User login

One in three children fall short of sleep recommendations

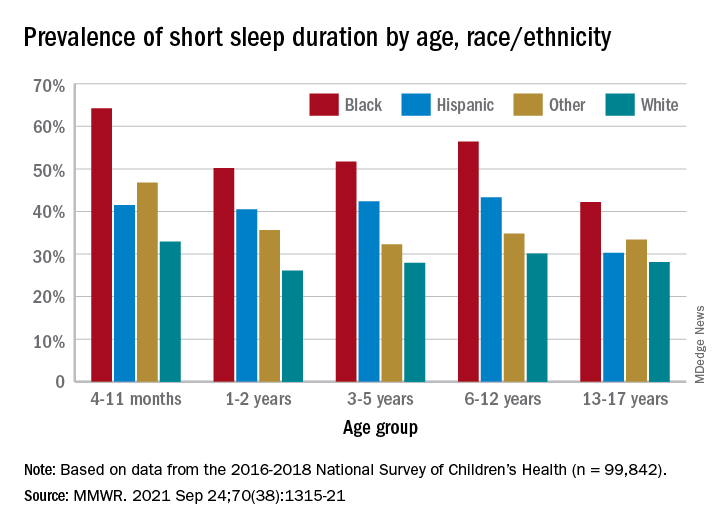

Just over one-third of children in the United States get less sleep than recommended, with higher rates occurring among several racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

, Anne G. Wheaton, PhD, and Angelika H. Claussen, PhD, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Unlike previous reports, this analysis showed that adolescents were less likely than infants to have short sleep duration, 31.2% vs. 40.3%. These latest data are based on the 2016-2018 editions of the National Survey of Children’s Health, and the “difference might be explained by NSCH’s reliance on parent report rather than self-report with Youth Risk Behavior Surveys,” they suggested.

Black children had the highest prevalence of any group included in the study, as parents reported that 50.8% of all ages were not getting the recommended amount of sleep, compared with 39.1% among Hispanics, 34.6% for other races, and 28.8% for Whites. The figure for Black infants was 64.2%, almost double the prevalence for White infants (32.9%), said Dr. Wheaton and Dr. Claussen of the CDC.

Short sleep duration also was more common in children from lower-income families and among those with less educated parents. Geography had an effect as well, with prevalence “highest in the Southeast, similar to geographic variation in adequate sleep observed for adults,” they noted.

Previous research has shown that “sleep disparity was associated with various social determinants of health (e.g., poverty, food insecurity, and perceived racism), which can increase chronic and acute stress and result in environmental and psychological factors that negatively affect sleep duration and can compound long-term health risks,” the investigators wrote.

Short sleep duration by age group was defined as less the following amounts: Twelve hours for infants (4-11 months), 11 hours for children aged 1-2 years, 10 hours for children aged 3-5 years, 9 hours for children aged 6-12, and 8 hours for adolescents (13-17 years), they explained. Responses for the survey’s sleep-duration question totaled 99,842 for the 3 years included.

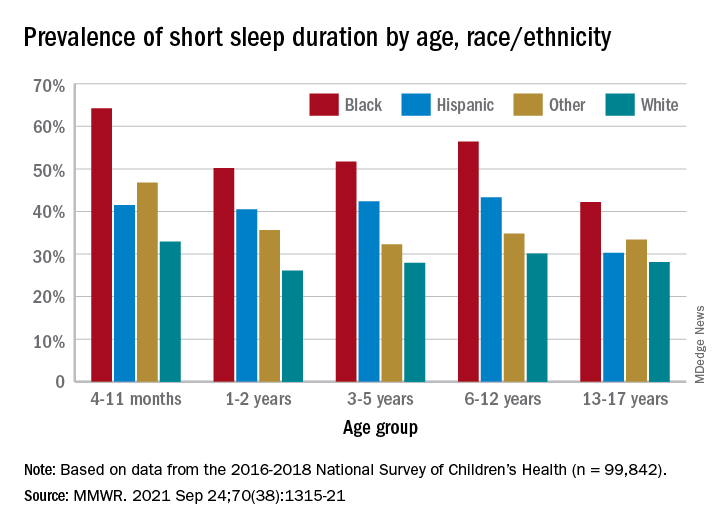

Just over one-third of children in the United States get less sleep than recommended, with higher rates occurring among several racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

, Anne G. Wheaton, PhD, and Angelika H. Claussen, PhD, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Unlike previous reports, this analysis showed that adolescents were less likely than infants to have short sleep duration, 31.2% vs. 40.3%. These latest data are based on the 2016-2018 editions of the National Survey of Children’s Health, and the “difference might be explained by NSCH’s reliance on parent report rather than self-report with Youth Risk Behavior Surveys,” they suggested.

Black children had the highest prevalence of any group included in the study, as parents reported that 50.8% of all ages were not getting the recommended amount of sleep, compared with 39.1% among Hispanics, 34.6% for other races, and 28.8% for Whites. The figure for Black infants was 64.2%, almost double the prevalence for White infants (32.9%), said Dr. Wheaton and Dr. Claussen of the CDC.

Short sleep duration also was more common in children from lower-income families and among those with less educated parents. Geography had an effect as well, with prevalence “highest in the Southeast, similar to geographic variation in adequate sleep observed for adults,” they noted.

Previous research has shown that “sleep disparity was associated with various social determinants of health (e.g., poverty, food insecurity, and perceived racism), which can increase chronic and acute stress and result in environmental and psychological factors that negatively affect sleep duration and can compound long-term health risks,” the investigators wrote.

Short sleep duration by age group was defined as less the following amounts: Twelve hours for infants (4-11 months), 11 hours for children aged 1-2 years, 10 hours for children aged 3-5 years, 9 hours for children aged 6-12, and 8 hours for adolescents (13-17 years), they explained. Responses for the survey’s sleep-duration question totaled 99,842 for the 3 years included.

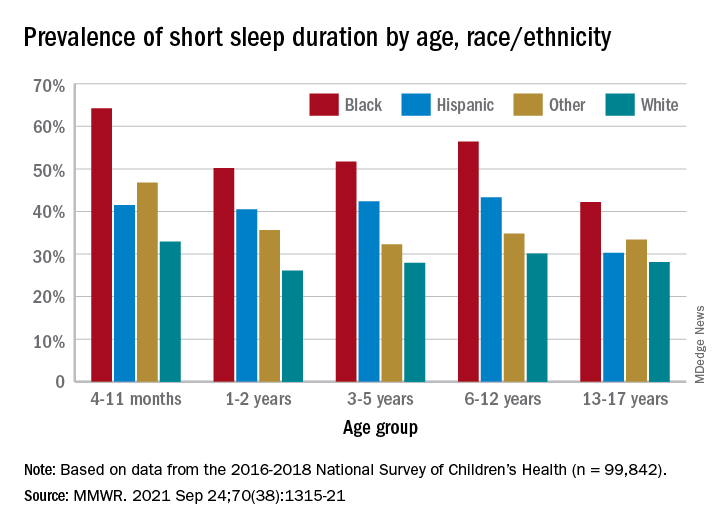

Just over one-third of children in the United States get less sleep than recommended, with higher rates occurring among several racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

, Anne G. Wheaton, PhD, and Angelika H. Claussen, PhD, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Unlike previous reports, this analysis showed that adolescents were less likely than infants to have short sleep duration, 31.2% vs. 40.3%. These latest data are based on the 2016-2018 editions of the National Survey of Children’s Health, and the “difference might be explained by NSCH’s reliance on parent report rather than self-report with Youth Risk Behavior Surveys,” they suggested.

Black children had the highest prevalence of any group included in the study, as parents reported that 50.8% of all ages were not getting the recommended amount of sleep, compared with 39.1% among Hispanics, 34.6% for other races, and 28.8% for Whites. The figure for Black infants was 64.2%, almost double the prevalence for White infants (32.9%), said Dr. Wheaton and Dr. Claussen of the CDC.

Short sleep duration also was more common in children from lower-income families and among those with less educated parents. Geography had an effect as well, with prevalence “highest in the Southeast, similar to geographic variation in adequate sleep observed for adults,” they noted.

Previous research has shown that “sleep disparity was associated with various social determinants of health (e.g., poverty, food insecurity, and perceived racism), which can increase chronic and acute stress and result in environmental and psychological factors that negatively affect sleep duration and can compound long-term health risks,” the investigators wrote.

Short sleep duration by age group was defined as less the following amounts: Twelve hours for infants (4-11 months), 11 hours for children aged 1-2 years, 10 hours for children aged 3-5 years, 9 hours for children aged 6-12, and 8 hours for adolescents (13-17 years), they explained. Responses for the survey’s sleep-duration question totaled 99,842 for the 3 years included.

FROM MMWR

New fellowship, no problem

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Feasibility of a Saliva-Based COVID-19 Screening Program in Abu Dhabi Primary Schools

From Health Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Virji and Aisha Al Hamiz), Public Health, Abu Dhabi Public Health Center, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Drs. Al Hajeri, Al Shehhi, Al Memari, and Ahlam Al Maskari), College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Department of Medicine, Sheikh Shakhbout Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Alhajri), Public Health Research Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, England, and the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England (Dr. Ali).

Objective: The pandemic has forced closures of primary schools, resulting in loss of learning time on a global scale. In addition to face coverings, social distancing, and hand hygiene, an efficient testing method is important to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in schools. We evaluated the feasibility of a saliva-based SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction testing program among 18 primary schools in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Qualitative results show that children 4 to 5 years old had difficulty producing an adequate saliva specimen compared to those 6 to 12 years old.

Methods: A short training video on saliva collection beforehand helps demystify the process for students and parents alike. Informed consent was challenging yet should be done beforehand by school health nurses or other medical professionals to reassure parents and maximize participation.

Results: Telephone interviews with school administrators resulted in an 83% response rate. Overall, 93% of school administrators had a positive experience with saliva testing and felt the program improved the safety of their schools. The ongoing use of saliva testing for SARS-CoV-2 was supported by 73% of respondents.

Conclusion: On-campus saliva testing is a feasible option for primary schools to screen for COVID-19 in their student population to help keep their campuses safe and open for learning.

Keywords: COVID-19; saliva testing; mitigation; primary school.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and continues to exhaust health care resources on a large scale.1 Efficient testing is critical to identify cases early and to help mitigate the deleterious effects of the pandemic.2 Saliva polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is more comfortable than nasopharyngeal (NP) NAAT and has been validated as a test for SARS-CoV-2.1 Although children are less susceptible to severe disease, primary schools are considered a vector for transmission and community spread.3 Efficient and scalable methods of routine testing are needed globally to help keep schools open. Saliva testing has proven a useful resource for this population.4,5

Abu Dhabi is the largest Emirate in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with an estimated population of 2.5 million.6 The first case of COVID-19 was discovered in the UAE on January 29, 2020.7 The UAE has been recognized worldwide for its robust pandemic response. Along with the coordinated and swift application of public health measures, the country has one of the highest COVID-19 testing rates per capita and one of the highest vaccination rates worldwide.8,9 The Abu Dhabi Public Health Center (ADPHC) works alongside the Ministry of Education (MOE) to establish testing, quarantine, and general safety guidelines for primary schools. In December 2020, the ADPHC partnered with a local, accredited diagnostic laboratory to test the feasibility of a saliva-based screening program for COVID-19 directly on school campuses for 18 primary schools in the Emirate.

Saliva-based PCR testing for COVID-19 was approved for use in schools in the UAE on January 24, 2021.10 As part of a greater mitigation strategy to reduce both school-based transmission and, hence, community spread, the ADPHC focused its on-site testing program on children aged 4 to 12 years. The program required collaboration among medical professionals, school administrators and teachers, students, and parents. Our study evaluates the feasibility of implementing a saliva-based COVID-19 screening program directly on primary school campuses involving children as young as 4 years of age.

Methods

The ADPHC, in collaboration with G42 Biogenix Labs, conducted a saliva SARS-CoV-2 NAAT testing program in 18 primary schools in the Emirate. Schools were selected based on outbreak prevalence at the time and focused on “hot spot” areas. The school on-site saliva testing program included children aged 4 to 12 years old in a “bubble” attendance model during the school day. This model involved children being assigned to groups or “pods.” This allowed us to limit a potential outbreak to a single pod, as opposed to risk exposing the entire school, should a single student test positive. The well-established SalivaDirect protocol developed at Yale University was used for testing and included an RNA extraction-free, RT-qPCR method for SARS-CoV-2 detection.11

We conducted a qualitative study involving telephone interviews of school administrators to evaluate their experience with the ADPHC testing program at their schools. In addition, we interviewed the G42 Biogenix Lab providers to understand the logistics that supported on-campus collection of saliva specimens for this age group. We also gathered the attitudes of school children before and after testing. This study was reviewed and approved by the Abu Dhabi Health Research and Technology Committee and the Institutional Review Board (IRB), New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD).

Sample and recruitment

The original sample collection of saliva specimens was performed by the ADPHC in collaboration with G42 Biogenix Lab providers on school campuses between December 6 and December 10, 2020. During this time, schools operated in a hybrid teaching model, where learning took place both online and in person. Infection control measures were deployed based on ADPHC standards and guidelines. Nurses utilized appropriate patient protective equipment, frequent hand hygiene, and social distancing during the collection process. Inclusion criteria included asymptomatic students aged 4 to 12 years attending in-person classes on campus. Students with respiratory symptoms who were asked to stay home or those not attending in-person classes were excluded.

Data collection

Data with regard to school children’s attitudes before and after testing were compiled through an online survey sent randomly to participants postintervention. Data from school administrators were collected through video and telephone interviews between April 14 and April 29, 2021. We first interviewed G42 Biogenix Lab providers to obtain previously acquired qualitative and quantitative data, which were collected during the intervention itself. After obtaining this information, we designed a questionnaire and proceeded with a structured interview process for school officials.

We interviewed school principals and administrators to collect their overall experiences with the saliva testing program. Before starting each interview, we established the interviewees preferred language, either English or Arabic. We then introduced the meeting attendees and provided study details, aims, and objectives, and described collaborating entities. We obtained verbal informed consent from a script approved by the NYUAD IRB and then proceeded with the interview, which included 4 questions. The first 3 questions were answered on a 5-point Likert scale model that consisted of 5 answer options: 5 being completely agree, 4 agree, 3 somewhat agree, 2 somewhat disagree, and 1 completely disagree. The fourth question invited open-ended feedback and comments on the following statements:

- I believe the COVID-19 saliva testing program improved the safety for my school campus.

- Our community had an overall positive experience with the COVID saliva testing.

- We would like to continue a saliva-based COVID testing program on our school campus.

- Please provide any additional comments you feel important about the program.

During the interview, we transcribed the answers as the interviewee was answering. We then translated those in Arabic into English and collected the data in 1 Excel spreadsheet. School interviewees and school names were de-identified in the collection and storage process.

Results

A total of 2011 saliva samples were collected from 18 different primary school campuses. Samples were sent the same day to G42 Biogenix Labs in Abu Dhabi for COVID PCR testing. A team consisting of 5 doctors providing general oversight, along with 2 to 6 nurses per site, were able to manage the collection process for all 18 school campuses. Samples were collected between 8

Sample stations were set up in either the school auditorium or gymnasium to ensure appropriate crowd control and ventilation. Teachers and other school staff, including public safety, were able to manage lines and the shuttling of students back and forth from classes to testing stations, which allowed medical staff to focus on sample collection.

Informed consent was obtained by prior electronic communication to parents from school staff, asking them to agree to allow their child to participate in the testing program. Informed consent was identified as a challenge: Getting parents to understand that saliva testing was more comfortable than NP testing, and that the results were only being used to help keep the school safe, took time. School staff are used to obtaining consent from parents for field trips, but this was clearly more challenging for them.

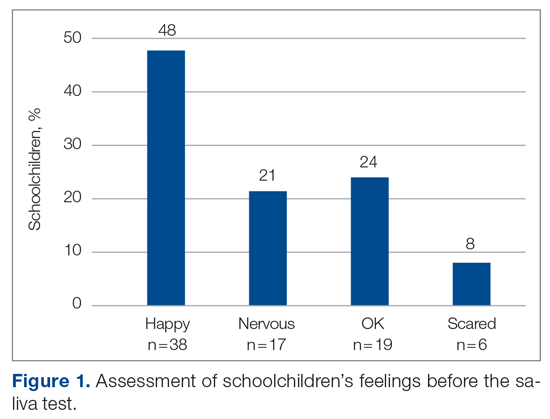

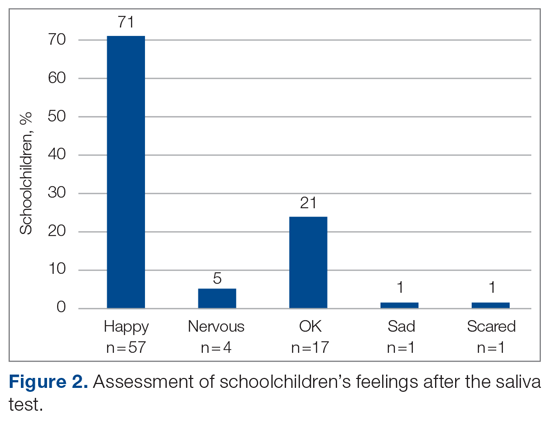

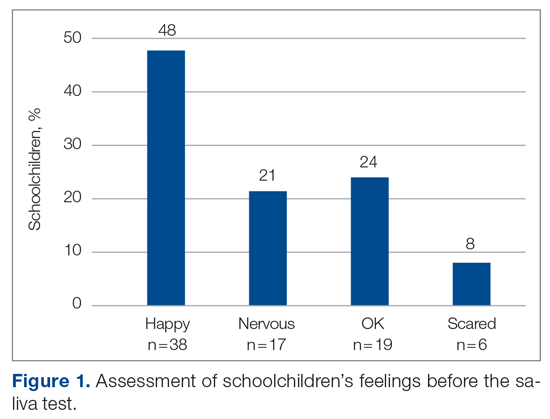

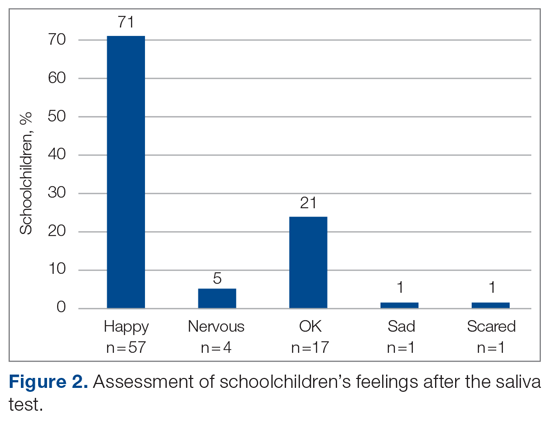

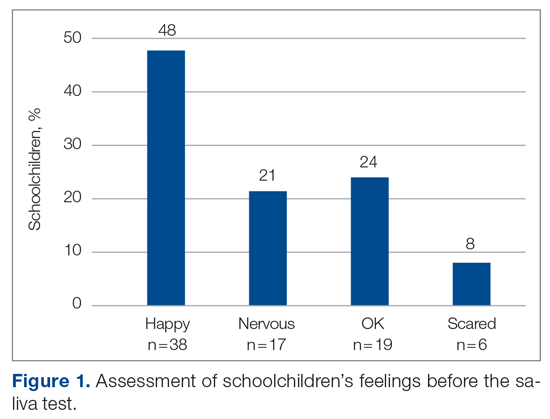

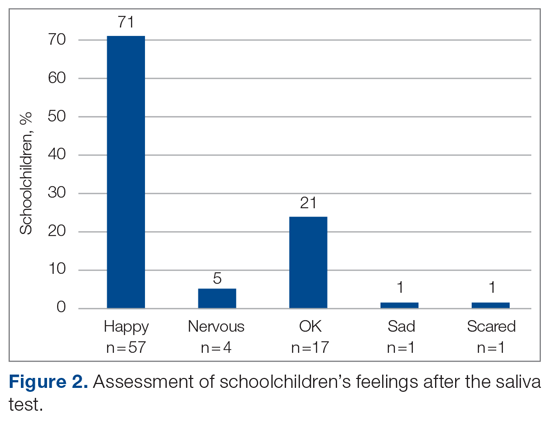

The saliva collection process per child took more time than expected. Children fasted for 45 minutes before saliva collection. We used an active drool technique, which required children to pool saliva in their mouth then express it into a collection tube. Adults can generally do this on command, but we found it took 10 to 12 minutes per child. Saliva production was cued by asking the children to think about food, and by showing them pictures and TV commercials depicting food. Children 4 to 5 years old had more difficulty with the process despite active cueing, while those 6 to 12 years old had an easier time with the process. We collected data on a cohort of 80 children regarding their attitudes pre (Figure 1) and post collection (Figure 2). Children felt happier, less nervous, and less scared after collection than before collection. This trend reassured us that future collections would be easier for students.

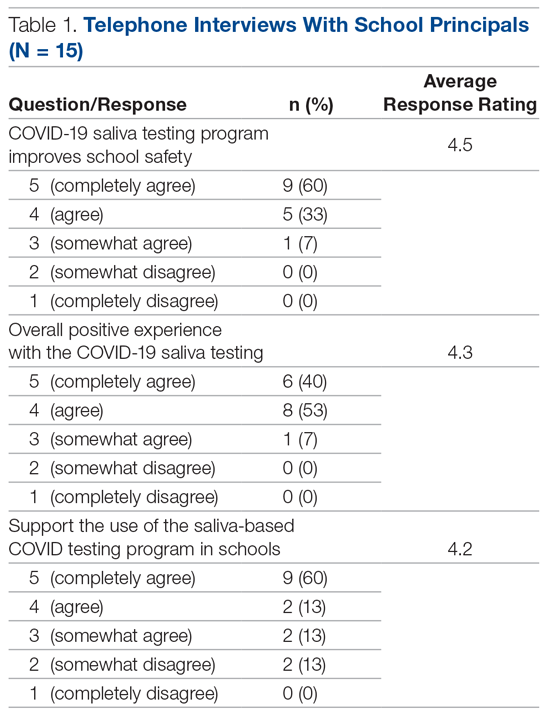

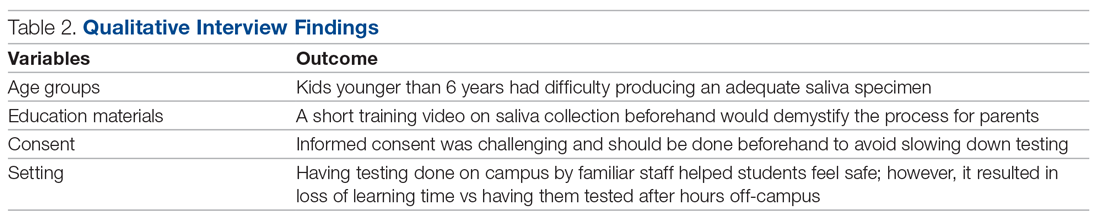

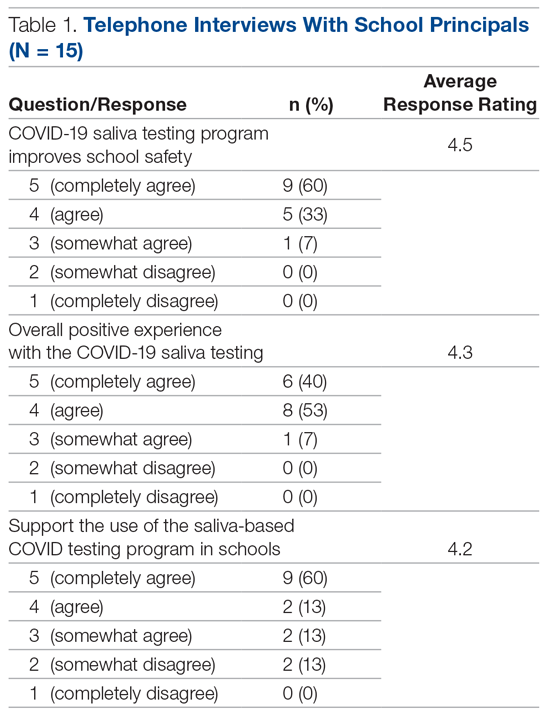

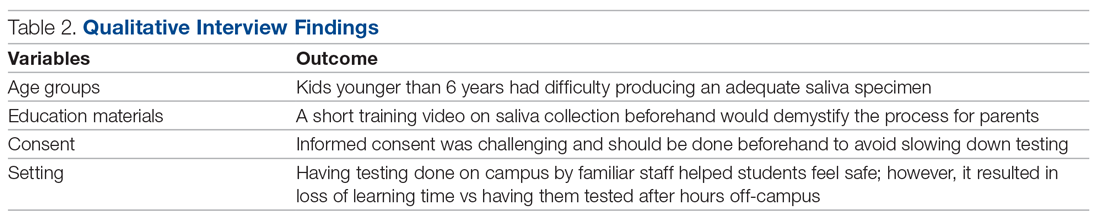

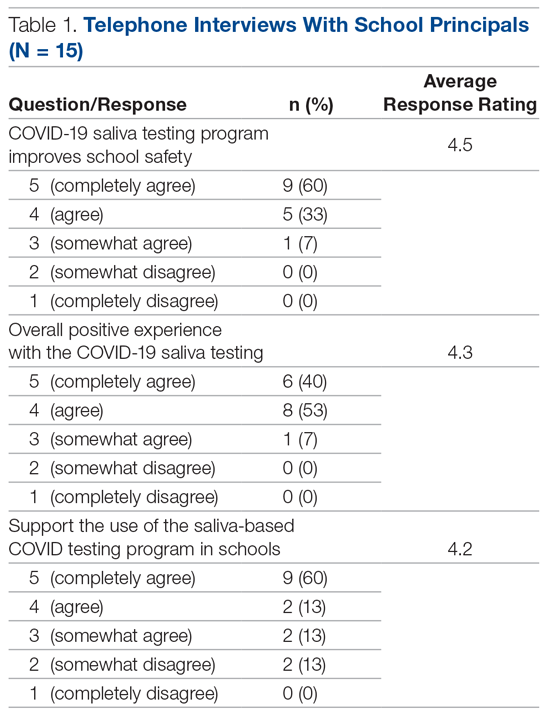

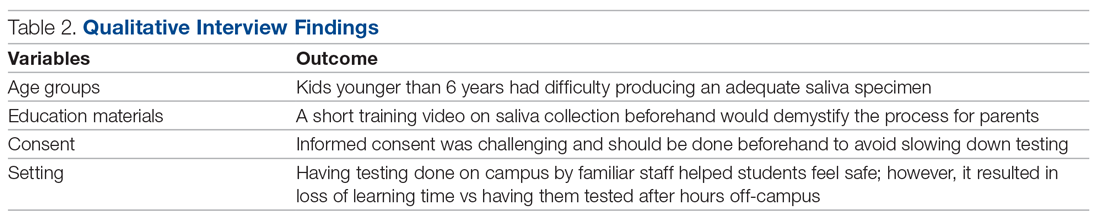

A total of 15 of 18 school principals completed the telephone interview, yielding a response rate of 83%. Overall, 93% of the school principals agreed or completely agreed that the COVID-19 saliva testing program improved school safety; 93% agreed or completely agreed that they had an overall positive experience with the program; and 73% supported the ongoing use of saliva testing in their schools (Table 1). Administrators’ open-ended comments on their experience were positive overall (Table 2).

Discussion

By March 2020, many kindergarten to grade 12 public and private schools suspended in-person classes due to the pandemic and turned to online learning platforms. The negative impact of school closures on academic achievement is projected to be significant.7,12,13 Ensuring schools can stay open and run operations safely will require routine SARS-CoV-2 testing. Our study investigated the feasibility of routine saliva testing on children aged 4 to 12 years on their school campuses. The ADPHC school on-site saliva testing program involved bringing lab providers onto 18 primary school campuses and required cooperation among parents, students, school administrators, and health care professionals.

Children younger than 6 years had difficulty producing an adequate saliva specimen, whereas those 6 to 12 years did so with relative ease when cued by thoughts or pictures of food while waiting in line for collection. Schools considering on-site testing programs should consider the age range of 6 to 12 years as a viable age range for saliva screening. Children should fast for a minimum of 45 minutes prior to saliva collection and should be cued by thoughts of food, food pictures, or food commercials. Setting up a sampling station close to the cafeteria where students can smell meal preparation may also help.14,15 Sampling before breakfast or lunch, when children are potentially at their hungriest, should also be considered.

The greatest challenge was obtaining informed consent from parents who were not yet familiar with the reliability of saliva testing as a tool for SARS-CoV-2 screening or with the saliva collection process as a whole. Informed consent was initially done electronically, lacking direct human interaction to answer parents’ questions. Parents who refused had a follow-up call from the school nurse to further explain the logistics and rationale for saliva screening. Having medical professionals directly answer parents’ questions was helpful. Parents were reassured that the process was painless, confidential, and only to be used for school safety purposes. Despite school administrators being experienced in obtaining consent from parents for field trips, obtaining informed consent for a medical testing procedure is more complicated, and parents aren’t accustomed to providing such consent in a school environment. Schools considering on-site testing should ensure that their school nurse or other health care providers are on the front line obtaining informed consent and allaying parents’ fears.

School staff were able to effectively provide crowd control for testing, and children felt at ease being in a familiar environment. Teachers and public safety officers are well-equipped at managing the shuttling of students to class, to lunch, to physical education, and, finally, to dismissal. They were equally equipped at handling the logistics of students to and from testing, including minimizing crowds and helping students feel at ease during the process. This effective collaboration allowed the lab personnel to focus on sample collection and storage, while school staff managed all other aspects of the children’s safety and care.

Conclusion

Overall, school administrators had a positive experience with the testing program, felt the program improved the safety of their schools, and supported the ongoing use of saliva testing for SARS-CoV-2 on their school campuses. Children aged 6 years and older were able to provide adequate saliva samples, and children felt happier and less nervous after the process, indicating repeatability. Our findings highlight the feasibility of an integrated on-site saliva testing model for primary school campuses. Further research is needed to determine the scalability of such a model and whether the added compliance and safety of on-site testing compensates for the potential loss of learning time that testing during school hours would require.

Corresponding author: Ayaz Virji, MD, New York University Abu Dhabi, PO Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Kuehn BM. Despite improvements, COVID-19’s health care disruptions persist. JAMA. 2021;325(23):2335. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.9134

2. National Institute on Aging. Why COVID-19 testing is the key to getting back to normal. September 4, 2020. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/why-covid-19-testing-key-getting-back-normal

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science brief: Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in K-12 schools. Updated July 9, 2021. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/transmission_k_12_schools.html

4. Butler-Laporte G, Lawandi A, Schiller I, et al. Comparison of saliva and nasopharyngeal swab nucleic acid amplification testing for detection of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(3):353-360. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8876

5. Al Suwaidi H, Senok A, Varghese R, et al. Saliva for molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2 in school-age children. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(9):1330-1335. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2021.02.009

6. Abu Dhabi. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/the-seven-emirates/abu-dhabi

7. Alsuwaidi AR, Al Hosani FI, Al Memari S, et al. Seroprevalence of COVID-19 infection in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: a population-based cross-sectional study. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50(4):1077-1090. doi:10.1093/ije/dyab077

8. Al Hosany F, Ganesan S, Al Memari S, et al. Response to COVID-19 pandemic in the UAE: a public health perspective. J Glob Health. 2021;11:03050. doi:10.7189/jogh.11.03050

9. Bremmer I. The best global responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 year later. Time Magazine. Updated February 23, 2021. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://time.com/5851633/best-global-responses-covid-19/

10. Department of Health, Abu Dhabi. Laboratory diagnostic test for COVID-19: update regarding saliva-based testing using RT-PCR test. 2021.

11. Vogels C, Brackney DE, Kalinich CC, et al. SalivaDirect: RNA extraction-free SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics. Protocols.io. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.protocols.io/view/salivadirect-rna-extraction-free-sars-cov-2-diagno-bh6jj9cn?version_warning=no

12. Education Endowment Foundation. Impact of school closures on the attainment gap: rapid evidence assessment. June 2020. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342501263_EEF_2020_-_Impact_of_School_Closures_on_the_Attainment_Gap

13. United Nations. Policy brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf

14. Schiffman SS, Miletic ID. Effect of taste and smell on secretion rate of salivary IgA in elderly and young persons. J Nutr Health Aging. 1999;3(3):158-164.

15. Lee VM, Linden RW. The effect of odours on stimulated parotid salivary flow in humans. Physiol Behav. 1992;52(6):1121-1125. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(92)90470-m

From Health Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Virji and Aisha Al Hamiz), Public Health, Abu Dhabi Public Health Center, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Drs. Al Hajeri, Al Shehhi, Al Memari, and Ahlam Al Maskari), College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Department of Medicine, Sheikh Shakhbout Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Alhajri), Public Health Research Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, England, and the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England (Dr. Ali).

Objective: The pandemic has forced closures of primary schools, resulting in loss of learning time on a global scale. In addition to face coverings, social distancing, and hand hygiene, an efficient testing method is important to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in schools. We evaluated the feasibility of a saliva-based SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction testing program among 18 primary schools in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Qualitative results show that children 4 to 5 years old had difficulty producing an adequate saliva specimen compared to those 6 to 12 years old.

Methods: A short training video on saliva collection beforehand helps demystify the process for students and parents alike. Informed consent was challenging yet should be done beforehand by school health nurses or other medical professionals to reassure parents and maximize participation.

Results: Telephone interviews with school administrators resulted in an 83% response rate. Overall, 93% of school administrators had a positive experience with saliva testing and felt the program improved the safety of their schools. The ongoing use of saliva testing for SARS-CoV-2 was supported by 73% of respondents.

Conclusion: On-campus saliva testing is a feasible option for primary schools to screen for COVID-19 in their student population to help keep their campuses safe and open for learning.

Keywords: COVID-19; saliva testing; mitigation; primary school.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and continues to exhaust health care resources on a large scale.1 Efficient testing is critical to identify cases early and to help mitigate the deleterious effects of the pandemic.2 Saliva polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is more comfortable than nasopharyngeal (NP) NAAT and has been validated as a test for SARS-CoV-2.1 Although children are less susceptible to severe disease, primary schools are considered a vector for transmission and community spread.3 Efficient and scalable methods of routine testing are needed globally to help keep schools open. Saliva testing has proven a useful resource for this population.4,5

Abu Dhabi is the largest Emirate in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with an estimated population of 2.5 million.6 The first case of COVID-19 was discovered in the UAE on January 29, 2020.7 The UAE has been recognized worldwide for its robust pandemic response. Along with the coordinated and swift application of public health measures, the country has one of the highest COVID-19 testing rates per capita and one of the highest vaccination rates worldwide.8,9 The Abu Dhabi Public Health Center (ADPHC) works alongside the Ministry of Education (MOE) to establish testing, quarantine, and general safety guidelines for primary schools. In December 2020, the ADPHC partnered with a local, accredited diagnostic laboratory to test the feasibility of a saliva-based screening program for COVID-19 directly on school campuses for 18 primary schools in the Emirate.

Saliva-based PCR testing for COVID-19 was approved for use in schools in the UAE on January 24, 2021.10 As part of a greater mitigation strategy to reduce both school-based transmission and, hence, community spread, the ADPHC focused its on-site testing program on children aged 4 to 12 years. The program required collaboration among medical professionals, school administrators and teachers, students, and parents. Our study evaluates the feasibility of implementing a saliva-based COVID-19 screening program directly on primary school campuses involving children as young as 4 years of age.

Methods

The ADPHC, in collaboration with G42 Biogenix Labs, conducted a saliva SARS-CoV-2 NAAT testing program in 18 primary schools in the Emirate. Schools were selected based on outbreak prevalence at the time and focused on “hot spot” areas. The school on-site saliva testing program included children aged 4 to 12 years old in a “bubble” attendance model during the school day. This model involved children being assigned to groups or “pods.” This allowed us to limit a potential outbreak to a single pod, as opposed to risk exposing the entire school, should a single student test positive. The well-established SalivaDirect protocol developed at Yale University was used for testing and included an RNA extraction-free, RT-qPCR method for SARS-CoV-2 detection.11

We conducted a qualitative study involving telephone interviews of school administrators to evaluate their experience with the ADPHC testing program at their schools. In addition, we interviewed the G42 Biogenix Lab providers to understand the logistics that supported on-campus collection of saliva specimens for this age group. We also gathered the attitudes of school children before and after testing. This study was reviewed and approved by the Abu Dhabi Health Research and Technology Committee and the Institutional Review Board (IRB), New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD).

Sample and recruitment

The original sample collection of saliva specimens was performed by the ADPHC in collaboration with G42 Biogenix Lab providers on school campuses between December 6 and December 10, 2020. During this time, schools operated in a hybrid teaching model, where learning took place both online and in person. Infection control measures were deployed based on ADPHC standards and guidelines. Nurses utilized appropriate patient protective equipment, frequent hand hygiene, and social distancing during the collection process. Inclusion criteria included asymptomatic students aged 4 to 12 years attending in-person classes on campus. Students with respiratory symptoms who were asked to stay home or those not attending in-person classes were excluded.

Data collection

Data with regard to school children’s attitudes before and after testing were compiled through an online survey sent randomly to participants postintervention. Data from school administrators were collected through video and telephone interviews between April 14 and April 29, 2021. We first interviewed G42 Biogenix Lab providers to obtain previously acquired qualitative and quantitative data, which were collected during the intervention itself. After obtaining this information, we designed a questionnaire and proceeded with a structured interview process for school officials.

We interviewed school principals and administrators to collect their overall experiences with the saliva testing program. Before starting each interview, we established the interviewees preferred language, either English or Arabic. We then introduced the meeting attendees and provided study details, aims, and objectives, and described collaborating entities. We obtained verbal informed consent from a script approved by the NYUAD IRB and then proceeded with the interview, which included 4 questions. The first 3 questions were answered on a 5-point Likert scale model that consisted of 5 answer options: 5 being completely agree, 4 agree, 3 somewhat agree, 2 somewhat disagree, and 1 completely disagree. The fourth question invited open-ended feedback and comments on the following statements:

- I believe the COVID-19 saliva testing program improved the safety for my school campus.

- Our community had an overall positive experience with the COVID saliva testing.

- We would like to continue a saliva-based COVID testing program on our school campus.

- Please provide any additional comments you feel important about the program.

During the interview, we transcribed the answers as the interviewee was answering. We then translated those in Arabic into English and collected the data in 1 Excel spreadsheet. School interviewees and school names were de-identified in the collection and storage process.

Results

A total of 2011 saliva samples were collected from 18 different primary school campuses. Samples were sent the same day to G42 Biogenix Labs in Abu Dhabi for COVID PCR testing. A team consisting of 5 doctors providing general oversight, along with 2 to 6 nurses per site, were able to manage the collection process for all 18 school campuses. Samples were collected between 8

Sample stations were set up in either the school auditorium or gymnasium to ensure appropriate crowd control and ventilation. Teachers and other school staff, including public safety, were able to manage lines and the shuttling of students back and forth from classes to testing stations, which allowed medical staff to focus on sample collection.

Informed consent was obtained by prior electronic communication to parents from school staff, asking them to agree to allow their child to participate in the testing program. Informed consent was identified as a challenge: Getting parents to understand that saliva testing was more comfortable than NP testing, and that the results were only being used to help keep the school safe, took time. School staff are used to obtaining consent from parents for field trips, but this was clearly more challenging for them.

The saliva collection process per child took more time than expected. Children fasted for 45 minutes before saliva collection. We used an active drool technique, which required children to pool saliva in their mouth then express it into a collection tube. Adults can generally do this on command, but we found it took 10 to 12 minutes per child. Saliva production was cued by asking the children to think about food, and by showing them pictures and TV commercials depicting food. Children 4 to 5 years old had more difficulty with the process despite active cueing, while those 6 to 12 years old had an easier time with the process. We collected data on a cohort of 80 children regarding their attitudes pre (Figure 1) and post collection (Figure 2). Children felt happier, less nervous, and less scared after collection than before collection. This trend reassured us that future collections would be easier for students.

A total of 15 of 18 school principals completed the telephone interview, yielding a response rate of 83%. Overall, 93% of the school principals agreed or completely agreed that the COVID-19 saliva testing program improved school safety; 93% agreed or completely agreed that they had an overall positive experience with the program; and 73% supported the ongoing use of saliva testing in their schools (Table 1). Administrators’ open-ended comments on their experience were positive overall (Table 2).

Discussion

By March 2020, many kindergarten to grade 12 public and private schools suspended in-person classes due to the pandemic and turned to online learning platforms. The negative impact of school closures on academic achievement is projected to be significant.7,12,13 Ensuring schools can stay open and run operations safely will require routine SARS-CoV-2 testing. Our study investigated the feasibility of routine saliva testing on children aged 4 to 12 years on their school campuses. The ADPHC school on-site saliva testing program involved bringing lab providers onto 18 primary school campuses and required cooperation among parents, students, school administrators, and health care professionals.

Children younger than 6 years had difficulty producing an adequate saliva specimen, whereas those 6 to 12 years did so with relative ease when cued by thoughts or pictures of food while waiting in line for collection. Schools considering on-site testing programs should consider the age range of 6 to 12 years as a viable age range for saliva screening. Children should fast for a minimum of 45 minutes prior to saliva collection and should be cued by thoughts of food, food pictures, or food commercials. Setting up a sampling station close to the cafeteria where students can smell meal preparation may also help.14,15 Sampling before breakfast or lunch, when children are potentially at their hungriest, should also be considered.

The greatest challenge was obtaining informed consent from parents who were not yet familiar with the reliability of saliva testing as a tool for SARS-CoV-2 screening or with the saliva collection process as a whole. Informed consent was initially done electronically, lacking direct human interaction to answer parents’ questions. Parents who refused had a follow-up call from the school nurse to further explain the logistics and rationale for saliva screening. Having medical professionals directly answer parents’ questions was helpful. Parents were reassured that the process was painless, confidential, and only to be used for school safety purposes. Despite school administrators being experienced in obtaining consent from parents for field trips, obtaining informed consent for a medical testing procedure is more complicated, and parents aren’t accustomed to providing such consent in a school environment. Schools considering on-site testing should ensure that their school nurse or other health care providers are on the front line obtaining informed consent and allaying parents’ fears.

School staff were able to effectively provide crowd control for testing, and children felt at ease being in a familiar environment. Teachers and public safety officers are well-equipped at managing the shuttling of students to class, to lunch, to physical education, and, finally, to dismissal. They were equally equipped at handling the logistics of students to and from testing, including minimizing crowds and helping students feel at ease during the process. This effective collaboration allowed the lab personnel to focus on sample collection and storage, while school staff managed all other aspects of the children’s safety and care.

Conclusion

Overall, school administrators had a positive experience with the testing program, felt the program improved the safety of their schools, and supported the ongoing use of saliva testing for SARS-CoV-2 on their school campuses. Children aged 6 years and older were able to provide adequate saliva samples, and children felt happier and less nervous after the process, indicating repeatability. Our findings highlight the feasibility of an integrated on-site saliva testing model for primary school campuses. Further research is needed to determine the scalability of such a model and whether the added compliance and safety of on-site testing compensates for the potential loss of learning time that testing during school hours would require.

Corresponding author: Ayaz Virji, MD, New York University Abu Dhabi, PO Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From Health Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Virji and Aisha Al Hamiz), Public Health, Abu Dhabi Public Health Center, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Drs. Al Hajeri, Al Shehhi, Al Memari, and Ahlam Al Maskari), College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Department of Medicine, Sheikh Shakhbout Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Dr. Alhajri), Public Health Research Center, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, England, and the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England (Dr. Ali).

Objective: The pandemic has forced closures of primary schools, resulting in loss of learning time on a global scale. In addition to face coverings, social distancing, and hand hygiene, an efficient testing method is important to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in schools. We evaluated the feasibility of a saliva-based SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction testing program among 18 primary schools in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Qualitative results show that children 4 to 5 years old had difficulty producing an adequate saliva specimen compared to those 6 to 12 years old.

Methods: A short training video on saliva collection beforehand helps demystify the process for students and parents alike. Informed consent was challenging yet should be done beforehand by school health nurses or other medical professionals to reassure parents and maximize participation.

Results: Telephone interviews with school administrators resulted in an 83% response rate. Overall, 93% of school administrators had a positive experience with saliva testing and felt the program improved the safety of their schools. The ongoing use of saliva testing for SARS-CoV-2 was supported by 73% of respondents.

Conclusion: On-campus saliva testing is a feasible option for primary schools to screen for COVID-19 in their student population to help keep their campuses safe and open for learning.

Keywords: COVID-19; saliva testing; mitigation; primary school.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and continues to exhaust health care resources on a large scale.1 Efficient testing is critical to identify cases early and to help mitigate the deleterious effects of the pandemic.2 Saliva polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is more comfortable than nasopharyngeal (NP) NAAT and has been validated as a test for SARS-CoV-2.1 Although children are less susceptible to severe disease, primary schools are considered a vector for transmission and community spread.3 Efficient and scalable methods of routine testing are needed globally to help keep schools open. Saliva testing has proven a useful resource for this population.4,5

Abu Dhabi is the largest Emirate in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with an estimated population of 2.5 million.6 The first case of COVID-19 was discovered in the UAE on January 29, 2020.7 The UAE has been recognized worldwide for its robust pandemic response. Along with the coordinated and swift application of public health measures, the country has one of the highest COVID-19 testing rates per capita and one of the highest vaccination rates worldwide.8,9 The Abu Dhabi Public Health Center (ADPHC) works alongside the Ministry of Education (MOE) to establish testing, quarantine, and general safety guidelines for primary schools. In December 2020, the ADPHC partnered with a local, accredited diagnostic laboratory to test the feasibility of a saliva-based screening program for COVID-19 directly on school campuses for 18 primary schools in the Emirate.

Saliva-based PCR testing for COVID-19 was approved for use in schools in the UAE on January 24, 2021.10 As part of a greater mitigation strategy to reduce both school-based transmission and, hence, community spread, the ADPHC focused its on-site testing program on children aged 4 to 12 years. The program required collaboration among medical professionals, school administrators and teachers, students, and parents. Our study evaluates the feasibility of implementing a saliva-based COVID-19 screening program directly on primary school campuses involving children as young as 4 years of age.

Methods

The ADPHC, in collaboration with G42 Biogenix Labs, conducted a saliva SARS-CoV-2 NAAT testing program in 18 primary schools in the Emirate. Schools were selected based on outbreak prevalence at the time and focused on “hot spot” areas. The school on-site saliva testing program included children aged 4 to 12 years old in a “bubble” attendance model during the school day. This model involved children being assigned to groups or “pods.” This allowed us to limit a potential outbreak to a single pod, as opposed to risk exposing the entire school, should a single student test positive. The well-established SalivaDirect protocol developed at Yale University was used for testing and included an RNA extraction-free, RT-qPCR method for SARS-CoV-2 detection.11

We conducted a qualitative study involving telephone interviews of school administrators to evaluate their experience with the ADPHC testing program at their schools. In addition, we interviewed the G42 Biogenix Lab providers to understand the logistics that supported on-campus collection of saliva specimens for this age group. We also gathered the attitudes of school children before and after testing. This study was reviewed and approved by the Abu Dhabi Health Research and Technology Committee and the Institutional Review Board (IRB), New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD).

Sample and recruitment

The original sample collection of saliva specimens was performed by the ADPHC in collaboration with G42 Biogenix Lab providers on school campuses between December 6 and December 10, 2020. During this time, schools operated in a hybrid teaching model, where learning took place both online and in person. Infection control measures were deployed based on ADPHC standards and guidelines. Nurses utilized appropriate patient protective equipment, frequent hand hygiene, and social distancing during the collection process. Inclusion criteria included asymptomatic students aged 4 to 12 years attending in-person classes on campus. Students with respiratory symptoms who were asked to stay home or those not attending in-person classes were excluded.

Data collection

Data with regard to school children’s attitudes before and after testing were compiled through an online survey sent randomly to participants postintervention. Data from school administrators were collected through video and telephone interviews between April 14 and April 29, 2021. We first interviewed G42 Biogenix Lab providers to obtain previously acquired qualitative and quantitative data, which were collected during the intervention itself. After obtaining this information, we designed a questionnaire and proceeded with a structured interview process for school officials.

We interviewed school principals and administrators to collect their overall experiences with the saliva testing program. Before starting each interview, we established the interviewees preferred language, either English or Arabic. We then introduced the meeting attendees and provided study details, aims, and objectives, and described collaborating entities. We obtained verbal informed consent from a script approved by the NYUAD IRB and then proceeded with the interview, which included 4 questions. The first 3 questions were answered on a 5-point Likert scale model that consisted of 5 answer options: 5 being completely agree, 4 agree, 3 somewhat agree, 2 somewhat disagree, and 1 completely disagree. The fourth question invited open-ended feedback and comments on the following statements:

- I believe the COVID-19 saliva testing program improved the safety for my school campus.

- Our community had an overall positive experience with the COVID saliva testing.

- We would like to continue a saliva-based COVID testing program on our school campus.

- Please provide any additional comments you feel important about the program.

During the interview, we transcribed the answers as the interviewee was answering. We then translated those in Arabic into English and collected the data in 1 Excel spreadsheet. School interviewees and school names were de-identified in the collection and storage process.

Results

A total of 2011 saliva samples were collected from 18 different primary school campuses. Samples were sent the same day to G42 Biogenix Labs in Abu Dhabi for COVID PCR testing. A team consisting of 5 doctors providing general oversight, along with 2 to 6 nurses per site, were able to manage the collection process for all 18 school campuses. Samples were collected between 8

Sample stations were set up in either the school auditorium or gymnasium to ensure appropriate crowd control and ventilation. Teachers and other school staff, including public safety, were able to manage lines and the shuttling of students back and forth from classes to testing stations, which allowed medical staff to focus on sample collection.

Informed consent was obtained by prior electronic communication to parents from school staff, asking them to agree to allow their child to participate in the testing program. Informed consent was identified as a challenge: Getting parents to understand that saliva testing was more comfortable than NP testing, and that the results were only being used to help keep the school safe, took time. School staff are used to obtaining consent from parents for field trips, but this was clearly more challenging for them.

The saliva collection process per child took more time than expected. Children fasted for 45 minutes before saliva collection. We used an active drool technique, which required children to pool saliva in their mouth then express it into a collection tube. Adults can generally do this on command, but we found it took 10 to 12 minutes per child. Saliva production was cued by asking the children to think about food, and by showing them pictures and TV commercials depicting food. Children 4 to 5 years old had more difficulty with the process despite active cueing, while those 6 to 12 years old had an easier time with the process. We collected data on a cohort of 80 children regarding their attitudes pre (Figure 1) and post collection (Figure 2). Children felt happier, less nervous, and less scared after collection than before collection. This trend reassured us that future collections would be easier for students.

A total of 15 of 18 school principals completed the telephone interview, yielding a response rate of 83%. Overall, 93% of the school principals agreed or completely agreed that the COVID-19 saliva testing program improved school safety; 93% agreed or completely agreed that they had an overall positive experience with the program; and 73% supported the ongoing use of saliva testing in their schools (Table 1). Administrators’ open-ended comments on their experience were positive overall (Table 2).

Discussion

By March 2020, many kindergarten to grade 12 public and private schools suspended in-person classes due to the pandemic and turned to online learning platforms. The negative impact of school closures on academic achievement is projected to be significant.7,12,13 Ensuring schools can stay open and run operations safely will require routine SARS-CoV-2 testing. Our study investigated the feasibility of routine saliva testing on children aged 4 to 12 years on their school campuses. The ADPHC school on-site saliva testing program involved bringing lab providers onto 18 primary school campuses and required cooperation among parents, students, school administrators, and health care professionals.

Children younger than 6 years had difficulty producing an adequate saliva specimen, whereas those 6 to 12 years did so with relative ease when cued by thoughts or pictures of food while waiting in line for collection. Schools considering on-site testing programs should consider the age range of 6 to 12 years as a viable age range for saliva screening. Children should fast for a minimum of 45 minutes prior to saliva collection and should be cued by thoughts of food, food pictures, or food commercials. Setting up a sampling station close to the cafeteria where students can smell meal preparation may also help.14,15 Sampling before breakfast or lunch, when children are potentially at their hungriest, should also be considered.

The greatest challenge was obtaining informed consent from parents who were not yet familiar with the reliability of saliva testing as a tool for SARS-CoV-2 screening or with the saliva collection process as a whole. Informed consent was initially done electronically, lacking direct human interaction to answer parents’ questions. Parents who refused had a follow-up call from the school nurse to further explain the logistics and rationale for saliva screening. Having medical professionals directly answer parents’ questions was helpful. Parents were reassured that the process was painless, confidential, and only to be used for school safety purposes. Despite school administrators being experienced in obtaining consent from parents for field trips, obtaining informed consent for a medical testing procedure is more complicated, and parents aren’t accustomed to providing such consent in a school environment. Schools considering on-site testing should ensure that their school nurse or other health care providers are on the front line obtaining informed consent and allaying parents’ fears.

School staff were able to effectively provide crowd control for testing, and children felt at ease being in a familiar environment. Teachers and public safety officers are well-equipped at managing the shuttling of students to class, to lunch, to physical education, and, finally, to dismissal. They were equally equipped at handling the logistics of students to and from testing, including minimizing crowds and helping students feel at ease during the process. This effective collaboration allowed the lab personnel to focus on sample collection and storage, while school staff managed all other aspects of the children’s safety and care.

Conclusion

Overall, school administrators had a positive experience with the testing program, felt the program improved the safety of their schools, and supported the ongoing use of saliva testing for SARS-CoV-2 on their school campuses. Children aged 6 years and older were able to provide adequate saliva samples, and children felt happier and less nervous after the process, indicating repeatability. Our findings highlight the feasibility of an integrated on-site saliva testing model for primary school campuses. Further research is needed to determine the scalability of such a model and whether the added compliance and safety of on-site testing compensates for the potential loss of learning time that testing during school hours would require.

Corresponding author: Ayaz Virji, MD, New York University Abu Dhabi, PO Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Kuehn BM. Despite improvements, COVID-19’s health care disruptions persist. JAMA. 2021;325(23):2335. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.9134