User login

HPV vaccine safety concerns up 80% from 2015 to 2018

Despite a decrease in reported adverse events after receiving the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, among parents of unvaccinated adolescents, concerns about the vaccine’s safety rose 80% from 2015 to 2018, according to research published September 17 in JAMA Network Open.

Since its approval in 2006 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, uptake of the HPV vaccine has consistently lagged behind that of other routine vaccinations. According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, released September 3, 58.6% of adolescents were considered up to date with their HPV vaccinations in 2020.

Trials prior to the vaccine’s FDA approval as well as an abundance of clinical and observational evidence after it hit the market demonstrate the vaccine’s efficacy and safety, said lead author Kalyani Sonawane, PhD, an assistant professor of management, policy, and community health at the UTHealth School of Public Health, in Houston, Texas, in an interview. Still, recent research suggests that safety concerns are a main reason why parents are hesitant to have their children vaccinated, she noted.

In the study, Dr. Sonawane and colleagues analyzed data from National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) from 2015 through 2018. NIS-Teen is a random-digit-dialed telephone survey conducted annually by the CDC to monitor routine vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13 to 17. The researchers identified 39,364 adolescents who had not received any HPV shots and reviewed the caregivers’ reasons for vaccine hesitancy. The research team also reviewed the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). They identified 16,621 reports that listed the HPV vaccine from 2015 through 2018.

The top five reasons caregivers cited for avoiding the HPV vaccine were the following:

- not needed or necessary

- safety concerns

- not recommended

- lack of knowledge

- not sexually active

Of these, safety concerns were the only factor that increased during the study period. They increased from 13.0% in 2015 to 23.4% in 2018. Concerns over vaccine safety rose in 30 states, with increases of over 200% in California, Hawaii, South Dakota, and Mississippi.

The proportion of unvaccinated adolescents whose caregivers thought the HPV vaccine was not needed or necessary remained steady at around 25%. Those whose caregivers listed “not recommended,” “lack of knowledge,” and “not sexually active” as reasons for avoiding vaccination decreased over the study period.

The reporting rate for adverse events following HPV vaccination decreased from 44.7 per 100,000 doses in 2015 to 29.4 per 100,000 doses in 2018. Of the reported 16,621 adverse events following HPV vaccination that occurred over the study period, 4.6% were serious, resulting in hospitalizations, disability, life-threatening events, or death. From 2015 through 2018, reporting rates for serious adverse events remained level at around 0.3 events per 100,000 doses.

This mismatch between increasing vaccine safety concerns and decreasing adverse events suggests that disinformation may be driving these concerns more than scientific fact, Nosayaba Osazuwa-Peters, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor in head and neck surgery and communication sciences at the Duke University School of Medicine, in Durham, North Carolina, told this news organization. He co-wrote an invited commentary on the study and was not involved with the research. Although there have always been people who are hesitant to receive vaccinations, he said, social media and the internet have undoubtedly played a role in spreading concern.

Dr. Sonawane agreed. Online, “there are a lot of antivaccine groups that are making unwarranted claims about the vaccine’s safety,” such as that the HPV vaccine causes autism or fertility problems in women, she said. “We believe that this growing antivaccine movement in the U.S. and across the globe – which the World Health Organization has declared as one of the biggest threats right now – is also contributing to safety concerns among U.S. parents, particularly HPV vaccine safety.”

Although the study did not address strategies to combat this misinformation, Dr. Osazuwa-Peters said clinicians need to improve their communication with parents and patients. One way to do that, he said, is by bolstering an online presence and by countering vaccine disinformation with evidence-based responses on the internet. Most people get their medical information online. “Many people are just afraid because they don’t trust the messages coming from health care,” he said. “So, we need to a better job of not just providing the facts but providing the facts in a way that the end users can understand and appreciate.”

Dr. Sonawane and Dr. Osazuwa-Peters report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite a decrease in reported adverse events after receiving the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, among parents of unvaccinated adolescents, concerns about the vaccine’s safety rose 80% from 2015 to 2018, according to research published September 17 in JAMA Network Open.

Since its approval in 2006 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, uptake of the HPV vaccine has consistently lagged behind that of other routine vaccinations. According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, released September 3, 58.6% of adolescents were considered up to date with their HPV vaccinations in 2020.

Trials prior to the vaccine’s FDA approval as well as an abundance of clinical and observational evidence after it hit the market demonstrate the vaccine’s efficacy and safety, said lead author Kalyani Sonawane, PhD, an assistant professor of management, policy, and community health at the UTHealth School of Public Health, in Houston, Texas, in an interview. Still, recent research suggests that safety concerns are a main reason why parents are hesitant to have their children vaccinated, she noted.

In the study, Dr. Sonawane and colleagues analyzed data from National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) from 2015 through 2018. NIS-Teen is a random-digit-dialed telephone survey conducted annually by the CDC to monitor routine vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13 to 17. The researchers identified 39,364 adolescents who had not received any HPV shots and reviewed the caregivers’ reasons for vaccine hesitancy. The research team also reviewed the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). They identified 16,621 reports that listed the HPV vaccine from 2015 through 2018.

The top five reasons caregivers cited for avoiding the HPV vaccine were the following:

- not needed or necessary

- safety concerns

- not recommended

- lack of knowledge

- not sexually active

Of these, safety concerns were the only factor that increased during the study period. They increased from 13.0% in 2015 to 23.4% in 2018. Concerns over vaccine safety rose in 30 states, with increases of over 200% in California, Hawaii, South Dakota, and Mississippi.

The proportion of unvaccinated adolescents whose caregivers thought the HPV vaccine was not needed or necessary remained steady at around 25%. Those whose caregivers listed “not recommended,” “lack of knowledge,” and “not sexually active” as reasons for avoiding vaccination decreased over the study period.

The reporting rate for adverse events following HPV vaccination decreased from 44.7 per 100,000 doses in 2015 to 29.4 per 100,000 doses in 2018. Of the reported 16,621 adverse events following HPV vaccination that occurred over the study period, 4.6% were serious, resulting in hospitalizations, disability, life-threatening events, or death. From 2015 through 2018, reporting rates for serious adverse events remained level at around 0.3 events per 100,000 doses.

This mismatch between increasing vaccine safety concerns and decreasing adverse events suggests that disinformation may be driving these concerns more than scientific fact, Nosayaba Osazuwa-Peters, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor in head and neck surgery and communication sciences at the Duke University School of Medicine, in Durham, North Carolina, told this news organization. He co-wrote an invited commentary on the study and was not involved with the research. Although there have always been people who are hesitant to receive vaccinations, he said, social media and the internet have undoubtedly played a role in spreading concern.

Dr. Sonawane agreed. Online, “there are a lot of antivaccine groups that are making unwarranted claims about the vaccine’s safety,” such as that the HPV vaccine causes autism or fertility problems in women, she said. “We believe that this growing antivaccine movement in the U.S. and across the globe – which the World Health Organization has declared as one of the biggest threats right now – is also contributing to safety concerns among U.S. parents, particularly HPV vaccine safety.”

Although the study did not address strategies to combat this misinformation, Dr. Osazuwa-Peters said clinicians need to improve their communication with parents and patients. One way to do that, he said, is by bolstering an online presence and by countering vaccine disinformation with evidence-based responses on the internet. Most people get their medical information online. “Many people are just afraid because they don’t trust the messages coming from health care,” he said. “So, we need to a better job of not just providing the facts but providing the facts in a way that the end users can understand and appreciate.”

Dr. Sonawane and Dr. Osazuwa-Peters report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite a decrease in reported adverse events after receiving the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, among parents of unvaccinated adolescents, concerns about the vaccine’s safety rose 80% from 2015 to 2018, according to research published September 17 in JAMA Network Open.

Since its approval in 2006 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, uptake of the HPV vaccine has consistently lagged behind that of other routine vaccinations. According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, released September 3, 58.6% of adolescents were considered up to date with their HPV vaccinations in 2020.

Trials prior to the vaccine’s FDA approval as well as an abundance of clinical and observational evidence after it hit the market demonstrate the vaccine’s efficacy and safety, said lead author Kalyani Sonawane, PhD, an assistant professor of management, policy, and community health at the UTHealth School of Public Health, in Houston, Texas, in an interview. Still, recent research suggests that safety concerns are a main reason why parents are hesitant to have their children vaccinated, she noted.

In the study, Dr. Sonawane and colleagues analyzed data from National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) from 2015 through 2018. NIS-Teen is a random-digit-dialed telephone survey conducted annually by the CDC to monitor routine vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13 to 17. The researchers identified 39,364 adolescents who had not received any HPV shots and reviewed the caregivers’ reasons for vaccine hesitancy. The research team also reviewed the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). They identified 16,621 reports that listed the HPV vaccine from 2015 through 2018.

The top five reasons caregivers cited for avoiding the HPV vaccine were the following:

- not needed or necessary

- safety concerns

- not recommended

- lack of knowledge

- not sexually active

Of these, safety concerns were the only factor that increased during the study period. They increased from 13.0% in 2015 to 23.4% in 2018. Concerns over vaccine safety rose in 30 states, with increases of over 200% in California, Hawaii, South Dakota, and Mississippi.

The proportion of unvaccinated adolescents whose caregivers thought the HPV vaccine was not needed or necessary remained steady at around 25%. Those whose caregivers listed “not recommended,” “lack of knowledge,” and “not sexually active” as reasons for avoiding vaccination decreased over the study period.

The reporting rate for adverse events following HPV vaccination decreased from 44.7 per 100,000 doses in 2015 to 29.4 per 100,000 doses in 2018. Of the reported 16,621 adverse events following HPV vaccination that occurred over the study period, 4.6% were serious, resulting in hospitalizations, disability, life-threatening events, or death. From 2015 through 2018, reporting rates for serious adverse events remained level at around 0.3 events per 100,000 doses.

This mismatch between increasing vaccine safety concerns and decreasing adverse events suggests that disinformation may be driving these concerns more than scientific fact, Nosayaba Osazuwa-Peters, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor in head and neck surgery and communication sciences at the Duke University School of Medicine, in Durham, North Carolina, told this news organization. He co-wrote an invited commentary on the study and was not involved with the research. Although there have always been people who are hesitant to receive vaccinations, he said, social media and the internet have undoubtedly played a role in spreading concern.

Dr. Sonawane agreed. Online, “there are a lot of antivaccine groups that are making unwarranted claims about the vaccine’s safety,” such as that the HPV vaccine causes autism or fertility problems in women, she said. “We believe that this growing antivaccine movement in the U.S. and across the globe – which the World Health Organization has declared as one of the biggest threats right now – is also contributing to safety concerns among U.S. parents, particularly HPV vaccine safety.”

Although the study did not address strategies to combat this misinformation, Dr. Osazuwa-Peters said clinicians need to improve their communication with parents and patients. One way to do that, he said, is by bolstering an online presence and by countering vaccine disinformation with evidence-based responses on the internet. Most people get their medical information online. “Many people are just afraid because they don’t trust the messages coming from health care,” he said. “So, we need to a better job of not just providing the facts but providing the facts in a way that the end users can understand and appreciate.”

Dr. Sonawane and Dr. Osazuwa-Peters report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adolescent immunizations and protecting our children from COVID-19

I began thinking of a topic for this column weeks ago determined to discuss anything except COVID-19. Yet, news reports from all sources blasted daily reminders of rising COVID-19 cases overall and specifically in children.

In August, school resumed for many of our patients and the battle over mandating masks for school attendance was in full swing. The fact that it is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation supported by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society fell on deaf ears. One day, I heard a report that over 25,000 students attending Texas public schools were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Aug. 23 and Aug. 29. This peak in activity occurred just 2 weeks after the start of school and led to the closure of 45 school districts. Texas does not have a monopoly on these rising cases. Delta, a more contagious variant, began circulating in June 2021 and by July it was the most predominant. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations have increased nationwide. During the latter 2 weeks of August 2021, COVID-19–related ED visits and hospitalizations for persons aged 0-17 years were 3.4 and 3.7 times higher in states with the lowest vaccination coverage, compared with states with high vaccination coverage (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1249-54). Specifically, the rates of hospitalization the week ending Aug. 14, 2021, were nearly 5 times the rates for the week ending June 26, 2021, for 0- to 17-year-olds and nearly 10 times the rates for children 0-4 years of age. Hospitalization rates were 10.1 times higher for unimmunized adolescents than for fully vaccinated ones (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1255-60).

Multiple elected state leaders have opposed interventions such as mandating masks in school, and our children are paying for it. These leaders have relinquished their responsibility to local school boards. Several have reinforced the no-mask mandate while others have had the courage and insight to ignore state government leaders and have established mask mandates.

How is this lack of enforcement of national recommendations affecting our patients? Let’s look at two neighboring school districts in Texas. School districts have COVID-19 dashboards that are updated daily and accessible to the general public. School District A requires masks for school entry. It serves 196,171 students and has 27,195 teachers and staff. Since school opened in August, 1,606 cumulative cases of COVID-19 in students (0.8%) and 282 in staff (1%) have been reported. Fifty-five percent of the student cases occurred in elementary schools. In contrast, School District B located in the adjacent county serves 64,517 students and has 3,906 teachers and staff with no mask mandate. Since August, there have been 4,506 cumulative COVID-19 cases in students (6.9%) and 578 (14.7%) in staff. Information regarding the specific school type was not provided; however, the dashboard indicates that 2,924 cases (64.8%) occurred in children younger than 11 years of age. County data indicate 62% of those older than 12 years of age were fully vaccinated in District A, compared with 54% of persons older than 12 years in District B. The county COVID-19 positivity rate in District A is 17.6% and in District B it is 20%. Both counties are experiencing increased COVID-19 activity yet have had strikingly different outcomes in the student/staff population. While supporting the case for wearing masks to prevent disease transmission, one can’t ignore the adolescents who were infected and vaccine eligible (District A: 706; District B: 1,582). Their vaccination status could not be determined.

As pediatricians we have played an integral part in the elimination of diseases through educating and administering vaccinations. Adolescents are relatively healthy, thus limiting the number of encounters with them. The majority complete the 11-year visit; however, many fail to return for the 16- to 18-year visit.

So how are we doing? CDC data from 10 U.S. jurisdictions demonstrated a substantial decrease in vaccine administration between March and May of 2020, compared with the same period in 2018 and 2019. A decline was anticipated because of the nationwide lockdown. Doses of HPV administered declined almost 64% and 71% for 9- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds, respectively. Tdap administration declined 66% and 61% for the same respective age groups. Although administered doses increased between June and September of 2020, it was not sufficient to achieve catch-up coverage. Compared to the same period in 2018-2019, administration of the HPV vaccine declined 12.8% and 28% (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) and for Tdap it was 21% and 30% lower (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:840-5).

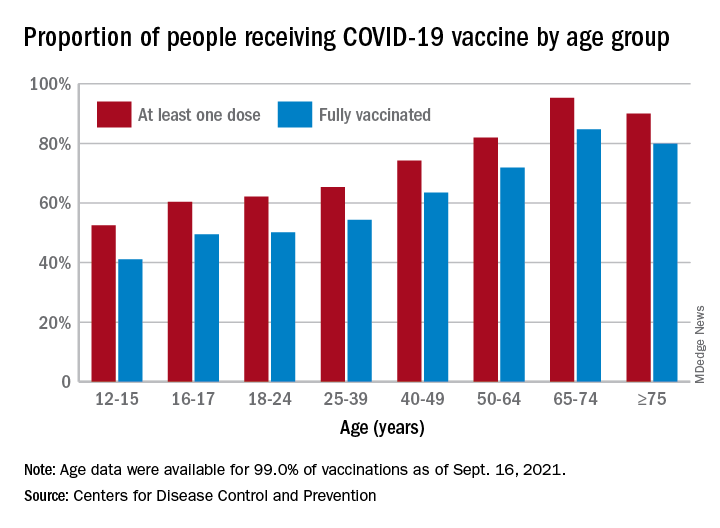

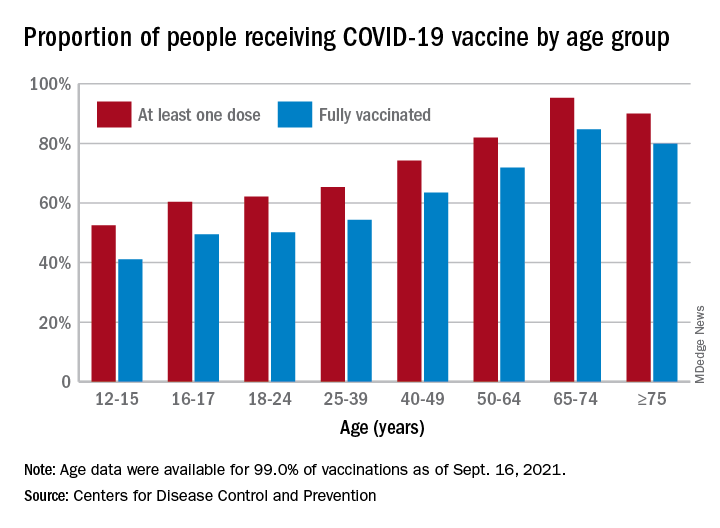

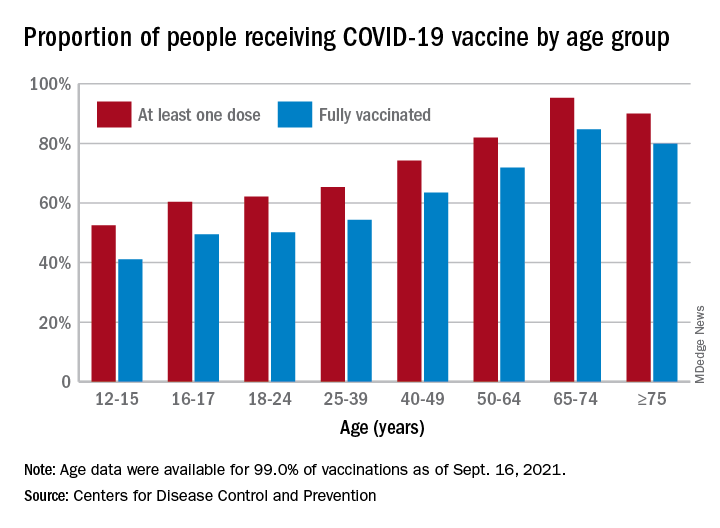

Now, we have another adolescent vaccine to discuss and encourage our patients to receive. We also need to address their concerns and/or to at least direct them to a reliable source to obtain accurate information. For the first time, a recommended vaccine may not be available at their medical home. Many don’t know where to go to receive it (http://www.vaccines.gov). Results of a Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 survey (August 2021) indicated that parents trusted their pediatricians most often (78%) for vaccine advice. The respondents voiced concern about trusting the location where the child would be immunized and long-term effects especially related to fertility. Parents who received communications regarding the benefits of vaccination were twice as likely to have their adolescents immunized. Finally, remember: Like parent, like child. An immunized parent is more likely to immunize the adolescent. (See Fig. 1.)

It is beyond the scope of this column to discuss the psychosocial aspects of this disease: children experiencing the death of teachers, classmates, family members, and those viewing the vitriol between pro- and antimask proponents often exhibited on school premises. And let’s not forget the child who wants to wear a mask but may be ostracized or bullied for doing so.

Our job is to do our very best to advocate for and to protect our patients by promoting mandatory masks at schools and encouraging vaccination of adolescents as we patiently wait for vaccines to become available for all of our children.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

I began thinking of a topic for this column weeks ago determined to discuss anything except COVID-19. Yet, news reports from all sources blasted daily reminders of rising COVID-19 cases overall and specifically in children.

In August, school resumed for many of our patients and the battle over mandating masks for school attendance was in full swing. The fact that it is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation supported by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society fell on deaf ears. One day, I heard a report that over 25,000 students attending Texas public schools were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Aug. 23 and Aug. 29. This peak in activity occurred just 2 weeks after the start of school and led to the closure of 45 school districts. Texas does not have a monopoly on these rising cases. Delta, a more contagious variant, began circulating in June 2021 and by July it was the most predominant. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations have increased nationwide. During the latter 2 weeks of August 2021, COVID-19–related ED visits and hospitalizations for persons aged 0-17 years were 3.4 and 3.7 times higher in states with the lowest vaccination coverage, compared with states with high vaccination coverage (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1249-54). Specifically, the rates of hospitalization the week ending Aug. 14, 2021, were nearly 5 times the rates for the week ending June 26, 2021, for 0- to 17-year-olds and nearly 10 times the rates for children 0-4 years of age. Hospitalization rates were 10.1 times higher for unimmunized adolescents than for fully vaccinated ones (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1255-60).

Multiple elected state leaders have opposed interventions such as mandating masks in school, and our children are paying for it. These leaders have relinquished their responsibility to local school boards. Several have reinforced the no-mask mandate while others have had the courage and insight to ignore state government leaders and have established mask mandates.

How is this lack of enforcement of national recommendations affecting our patients? Let’s look at two neighboring school districts in Texas. School districts have COVID-19 dashboards that are updated daily and accessible to the general public. School District A requires masks for school entry. It serves 196,171 students and has 27,195 teachers and staff. Since school opened in August, 1,606 cumulative cases of COVID-19 in students (0.8%) and 282 in staff (1%) have been reported. Fifty-five percent of the student cases occurred in elementary schools. In contrast, School District B located in the adjacent county serves 64,517 students and has 3,906 teachers and staff with no mask mandate. Since August, there have been 4,506 cumulative COVID-19 cases in students (6.9%) and 578 (14.7%) in staff. Information regarding the specific school type was not provided; however, the dashboard indicates that 2,924 cases (64.8%) occurred in children younger than 11 years of age. County data indicate 62% of those older than 12 years of age were fully vaccinated in District A, compared with 54% of persons older than 12 years in District B. The county COVID-19 positivity rate in District A is 17.6% and in District B it is 20%. Both counties are experiencing increased COVID-19 activity yet have had strikingly different outcomes in the student/staff population. While supporting the case for wearing masks to prevent disease transmission, one can’t ignore the adolescents who were infected and vaccine eligible (District A: 706; District B: 1,582). Their vaccination status could not be determined.

As pediatricians we have played an integral part in the elimination of diseases through educating and administering vaccinations. Adolescents are relatively healthy, thus limiting the number of encounters with them. The majority complete the 11-year visit; however, many fail to return for the 16- to 18-year visit.

So how are we doing? CDC data from 10 U.S. jurisdictions demonstrated a substantial decrease in vaccine administration between March and May of 2020, compared with the same period in 2018 and 2019. A decline was anticipated because of the nationwide lockdown. Doses of HPV administered declined almost 64% and 71% for 9- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds, respectively. Tdap administration declined 66% and 61% for the same respective age groups. Although administered doses increased between June and September of 2020, it was not sufficient to achieve catch-up coverage. Compared to the same period in 2018-2019, administration of the HPV vaccine declined 12.8% and 28% (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) and for Tdap it was 21% and 30% lower (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:840-5).

Now, we have another adolescent vaccine to discuss and encourage our patients to receive. We also need to address their concerns and/or to at least direct them to a reliable source to obtain accurate information. For the first time, a recommended vaccine may not be available at their medical home. Many don’t know where to go to receive it (http://www.vaccines.gov). Results of a Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 survey (August 2021) indicated that parents trusted their pediatricians most often (78%) for vaccine advice. The respondents voiced concern about trusting the location where the child would be immunized and long-term effects especially related to fertility. Parents who received communications regarding the benefits of vaccination were twice as likely to have their adolescents immunized. Finally, remember: Like parent, like child. An immunized parent is more likely to immunize the adolescent. (See Fig. 1.)

It is beyond the scope of this column to discuss the psychosocial aspects of this disease: children experiencing the death of teachers, classmates, family members, and those viewing the vitriol between pro- and antimask proponents often exhibited on school premises. And let’s not forget the child who wants to wear a mask but may be ostracized or bullied for doing so.

Our job is to do our very best to advocate for and to protect our patients by promoting mandatory masks at schools and encouraging vaccination of adolescents as we patiently wait for vaccines to become available for all of our children.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

I began thinking of a topic for this column weeks ago determined to discuss anything except COVID-19. Yet, news reports from all sources blasted daily reminders of rising COVID-19 cases overall and specifically in children.

In August, school resumed for many of our patients and the battle over mandating masks for school attendance was in full swing. The fact that it is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation supported by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society fell on deaf ears. One day, I heard a report that over 25,000 students attending Texas public schools were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Aug. 23 and Aug. 29. This peak in activity occurred just 2 weeks after the start of school and led to the closure of 45 school districts. Texas does not have a monopoly on these rising cases. Delta, a more contagious variant, began circulating in June 2021 and by July it was the most predominant. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations have increased nationwide. During the latter 2 weeks of August 2021, COVID-19–related ED visits and hospitalizations for persons aged 0-17 years were 3.4 and 3.7 times higher in states with the lowest vaccination coverage, compared with states with high vaccination coverage (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1249-54). Specifically, the rates of hospitalization the week ending Aug. 14, 2021, were nearly 5 times the rates for the week ending June 26, 2021, for 0- to 17-year-olds and nearly 10 times the rates for children 0-4 years of age. Hospitalization rates were 10.1 times higher for unimmunized adolescents than for fully vaccinated ones (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1255-60).

Multiple elected state leaders have opposed interventions such as mandating masks in school, and our children are paying for it. These leaders have relinquished their responsibility to local school boards. Several have reinforced the no-mask mandate while others have had the courage and insight to ignore state government leaders and have established mask mandates.

How is this lack of enforcement of national recommendations affecting our patients? Let’s look at two neighboring school districts in Texas. School districts have COVID-19 dashboards that are updated daily and accessible to the general public. School District A requires masks for school entry. It serves 196,171 students and has 27,195 teachers and staff. Since school opened in August, 1,606 cumulative cases of COVID-19 in students (0.8%) and 282 in staff (1%) have been reported. Fifty-five percent of the student cases occurred in elementary schools. In contrast, School District B located in the adjacent county serves 64,517 students and has 3,906 teachers and staff with no mask mandate. Since August, there have been 4,506 cumulative COVID-19 cases in students (6.9%) and 578 (14.7%) in staff. Information regarding the specific school type was not provided; however, the dashboard indicates that 2,924 cases (64.8%) occurred in children younger than 11 years of age. County data indicate 62% of those older than 12 years of age were fully vaccinated in District A, compared with 54% of persons older than 12 years in District B. The county COVID-19 positivity rate in District A is 17.6% and in District B it is 20%. Both counties are experiencing increased COVID-19 activity yet have had strikingly different outcomes in the student/staff population. While supporting the case for wearing masks to prevent disease transmission, one can’t ignore the adolescents who were infected and vaccine eligible (District A: 706; District B: 1,582). Their vaccination status could not be determined.

As pediatricians we have played an integral part in the elimination of diseases through educating and administering vaccinations. Adolescents are relatively healthy, thus limiting the number of encounters with them. The majority complete the 11-year visit; however, many fail to return for the 16- to 18-year visit.

So how are we doing? CDC data from 10 U.S. jurisdictions demonstrated a substantial decrease in vaccine administration between March and May of 2020, compared with the same period in 2018 and 2019. A decline was anticipated because of the nationwide lockdown. Doses of HPV administered declined almost 64% and 71% for 9- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds, respectively. Tdap administration declined 66% and 61% for the same respective age groups. Although administered doses increased between June and September of 2020, it was not sufficient to achieve catch-up coverage. Compared to the same period in 2018-2019, administration of the HPV vaccine declined 12.8% and 28% (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) and for Tdap it was 21% and 30% lower (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:840-5).

Now, we have another adolescent vaccine to discuss and encourage our patients to receive. We also need to address their concerns and/or to at least direct them to a reliable source to obtain accurate information. For the first time, a recommended vaccine may not be available at their medical home. Many don’t know where to go to receive it (http://www.vaccines.gov). Results of a Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 survey (August 2021) indicated that parents trusted their pediatricians most often (78%) for vaccine advice. The respondents voiced concern about trusting the location where the child would be immunized and long-term effects especially related to fertility. Parents who received communications regarding the benefits of vaccination were twice as likely to have their adolescents immunized. Finally, remember: Like parent, like child. An immunized parent is more likely to immunize the adolescent. (See Fig. 1.)

It is beyond the scope of this column to discuss the psychosocial aspects of this disease: children experiencing the death of teachers, classmates, family members, and those viewing the vitriol between pro- and antimask proponents often exhibited on school premises. And let’s not forget the child who wants to wear a mask but may be ostracized or bullied for doing so.

Our job is to do our very best to advocate for and to protect our patients by promoting mandatory masks at schools and encouraging vaccination of adolescents as we patiently wait for vaccines to become available for all of our children.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Navigating parenthood as pediatricians

PHM 2021 session

The Baby at Work or the Baby at Home: Navigating Parenthood as Pediatricians

Presenters

Jessica Gold, MD; Dana Foradori, MD, MEd; Nivedita Srinivas, MD; Honora Burnett, MD; Julie Pantaleoni, MD; and Barrett Fromme, MD, MHPE

Session summary

A group of physician-mothers from multiple academic children’s hospitals came together in a storytelling format to discuss topics relating to being a parent and pediatric hospitalist. Through short and poignant stories, the presenters shared their experiences and reviewed recent literature and policy changes relating to the topic. This mini-plenary focused on three themes:

1. Easing the transition back to work after the birth of a child.

2. Coping with the tension between being a parent and pediatrician.

3. The role that divisions, departments, and institutions can play in supporting parents and promoting workplace engagement.

The session concluded with a robust question-and-answer portion where participants built upon the themes above and shared their own experiences as pediatric hospitalist parents.

Key takeaways

- “Use your voice.” Physicians who are parents must continue having conversations about the challenging aspects of being a parent and hospitalist and advocate for the changes they would like to see.

- There will always be tension as a physician parent, but we can learn to embrace it while also learning how to ask for help, set boundaries, and share when we are struggling.

- There are numerous challenges for hospitalists who are parents because of poor parental leave policies in the United States, but this is slowly changing. For example, starting in July 2021, the ACGME mandated 6 weeks of parental leave during training without having to extend training.

- “You are not alone.” The presenters emphasized that their reason for hosting this session was to shed light on this topic and let all pediatric hospitalist parents know that they are not alone in this experience.

Dr. Scott is a second-year pediatric hospital medicine fellow at New York–Presbyterian Columbia/Cornell. Her academic interests are in curriculum development and evaluation in medical education with a focus on telemedicine.

PHM 2021 session

The Baby at Work or the Baby at Home: Navigating Parenthood as Pediatricians

Presenters

Jessica Gold, MD; Dana Foradori, MD, MEd; Nivedita Srinivas, MD; Honora Burnett, MD; Julie Pantaleoni, MD; and Barrett Fromme, MD, MHPE

Session summary

A group of physician-mothers from multiple academic children’s hospitals came together in a storytelling format to discuss topics relating to being a parent and pediatric hospitalist. Through short and poignant stories, the presenters shared their experiences and reviewed recent literature and policy changes relating to the topic. This mini-plenary focused on three themes:

1. Easing the transition back to work after the birth of a child.

2. Coping with the tension between being a parent and pediatrician.

3. The role that divisions, departments, and institutions can play in supporting parents and promoting workplace engagement.

The session concluded with a robust question-and-answer portion where participants built upon the themes above and shared their own experiences as pediatric hospitalist parents.

Key takeaways

- “Use your voice.” Physicians who are parents must continue having conversations about the challenging aspects of being a parent and hospitalist and advocate for the changes they would like to see.

- There will always be tension as a physician parent, but we can learn to embrace it while also learning how to ask for help, set boundaries, and share when we are struggling.

- There are numerous challenges for hospitalists who are parents because of poor parental leave policies in the United States, but this is slowly changing. For example, starting in July 2021, the ACGME mandated 6 weeks of parental leave during training without having to extend training.

- “You are not alone.” The presenters emphasized that their reason for hosting this session was to shed light on this topic and let all pediatric hospitalist parents know that they are not alone in this experience.

Dr. Scott is a second-year pediatric hospital medicine fellow at New York–Presbyterian Columbia/Cornell. Her academic interests are in curriculum development and evaluation in medical education with a focus on telemedicine.

PHM 2021 session

The Baby at Work or the Baby at Home: Navigating Parenthood as Pediatricians

Presenters

Jessica Gold, MD; Dana Foradori, MD, MEd; Nivedita Srinivas, MD; Honora Burnett, MD; Julie Pantaleoni, MD; and Barrett Fromme, MD, MHPE

Session summary

A group of physician-mothers from multiple academic children’s hospitals came together in a storytelling format to discuss topics relating to being a parent and pediatric hospitalist. Through short and poignant stories, the presenters shared their experiences and reviewed recent literature and policy changes relating to the topic. This mini-plenary focused on three themes:

1. Easing the transition back to work after the birth of a child.

2. Coping with the tension between being a parent and pediatrician.

3. The role that divisions, departments, and institutions can play in supporting parents and promoting workplace engagement.

The session concluded with a robust question-and-answer portion where participants built upon the themes above and shared their own experiences as pediatric hospitalist parents.

Key takeaways

- “Use your voice.” Physicians who are parents must continue having conversations about the challenging aspects of being a parent and hospitalist and advocate for the changes they would like to see.

- There will always be tension as a physician parent, but we can learn to embrace it while also learning how to ask for help, set boundaries, and share when we are struggling.

- There are numerous challenges for hospitalists who are parents because of poor parental leave policies in the United States, but this is slowly changing. For example, starting in July 2021, the ACGME mandated 6 weeks of parental leave during training without having to extend training.

- “You are not alone.” The presenters emphasized that their reason for hosting this session was to shed light on this topic and let all pediatric hospitalist parents know that they are not alone in this experience.

Dr. Scott is a second-year pediatric hospital medicine fellow at New York–Presbyterian Columbia/Cornell. Her academic interests are in curriculum development and evaluation in medical education with a focus on telemedicine.

COVID vaccine is safe, effective for children aged 5-11, Pfizer says

With record numbers of COVID-19 cases being reported in kids, Pfizer and its partner BioNTech have announced that their mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 is safe and appears to generate a protective immune response in children as young as 5.

The companies have been testing a lower dose of the vaccine -- just 10 milligrams -- in children between the ages of 5 and 11. That’s one-third the dose given to adults.

In a clinical trial that included more than 2,200 children, Pfizer says two doses of the vaccines given 3 weeks apart generated a high level of neutralizing antibodies, comparable to the level seen in older children who get a higher dose of the vaccine.

On the advice of its vaccine advisory committee, the Food and Drug Administration asked vaccine makers to include more children in these studies earlier this year.

Rather than testing whether the vaccines are preventing COVID-19 illness in children, as they did in adults, the pharmaceutical companies that make the COVID-19 vaccines are looking at the antibody levels generated by the vaccines instead. The FDA has approved the approach in hopes of speeding vaccines to children, who are now back in school full time in most parts of the United States.

With that in mind, Evan Anderson, MD, a doctor with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta who is an investigator for the trial — and is therefore kept in the dark about its results — said it’s important to keep in mind that the company didn’t share any efficacy data today.

“We don’t know whether there were cases of COVID-19 among children that were enrolled in the study and how those compared in those who received placebo versus those that received vaccine,” he said.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. The company said there were no cases of heart inflammation called myocarditis observed. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

“We are pleased to be able to submit data to regulatory authorities for this group of school-aged children before the start of the winter season,” Ugur Sahin, MD, CEO and co-founder of BioNTech, said in a news release. “The safety profile and immunogenicity data in children aged 5 to 11 years vaccinated at a lower dose are consistent with those we have observed with our vaccine in other older populations at a higher dose.”

When asked how soon the FDA might act on Pfizer’s application, Anderson said others had speculated about timelines of 4 to 6 weeks, but he also noted that the FDA could still exercise its authority to ask the company for more information, which could slow the process down.

“As a parent myself, I would love to see that timeline occurring quickly. However, I do want the FDA to fully review the data and ask the necessary questions,” he said. “It’s a little speculative to get too definitive with timelines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

With record numbers of COVID-19 cases being reported in kids, Pfizer and its partner BioNTech have announced that their mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 is safe and appears to generate a protective immune response in children as young as 5.

The companies have been testing a lower dose of the vaccine -- just 10 milligrams -- in children between the ages of 5 and 11. That’s one-third the dose given to adults.

In a clinical trial that included more than 2,200 children, Pfizer says two doses of the vaccines given 3 weeks apart generated a high level of neutralizing antibodies, comparable to the level seen in older children who get a higher dose of the vaccine.

On the advice of its vaccine advisory committee, the Food and Drug Administration asked vaccine makers to include more children in these studies earlier this year.

Rather than testing whether the vaccines are preventing COVID-19 illness in children, as they did in adults, the pharmaceutical companies that make the COVID-19 vaccines are looking at the antibody levels generated by the vaccines instead. The FDA has approved the approach in hopes of speeding vaccines to children, who are now back in school full time in most parts of the United States.

With that in mind, Evan Anderson, MD, a doctor with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta who is an investigator for the trial — and is therefore kept in the dark about its results — said it’s important to keep in mind that the company didn’t share any efficacy data today.

“We don’t know whether there were cases of COVID-19 among children that were enrolled in the study and how those compared in those who received placebo versus those that received vaccine,” he said.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. The company said there were no cases of heart inflammation called myocarditis observed. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

“We are pleased to be able to submit data to regulatory authorities for this group of school-aged children before the start of the winter season,” Ugur Sahin, MD, CEO and co-founder of BioNTech, said in a news release. “The safety profile and immunogenicity data in children aged 5 to 11 years vaccinated at a lower dose are consistent with those we have observed with our vaccine in other older populations at a higher dose.”

When asked how soon the FDA might act on Pfizer’s application, Anderson said others had speculated about timelines of 4 to 6 weeks, but he also noted that the FDA could still exercise its authority to ask the company for more information, which could slow the process down.

“As a parent myself, I would love to see that timeline occurring quickly. However, I do want the FDA to fully review the data and ask the necessary questions,” he said. “It’s a little speculative to get too definitive with timelines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

With record numbers of COVID-19 cases being reported in kids, Pfizer and its partner BioNTech have announced that their mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 is safe and appears to generate a protective immune response in children as young as 5.

The companies have been testing a lower dose of the vaccine -- just 10 milligrams -- in children between the ages of 5 and 11. That’s one-third the dose given to adults.

In a clinical trial that included more than 2,200 children, Pfizer says two doses of the vaccines given 3 weeks apart generated a high level of neutralizing antibodies, comparable to the level seen in older children who get a higher dose of the vaccine.

On the advice of its vaccine advisory committee, the Food and Drug Administration asked vaccine makers to include more children in these studies earlier this year.

Rather than testing whether the vaccines are preventing COVID-19 illness in children, as they did in adults, the pharmaceutical companies that make the COVID-19 vaccines are looking at the antibody levels generated by the vaccines instead. The FDA has approved the approach in hopes of speeding vaccines to children, who are now back in school full time in most parts of the United States.

With that in mind, Evan Anderson, MD, a doctor with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta who is an investigator for the trial — and is therefore kept in the dark about its results — said it’s important to keep in mind that the company didn’t share any efficacy data today.

“We don’t know whether there were cases of COVID-19 among children that were enrolled in the study and how those compared in those who received placebo versus those that received vaccine,” he said.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. The company said there were no cases of heart inflammation called myocarditis observed. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

“We are pleased to be able to submit data to regulatory authorities for this group of school-aged children before the start of the winter season,” Ugur Sahin, MD, CEO and co-founder of BioNTech, said in a news release. “The safety profile and immunogenicity data in children aged 5 to 11 years vaccinated at a lower dose are consistent with those we have observed with our vaccine in other older populations at a higher dose.”

When asked how soon the FDA might act on Pfizer’s application, Anderson said others had speculated about timelines of 4 to 6 weeks, but he also noted that the FDA could still exercise its authority to ask the company for more information, which could slow the process down.

“As a parent myself, I would love to see that timeline occurring quickly. However, I do want the FDA to fully review the data and ask the necessary questions,” he said. “It’s a little speculative to get too definitive with timelines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Parent-led intervention linked with decreased autism symptoms in at-risk infants

These findings, which were published in JAMA Pediatrics, were the first evidence worldwide that a preemptive intervention during infancy could lead to such a significant improvement in children’s social development, resulting in “three times fewer diagnoses of autism at age 3,” said lead author Andrew Whitehouse, PhD, in a statement.

“No trial of a preemptive infant intervention, applied prior to diagnosis, has to date shown such an effect to impact diagnostic outcomes – until now,” he said.

Study intervention is a nontraditonal approach

Dr. Whitehouse, who is professor of Autism Research at Telethon Kids and University of Western Australia, and Director of CliniKids in Perth, said the intervention is a departure from traditional approaches. “Traditionally, therapy seeks to train children to learn ‘typical’ behaviors,” he said in an email. “The difference of this therapy is that we help parents understand the unique abilities of their baby, and to use these strengths as a foundation for future development.”

Dr. Whitehouse’s study included 103 children (aged approximately 12 months), who displayed at least three of five behaviors indicating a high likelihood of ASD as defined by the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance–Revised (SACS-R) 12-month checklist. The infants were randomized to receive either usual care or the intervention, which is called the iBASIS–Video Interaction to Promote Positive Parenting (iBASIS-VIPP). Usual care was delivered by community physicians, whereas the intervention involved 10 sessions delivered at home by a trained therapist.

“The iBASIS-VIPP uses video-feedback as a means of helping parents recognize their baby’s communication cues so they can respond in a way that builds their social communication development,” Dr. Whitehouse explained in an interview. “The therapist then provides guidance to the parent as to how their baby is communicating with them, and they can communicate back to have back-and-forth conversations.”

“We know these back-and-forth conversations are crucial to support early social communication development, and are a precursor to more complex skills, such as verbal language,” he added.

Reassessment of the children at age 3 years showed a “small but enduring” benefit of the intervention, noted the authors. Children in the intervention group had a reduction in ASD symptom severity (P = .04), and reduced odds of ASD classification, compared with children receiving usual care (6.7% vs. 20.5%; odds ratio, 0.18; P = .02).

The findings provide “initial evidence of efficacy for a new clinical model that uses a specific developmentally focused intervention,” noted the authors. “The children falling below the diagnostic threshold still had developmental difficulties, but by working with each child’s unique differences, rather than trying to counter them, the therapy has effectively supported their development through the early childhood years,” noted Dr. Whitehouse in a statement.

Other research has shown benefits of new study approach

This is a “solid” study, “but, as acknowledged by the authors, the main effects are small in magnitude, and longer-term outcomes will be important to capture,” said Jessica Brian, PhD, C Psych, associate professor in the department of pediatrics at the University of Toronto, colead at the Autism Research Centre, and psychologist and clinician-investigator at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehab Hospital in Toronto.

Dr. Brian said she and her coauthors of a paper published in Autism Research and others have shown that the kind of approach used in the new study can be helpful for enhancing different areas of toddler development, but “the specific finding of reduced likelihood of a clinical ASD diagnosis is a bit different.”

The goal of reducing the likelihood of an ASD diagnosis “needs to be considered carefully, from the perspective of autism acceptance,” she added. “From an acceptance lens, the primary objective of early intervention in ASD might be better positioned as aiming to enhance or support a young child’s development, help them make developmental progress, build on their strengths, optimize outcomes, or reduce impairment. … I think the authors do a good job of balancing this perspective.”

New study shows value of parent-mediated interventions

Overall, Dr. Brian, who coauthored the Canadian Paediatric Society’s position statement on ASD diagnosis, lauded the findings as good news.

“It shows the value of using parent-mediated interventions, which are far less costly and are more resource-efficient than most therapist-delivered models.”

“In cases where parent-mediated approaches are made available to families prior to diagnosis, there is potential for strong effects, when the brain is most amenable to learning. Such models may also be an ideal fit before diagnosis, since they are less resource-intensive than therapist-delivered models, which may only be funded by governments once a diagnosis is confirmed,” she said.

“Finally, parent-mediated programs have the potential to support parents during what, for many families, is a particularly challenging time as they identify their child’s developmental differences or receive a diagnosis. Such programs have potential to increase parents’ confidence in parenting a young child with unique learning needs.”

What Dr. Brian thought was missing from the paper was acknowledgment that, “despite early developmental gains from parent-mediated interventions, it is likely that most children with ASD will need additional supports throughout development.”

This study was sponsored by the Telethon Kids Institute. Dr. Whitehouse reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Brian codeveloped a parent-mediated intervention for toddlers with probable or confirmed ASD (the Social ABCs), for which she does not receive any royalties.

These findings, which were published in JAMA Pediatrics, were the first evidence worldwide that a preemptive intervention during infancy could lead to such a significant improvement in children’s social development, resulting in “three times fewer diagnoses of autism at age 3,” said lead author Andrew Whitehouse, PhD, in a statement.

“No trial of a preemptive infant intervention, applied prior to diagnosis, has to date shown such an effect to impact diagnostic outcomes – until now,” he said.

Study intervention is a nontraditonal approach

Dr. Whitehouse, who is professor of Autism Research at Telethon Kids and University of Western Australia, and Director of CliniKids in Perth, said the intervention is a departure from traditional approaches. “Traditionally, therapy seeks to train children to learn ‘typical’ behaviors,” he said in an email. “The difference of this therapy is that we help parents understand the unique abilities of their baby, and to use these strengths as a foundation for future development.”

Dr. Whitehouse’s study included 103 children (aged approximately 12 months), who displayed at least three of five behaviors indicating a high likelihood of ASD as defined by the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance–Revised (SACS-R) 12-month checklist. The infants were randomized to receive either usual care or the intervention, which is called the iBASIS–Video Interaction to Promote Positive Parenting (iBASIS-VIPP). Usual care was delivered by community physicians, whereas the intervention involved 10 sessions delivered at home by a trained therapist.

“The iBASIS-VIPP uses video-feedback as a means of helping parents recognize their baby’s communication cues so they can respond in a way that builds their social communication development,” Dr. Whitehouse explained in an interview. “The therapist then provides guidance to the parent as to how their baby is communicating with them, and they can communicate back to have back-and-forth conversations.”

“We know these back-and-forth conversations are crucial to support early social communication development, and are a precursor to more complex skills, such as verbal language,” he added.

Reassessment of the children at age 3 years showed a “small but enduring” benefit of the intervention, noted the authors. Children in the intervention group had a reduction in ASD symptom severity (P = .04), and reduced odds of ASD classification, compared with children receiving usual care (6.7% vs. 20.5%; odds ratio, 0.18; P = .02).

The findings provide “initial evidence of efficacy for a new clinical model that uses a specific developmentally focused intervention,” noted the authors. “The children falling below the diagnostic threshold still had developmental difficulties, but by working with each child’s unique differences, rather than trying to counter them, the therapy has effectively supported their development through the early childhood years,” noted Dr. Whitehouse in a statement.

Other research has shown benefits of new study approach

This is a “solid” study, “but, as acknowledged by the authors, the main effects are small in magnitude, and longer-term outcomes will be important to capture,” said Jessica Brian, PhD, C Psych, associate professor in the department of pediatrics at the University of Toronto, colead at the Autism Research Centre, and psychologist and clinician-investigator at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehab Hospital in Toronto.

Dr. Brian said she and her coauthors of a paper published in Autism Research and others have shown that the kind of approach used in the new study can be helpful for enhancing different areas of toddler development, but “the specific finding of reduced likelihood of a clinical ASD diagnosis is a bit different.”

The goal of reducing the likelihood of an ASD diagnosis “needs to be considered carefully, from the perspective of autism acceptance,” she added. “From an acceptance lens, the primary objective of early intervention in ASD might be better positioned as aiming to enhance or support a young child’s development, help them make developmental progress, build on their strengths, optimize outcomes, or reduce impairment. … I think the authors do a good job of balancing this perspective.”

New study shows value of parent-mediated interventions

Overall, Dr. Brian, who coauthored the Canadian Paediatric Society’s position statement on ASD diagnosis, lauded the findings as good news.

“It shows the value of using parent-mediated interventions, which are far less costly and are more resource-efficient than most therapist-delivered models.”

“In cases where parent-mediated approaches are made available to families prior to diagnosis, there is potential for strong effects, when the brain is most amenable to learning. Such models may also be an ideal fit before diagnosis, since they are less resource-intensive than therapist-delivered models, which may only be funded by governments once a diagnosis is confirmed,” she said.

“Finally, parent-mediated programs have the potential to support parents during what, for many families, is a particularly challenging time as they identify their child’s developmental differences or receive a diagnosis. Such programs have potential to increase parents’ confidence in parenting a young child with unique learning needs.”

What Dr. Brian thought was missing from the paper was acknowledgment that, “despite early developmental gains from parent-mediated interventions, it is likely that most children with ASD will need additional supports throughout development.”

This study was sponsored by the Telethon Kids Institute. Dr. Whitehouse reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Brian codeveloped a parent-mediated intervention for toddlers with probable or confirmed ASD (the Social ABCs), for which she does not receive any royalties.

These findings, which were published in JAMA Pediatrics, were the first evidence worldwide that a preemptive intervention during infancy could lead to such a significant improvement in children’s social development, resulting in “three times fewer diagnoses of autism at age 3,” said lead author Andrew Whitehouse, PhD, in a statement.

“No trial of a preemptive infant intervention, applied prior to diagnosis, has to date shown such an effect to impact diagnostic outcomes – until now,” he said.

Study intervention is a nontraditonal approach

Dr. Whitehouse, who is professor of Autism Research at Telethon Kids and University of Western Australia, and Director of CliniKids in Perth, said the intervention is a departure from traditional approaches. “Traditionally, therapy seeks to train children to learn ‘typical’ behaviors,” he said in an email. “The difference of this therapy is that we help parents understand the unique abilities of their baby, and to use these strengths as a foundation for future development.”

Dr. Whitehouse’s study included 103 children (aged approximately 12 months), who displayed at least three of five behaviors indicating a high likelihood of ASD as defined by the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance–Revised (SACS-R) 12-month checklist. The infants were randomized to receive either usual care or the intervention, which is called the iBASIS–Video Interaction to Promote Positive Parenting (iBASIS-VIPP). Usual care was delivered by community physicians, whereas the intervention involved 10 sessions delivered at home by a trained therapist.

“The iBASIS-VIPP uses video-feedback as a means of helping parents recognize their baby’s communication cues so they can respond in a way that builds their social communication development,” Dr. Whitehouse explained in an interview. “The therapist then provides guidance to the parent as to how their baby is communicating with them, and they can communicate back to have back-and-forth conversations.”

“We know these back-and-forth conversations are crucial to support early social communication development, and are a precursor to more complex skills, such as verbal language,” he added.

Reassessment of the children at age 3 years showed a “small but enduring” benefit of the intervention, noted the authors. Children in the intervention group had a reduction in ASD symptom severity (P = .04), and reduced odds of ASD classification, compared with children receiving usual care (6.7% vs. 20.5%; odds ratio, 0.18; P = .02).

The findings provide “initial evidence of efficacy for a new clinical model that uses a specific developmentally focused intervention,” noted the authors. “The children falling below the diagnostic threshold still had developmental difficulties, but by working with each child’s unique differences, rather than trying to counter them, the therapy has effectively supported their development through the early childhood years,” noted Dr. Whitehouse in a statement.

Other research has shown benefits of new study approach

This is a “solid” study, “but, as acknowledged by the authors, the main effects are small in magnitude, and longer-term outcomes will be important to capture,” said Jessica Brian, PhD, C Psych, associate professor in the department of pediatrics at the University of Toronto, colead at the Autism Research Centre, and psychologist and clinician-investigator at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehab Hospital in Toronto.

Dr. Brian said she and her coauthors of a paper published in Autism Research and others have shown that the kind of approach used in the new study can be helpful for enhancing different areas of toddler development, but “the specific finding of reduced likelihood of a clinical ASD diagnosis is a bit different.”

The goal of reducing the likelihood of an ASD diagnosis “needs to be considered carefully, from the perspective of autism acceptance,” she added. “From an acceptance lens, the primary objective of early intervention in ASD might be better positioned as aiming to enhance or support a young child’s development, help them make developmental progress, build on their strengths, optimize outcomes, or reduce impairment. … I think the authors do a good job of balancing this perspective.”

New study shows value of parent-mediated interventions

Overall, Dr. Brian, who coauthored the Canadian Paediatric Society’s position statement on ASD diagnosis, lauded the findings as good news.

“It shows the value of using parent-mediated interventions, which are far less costly and are more resource-efficient than most therapist-delivered models.”

“In cases where parent-mediated approaches are made available to families prior to diagnosis, there is potential for strong effects, when the brain is most amenable to learning. Such models may also be an ideal fit before diagnosis, since they are less resource-intensive than therapist-delivered models, which may only be funded by governments once a diagnosis is confirmed,” she said.

“Finally, parent-mediated programs have the potential to support parents during what, for many families, is a particularly challenging time as they identify their child’s developmental differences or receive a diagnosis. Such programs have potential to increase parents’ confidence in parenting a young child with unique learning needs.”

What Dr. Brian thought was missing from the paper was acknowledgment that, “despite early developmental gains from parent-mediated interventions, it is likely that most children with ASD will need additional supports throughout development.”

This study was sponsored by the Telethon Kids Institute. Dr. Whitehouse reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Brian codeveloped a parent-mediated intervention for toddlers with probable or confirmed ASD (the Social ABCs), for which she does not receive any royalties.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

European agency recommends two new adalimumab biosimilars

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended marketing authorization this week for two new adalimumab biosimilars, Hukyndra and Libmyris.

The biosimilars, both developed by STADA Arzneimittel AG, will be available as a 40-mg solution for injection in a pre-filled syringe and pre-filled pen and 80-mg solution for injection in a pre-filled syringe. Both biosimilars will have 15 indications:

- rheumatoid arthritis

- polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- enthesitis-related arthritis

- ankylosing spondylitis

- axial spondyloarthritis without radiographic evidence of ankylosing spondylitis

- psoriatic arthritis

- chronic plaque psoriasis (adults and children)

- hidradenitis suppurativa

- Crohn’s disease (adults and children)

- ulcerative colitis (adults and children)

- uveitis (adults and children)

Data show that both Hukyndra and Libmyris are highly similar to the reference product Humira (adalimumab), a monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor alpha, and have comparable quality, safety, and efficacy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended marketing authorization this week for two new adalimumab biosimilars, Hukyndra and Libmyris.

The biosimilars, both developed by STADA Arzneimittel AG, will be available as a 40-mg solution for injection in a pre-filled syringe and pre-filled pen and 80-mg solution for injection in a pre-filled syringe. Both biosimilars will have 15 indications:

- rheumatoid arthritis

- polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- enthesitis-related arthritis

- ankylosing spondylitis

- axial spondyloarthritis without radiographic evidence of ankylosing spondylitis

- psoriatic arthritis

- chronic plaque psoriasis (adults and children)

- hidradenitis suppurativa

- Crohn’s disease (adults and children)

- ulcerative colitis (adults and children)

- uveitis (adults and children)

Data show that both Hukyndra and Libmyris are highly similar to the reference product Humira (adalimumab), a monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor alpha, and have comparable quality, safety, and efficacy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended marketing authorization this week for two new adalimumab biosimilars, Hukyndra and Libmyris.

The biosimilars, both developed by STADA Arzneimittel AG, will be available as a 40-mg solution for injection in a pre-filled syringe and pre-filled pen and 80-mg solution for injection in a pre-filled syringe. Both biosimilars will have 15 indications:

- rheumatoid arthritis

- polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- enthesitis-related arthritis

- ankylosing spondylitis

- axial spondyloarthritis without radiographic evidence of ankylosing spondylitis

- psoriatic arthritis

- chronic plaque psoriasis (adults and children)

- hidradenitis suppurativa

- Crohn’s disease (adults and children)

- ulcerative colitis (adults and children)

- uveitis (adults and children)

Data show that both Hukyndra and Libmyris are highly similar to the reference product Humira (adalimumab), a monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor alpha, and have comparable quality, safety, and efficacy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Higher than standard vitamin D dose provides no added benefits to children’s neurodevelopment

Prescribing higher doses of vitamin D may not provide any additional benefits to children’s brain development, a new study suggests.

New research published online in JAMA found that there were no differences in children’s developmental milestones or social-emotional problems when given a higher daily dose of 1,200 IU of vitamin D versus the standard dose of 400 IU.

Although past studies have looked into the relationship between vitamin D and neurodevelopment in children, the findings were inconsistent. A 2019 study published in Psychoneuroendocrinology found that vitamin D deficiency could be a biological risk factor for psychiatric disorders and that vitamin D acts as a neurosteroid with direct effect on brain development. However, a 2021 study published in Global Pediatric Health found no significant association between vitamin D levels and neurodevelopmental status in children at 2 years old.

Researchers of the current study said they expected to find a positive association between higher vitamin D levels and neurodevelopment.

“Our results highlight that the current recommendations, set forth mainly on the basis of bone health, also support healthy brain development,” said study author Kati Heinonen, PhD, associate professor of psychology and welfare sciences at Tampere (Finland) University. “Our results also point out that higher than currently recommended levels do not add to the benefits received from the vitamin D supplements.”

For the study, Dr. Heinonen and colleagues analyzed data from a double-blind, randomized clinical trial involving healthy infants born full-term between Jan. 1, 2013, and June 30, 2014, at a maternity hospital in Helsinki. They got follow-up information on 404 infants who were randomized to receive 400 IU of oral vitamin D supplements daily and 397 infants who received 1,200 IU of vitamin D supplements from 2 weeks to 24 months of age.

Researchers found no differences between the 400-IU group and the 1,200-IU group in the mean adjusted Ages and Stages Questionnaire total score at 12 months, a questionnaire that’s used to measure communication, problem solving, gross motor skills, fine motor skills, and personal and social skills. However, they did find that children receiving 1,200 IU of vitamin D supplementation had better developmental milestone scores in communication and problem-solving skills at 12 months.

Furthermore, they also found that higher vitamin D concentrations were associated with fewer sleeping problems at 24 months.

The researcher’s findings did not surprise Francis E. Rushton Jr., MD, a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, who was not involved in the study. “This study reveals that more is not always better,” Dr. Rushton said in an interview.

Dr. Rushton, who is also the medical director of the Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics network, said other ways to enhance early brain development include initiatives like infant home visitation and language enrichment programs like Reach Out and Read.

Dr. Heinonen noted that the study’s findings might be different if it had been conducted on infants from a different country.

“We have to remember that the participants were from northern European countries where several food products are also fortified by vitamin D,” Dr. Heinonen explained. “Thus, direct recommendations of the amount of the supplementation given for children from 2 weeks to 2 years in other countries should not be done on the basis of our study.”

Researchers also observed that the children receiving 1,200 IU of vitamin D supplementation had a risk of scoring higher on the externalizing symptoms scale at 24 months, meaning these infants are more likely to lose their temper and become physically aggressive.

“We could not fully exclude potential disadvantageous effects of higher doses. Even if minimal, the potential nonbeneficial effects of higher than standard doses warrant further studies,” she said.

Researchers said more studies are needed that follow children up to school age and adolescence, when higher cognitive abilities develop, to understand the long-term outcomes of early vitamin D supplementation.

Prescribing higher doses of vitamin D may not provide any additional benefits to children’s brain development, a new study suggests.

New research published online in JAMA found that there were no differences in children’s developmental milestones or social-emotional problems when given a higher daily dose of 1,200 IU of vitamin D versus the standard dose of 400 IU.

Although past studies have looked into the relationship between vitamin D and neurodevelopment in children, the findings were inconsistent. A 2019 study published in Psychoneuroendocrinology found that vitamin D deficiency could be a biological risk factor for psychiatric disorders and that vitamin D acts as a neurosteroid with direct effect on brain development. However, a 2021 study published in Global Pediatric Health found no significant association between vitamin D levels and neurodevelopmental status in children at 2 years old.

Researchers of the current study said they expected to find a positive association between higher vitamin D levels and neurodevelopment.

“Our results highlight that the current recommendations, set forth mainly on the basis of bone health, also support healthy brain development,” said study author Kati Heinonen, PhD, associate professor of psychology and welfare sciences at Tampere (Finland) University. “Our results also point out that higher than currently recommended levels do not add to the benefits received from the vitamin D supplements.”

For the study, Dr. Heinonen and colleagues analyzed data from a double-blind, randomized clinical trial involving healthy infants born full-term between Jan. 1, 2013, and June 30, 2014, at a maternity hospital in Helsinki. They got follow-up information on 404 infants who were randomized to receive 400 IU of oral vitamin D supplements daily and 397 infants who received 1,200 IU of vitamin D supplements from 2 weeks to 24 months of age.

Researchers found no differences between the 400-IU group and the 1,200-IU group in the mean adjusted Ages and Stages Questionnaire total score at 12 months, a questionnaire that’s used to measure communication, problem solving, gross motor skills, fine motor skills, and personal and social skills. However, they did find that children receiving 1,200 IU of vitamin D supplementation had better developmental milestone scores in communication and problem-solving skills at 12 months.

Furthermore, they also found that higher vitamin D concentrations were associated with fewer sleeping problems at 24 months.

The researcher’s findings did not surprise Francis E. Rushton Jr., MD, a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, who was not involved in the study. “This study reveals that more is not always better,” Dr. Rushton said in an interview.