User login

A pediatrician notices empty fields

The high school football team here in Brunswick has had winning years and losing years but the school has always fielded a competitive team. It has been state champion on several occasions and has weathered the challenge when soccer became the new and more popular sport shortly after it arrived in town several decades ago. But this year, on the heels of a strong winning season last year, the numbers are down significantly. The school is in jeopardy of not having enough players to field a junior varsity team.

This dearth of student athletes is a problem not just here in Brunswick. Schools across the state of Maine are being forced to shift to an eight man football format. Nor is it unique to football here in vacationland. A recent article in a Hudson Valley, N.Y., newspaper chronicles a broad-based decline in participation in high school sports including field hockey, tennis, and cross country (‘Covid,’ The Journal News, Nancy Haggerty, Sept. 5, 2021). In many situations the school may have enough players to field a varsity team but too few to play a junior varsity schedule. Without a supply of young talent coming up from the junior varsity, the future of any varsity program is on a shaky legs. Some of the coaches are referring to the decline in participation as a “COVID hangover” triggered in part by season disruptions, cancellations, and fluctuating remote learning formats.

I and some other coaches argue that the participation drought predates the pandemic and is the result of a wide range of unfortunate trends. First, is the general malaise and don’t-give-a-damn-about-anything attitude that has settled on the young people of this country, the causes of which are difficult to define. It may be that after years of sitting in front of a video screen, too many children have settled into the role of being spectators and find the energy it takes to participate just isn’t worth the effort.

Another contributor to the decline in participation is the heavy of emphasis on early specialization. Driven in many cases by unrealistic parental dreams, children are shepherded into elite travel teams with seasons that often stretch to lengths that make it difficult if not impossible for a child to participate in other sports. The child who may simply be a late bloomer or whose family can’t afford the time or money to buy into the travel team ethic quickly finds himself losing ground. Without the additional opportunities for skill development, many of the children noon travel teams eventually wonder if it is worth trying to catch up. Ironically, the trend toward early specialization is short-sighted because many college and professional coaches report that their best athletes shunned becoming one-trick ponies and played a variety of sports growing up.

Parental concerns about injury, particularly concussion, probably play a role in the trend of falling participation in sports, even those with minimal risk of head injury. Certainly our new awareness of the long-term effects of multiple concussions is long overdue. However, we as pediatricians must take some of the blame for often emphasizing the injury risk inherent in sports in general while neglecting to highlight the positive benefits of competitive sports such as fitness and team building. Are there situations where our emphasis on preparticipation physicals is acting as a deterrent?

There are exceptions to the general trend of falling participation, lacrosse being the most obvious example. However, as lacrosse becomes more popular across the country there are signs that it is already drifting into the larger and counterproductive elite travel team model. There have always been communities in which an individual coach or parent has created a team culture that is both inclusive and competitive. The two are not mutually exclusive.

Sadly, these exceptional programs are few and far between. I’m not sure where we can start to turn things around so that more children choose to be players rather than observers. But, we pediatricians certainly can play a more positive role in emphasizing the benefits of team play.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

The high school football team here in Brunswick has had winning years and losing years but the school has always fielded a competitive team. It has been state champion on several occasions and has weathered the challenge when soccer became the new and more popular sport shortly after it arrived in town several decades ago. But this year, on the heels of a strong winning season last year, the numbers are down significantly. The school is in jeopardy of not having enough players to field a junior varsity team.

This dearth of student athletes is a problem not just here in Brunswick. Schools across the state of Maine are being forced to shift to an eight man football format. Nor is it unique to football here in vacationland. A recent article in a Hudson Valley, N.Y., newspaper chronicles a broad-based decline in participation in high school sports including field hockey, tennis, and cross country (‘Covid,’ The Journal News, Nancy Haggerty, Sept. 5, 2021). In many situations the school may have enough players to field a varsity team but too few to play a junior varsity schedule. Without a supply of young talent coming up from the junior varsity, the future of any varsity program is on a shaky legs. Some of the coaches are referring to the decline in participation as a “COVID hangover” triggered in part by season disruptions, cancellations, and fluctuating remote learning formats.

I and some other coaches argue that the participation drought predates the pandemic and is the result of a wide range of unfortunate trends. First, is the general malaise and don’t-give-a-damn-about-anything attitude that has settled on the young people of this country, the causes of which are difficult to define. It may be that after years of sitting in front of a video screen, too many children have settled into the role of being spectators and find the energy it takes to participate just isn’t worth the effort.

Another contributor to the decline in participation is the heavy of emphasis on early specialization. Driven in many cases by unrealistic parental dreams, children are shepherded into elite travel teams with seasons that often stretch to lengths that make it difficult if not impossible for a child to participate in other sports. The child who may simply be a late bloomer or whose family can’t afford the time or money to buy into the travel team ethic quickly finds himself losing ground. Without the additional opportunities for skill development, many of the children noon travel teams eventually wonder if it is worth trying to catch up. Ironically, the trend toward early specialization is short-sighted because many college and professional coaches report that their best athletes shunned becoming one-trick ponies and played a variety of sports growing up.

Parental concerns about injury, particularly concussion, probably play a role in the trend of falling participation in sports, even those with minimal risk of head injury. Certainly our new awareness of the long-term effects of multiple concussions is long overdue. However, we as pediatricians must take some of the blame for often emphasizing the injury risk inherent in sports in general while neglecting to highlight the positive benefits of competitive sports such as fitness and team building. Are there situations where our emphasis on preparticipation physicals is acting as a deterrent?

There are exceptions to the general trend of falling participation, lacrosse being the most obvious example. However, as lacrosse becomes more popular across the country there are signs that it is already drifting into the larger and counterproductive elite travel team model. There have always been communities in which an individual coach or parent has created a team culture that is both inclusive and competitive. The two are not mutually exclusive.

Sadly, these exceptional programs are few and far between. I’m not sure where we can start to turn things around so that more children choose to be players rather than observers. But, we pediatricians certainly can play a more positive role in emphasizing the benefits of team play.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

The high school football team here in Brunswick has had winning years and losing years but the school has always fielded a competitive team. It has been state champion on several occasions and has weathered the challenge when soccer became the new and more popular sport shortly after it arrived in town several decades ago. But this year, on the heels of a strong winning season last year, the numbers are down significantly. The school is in jeopardy of not having enough players to field a junior varsity team.

This dearth of student athletes is a problem not just here in Brunswick. Schools across the state of Maine are being forced to shift to an eight man football format. Nor is it unique to football here in vacationland. A recent article in a Hudson Valley, N.Y., newspaper chronicles a broad-based decline in participation in high school sports including field hockey, tennis, and cross country (‘Covid,’ The Journal News, Nancy Haggerty, Sept. 5, 2021). In many situations the school may have enough players to field a varsity team but too few to play a junior varsity schedule. Without a supply of young talent coming up from the junior varsity, the future of any varsity program is on a shaky legs. Some of the coaches are referring to the decline in participation as a “COVID hangover” triggered in part by season disruptions, cancellations, and fluctuating remote learning formats.

I and some other coaches argue that the participation drought predates the pandemic and is the result of a wide range of unfortunate trends. First, is the general malaise and don’t-give-a-damn-about-anything attitude that has settled on the young people of this country, the causes of which are difficult to define. It may be that after years of sitting in front of a video screen, too many children have settled into the role of being spectators and find the energy it takes to participate just isn’t worth the effort.

Another contributor to the decline in participation is the heavy of emphasis on early specialization. Driven in many cases by unrealistic parental dreams, children are shepherded into elite travel teams with seasons that often stretch to lengths that make it difficult if not impossible for a child to participate in other sports. The child who may simply be a late bloomer or whose family can’t afford the time or money to buy into the travel team ethic quickly finds himself losing ground. Without the additional opportunities for skill development, many of the children noon travel teams eventually wonder if it is worth trying to catch up. Ironically, the trend toward early specialization is short-sighted because many college and professional coaches report that their best athletes shunned becoming one-trick ponies and played a variety of sports growing up.

Parental concerns about injury, particularly concussion, probably play a role in the trend of falling participation in sports, even those with minimal risk of head injury. Certainly our new awareness of the long-term effects of multiple concussions is long overdue. However, we as pediatricians must take some of the blame for often emphasizing the injury risk inherent in sports in general while neglecting to highlight the positive benefits of competitive sports such as fitness and team building. Are there situations where our emphasis on preparticipation physicals is acting as a deterrent?

There are exceptions to the general trend of falling participation, lacrosse being the most obvious example. However, as lacrosse becomes more popular across the country there are signs that it is already drifting into the larger and counterproductive elite travel team model. There have always been communities in which an individual coach or parent has created a team culture that is both inclusive and competitive. The two are not mutually exclusive.

Sadly, these exceptional programs are few and far between. I’m not sure where we can start to turn things around so that more children choose to be players rather than observers. But, we pediatricians certainly can play a more positive role in emphasizing the benefits of team play.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Hormone agonist therapy disrupts bone density in transgender youth

The use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists has a negative effect on bone mass in transgender youth, according to data from 172 individuals.

The onset of puberty and pubertal hormones contributes to the development of bone mass and body composition in adolescence, wrote Behdad Navabi, MD, and colleagues at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Canada. Although the safety and efficacy of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRHa) has been described in short-term studies of youth with gender dysphoria, concerns persist about suppression of bone mass accrual from extended use of GnRHas in this population, they noted.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 172 youth younger than 18 years of age who were treated with GNRHa and underwent at least one baseline dual-energy radiograph absorptiometry (DXA) measurement between January 2006 and April 2017 at a single center. The standard treatment protocol started with three doses of 7.5 mg leuprolide acetate, given intramuscularly every 4 weeks, followed by 11.25 mg intramuscularly every 12 weeks after puberty suppression was confirmed both clinically and biochemically. Areal bone mineral density (aBMD) measurement z scores were based on birth-assigned sex, age, and ethnicity, and assessed at baseline and every 12 months. In addition, volumetric bone mineral density was calculated as bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) at the lower spine, and the z score based on age-matched, birth-assigned gender BMAD.

Overall, 55.2% of the youth were vitamin D deficient or insufficient at baseline, but 87.3% were sufficient by the time of a third follow-up visit after treatment with 1,000-2,000 IU of vitamin D daily; no cases of vitamin D toxicity were reported.

At baseline, transgender females had lower z scores for the LS aBMD and BMAD compared to transgender males, reflecting a difference seen in previous studies of transgender youth and adult females, the researchers noted.

The researchers analyzed pre- and posttreatment DXA data in a subgroup of 36 transgender females and 80 transgender males to identify any changes associated with GnRHa. The average time between the DXA scans was 407 days. In this population, aBMD z scores at the lower lumbar spine (LS), left total hip (LTH), and total body less head (TBLH) decreased significantly from baseline in transgender males and females.

Among transgender males, LS bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) z scores also decreased significantly from baseline, but no such change occurred among transgender females. The most significant decrease in z scores occurred in the LS aBMD and BMAD of transgender males, with changes that reflect findings from previous studies and may be explained by decreased estrogen, the researchers wrote.

In terms of body composition, no significant changes occurred in body mass index z score from baseline to follow-up in transgender males or females, the researchers noted, and changes in both gynoid and android fat percentages were consistent with the individuals’ affirmed genders. No vertebral fractures were detected.

However, GnRHa was significantly associated with a decrease in total body fat percentage and a decrease in lean body mass (LBM) in transgender females.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of consistent baseline physical activity records, and limited analysis at follow-up of the possible role of physical activity in bone health and body composition, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the relatively large study population with baseline assessments, and by the pre- and posttreatment analysis, they added.

“Evidence on GnRHa-associated changes in body composition and BMD will help health care professionals involved in the care of youth with GD [gender dysphoria] to counsel appropriately and optimize their bone health,” the researchers said. “Given the absence of vertebral fractures detected in those with significant decreases in their LS z scores, the significance of BMD effects of GnRHa in transgender youth needs further study, as well as whether future spine radiographs are needed on the basis of BMD trajectory,” they concluded.

Balance bone health concerns with potential benefits

The effect of estrogen and testosterone on bone geometry in puberty varies, and the increase in the use of GnRHa as part of a multidisciplinary gender transition plan makes research on the skeletal impact of this therapy in transgender youth a top priority, Laura K. Bachrach, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and Catherine M. Gordon of Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The decrease in areal bone mineral density and in bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) z scores in the current study is not unexpected, but the key question is how much bone density recovers once the suppression therapy ends and transgender sex steroid use begins, they said. “Follow-up studies of young adults treated with GnRHa for precocious puberty in childhood are reassuring,” they wrote. “It is premature, however, to extrapolate from these findings to transgender youth,” because the impact of gender-affirming sex steroid therapy on the skeleton at older ages and stages of maturity are unclear, they emphasized.

In the absence of definitive answers, the editorial authors advised clinicians treating youth with gender dysphoria to provide a balanced view of the risks and benefits of hormone therapy, and encourage adequate intake of dietary vitamin D and calcium, along with weight-bearing physical activity, to promote general bone health. “Transgender teenagers and their parents should be reassured that some recovery from decreases in aBMD during pubertal suppression with GnRHa is likely,” the authors noted. Bone health should be monitored throughout all stages of treatment in transgender youth, but concerns about transient bone loss should not discourage gender transition therapy, they emphasized. “In this patient group, providing a pause in pubertal development offers a life-changing and, for some, a life-saving intervention,” they concluded.

Comparison to cisgender controls would add value

“This study is important because one of the major side effects of GnRH agonists is decreased bone density, especially the longer that patients are on them,” M. Brett Cooper, MD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center, said in an interview. The findings add to existing data to underscore the importance of screening for low bone density and low vitamin D levels, Dr. Cooper added.

Dr. Cooper said that he was not surprised by the study findings. “I think that this study supported what clinicians already knew, which is that GnRH agonists do potentially cause a decline in bone mineral density and thus, you need to support these patients as best you can with calcium, vitamin D, and weight-bearing exercise,” he noted.

Dr. Cooper emphasized two main take-home points from the study. “First, clinicians who prescribe GnRH agonists need to ensure that they are checking bone density and vitamin D measurements, and then optimizing these appropriately,” he said. “Second, when a bone density is found to be low or a vitamin level is low, clinicians need to ensure that they are monitored and treated appropriately.” Clinicians need to use these data when deciding when to start gender-affirming hormones so their patients have the best chance to recover bone density, he added.

“I think one confounding factor on this study is the ranges they used for vitamin D deficiency,” Dr. Cooper noted. “This study was done in Canada, and the scale used was in nmol/L, while most labs in the U.S. use ng/mL,” he said. “Most pediatric and adolescent societies in the United States use < 20 ng/mL as an indicator of vitamin D deficient and between 20 and 29 ng/mL as insufficient,” he explained, citing the position statement on recommended vitamin D intake for adolescents published by The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. In this study, the results converted to < 12 ng/mL as deficient and between 12 and 20 ng/mL as insufficient, respectively, on the U.S. scale, said Dr. Cooper.

“Therefore, I can see that there are cases where someone may have been labeled vitamin D insufficient in this study using their range, whereas in the U.S. these patients would be labeled as vitamin D deficient and treated with higher-dose supplementation,” he said. In addition, individuals with levels between 20 ng/mL and 29 ng/mL in the U.S. would still be treated with vitamin D supplementation, “whereas in their study those individuals would have been labeled as normal,” he noted.

As for future research, it would be useful to study whether bone mass in transgender young people differs from age- and gender-matched controls who are not gender diverse (cisgender), Dr. Cooper added. “It may be possible that the youth in this study are not different from their peers and maybe the GnRH agonist is not the culprit,” he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers, editorial authors, and Dr. Cooper had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists has a negative effect on bone mass in transgender youth, according to data from 172 individuals.

The onset of puberty and pubertal hormones contributes to the development of bone mass and body composition in adolescence, wrote Behdad Navabi, MD, and colleagues at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Canada. Although the safety and efficacy of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRHa) has been described in short-term studies of youth with gender dysphoria, concerns persist about suppression of bone mass accrual from extended use of GnRHas in this population, they noted.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 172 youth younger than 18 years of age who were treated with GNRHa and underwent at least one baseline dual-energy radiograph absorptiometry (DXA) measurement between January 2006 and April 2017 at a single center. The standard treatment protocol started with three doses of 7.5 mg leuprolide acetate, given intramuscularly every 4 weeks, followed by 11.25 mg intramuscularly every 12 weeks after puberty suppression was confirmed both clinically and biochemically. Areal bone mineral density (aBMD) measurement z scores were based on birth-assigned sex, age, and ethnicity, and assessed at baseline and every 12 months. In addition, volumetric bone mineral density was calculated as bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) at the lower spine, and the z score based on age-matched, birth-assigned gender BMAD.

Overall, 55.2% of the youth were vitamin D deficient or insufficient at baseline, but 87.3% were sufficient by the time of a third follow-up visit after treatment with 1,000-2,000 IU of vitamin D daily; no cases of vitamin D toxicity were reported.

At baseline, transgender females had lower z scores for the LS aBMD and BMAD compared to transgender males, reflecting a difference seen in previous studies of transgender youth and adult females, the researchers noted.

The researchers analyzed pre- and posttreatment DXA data in a subgroup of 36 transgender females and 80 transgender males to identify any changes associated with GnRHa. The average time between the DXA scans was 407 days. In this population, aBMD z scores at the lower lumbar spine (LS), left total hip (LTH), and total body less head (TBLH) decreased significantly from baseline in transgender males and females.

Among transgender males, LS bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) z scores also decreased significantly from baseline, but no such change occurred among transgender females. The most significant decrease in z scores occurred in the LS aBMD and BMAD of transgender males, with changes that reflect findings from previous studies and may be explained by decreased estrogen, the researchers wrote.

In terms of body composition, no significant changes occurred in body mass index z score from baseline to follow-up in transgender males or females, the researchers noted, and changes in both gynoid and android fat percentages were consistent with the individuals’ affirmed genders. No vertebral fractures were detected.

However, GnRHa was significantly associated with a decrease in total body fat percentage and a decrease in lean body mass (LBM) in transgender females.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of consistent baseline physical activity records, and limited analysis at follow-up of the possible role of physical activity in bone health and body composition, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the relatively large study population with baseline assessments, and by the pre- and posttreatment analysis, they added.

“Evidence on GnRHa-associated changes in body composition and BMD will help health care professionals involved in the care of youth with GD [gender dysphoria] to counsel appropriately and optimize their bone health,” the researchers said. “Given the absence of vertebral fractures detected in those with significant decreases in their LS z scores, the significance of BMD effects of GnRHa in transgender youth needs further study, as well as whether future spine radiographs are needed on the basis of BMD trajectory,” they concluded.

Balance bone health concerns with potential benefits

The effect of estrogen and testosterone on bone geometry in puberty varies, and the increase in the use of GnRHa as part of a multidisciplinary gender transition plan makes research on the skeletal impact of this therapy in transgender youth a top priority, Laura K. Bachrach, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and Catherine M. Gordon of Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The decrease in areal bone mineral density and in bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) z scores in the current study is not unexpected, but the key question is how much bone density recovers once the suppression therapy ends and transgender sex steroid use begins, they said. “Follow-up studies of young adults treated with GnRHa for precocious puberty in childhood are reassuring,” they wrote. “It is premature, however, to extrapolate from these findings to transgender youth,” because the impact of gender-affirming sex steroid therapy on the skeleton at older ages and stages of maturity are unclear, they emphasized.

In the absence of definitive answers, the editorial authors advised clinicians treating youth with gender dysphoria to provide a balanced view of the risks and benefits of hormone therapy, and encourage adequate intake of dietary vitamin D and calcium, along with weight-bearing physical activity, to promote general bone health. “Transgender teenagers and their parents should be reassured that some recovery from decreases in aBMD during pubertal suppression with GnRHa is likely,” the authors noted. Bone health should be monitored throughout all stages of treatment in transgender youth, but concerns about transient bone loss should not discourage gender transition therapy, they emphasized. “In this patient group, providing a pause in pubertal development offers a life-changing and, for some, a life-saving intervention,” they concluded.

Comparison to cisgender controls would add value

“This study is important because one of the major side effects of GnRH agonists is decreased bone density, especially the longer that patients are on them,” M. Brett Cooper, MD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center, said in an interview. The findings add to existing data to underscore the importance of screening for low bone density and low vitamin D levels, Dr. Cooper added.

Dr. Cooper said that he was not surprised by the study findings. “I think that this study supported what clinicians already knew, which is that GnRH agonists do potentially cause a decline in bone mineral density and thus, you need to support these patients as best you can with calcium, vitamin D, and weight-bearing exercise,” he noted.

Dr. Cooper emphasized two main take-home points from the study. “First, clinicians who prescribe GnRH agonists need to ensure that they are checking bone density and vitamin D measurements, and then optimizing these appropriately,” he said. “Second, when a bone density is found to be low or a vitamin level is low, clinicians need to ensure that they are monitored and treated appropriately.” Clinicians need to use these data when deciding when to start gender-affirming hormones so their patients have the best chance to recover bone density, he added.

“I think one confounding factor on this study is the ranges they used for vitamin D deficiency,” Dr. Cooper noted. “This study was done in Canada, and the scale used was in nmol/L, while most labs in the U.S. use ng/mL,” he said. “Most pediatric and adolescent societies in the United States use < 20 ng/mL as an indicator of vitamin D deficient and between 20 and 29 ng/mL as insufficient,” he explained, citing the position statement on recommended vitamin D intake for adolescents published by The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. In this study, the results converted to < 12 ng/mL as deficient and between 12 and 20 ng/mL as insufficient, respectively, on the U.S. scale, said Dr. Cooper.

“Therefore, I can see that there are cases where someone may have been labeled vitamin D insufficient in this study using their range, whereas in the U.S. these patients would be labeled as vitamin D deficient and treated with higher-dose supplementation,” he said. In addition, individuals with levels between 20 ng/mL and 29 ng/mL in the U.S. would still be treated with vitamin D supplementation, “whereas in their study those individuals would have been labeled as normal,” he noted.

As for future research, it would be useful to study whether bone mass in transgender young people differs from age- and gender-matched controls who are not gender diverse (cisgender), Dr. Cooper added. “It may be possible that the youth in this study are not different from their peers and maybe the GnRH agonist is not the culprit,” he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers, editorial authors, and Dr. Cooper had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists has a negative effect on bone mass in transgender youth, according to data from 172 individuals.

The onset of puberty and pubertal hormones contributes to the development of bone mass and body composition in adolescence, wrote Behdad Navabi, MD, and colleagues at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Canada. Although the safety and efficacy of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRHa) has been described in short-term studies of youth with gender dysphoria, concerns persist about suppression of bone mass accrual from extended use of GnRHas in this population, they noted.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 172 youth younger than 18 years of age who were treated with GNRHa and underwent at least one baseline dual-energy radiograph absorptiometry (DXA) measurement between January 2006 and April 2017 at a single center. The standard treatment protocol started with three doses of 7.5 mg leuprolide acetate, given intramuscularly every 4 weeks, followed by 11.25 mg intramuscularly every 12 weeks after puberty suppression was confirmed both clinically and biochemically. Areal bone mineral density (aBMD) measurement z scores were based on birth-assigned sex, age, and ethnicity, and assessed at baseline and every 12 months. In addition, volumetric bone mineral density was calculated as bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) at the lower spine, and the z score based on age-matched, birth-assigned gender BMAD.

Overall, 55.2% of the youth were vitamin D deficient or insufficient at baseline, but 87.3% were sufficient by the time of a third follow-up visit after treatment with 1,000-2,000 IU of vitamin D daily; no cases of vitamin D toxicity were reported.

At baseline, transgender females had lower z scores for the LS aBMD and BMAD compared to transgender males, reflecting a difference seen in previous studies of transgender youth and adult females, the researchers noted.

The researchers analyzed pre- and posttreatment DXA data in a subgroup of 36 transgender females and 80 transgender males to identify any changes associated with GnRHa. The average time between the DXA scans was 407 days. In this population, aBMD z scores at the lower lumbar spine (LS), left total hip (LTH), and total body less head (TBLH) decreased significantly from baseline in transgender males and females.

Among transgender males, LS bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) z scores also decreased significantly from baseline, but no such change occurred among transgender females. The most significant decrease in z scores occurred in the LS aBMD and BMAD of transgender males, with changes that reflect findings from previous studies and may be explained by decreased estrogen, the researchers wrote.

In terms of body composition, no significant changes occurred in body mass index z score from baseline to follow-up in transgender males or females, the researchers noted, and changes in both gynoid and android fat percentages were consistent with the individuals’ affirmed genders. No vertebral fractures were detected.

However, GnRHa was significantly associated with a decrease in total body fat percentage and a decrease in lean body mass (LBM) in transgender females.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of consistent baseline physical activity records, and limited analysis at follow-up of the possible role of physical activity in bone health and body composition, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the relatively large study population with baseline assessments, and by the pre- and posttreatment analysis, they added.

“Evidence on GnRHa-associated changes in body composition and BMD will help health care professionals involved in the care of youth with GD [gender dysphoria] to counsel appropriately and optimize their bone health,” the researchers said. “Given the absence of vertebral fractures detected in those with significant decreases in their LS z scores, the significance of BMD effects of GnRHa in transgender youth needs further study, as well as whether future spine radiographs are needed on the basis of BMD trajectory,” they concluded.

Balance bone health concerns with potential benefits

The effect of estrogen and testosterone on bone geometry in puberty varies, and the increase in the use of GnRHa as part of a multidisciplinary gender transition plan makes research on the skeletal impact of this therapy in transgender youth a top priority, Laura K. Bachrach, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and Catherine M. Gordon of Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The decrease in areal bone mineral density and in bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) z scores in the current study is not unexpected, but the key question is how much bone density recovers once the suppression therapy ends and transgender sex steroid use begins, they said. “Follow-up studies of young adults treated with GnRHa for precocious puberty in childhood are reassuring,” they wrote. “It is premature, however, to extrapolate from these findings to transgender youth,” because the impact of gender-affirming sex steroid therapy on the skeleton at older ages and stages of maturity are unclear, they emphasized.

In the absence of definitive answers, the editorial authors advised clinicians treating youth with gender dysphoria to provide a balanced view of the risks and benefits of hormone therapy, and encourage adequate intake of dietary vitamin D and calcium, along with weight-bearing physical activity, to promote general bone health. “Transgender teenagers and their parents should be reassured that some recovery from decreases in aBMD during pubertal suppression with GnRHa is likely,” the authors noted. Bone health should be monitored throughout all stages of treatment in transgender youth, but concerns about transient bone loss should not discourage gender transition therapy, they emphasized. “In this patient group, providing a pause in pubertal development offers a life-changing and, for some, a life-saving intervention,” they concluded.

Comparison to cisgender controls would add value

“This study is important because one of the major side effects of GnRH agonists is decreased bone density, especially the longer that patients are on them,” M. Brett Cooper, MD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center, said in an interview. The findings add to existing data to underscore the importance of screening for low bone density and low vitamin D levels, Dr. Cooper added.

Dr. Cooper said that he was not surprised by the study findings. “I think that this study supported what clinicians already knew, which is that GnRH agonists do potentially cause a decline in bone mineral density and thus, you need to support these patients as best you can with calcium, vitamin D, and weight-bearing exercise,” he noted.

Dr. Cooper emphasized two main take-home points from the study. “First, clinicians who prescribe GnRH agonists need to ensure that they are checking bone density and vitamin D measurements, and then optimizing these appropriately,” he said. “Second, when a bone density is found to be low or a vitamin level is low, clinicians need to ensure that they are monitored and treated appropriately.” Clinicians need to use these data when deciding when to start gender-affirming hormones so their patients have the best chance to recover bone density, he added.

“I think one confounding factor on this study is the ranges they used for vitamin D deficiency,” Dr. Cooper noted. “This study was done in Canada, and the scale used was in nmol/L, while most labs in the U.S. use ng/mL,” he said. “Most pediatric and adolescent societies in the United States use < 20 ng/mL as an indicator of vitamin D deficient and between 20 and 29 ng/mL as insufficient,” he explained, citing the position statement on recommended vitamin D intake for adolescents published by The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. In this study, the results converted to < 12 ng/mL as deficient and between 12 and 20 ng/mL as insufficient, respectively, on the U.S. scale, said Dr. Cooper.

“Therefore, I can see that there are cases where someone may have been labeled vitamin D insufficient in this study using their range, whereas in the U.S. these patients would be labeled as vitamin D deficient and treated with higher-dose supplementation,” he said. In addition, individuals with levels between 20 ng/mL and 29 ng/mL in the U.S. would still be treated with vitamin D supplementation, “whereas in their study those individuals would have been labeled as normal,” he noted.

As for future research, it would be useful to study whether bone mass in transgender young people differs from age- and gender-matched controls who are not gender diverse (cisgender), Dr. Cooper added. “It may be possible that the youth in this study are not different from their peers and maybe the GnRH agonist is not the culprit,” he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers, editorial authors, and Dr. Cooper had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Researchers warn young adults are at highest risk of obesity

Individuals aged 18-24 years are at the highest risk of weight gain and developing overweight or obesity over the next 10 years, compared with all other adults, and should be a target for obesity prevention policies, say U.K. researchers.

The research, published online Sept. 2, 2021, in The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, showed that factors more traditionally associated with obesity – such as socioeconomic status and ethnicity – play less of a role than age.

“Our results show clearly that age is the most important sociodemographic factor for BMI [body mass index] change,” lead author Michail Katsoulis, PhD, Institute of Health Informatics, University College London, said in a press release.

Cosenior author Claudia Langenberg, PhD, agreed, adding young people “go through big life changes. They may start work, go to university, or leave home for the first time,” and the habits formed during these years “may stick through adulthood.”

Current obesity prevention guidelines are mainly directed at individuals who already have obesity, the researchers said in their article.

“As the evidence presented in our study suggests, the opportunity to modify weight gain is greatest in individuals who are young and do not yet have obesity,” they observed.

“If we are serious about preventing obesity, then we should develop interventions that can be targeted and are relevant for young adults,” added Dr. Langenberg, of the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, (England), and Berlin Institute of Health.

Risks for higher BMI substantially greater in the youngest adults

The researchers gathered data on more than 2 million adults aged 18-74 years registered with general practitioners in England. Participants had BMI and weight measurements recorded between Jan. 1, 1998, and June 30, 2016, with at least 1 year of follow-up. Overall, 58% were women, 76% were White, 9% had prevalent cardiovascular disease, and 4% had prevalent cancer.

Changes in BMI were assessed at 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years.

At 10 years, adults aged 18-24 years had the highest risk of transitioning from normal weight to overweight or obesity, compared with adults aged 65-74 years, at a greatest absolute risk of 37% versus 24% (odds ratio, 4.22).

Moreover, the results showed that adults aged 18-24 years who were already overweight or obese had a greater risk of transitioning to a higher BMI category during follow-up versus the oldest participants.

They had an absolute risk of 42% versus 18% of transitioning from overweight to class 1 and 2 obesity (OR, 4.60), and an absolute risk of transitioning from class 1 and 2 obesity to class 3 obesity of 22% versus 5% (OR, 5.87).

Online risk calculator and YouTube video help explain findings

While factors other than age were associated with transitioning to a higher BMI category, the association was less pronounced.

For example, the OR of transitioning from normal weight to overweight or obesity in the most socially deprived versus the least deprived areas was 1.23 in men and 1.12 in women. The OR for making the same transition in Black versus White individuals was 1.13.

The findings allowed the researchers to develop a series of nomograms to determine an individual’s absolute risk of transitioning to a higher BMI category over 10 years based on their baseline BMI category, age, sex, and Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile.

“We show that, within each stratum, the risks for transitioning to higher BMI categories were substantially higher in the youngest adult age group than in older age groups,” the team writes.

From this, they developed an open-access online risk calculator to help individuals calculate their risk of weight change over the next 1, 5, and 10 years. The calculator takes into account current weight, height, age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic-area characteristics.

They have also posted a video on YouTube to help explain their findings.

COVID and obesity pandemics collide

Cosenior author Harry Hemingway, MD, PhD, also of University College London, believes that focusing on this young age group is especially critical now because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Calculating personal risk of transitioning to a higher weight category is important” as COVID-19 “collides with the obesity pandemic,” he said, noting that “people are exercising less and finding it harder to eat healthy diets during lockdowns.

“Health systems like the NHS [National Health Service] need to identify new ways to prevent obesity and its consequences,” he continued. “This study demonstrates that NHS data collected over time in primary care holds an important key to unlocking new insights for public health action.”

The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation, Health Data Research UK, the UK Medical Research Council, and the National Institute for Health Research. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Individuals aged 18-24 years are at the highest risk of weight gain and developing overweight or obesity over the next 10 years, compared with all other adults, and should be a target for obesity prevention policies, say U.K. researchers.

The research, published online Sept. 2, 2021, in The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, showed that factors more traditionally associated with obesity – such as socioeconomic status and ethnicity – play less of a role than age.

“Our results show clearly that age is the most important sociodemographic factor for BMI [body mass index] change,” lead author Michail Katsoulis, PhD, Institute of Health Informatics, University College London, said in a press release.

Cosenior author Claudia Langenberg, PhD, agreed, adding young people “go through big life changes. They may start work, go to university, or leave home for the first time,” and the habits formed during these years “may stick through adulthood.”

Current obesity prevention guidelines are mainly directed at individuals who already have obesity, the researchers said in their article.

“As the evidence presented in our study suggests, the opportunity to modify weight gain is greatest in individuals who are young and do not yet have obesity,” they observed.

“If we are serious about preventing obesity, then we should develop interventions that can be targeted and are relevant for young adults,” added Dr. Langenberg, of the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, (England), and Berlin Institute of Health.

Risks for higher BMI substantially greater in the youngest adults

The researchers gathered data on more than 2 million adults aged 18-74 years registered with general practitioners in England. Participants had BMI and weight measurements recorded between Jan. 1, 1998, and June 30, 2016, with at least 1 year of follow-up. Overall, 58% were women, 76% were White, 9% had prevalent cardiovascular disease, and 4% had prevalent cancer.

Changes in BMI were assessed at 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years.

At 10 years, adults aged 18-24 years had the highest risk of transitioning from normal weight to overweight or obesity, compared with adults aged 65-74 years, at a greatest absolute risk of 37% versus 24% (odds ratio, 4.22).

Moreover, the results showed that adults aged 18-24 years who were already overweight or obese had a greater risk of transitioning to a higher BMI category during follow-up versus the oldest participants.

They had an absolute risk of 42% versus 18% of transitioning from overweight to class 1 and 2 obesity (OR, 4.60), and an absolute risk of transitioning from class 1 and 2 obesity to class 3 obesity of 22% versus 5% (OR, 5.87).

Online risk calculator and YouTube video help explain findings

While factors other than age were associated with transitioning to a higher BMI category, the association was less pronounced.

For example, the OR of transitioning from normal weight to overweight or obesity in the most socially deprived versus the least deprived areas was 1.23 in men and 1.12 in women. The OR for making the same transition in Black versus White individuals was 1.13.

The findings allowed the researchers to develop a series of nomograms to determine an individual’s absolute risk of transitioning to a higher BMI category over 10 years based on their baseline BMI category, age, sex, and Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile.

“We show that, within each stratum, the risks for transitioning to higher BMI categories were substantially higher in the youngest adult age group than in older age groups,” the team writes.

From this, they developed an open-access online risk calculator to help individuals calculate their risk of weight change over the next 1, 5, and 10 years. The calculator takes into account current weight, height, age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic-area characteristics.

They have also posted a video on YouTube to help explain their findings.

COVID and obesity pandemics collide

Cosenior author Harry Hemingway, MD, PhD, also of University College London, believes that focusing on this young age group is especially critical now because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Calculating personal risk of transitioning to a higher weight category is important” as COVID-19 “collides with the obesity pandemic,” he said, noting that “people are exercising less and finding it harder to eat healthy diets during lockdowns.

“Health systems like the NHS [National Health Service] need to identify new ways to prevent obesity and its consequences,” he continued. “This study demonstrates that NHS data collected over time in primary care holds an important key to unlocking new insights for public health action.”

The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation, Health Data Research UK, the UK Medical Research Council, and the National Institute for Health Research. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Individuals aged 18-24 years are at the highest risk of weight gain and developing overweight or obesity over the next 10 years, compared with all other adults, and should be a target for obesity prevention policies, say U.K. researchers.

The research, published online Sept. 2, 2021, in The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, showed that factors more traditionally associated with obesity – such as socioeconomic status and ethnicity – play less of a role than age.

“Our results show clearly that age is the most important sociodemographic factor for BMI [body mass index] change,” lead author Michail Katsoulis, PhD, Institute of Health Informatics, University College London, said in a press release.

Cosenior author Claudia Langenberg, PhD, agreed, adding young people “go through big life changes. They may start work, go to university, or leave home for the first time,” and the habits formed during these years “may stick through adulthood.”

Current obesity prevention guidelines are mainly directed at individuals who already have obesity, the researchers said in their article.

“As the evidence presented in our study suggests, the opportunity to modify weight gain is greatest in individuals who are young and do not yet have obesity,” they observed.

“If we are serious about preventing obesity, then we should develop interventions that can be targeted and are relevant for young adults,” added Dr. Langenberg, of the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, (England), and Berlin Institute of Health.

Risks for higher BMI substantially greater in the youngest adults

The researchers gathered data on more than 2 million adults aged 18-74 years registered with general practitioners in England. Participants had BMI and weight measurements recorded between Jan. 1, 1998, and June 30, 2016, with at least 1 year of follow-up. Overall, 58% were women, 76% were White, 9% had prevalent cardiovascular disease, and 4% had prevalent cancer.

Changes in BMI were assessed at 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years.

At 10 years, adults aged 18-24 years had the highest risk of transitioning from normal weight to overweight or obesity, compared with adults aged 65-74 years, at a greatest absolute risk of 37% versus 24% (odds ratio, 4.22).

Moreover, the results showed that adults aged 18-24 years who were already overweight or obese had a greater risk of transitioning to a higher BMI category during follow-up versus the oldest participants.

They had an absolute risk of 42% versus 18% of transitioning from overweight to class 1 and 2 obesity (OR, 4.60), and an absolute risk of transitioning from class 1 and 2 obesity to class 3 obesity of 22% versus 5% (OR, 5.87).

Online risk calculator and YouTube video help explain findings

While factors other than age were associated with transitioning to a higher BMI category, the association was less pronounced.

For example, the OR of transitioning from normal weight to overweight or obesity in the most socially deprived versus the least deprived areas was 1.23 in men and 1.12 in women. The OR for making the same transition in Black versus White individuals was 1.13.

The findings allowed the researchers to develop a series of nomograms to determine an individual’s absolute risk of transitioning to a higher BMI category over 10 years based on their baseline BMI category, age, sex, and Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile.

“We show that, within each stratum, the risks for transitioning to higher BMI categories were substantially higher in the youngest adult age group than in older age groups,” the team writes.

From this, they developed an open-access online risk calculator to help individuals calculate their risk of weight change over the next 1, 5, and 10 years. The calculator takes into account current weight, height, age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic-area characteristics.

They have also posted a video on YouTube to help explain their findings.

COVID and obesity pandemics collide

Cosenior author Harry Hemingway, MD, PhD, also of University College London, believes that focusing on this young age group is especially critical now because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Calculating personal risk of transitioning to a higher weight category is important” as COVID-19 “collides with the obesity pandemic,” he said, noting that “people are exercising less and finding it harder to eat healthy diets during lockdowns.

“Health systems like the NHS [National Health Service] need to identify new ways to prevent obesity and its consequences,” he continued. “This study demonstrates that NHS data collected over time in primary care holds an important key to unlocking new insights for public health action.”

The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation, Health Data Research UK, the UK Medical Research Council, and the National Institute for Health Research. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

PHM 2021: Leading through adversity

PHM 2021 session

Leading through adversity

Presenter

Ilan Alhadeff, MD, MBA, SFHM, CLHM

Session summary

As the VP of hospitalist services and a practicing hospitalist in Boca Raton, Fla., Dr. Alhadeff shared an emotional journey where the impact of lives lost has led to organizational innovation and advocacy. He started this journey on the date of the Parkland High School shooting, Feb. 14, 2018. On this day, he lost his 14 year-old daughter Alyssa and described subsequent emotions of anger, sadness, hopelessness, and feeling the pressure to be the protector of his family. Despite receiving an outpouring of support through memorials, texts, letters, and social media posts, he was immersed in “survival mode.” He likens this to the experience many of us may be having during the pandemic. He described caring for patients with limited empathy and the impact this likely had on patient care. During this challenging time, the strongest supports became those that stated they couldn’t imagine how this event could have impacted Dr. Alhadeff’s life but offered support in any way needed – true empathic communication.

“It ain’t about how hard you hit. It’s about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward.” – Rocky Balboa (2006)

Despite the above, he and his wife founded Make Our Schools Safe (MOSS), a student-forward organization that promotes a culture of safety where all involved are counseled, “If you see something, say something.” Students are encouraged to use social media as an anonymous reporting tool. Likewise, this organization supports efforts for silent safety alerts in schools and fencing around schools to allow for 1-point entry. Lessons Dr. Alhadeff learned that might impact any pediatric hospitalist include the knowledge that mental health concerns aren’t going away; for example, after a school shooting any student affected should be provided counseling services as needed, the need to prevent triggering events, and turning grief into action can help.

“Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving.” – Albert Einstein (1930)

Dr. Alhadeff then described the process of “moving on” for him and his family. For his children, this initially meant “busying” their lives. They then gradually eased into therapy, and ultimately adopted a support dog. He experienced recurrent loss with his father passing away in March 2019, and he persevered in legislative advocacy in New Jersey and Florida and personal/professional development with work toward his MBA degree. Through this work, he collaborated with many legislators and two presidents. He describes resiliency as the ability to bounce back from adversity, with components including self-awareness, mindfulness, self-care, positive relationships, and purpose. While many of us have not had the great personal losses and challenge experienced by Dr. Alhadeff, we all are experiencing an once-in-a-lifetime transformation of health care with political and social interference. It is up to each of us to determine our role and how we can use our influence for positive change.

As noted by Dr. Alhadeff, “We are not all in the same boat. We ARE in the same storm.”

Key takeaways

- How PHM can promote MOSS: Allow children to be part of the work to keep schools safe. Advocate for local MOSS chapters. Support legislative advocacy for school safety.

- Despite adversity, we have the ability to demonstrate resilience. We do so through development of self-awareness, mindfulness, engagement in self-care, nurturing positive relationships, and continuing to pursue our greater purpose.

Dr. King is a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s MN and the director of medical education, an associate program director for the Pediatrics Residency program at the University of Minnesota. She received her medical degree from Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine and completed pediatric residency and chief residency at the University of Minnesota.

PHM 2021 session

Leading through adversity

Presenter

Ilan Alhadeff, MD, MBA, SFHM, CLHM

Session summary

As the VP of hospitalist services and a practicing hospitalist in Boca Raton, Fla., Dr. Alhadeff shared an emotional journey where the impact of lives lost has led to organizational innovation and advocacy. He started this journey on the date of the Parkland High School shooting, Feb. 14, 2018. On this day, he lost his 14 year-old daughter Alyssa and described subsequent emotions of anger, sadness, hopelessness, and feeling the pressure to be the protector of his family. Despite receiving an outpouring of support through memorials, texts, letters, and social media posts, he was immersed in “survival mode.” He likens this to the experience many of us may be having during the pandemic. He described caring for patients with limited empathy and the impact this likely had on patient care. During this challenging time, the strongest supports became those that stated they couldn’t imagine how this event could have impacted Dr. Alhadeff’s life but offered support in any way needed – true empathic communication.

“It ain’t about how hard you hit. It’s about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward.” – Rocky Balboa (2006)

Despite the above, he and his wife founded Make Our Schools Safe (MOSS), a student-forward organization that promotes a culture of safety where all involved are counseled, “If you see something, say something.” Students are encouraged to use social media as an anonymous reporting tool. Likewise, this organization supports efforts for silent safety alerts in schools and fencing around schools to allow for 1-point entry. Lessons Dr. Alhadeff learned that might impact any pediatric hospitalist include the knowledge that mental health concerns aren’t going away; for example, after a school shooting any student affected should be provided counseling services as needed, the need to prevent triggering events, and turning grief into action can help.

“Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving.” – Albert Einstein (1930)

Dr. Alhadeff then described the process of “moving on” for him and his family. For his children, this initially meant “busying” their lives. They then gradually eased into therapy, and ultimately adopted a support dog. He experienced recurrent loss with his father passing away in March 2019, and he persevered in legislative advocacy in New Jersey and Florida and personal/professional development with work toward his MBA degree. Through this work, he collaborated with many legislators and two presidents. He describes resiliency as the ability to bounce back from adversity, with components including self-awareness, mindfulness, self-care, positive relationships, and purpose. While many of us have not had the great personal losses and challenge experienced by Dr. Alhadeff, we all are experiencing an once-in-a-lifetime transformation of health care with political and social interference. It is up to each of us to determine our role and how we can use our influence for positive change.

As noted by Dr. Alhadeff, “We are not all in the same boat. We ARE in the same storm.”

Key takeaways

- How PHM can promote MOSS: Allow children to be part of the work to keep schools safe. Advocate for local MOSS chapters. Support legislative advocacy for school safety.

- Despite adversity, we have the ability to demonstrate resilience. We do so through development of self-awareness, mindfulness, engagement in self-care, nurturing positive relationships, and continuing to pursue our greater purpose.

Dr. King is a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s MN and the director of medical education, an associate program director for the Pediatrics Residency program at the University of Minnesota. She received her medical degree from Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine and completed pediatric residency and chief residency at the University of Minnesota.

PHM 2021 session

Leading through adversity

Presenter

Ilan Alhadeff, MD, MBA, SFHM, CLHM

Session summary

As the VP of hospitalist services and a practicing hospitalist in Boca Raton, Fla., Dr. Alhadeff shared an emotional journey where the impact of lives lost has led to organizational innovation and advocacy. He started this journey on the date of the Parkland High School shooting, Feb. 14, 2018. On this day, he lost his 14 year-old daughter Alyssa and described subsequent emotions of anger, sadness, hopelessness, and feeling the pressure to be the protector of his family. Despite receiving an outpouring of support through memorials, texts, letters, and social media posts, he was immersed in “survival mode.” He likens this to the experience many of us may be having during the pandemic. He described caring for patients with limited empathy and the impact this likely had on patient care. During this challenging time, the strongest supports became those that stated they couldn’t imagine how this event could have impacted Dr. Alhadeff’s life but offered support in any way needed – true empathic communication.

“It ain’t about how hard you hit. It’s about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward.” – Rocky Balboa (2006)

Despite the above, he and his wife founded Make Our Schools Safe (MOSS), a student-forward organization that promotes a culture of safety where all involved are counseled, “If you see something, say something.” Students are encouraged to use social media as an anonymous reporting tool. Likewise, this organization supports efforts for silent safety alerts in schools and fencing around schools to allow for 1-point entry. Lessons Dr. Alhadeff learned that might impact any pediatric hospitalist include the knowledge that mental health concerns aren’t going away; for example, after a school shooting any student affected should be provided counseling services as needed, the need to prevent triggering events, and turning grief into action can help.

“Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving.” – Albert Einstein (1930)

Dr. Alhadeff then described the process of “moving on” for him and his family. For his children, this initially meant “busying” their lives. They then gradually eased into therapy, and ultimately adopted a support dog. He experienced recurrent loss with his father passing away in March 2019, and he persevered in legislative advocacy in New Jersey and Florida and personal/professional development with work toward his MBA degree. Through this work, he collaborated with many legislators and two presidents. He describes resiliency as the ability to bounce back from adversity, with components including self-awareness, mindfulness, self-care, positive relationships, and purpose. While many of us have not had the great personal losses and challenge experienced by Dr. Alhadeff, we all are experiencing an once-in-a-lifetime transformation of health care with political and social interference. It is up to each of us to determine our role and how we can use our influence for positive change.

As noted by Dr. Alhadeff, “We are not all in the same boat. We ARE in the same storm.”

Key takeaways

- How PHM can promote MOSS: Allow children to be part of the work to keep schools safe. Advocate for local MOSS chapters. Support legislative advocacy for school safety.

- Despite adversity, we have the ability to demonstrate resilience. We do so through development of self-awareness, mindfulness, engagement in self-care, nurturing positive relationships, and continuing to pursue our greater purpose.

Dr. King is a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s MN and the director of medical education, an associate program director for the Pediatrics Residency program at the University of Minnesota. She received her medical degree from Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine and completed pediatric residency and chief residency at the University of Minnesota.

Urticaria and edema in a 2-year-old boy

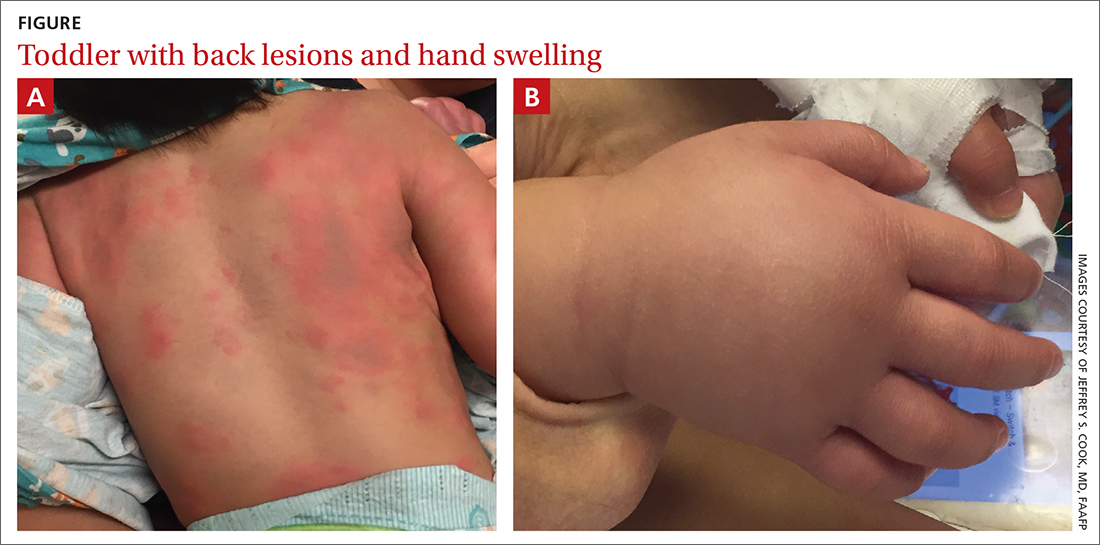

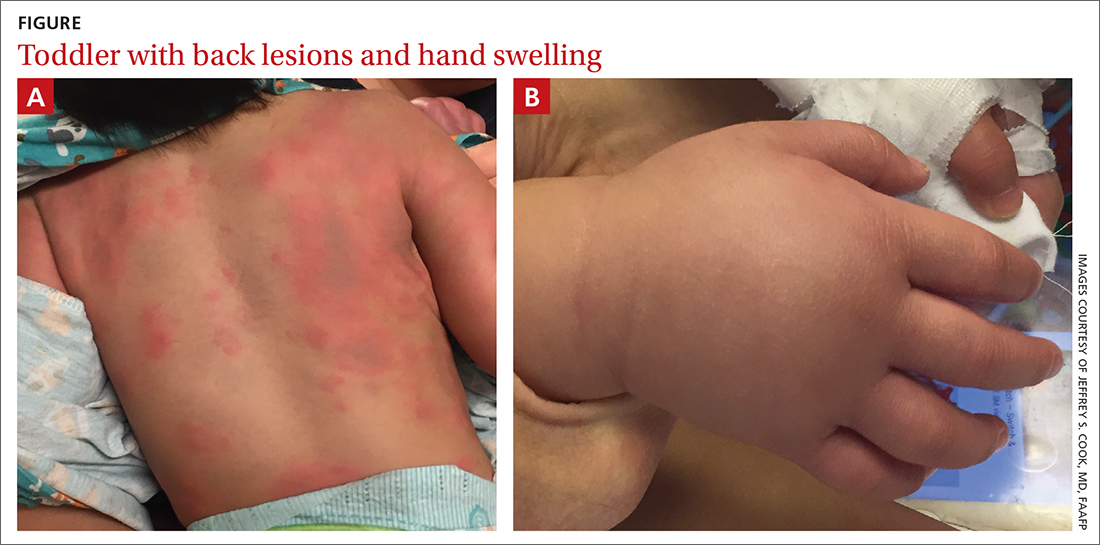

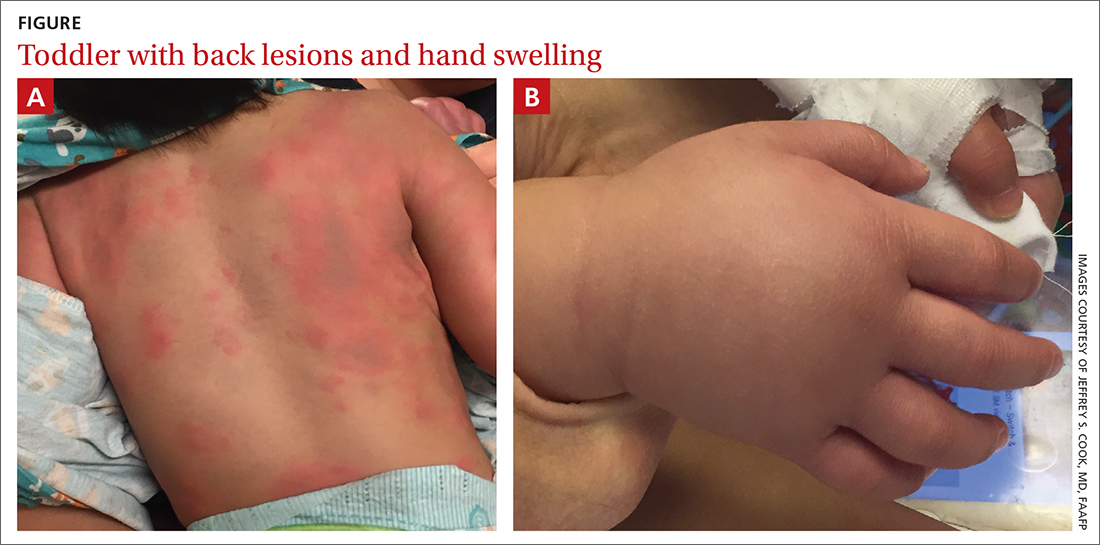

A 2-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the emergency room with a 1-day history of a diffuse, mildly pruritic rash and swelling of his knees, ankles, and feet following treatment of acute otitis media with amoxicillin for the previous 8 days. He was mildly febrile and consolable, but he was refusing to walk. His medical history was unremarkable.

Physical examination revealed erythematous annular wheals on his chest, face, back, and extremities. Lymphadenopathy and mucous membrane involvement were not present. A complete blood count (CBC) with differential, inflammatory marker tests, and a comprehensive metabolic panel were ordered. Given the joint swelling and rash, the patient was admitted for observation.

During his second day in the hospital, his skin lesions enlarged and several formed dusky blue centers (FIGURE 1A). He also developed swelling of his hands (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Urticaria multiforme

The patient’s lab work came back within normal range, except for an elevated white blood cell count (19,700/mm3; reference range, 4500-13,500/mm3). His mild systemic symptoms, skin lesions without blistering or necrosis, acral edema, and the absence of lymphadenopathy pointed to a diagnosis of urticaria multiforme.

Urticaria multiforme, also called acute annular urticaria or acute urticarial hypersensitivity syndrome, is a histamine-mediated hypersensitivity reaction characterized by transient annular, polycyclic, urticarial lesions with central ecchymosis. The incidence and prevalence are not known. Urticaria multiforme is considered common, but it is frequently misdiagnosed.1 It typically manifests in children ages 4 months to 4 years and begins with small erythematous macules, papules, and plaques that progress to large blanchable wheals with dusky blue centers.1-3 Lesions are usually located on the face, trunk, and extremities and are often pruritic (60%-94%).1-3 Individual lesions last less than 24 hours, but new ones may appear. The rash generally lasts 2 to 12 days.1,3

Patients often report a preceding viral illness, otitis media, recent use of antibiotics, or recent immunizations. Dermatographism due to mast cell–mediated cutaneous hypersensitivity at sites of minor skin trauma is common (44%).

The diagnosis is made clinically and should not require a skin biopsy or extensive laboratory testing.When performed, laboratory studies, including CBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and urinalysis are routinely normal.

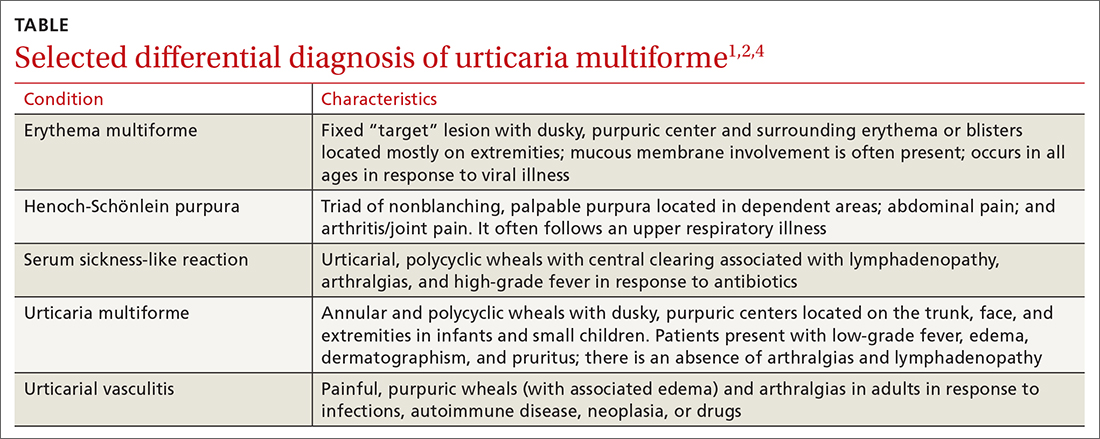

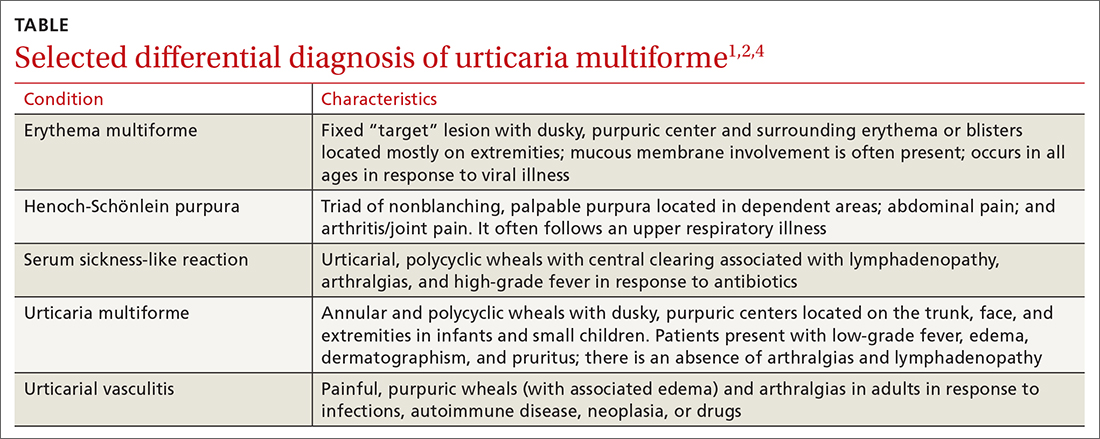

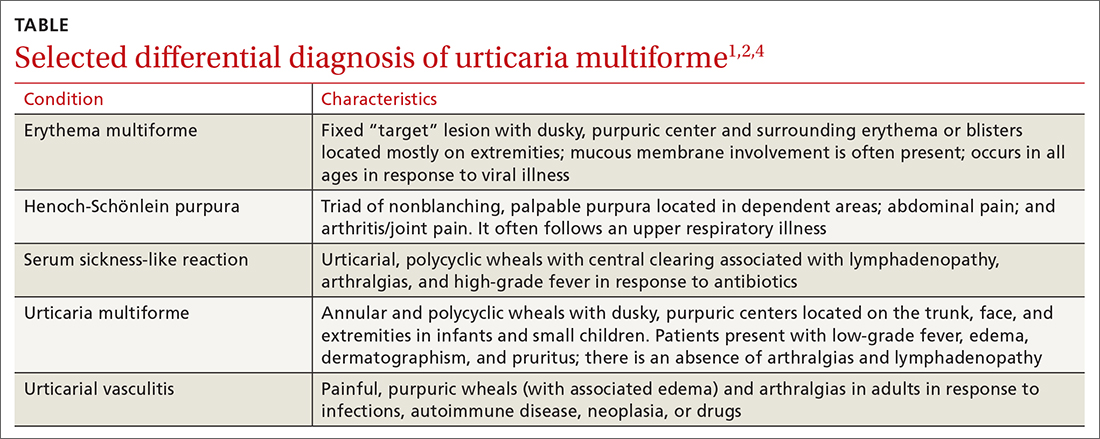

Erythema multiforme and urticarial vasculitis are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes erythema multiforme, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, serum sickness-like reaction, and urticarial vasculitis (TABLE1,2,4).

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme is a common misdiagnosis in patients with urticaria multiforme.1,2 The erythema multiforme rash has a “target” lesion with outer erythema and central ecchymosis, which may develop blisters or necrosis. Lesions are fixed and last 2 to 3 weeks. Unlike urticaria multiforme, patients with erythema multiforme commonly have mucous membrane erosions and occasionally ulcerations. Facial and acral edema is rare. Treatment is largely symptomatic and can include glucocorticoids. Antiviral medications may be used to treat recurrences.1,2

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is an immunoglobulin A–mediated vasculitis that affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and joints.4,5 Patients often present with arthralgias, gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain and bleeding, and a nonpruritic, erythematous rash that progresses to palpable purpura in dependent areas of the body. Treatment is generally symptomatic, but steroids may be used in severe cases.4,5

Serum sickness-like reaction can manifest with angioedema and a similar urticarial rash (with central clearing) that lasts 1 to 6 weeks.1,2,6,7 However, patients tend to have a high-grade fever, arthralgias, myalgias, and lymphadenopathy while dermatographism is absent. Treatment includes discontinuing the offending agent and the use of H1 and H2 antihistamines and steroids, in severe cases.

Urticarial vasculitis manifests as plaques or wheals lasting 1 to 7 days that may cause burning and pain but not pruritis.2,5 Purpura or hypopigmentation may develop as the hives resolve. Angioedema and arthralgias are common, but dermatographism is not present. Triggers include infections, autoimmune disease, malignancy, and the use of certain medications. H1 and H2 blockers and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are first-line therapy.2

Step 1: Discontinue offending agents; Step 2: Recommend antihistamines

Treatment consists of discontinuing any offending agent (if suspected) and using systemic H1 or H2 antihistamines for symptom relief. Systemic steroids should only be given in refractory cases.

Continue to: Our patient's amoxicillin

Our patient’s amoxicillin was discontinued, and he was started on a 14-day course of cetirizine 5 mg bid and hydroxyzine 10 mg at bedtime. He was also started on triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied twice daily for 1 week. During his 3-day hospital stay, his fever resolved and his rash and edema improved.

During an outpatient follow-up visit with a pediatric dermatologist 2 weeks after discharge, the patient’s rash was still present and dermatographism was noted. In light of this, his parents were instructed to continue giving the cetirizine and hydroxyzine once daily for an additional 2 weeks and to return as needed.

1. Shah KN, Honig PJ, Yan AC. “Urticaria multiforme”: a case series and review of acute annular urticarial hypersensitivity syndromes in children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1177-e1183. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1553

2. Emer JJ, Bernardo SG, Kovalerchik O, et al. Urticaria multiforme. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:34-39.

3. Starnes L, Patel T, Skinner RB. Urticaria multiforme – a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011; 28:436-438. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01311.x

4. Reamy BV, Williams PM, Lindsay TJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:697-704.

5. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Mosby, Elsevier Inc; 2016.

6. King BA, Geelhoed GC. Adverse skin and joint reactions associated with oral antibiotics in children: the role of cefaclor in serum sickness-like reactions. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:677-681. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00267.x

7. Misirlioglu ED, Duman H, Ozmen S, et al. Serum sickness-like reaction in children due to cefditoren. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;29:327-328. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01539.x

A 2-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the emergency room with a 1-day history of a diffuse, mildly pruritic rash and swelling of his knees, ankles, and feet following treatment of acute otitis media with amoxicillin for the previous 8 days. He was mildly febrile and consolable, but he was refusing to walk. His medical history was unremarkable.

Physical examination revealed erythematous annular wheals on his chest, face, back, and extremities. Lymphadenopathy and mucous membrane involvement were not present. A complete blood count (CBC) with differential, inflammatory marker tests, and a comprehensive metabolic panel were ordered. Given the joint swelling and rash, the patient was admitted for observation.

During his second day in the hospital, his skin lesions enlarged and several formed dusky blue centers (FIGURE 1A). He also developed swelling of his hands (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Urticaria multiforme

The patient’s lab work came back within normal range, except for an elevated white blood cell count (19,700/mm3; reference range, 4500-13,500/mm3). His mild systemic symptoms, skin lesions without blistering or necrosis, acral edema, and the absence of lymphadenopathy pointed to a diagnosis of urticaria multiforme.

Urticaria multiforme, also called acute annular urticaria or acute urticarial hypersensitivity syndrome, is a histamine-mediated hypersensitivity reaction characterized by transient annular, polycyclic, urticarial lesions with central ecchymosis. The incidence and prevalence are not known. Urticaria multiforme is considered common, but it is frequently misdiagnosed.1 It typically manifests in children ages 4 months to 4 years and begins with small erythematous macules, papules, and plaques that progress to large blanchable wheals with dusky blue centers.1-3 Lesions are usually located on the face, trunk, and extremities and are often pruritic (60%-94%).1-3 Individual lesions last less than 24 hours, but new ones may appear. The rash generally lasts 2 to 12 days.1,3

Patients often report a preceding viral illness, otitis media, recent use of antibiotics, or recent immunizations. Dermatographism due to mast cell–mediated cutaneous hypersensitivity at sites of minor skin trauma is common (44%).

The diagnosis is made clinically and should not require a skin biopsy or extensive laboratory testing.When performed, laboratory studies, including CBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and urinalysis are routinely normal.

Erythema multiforme and urticarial vasculitis are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis in this case includes erythema multiforme, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, serum sickness-like reaction, and urticarial vasculitis (TABLE1,2,4).

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme is a common misdiagnosis in patients with urticaria multiforme.1,2 The erythema multiforme rash has a “target” lesion with outer erythema and central ecchymosis, which may develop blisters or necrosis. Lesions are fixed and last 2 to 3 weeks. Unlike urticaria multiforme, patients with erythema multiforme commonly have mucous membrane erosions and occasionally ulcerations. Facial and acral edema is rare. Treatment is largely symptomatic and can include glucocorticoids. Antiviral medications may be used to treat recurrences.1,2

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is an immunoglobulin A–mediated vasculitis that affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and joints.4,5 Patients often present with arthralgias, gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain and bleeding, and a nonpruritic, erythematous rash that progresses to palpable purpura in dependent areas of the body. Treatment is generally symptomatic, but steroids may be used in severe cases.4,5