User login

Key differences found between pediatric- and adult-onset MS

WEST PALM BEACH, FLA. – , according to data presented at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Among patients with POMS, researchers also have observed an association between fatigue and mood disorders on one hand and DMT choice on the other hand. “These findings confirm the unique features of POMS and suggest that DMT choice in POMS and AOMS may influence the frequency of fatigue and mood disorders,” said Mary Rensel, MD, staff neurologist in neuroimmunology at Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for MS Treatment and Research, and colleagues.

POMS is defined as MS onset before age 18, and the disease characteristics of POMS and AOMS are distinct. The former diagnosis is rare, which has limited the amount of data collected on POMS to date.

MS Partners Advancing Technology and Health Solutions (MS-PATHS), sponsored by Biogen, is a multicenter initiative in which researchers collect MS performance measures longitudinally at each patient visit. MS-PATHS data include sociodemographic information, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), functional outcomes (FOs), MS phenotype, and DMT. Using MS-PATHS data, Dr. Rensel and colleagues sought to determine differences in sociodemographics, MS phenotype, PRO, FO, and DMT among patients with POMS and between patients with POMS and those with AOMS.

The investigators analyzed data cut 9 of the MS-PATHS database for their study. They included 637 participants with POMS and matched them with patients with AOMS, based on disease duration, in a 1:5 ratio. Dr. Rensel and colleagues categorized DMTs as high, mid, or low efficacy. They calculated descriptive statistics to characterize the study population. In addition, they compared MS FOs and PROs in the matched cohort using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Finally, linear regression analysis allowed the investigators to identify differences in the data set, while adjusting for important covariates.

The matched cohort included 5,857 patients with AOMS and 600 patients with POMS. The patients with AOMS had an average age of 49.8 years. About 87.5% of these patients were white, and 73.5% were female. The POMS patients had an average age of 31.49 years. Overall, 76.7% of these patients were white, and 73.2% were female. Dr. Rensel and colleagues found significant differences between the two groups in age at encounter, disease duration, race, insurance, Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS), education, employment, FOs, PROs, and DMT.

Patients with POMS used high-efficacy DMT more frequently than those with AOMS. The rate of depression was similar between patients with AOMS and those with POMS. Depression, anxiety, and fatigue were associated with DMT potency in AOMS, and anxiety and fatigue were associated with DMT groups in POMS.

Racial differences between POMS and AOMS have been reported previously, said Dr. Rensel. First-generation immigrant children have an increased risk of POMS, compared with other children. “In our data set, we had more Asians, more blacks, and fewer Caucasians in the POMS group,” said Dr. Rensel. People from a socioeconomically challenged environment have an increased risk of POMS, and this observation may explain the difference in insurance coverage between the POMS and AOMS groups, she added. Socioeconomic challenges also may explain the difference in the rate of higher education between the two groups.

“Why were the POMS cases associated with higher-efficacy DMT when only one oral MS DMT is [Food and Drug Administration]-approved for POMS?” Dr. Rensel asked. “This is likely due to the fact that POMS cases tend to have higher disease activity with more relapses and more brain lesions, leading to the choice of higher efficacy DMTs that are currently not FDA-approved for POMS.”

These data “may help [clinicians] caring for kids and teens, especially non-Caucasian [patients], to consider MS on the differential diagnosis,” Dr. Rensel added. “Mood disorders in POMS were as common as mood disorders in AOMS, so these should be screened for in this POMS population.”

Dr. Rensel has received funding for consulting, research, or patient education from Biogen, Genentech, Genzyme, Medimmune, MSAA, NMSS, Novartis, TSerono, and Teva.

SOURCE: Rensel M et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2020, Abstract P042.

WEST PALM BEACH, FLA. – , according to data presented at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Among patients with POMS, researchers also have observed an association between fatigue and mood disorders on one hand and DMT choice on the other hand. “These findings confirm the unique features of POMS and suggest that DMT choice in POMS and AOMS may influence the frequency of fatigue and mood disorders,” said Mary Rensel, MD, staff neurologist in neuroimmunology at Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for MS Treatment and Research, and colleagues.

POMS is defined as MS onset before age 18, and the disease characteristics of POMS and AOMS are distinct. The former diagnosis is rare, which has limited the amount of data collected on POMS to date.

MS Partners Advancing Technology and Health Solutions (MS-PATHS), sponsored by Biogen, is a multicenter initiative in which researchers collect MS performance measures longitudinally at each patient visit. MS-PATHS data include sociodemographic information, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), functional outcomes (FOs), MS phenotype, and DMT. Using MS-PATHS data, Dr. Rensel and colleagues sought to determine differences in sociodemographics, MS phenotype, PRO, FO, and DMT among patients with POMS and between patients with POMS and those with AOMS.

The investigators analyzed data cut 9 of the MS-PATHS database for their study. They included 637 participants with POMS and matched them with patients with AOMS, based on disease duration, in a 1:5 ratio. Dr. Rensel and colleagues categorized DMTs as high, mid, or low efficacy. They calculated descriptive statistics to characterize the study population. In addition, they compared MS FOs and PROs in the matched cohort using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Finally, linear regression analysis allowed the investigators to identify differences in the data set, while adjusting for important covariates.

The matched cohort included 5,857 patients with AOMS and 600 patients with POMS. The patients with AOMS had an average age of 49.8 years. About 87.5% of these patients were white, and 73.5% were female. The POMS patients had an average age of 31.49 years. Overall, 76.7% of these patients were white, and 73.2% were female. Dr. Rensel and colleagues found significant differences between the two groups in age at encounter, disease duration, race, insurance, Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS), education, employment, FOs, PROs, and DMT.

Patients with POMS used high-efficacy DMT more frequently than those with AOMS. The rate of depression was similar between patients with AOMS and those with POMS. Depression, anxiety, and fatigue were associated with DMT potency in AOMS, and anxiety and fatigue were associated with DMT groups in POMS.

Racial differences between POMS and AOMS have been reported previously, said Dr. Rensel. First-generation immigrant children have an increased risk of POMS, compared with other children. “In our data set, we had more Asians, more blacks, and fewer Caucasians in the POMS group,” said Dr. Rensel. People from a socioeconomically challenged environment have an increased risk of POMS, and this observation may explain the difference in insurance coverage between the POMS and AOMS groups, she added. Socioeconomic challenges also may explain the difference in the rate of higher education between the two groups.

“Why were the POMS cases associated with higher-efficacy DMT when only one oral MS DMT is [Food and Drug Administration]-approved for POMS?” Dr. Rensel asked. “This is likely due to the fact that POMS cases tend to have higher disease activity with more relapses and more brain lesions, leading to the choice of higher efficacy DMTs that are currently not FDA-approved for POMS.”

These data “may help [clinicians] caring for kids and teens, especially non-Caucasian [patients], to consider MS on the differential diagnosis,” Dr. Rensel added. “Mood disorders in POMS were as common as mood disorders in AOMS, so these should be screened for in this POMS population.”

Dr. Rensel has received funding for consulting, research, or patient education from Biogen, Genentech, Genzyme, Medimmune, MSAA, NMSS, Novartis, TSerono, and Teva.

SOURCE: Rensel M et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2020, Abstract P042.

WEST PALM BEACH, FLA. – , according to data presented at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Among patients with POMS, researchers also have observed an association between fatigue and mood disorders on one hand and DMT choice on the other hand. “These findings confirm the unique features of POMS and suggest that DMT choice in POMS and AOMS may influence the frequency of fatigue and mood disorders,” said Mary Rensel, MD, staff neurologist in neuroimmunology at Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for MS Treatment and Research, and colleagues.

POMS is defined as MS onset before age 18, and the disease characteristics of POMS and AOMS are distinct. The former diagnosis is rare, which has limited the amount of data collected on POMS to date.

MS Partners Advancing Technology and Health Solutions (MS-PATHS), sponsored by Biogen, is a multicenter initiative in which researchers collect MS performance measures longitudinally at each patient visit. MS-PATHS data include sociodemographic information, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), functional outcomes (FOs), MS phenotype, and DMT. Using MS-PATHS data, Dr. Rensel and colleagues sought to determine differences in sociodemographics, MS phenotype, PRO, FO, and DMT among patients with POMS and between patients with POMS and those with AOMS.

The investigators analyzed data cut 9 of the MS-PATHS database for their study. They included 637 participants with POMS and matched them with patients with AOMS, based on disease duration, in a 1:5 ratio. Dr. Rensel and colleagues categorized DMTs as high, mid, or low efficacy. They calculated descriptive statistics to characterize the study population. In addition, they compared MS FOs and PROs in the matched cohort using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Finally, linear regression analysis allowed the investigators to identify differences in the data set, while adjusting for important covariates.

The matched cohort included 5,857 patients with AOMS and 600 patients with POMS. The patients with AOMS had an average age of 49.8 years. About 87.5% of these patients were white, and 73.5% were female. The POMS patients had an average age of 31.49 years. Overall, 76.7% of these patients were white, and 73.2% were female. Dr. Rensel and colleagues found significant differences between the two groups in age at encounter, disease duration, race, insurance, Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS), education, employment, FOs, PROs, and DMT.

Patients with POMS used high-efficacy DMT more frequently than those with AOMS. The rate of depression was similar between patients with AOMS and those with POMS. Depression, anxiety, and fatigue were associated with DMT potency in AOMS, and anxiety and fatigue were associated with DMT groups in POMS.

Racial differences between POMS and AOMS have been reported previously, said Dr. Rensel. First-generation immigrant children have an increased risk of POMS, compared with other children. “In our data set, we had more Asians, more blacks, and fewer Caucasians in the POMS group,” said Dr. Rensel. People from a socioeconomically challenged environment have an increased risk of POMS, and this observation may explain the difference in insurance coverage between the POMS and AOMS groups, she added. Socioeconomic challenges also may explain the difference in the rate of higher education between the two groups.

“Why were the POMS cases associated with higher-efficacy DMT when only one oral MS DMT is [Food and Drug Administration]-approved for POMS?” Dr. Rensel asked. “This is likely due to the fact that POMS cases tend to have higher disease activity with more relapses and more brain lesions, leading to the choice of higher efficacy DMTs that are currently not FDA-approved for POMS.”

These data “may help [clinicians] caring for kids and teens, especially non-Caucasian [patients], to consider MS on the differential diagnosis,” Dr. Rensel added. “Mood disorders in POMS were as common as mood disorders in AOMS, so these should be screened for in this POMS population.”

Dr. Rensel has received funding for consulting, research, or patient education from Biogen, Genentech, Genzyme, Medimmune, MSAA, NMSS, Novartis, TSerono, and Teva.

SOURCE: Rensel M et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2020, Abstract P042.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2020

Community-wide initiative ups teen LARC adoption sixfold

In Rochester, N.Y., a comprehensive community initiative that raised awareness about and delivered training in the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) significantly upped LARC adoption among sexually active female high schoolers.

Over the course of the 3-year project, LARC use rose from about 4% to 24% in this group, a statistically significant increase (P less than .0001). During the same time period, LARC use increased nationally, as well, but at a lower rate, rising from 2% to 5% for the same population, while New York state saw LARC use rise from 2% to 5%.

In New York City, where an unrelated LARC awareness campaign was conducted, LARC use went from 3% to 5% over the study period for sexually active female high school students. Comparing the trend in LARC use in Rochester to the secular trend in these control groups showed significantly higher uptake over time in Rochester (P less than .0001).

Through a series of lunch-and-learn talks given to adults who work with adolescents in community-based settings and in medical settings, the Greater Rochester LARC Initiative reached more than 1,300 individuals during July 2014-June 2017, C. Andrew Aligne, MD, MPH, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and coauthors reported in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Of the 81 total talks delivered, 50 were in medical settings, reaching 703 attendees ranging from front-office personnel to primary care physicians, advanced practice clinicians, and nurses; the talks in community-based settings reached 662 attendees.

“We use the term ‘community detailing’ to describe the design of the intervention because it was an innovative hybrid of academic detailing and community health education,” explained Dr. Aligne and colleagues. This approach is a unique, feasible, and effective approach to unintended adolescent pregnancy programs. “The community detailing approach could be a useful complement to programs for preventing unintended adolescent pregnancy.”

The study’s primary outcome measure was LARC use among sexually active female high school students as identified by responses on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Statistics’ Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS).

YRBS data were examined for the years 2013, 2015, and 2017, spanning the period before and after the LARC initiative was begun. A separate question about LARC use wasn’t included in the 2013 YRBS survey, so the investigators used a generous estimate that two-thirds of respondents who reported using the “other” contraceptive category for that year were using LARCs. That category was chosen by a total of 6% of respondents, and encompassed LARC use along with use of the patch, ring, diaphragm, and fertility awareness, explained Dr. Aligne and collaborators.

Addressing the problem of failure to use a condom with LARC use, Dr. Aligne and collaborators found overall low rates of dual-method use, but higher rates in Rochester than in the comparison groups. In Rochester, 78% of respondents reported that they also did not use condoms. This figure was lower than the 91% reported for the United States as a whole, and also was lower than the 93% reported in New York City and the 85% reported in New York state. No increase in sexually transmitted infections was seen in Rochester’s sexually active high school females during the study period.

“Our main finding of increased LARC use is consistent with the literature demonstrating that many sexually active young women, including adolescents, will choose LARC if they are given access not only to birth control itself, but also to accurate information about various contraceptive methods,” concluded Dr. Aligne and his associates.

A practical strength of the Greater Rochester LARC initiative was that it capitalized on existing resources, such as New York state’s preexisting program for free access to contraception and similar provisions in the Affordable Care Act. Also, local Title X clinics that were enrolled in New York’s free contraception initiative already had practitioners who were trained and able to provide same-day LARC insertion.

Pediatricians engaged in the initiative were able to receive free training from LARC manufacturers, as mandated by the Food and Drug Administration. Through collaboration with implant manufacturers, Rochester LARC Initiative staff were able to piggyback on training sessions to add education about contraception counseling and the importance of offering access to all contraception methods.

Taken as a whole, the LARC Initiative could be scaled up, wrote Dr. Aligne and his coauthors, a potential boon in the 21 states where qualifying individuals younger than 19 years of age are eligible for Medicaid reimbursement for family planning services. “Even though easy LARC access is far from universal, there are vast areas of the nation where cost need not be seen as an insurmountable barrier.” Dr. Aligne and coauthors also addressed the fraught history of reproductive justice in the United States, cautioning that universal LARC adoption was not – and should not be – the goal of such initiatives. “There is a history of reproductive coercion in the U.S. including forced sterilization of women of color; therefore, it is critical that LARC methods not be imposed on any particular group. On the other hand, LARC should not be withheld deliberately from adolescents who want it, as this is another form of injustice,” they wrote. “The goal should be to empower individuals to decide what is right for them in a context of social and reproductive justice.”

Using the nationally administered YRBS was a significant strength of the study, commented Dr. Aligne and his collaborators. “This allowed us to employ the study design of pre-post with a nonrandomized control group,” the investigators noted, adding that the “relatively rigorous” methodology reduced the risk of problems with internal validity, and also allowed comparisons between changes in Rochester and those at the state and national level.

However, the researchers acknowledged that the study was not a randomized trial, and there’s always the possibility of unknown confounders contributing to LARC uptake during the study period. Also, the YRBS is a self-report instrument and only includes those enrolled in school.

Dr. Aligne reported that his spouse received compensation for providing contraceptive implant insertion training, as did two coauthors. The LARC initiative was supported by a grant from the Greater Rochester Health Foundation.

SOURCE: Aligne CA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan 22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.01.029.

In Rochester, N.Y., a comprehensive community initiative that raised awareness about and delivered training in the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) significantly upped LARC adoption among sexually active female high schoolers.

Over the course of the 3-year project, LARC use rose from about 4% to 24% in this group, a statistically significant increase (P less than .0001). During the same time period, LARC use increased nationally, as well, but at a lower rate, rising from 2% to 5% for the same population, while New York state saw LARC use rise from 2% to 5%.

In New York City, where an unrelated LARC awareness campaign was conducted, LARC use went from 3% to 5% over the study period for sexually active female high school students. Comparing the trend in LARC use in Rochester to the secular trend in these control groups showed significantly higher uptake over time in Rochester (P less than .0001).

Through a series of lunch-and-learn talks given to adults who work with adolescents in community-based settings and in medical settings, the Greater Rochester LARC Initiative reached more than 1,300 individuals during July 2014-June 2017, C. Andrew Aligne, MD, MPH, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and coauthors reported in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Of the 81 total talks delivered, 50 were in medical settings, reaching 703 attendees ranging from front-office personnel to primary care physicians, advanced practice clinicians, and nurses; the talks in community-based settings reached 662 attendees.

“We use the term ‘community detailing’ to describe the design of the intervention because it was an innovative hybrid of academic detailing and community health education,” explained Dr. Aligne and colleagues. This approach is a unique, feasible, and effective approach to unintended adolescent pregnancy programs. “The community detailing approach could be a useful complement to programs for preventing unintended adolescent pregnancy.”

The study’s primary outcome measure was LARC use among sexually active female high school students as identified by responses on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Statistics’ Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS).

YRBS data were examined for the years 2013, 2015, and 2017, spanning the period before and after the LARC initiative was begun. A separate question about LARC use wasn’t included in the 2013 YRBS survey, so the investigators used a generous estimate that two-thirds of respondents who reported using the “other” contraceptive category for that year were using LARCs. That category was chosen by a total of 6% of respondents, and encompassed LARC use along with use of the patch, ring, diaphragm, and fertility awareness, explained Dr. Aligne and collaborators.

Addressing the problem of failure to use a condom with LARC use, Dr. Aligne and collaborators found overall low rates of dual-method use, but higher rates in Rochester than in the comparison groups. In Rochester, 78% of respondents reported that they also did not use condoms. This figure was lower than the 91% reported for the United States as a whole, and also was lower than the 93% reported in New York City and the 85% reported in New York state. No increase in sexually transmitted infections was seen in Rochester’s sexually active high school females during the study period.

“Our main finding of increased LARC use is consistent with the literature demonstrating that many sexually active young women, including adolescents, will choose LARC if they are given access not only to birth control itself, but also to accurate information about various contraceptive methods,” concluded Dr. Aligne and his associates.

A practical strength of the Greater Rochester LARC initiative was that it capitalized on existing resources, such as New York state’s preexisting program for free access to contraception and similar provisions in the Affordable Care Act. Also, local Title X clinics that were enrolled in New York’s free contraception initiative already had practitioners who were trained and able to provide same-day LARC insertion.

Pediatricians engaged in the initiative were able to receive free training from LARC manufacturers, as mandated by the Food and Drug Administration. Through collaboration with implant manufacturers, Rochester LARC Initiative staff were able to piggyback on training sessions to add education about contraception counseling and the importance of offering access to all contraception methods.

Taken as a whole, the LARC Initiative could be scaled up, wrote Dr. Aligne and his coauthors, a potential boon in the 21 states where qualifying individuals younger than 19 years of age are eligible for Medicaid reimbursement for family planning services. “Even though easy LARC access is far from universal, there are vast areas of the nation where cost need not be seen as an insurmountable barrier.” Dr. Aligne and coauthors also addressed the fraught history of reproductive justice in the United States, cautioning that universal LARC adoption was not – and should not be – the goal of such initiatives. “There is a history of reproductive coercion in the U.S. including forced sterilization of women of color; therefore, it is critical that LARC methods not be imposed on any particular group. On the other hand, LARC should not be withheld deliberately from adolescents who want it, as this is another form of injustice,” they wrote. “The goal should be to empower individuals to decide what is right for them in a context of social and reproductive justice.”

Using the nationally administered YRBS was a significant strength of the study, commented Dr. Aligne and his collaborators. “This allowed us to employ the study design of pre-post with a nonrandomized control group,” the investigators noted, adding that the “relatively rigorous” methodology reduced the risk of problems with internal validity, and also allowed comparisons between changes in Rochester and those at the state and national level.

However, the researchers acknowledged that the study was not a randomized trial, and there’s always the possibility of unknown confounders contributing to LARC uptake during the study period. Also, the YRBS is a self-report instrument and only includes those enrolled in school.

Dr. Aligne reported that his spouse received compensation for providing contraceptive implant insertion training, as did two coauthors. The LARC initiative was supported by a grant from the Greater Rochester Health Foundation.

SOURCE: Aligne CA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan 22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.01.029.

In Rochester, N.Y., a comprehensive community initiative that raised awareness about and delivered training in the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) significantly upped LARC adoption among sexually active female high schoolers.

Over the course of the 3-year project, LARC use rose from about 4% to 24% in this group, a statistically significant increase (P less than .0001). During the same time period, LARC use increased nationally, as well, but at a lower rate, rising from 2% to 5% for the same population, while New York state saw LARC use rise from 2% to 5%.

In New York City, where an unrelated LARC awareness campaign was conducted, LARC use went from 3% to 5% over the study period for sexually active female high school students. Comparing the trend in LARC use in Rochester to the secular trend in these control groups showed significantly higher uptake over time in Rochester (P less than .0001).

Through a series of lunch-and-learn talks given to adults who work with adolescents in community-based settings and in medical settings, the Greater Rochester LARC Initiative reached more than 1,300 individuals during July 2014-June 2017, C. Andrew Aligne, MD, MPH, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and coauthors reported in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Of the 81 total talks delivered, 50 were in medical settings, reaching 703 attendees ranging from front-office personnel to primary care physicians, advanced practice clinicians, and nurses; the talks in community-based settings reached 662 attendees.

“We use the term ‘community detailing’ to describe the design of the intervention because it was an innovative hybrid of academic detailing and community health education,” explained Dr. Aligne and colleagues. This approach is a unique, feasible, and effective approach to unintended adolescent pregnancy programs. “The community detailing approach could be a useful complement to programs for preventing unintended adolescent pregnancy.”

The study’s primary outcome measure was LARC use among sexually active female high school students as identified by responses on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Statistics’ Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS).

YRBS data were examined for the years 2013, 2015, and 2017, spanning the period before and after the LARC initiative was begun. A separate question about LARC use wasn’t included in the 2013 YRBS survey, so the investigators used a generous estimate that two-thirds of respondents who reported using the “other” contraceptive category for that year were using LARCs. That category was chosen by a total of 6% of respondents, and encompassed LARC use along with use of the patch, ring, diaphragm, and fertility awareness, explained Dr. Aligne and collaborators.

Addressing the problem of failure to use a condom with LARC use, Dr. Aligne and collaborators found overall low rates of dual-method use, but higher rates in Rochester than in the comparison groups. In Rochester, 78% of respondents reported that they also did not use condoms. This figure was lower than the 91% reported for the United States as a whole, and also was lower than the 93% reported in New York City and the 85% reported in New York state. No increase in sexually transmitted infections was seen in Rochester’s sexually active high school females during the study period.

“Our main finding of increased LARC use is consistent with the literature demonstrating that many sexually active young women, including adolescents, will choose LARC if they are given access not only to birth control itself, but also to accurate information about various contraceptive methods,” concluded Dr. Aligne and his associates.

A practical strength of the Greater Rochester LARC initiative was that it capitalized on existing resources, such as New York state’s preexisting program for free access to contraception and similar provisions in the Affordable Care Act. Also, local Title X clinics that were enrolled in New York’s free contraception initiative already had practitioners who were trained and able to provide same-day LARC insertion.

Pediatricians engaged in the initiative were able to receive free training from LARC manufacturers, as mandated by the Food and Drug Administration. Through collaboration with implant manufacturers, Rochester LARC Initiative staff were able to piggyback on training sessions to add education about contraception counseling and the importance of offering access to all contraception methods.

Taken as a whole, the LARC Initiative could be scaled up, wrote Dr. Aligne and his coauthors, a potential boon in the 21 states where qualifying individuals younger than 19 years of age are eligible for Medicaid reimbursement for family planning services. “Even though easy LARC access is far from universal, there are vast areas of the nation where cost need not be seen as an insurmountable barrier.” Dr. Aligne and coauthors also addressed the fraught history of reproductive justice in the United States, cautioning that universal LARC adoption was not – and should not be – the goal of such initiatives. “There is a history of reproductive coercion in the U.S. including forced sterilization of women of color; therefore, it is critical that LARC methods not be imposed on any particular group. On the other hand, LARC should not be withheld deliberately from adolescents who want it, as this is another form of injustice,” they wrote. “The goal should be to empower individuals to decide what is right for them in a context of social and reproductive justice.”

Using the nationally administered YRBS was a significant strength of the study, commented Dr. Aligne and his collaborators. “This allowed us to employ the study design of pre-post with a nonrandomized control group,” the investigators noted, adding that the “relatively rigorous” methodology reduced the risk of problems with internal validity, and also allowed comparisons between changes in Rochester and those at the state and national level.

However, the researchers acknowledged that the study was not a randomized trial, and there’s always the possibility of unknown confounders contributing to LARC uptake during the study period. Also, the YRBS is a self-report instrument and only includes those enrolled in school.

Dr. Aligne reported that his spouse received compensation for providing contraceptive implant insertion training, as did two coauthors. The LARC initiative was supported by a grant from the Greater Rochester Health Foundation.

SOURCE: Aligne CA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan 22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.01.029.

FROM AJOG

Persistent Chlorotrichosis With Chronic Sun Exposure

To the Editor:

Chlorotrichosis, or green hair discoloration, is a dermatologic condition secondary to copper deposition on the hair. It most often is seen among swimmers who have prolonged exposure to chlorinated pools. The classic patient has predisposing chemical, heat, or mechanical damage to the hair shaft and usually lighter-colored hair.1-3 We present a case of chlorotrichosis in a young brunette patient who did not have predisposing factors except for chronic sun exposure.

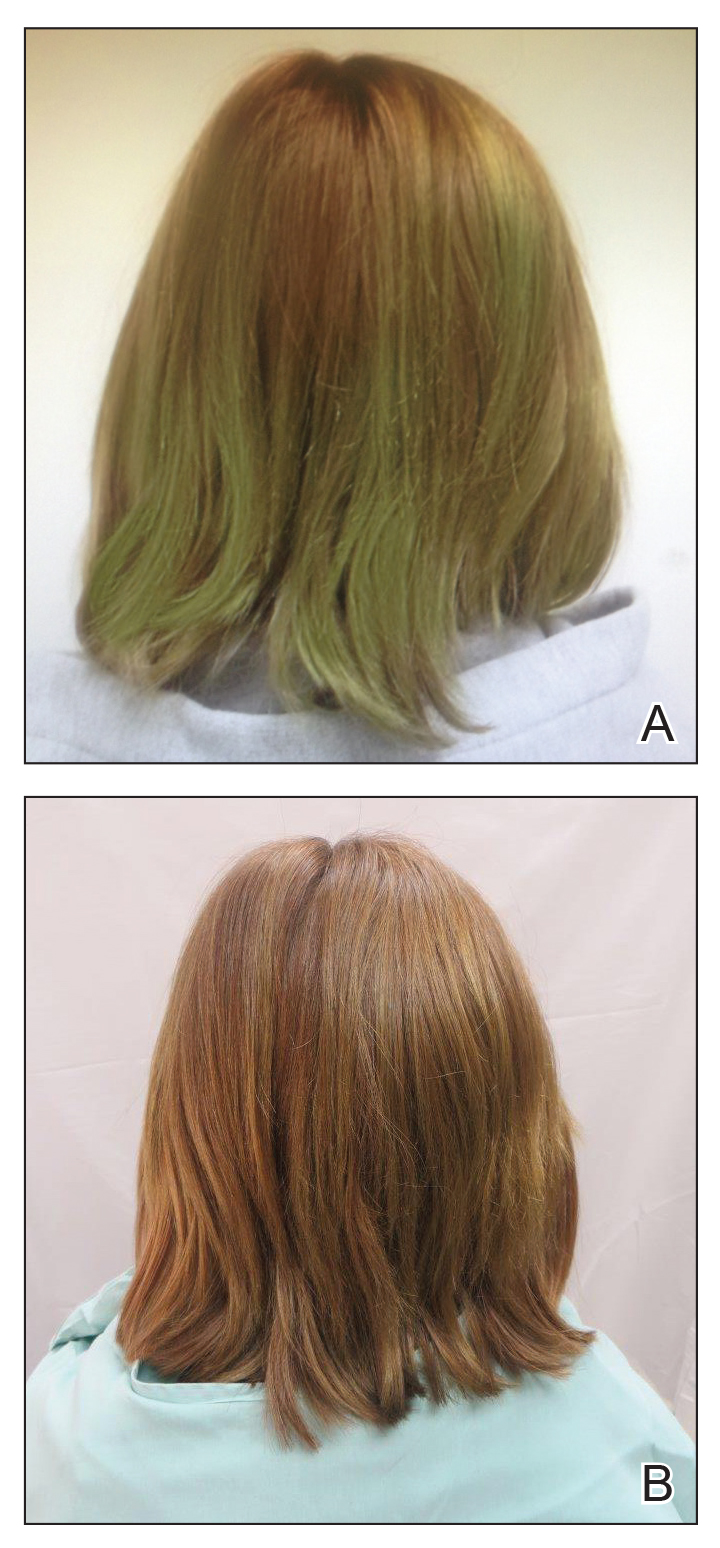

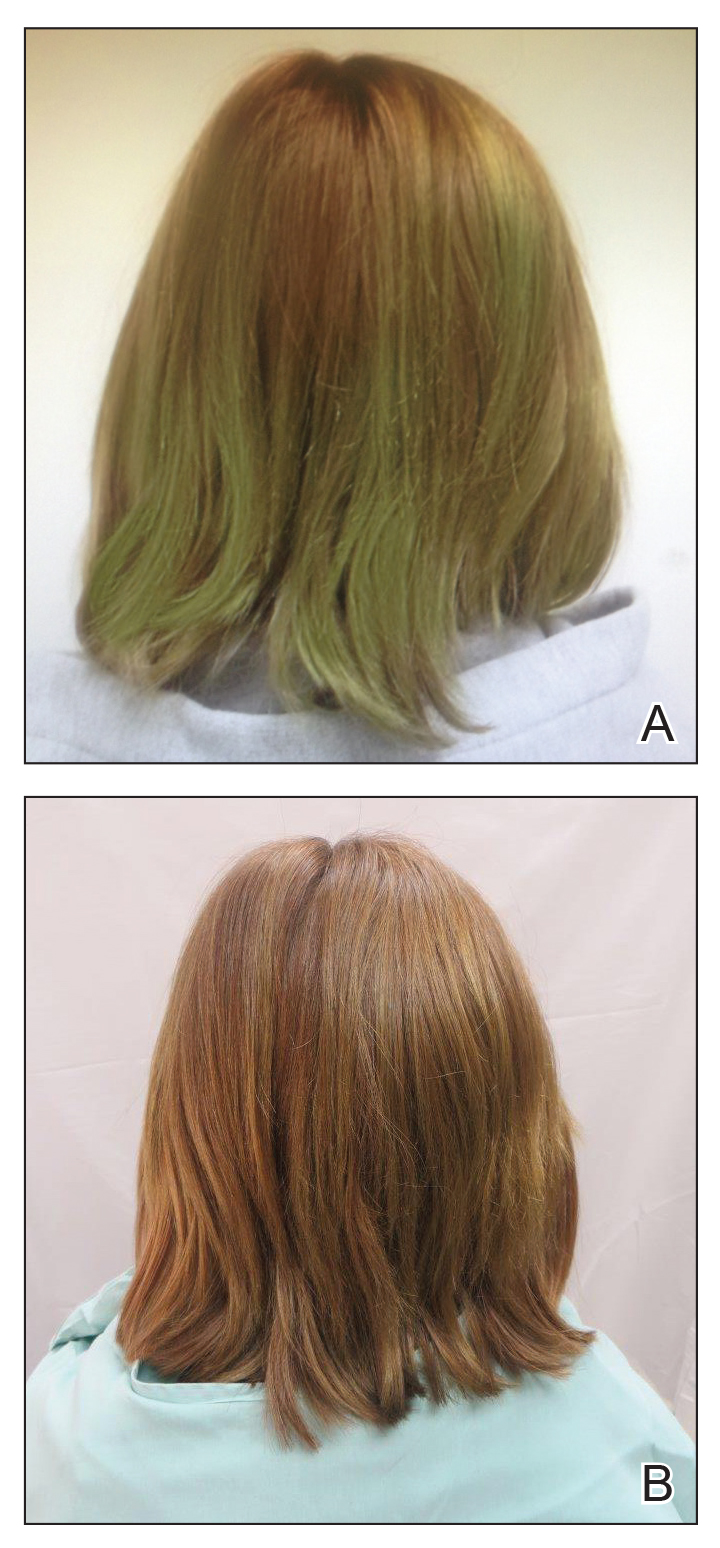

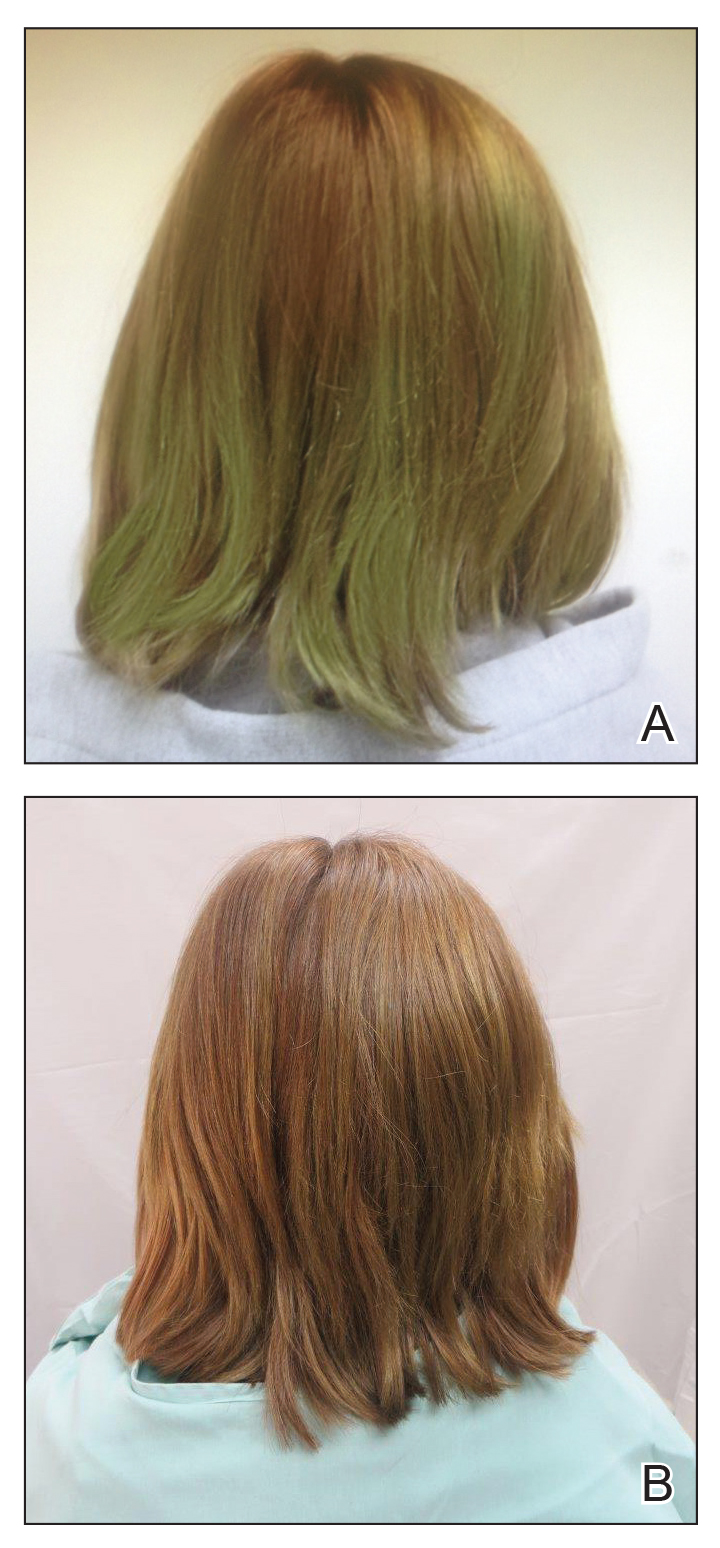

A 13-year-old healthy adolescent girl with brown hair presented with persistent green hair for 2 years (Figure 1A). She had first noted hair discoloration after swimming in a neighbor’s chlorinated outdoor pool during summertime but experienced year-round persistence even without swimming. She denied any history of typical risk factors for hair damage, including exposure to hair dye or bleach, styling products, heat, or mechanical damage from excessive brushing. Her sister had blonde hair with a history of similar activities and exposures, and although she did style her hair with heat, she did not develop hair discoloration. The patient lived in a newer home, and prior tap water testing did not show elevated levels of copper. She admitted to strictly wearing her hair down at all times, including during strenuous activity and swimming. Excessive teasing at school prompted her mother to seek advice from hair salons. Bleaching test strips of hair reportedly caused paradoxical intensification of green, and the patient declined recommendations for red hair dye. The patient also tried Internet-based suggestions such as topically applying crushed aspirin, lemon juice, tea tree oil, and clarifying shampoos, which all failed to result in notable improvement.

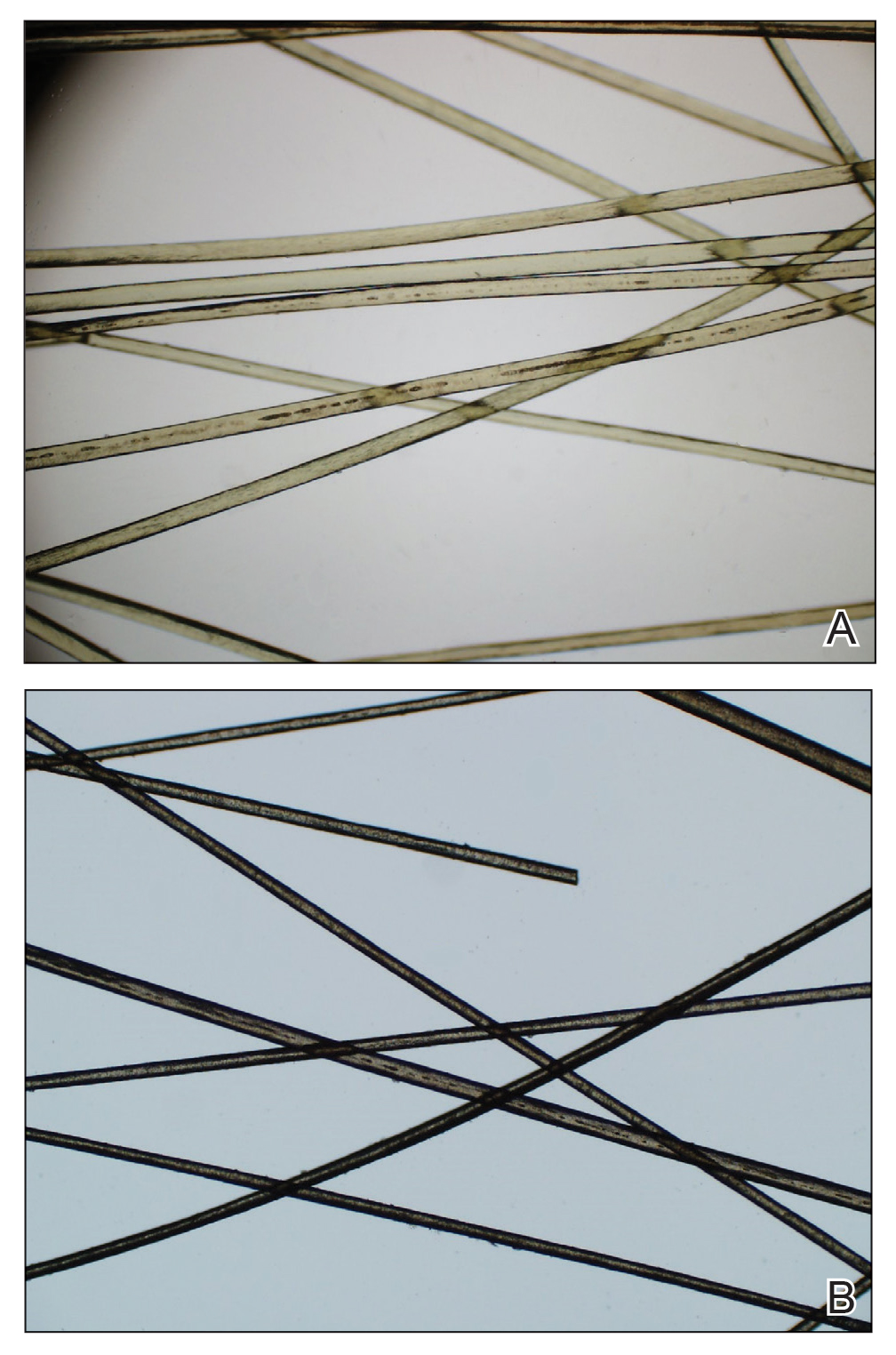

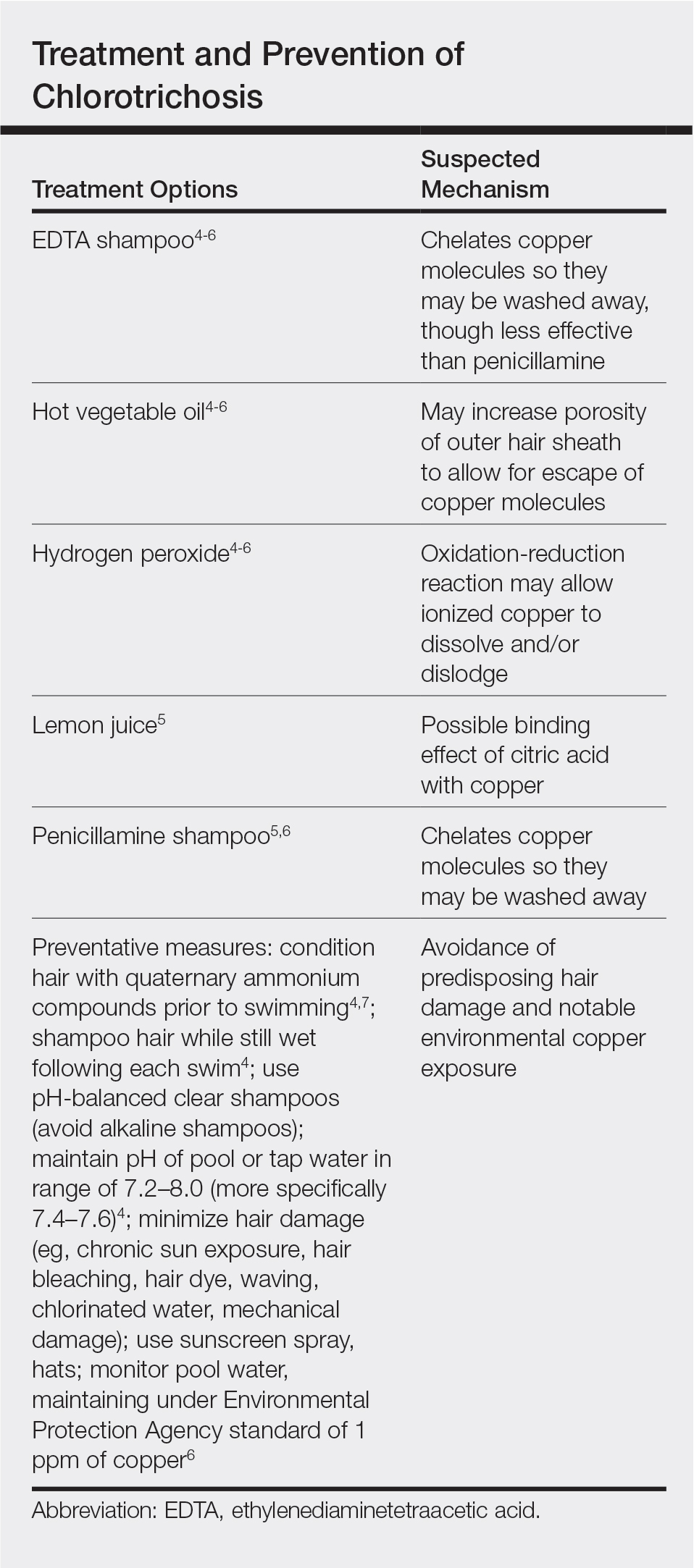

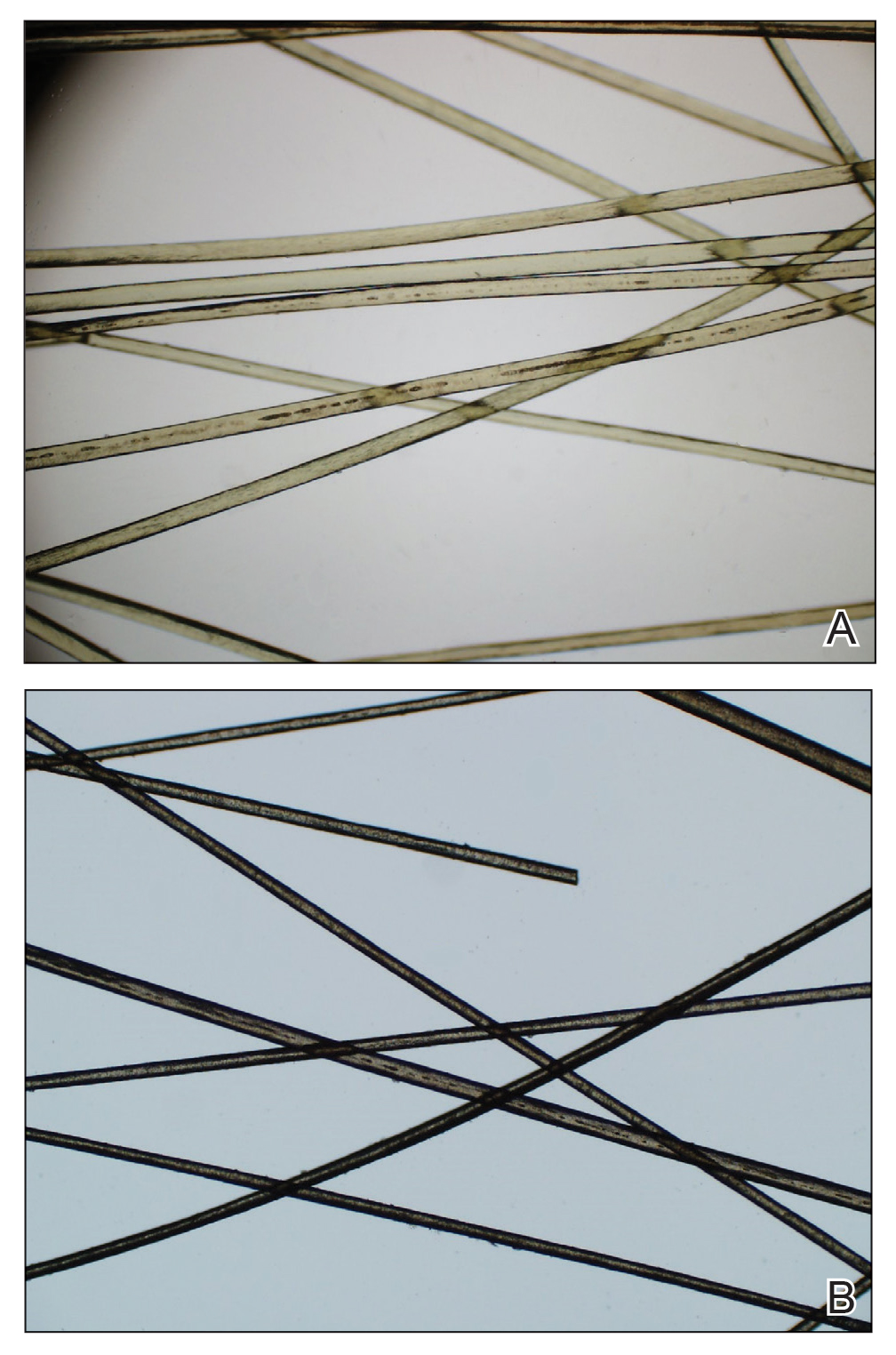

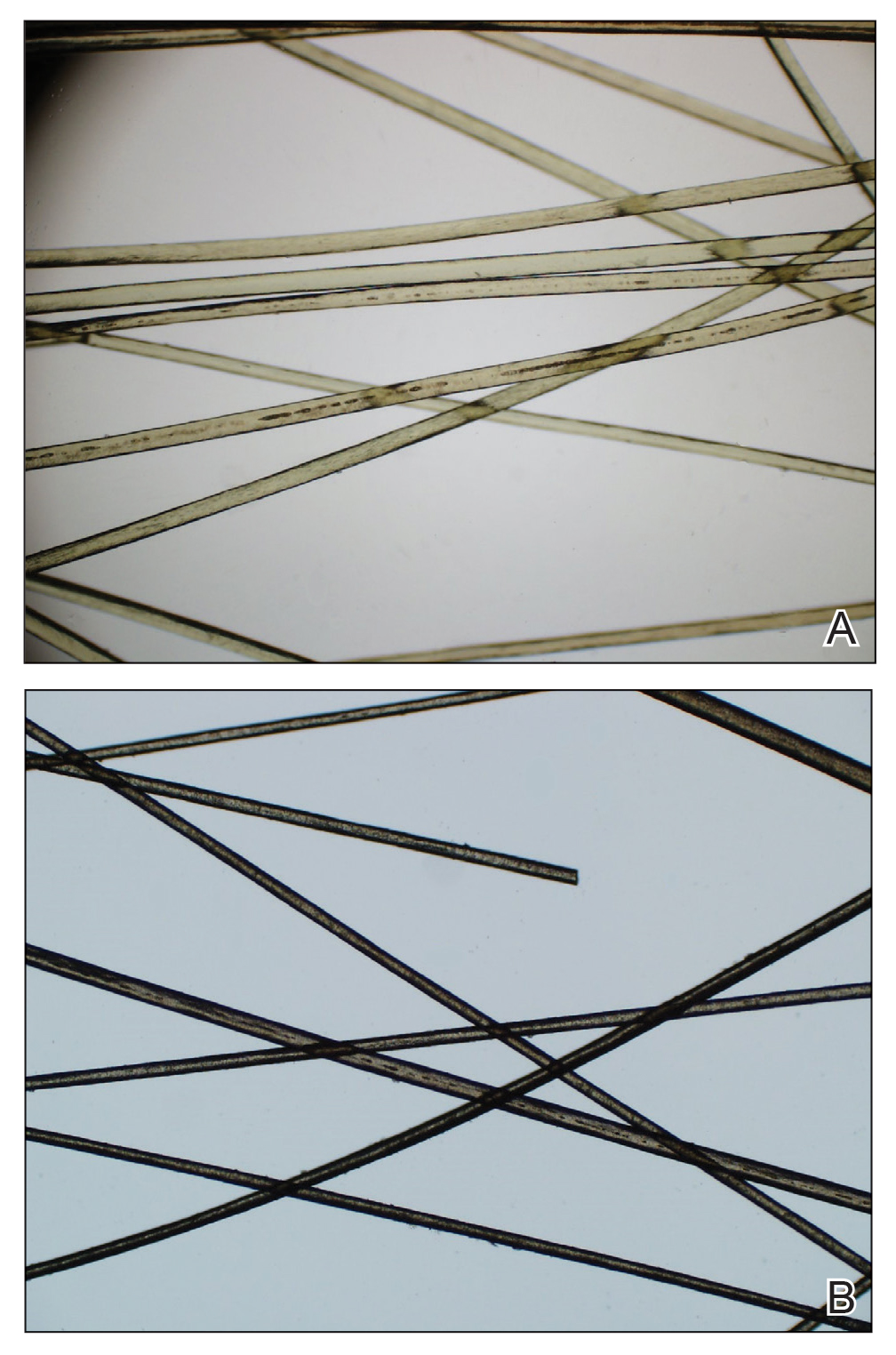

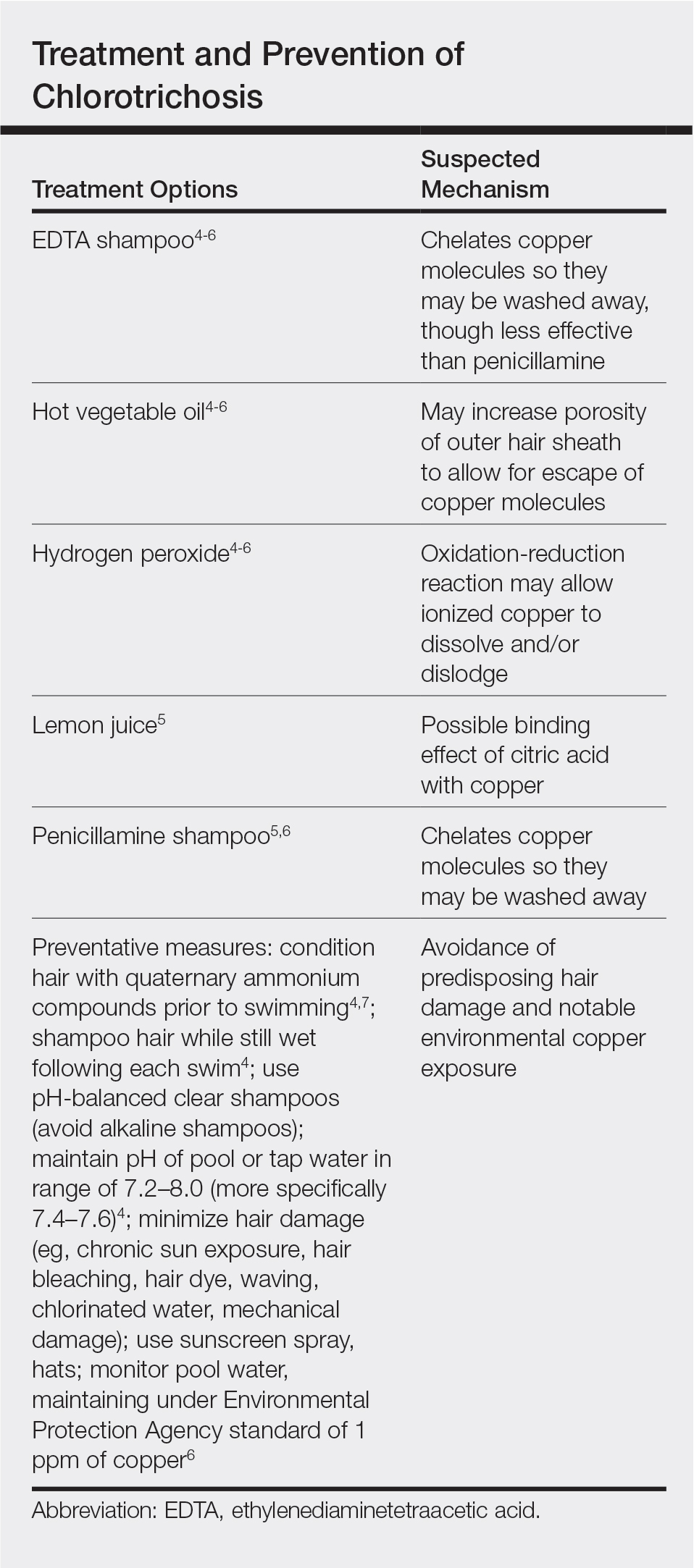

Physical examination revealed a sun-exposed distribution of ashy green hair that was worse at the distal hair ends and completely spared the roots. Trichoscopy of discolored hair (Figure 2A) revealed diffuse cuticle thinning, whereas unaffected hair appeared normal (Figure 2B). Because the patient reported slight improvement with tea tree oil, treatment was initiated with twice-weekly hot vegetable oil treatments applied for 20 minutes, which ultimately proved unsuccessful. Penicillamine shampoo (250-mg capsule of penicillamine into 5-mL purified water and 5-mL pH-balanced clear shampoo) was then recommended. At 3-month follow-up, the patient exhibited notable improvement of the hair discoloration, with only mild persistence at the distal ends of sun-damaged hair, visible only under fluorescent lighting (Figure 1B). Our recommendations thereafter were focused on prevention (Table).

The source of exogenous copper in chlorotrichosis commonly is tap water flowing through copper pipes or swimming pools rich in chlorine and copper-containing algaecides.2,4,8 The acidity of tap water is thought to cause the release of copper from the pipes.2,5 Such acidity could result from the effects of acid rain on water reservoirs or from water additives such as fluoride2 or those used in decalcification systems.5 Additionally, the attachment of electrical grounds to copper piping can cause copper to solubilize through an electric current, increasing water levels of copper.3 Although low pH facilitates copper solubility, high pH within the hair facilitates copper precipitation, which is quickly followed by adhesion to anionic molecules within hair shafts. Therefore, it is postulated that chlorotrichosis may persist in insufficiently rinsed hair with residual alkaline shampoo.6

Beyond pH flux in the induction of chlorotrichosis, other environmental agents have been suspected to play a role. A case report of green hair in a black patient following use of selenium sulfide 2.5% shampoo identified hair damage from tinea capitis infection as predisposing to chlorotrichosis.9 Other reports have cited tar shampoo and industrial exposure to cobalt, nickel, brass, mercury, or chromium as causative factors.2,3,6,7 Interestingly, green hair discoloration also has been observed in the metabolic disorder phenylketonuria.1

Few individuals exposed to elevated levels of copper will develop chlorotrichosis, which emphasizes the critical role of predisposing hair damage in its pathogenesis. With violation of the hair cuticle, chlorine can crystallize and copper can adhere to the hair shaft.10 Bleaching and waving of the hair also appear to alter the composition of keratin by increasing the number of cysteic acid and similar anionic sulfonate groups, which can bind copper.8

Although not harmful, chlorotrichosis may be aesthetically undesirable and lead to considerable social ostracism. Without intrinsic hair defects or obvious differences in predisposing factors, the question was raised as to why our patient, as a brunette, experienced dramatic hair discoloration while her blonde sister was entirely unaffected. We postulated that our patient’s persistent green hair may have been due to her unique predisposition to extensive sun-induced and mechanical hair damage because of her unwavering tendency to wear her hair down at all times. A variety of treatments of variable reported efficacy have been proposed (Table); fortunately, if treatments fail, the discoloration resolves with hair growth.

This case is unique in that it presented in a brunette patient with seemingly minimal hair damage with an unaffected blonde-haired sibling and with persistence over years. Furthermore, it lends credence to the use of penicillamine shampoo in treating chlorotrichosis, even in particularly difficult cases in which other treatments have failed.

- Holmes LB, Goldsmith LA. The man with green hair [letter]. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:1037.

Lampe RM, Henderson AL, Hansen GH. Green hair. JAMA. 1977;237:2092. - Nordlund JJ, Hartley C, Fister J. On the cause of green hair. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1700.

- Goldschmidt H. Green hair. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1288.

- Hinz T, Klingmuller K, Bieber T, et al. The mystery of green hair. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:409-410.

- Mascaro JM Jr, Ferrando J, Fontarnau R, et al. Green hair. Cutis. 1995;56:37-40.

- Bhat GR, Lukenbach ER, Kennedy RR, et al. The green hair problem: a preliminary investigation. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1979;30:1-8.

- Blanc D, Zultak M, Rochefort A, et al. Green hair: clinical, chemical and epidemiologic study. apropos of a case. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1988;115:807-812.

- Fitzgerald EA, Purcell SM, Goldman HM. Green hair discoloration due to selenium sulfide. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:238-239.

- Fair NB, Gupta BS. The chlorine-hair interaction. II. effect of chlorination at varied pH levels on hair properties. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1987;38:371-384.

To the Editor:

Chlorotrichosis, or green hair discoloration, is a dermatologic condition secondary to copper deposition on the hair. It most often is seen among swimmers who have prolonged exposure to chlorinated pools. The classic patient has predisposing chemical, heat, or mechanical damage to the hair shaft and usually lighter-colored hair.1-3 We present a case of chlorotrichosis in a young brunette patient who did not have predisposing factors except for chronic sun exposure.

A 13-year-old healthy adolescent girl with brown hair presented with persistent green hair for 2 years (Figure 1A). She had first noted hair discoloration after swimming in a neighbor’s chlorinated outdoor pool during summertime but experienced year-round persistence even without swimming. She denied any history of typical risk factors for hair damage, including exposure to hair dye or bleach, styling products, heat, or mechanical damage from excessive brushing. Her sister had blonde hair with a history of similar activities and exposures, and although she did style her hair with heat, she did not develop hair discoloration. The patient lived in a newer home, and prior tap water testing did not show elevated levels of copper. She admitted to strictly wearing her hair down at all times, including during strenuous activity and swimming. Excessive teasing at school prompted her mother to seek advice from hair salons. Bleaching test strips of hair reportedly caused paradoxical intensification of green, and the patient declined recommendations for red hair dye. The patient also tried Internet-based suggestions such as topically applying crushed aspirin, lemon juice, tea tree oil, and clarifying shampoos, which all failed to result in notable improvement.

Physical examination revealed a sun-exposed distribution of ashy green hair that was worse at the distal hair ends and completely spared the roots. Trichoscopy of discolored hair (Figure 2A) revealed diffuse cuticle thinning, whereas unaffected hair appeared normal (Figure 2B). Because the patient reported slight improvement with tea tree oil, treatment was initiated with twice-weekly hot vegetable oil treatments applied for 20 minutes, which ultimately proved unsuccessful. Penicillamine shampoo (250-mg capsule of penicillamine into 5-mL purified water and 5-mL pH-balanced clear shampoo) was then recommended. At 3-month follow-up, the patient exhibited notable improvement of the hair discoloration, with only mild persistence at the distal ends of sun-damaged hair, visible only under fluorescent lighting (Figure 1B). Our recommendations thereafter were focused on prevention (Table).

The source of exogenous copper in chlorotrichosis commonly is tap water flowing through copper pipes or swimming pools rich in chlorine and copper-containing algaecides.2,4,8 The acidity of tap water is thought to cause the release of copper from the pipes.2,5 Such acidity could result from the effects of acid rain on water reservoirs or from water additives such as fluoride2 or those used in decalcification systems.5 Additionally, the attachment of electrical grounds to copper piping can cause copper to solubilize through an electric current, increasing water levels of copper.3 Although low pH facilitates copper solubility, high pH within the hair facilitates copper precipitation, which is quickly followed by adhesion to anionic molecules within hair shafts. Therefore, it is postulated that chlorotrichosis may persist in insufficiently rinsed hair with residual alkaline shampoo.6

Beyond pH flux in the induction of chlorotrichosis, other environmental agents have been suspected to play a role. A case report of green hair in a black patient following use of selenium sulfide 2.5% shampoo identified hair damage from tinea capitis infection as predisposing to chlorotrichosis.9 Other reports have cited tar shampoo and industrial exposure to cobalt, nickel, brass, mercury, or chromium as causative factors.2,3,6,7 Interestingly, green hair discoloration also has been observed in the metabolic disorder phenylketonuria.1

Few individuals exposed to elevated levels of copper will develop chlorotrichosis, which emphasizes the critical role of predisposing hair damage in its pathogenesis. With violation of the hair cuticle, chlorine can crystallize and copper can adhere to the hair shaft.10 Bleaching and waving of the hair also appear to alter the composition of keratin by increasing the number of cysteic acid and similar anionic sulfonate groups, which can bind copper.8

Although not harmful, chlorotrichosis may be aesthetically undesirable and lead to considerable social ostracism. Without intrinsic hair defects or obvious differences in predisposing factors, the question was raised as to why our patient, as a brunette, experienced dramatic hair discoloration while her blonde sister was entirely unaffected. We postulated that our patient’s persistent green hair may have been due to her unique predisposition to extensive sun-induced and mechanical hair damage because of her unwavering tendency to wear her hair down at all times. A variety of treatments of variable reported efficacy have been proposed (Table); fortunately, if treatments fail, the discoloration resolves with hair growth.

This case is unique in that it presented in a brunette patient with seemingly minimal hair damage with an unaffected blonde-haired sibling and with persistence over years. Furthermore, it lends credence to the use of penicillamine shampoo in treating chlorotrichosis, even in particularly difficult cases in which other treatments have failed.

To the Editor:

Chlorotrichosis, or green hair discoloration, is a dermatologic condition secondary to copper deposition on the hair. It most often is seen among swimmers who have prolonged exposure to chlorinated pools. The classic patient has predisposing chemical, heat, or mechanical damage to the hair shaft and usually lighter-colored hair.1-3 We present a case of chlorotrichosis in a young brunette patient who did not have predisposing factors except for chronic sun exposure.

A 13-year-old healthy adolescent girl with brown hair presented with persistent green hair for 2 years (Figure 1A). She had first noted hair discoloration after swimming in a neighbor’s chlorinated outdoor pool during summertime but experienced year-round persistence even without swimming. She denied any history of typical risk factors for hair damage, including exposure to hair dye or bleach, styling products, heat, or mechanical damage from excessive brushing. Her sister had blonde hair with a history of similar activities and exposures, and although she did style her hair with heat, she did not develop hair discoloration. The patient lived in a newer home, and prior tap water testing did not show elevated levels of copper. She admitted to strictly wearing her hair down at all times, including during strenuous activity and swimming. Excessive teasing at school prompted her mother to seek advice from hair salons. Bleaching test strips of hair reportedly caused paradoxical intensification of green, and the patient declined recommendations for red hair dye. The patient also tried Internet-based suggestions such as topically applying crushed aspirin, lemon juice, tea tree oil, and clarifying shampoos, which all failed to result in notable improvement.

Physical examination revealed a sun-exposed distribution of ashy green hair that was worse at the distal hair ends and completely spared the roots. Trichoscopy of discolored hair (Figure 2A) revealed diffuse cuticle thinning, whereas unaffected hair appeared normal (Figure 2B). Because the patient reported slight improvement with tea tree oil, treatment was initiated with twice-weekly hot vegetable oil treatments applied for 20 minutes, which ultimately proved unsuccessful. Penicillamine shampoo (250-mg capsule of penicillamine into 5-mL purified water and 5-mL pH-balanced clear shampoo) was then recommended. At 3-month follow-up, the patient exhibited notable improvement of the hair discoloration, with only mild persistence at the distal ends of sun-damaged hair, visible only under fluorescent lighting (Figure 1B). Our recommendations thereafter were focused on prevention (Table).

The source of exogenous copper in chlorotrichosis commonly is tap water flowing through copper pipes or swimming pools rich in chlorine and copper-containing algaecides.2,4,8 The acidity of tap water is thought to cause the release of copper from the pipes.2,5 Such acidity could result from the effects of acid rain on water reservoirs or from water additives such as fluoride2 or those used in decalcification systems.5 Additionally, the attachment of electrical grounds to copper piping can cause copper to solubilize through an electric current, increasing water levels of copper.3 Although low pH facilitates copper solubility, high pH within the hair facilitates copper precipitation, which is quickly followed by adhesion to anionic molecules within hair shafts. Therefore, it is postulated that chlorotrichosis may persist in insufficiently rinsed hair with residual alkaline shampoo.6

Beyond pH flux in the induction of chlorotrichosis, other environmental agents have been suspected to play a role. A case report of green hair in a black patient following use of selenium sulfide 2.5% shampoo identified hair damage from tinea capitis infection as predisposing to chlorotrichosis.9 Other reports have cited tar shampoo and industrial exposure to cobalt, nickel, brass, mercury, or chromium as causative factors.2,3,6,7 Interestingly, green hair discoloration also has been observed in the metabolic disorder phenylketonuria.1

Few individuals exposed to elevated levels of copper will develop chlorotrichosis, which emphasizes the critical role of predisposing hair damage in its pathogenesis. With violation of the hair cuticle, chlorine can crystallize and copper can adhere to the hair shaft.10 Bleaching and waving of the hair also appear to alter the composition of keratin by increasing the number of cysteic acid and similar anionic sulfonate groups, which can bind copper.8

Although not harmful, chlorotrichosis may be aesthetically undesirable and lead to considerable social ostracism. Without intrinsic hair defects or obvious differences in predisposing factors, the question was raised as to why our patient, as a brunette, experienced dramatic hair discoloration while her blonde sister was entirely unaffected. We postulated that our patient’s persistent green hair may have been due to her unique predisposition to extensive sun-induced and mechanical hair damage because of her unwavering tendency to wear her hair down at all times. A variety of treatments of variable reported efficacy have been proposed (Table); fortunately, if treatments fail, the discoloration resolves with hair growth.

This case is unique in that it presented in a brunette patient with seemingly minimal hair damage with an unaffected blonde-haired sibling and with persistence over years. Furthermore, it lends credence to the use of penicillamine shampoo in treating chlorotrichosis, even in particularly difficult cases in which other treatments have failed.

- Holmes LB, Goldsmith LA. The man with green hair [letter]. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:1037.

Lampe RM, Henderson AL, Hansen GH. Green hair. JAMA. 1977;237:2092. - Nordlund JJ, Hartley C, Fister J. On the cause of green hair. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1700.

- Goldschmidt H. Green hair. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1288.

- Hinz T, Klingmuller K, Bieber T, et al. The mystery of green hair. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:409-410.

- Mascaro JM Jr, Ferrando J, Fontarnau R, et al. Green hair. Cutis. 1995;56:37-40.

- Bhat GR, Lukenbach ER, Kennedy RR, et al. The green hair problem: a preliminary investigation. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1979;30:1-8.

- Blanc D, Zultak M, Rochefort A, et al. Green hair: clinical, chemical and epidemiologic study. apropos of a case. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1988;115:807-812.

- Fitzgerald EA, Purcell SM, Goldman HM. Green hair discoloration due to selenium sulfide. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:238-239.

- Fair NB, Gupta BS. The chlorine-hair interaction. II. effect of chlorination at varied pH levels on hair properties. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1987;38:371-384.

- Holmes LB, Goldsmith LA. The man with green hair [letter]. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:1037.

Lampe RM, Henderson AL, Hansen GH. Green hair. JAMA. 1977;237:2092. - Nordlund JJ, Hartley C, Fister J. On the cause of green hair. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1700.

- Goldschmidt H. Green hair. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1288.

- Hinz T, Klingmuller K, Bieber T, et al. The mystery of green hair. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:409-410.

- Mascaro JM Jr, Ferrando J, Fontarnau R, et al. Green hair. Cutis. 1995;56:37-40.

- Bhat GR, Lukenbach ER, Kennedy RR, et al. The green hair problem: a preliminary investigation. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1979;30:1-8.

- Blanc D, Zultak M, Rochefort A, et al. Green hair: clinical, chemical and epidemiologic study. apropos of a case. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1988;115:807-812.

- Fitzgerald EA, Purcell SM, Goldman HM. Green hair discoloration due to selenium sulfide. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:238-239.

- Fair NB, Gupta BS. The chlorine-hair interaction. II. effect of chlorination at varied pH levels on hair properties. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1987;38:371-384.

Practice Points

- Chlorotrichosis is the deposition of copper onto hair, which causes a green discoloration and most commonly occurs in blonde patients with excessive exposure to chlorinated water.

- Hair cuticle damage from hair care practices, such as use of heat or chemicals, can predispose patients to the development of chlorotrichosis.

- Although a number of treatments have been proposed, the use of penicillamine shampoo seems to be particularly effective and works via chelation of the adherent copper molecules.

Unilateral Vesicular Eruption in a Neonate

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

A 4-day-old female neonate presented to the dermatology clinic with a vesicular eruption on the left leg of 1 day's duration. The eruption was asymptomatic without any extracutaneous findings. This term infant was born without complication, and the mother denied any symptoms consistent with herpes simplex virus infection. Physical examination revealed yellow-red vesicles on an erythematous base in a blaschkoid distribution on the left leg. The rest of the examination was unremarkable. Herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction testing was negative.

Prioritize oral health in children with DEB

LONDON – , pediatric dentist Susanne Krämer told attendees at the first EB World Congress.

While it may not be the first thing on the minds of families coming to terms with their children having a chronic and potentially debilitating skin disease, it is important to consider oral health early to ensure healthy dentition and mouth function, both of which will affect the ability to eat and thus nutrition.

When there are a lot of other health issues, “dentistry is not a priority,” Dr. Krämer acknowledged in an interview at the meeting, organized by the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Association (DEBRA).

Something as simple as brushing teeth can be very distressing for parents of a child with EB, she observed, especially if there is dysphagia and toothpaste may be getting into the airways accidentally.

Oral health was one of the topics that patients with EB and their families said would be good to have some guidance on when they were surveyed by DEBRA International. This led the charity to develop its first clinical practice guideline in 2012. Dr. Krämer was the lead author of the guidelines, which are about to be updated and republished.

The “Oral Health for Patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa – Best Clinical Practice Guidelines” (Int J Paediatr Dent. 2012;22 Suppl 1:1-35) are in the final stages of being revised, said Dr. Krämer, who is head of the department of pediatric dentistry at the University of Chile in Santiago. Although there is not much new evidence since the guidelines were first published, “we do have a lot of new technologies within dentistry that can aid the care of EB,” she said.

An important addition to the upcoming 2020 guidelines is a chapter on the patient-clinician partnership. This was added because “you can have fantastic technologies, but if you don’t have a confident relationship with the family and the patient, you won’t be able to proceed.” Dr. Krämer explained: “Patients with EB are so fragile and so afraid of being hurt that they won’t open their mouth unless there is a confidence with the clinician and they trust [him or her]; once they trust, they [will] open the mouth and you can work.”

Dr. Krämer noted that timing of the first dental appointment will depend on the referral pathway for every country and then every service. In her specialist practice the aim is to see newly diagnosed babies before the age of 3 months. “Lots of people would argue they don’t have teeth, but I need to educate the families on several aspects of oral health from early on.”

Older patients with EB may be more aware of the importance of a healthy mouth from a functional point of view and the need to eat and swallow normally, Dr. Krämer said, adding that the “social aspects of having a healthy smile are very important as well.”

Oral care in EB has come a long way since the 1970s when teeth extraction was recommended as the primary dental treatment option. “If you refer to literature in the 90s, that said we can actually restore the teeth in the patients with EB, and what we are now saying is that we have to prevent oral disease,” Dr. Krämer said.

Can oral disease be prevented completely? Yes, she said, but only in a few patients. “We still have decay in a lot of our patients, but far less than what we have had before. It will depend on the compliance of the family and the patient,” Dr. Krämer noted.

Compliance also is a factor in improving mouth function after surgery, which may be done to prevent the tongue from fusing to the bottom of the mouth and to relieve or prevent microstomia, which limits mouth opening.

“We are doing a lot of surgeries to release the fibrotic scars ... we have done it in both children and adults, but there have been better results in adults, because they are able to comply with the course of exercises” after surgery, Dr. Krämer said.

Results of an as-yet unpublished randomized controlled trial of postoperative mouth exercises demonstrate that patients who did the exercises, which involved using a device to stretch the mouth three times a day for 3 months, saw improvements in mouth opening. Once they stopped doing the exercises, however, these improvements faded. Considering the time spent on dressing changes and other exercises, this is perhaps understandable, she acknowledged.

Prevention, education, continual follow-up, and early referral are key to good oral health, Dr. Krämer emphasized. “If there is patient-clinician partnership confidence, they can have regular checkups with dental cleaning, with a fluoride varnish, different preventive strategies so they do not need to get to the point where they need general anesthesia or extractions.” Extractions still will be done, she added, but more for orthodontic reasons, because the teeth do not fit in the mouth. “That is our ideal world, that is where we want to go.”

LONDON – , pediatric dentist Susanne Krämer told attendees at the first EB World Congress.

While it may not be the first thing on the minds of families coming to terms with their children having a chronic and potentially debilitating skin disease, it is important to consider oral health early to ensure healthy dentition and mouth function, both of which will affect the ability to eat and thus nutrition.

When there are a lot of other health issues, “dentistry is not a priority,” Dr. Krämer acknowledged in an interview at the meeting, organized by the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Association (DEBRA).

Something as simple as brushing teeth can be very distressing for parents of a child with EB, she observed, especially if there is dysphagia and toothpaste may be getting into the airways accidentally.

Oral health was one of the topics that patients with EB and their families said would be good to have some guidance on when they were surveyed by DEBRA International. This led the charity to develop its first clinical practice guideline in 2012. Dr. Krämer was the lead author of the guidelines, which are about to be updated and republished.

The “Oral Health for Patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa – Best Clinical Practice Guidelines” (Int J Paediatr Dent. 2012;22 Suppl 1:1-35) are in the final stages of being revised, said Dr. Krämer, who is head of the department of pediatric dentistry at the University of Chile in Santiago. Although there is not much new evidence since the guidelines were first published, “we do have a lot of new technologies within dentistry that can aid the care of EB,” she said.

An important addition to the upcoming 2020 guidelines is a chapter on the patient-clinician partnership. This was added because “you can have fantastic technologies, but if you don’t have a confident relationship with the family and the patient, you won’t be able to proceed.” Dr. Krämer explained: “Patients with EB are so fragile and so afraid of being hurt that they won’t open their mouth unless there is a confidence with the clinician and they trust [him or her]; once they trust, they [will] open the mouth and you can work.”