User login

Risk factors found for respiratory AEs in children following OSA surgery

Underlying cardiac disease, airway anomalies, and younger age each independently boosted the risk of severe perioperative respiratory adverse events (PRAE) in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy to treat obstructive sleep apnea, in a review of 374 patients treated at a single Canadian tertiary-referral center.

In contrast, the analysis failed to show independent, significant effects from any assessed polysomnography or oximetry parameters on the rate of postoperative respiratory complications. The utility of preoperative polysomnography or oximetry for risk stratification is questionable for pediatric patients scheduled to adenotonsillectomy to treat obstructive sleep apnea, wrote Sherri L. Katz, MD, of the University of Ottawa, and associates in a recent report published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, although they also added that making these assessments may be “unavoidable” because of their need for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea and determining the need for surgery.

Despite this caveat, “overall our study results highlight the need to better define the complex interaction between comorbidities, age, nocturnal respiratory events, and gas exchange abnormalities in predicting risk for PRAE” after adenotonsillectomy, the researchers wrote. These findings “are consistent with existing clinical care guidelines,” and “cardiac and craniofacial conditions have been associated with risk of postoperative complications in other studies.”

The analysis used data collected from all children aged 0-18 years who underwent polysomnography assessment followed by adenotonsillectomy at one Canadian tertiary-referral center, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa, during 2010-2016. Their median age was just over 6 years, and 39 patients (10%) were younger than 3 years at the time of their surgery. More than three-quarters of the patients, 286, had at least one identified comorbidity, and nearly half had at least two comorbidities. Polysomnography identified sleep-disordered breathing in 344 of the children (92%), and diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea in 256 (68%), including 148 (43% of the full cohort) with a severe apnea-hypopnea index.

Sixty-six of the children (18%) had at least one severe PRAE that required intervention. Specifically these were either oxygen desaturations requiring intervention or need for airway or ventilatory support with interventions such as jaw thrust, oral or nasal airway placement, bag and mask ventilation, or endotracheal intubation.

A multivariate regression analysis of the measured comorbidity, polysomnography, and oximetry parameters, as well as age, identified three factors that independently linked with a statistically significant increase in the rate of severe PRAE: airway anomaly, underlying cardiac disease, and young age. Patients with an airway anomaly had a 219% increased rate of PRAE, compared with those with no anomaly; patients with underlying cardiac disease had a 109% increased rate, compared with those without cardiac disease; and patients aged younger than 3 years had a 310% higher rate of PRAE, compared with the children aged 6 years or older, while children aged 3-5 years had a 121% higher rate of PRAE, compared with older children.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Katz has received honoraria for speaking from Biogen that had no relevance to the study.

SOURCE: Katz SL et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 Jan 15;16(1):41-8.

This well-conducted, retrospective, chart-review study adds important information to the published literature about risk stratification for children in a tertiary-referral population undergoing adenotonsillectomy. Their findings indicate that younger children remain at higher risk as well as those children with complex comorbid medical disease. They also show that children with severe sleep apnea or significant oxyhemoglobin desaturation are likewise at higher risk of postoperative respiratory compromise – emphasizing the need for preoperative polysomnography – particularly in a tertiary setting where many patients have medical comorbidities.

Despite the strengths of this study in assessing perioperative risk for respiratory compromise in a referral population with highly prevalent medical comorbidities, this study does not provide significant insight into the management of otherwise healthy children in a community setting who are undergoing adenotonsillectomy. This is important because a large number of adenotonsillectomies are performed outside of a tertiary-referral center and many of these children may not have undergone preoperative polysomnography to stratify risk. The utility of preoperative polysomnography in the evaluation of all children undergoing adenotonsillectomy remains controversial, with diverging recommendations from two major U.S. medical groups.

This study does not address the utility of polysomnography in community-based populations of otherwise healthy children. It is imperative to accurately ascertain risk so perioperative planning can ensure the safety of children at higher risk following adenotonsillectomy; however, there remains a paucity of studies assessing the cost-effectiveness as well as the positive and negative predictive value of polysomnographic findings. This study highlights the need for community-based studies of otherwise healthy children undergoing adenotonsillectomy to ensure that children at risk receive appropriate monitoring in an inpatient setting whereas those at lesser risk are not unnecessarily hospitalized postoperatively.

Heidi V. Connolly, MD, and Laura E. Tomaselli, MD, are pediatric sleep medicine physicians, and Margo K. McKenna Benoit, MD, is an otolaryngologist at the University of Rochester (N.Y.). They made these comments in a commentary that accompanied the published report ( J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 Jan 15;16[1]:3-4 ). They had no disclosures.

This well-conducted, retrospective, chart-review study adds important information to the published literature about risk stratification for children in a tertiary-referral population undergoing adenotonsillectomy. Their findings indicate that younger children remain at higher risk as well as those children with complex comorbid medical disease. They also show that children with severe sleep apnea or significant oxyhemoglobin desaturation are likewise at higher risk of postoperative respiratory compromise – emphasizing the need for preoperative polysomnography – particularly in a tertiary setting where many patients have medical comorbidities.

Despite the strengths of this study in assessing perioperative risk for respiratory compromise in a referral population with highly prevalent medical comorbidities, this study does not provide significant insight into the management of otherwise healthy children in a community setting who are undergoing adenotonsillectomy. This is important because a large number of adenotonsillectomies are performed outside of a tertiary-referral center and many of these children may not have undergone preoperative polysomnography to stratify risk. The utility of preoperative polysomnography in the evaluation of all children undergoing adenotonsillectomy remains controversial, with diverging recommendations from two major U.S. medical groups.

This study does not address the utility of polysomnography in community-based populations of otherwise healthy children. It is imperative to accurately ascertain risk so perioperative planning can ensure the safety of children at higher risk following adenotonsillectomy; however, there remains a paucity of studies assessing the cost-effectiveness as well as the positive and negative predictive value of polysomnographic findings. This study highlights the need for community-based studies of otherwise healthy children undergoing adenotonsillectomy to ensure that children at risk receive appropriate monitoring in an inpatient setting whereas those at lesser risk are not unnecessarily hospitalized postoperatively.

Heidi V. Connolly, MD, and Laura E. Tomaselli, MD, are pediatric sleep medicine physicians, and Margo K. McKenna Benoit, MD, is an otolaryngologist at the University of Rochester (N.Y.). They made these comments in a commentary that accompanied the published report ( J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 Jan 15;16[1]:3-4 ). They had no disclosures.

This well-conducted, retrospective, chart-review study adds important information to the published literature about risk stratification for children in a tertiary-referral population undergoing adenotonsillectomy. Their findings indicate that younger children remain at higher risk as well as those children with complex comorbid medical disease. They also show that children with severe sleep apnea or significant oxyhemoglobin desaturation are likewise at higher risk of postoperative respiratory compromise – emphasizing the need for preoperative polysomnography – particularly in a tertiary setting where many patients have medical comorbidities.

Despite the strengths of this study in assessing perioperative risk for respiratory compromise in a referral population with highly prevalent medical comorbidities, this study does not provide significant insight into the management of otherwise healthy children in a community setting who are undergoing adenotonsillectomy. This is important because a large number of adenotonsillectomies are performed outside of a tertiary-referral center and many of these children may not have undergone preoperative polysomnography to stratify risk. The utility of preoperative polysomnography in the evaluation of all children undergoing adenotonsillectomy remains controversial, with diverging recommendations from two major U.S. medical groups.

This study does not address the utility of polysomnography in community-based populations of otherwise healthy children. It is imperative to accurately ascertain risk so perioperative planning can ensure the safety of children at higher risk following adenotonsillectomy; however, there remains a paucity of studies assessing the cost-effectiveness as well as the positive and negative predictive value of polysomnographic findings. This study highlights the need for community-based studies of otherwise healthy children undergoing adenotonsillectomy to ensure that children at risk receive appropriate monitoring in an inpatient setting whereas those at lesser risk are not unnecessarily hospitalized postoperatively.

Heidi V. Connolly, MD, and Laura E. Tomaselli, MD, are pediatric sleep medicine physicians, and Margo K. McKenna Benoit, MD, is an otolaryngologist at the University of Rochester (N.Y.). They made these comments in a commentary that accompanied the published report ( J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 Jan 15;16[1]:3-4 ). They had no disclosures.

Underlying cardiac disease, airway anomalies, and younger age each independently boosted the risk of severe perioperative respiratory adverse events (PRAE) in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy to treat obstructive sleep apnea, in a review of 374 patients treated at a single Canadian tertiary-referral center.

In contrast, the analysis failed to show independent, significant effects from any assessed polysomnography or oximetry parameters on the rate of postoperative respiratory complications. The utility of preoperative polysomnography or oximetry for risk stratification is questionable for pediatric patients scheduled to adenotonsillectomy to treat obstructive sleep apnea, wrote Sherri L. Katz, MD, of the University of Ottawa, and associates in a recent report published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, although they also added that making these assessments may be “unavoidable” because of their need for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea and determining the need for surgery.

Despite this caveat, “overall our study results highlight the need to better define the complex interaction between comorbidities, age, nocturnal respiratory events, and gas exchange abnormalities in predicting risk for PRAE” after adenotonsillectomy, the researchers wrote. These findings “are consistent with existing clinical care guidelines,” and “cardiac and craniofacial conditions have been associated with risk of postoperative complications in other studies.”

The analysis used data collected from all children aged 0-18 years who underwent polysomnography assessment followed by adenotonsillectomy at one Canadian tertiary-referral center, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa, during 2010-2016. Their median age was just over 6 years, and 39 patients (10%) were younger than 3 years at the time of their surgery. More than three-quarters of the patients, 286, had at least one identified comorbidity, and nearly half had at least two comorbidities. Polysomnography identified sleep-disordered breathing in 344 of the children (92%), and diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea in 256 (68%), including 148 (43% of the full cohort) with a severe apnea-hypopnea index.

Sixty-six of the children (18%) had at least one severe PRAE that required intervention. Specifically these were either oxygen desaturations requiring intervention or need for airway or ventilatory support with interventions such as jaw thrust, oral or nasal airway placement, bag and mask ventilation, or endotracheal intubation.

A multivariate regression analysis of the measured comorbidity, polysomnography, and oximetry parameters, as well as age, identified three factors that independently linked with a statistically significant increase in the rate of severe PRAE: airway anomaly, underlying cardiac disease, and young age. Patients with an airway anomaly had a 219% increased rate of PRAE, compared with those with no anomaly; patients with underlying cardiac disease had a 109% increased rate, compared with those without cardiac disease; and patients aged younger than 3 years had a 310% higher rate of PRAE, compared with the children aged 6 years or older, while children aged 3-5 years had a 121% higher rate of PRAE, compared with older children.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Katz has received honoraria for speaking from Biogen that had no relevance to the study.

SOURCE: Katz SL et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 Jan 15;16(1):41-8.

Underlying cardiac disease, airway anomalies, and younger age each independently boosted the risk of severe perioperative respiratory adverse events (PRAE) in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy to treat obstructive sleep apnea, in a review of 374 patients treated at a single Canadian tertiary-referral center.

In contrast, the analysis failed to show independent, significant effects from any assessed polysomnography or oximetry parameters on the rate of postoperative respiratory complications. The utility of preoperative polysomnography or oximetry for risk stratification is questionable for pediatric patients scheduled to adenotonsillectomy to treat obstructive sleep apnea, wrote Sherri L. Katz, MD, of the University of Ottawa, and associates in a recent report published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, although they also added that making these assessments may be “unavoidable” because of their need for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea and determining the need for surgery.

Despite this caveat, “overall our study results highlight the need to better define the complex interaction between comorbidities, age, nocturnal respiratory events, and gas exchange abnormalities in predicting risk for PRAE” after adenotonsillectomy, the researchers wrote. These findings “are consistent with existing clinical care guidelines,” and “cardiac and craniofacial conditions have been associated with risk of postoperative complications in other studies.”

The analysis used data collected from all children aged 0-18 years who underwent polysomnography assessment followed by adenotonsillectomy at one Canadian tertiary-referral center, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa, during 2010-2016. Their median age was just over 6 years, and 39 patients (10%) were younger than 3 years at the time of their surgery. More than three-quarters of the patients, 286, had at least one identified comorbidity, and nearly half had at least two comorbidities. Polysomnography identified sleep-disordered breathing in 344 of the children (92%), and diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea in 256 (68%), including 148 (43% of the full cohort) with a severe apnea-hypopnea index.

Sixty-six of the children (18%) had at least one severe PRAE that required intervention. Specifically these were either oxygen desaturations requiring intervention or need for airway or ventilatory support with interventions such as jaw thrust, oral or nasal airway placement, bag and mask ventilation, or endotracheal intubation.

A multivariate regression analysis of the measured comorbidity, polysomnography, and oximetry parameters, as well as age, identified three factors that independently linked with a statistically significant increase in the rate of severe PRAE: airway anomaly, underlying cardiac disease, and young age. Patients with an airway anomaly had a 219% increased rate of PRAE, compared with those with no anomaly; patients with underlying cardiac disease had a 109% increased rate, compared with those without cardiac disease; and patients aged younger than 3 years had a 310% higher rate of PRAE, compared with the children aged 6 years or older, while children aged 3-5 years had a 121% higher rate of PRAE, compared with older children.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Katz has received honoraria for speaking from Biogen that had no relevance to the study.

SOURCE: Katz SL et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020 Jan 15;16(1):41-8.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL SLEEP MEDICINE

Nail dystrophy and nail plate thinning

At a follow-up visit, a biopsy of the skin on the fingertips was performed, which showed lichenoid lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with associated hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis.

No fungal elements were seen. The findings were consistent with lichen planus.

The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine. It was recommended she start a 6-week course of oral prednisone, but the mother was opposed to systemic treatment because of potential side effects.

She continued topical betamethasone without much change. Topical tacrolimus later was recommended to use on off days of betamethasone, which led to no improvement. Narrow-band UVB also was started with minimal improvement. Unfortunately,

Nail lichen planus (NLP) in children is not a common condition.1 In a recent series from Chiheb et al., NLP was reported in 90 patients, of which 40% were children; a quarter of the patients reported having extracutaneous involvement as well.2 In another childhood LP series,14 % of the children presented with nail disease.3 It can be a severe disease that, if not treated aggressively, may lead to destruction of the nail bed. This condition seems to be more prevalent in boys than girls and more prevalent in African American children.3 Unfortunately, in this patient’s case, the mother was hesitant to use systemic therapy and aggressive treatment was delayed.

Possible but not clear associations with autoimmune conditions such as vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, myasthenia gravis, alopecia areata, thymoma, autoimmune polyendocrinopathy, atopic dermatitis, and lichen nitidus have been described in children with LP.

The clinical characteristics of NLP include nail plate thinning with longitudinal ridging and fissuring, with or without pterygium; trachyonychia; and erythema of the lunula when the nail matrix is involved. When the nail bed is affected, the patient can present with onycholysis with or without subungual hyperkeratosis and violaceous hue of the nail bed.4 NLP can have three different clinical presentations described by Tosti et al., which include typical NLP, 20‐nail dystrophy (trachyonychia), and idiopathic nail atrophy. Idiopathic nail atrophy is described solely in children as an acute and rapid progression that leads to destruction of the nail within months, which appears to be the clinical presentation in our patient.

The differential diagnosis of nail dystrophy in children includes infectious processes such as onychomycosis, especially when children present with onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis. Because of this, it is recommended to perform a nail culture or submit a sample of nail clippings for microscopic evaluation to confirm the diagnosis of onychomycosis prior to starting systemic therapy in children. Fingernail involvement without toenail involvement is an unusual presentation of onychomycosis.

Twenty-nail dystrophy – also known as trachyonychia – can be caused by several inflammatory skin conditions such as lichen planus, psoriasis, eczema, pemphigus vulgaris, and alopecia areata. Clinically, there is uniformly monomorphic thinning of the nail plate with longitudinal ridging without splitting or pterygium.1 This is a benign condition and should not cause scarring. About 10% of the cases of 20-nail dystrophy are caused by lichen planus.

Nail psoriasis is characterized by nail pitting, oil spots on the nail plate, leukonychia, subungual hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis, as well as nail crumbling, which were not seen in our patient. Although her initial presentation was of 20-nail dystrophy, which also can be a presentation of nail psoriasis, its rapid evolution with associated nail atrophy and pterygium make it unlikely to be psoriasis in this particular patient.

Patients with pachyonychia congenita – which is a genetic disorder or keratinization caused by mutations on several genes encoding keratin such as K6a, K16, K17, K6b, and possibly K6c – present with nail thickening (pachyonychia) and discoloration of the nails, as well as pincer nails. These patients also present with oral leukokeratosis and focal palmoplantar keratoderma.

The main treatment of lichen planus is potent topical corticosteroids.

For nail disease, topical treatment may not be effective and systemic treatment may be necessary. Systemic corticosteroids have been used in several pediatric series varying from a short course given at a dose of 1- 2 mg/kg per day for 2 weeks to a longer 3-month course followed by tapering.3 There are several protocols of intramuscular triamcinolone at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg in children in once a month injections for about 3 months that have been reported successful with minimal side effects.1 Other medications reported useful in patients with NLP include dapsone and acitretin. Other treatment options include narrow-band UVB and PUVA.3

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 2001 Aug;137(8):1027-32.

2. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Jan;142(1):21-5.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014 Jan-Feb;31(1):59-67.

4. Dermatological diseases, in “Nails: Diagnosis, Therapy, and Surgery,” 3rd ed. (Oxford: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, p. 105).

At a follow-up visit, a biopsy of the skin on the fingertips was performed, which showed lichenoid lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with associated hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis.

No fungal elements were seen. The findings were consistent with lichen planus.

The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine. It was recommended she start a 6-week course of oral prednisone, but the mother was opposed to systemic treatment because of potential side effects.

She continued topical betamethasone without much change. Topical tacrolimus later was recommended to use on off days of betamethasone, which led to no improvement. Narrow-band UVB also was started with minimal improvement. Unfortunately,

Nail lichen planus (NLP) in children is not a common condition.1 In a recent series from Chiheb et al., NLP was reported in 90 patients, of which 40% were children; a quarter of the patients reported having extracutaneous involvement as well.2 In another childhood LP series,14 % of the children presented with nail disease.3 It can be a severe disease that, if not treated aggressively, may lead to destruction of the nail bed. This condition seems to be more prevalent in boys than girls and more prevalent in African American children.3 Unfortunately, in this patient’s case, the mother was hesitant to use systemic therapy and aggressive treatment was delayed.

Possible but not clear associations with autoimmune conditions such as vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, myasthenia gravis, alopecia areata, thymoma, autoimmune polyendocrinopathy, atopic dermatitis, and lichen nitidus have been described in children with LP.

The clinical characteristics of NLP include nail plate thinning with longitudinal ridging and fissuring, with or without pterygium; trachyonychia; and erythema of the lunula when the nail matrix is involved. When the nail bed is affected, the patient can present with onycholysis with or without subungual hyperkeratosis and violaceous hue of the nail bed.4 NLP can have three different clinical presentations described by Tosti et al., which include typical NLP, 20‐nail dystrophy (trachyonychia), and idiopathic nail atrophy. Idiopathic nail atrophy is described solely in children as an acute and rapid progression that leads to destruction of the nail within months, which appears to be the clinical presentation in our patient.

The differential diagnosis of nail dystrophy in children includes infectious processes such as onychomycosis, especially when children present with onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis. Because of this, it is recommended to perform a nail culture or submit a sample of nail clippings for microscopic evaluation to confirm the diagnosis of onychomycosis prior to starting systemic therapy in children. Fingernail involvement without toenail involvement is an unusual presentation of onychomycosis.

Twenty-nail dystrophy – also known as trachyonychia – can be caused by several inflammatory skin conditions such as lichen planus, psoriasis, eczema, pemphigus vulgaris, and alopecia areata. Clinically, there is uniformly monomorphic thinning of the nail plate with longitudinal ridging without splitting or pterygium.1 This is a benign condition and should not cause scarring. About 10% of the cases of 20-nail dystrophy are caused by lichen planus.

Nail psoriasis is characterized by nail pitting, oil spots on the nail plate, leukonychia, subungual hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis, as well as nail crumbling, which were not seen in our patient. Although her initial presentation was of 20-nail dystrophy, which also can be a presentation of nail psoriasis, its rapid evolution with associated nail atrophy and pterygium make it unlikely to be psoriasis in this particular patient.

Patients with pachyonychia congenita – which is a genetic disorder or keratinization caused by mutations on several genes encoding keratin such as K6a, K16, K17, K6b, and possibly K6c – present with nail thickening (pachyonychia) and discoloration of the nails, as well as pincer nails. These patients also present with oral leukokeratosis and focal palmoplantar keratoderma.

The main treatment of lichen planus is potent topical corticosteroids.

For nail disease, topical treatment may not be effective and systemic treatment may be necessary. Systemic corticosteroids have been used in several pediatric series varying from a short course given at a dose of 1- 2 mg/kg per day for 2 weeks to a longer 3-month course followed by tapering.3 There are several protocols of intramuscular triamcinolone at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg in children in once a month injections for about 3 months that have been reported successful with minimal side effects.1 Other medications reported useful in patients with NLP include dapsone and acitretin. Other treatment options include narrow-band UVB and PUVA.3

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 2001 Aug;137(8):1027-32.

2. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Jan;142(1):21-5.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014 Jan-Feb;31(1):59-67.

4. Dermatological diseases, in “Nails: Diagnosis, Therapy, and Surgery,” 3rd ed. (Oxford: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, p. 105).

At a follow-up visit, a biopsy of the skin on the fingertips was performed, which showed lichenoid lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with associated hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis.

No fungal elements were seen. The findings were consistent with lichen planus.

The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine. It was recommended she start a 6-week course of oral prednisone, but the mother was opposed to systemic treatment because of potential side effects.

She continued topical betamethasone without much change. Topical tacrolimus later was recommended to use on off days of betamethasone, which led to no improvement. Narrow-band UVB also was started with minimal improvement. Unfortunately,

Nail lichen planus (NLP) in children is not a common condition.1 In a recent series from Chiheb et al., NLP was reported in 90 patients, of which 40% were children; a quarter of the patients reported having extracutaneous involvement as well.2 In another childhood LP series,14 % of the children presented with nail disease.3 It can be a severe disease that, if not treated aggressively, may lead to destruction of the nail bed. This condition seems to be more prevalent in boys than girls and more prevalent in African American children.3 Unfortunately, in this patient’s case, the mother was hesitant to use systemic therapy and aggressive treatment was delayed.

Possible but not clear associations with autoimmune conditions such as vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, myasthenia gravis, alopecia areata, thymoma, autoimmune polyendocrinopathy, atopic dermatitis, and lichen nitidus have been described in children with LP.

The clinical characteristics of NLP include nail plate thinning with longitudinal ridging and fissuring, with or without pterygium; trachyonychia; and erythema of the lunula when the nail matrix is involved. When the nail bed is affected, the patient can present with onycholysis with or without subungual hyperkeratosis and violaceous hue of the nail bed.4 NLP can have three different clinical presentations described by Tosti et al., which include typical NLP, 20‐nail dystrophy (trachyonychia), and idiopathic nail atrophy. Idiopathic nail atrophy is described solely in children as an acute and rapid progression that leads to destruction of the nail within months, which appears to be the clinical presentation in our patient.

The differential diagnosis of nail dystrophy in children includes infectious processes such as onychomycosis, especially when children present with onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis. Because of this, it is recommended to perform a nail culture or submit a sample of nail clippings for microscopic evaluation to confirm the diagnosis of onychomycosis prior to starting systemic therapy in children. Fingernail involvement without toenail involvement is an unusual presentation of onychomycosis.

Twenty-nail dystrophy – also known as trachyonychia – can be caused by several inflammatory skin conditions such as lichen planus, psoriasis, eczema, pemphigus vulgaris, and alopecia areata. Clinically, there is uniformly monomorphic thinning of the nail plate with longitudinal ridging without splitting or pterygium.1 This is a benign condition and should not cause scarring. About 10% of the cases of 20-nail dystrophy are caused by lichen planus.

Nail psoriasis is characterized by nail pitting, oil spots on the nail plate, leukonychia, subungual hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis, as well as nail crumbling, which were not seen in our patient. Although her initial presentation was of 20-nail dystrophy, which also can be a presentation of nail psoriasis, its rapid evolution with associated nail atrophy and pterygium make it unlikely to be psoriasis in this particular patient.

Patients with pachyonychia congenita – which is a genetic disorder or keratinization caused by mutations on several genes encoding keratin such as K6a, K16, K17, K6b, and possibly K6c – present with nail thickening (pachyonychia) and discoloration of the nails, as well as pincer nails. These patients also present with oral leukokeratosis and focal palmoplantar keratoderma.

The main treatment of lichen planus is potent topical corticosteroids.

For nail disease, topical treatment may not be effective and systemic treatment may be necessary. Systemic corticosteroids have been used in several pediatric series varying from a short course given at a dose of 1- 2 mg/kg per day for 2 weeks to a longer 3-month course followed by tapering.3 There are several protocols of intramuscular triamcinolone at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg in children in once a month injections for about 3 months that have been reported successful with minimal side effects.1 Other medications reported useful in patients with NLP include dapsone and acitretin. Other treatment options include narrow-band UVB and PUVA.3

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 2001 Aug;137(8):1027-32.

2. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Jan;142(1):21-5.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014 Jan-Feb;31(1):59-67.

4. Dermatological diseases, in “Nails: Diagnosis, Therapy, and Surgery,” 3rd ed. (Oxford: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, p. 105).

An 8-year-old female child comes to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of onychomycosis on her fingernails. The mother stated the child started developing funny-looking nails 1 year prior to the visit. It started with only two fingernails affected and now has spread to all her fingernails. Her toenails are not involved.

She denied any pain or itching. She initially was treated with topical antifungal medications as well as tea tree oil, apple cider vinegar, and a 6-week course of oral griseofulvin without any improvement. Her nails progressively have gotten much worse. She has no history of atopic dermatitis or any other skin conditions. She denied any joint pain, sun sensitivity, hair loss, or any other symptoms. The mother denied any family history of nail fungus, ringworm, psoriasis, or eczema.

She likes to play basketball and enjoys arts and crafts. She has a cat and a dog; neither of them have any skin problems.

On physical examination, there is nail dystrophy with nail plate thinning and longitudinal fissuring of all fingernails but not of the toenails. She also has hyperpigmented violaceous plaques on the surrounding periungual skin. There are no other skin lesions, and there are no oral or genital lesions. There is no scalp involvement or hair loss. At follow-up several months later, she had complete destruction of the nail plate with scar formation.

A fungal culture was performed, as well as microscopic analysis of the nail with periodic acid fast and giemsa stains, which showed no fungal organisms.

She initially was treated with topical betamethasone twice a day for 6 weeks and then 2 weeks on and 2 weeks off without much change.

Play it as it lies: Handling lying by kids

“Not my son!” your patient’s parent rants. “If he lies to me, he will regret it for a long time.” While your first reaction may be to agree that a child lying to a parent crosses a kind of moral line in the sand, lying is a far more nuanced part of parenting worth a deeper understanding.

In order to lie, a child has to develop cognitive and social understanding. Typically developing children look to see what is interesting to others, called “joint attention,” at around 12-18 months. Failure to do this is one of the early signs of autism reflecting atypical social understanding. At around 3.5 years, children may attempt to deceive if they have broken a rule. The study demonstrating this may sound a lot like home: Children are left alone with a tempting toy but told not to touch it. Although they do touch it while the adult is out of sight, they say rather sweetly (and eventually convincingly) that they did not, even though the toy was clearly moved! While boys generally have more behavior problems, girls and children with better verbal skills achieve deceit at an earlier age, some as young as 2 years. At this stage, children become aware that the adult can’t know exactly what they know. If the parent shows high emotion to what they consider a lie, this can be a topic for testing! Children with ADHD often lack the inhibition needed for early mastery of deception, and children with autism later or not at all. They don’t see the social point to lying nor can they fake a facial expression. They have a case of intractable honesty!

The inability to refrain from telling the truth can result in social rejection, for example when a child rats on a peer for a trivial misdeed in class. Even though he is speaking the truth and “following the (teacher’s) rules,” he did not see that the cost of breaking the (peer) social rules was more important. By age 6 years, children typically figure out that what another person thinks may not be true – their belief may be incorrect or a “false belief.” This understanding is called Theory of Mind, missing or delayed in autism. Only 40% of high-functioning children with autism passed false belief testing at ages 6- to 13-years-old, compared with 95% of typical age-matched peers (Physiol Behav. 2010 Jun 1;100[3]:268-76). The percentage of children on the spectrum understanding false beliefs more closely matched that of preschoolers (39%). At a later age and given extra time to think, some children with autism can do better at this kind of perspective taking, but many continue having difficulty understanding thoughts of others, especially social expectations or motivations (such as flirting, status seeking, and making an excuse) even as adults. This can impair social relationships even when desire to fit in and IQ are otherwise high.

On the other hand, ADHD is a common condition in which “lying” comes from saying the first thing that comes to mind even if the child knows otherwise. A wise parent of one of my patients with ADHD told me about her “30 second rule” where she would give her child that extra time and walk away briefly to “be sure that is what you wanted to say,” with praise rather than give a consequence for changing the story to the truth. This is an important concept we pediatricians need to know: Punishing lying in children tends to result in more, not less, lying and more sneakiness. Instead, parents need to be advised to recall the origins of the word discipline as being “to teach.”

When children lie there are four basic scenarios: They may not know the rules, they may know but have something they want more, they may be impulsive, or they may have developed an attitude of seeking to con the adults whom they feel are mean as a way to have some power in the relationship and get back at them. Clearly, we do not want to push children to this fourth resort by harsh reactions to lying. We have seen particular difficulty with harsh reactions to lying in parents from strong, rule-oriented careers such as police officers, military, and ministers. Asking “How would your parent have handled this?” often will reveal reasons for their tough but backfiring stance.

Lying can work to get what one wants and nearly all children try it. As with other new milestones, children practice this “skill,” much to parents’ dismay. Parents generally can tell if children are lying; they see it on their faces, hear the story from siblings, or see evidence of what happened. Lying provides an important opportunity for the adult to stop, take some breaths, touch the child, and empathize: “It is hard to admit a mistake. I know you did not mean to do it. But you are young, and I know that you are good and honest inside, and will get stronger and braver at telling the truth as you get older. Will you promise to try harder?” In some cases a consequence may be appropriate, for example if something was broken. Usually, simply empathizing and focusing on the expectation for improvement will increase the child’s desire to please the parents rather than get back at them. Actual rewards for honesty improve truth telling by 1.5 times if the reward is big enough.

But it is important to recognize that we all make split second tactical decisions about our actions based on how safe we feel in the situation and our knowledge of social rules and costs. Children over time need to learn that it is safe to tell the truth among family members and that they will not be harshly dealt with. It is a subtle task, but important to learn that deception is a tool that can be important used judiciously when required socially (I have a curfew) or in dangerous situations (I did not see the thug), but can undermine relationships and should not be used with your allies (family and friends).

But parenting involves lying also, which can be a model for the child. Sarcasm is a peculiar form of problematic adult lying. The adults say the opposite or an exaggeration of what they really mean, usually with a smirk or other nonverbal cue to their intent. This is confusing, if not infuriating, to immature children or those who do not understand this twisted communication. It is best to avoid sarcasm with children, or at least be sure to explain it so the children gain understanding over time.

Parents need to “lie” to their children to some extent to reassure and allow for development of confidence. What adult hasn’t said “It’s going to be all right” about a looming storm, car crash, or illness, when actually there is uncertainty. Children count on adults to keep them safe emotionally and physically from things they can’t yet handle. To move forward developmentally, children need adults to be brave leaders, even when the adults don’t feel confident. Some parents think their children must know the “truth” in every instance. Those children are often painfully anxious and overwhelmed.

There is plenty of time for more facts later when the child has the thinking and emotional power to handle the truth.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

“Not my son!” your patient’s parent rants. “If he lies to me, he will regret it for a long time.” While your first reaction may be to agree that a child lying to a parent crosses a kind of moral line in the sand, lying is a far more nuanced part of parenting worth a deeper understanding.

In order to lie, a child has to develop cognitive and social understanding. Typically developing children look to see what is interesting to others, called “joint attention,” at around 12-18 months. Failure to do this is one of the early signs of autism reflecting atypical social understanding. At around 3.5 years, children may attempt to deceive if they have broken a rule. The study demonstrating this may sound a lot like home: Children are left alone with a tempting toy but told not to touch it. Although they do touch it while the adult is out of sight, they say rather sweetly (and eventually convincingly) that they did not, even though the toy was clearly moved! While boys generally have more behavior problems, girls and children with better verbal skills achieve deceit at an earlier age, some as young as 2 years. At this stage, children become aware that the adult can’t know exactly what they know. If the parent shows high emotion to what they consider a lie, this can be a topic for testing! Children with ADHD often lack the inhibition needed for early mastery of deception, and children with autism later or not at all. They don’t see the social point to lying nor can they fake a facial expression. They have a case of intractable honesty!

The inability to refrain from telling the truth can result in social rejection, for example when a child rats on a peer for a trivial misdeed in class. Even though he is speaking the truth and “following the (teacher’s) rules,” he did not see that the cost of breaking the (peer) social rules was more important. By age 6 years, children typically figure out that what another person thinks may not be true – their belief may be incorrect or a “false belief.” This understanding is called Theory of Mind, missing or delayed in autism. Only 40% of high-functioning children with autism passed false belief testing at ages 6- to 13-years-old, compared with 95% of typical age-matched peers (Physiol Behav. 2010 Jun 1;100[3]:268-76). The percentage of children on the spectrum understanding false beliefs more closely matched that of preschoolers (39%). At a later age and given extra time to think, some children with autism can do better at this kind of perspective taking, but many continue having difficulty understanding thoughts of others, especially social expectations or motivations (such as flirting, status seeking, and making an excuse) even as adults. This can impair social relationships even when desire to fit in and IQ are otherwise high.

On the other hand, ADHD is a common condition in which “lying” comes from saying the first thing that comes to mind even if the child knows otherwise. A wise parent of one of my patients with ADHD told me about her “30 second rule” where she would give her child that extra time and walk away briefly to “be sure that is what you wanted to say,” with praise rather than give a consequence for changing the story to the truth. This is an important concept we pediatricians need to know: Punishing lying in children tends to result in more, not less, lying and more sneakiness. Instead, parents need to be advised to recall the origins of the word discipline as being “to teach.”

When children lie there are four basic scenarios: They may not know the rules, they may know but have something they want more, they may be impulsive, or they may have developed an attitude of seeking to con the adults whom they feel are mean as a way to have some power in the relationship and get back at them. Clearly, we do not want to push children to this fourth resort by harsh reactions to lying. We have seen particular difficulty with harsh reactions to lying in parents from strong, rule-oriented careers such as police officers, military, and ministers. Asking “How would your parent have handled this?” often will reveal reasons for their tough but backfiring stance.

Lying can work to get what one wants and nearly all children try it. As with other new milestones, children practice this “skill,” much to parents’ dismay. Parents generally can tell if children are lying; they see it on their faces, hear the story from siblings, or see evidence of what happened. Lying provides an important opportunity for the adult to stop, take some breaths, touch the child, and empathize: “It is hard to admit a mistake. I know you did not mean to do it. But you are young, and I know that you are good and honest inside, and will get stronger and braver at telling the truth as you get older. Will you promise to try harder?” In some cases a consequence may be appropriate, for example if something was broken. Usually, simply empathizing and focusing on the expectation for improvement will increase the child’s desire to please the parents rather than get back at them. Actual rewards for honesty improve truth telling by 1.5 times if the reward is big enough.

But it is important to recognize that we all make split second tactical decisions about our actions based on how safe we feel in the situation and our knowledge of social rules and costs. Children over time need to learn that it is safe to tell the truth among family members and that they will not be harshly dealt with. It is a subtle task, but important to learn that deception is a tool that can be important used judiciously when required socially (I have a curfew) or in dangerous situations (I did not see the thug), but can undermine relationships and should not be used with your allies (family and friends).

But parenting involves lying also, which can be a model for the child. Sarcasm is a peculiar form of problematic adult lying. The adults say the opposite or an exaggeration of what they really mean, usually with a smirk or other nonverbal cue to their intent. This is confusing, if not infuriating, to immature children or those who do not understand this twisted communication. It is best to avoid sarcasm with children, or at least be sure to explain it so the children gain understanding over time.

Parents need to “lie” to their children to some extent to reassure and allow for development of confidence. What adult hasn’t said “It’s going to be all right” about a looming storm, car crash, or illness, when actually there is uncertainty. Children count on adults to keep them safe emotionally and physically from things they can’t yet handle. To move forward developmentally, children need adults to be brave leaders, even when the adults don’t feel confident. Some parents think their children must know the “truth” in every instance. Those children are often painfully anxious and overwhelmed.

There is plenty of time for more facts later when the child has the thinking and emotional power to handle the truth.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

“Not my son!” your patient’s parent rants. “If he lies to me, he will regret it for a long time.” While your first reaction may be to agree that a child lying to a parent crosses a kind of moral line in the sand, lying is a far more nuanced part of parenting worth a deeper understanding.

In order to lie, a child has to develop cognitive and social understanding. Typically developing children look to see what is interesting to others, called “joint attention,” at around 12-18 months. Failure to do this is one of the early signs of autism reflecting atypical social understanding. At around 3.5 years, children may attempt to deceive if they have broken a rule. The study demonstrating this may sound a lot like home: Children are left alone with a tempting toy but told not to touch it. Although they do touch it while the adult is out of sight, they say rather sweetly (and eventually convincingly) that they did not, even though the toy was clearly moved! While boys generally have more behavior problems, girls and children with better verbal skills achieve deceit at an earlier age, some as young as 2 years. At this stage, children become aware that the adult can’t know exactly what they know. If the parent shows high emotion to what they consider a lie, this can be a topic for testing! Children with ADHD often lack the inhibition needed for early mastery of deception, and children with autism later or not at all. They don’t see the social point to lying nor can they fake a facial expression. They have a case of intractable honesty!

The inability to refrain from telling the truth can result in social rejection, for example when a child rats on a peer for a trivial misdeed in class. Even though he is speaking the truth and “following the (teacher’s) rules,” he did not see that the cost of breaking the (peer) social rules was more important. By age 6 years, children typically figure out that what another person thinks may not be true – their belief may be incorrect or a “false belief.” This understanding is called Theory of Mind, missing or delayed in autism. Only 40% of high-functioning children with autism passed false belief testing at ages 6- to 13-years-old, compared with 95% of typical age-matched peers (Physiol Behav. 2010 Jun 1;100[3]:268-76). The percentage of children on the spectrum understanding false beliefs more closely matched that of preschoolers (39%). At a later age and given extra time to think, some children with autism can do better at this kind of perspective taking, but many continue having difficulty understanding thoughts of others, especially social expectations or motivations (such as flirting, status seeking, and making an excuse) even as adults. This can impair social relationships even when desire to fit in and IQ are otherwise high.

On the other hand, ADHD is a common condition in which “lying” comes from saying the first thing that comes to mind even if the child knows otherwise. A wise parent of one of my patients with ADHD told me about her “30 second rule” where she would give her child that extra time and walk away briefly to “be sure that is what you wanted to say,” with praise rather than give a consequence for changing the story to the truth. This is an important concept we pediatricians need to know: Punishing lying in children tends to result in more, not less, lying and more sneakiness. Instead, parents need to be advised to recall the origins of the word discipline as being “to teach.”

When children lie there are four basic scenarios: They may not know the rules, they may know but have something they want more, they may be impulsive, or they may have developed an attitude of seeking to con the adults whom they feel are mean as a way to have some power in the relationship and get back at them. Clearly, we do not want to push children to this fourth resort by harsh reactions to lying. We have seen particular difficulty with harsh reactions to lying in parents from strong, rule-oriented careers such as police officers, military, and ministers. Asking “How would your parent have handled this?” often will reveal reasons for their tough but backfiring stance.

Lying can work to get what one wants and nearly all children try it. As with other new milestones, children practice this “skill,” much to parents’ dismay. Parents generally can tell if children are lying; they see it on their faces, hear the story from siblings, or see evidence of what happened. Lying provides an important opportunity for the adult to stop, take some breaths, touch the child, and empathize: “It is hard to admit a mistake. I know you did not mean to do it. But you are young, and I know that you are good and honest inside, and will get stronger and braver at telling the truth as you get older. Will you promise to try harder?” In some cases a consequence may be appropriate, for example if something was broken. Usually, simply empathizing and focusing on the expectation for improvement will increase the child’s desire to please the parents rather than get back at them. Actual rewards for honesty improve truth telling by 1.5 times if the reward is big enough.

But it is important to recognize that we all make split second tactical decisions about our actions based on how safe we feel in the situation and our knowledge of social rules and costs. Children over time need to learn that it is safe to tell the truth among family members and that they will not be harshly dealt with. It is a subtle task, but important to learn that deception is a tool that can be important used judiciously when required socially (I have a curfew) or in dangerous situations (I did not see the thug), but can undermine relationships and should not be used with your allies (family and friends).

But parenting involves lying also, which can be a model for the child. Sarcasm is a peculiar form of problematic adult lying. The adults say the opposite or an exaggeration of what they really mean, usually with a smirk or other nonverbal cue to their intent. This is confusing, if not infuriating, to immature children or those who do not understand this twisted communication. It is best to avoid sarcasm with children, or at least be sure to explain it so the children gain understanding over time.

Parents need to “lie” to their children to some extent to reassure and allow for development of confidence. What adult hasn’t said “It’s going to be all right” about a looming storm, car crash, or illness, when actually there is uncertainty. Children count on adults to keep them safe emotionally and physically from things they can’t yet handle. To move forward developmentally, children need adults to be brave leaders, even when the adults don’t feel confident. Some parents think their children must know the “truth” in every instance. Those children are often painfully anxious and overwhelmed.

There is plenty of time for more facts later when the child has the thinking and emotional power to handle the truth.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

Critical care admissions up for pediatric opioid poisonings

ORLANDO – The proportion of children and adolescents admitted to critical care for serious poisonings has increased in recent years, according to authors of a study of more than 750,000 reported opioid exposures.

Critical care units were involved in 10% of pediatric opioid poisoning cases registered in 2015-2018, up from 7% in 2005-2009, reported Megan E. Land, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and coinvestigators.

Attempted suicide has represented an increasingly large proportion of pediatric opioid poisonings from 2005 to 2018, according to the researchers, based on retrospective analysis of cases reported to U.S. poison centers.

Mortality related to these pediatric poisonings increased over time, and among children and adolescents admitted to a pediatric ICU, CPR and naloxone use also increased over time, Dr. Land and associates noted.

These said Dr. Land, who presented the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“I think that this really requires a two-pronged approach,” she explained. “One is that we need to increase mental health resources for kids to address adolescent suicidality, and secondly, we need to decrease access to opioids in the hands of pediatric patients by decreasing prescribing and then also getting those that are unused out of the homes.”

Jeffrey Zimmerman, MD, past president of SCCM, said these findings on pediatric opioid poisonings represent the “iceberg tip” of a much larger societal issue that has impacts well beyond critical care.

“I think acutely, we’re well equipped to deal with the situation in terms of interventions,” Dr. Zimmerman said in an interview. “The bigger issue is dealing with what happens afterward, when the patient leaves the ICU in the hospital.”

When the issue is chronic opioid use among adolescents or children, critical care specialists can help by initiating opioid tapering in the hospital setting, rather than allowing the complete weaning process to play out at home, he said.

All clinicians can help prevent future injury by asking questions of the child and family to ensure that any opiates and other prescription medications at home are locked up, he added.

“These aren’t very glamorous things, but they’re common sense, and there’s more need for this common sense now than there ever has been,” Dr. Zimmerman concluded.

The study by Dr. Land and colleagues included data on primary opioid ingestions registered at 55 poison control centers in the United States. They assessed trends over three time periods: 2005-2009, 2010-2014, and 2015-2018.

They found that children under 19 years of age accounted for 28% of the 753,592 opioid poisonings reported over that time period.

The overall number of reported opioid poisonings among children declined somewhat since about 2010. However, the proportion admitted to a critical care unit increased from 7% in the 2005-2009 period to 10% in the 2015-2018 period, said Dr. Land, who added that the probability of a moderate or major effect increased by 0.55% and 0.11% per year, respectively, over the 14 years studied.

Mortality – 0.21% overall – increased from 0.18% in the earliest era to 0.28% in the most recent era, according to the investigators.

Suicidal intent increased from 14% in the earliest era to 21% in the most recent era, and was linked to near tenfold odds of undergoing a pediatric ICU procedure, Dr. Land and colleagues reported.

Among those children admitted to a pediatric ICU, use of CPR increased from 1% to 3% in the earliest and latest time periods, respectively; likewise, naloxone administration increased from 42% to 51% over those two time periods. By contrast, there was no change in use of mechanical ventilation (12%) or vasopressors (3%) over time, they added.

The opioids most commonly linked to pediatric ICU procedures were fentanyl (odds ratio, 12), heroin (OR, 11), and methadone (OR, 15).

Some funding for the study came from the Georgia Poison Center. Dr. Land had no disclosures relevant to the research.

SOURCE: Land M et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000618708.38414.ea.

ORLANDO – The proportion of children and adolescents admitted to critical care for serious poisonings has increased in recent years, according to authors of a study of more than 750,000 reported opioid exposures.

Critical care units were involved in 10% of pediatric opioid poisoning cases registered in 2015-2018, up from 7% in 2005-2009, reported Megan E. Land, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and coinvestigators.

Attempted suicide has represented an increasingly large proportion of pediatric opioid poisonings from 2005 to 2018, according to the researchers, based on retrospective analysis of cases reported to U.S. poison centers.

Mortality related to these pediatric poisonings increased over time, and among children and adolescents admitted to a pediatric ICU, CPR and naloxone use also increased over time, Dr. Land and associates noted.

These said Dr. Land, who presented the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“I think that this really requires a two-pronged approach,” she explained. “One is that we need to increase mental health resources for kids to address adolescent suicidality, and secondly, we need to decrease access to opioids in the hands of pediatric patients by decreasing prescribing and then also getting those that are unused out of the homes.”

Jeffrey Zimmerman, MD, past president of SCCM, said these findings on pediatric opioid poisonings represent the “iceberg tip” of a much larger societal issue that has impacts well beyond critical care.

“I think acutely, we’re well equipped to deal with the situation in terms of interventions,” Dr. Zimmerman said in an interview. “The bigger issue is dealing with what happens afterward, when the patient leaves the ICU in the hospital.”

When the issue is chronic opioid use among adolescents or children, critical care specialists can help by initiating opioid tapering in the hospital setting, rather than allowing the complete weaning process to play out at home, he said.

All clinicians can help prevent future injury by asking questions of the child and family to ensure that any opiates and other prescription medications at home are locked up, he added.

“These aren’t very glamorous things, but they’re common sense, and there’s more need for this common sense now than there ever has been,” Dr. Zimmerman concluded.

The study by Dr. Land and colleagues included data on primary opioid ingestions registered at 55 poison control centers in the United States. They assessed trends over three time periods: 2005-2009, 2010-2014, and 2015-2018.

They found that children under 19 years of age accounted for 28% of the 753,592 opioid poisonings reported over that time period.

The overall number of reported opioid poisonings among children declined somewhat since about 2010. However, the proportion admitted to a critical care unit increased from 7% in the 2005-2009 period to 10% in the 2015-2018 period, said Dr. Land, who added that the probability of a moderate or major effect increased by 0.55% and 0.11% per year, respectively, over the 14 years studied.

Mortality – 0.21% overall – increased from 0.18% in the earliest era to 0.28% in the most recent era, according to the investigators.

Suicidal intent increased from 14% in the earliest era to 21% in the most recent era, and was linked to near tenfold odds of undergoing a pediatric ICU procedure, Dr. Land and colleagues reported.

Among those children admitted to a pediatric ICU, use of CPR increased from 1% to 3% in the earliest and latest time periods, respectively; likewise, naloxone administration increased from 42% to 51% over those two time periods. By contrast, there was no change in use of mechanical ventilation (12%) or vasopressors (3%) over time, they added.

The opioids most commonly linked to pediatric ICU procedures were fentanyl (odds ratio, 12), heroin (OR, 11), and methadone (OR, 15).

Some funding for the study came from the Georgia Poison Center. Dr. Land had no disclosures relevant to the research.

SOURCE: Land M et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000618708.38414.ea.

ORLANDO – The proportion of children and adolescents admitted to critical care for serious poisonings has increased in recent years, according to authors of a study of more than 750,000 reported opioid exposures.

Critical care units were involved in 10% of pediatric opioid poisoning cases registered in 2015-2018, up from 7% in 2005-2009, reported Megan E. Land, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and coinvestigators.

Attempted suicide has represented an increasingly large proportion of pediatric opioid poisonings from 2005 to 2018, according to the researchers, based on retrospective analysis of cases reported to U.S. poison centers.

Mortality related to these pediatric poisonings increased over time, and among children and adolescents admitted to a pediatric ICU, CPR and naloxone use also increased over time, Dr. Land and associates noted.

These said Dr. Land, who presented the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“I think that this really requires a two-pronged approach,” she explained. “One is that we need to increase mental health resources for kids to address adolescent suicidality, and secondly, we need to decrease access to opioids in the hands of pediatric patients by decreasing prescribing and then also getting those that are unused out of the homes.”

Jeffrey Zimmerman, MD, past president of SCCM, said these findings on pediatric opioid poisonings represent the “iceberg tip” of a much larger societal issue that has impacts well beyond critical care.

“I think acutely, we’re well equipped to deal with the situation in terms of interventions,” Dr. Zimmerman said in an interview. “The bigger issue is dealing with what happens afterward, when the patient leaves the ICU in the hospital.”

When the issue is chronic opioid use among adolescents or children, critical care specialists can help by initiating opioid tapering in the hospital setting, rather than allowing the complete weaning process to play out at home, he said.

All clinicians can help prevent future injury by asking questions of the child and family to ensure that any opiates and other prescription medications at home are locked up, he added.

“These aren’t very glamorous things, but they’re common sense, and there’s more need for this common sense now than there ever has been,” Dr. Zimmerman concluded.

The study by Dr. Land and colleagues included data on primary opioid ingestions registered at 55 poison control centers in the United States. They assessed trends over three time periods: 2005-2009, 2010-2014, and 2015-2018.

They found that children under 19 years of age accounted for 28% of the 753,592 opioid poisonings reported over that time period.

The overall number of reported opioid poisonings among children declined somewhat since about 2010. However, the proportion admitted to a critical care unit increased from 7% in the 2005-2009 period to 10% in the 2015-2018 period, said Dr. Land, who added that the probability of a moderate or major effect increased by 0.55% and 0.11% per year, respectively, over the 14 years studied.

Mortality – 0.21% overall – increased from 0.18% in the earliest era to 0.28% in the most recent era, according to the investigators.

Suicidal intent increased from 14% in the earliest era to 21% in the most recent era, and was linked to near tenfold odds of undergoing a pediatric ICU procedure, Dr. Land and colleagues reported.

Among those children admitted to a pediatric ICU, use of CPR increased from 1% to 3% in the earliest and latest time periods, respectively; likewise, naloxone administration increased from 42% to 51% over those two time periods. By contrast, there was no change in use of mechanical ventilation (12%) or vasopressors (3%) over time, they added.

The opioids most commonly linked to pediatric ICU procedures were fentanyl (odds ratio, 12), heroin (OR, 11), and methadone (OR, 15).

Some funding for the study came from the Georgia Poison Center. Dr. Land had no disclosures relevant to the research.

SOURCE: Land M et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000618708.38414.ea.

REPORTING FROM CCC49

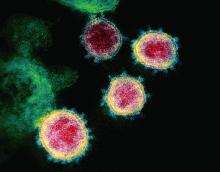

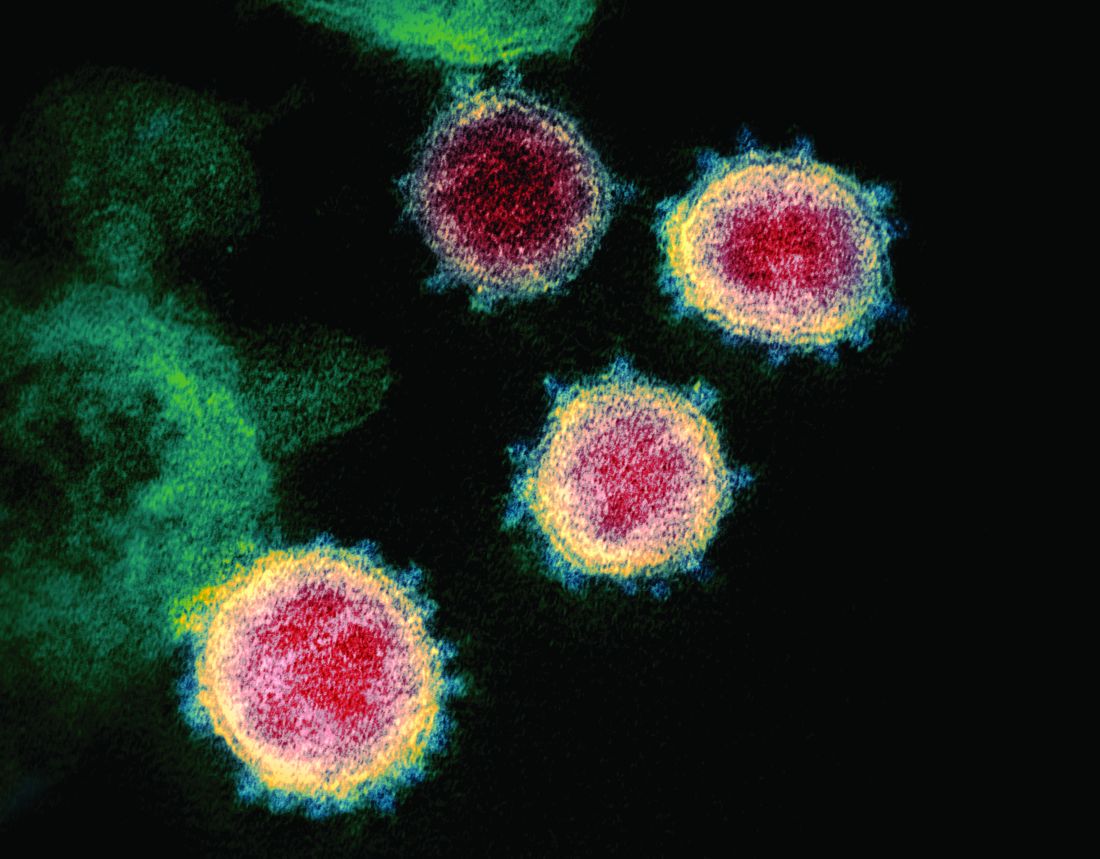

Infection with 2019 novel coronavirus extends to infants

between Dec. 8, 2019, and Feb. 6, 2020, based on data from the Chinese central government and local health departments.

“As of February 6, 2020, China reported 31,211 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 637 fatalities,” wrote Min Wei, MD, of Wuhan University, China, and colleagues. However, “few infections in children have been reported.”

In a research letter published in JAMA, the investigators reviewed data from nine infants aged 28 days to 1 year who were hospitalized with a diagnosis of COVID-19 between Dec. 8, 2019, and Feb. 6, 2020. The ages of the infants ranged from 1 month to 11 months, and seven were female. The patients included two children from Beijing, two from Hainan, and one each from the areas of Guangdong, Anhui, Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Guizhou.

All infected infants had at least one infected family member, and the infants’ infections occurred after the family members’ infections; seven infants lived in Wuhan or had family members who had visited Wuhan.

One of the infants had no symptoms but tested positive for the 2019 novel coronavirus, and two others had a diagnosis but missing information on any symptoms. Fever occurred in four patients, and mild upper respiratory tract symptoms occurred in two patients.

None of the infants died, and none reported severe complications or the need for intensive care or mechanical ventilation, the investigators said. The fact that most of the infants were female might suggest that they are more susceptible to the virus than males, although overall COVID-19 viral infections have been more common in adult men, especially those with chronic comorbidities, Dr. Wei and associates noted.

The study findings were limited by the small sample size and lack of symptom data for some patients, the researchers said. However, the results confirm that the COVID-19 virus is transmissible to infants younger than 1 year, and adult caregivers should exercise protective measures including wearing masks, washing hands before contact with infants, and routinely sterilizing toys and tableware, they emphasized.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Wei M et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 14. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2131.

between Dec. 8, 2019, and Feb. 6, 2020, based on data from the Chinese central government and local health departments.

“As of February 6, 2020, China reported 31,211 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 637 fatalities,” wrote Min Wei, MD, of Wuhan University, China, and colleagues. However, “few infections in children have been reported.”

In a research letter published in JAMA, the investigators reviewed data from nine infants aged 28 days to 1 year who were hospitalized with a diagnosis of COVID-19 between Dec. 8, 2019, and Feb. 6, 2020. The ages of the infants ranged from 1 month to 11 months, and seven were female. The patients included two children from Beijing, two from Hainan, and one each from the areas of Guangdong, Anhui, Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Guizhou.

All infected infants had at least one infected family member, and the infants’ infections occurred after the family members’ infections; seven infants lived in Wuhan or had family members who had visited Wuhan.

One of the infants had no symptoms but tested positive for the 2019 novel coronavirus, and two others had a diagnosis but missing information on any symptoms. Fever occurred in four patients, and mild upper respiratory tract symptoms occurred in two patients.

None of the infants died, and none reported severe complications or the need for intensive care or mechanical ventilation, the investigators said. The fact that most of the infants were female might suggest that they are more susceptible to the virus than males, although overall COVID-19 viral infections have been more common in adult men, especially those with chronic comorbidities, Dr. Wei and associates noted.

The study findings were limited by the small sample size and lack of symptom data for some patients, the researchers said. However, the results confirm that the COVID-19 virus is transmissible to infants younger than 1 year, and adult caregivers should exercise protective measures including wearing masks, washing hands before contact with infants, and routinely sterilizing toys and tableware, they emphasized.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Wei M et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 14. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2131.

between Dec. 8, 2019, and Feb. 6, 2020, based on data from the Chinese central government and local health departments.

“As of February 6, 2020, China reported 31,211 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 637 fatalities,” wrote Min Wei, MD, of Wuhan University, China, and colleagues. However, “few infections in children have been reported.”

In a research letter published in JAMA, the investigators reviewed data from nine infants aged 28 days to 1 year who were hospitalized with a diagnosis of COVID-19 between Dec. 8, 2019, and Feb. 6, 2020. The ages of the infants ranged from 1 month to 11 months, and seven were female. The patients included two children from Beijing, two from Hainan, and one each from the areas of Guangdong, Anhui, Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Guizhou.

All infected infants had at least one infected family member, and the infants’ infections occurred after the family members’ infections; seven infants lived in Wuhan or had family members who had visited Wuhan.

One of the infants had no symptoms but tested positive for the 2019 novel coronavirus, and two others had a diagnosis but missing information on any symptoms. Fever occurred in four patients, and mild upper respiratory tract symptoms occurred in two patients.

None of the infants died, and none reported severe complications or the need for intensive care or mechanical ventilation, the investigators said. The fact that most of the infants were female might suggest that they are more susceptible to the virus than males, although overall COVID-19 viral infections have been more common in adult men, especially those with chronic comorbidities, Dr. Wei and associates noted.

The study findings were limited by the small sample size and lack of symptom data for some patients, the researchers said. However, the results confirm that the COVID-19 virus is transmissible to infants younger than 1 year, and adult caregivers should exercise protective measures including wearing masks, washing hands before contact with infants, and routinely sterilizing toys and tableware, they emphasized.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Wei M et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 14. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2131.

FROM JAMA

Psychopharmacology for aggression? Our field’s ‘nonconsensus’ and the risks

A 13-year-old boy with ADHD, combined type, presents to his family physician with his parents. His parents called for an appointment outside of his routine follow-up care to discuss what they should do to address their son’s new “aggressive behaviors.” He will throw objects when angry, yell, and slam doors at home when he is told to turn off video games. He used to play soccer but doesn’t anymore. He has maintained very good grades and friends. There is not a concern for substance abuse at this time.He speaks in curt sentences during the appointment, and he has his arms crossed or is looking out of the window the entire time.

His parents share in front on him that he has always been a “difficult child” (their words), but they now are struggling to adjust to his aggressive tendencies as he ages. He is growing bigger and angrier. He will not attend therapy and will not see a consultation psychiatrist in the office. A variety of stimulant trials including Ritalin and amphetamine preparations to manage impulsivity in ADHD were ineffective to curb his aggression, and he doesn’t want to take any medication.

They ask, what do we do? They are not worried for their safety but living like this is eroding their quality of life as a family, and the dynamic seems destined to get worse before it gets better.

They wonder, is there a next medication step to manage his aggression?

A family physician presented the above situation to me in my role as a child and adolescent psychiatrist in the medical home. It led us to a fruitful discussion of aggression and what can be done to help families who are all too often in situations like the above, then in your office looking for immediate solutions. The questions are, what can be done with an aggressive child, even and especially without the child’s buy-in to work on that as a problem?