User login

Early maternal anxiety tied to adolescent hyperactivity

COPENHAGEN – Exposure to maternal somatic anxiety during pregnancy and toddlerhood increases a child’s risk of hyperactivity symptoms in adolescence, Blanca Bolea, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

In contrast, the children of mothers who were anxious were not at increased risk for subsequent inattention symptoms in an analysis of 8,725 mothers and their children participating in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a prospective epidemiologic cohort study ongoing in southwest England since 1991, said Dr. Bolea, a psychiatrist at the University of Toronto.

These findings have practical implications for clinical care: “If we know that women who are anxious in the perinatal period put their children at risk for hyperactivity later on, then we can tackle their anxiety in pregnancy or toddlerhood. And that’s easy to do: You can do group [cognitive-behavioral therapy]; you can give medications, so there are things you can do to reduce that risk. That’s relevant, because we don’t know much about how to reduce levels of ADHD. We know it has a genetic component, but we can’t touch that. You cannot change your genes, so far. But environmental things, we can change. So if we can identify the mothers who are more anxious during pregnancy and toddlerhood and give them resources to reduce their anxiety, then we can potentially reduce hyperactivity later on,” she explained in an interview.

In the Avon study, maternal anxiety was serially assessed from early pregnancy up until a child’s 5th birthday.

“We looked for maternal symptoms similar to panic disorder: shortness of breath, dizziness, sweating, things like that. These are symptoms that any clinician can identify by asking the mothers, so it’s not hard to identify the mothers who could be at risk,” according to the psychiatrist.

Children in the Avon study were assessed for symptoms of inattention at age 8.5 years using the Sky Search, Sky Search Dual Test, and Opposite Worlds subtests of the Tests of Everyday Attention for Children. Hyperactivity symptoms were assessed at age 16 years via the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

In an analysis adjusted for potentially confounding sociodemographic factors, adolescents whose mothers were rated by investigators as having moderate or high somatic anxiety during pregnancy and the toddlerhood years were at 2.1-fold increased risk of hyperactivity symptoms compared to those whose mothers had low or no anxiety, but increased maternal anxiety wasn’t associated with scores on any of the three tests of inattention.

Dr. Bolea cautioned that, while these Avon study findings document an association between early maternal anxiety and subsequent adolescent hyperactivity, that doesn’t prove causality. The findings are consistent, however, with the fetal origins hypothesis put forth by the late British epidemiologist David J. Barker, MD, PhD, which postulates that stressful fetal circumstances have profound effects later in life.

she said.

The hypothesis has been borne out in animal studies: Stress a pregnant rat, and her offspring will display hyperactivity.

Dr. Bolea reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study. The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children is funded by the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust.

COPENHAGEN – Exposure to maternal somatic anxiety during pregnancy and toddlerhood increases a child’s risk of hyperactivity symptoms in adolescence, Blanca Bolea, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

In contrast, the children of mothers who were anxious were not at increased risk for subsequent inattention symptoms in an analysis of 8,725 mothers and their children participating in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a prospective epidemiologic cohort study ongoing in southwest England since 1991, said Dr. Bolea, a psychiatrist at the University of Toronto.

These findings have practical implications for clinical care: “If we know that women who are anxious in the perinatal period put their children at risk for hyperactivity later on, then we can tackle their anxiety in pregnancy or toddlerhood. And that’s easy to do: You can do group [cognitive-behavioral therapy]; you can give medications, so there are things you can do to reduce that risk. That’s relevant, because we don’t know much about how to reduce levels of ADHD. We know it has a genetic component, but we can’t touch that. You cannot change your genes, so far. But environmental things, we can change. So if we can identify the mothers who are more anxious during pregnancy and toddlerhood and give them resources to reduce their anxiety, then we can potentially reduce hyperactivity later on,” she explained in an interview.

In the Avon study, maternal anxiety was serially assessed from early pregnancy up until a child’s 5th birthday.

“We looked for maternal symptoms similar to panic disorder: shortness of breath, dizziness, sweating, things like that. These are symptoms that any clinician can identify by asking the mothers, so it’s not hard to identify the mothers who could be at risk,” according to the psychiatrist.

Children in the Avon study were assessed for symptoms of inattention at age 8.5 years using the Sky Search, Sky Search Dual Test, and Opposite Worlds subtests of the Tests of Everyday Attention for Children. Hyperactivity symptoms were assessed at age 16 years via the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

In an analysis adjusted for potentially confounding sociodemographic factors, adolescents whose mothers were rated by investigators as having moderate or high somatic anxiety during pregnancy and the toddlerhood years were at 2.1-fold increased risk of hyperactivity symptoms compared to those whose mothers had low or no anxiety, but increased maternal anxiety wasn’t associated with scores on any of the three tests of inattention.

Dr. Bolea cautioned that, while these Avon study findings document an association between early maternal anxiety and subsequent adolescent hyperactivity, that doesn’t prove causality. The findings are consistent, however, with the fetal origins hypothesis put forth by the late British epidemiologist David J. Barker, MD, PhD, which postulates that stressful fetal circumstances have profound effects later in life.

she said.

The hypothesis has been borne out in animal studies: Stress a pregnant rat, and her offspring will display hyperactivity.

Dr. Bolea reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study. The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children is funded by the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust.

COPENHAGEN – Exposure to maternal somatic anxiety during pregnancy and toddlerhood increases a child’s risk of hyperactivity symptoms in adolescence, Blanca Bolea, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

In contrast, the children of mothers who were anxious were not at increased risk for subsequent inattention symptoms in an analysis of 8,725 mothers and their children participating in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a prospective epidemiologic cohort study ongoing in southwest England since 1991, said Dr. Bolea, a psychiatrist at the University of Toronto.

These findings have practical implications for clinical care: “If we know that women who are anxious in the perinatal period put their children at risk for hyperactivity later on, then we can tackle their anxiety in pregnancy or toddlerhood. And that’s easy to do: You can do group [cognitive-behavioral therapy]; you can give medications, so there are things you can do to reduce that risk. That’s relevant, because we don’t know much about how to reduce levels of ADHD. We know it has a genetic component, but we can’t touch that. You cannot change your genes, so far. But environmental things, we can change. So if we can identify the mothers who are more anxious during pregnancy and toddlerhood and give them resources to reduce their anxiety, then we can potentially reduce hyperactivity later on,” she explained in an interview.

In the Avon study, maternal anxiety was serially assessed from early pregnancy up until a child’s 5th birthday.

“We looked for maternal symptoms similar to panic disorder: shortness of breath, dizziness, sweating, things like that. These are symptoms that any clinician can identify by asking the mothers, so it’s not hard to identify the mothers who could be at risk,” according to the psychiatrist.

Children in the Avon study were assessed for symptoms of inattention at age 8.5 years using the Sky Search, Sky Search Dual Test, and Opposite Worlds subtests of the Tests of Everyday Attention for Children. Hyperactivity symptoms were assessed at age 16 years via the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

In an analysis adjusted for potentially confounding sociodemographic factors, adolescents whose mothers were rated by investigators as having moderate or high somatic anxiety during pregnancy and the toddlerhood years were at 2.1-fold increased risk of hyperactivity symptoms compared to those whose mothers had low or no anxiety, but increased maternal anxiety wasn’t associated with scores on any of the three tests of inattention.

Dr. Bolea cautioned that, while these Avon study findings document an association between early maternal anxiety and subsequent adolescent hyperactivity, that doesn’t prove causality. The findings are consistent, however, with the fetal origins hypothesis put forth by the late British epidemiologist David J. Barker, MD, PhD, which postulates that stressful fetal circumstances have profound effects later in life.

she said.

The hypothesis has been borne out in animal studies: Stress a pregnant rat, and her offspring will display hyperactivity.

Dr. Bolea reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study. The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children is funded by the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust.

REPORTING FROM ECNP 2019

Review looks at natural course of alopecia areata in young children

, according to a retrospective chart review of 125 children.

Almost 90% of the children presented between aged 2 and 4 years, compared with 11.9% between ages 1 and 2 years, and 1.6% aged under 1 year, “in keeping with the existing literature,” the study authors reported in Pediatric Dermatology. “A high percentage of patients continued to have mild, patchy alopecia at their follow‐up visits,” they added.

Epidemiologic studies of children with alopecia areata are few and have not focused on the youngest patients, said Sneha Rangu, of the section of dermatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and coauthors. They performed a retrospective chart review of 125 patients, who initially presented at the hospital with alopecia areata between Jan. 1, 2016, and June 1, 2018, when they were younger than 4 years. Patients who received systemic therapy or topical JAK inhibitors for alopecia were excluded. Severity was measured with the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score, to monitor progression of hair loss, analyzing scores at the initial presentation, at 3-6 months, at 1 year, and at 2 or more years.

Almost 70% were female, which the authors said was similar to other studies that have found alopecia areata is more prevalent in females; and 86.6% were between ages 2 and 4 years when they first presented. The initial diagnosis was alopecia areata in 72.0%, alopecia totalis in 8.8%, and alopecia universalis in 19.2%. Of the 41 boys, 39% had alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis, as did 22% of the girls, which suggested that boys presenting under aged 4 years were more likely to have more severe disease, or that “guardians of boys are more likely to present for therapy when disease is more severe,” the authors wrote.

About 40% of the children presented with a history of atopic dermatitis, and 4% had an autoimmune disease (vitiligo, celiac disease, or type 1 diabetes). Twenty-eight percent of patients had a family history of alopecia areata, 27.2% had a family history of other autoimmune diseases, and 32% had a family history of hypothyroidism.

At the first visit, 57.6% had patch‐stage alopecia and SALT scores in the mild range (0%‐24% hair loss), which was present in a high proportion of these patients at follow-up: 49.4% at 3-6 months, 39.5% at 1 year, and 42.9% at two or more years.

At the first visit, 28% had high SALT scores (50%-100% hair loss), increasing to 36% at 3-6 months, 41.8% at 1 year, and 46.4% at 2 or more years. They calculated that for those with more than 50% hair loss at the initial presentation, the likelihood of being in a high category of hair loss, as measured by increasing SALT scores, was significantly higher at 1 year (odds ratio, 1.85, P =.033) and at 2 or more years (OR, 2.29, P = .038).

“While there is a likelihood of increasing disease severity, those with higher severity at initial presentation are likely to stay severe after one or 2 years,” the authors noted.

They concluded that their results add to the understanding of the epidemiology of alopecia areata in children “and perhaps can provide clinicians and families with a better sense of prognosis for progression in the youngest patients presenting with alopecia areata.”

They said the retrospective design and small sample size were among the study’s limitations. They had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Rangu S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.1111/pde.13990.

, according to a retrospective chart review of 125 children.

Almost 90% of the children presented between aged 2 and 4 years, compared with 11.9% between ages 1 and 2 years, and 1.6% aged under 1 year, “in keeping with the existing literature,” the study authors reported in Pediatric Dermatology. “A high percentage of patients continued to have mild, patchy alopecia at their follow‐up visits,” they added.

Epidemiologic studies of children with alopecia areata are few and have not focused on the youngest patients, said Sneha Rangu, of the section of dermatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and coauthors. They performed a retrospective chart review of 125 patients, who initially presented at the hospital with alopecia areata between Jan. 1, 2016, and June 1, 2018, when they were younger than 4 years. Patients who received systemic therapy or topical JAK inhibitors for alopecia were excluded. Severity was measured with the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score, to monitor progression of hair loss, analyzing scores at the initial presentation, at 3-6 months, at 1 year, and at 2 or more years.

Almost 70% were female, which the authors said was similar to other studies that have found alopecia areata is more prevalent in females; and 86.6% were between ages 2 and 4 years when they first presented. The initial diagnosis was alopecia areata in 72.0%, alopecia totalis in 8.8%, and alopecia universalis in 19.2%. Of the 41 boys, 39% had alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis, as did 22% of the girls, which suggested that boys presenting under aged 4 years were more likely to have more severe disease, or that “guardians of boys are more likely to present for therapy when disease is more severe,” the authors wrote.

About 40% of the children presented with a history of atopic dermatitis, and 4% had an autoimmune disease (vitiligo, celiac disease, or type 1 diabetes). Twenty-eight percent of patients had a family history of alopecia areata, 27.2% had a family history of other autoimmune diseases, and 32% had a family history of hypothyroidism.

At the first visit, 57.6% had patch‐stage alopecia and SALT scores in the mild range (0%‐24% hair loss), which was present in a high proportion of these patients at follow-up: 49.4% at 3-6 months, 39.5% at 1 year, and 42.9% at two or more years.

At the first visit, 28% had high SALT scores (50%-100% hair loss), increasing to 36% at 3-6 months, 41.8% at 1 year, and 46.4% at 2 or more years. They calculated that for those with more than 50% hair loss at the initial presentation, the likelihood of being in a high category of hair loss, as measured by increasing SALT scores, was significantly higher at 1 year (odds ratio, 1.85, P =.033) and at 2 or more years (OR, 2.29, P = .038).

“While there is a likelihood of increasing disease severity, those with higher severity at initial presentation are likely to stay severe after one or 2 years,” the authors noted.

They concluded that their results add to the understanding of the epidemiology of alopecia areata in children “and perhaps can provide clinicians and families with a better sense of prognosis for progression in the youngest patients presenting with alopecia areata.”

They said the retrospective design and small sample size were among the study’s limitations. They had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Rangu S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.1111/pde.13990.

, according to a retrospective chart review of 125 children.

Almost 90% of the children presented between aged 2 and 4 years, compared with 11.9% between ages 1 and 2 years, and 1.6% aged under 1 year, “in keeping with the existing literature,” the study authors reported in Pediatric Dermatology. “A high percentage of patients continued to have mild, patchy alopecia at their follow‐up visits,” they added.

Epidemiologic studies of children with alopecia areata are few and have not focused on the youngest patients, said Sneha Rangu, of the section of dermatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and coauthors. They performed a retrospective chart review of 125 patients, who initially presented at the hospital with alopecia areata between Jan. 1, 2016, and June 1, 2018, when they were younger than 4 years. Patients who received systemic therapy or topical JAK inhibitors for alopecia were excluded. Severity was measured with the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score, to monitor progression of hair loss, analyzing scores at the initial presentation, at 3-6 months, at 1 year, and at 2 or more years.

Almost 70% were female, which the authors said was similar to other studies that have found alopecia areata is more prevalent in females; and 86.6% were between ages 2 and 4 years when they first presented. The initial diagnosis was alopecia areata in 72.0%, alopecia totalis in 8.8%, and alopecia universalis in 19.2%. Of the 41 boys, 39% had alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis, as did 22% of the girls, which suggested that boys presenting under aged 4 years were more likely to have more severe disease, or that “guardians of boys are more likely to present for therapy when disease is more severe,” the authors wrote.

About 40% of the children presented with a history of atopic dermatitis, and 4% had an autoimmune disease (vitiligo, celiac disease, or type 1 diabetes). Twenty-eight percent of patients had a family history of alopecia areata, 27.2% had a family history of other autoimmune diseases, and 32% had a family history of hypothyroidism.

At the first visit, 57.6% had patch‐stage alopecia and SALT scores in the mild range (0%‐24% hair loss), which was present in a high proportion of these patients at follow-up: 49.4% at 3-6 months, 39.5% at 1 year, and 42.9% at two or more years.

At the first visit, 28% had high SALT scores (50%-100% hair loss), increasing to 36% at 3-6 months, 41.8% at 1 year, and 46.4% at 2 or more years. They calculated that for those with more than 50% hair loss at the initial presentation, the likelihood of being in a high category of hair loss, as measured by increasing SALT scores, was significantly higher at 1 year (odds ratio, 1.85, P =.033) and at 2 or more years (OR, 2.29, P = .038).

“While there is a likelihood of increasing disease severity, those with higher severity at initial presentation are likely to stay severe after one or 2 years,” the authors noted.

They concluded that their results add to the understanding of the epidemiology of alopecia areata in children “and perhaps can provide clinicians and families with a better sense of prognosis for progression in the youngest patients presenting with alopecia areata.”

They said the retrospective design and small sample size were among the study’s limitations. They had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Rangu S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.1111/pde.13990.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Click for Credit: Psoriasis relief; Stress & CV problems; more

Here are 5 articles from the October issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Bronchiolitis is a feared complication of connective tissue disease

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2klWpRb

Expires April 8, 2020

2. Stress incontinence surgery improves sexual dysfunction

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2m0wb71

Expires April 10, 2020

3. Survey finds psoriasis patients seek relief with alternative therapies

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2lZZDtO

Expires April 10, 2020

4. New data further suggest that stress does a number on the CV system

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2lR31ax

Expires April 11, 2020

5. Rate of objects ingested by young children increased over last two decades

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2mmYptb

Expires April 12, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the October issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Bronchiolitis is a feared complication of connective tissue disease

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2klWpRb

Expires April 8, 2020

2. Stress incontinence surgery improves sexual dysfunction

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2m0wb71

Expires April 10, 2020

3. Survey finds psoriasis patients seek relief with alternative therapies

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2lZZDtO

Expires April 10, 2020

4. New data further suggest that stress does a number on the CV system

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2lR31ax

Expires April 11, 2020

5. Rate of objects ingested by young children increased over last two decades

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2mmYptb

Expires April 12, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the October issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Bronchiolitis is a feared complication of connective tissue disease

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2klWpRb

Expires April 8, 2020

2. Stress incontinence surgery improves sexual dysfunction

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2m0wb71

Expires April 10, 2020

3. Survey finds psoriasis patients seek relief with alternative therapies

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2lZZDtO

Expires April 10, 2020

4. New data further suggest that stress does a number on the CV system

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2lR31ax

Expires April 11, 2020

5. Rate of objects ingested by young children increased over last two decades

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2mmYptb

Expires April 12, 2020

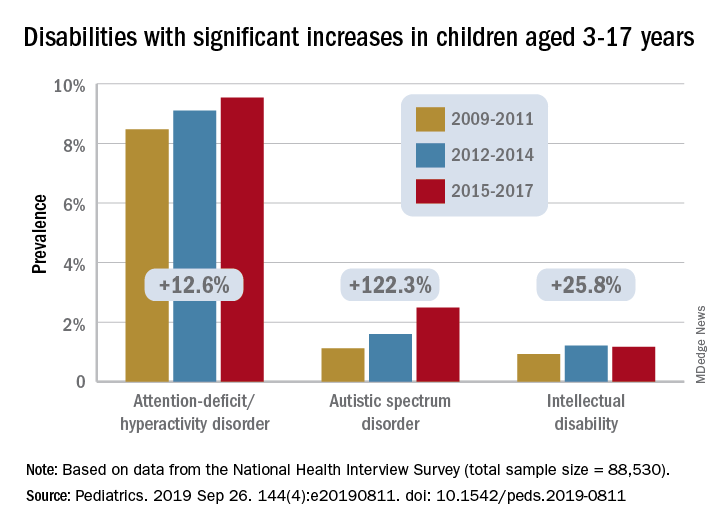

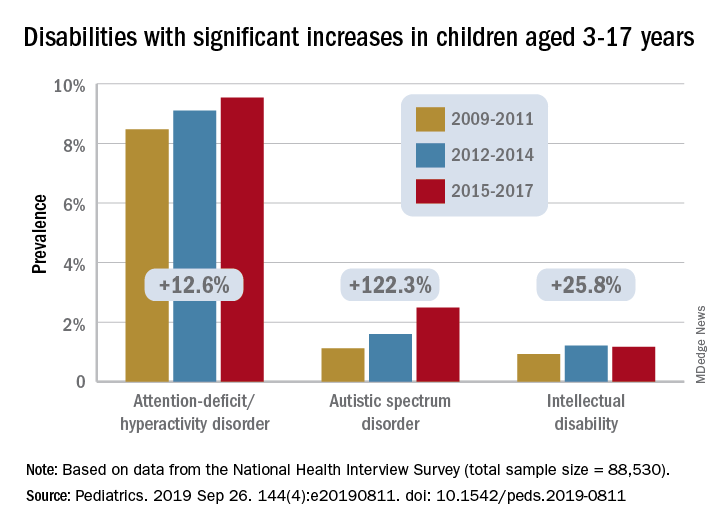

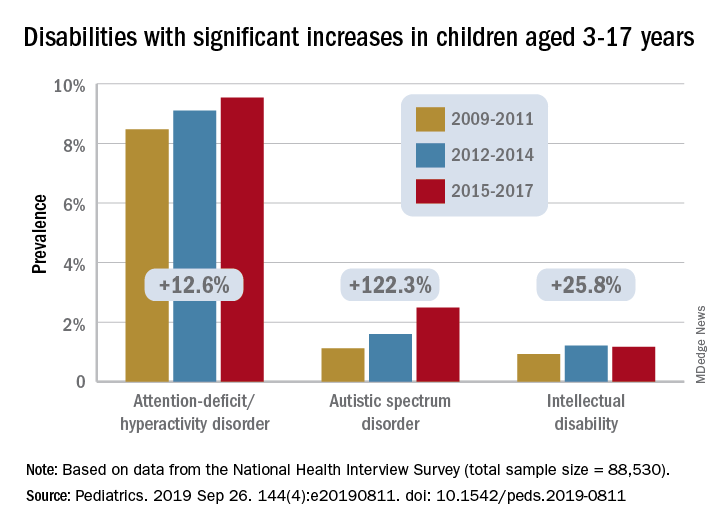

Prevalence of developmental disabilities up significantly since 2009

The significant increase in developmental disability prevalence in U.S. children from 2009 to 2017 may have been driven by factors such as better identification and availability of services, according to analysis of National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data.

The prevalence of any developmental disability rose from 16% in 2009 to 18% in 2017 in children aged 3-17 years, for an increase of 9.5%, Benjamin Zablotsky, PhD, of the National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md., and associates reported in Pediatrics.

Changes among the various conditions were not uniform, however, and most of the increase came from ADHD, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and intellectual disability, which were up by 12.6%, 122.3%, and 25.8%, respectively, they said, based on data for 88,530 children from the NHIS.

Because other studies have shown that the “prevalence of ADHD symptoms and impairment has remained steady over time,” the increase according to NHIS data “could be driven by better identification of children who meet criteria for ADHD, as current estimates of diagnosed prevalence are in line with community-based studies,” Dr. Zablotsky and associates wrote.

Improved identification, “related to increasing parental awareness and changing provider practices” also may account for much of the rise in ASD prevalence, they said.

It also may be related to changes in the survey itself, as “an increase of about 80% was seen in the 2014 NHIS following changes to the wording and ordering of the question capturing ASD.”

The investigators offered a similar explanation for the increase in intellectual disability prevalence, which increased by 72% from 2011 to 2013 when the phrasing of the NHIS question was changed from “mental retardation” to “intellectual disability, also known as mental retardation.”

The other specific conditions – blindness, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, learning disability, seizures, and stuttering/stammering – all saw nonsignificant changes during the study period, with one exception. “Other developmental delay” dropped by a significant 13%. “It is possible that parents have become less likely to select this category because their children have increasingly been diagnosed with another specified condition on the survey,” Dr. Zablotsky and associates said.

“These findings have major implications for pediatric training and workforce needs and more broadly for public health policies and resources to meet the complex medical and educational needs of the rising number of children with disabilities and their families,” Maureen S. Durkin, PhD, DrPH, said in an accompanying editorial.

The trends reported by Dr. Zablotsky and associates, which have been seen in other countries, are the result of improved survival among children, so, “in this sense, a rise in the prevalence of developmental disabilities may be seen as a global indicator of progress in children’s health and pediatric care,” said Dr. Durkin, a epidemiologist in Madison, Wis.

Dr. Zablotsky and coauthors said that there was no external funding for the study and that they had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Dr. Durkin said that she had no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Zablotsky B et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 26. 144(4):e20190811. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0811; Durkin MS. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 26. 144[4]:e20192005. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2005.

The significant increase in developmental disability prevalence in U.S. children from 2009 to 2017 may have been driven by factors such as better identification and availability of services, according to analysis of National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data.

The prevalence of any developmental disability rose from 16% in 2009 to 18% in 2017 in children aged 3-17 years, for an increase of 9.5%, Benjamin Zablotsky, PhD, of the National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md., and associates reported in Pediatrics.

Changes among the various conditions were not uniform, however, and most of the increase came from ADHD, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and intellectual disability, which were up by 12.6%, 122.3%, and 25.8%, respectively, they said, based on data for 88,530 children from the NHIS.

Because other studies have shown that the “prevalence of ADHD symptoms and impairment has remained steady over time,” the increase according to NHIS data “could be driven by better identification of children who meet criteria for ADHD, as current estimates of diagnosed prevalence are in line with community-based studies,” Dr. Zablotsky and associates wrote.

Improved identification, “related to increasing parental awareness and changing provider practices” also may account for much of the rise in ASD prevalence, they said.

It also may be related to changes in the survey itself, as “an increase of about 80% was seen in the 2014 NHIS following changes to the wording and ordering of the question capturing ASD.”

The investigators offered a similar explanation for the increase in intellectual disability prevalence, which increased by 72% from 2011 to 2013 when the phrasing of the NHIS question was changed from “mental retardation” to “intellectual disability, also known as mental retardation.”

The other specific conditions – blindness, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, learning disability, seizures, and stuttering/stammering – all saw nonsignificant changes during the study period, with one exception. “Other developmental delay” dropped by a significant 13%. “It is possible that parents have become less likely to select this category because their children have increasingly been diagnosed with another specified condition on the survey,” Dr. Zablotsky and associates said.

“These findings have major implications for pediatric training and workforce needs and more broadly for public health policies and resources to meet the complex medical and educational needs of the rising number of children with disabilities and their families,” Maureen S. Durkin, PhD, DrPH, said in an accompanying editorial.

The trends reported by Dr. Zablotsky and associates, which have been seen in other countries, are the result of improved survival among children, so, “in this sense, a rise in the prevalence of developmental disabilities may be seen as a global indicator of progress in children’s health and pediatric care,” said Dr. Durkin, a epidemiologist in Madison, Wis.

Dr. Zablotsky and coauthors said that there was no external funding for the study and that they had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Dr. Durkin said that she had no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Zablotsky B et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 26. 144(4):e20190811. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0811; Durkin MS. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 26. 144[4]:e20192005. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2005.

The significant increase in developmental disability prevalence in U.S. children from 2009 to 2017 may have been driven by factors such as better identification and availability of services, according to analysis of National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data.

The prevalence of any developmental disability rose from 16% in 2009 to 18% in 2017 in children aged 3-17 years, for an increase of 9.5%, Benjamin Zablotsky, PhD, of the National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md., and associates reported in Pediatrics.

Changes among the various conditions were not uniform, however, and most of the increase came from ADHD, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and intellectual disability, which were up by 12.6%, 122.3%, and 25.8%, respectively, they said, based on data for 88,530 children from the NHIS.

Because other studies have shown that the “prevalence of ADHD symptoms and impairment has remained steady over time,” the increase according to NHIS data “could be driven by better identification of children who meet criteria for ADHD, as current estimates of diagnosed prevalence are in line with community-based studies,” Dr. Zablotsky and associates wrote.

Improved identification, “related to increasing parental awareness and changing provider practices” also may account for much of the rise in ASD prevalence, they said.

It also may be related to changes in the survey itself, as “an increase of about 80% was seen in the 2014 NHIS following changes to the wording and ordering of the question capturing ASD.”

The investigators offered a similar explanation for the increase in intellectual disability prevalence, which increased by 72% from 2011 to 2013 when the phrasing of the NHIS question was changed from “mental retardation” to “intellectual disability, also known as mental retardation.”

The other specific conditions – blindness, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, learning disability, seizures, and stuttering/stammering – all saw nonsignificant changes during the study period, with one exception. “Other developmental delay” dropped by a significant 13%. “It is possible that parents have become less likely to select this category because their children have increasingly been diagnosed with another specified condition on the survey,” Dr. Zablotsky and associates said.

“These findings have major implications for pediatric training and workforce needs and more broadly for public health policies and resources to meet the complex medical and educational needs of the rising number of children with disabilities and their families,” Maureen S. Durkin, PhD, DrPH, said in an accompanying editorial.

The trends reported by Dr. Zablotsky and associates, which have been seen in other countries, are the result of improved survival among children, so, “in this sense, a rise in the prevalence of developmental disabilities may be seen as a global indicator of progress in children’s health and pediatric care,” said Dr. Durkin, a epidemiologist in Madison, Wis.

Dr. Zablotsky and coauthors said that there was no external funding for the study and that they had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Dr. Durkin said that she had no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Zablotsky B et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 26. 144(4):e20190811. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0811; Durkin MS. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 26. 144[4]:e20192005. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2005.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among U.S. children aged 3-17 years, prevalence of developmental disabilities increased by 9.5% from 2009 to 2017.

Study details: The sample from the National Health Interview Survey included 88,530 children.

Disclosures: The investigators said that there was no external funding for the study and that they had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Source: Zablotsky B et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 26. 144(4):e20190811. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0811.

RISE analyses highlight further youth vs. adult T2D differences

BARCELONA – Further differences in how adults and adolescents with type 2 diabetes respond to glucose and glucagon have been demonstrated by new data from the Restoring Insulin SEcretion (RISE) studies presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

In a comparison of responses to an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), youth (n = 85) were more likely than were adults (n = 353) to have a biphasic type of glucose response curve (18.8% vs. 8.2%, respectively), which is considered a more normal response curve. However, that “did not foretell an advantageous outcome to the RISE interventions in the younger age group,” said study investigator Silva Arslanian, MD, of UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

Fewer youth than adults had an incessant response (10.6% vs. 14.5%, respectively) or monophasic response to an OGTT (70.6% vs. 77.3%), and that was associated with lower beta-cell responses, compared with individuals with monophasic or biphasic glucose curves.

“Irrespective of curve type, insulin sensitivity was lower in youth than in adults,” Dr. Arslanian said. She added that beta-cell responses were greater in youth than in adults, except in youth with the worst incessant-increase curve type. In youth with the incessant-increase glucose curve, there was no evidence of beta-cell hypersecretion, which suggested youth “have more severe beta-cell dysfunction,” compared with adults.

There were also data presented on whether differences in alpha-cell function between youth and adults might be important. Those data showed that although fasting glucagon concentrations did not increase with fasting glucose in youth, they did in adults. It was found that fasting and stimulated glucagon concentrations were lower in youth than in adults, meaning that “alpha-cell function does not explain the beta-cell hyperresponsiveness seen in youth with impaired glucose tolerance or recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes,” reported study investigator Steven Kahn, MD, ChB, of VA Puget Sound Health Care System, University of Washington, Seattle.

“This is a batch of secondary analyses,” Philip Zeitler, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, said in an interview. Dr. Zeitler, who chaired the session at which the new findings were unveiled, noted that the main data from the RISE Pediatric Medication Study (RISE Peds) were published last year (Diabetes Care. 2018;41[8]:1717-25) and results from the RISE Adult Medication Study (RISE Adult) were just presented this year, and explained that the timing difference was because the adult study took longer to complete its target accrual.

Results of these studies showed that, compared with adults, youth were substantially more insulin resistant and had hyperresponsive beta cells. Furthermore, their beta-cell function deteriorated during and after treatment for type 2 diabetes, whereas it improved during treatment and remained stable after stopping treatment in adults (Diabetes. 2019;68:1670-80).

The idea for the RISE trials came about around 6 years ago, with the overall aim of trying to identify approaches that could preserve or improve beta-cell function in younger patients and adults with dysglycemia, Dr. Zeitler explained. When the trials were being planned it was known that young patients with type 2 diabetes often needed much higher doses of insulin, compared with their adult counterparts. So, it “wasn’t entirely unexpected” that they were found to be insulin resistant, particularly, as puberty is an insulin-resistant state, Dr. Zeitler observed.

“What was new, however, was that [the beta-cells of] youth were hyperresponsive and were really making large amounts of insulin.” Increased insulin production might be expected when there is insulin resistance, he added, but the level seen was “more than you would expect.” Over time, that might be toxic to the beta cells, and evidence from the earlier TODAY (Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth) studies suggested that the rate of beta-cell dysfunction was more rapid in youth than in adults.

Giving his perspective, as a pediatrician, on the new OGTT analyses from the RISE studies, Dr. Zeitler said that these data showed that the characteristic beta-cell hyperresponsiveness seen in youth “actually disappears as glycemia worsens.” In youth with the incessant glucose response pattern, “it shows that they cannot tolerate glucose, and their glucose levels just go up and up and up” until the beta cells fail.

This is a critical observation, Dr. Zeitler said, noting that it “sort of had to be the case, because sooner or later you had to lose beta cells ... this is probably the point where aggressive therapy is needed ... it was always a bit of a paradox, if these kids have such an aggressive course, how come they were starting out being so hyperresponsive?”

With regard to alpha-cell function, “these are really fresh data. We haven’t really had a long time to think about it,” said Dr. Zeitler. “What I find interesting is that there isn’t alpha-cell glucagon hypersecretion in youth like there is in adults.” That may be because youth are making so much insulin that they are suppressing glucagon production, but that’s not an entirely satisfying answer,” he said.

“The TODAY study demonstrated that diabetes in kids is aggressive; these RISE data now start to put some physiology around that, why is it more aggressive? Hyperresponsiveness, loss of beta-cell function over time, lack of response to intervention, compared with the adults.”

As for the clinical implications, Dr. Zeitler said that this is further evidence that the default approach to treating younger patients with greater caution than adults is perhaps not the best way to treat type 2 diabetes.

“These data are really showing that there is a very important toxic period that is occurring in these kids early on [and] that probably argues for more, not less, aggressive therapy,” than with adults. “Clearly, something is happening that is putting them at really big risk for rapid progression, and that’s your chance to treat much more aggressively, much earlier.”

The RISE studies are sponsored by the RISE Study Group in collaboration with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Zeitler disclosed that he had acted as a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Daiichi-Sankyo and Merck, Sharp & Dohme, and had received research support from Janssen. Dr. Arslanian stated that she has nothing to disclose. Dr. Khan did not provide any disclosure information.

SOURCES: Arslanian S. EASD 2019, Oral presentation S34.1; Kahn S. EASD 2019, Oral presentation S34.3

BARCELONA – Further differences in how adults and adolescents with type 2 diabetes respond to glucose and glucagon have been demonstrated by new data from the Restoring Insulin SEcretion (RISE) studies presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

In a comparison of responses to an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), youth (n = 85) were more likely than were adults (n = 353) to have a biphasic type of glucose response curve (18.8% vs. 8.2%, respectively), which is considered a more normal response curve. However, that “did not foretell an advantageous outcome to the RISE interventions in the younger age group,” said study investigator Silva Arslanian, MD, of UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

Fewer youth than adults had an incessant response (10.6% vs. 14.5%, respectively) or monophasic response to an OGTT (70.6% vs. 77.3%), and that was associated with lower beta-cell responses, compared with individuals with monophasic or biphasic glucose curves.

“Irrespective of curve type, insulin sensitivity was lower in youth than in adults,” Dr. Arslanian said. She added that beta-cell responses were greater in youth than in adults, except in youth with the worst incessant-increase curve type. In youth with the incessant-increase glucose curve, there was no evidence of beta-cell hypersecretion, which suggested youth “have more severe beta-cell dysfunction,” compared with adults.

There were also data presented on whether differences in alpha-cell function between youth and adults might be important. Those data showed that although fasting glucagon concentrations did not increase with fasting glucose in youth, they did in adults. It was found that fasting and stimulated glucagon concentrations were lower in youth than in adults, meaning that “alpha-cell function does not explain the beta-cell hyperresponsiveness seen in youth with impaired glucose tolerance or recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes,” reported study investigator Steven Kahn, MD, ChB, of VA Puget Sound Health Care System, University of Washington, Seattle.

“This is a batch of secondary analyses,” Philip Zeitler, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, said in an interview. Dr. Zeitler, who chaired the session at which the new findings were unveiled, noted that the main data from the RISE Pediatric Medication Study (RISE Peds) were published last year (Diabetes Care. 2018;41[8]:1717-25) and results from the RISE Adult Medication Study (RISE Adult) were just presented this year, and explained that the timing difference was because the adult study took longer to complete its target accrual.

Results of these studies showed that, compared with adults, youth were substantially more insulin resistant and had hyperresponsive beta cells. Furthermore, their beta-cell function deteriorated during and after treatment for type 2 diabetes, whereas it improved during treatment and remained stable after stopping treatment in adults (Diabetes. 2019;68:1670-80).

The idea for the RISE trials came about around 6 years ago, with the overall aim of trying to identify approaches that could preserve or improve beta-cell function in younger patients and adults with dysglycemia, Dr. Zeitler explained. When the trials were being planned it was known that young patients with type 2 diabetes often needed much higher doses of insulin, compared with their adult counterparts. So, it “wasn’t entirely unexpected” that they were found to be insulin resistant, particularly, as puberty is an insulin-resistant state, Dr. Zeitler observed.

“What was new, however, was that [the beta-cells of] youth were hyperresponsive and were really making large amounts of insulin.” Increased insulin production might be expected when there is insulin resistance, he added, but the level seen was “more than you would expect.” Over time, that might be toxic to the beta cells, and evidence from the earlier TODAY (Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth) studies suggested that the rate of beta-cell dysfunction was more rapid in youth than in adults.

Giving his perspective, as a pediatrician, on the new OGTT analyses from the RISE studies, Dr. Zeitler said that these data showed that the characteristic beta-cell hyperresponsiveness seen in youth “actually disappears as glycemia worsens.” In youth with the incessant glucose response pattern, “it shows that they cannot tolerate glucose, and their glucose levels just go up and up and up” until the beta cells fail.

This is a critical observation, Dr. Zeitler said, noting that it “sort of had to be the case, because sooner or later you had to lose beta cells ... this is probably the point where aggressive therapy is needed ... it was always a bit of a paradox, if these kids have such an aggressive course, how come they were starting out being so hyperresponsive?”

With regard to alpha-cell function, “these are really fresh data. We haven’t really had a long time to think about it,” said Dr. Zeitler. “What I find interesting is that there isn’t alpha-cell glucagon hypersecretion in youth like there is in adults.” That may be because youth are making so much insulin that they are suppressing glucagon production, but that’s not an entirely satisfying answer,” he said.

“The TODAY study demonstrated that diabetes in kids is aggressive; these RISE data now start to put some physiology around that, why is it more aggressive? Hyperresponsiveness, loss of beta-cell function over time, lack of response to intervention, compared with the adults.”

As for the clinical implications, Dr. Zeitler said that this is further evidence that the default approach to treating younger patients with greater caution than adults is perhaps not the best way to treat type 2 diabetes.

“These data are really showing that there is a very important toxic period that is occurring in these kids early on [and] that probably argues for more, not less, aggressive therapy,” than with adults. “Clearly, something is happening that is putting them at really big risk for rapid progression, and that’s your chance to treat much more aggressively, much earlier.”

The RISE studies are sponsored by the RISE Study Group in collaboration with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Zeitler disclosed that he had acted as a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Daiichi-Sankyo and Merck, Sharp & Dohme, and had received research support from Janssen. Dr. Arslanian stated that she has nothing to disclose. Dr. Khan did not provide any disclosure information.

SOURCES: Arslanian S. EASD 2019, Oral presentation S34.1; Kahn S. EASD 2019, Oral presentation S34.3

BARCELONA – Further differences in how adults and adolescents with type 2 diabetes respond to glucose and glucagon have been demonstrated by new data from the Restoring Insulin SEcretion (RISE) studies presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

In a comparison of responses to an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), youth (n = 85) were more likely than were adults (n = 353) to have a biphasic type of glucose response curve (18.8% vs. 8.2%, respectively), which is considered a more normal response curve. However, that “did not foretell an advantageous outcome to the RISE interventions in the younger age group,” said study investigator Silva Arslanian, MD, of UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

Fewer youth than adults had an incessant response (10.6% vs. 14.5%, respectively) or monophasic response to an OGTT (70.6% vs. 77.3%), and that was associated with lower beta-cell responses, compared with individuals with monophasic or biphasic glucose curves.

“Irrespective of curve type, insulin sensitivity was lower in youth than in adults,” Dr. Arslanian said. She added that beta-cell responses were greater in youth than in adults, except in youth with the worst incessant-increase curve type. In youth with the incessant-increase glucose curve, there was no evidence of beta-cell hypersecretion, which suggested youth “have more severe beta-cell dysfunction,” compared with adults.

There were also data presented on whether differences in alpha-cell function between youth and adults might be important. Those data showed that although fasting glucagon concentrations did not increase with fasting glucose in youth, they did in adults. It was found that fasting and stimulated glucagon concentrations were lower in youth than in adults, meaning that “alpha-cell function does not explain the beta-cell hyperresponsiveness seen in youth with impaired glucose tolerance or recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes,” reported study investigator Steven Kahn, MD, ChB, of VA Puget Sound Health Care System, University of Washington, Seattle.

“This is a batch of secondary analyses,” Philip Zeitler, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, said in an interview. Dr. Zeitler, who chaired the session at which the new findings were unveiled, noted that the main data from the RISE Pediatric Medication Study (RISE Peds) were published last year (Diabetes Care. 2018;41[8]:1717-25) and results from the RISE Adult Medication Study (RISE Adult) were just presented this year, and explained that the timing difference was because the adult study took longer to complete its target accrual.

Results of these studies showed that, compared with adults, youth were substantially more insulin resistant and had hyperresponsive beta cells. Furthermore, their beta-cell function deteriorated during and after treatment for type 2 diabetes, whereas it improved during treatment and remained stable after stopping treatment in adults (Diabetes. 2019;68:1670-80).

The idea for the RISE trials came about around 6 years ago, with the overall aim of trying to identify approaches that could preserve or improve beta-cell function in younger patients and adults with dysglycemia, Dr. Zeitler explained. When the trials were being planned it was known that young patients with type 2 diabetes often needed much higher doses of insulin, compared with their adult counterparts. So, it “wasn’t entirely unexpected” that they were found to be insulin resistant, particularly, as puberty is an insulin-resistant state, Dr. Zeitler observed.

“What was new, however, was that [the beta-cells of] youth were hyperresponsive and were really making large amounts of insulin.” Increased insulin production might be expected when there is insulin resistance, he added, but the level seen was “more than you would expect.” Over time, that might be toxic to the beta cells, and evidence from the earlier TODAY (Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth) studies suggested that the rate of beta-cell dysfunction was more rapid in youth than in adults.

Giving his perspective, as a pediatrician, on the new OGTT analyses from the RISE studies, Dr. Zeitler said that these data showed that the characteristic beta-cell hyperresponsiveness seen in youth “actually disappears as glycemia worsens.” In youth with the incessant glucose response pattern, “it shows that they cannot tolerate glucose, and their glucose levels just go up and up and up” until the beta cells fail.

This is a critical observation, Dr. Zeitler said, noting that it “sort of had to be the case, because sooner or later you had to lose beta cells ... this is probably the point where aggressive therapy is needed ... it was always a bit of a paradox, if these kids have such an aggressive course, how come they were starting out being so hyperresponsive?”

With regard to alpha-cell function, “these are really fresh data. We haven’t really had a long time to think about it,” said Dr. Zeitler. “What I find interesting is that there isn’t alpha-cell glucagon hypersecretion in youth like there is in adults.” That may be because youth are making so much insulin that they are suppressing glucagon production, but that’s not an entirely satisfying answer,” he said.

“The TODAY study demonstrated that diabetes in kids is aggressive; these RISE data now start to put some physiology around that, why is it more aggressive? Hyperresponsiveness, loss of beta-cell function over time, lack of response to intervention, compared with the adults.”

As for the clinical implications, Dr. Zeitler said that this is further evidence that the default approach to treating younger patients with greater caution than adults is perhaps not the best way to treat type 2 diabetes.

“These data are really showing that there is a very important toxic period that is occurring in these kids early on [and] that probably argues for more, not less, aggressive therapy,” than with adults. “Clearly, something is happening that is putting them at really big risk for rapid progression, and that’s your chance to treat much more aggressively, much earlier.”

The RISE studies are sponsored by the RISE Study Group in collaboration with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Zeitler disclosed that he had acted as a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Daiichi-Sankyo and Merck, Sharp & Dohme, and had received research support from Janssen. Dr. Arslanian stated that she has nothing to disclose. Dr. Khan did not provide any disclosure information.

SOURCES: Arslanian S. EASD 2019, Oral presentation S34.1; Kahn S. EASD 2019, Oral presentation S34.3

REPORTING FROM EASD 2019

Anakinra treatment for pediatric ‘cytokine storms’: Does one size fit all?

The biologic drug anakinra appears to be effective in treating children with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH)/macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), a dangerous “cytokine storm” that can emerge from infections, cancer, and rheumatic diseases.

Children with systematic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) and sHLH/MAS are especially good candidates for treatment with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra (Kineret), in whom its safety and benefits have been more widely explored than in pediatric patients with sHLH/MAS related to non-sJIA underlying conditions.

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, Esraa Eloseily, MD, and colleagues at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, looked at hospitalization records for 44 children (mean age, 10 years; n = 25 females) with sHLH/MAS. The children in the study had heterogeneous underlying conditions including leukemias, infections, and rheumatic diseases. About one-third of patients had no known rheumatic or autoimmune disorder.

Dr. Eloseily and colleagues found that early initiation of anakinra (within 5 days of hospitalization) was significantly associated with improved survival across the cohort, for which mortality was 27%. Thrombocytopenia (less than 100,000/mcL) and STXBP2 mutations were both seen significantly associated with mortality.

Patients with blood cancers – even those in remission at the time of treatment – did poorly. None of the three patients in the cohort with leukemia survived.

Importantly, no deaths were seen among the 13 patients with underlying SJIA who were treated with anakinra, suggesting particular benefit for this patient group.

“In addition to the 10% risk of developing overt MAS as part of sJIA, another 30%-40% of sJIA patients may have occult or subclinical MAS during a disease flare that can eventually lead to overt MAS,” Dr. Eloseily and colleagues wrote. “This association of MAS with sJIA suggested that anakinra would also be a valuable treatment for sJIA-MAS.”

The investigators acknowledged that their study was limited by its retrospective design and “nonuniform approach to therapy, lack of treatment controls, and variable follow-up period.” The authors also acknowledged the potential for selection bias favoring anakinra use in patients who are less severely ill.

In a comment accompanying Dr. Eloseily and colleagues’ study, Sarah Nikiforow, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and Nancy Berliner, MD, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, urged clinicians not to interpret the study results as supporting anakinra as “a carte blanche approach to hyperinflammatory syndromes.”

While the study supported the use of anakinra in sJIA with MAS or sHLH, “we posit that patients [with sHLH/MAS] in sepsis, cytokine release syndrome following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, and other hyperinflammatory syndromes still require individualized approaches to therapy,” Dr. Nikiforow and Dr. Berliner wrote, adding that, “in several studies and anecdotally in our institutional practice, cytotoxic chemotherapy was/is preferred over biologic agents in patients with evidence of more severe inflammatory activity.”

Outside sJIA, Dr. Nikiforow and Dr. Berliner wrote, “early anakinra therapy should be extended to treatment of other forms of sHLH with extreme caution. Specifically, the authors’ suggestion that cytotoxic therapy should be ‘considered’ only after anakinra therapy may be dangerous for some patients.”

Two of Dr. Eloseily’s coinvestigators reported financial and research support from Sobi, the manufacturer of anakinra. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCES: Eloseily E et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Sep 12. doi: 10.1002/art.41103; Nikiforow S, Berliner N. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Sep 16. doi: 10.1002/art.41106.

The biologic drug anakinra appears to be effective in treating children with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH)/macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), a dangerous “cytokine storm” that can emerge from infections, cancer, and rheumatic diseases.

Children with systematic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) and sHLH/MAS are especially good candidates for treatment with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra (Kineret), in whom its safety and benefits have been more widely explored than in pediatric patients with sHLH/MAS related to non-sJIA underlying conditions.

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, Esraa Eloseily, MD, and colleagues at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, looked at hospitalization records for 44 children (mean age, 10 years; n = 25 females) with sHLH/MAS. The children in the study had heterogeneous underlying conditions including leukemias, infections, and rheumatic diseases. About one-third of patients had no known rheumatic or autoimmune disorder.

Dr. Eloseily and colleagues found that early initiation of anakinra (within 5 days of hospitalization) was significantly associated with improved survival across the cohort, for which mortality was 27%. Thrombocytopenia (less than 100,000/mcL) and STXBP2 mutations were both seen significantly associated with mortality.

Patients with blood cancers – even those in remission at the time of treatment – did poorly. None of the three patients in the cohort with leukemia survived.

Importantly, no deaths were seen among the 13 patients with underlying SJIA who were treated with anakinra, suggesting particular benefit for this patient group.

“In addition to the 10% risk of developing overt MAS as part of sJIA, another 30%-40% of sJIA patients may have occult or subclinical MAS during a disease flare that can eventually lead to overt MAS,” Dr. Eloseily and colleagues wrote. “This association of MAS with sJIA suggested that anakinra would also be a valuable treatment for sJIA-MAS.”

The investigators acknowledged that their study was limited by its retrospective design and “nonuniform approach to therapy, lack of treatment controls, and variable follow-up period.” The authors also acknowledged the potential for selection bias favoring anakinra use in patients who are less severely ill.

In a comment accompanying Dr. Eloseily and colleagues’ study, Sarah Nikiforow, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and Nancy Berliner, MD, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, urged clinicians not to interpret the study results as supporting anakinra as “a carte blanche approach to hyperinflammatory syndromes.”

While the study supported the use of anakinra in sJIA with MAS or sHLH, “we posit that patients [with sHLH/MAS] in sepsis, cytokine release syndrome following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, and other hyperinflammatory syndromes still require individualized approaches to therapy,” Dr. Nikiforow and Dr. Berliner wrote, adding that, “in several studies and anecdotally in our institutional practice, cytotoxic chemotherapy was/is preferred over biologic agents in patients with evidence of more severe inflammatory activity.”

Outside sJIA, Dr. Nikiforow and Dr. Berliner wrote, “early anakinra therapy should be extended to treatment of other forms of sHLH with extreme caution. Specifically, the authors’ suggestion that cytotoxic therapy should be ‘considered’ only after anakinra therapy may be dangerous for some patients.”

Two of Dr. Eloseily’s coinvestigators reported financial and research support from Sobi, the manufacturer of anakinra. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCES: Eloseily E et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Sep 12. doi: 10.1002/art.41103; Nikiforow S, Berliner N. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Sep 16. doi: 10.1002/art.41106.

The biologic drug anakinra appears to be effective in treating children with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH)/macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), a dangerous “cytokine storm” that can emerge from infections, cancer, and rheumatic diseases.

Children with systematic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) and sHLH/MAS are especially good candidates for treatment with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra (Kineret), in whom its safety and benefits have been more widely explored than in pediatric patients with sHLH/MAS related to non-sJIA underlying conditions.

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, Esraa Eloseily, MD, and colleagues at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, looked at hospitalization records for 44 children (mean age, 10 years; n = 25 females) with sHLH/MAS. The children in the study had heterogeneous underlying conditions including leukemias, infections, and rheumatic diseases. About one-third of patients had no known rheumatic or autoimmune disorder.

Dr. Eloseily and colleagues found that early initiation of anakinra (within 5 days of hospitalization) was significantly associated with improved survival across the cohort, for which mortality was 27%. Thrombocytopenia (less than 100,000/mcL) and STXBP2 mutations were both seen significantly associated with mortality.

Patients with blood cancers – even those in remission at the time of treatment – did poorly. None of the three patients in the cohort with leukemia survived.

Importantly, no deaths were seen among the 13 patients with underlying SJIA who were treated with anakinra, suggesting particular benefit for this patient group.

“In addition to the 10% risk of developing overt MAS as part of sJIA, another 30%-40% of sJIA patients may have occult or subclinical MAS during a disease flare that can eventually lead to overt MAS,” Dr. Eloseily and colleagues wrote. “This association of MAS with sJIA suggested that anakinra would also be a valuable treatment for sJIA-MAS.”

The investigators acknowledged that their study was limited by its retrospective design and “nonuniform approach to therapy, lack of treatment controls, and variable follow-up period.” The authors also acknowledged the potential for selection bias favoring anakinra use in patients who are less severely ill.

In a comment accompanying Dr. Eloseily and colleagues’ study, Sarah Nikiforow, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and Nancy Berliner, MD, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, urged clinicians not to interpret the study results as supporting anakinra as “a carte blanche approach to hyperinflammatory syndromes.”

While the study supported the use of anakinra in sJIA with MAS or sHLH, “we posit that patients [with sHLH/MAS] in sepsis, cytokine release syndrome following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, and other hyperinflammatory syndromes still require individualized approaches to therapy,” Dr. Nikiforow and Dr. Berliner wrote, adding that, “in several studies and anecdotally in our institutional practice, cytotoxic chemotherapy was/is preferred over biologic agents in patients with evidence of more severe inflammatory activity.”

Outside sJIA, Dr. Nikiforow and Dr. Berliner wrote, “early anakinra therapy should be extended to treatment of other forms of sHLH with extreme caution. Specifically, the authors’ suggestion that cytotoxic therapy should be ‘considered’ only after anakinra therapy may be dangerous for some patients.”

Two of Dr. Eloseily’s coinvestigators reported financial and research support from Sobi, the manufacturer of anakinra. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCES: Eloseily E et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Sep 12. doi: 10.1002/art.41103; Nikiforow S, Berliner N. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Sep 16. doi: 10.1002/art.41106.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Parent survey sheds light on suboptimal compliance with eczema medications

of children with AD.

Perceived effectiveness was the main driver of this variation, Alan Schwartz PhD, and Korey Capozza, MPH, wrote in the study, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

“Responses suggest parents may be willing to use therapies with concerning side effects if they can see a clear benefit for their child’s eczema, but when anticipated improvements fail to materialize, they may change their usage, usually in the direction of using less medication or stopping,” observed Dr. Schwartz, of the University of Illinois, Chicago, and Ms. Capozza, of Global Parents for Eczema Research.

“Addressing expectations related to effectiveness, rather than concerns about medication use, may thus be more likely to lead to taking medication as directed.”

The researchers posted a 15-question survey on the Facebook page of Global Parents for Eczema Research, an international coalition of parents of children with AD. During the month that the survey was posted, 86 parents completed it; questions pertained to adherence to medications and reasons for changing treatments. The mean age of their children was 6 years, most (about 83%) had moderate or severe eczema, and about half lived in the United States.

More than half (55%) reported using the AD medications as directed. But 30% said they took or applied less than prescribed, 13% had stopped the prescribed medication altogether, and 2% took or applied more (or more often) than prescribed.

There were several reasons stated for this variance. Concern over side effects was the most common (46%) reason for not using medications as directed. The next most common reasons were that the child’s symptoms went away (28%); or the “medication was not helping or was not helping as much,” in 23%.

A lack of physician trust or not agreeing with the physician’s recommendations accounted for 18% of the concerns. The remainder thought it wasn’t important to take the medication as prescribed, it was inconvenient or too time consuming, that they forgot, it was too expensive, or they were confused about the directions.

To the question asking “What would have made you more likely to use the medication as prescribed?” the most common answer was a clearer indication of effectiveness (56%). The next most common was “access to research or evidence about benefit and side effect profile” (14%).

A good relationship between the physician and patient was associated with taking medication as directed

“Improvement in adherence to topical treatments among children with AD could yield large gains in quality-of-life improvements and reduce exposure to costlier and potentially more toxic systemic agents,” the authors noted. “Given the large, documented gains in disease improvement, and even remission, achieved with interventions that address adherence among patients with other chronic diseases, strategies that address the underlying causes for poor adherence among parents of children with atopic dermatitis stand to provide a significant, untapped benefit.”

No financial disclosures were noted.

SOURCE: Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 28. doi: 10.1111/pde.13991.

of children with AD.

Perceived effectiveness was the main driver of this variation, Alan Schwartz PhD, and Korey Capozza, MPH, wrote in the study, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

“Responses suggest parents may be willing to use therapies with concerning side effects if they can see a clear benefit for their child’s eczema, but when anticipated improvements fail to materialize, they may change their usage, usually in the direction of using less medication or stopping,” observed Dr. Schwartz, of the University of Illinois, Chicago, and Ms. Capozza, of Global Parents for Eczema Research.

“Addressing expectations related to effectiveness, rather than concerns about medication use, may thus be more likely to lead to taking medication as directed.”

The researchers posted a 15-question survey on the Facebook page of Global Parents for Eczema Research, an international coalition of parents of children with AD. During the month that the survey was posted, 86 parents completed it; questions pertained to adherence to medications and reasons for changing treatments. The mean age of their children was 6 years, most (about 83%) had moderate or severe eczema, and about half lived in the United States.

More than half (55%) reported using the AD medications as directed. But 30% said they took or applied less than prescribed, 13% had stopped the prescribed medication altogether, and 2% took or applied more (or more often) than prescribed.

There were several reasons stated for this variance. Concern over side effects was the most common (46%) reason for not using medications as directed. The next most common reasons were that the child’s symptoms went away (28%); or the “medication was not helping or was not helping as much,” in 23%.

A lack of physician trust or not agreeing with the physician’s recommendations accounted for 18% of the concerns. The remainder thought it wasn’t important to take the medication as prescribed, it was inconvenient or too time consuming, that they forgot, it was too expensive, or they were confused about the directions.

To the question asking “What would have made you more likely to use the medication as prescribed?” the most common answer was a clearer indication of effectiveness (56%). The next most common was “access to research or evidence about benefit and side effect profile” (14%).

A good relationship between the physician and patient was associated with taking medication as directed

“Improvement in adherence to topical treatments among children with AD could yield large gains in quality-of-life improvements and reduce exposure to costlier and potentially more toxic systemic agents,” the authors noted. “Given the large, documented gains in disease improvement, and even remission, achieved with interventions that address adherence among patients with other chronic diseases, strategies that address the underlying causes for poor adherence among parents of children with atopic dermatitis stand to provide a significant, untapped benefit.”

No financial disclosures were noted.

SOURCE: Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 28. doi: 10.1111/pde.13991.

of children with AD.

Perceived effectiveness was the main driver of this variation, Alan Schwartz PhD, and Korey Capozza, MPH, wrote in the study, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

“Responses suggest parents may be willing to use therapies with concerning side effects if they can see a clear benefit for their child’s eczema, but when anticipated improvements fail to materialize, they may change their usage, usually in the direction of using less medication or stopping,” observed Dr. Schwartz, of the University of Illinois, Chicago, and Ms. Capozza, of Global Parents for Eczema Research.

“Addressing expectations related to effectiveness, rather than concerns about medication use, may thus be more likely to lead to taking medication as directed.”

The researchers posted a 15-question survey on the Facebook page of Global Parents for Eczema Research, an international coalition of parents of children with AD. During the month that the survey was posted, 86 parents completed it; questions pertained to adherence to medications and reasons for changing treatments. The mean age of their children was 6 years, most (about 83%) had moderate or severe eczema, and about half lived in the United States.

More than half (55%) reported using the AD medications as directed. But 30% said they took or applied less than prescribed, 13% had stopped the prescribed medication altogether, and 2% took or applied more (or more often) than prescribed.

There were several reasons stated for this variance. Concern over side effects was the most common (46%) reason for not using medications as directed. The next most common reasons were that the child’s symptoms went away (28%); or the “medication was not helping or was not helping as much,” in 23%.

A lack of physician trust or not agreeing with the physician’s recommendations accounted for 18% of the concerns. The remainder thought it wasn’t important to take the medication as prescribed, it was inconvenient or too time consuming, that they forgot, it was too expensive, or they were confused about the directions.

To the question asking “What would have made you more likely to use the medication as prescribed?” the most common answer was a clearer indication of effectiveness (56%). The next most common was “access to research or evidence about benefit and side effect profile” (14%).

A good relationship between the physician and patient was associated with taking medication as directed

“Improvement in adherence to topical treatments among children with AD could yield large gains in quality-of-life improvements and reduce exposure to costlier and potentially more toxic systemic agents,” the authors noted. “Given the large, documented gains in disease improvement, and even remission, achieved with interventions that address adherence among patients with other chronic diseases, strategies that address the underlying causes for poor adherence among parents of children with atopic dermatitis stand to provide a significant, untapped benefit.”

No financial disclosures were noted.

SOURCE: Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 28. doi: 10.1111/pde.13991.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Impulsivity, screen time, and sleep

If you are still struggling to understand the ADHD phenomenon and its meteoric rise to prominence over the last 3 or 4 decades, a study published in the September 2019 Pediatrics may help you make sense of why you are spending a large part of your professional day counseling parents and treating children whose lives are disrupted by their impulsivity, distractibility, and inattentiveness (“24-hour movement behaviors and impulsivity.” doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0187). Researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (Canada) Research Institute used data collected over 10 years in 21 sites across the United States on more than 4,500 children aged 8-11 years, looking for possible associations between impulsivity and three factors – sleep duration, screen time, and physical activity.

They found that children who were exposed to fewer than 2 hours of recreational screen time each day and slept 9-11 hours nightly had significantly reduced scores on a range of impulsivity scores. While participating in at least 60 minutes of vigorous physical activity per day also was associated with less impulsivity, the effect added little to the benefit of the sleep/screen time combination. Although these nonpharmacologic strategies aimed at decreasing impulsivity may not be a cure-all for every child with symptoms that suggest ADHD, the data are compelling.

I hope that the associations these Canadian researchers have unearthed is not news to you. But their observation that 30% of the sample population met none of the recommendations for sleep, screen time, and activity and that only 5% of the sample did suggests that too few of us are delivering the message with sufficient enthusiasm and/or too many parents aren’t taking it seriously.

Over the last several years I have been encouraged to find sleep and screen time limits mentioned in articles on ADHD for both professionals and parents, but these potent contributors to impulsivity and distractibility always seem to be relegated to the oh-by-the-way category at the end of the article after a lengthy discussion of the relative values of medication and cognitive-behavioral therapy. And unfortunately, meeting these behavioral guidelines can be difficult to achieve and cannot be subcontracted out to a therapist or a pharmacist. They require parents to set and enforce limits. Saying no is difficult for all of us, particularly those without much prior experience.

How robustly have you bought into the idea that more sleep and less screen time are, if not THE answers, at least are the two we should start with? Where do your recommendations about screen time, sleep, and physical activity fit into the script when you are talking with parents about their child’s ADHD-ish behaviors? Have you put them in the oh-by-the-way category?