User login

Racial Limitations of Fitzpatrick Skin Type

Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) is the most commonly used classification system in dermatologic practice. It was developed by Thomas B. Fitzpatrick, MD, PhD, in 1975 to assess the propensity of the skin to burn during phototherapy.1 Fitzpatrick skin type also can be used to assess the clinical benefits and efficacy of cosmetic procedures, including laser hair removal, chemical peel and dermabrasion, tattoo removal, spray tanning, and laser resurfacing for acne scarring.2 The original FST classifications included skin types I through IV; skin types V and VI were later added to include individuals of Asian, Indian, and African origin.1 As a result, FST often is used by providers as a means of describing constitutive skin color and ethnicity.3

How did FST transition from describing the propensity of the skin to burn from UV light exposure to categorizing skin color, thereby becoming a proxy for race? It most likely occurred because there has not been another widely adopted classification system for describing skin color that can be applied to all skin types. Even when the FST classification scale is used as intended, there are inconsistencies with its accuracy; for example, self-reported FSTs have correlated poorly with sunburn risk as well as physician-reported FSTs.4,5 Although physician-reported FSTs have been demonstrated to correlate with race, race does not consistently correlate with objective measures of pigmentation or self-reported FSTs.5 For example, Japanese women often self-identify as FST type II, but Asian skin generally is considered to be nonwhite.1 Fitzpatrick himself acknowledged that race and ethnicity are cultural and political terms with no scientific basis.6 Fitzpatrick skin type also has been demonstrated to correlate poorly with constitutive skin color and minimal erythema dose values.7

We conducted an anonymous survey of dermatologists and dermatology trainees to evaluate how providers use FST in their clinical practice as well as how it is used to describe race and ethnicity.

Methods

The survey was distributed electronically to dermatologists and dermatology trainees from March 13 to March 28, 2019, using the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserv, as well as in person at the annual Skin of Color Society meeting in Washington, DC, on February 28, 2019. The 8-item survey included questions about physician demographics (ie, primary practice setting, board certification, and geographic location); whether the respondent identified as an individual with skin of color; and how the respondent utilized FST in clinical notes (ie, describing race/ethnicity, skin cancer risk, and constitutive [baseline] skin color; determining initial phototherapy dosage and suitability for laser treatments, and likelihood of skin burning). A t test was used to determine whether dermatologists who identified as having skin of color utilized FST differently.

Results

A total of 141 surveys were returned, and 140 respondents were included in the final analysis. Given the methods used to distribute the survey, a response rate could not be calculated. The respondents included more board-certified dermatologists (70%) than dermatology trainees (30%). Ninety-three percent of respondents indicated an academic institution as their primary practice location. Notably, 26% of respondents self-identified as having skin of color.

Forty-one percent of all respondents agreed that FST should be included in their clinical documentation. In response to the question “In what scenarios would you refer to FST in a clinical note?” 31% said they used FST to describe patients’ race or ethnicity, 47% used it to describe patients’ constitutive skin color, and 22% utilized it in both scenarios. Respondents who did not identify as having skin of color were more likely to use FST to describe constitutive skin color, though this finding was not statistically significant (P=.063). Anecdotally, providers also included FST in clinical notes on postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, and treatment with cryotherapy.

Comment

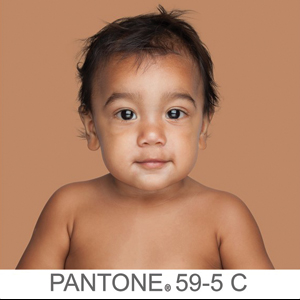

The US Census Bureau has estimated that half of the US population will be of non-European descent by 2050.8 As racial and ethnic distinctions continue to be blurred, attempts to include all nonwhite skin types under the umbrella term skin of color becomes increasingly problematic. The true number of skin colors is unknown but likely is infinite, as Brazilian artist Angélica Dass has demonstrated with her photographic project “Humanae” (Figure). Given this shift in demographics and the limitations of the FST, alternative methods of describing skin color must be developed.

© Angélica Dass | Humanae Work in Progress (Courtesy of the artist).

The results of our survey suggest that approximately one-third to half of academic dermatologists/dermatology trainees use FST to describe race/ethnicity and/or constitutive skin color. This misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color. Additionally, misuse of FST in academic settings may be problematic and confusing for medical students who may learn to use this common dermatologic tool outside of its original intent.

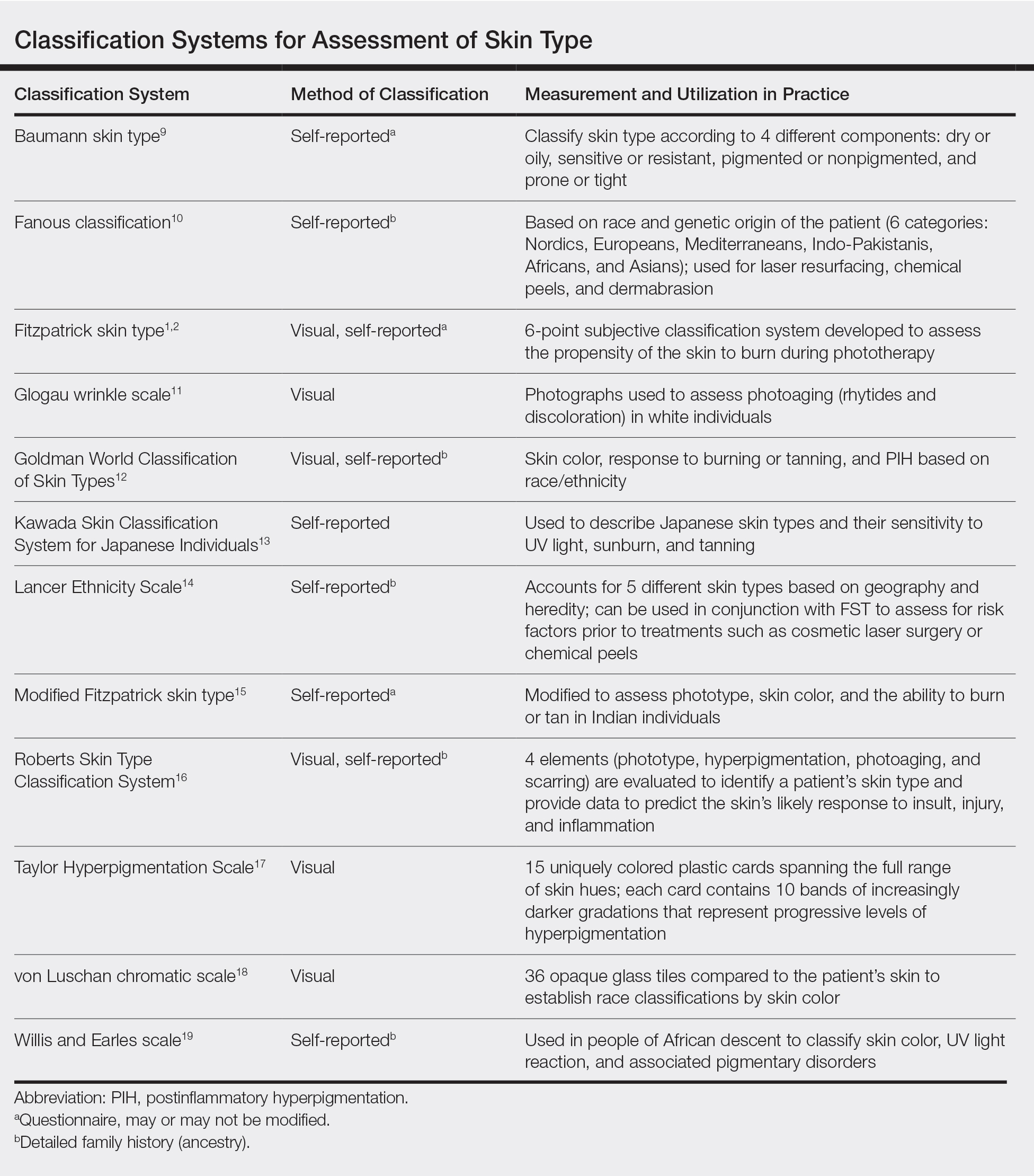

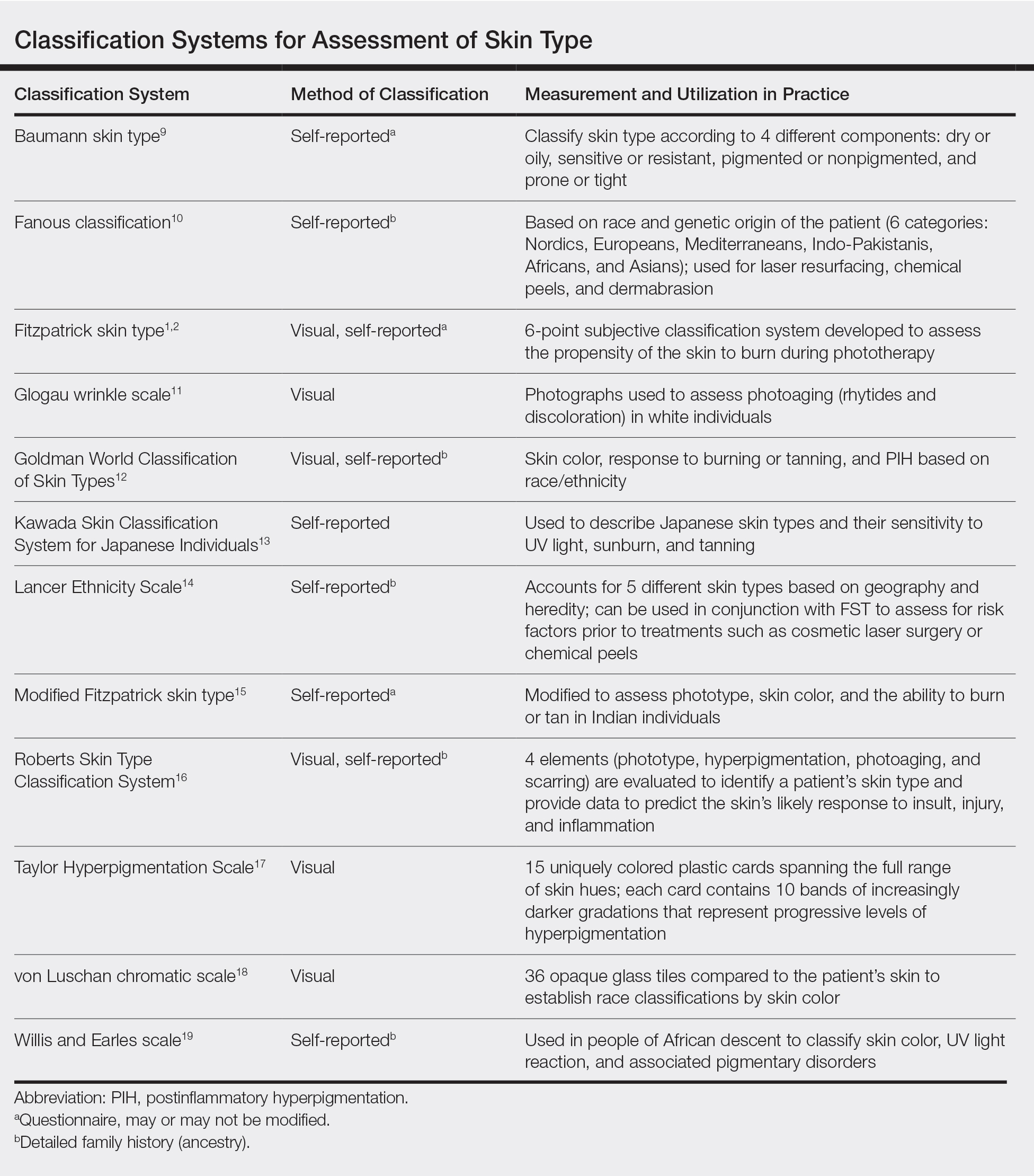

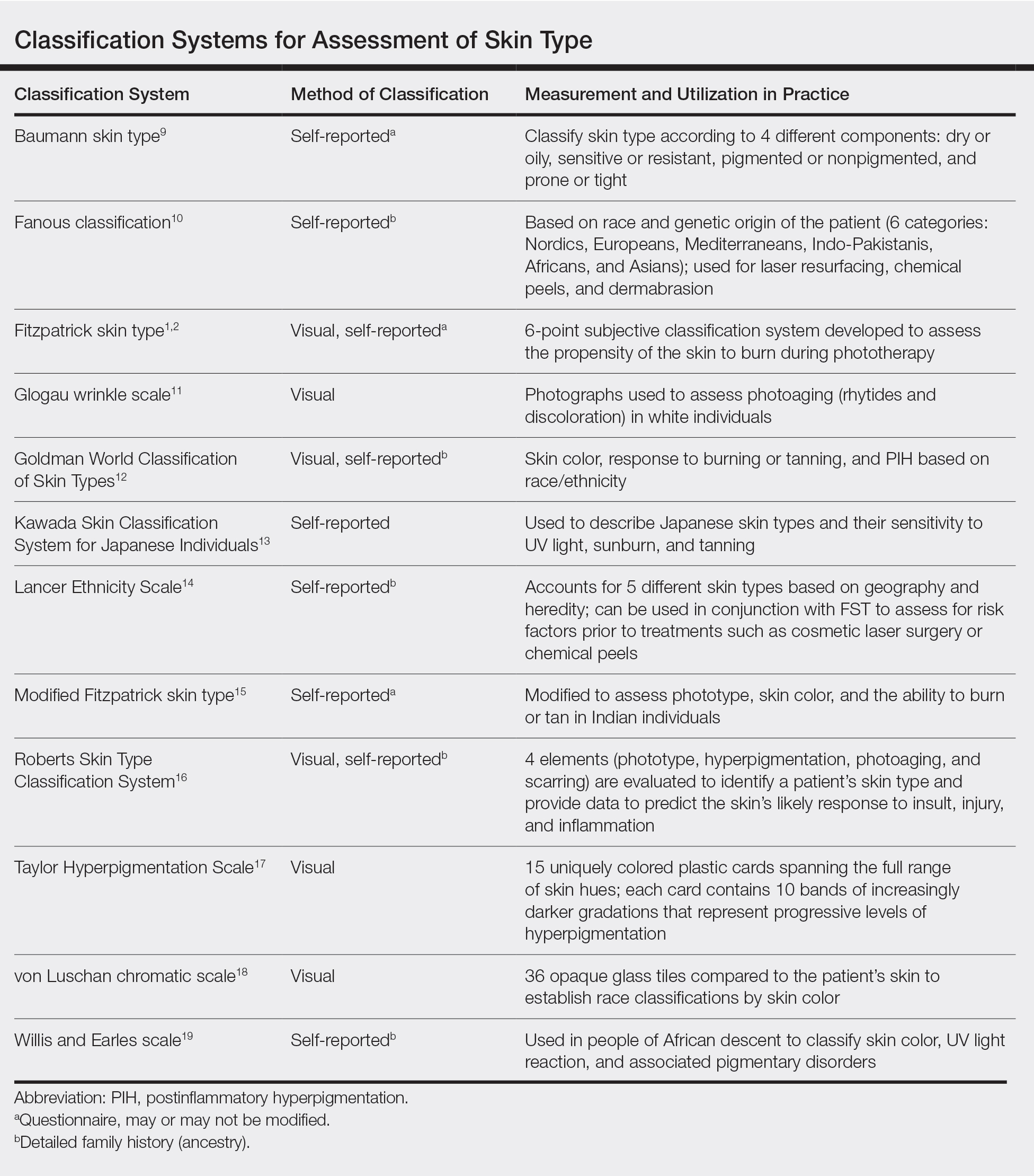

We acknowledge that the conundrum of how to classify individuals with nonwhite skin or skin of color is not simply answered. Several alternative skin classification models have been proposed to improve the sensitivity and specificity of identifying patients with skin of color (Table). Refining FST classification is one approach. Employing terms such as skin irritation, tenderness, itching, or skin becoming darker from sun exposure rather than painful burn or tanning may result in better identification.1,4 A study conducted in India modified the FST questionnaire to acknowledge cultural behaviors.15 Because lighter skin is culturally valued in this population, patient experience with purposeful sun exposure was limited; thus, the questionnaire was modified to remove questions on the use of tanning booths and/or creams as well as sun exposure and instead included more objective questions regarding dark brown eye color, black and dark brown hair color, and dark brown skin color.15 Other studies have suggested that patient-reported photosensitivity assessed via a questionnaire is a valid measure for assessing FST but is associated with an overestimation of skin color, known as “the dark shift.”20

Sharma et al15 utilized reflectance spectrophotometry as an objective measure of melanin and skin erythema. The melanin index consistently showed a positive correlation with FSTs as opposed to the erythema index, which correlated poorly.15 Although reflectance spectrometry accurately identifies skin color in patients with nonwhite skin,21,22 it is an impractical and cost-prohibitive tool for daily practice. A more practical tool for the clinical setting would be a visual color scale with skin hues spanning FST types I to VI, including bands of increasingly darker gradations that would be particularly useful in assessing skin of color. Once such tool is the Taylor Hyperpigmentation Scale.17 Although currently not widely available, this tool could be further refined with additional skin hues.

Conclusion

Other investigators have criticized the various limitations of FST, including physician vs patient assessment, interview vs questionnaire, and phrasing of questions on skin type.23 Our findings suggest that medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with FST. Two authors of this report (O.R.W. and J.E.D.) are medical students with skin of color and frequently have observed the addition of FST to the medical records of patients who were not receiving phototherapy as a proxy for race. We believe that more culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed and, in the interim, the original intent of FST should be emphasized and incorporated in medical school and resident education.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Adewole Adamson, MD (Austin, Texas), for discussion and feedback.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

- Everett JS, Budescu M, Sommers MS. Making sense of skin color in clinical care. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21:495-516.

- Eilers S, Bach DQ, Gaber R, et al. Accuracy of self-report in assessingFitzpatrick skin phototypes I through VI. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1289-1294.

- He SY, McCulloch CE, Boscardin WJ, et al. Self-reported pigmentary phenotypes and race are significant but incomplete predictors of Fitzpatrick skin phototype in an ethnically diverse population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:731-737.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Leenutaphong V. Relationship between skin color and cutaneous response to ultraviolet radiation in Thai. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1996;11:198-203.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

- Baumann L. Understanding and treating various skin types: the Baumann Skin Type Indicator. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:359-373.

- Fanous N. A new patient classification for laser resurfacing and peels: predicting responses, risks, and results. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26:99-104.

- Glogau RG. Chemical peeling and aging skin. J Geriatric Dermatol. 1994;2:30-35.

- Goldman M. Universal classification of skin type. In: Shiffman M, Mirrafati S, Lam S, et al, eds. Simplified Facial Rejuvenation. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008:47-50.

- Kawada A. UVB-induced erythema, delayed tanning, and UVA-induced immediate tanning in Japanese skin. Photodermatol. 1986;3:327-333.

- Lancer HA. Lancer Ethnicity Scale (LES). Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22:9.

- Sharma VK, Gupta V, Jangid BL, et al. Modification of the Fitzpatrick system of skin phototype classification for the Indian population, and its correlation with narrowband diffuse reflectance spectrophotometry. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:274-280.

- Roberts WE. The Roberts Skin Type Classification System. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:452-456.

- Taylor SC, Arsonnaud S, Czernielewski J. The Taylor hyperpigmentation scale: a new visual assessment tool for the evaluation of skin color and pigmentation. Cutis. 2005;76:270-274.

- Treesirichod A, Chansakulporn S, Wattanapan P. Correlation between skin color evaluation by skin color scale chart and narrowband reflectance spectrophotometer. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:339-342.

- Willis I, Earles RM. A new classification system relevant to people of African descent. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2005;18:209-216.

- Reeder AI, Hammond VA, Gray AR. Questionnaire items to assess skin color and erythemal sensitivity: reliability, validity, and “the dark shift.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1167-1173.

- Dwyer T, Muller HK, Blizzard L, et al. The use of spectrophotometry to estimate melanin density in Caucasians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:203-206.

- Pershing LK, Tirumala VP, Nelson JL, et al. Reflectance spectrophotometer: the dermatologists’ sphygmomanometer for skin phototyping? J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1633-1640.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) is the most commonly used classification system in dermatologic practice. It was developed by Thomas B. Fitzpatrick, MD, PhD, in 1975 to assess the propensity of the skin to burn during phototherapy.1 Fitzpatrick skin type also can be used to assess the clinical benefits and efficacy of cosmetic procedures, including laser hair removal, chemical peel and dermabrasion, tattoo removal, spray tanning, and laser resurfacing for acne scarring.2 The original FST classifications included skin types I through IV; skin types V and VI were later added to include individuals of Asian, Indian, and African origin.1 As a result, FST often is used by providers as a means of describing constitutive skin color and ethnicity.3

How did FST transition from describing the propensity of the skin to burn from UV light exposure to categorizing skin color, thereby becoming a proxy for race? It most likely occurred because there has not been another widely adopted classification system for describing skin color that can be applied to all skin types. Even when the FST classification scale is used as intended, there are inconsistencies with its accuracy; for example, self-reported FSTs have correlated poorly with sunburn risk as well as physician-reported FSTs.4,5 Although physician-reported FSTs have been demonstrated to correlate with race, race does not consistently correlate with objective measures of pigmentation or self-reported FSTs.5 For example, Japanese women often self-identify as FST type II, but Asian skin generally is considered to be nonwhite.1 Fitzpatrick himself acknowledged that race and ethnicity are cultural and political terms with no scientific basis.6 Fitzpatrick skin type also has been demonstrated to correlate poorly with constitutive skin color and minimal erythema dose values.7

We conducted an anonymous survey of dermatologists and dermatology trainees to evaluate how providers use FST in their clinical practice as well as how it is used to describe race and ethnicity.

Methods

The survey was distributed electronically to dermatologists and dermatology trainees from March 13 to March 28, 2019, using the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserv, as well as in person at the annual Skin of Color Society meeting in Washington, DC, on February 28, 2019. The 8-item survey included questions about physician demographics (ie, primary practice setting, board certification, and geographic location); whether the respondent identified as an individual with skin of color; and how the respondent utilized FST in clinical notes (ie, describing race/ethnicity, skin cancer risk, and constitutive [baseline] skin color; determining initial phototherapy dosage and suitability for laser treatments, and likelihood of skin burning). A t test was used to determine whether dermatologists who identified as having skin of color utilized FST differently.

Results

A total of 141 surveys were returned, and 140 respondents were included in the final analysis. Given the methods used to distribute the survey, a response rate could not be calculated. The respondents included more board-certified dermatologists (70%) than dermatology trainees (30%). Ninety-three percent of respondents indicated an academic institution as their primary practice location. Notably, 26% of respondents self-identified as having skin of color.

Forty-one percent of all respondents agreed that FST should be included in their clinical documentation. In response to the question “In what scenarios would you refer to FST in a clinical note?” 31% said they used FST to describe patients’ race or ethnicity, 47% used it to describe patients’ constitutive skin color, and 22% utilized it in both scenarios. Respondents who did not identify as having skin of color were more likely to use FST to describe constitutive skin color, though this finding was not statistically significant (P=.063). Anecdotally, providers also included FST in clinical notes on postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, and treatment with cryotherapy.

Comment

The US Census Bureau has estimated that half of the US population will be of non-European descent by 2050.8 As racial and ethnic distinctions continue to be blurred, attempts to include all nonwhite skin types under the umbrella term skin of color becomes increasingly problematic. The true number of skin colors is unknown but likely is infinite, as Brazilian artist Angélica Dass has demonstrated with her photographic project “Humanae” (Figure). Given this shift in demographics and the limitations of the FST, alternative methods of describing skin color must be developed.

© Angélica Dass | Humanae Work in Progress (Courtesy of the artist).

The results of our survey suggest that approximately one-third to half of academic dermatologists/dermatology trainees use FST to describe race/ethnicity and/or constitutive skin color. This misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color. Additionally, misuse of FST in academic settings may be problematic and confusing for medical students who may learn to use this common dermatologic tool outside of its original intent.

We acknowledge that the conundrum of how to classify individuals with nonwhite skin or skin of color is not simply answered. Several alternative skin classification models have been proposed to improve the sensitivity and specificity of identifying patients with skin of color (Table). Refining FST classification is one approach. Employing terms such as skin irritation, tenderness, itching, or skin becoming darker from sun exposure rather than painful burn or tanning may result in better identification.1,4 A study conducted in India modified the FST questionnaire to acknowledge cultural behaviors.15 Because lighter skin is culturally valued in this population, patient experience with purposeful sun exposure was limited; thus, the questionnaire was modified to remove questions on the use of tanning booths and/or creams as well as sun exposure and instead included more objective questions regarding dark brown eye color, black and dark brown hair color, and dark brown skin color.15 Other studies have suggested that patient-reported photosensitivity assessed via a questionnaire is a valid measure for assessing FST but is associated with an overestimation of skin color, known as “the dark shift.”20

Sharma et al15 utilized reflectance spectrophotometry as an objective measure of melanin and skin erythema. The melanin index consistently showed a positive correlation with FSTs as opposed to the erythema index, which correlated poorly.15 Although reflectance spectrometry accurately identifies skin color in patients with nonwhite skin,21,22 it is an impractical and cost-prohibitive tool for daily practice. A more practical tool for the clinical setting would be a visual color scale with skin hues spanning FST types I to VI, including bands of increasingly darker gradations that would be particularly useful in assessing skin of color. Once such tool is the Taylor Hyperpigmentation Scale.17 Although currently not widely available, this tool could be further refined with additional skin hues.

Conclusion

Other investigators have criticized the various limitations of FST, including physician vs patient assessment, interview vs questionnaire, and phrasing of questions on skin type.23 Our findings suggest that medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with FST. Two authors of this report (O.R.W. and J.E.D.) are medical students with skin of color and frequently have observed the addition of FST to the medical records of patients who were not receiving phototherapy as a proxy for race. We believe that more culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed and, in the interim, the original intent of FST should be emphasized and incorporated in medical school and resident education.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Adewole Adamson, MD (Austin, Texas), for discussion and feedback.

Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) is the most commonly used classification system in dermatologic practice. It was developed by Thomas B. Fitzpatrick, MD, PhD, in 1975 to assess the propensity of the skin to burn during phototherapy.1 Fitzpatrick skin type also can be used to assess the clinical benefits and efficacy of cosmetic procedures, including laser hair removal, chemical peel and dermabrasion, tattoo removal, spray tanning, and laser resurfacing for acne scarring.2 The original FST classifications included skin types I through IV; skin types V and VI were later added to include individuals of Asian, Indian, and African origin.1 As a result, FST often is used by providers as a means of describing constitutive skin color and ethnicity.3

How did FST transition from describing the propensity of the skin to burn from UV light exposure to categorizing skin color, thereby becoming a proxy for race? It most likely occurred because there has not been another widely adopted classification system for describing skin color that can be applied to all skin types. Even when the FST classification scale is used as intended, there are inconsistencies with its accuracy; for example, self-reported FSTs have correlated poorly with sunburn risk as well as physician-reported FSTs.4,5 Although physician-reported FSTs have been demonstrated to correlate with race, race does not consistently correlate with objective measures of pigmentation or self-reported FSTs.5 For example, Japanese women often self-identify as FST type II, but Asian skin generally is considered to be nonwhite.1 Fitzpatrick himself acknowledged that race and ethnicity are cultural and political terms with no scientific basis.6 Fitzpatrick skin type also has been demonstrated to correlate poorly with constitutive skin color and minimal erythema dose values.7

We conducted an anonymous survey of dermatologists and dermatology trainees to evaluate how providers use FST in their clinical practice as well as how it is used to describe race and ethnicity.

Methods

The survey was distributed electronically to dermatologists and dermatology trainees from March 13 to March 28, 2019, using the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserv, as well as in person at the annual Skin of Color Society meeting in Washington, DC, on February 28, 2019. The 8-item survey included questions about physician demographics (ie, primary practice setting, board certification, and geographic location); whether the respondent identified as an individual with skin of color; and how the respondent utilized FST in clinical notes (ie, describing race/ethnicity, skin cancer risk, and constitutive [baseline] skin color; determining initial phototherapy dosage and suitability for laser treatments, and likelihood of skin burning). A t test was used to determine whether dermatologists who identified as having skin of color utilized FST differently.

Results

A total of 141 surveys were returned, and 140 respondents were included in the final analysis. Given the methods used to distribute the survey, a response rate could not be calculated. The respondents included more board-certified dermatologists (70%) than dermatology trainees (30%). Ninety-three percent of respondents indicated an academic institution as their primary practice location. Notably, 26% of respondents self-identified as having skin of color.

Forty-one percent of all respondents agreed that FST should be included in their clinical documentation. In response to the question “In what scenarios would you refer to FST in a clinical note?” 31% said they used FST to describe patients’ race or ethnicity, 47% used it to describe patients’ constitutive skin color, and 22% utilized it in both scenarios. Respondents who did not identify as having skin of color were more likely to use FST to describe constitutive skin color, though this finding was not statistically significant (P=.063). Anecdotally, providers also included FST in clinical notes on postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, and treatment with cryotherapy.

Comment

The US Census Bureau has estimated that half of the US population will be of non-European descent by 2050.8 As racial and ethnic distinctions continue to be blurred, attempts to include all nonwhite skin types under the umbrella term skin of color becomes increasingly problematic. The true number of skin colors is unknown but likely is infinite, as Brazilian artist Angélica Dass has demonstrated with her photographic project “Humanae” (Figure). Given this shift in demographics and the limitations of the FST, alternative methods of describing skin color must be developed.

© Angélica Dass | Humanae Work in Progress (Courtesy of the artist).

The results of our survey suggest that approximately one-third to half of academic dermatologists/dermatology trainees use FST to describe race/ethnicity and/or constitutive skin color. This misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color. Additionally, misuse of FST in academic settings may be problematic and confusing for medical students who may learn to use this common dermatologic tool outside of its original intent.

We acknowledge that the conundrum of how to classify individuals with nonwhite skin or skin of color is not simply answered. Several alternative skin classification models have been proposed to improve the sensitivity and specificity of identifying patients with skin of color (Table). Refining FST classification is one approach. Employing terms such as skin irritation, tenderness, itching, or skin becoming darker from sun exposure rather than painful burn or tanning may result in better identification.1,4 A study conducted in India modified the FST questionnaire to acknowledge cultural behaviors.15 Because lighter skin is culturally valued in this population, patient experience with purposeful sun exposure was limited; thus, the questionnaire was modified to remove questions on the use of tanning booths and/or creams as well as sun exposure and instead included more objective questions regarding dark brown eye color, black and dark brown hair color, and dark brown skin color.15 Other studies have suggested that patient-reported photosensitivity assessed via a questionnaire is a valid measure for assessing FST but is associated with an overestimation of skin color, known as “the dark shift.”20

Sharma et al15 utilized reflectance spectrophotometry as an objective measure of melanin and skin erythema. The melanin index consistently showed a positive correlation with FSTs as opposed to the erythema index, which correlated poorly.15 Although reflectance spectrometry accurately identifies skin color in patients with nonwhite skin,21,22 it is an impractical and cost-prohibitive tool for daily practice. A more practical tool for the clinical setting would be a visual color scale with skin hues spanning FST types I to VI, including bands of increasingly darker gradations that would be particularly useful in assessing skin of color. Once such tool is the Taylor Hyperpigmentation Scale.17 Although currently not widely available, this tool could be further refined with additional skin hues.

Conclusion

Other investigators have criticized the various limitations of FST, including physician vs patient assessment, interview vs questionnaire, and phrasing of questions on skin type.23 Our findings suggest that medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with FST. Two authors of this report (O.R.W. and J.E.D.) are medical students with skin of color and frequently have observed the addition of FST to the medical records of patients who were not receiving phototherapy as a proxy for race. We believe that more culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed and, in the interim, the original intent of FST should be emphasized and incorporated in medical school and resident education.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Adewole Adamson, MD (Austin, Texas), for discussion and feedback.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

- Everett JS, Budescu M, Sommers MS. Making sense of skin color in clinical care. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21:495-516.

- Eilers S, Bach DQ, Gaber R, et al. Accuracy of self-report in assessingFitzpatrick skin phototypes I through VI. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1289-1294.

- He SY, McCulloch CE, Boscardin WJ, et al. Self-reported pigmentary phenotypes and race are significant but incomplete predictors of Fitzpatrick skin phototype in an ethnically diverse population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:731-737.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Leenutaphong V. Relationship between skin color and cutaneous response to ultraviolet radiation in Thai. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1996;11:198-203.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

- Baumann L. Understanding and treating various skin types: the Baumann Skin Type Indicator. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:359-373.

- Fanous N. A new patient classification for laser resurfacing and peels: predicting responses, risks, and results. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26:99-104.

- Glogau RG. Chemical peeling and aging skin. J Geriatric Dermatol. 1994;2:30-35.

- Goldman M. Universal classification of skin type. In: Shiffman M, Mirrafati S, Lam S, et al, eds. Simplified Facial Rejuvenation. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008:47-50.

- Kawada A. UVB-induced erythema, delayed tanning, and UVA-induced immediate tanning in Japanese skin. Photodermatol. 1986;3:327-333.

- Lancer HA. Lancer Ethnicity Scale (LES). Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22:9.

- Sharma VK, Gupta V, Jangid BL, et al. Modification of the Fitzpatrick system of skin phototype classification for the Indian population, and its correlation with narrowband diffuse reflectance spectrophotometry. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:274-280.

- Roberts WE. The Roberts Skin Type Classification System. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:452-456.

- Taylor SC, Arsonnaud S, Czernielewski J. The Taylor hyperpigmentation scale: a new visual assessment tool for the evaluation of skin color and pigmentation. Cutis. 2005;76:270-274.

- Treesirichod A, Chansakulporn S, Wattanapan P. Correlation between skin color evaluation by skin color scale chart and narrowband reflectance spectrophotometer. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:339-342.

- Willis I, Earles RM. A new classification system relevant to people of African descent. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2005;18:209-216.

- Reeder AI, Hammond VA, Gray AR. Questionnaire items to assess skin color and erythemal sensitivity: reliability, validity, and “the dark shift.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1167-1173.

- Dwyer T, Muller HK, Blizzard L, et al. The use of spectrophotometry to estimate melanin density in Caucasians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:203-206.

- Pershing LK, Tirumala VP, Nelson JL, et al. Reflectance spectrophotometer: the dermatologists’ sphygmomanometer for skin phototyping? J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1633-1640.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

- Everett JS, Budescu M, Sommers MS. Making sense of skin color in clinical care. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21:495-516.

- Eilers S, Bach DQ, Gaber R, et al. Accuracy of self-report in assessingFitzpatrick skin phototypes I through VI. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1289-1294.

- He SY, McCulloch CE, Boscardin WJ, et al. Self-reported pigmentary phenotypes and race are significant but incomplete predictors of Fitzpatrick skin phototype in an ethnically diverse population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:731-737.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869-871.

- Leenutaphong V. Relationship between skin color and cutaneous response to ultraviolet radiation in Thai. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1996;11:198-203.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

- Baumann L. Understanding and treating various skin types: the Baumann Skin Type Indicator. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:359-373.

- Fanous N. A new patient classification for laser resurfacing and peels: predicting responses, risks, and results. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26:99-104.

- Glogau RG. Chemical peeling and aging skin. J Geriatric Dermatol. 1994;2:30-35.

- Goldman M. Universal classification of skin type. In: Shiffman M, Mirrafati S, Lam S, et al, eds. Simplified Facial Rejuvenation. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2008:47-50.

- Kawada A. UVB-induced erythema, delayed tanning, and UVA-induced immediate tanning in Japanese skin. Photodermatol. 1986;3:327-333.

- Lancer HA. Lancer Ethnicity Scale (LES). Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22:9.

- Sharma VK, Gupta V, Jangid BL, et al. Modification of the Fitzpatrick system of skin phototype classification for the Indian population, and its correlation with narrowband diffuse reflectance spectrophotometry. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:274-280.

- Roberts WE. The Roberts Skin Type Classification System. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:452-456.

- Taylor SC, Arsonnaud S, Czernielewski J. The Taylor hyperpigmentation scale: a new visual assessment tool for the evaluation of skin color and pigmentation. Cutis. 2005;76:270-274.

- Treesirichod A, Chansakulporn S, Wattanapan P. Correlation between skin color evaluation by skin color scale chart and narrowband reflectance spectrophotometer. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:339-342.

- Willis I, Earles RM. A new classification system relevant to people of African descent. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2005;18:209-216.

- Reeder AI, Hammond VA, Gray AR. Questionnaire items to assess skin color and erythemal sensitivity: reliability, validity, and “the dark shift.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1167-1173.

- Dwyer T, Muller HK, Blizzard L, et al. The use of spectrophotometry to estimate melanin density in Caucasians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:203-206.

- Pershing LK, Tirumala VP, Nelson JL, et al. Reflectance spectrophotometer: the dermatologists’ sphygmomanometer for skin phototyping? J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1633-1640.

- Trakatelli M, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Correia O, et al. Clinical assessment of skin phototypes: watch your words! Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:615-619.

Practice Points

- Medical providers should be cognizant of conflating race and ethnicity with Fitzpatrick skin type (FST).

- Misuse of FST may occur more frequently among physicians who do not identify as having skin of color.

- Although alternative skin type classification systems have been proposed, more clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color need to be developed.

New Barbie lineup includes a doll with vitiligo

A new line of Barbie dolls unveiled by Mattel earlier this month includes one with vitiligo, much to the delight of clinicians who treat children and adolescents with the condition.

“When I see young children and adolescents with vitiligo, it is very common for me to feel their emotional suffering from their skin condition,” Seemal R. Desai, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas said in an interview. “Kids can be cruel. Name calling, social ostracizing, [and] effects on self-esteem are all things I have seen amongst my patients and their families in their own struggles with vitiligo.”

According to a brand communications representative from toymaker Mattel, which began manufacturing Barbie dolls in 1959, the company worked with a board-certified dermatologist to include a doll with vitiligo in its 2020 “Fashionistas” line. “As we continue to redefine what it means to be a ‘Barbie’ or look like Barbie, offering a doll with vitiligo in our main doll line allows kids to play out even more stories they see in the world around them,” the representative wrote in an email message. Other dolls debuting as part of the lineup include one with no hair, one with a darker skin tone that uses a gold prosthetic limb, and a Ken doll with long rooted hair (think Jeff Spicoli in “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” but about six inches longer).

Such efforts to celebrate diversity and inclusiveness go far in helping children and young adults to embrace their skin and their own identities, said Dr. Desai, the immediate past president of the Skin of Color Society and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology board of directors. “One nuance, perhaps even more important, is that the Barbie can help to break down barriers, create awareness, and potentially even reduce bullying, stigma, and lack of knowledge about vitiligo amongst the general public who don’t understand vitiligo,” he said. “I hope the public and social media will embrace this new Barbie. Who knows? Pretty soon, vitiligo may no longer be a ‘thing’ that causes ‘stares’ and ‘glares.’ ”

Referring to the Barbie with no hair in the new line of dolls, the Mattel statement said, “ if a girl is experiencing hair loss for any reason, she can see herself reflected in the line.”

In 2019, Mattel introduced a lineup of Barbie dolls reflecting permanent disabilities, including one with a prosthetic limb. For that effort, the company collaborated with then-12-year-old Jordan Reeves, the “Born Just Right” coauthor “who is on a mission to build creative solutions that help kids with disabilities, to create a play experience that is as representative as possible,” the Mattel representative wrote.

A new line of Barbie dolls unveiled by Mattel earlier this month includes one with vitiligo, much to the delight of clinicians who treat children and adolescents with the condition.

“When I see young children and adolescents with vitiligo, it is very common for me to feel their emotional suffering from their skin condition,” Seemal R. Desai, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas said in an interview. “Kids can be cruel. Name calling, social ostracizing, [and] effects on self-esteem are all things I have seen amongst my patients and their families in their own struggles with vitiligo.”

According to a brand communications representative from toymaker Mattel, which began manufacturing Barbie dolls in 1959, the company worked with a board-certified dermatologist to include a doll with vitiligo in its 2020 “Fashionistas” line. “As we continue to redefine what it means to be a ‘Barbie’ or look like Barbie, offering a doll with vitiligo in our main doll line allows kids to play out even more stories they see in the world around them,” the representative wrote in an email message. Other dolls debuting as part of the lineup include one with no hair, one with a darker skin tone that uses a gold prosthetic limb, and a Ken doll with long rooted hair (think Jeff Spicoli in “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” but about six inches longer).

Such efforts to celebrate diversity and inclusiveness go far in helping children and young adults to embrace their skin and their own identities, said Dr. Desai, the immediate past president of the Skin of Color Society and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology board of directors. “One nuance, perhaps even more important, is that the Barbie can help to break down barriers, create awareness, and potentially even reduce bullying, stigma, and lack of knowledge about vitiligo amongst the general public who don’t understand vitiligo,” he said. “I hope the public and social media will embrace this new Barbie. Who knows? Pretty soon, vitiligo may no longer be a ‘thing’ that causes ‘stares’ and ‘glares.’ ”

Referring to the Barbie with no hair in the new line of dolls, the Mattel statement said, “ if a girl is experiencing hair loss for any reason, she can see herself reflected in the line.”

In 2019, Mattel introduced a lineup of Barbie dolls reflecting permanent disabilities, including one with a prosthetic limb. For that effort, the company collaborated with then-12-year-old Jordan Reeves, the “Born Just Right” coauthor “who is on a mission to build creative solutions that help kids with disabilities, to create a play experience that is as representative as possible,” the Mattel representative wrote.

A new line of Barbie dolls unveiled by Mattel earlier this month includes one with vitiligo, much to the delight of clinicians who treat children and adolescents with the condition.

“When I see young children and adolescents with vitiligo, it is very common for me to feel their emotional suffering from their skin condition,” Seemal R. Desai, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas said in an interview. “Kids can be cruel. Name calling, social ostracizing, [and] effects on self-esteem are all things I have seen amongst my patients and their families in their own struggles with vitiligo.”

According to a brand communications representative from toymaker Mattel, which began manufacturing Barbie dolls in 1959, the company worked with a board-certified dermatologist to include a doll with vitiligo in its 2020 “Fashionistas” line. “As we continue to redefine what it means to be a ‘Barbie’ or look like Barbie, offering a doll with vitiligo in our main doll line allows kids to play out even more stories they see in the world around them,” the representative wrote in an email message. Other dolls debuting as part of the lineup include one with no hair, one with a darker skin tone that uses a gold prosthetic limb, and a Ken doll with long rooted hair (think Jeff Spicoli in “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” but about six inches longer).

Such efforts to celebrate diversity and inclusiveness go far in helping children and young adults to embrace their skin and their own identities, said Dr. Desai, the immediate past president of the Skin of Color Society and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology board of directors. “One nuance, perhaps even more important, is that the Barbie can help to break down barriers, create awareness, and potentially even reduce bullying, stigma, and lack of knowledge about vitiligo amongst the general public who don’t understand vitiligo,” he said. “I hope the public and social media will embrace this new Barbie. Who knows? Pretty soon, vitiligo may no longer be a ‘thing’ that causes ‘stares’ and ‘glares.’ ”

Referring to the Barbie with no hair in the new line of dolls, the Mattel statement said, “ if a girl is experiencing hair loss for any reason, she can see herself reflected in the line.”

In 2019, Mattel introduced a lineup of Barbie dolls reflecting permanent disabilities, including one with a prosthetic limb. For that effort, the company collaborated with then-12-year-old Jordan Reeves, the “Born Just Right” coauthor “who is on a mission to build creative solutions that help kids with disabilities, to create a play experience that is as representative as possible,” the Mattel representative wrote.

Albinism awareness goes global in dermatologists’ nonprofit work

A dermatologist-led nonprofit organization has entered into a

Representatives from the New York–based NYDG Foundation, including dermatologist David Colbert, MD, recently signed the agreement with the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. At the center of the inclusivity efforts is the foundation’s ColorFull campaign, which aims to shape a collective response to the discrimination and violence that individuals with albinism face around the world.

“We really need to build more inclusive and communal health care systems for all. Partnering with the United Nations will help us to reach our goals and build stronger bonds with those health care providers working with one of the most marginalized and vulnerable groups in Africa,” Dr. Colbert said in an interview.

Stylish images of individuals with albinism, including prominent model Diandra Forrest, anchor the ColorFull campaign’s messaging; Ms. Forrest is featured in a video posted by the United Nations in November announcing the joint human rights campaign. Because the consequences of albinism can be deadly serious for affected individuals in many parts of the world, awareness is desperately needed, participants in NYDG’s work and in Standing Voice, another nonprofit that provides resources for people with albinism in East Africa, emphasized in interviews.

Striving to do good work

Stephan Bognar, a seasoned leader of international nonprofits, has teamed up with Dr. Colbert, NYDG Foundation’s founding physician, to craft the international campaign to raise awareness of albinism and increase acceptance of those with the condition. “You don’t always have to stand alone to break down the walls of exclusion. The fight for social justice and human rights for persons with albinism requires a collective responsibility,” Mr. Bognar said in an interview.

Dr. Colbert, senior partner of the New York Dermatology Group, a large Manhattan-based practice, founded the nonprofit when he became involved in wound-care efforts in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake. The foundation has since supported such philanthropic efforts as helping people with albinism, offering scholarships, and raising awareness of the importance of sun protection among youth athletes.

“One day, 3 years ago or so, I was reading the New York Times and I came across this article – it was called ‘The Hunted,’ ” Dr. Colbert recalled. “It was something I knew nothing about. In Eastern Africa, people with albinism are often hunted down for body parts and their lives are at risk” from being hunted and murdered – but also because their body parts are used for witchcraft and magic, he noted.

“I was captivated by that, and I remember I called Stephan, and I said, ‘I have a project for you.’ ” Because of extensive previous work with international nongovernmental organizations and the United Nations, Mr. Bognar, who is now the executive director of the NYDG Foundation, “had the pedigree to make things happen instead of spinning our wheels,” Dr. Colbert said.

Albinism is more common by a factor of about 10 in certain sub-Saharan African populations in Tanzania and Malawi, compared with worldwide prevalence. The condition is stigmatized, but people with albinism are also believed to possess some magical powers. People with albinism are attacked, maimed, and even killed for their body parts, which are used by traditional “witch doctors” in ceremonies designed to generate wealth and good fortune. Raping a woman with albinism is thought by some to cure HIV/AIDS and infertility.

If African individuals with albinism escapes these horrors, they are still at high risk of developing a disfiguring, or even fatal, skin cancer. Even in higher-resource countries and in places farther from the equator, though, people with albinism still need stringent sun-exposure precautions and frequent dermatologic surveillance.

Philanthropic work in dermatology

Despite his busy practice, Dr. Colbert said he has found great satisfaction in pursuing philanthropic work. For physicians considering similar efforts, he said that genuine engagement with the issue is critical and global travel isn’t necessary to make a real difference.

“I think that, first, this should be something that you’re interested in and that you have the means to make some impact,” Dr. Colbert said. “Doing something doesn’t need to be a global campaign. You don’t need to have a home run – every little thing counts. Catching one squamous cell cancer on one patient with albinism makes a difference. But if you want to go bigger, you have to look at your community and see who has the resources and who might also be interested” in a cause you’re passionate about.

He added that a busy physician shouldn’t expect to do it all. “You have to find the right partner because we as physicians are taking care of our patients and paying the rent, so taking on a partner who is trained to do that can ... help you achieve what you envision.”

Though the NYDG Foundation has funded trips to Africa and participates in teledermatology there, Dr. Colbert said that the awareness campaign the NYDG is cosponsoring with the United Nations is of fundamental importance as well. “This is a really great example of the positive impact that social media can have on our society – in a good way, instead of a negative or self-serving way,” he said.

“I think that the ColorFull campaign will normalize the idea of people who are living without melanin in their skin. It keeps it out of the realm of ‘Don’t say anything.’ People don’t know what it means, so if we bring out the science, and show successful people who have normal lives, who have children, and we explain what it is, it demystifies it – and everybody wins. ... We’re all just people, no matter how many melanin granules we have.”

Dr. Colbert reported that he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Standing Voice also provides resources in East Africa

The work of other nongovernmental organizations is also making a difference for people in East Africa with albinism.

Standing Voice is a United Kingdom–based nonprofit that provides education and resources that include sunscreen, as well as assessment and treatment of skin conditions for people with albinism in Tanzania and Malawi.

This and other work by Standing Voice were on display in an exhibit at the World Congress of Dermatology meeting in Milan in June 2019. In an interview at the meeting, Dr. Sharp, who spent his childhood in East Africa, contrasted access to dermatology care in the United States and United Kingdom with that in Africa, where an entire country may have hardly more than a few dermatologists.

“I go about three times a year, for about a week,” explained Dr. Sharp. “I’ll do a workshop to teach basic skin surgery techniques – excisions and biopsies. Very simple stuff. I’ll teach skin grafting as well because some of these patients have large lesions that won’t close directly,” he said. “On the whole, we like to use good grafts, rather than flaps, because often a local flap is just moving sun-damaged skin.”

Many patients have to travel great distances to reach a facility where general anesthesia and a full operating room suite are available, resources that are in high demand in resource-restricted African nations, according to Dr. Sharp. Teaching African practitioners regional anesthesia techniques that can be used for skin cancer surgery also helps ensure that more patients with albinism and squamous cell carcinoma can be treated – and treated closer to home.

Dr. Sharp reported that he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

A dermatologist-led nonprofit organization has entered into a

Representatives from the New York–based NYDG Foundation, including dermatologist David Colbert, MD, recently signed the agreement with the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. At the center of the inclusivity efforts is the foundation’s ColorFull campaign, which aims to shape a collective response to the discrimination and violence that individuals with albinism face around the world.

“We really need to build more inclusive and communal health care systems for all. Partnering with the United Nations will help us to reach our goals and build stronger bonds with those health care providers working with one of the most marginalized and vulnerable groups in Africa,” Dr. Colbert said in an interview.

Stylish images of individuals with albinism, including prominent model Diandra Forrest, anchor the ColorFull campaign’s messaging; Ms. Forrest is featured in a video posted by the United Nations in November announcing the joint human rights campaign. Because the consequences of albinism can be deadly serious for affected individuals in many parts of the world, awareness is desperately needed, participants in NYDG’s work and in Standing Voice, another nonprofit that provides resources for people with albinism in East Africa, emphasized in interviews.

Striving to do good work

Stephan Bognar, a seasoned leader of international nonprofits, has teamed up with Dr. Colbert, NYDG Foundation’s founding physician, to craft the international campaign to raise awareness of albinism and increase acceptance of those with the condition. “You don’t always have to stand alone to break down the walls of exclusion. The fight for social justice and human rights for persons with albinism requires a collective responsibility,” Mr. Bognar said in an interview.

Dr. Colbert, senior partner of the New York Dermatology Group, a large Manhattan-based practice, founded the nonprofit when he became involved in wound-care efforts in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake. The foundation has since supported such philanthropic efforts as helping people with albinism, offering scholarships, and raising awareness of the importance of sun protection among youth athletes.

“One day, 3 years ago or so, I was reading the New York Times and I came across this article – it was called ‘The Hunted,’ ” Dr. Colbert recalled. “It was something I knew nothing about. In Eastern Africa, people with albinism are often hunted down for body parts and their lives are at risk” from being hunted and murdered – but also because their body parts are used for witchcraft and magic, he noted.

“I was captivated by that, and I remember I called Stephan, and I said, ‘I have a project for you.’ ” Because of extensive previous work with international nongovernmental organizations and the United Nations, Mr. Bognar, who is now the executive director of the NYDG Foundation, “had the pedigree to make things happen instead of spinning our wheels,” Dr. Colbert said.

Albinism is more common by a factor of about 10 in certain sub-Saharan African populations in Tanzania and Malawi, compared with worldwide prevalence. The condition is stigmatized, but people with albinism are also believed to possess some magical powers. People with albinism are attacked, maimed, and even killed for their body parts, which are used by traditional “witch doctors” in ceremonies designed to generate wealth and good fortune. Raping a woman with albinism is thought by some to cure HIV/AIDS and infertility.

If African individuals with albinism escapes these horrors, they are still at high risk of developing a disfiguring, or even fatal, skin cancer. Even in higher-resource countries and in places farther from the equator, though, people with albinism still need stringent sun-exposure precautions and frequent dermatologic surveillance.

Philanthropic work in dermatology

Despite his busy practice, Dr. Colbert said he has found great satisfaction in pursuing philanthropic work. For physicians considering similar efforts, he said that genuine engagement with the issue is critical and global travel isn’t necessary to make a real difference.

“I think that, first, this should be something that you’re interested in and that you have the means to make some impact,” Dr. Colbert said. “Doing something doesn’t need to be a global campaign. You don’t need to have a home run – every little thing counts. Catching one squamous cell cancer on one patient with albinism makes a difference. But if you want to go bigger, you have to look at your community and see who has the resources and who might also be interested” in a cause you’re passionate about.

He added that a busy physician shouldn’t expect to do it all. “You have to find the right partner because we as physicians are taking care of our patients and paying the rent, so taking on a partner who is trained to do that can ... help you achieve what you envision.”

Though the NYDG Foundation has funded trips to Africa and participates in teledermatology there, Dr. Colbert said that the awareness campaign the NYDG is cosponsoring with the United Nations is of fundamental importance as well. “This is a really great example of the positive impact that social media can have on our society – in a good way, instead of a negative or self-serving way,” he said.

“I think that the ColorFull campaign will normalize the idea of people who are living without melanin in their skin. It keeps it out of the realm of ‘Don’t say anything.’ People don’t know what it means, so if we bring out the science, and show successful people who have normal lives, who have children, and we explain what it is, it demystifies it – and everybody wins. ... We’re all just people, no matter how many melanin granules we have.”

Dr. Colbert reported that he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Standing Voice also provides resources in East Africa

The work of other nongovernmental organizations is also making a difference for people in East Africa with albinism.

Standing Voice is a United Kingdom–based nonprofit that provides education and resources that include sunscreen, as well as assessment and treatment of skin conditions for people with albinism in Tanzania and Malawi.

This and other work by Standing Voice were on display in an exhibit at the World Congress of Dermatology meeting in Milan in June 2019. In an interview at the meeting, Dr. Sharp, who spent his childhood in East Africa, contrasted access to dermatology care in the United States and United Kingdom with that in Africa, where an entire country may have hardly more than a few dermatologists.

“I go about three times a year, for about a week,” explained Dr. Sharp. “I’ll do a workshop to teach basic skin surgery techniques – excisions and biopsies. Very simple stuff. I’ll teach skin grafting as well because some of these patients have large lesions that won’t close directly,” he said. “On the whole, we like to use good grafts, rather than flaps, because often a local flap is just moving sun-damaged skin.”

Many patients have to travel great distances to reach a facility where general anesthesia and a full operating room suite are available, resources that are in high demand in resource-restricted African nations, according to Dr. Sharp. Teaching African practitioners regional anesthesia techniques that can be used for skin cancer surgery also helps ensure that more patients with albinism and squamous cell carcinoma can be treated – and treated closer to home.

Dr. Sharp reported that he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

A dermatologist-led nonprofit organization has entered into a

Representatives from the New York–based NYDG Foundation, including dermatologist David Colbert, MD, recently signed the agreement with the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. At the center of the inclusivity efforts is the foundation’s ColorFull campaign, which aims to shape a collective response to the discrimination and violence that individuals with albinism face around the world.

“We really need to build more inclusive and communal health care systems for all. Partnering with the United Nations will help us to reach our goals and build stronger bonds with those health care providers working with one of the most marginalized and vulnerable groups in Africa,” Dr. Colbert said in an interview.

Stylish images of individuals with albinism, including prominent model Diandra Forrest, anchor the ColorFull campaign’s messaging; Ms. Forrest is featured in a video posted by the United Nations in November announcing the joint human rights campaign. Because the consequences of albinism can be deadly serious for affected individuals in many parts of the world, awareness is desperately needed, participants in NYDG’s work and in Standing Voice, another nonprofit that provides resources for people with albinism in East Africa, emphasized in interviews.

Striving to do good work

Stephan Bognar, a seasoned leader of international nonprofits, has teamed up with Dr. Colbert, NYDG Foundation’s founding physician, to craft the international campaign to raise awareness of albinism and increase acceptance of those with the condition. “You don’t always have to stand alone to break down the walls of exclusion. The fight for social justice and human rights for persons with albinism requires a collective responsibility,” Mr. Bognar said in an interview.

Dr. Colbert, senior partner of the New York Dermatology Group, a large Manhattan-based practice, founded the nonprofit when he became involved in wound-care efforts in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake. The foundation has since supported such philanthropic efforts as helping people with albinism, offering scholarships, and raising awareness of the importance of sun protection among youth athletes.

“One day, 3 years ago or so, I was reading the New York Times and I came across this article – it was called ‘The Hunted,’ ” Dr. Colbert recalled. “It was something I knew nothing about. In Eastern Africa, people with albinism are often hunted down for body parts and their lives are at risk” from being hunted and murdered – but also because their body parts are used for witchcraft and magic, he noted.

“I was captivated by that, and I remember I called Stephan, and I said, ‘I have a project for you.’ ” Because of extensive previous work with international nongovernmental organizations and the United Nations, Mr. Bognar, who is now the executive director of the NYDG Foundation, “had the pedigree to make things happen instead of spinning our wheels,” Dr. Colbert said.

Albinism is more common by a factor of about 10 in certain sub-Saharan African populations in Tanzania and Malawi, compared with worldwide prevalence. The condition is stigmatized, but people with albinism are also believed to possess some magical powers. People with albinism are attacked, maimed, and even killed for their body parts, which are used by traditional “witch doctors” in ceremonies designed to generate wealth and good fortune. Raping a woman with albinism is thought by some to cure HIV/AIDS and infertility.

If African individuals with albinism escapes these horrors, they are still at high risk of developing a disfiguring, or even fatal, skin cancer. Even in higher-resource countries and in places farther from the equator, though, people with albinism still need stringent sun-exposure precautions and frequent dermatologic surveillance.

Philanthropic work in dermatology

Despite his busy practice, Dr. Colbert said he has found great satisfaction in pursuing philanthropic work. For physicians considering similar efforts, he said that genuine engagement with the issue is critical and global travel isn’t necessary to make a real difference.

“I think that, first, this should be something that you’re interested in and that you have the means to make some impact,” Dr. Colbert said. “Doing something doesn’t need to be a global campaign. You don’t need to have a home run – every little thing counts. Catching one squamous cell cancer on one patient with albinism makes a difference. But if you want to go bigger, you have to look at your community and see who has the resources and who might also be interested” in a cause you’re passionate about.

He added that a busy physician shouldn’t expect to do it all. “You have to find the right partner because we as physicians are taking care of our patients and paying the rent, so taking on a partner who is trained to do that can ... help you achieve what you envision.”

Though the NYDG Foundation has funded trips to Africa and participates in teledermatology there, Dr. Colbert said that the awareness campaign the NYDG is cosponsoring with the United Nations is of fundamental importance as well. “This is a really great example of the positive impact that social media can have on our society – in a good way, instead of a negative or self-serving way,” he said.

“I think that the ColorFull campaign will normalize the idea of people who are living without melanin in their skin. It keeps it out of the realm of ‘Don’t say anything.’ People don’t know what it means, so if we bring out the science, and show successful people who have normal lives, who have children, and we explain what it is, it demystifies it – and everybody wins. ... We’re all just people, no matter how many melanin granules we have.”

Dr. Colbert reported that he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Standing Voice also provides resources in East Africa

The work of other nongovernmental organizations is also making a difference for people in East Africa with albinism.

Standing Voice is a United Kingdom–based nonprofit that provides education and resources that include sunscreen, as well as assessment and treatment of skin conditions for people with albinism in Tanzania and Malawi.

This and other work by Standing Voice were on display in an exhibit at the World Congress of Dermatology meeting in Milan in June 2019. In an interview at the meeting, Dr. Sharp, who spent his childhood in East Africa, contrasted access to dermatology care in the United States and United Kingdom with that in Africa, where an entire country may have hardly more than a few dermatologists.

“I go about three times a year, for about a week,” explained Dr. Sharp. “I’ll do a workshop to teach basic skin surgery techniques – excisions and biopsies. Very simple stuff. I’ll teach skin grafting as well because some of these patients have large lesions that won’t close directly,” he said. “On the whole, we like to use good grafts, rather than flaps, because often a local flap is just moving sun-damaged skin.”

Many patients have to travel great distances to reach a facility where general anesthesia and a full operating room suite are available, resources that are in high demand in resource-restricted African nations, according to Dr. Sharp. Teaching African practitioners regional anesthesia techniques that can be used for skin cancer surgery also helps ensure that more patients with albinism and squamous cell carcinoma can be treated – and treated closer to home.

Dr. Sharp reported that he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

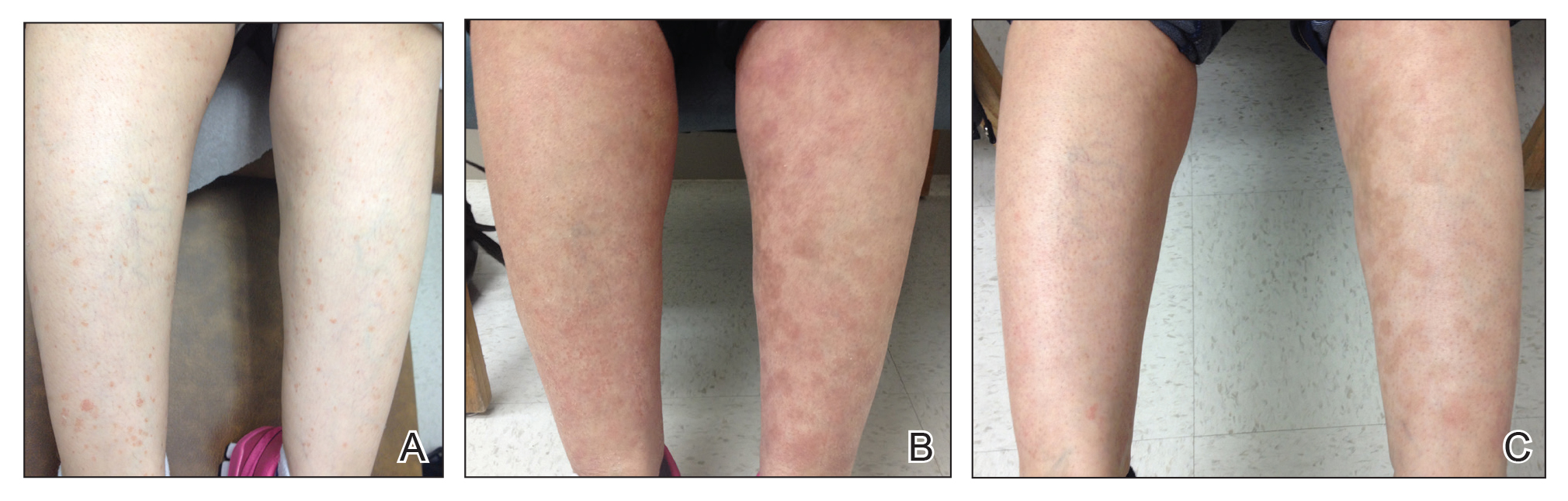

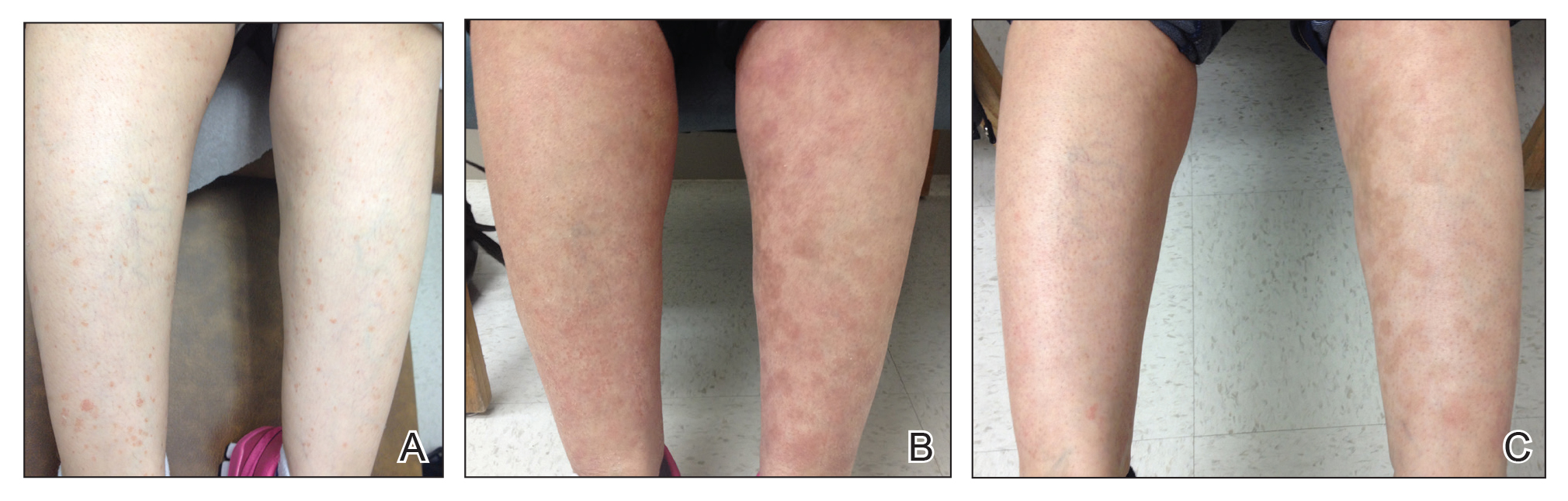

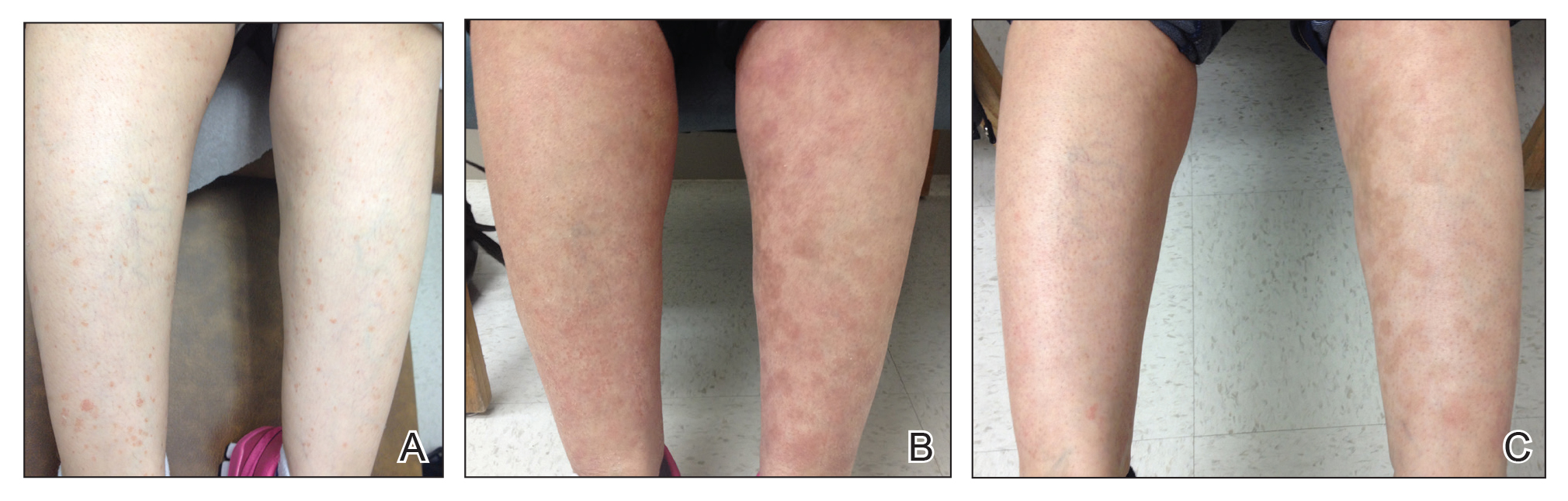

Nonablative laser improved PIH in patients with darker skin

Yoon‐Soo Cindy Bae, MD, and colleagues reported.

Among patients treated with the nonablative fractional 1,927 nm laser, there was a mean improvement of about 43% in hyperpigmented areas, and no side effects were reported, wrote Dr. Bae, of the department of dermatology at New York University and the Laser & Skin Surgery Center of New York, and coauthors in Lasers in Surgery and Medicine.

Lasers have not been the first choice for hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI, they pointed out. More commonly used treatments are hydroquinone and chemical peels that use glycolic acid or salicylic acid. But these are not always ideal options, Dr. Bae said in an interview.

“There are side effects to medical therapy. The drawbacks of medical therapy include compliance issues, risk of skin irritation from the product ... and a risk of hyperpigmentation specifically for hydroquinone. There are also risks to laser therapy, including dyspigmentation and scarring,” she added. “However, the laser we used is a low energy, nonablative type of laser, so the risk of scarring is extremely rare and the dyspigmentation is actually what we are aiming to treat.”

The retrospective study comprised 61 patients with PIH who had received more than one treatment with the low energy fractionated 1,927 nm diode laser between 2013 and 2016. Most were Fitzpatrick type IV (73.8%). The remainder were Type V (16.4%) and Type VI (9.8%). The most common treatment site was the face or cheeks (68.9%), followed by legs (13%), the rest of the cases were unspecified.

Patients had received treatment with the laser with fixed fluence at 5 mJ, fixed spot size of 140 micrometers, depth of 170 micrometers, and 5% coverage. They required several treatments: 15 had two, 14 had three, 16 had four, and the remainder had five or more. Topical treatment data were not collected. Photographs taken before treatment and before the last treatment were evaluated by dermatologists who had not treated the patients. Based on those evaluations, the mean improvement was a statistically significant 43.2%.

There did not, however, appear to be much difference between the treatment groups. The mean improvement among patients with two treatments was 44.5%; three treatments, 44.29%; four treatments, 40.63%; five or more treatments, 43.75%.

Although those with darker skin types tended to have better results, there were no statistically significant differences between the skin-type groups. Among those with Fitzpatrick skin type IV, the mean improvement was 40.39%; skin type V, 47.25%; and skin type VI, 57.92%.

“The fact that there was no correlation between Fitzpatrick skin type … and average percent improvement demonstrates that this laser is a viable treatment option for patients with very dark skin,” the authors wrote. “There were also no significant differences between the average percent improvements for people receiving different numbers of treatments. A trend was observed that favored treating patients with darker skin type; however, this lacked statistical significance. This may have been due to an underpowered study.”

Limitations of the study included the retrospective design and nonstandardization of photographs; “further studies with prospective controlled designs are needed to confirm our findings,” they added.

No funding or disclosure information was provided.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Bae YS et al. Lasers Surg Med. 2019 Oct 29. doi: 10.1002/lsm.23173.

Yoon‐Soo Cindy Bae, MD, and colleagues reported.

Among patients treated with the nonablative fractional 1,927 nm laser, there was a mean improvement of about 43% in hyperpigmented areas, and no side effects were reported, wrote Dr. Bae, of the department of dermatology at New York University and the Laser & Skin Surgery Center of New York, and coauthors in Lasers in Surgery and Medicine.

Lasers have not been the first choice for hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI, they pointed out. More commonly used treatments are hydroquinone and chemical peels that use glycolic acid or salicylic acid. But these are not always ideal options, Dr. Bae said in an interview.

“There are side effects to medical therapy. The drawbacks of medical therapy include compliance issues, risk of skin irritation from the product ... and a risk of hyperpigmentation specifically for hydroquinone. There are also risks to laser therapy, including dyspigmentation and scarring,” she added. “However, the laser we used is a low energy, nonablative type of laser, so the risk of scarring is extremely rare and the dyspigmentation is actually what we are aiming to treat.”

The retrospective study comprised 61 patients with PIH who had received more than one treatment with the low energy fractionated 1,927 nm diode laser between 2013 and 2016. Most were Fitzpatrick type IV (73.8%). The remainder were Type V (16.4%) and Type VI (9.8%). The most common treatment site was the face or cheeks (68.9%), followed by legs (13%), the rest of the cases were unspecified.

Patients had received treatment with the laser with fixed fluence at 5 mJ, fixed spot size of 140 micrometers, depth of 170 micrometers, and 5% coverage. They required several treatments: 15 had two, 14 had three, 16 had four, and the remainder had five or more. Topical treatment data were not collected. Photographs taken before treatment and before the last treatment were evaluated by dermatologists who had not treated the patients. Based on those evaluations, the mean improvement was a statistically significant 43.2%.

There did not, however, appear to be much difference between the treatment groups. The mean improvement among patients with two treatments was 44.5%; three treatments, 44.29%; four treatments, 40.63%; five or more treatments, 43.75%.

Although those with darker skin types tended to have better results, there were no statistically significant differences between the skin-type groups. Among those with Fitzpatrick skin type IV, the mean improvement was 40.39%; skin type V, 47.25%; and skin type VI, 57.92%.

“The fact that there was no correlation between Fitzpatrick skin type … and average percent improvement demonstrates that this laser is a viable treatment option for patients with very dark skin,” the authors wrote. “There were also no significant differences between the average percent improvements for people receiving different numbers of treatments. A trend was observed that favored treating patients with darker skin type; however, this lacked statistical significance. This may have been due to an underpowered study.”

Limitations of the study included the retrospective design and nonstandardization of photographs; “further studies with prospective controlled designs are needed to confirm our findings,” they added.

No funding or disclosure information was provided.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Bae YS et al. Lasers Surg Med. 2019 Oct 29. doi: 10.1002/lsm.23173.

Yoon‐Soo Cindy Bae, MD, and colleagues reported.

Among patients treated with the nonablative fractional 1,927 nm laser, there was a mean improvement of about 43% in hyperpigmented areas, and no side effects were reported, wrote Dr. Bae, of the department of dermatology at New York University and the Laser & Skin Surgery Center of New York, and coauthors in Lasers in Surgery and Medicine.

Lasers have not been the first choice for hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI, they pointed out. More commonly used treatments are hydroquinone and chemical peels that use glycolic acid or salicylic acid. But these are not always ideal options, Dr. Bae said in an interview.

“There are side effects to medical therapy. The drawbacks of medical therapy include compliance issues, risk of skin irritation from the product ... and a risk of hyperpigmentation specifically for hydroquinone. There are also risks to laser therapy, including dyspigmentation and scarring,” she added. “However, the laser we used is a low energy, nonablative type of laser, so the risk of scarring is extremely rare and the dyspigmentation is actually what we are aiming to treat.”

The retrospective study comprised 61 patients with PIH who had received more than one treatment with the low energy fractionated 1,927 nm diode laser between 2013 and 2016. Most were Fitzpatrick type IV (73.8%). The remainder were Type V (16.4%) and Type VI (9.8%). The most common treatment site was the face or cheeks (68.9%), followed by legs (13%), the rest of the cases were unspecified.

Patients had received treatment with the laser with fixed fluence at 5 mJ, fixed spot size of 140 micrometers, depth of 170 micrometers, and 5% coverage. They required several treatments: 15 had two, 14 had three, 16 had four, and the remainder had five or more. Topical treatment data were not collected. Photographs taken before treatment and before the last treatment were evaluated by dermatologists who had not treated the patients. Based on those evaluations, the mean improvement was a statistically significant 43.2%.

There did not, however, appear to be much difference between the treatment groups. The mean improvement among patients with two treatments was 44.5%; three treatments, 44.29%; four treatments, 40.63%; five or more treatments, 43.75%.

Although those with darker skin types tended to have better results, there were no statistically significant differences between the skin-type groups. Among those with Fitzpatrick skin type IV, the mean improvement was 40.39%; skin type V, 47.25%; and skin type VI, 57.92%.

“The fact that there was no correlation between Fitzpatrick skin type … and average percent improvement demonstrates that this laser is a viable treatment option for patients with very dark skin,” the authors wrote. “There were also no significant differences between the average percent improvements for people receiving different numbers of treatments. A trend was observed that favored treating patients with darker skin type; however, this lacked statistical significance. This may have been due to an underpowered study.”

Limitations of the study included the retrospective design and nonstandardization of photographs; “further studies with prospective controlled designs are needed to confirm our findings,” they added.

No funding or disclosure information was provided.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Bae YS et al. Lasers Surg Med. 2019 Oct 29. doi: 10.1002/lsm.23173.

FROM LASERS IN SURGERY AND MEDICINE

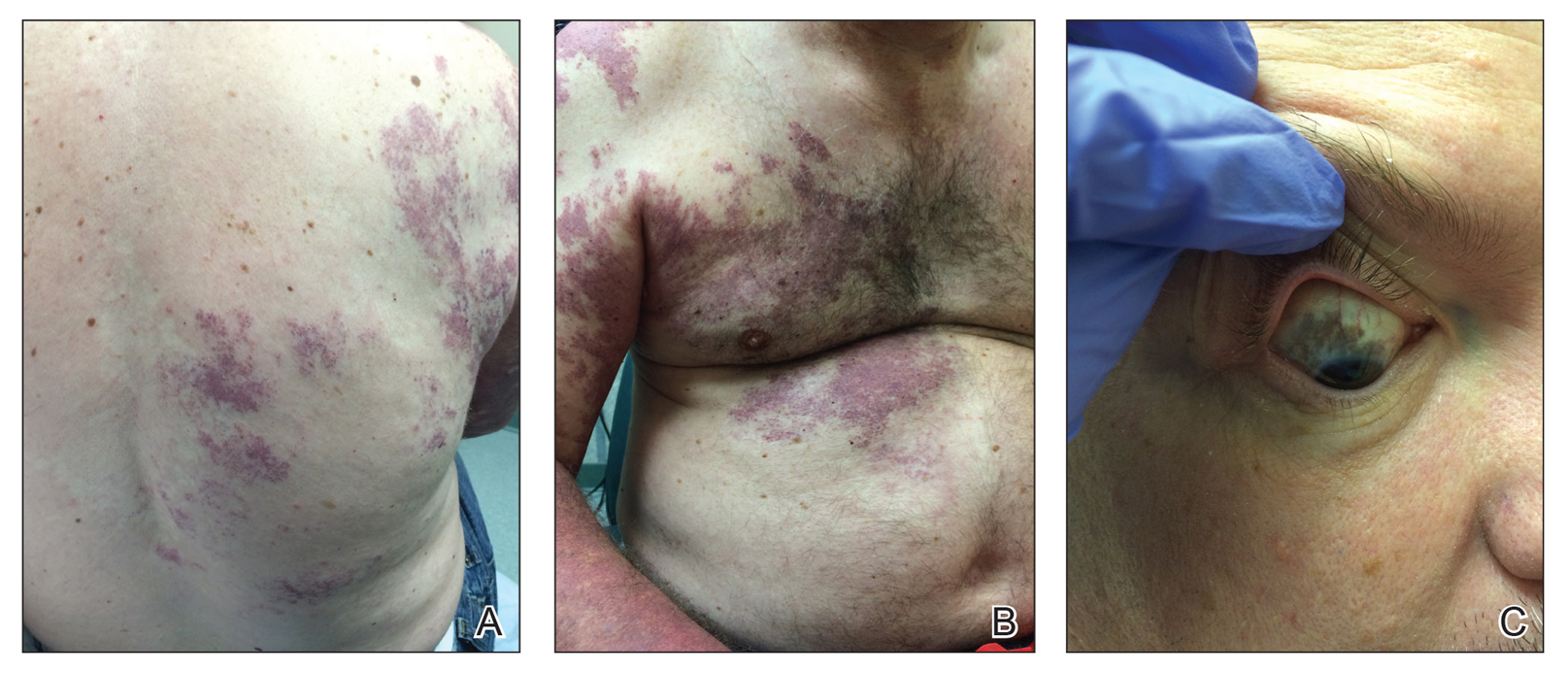

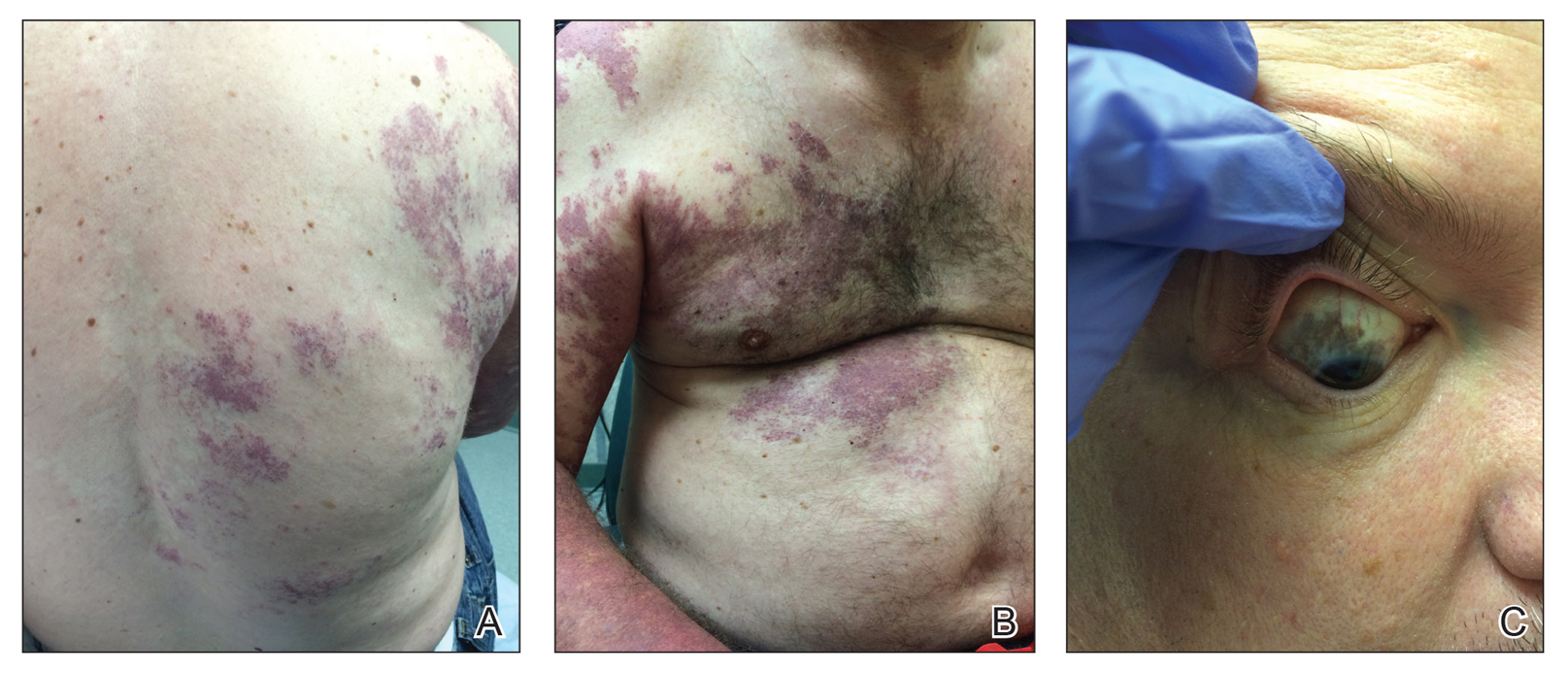

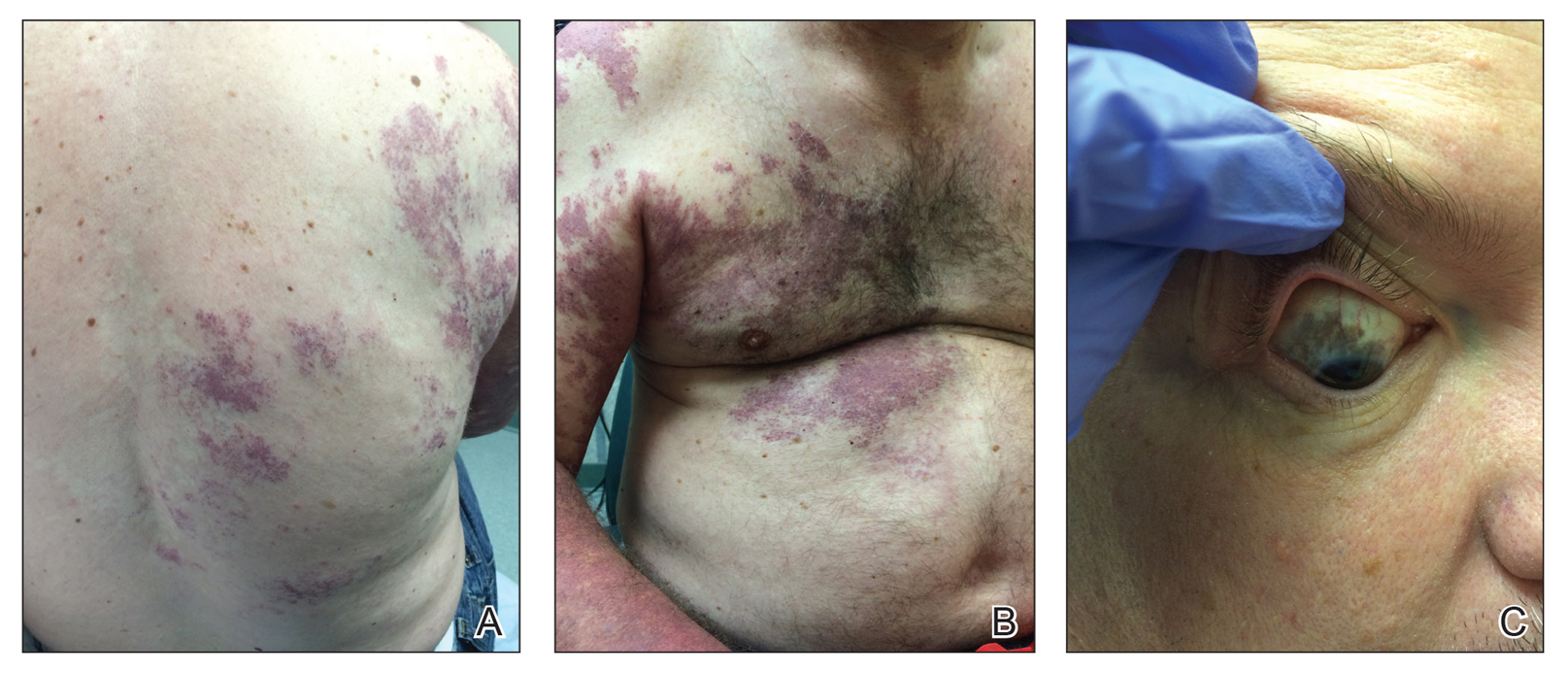

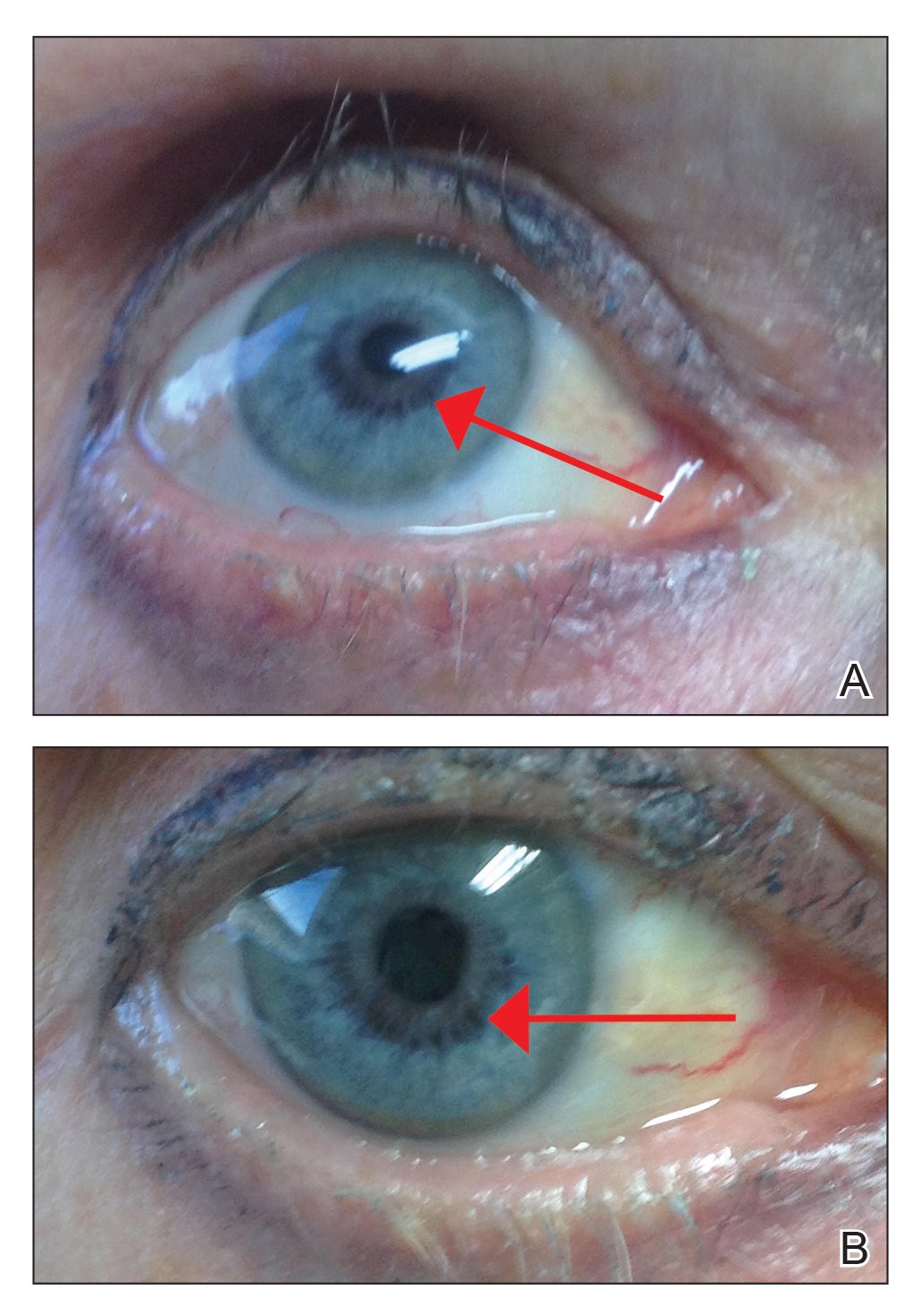

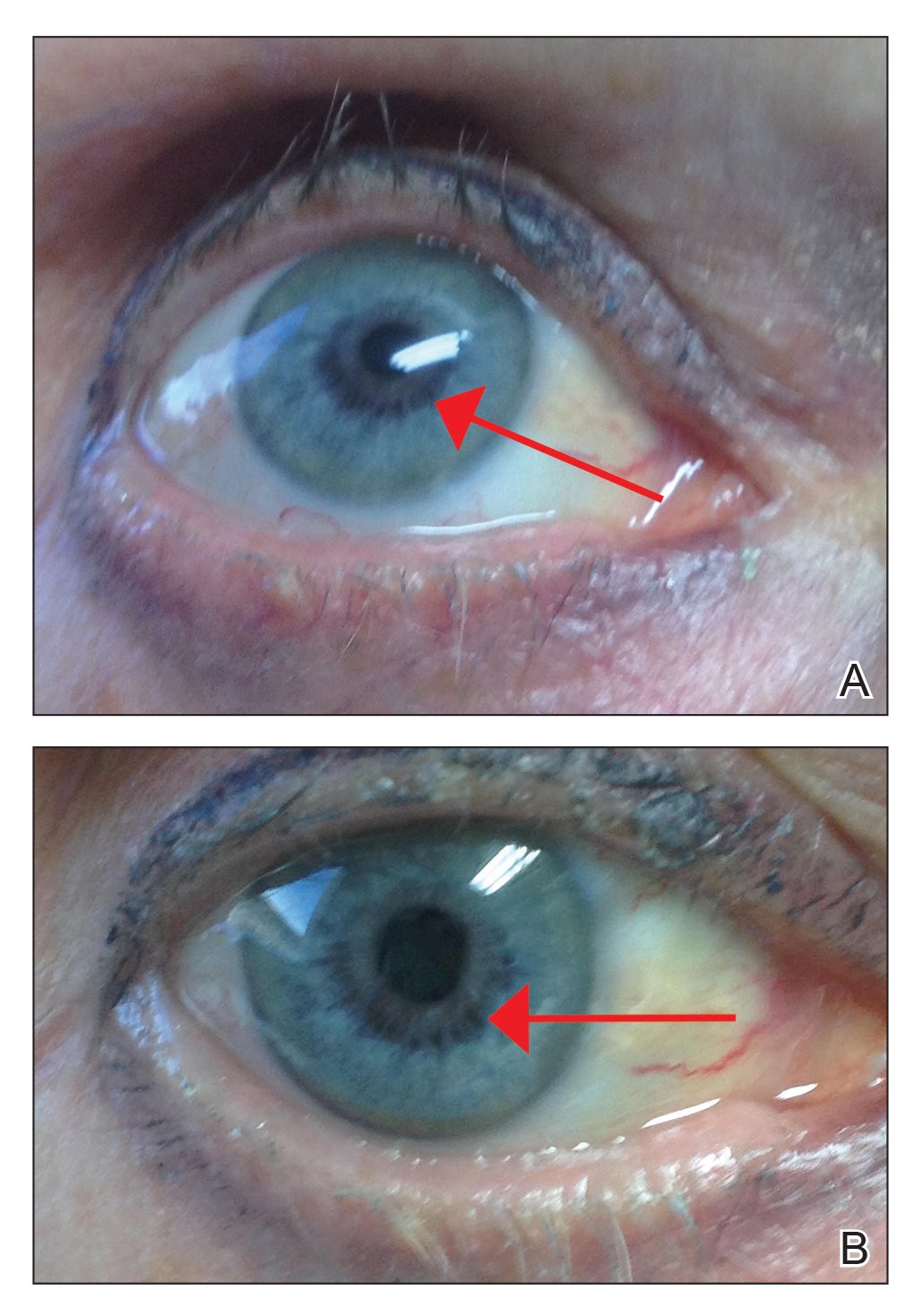

Vitiligo: First-ever RCT is smashing success

MADRID – cream for the treatment of vitiligo, Amit G. Pandya, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“I have been waiting 30 years for the first clinical trial for vitiligo. I know many of you dermatologists have been waiting for something for vitiligo, so I’m happy to present the results of the first randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective trial of a topical agent in history for vitiligo,” said Dr. Pandya, who was clearly overjoyed to present the final results of the 52-week trial.

Ruxolitinib is a Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and 2 inhibitor. Topical ruxolitinib is under study for vitiligo because this chronic autoimmune disease targeting melanocytes is now recognized as being driven by signaling through the JAK 1/2 pathways.

The interim 24-week results of the phase 2 trial, presented earlier in the year at the World Congress of Dermatology in Milan, showed significant repigmentation with ruxolitinib cream. Dr. Pandya’s key message at EADV 2019 was that continued treatment out to a year brought substantial further improvement, and with a benign safety profile indistinguishable from vehicle control.

“We see a tremendous difference between 6 months and 1 year,” said Dr. Pandya, professor of dermatology at the University of Texas, Dallas. “For the first time, we dare talk about F-VASI75 [Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index] and F-VASI90 responses. We don’t usually tell patients that they can get 75% or 90% of their color back, and yet the week-52 F-VASI75 rate was 51.5%, up from 30.3% at week 24. And the F-VASI90 response was 33.3%, versus 12.1% at week 24.”