User login

White Spots on the Extremities

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

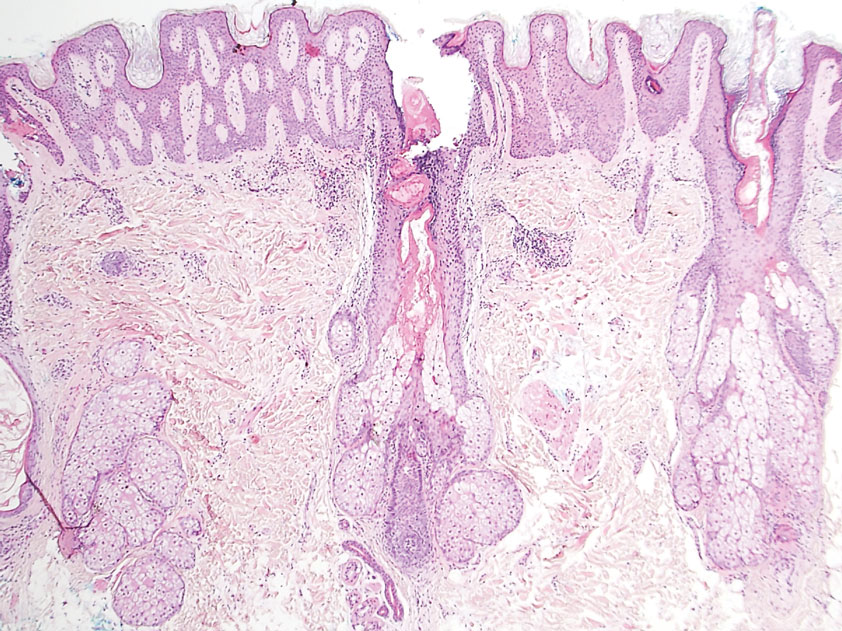

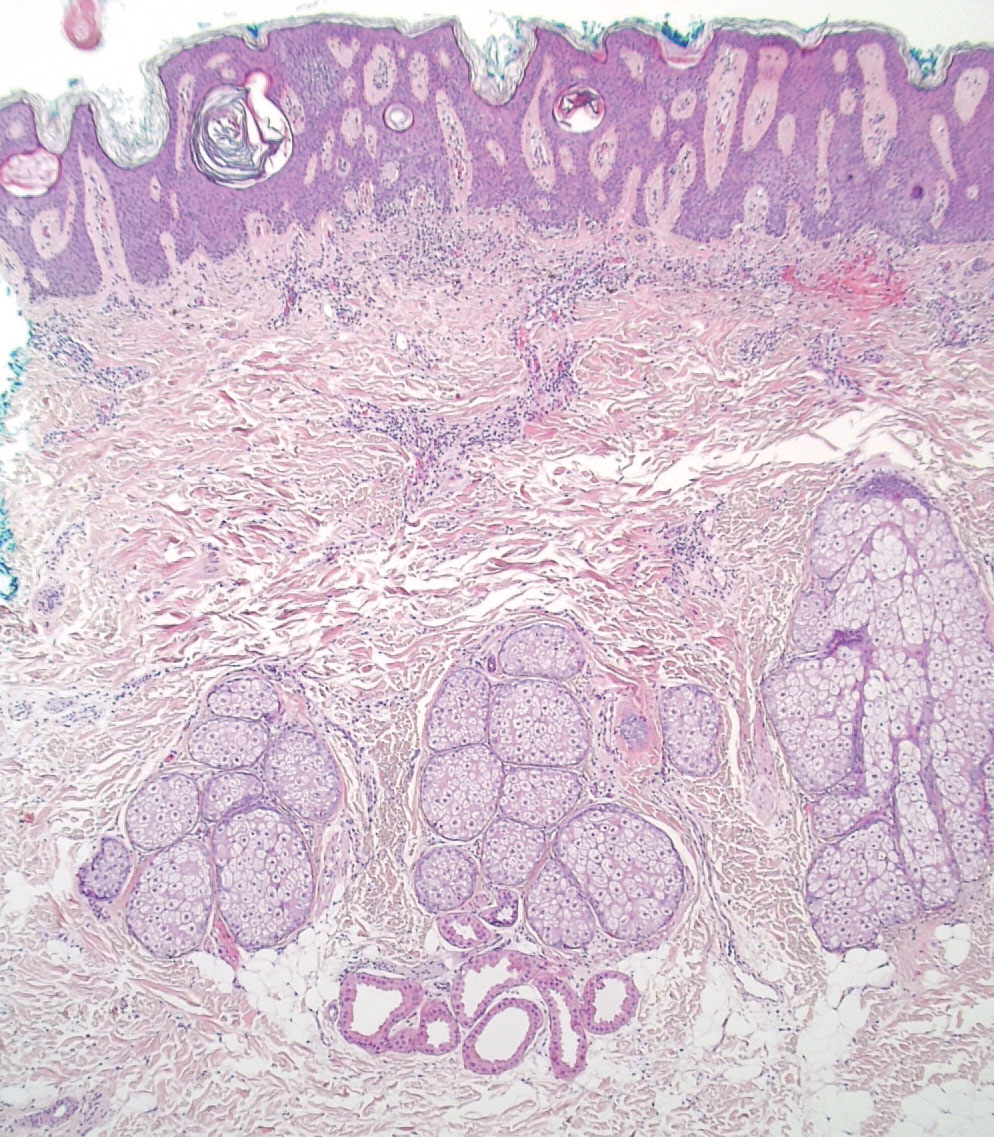

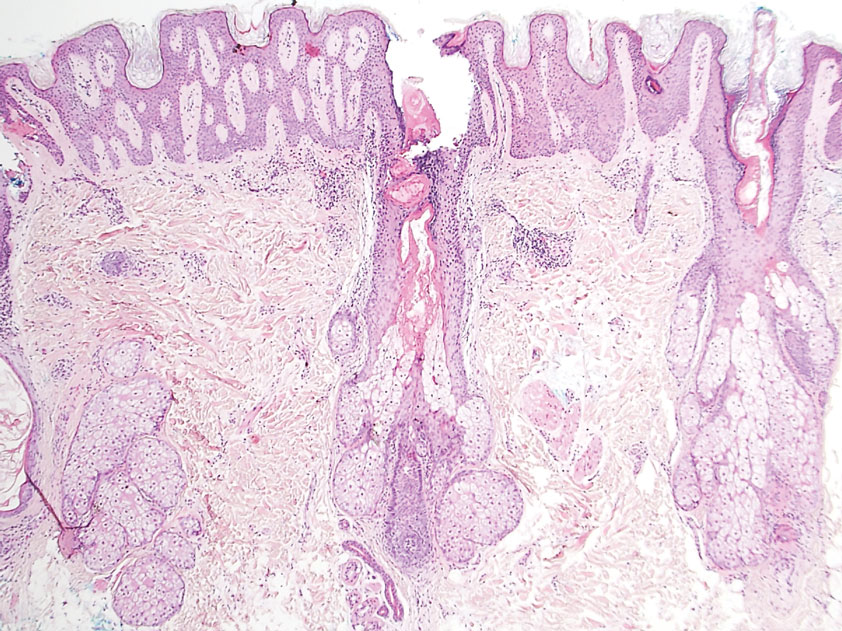

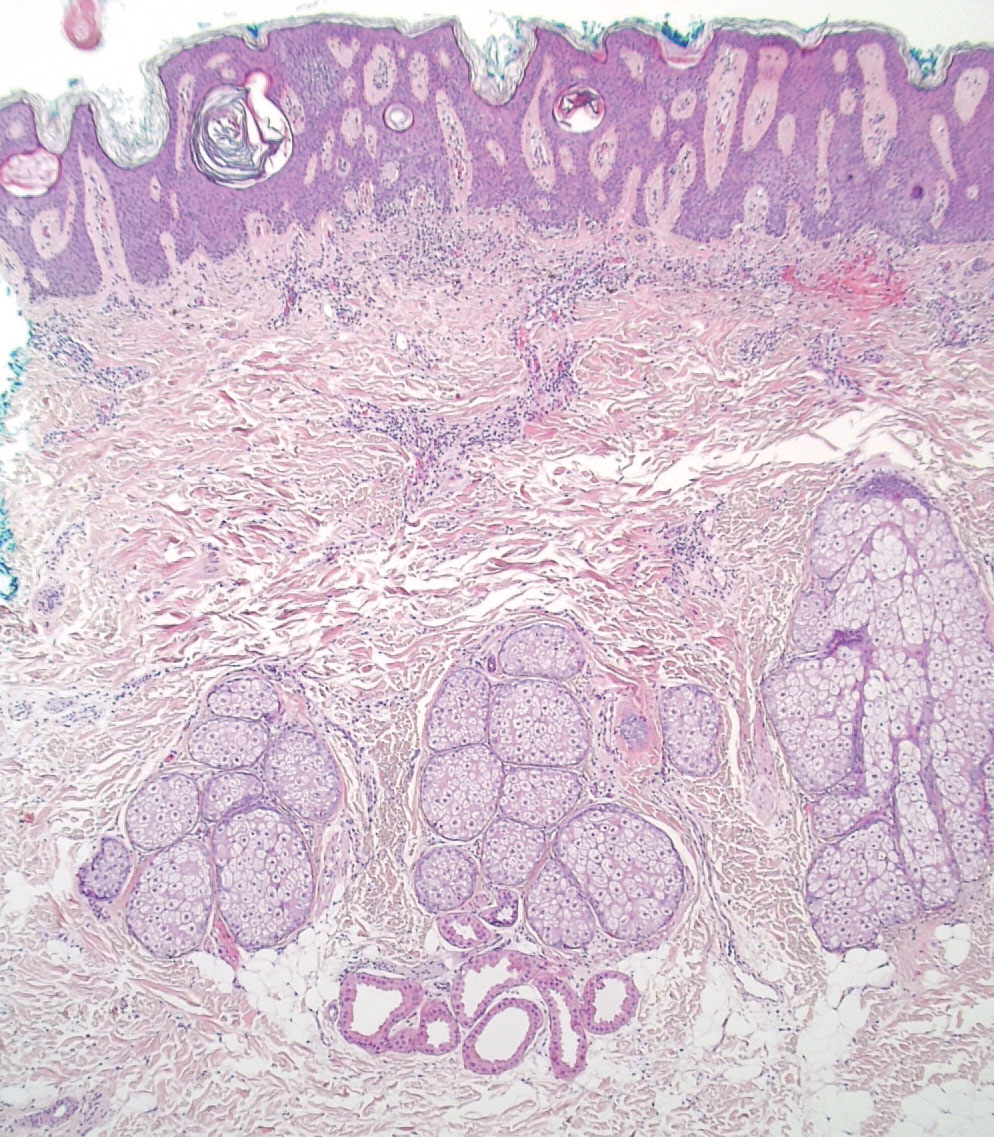

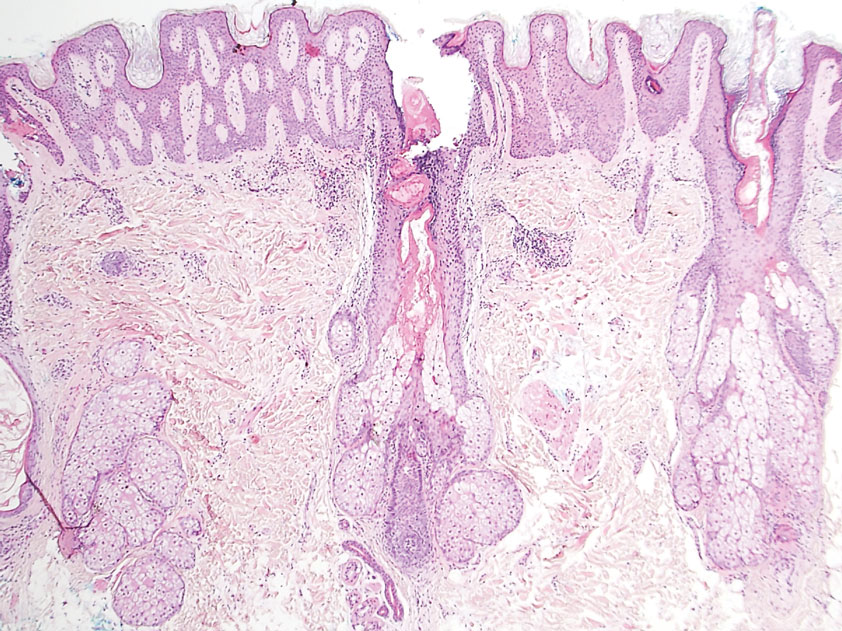

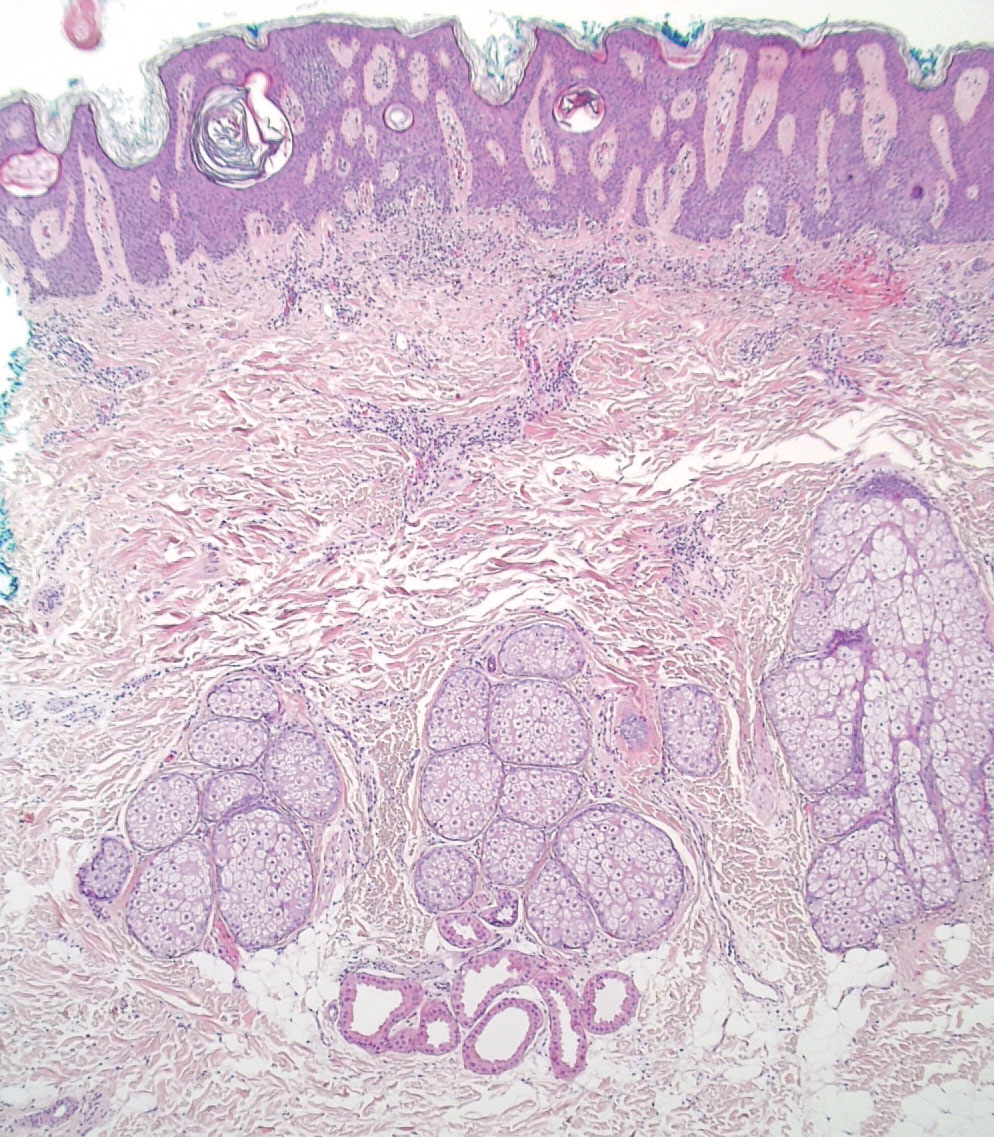

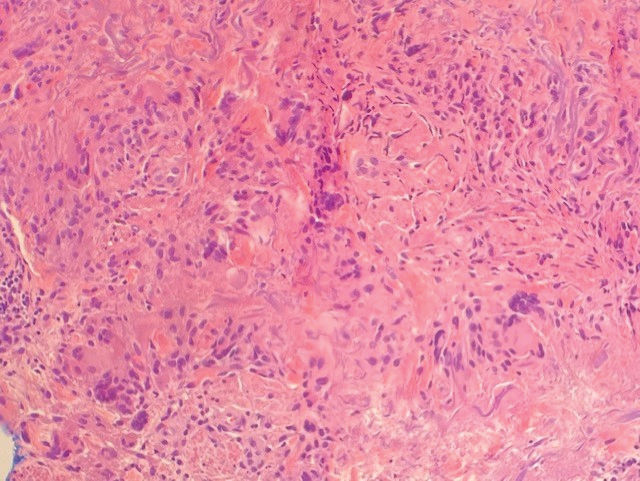

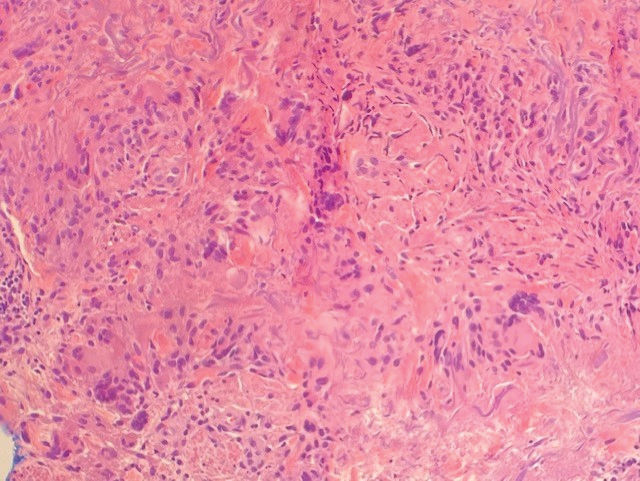

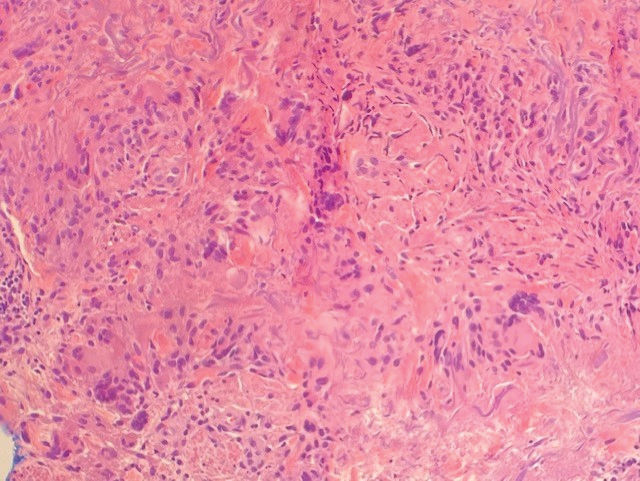

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

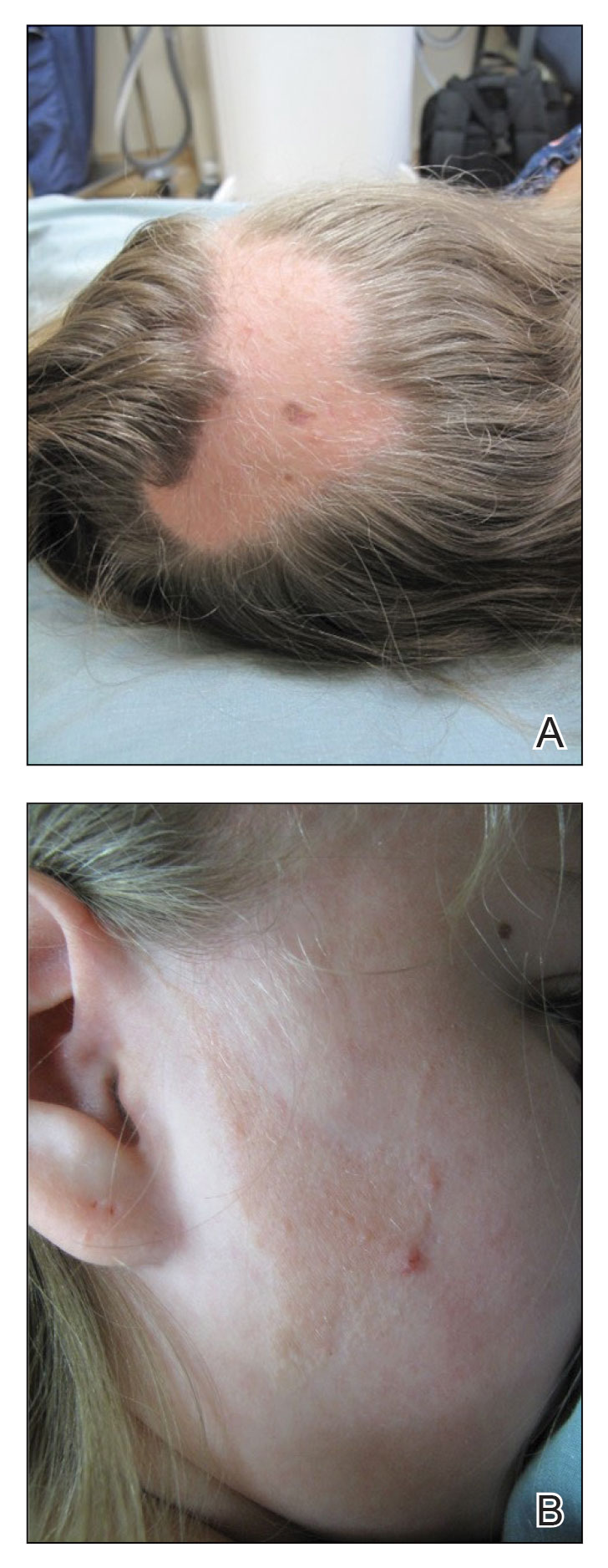

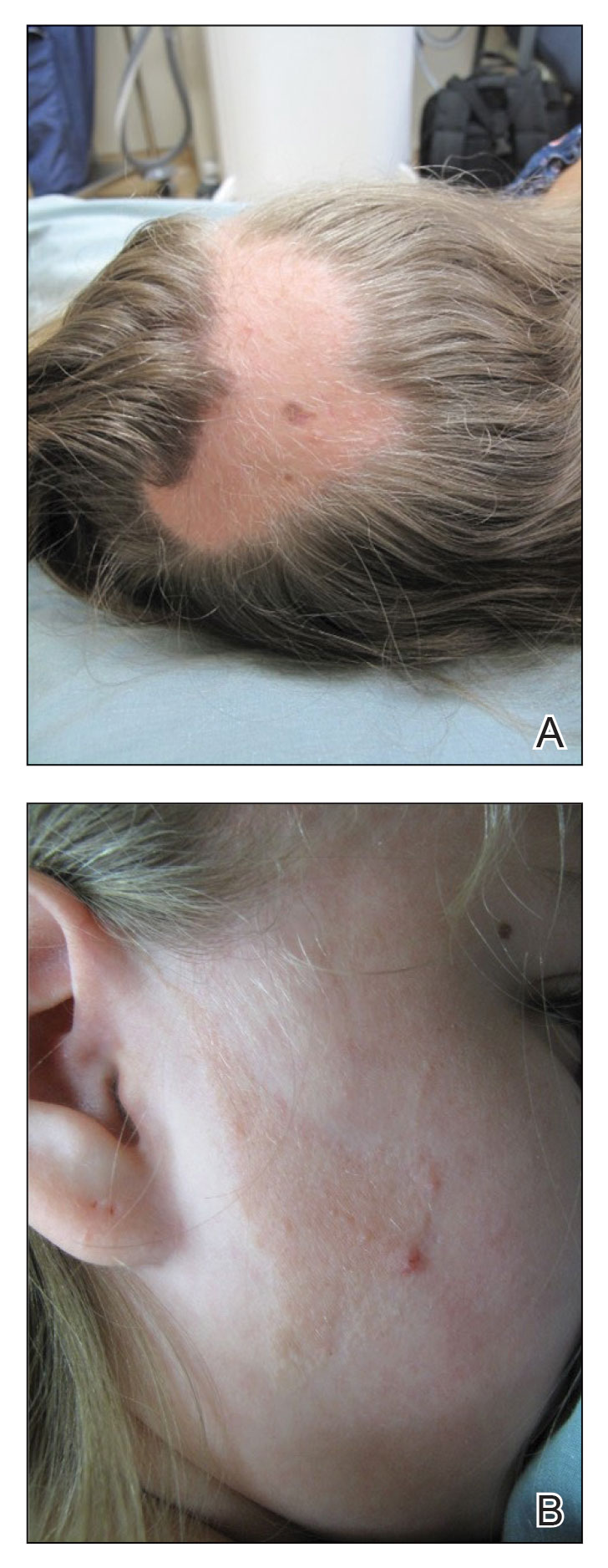

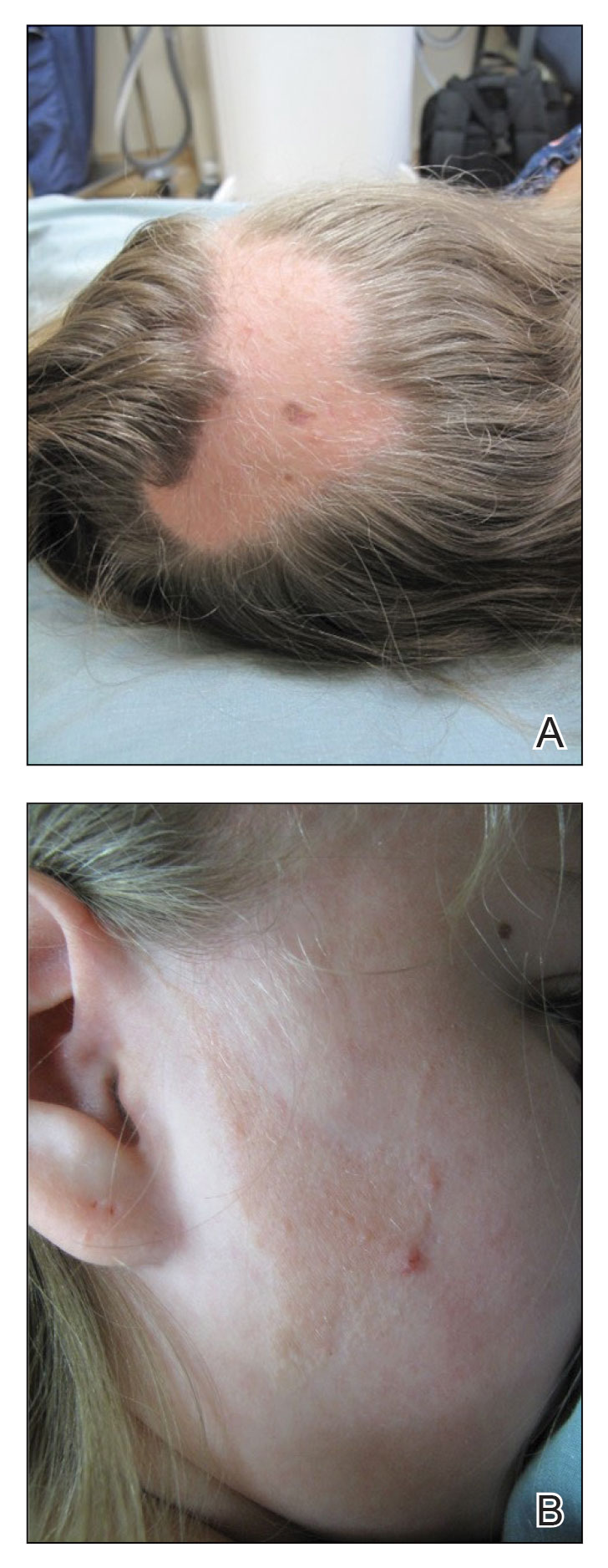

A 52-year-old Black woman presented with self-described whitened spots on the arms and legs of 2 years’ duration. She experienced no improvement with ketoconazole cream and topical calcineurin inhibitors prescribed during a prior dermatology visit at an outside institution. She denied pain or pruritus. A review of systems as well as the patient’s medical history were noncontributory. A prior biopsy at an outside institution revealed an interface dermatitis suggestive of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The patient noted social drinking and denied tobacco use. She had no known allergies to medications and currently was on tamoxifen for breast cancer following a right mastectomy. Physical examination showed hypopigmented macules and patches on the left upper arm and right proximal leg. The center of the lesions was not erythematous or scaly. Palpation did not reveal enlarged lymph nodes, and laboratory analyses ruled out low levels of red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets. Punch biopsies from the left arm and right thigh were performed.

Halting active inflammation key in treating PIH

CHICAGO –

Dr. Desai, clinical assistant professor in the department of dermatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, spoke at the Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium, provided by MedscapeLive!

Like all dermatologists, he said at the meeting, he sees lots of acne cases. However, PIH is often the presenting reason for the visit in his practice, which focuses predominantly on skin of color.

“Most of my patients come in not even worried about the acne,” he said. “They come in wanting me to fix the dark spots.”

Inflammation persists

Dermatologists, Dr. Desai said, should educate patients with active PIH resulting from acne or other diseases that even though the condition has been labeled post- inflammatory hyperpigmentation, the inflammation continues to be a problem.

He said, while patients may think PIH is “just scars,” the inflammation is still active and the condition needs to be treated from a skin-lightening perspective but, more importantly, with a focus on halting the inflammation. “If you were to biopsy the areas of hyperpigmentation, you would find a high density of active inflammatory behaviors still present in the skin,” he said.

When treating patients, it’s critical to first treat the underlying skin condition aggressively, he said. “Things like topical retinoids and azelaic acid mechanistically actually make a lot more sense for PIH than even hydroquinone, in some cases, because these therapies are actually anti-inflammatory for many of the diseases we treat.”

Dr. Desai noted that, in patients with darker skin tones, even diseases like seborrheic dermatitis and plaque psoriasis can result in PIH, while in patients with lighter skin tones, the same diseases may leave some residual postinflammatory erythema.

“I think it’s very important, particularly when you’re treating a darker skin–toned patient, to arrest the erythema early on to prevent that further worsening of hyperpigmentation,” he said.

Biopsies important

In cases of PIH, determining the best treatment requires finding out where the pigment is and how deep it is, Dr. Desai said.

He noted dermatologists are often worried about doing biopsies, particularly in patients with darker skin, because of the risk of scarring and keloid formation for those more prone to keloids. The preference is also for a therapeutic effect without using invasive procedures.

“But particularly with PIH, in patients who have been therapeutically challenging, I don’t hesitate to do very small biopsies – 2- and 3-mm punch biopsies – particularly if they are from the head and neck area.”

He suggests doing biopsies on part of the ear, lower jaw line, or the neck area, as these areas tend to heal nicely. “You don’t have to be so concerned about the scarring if you counsel appropriately,” he said.

The biopsy can be valuable in determining whether a very expensive treatment will reach the intended target.

Topical retinoids play an important role as anti-inflammatories for PIH, Dr. Desai said.

He gave an example of a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV or V with chronic acne and extensive PIH. “Are you going to effectively tell that patient to apply 4% hydroquinone triple-combination compound across 30 different areas of PIH on their face? The answer is that’s really not very efficient or effective.”

That’s why therapies, such as retinoids, that target the pathogenesis of PIH, particularly the inflammatory component, are important, he added.

Psychological burden

PIH comes with significant stigma and loss of quality of life loss that can last many years.

During another presentation at the meeting, Susan C. Taylor, MD, professor and vice chair of diversity, equity and inclusion in the department of dermatology, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, pointed out that in a 2016 study of 324 patients in seven Asian countries, acne-related PIH lasted longer than 1 year in 65.2% of patients and 5 years or longer in 22.3%, significantly affecting their quality of life.

Dr. Desai added that, in a paper recently published in the British Journal of Dermatology, on the impact of postacne hyperpigmentation in patients, the authors pointed out that the reported prevalence of PIH in patients with acne ranges between 45.5% and 87.2%, depending on skin phototype, and that in most cases, PIH takes more than a year to fade.

“Studies have demonstrated that patients with acne and resulting scarring often face stigmatization, leading to quality of life impairment, social withdrawal and body image disorders, which can further contribute to higher risk for depression and social anxiety,” the paper’s authors wrote.

Dr. Desai reported no financial disclosures relevant to his talk.

CHICAGO –

Dr. Desai, clinical assistant professor in the department of dermatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, spoke at the Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium, provided by MedscapeLive!

Like all dermatologists, he said at the meeting, he sees lots of acne cases. However, PIH is often the presenting reason for the visit in his practice, which focuses predominantly on skin of color.

“Most of my patients come in not even worried about the acne,” he said. “They come in wanting me to fix the dark spots.”

Inflammation persists

Dermatologists, Dr. Desai said, should educate patients with active PIH resulting from acne or other diseases that even though the condition has been labeled post- inflammatory hyperpigmentation, the inflammation continues to be a problem.

He said, while patients may think PIH is “just scars,” the inflammation is still active and the condition needs to be treated from a skin-lightening perspective but, more importantly, with a focus on halting the inflammation. “If you were to biopsy the areas of hyperpigmentation, you would find a high density of active inflammatory behaviors still present in the skin,” he said.

When treating patients, it’s critical to first treat the underlying skin condition aggressively, he said. “Things like topical retinoids and azelaic acid mechanistically actually make a lot more sense for PIH than even hydroquinone, in some cases, because these therapies are actually anti-inflammatory for many of the diseases we treat.”

Dr. Desai noted that, in patients with darker skin tones, even diseases like seborrheic dermatitis and plaque psoriasis can result in PIH, while in patients with lighter skin tones, the same diseases may leave some residual postinflammatory erythema.

“I think it’s very important, particularly when you’re treating a darker skin–toned patient, to arrest the erythema early on to prevent that further worsening of hyperpigmentation,” he said.

Biopsies important

In cases of PIH, determining the best treatment requires finding out where the pigment is and how deep it is, Dr. Desai said.

He noted dermatologists are often worried about doing biopsies, particularly in patients with darker skin, because of the risk of scarring and keloid formation for those more prone to keloids. The preference is also for a therapeutic effect without using invasive procedures.

“But particularly with PIH, in patients who have been therapeutically challenging, I don’t hesitate to do very small biopsies – 2- and 3-mm punch biopsies – particularly if they are from the head and neck area.”

He suggests doing biopsies on part of the ear, lower jaw line, or the neck area, as these areas tend to heal nicely. “You don’t have to be so concerned about the scarring if you counsel appropriately,” he said.

The biopsy can be valuable in determining whether a very expensive treatment will reach the intended target.

Topical retinoids play an important role as anti-inflammatories for PIH, Dr. Desai said.

He gave an example of a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV or V with chronic acne and extensive PIH. “Are you going to effectively tell that patient to apply 4% hydroquinone triple-combination compound across 30 different areas of PIH on their face? The answer is that’s really not very efficient or effective.”

That’s why therapies, such as retinoids, that target the pathogenesis of PIH, particularly the inflammatory component, are important, he added.

Psychological burden

PIH comes with significant stigma and loss of quality of life loss that can last many years.

During another presentation at the meeting, Susan C. Taylor, MD, professor and vice chair of diversity, equity and inclusion in the department of dermatology, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, pointed out that in a 2016 study of 324 patients in seven Asian countries, acne-related PIH lasted longer than 1 year in 65.2% of patients and 5 years or longer in 22.3%, significantly affecting their quality of life.

Dr. Desai added that, in a paper recently published in the British Journal of Dermatology, on the impact of postacne hyperpigmentation in patients, the authors pointed out that the reported prevalence of PIH in patients with acne ranges between 45.5% and 87.2%, depending on skin phototype, and that in most cases, PIH takes more than a year to fade.

“Studies have demonstrated that patients with acne and resulting scarring often face stigmatization, leading to quality of life impairment, social withdrawal and body image disorders, which can further contribute to higher risk for depression and social anxiety,” the paper’s authors wrote.

Dr. Desai reported no financial disclosures relevant to his talk.

CHICAGO –

Dr. Desai, clinical assistant professor in the department of dermatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, spoke at the Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium, provided by MedscapeLive!

Like all dermatologists, he said at the meeting, he sees lots of acne cases. However, PIH is often the presenting reason for the visit in his practice, which focuses predominantly on skin of color.

“Most of my patients come in not even worried about the acne,” he said. “They come in wanting me to fix the dark spots.”

Inflammation persists

Dermatologists, Dr. Desai said, should educate patients with active PIH resulting from acne or other diseases that even though the condition has been labeled post- inflammatory hyperpigmentation, the inflammation continues to be a problem.

He said, while patients may think PIH is “just scars,” the inflammation is still active and the condition needs to be treated from a skin-lightening perspective but, more importantly, with a focus on halting the inflammation. “If you were to biopsy the areas of hyperpigmentation, you would find a high density of active inflammatory behaviors still present in the skin,” he said.

When treating patients, it’s critical to first treat the underlying skin condition aggressively, he said. “Things like topical retinoids and azelaic acid mechanistically actually make a lot more sense for PIH than even hydroquinone, in some cases, because these therapies are actually anti-inflammatory for many of the diseases we treat.”

Dr. Desai noted that, in patients with darker skin tones, even diseases like seborrheic dermatitis and plaque psoriasis can result in PIH, while in patients with lighter skin tones, the same diseases may leave some residual postinflammatory erythema.

“I think it’s very important, particularly when you’re treating a darker skin–toned patient, to arrest the erythema early on to prevent that further worsening of hyperpigmentation,” he said.

Biopsies important

In cases of PIH, determining the best treatment requires finding out where the pigment is and how deep it is, Dr. Desai said.

He noted dermatologists are often worried about doing biopsies, particularly in patients with darker skin, because of the risk of scarring and keloid formation for those more prone to keloids. The preference is also for a therapeutic effect without using invasive procedures.

“But particularly with PIH, in patients who have been therapeutically challenging, I don’t hesitate to do very small biopsies – 2- and 3-mm punch biopsies – particularly if they are from the head and neck area.”

He suggests doing biopsies on part of the ear, lower jaw line, or the neck area, as these areas tend to heal nicely. “You don’t have to be so concerned about the scarring if you counsel appropriately,” he said.

The biopsy can be valuable in determining whether a very expensive treatment will reach the intended target.

Topical retinoids play an important role as anti-inflammatories for PIH, Dr. Desai said.

He gave an example of a patient with Fitzpatrick skin type IV or V with chronic acne and extensive PIH. “Are you going to effectively tell that patient to apply 4% hydroquinone triple-combination compound across 30 different areas of PIH on their face? The answer is that’s really not very efficient or effective.”

That’s why therapies, such as retinoids, that target the pathogenesis of PIH, particularly the inflammatory component, are important, he added.

Psychological burden

PIH comes with significant stigma and loss of quality of life loss that can last many years.

During another presentation at the meeting, Susan C. Taylor, MD, professor and vice chair of diversity, equity and inclusion in the department of dermatology, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, pointed out that in a 2016 study of 324 patients in seven Asian countries, acne-related PIH lasted longer than 1 year in 65.2% of patients and 5 years or longer in 22.3%, significantly affecting their quality of life.

Dr. Desai added that, in a paper recently published in the British Journal of Dermatology, on the impact of postacne hyperpigmentation in patients, the authors pointed out that the reported prevalence of PIH in patients with acne ranges between 45.5% and 87.2%, depending on skin phototype, and that in most cases, PIH takes more than a year to fade.

“Studies have demonstrated that patients with acne and resulting scarring often face stigmatization, leading to quality of life impairment, social withdrawal and body image disorders, which can further contribute to higher risk for depression and social anxiety,” the paper’s authors wrote.

Dr. Desai reported no financial disclosures relevant to his talk.

AT THE MEDSCAPELIVE! PIGMENTARY DISORDERS SYMPOSIUM

Macular dermal hyperpigmentation: Treatment tips from an expert

CHICAGO – based on cases she has treated in her practice.

Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, director of the skin of color division in the dermatology department at University of Miami, provided three general pointers.

- When in doubt, biopsy.

- For inflammatory disorders, always treat the inflammation in addition to the hyperpigmentation.

- Avoid long-term hydroquinone use in these patients.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd also reviewed examples of what she has found successful in treating her patients with these conditions.

Lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP)

“It’s one of the hardest things that we treat,” said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, who often sees cases of LPP in patients in their 30s, 40s, and 50s.

Lesions first appear as small, ill-defined oval-to-round macules, which later become confluent and form large areas of pigmentation. In different patients, the pigment on the face and neck, and sometimes on the forearms can be slate gray or brownish black.

In 2013, dermatologist N.C. Dlova, MD, at the University of KwaZulu‐Natal, Durban, South Africa, reported a link between frontal fibrosing alopecia and LPP in the British Journal of Dermatology. “I definitely see this connection in my practice,” said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, noting that “both conditions often result in the loss of both eyebrows.”

She recommends always using a topical anti-inflammatory that is safe for the face. One combination she uses is azelaic acid 20% plus hydrocortisone 2.5%.

“We do use a lot of azelaic acid in my practice because it’s affordable,” she said, at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLive! She added that the hardest area to treat in women is around the chin.

Two other conditions, ashy dermatosis and erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), are similar. Ashy dermatosis mimics LPP but occurs more prominently on the trunk and extremities. EDP often has a preceding ring of erythema.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said the term EDP is often used to cover both EDP and ashy dermatosis in North America because “ashy” can have a negative connotation.

She noted there is no consensus on effective therapy for LPP, ashy dermatosis, or EDP.

A review of the literature on EDP, which included 16 studies on treatment outcomes, found the following:

- Narrow-band ultraviolet B and tacrolimus were effective treatments with minimal side effects.

- Clofazimine was effective, but had side effects, which, ironically, included pigmentary changes.

- Griseofulvin, isotretinoin, and dapsone were comparatively ineffective as lesions recurred after discontinuation.

- Lasers were largely ineffective and can also result in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and fibrosis.

Ochronosis

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said she may see one to two patients a year with ochronosis, which is characterized by paradoxical darkening of the skin with long-term hydroquinone use. It usually starts with redness followed by blue-black patches on the face where hydroquinone is applied. In severe cases, blue-black papules and nodules can occur.

“When I give a patient hydroquinone, I always say: ‘I don’t want to see any redness,’” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said. “If you have any redness, please stop because ochronosis is typically preceded by this redness.”

But, she noted, “people will come in actively using hydroquinone, will have the dark brown or deep black papules or macules on their face, and then this background of redness because they are so inflamed.”

She said that ochronosis can occur in any skin type, not just in patients with darker skin tones. Dr. Woolery-Lloyd advised: “Do not hesitate to biopsy the face if ochronosis is suspected. I always biopsy ochronosis.”

There are two reasons for doing so, she explained. It can help with the diagnosis but it will also provide the patient with an incentive to stop using hydroquinone. “People who are using hydroquinone are addicted to it. They love it. They don’t want to stop. They keep using it despite the fact that their face is getting darker.” When they see a biopsy report, they may be convinced to stop.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said she does a 2-mm punch biopsy in the crow’s feet area because there’s almost always ochronosis in that area and it does not leave an obvious scar.

Eventually, she said, if the person stops using hydroquinone, it will clear up, “but it will take years.” Again, here she has had success with her “special formula” of azelaic acid 20% plus hydrocortisone 2.5%

“Don’t tell patients there’s no treatment. That’s the take-home,” she said.

Drug-induced facial hyperpigmentation

“I see this all the time in my African American patients,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said. The condition usually is characterized by dark brown hyperpigmentation on the face.

In this situation, the first question to ask is whether the patient is taking medication for hypertension, and the second question is whether it is “HCTZ.” It’s important to use the abbreviation for hydrochlorothiazide – the most common cause of drug-induced facial hyperpigmentation – because that’s what a patient sees on the bottle.

If they are taking HCTZ or another blood pressure medication associated with photosensitivity, they need to switch to a nonphotosensitizing antihypertensive agent (there are several options) and they should start treatment with a topical anti-inflammatory, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said. Then, she suggests introducing hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and a hydroquinone-free skin brightener (azelaic acid, for example).

Importantly, with any of these conditions, Dr Woolery-Lloyd said, dermatologists should talk with patients about realistic expectations. “It takes a long time for dermal pigment to clear,” she emphasized.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd has been a speaker for Ortho Dermatologics, L’Oreal, and EPI; has done research for Pfizer, Galderma, Allergan, Arcutis, Vyne, Merz, and Eirion; and has been on advisory boards for L’Oreal, Allergan, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, and Merz.

CHICAGO – based on cases she has treated in her practice.

Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, director of the skin of color division in the dermatology department at University of Miami, provided three general pointers.

- When in doubt, biopsy.

- For inflammatory disorders, always treat the inflammation in addition to the hyperpigmentation.

- Avoid long-term hydroquinone use in these patients.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd also reviewed examples of what she has found successful in treating her patients with these conditions.

Lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP)

“It’s one of the hardest things that we treat,” said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, who often sees cases of LPP in patients in their 30s, 40s, and 50s.

Lesions first appear as small, ill-defined oval-to-round macules, which later become confluent and form large areas of pigmentation. In different patients, the pigment on the face and neck, and sometimes on the forearms can be slate gray or brownish black.

In 2013, dermatologist N.C. Dlova, MD, at the University of KwaZulu‐Natal, Durban, South Africa, reported a link between frontal fibrosing alopecia and LPP in the British Journal of Dermatology. “I definitely see this connection in my practice,” said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, noting that “both conditions often result in the loss of both eyebrows.”

She recommends always using a topical anti-inflammatory that is safe for the face. One combination she uses is azelaic acid 20% plus hydrocortisone 2.5%.

“We do use a lot of azelaic acid in my practice because it’s affordable,” she said, at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLive! She added that the hardest area to treat in women is around the chin.

Two other conditions, ashy dermatosis and erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), are similar. Ashy dermatosis mimics LPP but occurs more prominently on the trunk and extremities. EDP often has a preceding ring of erythema.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said the term EDP is often used to cover both EDP and ashy dermatosis in North America because “ashy” can have a negative connotation.

She noted there is no consensus on effective therapy for LPP, ashy dermatosis, or EDP.

A review of the literature on EDP, which included 16 studies on treatment outcomes, found the following:

- Narrow-band ultraviolet B and tacrolimus were effective treatments with minimal side effects.

- Clofazimine was effective, but had side effects, which, ironically, included pigmentary changes.

- Griseofulvin, isotretinoin, and dapsone were comparatively ineffective as lesions recurred after discontinuation.

- Lasers were largely ineffective and can also result in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and fibrosis.

Ochronosis

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said she may see one to two patients a year with ochronosis, which is characterized by paradoxical darkening of the skin with long-term hydroquinone use. It usually starts with redness followed by blue-black patches on the face where hydroquinone is applied. In severe cases, blue-black papules and nodules can occur.

“When I give a patient hydroquinone, I always say: ‘I don’t want to see any redness,’” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said. “If you have any redness, please stop because ochronosis is typically preceded by this redness.”

But, she noted, “people will come in actively using hydroquinone, will have the dark brown or deep black papules or macules on their face, and then this background of redness because they are so inflamed.”

She said that ochronosis can occur in any skin type, not just in patients with darker skin tones. Dr. Woolery-Lloyd advised: “Do not hesitate to biopsy the face if ochronosis is suspected. I always biopsy ochronosis.”

There are two reasons for doing so, she explained. It can help with the diagnosis but it will also provide the patient with an incentive to stop using hydroquinone. “People who are using hydroquinone are addicted to it. They love it. They don’t want to stop. They keep using it despite the fact that their face is getting darker.” When they see a biopsy report, they may be convinced to stop.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said she does a 2-mm punch biopsy in the crow’s feet area because there’s almost always ochronosis in that area and it does not leave an obvious scar.

Eventually, she said, if the person stops using hydroquinone, it will clear up, “but it will take years.” Again, here she has had success with her “special formula” of azelaic acid 20% plus hydrocortisone 2.5%

“Don’t tell patients there’s no treatment. That’s the take-home,” she said.

Drug-induced facial hyperpigmentation

“I see this all the time in my African American patients,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said. The condition usually is characterized by dark brown hyperpigmentation on the face.

In this situation, the first question to ask is whether the patient is taking medication for hypertension, and the second question is whether it is “HCTZ.” It’s important to use the abbreviation for hydrochlorothiazide – the most common cause of drug-induced facial hyperpigmentation – because that’s what a patient sees on the bottle.

If they are taking HCTZ or another blood pressure medication associated with photosensitivity, they need to switch to a nonphotosensitizing antihypertensive agent (there are several options) and they should start treatment with a topical anti-inflammatory, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said. Then, she suggests introducing hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and a hydroquinone-free skin brightener (azelaic acid, for example).

Importantly, with any of these conditions, Dr Woolery-Lloyd said, dermatologists should talk with patients about realistic expectations. “It takes a long time for dermal pigment to clear,” she emphasized.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd has been a speaker for Ortho Dermatologics, L’Oreal, and EPI; has done research for Pfizer, Galderma, Allergan, Arcutis, Vyne, Merz, and Eirion; and has been on advisory boards for L’Oreal, Allergan, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, and Merz.

CHICAGO – based on cases she has treated in her practice.

Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, director of the skin of color division in the dermatology department at University of Miami, provided three general pointers.

- When in doubt, biopsy.

- For inflammatory disorders, always treat the inflammation in addition to the hyperpigmentation.

- Avoid long-term hydroquinone use in these patients.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd also reviewed examples of what she has found successful in treating her patients with these conditions.

Lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP)

“It’s one of the hardest things that we treat,” said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, who often sees cases of LPP in patients in their 30s, 40s, and 50s.

Lesions first appear as small, ill-defined oval-to-round macules, which later become confluent and form large areas of pigmentation. In different patients, the pigment on the face and neck, and sometimes on the forearms can be slate gray or brownish black.

In 2013, dermatologist N.C. Dlova, MD, at the University of KwaZulu‐Natal, Durban, South Africa, reported a link between frontal fibrosing alopecia and LPP in the British Journal of Dermatology. “I definitely see this connection in my practice,” said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, noting that “both conditions often result in the loss of both eyebrows.”

She recommends always using a topical anti-inflammatory that is safe for the face. One combination she uses is azelaic acid 20% plus hydrocortisone 2.5%.

“We do use a lot of azelaic acid in my practice because it’s affordable,” she said, at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLive! She added that the hardest area to treat in women is around the chin.

Two other conditions, ashy dermatosis and erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), are similar. Ashy dermatosis mimics LPP but occurs more prominently on the trunk and extremities. EDP often has a preceding ring of erythema.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said the term EDP is often used to cover both EDP and ashy dermatosis in North America because “ashy” can have a negative connotation.

She noted there is no consensus on effective therapy for LPP, ashy dermatosis, or EDP.

A review of the literature on EDP, which included 16 studies on treatment outcomes, found the following:

- Narrow-band ultraviolet B and tacrolimus were effective treatments with minimal side effects.

- Clofazimine was effective, but had side effects, which, ironically, included pigmentary changes.

- Griseofulvin, isotretinoin, and dapsone were comparatively ineffective as lesions recurred after discontinuation.

- Lasers were largely ineffective and can also result in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and fibrosis.

Ochronosis

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said she may see one to two patients a year with ochronosis, which is characterized by paradoxical darkening of the skin with long-term hydroquinone use. It usually starts with redness followed by blue-black patches on the face where hydroquinone is applied. In severe cases, blue-black papules and nodules can occur.

“When I give a patient hydroquinone, I always say: ‘I don’t want to see any redness,’” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said. “If you have any redness, please stop because ochronosis is typically preceded by this redness.”

But, she noted, “people will come in actively using hydroquinone, will have the dark brown or deep black papules or macules on their face, and then this background of redness because they are so inflamed.”

She said that ochronosis can occur in any skin type, not just in patients with darker skin tones. Dr. Woolery-Lloyd advised: “Do not hesitate to biopsy the face if ochronosis is suspected. I always biopsy ochronosis.”

There are two reasons for doing so, she explained. It can help with the diagnosis but it will also provide the patient with an incentive to stop using hydroquinone. “People who are using hydroquinone are addicted to it. They love it. They don’t want to stop. They keep using it despite the fact that their face is getting darker.” When they see a biopsy report, they may be convinced to stop.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said she does a 2-mm punch biopsy in the crow’s feet area because there’s almost always ochronosis in that area and it does not leave an obvious scar.

Eventually, she said, if the person stops using hydroquinone, it will clear up, “but it will take years.” Again, here she has had success with her “special formula” of azelaic acid 20% plus hydrocortisone 2.5%

“Don’t tell patients there’s no treatment. That’s the take-home,” she said.

Drug-induced facial hyperpigmentation

“I see this all the time in my African American patients,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said. The condition usually is characterized by dark brown hyperpigmentation on the face.

In this situation, the first question to ask is whether the patient is taking medication for hypertension, and the second question is whether it is “HCTZ.” It’s important to use the abbreviation for hydrochlorothiazide – the most common cause of drug-induced facial hyperpigmentation – because that’s what a patient sees on the bottle.

If they are taking HCTZ or another blood pressure medication associated with photosensitivity, they need to switch to a nonphotosensitizing antihypertensive agent (there are several options) and they should start treatment with a topical anti-inflammatory, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said. Then, she suggests introducing hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and a hydroquinone-free skin brightener (azelaic acid, for example).

Importantly, with any of these conditions, Dr Woolery-Lloyd said, dermatologists should talk with patients about realistic expectations. “It takes a long time for dermal pigment to clear,” she emphasized.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd has been a speaker for Ortho Dermatologics, L’Oreal, and EPI; has done research for Pfizer, Galderma, Allergan, Arcutis, Vyne, Merz, and Eirion; and has been on advisory boards for L’Oreal, Allergan, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, and Merz.

AT THE MEDSCAPELIVE! PIGMENTARY DISORDERS SYMPOSIUM

Tips, contraindications for superficial chemical peels reviewed

CHICAGO – Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, says she’s generally “risk averse,” but when it comes to superficial chemical peels, she’s in her comfort zone.

Superficial peeling is “one of the most common cosmetic procedures that I do,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, director of the skin of color division in the dermatology department at the University of Miami, said at the Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium.

In her practice, .

Contraindications are an active bacterial infection, open wounds, and active herpes simplex virus. “If someone looks like they even have a remnant of a cold sore, I tell them to come back,” she said.

Setting expectations for patients is critical, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said, as a series of superficial peels is needed before the desired results are evident.

The peel she uses most is salicylic acid, a beta-hydroxy acid, at a strength of 20%-30%. “It’s very effective on our acne patients,” she said at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLIVE! “If you’re just starting with peels, I think this is a very safe one. You don’t have to time it, and you don’t have to neutralize it,” and at lower concentrations, is “very safe.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd provided these other tips during her presentation:

- Even superficial peels can be uncomfortable, she noted, so she keeps a fan nearby to use when needed to help with discomfort.

- Find the peel you’re comfortable with, master that peel, and don’t jump from peel to peel. Get familiar with the side effects and how to predict results.

- Stop retinoids up to 7 days before a peel. Consider placing the patient on hydroquinone before the chemical peel to decrease the risk of hyperpigmentation.

- Before the procedure, prep the skin with acetone or alcohol. Applying petrolatum helps protect around the eyes, alar crease, and other sensitive areas, “or anywhere you’re concerned about the depth of the peel.”

- Application with rough gauze helps avoid the waste that comes with makeup sponges soaking up the product. It also helps add exfoliation.

- Have everything ready before starting the procedure, including (depending on the peel), a neutralizer or soapless cleanser. Although peels are generally safe, you want to be able to remove one quickly, if needed, without having to leave the room.

- Start with the lowest concentration (salicylic acid or glycolic acid) then titrate up. Ask patients about any reactions they experienced with the previous peel before making the decision on the next concentration.

- For a peel to treat hyperpigmentation, she recommends one peel about every 4 weeks for a series of 5-6 peels.

- After a peel, the patient should use a mineral sunscreen; chemical sunscreens will sting.

Know your comfort zone

Conference chair Pearl Grimes, MD, director of The Vitiligo & Pigmentation Institute of Southern California in Los Angeles, said superficial peels are best for dermatologists new to peeling until they gain comfort with experience.

Superficial and medium-depth peels work well for mild to moderate photoaging, she said at the meeting.

“We know that in darker skin we have more intrinsic aging rather than photoaging. We have more textural changes, hyperpigmentation,” Dr. Grimes said.

For Fitzpatrick skin types I-III, she said, “you can do superficial, medium, and deep peels.” For darker skin types, “I typically stay in the superficial, medium range.”

She said that she uses retinoids to exfoliate before a superficial peel but added, “you’ve got to stop them early because retinoids can make a superficial peel a medium-depth peel.”

Taking photos is important before any procedure, she said, as is spending time with patients clarifying their outcome expectations.

“I love peeling,” Dr. Grimes said. “And it’s cost effective. If you don’t want to spend a ton of money, it’s amazing what you can achieve with chemical peeling.”

When asked by a member of the audience whether they avoid superficial peels in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, both Dr. Woolery-Lloyd and Dr. Grimes said they do avoid them in those patients.

Dr. Grimes said she tells her patients, especially in the first trimester, “I am the most conservative woman on the planet. I do nothing during the first trimester.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd has been a speaker for Ortho Dermatologics, Loreal and EPI, and has done research for Pfizer, Galderma, Allergan, Arcutis, Vyne, Merz, and Eirion. She has been on advisory boards for Loreal, Allergan, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfize,r and Merz. Dr. Grimes reports grant/research Support from Clinuvel Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, Johnson & Johnson, LASEROPTEK, L’Oréal USA, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, skinbetter science, and Versicolor Technologies, and is on the speakers bureau/receives honoraria for non-CME for Incyte and Procter & Gamble; and is a consultant or is on the advisory board for L’Oréal USA and Procter & Gamble. She has stock options in Versicolor Technologies.

CHICAGO – Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, says she’s generally “risk averse,” but when it comes to superficial chemical peels, she’s in her comfort zone.

Superficial peeling is “one of the most common cosmetic procedures that I do,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, director of the skin of color division in the dermatology department at the University of Miami, said at the Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium.

In her practice, .

Contraindications are an active bacterial infection, open wounds, and active herpes simplex virus. “If someone looks like they even have a remnant of a cold sore, I tell them to come back,” she said.

Setting expectations for patients is critical, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said, as a series of superficial peels is needed before the desired results are evident.

The peel she uses most is salicylic acid, a beta-hydroxy acid, at a strength of 20%-30%. “It’s very effective on our acne patients,” she said at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLIVE! “If you’re just starting with peels, I think this is a very safe one. You don’t have to time it, and you don’t have to neutralize it,” and at lower concentrations, is “very safe.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd provided these other tips during her presentation:

- Even superficial peels can be uncomfortable, she noted, so she keeps a fan nearby to use when needed to help with discomfort.

- Find the peel you’re comfortable with, master that peel, and don’t jump from peel to peel. Get familiar with the side effects and how to predict results.

- Stop retinoids up to 7 days before a peel. Consider placing the patient on hydroquinone before the chemical peel to decrease the risk of hyperpigmentation.

- Before the procedure, prep the skin with acetone or alcohol. Applying petrolatum helps protect around the eyes, alar crease, and other sensitive areas, “or anywhere you’re concerned about the depth of the peel.”

- Application with rough gauze helps avoid the waste that comes with makeup sponges soaking up the product. It also helps add exfoliation.

- Have everything ready before starting the procedure, including (depending on the peel), a neutralizer or soapless cleanser. Although peels are generally safe, you want to be able to remove one quickly, if needed, without having to leave the room.

- Start with the lowest concentration (salicylic acid or glycolic acid) then titrate up. Ask patients about any reactions they experienced with the previous peel before making the decision on the next concentration.

- For a peel to treat hyperpigmentation, she recommends one peel about every 4 weeks for a series of 5-6 peels.

- After a peel, the patient should use a mineral sunscreen; chemical sunscreens will sting.

Know your comfort zone

Conference chair Pearl Grimes, MD, director of The Vitiligo & Pigmentation Institute of Southern California in Los Angeles, said superficial peels are best for dermatologists new to peeling until they gain comfort with experience.

Superficial and medium-depth peels work well for mild to moderate photoaging, she said at the meeting.

“We know that in darker skin we have more intrinsic aging rather than photoaging. We have more textural changes, hyperpigmentation,” Dr. Grimes said.

For Fitzpatrick skin types I-III, she said, “you can do superficial, medium, and deep peels.” For darker skin types, “I typically stay in the superficial, medium range.”

She said that she uses retinoids to exfoliate before a superficial peel but added, “you’ve got to stop them early because retinoids can make a superficial peel a medium-depth peel.”

Taking photos is important before any procedure, she said, as is spending time with patients clarifying their outcome expectations.

“I love peeling,” Dr. Grimes said. “And it’s cost effective. If you don’t want to spend a ton of money, it’s amazing what you can achieve with chemical peeling.”

When asked by a member of the audience whether they avoid superficial peels in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, both Dr. Woolery-Lloyd and Dr. Grimes said they do avoid them in those patients.

Dr. Grimes said she tells her patients, especially in the first trimester, “I am the most conservative woman on the planet. I do nothing during the first trimester.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd has been a speaker for Ortho Dermatologics, Loreal and EPI, and has done research for Pfizer, Galderma, Allergan, Arcutis, Vyne, Merz, and Eirion. She has been on advisory boards for Loreal, Allergan, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfize,r and Merz. Dr. Grimes reports grant/research Support from Clinuvel Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, Johnson & Johnson, LASEROPTEK, L’Oréal USA, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, skinbetter science, and Versicolor Technologies, and is on the speakers bureau/receives honoraria for non-CME for Incyte and Procter & Gamble; and is a consultant or is on the advisory board for L’Oréal USA and Procter & Gamble. She has stock options in Versicolor Technologies.

CHICAGO – Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, says she’s generally “risk averse,” but when it comes to superficial chemical peels, she’s in her comfort zone.

Superficial peeling is “one of the most common cosmetic procedures that I do,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, director of the skin of color division in the dermatology department at the University of Miami, said at the Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium.

In her practice, .

Contraindications are an active bacterial infection, open wounds, and active herpes simplex virus. “If someone looks like they even have a remnant of a cold sore, I tell them to come back,” she said.

Setting expectations for patients is critical, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said, as a series of superficial peels is needed before the desired results are evident.

The peel she uses most is salicylic acid, a beta-hydroxy acid, at a strength of 20%-30%. “It’s very effective on our acne patients,” she said at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLIVE! “If you’re just starting with peels, I think this is a very safe one. You don’t have to time it, and you don’t have to neutralize it,” and at lower concentrations, is “very safe.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd provided these other tips during her presentation:

- Even superficial peels can be uncomfortable, she noted, so she keeps a fan nearby to use when needed to help with discomfort.

- Find the peel you’re comfortable with, master that peel, and don’t jump from peel to peel. Get familiar with the side effects and how to predict results.

- Stop retinoids up to 7 days before a peel. Consider placing the patient on hydroquinone before the chemical peel to decrease the risk of hyperpigmentation.

- Before the procedure, prep the skin with acetone or alcohol. Applying petrolatum helps protect around the eyes, alar crease, and other sensitive areas, “or anywhere you’re concerned about the depth of the peel.”

- Application with rough gauze helps avoid the waste that comes with makeup sponges soaking up the product. It also helps add exfoliation.

- Have everything ready before starting the procedure, including (depending on the peel), a neutralizer or soapless cleanser. Although peels are generally safe, you want to be able to remove one quickly, if needed, without having to leave the room.

- Start with the lowest concentration (salicylic acid or glycolic acid) then titrate up. Ask patients about any reactions they experienced with the previous peel before making the decision on the next concentration.

- For a peel to treat hyperpigmentation, she recommends one peel about every 4 weeks for a series of 5-6 peels.

- After a peel, the patient should use a mineral sunscreen; chemical sunscreens will sting.

Know your comfort zone

Conference chair Pearl Grimes, MD, director of The Vitiligo & Pigmentation Institute of Southern California in Los Angeles, said superficial peels are best for dermatologists new to peeling until they gain comfort with experience.

Superficial and medium-depth peels work well for mild to moderate photoaging, she said at the meeting.

“We know that in darker skin we have more intrinsic aging rather than photoaging. We have more textural changes, hyperpigmentation,” Dr. Grimes said.

For Fitzpatrick skin types I-III, she said, “you can do superficial, medium, and deep peels.” For darker skin types, “I typically stay in the superficial, medium range.”

She said that she uses retinoids to exfoliate before a superficial peel but added, “you’ve got to stop them early because retinoids can make a superficial peel a medium-depth peel.”

Taking photos is important before any procedure, she said, as is spending time with patients clarifying their outcome expectations.

“I love peeling,” Dr. Grimes said. “And it’s cost effective. If you don’t want to spend a ton of money, it’s amazing what you can achieve with chemical peeling.”

When asked by a member of the audience whether they avoid superficial peels in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, both Dr. Woolery-Lloyd and Dr. Grimes said they do avoid them in those patients.

Dr. Grimes said she tells her patients, especially in the first trimester, “I am the most conservative woman on the planet. I do nothing during the first trimester.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd has been a speaker for Ortho Dermatologics, Loreal and EPI, and has done research for Pfizer, Galderma, Allergan, Arcutis, Vyne, Merz, and Eirion. She has been on advisory boards for Loreal, Allergan, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfize,r and Merz. Dr. Grimes reports grant/research Support from Clinuvel Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, Johnson & Johnson, LASEROPTEK, L’Oréal USA, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, skinbetter science, and Versicolor Technologies, and is on the speakers bureau/receives honoraria for non-CME for Incyte and Procter & Gamble; and is a consultant or is on the advisory board for L’Oréal USA and Procter & Gamble. She has stock options in Versicolor Technologies.

AT THE MEDSCAPE LIVE! PIGMENTARY DISORDERS SYMPOSIUM

SPF is only the start when recommending sunscreens

CHICAGO – at the inaugural Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium.

Among the first factors physicians should consider before recommending sunscreen are a patient’s Fitzpatrick skin type, risks for burning or tanning, underlying skin disorders, and medications the patient is taking, Dr. Taylor, professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLIVE! If patients are on hypertensives, for example, medications can make them more photosensitive.

Consider skin type

Dr. Taylor said she was dismayed by the results of a recent study, which found that 43% of dermatologists who responded to a survey reported that they never, rarely, or only sometimes took a patient’s skin type into account when making sunscreen recommendations. The article is referenced in a 2022 expert panel consensus paper she coauthored on photoprotection “for skin of all color.” But she pointed out that considering skin type alone is inadequate.

Questions for patients in joint decision-making should include lifestyle and work choices such as whether they work inside or outside, and how much sun exposure they get in a typical day. Heat and humidity levels should also be considered as should a patient’s susceptibility to dyspigmentation. “That could be overall darkening of the skin, mottled hyperpigmentation, actinic dyspigmentation, and, of course, propensity for skin cancer,” she said.

Use differs by race

Dr. Taylor, who is also vice chair for diversity, equity and inclusion in the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, pointed out that sunscreen use differs considerably by race.

In study of 8,952 adults in the United States who reported that they were sun sensitive found that a subset of adults with skin of color were significantly less likely to use sunscreen when compared with non-Hispanic White adults: Non-Hispanic Black (adjusted odds ratio, 0.43); non-Hispanic Asian (aOR. 0.54); and Hispanic (aOR, 0.70) adults.

In the study, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adults were significantly less likely to use sunscreens with an SPF greater than 15. In addition, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic adults were significantly more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to wear long sleeves when outside. Such differences are important to keep in mind when advising patients about sunscreens, she said.

Protection for lighter-colored skin

Dr. Taylor said that, for patients with lighter skin tones, “we really want to protect against ultraviolet B as well as ultraviolet A, particularly ultraviolet A2. Ultraviolet radiation is going to cause DNA damage.” Patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I, II, or III are most susceptible to the effects of UVB with sunburn inflammation, which will cause erythema and tanning, and immunosuppression.

“For those who are I, II, and III, we do want to recommend a broad-spectrum, photostable sunscreen with a critical wavelength of 370 nanometers, which is going to protect from both UVB and UVA2,” she said.

Sunscreen recommendations are meant to be paired with advice to avoid midday sun from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., wearing protective clothing and accessories, and seeking shade, she noted.

Dr. Taylor said, for those patients with lighter skin who are more susceptible to photodamage and premature aging, physicians should recommend sunscreens that contain DNA repair enzymes such as photolyases and sunscreens that contain antioxidants that can prevent or reverse DNA damage. “The exogenous form of these lyases have been manufactured and added to sunscreens,” Dr. Taylor said. “They’re readily available in the United States. That is something to consider for patients with significant photodamage.”

Retinoids can also help alleviate or reverse photodamage, she added.

Protection for darker-colored skin

“Many people of color do not believe they need sunscreen,” Dr. Taylor said. But studies show that, although there may be more intrinsic protection, sunscreen is still needed.

Over 30 years ago, Halder and colleagues reported that melanin in skin of color can filter two to five times more UV radiation, and in a paper on the photoprotective role of melanin, Kaidbey and colleagues found that skin types V and VI had an intrinsic SPF of 13 when compared with those who have lighter complexions, which had an SPF of 3.

Sunburns seem to occur less frequently in people with skin of color, but that may be because erythema is less apparent in people with darker skin tones or because of differences in personal definitions of sunburn, Dr. Taylor said.

“Skin of color can and does sustain sunburns and sunscreen will help prevent that,” she said, adding that a recommendation of an SPF 30 is likely sufficient for these patients. Dr. Taylor noted that sunscreens for patients with darker skin often cost substantially more than those for lighter skin, and that should be considered in recommendations.

Tinted sunscreens

Dr. Taylor said that, while broad-spectrum photostable sunscreens protect against UVB and UVA 2, they don’t protect from visible light and UVA1. Two methods to add that protection are using inorganic tinted sunscreens that contain iron oxide or pigmentary titanium dioxide. Dr. Taylor was a coauthor of a practical guide to tinted sunscreens published in 2022.

“For iron oxide, we want a concentration of 3% or greater,” she said, adding that the percentage often is not known because if it is contained in a sunscreen, it is listed as an inactive ingredient.

Another method to address visible light and UVA1 is the use of antioxidant-containing sunscreens with vitamin E, vitamin C, or licochalcone A, Dr. Taylor said.

During the question-and-answer period following her presentation, Amit Pandya, MD, adjunct professor of dermatology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, asked why “every makeup, every sunscreen, just says iron oxide,” since it is known that visible light will cause pigmentation, especially in those with darker skin tones.

He urged pushing for a law that would require listing the percentage of iron oxide on products to assure it is sufficient, according to what the literature recommends.

Conference Chair Pearl Grimes, MD, director of the Vitiligo and Pigmentation Institute of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that she recommends tinted sunscreens almost exclusively for her patients, but those with darker skin colors struggle to match color.

Dr. Taylor referred to an analysis published in 2022 of 58 over-the counter sunscreens, which found that only 38% of tinted sunscreens was available in more than one shade, “which is a problem for many of our patients.” She said that providing samples with different hues and tactile sensations may help patients find the right product.

Dr. Taylor disclosed being on the advisory boards for AbbVie, Avita Medical, Beiersdorf, Biorez, Eli Lily, EPI Health, Evolus, Galderma, Hugel America, Johnson and Johnson, L’Oreal USA, MedScape, Pfizer, Scientis US, UCB, Vichy Laboratories. She is a consultant for Arcutis Biothermapeutics, Beiersdorf, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cara Therapeutics, Dior, and Sanofi. She has done contracted research for Allergan Aesthetics, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Croma-Pharma, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer, and has an ownership interest in Armis Scientific, GloGetter, and Piction Health.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

CHICAGO – at the inaugural Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium.

Among the first factors physicians should consider before recommending sunscreen are a patient’s Fitzpatrick skin type, risks for burning or tanning, underlying skin disorders, and medications the patient is taking, Dr. Taylor, professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLIVE! If patients are on hypertensives, for example, medications can make them more photosensitive.

Consider skin type

Dr. Taylor said she was dismayed by the results of a recent study, which found that 43% of dermatologists who responded to a survey reported that they never, rarely, or only sometimes took a patient’s skin type into account when making sunscreen recommendations. The article is referenced in a 2022 expert panel consensus paper she coauthored on photoprotection “for skin of all color.” But she pointed out that considering skin type alone is inadequate.

Questions for patients in joint decision-making should include lifestyle and work choices such as whether they work inside or outside, and how much sun exposure they get in a typical day. Heat and humidity levels should also be considered as should a patient’s susceptibility to dyspigmentation. “That could be overall darkening of the skin, mottled hyperpigmentation, actinic dyspigmentation, and, of course, propensity for skin cancer,” she said.

Use differs by race

Dr. Taylor, who is also vice chair for diversity, equity and inclusion in the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, pointed out that sunscreen use differs considerably by race.

In study of 8,952 adults in the United States who reported that they were sun sensitive found that a subset of adults with skin of color were significantly less likely to use sunscreen when compared with non-Hispanic White adults: Non-Hispanic Black (adjusted odds ratio, 0.43); non-Hispanic Asian (aOR. 0.54); and Hispanic (aOR, 0.70) adults.

In the study, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adults were significantly less likely to use sunscreens with an SPF greater than 15. In addition, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic adults were significantly more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to wear long sleeves when outside. Such differences are important to keep in mind when advising patients about sunscreens, she said.

Protection for lighter-colored skin

Dr. Taylor said that, for patients with lighter skin tones, “we really want to protect against ultraviolet B as well as ultraviolet A, particularly ultraviolet A2. Ultraviolet radiation is going to cause DNA damage.” Patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I, II, or III are most susceptible to the effects of UVB with sunburn inflammation, which will cause erythema and tanning, and immunosuppression.

“For those who are I, II, and III, we do want to recommend a broad-spectrum, photostable sunscreen with a critical wavelength of 370 nanometers, which is going to protect from both UVB and UVA2,” she said.

Sunscreen recommendations are meant to be paired with advice to avoid midday sun from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., wearing protective clothing and accessories, and seeking shade, she noted.

Dr. Taylor said, for those patients with lighter skin who are more susceptible to photodamage and premature aging, physicians should recommend sunscreens that contain DNA repair enzymes such as photolyases and sunscreens that contain antioxidants that can prevent or reverse DNA damage. “The exogenous form of these lyases have been manufactured and added to sunscreens,” Dr. Taylor said. “They’re readily available in the United States. That is something to consider for patients with significant photodamage.”

Retinoids can also help alleviate or reverse photodamage, she added.

Protection for darker-colored skin

“Many people of color do not believe they need sunscreen,” Dr. Taylor said. But studies show that, although there may be more intrinsic protection, sunscreen is still needed.

Over 30 years ago, Halder and colleagues reported that melanin in skin of color can filter two to five times more UV radiation, and in a paper on the photoprotective role of melanin, Kaidbey and colleagues found that skin types V and VI had an intrinsic SPF of 13 when compared with those who have lighter complexions, which had an SPF of 3.

Sunburns seem to occur less frequently in people with skin of color, but that may be because erythema is less apparent in people with darker skin tones or because of differences in personal definitions of sunburn, Dr. Taylor said.

“Skin of color can and does sustain sunburns and sunscreen will help prevent that,” she said, adding that a recommendation of an SPF 30 is likely sufficient for these patients. Dr. Taylor noted that sunscreens for patients with darker skin often cost substantially more than those for lighter skin, and that should be considered in recommendations.

Tinted sunscreens

Dr. Taylor said that, while broad-spectrum photostable sunscreens protect against UVB and UVA 2, they don’t protect from visible light and UVA1. Two methods to add that protection are using inorganic tinted sunscreens that contain iron oxide or pigmentary titanium dioxide. Dr. Taylor was a coauthor of a practical guide to tinted sunscreens published in 2022.

“For iron oxide, we want a concentration of 3% or greater,” she said, adding that the percentage often is not known because if it is contained in a sunscreen, it is listed as an inactive ingredient.

Another method to address visible light and UVA1 is the use of antioxidant-containing sunscreens with vitamin E, vitamin C, or licochalcone A, Dr. Taylor said.

During the question-and-answer period following her presentation, Amit Pandya, MD, adjunct professor of dermatology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, asked why “every makeup, every sunscreen, just says iron oxide,” since it is known that visible light will cause pigmentation, especially in those with darker skin tones.

He urged pushing for a law that would require listing the percentage of iron oxide on products to assure it is sufficient, according to what the literature recommends.

Conference Chair Pearl Grimes, MD, director of the Vitiligo and Pigmentation Institute of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that she recommends tinted sunscreens almost exclusively for her patients, but those with darker skin colors struggle to match color.

Dr. Taylor referred to an analysis published in 2022 of 58 over-the counter sunscreens, which found that only 38% of tinted sunscreens was available in more than one shade, “which is a problem for many of our patients.” She said that providing samples with different hues and tactile sensations may help patients find the right product.