User login

Does Bariatric Surgery Also Improve Thyroid Function?

TOPLINE:

Metabolic/bariatric surgery (MBS) reduces thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free triiodothyronine (fT3) levels, and thyroid hormone resistance indices in patients with obesity, changes strongly correlated with improvement in body composition.

METHODOLOGY:

- Recent studies have linked obesity with increased levels of TSH and thyroid hormones; however, the role that body fat distribution plays in this association remains unclear.

- This retrospective observational study evaluated the effects of MBS on thyroid hormone levels and thyroid hormone resistance in euthyroid individuals with obesity, focusing on the correlation with changes in body composition.

- Researchers included 470 patients with obesity (mean age, 33.4 years; mean body mass index [BMI], 37.9; 63.2% women) and 118 control individuals without obesity (mean BMI, 21.8), who had had normal levels of TSH, fT3, and free thyroxine.

- Among the patients with obesity, 125 underwent MBS and had thyroid tests both before and ≥ 3 months after surgery.

- Data on body composition and thyroid function were collected, and correlations between baseline and changes in thyroid function and body composition were assessed.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with obesity had higher baseline TSH and fT3 levels (P < .001) and thyroid feedback quantile-based index (TFQI; P = .047) than those without obesity, with the values decreasing after MBS (all P < .001).

- Among individuals with obesity, preoperative TSH was positively correlated with the visceral fat area (VFA; P = .019) and body fat percentage (P = .013) and negatively correlated with skeletal muscle mass percentage (P = .024)

- The decrease in TSH post-surgery positively correlated with decreased VFA (P = .021) and decreased body fat percentage (P = .031).

- Decrease in VFA and body fat percentage after MBS was also associated with improved central thyroid hormone resistance indicated by TFQI.

IN PRACTICE:

“The relationship between obesity and [thyroid hormone] is bidirectional, indicating that addressing underlying thyroid disturbance could potentially benefit weight loss and metabolism,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Yu Yan, MD, Department of Pancreatic and Metabolic Surgery, Medical School of Southeast University, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Nanjing, China, and published online in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature of this study limited the ability to definitively attribute changes in thyroid function and thyroid hormone resistance to changes in body composition. The relatively short duration of the study and the exclusion of individuals taking medications affecting thyroid function may also limit the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the Fundings for Clinical Trials from the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Nanjing University Medical School, Nanjing, China. The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Metabolic/bariatric surgery (MBS) reduces thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free triiodothyronine (fT3) levels, and thyroid hormone resistance indices in patients with obesity, changes strongly correlated with improvement in body composition.

METHODOLOGY:

- Recent studies have linked obesity with increased levels of TSH and thyroid hormones; however, the role that body fat distribution plays in this association remains unclear.

- This retrospective observational study evaluated the effects of MBS on thyroid hormone levels and thyroid hormone resistance in euthyroid individuals with obesity, focusing on the correlation with changes in body composition.

- Researchers included 470 patients with obesity (mean age, 33.4 years; mean body mass index [BMI], 37.9; 63.2% women) and 118 control individuals without obesity (mean BMI, 21.8), who had had normal levels of TSH, fT3, and free thyroxine.

- Among the patients with obesity, 125 underwent MBS and had thyroid tests both before and ≥ 3 months after surgery.

- Data on body composition and thyroid function were collected, and correlations between baseline and changes in thyroid function and body composition were assessed.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with obesity had higher baseline TSH and fT3 levels (P < .001) and thyroid feedback quantile-based index (TFQI; P = .047) than those without obesity, with the values decreasing after MBS (all P < .001).

- Among individuals with obesity, preoperative TSH was positively correlated with the visceral fat area (VFA; P = .019) and body fat percentage (P = .013) and negatively correlated with skeletal muscle mass percentage (P = .024)

- The decrease in TSH post-surgery positively correlated with decreased VFA (P = .021) and decreased body fat percentage (P = .031).

- Decrease in VFA and body fat percentage after MBS was also associated with improved central thyroid hormone resistance indicated by TFQI.

IN PRACTICE:

“The relationship between obesity and [thyroid hormone] is bidirectional, indicating that addressing underlying thyroid disturbance could potentially benefit weight loss and metabolism,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Yu Yan, MD, Department of Pancreatic and Metabolic Surgery, Medical School of Southeast University, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Nanjing, China, and published online in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature of this study limited the ability to definitively attribute changes in thyroid function and thyroid hormone resistance to changes in body composition. The relatively short duration of the study and the exclusion of individuals taking medications affecting thyroid function may also limit the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the Fundings for Clinical Trials from the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Nanjing University Medical School, Nanjing, China. The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Metabolic/bariatric surgery (MBS) reduces thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free triiodothyronine (fT3) levels, and thyroid hormone resistance indices in patients with obesity, changes strongly correlated with improvement in body composition.

METHODOLOGY:

- Recent studies have linked obesity with increased levels of TSH and thyroid hormones; however, the role that body fat distribution plays in this association remains unclear.

- This retrospective observational study evaluated the effects of MBS on thyroid hormone levels and thyroid hormone resistance in euthyroid individuals with obesity, focusing on the correlation with changes in body composition.

- Researchers included 470 patients with obesity (mean age, 33.4 years; mean body mass index [BMI], 37.9; 63.2% women) and 118 control individuals without obesity (mean BMI, 21.8), who had had normal levels of TSH, fT3, and free thyroxine.

- Among the patients with obesity, 125 underwent MBS and had thyroid tests both before and ≥ 3 months after surgery.

- Data on body composition and thyroid function were collected, and correlations between baseline and changes in thyroid function and body composition were assessed.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals with obesity had higher baseline TSH and fT3 levels (P < .001) and thyroid feedback quantile-based index (TFQI; P = .047) than those without obesity, with the values decreasing after MBS (all P < .001).

- Among individuals with obesity, preoperative TSH was positively correlated with the visceral fat area (VFA; P = .019) and body fat percentage (P = .013) and negatively correlated with skeletal muscle mass percentage (P = .024)

- The decrease in TSH post-surgery positively correlated with decreased VFA (P = .021) and decreased body fat percentage (P = .031).

- Decrease in VFA and body fat percentage after MBS was also associated with improved central thyroid hormone resistance indicated by TFQI.

IN PRACTICE:

“The relationship between obesity and [thyroid hormone] is bidirectional, indicating that addressing underlying thyroid disturbance could potentially benefit weight loss and metabolism,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Yu Yan, MD, Department of Pancreatic and Metabolic Surgery, Medical School of Southeast University, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Nanjing, China, and published online in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature of this study limited the ability to definitively attribute changes in thyroid function and thyroid hormone resistance to changes in body composition. The relatively short duration of the study and the exclusion of individuals taking medications affecting thyroid function may also limit the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the Fundings for Clinical Trials from the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Nanjing University Medical School, Nanjing, China. The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Stones, Bones, Groans, and Moans: Could This Be Primary Hyperparathyroidism?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr. Paul Nelson Williams.

Paul, we’re going to talk about our primary hyperparathyroidism podcast with Dr. Lindsay Kuo. It’s a topic that I feel much more clear on now.

Now, Paul, in primary care, you see a lot of calcium that is just slightly high. Can we just blame that on thiazide diuretics?

Paul N. Williams, MD: It’s a place to start. As you’re starting to think about the possible etiologies, primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy are the two that roll right off the tongue, but it is worth going back to the patient’s medication list and making sure you’re not missing something.

Thiazides famously cause hypercalcemia, but in some of the reading I did for this episode, they may just uncover it a little bit early. Patients who are on thiazides who become hypercalcemic seem to go on to develop primary hyperthyroidism anyway. So I don’t think you can solely blame the thiazide.

Another medication that can be causative is lithium. So a good place to look first after you’ve repeated the labs and confirmed hypercalcemia is the patient’s medication list.

Dr. Watto: We’ve talked before about the basic workup for hypercalcemia, and determining whether it’s PTH dependent or PTH independent. On the podcast, we talk more about the full workup, but I wanted to talk about the classic symptoms. Our expert made the point that we don’t see them as much anymore, although we do see kidney stones. People used to present very late in the disease because they weren’t having labs done routinely.

The classic symptoms include osteoporosis and bone tumors. People can get nephrocalcinosis and kidney stones. I hadn’t really thought of it this way because we’re used to diagnosing it early now. Do you feel the same?

Dr. Williams: As labs have started routinely reporting calcium levels, this is more and more often how it’s picked up. The other aspect is that as we are screening for and finding osteoporosis, part of the workup almost always involves getting a parathyroid hormone and a calcium level. We’re seeing these lab abnormalities before we’re seeing symptoms, which is good.

But it also makes things more diagnostically thorny.

Dr. Watto: Dr. Lindsay Kuo made the point that when she sees patients before and after surgery, she’s aware of these nonclassic symptoms — the stones, bones, groans, and the psychiatric overtones that can be anything from fatigue or irritability to dysphoria.

Some people have a generalized weakness that’s very nonspecific. Dr. Kuo said that sometimes these symptoms will disappear after surgery. The patients may just have gotten used to them, or they thought these symptoms were caused by something else, but after surgery they went away.

There are these nonclassic symptoms that are harder to pin down. I was surprised by that.

Dr. Williams: She mentioned polydipsia and polyuria, which have been reported in other studies. It seems like it can be anything. You have to take a good history, but none of those things in and of themselves is an indication for operating unless the patient has the classic renal or bone manifestations.

Dr. Watto: The other thing we talked about is a normal calcium level in a patient with primary hyperparathyroidism, or the finding of a PTH level in the normal range but with a high calcium level that is inappropriate. Can you talk a little bit about those two situations?

Dr. Williams: They’re hard to say but kind of easy to manage because you treat them the same way as someone who has elevated calcium and PTH levels.

The normocalcemic patient is something we might stumble across with osteoporosis screening. Initially the calcium level is elevated, so you repeat it and it’s normal but with an elevated PTH level. You’re like, shoot. Now what?

It turns out that most endocrine surgeons say that the indications for surgery for the classic form of primary hyperparathyroidism apply to these patients as well, and it probably helps with the bone outcomes, which is one of the things they follow most closely. If you have hypercalcemia, you should have a suppressed PTH level, the so-called normohormonal hyperparathyroidism, which is not normal at all. So even if the PTH is in the normal range, it’s still relatively elevated compared with what it should be. That situation is treated in the same way as the classic elevated PTH and elevated calcium levels.

Dr. Watto: If the calcium is abnormal and the PTH is not quite what you’d expect it to be, you can always ask your friendly neighborhood endocrinologist to help you figure out whether the patient really has one of these conditions. You have to make sure that they don’t have a simple secondary cause like a low vitamin D level. In that case, you fix the vitamin D and then recheck the numbers to see if they’ve normalized. But I have found a bunch of these edge cases in which it has been helpful to confer with an endocrinologist, especially before you send someone to a surgeon to take out their parathyroid gland.

This was a really fantastic conversation. If you want to hear the full podcast episode, click here.

Dr. Watto, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania; Internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Williams, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for The Curbsiders, and has received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from The Curbsiders.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr. Paul Nelson Williams.

Paul, we’re going to talk about our primary hyperparathyroidism podcast with Dr. Lindsay Kuo. It’s a topic that I feel much more clear on now.

Now, Paul, in primary care, you see a lot of calcium that is just slightly high. Can we just blame that on thiazide diuretics?

Paul N. Williams, MD: It’s a place to start. As you’re starting to think about the possible etiologies, primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy are the two that roll right off the tongue, but it is worth going back to the patient’s medication list and making sure you’re not missing something.

Thiazides famously cause hypercalcemia, but in some of the reading I did for this episode, they may just uncover it a little bit early. Patients who are on thiazides who become hypercalcemic seem to go on to develop primary hyperthyroidism anyway. So I don’t think you can solely blame the thiazide.

Another medication that can be causative is lithium. So a good place to look first after you’ve repeated the labs and confirmed hypercalcemia is the patient’s medication list.

Dr. Watto: We’ve talked before about the basic workup for hypercalcemia, and determining whether it’s PTH dependent or PTH independent. On the podcast, we talk more about the full workup, but I wanted to talk about the classic symptoms. Our expert made the point that we don’t see them as much anymore, although we do see kidney stones. People used to present very late in the disease because they weren’t having labs done routinely.

The classic symptoms include osteoporosis and bone tumors. People can get nephrocalcinosis and kidney stones. I hadn’t really thought of it this way because we’re used to diagnosing it early now. Do you feel the same?

Dr. Williams: As labs have started routinely reporting calcium levels, this is more and more often how it’s picked up. The other aspect is that as we are screening for and finding osteoporosis, part of the workup almost always involves getting a parathyroid hormone and a calcium level. We’re seeing these lab abnormalities before we’re seeing symptoms, which is good.

But it also makes things more diagnostically thorny.

Dr. Watto: Dr. Lindsay Kuo made the point that when she sees patients before and after surgery, she’s aware of these nonclassic symptoms — the stones, bones, groans, and the psychiatric overtones that can be anything from fatigue or irritability to dysphoria.

Some people have a generalized weakness that’s very nonspecific. Dr. Kuo said that sometimes these symptoms will disappear after surgery. The patients may just have gotten used to them, or they thought these symptoms were caused by something else, but after surgery they went away.

There are these nonclassic symptoms that are harder to pin down. I was surprised by that.

Dr. Williams: She mentioned polydipsia and polyuria, which have been reported in other studies. It seems like it can be anything. You have to take a good history, but none of those things in and of themselves is an indication for operating unless the patient has the classic renal or bone manifestations.

Dr. Watto: The other thing we talked about is a normal calcium level in a patient with primary hyperparathyroidism, or the finding of a PTH level in the normal range but with a high calcium level that is inappropriate. Can you talk a little bit about those two situations?

Dr. Williams: They’re hard to say but kind of easy to manage because you treat them the same way as someone who has elevated calcium and PTH levels.

The normocalcemic patient is something we might stumble across with osteoporosis screening. Initially the calcium level is elevated, so you repeat it and it’s normal but with an elevated PTH level. You’re like, shoot. Now what?

It turns out that most endocrine surgeons say that the indications for surgery for the classic form of primary hyperparathyroidism apply to these patients as well, and it probably helps with the bone outcomes, which is one of the things they follow most closely. If you have hypercalcemia, you should have a suppressed PTH level, the so-called normohormonal hyperparathyroidism, which is not normal at all. So even if the PTH is in the normal range, it’s still relatively elevated compared with what it should be. That situation is treated in the same way as the classic elevated PTH and elevated calcium levels.

Dr. Watto: If the calcium is abnormal and the PTH is not quite what you’d expect it to be, you can always ask your friendly neighborhood endocrinologist to help you figure out whether the patient really has one of these conditions. You have to make sure that they don’t have a simple secondary cause like a low vitamin D level. In that case, you fix the vitamin D and then recheck the numbers to see if they’ve normalized. But I have found a bunch of these edge cases in which it has been helpful to confer with an endocrinologist, especially before you send someone to a surgeon to take out their parathyroid gland.

This was a really fantastic conversation. If you want to hear the full podcast episode, click here.

Dr. Watto, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania; Internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Williams, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for The Curbsiders, and has received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from The Curbsiders.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr. Paul Nelson Williams.

Paul, we’re going to talk about our primary hyperparathyroidism podcast with Dr. Lindsay Kuo. It’s a topic that I feel much more clear on now.

Now, Paul, in primary care, you see a lot of calcium that is just slightly high. Can we just blame that on thiazide diuretics?

Paul N. Williams, MD: It’s a place to start. As you’re starting to think about the possible etiologies, primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy are the two that roll right off the tongue, but it is worth going back to the patient’s medication list and making sure you’re not missing something.

Thiazides famously cause hypercalcemia, but in some of the reading I did for this episode, they may just uncover it a little bit early. Patients who are on thiazides who become hypercalcemic seem to go on to develop primary hyperthyroidism anyway. So I don’t think you can solely blame the thiazide.

Another medication that can be causative is lithium. So a good place to look first after you’ve repeated the labs and confirmed hypercalcemia is the patient’s medication list.

Dr. Watto: We’ve talked before about the basic workup for hypercalcemia, and determining whether it’s PTH dependent or PTH independent. On the podcast, we talk more about the full workup, but I wanted to talk about the classic symptoms. Our expert made the point that we don’t see them as much anymore, although we do see kidney stones. People used to present very late in the disease because they weren’t having labs done routinely.

The classic symptoms include osteoporosis and bone tumors. People can get nephrocalcinosis and kidney stones. I hadn’t really thought of it this way because we’re used to diagnosing it early now. Do you feel the same?

Dr. Williams: As labs have started routinely reporting calcium levels, this is more and more often how it’s picked up. The other aspect is that as we are screening for and finding osteoporosis, part of the workup almost always involves getting a parathyroid hormone and a calcium level. We’re seeing these lab abnormalities before we’re seeing symptoms, which is good.

But it also makes things more diagnostically thorny.

Dr. Watto: Dr. Lindsay Kuo made the point that when she sees patients before and after surgery, she’s aware of these nonclassic symptoms — the stones, bones, groans, and the psychiatric overtones that can be anything from fatigue or irritability to dysphoria.

Some people have a generalized weakness that’s very nonspecific. Dr. Kuo said that sometimes these symptoms will disappear after surgery. The patients may just have gotten used to them, or they thought these symptoms were caused by something else, but after surgery they went away.

There are these nonclassic symptoms that are harder to pin down. I was surprised by that.

Dr. Williams: She mentioned polydipsia and polyuria, which have been reported in other studies. It seems like it can be anything. You have to take a good history, but none of those things in and of themselves is an indication for operating unless the patient has the classic renal or bone manifestations.

Dr. Watto: The other thing we talked about is a normal calcium level in a patient with primary hyperparathyroidism, or the finding of a PTH level in the normal range but with a high calcium level that is inappropriate. Can you talk a little bit about those two situations?

Dr. Williams: They’re hard to say but kind of easy to manage because you treat them the same way as someone who has elevated calcium and PTH levels.

The normocalcemic patient is something we might stumble across with osteoporosis screening. Initially the calcium level is elevated, so you repeat it and it’s normal but with an elevated PTH level. You’re like, shoot. Now what?

It turns out that most endocrine surgeons say that the indications for surgery for the classic form of primary hyperparathyroidism apply to these patients as well, and it probably helps with the bone outcomes, which is one of the things they follow most closely. If you have hypercalcemia, you should have a suppressed PTH level, the so-called normohormonal hyperparathyroidism, which is not normal at all. So even if the PTH is in the normal range, it’s still relatively elevated compared with what it should be. That situation is treated in the same way as the classic elevated PTH and elevated calcium levels.

Dr. Watto: If the calcium is abnormal and the PTH is not quite what you’d expect it to be, you can always ask your friendly neighborhood endocrinologist to help you figure out whether the patient really has one of these conditions. You have to make sure that they don’t have a simple secondary cause like a low vitamin D level. In that case, you fix the vitamin D and then recheck the numbers to see if they’ve normalized. But I have found a bunch of these edge cases in which it has been helpful to confer with an endocrinologist, especially before you send someone to a surgeon to take out their parathyroid gland.

This was a really fantastic conversation. If you want to hear the full podcast episode, click here.

Dr. Watto, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania; Internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Williams, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for The Curbsiders, and has received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from The Curbsiders.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Simple Blood Test May Predict Cancer Risk in T2D

TOPLINE:

potentially enabling the identification of higher-risk individuals through a simple blood test.

METHODOLOGY:

- T2D is associated with an increased risk for obesity-related cancers, including breast, renal, uterine, thyroid, ovarian, and gastrointestinal cancers, as well as multiple myeloma, possibly because of chronic low-grade inflammation.

- Researchers explored whether the markers of inflammation IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) can serve as predictive biomarkers for obesity-related cancers in patients recently diagnosed with T2D.

- They identified patients with recent-onset T2D and no prior history of cancer participating in the ongoing Danish Centre for Strategic Research in Type 2 Diabetes cohort study.

- At study initiation, plasma levels of IL-6 and TNF-alpha were measured using Meso Scale Discovery assays, and serum levels of hsCRP were measured using immunofluorometric assays.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among 6,466 eligible patients (40.5% women; median age, 60.9 years), 327 developed obesity-related cancers over a median follow-up of 8.8 years.

- Each SD increase in log-transformed IL-6 levels increased the risk for obesity-related cancers by 19%.

- The researchers did not find a strong association between TNF-alpha or hsCRP and obesity-related cancers.

- The addition of baseline IL-6 levels to other well-known risk factors for obesity-related cancers improved the performance of a cancer prediction model from 0.685 to 0.693, translating to a small but important increase in the ability to predict whether an individual would develop one of these cancers.

IN PRACTICE:

“In future, a simple blood test could identify those at higher risk of the cancers,” said the study’s lead author in an accompanying press release.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Mathilde D. Bennetsen, Steno Diabetes Center Odense, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark, and published online on August 27 as an early release from the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2024 Annual Meeting.

LIMITATIONS:

No limitations were discussed in this abstract. However, the reliance on registry data may have introduced potential biases related to data accuracy and completeness.

DISCLOSURES:

The Danish Centre for Strategic Research in Type 2 Diabetes was supported by grants from the Danish Agency for Science and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

potentially enabling the identification of higher-risk individuals through a simple blood test.

METHODOLOGY:

- T2D is associated with an increased risk for obesity-related cancers, including breast, renal, uterine, thyroid, ovarian, and gastrointestinal cancers, as well as multiple myeloma, possibly because of chronic low-grade inflammation.

- Researchers explored whether the markers of inflammation IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) can serve as predictive biomarkers for obesity-related cancers in patients recently diagnosed with T2D.

- They identified patients with recent-onset T2D and no prior history of cancer participating in the ongoing Danish Centre for Strategic Research in Type 2 Diabetes cohort study.

- At study initiation, plasma levels of IL-6 and TNF-alpha were measured using Meso Scale Discovery assays, and serum levels of hsCRP were measured using immunofluorometric assays.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among 6,466 eligible patients (40.5% women; median age, 60.9 years), 327 developed obesity-related cancers over a median follow-up of 8.8 years.

- Each SD increase in log-transformed IL-6 levels increased the risk for obesity-related cancers by 19%.

- The researchers did not find a strong association between TNF-alpha or hsCRP and obesity-related cancers.

- The addition of baseline IL-6 levels to other well-known risk factors for obesity-related cancers improved the performance of a cancer prediction model from 0.685 to 0.693, translating to a small but important increase in the ability to predict whether an individual would develop one of these cancers.

IN PRACTICE:

“In future, a simple blood test could identify those at higher risk of the cancers,” said the study’s lead author in an accompanying press release.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Mathilde D. Bennetsen, Steno Diabetes Center Odense, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark, and published online on August 27 as an early release from the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2024 Annual Meeting.

LIMITATIONS:

No limitations were discussed in this abstract. However, the reliance on registry data may have introduced potential biases related to data accuracy and completeness.

DISCLOSURES:

The Danish Centre for Strategic Research in Type 2 Diabetes was supported by grants from the Danish Agency for Science and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

potentially enabling the identification of higher-risk individuals through a simple blood test.

METHODOLOGY:

- T2D is associated with an increased risk for obesity-related cancers, including breast, renal, uterine, thyroid, ovarian, and gastrointestinal cancers, as well as multiple myeloma, possibly because of chronic low-grade inflammation.

- Researchers explored whether the markers of inflammation IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) can serve as predictive biomarkers for obesity-related cancers in patients recently diagnosed with T2D.

- They identified patients with recent-onset T2D and no prior history of cancer participating in the ongoing Danish Centre for Strategic Research in Type 2 Diabetes cohort study.

- At study initiation, plasma levels of IL-6 and TNF-alpha were measured using Meso Scale Discovery assays, and serum levels of hsCRP were measured using immunofluorometric assays.

TAKEAWAY:

- Among 6,466 eligible patients (40.5% women; median age, 60.9 years), 327 developed obesity-related cancers over a median follow-up of 8.8 years.

- Each SD increase in log-transformed IL-6 levels increased the risk for obesity-related cancers by 19%.

- The researchers did not find a strong association between TNF-alpha or hsCRP and obesity-related cancers.

- The addition of baseline IL-6 levels to other well-known risk factors for obesity-related cancers improved the performance of a cancer prediction model from 0.685 to 0.693, translating to a small but important increase in the ability to predict whether an individual would develop one of these cancers.

IN PRACTICE:

“In future, a simple blood test could identify those at higher risk of the cancers,” said the study’s lead author in an accompanying press release.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Mathilde D. Bennetsen, Steno Diabetes Center Odense, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark, and published online on August 27 as an early release from the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2024 Annual Meeting.

LIMITATIONS:

No limitations were discussed in this abstract. However, the reliance on registry data may have introduced potential biases related to data accuracy and completeness.

DISCLOSURES:

The Danish Centre for Strategic Research in Type 2 Diabetes was supported by grants from the Danish Agency for Science and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Thyroid Resistance Ups Mortality in Euthyroid CKD Patients

TOPLINE:

An impaired central sensitivity to thyroid hormone may be associated with an increased risk for death in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and normal thyroid function.

METHODOLOGY:

- Previous studies have shown that abnormal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) are associated with a higher mortality risk in patients with CKD, but whether the risk extends to those with normal thyroid function remains controversial.

- Researchers investigated the association between central sensitivity to thyroid hormone and the risk for all-cause mortality in 1303 euthyroid patients with CKD (mean age, 60 years; 59% women) from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database (2007-2012).

- All participants had CKD stages I-IV, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and/or a urinary albumin to urinary creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g.

- The central sensitivity to thyroid hormone was primarily evaluated using a new central thyroid hormone resistance index, the Thyroid Feedback Quantile–based Index (TFQI), using free thyroxine and TSH concentrations.

- The participants were followed for a median duration of 115 months, during which 503 died.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients with CKD who died during the follow-up period had a significantly higher TFQI (P < .001) than those who survived.

- The rates of all-cause mortality increased from 26.61% in the lowest TFQI tertile to 40.89% in the highest tertile (P = .001).

- A per unit increase in the TFQI was associated with a 40% increased risk for all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.10-1.79).

- This association between TFQI level and all-cause mortality persisted in all subgroups stratified by age, gender, race, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and CKD stages.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study demonstrates that impaired sensitivity to thyroid hormone might be associated with all-cause mortality in CKD patients with normal thyroid function, independent of other traditional risk factors and comorbidities,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Qichao Yang and Ru Dong, Department of Endocrinology, Affiliated Wujin Hospital of Jiangsu University, Changzhou, China, and was published online on August 6, 2024, in BMC Public Health.

LIMITATIONS:

Thyroid function was measured only at baseline, and the changes in thyroid function over time were not measured. The study excluded people on thyroid hormone replacement therapy but did not consider other medication use that might have affected thyroid function, such as beta-blockers, steroids, and amiodarone. Thyroid-related antibodies, metabolic syndrome, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease were not included in the analysis as possible confounding factors. The US-based sample requires further validation.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Changzhou Health Commission. The authors declared no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

An impaired central sensitivity to thyroid hormone may be associated with an increased risk for death in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and normal thyroid function.

METHODOLOGY:

- Previous studies have shown that abnormal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) are associated with a higher mortality risk in patients with CKD, but whether the risk extends to those with normal thyroid function remains controversial.

- Researchers investigated the association between central sensitivity to thyroid hormone and the risk for all-cause mortality in 1303 euthyroid patients with CKD (mean age, 60 years; 59% women) from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database (2007-2012).

- All participants had CKD stages I-IV, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and/or a urinary albumin to urinary creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g.

- The central sensitivity to thyroid hormone was primarily evaluated using a new central thyroid hormone resistance index, the Thyroid Feedback Quantile–based Index (TFQI), using free thyroxine and TSH concentrations.

- The participants were followed for a median duration of 115 months, during which 503 died.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients with CKD who died during the follow-up period had a significantly higher TFQI (P < .001) than those who survived.

- The rates of all-cause mortality increased from 26.61% in the lowest TFQI tertile to 40.89% in the highest tertile (P = .001).

- A per unit increase in the TFQI was associated with a 40% increased risk for all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.10-1.79).

- This association between TFQI level and all-cause mortality persisted in all subgroups stratified by age, gender, race, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and CKD stages.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study demonstrates that impaired sensitivity to thyroid hormone might be associated with all-cause mortality in CKD patients with normal thyroid function, independent of other traditional risk factors and comorbidities,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Qichao Yang and Ru Dong, Department of Endocrinology, Affiliated Wujin Hospital of Jiangsu University, Changzhou, China, and was published online on August 6, 2024, in BMC Public Health.

LIMITATIONS:

Thyroid function was measured only at baseline, and the changes in thyroid function over time were not measured. The study excluded people on thyroid hormone replacement therapy but did not consider other medication use that might have affected thyroid function, such as beta-blockers, steroids, and amiodarone. Thyroid-related antibodies, metabolic syndrome, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease were not included in the analysis as possible confounding factors. The US-based sample requires further validation.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Changzhou Health Commission. The authors declared no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

An impaired central sensitivity to thyroid hormone may be associated with an increased risk for death in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and normal thyroid function.

METHODOLOGY:

- Previous studies have shown that abnormal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) are associated with a higher mortality risk in patients with CKD, but whether the risk extends to those with normal thyroid function remains controversial.

- Researchers investigated the association between central sensitivity to thyroid hormone and the risk for all-cause mortality in 1303 euthyroid patients with CKD (mean age, 60 years; 59% women) from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database (2007-2012).

- All participants had CKD stages I-IV, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and/or a urinary albumin to urinary creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g.

- The central sensitivity to thyroid hormone was primarily evaluated using a new central thyroid hormone resistance index, the Thyroid Feedback Quantile–based Index (TFQI), using free thyroxine and TSH concentrations.

- The participants were followed for a median duration of 115 months, during which 503 died.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients with CKD who died during the follow-up period had a significantly higher TFQI (P < .001) than those who survived.

- The rates of all-cause mortality increased from 26.61% in the lowest TFQI tertile to 40.89% in the highest tertile (P = .001).

- A per unit increase in the TFQI was associated with a 40% increased risk for all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.10-1.79).

- This association between TFQI level and all-cause mortality persisted in all subgroups stratified by age, gender, race, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and CKD stages.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study demonstrates that impaired sensitivity to thyroid hormone might be associated with all-cause mortality in CKD patients with normal thyroid function, independent of other traditional risk factors and comorbidities,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Qichao Yang and Ru Dong, Department of Endocrinology, Affiliated Wujin Hospital of Jiangsu University, Changzhou, China, and was published online on August 6, 2024, in BMC Public Health.

LIMITATIONS:

Thyroid function was measured only at baseline, and the changes in thyroid function over time were not measured. The study excluded people on thyroid hormone replacement therapy but did not consider other medication use that might have affected thyroid function, such as beta-blockers, steroids, and amiodarone. Thyroid-related antibodies, metabolic syndrome, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease were not included in the analysis as possible confounding factors. The US-based sample requires further validation.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Changzhou Health Commission. The authors declared no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A New Focus for Cushing Syndrome Screening in Obesity

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity is a key clinical feature of Cushing syndrome and shares many overlapping characteristics. An ongoing debate continues about the need to screen patients with obesity for the rare endocrine disease, but phenotypes known as metabolically healthy or unhealthy obesity may help better define an at-risk population.

- To assess the prevalence of Cushing syndrome by metabolic health status, researchers conducted a retrospective study of 1008 patients with obesity (mean age, 40 years; 83% women; body mass index ≥ 30) seen at an endocrinology outpatient clinic in Turkey between December 2020 and June 2022.

- They screened patients for Cushing syndrome with an overnight dexamethasone suppression test (1 mg DST), an oral dexamethasone dose given at 11 PM followed by a fasting blood sample for cortisol measurement the next morning. A serum cortisol level < 1.8 mcg/dL indicated normal suppression.

- Patients were categorized into those with metabolically healthy obesity (n = 229) or metabolically unhealthy obesity (n = 779) based on the absence or presence of comorbidities such as diabetes, prediabetes, coronary artery disease, hypertension, or dyslipidemia.

TAKEAWAY:

- The overall prevalence of Cushing syndrome in the study cohort was 0.2%, with only two patients definitively diagnosed after more tests and the remaining 10 classified as having subclinical hypercortisolism.

- Cortisol levels following the 1 mg DST were higher in the metabolically unhealthy obesity group than in the metabolically healthy obesity group (P = .001).

- Among the 12 patients with unsuppressed levels of cortisol, 11 belonged to the metabolically unhealthy obesity group, indicating a strong association between metabolic health and the levels of cortisol.

- The test demonstrated a specificity of 99% and sensitivity of 100% for screening Cushing syndrome in patients with obesity.

IN PRACTICE:

“Screening all patients with obesity for CS [Cushing syndrome] without considering any associated metabolic conditions appears impractical and unnecessary in everyday clinical practice,” the authors wrote. “However, it may be more reasonable and applicable to selectively screen the patients with obesity having comorbidities such as DM [diabetes mellitus], hypertension, dyslipidemia, or coronary artery disease, which lead to a metabolically unhealthy phenotype, rather than all individuals with obesity,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Sema Hepsen, Ankara Etlik City Hospital, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Ankara, Turkey, was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The single-center design of the study and inclusion of patients from a single racial group may limit the generalizability of the findings. The retrospective design prevented the retrieval of all relevant data on clinical features and fat distribution.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by an open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity is a key clinical feature of Cushing syndrome and shares many overlapping characteristics. An ongoing debate continues about the need to screen patients with obesity for the rare endocrine disease, but phenotypes known as metabolically healthy or unhealthy obesity may help better define an at-risk population.

- To assess the prevalence of Cushing syndrome by metabolic health status, researchers conducted a retrospective study of 1008 patients with obesity (mean age, 40 years; 83% women; body mass index ≥ 30) seen at an endocrinology outpatient clinic in Turkey between December 2020 and June 2022.

- They screened patients for Cushing syndrome with an overnight dexamethasone suppression test (1 mg DST), an oral dexamethasone dose given at 11 PM followed by a fasting blood sample for cortisol measurement the next morning. A serum cortisol level < 1.8 mcg/dL indicated normal suppression.

- Patients were categorized into those with metabolically healthy obesity (n = 229) or metabolically unhealthy obesity (n = 779) based on the absence or presence of comorbidities such as diabetes, prediabetes, coronary artery disease, hypertension, or dyslipidemia.

TAKEAWAY:

- The overall prevalence of Cushing syndrome in the study cohort was 0.2%, with only two patients definitively diagnosed after more tests and the remaining 10 classified as having subclinical hypercortisolism.

- Cortisol levels following the 1 mg DST were higher in the metabolically unhealthy obesity group than in the metabolically healthy obesity group (P = .001).

- Among the 12 patients with unsuppressed levels of cortisol, 11 belonged to the metabolically unhealthy obesity group, indicating a strong association between metabolic health and the levels of cortisol.

- The test demonstrated a specificity of 99% and sensitivity of 100% for screening Cushing syndrome in patients with obesity.

IN PRACTICE:

“Screening all patients with obesity for CS [Cushing syndrome] without considering any associated metabolic conditions appears impractical and unnecessary in everyday clinical practice,” the authors wrote. “However, it may be more reasonable and applicable to selectively screen the patients with obesity having comorbidities such as DM [diabetes mellitus], hypertension, dyslipidemia, or coronary artery disease, which lead to a metabolically unhealthy phenotype, rather than all individuals with obesity,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Sema Hepsen, Ankara Etlik City Hospital, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Ankara, Turkey, was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The single-center design of the study and inclusion of patients from a single racial group may limit the generalizability of the findings. The retrospective design prevented the retrieval of all relevant data on clinical features and fat distribution.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by an open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity is a key clinical feature of Cushing syndrome and shares many overlapping characteristics. An ongoing debate continues about the need to screen patients with obesity for the rare endocrine disease, but phenotypes known as metabolically healthy or unhealthy obesity may help better define an at-risk population.

- To assess the prevalence of Cushing syndrome by metabolic health status, researchers conducted a retrospective study of 1008 patients with obesity (mean age, 40 years; 83% women; body mass index ≥ 30) seen at an endocrinology outpatient clinic in Turkey between December 2020 and June 2022.

- They screened patients for Cushing syndrome with an overnight dexamethasone suppression test (1 mg DST), an oral dexamethasone dose given at 11 PM followed by a fasting blood sample for cortisol measurement the next morning. A serum cortisol level < 1.8 mcg/dL indicated normal suppression.

- Patients were categorized into those with metabolically healthy obesity (n = 229) or metabolically unhealthy obesity (n = 779) based on the absence or presence of comorbidities such as diabetes, prediabetes, coronary artery disease, hypertension, or dyslipidemia.

TAKEAWAY:

- The overall prevalence of Cushing syndrome in the study cohort was 0.2%, with only two patients definitively diagnosed after more tests and the remaining 10 classified as having subclinical hypercortisolism.

- Cortisol levels following the 1 mg DST were higher in the metabolically unhealthy obesity group than in the metabolically healthy obesity group (P = .001).

- Among the 12 patients with unsuppressed levels of cortisol, 11 belonged to the metabolically unhealthy obesity group, indicating a strong association between metabolic health and the levels of cortisol.

- The test demonstrated a specificity of 99% and sensitivity of 100% for screening Cushing syndrome in patients with obesity.

IN PRACTICE:

“Screening all patients with obesity for CS [Cushing syndrome] without considering any associated metabolic conditions appears impractical and unnecessary in everyday clinical practice,” the authors wrote. “However, it may be more reasonable and applicable to selectively screen the patients with obesity having comorbidities such as DM [diabetes mellitus], hypertension, dyslipidemia, or coronary artery disease, which lead to a metabolically unhealthy phenotype, rather than all individuals with obesity,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Sema Hepsen, Ankara Etlik City Hospital, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Ankara, Turkey, was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The single-center design of the study and inclusion of patients from a single racial group may limit the generalizability of the findings. The retrospective design prevented the retrieval of all relevant data on clinical features and fat distribution.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by an open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Step-by-Step Guide for Diagnosing Cushing Syndrome

“Moon face” is a term that’s become popular on social media, used to describe people with unusually round faces who are purported to have high levels of cortisol. But the term “moon face” isn’t new. It was actually coined in the 1930s by neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing, MD, who identified patients with a constellation of clinical characteristics — a condition that came to bear his name — which included rapidly developing facial adiposity. And indeed, elevated cortisol is a hallmark feature of Cushing syndrome (CS), but there are other reasons for elevated cortisol and other manifestations of CS.

Today, the term “moon face” has been replaced with “round face,” which is considered more encompassing and culturally sensitive, said Maria Fleseriu, MD, professor of medicine and neurological surgery and director of the Pituitary Center at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, Oregon.

Facial roundness can lead clinicians to be suspicious that their patient is experiencing CS. But because a round face is associated with several other conditions, it’s important to be familiar with its particular presentation in CS, as well as how to diagnose and treat CS.

Pathophysiology of CS

Dr. Fleseriu defined CS as “prolonged nonphysiologic increase in cortisol, due either to exogenous use of steroids (oral, topical, or inhaled) or to excess endogenous cortisol production.” She added that it’s important “to always exclude exogenous causes before conducting a further workup to determine the type and cause of cortisol excess.”

Dr. Fleseriu said. Other causes of CS are ectopic (caused by neuroendocrine tumors) or adrenal. CS affects primarily females and typically has an onset between ages 20 and 50 years, depending on the CS type.

Diagnosis of CS is “substantially delayed for most patients, due to metabolic syndrome phenotypic overlap and lack of a single pathognomonic symptom,” according to Dr. Fleseriu.

An accurate diagnosis should be on the basis of signs and symptoms, biochemical screening, other laboratory testing, and diagnostic imaging.

Look for Clinical Signs and Symptoms of CS

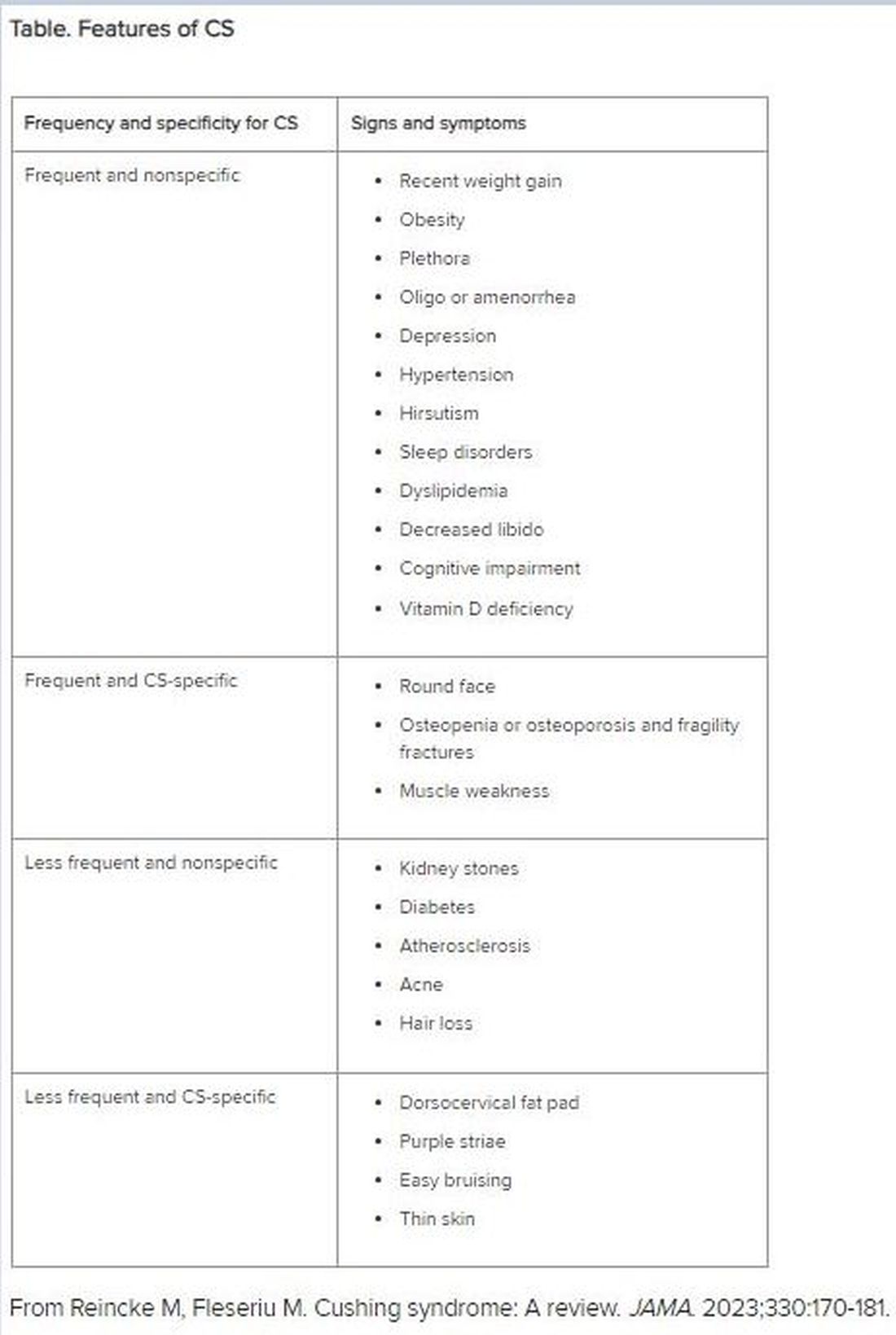

“CS mostly presents as a combination of two or more features,” Dr. Fleseriu stated. These include increased fat pads (in the face, neck, and trunk), skin changes, signs of protein catabolism, growth retardation and body weight increase in children, and metabolic dysregulations (Table).

“Biochemical screening should be performed in patients with a combination of symptoms, and therefore an increased pretest probability for CS,” Dr. Fleseriu advised.

A CS diagnosis requires not only biochemical confirmation of hypercortisolemia but also determination of the underlying cause of the excess endogenous cortisol production. This is a key step, as the management of CS is specific to its etiology.

Elevated plasma cortisol alone is insufficient for diagnosing CS, as several conditions can be associated with physiologic, nonneoplastic endogenous hypercortisolemia, according to the 2021 updated CS guidelines for which Dr. Fleseriu served as a coauthor. These include depression, alcohol dependence, glucocorticoid resistance, obesity, diabetes, pregnancy, prolonged physical exertion, malnutrition, and cortisol-binding globulin excess.

The diagnosis begins with the following screening tests:

- Late-night salivary cortisol (LNSC) to assess an abnormal circadian rhythm

According to the 2021 guideline, this is “based on the assumption that patients with CS lose the normal circadian nadir of cortisol secretion.”

- Overnight 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test (DST) to assess impaired glucocorticoid feedback

The authors noted that in healthy individuals, a supraphysiologic dexamethasone dose inhibits vasopressin and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion, leading to decreased cortisol concentration. Cortisol concentrations of < 1-8 μg/dL in the morning (after administration of the dexamethasone between 11 p.m. and midnight) are considered “normal,” and a negative result “strongly predicts” the absence of CS. But false-positive and false-negative results can occur. Thus, “it is imperative that first-line testing is elected on the basis of physiologic conditions and drug intake — for example, use of CYP2A4/5 inhibitors or stimulators and oral estrogen — as well as laboratory quality control measure, and special attention to night shift workers,” Dr. Fleseriu emphasized.

- A 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC) test to assess increased bioavailable cortisol

The guideline encourages conducting several 24-hour urine collections to account for intra-patient variability.

Dr. Fleseriu recommended utilizing at least two of the three screening tests, all of which have reasonable sensitivity and specificity.

“Two normal test results usually exclude the presence of CS, except in rare cyclic CS,” she added.

Conduct Additional Laboratory Testing

Additional laboratory abnormalities suggestive of CS include:

- Increased leukocytes with decreased lymphocytes, eosinophils, monocytes, and basophils

- Elevated glucose and insulin levels

- Hypokalemia

- Increased triglycerides and total cholesterol levels

- Elevated liver enzymes

- Changes in activated thromboplastin time and plasma concentrations of pro- and anticoagulant factors

- Hypercalciuria, hypocalcemia (rare), hypophosphatemia, decreased phosphate maximum resorption, and increased alkaline phosphatase activity

Dr. Fleseriu noted that, in most cases, a final CS diagnosis can be reached after confirmation of biochemical hypercortisolism, which is done after an initial positive screening test.

She added that plasma ACTH levels are “instrumental” in distinguishing ACTH-depending forms of CS — such as Cushing disease and ectopic CS — from adrenal cases. Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling is necessary in ACTH-dependent CS.

Utilize Diagnostic Imaging

There are several diagnostic imaging techniques that localize the origin of the hypercortisolism, thus informing the course of treatment.

- Pituitary MRI to detect corticotropin-secreting corticotroph adenomas, which are typically small lesions (< 6 mm in diameter)

- CT evaluation of the neck, thoracic cavity, and abdomen to diagnose ectopic CS, including lung neuroendocrine tumors and bronchial neuroendocrine tumors

- Cervical and thyroid ultrasonography to identify primary or metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma, and PET scans, which have greater sensitivity in detecting tumors, compared with CT scans

- Contrast-enhanced CT scans to detect adrenal adenomas and adrenocortical carcinomas

Management of CS

“The primary aim of treatment is eucortisolemia, and in those with endogenous CS, complete surgical resection of the underlying tumor is the primary method,” Dr. Fleseriu said.

It’s critical to monitor for biochemical remission following surgery, utilizing 24-hour UFC, LNSC, and DST “because clinical manifestations may lag behind biochemical evidence.”

In Cushing disease, almost half of patients will have either persistent or recurrent hypercortisolemia after surgery. In those cases, individualized adjuvant treatments are recommended. These include repeat surgery, bilateral adrenalectomy, radiation, or medical treatments, including pituitary-directed drugs, adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitors, or glucocorticoid receptor-blocking agents. The last two groups are used for other types of CS.

Dr. Fleseriu pointed out that CS is “associated with increased metabolic, cardiovascular, psychiatric, infectious, and musculoskeletal morbidity, which are only partially reversible with successful [CS] treatment.” These comorbidities need to be addressed via individualized therapies. Moreover, long-term mortality is increased in all forms of CS. Thus, patients require lifelong follow-up to detect recurrence at an early stage and to treat comorbidities.

“It is likely that delayed diagnosis might explain the long-term consequences of CS, including increased morbidity and mortality despite remission,” she said.

Familiarity with the presenting signs and symptoms of CS and ordering recommended screening and confirmatory tests will enable appropriate management of the condition, leading to better outcomes.

Dr. Fleseriu reported receiving research grants from Sparrow Pharmaceuticals to Oregon Health and Science University as principal investigator and receiving occasional fees for scientific consulting/advisory boards from Sparrow Pharmaceuticals, Recordati Rare Diseases Inc., and Xeris Biopharma Holdings Inc.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Moon face” is a term that’s become popular on social media, used to describe people with unusually round faces who are purported to have high levels of cortisol. But the term “moon face” isn’t new. It was actually coined in the 1930s by neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing, MD, who identified patients with a constellation of clinical characteristics — a condition that came to bear his name — which included rapidly developing facial adiposity. And indeed, elevated cortisol is a hallmark feature of Cushing syndrome (CS), but there are other reasons for elevated cortisol and other manifestations of CS.

Today, the term “moon face” has been replaced with “round face,” which is considered more encompassing and culturally sensitive, said Maria Fleseriu, MD, professor of medicine and neurological surgery and director of the Pituitary Center at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, Oregon.

Facial roundness can lead clinicians to be suspicious that their patient is experiencing CS. But because a round face is associated with several other conditions, it’s important to be familiar with its particular presentation in CS, as well as how to diagnose and treat CS.

Pathophysiology of CS

Dr. Fleseriu defined CS as “prolonged nonphysiologic increase in cortisol, due either to exogenous use of steroids (oral, topical, or inhaled) or to excess endogenous cortisol production.” She added that it’s important “to always exclude exogenous causes before conducting a further workup to determine the type and cause of cortisol excess.”

Dr. Fleseriu said. Other causes of CS are ectopic (caused by neuroendocrine tumors) or adrenal. CS affects primarily females and typically has an onset between ages 20 and 50 years, depending on the CS type.

Diagnosis of CS is “substantially delayed for most patients, due to metabolic syndrome phenotypic overlap and lack of a single pathognomonic symptom,” according to Dr. Fleseriu.

An accurate diagnosis should be on the basis of signs and symptoms, biochemical screening, other laboratory testing, and diagnostic imaging.

Look for Clinical Signs and Symptoms of CS

“CS mostly presents as a combination of two or more features,” Dr. Fleseriu stated. These include increased fat pads (in the face, neck, and trunk), skin changes, signs of protein catabolism, growth retardation and body weight increase in children, and metabolic dysregulations (Table).

“Biochemical screening should be performed in patients with a combination of symptoms, and therefore an increased pretest probability for CS,” Dr. Fleseriu advised.

A CS diagnosis requires not only biochemical confirmation of hypercortisolemia but also determination of the underlying cause of the excess endogenous cortisol production. This is a key step, as the management of CS is specific to its etiology.

Elevated plasma cortisol alone is insufficient for diagnosing CS, as several conditions can be associated with physiologic, nonneoplastic endogenous hypercortisolemia, according to the 2021 updated CS guidelines for which Dr. Fleseriu served as a coauthor. These include depression, alcohol dependence, glucocorticoid resistance, obesity, diabetes, pregnancy, prolonged physical exertion, malnutrition, and cortisol-binding globulin excess.

The diagnosis begins with the following screening tests:

- Late-night salivary cortisol (LNSC) to assess an abnormal circadian rhythm

According to the 2021 guideline, this is “based on the assumption that patients with CS lose the normal circadian nadir of cortisol secretion.”

- Overnight 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test (DST) to assess impaired glucocorticoid feedback

The authors noted that in healthy individuals, a supraphysiologic dexamethasone dose inhibits vasopressin and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion, leading to decreased cortisol concentration. Cortisol concentrations of < 1-8 μg/dL in the morning (after administration of the dexamethasone between 11 p.m. and midnight) are considered “normal,” and a negative result “strongly predicts” the absence of CS. But false-positive and false-negative results can occur. Thus, “it is imperative that first-line testing is elected on the basis of physiologic conditions and drug intake — for example, use of CYP2A4/5 inhibitors or stimulators and oral estrogen — as well as laboratory quality control measure, and special attention to night shift workers,” Dr. Fleseriu emphasized.

- A 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC) test to assess increased bioavailable cortisol

The guideline encourages conducting several 24-hour urine collections to account for intra-patient variability.

Dr. Fleseriu recommended utilizing at least two of the three screening tests, all of which have reasonable sensitivity and specificity.

“Two normal test results usually exclude the presence of CS, except in rare cyclic CS,” she added.

Conduct Additional Laboratory Testing

Additional laboratory abnormalities suggestive of CS include:

- Increased leukocytes with decreased lymphocytes, eosinophils, monocytes, and basophils

- Elevated glucose and insulin levels

- Hypokalemia

- Increased triglycerides and total cholesterol levels

- Elevated liver enzymes

- Changes in activated thromboplastin time and plasma concentrations of pro- and anticoagulant factors

- Hypercalciuria, hypocalcemia (rare), hypophosphatemia, decreased phosphate maximum resorption, and increased alkaline phosphatase activity

Dr. Fleseriu noted that, in most cases, a final CS diagnosis can be reached after confirmation of biochemical hypercortisolism, which is done after an initial positive screening test.

She added that plasma ACTH levels are “instrumental” in distinguishing ACTH-depending forms of CS — such as Cushing disease and ectopic CS — from adrenal cases. Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling is necessary in ACTH-dependent CS.

Utilize Diagnostic Imaging

There are several diagnostic imaging techniques that localize the origin of the hypercortisolism, thus informing the course of treatment.

- Pituitary MRI to detect corticotropin-secreting corticotroph adenomas, which are typically small lesions (< 6 mm in diameter)

- CT evaluation of the neck, thoracic cavity, and abdomen to diagnose ectopic CS, including lung neuroendocrine tumors and bronchial neuroendocrine tumors

- Cervical and thyroid ultrasonography to identify primary or metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma, and PET scans, which have greater sensitivity in detecting tumors, compared with CT scans

- Contrast-enhanced CT scans to detect adrenal adenomas and adrenocortical carcinomas

Management of CS

“The primary aim of treatment is eucortisolemia, and in those with endogenous CS, complete surgical resection of the underlying tumor is the primary method,” Dr. Fleseriu said.

It’s critical to monitor for biochemical remission following surgery, utilizing 24-hour UFC, LNSC, and DST “because clinical manifestations may lag behind biochemical evidence.”

In Cushing disease, almost half of patients will have either persistent or recurrent hypercortisolemia after surgery. In those cases, individualized adjuvant treatments are recommended. These include repeat surgery, bilateral adrenalectomy, radiation, or medical treatments, including pituitary-directed drugs, adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitors, or glucocorticoid receptor-blocking agents. The last two groups are used for other types of CS.

Dr. Fleseriu pointed out that CS is “associated with increased metabolic, cardiovascular, psychiatric, infectious, and musculoskeletal morbidity, which are only partially reversible with successful [CS] treatment.” These comorbidities need to be addressed via individualized therapies. Moreover, long-term mortality is increased in all forms of CS. Thus, patients require lifelong follow-up to detect recurrence at an early stage and to treat comorbidities.

“It is likely that delayed diagnosis might explain the long-term consequences of CS, including increased morbidity and mortality despite remission,” she said.

Familiarity with the presenting signs and symptoms of CS and ordering recommended screening and confirmatory tests will enable appropriate management of the condition, leading to better outcomes.

Dr. Fleseriu reported receiving research grants from Sparrow Pharmaceuticals to Oregon Health and Science University as principal investigator and receiving occasional fees for scientific consulting/advisory boards from Sparrow Pharmaceuticals, Recordati Rare Diseases Inc., and Xeris Biopharma Holdings Inc.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Moon face” is a term that’s become popular on social media, used to describe people with unusually round faces who are purported to have high levels of cortisol. But the term “moon face” isn’t new. It was actually coined in the 1930s by neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing, MD, who identified patients with a constellation of clinical characteristics — a condition that came to bear his name — which included rapidly developing facial adiposity. And indeed, elevated cortisol is a hallmark feature of Cushing syndrome (CS), but there are other reasons for elevated cortisol and other manifestations of CS.

Today, the term “moon face” has been replaced with “round face,” which is considered more encompassing and culturally sensitive, said Maria Fleseriu, MD, professor of medicine and neurological surgery and director of the Pituitary Center at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, Oregon.

Facial roundness can lead clinicians to be suspicious that their patient is experiencing CS. But because a round face is associated with several other conditions, it’s important to be familiar with its particular presentation in CS, as well as how to diagnose and treat CS.

Pathophysiology of CS

Dr. Fleseriu defined CS as “prolonged nonphysiologic increase in cortisol, due either to exogenous use of steroids (oral, topical, or inhaled) or to excess endogenous cortisol production.” She added that it’s important “to always exclude exogenous causes before conducting a further workup to determine the type and cause of cortisol excess.”

Dr. Fleseriu said. Other causes of CS are ectopic (caused by neuroendocrine tumors) or adrenal. CS affects primarily females and typically has an onset between ages 20 and 50 years, depending on the CS type.

Diagnosis of CS is “substantially delayed for most patients, due to metabolic syndrome phenotypic overlap and lack of a single pathognomonic symptom,” according to Dr. Fleseriu.

An accurate diagnosis should be on the basis of signs and symptoms, biochemical screening, other laboratory testing, and diagnostic imaging.

Look for Clinical Signs and Symptoms of CS

“CS mostly presents as a combination of two or more features,” Dr. Fleseriu stated. These include increased fat pads (in the face, neck, and trunk), skin changes, signs of protein catabolism, growth retardation and body weight increase in children, and metabolic dysregulations (Table).

“Biochemical screening should be performed in patients with a combination of symptoms, and therefore an increased pretest probability for CS,” Dr. Fleseriu advised.

A CS diagnosis requires not only biochemical confirmation of hypercortisolemia but also determination of the underlying cause of the excess endogenous cortisol production. This is a key step, as the management of CS is specific to its etiology.

Elevated plasma cortisol alone is insufficient for diagnosing CS, as several conditions can be associated with physiologic, nonneoplastic endogenous hypercortisolemia, according to the 2021 updated CS guidelines for which Dr. Fleseriu served as a coauthor. These include depression, alcohol dependence, glucocorticoid resistance, obesity, diabetes, pregnancy, prolonged physical exertion, malnutrition, and cortisol-binding globulin excess.

The diagnosis begins with the following screening tests:

- Late-night salivary cortisol (LNSC) to assess an abnormal circadian rhythm

According to the 2021 guideline, this is “based on the assumption that patients with CS lose the normal circadian nadir of cortisol secretion.”

- Overnight 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test (DST) to assess impaired glucocorticoid feedback

The authors noted that in healthy individuals, a supraphysiologic dexamethasone dose inhibits vasopressin and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion, leading to decreased cortisol concentration. Cortisol concentrations of < 1-8 μg/dL in the morning (after administration of the dexamethasone between 11 p.m. and midnight) are considered “normal,” and a negative result “strongly predicts” the absence of CS. But false-positive and false-negative results can occur. Thus, “it is imperative that first-line testing is elected on the basis of physiologic conditions and drug intake — for example, use of CYP2A4/5 inhibitors or stimulators and oral estrogen — as well as laboratory quality control measure, and special attention to night shift workers,” Dr. Fleseriu emphasized.

- A 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC) test to assess increased bioavailable cortisol

The guideline encourages conducting several 24-hour urine collections to account for intra-patient variability.

Dr. Fleseriu recommended utilizing at least two of the three screening tests, all of which have reasonable sensitivity and specificity.

“Two normal test results usually exclude the presence of CS, except in rare cyclic CS,” she added.

Conduct Additional Laboratory Testing

Additional laboratory abnormalities suggestive of CS include: