User login

NCCN survey shows ongoing chemo drug shortages

Although access to carboplatin and cisplatin has improved slightly since June, when 93% and 70% of 27 NCCN member institutions reported shortages of the two agents, supplies remain limited and other anticancer drugs remain scarce, an NCCN follow-up survey shows.

Of 29 institutions surveyed last month, 86% reported having difficulty obtaining at least one anticancer drug, and 72% and 59% reported ongoing shortages of carboplatin and cisplatin, respectively – drugs recommended for treating patients involved in hundreds of different cancer scenarios, according to the NCCN.

“Drug shortages aren’t new, but the widespread impact makes this one particularly alarming,” NCCN’s chief executive officer, Robert W. Carlson, MD, said in a press statement. “It is extremely concerning that this situation continues despite significant attention and effort over the past few months.”

The latest survey, conducted between Sept. 6 and 27, was sent to the 33 NCCN member institutions. Overall, most respondents reported “being able to continue treating every patient who needs carboplatin or cisplatin, despite lowered supply, primarily by implementing strict waste management strategies,” the network noted, adding that “the responses may not reflect any additional challenges experienced by smaller community practices serving rural and marginalized patients.”

In addition to carboplatin and cisplatin shortages, the survey results also revealed that centers are experiencing shortages of a host of other drugs, including methotrexate (66%), 5-flourouracil (55%), fludarabine (45%), hydrocortisone (41%), and dacarbazine (28%), according to the press release.

“These drug shortages are the result of decades of systemic challenges,” noted Alyssa Schatz, senior director of policy and advocacy for NCCN, in a press release. “We recognize that comprehensive solutions take time, and we appreciate everyone who has put forth proposals to improve investment in generics and our data infrastructure. At the same time, we have to acknowledge that the cancer drug shortage has been ongoing for months, which is unacceptable for anyone impacted by cancer today.”

Following the June survey, the NCCN called for action from the federal government, the pharmaceutical industry, providers, and payers, encouraging them “to work together to ensure quality, effective, equitable, and accessible cancer care” and has since worked with multiple stakeholders and policymaking organizations to “advocate for short- and long-term fixes.”

“These new survey results remind us that we are still in an ongoing crisis and must respond with appropriate urgency,” Ms. Shatz added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although access to carboplatin and cisplatin has improved slightly since June, when 93% and 70% of 27 NCCN member institutions reported shortages of the two agents, supplies remain limited and other anticancer drugs remain scarce, an NCCN follow-up survey shows.

Of 29 institutions surveyed last month, 86% reported having difficulty obtaining at least one anticancer drug, and 72% and 59% reported ongoing shortages of carboplatin and cisplatin, respectively – drugs recommended for treating patients involved in hundreds of different cancer scenarios, according to the NCCN.

“Drug shortages aren’t new, but the widespread impact makes this one particularly alarming,” NCCN’s chief executive officer, Robert W. Carlson, MD, said in a press statement. “It is extremely concerning that this situation continues despite significant attention and effort over the past few months.”

The latest survey, conducted between Sept. 6 and 27, was sent to the 33 NCCN member institutions. Overall, most respondents reported “being able to continue treating every patient who needs carboplatin or cisplatin, despite lowered supply, primarily by implementing strict waste management strategies,” the network noted, adding that “the responses may not reflect any additional challenges experienced by smaller community practices serving rural and marginalized patients.”

In addition to carboplatin and cisplatin shortages, the survey results also revealed that centers are experiencing shortages of a host of other drugs, including methotrexate (66%), 5-flourouracil (55%), fludarabine (45%), hydrocortisone (41%), and dacarbazine (28%), according to the press release.

“These drug shortages are the result of decades of systemic challenges,” noted Alyssa Schatz, senior director of policy and advocacy for NCCN, in a press release. “We recognize that comprehensive solutions take time, and we appreciate everyone who has put forth proposals to improve investment in generics and our data infrastructure. At the same time, we have to acknowledge that the cancer drug shortage has been ongoing for months, which is unacceptable for anyone impacted by cancer today.”

Following the June survey, the NCCN called for action from the federal government, the pharmaceutical industry, providers, and payers, encouraging them “to work together to ensure quality, effective, equitable, and accessible cancer care” and has since worked with multiple stakeholders and policymaking organizations to “advocate for short- and long-term fixes.”

“These new survey results remind us that we are still in an ongoing crisis and must respond with appropriate urgency,” Ms. Shatz added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although access to carboplatin and cisplatin has improved slightly since June, when 93% and 70% of 27 NCCN member institutions reported shortages of the two agents, supplies remain limited and other anticancer drugs remain scarce, an NCCN follow-up survey shows.

Of 29 institutions surveyed last month, 86% reported having difficulty obtaining at least one anticancer drug, and 72% and 59% reported ongoing shortages of carboplatin and cisplatin, respectively – drugs recommended for treating patients involved in hundreds of different cancer scenarios, according to the NCCN.

“Drug shortages aren’t new, but the widespread impact makes this one particularly alarming,” NCCN’s chief executive officer, Robert W. Carlson, MD, said in a press statement. “It is extremely concerning that this situation continues despite significant attention and effort over the past few months.”

The latest survey, conducted between Sept. 6 and 27, was sent to the 33 NCCN member institutions. Overall, most respondents reported “being able to continue treating every patient who needs carboplatin or cisplatin, despite lowered supply, primarily by implementing strict waste management strategies,” the network noted, adding that “the responses may not reflect any additional challenges experienced by smaller community practices serving rural and marginalized patients.”

In addition to carboplatin and cisplatin shortages, the survey results also revealed that centers are experiencing shortages of a host of other drugs, including methotrexate (66%), 5-flourouracil (55%), fludarabine (45%), hydrocortisone (41%), and dacarbazine (28%), according to the press release.

“These drug shortages are the result of decades of systemic challenges,” noted Alyssa Schatz, senior director of policy and advocacy for NCCN, in a press release. “We recognize that comprehensive solutions take time, and we appreciate everyone who has put forth proposals to improve investment in generics and our data infrastructure. At the same time, we have to acknowledge that the cancer drug shortage has been ongoing for months, which is unacceptable for anyone impacted by cancer today.”

Following the June survey, the NCCN called for action from the federal government, the pharmaceutical industry, providers, and payers, encouraging them “to work together to ensure quality, effective, equitable, and accessible cancer care” and has since worked with multiple stakeholders and policymaking organizations to “advocate for short- and long-term fixes.”

“These new survey results remind us that we are still in an ongoing crisis and must respond with appropriate urgency,” Ms. Shatz added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From scrubs to screens: Growing your patient base with social media

With physicians under increasing pressure to see more patients in shorter office visits, developing a social media presence may offer valuable opportunities to connect with patients, explain procedures, combat misinformation, talk through a published article, and even share a joke or meme.

But there are caveats for doctors posting on social media platforms. This news organization spoke to four doctors who successfully use social media.

Use social media for the right reasons

While you’re under no obligation to build a social media presence, if you’re going to do it, be sure your intentions are solid, said Don S. Dizon, MD, professor of medicine and professor of surgery at Brown University, Providence, R.I. Dr. Dizon, as @DoctorDon, has 44,700 TikTok followers and uses the platform to answer cancer-related questions.

“It should be your altruism that motivates you to post,” said Dr. Dizon, who is also associate director of community outreach and engagement at the Legorreta Cancer Center in Providence, R.I., and director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital. “What we can do for society at large is to provide our input into issues, add informed opinions where there’s controversy, and address misinformation.”

If you don’t know where to start, consider seeking a digital mentor to talk through your options.

“You may never meet this person, but you should choose them if you like their style, their content, their delivery, and their perspective,” Dr. Dizon said. “Find another doctor out there on social media whom you feel you can emulate. Take your time, too. Soon enough, you’ll develop your own style and your own online persona.”

Post clear, accurate information

If you want to be lighthearted on social media, that’s your choice. But Jennifer Trachtenberg, a pediatrician with nearly 7,000 Instagram followers in New York who posts as @askdrjen, prefers to offer vaccine scheduling tips, alert parents about COVID-19 rates, and offer advice on cold and flu prevention.

“Right now, I’m mainly doing this to educate patients and make them aware of topics that I think are important and that I see my patients needing more information on,” she said. “We have to be clear: People take what we say seriously. So, while it’s important to be relatable, it’s even more important to share evidence-based information.”

Many patients get their information on social media

While patients once came to the doctor armed with information sourced via “Doctor Google,” today, just as many patients use social media to learn about their condition or the medications they’re taking.

Unfortunately, a recent Ohio State University, Columbus, study found that the majority of gynecologic cancer advice on TikTok, for example, was either misleading or inaccurate.

“This misinformation should be a motivator for physicians to explore the social media space,” Dr. Dizon said. “Our voices need to be on there.”

Break down barriers – and make connections

Mike Natter, MD, an endocrinologist in New York, has type 1 diabetes. This informs his work – and his life – and he’s passionate about sharing it with his 117,000 followers as @mike.natter on Instagram.

“A lot of type 1s follow me, so there’s an advocacy component to what I do,” he said. “I enjoy being able to raise awareness and keep people up to date on the newest research and treatment.”

But that’s not all: Dr. Natter is also an artist who went to art school before he went to medical school, and his account is rife with his cartoons and illustrations about everything from valvular disease to diabetic ketoacidosis.

“I found that I was drawing a lot of my notes in medical school,” he said. “When I drew my notes, I did quite well, and I think that using art and illustration is a great tool. It breaks down barriers and makes health information all the more accessible to everyone.”

Share your expertise as a doctor – and a person

As a mom and pediatrician, Krupa Playforth, MD, who practices in Vienna, Va., knows that what she posts carries weight. So, whether she’s writing about backpack safety tips, choking hazards, or separation anxiety, her followers can rest assured that she’s posting responsibly.

“Pediatricians often underestimate how smart parents are,” said Dr. Playforth, who has three kids, ages 8, 5, and 2, and has 137,000 followers on @thepediatricianmom, her Instagram account. “Their anxiety comes from an understandable place, which is why I see my role as that of a parent and pediatrician who can translate the knowledge pediatricians have into something parents can understand.”

Dr. Playforth, who jumped on social media during COVID-19 and experienced a positive response in her local community, said being on social media is imperative if you’re a pediatrician.

“This is the future of pediatric medicine in particular,” she said. “A lot of pediatricians don’t want to embrace social media, but I think that’s a mistake. After all, while parents think pediatricians have all the answers, when we think of our own children, most doctors are like other parents – we can’t think objectively about our kids. It’s helpful for me to share that and to help parents feel less alone.”

If you’re not yet using social media to the best of your physician abilities, you might take a shot at becoming widely recognizable. Pick a preferred platform, answer common patient questions, dispel medical myths, provide pertinent information, and let your personality shine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With physicians under increasing pressure to see more patients in shorter office visits, developing a social media presence may offer valuable opportunities to connect with patients, explain procedures, combat misinformation, talk through a published article, and even share a joke or meme.

But there are caveats for doctors posting on social media platforms. This news organization spoke to four doctors who successfully use social media.

Use social media for the right reasons

While you’re under no obligation to build a social media presence, if you’re going to do it, be sure your intentions are solid, said Don S. Dizon, MD, professor of medicine and professor of surgery at Brown University, Providence, R.I. Dr. Dizon, as @DoctorDon, has 44,700 TikTok followers and uses the platform to answer cancer-related questions.

“It should be your altruism that motivates you to post,” said Dr. Dizon, who is also associate director of community outreach and engagement at the Legorreta Cancer Center in Providence, R.I., and director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital. “What we can do for society at large is to provide our input into issues, add informed opinions where there’s controversy, and address misinformation.”

If you don’t know where to start, consider seeking a digital mentor to talk through your options.

“You may never meet this person, but you should choose them if you like their style, their content, their delivery, and their perspective,” Dr. Dizon said. “Find another doctor out there on social media whom you feel you can emulate. Take your time, too. Soon enough, you’ll develop your own style and your own online persona.”

Post clear, accurate information

If you want to be lighthearted on social media, that’s your choice. But Jennifer Trachtenberg, a pediatrician with nearly 7,000 Instagram followers in New York who posts as @askdrjen, prefers to offer vaccine scheduling tips, alert parents about COVID-19 rates, and offer advice on cold and flu prevention.

“Right now, I’m mainly doing this to educate patients and make them aware of topics that I think are important and that I see my patients needing more information on,” she said. “We have to be clear: People take what we say seriously. So, while it’s important to be relatable, it’s even more important to share evidence-based information.”

Many patients get their information on social media

While patients once came to the doctor armed with information sourced via “Doctor Google,” today, just as many patients use social media to learn about their condition or the medications they’re taking.

Unfortunately, a recent Ohio State University, Columbus, study found that the majority of gynecologic cancer advice on TikTok, for example, was either misleading or inaccurate.

“This misinformation should be a motivator for physicians to explore the social media space,” Dr. Dizon said. “Our voices need to be on there.”

Break down barriers – and make connections

Mike Natter, MD, an endocrinologist in New York, has type 1 diabetes. This informs his work – and his life – and he’s passionate about sharing it with his 117,000 followers as @mike.natter on Instagram.

“A lot of type 1s follow me, so there’s an advocacy component to what I do,” he said. “I enjoy being able to raise awareness and keep people up to date on the newest research and treatment.”

But that’s not all: Dr. Natter is also an artist who went to art school before he went to medical school, and his account is rife with his cartoons and illustrations about everything from valvular disease to diabetic ketoacidosis.

“I found that I was drawing a lot of my notes in medical school,” he said. “When I drew my notes, I did quite well, and I think that using art and illustration is a great tool. It breaks down barriers and makes health information all the more accessible to everyone.”

Share your expertise as a doctor – and a person

As a mom and pediatrician, Krupa Playforth, MD, who practices in Vienna, Va., knows that what she posts carries weight. So, whether she’s writing about backpack safety tips, choking hazards, or separation anxiety, her followers can rest assured that she’s posting responsibly.

“Pediatricians often underestimate how smart parents are,” said Dr. Playforth, who has three kids, ages 8, 5, and 2, and has 137,000 followers on @thepediatricianmom, her Instagram account. “Their anxiety comes from an understandable place, which is why I see my role as that of a parent and pediatrician who can translate the knowledge pediatricians have into something parents can understand.”

Dr. Playforth, who jumped on social media during COVID-19 and experienced a positive response in her local community, said being on social media is imperative if you’re a pediatrician.

“This is the future of pediatric medicine in particular,” she said. “A lot of pediatricians don’t want to embrace social media, but I think that’s a mistake. After all, while parents think pediatricians have all the answers, when we think of our own children, most doctors are like other parents – we can’t think objectively about our kids. It’s helpful for me to share that and to help parents feel less alone.”

If you’re not yet using social media to the best of your physician abilities, you might take a shot at becoming widely recognizable. Pick a preferred platform, answer common patient questions, dispel medical myths, provide pertinent information, and let your personality shine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With physicians under increasing pressure to see more patients in shorter office visits, developing a social media presence may offer valuable opportunities to connect with patients, explain procedures, combat misinformation, talk through a published article, and even share a joke or meme.

But there are caveats for doctors posting on social media platforms. This news organization spoke to four doctors who successfully use social media.

Use social media for the right reasons

While you’re under no obligation to build a social media presence, if you’re going to do it, be sure your intentions are solid, said Don S. Dizon, MD, professor of medicine and professor of surgery at Brown University, Providence, R.I. Dr. Dizon, as @DoctorDon, has 44,700 TikTok followers and uses the platform to answer cancer-related questions.

“It should be your altruism that motivates you to post,” said Dr. Dizon, who is also associate director of community outreach and engagement at the Legorreta Cancer Center in Providence, R.I., and director of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital. “What we can do for society at large is to provide our input into issues, add informed opinions where there’s controversy, and address misinformation.”

If you don’t know where to start, consider seeking a digital mentor to talk through your options.

“You may never meet this person, but you should choose them if you like their style, their content, their delivery, and their perspective,” Dr. Dizon said. “Find another doctor out there on social media whom you feel you can emulate. Take your time, too. Soon enough, you’ll develop your own style and your own online persona.”

Post clear, accurate information

If you want to be lighthearted on social media, that’s your choice. But Jennifer Trachtenberg, a pediatrician with nearly 7,000 Instagram followers in New York who posts as @askdrjen, prefers to offer vaccine scheduling tips, alert parents about COVID-19 rates, and offer advice on cold and flu prevention.

“Right now, I’m mainly doing this to educate patients and make them aware of topics that I think are important and that I see my patients needing more information on,” she said. “We have to be clear: People take what we say seriously. So, while it’s important to be relatable, it’s even more important to share evidence-based information.”

Many patients get their information on social media

While patients once came to the doctor armed with information sourced via “Doctor Google,” today, just as many patients use social media to learn about their condition or the medications they’re taking.

Unfortunately, a recent Ohio State University, Columbus, study found that the majority of gynecologic cancer advice on TikTok, for example, was either misleading or inaccurate.

“This misinformation should be a motivator for physicians to explore the social media space,” Dr. Dizon said. “Our voices need to be on there.”

Break down barriers – and make connections

Mike Natter, MD, an endocrinologist in New York, has type 1 diabetes. This informs his work – and his life – and he’s passionate about sharing it with his 117,000 followers as @mike.natter on Instagram.

“A lot of type 1s follow me, so there’s an advocacy component to what I do,” he said. “I enjoy being able to raise awareness and keep people up to date on the newest research and treatment.”

But that’s not all: Dr. Natter is also an artist who went to art school before he went to medical school, and his account is rife with his cartoons and illustrations about everything from valvular disease to diabetic ketoacidosis.

“I found that I was drawing a lot of my notes in medical school,” he said. “When I drew my notes, I did quite well, and I think that using art and illustration is a great tool. It breaks down barriers and makes health information all the more accessible to everyone.”

Share your expertise as a doctor – and a person

As a mom and pediatrician, Krupa Playforth, MD, who practices in Vienna, Va., knows that what she posts carries weight. So, whether she’s writing about backpack safety tips, choking hazards, or separation anxiety, her followers can rest assured that she’s posting responsibly.

“Pediatricians often underestimate how smart parents are,” said Dr. Playforth, who has three kids, ages 8, 5, and 2, and has 137,000 followers on @thepediatricianmom, her Instagram account. “Their anxiety comes from an understandable place, which is why I see my role as that of a parent and pediatrician who can translate the knowledge pediatricians have into something parents can understand.”

Dr. Playforth, who jumped on social media during COVID-19 and experienced a positive response in her local community, said being on social media is imperative if you’re a pediatrician.

“This is the future of pediatric medicine in particular,” she said. “A lot of pediatricians don’t want to embrace social media, but I think that’s a mistake. After all, while parents think pediatricians have all the answers, when we think of our own children, most doctors are like other parents – we can’t think objectively about our kids. It’s helpful for me to share that and to help parents feel less alone.”

If you’re not yet using social media to the best of your physician abilities, you might take a shot at becoming widely recognizable. Pick a preferred platform, answer common patient questions, dispel medical myths, provide pertinent information, and let your personality shine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Advanced practice radiation therapists: Are they worth it?

An innovative care model involving in the radiation oncology department of Mount Sinai Health System in New York.

At a time when clinician burnout is rampant, a novel approach that brings value to both patients and health systems – and helps advance the careers of highly educated and skilled practitioners – represents a welcome step forward, according to Samantha Skubish, MS, RT, chief technical director of radiation oncology and Mount Sinai.

In the new care model, APRTs work alongside radiation oncologists and support “the care of resource-intensive patient populations,” according to the Association of Community Cancer Centers, which recently recognized the Mount Sinai Health System program as a 2023 ACCC Innovator Award winner.

The new and improved “model for continuity of care” with the APRT role has “helped improve the patient experience and create a more streamlined, efficient process while also alleviating some of the burden on our physicians,” Ms. Skubish said in the ACCC press release. She explained that APRTs possess the skills, knowledge, and judgment to provide an elevated level of care, as evidenced by decades of international research.

A 2022 systematic review of APRT-based care models outside the United States explored how the models have worked. Overall, the research shows that such models improve quality, efficiency, wellness, and administrative outcomes, according to investigators.

At Mount Sinai, the first health system to develop the APRT role in the United States, research to demonstrate the benefits of APRT model continues. In 2021, an APRT working group was established to “garner a network of individuals across the country focused on the work to prove the advanced practice radiation therapy model in the U.S.,” according to Danielle McDonagh, MS, RT, Mount Sinai’s clinical coordinator of radiation sciences education and research.

A paper published in May by Ms. McDonagh and colleagues underscored the potential for “positive change and impact” of the APRT care model in radiation oncology.

“We’re all in this current and longstanding crisis of clinician shortages,” Kimberly Smith, MPA, explained in a video introducing the Mount Sinai program.

“If you look at your therapists’ skill set and allow them to work at the top of their license, you can provide a cost-saving solution that lends itself to value-based care,” said Ms. Smith, vice president of radiation oncology services at Mount Sinai.

Indeed, Sheryl Green, MBBCh, professor and medical director of radiation oncology at Mount Sinai, noted that “the APRT has allowed us to really improve the quality of care that we deliver, primarily in the aspects of optimizing and personalizing the patient experience.”

Ms. Skubish and Ms. Smith will share details of the new care model at the ACCC’s upcoming National Oncology Conference.

An innovative care model involving in the radiation oncology department of Mount Sinai Health System in New York.

At a time when clinician burnout is rampant, a novel approach that brings value to both patients and health systems – and helps advance the careers of highly educated and skilled practitioners – represents a welcome step forward, according to Samantha Skubish, MS, RT, chief technical director of radiation oncology and Mount Sinai.

In the new care model, APRTs work alongside radiation oncologists and support “the care of resource-intensive patient populations,” according to the Association of Community Cancer Centers, which recently recognized the Mount Sinai Health System program as a 2023 ACCC Innovator Award winner.

The new and improved “model for continuity of care” with the APRT role has “helped improve the patient experience and create a more streamlined, efficient process while also alleviating some of the burden on our physicians,” Ms. Skubish said in the ACCC press release. She explained that APRTs possess the skills, knowledge, and judgment to provide an elevated level of care, as evidenced by decades of international research.

A 2022 systematic review of APRT-based care models outside the United States explored how the models have worked. Overall, the research shows that such models improve quality, efficiency, wellness, and administrative outcomes, according to investigators.

At Mount Sinai, the first health system to develop the APRT role in the United States, research to demonstrate the benefits of APRT model continues. In 2021, an APRT working group was established to “garner a network of individuals across the country focused on the work to prove the advanced practice radiation therapy model in the U.S.,” according to Danielle McDonagh, MS, RT, Mount Sinai’s clinical coordinator of radiation sciences education and research.

A paper published in May by Ms. McDonagh and colleagues underscored the potential for “positive change and impact” of the APRT care model in radiation oncology.

“We’re all in this current and longstanding crisis of clinician shortages,” Kimberly Smith, MPA, explained in a video introducing the Mount Sinai program.

“If you look at your therapists’ skill set and allow them to work at the top of their license, you can provide a cost-saving solution that lends itself to value-based care,” said Ms. Smith, vice president of radiation oncology services at Mount Sinai.

Indeed, Sheryl Green, MBBCh, professor and medical director of radiation oncology at Mount Sinai, noted that “the APRT has allowed us to really improve the quality of care that we deliver, primarily in the aspects of optimizing and personalizing the patient experience.”

Ms. Skubish and Ms. Smith will share details of the new care model at the ACCC’s upcoming National Oncology Conference.

An innovative care model involving in the radiation oncology department of Mount Sinai Health System in New York.

At a time when clinician burnout is rampant, a novel approach that brings value to both patients and health systems – and helps advance the careers of highly educated and skilled practitioners – represents a welcome step forward, according to Samantha Skubish, MS, RT, chief technical director of radiation oncology and Mount Sinai.

In the new care model, APRTs work alongside radiation oncologists and support “the care of resource-intensive patient populations,” according to the Association of Community Cancer Centers, which recently recognized the Mount Sinai Health System program as a 2023 ACCC Innovator Award winner.

The new and improved “model for continuity of care” with the APRT role has “helped improve the patient experience and create a more streamlined, efficient process while also alleviating some of the burden on our physicians,” Ms. Skubish said in the ACCC press release. She explained that APRTs possess the skills, knowledge, and judgment to provide an elevated level of care, as evidenced by decades of international research.

A 2022 systematic review of APRT-based care models outside the United States explored how the models have worked. Overall, the research shows that such models improve quality, efficiency, wellness, and administrative outcomes, according to investigators.

At Mount Sinai, the first health system to develop the APRT role in the United States, research to demonstrate the benefits of APRT model continues. In 2021, an APRT working group was established to “garner a network of individuals across the country focused on the work to prove the advanced practice radiation therapy model in the U.S.,” according to Danielle McDonagh, MS, RT, Mount Sinai’s clinical coordinator of radiation sciences education and research.

A paper published in May by Ms. McDonagh and colleagues underscored the potential for “positive change and impact” of the APRT care model in radiation oncology.

“We’re all in this current and longstanding crisis of clinician shortages,” Kimberly Smith, MPA, explained in a video introducing the Mount Sinai program.

“If you look at your therapists’ skill set and allow them to work at the top of their license, you can provide a cost-saving solution that lends itself to value-based care,” said Ms. Smith, vice president of radiation oncology services at Mount Sinai.

Indeed, Sheryl Green, MBBCh, professor and medical director of radiation oncology at Mount Sinai, noted that “the APRT has allowed us to really improve the quality of care that we deliver, primarily in the aspects of optimizing and personalizing the patient experience.”

Ms. Skubish and Ms. Smith will share details of the new care model at the ACCC’s upcoming National Oncology Conference.

What’s right and wrong for doctors on social media

She went by the name “Dr. Roxy” on social media and became something of a sensation on TikTok, where she livestreamed her patients’ operations. Ultimately, however, plastic surgeon Katharine Roxanne Grawe, MD, lost her medical license based partly on her “life-altering, reckless treatment,” heightened by her social media fame. In July, the Ohio state medical board permanently revoked Dr. Grawe’s license after twice reprimanding her for her failure to meet the standard of care. The board also determined that, by livestreaming procedures, she placed her patients in danger of immediate and serious harm.

Although most doctors don’t use social media to the degree that Dr. Grawe did, using the various platforms – from X (formerly Twitter) to Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok – can be a slippery slope. Medscape’s Physician Behavior Report 2023 revealed that doctors have seen their share of unprofessional or offensive social media use from their peers. Nearly 7 in 10 said it is unethical for a doctor to act rudely, offensively, or unprofessionally on social media, even if their medical practice isn’t mentioned. As one physician put it: “Professional is not a 9-to-5 descriptor.”

“There’s still a stigma attached,” said Liudmila Schafer, MD, an oncologist with The Doctor Connect, a career consulting firm. “Physicians face a tougher challenge due to societal expectations of perfection, with greater consequences for mistakes. We’re under constant ‘observation’ from peers, employers, and patients.”

Beverly Hills plastic surgeon Jay Calvert, MD, says he holds firm boundaries with how he uses social media. “I do comedy on the side, but it’s not acceptable for me as a doctor to share that on social media,” he said. “People want doctors who are professional, and I’m always concerned about how I present myself.”

Dr. Calvert said it is fairly easy to spot doctors who cross the line with social media. “You have to hold yourself back when posting. Doing things like dancing in the OR are out of whack with the profession.”

According to Dr. Schafer, a definite line to avoid crossing is offering medical advice or guidance on social media. “You also can’t discuss confidential practice details, respond to unfamiliar contacts, or discuss institutional policies without permission,” she said. “It’s important to add disclaimers if a personal scientific opinion is shared without reference [or] research or with unchecked sources.”

Navigating the many social media sites

Each social media platform has its pros and cons. Doctors need to determine why to use them and what the payback of each might be. Dr. Schafer uses multiple sites, including LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X, Threads, YouTube, and, to a lesser degree, Clubhouse. How and what she posts on each varies. “I use them almost 95% professionally,” she said. “It’s challenging to meet and engage in person, so that is where social media helps.”

Stephen Pribut, MD, a Washington-based podiatrist, likes to use X as an information source. He follows pretty simple rules when it comes to what he tweets and shares on various sites: “I stay away from politics and religion,” he said. “I also avoid controversial topics online, such as vaccines.”

Joseph Daibes, DO, who specializes in cardiovascular medicine at New Jersey Heart and Vein, Clifton, said he has changed how he uses social media. “Initially, I was a passive consumer, but as I recognized the importance of accurate medical information online, I became more active in weighing in responsibly, occasionally sharing studies, debunking myths, and engaging in meaningful conversations,” he said. “Social media can get dangerous, so we have a duty to use it responsibly, and I cannot stress that enough.”

For plastic surgeons like Dr. Calvert, the visual platforms such as Instagram can prove invaluable for marketing purposes. “I’ve been using Instagram since 2012, and it’s been my most positive experience,” he said. “I don’t generate business from it, but I use it to back up my qualifications as a surgeon.”

Potential patients like to scroll through posts by plastic surgeons to learn what their finished product looks like, Dr. Calvert said. In many cases, plastic surgeons hire social media experts to cultivate their content. “I’ve hired and fired social media managers over the years, ultimately deciding I should develop my own content,” he said. “I want people to see the same doctor on social media that they will see in the office. I like an authentic presentation, not glitzy.”

Social media gone wrong

Dr. Calvert said that in the world of plastic surgery, some doctors use social media to present “before and after” compilations that in his opinion aren’t necessarily fully authentic, and this rubs him wrong. “There’s a bit of ‘cheating’ in some of these posts, using filters, making the ‘befores’ particularly bad, and other tricks,” he said.

Dr. Daibes has also seen his share of social media misuse: ”Red flags include oversharing personal indulgences, engaging in online spats, or making unfounded medical claims,” he said. “It’s essential to remember our role as educators and advocates, and to present ourselves in a way that upholds the dignity of our profession.”

At the end of the day, social media can have positive uses for physicians, and it is clearly here to stay. The onus for responsible use ultimately falls to the physicians using it.

Dr. Daibes emphasizes the fact that a doctor’s words carry weight – perhaps more so than those of other professionals. “The added scrutiny is good because it keeps us accountable; it’s crucial that our information is accurate,” he said. “The downside is that the scrutiny can be stifling at times and lead to self-censorship, even on nonmedical matters.”

Physicians have suggested eight guidelines for doctors to follow when using social media:

- Remember that you represent your profession, even if posting on personal accounts.

- Never post from the operating room, the emergency department, or any sort of medical space.

- If you’re employed, before you post, check with your employer to see whether they have any rules or guidance surrounding social media.

- Never use social media to badmouth colleagues, hospitals, or other healthcare organizations.

- Never use social media to dispense medical advice.

- Steer clear of the obvious hot-button issues, like religion and politics.

- Always protect patient privacy when posting.

- Be careful with how and whom you engage on social media.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

She went by the name “Dr. Roxy” on social media and became something of a sensation on TikTok, where she livestreamed her patients’ operations. Ultimately, however, plastic surgeon Katharine Roxanne Grawe, MD, lost her medical license based partly on her “life-altering, reckless treatment,” heightened by her social media fame. In July, the Ohio state medical board permanently revoked Dr. Grawe’s license after twice reprimanding her for her failure to meet the standard of care. The board also determined that, by livestreaming procedures, she placed her patients in danger of immediate and serious harm.

Although most doctors don’t use social media to the degree that Dr. Grawe did, using the various platforms – from X (formerly Twitter) to Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok – can be a slippery slope. Medscape’s Physician Behavior Report 2023 revealed that doctors have seen their share of unprofessional or offensive social media use from their peers. Nearly 7 in 10 said it is unethical for a doctor to act rudely, offensively, or unprofessionally on social media, even if their medical practice isn’t mentioned. As one physician put it: “Professional is not a 9-to-5 descriptor.”

“There’s still a stigma attached,” said Liudmila Schafer, MD, an oncologist with The Doctor Connect, a career consulting firm. “Physicians face a tougher challenge due to societal expectations of perfection, with greater consequences for mistakes. We’re under constant ‘observation’ from peers, employers, and patients.”

Beverly Hills plastic surgeon Jay Calvert, MD, says he holds firm boundaries with how he uses social media. “I do comedy on the side, but it’s not acceptable for me as a doctor to share that on social media,” he said. “People want doctors who are professional, and I’m always concerned about how I present myself.”

Dr. Calvert said it is fairly easy to spot doctors who cross the line with social media. “You have to hold yourself back when posting. Doing things like dancing in the OR are out of whack with the profession.”

According to Dr. Schafer, a definite line to avoid crossing is offering medical advice or guidance on social media. “You also can’t discuss confidential practice details, respond to unfamiliar contacts, or discuss institutional policies without permission,” she said. “It’s important to add disclaimers if a personal scientific opinion is shared without reference [or] research or with unchecked sources.”

Navigating the many social media sites

Each social media platform has its pros and cons. Doctors need to determine why to use them and what the payback of each might be. Dr. Schafer uses multiple sites, including LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X, Threads, YouTube, and, to a lesser degree, Clubhouse. How and what she posts on each varies. “I use them almost 95% professionally,” she said. “It’s challenging to meet and engage in person, so that is where social media helps.”

Stephen Pribut, MD, a Washington-based podiatrist, likes to use X as an information source. He follows pretty simple rules when it comes to what he tweets and shares on various sites: “I stay away from politics and religion,” he said. “I also avoid controversial topics online, such as vaccines.”

Joseph Daibes, DO, who specializes in cardiovascular medicine at New Jersey Heart and Vein, Clifton, said he has changed how he uses social media. “Initially, I was a passive consumer, but as I recognized the importance of accurate medical information online, I became more active in weighing in responsibly, occasionally sharing studies, debunking myths, and engaging in meaningful conversations,” he said. “Social media can get dangerous, so we have a duty to use it responsibly, and I cannot stress that enough.”

For plastic surgeons like Dr. Calvert, the visual platforms such as Instagram can prove invaluable for marketing purposes. “I’ve been using Instagram since 2012, and it’s been my most positive experience,” he said. “I don’t generate business from it, but I use it to back up my qualifications as a surgeon.”

Potential patients like to scroll through posts by plastic surgeons to learn what their finished product looks like, Dr. Calvert said. In many cases, plastic surgeons hire social media experts to cultivate their content. “I’ve hired and fired social media managers over the years, ultimately deciding I should develop my own content,” he said. “I want people to see the same doctor on social media that they will see in the office. I like an authentic presentation, not glitzy.”

Social media gone wrong

Dr. Calvert said that in the world of plastic surgery, some doctors use social media to present “before and after” compilations that in his opinion aren’t necessarily fully authentic, and this rubs him wrong. “There’s a bit of ‘cheating’ in some of these posts, using filters, making the ‘befores’ particularly bad, and other tricks,” he said.

Dr. Daibes has also seen his share of social media misuse: ”Red flags include oversharing personal indulgences, engaging in online spats, or making unfounded medical claims,” he said. “It’s essential to remember our role as educators and advocates, and to present ourselves in a way that upholds the dignity of our profession.”

At the end of the day, social media can have positive uses for physicians, and it is clearly here to stay. The onus for responsible use ultimately falls to the physicians using it.

Dr. Daibes emphasizes the fact that a doctor’s words carry weight – perhaps more so than those of other professionals. “The added scrutiny is good because it keeps us accountable; it’s crucial that our information is accurate,” he said. “The downside is that the scrutiny can be stifling at times and lead to self-censorship, even on nonmedical matters.”

Physicians have suggested eight guidelines for doctors to follow when using social media:

- Remember that you represent your profession, even if posting on personal accounts.

- Never post from the operating room, the emergency department, or any sort of medical space.

- If you’re employed, before you post, check with your employer to see whether they have any rules or guidance surrounding social media.

- Never use social media to badmouth colleagues, hospitals, or other healthcare organizations.

- Never use social media to dispense medical advice.

- Steer clear of the obvious hot-button issues, like religion and politics.

- Always protect patient privacy when posting.

- Be careful with how and whom you engage on social media.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

She went by the name “Dr. Roxy” on social media and became something of a sensation on TikTok, where she livestreamed her patients’ operations. Ultimately, however, plastic surgeon Katharine Roxanne Grawe, MD, lost her medical license based partly on her “life-altering, reckless treatment,” heightened by her social media fame. In July, the Ohio state medical board permanently revoked Dr. Grawe’s license after twice reprimanding her for her failure to meet the standard of care. The board also determined that, by livestreaming procedures, she placed her patients in danger of immediate and serious harm.

Although most doctors don’t use social media to the degree that Dr. Grawe did, using the various platforms – from X (formerly Twitter) to Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok – can be a slippery slope. Medscape’s Physician Behavior Report 2023 revealed that doctors have seen their share of unprofessional or offensive social media use from their peers. Nearly 7 in 10 said it is unethical for a doctor to act rudely, offensively, or unprofessionally on social media, even if their medical practice isn’t mentioned. As one physician put it: “Professional is not a 9-to-5 descriptor.”

“There’s still a stigma attached,” said Liudmila Schafer, MD, an oncologist with The Doctor Connect, a career consulting firm. “Physicians face a tougher challenge due to societal expectations of perfection, with greater consequences for mistakes. We’re under constant ‘observation’ from peers, employers, and patients.”

Beverly Hills plastic surgeon Jay Calvert, MD, says he holds firm boundaries with how he uses social media. “I do comedy on the side, but it’s not acceptable for me as a doctor to share that on social media,” he said. “People want doctors who are professional, and I’m always concerned about how I present myself.”

Dr. Calvert said it is fairly easy to spot doctors who cross the line with social media. “You have to hold yourself back when posting. Doing things like dancing in the OR are out of whack with the profession.”

According to Dr. Schafer, a definite line to avoid crossing is offering medical advice or guidance on social media. “You also can’t discuss confidential practice details, respond to unfamiliar contacts, or discuss institutional policies without permission,” she said. “It’s important to add disclaimers if a personal scientific opinion is shared without reference [or] research or with unchecked sources.”

Navigating the many social media sites

Each social media platform has its pros and cons. Doctors need to determine why to use them and what the payback of each might be. Dr. Schafer uses multiple sites, including LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X, Threads, YouTube, and, to a lesser degree, Clubhouse. How and what she posts on each varies. “I use them almost 95% professionally,” she said. “It’s challenging to meet and engage in person, so that is where social media helps.”

Stephen Pribut, MD, a Washington-based podiatrist, likes to use X as an information source. He follows pretty simple rules when it comes to what he tweets and shares on various sites: “I stay away from politics and religion,” he said. “I also avoid controversial topics online, such as vaccines.”

Joseph Daibes, DO, who specializes in cardiovascular medicine at New Jersey Heart and Vein, Clifton, said he has changed how he uses social media. “Initially, I was a passive consumer, but as I recognized the importance of accurate medical information online, I became more active in weighing in responsibly, occasionally sharing studies, debunking myths, and engaging in meaningful conversations,” he said. “Social media can get dangerous, so we have a duty to use it responsibly, and I cannot stress that enough.”

For plastic surgeons like Dr. Calvert, the visual platforms such as Instagram can prove invaluable for marketing purposes. “I’ve been using Instagram since 2012, and it’s been my most positive experience,” he said. “I don’t generate business from it, but I use it to back up my qualifications as a surgeon.”

Potential patients like to scroll through posts by plastic surgeons to learn what their finished product looks like, Dr. Calvert said. In many cases, plastic surgeons hire social media experts to cultivate their content. “I’ve hired and fired social media managers over the years, ultimately deciding I should develop my own content,” he said. “I want people to see the same doctor on social media that they will see in the office. I like an authentic presentation, not glitzy.”

Social media gone wrong

Dr. Calvert said that in the world of plastic surgery, some doctors use social media to present “before and after” compilations that in his opinion aren’t necessarily fully authentic, and this rubs him wrong. “There’s a bit of ‘cheating’ in some of these posts, using filters, making the ‘befores’ particularly bad, and other tricks,” he said.

Dr. Daibes has also seen his share of social media misuse: ”Red flags include oversharing personal indulgences, engaging in online spats, or making unfounded medical claims,” he said. “It’s essential to remember our role as educators and advocates, and to present ourselves in a way that upholds the dignity of our profession.”

At the end of the day, social media can have positive uses for physicians, and it is clearly here to stay. The onus for responsible use ultimately falls to the physicians using it.

Dr. Daibes emphasizes the fact that a doctor’s words carry weight – perhaps more so than those of other professionals. “The added scrutiny is good because it keeps us accountable; it’s crucial that our information is accurate,” he said. “The downside is that the scrutiny can be stifling at times and lead to self-censorship, even on nonmedical matters.”

Physicians have suggested eight guidelines for doctors to follow when using social media:

- Remember that you represent your profession, even if posting on personal accounts.

- Never post from the operating room, the emergency department, or any sort of medical space.

- If you’re employed, before you post, check with your employer to see whether they have any rules or guidance surrounding social media.

- Never use social media to badmouth colleagues, hospitals, or other healthcare organizations.

- Never use social media to dispense medical advice.

- Steer clear of the obvious hot-button issues, like religion and politics.

- Always protect patient privacy when posting.

- Be careful with how and whom you engage on social media.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Update on Dermatology Reimbursement in 2024

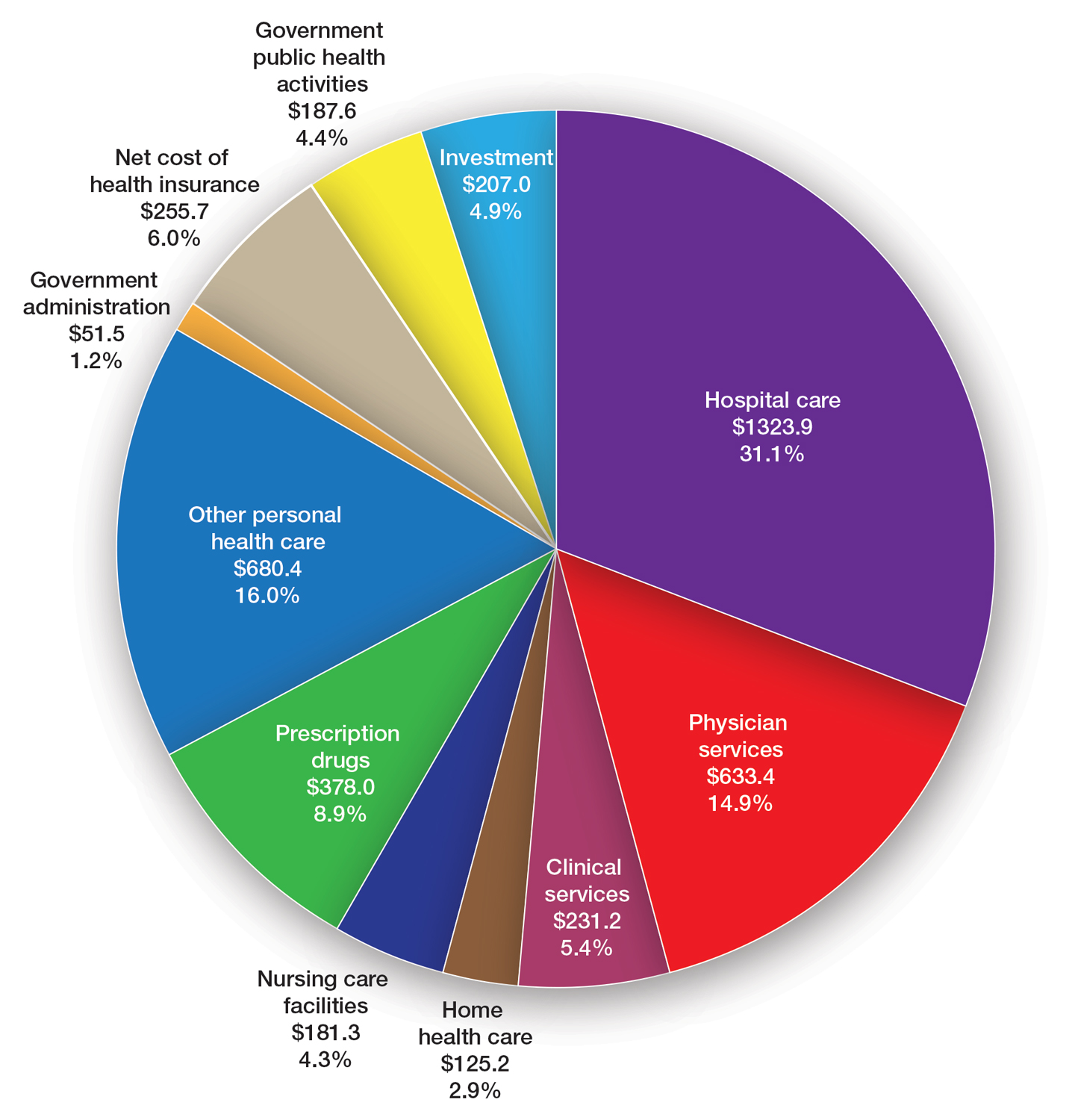

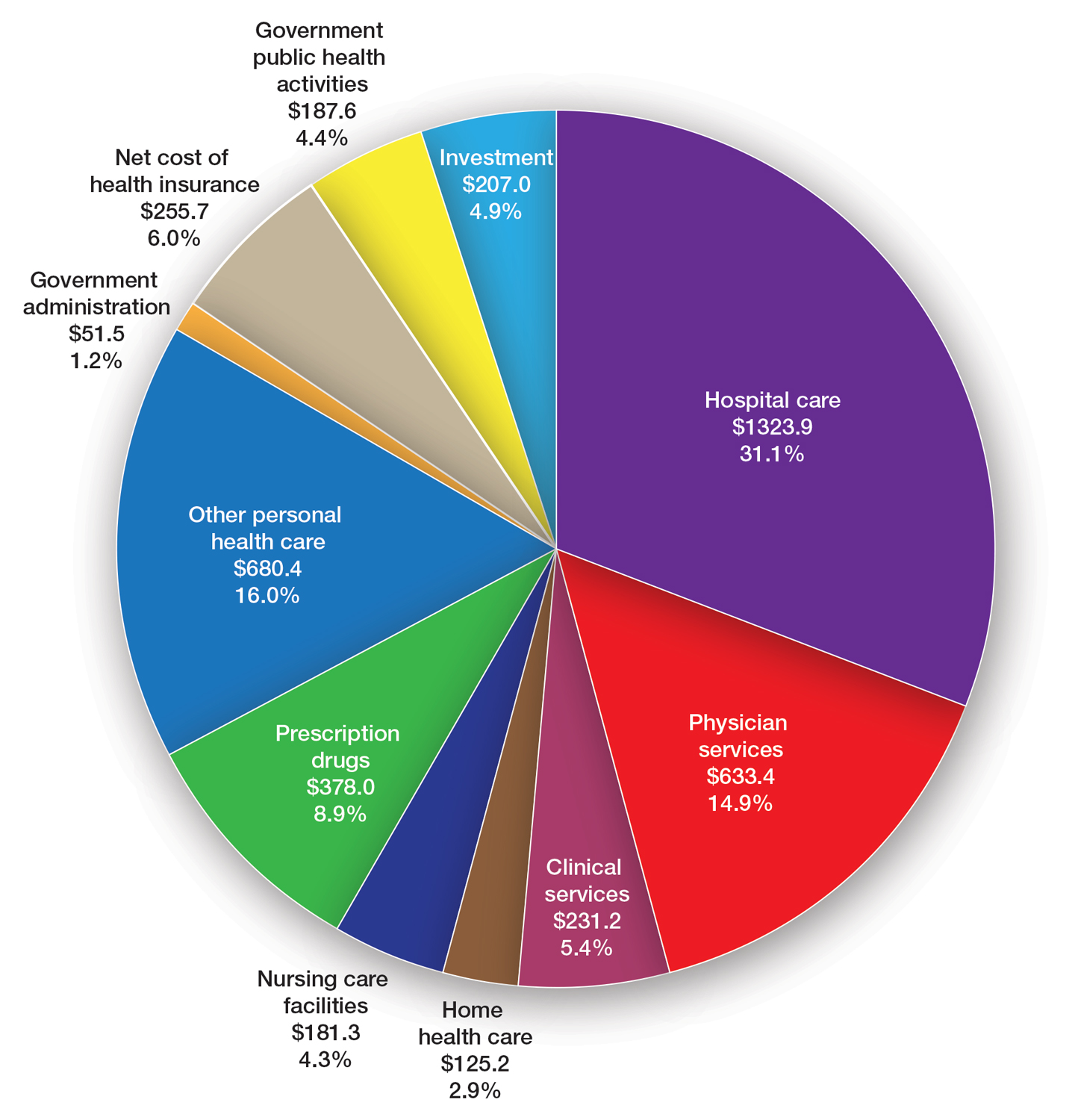

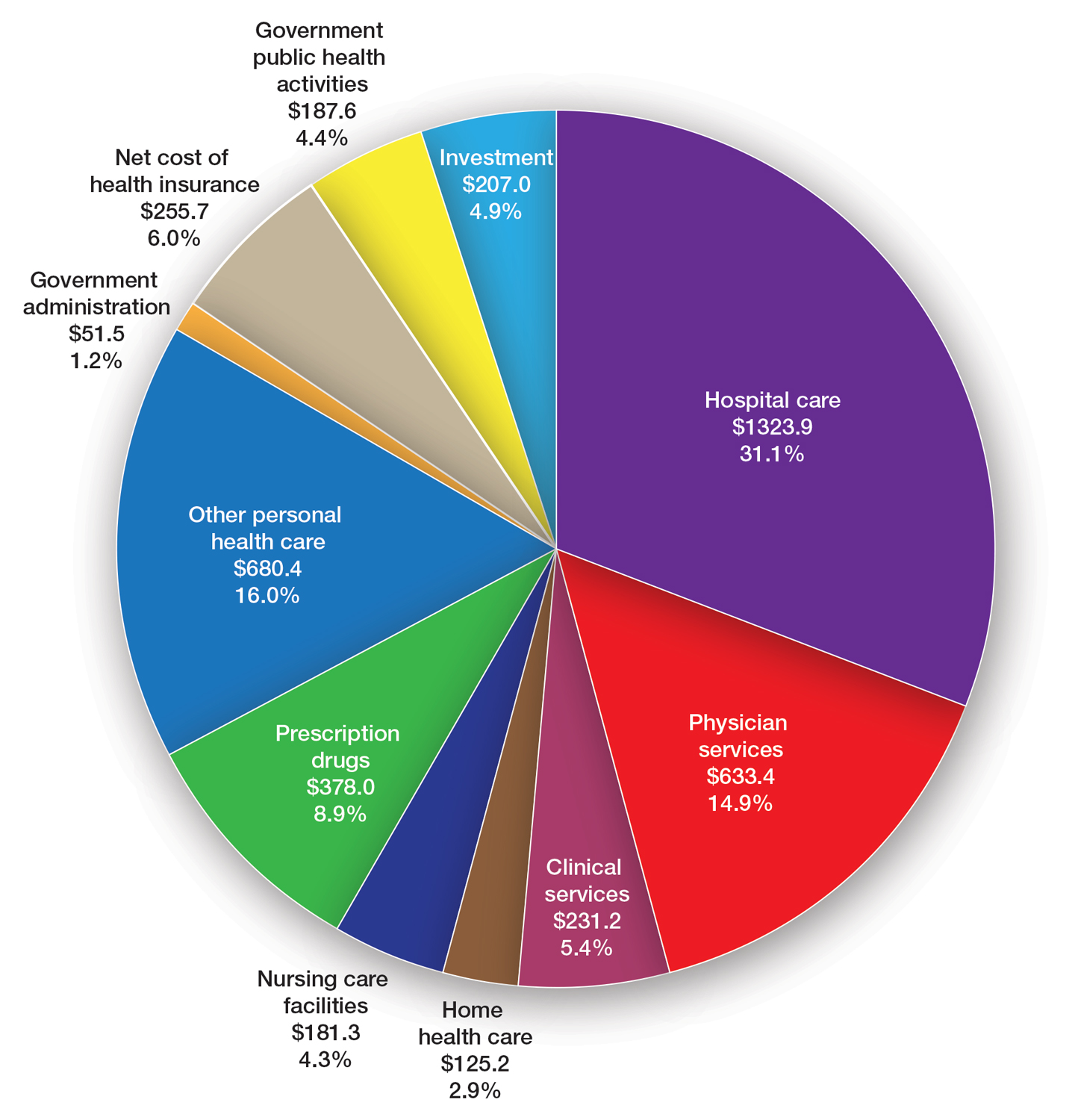

Health care spending in the United States remained relatively flat from 2019 to 2021 and only increased 2.7% in 2021, reaching $4.3 billion or $12,914 per person. Physician services account for 15% of health care spending (Figure). Relative value units (RVUs) signify the time it took a physician to complete a task multiplied by a conversion factor (CF). When RVUs initially were created in 1992 by what is now the Centers for Medicare &Medicaid Services (CMS), the CF was $32.00. Thirty-one years later, the CF is $33.89 in 2023; however, it would be $66.00 if the CF had increased with inflation.1 If the proposed 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule (MPFS) is adopted, the payment formula would decrease by 3.4% ($32.75) relative to the 2023 fee schedule ($33.89), which would be a 9% decrease relative to 2019 ($36.04).2,3 This reduction is due to the budget neutrality adjustment required by changes in RVUs, implementation of the evaluation and management (E/M) add-on code G2211, and proposed increases in primary are services.2,3 Since 2001, Medicare physician payment has declined by 26%.4 Adjustments to the CF typically are made based on 3 factors: (1) the Medicare Economic Index (MEI); (2) an expenditure target performance adjustment; and (3) miscellaneous adjustments, including those for budget neutrality required by law. Despite continued substantial increases in practice expenses, physicians’ reimbursement has remained flat while other service providers, such as those in skilled nursing facilities and hospitals, have received favorable payment increases compared to practice cost inflation and the Consumer Price Index.4

The CMS will not incorporate 2017 MEI cost weights for the RVUs in the MPFS rate setting for 2024 because all key measures of practice expenses in the MEI accelerated in 2022. Instead, the CMS is updating data on practice expense per hour to calculate payment for physician services with a survey for physician practices that launched on July 31, 2023.5 The American Medical Association contracted with Mathematica, an independent research company, to conduct a physician practice information survey that will be used to determine indirect practice expenses. Physicians should be on the lookout for emails regarding completion of these surveys and the appropriate financial expert in their practice should be contacted so the responses are accurate, as these data are key to future updates in the Medicare pay formula used to reimburse physicians.

Impact of Medicare Cuts

The recent congressional debt limit deal set spending caps for the next 2 fiscal years. Dermatology is facing an overall payment reduction of 1.87% (range, 1%–4%).2,3 The impact will depend on the services offered in an individual practice; for example, payment for a punch biopsy (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] code 11104) would decrease by 3.9%. Payment for benign destruction (CPT code 17110) would decrease by 2.8%, and payment for even simple E/M of an established patient (CPT code 99213) would decrease by 1.6%. Overall, there would be a reduction of 2.75% for dermatopathology services, with a decrease of 2% for CPT code 88305 global and decreases for the technical component of 1% and professional component of 3%.2,3

Medicare cuts have reached a critical level, and physicians cannot continue to absorb the costs to own and operate their practices.4 This has led to health market consolidation, which in turn limits competition and patient access while driving up health care costs and driving down the quality of care. Small independent rural practices as well as those caring for historically marginalized patients will be disproportionately affected.

Proposed Addition of E/M Code G2211

In the calendar year (CY) 2021 final rule, the CMS tried to adopt a new add-on code—G2211—patients with a serious or complex condition that typically require referral and coordination of multispecialty care. Per the CMS, the primary policy goal of G2211 is to increase payments to primary care physicians and to reimburse them more appropriately for the care provided to patients with a serious or complex condition.2,3 It can be reported in conjunction with all office and outpatient E/M visits to better account for additional resources associated with primary care, or similarly ongoing medical care related to a patient’s single, serious condition, or complex condition.3 Typically, G2211 would not be used by dermatologists, as this add-on code requires visit complexity inherent to E/M associated with medical care services that serve as the continuing focal point for all needed health care services and/or with medical care services that are part of ongoing care related to a patient’s single serious condition or a complex condition.2,3

Initially, the CMS assumed that G2211 would be reported with 90% of all office and outpatient E/M visit claims, which would account for a considerable portion of total MPFS schedule spending; however, the House of Medicine disagreed and believed it would be 75%.2,3 Given the extremely high utilization estimate, G2211 would have had a substantial effect on budget neutrality, accounting for an estimated increase of $3.3 billion and a corresponding 3.0% cut to the CY 2021 MPFS. Because of the potential payment reductions to physicians and a successful advocacy effort by organized medicine, including the American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA), Congress delayed implementation of G2211 until CY 2024. Modifier -25 cannot be reported with G2211. The CMS revised its utilization assumptions from 90% of all E/M services to an initial utilization of 38% and then 54% when fully adopted. The proposed 2024 payment for G2211 is an additional $16.05.2,3

Advancing Health Equity With Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System G Codes

The CMS is proposing coding and payment for several new services to help underserved populations, including addressing unmet health-related social needs that can potentially interfere with the diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions, which includes paying for certain caregiver training services as well as payment for community health integration services.2,3 These are the first MPFS services designed to include care involving community health workers, who link underserved communities with critical health care and social services in the community. Additionally, the rule also proposes coding and payment for evaluating the risks related to social factors that affect a patient’s health, such as access to affordable quality health care, that can take place during an annual wellness visit or in combination with an E/M visit.2,3 As dermatologists, we should be familiar with this set of G codes, as we will likely use them in practice for patients with transportation needs.

Advocacy Efforts on Medicare Payment Reform

Medicare physician payment reform needs to happen at a national level. Advocacy efforts by the AADA and other groups have been underway to mitigate the proposed 2024 cuts. The Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act (HR 2474) is a bill that was introduced by a bipartisan coalition of physicians to provide an inflation-based increase in Medicare payments in 2024 and beyond.6

Other Legislative Updates Affecting Dermatology

Modifier -25—Cigna’s policy requiring dermatologists to submit documentation to use modifier -25 when billing with E/M CPT codes 99212 through 99215 has been delayed indefinitely.7 If a payer denies a dermatologist payment, contact the AADA Patient Access and Payer Relations committee ([email protected]) for assistance.

Telehealth and Digital Pathology—Recent legislation authorized extension of many of the Medicare telehealth and digital pathology flexibilities that were put in place during the COVID-19 public health emergency through December 31, 2024.8,9 Seventeen newly approved CPT telemedicine codes for new and established patient audio-visual and audio-only visits recently were surveyed.2,3 The data from the survey will be used as a key element in assigning a specific RVU to the CMS and will be included in the MPFS.

Thirty additional new digital pathology add-on CPT category III codes for 2024 were added to the ones from 2023.2,3 These codes can be used to report additional clinical staff work and service requirements associated with digitizing glass microscope slides for primary diagnosis. They cannot be used for archival or educational purposes, clinical conferences, training, or validating artificial intelligence algorithms. Category III codes used for emerging technologies have no assigned RVUs or reimbursement.2,3

The Cures Act—The Cures Act aims to ensure that patients have timely access to their health information.10 It requires all physicians to make their office notes, laboratory results, and other diagnostic reports available to patients as soon as the office receives them. The rules went into effect on April 5, 2021, with a limited definition of electronic health information; on October 6, 2022, the Cures Act rule expanded to include all electronic health information. The AADA has urged the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to collaborate with stakeholder organizations to re-evaluate federal policies concerning the immediate release of electronic health information and information blocking, particularly in cases with life-altering diagnoses.10 They stressed the importance of prioritizing the well-being and emotional stability of patients and enhancing care by providing patients adequate time and support to process, comprehend, and discuss findings with their physician.

Proposed 2024 Medicare Quality Payment Program Requirements

The CMS proposed to increase the performance threshold in the quality payment program from 75 to 82 points for the 2024 Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) performance period, impacting the 2026 payment year.2,3,11 As a result of this increase, there could be more MIPS-eligible clinicians receiving penalties, which could be a reduction of up to 9%. The AADA will firmly oppose any increase in the threshold and strongly urge CMS to maintain the 75-point threshold. The performance category weights for the 2024 performance year will remain unchanged from the 2023 performance year.2,3,11

2024 Proposed Quality MIPS Measures Set—The CMS proposed to remove the topped-out MIPS measure 138 (coordination of care for melanoma).2,3,11 Additionally, it proposed to remove MIPS measure 402 (tobacco use and help with quitting among adolescents) as a quality measure from MIPS because the agency believes it is duplicative of measure 226 (preventive care and screening: tobacco use: screening and cessation intervention).2,3,11

MIPS Value Pathways—The CMS consolidated 2 previously established MIPS value pathways (MVPs): the Promoting Wellness MVP and the Optimizing Chronic Disease Management MVP.2,3,11 Proposed new MVPs for 2024 include Focusing on Women’s Health; Quality Care for the Treatment of Ear, Nose, and Throat Disorders; Prevention and Treatment of Infectious Disorders Including Hepatitis C and HIV; Quality Care in Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders; and Rehabilitative Support for Musculoskeletal Care. Dermatology is not impacted; however, the CMS plans to sunset traditional MIPS and replace it with MVPs—the future of MIPS.2,3,11 The AADA maintains that traditional MIPS should continue to be an option because MVPs have a limited number of measures for dermatologists.

Update on Reporting Suture Removal

There are 2 new CPT add-on codes—15853 and 15854—for the removal of sutures or staples not requiring anesthesia to be listed separately in addition to an appropriate E/M service. These add-on codes went into effect on January 1, 2023.12 These codes were created with the intent to capture and ensure remuneration for practice expenses that are not included in a stand-alone E/M encounter that occur after a 0-day procedure (eg, services reported with CPT codes 11102–11107 and 11300–11313) for wound check and suture removal where appropriate. These new add-on codes do not have physician work RVUs assigned to them because they are only for practice expenses (eg, clinical staff time, disposable supplies, use of equipment); CPT code 15853 is reported for the removal of sutures or staples, and CPT code 15854 is reported when both sutures and staples are removed. These codes can only be reported if an E/M service also is reported for the patient encounter.12

Final Thoughts

The AADA is working with the House of Medicine and the medical specialty community to develop specific proposals to reform the Medicare payment system.4 The proposed 2024 MPFS was released on July 13, 2023, and final regulations are expected in the late fall of 2023. The AADA will continue to engage with the CMS, but it is important for physicians to learn about and support advocacy priorities and efforts as well as join forces to protect their practices. As health care professionals, we have unique insights into the challenges and needs of our patients and the health care system. Advocacy can take various forms, such as supporting or opposing specific legislations, participating in grassroots campaigns, engaging with policymakers, and/or joining professional organizations that advocate for health care–related issues. Get involved, stay informed, and stay engaged through dermatology medical societies; together we can make a difference.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. NHE fact sheet. Updated September 6, 2023. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet

- Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2024 payment policies under the physician fee schedule and other changes to part B payment and coverage policies; Medicare shared savings program requirements; Medicare advantage; Medicare and Medicaid provider and supplier enrollment policies; and basic health program. Fed Regist. 2023;88:52262-53197. To be codified at 42 CFR §405, §410, §411, §414, §415, §418, §422, §423, §424, §425, §455, §489, §491, §495, §498, and §600. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/08/07/2023-14624/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-cy-2024-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-and-other

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule proposed rule. Published July 13, 2023. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2024-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-proposed-rule

- American Medical Association. Payment reform. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/health-care-advocacypayment-reform

- American Medical Association. Physician answers on this survey will shape future Medicare pay. Published July 31, 2023. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/medicare-medicaid/physician-answers-survey-will-shape-future -medicare-pay

- Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act, HR 2474, 118 Congress (2023-2024). https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2474

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Academy advocacy priorities. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/priorities

- College of American Pathologists. Remote sign-out of cases with digital pathology FAQs. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.cap.org/covid-19/remote-sign-out-faqs

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Telehealth. Updated September 6, 2023. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/coverage/telehealth

- The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. ONC’s Cures Act final rule. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/oncs-cures-act-final-rule

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar Year (CY) 2024 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) Notice of Proposed Rule Making Quality Payment Program Policy Overview: Proposals and Requests for Information. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://email.aadresources.org/e3t/Ctc/I6+113/cVKqx04/VVWzj43dDbctW8c23GW1ZLnJHW1xTZ7Q50Y DYN89Qzy5nCVhV3Zsc37CgFV9W5Ck4-D42qs9BW38PtXn4LSlNLW1QKpPL4xT8BMW6Mcwww3FdwCHN3vfGTMXbtF-W2-Zzfy5WHDg6W88tx1F1KgsgxW7zDzT46C2sFXW800vQJ3lLsS_W5D6f1d30-f3cN1njgZ_dX7xkW447ldH2-kgc5VCs7Xg1GY6dsN87pLVJqJG5XW8VWwD-7VxVkJN777f5fJL7jBW8RxkQM1lcSDjVV746T3C-stpN52V_S5xj7q6W3_vldf3p1Yk2Vbd4ZD3cPrHqW5Pwv9m567fkzW1vfDm51H-T7rW1jVrxl8gstXyW5RVTn8863CVFW8g6LgK2YdhpkW34HC4z3_pGYgW8V_qWH3g-tTlW4S3RD-1dKry7W4_rW8d1ssZ1fVwXQjQ9krVMW8Y0bTt8Nr5CNW6vbG0h3wyx59W8WCrNW50p5n6W1r-VBC2rKh93N4W2RyYr7vvm3kxG1

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Chapter III surgery: integumentary system CPT codes 10000-19999 for Medicare national correct coding initiative policy manual. Updated January 1, 2023. Accessed September 26, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-ncci-policy-manual-2023-chapter-3.pdf

Health care spending in the United States remained relatively flat from 2019 to 2021 and only increased 2.7% in 2021, reaching $4.3 billion or $12,914 per person. Physician services account for 15% of health care spending (Figure). Relative value units (RVUs) signify the time it took a physician to complete a task multiplied by a conversion factor (CF). When RVUs initially were created in 1992 by what is now the Centers for Medicare &Medicaid Services (CMS), the CF was $32.00. Thirty-one years later, the CF is $33.89 in 2023; however, it would be $66.00 if the CF had increased with inflation.1 If the proposed 2024 Medicare physician fee schedule (MPFS) is adopted, the payment formula would decrease by 3.4% ($32.75) relative to the 2023 fee schedule ($33.89), which would be a 9% decrease relative to 2019 ($36.04).2,3 This reduction is due to the budget neutrality adjustment required by changes in RVUs, implementation of the evaluation and management (E/M) add-on code G2211, and proposed increases in primary are services.2,3 Since 2001, Medicare physician payment has declined by 26%.4 Adjustments to the CF typically are made based on 3 factors: (1) the Medicare Economic Index (MEI); (2) an expenditure target performance adjustment; and (3) miscellaneous adjustments, including those for budget neutrality required by law. Despite continued substantial increases in practice expenses, physicians’ reimbursement has remained flat while other service providers, such as those in skilled nursing facilities and hospitals, have received favorable payment increases compared to practice cost inflation and the Consumer Price Index.4

The CMS will not incorporate 2017 MEI cost weights for the RVUs in the MPFS rate setting for 2024 because all key measures of practice expenses in the MEI accelerated in 2022. Instead, the CMS is updating data on practice expense per hour to calculate payment for physician services with a survey for physician practices that launched on July 31, 2023.5 The American Medical Association contracted with Mathematica, an independent research company, to conduct a physician practice information survey that will be used to determine indirect practice expenses. Physicians should be on the lookout for emails regarding completion of these surveys and the appropriate financial expert in their practice should be contacted so the responses are accurate, as these data are key to future updates in the Medicare pay formula used to reimburse physicians.

Impact of Medicare Cuts

The recent congressional debt limit deal set spending caps for the next 2 fiscal years. Dermatology is facing an overall payment reduction of 1.87% (range, 1%–4%).2,3 The impact will depend on the services offered in an individual practice; for example, payment for a punch biopsy (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] code 11104) would decrease by 3.9%. Payment for benign destruction (CPT code 17110) would decrease by 2.8%, and payment for even simple E/M of an established patient (CPT code 99213) would decrease by 1.6%. Overall, there would be a reduction of 2.75% for dermatopathology services, with a decrease of 2% for CPT code 88305 global and decreases for the technical component of 1% and professional component of 3%.2,3

Medicare cuts have reached a critical level, and physicians cannot continue to absorb the costs to own and operate their practices.4 This has led to health market consolidation, which in turn limits competition and patient access while driving up health care costs and driving down the quality of care. Small independent rural practices as well as those caring for historically marginalized patients will be disproportionately affected.

Proposed Addition of E/M Code G2211

In the calendar year (CY) 2021 final rule, the CMS tried to adopt a new add-on code—G2211—patients with a serious or complex condition that typically require referral and coordination of multispecialty care. Per the CMS, the primary policy goal of G2211 is to increase payments to primary care physicians and to reimburse them more appropriately for the care provided to patients with a serious or complex condition.2,3 It can be reported in conjunction with all office and outpatient E/M visits to better account for additional resources associated with primary care, or similarly ongoing medical care related to a patient’s single, serious condition, or complex condition.3 Typically, G2211 would not be used by dermatologists, as this add-on code requires visit complexity inherent to E/M associated with medical care services that serve as the continuing focal point for all needed health care services and/or with medical care services that are part of ongoing care related to a patient’s single serious condition or a complex condition.2,3

Initially, the CMS assumed that G2211 would be reported with 90% of all office and outpatient E/M visit claims, which would account for a considerable portion of total MPFS schedule spending; however, the House of Medicine disagreed and believed it would be 75%.2,3 Given the extremely high utilization estimate, G2211 would have had a substantial effect on budget neutrality, accounting for an estimated increase of $3.3 billion and a corresponding 3.0% cut to the CY 2021 MPFS. Because of the potential payment reductions to physicians and a successful advocacy effort by organized medicine, including the American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA), Congress delayed implementation of G2211 until CY 2024. Modifier -25 cannot be reported with G2211. The CMS revised its utilization assumptions from 90% of all E/M services to an initial utilization of 38% and then 54% when fully adopted. The proposed 2024 payment for G2211 is an additional $16.05.2,3

Advancing Health Equity With Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System G Codes

The CMS is proposing coding and payment for several new services to help underserved populations, including addressing unmet health-related social needs that can potentially interfere with the diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions, which includes paying for certain caregiver training services as well as payment for community health integration services.2,3 These are the first MPFS services designed to include care involving community health workers, who link underserved communities with critical health care and social services in the community. Additionally, the rule also proposes coding and payment for evaluating the risks related to social factors that affect a patient’s health, such as access to affordable quality health care, that can take place during an annual wellness visit or in combination with an E/M visit.2,3 As dermatologists, we should be familiar with this set of G codes, as we will likely use them in practice for patients with transportation needs.

Advocacy Efforts on Medicare Payment Reform

Medicare physician payment reform needs to happen at a national level. Advocacy efforts by the AADA and other groups have been underway to mitigate the proposed 2024 cuts. The Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act (HR 2474) is a bill that was introduced by a bipartisan coalition of physicians to provide an inflation-based increase in Medicare payments in 2024 and beyond.6

Other Legislative Updates Affecting Dermatology

Modifier -25—Cigna’s policy requiring dermatologists to submit documentation to use modifier -25 when billing with E/M CPT codes 99212 through 99215 has been delayed indefinitely.7 If a payer denies a dermatologist payment, contact the AADA Patient Access and Payer Relations committee ([email protected]) for assistance.

Telehealth and Digital Pathology—Recent legislation authorized extension of many of the Medicare telehealth and digital pathology flexibilities that were put in place during the COVID-19 public health emergency through December 31, 2024.8,9 Seventeen newly approved CPT telemedicine codes for new and established patient audio-visual and audio-only visits recently were surveyed.2,3 The data from the survey will be used as a key element in assigning a specific RVU to the CMS and will be included in the MPFS.