User login

Elevated type 2 diabetes risk seen in PsA patients

Patients with incident psoriatic arthritis are at a significantly increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes when compared against patients with psoriasis alone and with the general population, according to recent research published in Rheumatology.

Rachel Charlton, PhD, of the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath (England), and her colleagues performed an analysis of 6,783 incident cases of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink who were diagnosed during 1998-2014. Patients were between 18 years and 89 years old with a median age of 49 years at PsA diagnosis.

In the study, the researchers randomly matched PsA cases at a 1:4 ratio to either a cohort of general population patients with no PsA, psoriasis, or inflammatory arthritis or a cohort of patients with psoriasis but no PsA or inflammatory arthritis. Patients were followed from match to the point where they either no longer met inclusion criteria for the cohort or received a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), ischemic heart disease (IHD), or peripheral vascular disease (PVD) with a mean follow-up duration of approximately 5.5 years across all patient groups.

Patients in the PsA group had a significantly higher incidence of type 2 diabetes, compared with the general population (adjusted relative risk, 1.40; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.70; P = .0007) and psoriasis groups (adjusted RR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.19-1.97; P = .0009). In the PsA group, risk of CVD (adjusted RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.99-1.56; P = .06), IHD (adjusted RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.54; P = .02), and PVD (adjusted RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.02-1.92; P = .04) were significantly higher than in the general population but not when compared with the psoriasis group. The overall risk of cardiovascular disease (including CVD, IHD, and PVD) for the PsA group was significantly higher (adjusted RR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.48; P = .0005), compared with the general population.

“These results support the proposal in existing clinical guidelines that, in order to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with PsA, it is important to treat inflammatory disease as well as to screen and treat traditional risk factors early in the disease course,” Ms. Charlton and her colleagues wrote in their study.

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Charlton RA et al. Rheumatology. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key286.

Patients with incident psoriatic arthritis are at a significantly increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes when compared against patients with psoriasis alone and with the general population, according to recent research published in Rheumatology.

Rachel Charlton, PhD, of the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath (England), and her colleagues performed an analysis of 6,783 incident cases of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink who were diagnosed during 1998-2014. Patients were between 18 years and 89 years old with a median age of 49 years at PsA diagnosis.

In the study, the researchers randomly matched PsA cases at a 1:4 ratio to either a cohort of general population patients with no PsA, psoriasis, or inflammatory arthritis or a cohort of patients with psoriasis but no PsA or inflammatory arthritis. Patients were followed from match to the point where they either no longer met inclusion criteria for the cohort or received a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), ischemic heart disease (IHD), or peripheral vascular disease (PVD) with a mean follow-up duration of approximately 5.5 years across all patient groups.

Patients in the PsA group had a significantly higher incidence of type 2 diabetes, compared with the general population (adjusted relative risk, 1.40; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.70; P = .0007) and psoriasis groups (adjusted RR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.19-1.97; P = .0009). In the PsA group, risk of CVD (adjusted RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.99-1.56; P = .06), IHD (adjusted RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.54; P = .02), and PVD (adjusted RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.02-1.92; P = .04) were significantly higher than in the general population but not when compared with the psoriasis group. The overall risk of cardiovascular disease (including CVD, IHD, and PVD) for the PsA group was significantly higher (adjusted RR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.48; P = .0005), compared with the general population.

“These results support the proposal in existing clinical guidelines that, in order to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with PsA, it is important to treat inflammatory disease as well as to screen and treat traditional risk factors early in the disease course,” Ms. Charlton and her colleagues wrote in their study.

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Charlton RA et al. Rheumatology. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key286.

Patients with incident psoriatic arthritis are at a significantly increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes when compared against patients with psoriasis alone and with the general population, according to recent research published in Rheumatology.

Rachel Charlton, PhD, of the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath (England), and her colleagues performed an analysis of 6,783 incident cases of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink who were diagnosed during 1998-2014. Patients were between 18 years and 89 years old with a median age of 49 years at PsA diagnosis.

In the study, the researchers randomly matched PsA cases at a 1:4 ratio to either a cohort of general population patients with no PsA, psoriasis, or inflammatory arthritis or a cohort of patients with psoriasis but no PsA or inflammatory arthritis. Patients were followed from match to the point where they either no longer met inclusion criteria for the cohort or received a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), ischemic heart disease (IHD), or peripheral vascular disease (PVD) with a mean follow-up duration of approximately 5.5 years across all patient groups.

Patients in the PsA group had a significantly higher incidence of type 2 diabetes, compared with the general population (adjusted relative risk, 1.40; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.70; P = .0007) and psoriasis groups (adjusted RR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.19-1.97; P = .0009). In the PsA group, risk of CVD (adjusted RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.99-1.56; P = .06), IHD (adjusted RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.54; P = .02), and PVD (adjusted RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.02-1.92; P = .04) were significantly higher than in the general population but not when compared with the psoriasis group. The overall risk of cardiovascular disease (including CVD, IHD, and PVD) for the PsA group was significantly higher (adjusted RR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.48; P = .0005), compared with the general population.

“These results support the proposal in existing clinical guidelines that, in order to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with PsA, it is important to treat inflammatory disease as well as to screen and treat traditional risk factors early in the disease course,” Ms. Charlton and her colleagues wrote in their study.

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Charlton RA et al. Rheumatology. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key286.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: It is important to treat inflammatory disease as well as to screen and treat traditional cardiovascular risk factors early in the course of PsA.

Major finding: (adjusted RR = 1.53) and a general population control group (adjusted RR = 1.40).

Study details: An analysis of 6,783 patients with psoriatic arthritis in the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink who were diagnosed between 1998 and 2014.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Charlton RA et al. Rheumatology. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key286.

Infliximab biosimilar only moderately less expensive in Medicare Part D

The infliximab-dyyb biosimilar was only moderately less expensive than the originator infliximab product Remicade in the United States in 2017 under Medicare Part D, an analysis shows.

Infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra) cost 18% less than infliximab, with an annual cost exceeding $14,000 in an analysis published online Sept. 4 in JAMA by Jinoos Yazdany, MD, of the division of rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors.

However, “without biosimilar gap discounts in 2017, beneficiaries would have paid more than $5,100 for infliximab-dyyb, or nearly $1,700 more in projected out-of-pocket costs than infliximab,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors wrote.

Biologics represent only 2% of U.S. prescriptions but made up 38% of drug spending in 2015 and accounted for 70% of growth in drug spending from 2010 to 2015, according to Dr. Yazdany and her colleagues.

Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) cost more than $14,000 per year, and in 2015, 3 were among the top 15 drugs in terms of Medicare expenditures, they added.

While biosimilars are supposed to increase competition and lower prices, it’s an open question whether they actually reduce out-of-pocket expenditures for the 43 million individuals with drug benefits under Medicare Part D.

That uncertainty is due in part to the complex cost-sharing design of Part D, which includes an initial deductible, a coverage phase, a coverage gap, and catastrophic coverage.

In 2017, the plan included an initial $400 deductible, followed by the coverage phase, in which the patient paid 25% of drug costs. In the coverage gap, which started at $3,700 in total drug costs, the patient’s share of drug costs increased to 40% for biologics, and 51% for biosimilars. In the catastrophic coverage phase, triggered when out-of-pocket costs exceeded $4,950, the patient was responsible for 5% of drug costs.

“Currently, beneficiaries receive a 50% manufacturer discount during the gap for brand-name drugs and biologics, but not for biosimilars,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors said in the report.

To evaluate cost-sharing for infliximab-dyyb, which in 2016 became the first available RA biosimilar, the authors analyzed data for all Part D plans in the June 2017 Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information Files.

Out of 2,547 plans, only 10% covered the biosimilar, while 96% covered infliximab, the authors found.

The mean total cost of infliximab-dyyb was “modestly lower,” they reported. Eight-week prescription costs were $2,185 for infliximab-dyyb versus $2,667 for infliximab, while annual costs were $14,202 for the biosimilar and $17,335 for infliximab.

However, all plans required coinsurance cost-sharing for the biosimilar, they said. The mean coinsurance rate was 26.6% of the total drug cost for the biosimilar and 28.4% for infliximab.

For beneficiaries, projected annual out-of-pocket costs without the gap discount were $5,118 for infliximab-dyyb and $3,432 for infliximab, the researchers said.

Biosimilar gap discounts are set to start in 2019, according to the authors. However, they said those discounts may not substantially reduce out-of-pocket costs for Part D beneficiaries because of the high price of infliximab-dyyb and a coinsurance cost-sharing rate similar to that of infliximab.

“Further policies are needed to address affordability and access to specialty drugs,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors concluded.

The study was funded in part by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Robert L. Kroc Endowed Chair in Rheumatic and Connective Tissue Diseases, and other sources. Dr. Yazdany reported receiving an independent investigator award from Pfizer. Her coauthors reported no conflict of interest disclosures.

The infliximab-dyyb biosimilar was only moderately less expensive than the originator infliximab product Remicade in the United States in 2017 under Medicare Part D, an analysis shows.

Infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra) cost 18% less than infliximab, with an annual cost exceeding $14,000 in an analysis published online Sept. 4 in JAMA by Jinoos Yazdany, MD, of the division of rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors.

However, “without biosimilar gap discounts in 2017, beneficiaries would have paid more than $5,100 for infliximab-dyyb, or nearly $1,700 more in projected out-of-pocket costs than infliximab,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors wrote.

Biologics represent only 2% of U.S. prescriptions but made up 38% of drug spending in 2015 and accounted for 70% of growth in drug spending from 2010 to 2015, according to Dr. Yazdany and her colleagues.

Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) cost more than $14,000 per year, and in 2015, 3 were among the top 15 drugs in terms of Medicare expenditures, they added.

While biosimilars are supposed to increase competition and lower prices, it’s an open question whether they actually reduce out-of-pocket expenditures for the 43 million individuals with drug benefits under Medicare Part D.

That uncertainty is due in part to the complex cost-sharing design of Part D, which includes an initial deductible, a coverage phase, a coverage gap, and catastrophic coverage.

In 2017, the plan included an initial $400 deductible, followed by the coverage phase, in which the patient paid 25% of drug costs. In the coverage gap, which started at $3,700 in total drug costs, the patient’s share of drug costs increased to 40% for biologics, and 51% for biosimilars. In the catastrophic coverage phase, triggered when out-of-pocket costs exceeded $4,950, the patient was responsible for 5% of drug costs.

“Currently, beneficiaries receive a 50% manufacturer discount during the gap for brand-name drugs and biologics, but not for biosimilars,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors said in the report.

To evaluate cost-sharing for infliximab-dyyb, which in 2016 became the first available RA biosimilar, the authors analyzed data for all Part D plans in the June 2017 Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information Files.

Out of 2,547 plans, only 10% covered the biosimilar, while 96% covered infliximab, the authors found.

The mean total cost of infliximab-dyyb was “modestly lower,” they reported. Eight-week prescription costs were $2,185 for infliximab-dyyb versus $2,667 for infliximab, while annual costs were $14,202 for the biosimilar and $17,335 for infliximab.

However, all plans required coinsurance cost-sharing for the biosimilar, they said. The mean coinsurance rate was 26.6% of the total drug cost for the biosimilar and 28.4% for infliximab.

For beneficiaries, projected annual out-of-pocket costs without the gap discount were $5,118 for infliximab-dyyb and $3,432 for infliximab, the researchers said.

Biosimilar gap discounts are set to start in 2019, according to the authors. However, they said those discounts may not substantially reduce out-of-pocket costs for Part D beneficiaries because of the high price of infliximab-dyyb and a coinsurance cost-sharing rate similar to that of infliximab.

“Further policies are needed to address affordability and access to specialty drugs,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors concluded.

The study was funded in part by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Robert L. Kroc Endowed Chair in Rheumatic and Connective Tissue Diseases, and other sources. Dr. Yazdany reported receiving an independent investigator award from Pfizer. Her coauthors reported no conflict of interest disclosures.

The infliximab-dyyb biosimilar was only moderately less expensive than the originator infliximab product Remicade in the United States in 2017 under Medicare Part D, an analysis shows.

Infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra) cost 18% less than infliximab, with an annual cost exceeding $14,000 in an analysis published online Sept. 4 in JAMA by Jinoos Yazdany, MD, of the division of rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors.

However, “without biosimilar gap discounts in 2017, beneficiaries would have paid more than $5,100 for infliximab-dyyb, or nearly $1,700 more in projected out-of-pocket costs than infliximab,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors wrote.

Biologics represent only 2% of U.S. prescriptions but made up 38% of drug spending in 2015 and accounted for 70% of growth in drug spending from 2010 to 2015, according to Dr. Yazdany and her colleagues.

Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) cost more than $14,000 per year, and in 2015, 3 were among the top 15 drugs in terms of Medicare expenditures, they added.

While biosimilars are supposed to increase competition and lower prices, it’s an open question whether they actually reduce out-of-pocket expenditures for the 43 million individuals with drug benefits under Medicare Part D.

That uncertainty is due in part to the complex cost-sharing design of Part D, which includes an initial deductible, a coverage phase, a coverage gap, and catastrophic coverage.

In 2017, the plan included an initial $400 deductible, followed by the coverage phase, in which the patient paid 25% of drug costs. In the coverage gap, which started at $3,700 in total drug costs, the patient’s share of drug costs increased to 40% for biologics, and 51% for biosimilars. In the catastrophic coverage phase, triggered when out-of-pocket costs exceeded $4,950, the patient was responsible for 5% of drug costs.

“Currently, beneficiaries receive a 50% manufacturer discount during the gap for brand-name drugs and biologics, but not for biosimilars,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors said in the report.

To evaluate cost-sharing for infliximab-dyyb, which in 2016 became the first available RA biosimilar, the authors analyzed data for all Part D plans in the June 2017 Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information Files.

Out of 2,547 plans, only 10% covered the biosimilar, while 96% covered infliximab, the authors found.

The mean total cost of infliximab-dyyb was “modestly lower,” they reported. Eight-week prescription costs were $2,185 for infliximab-dyyb versus $2,667 for infliximab, while annual costs were $14,202 for the biosimilar and $17,335 for infliximab.

However, all plans required coinsurance cost-sharing for the biosimilar, they said. The mean coinsurance rate was 26.6% of the total drug cost for the biosimilar and 28.4% for infliximab.

For beneficiaries, projected annual out-of-pocket costs without the gap discount were $5,118 for infliximab-dyyb and $3,432 for infliximab, the researchers said.

Biosimilar gap discounts are set to start in 2019, according to the authors. However, they said those discounts may not substantially reduce out-of-pocket costs for Part D beneficiaries because of the high price of infliximab-dyyb and a coinsurance cost-sharing rate similar to that of infliximab.

“Further policies are needed to address affordability and access to specialty drugs,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors concluded.

The study was funded in part by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Robert L. Kroc Endowed Chair in Rheumatic and Connective Tissue Diseases, and other sources. Dr. Yazdany reported receiving an independent investigator award from Pfizer. Her coauthors reported no conflict of interest disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Infliximab-dyyb was 18% less costly than infliximab, with an annual cost exceeding $14,000.

Study details: Analysis of data for 2,547 Part D plans in the June 2017 Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information Files.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Robert L. Kroc Endowed Chair in Rheumatic and Connective Tissue Diseases, and other sources. One author reported receiving an independent investigator award from Pfizer.

Source: Yazdany J et al. JAMA. 2018;320(9):931-3.

Medication app boosts psoriasis patients’ short-term adherence

compared with those who did not use the app.

Treatment adherence remains a challenge in psoriasis, and although the field of electronic health interventions is growing, data on the effectiveness of such interventions are limited, wrote Mathias T. Svendsen, MD, of Odense University Hospital in Denmark, and his colleagues.

In a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology, 134 adults with psoriasis were randomized to use a smartphone app (68) or not (66) that provided daily medication reminders and daily information about the amount of treatment and number of product applications.

The primary outcome measure of treatment adherence was defined as once-daily application of topical medication – calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate cutaneous foam – for at least 80% of the days during the treatment period. A computer chip on the medication dispenser tracked patient use of the product and sent usage information to the patient’s smartphone via Bluetooth.

At 4 weeks, 65% of patients who used the app were adherent to treatment, versus 38% of those who didn’t use the app (P = .004).

In addition, patients who used the app showed significant improvement in disease severity, based on the secondary outcome measure of the Lattice System Physician’s Global Assessment (LS-PGA) at 4 weeks, with a mean change in score from baseline of 1.86 in the app group and 1.46 in the non-app group (P = .047). The LS-PGA and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) were measured at all visits. No significant differences on the DLQI appeared between the groups.

During a 22-week follow-up completed by 122 patients, the effects were similar, but the differences were not statistically significant at weeks 8 and 26.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of knowledge of the correct amount of medication needed for the full benefit of the topical treatment and a lack of data on patient satisfaction with the app, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that a medication reminder app improved disease severity as well as patient adherence rates in the short term, and that “there is potential for implementing patient-supporting apps in the dermatology clinic.”

The study was supported by LEO Pharma and by the Kirsten and Volmer Rask Nielsen’s Foundation; part of Dr. Svendsen’s salary during the study was paid by LEO Pharma, and several coauthors reported relationships with LEO Pharma.

SOURCE: Svendsen MT et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16667.

compared with those who did not use the app.

Treatment adherence remains a challenge in psoriasis, and although the field of electronic health interventions is growing, data on the effectiveness of such interventions are limited, wrote Mathias T. Svendsen, MD, of Odense University Hospital in Denmark, and his colleagues.

In a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology, 134 adults with psoriasis were randomized to use a smartphone app (68) or not (66) that provided daily medication reminders and daily information about the amount of treatment and number of product applications.

The primary outcome measure of treatment adherence was defined as once-daily application of topical medication – calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate cutaneous foam – for at least 80% of the days during the treatment period. A computer chip on the medication dispenser tracked patient use of the product and sent usage information to the patient’s smartphone via Bluetooth.

At 4 weeks, 65% of patients who used the app were adherent to treatment, versus 38% of those who didn’t use the app (P = .004).

In addition, patients who used the app showed significant improvement in disease severity, based on the secondary outcome measure of the Lattice System Physician’s Global Assessment (LS-PGA) at 4 weeks, with a mean change in score from baseline of 1.86 in the app group and 1.46 in the non-app group (P = .047). The LS-PGA and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) were measured at all visits. No significant differences on the DLQI appeared between the groups.

During a 22-week follow-up completed by 122 patients, the effects were similar, but the differences were not statistically significant at weeks 8 and 26.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of knowledge of the correct amount of medication needed for the full benefit of the topical treatment and a lack of data on patient satisfaction with the app, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that a medication reminder app improved disease severity as well as patient adherence rates in the short term, and that “there is potential for implementing patient-supporting apps in the dermatology clinic.”

The study was supported by LEO Pharma and by the Kirsten and Volmer Rask Nielsen’s Foundation; part of Dr. Svendsen’s salary during the study was paid by LEO Pharma, and several coauthors reported relationships with LEO Pharma.

SOURCE: Svendsen MT et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16667.

compared with those who did not use the app.

Treatment adherence remains a challenge in psoriasis, and although the field of electronic health interventions is growing, data on the effectiveness of such interventions are limited, wrote Mathias T. Svendsen, MD, of Odense University Hospital in Denmark, and his colleagues.

In a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology, 134 adults with psoriasis were randomized to use a smartphone app (68) or not (66) that provided daily medication reminders and daily information about the amount of treatment and number of product applications.

The primary outcome measure of treatment adherence was defined as once-daily application of topical medication – calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate cutaneous foam – for at least 80% of the days during the treatment period. A computer chip on the medication dispenser tracked patient use of the product and sent usage information to the patient’s smartphone via Bluetooth.

At 4 weeks, 65% of patients who used the app were adherent to treatment, versus 38% of those who didn’t use the app (P = .004).

In addition, patients who used the app showed significant improvement in disease severity, based on the secondary outcome measure of the Lattice System Physician’s Global Assessment (LS-PGA) at 4 weeks, with a mean change in score from baseline of 1.86 in the app group and 1.46 in the non-app group (P = .047). The LS-PGA and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) were measured at all visits. No significant differences on the DLQI appeared between the groups.

During a 22-week follow-up completed by 122 patients, the effects were similar, but the differences were not statistically significant at weeks 8 and 26.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of knowledge of the correct amount of medication needed for the full benefit of the topical treatment and a lack of data on patient satisfaction with the app, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that a medication reminder app improved disease severity as well as patient adherence rates in the short term, and that “there is potential for implementing patient-supporting apps in the dermatology clinic.”

The study was supported by LEO Pharma and by the Kirsten and Volmer Rask Nielsen’s Foundation; part of Dr. Svendsen’s salary during the study was paid by LEO Pharma, and several coauthors reported relationships with LEO Pharma.

SOURCE: Svendsen MT et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16667.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Using a smartphone app helped patients with psoriasis significantly improve their treatment adherence.

Major finding: Significantly more patients who used the app followed their topical treatment plan, compared with the no-app controls (65% vs. 38%).

Study details: The data come from 134 adults with psoriasis who were randomized to use an app or no app for 28 days.

Disclosures: The study was supported by LEO Pharma and by the Kirsten and Volmer Rask Nielsen’s Foundation; part of Dr. Svendsen’s salary during the study was paid by LEO Pharma, and several coauthors reported relationships with LEO Pharma.

Source: Svendsen MT et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16667.

Risankizumab proves more effective in psoriasis than ustekinumab

, according to results of a pair of head-to-head trials published in the Lancet.

The replicate phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator–controlled trials, UltIMMa-1 (NCT02684370) and UltIMMa-2 (NCT02684375) altogether randomized 997 patients to risankizumab, ustekinumab, or placebo. The coprimary endpoints were the proportions of patients achieving 90% reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 90) at 16 weeks and a static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) score of 0 or 1, and the 15 ranked secondary endpoints included proportions of those achieving PASI 100 or sPGA 0, both of which demonstrate total clearance of psoriasis, as well as measures of quality of life improvement.

Compared with those receiving either ustekinumab or placebo, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving risankizumab achieved the coprimary endpoints, and all secondary endpoints were met. In UltIMMA-1, 75.3% of risankizumab patients achieved PASI 90, compared with 4.9% of placebo patients and 42% of ustekinumab patients (P less than .0001 when comparing it with both placebo and ustekinumab); sPGA of 0 or 1 was achieved by 87.8% of risankizumab patients and only 7.8% of placebo patients and 63% of ustekinumab patients (P less than .0001 when comparing it with both placebo and ustekinumab). Results were similar in UltIMMA-2: 74.8% of risankizumab patients achieved PASI 90, and 83.7% of them achieved sPGA 0 or 1 (P less than .0001 when comparing them with placebo and ustekinumab). According to results of the secondary endpoints, both studies also showed greater rates of clearance and improvements in quality of life among patients receiving risankizumab than among those receiving either placebo or ustekinumab.

The safety profiles across treatment groups were similar in both studies, with the most common adverse events including upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and diarrhea.

Risankizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that targets the p19 subunit of only interleukin-23, unlike the studies’ active comparator, ustekinumab, which targets both interleukin-23 and interleukin-12. “Selectively blocking interleukin 23 with a p19 inhibitor appears to be one of the best ways to treat psoriasis,” commented Abigail Cline, MD, and Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, both of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., in an accompanying editorial (Lancet. 2018 Aug 7;392:616-71.).

The authors of the study reported relationships with various industry entities, including AbbVie, which sponsored the studies and developed risankizumab, and Boehringer Ingelheim, which collaborated in the studies. The authors of the editorial also disclosed relationships with entities, including AbbVie.

SOURCE: Gordon KB et al. Lancet. 2018 Aug 7;392:650-61.

, according to results of a pair of head-to-head trials published in the Lancet.

The replicate phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator–controlled trials, UltIMMa-1 (NCT02684370) and UltIMMa-2 (NCT02684375) altogether randomized 997 patients to risankizumab, ustekinumab, or placebo. The coprimary endpoints were the proportions of patients achieving 90% reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 90) at 16 weeks and a static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) score of 0 or 1, and the 15 ranked secondary endpoints included proportions of those achieving PASI 100 or sPGA 0, both of which demonstrate total clearance of psoriasis, as well as measures of quality of life improvement.

Compared with those receiving either ustekinumab or placebo, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving risankizumab achieved the coprimary endpoints, and all secondary endpoints were met. In UltIMMA-1, 75.3% of risankizumab patients achieved PASI 90, compared with 4.9% of placebo patients and 42% of ustekinumab patients (P less than .0001 when comparing it with both placebo and ustekinumab); sPGA of 0 or 1 was achieved by 87.8% of risankizumab patients and only 7.8% of placebo patients and 63% of ustekinumab patients (P less than .0001 when comparing it with both placebo and ustekinumab). Results were similar in UltIMMA-2: 74.8% of risankizumab patients achieved PASI 90, and 83.7% of them achieved sPGA 0 or 1 (P less than .0001 when comparing them with placebo and ustekinumab). According to results of the secondary endpoints, both studies also showed greater rates of clearance and improvements in quality of life among patients receiving risankizumab than among those receiving either placebo or ustekinumab.

The safety profiles across treatment groups were similar in both studies, with the most common adverse events including upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and diarrhea.

Risankizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that targets the p19 subunit of only interleukin-23, unlike the studies’ active comparator, ustekinumab, which targets both interleukin-23 and interleukin-12. “Selectively blocking interleukin 23 with a p19 inhibitor appears to be one of the best ways to treat psoriasis,” commented Abigail Cline, MD, and Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, both of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., in an accompanying editorial (Lancet. 2018 Aug 7;392:616-71.).

The authors of the study reported relationships with various industry entities, including AbbVie, which sponsored the studies and developed risankizumab, and Boehringer Ingelheim, which collaborated in the studies. The authors of the editorial also disclosed relationships with entities, including AbbVie.

SOURCE: Gordon KB et al. Lancet. 2018 Aug 7;392:650-61.

, according to results of a pair of head-to-head trials published in the Lancet.

The replicate phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator–controlled trials, UltIMMa-1 (NCT02684370) and UltIMMa-2 (NCT02684375) altogether randomized 997 patients to risankizumab, ustekinumab, or placebo. The coprimary endpoints were the proportions of patients achieving 90% reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 90) at 16 weeks and a static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) score of 0 or 1, and the 15 ranked secondary endpoints included proportions of those achieving PASI 100 or sPGA 0, both of which demonstrate total clearance of psoriasis, as well as measures of quality of life improvement.

Compared with those receiving either ustekinumab or placebo, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving risankizumab achieved the coprimary endpoints, and all secondary endpoints were met. In UltIMMA-1, 75.3% of risankizumab patients achieved PASI 90, compared with 4.9% of placebo patients and 42% of ustekinumab patients (P less than .0001 when comparing it with both placebo and ustekinumab); sPGA of 0 or 1 was achieved by 87.8% of risankizumab patients and only 7.8% of placebo patients and 63% of ustekinumab patients (P less than .0001 when comparing it with both placebo and ustekinumab). Results were similar in UltIMMA-2: 74.8% of risankizumab patients achieved PASI 90, and 83.7% of them achieved sPGA 0 or 1 (P less than .0001 when comparing them with placebo and ustekinumab). According to results of the secondary endpoints, both studies also showed greater rates of clearance and improvements in quality of life among patients receiving risankizumab than among those receiving either placebo or ustekinumab.

The safety profiles across treatment groups were similar in both studies, with the most common adverse events including upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and diarrhea.

Risankizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that targets the p19 subunit of only interleukin-23, unlike the studies’ active comparator, ustekinumab, which targets both interleukin-23 and interleukin-12. “Selectively blocking interleukin 23 with a p19 inhibitor appears to be one of the best ways to treat psoriasis,” commented Abigail Cline, MD, and Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, both of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., in an accompanying editorial (Lancet. 2018 Aug 7;392:616-71.).

The authors of the study reported relationships with various industry entities, including AbbVie, which sponsored the studies and developed risankizumab, and Boehringer Ingelheim, which collaborated in the studies. The authors of the editorial also disclosed relationships with entities, including AbbVie.

SOURCE: Gordon KB et al. Lancet. 2018 Aug 7;392:650-61.

FROM THE LANCET

Psoriasis registry study provides more data on infliximab’s infection risk

that led to hospitalization, the use of intravenous antimicrobial therapy, or death, according to a prospective cohort study of cases in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.

The new data suggest a risk associated with infliximab treatment that previous clinical trials and observational studies were insufficiently powered to detect, according to the investigators, led by Zenas Yiu, of the University of Manchester (England). They found no associations between infection risk and treatment with etanercept, adalimumab, or ustekinumab, and they noted that there are no such data yet on more recently approved biologic therapies for psoriasis, such as secukinumab or ixekizumab.

The British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) recommends infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–blocker, only for severe cases of psoriasis (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index greater than or equal to 20 and a Dermatology Life Quality Index greater than 18), or when other biologics fail or cannot be used.

To address the insufficient power of earlier studies, the researchers used data from the BAD Biologic Interventions Register (BADBIR), a large, prospective psoriasis registry in the United Kingdom and Ireland established in 2007. The analysis included 3,421 subjects in the nonbiologic systemic therapy cohort, and 422 subjects in the all-lines infliximab cohort. The median follow-up period was 1.49 person-years (interquartile range, 2.50 person-years) for the all-lines (not just first-line) infliximab group, and 1.51 person-years (1.84 person-years) for the nonbiologics group.*

Treatment with infliximab was associated with a statistically significant increased risk of serious infection (defined as an infection associated with prolonged hospitalization or use of IV antimicrobial therapy; or an infection that resulted in death), with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.95 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-3.75), compared with nonbiologic systemic treatments. The risk was higher in the first 6 months (adjusted HR, 3.49; 95% CI, 1.14-10.70), and from 6 months to 1 year (aHR, 2.99; 95% CI, 1.10-8.14,) but did not reach statistical significance at 1 year to 2 years (aHR, 2.03; 95% CI, 0.61-6.79).

There was also an increased risk of serious infection with infliximab compared with methotrexate (aHR, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.58-5.57).

“Given our findings of a higher risk of serious infection associated with infliximab, we provide real-world evidence to reinforce the position of infliximab in the psoriasis treatment hierarchy,” the authors wrote, adding that “patients with severe psoriasis who fulfill the criteria for the prescription of infliximab should be counseled” about the risk of serious infection.

Dr. Yiu disclosed having received nonfinancial support form Novartis, two authors had no disclosures, and the remainder had various disclosures related to pharmaceutical companies. BADBIR is funded by BAD, which receives funding from Pfizer, Janssen Cilag, AbbVie, Novartis, Samsung Bioepis and Eli Lilly for providing pharmacovigilance services.

SOURCE: Yiu ZZN et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17036.

*This article was updated to correctly indicate that the median follow-up period was 1.49 person-years (interquartile range, 2.50 person-years) for the all-lines (not just first-line) infliximab group, and 1.51 person-years (1.84 person-years) for the nonbiologics group.

that led to hospitalization, the use of intravenous antimicrobial therapy, or death, according to a prospective cohort study of cases in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.

The new data suggest a risk associated with infliximab treatment that previous clinical trials and observational studies were insufficiently powered to detect, according to the investigators, led by Zenas Yiu, of the University of Manchester (England). They found no associations between infection risk and treatment with etanercept, adalimumab, or ustekinumab, and they noted that there are no such data yet on more recently approved biologic therapies for psoriasis, such as secukinumab or ixekizumab.

The British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) recommends infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–blocker, only for severe cases of psoriasis (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index greater than or equal to 20 and a Dermatology Life Quality Index greater than 18), or when other biologics fail or cannot be used.

To address the insufficient power of earlier studies, the researchers used data from the BAD Biologic Interventions Register (BADBIR), a large, prospective psoriasis registry in the United Kingdom and Ireland established in 2007. The analysis included 3,421 subjects in the nonbiologic systemic therapy cohort, and 422 subjects in the all-lines infliximab cohort. The median follow-up period was 1.49 person-years (interquartile range, 2.50 person-years) for the all-lines (not just first-line) infliximab group, and 1.51 person-years (1.84 person-years) for the nonbiologics group.*

Treatment with infliximab was associated with a statistically significant increased risk of serious infection (defined as an infection associated with prolonged hospitalization or use of IV antimicrobial therapy; or an infection that resulted in death), with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.95 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-3.75), compared with nonbiologic systemic treatments. The risk was higher in the first 6 months (adjusted HR, 3.49; 95% CI, 1.14-10.70), and from 6 months to 1 year (aHR, 2.99; 95% CI, 1.10-8.14,) but did not reach statistical significance at 1 year to 2 years (aHR, 2.03; 95% CI, 0.61-6.79).

There was also an increased risk of serious infection with infliximab compared with methotrexate (aHR, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.58-5.57).

“Given our findings of a higher risk of serious infection associated with infliximab, we provide real-world evidence to reinforce the position of infliximab in the psoriasis treatment hierarchy,” the authors wrote, adding that “patients with severe psoriasis who fulfill the criteria for the prescription of infliximab should be counseled” about the risk of serious infection.

Dr. Yiu disclosed having received nonfinancial support form Novartis, two authors had no disclosures, and the remainder had various disclosures related to pharmaceutical companies. BADBIR is funded by BAD, which receives funding from Pfizer, Janssen Cilag, AbbVie, Novartis, Samsung Bioepis and Eli Lilly for providing pharmacovigilance services.

SOURCE: Yiu ZZN et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17036.

*This article was updated to correctly indicate that the median follow-up period was 1.49 person-years (interquartile range, 2.50 person-years) for the all-lines (not just first-line) infliximab group, and 1.51 person-years (1.84 person-years) for the nonbiologics group.

that led to hospitalization, the use of intravenous antimicrobial therapy, or death, according to a prospective cohort study of cases in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.

The new data suggest a risk associated with infliximab treatment that previous clinical trials and observational studies were insufficiently powered to detect, according to the investigators, led by Zenas Yiu, of the University of Manchester (England). They found no associations between infection risk and treatment with etanercept, adalimumab, or ustekinumab, and they noted that there are no such data yet on more recently approved biologic therapies for psoriasis, such as secukinumab or ixekizumab.

The British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) recommends infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–blocker, only for severe cases of psoriasis (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index greater than or equal to 20 and a Dermatology Life Quality Index greater than 18), or when other biologics fail or cannot be used.

To address the insufficient power of earlier studies, the researchers used data from the BAD Biologic Interventions Register (BADBIR), a large, prospective psoriasis registry in the United Kingdom and Ireland established in 2007. The analysis included 3,421 subjects in the nonbiologic systemic therapy cohort, and 422 subjects in the all-lines infliximab cohort. The median follow-up period was 1.49 person-years (interquartile range, 2.50 person-years) for the all-lines (not just first-line) infliximab group, and 1.51 person-years (1.84 person-years) for the nonbiologics group.*

Treatment with infliximab was associated with a statistically significant increased risk of serious infection (defined as an infection associated with prolonged hospitalization or use of IV antimicrobial therapy; or an infection that resulted in death), with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.95 (95% confidence interval, 1.01-3.75), compared with nonbiologic systemic treatments. The risk was higher in the first 6 months (adjusted HR, 3.49; 95% CI, 1.14-10.70), and from 6 months to 1 year (aHR, 2.99; 95% CI, 1.10-8.14,) but did not reach statistical significance at 1 year to 2 years (aHR, 2.03; 95% CI, 0.61-6.79).

There was also an increased risk of serious infection with infliximab compared with methotrexate (aHR, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.58-5.57).

“Given our findings of a higher risk of serious infection associated with infliximab, we provide real-world evidence to reinforce the position of infliximab in the psoriasis treatment hierarchy,” the authors wrote, adding that “patients with severe psoriasis who fulfill the criteria for the prescription of infliximab should be counseled” about the risk of serious infection.

Dr. Yiu disclosed having received nonfinancial support form Novartis, two authors had no disclosures, and the remainder had various disclosures related to pharmaceutical companies. BADBIR is funded by BAD, which receives funding from Pfizer, Janssen Cilag, AbbVie, Novartis, Samsung Bioepis and Eli Lilly for providing pharmacovigilance services.

SOURCE: Yiu ZZN et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17036.

*This article was updated to correctly indicate that the median follow-up period was 1.49 person-years (interquartile range, 2.50 person-years) for the all-lines (not just first-line) infliximab group, and 1.51 person-years (1.84 person-years) for the nonbiologics group.

FROM BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The study reinforces British guidelines that infliximab should be restricted to most severe cases.

Major finding: Infliximab was associated with a hazard ratio of 1.95 for severe infections, compared with non-biologic systemic therapies.

Study details: Prospective cohort analysis of a psoriasis treatment database of 3,843 individuals.

Disclosures: Dr. Yiu disclosed having received non-financial support form Novartis, two authors had no disclosures, and the remainder had various disclosures related to pharmaceutical companies. BADBIR is funded by BAD, which receives funding from Pfizer, Janssen Cilag, AbbVie, Novartis, Samsung Bioepis and Eli Lilly for providing pharmacovigilance services.

Source: Yiu ZZN et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17036.

Latex Allergy From Biologic Injectable Devices

Latex Hypersensitivity to Injection Devices for Biologic Therapies in Psoriasis Patients

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

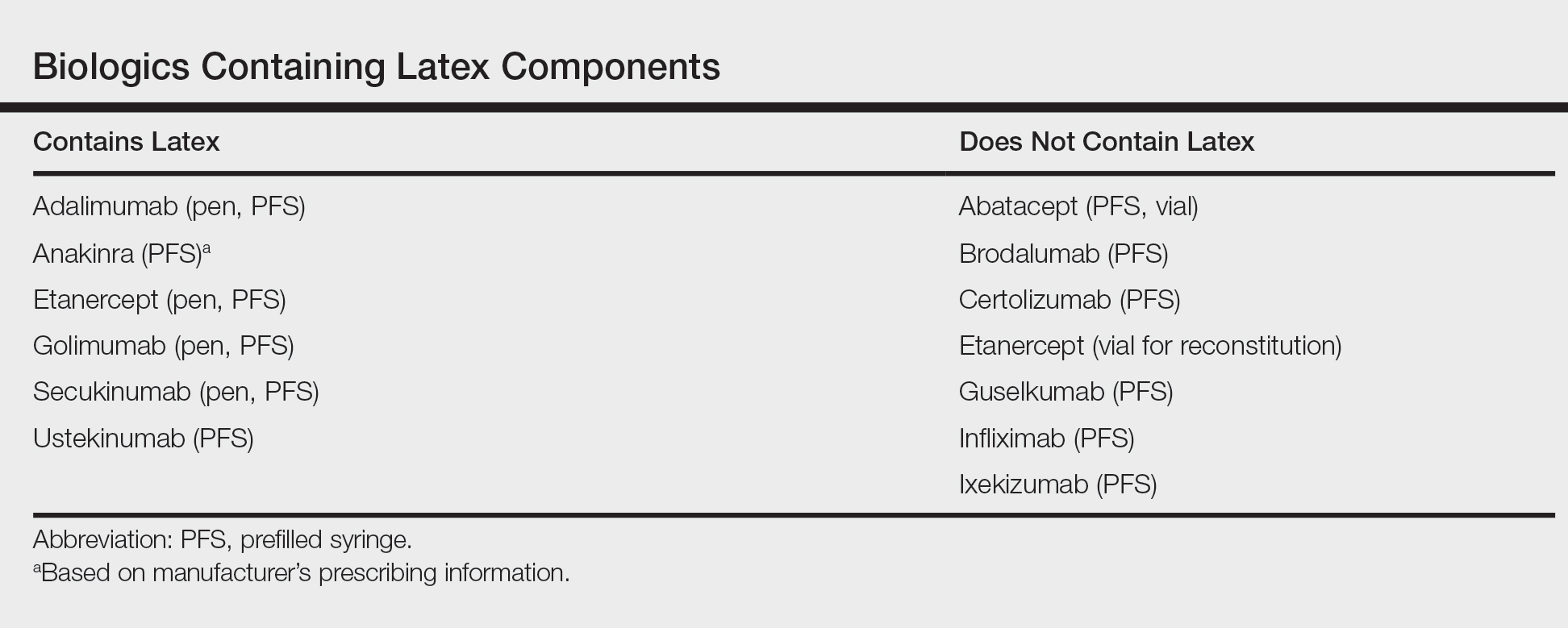

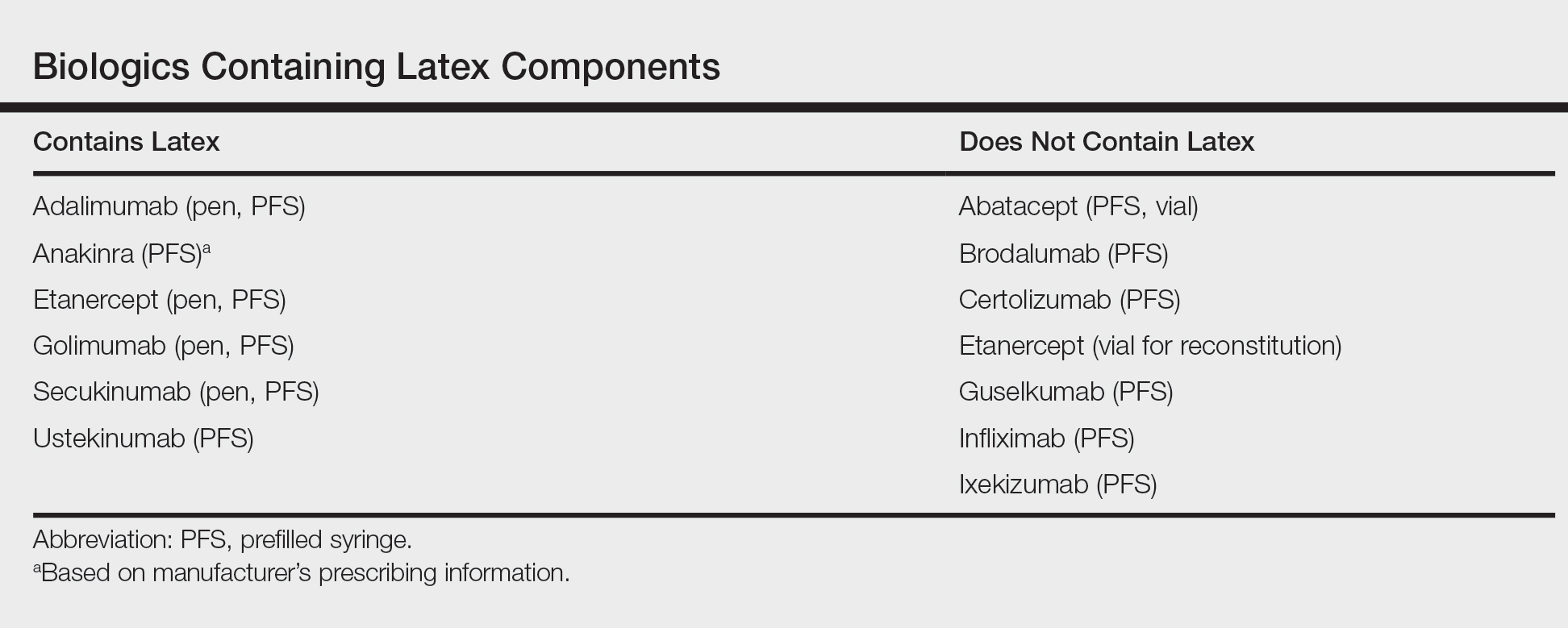

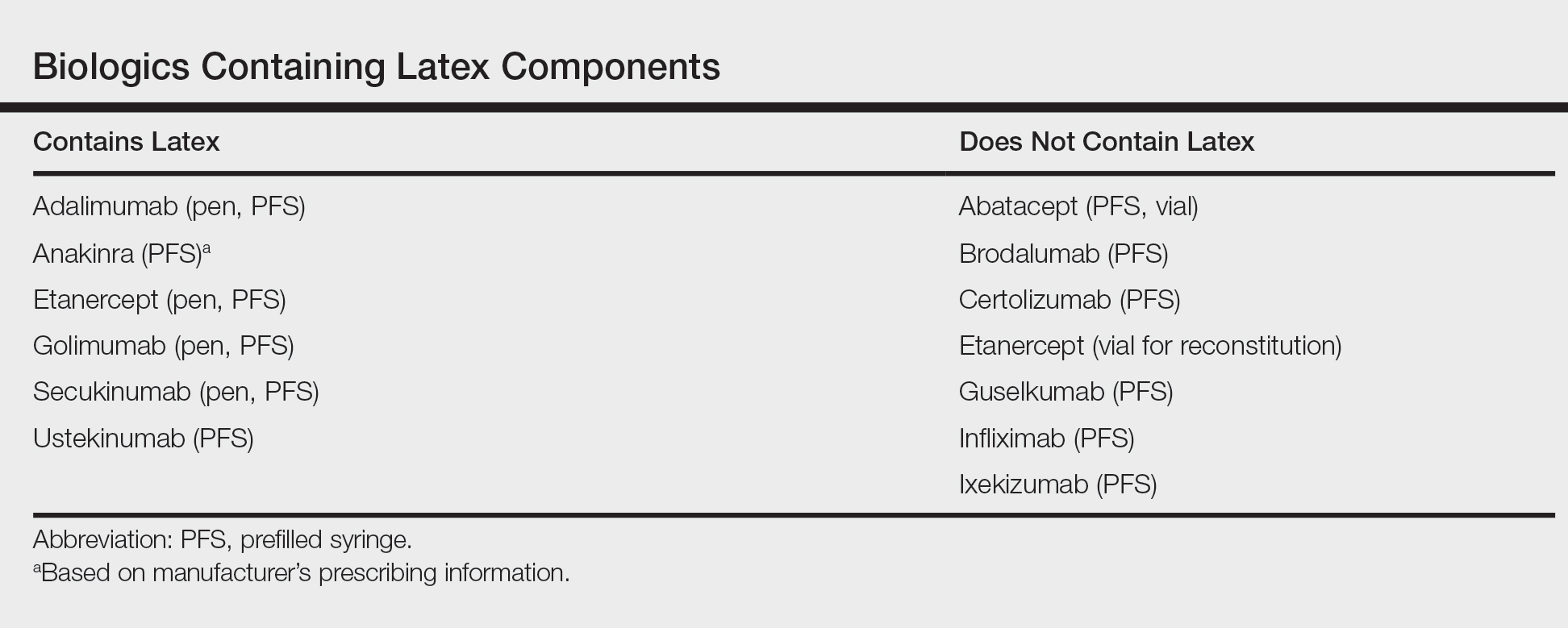

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

Inflammatory Linear Verrucous Epidermal Nevus Responsive to 308-nm Excimer Laser Treatment

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is a rare entity that presents with linear and pruritic psoriasiform plaques and most commonly occurs during childhood. It represents a dysregulation of keratinocytes exhibiting genetic mosaicism.1,2 Epidermal nevi may derive from keratinocytic, follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, or eccrine origin. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is classified under the keratinocytic type of epidermal nevus and represents approximately 6% of all epidermal nevi.3 The condition presents as erythematous and verrucous plaques along the lines of Blaschko.2,4 There is a predilection for the legs, and girls are 4 times more commonly affected than boys.1 Cases of ILVEN are predominantly sporadic, though rare familial cases have been reported.4

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is notoriously refractory to treatment. First-line therapies include topical agents such as corticosteroids, calcipotriol, retinoids, and 5-fluorouracil.3,4 Other treatments include intralesional corticosteroids, cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and surgical excision.3 Several case reports have shown promising results using the pulsed dye and ablative CO2 lasers.5-8

Case Report

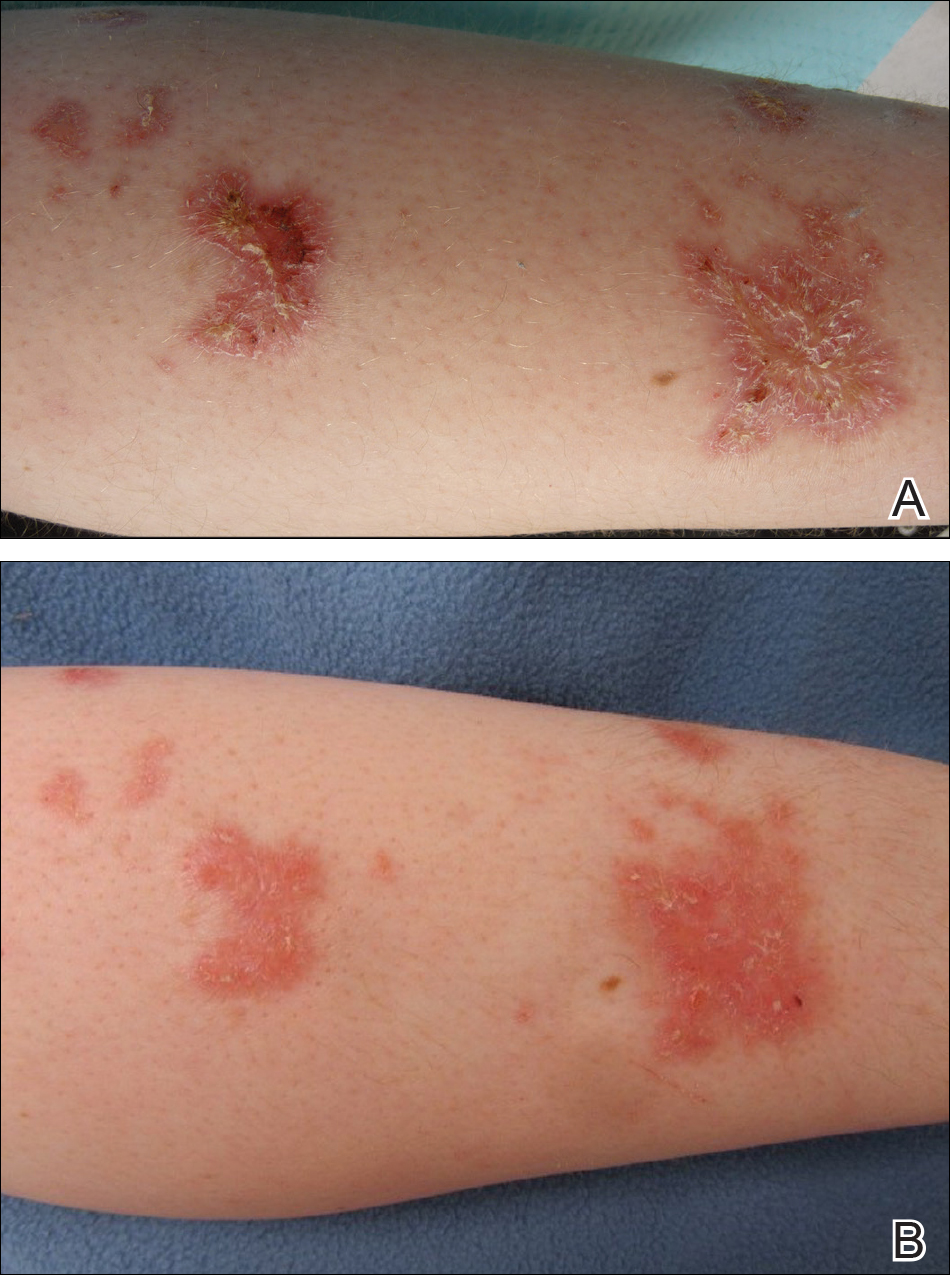

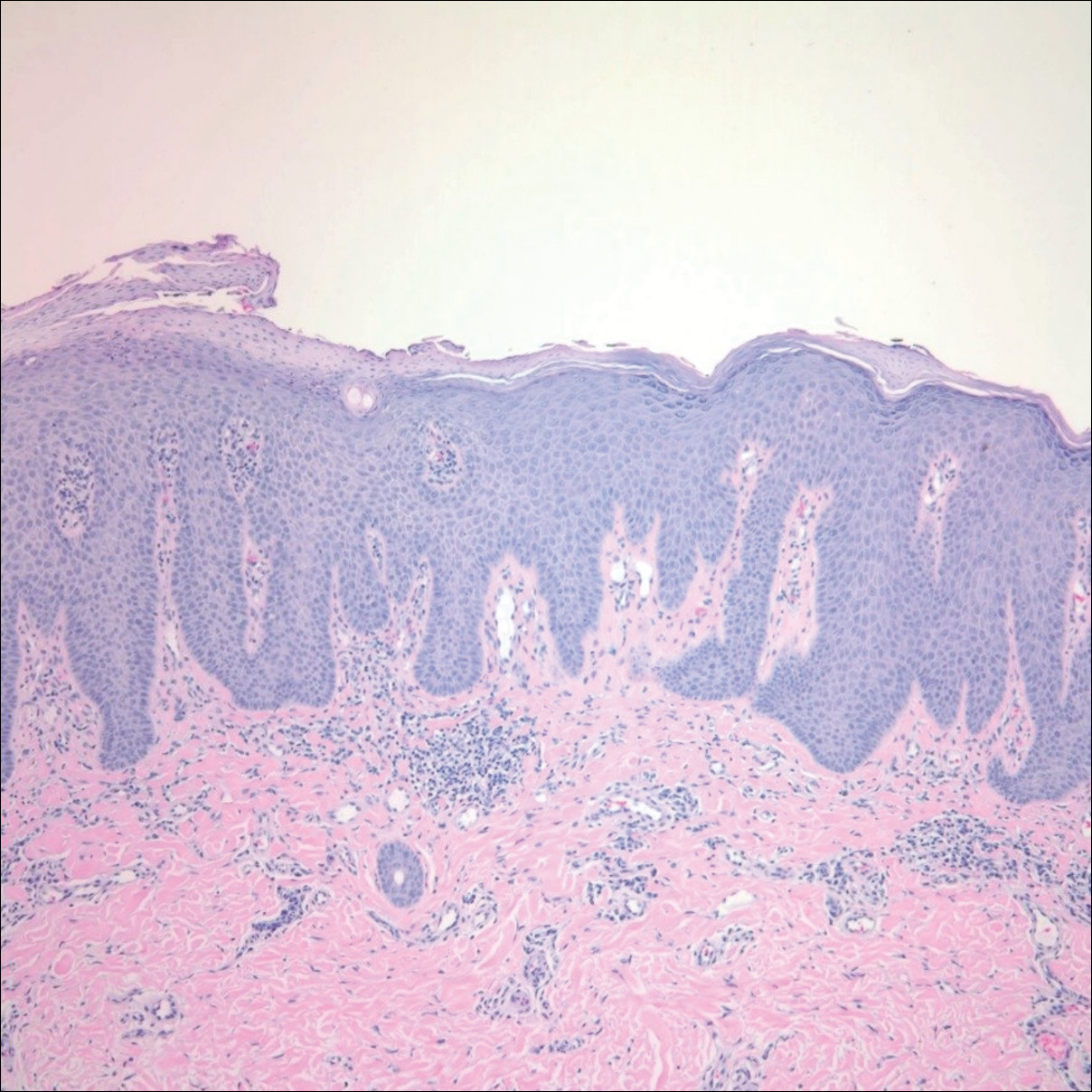

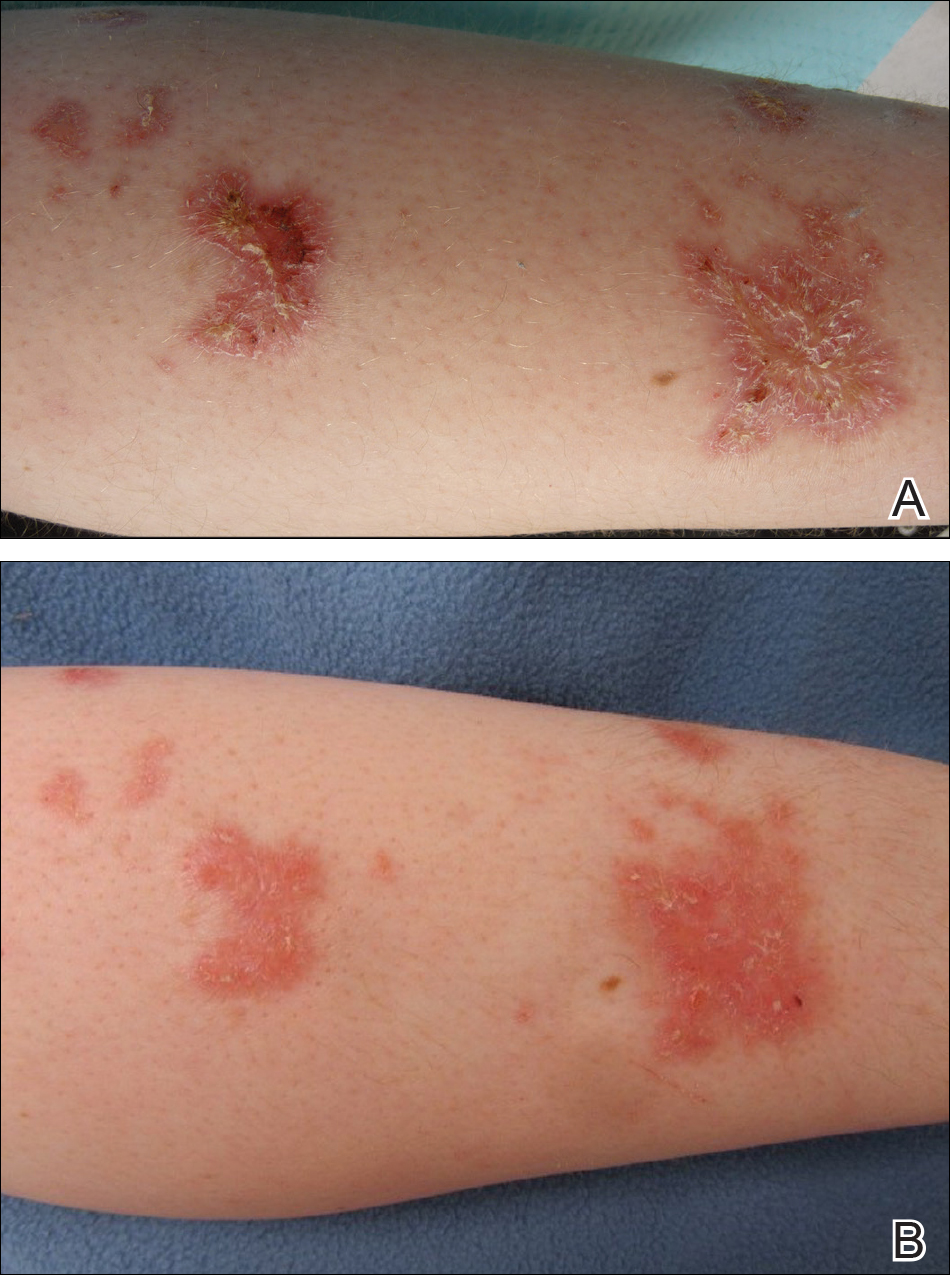

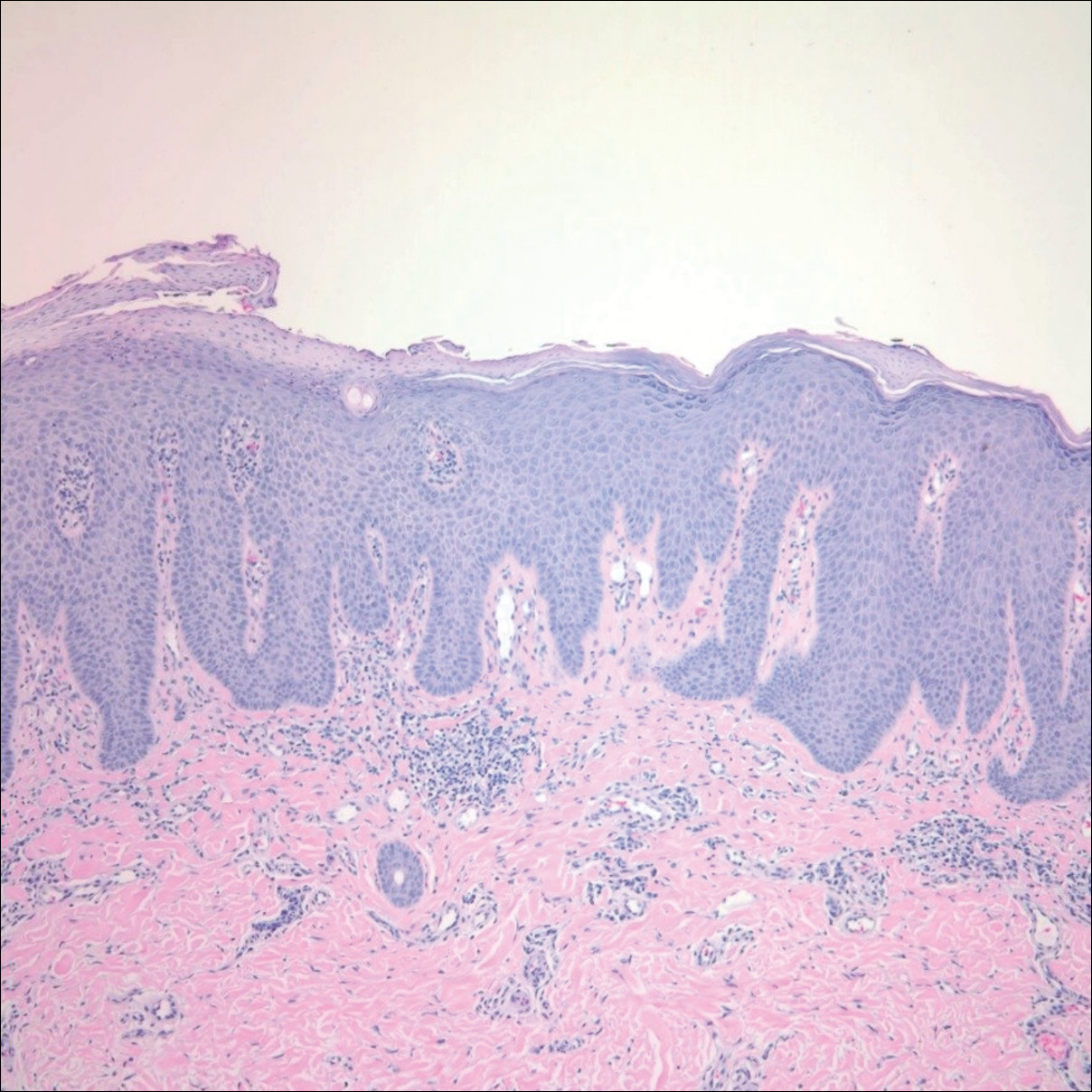

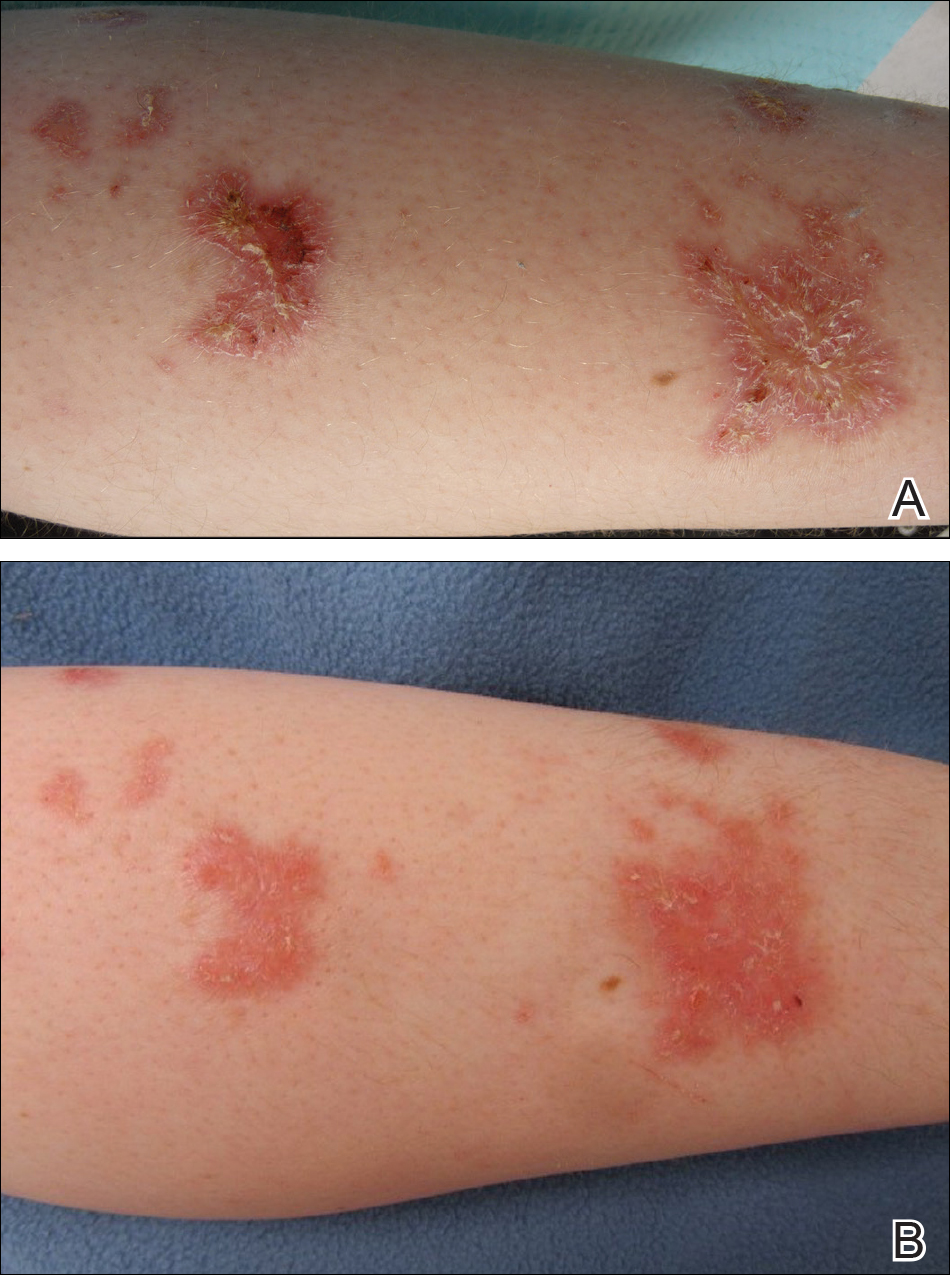

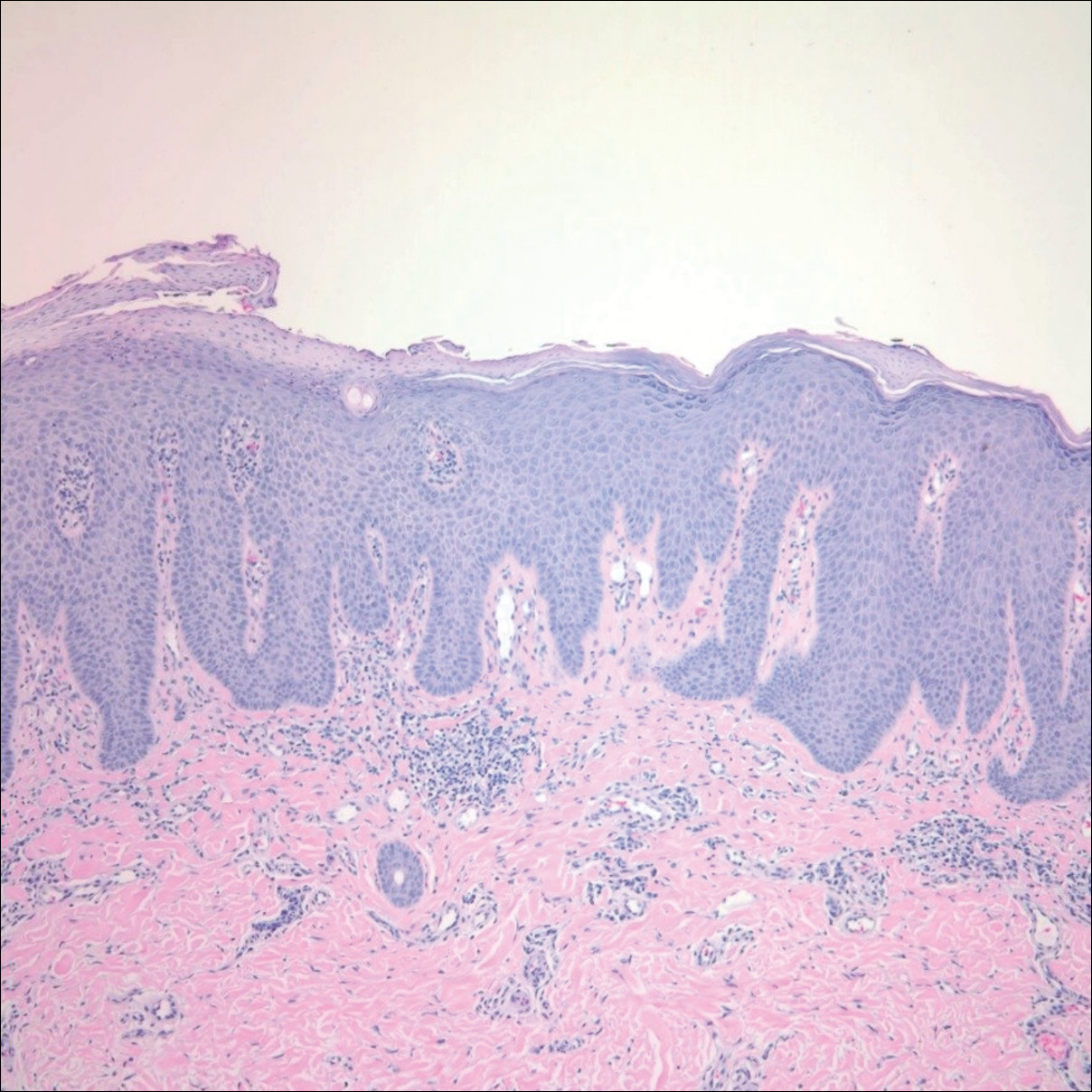

An otherwise healthy 20-year-old woman presented with dry, pruritic, red lesions on the right leg that had been present and stable since she was an infant (2 weeks of age). Her medical history included acne vulgaris, but she denied any personal or family history of psoriasis as well as any arthralgia or arthritis. Physical examination revealed discrete, oval, hyperkeratotic, scaly, red plaques on the lateral right leg with a larger hyperkeratotic, linear, red plaque extending from the right popliteal fossa to the posterior thigh (Figure 1A). The nails, scalp, buttocks, and upper extremities were unaffected. Bacterial culture of the right leg demonstrated Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Biopsy of the right popliteal fossa showed psoriasiform dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia, a slightly verruciform surface, broad zones of superficial pallor, and parakeratosis with conspicuous colonies of bacteria (Figure 2).

Following the positive bacterial culture, the patient was treated with a short course of oral doxycycline, which did not alter the clinical appearance of the lesions or improve symptoms of pruritus. Pruritus improved moderately with topical corticosteroid treatment, but clinically the lesions appeared unchanged. The plaque on the superior right leg was treated with a superpulsed CO2 laser and the plaque on the inferior right leg was treated with a fractional CO2 laser, both with minimal improvement.