User login

Complete Remission of Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Patient With Severe Psoriasis

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old white man presented with a skin lesion on the back of 1 to 2 weeks’ duration. The patient stated he was unaware of it, but his wife had recently noticed the new spot. He denied any bleeding, pain, pruritus, or other associated symptoms with the lesion. He also denied any prior treatment to the area. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for severe psoriasis involving more than 80% body surface area, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, coronary artery disease, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic keratoses. He had been on multiple treatment regimens over the last 20 years for control of psoriasis including topical corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA and UVB phototherapy, gold injections, acitretin, prednisone, efalizumab, ustekinumab, and alefacept upon evaluation of this new skin lesion. Utilization of immunosuppressive agents also provided an additional benefit of controlling the patient’s inflammatory arthritic disease.

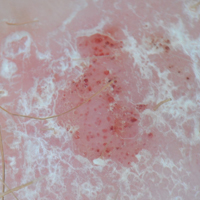

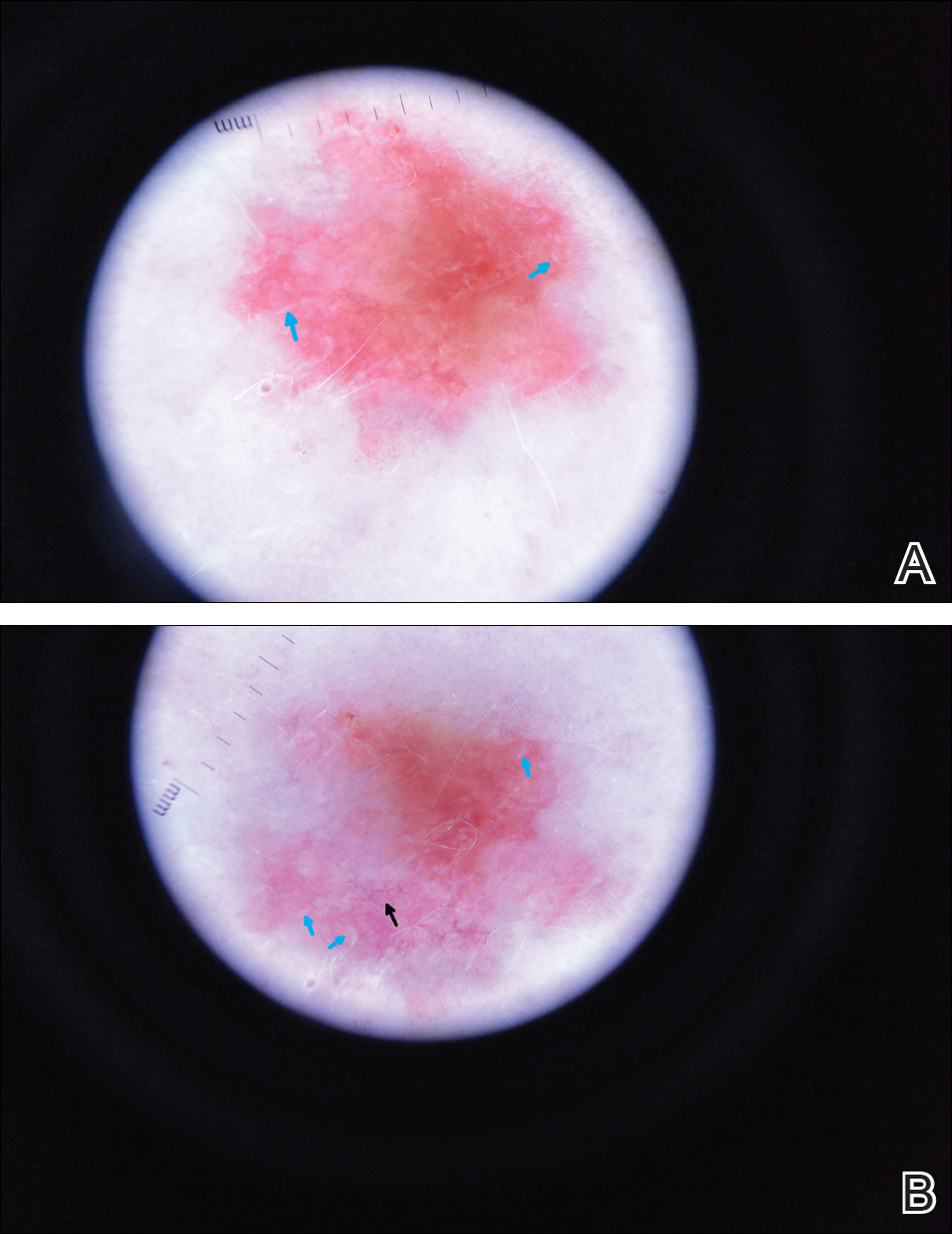

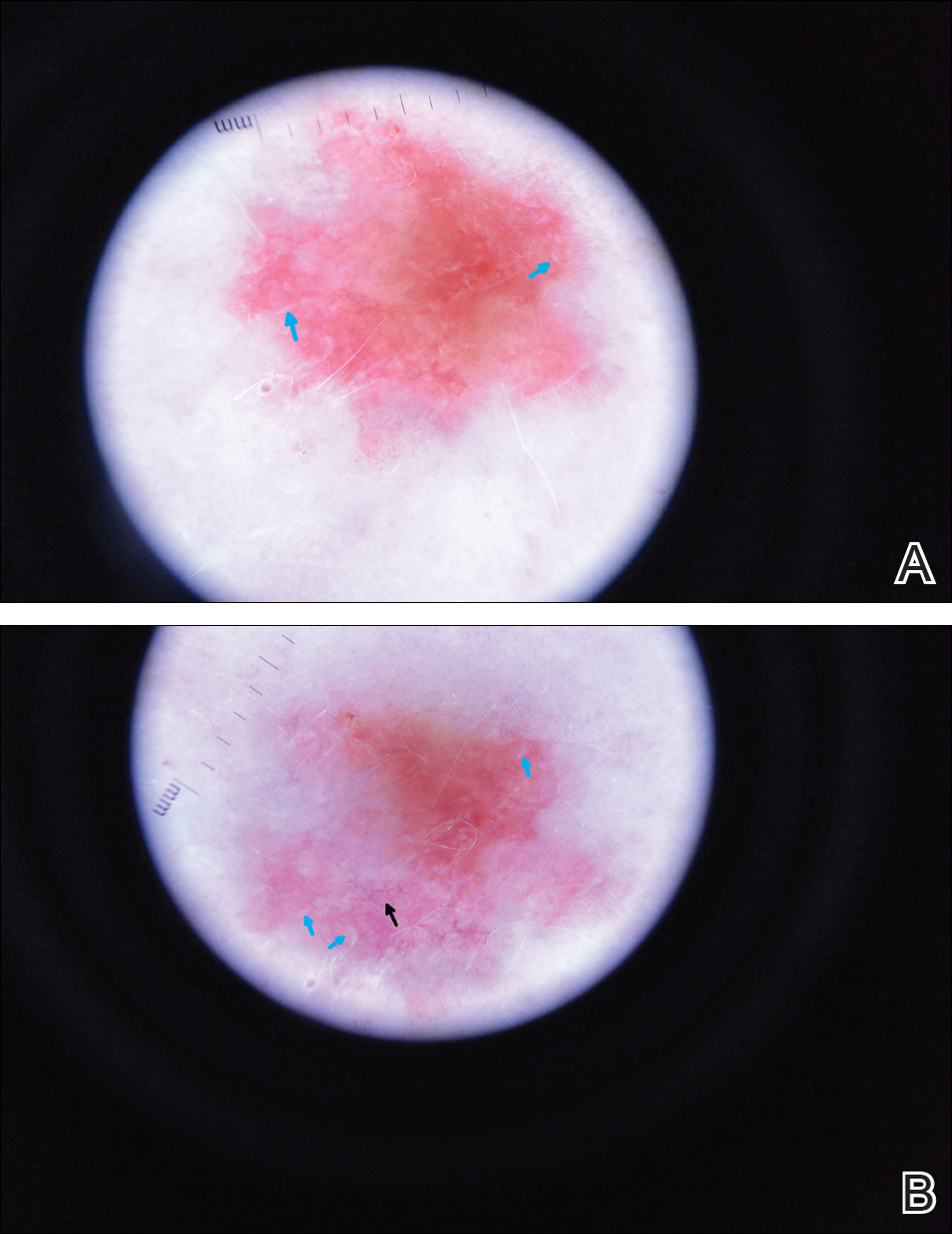

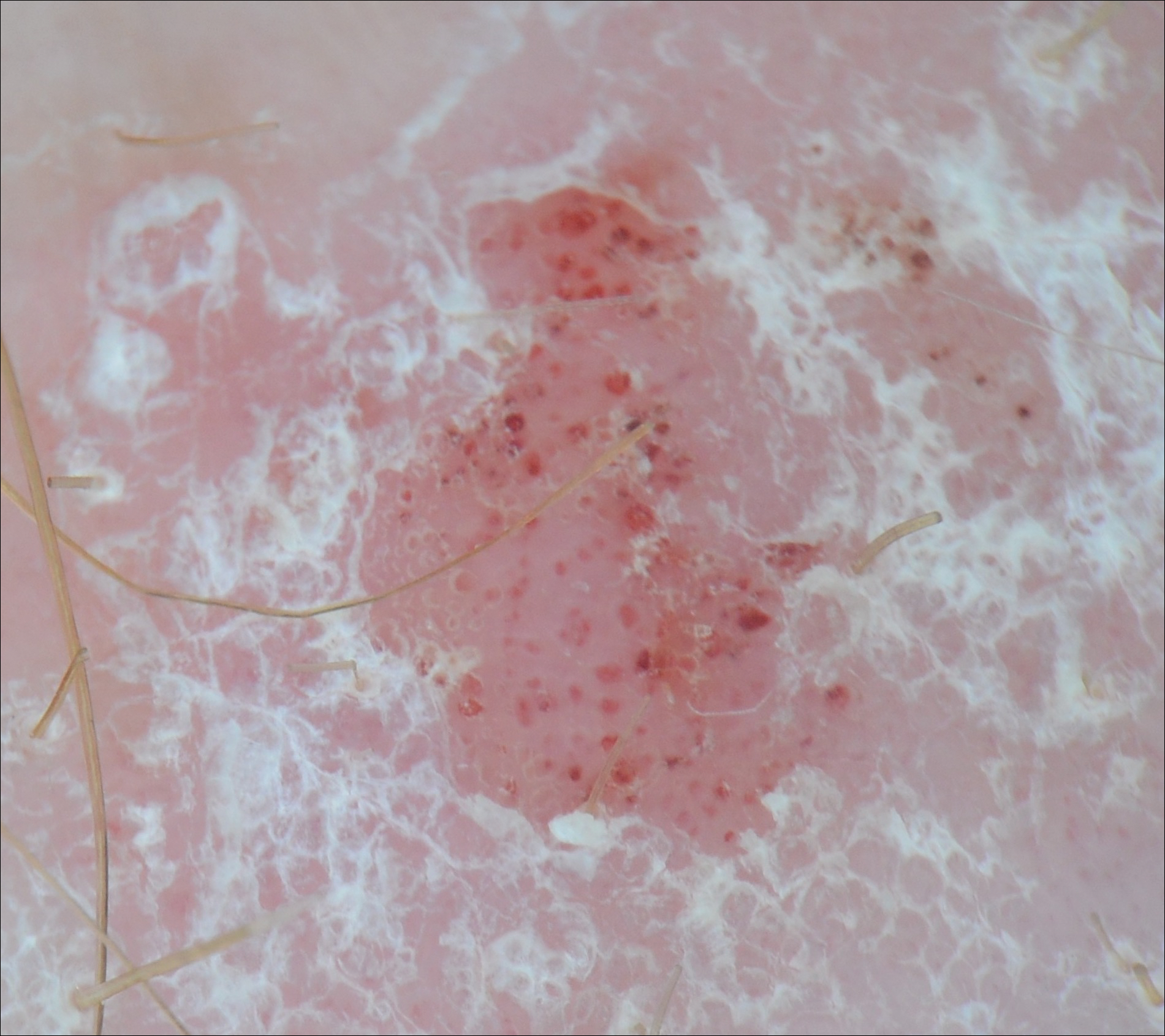

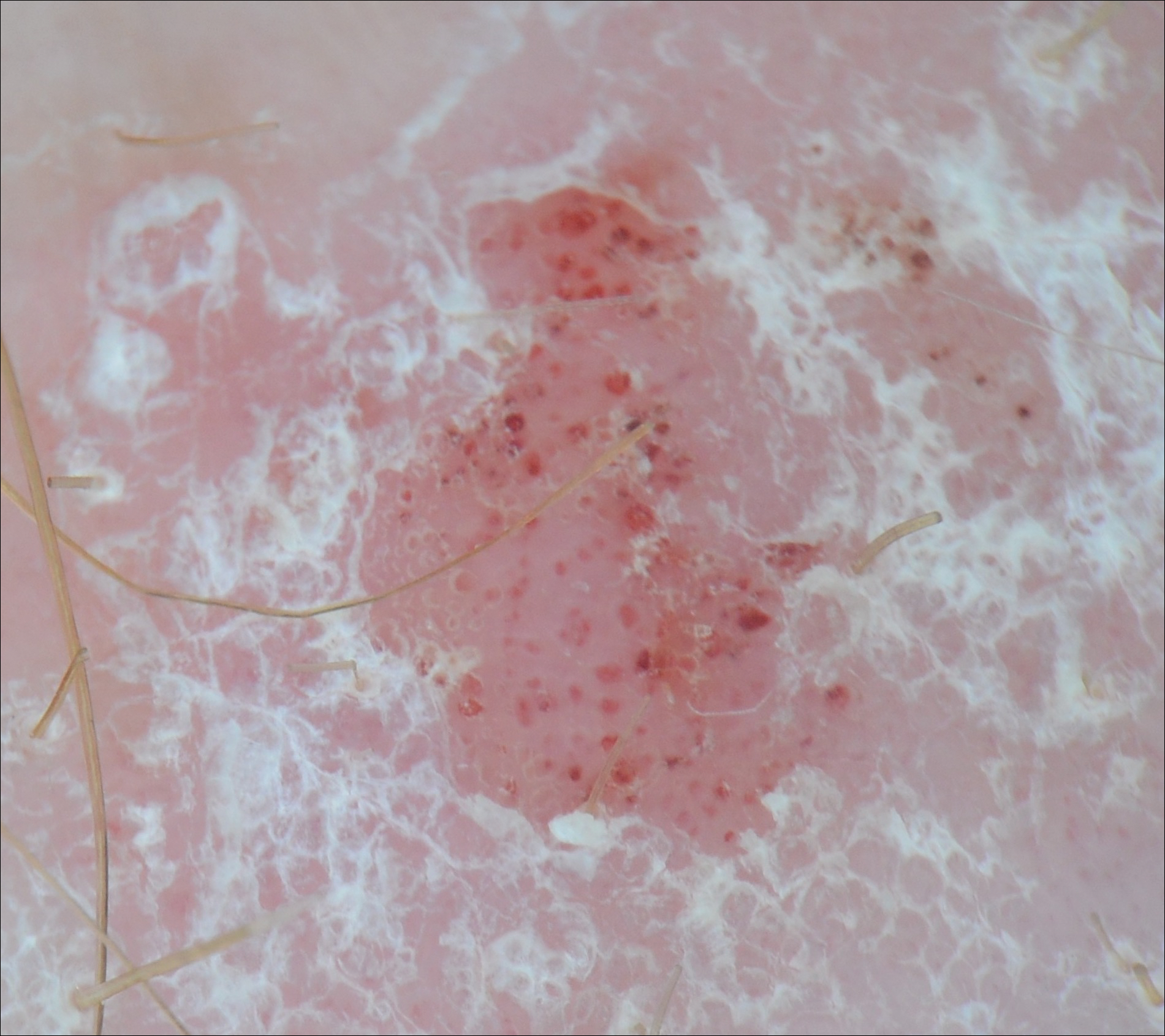

On physical examination a 0.6×0.7-cm, pink to erythematous, pearly papule with superficial telangiectases was noted on the right side of the dorsal thorax (Figure 1). Multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with silvery scale and areas of secondary excoriation were noted on the trunk and both legs consistent with the patient’s history of psoriasis.

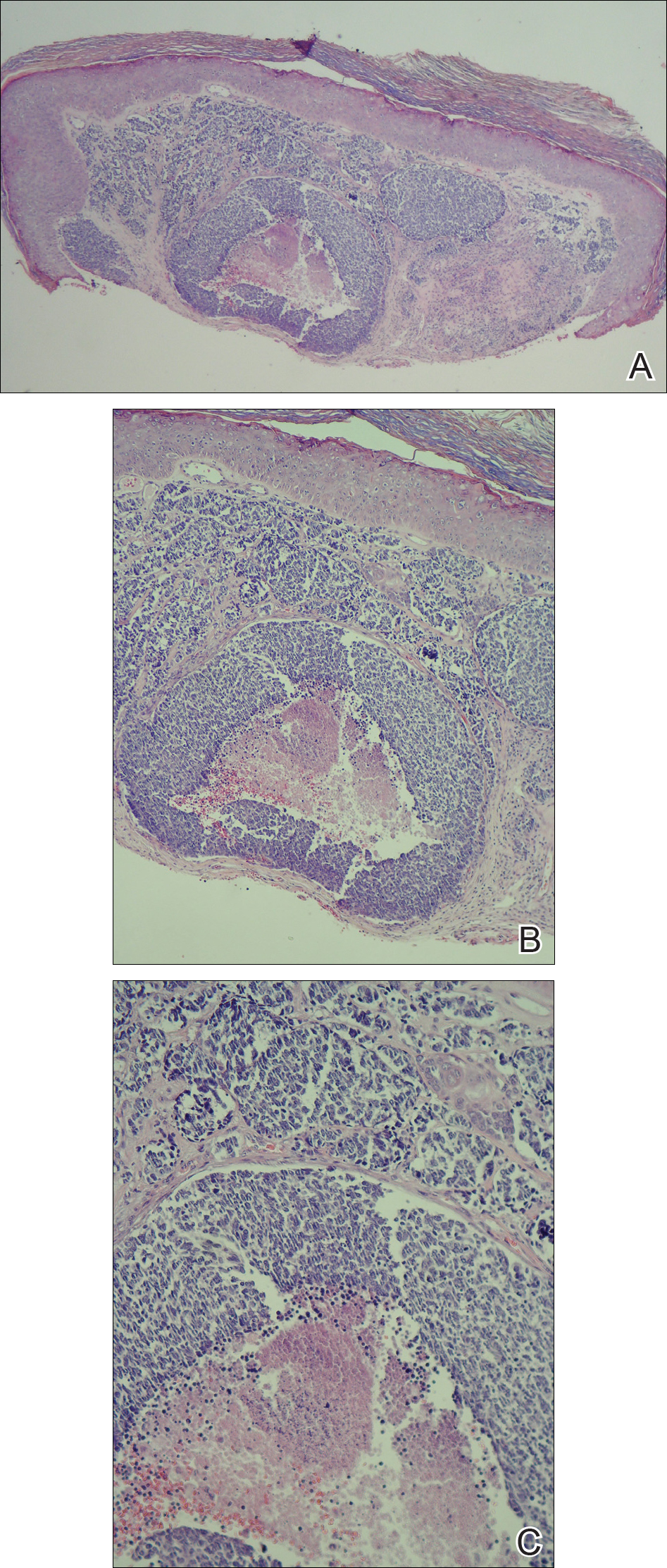

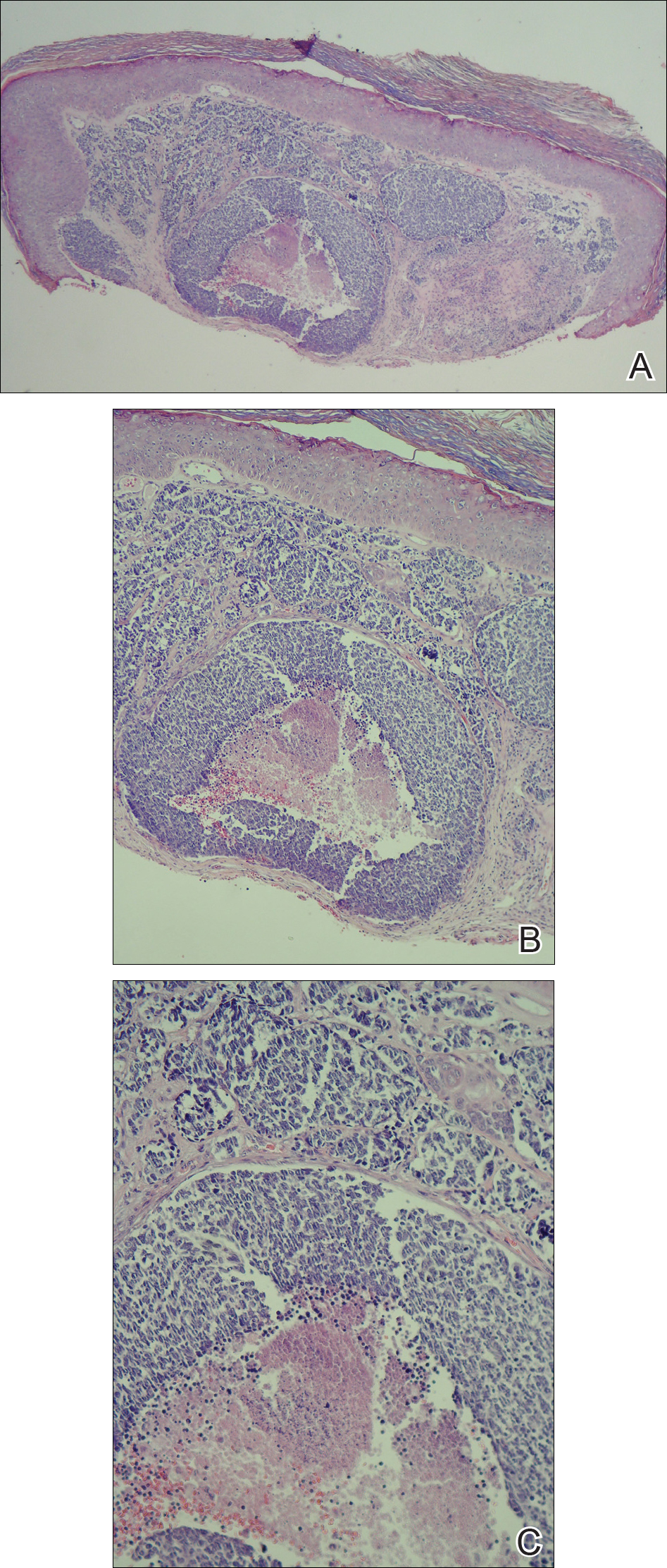

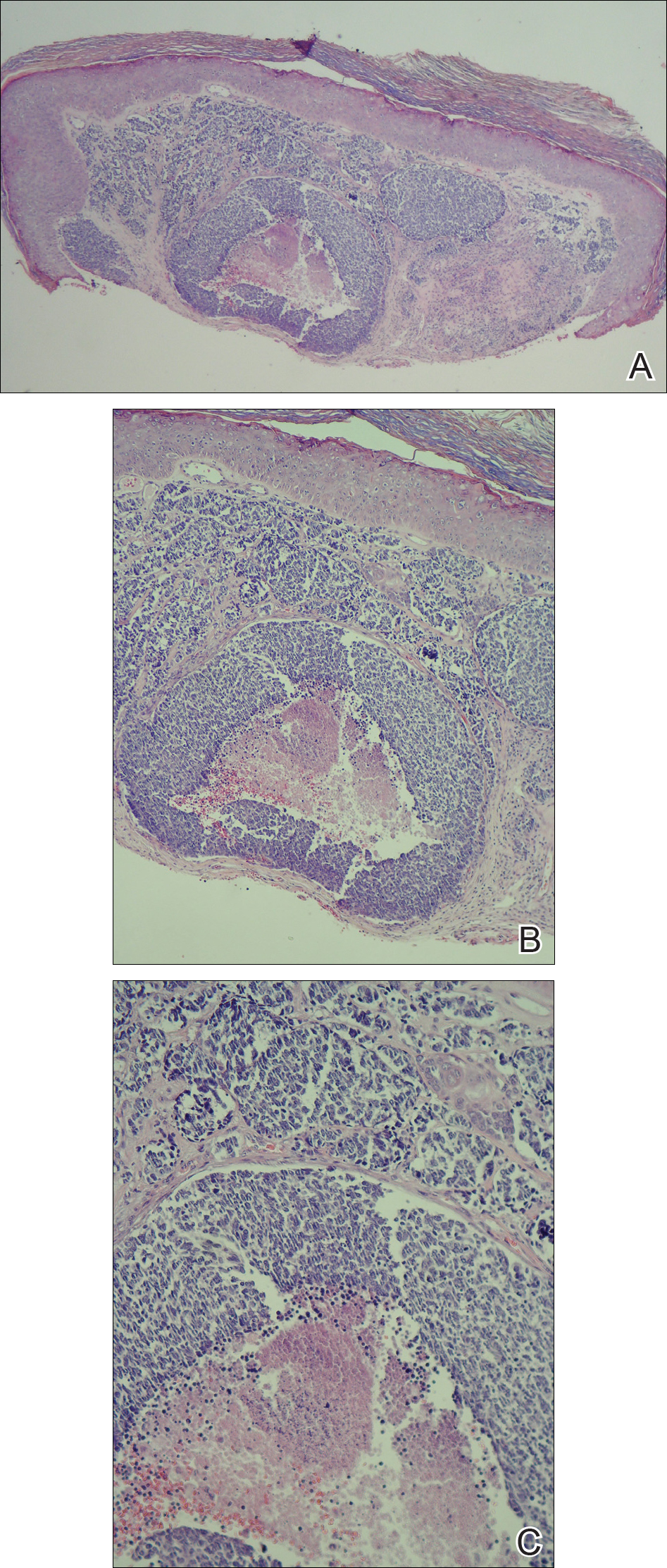

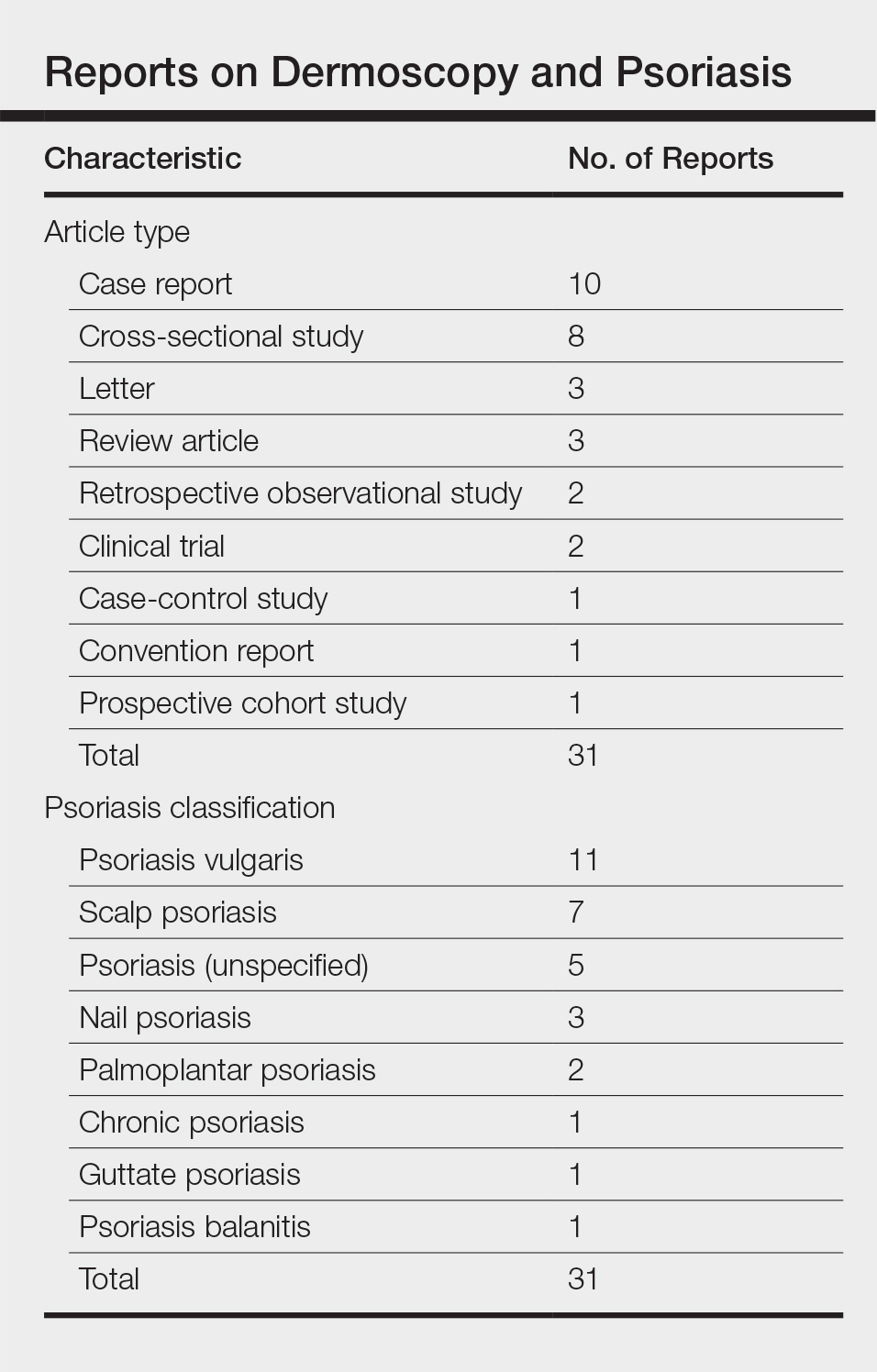

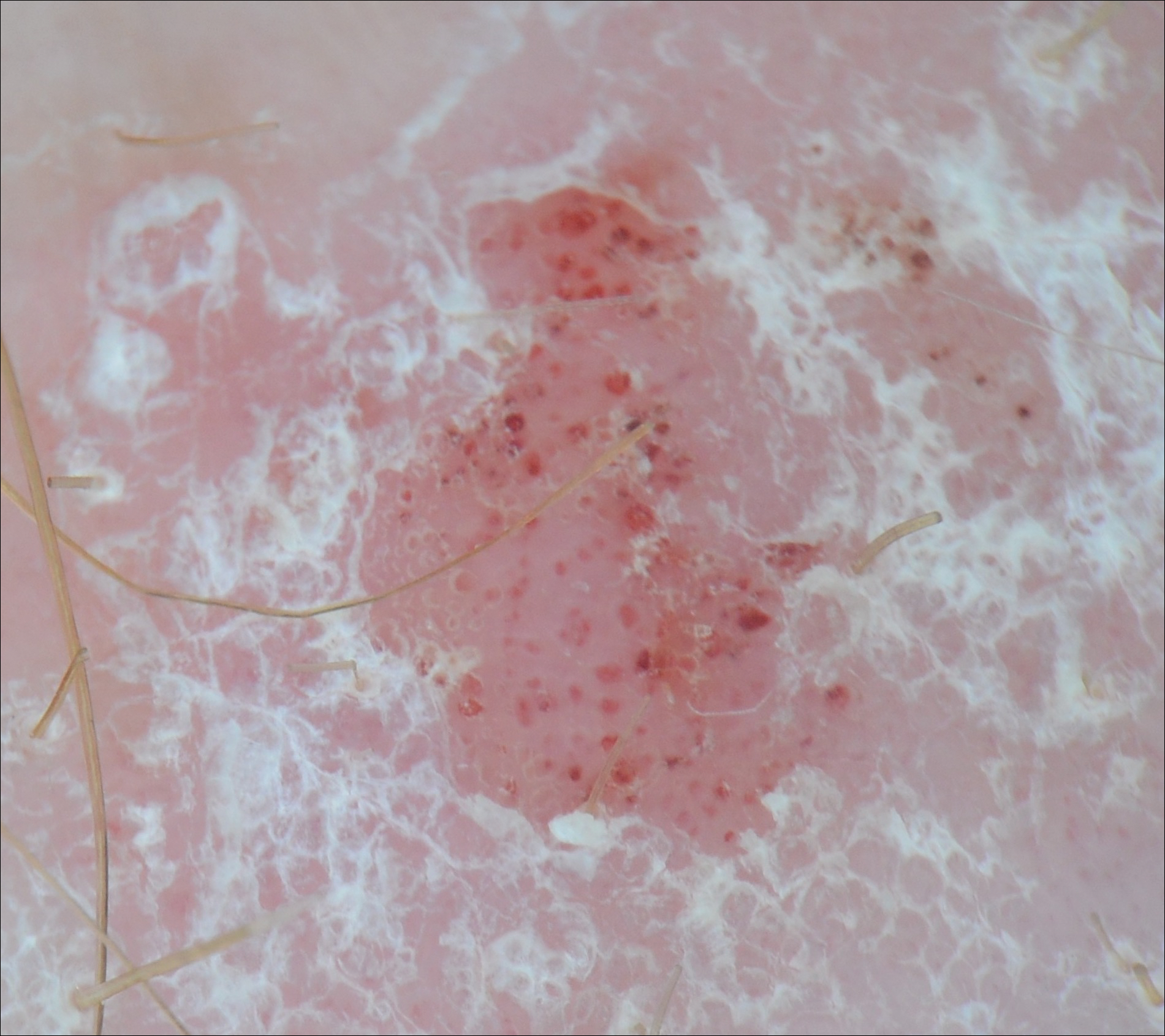

A shave biopsy was performed on the skin lesion on the right side of the dorsal thorax with a suspected clinical diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. Two weeks later the patient returned for a discussion of the pathology report, which revealed nodules of basaloid cells with tightly packed vesicular nuclei and scant cytoplasm in sheets within the superficial dermis, as well as areas of nuclear molding, numerous mitotic figures, and areas of focal necrosis (Figure 2). In addition, immunostaining was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 20 antibodies with a characteristic paranuclear dot uptake of the antibody. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). At that time, alefacept was discontinued and he was referred to a tertiary referral center for further evaluation and treatment.

The patient subsequently underwent wide excision with 1-cm margins of the MCC, with intraoperative lymphatic mapping/sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) of the right axillary nodal basin 1 month later, which he tolerated well without any associated complications. Further histopathologic examination revealed the deep, medial, and lateral surgical margins to be negative of residual neoplasm. However, one sentinel lymph node indicated positivity for micrometastatic MCC, consistent with stage IIIA disease progression.

He underwent a second procedure the following month for complete right axillary lymph node dissection. Histopathologic examination of the right axillary contents included 28 lymph nodes, which were negative for carcinoma. He continued to do well without any signs of clinical recurrence or distant metastasis at subsequent follow-up visits.

Approximately 2.5 years after the second procedure, the patient began to develop right upper quadrant abdominal pain of an unclear etiology. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, revealing areas of calcification and findings consistent with malignant lymphadenopathy. Multiple hepatic lesions also were noted including a 9-cm lesion in the posterior right hepatic lobe. Computed tomography–guided biopsy of the liver lesion was performed and the findings were consistent with metastatic MCC, indicating progression to stage IV disease.

The patient was subsequently started on combination chemotherapeutic treatment with carboplatin and VP-16, with a planned treatment course of 4 to 6 cycles. He was able to complete a total of 6 cycles over a 4-month period, tolerating the treatment regimen fairly well. Follow-up positron emission tomography–computed tomography was within normal limits with no evidence of any hypermetabolic activity noted, indicating a complete radiographic remission of MCC. He was seen approximately 1 month after completion of treatment for clinical follow-up and monthly thereafter.

While on chemotherapy, the patient experienced a notable improvement in the psoriasis and psoriatic joint disease. Upon completion of chemotherapy, he was restarted on the same treatment plan that was utilized prior to surgery including topical corticosteroids, calcitriol, intramuscular steroid injections, and UVB phototherapy, which provided substantial control of psoriasis and arthritic joint disease. The patient later died, likely due to his multiple comorbidities.

Merkel cells are slow-responding mechanoreceptors located within the basal layer of the epidermis and are the source of a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy.1 Merkel cell carcinoma was first noted in 1972 and termed trabecular carcinoma of the skin, and it accounts for less than 1% of all nonmelanoma skin cancer.2,3 This primary neuroendocrine carcinoma has remarkable metastatic potential (34%–75%) and can invade regional lymph nodes, as well as distant metastasis most commonly to the liver, lungs, bones, and brain.2 Approximately 25% of patients present with palpable lymphadenopathy and 5% with distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. This frequency of metastasis at diagnosis as well as the recurrence after treatment contributes to the poor prognosis of MCC. Local recurrence rates have been reported at 25% with lymph node involvement in 52% and metastasis in 34%, with most recurrences occurring within 2 years of diagnosis. Patient mortality is dependent on the aggressiveness of the tumor, with 5-year survival rates of 83.3% without lymph node involvement, 58.3% with lymph node involvement, and 31.3% in those with metastatic disease.4

The tumor classically presents as a red to violaceous, painless nodule with a smooth shiny surface most often on the head and neck region.4-6 Approximately 50% of MCC cases present in the head and neck region, 32% to 38% on the extremities, and 12% to 14% on the trunk.1 This nonspecific presentation may lead to diagnostic uncertainty and a consequent delay in treatment. Definitive diagnosis of MCC is achieved with a skin biopsy and allows for distinction from other clinically similar–appearing neoplasms. Merkel cell carcinoma presents histologically as small round basophilic cells penetrating through the dermis in 3 histologic patterns: the trabecular, intermediate (80% of cases), and small cell type.5 It may be differentiated immunohistochemically from other neoplasms, as it displays CK20 positivity (showing paranuclear dotlike depositions in the cytoplasm or cell membrane) and is negative for CK7. Chromagranin and synaptophysin positivity also may provide further histologic confirmation. In addition, absence of peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a fibromyxoid stroma allow for distinction from cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, which may display these features histologically. Other immunohistochemical markers that may be of value include thyroid transcription factor 1, which is typically positive in cutaneous metastasis of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung; S-100 and human melanoma black 45, which are positive in melanoma; and leukocyte common antigen (CD45), which can be positive in lymphoma. These stains are classically negative in MCC.3

Merkel cell carcinoma is commonly associated with the presence of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in tumor specimens, with a prevalence of 70% to 80% in all cases. Merkel cell polyomavirus is a class 2A carcinogen (ie, a probable carcinogen to humans) and is classified among a group of viruses that encode T antigens (ie, an antigen coded by a viral genome associated with transformation of infected cells by tumor viruses), which can lead to initiation of tumorigenesis through interference with cellular tumor suppressing proteins such as p53.5 In addition, several risk factors have been associated with the development of MCC including immunosuppression, older age (>50 years), and UV-exposed fair skin.7 One explanation for this phenomenon is the increase in MCPyV small T antigen transcripts induced by UV irradiation.5 In addition, as with other cancers induced by viruses, host immunity can impede tumor progression and development. Therefore, impairment of normal immune function likely creates a higher risk for MCC development and potential for a worse prognosis.3Although the exact incidence of MCC in immunosuppressed patients appears unclear, chronic immunosuppressive therapy may play a notable role in the pathogenesis of the tumor.3

Although each of these factors was observed in our patient, it also was possible that his associated comorbidities further contributed to disease presentation. In particular, rheumatoid arthritis has been shown to carry an increased risk for the development of MCC.8 In addition, inflammatory monocytes infected with MCPyV, as evidenced in a patient with a history of chronic psoriasis prior to diagnosis of MCC, also may contribute to the pathogenesis of MCC by traveling to inflammatory skin lesions, such as those seen in psoriasis, releasing MCPyV locally and infecting Merkel cells.9 Although MCPyV testing was never performed in our patient, it certainly would be prudent as well as further studies determining the correlation of MCC to these disease processes.

Although regression is rare, multiple cases have documented spontaneous regression of MCC after biopsy of these lesions.4,6,10 The exact mechanism is unclear, but apoptosis induced by T-cell immunity is suspected to play a role. Programmed cell death 1 protein (PD-1)–positive cells play a role. The PD-1 receptor is an inhibitory receptor expressed by T cells and in approximately half of tumor-infiltrating cells in MCC. It was found that in a regressed case of MCC there was a notably lower percentage of PD-1 positivity compared to cases with no apparent regression, suggesting that PD-1–positive cells suppress tumor immunity to MCC and that significant reduction in these cells may induce clinical regression.10 Additional investigation would be beneficial to examine the relationship of this phenomenon to tumor regression.

Initial evaluation of these patients should include a meticulous clinical examination with an emphasis on detection of cutaneous, lymph node, and distant metastasis. Due to the risk of metastatic potential, regional lymph node ultrasonography and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis typically are recommended at baseline. Other imaging modalities may be warranted based on clinical findings.3 Treatment modalities include various approaches, with surgical excision of the primary tumor with more than 1-cm margin to the fascial plane being the primary modality for uncomplicated cases.1,3,7 In addition, SLNB also should be performed at the time of the procedure. In the case of a positive SLNB or suspected regional lymph node involvement upon initial examination, radical regional lymph node dissection also is recommended.3 Although some authorities advocate postsurgical radiation therapy to minimize the risk of local recurrence, there does not appear to be a clear benefit in survival rate.3,5 However, radiation treatment as monotherapy has been advocated in certain instances, particularly in cases of unresectable tumors or patients who are poor surgical candidates.5,7 Cases of distant metastasis (stage IV disease) may include management with surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy. Although none of these modalities have consistently shown to improve survival, there appears to be up to a 60% response with chemotherapy in these patients.3

Because MCC tends to affect an older population, often with other notable comorbidities, important considerations involving a treatment plan include the cost, side effects, and convenience for patients. The combination of carboplatin and VP-16 (etoposide) was utilized and tolerated well in our patient, and it has been successful in achieving complete radiologic and clinical remission of his metastatic disease. This combination appears to prolong survival in patients with distant metastasis, as compared to those patients not receiving chemotherapy.1 Our patient has since died, but in these high-risk patients, close clinical monitoring is essential to help optimize their prognosis.

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare aggressive cutaneous neoplasm that most commonly affects the elderly, immunosuppressed, and those with chronic UV sun damage. An association between the oncogenesis of MCC and infection with MCPyV has been documented, but other underlying diseases also may play a role in this process including rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Although these risk factors were associated with our patient, his history of chronic immunosuppressive therapy for treatment of his psoriasis and inflammatory joint disease likely played a role in the pathogenesis of the tumor and should be an important point of discussion with any patient requiring this type of long-term management for disease control. Our unique clinical case highlights a patient with substantial comorbidities who developed metastatic MCC and achieved complete clinical and radiologic remission after treatment with surgery and chemotherapy.

- Timmer FC, Klop WM, Relyveld GN, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: emphasizing the risk of undertreatment [published online March 11, 2015]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1243-1252.

- Açıkalın A, Paydas¸ S, Güleç ÜK, et al. A unique case of Merkel cell carcinoma with ovarian metastasis [published online December 1, 2014]. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:356-359.

- Samimi M, Gardair C, Nicol JT, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma: clinical and therapeutic perspectives [published online Dec 31, 2014]. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:347-358.

- Grandhaye M, Teixeira PG, Henrot P, et al. Focus on Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis and staging [published online January 30, 2015]. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:777-786.

- Chatzinasiou F, Papadavid E, Korkolopoulou P, et al. An unusual case of diffuse Merkel cell carcinoma successfully treated with low dose radiotherapy [published online May 14, 2015]. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:282-286.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature [published online November 13, 2014]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- Kitamura N, Tomita R, Yamamoto M, et al. Complete remission of Merkel cell carcinoma on the upper lip treated with radiation monotherapy and a literature review of Japanese cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:152.

- Lanoy E, Engels EA. Skin cancers associated with autoimmune conditions among elderly adults [published online June 15, 2010]. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:112-114.

- Mertz KD, Junt T, Schmid M, et al. Inflammatory monocytes are a reservoir for Merkel cell polyomavirus [published online December 17, 2009]. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:1146-1151.

- Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, Kabuto M, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma showing regression after biopsy: evaluation of programmed cell death 1-positive cells [published online February 24, 2015]. J Dermatol. 2015;42:496-499.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old white man presented with a skin lesion on the back of 1 to 2 weeks’ duration. The patient stated he was unaware of it, but his wife had recently noticed the new spot. He denied any bleeding, pain, pruritus, or other associated symptoms with the lesion. He also denied any prior treatment to the area. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for severe psoriasis involving more than 80% body surface area, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, coronary artery disease, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic keratoses. He had been on multiple treatment regimens over the last 20 years for control of psoriasis including topical corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA and UVB phototherapy, gold injections, acitretin, prednisone, efalizumab, ustekinumab, and alefacept upon evaluation of this new skin lesion. Utilization of immunosuppressive agents also provided an additional benefit of controlling the patient’s inflammatory arthritic disease.

On physical examination a 0.6×0.7-cm, pink to erythematous, pearly papule with superficial telangiectases was noted on the right side of the dorsal thorax (Figure 1). Multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with silvery scale and areas of secondary excoriation were noted on the trunk and both legs consistent with the patient’s history of psoriasis.

A shave biopsy was performed on the skin lesion on the right side of the dorsal thorax with a suspected clinical diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. Two weeks later the patient returned for a discussion of the pathology report, which revealed nodules of basaloid cells with tightly packed vesicular nuclei and scant cytoplasm in sheets within the superficial dermis, as well as areas of nuclear molding, numerous mitotic figures, and areas of focal necrosis (Figure 2). In addition, immunostaining was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 20 antibodies with a characteristic paranuclear dot uptake of the antibody. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). At that time, alefacept was discontinued and he was referred to a tertiary referral center for further evaluation and treatment.

The patient subsequently underwent wide excision with 1-cm margins of the MCC, with intraoperative lymphatic mapping/sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) of the right axillary nodal basin 1 month later, which he tolerated well without any associated complications. Further histopathologic examination revealed the deep, medial, and lateral surgical margins to be negative of residual neoplasm. However, one sentinel lymph node indicated positivity for micrometastatic MCC, consistent with stage IIIA disease progression.

He underwent a second procedure the following month for complete right axillary lymph node dissection. Histopathologic examination of the right axillary contents included 28 lymph nodes, which were negative for carcinoma. He continued to do well without any signs of clinical recurrence or distant metastasis at subsequent follow-up visits.

Approximately 2.5 years after the second procedure, the patient began to develop right upper quadrant abdominal pain of an unclear etiology. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, revealing areas of calcification and findings consistent with malignant lymphadenopathy. Multiple hepatic lesions also were noted including a 9-cm lesion in the posterior right hepatic lobe. Computed tomography–guided biopsy of the liver lesion was performed and the findings were consistent with metastatic MCC, indicating progression to stage IV disease.

The patient was subsequently started on combination chemotherapeutic treatment with carboplatin and VP-16, with a planned treatment course of 4 to 6 cycles. He was able to complete a total of 6 cycles over a 4-month period, tolerating the treatment regimen fairly well. Follow-up positron emission tomography–computed tomography was within normal limits with no evidence of any hypermetabolic activity noted, indicating a complete radiographic remission of MCC. He was seen approximately 1 month after completion of treatment for clinical follow-up and monthly thereafter.

While on chemotherapy, the patient experienced a notable improvement in the psoriasis and psoriatic joint disease. Upon completion of chemotherapy, he was restarted on the same treatment plan that was utilized prior to surgery including topical corticosteroids, calcitriol, intramuscular steroid injections, and UVB phototherapy, which provided substantial control of psoriasis and arthritic joint disease. The patient later died, likely due to his multiple comorbidities.

Merkel cells are slow-responding mechanoreceptors located within the basal layer of the epidermis and are the source of a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy.1 Merkel cell carcinoma was first noted in 1972 and termed trabecular carcinoma of the skin, and it accounts for less than 1% of all nonmelanoma skin cancer.2,3 This primary neuroendocrine carcinoma has remarkable metastatic potential (34%–75%) and can invade regional lymph nodes, as well as distant metastasis most commonly to the liver, lungs, bones, and brain.2 Approximately 25% of patients present with palpable lymphadenopathy and 5% with distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. This frequency of metastasis at diagnosis as well as the recurrence after treatment contributes to the poor prognosis of MCC. Local recurrence rates have been reported at 25% with lymph node involvement in 52% and metastasis in 34%, with most recurrences occurring within 2 years of diagnosis. Patient mortality is dependent on the aggressiveness of the tumor, with 5-year survival rates of 83.3% without lymph node involvement, 58.3% with lymph node involvement, and 31.3% in those with metastatic disease.4

The tumor classically presents as a red to violaceous, painless nodule with a smooth shiny surface most often on the head and neck region.4-6 Approximately 50% of MCC cases present in the head and neck region, 32% to 38% on the extremities, and 12% to 14% on the trunk.1 This nonspecific presentation may lead to diagnostic uncertainty and a consequent delay in treatment. Definitive diagnosis of MCC is achieved with a skin biopsy and allows for distinction from other clinically similar–appearing neoplasms. Merkel cell carcinoma presents histologically as small round basophilic cells penetrating through the dermis in 3 histologic patterns: the trabecular, intermediate (80% of cases), and small cell type.5 It may be differentiated immunohistochemically from other neoplasms, as it displays CK20 positivity (showing paranuclear dotlike depositions in the cytoplasm or cell membrane) and is negative for CK7. Chromagranin and synaptophysin positivity also may provide further histologic confirmation. In addition, absence of peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a fibromyxoid stroma allow for distinction from cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, which may display these features histologically. Other immunohistochemical markers that may be of value include thyroid transcription factor 1, which is typically positive in cutaneous metastasis of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung; S-100 and human melanoma black 45, which are positive in melanoma; and leukocyte common antigen (CD45), which can be positive in lymphoma. These stains are classically negative in MCC.3

Merkel cell carcinoma is commonly associated with the presence of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in tumor specimens, with a prevalence of 70% to 80% in all cases. Merkel cell polyomavirus is a class 2A carcinogen (ie, a probable carcinogen to humans) and is classified among a group of viruses that encode T antigens (ie, an antigen coded by a viral genome associated with transformation of infected cells by tumor viruses), which can lead to initiation of tumorigenesis through interference with cellular tumor suppressing proteins such as p53.5 In addition, several risk factors have been associated with the development of MCC including immunosuppression, older age (>50 years), and UV-exposed fair skin.7 One explanation for this phenomenon is the increase in MCPyV small T antigen transcripts induced by UV irradiation.5 In addition, as with other cancers induced by viruses, host immunity can impede tumor progression and development. Therefore, impairment of normal immune function likely creates a higher risk for MCC development and potential for a worse prognosis.3Although the exact incidence of MCC in immunosuppressed patients appears unclear, chronic immunosuppressive therapy may play a notable role in the pathogenesis of the tumor.3

Although each of these factors was observed in our patient, it also was possible that his associated comorbidities further contributed to disease presentation. In particular, rheumatoid arthritis has been shown to carry an increased risk for the development of MCC.8 In addition, inflammatory monocytes infected with MCPyV, as evidenced in a patient with a history of chronic psoriasis prior to diagnosis of MCC, also may contribute to the pathogenesis of MCC by traveling to inflammatory skin lesions, such as those seen in psoriasis, releasing MCPyV locally and infecting Merkel cells.9 Although MCPyV testing was never performed in our patient, it certainly would be prudent as well as further studies determining the correlation of MCC to these disease processes.

Although regression is rare, multiple cases have documented spontaneous regression of MCC after biopsy of these lesions.4,6,10 The exact mechanism is unclear, but apoptosis induced by T-cell immunity is suspected to play a role. Programmed cell death 1 protein (PD-1)–positive cells play a role. The PD-1 receptor is an inhibitory receptor expressed by T cells and in approximately half of tumor-infiltrating cells in MCC. It was found that in a regressed case of MCC there was a notably lower percentage of PD-1 positivity compared to cases with no apparent regression, suggesting that PD-1–positive cells suppress tumor immunity to MCC and that significant reduction in these cells may induce clinical regression.10 Additional investigation would be beneficial to examine the relationship of this phenomenon to tumor regression.

Initial evaluation of these patients should include a meticulous clinical examination with an emphasis on detection of cutaneous, lymph node, and distant metastasis. Due to the risk of metastatic potential, regional lymph node ultrasonography and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis typically are recommended at baseline. Other imaging modalities may be warranted based on clinical findings.3 Treatment modalities include various approaches, with surgical excision of the primary tumor with more than 1-cm margin to the fascial plane being the primary modality for uncomplicated cases.1,3,7 In addition, SLNB also should be performed at the time of the procedure. In the case of a positive SLNB or suspected regional lymph node involvement upon initial examination, radical regional lymph node dissection also is recommended.3 Although some authorities advocate postsurgical radiation therapy to minimize the risk of local recurrence, there does not appear to be a clear benefit in survival rate.3,5 However, radiation treatment as monotherapy has been advocated in certain instances, particularly in cases of unresectable tumors or patients who are poor surgical candidates.5,7 Cases of distant metastasis (stage IV disease) may include management with surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy. Although none of these modalities have consistently shown to improve survival, there appears to be up to a 60% response with chemotherapy in these patients.3

Because MCC tends to affect an older population, often with other notable comorbidities, important considerations involving a treatment plan include the cost, side effects, and convenience for patients. The combination of carboplatin and VP-16 (etoposide) was utilized and tolerated well in our patient, and it has been successful in achieving complete radiologic and clinical remission of his metastatic disease. This combination appears to prolong survival in patients with distant metastasis, as compared to those patients not receiving chemotherapy.1 Our patient has since died, but in these high-risk patients, close clinical monitoring is essential to help optimize their prognosis.

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare aggressive cutaneous neoplasm that most commonly affects the elderly, immunosuppressed, and those with chronic UV sun damage. An association between the oncogenesis of MCC and infection with MCPyV has been documented, but other underlying diseases also may play a role in this process including rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Although these risk factors were associated with our patient, his history of chronic immunosuppressive therapy for treatment of his psoriasis and inflammatory joint disease likely played a role in the pathogenesis of the tumor and should be an important point of discussion with any patient requiring this type of long-term management for disease control. Our unique clinical case highlights a patient with substantial comorbidities who developed metastatic MCC and achieved complete clinical and radiologic remission after treatment with surgery and chemotherapy.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old white man presented with a skin lesion on the back of 1 to 2 weeks’ duration. The patient stated he was unaware of it, but his wife had recently noticed the new spot. He denied any bleeding, pain, pruritus, or other associated symptoms with the lesion. He also denied any prior treatment to the area. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for severe psoriasis involving more than 80% body surface area, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, coronary artery disease, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic keratoses. He had been on multiple treatment regimens over the last 20 years for control of psoriasis including topical corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA and UVB phototherapy, gold injections, acitretin, prednisone, efalizumab, ustekinumab, and alefacept upon evaluation of this new skin lesion. Utilization of immunosuppressive agents also provided an additional benefit of controlling the patient’s inflammatory arthritic disease.

On physical examination a 0.6×0.7-cm, pink to erythematous, pearly papule with superficial telangiectases was noted on the right side of the dorsal thorax (Figure 1). Multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with silvery scale and areas of secondary excoriation were noted on the trunk and both legs consistent with the patient’s history of psoriasis.

A shave biopsy was performed on the skin lesion on the right side of the dorsal thorax with a suspected clinical diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. Two weeks later the patient returned for a discussion of the pathology report, which revealed nodules of basaloid cells with tightly packed vesicular nuclei and scant cytoplasm in sheets within the superficial dermis, as well as areas of nuclear molding, numerous mitotic figures, and areas of focal necrosis (Figure 2). In addition, immunostaining was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 20 antibodies with a characteristic paranuclear dot uptake of the antibody. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). At that time, alefacept was discontinued and he was referred to a tertiary referral center for further evaluation and treatment.

The patient subsequently underwent wide excision with 1-cm margins of the MCC, with intraoperative lymphatic mapping/sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) of the right axillary nodal basin 1 month later, which he tolerated well without any associated complications. Further histopathologic examination revealed the deep, medial, and lateral surgical margins to be negative of residual neoplasm. However, one sentinel lymph node indicated positivity for micrometastatic MCC, consistent with stage IIIA disease progression.

He underwent a second procedure the following month for complete right axillary lymph node dissection. Histopathologic examination of the right axillary contents included 28 lymph nodes, which were negative for carcinoma. He continued to do well without any signs of clinical recurrence or distant metastasis at subsequent follow-up visits.

Approximately 2.5 years after the second procedure, the patient began to develop right upper quadrant abdominal pain of an unclear etiology. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, revealing areas of calcification and findings consistent with malignant lymphadenopathy. Multiple hepatic lesions also were noted including a 9-cm lesion in the posterior right hepatic lobe. Computed tomography–guided biopsy of the liver lesion was performed and the findings were consistent with metastatic MCC, indicating progression to stage IV disease.

The patient was subsequently started on combination chemotherapeutic treatment with carboplatin and VP-16, with a planned treatment course of 4 to 6 cycles. He was able to complete a total of 6 cycles over a 4-month period, tolerating the treatment regimen fairly well. Follow-up positron emission tomography–computed tomography was within normal limits with no evidence of any hypermetabolic activity noted, indicating a complete radiographic remission of MCC. He was seen approximately 1 month after completion of treatment for clinical follow-up and monthly thereafter.

While on chemotherapy, the patient experienced a notable improvement in the psoriasis and psoriatic joint disease. Upon completion of chemotherapy, he was restarted on the same treatment plan that was utilized prior to surgery including topical corticosteroids, calcitriol, intramuscular steroid injections, and UVB phototherapy, which provided substantial control of psoriasis and arthritic joint disease. The patient later died, likely due to his multiple comorbidities.

Merkel cells are slow-responding mechanoreceptors located within the basal layer of the epidermis and are the source of a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy.1 Merkel cell carcinoma was first noted in 1972 and termed trabecular carcinoma of the skin, and it accounts for less than 1% of all nonmelanoma skin cancer.2,3 This primary neuroendocrine carcinoma has remarkable metastatic potential (34%–75%) and can invade regional lymph nodes, as well as distant metastasis most commonly to the liver, lungs, bones, and brain.2 Approximately 25% of patients present with palpable lymphadenopathy and 5% with distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. This frequency of metastasis at diagnosis as well as the recurrence after treatment contributes to the poor prognosis of MCC. Local recurrence rates have been reported at 25% with lymph node involvement in 52% and metastasis in 34%, with most recurrences occurring within 2 years of diagnosis. Patient mortality is dependent on the aggressiveness of the tumor, with 5-year survival rates of 83.3% without lymph node involvement, 58.3% with lymph node involvement, and 31.3% in those with metastatic disease.4

The tumor classically presents as a red to violaceous, painless nodule with a smooth shiny surface most often on the head and neck region.4-6 Approximately 50% of MCC cases present in the head and neck region, 32% to 38% on the extremities, and 12% to 14% on the trunk.1 This nonspecific presentation may lead to diagnostic uncertainty and a consequent delay in treatment. Definitive diagnosis of MCC is achieved with a skin biopsy and allows for distinction from other clinically similar–appearing neoplasms. Merkel cell carcinoma presents histologically as small round basophilic cells penetrating through the dermis in 3 histologic patterns: the trabecular, intermediate (80% of cases), and small cell type.5 It may be differentiated immunohistochemically from other neoplasms, as it displays CK20 positivity (showing paranuclear dotlike depositions in the cytoplasm or cell membrane) and is negative for CK7. Chromagranin and synaptophysin positivity also may provide further histologic confirmation. In addition, absence of peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a fibromyxoid stroma allow for distinction from cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, which may display these features histologically. Other immunohistochemical markers that may be of value include thyroid transcription factor 1, which is typically positive in cutaneous metastasis of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung; S-100 and human melanoma black 45, which are positive in melanoma; and leukocyte common antigen (CD45), which can be positive in lymphoma. These stains are classically negative in MCC.3

Merkel cell carcinoma is commonly associated with the presence of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in tumor specimens, with a prevalence of 70% to 80% in all cases. Merkel cell polyomavirus is a class 2A carcinogen (ie, a probable carcinogen to humans) and is classified among a group of viruses that encode T antigens (ie, an antigen coded by a viral genome associated with transformation of infected cells by tumor viruses), which can lead to initiation of tumorigenesis through interference with cellular tumor suppressing proteins such as p53.5 In addition, several risk factors have been associated with the development of MCC including immunosuppression, older age (>50 years), and UV-exposed fair skin.7 One explanation for this phenomenon is the increase in MCPyV small T antigen transcripts induced by UV irradiation.5 In addition, as with other cancers induced by viruses, host immunity can impede tumor progression and development. Therefore, impairment of normal immune function likely creates a higher risk for MCC development and potential for a worse prognosis.3Although the exact incidence of MCC in immunosuppressed patients appears unclear, chronic immunosuppressive therapy may play a notable role in the pathogenesis of the tumor.3

Although each of these factors was observed in our patient, it also was possible that his associated comorbidities further contributed to disease presentation. In particular, rheumatoid arthritis has been shown to carry an increased risk for the development of MCC.8 In addition, inflammatory monocytes infected with MCPyV, as evidenced in a patient with a history of chronic psoriasis prior to diagnosis of MCC, also may contribute to the pathogenesis of MCC by traveling to inflammatory skin lesions, such as those seen in psoriasis, releasing MCPyV locally and infecting Merkel cells.9 Although MCPyV testing was never performed in our patient, it certainly would be prudent as well as further studies determining the correlation of MCC to these disease processes.

Although regression is rare, multiple cases have documented spontaneous regression of MCC after biopsy of these lesions.4,6,10 The exact mechanism is unclear, but apoptosis induced by T-cell immunity is suspected to play a role. Programmed cell death 1 protein (PD-1)–positive cells play a role. The PD-1 receptor is an inhibitory receptor expressed by T cells and in approximately half of tumor-infiltrating cells in MCC. It was found that in a regressed case of MCC there was a notably lower percentage of PD-1 positivity compared to cases with no apparent regression, suggesting that PD-1–positive cells suppress tumor immunity to MCC and that significant reduction in these cells may induce clinical regression.10 Additional investigation would be beneficial to examine the relationship of this phenomenon to tumor regression.

Initial evaluation of these patients should include a meticulous clinical examination with an emphasis on detection of cutaneous, lymph node, and distant metastasis. Due to the risk of metastatic potential, regional lymph node ultrasonography and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis typically are recommended at baseline. Other imaging modalities may be warranted based on clinical findings.3 Treatment modalities include various approaches, with surgical excision of the primary tumor with more than 1-cm margin to the fascial plane being the primary modality for uncomplicated cases.1,3,7 In addition, SLNB also should be performed at the time of the procedure. In the case of a positive SLNB or suspected regional lymph node involvement upon initial examination, radical regional lymph node dissection also is recommended.3 Although some authorities advocate postsurgical radiation therapy to minimize the risk of local recurrence, there does not appear to be a clear benefit in survival rate.3,5 However, radiation treatment as monotherapy has been advocated in certain instances, particularly in cases of unresectable tumors or patients who are poor surgical candidates.5,7 Cases of distant metastasis (stage IV disease) may include management with surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy. Although none of these modalities have consistently shown to improve survival, there appears to be up to a 60% response with chemotherapy in these patients.3

Because MCC tends to affect an older population, often with other notable comorbidities, important considerations involving a treatment plan include the cost, side effects, and convenience for patients. The combination of carboplatin and VP-16 (etoposide) was utilized and tolerated well in our patient, and it has been successful in achieving complete radiologic and clinical remission of his metastatic disease. This combination appears to prolong survival in patients with distant metastasis, as compared to those patients not receiving chemotherapy.1 Our patient has since died, but in these high-risk patients, close clinical monitoring is essential to help optimize their prognosis.

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare aggressive cutaneous neoplasm that most commonly affects the elderly, immunosuppressed, and those with chronic UV sun damage. An association between the oncogenesis of MCC and infection with MCPyV has been documented, but other underlying diseases also may play a role in this process including rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Although these risk factors were associated with our patient, his history of chronic immunosuppressive therapy for treatment of his psoriasis and inflammatory joint disease likely played a role in the pathogenesis of the tumor and should be an important point of discussion with any patient requiring this type of long-term management for disease control. Our unique clinical case highlights a patient with substantial comorbidities who developed metastatic MCC and achieved complete clinical and radiologic remission after treatment with surgery and chemotherapy.

- Timmer FC, Klop WM, Relyveld GN, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: emphasizing the risk of undertreatment [published online March 11, 2015]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1243-1252.

- Açıkalın A, Paydas¸ S, Güleç ÜK, et al. A unique case of Merkel cell carcinoma with ovarian metastasis [published online December 1, 2014]. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:356-359.

- Samimi M, Gardair C, Nicol JT, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma: clinical and therapeutic perspectives [published online Dec 31, 2014]. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:347-358.

- Grandhaye M, Teixeira PG, Henrot P, et al. Focus on Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis and staging [published online January 30, 2015]. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:777-786.

- Chatzinasiou F, Papadavid E, Korkolopoulou P, et al. An unusual case of diffuse Merkel cell carcinoma successfully treated with low dose radiotherapy [published online May 14, 2015]. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:282-286.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature [published online November 13, 2014]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- Kitamura N, Tomita R, Yamamoto M, et al. Complete remission of Merkel cell carcinoma on the upper lip treated with radiation monotherapy and a literature review of Japanese cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:152.

- Lanoy E, Engels EA. Skin cancers associated with autoimmune conditions among elderly adults [published online June 15, 2010]. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:112-114.

- Mertz KD, Junt T, Schmid M, et al. Inflammatory monocytes are a reservoir for Merkel cell polyomavirus [published online December 17, 2009]. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:1146-1151.

- Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, Kabuto M, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma showing regression after biopsy: evaluation of programmed cell death 1-positive cells [published online February 24, 2015]. J Dermatol. 2015;42:496-499.

- Timmer FC, Klop WM, Relyveld GN, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: emphasizing the risk of undertreatment [published online March 11, 2015]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1243-1252.

- Açıkalın A, Paydas¸ S, Güleç ÜK, et al. A unique case of Merkel cell carcinoma with ovarian metastasis [published online December 1, 2014]. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:356-359.

- Samimi M, Gardair C, Nicol JT, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma: clinical and therapeutic perspectives [published online Dec 31, 2014]. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:347-358.

- Grandhaye M, Teixeira PG, Henrot P, et al. Focus on Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis and staging [published online January 30, 2015]. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:777-786.

- Chatzinasiou F, Papadavid E, Korkolopoulou P, et al. An unusual case of diffuse Merkel cell carcinoma successfully treated with low dose radiotherapy [published online May 14, 2015]. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:282-286.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature [published online November 13, 2014]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- Kitamura N, Tomita R, Yamamoto M, et al. Complete remission of Merkel cell carcinoma on the upper lip treated with radiation monotherapy and a literature review of Japanese cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:152.

- Lanoy E, Engels EA. Skin cancers associated with autoimmune conditions among elderly adults [published online June 15, 2010]. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:112-114.

- Mertz KD, Junt T, Schmid M, et al. Inflammatory monocytes are a reservoir for Merkel cell polyomavirus [published online December 17, 2009]. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:1146-1151.

- Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, Kabuto M, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma showing regression after biopsy: evaluation of programmed cell death 1-positive cells [published online February 24, 2015]. J Dermatol. 2015;42:496-499.

Practice Points

- Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) has remarkable metastatic potential.

- Initial evaluation of patients with MCC should include clinical examination to detect cutaneous, lymph node, and distant metastasis.

- Risk factors associated with the development of MCC include immunosuppression, older age, and UV-exposed fair skin.

Meta-analysis: Lifestyle changes improve psoriasis

GENEVA – according to a systematic review and meta-analysis presented by Ching-Chi Chi, MD, at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

A plausible mechanism of benefit exists for these findings: “Fat tissue is known to be an endocrine organ that produces inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor. Reduce the amount of fat tissue and you reduce inflammation,” explained Dr. Chi, professor of dermatology at Chang Gung University in Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Among the key findings in the meta-analysis: Participation in dietary interventions provided obese psoriasis patients with a 66% increased likelihood of achieving a PASI 75 response at week 24, compared with controls, with a number needed to treat of 3. These low-calorie diets were typically rigorous, the dermatologist noted. For example, one entailed a food intake of 1,000 kcal/day or less, while another restricted intake by 500 kcal/day less than a patient’s calculated resting energy expenditure.

Also, participants in the dietary intervention studies averaged a 14.4-point improvement from baseline in Dermatologic Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores at week 24 versus a 2.2-point improvement in controls. Researchers consider a 5-point or greater improvement in the DLQI clinically meaningful.

A combined diet and exercise program resulted in a 45% increased likelihood that obese psoriasis patients would achieve a PASI 50 response at week 16, with a number needed to treat of 7. There was a trend in the active treatment arm for higher PASI 75 and PASI 100 responses than in controls as well, but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The one randomized trial of a walking exercise program coupled with continuous health education demonstrated a significant reduction in the rate of psoriasis flares, compared with controls, over a 3-year period.

In contrast, the studies of educational programs promoting a healthy lifestyle without an associated dietary or physical activity intervention failed to show a reduction in PASI scores.

Dr. Chi reported no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, which was funded by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

SOURCE: Chi C. EADV 2017.

GENEVA – according to a systematic review and meta-analysis presented by Ching-Chi Chi, MD, at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

A plausible mechanism of benefit exists for these findings: “Fat tissue is known to be an endocrine organ that produces inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor. Reduce the amount of fat tissue and you reduce inflammation,” explained Dr. Chi, professor of dermatology at Chang Gung University in Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Among the key findings in the meta-analysis: Participation in dietary interventions provided obese psoriasis patients with a 66% increased likelihood of achieving a PASI 75 response at week 24, compared with controls, with a number needed to treat of 3. These low-calorie diets were typically rigorous, the dermatologist noted. For example, one entailed a food intake of 1,000 kcal/day or less, while another restricted intake by 500 kcal/day less than a patient’s calculated resting energy expenditure.

Also, participants in the dietary intervention studies averaged a 14.4-point improvement from baseline in Dermatologic Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores at week 24 versus a 2.2-point improvement in controls. Researchers consider a 5-point or greater improvement in the DLQI clinically meaningful.

A combined diet and exercise program resulted in a 45% increased likelihood that obese psoriasis patients would achieve a PASI 50 response at week 16, with a number needed to treat of 7. There was a trend in the active treatment arm for higher PASI 75 and PASI 100 responses than in controls as well, but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The one randomized trial of a walking exercise program coupled with continuous health education demonstrated a significant reduction in the rate of psoriasis flares, compared with controls, over a 3-year period.

In contrast, the studies of educational programs promoting a healthy lifestyle without an associated dietary or physical activity intervention failed to show a reduction in PASI scores.

Dr. Chi reported no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, which was funded by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

SOURCE: Chi C. EADV 2017.

GENEVA – according to a systematic review and meta-analysis presented by Ching-Chi Chi, MD, at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

A plausible mechanism of benefit exists for these findings: “Fat tissue is known to be an endocrine organ that produces inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor. Reduce the amount of fat tissue and you reduce inflammation,” explained Dr. Chi, professor of dermatology at Chang Gung University in Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Among the key findings in the meta-analysis: Participation in dietary interventions provided obese psoriasis patients with a 66% increased likelihood of achieving a PASI 75 response at week 24, compared with controls, with a number needed to treat of 3. These low-calorie diets were typically rigorous, the dermatologist noted. For example, one entailed a food intake of 1,000 kcal/day or less, while another restricted intake by 500 kcal/day less than a patient’s calculated resting energy expenditure.

Also, participants in the dietary intervention studies averaged a 14.4-point improvement from baseline in Dermatologic Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores at week 24 versus a 2.2-point improvement in controls. Researchers consider a 5-point or greater improvement in the DLQI clinically meaningful.

A combined diet and exercise program resulted in a 45% increased likelihood that obese psoriasis patients would achieve a PASI 50 response at week 16, with a number needed to treat of 7. There was a trend in the active treatment arm for higher PASI 75 and PASI 100 responses than in controls as well, but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The one randomized trial of a walking exercise program coupled with continuous health education demonstrated a significant reduction in the rate of psoriasis flares, compared with controls, over a 3-year period.

In contrast, the studies of educational programs promoting a healthy lifestyle without an associated dietary or physical activity intervention failed to show a reduction in PASI scores.

Dr. Chi reported no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, which was funded by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

SOURCE: Chi C. EADV 2017.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Weight loss and exercise reduce psoriasis severity.

Major finding: The number needed to treat with a calorie-restricted diet in order for one additional obese patient with psoriasis on systemic therapy to achieve a PASI 75 response is 3.

Study details: This meta-analysis included 10 randomized, controlled trials totaling 1,163 patients with psoriasis.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, funded by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Source: Chi C. EADV 2017.

Ixekizumab beats ustekinumab for fingernail psoriasis, hands down

GENEVA – Ixekizumab improved fingernail psoriasis significantly faster and with a higher complete nail clearance rate by week 24 compared with ustekinumab in a head-to-head phase 3b randomized trial, Yves Dutronc, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This is a clinically important finding because – as dermatologists and psoriasis patients well know – nail and skin psoriasis are two different animals.

He presented a prespecified secondary analysis of the randomized, phase 3b, multicenter IXORA-S trial. The study pit the interleukin-17A inhibitor ixekizumab (Taltz) head-to-head against the interleukin 12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab (Stelara). The primary endpoint, which was the PASI 90 improvement rate, has previously been reported: 73% in the ixekizumab group versus 42% in the ustekinumab group at week 12, and 83% versus 59% at week 24. And ixekizumab’s superior efficacy was achieved with a safety profile similar to that of ustekinumab (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:1014-23).

However, change in PASI score or Investigator’s Global Assessment isn’t informative regarding a patient’s change in nail psoriasis status. This was the impetus for the secondary analysis focused on the IXORA-S subgroup with baseline fingernail psoriasis. For this purpose, Dr. Dutronc and his coinvestigators used as their metric the change over time in the Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) total score, which entails a quadrant-by-quadrant assessment of every fingernail.

By play of chance, the 84 patients randomized to ixekizumab had slightly more severe nail psoriasis at baseline than that of the 105 ustekinumab patients. Their mean baseline NAPSI total score was 28.3, compared with 24.8 for the ustekinumab group. More than one-quarter of patients in the ixekizumab arm had a baseline NAPSI score greater than 43, whereas the top quartile of nail psoriasis severity in the ustekinumab group began with a NAPSI score above 34.

Not surprisingly, not much happened in terms of improvement in nail appearance in the first 12 weeks, since new nail grows slowly. But by week 8 the between-group difference in improvement in NAPSI score had become significant in favor of ixekizumab, with a mean 12.9-point reduction from baseline versus a 5.6-point drop in the ustekinumab group. This difference continued to grow over time, such that at week 24 the ixekizumab had a mean 19.9-point reduction, compared with a 13.2-point decrease for the ustekinumab group.

At week 12, 15.5% of the ixekizumab group and 11.3% of the ustekinumab group had reached complete clearance of their fingernail psoriasis. At week 24, complete clearance had been achieved in 48.8% of the ixekizumab group and 22.9% of patients on ustekinumab.

This is an interim analysis. Final results of the IXORA-S nail psoriasis substudy will be reported at 52 weeks of follow-up.

SOURCE: Dutronc Y. https://eadvgeneva2017.org/

GENEVA – Ixekizumab improved fingernail psoriasis significantly faster and with a higher complete nail clearance rate by week 24 compared with ustekinumab in a head-to-head phase 3b randomized trial, Yves Dutronc, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This is a clinically important finding because – as dermatologists and psoriasis patients well know – nail and skin psoriasis are two different animals.

He presented a prespecified secondary analysis of the randomized, phase 3b, multicenter IXORA-S trial. The study pit the interleukin-17A inhibitor ixekizumab (Taltz) head-to-head against the interleukin 12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab (Stelara). The primary endpoint, which was the PASI 90 improvement rate, has previously been reported: 73% in the ixekizumab group versus 42% in the ustekinumab group at week 12, and 83% versus 59% at week 24. And ixekizumab’s superior efficacy was achieved with a safety profile similar to that of ustekinumab (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:1014-23).

However, change in PASI score or Investigator’s Global Assessment isn’t informative regarding a patient’s change in nail psoriasis status. This was the impetus for the secondary analysis focused on the IXORA-S subgroup with baseline fingernail psoriasis. For this purpose, Dr. Dutronc and his coinvestigators used as their metric the change over time in the Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) total score, which entails a quadrant-by-quadrant assessment of every fingernail.

By play of chance, the 84 patients randomized to ixekizumab had slightly more severe nail psoriasis at baseline than that of the 105 ustekinumab patients. Their mean baseline NAPSI total score was 28.3, compared with 24.8 for the ustekinumab group. More than one-quarter of patients in the ixekizumab arm had a baseline NAPSI score greater than 43, whereas the top quartile of nail psoriasis severity in the ustekinumab group began with a NAPSI score above 34.

Not surprisingly, not much happened in terms of improvement in nail appearance in the first 12 weeks, since new nail grows slowly. But by week 8 the between-group difference in improvement in NAPSI score had become significant in favor of ixekizumab, with a mean 12.9-point reduction from baseline versus a 5.6-point drop in the ustekinumab group. This difference continued to grow over time, such that at week 24 the ixekizumab had a mean 19.9-point reduction, compared with a 13.2-point decrease for the ustekinumab group.

At week 12, 15.5% of the ixekizumab group and 11.3% of the ustekinumab group had reached complete clearance of their fingernail psoriasis. At week 24, complete clearance had been achieved in 48.8% of the ixekizumab group and 22.9% of patients on ustekinumab.

This is an interim analysis. Final results of the IXORA-S nail psoriasis substudy will be reported at 52 weeks of follow-up.

SOURCE: Dutronc Y. https://eadvgeneva2017.org/

GENEVA – Ixekizumab improved fingernail psoriasis significantly faster and with a higher complete nail clearance rate by week 24 compared with ustekinumab in a head-to-head phase 3b randomized trial, Yves Dutronc, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This is a clinically important finding because – as dermatologists and psoriasis patients well know – nail and skin psoriasis are two different animals.

He presented a prespecified secondary analysis of the randomized, phase 3b, multicenter IXORA-S trial. The study pit the interleukin-17A inhibitor ixekizumab (Taltz) head-to-head against the interleukin 12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab (Stelara). The primary endpoint, which was the PASI 90 improvement rate, has previously been reported: 73% in the ixekizumab group versus 42% in the ustekinumab group at week 12, and 83% versus 59% at week 24. And ixekizumab’s superior efficacy was achieved with a safety profile similar to that of ustekinumab (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:1014-23).

However, change in PASI score or Investigator’s Global Assessment isn’t informative regarding a patient’s change in nail psoriasis status. This was the impetus for the secondary analysis focused on the IXORA-S subgroup with baseline fingernail psoriasis. For this purpose, Dr. Dutronc and his coinvestigators used as their metric the change over time in the Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) total score, which entails a quadrant-by-quadrant assessment of every fingernail.

By play of chance, the 84 patients randomized to ixekizumab had slightly more severe nail psoriasis at baseline than that of the 105 ustekinumab patients. Their mean baseline NAPSI total score was 28.3, compared with 24.8 for the ustekinumab group. More than one-quarter of patients in the ixekizumab arm had a baseline NAPSI score greater than 43, whereas the top quartile of nail psoriasis severity in the ustekinumab group began with a NAPSI score above 34.

Not surprisingly, not much happened in terms of improvement in nail appearance in the first 12 weeks, since new nail grows slowly. But by week 8 the between-group difference in improvement in NAPSI score had become significant in favor of ixekizumab, with a mean 12.9-point reduction from baseline versus a 5.6-point drop in the ustekinumab group. This difference continued to grow over time, such that at week 24 the ixekizumab had a mean 19.9-point reduction, compared with a 13.2-point decrease for the ustekinumab group.

At week 12, 15.5% of the ixekizumab group and 11.3% of the ustekinumab group had reached complete clearance of their fingernail psoriasis. At week 24, complete clearance had been achieved in 48.8% of the ixekizumab group and 22.9% of patients on ustekinumab.

This is an interim analysis. Final results of the IXORA-S nail psoriasis substudy will be reported at 52 weeks of follow-up.

SOURCE: Dutronc Y. https://eadvgeneva2017.org/

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At week 24, complete clearance of fingernail psoriasis was documented in 49% of patients on ixekizumab and 23% on ustekinumab.

Study details: This secondary analysis of the randomized, multicenter, prospective, phase 3b IXORA-S trial included 189 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with fingernail involvement.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and presented by a company employee.

Source: Dutronc Y. https://eadvgeneva2017.org

Pearls in Dermatology: 2017

The Pearls in Dermatology collection consists of our popular pearls from the year in one convenient file. Topics include:

- Nail psoriasis and psoriasis on the hands and feet

- Genital wart treatment

- Isotretinoin for acne

- Cosmeceuticals for rosacea

- Surgical technique with the flexible scalpel blade

Editor’s Commentary provided by Vincent A. DeLeo, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Cutis.

Save this collection, print it, and/or share it with your colleagues. We hope this comprehensive collection will positively impact how you manage patients.

The Pearls in Dermatology collection consists of our popular pearls from the year in one convenient file. Topics include:

- Nail psoriasis and psoriasis on the hands and feet

- Genital wart treatment

- Isotretinoin for acne

- Cosmeceuticals for rosacea

- Surgical technique with the flexible scalpel blade

Editor’s Commentary provided by Vincent A. DeLeo, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Cutis.

Save this collection, print it, and/or share it with your colleagues. We hope this comprehensive collection will positively impact how you manage patients.

The Pearls in Dermatology collection consists of our popular pearls from the year in one convenient file. Topics include:

- Nail psoriasis and psoriasis on the hands and feet

- Genital wart treatment

- Isotretinoin for acne

- Cosmeceuticals for rosacea

- Surgical technique with the flexible scalpel blade

Editor’s Commentary provided by Vincent A. DeLeo, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Cutis.

Save this collection, print it, and/or share it with your colleagues. We hope this comprehensive collection will positively impact how you manage patients.

Mood changes reported in cases of methotrexate use for dermatologic disease

, said Trisha Bhat and Carrie C. Coughlin, MD, both of Washington University, St. Louis.

Neurotoxicity with low-dose methotrexate often has been described when used to treat rheumatologic disease, the investigators said, but not in the dermatologic literature – although CNS symptoms such as dizziness and headache have been described in both.

An 8-year-old girl with psoriasis vulgaris and no prior psychiatric history began weekly subcutaneous methotrexate 12.5 mg (0.23 mg/kg) with folic acid supplementation 6 days per week after failing topical therapy. Her parents noticed severe irritability right away and fluctuating mood changes over the next 2 months. At first, she was angry and unsettled, with depressed mood; her irritability became less frequent later, but she said she wanted to hurt someone else. After stopping methotrexate, her mood returned to normal within 2 weeks.

It is unclear how methotrexate affects mood, but recent evidence suggests that abnormalities in synaptic plasticity are involved in mood changes, and there is evidence that mice treated with methotrexate show changes in synaptic plasticity. Methotrexate also increases extracellular adenosine, which affects neuronal excitability and synaptic plasticity, Ms. Bhat and Dr. Coughlin observed. Methotrexate also affects glucose metabolism in rats, and regional metabolic disturbances occur in a number of psychiatric disorders.

Read more at Pediatric Dermatology (2018 Jan 9. doi: 10.1111/pde.13406).

, said Trisha Bhat and Carrie C. Coughlin, MD, both of Washington University, St. Louis.

Neurotoxicity with low-dose methotrexate often has been described when used to treat rheumatologic disease, the investigators said, but not in the dermatologic literature – although CNS symptoms such as dizziness and headache have been described in both.

An 8-year-old girl with psoriasis vulgaris and no prior psychiatric history began weekly subcutaneous methotrexate 12.5 mg (0.23 mg/kg) with folic acid supplementation 6 days per week after failing topical therapy. Her parents noticed severe irritability right away and fluctuating mood changes over the next 2 months. At first, she was angry and unsettled, with depressed mood; her irritability became less frequent later, but she said she wanted to hurt someone else. After stopping methotrexate, her mood returned to normal within 2 weeks.

It is unclear how methotrexate affects mood, but recent evidence suggests that abnormalities in synaptic plasticity are involved in mood changes, and there is evidence that mice treated with methotrexate show changes in synaptic plasticity. Methotrexate also increases extracellular adenosine, which affects neuronal excitability and synaptic plasticity, Ms. Bhat and Dr. Coughlin observed. Methotrexate also affects glucose metabolism in rats, and regional metabolic disturbances occur in a number of psychiatric disorders.

Read more at Pediatric Dermatology (2018 Jan 9. doi: 10.1111/pde.13406).

, said Trisha Bhat and Carrie C. Coughlin, MD, both of Washington University, St. Louis.

Neurotoxicity with low-dose methotrexate often has been described when used to treat rheumatologic disease, the investigators said, but not in the dermatologic literature – although CNS symptoms such as dizziness and headache have been described in both.

An 8-year-old girl with psoriasis vulgaris and no prior psychiatric history began weekly subcutaneous methotrexate 12.5 mg (0.23 mg/kg) with folic acid supplementation 6 days per week after failing topical therapy. Her parents noticed severe irritability right away and fluctuating mood changes over the next 2 months. At first, she was angry and unsettled, with depressed mood; her irritability became less frequent later, but she said she wanted to hurt someone else. After stopping methotrexate, her mood returned to normal within 2 weeks.

It is unclear how methotrexate affects mood, but recent evidence suggests that abnormalities in synaptic plasticity are involved in mood changes, and there is evidence that mice treated with methotrexate show changes in synaptic plasticity. Methotrexate also increases extracellular adenosine, which affects neuronal excitability and synaptic plasticity, Ms. Bhat and Dr. Coughlin observed. Methotrexate also affects glucose metabolism in rats, and regional metabolic disturbances occur in a number of psychiatric disorders.

Read more at Pediatric Dermatology (2018 Jan 9. doi: 10.1111/pde.13406).

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Prior biologic exposure doesn’t diminish ixekizumab’s efficacy

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

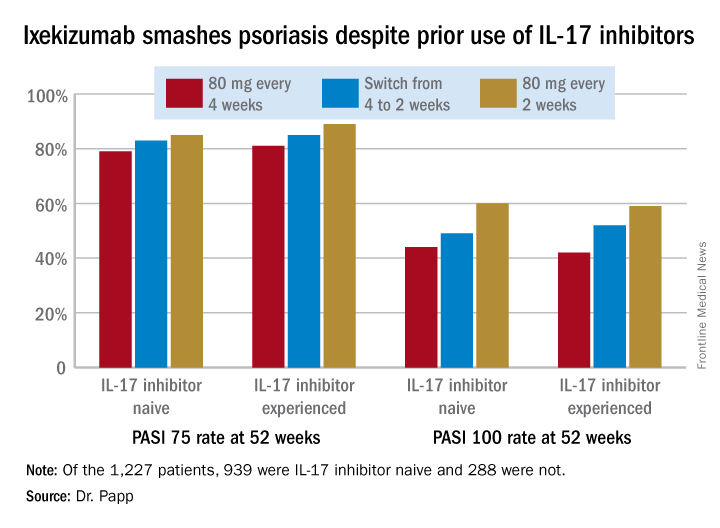

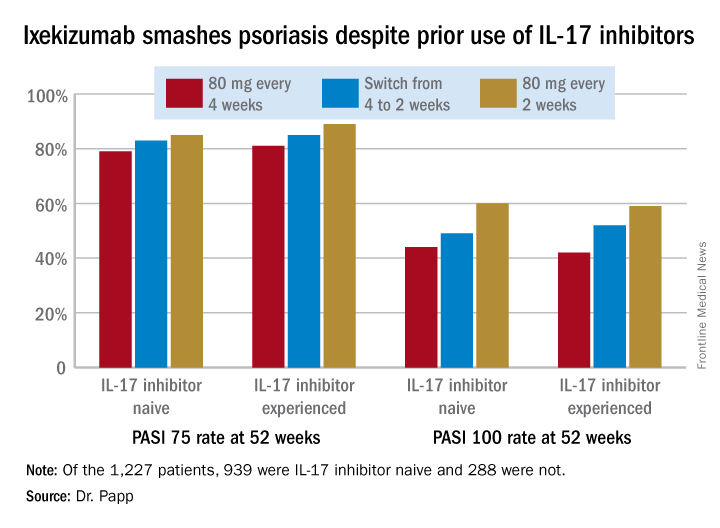

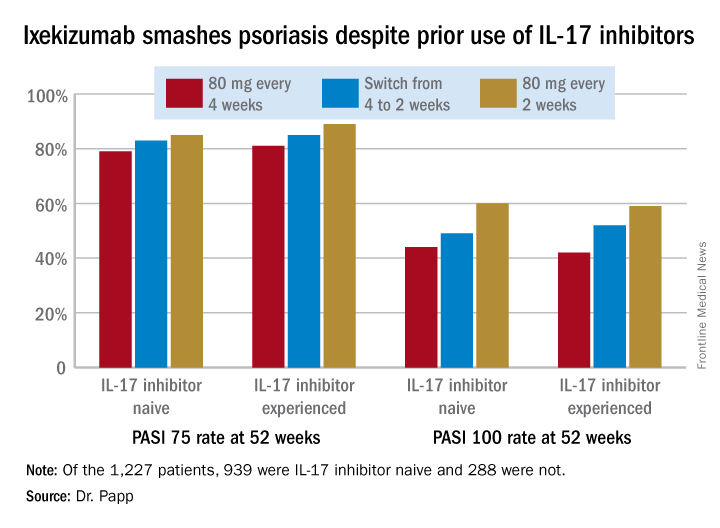

GENEVA – Psoriasis patients switched to ixekizumab after previous exposure to another interleukin-17 inhibitor respond as well as those who are IL-17 antagonist naive, Kim A. Papp, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This finding is of importance in real-world clinical practice because it’s not at all uncommon for psoriasis patients on one biologic to have to switch to another because of insufficient efficacy, side effects, or a change in insurance coverage. Physicians would like to know what sort of responses can be expected to whatever agent they prescribe next.

However, that was not a problem in this secondary analysis of a large clinical trial whose primary purpose was to evaluate the relative safety and efficacy of ixekizumab (Taltz) when dosed every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks.

“I think what we have seen here is a very compelling story: , nor for that matter does it appear to impact safety,” the dermatologist said.

He reported on 1,227 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who were randomized to ixekizumab at 80 mg every 2 or 4 weeks following an initial 160 mg loading dose. Among those who started out on ixekizumab every 4 weeks, 306 patients got a per-protocol dose adjustment to biweekly therapy because of an insufficient response to monthly dosing as defined by a Physician’s Global Assessment score of 2 or more on two consecutive office visits during study weeks 12-40.

A total of 939 patients were IL-17 inhibitor naive. The other 288 had previously been on the IL-17 antagonists brodalumab (Siliq) or secukinumab (Cosentyx). The two groups had similar baseline demographics with the exception that the experienced cohort had on average a 22.2-year duration of psoriasis, 3.7 years more than IL-17 antagonist-naive patients.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75, 90, and 100 responses at week 52 didn’t differ significantly between the IL-17 inhibitor-naive and -experienced groups. In fact, patients with prior exposure to other IL-17 antagonists showed a consistent trend for slightly higher response rates (see graphic).

It was clear from this analysis that dosing ixekizumab every 2 weeks provides significantly better efficacy than was dosing every 4 weeks, Dr. Papp noted. Yet the approved dosing is 160 mg at week 0, followed by 80 mg at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12, then 80 mg every 4 weeks.

No new safety issues arose in this study. The only difference between the naive and experienced groups was a lower rate of allergic reactions/hypersensitivity in the experienced group. For example, in patients on ixekizumab every 2 weeks for the entire 52-week study period the incidence of such reactions was 11.5% in the IL-17 antagonist-naive group, compared with 4.1% in the experienced cohort. This isn’t really surprising, according to Dr. Papp.

“Most injection site reactions occur in the newbies,” he said.

The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Papp serves as a consultant and/or adviser to Lilly and numerous other pharmaceutical companies involved in the development of dermatologic therapies.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

GENEVA – Psoriasis patients switched to ixekizumab after previous exposure to another interleukin-17 inhibitor respond as well as those who are IL-17 antagonist naive, Kim A. Papp, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This finding is of importance in real-world clinical practice because it’s not at all uncommon for psoriasis patients on one biologic to have to switch to another because of insufficient efficacy, side effects, or a change in insurance coverage. Physicians would like to know what sort of responses can be expected to whatever agent they prescribe next.

However, that was not a problem in this secondary analysis of a large clinical trial whose primary purpose was to evaluate the relative safety and efficacy of ixekizumab (Taltz) when dosed every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks.

“I think what we have seen here is a very compelling story: , nor for that matter does it appear to impact safety,” the dermatologist said.

He reported on 1,227 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who were randomized to ixekizumab at 80 mg every 2 or 4 weeks following an initial 160 mg loading dose. Among those who started out on ixekizumab every 4 weeks, 306 patients got a per-protocol dose adjustment to biweekly therapy because of an insufficient response to monthly dosing as defined by a Physician’s Global Assessment score of 2 or more on two consecutive office visits during study weeks 12-40.

A total of 939 patients were IL-17 inhibitor naive. The other 288 had previously been on the IL-17 antagonists brodalumab (Siliq) or secukinumab (Cosentyx). The two groups had similar baseline demographics with the exception that the experienced cohort had on average a 22.2-year duration of psoriasis, 3.7 years more than IL-17 antagonist-naive patients.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75, 90, and 100 responses at week 52 didn’t differ significantly between the IL-17 inhibitor-naive and -experienced groups. In fact, patients with prior exposure to other IL-17 antagonists showed a consistent trend for slightly higher response rates (see graphic).

It was clear from this analysis that dosing ixekizumab every 2 weeks provides significantly better efficacy than was dosing every 4 weeks, Dr. Papp noted. Yet the approved dosing is 160 mg at week 0, followed by 80 mg at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12, then 80 mg every 4 weeks.

No new safety issues arose in this study. The only difference between the naive and experienced groups was a lower rate of allergic reactions/hypersensitivity in the experienced group. For example, in patients on ixekizumab every 2 weeks for the entire 52-week study period the incidence of such reactions was 11.5% in the IL-17 antagonist-naive group, compared with 4.1% in the experienced cohort. This isn’t really surprising, according to Dr. Papp.

“Most injection site reactions occur in the newbies,” he said.

The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Papp serves as a consultant and/or adviser to Lilly and numerous other pharmaceutical companies involved in the development of dermatologic therapies.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

GENEVA – Psoriasis patients switched to ixekizumab after previous exposure to another interleukin-17 inhibitor respond as well as those who are IL-17 antagonist naive, Kim A. Papp, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This finding is of importance in real-world clinical practice because it’s not at all uncommon for psoriasis patients on one biologic to have to switch to another because of insufficient efficacy, side effects, or a change in insurance coverage. Physicians would like to know what sort of responses can be expected to whatever agent they prescribe next.

However, that was not a problem in this secondary analysis of a large clinical trial whose primary purpose was to evaluate the relative safety and efficacy of ixekizumab (Taltz) when dosed every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks.

“I think what we have seen here is a very compelling story: , nor for that matter does it appear to impact safety,” the dermatologist said.

He reported on 1,227 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who were randomized to ixekizumab at 80 mg every 2 or 4 weeks following an initial 160 mg loading dose. Among those who started out on ixekizumab every 4 weeks, 306 patients got a per-protocol dose adjustment to biweekly therapy because of an insufficient response to monthly dosing as defined by a Physician’s Global Assessment score of 2 or more on two consecutive office visits during study weeks 12-40.

A total of 939 patients were IL-17 inhibitor naive. The other 288 had previously been on the IL-17 antagonists brodalumab (Siliq) or secukinumab (Cosentyx). The two groups had similar baseline demographics with the exception that the experienced cohort had on average a 22.2-year duration of psoriasis, 3.7 years more than IL-17 antagonist-naive patients.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75, 90, and 100 responses at week 52 didn’t differ significantly between the IL-17 inhibitor-naive and -experienced groups. In fact, patients with prior exposure to other IL-17 antagonists showed a consistent trend for slightly higher response rates (see graphic).

It was clear from this analysis that dosing ixekizumab every 2 weeks provides significantly better efficacy than was dosing every 4 weeks, Dr. Papp noted. Yet the approved dosing is 160 mg at week 0, followed by 80 mg at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12, then 80 mg every 4 weeks.

No new safety issues arose in this study. The only difference between the naive and experienced groups was a lower rate of allergic reactions/hypersensitivity in the experienced group. For example, in patients on ixekizumab every 2 weeks for the entire 52-week study period the incidence of such reactions was 11.5% in the IL-17 antagonist-naive group, compared with 4.1% in the experienced cohort. This isn’t really surprising, according to Dr. Papp.

“Most injection site reactions occur in the newbies,” he said.

The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Papp serves as a consultant and/or adviser to Lilly and numerous other pharmaceutical companies involved in the development of dermatologic therapies.

Scaly Pink Patches: Differentiating Psoriasis From Basal Cell Carcinoma