User login

Biologics gaining traction in children with moderate to severe psoriasis

SAN DIEGO – Systemic therapies are increasingly being used for children with moderate to severe psoriasis; methotrexate is still the mainstay of systemic treatment, but biologics appear to achieve superior results with fewer side effects, Amy S. Paller, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Etanercept was approved in 2016 for children ages 6 and up, and ustekinumab was approved for use in patients aged 12 years or older in October 2017. Ongoing trials are examining adalimumab, apremilast, ustekinumab, and ixekizumab for use in adolescents and younger children. Trials are also being planned for other therapies that inhibit the Th17/IL-23 pathway, said Dr. Paller, the Walter J. Hamlin Professor and chair of dermatology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

Further, the study found that biologic agents, primarily etanercept, were used by 27%, acitretin by nearly 15%, cyclosporine by about 8%, and fumaric acid esters by 5%. More than 1 medication was used by 19%, according to the study results.

Adverse events affected the ability to tolerate therapy, and methotrexate and biologic agents were taken for a mean duration that was 2-fold greater than the mean duration for cyclosporine or fumaric acid esters. “A prospective registry is needed to track the long-term risks of systemic agents for pediatric psoriasis,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Paller reported that, in her practice, "we're still primarily using methotrexate. It takes time to see an effect with methotrexate, and you have to let people know this up front.” She pointed to a 2015 single-site prospective study of 25 children that found just 40% achieved Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 50 at 12 weeks, with that number rising to 80% by 36 weeks. (J Derm Treat 2015; 26: 406-12)

Dr. Paller recommends baseline and annual TB testing, updated vaccinations and pregnancy counseling for all patients taking immunosuppressant therapies.

"I don't use a lot of retinoids for plaque psoriasis in kids," Dr. Paller said, "but for pustular psoriasis, I use (them) quite a bit. The beauty of retinoids is that they are not immunosuppressants, and you can start and stop them without loss of efficacy. There are many potential side effects, primarily skin and mucosal dryness."

Cyclosporine "has the greatest potential toxicity, which leaves it lower on the therapeutic ladder," Dr. Paller said. "But it has a pretty good safety record. The nice thing we can say is that (cyclosporine has) been around a long time. We have decades of experience in children, and we're using a low dose."

Benefits of biologics include convenience, infrequent dosing, and, potentially, fewer lab tests, Dr. Paller said. She added that there's no consensus about whether lab tests beyond annual TB tests are a good idea for patients on biologics.

Long-term risks are unclear, however, and drug holidays could spell trouble for efficacy when kids return to the medications.

Dr. Paller noted that biologics can cost tens of thousands of dollars for several weeks of treatment, and insurers may not cover them.

A 2014 meta-analysis of 48 randomized, controlled trials of 16,696 adult patients with psoriasis put biologics as the most effective therapies, with infliximab at the top (risk difference 76%), followed by adalimumab (RD 61%) and ustekinumab (RD 63%).

“These biologics are more effective than etanercept and all conventional treatments. Head-to-head trials indicate the superiority of adalimumab and infliximab over methotrexate (MTX), the superiority of ustekinumab over etanercept …” the meta-analysis concluded. (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Feb;170(2):274-303)

Dr. Paller disclosed that she is an investigator for Abbvie; Celgene; Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Foundation; Novartis. She is a consultant with honorarium for Amgen; Celgene; Eli Lilly; and Novartis.

SOURCE: Paller, A. et al, Session F025 Update on systemic therapies and emerging treatments

SAN DIEGO – Systemic therapies are increasingly being used for children with moderate to severe psoriasis; methotrexate is still the mainstay of systemic treatment, but biologics appear to achieve superior results with fewer side effects, Amy S. Paller, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Etanercept was approved in 2016 for children ages 6 and up, and ustekinumab was approved for use in patients aged 12 years or older in October 2017. Ongoing trials are examining adalimumab, apremilast, ustekinumab, and ixekizumab for use in adolescents and younger children. Trials are also being planned for other therapies that inhibit the Th17/IL-23 pathway, said Dr. Paller, the Walter J. Hamlin Professor and chair of dermatology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

Further, the study found that biologic agents, primarily etanercept, were used by 27%, acitretin by nearly 15%, cyclosporine by about 8%, and fumaric acid esters by 5%. More than 1 medication was used by 19%, according to the study results.

Adverse events affected the ability to tolerate therapy, and methotrexate and biologic agents were taken for a mean duration that was 2-fold greater than the mean duration for cyclosporine or fumaric acid esters. “A prospective registry is needed to track the long-term risks of systemic agents for pediatric psoriasis,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Paller reported that, in her practice, "we're still primarily using methotrexate. It takes time to see an effect with methotrexate, and you have to let people know this up front.” She pointed to a 2015 single-site prospective study of 25 children that found just 40% achieved Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 50 at 12 weeks, with that number rising to 80% by 36 weeks. (J Derm Treat 2015; 26: 406-12)

Dr. Paller recommends baseline and annual TB testing, updated vaccinations and pregnancy counseling for all patients taking immunosuppressant therapies.

"I don't use a lot of retinoids for plaque psoriasis in kids," Dr. Paller said, "but for pustular psoriasis, I use (them) quite a bit. The beauty of retinoids is that they are not immunosuppressants, and you can start and stop them without loss of efficacy. There are many potential side effects, primarily skin and mucosal dryness."

Cyclosporine "has the greatest potential toxicity, which leaves it lower on the therapeutic ladder," Dr. Paller said. "But it has a pretty good safety record. The nice thing we can say is that (cyclosporine has) been around a long time. We have decades of experience in children, and we're using a low dose."

Benefits of biologics include convenience, infrequent dosing, and, potentially, fewer lab tests, Dr. Paller said. She added that there's no consensus about whether lab tests beyond annual TB tests are a good idea for patients on biologics.

Long-term risks are unclear, however, and drug holidays could spell trouble for efficacy when kids return to the medications.

Dr. Paller noted that biologics can cost tens of thousands of dollars for several weeks of treatment, and insurers may not cover them.

A 2014 meta-analysis of 48 randomized, controlled trials of 16,696 adult patients with psoriasis put biologics as the most effective therapies, with infliximab at the top (risk difference 76%), followed by adalimumab (RD 61%) and ustekinumab (RD 63%).

“These biologics are more effective than etanercept and all conventional treatments. Head-to-head trials indicate the superiority of adalimumab and infliximab over methotrexate (MTX), the superiority of ustekinumab over etanercept …” the meta-analysis concluded. (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Feb;170(2):274-303)

Dr. Paller disclosed that she is an investigator for Abbvie; Celgene; Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Foundation; Novartis. She is a consultant with honorarium for Amgen; Celgene; Eli Lilly; and Novartis.

SOURCE: Paller, A. et al, Session F025 Update on systemic therapies and emerging treatments

SAN DIEGO – Systemic therapies are increasingly being used for children with moderate to severe psoriasis; methotrexate is still the mainstay of systemic treatment, but biologics appear to achieve superior results with fewer side effects, Amy S. Paller, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Etanercept was approved in 2016 for children ages 6 and up, and ustekinumab was approved for use in patients aged 12 years or older in October 2017. Ongoing trials are examining adalimumab, apremilast, ustekinumab, and ixekizumab for use in adolescents and younger children. Trials are also being planned for other therapies that inhibit the Th17/IL-23 pathway, said Dr. Paller, the Walter J. Hamlin Professor and chair of dermatology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

Further, the study found that biologic agents, primarily etanercept, were used by 27%, acitretin by nearly 15%, cyclosporine by about 8%, and fumaric acid esters by 5%. More than 1 medication was used by 19%, according to the study results.

Adverse events affected the ability to tolerate therapy, and methotrexate and biologic agents were taken for a mean duration that was 2-fold greater than the mean duration for cyclosporine or fumaric acid esters. “A prospective registry is needed to track the long-term risks of systemic agents for pediatric psoriasis,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Paller reported that, in her practice, "we're still primarily using methotrexate. It takes time to see an effect with methotrexate, and you have to let people know this up front.” She pointed to a 2015 single-site prospective study of 25 children that found just 40% achieved Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 50 at 12 weeks, with that number rising to 80% by 36 weeks. (J Derm Treat 2015; 26: 406-12)

Dr. Paller recommends baseline and annual TB testing, updated vaccinations and pregnancy counseling for all patients taking immunosuppressant therapies.

"I don't use a lot of retinoids for plaque psoriasis in kids," Dr. Paller said, "but for pustular psoriasis, I use (them) quite a bit. The beauty of retinoids is that they are not immunosuppressants, and you can start and stop them without loss of efficacy. There are many potential side effects, primarily skin and mucosal dryness."

Cyclosporine "has the greatest potential toxicity, which leaves it lower on the therapeutic ladder," Dr. Paller said. "But it has a pretty good safety record. The nice thing we can say is that (cyclosporine has) been around a long time. We have decades of experience in children, and we're using a low dose."

Benefits of biologics include convenience, infrequent dosing, and, potentially, fewer lab tests, Dr. Paller said. She added that there's no consensus about whether lab tests beyond annual TB tests are a good idea for patients on biologics.

Long-term risks are unclear, however, and drug holidays could spell trouble for efficacy when kids return to the medications.

Dr. Paller noted that biologics can cost tens of thousands of dollars for several weeks of treatment, and insurers may not cover them.

A 2014 meta-analysis of 48 randomized, controlled trials of 16,696 adult patients with psoriasis put biologics as the most effective therapies, with infliximab at the top (risk difference 76%), followed by adalimumab (RD 61%) and ustekinumab (RD 63%).

“These biologics are more effective than etanercept and all conventional treatments. Head-to-head trials indicate the superiority of adalimumab and infliximab over methotrexate (MTX), the superiority of ustekinumab over etanercept …” the meta-analysis concluded. (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Feb;170(2):274-303)

Dr. Paller disclosed that she is an investigator for Abbvie; Celgene; Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Foundation; Novartis. She is a consultant with honorarium for Amgen; Celgene; Eli Lilly; and Novartis.

SOURCE: Paller, A. et al, Session F025 Update on systemic therapies and emerging treatments

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT AAD 18

Here comes bimekizumab, the newest IL-17 inhibitor

KAUAI, HAWAII –

And that’s not all: Much the same was true in patients with psoriatic arthritis in the parallel phase 2b BE ACTIVE study and for ankylosing spondylitis in the BE AGILE study. BE ABLE was a double-blind, 12-week, multicenter, five-arm, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of 250 psoriasis patients randomized to various doses of subcutaneous bimekizumab or placebo every 4 weeks. The primary outcome – the PASI 90 response rate at 12 weeks, rather than the lower-bar PASI 75 endpoint more typically used in clinical trials – was 79% at the optimal dose. The PASI 100 rate – complete clearance of disease – at 12 weeks was 60%, Craig L. Leonardi, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

lthough Dr. Leonardi is a distinguished psoriasis clinical trialist, he wasn’t involved in the BE ABLE study. Only top line results have been announced to date, although publication of the BE ABLE, BE AGILE, and BE ACTIVE results and presentations at major medical meetings are pending.

Bimekizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody which uniquely neutralizes both IL-17A and IL-17F. In contrast, secukinumab (Cosentyx) and ixekizumab (Taltz) specifically inhibit IL-17A, while brodalumab (Siliq) is a pan-IL-17 receptor antagonist, inhibiting the IL-17 A, A/F, E, F, and C receptors. The impressive clinical outcomes of the three BE phase 2b studies validate the notion that IL-17F is an important cytokine in tissue inflammation across a range of dermatologic and rheumatologic diseases.

A long-term extension of BE ABLE is ongoing. In addition, a phase 3 randomized trial of bimekizumab versus adalimumab (Humira) versus placebo in 450 psoriasis patients is now recruiting, as is a separate phase 3 placebo-controlled head to head comparison of bimekizumab versus ustekinumab (Stelara).

The BE ACTIVE study included 206 psoriatic arthritis patients. At the top dose of bimekizumab, the week 12 rate of at least a 50% improvement in joint symptoms, or ACR 50 response, was 46%, compared with 7% in placebo-treated controls. Patients with concomitant psoriasis over at least 3% of their body surface area demonstrated a 65% PASI 90 response rate at 12 weeks.

BE AGILE included 303 patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Forty-seven percent of those randomized to the top-performing dose of bimekizumab had at least a 40% improvement in their Ankylosing Spondylitis Activity Score, or ASAS 40, at week 12, as did 13% in the placebo arm.

Bimekizumab is being developed by UCB, which is planning additional studies advancing the biologic in all three diseases studied in the phase 2b trials.

Dr. Leonardi reported receiving research grants from well over a dozen pharmaceutical companies and serving as a consultant to UCB and others.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII –

And that’s not all: Much the same was true in patients with psoriatic arthritis in the parallel phase 2b BE ACTIVE study and for ankylosing spondylitis in the BE AGILE study. BE ABLE was a double-blind, 12-week, multicenter, five-arm, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of 250 psoriasis patients randomized to various doses of subcutaneous bimekizumab or placebo every 4 weeks. The primary outcome – the PASI 90 response rate at 12 weeks, rather than the lower-bar PASI 75 endpoint more typically used in clinical trials – was 79% at the optimal dose. The PASI 100 rate – complete clearance of disease – at 12 weeks was 60%, Craig L. Leonardi, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

lthough Dr. Leonardi is a distinguished psoriasis clinical trialist, he wasn’t involved in the BE ABLE study. Only top line results have been announced to date, although publication of the BE ABLE, BE AGILE, and BE ACTIVE results and presentations at major medical meetings are pending.

Bimekizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody which uniquely neutralizes both IL-17A and IL-17F. In contrast, secukinumab (Cosentyx) and ixekizumab (Taltz) specifically inhibit IL-17A, while brodalumab (Siliq) is a pan-IL-17 receptor antagonist, inhibiting the IL-17 A, A/F, E, F, and C receptors. The impressive clinical outcomes of the three BE phase 2b studies validate the notion that IL-17F is an important cytokine in tissue inflammation across a range of dermatologic and rheumatologic diseases.

A long-term extension of BE ABLE is ongoing. In addition, a phase 3 randomized trial of bimekizumab versus adalimumab (Humira) versus placebo in 450 psoriasis patients is now recruiting, as is a separate phase 3 placebo-controlled head to head comparison of bimekizumab versus ustekinumab (Stelara).

The BE ACTIVE study included 206 psoriatic arthritis patients. At the top dose of bimekizumab, the week 12 rate of at least a 50% improvement in joint symptoms, or ACR 50 response, was 46%, compared with 7% in placebo-treated controls. Patients with concomitant psoriasis over at least 3% of their body surface area demonstrated a 65% PASI 90 response rate at 12 weeks.

BE AGILE included 303 patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Forty-seven percent of those randomized to the top-performing dose of bimekizumab had at least a 40% improvement in their Ankylosing Spondylitis Activity Score, or ASAS 40, at week 12, as did 13% in the placebo arm.

Bimekizumab is being developed by UCB, which is planning additional studies advancing the biologic in all three diseases studied in the phase 2b trials.

Dr. Leonardi reported receiving research grants from well over a dozen pharmaceutical companies and serving as a consultant to UCB and others.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII –

And that’s not all: Much the same was true in patients with psoriatic arthritis in the parallel phase 2b BE ACTIVE study and for ankylosing spondylitis in the BE AGILE study. BE ABLE was a double-blind, 12-week, multicenter, five-arm, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of 250 psoriasis patients randomized to various doses of subcutaneous bimekizumab or placebo every 4 weeks. The primary outcome – the PASI 90 response rate at 12 weeks, rather than the lower-bar PASI 75 endpoint more typically used in clinical trials – was 79% at the optimal dose. The PASI 100 rate – complete clearance of disease – at 12 weeks was 60%, Craig L. Leonardi, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

lthough Dr. Leonardi is a distinguished psoriasis clinical trialist, he wasn’t involved in the BE ABLE study. Only top line results have been announced to date, although publication of the BE ABLE, BE AGILE, and BE ACTIVE results and presentations at major medical meetings are pending.

Bimekizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody which uniquely neutralizes both IL-17A and IL-17F. In contrast, secukinumab (Cosentyx) and ixekizumab (Taltz) specifically inhibit IL-17A, while brodalumab (Siliq) is a pan-IL-17 receptor antagonist, inhibiting the IL-17 A, A/F, E, F, and C receptors. The impressive clinical outcomes of the three BE phase 2b studies validate the notion that IL-17F is an important cytokine in tissue inflammation across a range of dermatologic and rheumatologic diseases.

A long-term extension of BE ABLE is ongoing. In addition, a phase 3 randomized trial of bimekizumab versus adalimumab (Humira) versus placebo in 450 psoriasis patients is now recruiting, as is a separate phase 3 placebo-controlled head to head comparison of bimekizumab versus ustekinumab (Stelara).

The BE ACTIVE study included 206 psoriatic arthritis patients. At the top dose of bimekizumab, the week 12 rate of at least a 50% improvement in joint symptoms, or ACR 50 response, was 46%, compared with 7% in placebo-treated controls. Patients with concomitant psoriasis over at least 3% of their body surface area demonstrated a 65% PASI 90 response rate at 12 weeks.

BE AGILE included 303 patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Forty-seven percent of those randomized to the top-performing dose of bimekizumab had at least a 40% improvement in their Ankylosing Spondylitis Activity Score, or ASAS 40, at week 12, as did 13% in the placebo arm.

Bimekizumab is being developed by UCB, which is planning additional studies advancing the biologic in all three diseases studied in the phase 2b trials.

Dr. Leonardi reported receiving research grants from well over a dozen pharmaceutical companies and serving as a consultant to UCB and others.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Tune in to cardiovascular risk in psoriasis

Stay attentive to cardiovascular disease risk in patients with psoriasis because effective treatment of psoriasis could improve their vascular risk as well, said Jeffrey M. Sobell, MD, of Tufts University in Boston.

he said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

The metabolic syndrome and its associated cardiovascular risk of myocardial infarction and stroke is significantly more prevalent in psoriasis patients, compared with controls, Dr. Sobell said at the meeting, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

A possible reason for this link may be that the chronic inflammation associated with psoriasis leads to atherosclerosis, Dr. Sobell noted. The inflammation is evident on PET imaging with a radiolabeled glucose known as fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography–computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) The technology, first used in cancer and neuroimaging, can detect early subclinical inflammation and allows for exact measurements of inflammatory activity, and measuring inflammation of the aorta can serve as a surrogate marker for treatment, he said.

Treating skin disease appears to impact vascular disease, Dr. Sobell said. In a study published in JAMA Cardiology, researchers followed 115 patients for 1 year using FDG-PET/CT (JAMA Cardiol. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.1213)

Overall, when psoriasis improved, so did signs of vascular inflammation. “When the skin is more severe and treated more aggressively with anti-TNF therapy, the reduction in vascular disease is stronger,” Dr. Sobell said.

Data from another large study presented as a late-breaker at the American Academy of Dermatology in 2017 showed that treatment of psoriasis with tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor therapy significantly reduced all-cause mortality in patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, he noted.

Psoriasis patients often are underscreened for cardiac risk factors, but identifying them can help guide treatment, Dr. Sobell said.

“Dermatologists should at minimum direct patients to primary care physicians for appropriate screening and assessment,” he emphasized.

Dr. Sobell disclosed relationships with Amgen, AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, and Sun Pharma.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Stay attentive to cardiovascular disease risk in patients with psoriasis because effective treatment of psoriasis could improve their vascular risk as well, said Jeffrey M. Sobell, MD, of Tufts University in Boston.

he said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

The metabolic syndrome and its associated cardiovascular risk of myocardial infarction and stroke is significantly more prevalent in psoriasis patients, compared with controls, Dr. Sobell said at the meeting, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

A possible reason for this link may be that the chronic inflammation associated with psoriasis leads to atherosclerosis, Dr. Sobell noted. The inflammation is evident on PET imaging with a radiolabeled glucose known as fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography–computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) The technology, first used in cancer and neuroimaging, can detect early subclinical inflammation and allows for exact measurements of inflammatory activity, and measuring inflammation of the aorta can serve as a surrogate marker for treatment, he said.

Treating skin disease appears to impact vascular disease, Dr. Sobell said. In a study published in JAMA Cardiology, researchers followed 115 patients for 1 year using FDG-PET/CT (JAMA Cardiol. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.1213)

Overall, when psoriasis improved, so did signs of vascular inflammation. “When the skin is more severe and treated more aggressively with anti-TNF therapy, the reduction in vascular disease is stronger,” Dr. Sobell said.

Data from another large study presented as a late-breaker at the American Academy of Dermatology in 2017 showed that treatment of psoriasis with tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor therapy significantly reduced all-cause mortality in patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, he noted.

Psoriasis patients often are underscreened for cardiac risk factors, but identifying them can help guide treatment, Dr. Sobell said.

“Dermatologists should at minimum direct patients to primary care physicians for appropriate screening and assessment,” he emphasized.

Dr. Sobell disclosed relationships with Amgen, AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, and Sun Pharma.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Stay attentive to cardiovascular disease risk in patients with psoriasis because effective treatment of psoriasis could improve their vascular risk as well, said Jeffrey M. Sobell, MD, of Tufts University in Boston.

he said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

The metabolic syndrome and its associated cardiovascular risk of myocardial infarction and stroke is significantly more prevalent in psoriasis patients, compared with controls, Dr. Sobell said at the meeting, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

A possible reason for this link may be that the chronic inflammation associated with psoriasis leads to atherosclerosis, Dr. Sobell noted. The inflammation is evident on PET imaging with a radiolabeled glucose known as fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography–computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) The technology, first used in cancer and neuroimaging, can detect early subclinical inflammation and allows for exact measurements of inflammatory activity, and measuring inflammation of the aorta can serve as a surrogate marker for treatment, he said.

Treating skin disease appears to impact vascular disease, Dr. Sobell said. In a study published in JAMA Cardiology, researchers followed 115 patients for 1 year using FDG-PET/CT (JAMA Cardiol. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.1213)

Overall, when psoriasis improved, so did signs of vascular inflammation. “When the skin is more severe and treated more aggressively with anti-TNF therapy, the reduction in vascular disease is stronger,” Dr. Sobell said.

Data from another large study presented as a late-breaker at the American Academy of Dermatology in 2017 showed that treatment of psoriasis with tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor therapy significantly reduced all-cause mortality in patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, he noted.

Psoriasis patients often are underscreened for cardiac risk factors, but identifying them can help guide treatment, Dr. Sobell said.

“Dermatologists should at minimum direct patients to primary care physicians for appropriate screening and assessment,” he emphasized.

Dr. Sobell disclosed relationships with Amgen, AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, and Sun Pharma.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARIBBEAN DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Get ready for certolizumab for psoriasis

KAUAI, HAWAII – When certolizumab pegol receives marketing approval for moderate to severe psoriasis – which experts say is a virtual lock – it will offer a singular advantage over current anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) biologics: strong evidence of safety in pregnancy.

“ ” Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, observed at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Lots of women and their families are understandably deeply concerned about using powerful, transformative medications during pregnancy, even though they know from experience how debilitating inadequately treated psoriasis can be.

“Many women of childbearing potential would find [certolizumab] to be a preferential agent if they’re planning to become pregnant,” said Dr. Gordon, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

He cited the CRIB (A Multicenter, Postmarketing Study Evaluating the Transfer of Cimzia From the Mother to the Infant via the Placenta) study results presented by Alexa B. Kimball, MD, at the 2017 annual meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology in Geneva as a major step forward in establishing the safety of certolizumab during pregnancy.

CRIB was a prospective postmarketing pharmacokinetic study that evaluated placental transfer of certolizumab from 16 pregnant women on the biologic to their infants. All of the mothers received their last dose of certolizumab for rheumatoid arthritis or other approved indications within 35 days of delivery. Blood samples were collected from mothers, newborns, and umbilical cords within 1 hour of delivery, and again from the infants at weeks 4 and 8 after delivery.

Only one infant had a detectable plasma level of certolizumab at birth, and it was barely measurable at 0.042 mcg/mL, as compared with 49.4 mcg/mL in the mother’s plasma. This is consistent with the fact that certolizumab’s pegylated arm allows only minimal or no placental transfer from mother to infant, so there is essentially no third trimester in utero fetal exposure. In contrast, as Dr. Kimball noted, other anti-TNF biologics lack a pegylated arm and thus preferentially cross the placenta, creating a theoretical increased risk of maternal pregnancy complications and/or congenital malformations.

Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and chief executive officer of Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston, also has been deeply involved in an ongoing registry (sponsored by certolizumab manufacturer UCB) of several hundred women on certolizumab in pregnancy. The data have reassuringly shown no increased risk of maternal pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or preterm birth, nor any increase in or pattern of congenital malformations, compared with background rates in the general population.

Dr. Gordon said that while he understands the concerns, he personally doesn’t think the class-wide safety of TNF inhibitors in pregnancy and lactation is a big issue.

“My argument is that anti-TNF agents have been used very frequently in women of childbearing age, and also in women who are pregnant or lactating. And there have not been any side effect signals from that,” he explained.

The prospects of gaining an expanded indication for certolizumab in psoriasis hinge in part on the impressive results of the pivotal phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled CIMPASI-1 and CIMPASI-2 trials. In CIMPASI-1, the week-48 Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75 and PASI 90 response rates were 87.1% and 60.2%, respectively, in patients on the biologic at 400 mg every 2 weeks; among those on certolizumab at 200 mg every 2 weeks, the rates were 67.2% and 42.8%. In CIMPASI-2, the PASI 75 and PASI 90 rates were 81.3% and 62.0% at 400 mg and 78.7% and 59.6% with 200 mg every 2 weeks.

There were no cases of tuberculosis or any other significant safety concerns through 48 weeks, Dr. Gordon said.

“Certolizumab is coming soon for psoriasis,” predicted Craig L. Leonardi, MD, a psoriasis researcher at Saint Louis University. “The data are very impressive. It’s a high-performance drug. There’s no reason why this drug shouldn’t be approved.”

Since Dr. Kimball’s presentation of the CRIB data at the 2017 annual meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, the study has been published (Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Feb;77[2]:228-33).

Dr. Gordon reported receiving research support from and serving as a paid consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies developing new psoriasis therapies.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – When certolizumab pegol receives marketing approval for moderate to severe psoriasis – which experts say is a virtual lock – it will offer a singular advantage over current anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) biologics: strong evidence of safety in pregnancy.

“ ” Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, observed at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Lots of women and their families are understandably deeply concerned about using powerful, transformative medications during pregnancy, even though they know from experience how debilitating inadequately treated psoriasis can be.

“Many women of childbearing potential would find [certolizumab] to be a preferential agent if they’re planning to become pregnant,” said Dr. Gordon, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

He cited the CRIB (A Multicenter, Postmarketing Study Evaluating the Transfer of Cimzia From the Mother to the Infant via the Placenta) study results presented by Alexa B. Kimball, MD, at the 2017 annual meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology in Geneva as a major step forward in establishing the safety of certolizumab during pregnancy.

CRIB was a prospective postmarketing pharmacokinetic study that evaluated placental transfer of certolizumab from 16 pregnant women on the biologic to their infants. All of the mothers received their last dose of certolizumab for rheumatoid arthritis or other approved indications within 35 days of delivery. Blood samples were collected from mothers, newborns, and umbilical cords within 1 hour of delivery, and again from the infants at weeks 4 and 8 after delivery.

Only one infant had a detectable plasma level of certolizumab at birth, and it was barely measurable at 0.042 mcg/mL, as compared with 49.4 mcg/mL in the mother’s plasma. This is consistent with the fact that certolizumab’s pegylated arm allows only minimal or no placental transfer from mother to infant, so there is essentially no third trimester in utero fetal exposure. In contrast, as Dr. Kimball noted, other anti-TNF biologics lack a pegylated arm and thus preferentially cross the placenta, creating a theoretical increased risk of maternal pregnancy complications and/or congenital malformations.

Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and chief executive officer of Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston, also has been deeply involved in an ongoing registry (sponsored by certolizumab manufacturer UCB) of several hundred women on certolizumab in pregnancy. The data have reassuringly shown no increased risk of maternal pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or preterm birth, nor any increase in or pattern of congenital malformations, compared with background rates in the general population.

Dr. Gordon said that while he understands the concerns, he personally doesn’t think the class-wide safety of TNF inhibitors in pregnancy and lactation is a big issue.

“My argument is that anti-TNF agents have been used very frequently in women of childbearing age, and also in women who are pregnant or lactating. And there have not been any side effect signals from that,” he explained.

The prospects of gaining an expanded indication for certolizumab in psoriasis hinge in part on the impressive results of the pivotal phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled CIMPASI-1 and CIMPASI-2 trials. In CIMPASI-1, the week-48 Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75 and PASI 90 response rates were 87.1% and 60.2%, respectively, in patients on the biologic at 400 mg every 2 weeks; among those on certolizumab at 200 mg every 2 weeks, the rates were 67.2% and 42.8%. In CIMPASI-2, the PASI 75 and PASI 90 rates were 81.3% and 62.0% at 400 mg and 78.7% and 59.6% with 200 mg every 2 weeks.

There were no cases of tuberculosis or any other significant safety concerns through 48 weeks, Dr. Gordon said.

“Certolizumab is coming soon for psoriasis,” predicted Craig L. Leonardi, MD, a psoriasis researcher at Saint Louis University. “The data are very impressive. It’s a high-performance drug. There’s no reason why this drug shouldn’t be approved.”

Since Dr. Kimball’s presentation of the CRIB data at the 2017 annual meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, the study has been published (Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Feb;77[2]:228-33).

Dr. Gordon reported receiving research support from and serving as a paid consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies developing new psoriasis therapies.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – When certolizumab pegol receives marketing approval for moderate to severe psoriasis – which experts say is a virtual lock – it will offer a singular advantage over current anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) biologics: strong evidence of safety in pregnancy.

“ ” Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, observed at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Lots of women and their families are understandably deeply concerned about using powerful, transformative medications during pregnancy, even though they know from experience how debilitating inadequately treated psoriasis can be.

“Many women of childbearing potential would find [certolizumab] to be a preferential agent if they’re planning to become pregnant,” said Dr. Gordon, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

He cited the CRIB (A Multicenter, Postmarketing Study Evaluating the Transfer of Cimzia From the Mother to the Infant via the Placenta) study results presented by Alexa B. Kimball, MD, at the 2017 annual meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology in Geneva as a major step forward in establishing the safety of certolizumab during pregnancy.

CRIB was a prospective postmarketing pharmacokinetic study that evaluated placental transfer of certolizumab from 16 pregnant women on the biologic to their infants. All of the mothers received their last dose of certolizumab for rheumatoid arthritis or other approved indications within 35 days of delivery. Blood samples were collected from mothers, newborns, and umbilical cords within 1 hour of delivery, and again from the infants at weeks 4 and 8 after delivery.

Only one infant had a detectable plasma level of certolizumab at birth, and it was barely measurable at 0.042 mcg/mL, as compared with 49.4 mcg/mL in the mother’s plasma. This is consistent with the fact that certolizumab’s pegylated arm allows only minimal or no placental transfer from mother to infant, so there is essentially no third trimester in utero fetal exposure. In contrast, as Dr. Kimball noted, other anti-TNF biologics lack a pegylated arm and thus preferentially cross the placenta, creating a theoretical increased risk of maternal pregnancy complications and/or congenital malformations.

Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and chief executive officer of Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston, also has been deeply involved in an ongoing registry (sponsored by certolizumab manufacturer UCB) of several hundred women on certolizumab in pregnancy. The data have reassuringly shown no increased risk of maternal pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or preterm birth, nor any increase in or pattern of congenital malformations, compared with background rates in the general population.

Dr. Gordon said that while he understands the concerns, he personally doesn’t think the class-wide safety of TNF inhibitors in pregnancy and lactation is a big issue.

“My argument is that anti-TNF agents have been used very frequently in women of childbearing age, and also in women who are pregnant or lactating. And there have not been any side effect signals from that,” he explained.

The prospects of gaining an expanded indication for certolizumab in psoriasis hinge in part on the impressive results of the pivotal phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled CIMPASI-1 and CIMPASI-2 trials. In CIMPASI-1, the week-48 Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75 and PASI 90 response rates were 87.1% and 60.2%, respectively, in patients on the biologic at 400 mg every 2 weeks; among those on certolizumab at 200 mg every 2 weeks, the rates were 67.2% and 42.8%. In CIMPASI-2, the PASI 75 and PASI 90 rates were 81.3% and 62.0% at 400 mg and 78.7% and 59.6% with 200 mg every 2 weeks.

There were no cases of tuberculosis or any other significant safety concerns through 48 weeks, Dr. Gordon said.

“Certolizumab is coming soon for psoriasis,” predicted Craig L. Leonardi, MD, a psoriasis researcher at Saint Louis University. “The data are very impressive. It’s a high-performance drug. There’s no reason why this drug shouldn’t be approved.”

Since Dr. Kimball’s presentation of the CRIB data at the 2017 annual meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, the study has been published (Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Feb;77[2]:228-33).

Dr. Gordon reported receiving research support from and serving as a paid consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies developing new psoriasis therapies.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

CV risk factors go undiagnosed, untreated in many psoriatic patients

A significant proportion of patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are underdiagnosed and undertreated for cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF), according to Lihi Eder, MD, of the University of Toronto, and her associates.

In a cross-sectional analysis published in the Journal of Rheumatology, researchers examined 2,254 patients (58.9% with PsA, 41.1% with psoriasis only) from eight centers in Canada, the United States, and Israel. They found that 1,017 of the patients had hypertension (PsA: 48.5%, psoriasis: 40.2%), including 233 who were not previously diagnosed with hypertension and were not taking any blood pressure–lowering medications (PsA: 19.9%, psoriasis: 39.1%). Many patients had low adherence to hypertension treatment recommendations: A total of 602 (PsA: 55.9%, psoriasis: 64.8%) were untreated or undertreated. Undertreatment of hypertension occurred in 60.9% patients with cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus.

“In this large international study, we found significant gaps in screening and treating CVRF in patients with psoriasis and PsA,” the researchers concluded. “Although questions exist regarding the optimal treatment targets for CVRF in psoriatic patients, adherence by physicians to, at a minimum, the general treatment recommendations for primary CV prevention is warranted.”

SOURCE: Eder L et al. J Rheumatol. 2018 Feb 1. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170379.

A significant proportion of patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are underdiagnosed and undertreated for cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF), according to Lihi Eder, MD, of the University of Toronto, and her associates.

In a cross-sectional analysis published in the Journal of Rheumatology, researchers examined 2,254 patients (58.9% with PsA, 41.1% with psoriasis only) from eight centers in Canada, the United States, and Israel. They found that 1,017 of the patients had hypertension (PsA: 48.5%, psoriasis: 40.2%), including 233 who were not previously diagnosed with hypertension and were not taking any blood pressure–lowering medications (PsA: 19.9%, psoriasis: 39.1%). Many patients had low adherence to hypertension treatment recommendations: A total of 602 (PsA: 55.9%, psoriasis: 64.8%) were untreated or undertreated. Undertreatment of hypertension occurred in 60.9% patients with cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus.

“In this large international study, we found significant gaps in screening and treating CVRF in patients with psoriasis and PsA,” the researchers concluded. “Although questions exist regarding the optimal treatment targets for CVRF in psoriatic patients, adherence by physicians to, at a minimum, the general treatment recommendations for primary CV prevention is warranted.”

SOURCE: Eder L et al. J Rheumatol. 2018 Feb 1. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170379.

A significant proportion of patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are underdiagnosed and undertreated for cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF), according to Lihi Eder, MD, of the University of Toronto, and her associates.

In a cross-sectional analysis published in the Journal of Rheumatology, researchers examined 2,254 patients (58.9% with PsA, 41.1% with psoriasis only) from eight centers in Canada, the United States, and Israel. They found that 1,017 of the patients had hypertension (PsA: 48.5%, psoriasis: 40.2%), including 233 who were not previously diagnosed with hypertension and were not taking any blood pressure–lowering medications (PsA: 19.9%, psoriasis: 39.1%). Many patients had low adherence to hypertension treatment recommendations: A total of 602 (PsA: 55.9%, psoriasis: 64.8%) were untreated or undertreated. Undertreatment of hypertension occurred in 60.9% patients with cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus.

“In this large international study, we found significant gaps in screening and treating CVRF in patients with psoriasis and PsA,” the researchers concluded. “Although questions exist regarding the optimal treatment targets for CVRF in psoriatic patients, adherence by physicians to, at a minimum, the general treatment recommendations for primary CV prevention is warranted.”

SOURCE: Eder L et al. J Rheumatol. 2018 Feb 1. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170379.

FROM JOURNAL OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Make a PEST of your psoriasis patients

KAUAI, HAWAII – for the rheumatologic disease once per year, advised Jashin J. Wu, MD. The PEST is a simple, validated, five-question yes/no screening tool. It’s geared towards nonrheumatologists who may not feel competent to diagnose psoriatic arthritis or who just don’t have time to do so. Three or more “yes” answers is deemed a positive result warranting consideration of referral to a rheumatologist, explained Dr. Wu, the director of the psoriasis clinic and director of dermatology research at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center.

The five PEST questions are:

- Have you ever had a swollen joint (or joints)?

- Has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis?

- Do your fingernails or toenails have holes or pits?

- Have you had pain in your heel?

- Have you had a finger or toe that was completely swollen and painful for no apparent reason?

The PEST has been shown to have 92% sensitivity and 78% specificity for diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009 May-Jun;27[3]:469-74).

Dr. Wu’s call for regular screening for psoriatic arthritis resonated with another psoriasis expert at the meeting, Craig L. Leonardi, MD.

“It’s our moral obligation to be on the lookout for that disease. Remember that patients who develop psoriatic arthritis usually have their skin disease for 10 years before they develop their first signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis. So that means they should be in the dermatologist’s office getting their skin treated as they start to have problems with their joints,” observed Dr. Leonardi, of Saint Louis University.

Dr. Wu reported receiving research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, and Regeneron.

The SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – for the rheumatologic disease once per year, advised Jashin J. Wu, MD. The PEST is a simple, validated, five-question yes/no screening tool. It’s geared towards nonrheumatologists who may not feel competent to diagnose psoriatic arthritis or who just don’t have time to do so. Three or more “yes” answers is deemed a positive result warranting consideration of referral to a rheumatologist, explained Dr. Wu, the director of the psoriasis clinic and director of dermatology research at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center.

The five PEST questions are:

- Have you ever had a swollen joint (or joints)?

- Has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis?

- Do your fingernails or toenails have holes or pits?

- Have you had pain in your heel?

- Have you had a finger or toe that was completely swollen and painful for no apparent reason?

The PEST has been shown to have 92% sensitivity and 78% specificity for diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009 May-Jun;27[3]:469-74).

Dr. Wu’s call for regular screening for psoriatic arthritis resonated with another psoriasis expert at the meeting, Craig L. Leonardi, MD.

“It’s our moral obligation to be on the lookout for that disease. Remember that patients who develop psoriatic arthritis usually have their skin disease for 10 years before they develop their first signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis. So that means they should be in the dermatologist’s office getting their skin treated as they start to have problems with their joints,” observed Dr. Leonardi, of Saint Louis University.

Dr. Wu reported receiving research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, and Regeneron.

The SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – for the rheumatologic disease once per year, advised Jashin J. Wu, MD. The PEST is a simple, validated, five-question yes/no screening tool. It’s geared towards nonrheumatologists who may not feel competent to diagnose psoriatic arthritis or who just don’t have time to do so. Three or more “yes” answers is deemed a positive result warranting consideration of referral to a rheumatologist, explained Dr. Wu, the director of the psoriasis clinic and director of dermatology research at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center.

The five PEST questions are:

- Have you ever had a swollen joint (or joints)?

- Has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis?

- Do your fingernails or toenails have holes or pits?

- Have you had pain in your heel?

- Have you had a finger or toe that was completely swollen and painful for no apparent reason?

The PEST has been shown to have 92% sensitivity and 78% specificity for diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009 May-Jun;27[3]:469-74).

Dr. Wu’s call for regular screening for psoriatic arthritis resonated with another psoriasis expert at the meeting, Craig L. Leonardi, MD.

“It’s our moral obligation to be on the lookout for that disease. Remember that patients who develop psoriatic arthritis usually have their skin disease for 10 years before they develop their first signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis. So that means they should be in the dermatologist’s office getting their skin treated as they start to have problems with their joints,” observed Dr. Leonardi, of Saint Louis University.

Dr. Wu reported receiving research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, and Regeneron.

The SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Molluscum Contagiosum in Immunocompromised Patients: AIDS Presenting as Molluscum Contagiosum in a Patient With Psoriasis on Biologic Therapy

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is a double-stranded DNA virus of the Poxviridae family, which commonly infects human keratinocytes resulting in small, umbilicated, flesh-colored papules. The greatest incidence of MC is seen in the pediatric population and sexually active young adults, and it is considered a self-limited disease in immunocompetent individuals.1 With the emergence of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and subsequent AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, a new population of immunocompromised individuals has been observed to be increasingly susceptible to MC with an atypical clinical presentation and a recalcitrant disease course.2 Although the increased prevalence of MC in the HIV population has been well-documented, it has been observed in other disease states or iatrogenically induced immunosuppression due to a deficiency in function or absolute number of T lymphocytes.

We present a case of a patient with long-standing psoriasis on biologic therapy who presented with MC with a subsequent workup that revealed AIDS. This case reiterates the importance of MC as a potential indicator of underlying immunosuppression. We review the literature to evaluate the occurrence of MC in immunosuppressed patients.

Case Report

A 33-year-old man initially presented for evaluation of severe plaque-type psoriasis associated with pain, erythema, and swelling of the joints of the hands of 10 years’ duration. He was started on methotrexate 5 mg weekly and topical corticosteroids but was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to headaches. He also had difficulty affording topical medications and adjunctive phototherapy. The patient was sporadically seen in follow-up with persistence of psoriatic plaques involving up to 60% body surface area (BSA) with the only treatment consisting of occasional topical steroids. Five years later, the patient was restarted on methotrexate 5 to 7.5 mg weekly, which resulted in moderate improvement. However, because of persistent elevation of liver enzymes, this treatment was stopped. Several months later he was evaluated for treatment with a biologic agent, and after a negative tuberculin skin test, he began treatment with etanercept 50 mg subcutaneous injection twice weekly, which provided notable improvement and allowed for reduction of dose frequency to once weekly.

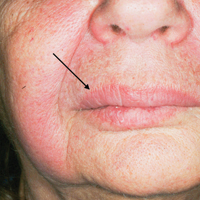

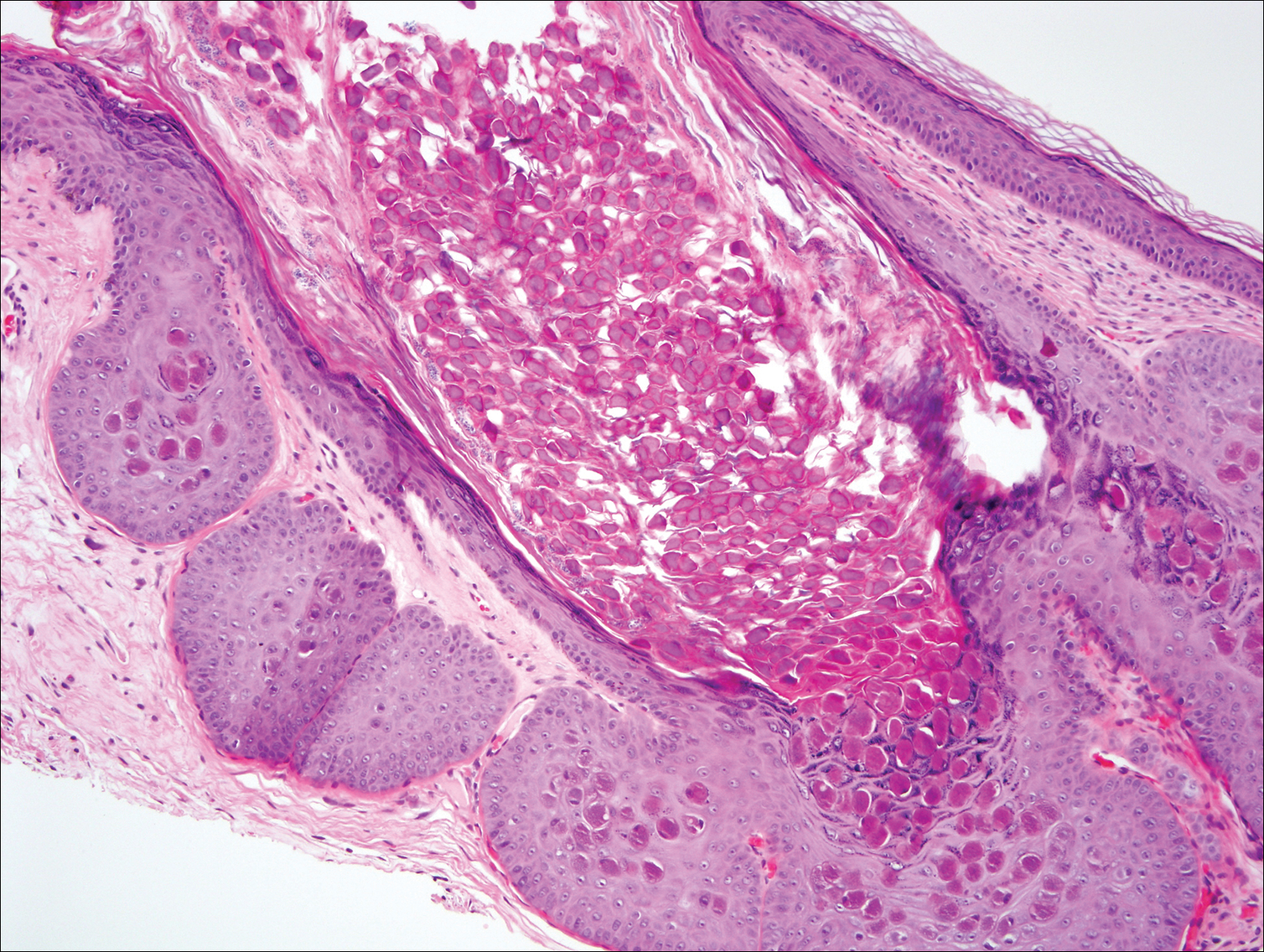

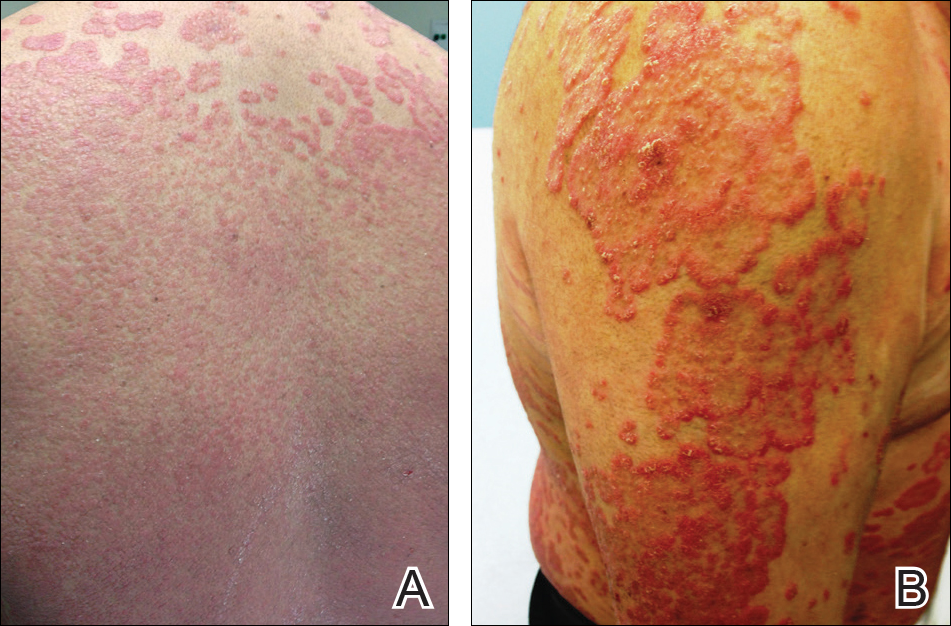

At follow-up 1 year later, the patient had continued improvement of psoriasis with approximately 30% BSA on a treatment regimen of etanercept 50 mg weekly injection and topical corticosteroids. However, on physical examination, there were multiple small semitranslucent papules with telangiectases on the chest and upper back (Figure 1). Biopsy of a representative papule on the chest revealed MC (Figure 2). The patient was subsequently advised to stop etanercept and to return immediately to the clinic for HIV testing. He returned for follow-up 3 months later with pronounced worsening of disease and a new onset of blurred vision of the right eye. Cutaneous examination revealed numerous large erythematous plaques with superficial scale and cerebriform surface on the chest, back, abdomen, and upper and lower extremities involving 80% BSA (Figure 3). Biopsy of a plaque demonstrated psoriasiform dermatitis with neutrophils and parakeratosis consistent with psoriasis. Extensive blood work was notable for reactive HIV antibody and lymphopenia, CD4 lymphocyte count of 60 cells/mm3, and an HIV viral load of 247,000 copies/mL, meeting diagnostic criteria for AIDS. Additionally, ophthalmologic evaluation revealed toxoplasma retinitis. Upon initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and continued use of topical corticosteroids, the patient experienced notable improvement of disease severity with approximately 20% BSA.

Comment

Molluscum contagiosum is a common skin infection. Among patients with HIV and other types of impaired cellular immunity, the prevalence of MC is estimated to be as high as 20%.3 The MC poxvirus survives and proliferates within the epidermis by interfering with tumor necrosis factor–induced apoptosis of virally infected cells; therefore, intact cell-mediated immunity is an important component of prevention and clearance of poxvirus infections. In immunocompromised patients, the presentation of MC varies widely, and the disease is often difficult to eradicate. This review will highlight the prevalence, presentation, and treatment of MC in the context of immunosuppressed states.

HIV/AIDS

Molluscum contagiosum in HIV-positive patients was first recognized in 1983,2 and its prevalence is estimated to range from 5% to 18% in AIDS patients.3 Molluscum contagiosum is a clinical sign of HIV progression, and its incidence appears to increase with reduced immune function (ie, a CD4 cell count <200/mm3).3 In a study of 456 patients with HIV-associated skin disorders, the majority of patients with MC had notable immunosuppression with a median survival time of 12 months. Thus, MC was not an independent prognostic marker but a clinical indicator of markedly reduced immune status.4

Molluscum contagiosum is transmitted in both sexual and nonsexual patterns in HIV-positive individuals, with the distribution of the latter involving primarily the face and neck. Although it may present with typical umbilicated papules, MC has a wide range of atypical clinical presentations in patients with AIDS that can make it difficult to diagnose. Complicated cases of eyelid MC have been reported in advanced HIV in both adults and children, resulting in obstruction of vision due to large lesions (up to 2 cm) or hundreds of confluent lesions.5 Giant MC, which appears as large exophytic nodules, is another presentation that has been frequently described in patients with advanced HIV. In these patients, the lesions often are too voluminous for conservative therapy and require excision.6 Atypical MC lesions also can resemble other dermatologic conditions, including condyloma acuminatum,7 nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn, ecthyma,8 and cutaneous horns,9,10 as well as other bacterial and fungal infections in HIV-positive patients, such as cutaneous Cryptococcus neoformans,11,12 disseminated histoplasmosis,13 and infections caused by Penicillium marneffei14 and Bartonella henselae.15 In most cases of MC in HIV-positive patients, diagnosis is dependent on the examination of biopsy specimens, which maintain the same histopathologic features regardless of immune status.

The management of MC in patients with HIV/AIDS is difficult. Molluscum contagiosum has shown no evidence of spontaneous resolution in patients with HIV, and treatment with one modality is often insufficient. Treatment is most successful when a combination approach is utilized with destructive procedures (eg, curettage, cryosurgery) and adjunctive agents (eg, retinoids, cantharidin, trichloroacetic acid). Imiquimod and cidofovir have been used off label for MC in AIDS patients.16 Imiquimod, which is used to treat genital warts, another cutaneous viral infection seen in patients with HIV, has demonstrated efficacy in treating MC.16 In a randomized controlled trial comparing imiquimod cream 5% to cryotherapy for MC in healthy children, imiquimod was slow acting but better suited than cryotherapy for patients with eruptions of many small lesions.17 For HIV patients, numerous reports have described successful treatment of disseminated or recalcitrant MC with topical imiquimod.18-20 Cidofovir, an antiviral used to treat cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS, is a promising antiviral agent against the poxvirus family. In a study of viral DNA polymerase genes of MC virus, cidofovir inhibited MC virus DNA polymerase activity.21 It has been used in both topical (1% to 3%) and intravenous form to successfully treat recalcitrant and exuberant giant MC.6,22 However, the use of cidofovir is limited by its high costs, especially when compounded into a topical formulation.23

From a systemic standpoint, numerous reports have shown that treating the underlying HIV by optimizing HAART is the most important first step in clearing MC.24-27 However, a special concern regarding the initiation of HAART in patients with MC as well as a markedly impaired immune function is the development of an inflammatory reaction called immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). This reaction is thought to be a result of immune recovery in severely immunosuppressed patients. During the initial phase of reconstitution when CD4 lymphocyte counts rise and viral load decreases, IRIS occurs due to an inflammatory reaction to microbial and autoimmune antigens, leading to temporary clinical deterioration.28 The incidence has been reported in up to 25% of patients starting HAART, and 52% to 78% of IRIS cases involve dermatologic manifestations such as varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus infections, genital warts, and MC.29,30 In a cohort study of 199 patients, 2% of patients developed MC within 6 months of initiating HAART.31 In a case of exuberant MC lesions after beginning HAART, the lesions spontaneously resolved with the progression of immune reconstitution.28

Malignancies

Patients with hematologic malignancies such as lymphoma and leukemia comprise another subset of patients at risk for atypical presentations of MC. Molluscum contagiosum has been described in patients with hematologic malignancies such as adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, multiple myeloma, chronic myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, lymphomatoid papulosis, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In a review of MC in children with cancer, 0.5% were diagnosed with MC.32,33 Reports also have documented eruptive MC in the presence of solid organ cancers, including lung cancer.34

In patients with malignancies, the differential diagnosis should include other common dermatologic conditions such as varicella, herpes simplex, papillomas, pyoderma, and cutaneous cryptococcosis, as well as MC. Similar to HIV-positive patients, the lesions of MC described in patients with malignancies do not tend to spontaneously resolve. In a report of a pediatric patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, MC presented as an ulcerated lesion without any classic features, requiring biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Only partial resolution was achieved with cryotherapy and crusting of the lesion in an attempt to slow the progression.35 In a series of 5 children with hematologic malignancies and MC, little improvement was noted after treatment with surgical scraping, liquid nitrogen, and salicylic acid ointment 5%. Similar to patients with HIV, improvement of immune status and function help clear the disease, and patients who reach remission and discontinue chemotherapeutic agents have a higher rate of spontaneous resolution of previously recalcitrant MC lesions.36

Transplant Patients

Molluscum contagiosum in transplant patients has features similar to patients with HIV/AIDS. In organ transplant recipients, there is an increased risk for cutaneous disease from iatrogenic immunosuppression or immunosuppression through infectious or neoplastic processes.37 As in other immunocompromised populations, MC often has an atypical presentation in transplant patients with more extensive involvement and recalcitrant, rapidly recurring lesions.

In a review of 145 pediatric organ transplant recipients, MC was the fourth most common skin infection after verruca vulgaris, tinea versicolor, and herpes simplex/zoster. Affecting 7% of patients, the majority of patients demonstrated clinically typical lesions; however, the disease was difficult to eradicate if multiple lesions were present.37 In other reports in adults, fulminant and giant MC have been described after renal and other solid organ transplants.38,39 Molluscum contagiosum also has been reported to mimic other skin diseases in transplant patients including tinea barbae40 and nodular basal cell carcinomas.41

The standard treatments are identical to those used in patients with HIV, including ablative methods via liquid nitrogen, electrocautery, cantharidin, trichloroacetic acid, and topical retinoids. Similar to MC in other immunocompromised states, treatment can be difficult and usually requires multiple modalities. For children, imiquimod cream 5% has been recommended due to high clearance rates (up to 92%) and the painless nature of the treatment.42,43

Other Iatrogenic Immunosuppressive States

Immunosuppression through the use of steroids, chemotherapeutic agents, and biologic drugs often is the result of treatment of various diseases. In patients with psoriasis treated with systemic immunosuppressive agents, there are numerous reports that describe the appearance of eruptive MC in association with methotrexate, cyclosporine, and biologics. Methotrexate acts as an immunosuppressive agent by binding to dihydrofolate reductase, which inhibits DNA synthesis in immunologically competent cells.44 It also may block host defense mechanisms against MC by suppressing the expression of serum inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ and suppressing the activity of TNF-α inducing apoptosis of virus-infected cells. Cyclosporine used in conjunction with methotrexate may exacerbate the insult to the immune system by inhibiting the production of IFN-γ.45 Biologics are an emerging class of drugs that have demonstrated efficacy in moderate to severe psoriasis by inhibiting TNF-α or other inflammatory molecules. Several published reports have described eruptive or atypical MC in patients on biologic medications. In one case, within 2 weeks after initiation of infliximab, a monoclonal antibody against TNF-α, a patient developed an eruption of MC involving the entire body.46 In another report, an anti–TNF-α agent for rheumatoid arthritis was associated with atypical MC with eyelid lesions.47

There are other skin disorders treated with immunosuppressive agents that also have been associated with MC. In a patient with pemphigus vulgaris treated with prednisolone, pimecrolimus, and azathioprine, MC lesions were observed on the face and within healed pemphigus vulgaris sites.48 Pimecrolimus and tacrolimus, corticosteroid-sparing agents, suppress cell-mediated immunity and inhibit inflammatory cytokines such as IL-2. The infection resolved with a gradual tapering of immunosuppressive therapy and 10 sessions of cryotherapy.48 In a case of topical pimecrolimus for pityriasis alba, the patient developed biopsy-proven MC within 2 weeks of initiating treatment in the areas that were treated with tacrolimus.49

In nontransplant patients with iatrogenic immunosuppression, MC treatment has not been documented to be as challenging as in patients with inherent immunosuppression. Most patients respond to either withdrawal of the drug alone or to simple ablative treatments such as cryotherapy.45,46,48 This important difference is most likely due to the presence of an otherwise intact immune system.

Conclusion

This case describes the appearance of MC in a patient with psoriasis treated with a TNF-α inhibitor who was ultimately diagnosed with AIDS. Although atypical MC infections have been documented in patients with psoriasis undergoing treatment with biologics, it is thought to be more common for MC to occur in more remarkably immunocompromised states such as AIDS. Thus, the persistence and progression of MC in our patient despite discontinuation of etanercept suggested a separate underlying process. Subsequent workup led to the diagnosis of AIDS along with the opportunistic ocular infection of toxoplasmosis retinitis. This clinical sequence consisting of psoriasis treated with a biologic agent, development of MC, and subsequent diagnosis of AIDS is unique and clinically significant to dermatologists. The presentation of psoriasis in patients with HIV can be diverse with different levels of severity and atypical clinical features. In many cases, HIV is known to exacerbate the classic clinical presentation of psoriasis. However, there are other particular presentations of psoriasis in HIV patients that have been observed, which include a predilection for scalp lesions, palmoplantar keratoderma, flexural involvement, and higher levels of immunodeficiency.50 Although tuberculin skin tests are required prior to initiating biologic therapy due to the potential for disease reactivation, there are no requirements for HIV antibody testing. In cases of severe recalcitrant psoriasis, an HIV test should be ordered during the workup to establish an early diagnosis so that an HIV-positive patient can avoid poor outcomes from either the disease processes, the use of certain therapeutic agents, or both. Furthermore, the benefit of avoiding possible harm to the patient and potential legal action outweighs the cost of performing surveillance HIV testing in this subset of patients. Thus, due to the potential additive immunosuppressive effect of HIV with biologic therapy, providers should always assess for risk factors and consider testing for HIV in all patients before initiating treatment with immunosuppressive agents such as biologics.

- Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:47-54.

- Reichert CM, O’Leary TJ, Levens DL, et al. Autopsy pathology in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Pathol. 1983;112:357-382.

- Czelusta A, Yen-Moore A, Van der Straten M, et al. An overview of sexually transmitted diseases. Part III. Sexually transmitted diseases in HIV-infected patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:409-432.

- Husak R, Garbe C, Orfanos CE. Mollusca contagiosa in HIV infection. Clinical manifestation, relation to immune status and prognostic value in 39 patients [in German]. Hautarzt. 1997;48:103-109.

- Averbuch D, Jaouni T, Pe’er J, et al. Confluent molluscum contagiosum covering the eyelids of an HIV-positive child. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;37:525-527.

- Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:652-654.

- Mastrolorenzo A, Urbano FG, Salimbeni L, et al. Atypical molluscum contagiosum infection in an HIV-infected patient. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:378-380.

- Itin PH, Gilli L. Molluscum contagiosum mimicking sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn, ecthyma and giant condylomata acuminata in HIV-infected patients. Dermatology. 1994;189:396-398.

- Sim JH, Lee ES. Molluscum contagiosum presenting as a cutaneous horn. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:262-263.

- Manchanda Y, Sethuraman G, Paderwani PP, et al. Molluscum contagiosum presenting as penile horn in an HIV positive patient. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:183-184.

- Miller SJ. Cutaneous cryptococcus resembling molluscum contagiosum in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 1988;41:411-412.

- Sornum A. A mistaken diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum in a HIV-positive patient in rural South Africa. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;14.

- Corti M, Villafañe MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

- Saikia L, Nath R, Hazarika D, et al. Atypical cutaneous lesions of Penicillium marneffei infection as a manifestation of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:45-48.

- de Souza JA. Molluscum or a mimic? Am J Med. 2006;119:927-929.

- Conant MA. Immunomodulatory therapy in the management of viral infections in patients with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:S27-S30.

- Gamble RG, Echols KF, Dellavalle RP. Imiquimod vs cryotherapy for molluscum contagiosum: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:109-112.

- Brown CW Jr, O’Donoghue M, Moore J, et al. Recalcitrant molluscum contagiosum in an HIV-afflicted male treated successfully with topical imiquimod. Cutis. 2000;65:363-366.

- Strauss RM, Doyle EL, Mohsen AH, et al. Successful treatment of molluscum contagiosum with topical imiquimod in a severely immunocompromised HIV-positive patient. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:264-266.

- Theiler M, Kempf W, Kerl K, et al. Disseminated molluscum contagiosum in a HIV-positive child. improvement after therapy with 5% imiquimod. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:19-23.

- Watanabe T, Tamaki K. Cidofovir diphosphate inhibits molluscum contagiosum virus DNA polymerase activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1327-1329.

- Calista D. Topical cidofovir for severe cutaneous human papillomavirus and molluscum contagiosum infections in patients with HIV/AIDS. a pilot study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:484-488.

- Toro JR, Sanchez S, Turiansky G, et al. Topical cidofovir for the treatment of dermatologic conditions: verruca, condyloma, intraepithelial neoplasia, herpes simplex and its potential use in smallpox. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:301-309.

- Calista D, Boschini A, Landi G. Resolution of disseminated molluscum contagiosum with highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with AIDS. Eur J Dermatol. 1999;9:211-213.

- Cattelan AM, Sasset L, Corti L, et al. A complete remission of recalcitrant molluscum contagiosum in an AIDS patient following highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). J Infect. 1999;38:58-60.

- Sen S, Bhaumik P. Resolution of giant molluscum contagiosum with antiretroviral therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:267-268.

- Sen S, Goswami BK, Karjyi N, et al. Disfiguring molluscum contagiosum in a HIV-positive patient responding to antiretroviral therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:180-182.

- Pereira B, Fernandes C, Nachiambo E, et al. Exuberant molluscum contagiosum as a manifestation of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:6.

- Osei-Sekyere B, Karstaedt AS. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome involving the skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:477-481.

- Sung KU, Lee HE, Choi WR, et al. Molluscum contagiosum as a skin manifestation of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in an AIDS patient who is receiving HAART. Korean J Fam Med. 2012;33:182-185.

- Ratnam I, Chiu C, Kandala NB, et al. Incidence and risk factors for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in an ethnically diverse HIV type 1-infected cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:418-427.

- Chen KW, Yang CF, Huang CT, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in a patient with adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2011;155:286.

- Fernandez KH, Bream M, Ali MA, et al. Investigation of molluscum contagiosum virus, orf and other parapoxviruses in lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1046-1047.

- Nakamura-Wakatsuki T, Kato Y, Miura T, et al. Eruptive molluscum contagiosums in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis and lung cancer. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:1117-1118.

- Ozyürek E, Sentürk N, Kefeli M, et al. Ulcerating molluscum contagiosum in a boy with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:E114-E116.

- Hughes WT, Parham DM. Molluscum contagiosum in children with cancer or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10:152-156.

- Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Cochat P, et al. Skin diseases in children with organ transplants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:932-939.

- Gardner LS, Ormond PJ. Treatment of multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant patient with imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:452-453.

- Mansur AT, Göktay F, Gündüz S, et al. Multiple giant molluscum contagiosum in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2004;6:120-123.

- Feldmeyer L, Kamarashev J, Boehler A, et al. Molluscum contagiosum folliculitis mimicking tinea barbae in a lung transplant recipient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:169-171.

- Tas¸kapan O, Yenicesu M, Aksu A. A giant solitary molluscum contagiosum, resembling nodular basal cell carcinoma, in a renal transplant recipient. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76:247-248.

- Tan HH, Goh CL. Viral infections affecting the skin in organ transplant recipients: epidemiology and current management strategies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:13-29.

- Al-Mutairi N, Al-Doukhi A, Al-Farag S, et al. Comparative study on the efficacy, safety, and acceptability of imiquimod 5% cream versus cryotherapy for molluscum contagiosum in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:388-394.

- Lim KS, Foo CC. Disseminated molluscum contagiosum in a patient with chronic plaque psoriasis taking methotrexate. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:591-593.

- Fotiadou C, Lazaridou E, Lekkas D, et al. Disseminated, eruptive molluscum contagiosum lesions in a psoriasis patient under treatment with methotrexate and cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:147-148.

- Antoniou C, Kosmadaki MG, Stratigos AJ, et al. Genital HPV lesions and molluscum contagiosum occurring in patients receiving anti-TNF-alpha therapy. Dermatology. 2008;216:364-365.

- Cursiefen C, Grunke M, Dechant C, et al. Multiple bilateral eyelid molluscum contagiosum lesions associated with TNFalpha-antibody and methotrexate therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:270-271.

- Heng YK, Lee JS, Neoh CY. Verrucous plaques in a pemphigus vulgaris patient on immunosuppressive therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1044-1046.

- Goksugur N, Ozbostanci B, Goksugur SB. Molluscum contagiosum infection associated with pimecrolimus use in pityriasis alba. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:E63-E65.

- Fernandes S, Pinto GM, Cardoso J. Particular clinical presentations of psoriasis in HIV patients. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22:653-654.