User login

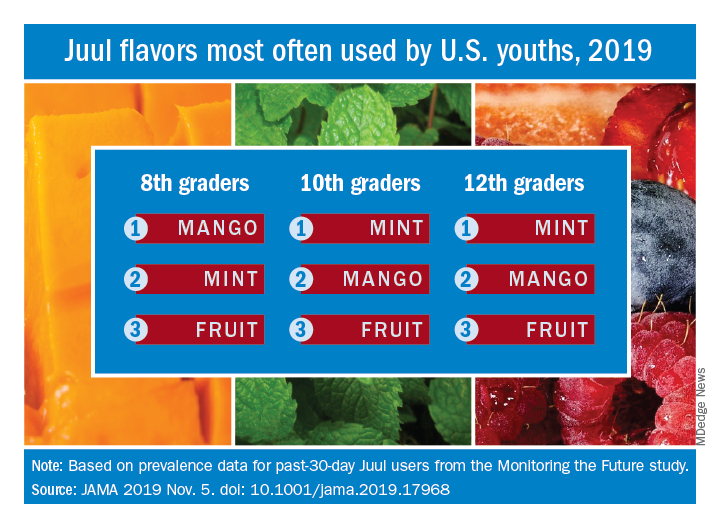

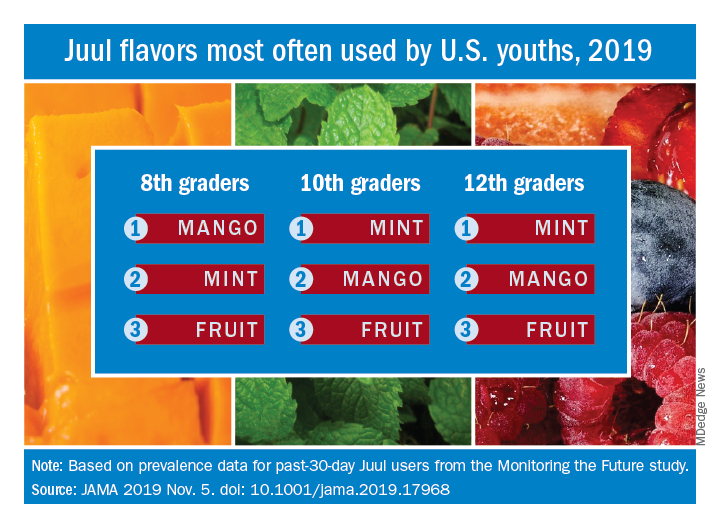

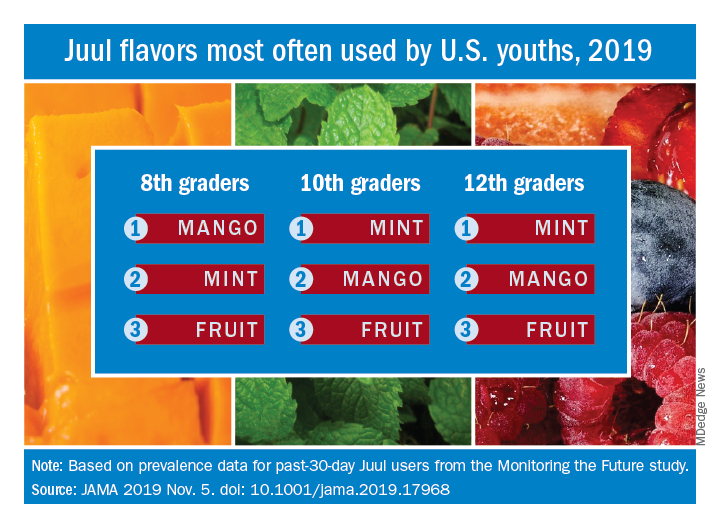

Student vapers make mint the most popular Juul flavor

according to data from the 2019 Monitoring the Future study.

Almost half (47.1%) of the 12th graders who had used Juul e-cigarettes in the past 30 days reported that mint was the flavor they most often used, compared with 23.8% for mango and 8.6% for fruit, which is a combination of flavors, Adam M. Leventhal, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates wrote in JAMA.

Mint was also the flavor most often used by 10th graders (43.5%), with mango again second at 27.3%, and fruit third at 10.8%. Eighth-grade students switched mango (33.5%) and mint (29.2%) but had fruit third again at 16.0%, the investigators reported, based on data for 1,739 respondents to the Monitoring the Future survey who had used a vaping product within the past 30 days.

Juul has suspended sales of four – mango, fruit, creme, and cucumber – of its original eight flavors, Dr. Leventhal and associates noted, and e-cigarette flavors other than tobacco, menthol, and mint have been prohibited by some local municipalities.

“The current findings raise uncertainty whether regulations or sales suspensions that exempt mint flavors are optimal strategies for reducing youth e-cigarette use,” they wrote.

As this article was being written, the Wall Street Journal had just reported that the Food and Drug Administration will ban mint and all other e-cigarette flavors except tobacco and menthol.

SOURCE: Leventhal AM et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17968.

according to data from the 2019 Monitoring the Future study.

Almost half (47.1%) of the 12th graders who had used Juul e-cigarettes in the past 30 days reported that mint was the flavor they most often used, compared with 23.8% for mango and 8.6% for fruit, which is a combination of flavors, Adam M. Leventhal, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates wrote in JAMA.

Mint was also the flavor most often used by 10th graders (43.5%), with mango again second at 27.3%, and fruit third at 10.8%. Eighth-grade students switched mango (33.5%) and mint (29.2%) but had fruit third again at 16.0%, the investigators reported, based on data for 1,739 respondents to the Monitoring the Future survey who had used a vaping product within the past 30 days.

Juul has suspended sales of four – mango, fruit, creme, and cucumber – of its original eight flavors, Dr. Leventhal and associates noted, and e-cigarette flavors other than tobacco, menthol, and mint have been prohibited by some local municipalities.

“The current findings raise uncertainty whether regulations or sales suspensions that exempt mint flavors are optimal strategies for reducing youth e-cigarette use,” they wrote.

As this article was being written, the Wall Street Journal had just reported that the Food and Drug Administration will ban mint and all other e-cigarette flavors except tobacco and menthol.

SOURCE: Leventhal AM et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17968.

according to data from the 2019 Monitoring the Future study.

Almost half (47.1%) of the 12th graders who had used Juul e-cigarettes in the past 30 days reported that mint was the flavor they most often used, compared with 23.8% for mango and 8.6% for fruit, which is a combination of flavors, Adam M. Leventhal, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates wrote in JAMA.

Mint was also the flavor most often used by 10th graders (43.5%), with mango again second at 27.3%, and fruit third at 10.8%. Eighth-grade students switched mango (33.5%) and mint (29.2%) but had fruit third again at 16.0%, the investigators reported, based on data for 1,739 respondents to the Monitoring the Future survey who had used a vaping product within the past 30 days.

Juul has suspended sales of four – mango, fruit, creme, and cucumber – of its original eight flavors, Dr. Leventhal and associates noted, and e-cigarette flavors other than tobacco, menthol, and mint have been prohibited by some local municipalities.

“The current findings raise uncertainty whether regulations or sales suspensions that exempt mint flavors are optimal strategies for reducing youth e-cigarette use,” they wrote.

As this article was being written, the Wall Street Journal had just reported that the Food and Drug Administration will ban mint and all other e-cigarette flavors except tobacco and menthol.

SOURCE: Leventhal AM et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17968.

FROM JAMA

Robotic bronchoscopy beat standard techniques for targeting lung nodules

NEW ORLEANS –

A prospective study in a cadaver model showed that robotic bronchoscopy targeted nodules more effectively than electromagnetic navigation or an ultrathin bronchoscope with radial endobronchial ultrasound (UTB-rEBUS).

“This is really the first study to randomize, blind, and compare procedural outcomes between existing technologies in advanced bronchoscopy,” said Lonny Yarmus, DO, of Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Yarmus described this study, PRECISION-1, at the annual meeting of the American Society of Chest Physicians. The study was designed to compare the following:

- UTB-rEBUS (3.0 mm outer diameter and 1.7 mm working channel).

- Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (Superdimension version 7.1).

- Robotic bronchoscopy (3.5 mm outer diameter and 2.0-mm working channel).

With all methods, a 21-gauge needle was used. For each nodule, UTB-rEBUS was done first to eliminate potential localization bias. The subsequent order of electromagnetic navigation and robotic bronchoscopy was determined based on block randomization.

Eight bronchoscopists performed a total of 60 procedures using each of the methods to target 20 nodules implanted in cadavers. The nodules were distributed across all lobes, 80% were in the outer third of the lung, and 50% had a positive bronchus sign on computed tomography (CT). The mean nodule size was 16.5 plus or minus 1.5 mm.

The study’s primary endpoint was the ability to localize and puncture target nodules within a maximum of three attempts per method. This includes center, peripheral, and distal punctures of nodules. Cone-beam CT was used to confirm that needles punctured the target lesions. The bronchoscopists were blinded to cone-beam CT results, and a blinded, independent investigator assessed whether nodule punctures were successful. The primary endpoint was met in 25% of UTB-rEBUS procedures, 45% of electromagnetic navigation procedures, and 80% of robotic bronchoscopy procedures.

The study’s secondary endpoint was localization success, which was defined as navigation to within needle biopsy distance of the nodule. This includes center, peripheral, and distal punctures of nodules, as well as adjacent punctures (touching the nodule but not within it). The secondary endpoint was met in 35% of UTB-rEBUS procedures, 65% of electromagnetic navigation procedures, and 90% of robotic bronchoscopy procedures.

The researchers also assessed successful navigation, which was defined as the provider localizing with software or radial ultrasound and passing the needle to make a biopsy attempt. Navigation was successful in 65% of UTB-rEBUS procedures, 85% of electromagnetic navigation procedures, and 100% of robotic bronchoscopy procedures.

“Utilization of robotic bronchoscopy with shape-sensing technology can significantly increase the ability to localize and puncture lesions when compared with standard existing technologies,” Dr. Yarmus said in closing.

He did note that this research was done in a cadaveric model, so “prospective, randomized, and comparative in vivo studies are needed.”

This study was funded by the Association of Interventional Pulmonary Program Directors. Dr. Yarmus disclosed government and societal funding and relationships with Boston Scientific, Veran, Medtronic, Intuitive, Auris, Erbe, Olympus, BD, Rocket, Ambu, Inspire Medical, and AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Yarmus L et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.311.

NEW ORLEANS –

A prospective study in a cadaver model showed that robotic bronchoscopy targeted nodules more effectively than electromagnetic navigation or an ultrathin bronchoscope with radial endobronchial ultrasound (UTB-rEBUS).

“This is really the first study to randomize, blind, and compare procedural outcomes between existing technologies in advanced bronchoscopy,” said Lonny Yarmus, DO, of Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Yarmus described this study, PRECISION-1, at the annual meeting of the American Society of Chest Physicians. The study was designed to compare the following:

- UTB-rEBUS (3.0 mm outer diameter and 1.7 mm working channel).

- Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (Superdimension version 7.1).

- Robotic bronchoscopy (3.5 mm outer diameter and 2.0-mm working channel).

With all methods, a 21-gauge needle was used. For each nodule, UTB-rEBUS was done first to eliminate potential localization bias. The subsequent order of electromagnetic navigation and robotic bronchoscopy was determined based on block randomization.

Eight bronchoscopists performed a total of 60 procedures using each of the methods to target 20 nodules implanted in cadavers. The nodules were distributed across all lobes, 80% were in the outer third of the lung, and 50% had a positive bronchus sign on computed tomography (CT). The mean nodule size was 16.5 plus or minus 1.5 mm.

The study’s primary endpoint was the ability to localize and puncture target nodules within a maximum of three attempts per method. This includes center, peripheral, and distal punctures of nodules. Cone-beam CT was used to confirm that needles punctured the target lesions. The bronchoscopists were blinded to cone-beam CT results, and a blinded, independent investigator assessed whether nodule punctures were successful. The primary endpoint was met in 25% of UTB-rEBUS procedures, 45% of electromagnetic navigation procedures, and 80% of robotic bronchoscopy procedures.

The study’s secondary endpoint was localization success, which was defined as navigation to within needle biopsy distance of the nodule. This includes center, peripheral, and distal punctures of nodules, as well as adjacent punctures (touching the nodule but not within it). The secondary endpoint was met in 35% of UTB-rEBUS procedures, 65% of electromagnetic navigation procedures, and 90% of robotic bronchoscopy procedures.

The researchers also assessed successful navigation, which was defined as the provider localizing with software or radial ultrasound and passing the needle to make a biopsy attempt. Navigation was successful in 65% of UTB-rEBUS procedures, 85% of electromagnetic navigation procedures, and 100% of robotic bronchoscopy procedures.

“Utilization of robotic bronchoscopy with shape-sensing technology can significantly increase the ability to localize and puncture lesions when compared with standard existing technologies,” Dr. Yarmus said in closing.

He did note that this research was done in a cadaveric model, so “prospective, randomized, and comparative in vivo studies are needed.”

This study was funded by the Association of Interventional Pulmonary Program Directors. Dr. Yarmus disclosed government and societal funding and relationships with Boston Scientific, Veran, Medtronic, Intuitive, Auris, Erbe, Olympus, BD, Rocket, Ambu, Inspire Medical, and AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Yarmus L et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.311.

NEW ORLEANS –

A prospective study in a cadaver model showed that robotic bronchoscopy targeted nodules more effectively than electromagnetic navigation or an ultrathin bronchoscope with radial endobronchial ultrasound (UTB-rEBUS).

“This is really the first study to randomize, blind, and compare procedural outcomes between existing technologies in advanced bronchoscopy,” said Lonny Yarmus, DO, of Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Yarmus described this study, PRECISION-1, at the annual meeting of the American Society of Chest Physicians. The study was designed to compare the following:

- UTB-rEBUS (3.0 mm outer diameter and 1.7 mm working channel).

- Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (Superdimension version 7.1).

- Robotic bronchoscopy (3.5 mm outer diameter and 2.0-mm working channel).

With all methods, a 21-gauge needle was used. For each nodule, UTB-rEBUS was done first to eliminate potential localization bias. The subsequent order of electromagnetic navigation and robotic bronchoscopy was determined based on block randomization.

Eight bronchoscopists performed a total of 60 procedures using each of the methods to target 20 nodules implanted in cadavers. The nodules were distributed across all lobes, 80% were in the outer third of the lung, and 50% had a positive bronchus sign on computed tomography (CT). The mean nodule size was 16.5 plus or minus 1.5 mm.

The study’s primary endpoint was the ability to localize and puncture target nodules within a maximum of three attempts per method. This includes center, peripheral, and distal punctures of nodules. Cone-beam CT was used to confirm that needles punctured the target lesions. The bronchoscopists were blinded to cone-beam CT results, and a blinded, independent investigator assessed whether nodule punctures were successful. The primary endpoint was met in 25% of UTB-rEBUS procedures, 45% of electromagnetic navigation procedures, and 80% of robotic bronchoscopy procedures.

The study’s secondary endpoint was localization success, which was defined as navigation to within needle biopsy distance of the nodule. This includes center, peripheral, and distal punctures of nodules, as well as adjacent punctures (touching the nodule but not within it). The secondary endpoint was met in 35% of UTB-rEBUS procedures, 65% of electromagnetic navigation procedures, and 90% of robotic bronchoscopy procedures.

The researchers also assessed successful navigation, which was defined as the provider localizing with software or radial ultrasound and passing the needle to make a biopsy attempt. Navigation was successful in 65% of UTB-rEBUS procedures, 85% of electromagnetic navigation procedures, and 100% of robotic bronchoscopy procedures.

“Utilization of robotic bronchoscopy with shape-sensing technology can significantly increase the ability to localize and puncture lesions when compared with standard existing technologies,” Dr. Yarmus said in closing.

He did note that this research was done in a cadaveric model, so “prospective, randomized, and comparative in vivo studies are needed.”

This study was funded by the Association of Interventional Pulmonary Program Directors. Dr. Yarmus disclosed government and societal funding and relationships with Boston Scientific, Veran, Medtronic, Intuitive, Auris, Erbe, Olympus, BD, Rocket, Ambu, Inspire Medical, and AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Yarmus L et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.311.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2019

Inhaled nitric oxide improves activity in pulmonary fibrosis patients at risk of PH

NEW ORLEANS – In patients with interstitial lung diseases at risk of pulmonary hypertension, inhaled nitric oxide produced meaningful improvements in activity that have been maintained over the long term, an investigator reported here.

Inhaled nitric oxide, which improved moderate to vigorous physical activity by 34% versus placebo in an 8-week controlled trial, has demonstrated long-term maintenance of activity parameters in open-label extension data, presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The treatment was safe and well tolerated in this cohort of subjects at risk of pulmonary hypertension associated with pulmonary fibrosis (PH-PF), said Steven D. Nathan, MD, director of the advanced lung disease and lung transplant program at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital.

The findings to date suggest inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) is a potentially effective treatment option for patients at risk for pulmonary hypertension, which is associated with poor outcomes in various forms of interstitial lung disease, Dr. Nathan said in his presentation, adding that a second cohort of PH-PF patients has been fully recruited and continue to be followed.

“Hopefully, once we show that iNO is positive and validate what we’ve seen with cohort one, then we’ll be moving on to cohort three, which will be a pivotal phase 3 clinical study with actigraphy activity–monitoring being the primary endpoint, and that has been agreed upon by the Food and Drug Administration,” he said.

The actigraph device used in the study, worn on the wrist of the nondominant arm, continuously measures patient movement in acceleration units and allows for categorization of intensity, from sedentary to vigorous, Dr. Nathan explained in this presentation.

“To me, actigraphy activity–monitoring is kind of a step beyond the 6-minute walk test,” he said. “We get a sense of how [patients] might function, based on the 6-minute walk test, but what actigraphy gives us is actually how they do function once they leave the clinic. So I think this is emerging as a very viable and valuable endpoint in clinical trials.”

Dr. Nathan reported on 23 patients with a variety of pulmonary fibrotic interstitial lung diseases randomized to receive iNO 30 mcg/kg based on their ideal body weight (IBW) per hour, and 18 who were randomized to placebo, for 8 weeks of blinded treatment. After that, patients from both arms transitioned to open-label treatment, stepping up to 45 mcg/kg IBW/hr for at least 8 weeks, and then to 75 mcg/kg IBW/hr.

After the 8 weeks of blinded treatment, activity as measured by actigraphy was maintained in the patients receiving iNO, and decreased in the placebo arm (P = .05), according to Dr. Nathan, who added that this difference was largely driven by changes in levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity, which improved in the treatment arm, while declining substantially in the placebo arm.

Clinically significant improvements in moderate to vigorous physical activity were seen in 23.1% of patients in the treatment arm and 0% of the placebo arm, while clinically significant declines in that measure were seen in 38.5% of the treatment group versus 71.4% of the placebo group.

Data from the open-label extension phase, which included a total of 18 patients, show that activity was “well maintained” over a total of 20 weeks, with patients formerly in the placebo arm demonstrating levels of activity comparable to what was achieved in the patients randomized to treatment: “We felt like this supports the clinical efficacy of the nitric oxide effect, that the placebo arm started to behave like the treatment arm,” Dr. Nathan said.

Some adverse events were reported in the study, but none were felt to be attributable to the iNO, according to Dr. Nathan.

Dr. Nathan provided disclosures related to Roche-Genentech, Boehringer Ingelheim, Promedior, Bellerophon, and United Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Nathan SD et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.308.

NEW ORLEANS – In patients with interstitial lung diseases at risk of pulmonary hypertension, inhaled nitric oxide produced meaningful improvements in activity that have been maintained over the long term, an investigator reported here.

Inhaled nitric oxide, which improved moderate to vigorous physical activity by 34% versus placebo in an 8-week controlled trial, has demonstrated long-term maintenance of activity parameters in open-label extension data, presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The treatment was safe and well tolerated in this cohort of subjects at risk of pulmonary hypertension associated with pulmonary fibrosis (PH-PF), said Steven D. Nathan, MD, director of the advanced lung disease and lung transplant program at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital.

The findings to date suggest inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) is a potentially effective treatment option for patients at risk for pulmonary hypertension, which is associated with poor outcomes in various forms of interstitial lung disease, Dr. Nathan said in his presentation, adding that a second cohort of PH-PF patients has been fully recruited and continue to be followed.

“Hopefully, once we show that iNO is positive and validate what we’ve seen with cohort one, then we’ll be moving on to cohort three, which will be a pivotal phase 3 clinical study with actigraphy activity–monitoring being the primary endpoint, and that has been agreed upon by the Food and Drug Administration,” he said.

The actigraph device used in the study, worn on the wrist of the nondominant arm, continuously measures patient movement in acceleration units and allows for categorization of intensity, from sedentary to vigorous, Dr. Nathan explained in this presentation.

“To me, actigraphy activity–monitoring is kind of a step beyond the 6-minute walk test,” he said. “We get a sense of how [patients] might function, based on the 6-minute walk test, but what actigraphy gives us is actually how they do function once they leave the clinic. So I think this is emerging as a very viable and valuable endpoint in clinical trials.”

Dr. Nathan reported on 23 patients with a variety of pulmonary fibrotic interstitial lung diseases randomized to receive iNO 30 mcg/kg based on their ideal body weight (IBW) per hour, and 18 who were randomized to placebo, for 8 weeks of blinded treatment. After that, patients from both arms transitioned to open-label treatment, stepping up to 45 mcg/kg IBW/hr for at least 8 weeks, and then to 75 mcg/kg IBW/hr.

After the 8 weeks of blinded treatment, activity as measured by actigraphy was maintained in the patients receiving iNO, and decreased in the placebo arm (P = .05), according to Dr. Nathan, who added that this difference was largely driven by changes in levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity, which improved in the treatment arm, while declining substantially in the placebo arm.

Clinically significant improvements in moderate to vigorous physical activity were seen in 23.1% of patients in the treatment arm and 0% of the placebo arm, while clinically significant declines in that measure were seen in 38.5% of the treatment group versus 71.4% of the placebo group.

Data from the open-label extension phase, which included a total of 18 patients, show that activity was “well maintained” over a total of 20 weeks, with patients formerly in the placebo arm demonstrating levels of activity comparable to what was achieved in the patients randomized to treatment: “We felt like this supports the clinical efficacy of the nitric oxide effect, that the placebo arm started to behave like the treatment arm,” Dr. Nathan said.

Some adverse events were reported in the study, but none were felt to be attributable to the iNO, according to Dr. Nathan.

Dr. Nathan provided disclosures related to Roche-Genentech, Boehringer Ingelheim, Promedior, Bellerophon, and United Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Nathan SD et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.308.

NEW ORLEANS – In patients with interstitial lung diseases at risk of pulmonary hypertension, inhaled nitric oxide produced meaningful improvements in activity that have been maintained over the long term, an investigator reported here.

Inhaled nitric oxide, which improved moderate to vigorous physical activity by 34% versus placebo in an 8-week controlled trial, has demonstrated long-term maintenance of activity parameters in open-label extension data, presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

The treatment was safe and well tolerated in this cohort of subjects at risk of pulmonary hypertension associated with pulmonary fibrosis (PH-PF), said Steven D. Nathan, MD, director of the advanced lung disease and lung transplant program at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital.

The findings to date suggest inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) is a potentially effective treatment option for patients at risk for pulmonary hypertension, which is associated with poor outcomes in various forms of interstitial lung disease, Dr. Nathan said in his presentation, adding that a second cohort of PH-PF patients has been fully recruited and continue to be followed.

“Hopefully, once we show that iNO is positive and validate what we’ve seen with cohort one, then we’ll be moving on to cohort three, which will be a pivotal phase 3 clinical study with actigraphy activity–monitoring being the primary endpoint, and that has been agreed upon by the Food and Drug Administration,” he said.

The actigraph device used in the study, worn on the wrist of the nondominant arm, continuously measures patient movement in acceleration units and allows for categorization of intensity, from sedentary to vigorous, Dr. Nathan explained in this presentation.

“To me, actigraphy activity–monitoring is kind of a step beyond the 6-minute walk test,” he said. “We get a sense of how [patients] might function, based on the 6-minute walk test, but what actigraphy gives us is actually how they do function once they leave the clinic. So I think this is emerging as a very viable and valuable endpoint in clinical trials.”

Dr. Nathan reported on 23 patients with a variety of pulmonary fibrotic interstitial lung diseases randomized to receive iNO 30 mcg/kg based on their ideal body weight (IBW) per hour, and 18 who were randomized to placebo, for 8 weeks of blinded treatment. After that, patients from both arms transitioned to open-label treatment, stepping up to 45 mcg/kg IBW/hr for at least 8 weeks, and then to 75 mcg/kg IBW/hr.

After the 8 weeks of blinded treatment, activity as measured by actigraphy was maintained in the patients receiving iNO, and decreased in the placebo arm (P = .05), according to Dr. Nathan, who added that this difference was largely driven by changes in levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity, which improved in the treatment arm, while declining substantially in the placebo arm.

Clinically significant improvements in moderate to vigorous physical activity were seen in 23.1% of patients in the treatment arm and 0% of the placebo arm, while clinically significant declines in that measure were seen in 38.5% of the treatment group versus 71.4% of the placebo group.

Data from the open-label extension phase, which included a total of 18 patients, show that activity was “well maintained” over a total of 20 weeks, with patients formerly in the placebo arm demonstrating levels of activity comparable to what was achieved in the patients randomized to treatment: “We felt like this supports the clinical efficacy of the nitric oxide effect, that the placebo arm started to behave like the treatment arm,” Dr. Nathan said.

Some adverse events were reported in the study, but none were felt to be attributable to the iNO, according to Dr. Nathan.

Dr. Nathan provided disclosures related to Roche-Genentech, Boehringer Ingelheim, Promedior, Bellerophon, and United Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Nathan SD et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.308.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2019

Fluoroscopic system can improve targeting of lung lesions

NEW ORLEANS – A novel according to an industry-sponsored, prospective study.

The system, which incorporates fluoroscopic navigation, increased the percentage of cases in which the target overlapped with the lesion, from 60% to 83%. The percentage of cases without any target overlap decreased from 32% to 5%.

“Tomosynthesis-based fluoroscopic navigation … improves the three-dimensional convergence between the virtual target and the actual target,” said Krish Bhadra, MD, of CHI Memorial Medical Group in Chattanooga, Tenn.

Dr. Bhadra presented results with this system at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

He and his colleagues conducted a study of Medtronic’s superDimension navigation system (version 7.2), which provides real-time imaging with three-dimensional fluoroscopy. The system has a “local registration” feature, which uses fluoroscopy and an algorithm to update the virtual target location during the procedure. This allows the user to reposition the catheter based on the location of the lesion.

The researchers tested the system in 50 patients from two centers (NCT03585959). Patients’ lesions had to be larger than 10 mm, not visible endobronchially, and not reachable by convex endobronchial ultrasound. Lesions within 10 mm of the diaphragm were excluded.

The median lesion size was 17.0 mm, 61.2% were smaller than 20 mm, 65.3% were in the upper lobe, and 53.1% had a bronchus sign present. The median distance from lesion to pleura was 5.9 mm.

Dr. Bhadra said the system performed as designed in all cases, and the protocol-defined technical success rate was 95.9% (47/49). Local registration was attempted in 49 patients and was successful in 47 patients (95.9%). In the unsuccessful cases, local registration was not completed based on the system design because the correction distance was greater than 3.0 cm.

The study’s primary endpoint was three-dimensional overlap of the virtual target and the actual lesion, as confirmed by cone-beam computed tomography. Success was defined as greater than 0% overlap after location correction. Target overlap was achieved in 59.6% (28/47) of cases before local registration and 83.0% (39/47) of cases after.

There were six cases in which local registration was successful, but these subjects weren’t evaluable because of failed procedure recording. When those subjects were excluded, target overlap was achieved in 95.1% (39/41) of cases after local registration.

The median percent overlap between the virtual target and the actual lesion was 11.4% before local registration and 32.8% after. The percentage of cases without any target overlap decreased from 31.7% (13/41) before local registration to 4.9% (2/41) after.

Focusing on the two cases without target overlap, Dr. Bhadra noted that he was able to get a biopsy that proved a malignancy in one of those patients. In the other patient, Dr. Bhadra was able to identify features of organizing pneumonia.

“Even though we did not have overlap, we must have been close enough that we were able to get malignant tissue in one [patient] and features of organizing pneumonia in a patient who’s got no history of organizing pneumonia,” Dr. Bhadra said.

He and his colleagues did not evaluate diagnostic yield in this study, but they did assess complications up to 7 days after the procedure.

The team reported one case of pneumothorax, but the patient didn’t require a chest tube. Additionally, there were two cases of bronchopulmonary hemorrhage, but the patients didn’t require any interventions.

This study was sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Bhadra disclosed relationships with Medtronic, Boston Scientific, BodyVision, Auris Surgical Robotics, Intuitive Surgical, Veracyte, Biodesix, Merit Medical Endotek, and Johnson & Johnson.

SOURCE: Bhadra K et al. CHEST 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.314.

NEW ORLEANS – A novel according to an industry-sponsored, prospective study.

The system, which incorporates fluoroscopic navigation, increased the percentage of cases in which the target overlapped with the lesion, from 60% to 83%. The percentage of cases without any target overlap decreased from 32% to 5%.

“Tomosynthesis-based fluoroscopic navigation … improves the three-dimensional convergence between the virtual target and the actual target,” said Krish Bhadra, MD, of CHI Memorial Medical Group in Chattanooga, Tenn.

Dr. Bhadra presented results with this system at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

He and his colleagues conducted a study of Medtronic’s superDimension navigation system (version 7.2), which provides real-time imaging with three-dimensional fluoroscopy. The system has a “local registration” feature, which uses fluoroscopy and an algorithm to update the virtual target location during the procedure. This allows the user to reposition the catheter based on the location of the lesion.

The researchers tested the system in 50 patients from two centers (NCT03585959). Patients’ lesions had to be larger than 10 mm, not visible endobronchially, and not reachable by convex endobronchial ultrasound. Lesions within 10 mm of the diaphragm were excluded.

The median lesion size was 17.0 mm, 61.2% were smaller than 20 mm, 65.3% were in the upper lobe, and 53.1% had a bronchus sign present. The median distance from lesion to pleura was 5.9 mm.

Dr. Bhadra said the system performed as designed in all cases, and the protocol-defined technical success rate was 95.9% (47/49). Local registration was attempted in 49 patients and was successful in 47 patients (95.9%). In the unsuccessful cases, local registration was not completed based on the system design because the correction distance was greater than 3.0 cm.

The study’s primary endpoint was three-dimensional overlap of the virtual target and the actual lesion, as confirmed by cone-beam computed tomography. Success was defined as greater than 0% overlap after location correction. Target overlap was achieved in 59.6% (28/47) of cases before local registration and 83.0% (39/47) of cases after.

There were six cases in which local registration was successful, but these subjects weren’t evaluable because of failed procedure recording. When those subjects were excluded, target overlap was achieved in 95.1% (39/41) of cases after local registration.

The median percent overlap between the virtual target and the actual lesion was 11.4% before local registration and 32.8% after. The percentage of cases without any target overlap decreased from 31.7% (13/41) before local registration to 4.9% (2/41) after.

Focusing on the two cases without target overlap, Dr. Bhadra noted that he was able to get a biopsy that proved a malignancy in one of those patients. In the other patient, Dr. Bhadra was able to identify features of organizing pneumonia.

“Even though we did not have overlap, we must have been close enough that we were able to get malignant tissue in one [patient] and features of organizing pneumonia in a patient who’s got no history of organizing pneumonia,” Dr. Bhadra said.

He and his colleagues did not evaluate diagnostic yield in this study, but they did assess complications up to 7 days after the procedure.

The team reported one case of pneumothorax, but the patient didn’t require a chest tube. Additionally, there were two cases of bronchopulmonary hemorrhage, but the patients didn’t require any interventions.

This study was sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Bhadra disclosed relationships with Medtronic, Boston Scientific, BodyVision, Auris Surgical Robotics, Intuitive Surgical, Veracyte, Biodesix, Merit Medical Endotek, and Johnson & Johnson.

SOURCE: Bhadra K et al. CHEST 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.314.

NEW ORLEANS – A novel according to an industry-sponsored, prospective study.

The system, which incorporates fluoroscopic navigation, increased the percentage of cases in which the target overlapped with the lesion, from 60% to 83%. The percentage of cases without any target overlap decreased from 32% to 5%.

“Tomosynthesis-based fluoroscopic navigation … improves the three-dimensional convergence between the virtual target and the actual target,” said Krish Bhadra, MD, of CHI Memorial Medical Group in Chattanooga, Tenn.

Dr. Bhadra presented results with this system at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

He and his colleagues conducted a study of Medtronic’s superDimension navigation system (version 7.2), which provides real-time imaging with three-dimensional fluoroscopy. The system has a “local registration” feature, which uses fluoroscopy and an algorithm to update the virtual target location during the procedure. This allows the user to reposition the catheter based on the location of the lesion.

The researchers tested the system in 50 patients from two centers (NCT03585959). Patients’ lesions had to be larger than 10 mm, not visible endobronchially, and not reachable by convex endobronchial ultrasound. Lesions within 10 mm of the diaphragm were excluded.

The median lesion size was 17.0 mm, 61.2% were smaller than 20 mm, 65.3% were in the upper lobe, and 53.1% had a bronchus sign present. The median distance from lesion to pleura was 5.9 mm.

Dr. Bhadra said the system performed as designed in all cases, and the protocol-defined technical success rate was 95.9% (47/49). Local registration was attempted in 49 patients and was successful in 47 patients (95.9%). In the unsuccessful cases, local registration was not completed based on the system design because the correction distance was greater than 3.0 cm.

The study’s primary endpoint was three-dimensional overlap of the virtual target and the actual lesion, as confirmed by cone-beam computed tomography. Success was defined as greater than 0% overlap after location correction. Target overlap was achieved in 59.6% (28/47) of cases before local registration and 83.0% (39/47) of cases after.

There were six cases in which local registration was successful, but these subjects weren’t evaluable because of failed procedure recording. When those subjects were excluded, target overlap was achieved in 95.1% (39/41) of cases after local registration.

The median percent overlap between the virtual target and the actual lesion was 11.4% before local registration and 32.8% after. The percentage of cases without any target overlap decreased from 31.7% (13/41) before local registration to 4.9% (2/41) after.

Focusing on the two cases without target overlap, Dr. Bhadra noted that he was able to get a biopsy that proved a malignancy in one of those patients. In the other patient, Dr. Bhadra was able to identify features of organizing pneumonia.

“Even though we did not have overlap, we must have been close enough that we were able to get malignant tissue in one [patient] and features of organizing pneumonia in a patient who’s got no history of organizing pneumonia,” Dr. Bhadra said.

He and his colleagues did not evaluate diagnostic yield in this study, but they did assess complications up to 7 days after the procedure.

The team reported one case of pneumothorax, but the patient didn’t require a chest tube. Additionally, there were two cases of bronchopulmonary hemorrhage, but the patients didn’t require any interventions.

This study was sponsored by Medtronic. Dr. Bhadra disclosed relationships with Medtronic, Boston Scientific, BodyVision, Auris Surgical Robotics, Intuitive Surgical, Veracyte, Biodesix, Merit Medical Endotek, and Johnson & Johnson.

SOURCE: Bhadra K et al. CHEST 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.314.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2019

Measles causes B-cell changes, leading to ‘immune amnesia’

“Our findings provide a biological explanation for the observed increase in childhood mortality and secondary infections several years after an episode of measles,” said Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors. The study was published in Science Immunology.

To determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression, the researchers investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IGHV-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IGHV genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IGHV genes, Dr. Petrova and associates said.

Finally, the researchers confirmed a hypothesis about the depletion of B memory cell clones during measles and a repopulation of new cells with less clonal expansion. The frequency of individual IGHV-J gene combinations before infection was correlated with a reduction after infection, “with the most frequent combinations undergoing the most marked depletion” and the result being an increase in genetic diversity.

To further test their findings, the researchers vaccinated two groups of four ferrets with live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and at 4 weeks infected one of the groups with canine distemper virus (CDV), a surrogate for MeV. At 14 weeks after vaccination, the uninfected group maintained high levels of influenza-specific neutralizing antibodies while the infected group saw impaired B cells and a subsequent reduction in neutralizing antibodies.

Understanding the impact of measles on the immune system

“How measles infection has such a long-lasting deleterious effect on the immune system while allowing robust immunity against itself has been a burning immunological question,” Duane R. Wesemann, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an accompanying editorial. The research from Petrova et al. begins to answer that question.

Among the observations he found most interesting was how “post-measles memory cells were more diverse than the pre-measles memory pool,” despite expectations that measles immunity would be dominant. He speculated that the void in memory cells is filled by a set of clones binding to unidentified or nonnative antigens, which may bring polyclonal diversity into B memory cells.

More research is needed to determine just what these findings mean, including looking beyond memory cell depletion and focusing on the impact of immature immunoglobulin repertoires in naive cells. But his broad takeaway is that measles remains both a public health concern and an opportunity to understand how the human body counters disease.

“The unique relationship measles has with the human immune system,” he said, “can illuminate aspects of its inner workings.”

The study was funded by grants to the investigators the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education, the Wellcome Trust, the German Centre for Infection Research, the Collaborative Research Centre of the German Research Foundation, the German Ministry of Health, and the Royal Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Wesemann reported receiving support from National Institutes of Health grants and an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; he also reports being a consultant for OpenBiome.

SOURCE: Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125; Wesemann DR. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz4195.

“Our findings provide a biological explanation for the observed increase in childhood mortality and secondary infections several years after an episode of measles,” said Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors. The study was published in Science Immunology.

To determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression, the researchers investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IGHV-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IGHV genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IGHV genes, Dr. Petrova and associates said.

Finally, the researchers confirmed a hypothesis about the depletion of B memory cell clones during measles and a repopulation of new cells with less clonal expansion. The frequency of individual IGHV-J gene combinations before infection was correlated with a reduction after infection, “with the most frequent combinations undergoing the most marked depletion” and the result being an increase in genetic diversity.

To further test their findings, the researchers vaccinated two groups of four ferrets with live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and at 4 weeks infected one of the groups with canine distemper virus (CDV), a surrogate for MeV. At 14 weeks after vaccination, the uninfected group maintained high levels of influenza-specific neutralizing antibodies while the infected group saw impaired B cells and a subsequent reduction in neutralizing antibodies.

Understanding the impact of measles on the immune system

“How measles infection has such a long-lasting deleterious effect on the immune system while allowing robust immunity against itself has been a burning immunological question,” Duane R. Wesemann, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an accompanying editorial. The research from Petrova et al. begins to answer that question.

Among the observations he found most interesting was how “post-measles memory cells were more diverse than the pre-measles memory pool,” despite expectations that measles immunity would be dominant. He speculated that the void in memory cells is filled by a set of clones binding to unidentified or nonnative antigens, which may bring polyclonal diversity into B memory cells.

More research is needed to determine just what these findings mean, including looking beyond memory cell depletion and focusing on the impact of immature immunoglobulin repertoires in naive cells. But his broad takeaway is that measles remains both a public health concern and an opportunity to understand how the human body counters disease.

“The unique relationship measles has with the human immune system,” he said, “can illuminate aspects of its inner workings.”

The study was funded by grants to the investigators the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education, the Wellcome Trust, the German Centre for Infection Research, the Collaborative Research Centre of the German Research Foundation, the German Ministry of Health, and the Royal Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Wesemann reported receiving support from National Institutes of Health grants and an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; he also reports being a consultant for OpenBiome.

SOURCE: Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125; Wesemann DR. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz4195.

“Our findings provide a biological explanation for the observed increase in childhood mortality and secondary infections several years after an episode of measles,” said Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors. The study was published in Science Immunology.

To determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression, the researchers investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IGHV-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IGHV genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IGHV genes, Dr. Petrova and associates said.

Finally, the researchers confirmed a hypothesis about the depletion of B memory cell clones during measles and a repopulation of new cells with less clonal expansion. The frequency of individual IGHV-J gene combinations before infection was correlated with a reduction after infection, “with the most frequent combinations undergoing the most marked depletion” and the result being an increase in genetic diversity.

To further test their findings, the researchers vaccinated two groups of four ferrets with live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and at 4 weeks infected one of the groups with canine distemper virus (CDV), a surrogate for MeV. At 14 weeks after vaccination, the uninfected group maintained high levels of influenza-specific neutralizing antibodies while the infected group saw impaired B cells and a subsequent reduction in neutralizing antibodies.

Understanding the impact of measles on the immune system

“How measles infection has such a long-lasting deleterious effect on the immune system while allowing robust immunity against itself has been a burning immunological question,” Duane R. Wesemann, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an accompanying editorial. The research from Petrova et al. begins to answer that question.

Among the observations he found most interesting was how “post-measles memory cells were more diverse than the pre-measles memory pool,” despite expectations that measles immunity would be dominant. He speculated that the void in memory cells is filled by a set of clones binding to unidentified or nonnative antigens, which may bring polyclonal diversity into B memory cells.

More research is needed to determine just what these findings mean, including looking beyond memory cell depletion and focusing on the impact of immature immunoglobulin repertoires in naive cells. But his broad takeaway is that measles remains both a public health concern and an opportunity to understand how the human body counters disease.

“The unique relationship measles has with the human immune system,” he said, “can illuminate aspects of its inner workings.”

The study was funded by grants to the investigators the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education, the Wellcome Trust, the German Centre for Infection Research, the Collaborative Research Centre of the German Research Foundation, the German Ministry of Health, and the Royal Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Wesemann reported receiving support from National Institutes of Health grants and an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; he also reports being a consultant for OpenBiome.

SOURCE: Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125; Wesemann DR. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz4195.

FROM SCIENCE IMMUNOTHERAPY

Click for Credit: Long-term antibiotics & stroke, CHD; Postvaccination seizures; more

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Poor response to statins hikes risk of cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2MVHlDR

Expires April 17, 2020

2. Postvaccination febrile seizures are no more severe than other febrile seizures

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VUJzaE

Expires April 19, 2020

3. Hydroxychloroquine adherence in SLE: worse than you thought

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2oT00Z9

Expires April 22, 2020

4. Long-term antibiotic use may heighten stroke, CHD risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OUUVu5

Expires April 28, 2020

5. Knowledge gaps about long-term osteoporosis drug therapy benefits, risks remain large

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Msgqkb

Expires May 1, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Poor response to statins hikes risk of cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2MVHlDR

Expires April 17, 2020

2. Postvaccination febrile seizures are no more severe than other febrile seizures

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VUJzaE

Expires April 19, 2020

3. Hydroxychloroquine adherence in SLE: worse than you thought

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2oT00Z9

Expires April 22, 2020

4. Long-term antibiotic use may heighten stroke, CHD risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OUUVu5

Expires April 28, 2020

5. Knowledge gaps about long-term osteoporosis drug therapy benefits, risks remain large

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Msgqkb

Expires May 1, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the November issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Poor response to statins hikes risk of cardiovascular events

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2MVHlDR

Expires April 17, 2020

2. Postvaccination febrile seizures are no more severe than other febrile seizures

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2VUJzaE

Expires April 19, 2020

3. Hydroxychloroquine adherence in SLE: worse than you thought

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2oT00Z9

Expires April 22, 2020

4. Long-term antibiotic use may heighten stroke, CHD risk

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2OUUVu5

Expires April 28, 2020

5. Knowledge gaps about long-term osteoporosis drug therapy benefits, risks remain large

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Msgqkb

Expires May 1, 2020

Brain abscess with lung infection? Think Nocardia

ST. LOUIS – according to University of California, San Francisco, investigators.

Nocardia – an ubiquitous gram-positive rod normally found in standing water, decaying plants, and soil, that can cause problems when it is inhaled as dust or introduced through a nick in the skin – is an underappreciated cause of brain abscess that is not covered by standard empiric therapy targeting the more common causes: Staphylococcus and Streptococcus bacteria, said senior investigator Megan Richie, MD, an assistant neurology professor at UCSF.

“Patients that have a lung infection with a new brain abscess should be started on empiric therapy not just for pyogenic organisms, but also for Nocardia pending biopsy and operative culture data, especially given that empiric therapy of high-dose Bactrim for Nocardia is relatively benign,” she said at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

The advice comes from a comparison of 14 Nocardia cases with 42 randomly selected Staph/Strep cases in a university radiologic database. Nine Nocardia cases were confirmed by operative specimen culture, the rest by lung, blood, or other tissue cultures.

Dr. Richie and colleagues suspected an association with lung infection, which has been reported anecdotally in the literature. The researchers wanted to take a quantitative look to see if it held up statistically after pushback on a brain abscess patient with a lung infection. “We were concerned this patient had Nocardia, but it took quite some time to convince other doctors that we really needed to start [Bactrim]. The patient was not immunocompromised and the infectious disease team said ‘Nocardia brain infections don’t happen in immunocompetent patients,’” Dr. Richie said,

The man did, however, turn out to have Nocardia, and of the 14 cases in the series, four patients (29%) were not immunosuppressed. “I think this would surprise [physicians] who have a little bit less experience with this organism,” Dr. Richie said.Patients with a Nocardia brain abscess were far more likely to have a concomitant lung infection (86% vs. 2%; odds ratio, 246; 95% confidence interval, 21-2953; P less than .0001). Staph/Strep brain abscess patients were more likely to have concomitant ear or sinus infections (40% versus 0%; P = .005). Immunosuppression did turn out to be more common in the Nocardia group, as well (71% vs. 19%; OR, 11; 95% CI, 3-43; P = .001), as did diabetes (36% vs. 10%; P = .03).

Nocardia patients were older (median age, 61 yrs vs. 46 yrs: P = .01) and more likely to be Hispanic (36% vs. 10%; P = .04). There were no differences in sex; neurosurgery history; intravenous drug use; or endocarditis.

On imaging, Nocardia brain abscesses were poorly circumscribed and tended to have multiple lobes, “often two in a figure-eight pattern,” Dr. Richie said. Nocardia diagnosis took longer (median, 7 vs. 4 days; P = .04), “which makes sense because it is a harder diagnosis to make,” she said.

Operative specimen culture was the most potent diagnostic tool. Blood cultures were positive in just one Nocardia patient and a few controls.

There was no external funding, and the investigators did not have any relevant disclosures.

ST. LOUIS – according to University of California, San Francisco, investigators.

Nocardia – an ubiquitous gram-positive rod normally found in standing water, decaying plants, and soil, that can cause problems when it is inhaled as dust or introduced through a nick in the skin – is an underappreciated cause of brain abscess that is not covered by standard empiric therapy targeting the more common causes: Staphylococcus and Streptococcus bacteria, said senior investigator Megan Richie, MD, an assistant neurology professor at UCSF.

“Patients that have a lung infection with a new brain abscess should be started on empiric therapy not just for pyogenic organisms, but also for Nocardia pending biopsy and operative culture data, especially given that empiric therapy of high-dose Bactrim for Nocardia is relatively benign,” she said at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

The advice comes from a comparison of 14 Nocardia cases with 42 randomly selected Staph/Strep cases in a university radiologic database. Nine Nocardia cases were confirmed by operative specimen culture, the rest by lung, blood, or other tissue cultures.

Dr. Richie and colleagues suspected an association with lung infection, which has been reported anecdotally in the literature. The researchers wanted to take a quantitative look to see if it held up statistically after pushback on a brain abscess patient with a lung infection. “We were concerned this patient had Nocardia, but it took quite some time to convince other doctors that we really needed to start [Bactrim]. The patient was not immunocompromised and the infectious disease team said ‘Nocardia brain infections don’t happen in immunocompetent patients,’” Dr. Richie said,

The man did, however, turn out to have Nocardia, and of the 14 cases in the series, four patients (29%) were not immunosuppressed. “I think this would surprise [physicians] who have a little bit less experience with this organism,” Dr. Richie said.Patients with a Nocardia brain abscess were far more likely to have a concomitant lung infection (86% vs. 2%; odds ratio, 246; 95% confidence interval, 21-2953; P less than .0001). Staph/Strep brain abscess patients were more likely to have concomitant ear or sinus infections (40% versus 0%; P = .005). Immunosuppression did turn out to be more common in the Nocardia group, as well (71% vs. 19%; OR, 11; 95% CI, 3-43; P = .001), as did diabetes (36% vs. 10%; P = .03).

Nocardia patients were older (median age, 61 yrs vs. 46 yrs: P = .01) and more likely to be Hispanic (36% vs. 10%; P = .04). There were no differences in sex; neurosurgery history; intravenous drug use; or endocarditis.

On imaging, Nocardia brain abscesses were poorly circumscribed and tended to have multiple lobes, “often two in a figure-eight pattern,” Dr. Richie said. Nocardia diagnosis took longer (median, 7 vs. 4 days; P = .04), “which makes sense because it is a harder diagnosis to make,” she said.

Operative specimen culture was the most potent diagnostic tool. Blood cultures were positive in just one Nocardia patient and a few controls.

There was no external funding, and the investigators did not have any relevant disclosures.

ST. LOUIS – according to University of California, San Francisco, investigators.

Nocardia – an ubiquitous gram-positive rod normally found in standing water, decaying plants, and soil, that can cause problems when it is inhaled as dust or introduced through a nick in the skin – is an underappreciated cause of brain abscess that is not covered by standard empiric therapy targeting the more common causes: Staphylococcus and Streptococcus bacteria, said senior investigator Megan Richie, MD, an assistant neurology professor at UCSF.

“Patients that have a lung infection with a new brain abscess should be started on empiric therapy not just for pyogenic organisms, but also for Nocardia pending biopsy and operative culture data, especially given that empiric therapy of high-dose Bactrim for Nocardia is relatively benign,” she said at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

The advice comes from a comparison of 14 Nocardia cases with 42 randomly selected Staph/Strep cases in a university radiologic database. Nine Nocardia cases were confirmed by operative specimen culture, the rest by lung, blood, or other tissue cultures.

Dr. Richie and colleagues suspected an association with lung infection, which has been reported anecdotally in the literature. The researchers wanted to take a quantitative look to see if it held up statistically after pushback on a brain abscess patient with a lung infection. “We were concerned this patient had Nocardia, but it took quite some time to convince other doctors that we really needed to start [Bactrim]. The patient was not immunocompromised and the infectious disease team said ‘Nocardia brain infections don’t happen in immunocompetent patients,’” Dr. Richie said,

The man did, however, turn out to have Nocardia, and of the 14 cases in the series, four patients (29%) were not immunosuppressed. “I think this would surprise [physicians] who have a little bit less experience with this organism,” Dr. Richie said.Patients with a Nocardia brain abscess were far more likely to have a concomitant lung infection (86% vs. 2%; odds ratio, 246; 95% confidence interval, 21-2953; P less than .0001). Staph/Strep brain abscess patients were more likely to have concomitant ear or sinus infections (40% versus 0%; P = .005). Immunosuppression did turn out to be more common in the Nocardia group, as well (71% vs. 19%; OR, 11; 95% CI, 3-43; P = .001), as did diabetes (36% vs. 10%; P = .03).

Nocardia patients were older (median age, 61 yrs vs. 46 yrs: P = .01) and more likely to be Hispanic (36% vs. 10%; P = .04). There were no differences in sex; neurosurgery history; intravenous drug use; or endocarditis.

On imaging, Nocardia brain abscesses were poorly circumscribed and tended to have multiple lobes, “often two in a figure-eight pattern,” Dr. Richie said. Nocardia diagnosis took longer (median, 7 vs. 4 days; P = .04), “which makes sense because it is a harder diagnosis to make,” she said.

Operative specimen culture was the most potent diagnostic tool. Blood cultures were positive in just one Nocardia patient and a few controls.

There was no external funding, and the investigators did not have any relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ANA 2019

Tips for helping children improve adherence to asthma treatment

NEW ORLEANS – Up to 50% of children with asthma struggle to control their condition, yet fewer than 5% of pediatric asthma is severe and truly resistant to therapy, according to Susan Laubach, MD.

Other factors may make asthma difficult to control and may be modifiable, especially nonadherence to recommended treatment. In fact, up to 70% of patients report poor adherence to recommended treatment, Dr. Laubach said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Barriers to adherence may be related to the treatments themselves,” she said. “These include complex treatment schedules, lack of an immediately discernible beneficial effect, adverse effects of the medication, and prohibitive costs.”

Dr. Laubach, who directs the allergy clinic at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, said that clinician-related barriers also influence patient adherence to recommended treatment, including difficulty scheduling appointments or seeing the same physician, a perceived lack of empathy, or failure to discuss the family’s concerns or answer questions. Common patient-related barriers include poor understanding of how the medication may help or how to use the inhalers.

“Some families have a lack of trust in the health care system, or certain beliefs about illness or medication that may hamper motivation to adhere,” she added. “Social issues such as poverty, lack of insurance, or a chaotic home environment may make it difficult for a patient to adhere to recommended treatment.”

In 2013, researchers led by Ted Klok, MD, PhD, of Princess Amalia Children’s Clinic in the Netherlands, explored practical ways to improve treatment adherence in children with pediatric respiratory disease (Breathe. 2013;9:268-77). One of their recommendations involves “five E’s” of ensuring optimal adherence. They include:

Ensure close and repeated follow-up to help build trust and partnership. “I’ll often follow up every month until I know a patient has gained good control of his or her asthma,” said Dr. Laubach, who was not involved in developing the recommendations. “Then I’ll follow up every 3 months.”

Explore the patient’s views, beliefs, and preferences. “You can do this by inviting questions or following up on comments or remarks made about the treatment plan,” she said. “This doesn’t have to take long. You can simply ask, ‘What are you concerned might happen if your child uses an inhaled corticosteroid?’ Or, ‘What have you heard about inhaled steroids?’ ”

Express empathy using active listening techniques tailored to the patient’s needs. Consider phrasing like, “I understand what you’re saying. In a perfect world, your child would not have to use any medications. But when he can’t sleep because he’s coughing so much, the benefit of this medication probably outweighs any potential risks.”

Exercise shared decision making. For example, if the parent of one of your patients has to leave for work very early in the morning, “maybe find a way to adjust to once-daily dosing so that appropriate doses can be given at bedtime when the parent is consistently available,” Dr. Laubach said.

Evaluate adherence in a nonjudgmental fashion. Evidence suggests that most patients with asthma miss a couple of medication doses now and then. She makes it a point to ask patients, “If you’re supposed to take 14 doses a week, how many do you think you actually take?” Their response “gives me an idea about their level of adherence and it opens a discussion into why they may miss doses, so that we can find a solution to help improve adherence.”

The Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) study found a significant reduction in height velocity in patients treated with budesonide, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2012;367[10]:904-12). “However, most of this reduction occurred in the first year of treatment, was not additive over time, and led in average to a 1-cm difference in height as an adult,” said Dr. Laubach, who is also of the department of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. “So while it must be acknowledged that high-dose inhaled corticosteroids may affect growth, who do we put on inhaled corticosteroids? People who can’t breathe.”

Studies have demonstrated that the regular use of inhaled corticosteroids is associated with a decreased risk of death from asthma (N Engl J Med. 2000;343:332-6). “I suspect that most parents would trade 1 cm of height to reduce the risk of death in their child,” Dr. Laubach said.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Up to 50% of children with asthma struggle to control their condition, yet fewer than 5% of pediatric asthma is severe and truly resistant to therapy, according to Susan Laubach, MD.

Other factors may make asthma difficult to control and may be modifiable, especially nonadherence to recommended treatment. In fact, up to 70% of patients report poor adherence to recommended treatment, Dr. Laubach said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Barriers to adherence may be related to the treatments themselves,” she said. “These include complex treatment schedules, lack of an immediately discernible beneficial effect, adverse effects of the medication, and prohibitive costs.”

Dr. Laubach, who directs the allergy clinic at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, said that clinician-related barriers also influence patient adherence to recommended treatment, including difficulty scheduling appointments or seeing the same physician, a perceived lack of empathy, or failure to discuss the family’s concerns or answer questions. Common patient-related barriers include poor understanding of how the medication may help or how to use the inhalers.

“Some families have a lack of trust in the health care system, or certain beliefs about illness or medication that may hamper motivation to adhere,” she added. “Social issues such as poverty, lack of insurance, or a chaotic home environment may make it difficult for a patient to adhere to recommended treatment.”

In 2013, researchers led by Ted Klok, MD, PhD, of Princess Amalia Children’s Clinic in the Netherlands, explored practical ways to improve treatment adherence in children with pediatric respiratory disease (Breathe. 2013;9:268-77). One of their recommendations involves “five E’s” of ensuring optimal adherence. They include:

Ensure close and repeated follow-up to help build trust and partnership. “I’ll often follow up every month until I know a patient has gained good control of his or her asthma,” said Dr. Laubach, who was not involved in developing the recommendations. “Then I’ll follow up every 3 months.”

Explore the patient’s views, beliefs, and preferences. “You can do this by inviting questions or following up on comments or remarks made about the treatment plan,” she said. “This doesn’t have to take long. You can simply ask, ‘What are you concerned might happen if your child uses an inhaled corticosteroid?’ Or, ‘What have you heard about inhaled steroids?’ ”

Express empathy using active listening techniques tailored to the patient’s needs. Consider phrasing like, “I understand what you’re saying. In a perfect world, your child would not have to use any medications. But when he can’t sleep because he’s coughing so much, the benefit of this medication probably outweighs any potential risks.”

Exercise shared decision making. For example, if the parent of one of your patients has to leave for work very early in the morning, “maybe find a way to adjust to once-daily dosing so that appropriate doses can be given at bedtime when the parent is consistently available,” Dr. Laubach said.

Evaluate adherence in a nonjudgmental fashion. Evidence suggests that most patients with asthma miss a couple of medication doses now and then. She makes it a point to ask patients, “If you’re supposed to take 14 doses a week, how many do you think you actually take?” Their response “gives me an idea about their level of adherence and it opens a discussion into why they may miss doses, so that we can find a solution to help improve adherence.”

The Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) study found a significant reduction in height velocity in patients treated with budesonide, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2012;367[10]:904-12). “However, most of this reduction occurred in the first year of treatment, was not additive over time, and led in average to a 1-cm difference in height as an adult,” said Dr. Laubach, who is also of the department of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. “So while it must be acknowledged that high-dose inhaled corticosteroids may affect growth, who do we put on inhaled corticosteroids? People who can’t breathe.”

Studies have demonstrated that the regular use of inhaled corticosteroids is associated with a decreased risk of death from asthma (N Engl J Med. 2000;343:332-6). “I suspect that most parents would trade 1 cm of height to reduce the risk of death in their child,” Dr. Laubach said.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Up to 50% of children with asthma struggle to control their condition, yet fewer than 5% of pediatric asthma is severe and truly resistant to therapy, according to Susan Laubach, MD.

Other factors may make asthma difficult to control and may be modifiable, especially nonadherence to recommended treatment. In fact, up to 70% of patients report poor adherence to recommended treatment, Dr. Laubach said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Barriers to adherence may be related to the treatments themselves,” she said. “These include complex treatment schedules, lack of an immediately discernible beneficial effect, adverse effects of the medication, and prohibitive costs.”

Dr. Laubach, who directs the allergy clinic at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, said that clinician-related barriers also influence patient adherence to recommended treatment, including difficulty scheduling appointments or seeing the same physician, a perceived lack of empathy, or failure to discuss the family’s concerns or answer questions. Common patient-related barriers include poor understanding of how the medication may help or how to use the inhalers.

“Some families have a lack of trust in the health care system, or certain beliefs about illness or medication that may hamper motivation to adhere,” she added. “Social issues such as poverty, lack of insurance, or a chaotic home environment may make it difficult for a patient to adhere to recommended treatment.”

In 2013, researchers led by Ted Klok, MD, PhD, of Princess Amalia Children’s Clinic in the Netherlands, explored practical ways to improve treatment adherence in children with pediatric respiratory disease (Breathe. 2013;9:268-77). One of their recommendations involves “five E’s” of ensuring optimal adherence. They include:

Ensure close and repeated follow-up to help build trust and partnership. “I’ll often follow up every month until I know a patient has gained good control of his or her asthma,” said Dr. Laubach, who was not involved in developing the recommendations. “Then I’ll follow up every 3 months.”

Explore the patient’s views, beliefs, and preferences. “You can do this by inviting questions or following up on comments or remarks made about the treatment plan,” she said. “This doesn’t have to take long. You can simply ask, ‘What are you concerned might happen if your child uses an inhaled corticosteroid?’ Or, ‘What have you heard about inhaled steroids?’ ”

Express empathy using active listening techniques tailored to the patient’s needs. Consider phrasing like, “I understand what you’re saying. In a perfect world, your child would not have to use any medications. But when he can’t sleep because he’s coughing so much, the benefit of this medication probably outweighs any potential risks.”

Exercise shared decision making. For example, if the parent of one of your patients has to leave for work very early in the morning, “maybe find a way to adjust to once-daily dosing so that appropriate doses can be given at bedtime when the parent is consistently available,” Dr. Laubach said.

Evaluate adherence in a nonjudgmental fashion. Evidence suggests that most patients with asthma miss a couple of medication doses now and then. She makes it a point to ask patients, “If you’re supposed to take 14 doses a week, how many do you think you actually take?” Their response “gives me an idea about their level of adherence and it opens a discussion into why they may miss doses, so that we can find a solution to help improve adherence.”

The Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) study found a significant reduction in height velocity in patients treated with budesonide, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2012;367[10]:904-12). “However, most of this reduction occurred in the first year of treatment, was not additive over time, and led in average to a 1-cm difference in height as an adult,” said Dr. Laubach, who is also of the department of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. “So while it must be acknowledged that high-dose inhaled corticosteroids may affect growth, who do we put on inhaled corticosteroids? People who can’t breathe.”