User login

High mortality rates trail tracheostomy patients

findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Current outcome prediction tools to support decision making regarding tracheostomies are limited, wrote Anuj B. Mehta, MD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues. “This study provides novel and in-depth insight into mortality and health care utilization following tracheostomy not previously described at the population-level.”

In a study published in Critical Care Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from 8,343 nonsurgical patients seen in California hospitals from 2012 to 2013 who received a tracheostomy for acute respiratory failure.

Overall, the 1-year mortality rate for patients who had tracheostomies (the primary outcome) was 46.5%, with in-hospital mortality of 18.9% and 30-day mortality of 22.1%. Pneumonia was the most common diagnosis for patients with respiratory failure (79%) and some had an additional diagnosis, such as severe sepsis (56%).

Patients aged 65 years and older had significantly higher mortality than those under 65 (54.7% vs. 36.5%). The average age of the patients was 65 years; approximately 46% were women and 48% were white. The median survival for adults aged 65 years and older was 175 days, compared with median survival of more than a year for younger patients.

Secondary outcomes included discharge destination, hospital readmission, and health care utilization. A majority (86%) of patients were discharged to a long-term care facility, while 11% were sent home and approximately 3% were discharged to other destinations.

Nearly two-thirds (60%) of patients were readmitted to the hospital within a year of tracheostomy, and readmission was more common among older adults, compared with younger (66% vs. 55%).

In addition, just over one-third of all patients (36%) spent more than 50% of their days alive in the hospital in short-term acute care, and this rate was significantly higher for patients aged 65 years and older, compared with those under 65 (43% vs. 29%). On average, the total hospital cost for patients who survived the first year after tracheostomy was $215,369, with no significant difference in average cost among age groups.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single state, possible misclassification of billing codes, and inability to measure quality of life, the researchers noted.

However, “our findings of high mortality, low median survival for older patients, high readmission rates, potentially burdensome cost, and informative outcome trajectories provide significant insight into long-term outcomes following tracheostomy,” they concluded.

Dr. Mehta and several colleagues reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Mehta AB et al. Crit Care Med. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003959.

findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Current outcome prediction tools to support decision making regarding tracheostomies are limited, wrote Anuj B. Mehta, MD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues. “This study provides novel and in-depth insight into mortality and health care utilization following tracheostomy not previously described at the population-level.”

In a study published in Critical Care Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from 8,343 nonsurgical patients seen in California hospitals from 2012 to 2013 who received a tracheostomy for acute respiratory failure.

Overall, the 1-year mortality rate for patients who had tracheostomies (the primary outcome) was 46.5%, with in-hospital mortality of 18.9% and 30-day mortality of 22.1%. Pneumonia was the most common diagnosis for patients with respiratory failure (79%) and some had an additional diagnosis, such as severe sepsis (56%).

Patients aged 65 years and older had significantly higher mortality than those under 65 (54.7% vs. 36.5%). The average age of the patients was 65 years; approximately 46% were women and 48% were white. The median survival for adults aged 65 years and older was 175 days, compared with median survival of more than a year for younger patients.

Secondary outcomes included discharge destination, hospital readmission, and health care utilization. A majority (86%) of patients were discharged to a long-term care facility, while 11% were sent home and approximately 3% were discharged to other destinations.

Nearly two-thirds (60%) of patients were readmitted to the hospital within a year of tracheostomy, and readmission was more common among older adults, compared with younger (66% vs. 55%).

In addition, just over one-third of all patients (36%) spent more than 50% of their days alive in the hospital in short-term acute care, and this rate was significantly higher for patients aged 65 years and older, compared with those under 65 (43% vs. 29%). On average, the total hospital cost for patients who survived the first year after tracheostomy was $215,369, with no significant difference in average cost among age groups.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single state, possible misclassification of billing codes, and inability to measure quality of life, the researchers noted.

However, “our findings of high mortality, low median survival for older patients, high readmission rates, potentially burdensome cost, and informative outcome trajectories provide significant insight into long-term outcomes following tracheostomy,” they concluded.

Dr. Mehta and several colleagues reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Mehta AB et al. Crit Care Med. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003959.

findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Current outcome prediction tools to support decision making regarding tracheostomies are limited, wrote Anuj B. Mehta, MD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues. “This study provides novel and in-depth insight into mortality and health care utilization following tracheostomy not previously described at the population-level.”

In a study published in Critical Care Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from 8,343 nonsurgical patients seen in California hospitals from 2012 to 2013 who received a tracheostomy for acute respiratory failure.

Overall, the 1-year mortality rate for patients who had tracheostomies (the primary outcome) was 46.5%, with in-hospital mortality of 18.9% and 30-day mortality of 22.1%. Pneumonia was the most common diagnosis for patients with respiratory failure (79%) and some had an additional diagnosis, such as severe sepsis (56%).

Patients aged 65 years and older had significantly higher mortality than those under 65 (54.7% vs. 36.5%). The average age of the patients was 65 years; approximately 46% were women and 48% were white. The median survival for adults aged 65 years and older was 175 days, compared with median survival of more than a year for younger patients.

Secondary outcomes included discharge destination, hospital readmission, and health care utilization. A majority (86%) of patients were discharged to a long-term care facility, while 11% were sent home and approximately 3% were discharged to other destinations.

Nearly two-thirds (60%) of patients were readmitted to the hospital within a year of tracheostomy, and readmission was more common among older adults, compared with younger (66% vs. 55%).

In addition, just over one-third of all patients (36%) spent more than 50% of their days alive in the hospital in short-term acute care, and this rate was significantly higher for patients aged 65 years and older, compared with those under 65 (43% vs. 29%). On average, the total hospital cost for patients who survived the first year after tracheostomy was $215,369, with no significant difference in average cost among age groups.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from a single state, possible misclassification of billing codes, and inability to measure quality of life, the researchers noted.

However, “our findings of high mortality, low median survival for older patients, high readmission rates, potentially burdensome cost, and informative outcome trajectories provide significant insight into long-term outcomes following tracheostomy,” they concluded.

Dr. Mehta and several colleagues reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Mehta AB et al. Crit Care Med. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003959.

FROM CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE

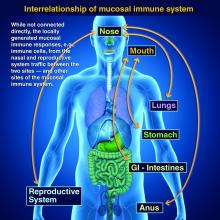

Taking vaccines to the next level via mucosal immunity

Vaccines are marvelous, and there are many well documented success stories, including rotavirus (RV) vaccines, where a live vaccine is administered to the gastrointestinal mucosa via oral drops. Antigens presented at the mucosal/epithelial surface not only induce systemic serum IgG – as do injectable vaccines – but also induce secretory IgA (sIgA), which is most helpful in diseases that directly affect the mucosa.

Mucosal vs. systemic immunity

Antibody being present on mucosal surfaces (point of initial pathogen contact) has a chance to neutralize the pathogen before it gains a foothold. Pathogen-specific mucosal lymphoid elements (e.g. in Peyer’s patches in the gut) also appear critical for optimal protection.1 The presence of both mucosal immune elements means that infection is severely limited or at times entirely prevented. So virus entering the GI tract causes minimal to no gut lining injury. Hence, there is no or mostly reduced vomiting/diarrhea. A downside of mucosally-administered live vaccines is that preexisting antibody to the vaccine antigens can reduce or block vaccine virus replication in the vaccinee, blunting or preventing protection. Note: Preexisting antibody also affects injectable live vaccines, such as the measles vaccine, similarly.

Classic injectable live or nonlive vaccines provide their most potent protection via systemic cellular responses antibody and/or antibodies in serum and extracellular fluid (ECF) where IgG and IgM are in highest concentrations. So even successful injectable vaccines still allow mucosal infection to start but then intercept further spread and prevent most of the downstream damage (think pertussis) or neutralize an infection-generated toxin (pertussis or tetanus). It usually is only after infection-induced damage occurs that systemic IgG and IgM gain better access to respiratory epithelial surfaces, but still only at a fraction of circulating concentrations. Indeed, pertussis vaccine–induced systemic immunity allows the pathogen to attack and replicate in/on host surface cells, causing toxin release and variable amounts of local mucosal injury/inflammation before vaccine-induced systemic immunity gains adequate access to the pathogen and/or to its toxin which may enter systemic circulation.

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) induces mucosal immunity

Another “standard” vaccine that induces mucosal immunity – LAIV – was developed to improve on protection afforded by injectable influenza vaccines (IIVs), but LAIV has had hiccups in the United States. One example is several years of negligible protection against H1N1 disease. As long as LAIV’s vaccine strain had reasonably matched the circulating strains, LAIV worked at least as well as injectable influenza vaccine, and even offered some cross-protection against mildly mismatched strains. But after a number of years of LAIV use, vaccine effectiveness in the United States vs. H1N1 strains appeared to fade due to previously undetected but significant changes in the circulating H1N1 strain. The lesson is that mucosal immunity’s advantages are lost if too much change occurs in the pathogen target for sIgA and mucosally-associated lymphoid tissue cells (MALT)).

Other vaccines likely need to induce mucosal immunity

Protection at the mucosal level will likely be needed for success against norovirus, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Neisseria gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Another helpful aspect of mucosal immunity is that immune cells and sIgA not only reside on the mucosa where the antigen was originally presented, but there is also a reasonable chance that these components will traffic to other mucosal surfaces.2

So intranasal vaccine could be expected to protect distant mucosal surfaces (urogenital, GI, and respiratory), leading to vaccine-induced systemic antibody plus mucosal immunity (sIGA and MALT responses) at each site.

Let’s look at a novel “two-site” chlamydia vaccine

Recently a phase 1 chlamydia vaccine that used a novel two-pronged administration site/schedule was successful at inducing both mucosal and systemic immunity in a proof-of-concept study – achieving the best of both worlds.3 This may be a template for vaccines in years to come. British investigators studied 50 healthy women aged 19-45 years in a double-blind, parallel, randomized, placebo-controlled trial that used a recombinant chlamydia protein subunit antigen (CTH522). The vaccine schedule involved three injectable priming doses followed soon thereafter by two intranasal boosting doses. There were three groups:

1. CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes (CTH522:CAF01).

2. CTH522 adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide (CTH522:AH).

3. Placebo (saline).

The intramuscular (IM) priming schedule was 0, 1, and 4 months. The intranasal vaccine booster doses or placebo were given at 4.5 and 5 months. No related serious adverse reactions occurred. For injectable dosing, the most frequent adverse event was mild local injection-site reactions in all subjects in both vaccine groups vs. in 60% of placebo recipients (P = .053). The adjuvants were the likely cause for local reactions. Intranasal doses had local reactions in 47% of both vaccine groups and 60% of placebo recipients; P = 1.000).

Both vaccines produced systemic IgG seroconversion (including neutralizing antibody) plus small amounts of IgG in the nasal cavity and genital tract in all vaccine recipients; no placebo recipient seroconverted. Interestingly, liposomally-adjuvanted vaccine produced a more rapid systemic IgG response and higher serum titers than the alum-adjuvanted vaccine. Likewise, the IM liposomal vaccine also induced higher but still small mucosal IgG antibody responses (P = .0091). Intranasal IM-induced IgG titers were not boosted by later intranasal vaccine dosing.

Subjects getting liposomal vaccine (but not alum vaccine or placebo) boosters had detectable sIgA titers in both nasal and genital tract secretions. Liposomal vaccine recipients also had fivefold to sixfold higher median titers than alum vaccine recipients after the priming dose, and these higher titers persisted to the end of the study. All liposomal vaccine recipients developed antichlamydial cell-mediated responses vs. 57% alum-adjuvanted vaccine recipients. (P = .01). So both use of two-site dosing and the liposomal adjuvant appeared critical to better responses.

In summary

While this candidate vaccine has hurdles to overcome before coming into routine use, the proof-of-principle that a combination injectable-intranasal vaccine schedule can induce robust systemic and mucosal immunity when given with an appropriate adjuvant is very promising. Adding more vaccines to the schedule then becomes an issue, but that is one of those “good” problems we can deal with later.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital-Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines, receives funding from GlaxoSmithKline for studies on pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, and from Pfizer for a study on pneumococcal vaccine on which Dr. Harrison is a sub-investigator. The hospital also receives Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus, and also for rotavirus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. PLOS Biology. 2012 Sep 1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001397.

2. Mucosal Immunity in the Human Female Reproductive Tract in “Mucosal Immunology,” 4th ed., Volume 2 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2015, pp. 2097-124).

3. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30279-8.

Vaccines are marvelous, and there are many well documented success stories, including rotavirus (RV) vaccines, where a live vaccine is administered to the gastrointestinal mucosa via oral drops. Antigens presented at the mucosal/epithelial surface not only induce systemic serum IgG – as do injectable vaccines – but also induce secretory IgA (sIgA), which is most helpful in diseases that directly affect the mucosa.

Mucosal vs. systemic immunity

Antibody being present on mucosal surfaces (point of initial pathogen contact) has a chance to neutralize the pathogen before it gains a foothold. Pathogen-specific mucosal lymphoid elements (e.g. in Peyer’s patches in the gut) also appear critical for optimal protection.1 The presence of both mucosal immune elements means that infection is severely limited or at times entirely prevented. So virus entering the GI tract causes minimal to no gut lining injury. Hence, there is no or mostly reduced vomiting/diarrhea. A downside of mucosally-administered live vaccines is that preexisting antibody to the vaccine antigens can reduce or block vaccine virus replication in the vaccinee, blunting or preventing protection. Note: Preexisting antibody also affects injectable live vaccines, such as the measles vaccine, similarly.

Classic injectable live or nonlive vaccines provide their most potent protection via systemic cellular responses antibody and/or antibodies in serum and extracellular fluid (ECF) where IgG and IgM are in highest concentrations. So even successful injectable vaccines still allow mucosal infection to start but then intercept further spread and prevent most of the downstream damage (think pertussis) or neutralize an infection-generated toxin (pertussis or tetanus). It usually is only after infection-induced damage occurs that systemic IgG and IgM gain better access to respiratory epithelial surfaces, but still only at a fraction of circulating concentrations. Indeed, pertussis vaccine–induced systemic immunity allows the pathogen to attack and replicate in/on host surface cells, causing toxin release and variable amounts of local mucosal injury/inflammation before vaccine-induced systemic immunity gains adequate access to the pathogen and/or to its toxin which may enter systemic circulation.

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) induces mucosal immunity

Another “standard” vaccine that induces mucosal immunity – LAIV – was developed to improve on protection afforded by injectable influenza vaccines (IIVs), but LAIV has had hiccups in the United States. One example is several years of negligible protection against H1N1 disease. As long as LAIV’s vaccine strain had reasonably matched the circulating strains, LAIV worked at least as well as injectable influenza vaccine, and even offered some cross-protection against mildly mismatched strains. But after a number of years of LAIV use, vaccine effectiveness in the United States vs. H1N1 strains appeared to fade due to previously undetected but significant changes in the circulating H1N1 strain. The lesson is that mucosal immunity’s advantages are lost if too much change occurs in the pathogen target for sIgA and mucosally-associated lymphoid tissue cells (MALT)).

Other vaccines likely need to induce mucosal immunity

Protection at the mucosal level will likely be needed for success against norovirus, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Neisseria gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Another helpful aspect of mucosal immunity is that immune cells and sIgA not only reside on the mucosa where the antigen was originally presented, but there is also a reasonable chance that these components will traffic to other mucosal surfaces.2

So intranasal vaccine could be expected to protect distant mucosal surfaces (urogenital, GI, and respiratory), leading to vaccine-induced systemic antibody plus mucosal immunity (sIGA and MALT responses) at each site.

Let’s look at a novel “two-site” chlamydia vaccine

Recently a phase 1 chlamydia vaccine that used a novel two-pronged administration site/schedule was successful at inducing both mucosal and systemic immunity in a proof-of-concept study – achieving the best of both worlds.3 This may be a template for vaccines in years to come. British investigators studied 50 healthy women aged 19-45 years in a double-blind, parallel, randomized, placebo-controlled trial that used a recombinant chlamydia protein subunit antigen (CTH522). The vaccine schedule involved three injectable priming doses followed soon thereafter by two intranasal boosting doses. There were three groups:

1. CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes (CTH522:CAF01).

2. CTH522 adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide (CTH522:AH).

3. Placebo (saline).

The intramuscular (IM) priming schedule was 0, 1, and 4 months. The intranasal vaccine booster doses or placebo were given at 4.5 and 5 months. No related serious adverse reactions occurred. For injectable dosing, the most frequent adverse event was mild local injection-site reactions in all subjects in both vaccine groups vs. in 60% of placebo recipients (P = .053). The adjuvants were the likely cause for local reactions. Intranasal doses had local reactions in 47% of both vaccine groups and 60% of placebo recipients; P = 1.000).

Both vaccines produced systemic IgG seroconversion (including neutralizing antibody) plus small amounts of IgG in the nasal cavity and genital tract in all vaccine recipients; no placebo recipient seroconverted. Interestingly, liposomally-adjuvanted vaccine produced a more rapid systemic IgG response and higher serum titers than the alum-adjuvanted vaccine. Likewise, the IM liposomal vaccine also induced higher but still small mucosal IgG antibody responses (P = .0091). Intranasal IM-induced IgG titers were not boosted by later intranasal vaccine dosing.

Subjects getting liposomal vaccine (but not alum vaccine or placebo) boosters had detectable sIgA titers in both nasal and genital tract secretions. Liposomal vaccine recipients also had fivefold to sixfold higher median titers than alum vaccine recipients after the priming dose, and these higher titers persisted to the end of the study. All liposomal vaccine recipients developed antichlamydial cell-mediated responses vs. 57% alum-adjuvanted vaccine recipients. (P = .01). So both use of two-site dosing and the liposomal adjuvant appeared critical to better responses.

In summary

While this candidate vaccine has hurdles to overcome before coming into routine use, the proof-of-principle that a combination injectable-intranasal vaccine schedule can induce robust systemic and mucosal immunity when given with an appropriate adjuvant is very promising. Adding more vaccines to the schedule then becomes an issue, but that is one of those “good” problems we can deal with later.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital-Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines, receives funding from GlaxoSmithKline for studies on pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, and from Pfizer for a study on pneumococcal vaccine on which Dr. Harrison is a sub-investigator. The hospital also receives Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus, and also for rotavirus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. PLOS Biology. 2012 Sep 1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001397.

2. Mucosal Immunity in the Human Female Reproductive Tract in “Mucosal Immunology,” 4th ed., Volume 2 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2015, pp. 2097-124).

3. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30279-8.

Vaccines are marvelous, and there are many well documented success stories, including rotavirus (RV) vaccines, where a live vaccine is administered to the gastrointestinal mucosa via oral drops. Antigens presented at the mucosal/epithelial surface not only induce systemic serum IgG – as do injectable vaccines – but also induce secretory IgA (sIgA), which is most helpful in diseases that directly affect the mucosa.

Mucosal vs. systemic immunity

Antibody being present on mucosal surfaces (point of initial pathogen contact) has a chance to neutralize the pathogen before it gains a foothold. Pathogen-specific mucosal lymphoid elements (e.g. in Peyer’s patches in the gut) also appear critical for optimal protection.1 The presence of both mucosal immune elements means that infection is severely limited or at times entirely prevented. So virus entering the GI tract causes minimal to no gut lining injury. Hence, there is no or mostly reduced vomiting/diarrhea. A downside of mucosally-administered live vaccines is that preexisting antibody to the vaccine antigens can reduce or block vaccine virus replication in the vaccinee, blunting or preventing protection. Note: Preexisting antibody also affects injectable live vaccines, such as the measles vaccine, similarly.

Classic injectable live or nonlive vaccines provide their most potent protection via systemic cellular responses antibody and/or antibodies in serum and extracellular fluid (ECF) where IgG and IgM are in highest concentrations. So even successful injectable vaccines still allow mucosal infection to start but then intercept further spread and prevent most of the downstream damage (think pertussis) or neutralize an infection-generated toxin (pertussis or tetanus). It usually is only after infection-induced damage occurs that systemic IgG and IgM gain better access to respiratory epithelial surfaces, but still only at a fraction of circulating concentrations. Indeed, pertussis vaccine–induced systemic immunity allows the pathogen to attack and replicate in/on host surface cells, causing toxin release and variable amounts of local mucosal injury/inflammation before vaccine-induced systemic immunity gains adequate access to the pathogen and/or to its toxin which may enter systemic circulation.

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) induces mucosal immunity

Another “standard” vaccine that induces mucosal immunity – LAIV – was developed to improve on protection afforded by injectable influenza vaccines (IIVs), but LAIV has had hiccups in the United States. One example is several years of negligible protection against H1N1 disease. As long as LAIV’s vaccine strain had reasonably matched the circulating strains, LAIV worked at least as well as injectable influenza vaccine, and even offered some cross-protection against mildly mismatched strains. But after a number of years of LAIV use, vaccine effectiveness in the United States vs. H1N1 strains appeared to fade due to previously undetected but significant changes in the circulating H1N1 strain. The lesson is that mucosal immunity’s advantages are lost if too much change occurs in the pathogen target for sIgA and mucosally-associated lymphoid tissue cells (MALT)).

Other vaccines likely need to induce mucosal immunity

Protection at the mucosal level will likely be needed for success against norovirus, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Neisseria gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Another helpful aspect of mucosal immunity is that immune cells and sIgA not only reside on the mucosa where the antigen was originally presented, but there is also a reasonable chance that these components will traffic to other mucosal surfaces.2

So intranasal vaccine could be expected to protect distant mucosal surfaces (urogenital, GI, and respiratory), leading to vaccine-induced systemic antibody plus mucosal immunity (sIGA and MALT responses) at each site.

Let’s look at a novel “two-site” chlamydia vaccine

Recently a phase 1 chlamydia vaccine that used a novel two-pronged administration site/schedule was successful at inducing both mucosal and systemic immunity in a proof-of-concept study – achieving the best of both worlds.3 This may be a template for vaccines in years to come. British investigators studied 50 healthy women aged 19-45 years in a double-blind, parallel, randomized, placebo-controlled trial that used a recombinant chlamydia protein subunit antigen (CTH522). The vaccine schedule involved three injectable priming doses followed soon thereafter by two intranasal boosting doses. There were three groups:

1. CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes (CTH522:CAF01).

2. CTH522 adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide (CTH522:AH).

3. Placebo (saline).

The intramuscular (IM) priming schedule was 0, 1, and 4 months. The intranasal vaccine booster doses or placebo were given at 4.5 and 5 months. No related serious adverse reactions occurred. For injectable dosing, the most frequent adverse event was mild local injection-site reactions in all subjects in both vaccine groups vs. in 60% of placebo recipients (P = .053). The adjuvants were the likely cause for local reactions. Intranasal doses had local reactions in 47% of both vaccine groups and 60% of placebo recipients; P = 1.000).

Both vaccines produced systemic IgG seroconversion (including neutralizing antibody) plus small amounts of IgG in the nasal cavity and genital tract in all vaccine recipients; no placebo recipient seroconverted. Interestingly, liposomally-adjuvanted vaccine produced a more rapid systemic IgG response and higher serum titers than the alum-adjuvanted vaccine. Likewise, the IM liposomal vaccine also induced higher but still small mucosal IgG antibody responses (P = .0091). Intranasal IM-induced IgG titers were not boosted by later intranasal vaccine dosing.

Subjects getting liposomal vaccine (but not alum vaccine or placebo) boosters had detectable sIgA titers in both nasal and genital tract secretions. Liposomal vaccine recipients also had fivefold to sixfold higher median titers than alum vaccine recipients after the priming dose, and these higher titers persisted to the end of the study. All liposomal vaccine recipients developed antichlamydial cell-mediated responses vs. 57% alum-adjuvanted vaccine recipients. (P = .01). So both use of two-site dosing and the liposomal adjuvant appeared critical to better responses.

In summary

While this candidate vaccine has hurdles to overcome before coming into routine use, the proof-of-principle that a combination injectable-intranasal vaccine schedule can induce robust systemic and mucosal immunity when given with an appropriate adjuvant is very promising. Adding more vaccines to the schedule then becomes an issue, but that is one of those “good” problems we can deal with later.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital-Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines, receives funding from GlaxoSmithKline for studies on pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, and from Pfizer for a study on pneumococcal vaccine on which Dr. Harrison is a sub-investigator. The hospital also receives Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus, and also for rotavirus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. PLOS Biology. 2012 Sep 1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001397.

2. Mucosal Immunity in the Human Female Reproductive Tract in “Mucosal Immunology,” 4th ed., Volume 2 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2015, pp. 2097-124).

3. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30279-8.

Growing vaping habit may lead to nicotine addiction in adolescents

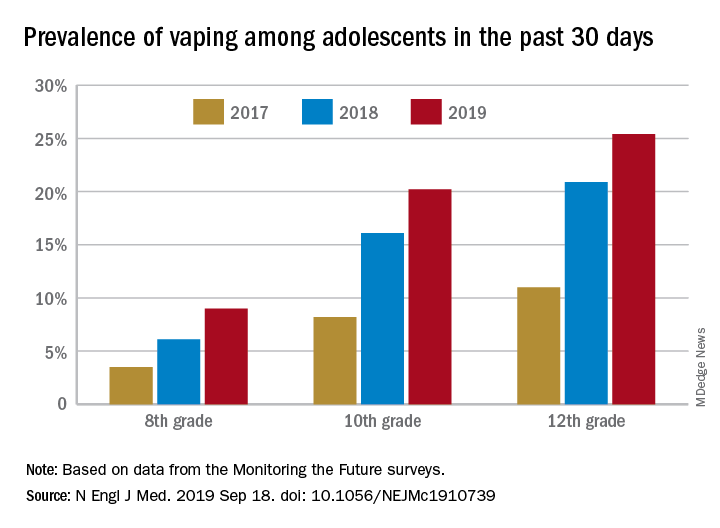

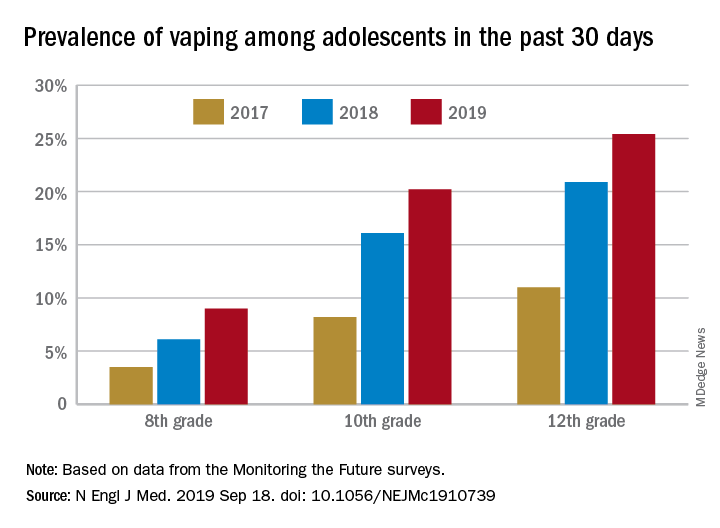

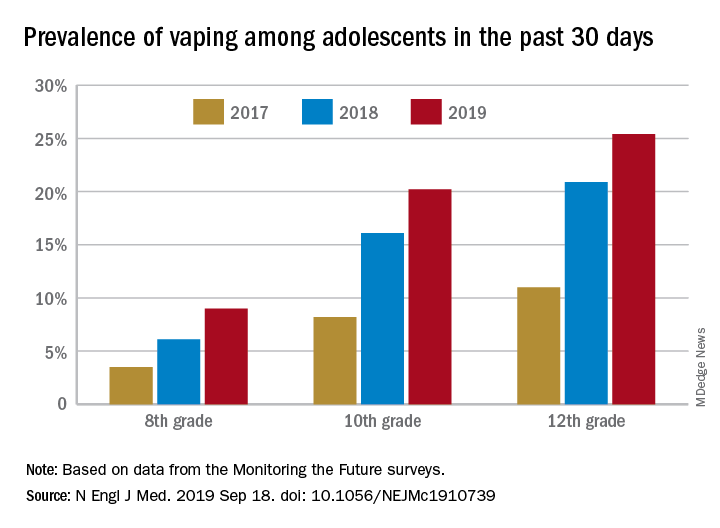

and in 2019 almost 12% of high school seniors reported that they were vaping every day, according to data from the Monitoring the Future surveys.

Daily use – defined as vaping on 20 or more of the previous 30 days – was reported by 6.9% of 10th-grade and 1.9% of 8th-grade respondents in the 2019 survey, which was the first time use in these age groups was assessed. “The substantial levels of daily vaping suggest the development of nicotine addiction,” Richard Miech, PhD, and associates said Sept. 18 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

From 2017 to 2019, e-cigarette use over the previous 30 days increased from 11.0% to 25.4% among 12th graders, from 8.2% to 20.2% in 10th graders, and from 3.5% to 9.0% of 8th graders, suggesting that “current efforts by the vaping industry, government agencies, and schools have thus far proved insufficient to stop the rapid spread of nicotine vaping among adolescents,” the investigators wrote.

By 2019, over 40% of 12th-grade students reported ever using e-cigarettes, along with more than 36% of 10th graders and almost 21% of 8th graders. Corresponding figures for past 12-month use were 35.1%, 31.1%, and 16.1%, they reported.

“New efforts are needed to protect youth from using nicotine during adolescence, when the developing brain is particularly susceptible to permanent changes from nicotine use and when almost all nicotine addiction is established,” the investigators wrote.

The analysis was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Miech.

SOURCE: Miech R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739.

and in 2019 almost 12% of high school seniors reported that they were vaping every day, according to data from the Monitoring the Future surveys.

Daily use – defined as vaping on 20 or more of the previous 30 days – was reported by 6.9% of 10th-grade and 1.9% of 8th-grade respondents in the 2019 survey, which was the first time use in these age groups was assessed. “The substantial levels of daily vaping suggest the development of nicotine addiction,” Richard Miech, PhD, and associates said Sept. 18 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

From 2017 to 2019, e-cigarette use over the previous 30 days increased from 11.0% to 25.4% among 12th graders, from 8.2% to 20.2% in 10th graders, and from 3.5% to 9.0% of 8th graders, suggesting that “current efforts by the vaping industry, government agencies, and schools have thus far proved insufficient to stop the rapid spread of nicotine vaping among adolescents,” the investigators wrote.

By 2019, over 40% of 12th-grade students reported ever using e-cigarettes, along with more than 36% of 10th graders and almost 21% of 8th graders. Corresponding figures for past 12-month use were 35.1%, 31.1%, and 16.1%, they reported.

“New efforts are needed to protect youth from using nicotine during adolescence, when the developing brain is particularly susceptible to permanent changes from nicotine use and when almost all nicotine addiction is established,” the investigators wrote.

The analysis was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Miech.

SOURCE: Miech R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739.

and in 2019 almost 12% of high school seniors reported that they were vaping every day, according to data from the Monitoring the Future surveys.

Daily use – defined as vaping on 20 or more of the previous 30 days – was reported by 6.9% of 10th-grade and 1.9% of 8th-grade respondents in the 2019 survey, which was the first time use in these age groups was assessed. “The substantial levels of daily vaping suggest the development of nicotine addiction,” Richard Miech, PhD, and associates said Sept. 18 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

From 2017 to 2019, e-cigarette use over the previous 30 days increased from 11.0% to 25.4% among 12th graders, from 8.2% to 20.2% in 10th graders, and from 3.5% to 9.0% of 8th graders, suggesting that “current efforts by the vaping industry, government agencies, and schools have thus far proved insufficient to stop the rapid spread of nicotine vaping among adolescents,” the investigators wrote.

By 2019, over 40% of 12th-grade students reported ever using e-cigarettes, along with more than 36% of 10th graders and almost 21% of 8th graders. Corresponding figures for past 12-month use were 35.1%, 31.1%, and 16.1%, they reported.

“New efforts are needed to protect youth from using nicotine during adolescence, when the developing brain is particularly susceptible to permanent changes from nicotine use and when almost all nicotine addiction is established,” the investigators wrote.

The analysis was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Miech.

SOURCE: Miech R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Adolescents who use e-cigarettes every day may be developing nicotine addiction.

Major finding: In 2019, almost 12% of high school seniors were vaping every day.

Study details: Monitoring the Future surveys nationally representative samples of 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students each year.

Disclosures: The analysis was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Miech.

Source: Miech R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739.

Wildfire smoke has acute cardiorespiratory impact, but long-term effects still under study

The 2019 wildfire season is underway in many locales across the United States, exposing millions of individuals to smoky conditions that will have health consequences ranging from stinging eyes to scratchy throats to a trip to the ED for asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation. Questions about long-term health impacts are on the minds of many, including physicians and their patients who live with cardiorespiratory conditions.

John R. Balmes, MD, a pulmonologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and an expert on the respiratory and cardiovascular effects of air pollutants, suggested that the best available published literature points to “pretty strong evidence for acute effects of wildfire smoke on respiratory health, meaning people with preexisting asthma and COPD are at risk for exacerbations, and probably for respiratory tract infections as well.” He said, “It’s a little less clear, but there’s good biological plausibility for increased risk of respiratory tract infections because when your alveolar macrophages are overloaded with carbon particles that are toxic to those cells, they don’t function as well as a first line of defense against bacterial infection, for example.”

The new normal of wildfires

Warmer, drier summers in recent years in the western United States and many other regions, attributed by climate experts to global climate change, have produced catastrophic wildfires (PNAS;2016 Oct 18;113[42]11770-5; Science 2006 Aug 18;313:940-3). The Camp Fire in Northern California broke out in November 2018, took the lives of at least 85 people, and cost more than $16 billion in damage. Smoke from that blaze reached hazardous levels in San Francisco, Sacramento, Fresno, and many other smaller towns. Other forest fires in that year caused heavy smoke conditions in Portland, Seattle, Vancouver, and Anchorage. Such events are expected to be repeated often in the coming years (Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Jul 6;16[13]).

Wildfire smoke can contain a wide range of substances, chemicals, and gases with known and unknown cardiorespiratory implications. “Smoke is composed primarily of carbon dioxide, water vapor, carbon monoxide, particulate matter, hydrocarbons and other organic chemicals, nitrogen oxides, trace minerals and several thousand other compounds,” according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Wildfire smoke: A guide for public health officials 2019. Washington, D.C.: EPA, 2019). The EPA report noted, “Particles with diameters less than 10 mcm (particulate matter, or PM10) can be inhaled into the lungs and affect the lungs, heart, and blood vessels. The smallest particles, those less than 2.5 mcm in diameter (PM2.5), are the greatest risk to public health because they can reach deep into the lungs and may even make it into the bloodstream.”

Research on health impact

In early June of 2008, Wayne Cascio, MD, awoke in his Greenville, N.C., home to the stench of smoke emanating from a large peat fire burning some 65 miles away. By the time he reached the parking lot at East Carolina University in Greenville to begin his workday as chief of cardiology, the haze of smoke had thickened to the point where he could only see a few feet in front of him.

Over the next several weeks, the fire scorched 41,000 acres and produced haze and air pollution that far exceeded National Ambient Air Quality Standards for particulate matter and blanketed rural communities in the state’s eastern region. The price tag for management of the blaze reached $20 million. Because of his interest in the health effects of wildfire smoke and because of his relationship with investigators at the EPA, Dr. Cascio initiated an epidemiology study to investigate the effects of exposure on cardiorespiratory outcomes in the population affected by the fire (Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Oct;119[10]:1415-20).

By combining satellite data with syndromic surveillance drawn from hospital records in 41 counties contained in the North Carolina Disease Event Tracking and Epidemiologic Collection Tool, he and his colleagues found that exposure to the peat wildfire smoke led to increases in the cumulative risk ratio for asthma (relative risk, 1.65), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (RR, 1.73), and pneumonia and acute bronchitis (RR, 1.59). ED visits related to cardiopulmonary symptoms and heart failure also were significantly increased (RR, 1.23 and 1.37, respectively). “That was really the first study to strongly identify a cardiac endpoint related to wildfire smoke exposure,” said Dr. Cascio, who now directs the EPA’s National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. “It really pointed out how little we knew about the health effects of wildfire up until that time.”

Those early findings have been replicated in subsequent research about the acute health effects of exposure to wildfire smoke, which contains PM2.5 and other toxic substances from structures, electronic devices, and automobiles destroyed in the path of flames, including heavy metals and asbestos. Most of the work has focused on smoke-related cardiovascular and respiratory ED visits and hospitalizations.

A study of the 2008 California wildfire impact on ED visits accounted for ozone levels in addition to PM2.5 in the smoke. During the active fire periods, PM2.5 was significantly associated with exacerbations of asthma and COPD and these effects remained after controlling for ozone levels. PM2.5 inhalation during the wildfires was associated with increased risk of an ED visit for asthma (RR, 1.112; 95% confidence interval, 1.087-1.138) for a 10 mcg/m3 increase in PM2.5 and COPD (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.019-1.0825), as well as for combined respiratory visits (RR, 1.035; 95% CI, 1.023-1.046) (Environ Int. 2109 Aug;129:291-8).

Researchers who evaluated the health impacts of wildfires in California during the 2015 fire season found an increase in all-cause cardiovascular and respiratory ED visits, especially among those aged 65 years and older during smoke days. The population-based study included 1,196,233 ED visits during May 1–Sept. 30 that year. PM2.5 concentrations were categorized as light, medium, or dense. Relative risk rose with the amount of smoke in the air. Rates of all-cause cardiovascular ED visits were elevated across levels of smoke density, with the greatest increase on dense smoke days and among those aged 65 years or older (RR,1.15; 95% CI, 1.09-1.22). All-cause cerebrovascular visits were associated with dense smoke days, especially among those aged 65 years and older (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.00-1.49). Respiratory conditions also were increased on dense smoke days (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08-1.28) (J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Apr 11;7:e007492. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007492).

Long-term effects unknown

When it comes to the long-term effects of wildfire smoke on human health outcomes, much less is known. In a recent literature review, Colleen E. Reid, PhD, and Melissa May Maestas, PhD, found only one study that investigated long-term respiratory health impacts of wildfire smoke, and only a few studies that have estimated future health impacts of wildfires under likely climate change scenarios (Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2019 Mar;25:179-87).

“We know that there are immediate respiratory health effects from wildfire smoke,” said Dr. Reid of the department of geography at the University of Colorado Boulder. “What’s less known is everything else. That’s challenging, because people want to know about the long-term health effects.”

Evidence from the scientific literature suggests that exposure to air pollution adversely affects cardiovascular health, but whether exposure to wildfire smoke confers a similar risk is less clear. “Until just a few years ago we haven’t been able to study wildfire exposure measures on a large scale,” said EPA scientist Ana G. Rappold, PhD, a statistician there in the environmental public health division of the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. “It’s also hard to predict wildfires, so it’s hard to plan for an epidemiologic study if you don’t know where they’re going to occur.”

Dr. Rappold and colleagues examined cardiopulmonary hospitalizations among adults aged 65 years and older in 692 U.S. counties within 200 km of 123 large wildfires during 2008-2010 (Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127[3]:37006. doi: 10.1289/EHP3860). They observed that an increased risk of PM2.5-related cardiopulmonary hospitalizations was similar on smoke and nonsmoke days across multiple lags and exposure metrics, while risk for asthma-related hospitalizations was higher during smoke days. “One hypothesis is that this was an older study population, so naturally if you’re inhaling smoke, the first organ that’s impacted in an older population is the lungs,” Dr. Rappold said. “If you go to the hospital for asthma, wheezing, or bronchitis, you are taken out of the risk pool for cardiovascular and other diseases. That could explain why in other studies we don’t see a clear cardiovascular signal as we have for air pollution studies in general. Another aspect to this study is, the exposure metric was PM2.5, but smoke contains many other components, particularly gases, which are respiratory irritants. It could be that this triggers a higher risk for respiratory [effects] than regular episodes of high PM2.5 exposure, just because of the additional gases that people are exposed to.”

Another complicating factor is the paucity of data about solutions to long-term exposure to wildfire smoke. “If you’re impacted by high-exposure levels for 60 days, that is not something we have experienced before,” Dr. Rappold noted. “What are the solutions for that community? What works? Can we show that by implementing community-level resilience plans with HEPA [high-efficiency particulate air] filters or other interventions, do the overall outcomes improve? Doctors are the first ones to talk with their patients about their symptoms and about how to take care of their conditions. They can clearly make a difference in emphasizing reducing exposures in a way that fits their patients individually, either reducing the amount of time spent outside, the duration of exposure, and the level of exposure. Maybe change activities based on the intensity of exposure. Don’t go for a run outside when it’s smoky, because your ventilation rate is higher and you will breathe in more smoke. Become aware of those things.”

Advising vulnerable patients

While research in this field advances, the unforgiving wildfire season looms, assuring more destruction of property and threats to cardiorespiratory health. “There are a lot of questions that research will have an opportunity to address as we go forward, including the utility and the benefit of N95 masks, the utility of HEPA filters used in the house, and even with HVAC [heating, ventilation, and air conditioning] systems,” Dr. Cascio said. “Can we really clean up the indoor air well enough to protect us from wildfire smoke?”

The way he sees it, the time is ripe for clinicians and officials in public and private practice settings to refine how they distribute information to people living in areas affected by wildfire smoke. “We can’t force people do anything, but at least if they’re informed, then they understand they can make an informed decision about how they might want to affect what they do that would limit their exposure,” he said. “As a patient, my health care system sends text and email messages to me. So, why couldn’t the hospital send out a text message or an email to all of the patients with COPD, coronary disease, and heart failure when an area is impacted by smoke, saying, ‘Check your air quality and take action if air quality is poor?’ Physicians don’t have time to do this kind of education in the office for all of their patients. I know that from experience. But if one were to only focus on those at highest risk, and encourage them to follow our guidelines, which might include doing HEPA filter treatment in the home, we probably would reduce the number of clinical events in a cost-effective way.”

The 2019 wildfire season is underway in many locales across the United States, exposing millions of individuals to smoky conditions that will have health consequences ranging from stinging eyes to scratchy throats to a trip to the ED for asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation. Questions about long-term health impacts are on the minds of many, including physicians and their patients who live with cardiorespiratory conditions.

John R. Balmes, MD, a pulmonologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and an expert on the respiratory and cardiovascular effects of air pollutants, suggested that the best available published literature points to “pretty strong evidence for acute effects of wildfire smoke on respiratory health, meaning people with preexisting asthma and COPD are at risk for exacerbations, and probably for respiratory tract infections as well.” He said, “It’s a little less clear, but there’s good biological plausibility for increased risk of respiratory tract infections because when your alveolar macrophages are overloaded with carbon particles that are toxic to those cells, they don’t function as well as a first line of defense against bacterial infection, for example.”

The new normal of wildfires

Warmer, drier summers in recent years in the western United States and many other regions, attributed by climate experts to global climate change, have produced catastrophic wildfires (PNAS;2016 Oct 18;113[42]11770-5; Science 2006 Aug 18;313:940-3). The Camp Fire in Northern California broke out in November 2018, took the lives of at least 85 people, and cost more than $16 billion in damage. Smoke from that blaze reached hazardous levels in San Francisco, Sacramento, Fresno, and many other smaller towns. Other forest fires in that year caused heavy smoke conditions in Portland, Seattle, Vancouver, and Anchorage. Such events are expected to be repeated often in the coming years (Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Jul 6;16[13]).

Wildfire smoke can contain a wide range of substances, chemicals, and gases with known and unknown cardiorespiratory implications. “Smoke is composed primarily of carbon dioxide, water vapor, carbon monoxide, particulate matter, hydrocarbons and other organic chemicals, nitrogen oxides, trace minerals and several thousand other compounds,” according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Wildfire smoke: A guide for public health officials 2019. Washington, D.C.: EPA, 2019). The EPA report noted, “Particles with diameters less than 10 mcm (particulate matter, or PM10) can be inhaled into the lungs and affect the lungs, heart, and blood vessels. The smallest particles, those less than 2.5 mcm in diameter (PM2.5), are the greatest risk to public health because they can reach deep into the lungs and may even make it into the bloodstream.”

Research on health impact

In early June of 2008, Wayne Cascio, MD, awoke in his Greenville, N.C., home to the stench of smoke emanating from a large peat fire burning some 65 miles away. By the time he reached the parking lot at East Carolina University in Greenville to begin his workday as chief of cardiology, the haze of smoke had thickened to the point where he could only see a few feet in front of him.

Over the next several weeks, the fire scorched 41,000 acres and produced haze and air pollution that far exceeded National Ambient Air Quality Standards for particulate matter and blanketed rural communities in the state’s eastern region. The price tag for management of the blaze reached $20 million. Because of his interest in the health effects of wildfire smoke and because of his relationship with investigators at the EPA, Dr. Cascio initiated an epidemiology study to investigate the effects of exposure on cardiorespiratory outcomes in the population affected by the fire (Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Oct;119[10]:1415-20).

By combining satellite data with syndromic surveillance drawn from hospital records in 41 counties contained in the North Carolina Disease Event Tracking and Epidemiologic Collection Tool, he and his colleagues found that exposure to the peat wildfire smoke led to increases in the cumulative risk ratio for asthma (relative risk, 1.65), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (RR, 1.73), and pneumonia and acute bronchitis (RR, 1.59). ED visits related to cardiopulmonary symptoms and heart failure also were significantly increased (RR, 1.23 and 1.37, respectively). “That was really the first study to strongly identify a cardiac endpoint related to wildfire smoke exposure,” said Dr. Cascio, who now directs the EPA’s National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. “It really pointed out how little we knew about the health effects of wildfire up until that time.”

Those early findings have been replicated in subsequent research about the acute health effects of exposure to wildfire smoke, which contains PM2.5 and other toxic substances from structures, electronic devices, and automobiles destroyed in the path of flames, including heavy metals and asbestos. Most of the work has focused on smoke-related cardiovascular and respiratory ED visits and hospitalizations.

A study of the 2008 California wildfire impact on ED visits accounted for ozone levels in addition to PM2.5 in the smoke. During the active fire periods, PM2.5 was significantly associated with exacerbations of asthma and COPD and these effects remained after controlling for ozone levels. PM2.5 inhalation during the wildfires was associated with increased risk of an ED visit for asthma (RR, 1.112; 95% confidence interval, 1.087-1.138) for a 10 mcg/m3 increase in PM2.5 and COPD (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.019-1.0825), as well as for combined respiratory visits (RR, 1.035; 95% CI, 1.023-1.046) (Environ Int. 2109 Aug;129:291-8).

Researchers who evaluated the health impacts of wildfires in California during the 2015 fire season found an increase in all-cause cardiovascular and respiratory ED visits, especially among those aged 65 years and older during smoke days. The population-based study included 1,196,233 ED visits during May 1–Sept. 30 that year. PM2.5 concentrations were categorized as light, medium, or dense. Relative risk rose with the amount of smoke in the air. Rates of all-cause cardiovascular ED visits were elevated across levels of smoke density, with the greatest increase on dense smoke days and among those aged 65 years or older (RR,1.15; 95% CI, 1.09-1.22). All-cause cerebrovascular visits were associated with dense smoke days, especially among those aged 65 years and older (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.00-1.49). Respiratory conditions also were increased on dense smoke days (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08-1.28) (J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Apr 11;7:e007492. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007492).

Long-term effects unknown

When it comes to the long-term effects of wildfire smoke on human health outcomes, much less is known. In a recent literature review, Colleen E. Reid, PhD, and Melissa May Maestas, PhD, found only one study that investigated long-term respiratory health impacts of wildfire smoke, and only a few studies that have estimated future health impacts of wildfires under likely climate change scenarios (Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2019 Mar;25:179-87).

“We know that there are immediate respiratory health effects from wildfire smoke,” said Dr. Reid of the department of geography at the University of Colorado Boulder. “What’s less known is everything else. That’s challenging, because people want to know about the long-term health effects.”

Evidence from the scientific literature suggests that exposure to air pollution adversely affects cardiovascular health, but whether exposure to wildfire smoke confers a similar risk is less clear. “Until just a few years ago we haven’t been able to study wildfire exposure measures on a large scale,” said EPA scientist Ana G. Rappold, PhD, a statistician there in the environmental public health division of the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. “It’s also hard to predict wildfires, so it’s hard to plan for an epidemiologic study if you don’t know where they’re going to occur.”

Dr. Rappold and colleagues examined cardiopulmonary hospitalizations among adults aged 65 years and older in 692 U.S. counties within 200 km of 123 large wildfires during 2008-2010 (Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127[3]:37006. doi: 10.1289/EHP3860). They observed that an increased risk of PM2.5-related cardiopulmonary hospitalizations was similar on smoke and nonsmoke days across multiple lags and exposure metrics, while risk for asthma-related hospitalizations was higher during smoke days. “One hypothesis is that this was an older study population, so naturally if you’re inhaling smoke, the first organ that’s impacted in an older population is the lungs,” Dr. Rappold said. “If you go to the hospital for asthma, wheezing, or bronchitis, you are taken out of the risk pool for cardiovascular and other diseases. That could explain why in other studies we don’t see a clear cardiovascular signal as we have for air pollution studies in general. Another aspect to this study is, the exposure metric was PM2.5, but smoke contains many other components, particularly gases, which are respiratory irritants. It could be that this triggers a higher risk for respiratory [effects] than regular episodes of high PM2.5 exposure, just because of the additional gases that people are exposed to.”

Another complicating factor is the paucity of data about solutions to long-term exposure to wildfire smoke. “If you’re impacted by high-exposure levels for 60 days, that is not something we have experienced before,” Dr. Rappold noted. “What are the solutions for that community? What works? Can we show that by implementing community-level resilience plans with HEPA [high-efficiency particulate air] filters or other interventions, do the overall outcomes improve? Doctors are the first ones to talk with their patients about their symptoms and about how to take care of their conditions. They can clearly make a difference in emphasizing reducing exposures in a way that fits their patients individually, either reducing the amount of time spent outside, the duration of exposure, and the level of exposure. Maybe change activities based on the intensity of exposure. Don’t go for a run outside when it’s smoky, because your ventilation rate is higher and you will breathe in more smoke. Become aware of those things.”

Advising vulnerable patients

While research in this field advances, the unforgiving wildfire season looms, assuring more destruction of property and threats to cardiorespiratory health. “There are a lot of questions that research will have an opportunity to address as we go forward, including the utility and the benefit of N95 masks, the utility of HEPA filters used in the house, and even with HVAC [heating, ventilation, and air conditioning] systems,” Dr. Cascio said. “Can we really clean up the indoor air well enough to protect us from wildfire smoke?”

The way he sees it, the time is ripe for clinicians and officials in public and private practice settings to refine how they distribute information to people living in areas affected by wildfire smoke. “We can’t force people do anything, but at least if they’re informed, then they understand they can make an informed decision about how they might want to affect what they do that would limit their exposure,” he said. “As a patient, my health care system sends text and email messages to me. So, why couldn’t the hospital send out a text message or an email to all of the patients with COPD, coronary disease, and heart failure when an area is impacted by smoke, saying, ‘Check your air quality and take action if air quality is poor?’ Physicians don’t have time to do this kind of education in the office for all of their patients. I know that from experience. But if one were to only focus on those at highest risk, and encourage them to follow our guidelines, which might include doing HEPA filter treatment in the home, we probably would reduce the number of clinical events in a cost-effective way.”

The 2019 wildfire season is underway in many locales across the United States, exposing millions of individuals to smoky conditions that will have health consequences ranging from stinging eyes to scratchy throats to a trip to the ED for asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation. Questions about long-term health impacts are on the minds of many, including physicians and their patients who live with cardiorespiratory conditions.

John R. Balmes, MD, a pulmonologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and an expert on the respiratory and cardiovascular effects of air pollutants, suggested that the best available published literature points to “pretty strong evidence for acute effects of wildfire smoke on respiratory health, meaning people with preexisting asthma and COPD are at risk for exacerbations, and probably for respiratory tract infections as well.” He said, “It’s a little less clear, but there’s good biological plausibility for increased risk of respiratory tract infections because when your alveolar macrophages are overloaded with carbon particles that are toxic to those cells, they don’t function as well as a first line of defense against bacterial infection, for example.”

The new normal of wildfires

Warmer, drier summers in recent years in the western United States and many other regions, attributed by climate experts to global climate change, have produced catastrophic wildfires (PNAS;2016 Oct 18;113[42]11770-5; Science 2006 Aug 18;313:940-3). The Camp Fire in Northern California broke out in November 2018, took the lives of at least 85 people, and cost more than $16 billion in damage. Smoke from that blaze reached hazardous levels in San Francisco, Sacramento, Fresno, and many other smaller towns. Other forest fires in that year caused heavy smoke conditions in Portland, Seattle, Vancouver, and Anchorage. Such events are expected to be repeated often in the coming years (Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Jul 6;16[13]).

Wildfire smoke can contain a wide range of substances, chemicals, and gases with known and unknown cardiorespiratory implications. “Smoke is composed primarily of carbon dioxide, water vapor, carbon monoxide, particulate matter, hydrocarbons and other organic chemicals, nitrogen oxides, trace minerals and several thousand other compounds,” according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Wildfire smoke: A guide for public health officials 2019. Washington, D.C.: EPA, 2019). The EPA report noted, “Particles with diameters less than 10 mcm (particulate matter, or PM10) can be inhaled into the lungs and affect the lungs, heart, and blood vessels. The smallest particles, those less than 2.5 mcm in diameter (PM2.5), are the greatest risk to public health because they can reach deep into the lungs and may even make it into the bloodstream.”

Research on health impact

In early June of 2008, Wayne Cascio, MD, awoke in his Greenville, N.C., home to the stench of smoke emanating from a large peat fire burning some 65 miles away. By the time he reached the parking lot at East Carolina University in Greenville to begin his workday as chief of cardiology, the haze of smoke had thickened to the point where he could only see a few feet in front of him.

Over the next several weeks, the fire scorched 41,000 acres and produced haze and air pollution that far exceeded National Ambient Air Quality Standards for particulate matter and blanketed rural communities in the state’s eastern region. The price tag for management of the blaze reached $20 million. Because of his interest in the health effects of wildfire smoke and because of his relationship with investigators at the EPA, Dr. Cascio initiated an epidemiology study to investigate the effects of exposure on cardiorespiratory outcomes in the population affected by the fire (Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Oct;119[10]:1415-20).

By combining satellite data with syndromic surveillance drawn from hospital records in 41 counties contained in the North Carolina Disease Event Tracking and Epidemiologic Collection Tool, he and his colleagues found that exposure to the peat wildfire smoke led to increases in the cumulative risk ratio for asthma (relative risk, 1.65), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (RR, 1.73), and pneumonia and acute bronchitis (RR, 1.59). ED visits related to cardiopulmonary symptoms and heart failure also were significantly increased (RR, 1.23 and 1.37, respectively). “That was really the first study to strongly identify a cardiac endpoint related to wildfire smoke exposure,” said Dr. Cascio, who now directs the EPA’s National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. “It really pointed out how little we knew about the health effects of wildfire up until that time.”

Those early findings have been replicated in subsequent research about the acute health effects of exposure to wildfire smoke, which contains PM2.5 and other toxic substances from structures, electronic devices, and automobiles destroyed in the path of flames, including heavy metals and asbestos. Most of the work has focused on smoke-related cardiovascular and respiratory ED visits and hospitalizations.

A study of the 2008 California wildfire impact on ED visits accounted for ozone levels in addition to PM2.5 in the smoke. During the active fire periods, PM2.5 was significantly associated with exacerbations of asthma and COPD and these effects remained after controlling for ozone levels. PM2.5 inhalation during the wildfires was associated with increased risk of an ED visit for asthma (RR, 1.112; 95% confidence interval, 1.087-1.138) for a 10 mcg/m3 increase in PM2.5 and COPD (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.019-1.0825), as well as for combined respiratory visits (RR, 1.035; 95% CI, 1.023-1.046) (Environ Int. 2109 Aug;129:291-8).

Researchers who evaluated the health impacts of wildfires in California during the 2015 fire season found an increase in all-cause cardiovascular and respiratory ED visits, especially among those aged 65 years and older during smoke days. The population-based study included 1,196,233 ED visits during May 1–Sept. 30 that year. PM2.5 concentrations were categorized as light, medium, or dense. Relative risk rose with the amount of smoke in the air. Rates of all-cause cardiovascular ED visits were elevated across levels of smoke density, with the greatest increase on dense smoke days and among those aged 65 years or older (RR,1.15; 95% CI, 1.09-1.22). All-cause cerebrovascular visits were associated with dense smoke days, especially among those aged 65 years and older (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.00-1.49). Respiratory conditions also were increased on dense smoke days (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08-1.28) (J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Apr 11;7:e007492. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007492).

Long-term effects unknown

When it comes to the long-term effects of wildfire smoke on human health outcomes, much less is known. In a recent literature review, Colleen E. Reid, PhD, and Melissa May Maestas, PhD, found only one study that investigated long-term respiratory health impacts of wildfire smoke, and only a few studies that have estimated future health impacts of wildfires under likely climate change scenarios (Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2019 Mar;25:179-87).

“We know that there are immediate respiratory health effects from wildfire smoke,” said Dr. Reid of the department of geography at the University of Colorado Boulder. “What’s less known is everything else. That’s challenging, because people want to know about the long-term health effects.”

Evidence from the scientific literature suggests that exposure to air pollution adversely affects cardiovascular health, but whether exposure to wildfire smoke confers a similar risk is less clear. “Until just a few years ago we haven’t been able to study wildfire exposure measures on a large scale,” said EPA scientist Ana G. Rappold, PhD, a statistician there in the environmental public health division of the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory. “It’s also hard to predict wildfires, so it’s hard to plan for an epidemiologic study if you don’t know where they’re going to occur.”

Dr. Rappold and colleagues examined cardiopulmonary hospitalizations among adults aged 65 years and older in 692 U.S. counties within 200 km of 123 large wildfires during 2008-2010 (Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127[3]:37006. doi: 10.1289/EHP3860). They observed that an increased risk of PM2.5-related cardiopulmonary hospitalizations was similar on smoke and nonsmoke days across multiple lags and exposure metrics, while risk for asthma-related hospitalizations was higher during smoke days. “One hypothesis is that this was an older study population, so naturally if you’re inhaling smoke, the first organ that’s impacted in an older population is the lungs,” Dr. Rappold said. “If you go to the hospital for asthma, wheezing, or bronchitis, you are taken out of the risk pool for cardiovascular and other diseases. That could explain why in other studies we don’t see a clear cardiovascular signal as we have for air pollution studies in general. Another aspect to this study is, the exposure metric was PM2.5, but smoke contains many other components, particularly gases, which are respiratory irritants. It could be that this triggers a higher risk for respiratory [effects] than regular episodes of high PM2.5 exposure, just because of the additional gases that people are exposed to.”

Another complicating factor is the paucity of data about solutions to long-term exposure to wildfire smoke. “If you’re impacted by high-exposure levels for 60 days, that is not something we have experienced before,” Dr. Rappold noted. “What are the solutions for that community? What works? Can we show that by implementing community-level resilience plans with HEPA [high-efficiency particulate air] filters or other interventions, do the overall outcomes improve? Doctors are the first ones to talk with their patients about their symptoms and about how to take care of their conditions. They can clearly make a difference in emphasizing reducing exposures in a way that fits their patients individually, either reducing the amount of time spent outside, the duration of exposure, and the level of exposure. Maybe change activities based on the intensity of exposure. Don’t go for a run outside when it’s smoky, because your ventilation rate is higher and you will breathe in more smoke. Become aware of those things.”

Advising vulnerable patients

While research in this field advances, the unforgiving wildfire season looms, assuring more destruction of property and threats to cardiorespiratory health. “There are a lot of questions that research will have an opportunity to address as we go forward, including the utility and the benefit of N95 masks, the utility of HEPA filters used in the house, and even with HVAC [heating, ventilation, and air conditioning] systems,” Dr. Cascio said. “Can we really clean up the indoor air well enough to protect us from wildfire smoke?”

The way he sees it, the time is ripe for clinicians and officials in public and private practice settings to refine how they distribute information to people living in areas affected by wildfire smoke. “We can’t force people do anything, but at least if they’re informed, then they understand they can make an informed decision about how they might want to affect what they do that would limit their exposure,” he said. “As a patient, my health care system sends text and email messages to me. So, why couldn’t the hospital send out a text message or an email to all of the patients with COPD, coronary disease, and heart failure when an area is impacted by smoke, saying, ‘Check your air quality and take action if air quality is poor?’ Physicians don’t have time to do this kind of education in the office for all of their patients. I know that from experience. But if one were to only focus on those at highest risk, and encourage them to follow our guidelines, which might include doing HEPA filter treatment in the home, we probably would reduce the number of clinical events in a cost-effective way.”

Benefits of peanut desensitization may not last

based on data from a phase 2 randomized trial of individuals with confirmed peanut allergies.

Previous studies have shown that desensitization to peanuts can be successful, but sustained response to oral immunotherapy after treatment reduction or discontinuation has not been well studied, wrote R. Sharon Chinthrajah, MD, of Stanford (Calif.)University, and colleagues.

“We found that OIT with peanut was able to desensitise people with peanut allergy to 4,000 mg of peanut protein, but that discontinuation of peanut, or even a reduction to 300 mg daily, increased the likelihood of regaining clinical reactivity to peanut,” they wrote. “With peanut allergy therapies in varying stages of clinical development, and some nearing [Food and Drug Administration] approval, vital questions remain regarding the durability of treatment effects and the appropriate maintenance doses.”

In the Peanut Oral Immunotherapy Study: Safety Efficacy and Discovery (POISED), published in The Lancet, the researchers randomized 120 participants to three groups:

• 60 patients built up to a maintenance dose of 4,000 mg of peanut protein for 104 weeks followed by total discontinuation (peanut-0).

• 35 patients built up to a maintenance dose of 4,000 mg of peanut protein for 104 weeks followed by a 300-mg maintenance dose of peanut protein in the form of peanut flour (peanut-300).

• 25 patients to an oat flour placebo.

All participants were trained on how and when to use epinephrine autoinjector devices to treat allergic symptoms such as respiratory problems (cough, shortness of breath, or change in voice), widespread hives or erythema, repetitive vomiting, persistent abdominal pain, angioedema of the face, or feeling faint.

The primary outcome was passing a double-blind, placebo-controlled, food challenge (DBPCFC) to 4,000 mg of peanut protein, which was measured at baseline and at weeks 104, 117, 130, 143, and 156.

Overall, 35% of the peanut-0 group passed the challenge at 104 and 117 weeks, compared with 4% of the placebo group. At week 156 after discontinuing OIT, 13% of the peanut-0 group met the DBPCFC challenge, compared with 4% of the placebo group. However, 37% of participants randomized to a reduced peanut protein dose of 300 mg passed the challenge at 156 weeks, suggesting that more data are needed on optimal maintenance dosing strategies.

Baseline demographics were similar across all groups. The median age at study enrollment was 11 years and the median allergy duration was 9 years. The most common adverse events were mild gastrointestinal and respiratory problems. Adverse events decreased over time in all three groups.

“Higher levels of peanut-specific IgE to total IgE ratio, peanut sIgE, Ara h 1, Ara h 2, and Ara h 1 IgE to peanut-specific IgE ratio at baseline in participants were associated with increased frequencies of adverse events during active peanut OIT,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the ability of participants to tolerate 4,000 mg of peanut protein after achieving a maintenance dose but conducting serial testing only for those who passed the challenge. In addition, the results may be limited to peanut and not generalizable to other food allergies, the researchers said.

However, the results suggest that OIT remains a promising treatment for peanut allergies, and the association of biomarkers with clinical outcomes “might help the practitioner in identifying good candidates for OIT and those individuals who warrant increased vigilance against allergic reactions during OIT,” they said.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Chinthrajah RS et al. Lancet. 2019 Sep 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31793-3.

based on data from a phase 2 randomized trial of individuals with confirmed peanut allergies.

Previous studies have shown that desensitization to peanuts can be successful, but sustained response to oral immunotherapy after treatment reduction or discontinuation has not been well studied, wrote R. Sharon Chinthrajah, MD, of Stanford (Calif.)University, and colleagues.

“We found that OIT with peanut was able to desensitise people with peanut allergy to 4,000 mg of peanut protein, but that discontinuation of peanut, or even a reduction to 300 mg daily, increased the likelihood of regaining clinical reactivity to peanut,” they wrote. “With peanut allergy therapies in varying stages of clinical development, and some nearing [Food and Drug Administration] approval, vital questions remain regarding the durability of treatment effects and the appropriate maintenance doses.”