User login

MIS-C follow-up proves challenging across pediatric hospitals

The discovery of any novel disease or condition means a steep learning curve as physicians must develop protocols for diagnosis, management, and follow-up on the fly in the midst of admitting and treating patients. Medical society task forces and committees often release interim guidance during the learning process, but each institution ultimately has to determine what works for them based on their resources, clinical experience, and patient population.

But when the novel condition demands the involvement of multiple different specialties, the challenge of management grows even more complex – as does follow-up after patients are discharged. Such has been the story with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a complication of COVID-19 that shares some features with Kawasaki disease.

The similarities to Kawasaki provided physicians a place to start in developing appropriate treatment regimens and involved a similar interdisciplinary team from, at the least, cardiology and rheumatology, plus infectious disease since MIS-C results from COVID-19.

“It literally has it in the name – multisystem essentially hints that there are multiple specialties involved, multiple hands in the pot trying to manage the kids, and so each specialty has their own kind of unique role in the patient’s care even on the outpatient side,” said Samina S. Bhumbra, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at Riley Hospital for Children and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University in Indianapolis. “This isn’t a disease that falls under one specialty.”

By July, the American College of Rheumatology had issued interim clinical guidance for management that most children’s hospitals have followed or slightly adapted. But ACR guidelines could not address how each institution should handle outpatient follow-up visits, especially since those visits required, again, at least cardiology and rheumatology if not infectious disease or other specialties as well.

“When their kids are admitted to the hospital, to be told at discharge you have to be followed up by all these specialists is a lot to handle,” Dr. Bhumbra said. But just as it’s difficult for parents to deal with the need to see several different doctors after discharge, it can be difficult at some institutions for physicians to design a follow-up schedule that can accommodate families, especially families who live far from the hospital in the first place.

“Some of our follow-up is disjointed because all of our clinics had never been on the same day just because of staff availability,” Dr. Bhumbra said. “But it can be a 2- to 3-hour drive for some of our patients, depending on how far they’re coming.”

Many of them can’t make that drive more than once in the same month, much less the same week.

“If you have multiple visits, it makes it more likely that they’re not showing up,” said Ryan M. Serrano, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Riley and assistant professor of pediatrics at Indiana University. Riley used telehealth when possible, especially if families could get labs done near home. But pediatric echocardiograms require technicians who have experience with children, so families need to come to the hospital.

Children’s hospitals have therefore had to adapt scheduling strategies or develop pediatric specialty clinics to coordinate across the multiple departments and accommodate a complex follow-up regimen that is still evolving as physicians learn more about MIS-C.

Determining a follow-up regimen

Even before determining how to coordinate appointments, hospitals had to decide what follow-up itself should be.

“How long do we follow these patients and how often do we follow them?” said Melissa S. Oliver, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University.

“We’re seeing that a lot of our patients rapidly respond when they get appropriate therapy, but we don’t know about long-term outcomes yet. We’re all still learning.”

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, infectious disease follows up 4-6 weeks post discharge. The cardiology division came up with a follow-up plan that has evolved over time, said Matthew Elias, MD, an attending cardiologist at CHOP’s Cardiac Center and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Patients get an EKG and echocardiogram at 2 weeks and, if their condition is stable, 6 weeks after discharge. After that, it depends on the patient’s clinical situation. Patients with moderately diminished left ventricular systolic function are recommended to get an MRI scan 3 months after discharge and, if old enough, exercise stress tests. Otherwise, they are seen at 6 months, but that appointment is optional for those whose prior echos have consistently been normal.

Other institutions, including Riley, are following a similar schedule of 2-week, 6-week, and 6-month postdischarge follow-ups, and most plan to do a 1-year follow-up as well, although that 1-year mark hasn’t arrived yet for most. Most do rheumatology labs at the 2-week appointment and use that to determine steroids management and whether labs are needed at the 6-week appointment. If labs have normalized, they aren’t done at 6 months. Small variations in follow-up management exist across institutions, but all are remaining open to changes. Riley, for example, is considering MRI screening for ongoing cardiac inflammation at 6 months to a year for all patients, Dr. Serrano said.

The dedicated clinic model

The two challenges Riley needed to address were the lack of a clear consensus on what MIS-C follow-up should look like and the need for continuity of care, Dr. Serrano said.

Regular discussion in departmental meetings at Riley “progressed from how do we take care of them and what treatments do we give them to how do we follow them and manage them in outpatient,” Dr. Oliver said. In the inpatient setting, they had an interdisciplinary team, but how could they maintain that for outpatients without overwhelming the families?

“I think the main challenge is for the families to identify who is leading the care for them,” said Martha M. Rodriguez, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University. That sometimes led to families picking which follow-up appointments they would attend and which they would skip if they could not make them all – and sometimes they skipped the more important ones. “They would go to the appointment with me and then miss the cardiology appointments and the echocardiogram, which was more important to follow any abnormalities in the heart,” Dr. Rodriguez said.

After trying to coordinate separate follow-up appointments for months, Riley ultimately decided to form a dedicated clinic for MIS-C follow-up – a “one-stop shop” single appointment at each follow-up, Dr. Bhumbra said, that covers labs, EKG, echocardiogram, and any other necessary tests.

“Our goal with the clinic is to make life easier for the families and to be able to coordinate the appointments,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “They will be able to see the three of us, and it would be easier for us to communicate with each other about their plan.”

The clinic began Feb. 11 and occurs twice a month. Though it’s just begun, Dr. Oliver said the first clinic went well, and it’s helping them figure out the role each specialty needs to play in follow-up care.

“For us with rheumatology, after lab values have returned to normal and they’re off steroids, sometimes we think there isn’t much more we can contribute to,” she said. And then there are the patients who didn’t see any rheumatologists while inpatients.

“That’s what we’re trying to figure out as well,” Dr. Oliver said. “Should we be seeing every single kid regardless of whether we were involved in their inpatient [stay] or only seeing the ones we’ve seen?” She expects the coming months will help them work that out.

Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston also uses a dedicated clinic, but they set it up before the first MIS-C patient came through the doors, said Sara Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Texas Children’s. The hospital already has other types of multidisciplinary clinics, and they anticipated the challenge of getting families to come to too many appointments in a short period of time.

“Getting someone to come back once is hard enough,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Getting them to come back twice is impossible.”

Infectious disease is less involved at Texas Children’s, so it’s primarily Dr. Sexson Tejtel and her rheumatologist colleague who see the patients. They hold the clinic once a week, twice if needed.

“It does make the appointment a little longer, but I think the patients appreciate that everything can be addressed with that one visit,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Being in the hospital as long as some of these kids are is so hard, so making any of that easy as possible is so helpful.” A single appointment also allows the doctors to work together on what labs are needed so that children don’t need multiple labs drawn.

At the appointment, she and the rheumatologist enter the patient’s room and take the patient’s history together.

“It’s nice because it makes the family not to have to repeat things and tell the same story over and over,” she said. “Sometimes I ask questions that then the rheumatologist jumps off of, and then sometimes he’ll ask questions, and I’ll think, ‘Ooh, I’ll ask more questions about that.’ ”

In fact, this team approach at all clinics has made her a more thoughtful, well-rounded physician, she said.

“I have learned so much going to all of my multidisciplinary clinics, and I think I’m able to better care for my patients because I’m not just thinking about it from a cardiac perspective,” she said. “It takes some work, but it’s not hard and I think it is beneficial both for the patient and for the physician. This team approach is definitely where we’re trying to live right now.”

Separate but coordinated appointments

A dedicated clinic isn’t the answer for all institutions, however. At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the size of the networks and all its satellites made a one-stop shop impractical.

“We talked about a consolidated clinic early on, when MIS-C was first emerging and all our groups were collaborating and coming up with our inpatient and outpatient care pathways,” said Sanjeev K. Swami, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at CHOP and associate professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania. But timing varies on when each specialist wants to see the families return, and existing clinic schedules and locations varied too much.

So CHOP coordinates appointments individually for each patient, depending on where the patient lives and sometimes stacking them on the same day when possible. Sometimes infectious disease or rheumatology use telehealth, and CHOP, like the other hospitals, prioritizes cardiology, especially for the patients who had cardiac abnormalities in the hospital, Dr. Swami said.

“All three of our groups try to be as flexible as possible. We’ve had a really good collaboration between our groups,” he said, and spreading out follow-up allows specialists to ask about concerns raised at previous appointments, ensuring stronger continuity of care.

“We can make sure things are getting followed up on,” Dr. Swami said. “I think that has been beneficial to make sure things aren’t falling through the cracks.”

CHOP cardiologist Dr. Elias said that ongoing communication, among providers and with families, has been absolutely crucial.

“Everyone’s been talking so frequently about our MIS-C patients while inpatient that by the time they’re an outpatient, it seems to work smoothly, where families are hearing similar items but with a different flair, one from infectious, one from rheumatology, and one from cardiology,” he said.

Children’s Mercy in Kansas City, Mo., also has multiple satellite clinics and follows a model similar to that of CHOP. They discussed having a dedicated multidisciplinary team for each MIS-C patient, but even the logistics of that were difficult, said Emily J. Fox, MD, a rheumatologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Instead, Children’s Mercy tries to coordinate follow-up appointments to be on the same day and often use telehealth for the rheumatology appointments. Families that live closer to the hospital’s location in Joplin, Mo., go in for their cardiology appointment there, and then Dr. Fox conducts a telehealth appointment with the help of nurses in Joplin.

“We really do try hard, especially since these kids are in the hospital for a long time, to make the coordination as easy as possible,” Dr. Fox said. “This was all was very new, especially in the beginning, but I think at least our group is getting a little bit more comfortable in managing these patients.”

Looking ahead

The biggest question that still looms is what happens to these children, if anything, down the line.

“What was unique about this was this was a new disease we were all learning about together with no baseline,” Dr. Swami said. “None of us had ever seen this condition before.”

So far, the prognosis for the vast majority of children is good. “Most of these kids survive, most of them are doing well, and they almost all recover,” Dr. Serrano said. Labs tend to normalize by 6 weeks post discharge, if not much earlier, and not much cardiac involvement is showing up at later follow-ups. But not even a year has passed, so there’s plenty to learn. “We don’t know if there’s long-term risk. I would not be surprised if 20 years down the road we’re finding out things about this that we had no idea” about, Dr. Serrano said. “Everybody wants answers, and nobody has any, and the answers we have may end up being wrong. That’s how it goes when you’re dealing with something you’ve never seen.”

Research underway will ideally begin providing those answers soon. CHOP is a participating site in an NIH-NHLBI–sponsored study, called COVID MUSIC, that is tracking long-term outcomes for MIS-C at 30 centers across the United States and Canada for 5 years.

“That will really definitely be helpful in answering some of the questions about long-term outcomes,” Dr. Elias said. “We hope this is going to be a transient issue and that patients won’t have any long-term manifestations, but we don’t know that yet.”

Meanwhile, one benefit that has come out of the pandemic is strong collaboration, Dr. Bhumbra said.

“The biggest thing we’re all eagerly waiting and hoping for is standard guidelines on how best to follow-up on these kids, but I know that’s a ways away,” Dr. Bhumbra said. So for now, each institution is doing what it can to develop protocols that they feel best serve the patients’ needs, such as Riley’s new dedicated MIS-C clinic. “It takes a village to take care of these kids, and MIS-C has proven that having a clinic with all three specialties at one clinic is going to be great for the families.”

Dr. Fox serves on a committee for Pfizer unrelated to MIS-C. No other doctors interviewed for this story had relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

The discovery of any novel disease or condition means a steep learning curve as physicians must develop protocols for diagnosis, management, and follow-up on the fly in the midst of admitting and treating patients. Medical society task forces and committees often release interim guidance during the learning process, but each institution ultimately has to determine what works for them based on their resources, clinical experience, and patient population.

But when the novel condition demands the involvement of multiple different specialties, the challenge of management grows even more complex – as does follow-up after patients are discharged. Such has been the story with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a complication of COVID-19 that shares some features with Kawasaki disease.

The similarities to Kawasaki provided physicians a place to start in developing appropriate treatment regimens and involved a similar interdisciplinary team from, at the least, cardiology and rheumatology, plus infectious disease since MIS-C results from COVID-19.

“It literally has it in the name – multisystem essentially hints that there are multiple specialties involved, multiple hands in the pot trying to manage the kids, and so each specialty has their own kind of unique role in the patient’s care even on the outpatient side,” said Samina S. Bhumbra, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at Riley Hospital for Children and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University in Indianapolis. “This isn’t a disease that falls under one specialty.”

By July, the American College of Rheumatology had issued interim clinical guidance for management that most children’s hospitals have followed or slightly adapted. But ACR guidelines could not address how each institution should handle outpatient follow-up visits, especially since those visits required, again, at least cardiology and rheumatology if not infectious disease or other specialties as well.

“When their kids are admitted to the hospital, to be told at discharge you have to be followed up by all these specialists is a lot to handle,” Dr. Bhumbra said. But just as it’s difficult for parents to deal with the need to see several different doctors after discharge, it can be difficult at some institutions for physicians to design a follow-up schedule that can accommodate families, especially families who live far from the hospital in the first place.

“Some of our follow-up is disjointed because all of our clinics had never been on the same day just because of staff availability,” Dr. Bhumbra said. “But it can be a 2- to 3-hour drive for some of our patients, depending on how far they’re coming.”

Many of them can’t make that drive more than once in the same month, much less the same week.

“If you have multiple visits, it makes it more likely that they’re not showing up,” said Ryan M. Serrano, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Riley and assistant professor of pediatrics at Indiana University. Riley used telehealth when possible, especially if families could get labs done near home. But pediatric echocardiograms require technicians who have experience with children, so families need to come to the hospital.

Children’s hospitals have therefore had to adapt scheduling strategies or develop pediatric specialty clinics to coordinate across the multiple departments and accommodate a complex follow-up regimen that is still evolving as physicians learn more about MIS-C.

Determining a follow-up regimen

Even before determining how to coordinate appointments, hospitals had to decide what follow-up itself should be.

“How long do we follow these patients and how often do we follow them?” said Melissa S. Oliver, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University.

“We’re seeing that a lot of our patients rapidly respond when they get appropriate therapy, but we don’t know about long-term outcomes yet. We’re all still learning.”

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, infectious disease follows up 4-6 weeks post discharge. The cardiology division came up with a follow-up plan that has evolved over time, said Matthew Elias, MD, an attending cardiologist at CHOP’s Cardiac Center and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Patients get an EKG and echocardiogram at 2 weeks and, if their condition is stable, 6 weeks after discharge. After that, it depends on the patient’s clinical situation. Patients with moderately diminished left ventricular systolic function are recommended to get an MRI scan 3 months after discharge and, if old enough, exercise stress tests. Otherwise, they are seen at 6 months, but that appointment is optional for those whose prior echos have consistently been normal.

Other institutions, including Riley, are following a similar schedule of 2-week, 6-week, and 6-month postdischarge follow-ups, and most plan to do a 1-year follow-up as well, although that 1-year mark hasn’t arrived yet for most. Most do rheumatology labs at the 2-week appointment and use that to determine steroids management and whether labs are needed at the 6-week appointment. If labs have normalized, they aren’t done at 6 months. Small variations in follow-up management exist across institutions, but all are remaining open to changes. Riley, for example, is considering MRI screening for ongoing cardiac inflammation at 6 months to a year for all patients, Dr. Serrano said.

The dedicated clinic model

The two challenges Riley needed to address were the lack of a clear consensus on what MIS-C follow-up should look like and the need for continuity of care, Dr. Serrano said.

Regular discussion in departmental meetings at Riley “progressed from how do we take care of them and what treatments do we give them to how do we follow them and manage them in outpatient,” Dr. Oliver said. In the inpatient setting, they had an interdisciplinary team, but how could they maintain that for outpatients without overwhelming the families?

“I think the main challenge is for the families to identify who is leading the care for them,” said Martha M. Rodriguez, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University. That sometimes led to families picking which follow-up appointments they would attend and which they would skip if they could not make them all – and sometimes they skipped the more important ones. “They would go to the appointment with me and then miss the cardiology appointments and the echocardiogram, which was more important to follow any abnormalities in the heart,” Dr. Rodriguez said.

After trying to coordinate separate follow-up appointments for months, Riley ultimately decided to form a dedicated clinic for MIS-C follow-up – a “one-stop shop” single appointment at each follow-up, Dr. Bhumbra said, that covers labs, EKG, echocardiogram, and any other necessary tests.

“Our goal with the clinic is to make life easier for the families and to be able to coordinate the appointments,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “They will be able to see the three of us, and it would be easier for us to communicate with each other about their plan.”

The clinic began Feb. 11 and occurs twice a month. Though it’s just begun, Dr. Oliver said the first clinic went well, and it’s helping them figure out the role each specialty needs to play in follow-up care.

“For us with rheumatology, after lab values have returned to normal and they’re off steroids, sometimes we think there isn’t much more we can contribute to,” she said. And then there are the patients who didn’t see any rheumatologists while inpatients.

“That’s what we’re trying to figure out as well,” Dr. Oliver said. “Should we be seeing every single kid regardless of whether we were involved in their inpatient [stay] or only seeing the ones we’ve seen?” She expects the coming months will help them work that out.

Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston also uses a dedicated clinic, but they set it up before the first MIS-C patient came through the doors, said Sara Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Texas Children’s. The hospital already has other types of multidisciplinary clinics, and they anticipated the challenge of getting families to come to too many appointments in a short period of time.

“Getting someone to come back once is hard enough,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Getting them to come back twice is impossible.”

Infectious disease is less involved at Texas Children’s, so it’s primarily Dr. Sexson Tejtel and her rheumatologist colleague who see the patients. They hold the clinic once a week, twice if needed.

“It does make the appointment a little longer, but I think the patients appreciate that everything can be addressed with that one visit,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Being in the hospital as long as some of these kids are is so hard, so making any of that easy as possible is so helpful.” A single appointment also allows the doctors to work together on what labs are needed so that children don’t need multiple labs drawn.

At the appointment, she and the rheumatologist enter the patient’s room and take the patient’s history together.

“It’s nice because it makes the family not to have to repeat things and tell the same story over and over,” she said. “Sometimes I ask questions that then the rheumatologist jumps off of, and then sometimes he’ll ask questions, and I’ll think, ‘Ooh, I’ll ask more questions about that.’ ”

In fact, this team approach at all clinics has made her a more thoughtful, well-rounded physician, she said.

“I have learned so much going to all of my multidisciplinary clinics, and I think I’m able to better care for my patients because I’m not just thinking about it from a cardiac perspective,” she said. “It takes some work, but it’s not hard and I think it is beneficial both for the patient and for the physician. This team approach is definitely where we’re trying to live right now.”

Separate but coordinated appointments

A dedicated clinic isn’t the answer for all institutions, however. At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the size of the networks and all its satellites made a one-stop shop impractical.

“We talked about a consolidated clinic early on, when MIS-C was first emerging and all our groups were collaborating and coming up with our inpatient and outpatient care pathways,” said Sanjeev K. Swami, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at CHOP and associate professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania. But timing varies on when each specialist wants to see the families return, and existing clinic schedules and locations varied too much.

So CHOP coordinates appointments individually for each patient, depending on where the patient lives and sometimes stacking them on the same day when possible. Sometimes infectious disease or rheumatology use telehealth, and CHOP, like the other hospitals, prioritizes cardiology, especially for the patients who had cardiac abnormalities in the hospital, Dr. Swami said.

“All three of our groups try to be as flexible as possible. We’ve had a really good collaboration between our groups,” he said, and spreading out follow-up allows specialists to ask about concerns raised at previous appointments, ensuring stronger continuity of care.

“We can make sure things are getting followed up on,” Dr. Swami said. “I think that has been beneficial to make sure things aren’t falling through the cracks.”

CHOP cardiologist Dr. Elias said that ongoing communication, among providers and with families, has been absolutely crucial.

“Everyone’s been talking so frequently about our MIS-C patients while inpatient that by the time they’re an outpatient, it seems to work smoothly, where families are hearing similar items but with a different flair, one from infectious, one from rheumatology, and one from cardiology,” he said.

Children’s Mercy in Kansas City, Mo., also has multiple satellite clinics and follows a model similar to that of CHOP. They discussed having a dedicated multidisciplinary team for each MIS-C patient, but even the logistics of that were difficult, said Emily J. Fox, MD, a rheumatologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Instead, Children’s Mercy tries to coordinate follow-up appointments to be on the same day and often use telehealth for the rheumatology appointments. Families that live closer to the hospital’s location in Joplin, Mo., go in for their cardiology appointment there, and then Dr. Fox conducts a telehealth appointment with the help of nurses in Joplin.

“We really do try hard, especially since these kids are in the hospital for a long time, to make the coordination as easy as possible,” Dr. Fox said. “This was all was very new, especially in the beginning, but I think at least our group is getting a little bit more comfortable in managing these patients.”

Looking ahead

The biggest question that still looms is what happens to these children, if anything, down the line.

“What was unique about this was this was a new disease we were all learning about together with no baseline,” Dr. Swami said. “None of us had ever seen this condition before.”

So far, the prognosis for the vast majority of children is good. “Most of these kids survive, most of them are doing well, and they almost all recover,” Dr. Serrano said. Labs tend to normalize by 6 weeks post discharge, if not much earlier, and not much cardiac involvement is showing up at later follow-ups. But not even a year has passed, so there’s plenty to learn. “We don’t know if there’s long-term risk. I would not be surprised if 20 years down the road we’re finding out things about this that we had no idea” about, Dr. Serrano said. “Everybody wants answers, and nobody has any, and the answers we have may end up being wrong. That’s how it goes when you’re dealing with something you’ve never seen.”

Research underway will ideally begin providing those answers soon. CHOP is a participating site in an NIH-NHLBI–sponsored study, called COVID MUSIC, that is tracking long-term outcomes for MIS-C at 30 centers across the United States and Canada for 5 years.

“That will really definitely be helpful in answering some of the questions about long-term outcomes,” Dr. Elias said. “We hope this is going to be a transient issue and that patients won’t have any long-term manifestations, but we don’t know that yet.”

Meanwhile, one benefit that has come out of the pandemic is strong collaboration, Dr. Bhumbra said.

“The biggest thing we’re all eagerly waiting and hoping for is standard guidelines on how best to follow-up on these kids, but I know that’s a ways away,” Dr. Bhumbra said. So for now, each institution is doing what it can to develop protocols that they feel best serve the patients’ needs, such as Riley’s new dedicated MIS-C clinic. “It takes a village to take care of these kids, and MIS-C has proven that having a clinic with all three specialties at one clinic is going to be great for the families.”

Dr. Fox serves on a committee for Pfizer unrelated to MIS-C. No other doctors interviewed for this story had relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

The discovery of any novel disease or condition means a steep learning curve as physicians must develop protocols for diagnosis, management, and follow-up on the fly in the midst of admitting and treating patients. Medical society task forces and committees often release interim guidance during the learning process, but each institution ultimately has to determine what works for them based on their resources, clinical experience, and patient population.

But when the novel condition demands the involvement of multiple different specialties, the challenge of management grows even more complex – as does follow-up after patients are discharged. Such has been the story with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a complication of COVID-19 that shares some features with Kawasaki disease.

The similarities to Kawasaki provided physicians a place to start in developing appropriate treatment regimens and involved a similar interdisciplinary team from, at the least, cardiology and rheumatology, plus infectious disease since MIS-C results from COVID-19.

“It literally has it in the name – multisystem essentially hints that there are multiple specialties involved, multiple hands in the pot trying to manage the kids, and so each specialty has their own kind of unique role in the patient’s care even on the outpatient side,” said Samina S. Bhumbra, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at Riley Hospital for Children and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University in Indianapolis. “This isn’t a disease that falls under one specialty.”

By July, the American College of Rheumatology had issued interim clinical guidance for management that most children’s hospitals have followed or slightly adapted. But ACR guidelines could not address how each institution should handle outpatient follow-up visits, especially since those visits required, again, at least cardiology and rheumatology if not infectious disease or other specialties as well.

“When their kids are admitted to the hospital, to be told at discharge you have to be followed up by all these specialists is a lot to handle,” Dr. Bhumbra said. But just as it’s difficult for parents to deal with the need to see several different doctors after discharge, it can be difficult at some institutions for physicians to design a follow-up schedule that can accommodate families, especially families who live far from the hospital in the first place.

“Some of our follow-up is disjointed because all of our clinics had never been on the same day just because of staff availability,” Dr. Bhumbra said. “But it can be a 2- to 3-hour drive for some of our patients, depending on how far they’re coming.”

Many of them can’t make that drive more than once in the same month, much less the same week.

“If you have multiple visits, it makes it more likely that they’re not showing up,” said Ryan M. Serrano, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Riley and assistant professor of pediatrics at Indiana University. Riley used telehealth when possible, especially if families could get labs done near home. But pediatric echocardiograms require technicians who have experience with children, so families need to come to the hospital.

Children’s hospitals have therefore had to adapt scheduling strategies or develop pediatric specialty clinics to coordinate across the multiple departments and accommodate a complex follow-up regimen that is still evolving as physicians learn more about MIS-C.

Determining a follow-up regimen

Even before determining how to coordinate appointments, hospitals had to decide what follow-up itself should be.

“How long do we follow these patients and how often do we follow them?” said Melissa S. Oliver, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University.

“We’re seeing that a lot of our patients rapidly respond when they get appropriate therapy, but we don’t know about long-term outcomes yet. We’re all still learning.”

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, infectious disease follows up 4-6 weeks post discharge. The cardiology division came up with a follow-up plan that has evolved over time, said Matthew Elias, MD, an attending cardiologist at CHOP’s Cardiac Center and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Patients get an EKG and echocardiogram at 2 weeks and, if their condition is stable, 6 weeks after discharge. After that, it depends on the patient’s clinical situation. Patients with moderately diminished left ventricular systolic function are recommended to get an MRI scan 3 months after discharge and, if old enough, exercise stress tests. Otherwise, they are seen at 6 months, but that appointment is optional for those whose prior echos have consistently been normal.

Other institutions, including Riley, are following a similar schedule of 2-week, 6-week, and 6-month postdischarge follow-ups, and most plan to do a 1-year follow-up as well, although that 1-year mark hasn’t arrived yet for most. Most do rheumatology labs at the 2-week appointment and use that to determine steroids management and whether labs are needed at the 6-week appointment. If labs have normalized, they aren’t done at 6 months. Small variations in follow-up management exist across institutions, but all are remaining open to changes. Riley, for example, is considering MRI screening for ongoing cardiac inflammation at 6 months to a year for all patients, Dr. Serrano said.

The dedicated clinic model

The two challenges Riley needed to address were the lack of a clear consensus on what MIS-C follow-up should look like and the need for continuity of care, Dr. Serrano said.

Regular discussion in departmental meetings at Riley “progressed from how do we take care of them and what treatments do we give them to how do we follow them and manage them in outpatient,” Dr. Oliver said. In the inpatient setting, they had an interdisciplinary team, but how could they maintain that for outpatients without overwhelming the families?

“I think the main challenge is for the families to identify who is leading the care for them,” said Martha M. Rodriguez, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University. That sometimes led to families picking which follow-up appointments they would attend and which they would skip if they could not make them all – and sometimes they skipped the more important ones. “They would go to the appointment with me and then miss the cardiology appointments and the echocardiogram, which was more important to follow any abnormalities in the heart,” Dr. Rodriguez said.

After trying to coordinate separate follow-up appointments for months, Riley ultimately decided to form a dedicated clinic for MIS-C follow-up – a “one-stop shop” single appointment at each follow-up, Dr. Bhumbra said, that covers labs, EKG, echocardiogram, and any other necessary tests.

“Our goal with the clinic is to make life easier for the families and to be able to coordinate the appointments,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “They will be able to see the three of us, and it would be easier for us to communicate with each other about their plan.”

The clinic began Feb. 11 and occurs twice a month. Though it’s just begun, Dr. Oliver said the first clinic went well, and it’s helping them figure out the role each specialty needs to play in follow-up care.

“For us with rheumatology, after lab values have returned to normal and they’re off steroids, sometimes we think there isn’t much more we can contribute to,” she said. And then there are the patients who didn’t see any rheumatologists while inpatients.

“That’s what we’re trying to figure out as well,” Dr. Oliver said. “Should we be seeing every single kid regardless of whether we were involved in their inpatient [stay] or only seeing the ones we’ve seen?” She expects the coming months will help them work that out.

Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston also uses a dedicated clinic, but they set it up before the first MIS-C patient came through the doors, said Sara Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Texas Children’s. The hospital already has other types of multidisciplinary clinics, and they anticipated the challenge of getting families to come to too many appointments in a short period of time.

“Getting someone to come back once is hard enough,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Getting them to come back twice is impossible.”

Infectious disease is less involved at Texas Children’s, so it’s primarily Dr. Sexson Tejtel and her rheumatologist colleague who see the patients. They hold the clinic once a week, twice if needed.

“It does make the appointment a little longer, but I think the patients appreciate that everything can be addressed with that one visit,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Being in the hospital as long as some of these kids are is so hard, so making any of that easy as possible is so helpful.” A single appointment also allows the doctors to work together on what labs are needed so that children don’t need multiple labs drawn.

At the appointment, she and the rheumatologist enter the patient’s room and take the patient’s history together.

“It’s nice because it makes the family not to have to repeat things and tell the same story over and over,” she said. “Sometimes I ask questions that then the rheumatologist jumps off of, and then sometimes he’ll ask questions, and I’ll think, ‘Ooh, I’ll ask more questions about that.’ ”

In fact, this team approach at all clinics has made her a more thoughtful, well-rounded physician, she said.

“I have learned so much going to all of my multidisciplinary clinics, and I think I’m able to better care for my patients because I’m not just thinking about it from a cardiac perspective,” she said. “It takes some work, but it’s not hard and I think it is beneficial both for the patient and for the physician. This team approach is definitely where we’re trying to live right now.”

Separate but coordinated appointments

A dedicated clinic isn’t the answer for all institutions, however. At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the size of the networks and all its satellites made a one-stop shop impractical.

“We talked about a consolidated clinic early on, when MIS-C was first emerging and all our groups were collaborating and coming up with our inpatient and outpatient care pathways,” said Sanjeev K. Swami, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at CHOP and associate professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania. But timing varies on when each specialist wants to see the families return, and existing clinic schedules and locations varied too much.

So CHOP coordinates appointments individually for each patient, depending on where the patient lives and sometimes stacking them on the same day when possible. Sometimes infectious disease or rheumatology use telehealth, and CHOP, like the other hospitals, prioritizes cardiology, especially for the patients who had cardiac abnormalities in the hospital, Dr. Swami said.

“All three of our groups try to be as flexible as possible. We’ve had a really good collaboration between our groups,” he said, and spreading out follow-up allows specialists to ask about concerns raised at previous appointments, ensuring stronger continuity of care.

“We can make sure things are getting followed up on,” Dr. Swami said. “I think that has been beneficial to make sure things aren’t falling through the cracks.”

CHOP cardiologist Dr. Elias said that ongoing communication, among providers and with families, has been absolutely crucial.

“Everyone’s been talking so frequently about our MIS-C patients while inpatient that by the time they’re an outpatient, it seems to work smoothly, where families are hearing similar items but with a different flair, one from infectious, one from rheumatology, and one from cardiology,” he said.

Children’s Mercy in Kansas City, Mo., also has multiple satellite clinics and follows a model similar to that of CHOP. They discussed having a dedicated multidisciplinary team for each MIS-C patient, but even the logistics of that were difficult, said Emily J. Fox, MD, a rheumatologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Instead, Children’s Mercy tries to coordinate follow-up appointments to be on the same day and often use telehealth for the rheumatology appointments. Families that live closer to the hospital’s location in Joplin, Mo., go in for their cardiology appointment there, and then Dr. Fox conducts a telehealth appointment with the help of nurses in Joplin.

“We really do try hard, especially since these kids are in the hospital for a long time, to make the coordination as easy as possible,” Dr. Fox said. “This was all was very new, especially in the beginning, but I think at least our group is getting a little bit more comfortable in managing these patients.”

Looking ahead

The biggest question that still looms is what happens to these children, if anything, down the line.

“What was unique about this was this was a new disease we were all learning about together with no baseline,” Dr. Swami said. “None of us had ever seen this condition before.”

So far, the prognosis for the vast majority of children is good. “Most of these kids survive, most of them are doing well, and they almost all recover,” Dr. Serrano said. Labs tend to normalize by 6 weeks post discharge, if not much earlier, and not much cardiac involvement is showing up at later follow-ups. But not even a year has passed, so there’s plenty to learn. “We don’t know if there’s long-term risk. I would not be surprised if 20 years down the road we’re finding out things about this that we had no idea” about, Dr. Serrano said. “Everybody wants answers, and nobody has any, and the answers we have may end up being wrong. That’s how it goes when you’re dealing with something you’ve never seen.”

Research underway will ideally begin providing those answers soon. CHOP is a participating site in an NIH-NHLBI–sponsored study, called COVID MUSIC, that is tracking long-term outcomes for MIS-C at 30 centers across the United States and Canada for 5 years.

“That will really definitely be helpful in answering some of the questions about long-term outcomes,” Dr. Elias said. “We hope this is going to be a transient issue and that patients won’t have any long-term manifestations, but we don’t know that yet.”

Meanwhile, one benefit that has come out of the pandemic is strong collaboration, Dr. Bhumbra said.

“The biggest thing we’re all eagerly waiting and hoping for is standard guidelines on how best to follow-up on these kids, but I know that’s a ways away,” Dr. Bhumbra said. So for now, each institution is doing what it can to develop protocols that they feel best serve the patients’ needs, such as Riley’s new dedicated MIS-C clinic. “It takes a village to take care of these kids, and MIS-C has proven that having a clinic with all three specialties at one clinic is going to be great for the families.”

Dr. Fox serves on a committee for Pfizer unrelated to MIS-C. No other doctors interviewed for this story had relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

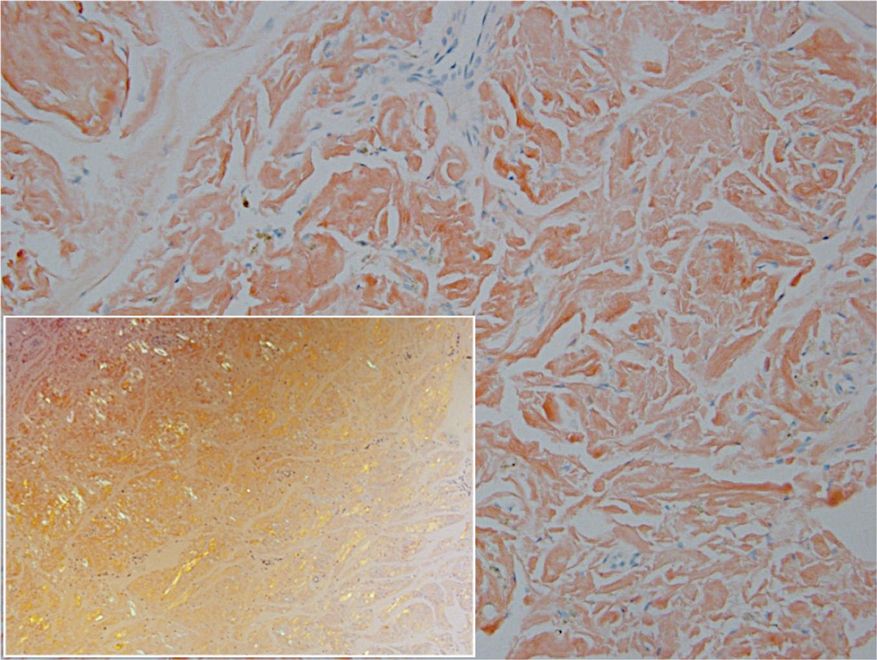

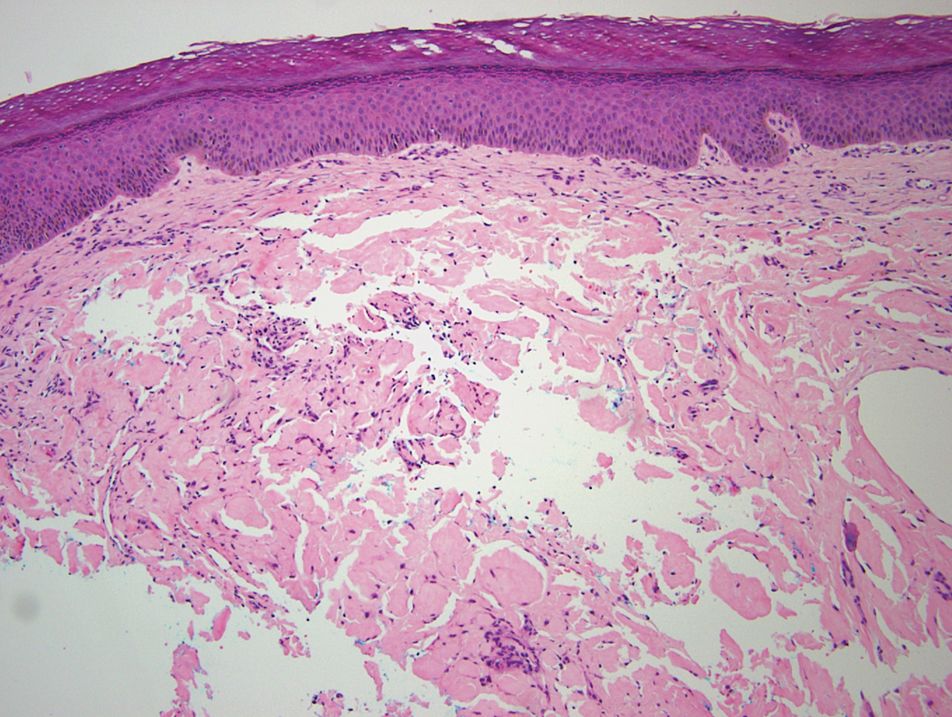

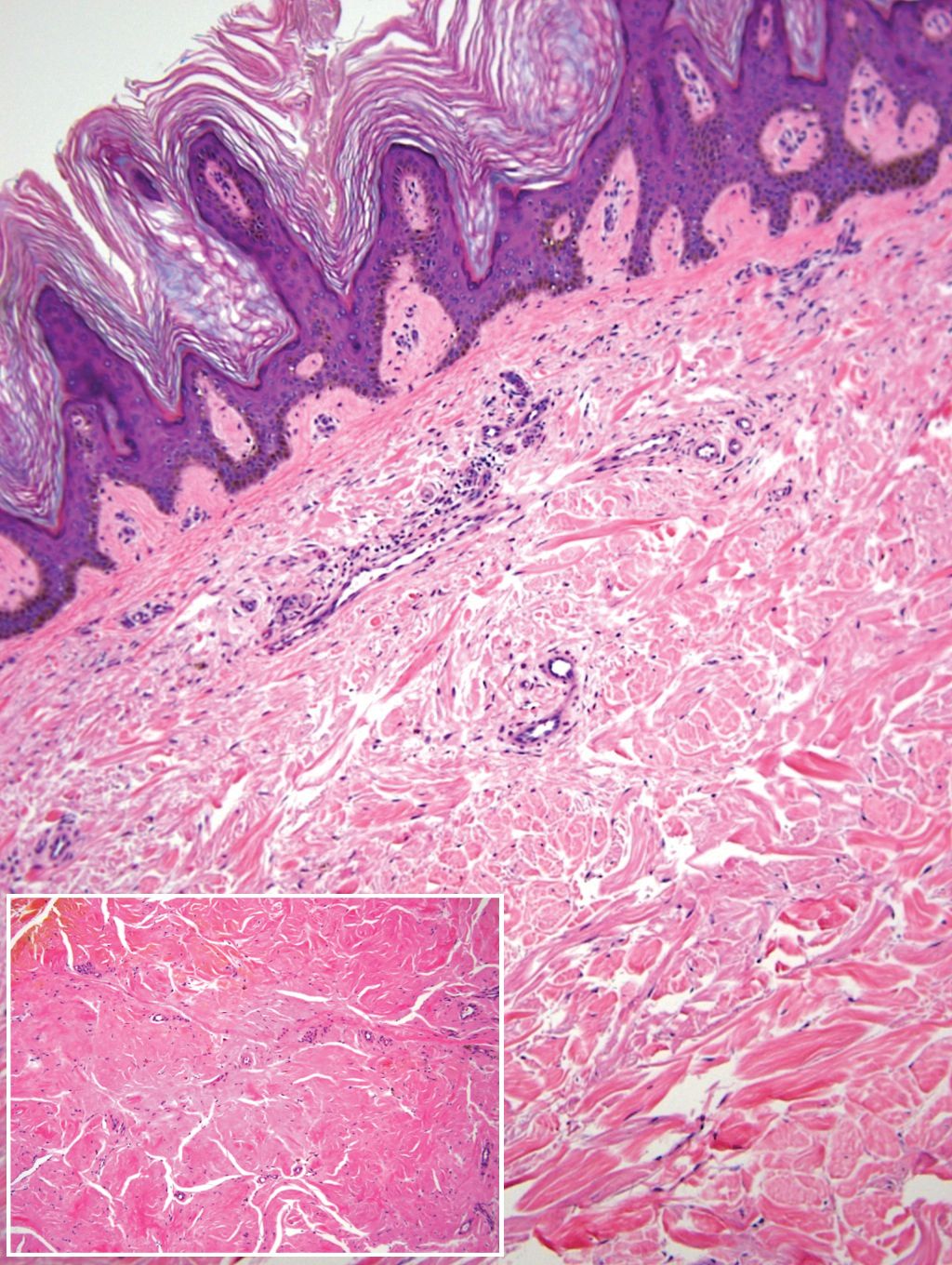

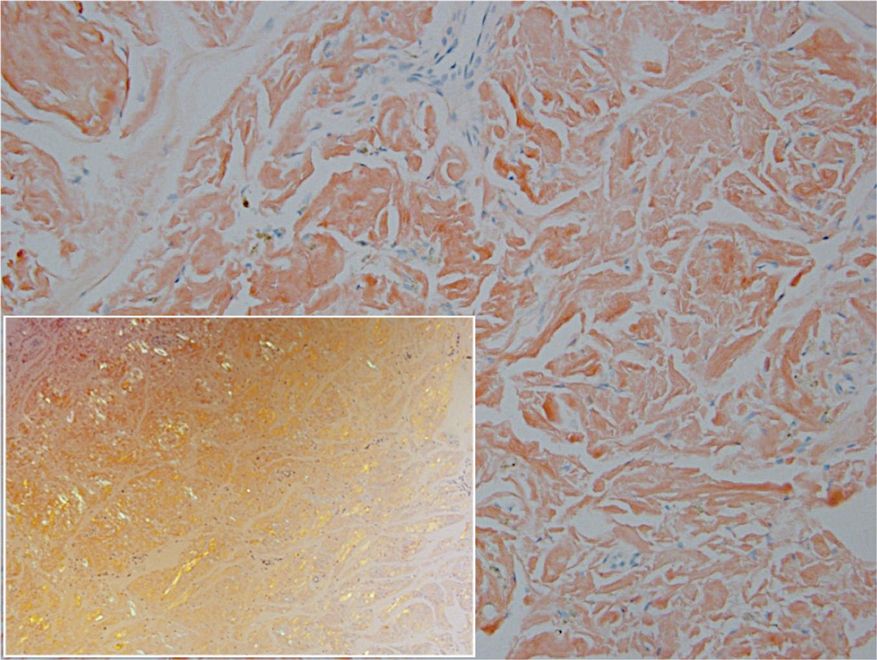

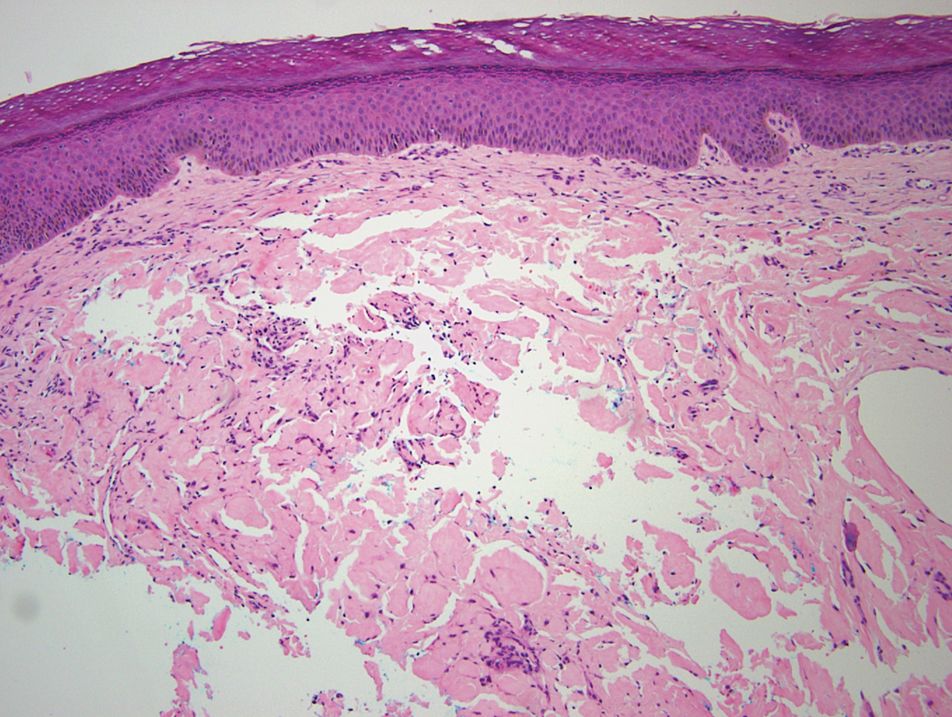

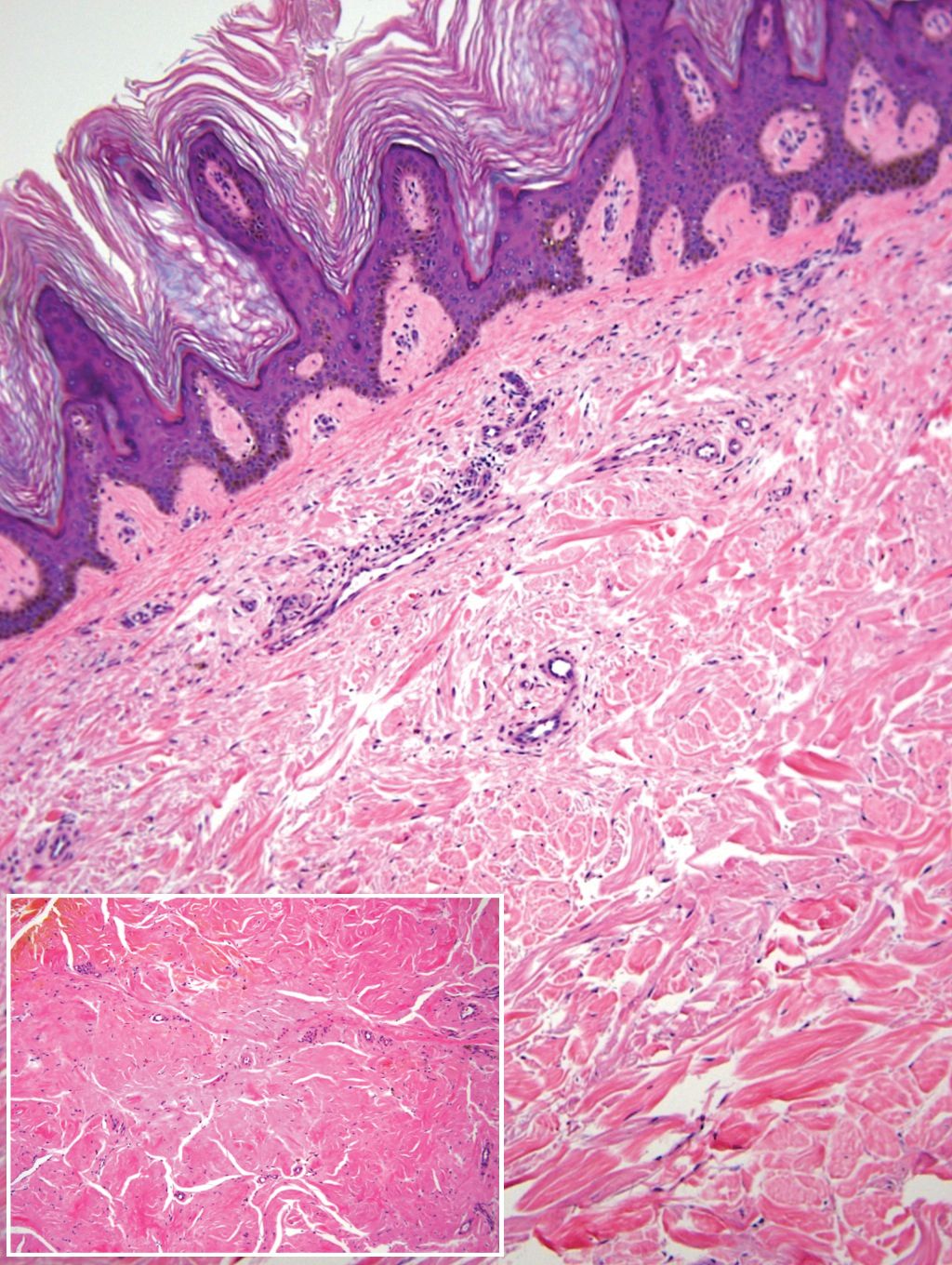

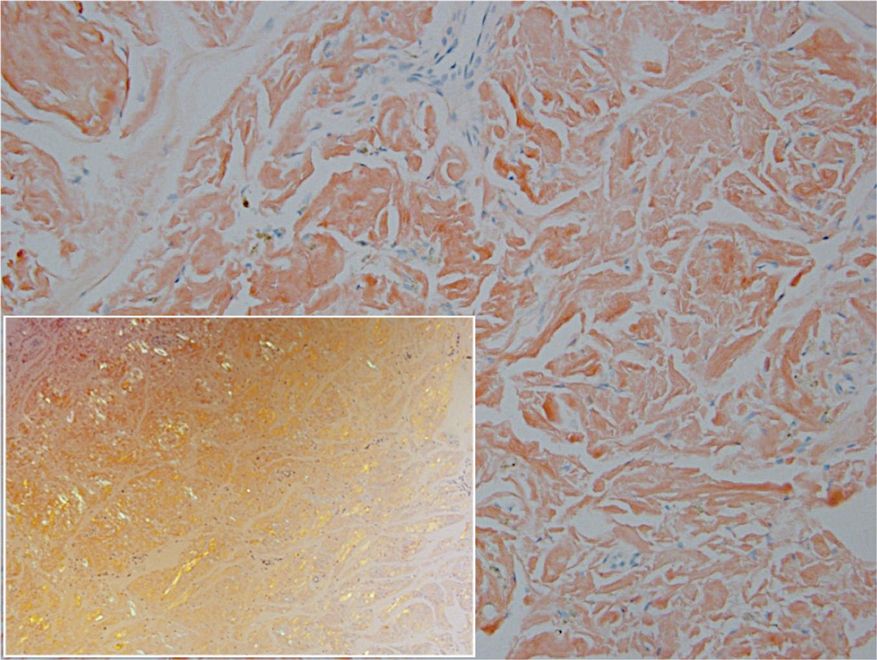

Tocilizumab (Actemra) scores FDA approval for systemic sclerosis–associated interstitial lung disease

The Food and Drug Administration has approved subcutaneously-injected tocilizumab (Actemra) to reduce the rate of pulmonary function decline in systemic sclerosis–associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) patients, according to a press release from manufacturer Genentech.

Tocilizumab is the first biologic to be approved by the agency for adults with SSc-ILD, a rare and potentially life-threatening condition that may affect up to 80% of SSc patients and lead to lung inflammation and scarring.

The approval was based primarily on data from a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial (the focuSSced trial) that included 212 adults with SSc. Although that study failed to meet its primary endpoint of change from baseline to 48 weeks in the modified Rodnan Skin Score, the researchers observed a significantly reduced lung function decline as measured by forced vital capacity (FVC) and percent predicted forced vital capacity (ppFVC) among tocilizumab-treated patients, compared with those who received placebo. A total of 68 patients (65%) in the tocilizumab group and 68 patients (64%) in the placebo group had SSc-ILD at baseline.

In a subgroup analysis, patients taking tocilizumab had a smaller decline in mean ppFVC, compared with placebo patients (0.07% vs. –6.4%; mean difference, 6.47%), and a smaller decline in FVC (mean change –14 mL vs. –255 mL with placebo; mean difference, 241 mL).

The mean change from baseline to week 48 in modified Rodnan Skin Score was –5.88 for patients on tocilizumab and –3.77 with placebo.

Safety data were similar between tocilizumab and placebo groups through 48 weeks, and similar for patients with and without SSc-ILD. In general, tocilizumab side effects include increased susceptibility to infections, and serious side effects may include stomach tears, hepatotoxicity, and increased risk of cancer and hepatitis B, according to the prescribing information. However, the most common side effects are upper respiratory tract infections, headache, hypertension, and injection-site reactions.

Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, is already approved for the treatment of adult patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis, as well as for adult patients with giant cell arteritis; patients aged 2 years and older with active polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis or active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis; and adults and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older with chimeric antigen receptor T-cell–induced severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome.

Prescribing information is available here.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved subcutaneously-injected tocilizumab (Actemra) to reduce the rate of pulmonary function decline in systemic sclerosis–associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) patients, according to a press release from manufacturer Genentech.

Tocilizumab is the first biologic to be approved by the agency for adults with SSc-ILD, a rare and potentially life-threatening condition that may affect up to 80% of SSc patients and lead to lung inflammation and scarring.

The approval was based primarily on data from a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial (the focuSSced trial) that included 212 adults with SSc. Although that study failed to meet its primary endpoint of change from baseline to 48 weeks in the modified Rodnan Skin Score, the researchers observed a significantly reduced lung function decline as measured by forced vital capacity (FVC) and percent predicted forced vital capacity (ppFVC) among tocilizumab-treated patients, compared with those who received placebo. A total of 68 patients (65%) in the tocilizumab group and 68 patients (64%) in the placebo group had SSc-ILD at baseline.

In a subgroup analysis, patients taking tocilizumab had a smaller decline in mean ppFVC, compared with placebo patients (0.07% vs. –6.4%; mean difference, 6.47%), and a smaller decline in FVC (mean change –14 mL vs. –255 mL with placebo; mean difference, 241 mL).

The mean change from baseline to week 48 in modified Rodnan Skin Score was –5.88 for patients on tocilizumab and –3.77 with placebo.

Safety data were similar between tocilizumab and placebo groups through 48 weeks, and similar for patients with and without SSc-ILD. In general, tocilizumab side effects include increased susceptibility to infections, and serious side effects may include stomach tears, hepatotoxicity, and increased risk of cancer and hepatitis B, according to the prescribing information. However, the most common side effects are upper respiratory tract infections, headache, hypertension, and injection-site reactions.

Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, is already approved for the treatment of adult patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis, as well as for adult patients with giant cell arteritis; patients aged 2 years and older with active polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis or active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis; and adults and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older with chimeric antigen receptor T-cell–induced severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome.

Prescribing information is available here.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved subcutaneously-injected tocilizumab (Actemra) to reduce the rate of pulmonary function decline in systemic sclerosis–associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) patients, according to a press release from manufacturer Genentech.

Tocilizumab is the first biologic to be approved by the agency for adults with SSc-ILD, a rare and potentially life-threatening condition that may affect up to 80% of SSc patients and lead to lung inflammation and scarring.

The approval was based primarily on data from a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial (the focuSSced trial) that included 212 adults with SSc. Although that study failed to meet its primary endpoint of change from baseline to 48 weeks in the modified Rodnan Skin Score, the researchers observed a significantly reduced lung function decline as measured by forced vital capacity (FVC) and percent predicted forced vital capacity (ppFVC) among tocilizumab-treated patients, compared with those who received placebo. A total of 68 patients (65%) in the tocilizumab group and 68 patients (64%) in the placebo group had SSc-ILD at baseline.

In a subgroup analysis, patients taking tocilizumab had a smaller decline in mean ppFVC, compared with placebo patients (0.07% vs. –6.4%; mean difference, 6.47%), and a smaller decline in FVC (mean change –14 mL vs. –255 mL with placebo; mean difference, 241 mL).

The mean change from baseline to week 48 in modified Rodnan Skin Score was –5.88 for patients on tocilizumab and –3.77 with placebo.

Safety data were similar between tocilizumab and placebo groups through 48 weeks, and similar for patients with and without SSc-ILD. In general, tocilizumab side effects include increased susceptibility to infections, and serious side effects may include stomach tears, hepatotoxicity, and increased risk of cancer and hepatitis B, according to the prescribing information. However, the most common side effects are upper respiratory tract infections, headache, hypertension, and injection-site reactions.

Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, is already approved for the treatment of adult patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis, as well as for adult patients with giant cell arteritis; patients aged 2 years and older with active polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis or active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis; and adults and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older with chimeric antigen receptor T-cell–induced severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome.

Prescribing information is available here.

FDA approves first targeted treatment for rare DMD mutation

, the agency has announced.

This particular mutation of the DMD gene “is amenable to exon 45 skipping,” the FDA noted in a press release. The agency added that this is its first approval of a targeted treatment for patients with the mutation.

“Developing drugs designed for patients with specific mutations is a critical part of personalized medicine,” Eric Bastings, MD, deputy director of the Office of Neuroscience at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

The approval was based on results from a 43-person randomized controlled trial. Patients who received casimersen had a greater increase in production of the muscle-fiber protein dystrophin compared with their counterparts who received placebo.

Approved – with cautions

The FDA noted that DMD prevalence worldwide is about 1 in 3,600 boys – although it can also affect girls in rare cases. Symptoms of the disorder are commonly first observed around age 3 years but worsen steadily over time. DMD gene mutations lead to a decrease in dystrophin.

As reported by Medscape Medical News in August, the FDA approved viltolarsen (Viltepso, NS Pharma) for the treatment of DMD in patients with a confirmed mutation amenable to exon 53 skipping, following approval of golodirsen injection (Vyondys 53, Sarepta Therapeutics) for the same indication in December 2019.

The DMD gene mutation that is amenable to exon 45 skipping is present in about 8% of patients with DMD.

The trial that carried weight with the FDA included 43 male participants with DMD aged 7-20 years. All were confirmed to have the exon 45-skipping gene mutation and all were randomly assigned 2:1 to received IV casimersen 30 mg/kg or matching placebo.

Results showed that, between baseline and 48 weeks post treatment, the casimersen group showed a significantly higher increase in levels of dystrophin protein than in the placebo group.

Upper respiratory tract infections, fever, joint and throat pain, headache, and cough were the most common adverse events experienced by the active-treatment group.

Although the clinical studies assessing casimersen did not show any reports of kidney toxicity, the adverse event was observed in some nonclinical studies. Therefore, clinicians should monitor kidney function in any patient receiving this treatment, the FDA recommended.

Overall, “the FDA has concluded that the data submitted by the applicant demonstrated an increase in dystrophin production that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit” in this patient population, the agency said in its press release.

However, it noted that definitive clinical benefits such as improved motor function were not “established.”

“In making this decision, the FDA considered the potential risks associated with the drug, the life-threatening and debilitating nature of the disease, and the lack of [other] available therapy,” the agency said.

It added that the manufacturer is currently conducting a multicenter study focused on the safety and efficacy of the drug in ambulatory patients with DMD.

The FDA approved casimersen using its Accelerated Approval pathway, granted Fast Track and Priority Review designations to its applications, and gave the treatment Orphan Drug designation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the agency has announced.

This particular mutation of the DMD gene “is amenable to exon 45 skipping,” the FDA noted in a press release. The agency added that this is its first approval of a targeted treatment for patients with the mutation.

“Developing drugs designed for patients with specific mutations is a critical part of personalized medicine,” Eric Bastings, MD, deputy director of the Office of Neuroscience at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

The approval was based on results from a 43-person randomized controlled trial. Patients who received casimersen had a greater increase in production of the muscle-fiber protein dystrophin compared with their counterparts who received placebo.

Approved – with cautions

The FDA noted that DMD prevalence worldwide is about 1 in 3,600 boys – although it can also affect girls in rare cases. Symptoms of the disorder are commonly first observed around age 3 years but worsen steadily over time. DMD gene mutations lead to a decrease in dystrophin.

As reported by Medscape Medical News in August, the FDA approved viltolarsen (Viltepso, NS Pharma) for the treatment of DMD in patients with a confirmed mutation amenable to exon 53 skipping, following approval of golodirsen injection (Vyondys 53, Sarepta Therapeutics) for the same indication in December 2019.

The DMD gene mutation that is amenable to exon 45 skipping is present in about 8% of patients with DMD.

The trial that carried weight with the FDA included 43 male participants with DMD aged 7-20 years. All were confirmed to have the exon 45-skipping gene mutation and all were randomly assigned 2:1 to received IV casimersen 30 mg/kg or matching placebo.

Results showed that, between baseline and 48 weeks post treatment, the casimersen group showed a significantly higher increase in levels of dystrophin protein than in the placebo group.

Upper respiratory tract infections, fever, joint and throat pain, headache, and cough were the most common adverse events experienced by the active-treatment group.

Although the clinical studies assessing casimersen did not show any reports of kidney toxicity, the adverse event was observed in some nonclinical studies. Therefore, clinicians should monitor kidney function in any patient receiving this treatment, the FDA recommended.

Overall, “the FDA has concluded that the data submitted by the applicant demonstrated an increase in dystrophin production that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit” in this patient population, the agency said in its press release.

However, it noted that definitive clinical benefits such as improved motor function were not “established.”

“In making this decision, the FDA considered the potential risks associated with the drug, the life-threatening and debilitating nature of the disease, and the lack of [other] available therapy,” the agency said.

It added that the manufacturer is currently conducting a multicenter study focused on the safety and efficacy of the drug in ambulatory patients with DMD.

The FDA approved casimersen using its Accelerated Approval pathway, granted Fast Track and Priority Review designations to its applications, and gave the treatment Orphan Drug designation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the agency has announced.

This particular mutation of the DMD gene “is amenable to exon 45 skipping,” the FDA noted in a press release. The agency added that this is its first approval of a targeted treatment for patients with the mutation.

“Developing drugs designed for patients with specific mutations is a critical part of personalized medicine,” Eric Bastings, MD, deputy director of the Office of Neuroscience at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement.

The approval was based on results from a 43-person randomized controlled trial. Patients who received casimersen had a greater increase in production of the muscle-fiber protein dystrophin compared with their counterparts who received placebo.

Approved – with cautions

The FDA noted that DMD prevalence worldwide is about 1 in 3,600 boys – although it can also affect girls in rare cases. Symptoms of the disorder are commonly first observed around age 3 years but worsen steadily over time. DMD gene mutations lead to a decrease in dystrophin.

As reported by Medscape Medical News in August, the FDA approved viltolarsen (Viltepso, NS Pharma) for the treatment of DMD in patients with a confirmed mutation amenable to exon 53 skipping, following approval of golodirsen injection (Vyondys 53, Sarepta Therapeutics) for the same indication in December 2019.

The DMD gene mutation that is amenable to exon 45 skipping is present in about 8% of patients with DMD.

The trial that carried weight with the FDA included 43 male participants with DMD aged 7-20 years. All were confirmed to have the exon 45-skipping gene mutation and all were randomly assigned 2:1 to received IV casimersen 30 mg/kg or matching placebo.

Results showed that, between baseline and 48 weeks post treatment, the casimersen group showed a significantly higher increase in levels of dystrophin protein than in the placebo group.

Upper respiratory tract infections, fever, joint and throat pain, headache, and cough were the most common adverse events experienced by the active-treatment group.

Although the clinical studies assessing casimersen did not show any reports of kidney toxicity, the adverse event was observed in some nonclinical studies. Therefore, clinicians should monitor kidney function in any patient receiving this treatment, the FDA recommended.

Overall, “the FDA has concluded that the data submitted by the applicant demonstrated an increase in dystrophin production that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit” in this patient population, the agency said in its press release.

However, it noted that definitive clinical benefits such as improved motor function were not “established.”

“In making this decision, the FDA considered the potential risks associated with the drug, the life-threatening and debilitating nature of the disease, and the lack of [other] available therapy,” the agency said.

It added that the manufacturer is currently conducting a multicenter study focused on the safety and efficacy of the drug in ambulatory patients with DMD.

The FDA approved casimersen using its Accelerated Approval pathway, granted Fast Track and Priority Review designations to its applications, and gave the treatment Orphan Drug designation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New steroid dosing regimen for myasthenia gravis

. The trial showed that the conventional slow tapering regimen enabled discontinuation of prednisone earlier than previously reported but the new rapid-tapering regimen enabled an even faster discontinuation.

Noting that although both regimens led to a comparable myasthenia gravis status and prednisone dose at 15 months, the authors stated: “We think that the reduction of the cumulative dose over a year (equivalent to 5 mg/day) is a clinically relevant reduction, since the risk of complications is proportional to the daily or cumulative doses of prednisone.

“Our results warrant testing of a more rapid-tapering regimen in a future trial. In the meantime, our trial provides useful information on how prednisone tapering could be managed in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis treated with azathioprine,” they concluded.

The trial was published online Feb. 8 in JAMA Neurology.

Myasthenia gravis is a disorder of neuromuscular transmission, resulting from autoantibodies to components of the neuromuscular junction, most commonly the acetylcholine receptor. The incidence ranges from 0.3 to 2.8 per 100,000, and it is estimated to affect more than 700,000 people worldwide.

The authors of the current paper, led by Tarek Sharshar, MD, PhD, Groupe Hospitalier Universitaire, Paris, explained that many patients whose symptoms are not controlled by cholinesterase inhibitors are treated with corticosteroids and an immunosuppressant, usually azathioprine. No specific dosing protocol for prednisone has been validated, but it is commonly gradually increased to 0.75 mg/kg on alternate days and reduced progressively when minimal manifestation status (MMS; no symptoms or functional limitations) is reached.

They noted that this regimen leads to high and prolonged corticosteroid treatment – often for several years – with the mean daily prednisone dose exceeding 30 mg/day at 15 months and 20 mg/day at 36 months. As long-term use of corticosteroids is often associated with significant complications, reducing or even discontinuing prednisone treatment without destabilizing myasthenia gravis is therefore a therapeutic goal.

Evaluating dosage regimens

To investigate whether different dosage regimens could help wean patients with generalized myasthenia gravis from corticosteroid therapy without compromising efficacy, the researchers conducted this study in which the current recommended regimen was compared with an approach using higher initial corticosteroid doses followed by rapid tapering.

In the conventional slow-tapering group (control group), prednisone was given on alternate days, starting at a dose of 10 mg then increased by increments of 10 mg every 2 days up to 1.5 mg/kg on alternate days without exceeding 100 mg. This dose was maintained until MMS was reached and then reduced by 10 mg every 2 weeks until a dosage of 40 mg was reached, with subsequent slowing of the taper to 5 mg monthly. If MMS was not maintained, the alternate-day prednisone dose was increased by 10 mg every 2 weeks until MMS was restored, and the tapering resumed 4 weeks later.

In the new rapid-tapering group, oral prednisone was immediately started at 0.75 mg/kg per day, and this was followed by an earlier and rapid decrease once improved myasthenia gravis status was attained. Three different tapering schedules were applied dependent on the improvement status of the patient.

First, If the patient reached MMS at 1 month, the dose of prednisone was reduced by 0.1 mg/kg every 10 days up to 0.45 mg/kg per day, then 0.05 mg/kg every 10 days up to 0.25 mg/kg per day, then in decrements of 1 mg by adjusting the duration of the decrements according to the participant’s weight with the aim of achieving complete cessation of corticosteroid therapy within 18-20 weeks for this third stage of tapering.

Second, if the state of MMS was not reached at 1 month but the participant had improved, a slower tapering was conducted, with the dosage reduced in a similar way to the first instance but with each reduction introduced every 20 days. If the participant reached MMS during this tapering process, the tapering of prednisone was similar to the sequence described in the first group.

Third, if MMS was not reached and the participant had not improved, the initial dose was maintained for the first 3 months; beyond that time, a decrease in the prednisone dose was undertaken as in the second group to a minimum dose of 0.25 mg/kg per day, after which the prednisone dose was not reduced further. If the patient improved, the tapering of prednisone followed the sequence described in the second category.

Reductions in prednisone dose could be accelerated in the case of severe prednisone adverse effects, according to the prescriber’s decision.

In the event of a myasthenia gravis exacerbation, the patient was hospitalized and the dose of prednisone was routinely doubled, or for a more moderate aggravation, the dose was increased to the previous dose recommended in the tapering regimen.

Azathioprine, up to a maximum dose of 3 mg/kg per day, was prescribed for all participants. In all, 117 patients were randomly assigned, and 113 completed the study.

The primary outcome was the proportion of participants having reached MMS without prednisone at 12 months and having not relapsed or taken prednisone between months 12 and 15. This was achieved by significantly more patients in the rapid-tapering group (39% vs. 9%; risk ratio, 3.61; P < .001).

Rapid tapering allowed sparing of a mean of 1,898 mg of prednisone over 1 year (5.3 mg/day) per patient.

The rate of myasthenia gravis exacerbation or worsening did not differ significantly between the two groups, nor did the use of plasmapheresis or IVIG or the doses of azathioprine.

The overall number of serious adverse events did not differ significantly between the two groups (slow tapering, 22% vs. rapid-tapering, 36%; P = .15).

The researchers said it is possible that prednisone tapering would differ with another immunosuppressive agent but as azathioprine is the first-line immunosuppressant usually recommended, these results are relevant for a large proportion of patients.

They said the better outcome of the intervention group could have been related to one or more of four differences in prednisone administration: An immediate high dose versus a slow increase of the prednisone dose; daily versus alternate-day dosing; earlier tapering initiation; and faster tapering. However, the structure of the study did not allow identification of which of these factors was responsible.

“Researching the best prednisone-tapering scheme is not only a major issue for patients with myasthenia gravis but also for other autoimmune or inflammatory diseases, because validated prednisone-tapering regimens are scarce,” the authors said.

The rapid tapering of prednisone therapy appears to be feasible, beneficial, and safe in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis and “warrants testing in other autoimmune diseases,” they added.

Particularly relevant to late-onset disease

Commenting on the study, Raffi Topakian, MD, Klinikum Wels-Grieskirchen, Wels, Austria, said the results showed that in patients with moderate to severe generalized myasthenia gravis requiring high-dose prednisone, azathioprine, a widely used immunosuppressant, may have a quicker steroid-sparing effect than previously thought, and that rapid steroid tapering can be achieved safely, resulting in a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose over a year despite higher initial doses.

Dr. Topakian, who was not involved with the research, pointed out that the median age was advanced (around 56 years), and the benefit of a regimen that leads to a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose over a year may be disproportionately larger for older, sicker patients with many comorbidities who are at considerably higher risk for a prednisone-induced increase in cardiovascular complications, osteoporotic fractures, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

“The study findings are particularly relevant for the management of late-onset myasthenia gravis (when first symptoms start after age 45-50 years), which is being encountered more frequently over the past years,” he said.

“But the holy grail of myasthenia gravis treatment has not been found yet,” Dr. Topakian noted. “Disappointingly, rapid tapering of steroids (compared to slow tapering) resulted in a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose only, but was not associated with better myasthenia gravis functional status or lower doses of steroids at 15 months. To my view, this finding points to the limited immunosuppressive efficacy of azathioprine.”

He added that the study findings should not be extrapolated to patients with mild presentations or to those with muscle-specific kinase myasthenia gravis.

Dr. Sharshar disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the study coauthors appear in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

. The trial showed that the conventional slow tapering regimen enabled discontinuation of prednisone earlier than previously reported but the new rapid-tapering regimen enabled an even faster discontinuation.

Noting that although both regimens led to a comparable myasthenia gravis status and prednisone dose at 15 months, the authors stated: “We think that the reduction of the cumulative dose over a year (equivalent to 5 mg/day) is a clinically relevant reduction, since the risk of complications is proportional to the daily or cumulative doses of prednisone.

“Our results warrant testing of a more rapid-tapering regimen in a future trial. In the meantime, our trial provides useful information on how prednisone tapering could be managed in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis treated with azathioprine,” they concluded.

The trial was published online Feb. 8 in JAMA Neurology.

Myasthenia gravis is a disorder of neuromuscular transmission, resulting from autoantibodies to components of the neuromuscular junction, most commonly the acetylcholine receptor. The incidence ranges from 0.3 to 2.8 per 100,000, and it is estimated to affect more than 700,000 people worldwide.

The authors of the current paper, led by Tarek Sharshar, MD, PhD, Groupe Hospitalier Universitaire, Paris, explained that many patients whose symptoms are not controlled by cholinesterase inhibitors are treated with corticosteroids and an immunosuppressant, usually azathioprine. No specific dosing protocol for prednisone has been validated, but it is commonly gradually increased to 0.75 mg/kg on alternate days and reduced progressively when minimal manifestation status (MMS; no symptoms or functional limitations) is reached.

They noted that this regimen leads to high and prolonged corticosteroid treatment – often for several years – with the mean daily prednisone dose exceeding 30 mg/day at 15 months and 20 mg/day at 36 months. As long-term use of corticosteroids is often associated with significant complications, reducing or even discontinuing prednisone treatment without destabilizing myasthenia gravis is therefore a therapeutic goal.

Evaluating dosage regimens

To investigate whether different dosage regimens could help wean patients with generalized myasthenia gravis from corticosteroid therapy without compromising efficacy, the researchers conducted this study in which the current recommended regimen was compared with an approach using higher initial corticosteroid doses followed by rapid tapering.

In the conventional slow-tapering group (control group), prednisone was given on alternate days, starting at a dose of 10 mg then increased by increments of 10 mg every 2 days up to 1.5 mg/kg on alternate days without exceeding 100 mg. This dose was maintained until MMS was reached and then reduced by 10 mg every 2 weeks until a dosage of 40 mg was reached, with subsequent slowing of the taper to 5 mg monthly. If MMS was not maintained, the alternate-day prednisone dose was increased by 10 mg every 2 weeks until MMS was restored, and the tapering resumed 4 weeks later.

In the new rapid-tapering group, oral prednisone was immediately started at 0.75 mg/kg per day, and this was followed by an earlier and rapid decrease once improved myasthenia gravis status was attained. Three different tapering schedules were applied dependent on the improvement status of the patient.

First, If the patient reached MMS at 1 month, the dose of prednisone was reduced by 0.1 mg/kg every 10 days up to 0.45 mg/kg per day, then 0.05 mg/kg every 10 days up to 0.25 mg/kg per day, then in decrements of 1 mg by adjusting the duration of the decrements according to the participant’s weight with the aim of achieving complete cessation of corticosteroid therapy within 18-20 weeks for this third stage of tapering.

Second, if the state of MMS was not reached at 1 month but the participant had improved, a slower tapering was conducted, with the dosage reduced in a similar way to the first instance but with each reduction introduced every 20 days. If the participant reached MMS during this tapering process, the tapering of prednisone was similar to the sequence described in the first group.

Third, if MMS was not reached and the participant had not improved, the initial dose was maintained for the first 3 months; beyond that time, a decrease in the prednisone dose was undertaken as in the second group to a minimum dose of 0.25 mg/kg per day, after which the prednisone dose was not reduced further. If the patient improved, the tapering of prednisone followed the sequence described in the second category.

Reductions in prednisone dose could be accelerated in the case of severe prednisone adverse effects, according to the prescriber’s decision.

In the event of a myasthenia gravis exacerbation, the patient was hospitalized and the dose of prednisone was routinely doubled, or for a more moderate aggravation, the dose was increased to the previous dose recommended in the tapering regimen.

Azathioprine, up to a maximum dose of 3 mg/kg per day, was prescribed for all participants. In all, 117 patients were randomly assigned, and 113 completed the study.

The primary outcome was the proportion of participants having reached MMS without prednisone at 12 months and having not relapsed or taken prednisone between months 12 and 15. This was achieved by significantly more patients in the rapid-tapering group (39% vs. 9%; risk ratio, 3.61; P < .001).

Rapid tapering allowed sparing of a mean of 1,898 mg of prednisone over 1 year (5.3 mg/day) per patient.