User login

Gynecologic and Obstetric Implications of Darier Disease: A Dermatologist’s Perspective

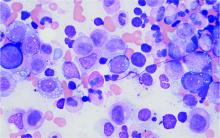

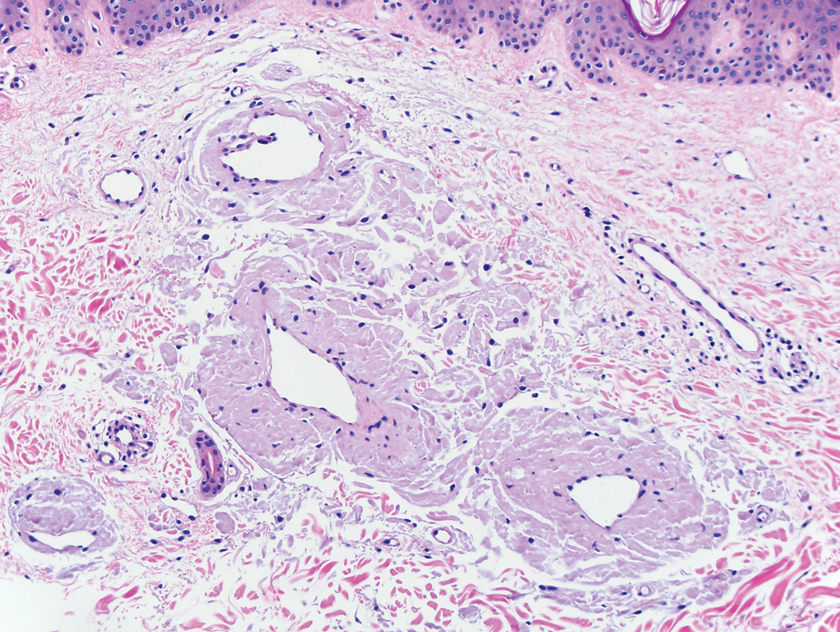

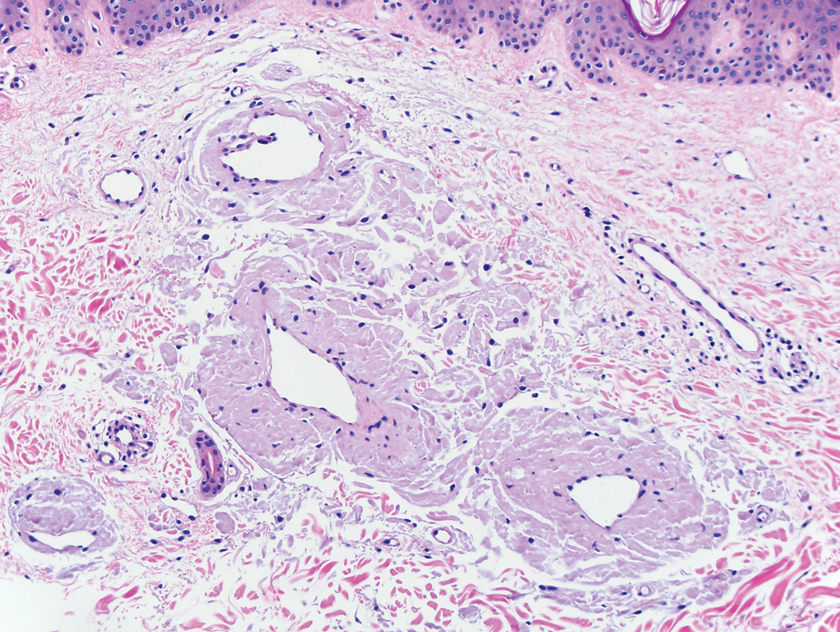

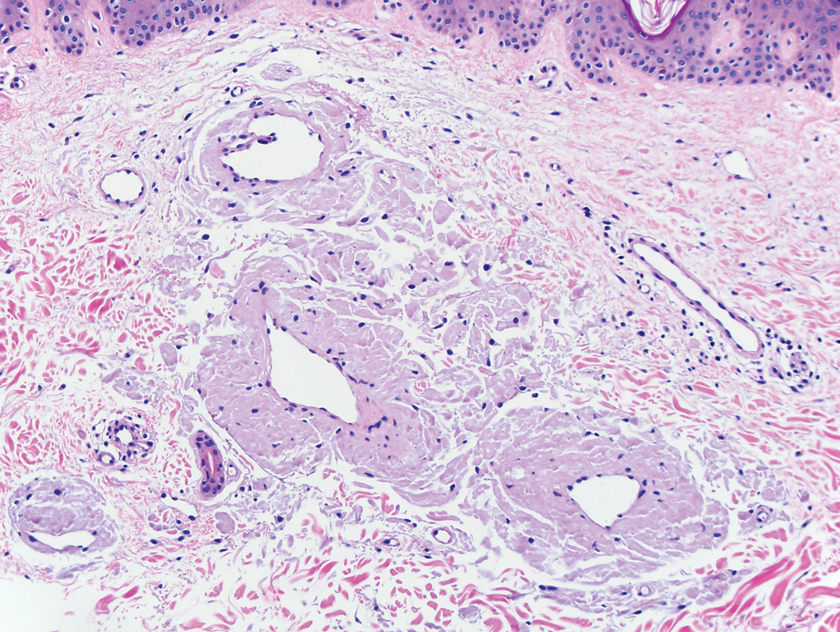

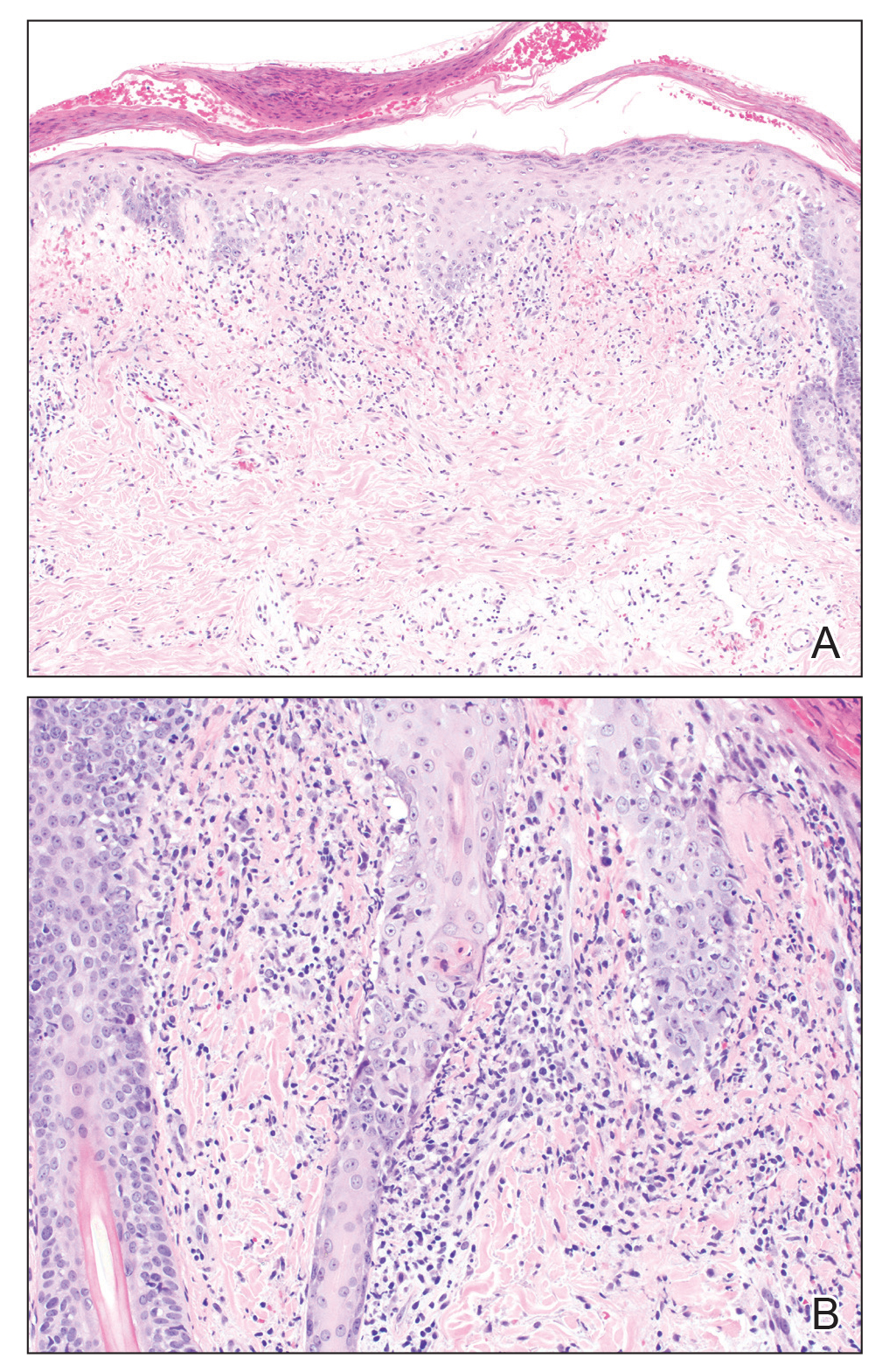

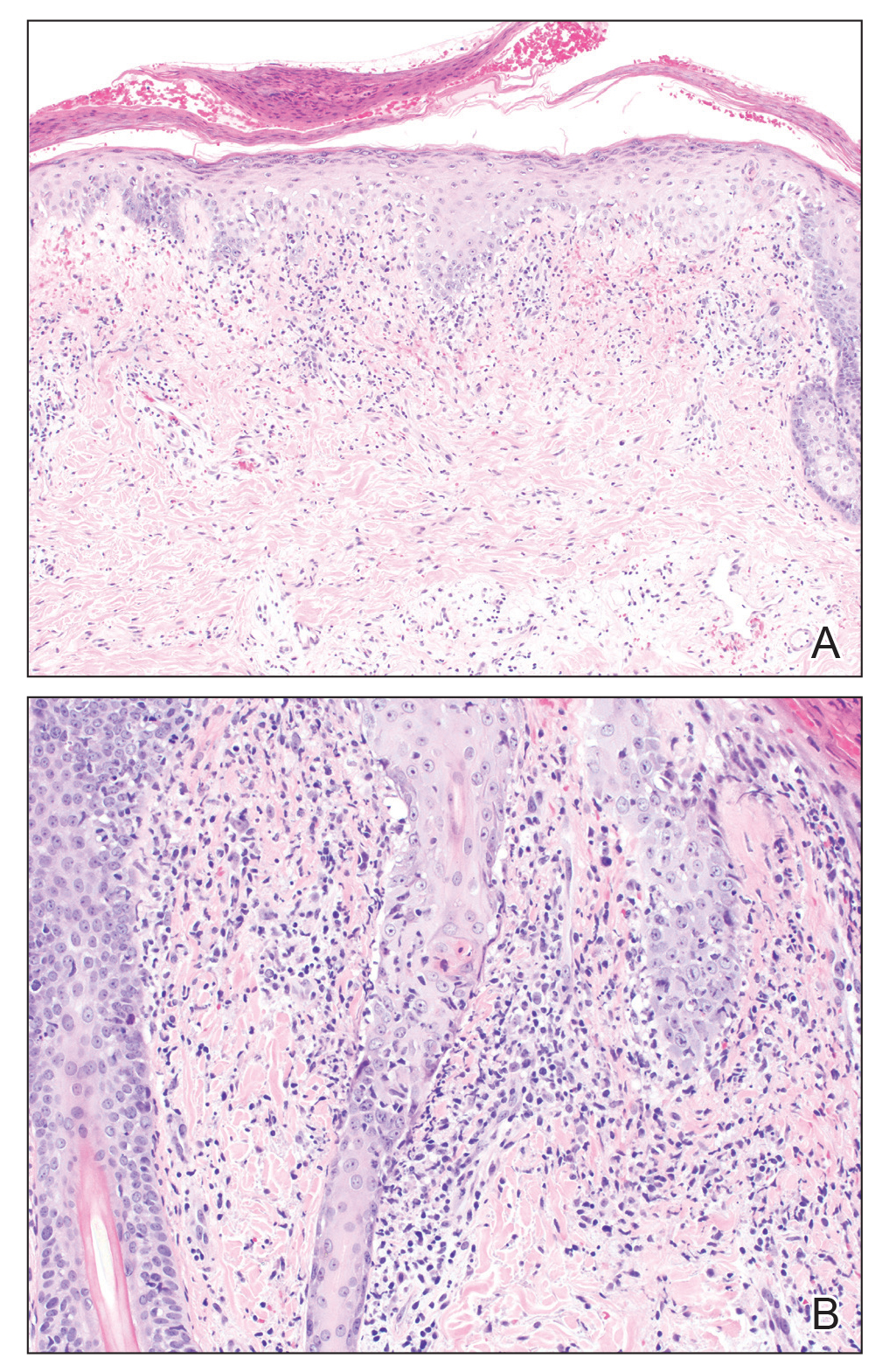

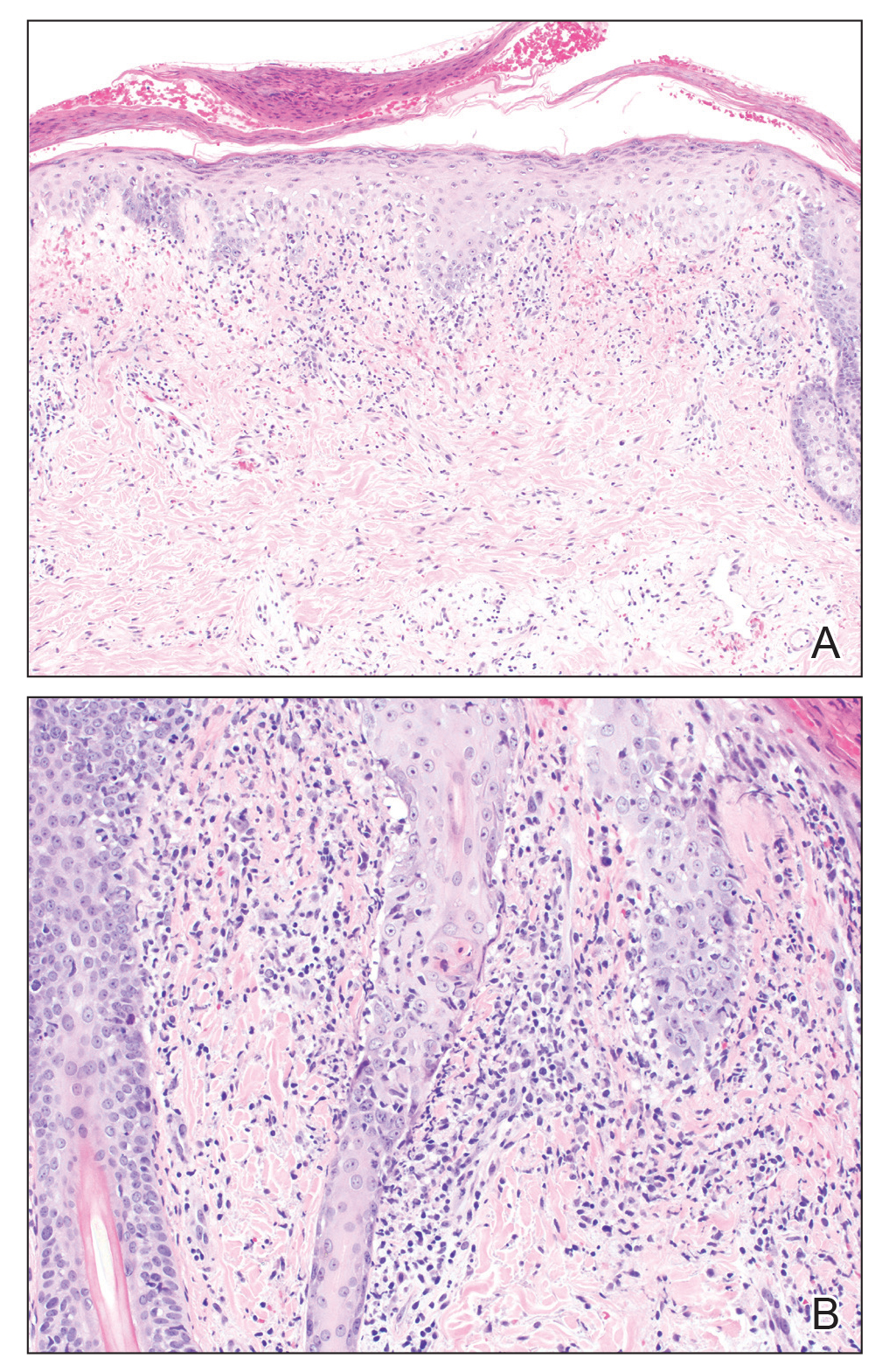

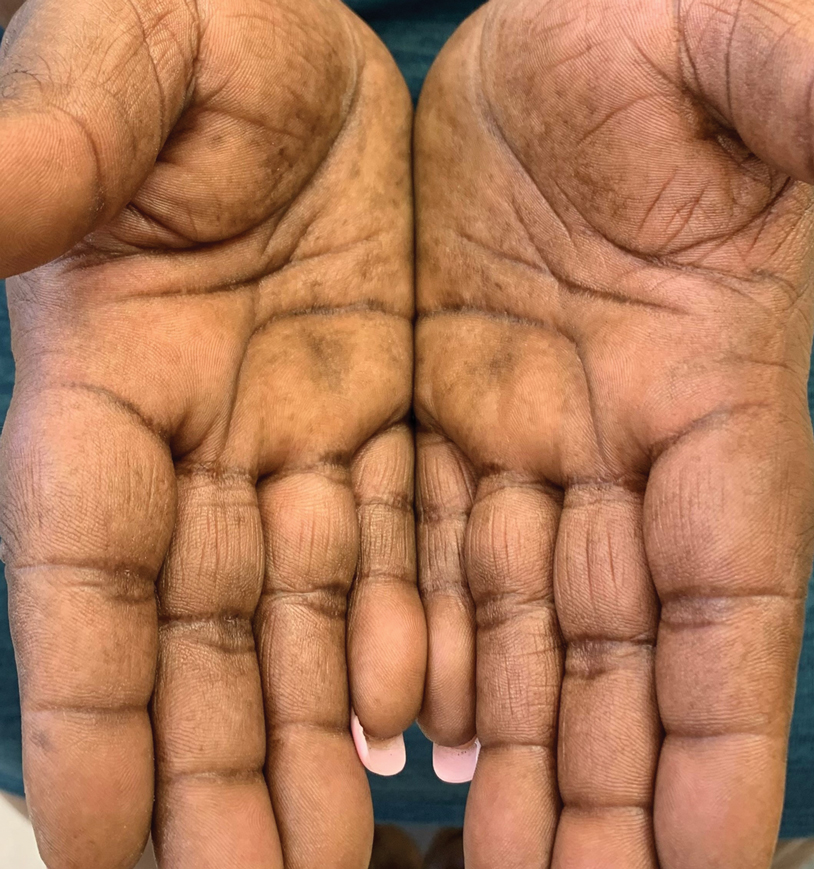

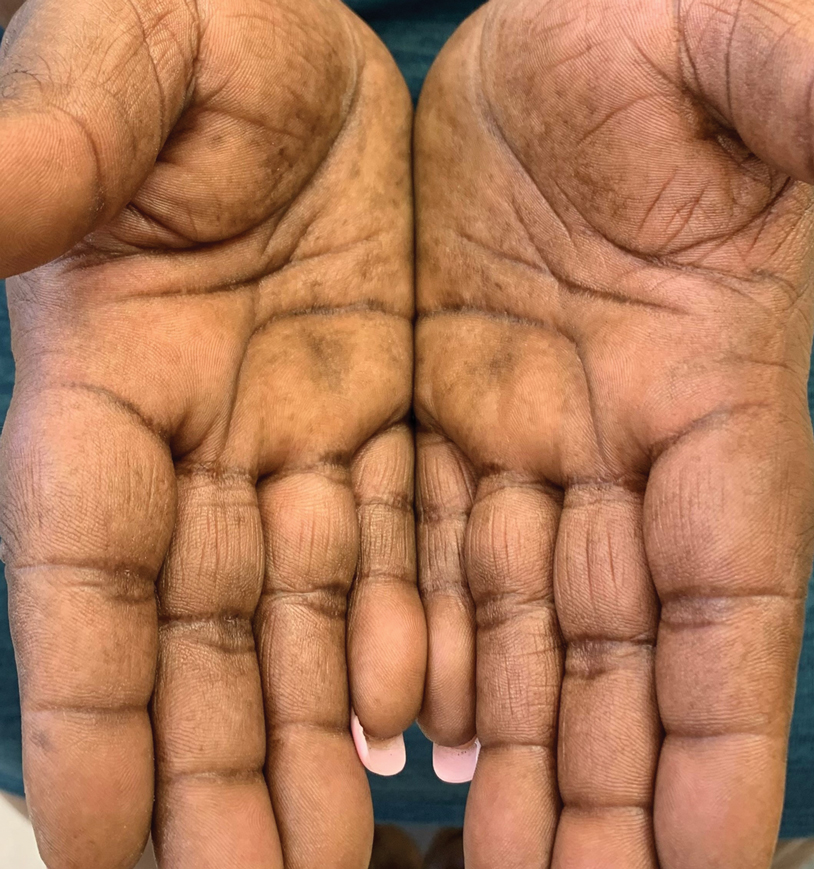

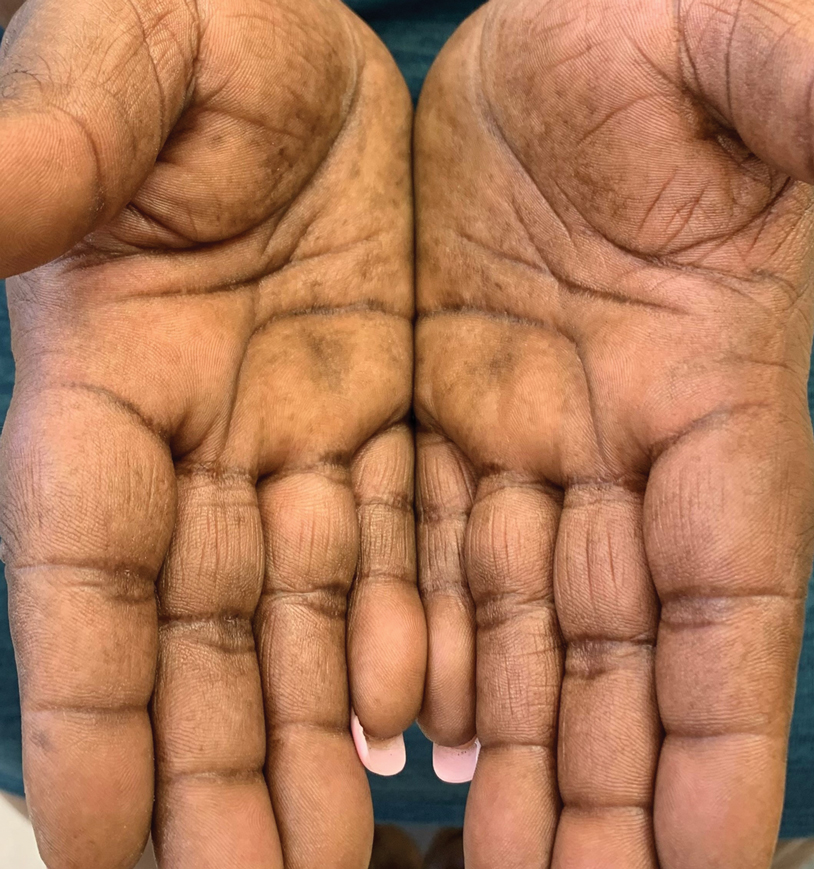

Darier disease (DD)(also known as dyskeratosis follicularis) is a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis characterized by greasy, rough, keratotic papules; typical nail abnormalities; mucosal changes; and characteristic dyskeratotic acantholysis that is called corps ronds and grains on histopathologic analysis. Darier disease is caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene on chromosome 12q23-24.1,2

Because of the autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance in DD, if either parent is affected by DD, approximately 50% of their offspring will have the disorder. Therefore, couples need to be offered genetic counseling at a preconception visit or early in pregnancy. Although penetrance of DD is complete, spontaneous mutations are frequent and expressivity is variable1; prenatal diagnosis, though available since the 1980s, is therefore unreliable in DD, given the considerable variation in phenotypic expressivity. Differing phenotypes underscore the importance of proper counseling by the treating dermatologist or other provider. Females with a mild or nearly undetectable phenotype can give birth to a child with severe disease.

Lack of clear understanding about the variable phenotypic expressivity of DD can cause considerable anger, anxiety, guilt, psychological trauma, and fear in parents, should their child later develop a severe phenotype. They may feel that they were not properly prepared for the outcome. The physician-parent or physician-patient relationship can be negatively impacted if ongoing counseling is inadequate.

Clinically, DD presents in early adolescence (age range, 6–20 years) in most patients, which means that the disease and female reproductive years are contemporaneous. However, gynecologic and obstetric issues and complications of DD rarely have been addressed.3 Oromucosal involvement in DD is reported in 13% to 50% of cases, yet vaginal and cervical mucosal involvement rarely has been described,4,5 likely due to underreporting. Therefore, in this rare disease, it is important to address these aspects so that the patients are provided with appropriate management options.

Implications for Cervical Screening and Papanicolaou Tests

Cytopathologic findings of a Papanicolaou test taken from a patient with DD can lead to erroneous diagnosis of a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion due to cervical involvement by the disease process; therefore, correct interpretation of a smear may be inappropriate and erroneous. The cytopathologist needs to be informed of the patient’s diagnosis of DD in advance for appropriate reporting.5,6

Obstetric Implications

Fertility is normal in DD patients, and pregnancy usually has a normal course; however, exacerbation and remission of disease have been reported. de la Rosa Carrillo7 reported a case of vegetating DD during pregnancy. He described it as an exacerbation with concurrent bacterial infection and bilateral external otitis.7 Spouge et al8 reported a case of a 58-year-old woman who was the mother of 4 DD patients. She experienced an exacerbation of DD during all 6 pregnancies but improved immediately postpartum.8 Espy et al9 evaluated 8 cases of women with DD and described spontaneous improvement of the disorder during pregnancy (1 case) or while taking an oral contraceptive (3 cases).

Prenatal Counseling

Women with DD should be encouraged to talk to their dermatologist, obstetrician, or other provider of prenatal care regarding plans for pregnancy, labor, and delivery, as these events might be affected by the disorder. During pregnancy, careful monitoring and self-care remain essential. Simple measures to reduce the impact of irritants on DD during pregnancy include keeping the skin cool, using a soothing moisturizer, applying photoprotection, and using sunscreen. Treatment with systemic retinoids must be avoided if pregnancy is planned.

Warty plaques and papules of DD can involve flexures (groin, vulva, and perineum), with resultant malodor and pruritus10 as well as the potential for (drug resistant) secondary infection (eg, Staphylococcus aureus, group B Streptococcus, viruses [eg, Kaposi varicelliform eruption]). Skin swabs should be taken for culture and susceptibility testing, and infection should be treated at the earliest sign.

Management Concerns During Pregnancy and Delivery

Because the benefits of treating DD might outweigh risk in certain cases, thorough discussion with the patient about options is recommended, including the following concerns:

• Because mucocutaneous elasticity of the birth canal, including the vulva, perineum, and groin, is essential for nontraumatic vaginal delivery, it might be necessary to schedule an elective cesarean delivery in DD patients in whom these regions are involved.11

• In females with lower abdominal lesions, using a Pfannenstiel-Kerr incision for cesarean delivery might be problematic.11

• A single case report has described successful anesthetic management of labor, delivery, and postpartum care in a DD patient.12 Involvement of the skin of the back might preclude safe administration of regional anesthesia; however, because DD lesions are considered noninfectious, the authors operatively administered a subarachnoid block at the L3-L4 interspace through a lesion-free area. Postpartum, the patient was observed in the intensive care unit. She and the baby remained stable; she did not develop infectious complications, including a central nervous system infection.12

•Mucosal involvement is relatively rare in DD and has not been reported to compromise airway management.8

Postnatal Considerations

Breastfeeding might have to be stopped early or withheld altogether if there is widespread involvement of the skin of the breast or the nipple.11 Darier disease has been associated with neuropsychiatric manifestations, including major depression (30%), suicide attempts (13%), suicidal thoughts (31%), cyclothymia, bipolar disorder (4%), and epilepsy (3%).13,14 Therefore, patients should be screened for postpartum psychiatric manifestations at an early follow-up visit.

Final Thoughts

Although the etiology of DD is well known, the gynelogic and obstretric implications of this genodermatosis have rarely been described. This brief commentary is an attempt to provide the important information to a practicing dermatologist for appropriate management of female DD patients.

- Bale SJ, Toro JR. Genetic basis of Darier-White disease: bad pumps cause bumps. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:103-106. doi:10.1177/120347540000400212

- Kansal NK, Hazarika N, Rao S. Familial case of Darier disease with guttate leukoderma: a case series from India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:62-63. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_52_17

- Lynch PJ. Vulvar dermatoses: the eczematous diseases. In: Black M, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Edwards L, Lynch P, eds. Obstetric and Gynecologic Dermatology. 3rd ed. Mosby-Elsevier; 2008:192-194.

- Adam AE. Ectopic Darier’s disease of the cervix: an extraordinary cause of an abnormal smear. Cytopathology. 1996;7:414-421. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2303.1996.tb00547.x

- Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Antúnez JR, Del Rio E, et al. Vaginal involvement in a woman with Darier’s disease: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:530-532. doi:10.1159/000326200

- Boon ME. Dr. Darier’s lesson: it can be advantageous to the patient to ignore evident cytonuclear changes. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:469-470. doi:10.1159/000326189

- de la Rosa Carrillo D. Vegetating Darier’s disease during pregnancy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:259-260. doi:10.2340/00015555-0066

- Spouge JD, Trott JR, Chesko G. Darier-White’s disease: a cause of white lesions of the mucosa. report of four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;21:441-457. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(66)90401-4

- Espy PD, Stone S, Jolly HW Jr. Hormonal dependency in Darier disease. Cutis. 1976;17:315-320.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Saikia UN. Uncommon flexural presentation of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:249-252. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.07035

- Quinlivan JA, O'Halloran LC. Darier’s disease and pregnancy. Dermatol Aspects. 2013;1:1-3. doi:10.7243/2053-5309-1-1

- Sharma R, Singh BP, Das SN. Anesthetic management of cesarean section in a parturient with Darier’s disease. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2010;48:158-159. doi:10.1016/S1875-4597(10)60051-3

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Dodiuk-Gad RP, Cohen-Barak E, Khayat M, et al. Darier disease in Israel: combined evaluation of genetic and neuropsychiatric aspects. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:562-568. doi:10.1111/bjd.14220

Darier disease (DD)(also known as dyskeratosis follicularis) is a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis characterized by greasy, rough, keratotic papules; typical nail abnormalities; mucosal changes; and characteristic dyskeratotic acantholysis that is called corps ronds and grains on histopathologic analysis. Darier disease is caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene on chromosome 12q23-24.1,2

Because of the autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance in DD, if either parent is affected by DD, approximately 50% of their offspring will have the disorder. Therefore, couples need to be offered genetic counseling at a preconception visit or early in pregnancy. Although penetrance of DD is complete, spontaneous mutations are frequent and expressivity is variable1; prenatal diagnosis, though available since the 1980s, is therefore unreliable in DD, given the considerable variation in phenotypic expressivity. Differing phenotypes underscore the importance of proper counseling by the treating dermatologist or other provider. Females with a mild or nearly undetectable phenotype can give birth to a child with severe disease.

Lack of clear understanding about the variable phenotypic expressivity of DD can cause considerable anger, anxiety, guilt, psychological trauma, and fear in parents, should their child later develop a severe phenotype. They may feel that they were not properly prepared for the outcome. The physician-parent or physician-patient relationship can be negatively impacted if ongoing counseling is inadequate.

Clinically, DD presents in early adolescence (age range, 6–20 years) in most patients, which means that the disease and female reproductive years are contemporaneous. However, gynecologic and obstetric issues and complications of DD rarely have been addressed.3 Oromucosal involvement in DD is reported in 13% to 50% of cases, yet vaginal and cervical mucosal involvement rarely has been described,4,5 likely due to underreporting. Therefore, in this rare disease, it is important to address these aspects so that the patients are provided with appropriate management options.

Implications for Cervical Screening and Papanicolaou Tests

Cytopathologic findings of a Papanicolaou test taken from a patient with DD can lead to erroneous diagnosis of a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion due to cervical involvement by the disease process; therefore, correct interpretation of a smear may be inappropriate and erroneous. The cytopathologist needs to be informed of the patient’s diagnosis of DD in advance for appropriate reporting.5,6

Obstetric Implications

Fertility is normal in DD patients, and pregnancy usually has a normal course; however, exacerbation and remission of disease have been reported. de la Rosa Carrillo7 reported a case of vegetating DD during pregnancy. He described it as an exacerbation with concurrent bacterial infection and bilateral external otitis.7 Spouge et al8 reported a case of a 58-year-old woman who was the mother of 4 DD patients. She experienced an exacerbation of DD during all 6 pregnancies but improved immediately postpartum.8 Espy et al9 evaluated 8 cases of women with DD and described spontaneous improvement of the disorder during pregnancy (1 case) or while taking an oral contraceptive (3 cases).

Prenatal Counseling

Women with DD should be encouraged to talk to their dermatologist, obstetrician, or other provider of prenatal care regarding plans for pregnancy, labor, and delivery, as these events might be affected by the disorder. During pregnancy, careful monitoring and self-care remain essential. Simple measures to reduce the impact of irritants on DD during pregnancy include keeping the skin cool, using a soothing moisturizer, applying photoprotection, and using sunscreen. Treatment with systemic retinoids must be avoided if pregnancy is planned.

Warty plaques and papules of DD can involve flexures (groin, vulva, and perineum), with resultant malodor and pruritus10 as well as the potential for (drug resistant) secondary infection (eg, Staphylococcus aureus, group B Streptococcus, viruses [eg, Kaposi varicelliform eruption]). Skin swabs should be taken for culture and susceptibility testing, and infection should be treated at the earliest sign.

Management Concerns During Pregnancy and Delivery

Because the benefits of treating DD might outweigh risk in certain cases, thorough discussion with the patient about options is recommended, including the following concerns:

• Because mucocutaneous elasticity of the birth canal, including the vulva, perineum, and groin, is essential for nontraumatic vaginal delivery, it might be necessary to schedule an elective cesarean delivery in DD patients in whom these regions are involved.11

• In females with lower abdominal lesions, using a Pfannenstiel-Kerr incision for cesarean delivery might be problematic.11

• A single case report has described successful anesthetic management of labor, delivery, and postpartum care in a DD patient.12 Involvement of the skin of the back might preclude safe administration of regional anesthesia; however, because DD lesions are considered noninfectious, the authors operatively administered a subarachnoid block at the L3-L4 interspace through a lesion-free area. Postpartum, the patient was observed in the intensive care unit. She and the baby remained stable; she did not develop infectious complications, including a central nervous system infection.12

•Mucosal involvement is relatively rare in DD and has not been reported to compromise airway management.8

Postnatal Considerations

Breastfeeding might have to be stopped early or withheld altogether if there is widespread involvement of the skin of the breast or the nipple.11 Darier disease has been associated with neuropsychiatric manifestations, including major depression (30%), suicide attempts (13%), suicidal thoughts (31%), cyclothymia, bipolar disorder (4%), and epilepsy (3%).13,14 Therefore, patients should be screened for postpartum psychiatric manifestations at an early follow-up visit.

Final Thoughts

Although the etiology of DD is well known, the gynelogic and obstretric implications of this genodermatosis have rarely been described. This brief commentary is an attempt to provide the important information to a practicing dermatologist for appropriate management of female DD patients.

Darier disease (DD)(also known as dyskeratosis follicularis) is a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis characterized by greasy, rough, keratotic papules; typical nail abnormalities; mucosal changes; and characteristic dyskeratotic acantholysis that is called corps ronds and grains on histopathologic analysis. Darier disease is caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene on chromosome 12q23-24.1,2

Because of the autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance in DD, if either parent is affected by DD, approximately 50% of their offspring will have the disorder. Therefore, couples need to be offered genetic counseling at a preconception visit or early in pregnancy. Although penetrance of DD is complete, spontaneous mutations are frequent and expressivity is variable1; prenatal diagnosis, though available since the 1980s, is therefore unreliable in DD, given the considerable variation in phenotypic expressivity. Differing phenotypes underscore the importance of proper counseling by the treating dermatologist or other provider. Females with a mild or nearly undetectable phenotype can give birth to a child with severe disease.

Lack of clear understanding about the variable phenotypic expressivity of DD can cause considerable anger, anxiety, guilt, psychological trauma, and fear in parents, should their child later develop a severe phenotype. They may feel that they were not properly prepared for the outcome. The physician-parent or physician-patient relationship can be negatively impacted if ongoing counseling is inadequate.

Clinically, DD presents in early adolescence (age range, 6–20 years) in most patients, which means that the disease and female reproductive years are contemporaneous. However, gynecologic and obstetric issues and complications of DD rarely have been addressed.3 Oromucosal involvement in DD is reported in 13% to 50% of cases, yet vaginal and cervical mucosal involvement rarely has been described,4,5 likely due to underreporting. Therefore, in this rare disease, it is important to address these aspects so that the patients are provided with appropriate management options.

Implications for Cervical Screening and Papanicolaou Tests

Cytopathologic findings of a Papanicolaou test taken from a patient with DD can lead to erroneous diagnosis of a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion due to cervical involvement by the disease process; therefore, correct interpretation of a smear may be inappropriate and erroneous. The cytopathologist needs to be informed of the patient’s diagnosis of DD in advance for appropriate reporting.5,6

Obstetric Implications

Fertility is normal in DD patients, and pregnancy usually has a normal course; however, exacerbation and remission of disease have been reported. de la Rosa Carrillo7 reported a case of vegetating DD during pregnancy. He described it as an exacerbation with concurrent bacterial infection and bilateral external otitis.7 Spouge et al8 reported a case of a 58-year-old woman who was the mother of 4 DD patients. She experienced an exacerbation of DD during all 6 pregnancies but improved immediately postpartum.8 Espy et al9 evaluated 8 cases of women with DD and described spontaneous improvement of the disorder during pregnancy (1 case) or while taking an oral contraceptive (3 cases).

Prenatal Counseling

Women with DD should be encouraged to talk to their dermatologist, obstetrician, or other provider of prenatal care regarding plans for pregnancy, labor, and delivery, as these events might be affected by the disorder. During pregnancy, careful monitoring and self-care remain essential. Simple measures to reduce the impact of irritants on DD during pregnancy include keeping the skin cool, using a soothing moisturizer, applying photoprotection, and using sunscreen. Treatment with systemic retinoids must be avoided if pregnancy is planned.

Warty plaques and papules of DD can involve flexures (groin, vulva, and perineum), with resultant malodor and pruritus10 as well as the potential for (drug resistant) secondary infection (eg, Staphylococcus aureus, group B Streptococcus, viruses [eg, Kaposi varicelliform eruption]). Skin swabs should be taken for culture and susceptibility testing, and infection should be treated at the earliest sign.

Management Concerns During Pregnancy and Delivery

Because the benefits of treating DD might outweigh risk in certain cases, thorough discussion with the patient about options is recommended, including the following concerns:

• Because mucocutaneous elasticity of the birth canal, including the vulva, perineum, and groin, is essential for nontraumatic vaginal delivery, it might be necessary to schedule an elective cesarean delivery in DD patients in whom these regions are involved.11

• In females with lower abdominal lesions, using a Pfannenstiel-Kerr incision for cesarean delivery might be problematic.11

• A single case report has described successful anesthetic management of labor, delivery, and postpartum care in a DD patient.12 Involvement of the skin of the back might preclude safe administration of regional anesthesia; however, because DD lesions are considered noninfectious, the authors operatively administered a subarachnoid block at the L3-L4 interspace through a lesion-free area. Postpartum, the patient was observed in the intensive care unit. She and the baby remained stable; she did not develop infectious complications, including a central nervous system infection.12

•Mucosal involvement is relatively rare in DD and has not been reported to compromise airway management.8

Postnatal Considerations

Breastfeeding might have to be stopped early or withheld altogether if there is widespread involvement of the skin of the breast or the nipple.11 Darier disease has been associated with neuropsychiatric manifestations, including major depression (30%), suicide attempts (13%), suicidal thoughts (31%), cyclothymia, bipolar disorder (4%), and epilepsy (3%).13,14 Therefore, patients should be screened for postpartum psychiatric manifestations at an early follow-up visit.

Final Thoughts

Although the etiology of DD is well known, the gynelogic and obstretric implications of this genodermatosis have rarely been described. This brief commentary is an attempt to provide the important information to a practicing dermatologist for appropriate management of female DD patients.

- Bale SJ, Toro JR. Genetic basis of Darier-White disease: bad pumps cause bumps. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:103-106. doi:10.1177/120347540000400212

- Kansal NK, Hazarika N, Rao S. Familial case of Darier disease with guttate leukoderma: a case series from India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:62-63. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_52_17

- Lynch PJ. Vulvar dermatoses: the eczematous diseases. In: Black M, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Edwards L, Lynch P, eds. Obstetric and Gynecologic Dermatology. 3rd ed. Mosby-Elsevier; 2008:192-194.

- Adam AE. Ectopic Darier’s disease of the cervix: an extraordinary cause of an abnormal smear. Cytopathology. 1996;7:414-421. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2303.1996.tb00547.x

- Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Antúnez JR, Del Rio E, et al. Vaginal involvement in a woman with Darier’s disease: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:530-532. doi:10.1159/000326200

- Boon ME. Dr. Darier’s lesson: it can be advantageous to the patient to ignore evident cytonuclear changes. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:469-470. doi:10.1159/000326189

- de la Rosa Carrillo D. Vegetating Darier’s disease during pregnancy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:259-260. doi:10.2340/00015555-0066

- Spouge JD, Trott JR, Chesko G. Darier-White’s disease: a cause of white lesions of the mucosa. report of four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;21:441-457. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(66)90401-4

- Espy PD, Stone S, Jolly HW Jr. Hormonal dependency in Darier disease. Cutis. 1976;17:315-320.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Saikia UN. Uncommon flexural presentation of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:249-252. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.07035

- Quinlivan JA, O'Halloran LC. Darier’s disease and pregnancy. Dermatol Aspects. 2013;1:1-3. doi:10.7243/2053-5309-1-1

- Sharma R, Singh BP, Das SN. Anesthetic management of cesarean section in a parturient with Darier’s disease. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2010;48:158-159. doi:10.1016/S1875-4597(10)60051-3

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Dodiuk-Gad RP, Cohen-Barak E, Khayat M, et al. Darier disease in Israel: combined evaluation of genetic and neuropsychiatric aspects. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:562-568. doi:10.1111/bjd.14220

- Bale SJ, Toro JR. Genetic basis of Darier-White disease: bad pumps cause bumps. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:103-106. doi:10.1177/120347540000400212

- Kansal NK, Hazarika N, Rao S. Familial case of Darier disease with guttate leukoderma: a case series from India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:62-63. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_52_17

- Lynch PJ. Vulvar dermatoses: the eczematous diseases. In: Black M, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Edwards L, Lynch P, eds. Obstetric and Gynecologic Dermatology. 3rd ed. Mosby-Elsevier; 2008:192-194.

- Adam AE. Ectopic Darier’s disease of the cervix: an extraordinary cause of an abnormal smear. Cytopathology. 1996;7:414-421. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2303.1996.tb00547.x

- Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Antúnez JR, Del Rio E, et al. Vaginal involvement in a woman with Darier’s disease: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:530-532. doi:10.1159/000326200

- Boon ME. Dr. Darier’s lesson: it can be advantageous to the patient to ignore evident cytonuclear changes. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:469-470. doi:10.1159/000326189

- de la Rosa Carrillo D. Vegetating Darier’s disease during pregnancy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:259-260. doi:10.2340/00015555-0066

- Spouge JD, Trott JR, Chesko G. Darier-White’s disease: a cause of white lesions of the mucosa. report of four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;21:441-457. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(66)90401-4

- Espy PD, Stone S, Jolly HW Jr. Hormonal dependency in Darier disease. Cutis. 1976;17:315-320.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Saikia UN. Uncommon flexural presentation of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:249-252. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.07035

- Quinlivan JA, O'Halloran LC. Darier’s disease and pregnancy. Dermatol Aspects. 2013;1:1-3. doi:10.7243/2053-5309-1-1

- Sharma R, Singh BP, Das SN. Anesthetic management of cesarean section in a parturient with Darier’s disease. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2010;48:158-159. doi:10.1016/S1875-4597(10)60051-3

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Dodiuk-Gad RP, Cohen-Barak E, Khayat M, et al. Darier disease in Israel: combined evaluation of genetic and neuropsychiatric aspects. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:562-568. doi:10.1111/bjd.14220

Practice Points

- Because Darier disease (DD) manifests during reproductive years, systemic retinoids should be used carefully in female patients.

- For a Papanicolaou test to be properly interpreted in a patient with DD, the cytopathologist must be informed of the DD diagnosis.

- Darier disease may be exacerbated or relieved during pregnancy.

Despite new ichthyosis treatment recommendations, ‘many questions still exist’

.

According to a consensus statement published in the February issue of Pediatric Dermatology, adequate data exist in the medical literature to demonstrate an improvement in use of systemic retinoids for select genotypes of congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, epidermolytic ichthyosis, erythrokeratodermia variabilis, harlequin ichthyosis, IFAP syndrome (ichthyosis with confetti, ichthyosis follicularis, atrichia, and photophobia), KID syndrome (keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness), KLICK syndrome (keratosis linearis with ichthyosis congenita and sclerosing keratoderma), lamellar ichthyosis, loricrin keratoderma, neutral lipid storage disease with ichthyosis, recessive X-linked ichthyosis, and Sjögren-Larsson syndrome.

At the same time, limited or no data exist to support the use of systemic retinoids for CHILD syndrome (congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects), CHIME syndrome (colobomas, heart defects, ichthyosiform dermatosis, intellectual disability, and either ear defects or epilepsy), Conradi-Hunermann-Happle syndrome, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis-sclerosis cholangitis, ichthyosis prematurity syndrome, MEDNIK syndrome (mental retardation, enteropathy, deafness, peripheral neuropathy, ichthyosis, and keratoderma), peeling skin disease, Refsum syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy, according to the statement.

“In particular, we did note that, with any disorder that was associated with atopy, the retinoids were often counterproductive,” one of the consensus statement cochairs, Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, said during the Society for Pediatric Dermatology pre-AAD meeting. “In Netherton syndrome, for example, retinoids seemed to make the skin fragility a lot worse, so typically, they would be avoided in those patients.”

The statement, which she assembled with cochair pediatric dermatologist Moise L. Levy, MD, professor of pediatrics, University of Texas at Austin, and 21 other multidisciplinary experts, recommends considering use of topical retinoids to help decrease scaling of the skin,“but [they] are particularly helpful for more localized complications of ichthyosis, such as digital contractures and ectropion,” said Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Penn State University, Hershey. “A lot of it has to do with the size and the volume of the tubes and getting enough [product] to be able to apply it over larger areas. We do tend to use them more focally.”

While systemic absorption can occur with widespread use, no specific lab monitoring is required. Dr. Zaenglein and her colleagues also recommend avoiding the use of tazarotene during pregnancy, since it is contraindicated in pregnancy (category X), but monthly pregnancy tests are not recommended.

During an overview of the document at the meeting, she noted that the recommended dosing for both isotretinoin and acitretin is 0.5-1.0 mg/kg per day and the side effects tend to be dose dependent, “except teratogenicity, which can occur with even low doses of systemic retinoid exposure and early on in pregnancy.” The authors also advise patients to consider drug holidays or lower doses “especially during warmer, more humid months, where you might not need the higher doses to achieve cutaneous effects,” she said.

They emphasized the importance of avoiding pregnancy for 3 years after completion of treatment with acitretin. “While the half-life of acitretin is 49 hours, it’s easily converted with any alcohol exposure to etretinate,” Dr. Zaenglein noted. “Then, the half-life is 120 days.”

The statement, which was sponsored by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PEDRA), also addresses the clinical considerations and consequences of long-term systemic retinoid use on bone health, such as premature epiphyseal closure in preadolescent children. “In general, this risk is greater with higher doses of therapies – above 1 mg/kg per day – and over prolonged periods of time, typically 4-6 years,” she said. Other potential effects on bone health include calcifications of tendons and ligaments, osteophytes or “bone spurs,” DISH (diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis), and potential alterations in bone density and growth.

“We also have to worry about concomitant effects of contraception, particularly if you’re using progestin-only formulations that carry a black box warning for osteoporosis,” Dr. Zaenglein said. “It is recommended that you limit their use to 3 years.” Other factors to consider include genetic risk and modifiable factors that affect bone health, such as diet and physical activity, which may impact susceptibility to systemic retinoid bone toxicity and should be discussed with the patient.

Recommended bone monitoring in children starts with a comprehensive family and personal medical history for skeletal toxicity risk factors, followed by an annual growth assessment (height, weight, body mass index, and growth curve), asking regularly about musculoskeletal symptoms, and following up with appropriate imaging. “Inquiring about their diet is recommended as well, so making sure they’re getting sufficient amounts of calcium and vitamin D, and no additional vitamin A sources that may compound the side effects from systemic retinoids,” Dr. Zaenglein said.

The document also advises that a baseline skeletal radiographic survey be performed in patients aged 16-18 years. This may include imaging of the lateral cervical and thoracic spine, lateral view of the calcanei to include Achilles tendon, hips and symptomatic areas, and bone density evaluation.

The statement addressed the psychiatric considerations and consequences of long-term systemic retinoid use. One cross-sectional study of children with ichthyosis found that 30% screened positive for depression and 38% screened positive for anxiety, “but the role of retinoids is unclear,” Dr. Zaenglein said. “It’s a complicated matter, but patients with a personal history of depression, anxiety, and other affective disorders prior to initiation of systemic retinoid treatment should be monitored carefully for exacerbation of symptoms. Comanagement with a mental health provider should be considered.”

As for contraception considerations with long-term systemic retinoid therapy use, the authors recommend that two forms of contraception be used. “Consider long-acting reversible contraception, especially in sexually active adolescents who have a history of noncompliance, or to remove the risk of teratogenicity for them,” she said. “We’re not sure what additive effects progestin/lower estrogen have on long-term cardiovascular health, including lipids and bone density.”

The authors noted that iPLEDGE is not designed for long-term use. “It’s really designed for the on-label use of systemic retinoids in severe acne, where you’re using it for 5-6 months, not for 5-6 years,” Dr. Zaenglein said. “iPLEDGE does impose significant and financial barriers for our patients. More advocacy is needed to adapt that program for our patients.”

She and her coauthors acknowledged practice gaps and unmet needs in patients with disorders of cornification/types of ichthyosis, including the optimal formulation of retinoids based on ichthyosis subtype, whether there is a benefit to intermittent therapy with respect to risk of toxicity and maintenance of efficacy, and how to minimize the bone-related changes that can occur with treatment. “These are some of the things that we can look further into,” she said. “For now, though, retinoids can improve function and quality of life in patients with ichthyosis and disorders of cornification. Many questions still exist, and more data and research are needed.”

Sun Pharmaceuticals and the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types (FIRST) provided an unrestricted grant for development of the recommendations.

Dr. Zaenglein disclosed that she is a consultant for Pfizer. She is also an advisory board member for Dermata, Sol-Gel, Regeneron, Verrica, and Cassiopea, and has conducted contracted research for AbbVie, Incyte, Arcutis, and Pfizer. The other authors disclosed serving as investigators, advisers, consultants, and/or had other relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

.

According to a consensus statement published in the February issue of Pediatric Dermatology, adequate data exist in the medical literature to demonstrate an improvement in use of systemic retinoids for select genotypes of congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, epidermolytic ichthyosis, erythrokeratodermia variabilis, harlequin ichthyosis, IFAP syndrome (ichthyosis with confetti, ichthyosis follicularis, atrichia, and photophobia), KID syndrome (keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness), KLICK syndrome (keratosis linearis with ichthyosis congenita and sclerosing keratoderma), lamellar ichthyosis, loricrin keratoderma, neutral lipid storage disease with ichthyosis, recessive X-linked ichthyosis, and Sjögren-Larsson syndrome.

At the same time, limited or no data exist to support the use of systemic retinoids for CHILD syndrome (congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects), CHIME syndrome (colobomas, heart defects, ichthyosiform dermatosis, intellectual disability, and either ear defects or epilepsy), Conradi-Hunermann-Happle syndrome, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis-sclerosis cholangitis, ichthyosis prematurity syndrome, MEDNIK syndrome (mental retardation, enteropathy, deafness, peripheral neuropathy, ichthyosis, and keratoderma), peeling skin disease, Refsum syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy, according to the statement.

“In particular, we did note that, with any disorder that was associated with atopy, the retinoids were often counterproductive,” one of the consensus statement cochairs, Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, said during the Society for Pediatric Dermatology pre-AAD meeting. “In Netherton syndrome, for example, retinoids seemed to make the skin fragility a lot worse, so typically, they would be avoided in those patients.”

The statement, which she assembled with cochair pediatric dermatologist Moise L. Levy, MD, professor of pediatrics, University of Texas at Austin, and 21 other multidisciplinary experts, recommends considering use of topical retinoids to help decrease scaling of the skin,“but [they] are particularly helpful for more localized complications of ichthyosis, such as digital contractures and ectropion,” said Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Penn State University, Hershey. “A lot of it has to do with the size and the volume of the tubes and getting enough [product] to be able to apply it over larger areas. We do tend to use them more focally.”

While systemic absorption can occur with widespread use, no specific lab monitoring is required. Dr. Zaenglein and her colleagues also recommend avoiding the use of tazarotene during pregnancy, since it is contraindicated in pregnancy (category X), but monthly pregnancy tests are not recommended.

During an overview of the document at the meeting, she noted that the recommended dosing for both isotretinoin and acitretin is 0.5-1.0 mg/kg per day and the side effects tend to be dose dependent, “except teratogenicity, which can occur with even low doses of systemic retinoid exposure and early on in pregnancy.” The authors also advise patients to consider drug holidays or lower doses “especially during warmer, more humid months, where you might not need the higher doses to achieve cutaneous effects,” she said.

They emphasized the importance of avoiding pregnancy for 3 years after completion of treatment with acitretin. “While the half-life of acitretin is 49 hours, it’s easily converted with any alcohol exposure to etretinate,” Dr. Zaenglein noted. “Then, the half-life is 120 days.”

The statement, which was sponsored by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PEDRA), also addresses the clinical considerations and consequences of long-term systemic retinoid use on bone health, such as premature epiphyseal closure in preadolescent children. “In general, this risk is greater with higher doses of therapies – above 1 mg/kg per day – and over prolonged periods of time, typically 4-6 years,” she said. Other potential effects on bone health include calcifications of tendons and ligaments, osteophytes or “bone spurs,” DISH (diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis), and potential alterations in bone density and growth.

“We also have to worry about concomitant effects of contraception, particularly if you’re using progestin-only formulations that carry a black box warning for osteoporosis,” Dr. Zaenglein said. “It is recommended that you limit their use to 3 years.” Other factors to consider include genetic risk and modifiable factors that affect bone health, such as diet and physical activity, which may impact susceptibility to systemic retinoid bone toxicity and should be discussed with the patient.

Recommended bone monitoring in children starts with a comprehensive family and personal medical history for skeletal toxicity risk factors, followed by an annual growth assessment (height, weight, body mass index, and growth curve), asking regularly about musculoskeletal symptoms, and following up with appropriate imaging. “Inquiring about their diet is recommended as well, so making sure they’re getting sufficient amounts of calcium and vitamin D, and no additional vitamin A sources that may compound the side effects from systemic retinoids,” Dr. Zaenglein said.

The document also advises that a baseline skeletal radiographic survey be performed in patients aged 16-18 years. This may include imaging of the lateral cervical and thoracic spine, lateral view of the calcanei to include Achilles tendon, hips and symptomatic areas, and bone density evaluation.

The statement addressed the psychiatric considerations and consequences of long-term systemic retinoid use. One cross-sectional study of children with ichthyosis found that 30% screened positive for depression and 38% screened positive for anxiety, “but the role of retinoids is unclear,” Dr. Zaenglein said. “It’s a complicated matter, but patients with a personal history of depression, anxiety, and other affective disorders prior to initiation of systemic retinoid treatment should be monitored carefully for exacerbation of symptoms. Comanagement with a mental health provider should be considered.”

As for contraception considerations with long-term systemic retinoid therapy use, the authors recommend that two forms of contraception be used. “Consider long-acting reversible contraception, especially in sexually active adolescents who have a history of noncompliance, or to remove the risk of teratogenicity for them,” she said. “We’re not sure what additive effects progestin/lower estrogen have on long-term cardiovascular health, including lipids and bone density.”

The authors noted that iPLEDGE is not designed for long-term use. “It’s really designed for the on-label use of systemic retinoids in severe acne, where you’re using it for 5-6 months, not for 5-6 years,” Dr. Zaenglein said. “iPLEDGE does impose significant and financial barriers for our patients. More advocacy is needed to adapt that program for our patients.”

She and her coauthors acknowledged practice gaps and unmet needs in patients with disorders of cornification/types of ichthyosis, including the optimal formulation of retinoids based on ichthyosis subtype, whether there is a benefit to intermittent therapy with respect to risk of toxicity and maintenance of efficacy, and how to minimize the bone-related changes that can occur with treatment. “These are some of the things that we can look further into,” she said. “For now, though, retinoids can improve function and quality of life in patients with ichthyosis and disorders of cornification. Many questions still exist, and more data and research are needed.”

Sun Pharmaceuticals and the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types (FIRST) provided an unrestricted grant for development of the recommendations.

Dr. Zaenglein disclosed that she is a consultant for Pfizer. She is also an advisory board member for Dermata, Sol-Gel, Regeneron, Verrica, and Cassiopea, and has conducted contracted research for AbbVie, Incyte, Arcutis, and Pfizer. The other authors disclosed serving as investigators, advisers, consultants, and/or had other relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

.

According to a consensus statement published in the February issue of Pediatric Dermatology, adequate data exist in the medical literature to demonstrate an improvement in use of systemic retinoids for select genotypes of congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, epidermolytic ichthyosis, erythrokeratodermia variabilis, harlequin ichthyosis, IFAP syndrome (ichthyosis with confetti, ichthyosis follicularis, atrichia, and photophobia), KID syndrome (keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness), KLICK syndrome (keratosis linearis with ichthyosis congenita and sclerosing keratoderma), lamellar ichthyosis, loricrin keratoderma, neutral lipid storage disease with ichthyosis, recessive X-linked ichthyosis, and Sjögren-Larsson syndrome.

At the same time, limited or no data exist to support the use of systemic retinoids for CHILD syndrome (congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects), CHIME syndrome (colobomas, heart defects, ichthyosiform dermatosis, intellectual disability, and either ear defects or epilepsy), Conradi-Hunermann-Happle syndrome, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis-sclerosis cholangitis, ichthyosis prematurity syndrome, MEDNIK syndrome (mental retardation, enteropathy, deafness, peripheral neuropathy, ichthyosis, and keratoderma), peeling skin disease, Refsum syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy, according to the statement.

“In particular, we did note that, with any disorder that was associated with atopy, the retinoids were often counterproductive,” one of the consensus statement cochairs, Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, said during the Society for Pediatric Dermatology pre-AAD meeting. “In Netherton syndrome, for example, retinoids seemed to make the skin fragility a lot worse, so typically, they would be avoided in those patients.”

The statement, which she assembled with cochair pediatric dermatologist Moise L. Levy, MD, professor of pediatrics, University of Texas at Austin, and 21 other multidisciplinary experts, recommends considering use of topical retinoids to help decrease scaling of the skin,“but [they] are particularly helpful for more localized complications of ichthyosis, such as digital contractures and ectropion,” said Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Penn State University, Hershey. “A lot of it has to do with the size and the volume of the tubes and getting enough [product] to be able to apply it over larger areas. We do tend to use them more focally.”

While systemic absorption can occur with widespread use, no specific lab monitoring is required. Dr. Zaenglein and her colleagues also recommend avoiding the use of tazarotene during pregnancy, since it is contraindicated in pregnancy (category X), but monthly pregnancy tests are not recommended.

During an overview of the document at the meeting, she noted that the recommended dosing for both isotretinoin and acitretin is 0.5-1.0 mg/kg per day and the side effects tend to be dose dependent, “except teratogenicity, which can occur with even low doses of systemic retinoid exposure and early on in pregnancy.” The authors also advise patients to consider drug holidays or lower doses “especially during warmer, more humid months, where you might not need the higher doses to achieve cutaneous effects,” she said.

They emphasized the importance of avoiding pregnancy for 3 years after completion of treatment with acitretin. “While the half-life of acitretin is 49 hours, it’s easily converted with any alcohol exposure to etretinate,” Dr. Zaenglein noted. “Then, the half-life is 120 days.”

The statement, which was sponsored by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PEDRA), also addresses the clinical considerations and consequences of long-term systemic retinoid use on bone health, such as premature epiphyseal closure in preadolescent children. “In general, this risk is greater with higher doses of therapies – above 1 mg/kg per day – and over prolonged periods of time, typically 4-6 years,” she said. Other potential effects on bone health include calcifications of tendons and ligaments, osteophytes or “bone spurs,” DISH (diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis), and potential alterations in bone density and growth.

“We also have to worry about concomitant effects of contraception, particularly if you’re using progestin-only formulations that carry a black box warning for osteoporosis,” Dr. Zaenglein said. “It is recommended that you limit their use to 3 years.” Other factors to consider include genetic risk and modifiable factors that affect bone health, such as diet and physical activity, which may impact susceptibility to systemic retinoid bone toxicity and should be discussed with the patient.

Recommended bone monitoring in children starts with a comprehensive family and personal medical history for skeletal toxicity risk factors, followed by an annual growth assessment (height, weight, body mass index, and growth curve), asking regularly about musculoskeletal symptoms, and following up with appropriate imaging. “Inquiring about their diet is recommended as well, so making sure they’re getting sufficient amounts of calcium and vitamin D, and no additional vitamin A sources that may compound the side effects from systemic retinoids,” Dr. Zaenglein said.

The document also advises that a baseline skeletal radiographic survey be performed in patients aged 16-18 years. This may include imaging of the lateral cervical and thoracic spine, lateral view of the calcanei to include Achilles tendon, hips and symptomatic areas, and bone density evaluation.

The statement addressed the psychiatric considerations and consequences of long-term systemic retinoid use. One cross-sectional study of children with ichthyosis found that 30% screened positive for depression and 38% screened positive for anxiety, “but the role of retinoids is unclear,” Dr. Zaenglein said. “It’s a complicated matter, but patients with a personal history of depression, anxiety, and other affective disorders prior to initiation of systemic retinoid treatment should be monitored carefully for exacerbation of symptoms. Comanagement with a mental health provider should be considered.”

As for contraception considerations with long-term systemic retinoid therapy use, the authors recommend that two forms of contraception be used. “Consider long-acting reversible contraception, especially in sexually active adolescents who have a history of noncompliance, or to remove the risk of teratogenicity for them,” she said. “We’re not sure what additive effects progestin/lower estrogen have on long-term cardiovascular health, including lipids and bone density.”

The authors noted that iPLEDGE is not designed for long-term use. “It’s really designed for the on-label use of systemic retinoids in severe acne, where you’re using it for 5-6 months, not for 5-6 years,” Dr. Zaenglein said. “iPLEDGE does impose significant and financial barriers for our patients. More advocacy is needed to adapt that program for our patients.”

She and her coauthors acknowledged practice gaps and unmet needs in patients with disorders of cornification/types of ichthyosis, including the optimal formulation of retinoids based on ichthyosis subtype, whether there is a benefit to intermittent therapy with respect to risk of toxicity and maintenance of efficacy, and how to minimize the bone-related changes that can occur with treatment. “These are some of the things that we can look further into,” she said. “For now, though, retinoids can improve function and quality of life in patients with ichthyosis and disorders of cornification. Many questions still exist, and more data and research are needed.”

Sun Pharmaceuticals and the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types (FIRST) provided an unrestricted grant for development of the recommendations.

Dr. Zaenglein disclosed that she is a consultant for Pfizer. She is also an advisory board member for Dermata, Sol-Gel, Regeneron, Verrica, and Cassiopea, and has conducted contracted research for AbbVie, Incyte, Arcutis, and Pfizer. The other authors disclosed serving as investigators, advisers, consultants, and/or had other relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE SPD PRE-AAD MEETING

VEXAS: A novel rheumatologic, hematologic syndrome that’s making waves

Older men with a novel adult-onset, severe autoinflammatory syndrome known by the acronym VEXAS are likely hiding in plain sight in many adult rheumatology, hematology, and dermatology practices. New clinical features are being described to fill out the clinical profile of such patients who may be currently misdiagnosed with other conditions, according to researchers who first described the syndrome in the last quarter of 2020.

VEXAS is often misdiagnosed as treatment-refractory relapsing polychondritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Sweet syndrome, or giant cell arteritis. These seemingly unrelated disorders are actually tied together by a single thread recently unraveled by David B. Beck, MD, PhD, a clinical fellow at the National Human Genome Research Institute, and colleagues, including rheumatologist Marcela Ferrada, MD, and others at institutes of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. The connection between these disparate clinical presentations lies in somatic mutations in UBA1, a gene that initiates cytoplasmic ubiquitylation, a process by which misfolded proteins are tagged for degradation. VEXAS appears primarily limited to men because the UBA1 gene lies on the X chromosome, although it may be possible for women to have it because of an acquired loss of X chromosome.

VEXAS is an acronym for:

- Vacuoles in bone marrow cells

- E-1 activating enzyme, which is what UBA1 encodes for

- X-linked

- Autoinflammatory

- Somatic mutation featuring hematologic mosaicism

Dr. Beck said that VEXAS is “probably affecting thousands of Americans,” but it is tough to say this early in the understanding of the disease. He estimated that the prevalence of VEXAS could be 1 per 20,000-30,000 individuals.

A new way of looking for disease

VEXAS has caused a major stir among geneticists because of the novel manner in which Dr. Beck and his coinvestigators made their discovery. Instead of starting out in the traditional path to discovery of a new genetic disease – that is, by looking for clinical similarities among patients with undiagnosed diseases and then conducting a search for a gene or genes that might explain the shared patient symptoms – the investigators took a genotype-first approach. They scanned the mapped genomic sequences of patients in the National Institutes of Health Undiagnosed Diseases Network, which led them to zero in on mutations in UBA1 as their top candidate.

“We targeted the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, because it has been implicated in many autoinflammatory diseases – for example, HA20 [A20 haploinsufficiency] and CANDLE syndrome [Chronic Atypical Neutrophilic Dermatosis with Lipodystrophy and Elevated temperature]. Many of these recurrent inflammatory diseases are caused by mutations within this pathway,” Dr. Beck said in an interview.

Next, they analyzed the genomes of patients in other NIH databases and patients from other study populations at the University College London and Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust in the United Kingdom in a search for UBA1 somatic mutations, eventually identifying 25 men with the shared features they called VEXAS. These 25 formed the basis for their initial report on the syndrome in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Most autoinflammatory diseases appear in childhood because they stem from germline mutations. VEXAS syndrome, because of somatic mutations with mosaicism, appears to manifest later in life: The median age of the initial 25-man cohort was 64 years, ranging from 45 to 80 years. It’s a severe disorder. By the time the investigators were preparing their paper for publication, 10 of the 25 patients, or 40%, had died.

“I think that somatic mutations may account for a significant percentage of severe. adult-onset rheumatologic diseases, and it may change the way we think about treating them based on having a genetic diagnosis,” Dr. Beck said.

“This approach could be expanded to look at other pathways we know are important in inflammation, or alternatively, it could be completely unbiased and look for any shared variation that occurs across undiagnosed patients with inflammatory diseases. I think that one thing that’s important about our study is that previously we had been looking for mutations that really in most cases were the same sort of germline mutations present in [pediatric] patients who have disease at early onset, but now we’re thinking about things differently. There may be a different type of genetics that drives adult-onset rheumatologic disease, and this would be somatic mutations which are not present in every cell of the body, just in the blood, and that’s why there’s just this blood-based disease.”

When to suspect VEXAS syndrome

Consider the possibility of VEXAS in middle-aged or older men in a rheumatology clinic with characteristics suggestive of treatment-refractory relapsing polychondritis, giant cell arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, or Sweet syndrome. In the original series of 25 men, 15 were diagnosed with relapsing polychondritis, 8 with Sweet syndrome, 3 with polyarteritis nodosa, and 1 with giant cell arteritis.

Men with VEXAS often have periodic fevers, pulmonary infiltrates, a history of unprovoked venous thromboembolic events, neutrophilic dermatoses, and/or hematologic abnormalities such as myelodysplastic syndrome, multiple myeloma, or monoclonal gammopathy of unknown origin.

Bone marrow biopsy will show vacuoles in myeloid and erythroid precursor cells. Inflammatory marker levels are very high: In the NIH series, the median C-reactive protein was 73 mg/L and median erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 97 mm/hr. The diagnosis of VEXAS can be confirmed by genetic testing performed by Dr. Beck and his NIH coworkers ([email protected]).

In interviews, Dr. Beck and Dr. Ferrada emphasized that management of VEXAS requires a multidisciplinary team of clinicians including rheumatologists, hematologists, and dermatologists.

Dr. Ferrada said that rheumatologists could suspect VEXAS in patients who have very high inflammatory markers and do not have a clear diagnosis or do not meet all criteria for other rheumatologic diseases, particularly in older men, but it’s possible in younger men as well. Hematologists could also consider VEXAS in patients with macrocytic anemia or macrocytosis without an explanation and inflammatory features, she said.

Dr. Ferrada, Dr. Beck, and colleagues also published a study in Arthritis & Rheumatology that presents a useful clinical algorithm for deciding whether to order genetic screening for VEXAS in patients with relapsing polychondritis.

First off, Dr. Ferrada and colleagues performed whole-exome sequencing and testing for UBA1 variants in an observational cohort of 92 relapsing polychondritis patients to determine the prevalence of VEXAS, which turned out to be 8%. They added an additional 6 patients with relapsing polychondritis and VEXAS from other cohorts, for a total of 13. The investigators determined that patients with VEXAS were older at disease onset, and more likely to have fever, ear chondritis, DVT, pulmonary infiltrates, skin involvement, and periorbital edema. In contrast, the RP cohort had a significantly higher prevalence of airway chondritis, joint involvement, and vestibular symptoms.

Dr. Ferrada’s algorithm for picking out VEXAS in patients who meet diagnostic criteria for relapsing polychondritis is based upon a few simple factors readily apparent in screening patient charts: male sex; age at onset older than 50 years; macrocytic anemia; and thrombocytopenia. Those four variables, when present, identify VEXAS within an RP cohort with 100% sensitivity and 96% specificity. “As we learn more about [VEXAS] and how it presents earlier, I think we are going to be able to find different manifestations or laboratory data that are going to allow us to diagnose these patients earlier,” she said. “The whole role of that algorithm was to guide clinicians who see patients with relapsing polychondritis to test these patients for the mutation, but I think over time that is going to evolve.”

Researchers are taking similar approaches for other clinical diagnoses to see which should be referred for UBA1 testing, Dr. Beck said.

Myelodysplastic syndrome and hematologic abnormalities

While patients with both myelodysplastic syndrome and relapsing polychondritis have been known in the literature for many years, it’s not until now that researchers are seeing a connection between the two, Dr. Ferrada said.

A majority of the VEXAS patients in the NEJM study had a workup for myelodysplastic syndrome, but only 24% met criteria. However, many were within the spectrum of myelodysplastic disease and some did not meet criteria because their anemia was attributed to a rheumatologic diagnosis and they did not have a known genetic driver of myelodysplastic syndrome, Dr. Beck said. It also fits with this new evidence that UBA1 is probably a driver of myelodysplastic syndrome in and of itself, and that anemia and hematologic involvement are not secondary to the rheumatologic disease; they are linked to the same disease process.

Dr. Beck said that there may be a subset of patients who present with primarily hematologic manifestations, noting the NEJM study could have ascertainment bias because the researchers analyzed mainly patients presenting to their clinic with relapsing polychondritis and severe inflammation. NIH researchers also are still looking in their cohort for any association with hematologic malignancies that preceded clinical manifestations, he said.

More cases reported

As of early April, another 27 cases had been reported in the literature as more researchers have begun to look for patients with UBA1 mutations, some with additional presenting clinical features associated with VEXAS, including chronic progressive inflammatory arthritis, Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease, spondyloarthritis, and bacterial pneumonia.

“Many times with rare diseases, we can’t get enough patients to understand the full spectrum of the disease, but this disease seems to be far more common than we would have expected. We’re actually getting many referrals,” Dr. Beck said.

It appears so far that the range of somatic UBA1 mutations that have been discovered in VEXAS patients does make a difference in the severity of clinical presentation and could potentially be useful in prognosis, Dr. Beck said.

Right now, NIH researchers are asking patients about their natural clinical course, assessing disease activity, and determining which treatments get a response, with the ultimate goal of a treatment trial at the NIH.

Treatment

Developing better treatments for VEXAS syndrome is a priority. In the initial report on VEXAS, the researchers found that the only reliably effective therapy is high-dose corticosteroids. Dr. Ferrada said that NIH investigators have begun thinking about agents that target both the hematologic and inflammatory features of VEXAS. “Most patients get exposed to treatments that are targeted to decrease the inflammatory process, and some of these treatments help partially but not completely to decrease the amount of steroids that patients are taking. For example, one of the medications is tocilizumab. [It was used in] patients who had previous diagnosis of relapsing polychondritis, but they still had to take steroids and their hematologic manifestations keep progressing. We’re in the process of figuring out medications that may help in treating both.” Dr. Ferrada added that because the source of the mutation is in the bone marrow, transplantation may be an effective option.

Laboratory work to identify potential treatments for VEXAS in studies of model organisms could identify treatments outside of the classic anti-inflammatory agents, such as targeting certain cell types in the bone marrow or the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, Dr. Beck said. “We think that however UBA1 works to initiate inflammation may be important not just in VEXAS but in other diseases. Rare diseases may be informing the mechanisms in common diseases.”

The VEXAS NEJM study was sponsored by the NIH Intramural Research Programs and by an EU Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program grant. Dr. Beck reported a patent pending on “Diagnosis and Treatment of VEXAS with Mosaic Missense Mutations in UBA1.”

Older men with a novel adult-onset, severe autoinflammatory syndrome known by the acronym VEXAS are likely hiding in plain sight in many adult rheumatology, hematology, and dermatology practices. New clinical features are being described to fill out the clinical profile of such patients who may be currently misdiagnosed with other conditions, according to researchers who first described the syndrome in the last quarter of 2020.

VEXAS is often misdiagnosed as treatment-refractory relapsing polychondritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Sweet syndrome, or giant cell arteritis. These seemingly unrelated disorders are actually tied together by a single thread recently unraveled by David B. Beck, MD, PhD, a clinical fellow at the National Human Genome Research Institute, and colleagues, including rheumatologist Marcela Ferrada, MD, and others at institutes of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. The connection between these disparate clinical presentations lies in somatic mutations in UBA1, a gene that initiates cytoplasmic ubiquitylation, a process by which misfolded proteins are tagged for degradation. VEXAS appears primarily limited to men because the UBA1 gene lies on the X chromosome, although it may be possible for women to have it because of an acquired loss of X chromosome.

VEXAS is an acronym for:

- Vacuoles in bone marrow cells

- E-1 activating enzyme, which is what UBA1 encodes for

- X-linked

- Autoinflammatory

- Somatic mutation featuring hematologic mosaicism

Dr. Beck said that VEXAS is “probably affecting thousands of Americans,” but it is tough to say this early in the understanding of the disease. He estimated that the prevalence of VEXAS could be 1 per 20,000-30,000 individuals.

A new way of looking for disease

VEXAS has caused a major stir among geneticists because of the novel manner in which Dr. Beck and his coinvestigators made their discovery. Instead of starting out in the traditional path to discovery of a new genetic disease – that is, by looking for clinical similarities among patients with undiagnosed diseases and then conducting a search for a gene or genes that might explain the shared patient symptoms – the investigators took a genotype-first approach. They scanned the mapped genomic sequences of patients in the National Institutes of Health Undiagnosed Diseases Network, which led them to zero in on mutations in UBA1 as their top candidate.

“We targeted the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, because it has been implicated in many autoinflammatory diseases – for example, HA20 [A20 haploinsufficiency] and CANDLE syndrome [Chronic Atypical Neutrophilic Dermatosis with Lipodystrophy and Elevated temperature]. Many of these recurrent inflammatory diseases are caused by mutations within this pathway,” Dr. Beck said in an interview.

Next, they analyzed the genomes of patients in other NIH databases and patients from other study populations at the University College London and Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust in the United Kingdom in a search for UBA1 somatic mutations, eventually identifying 25 men with the shared features they called VEXAS. These 25 formed the basis for their initial report on the syndrome in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Most autoinflammatory diseases appear in childhood because they stem from germline mutations. VEXAS syndrome, because of somatic mutations with mosaicism, appears to manifest later in life: The median age of the initial 25-man cohort was 64 years, ranging from 45 to 80 years. It’s a severe disorder. By the time the investigators were preparing their paper for publication, 10 of the 25 patients, or 40%, had died.

“I think that somatic mutations may account for a significant percentage of severe. adult-onset rheumatologic diseases, and it may change the way we think about treating them based on having a genetic diagnosis,” Dr. Beck said.

“This approach could be expanded to look at other pathways we know are important in inflammation, or alternatively, it could be completely unbiased and look for any shared variation that occurs across undiagnosed patients with inflammatory diseases. I think that one thing that’s important about our study is that previously we had been looking for mutations that really in most cases were the same sort of germline mutations present in [pediatric] patients who have disease at early onset, but now we’re thinking about things differently. There may be a different type of genetics that drives adult-onset rheumatologic disease, and this would be somatic mutations which are not present in every cell of the body, just in the blood, and that’s why there’s just this blood-based disease.”

When to suspect VEXAS syndrome

Consider the possibility of VEXAS in middle-aged or older men in a rheumatology clinic with characteristics suggestive of treatment-refractory relapsing polychondritis, giant cell arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, or Sweet syndrome. In the original series of 25 men, 15 were diagnosed with relapsing polychondritis, 8 with Sweet syndrome, 3 with polyarteritis nodosa, and 1 with giant cell arteritis.

Men with VEXAS often have periodic fevers, pulmonary infiltrates, a history of unprovoked venous thromboembolic events, neutrophilic dermatoses, and/or hematologic abnormalities such as myelodysplastic syndrome, multiple myeloma, or monoclonal gammopathy of unknown origin.

Bone marrow biopsy will show vacuoles in myeloid and erythroid precursor cells. Inflammatory marker levels are very high: In the NIH series, the median C-reactive protein was 73 mg/L and median erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 97 mm/hr. The diagnosis of VEXAS can be confirmed by genetic testing performed by Dr. Beck and his NIH coworkers ([email protected]).

In interviews, Dr. Beck and Dr. Ferrada emphasized that management of VEXAS requires a multidisciplinary team of clinicians including rheumatologists, hematologists, and dermatologists.

Dr. Ferrada said that rheumatologists could suspect VEXAS in patients who have very high inflammatory markers and do not have a clear diagnosis or do not meet all criteria for other rheumatologic diseases, particularly in older men, but it’s possible in younger men as well. Hematologists could also consider VEXAS in patients with macrocytic anemia or macrocytosis without an explanation and inflammatory features, she said.

Dr. Ferrada, Dr. Beck, and colleagues also published a study in Arthritis & Rheumatology that presents a useful clinical algorithm for deciding whether to order genetic screening for VEXAS in patients with relapsing polychondritis.

First off, Dr. Ferrada and colleagues performed whole-exome sequencing and testing for UBA1 variants in an observational cohort of 92 relapsing polychondritis patients to determine the prevalence of VEXAS, which turned out to be 8%. They added an additional 6 patients with relapsing polychondritis and VEXAS from other cohorts, for a total of 13. The investigators determined that patients with VEXAS were older at disease onset, and more likely to have fever, ear chondritis, DVT, pulmonary infiltrates, skin involvement, and periorbital edema. In contrast, the RP cohort had a significantly higher prevalence of airway chondritis, joint involvement, and vestibular symptoms.

Dr. Ferrada’s algorithm for picking out VEXAS in patients who meet diagnostic criteria for relapsing polychondritis is based upon a few simple factors readily apparent in screening patient charts: male sex; age at onset older than 50 years; macrocytic anemia; and thrombocytopenia. Those four variables, when present, identify VEXAS within an RP cohort with 100% sensitivity and 96% specificity. “As we learn more about [VEXAS] and how it presents earlier, I think we are going to be able to find different manifestations or laboratory data that are going to allow us to diagnose these patients earlier,” she said. “The whole role of that algorithm was to guide clinicians who see patients with relapsing polychondritis to test these patients for the mutation, but I think over time that is going to evolve.”

Researchers are taking similar approaches for other clinical diagnoses to see which should be referred for UBA1 testing, Dr. Beck said.

Myelodysplastic syndrome and hematologic abnormalities

While patients with both myelodysplastic syndrome and relapsing polychondritis have been known in the literature for many years, it’s not until now that researchers are seeing a connection between the two, Dr. Ferrada said.

A majority of the VEXAS patients in the NEJM study had a workup for myelodysplastic syndrome, but only 24% met criteria. However, many were within the spectrum of myelodysplastic disease and some did not meet criteria because their anemia was attributed to a rheumatologic diagnosis and they did not have a known genetic driver of myelodysplastic syndrome, Dr. Beck said. It also fits with this new evidence that UBA1 is probably a driver of myelodysplastic syndrome in and of itself, and that anemia and hematologic involvement are not secondary to the rheumatologic disease; they are linked to the same disease process.

Dr. Beck said that there may be a subset of patients who present with primarily hematologic manifestations, noting the NEJM study could have ascertainment bias because the researchers analyzed mainly patients presenting to their clinic with relapsing polychondritis and severe inflammation. NIH researchers also are still looking in their cohort for any association with hematologic malignancies that preceded clinical manifestations, he said.

More cases reported

As of early April, another 27 cases had been reported in the literature as more researchers have begun to look for patients with UBA1 mutations, some with additional presenting clinical features associated with VEXAS, including chronic progressive inflammatory arthritis, Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease, spondyloarthritis, and bacterial pneumonia.

“Many times with rare diseases, we can’t get enough patients to understand the full spectrum of the disease, but this disease seems to be far more common than we would have expected. We’re actually getting many referrals,” Dr. Beck said.

It appears so far that the range of somatic UBA1 mutations that have been discovered in VEXAS patients does make a difference in the severity of clinical presentation and could potentially be useful in prognosis, Dr. Beck said.

Right now, NIH researchers are asking patients about their natural clinical course, assessing disease activity, and determining which treatments get a response, with the ultimate goal of a treatment trial at the NIH.

Treatment

Developing better treatments for VEXAS syndrome is a priority. In the initial report on VEXAS, the researchers found that the only reliably effective therapy is high-dose corticosteroids. Dr. Ferrada said that NIH investigators have begun thinking about agents that target both the hematologic and inflammatory features of VEXAS. “Most patients get exposed to treatments that are targeted to decrease the inflammatory process, and some of these treatments help partially but not completely to decrease the amount of steroids that patients are taking. For example, one of the medications is tocilizumab. [It was used in] patients who had previous diagnosis of relapsing polychondritis, but they still had to take steroids and their hematologic manifestations keep progressing. We’re in the process of figuring out medications that may help in treating both.” Dr. Ferrada added that because the source of the mutation is in the bone marrow, transplantation may be an effective option.

Laboratory work to identify potential treatments for VEXAS in studies of model organisms could identify treatments outside of the classic anti-inflammatory agents, such as targeting certain cell types in the bone marrow or the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, Dr. Beck said. “We think that however UBA1 works to initiate inflammation may be important not just in VEXAS but in other diseases. Rare diseases may be informing the mechanisms in common diseases.”

The VEXAS NEJM study was sponsored by the NIH Intramural Research Programs and by an EU Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program grant. Dr. Beck reported a patent pending on “Diagnosis and Treatment of VEXAS with Mosaic Missense Mutations in UBA1.”

Older men with a novel adult-onset, severe autoinflammatory syndrome known by the acronym VEXAS are likely hiding in plain sight in many adult rheumatology, hematology, and dermatology practices. New clinical features are being described to fill out the clinical profile of such patients who may be currently misdiagnosed with other conditions, according to researchers who first described the syndrome in the last quarter of 2020.

VEXAS is often misdiagnosed as treatment-refractory relapsing polychondritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Sweet syndrome, or giant cell arteritis. These seemingly unrelated disorders are actually tied together by a single thread recently unraveled by David B. Beck, MD, PhD, a clinical fellow at the National Human Genome Research Institute, and colleagues, including rheumatologist Marcela Ferrada, MD, and others at institutes of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. The connection between these disparate clinical presentations lies in somatic mutations in UBA1, a gene that initiates cytoplasmic ubiquitylation, a process by which misfolded proteins are tagged for degradation. VEXAS appears primarily limited to men because the UBA1 gene lies on the X chromosome, although it may be possible for women to have it because of an acquired loss of X chromosome.

VEXAS is an acronym for:

- Vacuoles in bone marrow cells

- E-1 activating enzyme, which is what UBA1 encodes for

- X-linked

- Autoinflammatory

- Somatic mutation featuring hematologic mosaicism

Dr. Beck said that VEXAS is “probably affecting thousands of Americans,” but it is tough to say this early in the understanding of the disease. He estimated that the prevalence of VEXAS could be 1 per 20,000-30,000 individuals.

A new way of looking for disease

VEXAS has caused a major stir among geneticists because of the novel manner in which Dr. Beck and his coinvestigators made their discovery. Instead of starting out in the traditional path to discovery of a new genetic disease – that is, by looking for clinical similarities among patients with undiagnosed diseases and then conducting a search for a gene or genes that might explain the shared patient symptoms – the investigators took a genotype-first approach. They scanned the mapped genomic sequences of patients in the National Institutes of Health Undiagnosed Diseases Network, which led them to zero in on mutations in UBA1 as their top candidate.

“We targeted the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, because it has been implicated in many autoinflammatory diseases – for example, HA20 [A20 haploinsufficiency] and CANDLE syndrome [Chronic Atypical Neutrophilic Dermatosis with Lipodystrophy and Elevated temperature]. Many of these recurrent inflammatory diseases are caused by mutations within this pathway,” Dr. Beck said in an interview.