User login

Pazopanib extended PFS in patients with carcinoid tumors

CHICAGO – Pazopanib significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with progressive carcinoid tumors who were enrolled in a prospective randomized phase 2 trial.*

Median PFS was 11.6 months for patients receiving the small molecule VEGF inhibitor, versus 8.5 months for those receiving placebo (P = .0005), according to results of the Alliance A021202 trial.

This is the first randomized study to show that the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway may be a valid therapeutic target in carcinoid tumors, said investigator Emily K. Bergsland, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

However, the potential benefits of pazopanib need to be viewed in light of toxicity risks, including an excess of hypertension, Dr. Bergsland said in an oral abstract presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The efficacy results suggest that pazopanib is another promising systemic option for carcinoid tumors, according to William P. Harris, MD, of the University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

“Pazopanib does inhibit other targets, including [fibroblast growth factor receptors], which may be of relevance in carcinoid,” Dr. Harris noted in a podium discussion of the A021202 trial results.

Other promising systemic options under investigation include cabozantinib, which he said will be evaluated in phase 3 trials, lenvatinib, and ramucirumab plus a somatostatin analogue.

The CDK4/6 inhibition is of interest and will be pursued in future trials, though unfortunately the role of checkpoint inhibitors is “unclear” in this tumor type, he said.

In the present randomized study of pazopanib, a computer error resulted in slightly more patients being randomized to the pazopanib arm – 89 patients – while 72 were randomized to placebo, according to the investigator.

The rate of grade 3 or greater toxicities was 73.0% for pazopanib, and 7.9% for placebo in the study. Notably, there was a relatively high rate of grade 3 or greater hypertension, at 26.9% versus 4.2% for placebo, though only one case in the pazopanib arm was grade 4, Dr. Bergsland said.

Pazopanib was also associated with more symptoms such as diarrhea, appetite loss, and fatigue, but the overall quality of life was similar between the groups in preliminary analyses, said Dr. Bergsland.

Despite the improved PFS in the pazopanib arm, there was no improvement in overall survival. That’s likely because placebo-treated patients were allowed to cross over to pazopanib upon progression, and two-thirds of them did so, said Dr. Bergsland. The resulting median overall survival was 41.3 months for pazopanib and 42.4 months for placebo.

“Additional work is needed to identify strategies for mitigating toxicity and/or selecting patients most likely to benefit,” Dr. Bergsland said in her presentation.

Toward that end, investigators are looking at strategies including angiome profiling, assessment of tumor growth rate, and textural image analysis, she added.

Dr. Bergsland reported disclosures related to More Health, UpToDate, Advanced Accelerator Applications, Lexicon, Merck, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Bergsland EK, et al. ASCO 2019. Abstract 4005.

Correction, 6/17/19: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the study type.

CHICAGO – Pazopanib significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with progressive carcinoid tumors who were enrolled in a prospective randomized phase 2 trial.*

Median PFS was 11.6 months for patients receiving the small molecule VEGF inhibitor, versus 8.5 months for those receiving placebo (P = .0005), according to results of the Alliance A021202 trial.

This is the first randomized study to show that the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway may be a valid therapeutic target in carcinoid tumors, said investigator Emily K. Bergsland, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

However, the potential benefits of pazopanib need to be viewed in light of toxicity risks, including an excess of hypertension, Dr. Bergsland said in an oral abstract presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The efficacy results suggest that pazopanib is another promising systemic option for carcinoid tumors, according to William P. Harris, MD, of the University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

“Pazopanib does inhibit other targets, including [fibroblast growth factor receptors], which may be of relevance in carcinoid,” Dr. Harris noted in a podium discussion of the A021202 trial results.

Other promising systemic options under investigation include cabozantinib, which he said will be evaluated in phase 3 trials, lenvatinib, and ramucirumab plus a somatostatin analogue.

The CDK4/6 inhibition is of interest and will be pursued in future trials, though unfortunately the role of checkpoint inhibitors is “unclear” in this tumor type, he said.

In the present randomized study of pazopanib, a computer error resulted in slightly more patients being randomized to the pazopanib arm – 89 patients – while 72 were randomized to placebo, according to the investigator.

The rate of grade 3 or greater toxicities was 73.0% for pazopanib, and 7.9% for placebo in the study. Notably, there was a relatively high rate of grade 3 or greater hypertension, at 26.9% versus 4.2% for placebo, though only one case in the pazopanib arm was grade 4, Dr. Bergsland said.

Pazopanib was also associated with more symptoms such as diarrhea, appetite loss, and fatigue, but the overall quality of life was similar between the groups in preliminary analyses, said Dr. Bergsland.

Despite the improved PFS in the pazopanib arm, there was no improvement in overall survival. That’s likely because placebo-treated patients were allowed to cross over to pazopanib upon progression, and two-thirds of them did so, said Dr. Bergsland. The resulting median overall survival was 41.3 months for pazopanib and 42.4 months for placebo.

“Additional work is needed to identify strategies for mitigating toxicity and/or selecting patients most likely to benefit,” Dr. Bergsland said in her presentation.

Toward that end, investigators are looking at strategies including angiome profiling, assessment of tumor growth rate, and textural image analysis, she added.

Dr. Bergsland reported disclosures related to More Health, UpToDate, Advanced Accelerator Applications, Lexicon, Merck, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Bergsland EK, et al. ASCO 2019. Abstract 4005.

Correction, 6/17/19: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the study type.

CHICAGO – Pazopanib significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with progressive carcinoid tumors who were enrolled in a prospective randomized phase 2 trial.*

Median PFS was 11.6 months for patients receiving the small molecule VEGF inhibitor, versus 8.5 months for those receiving placebo (P = .0005), according to results of the Alliance A021202 trial.

This is the first randomized study to show that the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway may be a valid therapeutic target in carcinoid tumors, said investigator Emily K. Bergsland, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

However, the potential benefits of pazopanib need to be viewed in light of toxicity risks, including an excess of hypertension, Dr. Bergsland said in an oral abstract presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The efficacy results suggest that pazopanib is another promising systemic option for carcinoid tumors, according to William P. Harris, MD, of the University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

“Pazopanib does inhibit other targets, including [fibroblast growth factor receptors], which may be of relevance in carcinoid,” Dr. Harris noted in a podium discussion of the A021202 trial results.

Other promising systemic options under investigation include cabozantinib, which he said will be evaluated in phase 3 trials, lenvatinib, and ramucirumab plus a somatostatin analogue.

The CDK4/6 inhibition is of interest and will be pursued in future trials, though unfortunately the role of checkpoint inhibitors is “unclear” in this tumor type, he said.

In the present randomized study of pazopanib, a computer error resulted in slightly more patients being randomized to the pazopanib arm – 89 patients – while 72 were randomized to placebo, according to the investigator.

The rate of grade 3 or greater toxicities was 73.0% for pazopanib, and 7.9% for placebo in the study. Notably, there was a relatively high rate of grade 3 or greater hypertension, at 26.9% versus 4.2% for placebo, though only one case in the pazopanib arm was grade 4, Dr. Bergsland said.

Pazopanib was also associated with more symptoms such as diarrhea, appetite loss, and fatigue, but the overall quality of life was similar between the groups in preliminary analyses, said Dr. Bergsland.

Despite the improved PFS in the pazopanib arm, there was no improvement in overall survival. That’s likely because placebo-treated patients were allowed to cross over to pazopanib upon progression, and two-thirds of them did so, said Dr. Bergsland. The resulting median overall survival was 41.3 months for pazopanib and 42.4 months for placebo.

“Additional work is needed to identify strategies for mitigating toxicity and/or selecting patients most likely to benefit,” Dr. Bergsland said in her presentation.

Toward that end, investigators are looking at strategies including angiome profiling, assessment of tumor growth rate, and textural image analysis, she added.

Dr. Bergsland reported disclosures related to More Health, UpToDate, Advanced Accelerator Applications, Lexicon, Merck, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Bergsland EK, et al. ASCO 2019. Abstract 4005.

Correction, 6/17/19: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the study type.

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2019

A longing for belonging

As I watched my grandson and his team warm up for their Saturday morning lacrosse game, a long parade of mostly purple-shirted adults and children of all ages began to weave its way around the periphery of the athletic field complex. A quick reading of the hand-lettered and machine-printed shirts made it clear that I was watching a charity walk for cystic fibrosis. There must have been several hundred walkers strolling by, laughing and chatting with one another. It lent a festive atmosphere to the park. I suspect that for most of the participants this was not their first fundraising event for cystic fibrosis.

The motley mix of marchers probably included several handfuls of parents of children with cystic fibrosis. I wonder how many of those parents realized how fortunate they were. Cystic fibrosis isn’t a great diagnosis. But at least it is a diagnosis, and with the diagnosis comes a community.

Reading a front-page article on DNA testing in a recent Wall Street Journal issue had primed me to reconsider how even an unfortunate diagnosis can be extremely valuable for a family (“The Unfulfilled Promise of DNA Testing,” by Amy Dockser Marcus, May 18, 2019).The focus of the article was on the confusion and disappointment that are the predictable consequences of our current inability to accurately correlate genetic code “mistakes” with phenotypic abnormalities. Of course there have been a few successes, but we aren’t even close to the promise that many have predicted in the wake of sequencing the human genome. The family featured in the article has a ridden roller coaster ride through two failed attributions of genetic syndromes that appeared to provide their now 8-year-old daughter with a diagnosis for her epilepsy and developmental delay.

In each case, the mother had searched out other families with children who shared the same genetic code errors. She formed support groups and created foundations to promote research for these rare disorders only to learn that her daughter didn’t really fit into the phenotype exhibited by the other children. As the article indicates this mother had “found a genetic home, only to feel that she no longer belonged.” She had made “intense friendships” and for “2 years, the community was her main emotional support.” Since the second diagnosis has evaporated, she has struggled with whether to remain with that community, having already left one behind. She has been encouraged to stay involved by another mother whose son does have the diagnosis. Understandably, she is still seeking the correct diagnosis, and I suspect will form or join a new community when she finds it.

We all want to belong to a community. And with that ticket comes the opportunity to share the frustrations and difficulties unique to children with that diagnosis, and the comfort that there are other people who look, behave, and feel the way we do. We hear repeatedly about the value of diversity and how wonderful it is to be all inclusive. And certainly we should continue to be as accepting as we can of people who are different. But the truth is that we will always fall short because we seem to be hardwired to notice what is different. And the power of the longing to belong is often stronger than our will to be inclusive.

The revolution that resulted in the disappearance of the label “mental retardation” and the widespread adoption of the diagnosis of autism are examples of how a community can form around a diagnosis. But not every child who is labeled as autistic will actually fit the diagnosis. Yet even a less-than-perfect attribution can provide a place where a family and a patient can feel that they belong.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

As I watched my grandson and his team warm up for their Saturday morning lacrosse game, a long parade of mostly purple-shirted adults and children of all ages began to weave its way around the periphery of the athletic field complex. A quick reading of the hand-lettered and machine-printed shirts made it clear that I was watching a charity walk for cystic fibrosis. There must have been several hundred walkers strolling by, laughing and chatting with one another. It lent a festive atmosphere to the park. I suspect that for most of the participants this was not their first fundraising event for cystic fibrosis.

The motley mix of marchers probably included several handfuls of parents of children with cystic fibrosis. I wonder how many of those parents realized how fortunate they were. Cystic fibrosis isn’t a great diagnosis. But at least it is a diagnosis, and with the diagnosis comes a community.

Reading a front-page article on DNA testing in a recent Wall Street Journal issue had primed me to reconsider how even an unfortunate diagnosis can be extremely valuable for a family (“The Unfulfilled Promise of DNA Testing,” by Amy Dockser Marcus, May 18, 2019).The focus of the article was on the confusion and disappointment that are the predictable consequences of our current inability to accurately correlate genetic code “mistakes” with phenotypic abnormalities. Of course there have been a few successes, but we aren’t even close to the promise that many have predicted in the wake of sequencing the human genome. The family featured in the article has a ridden roller coaster ride through two failed attributions of genetic syndromes that appeared to provide their now 8-year-old daughter with a diagnosis for her epilepsy and developmental delay.

In each case, the mother had searched out other families with children who shared the same genetic code errors. She formed support groups and created foundations to promote research for these rare disorders only to learn that her daughter didn’t really fit into the phenotype exhibited by the other children. As the article indicates this mother had “found a genetic home, only to feel that she no longer belonged.” She had made “intense friendships” and for “2 years, the community was her main emotional support.” Since the second diagnosis has evaporated, she has struggled with whether to remain with that community, having already left one behind. She has been encouraged to stay involved by another mother whose son does have the diagnosis. Understandably, she is still seeking the correct diagnosis, and I suspect will form or join a new community when she finds it.

We all want to belong to a community. And with that ticket comes the opportunity to share the frustrations and difficulties unique to children with that diagnosis, and the comfort that there are other people who look, behave, and feel the way we do. We hear repeatedly about the value of diversity and how wonderful it is to be all inclusive. And certainly we should continue to be as accepting as we can of people who are different. But the truth is that we will always fall short because we seem to be hardwired to notice what is different. And the power of the longing to belong is often stronger than our will to be inclusive.

The revolution that resulted in the disappearance of the label “mental retardation” and the widespread adoption of the diagnosis of autism are examples of how a community can form around a diagnosis. But not every child who is labeled as autistic will actually fit the diagnosis. Yet even a less-than-perfect attribution can provide a place where a family and a patient can feel that they belong.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

As I watched my grandson and his team warm up for their Saturday morning lacrosse game, a long parade of mostly purple-shirted adults and children of all ages began to weave its way around the periphery of the athletic field complex. A quick reading of the hand-lettered and machine-printed shirts made it clear that I was watching a charity walk for cystic fibrosis. There must have been several hundred walkers strolling by, laughing and chatting with one another. It lent a festive atmosphere to the park. I suspect that for most of the participants this was not their first fundraising event for cystic fibrosis.

The motley mix of marchers probably included several handfuls of parents of children with cystic fibrosis. I wonder how many of those parents realized how fortunate they were. Cystic fibrosis isn’t a great diagnosis. But at least it is a diagnosis, and with the diagnosis comes a community.

Reading a front-page article on DNA testing in a recent Wall Street Journal issue had primed me to reconsider how even an unfortunate diagnosis can be extremely valuable for a family (“The Unfulfilled Promise of DNA Testing,” by Amy Dockser Marcus, May 18, 2019).The focus of the article was on the confusion and disappointment that are the predictable consequences of our current inability to accurately correlate genetic code “mistakes” with phenotypic abnormalities. Of course there have been a few successes, but we aren’t even close to the promise that many have predicted in the wake of sequencing the human genome. The family featured in the article has a ridden roller coaster ride through two failed attributions of genetic syndromes that appeared to provide their now 8-year-old daughter with a diagnosis for her epilepsy and developmental delay.

In each case, the mother had searched out other families with children who shared the same genetic code errors. She formed support groups and created foundations to promote research for these rare disorders only to learn that her daughter didn’t really fit into the phenotype exhibited by the other children. As the article indicates this mother had “found a genetic home, only to feel that she no longer belonged.” She had made “intense friendships” and for “2 years, the community was her main emotional support.” Since the second diagnosis has evaporated, she has struggled with whether to remain with that community, having already left one behind. She has been encouraged to stay involved by another mother whose son does have the diagnosis. Understandably, she is still seeking the correct diagnosis, and I suspect will form or join a new community when she finds it.

We all want to belong to a community. And with that ticket comes the opportunity to share the frustrations and difficulties unique to children with that diagnosis, and the comfort that there are other people who look, behave, and feel the way we do. We hear repeatedly about the value of diversity and how wonderful it is to be all inclusive. And certainly we should continue to be as accepting as we can of people who are different. But the truth is that we will always fall short because we seem to be hardwired to notice what is different. And the power of the longing to belong is often stronger than our will to be inclusive.

The revolution that resulted in the disappearance of the label “mental retardation” and the widespread adoption of the diagnosis of autism are examples of how a community can form around a diagnosis. But not every child who is labeled as autistic will actually fit the diagnosis. Yet even a less-than-perfect attribution can provide a place where a family and a patient can feel that they belong.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

New tickborne virus emerges in China

A new virus has been associated with febrile illness in China in patients with histories of tick bites. The data on the discovery, isolation, and characterization of the virus were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The segmented RNA virus now known as Alongshan virus (ALSV) “belongs to the unclassified jingmenvirus group in the family Flaviviridae, which includes the genera flavivirus, pestivirus, hepacivirus, and pegivirus,” wrote Ze-Dong Wang, PhD, of Foshan (China) University, and colleagues.

The index patient with ALSV was a 42-year-old female farmer from the town of Alongshan, China, who presented to a regional hospital in April 2017 with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites. The initial clinical features were similar to those seen in tickborne diseases, but a blood sample showed no RNA or antibodies for tickborne encephalitis virus. Investigators obtained a blood specimen from the index patient 4 days after the onset of illness. After culturing the sample, the investigators extracted the viral RNA genome and sequenced it.

Sequence analysis found that the new pathogen was related to segmented viruses in the jingmenvirus group of the family Flaviviridae; however, “comparison of the amino acids further confirmed that ALSV is genetically distinct from other jingmenviruses,” the investigators said.

The investigators identified 374 patients who presented to the hospital with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites during May 2017–September 2017; 86 patients had confirmed ALSV infections via nested reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing. Of these, 63 were men and 84 were farmers or forestry workers. Although ticks were common in the patients’ environments, no other evidence of tickborne diseases was noted. The patients ranged in age from 24 to 77 years, and the average duration of the infection was 3-7 days.

Symptoms were nonspecific and included fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, cough, and sore throat. All 86 patients were treated with intravenous ribavirin (0.5 g/day), and intramuscular benzylpenicillin sodium (2 million U/day) for 3-5 days. The median hospital stay was 11 days, and no deaths or long-term clinical complications occurred in the confirmed ALSV patients.

ALSV is similar to other jingmenviruses, but is distinct from other infections in part because of the absence of a rash or jaundice, the investigators said.

Although the investigators said they suspected the disease was carried by ticks, they would not rule out mosquitoes as a possible carrier because ALSV RNA was found in mosquitoes in a Northeastern province of China, and the RNA from those mosquitoes was found to be genetically related to the RNA assessed in this study.

Overall, “our findings suggest that ALSV may be the cause of a previously unknown febrile disease, and more studies should be conducted to determine the geographic distribution of this disease outside its current areas of identification,” they said.

The research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

SOURCE: Wang Z et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805068.

New technology and genomic surveys will continue to help identify emerging pathogens, however, “they may provide limited value in understanding the mechanisms of disease emergence,” wrote Nikos Vasilakis, PhD, and David H. Walker, MD, in an accompanying editorial. An active surveillance program allowed the investigators of the previously unknown tickborne pathogen in China to identify a group of patients with similar history. The new pathogen was classified as one of the jingmenviruses, which “reveal that RNA virus segmentation is an evolutionary process that has occurred in previously unanticipated circumstances.” This study by Wang et al. shows that these viruses are not limited to arthropod hosts but can be dangerous to humans.

The new pathogen had likely been evolving for some time before it was discovered, the editorialists said. “The key to making such discoveries is the study of ill persons, isolation of the etiologic agent, use of tools that will reveal the nature of the agent (e.g., electron microscopy), and application of the appropriate tools for definitive characterization (e.g., sequencing of the RNA genome),” they emphasized. However, to mitigate outbreaks, “proactive, real-time surveillance” may be more cost effective than extensive genomic surveys, they noted (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1901212).

Dr. Vasilakis and Dr. Walker are affiliated with the department of pathology, Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Center for Tropical Diseases, and the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

New technology and genomic surveys will continue to help identify emerging pathogens, however, “they may provide limited value in understanding the mechanisms of disease emergence,” wrote Nikos Vasilakis, PhD, and David H. Walker, MD, in an accompanying editorial. An active surveillance program allowed the investigators of the previously unknown tickborne pathogen in China to identify a group of patients with similar history. The new pathogen was classified as one of the jingmenviruses, which “reveal that RNA virus segmentation is an evolutionary process that has occurred in previously unanticipated circumstances.” This study by Wang et al. shows that these viruses are not limited to arthropod hosts but can be dangerous to humans.

The new pathogen had likely been evolving for some time before it was discovered, the editorialists said. “The key to making such discoveries is the study of ill persons, isolation of the etiologic agent, use of tools that will reveal the nature of the agent (e.g., electron microscopy), and application of the appropriate tools for definitive characterization (e.g., sequencing of the RNA genome),” they emphasized. However, to mitigate outbreaks, “proactive, real-time surveillance” may be more cost effective than extensive genomic surveys, they noted (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1901212).

Dr. Vasilakis and Dr. Walker are affiliated with the department of pathology, Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Center for Tropical Diseases, and the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

New technology and genomic surveys will continue to help identify emerging pathogens, however, “they may provide limited value in understanding the mechanisms of disease emergence,” wrote Nikos Vasilakis, PhD, and David H. Walker, MD, in an accompanying editorial. An active surveillance program allowed the investigators of the previously unknown tickborne pathogen in China to identify a group of patients with similar history. The new pathogen was classified as one of the jingmenviruses, which “reveal that RNA virus segmentation is an evolutionary process that has occurred in previously unanticipated circumstances.” This study by Wang et al. shows that these viruses are not limited to arthropod hosts but can be dangerous to humans.

The new pathogen had likely been evolving for some time before it was discovered, the editorialists said. “The key to making such discoveries is the study of ill persons, isolation of the etiologic agent, use of tools that will reveal the nature of the agent (e.g., electron microscopy), and application of the appropriate tools for definitive characterization (e.g., sequencing of the RNA genome),” they emphasized. However, to mitigate outbreaks, “proactive, real-time surveillance” may be more cost effective than extensive genomic surveys, they noted (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1901212).

Dr. Vasilakis and Dr. Walker are affiliated with the department of pathology, Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Center for Tropical Diseases, and the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A new virus has been associated with febrile illness in China in patients with histories of tick bites. The data on the discovery, isolation, and characterization of the virus were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The segmented RNA virus now known as Alongshan virus (ALSV) “belongs to the unclassified jingmenvirus group in the family Flaviviridae, which includes the genera flavivirus, pestivirus, hepacivirus, and pegivirus,” wrote Ze-Dong Wang, PhD, of Foshan (China) University, and colleagues.

The index patient with ALSV was a 42-year-old female farmer from the town of Alongshan, China, who presented to a regional hospital in April 2017 with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites. The initial clinical features were similar to those seen in tickborne diseases, but a blood sample showed no RNA or antibodies for tickborne encephalitis virus. Investigators obtained a blood specimen from the index patient 4 days after the onset of illness. After culturing the sample, the investigators extracted the viral RNA genome and sequenced it.

Sequence analysis found that the new pathogen was related to segmented viruses in the jingmenvirus group of the family Flaviviridae; however, “comparison of the amino acids further confirmed that ALSV is genetically distinct from other jingmenviruses,” the investigators said.

The investigators identified 374 patients who presented to the hospital with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites during May 2017–September 2017; 86 patients had confirmed ALSV infections via nested reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing. Of these, 63 were men and 84 were farmers or forestry workers. Although ticks were common in the patients’ environments, no other evidence of tickborne diseases was noted. The patients ranged in age from 24 to 77 years, and the average duration of the infection was 3-7 days.

Symptoms were nonspecific and included fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, cough, and sore throat. All 86 patients were treated with intravenous ribavirin (0.5 g/day), and intramuscular benzylpenicillin sodium (2 million U/day) for 3-5 days. The median hospital stay was 11 days, and no deaths or long-term clinical complications occurred in the confirmed ALSV patients.

ALSV is similar to other jingmenviruses, but is distinct from other infections in part because of the absence of a rash or jaundice, the investigators said.

Although the investigators said they suspected the disease was carried by ticks, they would not rule out mosquitoes as a possible carrier because ALSV RNA was found in mosquitoes in a Northeastern province of China, and the RNA from those mosquitoes was found to be genetically related to the RNA assessed in this study.

Overall, “our findings suggest that ALSV may be the cause of a previously unknown febrile disease, and more studies should be conducted to determine the geographic distribution of this disease outside its current areas of identification,” they said.

The research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

SOURCE: Wang Z et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805068.

A new virus has been associated with febrile illness in China in patients with histories of tick bites. The data on the discovery, isolation, and characterization of the virus were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The segmented RNA virus now known as Alongshan virus (ALSV) “belongs to the unclassified jingmenvirus group in the family Flaviviridae, which includes the genera flavivirus, pestivirus, hepacivirus, and pegivirus,” wrote Ze-Dong Wang, PhD, of Foshan (China) University, and colleagues.

The index patient with ALSV was a 42-year-old female farmer from the town of Alongshan, China, who presented to a regional hospital in April 2017 with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites. The initial clinical features were similar to those seen in tickborne diseases, but a blood sample showed no RNA or antibodies for tickborne encephalitis virus. Investigators obtained a blood specimen from the index patient 4 days after the onset of illness. After culturing the sample, the investigators extracted the viral RNA genome and sequenced it.

Sequence analysis found that the new pathogen was related to segmented viruses in the jingmenvirus group of the family Flaviviridae; however, “comparison of the amino acids further confirmed that ALSV is genetically distinct from other jingmenviruses,” the investigators said.

The investigators identified 374 patients who presented to the hospital with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites during May 2017–September 2017; 86 patients had confirmed ALSV infections via nested reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing. Of these, 63 were men and 84 were farmers or forestry workers. Although ticks were common in the patients’ environments, no other evidence of tickborne diseases was noted. The patients ranged in age from 24 to 77 years, and the average duration of the infection was 3-7 days.

Symptoms were nonspecific and included fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, cough, and sore throat. All 86 patients were treated with intravenous ribavirin (0.5 g/day), and intramuscular benzylpenicillin sodium (2 million U/day) for 3-5 days. The median hospital stay was 11 days, and no deaths or long-term clinical complications occurred in the confirmed ALSV patients.

ALSV is similar to other jingmenviruses, but is distinct from other infections in part because of the absence of a rash or jaundice, the investigators said.

Although the investigators said they suspected the disease was carried by ticks, they would not rule out mosquitoes as a possible carrier because ALSV RNA was found in mosquitoes in a Northeastern province of China, and the RNA from those mosquitoes was found to be genetically related to the RNA assessed in this study.

Overall, “our findings suggest that ALSV may be the cause of a previously unknown febrile disease, and more studies should be conducted to determine the geographic distribution of this disease outside its current areas of identification,” they said.

The research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

SOURCE: Wang Z et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805068.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Do You Know Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever When You See It?

In 2017, the number of cases of tickborne spotted fever rickettsiosis (SFR) reported to the CDC jumped 46%—from 4,269 in 2016 to a “record” 6,248 cases. The New England, East North Central, and Mid-Atlantic regions in 2017 alone experienced a 215%, 78%, and 65% increase, respectively, although they typically report only a handful of cases each year.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is the most severe of the SFR. It begins with nonspecific symptoms such as fever and headache, and sometimes rash, but when left untreated, the disease can have serious consequences, including amputation. Roughly 1 in 5 untreated cases is fatal; half of those deaths occur within the first 8 days of illness.

However, RMSF is treatable with doxycycline, which can prevent disability and death if prescribed within the first 5 days of illness, meaning that early recognition and treatment can save lives. Yet cases “often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases,” says CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD. Less than 1% of the reported SFR cases in 2017 had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. And although the annual incidence of SFR in the US increased from 6.4 to 19.2 cases per million persons between years 2010 and 2017, the proportion of confirmed cases went down.

Citing the need to train health care providers (HCPs) on the best methods to diagnose tickborne diseases, the CDC has created a “first of its kind” clinical education tool that uses scenarios based on real cases to help clinicians recognize and differentiate among the various possibilities. The module is self-directed with knowledge checks, reference materials, and an interactive rash identification tool that allows HCPs to compare the rash seen in RMSF with that of other illnesses.

Continuing education credit is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators. To access the module, go to https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/resources/module.html

In 2017, the number of cases of tickborne spotted fever rickettsiosis (SFR) reported to the CDC jumped 46%—from 4,269 in 2016 to a “record” 6,248 cases. The New England, East North Central, and Mid-Atlantic regions in 2017 alone experienced a 215%, 78%, and 65% increase, respectively, although they typically report only a handful of cases each year.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is the most severe of the SFR. It begins with nonspecific symptoms such as fever and headache, and sometimes rash, but when left untreated, the disease can have serious consequences, including amputation. Roughly 1 in 5 untreated cases is fatal; half of those deaths occur within the first 8 days of illness.

However, RMSF is treatable with doxycycline, which can prevent disability and death if prescribed within the first 5 days of illness, meaning that early recognition and treatment can save lives. Yet cases “often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases,” says CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD. Less than 1% of the reported SFR cases in 2017 had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. And although the annual incidence of SFR in the US increased from 6.4 to 19.2 cases per million persons between years 2010 and 2017, the proportion of confirmed cases went down.

Citing the need to train health care providers (HCPs) on the best methods to diagnose tickborne diseases, the CDC has created a “first of its kind” clinical education tool that uses scenarios based on real cases to help clinicians recognize and differentiate among the various possibilities. The module is self-directed with knowledge checks, reference materials, and an interactive rash identification tool that allows HCPs to compare the rash seen in RMSF with that of other illnesses.

Continuing education credit is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators. To access the module, go to https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/resources/module.html

In 2017, the number of cases of tickborne spotted fever rickettsiosis (SFR) reported to the CDC jumped 46%—from 4,269 in 2016 to a “record” 6,248 cases. The New England, East North Central, and Mid-Atlantic regions in 2017 alone experienced a 215%, 78%, and 65% increase, respectively, although they typically report only a handful of cases each year.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is the most severe of the SFR. It begins with nonspecific symptoms such as fever and headache, and sometimes rash, but when left untreated, the disease can have serious consequences, including amputation. Roughly 1 in 5 untreated cases is fatal; half of those deaths occur within the first 8 days of illness.

However, RMSF is treatable with doxycycline, which can prevent disability and death if prescribed within the first 5 days of illness, meaning that early recognition and treatment can save lives. Yet cases “often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases,” says CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD. Less than 1% of the reported SFR cases in 2017 had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. And although the annual incidence of SFR in the US increased from 6.4 to 19.2 cases per million persons between years 2010 and 2017, the proportion of confirmed cases went down.

Citing the need to train health care providers (HCPs) on the best methods to diagnose tickborne diseases, the CDC has created a “first of its kind” clinical education tool that uses scenarios based on real cases to help clinicians recognize and differentiate among the various possibilities. The module is self-directed with knowledge checks, reference materials, and an interactive rash identification tool that allows HCPs to compare the rash seen in RMSF with that of other illnesses.

Continuing education credit is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators. To access the module, go to https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/resources/module.html

FDA approves Zolgensma for infantile-onset SMA treatment

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi), the first gene therapy for the treatment of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy in children aged less than 2 years.

The FDA granted the approval of Zolgensma to AveXis Inc.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the SMN1 gene, which encodes the survival motor neuron protein. This protein is necessary for motor function throughout the body; without it, motor neurons die, causing severe, often fatal muscle weakness. Infantile-onset SMA is the most severe and most common form of the disease; children will have difficulty holding their head up, swallowing, or breathing. Symptoms can be present at birth or appear by 6 months.

FDA approval of Zolgensma is based on results of a pair of clinical trials – one ongoing, one completed – comprising 36 patients with infantile-onset SMA aged between 2 weeks and 8 months at study entry. Of the 21 patients initially enrolled in the ongoing trial, 19 remain, aged between 9.4 and 18.5 months; most of these patients are at least 14 months. Compared with natural disease course, patients treated with Zolgensma are more likely to reach developmental motor milestones such as head control and the ability to sit without support.

The most common adverse events associated with Zolgensma include elevated liver enzymes and vomiting. The labeling includes a warning that acute serious liver injury can occur, and patients with preexisting liver conditions are at a higher risk for serious liver injury. Liver function should be monitored for at least 3 months following initiation of Zolgensma treatment.

“Children with SMA experience difficulty performing essential functions of life. Most children with this disease do not survive past early childhood due to respiratory failure. Patients with SMA now have another treatment option to minimize the progression of SMA and improve survival,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi), the first gene therapy for the treatment of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy in children aged less than 2 years.

The FDA granted the approval of Zolgensma to AveXis Inc.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the SMN1 gene, which encodes the survival motor neuron protein. This protein is necessary for motor function throughout the body; without it, motor neurons die, causing severe, often fatal muscle weakness. Infantile-onset SMA is the most severe and most common form of the disease; children will have difficulty holding their head up, swallowing, or breathing. Symptoms can be present at birth or appear by 6 months.

FDA approval of Zolgensma is based on results of a pair of clinical trials – one ongoing, one completed – comprising 36 patients with infantile-onset SMA aged between 2 weeks and 8 months at study entry. Of the 21 patients initially enrolled in the ongoing trial, 19 remain, aged between 9.4 and 18.5 months; most of these patients are at least 14 months. Compared with natural disease course, patients treated with Zolgensma are more likely to reach developmental motor milestones such as head control and the ability to sit without support.

The most common adverse events associated with Zolgensma include elevated liver enzymes and vomiting. The labeling includes a warning that acute serious liver injury can occur, and patients with preexisting liver conditions are at a higher risk for serious liver injury. Liver function should be monitored for at least 3 months following initiation of Zolgensma treatment.

“Children with SMA experience difficulty performing essential functions of life. Most children with this disease do not survive past early childhood due to respiratory failure. Patients with SMA now have another treatment option to minimize the progression of SMA and improve survival,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi), the first gene therapy for the treatment of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy in children aged less than 2 years.

The FDA granted the approval of Zolgensma to AveXis Inc.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the SMN1 gene, which encodes the survival motor neuron protein. This protein is necessary for motor function throughout the body; without it, motor neurons die, causing severe, often fatal muscle weakness. Infantile-onset SMA is the most severe and most common form of the disease; children will have difficulty holding their head up, swallowing, or breathing. Symptoms can be present at birth or appear by 6 months.

FDA approval of Zolgensma is based on results of a pair of clinical trials – one ongoing, one completed – comprising 36 patients with infantile-onset SMA aged between 2 weeks and 8 months at study entry. Of the 21 patients initially enrolled in the ongoing trial, 19 remain, aged between 9.4 and 18.5 months; most of these patients are at least 14 months. Compared with natural disease course, patients treated with Zolgensma are more likely to reach developmental motor milestones such as head control and the ability to sit without support.

The most common adverse events associated with Zolgensma include elevated liver enzymes and vomiting. The labeling includes a warning that acute serious liver injury can occur, and patients with preexisting liver conditions are at a higher risk for serious liver injury. Liver function should be monitored for at least 3 months following initiation of Zolgensma treatment.

“Children with SMA experience difficulty performing essential functions of life. Most children with this disease do not survive past early childhood due to respiratory failure. Patients with SMA now have another treatment option to minimize the progression of SMA and improve survival,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome and Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy of the skin that is thought to arise from neural crest cells. It has an estimated annual incidence of 0.6 per 100,000 individuals, typically occurs in the elderly population, and is most common in white males.1 The tumor presents as a rapidly growing, violaceous nodule in sun-exposed areas of the skin; early in the course, it can be mistaken for a benign entity such as an epidermal cyst.2 Merkel cell carcinoma has a propensity to spread to regional lymph nodes, and in some cases, it occurs in the absence of skin findings.3 Histologically, MCC is nearly indistinguishable from small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC).4 The overall prognosis for patients with MCC is poor and largely dependent on the stage at diagnosis. Patients with regional and distant metastases have a 5-year survival rate of 26% to 42% and 18%, respectively.3

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) is a paraneoplastic or autoimmune disorder of the neuromuscular junction that is found in 3% of cases of SCLC.4 Reported cases of LEMS in patients with MCC are exceedingly rare.5-8 We provide a full report and longitudinal clinical follow-up of a case that was briefly discussed by Simmons et al,8 and we review the literature regarding paraneoplastic syndromes associated with MCC and other extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas (EPSCCs).

Case Report

A 63-year-old man was evaluated in the neurology clinic due to difficulty walking, climbing stairs, and performing push-ups over the last month. Prior to the onset of symptoms, he was otherwise healthy, walking 3 miles daily; however, at presentation he required use of a cane. Leg weakness worsened as the day progressed. In addition, he reported constipation, urinary urgency, dry mouth, mild dysphagia, reduced sensation below the knees, and a nasal quality in his speech. He had no ptosis, diplopia, dysarthria, muscle cramps, myalgia, or facial weakness. He denied fevers, chills, and night sweats but did admit to an unintentional 10- to 15-lb weight loss over the preceding few months.

The neurologic examination revealed mild proximal upper extremity weakness in the bilateral shoulder abductors, infraspinatus, hip extensors, and hip flexors (Medical Research Council muscle scale grade 4). All deep tendon reflexes, except the Achilles reflex, were present. Despite subjective sensory concerns, objective examination of all sensory modalities was normal. Cranial nerve examination was normal, except for a slight nasal quality to his voice.

A qualitative assay was positive for the presence of P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channel (VGCC) antibodies. Other laboratory studies were within reference range, including acetylcholine-receptor antibodies (blocking, binding, and modulating) and muscle-specific kinase antibodies.

Lumbar and cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging revealed multilevel neuroforaminal stenosis without spinal canal stenosis or myelopathy. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest was notable for 2 pathologically enlarged lymph nodes in the left axilla and no evidence of primary pulmonary malignancy. Nerve-conduction studies (NCSs) in conjunction with other clinical findings were consistent with the diagnosis of LEMS.

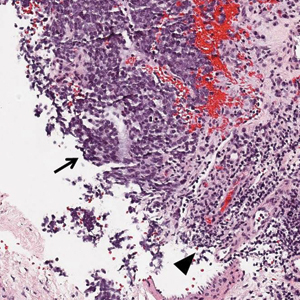

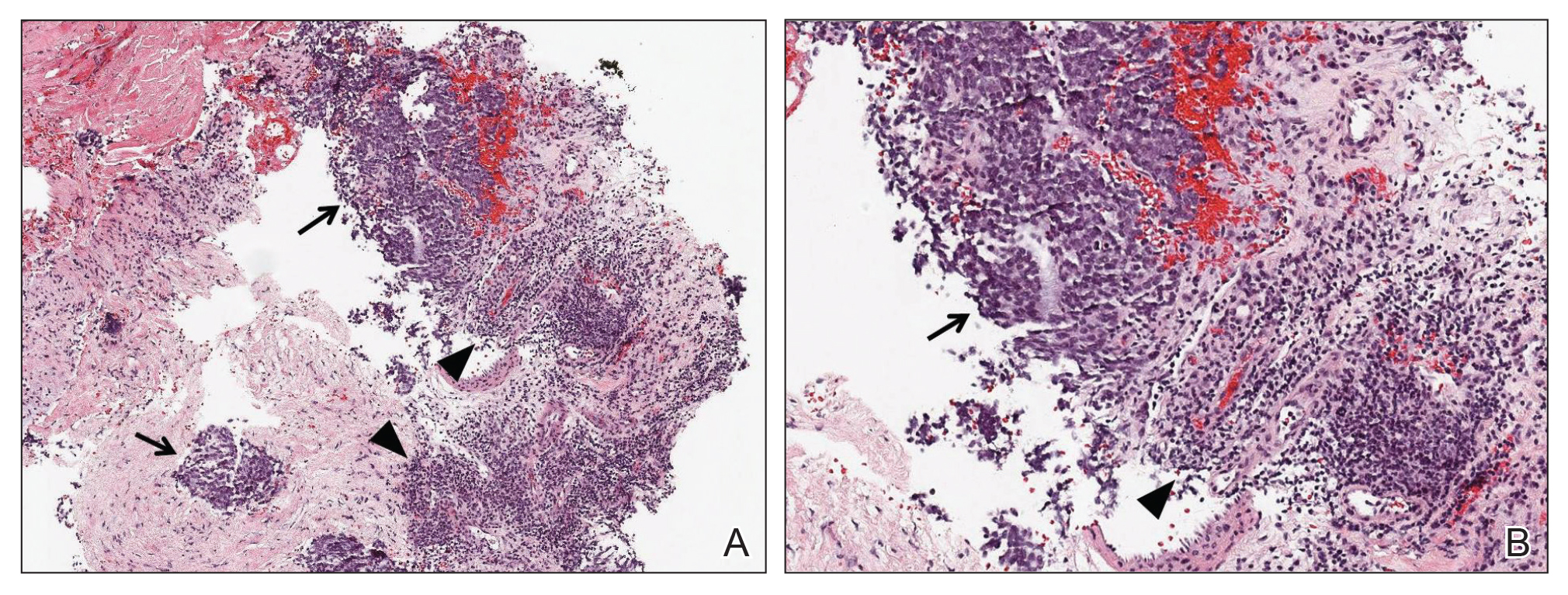

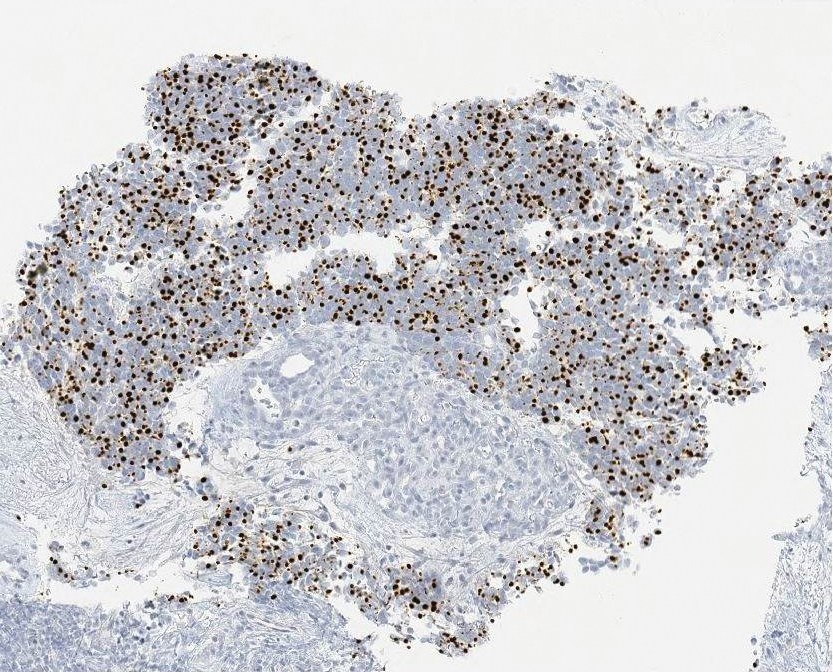

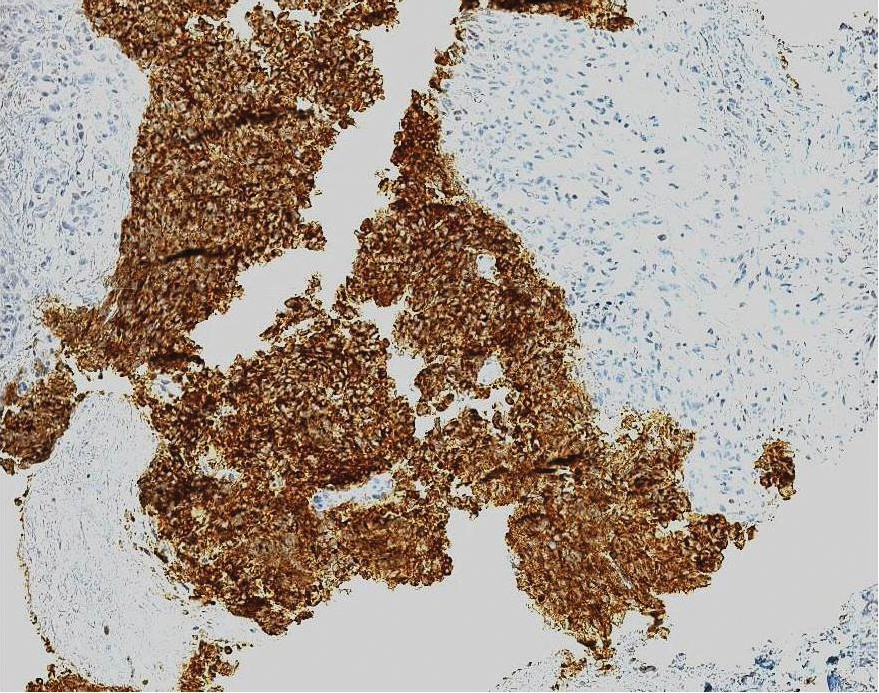

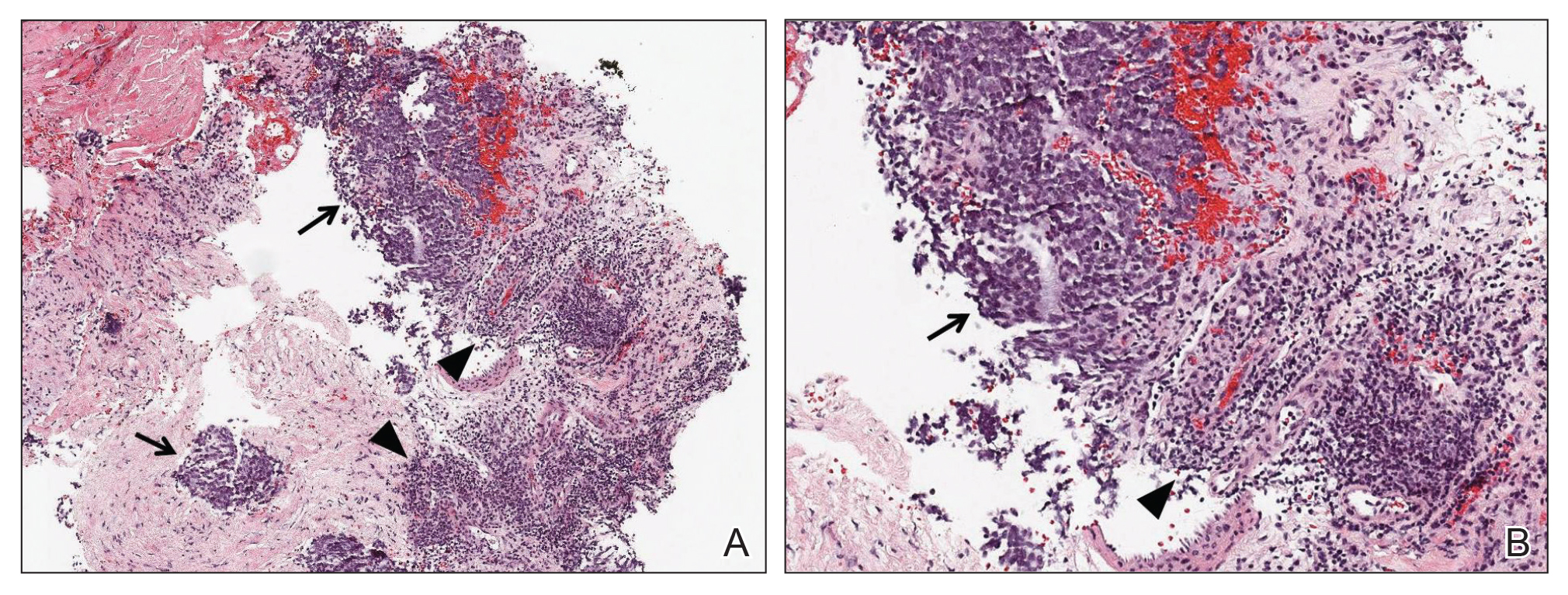

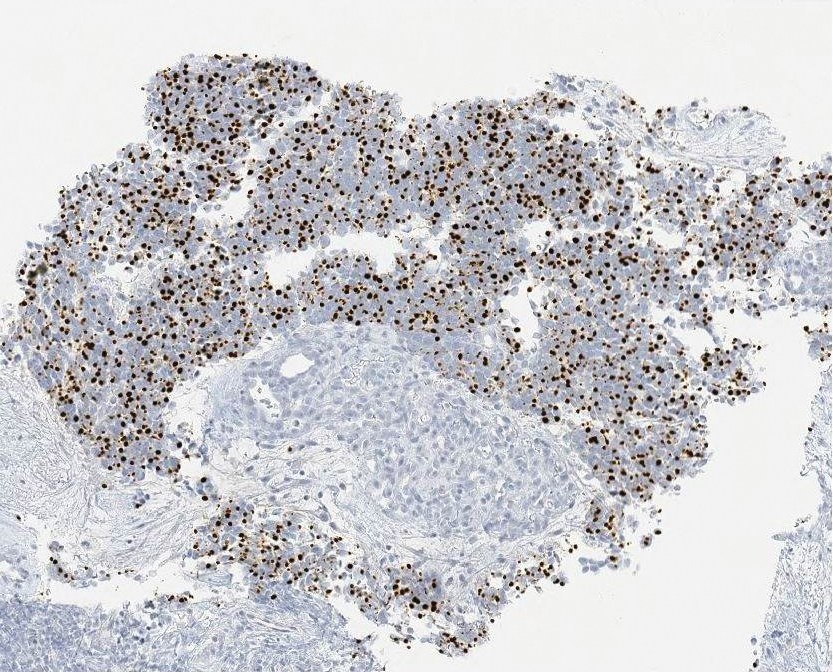

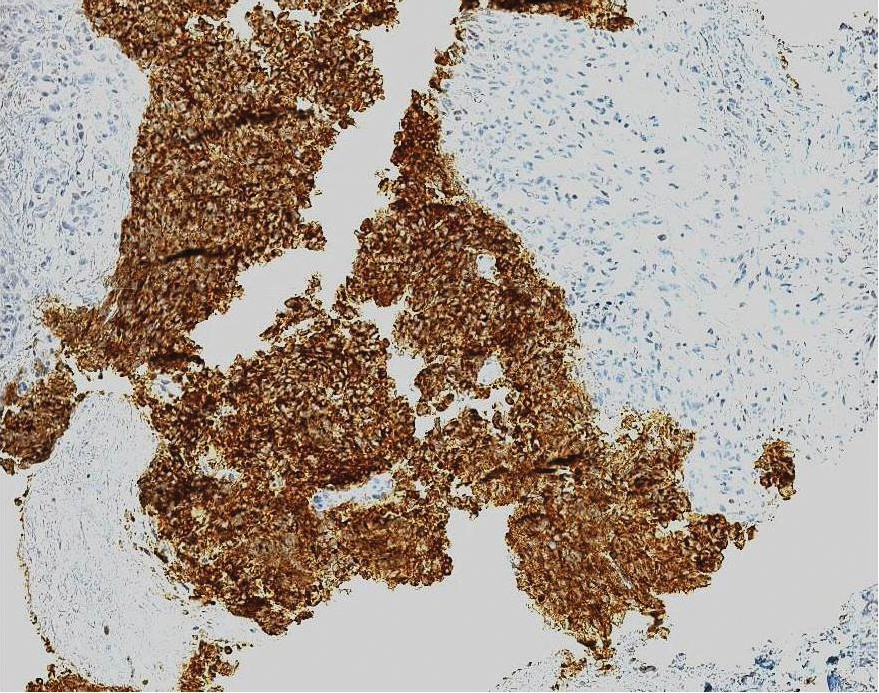

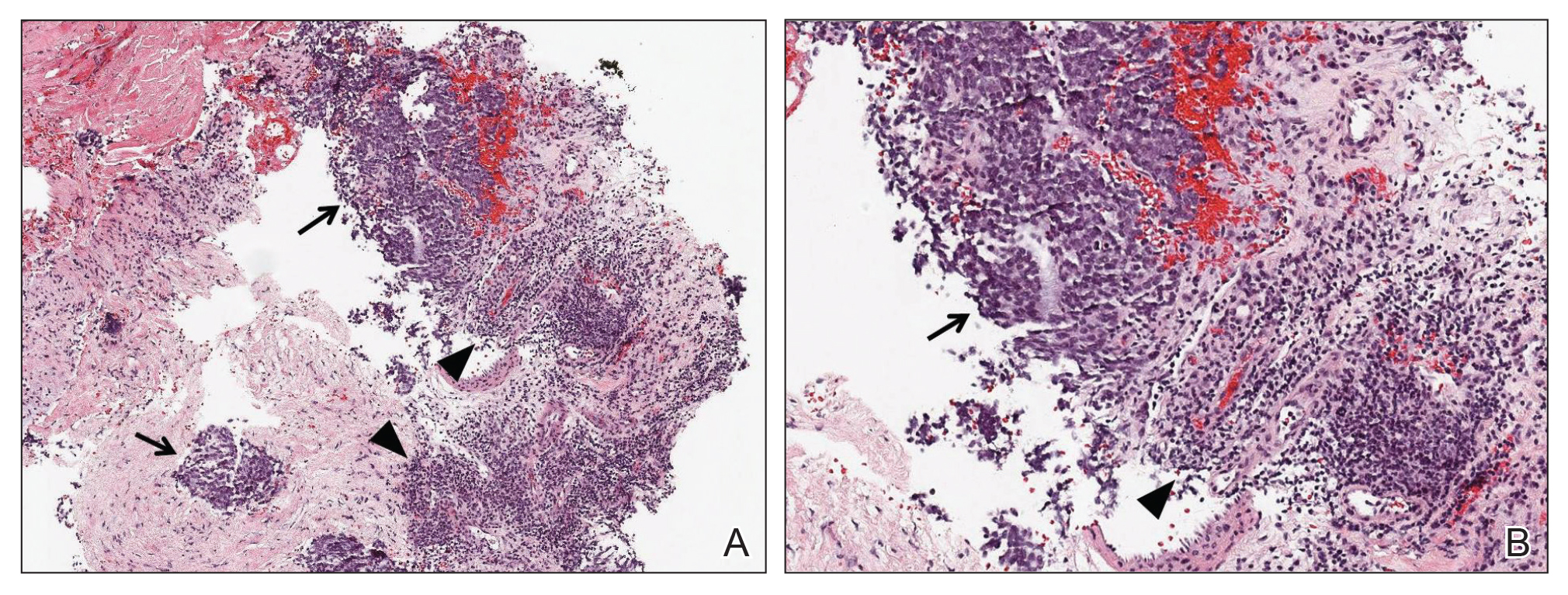

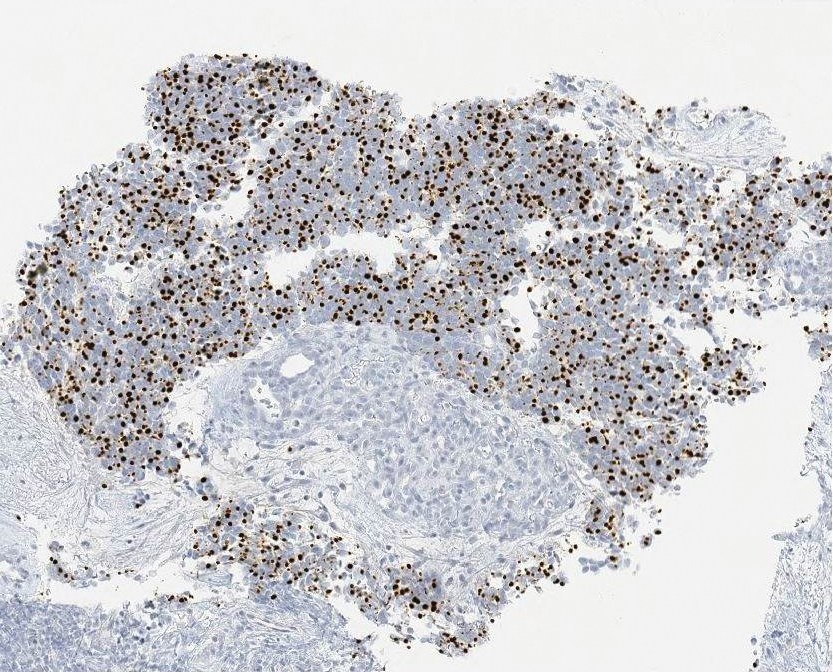

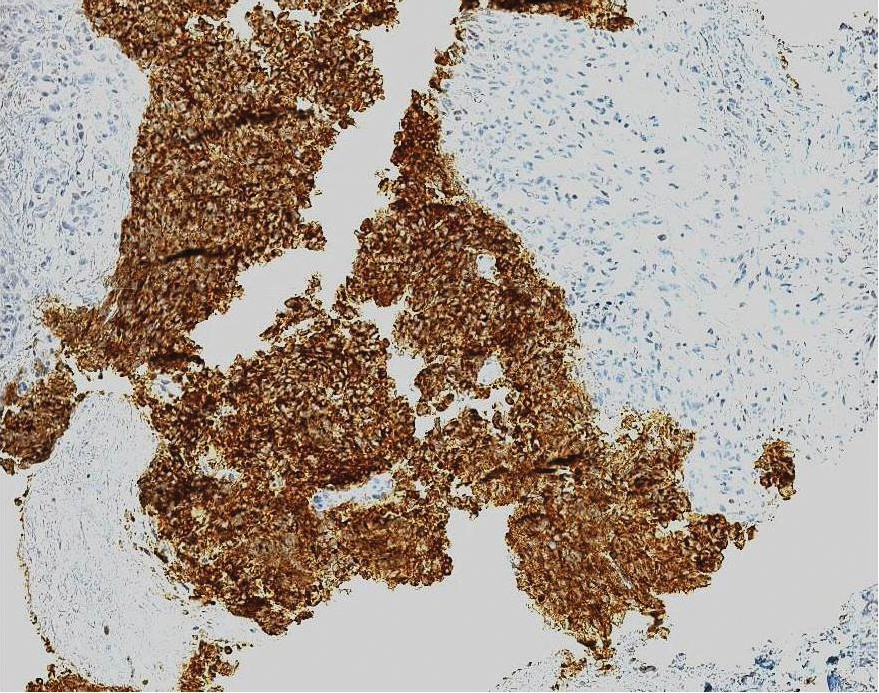

Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the enlarged axillary lymph nodes demonstrated sheets and nests of small round blue tumor cells with minimal cytoplasm, high mitotic rate, and foci of necrosis (Figure 1). The tumor cells were positive for pancytokeratin (Lu-5) and cytokeratin (CK) 20 in a perinuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2), as well as for the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin (Figure 3), chromogranin A, and CD56. The tumor cells showed no immunoreactivity for CK7, thyroid transcription factor 1, CD3, CD5, or CD20. Flow cytometry demonstrated low cellularity, low specimen viability, and no evidence of an abnormal B-cell population. These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of MCC.

The patient underwent surgical excision of the involved lymph nodes. Four weeks after surgery, he reported dramatic improvement in strength, with complete resolution of the nasal speech, dysphagia, dry mouth, urinary retention, and constipation. Two months after surgery, his strength had normalized, except for slight persistent weakness in the bilateral shoulder abductors, trace weakness in the hip flexors, and a slight Trendelenburg gait. He was able to rise from a chair without using his arms and no longer required a cane for ambulation.

The patient underwent adjuvant radiation therapy after 2-month surgical follow-up with 5000-cGy radiation treatment to the left axillary region. Six months following primary definitive surgery and 4 months following adjuvant radiation therapy, he reported a 95% subjective return of physical strength. The patient was able to return to near-baseline physical activity. He continued to deny symptoms of dry mouth, incontinence, or constipation. Objectively, he had no focal neurologic deficits or weakness; no evidence of new skin lesions or lymphadenopathy was noted.

Comment

MCC vs SCLC

Merkel cell carcinoma is classified as a type of EPSCC. The histologic appearance of MCC is indistinguishable from SCLC. Both tumors are composed of uniform sheets of small round cells with a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, and both can express neuroendocrine markers, such as neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin.9 Immunohistochemical positivity for CK20 and neurofilaments in combination with negative staining for thyroid transcription factor 1 and CK7 effectively differentiate MCC from SCLC.9 In addition, MCC often displays CK20 positivity in a perinuclear dotlike or punctate pattern, which is characteristic of this tumor.3,9,10 Negative immunohistochemical markers for B cells (CD20) and T cells (CD3) are important in excluding lymphoma.

LEMS Diagnosis

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome is a paraneoplastic or autoimmune disorder involving the neuromuscular junction. Autoantibodies to VGCC impair calcium influx into the presynaptic terminal, resulting in marked reduction of acetylcholine release into the synaptic cleft. The reduction in acetylcholine activity impairs production of muscle fiber action potentials, resulting in clinical weakness. The diagnosis of LEMS rests on clinical presentation, positive serology, and confirmatory neurophysiologic testing by NCS. Clinically, patients present with proximal weakness, hyporeflexia or areflexia, and autonomic dysfunction. Antibodies to P/Q-type VGCCs are found in 85% to 90% of cases of LEMS and are thought to play a direct causative role in the development of weakness.11 The finding of postexercise facilitation on motor NCS is the neurophysiologic hallmark and is highly specific for the diagnosis.

Approximately 50% to 60% of patients who present with LEMS have an underlying tumor, the vast majority of which are SCLC.11 There are a few reports of LEMS associated with other malignancies, including lymphoma; thymoma; neuroblastoma; and carcinoma of the breast, stomach, prostate, bladder, kidney, and gallbladder.12 Patients with nontumor or autoimmune LEMS tend to be younger, and there is no male predominance, as there is in paraneoplastic LEMS.13 Given the risk of underlying malignancy in LEMS, Titulaer et al14 proposed a screening protocol for patients presenting with LEMS, recommending initial primary screening using CT of the chest. If the CT scan is negative, total-body fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography should be performed to assess for fludeoxyglucose avid lesions. If both initial studies are negative, routine follow-up with CT of the chest at 6-month intervals for a minimum of 2 to 4 years after the initial diagnosis of LEMS was recommended. An exception to this protocol was suggested to allow consideration to stop screening after the first 6-month follow-up chest CT for patients younger than 45 years who have never smoked and who have an HLA 8.1 haplotype for which nontumor LEMS would be a more probable diagnosis.14

In addition to a screening protocol, a validated prediction tool, the Dutch-English LEMS Tumor Association prediction score, was developed. It uses common signs and symptoms of LEMS and risk factors for SCLC to help guide the need for further screening.15

Paraneoplastic Syndromes Associated With MCC

Other paraneoplastic syndromes have been reported in association with MCC. A patient with brainstem encephalitis associated with MCC was reported in a trial of a novel immunotherapy for paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes.16,17 A syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion was reported in a patient with N-type calcium channel antibodies.18 Two cases of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration have been reported; the first was associated with a novel 70-kD antibody,19 and the second was associated with the P/Q-type VGCC antibody.20 Anti-Hu antibodies have been found in a handful of reports of neurologic deterioration in patients with MCC. Hocar et al21 reported a severe necrotizing myopathy; Greenlee et al22 described a syndrome of progressive sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathy with encephalopathy; and Lopez et al23 described a constellation of vision changes, gait imbalance, and proximal weakness. Support for a pathophysiologic connection among these 3 cases is suggested by the finding of Hu antigen expression by MCC in 2 studies.24,25 Because MCC can present with occult lymph node involvement in the absence of primary cutaneous findings,3 there are more cases of paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes that were not recognized.

Extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas such as MCC are morphologically indistinguishable from their pulmonary counterparts and have been reported in most anatomic regions of the body, including gynecologic organs (eg, ovaries, cervix), genitourinary organs (eg, bladder, prostate), the gastrointestinal tract (eg, esophagus), skin (eg, MCC), and the head and neck region. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma is a rare entity, with the most common form found in the gynecologic tract, representing only 2% of gynecologic malignancies.26

Paraneoplastic syndromes of EPSCC are rare given the paucity of the malignancy. Several case reports discuss findings of SIADH in EPSCC of the cervix, as well as hypercalcemia, polyneuropathy, Cushing syndrome, limbic encephalitis, and peripheral neuropathy in EPSCC of the prostate.27,28 In contrast, SCLC has long been associated with paraneoplastic syndromes. Numerous case reports have been published describing SCLC-associated paraneoplastic syndromes to include hypercalcemia, Cushing syndrome, SIADH, vasoactive peptide production, cerebellar degeneration, limbic encephalitis, visceral plexopathy, autonomic dysfunction, and LEMS.29 As more cases of EPSCC with paraneoplastic syndromes are identified and reported, we might gain a better understanding of this interesting phenomenon.

Conclusion

Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy associated with paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes, including LEMS. A thorough search for an underlying malignancy is highly recommended in patients with diagnosed LEMS without clear cause. Early identification and treatment of the primary tumor can lead to improvement of neurologic symptoms.

We present a case of LEMS with no clearly identifiable cause on presentation with later diagnosis of metastatic MCC of unknown primary origin. After surgical excision of affected lymph nodes and adjuvant radiation therapy, the patient had near-complete resolution of LEMS symptoms at 6-month follow-up, without additional findings of lymphadenopathy or skin lesions. Although this patient is not undergoing routine surveillance imaging to monitor for recurrence of MCC, a chest CT or positron emission tomography–CT for secondary screening would be considered if the patient experienced clinical symptoms consistent with LEMS.

In cases of LEMS without pulmonary malignancy, we recommend considering MCC in the differential diagnosis during the workup of an underlying malignancy

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-27.

- Senchenkov A, Moran SL. Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis, management, and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:E771-E778.

- Han SY, North JP, Canavan T, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2012;26:1351-1374.

- Vernino S. Paraneoplastic disorders affecting the neuromuscular junction or anterior horn cell. CONTINUUM Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2009;15:132-146.

- Eggers SD, Salomao DR, Dinapoli RP, et al. Paraneoplastic and metastatic neurologic complications of Merkel cell carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:327-330.

- Siau RT, Morris A, Karoo RO. Surgery results in complete cure of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome in a patient with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:e162-e164.

- Bombelli F, Lispi L, Calabrò F, et al. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome associated to Merkel cell carcinoma: report of a case. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:1491-1492.

- Simmons DB, Duginski TM, McClean JC, et al. Lambert-eaton myasthenic syndrome and merkel cell carcinoma. Muscle Nerve. 2015;53:325-326.

- Bobos M, Hytiroglou P, Kostopoulos I, et al. Immunohistochemical distinction between Merkel cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma of the lung. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:99-104.

- Jensen K, Kohler S, Rouse RV. Cytokeratin staining in Merkel cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study of cytokeratins 5/6, 7, 17, and 20. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2000;8:310-315.

- Titulaer MJ, Lang B, Verschuuren JJ. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: from clinical characteristics to therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:1098-1107.

- Sanders DB. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. In: Daroff R, Aminoff MJ, eds. Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2009:819-822.

- Wirtz PW, Smallegange TM, Wintzen AR, et al. Differences in clinical features between the Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome with and without cancer: an analysis of 227 published cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2002;104:359-363.

- Titulaer MJ, Wirtz PW, Willems LN, et al. Screening for small-cell lung cancer: a follow-up study of patients with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4276-4281.

- Titulaer MJ, Maddison P, Sont JK, et al. Clinical Dutch-English Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS) Tumor Association prediction score accurately predicts small-cell lung cancer in the LEMS. J Clin Oncol. 2011;7:902-908.

- Cher LM, Hochberg FH, Teruya J, et al. Therapy for paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes in six patients with protein A column immunoadsorption. Cancer. 1995;75:1678-1683.

- Batchelor TT, Platten M, Hochberg FH. Immunoadsorption therapy for paraneoplastic syndromes. J Neurooncol. 1998;40:131-136.

- Blondin NA, Vortmeyer AO, Harel NY. Paraneoplastic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone mimicking limbic encephalitis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1591-1594.

- Balegno S, Ceroni M, Corato M, et al. Antibodies to cerebellar nerve fibres in two patients with paraneoplastic cerebellar ataxia. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3211-3214.

- Zhang C, Emery L, Lancaster E. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration associated with noncutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2014;1:e17.

- Hocar O, Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Faye O, et al. Severe necrotizing myopathy subsequent to Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:130-134.

- Greenlee JE, Steffens JD, Clawson SA, et al. Anti-Hu antibodies in Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:111-115.

- Lopez MC, Pericay C, Agustí M, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma associated with a paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome. Histopathology. 2004;44:628-629.

- Dalmau J, Furneaux HM, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. The expression of the Hu (paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis/sensory neuronopathy) antigen in human normal and tumor tissues. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:881-886.

- Gultekin SH, Rosai J, Demopoulos A, et al. Hu immunolabeling as a marker of neural and neuroendocrine differentiation in normal and neoplastic human tissues: assessment using a recombinant anti-Hu Fab fragment. Int J Surg Pathol. 2000;8:109-117.

- Zheng X, Liu D, Fallon JT, et al. Distinct genetic alterations in small cell carcinoma from different anatomic sites. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2015;4:2.

- Kim D, Yun H, Lee Y, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix presenting with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:420-425.

- Venkatesh PK, Motwani B, Sherman N, et al. Metastatic pure small-cell carcinoma of prostate. Am J Med Sci. 2004;328:286-289.

- Kaltsas G, Androulakis II, de Herder WW, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes secondary to neuroendocrine tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R173-R193.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy of the skin that is thought to arise from neural crest cells. It has an estimated annual incidence of 0.6 per 100,000 individuals, typically occurs in the elderly population, and is most common in white males.1 The tumor presents as a rapidly growing, violaceous nodule in sun-exposed areas of the skin; early in the course, it can be mistaken for a benign entity such as an epidermal cyst.2 Merkel cell carcinoma has a propensity to spread to regional lymph nodes, and in some cases, it occurs in the absence of skin findings.3 Histologically, MCC is nearly indistinguishable from small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC).4 The overall prognosis for patients with MCC is poor and largely dependent on the stage at diagnosis. Patients with regional and distant metastases have a 5-year survival rate of 26% to 42% and 18%, respectively.3

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) is a paraneoplastic or autoimmune disorder of the neuromuscular junction that is found in 3% of cases of SCLC.4 Reported cases of LEMS in patients with MCC are exceedingly rare.5-8 We provide a full report and longitudinal clinical follow-up of a case that was briefly discussed by Simmons et al,8 and we review the literature regarding paraneoplastic syndromes associated with MCC and other extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas (EPSCCs).

Case Report

A 63-year-old man was evaluated in the neurology clinic due to difficulty walking, climbing stairs, and performing push-ups over the last month. Prior to the onset of symptoms, he was otherwise healthy, walking 3 miles daily; however, at presentation he required use of a cane. Leg weakness worsened as the day progressed. In addition, he reported constipation, urinary urgency, dry mouth, mild dysphagia, reduced sensation below the knees, and a nasal quality in his speech. He had no ptosis, diplopia, dysarthria, muscle cramps, myalgia, or facial weakness. He denied fevers, chills, and night sweats but did admit to an unintentional 10- to 15-lb weight loss over the preceding few months.

The neurologic examination revealed mild proximal upper extremity weakness in the bilateral shoulder abductors, infraspinatus, hip extensors, and hip flexors (Medical Research Council muscle scale grade 4). All deep tendon reflexes, except the Achilles reflex, were present. Despite subjective sensory concerns, objective examination of all sensory modalities was normal. Cranial nerve examination was normal, except for a slight nasal quality to his voice.

A qualitative assay was positive for the presence of P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channel (VGCC) antibodies. Other laboratory studies were within reference range, including acetylcholine-receptor antibodies (blocking, binding, and modulating) and muscle-specific kinase antibodies.

Lumbar and cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging revealed multilevel neuroforaminal stenosis without spinal canal stenosis or myelopathy. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest was notable for 2 pathologically enlarged lymph nodes in the left axilla and no evidence of primary pulmonary malignancy. Nerve-conduction studies (NCSs) in conjunction with other clinical findings were consistent with the diagnosis of LEMS.

Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the enlarged axillary lymph nodes demonstrated sheets and nests of small round blue tumor cells with minimal cytoplasm, high mitotic rate, and foci of necrosis (Figure 1). The tumor cells were positive for pancytokeratin (Lu-5) and cytokeratin (CK) 20 in a perinuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2), as well as for the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin (Figure 3), chromogranin A, and CD56. The tumor cells showed no immunoreactivity for CK7, thyroid transcription factor 1, CD3, CD5, or CD20. Flow cytometry demonstrated low cellularity, low specimen viability, and no evidence of an abnormal B-cell population. These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of MCC.

The patient underwent surgical excision of the involved lymph nodes. Four weeks after surgery, he reported dramatic improvement in strength, with complete resolution of the nasal speech, dysphagia, dry mouth, urinary retention, and constipation. Two months after surgery, his strength had normalized, except for slight persistent weakness in the bilateral shoulder abductors, trace weakness in the hip flexors, and a slight Trendelenburg gait. He was able to rise from a chair without using his arms and no longer required a cane for ambulation.

The patient underwent adjuvant radiation therapy after 2-month surgical follow-up with 5000-cGy radiation treatment to the left axillary region. Six months following primary definitive surgery and 4 months following adjuvant radiation therapy, he reported a 95% subjective return of physical strength. The patient was able to return to near-baseline physical activity. He continued to deny symptoms of dry mouth, incontinence, or constipation. Objectively, he had no focal neurologic deficits or weakness; no evidence of new skin lesions or lymphadenopathy was noted.

Comment

MCC vs SCLC

Merkel cell carcinoma is classified as a type of EPSCC. The histologic appearance of MCC is indistinguishable from SCLC. Both tumors are composed of uniform sheets of small round cells with a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, and both can express neuroendocrine markers, such as neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin.9 Immunohistochemical positivity for CK20 and neurofilaments in combination with negative staining for thyroid transcription factor 1 and CK7 effectively differentiate MCC from SCLC.9 In addition, MCC often displays CK20 positivity in a perinuclear dotlike or punctate pattern, which is characteristic of this tumor.3,9,10 Negative immunohistochemical markers for B cells (CD20) and T cells (CD3) are important in excluding lymphoma.

LEMS Diagnosis

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome is a paraneoplastic or autoimmune disorder involving the neuromuscular junction. Autoantibodies to VGCC impair calcium influx into the presynaptic terminal, resulting in marked reduction of acetylcholine release into the synaptic cleft. The reduction in acetylcholine activity impairs production of muscle fiber action potentials, resulting in clinical weakness. The diagnosis of LEMS rests on clinical presentation, positive serology, and confirmatory neurophysiologic testing by NCS. Clinically, patients present with proximal weakness, hyporeflexia or areflexia, and autonomic dysfunction. Antibodies to P/Q-type VGCCs are found in 85% to 90% of cases of LEMS and are thought to play a direct causative role in the development of weakness.11 The finding of postexercise facilitation on motor NCS is the neurophysiologic hallmark and is highly specific for the diagnosis.

Approximately 50% to 60% of patients who present with LEMS have an underlying tumor, the vast majority of which are SCLC.11 There are a few reports of LEMS associated with other malignancies, including lymphoma; thymoma; neuroblastoma; and carcinoma of the breast, stomach, prostate, bladder, kidney, and gallbladder.12 Patients with nontumor or autoimmune LEMS tend to be younger, and there is no male predominance, as there is in paraneoplastic LEMS.13 Given the risk of underlying malignancy in LEMS, Titulaer et al14 proposed a screening protocol for patients presenting with LEMS, recommending initial primary screening using CT of the chest. If the CT scan is negative, total-body fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography should be performed to assess for fludeoxyglucose avid lesions. If both initial studies are negative, routine follow-up with CT of the chest at 6-month intervals for a minimum of 2 to 4 years after the initial diagnosis of LEMS was recommended. An exception to this protocol was suggested to allow consideration to stop screening after the first 6-month follow-up chest CT for patients younger than 45 years who have never smoked and who have an HLA 8.1 haplotype for which nontumor LEMS would be a more probable diagnosis.14

In addition to a screening protocol, a validated prediction tool, the Dutch-English LEMS Tumor Association prediction score, was developed. It uses common signs and symptoms of LEMS and risk factors for SCLC to help guide the need for further screening.15

Paraneoplastic Syndromes Associated With MCC

Other paraneoplastic syndromes have been reported in association with MCC. A patient with brainstem encephalitis associated with MCC was reported in a trial of a novel immunotherapy for paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes.16,17 A syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion was reported in a patient with N-type calcium channel antibodies.18 Two cases of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration have been reported; the first was associated with a novel 70-kD antibody,19 and the second was associated with the P/Q-type VGCC antibody.20 Anti-Hu antibodies have been found in a handful of reports of neurologic deterioration in patients with MCC. Hocar et al21 reported a severe necrotizing myopathy; Greenlee et al22 described a syndrome of progressive sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathy with encephalopathy; and Lopez et al23 described a constellation of vision changes, gait imbalance, and proximal weakness. Support for a pathophysiologic connection among these 3 cases is suggested by the finding of Hu antigen expression by MCC in 2 studies.24,25 Because MCC can present with occult lymph node involvement in the absence of primary cutaneous findings,3 there are more cases of paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes that were not recognized.

Extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas such as MCC are morphologically indistinguishable from their pulmonary counterparts and have been reported in most anatomic regions of the body, including gynecologic organs (eg, ovaries, cervix), genitourinary organs (eg, bladder, prostate), the gastrointestinal tract (eg, esophagus), skin (eg, MCC), and the head and neck region. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma is a rare entity, with the most common form found in the gynecologic tract, representing only 2% of gynecologic malignancies.26

Paraneoplastic syndromes of EPSCC are rare given the paucity of the malignancy. Several case reports discuss findings of SIADH in EPSCC of the cervix, as well as hypercalcemia, polyneuropathy, Cushing syndrome, limbic encephalitis, and peripheral neuropathy in EPSCC of the prostate.27,28 In contrast, SCLC has long been associated with paraneoplastic syndromes. Numerous case reports have been published describing SCLC-associated paraneoplastic syndromes to include hypercalcemia, Cushing syndrome, SIADH, vasoactive peptide production, cerebellar degeneration, limbic encephalitis, visceral plexopathy, autonomic dysfunction, and LEMS.29 As more cases of EPSCC with paraneoplastic syndromes are identified and reported, we might gain a better understanding of this interesting phenomenon.

Conclusion

Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy associated with paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes, including LEMS. A thorough search for an underlying malignancy is highly recommended in patients with diagnosed LEMS without clear cause. Early identification and treatment of the primary tumor can lead to improvement of neurologic symptoms.

We present a case of LEMS with no clearly identifiable cause on presentation with later diagnosis of metastatic MCC of unknown primary origin. After surgical excision of affected lymph nodes and adjuvant radiation therapy, the patient had near-complete resolution of LEMS symptoms at 6-month follow-up, without additional findings of lymphadenopathy or skin lesions. Although this patient is not undergoing routine surveillance imaging to monitor for recurrence of MCC, a chest CT or positron emission tomography–CT for secondary screening would be considered if the patient experienced clinical symptoms consistent with LEMS.

In cases of LEMS without pulmonary malignancy, we recommend considering MCC in the differential diagnosis during the workup of an underlying malignancy