User login

Focus groups seek transgender experience with HIV prevention

A pair of focus groups explored the experience of transgender patients with HIV prevention, finding many were discouraged by experiences of care that was not culturally competent and affirming.

The findings, including other important themes, were published in Pediatrics.

The pair of online asynchronous focus groups, conducted by Holly B. Fontenot, PhD, RN/NP, of the Fenway Institute in Boston, and colleagues, sought input from 30 transgender participants from across the United States. Eleven were aged 13-18 years, and 19 were aged 18-24 years, with an average age of 19. Most (70%) were white, and the remainder were African American (7%), Asian American (3%), multiracial (17%), and other (3%); 10% identified as Hispanic. Participants were given multiple options for reporting gender identity; 27% reported identifying as transgender males, 17% reported identifying as transgender females, and the rest identified with other terms, including 27% using one or more terms.

The quantitative analysis found four common themes, which the study explored in depth: “barriers to self-efficacy in sexual decision making; safety concerns, fear, and other challenges in forming romantic and/or sexual relationships; need for support and education; and desire for affirmative and culturally competent experiences and interactions.”

Based on their findings, the authors suggested ways of improving transgender youth experiences:

- Increasing provider knowledge and skills in providing affirming care through transgender health education programs.

- Addressing the barriers, such as stigma and lack of accessibility.

- Expanding sexual health education to be more inclusive regarding gender identities, sexual orientations, and definitions of sex.

Providers also need to include information on sexually transmitted infection and HIV prevention, including “discussion of safer sexual behaviors, negotiation and consent, sexual and physical assault, condoms, lubrication, STI and HIV testing, human papillomavirus vaccination, and PrEP [preexposure prophylaxis]” the authors emphasized.

Dr. Fontenot and associates determined that this study’s findings were consistent with what’s known about adult transgender patients, but this study provides more context regarding transgender youth experiences.

“It is important to elicit transgender youth experiences and perspectives related to HIV risk and preventive services,” they concluded. “This study provided a greater understanding of barriers to and facilitators of youth obtaining HIV preventive services and sexual health education.”

Limitations of the study included that non–English speaking participants were excluded, and that participants were predominantly white, non-Hispanic, and assigned female sex at birth.

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and NORC at The University of Chicago. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fontenot HB et al., Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2204.

A pair of focus groups explored the experience of transgender patients with HIV prevention, finding many were discouraged by experiences of care that was not culturally competent and affirming.

The findings, including other important themes, were published in Pediatrics.

The pair of online asynchronous focus groups, conducted by Holly B. Fontenot, PhD, RN/NP, of the Fenway Institute in Boston, and colleagues, sought input from 30 transgender participants from across the United States. Eleven were aged 13-18 years, and 19 were aged 18-24 years, with an average age of 19. Most (70%) were white, and the remainder were African American (7%), Asian American (3%), multiracial (17%), and other (3%); 10% identified as Hispanic. Participants were given multiple options for reporting gender identity; 27% reported identifying as transgender males, 17% reported identifying as transgender females, and the rest identified with other terms, including 27% using one or more terms.

The quantitative analysis found four common themes, which the study explored in depth: “barriers to self-efficacy in sexual decision making; safety concerns, fear, and other challenges in forming romantic and/or sexual relationships; need for support and education; and desire for affirmative and culturally competent experiences and interactions.”

Based on their findings, the authors suggested ways of improving transgender youth experiences:

- Increasing provider knowledge and skills in providing affirming care through transgender health education programs.

- Addressing the barriers, such as stigma and lack of accessibility.

- Expanding sexual health education to be more inclusive regarding gender identities, sexual orientations, and definitions of sex.

Providers also need to include information on sexually transmitted infection and HIV prevention, including “discussion of safer sexual behaviors, negotiation and consent, sexual and physical assault, condoms, lubrication, STI and HIV testing, human papillomavirus vaccination, and PrEP [preexposure prophylaxis]” the authors emphasized.

Dr. Fontenot and associates determined that this study’s findings were consistent with what’s known about adult transgender patients, but this study provides more context regarding transgender youth experiences.

“It is important to elicit transgender youth experiences and perspectives related to HIV risk and preventive services,” they concluded. “This study provided a greater understanding of barriers to and facilitators of youth obtaining HIV preventive services and sexual health education.”

Limitations of the study included that non–English speaking participants were excluded, and that participants were predominantly white, non-Hispanic, and assigned female sex at birth.

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and NORC at The University of Chicago. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fontenot HB et al., Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2204.

A pair of focus groups explored the experience of transgender patients with HIV prevention, finding many were discouraged by experiences of care that was not culturally competent and affirming.

The findings, including other important themes, were published in Pediatrics.

The pair of online asynchronous focus groups, conducted by Holly B. Fontenot, PhD, RN/NP, of the Fenway Institute in Boston, and colleagues, sought input from 30 transgender participants from across the United States. Eleven were aged 13-18 years, and 19 were aged 18-24 years, with an average age of 19. Most (70%) were white, and the remainder were African American (7%), Asian American (3%), multiracial (17%), and other (3%); 10% identified as Hispanic. Participants were given multiple options for reporting gender identity; 27% reported identifying as transgender males, 17% reported identifying as transgender females, and the rest identified with other terms, including 27% using one or more terms.

The quantitative analysis found four common themes, which the study explored in depth: “barriers to self-efficacy in sexual decision making; safety concerns, fear, and other challenges in forming romantic and/or sexual relationships; need for support and education; and desire for affirmative and culturally competent experiences and interactions.”

Based on their findings, the authors suggested ways of improving transgender youth experiences:

- Increasing provider knowledge and skills in providing affirming care through transgender health education programs.

- Addressing the barriers, such as stigma and lack of accessibility.

- Expanding sexual health education to be more inclusive regarding gender identities, sexual orientations, and definitions of sex.

Providers also need to include information on sexually transmitted infection and HIV prevention, including “discussion of safer sexual behaviors, negotiation and consent, sexual and physical assault, condoms, lubrication, STI and HIV testing, human papillomavirus vaccination, and PrEP [preexposure prophylaxis]” the authors emphasized.

Dr. Fontenot and associates determined that this study’s findings were consistent with what’s known about adult transgender patients, but this study provides more context regarding transgender youth experiences.

“It is important to elicit transgender youth experiences and perspectives related to HIV risk and preventive services,” they concluded. “This study provided a greater understanding of barriers to and facilitators of youth obtaining HIV preventive services and sexual health education.”

Limitations of the study included that non–English speaking participants were excluded, and that participants were predominantly white, non-Hispanic, and assigned female sex at birth.

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and NORC at The University of Chicago. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Fontenot HB et al., Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2204.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Requests for crowd diagnoses of STDs common on social media

Requests for crowd diagnosis of sexually transmitted diseases were frequent on a social media website, new research found.

The social media website Reddit, which currently has 330 million monthly active users, is home to more than 230 health-related subreddits, including r/STD, a forum that allows users to publicly share “stories, concerns, and questions” about “anything and everything STD related,” Alicia L. Nobles, PhD, of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, and associates wrote in a research letter published in JAMA.

Dr. Noble and associates conducted an analysis of all posts published to r/STD from the subreddit’s inception during November 2010–February 2019, a total of 16,979 posts. Three coauthors independently coded each post, recording whether or not a post requested a crowd diagnosis, and if so, whether that request was made to obtain a second opinion after a visit to a health care professional.

About 58% of posts requested a crowd diagnosis, 31% of which included an image of the physical signs. One-fifth of the requests for a crowd diagnosis were seeking a second opinion after a previous diagnosis by a health care professional. Nearly 90% of all crowd-diagnosis requests received at least one reply (mean responses, 1.7), with a median response time of 3.04 hours. About 80% of requests were answered in less than 1 day.

While crowd diagnoses do seem to be popular and have the benefits of anonymity, rapid response, and multiple opinions, the accuracy of crowd diagnoses is unknown given the limited information responders operate with and the potential lack of responder medical training, the study authors noted. Misdiagnosis could allow further disease transmission, and third parties viewing posts could incorrectly self-diagnose their own condition.

“Health care professionals could partner with social media outlets to promote the potential benefits of crowd diagnosis while suppressing potential harms, for example by having trained professionals respond to posts to better diagnose and make referrals to health care centers,” Dr. Nobles and associates concluded.

One coauthor reported receiving personal fees from Bloomberg and Good Analytics, and another reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health; no other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Nobles AL et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 5;322(17):1712-3.

Requests for crowd diagnosis of sexually transmitted diseases were frequent on a social media website, new research found.

The social media website Reddit, which currently has 330 million monthly active users, is home to more than 230 health-related subreddits, including r/STD, a forum that allows users to publicly share “stories, concerns, and questions” about “anything and everything STD related,” Alicia L. Nobles, PhD, of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, and associates wrote in a research letter published in JAMA.

Dr. Noble and associates conducted an analysis of all posts published to r/STD from the subreddit’s inception during November 2010–February 2019, a total of 16,979 posts. Three coauthors independently coded each post, recording whether or not a post requested a crowd diagnosis, and if so, whether that request was made to obtain a second opinion after a visit to a health care professional.

About 58% of posts requested a crowd diagnosis, 31% of which included an image of the physical signs. One-fifth of the requests for a crowd diagnosis were seeking a second opinion after a previous diagnosis by a health care professional. Nearly 90% of all crowd-diagnosis requests received at least one reply (mean responses, 1.7), with a median response time of 3.04 hours. About 80% of requests were answered in less than 1 day.

While crowd diagnoses do seem to be popular and have the benefits of anonymity, rapid response, and multiple opinions, the accuracy of crowd diagnoses is unknown given the limited information responders operate with and the potential lack of responder medical training, the study authors noted. Misdiagnosis could allow further disease transmission, and third parties viewing posts could incorrectly self-diagnose their own condition.

“Health care professionals could partner with social media outlets to promote the potential benefits of crowd diagnosis while suppressing potential harms, for example by having trained professionals respond to posts to better diagnose and make referrals to health care centers,” Dr. Nobles and associates concluded.

One coauthor reported receiving personal fees from Bloomberg and Good Analytics, and another reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health; no other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Nobles AL et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 5;322(17):1712-3.

Requests for crowd diagnosis of sexually transmitted diseases were frequent on a social media website, new research found.

The social media website Reddit, which currently has 330 million monthly active users, is home to more than 230 health-related subreddits, including r/STD, a forum that allows users to publicly share “stories, concerns, and questions” about “anything and everything STD related,” Alicia L. Nobles, PhD, of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, and associates wrote in a research letter published in JAMA.

Dr. Noble and associates conducted an analysis of all posts published to r/STD from the subreddit’s inception during November 2010–February 2019, a total of 16,979 posts. Three coauthors independently coded each post, recording whether or not a post requested a crowd diagnosis, and if so, whether that request was made to obtain a second opinion after a visit to a health care professional.

About 58% of posts requested a crowd diagnosis, 31% of which included an image of the physical signs. One-fifth of the requests for a crowd diagnosis were seeking a second opinion after a previous diagnosis by a health care professional. Nearly 90% of all crowd-diagnosis requests received at least one reply (mean responses, 1.7), with a median response time of 3.04 hours. About 80% of requests were answered in less than 1 day.

While crowd diagnoses do seem to be popular and have the benefits of anonymity, rapid response, and multiple opinions, the accuracy of crowd diagnoses is unknown given the limited information responders operate with and the potential lack of responder medical training, the study authors noted. Misdiagnosis could allow further disease transmission, and third parties viewing posts could incorrectly self-diagnose their own condition.

“Health care professionals could partner with social media outlets to promote the potential benefits of crowd diagnosis while suppressing potential harms, for example by having trained professionals respond to posts to better diagnose and make referrals to health care centers,” Dr. Nobles and associates concluded.

One coauthor reported receiving personal fees from Bloomberg and Good Analytics, and another reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health; no other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Nobles AL et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 5;322(17):1712-3.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Crowd-diagnosis requests of STDs are popular on a social media–based health forum.

Major finding: Nearly 60% of r/STD posts were a request for diagnosis, 87% of which received a reply (mean responses, 1.7; mean response time, 3.0 hours).

Study details: A review of 16,979 posts on the subreddit r/STD.

Disclosures: One coauthor reported receiving personal fees from Bloomberg and Good Analytics, and another reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health; no other disclosures were reported.Source: Nobles AL et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 5;322(17):1712-3.

Survey: Most physicians who treat STIs in their offices lack key injectable drugs

The majority of physicians surveyed who treat sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in their offices reported that they did not have on-site availability of the two primary injectable drugs for syphilis and gonorrhea, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This lack of drug availability for immediate treatment is significant because STIs are on the rise in the United States. The numbers of reported cases of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Treponema pallidum infections dramatically increased between 2013 and 2017, at 75% higher for gonorrhea and 153% higher for syphilis (primary and secondary), according to a research letter in the November issue of Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Optimal, same-day treatment of bacterial STIs with a highly effective regimen is critical for national STI control efforts and can help mitigate the development of drug resistance, the researchers stated. The recommended first-line treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea is intramuscular ceftriaxone (250 mg), and for primary and secondary syphilis, it’s intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (2.5 million units), instead of using oral antimicrobial drug alternatives, which have been known to facilitate the development of drug resistance.

William S. Pearson, PhD, of the CDC and colleagues examined the on-site availability of the two injectable therapeutic agents among physicians who treated STIs in their office. They used the 2016 Physician Induction File of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey to assess the number of physicians who treat patients with STIs and had injectable antimicrobial drugs available on site. A total of 1,030 physicians (46.2% unweighted response rate), which represents an estimated 330,581 physicians in the United States, completed the Physician Induction File in 2016.

In this survey, physicians who reported evaluating or treating patients for STIs were asked which antimicrobial drugs they had available on site for same-day management of gonorrhea and syphilis, including intramuscular ceftriaxone and penicillin G benzathine at the recommended doses.

The researchers used this information to determine national estimates of reported on-site, same-day availability for these antimicrobial drugs and stratified results by patient-centered medical homes (PCMH) designation and U.S. region. They used multiple logistic regression models to determine if PCMH designation and region were predictive of on-site availability of the two medications.

An estimated 45.2% (149,483) of office-based physicians indicated that they evaluate patients for STIs in their offices. Of these, 77.9% reported not having penicillin G benzathine available on site, and 56.1% reported not having ceftriaxone.

Geographic differences in drug availability were not statistically significant. In addition, physicians in offices not designated PCMHs were more likely than those in offices designated as PCMHs to report lacking on-site availability of ceftriaxone (odds ratio, 2.03) and penicillin G benzathine (OR, 3.20).

“The costs of obtaining and carrying these medications, as well as issues of storage and shelf-life, should be explored to determine if these factors are barriers. In addition, the implications of prescribing alternative treatments or delaying care in situations when medications are not readily available on site should be further explored. Mitigating the lack of medication availability to treat these infections will help public health officials stop the rise in STI disease,” the researchers concluded.

The authors are all employees of the CDC and did not provide other disclosures.

SOURCE: Pearson WS et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.3201/eid2511.190764.

The majority of physicians surveyed who treat sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in their offices reported that they did not have on-site availability of the two primary injectable drugs for syphilis and gonorrhea, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This lack of drug availability for immediate treatment is significant because STIs are on the rise in the United States. The numbers of reported cases of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Treponema pallidum infections dramatically increased between 2013 and 2017, at 75% higher for gonorrhea and 153% higher for syphilis (primary and secondary), according to a research letter in the November issue of Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Optimal, same-day treatment of bacterial STIs with a highly effective regimen is critical for national STI control efforts and can help mitigate the development of drug resistance, the researchers stated. The recommended first-line treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea is intramuscular ceftriaxone (250 mg), and for primary and secondary syphilis, it’s intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (2.5 million units), instead of using oral antimicrobial drug alternatives, which have been known to facilitate the development of drug resistance.

William S. Pearson, PhD, of the CDC and colleagues examined the on-site availability of the two injectable therapeutic agents among physicians who treated STIs in their office. They used the 2016 Physician Induction File of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey to assess the number of physicians who treat patients with STIs and had injectable antimicrobial drugs available on site. A total of 1,030 physicians (46.2% unweighted response rate), which represents an estimated 330,581 physicians in the United States, completed the Physician Induction File in 2016.

In this survey, physicians who reported evaluating or treating patients for STIs were asked which antimicrobial drugs they had available on site for same-day management of gonorrhea and syphilis, including intramuscular ceftriaxone and penicillin G benzathine at the recommended doses.

The researchers used this information to determine national estimates of reported on-site, same-day availability for these antimicrobial drugs and stratified results by patient-centered medical homes (PCMH) designation and U.S. region. They used multiple logistic regression models to determine if PCMH designation and region were predictive of on-site availability of the two medications.

An estimated 45.2% (149,483) of office-based physicians indicated that they evaluate patients for STIs in their offices. Of these, 77.9% reported not having penicillin G benzathine available on site, and 56.1% reported not having ceftriaxone.

Geographic differences in drug availability were not statistically significant. In addition, physicians in offices not designated PCMHs were more likely than those in offices designated as PCMHs to report lacking on-site availability of ceftriaxone (odds ratio, 2.03) and penicillin G benzathine (OR, 3.20).

“The costs of obtaining and carrying these medications, as well as issues of storage and shelf-life, should be explored to determine if these factors are barriers. In addition, the implications of prescribing alternative treatments or delaying care in situations when medications are not readily available on site should be further explored. Mitigating the lack of medication availability to treat these infections will help public health officials stop the rise in STI disease,” the researchers concluded.

The authors are all employees of the CDC and did not provide other disclosures.

SOURCE: Pearson WS et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.3201/eid2511.190764.

The majority of physicians surveyed who treat sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in their offices reported that they did not have on-site availability of the two primary injectable drugs for syphilis and gonorrhea, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This lack of drug availability for immediate treatment is significant because STIs are on the rise in the United States. The numbers of reported cases of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Treponema pallidum infections dramatically increased between 2013 and 2017, at 75% higher for gonorrhea and 153% higher for syphilis (primary and secondary), according to a research letter in the November issue of Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Optimal, same-day treatment of bacterial STIs with a highly effective regimen is critical for national STI control efforts and can help mitigate the development of drug resistance, the researchers stated. The recommended first-line treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea is intramuscular ceftriaxone (250 mg), and for primary and secondary syphilis, it’s intramuscular penicillin G benzathine (2.5 million units), instead of using oral antimicrobial drug alternatives, which have been known to facilitate the development of drug resistance.

William S. Pearson, PhD, of the CDC and colleagues examined the on-site availability of the two injectable therapeutic agents among physicians who treated STIs in their office. They used the 2016 Physician Induction File of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey to assess the number of physicians who treat patients with STIs and had injectable antimicrobial drugs available on site. A total of 1,030 physicians (46.2% unweighted response rate), which represents an estimated 330,581 physicians in the United States, completed the Physician Induction File in 2016.

In this survey, physicians who reported evaluating or treating patients for STIs were asked which antimicrobial drugs they had available on site for same-day management of gonorrhea and syphilis, including intramuscular ceftriaxone and penicillin G benzathine at the recommended doses.

The researchers used this information to determine national estimates of reported on-site, same-day availability for these antimicrobial drugs and stratified results by patient-centered medical homes (PCMH) designation and U.S. region. They used multiple logistic regression models to determine if PCMH designation and region were predictive of on-site availability of the two medications.

An estimated 45.2% (149,483) of office-based physicians indicated that they evaluate patients for STIs in their offices. Of these, 77.9% reported not having penicillin G benzathine available on site, and 56.1% reported not having ceftriaxone.

Geographic differences in drug availability were not statistically significant. In addition, physicians in offices not designated PCMHs were more likely than those in offices designated as PCMHs to report lacking on-site availability of ceftriaxone (odds ratio, 2.03) and penicillin G benzathine (OR, 3.20).

“The costs of obtaining and carrying these medications, as well as issues of storage and shelf-life, should be explored to determine if these factors are barriers. In addition, the implications of prescribing alternative treatments or delaying care in situations when medications are not readily available on site should be further explored. Mitigating the lack of medication availability to treat these infections will help public health officials stop the rise in STI disease,” the researchers concluded.

The authors are all employees of the CDC and did not provide other disclosures.

SOURCE: Pearson WS et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019. doi: 10.3201/eid2511.190764.

FROM EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Short-term statin use linked to risk of skin and soft tissue infections

according to a sequence symmetry analysis of prescription claims over a 10-year period reported in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

In the study, statin use for as little as 91 days was linked with elevated risks of SSTIs and diabetes. However, the increased risk of infection was seen in individuals who did and did not develop diabetes, wrote Humphrey Ko, of the school of pharmacy and biomedical sciences, Curtin University, Perth, Australia, and colleagues.

The current literature on the impact of statins on SSTIs is conflicted, they noted. Previous research shows that statins “may reduce the risk of community-acquired [Staphylococcus aureus] bacteremia and exert antibacterial effects against S. aureus,” and therefore may have potential for reducing SSTI risk “or evolve into promising novel treatments for SSTIs,” the researchers said; they noted, however, that other data show that statins may induce new-onset diabetes.

They examined prescription claims (for statins, antidiabetic medications, and antistaphylococcal antibiotics) from 2001 to 2011 from the Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs that included more than 228,000 veterans, war widows, and widowers. Prescriptions for antistaphylococcal antibiotics were used as a marker of SSTIs.

Overall, statins were significantly associated with an increased risk of SSTIs at 91 days (adjusted sequence ratio, 1.40). The risk of SSTIs from statin use was similar at 182 (ASR, 1.41) and 365 days (ASR, 1.40). In this case, the ASRs represent the incidence rate ratios of prescribing antibiotics in statin-exposed versus statin-nonexposed person-time.

Statins were associated with a significantly increased risk of new onset diabetes, but the SSTI risk was not significantly different between statin users with and without diabetes. Statin users who did not have diabetes had significant SSTI risks at 91, 182, and 365 days (ASR, 1.39, 1.41, and 1.37, respectively) and statin users with diabetes had similarly significant risks of SSTIs (ASR,1.43, 1.42, and 1.49, respectively).

In addition, socioeconomic status appeared to have no significant effect on the relationship between statin use, SSTIs, and diabetes, the researchers noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including the inability to account for patient compliance in taking the medications, a lack of dosage data to determine the impact of dosage on outcomes, and potential confounding by the presence of diabetes, they said. However, the results suggest that “it would seem prudent for clinicians to monitor blood glucose levels of statin users who are predisposed to diabetes, and be mindful of possible increased SSTI risks in such patients,” they concluded. Statins, they added, “may increase SSTI risk via direct or indirect mechanisms.”

More clinical trials are needed to confirm the mechanisms, and “to ascertain the effect of statins on gut dysbiosis, impaired bile acid metabolism, vitamin D levels, and cholesterol inhibition on skin function,” they wrote.

The study was supported in part by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, the Curtin Health Innovation Research Institute Biosciences Research Precinct Core Facility, and the School of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences (Curtin University). The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Ko H et al. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14077.

according to a sequence symmetry analysis of prescription claims over a 10-year period reported in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

In the study, statin use for as little as 91 days was linked with elevated risks of SSTIs and diabetes. However, the increased risk of infection was seen in individuals who did and did not develop diabetes, wrote Humphrey Ko, of the school of pharmacy and biomedical sciences, Curtin University, Perth, Australia, and colleagues.

The current literature on the impact of statins on SSTIs is conflicted, they noted. Previous research shows that statins “may reduce the risk of community-acquired [Staphylococcus aureus] bacteremia and exert antibacterial effects against S. aureus,” and therefore may have potential for reducing SSTI risk “or evolve into promising novel treatments for SSTIs,” the researchers said; they noted, however, that other data show that statins may induce new-onset diabetes.

They examined prescription claims (for statins, antidiabetic medications, and antistaphylococcal antibiotics) from 2001 to 2011 from the Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs that included more than 228,000 veterans, war widows, and widowers. Prescriptions for antistaphylococcal antibiotics were used as a marker of SSTIs.

Overall, statins were significantly associated with an increased risk of SSTIs at 91 days (adjusted sequence ratio, 1.40). The risk of SSTIs from statin use was similar at 182 (ASR, 1.41) and 365 days (ASR, 1.40). In this case, the ASRs represent the incidence rate ratios of prescribing antibiotics in statin-exposed versus statin-nonexposed person-time.

Statins were associated with a significantly increased risk of new onset diabetes, but the SSTI risk was not significantly different between statin users with and without diabetes. Statin users who did not have diabetes had significant SSTI risks at 91, 182, and 365 days (ASR, 1.39, 1.41, and 1.37, respectively) and statin users with diabetes had similarly significant risks of SSTIs (ASR,1.43, 1.42, and 1.49, respectively).

In addition, socioeconomic status appeared to have no significant effect on the relationship between statin use, SSTIs, and diabetes, the researchers noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including the inability to account for patient compliance in taking the medications, a lack of dosage data to determine the impact of dosage on outcomes, and potential confounding by the presence of diabetes, they said. However, the results suggest that “it would seem prudent for clinicians to monitor blood glucose levels of statin users who are predisposed to diabetes, and be mindful of possible increased SSTI risks in such patients,” they concluded. Statins, they added, “may increase SSTI risk via direct or indirect mechanisms.”

More clinical trials are needed to confirm the mechanisms, and “to ascertain the effect of statins on gut dysbiosis, impaired bile acid metabolism, vitamin D levels, and cholesterol inhibition on skin function,” they wrote.

The study was supported in part by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, the Curtin Health Innovation Research Institute Biosciences Research Precinct Core Facility, and the School of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences (Curtin University). The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Ko H et al. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14077.

according to a sequence symmetry analysis of prescription claims over a 10-year period reported in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

In the study, statin use for as little as 91 days was linked with elevated risks of SSTIs and diabetes. However, the increased risk of infection was seen in individuals who did and did not develop diabetes, wrote Humphrey Ko, of the school of pharmacy and biomedical sciences, Curtin University, Perth, Australia, and colleagues.

The current literature on the impact of statins on SSTIs is conflicted, they noted. Previous research shows that statins “may reduce the risk of community-acquired [Staphylococcus aureus] bacteremia and exert antibacterial effects against S. aureus,” and therefore may have potential for reducing SSTI risk “or evolve into promising novel treatments for SSTIs,” the researchers said; they noted, however, that other data show that statins may induce new-onset diabetes.

They examined prescription claims (for statins, antidiabetic medications, and antistaphylococcal antibiotics) from 2001 to 2011 from the Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs that included more than 228,000 veterans, war widows, and widowers. Prescriptions for antistaphylococcal antibiotics were used as a marker of SSTIs.

Overall, statins were significantly associated with an increased risk of SSTIs at 91 days (adjusted sequence ratio, 1.40). The risk of SSTIs from statin use was similar at 182 (ASR, 1.41) and 365 days (ASR, 1.40). In this case, the ASRs represent the incidence rate ratios of prescribing antibiotics in statin-exposed versus statin-nonexposed person-time.

Statins were associated with a significantly increased risk of new onset diabetes, but the SSTI risk was not significantly different between statin users with and without diabetes. Statin users who did not have diabetes had significant SSTI risks at 91, 182, and 365 days (ASR, 1.39, 1.41, and 1.37, respectively) and statin users with diabetes had similarly significant risks of SSTIs (ASR,1.43, 1.42, and 1.49, respectively).

In addition, socioeconomic status appeared to have no significant effect on the relationship between statin use, SSTIs, and diabetes, the researchers noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including the inability to account for patient compliance in taking the medications, a lack of dosage data to determine the impact of dosage on outcomes, and potential confounding by the presence of diabetes, they said. However, the results suggest that “it would seem prudent for clinicians to monitor blood glucose levels of statin users who are predisposed to diabetes, and be mindful of possible increased SSTI risks in such patients,” they concluded. Statins, they added, “may increase SSTI risk via direct or indirect mechanisms.”

More clinical trials are needed to confirm the mechanisms, and “to ascertain the effect of statins on gut dysbiosis, impaired bile acid metabolism, vitamin D levels, and cholesterol inhibition on skin function,” they wrote.

The study was supported in part by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, the Curtin Health Innovation Research Institute Biosciences Research Precinct Core Facility, and the School of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences (Curtin University). The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Ko H et al. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14077.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

ID Blog: The story of syphilis, part III

The tortured road to successful treatment

It is rare in this modern era for medicine to confront an infectious disease for which there is no cure. Today, there are comparatively few infectious diseases (in the developed world and in places where money is no object) for which medicine cannot offer at least a glimmer of hope to infected patients. Even at its most futile, modern medicine has achieved vast improvements in the efficacy of palliative care. But it wasn’t that long ago that HIV infection was a nearly inevitable death sentence from the complications of AIDS, with no available treatments. And however monstrous that suffering and death, which still continues in many areas of the developing world, it was decades rather than centuries before modern medicine came up with effective treatments. Recently, there is even significant hope on the Ebola virus front that curative treatments may soon become available.

Medicine has always been in the business of hope, even when true cures were not available. Today that hope is less often misplaced. But in previous centuries, the need to offer hope to – and perhaps to make money from – desperate patients was a hallmark of the doctor’s trade.

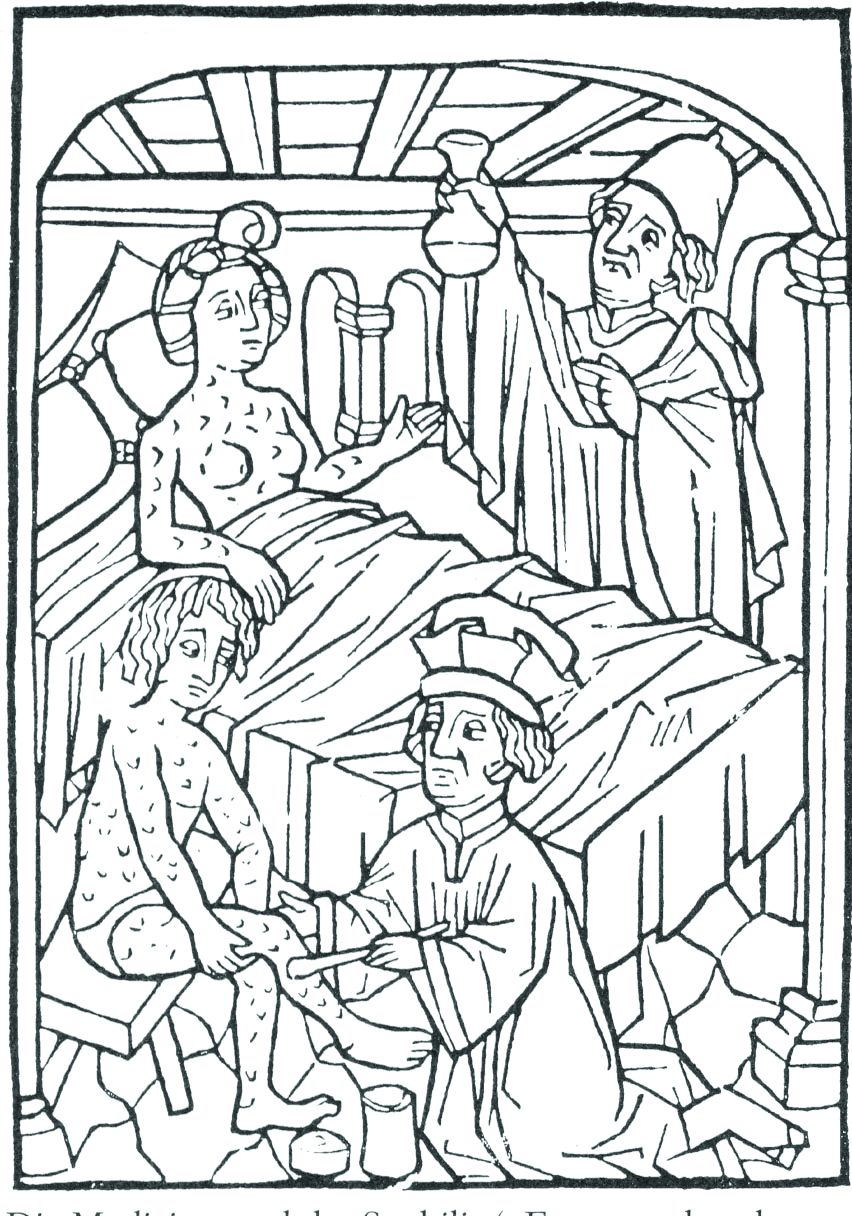

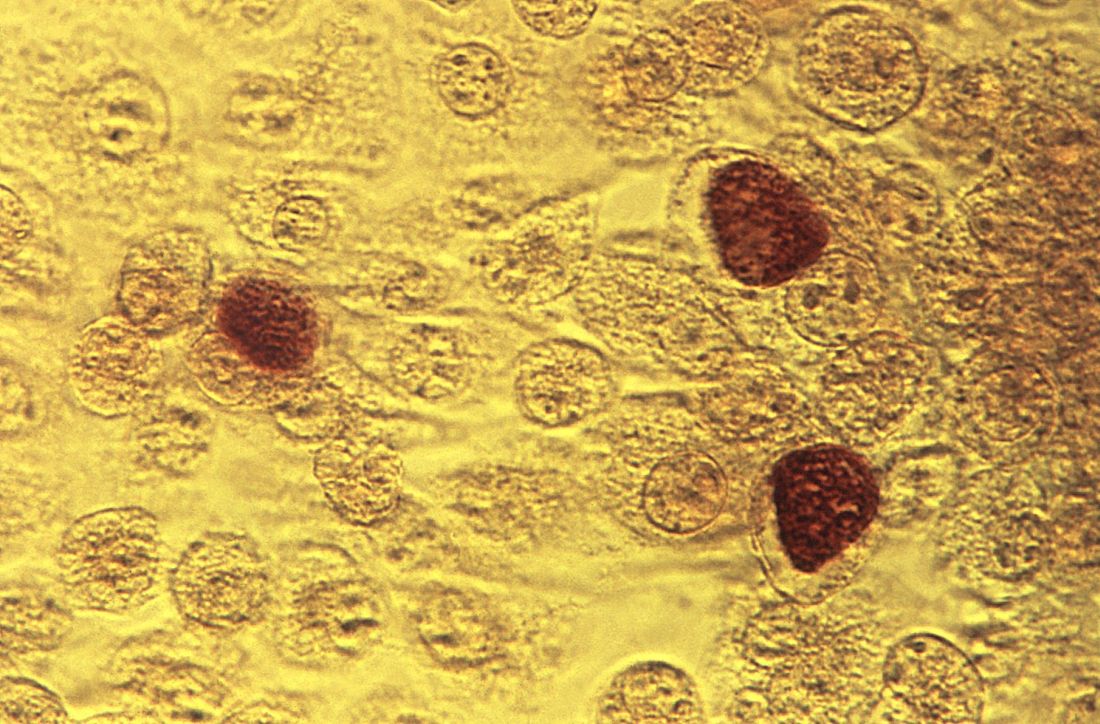

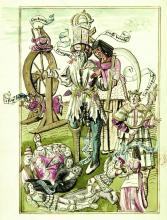

It was this need to give patients hope and for doctors to feel that they were being effective that led to some highly dubious and desperate efforts to cure syphilis throughout history. These efforts meant centuries of fruitless torture for countless patients until the rise of modern antibiotics.

For the most part, what we now look upon as horrors and insanity in treatment were the result of misguided scientific theories, half-baked folk wisdom, and the generally well-intentioned efforts of medical practitioners at a cure. There were the charlatans as well, seeking a quick buck from the truly hopeless.

However, the social stigma of syphilis as a venereal disease played a role in the courses of treatment.

By the 15th century, syphilis was recognized as being spread by sexual intercourse, and in a situation analogous with the early AIDS epidemic, “16th- and 17th-century writers and physicians were divided on the moral aspects of syphilis. Some thought it was a divine punishment for sin – and as such only harsh treatments would cure it – or that people with syphilis shouldn’t be treated at all.”

Mercury rising

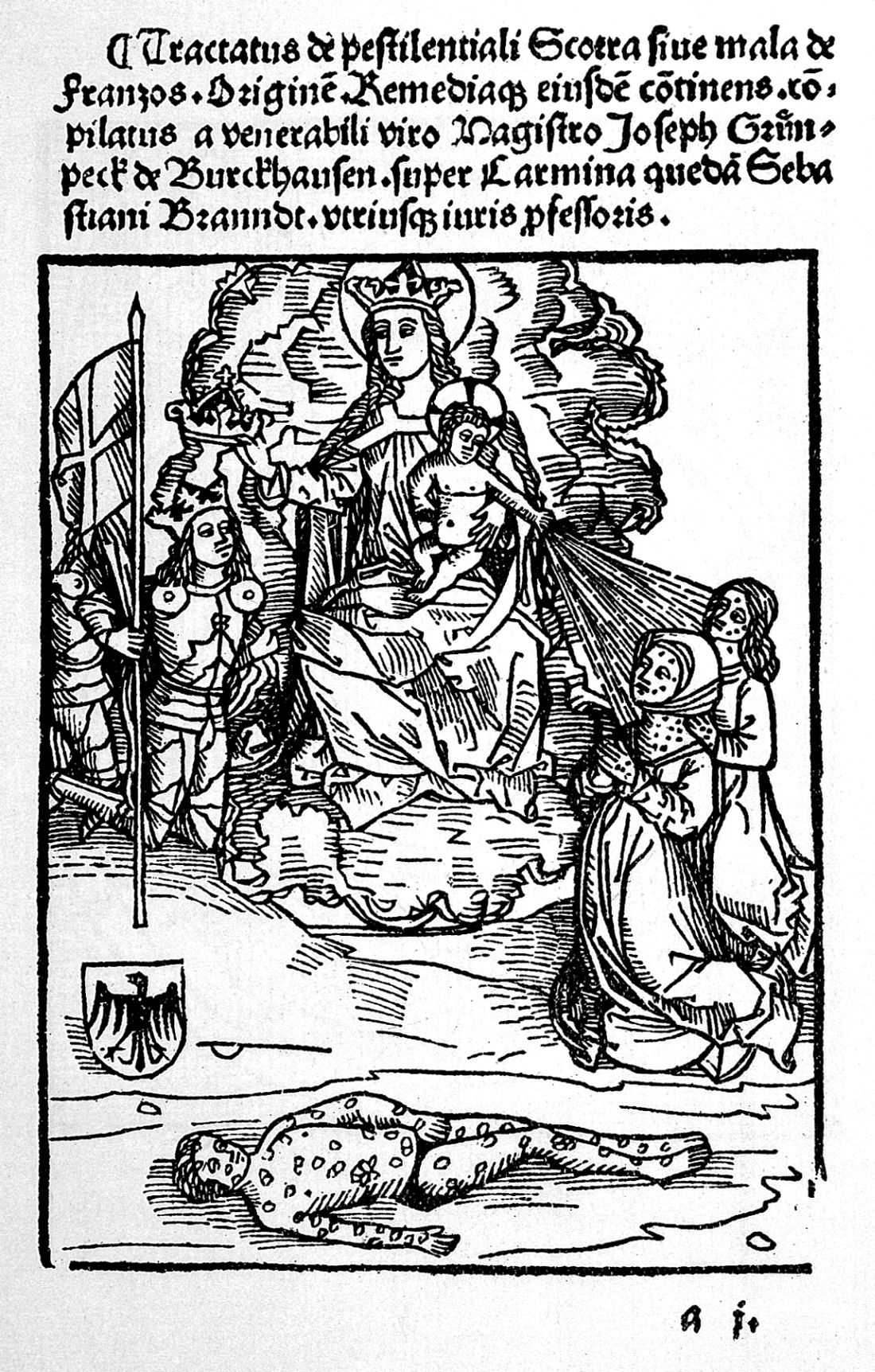

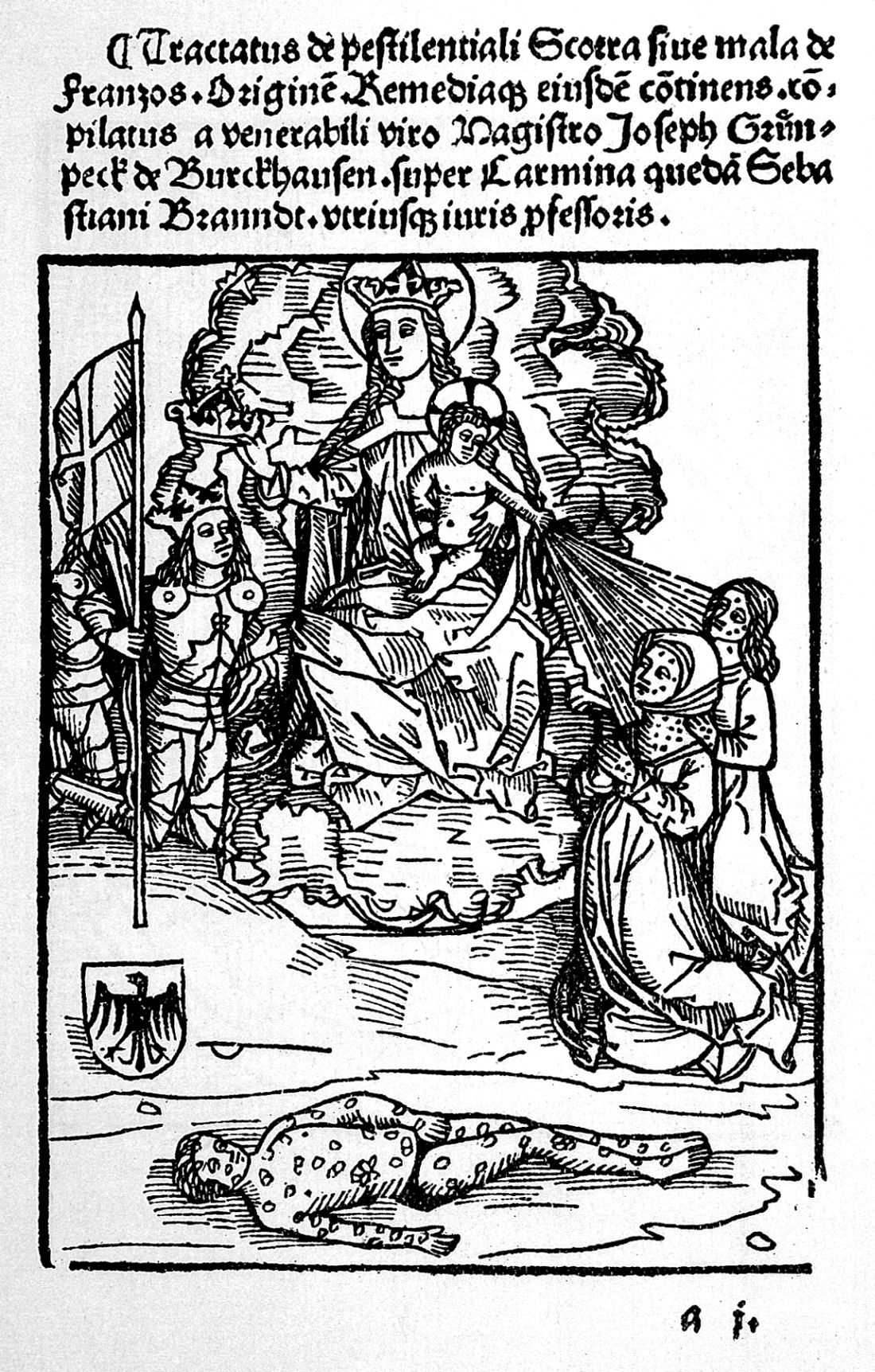

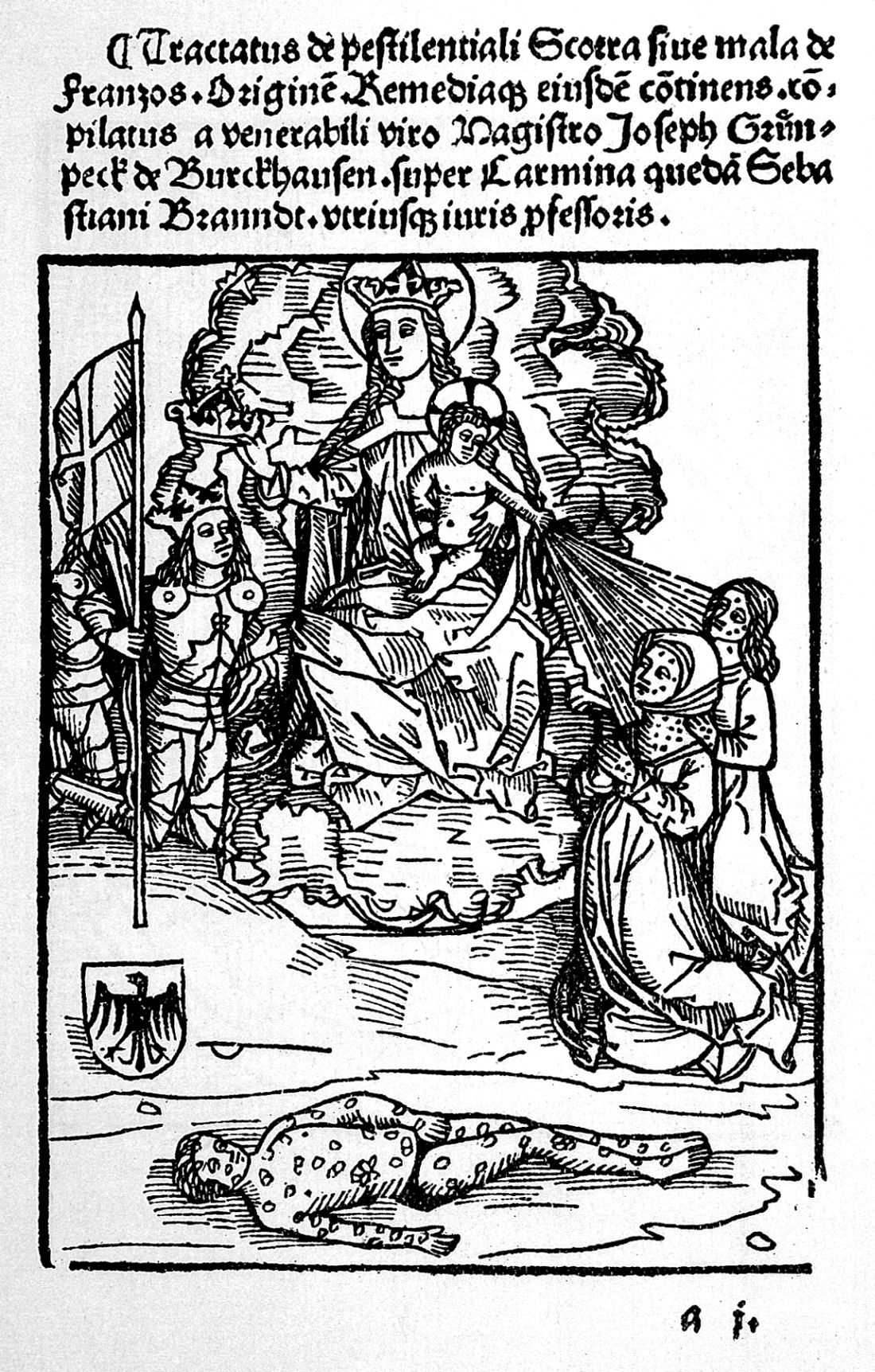

In its earliest manifestations, syphilis was considered untreatable. In 1496, Sebastian Brandt, wrote a poem entitled “De pestilentiali Scorra sive mala de Franzos” detailing the disease’s early spread across Europe and how doctors had no remedy for it.

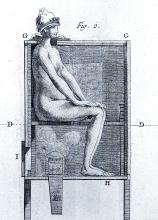

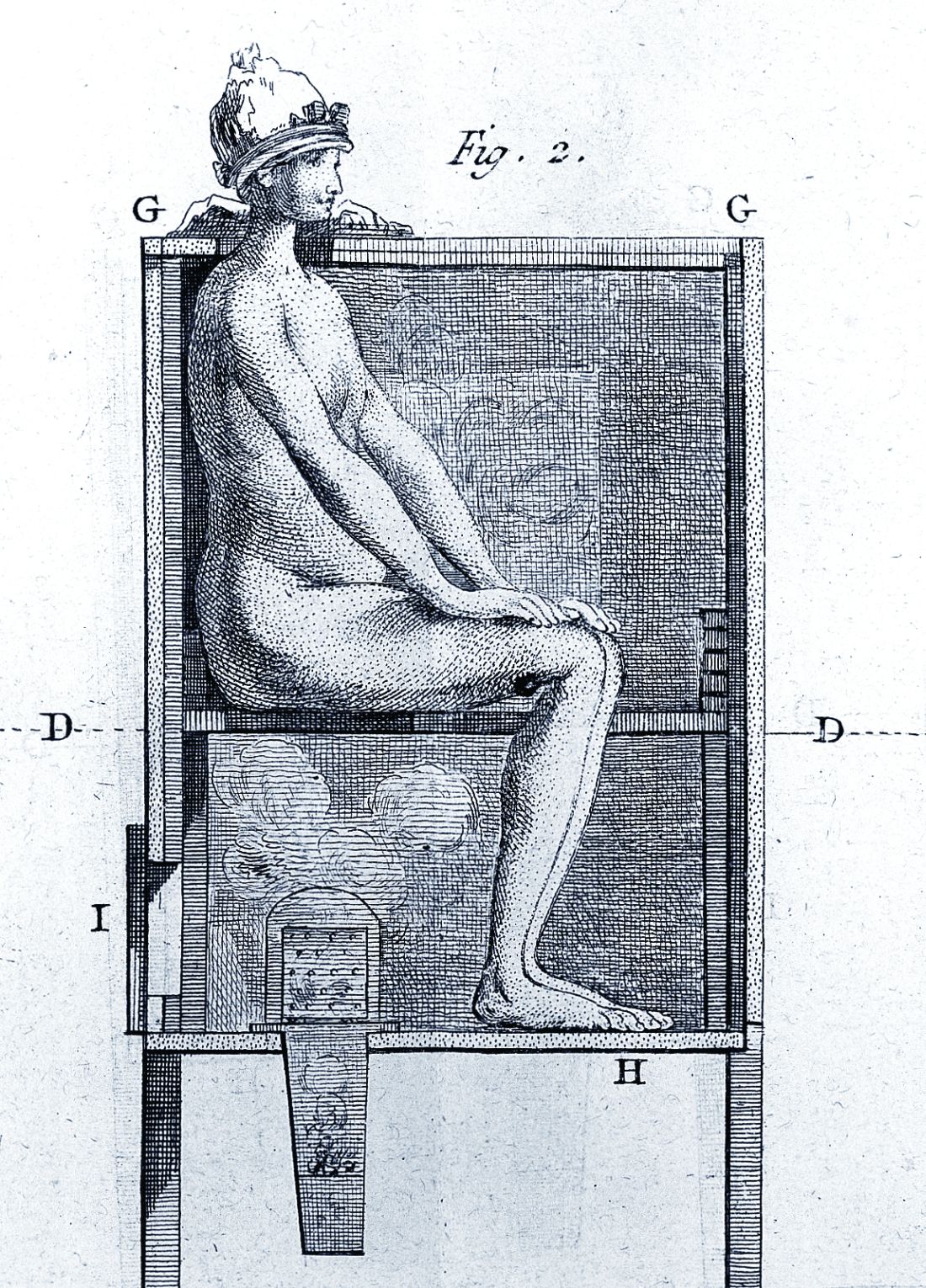

However, it wasn’t long before desperate physicians turned their quest for a cure to a reliable old standby treatment of the period – mercury, which had a history of being used for skin diseases. Mercury salves had been in use in the Arab world for leprosy and eczema, among other skin afflictions, and had been brought to Europe with the return of the medieval crusaders. Another way elemental mercury was administered was through the use of heated cinnabar (HgS), which gave off mercury vapors that could be absorbed by breathing and through the skin. In the 16th century, doctors would place a syphilis-infected individual inside an ovenlike chamber over pans of cinnabar, which were then heated at the person’s feet.

Oral mercury treatments were promoted by Paracelsus (1493?-1541), an alchemist and physician who prescribed calomel (HgCl), or mercury chloride, pills. Mercury treatment, administered at almost inevitably toxic doses, led to ulcerations of the lips, tongue, palate, and jaw; tooth loss; and fetid breath and excessive salivation. This last symptom was, in fact, considered the endpoint in mercury therapy for syphilis, which was “originally judged to be a copious secretion of saliva – ‘some few liters per diem.’ ” Even as recent as the late 19th century and early 20th century, syphilitic patients such as Oscar Wilde (whose teeth were blackened by the treatment), were prescribed calomel.

Looking to the “holy wood”

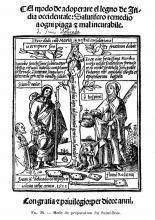

By 1519, an alternative treatment to mercury was available. In that year, Ulrich von Hutton, a German scholar who suffered from the “great pox,” described its treatment with guaiacum sanctum, or holy wood, in “De Morbo Gallico.” Four years later, despite such treatment, he was dead from the disease himself. But the lack of efficacy did not stop the faith that doctors placed in this botanical cure.

Holy wood was an herbal treatment derived from the bark of trees from the Guaiacum family. It was brought back on trading ships from the Caribbean and South America, the origin of syphilis’s foothold in Europe and the rest of the world. The use of holy wood matched a then-current theory that the cure to a disease could be found in the area from which it came. Other botanicals from around the world were also tried, but never came into routine use.

Guaiacum was the first treatment given to sufferers of syphilis in the Blatterhaus (pox hospital) in Augsburg after 1522, according to information from the archives at the Edward Worth Library in Dublin. The botanical therapy was given as a hot drink and followed by a sweating cure. Guaiacum extract acted as a sudorific, a compound which induces sweating when ingested. Even though the use of Guaiacum was initially popular, it was replaced almost exclusively by the use of mercury.

“Give me fever”

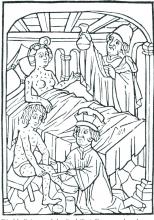

In the late 1800s, Julius Wagner von Jauregg (1857-1940), a Viennese neurologist, observed that Austrian army officers with neurosyphilis did not become partially paralyzed if they had also contracted malaria or relapsing fever. He initiated clinical trials in which he induced fever in syphilitics with tuberculin (1-10 mg) and observed in many the remissions their neuropsychiatric symptoms and signs. He also injected neurosyphilitic patients with a mild form of malaria to induce fever, which could then be suppressed with quinine treatment.

“Other physicians soon began using malariotherapy in uncontrolled studies of neurosyphilitics and reported clinical success rates of 33%-51% and only a 5% mortality. Persons with tabes dorsalis (the “wasting” paralysis of neurosyphilis) were hospitalized for 3 weeks of alternate-day fever therapy involving 5-hour long hot baths and extended periods wrapped in heavy blankets,” according to C.T. Ambrose, MD, of the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

A 1931 medical text summarizes in 35 studies involving 2,356 cases of general paresis treated with malaria and reported a 27.5% “full remission,” he added. A bacterial treatment developed in this period used a course of 18-23 injections of killed typhoid cells administered every 2-3 days in order to produce a fever of 103°–104°F. Animal studies of rabbits infected with syphilis showed that high temperatures could be curative.

Dr. Ambrose suggests that 16th-century syphilitics who had been subjected to mercury fumigation in ovenlike chambers endured severe sweating conditions and – for those who survived – the prolonged elevated body temperature (not the mercury) may have proved curative. Fever “was the common therapeutic denominator in the cinnabar-oven treatment, botanical sudorifics (guaiacum, China root), malarial infections (natural and iatrogenic), and bacterial (tuberculin) vaccine therapy.”

Prelude to modern antibiotics

German bacteriologist/immunologist Paul Ehrlich, MD, (1854-1915) investigated the use of atoxyl (sodium arsanilate) in syphilis, but the metallic drug had severe side effects, injuring the optic nerve and causing blindness. To overcome this problem, Ehrlich and his coworkers synthesized and tested related organic arsenicals. The antisyphilitic activity of arsphenamine (compound 606) was discovered by Sahachiro Hata, MD, (1879-1938) in 1909. This compound, known as Salvarsan, became “Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet,” for the treatment of syphilis in the 1910s, and it, and later, the less-toxic compound neoarsphenamine (compound 914) became mainstays of successful clinical treatment until the development and use of penicillin in the 1940s.

Selected sources

Ambrose, CT. Pre-antibiotic therapy of syphilis. NESSA J Infect Dis Immunology. 2016. 1(1);1-20.

Frith J. Syphilis: Its early history and treatment until penicillin and the debate on its origins. J Mil Veterans Health. 2012;20(4):49-58.

Tognotti B. The rise and fall of syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 2009 Jun;30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor in the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

The tortured road to successful treatment

The tortured road to successful treatment

It is rare in this modern era for medicine to confront an infectious disease for which there is no cure. Today, there are comparatively few infectious diseases (in the developed world and in places where money is no object) for which medicine cannot offer at least a glimmer of hope to infected patients. Even at its most futile, modern medicine has achieved vast improvements in the efficacy of palliative care. But it wasn’t that long ago that HIV infection was a nearly inevitable death sentence from the complications of AIDS, with no available treatments. And however monstrous that suffering and death, which still continues in many areas of the developing world, it was decades rather than centuries before modern medicine came up with effective treatments. Recently, there is even significant hope on the Ebola virus front that curative treatments may soon become available.

Medicine has always been in the business of hope, even when true cures were not available. Today that hope is less often misplaced. But in previous centuries, the need to offer hope to – and perhaps to make money from – desperate patients was a hallmark of the doctor’s trade.

It was this need to give patients hope and for doctors to feel that they were being effective that led to some highly dubious and desperate efforts to cure syphilis throughout history. These efforts meant centuries of fruitless torture for countless patients until the rise of modern antibiotics.

For the most part, what we now look upon as horrors and insanity in treatment were the result of misguided scientific theories, half-baked folk wisdom, and the generally well-intentioned efforts of medical practitioners at a cure. There were the charlatans as well, seeking a quick buck from the truly hopeless.

However, the social stigma of syphilis as a venereal disease played a role in the courses of treatment.

By the 15th century, syphilis was recognized as being spread by sexual intercourse, and in a situation analogous with the early AIDS epidemic, “16th- and 17th-century writers and physicians were divided on the moral aspects of syphilis. Some thought it was a divine punishment for sin – and as such only harsh treatments would cure it – or that people with syphilis shouldn’t be treated at all.”

Mercury rising

In its earliest manifestations, syphilis was considered untreatable. In 1496, Sebastian Brandt, wrote a poem entitled “De pestilentiali Scorra sive mala de Franzos” detailing the disease’s early spread across Europe and how doctors had no remedy for it.

However, it wasn’t long before desperate physicians turned their quest for a cure to a reliable old standby treatment of the period – mercury, which had a history of being used for skin diseases. Mercury salves had been in use in the Arab world for leprosy and eczema, among other skin afflictions, and had been brought to Europe with the return of the medieval crusaders. Another way elemental mercury was administered was through the use of heated cinnabar (HgS), which gave off mercury vapors that could be absorbed by breathing and through the skin. In the 16th century, doctors would place a syphilis-infected individual inside an ovenlike chamber over pans of cinnabar, which were then heated at the person’s feet.

Oral mercury treatments were promoted by Paracelsus (1493?-1541), an alchemist and physician who prescribed calomel (HgCl), or mercury chloride, pills. Mercury treatment, administered at almost inevitably toxic doses, led to ulcerations of the lips, tongue, palate, and jaw; tooth loss; and fetid breath and excessive salivation. This last symptom was, in fact, considered the endpoint in mercury therapy for syphilis, which was “originally judged to be a copious secretion of saliva – ‘some few liters per diem.’ ” Even as recent as the late 19th century and early 20th century, syphilitic patients such as Oscar Wilde (whose teeth were blackened by the treatment), were prescribed calomel.

Looking to the “holy wood”

By 1519, an alternative treatment to mercury was available. In that year, Ulrich von Hutton, a German scholar who suffered from the “great pox,” described its treatment with guaiacum sanctum, or holy wood, in “De Morbo Gallico.” Four years later, despite such treatment, he was dead from the disease himself. But the lack of efficacy did not stop the faith that doctors placed in this botanical cure.

Holy wood was an herbal treatment derived from the bark of trees from the Guaiacum family. It was brought back on trading ships from the Caribbean and South America, the origin of syphilis’s foothold in Europe and the rest of the world. The use of holy wood matched a then-current theory that the cure to a disease could be found in the area from which it came. Other botanicals from around the world were also tried, but never came into routine use.

Guaiacum was the first treatment given to sufferers of syphilis in the Blatterhaus (pox hospital) in Augsburg after 1522, according to information from the archives at the Edward Worth Library in Dublin. The botanical therapy was given as a hot drink and followed by a sweating cure. Guaiacum extract acted as a sudorific, a compound which induces sweating when ingested. Even though the use of Guaiacum was initially popular, it was replaced almost exclusively by the use of mercury.

“Give me fever”

In the late 1800s, Julius Wagner von Jauregg (1857-1940), a Viennese neurologist, observed that Austrian army officers with neurosyphilis did not become partially paralyzed if they had also contracted malaria or relapsing fever. He initiated clinical trials in which he induced fever in syphilitics with tuberculin (1-10 mg) and observed in many the remissions their neuropsychiatric symptoms and signs. He also injected neurosyphilitic patients with a mild form of malaria to induce fever, which could then be suppressed with quinine treatment.

“Other physicians soon began using malariotherapy in uncontrolled studies of neurosyphilitics and reported clinical success rates of 33%-51% and only a 5% mortality. Persons with tabes dorsalis (the “wasting” paralysis of neurosyphilis) were hospitalized for 3 weeks of alternate-day fever therapy involving 5-hour long hot baths and extended periods wrapped in heavy blankets,” according to C.T. Ambrose, MD, of the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

A 1931 medical text summarizes in 35 studies involving 2,356 cases of general paresis treated with malaria and reported a 27.5% “full remission,” he added. A bacterial treatment developed in this period used a course of 18-23 injections of killed typhoid cells administered every 2-3 days in order to produce a fever of 103°–104°F. Animal studies of rabbits infected with syphilis showed that high temperatures could be curative.

Dr. Ambrose suggests that 16th-century syphilitics who had been subjected to mercury fumigation in ovenlike chambers endured severe sweating conditions and – for those who survived – the prolonged elevated body temperature (not the mercury) may have proved curative. Fever “was the common therapeutic denominator in the cinnabar-oven treatment, botanical sudorifics (guaiacum, China root), malarial infections (natural and iatrogenic), and bacterial (tuberculin) vaccine therapy.”

Prelude to modern antibiotics

German bacteriologist/immunologist Paul Ehrlich, MD, (1854-1915) investigated the use of atoxyl (sodium arsanilate) in syphilis, but the metallic drug had severe side effects, injuring the optic nerve and causing blindness. To overcome this problem, Ehrlich and his coworkers synthesized and tested related organic arsenicals. The antisyphilitic activity of arsphenamine (compound 606) was discovered by Sahachiro Hata, MD, (1879-1938) in 1909. This compound, known as Salvarsan, became “Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet,” for the treatment of syphilis in the 1910s, and it, and later, the less-toxic compound neoarsphenamine (compound 914) became mainstays of successful clinical treatment until the development and use of penicillin in the 1940s.

Selected sources

Ambrose, CT. Pre-antibiotic therapy of syphilis. NESSA J Infect Dis Immunology. 2016. 1(1);1-20.

Frith J. Syphilis: Its early history and treatment until penicillin and the debate on its origins. J Mil Veterans Health. 2012;20(4):49-58.

Tognotti B. The rise and fall of syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 2009 Jun;30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor in the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

It is rare in this modern era for medicine to confront an infectious disease for which there is no cure. Today, there are comparatively few infectious diseases (in the developed world and in places where money is no object) for which medicine cannot offer at least a glimmer of hope to infected patients. Even at its most futile, modern medicine has achieved vast improvements in the efficacy of palliative care. But it wasn’t that long ago that HIV infection was a nearly inevitable death sentence from the complications of AIDS, with no available treatments. And however monstrous that suffering and death, which still continues in many areas of the developing world, it was decades rather than centuries before modern medicine came up with effective treatments. Recently, there is even significant hope on the Ebola virus front that curative treatments may soon become available.

Medicine has always been in the business of hope, even when true cures were not available. Today that hope is less often misplaced. But in previous centuries, the need to offer hope to – and perhaps to make money from – desperate patients was a hallmark of the doctor’s trade.

It was this need to give patients hope and for doctors to feel that they were being effective that led to some highly dubious and desperate efforts to cure syphilis throughout history. These efforts meant centuries of fruitless torture for countless patients until the rise of modern antibiotics.

For the most part, what we now look upon as horrors and insanity in treatment were the result of misguided scientific theories, half-baked folk wisdom, and the generally well-intentioned efforts of medical practitioners at a cure. There were the charlatans as well, seeking a quick buck from the truly hopeless.

However, the social stigma of syphilis as a venereal disease played a role in the courses of treatment.

By the 15th century, syphilis was recognized as being spread by sexual intercourse, and in a situation analogous with the early AIDS epidemic, “16th- and 17th-century writers and physicians were divided on the moral aspects of syphilis. Some thought it was a divine punishment for sin – and as such only harsh treatments would cure it – or that people with syphilis shouldn’t be treated at all.”

Mercury rising

In its earliest manifestations, syphilis was considered untreatable. In 1496, Sebastian Brandt, wrote a poem entitled “De pestilentiali Scorra sive mala de Franzos” detailing the disease’s early spread across Europe and how doctors had no remedy for it.

However, it wasn’t long before desperate physicians turned their quest for a cure to a reliable old standby treatment of the period – mercury, which had a history of being used for skin diseases. Mercury salves had been in use in the Arab world for leprosy and eczema, among other skin afflictions, and had been brought to Europe with the return of the medieval crusaders. Another way elemental mercury was administered was through the use of heated cinnabar (HgS), which gave off mercury vapors that could be absorbed by breathing and through the skin. In the 16th century, doctors would place a syphilis-infected individual inside an ovenlike chamber over pans of cinnabar, which were then heated at the person’s feet.

Oral mercury treatments were promoted by Paracelsus (1493?-1541), an alchemist and physician who prescribed calomel (HgCl), or mercury chloride, pills. Mercury treatment, administered at almost inevitably toxic doses, led to ulcerations of the lips, tongue, palate, and jaw; tooth loss; and fetid breath and excessive salivation. This last symptom was, in fact, considered the endpoint in mercury therapy for syphilis, which was “originally judged to be a copious secretion of saliva – ‘some few liters per diem.’ ” Even as recent as the late 19th century and early 20th century, syphilitic patients such as Oscar Wilde (whose teeth were blackened by the treatment), were prescribed calomel.

Looking to the “holy wood”

By 1519, an alternative treatment to mercury was available. In that year, Ulrich von Hutton, a German scholar who suffered from the “great pox,” described its treatment with guaiacum sanctum, or holy wood, in “De Morbo Gallico.” Four years later, despite such treatment, he was dead from the disease himself. But the lack of efficacy did not stop the faith that doctors placed in this botanical cure.

Holy wood was an herbal treatment derived from the bark of trees from the Guaiacum family. It was brought back on trading ships from the Caribbean and South America, the origin of syphilis’s foothold in Europe and the rest of the world. The use of holy wood matched a then-current theory that the cure to a disease could be found in the area from which it came. Other botanicals from around the world were also tried, but never came into routine use.

Guaiacum was the first treatment given to sufferers of syphilis in the Blatterhaus (pox hospital) in Augsburg after 1522, according to information from the archives at the Edward Worth Library in Dublin. The botanical therapy was given as a hot drink and followed by a sweating cure. Guaiacum extract acted as a sudorific, a compound which induces sweating when ingested. Even though the use of Guaiacum was initially popular, it was replaced almost exclusively by the use of mercury.

“Give me fever”

In the late 1800s, Julius Wagner von Jauregg (1857-1940), a Viennese neurologist, observed that Austrian army officers with neurosyphilis did not become partially paralyzed if they had also contracted malaria or relapsing fever. He initiated clinical trials in which he induced fever in syphilitics with tuberculin (1-10 mg) and observed in many the remissions their neuropsychiatric symptoms and signs. He also injected neurosyphilitic patients with a mild form of malaria to induce fever, which could then be suppressed with quinine treatment.

“Other physicians soon began using malariotherapy in uncontrolled studies of neurosyphilitics and reported clinical success rates of 33%-51% and only a 5% mortality. Persons with tabes dorsalis (the “wasting” paralysis of neurosyphilis) were hospitalized for 3 weeks of alternate-day fever therapy involving 5-hour long hot baths and extended periods wrapped in heavy blankets,” according to C.T. Ambrose, MD, of the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

A 1931 medical text summarizes in 35 studies involving 2,356 cases of general paresis treated with malaria and reported a 27.5% “full remission,” he added. A bacterial treatment developed in this period used a course of 18-23 injections of killed typhoid cells administered every 2-3 days in order to produce a fever of 103°–104°F. Animal studies of rabbits infected with syphilis showed that high temperatures could be curative.

Dr. Ambrose suggests that 16th-century syphilitics who had been subjected to mercury fumigation in ovenlike chambers endured severe sweating conditions and – for those who survived – the prolonged elevated body temperature (not the mercury) may have proved curative. Fever “was the common therapeutic denominator in the cinnabar-oven treatment, botanical sudorifics (guaiacum, China root), malarial infections (natural and iatrogenic), and bacterial (tuberculin) vaccine therapy.”

Prelude to modern antibiotics

German bacteriologist/immunologist Paul Ehrlich, MD, (1854-1915) investigated the use of atoxyl (sodium arsanilate) in syphilis, but the metallic drug had severe side effects, injuring the optic nerve and causing blindness. To overcome this problem, Ehrlich and his coworkers synthesized and tested related organic arsenicals. The antisyphilitic activity of arsphenamine (compound 606) was discovered by Sahachiro Hata, MD, (1879-1938) in 1909. This compound, known as Salvarsan, became “Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet,” for the treatment of syphilis in the 1910s, and it, and later, the less-toxic compound neoarsphenamine (compound 914) became mainstays of successful clinical treatment until the development and use of penicillin in the 1940s.

Selected sources

Ambrose, CT. Pre-antibiotic therapy of syphilis. NESSA J Infect Dis Immunology. 2016. 1(1);1-20.

Frith J. Syphilis: Its early history and treatment until penicillin and the debate on its origins. J Mil Veterans Health. 2012;20(4):49-58.

Tognotti B. The rise and fall of syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 2009 Jun;30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor in the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

Does this patient have bacterial conjunctivitis?

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.