User login

Botanical Briefs: Contact Dermatitis Induced by Western Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii)

Clinical Importance

Western poison ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii) is responsible for many of the cases of Toxicodendron contact dermatitis (TCD) reported in the western and northern United States. Toxicodendron plants cause more cases of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in North America than any other allergen1; 9 million Americans present to physician offices and 1.6 million present to emergency departments annually for ACD, emphasizing the notable medical burden of this condition.2,3 Exposure to urushiol, a plant resin containing potent allergens, precipitates this form of ACD.

An estimated 50% to 75% of adults in the United States demonstrate clinical sensitivity and exhibit ACD following contact with T rydbergii.4 Campers, hikers, firefighters, and forest workers often risk increased exposure through physical contact or aerosolized allergens in smoke. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the incidence of visits to US emergency departments for TCD nearly doubled from 2002 to 2012,5 which may be explained by atmospheric CO2 levels that both promote increased growth of Toxicodendron species and augment their toxicity.6

Cutaneous Manifestations

The clinical presentation of T rydbergii contact dermatitis is similar to other allergenic members of the Toxicodendron genus. Patients sensitive to urushiol typically develop a pruritic erythematous rash within 1 to 2 days of exposure (range, 5 hours to 15 days).7 Erythematous and edematous streaks initially manifest on the extremities and often progress to bullae and oozing papulovesicles. In early disease, patients also may display black lesions on or near the rash8 (so-called black-dot dermatitis) caused by oxidized urushiol deposited on the skin—an uncommon yet classic presentation of TCD. Generally, symptoms resolve without complications and with few sequalae, though hyperpigmentation or a secondary infection can develop on or near affected areas.9,10

Taxonomy

The Toxicodendron genus belongs to the Anacardiaceae family, which includes pistachios, mangos, and cashews, and causes more cases of ACD than every other plant combined.4 (Shelled pistachios and cashews do not possess cross-reacting allergens and should not worry consumers; mango skin does contain urushiol.)

Toxicodendron (formerly part of the Rhus genus) includes several species of poison oak, poison ivy, and poison sumac and can be found in shrubs (T rydbergii and Toxicodendron diversilobum), vines (Toxicodendron radicans and Toxicodendron pubescens), and trees (Toxicodendron vernix). In addition, Toxicodendron taxa can hybridize with other taxa in close geographic proximity to form morphologic intermediates. Some individual plants have features of multiple species.11

Etymology

The common name of T rydbergii—western poison ivy—misleads the public; the plant contains no poison that can cause death and does not grow as ivy by wrapping around trees, as T radicans and English ivy (Hedera helix) do. Its formal genus, Toxicodendron, means “poison tree” in Greek and was given its generic name by the English botanist Phillip Miller in 1768,12 which caused the renaming of Rhus rydbergii as T rydbergii. The species name honors Per Axel Rydberg, a 19th and 20th century Swedish-American botanist.

Distribution

Toxicodendron rydbergii grows in California and other states in the western half of the United States as well as the states bordering Canada and Mexico. In Canada, it reigns as the most dominant form of poison ivy.13 Hikers and campers find T rydbergii in a variety of areas, including roadsides, river bottoms, sandy shores, talus slopes, precipices, and floodplains.11 This taxon grows under a variety of conditions and in distinct regions, and it thrives in both full sun or shade.

Identifying Features

Toxicodendron rydbergii turns red earlier than most plants; early red summer leaves should serve as a warning sign to hikers from a distance (Figure 1). It displays trifoliate ovate leaves (ie, each leaf contains 3 leaflets) on a dwarf nonclimbing shrub (Figure 2). Although the plant shares common features with its cousin T radicans (eastern poison ivy), T rydbergii is easily distinguished by its thicker stems, absence of aerial rootlets (abundant in T radicans), and short (approximately 1 meter) height.4

Curly hairs occupy the underside of T rydbergii leaflets and along the midrib; leaflet margins appear lobed or rounded. Lenticels appear as small holes in the bark that turn gray in the cold and become brighter come spring.13

The plant bears glabrous long petioles (leaf stems) and densely grouped clusters of yellow flowers. In autumn, the globose fruit—formed in clusters between each twig and leaf petiole (known as an axillary position)—change from yellow-green to tan (Figure 3). When urushiol exudes from damaged leaflets or other plant parts, it oxidizes on exposure to air and creates hardened black deposits on the plant. Even when grown in garden pots, T rydbergii maintains its distinguishing features.11

Dermatitis-Inducing Plant Parts

All parts of T rydbergii including leaves, stems, roots, and fruit contain the allergenic sap throughout the year.14 A person must damage or bruise the plant for urushiol to be released and produce its allergenic effects; softly brushing against undamaged plants typically does not induce dermatitis.4

Pathophysiology of Urushiol

Urushiol, a pale yellow, oily mixture of organic compounds conserved throughout all Toxicodendron species, contains highly allergenic alkyl catechols. These catechols possess hydroxyl groups at positions 1 and 2 on a benzene ring; the hydrocarbon side chain of poison ivies (typically 15–carbon atoms long) attaches at position 3.15 The catechols and the aliphatic side chain contribute to the plant’s antigenic and dermatitis-inducing properties.16

The high lipophilicity of urushiol allows for rapid and unforgiving absorption into the skin, notwithstanding attempts to wash it off. Upon direct contact, catechols of urushiol penetrate the epidermis and become oxidized to quinone intermediates that bind to antigen-presenting cells in the epidermis and dermis. Epidermal Langerhans cells and dermal macrophages internalize and present the antigen to CD4+ T cells in nearby lymph nodes. This sequence results in production of inflammatory mediators, clonal expansion of T-effector and T-memory cells specific to the allergenic catechols, and an ensuing cytotoxic response against epidermal cells and the dermal vasculature. Keratinocytes and monocytes mediate the inflammatory response by releasing other cytokines.4,17

Sensitization to urushiol generally occurs at 8 to 14 years of age; therefore, infants have lower susceptibility to dermatitis upon contact with T rydbergii.18 Most animals do not experience sensitization upon contact; in fact, birds and forest animals consume the urushiol-rich fruit of T rydbergii without harm.3

Prevention and Treatment

Toxicodendron dermatitis typically lasts 1 to 3 weeks but can remain for as long as 6 weeks without treatment.19 Recognition and physical avoidance of the plant provides the most promising preventive strategy. Immediate rinsing with soap and water can prevent TCD by breaking down urushiol and its allergenic components; however, this is an option for only a short time, as the skin absorbs 50% of urushiol within 10 minutes after contact.20 Nevertheless, patients must seize the earliest opportunity to wash off the affected area and remove any residual urushiol. Patients must be cautious when removing and washing clothing to prevent further contact.

Most health care providers treat TCD with a corticosteroid to reduce inflammation and intense pruritus. A high-potency topical corticosteroid (eg, clobetasol) may prove effective in providing early therapeutic relief in mild disease.21 A short course of a systemic steroid quickly and effectively quenches intense itching and should not be limited to what the clinician considers severe disease. Do not underestimate the patient’s symptoms with this eruption.

Prednisone dosing begins at 1 mg/kg daily and is then tapered slowly over 2 weeks (no shorter a time) for an optimal treatment course of 15 days.22 Prescribing an inadequate dosage and course of a corticosteroid leaves the patient susceptible to rebound dermatitis—and loss of trust in their provider.

Intramuscular injection of the long-acting corticosteroid triamcinolone acetonide with rapid-onset betamethasone provides rapid relief and fewer adverse effects than an oral corticosteroid.22 Despite the long-standing use of sedating oral antihistamines by clinicians, these drugs provide no benefit for pruritus or sleep because the histamine does not cause the itching of TCD, and antihistamines disrupt normal sleep architecture.23-25

Patients can consider several over-the-counter products that have varying degrees of efficacy.4,26 The few products for which prospective studies support their use include Tecnu (Tec Laboraties Inc), Zanfel (RhusTox), and the well-known soaps Dial (Henkel Corporation) and Goop (Critzas Industries, Inc).27,28

Aside from treating the direct effects of TCD, clinicians also must take note of any look for signs of secondary infection and occasionally should consider supplementing treatment with an antibiotic.

- Lofgran T, Mahabal GD. Toxicodendron toxicity. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated May 16, 2023. Accessed December 23, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557866/

- The Lewin Group. The Burden of Skin Diseases 2005. Society for Investigative Dermatology and American Academy of Dermatology Association; 2005:37-40. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://www.lewin.com/content/dam/Lewin/Resources/Site_Sections/Publications/april2005skindisease.pdf

- Monroe J. Toxicodendron contact dermatitis: a case report and brief review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(9 Suppl 1):S29-S34.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128. doi:10.1580/pr31-05.1

- Fretwell S. Poison ivy cases on the rise. The State. Updated May 15,2017. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://www.thestate.com/news/local/article150403932.html

- Mohan JE, Ziska LH, Schlesinger WH, et al. Biomass and toxicity responses of poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) to elevated atmospheric CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9086-9089. doi:10.1073/pnas.0602392103

- Williams JV, Light J, Marks JG Jr. Individual variations in allergic contact dermatitis from urushiol. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1002-1003. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.8.1002

- Kurlan JG, Lucky AW. Black spot poison ivy: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:246-249. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.114295

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak/sumac. part II: specific features. Cutis. 1996;58:22-24.

- Brook I, Frazier EH, Yeager JK. Microbiology of infected poison ivy dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:943-946. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03475.x

- Gillis WT. The systematics and ecology of poison-ivy and the poison-oaks (Toxicodendron, Anacardiaceae). Rhodora. 1971;73:370-443.

- Reveal JL. Typification of six Philip Miller names of temperate North American Toxicodendron (Anacardiaceae) with proposals (999-1000) to reject T. crenatum and T. volubile. TAXON. 1991;40:333-335. doi:10.2307/1222994

- Guin JD, Gillis WT, Beaman JH. Recognizing the Toxicodendrons (poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:99-114. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70014-8

- Lee NP, Arriola ER. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis. West J Med. 1999;171:354-355.

- Marks JG Jr, Anderson BE, DeLeo VA, eds. Contact and Occupational Dermatology. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Ltd; 2016.

- Dawson CR. The chemistry of poison ivy. Trans N Y Acad Sci. 1956;18:427-443. doi:10.1111/j.2164-0947.1956.tb00465.x

- Kalish RS. Recent developments in the pathogenesis of allergic contact dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1558-1563.

- Fisher AA, Mitchell J. Toxicodendron plants and spices. In: Rietschel RL, Fowler JF Jr. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. 4th ed. Williams & Wilkins; 1995:461-523.

- Labib A, Yosipovitch G. Itchy Toxicodendron plant dermatitis. Allergies. 2022;2:16-22. doi:10.3390/allergies2010002

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak dermatitis part I: prevention—soap and water, topical barriers, hyposensitization. Cutis. 1996;57:384-386.

- Kim Y, Flamm A, ElSohly MA, et al. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis: what is known and what is new? 2019;30:183-190. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000472

- Prok L, McGovern T. Poison ivy (Toxicodendron) dermatitis. UpToDate. Updated October 16, 2023. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/poison-ivy-toxicodendron-dermatitis

- Klein PA, Clark RA. An evidence-based review of the efficacy of antihistamines in relieving pruritus in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1522-1525. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.12.1522

- He A, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. An assessment of the use of antihistamines in the management of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:92-96. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.077

- van Zuuren EJ, Apfelbacher CJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. No high level evidence to support the use of oral H1 antihistamines as monotherapy for eczema: a summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Syst Rev. 2014;3:25. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-25

- Neill BC, Neill JA, Brauker J, et al. Postexposure prevention of Toxicodendron dermatitis by early forceful unidirectional washing with liquid dishwashing soap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:E25. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.081

- Stibich AS, Yagan M, Sharma V, et al. Cost-effective post-exposure prevention of poison ivy dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:515-518. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00003.x

- Davila A, Laurora M, Fulton J, et al. A new topical agent, Zanfel, ameliorates urushiol-induced Toxicodendron allergic contact dermatitis [abstract]. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:S98.

Clinical Importance

Western poison ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii) is responsible for many of the cases of Toxicodendron contact dermatitis (TCD) reported in the western and northern United States. Toxicodendron plants cause more cases of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in North America than any other allergen1; 9 million Americans present to physician offices and 1.6 million present to emergency departments annually for ACD, emphasizing the notable medical burden of this condition.2,3 Exposure to urushiol, a plant resin containing potent allergens, precipitates this form of ACD.

An estimated 50% to 75% of adults in the United States demonstrate clinical sensitivity and exhibit ACD following contact with T rydbergii.4 Campers, hikers, firefighters, and forest workers often risk increased exposure through physical contact or aerosolized allergens in smoke. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the incidence of visits to US emergency departments for TCD nearly doubled from 2002 to 2012,5 which may be explained by atmospheric CO2 levels that both promote increased growth of Toxicodendron species and augment their toxicity.6

Cutaneous Manifestations

The clinical presentation of T rydbergii contact dermatitis is similar to other allergenic members of the Toxicodendron genus. Patients sensitive to urushiol typically develop a pruritic erythematous rash within 1 to 2 days of exposure (range, 5 hours to 15 days).7 Erythematous and edematous streaks initially manifest on the extremities and often progress to bullae and oozing papulovesicles. In early disease, patients also may display black lesions on or near the rash8 (so-called black-dot dermatitis) caused by oxidized urushiol deposited on the skin—an uncommon yet classic presentation of TCD. Generally, symptoms resolve without complications and with few sequalae, though hyperpigmentation or a secondary infection can develop on or near affected areas.9,10

Taxonomy

The Toxicodendron genus belongs to the Anacardiaceae family, which includes pistachios, mangos, and cashews, and causes more cases of ACD than every other plant combined.4 (Shelled pistachios and cashews do not possess cross-reacting allergens and should not worry consumers; mango skin does contain urushiol.)

Toxicodendron (formerly part of the Rhus genus) includes several species of poison oak, poison ivy, and poison sumac and can be found in shrubs (T rydbergii and Toxicodendron diversilobum), vines (Toxicodendron radicans and Toxicodendron pubescens), and trees (Toxicodendron vernix). In addition, Toxicodendron taxa can hybridize with other taxa in close geographic proximity to form morphologic intermediates. Some individual plants have features of multiple species.11

Etymology

The common name of T rydbergii—western poison ivy—misleads the public; the plant contains no poison that can cause death and does not grow as ivy by wrapping around trees, as T radicans and English ivy (Hedera helix) do. Its formal genus, Toxicodendron, means “poison tree” in Greek and was given its generic name by the English botanist Phillip Miller in 1768,12 which caused the renaming of Rhus rydbergii as T rydbergii. The species name honors Per Axel Rydberg, a 19th and 20th century Swedish-American botanist.

Distribution

Toxicodendron rydbergii grows in California and other states in the western half of the United States as well as the states bordering Canada and Mexico. In Canada, it reigns as the most dominant form of poison ivy.13 Hikers and campers find T rydbergii in a variety of areas, including roadsides, river bottoms, sandy shores, talus slopes, precipices, and floodplains.11 This taxon grows under a variety of conditions and in distinct regions, and it thrives in both full sun or shade.

Identifying Features

Toxicodendron rydbergii turns red earlier than most plants; early red summer leaves should serve as a warning sign to hikers from a distance (Figure 1). It displays trifoliate ovate leaves (ie, each leaf contains 3 leaflets) on a dwarf nonclimbing shrub (Figure 2). Although the plant shares common features with its cousin T radicans (eastern poison ivy), T rydbergii is easily distinguished by its thicker stems, absence of aerial rootlets (abundant in T radicans), and short (approximately 1 meter) height.4

Curly hairs occupy the underside of T rydbergii leaflets and along the midrib; leaflet margins appear lobed or rounded. Lenticels appear as small holes in the bark that turn gray in the cold and become brighter come spring.13

The plant bears glabrous long petioles (leaf stems) and densely grouped clusters of yellow flowers. In autumn, the globose fruit—formed in clusters between each twig and leaf petiole (known as an axillary position)—change from yellow-green to tan (Figure 3). When urushiol exudes from damaged leaflets or other plant parts, it oxidizes on exposure to air and creates hardened black deposits on the plant. Even when grown in garden pots, T rydbergii maintains its distinguishing features.11

Dermatitis-Inducing Plant Parts

All parts of T rydbergii including leaves, stems, roots, and fruit contain the allergenic sap throughout the year.14 A person must damage or bruise the plant for urushiol to be released and produce its allergenic effects; softly brushing against undamaged plants typically does not induce dermatitis.4

Pathophysiology of Urushiol

Urushiol, a pale yellow, oily mixture of organic compounds conserved throughout all Toxicodendron species, contains highly allergenic alkyl catechols. These catechols possess hydroxyl groups at positions 1 and 2 on a benzene ring; the hydrocarbon side chain of poison ivies (typically 15–carbon atoms long) attaches at position 3.15 The catechols and the aliphatic side chain contribute to the plant’s antigenic and dermatitis-inducing properties.16

The high lipophilicity of urushiol allows for rapid and unforgiving absorption into the skin, notwithstanding attempts to wash it off. Upon direct contact, catechols of urushiol penetrate the epidermis and become oxidized to quinone intermediates that bind to antigen-presenting cells in the epidermis and dermis. Epidermal Langerhans cells and dermal macrophages internalize and present the antigen to CD4+ T cells in nearby lymph nodes. This sequence results in production of inflammatory mediators, clonal expansion of T-effector and T-memory cells specific to the allergenic catechols, and an ensuing cytotoxic response against epidermal cells and the dermal vasculature. Keratinocytes and monocytes mediate the inflammatory response by releasing other cytokines.4,17

Sensitization to urushiol generally occurs at 8 to 14 years of age; therefore, infants have lower susceptibility to dermatitis upon contact with T rydbergii.18 Most animals do not experience sensitization upon contact; in fact, birds and forest animals consume the urushiol-rich fruit of T rydbergii without harm.3

Prevention and Treatment

Toxicodendron dermatitis typically lasts 1 to 3 weeks but can remain for as long as 6 weeks without treatment.19 Recognition and physical avoidance of the plant provides the most promising preventive strategy. Immediate rinsing with soap and water can prevent TCD by breaking down urushiol and its allergenic components; however, this is an option for only a short time, as the skin absorbs 50% of urushiol within 10 minutes after contact.20 Nevertheless, patients must seize the earliest opportunity to wash off the affected area and remove any residual urushiol. Patients must be cautious when removing and washing clothing to prevent further contact.

Most health care providers treat TCD with a corticosteroid to reduce inflammation and intense pruritus. A high-potency topical corticosteroid (eg, clobetasol) may prove effective in providing early therapeutic relief in mild disease.21 A short course of a systemic steroid quickly and effectively quenches intense itching and should not be limited to what the clinician considers severe disease. Do not underestimate the patient’s symptoms with this eruption.

Prednisone dosing begins at 1 mg/kg daily and is then tapered slowly over 2 weeks (no shorter a time) for an optimal treatment course of 15 days.22 Prescribing an inadequate dosage and course of a corticosteroid leaves the patient susceptible to rebound dermatitis—and loss of trust in their provider.

Intramuscular injection of the long-acting corticosteroid triamcinolone acetonide with rapid-onset betamethasone provides rapid relief and fewer adverse effects than an oral corticosteroid.22 Despite the long-standing use of sedating oral antihistamines by clinicians, these drugs provide no benefit for pruritus or sleep because the histamine does not cause the itching of TCD, and antihistamines disrupt normal sleep architecture.23-25

Patients can consider several over-the-counter products that have varying degrees of efficacy.4,26 The few products for which prospective studies support their use include Tecnu (Tec Laboraties Inc), Zanfel (RhusTox), and the well-known soaps Dial (Henkel Corporation) and Goop (Critzas Industries, Inc).27,28

Aside from treating the direct effects of TCD, clinicians also must take note of any look for signs of secondary infection and occasionally should consider supplementing treatment with an antibiotic.

Clinical Importance

Western poison ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii) is responsible for many of the cases of Toxicodendron contact dermatitis (TCD) reported in the western and northern United States. Toxicodendron plants cause more cases of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in North America than any other allergen1; 9 million Americans present to physician offices and 1.6 million present to emergency departments annually for ACD, emphasizing the notable medical burden of this condition.2,3 Exposure to urushiol, a plant resin containing potent allergens, precipitates this form of ACD.

An estimated 50% to 75% of adults in the United States demonstrate clinical sensitivity and exhibit ACD following contact with T rydbergii.4 Campers, hikers, firefighters, and forest workers often risk increased exposure through physical contact or aerosolized allergens in smoke. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the incidence of visits to US emergency departments for TCD nearly doubled from 2002 to 2012,5 which may be explained by atmospheric CO2 levels that both promote increased growth of Toxicodendron species and augment their toxicity.6

Cutaneous Manifestations

The clinical presentation of T rydbergii contact dermatitis is similar to other allergenic members of the Toxicodendron genus. Patients sensitive to urushiol typically develop a pruritic erythematous rash within 1 to 2 days of exposure (range, 5 hours to 15 days).7 Erythematous and edematous streaks initially manifest on the extremities and often progress to bullae and oozing papulovesicles. In early disease, patients also may display black lesions on or near the rash8 (so-called black-dot dermatitis) caused by oxidized urushiol deposited on the skin—an uncommon yet classic presentation of TCD. Generally, symptoms resolve without complications and with few sequalae, though hyperpigmentation or a secondary infection can develop on or near affected areas.9,10

Taxonomy

The Toxicodendron genus belongs to the Anacardiaceae family, which includes pistachios, mangos, and cashews, and causes more cases of ACD than every other plant combined.4 (Shelled pistachios and cashews do not possess cross-reacting allergens and should not worry consumers; mango skin does contain urushiol.)

Toxicodendron (formerly part of the Rhus genus) includes several species of poison oak, poison ivy, and poison sumac and can be found in shrubs (T rydbergii and Toxicodendron diversilobum), vines (Toxicodendron radicans and Toxicodendron pubescens), and trees (Toxicodendron vernix). In addition, Toxicodendron taxa can hybridize with other taxa in close geographic proximity to form morphologic intermediates. Some individual plants have features of multiple species.11

Etymology

The common name of T rydbergii—western poison ivy—misleads the public; the plant contains no poison that can cause death and does not grow as ivy by wrapping around trees, as T radicans and English ivy (Hedera helix) do. Its formal genus, Toxicodendron, means “poison tree” in Greek and was given its generic name by the English botanist Phillip Miller in 1768,12 which caused the renaming of Rhus rydbergii as T rydbergii. The species name honors Per Axel Rydberg, a 19th and 20th century Swedish-American botanist.

Distribution

Toxicodendron rydbergii grows in California and other states in the western half of the United States as well as the states bordering Canada and Mexico. In Canada, it reigns as the most dominant form of poison ivy.13 Hikers and campers find T rydbergii in a variety of areas, including roadsides, river bottoms, sandy shores, talus slopes, precipices, and floodplains.11 This taxon grows under a variety of conditions and in distinct regions, and it thrives in both full sun or shade.

Identifying Features

Toxicodendron rydbergii turns red earlier than most plants; early red summer leaves should serve as a warning sign to hikers from a distance (Figure 1). It displays trifoliate ovate leaves (ie, each leaf contains 3 leaflets) on a dwarf nonclimbing shrub (Figure 2). Although the plant shares common features with its cousin T radicans (eastern poison ivy), T rydbergii is easily distinguished by its thicker stems, absence of aerial rootlets (abundant in T radicans), and short (approximately 1 meter) height.4

Curly hairs occupy the underside of T rydbergii leaflets and along the midrib; leaflet margins appear lobed or rounded. Lenticels appear as small holes in the bark that turn gray in the cold and become brighter come spring.13

The plant bears glabrous long petioles (leaf stems) and densely grouped clusters of yellow flowers. In autumn, the globose fruit—formed in clusters between each twig and leaf petiole (known as an axillary position)—change from yellow-green to tan (Figure 3). When urushiol exudes from damaged leaflets or other plant parts, it oxidizes on exposure to air and creates hardened black deposits on the plant. Even when grown in garden pots, T rydbergii maintains its distinguishing features.11

Dermatitis-Inducing Plant Parts

All parts of T rydbergii including leaves, stems, roots, and fruit contain the allergenic sap throughout the year.14 A person must damage or bruise the plant for urushiol to be released and produce its allergenic effects; softly brushing against undamaged plants typically does not induce dermatitis.4

Pathophysiology of Urushiol

Urushiol, a pale yellow, oily mixture of organic compounds conserved throughout all Toxicodendron species, contains highly allergenic alkyl catechols. These catechols possess hydroxyl groups at positions 1 and 2 on a benzene ring; the hydrocarbon side chain of poison ivies (typically 15–carbon atoms long) attaches at position 3.15 The catechols and the aliphatic side chain contribute to the plant’s antigenic and dermatitis-inducing properties.16

The high lipophilicity of urushiol allows for rapid and unforgiving absorption into the skin, notwithstanding attempts to wash it off. Upon direct contact, catechols of urushiol penetrate the epidermis and become oxidized to quinone intermediates that bind to antigen-presenting cells in the epidermis and dermis. Epidermal Langerhans cells and dermal macrophages internalize and present the antigen to CD4+ T cells in nearby lymph nodes. This sequence results in production of inflammatory mediators, clonal expansion of T-effector and T-memory cells specific to the allergenic catechols, and an ensuing cytotoxic response against epidermal cells and the dermal vasculature. Keratinocytes and monocytes mediate the inflammatory response by releasing other cytokines.4,17

Sensitization to urushiol generally occurs at 8 to 14 years of age; therefore, infants have lower susceptibility to dermatitis upon contact with T rydbergii.18 Most animals do not experience sensitization upon contact; in fact, birds and forest animals consume the urushiol-rich fruit of T rydbergii without harm.3

Prevention and Treatment

Toxicodendron dermatitis typically lasts 1 to 3 weeks but can remain for as long as 6 weeks without treatment.19 Recognition and physical avoidance of the plant provides the most promising preventive strategy. Immediate rinsing with soap and water can prevent TCD by breaking down urushiol and its allergenic components; however, this is an option for only a short time, as the skin absorbs 50% of urushiol within 10 minutes after contact.20 Nevertheless, patients must seize the earliest opportunity to wash off the affected area and remove any residual urushiol. Patients must be cautious when removing and washing clothing to prevent further contact.

Most health care providers treat TCD with a corticosteroid to reduce inflammation and intense pruritus. A high-potency topical corticosteroid (eg, clobetasol) may prove effective in providing early therapeutic relief in mild disease.21 A short course of a systemic steroid quickly and effectively quenches intense itching and should not be limited to what the clinician considers severe disease. Do not underestimate the patient’s symptoms with this eruption.

Prednisone dosing begins at 1 mg/kg daily and is then tapered slowly over 2 weeks (no shorter a time) for an optimal treatment course of 15 days.22 Prescribing an inadequate dosage and course of a corticosteroid leaves the patient susceptible to rebound dermatitis—and loss of trust in their provider.

Intramuscular injection of the long-acting corticosteroid triamcinolone acetonide with rapid-onset betamethasone provides rapid relief and fewer adverse effects than an oral corticosteroid.22 Despite the long-standing use of sedating oral antihistamines by clinicians, these drugs provide no benefit for pruritus or sleep because the histamine does not cause the itching of TCD, and antihistamines disrupt normal sleep architecture.23-25

Patients can consider several over-the-counter products that have varying degrees of efficacy.4,26 The few products for which prospective studies support their use include Tecnu (Tec Laboraties Inc), Zanfel (RhusTox), and the well-known soaps Dial (Henkel Corporation) and Goop (Critzas Industries, Inc).27,28

Aside from treating the direct effects of TCD, clinicians also must take note of any look for signs of secondary infection and occasionally should consider supplementing treatment with an antibiotic.

- Lofgran T, Mahabal GD. Toxicodendron toxicity. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated May 16, 2023. Accessed December 23, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557866/

- The Lewin Group. The Burden of Skin Diseases 2005. Society for Investigative Dermatology and American Academy of Dermatology Association; 2005:37-40. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://www.lewin.com/content/dam/Lewin/Resources/Site_Sections/Publications/april2005skindisease.pdf

- Monroe J. Toxicodendron contact dermatitis: a case report and brief review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(9 Suppl 1):S29-S34.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128. doi:10.1580/pr31-05.1

- Fretwell S. Poison ivy cases on the rise. The State. Updated May 15,2017. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://www.thestate.com/news/local/article150403932.html

- Mohan JE, Ziska LH, Schlesinger WH, et al. Biomass and toxicity responses of poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) to elevated atmospheric CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9086-9089. doi:10.1073/pnas.0602392103

- Williams JV, Light J, Marks JG Jr. Individual variations in allergic contact dermatitis from urushiol. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1002-1003. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.8.1002

- Kurlan JG, Lucky AW. Black spot poison ivy: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:246-249. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.114295

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak/sumac. part II: specific features. Cutis. 1996;58:22-24.

- Brook I, Frazier EH, Yeager JK. Microbiology of infected poison ivy dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:943-946. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03475.x

- Gillis WT. The systematics and ecology of poison-ivy and the poison-oaks (Toxicodendron, Anacardiaceae). Rhodora. 1971;73:370-443.

- Reveal JL. Typification of six Philip Miller names of temperate North American Toxicodendron (Anacardiaceae) with proposals (999-1000) to reject T. crenatum and T. volubile. TAXON. 1991;40:333-335. doi:10.2307/1222994

- Guin JD, Gillis WT, Beaman JH. Recognizing the Toxicodendrons (poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:99-114. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70014-8

- Lee NP, Arriola ER. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis. West J Med. 1999;171:354-355.

- Marks JG Jr, Anderson BE, DeLeo VA, eds. Contact and Occupational Dermatology. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Ltd; 2016.

- Dawson CR. The chemistry of poison ivy. Trans N Y Acad Sci. 1956;18:427-443. doi:10.1111/j.2164-0947.1956.tb00465.x

- Kalish RS. Recent developments in the pathogenesis of allergic contact dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1558-1563.

- Fisher AA, Mitchell J. Toxicodendron plants and spices. In: Rietschel RL, Fowler JF Jr. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. 4th ed. Williams & Wilkins; 1995:461-523.

- Labib A, Yosipovitch G. Itchy Toxicodendron plant dermatitis. Allergies. 2022;2:16-22. doi:10.3390/allergies2010002

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak dermatitis part I: prevention—soap and water, topical barriers, hyposensitization. Cutis. 1996;57:384-386.

- Kim Y, Flamm A, ElSohly MA, et al. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis: what is known and what is new? 2019;30:183-190. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000472

- Prok L, McGovern T. Poison ivy (Toxicodendron) dermatitis. UpToDate. Updated October 16, 2023. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/poison-ivy-toxicodendron-dermatitis

- Klein PA, Clark RA. An evidence-based review of the efficacy of antihistamines in relieving pruritus in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1522-1525. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.12.1522

- He A, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. An assessment of the use of antihistamines in the management of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:92-96. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.077

- van Zuuren EJ, Apfelbacher CJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. No high level evidence to support the use of oral H1 antihistamines as monotherapy for eczema: a summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Syst Rev. 2014;3:25. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-25

- Neill BC, Neill JA, Brauker J, et al. Postexposure prevention of Toxicodendron dermatitis by early forceful unidirectional washing with liquid dishwashing soap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:E25. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.081

- Stibich AS, Yagan M, Sharma V, et al. Cost-effective post-exposure prevention of poison ivy dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:515-518. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00003.x

- Davila A, Laurora M, Fulton J, et al. A new topical agent, Zanfel, ameliorates urushiol-induced Toxicodendron allergic contact dermatitis [abstract]. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:S98.

- Lofgran T, Mahabal GD. Toxicodendron toxicity. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated May 16, 2023. Accessed December 23, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557866/

- The Lewin Group. The Burden of Skin Diseases 2005. Society for Investigative Dermatology and American Academy of Dermatology Association; 2005:37-40. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://www.lewin.com/content/dam/Lewin/Resources/Site_Sections/Publications/april2005skindisease.pdf

- Monroe J. Toxicodendron contact dermatitis: a case report and brief review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(9 Suppl 1):S29-S34.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128. doi:10.1580/pr31-05.1

- Fretwell S. Poison ivy cases on the rise. The State. Updated May 15,2017. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://www.thestate.com/news/local/article150403932.html

- Mohan JE, Ziska LH, Schlesinger WH, et al. Biomass and toxicity responses of poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) to elevated atmospheric CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9086-9089. doi:10.1073/pnas.0602392103

- Williams JV, Light J, Marks JG Jr. Individual variations in allergic contact dermatitis from urushiol. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1002-1003. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.8.1002

- Kurlan JG, Lucky AW. Black spot poison ivy: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:246-249. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.114295

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak/sumac. part II: specific features. Cutis. 1996;58:22-24.

- Brook I, Frazier EH, Yeager JK. Microbiology of infected poison ivy dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:943-946. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03475.x

- Gillis WT. The systematics and ecology of poison-ivy and the poison-oaks (Toxicodendron, Anacardiaceae). Rhodora. 1971;73:370-443.

- Reveal JL. Typification of six Philip Miller names of temperate North American Toxicodendron (Anacardiaceae) with proposals (999-1000) to reject T. crenatum and T. volubile. TAXON. 1991;40:333-335. doi:10.2307/1222994

- Guin JD, Gillis WT, Beaman JH. Recognizing the Toxicodendrons (poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:99-114. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70014-8

- Lee NP, Arriola ER. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis. West J Med. 1999;171:354-355.

- Marks JG Jr, Anderson BE, DeLeo VA, eds. Contact and Occupational Dermatology. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Ltd; 2016.

- Dawson CR. The chemistry of poison ivy. Trans N Y Acad Sci. 1956;18:427-443. doi:10.1111/j.2164-0947.1956.tb00465.x

- Kalish RS. Recent developments in the pathogenesis of allergic contact dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1558-1563.

- Fisher AA, Mitchell J. Toxicodendron plants and spices. In: Rietschel RL, Fowler JF Jr. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. 4th ed. Williams & Wilkins; 1995:461-523.

- Labib A, Yosipovitch G. Itchy Toxicodendron plant dermatitis. Allergies. 2022;2:16-22. doi:10.3390/allergies2010002

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak dermatitis part I: prevention—soap and water, topical barriers, hyposensitization. Cutis. 1996;57:384-386.

- Kim Y, Flamm A, ElSohly MA, et al. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis: what is known and what is new? 2019;30:183-190. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000472

- Prok L, McGovern T. Poison ivy (Toxicodendron) dermatitis. UpToDate. Updated October 16, 2023. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/poison-ivy-toxicodendron-dermatitis

- Klein PA, Clark RA. An evidence-based review of the efficacy of antihistamines in relieving pruritus in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1522-1525. doi:10.1001/archderm.135.12.1522

- He A, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. An assessment of the use of antihistamines in the management of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:92-96. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.077

- van Zuuren EJ, Apfelbacher CJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. No high level evidence to support the use of oral H1 antihistamines as monotherapy for eczema: a summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Syst Rev. 2014;3:25. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-25

- Neill BC, Neill JA, Brauker J, et al. Postexposure prevention of Toxicodendron dermatitis by early forceful unidirectional washing with liquid dishwashing soap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:E25. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.081

- Stibich AS, Yagan M, Sharma V, et al. Cost-effective post-exposure prevention of poison ivy dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:515-518. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00003.x

- Davila A, Laurora M, Fulton J, et al. A new topical agent, Zanfel, ameliorates urushiol-induced Toxicodendron allergic contact dermatitis [abstract]. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:S98.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Western poison ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii) accounts for many of the cases of Toxicodendron contact dermatitis (TCD) in the western and northern United States. Individuals in these regions should be educated on how to identify T rydbergii to avoid TCD.

- Dermatologists should include TCD in the differential diagnosis when a patient presents with an erythematous pruritic rash in a linear pattern with sharp borders.

- Most patients who experience intense itching and pain from TCD benefit greatly from prompt treatment with an oral or intramuscular corticosteroid. Topical steroids rarely provide relief; oral antihistamines provide no benefit.

Multiple New-Onset Pyogenic Granulomas During Treatment With Paclitaxel and Ramucirumab

To the Editor:

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor that clinically is characterized as a small eruptive friable papule.1 Lesions typically are solitary and most commonly occur in children but also are associated with pregnancy; trauma to the skin or mucosa; and use of certain medications such as isotretinoin, capecitabine, vemurafenib, or indinavir.1 Numerous antineoplastic medications have been associated with the development of solitary PGs, including the taxane mitotic inhibitor paclitaxel (PTX) and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) monoclonal antibody ramucirumab.2 We report a case of multiple PGs in a patient undergoing treatment with PTX and ramucirumab.

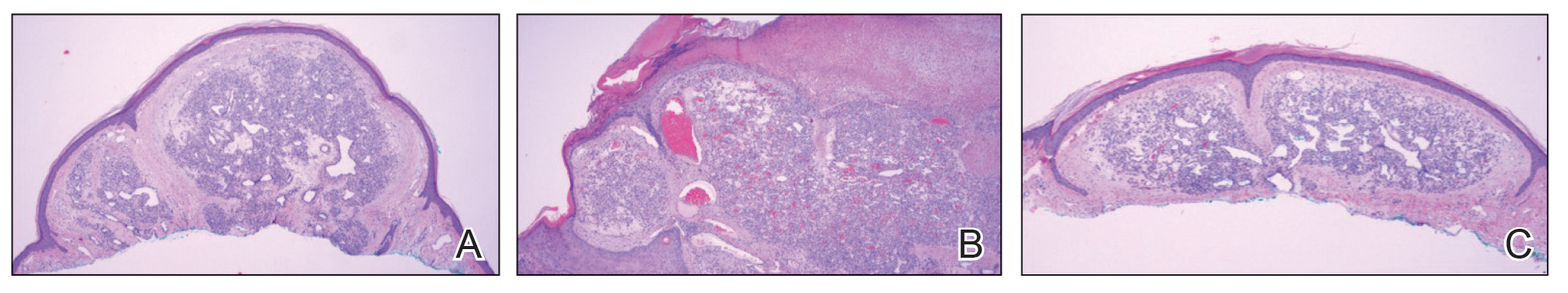

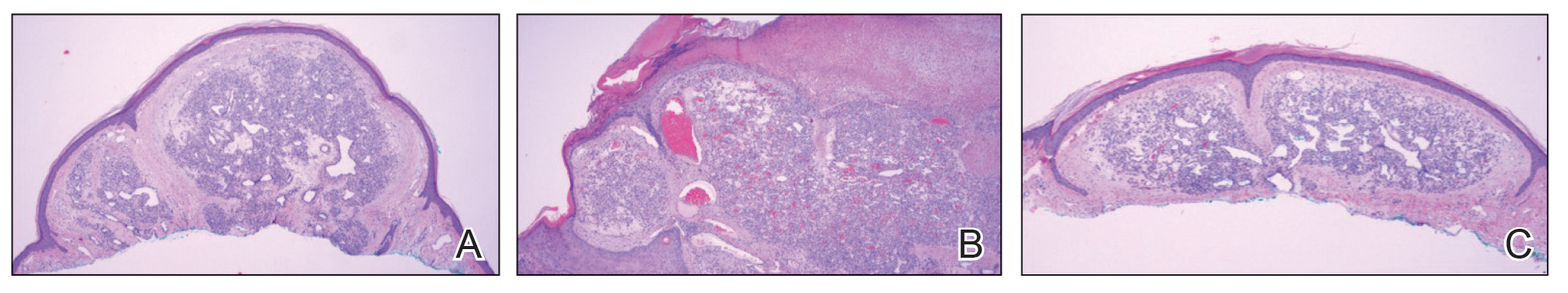

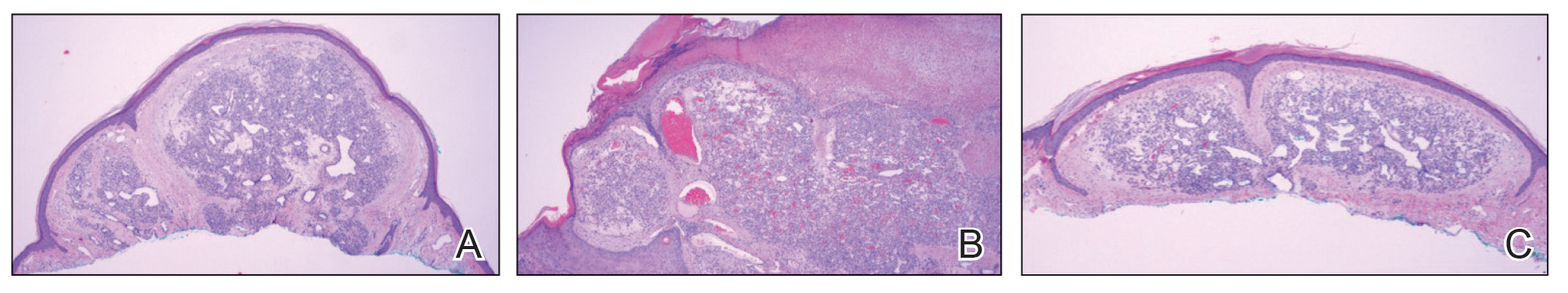

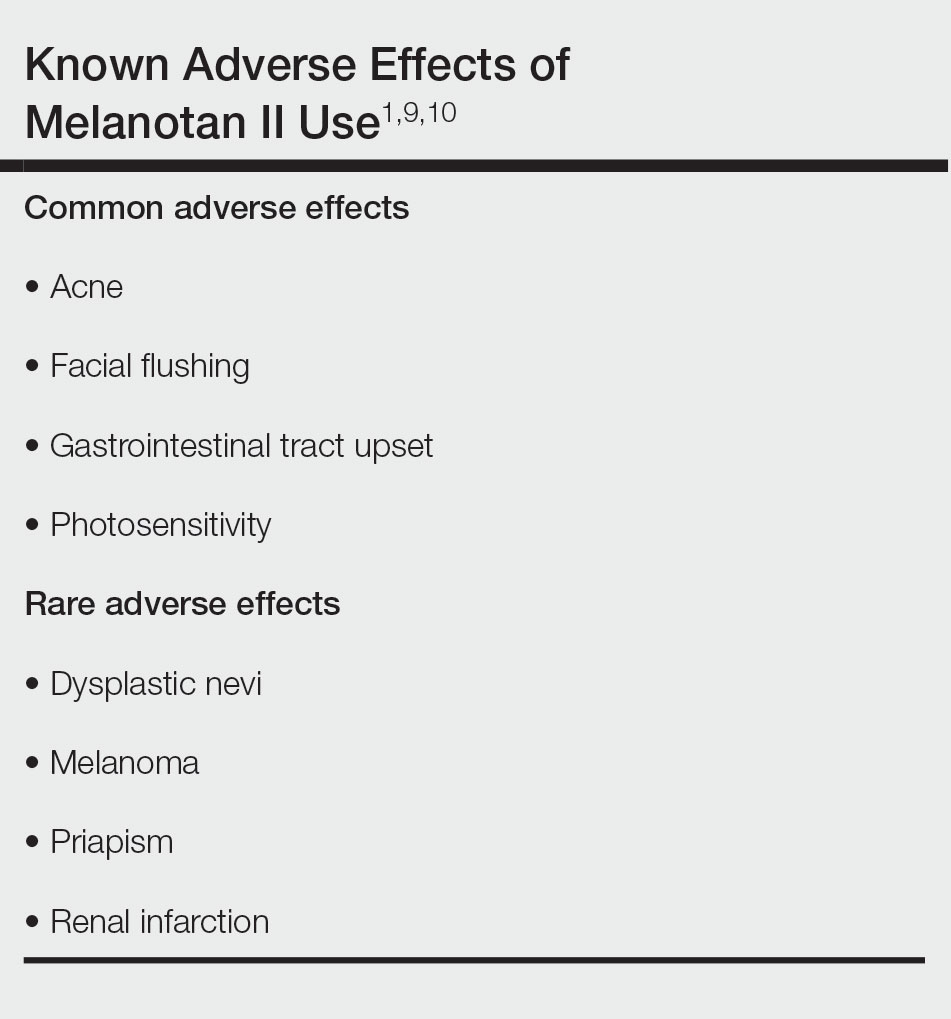

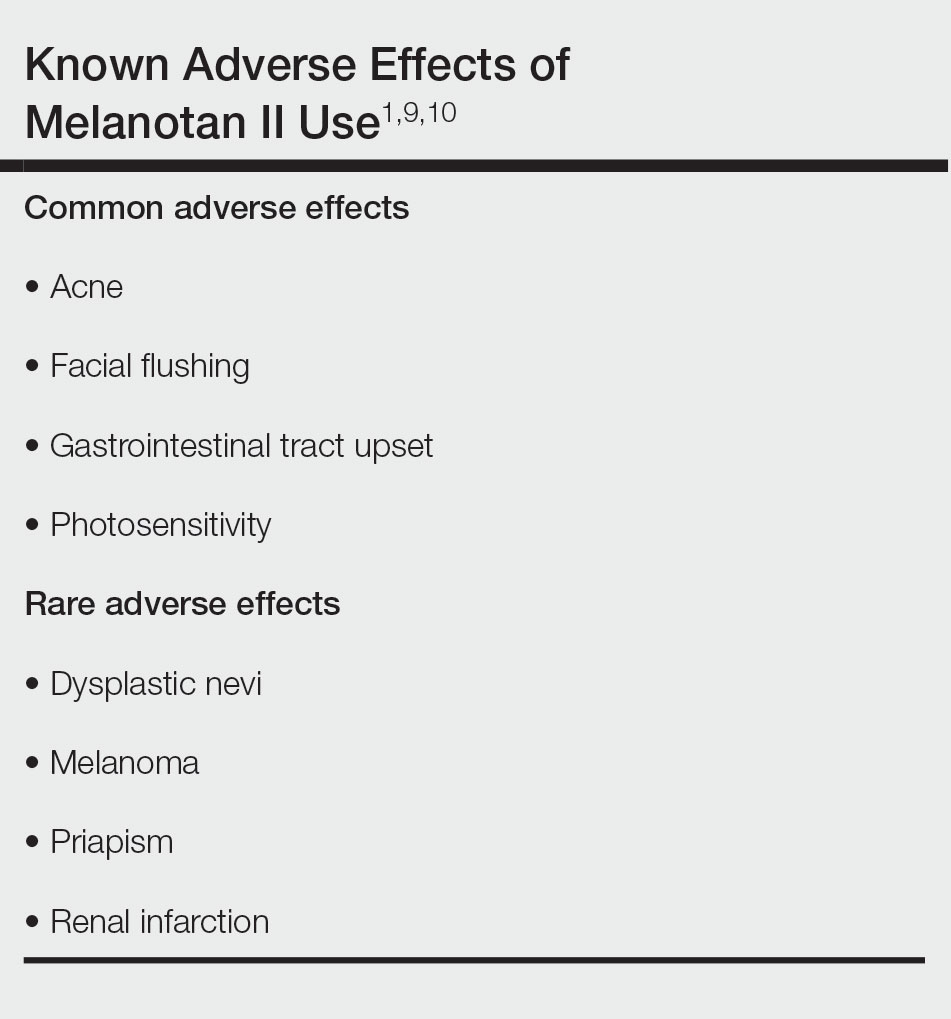

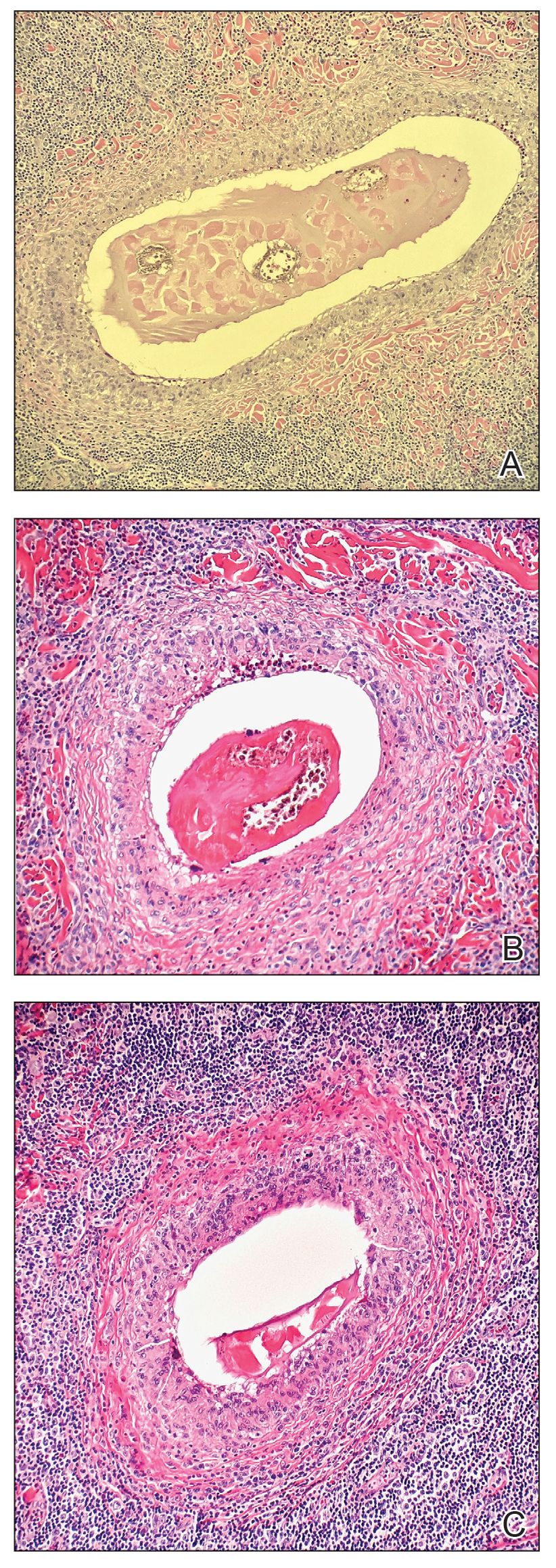

A 59-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with red, itchy, bleeding skin lesions on the breast, superior chest, left cheek, and forearm of 1 month’s duration. She denied any preceding trauma to the areas. Her medical history was notable for gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma diagnosed more than 2 years prior to presentation. Her original treatment regimen included nivolumab, which was discontinued for unknown reasons 5 months prior to presentation, and she was started on combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab at that time. She noted the formation of small red papules 2 months after the initiation of PTX-ramucirumab combination therapy, which grew larger over the course of the next month. Physical examination revealed 5 friable hemorrhagic papules and nodules ranging in size from 3 to 10 mm on the chest, cheek, and forearm consistent with PGs (Figure 1). Several scattered cherry angiomas were noted on the scalp and torso, but the patient reported these were not new. Biopsies of the PGs demonstrated lobular aggregates of small-caliber vessels set in an edematous inflamed stroma and partially enclosed by small collarettes of adnexal epithelium, confirming the clinical diagnosis of multiple PGs (Figure 2).

The first case of PTX-associated PG was reported in 2012.3 Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pyogenic granuloma, lobular capillary hemangioma, paclitaxel, taxane, and ramucirumab, there have been 9 cases of solitary PG development in the setting of PTX alone or in combination with ramucirumab since 2019 (Table).3-8 Pyogenic granulomas reported in patients who were treated exclusively with PTX were subungual, while the cases resulting from combined therapy were present on the scalp, face, oral mucosa, and surfaces of the hands sparing the nails. Ibe et al6 reported PG in a patient who received ramucirumab therapy without PTX but in combination with another taxane, docetaxel, which itself has been reported to cause subungual PG when used alone.9 Our case of the simultaneous development of multiple PGs in the setting of combined PTX and ramucirumab therapy added to the cutaneous distributions for which therapy-induced PGs have been observed (Table).

The development of PG, a vascular tumor, during treatment with the VEGFR2 inhibitor ramucirumab—whose mechanism of action is to inhibit angioneogenesis—is inherently paradoxical. In 2015, a rapidly expanding angioma with a mutation in the kinase domain receptor gene, KDR, that encodes VEGFR2 was identified in a patient undergoing ramucirumab therapy. The authors suggested that KDR mutation resulted in paradoxical activation of VEGFR2 in the setting of ramucirumab therapy.10 Since then, ramucirumab and PTX were suggested to have a synergistic effect in vascular proliferation,5 though an exact mechanism has not been proposed. Other authors have identified increased expression of VEGFR2 in biopsy specimens of PG during combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy.6 Although genetic studies have not been used to evaluate for the presence of KDR mutations specifically in our patient population, it is possible that patients who develop PG and other vascular tumors during combined taxane and ramucirumab therapy have a mutation that makes them more susceptible to VEGFR2 upregulation. UV exposure may have a role in the formation of PG in patients on combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy7; however, our patient’s lesions were distributed on both sun-exposed and unexposed areas. Although potential clinical implications have not yet been thoroughly investigated, following long-term outcomes for these patients may provide important information on the efficacy of the antineoplastic regimen in the subset of patients who develop cutaneous vascular tumors during antiangiogenic treatment.

Combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab has been associated with the paradoxical development of cutaneous vascular tumors. We report a case of multiple new-onset PGs in a patient undergoing this treatment regimen.

- Elston D, Neuhaus I, James WD, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Pierson JC. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma) clinical presentation. Medscape. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1084701-clinical#showall

- Paul LJ, Cohen PR. Paclitaxel-associated subungual pyogenic granuloma: report in a patient with breast cancer receiving paclitaxel and review of drug-induced pyogenic granulomas adjacent to and beneath the nail. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:262-268.

- Alessandrini A, Starace M, Cerè G, et al. Management and outcome of taxane-induced nail side effects: experience of 79 patients from a single centre. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:276-282.

- Watanabe R, Nakano E, Kawazoe A, et al. Four cases of paradoxical cephalocervical pyogenic granuloma during treatment with paclitaxel and ramucirumab. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E178-E180.

- Ibe T, Hamamoto Y, Takabatake M, et al. Development of pyogenic granuloma with strong vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 expression during ramucirumab treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231464.

- Choi YH, Byun HJ, Lee JH, et al. Multiple cherry angiomas and pyogenic granuloma in a patient treated with ramucirumab and paclitaxel. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:199-202.

- Aragaki T, Tomomatsu N, Michi Y, et al. Ramucirumab-related oral pyogenic granuloma: a report of two cases [published online March 8, 2021]. Intern Med. 2021;60:2601-2605. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.6650-20

- Devillers C, Vanhooteghem O, Henrijean A, et al. Subungual pyogenic granuloma secondary to docetaxel therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:251-252.

- Lim YH, Odell ID, Ko CJ, et al. Somatic p.T771R KDR (VEGFR2) mutation arising in a sporadic angioma during ramucirumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1240-1243.

To the Editor:

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor that clinically is characterized as a small eruptive friable papule.1 Lesions typically are solitary and most commonly occur in children but also are associated with pregnancy; trauma to the skin or mucosa; and use of certain medications such as isotretinoin, capecitabine, vemurafenib, or indinavir.1 Numerous antineoplastic medications have been associated with the development of solitary PGs, including the taxane mitotic inhibitor paclitaxel (PTX) and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) monoclonal antibody ramucirumab.2 We report a case of multiple PGs in a patient undergoing treatment with PTX and ramucirumab.

A 59-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with red, itchy, bleeding skin lesions on the breast, superior chest, left cheek, and forearm of 1 month’s duration. She denied any preceding trauma to the areas. Her medical history was notable for gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma diagnosed more than 2 years prior to presentation. Her original treatment regimen included nivolumab, which was discontinued for unknown reasons 5 months prior to presentation, and she was started on combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab at that time. She noted the formation of small red papules 2 months after the initiation of PTX-ramucirumab combination therapy, which grew larger over the course of the next month. Physical examination revealed 5 friable hemorrhagic papules and nodules ranging in size from 3 to 10 mm on the chest, cheek, and forearm consistent with PGs (Figure 1). Several scattered cherry angiomas were noted on the scalp and torso, but the patient reported these were not new. Biopsies of the PGs demonstrated lobular aggregates of small-caliber vessels set in an edematous inflamed stroma and partially enclosed by small collarettes of adnexal epithelium, confirming the clinical diagnosis of multiple PGs (Figure 2).

The first case of PTX-associated PG was reported in 2012.3 Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pyogenic granuloma, lobular capillary hemangioma, paclitaxel, taxane, and ramucirumab, there have been 9 cases of solitary PG development in the setting of PTX alone or in combination with ramucirumab since 2019 (Table).3-8 Pyogenic granulomas reported in patients who were treated exclusively with PTX were subungual, while the cases resulting from combined therapy were present on the scalp, face, oral mucosa, and surfaces of the hands sparing the nails. Ibe et al6 reported PG in a patient who received ramucirumab therapy without PTX but in combination with another taxane, docetaxel, which itself has been reported to cause subungual PG when used alone.9 Our case of the simultaneous development of multiple PGs in the setting of combined PTX and ramucirumab therapy added to the cutaneous distributions for which therapy-induced PGs have been observed (Table).

The development of PG, a vascular tumor, during treatment with the VEGFR2 inhibitor ramucirumab—whose mechanism of action is to inhibit angioneogenesis—is inherently paradoxical. In 2015, a rapidly expanding angioma with a mutation in the kinase domain receptor gene, KDR, that encodes VEGFR2 was identified in a patient undergoing ramucirumab therapy. The authors suggested that KDR mutation resulted in paradoxical activation of VEGFR2 in the setting of ramucirumab therapy.10 Since then, ramucirumab and PTX were suggested to have a synergistic effect in vascular proliferation,5 though an exact mechanism has not been proposed. Other authors have identified increased expression of VEGFR2 in biopsy specimens of PG during combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy.6 Although genetic studies have not been used to evaluate for the presence of KDR mutations specifically in our patient population, it is possible that patients who develop PG and other vascular tumors during combined taxane and ramucirumab therapy have a mutation that makes them more susceptible to VEGFR2 upregulation. UV exposure may have a role in the formation of PG in patients on combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy7; however, our patient’s lesions were distributed on both sun-exposed and unexposed areas. Although potential clinical implications have not yet been thoroughly investigated, following long-term outcomes for these patients may provide important information on the efficacy of the antineoplastic regimen in the subset of patients who develop cutaneous vascular tumors during antiangiogenic treatment.

Combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab has been associated with the paradoxical development of cutaneous vascular tumors. We report a case of multiple new-onset PGs in a patient undergoing this treatment regimen.

To the Editor:

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor that clinically is characterized as a small eruptive friable papule.1 Lesions typically are solitary and most commonly occur in children but also are associated with pregnancy; trauma to the skin or mucosa; and use of certain medications such as isotretinoin, capecitabine, vemurafenib, or indinavir.1 Numerous antineoplastic medications have been associated with the development of solitary PGs, including the taxane mitotic inhibitor paclitaxel (PTX) and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) monoclonal antibody ramucirumab.2 We report a case of multiple PGs in a patient undergoing treatment with PTX and ramucirumab.

A 59-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with red, itchy, bleeding skin lesions on the breast, superior chest, left cheek, and forearm of 1 month’s duration. She denied any preceding trauma to the areas. Her medical history was notable for gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma diagnosed more than 2 years prior to presentation. Her original treatment regimen included nivolumab, which was discontinued for unknown reasons 5 months prior to presentation, and she was started on combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab at that time. She noted the formation of small red papules 2 months after the initiation of PTX-ramucirumab combination therapy, which grew larger over the course of the next month. Physical examination revealed 5 friable hemorrhagic papules and nodules ranging in size from 3 to 10 mm on the chest, cheek, and forearm consistent with PGs (Figure 1). Several scattered cherry angiomas were noted on the scalp and torso, but the patient reported these were not new. Biopsies of the PGs demonstrated lobular aggregates of small-caliber vessels set in an edematous inflamed stroma and partially enclosed by small collarettes of adnexal epithelium, confirming the clinical diagnosis of multiple PGs (Figure 2).

The first case of PTX-associated PG was reported in 2012.3 Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pyogenic granuloma, lobular capillary hemangioma, paclitaxel, taxane, and ramucirumab, there have been 9 cases of solitary PG development in the setting of PTX alone or in combination with ramucirumab since 2019 (Table).3-8 Pyogenic granulomas reported in patients who were treated exclusively with PTX were subungual, while the cases resulting from combined therapy were present on the scalp, face, oral mucosa, and surfaces of the hands sparing the nails. Ibe et al6 reported PG in a patient who received ramucirumab therapy without PTX but in combination with another taxane, docetaxel, which itself has been reported to cause subungual PG when used alone.9 Our case of the simultaneous development of multiple PGs in the setting of combined PTX and ramucirumab therapy added to the cutaneous distributions for which therapy-induced PGs have been observed (Table).

The development of PG, a vascular tumor, during treatment with the VEGFR2 inhibitor ramucirumab—whose mechanism of action is to inhibit angioneogenesis—is inherently paradoxical. In 2015, a rapidly expanding angioma with a mutation in the kinase domain receptor gene, KDR, that encodes VEGFR2 was identified in a patient undergoing ramucirumab therapy. The authors suggested that KDR mutation resulted in paradoxical activation of VEGFR2 in the setting of ramucirumab therapy.10 Since then, ramucirumab and PTX were suggested to have a synergistic effect in vascular proliferation,5 though an exact mechanism has not been proposed. Other authors have identified increased expression of VEGFR2 in biopsy specimens of PG during combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy.6 Although genetic studies have not been used to evaluate for the presence of KDR mutations specifically in our patient population, it is possible that patients who develop PG and other vascular tumors during combined taxane and ramucirumab therapy have a mutation that makes them more susceptible to VEGFR2 upregulation. UV exposure may have a role in the formation of PG in patients on combined ramucirumab and taxane therapy7; however, our patient’s lesions were distributed on both sun-exposed and unexposed areas. Although potential clinical implications have not yet been thoroughly investigated, following long-term outcomes for these patients may provide important information on the efficacy of the antineoplastic regimen in the subset of patients who develop cutaneous vascular tumors during antiangiogenic treatment.

Combination therapy with PTX and ramucirumab has been associated with the paradoxical development of cutaneous vascular tumors. We report a case of multiple new-onset PGs in a patient undergoing this treatment regimen.

- Elston D, Neuhaus I, James WD, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Pierson JC. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma) clinical presentation. Medscape. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1084701-clinical#showall

- Paul LJ, Cohen PR. Paclitaxel-associated subungual pyogenic granuloma: report in a patient with breast cancer receiving paclitaxel and review of drug-induced pyogenic granulomas adjacent to and beneath the nail. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:262-268.

- Alessandrini A, Starace M, Cerè G, et al. Management and outcome of taxane-induced nail side effects: experience of 79 patients from a single centre. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:276-282.

- Watanabe R, Nakano E, Kawazoe A, et al. Four cases of paradoxical cephalocervical pyogenic granuloma during treatment with paclitaxel and ramucirumab. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E178-E180.

- Ibe T, Hamamoto Y, Takabatake M, et al. Development of pyogenic granuloma with strong vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 expression during ramucirumab treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231464.

- Choi YH, Byun HJ, Lee JH, et al. Multiple cherry angiomas and pyogenic granuloma in a patient treated with ramucirumab and paclitaxel. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:199-202.

- Aragaki T, Tomomatsu N, Michi Y, et al. Ramucirumab-related oral pyogenic granuloma: a report of two cases [published online March 8, 2021]. Intern Med. 2021;60:2601-2605. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.6650-20

- Devillers C, Vanhooteghem O, Henrijean A, et al. Subungual pyogenic granuloma secondary to docetaxel therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:251-252.

- Lim YH, Odell ID, Ko CJ, et al. Somatic p.T771R KDR (VEGFR2) mutation arising in a sporadic angioma during ramucirumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1240-1243.

- Elston D, Neuhaus I, James WD, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Pierson JC. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma) clinical presentation. Medscape. Updated February 21, 2020. Accessed December 26, 2023. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1084701-clinical#showall

- Paul LJ, Cohen PR. Paclitaxel-associated subungual pyogenic granuloma: report in a patient with breast cancer receiving paclitaxel and review of drug-induced pyogenic granulomas adjacent to and beneath the nail. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:262-268.

- Alessandrini A, Starace M, Cerè G, et al. Management and outcome of taxane-induced nail side effects: experience of 79 patients from a single centre. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:276-282.

- Watanabe R, Nakano E, Kawazoe A, et al. Four cases of paradoxical cephalocervical pyogenic granuloma during treatment with paclitaxel and ramucirumab. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E178-E180.

- Ibe T, Hamamoto Y, Takabatake M, et al. Development of pyogenic granuloma with strong vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 expression during ramucirumab treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231464.

- Choi YH, Byun HJ, Lee JH, et al. Multiple cherry angiomas and pyogenic granuloma in a patient treated with ramucirumab and paclitaxel. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:199-202.

- Aragaki T, Tomomatsu N, Michi Y, et al. Ramucirumab-related oral pyogenic granuloma: a report of two cases [published online March 8, 2021]. Intern Med. 2021;60:2601-2605. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.6650-20

- Devillers C, Vanhooteghem O, Henrijean A, et al. Subungual pyogenic granuloma secondary to docetaxel therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:251-252.

- Lim YH, Odell ID, Ko CJ, et al. Somatic p.T771R KDR (VEGFR2) mutation arising in a sporadic angioma during ramucirumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1240-1243.

Practice Points

- Pyogenic granulomas (PGs) are benign vascular tumors that clinically are characterized as small, eruptive, friable papules.

- Ramucirumab is a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

- Some patients experience paradoxical formation of vascular tumors such as PGs when treated with combination therapy with ramucirumab and a taxane such as paclitaxel.

Cemiplimab-Associated Eruption of Generalized Eruptive Keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski

To the Editor:

Treatment of cancer, including cutaneous malignancy, has been transformed by the use of immunotherapeutic agents such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1), or programmed cell-death ligand 1 (PD-L1). However, these drugs are associated with a distinct set of immune-related adverse events (IRAEs). We present a case of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski associated with the ICI cemiplimab.

A 94-year-old White woman presented to the dermatology clinic with acute onset of extensive, locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) of the upper right posterolateral calf as well as multiple noninvasive cSCCs of the arms and legs. Her medical history was remarkable for widespread actinic keratoses and numerous cSCCs. The patient had no personal or family history of melanoma. Various cSCCs had required treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage, topical or intralesional 5-fluorouracil, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Approximately 1 year prior to presentation, oral acitretin was initiated to help control the cSCC. Given the extent of locally advanced disease, which was considered unresectable, she was referred to oncology but continued to follow up with dermatology. Positron emission tomography was remarkable for hypermetabolic cutaneous thickening in the upper right posterolateral calf with no evidence of visceral disease.

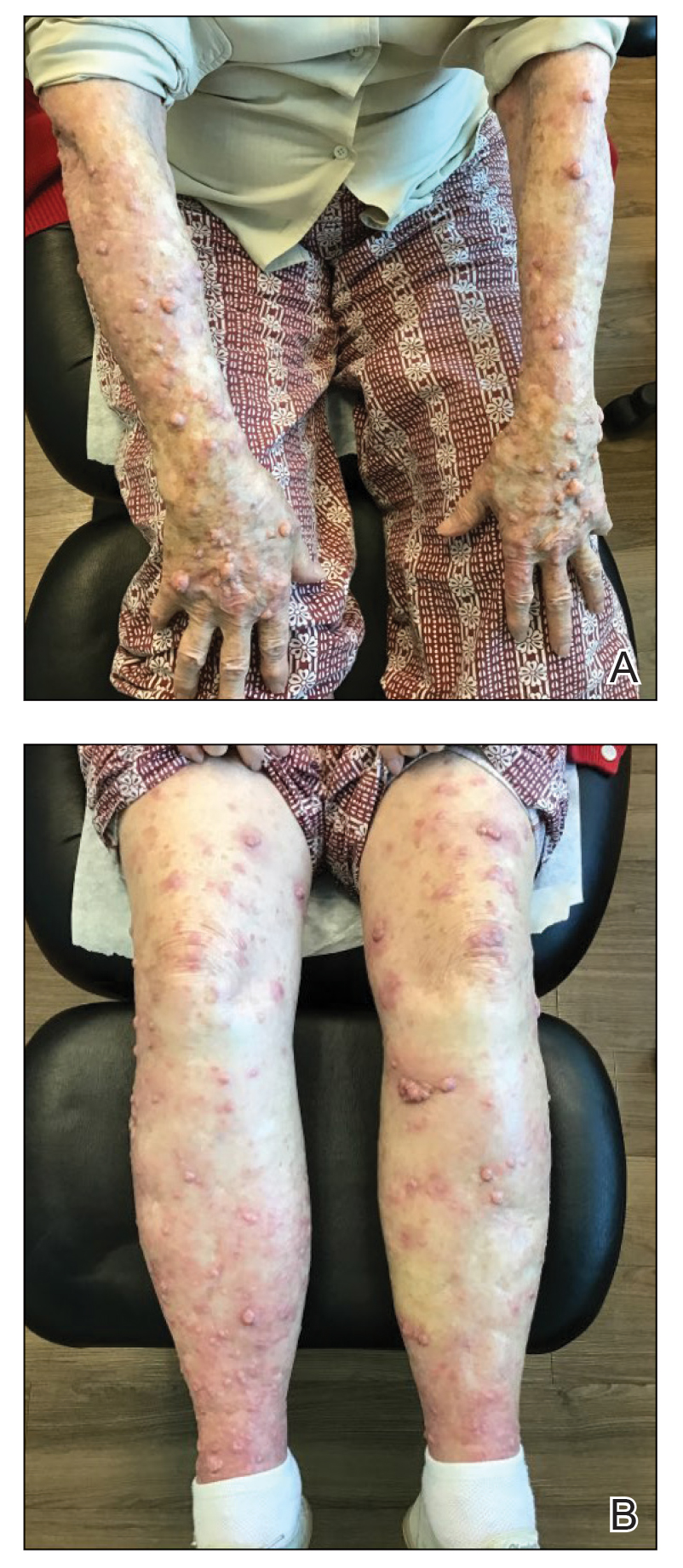

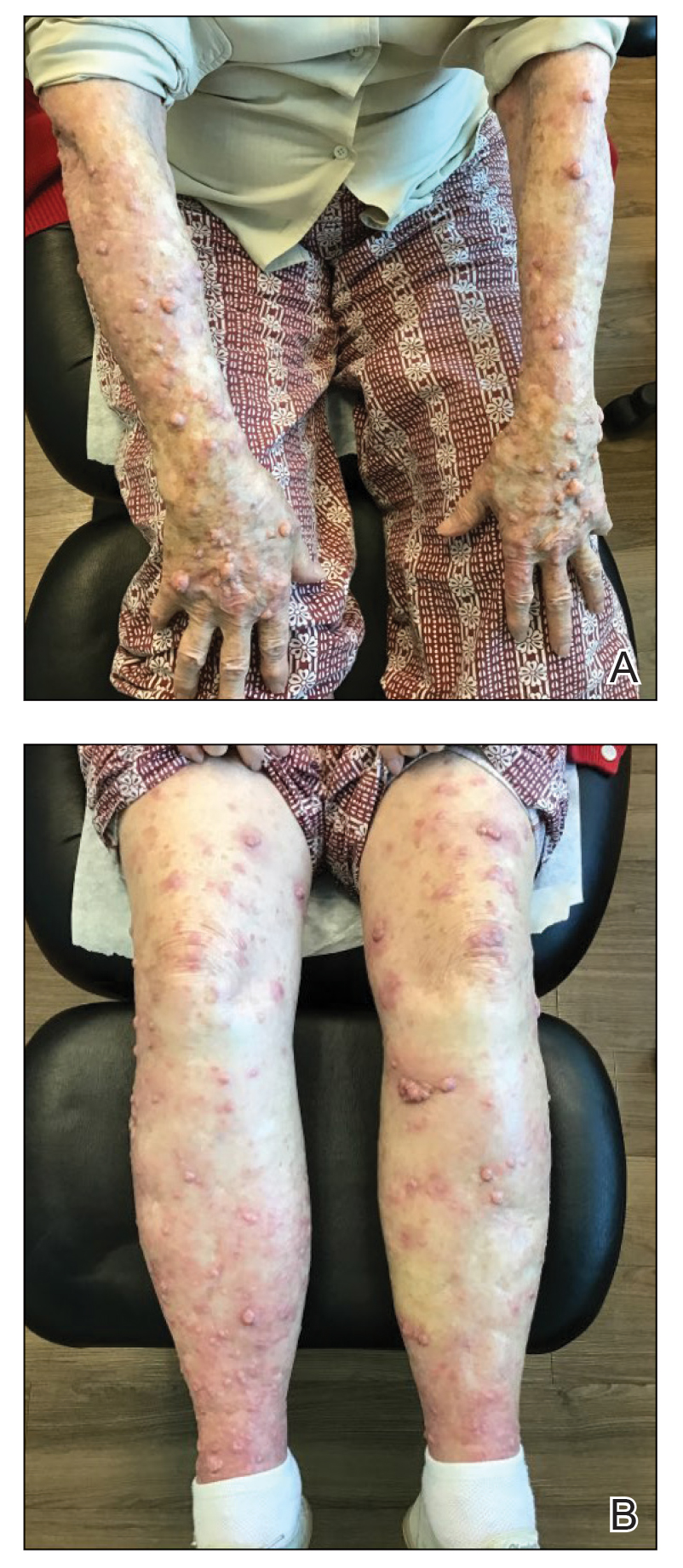

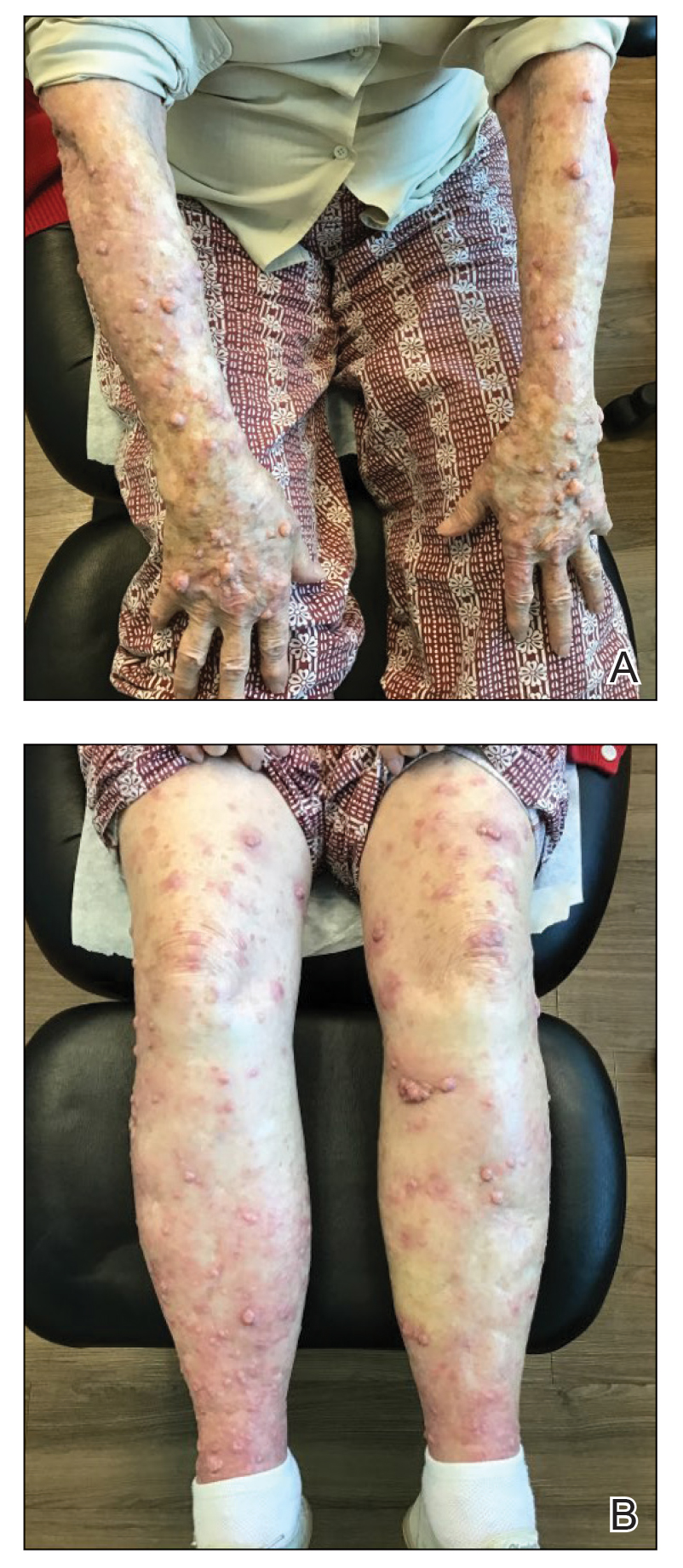

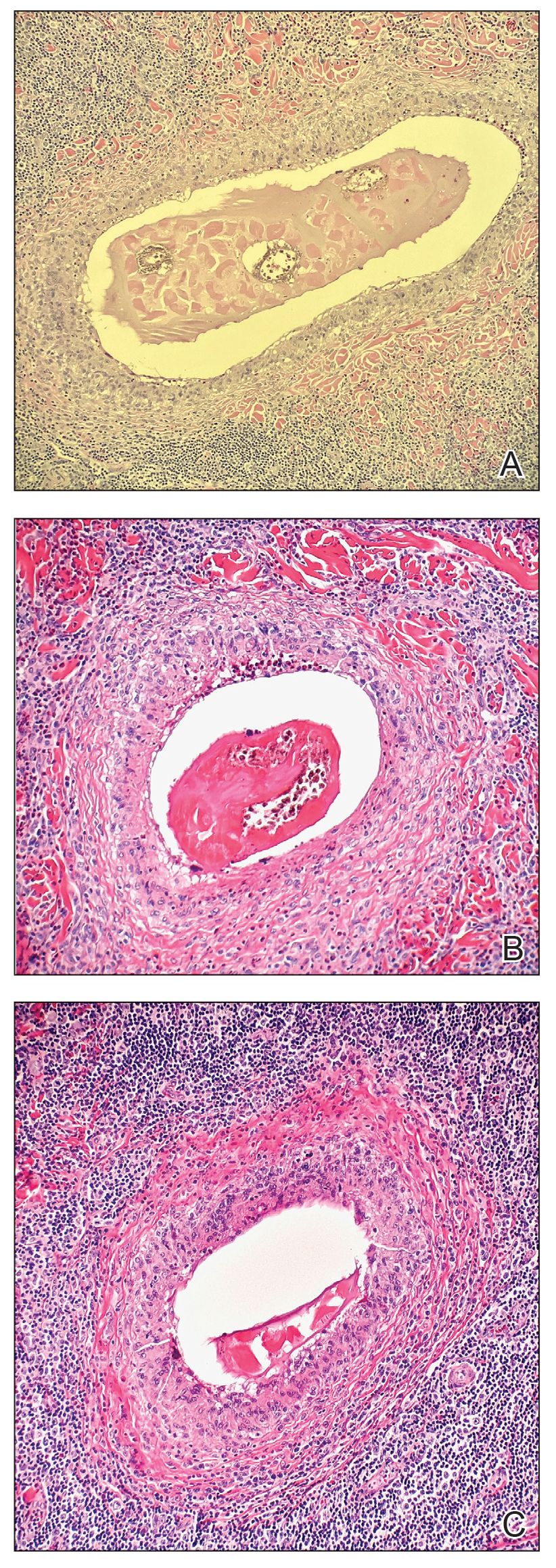

The patient was started on cemiplimab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody ICI indicated for the treatment of both metastatic and advanced cSCC. After 4 cycles of intravenous cemiplimab, the patient developed widespread nodules covering the arms and legs (Figure 1) as well as associated tenderness and pruritus. Biopsies of nodules revealed superficially invasive, well-differentiated cSCC consistent with keratoacanthoma. Although a lymphocytic infiltrate was present, no other specific reaction pattern, such as a lichenoid infiltrate, was present (Figure 2).

Positron emission tomography was repeated, demonstrating resolution of the right calf lesion; however, new diffuse cutaneous lesions and inguinal lymph node involvement were present, again without evidence of visceral disease. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski was made. Cemiplimab was discontinued after the fifth cycle. The patient declined further systemic treatment, instead choosing a regimen of topical steroids and an emollient.

Immunotherapeutics have transformed cancer therapy, which includes ICIs that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, PD-1, or PD-L1. Increased activity of these checkpoints allows tumor cells to downregulate T-cell activation, thereby evading immune destruction. When PD-1 on T cells binds PD-L1 on tumor cells, T lymphocytes are inhibited from cytotoxic-mediated killing. Therefore, anti-PD-1 ICIs such as cemiplimab permit T-lymphocyte activation and destruction of malignant cells. However, this unique mechanism of immunotherapy is associated with an array of IRAEs, which often manifest in a delayed and prolonged fashion.1 Immune-related adverse events most commonly affect the gastrointestinal tract as well as the endocrine and dermatologic systems.2 Notably, patients with certain tumors who experience these adverse effects might be more likely to have superior overall survival; therefore, IRAEs are sometimes used as an indicator of favorable treatment response.2,3

Dermatologic IRAEs associated with the use of a PD-1 inhibitor include lichenoid reactions, pruritus, morbilliform eruptions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid.4,5 Eruptions of keratoacanthoma rarely have been reported following treatment with the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab.3,6,7 In our patient, we believe the profound and generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma—a well-differentiated cSCC variant—was related to treatment of locally advanced cSCC with cemiplimab. The mechanism underlying the formation of anti-PD-1 eruptive keratoacanthoma is not well understood. In susceptible patients, it is plausible that the inflammatory environment permitted by ICIs paradoxically induces regression of tumors such as locally invasive cSCC and simultaneously promotes formation of keratoacanthoma.

The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis and progression of cSCC is complex and possibly involves contrasting roles of leukocyte subpopulations.8 The increased incidence of cSCC in the immunocompromised population,8 PD-L1 overexpression in cSCC,9,10 and successful treatment of cSCC with PD-1 inhibition10 all suggest that inhibition of specific inflammatory pathways is pivotal in tumor pathogenesis. However, increased inflammation, particularly inflammation driven by T lymphocytes and Langerhans cells, also is believed to play a key role in the formation of cSCCs, including the degeneration of actinic keratosis into cSCC. Moreover, because keratoacanthomas are believed to be a cSCC variant and also are associated with PD-L1 overexpression,9 it is perplexing that PD-1 blockade may result in eruptive keratoacanthoma in some patients while also treating locally advanced cSCC, as seen in our patient. Successful treatment of keratoacanthoma with anti-inflammatory intralesional or topical corticosteroids adds to this complicated picture.3

We hypothesize that the pathogenesis of invasive cSCC and keratoacanthoma shares certain immune-mediated mechanisms but also differs in distinct manners. To understand the relationship between systemic treatment of cSCC and eruptive keratoacanthoma, further research is required.

In addition, the RAS/BRAF/MEK oncogenic pathway may be involved in the development of cSCCs associated with anti-PD-1. It is hypothesized that BRAF and MEK inhibition increases T-cell infiltration and increases PD-L1 expression on tumor cells,11 thus increasing the susceptibility of those cells to PD-1 blockade. Further supporting a relationship between the RAS/BRAF/MEK and PD-1 pathways, BRAF inhibitors are associated with development of SCCs and verrucal keratosis by upregulation of the RAS pathway.12,13 Perhaps a common mechanism underlying these pathways results in their shared association for an increased risk for cSCC upon blockade. More research is needed to fully elucidate the underlying biochemical mechanism of immunotherapy and formation of SCCs, such as keratoacanthoma.

Treatment of solitary keratoacanthoma often involves surgical excision; however, the sheer number of lesions in eruptive keratoacanthoma presents a larger dilemma. Because oral systemic retinoids have been shown to be most effective for treating eruptive keratoacanthoma, they are considered first-line therapy as monotherapy or in combination with surgical excision.3 Other treatment options include intralesional or topical corticosteroids, cyclosporine, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, and cryotherapy.3,6

The development of ICIs has revolutionized the treatment of cutaneous malignancy, yet we have a great deal more to comprehend on the systemic effects of these medications. Although IRAEs may signal a better response to therapy, some of these effects regrettably can be dose limiting. In our patient, cemiplimab was successful in treating locally advanced cSCC, but treatment also resulted in devastating widespread eruptive keratoacanthoma. The mechanism of this kind of eruption has yet to be understood; we hypothesize that it likely involves T lymphocyte–driven inflammation and the interplay of molecular and immune-mediated pathways.

- Ramos-Casals M, Brahmer JR, Callahan MK, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:38. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6

- Das S, Johnson DB. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:306. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8

- Freites-Martinez A, Kwong BY, Rieger KE, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:694-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0989

- Shen J, Chang J, Mendenhall M, et al. Diverse cutaneous adverse eruptions caused by anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and anti-programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) immunotherapies: clinicalfeatures and management. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758834017751634. doi:10.1177/1758834017751634

- Bandino JP, Perry DM, Clarke CE, et al. Two cases of anti-programmed cell death 1-associated bullous pemphigoid-like disease and eruptive keratoacanthomas featuring combined histopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E378-E380. doi:10.1111/jdv.14179

- Marsh RL, Kolodney JA, Iyengar S, et al. Formation of eruptive cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas after programmed cell death protein-1 blockade. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:390-393. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.024

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Bottomley MJ, Thomson J, Harwood C, et al. The role of the immune system in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2009. doi:10.3390/ijms20082009

- Gambichler T, Gnielka M, Rüddel I, et al. Expression of PD-L1 in keratoacanthoma and different stages of progression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1199-1204. doi:10.1007/s00262-017-2015-x

- Patel R, Chang ALS. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for treating advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:477-482. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00426-w

- Rozeman EA, Blank CU. Combining checkpoint inhibition and targeted therapy in melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:879-882. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0482-7

- Dubauskas Z, Kunishige J, Prieto VG, Jonasch E, Hwu P, Tannir NM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and inflammation of actinic keratoses associated with sorafenib. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2009;7:20-23. doi:10.3816/CGC.2009.n.003

- Chen P, Chen F, Zhou B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of dermatological toxicities associated with vemurafenib treatment in patients with melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:243-251. doi:10.1111/ced.13751

To the Editor:

Treatment of cancer, including cutaneous malignancy, has been transformed by the use of immunotherapeutic agents such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1), or programmed cell-death ligand 1 (PD-L1). However, these drugs are associated with a distinct set of immune-related adverse events (IRAEs). We present a case of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski associated with the ICI cemiplimab.

A 94-year-old White woman presented to the dermatology clinic with acute onset of extensive, locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) of the upper right posterolateral calf as well as multiple noninvasive cSCCs of the arms and legs. Her medical history was remarkable for widespread actinic keratoses and numerous cSCCs. The patient had no personal or family history of melanoma. Various cSCCs had required treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage, topical or intralesional 5-fluorouracil, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Approximately 1 year prior to presentation, oral acitretin was initiated to help control the cSCC. Given the extent of locally advanced disease, which was considered unresectable, she was referred to oncology but continued to follow up with dermatology. Positron emission tomography was remarkable for hypermetabolic cutaneous thickening in the upper right posterolateral calf with no evidence of visceral disease.

The patient was started on cemiplimab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody ICI indicated for the treatment of both metastatic and advanced cSCC. After 4 cycles of intravenous cemiplimab, the patient developed widespread nodules covering the arms and legs (Figure 1) as well as associated tenderness and pruritus. Biopsies of nodules revealed superficially invasive, well-differentiated cSCC consistent with keratoacanthoma. Although a lymphocytic infiltrate was present, no other specific reaction pattern, such as a lichenoid infiltrate, was present (Figure 2).

Positron emission tomography was repeated, demonstrating resolution of the right calf lesion; however, new diffuse cutaneous lesions and inguinal lymph node involvement were present, again without evidence of visceral disease. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski was made. Cemiplimab was discontinued after the fifth cycle. The patient declined further systemic treatment, instead choosing a regimen of topical steroids and an emollient.

Immunotherapeutics have transformed cancer therapy, which includes ICIs that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, PD-1, or PD-L1. Increased activity of these checkpoints allows tumor cells to downregulate T-cell activation, thereby evading immune destruction. When PD-1 on T cells binds PD-L1 on tumor cells, T lymphocytes are inhibited from cytotoxic-mediated killing. Therefore, anti-PD-1 ICIs such as cemiplimab permit T-lymphocyte activation and destruction of malignant cells. However, this unique mechanism of immunotherapy is associated with an array of IRAEs, which often manifest in a delayed and prolonged fashion.1 Immune-related adverse events most commonly affect the gastrointestinal tract as well as the endocrine and dermatologic systems.2 Notably, patients with certain tumors who experience these adverse effects might be more likely to have superior overall survival; therefore, IRAEs are sometimes used as an indicator of favorable treatment response.2,3

Dermatologic IRAEs associated with the use of a PD-1 inhibitor include lichenoid reactions, pruritus, morbilliform eruptions, vitiligo, and bullous pemphigoid.4,5 Eruptions of keratoacanthoma rarely have been reported following treatment with the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab.3,6,7 In our patient, we believe the profound and generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma—a well-differentiated cSCC variant—was related to treatment of locally advanced cSCC with cemiplimab. The mechanism underlying the formation of anti-PD-1 eruptive keratoacanthoma is not well understood. In susceptible patients, it is plausible that the inflammatory environment permitted by ICIs paradoxically induces regression of tumors such as locally invasive cSCC and simultaneously promotes formation of keratoacanthoma.