User login

In the Future, a Robot Intensivist May Save Your Life

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

They call it the “golden hour”: 60 minutes, give or take, when the chance to save the life of a trauma victim is at its greatest. If the patient can be resuscitated and stabilized in that time window, they stand a good chance of surviving. If not, well, they don’t.

But resuscitation is complicated. It requires blood products, fluids, vasopressors — all given in precise doses in response to rapidly changing hemodynamics. To do it right takes specialized training, advanced life support (ALS). If the patient is in a remote area or an area without ALS-certified emergency medical services, or is far from the nearest trauma center, that golden hour is lost. And the patient may be as well.

But we live in the future. We have robots in factories, self-driving cars, autonomous drones. Why not an autonomous trauma doctor? If you are in a life-threatening accident, would you want to be treated ... by a robot?

Enter “resuscitation based on functional hemodynamic monitoring,” or “ReFit,” introduced in this article appearing in the journal Intensive Care Medicine Experimental.

The idea behind ReFit is straightforward. Resuscitation after trauma should be based on hitting key hemodynamic targets using the tools we have available in the field: blood, fluids, pressors. The researchers wanted to develop a closed-loop system, something that could be used by minimally trained personnel. The input to the system? Hemodynamic data, provided through a single measurement device, an arterial catheter. The output: blood, fluids, and pressors, delivered intravenously.

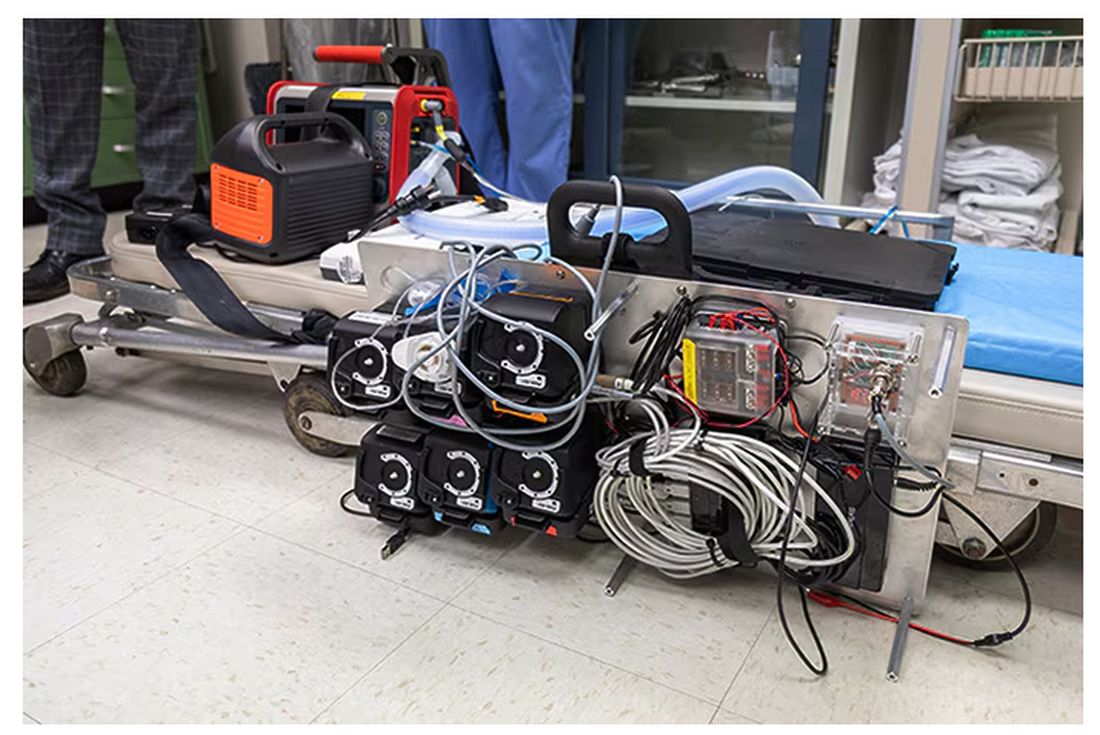

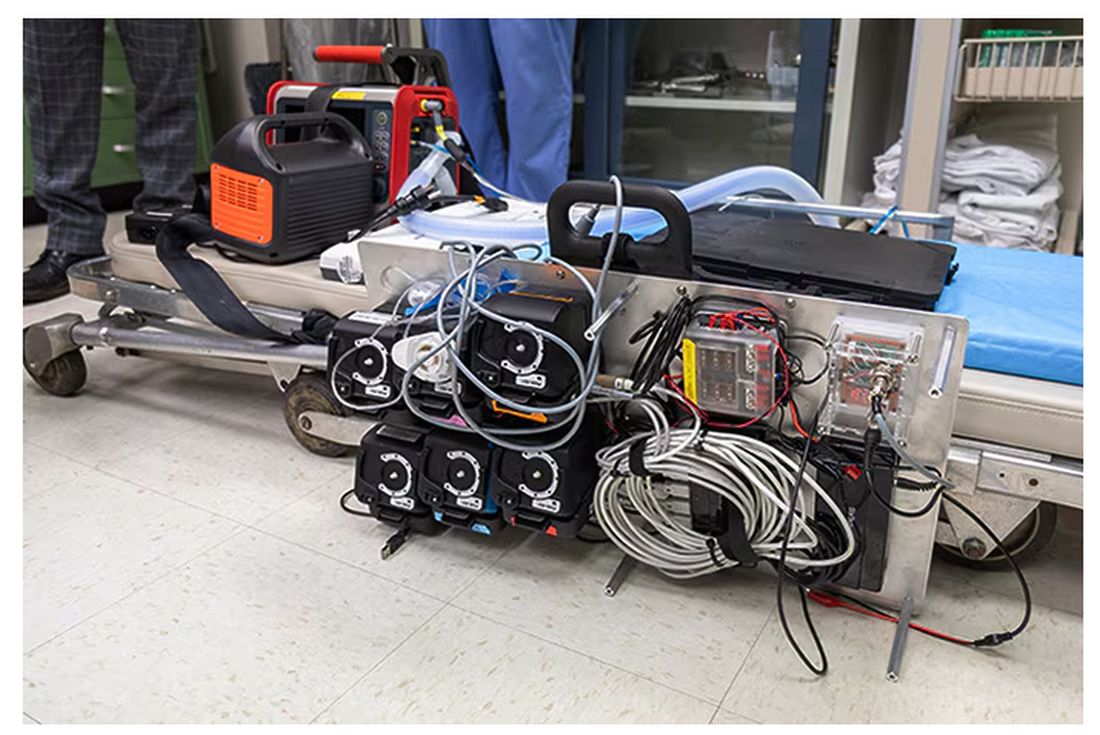

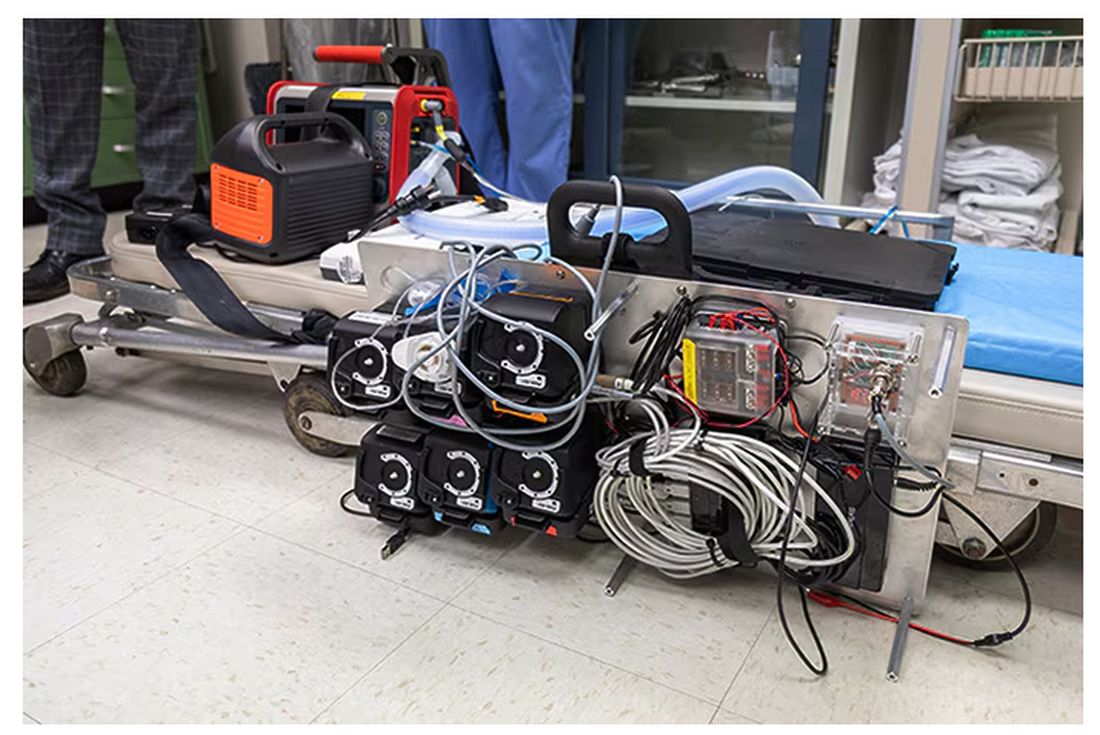

The body (a prototype) of the system looks like this. You can see various pumps labeled with various fluids, electronic controllers, and so forth.

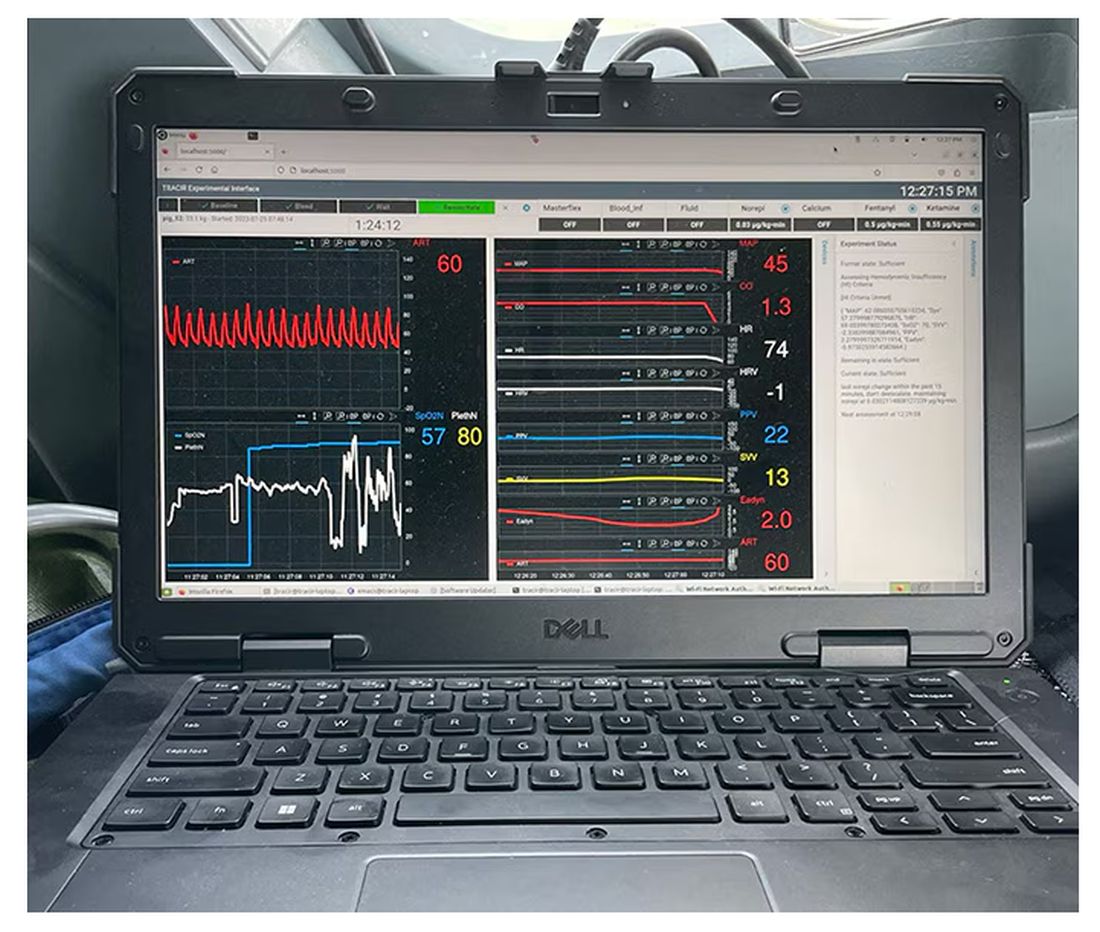

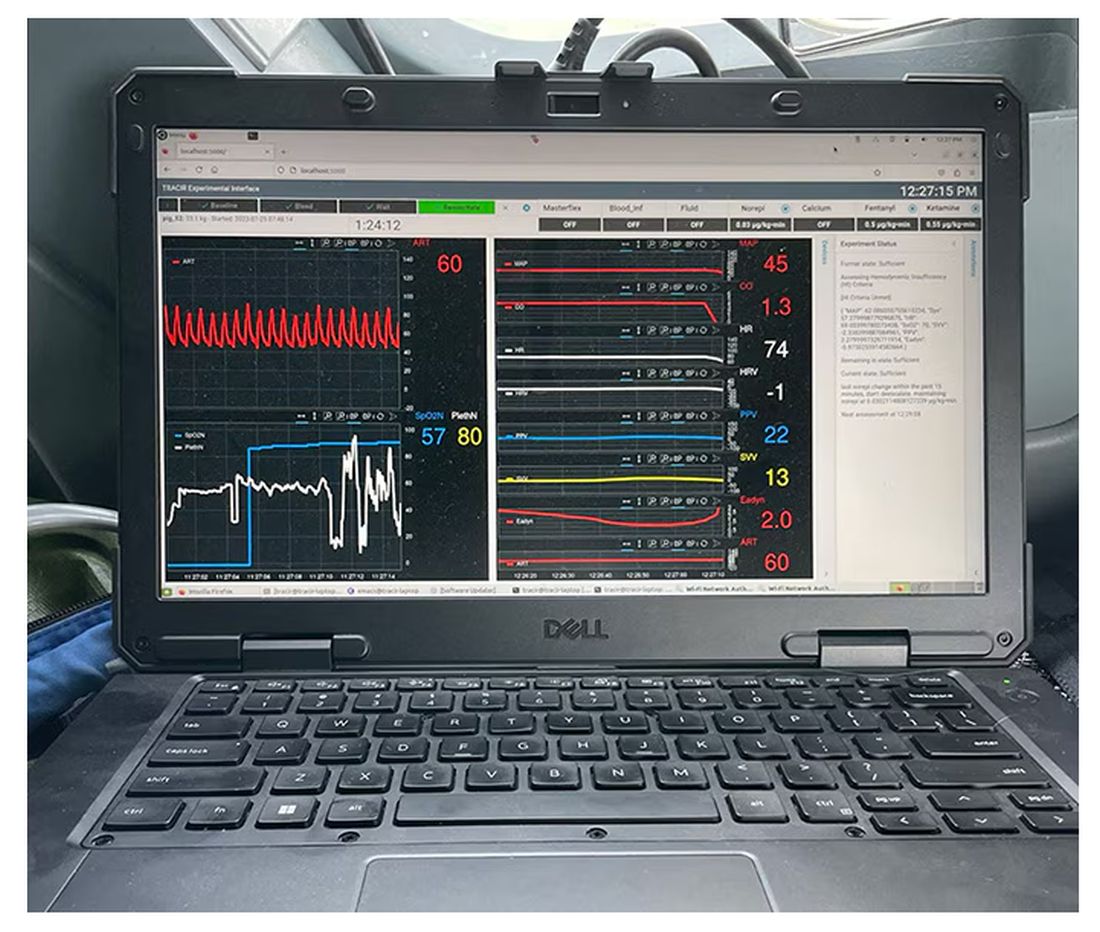

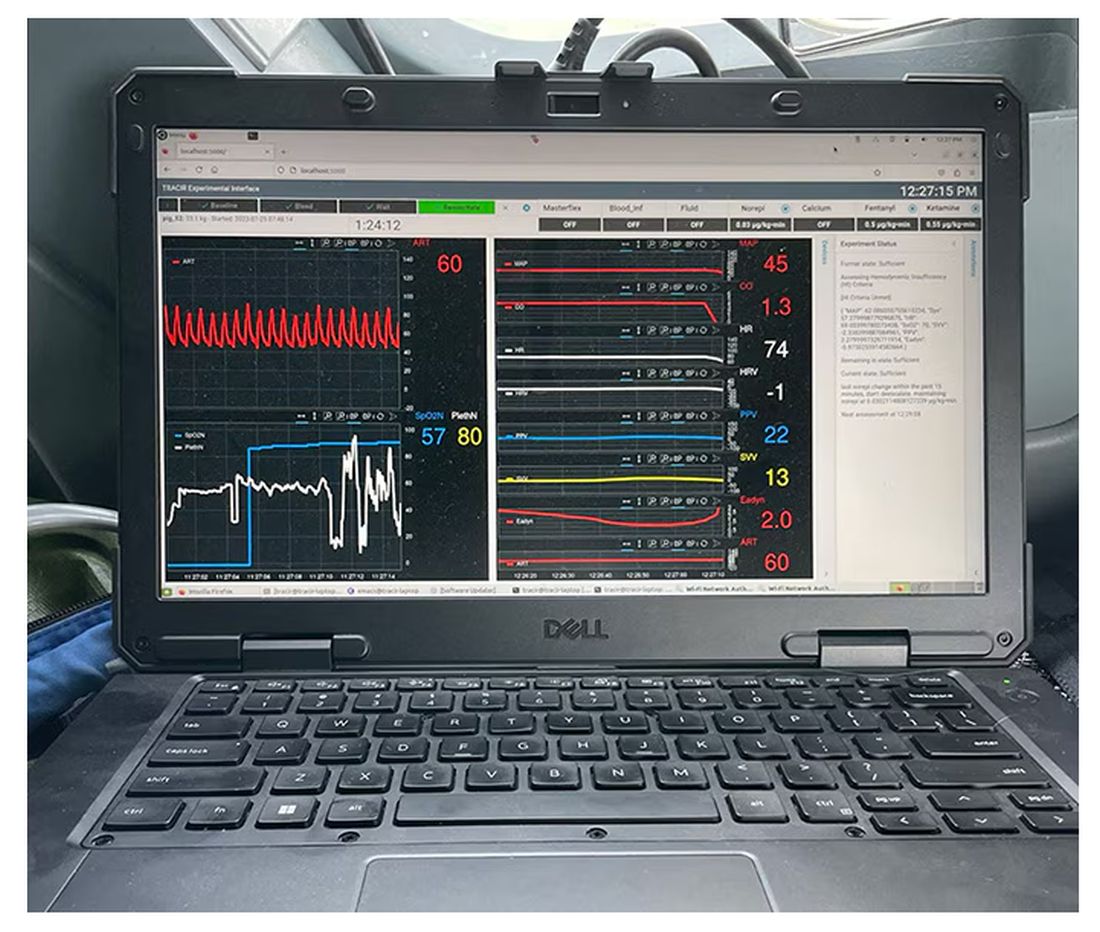

If that’s the body, then this is the brain – a ruggedized laptop interpreting a readout of that arterial catheter.

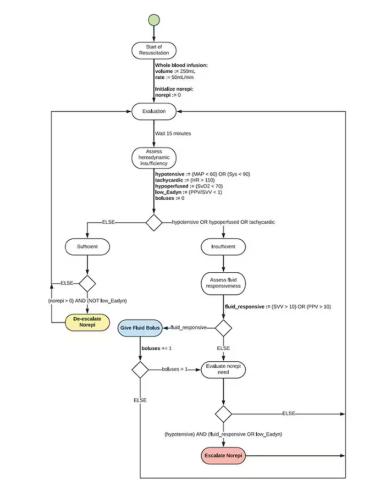

If that’s the brain, then the ReFit algorithm is the mind. The algorithm does its best to leverage all the data it can, so I want to walk through it in a bit of detail.

First, check to see whether the patient is stable, defined as a heart rate < 110 beats/min and a mean arterial pressure > 60 mm Hg. If not, you’re off to the races, starting with a bolus of whole blood.

Next, the algorithm gets really interesting. If the patient is still unstable, the computer assesses fluid responsiveness by giving a test dose of fluid and measuring the pulse pressure variation. Greater pulse pressure variation means more fluid responsiveness and the algorithm gives more fluid. Less pulse pressure variation leads the algorithm to uptitrate pressors — in this case, norepinephrine.

This cycle of evaluation and response keeps repeating. The computer titrates fluids and pressors up and down entirely on its own, in theory freeing the human team members to do other things, like getting the patient to a trauma center for definitive care.

So, how do you test whether something like this works? Clearly, you don’t want the trial run of a system like this to be used on a real human suffering from a real traumatic injury.

Once again, we have animals to thank for research advances — in this case, pigs. Fifteen pigs are described in the study. To simulate a severe, hemorrhagic trauma, they were anesthetized and the liver was lacerated. They were then observed passively until the mean arterial pressure had dropped to below 40 mm Hg.

This is a pretty severe injury. Three unfortunate animals served as controls, two of which died within the 3-hour time window of the study. Eight animals were plugged into the ReFit system.

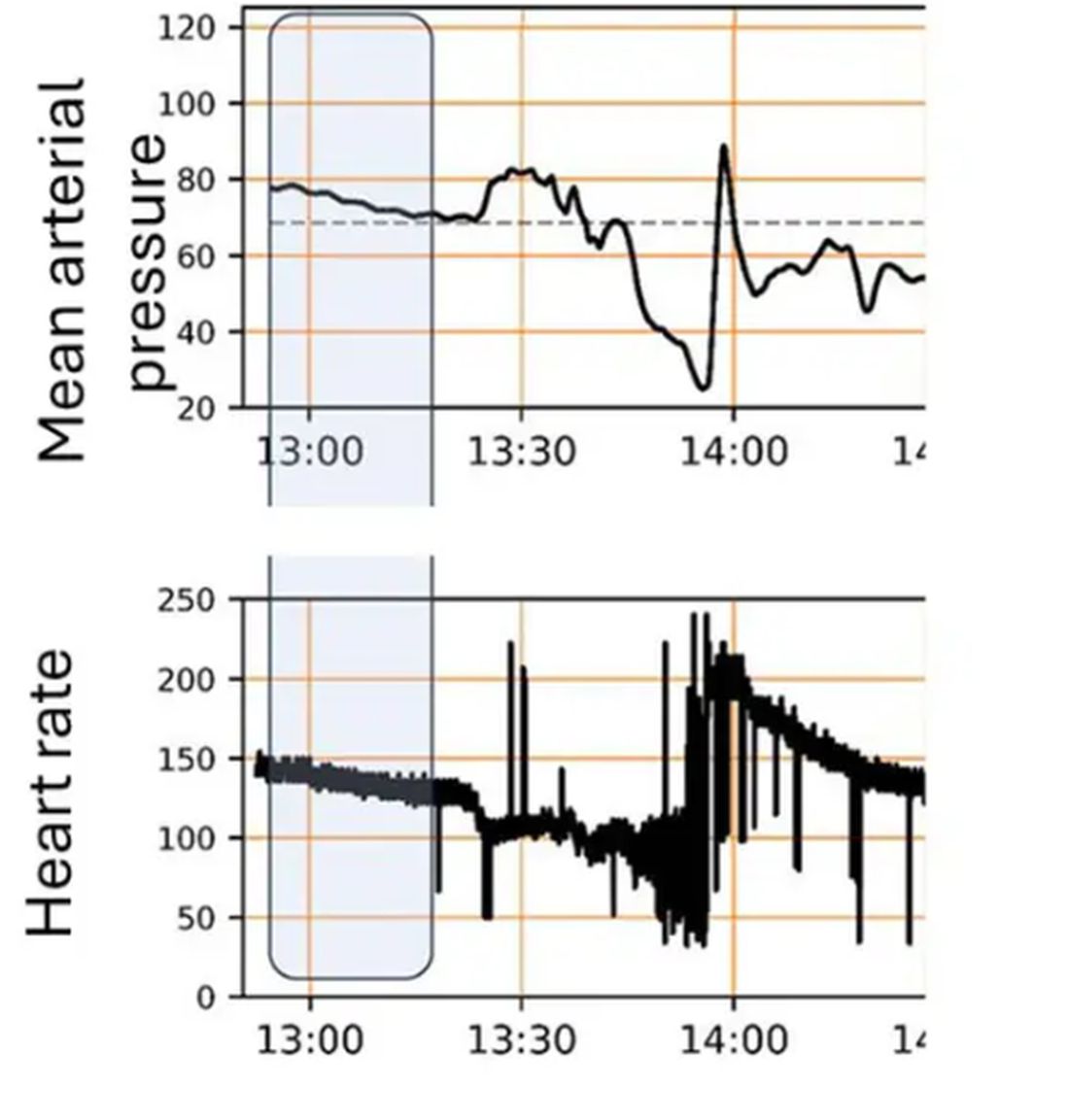

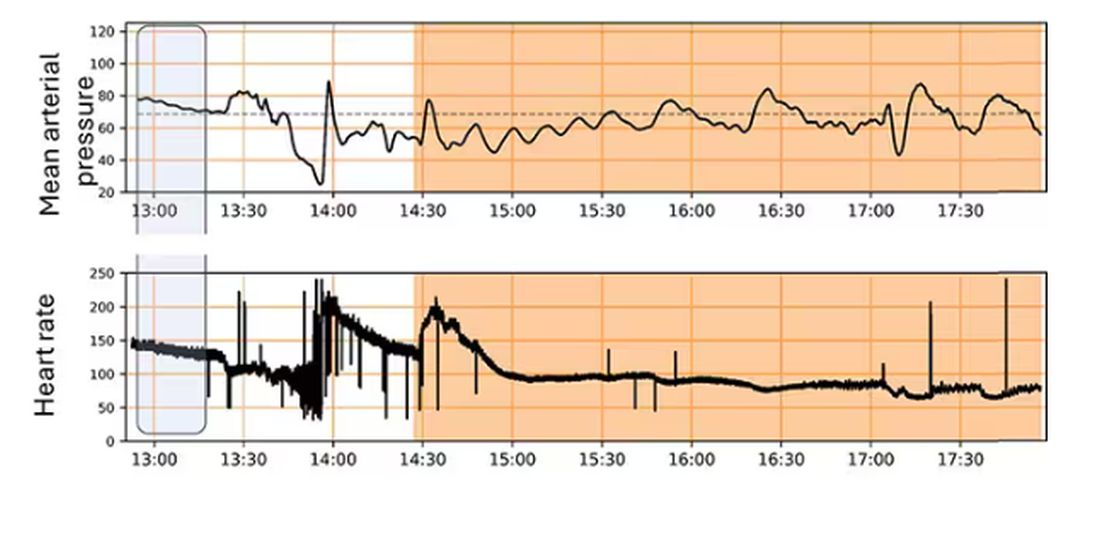

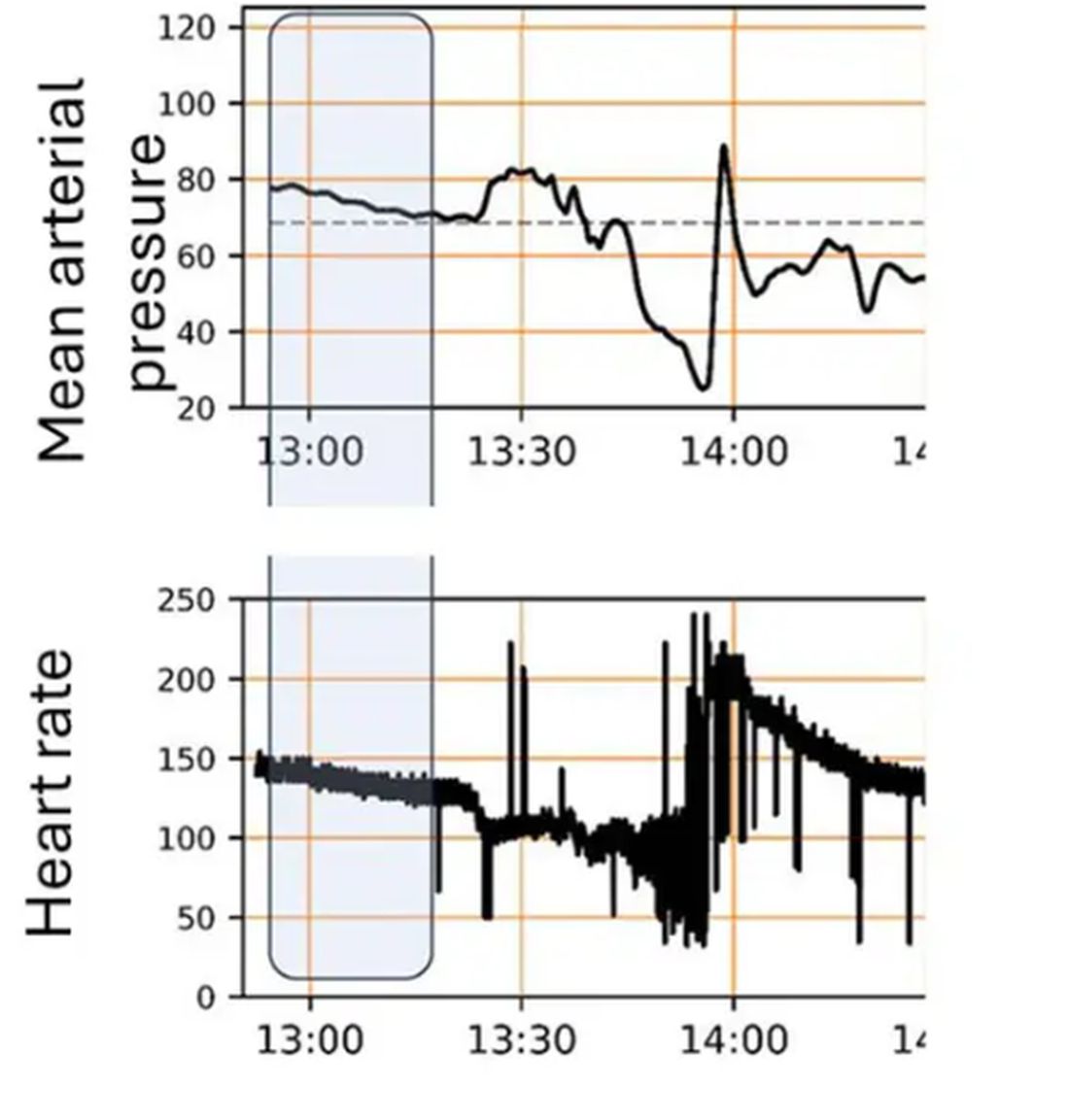

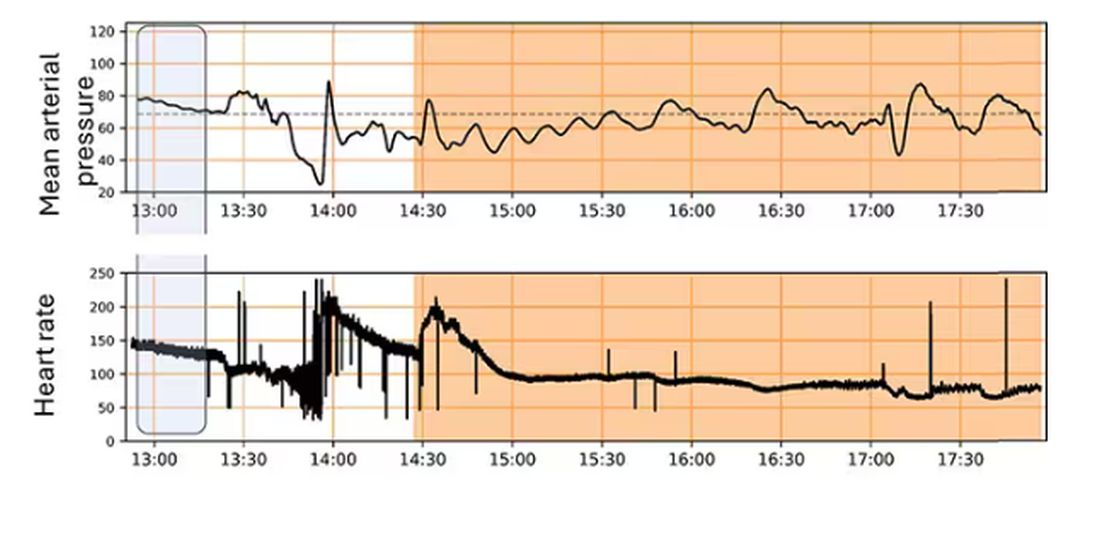

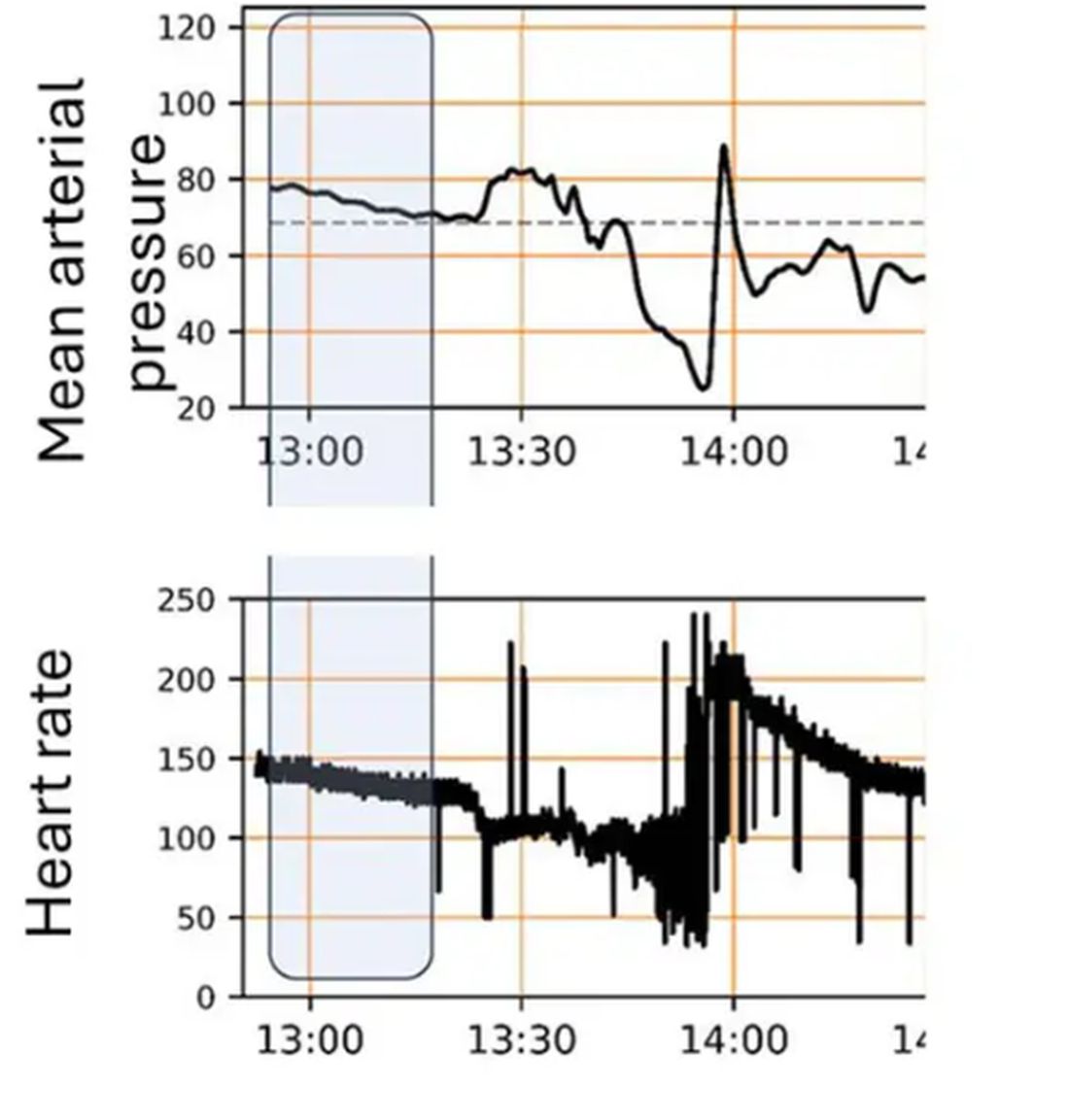

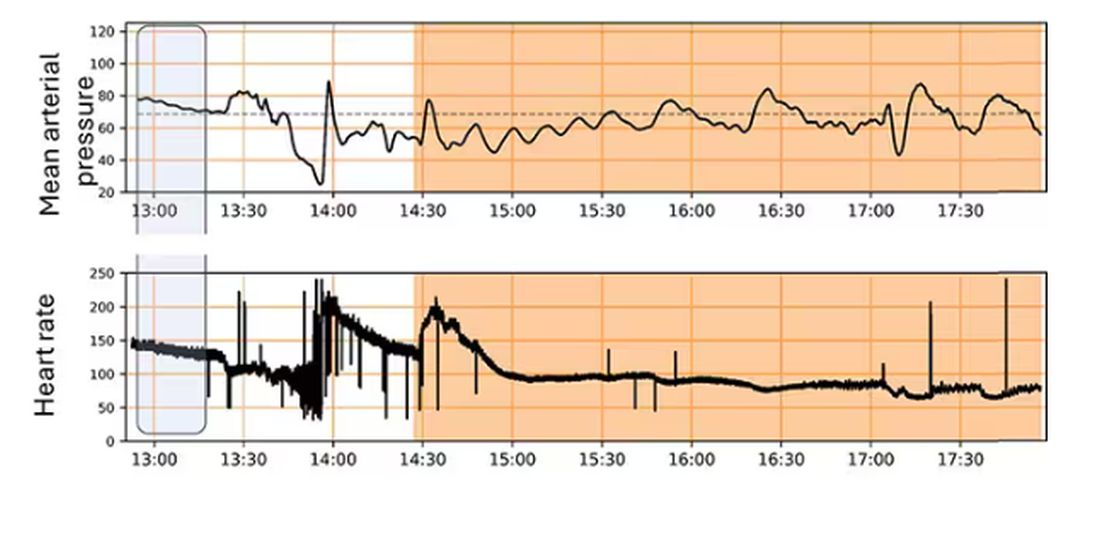

For a window into what happens during this process, let’s take a look at the mean arterial pressure and heart rate readouts for one of the animals. You see that the blood pressure starts to fall precipitously after the liver laceration. The heart rate quickly picks up to compensate, raising the mean arterial pressure a bit, but this would be unsustainable with ongoing bleeding.

Here, the ReFit system takes over. Autonomously, the system administers two units of blood, followed by fluids, and then norepinephrine or further fluids per the protocol I described earlier.

The practical upshot of all of this is stabilization, despite an as-yet untreated liver laceration.

Could an experienced ALS provider do this? Of course. But, as I mentioned before, you aren’t always near an experienced ALS provider.

This is all well and good in the lab, but in the real world, you actually need to transport a trauma patient. The researchers tried this also. To prove feasibility, four pigs were taken from the lab to the top of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, flown to Allegheny County Airport and back. Total time before liver laceration repair? Three hours. And all four survived.

It won’t surprise you to hear that this work was funded by the Department of Defense. You can see how a system like this, made a bit more rugged, a bit smaller, and a bit more self-contained could have real uses in the battlefield. But trauma is not unique to war, and something that can extend the time you have to safely transport a patient to definitive care — well, that’s worth its weight in golden hours.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

They call it the “golden hour”: 60 minutes, give or take, when the chance to save the life of a trauma victim is at its greatest. If the patient can be resuscitated and stabilized in that time window, they stand a good chance of surviving. If not, well, they don’t.

But resuscitation is complicated. It requires blood products, fluids, vasopressors — all given in precise doses in response to rapidly changing hemodynamics. To do it right takes specialized training, advanced life support (ALS). If the patient is in a remote area or an area without ALS-certified emergency medical services, or is far from the nearest trauma center, that golden hour is lost. And the patient may be as well.

But we live in the future. We have robots in factories, self-driving cars, autonomous drones. Why not an autonomous trauma doctor? If you are in a life-threatening accident, would you want to be treated ... by a robot?

Enter “resuscitation based on functional hemodynamic monitoring,” or “ReFit,” introduced in this article appearing in the journal Intensive Care Medicine Experimental.

The idea behind ReFit is straightforward. Resuscitation after trauma should be based on hitting key hemodynamic targets using the tools we have available in the field: blood, fluids, pressors. The researchers wanted to develop a closed-loop system, something that could be used by minimally trained personnel. The input to the system? Hemodynamic data, provided through a single measurement device, an arterial catheter. The output: blood, fluids, and pressors, delivered intravenously.

The body (a prototype) of the system looks like this. You can see various pumps labeled with various fluids, electronic controllers, and so forth.

If that’s the body, then this is the brain – a ruggedized laptop interpreting a readout of that arterial catheter.

If that’s the brain, then the ReFit algorithm is the mind. The algorithm does its best to leverage all the data it can, so I want to walk through it in a bit of detail.

First, check to see whether the patient is stable, defined as a heart rate < 110 beats/min and a mean arterial pressure > 60 mm Hg. If not, you’re off to the races, starting with a bolus of whole blood.

Next, the algorithm gets really interesting. If the patient is still unstable, the computer assesses fluid responsiveness by giving a test dose of fluid and measuring the pulse pressure variation. Greater pulse pressure variation means more fluid responsiveness and the algorithm gives more fluid. Less pulse pressure variation leads the algorithm to uptitrate pressors — in this case, norepinephrine.

This cycle of evaluation and response keeps repeating. The computer titrates fluids and pressors up and down entirely on its own, in theory freeing the human team members to do other things, like getting the patient to a trauma center for definitive care.

So, how do you test whether something like this works? Clearly, you don’t want the trial run of a system like this to be used on a real human suffering from a real traumatic injury.

Once again, we have animals to thank for research advances — in this case, pigs. Fifteen pigs are described in the study. To simulate a severe, hemorrhagic trauma, they were anesthetized and the liver was lacerated. They were then observed passively until the mean arterial pressure had dropped to below 40 mm Hg.

This is a pretty severe injury. Three unfortunate animals served as controls, two of which died within the 3-hour time window of the study. Eight animals were plugged into the ReFit system.

For a window into what happens during this process, let’s take a look at the mean arterial pressure and heart rate readouts for one of the animals. You see that the blood pressure starts to fall precipitously after the liver laceration. The heart rate quickly picks up to compensate, raising the mean arterial pressure a bit, but this would be unsustainable with ongoing bleeding.

Here, the ReFit system takes over. Autonomously, the system administers two units of blood, followed by fluids, and then norepinephrine or further fluids per the protocol I described earlier.

The practical upshot of all of this is stabilization, despite an as-yet untreated liver laceration.

Could an experienced ALS provider do this? Of course. But, as I mentioned before, you aren’t always near an experienced ALS provider.

This is all well and good in the lab, but in the real world, you actually need to transport a trauma patient. The researchers tried this also. To prove feasibility, four pigs were taken from the lab to the top of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, flown to Allegheny County Airport and back. Total time before liver laceration repair? Three hours. And all four survived.

It won’t surprise you to hear that this work was funded by the Department of Defense. You can see how a system like this, made a bit more rugged, a bit smaller, and a bit more self-contained could have real uses in the battlefield. But trauma is not unique to war, and something that can extend the time you have to safely transport a patient to definitive care — well, that’s worth its weight in golden hours.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

They call it the “golden hour”: 60 minutes, give or take, when the chance to save the life of a trauma victim is at its greatest. If the patient can be resuscitated and stabilized in that time window, they stand a good chance of surviving. If not, well, they don’t.

But resuscitation is complicated. It requires blood products, fluids, vasopressors — all given in precise doses in response to rapidly changing hemodynamics. To do it right takes specialized training, advanced life support (ALS). If the patient is in a remote area or an area without ALS-certified emergency medical services, or is far from the nearest trauma center, that golden hour is lost. And the patient may be as well.

But we live in the future. We have robots in factories, self-driving cars, autonomous drones. Why not an autonomous trauma doctor? If you are in a life-threatening accident, would you want to be treated ... by a robot?

Enter “resuscitation based on functional hemodynamic monitoring,” or “ReFit,” introduced in this article appearing in the journal Intensive Care Medicine Experimental.

The idea behind ReFit is straightforward. Resuscitation after trauma should be based on hitting key hemodynamic targets using the tools we have available in the field: blood, fluids, pressors. The researchers wanted to develop a closed-loop system, something that could be used by minimally trained personnel. The input to the system? Hemodynamic data, provided through a single measurement device, an arterial catheter. The output: blood, fluids, and pressors, delivered intravenously.

The body (a prototype) of the system looks like this. You can see various pumps labeled with various fluids, electronic controllers, and so forth.

If that’s the body, then this is the brain – a ruggedized laptop interpreting a readout of that arterial catheter.

If that’s the brain, then the ReFit algorithm is the mind. The algorithm does its best to leverage all the data it can, so I want to walk through it in a bit of detail.

First, check to see whether the patient is stable, defined as a heart rate < 110 beats/min and a mean arterial pressure > 60 mm Hg. If not, you’re off to the races, starting with a bolus of whole blood.

Next, the algorithm gets really interesting. If the patient is still unstable, the computer assesses fluid responsiveness by giving a test dose of fluid and measuring the pulse pressure variation. Greater pulse pressure variation means more fluid responsiveness and the algorithm gives more fluid. Less pulse pressure variation leads the algorithm to uptitrate pressors — in this case, norepinephrine.

This cycle of evaluation and response keeps repeating. The computer titrates fluids and pressors up and down entirely on its own, in theory freeing the human team members to do other things, like getting the patient to a trauma center for definitive care.

So, how do you test whether something like this works? Clearly, you don’t want the trial run of a system like this to be used on a real human suffering from a real traumatic injury.

Once again, we have animals to thank for research advances — in this case, pigs. Fifteen pigs are described in the study. To simulate a severe, hemorrhagic trauma, they were anesthetized and the liver was lacerated. They were then observed passively until the mean arterial pressure had dropped to below 40 mm Hg.

This is a pretty severe injury. Three unfortunate animals served as controls, two of which died within the 3-hour time window of the study. Eight animals were plugged into the ReFit system.

For a window into what happens during this process, let’s take a look at the mean arterial pressure and heart rate readouts for one of the animals. You see that the blood pressure starts to fall precipitously after the liver laceration. The heart rate quickly picks up to compensate, raising the mean arterial pressure a bit, but this would be unsustainable with ongoing bleeding.

Here, the ReFit system takes over. Autonomously, the system administers two units of blood, followed by fluids, and then norepinephrine or further fluids per the protocol I described earlier.

The practical upshot of all of this is stabilization, despite an as-yet untreated liver laceration.

Could an experienced ALS provider do this? Of course. But, as I mentioned before, you aren’t always near an experienced ALS provider.

This is all well and good in the lab, but in the real world, you actually need to transport a trauma patient. The researchers tried this also. To prove feasibility, four pigs were taken from the lab to the top of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, flown to Allegheny County Airport and back. Total time before liver laceration repair? Three hours. And all four survived.

It won’t surprise you to hear that this work was funded by the Department of Defense. You can see how a system like this, made a bit more rugged, a bit smaller, and a bit more self-contained could have real uses in the battlefield. But trauma is not unique to war, and something that can extend the time you have to safely transport a patient to definitive care — well, that’s worth its weight in golden hours.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

When It Comes to Medicine, ‘Women Are Not Small Men’

Welcome everyone. I’m Dr. John White. I’m the chief medical officer at WebMD. Does your biologic sex impact your health? Does it have any play in how you’re diagnosed, how you’re treated in terms of what symptoms you have? Of course it does. We all know that. But that’s not something that many people believed 5, 10 years ago, certainly not 20 years ago. And it was only because of leaders like my guest today, Phyllis Greenberger, who really championed the need for research on women’s health. She has a new book out, which I love. It’s called Sex Cells: the Fight to Overcome Bias and Discrimination in Women’s Healthcare. Please welcome my very good friend, Phyllis Greenberger.

Thank you.

Phyllis, It’s great to see you today.

It’s great to see you as well.

Now, you and I have been talking about this for easily 2 decades.

At least.

And some people think, oh, of course it makes sense. Although I saw you disagreeing that not everyone still believes that. But what has been that journey? Why has it been so hard to make people understand, as you point out early on in your book, women are not smaller men?

I think the basic reason was that it was just believed that men and women were the same except for their reproductive organs. So minus the reproductive organs, whether it was a device, a diagnostic, or therapeutic, if it was used and successful on a male, that it would be successful on a female. We’re really very far from understanding the differences, and there’s still a lot of distrust and disbelief and ignorance about it. And so there’s still a long way to go.

But you talk about that in the book, that there’s still a long way to go. Why is that? What’s the biggest obstacle? Is it just misinformation, lack of information? People don’t understand the science? There’s still resistance in some areas. Why is that?

I think it’s misinformation, and I gave a presentation, I don’t know how many years ago, at least 20 years ago, about the curriculum. And at the time, there was no women’s health in the curriculum. It was health. So if it was on cardiovascular issues or on osteoporosis, it was sort of the basic. And at the time, there would maybe be one woman whose job was women’s health, and she’d have an office, and otherwise there was nothing. And maybe they talked about breast cancer, who knows. But I spoke to someone just the other day, in view of all the attention that the book is getting now, whether that’s changed, whether it’s necessary and required. And she said it’s not. So, it’s not necessarily on the curriculum of all research and medical institutions, and even if women’s health, quote unquote, is on the curriculum, it doesn’t mean that they’re really looking at sex differences. And the difference is obvious. I mean, gender is really, it’s a social construct, but biological sex is how disease occurs and develops. And so if you’re not looking, and because there’s so little research now on sex differences that I don’t even know, I mean, how much you could actually teach.

So what needs to change? This book is a manifesto in many ways in how we need to include women; we need to make research more inclusive of everyone. But we’re not there yet. So what needs to change, Phyllis?

During this whole saga of trying to get people to listen to me and to the society, we really started out just looking at clinical trials and that, as you mentioned, I mean, there are issues in rural communities. There’s travel issues for women and child care. There’s a lot of disbelief or fear of clinical trials in some ethnicities. I do think, going to the future, that technology can help that. I mean, if people have broadband, which of course is also an issue in rural areas.

What could women do today? What should women listeners hear and then be doing? Should they be saying something to their doctor? Should they be asking specific questions? When they interact with the health care system, how can they make sure they’re getting the best care that’s appropriate for them when we know that sex cells matter?

Well, that’s a good question. It depends on, frankly, if your doctor is aware of this, if he or she has learned anything about this in school, which, I had already said, we’re not sure about that because research is still ongoing and there’s so much we don’t know. So I mean, you used to think, or I used to think, that you go to, you want a physician who’s older and more experienced. But now I think you should be going to a physician who’s younger and hopefully has learned about this, because the physicians that were educated years ago and have been practicing for 20, 30 years, I don’t know how much they know about this, whether they’re even aware of it.

Phyllis, you are a woman of action. You’ve lived in the DC area. You have championed legislative reforms, executive agendas. What do you want done now? What needs to be changed today? The curriculum is going to take time, but what else needs to change?

That’s a good question. I mean, if curriculum is going to take a while and you can ask your doctor if he prescribes the medication, whether it’s been tested on women, but then if it hasn’t been tested on women, but it’s the only thing that there is for your condition, I mean, so it’s very difficult. The Biden administration, as you know, just allocated a hundred million dollars for women’s health research.

What do you hope to accomplish with this book?

Well, what I’m hoping is that I spoke to someone at AMWA and I’m hoping — and AMWA is an association for women medical students. And I’m hoping that’s the audience. The audience needs to be. I mean, obviously everybody that I know that’s not a doctor that’s read it, found it fascinating and didn’t know a lot of the stuff that was in it. So I think it’s an interesting book anyway, and I think women should be aware of it. But really I think it needs to be for medical students.

And to your credit, you built the Society for Women’s Health Research into a powerful force in Washington under your tenure in really promoting the need for Office of Women’s Health and Research in general. The book is entitled Sex Cells, the Fight to Overcome Bias and Discrimination in Women’s Healthcare. Phyllis Greenberger, thank you so much for all that you’ve done for women’s health, for women’s research. We wouldn’t be where we are today if it wasn’t for you. So thanks.

Thank you very much, John. Thank you. I appreciate the opportunity.

Dr. Whyte, is chief medical officer, WebMD, New York, NY. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Ms. Greenberger is a women’s health advocate and author of “Sex Cells: The Fight to Overcome Bias and Discrimination in Women’s Healthcare”

This interview originally appeared on WebMD on May 23, 2024. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Welcome everyone. I’m Dr. John White. I’m the chief medical officer at WebMD. Does your biologic sex impact your health? Does it have any play in how you’re diagnosed, how you’re treated in terms of what symptoms you have? Of course it does. We all know that. But that’s not something that many people believed 5, 10 years ago, certainly not 20 years ago. And it was only because of leaders like my guest today, Phyllis Greenberger, who really championed the need for research on women’s health. She has a new book out, which I love. It’s called Sex Cells: the Fight to Overcome Bias and Discrimination in Women’s Healthcare. Please welcome my very good friend, Phyllis Greenberger.

Thank you.

Phyllis, It’s great to see you today.

It’s great to see you as well.

Now, you and I have been talking about this for easily 2 decades.

At least.

And some people think, oh, of course it makes sense. Although I saw you disagreeing that not everyone still believes that. But what has been that journey? Why has it been so hard to make people understand, as you point out early on in your book, women are not smaller men?

I think the basic reason was that it was just believed that men and women were the same except for their reproductive organs. So minus the reproductive organs, whether it was a device, a diagnostic, or therapeutic, if it was used and successful on a male, that it would be successful on a female. We’re really very far from understanding the differences, and there’s still a lot of distrust and disbelief and ignorance about it. And so there’s still a long way to go.

But you talk about that in the book, that there’s still a long way to go. Why is that? What’s the biggest obstacle? Is it just misinformation, lack of information? People don’t understand the science? There’s still resistance in some areas. Why is that?

I think it’s misinformation, and I gave a presentation, I don’t know how many years ago, at least 20 years ago, about the curriculum. And at the time, there was no women’s health in the curriculum. It was health. So if it was on cardiovascular issues or on osteoporosis, it was sort of the basic. And at the time, there would maybe be one woman whose job was women’s health, and she’d have an office, and otherwise there was nothing. And maybe they talked about breast cancer, who knows. But I spoke to someone just the other day, in view of all the attention that the book is getting now, whether that’s changed, whether it’s necessary and required. And she said it’s not. So, it’s not necessarily on the curriculum of all research and medical institutions, and even if women’s health, quote unquote, is on the curriculum, it doesn’t mean that they’re really looking at sex differences. And the difference is obvious. I mean, gender is really, it’s a social construct, but biological sex is how disease occurs and develops. And so if you’re not looking, and because there’s so little research now on sex differences that I don’t even know, I mean, how much you could actually teach.

So what needs to change? This book is a manifesto in many ways in how we need to include women; we need to make research more inclusive of everyone. But we’re not there yet. So what needs to change, Phyllis?

During this whole saga of trying to get people to listen to me and to the society, we really started out just looking at clinical trials and that, as you mentioned, I mean, there are issues in rural communities. There’s travel issues for women and child care. There’s a lot of disbelief or fear of clinical trials in some ethnicities. I do think, going to the future, that technology can help that. I mean, if people have broadband, which of course is also an issue in rural areas.

What could women do today? What should women listeners hear and then be doing? Should they be saying something to their doctor? Should they be asking specific questions? When they interact with the health care system, how can they make sure they’re getting the best care that’s appropriate for them when we know that sex cells matter?

Well, that’s a good question. It depends on, frankly, if your doctor is aware of this, if he or she has learned anything about this in school, which, I had already said, we’re not sure about that because research is still ongoing and there’s so much we don’t know. So I mean, you used to think, or I used to think, that you go to, you want a physician who’s older and more experienced. But now I think you should be going to a physician who’s younger and hopefully has learned about this, because the physicians that were educated years ago and have been practicing for 20, 30 years, I don’t know how much they know about this, whether they’re even aware of it.

Phyllis, you are a woman of action. You’ve lived in the DC area. You have championed legislative reforms, executive agendas. What do you want done now? What needs to be changed today? The curriculum is going to take time, but what else needs to change?

That’s a good question. I mean, if curriculum is going to take a while and you can ask your doctor if he prescribes the medication, whether it’s been tested on women, but then if it hasn’t been tested on women, but it’s the only thing that there is for your condition, I mean, so it’s very difficult. The Biden administration, as you know, just allocated a hundred million dollars for women’s health research.

What do you hope to accomplish with this book?

Well, what I’m hoping is that I spoke to someone at AMWA and I’m hoping — and AMWA is an association for women medical students. And I’m hoping that’s the audience. The audience needs to be. I mean, obviously everybody that I know that’s not a doctor that’s read it, found it fascinating and didn’t know a lot of the stuff that was in it. So I think it’s an interesting book anyway, and I think women should be aware of it. But really I think it needs to be for medical students.

And to your credit, you built the Society for Women’s Health Research into a powerful force in Washington under your tenure in really promoting the need for Office of Women’s Health and Research in general. The book is entitled Sex Cells, the Fight to Overcome Bias and Discrimination in Women’s Healthcare. Phyllis Greenberger, thank you so much for all that you’ve done for women’s health, for women’s research. We wouldn’t be where we are today if it wasn’t for you. So thanks.

Thank you very much, John. Thank you. I appreciate the opportunity.

Dr. Whyte, is chief medical officer, WebMD, New York, NY. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Ms. Greenberger is a women’s health advocate and author of “Sex Cells: The Fight to Overcome Bias and Discrimination in Women’s Healthcare”

This interview originally appeared on WebMD on May 23, 2024. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Welcome everyone. I’m Dr. John White. I’m the chief medical officer at WebMD. Does your biologic sex impact your health? Does it have any play in how you’re diagnosed, how you’re treated in terms of what symptoms you have? Of course it does. We all know that. But that’s not something that many people believed 5, 10 years ago, certainly not 20 years ago. And it was only because of leaders like my guest today, Phyllis Greenberger, who really championed the need for research on women’s health. She has a new book out, which I love. It’s called Sex Cells: the Fight to Overcome Bias and Discrimination in Women’s Healthcare. Please welcome my very good friend, Phyllis Greenberger.

Thank you.

Phyllis, It’s great to see you today.

It’s great to see you as well.

Now, you and I have been talking about this for easily 2 decades.

At least.

And some people think, oh, of course it makes sense. Although I saw you disagreeing that not everyone still believes that. But what has been that journey? Why has it been so hard to make people understand, as you point out early on in your book, women are not smaller men?

I think the basic reason was that it was just believed that men and women were the same except for their reproductive organs. So minus the reproductive organs, whether it was a device, a diagnostic, or therapeutic, if it was used and successful on a male, that it would be successful on a female. We’re really very far from understanding the differences, and there’s still a lot of distrust and disbelief and ignorance about it. And so there’s still a long way to go.

But you talk about that in the book, that there’s still a long way to go. Why is that? What’s the biggest obstacle? Is it just misinformation, lack of information? People don’t understand the science? There’s still resistance in some areas. Why is that?

I think it’s misinformation, and I gave a presentation, I don’t know how many years ago, at least 20 years ago, about the curriculum. And at the time, there was no women’s health in the curriculum. It was health. So if it was on cardiovascular issues or on osteoporosis, it was sort of the basic. And at the time, there would maybe be one woman whose job was women’s health, and she’d have an office, and otherwise there was nothing. And maybe they talked about breast cancer, who knows. But I spoke to someone just the other day, in view of all the attention that the book is getting now, whether that’s changed, whether it’s necessary and required. And she said it’s not. So, it’s not necessarily on the curriculum of all research and medical institutions, and even if women’s health, quote unquote, is on the curriculum, it doesn’t mean that they’re really looking at sex differences. And the difference is obvious. I mean, gender is really, it’s a social construct, but biological sex is how disease occurs and develops. And so if you’re not looking, and because there’s so little research now on sex differences that I don’t even know, I mean, how much you could actually teach.

So what needs to change? This book is a manifesto in many ways in how we need to include women; we need to make research more inclusive of everyone. But we’re not there yet. So what needs to change, Phyllis?

During this whole saga of trying to get people to listen to me and to the society, we really started out just looking at clinical trials and that, as you mentioned, I mean, there are issues in rural communities. There’s travel issues for women and child care. There’s a lot of disbelief or fear of clinical trials in some ethnicities. I do think, going to the future, that technology can help that. I mean, if people have broadband, which of course is also an issue in rural areas.

What could women do today? What should women listeners hear and then be doing? Should they be saying something to their doctor? Should they be asking specific questions? When they interact with the health care system, how can they make sure they’re getting the best care that’s appropriate for them when we know that sex cells matter?

Well, that’s a good question. It depends on, frankly, if your doctor is aware of this, if he or she has learned anything about this in school, which, I had already said, we’re not sure about that because research is still ongoing and there’s so much we don’t know. So I mean, you used to think, or I used to think, that you go to, you want a physician who’s older and more experienced. But now I think you should be going to a physician who’s younger and hopefully has learned about this, because the physicians that were educated years ago and have been practicing for 20, 30 years, I don’t know how much they know about this, whether they’re even aware of it.

Phyllis, you are a woman of action. You’ve lived in the DC area. You have championed legislative reforms, executive agendas. What do you want done now? What needs to be changed today? The curriculum is going to take time, but what else needs to change?

That’s a good question. I mean, if curriculum is going to take a while and you can ask your doctor if he prescribes the medication, whether it’s been tested on women, but then if it hasn’t been tested on women, but it’s the only thing that there is for your condition, I mean, so it’s very difficult. The Biden administration, as you know, just allocated a hundred million dollars for women’s health research.

What do you hope to accomplish with this book?

Well, what I’m hoping is that I spoke to someone at AMWA and I’m hoping — and AMWA is an association for women medical students. And I’m hoping that’s the audience. The audience needs to be. I mean, obviously everybody that I know that’s not a doctor that’s read it, found it fascinating and didn’t know a lot of the stuff that was in it. So I think it’s an interesting book anyway, and I think women should be aware of it. But really I think it needs to be for medical students.

And to your credit, you built the Society for Women’s Health Research into a powerful force in Washington under your tenure in really promoting the need for Office of Women’s Health and Research in general. The book is entitled Sex Cells, the Fight to Overcome Bias and Discrimination in Women’s Healthcare. Phyllis Greenberger, thank you so much for all that you’ve done for women’s health, for women’s research. We wouldn’t be where we are today if it wasn’t for you. So thanks.

Thank you very much, John. Thank you. I appreciate the opportunity.

Dr. Whyte, is chief medical officer, WebMD, New York, NY. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Ms. Greenberger is a women’s health advocate and author of “Sex Cells: The Fight to Overcome Bias and Discrimination in Women’s Healthcare”

This interview originally appeared on WebMD on May 23, 2024. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Staving Off Obsolescence

I don’t write many checks anymore.

When I started my practice in 2000 I wrote a lot. Paychecks for my staff, my rent, insurance, IRA contributions, federal & state withholding, payments on my EMG machine, pretty much everything.

Checks are old. We’ve been using them in some form for roughly 2000 years.

But the online world has changed a lot of that. Now I write maybe 2-3 a month. I could probably do fewer, but haven’t bothered to set those accounts up that way.

I recently was down to my last few checks, so ordered replacements. The minimum order was 600. As I unpacked the box I realized they’re probably the last ones I’ll need, both because checks are gradually passing by and because there are more days behind in my neurology career than ahead.

The checks are a minor thing, but they do make you think. Certainly we’re in the last generation of people who will ever need to use paper checks. Some phrases like “blank check” will likely be with us long after they’re gone (like “dialing a phone”), but the real deal is heading the same way as 8-Track and VHS tapes.

As my 600 checks dwindle down, realistically, so will my career. There is no rewind button on life. I have no desire to leave medicine right now, but the passage of time changes things.

Does that mean I, like my checks, am also getting obsolete?

I hope not. I’d like to think I still have something to offer. I have 30 years of neurology experience behind me, and try to keep up to date on my field. My patients and staff depend on me to bring my best to the office every day.

I hope to stay that way to the end. I’d rather leave voluntarily, still at the top of my game. Even if I end up leaving a few unused checks behind.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

I don’t write many checks anymore.

When I started my practice in 2000 I wrote a lot. Paychecks for my staff, my rent, insurance, IRA contributions, federal & state withholding, payments on my EMG machine, pretty much everything.

Checks are old. We’ve been using them in some form for roughly 2000 years.

But the online world has changed a lot of that. Now I write maybe 2-3 a month. I could probably do fewer, but haven’t bothered to set those accounts up that way.

I recently was down to my last few checks, so ordered replacements. The minimum order was 600. As I unpacked the box I realized they’re probably the last ones I’ll need, both because checks are gradually passing by and because there are more days behind in my neurology career than ahead.

The checks are a minor thing, but they do make you think. Certainly we’re in the last generation of people who will ever need to use paper checks. Some phrases like “blank check” will likely be with us long after they’re gone (like “dialing a phone”), but the real deal is heading the same way as 8-Track and VHS tapes.

As my 600 checks dwindle down, realistically, so will my career. There is no rewind button on life. I have no desire to leave medicine right now, but the passage of time changes things.

Does that mean I, like my checks, am also getting obsolete?

I hope not. I’d like to think I still have something to offer. I have 30 years of neurology experience behind me, and try to keep up to date on my field. My patients and staff depend on me to bring my best to the office every day.

I hope to stay that way to the end. I’d rather leave voluntarily, still at the top of my game. Even if I end up leaving a few unused checks behind.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

I don’t write many checks anymore.

When I started my practice in 2000 I wrote a lot. Paychecks for my staff, my rent, insurance, IRA contributions, federal & state withholding, payments on my EMG machine, pretty much everything.

Checks are old. We’ve been using them in some form for roughly 2000 years.

But the online world has changed a lot of that. Now I write maybe 2-3 a month. I could probably do fewer, but haven’t bothered to set those accounts up that way.

I recently was down to my last few checks, so ordered replacements. The minimum order was 600. As I unpacked the box I realized they’re probably the last ones I’ll need, both because checks are gradually passing by and because there are more days behind in my neurology career than ahead.

The checks are a minor thing, but they do make you think. Certainly we’re in the last generation of people who will ever need to use paper checks. Some phrases like “blank check” will likely be with us long after they’re gone (like “dialing a phone”), but the real deal is heading the same way as 8-Track and VHS tapes.

As my 600 checks dwindle down, realistically, so will my career. There is no rewind button on life. I have no desire to leave medicine right now, but the passage of time changes things.

Does that mean I, like my checks, am also getting obsolete?

I hope not. I’d like to think I still have something to offer. I have 30 years of neurology experience behind me, and try to keep up to date on my field. My patients and staff depend on me to bring my best to the office every day.

I hope to stay that way to the end. I’d rather leave voluntarily, still at the top of my game. Even if I end up leaving a few unused checks behind.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Rethinking the Rebels

Each month I set out on an expedition to find a topic for this column. I came across a new book Rebel Health by Susannah Fox that I thought might be a good one. It’s both a treatise on the shortcomings of healthcare and a Baedeker for patients on how to find their way to being better served. Her argument is that many patients’ needs are unmet and their conditions are often invisible to us in mainstream healthcare. We fail to find solutions to help them. Patients would benefit from more open access to their records and more resources to take control of their own health, she argues. A few chapters in, I thought, “Oh, here we go, another diatribe on doctors and how we care most about how to keep patients in their rightful, subordinate place.” The “Rebel” title is provocative and implies patients need to overthrow the status quo. Well, I am part of the establishment. I stopped reading. This book doesn’t apply to me, I thought.

After all, I’m a healthcare progressive, right? My notes and results have been open for years. I encourage shared decision-making and try to empower patients as much as treat them. The idea that I or my colleagues are unwilling to do whatever is necessary to meet our patients’ needs was maddening. We dedicate our lives to it. My young daughter often greets me in the morning by asking if I’ll be working tonight. Most nights, I am — answering patient messages, collaborating with colleagues to help patients, keeping up with medical knowledge. I was angry at what felt like unjust criticism, especially that we’d neglect patients because their problems are not obvious or worse, there is not enough money to be made helping them. Harrumph.

That’s when I realized the best thing for me was to read the entire book and digest the arguments. I pride myself on being well-read, but I fall into a common trap: the podcasts I listen to, news I consume, and books I read mostly affirm my beliefs. It is a healthy choice to seek dispositive data and contrasting stories rather than always feeding our personal opinions.

Rebel Health was not written by Robespierre. It was penned by a thoughtful, articulate patient advocate with over 20 years experience. She has far more bona fides than I could achieve in two lifetimes. In the book, she reminds us that She describes four patient archetypes: seekers, networkers, solvers, and champions, and offers a four-quadrant model to visualize how some patients are unhelped by our current healthcare system. She advocates for frictionless, open access to health data and tries to inspire patients to connect, innovate, and create to fill the voids that exist in healthcare. We have come a long way from the immured system of a decade ago; much of that is the result of patient advocates. But healthcare is still too costly, too fragmented and too many patients unhelped. “Community is a superpower,” she writes. I agree, we should assemble all the heroes in the universe for this challenge.

Fox also tells stories of patients who solved diagnostic dilemmas through their own research and advocacy. I thought of my own contrasting experiences of patients whose DIY care was based on misinformation and how their false confidence led to poorer outcomes for them. I want to share with her readers how physicians feel hurt when patients question our competence or place the opinion of an adversarial Redditor over ours. Physicians are sometimes wrong and often in doubt. Most of us care deeply about our patients regardless of how visible their diagnosis or how easy they are to appease.

We don’t have time to engage back-and-forth on an insignificantly abnormal test they find in their open chart or why B12 and hormone testing would not be helpful for their disease. It’s also not the patients’ fault. Having unfettered access to their data might add work, but it also adds value. They are trying to learn and be active in their care. Physicians are frustrated mostly because we don’t have time to meet these unmet needs. Everyone is trying their best and we all want the same thing: patients to be satisfied and well.

As for learning the skill of being open-minded, an excellent reference is Adam Grant’s Think Again. It’s inspiring and instructive of how we can all be more open, including how to have productive arguments rather than fruitless fights. We live in divisive times. Perhaps if we all put in effort to be open-minded, push down righteous indignation, and advance more honest humility we’d all be a bit better off.

Patients are the primary audience for the Rebel Health book. Yet, as we care about them and we all want to make healthcare better, it is worth reading in its entirety. I told my daughter I don’t have to work tonight because I’ve written my article this month. When she’s a little older, I’ll tell her all about it. To be successful, she’ll have to be as open-minded as she is smart. She can learn both.

I have no conflict of interest in the book.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Each month I set out on an expedition to find a topic for this column. I came across a new book Rebel Health by Susannah Fox that I thought might be a good one. It’s both a treatise on the shortcomings of healthcare and a Baedeker for patients on how to find their way to being better served. Her argument is that many patients’ needs are unmet and their conditions are often invisible to us in mainstream healthcare. We fail to find solutions to help them. Patients would benefit from more open access to their records and more resources to take control of their own health, she argues. A few chapters in, I thought, “Oh, here we go, another diatribe on doctors and how we care most about how to keep patients in their rightful, subordinate place.” The “Rebel” title is provocative and implies patients need to overthrow the status quo. Well, I am part of the establishment. I stopped reading. This book doesn’t apply to me, I thought.

After all, I’m a healthcare progressive, right? My notes and results have been open for years. I encourage shared decision-making and try to empower patients as much as treat them. The idea that I or my colleagues are unwilling to do whatever is necessary to meet our patients’ needs was maddening. We dedicate our lives to it. My young daughter often greets me in the morning by asking if I’ll be working tonight. Most nights, I am — answering patient messages, collaborating with colleagues to help patients, keeping up with medical knowledge. I was angry at what felt like unjust criticism, especially that we’d neglect patients because their problems are not obvious or worse, there is not enough money to be made helping them. Harrumph.

That’s when I realized the best thing for me was to read the entire book and digest the arguments. I pride myself on being well-read, but I fall into a common trap: the podcasts I listen to, news I consume, and books I read mostly affirm my beliefs. It is a healthy choice to seek dispositive data and contrasting stories rather than always feeding our personal opinions.

Rebel Health was not written by Robespierre. It was penned by a thoughtful, articulate patient advocate with over 20 years experience. She has far more bona fides than I could achieve in two lifetimes. In the book, she reminds us that She describes four patient archetypes: seekers, networkers, solvers, and champions, and offers a four-quadrant model to visualize how some patients are unhelped by our current healthcare system. She advocates for frictionless, open access to health data and tries to inspire patients to connect, innovate, and create to fill the voids that exist in healthcare. We have come a long way from the immured system of a decade ago; much of that is the result of patient advocates. But healthcare is still too costly, too fragmented and too many patients unhelped. “Community is a superpower,” she writes. I agree, we should assemble all the heroes in the universe for this challenge.

Fox also tells stories of patients who solved diagnostic dilemmas through their own research and advocacy. I thought of my own contrasting experiences of patients whose DIY care was based on misinformation and how their false confidence led to poorer outcomes for them. I want to share with her readers how physicians feel hurt when patients question our competence or place the opinion of an adversarial Redditor over ours. Physicians are sometimes wrong and often in doubt. Most of us care deeply about our patients regardless of how visible their diagnosis or how easy they are to appease.

We don’t have time to engage back-and-forth on an insignificantly abnormal test they find in their open chart or why B12 and hormone testing would not be helpful for their disease. It’s also not the patients’ fault. Having unfettered access to their data might add work, but it also adds value. They are trying to learn and be active in their care. Physicians are frustrated mostly because we don’t have time to meet these unmet needs. Everyone is trying their best and we all want the same thing: patients to be satisfied and well.

As for learning the skill of being open-minded, an excellent reference is Adam Grant’s Think Again. It’s inspiring and instructive of how we can all be more open, including how to have productive arguments rather than fruitless fights. We live in divisive times. Perhaps if we all put in effort to be open-minded, push down righteous indignation, and advance more honest humility we’d all be a bit better off.

Patients are the primary audience for the Rebel Health book. Yet, as we care about them and we all want to make healthcare better, it is worth reading in its entirety. I told my daughter I don’t have to work tonight because I’ve written my article this month. When she’s a little older, I’ll tell her all about it. To be successful, she’ll have to be as open-minded as she is smart. She can learn both.

I have no conflict of interest in the book.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Each month I set out on an expedition to find a topic for this column. I came across a new book Rebel Health by Susannah Fox that I thought might be a good one. It’s both a treatise on the shortcomings of healthcare and a Baedeker for patients on how to find their way to being better served. Her argument is that many patients’ needs are unmet and their conditions are often invisible to us in mainstream healthcare. We fail to find solutions to help them. Patients would benefit from more open access to their records and more resources to take control of their own health, she argues. A few chapters in, I thought, “Oh, here we go, another diatribe on doctors and how we care most about how to keep patients in their rightful, subordinate place.” The “Rebel” title is provocative and implies patients need to overthrow the status quo. Well, I am part of the establishment. I stopped reading. This book doesn’t apply to me, I thought.

After all, I’m a healthcare progressive, right? My notes and results have been open for years. I encourage shared decision-making and try to empower patients as much as treat them. The idea that I or my colleagues are unwilling to do whatever is necessary to meet our patients’ needs was maddening. We dedicate our lives to it. My young daughter often greets me in the morning by asking if I’ll be working tonight. Most nights, I am — answering patient messages, collaborating with colleagues to help patients, keeping up with medical knowledge. I was angry at what felt like unjust criticism, especially that we’d neglect patients because their problems are not obvious or worse, there is not enough money to be made helping them. Harrumph.

That’s when I realized the best thing for me was to read the entire book and digest the arguments. I pride myself on being well-read, but I fall into a common trap: the podcasts I listen to, news I consume, and books I read mostly affirm my beliefs. It is a healthy choice to seek dispositive data and contrasting stories rather than always feeding our personal opinions.

Rebel Health was not written by Robespierre. It was penned by a thoughtful, articulate patient advocate with over 20 years experience. She has far more bona fides than I could achieve in two lifetimes. In the book, she reminds us that She describes four patient archetypes: seekers, networkers, solvers, and champions, and offers a four-quadrant model to visualize how some patients are unhelped by our current healthcare system. She advocates for frictionless, open access to health data and tries to inspire patients to connect, innovate, and create to fill the voids that exist in healthcare. We have come a long way from the immured system of a decade ago; much of that is the result of patient advocates. But healthcare is still too costly, too fragmented and too many patients unhelped. “Community is a superpower,” she writes. I agree, we should assemble all the heroes in the universe for this challenge.

Fox also tells stories of patients who solved diagnostic dilemmas through their own research and advocacy. I thought of my own contrasting experiences of patients whose DIY care was based on misinformation and how their false confidence led to poorer outcomes for them. I want to share with her readers how physicians feel hurt when patients question our competence or place the opinion of an adversarial Redditor over ours. Physicians are sometimes wrong and often in doubt. Most of us care deeply about our patients regardless of how visible their diagnosis or how easy they are to appease.

We don’t have time to engage back-and-forth on an insignificantly abnormal test they find in their open chart or why B12 and hormone testing would not be helpful for their disease. It’s also not the patients’ fault. Having unfettered access to their data might add work, but it also adds value. They are trying to learn and be active in their care. Physicians are frustrated mostly because we don’t have time to meet these unmet needs. Everyone is trying their best and we all want the same thing: patients to be satisfied and well.

As for learning the skill of being open-minded, an excellent reference is Adam Grant’s Think Again. It’s inspiring and instructive of how we can all be more open, including how to have productive arguments rather than fruitless fights. We live in divisive times. Perhaps if we all put in effort to be open-minded, push down righteous indignation, and advance more honest humility we’d all be a bit better off.

Patients are the primary audience for the Rebel Health book. Yet, as we care about them and we all want to make healthcare better, it is worth reading in its entirety. I told my daughter I don’t have to work tonight because I’ve written my article this month. When she’s a little older, I’ll tell her all about it. To be successful, she’ll have to be as open-minded as she is smart. She can learn both.

I have no conflict of interest in the book.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Access to Perinatal Mental Healthcare: What Exactly Are The Obstacles?

The first of May is marked as the World Maternal Mental Health Day, a time for patient groups, medical societies, clinicians, and other colleagues who care for women to highlight maternal mental health and to advocate for increased awareness, enhanced access to care, decrease in stigma, and development of the most effective treatments.

In this spirit, and within the context of greater mental health awareness, I wanted to highlight the ironic dichotomy we see in reproductive psychiatry today. Namely, although we have many useful treatments available in the field to treat maternal psychiatric illness, there are barriers to accessing mental healthcare that prevent women from receiving treatment and getting well.

Thinking back on the last few years from the other side of the pandemic, when COVID concerns turned the experience of motherhood on its side in so many ways, we can only acknowledge that it is an important time in the field of reproductive psychiatry. We have seen not only the development of new pharmacologic (neurosteroids) and nonpharmacologic therapies (transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive-behaviorial therapy for perinatal depression), but also the focus on new digital apps for perinatal depression that may be scalable and that may help bridge the voids in access to effective treatment from the most rural to the most urban settings.

In a previous column, I wrote about the potential difficulties of identifying at-risk women with postpartum psychiatric illness, particularly within the context of disparate data collection methods and management of data. Hospital systems that favor paper screening methods rather than digital platforms pose special problems. I also noted an even larger concern: namely, once screened, it can be very challenging to engage women with postpartum depression in treatment, and women may ultimately not navigate to care for a variety of reasons. These components are but one part of the so-called “perinatal treatment cascade.” When we look at access to care, patients would ideally move from depression screening as an example and, following endorsement of significant symptoms, would receive a referral, which would result in the patient being seen, followed up, and getting well. But that is not what is happening.

A recent preliminary study published as a short communication in the Archives of Women’s Mental Health highlighted this issue. The authors used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to follow symptoms of depression in 145 pregnant women in ob.gyn. services, and found that there were low levels of adherence to psychiatric screenings and referrals in the perinatal period. Another study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry found 30.8% of women with postpartum depression were identified clinically, 15.8% received treatment, and 3.2% achieved remission. That is the gulf, in 2024, that we have not managed to bridge.

The findings show the difficulty women experience accessing perinatal mental health resources. While we’ve known for a long time that the “perinatal treatment cascade” is real, what we don’t understand are the variables in the mix, particularly for patients in marginalized groups. We also do not know where women fall off the curve with regard to accessing care. In my mind, if we’re going to make a difference, we need to know the answer to that question.

Part of the issue is that the research into understanding why women fall off the curve is incomplete. You cannot simply hand a sheet to a woman with an EPDS score of 12 who’s depressed and has a newborn and expect her to navigate to care. What we should really be doing is investing in care navigation for women.

The situation is analogous to diagnosing and treating cardiac abnormalities in a catheterization laboratory. If a patient has a blocked coronary artery and needs a stent, then they need to go to the cath lab. We haven’t yet figured out the process in reproductive psychiatry to optimize the likelihood that patients will be screened and then referred to receive the best available treatment.

Some of our ob.gyn. colleagues have been working to improve access to perinatal mental health services, such as offering on-site services, and offering training and services to patients and providers on screening, assessment, and treatment. At the Center for Women’s Mental Health, we are conducting the Screening and Treatment Enhancement for Postpartum Depression study, which is a universal screening and referral program for women at our center. While some progress is being made, there are still far too many women who are falling through the cracks and not receiving the care they need.

It is both ironic and sad that the growing number of available treatments in reproductive psychiatry are scalable, yet we haven’t figured out how to facilitate access to care. While we should be excited about new treatments, we also need to take the time to understand what the barriers are for at-risk women accessing mental healthcare in the postpartum period.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. STEPS for PPD is funded by the Marriott Foundation. Full disclosure information for Dr. Cohen is available at womensmentalhealth.org. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

The first of May is marked as the World Maternal Mental Health Day, a time for patient groups, medical societies, clinicians, and other colleagues who care for women to highlight maternal mental health and to advocate for increased awareness, enhanced access to care, decrease in stigma, and development of the most effective treatments.

In this spirit, and within the context of greater mental health awareness, I wanted to highlight the ironic dichotomy we see in reproductive psychiatry today. Namely, although we have many useful treatments available in the field to treat maternal psychiatric illness, there are barriers to accessing mental healthcare that prevent women from receiving treatment and getting well.

Thinking back on the last few years from the other side of the pandemic, when COVID concerns turned the experience of motherhood on its side in so many ways, we can only acknowledge that it is an important time in the field of reproductive psychiatry. We have seen not only the development of new pharmacologic (neurosteroids) and nonpharmacologic therapies (transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive-behaviorial therapy for perinatal depression), but also the focus on new digital apps for perinatal depression that may be scalable and that may help bridge the voids in access to effective treatment from the most rural to the most urban settings.

In a previous column, I wrote about the potential difficulties of identifying at-risk women with postpartum psychiatric illness, particularly within the context of disparate data collection methods and management of data. Hospital systems that favor paper screening methods rather than digital platforms pose special problems. I also noted an even larger concern: namely, once screened, it can be very challenging to engage women with postpartum depression in treatment, and women may ultimately not navigate to care for a variety of reasons. These components are but one part of the so-called “perinatal treatment cascade.” When we look at access to care, patients would ideally move from depression screening as an example and, following endorsement of significant symptoms, would receive a referral, which would result in the patient being seen, followed up, and getting well. But that is not what is happening.

A recent preliminary study published as a short communication in the Archives of Women’s Mental Health highlighted this issue. The authors used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to follow symptoms of depression in 145 pregnant women in ob.gyn. services, and found that there were low levels of adherence to psychiatric screenings and referrals in the perinatal period. Another study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry found 30.8% of women with postpartum depression were identified clinically, 15.8% received treatment, and 3.2% achieved remission. That is the gulf, in 2024, that we have not managed to bridge.

The findings show the difficulty women experience accessing perinatal mental health resources. While we’ve known for a long time that the “perinatal treatment cascade” is real, what we don’t understand are the variables in the mix, particularly for patients in marginalized groups. We also do not know where women fall off the curve with regard to accessing care. In my mind, if we’re going to make a difference, we need to know the answer to that question.

Part of the issue is that the research into understanding why women fall off the curve is incomplete. You cannot simply hand a sheet to a woman with an EPDS score of 12 who’s depressed and has a newborn and expect her to navigate to care. What we should really be doing is investing in care navigation for women.

The situation is analogous to diagnosing and treating cardiac abnormalities in a catheterization laboratory. If a patient has a blocked coronary artery and needs a stent, then they need to go to the cath lab. We haven’t yet figured out the process in reproductive psychiatry to optimize the likelihood that patients will be screened and then referred to receive the best available treatment.

Some of our ob.gyn. colleagues have been working to improve access to perinatal mental health services, such as offering on-site services, and offering training and services to patients and providers on screening, assessment, and treatment. At the Center for Women’s Mental Health, we are conducting the Screening and Treatment Enhancement for Postpartum Depression study, which is a universal screening and referral program for women at our center. While some progress is being made, there are still far too many women who are falling through the cracks and not receiving the care they need.

It is both ironic and sad that the growing number of available treatments in reproductive psychiatry are scalable, yet we haven’t figured out how to facilitate access to care. While we should be excited about new treatments, we also need to take the time to understand what the barriers are for at-risk women accessing mental healthcare in the postpartum period.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. STEPS for PPD is funded by the Marriott Foundation. Full disclosure information for Dr. Cohen is available at womensmentalhealth.org. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

The first of May is marked as the World Maternal Mental Health Day, a time for patient groups, medical societies, clinicians, and other colleagues who care for women to highlight maternal mental health and to advocate for increased awareness, enhanced access to care, decrease in stigma, and development of the most effective treatments.

In this spirit, and within the context of greater mental health awareness, I wanted to highlight the ironic dichotomy we see in reproductive psychiatry today. Namely, although we have many useful treatments available in the field to treat maternal psychiatric illness, there are barriers to accessing mental healthcare that prevent women from receiving treatment and getting well.

Thinking back on the last few years from the other side of the pandemic, when COVID concerns turned the experience of motherhood on its side in so many ways, we can only acknowledge that it is an important time in the field of reproductive psychiatry. We have seen not only the development of new pharmacologic (neurosteroids) and nonpharmacologic therapies (transcranial magnetic stimulation, cognitive-behaviorial therapy for perinatal depression), but also the focus on new digital apps for perinatal depression that may be scalable and that may help bridge the voids in access to effective treatment from the most rural to the most urban settings.

In a previous column, I wrote about the potential difficulties of identifying at-risk women with postpartum psychiatric illness, particularly within the context of disparate data collection methods and management of data. Hospital systems that favor paper screening methods rather than digital platforms pose special problems. I also noted an even larger concern: namely, once screened, it can be very challenging to engage women with postpartum depression in treatment, and women may ultimately not navigate to care for a variety of reasons. These components are but one part of the so-called “perinatal treatment cascade.” When we look at access to care, patients would ideally move from depression screening as an example and, following endorsement of significant symptoms, would receive a referral, which would result in the patient being seen, followed up, and getting well. But that is not what is happening.

A recent preliminary study published as a short communication in the Archives of Women’s Mental Health highlighted this issue. The authors used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to follow symptoms of depression in 145 pregnant women in ob.gyn. services, and found that there were low levels of adherence to psychiatric screenings and referrals in the perinatal period. Another study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry found 30.8% of women with postpartum depression were identified clinically, 15.8% received treatment, and 3.2% achieved remission. That is the gulf, in 2024, that we have not managed to bridge.

The findings show the difficulty women experience accessing perinatal mental health resources. While we’ve known for a long time that the “perinatal treatment cascade” is real, what we don’t understand are the variables in the mix, particularly for patients in marginalized groups. We also do not know where women fall off the curve with regard to accessing care. In my mind, if we’re going to make a difference, we need to know the answer to that question.

Part of the issue is that the research into understanding why women fall off the curve is incomplete. You cannot simply hand a sheet to a woman with an EPDS score of 12 who’s depressed and has a newborn and expect her to navigate to care. What we should really be doing is investing in care navigation for women.

The situation is analogous to diagnosing and treating cardiac abnormalities in a catheterization laboratory. If a patient has a blocked coronary artery and needs a stent, then they need to go to the cath lab. We haven’t yet figured out the process in reproductive psychiatry to optimize the likelihood that patients will be screened and then referred to receive the best available treatment.

Some of our ob.gyn. colleagues have been working to improve access to perinatal mental health services, such as offering on-site services, and offering training and services to patients and providers on screening, assessment, and treatment. At the Center for Women’s Mental Health, we are conducting the Screening and Treatment Enhancement for Postpartum Depression study, which is a universal screening and referral program for women at our center. While some progress is being made, there are still far too many women who are falling through the cracks and not receiving the care they need.

It is both ironic and sad that the growing number of available treatments in reproductive psychiatry are scalable, yet we haven’t figured out how to facilitate access to care. While we should be excited about new treatments, we also need to take the time to understand what the barriers are for at-risk women accessing mental healthcare in the postpartum period.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. STEPS for PPD is funded by the Marriott Foundation. Full disclosure information for Dr. Cohen is available at womensmentalhealth.org. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Will the Federal Non-Compete Ban Take Effect?

(with very limited exceptions). The final rule will not go into effect until 120 days after its publication in the Federal Register, which took place on May 7, and numerous legal challenges appear to be on the horizon.

The principal components of the rule are as follows:

- After the effective date, most non-compete agreements (which prevent departing employees from signing with a new employer for a defined period within a specific geographic area) are banned nationwide.

- The rule exempts certain “senior executives,” ie individuals who earn more than $151,164 annually and serve in policy-making positions.

- There is another major exception for non-competes connected with a sale of a business.

- While not explicitly stated, the rule arguably exempts non-profits, tax-exempt hospitals, and other tax-exempt entities.

- Employers must provide verbal and written notice to employees regarding existing agreements, which would be voided under the rule.

The final rule is the latest skirmish in an ongoing, years-long debate. Twelve states have already put non-compete bans in place, according to a recent paper, and they may serve as a harbinger of things to come should the federal ban go into effect. Each state rule varies in its specifics as states respond to local market conditions. While some states ban all non-compete agreements outright, others limit them based on variables, such as income and employment circumstances. Of course, should the federal ban take effect, it will supersede whatever rules the individual states have in place.

In drafting the rule, the FTC reasoned that non-compete clauses constitute restraint of trade, and eliminating them could potentially increase worker earnings as well as lower health care costs by billions of dollars. In its statements on the proposed ban, the FTC claimed that it could lower health spending across the board by almost $150 billion per year and return $300 million to workers each year in earnings. The agency cited a large body of research that non-competes make it harder for workers to move between jobs and can raise prices for goods and services, while suppressing wages for workers and inhibiting the creation of new businesses.

Most physicians affected by non-compete agreements heavily favor the new rule, because it would give them more control over their careers and expand their practice and income opportunities. It would allow them to get a new job with a competing organization, bucking a long-standing trend that hospitals and health care systems have heavily relied on to keep staff in place.

The rule would, however, keep in place “non-solicitation” rules that many health care organizations have put in place. That means that if a physician leaves an employer, he or she cannot reach out to former patients and colleagues to bring them along or invite them to join him or her at the new employment venue.

Within that clause, however, the FTC has specified that if such non-solicitation agreement has the “equivalent effect” of a non-compete, the agency would deem it such. That means, even if that rule stands, it could be contested and may be interpreted as violating the non-compete provision. So, there is value in reading all the fine print should the rule move forward.

Physicians in independent practices who employ physician assistants and nurse practitioners have expressed concerns that their expensively trained employees might be tempted to accept a nearby, higher-paying position. The “non-solicitation” clause would theoretically prevent them from taking patients and co-workers with them — unless it were successfully contested. Many questions remain.