User login

Magnesium Sulfate for Fetal Neuroprotection in Preterm Birth

Introduction: The Many Lanes of Research on Magnesium Sulfate

The research that improves human health in the most expedient and most impactful ways is multitiered, with basic or fundamental research, translational research, interventional studies, and retrospective research often occurring simultaneously. There should be no “single lane” of research and one type of research does not preclude the other.

Too often, we fall short in one of these lanes. While we have achieved many moonshots in obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine, we have tended not to place a high priority on basic research, which can provide a strong understanding of the biology of major diseases and conditions affecting women and their offspring. When conducted with proper commitment and funding, such research can lead to biologically directed therapy.

Within our specialty, research on how we can effectively prevent preterm birth, prematurity, and preeclampsia has taken a long road, with various types of therapies being tried, but none being overwhelmingly effective — with an ongoing need for more basic or fundamental research. Nevertheless, we can benefit and gain great insights from retrospective and interventional studies associated with clinical therapies used to treat premature labor and preeclampsia when these therapies have an unanticipated and important secondary benefit.

This month our Master Class is focused on the neuroprotection of prematurity. Magnesium sulfate is a valuable tool for the treatment of both premature labor and preeclampsia, and more recently, also for neuroprotection of the fetus. Interestingly, this use stemmed from researchers looking retrospectively at outcomes in women who received the compound for other reasons. It took many years for researchers to prove its neuroprotective value through interventional trials, while researchers simultaneously strove to understand on a basic biologic level how magnesium sulfate works to prevent outcomes such as cerebral palsy.

Basic research underway today continues to improve our understanding of its precise mechanisms of action. Combined with other tiers of research — including more interventional studies and more translational research — we can improve its utility for the neuroprotection of prematurity. Alternatively, ongoing research may lead to different, even more effective treatments.

Our guest author is Irina Burd, MD, PhD, Sylvan Freiman, MD Endowed Professor and Chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.* Dr. Burd is also a physician-scientist. She recounts the important story of magnesium sulfate and what is currently known about its biologic plausibility in neuroprotection — including through her own studies – as well as what may be coming in the future.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Magnesium Sulfate for Fetal Neuroprotection in Preterm Birth

Without a doubt, magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) given before anticipated preterm birth reduces the risk of cerebral palsy. It is a valuable tool for fetal neuroprotection at a time when there are no proven alternatives. Yet without the persistent research that occurred over more than 20 years, it may not have won the endorsement of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists in 2010 and worked its way into routine practice.

Its history is worthy of reflection. It took years of observational trials (not all of which showed neuroprotective effects), six randomized controlled trials (none of which met their primary endpoint), three meta-analyses, and a Cochrane Database Systematic Review to arrive at the conclusion that antenatal magnesium sulfate therapy given to women at risk of preterm birth has definitive neuroprotective benefit.

This history also holds lessons for our specialty given the dearth of drugs approved for use in pregnancy and the recent withdrawal from the market of Makena — one of only nine drugs to ever be approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in pregnancy — after a second trial showed lack of benefit in preventing recurrent preterm birth. The story of MgSO4 tells us it’s acceptable to have major stumbling blocks: At one point, MgSO4 was considered to be not only not helpful, but harmful, causing neonatal death. Further research disproved this initial finding.

Moreover, the MgSO4 story is one that remains unfinished, as my laboratory and other researchers work to better understand its biologic plausibility and to discover additional neuroprotective agents for anticipated preterm birth that may further reduce the risk of cerebral palsy. This leading cause of chronic childhood disability is estimated by the United Cerebral Palsy Foundation to affect approximately 800,000 people in the United States.

Origins and Biologic Plausibility

The MgSO4 story is rooted in the late seventeenth century discovery by physician Nehemiah Grew that the compound was the key component of the then-famous medicinal spring waters in Epsom, England.1 MgSO4 was first used for eclampsia in 1906,2 and was first reported in the American literature for eclampsia in 1925.3 In 1959, its effect as a tocolytic agent was reported.4

More than 30 years later, in 1995, an observational study coauthored by Karin B. Nelson, MD, and Judith K. Grether, PhD of the National Institutes of Health, showed a reduced risk of cerebral palsy in very-low-birth-weight infants (VLBW).5 The report marked a turning point in research interest on neuroprotection for anticipated preterm birth.

The precise molecular mechanisms of action of MgSO4 for neuroprotection are still not well understood. However, research findings from the University of Maryland and other institutions have provided biologic plausibility for its use to prevent cerebral palsy. Our current thinking is that it involves the prevention of periventricular white matter injury and/or the prevention of oxidative stress and a neuronal injury mechanism called excitotoxicity.

Periventricular white matter injury involving injury to preoligodendrocytes before 32 weeks’ gestation is the most prevalent injury seen in cerebral palsy; preoligodendrocytes are precursors of myelinating oligodendrocytes, which constitute a major glial population in the white matter. Our research in a mouse model demonstrated that the intrauterine inflammation frequently associated with preterm birth can lead to neuronal injury as well as white matter damage, and that MgSO4 may ameliorate both.6,7

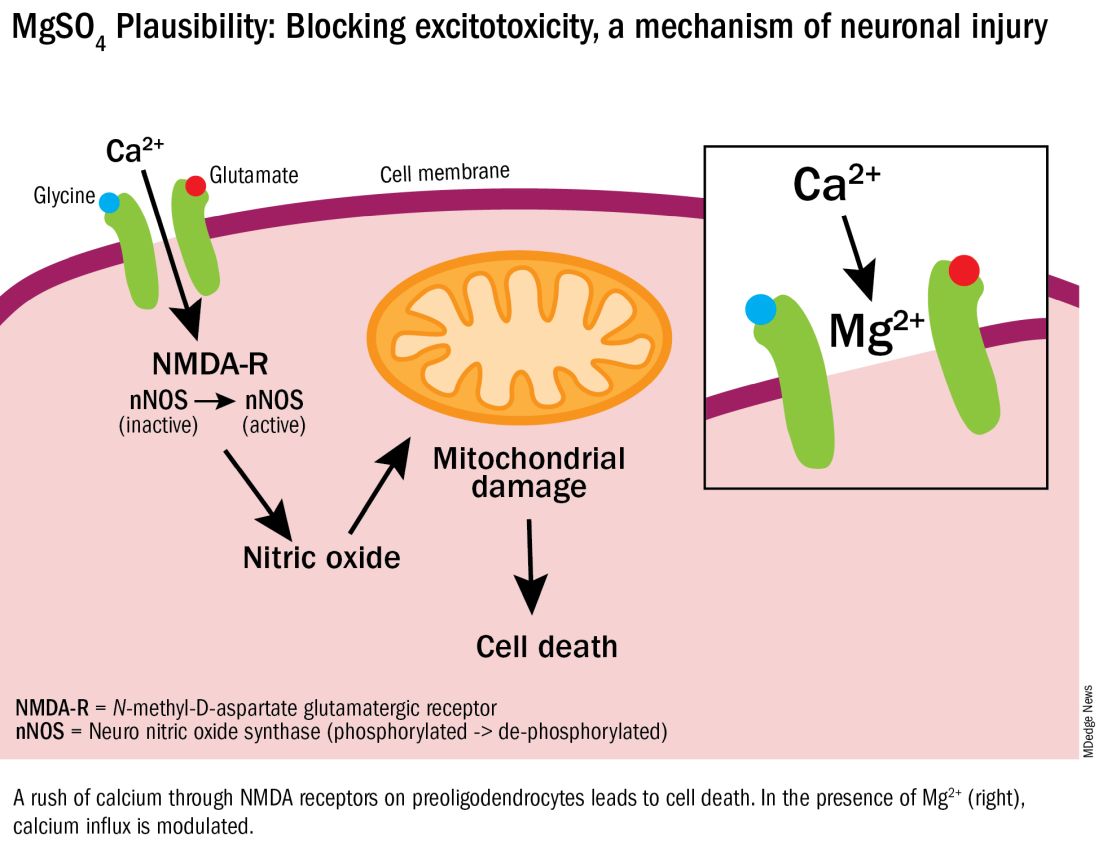

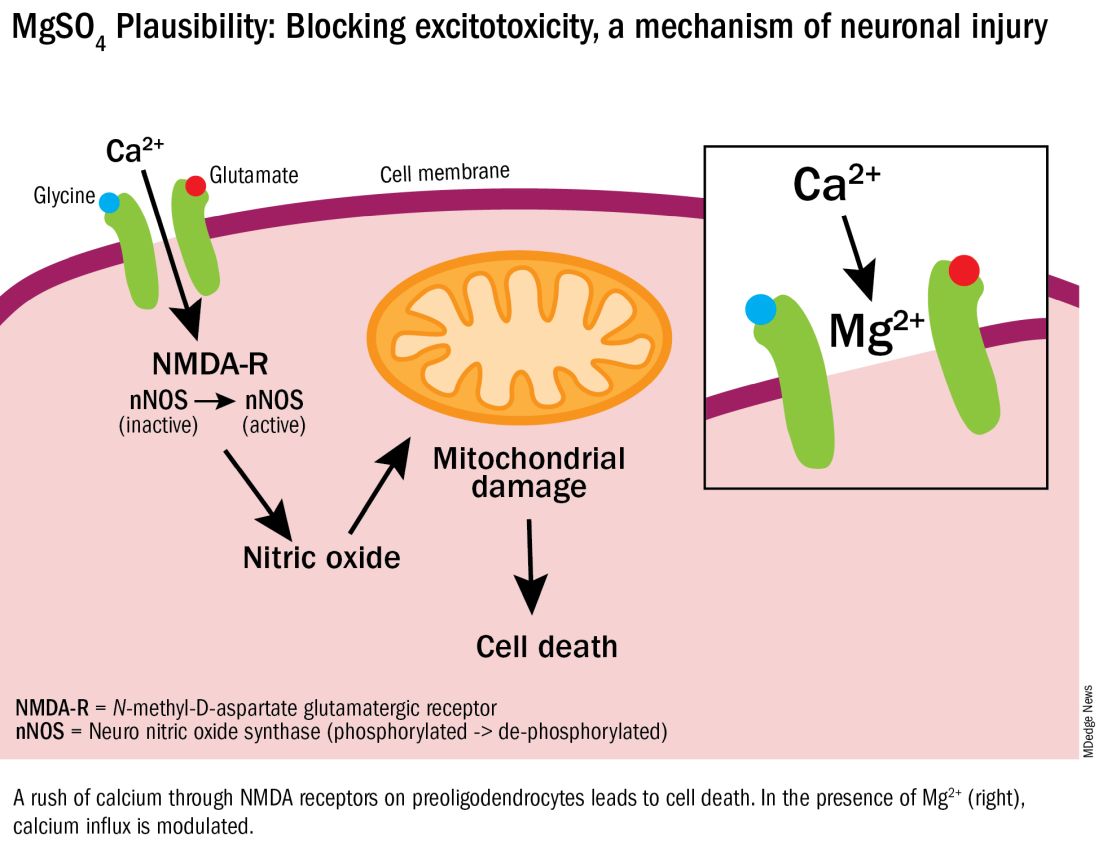

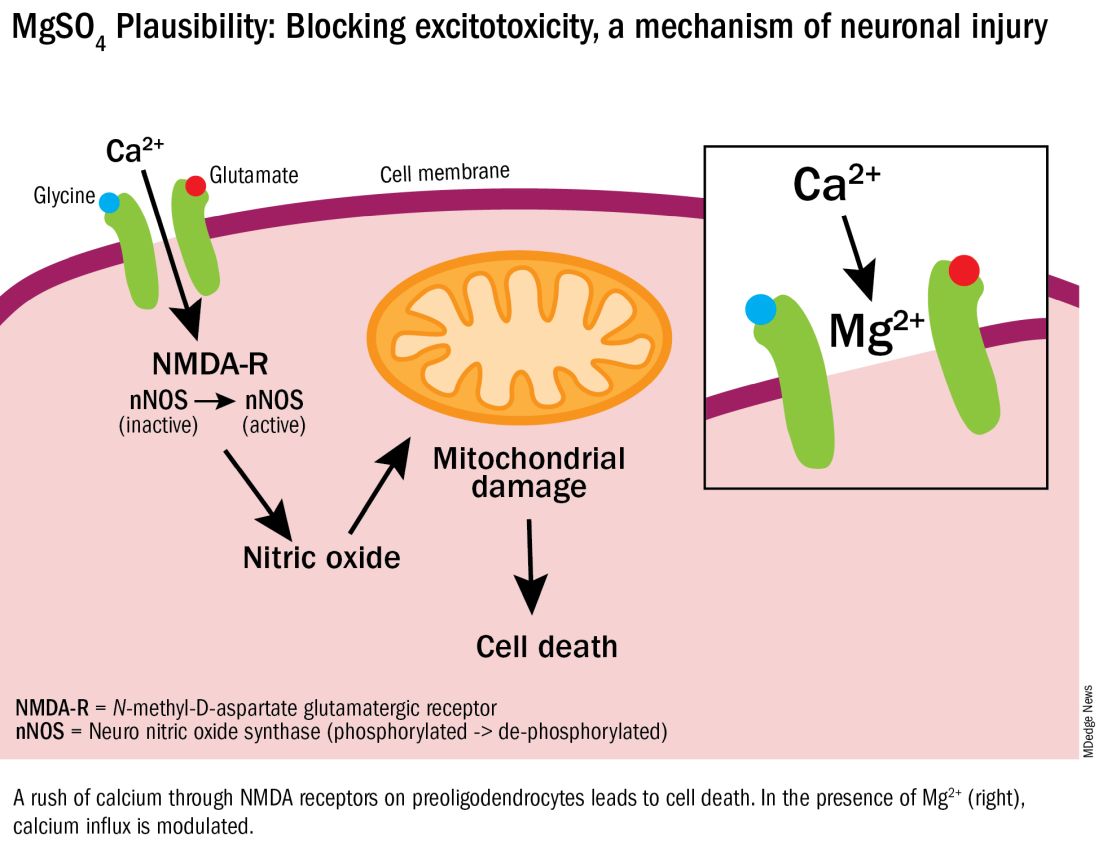

Excitotoxicity results from excessive stimulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamatergic receptors on preoligodendrocytes and a rush of calcium through the voltage-gated channels. This calcium influx leads to the production of nitric oxide, oxidative stress, and subsequent mitochondrial damage and cell death. As a bivalent ion, MgSO4 sits in the voltage-gated channels of the NMDA receptors and reduces glutamatergic signaling, thus serving as a calcium antagonist and modulating calcium influx (See Figure).

In vitro research in our laboratory has also shown that MgSO4 may dampen inflammatory reactions driven by intrauterine infections, which, like preterm birth, increase the risk of cerebral palsy and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes.8 MgSO4 appears to do so by blocking the voltage-gated P2X7 receptor in umbilical vein endothelial cells, thus blocking endothelial secretion of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)–1beta. Much more research is needed to determine whether MgSO4 could help prevent cerebral palsy through this mechanism.

The Long Route of Research

The 1995 Nelson-Grether study compared VLBW (< 1500 g) infants who survived and developed moderate/severe cerebral palsy within 3 years to randomly selected VLBW controls with respect to whether their mothers had received MgSO4 to prevent seizures in preeclampsia or as a tocolytic agent.5 In a population of more than 155,000 children born between 1983 and 1985, in utero exposure to MgSO4 was reported in 7.1% of 42 VLBW infants with cerebral palsy and 36% of 75 VLBW controls (odds ratio [OR], 0.14; 95% CI, 0.05-0.51). In women without preeclampsia the OR increased to 0.25.

This motivating study had been preceded by several observational studies showing that infants born to women with preeclampsia who received MgSO4 had significantly lower risks of developing intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) and germinal matrix hemorrhage (GMH). In one of these studies, published in 1992, Karl C. Kuban, MD, and coauthors reported that “maternal receipt of magnesium sulfate was associated with diminished risk of GMH-IVH even in those babies born to mothers who apparently did not have preeclampsia.”9

In the several years following the 1995 Nelson-Grether study, several other case-control/observational studies were reported, with conflicting conclusions, and investigators around the world began designing and conducting needed randomized controlled trials.

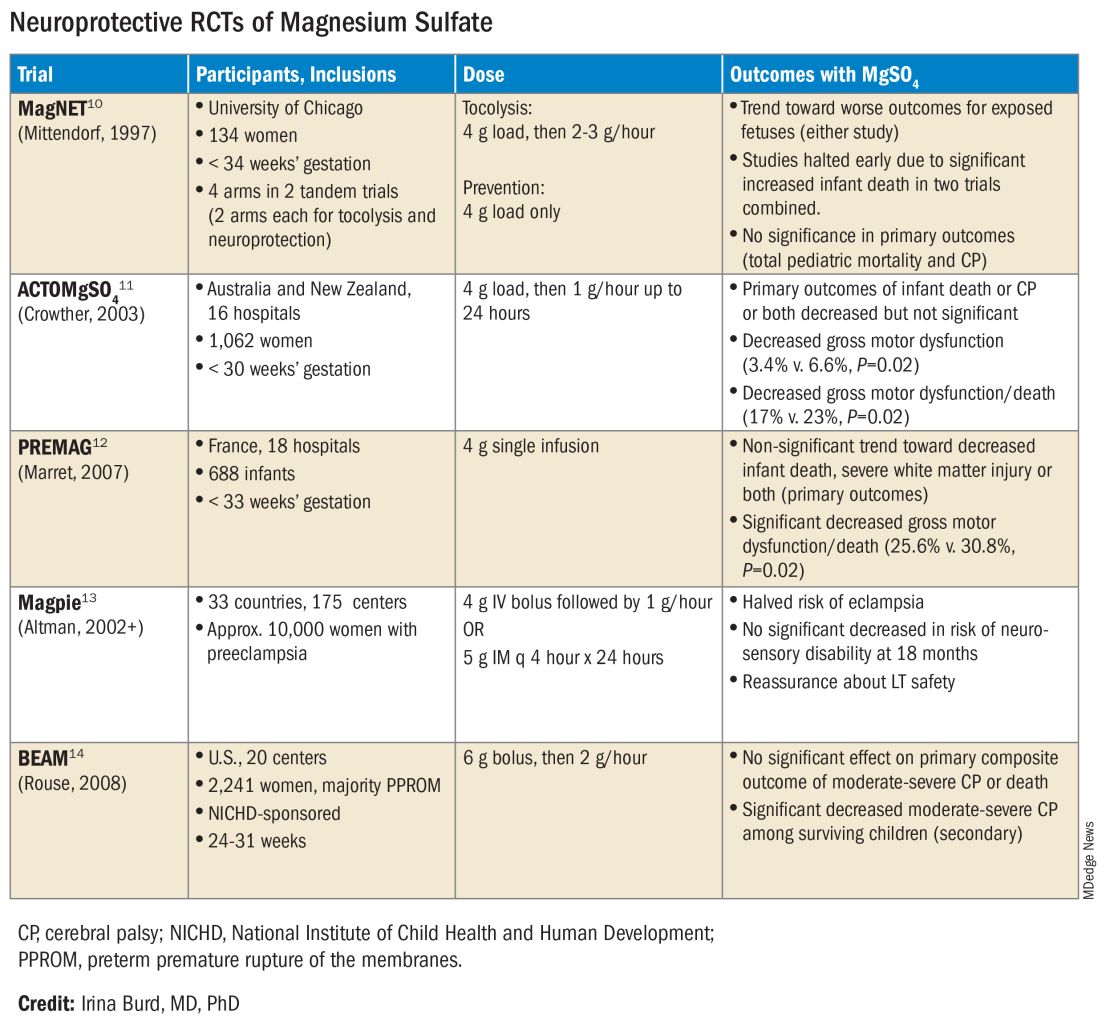

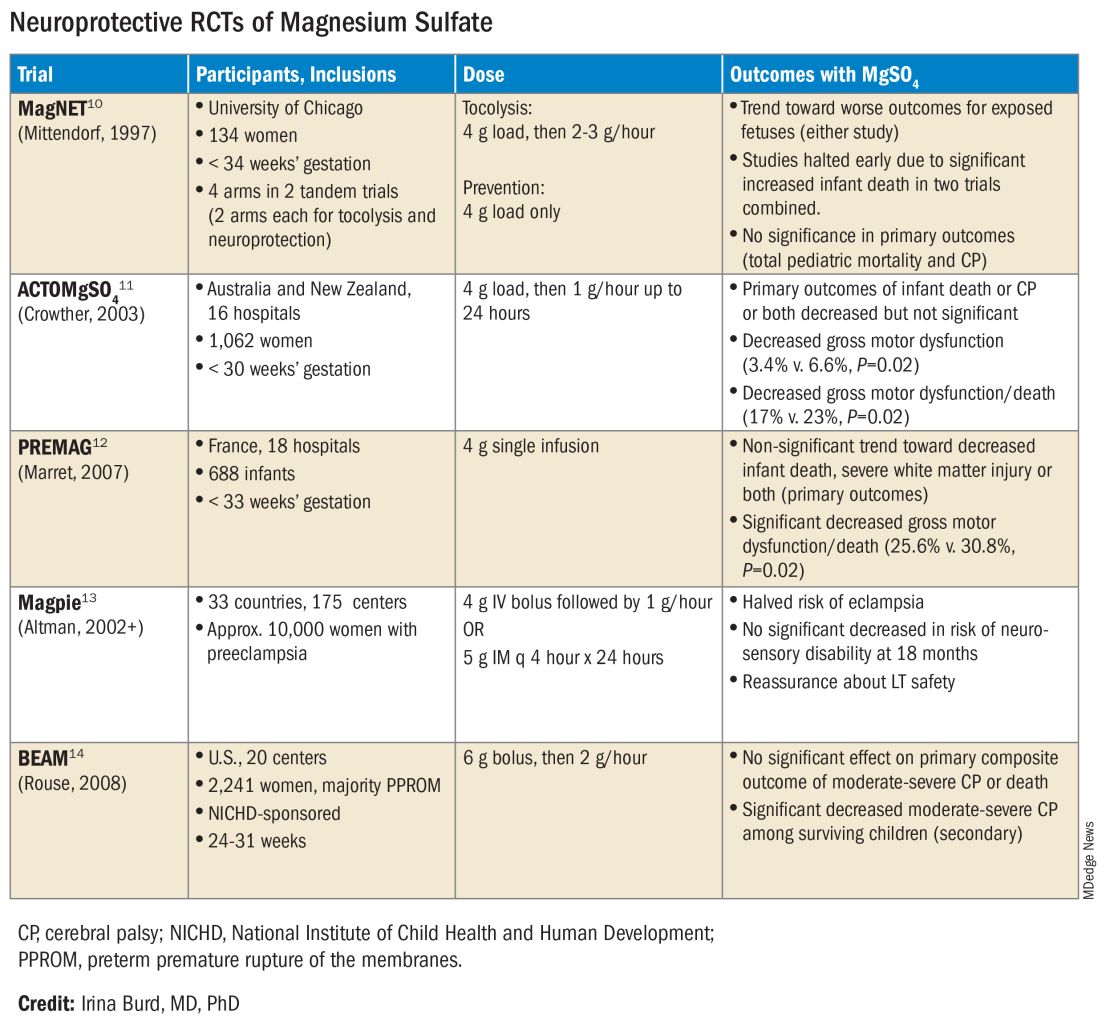

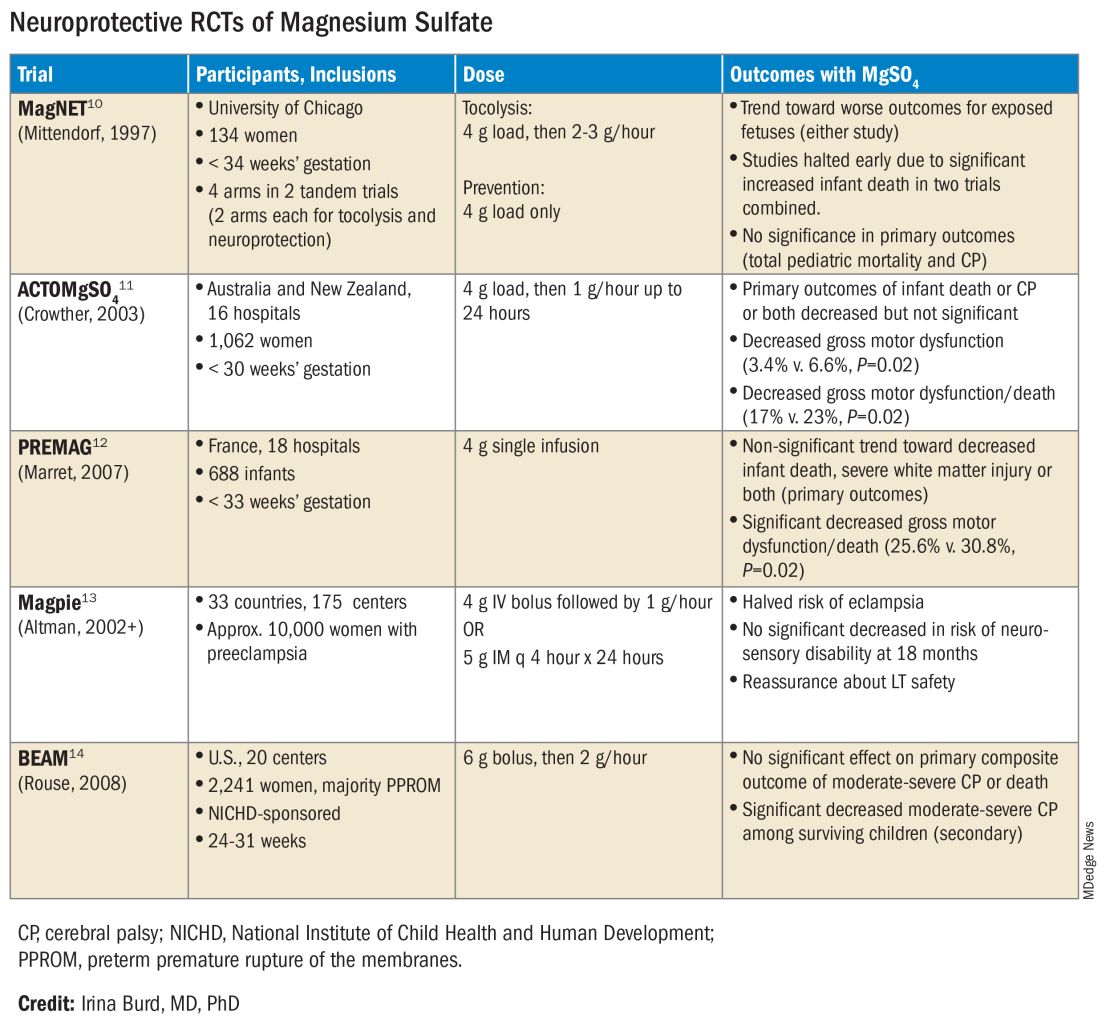

The six published randomized controlled trials looking at MgSO4 and neuroprotection varied in their inclusion and exclusion criteria, their recruitment and enrollment style, the gestational ages for MgSO4 administration, loading and maintenance doses, how cerebral palsy or neuroprotection was assessed, and other factors (See Table for RCT characteristics and main outcomes).10-14 One of the trials aimed primarily at evaluating the efficacy of MgSO4 for preventing preeclampsia.

Again, none of the randomized controlled trials demonstrated statistical significance for their primary outcomes or concluded that there was a significant neuroprotective effect for cerebral palsy. Rather, most suggested benefit through secondary analyses. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, research that proceeded after the first published randomized controlled trial — the Magnesium and Neurologic Endpoints (MAGnet) trial — was suspended early when an interim analysis showed a significantly increased risk of mortality in MgSO4-exposed fetuses. All told, it wasn’t until researchers obtained unpublished data and conducted meta-analyses and systematic reviews that a significant effect of MgSO4 on cerebral palsy could be seen.

The three systematic reviews and the Cochrane review, each of which used slightly different methodologies, were published in rapid succession in 2009. One review calculated a relative risk of cerebral palsy of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.55-0.91) — and a relative risk for the combined outcome of death and cerebral palsy at 0.85 (95% CI, 0.74-0.98) — when women at risk of preterm birth were given MgSO4.15 The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one case of cerebral palsy was 63, investigators determined, and the NNT to prevent one case of cerebral palsy or infant death was 44.

Another review estimated the NNT for prevention of one case of cerebral palsy at 52 when MgSO4 is given at less than 34 weeks’ gestation, and similarly concluded that MgSO4 is associated with a significantly “reduced risk of moderate/severe CP and substantial gross motor dysfunction without any statistically significant effect on the risk of total pediatric mortality.”16

A third review, from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network (MFMU), estimated an NNT of 46 to prevent one case of cerebral palsy in infants exposed to MgSO4 before 30 weeks, and an NNT of 56 when exposure occurs before 32-34 weeks.17

The Cochrane Review, meanwhile, reported a relative reduction in the risk of cerebral palsy of 0.68 (95% CI, 0.54-0.87) when antenatal MgSO4 is given at less than 37 weeks’ gestation, as well as a significant reduction in the rate of substantial gross motor dysfunction (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.44-0.85).18 The NNT to avoid one case of cerebral palsy, researchers reported, was 63.

Moving Forward

The NNTs calculated in these reviews — ranging from 44 to 63 — are convincing, and are comparable with evidence-based medicine data for prevention of other common diseases.19 For instance, the NNT for a life saved when aspirin is given immediately after a heart attack is 42. Statins given for 5 years in people with known heart disease have an NNT of 83 to save one life, an NNT of 39 to prevent one nonfatal heart attack, and an NNT of 125 to prevent one stroke. For oral anticoagulants used in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation for primary stroke prevention, the NNTs to prevent one stroke, and one death, are 22 and 42, respectively.19

In its 2010 Committee Opinion on Magnesium Sulfate Before Anticipated Preterm Birth for Neuroprotection (reaffirmed in 2020), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists left it to institutions to develop their own guidelines “regarding inclusion criteria, treatment regimens, concurrent tocolysis, and monitoring in accordance with one of the larger trials.”20

Not surprisingly, most if not all hospitals have chosen a higher dose of MgSO4 administered up to 31 weeks’ gestation in keeping with the protocols employed in the NICHD-sponsored BEAM trial (See Table).

The hope moving forward is to expand treatment options for neuroprotection in cases of imminent preterm birth. Researchers have been assessing the ability of melatonin to provide neuroprotection in cases of growth restriction and neonatal asphyxia. Melatonin has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties and is known to mediate neuronal generation and synaptic plasticity.21

N-acetyl-L-cysteine is another potential neuroprotective agent. It acts as an antioxidant, a precursor to glutathione, and a modulator of the glutamate system and has been studied as a neuroprotective agent in cases of maternal chorioamnionitis.21 Both melatonin and N-acetyl-L-cysteine are regarded as safe in pregnancy, but much more clinical study is needed to prove their neuroprotective potential when given shortly before birth or earlier.

Dr. Burd is the Sylvan Freiman, MD Endowed Professor and Chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. She has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Clio Med. 1984;19(1-2):1-21.

2. Medicinsk Rev. (Bergen) 1906;32:264-272.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(4):1390-1391.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;78(1):27-32.

5. Pediatrics. 1995;95(2):263-269.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(3):279.e1-279.e8.

7. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):292.e1-292.e9.

8. Pediatr Res. 2020;87(3):463-471.

9. J Child Neurol. 1992;7(1):70-76.

10. Lancet. 1997;350:1517-1518.

11. JAMA. 2003;290:2669-2676.

12. BJOG. 2007;114(3):310-318.

13. Lancet. 2002;359(9321):1877-1890.

14. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:895-905.

15. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(6):1327-1333.

16. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(6):595-609.

17. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:354-364.

18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jan 21:(1):CD004661.

19. www.thennt.com.

20. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:669-671.

21. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2012;13:680899.

*This story was corrected on June 10, 2024.

Introduction: The Many Lanes of Research on Magnesium Sulfate

The research that improves human health in the most expedient and most impactful ways is multitiered, with basic or fundamental research, translational research, interventional studies, and retrospective research often occurring simultaneously. There should be no “single lane” of research and one type of research does not preclude the other.

Too often, we fall short in one of these lanes. While we have achieved many moonshots in obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine, we have tended not to place a high priority on basic research, which can provide a strong understanding of the biology of major diseases and conditions affecting women and their offspring. When conducted with proper commitment and funding, such research can lead to biologically directed therapy.

Within our specialty, research on how we can effectively prevent preterm birth, prematurity, and preeclampsia has taken a long road, with various types of therapies being tried, but none being overwhelmingly effective — with an ongoing need for more basic or fundamental research. Nevertheless, we can benefit and gain great insights from retrospective and interventional studies associated with clinical therapies used to treat premature labor and preeclampsia when these therapies have an unanticipated and important secondary benefit.

This month our Master Class is focused on the neuroprotection of prematurity. Magnesium sulfate is a valuable tool for the treatment of both premature labor and preeclampsia, and more recently, also for neuroprotection of the fetus. Interestingly, this use stemmed from researchers looking retrospectively at outcomes in women who received the compound for other reasons. It took many years for researchers to prove its neuroprotective value through interventional trials, while researchers simultaneously strove to understand on a basic biologic level how magnesium sulfate works to prevent outcomes such as cerebral palsy.

Basic research underway today continues to improve our understanding of its precise mechanisms of action. Combined with other tiers of research — including more interventional studies and more translational research — we can improve its utility for the neuroprotection of prematurity. Alternatively, ongoing research may lead to different, even more effective treatments.

Our guest author is Irina Burd, MD, PhD, Sylvan Freiman, MD Endowed Professor and Chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.* Dr. Burd is also a physician-scientist. She recounts the important story of magnesium sulfate and what is currently known about its biologic plausibility in neuroprotection — including through her own studies – as well as what may be coming in the future.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Magnesium Sulfate for Fetal Neuroprotection in Preterm Birth

Without a doubt, magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) given before anticipated preterm birth reduces the risk of cerebral palsy. It is a valuable tool for fetal neuroprotection at a time when there are no proven alternatives. Yet without the persistent research that occurred over more than 20 years, it may not have won the endorsement of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists in 2010 and worked its way into routine practice.

Its history is worthy of reflection. It took years of observational trials (not all of which showed neuroprotective effects), six randomized controlled trials (none of which met their primary endpoint), three meta-analyses, and a Cochrane Database Systematic Review to arrive at the conclusion that antenatal magnesium sulfate therapy given to women at risk of preterm birth has definitive neuroprotective benefit.

This history also holds lessons for our specialty given the dearth of drugs approved for use in pregnancy and the recent withdrawal from the market of Makena — one of only nine drugs to ever be approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in pregnancy — after a second trial showed lack of benefit in preventing recurrent preterm birth. The story of MgSO4 tells us it’s acceptable to have major stumbling blocks: At one point, MgSO4 was considered to be not only not helpful, but harmful, causing neonatal death. Further research disproved this initial finding.

Moreover, the MgSO4 story is one that remains unfinished, as my laboratory and other researchers work to better understand its biologic plausibility and to discover additional neuroprotective agents for anticipated preterm birth that may further reduce the risk of cerebral palsy. This leading cause of chronic childhood disability is estimated by the United Cerebral Palsy Foundation to affect approximately 800,000 people in the United States.

Origins and Biologic Plausibility

The MgSO4 story is rooted in the late seventeenth century discovery by physician Nehemiah Grew that the compound was the key component of the then-famous medicinal spring waters in Epsom, England.1 MgSO4 was first used for eclampsia in 1906,2 and was first reported in the American literature for eclampsia in 1925.3 In 1959, its effect as a tocolytic agent was reported.4

More than 30 years later, in 1995, an observational study coauthored by Karin B. Nelson, MD, and Judith K. Grether, PhD of the National Institutes of Health, showed a reduced risk of cerebral palsy in very-low-birth-weight infants (VLBW).5 The report marked a turning point in research interest on neuroprotection for anticipated preterm birth.

The precise molecular mechanisms of action of MgSO4 for neuroprotection are still not well understood. However, research findings from the University of Maryland and other institutions have provided biologic plausibility for its use to prevent cerebral palsy. Our current thinking is that it involves the prevention of periventricular white matter injury and/or the prevention of oxidative stress and a neuronal injury mechanism called excitotoxicity.

Periventricular white matter injury involving injury to preoligodendrocytes before 32 weeks’ gestation is the most prevalent injury seen in cerebral palsy; preoligodendrocytes are precursors of myelinating oligodendrocytes, which constitute a major glial population in the white matter. Our research in a mouse model demonstrated that the intrauterine inflammation frequently associated with preterm birth can lead to neuronal injury as well as white matter damage, and that MgSO4 may ameliorate both.6,7

Excitotoxicity results from excessive stimulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamatergic receptors on preoligodendrocytes and a rush of calcium through the voltage-gated channels. This calcium influx leads to the production of nitric oxide, oxidative stress, and subsequent mitochondrial damage and cell death. As a bivalent ion, MgSO4 sits in the voltage-gated channels of the NMDA receptors and reduces glutamatergic signaling, thus serving as a calcium antagonist and modulating calcium influx (See Figure).

In vitro research in our laboratory has also shown that MgSO4 may dampen inflammatory reactions driven by intrauterine infections, which, like preterm birth, increase the risk of cerebral palsy and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes.8 MgSO4 appears to do so by blocking the voltage-gated P2X7 receptor in umbilical vein endothelial cells, thus blocking endothelial secretion of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)–1beta. Much more research is needed to determine whether MgSO4 could help prevent cerebral palsy through this mechanism.

The Long Route of Research

The 1995 Nelson-Grether study compared VLBW (< 1500 g) infants who survived and developed moderate/severe cerebral palsy within 3 years to randomly selected VLBW controls with respect to whether their mothers had received MgSO4 to prevent seizures in preeclampsia or as a tocolytic agent.5 In a population of more than 155,000 children born between 1983 and 1985, in utero exposure to MgSO4 was reported in 7.1% of 42 VLBW infants with cerebral palsy and 36% of 75 VLBW controls (odds ratio [OR], 0.14; 95% CI, 0.05-0.51). In women without preeclampsia the OR increased to 0.25.

This motivating study had been preceded by several observational studies showing that infants born to women with preeclampsia who received MgSO4 had significantly lower risks of developing intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) and germinal matrix hemorrhage (GMH). In one of these studies, published in 1992, Karl C. Kuban, MD, and coauthors reported that “maternal receipt of magnesium sulfate was associated with diminished risk of GMH-IVH even in those babies born to mothers who apparently did not have preeclampsia.”9

In the several years following the 1995 Nelson-Grether study, several other case-control/observational studies were reported, with conflicting conclusions, and investigators around the world began designing and conducting needed randomized controlled trials.

The six published randomized controlled trials looking at MgSO4 and neuroprotection varied in their inclusion and exclusion criteria, their recruitment and enrollment style, the gestational ages for MgSO4 administration, loading and maintenance doses, how cerebral palsy or neuroprotection was assessed, and other factors (See Table for RCT characteristics and main outcomes).10-14 One of the trials aimed primarily at evaluating the efficacy of MgSO4 for preventing preeclampsia.

Again, none of the randomized controlled trials demonstrated statistical significance for their primary outcomes or concluded that there was a significant neuroprotective effect for cerebral palsy. Rather, most suggested benefit through secondary analyses. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, research that proceeded after the first published randomized controlled trial — the Magnesium and Neurologic Endpoints (MAGnet) trial — was suspended early when an interim analysis showed a significantly increased risk of mortality in MgSO4-exposed fetuses. All told, it wasn’t until researchers obtained unpublished data and conducted meta-analyses and systematic reviews that a significant effect of MgSO4 on cerebral palsy could be seen.

The three systematic reviews and the Cochrane review, each of which used slightly different methodologies, were published in rapid succession in 2009. One review calculated a relative risk of cerebral palsy of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.55-0.91) — and a relative risk for the combined outcome of death and cerebral palsy at 0.85 (95% CI, 0.74-0.98) — when women at risk of preterm birth were given MgSO4.15 The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one case of cerebral palsy was 63, investigators determined, and the NNT to prevent one case of cerebral palsy or infant death was 44.

Another review estimated the NNT for prevention of one case of cerebral palsy at 52 when MgSO4 is given at less than 34 weeks’ gestation, and similarly concluded that MgSO4 is associated with a significantly “reduced risk of moderate/severe CP and substantial gross motor dysfunction without any statistically significant effect on the risk of total pediatric mortality.”16

A third review, from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network (MFMU), estimated an NNT of 46 to prevent one case of cerebral palsy in infants exposed to MgSO4 before 30 weeks, and an NNT of 56 when exposure occurs before 32-34 weeks.17

The Cochrane Review, meanwhile, reported a relative reduction in the risk of cerebral palsy of 0.68 (95% CI, 0.54-0.87) when antenatal MgSO4 is given at less than 37 weeks’ gestation, as well as a significant reduction in the rate of substantial gross motor dysfunction (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.44-0.85).18 The NNT to avoid one case of cerebral palsy, researchers reported, was 63.

Moving Forward

The NNTs calculated in these reviews — ranging from 44 to 63 — are convincing, and are comparable with evidence-based medicine data for prevention of other common diseases.19 For instance, the NNT for a life saved when aspirin is given immediately after a heart attack is 42. Statins given for 5 years in people with known heart disease have an NNT of 83 to save one life, an NNT of 39 to prevent one nonfatal heart attack, and an NNT of 125 to prevent one stroke. For oral anticoagulants used in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation for primary stroke prevention, the NNTs to prevent one stroke, and one death, are 22 and 42, respectively.19

In its 2010 Committee Opinion on Magnesium Sulfate Before Anticipated Preterm Birth for Neuroprotection (reaffirmed in 2020), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists left it to institutions to develop their own guidelines “regarding inclusion criteria, treatment regimens, concurrent tocolysis, and monitoring in accordance with one of the larger trials.”20

Not surprisingly, most if not all hospitals have chosen a higher dose of MgSO4 administered up to 31 weeks’ gestation in keeping with the protocols employed in the NICHD-sponsored BEAM trial (See Table).

The hope moving forward is to expand treatment options for neuroprotection in cases of imminent preterm birth. Researchers have been assessing the ability of melatonin to provide neuroprotection in cases of growth restriction and neonatal asphyxia. Melatonin has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties and is known to mediate neuronal generation and synaptic plasticity.21

N-acetyl-L-cysteine is another potential neuroprotective agent. It acts as an antioxidant, a precursor to glutathione, and a modulator of the glutamate system and has been studied as a neuroprotective agent in cases of maternal chorioamnionitis.21 Both melatonin and N-acetyl-L-cysteine are regarded as safe in pregnancy, but much more clinical study is needed to prove their neuroprotective potential when given shortly before birth or earlier.

Dr. Burd is the Sylvan Freiman, MD Endowed Professor and Chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. She has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Clio Med. 1984;19(1-2):1-21.

2. Medicinsk Rev. (Bergen) 1906;32:264-272.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(4):1390-1391.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;78(1):27-32.

5. Pediatrics. 1995;95(2):263-269.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(3):279.e1-279.e8.

7. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):292.e1-292.e9.

8. Pediatr Res. 2020;87(3):463-471.

9. J Child Neurol. 1992;7(1):70-76.

10. Lancet. 1997;350:1517-1518.

11. JAMA. 2003;290:2669-2676.

12. BJOG. 2007;114(3):310-318.

13. Lancet. 2002;359(9321):1877-1890.

14. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:895-905.

15. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(6):1327-1333.

16. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(6):595-609.

17. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:354-364.

18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jan 21:(1):CD004661.

19. www.thennt.com.

20. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:669-671.

21. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2012;13:680899.

*This story was corrected on June 10, 2024.

Introduction: The Many Lanes of Research on Magnesium Sulfate

The research that improves human health in the most expedient and most impactful ways is multitiered, with basic or fundamental research, translational research, interventional studies, and retrospective research often occurring simultaneously. There should be no “single lane” of research and one type of research does not preclude the other.

Too often, we fall short in one of these lanes. While we have achieved many moonshots in obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine, we have tended not to place a high priority on basic research, which can provide a strong understanding of the biology of major diseases and conditions affecting women and their offspring. When conducted with proper commitment and funding, such research can lead to biologically directed therapy.

Within our specialty, research on how we can effectively prevent preterm birth, prematurity, and preeclampsia has taken a long road, with various types of therapies being tried, but none being overwhelmingly effective — with an ongoing need for more basic or fundamental research. Nevertheless, we can benefit and gain great insights from retrospective and interventional studies associated with clinical therapies used to treat premature labor and preeclampsia when these therapies have an unanticipated and important secondary benefit.

This month our Master Class is focused on the neuroprotection of prematurity. Magnesium sulfate is a valuable tool for the treatment of both premature labor and preeclampsia, and more recently, also for neuroprotection of the fetus. Interestingly, this use stemmed from researchers looking retrospectively at outcomes in women who received the compound for other reasons. It took many years for researchers to prove its neuroprotective value through interventional trials, while researchers simultaneously strove to understand on a basic biologic level how magnesium sulfate works to prevent outcomes such as cerebral palsy.

Basic research underway today continues to improve our understanding of its precise mechanisms of action. Combined with other tiers of research — including more interventional studies and more translational research — we can improve its utility for the neuroprotection of prematurity. Alternatively, ongoing research may lead to different, even more effective treatments.

Our guest author is Irina Burd, MD, PhD, Sylvan Freiman, MD Endowed Professor and Chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.* Dr. Burd is also a physician-scientist. She recounts the important story of magnesium sulfate and what is currently known about its biologic plausibility in neuroprotection — including through her own studies – as well as what may be coming in the future.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Magnesium Sulfate for Fetal Neuroprotection in Preterm Birth

Without a doubt, magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) given before anticipated preterm birth reduces the risk of cerebral palsy. It is a valuable tool for fetal neuroprotection at a time when there are no proven alternatives. Yet without the persistent research that occurred over more than 20 years, it may not have won the endorsement of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists in 2010 and worked its way into routine practice.

Its history is worthy of reflection. It took years of observational trials (not all of which showed neuroprotective effects), six randomized controlled trials (none of which met their primary endpoint), three meta-analyses, and a Cochrane Database Systematic Review to arrive at the conclusion that antenatal magnesium sulfate therapy given to women at risk of preterm birth has definitive neuroprotective benefit.

This history also holds lessons for our specialty given the dearth of drugs approved for use in pregnancy and the recent withdrawal from the market of Makena — one of only nine drugs to ever be approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in pregnancy — after a second trial showed lack of benefit in preventing recurrent preterm birth. The story of MgSO4 tells us it’s acceptable to have major stumbling blocks: At one point, MgSO4 was considered to be not only not helpful, but harmful, causing neonatal death. Further research disproved this initial finding.

Moreover, the MgSO4 story is one that remains unfinished, as my laboratory and other researchers work to better understand its biologic plausibility and to discover additional neuroprotective agents for anticipated preterm birth that may further reduce the risk of cerebral palsy. This leading cause of chronic childhood disability is estimated by the United Cerebral Palsy Foundation to affect approximately 800,000 people in the United States.

Origins and Biologic Plausibility

The MgSO4 story is rooted in the late seventeenth century discovery by physician Nehemiah Grew that the compound was the key component of the then-famous medicinal spring waters in Epsom, England.1 MgSO4 was first used for eclampsia in 1906,2 and was first reported in the American literature for eclampsia in 1925.3 In 1959, its effect as a tocolytic agent was reported.4

More than 30 years later, in 1995, an observational study coauthored by Karin B. Nelson, MD, and Judith K. Grether, PhD of the National Institutes of Health, showed a reduced risk of cerebral palsy in very-low-birth-weight infants (VLBW).5 The report marked a turning point in research interest on neuroprotection for anticipated preterm birth.

The precise molecular mechanisms of action of MgSO4 for neuroprotection are still not well understood. However, research findings from the University of Maryland and other institutions have provided biologic plausibility for its use to prevent cerebral palsy. Our current thinking is that it involves the prevention of periventricular white matter injury and/or the prevention of oxidative stress and a neuronal injury mechanism called excitotoxicity.

Periventricular white matter injury involving injury to preoligodendrocytes before 32 weeks’ gestation is the most prevalent injury seen in cerebral palsy; preoligodendrocytes are precursors of myelinating oligodendrocytes, which constitute a major glial population in the white matter. Our research in a mouse model demonstrated that the intrauterine inflammation frequently associated with preterm birth can lead to neuronal injury as well as white matter damage, and that MgSO4 may ameliorate both.6,7

Excitotoxicity results from excessive stimulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamatergic receptors on preoligodendrocytes and a rush of calcium through the voltage-gated channels. This calcium influx leads to the production of nitric oxide, oxidative stress, and subsequent mitochondrial damage and cell death. As a bivalent ion, MgSO4 sits in the voltage-gated channels of the NMDA receptors and reduces glutamatergic signaling, thus serving as a calcium antagonist and modulating calcium influx (See Figure).

In vitro research in our laboratory has also shown that MgSO4 may dampen inflammatory reactions driven by intrauterine infections, which, like preterm birth, increase the risk of cerebral palsy and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes.8 MgSO4 appears to do so by blocking the voltage-gated P2X7 receptor in umbilical vein endothelial cells, thus blocking endothelial secretion of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)–1beta. Much more research is needed to determine whether MgSO4 could help prevent cerebral palsy through this mechanism.

The Long Route of Research

The 1995 Nelson-Grether study compared VLBW (< 1500 g) infants who survived and developed moderate/severe cerebral palsy within 3 years to randomly selected VLBW controls with respect to whether their mothers had received MgSO4 to prevent seizures in preeclampsia or as a tocolytic agent.5 In a population of more than 155,000 children born between 1983 and 1985, in utero exposure to MgSO4 was reported in 7.1% of 42 VLBW infants with cerebral palsy and 36% of 75 VLBW controls (odds ratio [OR], 0.14; 95% CI, 0.05-0.51). In women without preeclampsia the OR increased to 0.25.

This motivating study had been preceded by several observational studies showing that infants born to women with preeclampsia who received MgSO4 had significantly lower risks of developing intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) and germinal matrix hemorrhage (GMH). In one of these studies, published in 1992, Karl C. Kuban, MD, and coauthors reported that “maternal receipt of magnesium sulfate was associated with diminished risk of GMH-IVH even in those babies born to mothers who apparently did not have preeclampsia.”9

In the several years following the 1995 Nelson-Grether study, several other case-control/observational studies were reported, with conflicting conclusions, and investigators around the world began designing and conducting needed randomized controlled trials.

The six published randomized controlled trials looking at MgSO4 and neuroprotection varied in their inclusion and exclusion criteria, their recruitment and enrollment style, the gestational ages for MgSO4 administration, loading and maintenance doses, how cerebral palsy or neuroprotection was assessed, and other factors (See Table for RCT characteristics and main outcomes).10-14 One of the trials aimed primarily at evaluating the efficacy of MgSO4 for preventing preeclampsia.

Again, none of the randomized controlled trials demonstrated statistical significance for their primary outcomes or concluded that there was a significant neuroprotective effect for cerebral palsy. Rather, most suggested benefit through secondary analyses. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, research that proceeded after the first published randomized controlled trial — the Magnesium and Neurologic Endpoints (MAGnet) trial — was suspended early when an interim analysis showed a significantly increased risk of mortality in MgSO4-exposed fetuses. All told, it wasn’t until researchers obtained unpublished data and conducted meta-analyses and systematic reviews that a significant effect of MgSO4 on cerebral palsy could be seen.

The three systematic reviews and the Cochrane review, each of which used slightly different methodologies, were published in rapid succession in 2009. One review calculated a relative risk of cerebral palsy of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.55-0.91) — and a relative risk for the combined outcome of death and cerebral palsy at 0.85 (95% CI, 0.74-0.98) — when women at risk of preterm birth were given MgSO4.15 The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one case of cerebral palsy was 63, investigators determined, and the NNT to prevent one case of cerebral palsy or infant death was 44.

Another review estimated the NNT for prevention of one case of cerebral palsy at 52 when MgSO4 is given at less than 34 weeks’ gestation, and similarly concluded that MgSO4 is associated with a significantly “reduced risk of moderate/severe CP and substantial gross motor dysfunction without any statistically significant effect on the risk of total pediatric mortality.”16

A third review, from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network (MFMU), estimated an NNT of 46 to prevent one case of cerebral palsy in infants exposed to MgSO4 before 30 weeks, and an NNT of 56 when exposure occurs before 32-34 weeks.17

The Cochrane Review, meanwhile, reported a relative reduction in the risk of cerebral palsy of 0.68 (95% CI, 0.54-0.87) when antenatal MgSO4 is given at less than 37 weeks’ gestation, as well as a significant reduction in the rate of substantial gross motor dysfunction (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.44-0.85).18 The NNT to avoid one case of cerebral palsy, researchers reported, was 63.

Moving Forward

The NNTs calculated in these reviews — ranging from 44 to 63 — are convincing, and are comparable with evidence-based medicine data for prevention of other common diseases.19 For instance, the NNT for a life saved when aspirin is given immediately after a heart attack is 42. Statins given for 5 years in people with known heart disease have an NNT of 83 to save one life, an NNT of 39 to prevent one nonfatal heart attack, and an NNT of 125 to prevent one stroke. For oral anticoagulants used in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation for primary stroke prevention, the NNTs to prevent one stroke, and one death, are 22 and 42, respectively.19

In its 2010 Committee Opinion on Magnesium Sulfate Before Anticipated Preterm Birth for Neuroprotection (reaffirmed in 2020), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists left it to institutions to develop their own guidelines “regarding inclusion criteria, treatment regimens, concurrent tocolysis, and monitoring in accordance with one of the larger trials.”20

Not surprisingly, most if not all hospitals have chosen a higher dose of MgSO4 administered up to 31 weeks’ gestation in keeping with the protocols employed in the NICHD-sponsored BEAM trial (See Table).

The hope moving forward is to expand treatment options for neuroprotection in cases of imminent preterm birth. Researchers have been assessing the ability of melatonin to provide neuroprotection in cases of growth restriction and neonatal asphyxia. Melatonin has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties and is known to mediate neuronal generation and synaptic plasticity.21

N-acetyl-L-cysteine is another potential neuroprotective agent. It acts as an antioxidant, a precursor to glutathione, and a modulator of the glutamate system and has been studied as a neuroprotective agent in cases of maternal chorioamnionitis.21 Both melatonin and N-acetyl-L-cysteine are regarded as safe in pregnancy, but much more clinical study is needed to prove their neuroprotective potential when given shortly before birth or earlier.

Dr. Burd is the Sylvan Freiman, MD Endowed Professor and Chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. She has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Clio Med. 1984;19(1-2):1-21.

2. Medicinsk Rev. (Bergen) 1906;32:264-272.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(4):1390-1391.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;78(1):27-32.

5. Pediatrics. 1995;95(2):263-269.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(3):279.e1-279.e8.

7. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):292.e1-292.e9.

8. Pediatr Res. 2020;87(3):463-471.

9. J Child Neurol. 1992;7(1):70-76.

10. Lancet. 1997;350:1517-1518.

11. JAMA. 2003;290:2669-2676.

12. BJOG. 2007;114(3):310-318.

13. Lancet. 2002;359(9321):1877-1890.

14. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:895-905.

15. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(6):1327-1333.

16. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(6):595-609.

17. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:354-364.

18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jan 21:(1):CD004661.

19. www.thennt.com.

20. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:669-671.

21. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2012;13:680899.

*This story was corrected on June 10, 2024.

A 27-year-old Haitian woman presented with a painful umbilical mass which had been growing in size for 5 months

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial tissue outside of the uterine cavity, commonly occurring in women of reproductive age. The condition usually affects the adnexa (ovaries, Fallopian tubes, and associated ligaments and connective tissue) but can also be seen in extrapelvic structures.

Cutaneous endometriosis is an uncommon subtype that accounts for 1% of endometriosis cases and occurs when endometrial tissue is found on the surface of the skin. It is divided into primary and secondary cutaneous endometriosis. The that may lead to seeding of endometrial tissue on the skin. In the case of our patient, it appears that her laparoscopic procedure 2 years ago was the cause of endometrial seeding in the umbilicus.

Clinically, the condition may present with a palpable mass, cyclic pain, and bloody discharge from the affected area. Due to the rarity of cutaneous endometriosis, it may be hard to distinguish from other diagnoses such as keloids, dermatofibromas, hernias, or cutaneous metastasis of cancers (Sister Mary Joseph nodules).

The definitive diagnosis can be made by biopsy and histopathological assessment showing a mixture of endometrial glands and stromal tissue. Imaging studies such as computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are helpful in excluding more common diagnoses such as hernia or cutaneous metastasis. In this patient, the mass was surgically excised. Histopathological assessment established the diagnosis of cutaneous endometriosis.

Treatment options include surgical excision and medical therapy. Medical therapy entails the use of hormonal agents such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, danazol (a pituitary gonadotropin inhibitor), and oral contraceptives, which reduce the cyclical proliferation of endothelial tissue. These agents can be used preoperatively to reduce the size of the cutaneous mass before surgical excision, or as an alternative treatment for patients who wish to avoid surgery. The rate of recurrence is observed to be higher with medical therapy rather than surgical treatment.

The case and photo were submitted by Mina Ahmed, MBBS, Brooke Resh Sateesh MD, and Nathan Uebelhoer MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology, San Diego, California. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Gonzalez RH et al. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e932493-1–e932493-4.

2. Raffi L et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Dec;5(5):384-386.

3. Sharma A, Apostol R. Cutaneous endometriosis. Treasure Island, Fla: Statpearls Publishing, 2023.

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial tissue outside of the uterine cavity, commonly occurring in women of reproductive age. The condition usually affects the adnexa (ovaries, Fallopian tubes, and associated ligaments and connective tissue) but can also be seen in extrapelvic structures.

Cutaneous endometriosis is an uncommon subtype that accounts for 1% of endometriosis cases and occurs when endometrial tissue is found on the surface of the skin. It is divided into primary and secondary cutaneous endometriosis. The that may lead to seeding of endometrial tissue on the skin. In the case of our patient, it appears that her laparoscopic procedure 2 years ago was the cause of endometrial seeding in the umbilicus.

Clinically, the condition may present with a palpable mass, cyclic pain, and bloody discharge from the affected area. Due to the rarity of cutaneous endometriosis, it may be hard to distinguish from other diagnoses such as keloids, dermatofibromas, hernias, or cutaneous metastasis of cancers (Sister Mary Joseph nodules).

The definitive diagnosis can be made by biopsy and histopathological assessment showing a mixture of endometrial glands and stromal tissue. Imaging studies such as computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are helpful in excluding more common diagnoses such as hernia or cutaneous metastasis. In this patient, the mass was surgically excised. Histopathological assessment established the diagnosis of cutaneous endometriosis.

Treatment options include surgical excision and medical therapy. Medical therapy entails the use of hormonal agents such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, danazol (a pituitary gonadotropin inhibitor), and oral contraceptives, which reduce the cyclical proliferation of endothelial tissue. These agents can be used preoperatively to reduce the size of the cutaneous mass before surgical excision, or as an alternative treatment for patients who wish to avoid surgery. The rate of recurrence is observed to be higher with medical therapy rather than surgical treatment.

The case and photo were submitted by Mina Ahmed, MBBS, Brooke Resh Sateesh MD, and Nathan Uebelhoer MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology, San Diego, California. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Gonzalez RH et al. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e932493-1–e932493-4.

2. Raffi L et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Dec;5(5):384-386.

3. Sharma A, Apostol R. Cutaneous endometriosis. Treasure Island, Fla: Statpearls Publishing, 2023.

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial tissue outside of the uterine cavity, commonly occurring in women of reproductive age. The condition usually affects the adnexa (ovaries, Fallopian tubes, and associated ligaments and connective tissue) but can also be seen in extrapelvic structures.

Cutaneous endometriosis is an uncommon subtype that accounts for 1% of endometriosis cases and occurs when endometrial tissue is found on the surface of the skin. It is divided into primary and secondary cutaneous endometriosis. The that may lead to seeding of endometrial tissue on the skin. In the case of our patient, it appears that her laparoscopic procedure 2 years ago was the cause of endometrial seeding in the umbilicus.

Clinically, the condition may present with a palpable mass, cyclic pain, and bloody discharge from the affected area. Due to the rarity of cutaneous endometriosis, it may be hard to distinguish from other diagnoses such as keloids, dermatofibromas, hernias, or cutaneous metastasis of cancers (Sister Mary Joseph nodules).

The definitive diagnosis can be made by biopsy and histopathological assessment showing a mixture of endometrial glands and stromal tissue. Imaging studies such as computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are helpful in excluding more common diagnoses such as hernia or cutaneous metastasis. In this patient, the mass was surgically excised. Histopathological assessment established the diagnosis of cutaneous endometriosis.

Treatment options include surgical excision and medical therapy. Medical therapy entails the use of hormonal agents such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, danazol (a pituitary gonadotropin inhibitor), and oral contraceptives, which reduce the cyclical proliferation of endothelial tissue. These agents can be used preoperatively to reduce the size of the cutaneous mass before surgical excision, or as an alternative treatment for patients who wish to avoid surgery. The rate of recurrence is observed to be higher with medical therapy rather than surgical treatment.

The case and photo were submitted by Mina Ahmed, MBBS, Brooke Resh Sateesh MD, and Nathan Uebelhoer MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology, San Diego, California. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Gonzalez RH et al. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e932493-1–e932493-4.

2. Raffi L et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Dec;5(5):384-386.

3. Sharma A, Apostol R. Cutaneous endometriosis. Treasure Island, Fla: Statpearls Publishing, 2023.

Pet Peeves About the State of Primary Care – Part 2

I have received lots of notes from readers about other pet peeves they have about practicing primary care in our current environment and wanted to share some of them. I appreciate all the emails I received on this topic.

- The rapid increase in the number of hospital administrators in the last 50 years

This has increased health system costs without providing any relief for practicing physicians, and often has led to policies that have been harmful and detrimental. This would be a great place to start cutting back to get true savings without affecting quality of care.

- Emergency physicians and specialists who refer my patient elsewhere for a service we provide in our office

It is expensive for patients to go to a specialty provider for a simple procedure that can be easily done in a primary care practice, or to be referred to see a specialist for a problem that does not need specialty care. This creates further problems accessing specialists.

- Online reviews of practices, including reviews from people who have never been patients

I am concerned about the accuracy and intent of online reviews. If a patient is upset because they did not receive an antibiotic or narcotic, they can vent their frustration in a review, when what the medical professional was actually doing was good medicine. More concerning to me is that some organizations use these reviews to determine compensation, promotion, and support. These reviews are not evidence based or accurately collected.

- Offices and organizations being dropped by insurance carriers

Insurance companies are running amok. They make their own rules, which can devastate practices and patients. They can change fees paid unilaterally, and drop practices without explanation or valid reasons. Patients suffer terribly because they now cannot see their long-time physicians or they have to pay much more to see them as they are suddenly “out of network.”

- The lack of appreciation by organizations as well as the general public of the enormous cost savings primary care professionals contribute to the healthcare system

There are many studies showing that patients who see a primary care physician save the system money and have better health outcomes. US adults who regularly see a primary care physician have 33% lower healthcare costs and 19% lower odds of dying prematurely than those who see only a specialist.1

In one study, for every $1 invested in primary care, there was $13 in savings in healthcare costs.2 I had a patient a few years ago complain about the “enormous” bill she received for a visit where I had done an annual exam, cryotherapy for three actinic keratoses, and a steroid injection for her ailing knee. The cost savings was well over $700 (the new patient cost for two specialty visits). There is no doubt that patients who have stable primary care save money themselves and for the whole medical system.

- The stress of being witness to a dysfunctional system

It is really hard to see the hurt and difficulty our patients go through on a daily basis while trying to navigate a broken system. We bear witness to them and listen to all the stories when things have gone wrong. This also takes its toll on us, as we are part of the system, and our patients’ frustrations sometimes boil over. We are also the ones who care for the whole patient, so every bad experience with a specialty clinic is shared with us.

Many thanks extended to those who wrote to share their ideas (Drs. Sylvia Androne, Bhawna Bahethi, Pierre Ghassibi, Richard Katz, Louis Kasunic, Rebecca Keenan, David Kosnosky, Gregory Miller, and James Wilkens).

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington, Seattle. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Forbes.com. Why Primary Care Matters, and What We Can Do To Increase It. 2023 Nov 27.

2. Washingtonpost.com. A Health Care Solution We Can’t Afford to Ignore: Primary Care.

I have received lots of notes from readers about other pet peeves they have about practicing primary care in our current environment and wanted to share some of them. I appreciate all the emails I received on this topic.

- The rapid increase in the number of hospital administrators in the last 50 years

This has increased health system costs without providing any relief for practicing physicians, and often has led to policies that have been harmful and detrimental. This would be a great place to start cutting back to get true savings without affecting quality of care.

- Emergency physicians and specialists who refer my patient elsewhere for a service we provide in our office

It is expensive for patients to go to a specialty provider for a simple procedure that can be easily done in a primary care practice, or to be referred to see a specialist for a problem that does not need specialty care. This creates further problems accessing specialists.

- Online reviews of practices, including reviews from people who have never been patients

I am concerned about the accuracy and intent of online reviews. If a patient is upset because they did not receive an antibiotic or narcotic, they can vent their frustration in a review, when what the medical professional was actually doing was good medicine. More concerning to me is that some organizations use these reviews to determine compensation, promotion, and support. These reviews are not evidence based or accurately collected.

- Offices and organizations being dropped by insurance carriers

Insurance companies are running amok. They make their own rules, which can devastate practices and patients. They can change fees paid unilaterally, and drop practices without explanation or valid reasons. Patients suffer terribly because they now cannot see their long-time physicians or they have to pay much more to see them as they are suddenly “out of network.”

- The lack of appreciation by organizations as well as the general public of the enormous cost savings primary care professionals contribute to the healthcare system

There are many studies showing that patients who see a primary care physician save the system money and have better health outcomes. US adults who regularly see a primary care physician have 33% lower healthcare costs and 19% lower odds of dying prematurely than those who see only a specialist.1

In one study, for every $1 invested in primary care, there was $13 in savings in healthcare costs.2 I had a patient a few years ago complain about the “enormous” bill she received for a visit where I had done an annual exam, cryotherapy for three actinic keratoses, and a steroid injection for her ailing knee. The cost savings was well over $700 (the new patient cost for two specialty visits). There is no doubt that patients who have stable primary care save money themselves and for the whole medical system.

- The stress of being witness to a dysfunctional system

It is really hard to see the hurt and difficulty our patients go through on a daily basis while trying to navigate a broken system. We bear witness to them and listen to all the stories when things have gone wrong. This also takes its toll on us, as we are part of the system, and our patients’ frustrations sometimes boil over. We are also the ones who care for the whole patient, so every bad experience with a specialty clinic is shared with us.

Many thanks extended to those who wrote to share their ideas (Drs. Sylvia Androne, Bhawna Bahethi, Pierre Ghassibi, Richard Katz, Louis Kasunic, Rebecca Keenan, David Kosnosky, Gregory Miller, and James Wilkens).

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington, Seattle. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Forbes.com. Why Primary Care Matters, and What We Can Do To Increase It. 2023 Nov 27.

2. Washingtonpost.com. A Health Care Solution We Can’t Afford to Ignore: Primary Care.

I have received lots of notes from readers about other pet peeves they have about practicing primary care in our current environment and wanted to share some of them. I appreciate all the emails I received on this topic.

- The rapid increase in the number of hospital administrators in the last 50 years

This has increased health system costs without providing any relief for practicing physicians, and often has led to policies that have been harmful and detrimental. This would be a great place to start cutting back to get true savings without affecting quality of care.

- Emergency physicians and specialists who refer my patient elsewhere for a service we provide in our office

It is expensive for patients to go to a specialty provider for a simple procedure that can be easily done in a primary care practice, or to be referred to see a specialist for a problem that does not need specialty care. This creates further problems accessing specialists.

- Online reviews of practices, including reviews from people who have never been patients

I am concerned about the accuracy and intent of online reviews. If a patient is upset because they did not receive an antibiotic or narcotic, they can vent their frustration in a review, when what the medical professional was actually doing was good medicine. More concerning to me is that some organizations use these reviews to determine compensation, promotion, and support. These reviews are not evidence based or accurately collected.

- Offices and organizations being dropped by insurance carriers

Insurance companies are running amok. They make their own rules, which can devastate practices and patients. They can change fees paid unilaterally, and drop practices without explanation or valid reasons. Patients suffer terribly because they now cannot see their long-time physicians or they have to pay much more to see them as they are suddenly “out of network.”

- The lack of appreciation by organizations as well as the general public of the enormous cost savings primary care professionals contribute to the healthcare system

There are many studies showing that patients who see a primary care physician save the system money and have better health outcomes. US adults who regularly see a primary care physician have 33% lower healthcare costs and 19% lower odds of dying prematurely than those who see only a specialist.1

In one study, for every $1 invested in primary care, there was $13 in savings in healthcare costs.2 I had a patient a few years ago complain about the “enormous” bill she received for a visit where I had done an annual exam, cryotherapy for three actinic keratoses, and a steroid injection for her ailing knee. The cost savings was well over $700 (the new patient cost for two specialty visits). There is no doubt that patients who have stable primary care save money themselves and for the whole medical system.

- The stress of being witness to a dysfunctional system

It is really hard to see the hurt and difficulty our patients go through on a daily basis while trying to navigate a broken system. We bear witness to them and listen to all the stories when things have gone wrong. This also takes its toll on us, as we are part of the system, and our patients’ frustrations sometimes boil over. We are also the ones who care for the whole patient, so every bad experience with a specialty clinic is shared with us.

Many thanks extended to those who wrote to share their ideas (Drs. Sylvia Androne, Bhawna Bahethi, Pierre Ghassibi, Richard Katz, Louis Kasunic, Rebecca Keenan, David Kosnosky, Gregory Miller, and James Wilkens).

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington, Seattle. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Forbes.com. Why Primary Care Matters, and What We Can Do To Increase It. 2023 Nov 27.

2. Washingtonpost.com. A Health Care Solution We Can’t Afford to Ignore: Primary Care.

Zoom: Convenient and Imperfect

Making eye contact is important in human interactions. It shows attention and comprehension. It also helps us read the nuances of another’s facial expressions when interacting.

Although the idea of video phone calls isn’t new — I remember it from my childhood in “house of the future” TV shows — it certainly didn’t take off until the advent of high-speed Internet, computers, and phones with cameras. Then Facetime, Skype, Zoom, Teams, and others.

Of course, it all still took a back seat to actually seeing people and having meetings in person. Until the pandemic made that the least attractive option. Then the adoption of such things went into hyperdrive and has stayed there ever since.

And ya know, I don’t have too many complaints. Between clinical trials and legal cases, both of which involve A LOT of meetings, it’s made my life easier. I no longer have to leave the office, allow time to drive somewhere and back, fight traffic, burn gas, and find parking. I move from a patient to the meeting and back to a patient from the cozy confines of my office, all without my tea getting cold.

But you can’t really make eye contact on Zoom. Instinctively, we generally look directly at the eyes of the person we’re speaking to, but in the virtual world we really don’t do that. On their end you’re on a screen, your gaze fixed somewhere below the level of your camera.

Try talking directly to the camera on Zoom — or any video platform. It doesn’t work. You feel like Dave addressing HAL’s red light in 2001. Inevitably your eyes are drawn back to the other person’s face, which is what you’re programmed to do. If they’re speaking you look at them, even though the sound is really coming from your speakers.

Interestingly, though, it seems something is lost in there. A recent perspective noted that Zoom meetings seemed to stifle creativity and produced fewer ideas than in person.

An interesting study compared neural response signals of people seeing a presentation on Zoom versus the same talk in person. When looking at a “real” speaker, there was synchronized neural activity, a higher level of engagement, and increased activation of the dorsal-parietal cortex.

Without actual eye contact it’s harder to read subtle facial expressions. Hand gestures and other body language may be out of the camera frame, or absent altogether. The nuances of voice pitch, timbre, and tone may not be the same over the speaker.

Our brains have spent several million of years developing facial recognition and reading, knowing friend from foe, and understanding what’s meant not just in what sounds are used but how they’re conveyed.

I’m not saying we should stop using Zoom altogether — it makes meetings more convenient for most people, including myself. But we also need to keep in mind that what it doesn’t convey is as important as what it does, and that virtual is never a perfect substitute for reality.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Making eye contact is important in human interactions. It shows attention and comprehension. It also helps us read the nuances of another’s facial expressions when interacting.

Although the idea of video phone calls isn’t new — I remember it from my childhood in “house of the future” TV shows — it certainly didn’t take off until the advent of high-speed Internet, computers, and phones with cameras. Then Facetime, Skype, Zoom, Teams, and others.

Of course, it all still took a back seat to actually seeing people and having meetings in person. Until the pandemic made that the least attractive option. Then the adoption of such things went into hyperdrive and has stayed there ever since.

And ya know, I don’t have too many complaints. Between clinical trials and legal cases, both of which involve A LOT of meetings, it’s made my life easier. I no longer have to leave the office, allow time to drive somewhere and back, fight traffic, burn gas, and find parking. I move from a patient to the meeting and back to a patient from the cozy confines of my office, all without my tea getting cold.

But you can’t really make eye contact on Zoom. Instinctively, we generally look directly at the eyes of the person we’re speaking to, but in the virtual world we really don’t do that. On their end you’re on a screen, your gaze fixed somewhere below the level of your camera.

Try talking directly to the camera on Zoom — or any video platform. It doesn’t work. You feel like Dave addressing HAL’s red light in 2001. Inevitably your eyes are drawn back to the other person’s face, which is what you’re programmed to do. If they’re speaking you look at them, even though the sound is really coming from your speakers.

Interestingly, though, it seems something is lost in there. A recent perspective noted that Zoom meetings seemed to stifle creativity and produced fewer ideas than in person.

An interesting study compared neural response signals of people seeing a presentation on Zoom versus the same talk in person. When looking at a “real” speaker, there was synchronized neural activity, a higher level of engagement, and increased activation of the dorsal-parietal cortex.

Without actual eye contact it’s harder to read subtle facial expressions. Hand gestures and other body language may be out of the camera frame, or absent altogether. The nuances of voice pitch, timbre, and tone may not be the same over the speaker.

Our brains have spent several million of years developing facial recognition and reading, knowing friend from foe, and understanding what’s meant not just in what sounds are used but how they’re conveyed.

I’m not saying we should stop using Zoom altogether — it makes meetings more convenient for most people, including myself. But we also need to keep in mind that what it doesn’t convey is as important as what it does, and that virtual is never a perfect substitute for reality.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Making eye contact is important in human interactions. It shows attention and comprehension. It also helps us read the nuances of another’s facial expressions when interacting.

Although the idea of video phone calls isn’t new — I remember it from my childhood in “house of the future” TV shows — it certainly didn’t take off until the advent of high-speed Internet, computers, and phones with cameras. Then Facetime, Skype, Zoom, Teams, and others.

Of course, it all still took a back seat to actually seeing people and having meetings in person. Until the pandemic made that the least attractive option. Then the adoption of such things went into hyperdrive and has stayed there ever since.

And ya know, I don’t have too many complaints. Between clinical trials and legal cases, both of which involve A LOT of meetings, it’s made my life easier. I no longer have to leave the office, allow time to drive somewhere and back, fight traffic, burn gas, and find parking. I move from a patient to the meeting and back to a patient from the cozy confines of my office, all without my tea getting cold.

But you can’t really make eye contact on Zoom. Instinctively, we generally look directly at the eyes of the person we’re speaking to, but in the virtual world we really don’t do that. On their end you’re on a screen, your gaze fixed somewhere below the level of your camera.

Try talking directly to the camera on Zoom — or any video platform. It doesn’t work. You feel like Dave addressing HAL’s red light in 2001. Inevitably your eyes are drawn back to the other person’s face, which is what you’re programmed to do. If they’re speaking you look at them, even though the sound is really coming from your speakers.

Interestingly, though, it seems something is lost in there. A recent perspective noted that Zoom meetings seemed to stifle creativity and produced fewer ideas than in person.

An interesting study compared neural response signals of people seeing a presentation on Zoom versus the same talk in person. When looking at a “real” speaker, there was synchronized neural activity, a higher level of engagement, and increased activation of the dorsal-parietal cortex.

Without actual eye contact it’s harder to read subtle facial expressions. Hand gestures and other body language may be out of the camera frame, or absent altogether. The nuances of voice pitch, timbre, and tone may not be the same over the speaker.

Our brains have spent several million of years developing facial recognition and reading, knowing friend from foe, and understanding what’s meant not just in what sounds are used but how they’re conveyed.

I’m not saying we should stop using Zoom altogether — it makes meetings more convenient for most people, including myself. But we also need to keep in mind that what it doesn’t convey is as important as what it does, and that virtual is never a perfect substitute for reality.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A Counterintuitive Approach to Lowering Cholesterol in Children

With the flip of the calendar a few short weeks ago, gyms and fitness centers began ramping up their advertising campaigns in hopes of attracting the horde of resolution makers searching for a place where they can inject some exercise into their sedentary lives. A recent survey by C.S. Mott’s Children’s Hospital found that even young people are setting health-related goals with more than half of the parents of 11- to 18-year-olds reporting their children were setting personal goals for themselves. More than 40% of the young people listed more exercise as a target.

However, our personal and professional experiences have taught us that achieving goals, particularly when it comes to exercise, is far more difficult than setting the target. Finding an exercise buddy can be an important motivator on the days when just lacing up one’s sneakers is a stumbling block. Investing in a gym membership and sweating with a peer group can help. However, it is an investment that rarely pays a dividend. Exercise isn’t fun for everyone. For adults, showing up at a gym may be just one more reminder of how they have already lost their competitive edge over their leaner and fitter peers. If they aren’t lucky enough to find a sport or activity that they enjoy, the loneliness of the long-distance runner has little appeal.

A recent study on children in the United Kingdom suggests that at least when it comes to teens and young adults we as physicians may actually have been making things worse for our obese patients by urging them to accept unrealistic activity goals. While it is already known that sedentary time is responsible for 70% of the total increase in cholesterol as children advance to young adulthood an unqualified recommendation for more exercise may not be the best advice.