User login

AAN calls oral cannabinoids effective for MS pain, spasticity

An expert panel organized by the American Academy of Neurology called oral cannabis extract the only complementary and alternative medicine unequivocally effective for helping patients with multiple sclerosis, specifically easing their pain and symptoms of spasticity, possibly for as long as 1 year of treatment.

The academy’s Guideline Development Subcommittee also found existing evidence "insufficient to support or refute the effectiveness" of 25 other complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments, including acupuncture, chelation therapy, mindfulness training, and muscle-relaxation therapy. The panel noted that two of these inadequately assessed treatments – dental amalgam removal and transdermal histamine – have received substantial media attention despite having "little or no evidence to support recommendations."

Aside from various forms and delivery methods for cannabinoids, the nine-member panel found six other treatments with adequate evidence to develop practice recommendations that either endorsed their efficacy or lack of effect. Ginkgo biloba, reflexology, and magnetic therapy all had some proven level of efficacy, while bee venom, low-fat diet with omega-3 supplementation, and lofepramine plus L-phenylalanine with B12 were all found ineffective, the subcommittee said in guidelines released on March 24 (Neurology 2014;82:1083-92).

The efficacy of CAM therapies in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) is an important clinical issue. Ten reports cited by the subcommittee and published during 1999-2009 documented that anywhere from a third to 80% of MS patients – particularly women, patients with higher education levels, and patients who report poorer health – used one or more CAM therapies, according to the panel, which was led by Dr. Vijayshree Yadav of the department of neurology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and the Portland VA Medical Center.

The group also determined that oral cannabis extract and another orally delivered cannabinoid, synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), were possibly effective for reducing symptoms and objective measures of spasticity during treatment beyond 1 year, and that THC is probably effective for reducing symptoms of spasticity and pain during the first year of treatment. The panel decided that, based on existing evidence, both of these oral agents are "probably ineffective" for reducing both objective spasticity measures and MS-related tremor symptoms.

The subcommittee reviewed two other delivery forms of cannabinoids. The members concluded that Sativex oromucosal cannabinoid spray is probably effective for improving subjective spasticity symptoms for periods of 5-10 weeks and possibly ineffective when used for longer periods or for reducing MS-related tremor. When it came to smoked cannabis, the panel decided that the data were inadequate to draw any conclusions on safety or efficacy.

It also deemed the evidence inadequate to draw conclusions about oral cannabis extract or THC for bladder-urge incontinence or for treating overall symptoms; synthetic THC for central neuropathic pain; and Sativex spray for overall bladder symptoms, anxiety, sleep problems, cognitive symptoms, quality of life, or fatigue.

In addition, cannabinoid studies have been of short duration (6-15 weeks), and central side effects may have caused unblinding in studies. The panel cautioned clinicians to counsel patients about potential psychopathologic effects, cognitive effects, or both with cannabinoid use, and cautioned against extrapolating from findings with standardized oral cannabis extract to other, nonstandardized cannabis extracts.

For other treatments with an adequate evidence base, the panel concluded that magnetic therapy is probably effective for reducing fatigue and probably ineffective for reducing depression, with inadequate data to support or refute other effects in MS patients.

The subcommittee said that study findings established Ginkgo biloba as ineffective for improving cognitive function in patients with MS but possibly effective during 4 weeks of treatment to reduce fatigue. The members also warned that Ginkgo biloba and other supplements not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration may vary considerably in efficacy and adverse effects and may interact with other medications, especially disease-modifying therapies for MS.

The panel called low-fat diet with omega-3 fatty acid supplementation probably ineffective for reducing MS relapses, disability, or MRI lesions, or for improving fatigue or quality of life. It found lofepramine plus L-phenylalanine and vitamin B12 possibly ineffective for treating disability, symptoms, depression, or fatigue, and bee-sting therapy possibly ineffective for reducing relapses, disability, fatigue, total MRI-lesion burden, and gadolinium-enhancing lesion volume, or for improving health-related quality of life.

The subcommittee said that reflexology is possibly effective for reducing MS-associated paresthesia during 11 weeks of treatment, but that data were inadequate to support or refute its use for pain, spasticity, fatigue, anxiety, or several other MS manifestations.

The guidelines were funded by the American Academy of Neurology. Most of the panel members reported some potential conflicts of interest in relationships with pharmaceutical companies that market drugs for MS as well as ties to MS medical societies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

An expert panel organized by the American Academy of Neurology called oral cannabis extract the only complementary and alternative medicine unequivocally effective for helping patients with multiple sclerosis, specifically easing their pain and symptoms of spasticity, possibly for as long as 1 year of treatment.

The academy’s Guideline Development Subcommittee also found existing evidence "insufficient to support or refute the effectiveness" of 25 other complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments, including acupuncture, chelation therapy, mindfulness training, and muscle-relaxation therapy. The panel noted that two of these inadequately assessed treatments – dental amalgam removal and transdermal histamine – have received substantial media attention despite having "little or no evidence to support recommendations."

Aside from various forms and delivery methods for cannabinoids, the nine-member panel found six other treatments with adequate evidence to develop practice recommendations that either endorsed their efficacy or lack of effect. Ginkgo biloba, reflexology, and magnetic therapy all had some proven level of efficacy, while bee venom, low-fat diet with omega-3 supplementation, and lofepramine plus L-phenylalanine with B12 were all found ineffective, the subcommittee said in guidelines released on March 24 (Neurology 2014;82:1083-92).

The efficacy of CAM therapies in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) is an important clinical issue. Ten reports cited by the subcommittee and published during 1999-2009 documented that anywhere from a third to 80% of MS patients – particularly women, patients with higher education levels, and patients who report poorer health – used one or more CAM therapies, according to the panel, which was led by Dr. Vijayshree Yadav of the department of neurology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and the Portland VA Medical Center.

The group also determined that oral cannabis extract and another orally delivered cannabinoid, synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), were possibly effective for reducing symptoms and objective measures of spasticity during treatment beyond 1 year, and that THC is probably effective for reducing symptoms of spasticity and pain during the first year of treatment. The panel decided that, based on existing evidence, both of these oral agents are "probably ineffective" for reducing both objective spasticity measures and MS-related tremor symptoms.

The subcommittee reviewed two other delivery forms of cannabinoids. The members concluded that Sativex oromucosal cannabinoid spray is probably effective for improving subjective spasticity symptoms for periods of 5-10 weeks and possibly ineffective when used for longer periods or for reducing MS-related tremor. When it came to smoked cannabis, the panel decided that the data were inadequate to draw any conclusions on safety or efficacy.

It also deemed the evidence inadequate to draw conclusions about oral cannabis extract or THC for bladder-urge incontinence or for treating overall symptoms; synthetic THC for central neuropathic pain; and Sativex spray for overall bladder symptoms, anxiety, sleep problems, cognitive symptoms, quality of life, or fatigue.

In addition, cannabinoid studies have been of short duration (6-15 weeks), and central side effects may have caused unblinding in studies. The panel cautioned clinicians to counsel patients about potential psychopathologic effects, cognitive effects, or both with cannabinoid use, and cautioned against extrapolating from findings with standardized oral cannabis extract to other, nonstandardized cannabis extracts.

For other treatments with an adequate evidence base, the panel concluded that magnetic therapy is probably effective for reducing fatigue and probably ineffective for reducing depression, with inadequate data to support or refute other effects in MS patients.

The subcommittee said that study findings established Ginkgo biloba as ineffective for improving cognitive function in patients with MS but possibly effective during 4 weeks of treatment to reduce fatigue. The members also warned that Ginkgo biloba and other supplements not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration may vary considerably in efficacy and adverse effects and may interact with other medications, especially disease-modifying therapies for MS.

The panel called low-fat diet with omega-3 fatty acid supplementation probably ineffective for reducing MS relapses, disability, or MRI lesions, or for improving fatigue or quality of life. It found lofepramine plus L-phenylalanine and vitamin B12 possibly ineffective for treating disability, symptoms, depression, or fatigue, and bee-sting therapy possibly ineffective for reducing relapses, disability, fatigue, total MRI-lesion burden, and gadolinium-enhancing lesion volume, or for improving health-related quality of life.

The subcommittee said that reflexology is possibly effective for reducing MS-associated paresthesia during 11 weeks of treatment, but that data were inadequate to support or refute its use for pain, spasticity, fatigue, anxiety, or several other MS manifestations.

The guidelines were funded by the American Academy of Neurology. Most of the panel members reported some potential conflicts of interest in relationships with pharmaceutical companies that market drugs for MS as well as ties to MS medical societies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

An expert panel organized by the American Academy of Neurology called oral cannabis extract the only complementary and alternative medicine unequivocally effective for helping patients with multiple sclerosis, specifically easing their pain and symptoms of spasticity, possibly for as long as 1 year of treatment.

The academy’s Guideline Development Subcommittee also found existing evidence "insufficient to support or refute the effectiveness" of 25 other complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments, including acupuncture, chelation therapy, mindfulness training, and muscle-relaxation therapy. The panel noted that two of these inadequately assessed treatments – dental amalgam removal and transdermal histamine – have received substantial media attention despite having "little or no evidence to support recommendations."

Aside from various forms and delivery methods for cannabinoids, the nine-member panel found six other treatments with adequate evidence to develop practice recommendations that either endorsed their efficacy or lack of effect. Ginkgo biloba, reflexology, and magnetic therapy all had some proven level of efficacy, while bee venom, low-fat diet with omega-3 supplementation, and lofepramine plus L-phenylalanine with B12 were all found ineffective, the subcommittee said in guidelines released on March 24 (Neurology 2014;82:1083-92).

The efficacy of CAM therapies in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) is an important clinical issue. Ten reports cited by the subcommittee and published during 1999-2009 documented that anywhere from a third to 80% of MS patients – particularly women, patients with higher education levels, and patients who report poorer health – used one or more CAM therapies, according to the panel, which was led by Dr. Vijayshree Yadav of the department of neurology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and the Portland VA Medical Center.

The group also determined that oral cannabis extract and another orally delivered cannabinoid, synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), were possibly effective for reducing symptoms and objective measures of spasticity during treatment beyond 1 year, and that THC is probably effective for reducing symptoms of spasticity and pain during the first year of treatment. The panel decided that, based on existing evidence, both of these oral agents are "probably ineffective" for reducing both objective spasticity measures and MS-related tremor symptoms.

The subcommittee reviewed two other delivery forms of cannabinoids. The members concluded that Sativex oromucosal cannabinoid spray is probably effective for improving subjective spasticity symptoms for periods of 5-10 weeks and possibly ineffective when used for longer periods or for reducing MS-related tremor. When it came to smoked cannabis, the panel decided that the data were inadequate to draw any conclusions on safety or efficacy.

It also deemed the evidence inadequate to draw conclusions about oral cannabis extract or THC for bladder-urge incontinence or for treating overall symptoms; synthetic THC for central neuropathic pain; and Sativex spray for overall bladder symptoms, anxiety, sleep problems, cognitive symptoms, quality of life, or fatigue.

In addition, cannabinoid studies have been of short duration (6-15 weeks), and central side effects may have caused unblinding in studies. The panel cautioned clinicians to counsel patients about potential psychopathologic effects, cognitive effects, or both with cannabinoid use, and cautioned against extrapolating from findings with standardized oral cannabis extract to other, nonstandardized cannabis extracts.

For other treatments with an adequate evidence base, the panel concluded that magnetic therapy is probably effective for reducing fatigue and probably ineffective for reducing depression, with inadequate data to support or refute other effects in MS patients.

The subcommittee said that study findings established Ginkgo biloba as ineffective for improving cognitive function in patients with MS but possibly effective during 4 weeks of treatment to reduce fatigue. The members also warned that Ginkgo biloba and other supplements not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration may vary considerably in efficacy and adverse effects and may interact with other medications, especially disease-modifying therapies for MS.

The panel called low-fat diet with omega-3 fatty acid supplementation probably ineffective for reducing MS relapses, disability, or MRI lesions, or for improving fatigue or quality of life. It found lofepramine plus L-phenylalanine and vitamin B12 possibly ineffective for treating disability, symptoms, depression, or fatigue, and bee-sting therapy possibly ineffective for reducing relapses, disability, fatigue, total MRI-lesion burden, and gadolinium-enhancing lesion volume, or for improving health-related quality of life.

The subcommittee said that reflexology is possibly effective for reducing MS-associated paresthesia during 11 weeks of treatment, but that data were inadequate to support or refute its use for pain, spasticity, fatigue, anxiety, or several other MS manifestations.

The guidelines were funded by the American Academy of Neurology. Most of the panel members reported some potential conflicts of interest in relationships with pharmaceutical companies that market drugs for MS as well as ties to MS medical societies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

FROM NEUROLOGY

New cholesterol guidelines would add 13 million new statin users

Strict adherence to the new risk-based American College of Cardiology–American Heart Association guidelines for managing cholesterol would increase the number of adults eligible for statin therapy by nearly 13 million, a study suggests.

Most of the increase would be among older adults without cardiovascular disease, Michael J. Pencina, Ph.D., of the Duke Clinical Research Institute of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues reported online March 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigators used fasting data from 3,773 adults aged 40-75 years who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of 2005-2010 to estimate the number of individuals for whom statin therapy would be recommended under the new guidelines, published in November 2013, compared with the previously recommended 2007 guidelines from the Third Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program.

After extrapolating the results to the estimated population of U.S. adults aged 40-75 years (115.4 million adults), they determined that 14.4 million adults would be newly eligible for statin therapy based on the new guidelines, and that 1.6 million previously eligible adults would become ineligible under the new guidelines, for a net increase in the number of adults receiving or eligible for statin therapy from 43.2 million (38%) to 56.0 million (49%), the investigators said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315665]).

Of the 12.8 million additional eligible adults, 10.4 million would be individuals without existing cardiovascular disease, and 8.4 million of those would be aged 60-75 years; among the 60- to 75-year-olds without cardiovascular disease, the percentage eligible would increase from 30% to 87% for men, and from 21% to 54% for women.

"The median age of adults who would be newly eligible for statin therapy under the new ACC-AHA guidelines would be 63.4 years, and 61.7% would be men. The median LDL cholesterol level for these adults is 105.2 mg per deciliter," the investigators wrote, adding that the new guidelines increase the estimated number of adults who would be eligible across all categories.

The largest increase would occur among adults who have an indication for primary prevention on the basis of their 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease (15.1 million by the new guidelines vs. 6.9 million by ATP III), they said.

"Furthermore, 2.4 million adults with prevalent cardiovascular disease and LDL cholesterol levels of less than 100 mg per deciliter who would not be eligible for statin therapy according to the ATP III guidelines would be eligible under the new ACC-AHA guidelines. Finally, the number of adults with diabetes who are eligible for statin therapy would increase from 4.5 million to 6.7 million as a result of the lowering of the threshold for LDL cholesterol treatment from 100 to 70 mg per deciliter," the investigators wrote.

According to the ATP III guidelines, patients with established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and LDL cholesterol levels of 100 mg/dL or higher were eligible for statin therapy. Those guidelines also recommended statins for primary prevention in patients on the basis of a combined assessment of LDL cholesterol and a 10-year risk of coronary heart disease.

The new ACC-AHA guidelines differ substantially from the ATP III guidelines in that they expand the treatment recommendation to all adults with known cardiovascular disease, regardless of LDL cholesterol level, and for primary prevention they recommend statin therapy for all those with an LDL cholesterol level of 70 mg/dL or higher and who also have diabetes or a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease of 7.5% or greater based on new pooled-cohort equations.

"These new treatment recommendations have a larger effect in the older age group (60 to 75 years) than in the younger age group (40 to 59 years). Although up to 30% of adults in the younger age group without cardiovascular disease would be eligible for statin therapy for primary prevention, more than 77% of those in the older age group would be eligible. This difference might be partially explained by the addition of stroke to coronary heart disease as a target for prevention in the new pooled-cohort equations," they wrote. Because the prevalence of cardiovascular disease rises markedly with age, the large proportion of older adults who would be eligible for statin therapy may be justifiable, they added.

"Further research is required to determine whether more aggressive preventive strategies are needed for younger adults," they said.

Though limited by a number of factors, such as the extrapolation of data from 3,773 NHANES participants to 115.4 million U.S. adults, and by an inability to accurately quantify the effects of the new and old guidelines on patients currently receiving lipid-lowering therapy (since it was unclear why therapy was initiated), the findings nonetheless suggest a need for personalization with respect to applying the new guidelines.

The new guidelines "treat risk as the predominant reason for treating patients," according to one of the study’s lead authors, Dr. Eric D. Peterson of Duke University.

However, there is a paucity of data on the whether this approach works for older adults, Dr. Peterson said in an interview.

"I’m not willing to say we will be overtreating these patients [based on the new guidelines], but we need more data; this is a pretty big leap," he said.

Conversely, the new guidelines could lead to undertreatment of younger patients with high lipid levels, he added.

"This is kind of frightening," Dr. Peterson said, explaining that a younger patient who appears to have a relatively low 10-year risk of developing cardiovascular disease, but who has high lipid levels, would not be recommended for intervention – even though such a patient has a high likelihood of eventually developing cardiovascular disease.

"There is good research saying we should treat these patients, but these guidelines don’t recommend that. If we strictly follow the guidelines, we will undertreat younger patients," he said.

It is important to remember that the new guidelines are not "the letter of law," but rather are guides.

"Some degree of personalization for the patient in front of us is definitely needed right now," he said.

Dr. Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, cochair of the ACC-AHA guidelines, said he "agrees with the careful analysis" by Dr. Pencina, Dr. Peterson, and their colleagues.

"These findings are consistent with the analyses we reported in the guideline documents using NHANES data," said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, senior associate dean and professor and chair of preventive medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

Of note, the majority of the difference between the estimates based on the ATP III guidelines and the ACC-AHA guidelines is due to the lower threshold for consideration of treatment, which was derived directly from the evidence base from newer primary-prevention randomized clinical trials, he said.

"The authors recognized that the reported estimate is the maximum estimate of the increase in the number of people potentially eligible for statin therapy, because the guideline recommendation is for the clinician and patient to use the risk equations as the starting point for a risk discussion, not to mandate a statin prescription," he said.

Additionally, the results "refute the alarmist claims that we saw from a number of commentators in the media a few months ago that 70-100 million Americans would be put on statin therapy as a result of the new guidelines," Dr. Lloyd-Jones said.

"With one in three Americans dying of a preventable or postponable cardiovascular event, and more than half experiencing a major vascular event before they die, evidence-based guidelines that recommend that statins be considered for about half of American adults seem about right. Furthermore, we currently recommend that about 70 million Americans be treated for hypertension, so recommending that about 50 million should be considered for statins also seems about right," he said.

This study was funded by the Duke Clinical Research Institute and by grants from M. Jean de Granpre and Louis and Sylvia Vogel. Dr. Pencina reported receiving research fees (unrelated to this study) from McGill University Health Center and AbbVie. Dr. Peterson reported receiving grants from Eli Lilly and grant support and/or personal fees from Janssen and Boehringer Ingelheim. The remaining authors reported having nothing to disclose.

Strict adherence to the new risk-based American College of Cardiology–American Heart Association guidelines for managing cholesterol would increase the number of adults eligible for statin therapy by nearly 13 million, a study suggests.

Most of the increase would be among older adults without cardiovascular disease, Michael J. Pencina, Ph.D., of the Duke Clinical Research Institute of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues reported online March 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigators used fasting data from 3,773 adults aged 40-75 years who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of 2005-2010 to estimate the number of individuals for whom statin therapy would be recommended under the new guidelines, published in November 2013, compared with the previously recommended 2007 guidelines from the Third Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program.

After extrapolating the results to the estimated population of U.S. adults aged 40-75 years (115.4 million adults), they determined that 14.4 million adults would be newly eligible for statin therapy based on the new guidelines, and that 1.6 million previously eligible adults would become ineligible under the new guidelines, for a net increase in the number of adults receiving or eligible for statin therapy from 43.2 million (38%) to 56.0 million (49%), the investigators said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315665]).

Of the 12.8 million additional eligible adults, 10.4 million would be individuals without existing cardiovascular disease, and 8.4 million of those would be aged 60-75 years; among the 60- to 75-year-olds without cardiovascular disease, the percentage eligible would increase from 30% to 87% for men, and from 21% to 54% for women.

"The median age of adults who would be newly eligible for statin therapy under the new ACC-AHA guidelines would be 63.4 years, and 61.7% would be men. The median LDL cholesterol level for these adults is 105.2 mg per deciliter," the investigators wrote, adding that the new guidelines increase the estimated number of adults who would be eligible across all categories.

The largest increase would occur among adults who have an indication for primary prevention on the basis of their 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease (15.1 million by the new guidelines vs. 6.9 million by ATP III), they said.

"Furthermore, 2.4 million adults with prevalent cardiovascular disease and LDL cholesterol levels of less than 100 mg per deciliter who would not be eligible for statin therapy according to the ATP III guidelines would be eligible under the new ACC-AHA guidelines. Finally, the number of adults with diabetes who are eligible for statin therapy would increase from 4.5 million to 6.7 million as a result of the lowering of the threshold for LDL cholesterol treatment from 100 to 70 mg per deciliter," the investigators wrote.

According to the ATP III guidelines, patients with established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and LDL cholesterol levels of 100 mg/dL or higher were eligible for statin therapy. Those guidelines also recommended statins for primary prevention in patients on the basis of a combined assessment of LDL cholesterol and a 10-year risk of coronary heart disease.

The new ACC-AHA guidelines differ substantially from the ATP III guidelines in that they expand the treatment recommendation to all adults with known cardiovascular disease, regardless of LDL cholesterol level, and for primary prevention they recommend statin therapy for all those with an LDL cholesterol level of 70 mg/dL or higher and who also have diabetes or a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease of 7.5% or greater based on new pooled-cohort equations.

"These new treatment recommendations have a larger effect in the older age group (60 to 75 years) than in the younger age group (40 to 59 years). Although up to 30% of adults in the younger age group without cardiovascular disease would be eligible for statin therapy for primary prevention, more than 77% of those in the older age group would be eligible. This difference might be partially explained by the addition of stroke to coronary heart disease as a target for prevention in the new pooled-cohort equations," they wrote. Because the prevalence of cardiovascular disease rises markedly with age, the large proportion of older adults who would be eligible for statin therapy may be justifiable, they added.

"Further research is required to determine whether more aggressive preventive strategies are needed for younger adults," they said.

Though limited by a number of factors, such as the extrapolation of data from 3,773 NHANES participants to 115.4 million U.S. adults, and by an inability to accurately quantify the effects of the new and old guidelines on patients currently receiving lipid-lowering therapy (since it was unclear why therapy was initiated), the findings nonetheless suggest a need for personalization with respect to applying the new guidelines.

The new guidelines "treat risk as the predominant reason for treating patients," according to one of the study’s lead authors, Dr. Eric D. Peterson of Duke University.

However, there is a paucity of data on the whether this approach works for older adults, Dr. Peterson said in an interview.

"I’m not willing to say we will be overtreating these patients [based on the new guidelines], but we need more data; this is a pretty big leap," he said.

Conversely, the new guidelines could lead to undertreatment of younger patients with high lipid levels, he added.

"This is kind of frightening," Dr. Peterson said, explaining that a younger patient who appears to have a relatively low 10-year risk of developing cardiovascular disease, but who has high lipid levels, would not be recommended for intervention – even though such a patient has a high likelihood of eventually developing cardiovascular disease.

"There is good research saying we should treat these patients, but these guidelines don’t recommend that. If we strictly follow the guidelines, we will undertreat younger patients," he said.

It is important to remember that the new guidelines are not "the letter of law," but rather are guides.

"Some degree of personalization for the patient in front of us is definitely needed right now," he said.

Dr. Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, cochair of the ACC-AHA guidelines, said he "agrees with the careful analysis" by Dr. Pencina, Dr. Peterson, and their colleagues.

"These findings are consistent with the analyses we reported in the guideline documents using NHANES data," said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, senior associate dean and professor and chair of preventive medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

Of note, the majority of the difference between the estimates based on the ATP III guidelines and the ACC-AHA guidelines is due to the lower threshold for consideration of treatment, which was derived directly from the evidence base from newer primary-prevention randomized clinical trials, he said.

"The authors recognized that the reported estimate is the maximum estimate of the increase in the number of people potentially eligible for statin therapy, because the guideline recommendation is for the clinician and patient to use the risk equations as the starting point for a risk discussion, not to mandate a statin prescription," he said.

Additionally, the results "refute the alarmist claims that we saw from a number of commentators in the media a few months ago that 70-100 million Americans would be put on statin therapy as a result of the new guidelines," Dr. Lloyd-Jones said.

"With one in three Americans dying of a preventable or postponable cardiovascular event, and more than half experiencing a major vascular event before they die, evidence-based guidelines that recommend that statins be considered for about half of American adults seem about right. Furthermore, we currently recommend that about 70 million Americans be treated for hypertension, so recommending that about 50 million should be considered for statins also seems about right," he said.

This study was funded by the Duke Clinical Research Institute and by grants from M. Jean de Granpre and Louis and Sylvia Vogel. Dr. Pencina reported receiving research fees (unrelated to this study) from McGill University Health Center and AbbVie. Dr. Peterson reported receiving grants from Eli Lilly and grant support and/or personal fees from Janssen and Boehringer Ingelheim. The remaining authors reported having nothing to disclose.

Strict adherence to the new risk-based American College of Cardiology–American Heart Association guidelines for managing cholesterol would increase the number of adults eligible for statin therapy by nearly 13 million, a study suggests.

Most of the increase would be among older adults without cardiovascular disease, Michael J. Pencina, Ph.D., of the Duke Clinical Research Institute of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues reported online March 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The investigators used fasting data from 3,773 adults aged 40-75 years who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of 2005-2010 to estimate the number of individuals for whom statin therapy would be recommended under the new guidelines, published in November 2013, compared with the previously recommended 2007 guidelines from the Third Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program.

After extrapolating the results to the estimated population of U.S. adults aged 40-75 years (115.4 million adults), they determined that 14.4 million adults would be newly eligible for statin therapy based on the new guidelines, and that 1.6 million previously eligible adults would become ineligible under the new guidelines, for a net increase in the number of adults receiving or eligible for statin therapy from 43.2 million (38%) to 56.0 million (49%), the investigators said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 March 19 [doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315665]).

Of the 12.8 million additional eligible adults, 10.4 million would be individuals without existing cardiovascular disease, and 8.4 million of those would be aged 60-75 years; among the 60- to 75-year-olds without cardiovascular disease, the percentage eligible would increase from 30% to 87% for men, and from 21% to 54% for women.

"The median age of adults who would be newly eligible for statin therapy under the new ACC-AHA guidelines would be 63.4 years, and 61.7% would be men. The median LDL cholesterol level for these adults is 105.2 mg per deciliter," the investigators wrote, adding that the new guidelines increase the estimated number of adults who would be eligible across all categories.

The largest increase would occur among adults who have an indication for primary prevention on the basis of their 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease (15.1 million by the new guidelines vs. 6.9 million by ATP III), they said.

"Furthermore, 2.4 million adults with prevalent cardiovascular disease and LDL cholesterol levels of less than 100 mg per deciliter who would not be eligible for statin therapy according to the ATP III guidelines would be eligible under the new ACC-AHA guidelines. Finally, the number of adults with diabetes who are eligible for statin therapy would increase from 4.5 million to 6.7 million as a result of the lowering of the threshold for LDL cholesterol treatment from 100 to 70 mg per deciliter," the investigators wrote.

According to the ATP III guidelines, patients with established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and LDL cholesterol levels of 100 mg/dL or higher were eligible for statin therapy. Those guidelines also recommended statins for primary prevention in patients on the basis of a combined assessment of LDL cholesterol and a 10-year risk of coronary heart disease.

The new ACC-AHA guidelines differ substantially from the ATP III guidelines in that they expand the treatment recommendation to all adults with known cardiovascular disease, regardless of LDL cholesterol level, and for primary prevention they recommend statin therapy for all those with an LDL cholesterol level of 70 mg/dL or higher and who also have diabetes or a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease of 7.5% or greater based on new pooled-cohort equations.

"These new treatment recommendations have a larger effect in the older age group (60 to 75 years) than in the younger age group (40 to 59 years). Although up to 30% of adults in the younger age group without cardiovascular disease would be eligible for statin therapy for primary prevention, more than 77% of those in the older age group would be eligible. This difference might be partially explained by the addition of stroke to coronary heart disease as a target for prevention in the new pooled-cohort equations," they wrote. Because the prevalence of cardiovascular disease rises markedly with age, the large proportion of older adults who would be eligible for statin therapy may be justifiable, they added.

"Further research is required to determine whether more aggressive preventive strategies are needed for younger adults," they said.

Though limited by a number of factors, such as the extrapolation of data from 3,773 NHANES participants to 115.4 million U.S. adults, and by an inability to accurately quantify the effects of the new and old guidelines on patients currently receiving lipid-lowering therapy (since it was unclear why therapy was initiated), the findings nonetheless suggest a need for personalization with respect to applying the new guidelines.

The new guidelines "treat risk as the predominant reason for treating patients," according to one of the study’s lead authors, Dr. Eric D. Peterson of Duke University.

However, there is a paucity of data on the whether this approach works for older adults, Dr. Peterson said in an interview.

"I’m not willing to say we will be overtreating these patients [based on the new guidelines], but we need more data; this is a pretty big leap," he said.

Conversely, the new guidelines could lead to undertreatment of younger patients with high lipid levels, he added.

"This is kind of frightening," Dr. Peterson said, explaining that a younger patient who appears to have a relatively low 10-year risk of developing cardiovascular disease, but who has high lipid levels, would not be recommended for intervention – even though such a patient has a high likelihood of eventually developing cardiovascular disease.

"There is good research saying we should treat these patients, but these guidelines don’t recommend that. If we strictly follow the guidelines, we will undertreat younger patients," he said.

It is important to remember that the new guidelines are not "the letter of law," but rather are guides.

"Some degree of personalization for the patient in front of us is definitely needed right now," he said.

Dr. Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, cochair of the ACC-AHA guidelines, said he "agrees with the careful analysis" by Dr. Pencina, Dr. Peterson, and their colleagues.

"These findings are consistent with the analyses we reported in the guideline documents using NHANES data," said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, senior associate dean and professor and chair of preventive medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

Of note, the majority of the difference between the estimates based on the ATP III guidelines and the ACC-AHA guidelines is due to the lower threshold for consideration of treatment, which was derived directly from the evidence base from newer primary-prevention randomized clinical trials, he said.

"The authors recognized that the reported estimate is the maximum estimate of the increase in the number of people potentially eligible for statin therapy, because the guideline recommendation is for the clinician and patient to use the risk equations as the starting point for a risk discussion, not to mandate a statin prescription," he said.

Additionally, the results "refute the alarmist claims that we saw from a number of commentators in the media a few months ago that 70-100 million Americans would be put on statin therapy as a result of the new guidelines," Dr. Lloyd-Jones said.

"With one in three Americans dying of a preventable or postponable cardiovascular event, and more than half experiencing a major vascular event before they die, evidence-based guidelines that recommend that statins be considered for about half of American adults seem about right. Furthermore, we currently recommend that about 70 million Americans be treated for hypertension, so recommending that about 50 million should be considered for statins also seems about right," he said.

This study was funded by the Duke Clinical Research Institute and by grants from M. Jean de Granpre and Louis and Sylvia Vogel. Dr. Pencina reported receiving research fees (unrelated to this study) from McGill University Health Center and AbbVie. Dr. Peterson reported receiving grants from Eli Lilly and grant support and/or personal fees from Janssen and Boehringer Ingelheim. The remaining authors reported having nothing to disclose.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Major finding: The new ACC-AHA cholesterol guidelines could increase number of statin users by 13 million.

Data source: Extrapolation of NHANES data for the U.S. adult population aged 40-75 years.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Duke Clinical Research Institute and by grants from M. Jean de Granpre and Louis and Sylvia Vogel. Dr. Pencina reported receiving research fees (unrelated to this study) from McGill University Health Center and AbbVie. Dr. Peterson reported receiving grants from Eli Lilly and grant support and/or personal fees from Janssen and Boehringer Ingelheim. The remaining authors reported having nothing to disclose.

Two definitions of Gulf War illness recommended

An Institute of Medicine committee could not reach consensus on a single definition of Gulf War illness and recommended in a new report that clinicians and researchers at least narrow it down to two definitions.

That’s the preferred term – Gulf War illness – for a slew of health problems that occur at a higher rate in the approximately 697,000 U.S. veterans who served in the 1990-1991 Gulf War than in other veterans, the committee said. Gulf War illness is widely used and is more accurate than other terms used over the years for the same problems, including Gulf War syndrome, chronic multisystem illness, unexplained illness, medically unexplained symptoms, and medically unexplained physical symptoms, the report stated.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) drafted a committee of 16 experts at the request of the Department of Veterans Affairs to try to develop a case definition for what's now called Gulf War illness in order to help standardize diagnosis, inclusion in research studies, and treatments. The committee's 120-page report, "Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined," is available on the IOM website.

Unable to find validation for one definition because of methodologic limitations in the studies, the committee recommended using either a broader definition from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or a more restrictive one from studies of Kansas veterans, depending on the situation. Between the two of them, the definitions capture the most common symptoms of Gulf War illness and provide a framework for more focused research and treatment, the report said.

The committee found 2,033 articles in the literature focused on Gulf War illness symptoms and closely reviewed 718 of them. It found no objective diagnostic criteria but saw cumulative evidence that Gulf War illness is real. Fatigue, pain, and neurocognitive, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and/or dermatologic symptoms were reported with higher frequency in Gulf War veterans than in veterans of the same era who had not been deployed or were deployed elsewhere.

To identify the illness in a Gulf War veteran, the CDC definition requires one or more symptoms in at least two of the following categories: fatigue, pain, or mood and cognition. The Kansas definition requires symptoms in at least three of the following domains: fatigue or sleep, pain, neurologic or cognitive or mood symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, respiratory symptoms, and skin symptoms.

The CDC definition identified the illness in 29%-60% of Gulf War veterans, depending on the population studied. The Kansas definition identified the illness in 34% of Kansas veterans of the Gulf War.

The reason the committee couldn’t compile a single case definition is that the studies in the literature do not report on key features of the illness including onset, duration, severity, frequency of symptoms, and exclusionary criteria. The Department of Veterans Affairs should boost efforts to collect these kinds of data, conduct earlier in-depth assessments after deployment when unexpected complaints occur, and track troops’ exposures to vaccinations, drugs, and environmental factors, the report recommends.

The name Gulf War illness won out over Gulf War syndrome because "syndrome" indicates a new group of signs and symptoms, while the types and patterns of symptoms in this illness commonly are seen with other illnesses. The committee rejected "chronic multisymptom illness" because the phrase is not specific to Gulf War veterans.

The committee included experts in clinical medicine, toxicology, psychiatry, neurology, gastroenterology, epidemiology, sociology, psychometrics, biostatistics, occupational medicine, and basic science.

The report does not include potential disclosures of conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

There has long been debate about whether Gulf War syndrome or Gulf War illness existed. If you remember the time of the Gulf War and shortly afterwards, there were a lot of questions about whether this was "all in their heads." Nobody ever found the sources of the illness. This report says to me that it’s final – that this august institution says, yes, this illness does exist. Whether you use the wider or narrower definition, this is to be taken seriously. That’s very important for physicians to know.

In terms of the two definitions – one narrower to be used for research and one broader to be used clinically – I think this gives people a little bit of latitude, depending on where they fit. The take-home piece is that, since there has been such a smorgasbord of opinions, thoughts, and descriptions, this should help the field by solidifying it further. We do still have two working definitions and we still don’t know a lot such as onset, duration, severity, frequency, and exclusionary criteria. Certainly, more needs to be done, but I think this is a very important step.

|

|

Finally, I think it’s also important that they said "Gulf War illness" rather than "chronic multisymptom illness." Again, I think that lends credibility to the claims of the veterans who have been there. This committee is willing to say, yes, there is something about having been deployed to the first Gulf War at a particular time that helps us understand your medical history. That’s not as far as we’d like to go, but it’s certainly some steps in the right direction.

That was a very short war a long time ago. Now, we’ve had 12 years of a very long war with multiple deployments, yet we haven’t really seen Gulf War illness or its equivalent in this generation of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. I have expected that at some point we’re going to see these psychosomatic, vague symptoms coming out of this current war. I definitely think there’s time. Traumatic brain injury seems like the cardinal disorder from these wars, but I think we’re going to see some psychosomatic reactions over time.

Dr. Elspeth Cameron Ritchie is an expert on military health issues who retired as a colonel after 28 years in the U.S. Army. These are excerpts of an interview in which she spoke as an individual, not in her current roles as chief clinical officer of the Department of Behavioral Health for the District of Columbia and professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and at Georgetown University, Washington. She reported having no financial disclosures.

There has long been debate about whether Gulf War syndrome or Gulf War illness existed. If you remember the time of the Gulf War and shortly afterwards, there were a lot of questions about whether this was "all in their heads." Nobody ever found the sources of the illness. This report says to me that it’s final – that this august institution says, yes, this illness does exist. Whether you use the wider or narrower definition, this is to be taken seriously. That’s very important for physicians to know.

In terms of the two definitions – one narrower to be used for research and one broader to be used clinically – I think this gives people a little bit of latitude, depending on where they fit. The take-home piece is that, since there has been such a smorgasbord of opinions, thoughts, and descriptions, this should help the field by solidifying it further. We do still have two working definitions and we still don’t know a lot such as onset, duration, severity, frequency, and exclusionary criteria. Certainly, more needs to be done, but I think this is a very important step.

|

|

Finally, I think it’s also important that they said "Gulf War illness" rather than "chronic multisymptom illness." Again, I think that lends credibility to the claims of the veterans who have been there. This committee is willing to say, yes, there is something about having been deployed to the first Gulf War at a particular time that helps us understand your medical history. That’s not as far as we’d like to go, but it’s certainly some steps in the right direction.

That was a very short war a long time ago. Now, we’ve had 12 years of a very long war with multiple deployments, yet we haven’t really seen Gulf War illness or its equivalent in this generation of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. I have expected that at some point we’re going to see these psychosomatic, vague symptoms coming out of this current war. I definitely think there’s time. Traumatic brain injury seems like the cardinal disorder from these wars, but I think we’re going to see some psychosomatic reactions over time.

Dr. Elspeth Cameron Ritchie is an expert on military health issues who retired as a colonel after 28 years in the U.S. Army. These are excerpts of an interview in which she spoke as an individual, not in her current roles as chief clinical officer of the Department of Behavioral Health for the District of Columbia and professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and at Georgetown University, Washington. She reported having no financial disclosures.

There has long been debate about whether Gulf War syndrome or Gulf War illness existed. If you remember the time of the Gulf War and shortly afterwards, there were a lot of questions about whether this was "all in their heads." Nobody ever found the sources of the illness. This report says to me that it’s final – that this august institution says, yes, this illness does exist. Whether you use the wider or narrower definition, this is to be taken seriously. That’s very important for physicians to know.

In terms of the two definitions – one narrower to be used for research and one broader to be used clinically – I think this gives people a little bit of latitude, depending on where they fit. The take-home piece is that, since there has been such a smorgasbord of opinions, thoughts, and descriptions, this should help the field by solidifying it further. We do still have two working definitions and we still don’t know a lot such as onset, duration, severity, frequency, and exclusionary criteria. Certainly, more needs to be done, but I think this is a very important step.

|

|

Finally, I think it’s also important that they said "Gulf War illness" rather than "chronic multisymptom illness." Again, I think that lends credibility to the claims of the veterans who have been there. This committee is willing to say, yes, there is something about having been deployed to the first Gulf War at a particular time that helps us understand your medical history. That’s not as far as we’d like to go, but it’s certainly some steps in the right direction.

That was a very short war a long time ago. Now, we’ve had 12 years of a very long war with multiple deployments, yet we haven’t really seen Gulf War illness or its equivalent in this generation of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. I have expected that at some point we’re going to see these psychosomatic, vague symptoms coming out of this current war. I definitely think there’s time. Traumatic brain injury seems like the cardinal disorder from these wars, but I think we’re going to see some psychosomatic reactions over time.

Dr. Elspeth Cameron Ritchie is an expert on military health issues who retired as a colonel after 28 years in the U.S. Army. These are excerpts of an interview in which she spoke as an individual, not in her current roles as chief clinical officer of the Department of Behavioral Health for the District of Columbia and professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and at Georgetown University, Washington. She reported having no financial disclosures.

An Institute of Medicine committee could not reach consensus on a single definition of Gulf War illness and recommended in a new report that clinicians and researchers at least narrow it down to two definitions.

That’s the preferred term – Gulf War illness – for a slew of health problems that occur at a higher rate in the approximately 697,000 U.S. veterans who served in the 1990-1991 Gulf War than in other veterans, the committee said. Gulf War illness is widely used and is more accurate than other terms used over the years for the same problems, including Gulf War syndrome, chronic multisystem illness, unexplained illness, medically unexplained symptoms, and medically unexplained physical symptoms, the report stated.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) drafted a committee of 16 experts at the request of the Department of Veterans Affairs to try to develop a case definition for what's now called Gulf War illness in order to help standardize diagnosis, inclusion in research studies, and treatments. The committee's 120-page report, "Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined," is available on the IOM website.

Unable to find validation for one definition because of methodologic limitations in the studies, the committee recommended using either a broader definition from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or a more restrictive one from studies of Kansas veterans, depending on the situation. Between the two of them, the definitions capture the most common symptoms of Gulf War illness and provide a framework for more focused research and treatment, the report said.

The committee found 2,033 articles in the literature focused on Gulf War illness symptoms and closely reviewed 718 of them. It found no objective diagnostic criteria but saw cumulative evidence that Gulf War illness is real. Fatigue, pain, and neurocognitive, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and/or dermatologic symptoms were reported with higher frequency in Gulf War veterans than in veterans of the same era who had not been deployed or were deployed elsewhere.

To identify the illness in a Gulf War veteran, the CDC definition requires one or more symptoms in at least two of the following categories: fatigue, pain, or mood and cognition. The Kansas definition requires symptoms in at least three of the following domains: fatigue or sleep, pain, neurologic or cognitive or mood symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, respiratory symptoms, and skin symptoms.

The CDC definition identified the illness in 29%-60% of Gulf War veterans, depending on the population studied. The Kansas definition identified the illness in 34% of Kansas veterans of the Gulf War.

The reason the committee couldn’t compile a single case definition is that the studies in the literature do not report on key features of the illness including onset, duration, severity, frequency of symptoms, and exclusionary criteria. The Department of Veterans Affairs should boost efforts to collect these kinds of data, conduct earlier in-depth assessments after deployment when unexpected complaints occur, and track troops’ exposures to vaccinations, drugs, and environmental factors, the report recommends.

The name Gulf War illness won out over Gulf War syndrome because "syndrome" indicates a new group of signs and symptoms, while the types and patterns of symptoms in this illness commonly are seen with other illnesses. The committee rejected "chronic multisymptom illness" because the phrase is not specific to Gulf War veterans.

The committee included experts in clinical medicine, toxicology, psychiatry, neurology, gastroenterology, epidemiology, sociology, psychometrics, biostatistics, occupational medicine, and basic science.

The report does not include potential disclosures of conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

An Institute of Medicine committee could not reach consensus on a single definition of Gulf War illness and recommended in a new report that clinicians and researchers at least narrow it down to two definitions.

That’s the preferred term – Gulf War illness – for a slew of health problems that occur at a higher rate in the approximately 697,000 U.S. veterans who served in the 1990-1991 Gulf War than in other veterans, the committee said. Gulf War illness is widely used and is more accurate than other terms used over the years for the same problems, including Gulf War syndrome, chronic multisystem illness, unexplained illness, medically unexplained symptoms, and medically unexplained physical symptoms, the report stated.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) drafted a committee of 16 experts at the request of the Department of Veterans Affairs to try to develop a case definition for what's now called Gulf War illness in order to help standardize diagnosis, inclusion in research studies, and treatments. The committee's 120-page report, "Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined," is available on the IOM website.

Unable to find validation for one definition because of methodologic limitations in the studies, the committee recommended using either a broader definition from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or a more restrictive one from studies of Kansas veterans, depending on the situation. Between the two of them, the definitions capture the most common symptoms of Gulf War illness and provide a framework for more focused research and treatment, the report said.

The committee found 2,033 articles in the literature focused on Gulf War illness symptoms and closely reviewed 718 of them. It found no objective diagnostic criteria but saw cumulative evidence that Gulf War illness is real. Fatigue, pain, and neurocognitive, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and/or dermatologic symptoms were reported with higher frequency in Gulf War veterans than in veterans of the same era who had not been deployed or were deployed elsewhere.

To identify the illness in a Gulf War veteran, the CDC definition requires one or more symptoms in at least two of the following categories: fatigue, pain, or mood and cognition. The Kansas definition requires symptoms in at least three of the following domains: fatigue or sleep, pain, neurologic or cognitive or mood symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, respiratory symptoms, and skin symptoms.

The CDC definition identified the illness in 29%-60% of Gulf War veterans, depending on the population studied. The Kansas definition identified the illness in 34% of Kansas veterans of the Gulf War.

The reason the committee couldn’t compile a single case definition is that the studies in the literature do not report on key features of the illness including onset, duration, severity, frequency of symptoms, and exclusionary criteria. The Department of Veterans Affairs should boost efforts to collect these kinds of data, conduct earlier in-depth assessments after deployment when unexpected complaints occur, and track troops’ exposures to vaccinations, drugs, and environmental factors, the report recommends.

The name Gulf War illness won out over Gulf War syndrome because "syndrome" indicates a new group of signs and symptoms, while the types and patterns of symptoms in this illness commonly are seen with other illnesses. The committee rejected "chronic multisymptom illness" because the phrase is not specific to Gulf War veterans.

The committee included experts in clinical medicine, toxicology, psychiatry, neurology, gastroenterology, epidemiology, sociology, psychometrics, biostatistics, occupational medicine, and basic science.

The report does not include potential disclosures of conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Consensus Recommendations From the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the Management of Rosacea, Part 5: A Guide on the Management of Rosacea

Latest heart failure guidelines break new ground

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The latest heart failure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association place a new emphasis on aldosterone antagonists as a central aspect of the management of symptomatic or previously symptomatic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction – while underscoring important caveats to their use.

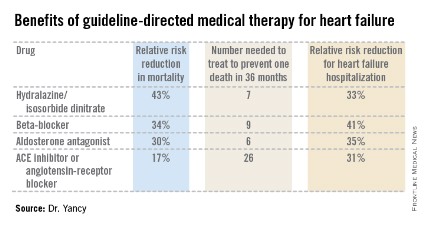

Aldosterone antagonist therapy earns the strongest possible designation in the guidelines: a Class I/Level of Evidence A recommendation. This is based on data from multiple randomized trials showing that, used appropriately, these agents result in a 30% relative risk reduction in mortality and a 35% reduction in the relative risk of heart failure hospitalization, with a number needed to treat for 36 months of just six patients to prevent one additional death. Those figures place the aldosterone antagonists on a par with the other Class I/A heart failure medications – beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate in African Americans – in terms of benefits (see chart).

"These data are quite striking," Dr. Clyde W. Yancy observed in presenting highlights of the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

"For many years, we’ve functioned in a space where we thought there’s not that much we can do for heart failure, and I would now argue stridently against that. You can see the incredibly low numbers needed to treat here. Only a handful of patients need to be exposed to these therapies to derive a significant benefit on mortality. These are data we should incorporate in our clinical practice without exclusion," declared Dr. Yancy, who chaired the heart failure guideline-writing committee.

The important caveat regarding the aldosterone antagonists is that they should be used only in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate greater than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and a serum potassium level below 5.0 mEq/dL. Otherwise that Class I/A recommendation plummets to III/B, meaning the treatment is inappropriate and potentially harmful, continued Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and of medical social sciences and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The guidelines emphasize the imperative to implement what has come to be termed guideline-directed medical therapy, known by the acronym GDMT. The panel found persuasive an analysis showing that heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction who were on two of seven evidence-based, guideline-directed management interventions had an adjusted 38% reduction in 2-year mortality risk compared with those on none or one, while those on three interventions had a 62% decrease in the odds of mortality and patients on four or more had mortality reductions of about 70% (J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2012;1:16-26).

The seven interventions are beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors or ARBs, aldosterone antagonists, anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation, cardiac resynchronization therapy, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, and heart failure education for eligible patients.

The guidelines advise strongly against the combined use of an ACE inhibitor and ARB. It’s an either/or treatment strategy. Studies indicate there is no additive benefit with the combination, only an increased risk of side effects.

An important innovation in the guidelines is the new prominence afforded to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, known as HFpEF (pronounced heff-peff).

"What’s most different in the new heart failure guidelines is that we have uploaded HFpEF to the front page," said Dr. Yancy. "We want you to appreciate how important it is. We recognize that there’s no evidence-based intervention that changes its natural history; rather, the focus is on identification and treatment of the comorbidities. It’s important to emphasize that this is a novel way of thinking about heart failure for a very important iteration of that disease."

Among the other highlights of the guidelines is a clarification of the current role for biomarker-guided heart failure therapy. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP measurements are deemed useful in making the diagnosis of heart failure as well as in establishing prognosis. Serial measurements can be used to titrate GDMT to optimal doses. But there are as yet no data to show that using the biomarkers to titrate GDMT to higher doses improves mortality.

The 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure was developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Chest Physicians, the Heart Rhythm Society, and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62:e147-e239).

Dr. Yancy reported having no financial conflicts.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The latest heart failure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association place a new emphasis on aldosterone antagonists as a central aspect of the management of symptomatic or previously symptomatic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction – while underscoring important caveats to their use.

Aldosterone antagonist therapy earns the strongest possible designation in the guidelines: a Class I/Level of Evidence A recommendation. This is based on data from multiple randomized trials showing that, used appropriately, these agents result in a 30% relative risk reduction in mortality and a 35% reduction in the relative risk of heart failure hospitalization, with a number needed to treat for 36 months of just six patients to prevent one additional death. Those figures place the aldosterone antagonists on a par with the other Class I/A heart failure medications – beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate in African Americans – in terms of benefits (see chart).

"These data are quite striking," Dr. Clyde W. Yancy observed in presenting highlights of the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

"For many years, we’ve functioned in a space where we thought there’s not that much we can do for heart failure, and I would now argue stridently against that. You can see the incredibly low numbers needed to treat here. Only a handful of patients need to be exposed to these therapies to derive a significant benefit on mortality. These are data we should incorporate in our clinical practice without exclusion," declared Dr. Yancy, who chaired the heart failure guideline-writing committee.

The important caveat regarding the aldosterone antagonists is that they should be used only in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate greater than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and a serum potassium level below 5.0 mEq/dL. Otherwise that Class I/A recommendation plummets to III/B, meaning the treatment is inappropriate and potentially harmful, continued Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and of medical social sciences and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The guidelines emphasize the imperative to implement what has come to be termed guideline-directed medical therapy, known by the acronym GDMT. The panel found persuasive an analysis showing that heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction who were on two of seven evidence-based, guideline-directed management interventions had an adjusted 38% reduction in 2-year mortality risk compared with those on none or one, while those on three interventions had a 62% decrease in the odds of mortality and patients on four or more had mortality reductions of about 70% (J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2012;1:16-26).

The seven interventions are beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors or ARBs, aldosterone antagonists, anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation, cardiac resynchronization therapy, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, and heart failure education for eligible patients.

The guidelines advise strongly against the combined use of an ACE inhibitor and ARB. It’s an either/or treatment strategy. Studies indicate there is no additive benefit with the combination, only an increased risk of side effects.

An important innovation in the guidelines is the new prominence afforded to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, known as HFpEF (pronounced heff-peff).

"What’s most different in the new heart failure guidelines is that we have uploaded HFpEF to the front page," said Dr. Yancy. "We want you to appreciate how important it is. We recognize that there’s no evidence-based intervention that changes its natural history; rather, the focus is on identification and treatment of the comorbidities. It’s important to emphasize that this is a novel way of thinking about heart failure for a very important iteration of that disease."

Among the other highlights of the guidelines is a clarification of the current role for biomarker-guided heart failure therapy. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP measurements are deemed useful in making the diagnosis of heart failure as well as in establishing prognosis. Serial measurements can be used to titrate GDMT to optimal doses. But there are as yet no data to show that using the biomarkers to titrate GDMT to higher doses improves mortality.

The 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure was developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Chest Physicians, the Heart Rhythm Society, and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62:e147-e239).

Dr. Yancy reported having no financial conflicts.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The latest heart failure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association place a new emphasis on aldosterone antagonists as a central aspect of the management of symptomatic or previously symptomatic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction – while underscoring important caveats to their use.

Aldosterone antagonist therapy earns the strongest possible designation in the guidelines: a Class I/Level of Evidence A recommendation. This is based on data from multiple randomized trials showing that, used appropriately, these agents result in a 30% relative risk reduction in mortality and a 35% reduction in the relative risk of heart failure hospitalization, with a number needed to treat for 36 months of just six patients to prevent one additional death. Those figures place the aldosterone antagonists on a par with the other Class I/A heart failure medications – beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate in African Americans – in terms of benefits (see chart).

"These data are quite striking," Dr. Clyde W. Yancy observed in presenting highlights of the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

"For many years, we’ve functioned in a space where we thought there’s not that much we can do for heart failure, and I would now argue stridently against that. You can see the incredibly low numbers needed to treat here. Only a handful of patients need to be exposed to these therapies to derive a significant benefit on mortality. These are data we should incorporate in our clinical practice without exclusion," declared Dr. Yancy, who chaired the heart failure guideline-writing committee.

The important caveat regarding the aldosterone antagonists is that they should be used only in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate greater than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and a serum potassium level below 5.0 mEq/dL. Otherwise that Class I/A recommendation plummets to III/B, meaning the treatment is inappropriate and potentially harmful, continued Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and of medical social sciences and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The guidelines emphasize the imperative to implement what has come to be termed guideline-directed medical therapy, known by the acronym GDMT. The panel found persuasive an analysis showing that heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction who were on two of seven evidence-based, guideline-directed management interventions had an adjusted 38% reduction in 2-year mortality risk compared with those on none or one, while those on three interventions had a 62% decrease in the odds of mortality and patients on four or more had mortality reductions of about 70% (J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2012;1:16-26).

The seven interventions are beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors or ARBs, aldosterone antagonists, anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation, cardiac resynchronization therapy, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, and heart failure education for eligible patients.

The guidelines advise strongly against the combined use of an ACE inhibitor and ARB. It’s an either/or treatment strategy. Studies indicate there is no additive benefit with the combination, only an increased risk of side effects.

An important innovation in the guidelines is the new prominence afforded to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, known as HFpEF (pronounced heff-peff).

"What’s most different in the new heart failure guidelines is that we have uploaded HFpEF to the front page," said Dr. Yancy. "We want you to appreciate how important it is. We recognize that there’s no evidence-based intervention that changes its natural history; rather, the focus is on identification and treatment of the comorbidities. It’s important to emphasize that this is a novel way of thinking about heart failure for a very important iteration of that disease."

Among the other highlights of the guidelines is a clarification of the current role for biomarker-guided heart failure therapy. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP measurements are deemed useful in making the diagnosis of heart failure as well as in establishing prognosis. Serial measurements can be used to titrate GDMT to optimal doses. But there are as yet no data to show that using the biomarkers to titrate GDMT to higher doses improves mortality.

The 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure was developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Chest Physicians, the Heart Rhythm Society, and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62:e147-e239).

Dr. Yancy reported having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

AAN issues nonvalvular atrial fibrillation stroke prevention guideline

A new evidence-based guideline on how to identify and treat patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation to prevent cardioembolic stroke from the American Academy of Neurology suggests when to conduct cardiac rhythm monitoring and offer anticoagulation, including newer agents in place of warfarin.

But the guideline might already be outdated in not considering the results of the recent CRYSTAL-AF study, in which long-term cardiac rhythm monitoring of patients with a previous cryptogenic stroke detected asymptomatic patients at a significantly higher rate than did standard monitoring methods.

The guideline also extends the routine use of anticoagulation for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) who are generally undertreated or whose health was thought a possible barrier to their use, such as those aged 75 years or older, those with mild dementia, and those at moderate risk of falls.

"Cognizant of the global reach of the AAN [American Academy of Neurology], the guideline also examines the evidence base for a treatment alternative to warfarin or its analogues for patients in developing countries who may not have access to the new oral anticoagulants," said lead author Dr. Antonio Culebras in an interview.

"The World Health Organization has determined that atrial fibrillation has reached near-epidemic proportions," observed Dr. Culebras of the State University of New York, Syracuse. "Approximately 1 in 20 individuals with AF will have a stroke unless treated appropriately."