User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

COVID attacks DNA in heart, unlike flu, study says

, according to a study published in Immunology.

The study looked at the hearts of patients who died from COVID-19, the flu, and other causes. The findings could provide clues about why coronavirus has led to complications such as ongoing heart issues.

“We found a lot of DNA damage that was unique to the COVID-19 patients, which wasn’t present in the flu patients,” Arutha Kulasinghe, one of the lead study authors and a research fellow at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, told the Brisbane Times.

“So in this study, COVID-19 and flu look very different in the way they affect the heart,” he said.

Dr. Kulasinghe and colleagues analyzed the hearts of seven COVID-19 patients, two flu patients, and six patients who died from other causes. They used transcriptomic profiling, which looks at the DNA landscape of an organ, to investigate heart tissue from the patients.

Because of previous studies about heart problems associated with COVID-19, he and colleagues expected to find extreme inflammation in the heart. Instead, they found that inflammation signals had been suppressed in the heart, and markers for DNA damage and repair were much higher. They’re still unsure of the underlying cause.

“The indications here are that there’s DNA damage here, it’s not inflammation,” Dr. Kulasinghe said. “There’s something else going on that we need to figure out.”

The damage was similar to the way chronic diseases such as diabetes and cancer appear in the heart, he said, with heart tissue showing DNA damage signals.

Dr. Kulasinghe said he hopes other studies can build on the findings to develop risk models to understand which patients may face a higher risk of serious COVID-19 complications. In turn, this could help doctors provide early treatment. For instance, all seven COVID-19 patients had other chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease.

“Ideally in the future, if you have cardiovascular disease, if you’re obese or have other complications, and you’ve got a signature in your blood that indicates you are at risk of severe disease, then we can risk-stratify patients when they are diagnosed,” he said.

The research is a preliminary step, Dr. Kulasinghe said, because of the small sample size. This type of study is often difficult to conduct because researchers have to wait for the availability of organs, as well as request permission from families for postmortem autopsies and biopsies, to be able to look at the effects on dead tissues.

“Our challenge now is to draw a clinical finding from this, which we can’t at this stage,” he added. “But it’s a really fundamental biological difference we’re observing [between COVID-19 and flu], which we need to validate with larger studies.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a study published in Immunology.

The study looked at the hearts of patients who died from COVID-19, the flu, and other causes. The findings could provide clues about why coronavirus has led to complications such as ongoing heart issues.

“We found a lot of DNA damage that was unique to the COVID-19 patients, which wasn’t present in the flu patients,” Arutha Kulasinghe, one of the lead study authors and a research fellow at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, told the Brisbane Times.

“So in this study, COVID-19 and flu look very different in the way they affect the heart,” he said.

Dr. Kulasinghe and colleagues analyzed the hearts of seven COVID-19 patients, two flu patients, and six patients who died from other causes. They used transcriptomic profiling, which looks at the DNA landscape of an organ, to investigate heart tissue from the patients.

Because of previous studies about heart problems associated with COVID-19, he and colleagues expected to find extreme inflammation in the heart. Instead, they found that inflammation signals had been suppressed in the heart, and markers for DNA damage and repair were much higher. They’re still unsure of the underlying cause.

“The indications here are that there’s DNA damage here, it’s not inflammation,” Dr. Kulasinghe said. “There’s something else going on that we need to figure out.”

The damage was similar to the way chronic diseases such as diabetes and cancer appear in the heart, he said, with heart tissue showing DNA damage signals.

Dr. Kulasinghe said he hopes other studies can build on the findings to develop risk models to understand which patients may face a higher risk of serious COVID-19 complications. In turn, this could help doctors provide early treatment. For instance, all seven COVID-19 patients had other chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease.

“Ideally in the future, if you have cardiovascular disease, if you’re obese or have other complications, and you’ve got a signature in your blood that indicates you are at risk of severe disease, then we can risk-stratify patients when they are diagnosed,” he said.

The research is a preliminary step, Dr. Kulasinghe said, because of the small sample size. This type of study is often difficult to conduct because researchers have to wait for the availability of organs, as well as request permission from families for postmortem autopsies and biopsies, to be able to look at the effects on dead tissues.

“Our challenge now is to draw a clinical finding from this, which we can’t at this stage,” he added. “But it’s a really fundamental biological difference we’re observing [between COVID-19 and flu], which we need to validate with larger studies.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a study published in Immunology.

The study looked at the hearts of patients who died from COVID-19, the flu, and other causes. The findings could provide clues about why coronavirus has led to complications such as ongoing heart issues.

“We found a lot of DNA damage that was unique to the COVID-19 patients, which wasn’t present in the flu patients,” Arutha Kulasinghe, one of the lead study authors and a research fellow at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, told the Brisbane Times.

“So in this study, COVID-19 and flu look very different in the way they affect the heart,” he said.

Dr. Kulasinghe and colleagues analyzed the hearts of seven COVID-19 patients, two flu patients, and six patients who died from other causes. They used transcriptomic profiling, which looks at the DNA landscape of an organ, to investigate heart tissue from the patients.

Because of previous studies about heart problems associated with COVID-19, he and colleagues expected to find extreme inflammation in the heart. Instead, they found that inflammation signals had been suppressed in the heart, and markers for DNA damage and repair were much higher. They’re still unsure of the underlying cause.

“The indications here are that there’s DNA damage here, it’s not inflammation,” Dr. Kulasinghe said. “There’s something else going on that we need to figure out.”

The damage was similar to the way chronic diseases such as diabetes and cancer appear in the heart, he said, with heart tissue showing DNA damage signals.

Dr. Kulasinghe said he hopes other studies can build on the findings to develop risk models to understand which patients may face a higher risk of serious COVID-19 complications. In turn, this could help doctors provide early treatment. For instance, all seven COVID-19 patients had other chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease.

“Ideally in the future, if you have cardiovascular disease, if you’re obese or have other complications, and you’ve got a signature in your blood that indicates you are at risk of severe disease, then we can risk-stratify patients when they are diagnosed,” he said.

The research is a preliminary step, Dr. Kulasinghe said, because of the small sample size. This type of study is often difficult to conduct because researchers have to wait for the availability of organs, as well as request permission from families for postmortem autopsies and biopsies, to be able to look at the effects on dead tissues.

“Our challenge now is to draw a clinical finding from this, which we can’t at this stage,” he added. “But it’s a really fundamental biological difference we’re observing [between COVID-19 and flu], which we need to validate with larger studies.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM IMMUNOLOGY

Strong link found between enterovirus and type 1 diabetes

STOCKHOLM – Enterovirus infection appears to be strongly linked to both type 1 diabetes and islet cell autoantibodies, new research suggests.

The strength of the relationship, particularly within the first month of type 1 diabetes diagnosis, “further supports the rationale for development of enterovirus-targeted vaccines and antiviral therapy to prevent and reduce the impact of type 1 diabetes,” according to lead investigator Sonia Isaacs, MD, of the department of pediatrics and child health at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Enteroviruses are a large family of viruses responsible for many infections in children. These live in the intestinal tract but can cause a wide variety of illnesses. There are more than 70 different strains, which include the group A and group B coxsackieviruses, the polioviruses, hepatitis A virus, and several strains that just go by the name enterovirus.

Dr. Isaacs presented the data, from a meta-analysis of studies using modern molecular techniques, at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

The findings raise the question of whether people should be routinely tested for enterovirus at the time of type 1 diabetes diagnosis, she said during her presentation.

Asked by this news organization about the implications for first-degree relatives of people with type 1 diabetes, Dr. Isaacs said that they are “definitely a population to watch out for,” with regard to enteroviral infections. “Type 1 diabetes is very diverse and has different endotypes. Different environmental factors may be implicated in these different endotypes, and it may be that the enteroviruses are quite important in the first-degree relative group.”

Asked to comment, session moderator Kamlesh Khunti, MD, PhD, told this news organization that the data were “compelling,” particularly in the short term after type 1 diabetes diagnosis. “It seems that there may be plausibility for enterovirus associated with the development of type 1 diabetes ... Are there methods by which we can reduce this risk with either antivirals or vaccinations? I think that needs to be tested.”

And in regard to first-degree relatives, “I think that’s the group to go for because the association is so highly correlated. I think that’s the group worth testing with any interventions,” said Dr. Khunti, professor of primary care diabetes and vascular medicine at the University of Leicester, England.

Link stronger a month after diagnosis, in close relatives, in Europe

The new meta-analysis is an update to a prior review published in 2011 by Dr. Isaacs’ group, which found that people with islet cell autoimmunity were more than four times as likely as were controls to have an enterovirus infection, and people with type 1 diabetes were almost 10 times as likely.

This new analysis focuses on studies using more modern molecular techniques for detecting viruses, including high throughput sequencing and single-cell technologies.

The analysis identified 60 studies with a total of 12,077 participants, of whom 900 had islet autoimmunity, 5,081 had type 1 diabetes, and 6,096 were controls. Thirty-five of the studies were from Europe, while others were from the United States, Asia, and the Middle East.

Of 16 studies examining enterovirus infection in islet autoimmunity, cases with islet autoimmunity were twice as likely to have an enterovirus infection at any time point compared to controls, a significant difference (odds ratio [OR], 2.07, P = .002.)

Among 48 studies reporting enterovirus infection in type 1 diabetes, those with type 1 diabetes were eight times as likely to have an enterovirus infection compared with controls (OR, 8.0, P < .00001).

In 25 studies including 2,977 participants with onset of type 1 diabetes within the prior month, those individuals were more than 16 times more likely to present with an enterovirus infection (OR, 16.2, P < .00001).

“The strength of this is association is greater than previously reported by both us and others,” Dr. Isaacs noted.

The association between enterovirus infection and islet autoimmunity was greater in individuals who later progressed to type 1 diabetes, with odds ratio 5.1 vs. 2.0 for those who didn’t. The association was most evident at or shortly after seroconversion (5.1), was stronger in Europe (3.2) than in other regions (1.9), and was stronger among those with a first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes (9.8) than those recruited via a high-risk human leukocyte antigen (HLA), in whom the relationship wasn’t significant.

Having multiple or consecutive enteroviral infections was also associated with islet autoimmunity (2.0).

With type 1 diabetes, the relationship with enterovirus was greater in children (9.0) than in adults (4.1), and was greater for type 1 diabetes onset within 1 year (13.8) and within 1 month (16.2) than for those with established type 1 diabetes (7.0). Here, too, the relationship was stronger in Europe (10.2) than outside Europe (7.5).

The link with type 1 diabetes and enterovirus was particularly strong for those with both a first-degree relative and a high-risk HLA (141.4).

The relationship with type 1 diabetes was significant for enterovirus species A (3.7), B (12.7) and C (13.8), including coxsackie virus genotypes, but not D.

“Future studies should focus on characterizing enterovirus genomes in at-risk cohorts rather than just the presence or absence of the virus,” Dr. Isaacs said.

However, she added, “type 1 diabetes is such a heterogenous condition, viruses may be implicated more in one type than another. It’s important that we start to look into this.”

Dr. Isaacs reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Khunti disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Berlin-Chemie AG / Menarini Group, Janssen, and Napp.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – Enterovirus infection appears to be strongly linked to both type 1 diabetes and islet cell autoantibodies, new research suggests.

The strength of the relationship, particularly within the first month of type 1 diabetes diagnosis, “further supports the rationale for development of enterovirus-targeted vaccines and antiviral therapy to prevent and reduce the impact of type 1 diabetes,” according to lead investigator Sonia Isaacs, MD, of the department of pediatrics and child health at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Enteroviruses are a large family of viruses responsible for many infections in children. These live in the intestinal tract but can cause a wide variety of illnesses. There are more than 70 different strains, which include the group A and group B coxsackieviruses, the polioviruses, hepatitis A virus, and several strains that just go by the name enterovirus.

Dr. Isaacs presented the data, from a meta-analysis of studies using modern molecular techniques, at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

The findings raise the question of whether people should be routinely tested for enterovirus at the time of type 1 diabetes diagnosis, she said during her presentation.

Asked by this news organization about the implications for first-degree relatives of people with type 1 diabetes, Dr. Isaacs said that they are “definitely a population to watch out for,” with regard to enteroviral infections. “Type 1 diabetes is very diverse and has different endotypes. Different environmental factors may be implicated in these different endotypes, and it may be that the enteroviruses are quite important in the first-degree relative group.”

Asked to comment, session moderator Kamlesh Khunti, MD, PhD, told this news organization that the data were “compelling,” particularly in the short term after type 1 diabetes diagnosis. “It seems that there may be plausibility for enterovirus associated with the development of type 1 diabetes ... Are there methods by which we can reduce this risk with either antivirals or vaccinations? I think that needs to be tested.”

And in regard to first-degree relatives, “I think that’s the group to go for because the association is so highly correlated. I think that’s the group worth testing with any interventions,” said Dr. Khunti, professor of primary care diabetes and vascular medicine at the University of Leicester, England.

Link stronger a month after diagnosis, in close relatives, in Europe

The new meta-analysis is an update to a prior review published in 2011 by Dr. Isaacs’ group, which found that people with islet cell autoimmunity were more than four times as likely as were controls to have an enterovirus infection, and people with type 1 diabetes were almost 10 times as likely.

This new analysis focuses on studies using more modern molecular techniques for detecting viruses, including high throughput sequencing and single-cell technologies.

The analysis identified 60 studies with a total of 12,077 participants, of whom 900 had islet autoimmunity, 5,081 had type 1 diabetes, and 6,096 were controls. Thirty-five of the studies were from Europe, while others were from the United States, Asia, and the Middle East.

Of 16 studies examining enterovirus infection in islet autoimmunity, cases with islet autoimmunity were twice as likely to have an enterovirus infection at any time point compared to controls, a significant difference (odds ratio [OR], 2.07, P = .002.)

Among 48 studies reporting enterovirus infection in type 1 diabetes, those with type 1 diabetes were eight times as likely to have an enterovirus infection compared with controls (OR, 8.0, P < .00001).

In 25 studies including 2,977 participants with onset of type 1 diabetes within the prior month, those individuals were more than 16 times more likely to present with an enterovirus infection (OR, 16.2, P < .00001).

“The strength of this is association is greater than previously reported by both us and others,” Dr. Isaacs noted.

The association between enterovirus infection and islet autoimmunity was greater in individuals who later progressed to type 1 diabetes, with odds ratio 5.1 vs. 2.0 for those who didn’t. The association was most evident at or shortly after seroconversion (5.1), was stronger in Europe (3.2) than in other regions (1.9), and was stronger among those with a first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes (9.8) than those recruited via a high-risk human leukocyte antigen (HLA), in whom the relationship wasn’t significant.

Having multiple or consecutive enteroviral infections was also associated with islet autoimmunity (2.0).

With type 1 diabetes, the relationship with enterovirus was greater in children (9.0) than in adults (4.1), and was greater for type 1 diabetes onset within 1 year (13.8) and within 1 month (16.2) than for those with established type 1 diabetes (7.0). Here, too, the relationship was stronger in Europe (10.2) than outside Europe (7.5).

The link with type 1 diabetes and enterovirus was particularly strong for those with both a first-degree relative and a high-risk HLA (141.4).

The relationship with type 1 diabetes was significant for enterovirus species A (3.7), B (12.7) and C (13.8), including coxsackie virus genotypes, but not D.

“Future studies should focus on characterizing enterovirus genomes in at-risk cohorts rather than just the presence or absence of the virus,” Dr. Isaacs said.

However, she added, “type 1 diabetes is such a heterogenous condition, viruses may be implicated more in one type than another. It’s important that we start to look into this.”

Dr. Isaacs reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Khunti disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Berlin-Chemie AG / Menarini Group, Janssen, and Napp.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – Enterovirus infection appears to be strongly linked to both type 1 diabetes and islet cell autoantibodies, new research suggests.

The strength of the relationship, particularly within the first month of type 1 diabetes diagnosis, “further supports the rationale for development of enterovirus-targeted vaccines and antiviral therapy to prevent and reduce the impact of type 1 diabetes,” according to lead investigator Sonia Isaacs, MD, of the department of pediatrics and child health at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Enteroviruses are a large family of viruses responsible for many infections in children. These live in the intestinal tract but can cause a wide variety of illnesses. There are more than 70 different strains, which include the group A and group B coxsackieviruses, the polioviruses, hepatitis A virus, and several strains that just go by the name enterovirus.

Dr. Isaacs presented the data, from a meta-analysis of studies using modern molecular techniques, at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

The findings raise the question of whether people should be routinely tested for enterovirus at the time of type 1 diabetes diagnosis, she said during her presentation.

Asked by this news organization about the implications for first-degree relatives of people with type 1 diabetes, Dr. Isaacs said that they are “definitely a population to watch out for,” with regard to enteroviral infections. “Type 1 diabetes is very diverse and has different endotypes. Different environmental factors may be implicated in these different endotypes, and it may be that the enteroviruses are quite important in the first-degree relative group.”

Asked to comment, session moderator Kamlesh Khunti, MD, PhD, told this news organization that the data were “compelling,” particularly in the short term after type 1 diabetes diagnosis. “It seems that there may be plausibility for enterovirus associated with the development of type 1 diabetes ... Are there methods by which we can reduce this risk with either antivirals or vaccinations? I think that needs to be tested.”

And in regard to first-degree relatives, “I think that’s the group to go for because the association is so highly correlated. I think that’s the group worth testing with any interventions,” said Dr. Khunti, professor of primary care diabetes and vascular medicine at the University of Leicester, England.

Link stronger a month after diagnosis, in close relatives, in Europe

The new meta-analysis is an update to a prior review published in 2011 by Dr. Isaacs’ group, which found that people with islet cell autoimmunity were more than four times as likely as were controls to have an enterovirus infection, and people with type 1 diabetes were almost 10 times as likely.

This new analysis focuses on studies using more modern molecular techniques for detecting viruses, including high throughput sequencing and single-cell technologies.

The analysis identified 60 studies with a total of 12,077 participants, of whom 900 had islet autoimmunity, 5,081 had type 1 diabetes, and 6,096 were controls. Thirty-five of the studies were from Europe, while others were from the United States, Asia, and the Middle East.

Of 16 studies examining enterovirus infection in islet autoimmunity, cases with islet autoimmunity were twice as likely to have an enterovirus infection at any time point compared to controls, a significant difference (odds ratio [OR], 2.07, P = .002.)

Among 48 studies reporting enterovirus infection in type 1 diabetes, those with type 1 diabetes were eight times as likely to have an enterovirus infection compared with controls (OR, 8.0, P < .00001).

In 25 studies including 2,977 participants with onset of type 1 diabetes within the prior month, those individuals were more than 16 times more likely to present with an enterovirus infection (OR, 16.2, P < .00001).

“The strength of this is association is greater than previously reported by both us and others,” Dr. Isaacs noted.

The association between enterovirus infection and islet autoimmunity was greater in individuals who later progressed to type 1 diabetes, with odds ratio 5.1 vs. 2.0 for those who didn’t. The association was most evident at or shortly after seroconversion (5.1), was stronger in Europe (3.2) than in other regions (1.9), and was stronger among those with a first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes (9.8) than those recruited via a high-risk human leukocyte antigen (HLA), in whom the relationship wasn’t significant.

Having multiple or consecutive enteroviral infections was also associated with islet autoimmunity (2.0).

With type 1 diabetes, the relationship with enterovirus was greater in children (9.0) than in adults (4.1), and was greater for type 1 diabetes onset within 1 year (13.8) and within 1 month (16.2) than for those with established type 1 diabetes (7.0). Here, too, the relationship was stronger in Europe (10.2) than outside Europe (7.5).

The link with type 1 diabetes and enterovirus was particularly strong for those with both a first-degree relative and a high-risk HLA (141.4).

The relationship with type 1 diabetes was significant for enterovirus species A (3.7), B (12.7) and C (13.8), including coxsackie virus genotypes, but not D.

“Future studies should focus on characterizing enterovirus genomes in at-risk cohorts rather than just the presence or absence of the virus,” Dr. Isaacs said.

However, she added, “type 1 diabetes is such a heterogenous condition, viruses may be implicated more in one type than another. It’s important that we start to look into this.”

Dr. Isaacs reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Khunti disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Berlin-Chemie AG / Menarini Group, Janssen, and Napp.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT EASD 2022

Cutaneous Eruption in an Immunocompromised Patient

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

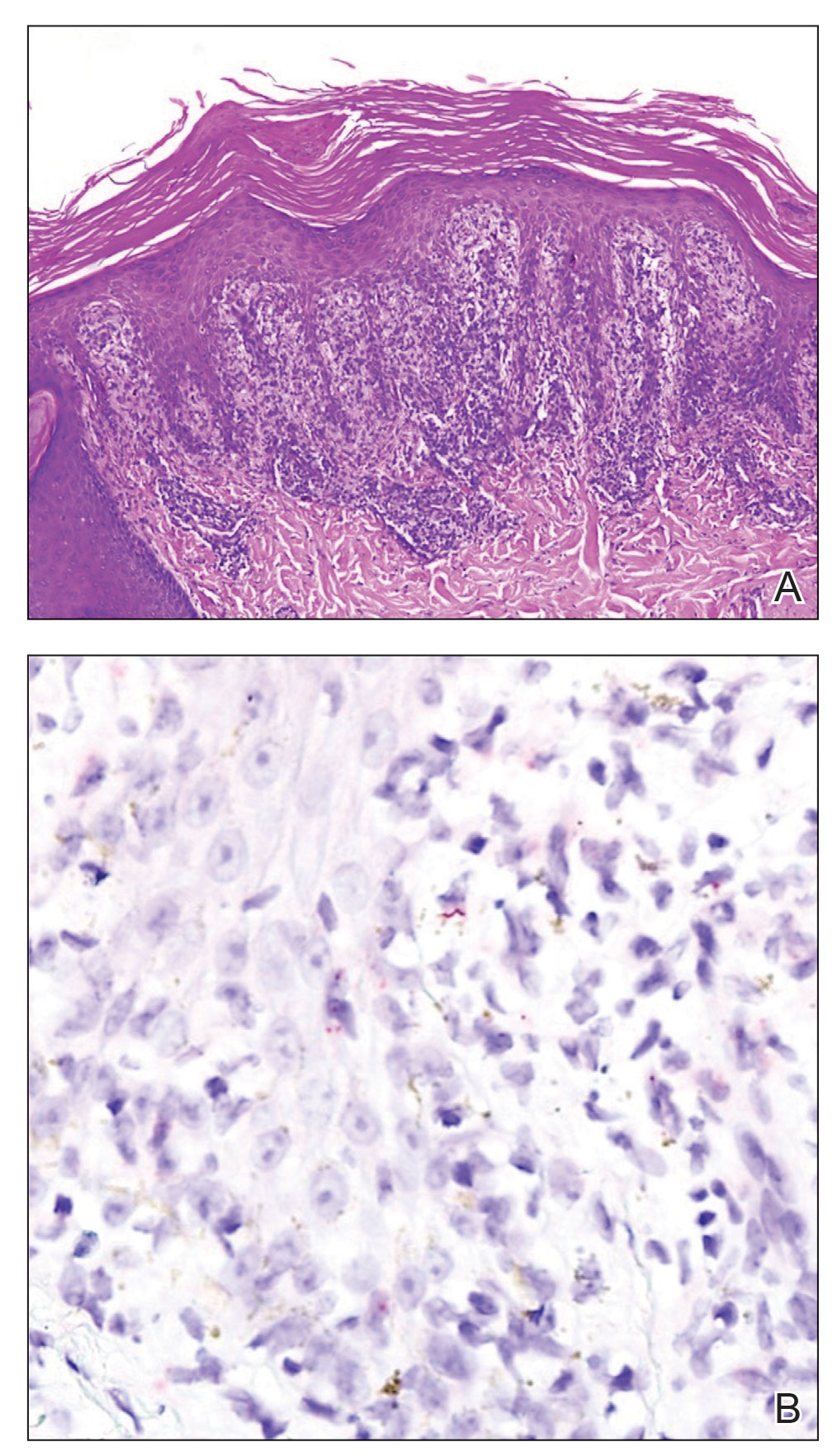

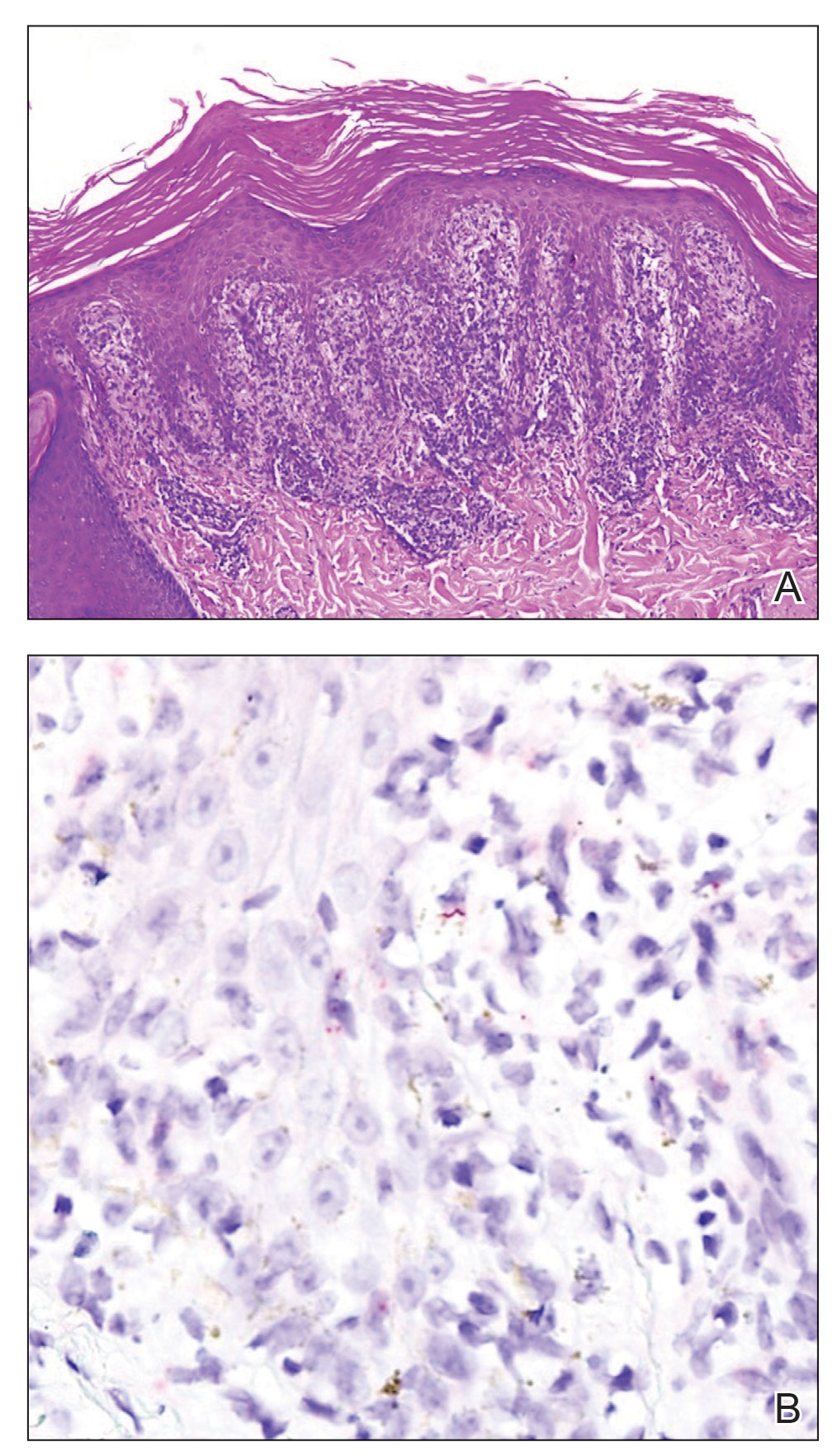

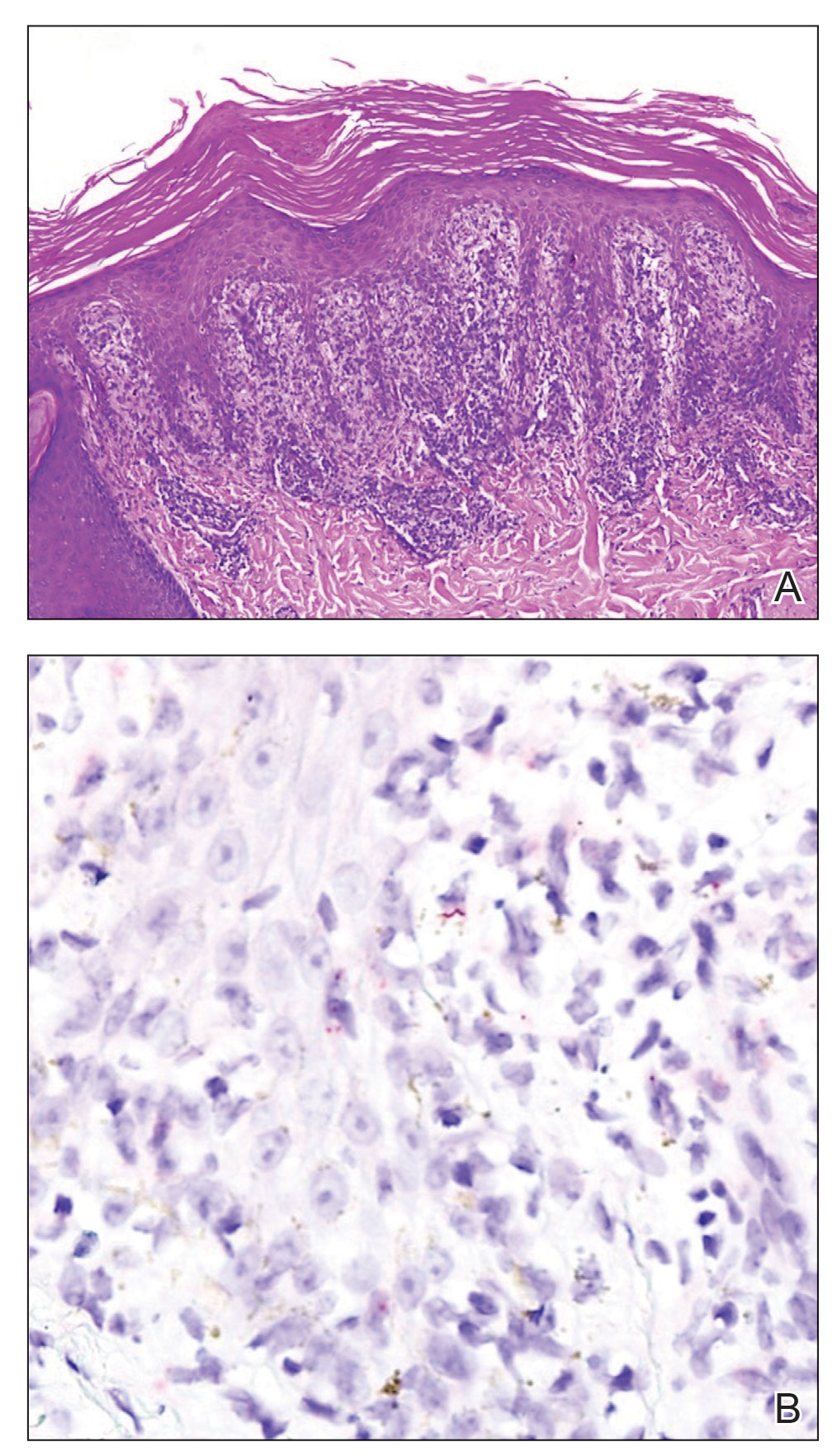

Histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia (Figure 1A). A single spirochete was identified using immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1B). Laboratory workup revealed positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies and reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:2048. A VDRL test performed on a cerebrospinal fluid specimen also was reactive at 1:8. A diagnosis of secondary syphilis with neurologic involvement was made, and the patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G for 14 days. Following treatment, his rapid plasma reagin decreased 4-fold with an improvement in his ocular and cutaneous symptoms.

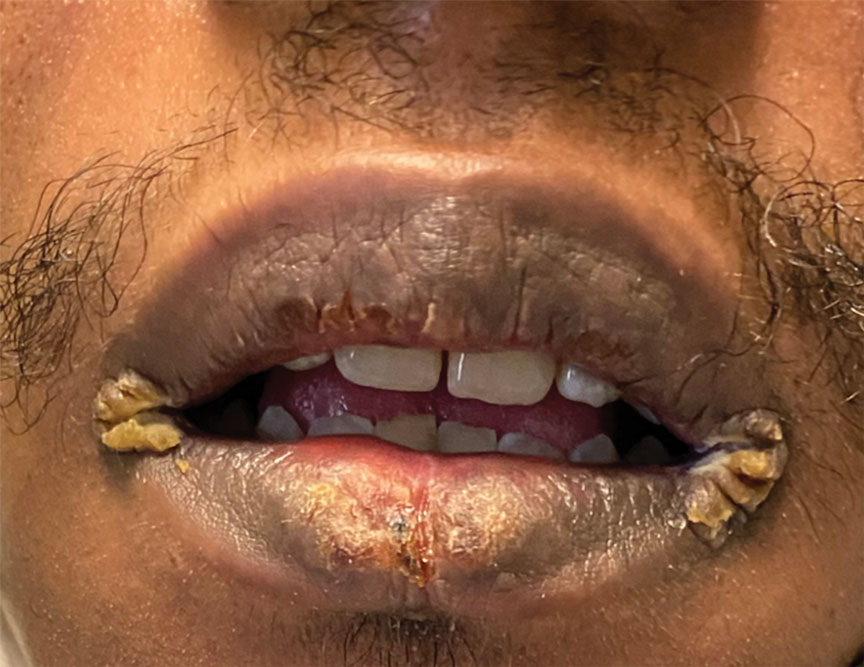

Mucocutaneus manifestations of secondary syphilis are multitudinous. As in our patient, the classic presentation is a generalized morbilliform and papulosquamous eruption involving the palms (Figure 2) and soles. Split papules at the oral commissures, mucosal patches, and condyloma lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis.1 Patchy nonscarring alopecia is not uncommon and can be the only manifestation of secondary syphilis.2 The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis vary depending on the location and type of the skin eruption. Psoriasiform or lichenoid changes commonly occur in the epidermis and dermoepidermal junction.3 The dermal inflammatory patterns that have been described include granulomatous, nodular, and superficial and deep perivascular inflammation. The infiltrate often is composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes. Reactive endothelial cells and perineural plasma cell infiltrates also are common histologic features.3,4 Spirochetes can be identified in most cases using immunohistochemical staining; however, the absence of spirochetes does not exclude syphilis.3 The sensitivity of immunohistochemical staining in secondary syphilis is reported to be 71% to 100% with a very high specificity.5 The treatment for all stages of syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, and the route of administration and duration of treatment depend on the stage of disease.6

A broad differential diagnosis must be considered when encountering skin eruptions in patients with HIV. Psoriasis usually presents as circumscribed erythematous plaques with dry and silvery scaling and a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the limbs, sacrum, scalp, and nails. Nail manifestations include distal onycholysis, irregular pitting, oil spots, salmon patches, and subungual hyperkeratosis. Alopecia occasionally may be seen within scalp lesions7; however, the constellation of alopecia with a moth-eaten appearance, subungual hyperkeratosis, papulosquamous eruption, and split papules was more suggestive of secondary syphilis in our patient. In immunocompromised patients, crusted scabies can be considered for the diagnosis of papulosquamous eruptions involving the palms and soles. It often presents with symmetric, mildly pruritic, psoriasiform dermatitis that favors acral sites, but widespread involvement can be observed.8 Areas of the scalp and face can be affected in infants, elderly patients, and immunocompromised individuals. Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in scabies.

Sarcoidosis is common in Black individuals, and similar to syphilis, it is considered a great imitator of other dermatologic diseases. Frequently, it presents as redviolaceous papules, nodules, or plaques; however, rare variants including psoriasiform, ichthyosiform, verrucous, and lichenoid skin eruptions can occur. Nail dystrophy, split papules, and alopecia also have been observed.9 Ocular involvement is common and frequently presents as uveitis.10 The pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis is noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, which also may occur in syphilitic lesions9; however, a papulosquamous eruption involving the palms and soles, positive serology, and the finding of interface lichenoid dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia confirmed the diagnosis of secondary syphilis in our patient. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare papulosquamous disorder that can be associated with HIV (type VI/HIVassociated follicular syndrome). It presents with generalized red-orange keratotic papules and often is associated with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen spinulosus.11 Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in pityriasis rubra pilaris.

This case highlights many classical findings of secondary syphilis and demonstrates that, while helpful, routine skin biopsy may not be required. Treatment should be guided by clinical presentation and serologic testing while reserving skin biopsy for equivocal cases.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:595-599.

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention [published online February 8, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

- Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.e1-718.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part II. extracutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:719.e1-730.

- Miralles E, Núñez M, De Las Heras M, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:990-993.

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia (Figure 1A). A single spirochete was identified using immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1B). Laboratory workup revealed positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies and reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:2048. A VDRL test performed on a cerebrospinal fluid specimen also was reactive at 1:8. A diagnosis of secondary syphilis with neurologic involvement was made, and the patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G for 14 days. Following treatment, his rapid plasma reagin decreased 4-fold with an improvement in his ocular and cutaneous symptoms.

Mucocutaneus manifestations of secondary syphilis are multitudinous. As in our patient, the classic presentation is a generalized morbilliform and papulosquamous eruption involving the palms (Figure 2) and soles. Split papules at the oral commissures, mucosal patches, and condyloma lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis.1 Patchy nonscarring alopecia is not uncommon and can be the only manifestation of secondary syphilis.2 The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis vary depending on the location and type of the skin eruption. Psoriasiform or lichenoid changes commonly occur in the epidermis and dermoepidermal junction.3 The dermal inflammatory patterns that have been described include granulomatous, nodular, and superficial and deep perivascular inflammation. The infiltrate often is composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes. Reactive endothelial cells and perineural plasma cell infiltrates also are common histologic features.3,4 Spirochetes can be identified in most cases using immunohistochemical staining; however, the absence of spirochetes does not exclude syphilis.3 The sensitivity of immunohistochemical staining in secondary syphilis is reported to be 71% to 100% with a very high specificity.5 The treatment for all stages of syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, and the route of administration and duration of treatment depend on the stage of disease.6

A broad differential diagnosis must be considered when encountering skin eruptions in patients with HIV. Psoriasis usually presents as circumscribed erythematous plaques with dry and silvery scaling and a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the limbs, sacrum, scalp, and nails. Nail manifestations include distal onycholysis, irregular pitting, oil spots, salmon patches, and subungual hyperkeratosis. Alopecia occasionally may be seen within scalp lesions7; however, the constellation of alopecia with a moth-eaten appearance, subungual hyperkeratosis, papulosquamous eruption, and split papules was more suggestive of secondary syphilis in our patient. In immunocompromised patients, crusted scabies can be considered for the diagnosis of papulosquamous eruptions involving the palms and soles. It often presents with symmetric, mildly pruritic, psoriasiform dermatitis that favors acral sites, but widespread involvement can be observed.8 Areas of the scalp and face can be affected in infants, elderly patients, and immunocompromised individuals. Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in scabies.

Sarcoidosis is common in Black individuals, and similar to syphilis, it is considered a great imitator of other dermatologic diseases. Frequently, it presents as redviolaceous papules, nodules, or plaques; however, rare variants including psoriasiform, ichthyosiform, verrucous, and lichenoid skin eruptions can occur. Nail dystrophy, split papules, and alopecia also have been observed.9 Ocular involvement is common and frequently presents as uveitis.10 The pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis is noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, which also may occur in syphilitic lesions9; however, a papulosquamous eruption involving the palms and soles, positive serology, and the finding of interface lichenoid dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia confirmed the diagnosis of secondary syphilis in our patient. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare papulosquamous disorder that can be associated with HIV (type VI/HIVassociated follicular syndrome). It presents with generalized red-orange keratotic papules and often is associated with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen spinulosus.11 Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in pityriasis rubra pilaris.

This case highlights many classical findings of secondary syphilis and demonstrates that, while helpful, routine skin biopsy may not be required. Treatment should be guided by clinical presentation and serologic testing while reserving skin biopsy for equivocal cases.

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia (Figure 1A). A single spirochete was identified using immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1B). Laboratory workup revealed positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies and reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:2048. A VDRL test performed on a cerebrospinal fluid specimen also was reactive at 1:8. A diagnosis of secondary syphilis with neurologic involvement was made, and the patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G for 14 days. Following treatment, his rapid plasma reagin decreased 4-fold with an improvement in his ocular and cutaneous symptoms.

Mucocutaneus manifestations of secondary syphilis are multitudinous. As in our patient, the classic presentation is a generalized morbilliform and papulosquamous eruption involving the palms (Figure 2) and soles. Split papules at the oral commissures, mucosal patches, and condyloma lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis.1 Patchy nonscarring alopecia is not uncommon and can be the only manifestation of secondary syphilis.2 The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis vary depending on the location and type of the skin eruption. Psoriasiform or lichenoid changes commonly occur in the epidermis and dermoepidermal junction.3 The dermal inflammatory patterns that have been described include granulomatous, nodular, and superficial and deep perivascular inflammation. The infiltrate often is composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes. Reactive endothelial cells and perineural plasma cell infiltrates also are common histologic features.3,4 Spirochetes can be identified in most cases using immunohistochemical staining; however, the absence of spirochetes does not exclude syphilis.3 The sensitivity of immunohistochemical staining in secondary syphilis is reported to be 71% to 100% with a very high specificity.5 The treatment for all stages of syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, and the route of administration and duration of treatment depend on the stage of disease.6

A broad differential diagnosis must be considered when encountering skin eruptions in patients with HIV. Psoriasis usually presents as circumscribed erythematous plaques with dry and silvery scaling and a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the limbs, sacrum, scalp, and nails. Nail manifestations include distal onycholysis, irregular pitting, oil spots, salmon patches, and subungual hyperkeratosis. Alopecia occasionally may be seen within scalp lesions7; however, the constellation of alopecia with a moth-eaten appearance, subungual hyperkeratosis, papulosquamous eruption, and split papules was more suggestive of secondary syphilis in our patient. In immunocompromised patients, crusted scabies can be considered for the diagnosis of papulosquamous eruptions involving the palms and soles. It often presents with symmetric, mildly pruritic, psoriasiform dermatitis that favors acral sites, but widespread involvement can be observed.8 Areas of the scalp and face can be affected in infants, elderly patients, and immunocompromised individuals. Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in scabies.

Sarcoidosis is common in Black individuals, and similar to syphilis, it is considered a great imitator of other dermatologic diseases. Frequently, it presents as redviolaceous papules, nodules, or plaques; however, rare variants including psoriasiform, ichthyosiform, verrucous, and lichenoid skin eruptions can occur. Nail dystrophy, split papules, and alopecia also have been observed.9 Ocular involvement is common and frequently presents as uveitis.10 The pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis is noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, which also may occur in syphilitic lesions9; however, a papulosquamous eruption involving the palms and soles, positive serology, and the finding of interface lichenoid dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia confirmed the diagnosis of secondary syphilis in our patient. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare papulosquamous disorder that can be associated with HIV (type VI/HIVassociated follicular syndrome). It presents with generalized red-orange keratotic papules and often is associated with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen spinulosus.11 Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in pityriasis rubra pilaris.

This case highlights many classical findings of secondary syphilis and demonstrates that, while helpful, routine skin biopsy may not be required. Treatment should be guided by clinical presentation and serologic testing while reserving skin biopsy for equivocal cases.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:595-599.

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention [published online February 8, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

- Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.e1-718.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part II. extracutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:719.e1-730.

- Miralles E, Núñez M, De Las Heras M, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:990-993.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:595-599.

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention [published online February 8, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

- Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.e1-718.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part II. extracutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:719.e1-730.

- Miralles E, Núñez M, De Las Heras M, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:990-993.

A 29-year-old Black man with long-standing untreated HIV presented with mildly pruritic, scaly plaques on the palms and soles of 2 weeks’ duration. His medical history was notable for primary syphilis treated approximately 1 year prior. A review of symptoms was positive for blurry vision and floaters but negative for constitutional symptoms. Physical examination revealed well-defined scaly plaques over the palms, soles, and elbows with subungual hyperkeratosis. Patches of nonscarring alopecia over the scalp and split papules at the oral commissures also were noted. There were no palpable lymph nodes or genital involvement. Eye examination showed conjunctival injection and 20 cells per field in the vitreous humor. Laboratory evaluation revealed an HIV viral load of 31,623 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 47 cells/μL (reference range, 362–1531 cells/μL). A shave biopsy of the left elbow was performed for histopathologic evaluation.

BREEZE-AD-PEDS: First data for baricitinib in childhood eczema reported

The oral Janus kinase

After 16 weeks of treatment, the primary endpoint – an Investigators Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 with at least a 2-point improvement from baseline – was met by 41.7% of patients given 2 mg (those younger than age 10) or 4 mg of baricitinib (those aged 10-17 years), the highest dose studied in each of those two age groups.

By comparison, the primary endpoint was met in 16.4% of children in the placebo group (P < .001).

Baricitinib is approved for the treatment of AD in adults in many countries, Antonio Torrelo, MD, of the Hospital Infantil Niño Jesús, Madrid, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating adults with severe alopecia areata in June and is under FDA review for the treatment of AD.

The phase 3 BREEZE-AD-PEDS trial

BREEZE-AD-PEDS was a randomized, double-blind trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of baricitinib in 483 children and adolescents with moderate to severe AD. Participants were aged 2-17 years. Those aged 2-5 years had been diagnosed with AD for at least 6 months; if they were older, they had been diagnosed for at least 12 months.

Three dosing levels of baricitinib were tested: 121 patients were given a low dose, which was 0.5 mg/day in children aged 2 to less than 10 years and 1 mg/day in those aged 10 to less than 18 years. A medium dose – 1 mg/day in the younger children and 2 mg/day in the older children – was given to 120 children, while a high dose – 2 mg/day and 4 mg/day, respectively – was given to another 120 children.

Topical treatments were permitted, although for entry into the trial, participants had to have had an inadequate response to steroids and an inadequate or no response to topical calcineurin inhibitors. In all groups, age, gender, race, geographic region, age at diagnosis of AD, and duration of AD “were more or less similar,” Dr. Torello said.

Good results, but only with highest dose

The primary IGA endpoint was reached by 25.8% of children in the medium-dose group and by 18.2% in the low-dose group. Neither result was statistically significant in comparison with placebo (16.4%).

When breaking down the results between different ages, “the results in the IGA scores are consistent in both age subgroups – below 10 years and over 10 years,” Dr. Torello noted. The results are also consistent across body weights (< 20 kg, 20-60 kg, and > 60 kg), he added.

Among those treated with the high dose of baricitinib, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) 75% and 95% improvement scores were reached in 52.5% and 30% of patients, respectively. Corresponding figures for the medium dose were 40% and 21.7%; for the low baricitinib dose, 32.2% and 11.6%; and for placebo, 32% and 12.3%. Again, only the results for the highest baricitinib dose were significant in comparison with placebo.

A similar pattern was seen for improvement in itch, and there was a 75% improvement in Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD75) results.

Safety of baricitinib in children

The labeling for JAK inhibitors that have been approved to date, including baricitinib, include a boxed warning regarding risks for thrombosis, major adverse cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality. The warning is based on use by patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Torello summarized baricitinib’s safety profile in the trial as being “consistent with the well-known safety profile for baricitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.”

In the study, no severe adverse effects were noted, and no new safety signals were observed, he said. The rate of any treatment-emergent effect among patients was around 50% and was similar across all baricitinib and placebo groups. Study discontinuations because of a side effect were more frequent in the placebo arm (1.6% of patients) than in the baricitinib low-, medium-, and high-dose arms (0.8%, 0%, and 0.8%, respectively).

There were no cases of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or other adverse effects of special interest, including major adverse cardiovascular events, gastrointestinal perforations, and opportunistic infections, Dr. Torrelo said.

No patient experienced elevations in liver enzyme levels, although there were some cases of elevated creatinine phosphokinase levels (16% in the placebo group and 19% in the baricitinib arms altogether) that were not from muscle injury. There was a possible increase in low-density cholesterol level (3.3% of those taking placebo vs. 10.1% of baricitinib-treated patients).

Is there a role for baricitinib?

“Baricitinib is a potential therapeutic option with a favorable benefit-to-risk profile for children between 2 and 18 years who have moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, and candidates for systemic therapy,” Dr. Torrelo said. “No single drug is capable to treat every patient with atopic dermatitis,” he added in discussing the possible place of baricitinib in pediatric practice.

“There are patients who do not respond to dupilumab, who apparently respond later to JAK inhibitors,” he noted.

“We are trying to work phenotypically, trying to learn what kind of patients – especially children who have a more heterogeneous disease than adults – can be better treated with JAK inhibitors or dupilumab.” There may be other important considerations in choosing a treatment in children, Dr. Torrelo said, including that JAK inhibitors can be given orally, while dupilumab is administered by injection.

Asked to comment on the results, Jashin J. Wu, MD, founder and CEO of the Dermatology Research and Education Foundation in Irvine, Calif., pointed out that “only the higher dose is significantly more effective than placebo.”

In his view, “the potentially severe adverse events are not worth the risk compared to more effective agents, such as dupilumab, in this pediatric population,” added Dr. Wu, who recently authored a review of the role of JAK inhibitors in skin disease. He was not involved with the baricitinib study.

The study was funded by Eli Lilly in collaboration with Incyte. Dr. Torello has participated in advisory boards and/or has served as a principal investigator in clinical trials for AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi. Dr. Wu has been an investigator, consultant, or speaker for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The oral Janus kinase

After 16 weeks of treatment, the primary endpoint – an Investigators Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 with at least a 2-point improvement from baseline – was met by 41.7% of patients given 2 mg (those younger than age 10) or 4 mg of baricitinib (those aged 10-17 years), the highest dose studied in each of those two age groups.

By comparison, the primary endpoint was met in 16.4% of children in the placebo group (P < .001).

Baricitinib is approved for the treatment of AD in adults in many countries, Antonio Torrelo, MD, of the Hospital Infantil Niño Jesús, Madrid, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating adults with severe alopecia areata in June and is under FDA review for the treatment of AD.

The phase 3 BREEZE-AD-PEDS trial

BREEZE-AD-PEDS was a randomized, double-blind trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of baricitinib in 483 children and adolescents with moderate to severe AD. Participants were aged 2-17 years. Those aged 2-5 years had been diagnosed with AD for at least 6 months; if they were older, they had been diagnosed for at least 12 months.

Three dosing levels of baricitinib were tested: 121 patients were given a low dose, which was 0.5 mg/day in children aged 2 to less than 10 years and 1 mg/day in those aged 10 to less than 18 years. A medium dose – 1 mg/day in the younger children and 2 mg/day in the older children – was given to 120 children, while a high dose – 2 mg/day and 4 mg/day, respectively – was given to another 120 children.

Topical treatments were permitted, although for entry into the trial, participants had to have had an inadequate response to steroids and an inadequate or no response to topical calcineurin inhibitors. In all groups, age, gender, race, geographic region, age at diagnosis of AD, and duration of AD “were more or less similar,” Dr. Torello said.

Good results, but only with highest dose

The primary IGA endpoint was reached by 25.8% of children in the medium-dose group and by 18.2% in the low-dose group. Neither result was statistically significant in comparison with placebo (16.4%).

When breaking down the results between different ages, “the results in the IGA scores are consistent in both age subgroups – below 10 years and over 10 years,” Dr. Torello noted. The results are also consistent across body weights (< 20 kg, 20-60 kg, and > 60 kg), he added.

Among those treated with the high dose of baricitinib, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) 75% and 95% improvement scores were reached in 52.5% and 30% of patients, respectively. Corresponding figures for the medium dose were 40% and 21.7%; for the low baricitinib dose, 32.2% and 11.6%; and for placebo, 32% and 12.3%. Again, only the results for the highest baricitinib dose were significant in comparison with placebo.

A similar pattern was seen for improvement in itch, and there was a 75% improvement in Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD75) results.

Safety of baricitinib in children

The labeling for JAK inhibitors that have been approved to date, including baricitinib, include a boxed warning regarding risks for thrombosis, major adverse cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality. The warning is based on use by patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Torello summarized baricitinib’s safety profile in the trial as being “consistent with the well-known safety profile for baricitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.”

In the study, no severe adverse effects were noted, and no new safety signals were observed, he said. The rate of any treatment-emergent effect among patients was around 50% and was similar across all baricitinib and placebo groups. Study discontinuations because of a side effect were more frequent in the placebo arm (1.6% of patients) than in the baricitinib low-, medium-, and high-dose arms (0.8%, 0%, and 0.8%, respectively).

There were no cases of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or other adverse effects of special interest, including major adverse cardiovascular events, gastrointestinal perforations, and opportunistic infections, Dr. Torrelo said.

No patient experienced elevations in liver enzyme levels, although there were some cases of elevated creatinine phosphokinase levels (16% in the placebo group and 19% in the baricitinib arms altogether) that were not from muscle injury. There was a possible increase in low-density cholesterol level (3.3% of those taking placebo vs. 10.1% of baricitinib-treated patients).

Is there a role for baricitinib?

“Baricitinib is a potential therapeutic option with a favorable benefit-to-risk profile for children between 2 and 18 years who have moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, and candidates for systemic therapy,” Dr. Torrelo said. “No single drug is capable to treat every patient with atopic dermatitis,” he added in discussing the possible place of baricitinib in pediatric practice.

“There are patients who do not respond to dupilumab, who apparently respond later to JAK inhibitors,” he noted.

“We are trying to work phenotypically, trying to learn what kind of patients – especially children who have a more heterogeneous disease than adults – can be better treated with JAK inhibitors or dupilumab.” There may be other important considerations in choosing a treatment in children, Dr. Torrelo said, including that JAK inhibitors can be given orally, while dupilumab is administered by injection.

Asked to comment on the results, Jashin J. Wu, MD, founder and CEO of the Dermatology Research and Education Foundation in Irvine, Calif., pointed out that “only the higher dose is significantly more effective than placebo.”

In his view, “the potentially severe adverse events are not worth the risk compared to more effective agents, such as dupilumab, in this pediatric population,” added Dr. Wu, who recently authored a review of the role of JAK inhibitors in skin disease. He was not involved with the baricitinib study.

The study was funded by Eli Lilly in collaboration with Incyte. Dr. Torello has participated in advisory boards and/or has served as a principal investigator in clinical trials for AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi. Dr. Wu has been an investigator, consultant, or speaker for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The oral Janus kinase

After 16 weeks of treatment, the primary endpoint – an Investigators Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 with at least a 2-point improvement from baseline – was met by 41.7% of patients given 2 mg (those younger than age 10) or 4 mg of baricitinib (those aged 10-17 years), the highest dose studied in each of those two age groups.

By comparison, the primary endpoint was met in 16.4% of children in the placebo group (P < .001).

Baricitinib is approved for the treatment of AD in adults in many countries, Antonio Torrelo, MD, of the Hospital Infantil Niño Jesús, Madrid, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating adults with severe alopecia areata in June and is under FDA review for the treatment of AD.

The phase 3 BREEZE-AD-PEDS trial

BREEZE-AD-PEDS was a randomized, double-blind trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of baricitinib in 483 children and adolescents with moderate to severe AD. Participants were aged 2-17 years. Those aged 2-5 years had been diagnosed with AD for at least 6 months; if they were older, they had been diagnosed for at least 12 months.

Three dosing levels of baricitinib were tested: 121 patients were given a low dose, which was 0.5 mg/day in children aged 2 to less than 10 years and 1 mg/day in those aged 10 to less than 18 years. A medium dose – 1 mg/day in the younger children and 2 mg/day in the older children – was given to 120 children, while a high dose – 2 mg/day and 4 mg/day, respectively – was given to another 120 children.

Topical treatments were permitted, although for entry into the trial, participants had to have had an inadequate response to steroids and an inadequate or no response to topical calcineurin inhibitors. In all groups, age, gender, race, geographic region, age at diagnosis of AD, and duration of AD “were more or less similar,” Dr. Torello said.

Good results, but only with highest dose

The primary IGA endpoint was reached by 25.8% of children in the medium-dose group and by 18.2% in the low-dose group. Neither result was statistically significant in comparison with placebo (16.4%).

When breaking down the results between different ages, “the results in the IGA scores are consistent in both age subgroups – below 10 years and over 10 years,” Dr. Torello noted. The results are also consistent across body weights (< 20 kg, 20-60 kg, and > 60 kg), he added.

Among those treated with the high dose of baricitinib, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) 75% and 95% improvement scores were reached in 52.5% and 30% of patients, respectively. Corresponding figures for the medium dose were 40% and 21.7%; for the low baricitinib dose, 32.2% and 11.6%; and for placebo, 32% and 12.3%. Again, only the results for the highest baricitinib dose were significant in comparison with placebo.

A similar pattern was seen for improvement in itch, and there was a 75% improvement in Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD75) results.

Safety of baricitinib in children

The labeling for JAK inhibitors that have been approved to date, including baricitinib, include a boxed warning regarding risks for thrombosis, major adverse cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality. The warning is based on use by patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Torello summarized baricitinib’s safety profile in the trial as being “consistent with the well-known safety profile for baricitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.”

In the study, no severe adverse effects were noted, and no new safety signals were observed, he said. The rate of any treatment-emergent effect among patients was around 50% and was similar across all baricitinib and placebo groups. Study discontinuations because of a side effect were more frequent in the placebo arm (1.6% of patients) than in the baricitinib low-, medium-, and high-dose arms (0.8%, 0%, and 0.8%, respectively).

There were no cases of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or other adverse effects of special interest, including major adverse cardiovascular events, gastrointestinal perforations, and opportunistic infections, Dr. Torrelo said.

No patient experienced elevations in liver enzyme levels, although there were some cases of elevated creatinine phosphokinase levels (16% in the placebo group and 19% in the baricitinib arms altogether) that were not from muscle injury. There was a possible increase in low-density cholesterol level (3.3% of those taking placebo vs. 10.1% of baricitinib-treated patients).

Is there a role for baricitinib?

“Baricitinib is a potential therapeutic option with a favorable benefit-to-risk profile for children between 2 and 18 years who have moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, and candidates for systemic therapy,” Dr. Torrelo said. “No single drug is capable to treat every patient with atopic dermatitis,” he added in discussing the possible place of baricitinib in pediatric practice.

“There are patients who do not respond to dupilumab, who apparently respond later to JAK inhibitors,” he noted.

“We are trying to work phenotypically, trying to learn what kind of patients – especially children who have a more heterogeneous disease than adults – can be better treated with JAK inhibitors or dupilumab.” There may be other important considerations in choosing a treatment in children, Dr. Torrelo said, including that JAK inhibitors can be given orally, while dupilumab is administered by injection.

Asked to comment on the results, Jashin J. Wu, MD, founder and CEO of the Dermatology Research and Education Foundation in Irvine, Calif., pointed out that “only the higher dose is significantly more effective than placebo.”

In his view, “the potentially severe adverse events are not worth the risk compared to more effective agents, such as dupilumab, in this pediatric population,” added Dr. Wu, who recently authored a review of the role of JAK inhibitors in skin disease. He was not involved with the baricitinib study.

The study was funded by Eli Lilly in collaboration with Incyte. Dr. Torello has participated in advisory boards and/or has served as a principal investigator in clinical trials for AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi. Dr. Wu has been an investigator, consultant, or speaker for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

What’s the true role of Demodex mites in the development of papulopustular rosacea?

, a narrative review proposes.

According to the author, Fabienne Forton, MD, PhD, a dermatologist based in Brussels, recent studies suggest that Demodex induces two opposite actions on host immunity: A defensive immune response aimed at eliminating the mite and an immunosuppressive action aimed at favoring its own proliferation. “Moreover, the initial defensive immune response is likely diverted towards benefit for the mite, via T-cell exhaustion induced by the immunosuppressive properties of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which may also explain the favorable influence that the altered vascular background of rosacea seems to exert on Demodex proliferation,” she wrote in the review, which was published in JEADV, the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

She presented several arguments for and against a causal role of Demodex in rosacea. Three on the “for” side are:

High Demodex densities (Dds) are observed in almost all cases of rosacea with papulopustules (PPR). Dr. Forton pointed out that Demodex proliferation presents in as many as 98.6% of cases of PPR when two consecutive standardized skin surface biopsies (SSSBs) are performed (Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:242-8). “Dds in patients with PPR are as high as those in patients with demodicosis, much higher than in healthy skin and other facial dermatoses (except when these are associated with demodicosis [as is often the case with seborrheic dermatitis and acne vulgaris]),” she wrote.

The Demodex mite has the elements necessary to stimulate the host’s innate and adaptative immune system. Dr. Forton characterized Demodex as “the only microorganism found in abundance in almost all subjects with PPR, which can, in addition, alter the skin barrier. To feed and move around, Demodex mites attack the epidermal wall of the pilosebaceous follicles mechanically (via their stylets, mouth palps and motor palps) and chemically (through enzymes secreted from salivary glands for pre-oral digestion).”

The Demodex mite stimulates the immune system (which ultimately results in phymatous changes). A healthy immune system, including T helper 17 cells, seems necessary to adequately control mite proliferation. Dr. Forton noted that researchers have observed a perivascular and perifollicular infiltrate in people with rosacea, “which invades the epidermis and is often associated with the presence of Demodex. The lympho-histiocytic perifollicular infiltrate is correlated with the presence and the numbers of mites inside the follicles, and giant cell granulomas can be seen around intradermal Demodex mites, which attempt to phagocytize the mites.”

The three arguments that she presented against a causal role of Demodex in rosacea are the following:

No relationship with the mite was observed in two early histological studies. Rosacea biopsies conducted in these two analyses, published in 1969 and 1988, showed only mild infiltrate, with few parasites and no inflammation around the infested follicles.

However, she countered, “these data are now obsolete, because it has since been clearly demonstrated that the perifollicular infiltrate is a characteristic of rosacea, that this infiltrate is statistically related to the presence and the number of Demodex mites, and that high Dds are observed in almost all subjects with PPR.”

Demodex is not always associated with inflammatory symptoms. This argument holds that Demodex is present in all individuals and can be observed in very high densities without causing significant symptoms. Studies that support this viewpoint include the following: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:441–4 and J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:998-1007.

However, Dr. Forton pointed out that the normal, low-density presence of Demodex in the skin “does not contradict a pathogenic effect when it proliferates excessively or penetrates into the dermis. The absence of intense inflammatory symptoms when the Dd is very high does not negate its potential pathogenicity.”

Demodex proliferation could be a consequence rather than a cause. Dr. Forton cited a study, suggesting that inflammation could be responsible for alteration of the skin barrier, “which, secondarily, would favor proliferation of the parasites, as with skin affected by atopic dermatitis that becomes superinfected by Staphylococcus aureus”. On the other hand, she argued, “unlike S. aureus, Demodex does not require alteration of the skin barrier to implant or proliferate. It also does not require an inflammatory background.” She added that if mite proliferation was a consequence of clinical lesions, “the Demodex mite should logically proliferate in other inflammatory facial skin conditions, which is not the case.”

A Sept. 14 National Rosacea Society (NRS) press release featured the paper by Dr. Forton, titled, “Which Comes First, The Rosacea Blemish or The Mite?” In the release, Richard Gallo, MD, PhD, who chaired the NRS Expert Committee that updated the standard classification of rosacea in 2018, said that “growing knowledge of rosacea’s pathophysiology has established that a consistent multivariate disease process underlies its potential manifestations, and the clinical significance of each of these elements is increasing as more is understood.”

While the potential role of Demodex in rosacea has been controversial in the past, “these new insights suggest where it may play a role as a meaningful cofactor in the development of the disorder,” added Dr. Gallo, chair of the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Forton reported having no financial disclosures.

, a narrative review proposes.

According to the author, Fabienne Forton, MD, PhD, a dermatologist based in Brussels, recent studies suggest that Demodex induces two opposite actions on host immunity: A defensive immune response aimed at eliminating the mite and an immunosuppressive action aimed at favoring its own proliferation. “Moreover, the initial defensive immune response is likely diverted towards benefit for the mite, via T-cell exhaustion induced by the immunosuppressive properties of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which may also explain the favorable influence that the altered vascular background of rosacea seems to exert on Demodex proliferation,” she wrote in the review, which was published in JEADV, the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

She presented several arguments for and against a causal role of Demodex in rosacea. Three on the “for” side are:

High Demodex densities (Dds) are observed in almost all cases of rosacea with papulopustules (PPR). Dr. Forton pointed out that Demodex proliferation presents in as many as 98.6% of cases of PPR when two consecutive standardized skin surface biopsies (SSSBs) are performed (Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:242-8). “Dds in patients with PPR are as high as those in patients with demodicosis, much higher than in healthy skin and other facial dermatoses (except when these are associated with demodicosis [as is often the case with seborrheic dermatitis and acne vulgaris]),” she wrote.

The Demodex mite has the elements necessary to stimulate the host’s innate and adaptative immune system. Dr. Forton characterized Demodex as “the only microorganism found in abundance in almost all subjects with PPR, which can, in addition, alter the skin barrier. To feed and move around, Demodex mites attack the epidermal wall of the pilosebaceous follicles mechanically (via their stylets, mouth palps and motor palps) and chemically (through enzymes secreted from salivary glands for pre-oral digestion).”

The Demodex mite stimulates the immune system (which ultimately results in phymatous changes). A healthy immune system, including T helper 17 cells, seems necessary to adequately control mite proliferation. Dr. Forton noted that researchers have observed a perivascular and perifollicular infiltrate in people with rosacea, “which invades the epidermis and is often associated with the presence of Demodex. The lympho-histiocytic perifollicular infiltrate is correlated with the presence and the numbers of mites inside the follicles, and giant cell granulomas can be seen around intradermal Demodex mites, which attempt to phagocytize the mites.”

The three arguments that she presented against a causal role of Demodex in rosacea are the following:

No relationship with the mite was observed in two early histological studies. Rosacea biopsies conducted in these two analyses, published in 1969 and 1988, showed only mild infiltrate, with few parasites and no inflammation around the infested follicles.

However, she countered, “these data are now obsolete, because it has since been clearly demonstrated that the perifollicular infiltrate is a characteristic of rosacea, that this infiltrate is statistically related to the presence and the number of Demodex mites, and that high Dds are observed in almost all subjects with PPR.”

Demodex is not always associated with inflammatory symptoms. This argument holds that Demodex is present in all individuals and can be observed in very high densities without causing significant symptoms. Studies that support this viewpoint include the following: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:441–4 and J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:998-1007.

However, Dr. Forton pointed out that the normal, low-density presence of Demodex in the skin “does not contradict a pathogenic effect when it proliferates excessively or penetrates into the dermis. The absence of intense inflammatory symptoms when the Dd is very high does not negate its potential pathogenicity.”

Demodex proliferation could be a consequence rather than a cause. Dr. Forton cited a study, suggesting that inflammation could be responsible for alteration of the skin barrier, “which, secondarily, would favor proliferation of the parasites, as with skin affected by atopic dermatitis that becomes superinfected by Staphylococcus aureus”. On the other hand, she argued, “unlike S. aureus, Demodex does not require alteration of the skin barrier to implant or proliferate. It also does not require an inflammatory background.” She added that if mite proliferation was a consequence of clinical lesions, “the Demodex mite should logically proliferate in other inflammatory facial skin conditions, which is not the case.”

A Sept. 14 National Rosacea Society (NRS) press release featured the paper by Dr. Forton, titled, “Which Comes First, The Rosacea Blemish or The Mite?” In the release, Richard Gallo, MD, PhD, who chaired the NRS Expert Committee that updated the standard classification of rosacea in 2018, said that “growing knowledge of rosacea’s pathophysiology has established that a consistent multivariate disease process underlies its potential manifestations, and the clinical significance of each of these elements is increasing as more is understood.”

While the potential role of Demodex in rosacea has been controversial in the past, “these new insights suggest where it may play a role as a meaningful cofactor in the development of the disorder,” added Dr. Gallo, chair of the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Forton reported having no financial disclosures.

, a narrative review proposes.