User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Does using A1c to diagnose diabetes miss some patients?

The introduction of hemoglobin A1c as an option for diagnosing type 2 diabetes over a decade ago may have resulted in underdiagnosis, new research indicates.

In 2011, the World Health Organization advised that A1c measurement, with a cutoff value of 6.5%, could be used to diagnose diabetes. The American Diabetes Association had issued similar guidance in 2010.

Prior to that time, the less-convenient 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and fasting blood glucose (FBG) were the only recommended tests. While WHO made no recommendations for interpreting values below 6.5%, the ADA designated 5.7%-6.4% as prediabetes.

The new study, published online in The Lancet Regional Health–Europe, showed that the incidence of type 2 diabetes in Denmark had been increasing prior to the 2012 adoption of A1c as a diagnostic option but declined thereafter. And all-cause mortality among people with type 2 diabetes, which had been dropping, began to increase after that time.

“Our findings suggest that fewer patients have been diagnosed with [type 2 diabetes] since A1c testing was introduced as a convenient diagnostic option. We may thus be missing a group with borderline increased A1c values that is still at high metabolic and cardiovascular risk,” Jakob S. Knudsen, MD, of the department of clinical epidemiology, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, and colleagues wrote.

Therefore, Dr. Knudsen said in an interview, clinicians should “consider testing with FBG or OGTT when presented with borderline A1c values.”

The reason for the increase in mortality after incident type 2 diabetes diagnosis, he said, “is that the patients who would have reduced the average mortality are no longer diagnosed...This does not reflect that we are treating already diagnosed patients any worse, rather some patients are not diagnosed.”

But M. Sue Kirkman, MD, emeritus professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was part of the writing group for the 2010 ADA guidelines, isn’t convinced.

“This is an interesting paper, but it is a bit hard to believe that a change in WHO recommendations would have such a large and almost immediate impact on incidence and mortality. It seems likely that ... factors [other] than just the changes in recommendations for the diagnostic test account for these findings,” she said.

Dr. Kirkman pointed to new data just out from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Jan. 26 that don›t show evidence of a higher proportion of people in the United States who have undiagnosed diabetes, “which would be expected if more cases were being ‘missed’ by A1c.”

She added that the CDC incidence data “show a continuing steady rate of decline in incidence that began in 2008, before any organizations recommended using A1c to screen for or diagnose diabetes.” Moreover, “there is evidence that type 2 diabetes incidence has fallen or plateaued in many countries since 2006, well before the WHO recommendation, with most of the studies from developed countries.”

But Dr. Knudsen also cited other data, including a study that showed a drop or stabilization in diagnosed diabetes incidence in high-income countries since 2010.

“That study concluded that the reasons for the declines in the incidence of diagnosed diabetes warrant further investigation with appropriate data sources, which was a main objective of our study,” wrote Dr. Knudsen and coauthors.

Dr. Knudsen said in an interview: “We are not the first to make the point that this sudden change is related to A1c introduction...but we are the first to have the data to clearly show that is the case.”

Diabetes incidence dropped but mortality rose after 2010

The population-based longitudinal study used four Danish medical databases and included 415,553 patients treated for type 2 diabetes for the first time from 1995-2018 and 2,060,279 matched comparators not treated for diabetes.

From 1995 until the 2012 introduction of A1c as a diagnostic option, the annual standardized incidence rates of type 2 diabetes more than doubled, from 193 per 100,000 population to 396 per 100,000 population, at a rate of 4.1% per year.

But from 2011 to 2018, the annual standardized incidence rate declined by 36%, to 253 per 100,000 population, a 5.7% annualized decrease.

The increase prior to 2011 occurred in both men and women and in all age groups, while the subsequent decline was seen primarily in the older age groups. The all-cause mortality risk within the first year after diabetes diagnosis was higher than subsequent 1-year mortality risks and not different between men and women.

From the periods 1995-1997 to 2010-2012, the adjusted mortality rate among those with type 2 diabetes decreased by 44%, from 72 deaths per 1000 person-years to 40 deaths per 1000 person-years (adjusted mortality rate ratio, 0.55). After that low level in 2010-2012, mortality increased by 27% to 48 per 1000 person-years (adjusted mortality rate ratio 0.69, compared with 1995-1997).

The reversed mortality trend after 2010-2012 was caused almost entirely by the increase in the first year after diabetes diagnosis, Dr. Knudsen and colleagues noted.

According to Dr. Kirkman, “A1c is strongly predictive of complications and mortality. That plus its ease of use and the fact that more people may be screened mean it’s still a good option. But for any of these tests, people who are slightly below the cut-point should not be considered normal or low risk.”

Indeed, Dr. Knudsen and colleagues said, “these findings may have implications for clinical practice and suggest that a more multifactorial view of metabolic risk is needed.”

Dr. Knudsen and Dr. Kirkman have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The introduction of hemoglobin A1c as an option for diagnosing type 2 diabetes over a decade ago may have resulted in underdiagnosis, new research indicates.

In 2011, the World Health Organization advised that A1c measurement, with a cutoff value of 6.5%, could be used to diagnose diabetes. The American Diabetes Association had issued similar guidance in 2010.

Prior to that time, the less-convenient 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and fasting blood glucose (FBG) were the only recommended tests. While WHO made no recommendations for interpreting values below 6.5%, the ADA designated 5.7%-6.4% as prediabetes.

The new study, published online in The Lancet Regional Health–Europe, showed that the incidence of type 2 diabetes in Denmark had been increasing prior to the 2012 adoption of A1c as a diagnostic option but declined thereafter. And all-cause mortality among people with type 2 diabetes, which had been dropping, began to increase after that time.

“Our findings suggest that fewer patients have been diagnosed with [type 2 diabetes] since A1c testing was introduced as a convenient diagnostic option. We may thus be missing a group with borderline increased A1c values that is still at high metabolic and cardiovascular risk,” Jakob S. Knudsen, MD, of the department of clinical epidemiology, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, and colleagues wrote.

Therefore, Dr. Knudsen said in an interview, clinicians should “consider testing with FBG or OGTT when presented with borderline A1c values.”

The reason for the increase in mortality after incident type 2 diabetes diagnosis, he said, “is that the patients who would have reduced the average mortality are no longer diagnosed...This does not reflect that we are treating already diagnosed patients any worse, rather some patients are not diagnosed.”

But M. Sue Kirkman, MD, emeritus professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was part of the writing group for the 2010 ADA guidelines, isn’t convinced.

“This is an interesting paper, but it is a bit hard to believe that a change in WHO recommendations would have such a large and almost immediate impact on incidence and mortality. It seems likely that ... factors [other] than just the changes in recommendations for the diagnostic test account for these findings,” she said.

Dr. Kirkman pointed to new data just out from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Jan. 26 that don›t show evidence of a higher proportion of people in the United States who have undiagnosed diabetes, “which would be expected if more cases were being ‘missed’ by A1c.”

She added that the CDC incidence data “show a continuing steady rate of decline in incidence that began in 2008, before any organizations recommended using A1c to screen for or diagnose diabetes.” Moreover, “there is evidence that type 2 diabetes incidence has fallen or plateaued in many countries since 2006, well before the WHO recommendation, with most of the studies from developed countries.”

But Dr. Knudsen also cited other data, including a study that showed a drop or stabilization in diagnosed diabetes incidence in high-income countries since 2010.

“That study concluded that the reasons for the declines in the incidence of diagnosed diabetes warrant further investigation with appropriate data sources, which was a main objective of our study,” wrote Dr. Knudsen and coauthors.

Dr. Knudsen said in an interview: “We are not the first to make the point that this sudden change is related to A1c introduction...but we are the first to have the data to clearly show that is the case.”

Diabetes incidence dropped but mortality rose after 2010

The population-based longitudinal study used four Danish medical databases and included 415,553 patients treated for type 2 diabetes for the first time from 1995-2018 and 2,060,279 matched comparators not treated for diabetes.

From 1995 until the 2012 introduction of A1c as a diagnostic option, the annual standardized incidence rates of type 2 diabetes more than doubled, from 193 per 100,000 population to 396 per 100,000 population, at a rate of 4.1% per year.

But from 2011 to 2018, the annual standardized incidence rate declined by 36%, to 253 per 100,000 population, a 5.7% annualized decrease.

The increase prior to 2011 occurred in both men and women and in all age groups, while the subsequent decline was seen primarily in the older age groups. The all-cause mortality risk within the first year after diabetes diagnosis was higher than subsequent 1-year mortality risks and not different between men and women.

From the periods 1995-1997 to 2010-2012, the adjusted mortality rate among those with type 2 diabetes decreased by 44%, from 72 deaths per 1000 person-years to 40 deaths per 1000 person-years (adjusted mortality rate ratio, 0.55). After that low level in 2010-2012, mortality increased by 27% to 48 per 1000 person-years (adjusted mortality rate ratio 0.69, compared with 1995-1997).

The reversed mortality trend after 2010-2012 was caused almost entirely by the increase in the first year after diabetes diagnosis, Dr. Knudsen and colleagues noted.

According to Dr. Kirkman, “A1c is strongly predictive of complications and mortality. That plus its ease of use and the fact that more people may be screened mean it’s still a good option. But for any of these tests, people who are slightly below the cut-point should not be considered normal or low risk.”

Indeed, Dr. Knudsen and colleagues said, “these findings may have implications for clinical practice and suggest that a more multifactorial view of metabolic risk is needed.”

Dr. Knudsen and Dr. Kirkman have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The introduction of hemoglobin A1c as an option for diagnosing type 2 diabetes over a decade ago may have resulted in underdiagnosis, new research indicates.

In 2011, the World Health Organization advised that A1c measurement, with a cutoff value of 6.5%, could be used to diagnose diabetes. The American Diabetes Association had issued similar guidance in 2010.

Prior to that time, the less-convenient 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and fasting blood glucose (FBG) were the only recommended tests. While WHO made no recommendations for interpreting values below 6.5%, the ADA designated 5.7%-6.4% as prediabetes.

The new study, published online in The Lancet Regional Health–Europe, showed that the incidence of type 2 diabetes in Denmark had been increasing prior to the 2012 adoption of A1c as a diagnostic option but declined thereafter. And all-cause mortality among people with type 2 diabetes, which had been dropping, began to increase after that time.

“Our findings suggest that fewer patients have been diagnosed with [type 2 diabetes] since A1c testing was introduced as a convenient diagnostic option. We may thus be missing a group with borderline increased A1c values that is still at high metabolic and cardiovascular risk,” Jakob S. Knudsen, MD, of the department of clinical epidemiology, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, and colleagues wrote.

Therefore, Dr. Knudsen said in an interview, clinicians should “consider testing with FBG or OGTT when presented with borderline A1c values.”

The reason for the increase in mortality after incident type 2 diabetes diagnosis, he said, “is that the patients who would have reduced the average mortality are no longer diagnosed...This does not reflect that we are treating already diagnosed patients any worse, rather some patients are not diagnosed.”

But M. Sue Kirkman, MD, emeritus professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was part of the writing group for the 2010 ADA guidelines, isn’t convinced.

“This is an interesting paper, but it is a bit hard to believe that a change in WHO recommendations would have such a large and almost immediate impact on incidence and mortality. It seems likely that ... factors [other] than just the changes in recommendations for the diagnostic test account for these findings,” she said.

Dr. Kirkman pointed to new data just out from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Jan. 26 that don›t show evidence of a higher proportion of people in the United States who have undiagnosed diabetes, “which would be expected if more cases were being ‘missed’ by A1c.”

She added that the CDC incidence data “show a continuing steady rate of decline in incidence that began in 2008, before any organizations recommended using A1c to screen for or diagnose diabetes.” Moreover, “there is evidence that type 2 diabetes incidence has fallen or plateaued in many countries since 2006, well before the WHO recommendation, with most of the studies from developed countries.”

But Dr. Knudsen also cited other data, including a study that showed a drop or stabilization in diagnosed diabetes incidence in high-income countries since 2010.

“That study concluded that the reasons for the declines in the incidence of diagnosed diabetes warrant further investigation with appropriate data sources, which was a main objective of our study,” wrote Dr. Knudsen and coauthors.

Dr. Knudsen said in an interview: “We are not the first to make the point that this sudden change is related to A1c introduction...but we are the first to have the data to clearly show that is the case.”

Diabetes incidence dropped but mortality rose after 2010

The population-based longitudinal study used four Danish medical databases and included 415,553 patients treated for type 2 diabetes for the first time from 1995-2018 and 2,060,279 matched comparators not treated for diabetes.

From 1995 until the 2012 introduction of A1c as a diagnostic option, the annual standardized incidence rates of type 2 diabetes more than doubled, from 193 per 100,000 population to 396 per 100,000 population, at a rate of 4.1% per year.

But from 2011 to 2018, the annual standardized incidence rate declined by 36%, to 253 per 100,000 population, a 5.7% annualized decrease.

The increase prior to 2011 occurred in both men and women and in all age groups, while the subsequent decline was seen primarily in the older age groups. The all-cause mortality risk within the first year after diabetes diagnosis was higher than subsequent 1-year mortality risks and not different between men and women.

From the periods 1995-1997 to 2010-2012, the adjusted mortality rate among those with type 2 diabetes decreased by 44%, from 72 deaths per 1000 person-years to 40 deaths per 1000 person-years (adjusted mortality rate ratio, 0.55). After that low level in 2010-2012, mortality increased by 27% to 48 per 1000 person-years (adjusted mortality rate ratio 0.69, compared with 1995-1997).

The reversed mortality trend after 2010-2012 was caused almost entirely by the increase in the first year after diabetes diagnosis, Dr. Knudsen and colleagues noted.

According to Dr. Kirkman, “A1c is strongly predictive of complications and mortality. That plus its ease of use and the fact that more people may be screened mean it’s still a good option. But for any of these tests, people who are slightly below the cut-point should not be considered normal or low risk.”

Indeed, Dr. Knudsen and colleagues said, “these findings may have implications for clinical practice and suggest that a more multifactorial view of metabolic risk is needed.”

Dr. Knudsen and Dr. Kirkman have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET REGIONAL HEALTH–EUROPE

No COVID vax, no transplant: Unfair or good medicine?

Right now, more than 106,600 people in the United States are on the national transplant waiting list, each hoping to hear soon that a lung, kidney, heart, or other vital organ has been found for them. It’s the promise not just of a new organ, but a new life.

Well before they are placed on that list, transplant candidates, as they’re known, are evaluated with a battery of tests and exams to be sure they are infection free, their other organs are healthy, and that all their vaccinations are up to date.

In January, a 31-year-old Boston father of two declined to get the COVID-19 vaccine, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital officials removed him from the heart transplant waiting list. And in North Carolina, a 38-year-old man in need of a kidney transplant said he, too, was denied the organ when he declined to get the vaccination.

Those are just two of the most recent cases. The decisions by the transplant centers to remove the candidates from the waiting list have set off a national debate among ethicists, family members, doctors, patients, and others.

On social media and in conversation, the question persists: Is removing them from the list unfair and cruel, or simply business as usual to keep the patient as healthy as possible and the transplant as successful as possible?

Two recent tweets sum up the debate.

“The people responsible for this should be charged with attempted homicide,” one Twitter user said, while another suggested that the more accurate way to headline the news about a transplant candidate refusing the COVID-19 vaccine would be: “Patient voluntarily forfeits donor organ.”

Doctors and ethics experts, as well as other patients on the waiting list, say it’s simply good medicine to require the COVID vaccine, along with a host of other pretransplant requirements.

Transplant protocols

“Transplant medicine has always been a strong promoter of vaccination,” said Silas Prescod Norman, MD, a clinical associate professor of nephrology and internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He is a kidney specialist who works in the university’s transplant clinic.

Requiring the COVID vaccine is in line with requirements to get numerous other vaccines, he said.“Promoting the COVID vaccine among our transplant candidates and recipients is just an extension of our usual practice.

“In transplantation, first and foremost is patient safety,” Dr. Norman said. “And we know that solid organ transplant patients are at substantially higher risk of contracting COVID than nontransplant patients.”

After the transplant, they are placed on immunosuppressant drugs, that weaken the immune system while also decreasing the body’s ability to reject the new organ.

“We know now, because there is good data about the vaccine to show that people who are on transplant medications are less likely to make detectable antibodies after vaccination,” said Dr. Norman, who’s also a medical adviser for the American Kidney Fund, a nonprofit that provides kidney health information and financial assistance for dialysis.

And this is not a surprise because of the immunosuppressive effects, he said. “So it only makes sense to get people vaccinated before transplantation.”

Researchers compared the cases of more than 17,000 people who had received organ transplants and were hospitalized from April to November 2020, either for COVID (1,682 of them) or other health issues. Those who had COVID were more likely to have complications and to die in the hospital than those who did not have it.

Vaccination guidelines, policies

Federal COVID-19 treatment guidelines from the National Institutes of Health state that transplant patients on immunosuppressant drugs used after the procedure should be considered at a higher risk of getting severe COVID if infected.

In a joint statement from the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, the American Society of Transplantation, and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, the organizations say they “strongly recommend that all eligible children and adult transplant candidates and recipients be vaccinated with a COVID-19 vaccine [and booster] that is approved or authorized in their jurisdiction. Whenever possible, vaccination should occur prior to transplantation.” Ideally, it should be completed at least 2 weeks before the transplant.

The organizations also “support the development of institutional policies regarding pretransplant vaccination. We believe that this is in the best interest of the transplant candidate, optimizing their chances of getting through the perioperative and posttransplant periods without severe COVID-19 disease, especially at times of greater infection prevalence.”

Officials at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where the 31-year-old father was removed from the list, issued a statement that reads, in part: “Our Mass General Brigham health care system requires several [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]-recommended vaccines, including the COVID-19 vaccine, and lifestyle behaviors for transplant candidates to create both the best chance for a successful operation and to optimize the patient’s survival after transplantation, given that their immune system is drastically suppressed. Patients are not active on the wait list without this.”

Ethics amid organ shortage

“Organs are scarce,” said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of the division of medical ethics at New York University Langone Medical Center. That makes the goal of choosing the very best candidates for success even more crucial.

“You try to maximize the chance the organ will work,” he said. Pretransplant vaccination is one way.

The shortage is most severe for kidney transplants. In 2020, according to federal statistics, more than 91,000 kidney transplants were needed, but fewer than 23,000 were received. During 2021, 41,354 transplants were done, an increase of nearly 6% over the previous year. The total includes kidneys, hearts, lungs, and other organs, with kidneys accounting for more than 24,000 of the total.

Even with the rise in transplant numbers, supply does not meet demand. According to federal statistics, 17 people in the United States die each day waiting for an organ transplant. Every 9 minutes, someone is added to the waiting list.

“This isn’t and it shouldn’t be a fight about the COVID vaccine,” Dr. Caplan said. “This isn’t an issue about punishing non-COVID vaccinators. It’s deciding who is going to get a scarce organ.”

“A lot of people [opposed to removing the nonvaccinated from the list] think: ‘Oh, they are just killing those people who won’t take a COVID vaccine.’ That’s not what is going on.”

The transplant candidate must be in the best possible shape overall, Dr. Caplan and doctors agreed. Someone who is smoking, drinking heavily, or abusing drugs isn’t going to the top of the list either. And for other procedures, such as bariatric surgery or knee surgery, some patients are told first to lose weight before a surgeon will operate.

The worry about side effects from the vaccine, which some patients have cited as a concern, is misplaced, Dr. Caplan said. What transplant candidates who refuse the COVID vaccine may not be thinking about is that they are facing a serious operation and will be on numerous anti-rejection drugs, with side effects, after the surgery.

“So to be worried about the side effects of a COVID vaccine is irrational,” he said.

Transplants: The process

The patients who were recently removed from the transplant list could seek care and a transplant at an alternate center, said Anne Paschke, a spokesperson for the United Network for Organ Sharing, a nonprofit group that is under contract with the federal government and operates the national Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN).

“Transplant hospitals decide which patients to add to the wait list based on their own criteria and medical judgment to create the best chance for a positive transplant outcome,” she said. That’s done with the understanding that patients will help with their medical care.

So, if one program won’t accept a patient, another may. But, if a patient turned down at one center due to refusing to get the COVID vaccine tries another center, the requirements at that hospital may be the same, she said.

OPTN maintains a list of transplant centers. As of Jan. 28, there were 251 transplant centers, according to UNOS, which manages the waiting list, matches donors and recipients, and strives for equity, among other duties.

Pretransplant refusers not typical

“The cases we are seeing are outliers,” Dr. Caplan said of the handful of known candidates who have refused the vaccine. Most ask their doctor exactly what they need to do to live and follow those instructions.

Dr. Norman agreed. Most of the kidney patients he cares for who are hoping for a transplant have been on dialysis, “which they do not like. They are doing whatever they can to make sure they don’t go back on dialysis. As a group, they tend to be very adherent, very safety conscious because they understand their risk and they understand the gift they have received [or will receive] through transplantation. They want to do everything they can to respect and protect that gift.”

Not surprisingly, some on the transplant list who are vaccinated have strong opinions about those who refuse to get the vaccine. Dana J. Ufkes, 61, a Seattle realtor, has been on the kidney transplant list – this time – since 2003, hoping for her third transplant. When asked if potential recipients should be removed from the list if they refuse the COVID vaccine, her answer was immediate: “Absolutely.”

At age 17, Ms. Ufkes got a serious kidney infection that went undiagnosed and untreated. Her kidney health worsened, and she needed a transplant. She got her first one in 1986, then again in 1992.

“They last longer than they used to,” she said. But not forever. (According to the American Kidney Fund, transplants from a living kidney donor last about 15-20 years; from a deceased donor, 10-15.)

The decision to decline the vaccine is, of course, each person’s choice, Ms. Ufkes said. But “if they don’t want to be vaccinated [and still want to be on the list], I think that’s BS.”

Citing the lack of organs, “it’s not like they are handing these out like jellybeans.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Right now, more than 106,600 people in the United States are on the national transplant waiting list, each hoping to hear soon that a lung, kidney, heart, or other vital organ has been found for them. It’s the promise not just of a new organ, but a new life.

Well before they are placed on that list, transplant candidates, as they’re known, are evaluated with a battery of tests and exams to be sure they are infection free, their other organs are healthy, and that all their vaccinations are up to date.

In January, a 31-year-old Boston father of two declined to get the COVID-19 vaccine, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital officials removed him from the heart transplant waiting list. And in North Carolina, a 38-year-old man in need of a kidney transplant said he, too, was denied the organ when he declined to get the vaccination.

Those are just two of the most recent cases. The decisions by the transplant centers to remove the candidates from the waiting list have set off a national debate among ethicists, family members, doctors, patients, and others.

On social media and in conversation, the question persists: Is removing them from the list unfair and cruel, or simply business as usual to keep the patient as healthy as possible and the transplant as successful as possible?

Two recent tweets sum up the debate.

“The people responsible for this should be charged with attempted homicide,” one Twitter user said, while another suggested that the more accurate way to headline the news about a transplant candidate refusing the COVID-19 vaccine would be: “Patient voluntarily forfeits donor organ.”

Doctors and ethics experts, as well as other patients on the waiting list, say it’s simply good medicine to require the COVID vaccine, along with a host of other pretransplant requirements.

Transplant protocols

“Transplant medicine has always been a strong promoter of vaccination,” said Silas Prescod Norman, MD, a clinical associate professor of nephrology and internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He is a kidney specialist who works in the university’s transplant clinic.

Requiring the COVID vaccine is in line with requirements to get numerous other vaccines, he said.“Promoting the COVID vaccine among our transplant candidates and recipients is just an extension of our usual practice.

“In transplantation, first and foremost is patient safety,” Dr. Norman said. “And we know that solid organ transplant patients are at substantially higher risk of contracting COVID than nontransplant patients.”

After the transplant, they are placed on immunosuppressant drugs, that weaken the immune system while also decreasing the body’s ability to reject the new organ.

“We know now, because there is good data about the vaccine to show that people who are on transplant medications are less likely to make detectable antibodies after vaccination,” said Dr. Norman, who’s also a medical adviser for the American Kidney Fund, a nonprofit that provides kidney health information and financial assistance for dialysis.

And this is not a surprise because of the immunosuppressive effects, he said. “So it only makes sense to get people vaccinated before transplantation.”

Researchers compared the cases of more than 17,000 people who had received organ transplants and were hospitalized from April to November 2020, either for COVID (1,682 of them) or other health issues. Those who had COVID were more likely to have complications and to die in the hospital than those who did not have it.

Vaccination guidelines, policies

Federal COVID-19 treatment guidelines from the National Institutes of Health state that transplant patients on immunosuppressant drugs used after the procedure should be considered at a higher risk of getting severe COVID if infected.

In a joint statement from the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, the American Society of Transplantation, and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, the organizations say they “strongly recommend that all eligible children and adult transplant candidates and recipients be vaccinated with a COVID-19 vaccine [and booster] that is approved or authorized in their jurisdiction. Whenever possible, vaccination should occur prior to transplantation.” Ideally, it should be completed at least 2 weeks before the transplant.

The organizations also “support the development of institutional policies regarding pretransplant vaccination. We believe that this is in the best interest of the transplant candidate, optimizing their chances of getting through the perioperative and posttransplant periods without severe COVID-19 disease, especially at times of greater infection prevalence.”

Officials at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where the 31-year-old father was removed from the list, issued a statement that reads, in part: “Our Mass General Brigham health care system requires several [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]-recommended vaccines, including the COVID-19 vaccine, and lifestyle behaviors for transplant candidates to create both the best chance for a successful operation and to optimize the patient’s survival after transplantation, given that their immune system is drastically suppressed. Patients are not active on the wait list without this.”

Ethics amid organ shortage

“Organs are scarce,” said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of the division of medical ethics at New York University Langone Medical Center. That makes the goal of choosing the very best candidates for success even more crucial.

“You try to maximize the chance the organ will work,” he said. Pretransplant vaccination is one way.

The shortage is most severe for kidney transplants. In 2020, according to federal statistics, more than 91,000 kidney transplants were needed, but fewer than 23,000 were received. During 2021, 41,354 transplants were done, an increase of nearly 6% over the previous year. The total includes kidneys, hearts, lungs, and other organs, with kidneys accounting for more than 24,000 of the total.

Even with the rise in transplant numbers, supply does not meet demand. According to federal statistics, 17 people in the United States die each day waiting for an organ transplant. Every 9 minutes, someone is added to the waiting list.

“This isn’t and it shouldn’t be a fight about the COVID vaccine,” Dr. Caplan said. “This isn’t an issue about punishing non-COVID vaccinators. It’s deciding who is going to get a scarce organ.”

“A lot of people [opposed to removing the nonvaccinated from the list] think: ‘Oh, they are just killing those people who won’t take a COVID vaccine.’ That’s not what is going on.”

The transplant candidate must be in the best possible shape overall, Dr. Caplan and doctors agreed. Someone who is smoking, drinking heavily, or abusing drugs isn’t going to the top of the list either. And for other procedures, such as bariatric surgery or knee surgery, some patients are told first to lose weight before a surgeon will operate.

The worry about side effects from the vaccine, which some patients have cited as a concern, is misplaced, Dr. Caplan said. What transplant candidates who refuse the COVID vaccine may not be thinking about is that they are facing a serious operation and will be on numerous anti-rejection drugs, with side effects, after the surgery.

“So to be worried about the side effects of a COVID vaccine is irrational,” he said.

Transplants: The process

The patients who were recently removed from the transplant list could seek care and a transplant at an alternate center, said Anne Paschke, a spokesperson for the United Network for Organ Sharing, a nonprofit group that is under contract with the federal government and operates the national Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN).

“Transplant hospitals decide which patients to add to the wait list based on their own criteria and medical judgment to create the best chance for a positive transplant outcome,” she said. That’s done with the understanding that patients will help with their medical care.

So, if one program won’t accept a patient, another may. But, if a patient turned down at one center due to refusing to get the COVID vaccine tries another center, the requirements at that hospital may be the same, she said.

OPTN maintains a list of transplant centers. As of Jan. 28, there were 251 transplant centers, according to UNOS, which manages the waiting list, matches donors and recipients, and strives for equity, among other duties.

Pretransplant refusers not typical

“The cases we are seeing are outliers,” Dr. Caplan said of the handful of known candidates who have refused the vaccine. Most ask their doctor exactly what they need to do to live and follow those instructions.

Dr. Norman agreed. Most of the kidney patients he cares for who are hoping for a transplant have been on dialysis, “which they do not like. They are doing whatever they can to make sure they don’t go back on dialysis. As a group, they tend to be very adherent, very safety conscious because they understand their risk and they understand the gift they have received [or will receive] through transplantation. They want to do everything they can to respect and protect that gift.”

Not surprisingly, some on the transplant list who are vaccinated have strong opinions about those who refuse to get the vaccine. Dana J. Ufkes, 61, a Seattle realtor, has been on the kidney transplant list – this time – since 2003, hoping for her third transplant. When asked if potential recipients should be removed from the list if they refuse the COVID vaccine, her answer was immediate: “Absolutely.”

At age 17, Ms. Ufkes got a serious kidney infection that went undiagnosed and untreated. Her kidney health worsened, and she needed a transplant. She got her first one in 1986, then again in 1992.

“They last longer than they used to,” she said. But not forever. (According to the American Kidney Fund, transplants from a living kidney donor last about 15-20 years; from a deceased donor, 10-15.)

The decision to decline the vaccine is, of course, each person’s choice, Ms. Ufkes said. But “if they don’t want to be vaccinated [and still want to be on the list], I think that’s BS.”

Citing the lack of organs, “it’s not like they are handing these out like jellybeans.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Right now, more than 106,600 people in the United States are on the national transplant waiting list, each hoping to hear soon that a lung, kidney, heart, or other vital organ has been found for them. It’s the promise not just of a new organ, but a new life.

Well before they are placed on that list, transplant candidates, as they’re known, are evaluated with a battery of tests and exams to be sure they are infection free, their other organs are healthy, and that all their vaccinations are up to date.

In January, a 31-year-old Boston father of two declined to get the COVID-19 vaccine, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital officials removed him from the heart transplant waiting list. And in North Carolina, a 38-year-old man in need of a kidney transplant said he, too, was denied the organ when he declined to get the vaccination.

Those are just two of the most recent cases. The decisions by the transplant centers to remove the candidates from the waiting list have set off a national debate among ethicists, family members, doctors, patients, and others.

On social media and in conversation, the question persists: Is removing them from the list unfair and cruel, or simply business as usual to keep the patient as healthy as possible and the transplant as successful as possible?

Two recent tweets sum up the debate.

“The people responsible for this should be charged with attempted homicide,” one Twitter user said, while another suggested that the more accurate way to headline the news about a transplant candidate refusing the COVID-19 vaccine would be: “Patient voluntarily forfeits donor organ.”

Doctors and ethics experts, as well as other patients on the waiting list, say it’s simply good medicine to require the COVID vaccine, along with a host of other pretransplant requirements.

Transplant protocols

“Transplant medicine has always been a strong promoter of vaccination,” said Silas Prescod Norman, MD, a clinical associate professor of nephrology and internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He is a kidney specialist who works in the university’s transplant clinic.

Requiring the COVID vaccine is in line with requirements to get numerous other vaccines, he said.“Promoting the COVID vaccine among our transplant candidates and recipients is just an extension of our usual practice.

“In transplantation, first and foremost is patient safety,” Dr. Norman said. “And we know that solid organ transplant patients are at substantially higher risk of contracting COVID than nontransplant patients.”

After the transplant, they are placed on immunosuppressant drugs, that weaken the immune system while also decreasing the body’s ability to reject the new organ.

“We know now, because there is good data about the vaccine to show that people who are on transplant medications are less likely to make detectable antibodies after vaccination,” said Dr. Norman, who’s also a medical adviser for the American Kidney Fund, a nonprofit that provides kidney health information and financial assistance for dialysis.

And this is not a surprise because of the immunosuppressive effects, he said. “So it only makes sense to get people vaccinated before transplantation.”

Researchers compared the cases of more than 17,000 people who had received organ transplants and were hospitalized from April to November 2020, either for COVID (1,682 of them) or other health issues. Those who had COVID were more likely to have complications and to die in the hospital than those who did not have it.

Vaccination guidelines, policies

Federal COVID-19 treatment guidelines from the National Institutes of Health state that transplant patients on immunosuppressant drugs used after the procedure should be considered at a higher risk of getting severe COVID if infected.

In a joint statement from the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, the American Society of Transplantation, and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, the organizations say they “strongly recommend that all eligible children and adult transplant candidates and recipients be vaccinated with a COVID-19 vaccine [and booster] that is approved or authorized in their jurisdiction. Whenever possible, vaccination should occur prior to transplantation.” Ideally, it should be completed at least 2 weeks before the transplant.

The organizations also “support the development of institutional policies regarding pretransplant vaccination. We believe that this is in the best interest of the transplant candidate, optimizing their chances of getting through the perioperative and posttransplant periods without severe COVID-19 disease, especially at times of greater infection prevalence.”

Officials at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where the 31-year-old father was removed from the list, issued a statement that reads, in part: “Our Mass General Brigham health care system requires several [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]-recommended vaccines, including the COVID-19 vaccine, and lifestyle behaviors for transplant candidates to create both the best chance for a successful operation and to optimize the patient’s survival after transplantation, given that their immune system is drastically suppressed. Patients are not active on the wait list without this.”

Ethics amid organ shortage

“Organs are scarce,” said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of the division of medical ethics at New York University Langone Medical Center. That makes the goal of choosing the very best candidates for success even more crucial.

“You try to maximize the chance the organ will work,” he said. Pretransplant vaccination is one way.

The shortage is most severe for kidney transplants. In 2020, according to federal statistics, more than 91,000 kidney transplants were needed, but fewer than 23,000 were received. During 2021, 41,354 transplants were done, an increase of nearly 6% over the previous year. The total includes kidneys, hearts, lungs, and other organs, with kidneys accounting for more than 24,000 of the total.

Even with the rise in transplant numbers, supply does not meet demand. According to federal statistics, 17 people in the United States die each day waiting for an organ transplant. Every 9 minutes, someone is added to the waiting list.

“This isn’t and it shouldn’t be a fight about the COVID vaccine,” Dr. Caplan said. “This isn’t an issue about punishing non-COVID vaccinators. It’s deciding who is going to get a scarce organ.”

“A lot of people [opposed to removing the nonvaccinated from the list] think: ‘Oh, they are just killing those people who won’t take a COVID vaccine.’ That’s not what is going on.”

The transplant candidate must be in the best possible shape overall, Dr. Caplan and doctors agreed. Someone who is smoking, drinking heavily, or abusing drugs isn’t going to the top of the list either. And for other procedures, such as bariatric surgery or knee surgery, some patients are told first to lose weight before a surgeon will operate.

The worry about side effects from the vaccine, which some patients have cited as a concern, is misplaced, Dr. Caplan said. What transplant candidates who refuse the COVID vaccine may not be thinking about is that they are facing a serious operation and will be on numerous anti-rejection drugs, with side effects, after the surgery.

“So to be worried about the side effects of a COVID vaccine is irrational,” he said.

Transplants: The process

The patients who were recently removed from the transplant list could seek care and a transplant at an alternate center, said Anne Paschke, a spokesperson for the United Network for Organ Sharing, a nonprofit group that is under contract with the federal government and operates the national Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN).

“Transplant hospitals decide which patients to add to the wait list based on their own criteria and medical judgment to create the best chance for a positive transplant outcome,” she said. That’s done with the understanding that patients will help with their medical care.

So, if one program won’t accept a patient, another may. But, if a patient turned down at one center due to refusing to get the COVID vaccine tries another center, the requirements at that hospital may be the same, she said.

OPTN maintains a list of transplant centers. As of Jan. 28, there were 251 transplant centers, according to UNOS, which manages the waiting list, matches donors and recipients, and strives for equity, among other duties.

Pretransplant refusers not typical

“The cases we are seeing are outliers,” Dr. Caplan said of the handful of known candidates who have refused the vaccine. Most ask their doctor exactly what they need to do to live and follow those instructions.

Dr. Norman agreed. Most of the kidney patients he cares for who are hoping for a transplant have been on dialysis, “which they do not like. They are doing whatever they can to make sure they don’t go back on dialysis. As a group, they tend to be very adherent, very safety conscious because they understand their risk and they understand the gift they have received [or will receive] through transplantation. They want to do everything they can to respect and protect that gift.”

Not surprisingly, some on the transplant list who are vaccinated have strong opinions about those who refuse to get the vaccine. Dana J. Ufkes, 61, a Seattle realtor, has been on the kidney transplant list – this time – since 2003, hoping for her third transplant. When asked if potential recipients should be removed from the list if they refuse the COVID vaccine, her answer was immediate: “Absolutely.”

At age 17, Ms. Ufkes got a serious kidney infection that went undiagnosed and untreated. Her kidney health worsened, and she needed a transplant. She got her first one in 1986, then again in 1992.

“They last longer than they used to,” she said. But not forever. (According to the American Kidney Fund, transplants from a living kidney donor last about 15-20 years; from a deceased donor, 10-15.)

The decision to decline the vaccine is, of course, each person’s choice, Ms. Ufkes said. But “if they don’t want to be vaccinated [and still want to be on the list], I think that’s BS.”

Citing the lack of organs, “it’s not like they are handing these out like jellybeans.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Disseminated Erythematous-Violet Edematous Plaques and Necrotic Nodules

The Diagnosis: Histiocytoid Sweet Syndrome

The patient was admitted for clinical study and treatment monitoring. During the first 72 hours of admittance, the lesions and general malaise further developed along with C-reactive protein elevation (126 mg/L). Administration of intravenous prednisone at a dosage of 1 mg/kg daily was accompanied by substantial improvement after 1 week of treatment, with subsequent follow-up and outpatient monitoring. An underlying neoplasia was ruled out after review of medical history, physical examination, complete blood cell count, chest radiography, abdominal ultrasonography, colonoscopy, and bone marrow aspiration.

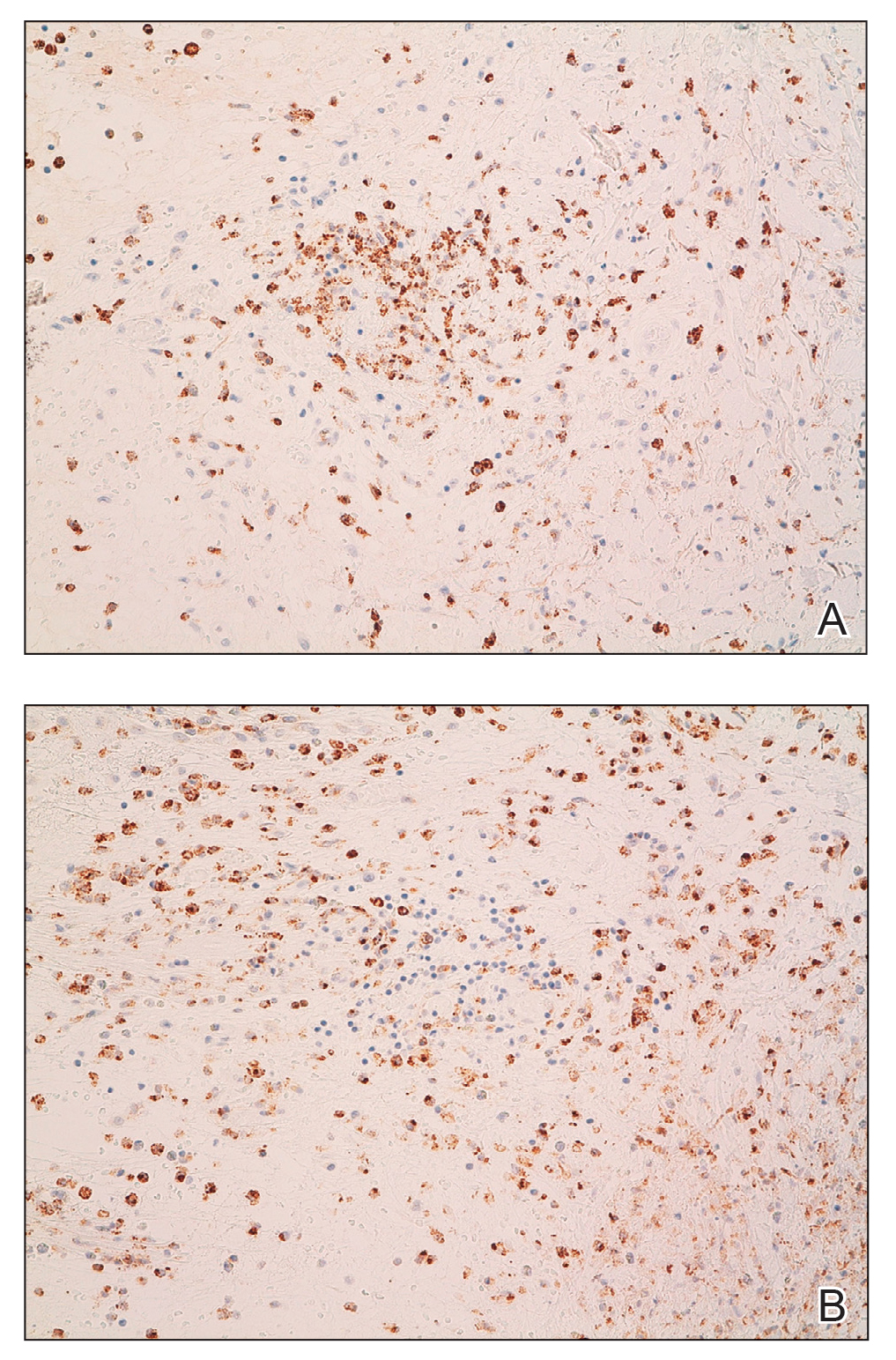

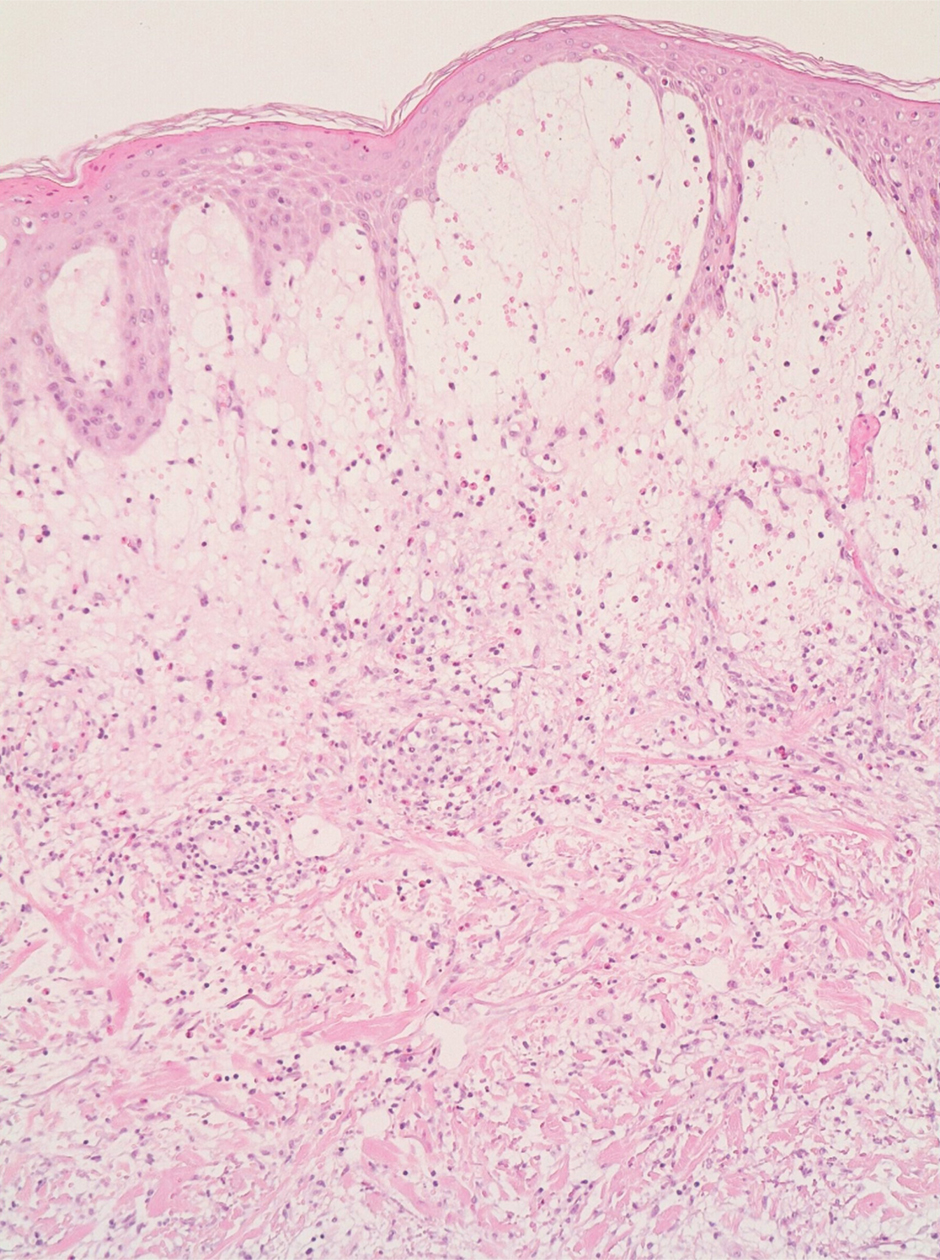

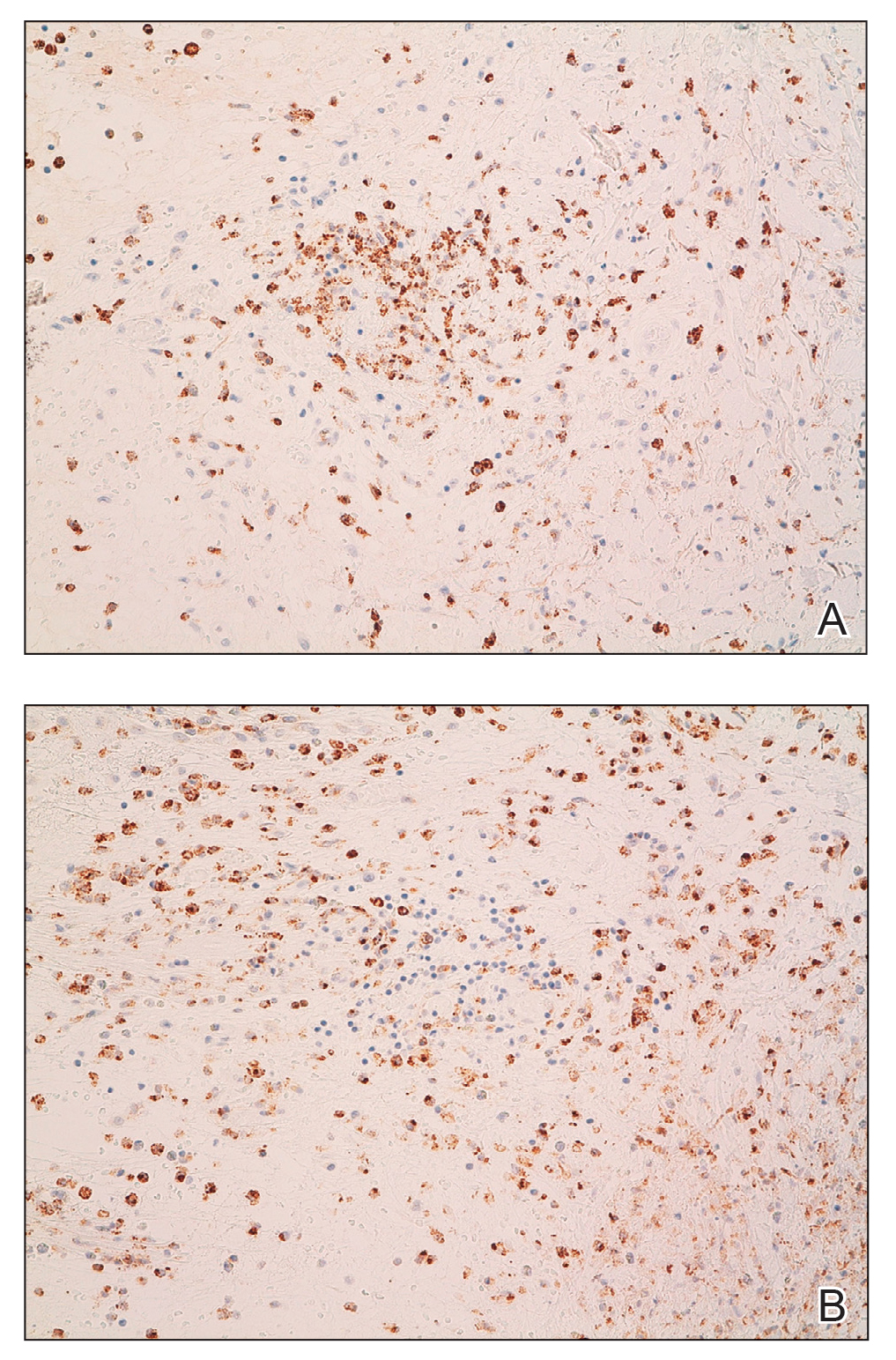

A 4-mm skin biopsy was performed from a lesion on the neck (Figure 1). Histology revealed a dermis with prominent edema alongside superficial, deep, and periadnexal perivascular inflammatory infiltrates, as well as predominant lymphocytes and cells with a histiocytoid profile (Figure 2). These findings were accompanied by isolated neutrophil foci. The absence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis was noted. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that the histiocyte population was positive for myeloperoxidase and CD68, which categorized them as immature cells of myeloid origin (Figure 3). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to a definitive diagnosis of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome (SS). Sweet syndrome consists of a neutrophilic dermatosis profile. Clinically, it manifests as a sudden onset of painful nodules and plaques accompanied by fever, malaise, and leukocytosis.

Histiocytoid SS is a rare histologic variant of SS initially described by Requena et al1 in 2005. In histiocytoid SS, the main inflammatory infiltrates are promyelocytes and myelocytes.2 Immunohistochemistry shows positivity for myeloperoxidase, CD15, CD43, CD45, CD68, MAC-386, and HAM56.1 The diagnosis is determined by exclusion after adequate clinical and histopathologic correlation, which also should exclude other diagnoses such as leukemia cutis and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis.3 Histiocytoid SS may be related to an increased risk for underlying malignancy. Haber et al4 performed a systematic review in which they concluded that approximately 40% of patients newly diagnosed with histiocytoid SS subsequently were diagnosed or already were diagnosed with a hematologic or solid cancer vs 21% in the classical neutrophilic infiltrate of SS (NSS). Histiocytoid SS more commonly was associated with myelodysplastic syndrome (46% vs 2.5% in NSS) and hematologic malignancies (42.5% vs 25% in SS).

The initial differential diagnoses include inflammatory dermatoses, infections, neoplasms, and systemic diseases. In exudative erythema multiforme, early lesions are composed of typical target lesions with mucosal involvement in 25% to 60% of patients.5 Erythema elevatum diutinum is a chronic dermatosis characterized by asymptomatic papules and red-violet nodules. The most characteristic histologic finding is leukocytoclastic vasculitis.6 The absence of vasculitis is part of the major diagnostic criteria for SS.7 Wells syndrome is associated with general malaise, and edematous and erythematous-violet plaques or nodules appear on the limbs; however, it frequently is associated with eosinophilia in peripheral blood, and histology shows that the main cell population of the inflammatory infiltrate also is eosinophilic.8 Painful, superficial, and erosive blisters appear preferentially on the face and backs of the arms in bullous pyoderma gangrenosum. It usually is not associated with the typical systemic manifestations of SS (ie, fever, arthralgia, damage to target organs). On histopathology, the neutrophilic infiltrate is accompanied by subepidermal vesicles.9

Histiocytoid SS responds dramatically to corticosteroids. Other first-line treatments that avoid use of corticosteroids are colchicine, dapsone, and potassium iodide. Multiple treatments were attempted in our patient, including corticosteroids, methotrexate, dapsone, colchicine, and anakinra. Despite patients responding well to treatment, a possible underlying neoplasm, most frequently of hematologic origin, must be excluded.10

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842. doi:10.1001/archderm.141.7.834

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6092

- Llamas-Velasco M, Concha-Garzón MJ, Fraga J, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome related to bortezomib: a mimicker of cutaneous infiltration by myeloma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015; 81:305-306. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.152743

- Haber R, Feghali J, El Gemayel M. Risk of malignancy in histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a systematic review and reappraisal [published online February 21, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:661-663. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.048

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05348.x

- Newburger J, Schmieder GJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov /books/NBK448069/

- Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

- Weins AB, Biedermann T, Weiss T, et al. Wells syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:989-993. doi:10.1111/ddg.13132

- Powell FC, Su WP, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: classification and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:395-409; quiz 410-412. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90428-4

- Villarreal-Villarreal CD, Ocampo-Candiani J, Villarreal-Martínez A. Sweet syndrome: a review and update. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:369-378. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2015.12.001

The Diagnosis: Histiocytoid Sweet Syndrome

The patient was admitted for clinical study and treatment monitoring. During the first 72 hours of admittance, the lesions and general malaise further developed along with C-reactive protein elevation (126 mg/L). Administration of intravenous prednisone at a dosage of 1 mg/kg daily was accompanied by substantial improvement after 1 week of treatment, with subsequent follow-up and outpatient monitoring. An underlying neoplasia was ruled out after review of medical history, physical examination, complete blood cell count, chest radiography, abdominal ultrasonography, colonoscopy, and bone marrow aspiration.

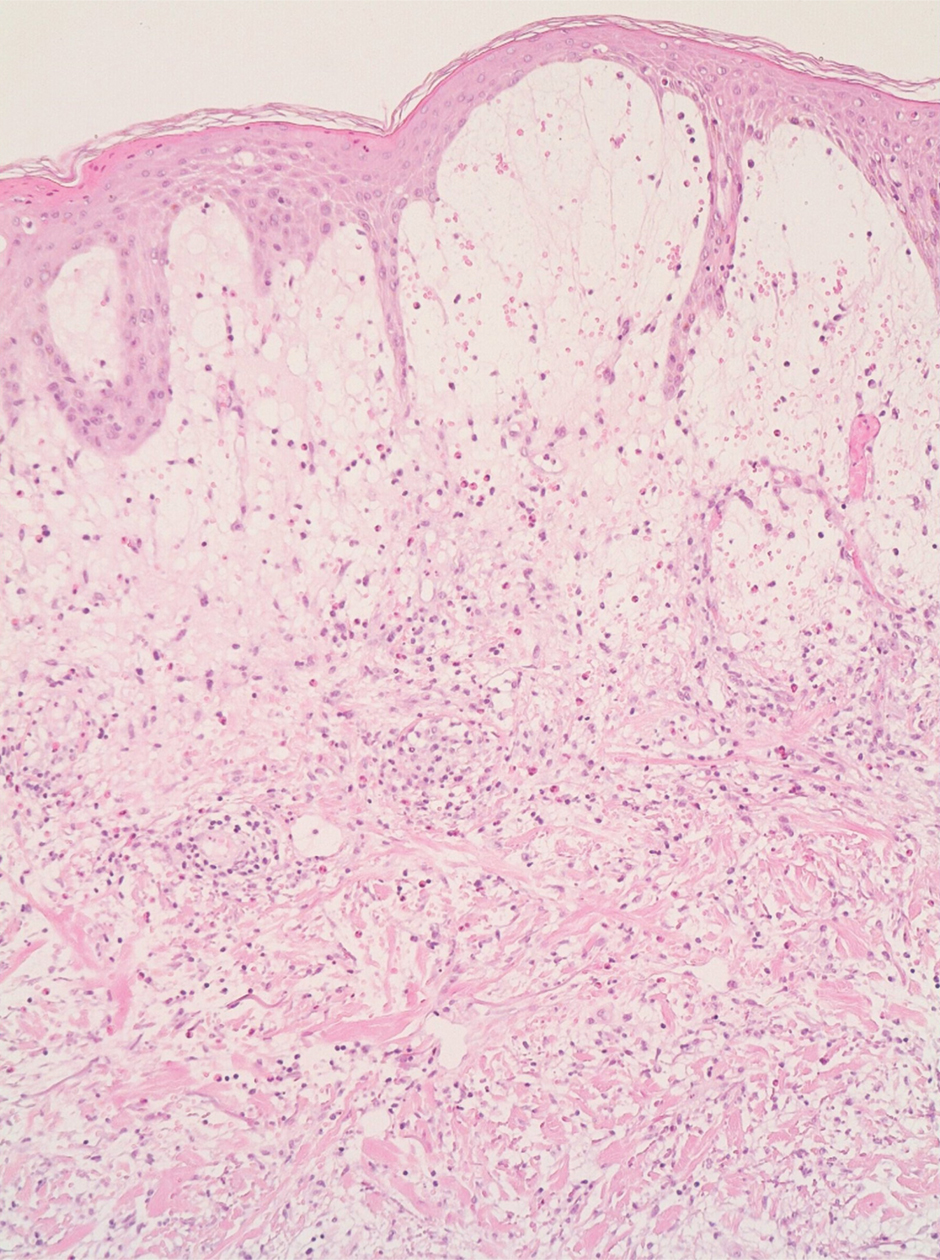

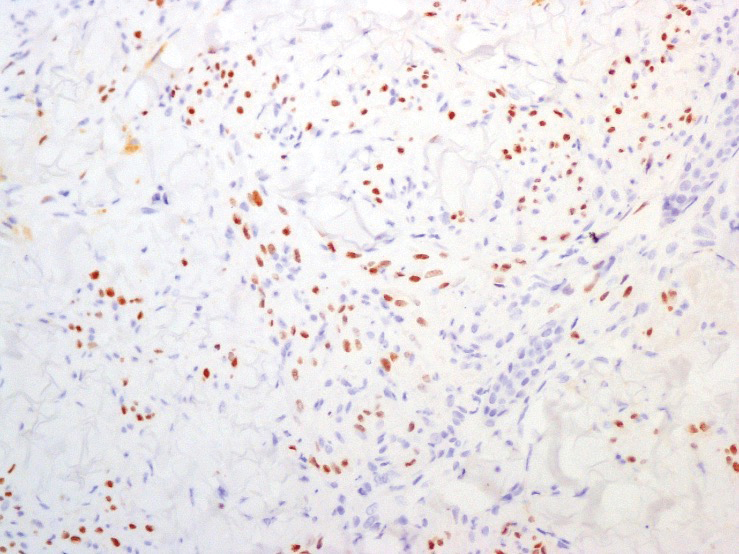

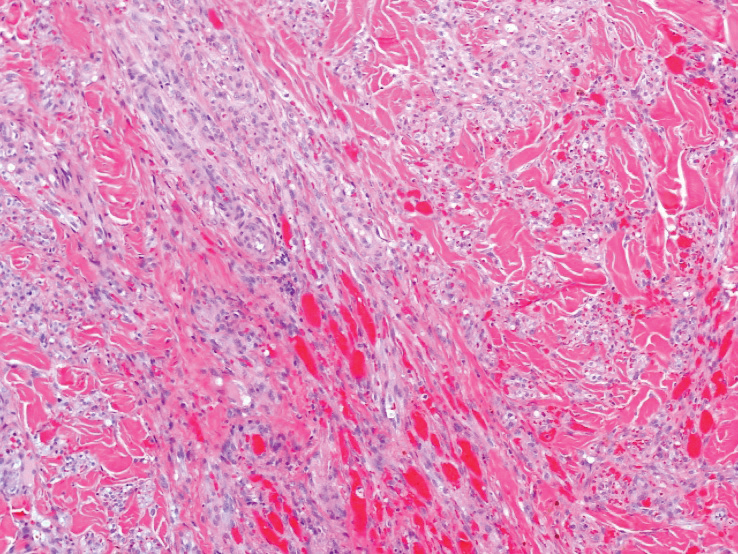

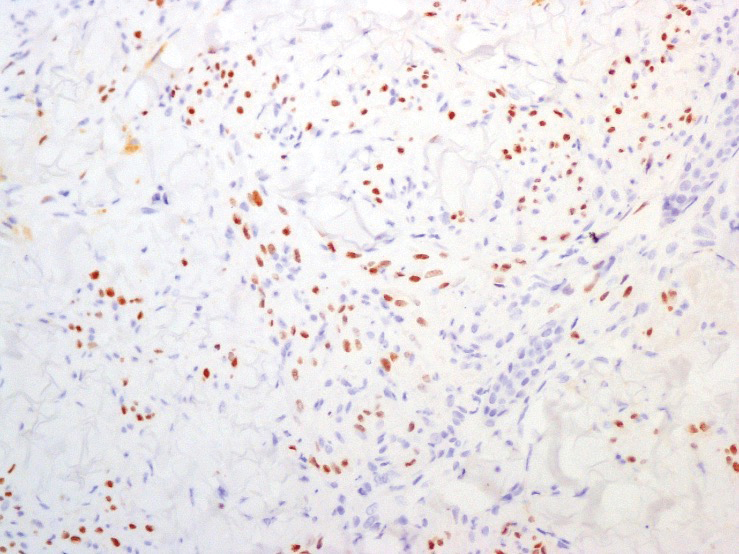

A 4-mm skin biopsy was performed from a lesion on the neck (Figure 1). Histology revealed a dermis with prominent edema alongside superficial, deep, and periadnexal perivascular inflammatory infiltrates, as well as predominant lymphocytes and cells with a histiocytoid profile (Figure 2). These findings were accompanied by isolated neutrophil foci. The absence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis was noted. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that the histiocyte population was positive for myeloperoxidase and CD68, which categorized them as immature cells of myeloid origin (Figure 3). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to a definitive diagnosis of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome (SS). Sweet syndrome consists of a neutrophilic dermatosis profile. Clinically, it manifests as a sudden onset of painful nodules and plaques accompanied by fever, malaise, and leukocytosis.

Histiocytoid SS is a rare histologic variant of SS initially described by Requena et al1 in 2005. In histiocytoid SS, the main inflammatory infiltrates are promyelocytes and myelocytes.2 Immunohistochemistry shows positivity for myeloperoxidase, CD15, CD43, CD45, CD68, MAC-386, and HAM56.1 The diagnosis is determined by exclusion after adequate clinical and histopathologic correlation, which also should exclude other diagnoses such as leukemia cutis and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis.3 Histiocytoid SS may be related to an increased risk for underlying malignancy. Haber et al4 performed a systematic review in which they concluded that approximately 40% of patients newly diagnosed with histiocytoid SS subsequently were diagnosed or already were diagnosed with a hematologic or solid cancer vs 21% in the classical neutrophilic infiltrate of SS (NSS). Histiocytoid SS more commonly was associated with myelodysplastic syndrome (46% vs 2.5% in NSS) and hematologic malignancies (42.5% vs 25% in SS).

The initial differential diagnoses include inflammatory dermatoses, infections, neoplasms, and systemic diseases. In exudative erythema multiforme, early lesions are composed of typical target lesions with mucosal involvement in 25% to 60% of patients.5 Erythema elevatum diutinum is a chronic dermatosis characterized by asymptomatic papules and red-violet nodules. The most characteristic histologic finding is leukocytoclastic vasculitis.6 The absence of vasculitis is part of the major diagnostic criteria for SS.7 Wells syndrome is associated with general malaise, and edematous and erythematous-violet plaques or nodules appear on the limbs; however, it frequently is associated with eosinophilia in peripheral blood, and histology shows that the main cell population of the inflammatory infiltrate also is eosinophilic.8 Painful, superficial, and erosive blisters appear preferentially on the face and backs of the arms in bullous pyoderma gangrenosum. It usually is not associated with the typical systemic manifestations of SS (ie, fever, arthralgia, damage to target organs). On histopathology, the neutrophilic infiltrate is accompanied by subepidermal vesicles.9

Histiocytoid SS responds dramatically to corticosteroids. Other first-line treatments that avoid use of corticosteroids are colchicine, dapsone, and potassium iodide. Multiple treatments were attempted in our patient, including corticosteroids, methotrexate, dapsone, colchicine, and anakinra. Despite patients responding well to treatment, a possible underlying neoplasm, most frequently of hematologic origin, must be excluded.10

The Diagnosis: Histiocytoid Sweet Syndrome

The patient was admitted for clinical study and treatment monitoring. During the first 72 hours of admittance, the lesions and general malaise further developed along with C-reactive protein elevation (126 mg/L). Administration of intravenous prednisone at a dosage of 1 mg/kg daily was accompanied by substantial improvement after 1 week of treatment, with subsequent follow-up and outpatient monitoring. An underlying neoplasia was ruled out after review of medical history, physical examination, complete blood cell count, chest radiography, abdominal ultrasonography, colonoscopy, and bone marrow aspiration.

A 4-mm skin biopsy was performed from a lesion on the neck (Figure 1). Histology revealed a dermis with prominent edema alongside superficial, deep, and periadnexal perivascular inflammatory infiltrates, as well as predominant lymphocytes and cells with a histiocytoid profile (Figure 2). These findings were accompanied by isolated neutrophil foci. The absence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis was noted. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that the histiocyte population was positive for myeloperoxidase and CD68, which categorized them as immature cells of myeloid origin (Figure 3). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to a definitive diagnosis of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome (SS). Sweet syndrome consists of a neutrophilic dermatosis profile. Clinically, it manifests as a sudden onset of painful nodules and plaques accompanied by fever, malaise, and leukocytosis.

Histiocytoid SS is a rare histologic variant of SS initially described by Requena et al1 in 2005. In histiocytoid SS, the main inflammatory infiltrates are promyelocytes and myelocytes.2 Immunohistochemistry shows positivity for myeloperoxidase, CD15, CD43, CD45, CD68, MAC-386, and HAM56.1 The diagnosis is determined by exclusion after adequate clinical and histopathologic correlation, which also should exclude other diagnoses such as leukemia cutis and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis.3 Histiocytoid SS may be related to an increased risk for underlying malignancy. Haber et al4 performed a systematic review in which they concluded that approximately 40% of patients newly diagnosed with histiocytoid SS subsequently were diagnosed or already were diagnosed with a hematologic or solid cancer vs 21% in the classical neutrophilic infiltrate of SS (NSS). Histiocytoid SS more commonly was associated with myelodysplastic syndrome (46% vs 2.5% in NSS) and hematologic malignancies (42.5% vs 25% in SS).

The initial differential diagnoses include inflammatory dermatoses, infections, neoplasms, and systemic diseases. In exudative erythema multiforme, early lesions are composed of typical target lesions with mucosal involvement in 25% to 60% of patients.5 Erythema elevatum diutinum is a chronic dermatosis characterized by asymptomatic papules and red-violet nodules. The most characteristic histologic finding is leukocytoclastic vasculitis.6 The absence of vasculitis is part of the major diagnostic criteria for SS.7 Wells syndrome is associated with general malaise, and edematous and erythematous-violet plaques or nodules appear on the limbs; however, it frequently is associated with eosinophilia in peripheral blood, and histology shows that the main cell population of the inflammatory infiltrate also is eosinophilic.8 Painful, superficial, and erosive blisters appear preferentially on the face and backs of the arms in bullous pyoderma gangrenosum. It usually is not associated with the typical systemic manifestations of SS (ie, fever, arthralgia, damage to target organs). On histopathology, the neutrophilic infiltrate is accompanied by subepidermal vesicles.9

Histiocytoid SS responds dramatically to corticosteroids. Other first-line treatments that avoid use of corticosteroids are colchicine, dapsone, and potassium iodide. Multiple treatments were attempted in our patient, including corticosteroids, methotrexate, dapsone, colchicine, and anakinra. Despite patients responding well to treatment, a possible underlying neoplasm, most frequently of hematologic origin, must be excluded.10

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842. doi:10.1001/archderm.141.7.834

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6092

- Llamas-Velasco M, Concha-Garzón MJ, Fraga J, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome related to bortezomib: a mimicker of cutaneous infiltration by myeloma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015; 81:305-306. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.152743

- Haber R, Feghali J, El Gemayel M. Risk of malignancy in histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a systematic review and reappraisal [published online February 21, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:661-663. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.048

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05348.x

- Newburger J, Schmieder GJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov /books/NBK448069/

- Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

- Weins AB, Biedermann T, Weiss T, et al. Wells syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:989-993. doi:10.1111/ddg.13132

- Powell FC, Su WP, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: classification and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:395-409; quiz 410-412. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90428-4

- Villarreal-Villarreal CD, Ocampo-Candiani J, Villarreal-Martínez A. Sweet syndrome: a review and update. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:369-378. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2015.12.001

- Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:834-842. doi:10.1001/archderm.141.7.834

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6092

- Llamas-Velasco M, Concha-Garzón MJ, Fraga J, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome related to bortezomib: a mimicker of cutaneous infiltration by myeloma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015; 81:305-306. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.152743

- Haber R, Feghali J, El Gemayel M. Risk of malignancy in histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a systematic review and reappraisal [published online February 21, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:661-663. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.048

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05348.x

- Newburger J, Schmieder GJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov /books/NBK448069/

- Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

- Weins AB, Biedermann T, Weiss T, et al. Wells syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:989-993. doi:10.1111/ddg.13132

- Powell FC, Su WP, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: classification and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:395-409; quiz 410-412. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90428-4

- Villarreal-Villarreal CD, Ocampo-Candiani J, Villarreal-Martínez A. Sweet syndrome: a review and update. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:369-378. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2015.12.001

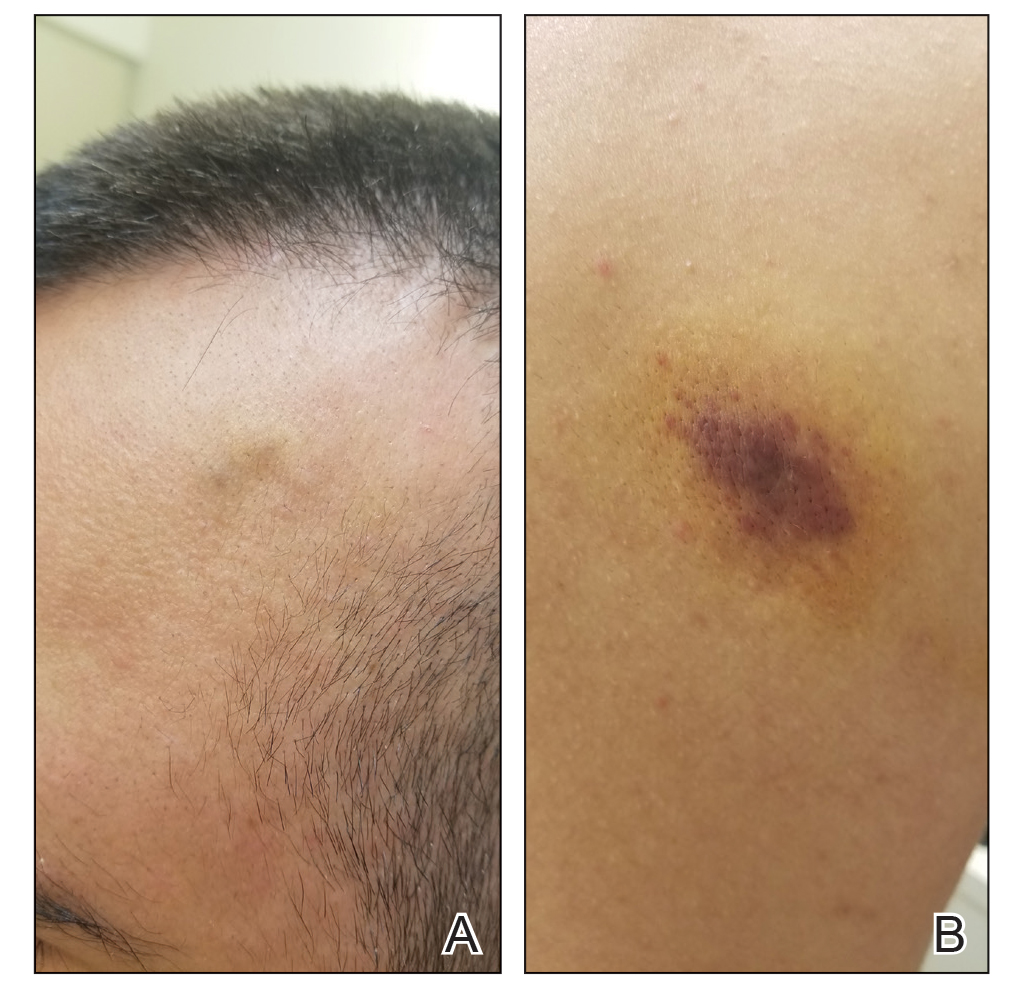

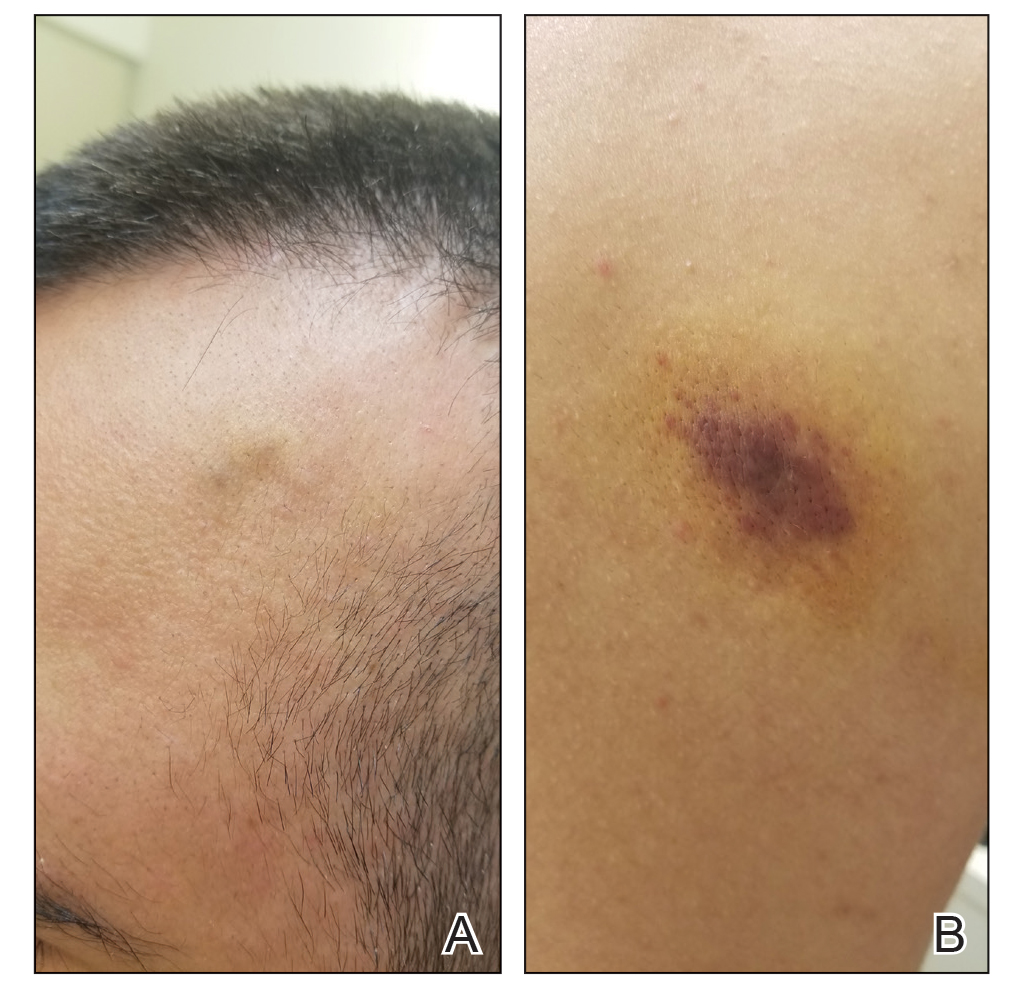

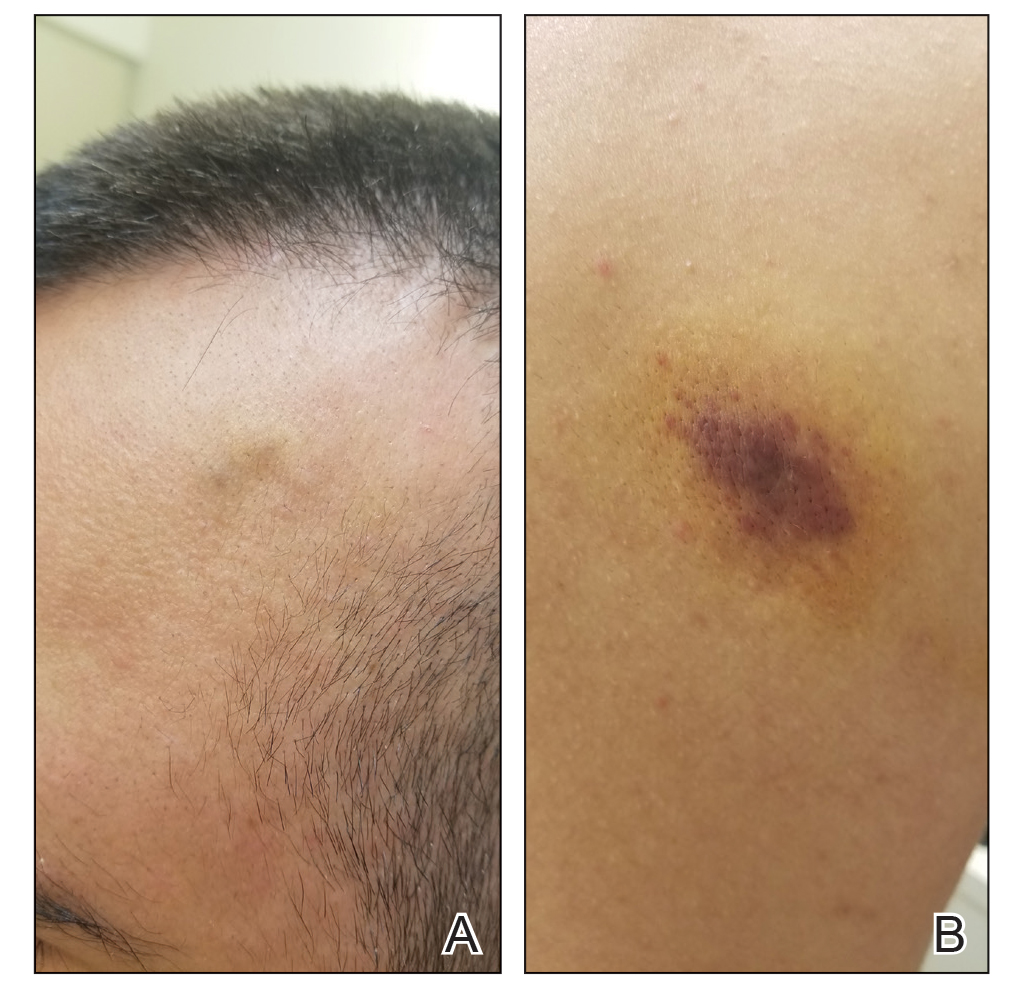

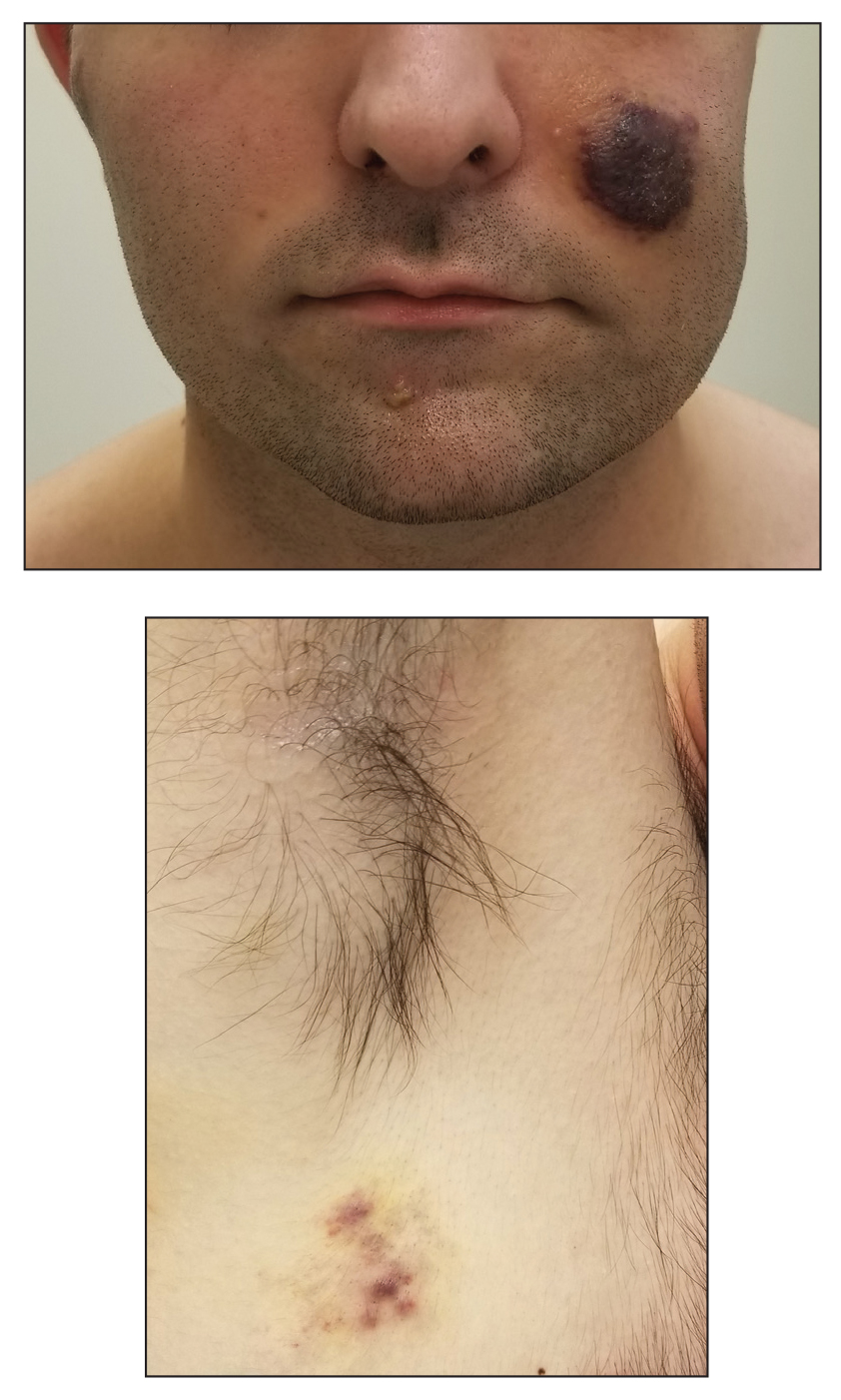

A 53-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a fever and painful skin lesions of 2 days’ duration. He reported a medical history of an upper respiratory infection 4 weeks prior. Physical examination was notable for erythematous-violet edematous papules, necrotic lesions, and pseudovesicles located on the face (top), head, neck, arms, and legs (bottom). Hemorrhagic splinters were evidenced in multiple nail sections. Urgent blood work revealed microcytic anemia (hemoglobin, 12.6 g/dL [reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL]) and elevated C-reactive protein (58 mg/L [reference range, 0.0–5.0 mg/L]).

Indurated Violaceous Lesions on the Face, Trunk, and Legs

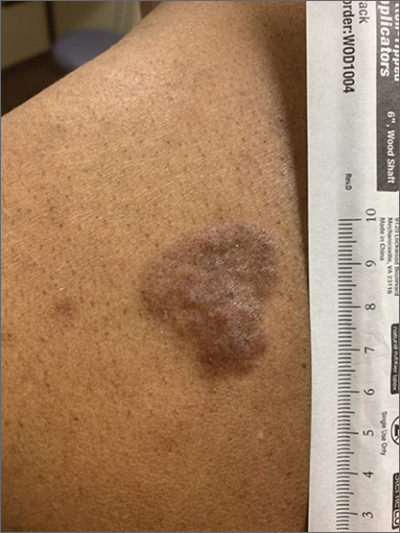

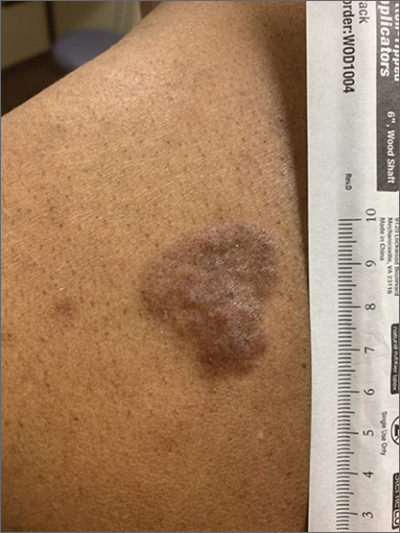

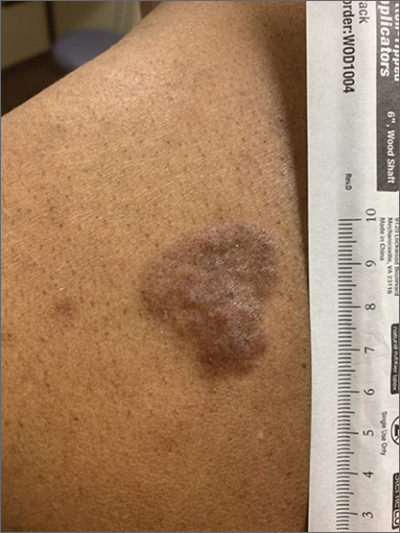

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

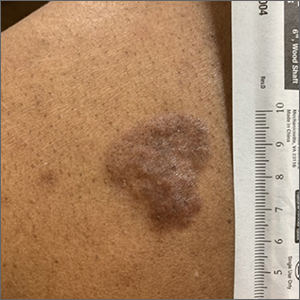

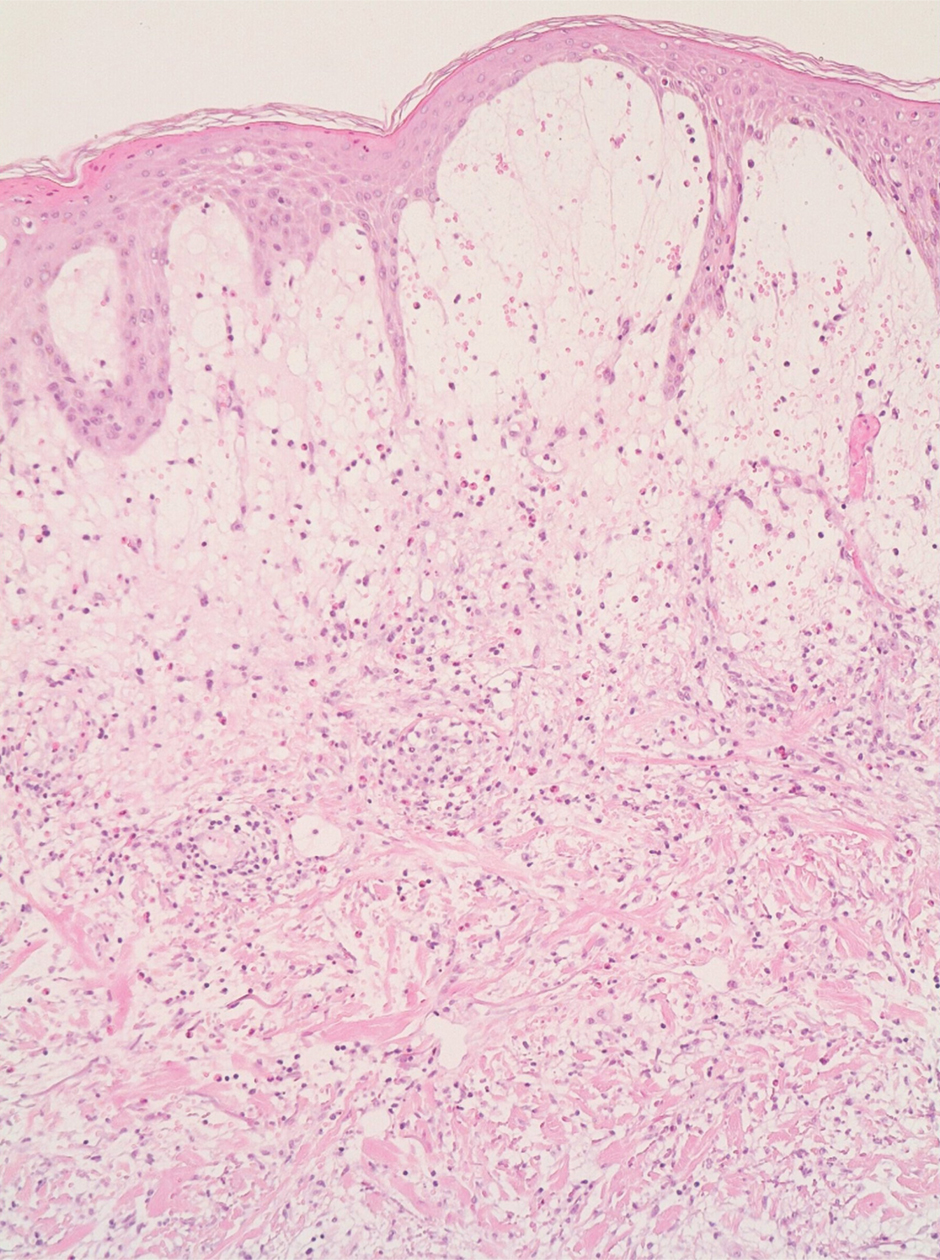

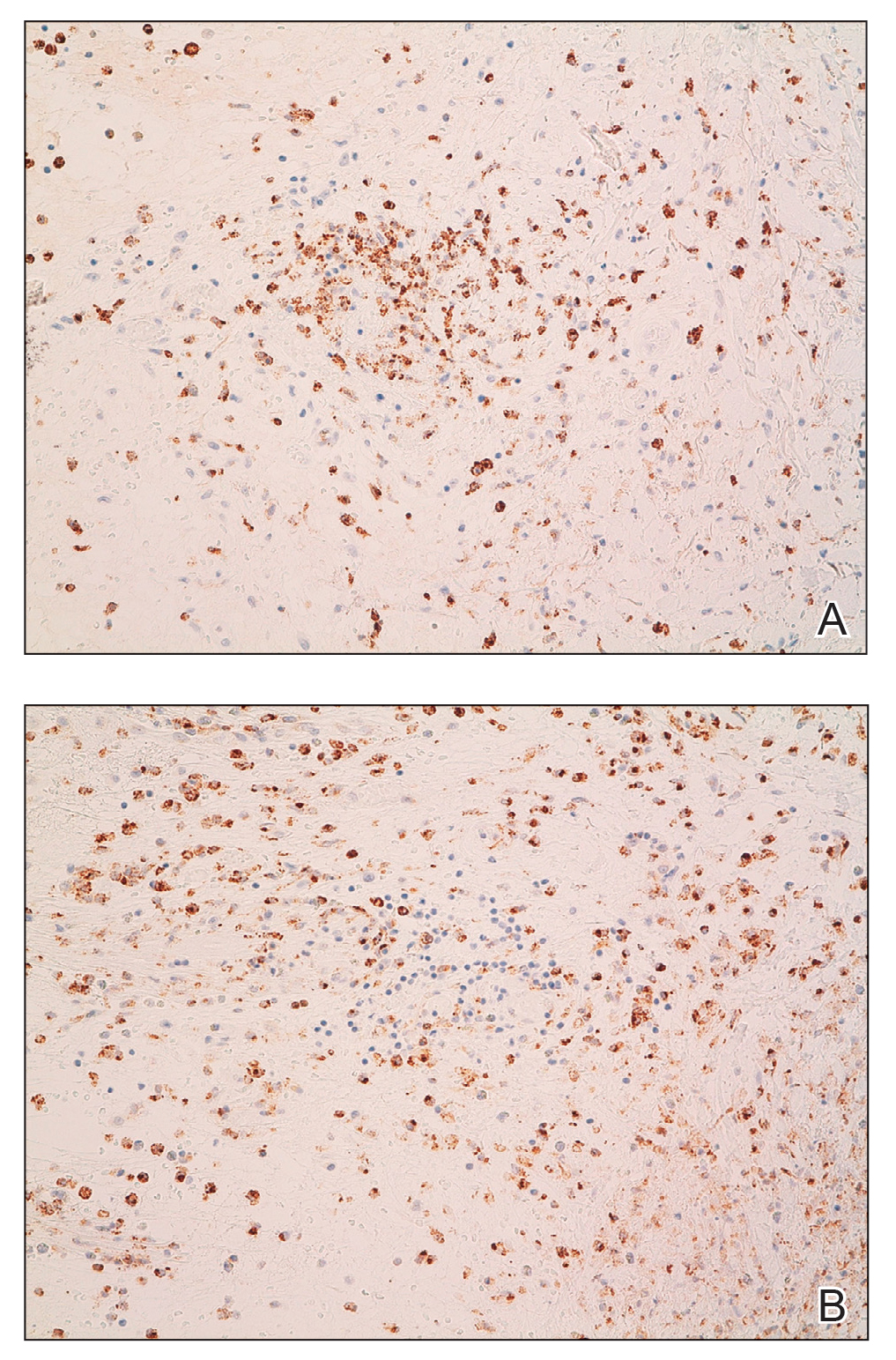

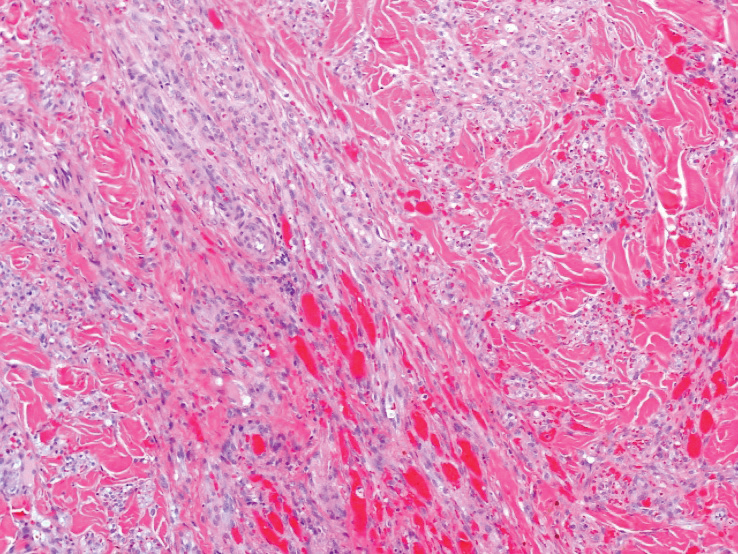

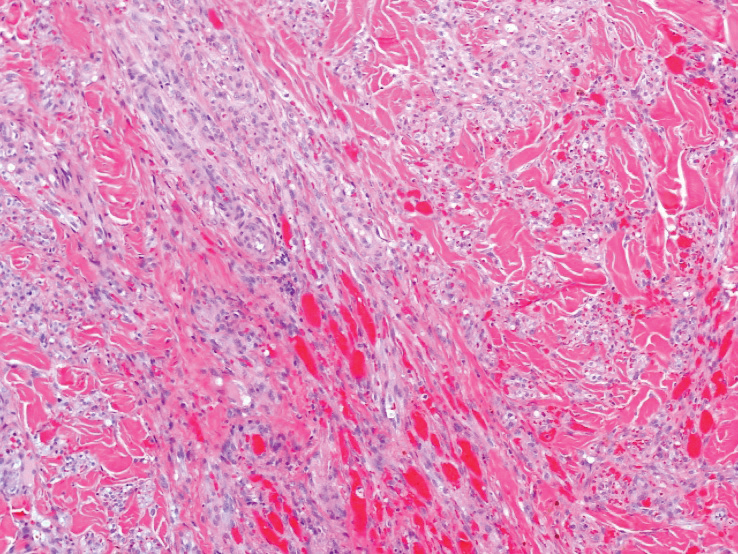

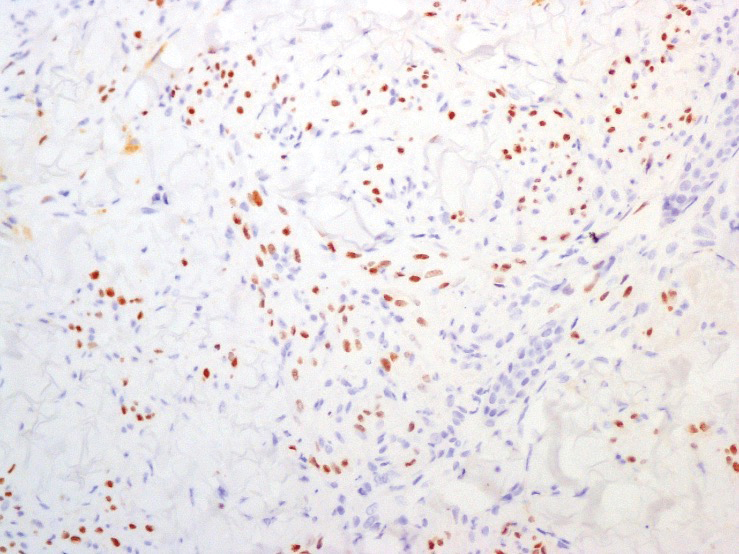

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative, AIDSdefining disease associated with HHV-8. There are 4 types of KS as defined by the populations they affect. AIDS-associated KS occurs in individuals with HIV, as seen in our patient. It often is accompanied by extensive mucocutaneous and visceral lesions, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and diarrhea.1 Classic KS is a variant that presents in older men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and South American descent. Cutaneous lesions typically are distributed on the lower extremities.2,3 Endemic (African) KS is seen in HIV-negative children and young adults in equatorial Africa. It most commonly affects the lower extremities or lymph nodes and usually follows a more aggressive course.2 Lastly, iatrogenic KS is associated with immunosuppressive medications or conditions, such as organ transplantation, chemotherapy, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4

Kaposi sarcoma commonly presents as violaceous or dark red macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules on various parts of the body (Figure 3). Lesions typically begin as macules and progress into plaques or nodules. Our patient presented as a deceptively healthy young man with lesions at various stages of development. In addition to the skin and oral mucosa, the lungs, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract commonly are involved in AIDS-associated KS.5 Patients may experience symptoms of internal involvement, including bleeding, hematochezia, odynophagia, or dyspnea.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that can mimic KS, including bacillary angiomatosis, angioinvasive fungal disease, sarcoid, and other malignancies. A skin biopsy is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of KS. Histopathology shows a vascular proliferation in the dermis and spindle cell proliferation.6 Kaposi sarcoma stains positively for factor VIII–related antigen, CD31, and CD34.2 Additionally, staining for HHV-8 gene products, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen 1, is helpful in differentiating KS from other conditions.7

In HIV-associated KS, the mainstay of treatment is initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Typically, as the CD4 count rises with treatment, the tumor burden classic KS, effective treatment options include recurrent cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutics, such as vincristine, for localized lesions; for widespread disease, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or radiation have been found to be effective options. Lastly, for patients with iatrogenic KS, reducing immunosuppressive medications is a reasonable first step in management. If this does not yield adequate improvement, transitioning from calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine) to proliferation signal inhibitors (eg, sirolimus) may lead to resolution.7

- Friedman-Kien AE, Saltzman BR. Clinical manifestations of classical, endemic African, and epidemic AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1237-1250.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542.

- Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy. a 5‐year material of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Norway. Cancer. 1978;42:2626-2630.

- Lemlich G, Schwam L, Lebwohl M. Kaposi’s sarcoma and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: postmortem findings in twenty-four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:319-325.

- Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:10.

- Curtiss P, Strazzulla LC, Friedman-Kien AE. An update on Kaposi’s sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:465-470.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative, AIDSdefining disease associated with HHV-8. There are 4 types of KS as defined by the populations they affect. AIDS-associated KS occurs in individuals with HIV, as seen in our patient. It often is accompanied by extensive mucocutaneous and visceral lesions, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and diarrhea.1 Classic KS is a variant that presents in older men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and South American descent. Cutaneous lesions typically are distributed on the lower extremities.2,3 Endemic (African) KS is seen in HIV-negative children and young adults in equatorial Africa. It most commonly affects the lower extremities or lymph nodes and usually follows a more aggressive course.2 Lastly, iatrogenic KS is associated with immunosuppressive medications or conditions, such as organ transplantation, chemotherapy, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4

Kaposi sarcoma commonly presents as violaceous or dark red macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules on various parts of the body (Figure 3). Lesions typically begin as macules and progress into plaques or nodules. Our patient presented as a deceptively healthy young man with lesions at various stages of development. In addition to the skin and oral mucosa, the lungs, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract commonly are involved in AIDS-associated KS.5 Patients may experience symptoms of internal involvement, including bleeding, hematochezia, odynophagia, or dyspnea.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that can mimic KS, including bacillary angiomatosis, angioinvasive fungal disease, sarcoid, and other malignancies. A skin biopsy is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of KS. Histopathology shows a vascular proliferation in the dermis and spindle cell proliferation.6 Kaposi sarcoma stains positively for factor VIII–related antigen, CD31, and CD34.2 Additionally, staining for HHV-8 gene products, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen 1, is helpful in differentiating KS from other conditions.7

In HIV-associated KS, the mainstay of treatment is initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Typically, as the CD4 count rises with treatment, the tumor burden classic KS, effective treatment options include recurrent cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutics, such as vincristine, for localized lesions; for widespread disease, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or radiation have been found to be effective options. Lastly, for patients with iatrogenic KS, reducing immunosuppressive medications is a reasonable first step in management. If this does not yield adequate improvement, transitioning from calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine) to proliferation signal inhibitors (eg, sirolimus) may lead to resolution.7

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.