User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Sustained response at 2 years reported for newly approved oral psoriasis agent

MILAN – The day after deucravacitinib became the first TYK2 inhibitor approved for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis, long-term data were presented at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, suggesting that a high degree of benefit persists for at least 2 years, making this oral drug a potential competitor for biologics.

,” said Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, professor of dermatology and dean of clinical therapeutics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Just 2 months after the 52-week data from the phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial were published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, a long-term extension study found essentially no loss of benefit at 112 weeks, according to Dr. Lebwohl.

One of the two co-primary endpoints was a 75% clearance on the Psoriasis and Severity Index (PASI75) score. At 52 weeks, 80.2% of patients on deucravacitinib had met this criterion of benefit. At 112 weeks, the proportion was 84.4%.

The other primary endpoint was a static Physician’s Global Assessment (sPGA) score of clear or almost clear skin. The proportion of patients meeting this criterion at weeks 52 and 112 weeks were 65.6% and 67.6%, respectively.

When assessed by Treatment Failure Rule (TFR) or modified nonresponder imputation (mNRI), results were similar. For both, the primary endpoints at every time interval were just one or two percentage points lower but not clinically meaningfully different, according to Dr. Lebwohl.

The same type of sustained response out to 112 weeks was observed in multiple analyses. When the researchers isolated the subgroup of patients who had achieved a PASI 75 response at 16 weeks (100%), there was a modest decline in the PASI 75 rate at week 52 (90.2%) but then no additional decline at week 112 (91.3%).

There were essentially no changes in the PASI 90 rates at week 16 (63%), week 52 (65.3%), and week 112 (63.1%), Dr. Lebwohl reported. PASI 100 rates, once achieved, were sustained long term.

The target, TYK2, is one of four Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. Until now, almost all JAK inhibitors have had greater relative specificity for JAK 1, JAK 2, and JAK 3, but several inhibitors of TYK2 inhibitors other than deucravacitinib are in development for inflammatory diseases. Deucravacitinib (Sotyktu), approved by the Food and Drug Administration on Sept. 9, is the only TYK2 inhibitor with regulatory approval for plaque psoriasis.

In the POETYK PSO-1 trial, 666 patients were initially randomized in a 2:1:1 ratio to 6 mg deucravacitinib (now the approved dose), placebo, or the oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor apremilast. At week 16, patients on placebo were switched over to deucravacitinib. At week 24, patients who did not achieve a PASI 50 on apremilast (which had been titrated to 10 mg daily to 30 mg twice a day over the first 5 days of dosing) were switched to deucravacitinib.

In the previously reported data, deucravacitinib was superior for all efficacy endpoints at week 16, including an analysis of quality of life when compared with placebo (P < .0001) or apremilast (P = .0088). At week 52, after having been switched to deucravacitinib at week 16, patients on placebo achieved comparable responses on the efficacy measures in this study, including PASI75.

Relative to JAK inhibitors commonly used in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases, the greater specificity of deucravacitinib for TYK2 appears to have meaningful safety advantages, according to Dr. Lebwohl. Targeted mostly on the TYK2 regulatory domain, deucravacitinib largely avoids inhibition of the JAK 1, 2, and 3 subtypes. Dr. Lebwohl said this explains why deucravacitinib labeling does not share the boxed warnings about off-target effects, such as those on the cardiovascular system, that can be found in the labeling of other JAK inhibitors.

In the published 52-week data, the discontinuation rate for adverse events was lower in the group randomized to deucravacitinib arm than in the placebo arm. In the extended follow-up, there were no new signals for adverse events, including those involving the CV system or immune function.

The key message so far from the long-term follow-up, which is ongoing, is that “continuous treatment with deucravacitinib is associated with durable efficacy,” Dr. Lebwohl said. It is this combination of sustained efficacy and safety that led Dr. Lebwohl to suggest it as a reasonable oral competitor to injectable biologics.

“Patients now have a choice,” he said.

Jashin J. Wu, MD, a board member of the National Psoriasis Foundation and an associate professor in the department of dermatology, University of Miami, has been following the development of deucravacitinib. He said that the recent FDA approval validates the clinical evidence of benefit and safety, while the long-term data presented at the EADV congress support its role in expanding treatment options.

“Deucravacitinib is a very effective oral agent for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with strong maintenance of effect through week 112,” he said. Differentiating it from other JAK inhibitors, the FDA approval “confirms the safety of this agent as there is no boxed warning,” he added.

Dr. Lebwohl reports financial relationships with more than 30 pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, the manufacturer of deucravacitinib. Dr. Wu has financial relationships with 14 pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, but he was not an investigator for the phase 3 trials of deucravacitinib.

MILAN – The day after deucravacitinib became the first TYK2 inhibitor approved for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis, long-term data were presented at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, suggesting that a high degree of benefit persists for at least 2 years, making this oral drug a potential competitor for biologics.

,” said Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, professor of dermatology and dean of clinical therapeutics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Just 2 months after the 52-week data from the phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial were published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, a long-term extension study found essentially no loss of benefit at 112 weeks, according to Dr. Lebwohl.

One of the two co-primary endpoints was a 75% clearance on the Psoriasis and Severity Index (PASI75) score. At 52 weeks, 80.2% of patients on deucravacitinib had met this criterion of benefit. At 112 weeks, the proportion was 84.4%.

The other primary endpoint was a static Physician’s Global Assessment (sPGA) score of clear or almost clear skin. The proportion of patients meeting this criterion at weeks 52 and 112 weeks were 65.6% and 67.6%, respectively.

When assessed by Treatment Failure Rule (TFR) or modified nonresponder imputation (mNRI), results were similar. For both, the primary endpoints at every time interval were just one or two percentage points lower but not clinically meaningfully different, according to Dr. Lebwohl.

The same type of sustained response out to 112 weeks was observed in multiple analyses. When the researchers isolated the subgroup of patients who had achieved a PASI 75 response at 16 weeks (100%), there was a modest decline in the PASI 75 rate at week 52 (90.2%) but then no additional decline at week 112 (91.3%).

There were essentially no changes in the PASI 90 rates at week 16 (63%), week 52 (65.3%), and week 112 (63.1%), Dr. Lebwohl reported. PASI 100 rates, once achieved, were sustained long term.

The target, TYK2, is one of four Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. Until now, almost all JAK inhibitors have had greater relative specificity for JAK 1, JAK 2, and JAK 3, but several inhibitors of TYK2 inhibitors other than deucravacitinib are in development for inflammatory diseases. Deucravacitinib (Sotyktu), approved by the Food and Drug Administration on Sept. 9, is the only TYK2 inhibitor with regulatory approval for plaque psoriasis.

In the POETYK PSO-1 trial, 666 patients were initially randomized in a 2:1:1 ratio to 6 mg deucravacitinib (now the approved dose), placebo, or the oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor apremilast. At week 16, patients on placebo were switched over to deucravacitinib. At week 24, patients who did not achieve a PASI 50 on apremilast (which had been titrated to 10 mg daily to 30 mg twice a day over the first 5 days of dosing) were switched to deucravacitinib.

In the previously reported data, deucravacitinib was superior for all efficacy endpoints at week 16, including an analysis of quality of life when compared with placebo (P < .0001) or apremilast (P = .0088). At week 52, after having been switched to deucravacitinib at week 16, patients on placebo achieved comparable responses on the efficacy measures in this study, including PASI75.

Relative to JAK inhibitors commonly used in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases, the greater specificity of deucravacitinib for TYK2 appears to have meaningful safety advantages, according to Dr. Lebwohl. Targeted mostly on the TYK2 regulatory domain, deucravacitinib largely avoids inhibition of the JAK 1, 2, and 3 subtypes. Dr. Lebwohl said this explains why deucravacitinib labeling does not share the boxed warnings about off-target effects, such as those on the cardiovascular system, that can be found in the labeling of other JAK inhibitors.

In the published 52-week data, the discontinuation rate for adverse events was lower in the group randomized to deucravacitinib arm than in the placebo arm. In the extended follow-up, there were no new signals for adverse events, including those involving the CV system or immune function.

The key message so far from the long-term follow-up, which is ongoing, is that “continuous treatment with deucravacitinib is associated with durable efficacy,” Dr. Lebwohl said. It is this combination of sustained efficacy and safety that led Dr. Lebwohl to suggest it as a reasonable oral competitor to injectable biologics.

“Patients now have a choice,” he said.

Jashin J. Wu, MD, a board member of the National Psoriasis Foundation and an associate professor in the department of dermatology, University of Miami, has been following the development of deucravacitinib. He said that the recent FDA approval validates the clinical evidence of benefit and safety, while the long-term data presented at the EADV congress support its role in expanding treatment options.

“Deucravacitinib is a very effective oral agent for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with strong maintenance of effect through week 112,” he said. Differentiating it from other JAK inhibitors, the FDA approval “confirms the safety of this agent as there is no boxed warning,” he added.

Dr. Lebwohl reports financial relationships with more than 30 pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, the manufacturer of deucravacitinib. Dr. Wu has financial relationships with 14 pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, but he was not an investigator for the phase 3 trials of deucravacitinib.

MILAN – The day after deucravacitinib became the first TYK2 inhibitor approved for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis, long-term data were presented at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, suggesting that a high degree of benefit persists for at least 2 years, making this oral drug a potential competitor for biologics.

,” said Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, professor of dermatology and dean of clinical therapeutics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Just 2 months after the 52-week data from the phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial were published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, a long-term extension study found essentially no loss of benefit at 112 weeks, according to Dr. Lebwohl.

One of the two co-primary endpoints was a 75% clearance on the Psoriasis and Severity Index (PASI75) score. At 52 weeks, 80.2% of patients on deucravacitinib had met this criterion of benefit. At 112 weeks, the proportion was 84.4%.

The other primary endpoint was a static Physician’s Global Assessment (sPGA) score of clear or almost clear skin. The proportion of patients meeting this criterion at weeks 52 and 112 weeks were 65.6% and 67.6%, respectively.

When assessed by Treatment Failure Rule (TFR) or modified nonresponder imputation (mNRI), results were similar. For both, the primary endpoints at every time interval were just one or two percentage points lower but not clinically meaningfully different, according to Dr. Lebwohl.

The same type of sustained response out to 112 weeks was observed in multiple analyses. When the researchers isolated the subgroup of patients who had achieved a PASI 75 response at 16 weeks (100%), there was a modest decline in the PASI 75 rate at week 52 (90.2%) but then no additional decline at week 112 (91.3%).

There were essentially no changes in the PASI 90 rates at week 16 (63%), week 52 (65.3%), and week 112 (63.1%), Dr. Lebwohl reported. PASI 100 rates, once achieved, were sustained long term.

The target, TYK2, is one of four Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. Until now, almost all JAK inhibitors have had greater relative specificity for JAK 1, JAK 2, and JAK 3, but several inhibitors of TYK2 inhibitors other than deucravacitinib are in development for inflammatory diseases. Deucravacitinib (Sotyktu), approved by the Food and Drug Administration on Sept. 9, is the only TYK2 inhibitor with regulatory approval for plaque psoriasis.

In the POETYK PSO-1 trial, 666 patients were initially randomized in a 2:1:1 ratio to 6 mg deucravacitinib (now the approved dose), placebo, or the oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor apremilast. At week 16, patients on placebo were switched over to deucravacitinib. At week 24, patients who did not achieve a PASI 50 on apremilast (which had been titrated to 10 mg daily to 30 mg twice a day over the first 5 days of dosing) were switched to deucravacitinib.

In the previously reported data, deucravacitinib was superior for all efficacy endpoints at week 16, including an analysis of quality of life when compared with placebo (P < .0001) or apremilast (P = .0088). At week 52, after having been switched to deucravacitinib at week 16, patients on placebo achieved comparable responses on the efficacy measures in this study, including PASI75.

Relative to JAK inhibitors commonly used in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases, the greater specificity of deucravacitinib for TYK2 appears to have meaningful safety advantages, according to Dr. Lebwohl. Targeted mostly on the TYK2 regulatory domain, deucravacitinib largely avoids inhibition of the JAK 1, 2, and 3 subtypes. Dr. Lebwohl said this explains why deucravacitinib labeling does not share the boxed warnings about off-target effects, such as those on the cardiovascular system, that can be found in the labeling of other JAK inhibitors.

In the published 52-week data, the discontinuation rate for adverse events was lower in the group randomized to deucravacitinib arm than in the placebo arm. In the extended follow-up, there were no new signals for adverse events, including those involving the CV system or immune function.

The key message so far from the long-term follow-up, which is ongoing, is that “continuous treatment with deucravacitinib is associated with durable efficacy,” Dr. Lebwohl said. It is this combination of sustained efficacy and safety that led Dr. Lebwohl to suggest it as a reasonable oral competitor to injectable biologics.

“Patients now have a choice,” he said.

Jashin J. Wu, MD, a board member of the National Psoriasis Foundation and an associate professor in the department of dermatology, University of Miami, has been following the development of deucravacitinib. He said that the recent FDA approval validates the clinical evidence of benefit and safety, while the long-term data presented at the EADV congress support its role in expanding treatment options.

“Deucravacitinib is a very effective oral agent for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with strong maintenance of effect through week 112,” he said. Differentiating it from other JAK inhibitors, the FDA approval “confirms the safety of this agent as there is no boxed warning,” he added.

Dr. Lebwohl reports financial relationships with more than 30 pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, the manufacturer of deucravacitinib. Dr. Wu has financial relationships with 14 pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, but he was not an investigator for the phase 3 trials of deucravacitinib.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

‘Dr. Caveman’ had a leg up on amputation

Monkey see, monkey do (advanced medical procedures)

We don’t tend to think too kindly of our prehistoric ancestors. We throw around the word “caveman” – hardly a term of endearment – and depictions of Paleolithic humans rarely flatter their subjects. In many ways, though, our conceptions are correct. Humans of the Stone Age lived short, often brutish lives, but civilization had to start somewhere, and our prehistoric ancestors were often far more capable than we give them credit for.

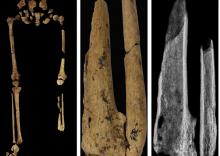

Case in point is a recent discovery from an archaeological dig in Borneo: A young adult who lived 31,000 years ago was discovered with the lower third of their left leg amputated. Save the clever retort about the person’s untimely death, because this individual did not die from the surgery. The amputation occurred when the individual was a child and the subject lived for several years after the operation.

Amputation is usually unnecessary given our current level of medical technology, but it’s actually quite an advanced procedure, and this example predates the previous first case of amputation by nearly 25,000 years. Not only did the surgeon need to cut at an appropriate place, they needed to understand blood loss, the risk of infection, and the need to preserve skin in order to seal the wound back up. That’s quite a lot for our Paleolithic doctor to know, and it’s even more impressive considering the, shall we say, limited tools they would have had available to perform the operation.

Rocks. They cut off the leg with a rock. And it worked.

This discovery also gives insight into the amputee’s society. Someone knew that amputation was the right move for this person, indicating that it had been done before. In addition, the individual would not have been able to spring back into action hunting mammoths right away, they would require care for the rest of their lives. And clearly the community provided, given the individual’s continued life post operation and their burial in a place of honor.

If only the American health care system was capable of such feats of compassion, but that would require the majority of politicians to be as clever as cavemen. We’re not hopeful on those odds.

The first step is admitting you have a crying baby. The second step is … a step

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Crying baby.

Crying baby who?

Crying baby who … umm … doesn’t have a punchline. Let’s try this again.

A priest, a rabbi, and a crying baby walk into a bar and … nope, that’s not going to work.

Why did the crying baby cross the road? Ugh, never mind.

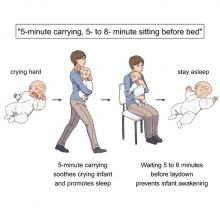

Clearly, crying babies are no laughing matter. What crying babies need is science. And the latest innovation – it’s fresh from a study conducted at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science in Saitama, Japan – in the science of crying babies is … walking. Researchers observed 21 unhappy infants and compared their responses to four strategies: being held by their walking mothers, held by their sitting mothers, lying in a motionless crib, or lying in a rocking cot.

The best strategy is for the mother – the experiment only involved mothers, but the results should apply to any caregiver – to pick up the crying baby, walk around for 5 minutes, sit for another 5-8 minutes, and then put the infant back to bed, the researchers said in a written statement.

The walking strategy, however, isn’t perfect. “Walking for 5 minutes promoted sleep, but only for crying infants. Surprisingly, this effect was absent when babies were already calm beforehand,” lead author Kumi O. Kuroda, MD, PhD, explained in a separate statement from the center.

It also doesn’t work on adults. We could not get a crying LOTME writer to fall asleep no matter how long his mother carried him around the office.

New way to detect Parkinson’s has already passed the sniff test

We humans aren’t generally known for our superpowers, but a woman from Scotland may just be the Smelling Superhero. Not only was she able to literally smell Parkinson’s disease (PD) on her husband 12 years before his diagnosis; she is also the reason that scientists have found a new way to test for PD.

Joy Milne, a retired nurse, told the BBC that her husband “had this musty rather unpleasant smell especially round his shoulders and the back of his neck and his skin had definitely changed.” She put two and two together after he had been diagnosed with PD and she came in contact with others with the same scent at a support group.

Researchers at the University of Manchester, working with Ms. Milne, have now created a skin test that uses mass spectroscopy to analyze a sample of the patient’s sebum in just 3 minutes and is 95% accurate. They tested 79 people with Parkinson’s and 71 without using this method and found “specific compounds unique to PD sebum samples when compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, we have identified two classes of lipids, namely, triacylglycerides and diglycerides, as components of human sebum that are significantly differentially expressed in PD,” they said in JACS Au.

This test could be available to general physicians within 2 years, which would provide new opportunities to the people who are waiting in line for neurologic consults. Ms. Milne’s husband passed away in 2015, but her courageous help and amazing nasal abilities may help millions down the line.

The power of flirting

It’s a common office stereotype: Women flirt with the boss to get ahead in the workplace, while men in power sexually harass women in subordinate positions. Nobody ever suspects the guys in the cubicles. A recent study takes a different look and paints a different picture.

The investigators conducted multiple online and lab experiments in how social sexual identity drives behavior in a workplace setting in relation to job placement. They found that it was most often men in lower-power positions who are insecure about their roles who initiate social sexual behavior, even though they know it’s offensive. Why? Power.

They randomly paired over 200 undergraduate students in a male/female fashion, placed them in subordinate and boss-like roles, and asked them to choose from a series of social sexual questions they wanted to ask their teammate. Male participants who were placed in subordinate positions to a female boss chose social sexual questions more often than did male bosses, female subordinates, and female bosses.

So what does this say about the threat of workplace harassment? The researchers found that men and women differ in their strategy for flirtation. For men, it’s a way to gain more power. But problems arise when they rationalize their behavior with a character trait like being a “big flirt.”

“When we take on that identity, it leads to certain behavioral patterns that reinforce the identity. And then, people use that identity as an excuse,” lead author Laura Kray of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement from the school.

The researchers make a point to note that the study isn’t about whether flirting is good or bad, nor are they suggesting that people in powerful positions don’t sexually harass underlings. It’s meant to provide insight to improve corporate sexual harassment training. A comment or conversation held in jest could potentially be a warning sign for future behavior.

Monkey see, monkey do (advanced medical procedures)

We don’t tend to think too kindly of our prehistoric ancestors. We throw around the word “caveman” – hardly a term of endearment – and depictions of Paleolithic humans rarely flatter their subjects. In many ways, though, our conceptions are correct. Humans of the Stone Age lived short, often brutish lives, but civilization had to start somewhere, and our prehistoric ancestors were often far more capable than we give them credit for.

Case in point is a recent discovery from an archaeological dig in Borneo: A young adult who lived 31,000 years ago was discovered with the lower third of their left leg amputated. Save the clever retort about the person’s untimely death, because this individual did not die from the surgery. The amputation occurred when the individual was a child and the subject lived for several years after the operation.

Amputation is usually unnecessary given our current level of medical technology, but it’s actually quite an advanced procedure, and this example predates the previous first case of amputation by nearly 25,000 years. Not only did the surgeon need to cut at an appropriate place, they needed to understand blood loss, the risk of infection, and the need to preserve skin in order to seal the wound back up. That’s quite a lot for our Paleolithic doctor to know, and it’s even more impressive considering the, shall we say, limited tools they would have had available to perform the operation.

Rocks. They cut off the leg with a rock. And it worked.

This discovery also gives insight into the amputee’s society. Someone knew that amputation was the right move for this person, indicating that it had been done before. In addition, the individual would not have been able to spring back into action hunting mammoths right away, they would require care for the rest of their lives. And clearly the community provided, given the individual’s continued life post operation and their burial in a place of honor.

If only the American health care system was capable of such feats of compassion, but that would require the majority of politicians to be as clever as cavemen. We’re not hopeful on those odds.

The first step is admitting you have a crying baby. The second step is … a step

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Crying baby.

Crying baby who?

Crying baby who … umm … doesn’t have a punchline. Let’s try this again.

A priest, a rabbi, and a crying baby walk into a bar and … nope, that’s not going to work.

Why did the crying baby cross the road? Ugh, never mind.

Clearly, crying babies are no laughing matter. What crying babies need is science. And the latest innovation – it’s fresh from a study conducted at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science in Saitama, Japan – in the science of crying babies is … walking. Researchers observed 21 unhappy infants and compared their responses to four strategies: being held by their walking mothers, held by their sitting mothers, lying in a motionless crib, or lying in a rocking cot.

The best strategy is for the mother – the experiment only involved mothers, but the results should apply to any caregiver – to pick up the crying baby, walk around for 5 minutes, sit for another 5-8 minutes, and then put the infant back to bed, the researchers said in a written statement.

The walking strategy, however, isn’t perfect. “Walking for 5 minutes promoted sleep, but only for crying infants. Surprisingly, this effect was absent when babies were already calm beforehand,” lead author Kumi O. Kuroda, MD, PhD, explained in a separate statement from the center.

It also doesn’t work on adults. We could not get a crying LOTME writer to fall asleep no matter how long his mother carried him around the office.

New way to detect Parkinson’s has already passed the sniff test

We humans aren’t generally known for our superpowers, but a woman from Scotland may just be the Smelling Superhero. Not only was she able to literally smell Parkinson’s disease (PD) on her husband 12 years before his diagnosis; she is also the reason that scientists have found a new way to test for PD.

Joy Milne, a retired nurse, told the BBC that her husband “had this musty rather unpleasant smell especially round his shoulders and the back of his neck and his skin had definitely changed.” She put two and two together after he had been diagnosed with PD and she came in contact with others with the same scent at a support group.

Researchers at the University of Manchester, working with Ms. Milne, have now created a skin test that uses mass spectroscopy to analyze a sample of the patient’s sebum in just 3 minutes and is 95% accurate. They tested 79 people with Parkinson’s and 71 without using this method and found “specific compounds unique to PD sebum samples when compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, we have identified two classes of lipids, namely, triacylglycerides and diglycerides, as components of human sebum that are significantly differentially expressed in PD,” they said in JACS Au.

This test could be available to general physicians within 2 years, which would provide new opportunities to the people who are waiting in line for neurologic consults. Ms. Milne’s husband passed away in 2015, but her courageous help and amazing nasal abilities may help millions down the line.

The power of flirting

It’s a common office stereotype: Women flirt with the boss to get ahead in the workplace, while men in power sexually harass women in subordinate positions. Nobody ever suspects the guys in the cubicles. A recent study takes a different look and paints a different picture.

The investigators conducted multiple online and lab experiments in how social sexual identity drives behavior in a workplace setting in relation to job placement. They found that it was most often men in lower-power positions who are insecure about their roles who initiate social sexual behavior, even though they know it’s offensive. Why? Power.

They randomly paired over 200 undergraduate students in a male/female fashion, placed them in subordinate and boss-like roles, and asked them to choose from a series of social sexual questions they wanted to ask their teammate. Male participants who were placed in subordinate positions to a female boss chose social sexual questions more often than did male bosses, female subordinates, and female bosses.

So what does this say about the threat of workplace harassment? The researchers found that men and women differ in their strategy for flirtation. For men, it’s a way to gain more power. But problems arise when they rationalize their behavior with a character trait like being a “big flirt.”

“When we take on that identity, it leads to certain behavioral patterns that reinforce the identity. And then, people use that identity as an excuse,” lead author Laura Kray of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement from the school.

The researchers make a point to note that the study isn’t about whether flirting is good or bad, nor are they suggesting that people in powerful positions don’t sexually harass underlings. It’s meant to provide insight to improve corporate sexual harassment training. A comment or conversation held in jest could potentially be a warning sign for future behavior.

Monkey see, monkey do (advanced medical procedures)

We don’t tend to think too kindly of our prehistoric ancestors. We throw around the word “caveman” – hardly a term of endearment – and depictions of Paleolithic humans rarely flatter their subjects. In many ways, though, our conceptions are correct. Humans of the Stone Age lived short, often brutish lives, but civilization had to start somewhere, and our prehistoric ancestors were often far more capable than we give them credit for.

Case in point is a recent discovery from an archaeological dig in Borneo: A young adult who lived 31,000 years ago was discovered with the lower third of their left leg amputated. Save the clever retort about the person’s untimely death, because this individual did not die from the surgery. The amputation occurred when the individual was a child and the subject lived for several years after the operation.

Amputation is usually unnecessary given our current level of medical technology, but it’s actually quite an advanced procedure, and this example predates the previous first case of amputation by nearly 25,000 years. Not only did the surgeon need to cut at an appropriate place, they needed to understand blood loss, the risk of infection, and the need to preserve skin in order to seal the wound back up. That’s quite a lot for our Paleolithic doctor to know, and it’s even more impressive considering the, shall we say, limited tools they would have had available to perform the operation.

Rocks. They cut off the leg with a rock. And it worked.

This discovery also gives insight into the amputee’s society. Someone knew that amputation was the right move for this person, indicating that it had been done before. In addition, the individual would not have been able to spring back into action hunting mammoths right away, they would require care for the rest of their lives. And clearly the community provided, given the individual’s continued life post operation and their burial in a place of honor.

If only the American health care system was capable of such feats of compassion, but that would require the majority of politicians to be as clever as cavemen. We’re not hopeful on those odds.

The first step is admitting you have a crying baby. The second step is … a step

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Crying baby.

Crying baby who?

Crying baby who … umm … doesn’t have a punchline. Let’s try this again.

A priest, a rabbi, and a crying baby walk into a bar and … nope, that’s not going to work.

Why did the crying baby cross the road? Ugh, never mind.

Clearly, crying babies are no laughing matter. What crying babies need is science. And the latest innovation – it’s fresh from a study conducted at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science in Saitama, Japan – in the science of crying babies is … walking. Researchers observed 21 unhappy infants and compared their responses to four strategies: being held by their walking mothers, held by their sitting mothers, lying in a motionless crib, or lying in a rocking cot.

The best strategy is for the mother – the experiment only involved mothers, but the results should apply to any caregiver – to pick up the crying baby, walk around for 5 minutes, sit for another 5-8 minutes, and then put the infant back to bed, the researchers said in a written statement.

The walking strategy, however, isn’t perfect. “Walking for 5 minutes promoted sleep, but only for crying infants. Surprisingly, this effect was absent when babies were already calm beforehand,” lead author Kumi O. Kuroda, MD, PhD, explained in a separate statement from the center.

It also doesn’t work on adults. We could not get a crying LOTME writer to fall asleep no matter how long his mother carried him around the office.

New way to detect Parkinson’s has already passed the sniff test

We humans aren’t generally known for our superpowers, but a woman from Scotland may just be the Smelling Superhero. Not only was she able to literally smell Parkinson’s disease (PD) on her husband 12 years before his diagnosis; she is also the reason that scientists have found a new way to test for PD.

Joy Milne, a retired nurse, told the BBC that her husband “had this musty rather unpleasant smell especially round his shoulders and the back of his neck and his skin had definitely changed.” She put two and two together after he had been diagnosed with PD and she came in contact with others with the same scent at a support group.

Researchers at the University of Manchester, working with Ms. Milne, have now created a skin test that uses mass spectroscopy to analyze a sample of the patient’s sebum in just 3 minutes and is 95% accurate. They tested 79 people with Parkinson’s and 71 without using this method and found “specific compounds unique to PD sebum samples when compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, we have identified two classes of lipids, namely, triacylglycerides and diglycerides, as components of human sebum that are significantly differentially expressed in PD,” they said in JACS Au.

This test could be available to general physicians within 2 years, which would provide new opportunities to the people who are waiting in line for neurologic consults. Ms. Milne’s husband passed away in 2015, but her courageous help and amazing nasal abilities may help millions down the line.

The power of flirting

It’s a common office stereotype: Women flirt with the boss to get ahead in the workplace, while men in power sexually harass women in subordinate positions. Nobody ever suspects the guys in the cubicles. A recent study takes a different look and paints a different picture.

The investigators conducted multiple online and lab experiments in how social sexual identity drives behavior in a workplace setting in relation to job placement. They found that it was most often men in lower-power positions who are insecure about their roles who initiate social sexual behavior, even though they know it’s offensive. Why? Power.

They randomly paired over 200 undergraduate students in a male/female fashion, placed them in subordinate and boss-like roles, and asked them to choose from a series of social sexual questions they wanted to ask their teammate. Male participants who were placed in subordinate positions to a female boss chose social sexual questions more often than did male bosses, female subordinates, and female bosses.

So what does this say about the threat of workplace harassment? The researchers found that men and women differ in their strategy for flirtation. For men, it’s a way to gain more power. But problems arise when they rationalize their behavior with a character trait like being a “big flirt.”

“When we take on that identity, it leads to certain behavioral patterns that reinforce the identity. And then, people use that identity as an excuse,” lead author Laura Kray of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement from the school.

The researchers make a point to note that the study isn’t about whether flirting is good or bad, nor are they suggesting that people in powerful positions don’t sexually harass underlings. It’s meant to provide insight to improve corporate sexual harassment training. A comment or conversation held in jest could potentially be a warning sign for future behavior.

Targeted anti-IgE therapy found safe and effective for chronic urticaria

MILAN – The therapeutic .

Both doses of ligelizumab evaluated met the primary endpoint of superiority to placebo for a complete response at 16 weeks of therapy, reported Marcus Maurer, MD, director of the Urticaria Center for Reference and Excellence at the Charité Hospital, Berlin.

The data from the two identically designed trials, PEARL 1 and PEARL 2, were presented at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. The two ligelizumab experimental arms (72 mg or 120 mg administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks) and the active comparative arm of omalizumab (300 mg administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks) demonstrated similar efficacy, all three of which were highly superior to placebo.

The data show that “another anti-IgE therapy – ligelizumab – is effective in CSU,” Dr. Maurer said.

“While the benefit was not different from omalizumab, ligelizumab showed remarkable results in disease activity and by demonstrating just how many patients achieved what we want them to achieve, which is to have no more signs and symptoms,” he added.

Majority of participants with severe urticaria

All of the patients entered into the two trials had severe (about 65%) or moderate (about 35%) symptoms at baseline. The results of the two trials were almost identical. In the randomization arms, a weekly Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7) of 0, which was the primary endpoint, was achieved at week 16 by 31.0% of those receiving 72-mg ligelizumab, 38.3% of those receiving 120-mg ligelizumab, and 34.1% of those receiving omalizumab (Xolair). The placebo response was 5.7%.

The UAS7 score is drawn from two components, wheals and itch. The range is 0 (no symptoms) to 42 (most severe). At baseline, the average patients’ scores were about 30, which correlates with a substantial symptom burden, according to Dr. Maurer.

The mean reduction in the UAS7 score in PEARL 2, which differed from PEARL 1 by no more than 0.4 points for any treatment group, was 19.2 points in the 72-mg ligelizumab group, 19.3 points in the 120-mg ligelizumab group, 19.6 points in the omalizumab group, and 9.2 points in the placebo group. There were no significant differences between any active treatment arm.

Complete symptom relief, meaning a UAS7 score of 0, was selected as the primary endpoint, because Dr. Maurer said that this is the goal of treatment. Although he admitted that a UAS7 score of 0 is analogous to a PASI score in psoriasis of 100 (complete clearing), he said, “Chronic urticaria is a debilitating disease, and we want to eliminate the symptoms. Gone is gone.”

Combined, the two phase 3 trials represent “the biggest chronic urticaria program ever,” according to Dr. Maurer. The 1,034 patients enrolled in PEARL 1 and the 1,023 enrolled in PEARL 2 were randomized in a 3:3:3:1 ratio with placebo representing the smaller group.

The planned follow-up is 52 weeks, but the placebo group will be switched to 120 mg ligelizumab every 4 weeks at the end of 24 weeks. The switch is required because “you cannot maintain patients with this disease on placebo over a long period,” Dr. Maurer said.

Ligelizumab associated with low discontinuation rate

Adverse events overall and stratified by severity have been similar across treatment arms, including placebo. The possible exception was a lower rate of moderate events (16.5%) in the placebo arm relative to the 72-mg ligelizumab arm (19.8%), the 120-mg ligelizumab arm (21.6%), and the omalizumab arm (22.3%). Discontinuations because of an adverse event were under 4% in every treatment arm.

Although Dr. Maurer did not present outcomes at 52 weeks, he did note that “only 15% of those who enrolled in these trials have discontinued treatment.” He considered this remarkable in that the study was conducted in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it appears that at least some of those left the trial did so because of concern for clinic visits.

Despite the similar benefit provided by ligelizumab and omalizumab, Dr. Maurer said that subgroup analyses will be coming. The possibility that some patients benefit more from one than the another cannot yet be ruled out. There are also, as of yet, no data to determine whether at least some patients respond to one after an inadequate response to the other.

Still, given the efficacy and the safety of ligelizumab, Dr. Maurer indicated that the drug is likely to find a role in routine management of CSU if approved.

“We only have two options for chronic spontaneous urticaria. There are antihistamines, which do not usually work, and omalizumab,” he said. “It is very important we develop more treatment options.”

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, agreed.

“More therapeutic options, especially for disease states that have a small armament – even if equivalent in efficacy to established therapies – is always a win for patients as it almost always increases access to treatment,” Dr. Friedman said in an interview.

“Furthermore, the heterogeneous nature of inflammatory skin diseases is often not captured in even phase 3 studies. Therefore, having additional options could offer relief where previous therapies have failed,” he added.

Dr. Maurer reports financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis, which is developing ligelizumab. Dr. Friedman has a financial relationship with more than 20 pharmaceutical companies but has no current financial association with Novartis and was not involved in the PEARL 1 and 2 trials.

MILAN – The therapeutic .

Both doses of ligelizumab evaluated met the primary endpoint of superiority to placebo for a complete response at 16 weeks of therapy, reported Marcus Maurer, MD, director of the Urticaria Center for Reference and Excellence at the Charité Hospital, Berlin.

The data from the two identically designed trials, PEARL 1 and PEARL 2, were presented at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. The two ligelizumab experimental arms (72 mg or 120 mg administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks) and the active comparative arm of omalizumab (300 mg administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks) demonstrated similar efficacy, all three of which were highly superior to placebo.

The data show that “another anti-IgE therapy – ligelizumab – is effective in CSU,” Dr. Maurer said.

“While the benefit was not different from omalizumab, ligelizumab showed remarkable results in disease activity and by demonstrating just how many patients achieved what we want them to achieve, which is to have no more signs and symptoms,” he added.

Majority of participants with severe urticaria

All of the patients entered into the two trials had severe (about 65%) or moderate (about 35%) symptoms at baseline. The results of the two trials were almost identical. In the randomization arms, a weekly Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7) of 0, which was the primary endpoint, was achieved at week 16 by 31.0% of those receiving 72-mg ligelizumab, 38.3% of those receiving 120-mg ligelizumab, and 34.1% of those receiving omalizumab (Xolair). The placebo response was 5.7%.

The UAS7 score is drawn from two components, wheals and itch. The range is 0 (no symptoms) to 42 (most severe). At baseline, the average patients’ scores were about 30, which correlates with a substantial symptom burden, according to Dr. Maurer.

The mean reduction in the UAS7 score in PEARL 2, which differed from PEARL 1 by no more than 0.4 points for any treatment group, was 19.2 points in the 72-mg ligelizumab group, 19.3 points in the 120-mg ligelizumab group, 19.6 points in the omalizumab group, and 9.2 points in the placebo group. There were no significant differences between any active treatment arm.

Complete symptom relief, meaning a UAS7 score of 0, was selected as the primary endpoint, because Dr. Maurer said that this is the goal of treatment. Although he admitted that a UAS7 score of 0 is analogous to a PASI score in psoriasis of 100 (complete clearing), he said, “Chronic urticaria is a debilitating disease, and we want to eliminate the symptoms. Gone is gone.”

Combined, the two phase 3 trials represent “the biggest chronic urticaria program ever,” according to Dr. Maurer. The 1,034 patients enrolled in PEARL 1 and the 1,023 enrolled in PEARL 2 were randomized in a 3:3:3:1 ratio with placebo representing the smaller group.

The planned follow-up is 52 weeks, but the placebo group will be switched to 120 mg ligelizumab every 4 weeks at the end of 24 weeks. The switch is required because “you cannot maintain patients with this disease on placebo over a long period,” Dr. Maurer said.

Ligelizumab associated with low discontinuation rate

Adverse events overall and stratified by severity have been similar across treatment arms, including placebo. The possible exception was a lower rate of moderate events (16.5%) in the placebo arm relative to the 72-mg ligelizumab arm (19.8%), the 120-mg ligelizumab arm (21.6%), and the omalizumab arm (22.3%). Discontinuations because of an adverse event were under 4% in every treatment arm.

Although Dr. Maurer did not present outcomes at 52 weeks, he did note that “only 15% of those who enrolled in these trials have discontinued treatment.” He considered this remarkable in that the study was conducted in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it appears that at least some of those left the trial did so because of concern for clinic visits.

Despite the similar benefit provided by ligelizumab and omalizumab, Dr. Maurer said that subgroup analyses will be coming. The possibility that some patients benefit more from one than the another cannot yet be ruled out. There are also, as of yet, no data to determine whether at least some patients respond to one after an inadequate response to the other.

Still, given the efficacy and the safety of ligelizumab, Dr. Maurer indicated that the drug is likely to find a role in routine management of CSU if approved.

“We only have two options for chronic spontaneous urticaria. There are antihistamines, which do not usually work, and omalizumab,” he said. “It is very important we develop more treatment options.”

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, agreed.

“More therapeutic options, especially for disease states that have a small armament – even if equivalent in efficacy to established therapies – is always a win for patients as it almost always increases access to treatment,” Dr. Friedman said in an interview.

“Furthermore, the heterogeneous nature of inflammatory skin diseases is often not captured in even phase 3 studies. Therefore, having additional options could offer relief where previous therapies have failed,” he added.

Dr. Maurer reports financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis, which is developing ligelizumab. Dr. Friedman has a financial relationship with more than 20 pharmaceutical companies but has no current financial association with Novartis and was not involved in the PEARL 1 and 2 trials.

MILAN – The therapeutic .

Both doses of ligelizumab evaluated met the primary endpoint of superiority to placebo for a complete response at 16 weeks of therapy, reported Marcus Maurer, MD, director of the Urticaria Center for Reference and Excellence at the Charité Hospital, Berlin.

The data from the two identically designed trials, PEARL 1 and PEARL 2, were presented at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. The two ligelizumab experimental arms (72 mg or 120 mg administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks) and the active comparative arm of omalizumab (300 mg administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks) demonstrated similar efficacy, all three of which were highly superior to placebo.

The data show that “another anti-IgE therapy – ligelizumab – is effective in CSU,” Dr. Maurer said.

“While the benefit was not different from omalizumab, ligelizumab showed remarkable results in disease activity and by demonstrating just how many patients achieved what we want them to achieve, which is to have no more signs and symptoms,” he added.

Majority of participants with severe urticaria

All of the patients entered into the two trials had severe (about 65%) or moderate (about 35%) symptoms at baseline. The results of the two trials were almost identical. In the randomization arms, a weekly Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7) of 0, which was the primary endpoint, was achieved at week 16 by 31.0% of those receiving 72-mg ligelizumab, 38.3% of those receiving 120-mg ligelizumab, and 34.1% of those receiving omalizumab (Xolair). The placebo response was 5.7%.

The UAS7 score is drawn from two components, wheals and itch. The range is 0 (no symptoms) to 42 (most severe). At baseline, the average patients’ scores were about 30, which correlates with a substantial symptom burden, according to Dr. Maurer.

The mean reduction in the UAS7 score in PEARL 2, which differed from PEARL 1 by no more than 0.4 points for any treatment group, was 19.2 points in the 72-mg ligelizumab group, 19.3 points in the 120-mg ligelizumab group, 19.6 points in the omalizumab group, and 9.2 points in the placebo group. There were no significant differences between any active treatment arm.

Complete symptom relief, meaning a UAS7 score of 0, was selected as the primary endpoint, because Dr. Maurer said that this is the goal of treatment. Although he admitted that a UAS7 score of 0 is analogous to a PASI score in psoriasis of 100 (complete clearing), he said, “Chronic urticaria is a debilitating disease, and we want to eliminate the symptoms. Gone is gone.”

Combined, the two phase 3 trials represent “the biggest chronic urticaria program ever,” according to Dr. Maurer. The 1,034 patients enrolled in PEARL 1 and the 1,023 enrolled in PEARL 2 were randomized in a 3:3:3:1 ratio with placebo representing the smaller group.

The planned follow-up is 52 weeks, but the placebo group will be switched to 120 mg ligelizumab every 4 weeks at the end of 24 weeks. The switch is required because “you cannot maintain patients with this disease on placebo over a long period,” Dr. Maurer said.

Ligelizumab associated with low discontinuation rate

Adverse events overall and stratified by severity have been similar across treatment arms, including placebo. The possible exception was a lower rate of moderate events (16.5%) in the placebo arm relative to the 72-mg ligelizumab arm (19.8%), the 120-mg ligelizumab arm (21.6%), and the omalizumab arm (22.3%). Discontinuations because of an adverse event were under 4% in every treatment arm.

Although Dr. Maurer did not present outcomes at 52 weeks, he did note that “only 15% of those who enrolled in these trials have discontinued treatment.” He considered this remarkable in that the study was conducted in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it appears that at least some of those left the trial did so because of concern for clinic visits.

Despite the similar benefit provided by ligelizumab and omalizumab, Dr. Maurer said that subgroup analyses will be coming. The possibility that some patients benefit more from one than the another cannot yet be ruled out. There are also, as of yet, no data to determine whether at least some patients respond to one after an inadequate response to the other.

Still, given the efficacy and the safety of ligelizumab, Dr. Maurer indicated that the drug is likely to find a role in routine management of CSU if approved.

“We only have two options for chronic spontaneous urticaria. There are antihistamines, which do not usually work, and omalizumab,” he said. “It is very important we develop more treatment options.”

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, agreed.

“More therapeutic options, especially for disease states that have a small armament – even if equivalent in efficacy to established therapies – is always a win for patients as it almost always increases access to treatment,” Dr. Friedman said in an interview.

“Furthermore, the heterogeneous nature of inflammatory skin diseases is often not captured in even phase 3 studies. Therefore, having additional options could offer relief where previous therapies have failed,” he added.

Dr. Maurer reports financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis, which is developing ligelizumab. Dr. Friedman has a financial relationship with more than 20 pharmaceutical companies but has no current financial association with Novartis and was not involved in the PEARL 1 and 2 trials.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

One in three MS patients reports chronic itch

, according to investigators.

Itch is historically underrecognized as a symptom of MS, but physicians should know that it is common and may negatively impact quality of life, reported lead author Giuseppe Ingrasci, MD, a dermatology research fellow at the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, and colleagues.

While previous publications suggest that pruritus occurs in just 2%-6% of patients with MS, principal author Gil Yosipovitch, MD, professor, Stiefel Chair of Medical Dermatology, and director of the Miami Itch Center in the Dr. Phillip Frost department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, encountered itch in enough patients with MS that he presented his observations to a group of neurologists.

Most of them dismissed him, he recalled in an interview: “The neurologists said, ‘Very interesting, but we don’t really see it.’ ”

One of those neurologists, however, decided to take a closer look.

Andrew Brown, MD, assistant professor of clinical neurology and chief of the general neurology division at the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, began asking his patients with MS if they were experiencing itch and soon found that it was “a very common problem,” according to Dr. Yosipovitch.

Dr. Yosipovitch, who was the first to report pruritus in patients with psoriasis, launched the present investigation with Dr. Brown to determine if itch is also a blind spot in the world of MS. Their results, and their uphill battle to publication, suggest that it very well could be.

After being rejected from six neurology journals, with one editor suggesting that itch is “not relevant at all to neurology,” their findings were published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology & Venereology.

A common problem that may indicate more severe disease

At the Multiple Sclerosis Center of Excellence in Miami, 27 out of 79 outpatients with MS (35%) reported pruritus, with an average severity of 5.42 out of 10. Among those with itch, the extremities were affected in about half of the patients, while the face, scalp, and trunk were affected in about one-third of the patients. Many described paroxysmal itch that was aggravated by heat, and about half experienced itch on a weekly basis.

Further investigation showed that itch was associated with more severe MS. Compared with patients not experiencing itch, those with itch were significantly more likely to report fatigue (77% vs. 44%), anxiety or depression (48% vs. 16%), and cognitive impairment (62% vs. 26%).

MRI findings backed up these clinical results. Compared with patients not experiencing itch, patients with itch had significantly more T2 hyperintensities in the posterior cervical cord (74.1% vs. 46.0%) and anterior pons/ventromedial medulla (62% vs. 26%). These hyperintensities in the medulla were also associated with an 11-fold increased rate of itch on the face or scalp (odds ratio, 11.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.6-78.6, P = 0.025).

“Health care providers should be aware of episodes of localized, neuropathic itch in MS patients, as they appear to be more prevalent than previously thought and may impair these patients’ quality of life,” the investigators concluded.

Challenges with symptom characterization, management

“This is an important study for both patients and clinicians,” said Justin Abbatemarco, MD, of Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis, in a written comment. “As the authors mention, many of our patients experience transient symptoms, including many different types of sensory disturbance (that is, pins & needles, burning, electrical shocks, and itching). These symptoms can be really distressing for patients and their caregivers.”

While Dr. Abbatemarco has encountered severe itching in “several patients” with MS, he maintained that it is “relatively uncommon” and noted that MS symptomatology is an inherently cloudy subject.

“I think it is difficult to be definite in any opinion on this topic,” Dr. Abbatemarco said. “How patients experience these symptoms is very subjective and can be difficult to describe/characterize.”

Dr. Abbatemarco emphasized that transient symptoms “do not usually represent MS relapse/flare or new inflammatory disease activity. Instead, we believe these symptoms are related to old areas of injury or demyelination.”

Symptom management can be challenging, he added. He recommended setting realistic expectations, and in the case of pruritus, asking dermatologists to rule out other causes of itch, and to offer “unique treatment approaches.”

Cool the itch?

Noting how heat appears to aggravate itch in patients with MS, Dr. Yosipovitch suggested that one of those unique – and simple – treatment approaches may be cooling itchy areas. Alternatively, clinicians may consider oral agents, like gabapentin to dampen neural transmission, or compounded formulations applied to the skin to reduce neural sensitivity, such as topical ketamine. Finally, Dr. Yosipovitch speculated that newer antibody agents for MS could potentially reduce itch.

All these treatment suggestions are purely hypothetical, he said, and require further investigation before they can be recommended with confidence.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Galderma, Pfizer, Novartis, and others. Dr. Abbatemarco disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Correction, 9/19/22: An earlier version of this article misidentified the photo of Dr. Justin Abbatemarco.

, according to investigators.

Itch is historically underrecognized as a symptom of MS, but physicians should know that it is common and may negatively impact quality of life, reported lead author Giuseppe Ingrasci, MD, a dermatology research fellow at the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, and colleagues.

While previous publications suggest that pruritus occurs in just 2%-6% of patients with MS, principal author Gil Yosipovitch, MD, professor, Stiefel Chair of Medical Dermatology, and director of the Miami Itch Center in the Dr. Phillip Frost department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, encountered itch in enough patients with MS that he presented his observations to a group of neurologists.

Most of them dismissed him, he recalled in an interview: “The neurologists said, ‘Very interesting, but we don’t really see it.’ ”

One of those neurologists, however, decided to take a closer look.

Andrew Brown, MD, assistant professor of clinical neurology and chief of the general neurology division at the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, began asking his patients with MS if they were experiencing itch and soon found that it was “a very common problem,” according to Dr. Yosipovitch.

Dr. Yosipovitch, who was the first to report pruritus in patients with psoriasis, launched the present investigation with Dr. Brown to determine if itch is also a blind spot in the world of MS. Their results, and their uphill battle to publication, suggest that it very well could be.

After being rejected from six neurology journals, with one editor suggesting that itch is “not relevant at all to neurology,” their findings were published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology & Venereology.

A common problem that may indicate more severe disease

At the Multiple Sclerosis Center of Excellence in Miami, 27 out of 79 outpatients with MS (35%) reported pruritus, with an average severity of 5.42 out of 10. Among those with itch, the extremities were affected in about half of the patients, while the face, scalp, and trunk were affected in about one-third of the patients. Many described paroxysmal itch that was aggravated by heat, and about half experienced itch on a weekly basis.

Further investigation showed that itch was associated with more severe MS. Compared with patients not experiencing itch, those with itch were significantly more likely to report fatigue (77% vs. 44%), anxiety or depression (48% vs. 16%), and cognitive impairment (62% vs. 26%).

MRI findings backed up these clinical results. Compared with patients not experiencing itch, patients with itch had significantly more T2 hyperintensities in the posterior cervical cord (74.1% vs. 46.0%) and anterior pons/ventromedial medulla (62% vs. 26%). These hyperintensities in the medulla were also associated with an 11-fold increased rate of itch on the face or scalp (odds ratio, 11.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.6-78.6, P = 0.025).

“Health care providers should be aware of episodes of localized, neuropathic itch in MS patients, as they appear to be more prevalent than previously thought and may impair these patients’ quality of life,” the investigators concluded.

Challenges with symptom characterization, management

“This is an important study for both patients and clinicians,” said Justin Abbatemarco, MD, of Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis, in a written comment. “As the authors mention, many of our patients experience transient symptoms, including many different types of sensory disturbance (that is, pins & needles, burning, electrical shocks, and itching). These symptoms can be really distressing for patients and their caregivers.”

While Dr. Abbatemarco has encountered severe itching in “several patients” with MS, he maintained that it is “relatively uncommon” and noted that MS symptomatology is an inherently cloudy subject.

“I think it is difficult to be definite in any opinion on this topic,” Dr. Abbatemarco said. “How patients experience these symptoms is very subjective and can be difficult to describe/characterize.”

Dr. Abbatemarco emphasized that transient symptoms “do not usually represent MS relapse/flare or new inflammatory disease activity. Instead, we believe these symptoms are related to old areas of injury or demyelination.”

Symptom management can be challenging, he added. He recommended setting realistic expectations, and in the case of pruritus, asking dermatologists to rule out other causes of itch, and to offer “unique treatment approaches.”

Cool the itch?

Noting how heat appears to aggravate itch in patients with MS, Dr. Yosipovitch suggested that one of those unique – and simple – treatment approaches may be cooling itchy areas. Alternatively, clinicians may consider oral agents, like gabapentin to dampen neural transmission, or compounded formulations applied to the skin to reduce neural sensitivity, such as topical ketamine. Finally, Dr. Yosipovitch speculated that newer antibody agents for MS could potentially reduce itch.

All these treatment suggestions are purely hypothetical, he said, and require further investigation before they can be recommended with confidence.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Galderma, Pfizer, Novartis, and others. Dr. Abbatemarco disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Correction, 9/19/22: An earlier version of this article misidentified the photo of Dr. Justin Abbatemarco.

, according to investigators.

Itch is historically underrecognized as a symptom of MS, but physicians should know that it is common and may negatively impact quality of life, reported lead author Giuseppe Ingrasci, MD, a dermatology research fellow at the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, and colleagues.

While previous publications suggest that pruritus occurs in just 2%-6% of patients with MS, principal author Gil Yosipovitch, MD, professor, Stiefel Chair of Medical Dermatology, and director of the Miami Itch Center in the Dr. Phillip Frost department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, encountered itch in enough patients with MS that he presented his observations to a group of neurologists.

Most of them dismissed him, he recalled in an interview: “The neurologists said, ‘Very interesting, but we don’t really see it.’ ”

One of those neurologists, however, decided to take a closer look.

Andrew Brown, MD, assistant professor of clinical neurology and chief of the general neurology division at the University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, began asking his patients with MS if they were experiencing itch and soon found that it was “a very common problem,” according to Dr. Yosipovitch.

Dr. Yosipovitch, who was the first to report pruritus in patients with psoriasis, launched the present investigation with Dr. Brown to determine if itch is also a blind spot in the world of MS. Their results, and their uphill battle to publication, suggest that it very well could be.

After being rejected from six neurology journals, with one editor suggesting that itch is “not relevant at all to neurology,” their findings were published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology & Venereology.

A common problem that may indicate more severe disease

At the Multiple Sclerosis Center of Excellence in Miami, 27 out of 79 outpatients with MS (35%) reported pruritus, with an average severity of 5.42 out of 10. Among those with itch, the extremities were affected in about half of the patients, while the face, scalp, and trunk were affected in about one-third of the patients. Many described paroxysmal itch that was aggravated by heat, and about half experienced itch on a weekly basis.

Further investigation showed that itch was associated with more severe MS. Compared with patients not experiencing itch, those with itch were significantly more likely to report fatigue (77% vs. 44%), anxiety or depression (48% vs. 16%), and cognitive impairment (62% vs. 26%).

MRI findings backed up these clinical results. Compared with patients not experiencing itch, patients with itch had significantly more T2 hyperintensities in the posterior cervical cord (74.1% vs. 46.0%) and anterior pons/ventromedial medulla (62% vs. 26%). These hyperintensities in the medulla were also associated with an 11-fold increased rate of itch on the face or scalp (odds ratio, 11.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.6-78.6, P = 0.025).

“Health care providers should be aware of episodes of localized, neuropathic itch in MS patients, as they appear to be more prevalent than previously thought and may impair these patients’ quality of life,” the investigators concluded.

Challenges with symptom characterization, management

“This is an important study for both patients and clinicians,” said Justin Abbatemarco, MD, of Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis, in a written comment. “As the authors mention, many of our patients experience transient symptoms, including many different types of sensory disturbance (that is, pins & needles, burning, electrical shocks, and itching). These symptoms can be really distressing for patients and their caregivers.”

While Dr. Abbatemarco has encountered severe itching in “several patients” with MS, he maintained that it is “relatively uncommon” and noted that MS symptomatology is an inherently cloudy subject.

“I think it is difficult to be definite in any opinion on this topic,” Dr. Abbatemarco said. “How patients experience these symptoms is very subjective and can be difficult to describe/characterize.”

Dr. Abbatemarco emphasized that transient symptoms “do not usually represent MS relapse/flare or new inflammatory disease activity. Instead, we believe these symptoms are related to old areas of injury or demyelination.”

Symptom management can be challenging, he added. He recommended setting realistic expectations, and in the case of pruritus, asking dermatologists to rule out other causes of itch, and to offer “unique treatment approaches.”

Cool the itch?

Noting how heat appears to aggravate itch in patients with MS, Dr. Yosipovitch suggested that one of those unique – and simple – treatment approaches may be cooling itchy areas. Alternatively, clinicians may consider oral agents, like gabapentin to dampen neural transmission, or compounded formulations applied to the skin to reduce neural sensitivity, such as topical ketamine. Finally, Dr. Yosipovitch speculated that newer antibody agents for MS could potentially reduce itch.

All these treatment suggestions are purely hypothetical, he said, and require further investigation before they can be recommended with confidence.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Galderma, Pfizer, Novartis, and others. Dr. Abbatemarco disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Correction, 9/19/22: An earlier version of this article misidentified the photo of Dr. Justin Abbatemarco.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE EUROPEAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY & VENEREOLOGY

Not just what, but when: Neoadjuvant pembrolizumab in melanoma

PARIS – “It’s not just what you give, it’s when you give it,” said the investigator reporting “that the same treatment for resectable melanoma given in a different sequence can generate lower rates of melanoma recurrence.”

Sapna Patel, MD, associate professor of melanoma medical oncology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, reported the results from the SWOG S1801 trial, which showed that than patients who received pembrolizumab after surgery only.

At a median follow-up of almost 15 months, there was a 42% lower rate of recurrence or death.

“Compared to the same treatment given entirely in the adjuvant setting, neoadjuvant pembrolizumab followed by adjuvant pembrolizumab improves event-free survival in resectable melanoma,” Dr. Patel commented.

She suggested that the explanation for the findings was that “inhibiting the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoints before surgery gives an antitumor response at local and distant sites, and this occurs before resection of the tumor bed. This approach tends to leave behind a larger number of anti-tumor T cells ... [and] these T cells can be activated and circulated systematically to recognize and attack micro-metastatic melanoma tumors.”

The findings were presented during a presidential symposium at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2022, Paris.

“This trial provides us with more evidence of when one strategy may be preferred over the other,” commented Maya Dimitrova, MD, medical oncologist at NYU Langone Perlmutter Cancer Center. She was not involved with the trial.

“Neoadjuvant immunotherapy has elicited impressive complete pathologic responses, which thus far have proven to be associated with a durable response. Neoadjuvant therapy may help identify patients who will respond well to checkpoint inhibitors and allow for de-escalation of therapy,” she told this news organization when approached for comment.

“As with all neoadjuvant therapy, we don’t want the treatment to compromise the outcomes of surgery when the intent is curative, and we once again have evidence that this is not the case when it comes to immune therapy,” she said. However, she added that “we will need further survival data to really change the standard of practice in high-risk melanoma and demonstrate whether there is a superior sequence of therapy and surgery.”

Details of the new results

The S1801 clinical trial enrolled 345 participants with stage IIIB through stage IV melanoma considered resectable. The cohort was randomized to receive either upfront surgery followed by 18 doses of pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks for a total of 18 doses or neoadjuvant therapy with pembrolizumab 200 mg (3 doses) followed by 15 doses of adjuvant pembrolizumab.

The primary endpoint was event-free survival (EFS), defined as the time from randomization to the occurrence of one of the following: disease progression or toxicity that resulted in not receiving surgery, failure to begin adjuvant therapy within 84 days of surgery, melanoma recurrence after surgery, or death from any cause.

At a median follow-up of 14.7 months, EFS was significantly higher for patients in the neoadjuvant group, compared with those receiving adjuvant therapy only (HR, 0.58; one-sided log-rank P = .004). A total of 36 participants died in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant groups (14 and 22 patients, extrapolating to a hazard ratio of 0.63; one-sided P = .091).

“With a limited number of events, overall survival is not statistically different at this time,” Dr. Patel said. “Landmark 2-year survival was 72% in the neoadjuvant arm and 49% in the adjuvant arm.”

The authors note that the benefit of neoadjuvant therapy remained consistent across a range of factors, including patient age, sex, performance status, stage of disease, ulceration, and BRAF status. The same proportion of patients in both groups received adjuvant pembrolizumab following surgery.

Rates of adverse events were similar in both groups, and neoadjuvant pembrolizumab did not result in an increase in adverse events related to surgery. In the neoadjuvant group, 28 patients (21%) with submitted pathology reports were noted to have had a complete pathologic response (0% viable tumor) on local review.

Questions remain

Invited discussant James Larkin, PhD, FRCP, FMedSci, a clinical researcher at The Royal Marsden Hospital, London, noted that the study had “striking results” and was a landmark trial with a simple but powerful design.

However, he pointed to some questions which need to be addressed in the future. “One important question is what is the optimal duration of neoadjuvant treatment, and can we individualize it?”

Another question is just how much postoperative treatment is really needed and whether pathology help determine that. “Can surgery be safely avoided altogether?” he asked. “Another issue is the need for anti-CTL4 therapy – which patients might benefit from anti-CTL4, in addition to anti-PD-1?”

“And by extension, this paradigm provides a great platform for testing new agents, including combinations in cases where PD-1 is not sufficient to achieve a sufficient response,” said Dr. Larkin. “In the future, trials addressing these questions hand us a major opportunity to individualize and rationally de-escalate treatment.”