User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Topical PDE4 Inhibitor Now Approved for Atopic Dermatitis in Children, Adults

On July 9, the aged 6 years or older.

Roflumilast cream 0.15%, which has been developed by Arcutis Biotherapeutics and is marketed under the brand name Zoryve, is a steroid-free topical phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor that was previously approved in a higher concentration to treat seborrheic dermatitis and plaque psoriasis.

According to a press release from Arcutis, approval for AD was supported by positive results from three phase 3 studies, a phase 2 dose-ranging study, and two phase 1 pharmacokinetic trials. In two identical phase 3 studies known as INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2, about 40% of children and adults treated with roflumilast cream 0.15% achieved a Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) at week 4 (INTEGUMENT-1: 41.5% vs 25.2%; P < .0001; INTEGUMENT-2: 39% vs 16.9%; P < .0001), with significant improvement as early as week 1 (P < .0001).

Among children and adults who participated in the INTEGUMENT studies for 28 and 56 weeks, 61.3% and 65.7% achieved a 75% reduction in their Eczema Area and Severity Index scores, respectively. According to the company, there were no adverse reactions in the combined phase 3 pivotal trials that occurred in more than 2.9% of participants in either arm. The most common adverse reactions included headache (2.9%), nausea (1.9%), application-site pain (1.5%), diarrhea (1.5%), and vomiting (1.5%).

The product is expected to be available commercially at the end of July 2024, according to Arcutis. Roflumilast cream 0.3% is indicated for topical treatment of plaque psoriasis, including intertriginous areas, in adult and pediatric patients aged 6 years or older; roflumilast foam 0.3% is indicated for the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in adult and pediatric patients aged 9 years or older.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On July 9, the aged 6 years or older.

Roflumilast cream 0.15%, which has been developed by Arcutis Biotherapeutics and is marketed under the brand name Zoryve, is a steroid-free topical phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor that was previously approved in a higher concentration to treat seborrheic dermatitis and plaque psoriasis.

According to a press release from Arcutis, approval for AD was supported by positive results from three phase 3 studies, a phase 2 dose-ranging study, and two phase 1 pharmacokinetic trials. In two identical phase 3 studies known as INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2, about 40% of children and adults treated with roflumilast cream 0.15% achieved a Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) at week 4 (INTEGUMENT-1: 41.5% vs 25.2%; P < .0001; INTEGUMENT-2: 39% vs 16.9%; P < .0001), with significant improvement as early as week 1 (P < .0001).

Among children and adults who participated in the INTEGUMENT studies for 28 and 56 weeks, 61.3% and 65.7% achieved a 75% reduction in their Eczema Area and Severity Index scores, respectively. According to the company, there were no adverse reactions in the combined phase 3 pivotal trials that occurred in more than 2.9% of participants in either arm. The most common adverse reactions included headache (2.9%), nausea (1.9%), application-site pain (1.5%), diarrhea (1.5%), and vomiting (1.5%).

The product is expected to be available commercially at the end of July 2024, according to Arcutis. Roflumilast cream 0.3% is indicated for topical treatment of plaque psoriasis, including intertriginous areas, in adult and pediatric patients aged 6 years or older; roflumilast foam 0.3% is indicated for the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in adult and pediatric patients aged 9 years or older.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On July 9, the aged 6 years or older.

Roflumilast cream 0.15%, which has been developed by Arcutis Biotherapeutics and is marketed under the brand name Zoryve, is a steroid-free topical phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor that was previously approved in a higher concentration to treat seborrheic dermatitis and plaque psoriasis.

According to a press release from Arcutis, approval for AD was supported by positive results from three phase 3 studies, a phase 2 dose-ranging study, and two phase 1 pharmacokinetic trials. In two identical phase 3 studies known as INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2, about 40% of children and adults treated with roflumilast cream 0.15% achieved a Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) at week 4 (INTEGUMENT-1: 41.5% vs 25.2%; P < .0001; INTEGUMENT-2: 39% vs 16.9%; P < .0001), with significant improvement as early as week 1 (P < .0001).

Among children and adults who participated in the INTEGUMENT studies for 28 and 56 weeks, 61.3% and 65.7% achieved a 75% reduction in their Eczema Area and Severity Index scores, respectively. According to the company, there were no adverse reactions in the combined phase 3 pivotal trials that occurred in more than 2.9% of participants in either arm. The most common adverse reactions included headache (2.9%), nausea (1.9%), application-site pain (1.5%), diarrhea (1.5%), and vomiting (1.5%).

The product is expected to be available commercially at the end of July 2024, according to Arcutis. Roflumilast cream 0.3% is indicated for topical treatment of plaque psoriasis, including intertriginous areas, in adult and pediatric patients aged 6 years or older; roflumilast foam 0.3% is indicated for the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in adult and pediatric patients aged 9 years or older.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Brazilian Peppertree: Watch Out for This Lesser-Known Relative of Poison Ivy

Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia), a member of the Anacardiaceae family, is an internationally invasive plant that causes allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in susceptible individuals. This noxious weed has settled into the landscape of the southern United States and continues to expand. Its key identifying features include its year-round white flowers as well as a peppery and turpentinelike aroma created by cracking its bright red berries. The ACD associated with contact—primarily with the plant’s sap—stems from known alkenyl phenols, cardol and cardanol. Treatment of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD parallels that for poison ivy. As this pest increases its range, dermatologists living in endemic areas should familiarize themselves with Brazilian peppertree and its potential for harm.

Brazilian Peppertree Morphology and Geography

Plants in the Anacardiaceae family contribute to more ACD than any other family, and its 80 genera include most of the urushiol-containing plants, such as Toxicodendron (poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac, Japanese lacquer tree), Anacardium (cashew tree), Mangifera (mango fruit), Semecarpus (India marking nut tree), and Schinus (Brazilian peppertree). Deciduous and evergreen tree members of the Anacardiaceae family grow primarily in tropical and subtropical locations and produce thick resins, 5-petalled flowers, and small fruit known as drupes. The genus name for Brazilian peppertree, Schinus, derives from Latin and Greek words meaning “mastic tree,” a relative of the pistachio tree that the Brazilian peppertree resembles.1 Brazilian peppertree leaves look and smell similar to Pistacia terebinthus (turpentine tree or terebinth), from which the species name terebinthifolia derives.2

Brazilian peppertree originated in South America, particularly Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina.3 Since the 1840s,4 it has been an invasive weed in the United States, notably in Florida, California, Hawaii, Alabama, Georgia,5 Arizona,6 Nevada,3 and Texas.5,7 The plant also grows throughout the world, including parts of Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe,6 New Zealand,8 Australia, and various islands.9 The plant expertly outcompetes neighboring plants and has prompted control and eradication efforts in many locations.3

Identifying Features and Allergenic Plant Parts

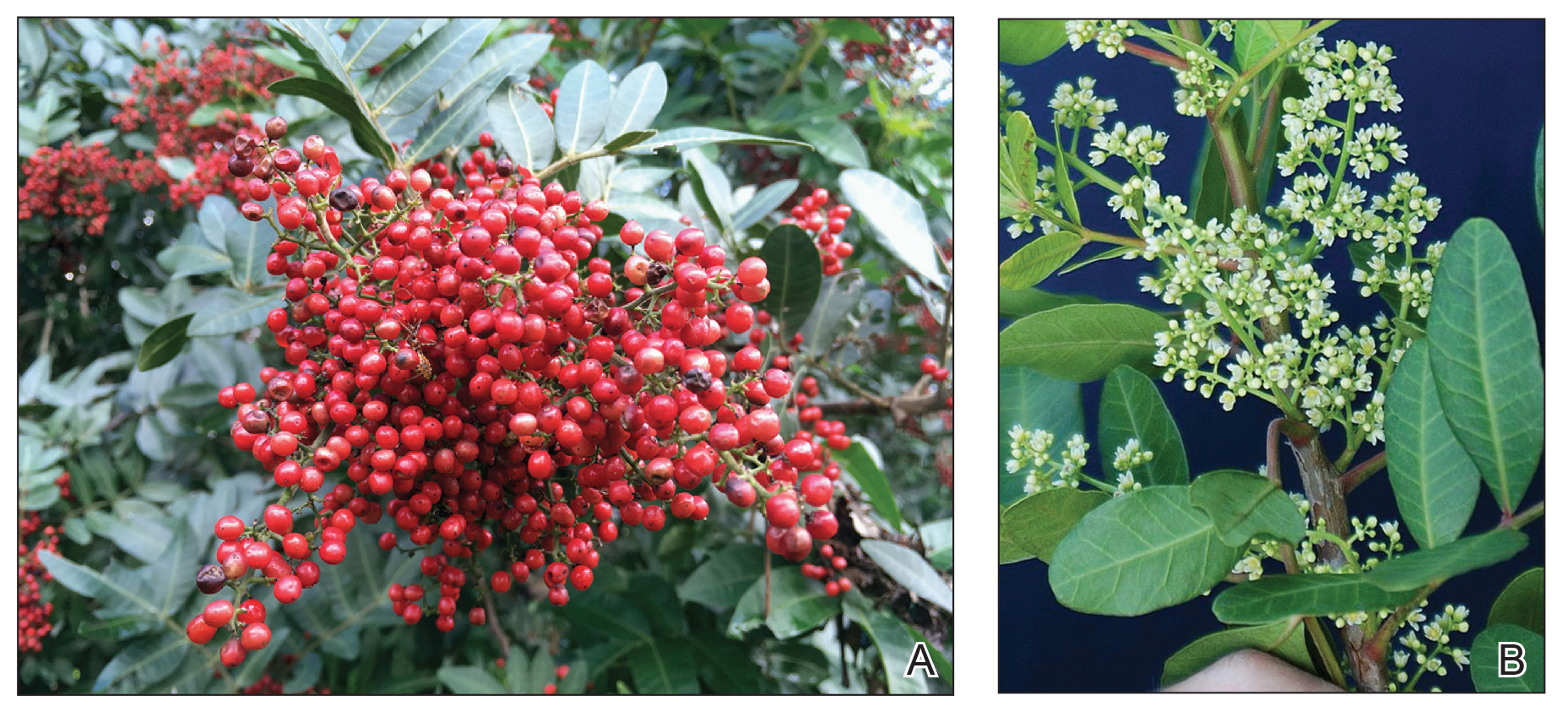

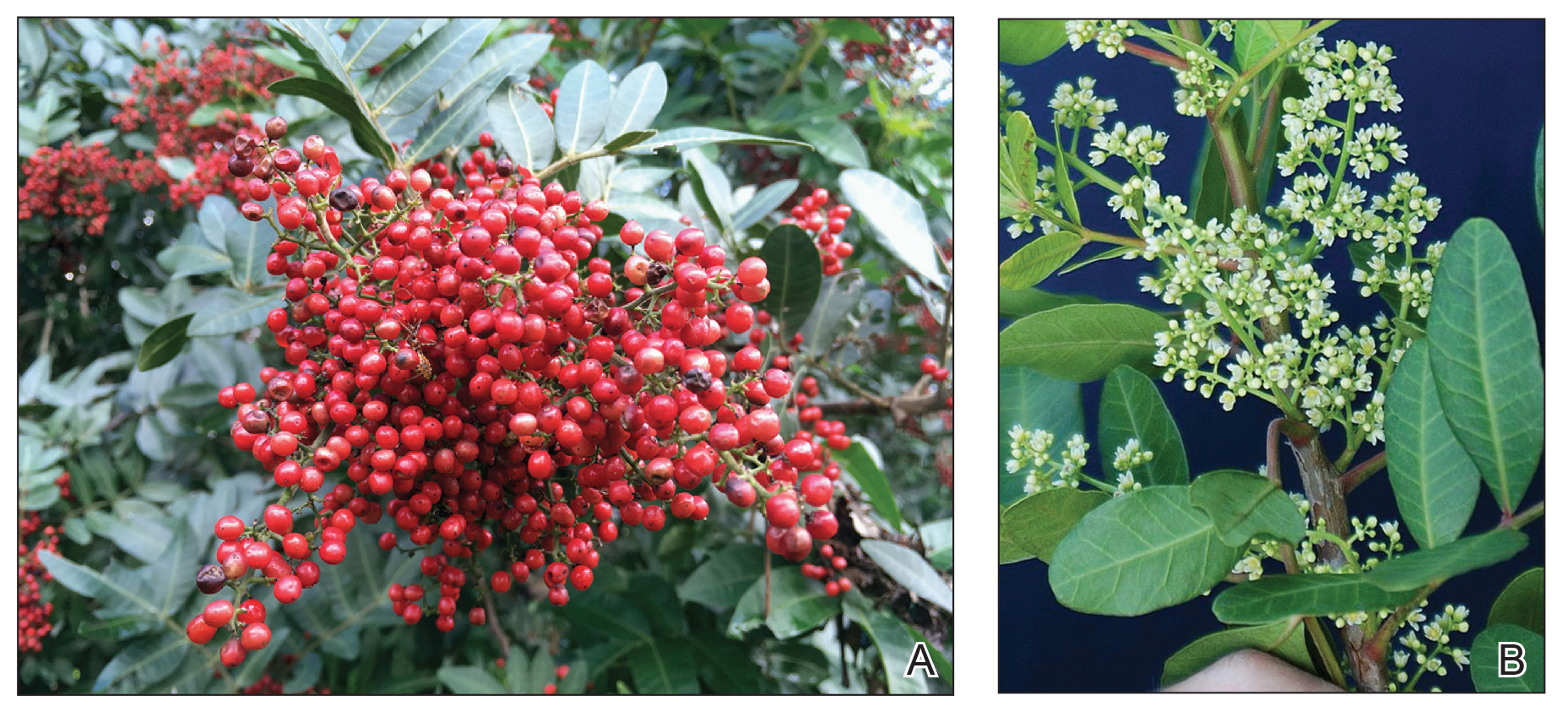

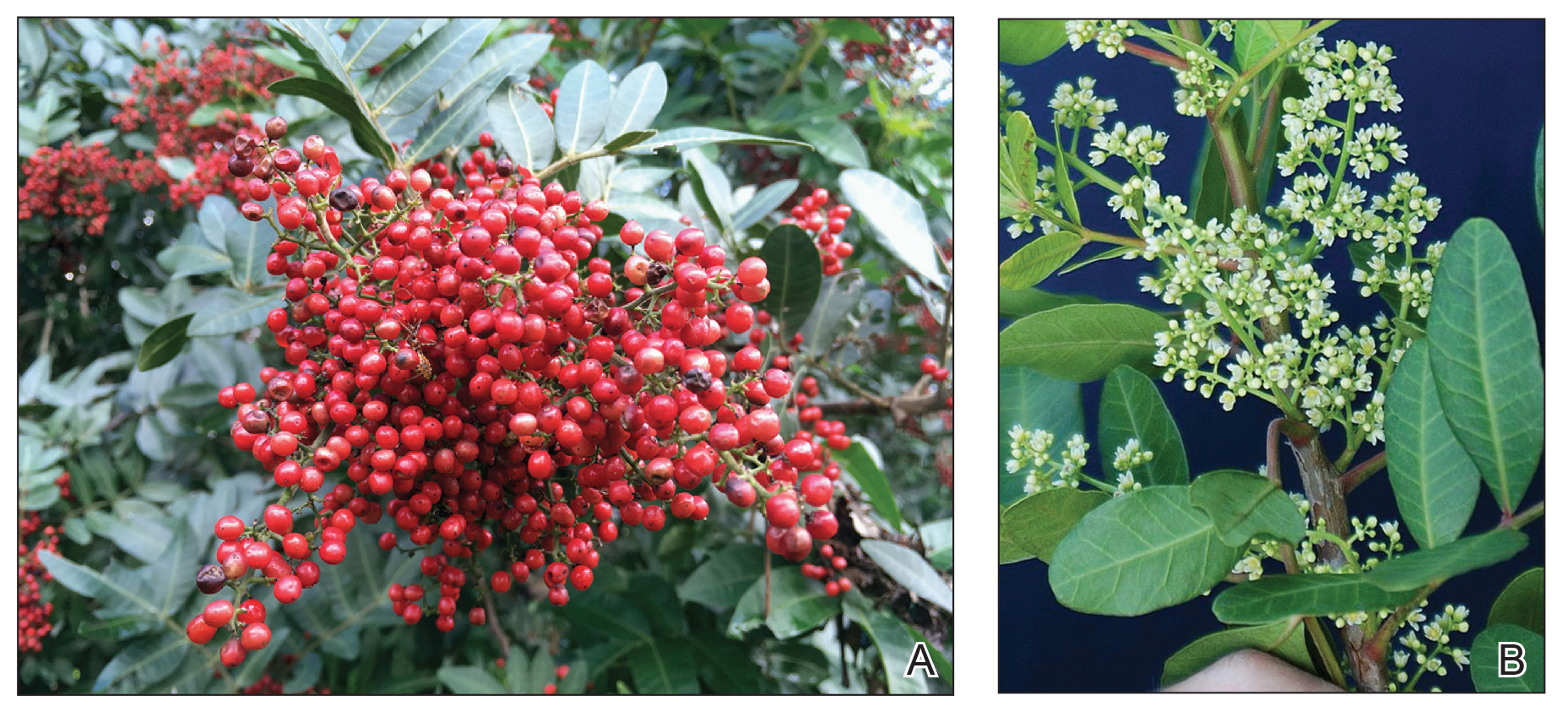

Brazilian peppertree can be either a shrub or tree up to 30 feet tall.4 As an evergreen, it retains its leaves year-round. During fruiting seasons (primarily December through March7), bright red or pink (depending on the variety3) berries appear (Figure 1A) and contribute to its nickname “Florida holly.” Although generally considered an unwelcome guest in Florida, it does display white flowers (Figure 1B) year-round, especially from September to November.9 It characteristically exhibits 3 to 13 leaflets per leaf.10 The leaflets’ ovoid and ridged edges, netlike vasculature, shiny hue, and aroma can help identify the plant (Figure 2A). For decades, the sap of the Brazilian peppertree has been associated with skin irritation (Figure 2B).6 Although the sap of the plant serves as the main culprit of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD, it appears that other parts of the plant, including the fruit, can cause irritating effects to skin on contact.11,12 The leaves, trunk, and fruit can be harmful to both humans and animals.6 Chemicals from flowers and crushed fruit also can lead to irritating effects in the respiratory tract if aspirated.13

Urushiol, an oily resin present in most plants of the Anacardiaceae family,14 contains many chemicals, including allergenic phenols, catechols, and resorcinols.15 Urushiol-allergic individuals develop dermatitis upon exposure to Brazilian peppertree sap.6 Alkenyl phenols found in Brazilian peppertree lead to the cutaneous manifestations in sensitized patients.11,12 In 1983, Stahl et al11 identified a phenol, cardanol (chemical name 3-pentadecylphenol16) C15:1, in Brazilian peppertree fruit. The group further tested this compound’s effect on skin via patch testing, which showed an allergic response.11 Cashew nut shells (Anacardium occidentale) contain cardanol, anacardic acid (a phenolic acid), and cardol (a phenol with the chemical name 5-pentadecylresorcinol),15,16 though Stahl et al11 were unable to extract these 2 substances (if present) from Brazilian peppertree fruit. When exposed to cardol and anacardic acid, those allergic to poison ivy often develop ACD,15 and these 2 substances are more irritating than cardanol.11 A later study did identify cardol in addition to cardanol in Brazilian peppertree.12

Cutaneous Manifestations

Brazilian peppertree–induced ACD appears similar to other plant-induced ACD with linear streaks of erythema, juicy papules, vesicles, coalescing erythematous plaques, and/or occasional edema and bullae accompanied by intense pruritus.

Treatment

Avoiding contact with Brazilian peppertree is the first line of defense, and treatment for a reaction associated with exposure is similar to that of poison ivy.17 Application of cool compresses, calamine lotion, and topical astringents offer symptom alleviation, and topical steroids (eg, clobetasol propionate 0.05% twice daily) can improve mild localized ACD when given prior to formation of blisters. For more severe and diffuse ACD, oral steroids (eg, prednisone 1 mg/kg/d tapered over 2–3 weeks) likely are necessary, though intramuscular options greatly alleviate discomfort in more severe cases (eg, intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide 1 mg/kg combined with betamethasone 0.1 mg/kg). Physicians should monitor sites for any signs of superimposed bacterial infection and initiate antibiotics as necessary.17

- Zona S. The correct gender of Schinus (Anacardiaceae). Phytotaxa. 2015;222:075-077.

- Terebinth. Encyclopedia.com website. Updated May 17, 2018. Accessed July 9, 2024. https://www.encyclopedia.com/plants-and-animals/plants/plants/terebinth

- Brazilian pepper tree. iNaturalist website. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/841531#:~:text=Throughout% 20South%20and%20Central%20America,and%20as%20a%20topical%20antiseptic

- Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Schinus terebinthifolia. Brazilian peppertree. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/schinus-terebinthifolia/#:~:text=Species%20Overview&text=People%20sensitive%20to%20poison%20ivy,associated%20with%20its%20bloom%20period

- Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia). Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.eddmaps.org/distribution/usstate.cfm?sub=78819

- Morton F. Brazilian pepper: its impact on people, animals, and the environment. Econ Bot. 1978;32:353-359.

- Fire Effects Information System. Schinus terebinthifolius. US Department of Agriculture website. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/shrub/schter/all.html

- New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. Schinus terebinthifolius. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.nzpcn.org.nz/flora/species/schinus-terebinthifolius

- Rojas-Sandoval J, Acevedo-Rodriguez P. Schinus terebinthifolius (Brazilian pepper tree). CABI Compendium. July 23, 2014. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/10.1079/cabicompendium.49031

- Patocka J, Diz de Almeida J. Brazilian peppertree: review of pharmacology. Mil Med Sci Lett. 2017;86:32-41.

- Stahl E, Keller K, Blinn C. Cardanol, a skin irritant in pink pepper. Plant Medica. 1983;48:5-9.

- Skopp G, Opferkuch H-J, Schqenker G. n-Alkylphenols from Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae). In German. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 1987;42:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1515/znc-1987-1-203.

- Lloyd HA, Jaouni TM, Evans SL, et al. Terpenes of Schinus terebinthifolius. Phytochemistry. 1977;16:1301-1302.

- Goon ATJ, Goh CL. Plant dermatitis: Asian perspective. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:707-710.

- Rozas-Muñoz E, Lepoittevin JP, Pujol RM, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to plants: understanding the chemistry will help our diagnostic approach. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:456-477.

- Caillol S. Cardanol: a promising building block for biobased polymers and additives. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2018;14: 26-32.

- Prok L, McGovern T. Poison ivy (Toxicodendron) dermatitis. UpToDate. Updated June 21, 2024. Accessed July 7, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/poison-ivy-toxicodendron-dermatitis#

Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia), a member of the Anacardiaceae family, is an internationally invasive plant that causes allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in susceptible individuals. This noxious weed has settled into the landscape of the southern United States and continues to expand. Its key identifying features include its year-round white flowers as well as a peppery and turpentinelike aroma created by cracking its bright red berries. The ACD associated with contact—primarily with the plant’s sap—stems from known alkenyl phenols, cardol and cardanol. Treatment of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD parallels that for poison ivy. As this pest increases its range, dermatologists living in endemic areas should familiarize themselves with Brazilian peppertree and its potential for harm.

Brazilian Peppertree Morphology and Geography

Plants in the Anacardiaceae family contribute to more ACD than any other family, and its 80 genera include most of the urushiol-containing plants, such as Toxicodendron (poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac, Japanese lacquer tree), Anacardium (cashew tree), Mangifera (mango fruit), Semecarpus (India marking nut tree), and Schinus (Brazilian peppertree). Deciduous and evergreen tree members of the Anacardiaceae family grow primarily in tropical and subtropical locations and produce thick resins, 5-petalled flowers, and small fruit known as drupes. The genus name for Brazilian peppertree, Schinus, derives from Latin and Greek words meaning “mastic tree,” a relative of the pistachio tree that the Brazilian peppertree resembles.1 Brazilian peppertree leaves look and smell similar to Pistacia terebinthus (turpentine tree or terebinth), from which the species name terebinthifolia derives.2

Brazilian peppertree originated in South America, particularly Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina.3 Since the 1840s,4 it has been an invasive weed in the United States, notably in Florida, California, Hawaii, Alabama, Georgia,5 Arizona,6 Nevada,3 and Texas.5,7 The plant also grows throughout the world, including parts of Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe,6 New Zealand,8 Australia, and various islands.9 The plant expertly outcompetes neighboring plants and has prompted control and eradication efforts in many locations.3

Identifying Features and Allergenic Plant Parts

Brazilian peppertree can be either a shrub or tree up to 30 feet tall.4 As an evergreen, it retains its leaves year-round. During fruiting seasons (primarily December through March7), bright red or pink (depending on the variety3) berries appear (Figure 1A) and contribute to its nickname “Florida holly.” Although generally considered an unwelcome guest in Florida, it does display white flowers (Figure 1B) year-round, especially from September to November.9 It characteristically exhibits 3 to 13 leaflets per leaf.10 The leaflets’ ovoid and ridged edges, netlike vasculature, shiny hue, and aroma can help identify the plant (Figure 2A). For decades, the sap of the Brazilian peppertree has been associated with skin irritation (Figure 2B).6 Although the sap of the plant serves as the main culprit of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD, it appears that other parts of the plant, including the fruit, can cause irritating effects to skin on contact.11,12 The leaves, trunk, and fruit can be harmful to both humans and animals.6 Chemicals from flowers and crushed fruit also can lead to irritating effects in the respiratory tract if aspirated.13

Urushiol, an oily resin present in most plants of the Anacardiaceae family,14 contains many chemicals, including allergenic phenols, catechols, and resorcinols.15 Urushiol-allergic individuals develop dermatitis upon exposure to Brazilian peppertree sap.6 Alkenyl phenols found in Brazilian peppertree lead to the cutaneous manifestations in sensitized patients.11,12 In 1983, Stahl et al11 identified a phenol, cardanol (chemical name 3-pentadecylphenol16) C15:1, in Brazilian peppertree fruit. The group further tested this compound’s effect on skin via patch testing, which showed an allergic response.11 Cashew nut shells (Anacardium occidentale) contain cardanol, anacardic acid (a phenolic acid), and cardol (a phenol with the chemical name 5-pentadecylresorcinol),15,16 though Stahl et al11 were unable to extract these 2 substances (if present) from Brazilian peppertree fruit. When exposed to cardol and anacardic acid, those allergic to poison ivy often develop ACD,15 and these 2 substances are more irritating than cardanol.11 A later study did identify cardol in addition to cardanol in Brazilian peppertree.12

Cutaneous Manifestations

Brazilian peppertree–induced ACD appears similar to other plant-induced ACD with linear streaks of erythema, juicy papules, vesicles, coalescing erythematous plaques, and/or occasional edema and bullae accompanied by intense pruritus.

Treatment

Avoiding contact with Brazilian peppertree is the first line of defense, and treatment for a reaction associated with exposure is similar to that of poison ivy.17 Application of cool compresses, calamine lotion, and topical astringents offer symptom alleviation, and topical steroids (eg, clobetasol propionate 0.05% twice daily) can improve mild localized ACD when given prior to formation of blisters. For more severe and diffuse ACD, oral steroids (eg, prednisone 1 mg/kg/d tapered over 2–3 weeks) likely are necessary, though intramuscular options greatly alleviate discomfort in more severe cases (eg, intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide 1 mg/kg combined with betamethasone 0.1 mg/kg). Physicians should monitor sites for any signs of superimposed bacterial infection and initiate antibiotics as necessary.17

Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia), a member of the Anacardiaceae family, is an internationally invasive plant that causes allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in susceptible individuals. This noxious weed has settled into the landscape of the southern United States and continues to expand. Its key identifying features include its year-round white flowers as well as a peppery and turpentinelike aroma created by cracking its bright red berries. The ACD associated with contact—primarily with the plant’s sap—stems from known alkenyl phenols, cardol and cardanol. Treatment of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD parallels that for poison ivy. As this pest increases its range, dermatologists living in endemic areas should familiarize themselves with Brazilian peppertree and its potential for harm.

Brazilian Peppertree Morphology and Geography

Plants in the Anacardiaceae family contribute to more ACD than any other family, and its 80 genera include most of the urushiol-containing plants, such as Toxicodendron (poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac, Japanese lacquer tree), Anacardium (cashew tree), Mangifera (mango fruit), Semecarpus (India marking nut tree), and Schinus (Brazilian peppertree). Deciduous and evergreen tree members of the Anacardiaceae family grow primarily in tropical and subtropical locations and produce thick resins, 5-petalled flowers, and small fruit known as drupes. The genus name for Brazilian peppertree, Schinus, derives from Latin and Greek words meaning “mastic tree,” a relative of the pistachio tree that the Brazilian peppertree resembles.1 Brazilian peppertree leaves look and smell similar to Pistacia terebinthus (turpentine tree or terebinth), from which the species name terebinthifolia derives.2

Brazilian peppertree originated in South America, particularly Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina.3 Since the 1840s,4 it has been an invasive weed in the United States, notably in Florida, California, Hawaii, Alabama, Georgia,5 Arizona,6 Nevada,3 and Texas.5,7 The plant also grows throughout the world, including parts of Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe,6 New Zealand,8 Australia, and various islands.9 The plant expertly outcompetes neighboring plants and has prompted control and eradication efforts in many locations.3

Identifying Features and Allergenic Plant Parts

Brazilian peppertree can be either a shrub or tree up to 30 feet tall.4 As an evergreen, it retains its leaves year-round. During fruiting seasons (primarily December through March7), bright red or pink (depending on the variety3) berries appear (Figure 1A) and contribute to its nickname “Florida holly.” Although generally considered an unwelcome guest in Florida, it does display white flowers (Figure 1B) year-round, especially from September to November.9 It characteristically exhibits 3 to 13 leaflets per leaf.10 The leaflets’ ovoid and ridged edges, netlike vasculature, shiny hue, and aroma can help identify the plant (Figure 2A). For decades, the sap of the Brazilian peppertree has been associated with skin irritation (Figure 2B).6 Although the sap of the plant serves as the main culprit of Brazilian peppertree–associated ACD, it appears that other parts of the plant, including the fruit, can cause irritating effects to skin on contact.11,12 The leaves, trunk, and fruit can be harmful to both humans and animals.6 Chemicals from flowers and crushed fruit also can lead to irritating effects in the respiratory tract if aspirated.13

Urushiol, an oily resin present in most plants of the Anacardiaceae family,14 contains many chemicals, including allergenic phenols, catechols, and resorcinols.15 Urushiol-allergic individuals develop dermatitis upon exposure to Brazilian peppertree sap.6 Alkenyl phenols found in Brazilian peppertree lead to the cutaneous manifestations in sensitized patients.11,12 In 1983, Stahl et al11 identified a phenol, cardanol (chemical name 3-pentadecylphenol16) C15:1, in Brazilian peppertree fruit. The group further tested this compound’s effect on skin via patch testing, which showed an allergic response.11 Cashew nut shells (Anacardium occidentale) contain cardanol, anacardic acid (a phenolic acid), and cardol (a phenol with the chemical name 5-pentadecylresorcinol),15,16 though Stahl et al11 were unable to extract these 2 substances (if present) from Brazilian peppertree fruit. When exposed to cardol and anacardic acid, those allergic to poison ivy often develop ACD,15 and these 2 substances are more irritating than cardanol.11 A later study did identify cardol in addition to cardanol in Brazilian peppertree.12

Cutaneous Manifestations

Brazilian peppertree–induced ACD appears similar to other plant-induced ACD with linear streaks of erythema, juicy papules, vesicles, coalescing erythematous plaques, and/or occasional edema and bullae accompanied by intense pruritus.

Treatment

Avoiding contact with Brazilian peppertree is the first line of defense, and treatment for a reaction associated with exposure is similar to that of poison ivy.17 Application of cool compresses, calamine lotion, and topical astringents offer symptom alleviation, and topical steroids (eg, clobetasol propionate 0.05% twice daily) can improve mild localized ACD when given prior to formation of blisters. For more severe and diffuse ACD, oral steroids (eg, prednisone 1 mg/kg/d tapered over 2–3 weeks) likely are necessary, though intramuscular options greatly alleviate discomfort in more severe cases (eg, intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide 1 mg/kg combined with betamethasone 0.1 mg/kg). Physicians should monitor sites for any signs of superimposed bacterial infection and initiate antibiotics as necessary.17

- Zona S. The correct gender of Schinus (Anacardiaceae). Phytotaxa. 2015;222:075-077.

- Terebinth. Encyclopedia.com website. Updated May 17, 2018. Accessed July 9, 2024. https://www.encyclopedia.com/plants-and-animals/plants/plants/terebinth

- Brazilian pepper tree. iNaturalist website. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/841531#:~:text=Throughout% 20South%20and%20Central%20America,and%20as%20a%20topical%20antiseptic

- Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Schinus terebinthifolia. Brazilian peppertree. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/schinus-terebinthifolia/#:~:text=Species%20Overview&text=People%20sensitive%20to%20poison%20ivy,associated%20with%20its%20bloom%20period

- Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia). Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.eddmaps.org/distribution/usstate.cfm?sub=78819

- Morton F. Brazilian pepper: its impact on people, animals, and the environment. Econ Bot. 1978;32:353-359.

- Fire Effects Information System. Schinus terebinthifolius. US Department of Agriculture website. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/shrub/schter/all.html

- New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. Schinus terebinthifolius. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.nzpcn.org.nz/flora/species/schinus-terebinthifolius

- Rojas-Sandoval J, Acevedo-Rodriguez P. Schinus terebinthifolius (Brazilian pepper tree). CABI Compendium. July 23, 2014. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/10.1079/cabicompendium.49031

- Patocka J, Diz de Almeida J. Brazilian peppertree: review of pharmacology. Mil Med Sci Lett. 2017;86:32-41.

- Stahl E, Keller K, Blinn C. Cardanol, a skin irritant in pink pepper. Plant Medica. 1983;48:5-9.

- Skopp G, Opferkuch H-J, Schqenker G. n-Alkylphenols from Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae). In German. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 1987;42:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1515/znc-1987-1-203.

- Lloyd HA, Jaouni TM, Evans SL, et al. Terpenes of Schinus terebinthifolius. Phytochemistry. 1977;16:1301-1302.

- Goon ATJ, Goh CL. Plant dermatitis: Asian perspective. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:707-710.

- Rozas-Muñoz E, Lepoittevin JP, Pujol RM, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to plants: understanding the chemistry will help our diagnostic approach. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:456-477.

- Caillol S. Cardanol: a promising building block for biobased polymers and additives. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2018;14: 26-32.

- Prok L, McGovern T. Poison ivy (Toxicodendron) dermatitis. UpToDate. Updated June 21, 2024. Accessed July 7, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/poison-ivy-toxicodendron-dermatitis#

- Zona S. The correct gender of Schinus (Anacardiaceae). Phytotaxa. 2015;222:075-077.

- Terebinth. Encyclopedia.com website. Updated May 17, 2018. Accessed July 9, 2024. https://www.encyclopedia.com/plants-and-animals/plants/plants/terebinth

- Brazilian pepper tree. iNaturalist website. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/841531#:~:text=Throughout% 20South%20and%20Central%20America,and%20as%20a%20topical%20antiseptic

- Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Schinus terebinthifolia. Brazilian peppertree. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/schinus-terebinthifolia/#:~:text=Species%20Overview&text=People%20sensitive%20to%20poison%20ivy,associated%20with%20its%20bloom%20period

- Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia). Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.eddmaps.org/distribution/usstate.cfm?sub=78819

- Morton F. Brazilian pepper: its impact on people, animals, and the environment. Econ Bot. 1978;32:353-359.

- Fire Effects Information System. Schinus terebinthifolius. US Department of Agriculture website. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/shrub/schter/all.html

- New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. Schinus terebinthifolius. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.nzpcn.org.nz/flora/species/schinus-terebinthifolius

- Rojas-Sandoval J, Acevedo-Rodriguez P. Schinus terebinthifolius (Brazilian pepper tree). CABI Compendium. July 23, 2014. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/10.1079/cabicompendium.49031

- Patocka J, Diz de Almeida J. Brazilian peppertree: review of pharmacology. Mil Med Sci Lett. 2017;86:32-41.

- Stahl E, Keller K, Blinn C. Cardanol, a skin irritant in pink pepper. Plant Medica. 1983;48:5-9.

- Skopp G, Opferkuch H-J, Schqenker G. n-Alkylphenols from Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae). In German. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 1987;42:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1515/znc-1987-1-203.

- Lloyd HA, Jaouni TM, Evans SL, et al. Terpenes of Schinus terebinthifolius. Phytochemistry. 1977;16:1301-1302.

- Goon ATJ, Goh CL. Plant dermatitis: Asian perspective. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:707-710.

- Rozas-Muñoz E, Lepoittevin JP, Pujol RM, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to plants: understanding the chemistry will help our diagnostic approach. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:456-477.

- Caillol S. Cardanol: a promising building block for biobased polymers and additives. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2018;14: 26-32.

- Prok L, McGovern T. Poison ivy (Toxicodendron) dermatitis. UpToDate. Updated June 21, 2024. Accessed July 7, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/poison-ivy-toxicodendron-dermatitis#

Practice Points

- The Anacardiaceae family contains several plants, including Brazilian peppertree and poison ivy, that have the potential to cause allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

- Hot spots for Brazilian peppertree include Florida and California, though it also has been reported in Texas, Hawaii, Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas, Nevada, and Arizona.

- Alkenyl phenols (eg, cardol, cardanol) are the key sensitizers found in Brazilian peppertree.

- Treatment consists of supportive care and either topical, oral, or intramuscular steroids depending on the extent and severity of the ACD.

Barriers to Mohs Micrographic Surgery in Japanese Patients With Basal Cell Carcinoma

Margin-controlled surgery for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the lower lip was first performed by Dr. Frederic Mohs on June 30, 1936. Since then, thousands of skin cancer surgeons have refined and adopted the technique. Due to the high cure rate and sparing of normal tissue, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has become the gold standard treatment for facial and special-site nonmelanoma skin cancer worldwide. Mohs micrographic surgery is performed on more than 876,000 tumors annually in the United States.1 Among 3.5 million Americans diagnosed with nonmelanoma skin cancer in 2006, one-quarter were treated with MMS.2 In Japan, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin malignancy, with an incidence of 3.34 cases per 100,000 individuals; SCC is the second most common, with an incidence of 2.5 cases per 100,000 individuals.3

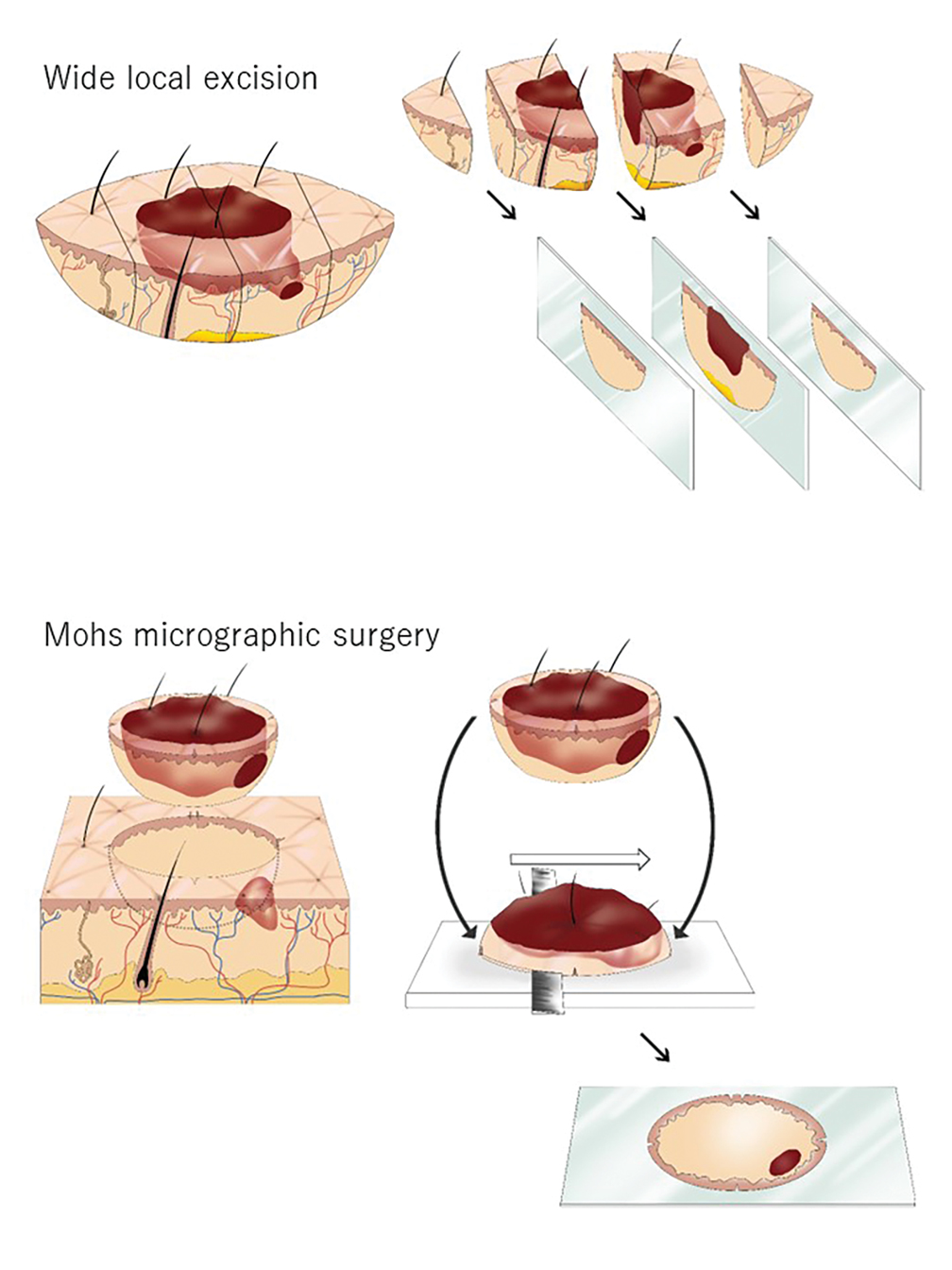

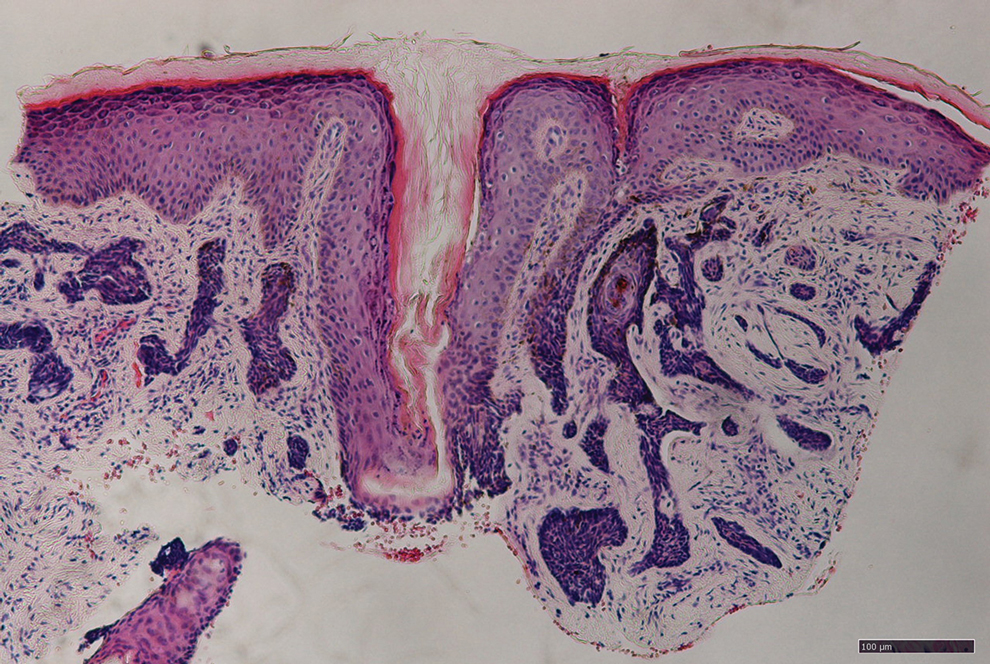

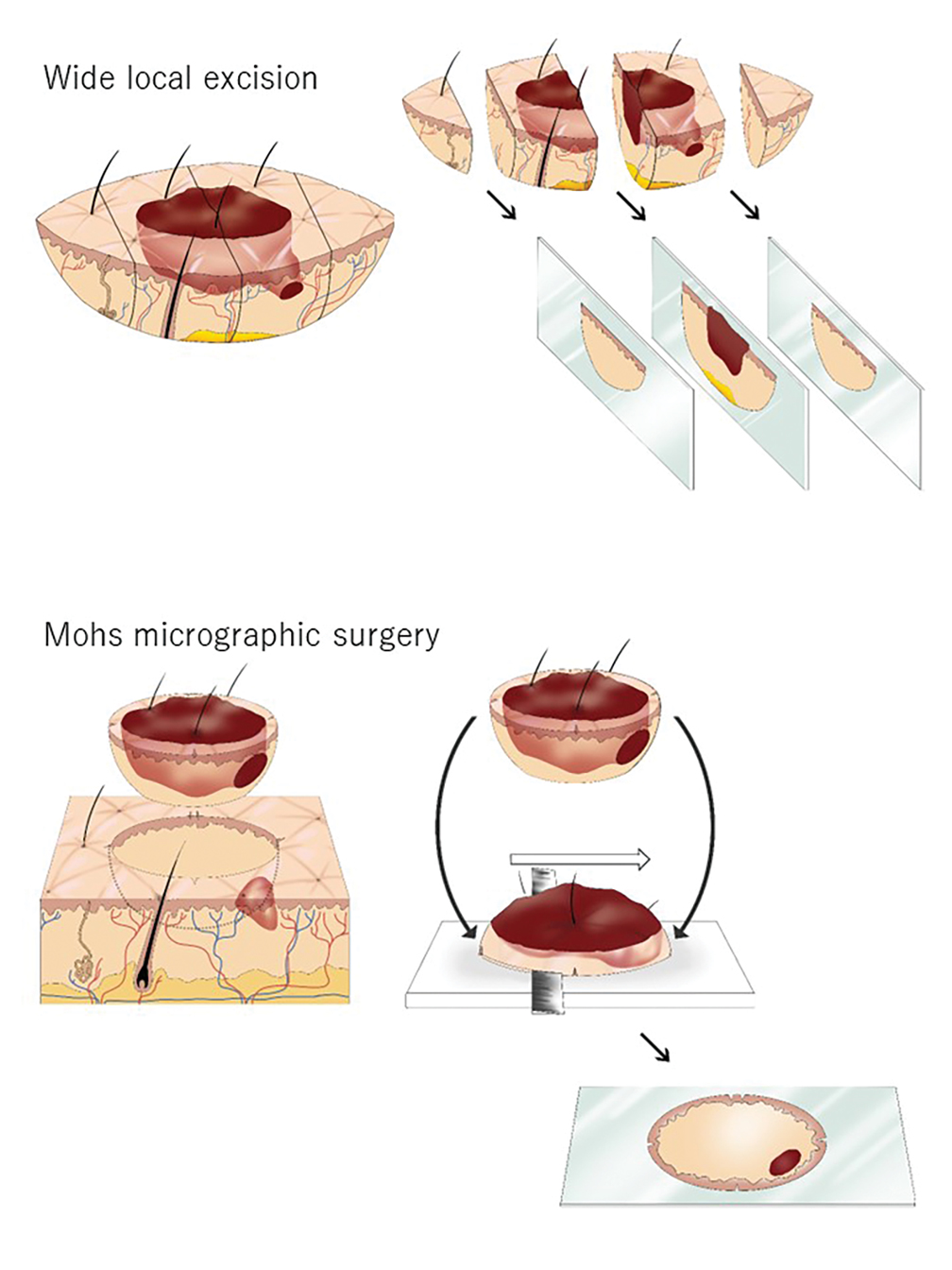

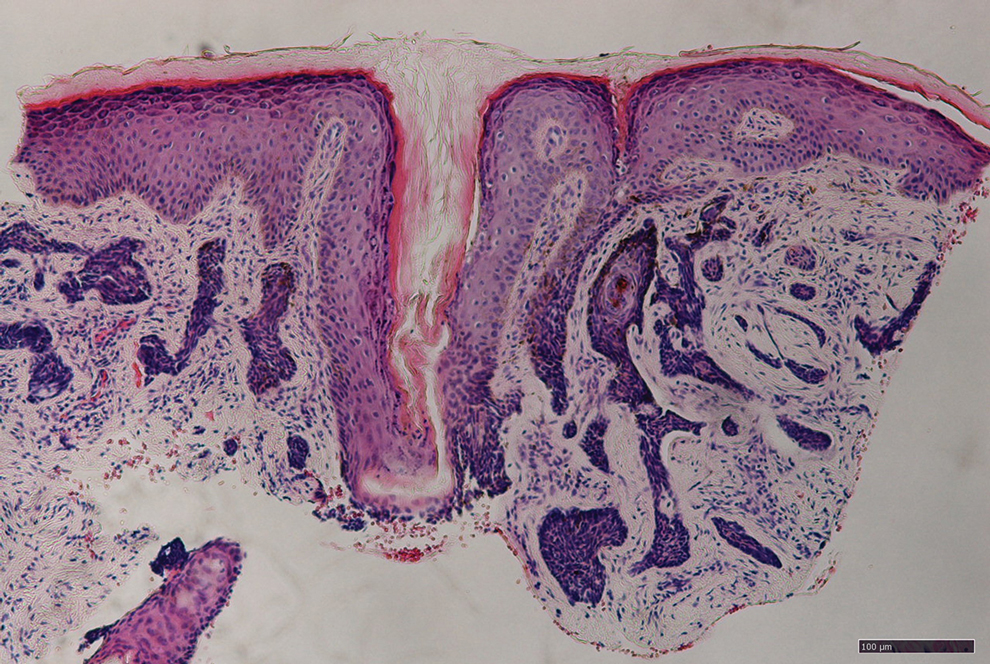

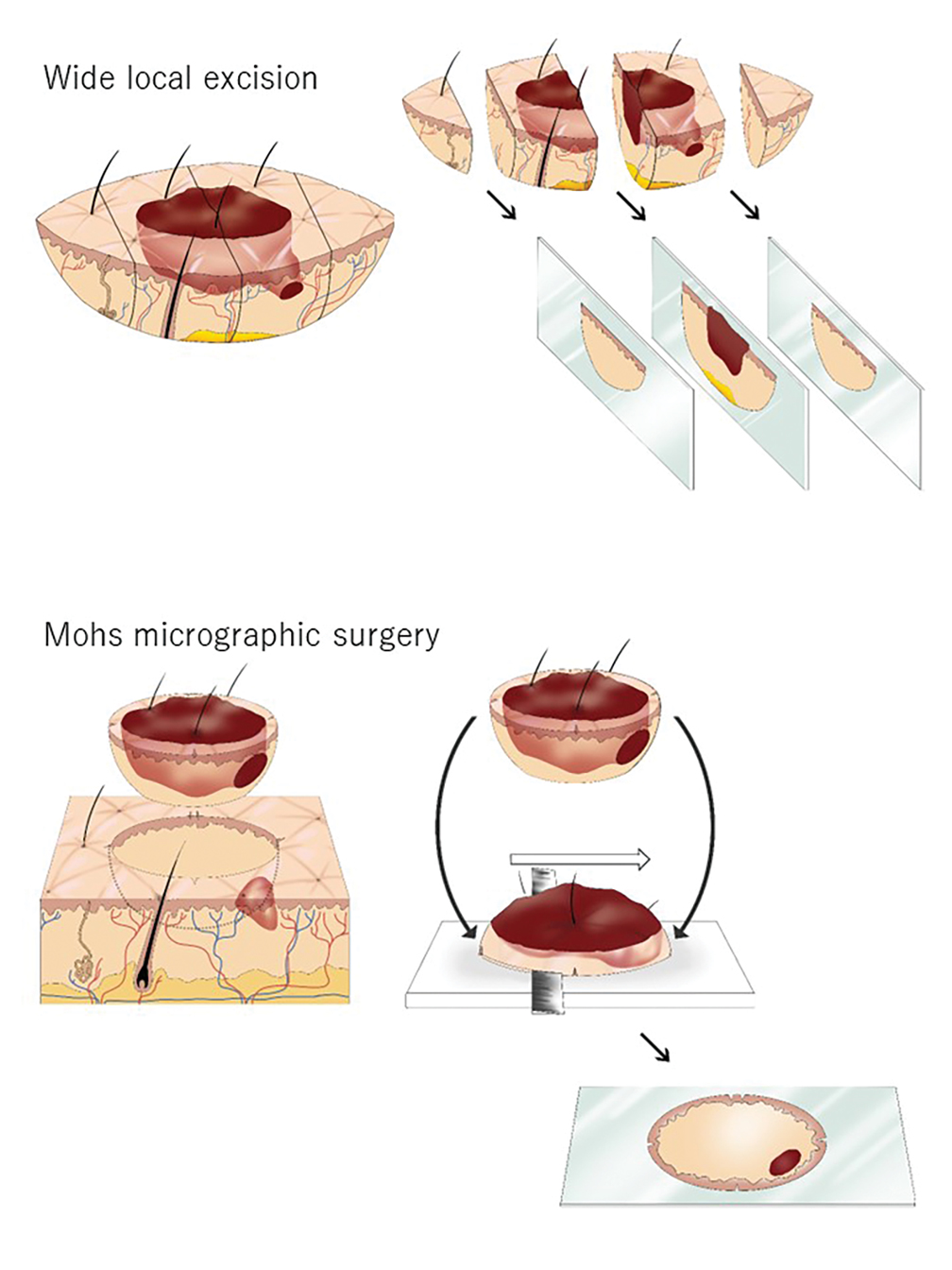

The essential element that makes MMS unique is the careful microscopic examination of the entire margin of the removed specimen. Tissue processing is done with careful en face orientation to ensure that circumferential and deep margins are entirely visible. The surgeon interprets the slides and proceeds to remove the additional tumor as necessary. Because the same physician performs both the surgery and the pathologic assessment throughout the procedure, a precise correlation between the microscopic and surgical findings can be made. The surgeon can begin with smaller margins, removing minimal healthy tissue while removing all the cancer cells, which results in the smallest-possible skin defect and the best prognosis for the malignancy (Figure 1).

At the only facility in Japan offering MMS, the lead author (S.S.) has treated 52 lesions with MMS in 46 patients (2020-2022). Of these patients, 40 were White, 5 were Japanese, and 1 was of African descent. In this case series, we present 5 Japanese patients who had BCC treated with MMS.

Case Series

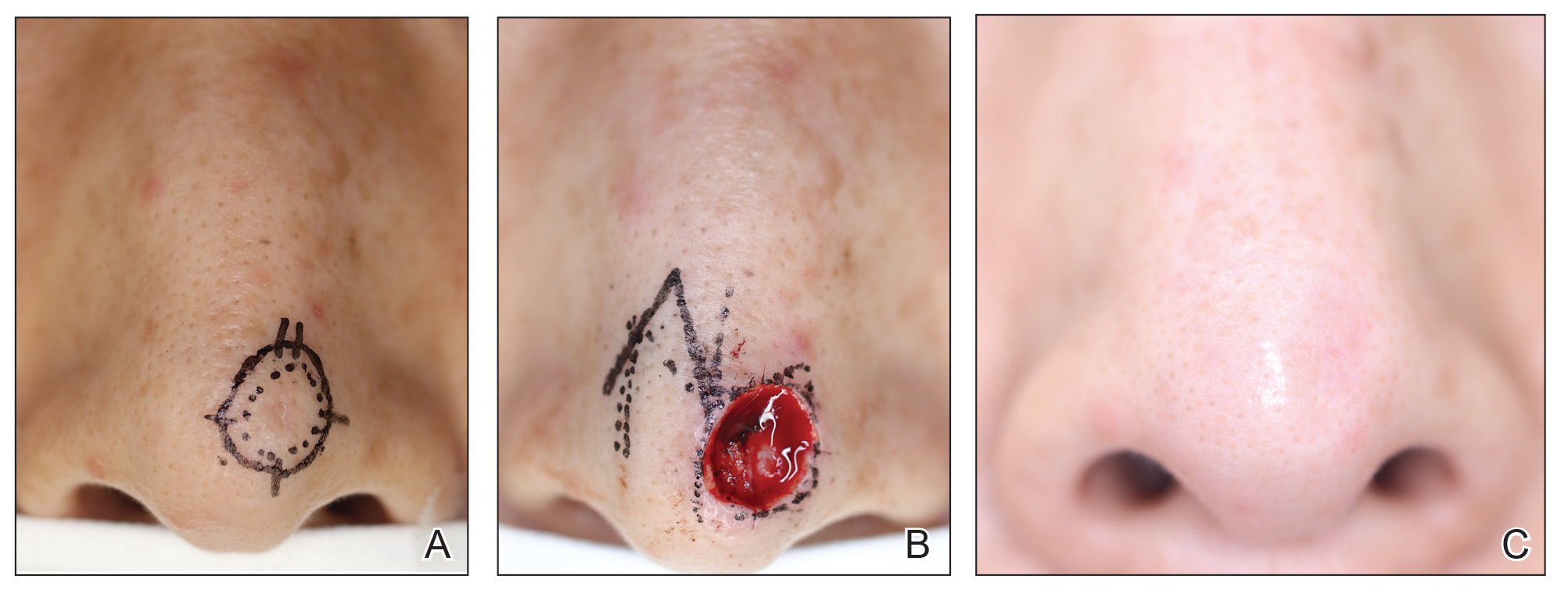

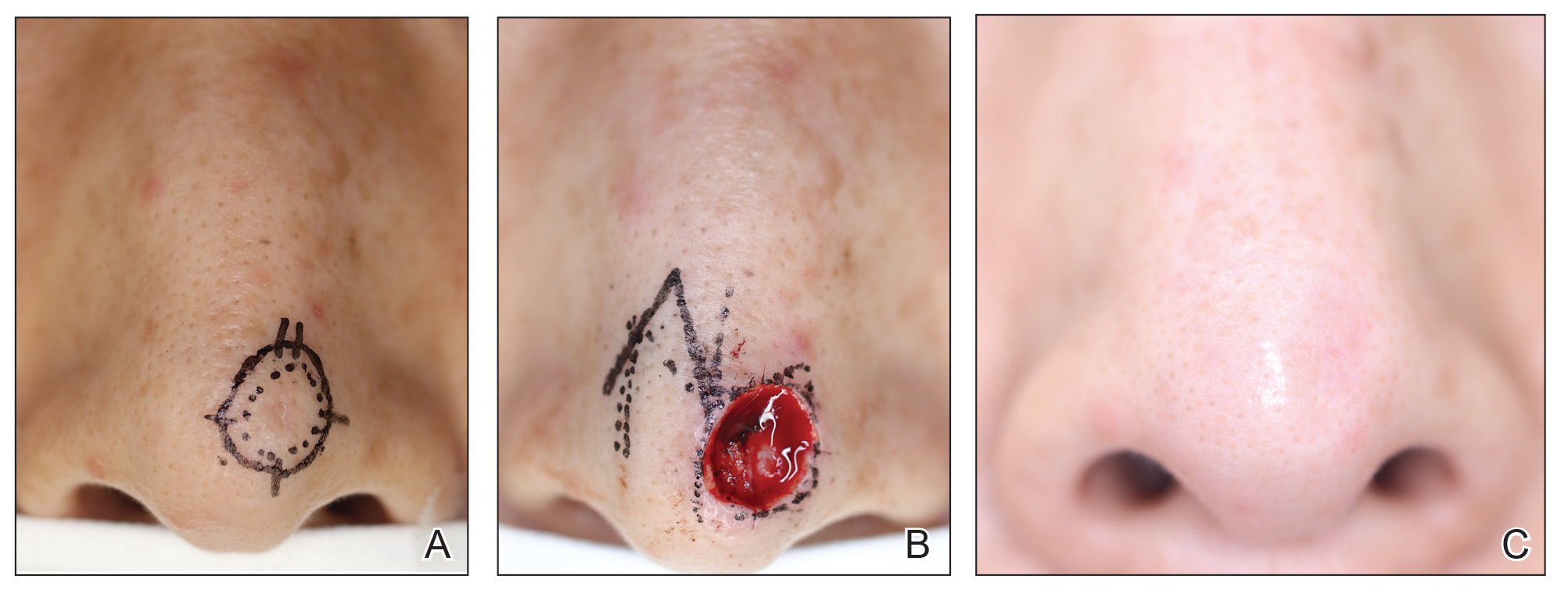

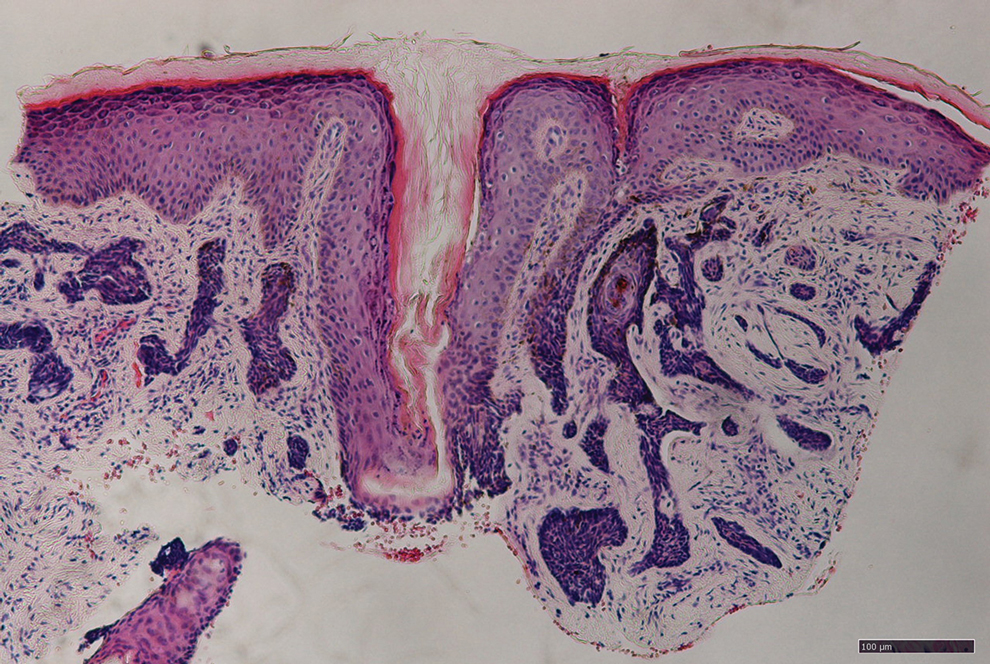

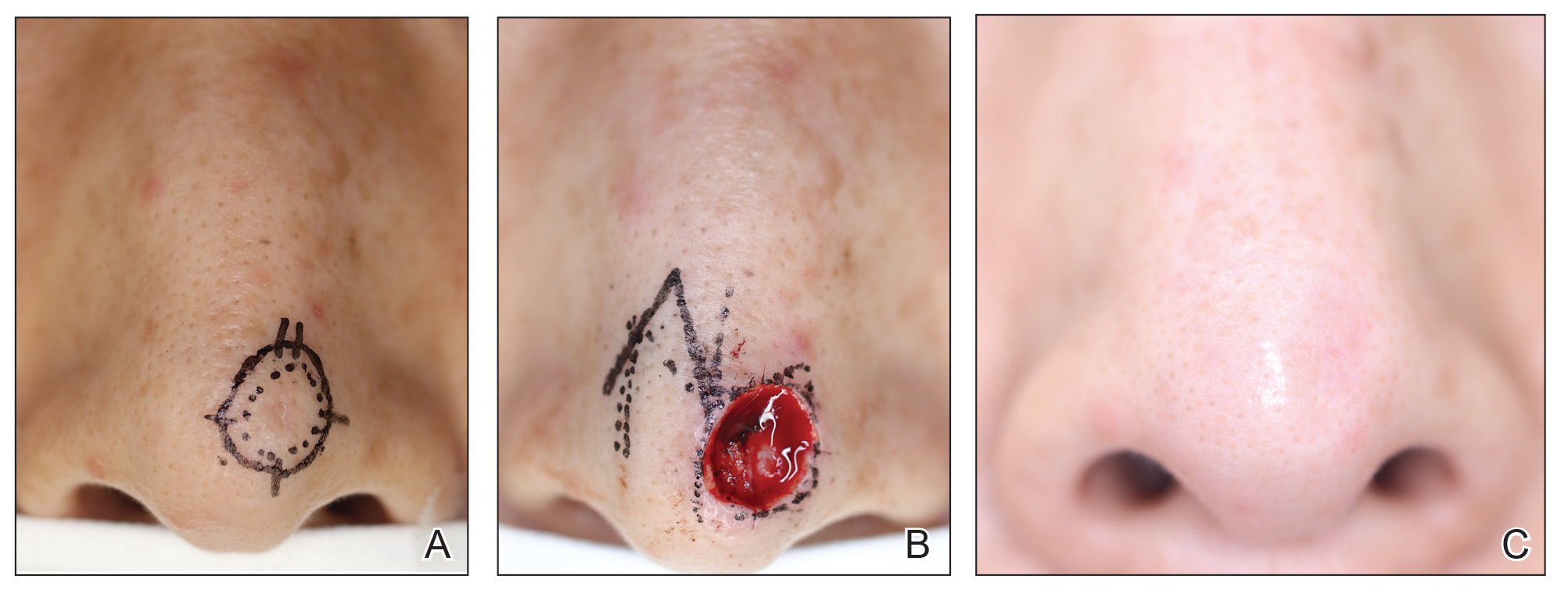

Patient 1—A 50-year-old Japanese woman presented to dermatology with a brown papule on the nasal tip of 1.25 year’s duration (Figure 2). A biopsy revealed infiltrative BCC (Figure 3), and the patient was referred to the dermatology department at a nearby university hospital. Because the BCC was an aggressive variant, wide local excision (WLE) with subsequent flap reconstruction was recommended as well as radiation therapy. The patient learned about MMS through an internet search and refused both options, seeking MMS treatment at our clinic. Although Japanese health insurance does not cover MMS, the patient had supplemental private insurance that did cover the cost. She provided consent to undergo the procedure. Physical examination revealed a 7.5×6-mm, brown-red macule with ill-defined borders on the tip of the nose. We used a 1.5-mm margin for the first stage of MMS (Figure 4A). The frozen section revealed that the tumor had been entirely excised in the first stage, leaving only a 10.5×9-mm skin defect that was reconstructed with a Dufourmentel flap (Figure 4B). No signs of recurrence were noted at 3.5-year follow-up, and the cosmetic outcome was favorable (Figure 4C). National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend a margin greater than 4 mm for infiltrative BCCs4; therefore, our technique reduced the total defect by at least 4 mm in a cosmetically sensitive area. The patient also did not need radiation therapy, which reduced morbidity. She continues to be recurrence free at 3.5-year follow-up.

Patient 2—A 63-year-old Japanese man presented to dermatology with a brown macule on the right lower eyelid of 2 years’ duration. A biopsy of the lesion was positive for nodular BCC. After being advised to undergo WLE and extensive reconstruction with plastic surgery, the patient learned of MMS through an internet search and found our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 7×5-mm brown macule on the right lower eyelid. The patient had supplemental private insurance that covered the cost of MMS, and he provided consent for the procedure. A 1.5-mm margin was taken for the first stage, resulting in a 10×8-mm defect superficial to the orbicularis oculi muscle. The frozen section revealed residual tumor exposure in the dermis at the 9- to 10-o’clock position. A second-stage excision was performed to remove an additional 1.5 mm of skin at the 9- to 12-o’clock position with a thin layer of the orbicularis oculi muscle. The subsequent histologic examination revealed no residual BCC, and the final 13×9-mm skin defect was reconstructed with a rotation flap. There were no signs of recurrence at 2.5-year follow-up with an excellent cosmetic outcome.

Patient 3—A 73-year-old Japanese man presented to a local university dermatology clinic with a new papule on the nose. The dermatologist suggested WLE with 4-mm margins and reconstruction of the skin defect 2 weeks later by a plastic surgeon. The patient was not satisfied with the proposed surgical plan, which led him to learn about MMS on the internet; he subsequently found our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 4×3.5-mm brown papule on the tip of the nose. He understood the nature of MMS and chose to pay out-of-pocket because Japanese health insurance did not cover the procedure. We used a 2-mm margin for the first stage, which created a 7.5×7-mm skin defect. The frozen section pathology revealed no residual BCC at the cut surface. The skin defect was reconstructed with a Limberg rhombic flap. There were no signs of recurrence at 1.5-year follow-up with a favorable cosmetic outcome.

Patient 4—A 45-year-old man presented to a dermatology clinic with a papule on the right side of the nose of 1 year’s duration. A biopsy revealed the lesion was a nodular BCC. The dermatologist recommended WLE at a general hospital, but the patient refused after learning about MMS. He subsequently made an appointment with our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 7×4-mm white papule on the right side of the nose. The patient had private insurance that covered the cost of MMS. The first stage was performed with 1.5-mm margins and was clear of residual tumor. A Limberg rhombic flap from the adjacent cheek was used to repair the final 10×7-mm skin defect. There were no signs of recurrence at 1 year and 9 months’ follow-up with a favorable cosmetic outcome.

Patient 5—A 76-year-old Japanese woman presented to a university hospital near Tokyo with a black papule on the left cutaneous lip of 5 years’ duration. A biopsy revealed nodular BCC, and WLE with flap reconstruction was recommended. The patient’s son learned about MMS through internet research and referred her to our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 7×5-mm black papule on the left upper lip. The patient’s private insurance covered the cost of MMS, and she consented to the procedure. We used a 2-mm initial margin, and the immediate frozen section revealed no signs of BCC at the cut surface. The 11×9-mm skin defect was reconstructed with a Limberg rhombic flap. There were no signs of recurrence at 1.5-year follow-up with a favorable cosmetic outcome.

Comment

We presented 5 cases of MMS in Japanese patients with BCC. More than 7000 new cases of nonmelanoma skin cancer occur every year in Japan.3 Only 0.04% of these cases—the 5 cases presented here—were treated with MMS in Japan in 2020 and 2021, in contrast to 25% in the United States in 2006.2

MMS vs Other BCC Treatments—Mohs micrographic surgery offers 2 distinct advantages over conventional excision: an improved cure rate while achieving a smaller final defect size, generally leading to better cosmetic outcomes. Overall 5-year recurrence rates of BCC are 10% for conventional surgical excision vs 1% for MMS, while the recurrence rates for SCC are 8% and 3%, respectively.5 A study of well-demarcated BCCs smaller than 2 cm that were treated with MMS with 2-mm increments revealed that 95% of the cases were free of malignancy within a 4-mm margin of the normal-appearing skin surrounding the tumor.6 Several articles have reported a 95% cure rate or higher with conventional excision of localized BCC,7 but 4- to 5-mm excision margins are required, resulting in a greater skin defect and a lower cure rate compared to MMS.

Aggressive subtypes of BCC have a higher recurrence rate. Rowe et al8 reported the following 5-year recurrence rates: 5.6% for MMS, 17.4% for conventional surgical excision, 40.0% for curettage and electrodesiccation, and 9.8% for radiation therapy. Primary BCCs with high-risk histologic subtypes has a 10-year recurrence rate of 4.4% with MMS vs 12.2% with conventional excision.9 These findings reveal that MMS yields a better prognosis compared to traditional treatment methods for recurrent BCCs and BCCs of high-risk histologic subtypes.

The primary reason for the excellent cure rate seen in MMS is the ability to perform complete margin assessment. Peripheral and deep en face margin assessment (PDEMA) is crucial in achieving high cure rates with narrow margins. In WLE (Figure 1), vertical sectioning (also known as bread-loafing) does not achieve direct visualization of the entire surgical margin, as this technique only evaluates random sections and does not achieve PDEMA.10 The bread-loafing method is used almost exclusively in Japan and visualizes only 0.1% of the entire margin compared to 100% with MMS.11 Beyond the superior cure rate, the MMS technique often yields smaller final defects compared to WLE. All 5 of our patients achieved complete tumor removal while sparing more normal tissue compared to conventional WLE, which takes at least a 4-mm margin in all directions.

Barriers to Adopting MMS in Japan—There are many barriers to the broader adoption of MMS in Japan. A guideline of the Japanese Dermatological Association says, MMS “is complicated, requires special training for acquisition, and requires time and labor for implementation of a series of processes, and it has not gained wide acceptance in Japan because of these disadvantages.”3 There currently are no MMS training programs in Japan. We refute this statement from the Japanese Dermatological Association because, in our experience, only 1 surgeon plus a single histotechnician familiar with MMS is sufficient for a facility to offer the procedure (the lead author of this study [S.S.] acts as both the surgeon and the histotechnician). Another misconception among some physicians in Japan is that cancer on ethnically Japanese skin is uniquely suited to excision without microscopic verification of tumor clearance because the borders of the tumors are easily identified, which was based on good cure rates for the excision of well-demarcated pigmented BCCs in a Japanese cohort. This study of a Japanese cohort investigated the specimens with the conventional bread-loafing technique but not with the PDEMA.12

Eighty percent (4/5) of our patients presented with nodular BCC, and only 1 required a second stage. In comparison, we also treated 16 White patients with nodular BCC with MMS during the same period, and 31% (5/16) required more than 1 stage, with 1 patient requiring 3 stages. This cohort, however, is too small to demonstrate a statistically significant difference (S.S., unpublished data, 2020-2022).

A study in Singapore reported the postsurgical complication rate and 5-year recurrence rate for 481 tumors (92% BCC and 7.5% SCC). The median follow-up duration after MMS was 36 months, and the recurrence rate was 0.6%. The postsurgical complications included 11 (2.3%) cases with superficial tip necrosis of surgical flaps/grafts, 2 (0.4%) with mild wound dehiscence, 1 (0.2%) with minor surgical site bleeding, and 1 (0.2%) with minor wound infection.13 This study supports the notion that MMS is equally effective for Asian patients.

Awareness of MMS in Japan is lacking, and most Japanese dermatologists do not know about the technique. All 5 patients in our case series asked their dermatologists about alternative treatment options and were not offered MMS. In each case, the patients learned of the technique through internet research.

The lack of insurance reimbursement for MMS in Japan is another barrier. Because the national health insurance does not reimburse for MMS, the procedure is relatively unavailable to most Japanese citizens who cannot pay out-of-pocket for the treatment and do not have supplemental insurance. Mohs micrographic surgery may seem expensive compared to WLE followed by repair; however, in the authors’ experience, in Japan, excision without MMS may require general sedation and multiple surgeries to reconstruct larger skin defects, leading to greater morbidity and risk for the patient.

Conclusion

Mohs micrographic surgery in Japan is in its infancy, and further studies showing recurrence rates and long-term prognosis are needed. Such data should help increase awareness of MMS among Japanese physicians as an excellent treatment option for their patients. Furthermore, as Japan becomes more heterogenous as a society and the US Military increases its presence in the region, the need for MMS is likely to increase.

Acknowledgments—We appreciate the proofreading support by Mark Bivens, MBA, MSc (Tokyo, Japan), as well as the technical support from Ben Tallon, MBChB, and Robyn Mason (both in Tauranga, New Zealand) to start MMS at our clinic.

- Asgari MM, Olson J, Alam M. Needs assessment for Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:167-175. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.010

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Baker DR, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Ansai SI, Umebayashi Y, Katsumata N, et al. Japanese Dermatological Association Guidelines: outlines of guidelines for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma 2020. J Dermatol. 2021;48:E288-E311.

- Schmults CD, Blitzblau R, Aasi SZ, et at. Basal cell skin cancer, version 2.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:1181-1203. doi:10.6004/jncn.2023.0056

- Snow SN, Gunkel J. Mohs surgery. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:2445-2455. doi:10.1016/b978-0-070-94171-3.00041-7

- Wolf DJ, Zitelli JA. Surgical margins for basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:340-344.

- Quazi SJ, Aslam N, Saleem H, et al. Surgical margin of excision in basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review of literature. Cureus. 2020;12:E9211.

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day Jus CL. Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice for recurrent (previously treated) basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:424-431.

- Van Loo, Mosterd K, Krekels GA. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

- Schmults CD, Blitzblau R, Aasi SZ, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Squamous Cell Skin Cancer, Version 1.2022. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:1382-1394.

- Hui AM, Jacobson M, Markowitz O, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of melanoma. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:503-515.

- Ito T, Inatomi Y, Nagae K, et al. Narrow-margin excision is a safe, reliable treatment for well-defined, primary pigmented basal cell carcinoma: an analysis of 288 lesions in Japan. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1828-1831.

- Ho WYB, Zhao X, Tan WPM. Mohs micrographic surgery in Singapore: a long-term follow-up review. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2021;50:922-923.

Margin-controlled surgery for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the lower lip was first performed by Dr. Frederic Mohs on June 30, 1936. Since then, thousands of skin cancer surgeons have refined and adopted the technique. Due to the high cure rate and sparing of normal tissue, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has become the gold standard treatment for facial and special-site nonmelanoma skin cancer worldwide. Mohs micrographic surgery is performed on more than 876,000 tumors annually in the United States.1 Among 3.5 million Americans diagnosed with nonmelanoma skin cancer in 2006, one-quarter were treated with MMS.2 In Japan, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin malignancy, with an incidence of 3.34 cases per 100,000 individuals; SCC is the second most common, with an incidence of 2.5 cases per 100,000 individuals.3

The essential element that makes MMS unique is the careful microscopic examination of the entire margin of the removed specimen. Tissue processing is done with careful en face orientation to ensure that circumferential and deep margins are entirely visible. The surgeon interprets the slides and proceeds to remove the additional tumor as necessary. Because the same physician performs both the surgery and the pathologic assessment throughout the procedure, a precise correlation between the microscopic and surgical findings can be made. The surgeon can begin with smaller margins, removing minimal healthy tissue while removing all the cancer cells, which results in the smallest-possible skin defect and the best prognosis for the malignancy (Figure 1).

At the only facility in Japan offering MMS, the lead author (S.S.) has treated 52 lesions with MMS in 46 patients (2020-2022). Of these patients, 40 were White, 5 were Japanese, and 1 was of African descent. In this case series, we present 5 Japanese patients who had BCC treated with MMS.

Case Series

Patient 1—A 50-year-old Japanese woman presented to dermatology with a brown papule on the nasal tip of 1.25 year’s duration (Figure 2). A biopsy revealed infiltrative BCC (Figure 3), and the patient was referred to the dermatology department at a nearby university hospital. Because the BCC was an aggressive variant, wide local excision (WLE) with subsequent flap reconstruction was recommended as well as radiation therapy. The patient learned about MMS through an internet search and refused both options, seeking MMS treatment at our clinic. Although Japanese health insurance does not cover MMS, the patient had supplemental private insurance that did cover the cost. She provided consent to undergo the procedure. Physical examination revealed a 7.5×6-mm, brown-red macule with ill-defined borders on the tip of the nose. We used a 1.5-mm margin for the first stage of MMS (Figure 4A). The frozen section revealed that the tumor had been entirely excised in the first stage, leaving only a 10.5×9-mm skin defect that was reconstructed with a Dufourmentel flap (Figure 4B). No signs of recurrence were noted at 3.5-year follow-up, and the cosmetic outcome was favorable (Figure 4C). National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend a margin greater than 4 mm for infiltrative BCCs4; therefore, our technique reduced the total defect by at least 4 mm in a cosmetically sensitive area. The patient also did not need radiation therapy, which reduced morbidity. She continues to be recurrence free at 3.5-year follow-up.

Patient 2—A 63-year-old Japanese man presented to dermatology with a brown macule on the right lower eyelid of 2 years’ duration. A biopsy of the lesion was positive for nodular BCC. After being advised to undergo WLE and extensive reconstruction with plastic surgery, the patient learned of MMS through an internet search and found our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 7×5-mm brown macule on the right lower eyelid. The patient had supplemental private insurance that covered the cost of MMS, and he provided consent for the procedure. A 1.5-mm margin was taken for the first stage, resulting in a 10×8-mm defect superficial to the orbicularis oculi muscle. The frozen section revealed residual tumor exposure in the dermis at the 9- to 10-o’clock position. A second-stage excision was performed to remove an additional 1.5 mm of skin at the 9- to 12-o’clock position with a thin layer of the orbicularis oculi muscle. The subsequent histologic examination revealed no residual BCC, and the final 13×9-mm skin defect was reconstructed with a rotation flap. There were no signs of recurrence at 2.5-year follow-up with an excellent cosmetic outcome.

Patient 3—A 73-year-old Japanese man presented to a local university dermatology clinic with a new papule on the nose. The dermatologist suggested WLE with 4-mm margins and reconstruction of the skin defect 2 weeks later by a plastic surgeon. The patient was not satisfied with the proposed surgical plan, which led him to learn about MMS on the internet; he subsequently found our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 4×3.5-mm brown papule on the tip of the nose. He understood the nature of MMS and chose to pay out-of-pocket because Japanese health insurance did not cover the procedure. We used a 2-mm margin for the first stage, which created a 7.5×7-mm skin defect. The frozen section pathology revealed no residual BCC at the cut surface. The skin defect was reconstructed with a Limberg rhombic flap. There were no signs of recurrence at 1.5-year follow-up with a favorable cosmetic outcome.

Patient 4—A 45-year-old man presented to a dermatology clinic with a papule on the right side of the nose of 1 year’s duration. A biopsy revealed the lesion was a nodular BCC. The dermatologist recommended WLE at a general hospital, but the patient refused after learning about MMS. He subsequently made an appointment with our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 7×4-mm white papule on the right side of the nose. The patient had private insurance that covered the cost of MMS. The first stage was performed with 1.5-mm margins and was clear of residual tumor. A Limberg rhombic flap from the adjacent cheek was used to repair the final 10×7-mm skin defect. There were no signs of recurrence at 1 year and 9 months’ follow-up with a favorable cosmetic outcome.

Patient 5—A 76-year-old Japanese woman presented to a university hospital near Tokyo with a black papule on the left cutaneous lip of 5 years’ duration. A biopsy revealed nodular BCC, and WLE with flap reconstruction was recommended. The patient’s son learned about MMS through internet research and referred her to our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 7×5-mm black papule on the left upper lip. The patient’s private insurance covered the cost of MMS, and she consented to the procedure. We used a 2-mm initial margin, and the immediate frozen section revealed no signs of BCC at the cut surface. The 11×9-mm skin defect was reconstructed with a Limberg rhombic flap. There were no signs of recurrence at 1.5-year follow-up with a favorable cosmetic outcome.

Comment

We presented 5 cases of MMS in Japanese patients with BCC. More than 7000 new cases of nonmelanoma skin cancer occur every year in Japan.3 Only 0.04% of these cases—the 5 cases presented here—were treated with MMS in Japan in 2020 and 2021, in contrast to 25% in the United States in 2006.2

MMS vs Other BCC Treatments—Mohs micrographic surgery offers 2 distinct advantages over conventional excision: an improved cure rate while achieving a smaller final defect size, generally leading to better cosmetic outcomes. Overall 5-year recurrence rates of BCC are 10% for conventional surgical excision vs 1% for MMS, while the recurrence rates for SCC are 8% and 3%, respectively.5 A study of well-demarcated BCCs smaller than 2 cm that were treated with MMS with 2-mm increments revealed that 95% of the cases were free of malignancy within a 4-mm margin of the normal-appearing skin surrounding the tumor.6 Several articles have reported a 95% cure rate or higher with conventional excision of localized BCC,7 but 4- to 5-mm excision margins are required, resulting in a greater skin defect and a lower cure rate compared to MMS.

Aggressive subtypes of BCC have a higher recurrence rate. Rowe et al8 reported the following 5-year recurrence rates: 5.6% for MMS, 17.4% for conventional surgical excision, 40.0% for curettage and electrodesiccation, and 9.8% for radiation therapy. Primary BCCs with high-risk histologic subtypes has a 10-year recurrence rate of 4.4% with MMS vs 12.2% with conventional excision.9 These findings reveal that MMS yields a better prognosis compared to traditional treatment methods for recurrent BCCs and BCCs of high-risk histologic subtypes.

The primary reason for the excellent cure rate seen in MMS is the ability to perform complete margin assessment. Peripheral and deep en face margin assessment (PDEMA) is crucial in achieving high cure rates with narrow margins. In WLE (Figure 1), vertical sectioning (also known as bread-loafing) does not achieve direct visualization of the entire surgical margin, as this technique only evaluates random sections and does not achieve PDEMA.10 The bread-loafing method is used almost exclusively in Japan and visualizes only 0.1% of the entire margin compared to 100% with MMS.11 Beyond the superior cure rate, the MMS technique often yields smaller final defects compared to WLE. All 5 of our patients achieved complete tumor removal while sparing more normal tissue compared to conventional WLE, which takes at least a 4-mm margin in all directions.

Barriers to Adopting MMS in Japan—There are many barriers to the broader adoption of MMS in Japan. A guideline of the Japanese Dermatological Association says, MMS “is complicated, requires special training for acquisition, and requires time and labor for implementation of a series of processes, and it has not gained wide acceptance in Japan because of these disadvantages.”3 There currently are no MMS training programs in Japan. We refute this statement from the Japanese Dermatological Association because, in our experience, only 1 surgeon plus a single histotechnician familiar with MMS is sufficient for a facility to offer the procedure (the lead author of this study [S.S.] acts as both the surgeon and the histotechnician). Another misconception among some physicians in Japan is that cancer on ethnically Japanese skin is uniquely suited to excision without microscopic verification of tumor clearance because the borders of the tumors are easily identified, which was based on good cure rates for the excision of well-demarcated pigmented BCCs in a Japanese cohort. This study of a Japanese cohort investigated the specimens with the conventional bread-loafing technique but not with the PDEMA.12

Eighty percent (4/5) of our patients presented with nodular BCC, and only 1 required a second stage. In comparison, we also treated 16 White patients with nodular BCC with MMS during the same period, and 31% (5/16) required more than 1 stage, with 1 patient requiring 3 stages. This cohort, however, is too small to demonstrate a statistically significant difference (S.S., unpublished data, 2020-2022).

A study in Singapore reported the postsurgical complication rate and 5-year recurrence rate for 481 tumors (92% BCC and 7.5% SCC). The median follow-up duration after MMS was 36 months, and the recurrence rate was 0.6%. The postsurgical complications included 11 (2.3%) cases with superficial tip necrosis of surgical flaps/grafts, 2 (0.4%) with mild wound dehiscence, 1 (0.2%) with minor surgical site bleeding, and 1 (0.2%) with minor wound infection.13 This study supports the notion that MMS is equally effective for Asian patients.

Awareness of MMS in Japan is lacking, and most Japanese dermatologists do not know about the technique. All 5 patients in our case series asked their dermatologists about alternative treatment options and were not offered MMS. In each case, the patients learned of the technique through internet research.

The lack of insurance reimbursement for MMS in Japan is another barrier. Because the national health insurance does not reimburse for MMS, the procedure is relatively unavailable to most Japanese citizens who cannot pay out-of-pocket for the treatment and do not have supplemental insurance. Mohs micrographic surgery may seem expensive compared to WLE followed by repair; however, in the authors’ experience, in Japan, excision without MMS may require general sedation and multiple surgeries to reconstruct larger skin defects, leading to greater morbidity and risk for the patient.

Conclusion

Mohs micrographic surgery in Japan is in its infancy, and further studies showing recurrence rates and long-term prognosis are needed. Such data should help increase awareness of MMS among Japanese physicians as an excellent treatment option for their patients. Furthermore, as Japan becomes more heterogenous as a society and the US Military increases its presence in the region, the need for MMS is likely to increase.

Acknowledgments—We appreciate the proofreading support by Mark Bivens, MBA, MSc (Tokyo, Japan), as well as the technical support from Ben Tallon, MBChB, and Robyn Mason (both in Tauranga, New Zealand) to start MMS at our clinic.

Margin-controlled surgery for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on the lower lip was first performed by Dr. Frederic Mohs on June 30, 1936. Since then, thousands of skin cancer surgeons have refined and adopted the technique. Due to the high cure rate and sparing of normal tissue, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has become the gold standard treatment for facial and special-site nonmelanoma skin cancer worldwide. Mohs micrographic surgery is performed on more than 876,000 tumors annually in the United States.1 Among 3.5 million Americans diagnosed with nonmelanoma skin cancer in 2006, one-quarter were treated with MMS.2 In Japan, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin malignancy, with an incidence of 3.34 cases per 100,000 individuals; SCC is the second most common, with an incidence of 2.5 cases per 100,000 individuals.3

The essential element that makes MMS unique is the careful microscopic examination of the entire margin of the removed specimen. Tissue processing is done with careful en face orientation to ensure that circumferential and deep margins are entirely visible. The surgeon interprets the slides and proceeds to remove the additional tumor as necessary. Because the same physician performs both the surgery and the pathologic assessment throughout the procedure, a precise correlation between the microscopic and surgical findings can be made. The surgeon can begin with smaller margins, removing minimal healthy tissue while removing all the cancer cells, which results in the smallest-possible skin defect and the best prognosis for the malignancy (Figure 1).

At the only facility in Japan offering MMS, the lead author (S.S.) has treated 52 lesions with MMS in 46 patients (2020-2022). Of these patients, 40 were White, 5 were Japanese, and 1 was of African descent. In this case series, we present 5 Japanese patients who had BCC treated with MMS.

Case Series

Patient 1—A 50-year-old Japanese woman presented to dermatology with a brown papule on the nasal tip of 1.25 year’s duration (Figure 2). A biopsy revealed infiltrative BCC (Figure 3), and the patient was referred to the dermatology department at a nearby university hospital. Because the BCC was an aggressive variant, wide local excision (WLE) with subsequent flap reconstruction was recommended as well as radiation therapy. The patient learned about MMS through an internet search and refused both options, seeking MMS treatment at our clinic. Although Japanese health insurance does not cover MMS, the patient had supplemental private insurance that did cover the cost. She provided consent to undergo the procedure. Physical examination revealed a 7.5×6-mm, brown-red macule with ill-defined borders on the tip of the nose. We used a 1.5-mm margin for the first stage of MMS (Figure 4A). The frozen section revealed that the tumor had been entirely excised in the first stage, leaving only a 10.5×9-mm skin defect that was reconstructed with a Dufourmentel flap (Figure 4B). No signs of recurrence were noted at 3.5-year follow-up, and the cosmetic outcome was favorable (Figure 4C). National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend a margin greater than 4 mm for infiltrative BCCs4; therefore, our technique reduced the total defect by at least 4 mm in a cosmetically sensitive area. The patient also did not need radiation therapy, which reduced morbidity. She continues to be recurrence free at 3.5-year follow-up.

Patient 2—A 63-year-old Japanese man presented to dermatology with a brown macule on the right lower eyelid of 2 years’ duration. A biopsy of the lesion was positive for nodular BCC. After being advised to undergo WLE and extensive reconstruction with plastic surgery, the patient learned of MMS through an internet search and found our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 7×5-mm brown macule on the right lower eyelid. The patient had supplemental private insurance that covered the cost of MMS, and he provided consent for the procedure. A 1.5-mm margin was taken for the first stage, resulting in a 10×8-mm defect superficial to the orbicularis oculi muscle. The frozen section revealed residual tumor exposure in the dermis at the 9- to 10-o’clock position. A second-stage excision was performed to remove an additional 1.5 mm of skin at the 9- to 12-o’clock position with a thin layer of the orbicularis oculi muscle. The subsequent histologic examination revealed no residual BCC, and the final 13×9-mm skin defect was reconstructed with a rotation flap. There were no signs of recurrence at 2.5-year follow-up with an excellent cosmetic outcome.

Patient 3—A 73-year-old Japanese man presented to a local university dermatology clinic with a new papule on the nose. The dermatologist suggested WLE with 4-mm margins and reconstruction of the skin defect 2 weeks later by a plastic surgeon. The patient was not satisfied with the proposed surgical plan, which led him to learn about MMS on the internet; he subsequently found our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 4×3.5-mm brown papule on the tip of the nose. He understood the nature of MMS and chose to pay out-of-pocket because Japanese health insurance did not cover the procedure. We used a 2-mm margin for the first stage, which created a 7.5×7-mm skin defect. The frozen section pathology revealed no residual BCC at the cut surface. The skin defect was reconstructed with a Limberg rhombic flap. There were no signs of recurrence at 1.5-year follow-up with a favorable cosmetic outcome.

Patient 4—A 45-year-old man presented to a dermatology clinic with a papule on the right side of the nose of 1 year’s duration. A biopsy revealed the lesion was a nodular BCC. The dermatologist recommended WLE at a general hospital, but the patient refused after learning about MMS. He subsequently made an appointment with our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 7×4-mm white papule on the right side of the nose. The patient had private insurance that covered the cost of MMS. The first stage was performed with 1.5-mm margins and was clear of residual tumor. A Limberg rhombic flap from the adjacent cheek was used to repair the final 10×7-mm skin defect. There were no signs of recurrence at 1 year and 9 months’ follow-up with a favorable cosmetic outcome.

Patient 5—A 76-year-old Japanese woman presented to a university hospital near Tokyo with a black papule on the left cutaneous lip of 5 years’ duration. A biopsy revealed nodular BCC, and WLE with flap reconstruction was recommended. The patient’s son learned about MMS through internet research and referred her to our clinic. Physical examination revealed a 7×5-mm black papule on the left upper lip. The patient’s private insurance covered the cost of MMS, and she consented to the procedure. We used a 2-mm initial margin, and the immediate frozen section revealed no signs of BCC at the cut surface. The 11×9-mm skin defect was reconstructed with a Limberg rhombic flap. There were no signs of recurrence at 1.5-year follow-up with a favorable cosmetic outcome.

Comment

We presented 5 cases of MMS in Japanese patients with BCC. More than 7000 new cases of nonmelanoma skin cancer occur every year in Japan.3 Only 0.04% of these cases—the 5 cases presented here—were treated with MMS in Japan in 2020 and 2021, in contrast to 25% in the United States in 2006.2

MMS vs Other BCC Treatments—Mohs micrographic surgery offers 2 distinct advantages over conventional excision: an improved cure rate while achieving a smaller final defect size, generally leading to better cosmetic outcomes. Overall 5-year recurrence rates of BCC are 10% for conventional surgical excision vs 1% for MMS, while the recurrence rates for SCC are 8% and 3%, respectively.5 A study of well-demarcated BCCs smaller than 2 cm that were treated with MMS with 2-mm increments revealed that 95% of the cases were free of malignancy within a 4-mm margin of the normal-appearing skin surrounding the tumor.6 Several articles have reported a 95% cure rate or higher with conventional excision of localized BCC,7 but 4- to 5-mm excision margins are required, resulting in a greater skin defect and a lower cure rate compared to MMS.

Aggressive subtypes of BCC have a higher recurrence rate. Rowe et al8 reported the following 5-year recurrence rates: 5.6% for MMS, 17.4% for conventional surgical excision, 40.0% for curettage and electrodesiccation, and 9.8% for radiation therapy. Primary BCCs with high-risk histologic subtypes has a 10-year recurrence rate of 4.4% with MMS vs 12.2% with conventional excision.9 These findings reveal that MMS yields a better prognosis compared to traditional treatment methods for recurrent BCCs and BCCs of high-risk histologic subtypes.

The primary reason for the excellent cure rate seen in MMS is the ability to perform complete margin assessment. Peripheral and deep en face margin assessment (PDEMA) is crucial in achieving high cure rates with narrow margins. In WLE (Figure 1), vertical sectioning (also known as bread-loafing) does not achieve direct visualization of the entire surgical margin, as this technique only evaluates random sections and does not achieve PDEMA.10 The bread-loafing method is used almost exclusively in Japan and visualizes only 0.1% of the entire margin compared to 100% with MMS.11 Beyond the superior cure rate, the MMS technique often yields smaller final defects compared to WLE. All 5 of our patients achieved complete tumor removal while sparing more normal tissue compared to conventional WLE, which takes at least a 4-mm margin in all directions.

Barriers to Adopting MMS in Japan—There are many barriers to the broader adoption of MMS in Japan. A guideline of the Japanese Dermatological Association says, MMS “is complicated, requires special training for acquisition, and requires time and labor for implementation of a series of processes, and it has not gained wide acceptance in Japan because of these disadvantages.”3 There currently are no MMS training programs in Japan. We refute this statement from the Japanese Dermatological Association because, in our experience, only 1 surgeon plus a single histotechnician familiar with MMS is sufficient for a facility to offer the procedure (the lead author of this study [S.S.] acts as both the surgeon and the histotechnician). Another misconception among some physicians in Japan is that cancer on ethnically Japanese skin is uniquely suited to excision without microscopic verification of tumor clearance because the borders of the tumors are easily identified, which was based on good cure rates for the excision of well-demarcated pigmented BCCs in a Japanese cohort. This study of a Japanese cohort investigated the specimens with the conventional bread-loafing technique but not with the PDEMA.12

Eighty percent (4/5) of our patients presented with nodular BCC, and only 1 required a second stage. In comparison, we also treated 16 White patients with nodular BCC with MMS during the same period, and 31% (5/16) required more than 1 stage, with 1 patient requiring 3 stages. This cohort, however, is too small to demonstrate a statistically significant difference (S.S., unpublished data, 2020-2022).

A study in Singapore reported the postsurgical complication rate and 5-year recurrence rate for 481 tumors (92% BCC and 7.5% SCC). The median follow-up duration after MMS was 36 months, and the recurrence rate was 0.6%. The postsurgical complications included 11 (2.3%) cases with superficial tip necrosis of surgical flaps/grafts, 2 (0.4%) with mild wound dehiscence, 1 (0.2%) with minor surgical site bleeding, and 1 (0.2%) with minor wound infection.13 This study supports the notion that MMS is equally effective for Asian patients.

Awareness of MMS in Japan is lacking, and most Japanese dermatologists do not know about the technique. All 5 patients in our case series asked their dermatologists about alternative treatment options and were not offered MMS. In each case, the patients learned of the technique through internet research.

The lack of insurance reimbursement for MMS in Japan is another barrier. Because the national health insurance does not reimburse for MMS, the procedure is relatively unavailable to most Japanese citizens who cannot pay out-of-pocket for the treatment and do not have supplemental insurance. Mohs micrographic surgery may seem expensive compared to WLE followed by repair; however, in the authors’ experience, in Japan, excision without MMS may require general sedation and multiple surgeries to reconstruct larger skin defects, leading to greater morbidity and risk for the patient.

Conclusion

Mohs micrographic surgery in Japan is in its infancy, and further studies showing recurrence rates and long-term prognosis are needed. Such data should help increase awareness of MMS among Japanese physicians as an excellent treatment option for their patients. Furthermore, as Japan becomes more heterogenous as a society and the US Military increases its presence in the region, the need for MMS is likely to increase.

Acknowledgments—We appreciate the proofreading support by Mark Bivens, MBA, MSc (Tokyo, Japan), as well as the technical support from Ben Tallon, MBChB, and Robyn Mason (both in Tauranga, New Zealand) to start MMS at our clinic.

- Asgari MM, Olson J, Alam M. Needs assessment for Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:167-175. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.010

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Baker DR, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Ansai SI, Umebayashi Y, Katsumata N, et al. Japanese Dermatological Association Guidelines: outlines of guidelines for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma 2020. J Dermatol. 2021;48:E288-E311.

- Schmults CD, Blitzblau R, Aasi SZ, et at. Basal cell skin cancer, version 2.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:1181-1203. doi:10.6004/jncn.2023.0056

- Snow SN, Gunkel J. Mohs surgery. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:2445-2455. doi:10.1016/b978-0-070-94171-3.00041-7

- Wolf DJ, Zitelli JA. Surgical margins for basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:340-344.

- Quazi SJ, Aslam N, Saleem H, et al. Surgical margin of excision in basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review of literature. Cureus. 2020;12:E9211.

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day Jus CL. Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice for recurrent (previously treated) basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:424-431.

- Van Loo, Mosterd K, Krekels GA. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

- Schmults CD, Blitzblau R, Aasi SZ, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Squamous Cell Skin Cancer, Version 1.2022. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:1382-1394.

- Hui AM, Jacobson M, Markowitz O, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of melanoma. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:503-515.

- Ito T, Inatomi Y, Nagae K, et al. Narrow-margin excision is a safe, reliable treatment for well-defined, primary pigmented basal cell carcinoma: an analysis of 288 lesions in Japan. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1828-1831.

- Ho WYB, Zhao X, Tan WPM. Mohs micrographic surgery in Singapore: a long-term follow-up review. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2021;50:922-923.

- Asgari MM, Olson J, Alam M. Needs assessment for Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:167-175. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.010

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Baker DR, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Ansai SI, Umebayashi Y, Katsumata N, et al. Japanese Dermatological Association Guidelines: outlines of guidelines for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma 2020. J Dermatol. 2021;48:E288-E311.

- Schmults CD, Blitzblau R, Aasi SZ, et at. Basal cell skin cancer, version 2.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:1181-1203. doi:10.6004/jncn.2023.0056

- Snow SN, Gunkel J. Mohs surgery. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:2445-2455. doi:10.1016/b978-0-070-94171-3.00041-7

- Wolf DJ, Zitelli JA. Surgical margins for basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:340-344.

- Quazi SJ, Aslam N, Saleem H, et al. Surgical margin of excision in basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review of literature. Cureus. 2020;12:E9211.

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day Jus CL. Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice for recurrent (previously treated) basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:424-431.

- Van Loo, Mosterd K, Krekels GA. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

- Schmults CD, Blitzblau R, Aasi SZ, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Squamous Cell Skin Cancer, Version 1.2022. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:1382-1394.

- Hui AM, Jacobson M, Markowitz O, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of melanoma. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:503-515.

- Ito T, Inatomi Y, Nagae K, et al. Narrow-margin excision is a safe, reliable treatment for well-defined, primary pigmented basal cell carcinoma: an analysis of 288 lesions in Japan. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1828-1831.