User login

In Case You Missed It: COVID

New-onset arrhythmias low in COVID-19 and flu

Among 3,970 patients treated during the early months of the pandemic, new onset AF/AFL was seen in 4%, matching the 4% incidence found in a historic cohort of patients hospitalized with influenza.

On the other hand, mortality was similarly high in both groups of patients studied with AF/AFL, showing a 77% increased risk of death in COVID-19 and a 78% increased risk in influenza, a team from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York reported.

“We saw new onset Afib and flutter in a minority of patients and it was associated with much higher mortality, but the point is that this increase is basically the same as what you see in influenza, which we feel is an indication that this is more of a generalized response to the inflammatory milieu of such a severe viral illness, as opposed to something specific to COVID,” Vivek Y. Reddy, MD, said in the report, published online Feb. 25 in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

“Here we see, with a similar respiratory virus used as controls, that the results are exactly what I would have expected to see, which is that where there is a lot of inflammation, we see Afib,” said John Mandrola, MD, of Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky., who was not involved with the study.

“We need more studies like this one because we know SARS-CoV-2 is a bad virus that may have important effects on the heart, but all the of research done so far has been problematic because it didn’t include controls.”

Atrial arrhythmias in COVID and flu

Dr. Reddy and coinvestigators performed a retrospective analysis of a large cohort of patients admitted with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 during Feb. 4-April 22, 2020, to one of five hospitals within the Mount Sinai Health System.

Their comparator arm included 1,420 patients with confirmed influenza A or B hospitalized between Jan. 1, 2017, and Jan. 1, 2020. For both cohorts, automated electronic record abstraction was used and all patient data were de-identified prior to analysis. In the COVID-19 cohort, a manual review of 1,110 charts was also performed.

Compared with those who did not develop AF/AFL, COVID-19 patients with newly detected AF/AFL and COVID-19 were older (74 vs. 66 years; P < .01) and had higher levels of inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, and higher troponin and D-dimer levels (all P < .01).

Overall, including those with a history of atrial arrhythmias, 10% of patients with hospitalized COVID-19 (13% in the manual review) and 12% of those with influenza had AF/AFL detected during their hospitalization.

Mortality at 30 days was higher in COVID-19 patients with AF/AFL compared to those without (46% vs. 26%; P < .01), as were the rates of intubation (27% vs. 15%; relative risk, 1.8; P < .01), and stroke (1.6% vs. 0.6%, RR, 2.7; P = .05).

Despite having more comorbidities, in-hospital mortality was significantly lower in the influenza cohort overall, compared to the COVID-19 cohort (9% vs. 29%; P < .01), reflecting the higher case fatality rate in COVID-19, Dr. Reddy, director of cardiac arrhythmia services at Mount Sinai Hospital, said in an interview.

But as with COVID-19, those influenza patients who had in-hospital AF/AFL were more likely to require intubation (14% vs. 7%; P = .004) or die (16% vs. 10%; P = .003).

“The data are not perfect and there are always limitations when doing an observational study using historic controls, but my guess would be that if we looked at other databases and other populations hospitalized for severe illness, we’d likely see something similar because when the body is inflamed, you’re more likely to see Afib,” said Dr. Mandrola.

Dr. Reddy concurred, noting that they considered comparing other populations to COVID-19 patients, including those with “just generalized severe illness,” but in the end felt there were many similarities between influenza and COVID-19, even though mortality in the latter is higher.

“It would be interesting for people to look at other illnesses and see if they find the same thing,” he said.

Dr. Reddy reported having no disclosures relevant to COVID-19. Dr. Mandrola is chief cardiology correspondent for Medscape.com. He reported having no relevant disclosures. MDedge is a member of the Medscape Professional Network.

Among 3,970 patients treated during the early months of the pandemic, new onset AF/AFL was seen in 4%, matching the 4% incidence found in a historic cohort of patients hospitalized with influenza.

On the other hand, mortality was similarly high in both groups of patients studied with AF/AFL, showing a 77% increased risk of death in COVID-19 and a 78% increased risk in influenza, a team from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York reported.

“We saw new onset Afib and flutter in a minority of patients and it was associated with much higher mortality, but the point is that this increase is basically the same as what you see in influenza, which we feel is an indication that this is more of a generalized response to the inflammatory milieu of such a severe viral illness, as opposed to something specific to COVID,” Vivek Y. Reddy, MD, said in the report, published online Feb. 25 in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

“Here we see, with a similar respiratory virus used as controls, that the results are exactly what I would have expected to see, which is that where there is a lot of inflammation, we see Afib,” said John Mandrola, MD, of Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky., who was not involved with the study.

“We need more studies like this one because we know SARS-CoV-2 is a bad virus that may have important effects on the heart, but all the of research done so far has been problematic because it didn’t include controls.”

Atrial arrhythmias in COVID and flu

Dr. Reddy and coinvestigators performed a retrospective analysis of a large cohort of patients admitted with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 during Feb. 4-April 22, 2020, to one of five hospitals within the Mount Sinai Health System.

Their comparator arm included 1,420 patients with confirmed influenza A or B hospitalized between Jan. 1, 2017, and Jan. 1, 2020. For both cohorts, automated electronic record abstraction was used and all patient data were de-identified prior to analysis. In the COVID-19 cohort, a manual review of 1,110 charts was also performed.

Compared with those who did not develop AF/AFL, COVID-19 patients with newly detected AF/AFL and COVID-19 were older (74 vs. 66 years; P < .01) and had higher levels of inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, and higher troponin and D-dimer levels (all P < .01).

Overall, including those with a history of atrial arrhythmias, 10% of patients with hospitalized COVID-19 (13% in the manual review) and 12% of those with influenza had AF/AFL detected during their hospitalization.

Mortality at 30 days was higher in COVID-19 patients with AF/AFL compared to those without (46% vs. 26%; P < .01), as were the rates of intubation (27% vs. 15%; relative risk, 1.8; P < .01), and stroke (1.6% vs. 0.6%, RR, 2.7; P = .05).

Despite having more comorbidities, in-hospital mortality was significantly lower in the influenza cohort overall, compared to the COVID-19 cohort (9% vs. 29%; P < .01), reflecting the higher case fatality rate in COVID-19, Dr. Reddy, director of cardiac arrhythmia services at Mount Sinai Hospital, said in an interview.

But as with COVID-19, those influenza patients who had in-hospital AF/AFL were more likely to require intubation (14% vs. 7%; P = .004) or die (16% vs. 10%; P = .003).

“The data are not perfect and there are always limitations when doing an observational study using historic controls, but my guess would be that if we looked at other databases and other populations hospitalized for severe illness, we’d likely see something similar because when the body is inflamed, you’re more likely to see Afib,” said Dr. Mandrola.

Dr. Reddy concurred, noting that they considered comparing other populations to COVID-19 patients, including those with “just generalized severe illness,” but in the end felt there were many similarities between influenza and COVID-19, even though mortality in the latter is higher.

“It would be interesting for people to look at other illnesses and see if they find the same thing,” he said.

Dr. Reddy reported having no disclosures relevant to COVID-19. Dr. Mandrola is chief cardiology correspondent for Medscape.com. He reported having no relevant disclosures. MDedge is a member of the Medscape Professional Network.

Among 3,970 patients treated during the early months of the pandemic, new onset AF/AFL was seen in 4%, matching the 4% incidence found in a historic cohort of patients hospitalized with influenza.

On the other hand, mortality was similarly high in both groups of patients studied with AF/AFL, showing a 77% increased risk of death in COVID-19 and a 78% increased risk in influenza, a team from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York reported.

“We saw new onset Afib and flutter in a minority of patients and it was associated with much higher mortality, but the point is that this increase is basically the same as what you see in influenza, which we feel is an indication that this is more of a generalized response to the inflammatory milieu of such a severe viral illness, as opposed to something specific to COVID,” Vivek Y. Reddy, MD, said in the report, published online Feb. 25 in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

“Here we see, with a similar respiratory virus used as controls, that the results are exactly what I would have expected to see, which is that where there is a lot of inflammation, we see Afib,” said John Mandrola, MD, of Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky., who was not involved with the study.

“We need more studies like this one because we know SARS-CoV-2 is a bad virus that may have important effects on the heart, but all the of research done so far has been problematic because it didn’t include controls.”

Atrial arrhythmias in COVID and flu

Dr. Reddy and coinvestigators performed a retrospective analysis of a large cohort of patients admitted with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 during Feb. 4-April 22, 2020, to one of five hospitals within the Mount Sinai Health System.

Their comparator arm included 1,420 patients with confirmed influenza A or B hospitalized between Jan. 1, 2017, and Jan. 1, 2020. For both cohorts, automated electronic record abstraction was used and all patient data were de-identified prior to analysis. In the COVID-19 cohort, a manual review of 1,110 charts was also performed.

Compared with those who did not develop AF/AFL, COVID-19 patients with newly detected AF/AFL and COVID-19 were older (74 vs. 66 years; P < .01) and had higher levels of inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, and higher troponin and D-dimer levels (all P < .01).

Overall, including those with a history of atrial arrhythmias, 10% of patients with hospitalized COVID-19 (13% in the manual review) and 12% of those with influenza had AF/AFL detected during their hospitalization.

Mortality at 30 days was higher in COVID-19 patients with AF/AFL compared to those without (46% vs. 26%; P < .01), as were the rates of intubation (27% vs. 15%; relative risk, 1.8; P < .01), and stroke (1.6% vs. 0.6%, RR, 2.7; P = .05).

Despite having more comorbidities, in-hospital mortality was significantly lower in the influenza cohort overall, compared to the COVID-19 cohort (9% vs. 29%; P < .01), reflecting the higher case fatality rate in COVID-19, Dr. Reddy, director of cardiac arrhythmia services at Mount Sinai Hospital, said in an interview.

But as with COVID-19, those influenza patients who had in-hospital AF/AFL were more likely to require intubation (14% vs. 7%; P = .004) or die (16% vs. 10%; P = .003).

“The data are not perfect and there are always limitations when doing an observational study using historic controls, but my guess would be that if we looked at other databases and other populations hospitalized for severe illness, we’d likely see something similar because when the body is inflamed, you’re more likely to see Afib,” said Dr. Mandrola.

Dr. Reddy concurred, noting that they considered comparing other populations to COVID-19 patients, including those with “just generalized severe illness,” but in the end felt there were many similarities between influenza and COVID-19, even though mortality in the latter is higher.

“It would be interesting for people to look at other illnesses and see if they find the same thing,” he said.

Dr. Reddy reported having no disclosures relevant to COVID-19. Dr. Mandrola is chief cardiology correspondent for Medscape.com. He reported having no relevant disclosures. MDedge is a member of the Medscape Professional Network.

FROM JACC: CLINICAL ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY

Variant found in NYC, Northeast

, according to CNN.

The variant, called B.1.526, has appeared in diverse neighborhoods in New York City and is “scattered in the Northeast,” the researchers said.

“We observed a steady increase in the detection rate from late December to mid-February, with an alarming rise to 12.7% in the past two weeks,” researchers from Columbia University Medical Center wrote in a report, which was published as a preprint Feb. 25.

On Feb. 22, the team released another preprint about the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants first identified in the United Kingdom and South Africa, respectively, which also mentions the B.1.526 variant in the U.S. Neither report has been peer reviewed.

Viruses mutate often, and several coronavirus variants have been identified and followed during the pandemic. Not all mutations are significant or are necessarily more contagious or dangerous. Researchers have been tracking the B.1.526 variant in the U.S. to find out if there are significant mutations that could be a cause for concern.

In the most recent preprints, the variant appears to have the same mutation found in B.1.351, called E484K, which may allow the virus to evade vaccines and the body’s natural immune response. The E484K mutation has shown up in at least 59 lines of the coronavirus, the research team said. That means the virus is evolving independently across the country and world, which could give the virus an advantage.

“A concern is that it might be beginning to overtake other strains, just like the U.K. and South African variants,” David Ho, MD, the lead study author and director of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center at Columbia, told CNN.

“However, we don’t have enough data to firm up this point now,” he said.

In a separate preprint posted Feb. 23, a research team at the California Institute of Technology developed a software tool that noticed the rise of B.1.526 in the New York region. The preprint hasn’t yet been peer reviewed.

“It appears that the frequency of lineage B.1.526 has increased rapidly in New York,” they wrote.

Both teams also reported on another variant, called B.1.427/B.1.429, which appears to be increasing in California. The variant could be more contagious and cause more severe disease, they said, but the research is still in the early stages.

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, have tested virus samples from recent outbreaks in California and also found that the variant is becoming more common. The variant didn’t appear in samples from September but was in half of the samples by late January. It has a different pattern of mutations than other variants, and one called L452R may affect the spike protein on the virus and allow it attach to cells more easily.

“Our data shows that this is likely the key mutation that makes this variant more infectious,” Charles Chiu, MD, associate director of the clinical microbiology lab at UCSF, told CNN.

The team also noticed that patients with a B.1.427/B.1.429 infection had more severe COVID-19 cases and needed more oxygen, CNN reported. The team plans to post a preprint once public health officials in San Francisco review the report.

Right now, the CDC provides public data for three variants: B.1.1.7, B.1.351, and P.1, which was first identified in Brazil. The U.S. has reported 1,881 B.1.1.7 cases across 45 states, 46 B.1.351 cases in 14 states, and five P.1 cases in four states, according to a CDC tally as of Feb. 23.

At the moment, lab officials aren’t able to tell patients or doctors whether someone has been infected by a variant, according to Kaiser Health News. High-level labs conduct genomic sequencing on samples and aren’t able to communicate information back to individual people.

But the Association of Public Health Laboratories and public health officials in several states are pushing for federal authorization of a test that could sequence the full genome and notify doctors. The test could be available in coming weeks, the news outlet reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to CNN.

The variant, called B.1.526, has appeared in diverse neighborhoods in New York City and is “scattered in the Northeast,” the researchers said.

“We observed a steady increase in the detection rate from late December to mid-February, with an alarming rise to 12.7% in the past two weeks,” researchers from Columbia University Medical Center wrote in a report, which was published as a preprint Feb. 25.

On Feb. 22, the team released another preprint about the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants first identified in the United Kingdom and South Africa, respectively, which also mentions the B.1.526 variant in the U.S. Neither report has been peer reviewed.

Viruses mutate often, and several coronavirus variants have been identified and followed during the pandemic. Not all mutations are significant or are necessarily more contagious or dangerous. Researchers have been tracking the B.1.526 variant in the U.S. to find out if there are significant mutations that could be a cause for concern.

In the most recent preprints, the variant appears to have the same mutation found in B.1.351, called E484K, which may allow the virus to evade vaccines and the body’s natural immune response. The E484K mutation has shown up in at least 59 lines of the coronavirus, the research team said. That means the virus is evolving independently across the country and world, which could give the virus an advantage.

“A concern is that it might be beginning to overtake other strains, just like the U.K. and South African variants,” David Ho, MD, the lead study author and director of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center at Columbia, told CNN.

“However, we don’t have enough data to firm up this point now,” he said.

In a separate preprint posted Feb. 23, a research team at the California Institute of Technology developed a software tool that noticed the rise of B.1.526 in the New York region. The preprint hasn’t yet been peer reviewed.

“It appears that the frequency of lineage B.1.526 has increased rapidly in New York,” they wrote.

Both teams also reported on another variant, called B.1.427/B.1.429, which appears to be increasing in California. The variant could be more contagious and cause more severe disease, they said, but the research is still in the early stages.

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, have tested virus samples from recent outbreaks in California and also found that the variant is becoming more common. The variant didn’t appear in samples from September but was in half of the samples by late January. It has a different pattern of mutations than other variants, and one called L452R may affect the spike protein on the virus and allow it attach to cells more easily.

“Our data shows that this is likely the key mutation that makes this variant more infectious,” Charles Chiu, MD, associate director of the clinical microbiology lab at UCSF, told CNN.

The team also noticed that patients with a B.1.427/B.1.429 infection had more severe COVID-19 cases and needed more oxygen, CNN reported. The team plans to post a preprint once public health officials in San Francisco review the report.

Right now, the CDC provides public data for three variants: B.1.1.7, B.1.351, and P.1, which was first identified in Brazil. The U.S. has reported 1,881 B.1.1.7 cases across 45 states, 46 B.1.351 cases in 14 states, and five P.1 cases in four states, according to a CDC tally as of Feb. 23.

At the moment, lab officials aren’t able to tell patients or doctors whether someone has been infected by a variant, according to Kaiser Health News. High-level labs conduct genomic sequencing on samples and aren’t able to communicate information back to individual people.

But the Association of Public Health Laboratories and public health officials in several states are pushing for federal authorization of a test that could sequence the full genome and notify doctors. The test could be available in coming weeks, the news outlet reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to CNN.

The variant, called B.1.526, has appeared in diverse neighborhoods in New York City and is “scattered in the Northeast,” the researchers said.

“We observed a steady increase in the detection rate from late December to mid-February, with an alarming rise to 12.7% in the past two weeks,” researchers from Columbia University Medical Center wrote in a report, which was published as a preprint Feb. 25.

On Feb. 22, the team released another preprint about the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants first identified in the United Kingdom and South Africa, respectively, which also mentions the B.1.526 variant in the U.S. Neither report has been peer reviewed.

Viruses mutate often, and several coronavirus variants have been identified and followed during the pandemic. Not all mutations are significant or are necessarily more contagious or dangerous. Researchers have been tracking the B.1.526 variant in the U.S. to find out if there are significant mutations that could be a cause for concern.

In the most recent preprints, the variant appears to have the same mutation found in B.1.351, called E484K, which may allow the virus to evade vaccines and the body’s natural immune response. The E484K mutation has shown up in at least 59 lines of the coronavirus, the research team said. That means the virus is evolving independently across the country and world, which could give the virus an advantage.

“A concern is that it might be beginning to overtake other strains, just like the U.K. and South African variants,” David Ho, MD, the lead study author and director of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center at Columbia, told CNN.

“However, we don’t have enough data to firm up this point now,” he said.

In a separate preprint posted Feb. 23, a research team at the California Institute of Technology developed a software tool that noticed the rise of B.1.526 in the New York region. The preprint hasn’t yet been peer reviewed.

“It appears that the frequency of lineage B.1.526 has increased rapidly in New York,” they wrote.

Both teams also reported on another variant, called B.1.427/B.1.429, which appears to be increasing in California. The variant could be more contagious and cause more severe disease, they said, but the research is still in the early stages.

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, have tested virus samples from recent outbreaks in California and also found that the variant is becoming more common. The variant didn’t appear in samples from September but was in half of the samples by late January. It has a different pattern of mutations than other variants, and one called L452R may affect the spike protein on the virus and allow it attach to cells more easily.

“Our data shows that this is likely the key mutation that makes this variant more infectious,” Charles Chiu, MD, associate director of the clinical microbiology lab at UCSF, told CNN.

The team also noticed that patients with a B.1.427/B.1.429 infection had more severe COVID-19 cases and needed more oxygen, CNN reported. The team plans to post a preprint once public health officials in San Francisco review the report.

Right now, the CDC provides public data for three variants: B.1.1.7, B.1.351, and P.1, which was first identified in Brazil. The U.S. has reported 1,881 B.1.1.7 cases across 45 states, 46 B.1.351 cases in 14 states, and five P.1 cases in four states, according to a CDC tally as of Feb. 23.

At the moment, lab officials aren’t able to tell patients or doctors whether someone has been infected by a variant, according to Kaiser Health News. High-level labs conduct genomic sequencing on samples and aren’t able to communicate information back to individual people.

But the Association of Public Health Laboratories and public health officials in several states are pushing for federal authorization of a test that could sequence the full genome and notify doctors. The test could be available in coming weeks, the news outlet reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Heroes: Nurses’ sacrifice in the age of COVID-19

This past year, the referrals to my private practice have taken a noticeable shift and caused me to pause.

More calls have come from nurses, many who work directly with COVID-19 patients, understandably seeking mental health treatment, or support. Especially in this time, nurses are facing trauma and stress that is unimaginable to many, myself included. Despite the collective efforts we have made as a society to recognize their work, I do not think we have given enough consideration to the enormous sacrifice nurses are currently undertaking to save our collective psyche.

As physicians and mental health providers, we have a glimpse into the complexities and stressors of medical treatment. In our line of work, we support patients with trauma on a regular basis. We feel deeply connected to patients, some of whom we have treated until the end of their lives. Despite that, I am not sure that I, or anyone, can truly comprehend what nurses face in today’s climate of care.

There is no denying that doctors are of value to our system, but our service has limits; nurses and doctors operate as two sides to a shared coin. As doctors, we diagnose and prescribe, while nurses explain and dispense. As doctors, we talk to patients, while nurses comfort them. Imagine spending an entire year working in a hospital diligently wiping endotracheal tubes that are responsible for maintaining someone’s life. Imagine spending an entire year laboring through the heavy task of lifting patients to prone them in a position that may save their lives. Imagine spending an entire year holding the hands of comatose patients in hopes of maintaining a sense of humanity.

And this only begins to describe the tasks bestowed upon nurses. While doctors answer pagers or complete insurance authorization forms, nurses empathize and reassure scared and isolated patients. Imagine spending an entire year updating crying family members who cannot see their loved ones. Imagine spending an entire year explaining and pleading to the outside world that wearing a mask and washing hands would reduce the suffering that takes place inside the hospital walls.

Despite the uncertainties, pressures, and demands, nurses have continued, and will continue, to show up for their patients, shift by shift. It takes a tragic number of deaths for the nurses I see in my practice to share that they have lost count. These numbers reflect people they held to feed, carried to prevent ulcers, wiped for decency, caressed for compassion, probed with IVs and tubes, monitored for signs of life, and warmed with blankets. If love were in any job description, it would fall under that of a nurse.

And we can’t ignore the fact that all the lives lost by COVID-19 had family. Family members who, without ever stepping foot in the hospital, needed a place to be heard, a place to receive explanation, and a place for reassurance. This invaluable place is cultivated by nurses. Through Zoom and phone calls, nurses share messages of hope, love, and fear between patients and family. Through Zoom and phone calls, nurses orchestrate visits and last goodbyes.

There is no denying that we have all been affected by this shared human experience. But the pause we owe our nurses feels long overdue, and of great importance. Nurses need a space to be heard, to be comforted, to be recognized. They come to our practices, trying to contain the world’s angst, while also navigating for themselves what it means to go through what they are going through. They hope that by coming to see us, they will find the strength to go back another day, another week, another month. Sometimes, they come to talk about everything but the job, in hopes that by talking about more mundane problems, they will feel “normal” and reconnected.

I hope that our empathy, congruence, and unconditional positive regard will allow them to feel heard.1 I hope that our warmth, concern, and hopefulness provide a welcoming place to voice sadness, anger, and fears.2 I hope that our processing of traumatic memory, our challenge to avoid inaccurate self-blaming beliefs, and our encouragement to create more thought-out conclusions will allow them to understand what is happening more accurately.3

Yet, I worry. I worry that society hasn’t been particularly successful with helping prior generations of heroes. From war veterans, to Sept. 11, 2001, firefighters, it seems that we have repeated mistakes. My experience with veterans in particular has taught me that for many who are suffering, it feels like society has broken its very fabric by being bystanders to the pain.

But suffering and tragedy are an inevitable part of the human experience that we share. What we can keep sight of is this: As physicians, we work with nurses. We are witnessing firsthand the impossible sacrifice they are taking and the limits of resilience. Let us not be too busy to stop and give recognition where and when it is due. Let us listen and learn from our past, and present, heroes. And let us never forget to extend our own hand to those who make a living extending theirs.

Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com.

References

1. Rogers CR. J Consult Psychol. 1957;21(2):95-103.

2. Mallo CJ, Mintz DL. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2013 Mar;41(1):13-37.

3. Resick PA et al. Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: A Comprehensive Manual. Guilford Publications, 2016.

This past year, the referrals to my private practice have taken a noticeable shift and caused me to pause.

More calls have come from nurses, many who work directly with COVID-19 patients, understandably seeking mental health treatment, or support. Especially in this time, nurses are facing trauma and stress that is unimaginable to many, myself included. Despite the collective efforts we have made as a society to recognize their work, I do not think we have given enough consideration to the enormous sacrifice nurses are currently undertaking to save our collective psyche.

As physicians and mental health providers, we have a glimpse into the complexities and stressors of medical treatment. In our line of work, we support patients with trauma on a regular basis. We feel deeply connected to patients, some of whom we have treated until the end of their lives. Despite that, I am not sure that I, or anyone, can truly comprehend what nurses face in today’s climate of care.

There is no denying that doctors are of value to our system, but our service has limits; nurses and doctors operate as two sides to a shared coin. As doctors, we diagnose and prescribe, while nurses explain and dispense. As doctors, we talk to patients, while nurses comfort them. Imagine spending an entire year working in a hospital diligently wiping endotracheal tubes that are responsible for maintaining someone’s life. Imagine spending an entire year laboring through the heavy task of lifting patients to prone them in a position that may save their lives. Imagine spending an entire year holding the hands of comatose patients in hopes of maintaining a sense of humanity.

And this only begins to describe the tasks bestowed upon nurses. While doctors answer pagers or complete insurance authorization forms, nurses empathize and reassure scared and isolated patients. Imagine spending an entire year updating crying family members who cannot see their loved ones. Imagine spending an entire year explaining and pleading to the outside world that wearing a mask and washing hands would reduce the suffering that takes place inside the hospital walls.

Despite the uncertainties, pressures, and demands, nurses have continued, and will continue, to show up for their patients, shift by shift. It takes a tragic number of deaths for the nurses I see in my practice to share that they have lost count. These numbers reflect people they held to feed, carried to prevent ulcers, wiped for decency, caressed for compassion, probed with IVs and tubes, monitored for signs of life, and warmed with blankets. If love were in any job description, it would fall under that of a nurse.

And we can’t ignore the fact that all the lives lost by COVID-19 had family. Family members who, without ever stepping foot in the hospital, needed a place to be heard, a place to receive explanation, and a place for reassurance. This invaluable place is cultivated by nurses. Through Zoom and phone calls, nurses share messages of hope, love, and fear between patients and family. Through Zoom and phone calls, nurses orchestrate visits and last goodbyes.

There is no denying that we have all been affected by this shared human experience. But the pause we owe our nurses feels long overdue, and of great importance. Nurses need a space to be heard, to be comforted, to be recognized. They come to our practices, trying to contain the world’s angst, while also navigating for themselves what it means to go through what they are going through. They hope that by coming to see us, they will find the strength to go back another day, another week, another month. Sometimes, they come to talk about everything but the job, in hopes that by talking about more mundane problems, they will feel “normal” and reconnected.

I hope that our empathy, congruence, and unconditional positive regard will allow them to feel heard.1 I hope that our warmth, concern, and hopefulness provide a welcoming place to voice sadness, anger, and fears.2 I hope that our processing of traumatic memory, our challenge to avoid inaccurate self-blaming beliefs, and our encouragement to create more thought-out conclusions will allow them to understand what is happening more accurately.3

Yet, I worry. I worry that society hasn’t been particularly successful with helping prior generations of heroes. From war veterans, to Sept. 11, 2001, firefighters, it seems that we have repeated mistakes. My experience with veterans in particular has taught me that for many who are suffering, it feels like society has broken its very fabric by being bystanders to the pain.

But suffering and tragedy are an inevitable part of the human experience that we share. What we can keep sight of is this: As physicians, we work with nurses. We are witnessing firsthand the impossible sacrifice they are taking and the limits of resilience. Let us not be too busy to stop and give recognition where and when it is due. Let us listen and learn from our past, and present, heroes. And let us never forget to extend our own hand to those who make a living extending theirs.

Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com.

References

1. Rogers CR. J Consult Psychol. 1957;21(2):95-103.

2. Mallo CJ, Mintz DL. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2013 Mar;41(1):13-37.

3. Resick PA et al. Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: A Comprehensive Manual. Guilford Publications, 2016.

This past year, the referrals to my private practice have taken a noticeable shift and caused me to pause.

More calls have come from nurses, many who work directly with COVID-19 patients, understandably seeking mental health treatment, or support. Especially in this time, nurses are facing trauma and stress that is unimaginable to many, myself included. Despite the collective efforts we have made as a society to recognize their work, I do not think we have given enough consideration to the enormous sacrifice nurses are currently undertaking to save our collective psyche.

As physicians and mental health providers, we have a glimpse into the complexities and stressors of medical treatment. In our line of work, we support patients with trauma on a regular basis. We feel deeply connected to patients, some of whom we have treated until the end of their lives. Despite that, I am not sure that I, or anyone, can truly comprehend what nurses face in today’s climate of care.

There is no denying that doctors are of value to our system, but our service has limits; nurses and doctors operate as two sides to a shared coin. As doctors, we diagnose and prescribe, while nurses explain and dispense. As doctors, we talk to patients, while nurses comfort them. Imagine spending an entire year working in a hospital diligently wiping endotracheal tubes that are responsible for maintaining someone’s life. Imagine spending an entire year laboring through the heavy task of lifting patients to prone them in a position that may save their lives. Imagine spending an entire year holding the hands of comatose patients in hopes of maintaining a sense of humanity.

And this only begins to describe the tasks bestowed upon nurses. While doctors answer pagers or complete insurance authorization forms, nurses empathize and reassure scared and isolated patients. Imagine spending an entire year updating crying family members who cannot see their loved ones. Imagine spending an entire year explaining and pleading to the outside world that wearing a mask and washing hands would reduce the suffering that takes place inside the hospital walls.

Despite the uncertainties, pressures, and demands, nurses have continued, and will continue, to show up for their patients, shift by shift. It takes a tragic number of deaths for the nurses I see in my practice to share that they have lost count. These numbers reflect people they held to feed, carried to prevent ulcers, wiped for decency, caressed for compassion, probed with IVs and tubes, monitored for signs of life, and warmed with blankets. If love were in any job description, it would fall under that of a nurse.

And we can’t ignore the fact that all the lives lost by COVID-19 had family. Family members who, without ever stepping foot in the hospital, needed a place to be heard, a place to receive explanation, and a place for reassurance. This invaluable place is cultivated by nurses. Through Zoom and phone calls, nurses share messages of hope, love, and fear between patients and family. Through Zoom and phone calls, nurses orchestrate visits and last goodbyes.

There is no denying that we have all been affected by this shared human experience. But the pause we owe our nurses feels long overdue, and of great importance. Nurses need a space to be heard, to be comforted, to be recognized. They come to our practices, trying to contain the world’s angst, while also navigating for themselves what it means to go through what they are going through. They hope that by coming to see us, they will find the strength to go back another day, another week, another month. Sometimes, they come to talk about everything but the job, in hopes that by talking about more mundane problems, they will feel “normal” and reconnected.

I hope that our empathy, congruence, and unconditional positive regard will allow them to feel heard.1 I hope that our warmth, concern, and hopefulness provide a welcoming place to voice sadness, anger, and fears.2 I hope that our processing of traumatic memory, our challenge to avoid inaccurate self-blaming beliefs, and our encouragement to create more thought-out conclusions will allow them to understand what is happening more accurately.3

Yet, I worry. I worry that society hasn’t been particularly successful with helping prior generations of heroes. From war veterans, to Sept. 11, 2001, firefighters, it seems that we have repeated mistakes. My experience with veterans in particular has taught me that for many who are suffering, it feels like society has broken its very fabric by being bystanders to the pain.

But suffering and tragedy are an inevitable part of the human experience that we share. What we can keep sight of is this: As physicians, we work with nurses. We are witnessing firsthand the impossible sacrifice they are taking and the limits of resilience. Let us not be too busy to stop and give recognition where and when it is due. Let us listen and learn from our past, and present, heroes. And let us never forget to extend our own hand to those who make a living extending theirs.

Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com.

References

1. Rogers CR. J Consult Psychol. 1957;21(2):95-103.

2. Mallo CJ, Mintz DL. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2013 Mar;41(1):13-37.

3. Resick PA et al. Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: A Comprehensive Manual. Guilford Publications, 2016.

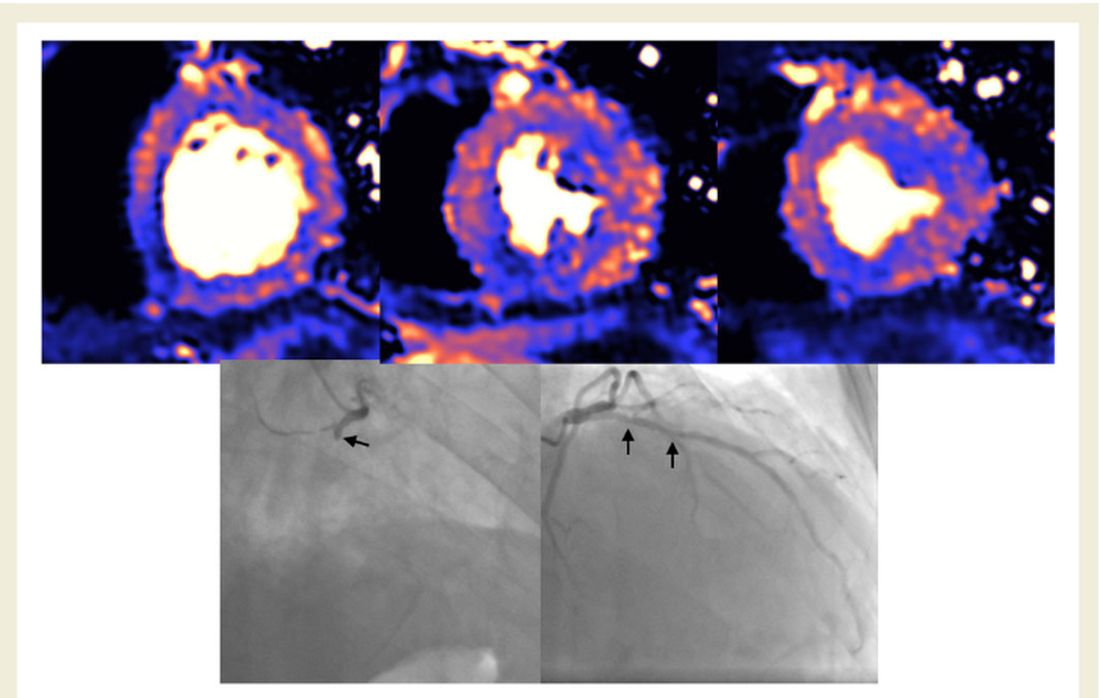

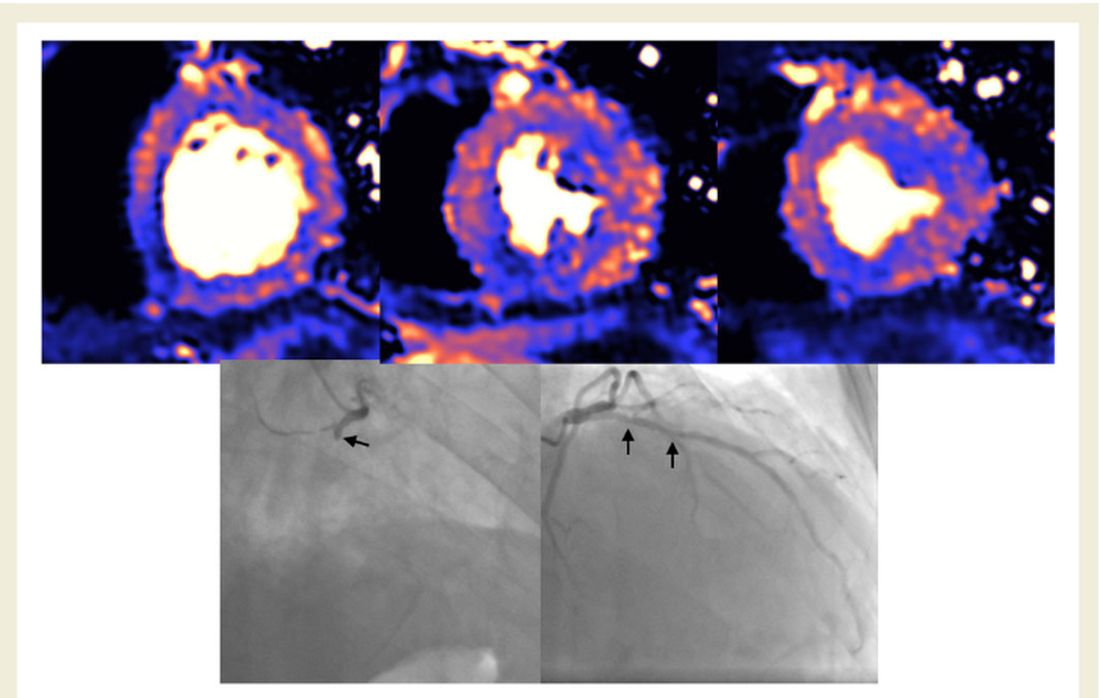

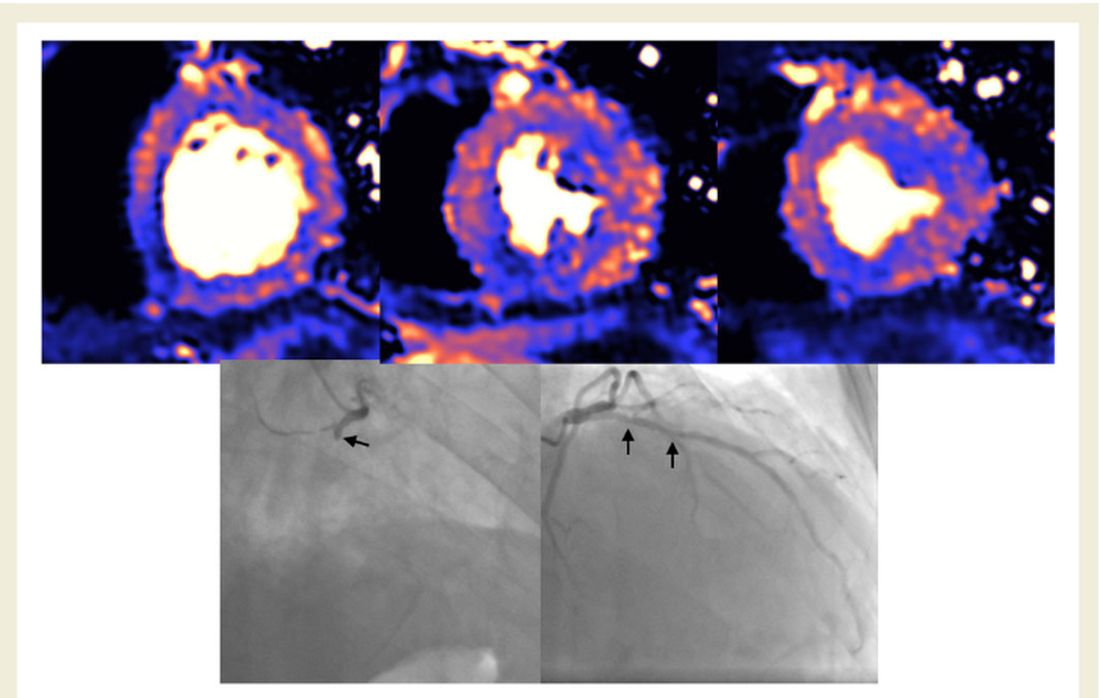

Myocardial injury seen on MRI in 54% of recovered COVID-19 patients

About half of 148 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection and elevated troponin levels had at least some evidence of myocardial injury on cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging 2 months later, a new study shows.

“Our results demonstrate that in this subset of patients surviving severe COVID-19 and with troponin elevation, ongoing localized myocardial inflammation, whilst less frequent than previously reported, remains present in a proportion of patients and may represent an emerging issue of clinical relevance,” wrote Marianna Fontana, MD, PhD, of University College London, and colleagues.

The cardiac abnormalities identified were classified as nonischemic (including “myocarditis-like” late gadolinium enhancement [LGE]) in 26% of the cohort; as related to ischemic heart disease (infarction or inducible ischemia) in 22%; and as dual pathology in 6%.

Left ventricular (LV) function was normal in 89% of the 148 patients. In the 17 patients (11%) with LV dysfunction, only four had an ejection fraction below 35%. Of the nine patients whose LV dysfunction was related to myocardial infarction, six had a known history of ischemic heart disease.

No patients with “myocarditis-pattern” LGE had regional wall motion abnormalities, and neither admission nor peak troponin values were predictive of the diagnosis of myocarditis.

The results were published online Feb. 18 in the European Heart Journal.

Glass half full

Taking a “glass half full” approach, co–senior author Graham D. Cole, MD, PhD, noted on Twitter that nearly half the patients had no major cardiac abnormalities on CMR just 2 months after a bout with troponin-positive COVID-19.

“We think this is important: Even in a group who had been very sick with raised troponin, it was common to find no evidence of heart damage,” said Dr. Cole, of the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust.

“We believe our data challenge the hypothesis that chronic inflammation, diffuse fibrosis, or long-term LV dysfunction is a dominant feature in those surviving COVID-19,” the investigators concluded in their report.

In an interview, Dr. Fontana explained further: “It has been reported in an early ‘pathfinder’ study that two-thirds of patients recovered from COVID-19 had CMR evidence of abnormal findings with a high incidence of elevated T1 and T2 in keeping with diffuse fibrosis and edema. Our findings with a larger, multicenter study and better controls show low rates of heart impairment and much less ongoing inflammation, which is reassuring.”

She also noted that the different patterns of injury suggest that different mechanisms are at play, including the possibility that “at least some of the found damage might have been preexisting, because people with heart damage are more likely to get severe disease.”

The investigators, including first author Tushar Kotecha, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, also noted that myocarditis-like injury was limited to three or fewer myocardial segments in 88% of cases with no associated ventricular dysfunction, and that biventricular function was no different than in those without myocarditis.

“We use the word ‘myocarditis-like’ but we don’t have histology,” Dr. Fontana said. “Our group actually suspects a lot of this will be microvascular clotting (microangiopathic thrombosis). This is exciting, as newer anticoagulation strategies – for example, those being tried in RECOVERY – may have benefit.”

Aloke V. Finn, MD, of the CVPath Institute in Gaithersburg, Md., wishes researchers would stop using the term myocarditis altogether to describe clinical or imaging findings in COVID-19.

“MRI can’t diagnose myocarditis. It is a specific diagnosis that requires, ideally, histology, as the investigators acknowledged,” Dr. Finn said in an interview.

His group at CVPath recently published data showing pathologic evidence of myocarditis after SARS-CoV-2 infection, as reported by theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

“As a clinician, when I think of myocarditis, I look at the echo and an LV gram, and I see if there is a wall motion abnormality and troponin elevation, but with normal coronary arteries. And if all that is there, then I think about myocarditis in my differential diagnosis,” he said. “But in most of these cases, as the authors rightly point out, most patients did not have what is necessary to really entertain a diagnosis of myocarditis.”

He agreed with Dr. Fontana’s suggestion that what the CMR might be picking up in these survivors is microthrombi, as his group saw in their recent autopsy study.

“It’s very possible these findings are concordant with the recent autopsy studies done by my group and others in terms of detecting the presence of microthrombi, but we don’t know this for certain because no one has ever studied this entity before in the clinic and we don’t really know how microthrombi might appear on CMR.”

Largest study to date

The 148 participants (mean age, 64 years; 70% male) in the largest study to date to investigate convalescing COVID-19 patients who had elevated troponins – something identified early in the pandemic as a risk factor for worse outcomes in COVID-19 – were treated at one of six hospitals in London.

Patients who had abnormal troponin levels were offered an MRI scan of the heart after discharge and were compared with those from a control group of patients who had not had COVID-19 and with 40 healthy volunteers.

Median length of stay was 9 days, and 32% of patients required ventilatory support in the intensive care unit.

Just over half the patients (57%) had hypertension, 7% had had a previous myocardial infarction, 34% had diabetes, 46% had hypercholesterolemia, and 24% were smokers. Mean body mass index was 28.5 kg/m2.

CMR follow-up was conducted a median of 68 days after confirmation of a COVID-19 diagnosis.

On Twitter, Dr. Cole noted that the findings are subject to both survivor bias and referral bias. “We didn’t scan frail patients where the clinician felt [CMR] was unlikely to inform management.”

The findings, said Dr. Fontana, “say nothing about what happens to people who are not hospitalized with COVID, or those who are hospitalized but without elevated troponin.”

What they do offer, particularly if replicated, is a way forward in identifying patients at higher or lower risk for long-term sequelae and inform strategies that could improve outcomes, she added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About half of 148 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection and elevated troponin levels had at least some evidence of myocardial injury on cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging 2 months later, a new study shows.

“Our results demonstrate that in this subset of patients surviving severe COVID-19 and with troponin elevation, ongoing localized myocardial inflammation, whilst less frequent than previously reported, remains present in a proportion of patients and may represent an emerging issue of clinical relevance,” wrote Marianna Fontana, MD, PhD, of University College London, and colleagues.

The cardiac abnormalities identified were classified as nonischemic (including “myocarditis-like” late gadolinium enhancement [LGE]) in 26% of the cohort; as related to ischemic heart disease (infarction or inducible ischemia) in 22%; and as dual pathology in 6%.

Left ventricular (LV) function was normal in 89% of the 148 patients. In the 17 patients (11%) with LV dysfunction, only four had an ejection fraction below 35%. Of the nine patients whose LV dysfunction was related to myocardial infarction, six had a known history of ischemic heart disease.

No patients with “myocarditis-pattern” LGE had regional wall motion abnormalities, and neither admission nor peak troponin values were predictive of the diagnosis of myocarditis.

The results were published online Feb. 18 in the European Heart Journal.

Glass half full

Taking a “glass half full” approach, co–senior author Graham D. Cole, MD, PhD, noted on Twitter that nearly half the patients had no major cardiac abnormalities on CMR just 2 months after a bout with troponin-positive COVID-19.

“We think this is important: Even in a group who had been very sick with raised troponin, it was common to find no evidence of heart damage,” said Dr. Cole, of the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust.

“We believe our data challenge the hypothesis that chronic inflammation, diffuse fibrosis, or long-term LV dysfunction is a dominant feature in those surviving COVID-19,” the investigators concluded in their report.

In an interview, Dr. Fontana explained further: “It has been reported in an early ‘pathfinder’ study that two-thirds of patients recovered from COVID-19 had CMR evidence of abnormal findings with a high incidence of elevated T1 and T2 in keeping with diffuse fibrosis and edema. Our findings with a larger, multicenter study and better controls show low rates of heart impairment and much less ongoing inflammation, which is reassuring.”

She also noted that the different patterns of injury suggest that different mechanisms are at play, including the possibility that “at least some of the found damage might have been preexisting, because people with heart damage are more likely to get severe disease.”

The investigators, including first author Tushar Kotecha, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, also noted that myocarditis-like injury was limited to three or fewer myocardial segments in 88% of cases with no associated ventricular dysfunction, and that biventricular function was no different than in those without myocarditis.

“We use the word ‘myocarditis-like’ but we don’t have histology,” Dr. Fontana said. “Our group actually suspects a lot of this will be microvascular clotting (microangiopathic thrombosis). This is exciting, as newer anticoagulation strategies – for example, those being tried in RECOVERY – may have benefit.”

Aloke V. Finn, MD, of the CVPath Institute in Gaithersburg, Md., wishes researchers would stop using the term myocarditis altogether to describe clinical or imaging findings in COVID-19.

“MRI can’t diagnose myocarditis. It is a specific diagnosis that requires, ideally, histology, as the investigators acknowledged,” Dr. Finn said in an interview.

His group at CVPath recently published data showing pathologic evidence of myocarditis after SARS-CoV-2 infection, as reported by theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

“As a clinician, when I think of myocarditis, I look at the echo and an LV gram, and I see if there is a wall motion abnormality and troponin elevation, but with normal coronary arteries. And if all that is there, then I think about myocarditis in my differential diagnosis,” he said. “But in most of these cases, as the authors rightly point out, most patients did not have what is necessary to really entertain a diagnosis of myocarditis.”

He agreed with Dr. Fontana’s suggestion that what the CMR might be picking up in these survivors is microthrombi, as his group saw in their recent autopsy study.

“It’s very possible these findings are concordant with the recent autopsy studies done by my group and others in terms of detecting the presence of microthrombi, but we don’t know this for certain because no one has ever studied this entity before in the clinic and we don’t really know how microthrombi might appear on CMR.”

Largest study to date

The 148 participants (mean age, 64 years; 70% male) in the largest study to date to investigate convalescing COVID-19 patients who had elevated troponins – something identified early in the pandemic as a risk factor for worse outcomes in COVID-19 – were treated at one of six hospitals in London.

Patients who had abnormal troponin levels were offered an MRI scan of the heart after discharge and were compared with those from a control group of patients who had not had COVID-19 and with 40 healthy volunteers.

Median length of stay was 9 days, and 32% of patients required ventilatory support in the intensive care unit.

Just over half the patients (57%) had hypertension, 7% had had a previous myocardial infarction, 34% had diabetes, 46% had hypercholesterolemia, and 24% were smokers. Mean body mass index was 28.5 kg/m2.

CMR follow-up was conducted a median of 68 days after confirmation of a COVID-19 diagnosis.

On Twitter, Dr. Cole noted that the findings are subject to both survivor bias and referral bias. “We didn’t scan frail patients where the clinician felt [CMR] was unlikely to inform management.”

The findings, said Dr. Fontana, “say nothing about what happens to people who are not hospitalized with COVID, or those who are hospitalized but without elevated troponin.”

What they do offer, particularly if replicated, is a way forward in identifying patients at higher or lower risk for long-term sequelae and inform strategies that could improve outcomes, she added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About half of 148 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection and elevated troponin levels had at least some evidence of myocardial injury on cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging 2 months later, a new study shows.

“Our results demonstrate that in this subset of patients surviving severe COVID-19 and with troponin elevation, ongoing localized myocardial inflammation, whilst less frequent than previously reported, remains present in a proportion of patients and may represent an emerging issue of clinical relevance,” wrote Marianna Fontana, MD, PhD, of University College London, and colleagues.

The cardiac abnormalities identified were classified as nonischemic (including “myocarditis-like” late gadolinium enhancement [LGE]) in 26% of the cohort; as related to ischemic heart disease (infarction or inducible ischemia) in 22%; and as dual pathology in 6%.

Left ventricular (LV) function was normal in 89% of the 148 patients. In the 17 patients (11%) with LV dysfunction, only four had an ejection fraction below 35%. Of the nine patients whose LV dysfunction was related to myocardial infarction, six had a known history of ischemic heart disease.

No patients with “myocarditis-pattern” LGE had regional wall motion abnormalities, and neither admission nor peak troponin values were predictive of the diagnosis of myocarditis.

The results were published online Feb. 18 in the European Heart Journal.

Glass half full

Taking a “glass half full” approach, co–senior author Graham D. Cole, MD, PhD, noted on Twitter that nearly half the patients had no major cardiac abnormalities on CMR just 2 months after a bout with troponin-positive COVID-19.

“We think this is important: Even in a group who had been very sick with raised troponin, it was common to find no evidence of heart damage,” said Dr. Cole, of the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust.

“We believe our data challenge the hypothesis that chronic inflammation, diffuse fibrosis, or long-term LV dysfunction is a dominant feature in those surviving COVID-19,” the investigators concluded in their report.

In an interview, Dr. Fontana explained further: “It has been reported in an early ‘pathfinder’ study that two-thirds of patients recovered from COVID-19 had CMR evidence of abnormal findings with a high incidence of elevated T1 and T2 in keeping with diffuse fibrosis and edema. Our findings with a larger, multicenter study and better controls show low rates of heart impairment and much less ongoing inflammation, which is reassuring.”

She also noted that the different patterns of injury suggest that different mechanisms are at play, including the possibility that “at least some of the found damage might have been preexisting, because people with heart damage are more likely to get severe disease.”

The investigators, including first author Tushar Kotecha, MBChB, PhD, of the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, also noted that myocarditis-like injury was limited to three or fewer myocardial segments in 88% of cases with no associated ventricular dysfunction, and that biventricular function was no different than in those without myocarditis.

“We use the word ‘myocarditis-like’ but we don’t have histology,” Dr. Fontana said. “Our group actually suspects a lot of this will be microvascular clotting (microangiopathic thrombosis). This is exciting, as newer anticoagulation strategies – for example, those being tried in RECOVERY – may have benefit.”

Aloke V. Finn, MD, of the CVPath Institute in Gaithersburg, Md., wishes researchers would stop using the term myocarditis altogether to describe clinical or imaging findings in COVID-19.

“MRI can’t diagnose myocarditis. It is a specific diagnosis that requires, ideally, histology, as the investigators acknowledged,” Dr. Finn said in an interview.

His group at CVPath recently published data showing pathologic evidence of myocarditis after SARS-CoV-2 infection, as reported by theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

“As a clinician, when I think of myocarditis, I look at the echo and an LV gram, and I see if there is a wall motion abnormality and troponin elevation, but with normal coronary arteries. And if all that is there, then I think about myocarditis in my differential diagnosis,” he said. “But in most of these cases, as the authors rightly point out, most patients did not have what is necessary to really entertain a diagnosis of myocarditis.”

He agreed with Dr. Fontana’s suggestion that what the CMR might be picking up in these survivors is microthrombi, as his group saw in their recent autopsy study.

“It’s very possible these findings are concordant with the recent autopsy studies done by my group and others in terms of detecting the presence of microthrombi, but we don’t know this for certain because no one has ever studied this entity before in the clinic and we don’t really know how microthrombi might appear on CMR.”

Largest study to date

The 148 participants (mean age, 64 years; 70% male) in the largest study to date to investigate convalescing COVID-19 patients who had elevated troponins – something identified early in the pandemic as a risk factor for worse outcomes in COVID-19 – were treated at one of six hospitals in London.

Patients who had abnormal troponin levels were offered an MRI scan of the heart after discharge and were compared with those from a control group of patients who had not had COVID-19 and with 40 healthy volunteers.

Median length of stay was 9 days, and 32% of patients required ventilatory support in the intensive care unit.

Just over half the patients (57%) had hypertension, 7% had had a previous myocardial infarction, 34% had diabetes, 46% had hypercholesterolemia, and 24% were smokers. Mean body mass index was 28.5 kg/m2.

CMR follow-up was conducted a median of 68 days after confirmation of a COVID-19 diagnosis.

On Twitter, Dr. Cole noted that the findings are subject to both survivor bias and referral bias. “We didn’t scan frail patients where the clinician felt [CMR] was unlikely to inform management.”

The findings, said Dr. Fontana, “say nothing about what happens to people who are not hospitalized with COVID, or those who are hospitalized but without elevated troponin.”

What they do offer, particularly if replicated, is a way forward in identifying patients at higher or lower risk for long-term sequelae and inform strategies that could improve outcomes, she added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatric COVID-19: Data to guide practice

With the daily stream of new information, it is difficult to keep up with data on how the coronavirus epidemic affects children and school attendance, as well as how pediatricians can advise parents. The following is a summary of recently published information about birth and infant outcomes, and symptoms seen in infants and children, along with a review of recent information on transmission in schools.

COVID-19 in newborns

In November 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published data from 16 jurisdictions detailing pregnancy and infant outcomes of more than 5,000 women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The data were collected from March to October 2020. More than 80% of the women found to be positive for SARS-CoV-2 were identified during their third trimester. The surveillance found that 12.9% of infants born to infected mothers were born preterm, compared with an expected rate in the population of approximately 10%, suggesting that third-trimester infection may be associated with an increase in premature birth. Among 610 infants born to infected mothers and tested for SARS-CoV-2 during their nursery stay, 2.6% were positive. The infant positivity rate was as high as 4.3% among infants who were born to women with a documented SARS-CoV-2 infection within 2 weeks of the delivery date. No newborn infections were found among the infants whose mothers’ infection occurred more than 14 days before delivery. Current CDC and American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations are to test infants born to mothers with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Data on clinical characteristics of a series of hospitalized infants in Montreal was published in December 2020. The study identified infants 0-12 months old who were diagnosed or treated at a single Montreal hospital from February until May 2020. In all, 25 (2.0%) of 1,165 infants were confirmed to have SARS-CoV-2, and approximately 8 of those were hospitalized; 85% had gastrointestinal symptoms and 81% had a fever. Upper respiratory tract symptoms were present in 59%, and none of the hospitalized infants required supplemental oxygen. The data overall support the idea that infants are generally only mildly symptomatic when infected, and respiratory symptoms do not appear to be the most prevalent finding.

COVID-19 in children

The lack of prominent respiratory symptoms among children with SARS-CoV-2 infection symptoms was echoed in another study that evaluated more than 2,400 children in Alberta, Canada. Among the 1,987 children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, one-third (35.9%) were asymptomatic. Some symptoms were not helpful in differentiating children who tested positive vs. those who tested negative. The frequency of muscle or joint pain, myalgia, malaise, and respiratory symptoms such as nasal congestion, difficulty breathing, and sore throat was indistinguishable between the SARS-CoV-2–infected and –noninfected children. However, anosmia was much more prevalent (7.7%) among those who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, compared with 1.1% of those who were negative. Headache was present in 15.7% of those who were positive vs. 6.3% of those who were negative. Fever was slightly more prevalent, at 25.5% among the positive patients and 15% of the negative patients.

The authors calculated likelihood ratios for individual symptoms and found that almost all individual symptoms had likelihood ratios of 1:1.8 for testing positive. However, nausea and vomiting had a likelihood ratio of 5.5, and for anosmia it was 7.3. The combination of symptoms of nausea, nausea and vomiting, and headache produced a likelihood ratio of nearly 66. The authors suggest that these data on ambulatory children indicate that, in general, respiratory symptoms are not helpful for distinguishing patients who are likely to be positive, although the symptoms of nausea, headache, and both along with fever can be highly predictive. The authors propose that it may be more helpful for schools to focus on identifying children with combinations of these high-yield symptoms for potential testing and exclusion from school rather than on random or isolated respiratory symptoms.

COVID-19 in schools

Transmission risk in different settings is certainly something parents quiz pediatricians about, so data released in January and February 2021 may help provide some context. A CDC report on the experience of 17 schools in Wisconsin from August to November 2020 is illuminating. In that study, the SARS-CoV-2 case rate in students, school teachers, and staff members was 63% of the rate in the general public at the time, suggesting that the mitigation strategies used by the schools were effective. In addition, among the students who contracted SARS-CoV-2, only 5% of cases were attributable to school exposure. No cases of SARS-CoV-2 among faculty or staff were linked to school exposure.

Indeed, data released on Feb. 2, 2021, demonstrate that younger adults are the largest source of sustaining the epidemic. On the basis of data from August to October 2020, the opening of schools does not appear to be associated with population-level changes in SARS-CoV-2–attributable deaths. For October 2020, the authors estimate that 2.7% of infections were from children 0-9 years old, 7.1% from those ages 10-19 years, but 34% from those 20-34 years old and 38% from those 35-49 years old, by far the largest two groups contributing to spread. It should be noted that ages 20-49 years are the peak working years for adults, but the source of the data did not allow the authors to conclude whether infections were work related or social activity related. Their data do suggest that prioritizing vaccination of younger working-age adults may put more of a dent in the pandemic spread than vaccinating older individuals.

In a similar vein, a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent studies looked at household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and demonstrated an attack rate within households of 16.6%. Of note, secondary household attack rates were only 0.7% from asymptomatic cases and 18% from symptomatic cases, with spouses and adult household contacts having higher secondary attack rates than children in the household.

COVID-19 in student athletes

A recent MMWR report described a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak associated with a series of wrestling tournaments in Florida, held in December and January 2021. While everyone would like children to be able to participate in sports, such events potentially violate several of the precepts for preventing spread: Avoid close contact and don’t mix contacts from different schools. Moreover, the events occurred during some of the highest incident case rates in the counties where the tournaments took place.

On Dec. 4, 2020, the AAP released updated guidance for athletic activities and recommended cloth face coverings for student athletes during training, in competition, while traveling, and even while waiting on the sidelines and not actively playing. Notable exceptions to the recommendation were competitive cheerleading, gymnastics, wrestling, and water sports, where the risk for entanglement from face coverings was too high or was not practical.

Taken as a whole, the evolving data continue to show that school mitigation practices can be effective in reducing the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 rates among schoolchildren more closely mirror community rates and are probably more influenced by what happens outside the schools than inside the schools.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With the daily stream of new information, it is difficult to keep up with data on how the coronavirus epidemic affects children and school attendance, as well as how pediatricians can advise parents. The following is a summary of recently published information about birth and infant outcomes, and symptoms seen in infants and children, along with a review of recent information on transmission in schools.

COVID-19 in newborns

In November 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published data from 16 jurisdictions detailing pregnancy and infant outcomes of more than 5,000 women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The data were collected from March to October 2020. More than 80% of the women found to be positive for SARS-CoV-2 were identified during their third trimester. The surveillance found that 12.9% of infants born to infected mothers were born preterm, compared with an expected rate in the population of approximately 10%, suggesting that third-trimester infection may be associated with an increase in premature birth. Among 610 infants born to infected mothers and tested for SARS-CoV-2 during their nursery stay, 2.6% were positive. The infant positivity rate was as high as 4.3% among infants who were born to women with a documented SARS-CoV-2 infection within 2 weeks of the delivery date. No newborn infections were found among the infants whose mothers’ infection occurred more than 14 days before delivery. Current CDC and American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations are to test infants born to mothers with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Data on clinical characteristics of a series of hospitalized infants in Montreal was published in December 2020. The study identified infants 0-12 months old who were diagnosed or treated at a single Montreal hospital from February until May 2020. In all, 25 (2.0%) of 1,165 infants were confirmed to have SARS-CoV-2, and approximately 8 of those were hospitalized; 85% had gastrointestinal symptoms and 81% had a fever. Upper respiratory tract symptoms were present in 59%, and none of the hospitalized infants required supplemental oxygen. The data overall support the idea that infants are generally only mildly symptomatic when infected, and respiratory symptoms do not appear to be the most prevalent finding.

COVID-19 in children

The lack of prominent respiratory symptoms among children with SARS-CoV-2 infection symptoms was echoed in another study that evaluated more than 2,400 children in Alberta, Canada. Among the 1,987 children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, one-third (35.9%) were asymptomatic. Some symptoms were not helpful in differentiating children who tested positive vs. those who tested negative. The frequency of muscle or joint pain, myalgia, malaise, and respiratory symptoms such as nasal congestion, difficulty breathing, and sore throat was indistinguishable between the SARS-CoV-2–infected and –noninfected children. However, anosmia was much more prevalent (7.7%) among those who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, compared with 1.1% of those who were negative. Headache was present in 15.7% of those who were positive vs. 6.3% of those who were negative. Fever was slightly more prevalent, at 25.5% among the positive patients and 15% of the negative patients.

The authors calculated likelihood ratios for individual symptoms and found that almost all individual symptoms had likelihood ratios of 1:1.8 for testing positive. However, nausea and vomiting had a likelihood ratio of 5.5, and for anosmia it was 7.3. The combination of symptoms of nausea, nausea and vomiting, and headache produced a likelihood ratio of nearly 66. The authors suggest that these data on ambulatory children indicate that, in general, respiratory symptoms are not helpful for distinguishing patients who are likely to be positive, although the symptoms of nausea, headache, and both along with fever can be highly predictive. The authors propose that it may be more helpful for schools to focus on identifying children with combinations of these high-yield symptoms for potential testing and exclusion from school rather than on random or isolated respiratory symptoms.

COVID-19 in schools

Transmission risk in different settings is certainly something parents quiz pediatricians about, so data released in January and February 2021 may help provide some context. A CDC report on the experience of 17 schools in Wisconsin from August to November 2020 is illuminating. In that study, the SARS-CoV-2 case rate in students, school teachers, and staff members was 63% of the rate in the general public at the time, suggesting that the mitigation strategies used by the schools were effective. In addition, among the students who contracted SARS-CoV-2, only 5% of cases were attributable to school exposure. No cases of SARS-CoV-2 among faculty or staff were linked to school exposure.

Indeed, data released on Feb. 2, 2021, demonstrate that younger adults are the largest source of sustaining the epidemic. On the basis of data from August to October 2020, the opening of schools does not appear to be associated with population-level changes in SARS-CoV-2–attributable deaths. For October 2020, the authors estimate that 2.7% of infections were from children 0-9 years old, 7.1% from those ages 10-19 years, but 34% from those 20-34 years old and 38% from those 35-49 years old, by far the largest two groups contributing to spread. It should be noted that ages 20-49 years are the peak working years for adults, but the source of the data did not allow the authors to conclude whether infections were work related or social activity related. Their data do suggest that prioritizing vaccination of younger working-age adults may put more of a dent in the pandemic spread than vaccinating older individuals.

In a similar vein, a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent studies looked at household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and demonstrated an attack rate within households of 16.6%. Of note, secondary household attack rates were only 0.7% from asymptomatic cases and 18% from symptomatic cases, with spouses and adult household contacts having higher secondary attack rates than children in the household.

COVID-19 in student athletes

A recent MMWR report described a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak associated with a series of wrestling tournaments in Florida, held in December and January 2021. While everyone would like children to be able to participate in sports, such events potentially violate several of the precepts for preventing spread: Avoid close contact and don’t mix contacts from different schools. Moreover, the events occurred during some of the highest incident case rates in the counties where the tournaments took place.

On Dec. 4, 2020, the AAP released updated guidance for athletic activities and recommended cloth face coverings for student athletes during training, in competition, while traveling, and even while waiting on the sidelines and not actively playing. Notable exceptions to the recommendation were competitive cheerleading, gymnastics, wrestling, and water sports, where the risk for entanglement from face coverings was too high or was not practical.

Taken as a whole, the evolving data continue to show that school mitigation practices can be effective in reducing the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 rates among schoolchildren more closely mirror community rates and are probably more influenced by what happens outside the schools than inside the schools.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With the daily stream of new information, it is difficult to keep up with data on how the coronavirus epidemic affects children and school attendance, as well as how pediatricians can advise parents. The following is a summary of recently published information about birth and infant outcomes, and symptoms seen in infants and children, along with a review of recent information on transmission in schools.

COVID-19 in newborns

In November 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published data from 16 jurisdictions detailing pregnancy and infant outcomes of more than 5,000 women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The data were collected from March to October 2020. More than 80% of the women found to be positive for SARS-CoV-2 were identified during their third trimester. The surveillance found that 12.9% of infants born to infected mothers were born preterm, compared with an expected rate in the population of approximately 10%, suggesting that third-trimester infection may be associated with an increase in premature birth. Among 610 infants born to infected mothers and tested for SARS-CoV-2 during their nursery stay, 2.6% were positive. The infant positivity rate was as high as 4.3% among infants who were born to women with a documented SARS-CoV-2 infection within 2 weeks of the delivery date. No newborn infections were found among the infants whose mothers’ infection occurred more than 14 days before delivery. Current CDC and American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations are to test infants born to mothers with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.