User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

COVID in pregnancy may affect boys’ neurodevelopment: Study

Boys born to mothers infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy may be more likely to receive a diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental disorder by age 12 months, according to new research.

Andrea G. Edlow, MD, MSc, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues examined data from 18,355 births between March 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, at eight hospitals across two health systems in Massachusetts.

Of these births, 883 (4.8%) were to individuals who tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy. Among the children exposed to SARS‐CoV‐2 in the womb, 26 (3%) received a neurodevelopmental diagnosis, including disorders of motor function, speech and language, and psychological development, by age 1 year. In the group unexposed to the virus, 1.8% received such a diagnosis.

After adjusting for factors such as race, insurance, maternal age, and preterm birth, Dr. Edlow’s group found that a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for neurodevelopmental diagnoses at 12 months among boys (adjusted odds ratio, 1.94; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-3.17; P = .01), but not among girls.

In a subset of children with data available at 18 months, the correlation among boys at that age was less pronounced and not statistically significant (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.92-2.11; P = .10).

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open

Prior epidemiological research has suggested that maternal infection during pregnancy is associated with heightened risk for a range of neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism and schizophrenia, in offspring, the authors wrote.

“The neurodevelopmental risk associated with maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection was disproportionately high in male infants, consistent with the known increased vulnerability of males in the face of prenatal adverse exposures,” Dr. Edlow said in a news release about the findings.

Larger studies and longer follow‐up are needed to confirm and reliably estimate the risk, the researchers said.

“It is not clear that the changes we can detect at 12 and 18 months will be indicative of persistent risks for disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or schizophrenia,” they write.

New data published online by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that in 11 communities in 2020, 1 in 36 (2.8%) 8-year-old children had been identified with autism spectrum disorder, an increase from 2.3% in 2018. The data also show that the early months of the pandemic may have disrupted autism detection efforts among 4-year-olds.

The investigators were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative. Coauthors disclosed consulting for or receiving personal fees from biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Boys born to mothers infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy may be more likely to receive a diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental disorder by age 12 months, according to new research.

Andrea G. Edlow, MD, MSc, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues examined data from 18,355 births between March 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, at eight hospitals across two health systems in Massachusetts.

Of these births, 883 (4.8%) were to individuals who tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy. Among the children exposed to SARS‐CoV‐2 in the womb, 26 (3%) received a neurodevelopmental diagnosis, including disorders of motor function, speech and language, and psychological development, by age 1 year. In the group unexposed to the virus, 1.8% received such a diagnosis.

After adjusting for factors such as race, insurance, maternal age, and preterm birth, Dr. Edlow’s group found that a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for neurodevelopmental diagnoses at 12 months among boys (adjusted odds ratio, 1.94; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-3.17; P = .01), but not among girls.

In a subset of children with data available at 18 months, the correlation among boys at that age was less pronounced and not statistically significant (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.92-2.11; P = .10).

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open

Prior epidemiological research has suggested that maternal infection during pregnancy is associated with heightened risk for a range of neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism and schizophrenia, in offspring, the authors wrote.

“The neurodevelopmental risk associated with maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection was disproportionately high in male infants, consistent with the known increased vulnerability of males in the face of prenatal adverse exposures,” Dr. Edlow said in a news release about the findings.

Larger studies and longer follow‐up are needed to confirm and reliably estimate the risk, the researchers said.

“It is not clear that the changes we can detect at 12 and 18 months will be indicative of persistent risks for disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or schizophrenia,” they write.

New data published online by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that in 11 communities in 2020, 1 in 36 (2.8%) 8-year-old children had been identified with autism spectrum disorder, an increase from 2.3% in 2018. The data also show that the early months of the pandemic may have disrupted autism detection efforts among 4-year-olds.

The investigators were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative. Coauthors disclosed consulting for or receiving personal fees from biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Boys born to mothers infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy may be more likely to receive a diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental disorder by age 12 months, according to new research.

Andrea G. Edlow, MD, MSc, with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues examined data from 18,355 births between March 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, at eight hospitals across two health systems in Massachusetts.

Of these births, 883 (4.8%) were to individuals who tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 during pregnancy. Among the children exposed to SARS‐CoV‐2 in the womb, 26 (3%) received a neurodevelopmental diagnosis, including disorders of motor function, speech and language, and psychological development, by age 1 year. In the group unexposed to the virus, 1.8% received such a diagnosis.

After adjusting for factors such as race, insurance, maternal age, and preterm birth, Dr. Edlow’s group found that a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for neurodevelopmental diagnoses at 12 months among boys (adjusted odds ratio, 1.94; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-3.17; P = .01), but not among girls.

In a subset of children with data available at 18 months, the correlation among boys at that age was less pronounced and not statistically significant (aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.92-2.11; P = .10).

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open

Prior epidemiological research has suggested that maternal infection during pregnancy is associated with heightened risk for a range of neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism and schizophrenia, in offspring, the authors wrote.

“The neurodevelopmental risk associated with maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection was disproportionately high in male infants, consistent with the known increased vulnerability of males in the face of prenatal adverse exposures,” Dr. Edlow said in a news release about the findings.

Larger studies and longer follow‐up are needed to confirm and reliably estimate the risk, the researchers said.

“It is not clear that the changes we can detect at 12 and 18 months will be indicative of persistent risks for disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or schizophrenia,” they write.

New data published online by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that in 11 communities in 2020, 1 in 36 (2.8%) 8-year-old children had been identified with autism spectrum disorder, an increase from 2.3% in 2018. The data also show that the early months of the pandemic may have disrupted autism detection efforts among 4-year-olds.

The investigators were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative. Coauthors disclosed consulting for or receiving personal fees from biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Headache before the revolution: A clinician looks back

Headache treatment before the early 1990s was marked by decades of improvisation with mostly unapproved agents, followed by an explosion of scientific interest and new treatments developed specifically for migraine.

But this is largely thanks to the sea change that occurred 30 years ago.

In an interview, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, past president of the International Headache Society and clinical professor of neurology at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine in Los Angeles, recalled what it was like to treat patients before and after triptan medications came onto the market.

After the first of these anti-migraine agents, sumatriptan, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in late December 1992, headache specialists found themselves with a powerful, approved treatment that validated their commitment to solving the disorder, and helped put to rest a persistent but mistaken notion that migraine was a psychiatric condition affecting young women.

But in the 1970s and 1980s, “there wasn’t great science explaining the pathophysiology of common primary headaches like tension-type headache, cluster headache, and migraine,” Dr. Rapoport recalled. “There is often comorbid depression and anxiety with migraine, and sometimes more serious psychiatric disease, but it doesn’t mean migraine is caused by psychological issues. Now we see it clearly as a disease of the brain, but it took years of investigation to prove that.”

The early years

Dr. Rapoport’s journey with headache began in 1972, when he joined a private neurology practice in Stamford and Greenwich, Conn. Neurologists were frowned upon then for having too much interest in headache, he said. There was poor remuneration for doctors treating headache patients, who were hard to properly diagnose and effectively care for. Few medications could effectively stop a migraine attack or reliably reduce the frequency of headaches or the disability they caused.

On weekends Dr. Rapoport covered emergency departments and ICUs at three hospitals, where standard treatment for a migraine attack was injectable opiates. Not only did this treatment aggravate nausea, a common migraine symptom, “but it did not stop the migraine process.” Once the pain relief wore off, patients woke up with the same headache, Dr. Rapoport recalled. “The other drug that was available was ergotamine tartrate” – a fungal alkaloid used since medieval times to treat headache – “given sublingually. It helped the headache slightly but increased the nausea. DHE, or dihydroergotamine, was available only by injection and not used very much.”

DHE, a semi-synthetic molecule based on ergotamine, had FDA approval for migraine, but was complicated to administer. Like the opioids, it provoked vomiting when given intravenously, in patients already suffering migraine-induced nausea. But Dr. Rapoport, along with some of his colleagues, felt that there was a role for DHE for the most severe subtypes of patients, those with long histories of frequent migraines.

“We put people in the hospital and we gave them intravenous DHE. Eventually I got the idea to give it intramuscularly or subcutaneously in the emergency room or my office. When you give it that way, it doesn’t work as quickly but has fewer side effects.” Dr. Rapoport designed a cocktail by coadministering promethazine for nausea, and eventually added a steroid, dexamethasone. The triple shots worked on most patients experiencing severe daily or near-daily migraine attacks, Dr. Rapoport saw, and he began administering the drug combination at The New England Center for Headache in Stamford and Greenwich, Conn., which he opened with Dr. Fred D. Sheftell in 1979.

“The triple shots really worked,” Dr. Rapoport recalled. “There was no need to keep patients in the office or emergency room for intravenous therapy. The patients never called to complain or came back the next day,” he said, as often occurred with opioid treatment.

Dr. Rapoport had learned early in his residency, in the late 1960s, from Dr. David R. Coddon, a neurologist at Mount Sinai hospital in New York, that a tricyclic antidepressant, imipramine, could be helpful in some patients with frequent migraine attacks. As evidence trickled in that other antidepressants, beta-blockers, and antiepileptic drugs might have preventive properties, Dr. Rapoport and others prescribed them for certain patients. But of all the drugs in the headache specialists’ repertoire, few were approved for either treatment or prevention. “And this continued until the triptans,” Dr. Rapoport said.

The triptan era

Sumatriptan was developed by Glaxo for the acute treatment of migraine. The medication, first available only as self-administered subcutaneous injections, was originally designed to bind to vascular serotonin receptors to allow selective constriction of cranial vessels that dilate, causing pain, during a migraine attack. (Years later it was discovered that triptans also worked as anti-inflammatory agents that decreased the release of the neurotransmitter calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP.)

Triptans “changed the world for migraine patients and for me,” Dr. Rapoport said. “I could now prescribe a medication that people could take at home to decrease or stop the migraine process in an hour or two.” The success of the triptans prompted pharmaceutical companies to search for new, more effective ways to treat migraine attacks, with better tolerability.

Seven different triptans were developed, some as injections or tablets and others as nasal sprays. “If one triptan didn’t work, we’d give a second and rarely a third,” Dr. Rapoport said. “We learned that if oral triptans did not work, the most likely issue was that it was not rapidly absorbed from the small intestine, as migraine patients have nausea, poor GI absorption, and slow transit times. This prompted the greater use of injections and nasal sprays.” Headache specialists began combining triptan treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, offering further relief for the acute care of migraine.

Medication overuse headache

The years between 1993 and 2000, which saw all the current triptan drugs come onto the market, was an exhilarating one for headache specialists. But even those who were thrilled by the possibilities of the triptans, like Dr. Rapoport, soon came to recognize their limitations, in terms of side effects and poor tolerability for some patients.

Specialists also noticed something unsettling about the triptans: that patients’ headaches seemed to recur within a day, or occur more frequently over time, with higher medication use.

Medication overuse headache (MOH) was known to occur when patients treated migraine too often with acute care medications, especially over-the-counter analgesics and prescription opioids and barbiturates. Dr. Rapoport began warning at conferences and in seminars that MOH seemed to occur with the triptans as well. “In the beginning other doctors didn’t think the triptans could cause MOH, but I observed that patients who were taking triptans daily or almost daily were having increased headache frequency and the triptans stopped being effective. If they didn’t take the drug they were overusing, they were going to get much worse, almost like a withdrawal.”

Today, all seven triptans are now generic, and they remain a mainstay of migraine treatment: “Almost all of my patients are using, or have used a triptan,” Dr. Rapoport said. Yet researchers came to recognize the need for treatments targeting different pathways, both for prevention and acute care.

The next revolution: CGRP and gepants

Studies in the early 2000s began to show a link between the release of one ubiquitous nervous system neurotransmitter, calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP, and migraine. They also noticed that blocking meningeal inflammation could lead to improvement in headache. Two new drug classes emerged from this science: monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or its receptor that had to be given by injection, and oral CGRP receptor blockers that could be used both as a preventive or as an acute care medication.

In 2018 the first monoclonal antibody against the CGRP receptor, erenumab (Aimovig, marketed by Amgen), delivered by injection, was approved for migraine prevention. Three others followed, most given by autoinjector, and one by IV infusion in office or hospital settings. “Those drugs are great,” Dr. Rapoport said. “You take one shot a month or every 3 months, and your headaches drop by 50% or more with very few side effects. Some patients actually see their migraines disappear.”

The following year ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, marketed by AbbVie), the first of a novel class of oral CGRP receptor blockers known as “gepants,” was approved to treat acute migraine. The FDA soon approved another gepant, rimegepant (Nurtec, marketed by Pfizer), which received indications both for prevention and for stopping a migraine attack acutely.

Both classes of therapies – the antibodies and the gepants – are far costlier than the triptans, which are all generic, and may not be needed for every migraine patient. With the gepants, for example, insurers may restrict use to people who have not responded to triptans or for whom triptans are contraindicated or cause too many adverse events. But the CGRP-targeted therapies as a whole “have been every bit as revolutionary” as the triptans, Dr. Rapoport said. The treatments work quickly to resolve headache and disability and get the patient functioning within an hour or two, and there are fewer side effects.

In a review article published in CNS Drugs in 2021, Dr. Rapoport and his colleagues reported that the anti-CGRP treatment with gepants did not appear linked to medication overuse headache, as virtually all previous acute care medication classes did, and could be used in patients who had previously reported MOH. “I am confident that over the next few years, more people will be using them as insurance coverage will improve for patients living with migraine,” he said.

Headache treatment today

Migraine specialists and patients now have a staggering range of therapeutic options. Approved treatments now include prevention of migraine with onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox, marketed by the Allergan division of AbbVie) injections, which work alone and with other medicines; acute care treatment with ditans like lasmiditan (Reyvow, marketed by Lilly*), a category of acute care medicines that work like triptans but target different serotonin receptors. Five devices have been cleared for migraine and other types of headache by the FDA. These work alone or along with medication and can be used acutely or preventively. The devices “should be used more,” Dr. Rapoport said, but are not yet well covered by insurance.

Thirty years after the triptans, scientists and researchers continue to explore the pathophysiology of headache disorders, finding new pathways and identifying new potential targets.

“There are many parts of the brain and brain stem that are involved, as well as the thalamus and hypothalamus,” Dr. Rapoport said. “It’s interesting that the newer medications, and some of the older ones, work in the peripheral nervous system, outside the brain stem in the trigeminovascular system, to modulate the central nervous system. We also know that the CGRP system is involved with cellular second-order messengers. Stimulating and blocking this chain of reactions with newer drugs may become treatments in the future.”

Recent research has focused on a blood vessel dilating neurotransmitter, pituitary adenylate-cyclase-activating polypeptide, or PACAP-38, as a potential therapeutic target. Psychedelic medications such as psilocybin, strong pain medications such as ketamine, and even cannabinoids such as marijuana have all been investigated in migraine. Biofeedback therapies, mindfulness, and other behavioral interventions also have proved effective.

“I expect the next 2-5 years to bring us many important clinical trials on new types of pharmacological treatments,” Dr. Rapoport said. “This is a wonderful time to be a doctor or nurse treating patients living with migraine. When I started out treating headache, 51 years ago, we had only ergotamine tartrate. Today we have so many therapies and combinations of therapies that I hardly know where to start.”

Dr. Rapoport has served as a consultant to or speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Cala Health, Lundbeck, Satsuma, and Teva, among others.

*Correction, 3/30/23: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the company that markets Reyvow.

Headache treatment before the early 1990s was marked by decades of improvisation with mostly unapproved agents, followed by an explosion of scientific interest and new treatments developed specifically for migraine.

But this is largely thanks to the sea change that occurred 30 years ago.

In an interview, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, past president of the International Headache Society and clinical professor of neurology at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine in Los Angeles, recalled what it was like to treat patients before and after triptan medications came onto the market.

After the first of these anti-migraine agents, sumatriptan, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in late December 1992, headache specialists found themselves with a powerful, approved treatment that validated their commitment to solving the disorder, and helped put to rest a persistent but mistaken notion that migraine was a psychiatric condition affecting young women.

But in the 1970s and 1980s, “there wasn’t great science explaining the pathophysiology of common primary headaches like tension-type headache, cluster headache, and migraine,” Dr. Rapoport recalled. “There is often comorbid depression and anxiety with migraine, and sometimes more serious psychiatric disease, but it doesn’t mean migraine is caused by psychological issues. Now we see it clearly as a disease of the brain, but it took years of investigation to prove that.”

The early years

Dr. Rapoport’s journey with headache began in 1972, when he joined a private neurology practice in Stamford and Greenwich, Conn. Neurologists were frowned upon then for having too much interest in headache, he said. There was poor remuneration for doctors treating headache patients, who were hard to properly diagnose and effectively care for. Few medications could effectively stop a migraine attack or reliably reduce the frequency of headaches or the disability they caused.

On weekends Dr. Rapoport covered emergency departments and ICUs at three hospitals, where standard treatment for a migraine attack was injectable opiates. Not only did this treatment aggravate nausea, a common migraine symptom, “but it did not stop the migraine process.” Once the pain relief wore off, patients woke up with the same headache, Dr. Rapoport recalled. “The other drug that was available was ergotamine tartrate” – a fungal alkaloid used since medieval times to treat headache – “given sublingually. It helped the headache slightly but increased the nausea. DHE, or dihydroergotamine, was available only by injection and not used very much.”

DHE, a semi-synthetic molecule based on ergotamine, had FDA approval for migraine, but was complicated to administer. Like the opioids, it provoked vomiting when given intravenously, in patients already suffering migraine-induced nausea. But Dr. Rapoport, along with some of his colleagues, felt that there was a role for DHE for the most severe subtypes of patients, those with long histories of frequent migraines.

“We put people in the hospital and we gave them intravenous DHE. Eventually I got the idea to give it intramuscularly or subcutaneously in the emergency room or my office. When you give it that way, it doesn’t work as quickly but has fewer side effects.” Dr. Rapoport designed a cocktail by coadministering promethazine for nausea, and eventually added a steroid, dexamethasone. The triple shots worked on most patients experiencing severe daily or near-daily migraine attacks, Dr. Rapoport saw, and he began administering the drug combination at The New England Center for Headache in Stamford and Greenwich, Conn., which he opened with Dr. Fred D. Sheftell in 1979.

“The triple shots really worked,” Dr. Rapoport recalled. “There was no need to keep patients in the office or emergency room for intravenous therapy. The patients never called to complain or came back the next day,” he said, as often occurred with opioid treatment.

Dr. Rapoport had learned early in his residency, in the late 1960s, from Dr. David R. Coddon, a neurologist at Mount Sinai hospital in New York, that a tricyclic antidepressant, imipramine, could be helpful in some patients with frequent migraine attacks. As evidence trickled in that other antidepressants, beta-blockers, and antiepileptic drugs might have preventive properties, Dr. Rapoport and others prescribed them for certain patients. But of all the drugs in the headache specialists’ repertoire, few were approved for either treatment or prevention. “And this continued until the triptans,” Dr. Rapoport said.

The triptan era

Sumatriptan was developed by Glaxo for the acute treatment of migraine. The medication, first available only as self-administered subcutaneous injections, was originally designed to bind to vascular serotonin receptors to allow selective constriction of cranial vessels that dilate, causing pain, during a migraine attack. (Years later it was discovered that triptans also worked as anti-inflammatory agents that decreased the release of the neurotransmitter calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP.)

Triptans “changed the world for migraine patients and for me,” Dr. Rapoport said. “I could now prescribe a medication that people could take at home to decrease or stop the migraine process in an hour or two.” The success of the triptans prompted pharmaceutical companies to search for new, more effective ways to treat migraine attacks, with better tolerability.

Seven different triptans were developed, some as injections or tablets and others as nasal sprays. “If one triptan didn’t work, we’d give a second and rarely a third,” Dr. Rapoport said. “We learned that if oral triptans did not work, the most likely issue was that it was not rapidly absorbed from the small intestine, as migraine patients have nausea, poor GI absorption, and slow transit times. This prompted the greater use of injections and nasal sprays.” Headache specialists began combining triptan treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, offering further relief for the acute care of migraine.

Medication overuse headache

The years between 1993 and 2000, which saw all the current triptan drugs come onto the market, was an exhilarating one for headache specialists. But even those who were thrilled by the possibilities of the triptans, like Dr. Rapoport, soon came to recognize their limitations, in terms of side effects and poor tolerability for some patients.

Specialists also noticed something unsettling about the triptans: that patients’ headaches seemed to recur within a day, or occur more frequently over time, with higher medication use.

Medication overuse headache (MOH) was known to occur when patients treated migraine too often with acute care medications, especially over-the-counter analgesics and prescription opioids and barbiturates. Dr. Rapoport began warning at conferences and in seminars that MOH seemed to occur with the triptans as well. “In the beginning other doctors didn’t think the triptans could cause MOH, but I observed that patients who were taking triptans daily or almost daily were having increased headache frequency and the triptans stopped being effective. If they didn’t take the drug they were overusing, they were going to get much worse, almost like a withdrawal.”

Today, all seven triptans are now generic, and they remain a mainstay of migraine treatment: “Almost all of my patients are using, or have used a triptan,” Dr. Rapoport said. Yet researchers came to recognize the need for treatments targeting different pathways, both for prevention and acute care.

The next revolution: CGRP and gepants

Studies in the early 2000s began to show a link between the release of one ubiquitous nervous system neurotransmitter, calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP, and migraine. They also noticed that blocking meningeal inflammation could lead to improvement in headache. Two new drug classes emerged from this science: monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or its receptor that had to be given by injection, and oral CGRP receptor blockers that could be used both as a preventive or as an acute care medication.

In 2018 the first monoclonal antibody against the CGRP receptor, erenumab (Aimovig, marketed by Amgen), delivered by injection, was approved for migraine prevention. Three others followed, most given by autoinjector, and one by IV infusion in office or hospital settings. “Those drugs are great,” Dr. Rapoport said. “You take one shot a month or every 3 months, and your headaches drop by 50% or more with very few side effects. Some patients actually see their migraines disappear.”

The following year ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, marketed by AbbVie), the first of a novel class of oral CGRP receptor blockers known as “gepants,” was approved to treat acute migraine. The FDA soon approved another gepant, rimegepant (Nurtec, marketed by Pfizer), which received indications both for prevention and for stopping a migraine attack acutely.

Both classes of therapies – the antibodies and the gepants – are far costlier than the triptans, which are all generic, and may not be needed for every migraine patient. With the gepants, for example, insurers may restrict use to people who have not responded to triptans or for whom triptans are contraindicated or cause too many adverse events. But the CGRP-targeted therapies as a whole “have been every bit as revolutionary” as the triptans, Dr. Rapoport said. The treatments work quickly to resolve headache and disability and get the patient functioning within an hour or two, and there are fewer side effects.

In a review article published in CNS Drugs in 2021, Dr. Rapoport and his colleagues reported that the anti-CGRP treatment with gepants did not appear linked to medication overuse headache, as virtually all previous acute care medication classes did, and could be used in patients who had previously reported MOH. “I am confident that over the next few years, more people will be using them as insurance coverage will improve for patients living with migraine,” he said.

Headache treatment today

Migraine specialists and patients now have a staggering range of therapeutic options. Approved treatments now include prevention of migraine with onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox, marketed by the Allergan division of AbbVie) injections, which work alone and with other medicines; acute care treatment with ditans like lasmiditan (Reyvow, marketed by Lilly*), a category of acute care medicines that work like triptans but target different serotonin receptors. Five devices have been cleared for migraine and other types of headache by the FDA. These work alone or along with medication and can be used acutely or preventively. The devices “should be used more,” Dr. Rapoport said, but are not yet well covered by insurance.

Thirty years after the triptans, scientists and researchers continue to explore the pathophysiology of headache disorders, finding new pathways and identifying new potential targets.

“There are many parts of the brain and brain stem that are involved, as well as the thalamus and hypothalamus,” Dr. Rapoport said. “It’s interesting that the newer medications, and some of the older ones, work in the peripheral nervous system, outside the brain stem in the trigeminovascular system, to modulate the central nervous system. We also know that the CGRP system is involved with cellular second-order messengers. Stimulating and blocking this chain of reactions with newer drugs may become treatments in the future.”

Recent research has focused on a blood vessel dilating neurotransmitter, pituitary adenylate-cyclase-activating polypeptide, or PACAP-38, as a potential therapeutic target. Psychedelic medications such as psilocybin, strong pain medications such as ketamine, and even cannabinoids such as marijuana have all been investigated in migraine. Biofeedback therapies, mindfulness, and other behavioral interventions also have proved effective.

“I expect the next 2-5 years to bring us many important clinical trials on new types of pharmacological treatments,” Dr. Rapoport said. “This is a wonderful time to be a doctor or nurse treating patients living with migraine. When I started out treating headache, 51 years ago, we had only ergotamine tartrate. Today we have so many therapies and combinations of therapies that I hardly know where to start.”

Dr. Rapoport has served as a consultant to or speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Cala Health, Lundbeck, Satsuma, and Teva, among others.

*Correction, 3/30/23: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the company that markets Reyvow.

Headache treatment before the early 1990s was marked by decades of improvisation with mostly unapproved agents, followed by an explosion of scientific interest and new treatments developed specifically for migraine.

But this is largely thanks to the sea change that occurred 30 years ago.

In an interview, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, past president of the International Headache Society and clinical professor of neurology at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine in Los Angeles, recalled what it was like to treat patients before and after triptan medications came onto the market.

After the first of these anti-migraine agents, sumatriptan, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in late December 1992, headache specialists found themselves with a powerful, approved treatment that validated their commitment to solving the disorder, and helped put to rest a persistent but mistaken notion that migraine was a psychiatric condition affecting young women.

But in the 1970s and 1980s, “there wasn’t great science explaining the pathophysiology of common primary headaches like tension-type headache, cluster headache, and migraine,” Dr. Rapoport recalled. “There is often comorbid depression and anxiety with migraine, and sometimes more serious psychiatric disease, but it doesn’t mean migraine is caused by psychological issues. Now we see it clearly as a disease of the brain, but it took years of investigation to prove that.”

The early years

Dr. Rapoport’s journey with headache began in 1972, when he joined a private neurology practice in Stamford and Greenwich, Conn. Neurologists were frowned upon then for having too much interest in headache, he said. There was poor remuneration for doctors treating headache patients, who were hard to properly diagnose and effectively care for. Few medications could effectively stop a migraine attack or reliably reduce the frequency of headaches or the disability they caused.

On weekends Dr. Rapoport covered emergency departments and ICUs at three hospitals, where standard treatment for a migraine attack was injectable opiates. Not only did this treatment aggravate nausea, a common migraine symptom, “but it did not stop the migraine process.” Once the pain relief wore off, patients woke up with the same headache, Dr. Rapoport recalled. “The other drug that was available was ergotamine tartrate” – a fungal alkaloid used since medieval times to treat headache – “given sublingually. It helped the headache slightly but increased the nausea. DHE, or dihydroergotamine, was available only by injection and not used very much.”

DHE, a semi-synthetic molecule based on ergotamine, had FDA approval for migraine, but was complicated to administer. Like the opioids, it provoked vomiting when given intravenously, in patients already suffering migraine-induced nausea. But Dr. Rapoport, along with some of his colleagues, felt that there was a role for DHE for the most severe subtypes of patients, those with long histories of frequent migraines.

“We put people in the hospital and we gave them intravenous DHE. Eventually I got the idea to give it intramuscularly or subcutaneously in the emergency room or my office. When you give it that way, it doesn’t work as quickly but has fewer side effects.” Dr. Rapoport designed a cocktail by coadministering promethazine for nausea, and eventually added a steroid, dexamethasone. The triple shots worked on most patients experiencing severe daily or near-daily migraine attacks, Dr. Rapoport saw, and he began administering the drug combination at The New England Center for Headache in Stamford and Greenwich, Conn., which he opened with Dr. Fred D. Sheftell in 1979.

“The triple shots really worked,” Dr. Rapoport recalled. “There was no need to keep patients in the office or emergency room for intravenous therapy. The patients never called to complain or came back the next day,” he said, as often occurred with opioid treatment.

Dr. Rapoport had learned early in his residency, in the late 1960s, from Dr. David R. Coddon, a neurologist at Mount Sinai hospital in New York, that a tricyclic antidepressant, imipramine, could be helpful in some patients with frequent migraine attacks. As evidence trickled in that other antidepressants, beta-blockers, and antiepileptic drugs might have preventive properties, Dr. Rapoport and others prescribed them for certain patients. But of all the drugs in the headache specialists’ repertoire, few were approved for either treatment or prevention. “And this continued until the triptans,” Dr. Rapoport said.

The triptan era

Sumatriptan was developed by Glaxo for the acute treatment of migraine. The medication, first available only as self-administered subcutaneous injections, was originally designed to bind to vascular serotonin receptors to allow selective constriction of cranial vessels that dilate, causing pain, during a migraine attack. (Years later it was discovered that triptans also worked as anti-inflammatory agents that decreased the release of the neurotransmitter calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP.)

Triptans “changed the world for migraine patients and for me,” Dr. Rapoport said. “I could now prescribe a medication that people could take at home to decrease or stop the migraine process in an hour or two.” The success of the triptans prompted pharmaceutical companies to search for new, more effective ways to treat migraine attacks, with better tolerability.

Seven different triptans were developed, some as injections or tablets and others as nasal sprays. “If one triptan didn’t work, we’d give a second and rarely a third,” Dr. Rapoport said. “We learned that if oral triptans did not work, the most likely issue was that it was not rapidly absorbed from the small intestine, as migraine patients have nausea, poor GI absorption, and slow transit times. This prompted the greater use of injections and nasal sprays.” Headache specialists began combining triptan treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, offering further relief for the acute care of migraine.

Medication overuse headache

The years between 1993 and 2000, which saw all the current triptan drugs come onto the market, was an exhilarating one for headache specialists. But even those who were thrilled by the possibilities of the triptans, like Dr. Rapoport, soon came to recognize their limitations, in terms of side effects and poor tolerability for some patients.

Specialists also noticed something unsettling about the triptans: that patients’ headaches seemed to recur within a day, or occur more frequently over time, with higher medication use.

Medication overuse headache (MOH) was known to occur when patients treated migraine too often with acute care medications, especially over-the-counter analgesics and prescription opioids and barbiturates. Dr. Rapoport began warning at conferences and in seminars that MOH seemed to occur with the triptans as well. “In the beginning other doctors didn’t think the triptans could cause MOH, but I observed that patients who were taking triptans daily or almost daily were having increased headache frequency and the triptans stopped being effective. If they didn’t take the drug they were overusing, they were going to get much worse, almost like a withdrawal.”

Today, all seven triptans are now generic, and they remain a mainstay of migraine treatment: “Almost all of my patients are using, or have used a triptan,” Dr. Rapoport said. Yet researchers came to recognize the need for treatments targeting different pathways, both for prevention and acute care.

The next revolution: CGRP and gepants

Studies in the early 2000s began to show a link between the release of one ubiquitous nervous system neurotransmitter, calcitonin gene-related peptide, or CGRP, and migraine. They also noticed that blocking meningeal inflammation could lead to improvement in headache. Two new drug classes emerged from this science: monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or its receptor that had to be given by injection, and oral CGRP receptor blockers that could be used both as a preventive or as an acute care medication.

In 2018 the first monoclonal antibody against the CGRP receptor, erenumab (Aimovig, marketed by Amgen), delivered by injection, was approved for migraine prevention. Three others followed, most given by autoinjector, and one by IV infusion in office or hospital settings. “Those drugs are great,” Dr. Rapoport said. “You take one shot a month or every 3 months, and your headaches drop by 50% or more with very few side effects. Some patients actually see their migraines disappear.”

The following year ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, marketed by AbbVie), the first of a novel class of oral CGRP receptor blockers known as “gepants,” was approved to treat acute migraine. The FDA soon approved another gepant, rimegepant (Nurtec, marketed by Pfizer), which received indications both for prevention and for stopping a migraine attack acutely.

Both classes of therapies – the antibodies and the gepants – are far costlier than the triptans, which are all generic, and may not be needed for every migraine patient. With the gepants, for example, insurers may restrict use to people who have not responded to triptans or for whom triptans are contraindicated or cause too many adverse events. But the CGRP-targeted therapies as a whole “have been every bit as revolutionary” as the triptans, Dr. Rapoport said. The treatments work quickly to resolve headache and disability and get the patient functioning within an hour or two, and there are fewer side effects.

In a review article published in CNS Drugs in 2021, Dr. Rapoport and his colleagues reported that the anti-CGRP treatment with gepants did not appear linked to medication overuse headache, as virtually all previous acute care medication classes did, and could be used in patients who had previously reported MOH. “I am confident that over the next few years, more people will be using them as insurance coverage will improve for patients living with migraine,” he said.

Headache treatment today

Migraine specialists and patients now have a staggering range of therapeutic options. Approved treatments now include prevention of migraine with onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox, marketed by the Allergan division of AbbVie) injections, which work alone and with other medicines; acute care treatment with ditans like lasmiditan (Reyvow, marketed by Lilly*), a category of acute care medicines that work like triptans but target different serotonin receptors. Five devices have been cleared for migraine and other types of headache by the FDA. These work alone or along with medication and can be used acutely or preventively. The devices “should be used more,” Dr. Rapoport said, but are not yet well covered by insurance.

Thirty years after the triptans, scientists and researchers continue to explore the pathophysiology of headache disorders, finding new pathways and identifying new potential targets.

“There are many parts of the brain and brain stem that are involved, as well as the thalamus and hypothalamus,” Dr. Rapoport said. “It’s interesting that the newer medications, and some of the older ones, work in the peripheral nervous system, outside the brain stem in the trigeminovascular system, to modulate the central nervous system. We also know that the CGRP system is involved with cellular second-order messengers. Stimulating and blocking this chain of reactions with newer drugs may become treatments in the future.”

Recent research has focused on a blood vessel dilating neurotransmitter, pituitary adenylate-cyclase-activating polypeptide, or PACAP-38, as a potential therapeutic target. Psychedelic medications such as psilocybin, strong pain medications such as ketamine, and even cannabinoids such as marijuana have all been investigated in migraine. Biofeedback therapies, mindfulness, and other behavioral interventions also have proved effective.

“I expect the next 2-5 years to bring us many important clinical trials on new types of pharmacological treatments,” Dr. Rapoport said. “This is a wonderful time to be a doctor or nurse treating patients living with migraine. When I started out treating headache, 51 years ago, we had only ergotamine tartrate. Today we have so many therapies and combinations of therapies that I hardly know where to start.”

Dr. Rapoport has served as a consultant to or speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Cala Health, Lundbeck, Satsuma, and Teva, among others.

*Correction, 3/30/23: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the company that markets Reyvow.

Tooth loss and diabetes together hasten mental decline

most specifically in those 65-74 years of age, new findings suggest.

The data come from a 12-year follow-up of older adults in a nationally representative U.S. survey.

“From a clinical perspective, our study demonstrates the importance of improving access to dental health care and integrating primary dental and medical care. Health care professionals and family caregivers should pay close attention to the cognitive status of diabetic older adults with poor oral health status,” lead author Bei Wu, PhD, of New York University, said in an interview. Dr. Wu is the Dean’s Professor in Global Health and codirector of the NYU Aging Incubator.

Moreover, said Dr. Wu: “For individuals with both poor oral health and diabetes, regular dental visits should be encouraged in addition to adherence to the diabetes self-care protocol.”

Diabetes has long been recognized as a risk factor for cognitive decline, but the findings have been inconsistent for different age groups. Tooth loss has also been linked to cognitive decline and dementia, as well as diabetes.

The mechanisms aren’t entirely clear, but “co-occurring diabetes and poor oral health may increase the risk for dementia, possibly via the potentially interrelated pathways of chronic inflammation and cardiovascular risk factors,” Dr. Wu said.

The new study, published in the Journal of Dental Research, is the first to examine the relationships between all three conditions by age group.

Diabetes, edentulism, and cognitive decline

The data came from a total of 9,948 participants in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) from 2006 to 2018. At baseline, 5,440 participants were aged 65-74 years, 3,300 were aged 75-84, and 1,208 were aged 85 years or older.

They were assessed every 2 years using the 35-point Telephone Survey for Cognitive Status, which included tests of immediate and delayed word recall, repeated subtracting by 7, counting backward from 20, naming objects, and naming the president and vice president of the U.S. As might be expected, the youngest group scored the highest, averaging 23 points, while the oldest group scored lowest, at 18.5 points.

Participants were also asked if they had ever been told by a doctor that they have diabetes. Another question was: “Have you lost all of your upper and lower natural permanent teeth?”

The condition of having no teeth is known as edentulism.

The percentages of participants who reported having both diabetes and edentulism were 6.0%, 6.7%, and 5.0% for those aged 65-74 years, 75-84 years, and 85 years or older, respectively. The proportions with neither of those conditions were 63.5%, 60.4%, and 58.3% in those three age groups, respectively (P < .001).

Compared with their counterparts with neither diabetes nor edentulism at baseline, older adults with both conditions aged 65-74 years (P < .001) and aged 75-84 years had worse cognitive function (P < .001).

In terms of the rate of cognitive decline, compared with those with neither condition from the same age cohort, older adults aged 65-74 years with both conditions declined at a higher rate (P < .001).

Having diabetes alone led to accelerated cognitive decline in older adults aged 65-74 years (P < .001). Having edentulism alone led to accelerated decline in older adults aged 65-74 years (P < .001) and older adults aged 75-84 years (P < 0.01).

“Our study finds the co-occurrence of diabetes and edentulism led to a worse cognitive function and a faster cognitive decline in older adults aged 65-74 years,” say Wu and colleagues.

Study limitations: Better data needed

The study has several limitations, most of them due to the data source. For example, while the HRS collects detailed information on cognitive status, edentulism is its only measure of oral health. There were no data on whether individuals had replacements such as dentures or implants that would affect their ability to eat, which could influence other health factors.

“I have made repeated appeals for federal funding to collect more oral health-related information in large national surveys,” Dr. Wu told this news organization.

Similarly, assessments of diabetes status such as hemoglobin A1c were only available for small subsets and not sufficient to demonstrate statistical significance, she explained.

Dr. Wu suggested that both oral health and cognitive screening might be included in the “Welcome to Medicare” preventive visit. In addition, “Oral hygiene practice should also be highlighted to improve cognitive health. Developing dental care interventions and programs are needed for reducing the societal cost of dementia.”

The study was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

most specifically in those 65-74 years of age, new findings suggest.

The data come from a 12-year follow-up of older adults in a nationally representative U.S. survey.

“From a clinical perspective, our study demonstrates the importance of improving access to dental health care and integrating primary dental and medical care. Health care professionals and family caregivers should pay close attention to the cognitive status of diabetic older adults with poor oral health status,” lead author Bei Wu, PhD, of New York University, said in an interview. Dr. Wu is the Dean’s Professor in Global Health and codirector of the NYU Aging Incubator.

Moreover, said Dr. Wu: “For individuals with both poor oral health and diabetes, regular dental visits should be encouraged in addition to adherence to the diabetes self-care protocol.”

Diabetes has long been recognized as a risk factor for cognitive decline, but the findings have been inconsistent for different age groups. Tooth loss has also been linked to cognitive decline and dementia, as well as diabetes.

The mechanisms aren’t entirely clear, but “co-occurring diabetes and poor oral health may increase the risk for dementia, possibly via the potentially interrelated pathways of chronic inflammation and cardiovascular risk factors,” Dr. Wu said.

The new study, published in the Journal of Dental Research, is the first to examine the relationships between all three conditions by age group.

Diabetes, edentulism, and cognitive decline

The data came from a total of 9,948 participants in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) from 2006 to 2018. At baseline, 5,440 participants were aged 65-74 years, 3,300 were aged 75-84, and 1,208 were aged 85 years or older.

They were assessed every 2 years using the 35-point Telephone Survey for Cognitive Status, which included tests of immediate and delayed word recall, repeated subtracting by 7, counting backward from 20, naming objects, and naming the president and vice president of the U.S. As might be expected, the youngest group scored the highest, averaging 23 points, while the oldest group scored lowest, at 18.5 points.

Participants were also asked if they had ever been told by a doctor that they have diabetes. Another question was: “Have you lost all of your upper and lower natural permanent teeth?”

The condition of having no teeth is known as edentulism.

The percentages of participants who reported having both diabetes and edentulism were 6.0%, 6.7%, and 5.0% for those aged 65-74 years, 75-84 years, and 85 years or older, respectively. The proportions with neither of those conditions were 63.5%, 60.4%, and 58.3% in those three age groups, respectively (P < .001).

Compared with their counterparts with neither diabetes nor edentulism at baseline, older adults with both conditions aged 65-74 years (P < .001) and aged 75-84 years had worse cognitive function (P < .001).

In terms of the rate of cognitive decline, compared with those with neither condition from the same age cohort, older adults aged 65-74 years with both conditions declined at a higher rate (P < .001).

Having diabetes alone led to accelerated cognitive decline in older adults aged 65-74 years (P < .001). Having edentulism alone led to accelerated decline in older adults aged 65-74 years (P < .001) and older adults aged 75-84 years (P < 0.01).

“Our study finds the co-occurrence of diabetes and edentulism led to a worse cognitive function and a faster cognitive decline in older adults aged 65-74 years,” say Wu and colleagues.

Study limitations: Better data needed

The study has several limitations, most of them due to the data source. For example, while the HRS collects detailed information on cognitive status, edentulism is its only measure of oral health. There were no data on whether individuals had replacements such as dentures or implants that would affect their ability to eat, which could influence other health factors.

“I have made repeated appeals for federal funding to collect more oral health-related information in large national surveys,” Dr. Wu told this news organization.

Similarly, assessments of diabetes status such as hemoglobin A1c were only available for small subsets and not sufficient to demonstrate statistical significance, she explained.

Dr. Wu suggested that both oral health and cognitive screening might be included in the “Welcome to Medicare” preventive visit. In addition, “Oral hygiene practice should also be highlighted to improve cognitive health. Developing dental care interventions and programs are needed for reducing the societal cost of dementia.”

The study was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

most specifically in those 65-74 years of age, new findings suggest.

The data come from a 12-year follow-up of older adults in a nationally representative U.S. survey.

“From a clinical perspective, our study demonstrates the importance of improving access to dental health care and integrating primary dental and medical care. Health care professionals and family caregivers should pay close attention to the cognitive status of diabetic older adults with poor oral health status,” lead author Bei Wu, PhD, of New York University, said in an interview. Dr. Wu is the Dean’s Professor in Global Health and codirector of the NYU Aging Incubator.

Moreover, said Dr. Wu: “For individuals with both poor oral health and diabetes, regular dental visits should be encouraged in addition to adherence to the diabetes self-care protocol.”

Diabetes has long been recognized as a risk factor for cognitive decline, but the findings have been inconsistent for different age groups. Tooth loss has also been linked to cognitive decline and dementia, as well as diabetes.

The mechanisms aren’t entirely clear, but “co-occurring diabetes and poor oral health may increase the risk for dementia, possibly via the potentially interrelated pathways of chronic inflammation and cardiovascular risk factors,” Dr. Wu said.

The new study, published in the Journal of Dental Research, is the first to examine the relationships between all three conditions by age group.

Diabetes, edentulism, and cognitive decline

The data came from a total of 9,948 participants in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) from 2006 to 2018. At baseline, 5,440 participants were aged 65-74 years, 3,300 were aged 75-84, and 1,208 were aged 85 years or older.

They were assessed every 2 years using the 35-point Telephone Survey for Cognitive Status, which included tests of immediate and delayed word recall, repeated subtracting by 7, counting backward from 20, naming objects, and naming the president and vice president of the U.S. As might be expected, the youngest group scored the highest, averaging 23 points, while the oldest group scored lowest, at 18.5 points.

Participants were also asked if they had ever been told by a doctor that they have diabetes. Another question was: “Have you lost all of your upper and lower natural permanent teeth?”

The condition of having no teeth is known as edentulism.

The percentages of participants who reported having both diabetes and edentulism were 6.0%, 6.7%, and 5.0% for those aged 65-74 years, 75-84 years, and 85 years or older, respectively. The proportions with neither of those conditions were 63.5%, 60.4%, and 58.3% in those three age groups, respectively (P < .001).

Compared with their counterparts with neither diabetes nor edentulism at baseline, older adults with both conditions aged 65-74 years (P < .001) and aged 75-84 years had worse cognitive function (P < .001).

In terms of the rate of cognitive decline, compared with those with neither condition from the same age cohort, older adults aged 65-74 years with both conditions declined at a higher rate (P < .001).

Having diabetes alone led to accelerated cognitive decline in older adults aged 65-74 years (P < .001). Having edentulism alone led to accelerated decline in older adults aged 65-74 years (P < .001) and older adults aged 75-84 years (P < 0.01).

“Our study finds the co-occurrence of diabetes and edentulism led to a worse cognitive function and a faster cognitive decline in older adults aged 65-74 years,” say Wu and colleagues.

Study limitations: Better data needed

The study has several limitations, most of them due to the data source. For example, while the HRS collects detailed information on cognitive status, edentulism is its only measure of oral health. There were no data on whether individuals had replacements such as dentures or implants that would affect their ability to eat, which could influence other health factors.

“I have made repeated appeals for federal funding to collect more oral health-related information in large national surveys,” Dr. Wu told this news organization.

Similarly, assessments of diabetes status such as hemoglobin A1c were only available for small subsets and not sufficient to demonstrate statistical significance, she explained.

Dr. Wu suggested that both oral health and cognitive screening might be included in the “Welcome to Medicare” preventive visit. In addition, “Oral hygiene practice should also be highlighted to improve cognitive health. Developing dental care interventions and programs are needed for reducing the societal cost of dementia.”

The study was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF DENTAL RESEARCH

Mortality risk in epilepsy: New data

new research shows.

“To our knowledge, this is the only study that has assessed the cause-specific mortality risk among people with epilepsy according to age and disease course,” investigators led by Seo-Young Lee, MD, PhD, of Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, South Korea, write. “Understanding cause-specific mortality risk, particularly the risk of external causes, is important because they are mostly preventable.”

The findings were published online in Neurology.

Higher mortality risk

For the study, researchers analyzed data from the National Health Insurance Service database in Korea from 2006 to 2017 and vital statistics from Statistics Korea from 2008 to 2017.

The study population included 138,998 patients with newly treated epilepsy, with an average at diagnosis of 48.6 years.

Over 665,928 person years of follow-up (mean follow-up, 4.79 years), 20.095 patients died.

People with epilepsy had more than twice the risk for death, compared with the overall population (standardized mortality ratio, 2.25; 95% confidence interval, 2.22-2.28). Mortality was highest in children aged 4 years or younger and was higher in the first year after diagnosis and in women at all age points.

People with epilepsy had a higher mortality risk, compared with the general public, regardless of how many anti-seizure medications they were taking. Those taking only one medication had a 156% higher risk for death (SMR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.53-1.60), compared with 493% higher risk in those taking four or more medications (SMR, 4.93; 95% CI, 4.76-5.10).

Where patients lived also played a role in mortality risk. Living in a rural area was associated with a 247% higher risk for death, compared with people without epilepsy who lived in the same area (SMR, 2.47; 95% CI, 2.41-2.53), and the risk was 203% higher risk among those living in urban centers (SMR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.98-2.09).

Although people with comorbidities had higher mortality rates, even those without any other health conditions had a 161% higher risk for death, compared with people without epilepsy (SMR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.50-1.72).

Causes of death

The most frequent causes of death were malignant neoplasm and cerebrovascular disease, which researchers noted are thought to be underlying causes of epilepsy.

Among external causes of death, suicide was the most common cause (2.6%). The suicide rate was highest among younger patients and gradually decreased with age.

Deaths tied directly to epilepsy, transport accidents, or falls were lower in this study than had been previously reported, which may be due to adequate seizure control or because the number of older people with epilepsy and comorbidities is higher in Korea than that reported in other countries.

“To reduce mortality in people with epilepsy, comprehensive efforts [are needed], including a national policy against stigma of epilepsy and clinicians’ total management such as risk stratification, education about injury prevention, and monitoring for suicidal ideation with psychological intervention, as well as active control of seizures,” the authors write.

Generalizable findings

Joseph Sirven, MD, professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic Florida, Jacksonville, said that although the study included only Korean patients, the findings are applicable to other counties.

That researchers found patients with epilepsy were more than twice as likely to die prematurely, compared with the general population wasn’t particularly surprising, Dr. Sirven said.

“What struck me the most was the fact that even patients who were on a single drug and seemingly well controlled also had excess mortality reported,” Dr. Sirven said. “That these risks occur should be part of what we tell all patients with epilepsy so that they can better arm themselves with information and help to address some of the risks that this study showed.”

Another important finding is the risk for suicide in patients with epilepsy, especially those who are newly diagnosed, he said.

“When we treat a patient with epilepsy, it should not just be about seizures, but we need to inquire about the psychiatric comorbidities and more importantly manage them in a comprehensive manner,” Dr. Sirven said.

The study was funded by Soonchunhyang University Research Fund and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project. The study authors and Dr. Sirven report no relevant financial conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

“To our knowledge, this is the only study that has assessed the cause-specific mortality risk among people with epilepsy according to age and disease course,” investigators led by Seo-Young Lee, MD, PhD, of Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, South Korea, write. “Understanding cause-specific mortality risk, particularly the risk of external causes, is important because they are mostly preventable.”

The findings were published online in Neurology.

Higher mortality risk

For the study, researchers analyzed data from the National Health Insurance Service database in Korea from 2006 to 2017 and vital statistics from Statistics Korea from 2008 to 2017.

The study population included 138,998 patients with newly treated epilepsy, with an average at diagnosis of 48.6 years.

Over 665,928 person years of follow-up (mean follow-up, 4.79 years), 20.095 patients died.

People with epilepsy had more than twice the risk for death, compared with the overall population (standardized mortality ratio, 2.25; 95% confidence interval, 2.22-2.28). Mortality was highest in children aged 4 years or younger and was higher in the first year after diagnosis and in women at all age points.

People with epilepsy had a higher mortality risk, compared with the general public, regardless of how many anti-seizure medications they were taking. Those taking only one medication had a 156% higher risk for death (SMR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.53-1.60), compared with 493% higher risk in those taking four or more medications (SMR, 4.93; 95% CI, 4.76-5.10).

Where patients lived also played a role in mortality risk. Living in a rural area was associated with a 247% higher risk for death, compared with people without epilepsy who lived in the same area (SMR, 2.47; 95% CI, 2.41-2.53), and the risk was 203% higher risk among those living in urban centers (SMR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.98-2.09).

Although people with comorbidities had higher mortality rates, even those without any other health conditions had a 161% higher risk for death, compared with people without epilepsy (SMR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.50-1.72).

Causes of death

The most frequent causes of death were malignant neoplasm and cerebrovascular disease, which researchers noted are thought to be underlying causes of epilepsy.

Among external causes of death, suicide was the most common cause (2.6%). The suicide rate was highest among younger patients and gradually decreased with age.

Deaths tied directly to epilepsy, transport accidents, or falls were lower in this study than had been previously reported, which may be due to adequate seizure control or because the number of older people with epilepsy and comorbidities is higher in Korea than that reported in other countries.

“To reduce mortality in people with epilepsy, comprehensive efforts [are needed], including a national policy against stigma of epilepsy and clinicians’ total management such as risk stratification, education about injury prevention, and monitoring for suicidal ideation with psychological intervention, as well as active control of seizures,” the authors write.

Generalizable findings

Joseph Sirven, MD, professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic Florida, Jacksonville, said that although the study included only Korean patients, the findings are applicable to other counties.

That researchers found patients with epilepsy were more than twice as likely to die prematurely, compared with the general population wasn’t particularly surprising, Dr. Sirven said.

“What struck me the most was the fact that even patients who were on a single drug and seemingly well controlled also had excess mortality reported,” Dr. Sirven said. “That these risks occur should be part of what we tell all patients with epilepsy so that they can better arm themselves with information and help to address some of the risks that this study showed.”

Another important finding is the risk for suicide in patients with epilepsy, especially those who are newly diagnosed, he said.

“When we treat a patient with epilepsy, it should not just be about seizures, but we need to inquire about the psychiatric comorbidities and more importantly manage them in a comprehensive manner,” Dr. Sirven said.

The study was funded by Soonchunhyang University Research Fund and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project. The study authors and Dr. Sirven report no relevant financial conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

“To our knowledge, this is the only study that has assessed the cause-specific mortality risk among people with epilepsy according to age and disease course,” investigators led by Seo-Young Lee, MD, PhD, of Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, South Korea, write. “Understanding cause-specific mortality risk, particularly the risk of external causes, is important because they are mostly preventable.”

The findings were published online in Neurology.

Higher mortality risk

For the study, researchers analyzed data from the National Health Insurance Service database in Korea from 2006 to 2017 and vital statistics from Statistics Korea from 2008 to 2017.

The study population included 138,998 patients with newly treated epilepsy, with an average at diagnosis of 48.6 years.

Over 665,928 person years of follow-up (mean follow-up, 4.79 years), 20.095 patients died.

People with epilepsy had more than twice the risk for death, compared with the overall population (standardized mortality ratio, 2.25; 95% confidence interval, 2.22-2.28). Mortality was highest in children aged 4 years or younger and was higher in the first year after diagnosis and in women at all age points.

People with epilepsy had a higher mortality risk, compared with the general public, regardless of how many anti-seizure medications they were taking. Those taking only one medication had a 156% higher risk for death (SMR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.53-1.60), compared with 493% higher risk in those taking four or more medications (SMR, 4.93; 95% CI, 4.76-5.10).

Where patients lived also played a role in mortality risk. Living in a rural area was associated with a 247% higher risk for death, compared with people without epilepsy who lived in the same area (SMR, 2.47; 95% CI, 2.41-2.53), and the risk was 203% higher risk among those living in urban centers (SMR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.98-2.09).

Although people with comorbidities had higher mortality rates, even those without any other health conditions had a 161% higher risk for death, compared with people without epilepsy (SMR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.50-1.72).

Causes of death

The most frequent causes of death were malignant neoplasm and cerebrovascular disease, which researchers noted are thought to be underlying causes of epilepsy.

Among external causes of death, suicide was the most common cause (2.6%). The suicide rate was highest among younger patients and gradually decreased with age.

Deaths tied directly to epilepsy, transport accidents, or falls were lower in this study than had been previously reported, which may be due to adequate seizure control or because the number of older people with epilepsy and comorbidities is higher in Korea than that reported in other countries.

“To reduce mortality in people with epilepsy, comprehensive efforts [are needed], including a national policy against stigma of epilepsy and clinicians’ total management such as risk stratification, education about injury prevention, and monitoring for suicidal ideation with psychological intervention, as well as active control of seizures,” the authors write.

Generalizable findings

Joseph Sirven, MD, professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic Florida, Jacksonville, said that although the study included only Korean patients, the findings are applicable to other counties.

That researchers found patients with epilepsy were more than twice as likely to die prematurely, compared with the general population wasn’t particularly surprising, Dr. Sirven said.

“What struck me the most was the fact that even patients who were on a single drug and seemingly well controlled also had excess mortality reported,” Dr. Sirven said. “That these risks occur should be part of what we tell all patients with epilepsy so that they can better arm themselves with information and help to address some of the risks that this study showed.”

Another important finding is the risk for suicide in patients with epilepsy, especially those who are newly diagnosed, he said.

“When we treat a patient with epilepsy, it should not just be about seizures, but we need to inquire about the psychiatric comorbidities and more importantly manage them in a comprehensive manner,” Dr. Sirven said.

The study was funded by Soonchunhyang University Research Fund and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project. The study authors and Dr. Sirven report no relevant financial conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Celebrity death finally solved – with locks of hair

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m going to open this week with a case.

A 56-year-old musician presents with diffuse abdominal pain, cramping, and jaundice. His medical history is notable for years of diffuse abdominal complaints, characterized by disabling bouts of diarrhea.

In addition to the jaundice, this acute illness was accompanied by fever as well as diffuse edema and ascites. The patient underwent several abdominal paracenteses to drain excess fluid. One consulting physician administered alcohol to relieve pain, to little avail.

The patient succumbed to his illness. An autopsy showed diffuse liver injury, as well as papillary necrosis of the kidneys. Notably, the nerves of his auditory canal were noted to be thickened, along with the bony part of the skull, consistent with Paget disease of the bone and explaining, potentially, why the talented musician had gone deaf at such a young age.

An interesting note on social history: The patient had apparently developed some feelings for the niece of that doctor who prescribed alcohol. Her name was Therese, perhaps mistranscribed as Elise, and it seems that he may have written this song for her.

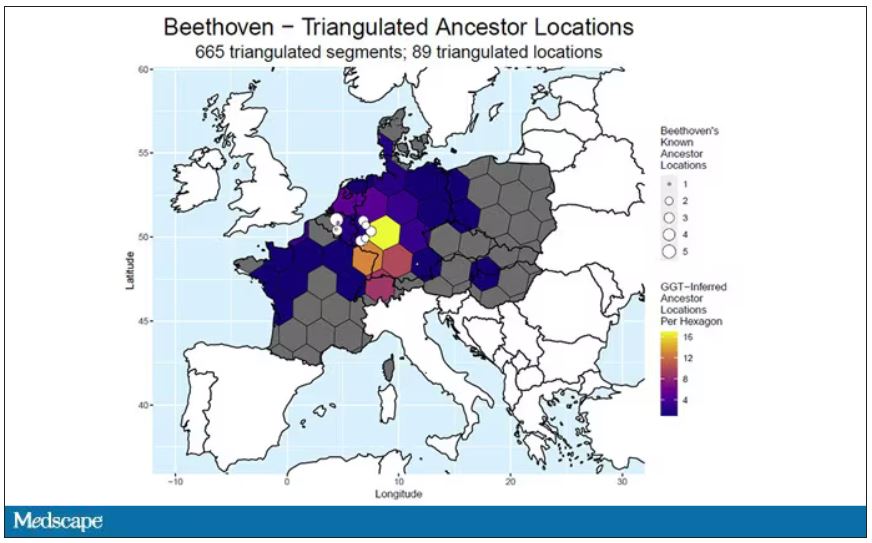

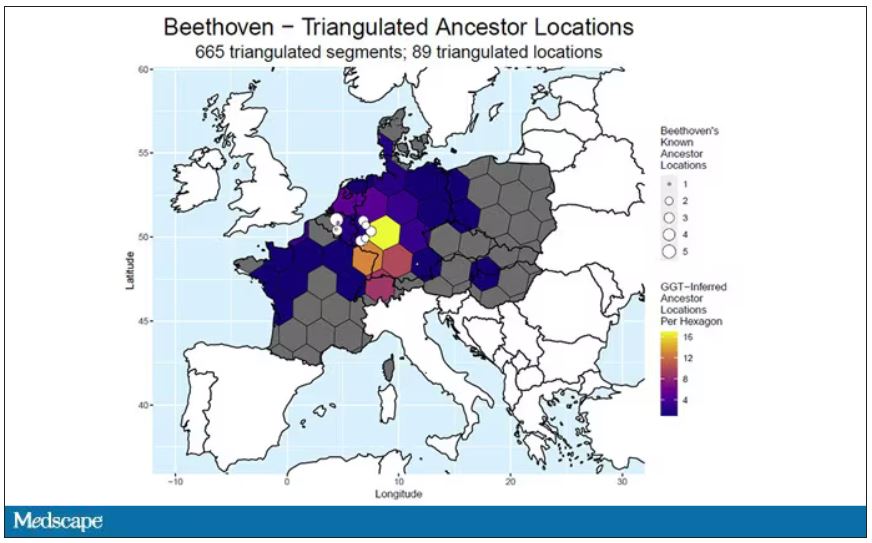

We’re talking about this paper in Current Biology, by Tristan Begg and colleagues, which gives us a look into the very genome of what some would argue is the world’s greatest composer.

The ability to extract DNA from older specimens has transformed the fields of anthropology, archaeology, and history, and now, perhaps, musicology as well.

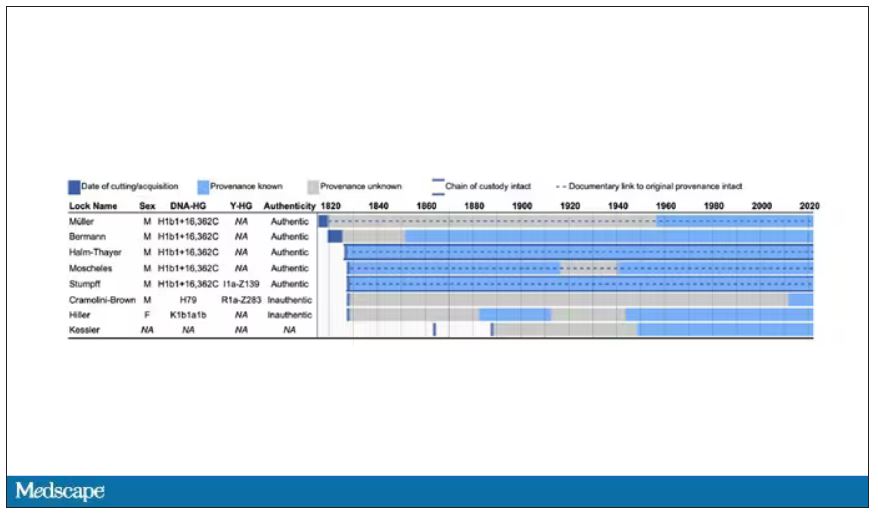

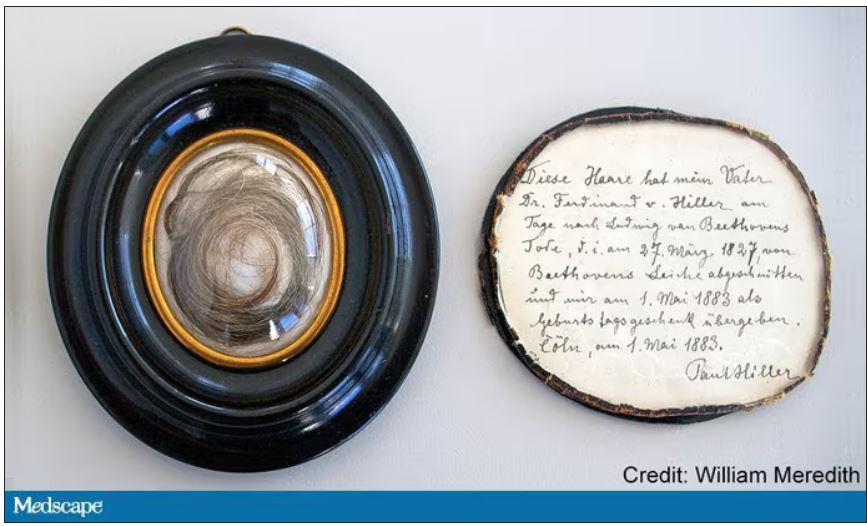

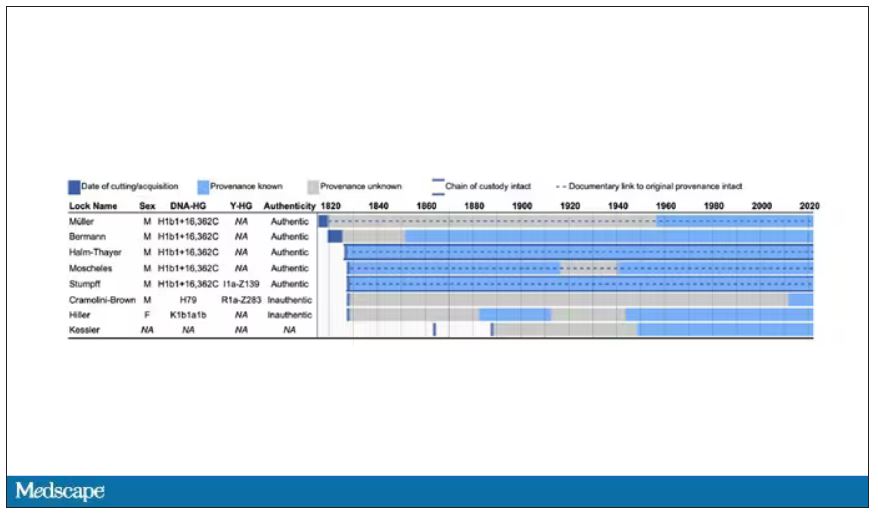

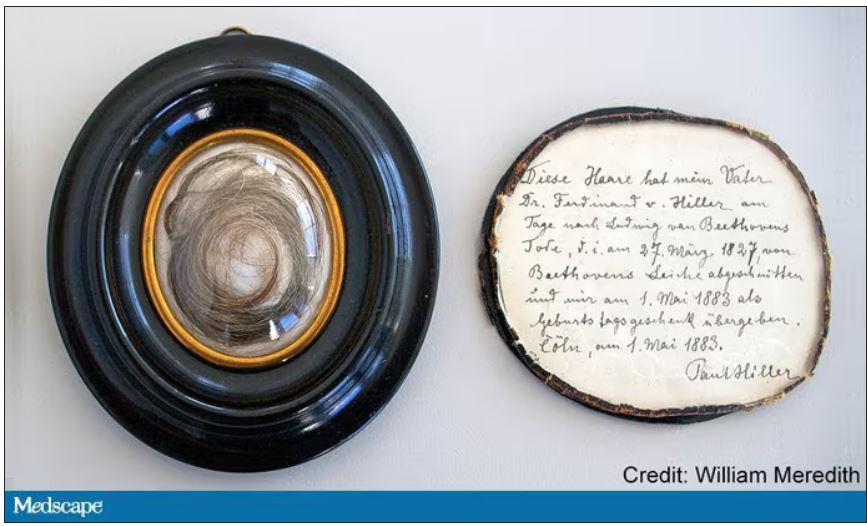

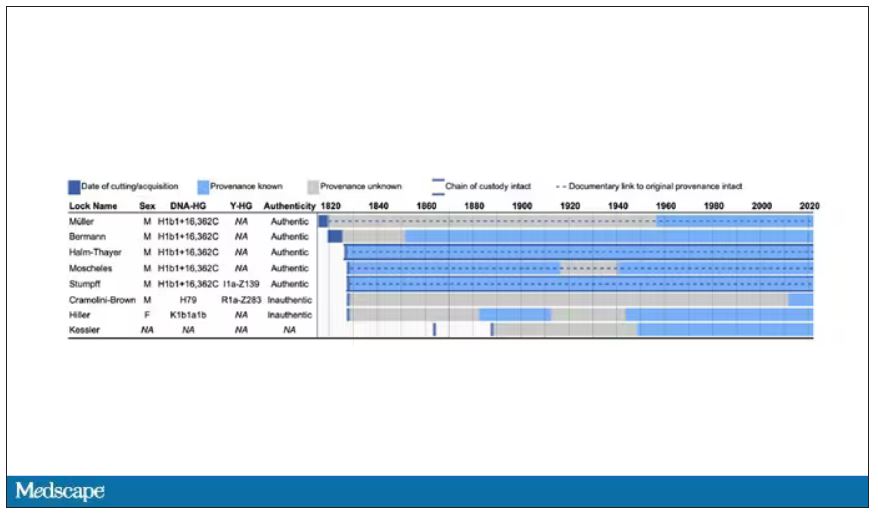

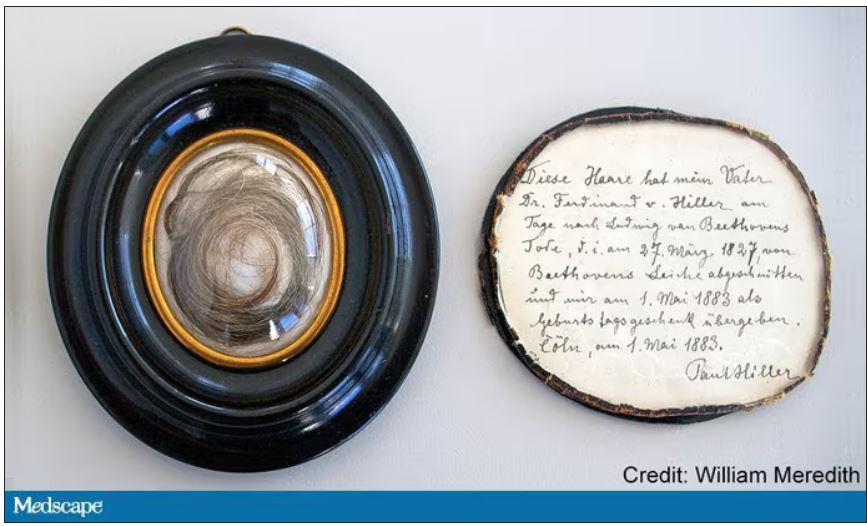

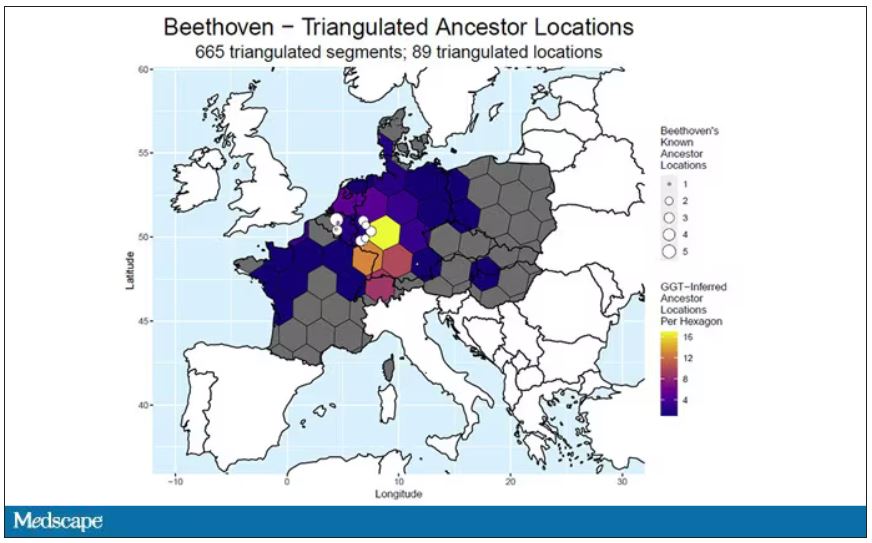

The researchers identified eight locks of hair in private and public collections, all attributed to the maestro.

Four of the samples had an intact chain of custody from the time the hair was cut. DNA sequencing on these four and an additional one of the eight locks came from the same individual, a male of European heritage.

The three locks with less documentation came from three other unrelated individuals. Interestingly, analysis of one of those hair samples – the so-called Hiller Lock – had shown high levels of lead, leading historians to speculate that lead poisoning could account for some of Beethoven’s symptoms.

DNA analysis of that hair reveals it to have come from a woman likely of North African, Middle Eastern, or Jewish ancestry. We can no longer presume that plumbism was involved in Beethoven’s death. Beethoven’s ancestry turns out to be less exotic and maps quite well to ethnic German populations today.