User login

Large cohort study finds isotretinoin not associated with IBD

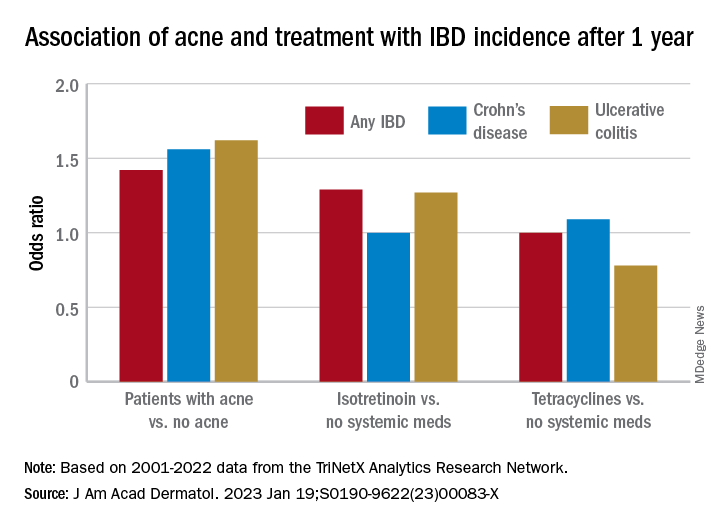

that also found no significant association of oral tetracycline-class antibiotics with IBD – and a small but statistically significant association of acne itself with the inflammatory disorders that make up IBD.

For the study, senior author John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, of the department of dermatology, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues used data from the TriNetX global research platform, which mines patient-level electronic medical record data from dozens of health care organizations, mainly in the United States. The network includes over 106 million patients. They looked at four cohorts: Patients without acne; those with acne but no current or prior use of systemic medications; those with acne managed with isotretinoin (and no prior use of oral tetracycline-class antibiotics); and those with acne managed with oral tetracycline-class antibiotics (and no exposure to isotretinoin).

For the acne cohorts, the investigators captured first encounters with a diagnosis of acne and first prescriptions of interest. And studywide, they used propensity score matching to balance cohorts for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and combined oral contraceptive use.

“These data should provide more reassurance to patients and prescribers that isotretinoin does not appear to result in a meaningfully increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease,” they wrote in the study, published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“These are important findings as isotretinoin is a valuable treatment for acne that can result in a durable remission of disease activity, prevent acne scarring, and reduce our overreliance on oral antibiotics for acne,” they added.

Indeed, dermatologist Jonathan S. Weiss, MD, who was not involved in the research and was asked to comment on the study, said that the findings “are reassuring given the large numbers of patients evaluated and treated.” The smallest cohort – the isotretinoin group – had over 11,000 patients, and the other cohorts had over 100,000 patients each, he said in an interview.

“At this point, I’m not sure we need any other immediate information to feel comfortable using isotretinoin with respect to a potential to cause IBD, but it would be nice to see some longitudinal follow-up data for longer-term reassurance,” added Dr. Weiss, who practices in Snellville, Georgia, and is on the board of the directors of the American Acne and Rosacea Society.

The findings: Risk with acne

To assess the potential association between acne and IBD, the researchers identified more than 350,000 patients with acne managed without systemic medications, and propensity score matched them with patients who did not have acne. Altogether, their mean age was 22; 32.1% were male, and 59.6% were White.

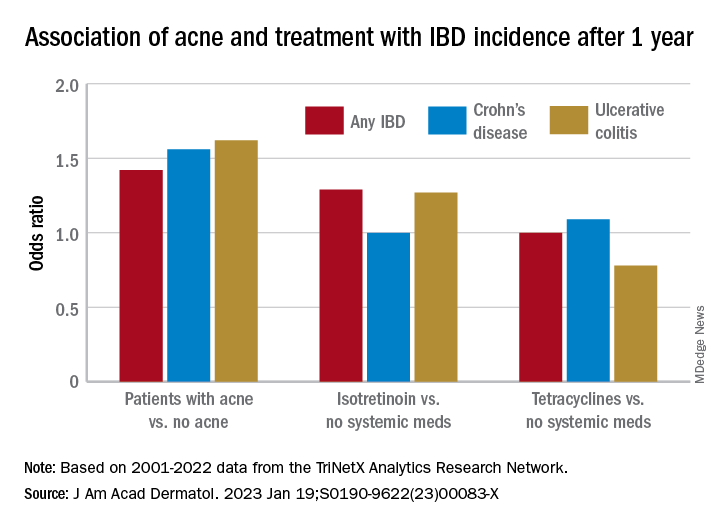

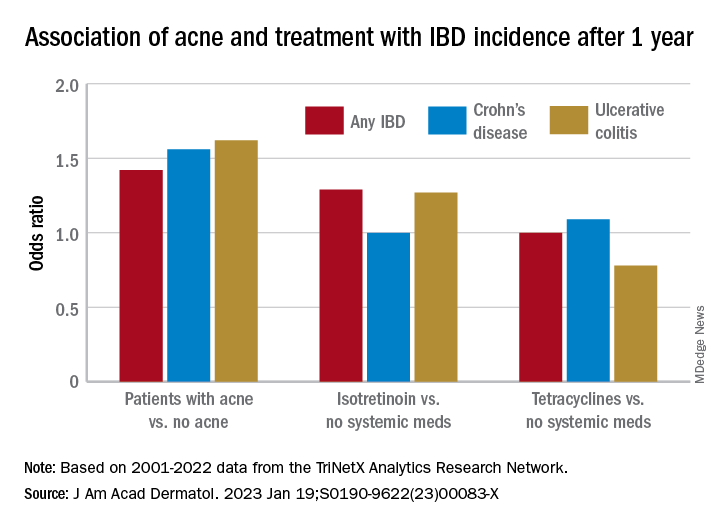

Compared with the controls who did not have acne, they found a statistically significant association between acne and risk of incident IBD (odds ratio, 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.65) and an absolute risk difference of .04%. Separated into Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), ORs were 1.56 and 1.62, respectively.

Tetracyclines

To assess the association of oral tetracycline use and IBD, they compared more than 144,000 patients whose acne was managed with antibiotics with patients whose acne was managed without systemic medications. The patients had a mean age of 24.4; 34.7% were male, and 68.2% were White.

Compared with the patients who were not on systemic medications, there were no significant associations among those on oral tetracyclines, with an OR for incident IBD of 1 (95% CI, 0.82-1.22), an OR for incident CD of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.86-1.38), and an OR for UC of 0.78 (95% CI, 0.61-1.00).

Isotretinoin

To evaluate the association of isotretinoin and IBD, the researchers compared more than 11,000 patients treated with isotretinoin with two matched groups: patients with acne managed without systemic medications, and patients with acne managed with oral tetracyclines. The latter comparison was made to minimize potential confounding by acne severity. These patients had a mean age of 21.1; 49.5% were male, and 75.3% were White.

In the first comparison, compared with patients not treated with systemic medications, the OR for 1-year incidence of IBD among patients treated with isotretinoin was 1.29 (95% CI, 0.64-2.59), with an absolute risk difference of .036%. The ORs for CD and UC were 1.00 (95% CI, 0.45-2.23) and 1.27 (95% CI, .58-2.80), respectively.

And compared with the antibiotic-managed group, the OR for incident IBD among those on isotretinoin was 1.13 (95% CI, 0.57-2.21), with an absolute risk difference of .018%. The OR for CD was 1.00 (95% CI, 0.45-2.23). The OR for UC could not be accurately estimated because of an insufficient number of events in the tetracycline-treated group.

‘Challenging’ area of research

Researching acne treatments and the potential risk of IBD has been a methodologically “challenging topic to study” because of possible confounding and surveillance bias depending on study designs, Dr. Barbieri, director of the Brigham and Women’s Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic, said in an interview.

Studies that have identified a potential association between isotretinoin and IBD often have not adequately controlled for prior antibiotic exposure, for instance. And other studies, including a retrospective cohort study also published recently in JAAD using the same TriNetX database, have found 6-month isotretinoin-related risks of IBD but no increased risk at 1 year or more of follow-up – a finding that suggests a role of surveillance bias, Dr. Barbieri said.

The follow-up period of 1 year in their new study was chosen to minimize the risk of such bias. “Since patients on isotretinoin are seen more often, and since there are historical concerns about isotretinoin and IBD, patients on isotretinoin may be more likely to be screened earlier and thus could be diagnosed sooner than those not on [the medication],” he said.

He and his coauthors considered similar potential bias in designing the no-acne cohort, choosing patients who had routine primary care visits without abnormal findings in order to “reduce potential for bias due to frequency of interaction with the health care system,” they noted in their paper. (Patients had no prior encounters for acne and no history of acne treatments.)

Antibiotics, acne itself

Research on antibiotic use for acne and risk of IBD is scant, and the few studies that have been published show conflicting findings, Dr. Barbieri noted. In the meantime, studies and meta-analyses in the general medical literature – not involving acne – have identified an association between lifetime oral antibiotic exposure and IBD, he said.

While the results of the new study “are reassuring that oral tetracycline-class exposure for acne may not be associated with a significant absolute risk of inflammatory bowel disease, given the potential for antibiotic resistance and other antibiotic-associated complications, it remains important to be judicious” with their use in acne management, he and his coauthors wrote in the study.

The potential association between antibiotics for acne and IBD needs further study, preferably with longer follow-up duration, Dr. Barbieri said in the interview, but researchers are challenged by the lack of datasets with high-quality longitudinal data “beyond a few years of follow-up.”

The extent to which acne itself is associated with IBD is another area ripe for more research. Thus far, it seems that IBD and acne – and other chronic inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis – involve similar pathogenic pathways. “We know that in IBD Th17 and TNF immunologic pathways are important, so it’s not surprising that there may be associations,” he said.

In their paper, Dr. Barbieri and his coauthors emphasize, however, that the absolute risk difference between acne and IBD is small. It’s “unlikely that population level screening is warranted among patients with acne,” they wrote.

A second new study

The other study, also published recently in JAAD, used the same TriNetX research platform to identify approximately 77,000 patients with acne starting isotretinoin and matched them with patients starting oral antibiotics.

The investigators, Khalaf Kridin MD, PhD, and Ralf J. Ludwig, MD, of the Lübeck Institute of Experimental Dermatology, University of Lübeck (Germany), found that the lifetime risks (greater than 6 months) for patients on isotretinoin were not significantly elevated, compared with those on oral antibiotics for either CD (hazard ratio 1.05; 95% CI, 0.89-1.24, P = .583) or UC (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.95-1.34; P = .162) They also looked at the risk of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and found a lower lifetime risk in the isotretinoin group.

In the short term, during the first 6 months after drug initiation, there was a significant, but slight increase in UC in the isotretinoin group. But this risk decreased to the level of the antibiotic group with longer follow up. “The absolute incidence rates [of IBD] and the risk difference of UC within the first 6 months are of limited clinical significance,” they wrote.

It may be, Dr. Weiss said in commenting on this study, “that isotretinoin unmasks an already-existing genetic tendency to UC early on in the course of treatment, but that it does not truly cause an increased incidence of any type of IBD.”

Both studies, said Dr. Barbieri, “add to an extensive body of literature that supports that isotretinoin is not associated with IBD.”

Dr. Barbieri had no disclosures for the study, for which Matthew T. Taylor served as first author. Coauthor Shawn Kwatra, MD, disclosed that he is an advisory board member/consultant for numerous pharmaceutical companies and has served as an investigator for several. Both are supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The other authors had no disclosures. Dr. Kridin and Dr. Ludwig had no disclosures for their study. Dr. Weiss had no disclosures.

that also found no significant association of oral tetracycline-class antibiotics with IBD – and a small but statistically significant association of acne itself with the inflammatory disorders that make up IBD.

For the study, senior author John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, of the department of dermatology, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues used data from the TriNetX global research platform, which mines patient-level electronic medical record data from dozens of health care organizations, mainly in the United States. The network includes over 106 million patients. They looked at four cohorts: Patients without acne; those with acne but no current or prior use of systemic medications; those with acne managed with isotretinoin (and no prior use of oral tetracycline-class antibiotics); and those with acne managed with oral tetracycline-class antibiotics (and no exposure to isotretinoin).

For the acne cohorts, the investigators captured first encounters with a diagnosis of acne and first prescriptions of interest. And studywide, they used propensity score matching to balance cohorts for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and combined oral contraceptive use.

“These data should provide more reassurance to patients and prescribers that isotretinoin does not appear to result in a meaningfully increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease,” they wrote in the study, published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“These are important findings as isotretinoin is a valuable treatment for acne that can result in a durable remission of disease activity, prevent acne scarring, and reduce our overreliance on oral antibiotics for acne,” they added.

Indeed, dermatologist Jonathan S. Weiss, MD, who was not involved in the research and was asked to comment on the study, said that the findings “are reassuring given the large numbers of patients evaluated and treated.” The smallest cohort – the isotretinoin group – had over 11,000 patients, and the other cohorts had over 100,000 patients each, he said in an interview.

“At this point, I’m not sure we need any other immediate information to feel comfortable using isotretinoin with respect to a potential to cause IBD, but it would be nice to see some longitudinal follow-up data for longer-term reassurance,” added Dr. Weiss, who practices in Snellville, Georgia, and is on the board of the directors of the American Acne and Rosacea Society.

The findings: Risk with acne

To assess the potential association between acne and IBD, the researchers identified more than 350,000 patients with acne managed without systemic medications, and propensity score matched them with patients who did not have acne. Altogether, their mean age was 22; 32.1% were male, and 59.6% were White.

Compared with the controls who did not have acne, they found a statistically significant association between acne and risk of incident IBD (odds ratio, 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.65) and an absolute risk difference of .04%. Separated into Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), ORs were 1.56 and 1.62, respectively.

Tetracyclines

To assess the association of oral tetracycline use and IBD, they compared more than 144,000 patients whose acne was managed with antibiotics with patients whose acne was managed without systemic medications. The patients had a mean age of 24.4; 34.7% were male, and 68.2% were White.

Compared with the patients who were not on systemic medications, there were no significant associations among those on oral tetracyclines, with an OR for incident IBD of 1 (95% CI, 0.82-1.22), an OR for incident CD of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.86-1.38), and an OR for UC of 0.78 (95% CI, 0.61-1.00).

Isotretinoin

To evaluate the association of isotretinoin and IBD, the researchers compared more than 11,000 patients treated with isotretinoin with two matched groups: patients with acne managed without systemic medications, and patients with acne managed with oral tetracyclines. The latter comparison was made to minimize potential confounding by acne severity. These patients had a mean age of 21.1; 49.5% were male, and 75.3% were White.

In the first comparison, compared with patients not treated with systemic medications, the OR for 1-year incidence of IBD among patients treated with isotretinoin was 1.29 (95% CI, 0.64-2.59), with an absolute risk difference of .036%. The ORs for CD and UC were 1.00 (95% CI, 0.45-2.23) and 1.27 (95% CI, .58-2.80), respectively.

And compared with the antibiotic-managed group, the OR for incident IBD among those on isotretinoin was 1.13 (95% CI, 0.57-2.21), with an absolute risk difference of .018%. The OR for CD was 1.00 (95% CI, 0.45-2.23). The OR for UC could not be accurately estimated because of an insufficient number of events in the tetracycline-treated group.

‘Challenging’ area of research

Researching acne treatments and the potential risk of IBD has been a methodologically “challenging topic to study” because of possible confounding and surveillance bias depending on study designs, Dr. Barbieri, director of the Brigham and Women’s Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic, said in an interview.

Studies that have identified a potential association between isotretinoin and IBD often have not adequately controlled for prior antibiotic exposure, for instance. And other studies, including a retrospective cohort study also published recently in JAAD using the same TriNetX database, have found 6-month isotretinoin-related risks of IBD but no increased risk at 1 year or more of follow-up – a finding that suggests a role of surveillance bias, Dr. Barbieri said.

The follow-up period of 1 year in their new study was chosen to minimize the risk of such bias. “Since patients on isotretinoin are seen more often, and since there are historical concerns about isotretinoin and IBD, patients on isotretinoin may be more likely to be screened earlier and thus could be diagnosed sooner than those not on [the medication],” he said.

He and his coauthors considered similar potential bias in designing the no-acne cohort, choosing patients who had routine primary care visits without abnormal findings in order to “reduce potential for bias due to frequency of interaction with the health care system,” they noted in their paper. (Patients had no prior encounters for acne and no history of acne treatments.)

Antibiotics, acne itself

Research on antibiotic use for acne and risk of IBD is scant, and the few studies that have been published show conflicting findings, Dr. Barbieri noted. In the meantime, studies and meta-analyses in the general medical literature – not involving acne – have identified an association between lifetime oral antibiotic exposure and IBD, he said.

While the results of the new study “are reassuring that oral tetracycline-class exposure for acne may not be associated with a significant absolute risk of inflammatory bowel disease, given the potential for antibiotic resistance and other antibiotic-associated complications, it remains important to be judicious” with their use in acne management, he and his coauthors wrote in the study.

The potential association between antibiotics for acne and IBD needs further study, preferably with longer follow-up duration, Dr. Barbieri said in the interview, but researchers are challenged by the lack of datasets with high-quality longitudinal data “beyond a few years of follow-up.”

The extent to which acne itself is associated with IBD is another area ripe for more research. Thus far, it seems that IBD and acne – and other chronic inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis – involve similar pathogenic pathways. “We know that in IBD Th17 and TNF immunologic pathways are important, so it’s not surprising that there may be associations,” he said.

In their paper, Dr. Barbieri and his coauthors emphasize, however, that the absolute risk difference between acne and IBD is small. It’s “unlikely that population level screening is warranted among patients with acne,” they wrote.

A second new study

The other study, also published recently in JAAD, used the same TriNetX research platform to identify approximately 77,000 patients with acne starting isotretinoin and matched them with patients starting oral antibiotics.

The investigators, Khalaf Kridin MD, PhD, and Ralf J. Ludwig, MD, of the Lübeck Institute of Experimental Dermatology, University of Lübeck (Germany), found that the lifetime risks (greater than 6 months) for patients on isotretinoin were not significantly elevated, compared with those on oral antibiotics for either CD (hazard ratio 1.05; 95% CI, 0.89-1.24, P = .583) or UC (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.95-1.34; P = .162) They also looked at the risk of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and found a lower lifetime risk in the isotretinoin group.

In the short term, during the first 6 months after drug initiation, there was a significant, but slight increase in UC in the isotretinoin group. But this risk decreased to the level of the antibiotic group with longer follow up. “The absolute incidence rates [of IBD] and the risk difference of UC within the first 6 months are of limited clinical significance,” they wrote.

It may be, Dr. Weiss said in commenting on this study, “that isotretinoin unmasks an already-existing genetic tendency to UC early on in the course of treatment, but that it does not truly cause an increased incidence of any type of IBD.”

Both studies, said Dr. Barbieri, “add to an extensive body of literature that supports that isotretinoin is not associated with IBD.”

Dr. Barbieri had no disclosures for the study, for which Matthew T. Taylor served as first author. Coauthor Shawn Kwatra, MD, disclosed that he is an advisory board member/consultant for numerous pharmaceutical companies and has served as an investigator for several. Both are supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The other authors had no disclosures. Dr. Kridin and Dr. Ludwig had no disclosures for their study. Dr. Weiss had no disclosures.

that also found no significant association of oral tetracycline-class antibiotics with IBD – and a small but statistically significant association of acne itself with the inflammatory disorders that make up IBD.

For the study, senior author John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, of the department of dermatology, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues used data from the TriNetX global research platform, which mines patient-level electronic medical record data from dozens of health care organizations, mainly in the United States. The network includes over 106 million patients. They looked at four cohorts: Patients without acne; those with acne but no current or prior use of systemic medications; those with acne managed with isotretinoin (and no prior use of oral tetracycline-class antibiotics); and those with acne managed with oral tetracycline-class antibiotics (and no exposure to isotretinoin).

For the acne cohorts, the investigators captured first encounters with a diagnosis of acne and first prescriptions of interest. And studywide, they used propensity score matching to balance cohorts for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and combined oral contraceptive use.

“These data should provide more reassurance to patients and prescribers that isotretinoin does not appear to result in a meaningfully increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease,” they wrote in the study, published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“These are important findings as isotretinoin is a valuable treatment for acne that can result in a durable remission of disease activity, prevent acne scarring, and reduce our overreliance on oral antibiotics for acne,” they added.

Indeed, dermatologist Jonathan S. Weiss, MD, who was not involved in the research and was asked to comment on the study, said that the findings “are reassuring given the large numbers of patients evaluated and treated.” The smallest cohort – the isotretinoin group – had over 11,000 patients, and the other cohorts had over 100,000 patients each, he said in an interview.

“At this point, I’m not sure we need any other immediate information to feel comfortable using isotretinoin with respect to a potential to cause IBD, but it would be nice to see some longitudinal follow-up data for longer-term reassurance,” added Dr. Weiss, who practices in Snellville, Georgia, and is on the board of the directors of the American Acne and Rosacea Society.

The findings: Risk with acne

To assess the potential association between acne and IBD, the researchers identified more than 350,000 patients with acne managed without systemic medications, and propensity score matched them with patients who did not have acne. Altogether, their mean age was 22; 32.1% were male, and 59.6% were White.

Compared with the controls who did not have acne, they found a statistically significant association between acne and risk of incident IBD (odds ratio, 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.65) and an absolute risk difference of .04%. Separated into Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), ORs were 1.56 and 1.62, respectively.

Tetracyclines

To assess the association of oral tetracycline use and IBD, they compared more than 144,000 patients whose acne was managed with antibiotics with patients whose acne was managed without systemic medications. The patients had a mean age of 24.4; 34.7% were male, and 68.2% were White.

Compared with the patients who were not on systemic medications, there were no significant associations among those on oral tetracyclines, with an OR for incident IBD of 1 (95% CI, 0.82-1.22), an OR for incident CD of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.86-1.38), and an OR for UC of 0.78 (95% CI, 0.61-1.00).

Isotretinoin

To evaluate the association of isotretinoin and IBD, the researchers compared more than 11,000 patients treated with isotretinoin with two matched groups: patients with acne managed without systemic medications, and patients with acne managed with oral tetracyclines. The latter comparison was made to minimize potential confounding by acne severity. These patients had a mean age of 21.1; 49.5% were male, and 75.3% were White.

In the first comparison, compared with patients not treated with systemic medications, the OR for 1-year incidence of IBD among patients treated with isotretinoin was 1.29 (95% CI, 0.64-2.59), with an absolute risk difference of .036%. The ORs for CD and UC were 1.00 (95% CI, 0.45-2.23) and 1.27 (95% CI, .58-2.80), respectively.

And compared with the antibiotic-managed group, the OR for incident IBD among those on isotretinoin was 1.13 (95% CI, 0.57-2.21), with an absolute risk difference of .018%. The OR for CD was 1.00 (95% CI, 0.45-2.23). The OR for UC could not be accurately estimated because of an insufficient number of events in the tetracycline-treated group.

‘Challenging’ area of research

Researching acne treatments and the potential risk of IBD has been a methodologically “challenging topic to study” because of possible confounding and surveillance bias depending on study designs, Dr. Barbieri, director of the Brigham and Women’s Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic, said in an interview.

Studies that have identified a potential association between isotretinoin and IBD often have not adequately controlled for prior antibiotic exposure, for instance. And other studies, including a retrospective cohort study also published recently in JAAD using the same TriNetX database, have found 6-month isotretinoin-related risks of IBD but no increased risk at 1 year or more of follow-up – a finding that suggests a role of surveillance bias, Dr. Barbieri said.

The follow-up period of 1 year in their new study was chosen to minimize the risk of such bias. “Since patients on isotretinoin are seen more often, and since there are historical concerns about isotretinoin and IBD, patients on isotretinoin may be more likely to be screened earlier and thus could be diagnosed sooner than those not on [the medication],” he said.

He and his coauthors considered similar potential bias in designing the no-acne cohort, choosing patients who had routine primary care visits without abnormal findings in order to “reduce potential for bias due to frequency of interaction with the health care system,” they noted in their paper. (Patients had no prior encounters for acne and no history of acne treatments.)

Antibiotics, acne itself

Research on antibiotic use for acne and risk of IBD is scant, and the few studies that have been published show conflicting findings, Dr. Barbieri noted. In the meantime, studies and meta-analyses in the general medical literature – not involving acne – have identified an association between lifetime oral antibiotic exposure and IBD, he said.

While the results of the new study “are reassuring that oral tetracycline-class exposure for acne may not be associated with a significant absolute risk of inflammatory bowel disease, given the potential for antibiotic resistance and other antibiotic-associated complications, it remains important to be judicious” with their use in acne management, he and his coauthors wrote in the study.

The potential association between antibiotics for acne and IBD needs further study, preferably with longer follow-up duration, Dr. Barbieri said in the interview, but researchers are challenged by the lack of datasets with high-quality longitudinal data “beyond a few years of follow-up.”

The extent to which acne itself is associated with IBD is another area ripe for more research. Thus far, it seems that IBD and acne – and other chronic inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis – involve similar pathogenic pathways. “We know that in IBD Th17 and TNF immunologic pathways are important, so it’s not surprising that there may be associations,” he said.

In their paper, Dr. Barbieri and his coauthors emphasize, however, that the absolute risk difference between acne and IBD is small. It’s “unlikely that population level screening is warranted among patients with acne,” they wrote.

A second new study

The other study, also published recently in JAAD, used the same TriNetX research platform to identify approximately 77,000 patients with acne starting isotretinoin and matched them with patients starting oral antibiotics.

The investigators, Khalaf Kridin MD, PhD, and Ralf J. Ludwig, MD, of the Lübeck Institute of Experimental Dermatology, University of Lübeck (Germany), found that the lifetime risks (greater than 6 months) for patients on isotretinoin were not significantly elevated, compared with those on oral antibiotics for either CD (hazard ratio 1.05; 95% CI, 0.89-1.24, P = .583) or UC (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.95-1.34; P = .162) They also looked at the risk of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and found a lower lifetime risk in the isotretinoin group.

In the short term, during the first 6 months after drug initiation, there was a significant, but slight increase in UC in the isotretinoin group. But this risk decreased to the level of the antibiotic group with longer follow up. “The absolute incidence rates [of IBD] and the risk difference of UC within the first 6 months are of limited clinical significance,” they wrote.

It may be, Dr. Weiss said in commenting on this study, “that isotretinoin unmasks an already-existing genetic tendency to UC early on in the course of treatment, but that it does not truly cause an increased incidence of any type of IBD.”

Both studies, said Dr. Barbieri, “add to an extensive body of literature that supports that isotretinoin is not associated with IBD.”

Dr. Barbieri had no disclosures for the study, for which Matthew T. Taylor served as first author. Coauthor Shawn Kwatra, MD, disclosed that he is an advisory board member/consultant for numerous pharmaceutical companies and has served as an investigator for several. Both are supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The other authors had no disclosures. Dr. Kridin and Dr. Ludwig had no disclosures for their study. Dr. Weiss had no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Almonds may be a good diet option

according to researchers at the University of South Australia’s Alliance for Research in Exercise, Nutrition and Activity.

What to know

People who consume as few as 30-50 g of almonds, as opposed to an energy-equivalent carbohydrate snack, can lower their energy intake significantly at the subsequent meal.

People who eat almonds can experience changes in their appetite-regulating hormones that may contribute to less food intake.

Almond consumption can lower C-peptide responses, which can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce the risk of developing diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Eating almonds can raise levels of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide glucagon, which can send satiety signals to the brain, and pancreatic polypeptide, which slows digestion, which may reduce food intake, supporting weight loss.

Almonds are high in protein, fiber, and unsaturated fatty acids, which may contribute to their satiating properties and help explain why fewer calories are consumed.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This is a summary of the article “Acute Feeding With Almonds Compared to a Carbohydrate-Based Snack Improves Appetite-Regulating Hormones With No Effect on Self-reported Appetite Sensations: A Randomised Controlled Trial,” published in the European Journal of Nutrition on Oct. 11, 2022. The full article can be found on link.springer.com.

according to researchers at the University of South Australia’s Alliance for Research in Exercise, Nutrition and Activity.

What to know

People who consume as few as 30-50 g of almonds, as opposed to an energy-equivalent carbohydrate snack, can lower their energy intake significantly at the subsequent meal.

People who eat almonds can experience changes in their appetite-regulating hormones that may contribute to less food intake.

Almond consumption can lower C-peptide responses, which can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce the risk of developing diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Eating almonds can raise levels of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide glucagon, which can send satiety signals to the brain, and pancreatic polypeptide, which slows digestion, which may reduce food intake, supporting weight loss.

Almonds are high in protein, fiber, and unsaturated fatty acids, which may contribute to their satiating properties and help explain why fewer calories are consumed.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This is a summary of the article “Acute Feeding With Almonds Compared to a Carbohydrate-Based Snack Improves Appetite-Regulating Hormones With No Effect on Self-reported Appetite Sensations: A Randomised Controlled Trial,” published in the European Journal of Nutrition on Oct. 11, 2022. The full article can be found on link.springer.com.

according to researchers at the University of South Australia’s Alliance for Research in Exercise, Nutrition and Activity.

What to know

People who consume as few as 30-50 g of almonds, as opposed to an energy-equivalent carbohydrate snack, can lower their energy intake significantly at the subsequent meal.

People who eat almonds can experience changes in their appetite-regulating hormones that may contribute to less food intake.

Almond consumption can lower C-peptide responses, which can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce the risk of developing diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Eating almonds can raise levels of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide glucagon, which can send satiety signals to the brain, and pancreatic polypeptide, which slows digestion, which may reduce food intake, supporting weight loss.

Almonds are high in protein, fiber, and unsaturated fatty acids, which may contribute to their satiating properties and help explain why fewer calories are consumed.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This is a summary of the article “Acute Feeding With Almonds Compared to a Carbohydrate-Based Snack Improves Appetite-Regulating Hormones With No Effect on Self-reported Appetite Sensations: A Randomised Controlled Trial,” published in the European Journal of Nutrition on Oct. 11, 2022. The full article can be found on link.springer.com.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF NUTRITION

Colorectal cancer treatment outcomes in older adults

A phase 2, multi-institutional feasibility study found a completion rate of 67.3%, while a prospective study found that completion was associated with improved disease-free survival.

Both studies were presented in January at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium 2023.

In HiSCO-04, Japanese researchers found that of 64 older patients with stage 3A colorectal cancer who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy, 53% completed the treatment with an improvement in disease-free survival. Patients who completed adjuvant chemotherapy had better disease-free survival (P = .03), while the survival was lower among those who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy, and lowest among those who discontinued adjuvant chemotherapy.

“The results showed that adjuvant chemotherapy is not always recommended for elderly patients, and that patients who are able to complete treatment may have a better prognosis for survival. However, the results do not indicate which patients are unable to complete chemotherapy, and it will be necessary to identify patients who are intolerant of chemotherapy,” said the study’s lead author Manabu Shimomura, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of gastroenterological and transplant surgery at the Hiroshima University Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences in Japan.

The study, which was conducted between 2013 and 2021, enrolled 214 patients (99 men, 115 women, 80-101 years old) who were in stage 3 cancer (27 cases 3A, 158 cases 3B, and 29 cases 3C). A total of 41 patients were ineligible for chemotherapy. Of the remaining patients, 65 received adjuvant chemotherapy and 108 did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy.

The 3-year disease-free survival was 63.6%, the 3-year overall survival was 76.9%, and the 3-year relapse-free survival was 63.1%. Thirty-six patients died because of colorectal cancer, and 30 patients died of other causes. There was recurrence in 58 cases and secondary cancers were observed in 17 cases during the 42.5 months–long follow-up period.

There were few reports of serious adverse events, but some cases of treatment discontinuation were because of adverse events.

In a second study presented by Dr. Shimomura’s group, called HiSCO-03, 65 patients (33 female) underwent curative resection and received five courses of uracil-tegafur and leucovorin (UFT/LV).

The completion rate of 67.3% had a 95% lower bound of 54.9%, which were lower than the predefined thresholds of 75% completion and a lower bound of 60%. “Based on the results of a previous (ACTS-CC phase III) study, we set the expected value of UFT/LV therapy in patients over 80 years of age at 75% and the threshold at 60%. Since the target age group of previous study was 75 years or younger, we concluded from the results of the current study that UFT/LV therapy is less well tolerated in patients 80 years of age and older than in patients 75 years of age and younger,” Dr. Shimomura said.

The treatment completion rate trended higher in males than females (77.6% versus 57.2%; P = .06) and performance status of 0 versus 1 or 2 (74.3% versus 58.9%; P = .10). The most common adverse events were anorexia (33.8%), diarrhea (30.8%), and anemia (24.6%). The median relative dose intensity was 84% for UFT and 100% for LV.

The challenges of treating older patients

If and how older patients with colorectal cancer should be treated is not clear cut. While 20% of patients in the United States who have colorectal cancer are over 80 years old, each case should be evaluated individually, experts say.

Writing in a 2015 review of colorectal cancer treatment in older adults, Monica Millan, MD, PhD, of Joan XXIII University Hospital, Tarragona, Spain, and colleagues, wrote that physiological heterogeneity and coexisting medical conditions make treating older patients with colorectal cancer challenging.

“Age in itself should not be an exclusion criterion for radical treatment, but there will be many elderly patients that will not tolerate or respond well to standard therapies. These patients need to be properly assessed before proposing treatment, and a tailored, individualized approach should be offered in a multidisciplinary setting,” wrote Dr. Millan, who is a colorectal surgeon.

The authors suggest that older patients who are fit could be treated similarly to younger patients, but there remain uncertainties about how to proceed in frail older adults with comorbidities.

“Most elderly patients with cancer will have priorities besides simply prolonging their lives. Surveys have found that their top concerns include avoiding suffering, strengthening relationships with family and friends, being mentally aware, not being a burden on others, and achieving a sense that their life is complete. The treatment plan should be comprehensive: cancer-specific treatment, symptom-specific treatment, supportive treatment modalities, and end-of-life care,” they wrote.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends colorectal cancer screening for men and women who are between 45 and 75 years old; however, screening for patients between 76 and 85 years old should be done on a case-by-case basis based on a patient’s overall health, screening history, and the patient’s preferences.

Colorectal cancer incidence rates have been declining since the mid-1980s because of an increase in screening among adults 50 years and older, according to the American Cancer Society. Likewise, mortality rates have dropped from 29.2% in 1970 to 12.6% in 2020 – mostly because of screening.

Dr. Shimomura has no relevant financial disclosures.

The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

A phase 2, multi-institutional feasibility study found a completion rate of 67.3%, while a prospective study found that completion was associated with improved disease-free survival.

Both studies were presented in January at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium 2023.

In HiSCO-04, Japanese researchers found that of 64 older patients with stage 3A colorectal cancer who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy, 53% completed the treatment with an improvement in disease-free survival. Patients who completed adjuvant chemotherapy had better disease-free survival (P = .03), while the survival was lower among those who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy, and lowest among those who discontinued adjuvant chemotherapy.

“The results showed that adjuvant chemotherapy is not always recommended for elderly patients, and that patients who are able to complete treatment may have a better prognosis for survival. However, the results do not indicate which patients are unable to complete chemotherapy, and it will be necessary to identify patients who are intolerant of chemotherapy,” said the study’s lead author Manabu Shimomura, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of gastroenterological and transplant surgery at the Hiroshima University Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences in Japan.

The study, which was conducted between 2013 and 2021, enrolled 214 patients (99 men, 115 women, 80-101 years old) who were in stage 3 cancer (27 cases 3A, 158 cases 3B, and 29 cases 3C). A total of 41 patients were ineligible for chemotherapy. Of the remaining patients, 65 received adjuvant chemotherapy and 108 did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy.

The 3-year disease-free survival was 63.6%, the 3-year overall survival was 76.9%, and the 3-year relapse-free survival was 63.1%. Thirty-six patients died because of colorectal cancer, and 30 patients died of other causes. There was recurrence in 58 cases and secondary cancers were observed in 17 cases during the 42.5 months–long follow-up period.

There were few reports of serious adverse events, but some cases of treatment discontinuation were because of adverse events.

In a second study presented by Dr. Shimomura’s group, called HiSCO-03, 65 patients (33 female) underwent curative resection and received five courses of uracil-tegafur and leucovorin (UFT/LV).

The completion rate of 67.3% had a 95% lower bound of 54.9%, which were lower than the predefined thresholds of 75% completion and a lower bound of 60%. “Based on the results of a previous (ACTS-CC phase III) study, we set the expected value of UFT/LV therapy in patients over 80 years of age at 75% and the threshold at 60%. Since the target age group of previous study was 75 years or younger, we concluded from the results of the current study that UFT/LV therapy is less well tolerated in patients 80 years of age and older than in patients 75 years of age and younger,” Dr. Shimomura said.

The treatment completion rate trended higher in males than females (77.6% versus 57.2%; P = .06) and performance status of 0 versus 1 or 2 (74.3% versus 58.9%; P = .10). The most common adverse events were anorexia (33.8%), diarrhea (30.8%), and anemia (24.6%). The median relative dose intensity was 84% for UFT and 100% for LV.

The challenges of treating older patients

If and how older patients with colorectal cancer should be treated is not clear cut. While 20% of patients in the United States who have colorectal cancer are over 80 years old, each case should be evaluated individually, experts say.

Writing in a 2015 review of colorectal cancer treatment in older adults, Monica Millan, MD, PhD, of Joan XXIII University Hospital, Tarragona, Spain, and colleagues, wrote that physiological heterogeneity and coexisting medical conditions make treating older patients with colorectal cancer challenging.

“Age in itself should not be an exclusion criterion for radical treatment, but there will be many elderly patients that will not tolerate or respond well to standard therapies. These patients need to be properly assessed before proposing treatment, and a tailored, individualized approach should be offered in a multidisciplinary setting,” wrote Dr. Millan, who is a colorectal surgeon.

The authors suggest that older patients who are fit could be treated similarly to younger patients, but there remain uncertainties about how to proceed in frail older adults with comorbidities.

“Most elderly patients with cancer will have priorities besides simply prolonging their lives. Surveys have found that their top concerns include avoiding suffering, strengthening relationships with family and friends, being mentally aware, not being a burden on others, and achieving a sense that their life is complete. The treatment plan should be comprehensive: cancer-specific treatment, symptom-specific treatment, supportive treatment modalities, and end-of-life care,” they wrote.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends colorectal cancer screening for men and women who are between 45 and 75 years old; however, screening for patients between 76 and 85 years old should be done on a case-by-case basis based on a patient’s overall health, screening history, and the patient’s preferences.

Colorectal cancer incidence rates have been declining since the mid-1980s because of an increase in screening among adults 50 years and older, according to the American Cancer Society. Likewise, mortality rates have dropped from 29.2% in 1970 to 12.6% in 2020 – mostly because of screening.

Dr. Shimomura has no relevant financial disclosures.

The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

A phase 2, multi-institutional feasibility study found a completion rate of 67.3%, while a prospective study found that completion was associated with improved disease-free survival.

Both studies were presented in January at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium 2023.

In HiSCO-04, Japanese researchers found that of 64 older patients with stage 3A colorectal cancer who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy, 53% completed the treatment with an improvement in disease-free survival. Patients who completed adjuvant chemotherapy had better disease-free survival (P = .03), while the survival was lower among those who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy, and lowest among those who discontinued adjuvant chemotherapy.

“The results showed that adjuvant chemotherapy is not always recommended for elderly patients, and that patients who are able to complete treatment may have a better prognosis for survival. However, the results do not indicate which patients are unable to complete chemotherapy, and it will be necessary to identify patients who are intolerant of chemotherapy,” said the study’s lead author Manabu Shimomura, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of gastroenterological and transplant surgery at the Hiroshima University Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences in Japan.

The study, which was conducted between 2013 and 2021, enrolled 214 patients (99 men, 115 women, 80-101 years old) who were in stage 3 cancer (27 cases 3A, 158 cases 3B, and 29 cases 3C). A total of 41 patients were ineligible for chemotherapy. Of the remaining patients, 65 received adjuvant chemotherapy and 108 did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy.

The 3-year disease-free survival was 63.6%, the 3-year overall survival was 76.9%, and the 3-year relapse-free survival was 63.1%. Thirty-six patients died because of colorectal cancer, and 30 patients died of other causes. There was recurrence in 58 cases and secondary cancers were observed in 17 cases during the 42.5 months–long follow-up period.

There were few reports of serious adverse events, but some cases of treatment discontinuation were because of adverse events.

In a second study presented by Dr. Shimomura’s group, called HiSCO-03, 65 patients (33 female) underwent curative resection and received five courses of uracil-tegafur and leucovorin (UFT/LV).

The completion rate of 67.3% had a 95% lower bound of 54.9%, which were lower than the predefined thresholds of 75% completion and a lower bound of 60%. “Based on the results of a previous (ACTS-CC phase III) study, we set the expected value of UFT/LV therapy in patients over 80 years of age at 75% and the threshold at 60%. Since the target age group of previous study was 75 years or younger, we concluded from the results of the current study that UFT/LV therapy is less well tolerated in patients 80 years of age and older than in patients 75 years of age and younger,” Dr. Shimomura said.

The treatment completion rate trended higher in males than females (77.6% versus 57.2%; P = .06) and performance status of 0 versus 1 or 2 (74.3% versus 58.9%; P = .10). The most common adverse events were anorexia (33.8%), diarrhea (30.8%), and anemia (24.6%). The median relative dose intensity was 84% for UFT and 100% for LV.

The challenges of treating older patients

If and how older patients with colorectal cancer should be treated is not clear cut. While 20% of patients in the United States who have colorectal cancer are over 80 years old, each case should be evaluated individually, experts say.

Writing in a 2015 review of colorectal cancer treatment in older adults, Monica Millan, MD, PhD, of Joan XXIII University Hospital, Tarragona, Spain, and colleagues, wrote that physiological heterogeneity and coexisting medical conditions make treating older patients with colorectal cancer challenging.

“Age in itself should not be an exclusion criterion for radical treatment, but there will be many elderly patients that will not tolerate or respond well to standard therapies. These patients need to be properly assessed before proposing treatment, and a tailored, individualized approach should be offered in a multidisciplinary setting,” wrote Dr. Millan, who is a colorectal surgeon.

The authors suggest that older patients who are fit could be treated similarly to younger patients, but there remain uncertainties about how to proceed in frail older adults with comorbidities.

“Most elderly patients with cancer will have priorities besides simply prolonging their lives. Surveys have found that their top concerns include avoiding suffering, strengthening relationships with family and friends, being mentally aware, not being a burden on others, and achieving a sense that their life is complete. The treatment plan should be comprehensive: cancer-specific treatment, symptom-specific treatment, supportive treatment modalities, and end-of-life care,” they wrote.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends colorectal cancer screening for men and women who are between 45 and 75 years old; however, screening for patients between 76 and 85 years old should be done on a case-by-case basis based on a patient’s overall health, screening history, and the patient’s preferences.

Colorectal cancer incidence rates have been declining since the mid-1980s because of an increase in screening among adults 50 years and older, according to the American Cancer Society. Likewise, mortality rates have dropped from 29.2% in 1970 to 12.6% in 2020 – mostly because of screening.

Dr. Shimomura has no relevant financial disclosures.

The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

FROM ASCO GI 2023

FDA OKs sacituzumab govitecan for HR+ metastatic breast cancer

for patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic hormone receptor (HR)–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer after endocrine-based therapy and at least two additional systemic therapies for metastatic disease.

Label expansion for the Trop-2–directed antibody-drug conjugate was based on the TROPICS-02 trial, which randomized 543 adults 1:1 to either sacituzumab govitecan 10 mg/kg IV on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle or single agent chemotherapy, most often eribulin but also vinorelbine, gemcitabine, or capecitabine.

Median progression free survival was 5.5 months with sacituzumab govitecan versus 4 months with single agent chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.66; P = .0003). Median overall survival was 14.4 months in the sacituzumab govitecan group versus 11.2 months with chemotherapy (HR, 0.79), according to an FDA press release announcing the approval.

In a Gilead press release, Hope Rugo, MD, a breast cancer specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, and principal investigator for TROPICS-02, said the approval “is significant for the breast cancer community. We have had limited options to offer patients after endocrine-based therapy and chemotherapy, and to see a clinically meaningful survival benefit of more than 3 months with a quality-of-life benefit for these women is exceptional.”

The most common adverse events associated with sacituzumab govitecan in the trial, occurring in a quarter or more of participants, were decreased leukocyte count, decreased neutrophil count, decreased hemoglobin, decreased lymphocyte count, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, alopecia, glucose elevation, constipation, and decreased albumin.

Labeling for the agent carries a boxedwarning of severe or life-threatening neutropenia and severe diarrhea.

The recommended dose is the trial dose: 10 mg/kg IV on days 1 and 8 of 21-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Sacituzumab govitecan was previously approved for unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer after two or more prior systemic therapies and locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer after platinum-based chemotherapy and either a PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

for patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic hormone receptor (HR)–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer after endocrine-based therapy and at least two additional systemic therapies for metastatic disease.

Label expansion for the Trop-2–directed antibody-drug conjugate was based on the TROPICS-02 trial, which randomized 543 adults 1:1 to either sacituzumab govitecan 10 mg/kg IV on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle or single agent chemotherapy, most often eribulin but also vinorelbine, gemcitabine, or capecitabine.

Median progression free survival was 5.5 months with sacituzumab govitecan versus 4 months with single agent chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.66; P = .0003). Median overall survival was 14.4 months in the sacituzumab govitecan group versus 11.2 months with chemotherapy (HR, 0.79), according to an FDA press release announcing the approval.

In a Gilead press release, Hope Rugo, MD, a breast cancer specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, and principal investigator for TROPICS-02, said the approval “is significant for the breast cancer community. We have had limited options to offer patients after endocrine-based therapy and chemotherapy, and to see a clinically meaningful survival benefit of more than 3 months with a quality-of-life benefit for these women is exceptional.”

The most common adverse events associated with sacituzumab govitecan in the trial, occurring in a quarter or more of participants, were decreased leukocyte count, decreased neutrophil count, decreased hemoglobin, decreased lymphocyte count, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, alopecia, glucose elevation, constipation, and decreased albumin.

Labeling for the agent carries a boxedwarning of severe or life-threatening neutropenia and severe diarrhea.

The recommended dose is the trial dose: 10 mg/kg IV on days 1 and 8 of 21-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Sacituzumab govitecan was previously approved for unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer after two or more prior systemic therapies and locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer after platinum-based chemotherapy and either a PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

for patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic hormone receptor (HR)–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer after endocrine-based therapy and at least two additional systemic therapies for metastatic disease.

Label expansion for the Trop-2–directed antibody-drug conjugate was based on the TROPICS-02 trial, which randomized 543 adults 1:1 to either sacituzumab govitecan 10 mg/kg IV on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle or single agent chemotherapy, most often eribulin but also vinorelbine, gemcitabine, or capecitabine.

Median progression free survival was 5.5 months with sacituzumab govitecan versus 4 months with single agent chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.66; P = .0003). Median overall survival was 14.4 months in the sacituzumab govitecan group versus 11.2 months with chemotherapy (HR, 0.79), according to an FDA press release announcing the approval.

In a Gilead press release, Hope Rugo, MD, a breast cancer specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, and principal investigator for TROPICS-02, said the approval “is significant for the breast cancer community. We have had limited options to offer patients after endocrine-based therapy and chemotherapy, and to see a clinically meaningful survival benefit of more than 3 months with a quality-of-life benefit for these women is exceptional.”

The most common adverse events associated with sacituzumab govitecan in the trial, occurring in a quarter or more of participants, were decreased leukocyte count, decreased neutrophil count, decreased hemoglobin, decreased lymphocyte count, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, alopecia, glucose elevation, constipation, and decreased albumin.

Labeling for the agent carries a boxedwarning of severe or life-threatening neutropenia and severe diarrhea.

The recommended dose is the trial dose: 10 mg/kg IV on days 1 and 8 of 21-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Sacituzumab govitecan was previously approved for unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer after two or more prior systemic therapies and locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer after platinum-based chemotherapy and either a PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immunotherapy with antibiotics doesn’t worsen biliary tract cancer outcomes

according to a new analysis of the landmark TOPAZ-1 clinical trial.

The findings, released at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium 2023, suggest that “people with advanced biliary tract cancer can safely be treated with antibiotics while still benefiting from treatment with durvalumab plus chemotherapy,” said lead author Aiwu Ruth He, MD, PhD, a gastrointestinal oncologist with MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington.

Antibiotic use during immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been associated with poorer outcomes. A review of 12 studies published in Frontiers in Oncology found that antibiotic use was associated with worse progression-free and overall survival.

“Patients with biliary tract cancer have the increased risk of biliary tract infection as the result of biliary tract obstruction, and they often receive antibiotics,” Dr. He said.

A 2020 report in eCancer suggested that antibiotics may disrupt gut bacteria and, as a result, interfere with the immune system’s responsiveness. “It has been a consensus that the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics should be avoided during the use of immunotherapy whenever possible,” the report authors wrote. “In addition, antibiotics should be prescribed only when properly indicated.”

However, cutting down on antibiotic use may be especially difficult in cancer patients since they frequently suffer from infections. “An antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection may cause serious issues for a cancer patient, who likely already has a suppressed immune system,” according to a 2017 information sheet posted by the Cancer Treatment Centers of America. “Chemotherapy may cause neutropenia, a reduction of white blood cells that help fight infections and viruses. Radiation therapy may damage the skin and cause irritation and wounds. Immunotherapy or targeted therapy drugs may trigger side effects that may lead to infections. Incisions from surgery or to insert ports or catheters may be vulnerable to infections.”

The new study

For the new subgroup analysis, researchers analyzed data from the phase 3 TOPAZ-1 clinical trial, which was a double-blinded analysis of durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer. The previously reported main findings from the study were positive with a median overall survival of 12.8 months in the durvalumab arm versus 11.5 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.80; P = .021). These findings contributed to the Food and Drug Administration’s decision in 2022 to approve the treatment for use in locally advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancer.

Of 341 patients who received durvalumab treatment, 167 also took antibiotics. The median overall survival in the antibiotic and nonantibiotic groups were similar at 12.6 months (95% confidence interval, 9.7-14.8 months) and 13 months (95% CI, 10.8-14.7 months), respectively. Median progression-free survival was 7.3 months (95% CI, 6.5-7.7 months) and 7.2 months (95% CI, 5.9-7.4 months), respectively.

“The results support that advanced patients’ risk of death, and the risk that their cancer would grow, spread, or get worse, was not meaningfully different between patients who used antibiotics and those who did not use antibiotics at the same time as they were receiving durvalumab-based treatment,” Dr. He said. “The result is not surprising to me since it is not clear to me how and why antibiotics may affect the effectiveness of immunotherapy.”

Moving forward, she said, “additional studies are needed to further investigator the relationship between antibiotics use and effectiveness of immunotherapy. We need to understand why use of antibiotics during treatment with immunotherapy is correlated with poor outcomes in some circumstances but not in other circumstances.”

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

according to a new analysis of the landmark TOPAZ-1 clinical trial.

The findings, released at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium 2023, suggest that “people with advanced biliary tract cancer can safely be treated with antibiotics while still benefiting from treatment with durvalumab plus chemotherapy,” said lead author Aiwu Ruth He, MD, PhD, a gastrointestinal oncologist with MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington.

Antibiotic use during immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been associated with poorer outcomes. A review of 12 studies published in Frontiers in Oncology found that antibiotic use was associated with worse progression-free and overall survival.

“Patients with biliary tract cancer have the increased risk of biliary tract infection as the result of biliary tract obstruction, and they often receive antibiotics,” Dr. He said.

A 2020 report in eCancer suggested that antibiotics may disrupt gut bacteria and, as a result, interfere with the immune system’s responsiveness. “It has been a consensus that the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics should be avoided during the use of immunotherapy whenever possible,” the report authors wrote. “In addition, antibiotics should be prescribed only when properly indicated.”

However, cutting down on antibiotic use may be especially difficult in cancer patients since they frequently suffer from infections. “An antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection may cause serious issues for a cancer patient, who likely already has a suppressed immune system,” according to a 2017 information sheet posted by the Cancer Treatment Centers of America. “Chemotherapy may cause neutropenia, a reduction of white blood cells that help fight infections and viruses. Radiation therapy may damage the skin and cause irritation and wounds. Immunotherapy or targeted therapy drugs may trigger side effects that may lead to infections. Incisions from surgery or to insert ports or catheters may be vulnerable to infections.”

The new study

For the new subgroup analysis, researchers analyzed data from the phase 3 TOPAZ-1 clinical trial, which was a double-blinded analysis of durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer. The previously reported main findings from the study were positive with a median overall survival of 12.8 months in the durvalumab arm versus 11.5 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.80; P = .021). These findings contributed to the Food and Drug Administration’s decision in 2022 to approve the treatment for use in locally advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancer.

Of 341 patients who received durvalumab treatment, 167 also took antibiotics. The median overall survival in the antibiotic and nonantibiotic groups were similar at 12.6 months (95% confidence interval, 9.7-14.8 months) and 13 months (95% CI, 10.8-14.7 months), respectively. Median progression-free survival was 7.3 months (95% CI, 6.5-7.7 months) and 7.2 months (95% CI, 5.9-7.4 months), respectively.

“The results support that advanced patients’ risk of death, and the risk that their cancer would grow, spread, or get worse, was not meaningfully different between patients who used antibiotics and those who did not use antibiotics at the same time as they were receiving durvalumab-based treatment,” Dr. He said. “The result is not surprising to me since it is not clear to me how and why antibiotics may affect the effectiveness of immunotherapy.”

Moving forward, she said, “additional studies are needed to further investigator the relationship between antibiotics use and effectiveness of immunotherapy. We need to understand why use of antibiotics during treatment with immunotherapy is correlated with poor outcomes in some circumstances but not in other circumstances.”

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

according to a new analysis of the landmark TOPAZ-1 clinical trial.

The findings, released at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium 2023, suggest that “people with advanced biliary tract cancer can safely be treated with antibiotics while still benefiting from treatment with durvalumab plus chemotherapy,” said lead author Aiwu Ruth He, MD, PhD, a gastrointestinal oncologist with MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington.

Antibiotic use during immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been associated with poorer outcomes. A review of 12 studies published in Frontiers in Oncology found that antibiotic use was associated with worse progression-free and overall survival.

“Patients with biliary tract cancer have the increased risk of biliary tract infection as the result of biliary tract obstruction, and they often receive antibiotics,” Dr. He said.

A 2020 report in eCancer suggested that antibiotics may disrupt gut bacteria and, as a result, interfere with the immune system’s responsiveness. “It has been a consensus that the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics should be avoided during the use of immunotherapy whenever possible,” the report authors wrote. “In addition, antibiotics should be prescribed only when properly indicated.”

However, cutting down on antibiotic use may be especially difficult in cancer patients since they frequently suffer from infections. “An antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection may cause serious issues for a cancer patient, who likely already has a suppressed immune system,” according to a 2017 information sheet posted by the Cancer Treatment Centers of America. “Chemotherapy may cause neutropenia, a reduction of white blood cells that help fight infections and viruses. Radiation therapy may damage the skin and cause irritation and wounds. Immunotherapy or targeted therapy drugs may trigger side effects that may lead to infections. Incisions from surgery or to insert ports or catheters may be vulnerable to infections.”

The new study

For the new subgroup analysis, researchers analyzed data from the phase 3 TOPAZ-1 clinical trial, which was a double-blinded analysis of durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer. The previously reported main findings from the study were positive with a median overall survival of 12.8 months in the durvalumab arm versus 11.5 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio, 0.80; P = .021). These findings contributed to the Food and Drug Administration’s decision in 2022 to approve the treatment for use in locally advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancer.

Of 341 patients who received durvalumab treatment, 167 also took antibiotics. The median overall survival in the antibiotic and nonantibiotic groups were similar at 12.6 months (95% confidence interval, 9.7-14.8 months) and 13 months (95% CI, 10.8-14.7 months), respectively. Median progression-free survival was 7.3 months (95% CI, 6.5-7.7 months) and 7.2 months (95% CI, 5.9-7.4 months), respectively.

“The results support that advanced patients’ risk of death, and the risk that their cancer would grow, spread, or get worse, was not meaningfully different between patients who used antibiotics and those who did not use antibiotics at the same time as they were receiving durvalumab-based treatment,” Dr. He said. “The result is not surprising to me since it is not clear to me how and why antibiotics may affect the effectiveness of immunotherapy.”

Moving forward, she said, “additional studies are needed to further investigator the relationship between antibiotics use and effectiveness of immunotherapy. We need to understand why use of antibiotics during treatment with immunotherapy is correlated with poor outcomes in some circumstances but not in other circumstances.”

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

FROM ASCO GI 2023

Race and geography tied to breast cancer care delays

suggesting the need to target high-risk geographic regions and patient groups to ensure timely care, new research suggests.

Among nearly 33,000 women from North Carolina with stage I-III breast cancer, Black patients were nearly twice as likely has non-Black patients to experience treatment delays of more than 60 days, researchers found.

“Our findings suggest that treatment delays are alarmingly common in patients at high risk for breast cancer death, including young Black women and patients with stage III disease,” the authors note in their article, which was published online in Cancer.

Research shows that breast cancer treatment delays of 30-60 days can lower survival, and Black patients face a “disproportionate risk of treatment delays across the breast cancer care delivery spectrum,” the authors explain.

However, studies exploring whether or how racial disparities in treatment delays relate to geography are more limited.

In the current analysis, researchers amassed a retrospective cohort of all patients with stage I-III breast cancer between 2004 and 2015 in the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry and explored the risk of treatment delay by race and geographic subregion.

The cohort included 32,626 women, 6,190 (19.0%) of whom were Black. Counties were divided into the nine Area Health Education Center regions for North Carolina.

Compared with non‐Black patients, Black patients were more likely to have stage III disease (15.2% vs. 9.3%), hormone receptor–negative tumors (29.3% vs. 15.6%), Medicaid insurance (46.7% vs. 14.9%), and to live within 5 miles of their treatment site (30.6% vs. 25.2%).

Overall, Black patients were almost two times more likely to experience a treatment delay of more than 60 days (15% vs. 8%).

On average, about one in seven Black women experienced a lengthy delay, but the risk varied depending on geographic location. Patients living in certain regions of the state were more likely to experience delays; those in the highest-risk region were about twice as likely to experience a delay as those in the lowest-risk region (relative risk, 2.1 among Black patients; and RR, 1.9 among non-Black patients).

The magnitude of the racial gap in treatment delay varied by region – from 0% to 9.4%. But overall, of patients who experienced treatment delays, a significantly greater proportion were Black patients in every region except region 2, where only 2.7% (93 of 3,362) of patients were Black.

Notably, two regions with the greatest disparities in treatment delay, as well as the highest absolute risk of treatment delay for Black patients, surround large cities.

“These delays weren’t explained by the patients’ distance from cancer treatment facilities, their specific stage of cancer or type of treatment, or what insurance they had,” lead author Katherine Reeder-Hayes, MD, with the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, Chapel Hill, said in a news release.

Instead, Dr. Reeder-Hayes said, the findings suggest that the structure of local health care systems, rather than patient characteristics, may better explain why some patients experience treatment delays.

In other words, “if cancer care teams in certain areas say, ‘Oh, it’s particularly hard to treat breast cancer in our area because people are poor or have really advanced stages of cancer when they come in,’ our research does not bear out that explanation,” Dr. Reeder-Hayes said in email to this news organization.

This study “highlights the persistent disparities in treatment delays Black women encounter, which often lead to worse outcomes,” said Kathie-Ann Joseph, MD, MPH, who was not involved in the research.

“Interestingly, the authors could not attribute these delays in treatment to patient-level factors,” said Dr. Joseph, a breast cancer surgeon at NYU Langone Perlmutter Cancer Center, New York. But the authors “did find substantial geographic variation, which suggests the need to address structural barriers contributing to treatment delays in Black women.”

Sara P. Cate, MD, who was not involved with the research, also noted that the study highlights a known issue – “that racial minorities have longer delays in cancer treatment.” And notably, she said, the findings reveal that this disparity persists in areas where access to care is better and more robust.

“The nuances of the delays to care are multifactorial,” said Dr. Cate, a breast cancer surgeon and director of the Breast Surgery Quality Program at Mount Sinai in New York. “We need to do better with this population, and it is a multilevel solution of financial assistance, social work, and patient navigation.”

The study was supported in part by grants from the Susan G. Komen Foundation and the NC State Employees’ Credit Union. Dr. Reeder-Hayes, Dr. Cate, and Dr. Joseph have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

suggesting the need to target high-risk geographic regions and patient groups to ensure timely care, new research suggests.

Among nearly 33,000 women from North Carolina with stage I-III breast cancer, Black patients were nearly twice as likely has non-Black patients to experience treatment delays of more than 60 days, researchers found.

“Our findings suggest that treatment delays are alarmingly common in patients at high risk for breast cancer death, including young Black women and patients with stage III disease,” the authors note in their article, which was published online in Cancer.

Research shows that breast cancer treatment delays of 30-60 days can lower survival, and Black patients face a “disproportionate risk of treatment delays across the breast cancer care delivery spectrum,” the authors explain.

However, studies exploring whether or how racial disparities in treatment delays relate to geography are more limited.

In the current analysis, researchers amassed a retrospective cohort of all patients with stage I-III breast cancer between 2004 and 2015 in the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry and explored the risk of treatment delay by race and geographic subregion.

The cohort included 32,626 women, 6,190 (19.0%) of whom were Black. Counties were divided into the nine Area Health Education Center regions for North Carolina.

Compared with non‐Black patients, Black patients were more likely to have stage III disease (15.2% vs. 9.3%), hormone receptor–negative tumors (29.3% vs. 15.6%), Medicaid insurance (46.7% vs. 14.9%), and to live within 5 miles of their treatment site (30.6% vs. 25.2%).

Overall, Black patients were almost two times more likely to experience a treatment delay of more than 60 days (15% vs. 8%).

On average, about one in seven Black women experienced a lengthy delay, but the risk varied depending on geographic location. Patients living in certain regions of the state were more likely to experience delays; those in the highest-risk region were about twice as likely to experience a delay as those in the lowest-risk region (relative risk, 2.1 among Black patients; and RR, 1.9 among non-Black patients).