User login

Erythematous Papules on the Ears

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

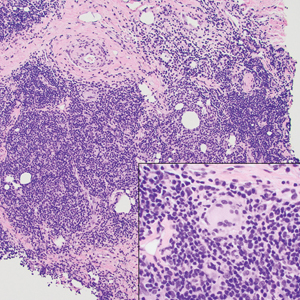

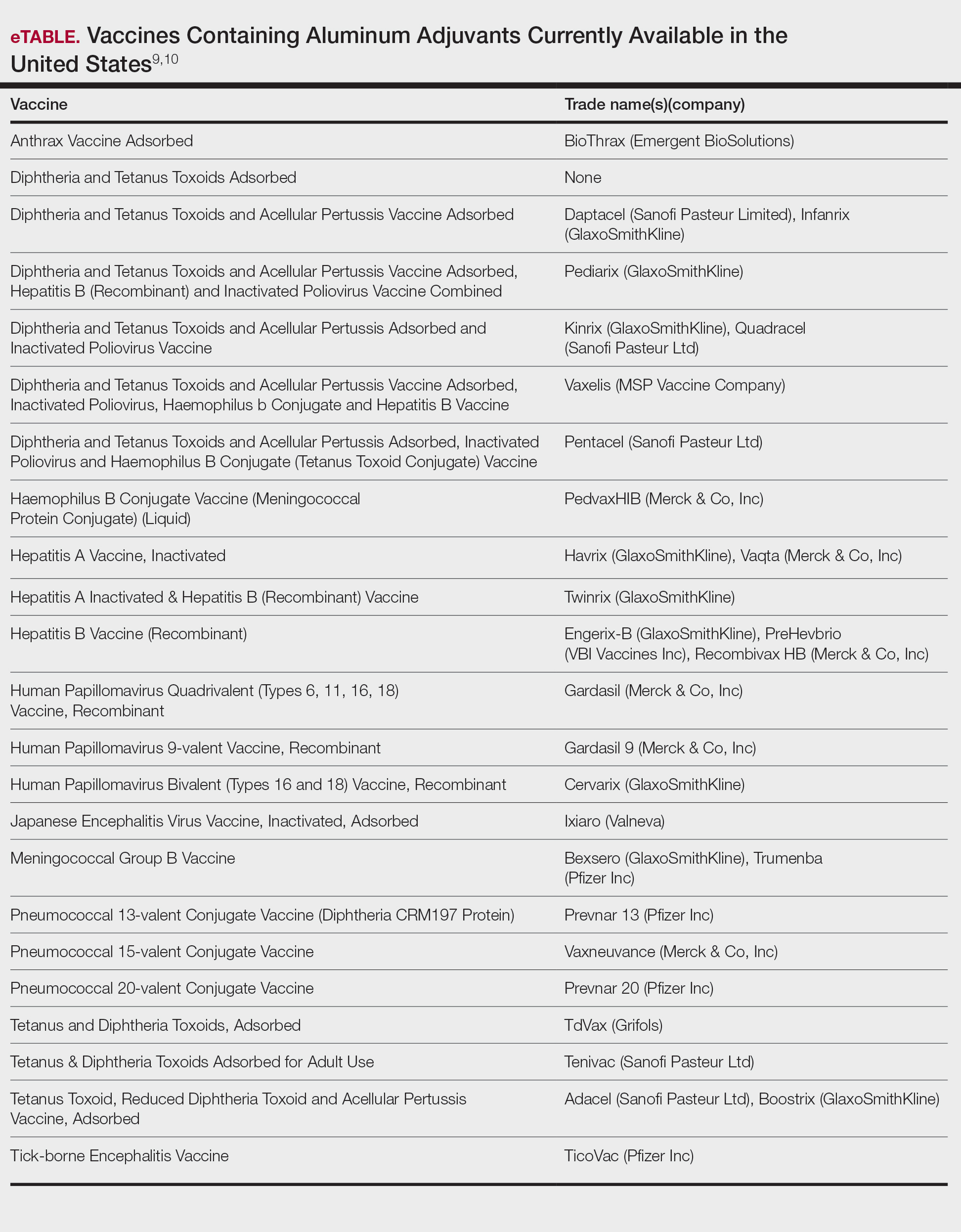

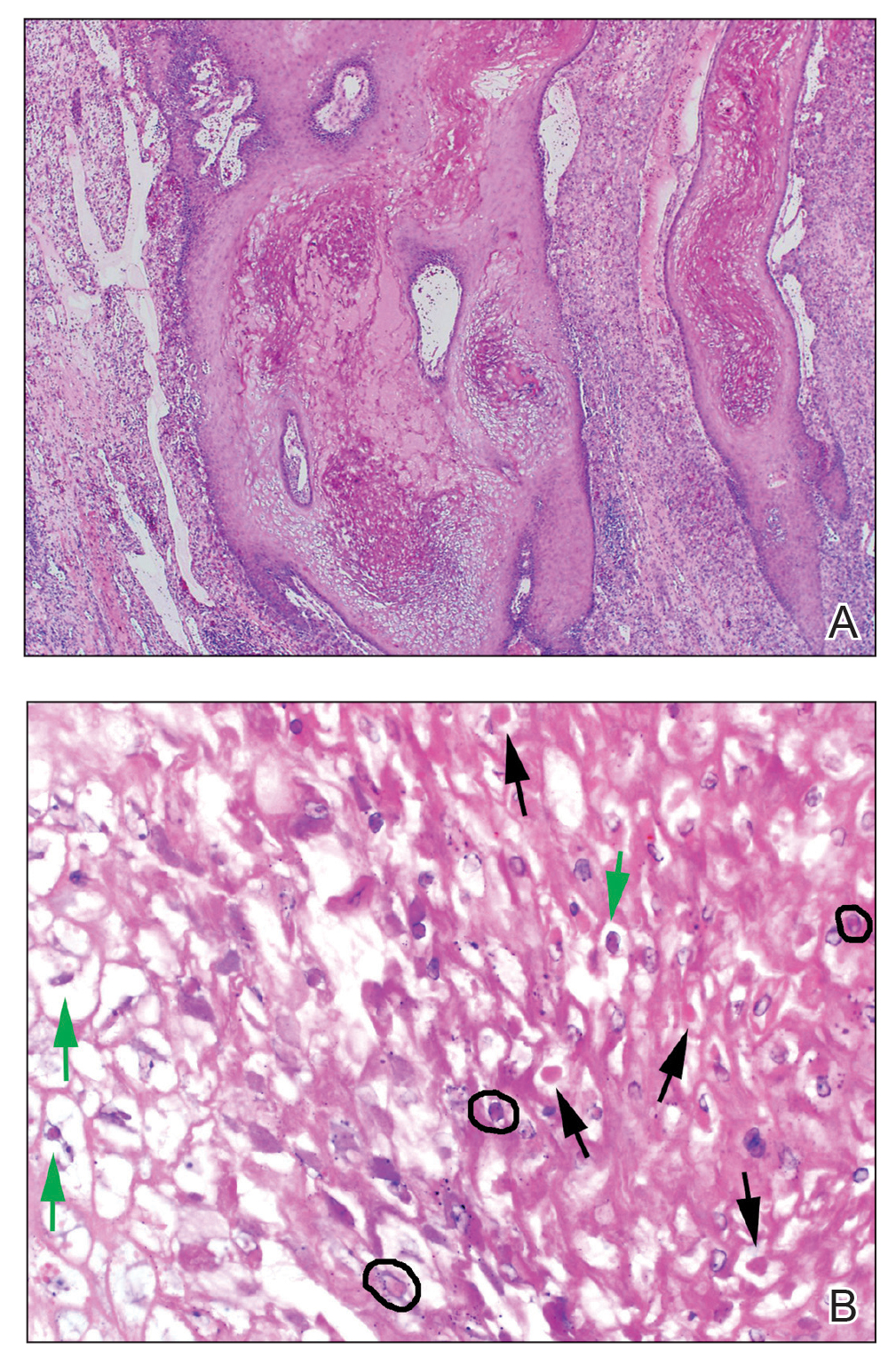

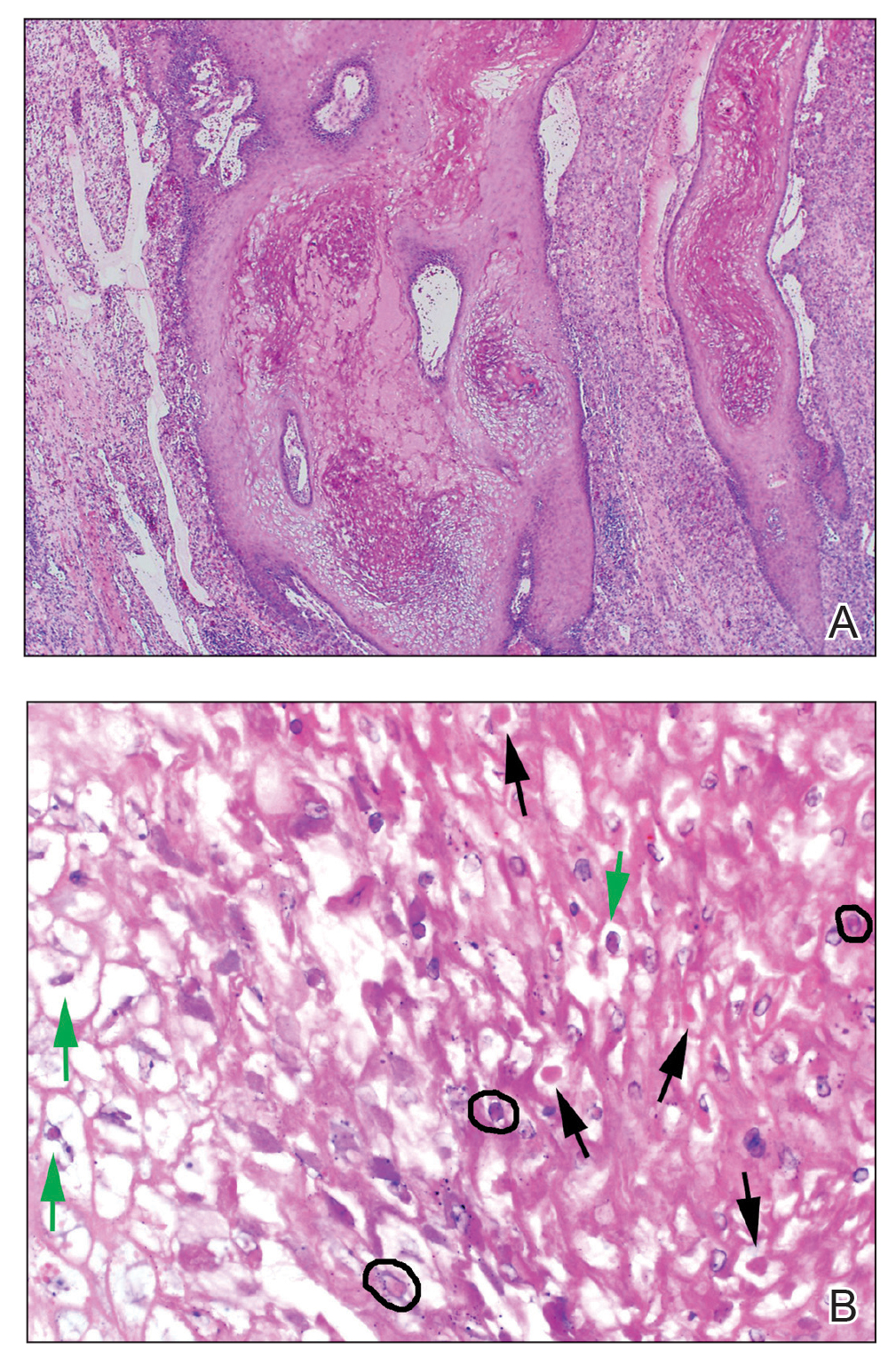

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

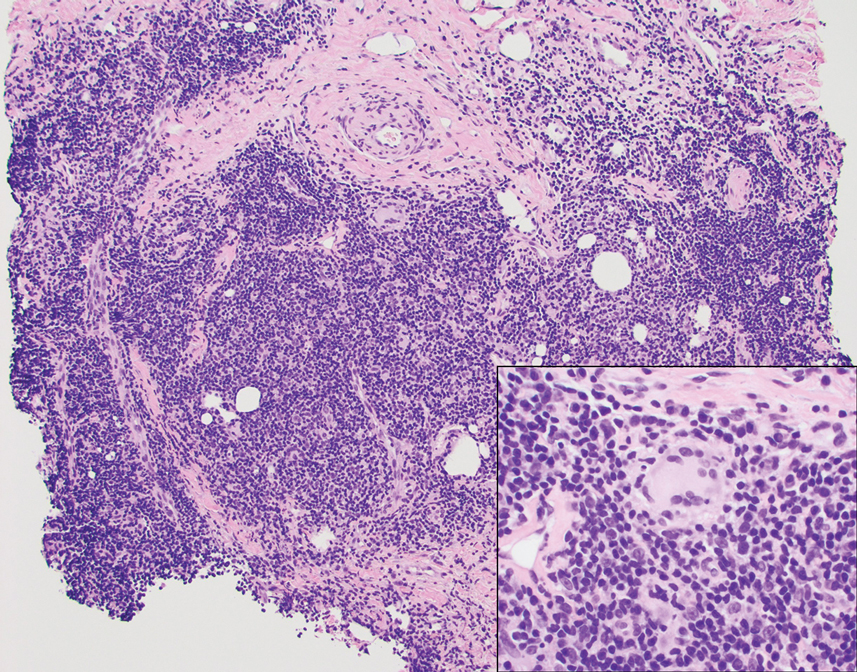

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

A 53-year-old man with a history of atopic dermatitis presented with pain and redness of the lobules of both ears of 9 months’ duration. He had no known allergies and took no medications. He lived in suburban Virginia and had not recently traveled outside of the region. Physical examination revealed tender erythematous and edematous nodules on the lobules of both ears (top). There was no evidence of arthritis or neurologic deficits. A punch biopsy was performed (bottom).

If nuclear disaster strikes, U.S. hematologists stand ready

For many Americans – especially those too young to know much about the Cold War or Hiroshima – Russia’s invasion of Ukraine might mark the first time they’ve truly considered the dangers of nuclear weapons. But dozens of hematologists in the United States already know the drill and have placed themselves on the front lines. These physicians stand prepared to treat patients exposed to radiation caused by nuclear accidents or attacks on U.S. soil.

They work nationwide at 74 medical centers that make up the Radiation Injury Treatment Network, ready to manage cases of acute radiation syndrome (ARS) during disasters. While RITN keeps a low profile, it’s been in the news lately amid anxieties about the Ukraine conflict, nuclear plant accidents, and the potential launching of nuclear weapons by foreign adversaries.

“The Radiation Injury Treatment Network helps plan responses for disaster scenarios where a person’s cells would be damaged after having been exposed to ionizing radiation,” program director Cullen Case Jr., MPA, said in an interview.

A U.S. Army veteran who took part in hurricane response early in his career, Mr. Case now oversees preparedness activities among all RITN hospitals, blood donor centers, and cord blood banks, in readiness for a mass casualty radiological incident. He also serves as a senior manager of the National Marrow Donor Program/Be a Match Marrow Registry.

Intense preparation for nuclear attacks or accidents is necessary, Mr. Case said, despite the doomsday scenarios disseminated on television shows and movies.

“The most frequent misconception we hear is that a nuclear disaster will encompass the whole world and be so complete that preparedness isn’t useful. However, many planning scenarios include smaller-scale incidents where survivors will need prompt and expert care,” he said.

In the wake of 9/11, the National Marrow Donor Program and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation established the RITN in 2006, with a mission to prepare for nuclear disaster and help manage the response if one occurs.

“The widespread availability of radioactive material has made future exposure events, accidental or intentional, nearly inevitable,” RITN leaders warned in a 2008 report. “Hematologists, oncologists, and HSCT [hematopoietic stem cell transplantation] physicians are uniquely suited to care for victims of radiation exposure, creating a collective responsibility to prepare for a variety of contingencies.”

RITN doesn’t just train physicians, Mr. Case noted. All medical centers within the RITN are required to conduct an annual tabletop exercise where a radiation disaster scenario and a set of discussion questions are presented to the team.

Hematologists specially equipped to treat radiation injuries

Why are hematologists involved in treating people exposed to dangerously high levels of radiation? The answer has to do with how radiation harms the body, said Dr. Ann A. Jakubowski, a hematologist/oncologist and transplant physician at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, who serves as a medical director for RITN.

“One of the most common toxicities from radiation exposure and a major player in acute radiation syndrome is hematologic toxicity– damage to the bone marrow by the radiation, with a resultant decrease in peripheral blood counts,” she said in an interview. “This is similar to what is often seen in the treatment of cancers with radiation and/or chemotherapy.”

In cases of severe and nonreversible radiation damage to the bone marrow, Dr. Jakubowski noted, “patients can be considered for a stem cell transplant to provide new healthy cells to repopulate the bone marrow, which provides recovery of peripheral blood counts. Hematologist/oncologists are the physicians who manage stem cell transplants.”

The crucial role of hematologists in radiation injuries is not new. In fact, these physicians have been closely intertwined with nuclear research since the dawn of the atomic age. The work of developing atomic bombs also led investigators to an understanding of the structure and processes of hematopoiesis and helped them to identify hematopoietic stem cells and prove their existence in humans.

Disaster response poses multiple challenges

As noted in a recent article in ASH Clinical News, the challenges of treating radiation injuries would be intense, especially in the event of a nuclear accident or attack that affects a wide area. For starters, how quickly can medical professionals be mobilized, and will there be enough physicians comfortable treating patients? Fortunately, irradiated patients should not pose a direct risk to medical professionals who treat them.

“The expectation is that the patients will all be decontaminated,” said Nelson Chao, MD, MBA, one of the founders of RITN and a hematologist/oncologist and transplant physician at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Dr. Jakubowski questions whether there will be adequate resources to handle the influx of patients who need more intensive treatment, as well as outpatients who “received lower doses of radiation and may experience a period of low blood counts but are expected to eventually recover blood counts.”

And if many people are injured, Dr. Chao asks, how will physicians “adopt altered standards of care to treat large numbers of patients?”

There will also be a need for physicians who aren’t hematologists, Dr. Jakubowski said. “There may be many victims who have both radiation exposure and traumatic or burn injuries, which need to be addressed first, before the hematologist can start addressing the consequences of ARS. Traumatic and burn injuries will require surgical resources.”

In addition, ARS affects the gastrointestinal track and central nervous system/cardiovascular, and it has multiple stages, she noted.

“Although we have methods of supporting the hematopoietic system – transfusions and growth factors – and even replacing it with a stem cell transplant, this will not necessarily fix the badly damaged other organs, Dr. Jakubowski said. “Also, not all radioactive isotopes are equal in their effects, nor are the various types of radiation exposure.”

Training goes beyond transplants and drugs

RITN offers individual hematologists specialized education about treating radiation injuries through annual exercises, modules, and “just-in-time” training.

For example, the RITN webpage devoted to triage includes guidelines for transferring radiation injury patients, triage guidelines for cytokine administration in cases of ARS, an exposure and symptom triage tool, and more. The treatment page includes details about subjects such as when human leukocyte antigen typing of casualties is appropriate and how to keep yourself safe while treating patients.

Another focus is teaching hematologists to react quickly in disasters, Mr. Case said. “The vast majority of hematologists have little to no experience in responding to disasters and making decisions with imperfect or incomplete information, as emergency medicine practitioners must do regularly.”

“Some of the RITN tabletop exercises present physicians and advanced practitioners with an incomplete set of patient information and ask physicians to then determine and prioritize their care,” Mr. Case said. “The resulting discussions help to lay the groundwork for being able to shift to the crisis standards of care mindset that would be necessary during a radiological disaster.”

Here’s how hematologists can get involved

If you want to help improve the nation’s response to radiation injuries, Mr. Case suggests checking RITN’s list of participating hospitals. If your facility is already part of this network, he said, contact its bone marrow transplant unit for more information.

In such cases, Dr. Jakubowski suggests that you “consider periodically giving a presentation to staff on the basics of radiation injury and the center’s role in RITN.” And if you’re not part of RITN, she said, consider contacting the network about becoming a member.

Hematologists, Mr. Case said, can also take advantage of RITN’s free short overview courses, review the RITN Treatment Guidelines, or watch short videos on the RITN’s YouTube channel.

He highlighted the Radiation Emergency Medical Management website administered by the Department of Health & Human Services, the Center for Disease Control’s radiation emergencies webpage, and the Department of Energy’s Radiation Emergency Assistance Center/Training Site.

For many Americans – especially those too young to know much about the Cold War or Hiroshima – Russia’s invasion of Ukraine might mark the first time they’ve truly considered the dangers of nuclear weapons. But dozens of hematologists in the United States already know the drill and have placed themselves on the front lines. These physicians stand prepared to treat patients exposed to radiation caused by nuclear accidents or attacks on U.S. soil.

They work nationwide at 74 medical centers that make up the Radiation Injury Treatment Network, ready to manage cases of acute radiation syndrome (ARS) during disasters. While RITN keeps a low profile, it’s been in the news lately amid anxieties about the Ukraine conflict, nuclear plant accidents, and the potential launching of nuclear weapons by foreign adversaries.

“The Radiation Injury Treatment Network helps plan responses for disaster scenarios where a person’s cells would be damaged after having been exposed to ionizing radiation,” program director Cullen Case Jr., MPA, said in an interview.

A U.S. Army veteran who took part in hurricane response early in his career, Mr. Case now oversees preparedness activities among all RITN hospitals, blood donor centers, and cord blood banks, in readiness for a mass casualty radiological incident. He also serves as a senior manager of the National Marrow Donor Program/Be a Match Marrow Registry.

Intense preparation for nuclear attacks or accidents is necessary, Mr. Case said, despite the doomsday scenarios disseminated on television shows and movies.

“The most frequent misconception we hear is that a nuclear disaster will encompass the whole world and be so complete that preparedness isn’t useful. However, many planning scenarios include smaller-scale incidents where survivors will need prompt and expert care,” he said.

In the wake of 9/11, the National Marrow Donor Program and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation established the RITN in 2006, with a mission to prepare for nuclear disaster and help manage the response if one occurs.

“The widespread availability of radioactive material has made future exposure events, accidental or intentional, nearly inevitable,” RITN leaders warned in a 2008 report. “Hematologists, oncologists, and HSCT [hematopoietic stem cell transplantation] physicians are uniquely suited to care for victims of radiation exposure, creating a collective responsibility to prepare for a variety of contingencies.”

RITN doesn’t just train physicians, Mr. Case noted. All medical centers within the RITN are required to conduct an annual tabletop exercise where a radiation disaster scenario and a set of discussion questions are presented to the team.

Hematologists specially equipped to treat radiation injuries

Why are hematologists involved in treating people exposed to dangerously high levels of radiation? The answer has to do with how radiation harms the body, said Dr. Ann A. Jakubowski, a hematologist/oncologist and transplant physician at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, who serves as a medical director for RITN.

“One of the most common toxicities from radiation exposure and a major player in acute radiation syndrome is hematologic toxicity– damage to the bone marrow by the radiation, with a resultant decrease in peripheral blood counts,” she said in an interview. “This is similar to what is often seen in the treatment of cancers with radiation and/or chemotherapy.”

In cases of severe and nonreversible radiation damage to the bone marrow, Dr. Jakubowski noted, “patients can be considered for a stem cell transplant to provide new healthy cells to repopulate the bone marrow, which provides recovery of peripheral blood counts. Hematologist/oncologists are the physicians who manage stem cell transplants.”

The crucial role of hematologists in radiation injuries is not new. In fact, these physicians have been closely intertwined with nuclear research since the dawn of the atomic age. The work of developing atomic bombs also led investigators to an understanding of the structure and processes of hematopoiesis and helped them to identify hematopoietic stem cells and prove their existence in humans.

Disaster response poses multiple challenges

As noted in a recent article in ASH Clinical News, the challenges of treating radiation injuries would be intense, especially in the event of a nuclear accident or attack that affects a wide area. For starters, how quickly can medical professionals be mobilized, and will there be enough physicians comfortable treating patients? Fortunately, irradiated patients should not pose a direct risk to medical professionals who treat them.

“The expectation is that the patients will all be decontaminated,” said Nelson Chao, MD, MBA, one of the founders of RITN and a hematologist/oncologist and transplant physician at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Dr. Jakubowski questions whether there will be adequate resources to handle the influx of patients who need more intensive treatment, as well as outpatients who “received lower doses of radiation and may experience a period of low blood counts but are expected to eventually recover blood counts.”

And if many people are injured, Dr. Chao asks, how will physicians “adopt altered standards of care to treat large numbers of patients?”

There will also be a need for physicians who aren’t hematologists, Dr. Jakubowski said. “There may be many victims who have both radiation exposure and traumatic or burn injuries, which need to be addressed first, before the hematologist can start addressing the consequences of ARS. Traumatic and burn injuries will require surgical resources.”

In addition, ARS affects the gastrointestinal track and central nervous system/cardiovascular, and it has multiple stages, she noted.

“Although we have methods of supporting the hematopoietic system – transfusions and growth factors – and even replacing it with a stem cell transplant, this will not necessarily fix the badly damaged other organs, Dr. Jakubowski said. “Also, not all radioactive isotopes are equal in their effects, nor are the various types of radiation exposure.”

Training goes beyond transplants and drugs

RITN offers individual hematologists specialized education about treating radiation injuries through annual exercises, modules, and “just-in-time” training.

For example, the RITN webpage devoted to triage includes guidelines for transferring radiation injury patients, triage guidelines for cytokine administration in cases of ARS, an exposure and symptom triage tool, and more. The treatment page includes details about subjects such as when human leukocyte antigen typing of casualties is appropriate and how to keep yourself safe while treating patients.

Another focus is teaching hematologists to react quickly in disasters, Mr. Case said. “The vast majority of hematologists have little to no experience in responding to disasters and making decisions with imperfect or incomplete information, as emergency medicine practitioners must do regularly.”

“Some of the RITN tabletop exercises present physicians and advanced practitioners with an incomplete set of patient information and ask physicians to then determine and prioritize their care,” Mr. Case said. “The resulting discussions help to lay the groundwork for being able to shift to the crisis standards of care mindset that would be necessary during a radiological disaster.”

Here’s how hematologists can get involved

If you want to help improve the nation’s response to radiation injuries, Mr. Case suggests checking RITN’s list of participating hospitals. If your facility is already part of this network, he said, contact its bone marrow transplant unit for more information.

In such cases, Dr. Jakubowski suggests that you “consider periodically giving a presentation to staff on the basics of radiation injury and the center’s role in RITN.” And if you’re not part of RITN, she said, consider contacting the network about becoming a member.

Hematologists, Mr. Case said, can also take advantage of RITN’s free short overview courses, review the RITN Treatment Guidelines, or watch short videos on the RITN’s YouTube channel.

He highlighted the Radiation Emergency Medical Management website administered by the Department of Health & Human Services, the Center for Disease Control’s radiation emergencies webpage, and the Department of Energy’s Radiation Emergency Assistance Center/Training Site.

For many Americans – especially those too young to know much about the Cold War or Hiroshima – Russia’s invasion of Ukraine might mark the first time they’ve truly considered the dangers of nuclear weapons. But dozens of hematologists in the United States already know the drill and have placed themselves on the front lines. These physicians stand prepared to treat patients exposed to radiation caused by nuclear accidents or attacks on U.S. soil.

They work nationwide at 74 medical centers that make up the Radiation Injury Treatment Network, ready to manage cases of acute radiation syndrome (ARS) during disasters. While RITN keeps a low profile, it’s been in the news lately amid anxieties about the Ukraine conflict, nuclear plant accidents, and the potential launching of nuclear weapons by foreign adversaries.

“The Radiation Injury Treatment Network helps plan responses for disaster scenarios where a person’s cells would be damaged after having been exposed to ionizing radiation,” program director Cullen Case Jr., MPA, said in an interview.

A U.S. Army veteran who took part in hurricane response early in his career, Mr. Case now oversees preparedness activities among all RITN hospitals, blood donor centers, and cord blood banks, in readiness for a mass casualty radiological incident. He also serves as a senior manager of the National Marrow Donor Program/Be a Match Marrow Registry.

Intense preparation for nuclear attacks or accidents is necessary, Mr. Case said, despite the doomsday scenarios disseminated on television shows and movies.

“The most frequent misconception we hear is that a nuclear disaster will encompass the whole world and be so complete that preparedness isn’t useful. However, many planning scenarios include smaller-scale incidents where survivors will need prompt and expert care,” he said.

In the wake of 9/11, the National Marrow Donor Program and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation established the RITN in 2006, with a mission to prepare for nuclear disaster and help manage the response if one occurs.

“The widespread availability of radioactive material has made future exposure events, accidental or intentional, nearly inevitable,” RITN leaders warned in a 2008 report. “Hematologists, oncologists, and HSCT [hematopoietic stem cell transplantation] physicians are uniquely suited to care for victims of radiation exposure, creating a collective responsibility to prepare for a variety of contingencies.”

RITN doesn’t just train physicians, Mr. Case noted. All medical centers within the RITN are required to conduct an annual tabletop exercise where a radiation disaster scenario and a set of discussion questions are presented to the team.

Hematologists specially equipped to treat radiation injuries

Why are hematologists involved in treating people exposed to dangerously high levels of radiation? The answer has to do with how radiation harms the body, said Dr. Ann A. Jakubowski, a hematologist/oncologist and transplant physician at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, who serves as a medical director for RITN.

“One of the most common toxicities from radiation exposure and a major player in acute radiation syndrome is hematologic toxicity– damage to the bone marrow by the radiation, with a resultant decrease in peripheral blood counts,” she said in an interview. “This is similar to what is often seen in the treatment of cancers with radiation and/or chemotherapy.”

In cases of severe and nonreversible radiation damage to the bone marrow, Dr. Jakubowski noted, “patients can be considered for a stem cell transplant to provide new healthy cells to repopulate the bone marrow, which provides recovery of peripheral blood counts. Hematologist/oncologists are the physicians who manage stem cell transplants.”

The crucial role of hematologists in radiation injuries is not new. In fact, these physicians have been closely intertwined with nuclear research since the dawn of the atomic age. The work of developing atomic bombs also led investigators to an understanding of the structure and processes of hematopoiesis and helped them to identify hematopoietic stem cells and prove their existence in humans.

Disaster response poses multiple challenges

As noted in a recent article in ASH Clinical News, the challenges of treating radiation injuries would be intense, especially in the event of a nuclear accident or attack that affects a wide area. For starters, how quickly can medical professionals be mobilized, and will there be enough physicians comfortable treating patients? Fortunately, irradiated patients should not pose a direct risk to medical professionals who treat them.

“The expectation is that the patients will all be decontaminated,” said Nelson Chao, MD, MBA, one of the founders of RITN and a hematologist/oncologist and transplant physician at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Dr. Jakubowski questions whether there will be adequate resources to handle the influx of patients who need more intensive treatment, as well as outpatients who “received lower doses of radiation and may experience a period of low blood counts but are expected to eventually recover blood counts.”

And if many people are injured, Dr. Chao asks, how will physicians “adopt altered standards of care to treat large numbers of patients?”

There will also be a need for physicians who aren’t hematologists, Dr. Jakubowski said. “There may be many victims who have both radiation exposure and traumatic or burn injuries, which need to be addressed first, before the hematologist can start addressing the consequences of ARS. Traumatic and burn injuries will require surgical resources.”

In addition, ARS affects the gastrointestinal track and central nervous system/cardiovascular, and it has multiple stages, she noted.

“Although we have methods of supporting the hematopoietic system – transfusions and growth factors – and even replacing it with a stem cell transplant, this will not necessarily fix the badly damaged other organs, Dr. Jakubowski said. “Also, not all radioactive isotopes are equal in their effects, nor are the various types of radiation exposure.”

Training goes beyond transplants and drugs

RITN offers individual hematologists specialized education about treating radiation injuries through annual exercises, modules, and “just-in-time” training.

For example, the RITN webpage devoted to triage includes guidelines for transferring radiation injury patients, triage guidelines for cytokine administration in cases of ARS, an exposure and symptom triage tool, and more. The treatment page includes details about subjects such as when human leukocyte antigen typing of casualties is appropriate and how to keep yourself safe while treating patients.

Another focus is teaching hematologists to react quickly in disasters, Mr. Case said. “The vast majority of hematologists have little to no experience in responding to disasters and making decisions with imperfect or incomplete information, as emergency medicine practitioners must do regularly.”

“Some of the RITN tabletop exercises present physicians and advanced practitioners with an incomplete set of patient information and ask physicians to then determine and prioritize their care,” Mr. Case said. “The resulting discussions help to lay the groundwork for being able to shift to the crisis standards of care mindset that would be necessary during a radiological disaster.”

Here’s how hematologists can get involved

If you want to help improve the nation’s response to radiation injuries, Mr. Case suggests checking RITN’s list of participating hospitals. If your facility is already part of this network, he said, contact its bone marrow transplant unit for more information.

In such cases, Dr. Jakubowski suggests that you “consider periodically giving a presentation to staff on the basics of radiation injury and the center’s role in RITN.” And if you’re not part of RITN, she said, consider contacting the network about becoming a member.

Hematologists, Mr. Case said, can also take advantage of RITN’s free short overview courses, review the RITN Treatment Guidelines, or watch short videos on the RITN’s YouTube channel.

He highlighted the Radiation Emergency Medical Management website administered by the Department of Health & Human Services, the Center for Disease Control’s radiation emergencies webpage, and the Department of Energy’s Radiation Emergency Assistance Center/Training Site.

Chest Infections & Disaster Response Network

Disaster Response and Global Health Section

Physician response to Ukraine and beyond

Displaced persons, international refugee crises, gun violence, and other disasters remain prevalent in current news. Recent events highlight the need for continued civilian physician leadership and response to disasters.

Before the Ukraine crisis, the United Nations Refugee Agency estimated displaced persons more than doubled to greater than 82 million persons over the last decade (unhcr.org). Since that analysis, there have been over 6.5 million externally displaced persons, 7.5 million internally displaced persons, and significant numbers of injured patients from the Ukraine crisis alone. The Ukraine Ministry of Health has shown preparedness in its ability to handle significant patient surges with minimal assistance.

However, organizations like the Ukraine Medical Association of North America, Razom for Ukraine, Doctors Without Borders (MSF), MedGlobal, Samaritan’s Purse, Global Response Management, and many more have deployed to assist in Ukraine. These NGOs continue to help with medical care, fulfill critical supply needs, and provide training in cutting-edge medicine (POCUS, trauma updates).

Challenges posed by unstable environments, from wars to active shooter situations, further underscore the need for continued education, advances in technology, and preparedness. Providers responding to these events often treat vulnerable populations suffering from physical and mental violence, requiring physicians to step out of their comfort zone.

Physicians should continue to be leaders in the care of vulnerable displaced persons.

Christopher Miller, DO, MPH

Fellow-in-Training Member

Thomas Marston, MD

Member-at-Large

Disaster Response and Global Health Section

Physician response to Ukraine and beyond

Displaced persons, international refugee crises, gun violence, and other disasters remain prevalent in current news. Recent events highlight the need for continued civilian physician leadership and response to disasters.

Before the Ukraine crisis, the United Nations Refugee Agency estimated displaced persons more than doubled to greater than 82 million persons over the last decade (unhcr.org). Since that analysis, there have been over 6.5 million externally displaced persons, 7.5 million internally displaced persons, and significant numbers of injured patients from the Ukraine crisis alone. The Ukraine Ministry of Health has shown preparedness in its ability to handle significant patient surges with minimal assistance.

However, organizations like the Ukraine Medical Association of North America, Razom for Ukraine, Doctors Without Borders (MSF), MedGlobal, Samaritan’s Purse, Global Response Management, and many more have deployed to assist in Ukraine. These NGOs continue to help with medical care, fulfill critical supply needs, and provide training in cutting-edge medicine (POCUS, trauma updates).

Challenges posed by unstable environments, from wars to active shooter situations, further underscore the need for continued education, advances in technology, and preparedness. Providers responding to these events often treat vulnerable populations suffering from physical and mental violence, requiring physicians to step out of their comfort zone.

Physicians should continue to be leaders in the care of vulnerable displaced persons.

Christopher Miller, DO, MPH

Fellow-in-Training Member

Thomas Marston, MD

Member-at-Large

Disaster Response and Global Health Section

Physician response to Ukraine and beyond

Displaced persons, international refugee crises, gun violence, and other disasters remain prevalent in current news. Recent events highlight the need for continued civilian physician leadership and response to disasters.

Before the Ukraine crisis, the United Nations Refugee Agency estimated displaced persons more than doubled to greater than 82 million persons over the last decade (unhcr.org). Since that analysis, there have been over 6.5 million externally displaced persons, 7.5 million internally displaced persons, and significant numbers of injured patients from the Ukraine crisis alone. The Ukraine Ministry of Health has shown preparedness in its ability to handle significant patient surges with minimal assistance.

However, organizations like the Ukraine Medical Association of North America, Razom for Ukraine, Doctors Without Borders (MSF), MedGlobal, Samaritan’s Purse, Global Response Management, and many more have deployed to assist in Ukraine. These NGOs continue to help with medical care, fulfill critical supply needs, and provide training in cutting-edge medicine (POCUS, trauma updates).

Challenges posed by unstable environments, from wars to active shooter situations, further underscore the need for continued education, advances in technology, and preparedness. Providers responding to these events often treat vulnerable populations suffering from physical and mental violence, requiring physicians to step out of their comfort zone.

Physicians should continue to be leaders in the care of vulnerable displaced persons.

Christopher Miller, DO, MPH

Fellow-in-Training Member

Thomas Marston, MD

Member-at-Large

Early childhood allergies linked with ADHD and ASD

, according to a large retrospective study.

“Our study provides strong evidence for the association between allergic disorders in early childhood and the development of ADHD,” Shay Nemet, MD, of the Kaplan Medical Center, Rehovot, Israel, and colleagues write in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. “The risk of those children to develop ASD was less significant.”

The researchers analyzed data from 117,022 consecutive children diagnosed with at least one allergic disorder – asthma, conjunctivitis, rhinitis, and drug, food, or skin allergy – and 116,968 children without allergies in the Clalit Health Services pediatric database. The children had been treated from 2000 to 2018; the mean follow-up period was 11 years.

The children who were diagnosed with one or more allergies (mean age, 4.5 years) were significantly more likely to develop ADHD (odds ratio, 2.45; 95% confidence interval, 2.39-2.51), ASD (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.08-1.27), or both ADHD and ASD (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.35-1.79) than were the control children who did not have allergies.

Children diagnosed with rhinitis (OR, 3.96; 95% CI, 3.80-4.12) and conjunctivitis (OR, 3.63; 95% CI, 3.53-3.74) were the most likely to develop ADHD.

Allergy correlation with ADHD and ASD

Cy B. Nadler, PhD, a clinical psychologist and the director of Autism Services at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Missouri, told this news organization that children and adults with neurodevelopmental differences are also more likely to have other health problems.

“Clinicians practicing in subspecialties such as allergy and immunology may have opportunities to help psychologists identify developmental and behavioral concerns early in childhood,” he added.

“Studies like this can’t be accomplished without large health care databases, but this approach has drawbacks, too,” Dr. Nadler said in an email. “Without more information about these patients’ co-occurring medical and behavioral conditions, we are almost certainly missing important contributors to the observed associations.”

Dr. Nadler, who was not involved in the study, noted that in the multivariable analysis that controlled for age at study entry, gender, and number of annual visits, the link between allergy and ASD diagnosis was not significant.

“It is important to remember not to interpret these study results as causal,” he added.

Desha M. Jordan, MD, FAAP, an assistant professor of pediatrics at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, called the study “an interesting new area that has been speculated about for some time” and “one of the first I have seen with statistically significant correlations found between ADHD, ASD, and allergic conditions.”

More questions for future studies

Health care providers need to understand the potential sequelae of allergic conditions so that they can manage their patients appropriately, she advised.

Although symptoms and diagnoses were confirmed for all patients, the study’s retrospective design and the possibility of recall bias were limitations, said Dr. Jordan in an email. She also was not involved in the study.

“For example, the family of a child diagnosed with ADHD or ASD may have been more mindful of anything out of the norm in that child’s past, while the family of a child without these conditions may not have recalled allergic symptoms as important,” she explained.

Another question that arises is whether some patients were treated and managed well while others were not and whether this disparity in care affected the development or severity of ADHD or ASD, she added.

“Is a patient with a well-controlled allergic condition less likely to develop ADHD or ASD than a patient with an uncontrolled allergic condition? Does a well-controlled patient ever return to the same probability of getting ADHD or ASD as a nonallergic patient?”

“While this study expands our understanding of these conditions and their interrelationships, it also brings up many additional questions and opens a new segment of research,” Dr. Jordan said. “More studies in this area are necessary to confirm the findings of this paper.”

The study was partially funded by the Israel Ambulatory Pediatric Association. The authors, Dr. Nadler, and Dr. Jordan report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a large retrospective study.

“Our study provides strong evidence for the association between allergic disorders in early childhood and the development of ADHD,” Shay Nemet, MD, of the Kaplan Medical Center, Rehovot, Israel, and colleagues write in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. “The risk of those children to develop ASD was less significant.”

The researchers analyzed data from 117,022 consecutive children diagnosed with at least one allergic disorder – asthma, conjunctivitis, rhinitis, and drug, food, or skin allergy – and 116,968 children without allergies in the Clalit Health Services pediatric database. The children had been treated from 2000 to 2018; the mean follow-up period was 11 years.

The children who were diagnosed with one or more allergies (mean age, 4.5 years) were significantly more likely to develop ADHD (odds ratio, 2.45; 95% confidence interval, 2.39-2.51), ASD (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.08-1.27), or both ADHD and ASD (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.35-1.79) than were the control children who did not have allergies.

Children diagnosed with rhinitis (OR, 3.96; 95% CI, 3.80-4.12) and conjunctivitis (OR, 3.63; 95% CI, 3.53-3.74) were the most likely to develop ADHD.

Allergy correlation with ADHD and ASD

Cy B. Nadler, PhD, a clinical psychologist and the director of Autism Services at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Missouri, told this news organization that children and adults with neurodevelopmental differences are also more likely to have other health problems.

“Clinicians practicing in subspecialties such as allergy and immunology may have opportunities to help psychologists identify developmental and behavioral concerns early in childhood,” he added.

“Studies like this can’t be accomplished without large health care databases, but this approach has drawbacks, too,” Dr. Nadler said in an email. “Without more information about these patients’ co-occurring medical and behavioral conditions, we are almost certainly missing important contributors to the observed associations.”

Dr. Nadler, who was not involved in the study, noted that in the multivariable analysis that controlled for age at study entry, gender, and number of annual visits, the link between allergy and ASD diagnosis was not significant.

“It is important to remember not to interpret these study results as causal,” he added.

Desha M. Jordan, MD, FAAP, an assistant professor of pediatrics at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, called the study “an interesting new area that has been speculated about for some time” and “one of the first I have seen with statistically significant correlations found between ADHD, ASD, and allergic conditions.”

More questions for future studies

Health care providers need to understand the potential sequelae of allergic conditions so that they can manage their patients appropriately, she advised.

Although symptoms and diagnoses were confirmed for all patients, the study’s retrospective design and the possibility of recall bias were limitations, said Dr. Jordan in an email. She also was not involved in the study.

“For example, the family of a child diagnosed with ADHD or ASD may have been more mindful of anything out of the norm in that child’s past, while the family of a child without these conditions may not have recalled allergic symptoms as important,” she explained.

Another question that arises is whether some patients were treated and managed well while others were not and whether this disparity in care affected the development or severity of ADHD or ASD, she added.

“Is a patient with a well-controlled allergic condition less likely to develop ADHD or ASD than a patient with an uncontrolled allergic condition? Does a well-controlled patient ever return to the same probability of getting ADHD or ASD as a nonallergic patient?”

“While this study expands our understanding of these conditions and their interrelationships, it also brings up many additional questions and opens a new segment of research,” Dr. Jordan said. “More studies in this area are necessary to confirm the findings of this paper.”

The study was partially funded by the Israel Ambulatory Pediatric Association. The authors, Dr. Nadler, and Dr. Jordan report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a large retrospective study.

“Our study provides strong evidence for the association between allergic disorders in early childhood and the development of ADHD,” Shay Nemet, MD, of the Kaplan Medical Center, Rehovot, Israel, and colleagues write in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. “The risk of those children to develop ASD was less significant.”

The researchers analyzed data from 117,022 consecutive children diagnosed with at least one allergic disorder – asthma, conjunctivitis, rhinitis, and drug, food, or skin allergy – and 116,968 children without allergies in the Clalit Health Services pediatric database. The children had been treated from 2000 to 2018; the mean follow-up period was 11 years.

The children who were diagnosed with one or more allergies (mean age, 4.5 years) were significantly more likely to develop ADHD (odds ratio, 2.45; 95% confidence interval, 2.39-2.51), ASD (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.08-1.27), or both ADHD and ASD (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.35-1.79) than were the control children who did not have allergies.

Children diagnosed with rhinitis (OR, 3.96; 95% CI, 3.80-4.12) and conjunctivitis (OR, 3.63; 95% CI, 3.53-3.74) were the most likely to develop ADHD.

Allergy correlation with ADHD and ASD

Cy B. Nadler, PhD, a clinical psychologist and the director of Autism Services at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Missouri, told this news organization that children and adults with neurodevelopmental differences are also more likely to have other health problems.

“Clinicians practicing in subspecialties such as allergy and immunology may have opportunities to help psychologists identify developmental and behavioral concerns early in childhood,” he added.

“Studies like this can’t be accomplished without large health care databases, but this approach has drawbacks, too,” Dr. Nadler said in an email. “Without more information about these patients’ co-occurring medical and behavioral conditions, we are almost certainly missing important contributors to the observed associations.”

Dr. Nadler, who was not involved in the study, noted that in the multivariable analysis that controlled for age at study entry, gender, and number of annual visits, the link between allergy and ASD diagnosis was not significant.

“It is important to remember not to interpret these study results as causal,” he added.

Desha M. Jordan, MD, FAAP, an assistant professor of pediatrics at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, called the study “an interesting new area that has been speculated about for some time” and “one of the first I have seen with statistically significant correlations found between ADHD, ASD, and allergic conditions.”

More questions for future studies

Health care providers need to understand the potential sequelae of allergic conditions so that they can manage their patients appropriately, she advised.

Although symptoms and diagnoses were confirmed for all patients, the study’s retrospective design and the possibility of recall bias were limitations, said Dr. Jordan in an email. She also was not involved in the study.

“For example, the family of a child diagnosed with ADHD or ASD may have been more mindful of anything out of the norm in that child’s past, while the family of a child without these conditions may not have recalled allergic symptoms as important,” she explained.

Another question that arises is whether some patients were treated and managed well while others were not and whether this disparity in care affected the development or severity of ADHD or ASD, she added.

“Is a patient with a well-controlled allergic condition less likely to develop ADHD or ASD than a patient with an uncontrolled allergic condition? Does a well-controlled patient ever return to the same probability of getting ADHD or ASD as a nonallergic patient?”

“While this study expands our understanding of these conditions and their interrelationships, it also brings up many additional questions and opens a new segment of research,” Dr. Jordan said. “More studies in this area are necessary to confirm the findings of this paper.”

The study was partially funded by the Israel Ambulatory Pediatric Association. The authors, Dr. Nadler, and Dr. Jordan report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PEDIATRIC ALLERGY AND IMMUNOLOGY

Botanical Briefs: Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba)

An ancient tree of the Ginkgoaceae family, Ginkgo biloba is known as a living fossil because its genome has been identified in fossils older than 200 million years.1 An individual tree can live longer than 1000 years. Originating in China, G biloba (here, “ginkgo”) is cultivated worldwide for its attractive foliage (Figure 1). Ginkgo extract has long been used in traditional Chinese medicine; however, contact with the plant proper can provoke allergic contact dermatitis.

Dermatitis-Inducing Components

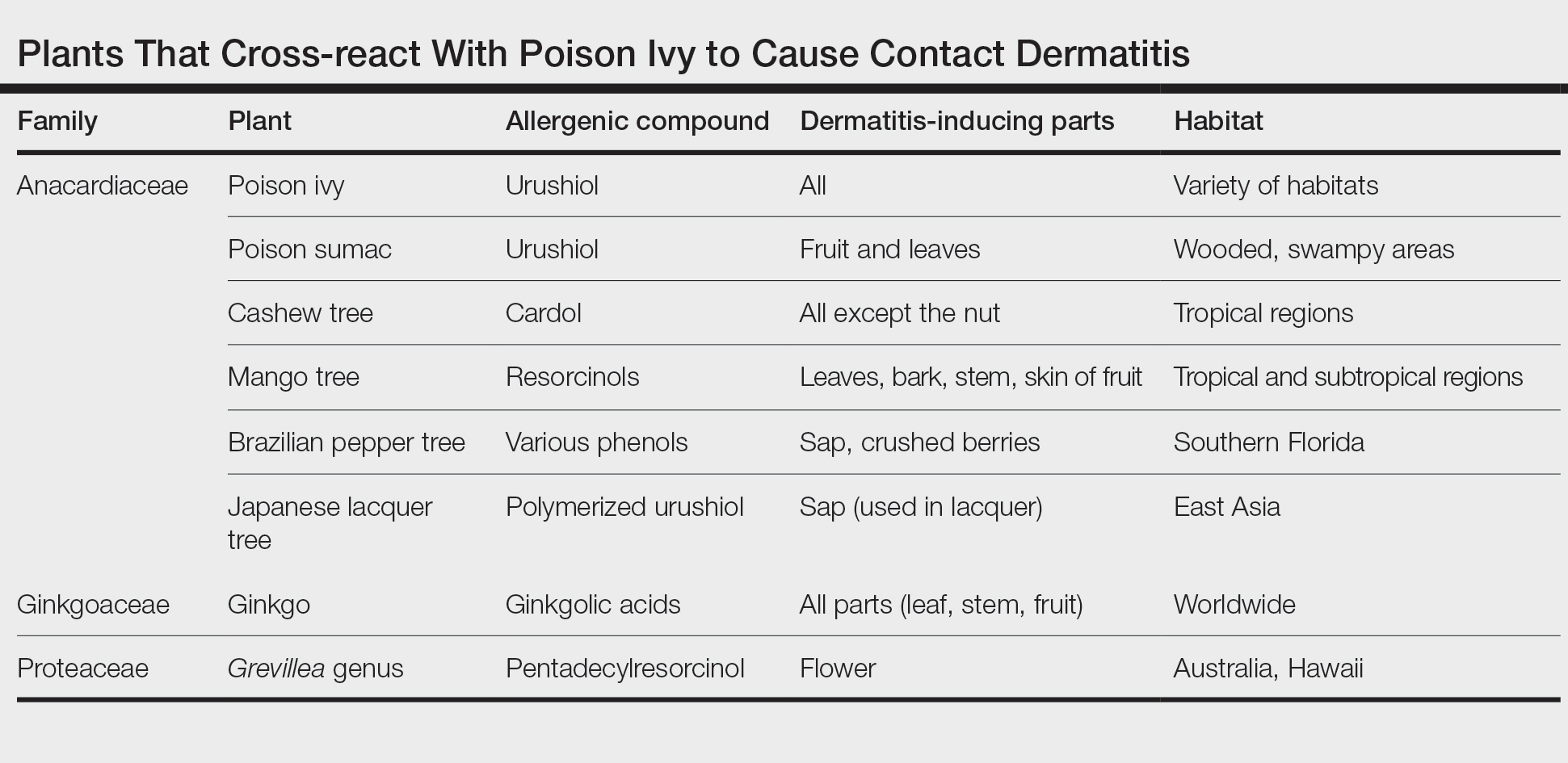

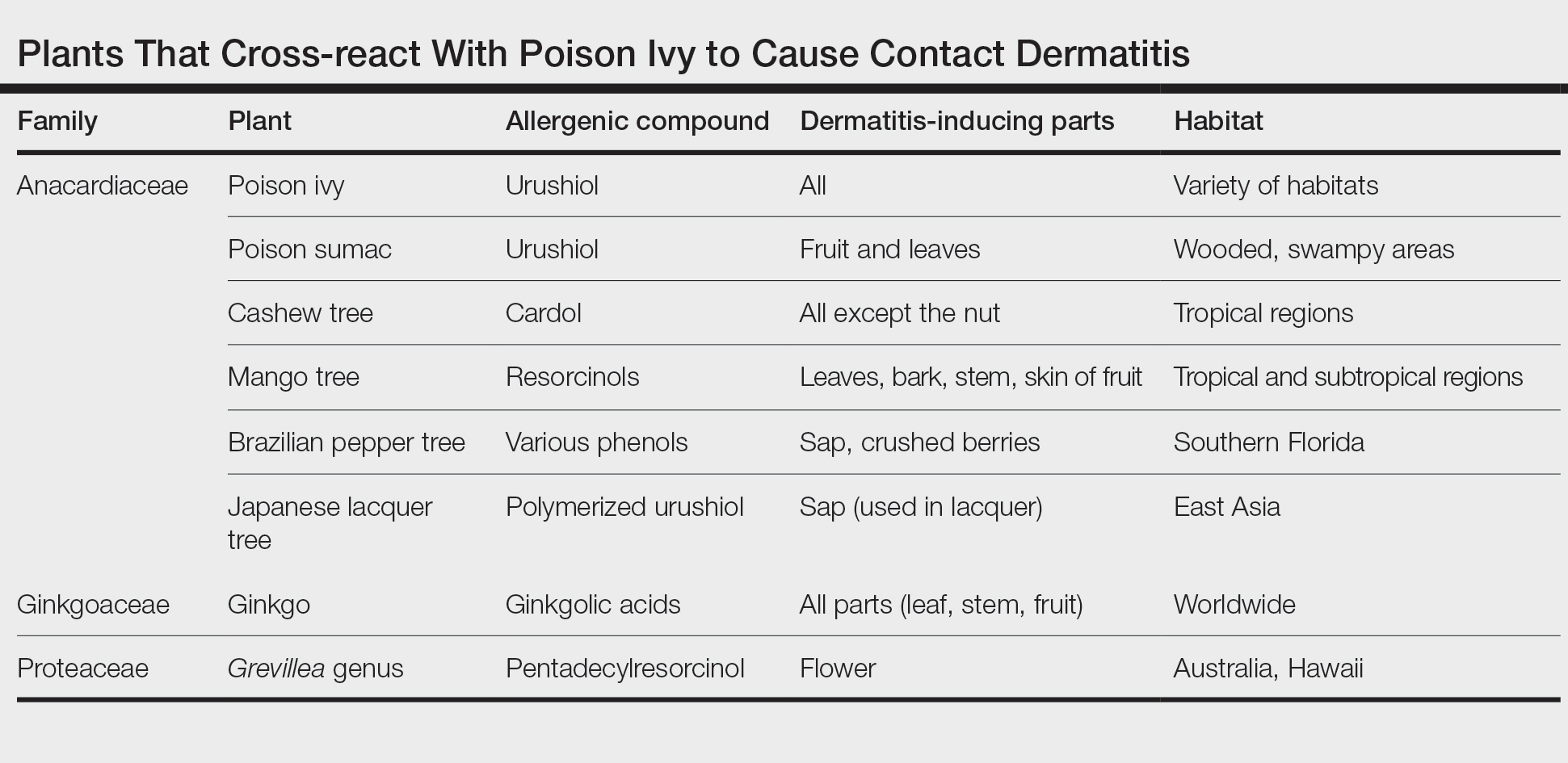

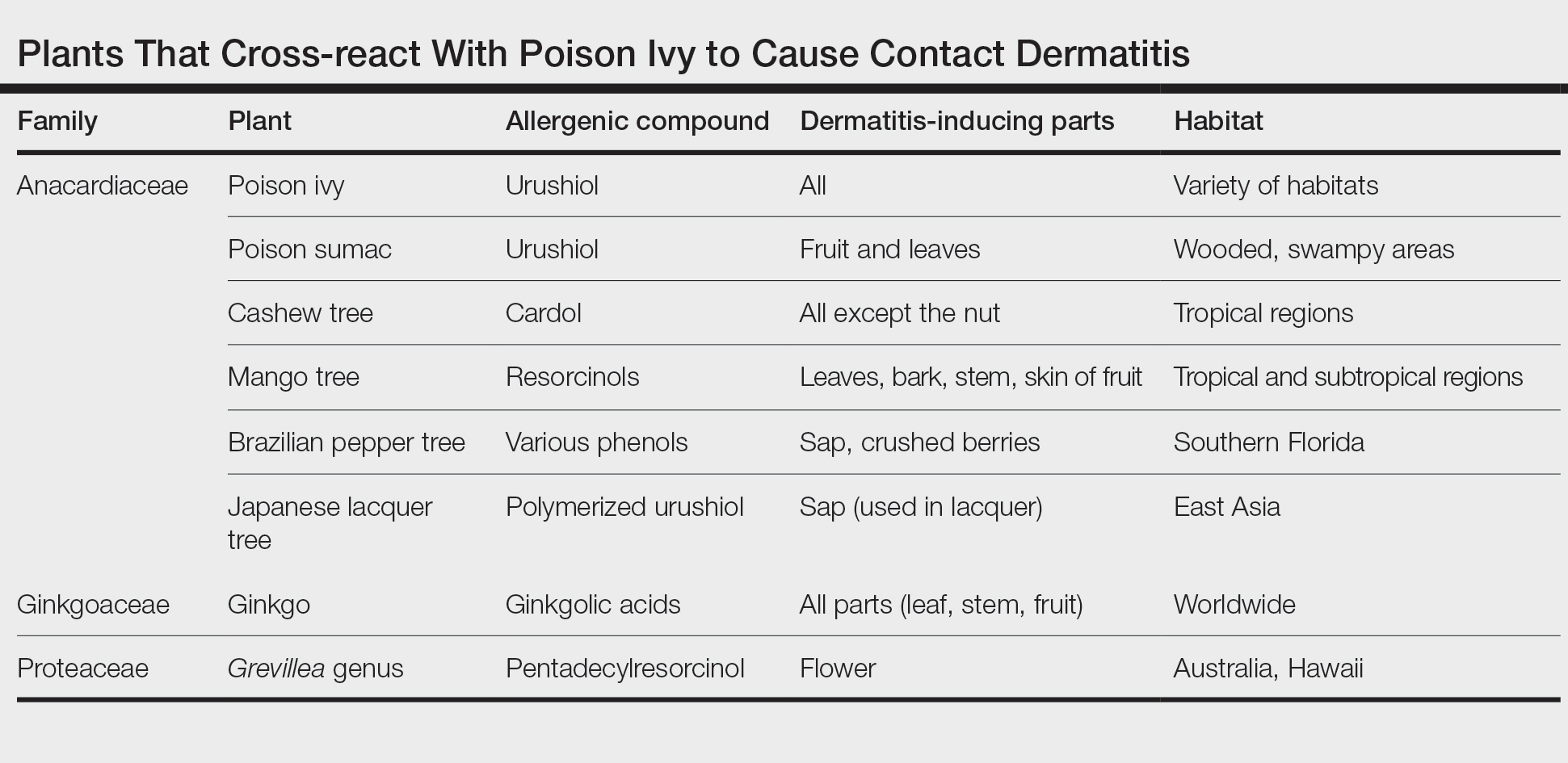

The allergenic component of the ginkgo tree is ginkgolic acid, which is structurally similar to urushiol and anacardic acid.2,3 This compound can cause a cross-reaction in a person previously sensitized by contact with other plants. Urushiol is found in poison ivy(Toxicodendron radicans); anacardic acid is found in the cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale). Both plants belong to the family Anacardiaceae, commonly known as the cashew family.

Members of Anacardiaceae are the most common causes of plant-induced allergic contact dermatitis and include the cashew tree, mango tree, poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. These plants can cross-react to cause contact dermatitis (Table).3 Patch tests have revealed that some individuals who are sensitive to components of the ginkgo tree also demonstrate sensitivity to poison ivy and poison sumac4,5; countering this finding, Lepoittevin and colleagues6 demonstrated in animal studies that there was no cross-reactivity between ginkgo and urushiol, suggesting that patients with a reported cross-reaction might truly have been previously sensitized to both plants. In general, patients who have a history of a reaction to any Anacardiaceae plant should take precautions when handling them.

Therapeutic Benefit of Ginkgo

Ginkgo extract is sold as the herbal supplement EGB761, which acts as an antioxidant.7 In France, Germany, and China, it is a commonly prescribed herbal medicine.8 It is purported to support memory and attention; studies have shown improvement in cognition and in involvement with activities of daily living for patients with dementia.9,10 Ginkgo extract might lessen peripheral vascular disease and cerebral circulatory disease, having been shown in vitro and in animal models to prevent platelet aggregation induced by platelet-activating factor and to stimulate vasodilation by increasing production of nitric oxide.11,12

Furthermore, purified ginkgo extract might have beneficial effects on skin. A study in rats showed that when intraperitoneal ginkgo extract was given prior to radiation therapy, 100% of rats receiving placebo developed radiation dermatitis vs 13% of those that received ginkgo extract (P<.0001). An excisional skin biopsy showed a decrease in markers of oxidative stress in rats that received ginkgo extract prior to radiation.7

A randomized, double-blind clinical trial showed a significant reduction in disease progression in vitiligo patients assigned to receive ginkgo extract orally compared to placebo (P=.006).13 Research for many possible uses of ginkgo extract is ongoing.

Cutaneous Manifestations

Contact with the fruit of the ginkgo tree can induce allergic contact dermatitis,14 most often as erythematous papules, vesicles, and in some cases edema.5,15

Exposures While Picking Berries—In 1939, Bolus15 reported the case of a patient who presented with edema, erythema, and vesicular lesions involving the hands and face after picking berries from a ginkgo tree. Later, patch testing on this patient, using ginkgo fruit, resulted in burning and stinging that necessitated removal of the patch, suggesting an irritant reaction. This was followed by a vesicular reaction that then developed within 24 hours, which was more consistent with allergy. Similarly, in 1988, a case series of contact dermatitis was reported in 3 patients after gathering ginkgo fruit.5

Incidental Exposure While Walking—In 1965, dermatitis broke out in 35 high school students, mainly affecting exposed portions of the leg, after ginkgo fruit fell and its pulp was exposed on a path at their school.4 Subsequently, patch testing was performed on 29 volunteers—some who had been exposed to ginkgo on that path, others without prior exposure. It was established that testing with ginkgo pulp directly caused an irritant reaction in all students, regardless of prior ginkgo exposure, but all prior ginkgo-exposed students in this study reacted positively to an acetone extract of ginkgo pulp and either poison ivy extract or pentadecylcatechol.4

Systemic Contact After Eating Fruit—An illustrative case of dermatitis, stomatitis, and proctitis was reported in a man with history of poison oak contact dermatitis who had eaten fruit from a ginkgo tree, suggesting systemic contact dermatitis. Weeks after resolution of symptoms, he reacted positively to ginkgo fruit and poison ivy extracts on patch testing.16

Ginkgo dermatitis tends to resolve upon removal of the inciting agent and application of a topical steroid.8,17 Although many reported cases involve the fruit, allergic contact dermatitis can result from exposure to any part of the plant. In a reported case, a woman developed airborne contact dermatitis from working with sarcotesta of the ginkgo plant.18 Despite wearing rubber gloves, she broke out 1 week after exposure with erythema on the face and arms and severe facial edema.

Ginkgo leaves also can cause allergic contact dermatitis.19 Precautions should be taken when handling any component of the ginkgo tree.

Oral ginkgo supplementation has been implicated in a variety of other cutaneous reactions—from benign to life-threatening. When the ginkgo allergen concentration is too high within the supplement, as has been noted in some formulations, patients have presented with a diffuse morbilliform eruption within 1 or 2 weeks after taking ginkgo.20 One patient—who was not taking any other medication—experienced an episode of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis 48 hours after taking ginkgo.21 Ingestion of ginkgo extract also has been associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome.22-24

Other Adverse Reactions

The adverse effects of ginkgo supplement vary widely. In addition to dermatitis, ginkgo supplement can cause headaches, palpitations, tachycardia, vasculitis, nausea, and other symptoms.14

Metabolic Disturbance—One patient taking ginkgo who died after a seizure was found to have subtherapeutic levels of valproate and phenytoin,25 which could be due to ginkgo’s effect on cytochrome p450 enzyme CYP2C19.26 Ginkgo interactions with many cytochrome enzymes have been studied for potential drug interactions. Any other direct effects remain variable and controversial.27,28

Hemorrhage—Another serious effect associated with taking ginkgo supplements is hemorrhage, often in conjunction with warfarin14; however, a meta-analysis indicated that ginkgo generally does not increase the risk of bleeding.29 Other studies have shown that taking ginkgo with warfarin showed no difference in clotting status, and ginkgo with aspirin resulted in no clinically significant difference in bruising, bleeding, or platelet function in an analysis over a period of 1 month.30,31 These findings notwithstanding, pregnant women, surgical patients, and those taking a blood thinner are advised as a general precaution not to take ginkgo extract.

Carcinogenesis—Ginkgo extract has antioxidant properties, but there is evidence that it might act as a carcinogen. An animal study reported by the US National Toxicology Program found that ginkgo induced mutagenic activity in the liver, thyroid, and nose of mice and rats. Over time, rodent liver underwent changes consistent with hepatic enzyme induction.32 More research is needed to clarify the role of ginkgo in this process.

Toxicity by Ingestion—Ginkgo seeds can cause food poisoning due to the compound 4’-O-methylpyridoxine (also known as ginkgotoxin).33 Because methylpyridoxine can cause depletion of pyridoxal phosphate (a form of vitamin B6 necessary for the synthesis of γ-aminobutyric acid), overconsumption of ginkgo seeds, even when fully cooked, might result in convulsions and even death.33

Nomenclature and Distribution of Plants

Gingko biloba belongs to the Ginkgoaceae family (class Ginkgophytes). The tree originated in China but might no longer exist in a truly wild form. It is grown worldwide for its beauty and longevity. The female ginkgo tree is a gymnosperm, producing fruit with seeds that are not coated by an ovary wall15; male (nonfruiting) trees are preferentially planted because the fruit is surrounded by a pulp that, when dropped, emits a sour smell described variously as rancid butter, vomit, or excrement.5

Identifying Features and Plant Facts

The deciduous ginkgo tree has unique fan-shaped leaves and is cultivated for its beauty and resistance to disease (Figure 2).4,34 It is nicknamed the maidenhair tree because the leaves are similar to the pinnae of the maidenhair fern.34 Because G biloba is resistant to pollution, it often is planted along city streets.17 The leaf—5- to 8-cm wide and a symbol of the city of Tokyo, Japan34—grows in clusters (Figure 3)5 and is green but turns yellow before it falls in autumn.34 Leaf veins branch out into the blade without anastomosing.34

Male flowers grow in a catkinlike pattern; female flowers grow on long stems.5 The fruit is small, dark, and shriveled, with a hint of silver4; it typically is 2 to 2.5 cm in diameter and contains the ginkgo nut or seed. The kernel of the ginkgo nut is edible when roasted and is used in traditional Chinese and Japanese cuisine as a dish served on special occasions in autumn.33

Final Thoughts

Given that G biloba is a beautiful, commonly planted ornamental tree, gardeners and landscapers should be aware of the risk for allergic contact dermatitis and use proper protection. Dermatologists should be aware of its cross-reactivity with other common plants such as poison ivy and poison oak to help patients identify the cause of their reactions and avoid the inciting agent. Because ginkgo extract also can cause a cutaneous reaction or interact with other medications, providers should remember to take a thorough medication history that includes herbal medicines and supplements.

- Lyu J. Ginkgo history told by genomes. Nat Plants. 2019;5:1029. doi:10.1038/s41477-019-0529-2

- ElSohly MA, Adawadkar PD, Benigni DA, et al. Analogues of poison ivy urushiol. Synthesis and biological activity of disubstituted n-alkylbenzenes. J Med Chem. 1986;29:606-611. doi:10.1021/jm00155a003

- He X, Bernart MW, Nolan GS, et al. High-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry study of ginkgolic acid in the leaves and fruits of the ginkgo tree (Ginkgo biloba). J Chromatogr Sci. 2000;38:169-173. doi:10.1093/chromsci/38.4.169

- Sowers WF, Weary PE, Collins OD, et al. Ginkgo-tree dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1965;91:452-456. doi:10.1001/archderm.1965.01600110038009

- Tomb RR, Foussereau J, Sell Y. Mini-epidemic of contact dermatitis from ginkgo tree fruit (Ginkgo biloba L.). Contact Dermatitis. 1988;19:281-283. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1988.tb02928.x

- Lepoittevin J-P, Benezra C, Asakawa Y. Allergic contact dermatitis to Ginkgo biloba L.: relationship with urushiol. Arch Dermatol Res. 1989;281:227-230. doi:10.1007/BF00431055

- Yirmibesoglu E, Karahacioglu E, Kilic D, et al. The protective effects of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb-761) on radiation-induced dermatitis: an experimental study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:387-394. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04253.x