User login

A ‘crisis’ of suicidal thoughts, attempts in transgender youth

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

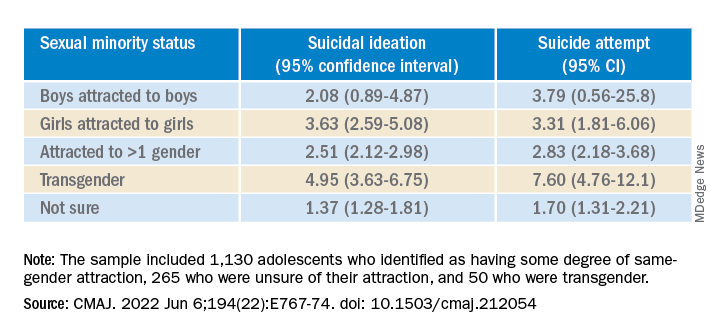

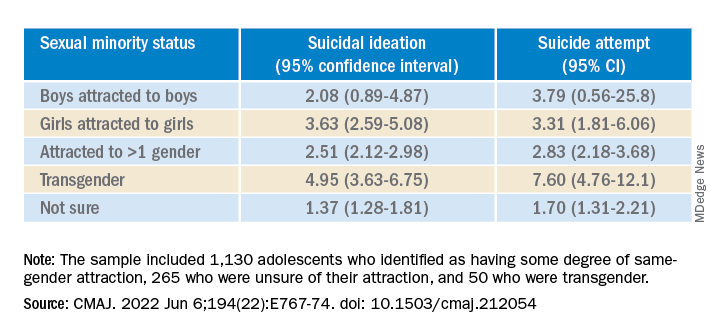

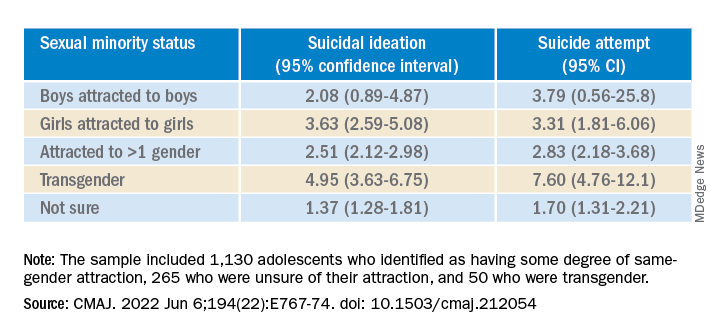

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

New studies show growing number of trans, nonbinary youth in U.S.

Two new studies point to an ever-increasing number of young people in the United States who identify as transgender and nonbinary, with the figures doubling among 18- to 24-year-olds in one institute’s research – from 0.66% of the population in 2016 to 1.3% (398,900) in 2022.

In addition, 1.4% (300,100) of 13- to 17-year-olds identify as trans or nonbinary, according to the report from that group, the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law.

Williams, which conducts independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, did not contain data on 13- to 17-year-olds in its 2016 study, so the growth in that group over the past 5+ years is not as well documented.

Overall, some 1.6 million Americans older than age 13 now identify as transgender, reported the Williams researchers.

And in a new Pew Research Center survey, 2% of adults aged 18-29 identify as transgender and 3% identify as nonbinary, a far greater number than in other age cohorts.

These reports are likely underestimates. The Human Rights Campaign estimates that some 2 million Americans of all ages identify as transgender.

The Pew survey is weighted to be representative but still has limitations, said the organization. The Williams analysis, based on responses to two CDC surveys – the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) – is incomplete, say researchers, because not every state collects data on gender identity.

Transgender identities more predominant among youth

The Williams researchers report that 18.3% of those who identified as trans were 13- to 17-year-olds; that age group makes up 7.6% of the United States population 13 and older.

And despite not having firm figures from earlier reports, they comment: “Youth ages 13-17 comprise a larger share of the transgender-identified population than we previously estimated, currently comprising about 18% of the transgender-identified population in the United State, up from 10% previously.”

About one-quarter of those who identified as trans in the new 2022 report were aged 18-24; that age cohort accounts for 11% of Americans.

The number of older Americans who identify as trans are more proportionate to their representation in the population, according to Williams. Overall, about half of those who said they were trans were aged 25-64; that group accounts for 62% of the overall American population. Some 10% of trans-identified individuals were over age 65. About 20% of Americans are 65 or older, said the researchers.

The Pew research – based on the responses of 10,188 individuals surveyed in May – also found growing numbers of young people who identify as trans. “The share of U.S. adults who are transgender is particularly high among adults younger than 25,” reported Pew in a blog post.

In the 18- to 25-year-old group, 3.1% identified as a trans man or a trans woman, compared with just 0.5% of those ages 25-29.

That compares to 0.3% of those aged 30-49 and 0.2% of those older than 50.

Racial and state-by-state variation

Similar percentages of youth aged 13-17 of all races and ethnicities in the Williams study report they are transgender, ranging from 1% of those who are Asian, to 1.3% of White youth, 1.4% of Black youth, 1.8% of American Indian or Alaska Native, and 1.8% of Latinx youth. The institute reported that 1.5% of biracial and multiracial youth identified as transgender.

The researchers said, however, that “transgender-identified youth and adults appear more likely to report being Latinx and less likely to report being White, as compared to the United States population.”

Transgender individuals live in every state, with the greatest percentage of both youth and adults in the Northeast and West, and lesser percentages in the Midwest and South, reported the Williams Institute.

Williams estimates as many as 3% of 13- to 17-year-olds in New York identify as trans, while just 0.6% of that age group in Wyoming is transgender. A total of 2%-2.5% of those aged 13-17 are transgender in Hawaii, New Mexico, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

Among the states with higher percentages of trans-identifying 18- to 24-year-olds: Arizona (1.9%), Arkansas (3.6%), Colorado (2%), Delaware (2.4%), Illinois (1.9%), Maryland (1.9%), North Carolina (2.5%), Oklahoma (2.5%), Massachusetts (2.3%), Rhode Island (2.1%), and Washington (2%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two new studies point to an ever-increasing number of young people in the United States who identify as transgender and nonbinary, with the figures doubling among 18- to 24-year-olds in one institute’s research – from 0.66% of the population in 2016 to 1.3% (398,900) in 2022.

In addition, 1.4% (300,100) of 13- to 17-year-olds identify as trans or nonbinary, according to the report from that group, the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law.

Williams, which conducts independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, did not contain data on 13- to 17-year-olds in its 2016 study, so the growth in that group over the past 5+ years is not as well documented.

Overall, some 1.6 million Americans older than age 13 now identify as transgender, reported the Williams researchers.

And in a new Pew Research Center survey, 2% of adults aged 18-29 identify as transgender and 3% identify as nonbinary, a far greater number than in other age cohorts.

These reports are likely underestimates. The Human Rights Campaign estimates that some 2 million Americans of all ages identify as transgender.

The Pew survey is weighted to be representative but still has limitations, said the organization. The Williams analysis, based on responses to two CDC surveys – the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) – is incomplete, say researchers, because not every state collects data on gender identity.

Transgender identities more predominant among youth

The Williams researchers report that 18.3% of those who identified as trans were 13- to 17-year-olds; that age group makes up 7.6% of the United States population 13 and older.

And despite not having firm figures from earlier reports, they comment: “Youth ages 13-17 comprise a larger share of the transgender-identified population than we previously estimated, currently comprising about 18% of the transgender-identified population in the United State, up from 10% previously.”

About one-quarter of those who identified as trans in the new 2022 report were aged 18-24; that age cohort accounts for 11% of Americans.

The number of older Americans who identify as trans are more proportionate to their representation in the population, according to Williams. Overall, about half of those who said they were trans were aged 25-64; that group accounts for 62% of the overall American population. Some 10% of trans-identified individuals were over age 65. About 20% of Americans are 65 or older, said the researchers.

The Pew research – based on the responses of 10,188 individuals surveyed in May – also found growing numbers of young people who identify as trans. “The share of U.S. adults who are transgender is particularly high among adults younger than 25,” reported Pew in a blog post.

In the 18- to 25-year-old group, 3.1% identified as a trans man or a trans woman, compared with just 0.5% of those ages 25-29.

That compares to 0.3% of those aged 30-49 and 0.2% of those older than 50.

Racial and state-by-state variation

Similar percentages of youth aged 13-17 of all races and ethnicities in the Williams study report they are transgender, ranging from 1% of those who are Asian, to 1.3% of White youth, 1.4% of Black youth, 1.8% of American Indian or Alaska Native, and 1.8% of Latinx youth. The institute reported that 1.5% of biracial and multiracial youth identified as transgender.

The researchers said, however, that “transgender-identified youth and adults appear more likely to report being Latinx and less likely to report being White, as compared to the United States population.”

Transgender individuals live in every state, with the greatest percentage of both youth and adults in the Northeast and West, and lesser percentages in the Midwest and South, reported the Williams Institute.

Williams estimates as many as 3% of 13- to 17-year-olds in New York identify as trans, while just 0.6% of that age group in Wyoming is transgender. A total of 2%-2.5% of those aged 13-17 are transgender in Hawaii, New Mexico, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

Among the states with higher percentages of trans-identifying 18- to 24-year-olds: Arizona (1.9%), Arkansas (3.6%), Colorado (2%), Delaware (2.4%), Illinois (1.9%), Maryland (1.9%), North Carolina (2.5%), Oklahoma (2.5%), Massachusetts (2.3%), Rhode Island (2.1%), and Washington (2%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two new studies point to an ever-increasing number of young people in the United States who identify as transgender and nonbinary, with the figures doubling among 18- to 24-year-olds in one institute’s research – from 0.66% of the population in 2016 to 1.3% (398,900) in 2022.

In addition, 1.4% (300,100) of 13- to 17-year-olds identify as trans or nonbinary, according to the report from that group, the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law.

Williams, which conducts independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, did not contain data on 13- to 17-year-olds in its 2016 study, so the growth in that group over the past 5+ years is not as well documented.

Overall, some 1.6 million Americans older than age 13 now identify as transgender, reported the Williams researchers.

And in a new Pew Research Center survey, 2% of adults aged 18-29 identify as transgender and 3% identify as nonbinary, a far greater number than in other age cohorts.

These reports are likely underestimates. The Human Rights Campaign estimates that some 2 million Americans of all ages identify as transgender.

The Pew survey is weighted to be representative but still has limitations, said the organization. The Williams analysis, based on responses to two CDC surveys – the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) – is incomplete, say researchers, because not every state collects data on gender identity.

Transgender identities more predominant among youth

The Williams researchers report that 18.3% of those who identified as trans were 13- to 17-year-olds; that age group makes up 7.6% of the United States population 13 and older.

And despite not having firm figures from earlier reports, they comment: “Youth ages 13-17 comprise a larger share of the transgender-identified population than we previously estimated, currently comprising about 18% of the transgender-identified population in the United State, up from 10% previously.”

About one-quarter of those who identified as trans in the new 2022 report were aged 18-24; that age cohort accounts for 11% of Americans.

The number of older Americans who identify as trans are more proportionate to their representation in the population, according to Williams. Overall, about half of those who said they were trans were aged 25-64; that group accounts for 62% of the overall American population. Some 10% of trans-identified individuals were over age 65. About 20% of Americans are 65 or older, said the researchers.

The Pew research – based on the responses of 10,188 individuals surveyed in May – also found growing numbers of young people who identify as trans. “The share of U.S. adults who are transgender is particularly high among adults younger than 25,” reported Pew in a blog post.

In the 18- to 25-year-old group, 3.1% identified as a trans man or a trans woman, compared with just 0.5% of those ages 25-29.

That compares to 0.3% of those aged 30-49 and 0.2% of those older than 50.

Racial and state-by-state variation

Similar percentages of youth aged 13-17 of all races and ethnicities in the Williams study report they are transgender, ranging from 1% of those who are Asian, to 1.3% of White youth, 1.4% of Black youth, 1.8% of American Indian or Alaska Native, and 1.8% of Latinx youth. The institute reported that 1.5% of biracial and multiracial youth identified as transgender.

The researchers said, however, that “transgender-identified youth and adults appear more likely to report being Latinx and less likely to report being White, as compared to the United States population.”

Transgender individuals live in every state, with the greatest percentage of both youth and adults in the Northeast and West, and lesser percentages in the Midwest and South, reported the Williams Institute.

Williams estimates as many as 3% of 13- to 17-year-olds in New York identify as trans, while just 0.6% of that age group in Wyoming is transgender. A total of 2%-2.5% of those aged 13-17 are transgender in Hawaii, New Mexico, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.

Among the states with higher percentages of trans-identifying 18- to 24-year-olds: Arizona (1.9%), Arkansas (3.6%), Colorado (2%), Delaware (2.4%), Illinois (1.9%), Maryland (1.9%), North Carolina (2.5%), Oklahoma (2.5%), Massachusetts (2.3%), Rhode Island (2.1%), and Washington (2%).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physician convicted in $10M veteran insurance fraud scheme

A federal jury found Alexander, Ark., family physician Joe David May, MD, known locally as “Jay,” guilty on all 22 counts for which he was indicted in a multi-million-dollar conspiracy to defraud TRICARE, the federal insurance program for U.S. veterans.

. A pharmacy promoter paid recruiters to find TRICARE beneficiaries, then paid Dr. May and other medical professionals to rubber-stamp prescriptions for pain cream, whether or not the patients needed it.

As a result of this scheme, TRICARE paid more than $12 million for compounded drugs. Dr. May, according to evidence presented at the trial, wrote 226 prescriptions over the course of 10 months, costing TRICARE $4.63 million. All but one of these prescriptions were supplied by pharmaceutical sales representatives Glenn Hudson and Derek Clifton, according to federal officials. The sales reps passed the prescriptions to the providers, including Dr. May.

Dr. May accepted $15,000 in cash bribes and signed off on the prescriptions without consulting or examining patients to determine whether or not the prescriptions were needed. Mr. Hudson and Mr. Clifton have pleaded guilty in the scheme, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

The conspiracy was complex and involved recruiting patients. According to prosecutors, one recruiter, for example, hosted a meeting at the Fisher Armory in North Little Rock, Ark., where he signed up patients for the drugs and offered to pay them $1,000. Thirteen of the patients from this meeting were sent to Dr. May, who signed the prescriptions. This group alone cost the veterans’ insurance program $370,000, say prosecutors. When the conspirators learned that reimbursements from TRICARE were set to decrease in May 2015, they rushed to profit from the scheme while there was still time. In April 2015 alone, Dr. May signed 59 prescriptions, contributing to the bilking of TRICARE for another $1.4 million.

According to a report in the Arkansas Democrat Gazette, Dr. May and Mr. Clifton, a former basketball coach, were longtime friends. Alexander Morgan, U.S. Attorney and one of the prosecutors in the case, said that Dr. May signed the prescriptions at the behest of Mr. Clifton. According to the Gazette report, Mr. Morgan said the scheme was successful for as long as it was because “TRICARE is not in the business of catching fraud. Tricare is in the business of delivering health care to our nation’s veterans. They trust the professionals to do the right thing.”

Dr. May is currently licensed in Arkansas to practice family medicine and emergency medicine and as a hospitalist. His license expires in September.

Dr. May is free pending a presentencing report. In addition to sentences imposed for fraud, mail fraud, falsifying records, and violation of anti kickback laws, for which he faces up to 20 years in prison, Dr. May will serve an additional 4 years for convictions on two counts of aggravated identity theft.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A federal jury found Alexander, Ark., family physician Joe David May, MD, known locally as “Jay,” guilty on all 22 counts for which he was indicted in a multi-million-dollar conspiracy to defraud TRICARE, the federal insurance program for U.S. veterans.

. A pharmacy promoter paid recruiters to find TRICARE beneficiaries, then paid Dr. May and other medical professionals to rubber-stamp prescriptions for pain cream, whether or not the patients needed it.

As a result of this scheme, TRICARE paid more than $12 million for compounded drugs. Dr. May, according to evidence presented at the trial, wrote 226 prescriptions over the course of 10 months, costing TRICARE $4.63 million. All but one of these prescriptions were supplied by pharmaceutical sales representatives Glenn Hudson and Derek Clifton, according to federal officials. The sales reps passed the prescriptions to the providers, including Dr. May.

Dr. May accepted $15,000 in cash bribes and signed off on the prescriptions without consulting or examining patients to determine whether or not the prescriptions were needed. Mr. Hudson and Mr. Clifton have pleaded guilty in the scheme, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

The conspiracy was complex and involved recruiting patients. According to prosecutors, one recruiter, for example, hosted a meeting at the Fisher Armory in North Little Rock, Ark., where he signed up patients for the drugs and offered to pay them $1,000. Thirteen of the patients from this meeting were sent to Dr. May, who signed the prescriptions. This group alone cost the veterans’ insurance program $370,000, say prosecutors. When the conspirators learned that reimbursements from TRICARE were set to decrease in May 2015, they rushed to profit from the scheme while there was still time. In April 2015 alone, Dr. May signed 59 prescriptions, contributing to the bilking of TRICARE for another $1.4 million.

According to a report in the Arkansas Democrat Gazette, Dr. May and Mr. Clifton, a former basketball coach, were longtime friends. Alexander Morgan, U.S. Attorney and one of the prosecutors in the case, said that Dr. May signed the prescriptions at the behest of Mr. Clifton. According to the Gazette report, Mr. Morgan said the scheme was successful for as long as it was because “TRICARE is not in the business of catching fraud. Tricare is in the business of delivering health care to our nation’s veterans. They trust the professionals to do the right thing.”

Dr. May is currently licensed in Arkansas to practice family medicine and emergency medicine and as a hospitalist. His license expires in September.

Dr. May is free pending a presentencing report. In addition to sentences imposed for fraud, mail fraud, falsifying records, and violation of anti kickback laws, for which he faces up to 20 years in prison, Dr. May will serve an additional 4 years for convictions on two counts of aggravated identity theft.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A federal jury found Alexander, Ark., family physician Joe David May, MD, known locally as “Jay,” guilty on all 22 counts for which he was indicted in a multi-million-dollar conspiracy to defraud TRICARE, the federal insurance program for U.S. veterans.

. A pharmacy promoter paid recruiters to find TRICARE beneficiaries, then paid Dr. May and other medical professionals to rubber-stamp prescriptions for pain cream, whether or not the patients needed it.

As a result of this scheme, TRICARE paid more than $12 million for compounded drugs. Dr. May, according to evidence presented at the trial, wrote 226 prescriptions over the course of 10 months, costing TRICARE $4.63 million. All but one of these prescriptions were supplied by pharmaceutical sales representatives Glenn Hudson and Derek Clifton, according to federal officials. The sales reps passed the prescriptions to the providers, including Dr. May.

Dr. May accepted $15,000 in cash bribes and signed off on the prescriptions without consulting or examining patients to determine whether or not the prescriptions were needed. Mr. Hudson and Mr. Clifton have pleaded guilty in the scheme, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

The conspiracy was complex and involved recruiting patients. According to prosecutors, one recruiter, for example, hosted a meeting at the Fisher Armory in North Little Rock, Ark., where he signed up patients for the drugs and offered to pay them $1,000. Thirteen of the patients from this meeting were sent to Dr. May, who signed the prescriptions. This group alone cost the veterans’ insurance program $370,000, say prosecutors. When the conspirators learned that reimbursements from TRICARE were set to decrease in May 2015, they rushed to profit from the scheme while there was still time. In April 2015 alone, Dr. May signed 59 prescriptions, contributing to the bilking of TRICARE for another $1.4 million.

According to a report in the Arkansas Democrat Gazette, Dr. May and Mr. Clifton, a former basketball coach, were longtime friends. Alexander Morgan, U.S. Attorney and one of the prosecutors in the case, said that Dr. May signed the prescriptions at the behest of Mr. Clifton. According to the Gazette report, Mr. Morgan said the scheme was successful for as long as it was because “TRICARE is not in the business of catching fraud. Tricare is in the business of delivering health care to our nation’s veterans. They trust the professionals to do the right thing.”

Dr. May is currently licensed in Arkansas to practice family medicine and emergency medicine and as a hospitalist. His license expires in September.

Dr. May is free pending a presentencing report. In addition to sentences imposed for fraud, mail fraud, falsifying records, and violation of anti kickback laws, for which he faces up to 20 years in prison, Dr. May will serve an additional 4 years for convictions on two counts of aggravated identity theft.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Surgery during a pandemic? COVID vaccination status matters – or not

An online survey captured mixed information about people’s willingness to undergo surgery during a viral pandemic in relation to the vaccine status of the patient and staff. The findings showcase opportunities for public education and “skillful messaging,” researchers report.

In survey scenarios that asked people to imagine their vaccination status, people were more willing to undergo surgery if it was lifesaving, rather than elective, especially if vaccinated. The prospect of no hospital stay tipped the scales further toward surgery. The vaccination status of hospital staff played only a minor role in decision making, according to the study, which was published in Vaccine.

But as a post hoc analysis revealed, it was participants who were not vaccinated against COVID-19 in real life who were more willing to undergo surgery, compared with those who had one or two shots.

In either case, too many people were unwilling to undergo lifesaving surgery, even though the risk of hospital-acquired COVID-19 is low. “Making this choice for an actual health problem would result in an unacceptably high rate of potential morbidity attributable to pandemic-related fears, the authors wrote.

In an unusual approach, the researchers used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to electronically recruit 2,006 adults. The participants answered a 26-item survey about a hypothetical surgery in an unnamed pandemic with different combinations of vaccine status for patient and staff.

Coauthor and anesthesiologist Keith J. Ruskin, MD, of the University of Chicago, told this news organization that they “wanted to make this timeless” and independent of COVID “so that when the next thing came about, the paper would still be relevant.”

The researchers were surprised by the findings at the extreme ends of attitudes toward surgery. Some were still willing to have elective surgery with (hypothetically) unvaccinated patients and staff.

“And people at the other end, even though they are vaccinated, the hospital staff is vaccinated, and the surgery is lifesaving, they absolutely won’t have surgery,” Dr. Ruskin said.

He viewed these two groups as opportunities for education. “You can present information in the most positive light to get them to do the right thing with what’s best for themselves,” he said.

As an example, Dr. Ruskin pointed to an ad in Illinois. “It’s not only people saying I’m getting vaccinated for myself and my family, but there are people who said I got vaccinated and I still got COVID, but it could have been much worse. Please, if you’re on the fence, just get vaccinated,” he said.

Coauthor Anna Clebone Ruskin, MD, an anesthesiologist at the University of Chicago, said, “Humans are programmed to see things in extremes. With surgery, people tend to think of surgery as a monolith – surgery is all good, or surgery is all bad, where there is a huge in between. So we saw those extremes. ... Seeing that dichotomy with people on either end was pretty surprising.

“Getting surgery is not always good. Getting surgery is not always bad. It’s a risk-versus-benefit analysis and educating the public to consider the risks and benefits of medical decisions, in general, would be enormously beneficial,” she said.

A post hoc analysis found that “participants who were not actually vaccinated against COVID-19 were generally more willing to undergo surgery compared to those who had one vaccination or two vaccinations,” the authors wrote.

In a second post hoc finding, participants who reported high wariness of vaccines were generally more likely to be willing to undergo surgery. Notably, 15% of participants “were unwilling to undergo lifesaving surgery during a pandemic even when they and the health care staff were vaccinated,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Keith J. Ruskin hypothesized about this result, saying, “What we think is that potentially actually getting vaccinated against COVID-19 may indicate that you have a lower risk tolerance. So you may be less likely to do anything you perceive to be risky if you’re vaccinated against COVID-19.”

The authors stated that “the risk of hospital-acquired COVID-19 even prior to vaccination is vanishingly small.” The risk of nosocomial COVID varies among different studies. An EPIC-based study between April 2020 and October 2021 found the risk to be 1.8%; EPIC describes the fears of a patient catching COVID at a hospital as “likely unfounded.”

In the United Kingdom, the risk was as high as 24% earlier in the pandemic and then declined to approximately 5% a year ago. Omicron also brought more infections. Rates varied significantly among hospitals – and, notably, the risk of death from a nosocomial COVID infection was 21% in April-September 2020.

Emily Landon, MD, an epidemiologist and executive medical director for infection prevention and control at the University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization that the study’s data were collected during Delta, a “time when we thought that this was a pandemic of the unvaccinated. But there was serious politicization of the vaccine.”

Dr. Landon said one of the study’s strengths was the large number of participants. A limitation was, “You’re going to have less participants who are generally poor and indigent, and fewer old participants, probably because they’re less likely to respond to an online survey.

“But the most interesting results are that people who were wary of vaccines or who hadn’t been vaccinated, were much more willing to undergo surgical procedures in the time of a pandemic, regardless of status, which reflects the fact that not being vaccinated correlates with not worrying much about COVID. Vaccinated individuals had a lot more wariness about undergoing surgical procedures during a pandemic.”

It appeared “individuals who were vaccinated in real life [were] worried about staff vaccination,” Dr. Landon noted. She concluded, “I think it supports the need for mandatory vaccinations in health care workers.”

The study has implications for hospital vaccination policies and practices. In Cumberland, Md., when COVID was high and vaccines first became available, the Maryland Hospital Association said that all health care staff should be vaccinated. The local hospital, UPMC–Western Maryland Hospital, refused.

Two months later, the local news reporter, Teresa McMinn, wrote, “While Maryland’s largest hospital systems have ‘led by example by mandating vaccines for all of their hospital staff,’ other facilities – including UPMC Western Maryland and Garrett Regional Medical Center – have taken no such action even though it’s been 8 months since vaccines were made available to health care workers.”

The hospital would not tell patients whether staff were vaccinated, either. An ongoing concern for members of the community is the lack of communication with UPMC, which erodes trust in the health system – the only hospital available in this rural community.

This vaccine study supports that the vaccination status of the staff may influence some patients’ decision on whether to have surgery.

The Ruskins and Dr. Landon have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An online survey captured mixed information about people’s willingness to undergo surgery during a viral pandemic in relation to the vaccine status of the patient and staff. The findings showcase opportunities for public education and “skillful messaging,” researchers report.

In survey scenarios that asked people to imagine their vaccination status, people were more willing to undergo surgery if it was lifesaving, rather than elective, especially if vaccinated. The prospect of no hospital stay tipped the scales further toward surgery. The vaccination status of hospital staff played only a minor role in decision making, according to the study, which was published in Vaccine.

But as a post hoc analysis revealed, it was participants who were not vaccinated against COVID-19 in real life who were more willing to undergo surgery, compared with those who had one or two shots.

In either case, too many people were unwilling to undergo lifesaving surgery, even though the risk of hospital-acquired COVID-19 is low. “Making this choice for an actual health problem would result in an unacceptably high rate of potential morbidity attributable to pandemic-related fears, the authors wrote.

In an unusual approach, the researchers used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to electronically recruit 2,006 adults. The participants answered a 26-item survey about a hypothetical surgery in an unnamed pandemic with different combinations of vaccine status for patient and staff.

Coauthor and anesthesiologist Keith J. Ruskin, MD, of the University of Chicago, told this news organization that they “wanted to make this timeless” and independent of COVID “so that when the next thing came about, the paper would still be relevant.”

The researchers were surprised by the findings at the extreme ends of attitudes toward surgery. Some were still willing to have elective surgery with (hypothetically) unvaccinated patients and staff.

“And people at the other end, even though they are vaccinated, the hospital staff is vaccinated, and the surgery is lifesaving, they absolutely won’t have surgery,” Dr. Ruskin said.

He viewed these two groups as opportunities for education. “You can present information in the most positive light to get them to do the right thing with what’s best for themselves,” he said.

As an example, Dr. Ruskin pointed to an ad in Illinois. “It’s not only people saying I’m getting vaccinated for myself and my family, but there are people who said I got vaccinated and I still got COVID, but it could have been much worse. Please, if you’re on the fence, just get vaccinated,” he said.

Coauthor Anna Clebone Ruskin, MD, an anesthesiologist at the University of Chicago, said, “Humans are programmed to see things in extremes. With surgery, people tend to think of surgery as a monolith – surgery is all good, or surgery is all bad, where there is a huge in between. So we saw those extremes. ... Seeing that dichotomy with people on either end was pretty surprising.

“Getting surgery is not always good. Getting surgery is not always bad. It’s a risk-versus-benefit analysis and educating the public to consider the risks and benefits of medical decisions, in general, would be enormously beneficial,” she said.

A post hoc analysis found that “participants who were not actually vaccinated against COVID-19 were generally more willing to undergo surgery compared to those who had one vaccination or two vaccinations,” the authors wrote.

In a second post hoc finding, participants who reported high wariness of vaccines were generally more likely to be willing to undergo surgery. Notably, 15% of participants “were unwilling to undergo lifesaving surgery during a pandemic even when they and the health care staff were vaccinated,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Keith J. Ruskin hypothesized about this result, saying, “What we think is that potentially actually getting vaccinated against COVID-19 may indicate that you have a lower risk tolerance. So you may be less likely to do anything you perceive to be risky if you’re vaccinated against COVID-19.”

The authors stated that “the risk of hospital-acquired COVID-19 even prior to vaccination is vanishingly small.” The risk of nosocomial COVID varies among different studies. An EPIC-based study between April 2020 and October 2021 found the risk to be 1.8%; EPIC describes the fears of a patient catching COVID at a hospital as “likely unfounded.”

In the United Kingdom, the risk was as high as 24% earlier in the pandemic and then declined to approximately 5% a year ago. Omicron also brought more infections. Rates varied significantly among hospitals – and, notably, the risk of death from a nosocomial COVID infection was 21% in April-September 2020.

Emily Landon, MD, an epidemiologist and executive medical director for infection prevention and control at the University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization that the study’s data were collected during Delta, a “time when we thought that this was a pandemic of the unvaccinated. But there was serious politicization of the vaccine.”

Dr. Landon said one of the study’s strengths was the large number of participants. A limitation was, “You’re going to have less participants who are generally poor and indigent, and fewer old participants, probably because they’re less likely to respond to an online survey.

“But the most interesting results are that people who were wary of vaccines or who hadn’t been vaccinated, were much more willing to undergo surgical procedures in the time of a pandemic, regardless of status, which reflects the fact that not being vaccinated correlates with not worrying much about COVID. Vaccinated individuals had a lot more wariness about undergoing surgical procedures during a pandemic.”

It appeared “individuals who were vaccinated in real life [were] worried about staff vaccination,” Dr. Landon noted. She concluded, “I think it supports the need for mandatory vaccinations in health care workers.”

The study has implications for hospital vaccination policies and practices. In Cumberland, Md., when COVID was high and vaccines first became available, the Maryland Hospital Association said that all health care staff should be vaccinated. The local hospital, UPMC–Western Maryland Hospital, refused.

Two months later, the local news reporter, Teresa McMinn, wrote, “While Maryland’s largest hospital systems have ‘led by example by mandating vaccines for all of their hospital staff,’ other facilities – including UPMC Western Maryland and Garrett Regional Medical Center – have taken no such action even though it’s been 8 months since vaccines were made available to health care workers.”

The hospital would not tell patients whether staff were vaccinated, either. An ongoing concern for members of the community is the lack of communication with UPMC, which erodes trust in the health system – the only hospital available in this rural community.

This vaccine study supports that the vaccination status of the staff may influence some patients’ decision on whether to have surgery.

The Ruskins and Dr. Landon have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An online survey captured mixed information about people’s willingness to undergo surgery during a viral pandemic in relation to the vaccine status of the patient and staff. The findings showcase opportunities for public education and “skillful messaging,” researchers report.

In survey scenarios that asked people to imagine their vaccination status, people were more willing to undergo surgery if it was lifesaving, rather than elective, especially if vaccinated. The prospect of no hospital stay tipped the scales further toward surgery. The vaccination status of hospital staff played only a minor role in decision making, according to the study, which was published in Vaccine.

But as a post hoc analysis revealed, it was participants who were not vaccinated against COVID-19 in real life who were more willing to undergo surgery, compared with those who had one or two shots.

In either case, too many people were unwilling to undergo lifesaving surgery, even though the risk of hospital-acquired COVID-19 is low. “Making this choice for an actual health problem would result in an unacceptably high rate of potential morbidity attributable to pandemic-related fears, the authors wrote.

In an unusual approach, the researchers used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to electronically recruit 2,006 adults. The participants answered a 26-item survey about a hypothetical surgery in an unnamed pandemic with different combinations of vaccine status for patient and staff.

Coauthor and anesthesiologist Keith J. Ruskin, MD, of the University of Chicago, told this news organization that they “wanted to make this timeless” and independent of COVID “so that when the next thing came about, the paper would still be relevant.”

The researchers were surprised by the findings at the extreme ends of attitudes toward surgery. Some were still willing to have elective surgery with (hypothetically) unvaccinated patients and staff.

“And people at the other end, even though they are vaccinated, the hospital staff is vaccinated, and the surgery is lifesaving, they absolutely won’t have surgery,” Dr. Ruskin said.

He viewed these two groups as opportunities for education. “You can present information in the most positive light to get them to do the right thing with what’s best for themselves,” he said.

As an example, Dr. Ruskin pointed to an ad in Illinois. “It’s not only people saying I’m getting vaccinated for myself and my family, but there are people who said I got vaccinated and I still got COVID, but it could have been much worse. Please, if you’re on the fence, just get vaccinated,” he said.

Coauthor Anna Clebone Ruskin, MD, an anesthesiologist at the University of Chicago, said, “Humans are programmed to see things in extremes. With surgery, people tend to think of surgery as a monolith – surgery is all good, or surgery is all bad, where there is a huge in between. So we saw those extremes. ... Seeing that dichotomy with people on either end was pretty surprising.

“Getting surgery is not always good. Getting surgery is not always bad. It’s a risk-versus-benefit analysis and educating the public to consider the risks and benefits of medical decisions, in general, would be enormously beneficial,” she said.

A post hoc analysis found that “participants who were not actually vaccinated against COVID-19 were generally more willing to undergo surgery compared to those who had one vaccination or two vaccinations,” the authors wrote.

In a second post hoc finding, participants who reported high wariness of vaccines were generally more likely to be willing to undergo surgery. Notably, 15% of participants “were unwilling to undergo lifesaving surgery during a pandemic even when they and the health care staff were vaccinated,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Keith J. Ruskin hypothesized about this result, saying, “What we think is that potentially actually getting vaccinated against COVID-19 may indicate that you have a lower risk tolerance. So you may be less likely to do anything you perceive to be risky if you’re vaccinated against COVID-19.”

The authors stated that “the risk of hospital-acquired COVID-19 even prior to vaccination is vanishingly small.” The risk of nosocomial COVID varies among different studies. An EPIC-based study between April 2020 and October 2021 found the risk to be 1.8%; EPIC describes the fears of a patient catching COVID at a hospital as “likely unfounded.”

In the United Kingdom, the risk was as high as 24% earlier in the pandemic and then declined to approximately 5% a year ago. Omicron also brought more infections. Rates varied significantly among hospitals – and, notably, the risk of death from a nosocomial COVID infection was 21% in April-September 2020.

Emily Landon, MD, an epidemiologist and executive medical director for infection prevention and control at the University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization that the study’s data were collected during Delta, a “time when we thought that this was a pandemic of the unvaccinated. But there was serious politicization of the vaccine.”

Dr. Landon said one of the study’s strengths was the large number of participants. A limitation was, “You’re going to have less participants who are generally poor and indigent, and fewer old participants, probably because they’re less likely to respond to an online survey.

“But the most interesting results are that people who were wary of vaccines or who hadn’t been vaccinated, were much more willing to undergo surgical procedures in the time of a pandemic, regardless of status, which reflects the fact that not being vaccinated correlates with not worrying much about COVID. Vaccinated individuals had a lot more wariness about undergoing surgical procedures during a pandemic.”

It appeared “individuals who were vaccinated in real life [were] worried about staff vaccination,” Dr. Landon noted. She concluded, “I think it supports the need for mandatory vaccinations in health care workers.”

The study has implications for hospital vaccination policies and practices. In Cumberland, Md., when COVID was high and vaccines first became available, the Maryland Hospital Association said that all health care staff should be vaccinated. The local hospital, UPMC–Western Maryland Hospital, refused.

Two months later, the local news reporter, Teresa McMinn, wrote, “While Maryland’s largest hospital systems have ‘led by example by mandating vaccines for all of their hospital staff,’ other facilities – including UPMC Western Maryland and Garrett Regional Medical Center – have taken no such action even though it’s been 8 months since vaccines were made available to health care workers.”

The hospital would not tell patients whether staff were vaccinated, either. An ongoing concern for members of the community is the lack of communication with UPMC, which erodes trust in the health system – the only hospital available in this rural community.

This vaccine study supports that the vaccination status of the staff may influence some patients’ decision on whether to have surgery.

The Ruskins and Dr. Landon have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hormonal contraceptives protective against suicide?

Contrary to previous analyses, new research suggests.

In a study of more than 800 women younger than age 50 who attempted suicide and more than 3,000 age-matched peers, results showed those who took hormonal contraceptives had a 27% reduced risk for attempted suicide.

Further analysis showed this was confined to women without a history of psychiatric illness and the reduction in risk rose to 43% among those who took combined hormonal contraceptives rather than progestin-only versions.

The protective effect against attempted suicide increased further to 46% if ethinyl estradiol (EE)–containing preparations were used. Moreover, the beneficial effect of contraceptive use increased over time.

The main message is the “current use of hormonal contraceptives is not associated with an increased risk of attempted suicide in our population,” study presenter Elena Toffol, MD, PhD, department of public health, University of Helsinki, told meeting attendees at the European Psychiatric Association 2022 Congress.

Age range differences

Dr. Toffol said there could be “several reasons” why the results are different from those in previous studies, including that the researchers included a “larger age range.” She noted it is known that “older women have a lower rate of attempted suicide and use different types of contraceptives.”

Dr. Toffol said in an interview that, although it’s “hard to estimate any causality” because this is an observational study, it is “tempting to speculate, and it is plausible, that hormones partly play a role with some, but not all, women being more sensitive to hormonal influences.”

However, the results “may also reflect life choices or a protective life status; for example, more stable relationships or more conscious and health-focused behaviors,” she said.

“It may also be that the underlying characteristics of women who are prescribed or opt for certain types of contraceptives are somehow related to their suicidal risk,” she added.

In 2019, the global age-standardized suicide rate was 9.0 per 100,000, which translates into more than 700,000 deaths every year, Dr. Toffol noted.

However, she emphasized the World Health Organization has calculated that, for every adult who dies by suicide, more than 20 people attempt suicide. In addition, data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that attempted suicides are three times more common among young women than in men.

“What are the reasons for this gender gap?” Dr. Toffol asked during her presentation.

“It is known that the major risk factor for suicidal behavior is a psychiatric disorder, and in particular depression and mood disorders. And depression and mood disorders are more common in women than in men,” she said.

However, there is also “growing interest into the role of biological factors” in the risk for suicide, including hormones and hormonal contraception. Some studies have also suggested that there is an increased risk for depression and “both completed and attempted suicide” after starting hormonal contraception.

Dr. Toffol added that about 70% of European women use some form of contraception and, among Finnish women, 40% choose a hormonal contraceptive.

Nested analysis

The researchers conducted a nested case-control analysis combining 2017 national prescription data on 587,823 women aged 15-49 years with information from general and primary healthcare registers for the years 2018 to 2019.

They were able to identify 818 cases of attempted suicide among the women. These were matched 4:1 with 3,272 age-matched healthy women who acted as the control group. Use of hormonal contraceptives in the previous 180 days was determined for the whole cohort.

Among users of hormonal contraceptives, there were 344 attempted suicides in 2017, at an incidence rate of 0.59 per 1,000 person-years. This compared with 474 attempted suicides among nonusers, at an incidence rate of 0.81 per 1000 person-years.

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed there was a significant difference in rates for attempted suicide among hormonal contraceptive users versus nonusers, at an incidence rate ratio of 0.73 (P < .0001) – and the difference increased over time.

In addition, the incidence of attempted suicide decreased with increasing age, with the highest incidence rate in women aged 15-19 years (1.62 per 1,000 person-years).

Conditional logistic regression analysis that controlled for education, marital status, chronic disease, recent psychiatric hospitalization, and current use of psychotropic medication showed hormonal contraceptive use was not linked to an increased risk of attempted suicide overall, at an odds ratio of 0.79 (95% confidence interval, 0.56-1.11).

However, when they looked specifically at women without a history of psychiatric illness, the association became significant, at an OR of 0.73 for attempted suicide among hormonal contraceptive users (95% CI, 0.58-0.91), while the relationship remained nonsignificant in women with a history of psychiatric disorders.

Further analysis suggested the significant association was confined to women taking combined hormonal contraceptives, at an OR of 0.57 for suicide attempt versus nonusers (95% CI, 0.44-0.75), and those use EE-containing preparations (OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.40-0.73).

There was a suggestion in the data that hormonal contraceptives containing desogestrel or drospirenone alongside EE may offer the greatest reduction in attempted suicide risk, but that did not survive multivariate analysis.

Dr. Toffol also noted that they were not able to capture data on use of intrauterine devices in their analysis.

“There is a growing number of municipalities in Finland that are providing free-of-charge contraception to young women” that is often an intrauterine device, she said. The researchers hope to include these women in a future analysis.

‘Age matters’

Commenting on the findings, Alexis C. Edwards, PhD, Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, said the current study’s findings “made a lot of sense.” Dr. Edwards wasn’t involved with this study but conducted a previous study of 216,702 Swedish women aged 15-22 years that showed use of combination or progestin-only oral contraceptives was associated with an increased risk for suicidal behavior.

She agreed with Dr. Toffol that the “much larger age range” in the new study may have played a role in showing the opposite result.

“The trajectory that we saw if we had been able to continue following the women for longer – which we couldn’t, due to limitations of the registries – [was that] using hormonal contraceptives was going to end up being protective, so I do think that it matters what age you’re looking at,” she said.

Dr. Edwards noted the takeaway from both studies “is that, even if there is a slight increase in risk from using hormonal contraceptives, it’s short lived and it’s probably specific to young women, which is important.”

She suggested the hormonal benefit from extended contraceptive use could come from the regulation of mood, as it offers a “more stable hormonal course than what their body might be putting them through in the absence of using the pill.”

Overall, it is “really lovely to see very well-executed studies on this, providing more empirical evidence on this question, because it is something that’s relevant to anyone who’s potentially going to be using hormonal contraception,” Dr. Edwards said.

Clinical implications?

Andrea Fiorillo, MD, PhD, department of psychiatry, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli,” Naples, Italy, said in a press release that the “striking” findings of the current study need “careful evaluation.”

They also need to be replicated in “different cohorts of women and controlled for the impact of several psychosocial stressors, such as economic upheavals, social insecurity, and uncertainty due to the COVID pandemic,” said Dr. Fiorillo, who was not involved with the research.

Nevertheless, she believes the “clinical implications of the study are obvious and may help to destigmatize the use of hormonal contraceptives.”

The study was funded by the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, the Avohoidon Tsukimis äätiö (Foundation for Primary Care Research), the Yrj ö Jahnsson Foundation, and the Finnish Cultural Foundation. No relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Contrary to previous analyses, new research suggests.

In a study of more than 800 women younger than age 50 who attempted suicide and more than 3,000 age-matched peers, results showed those who took hormonal contraceptives had a 27% reduced risk for attempted suicide.

Further analysis showed this was confined to women without a history of psychiatric illness and the reduction in risk rose to 43% among those who took combined hormonal contraceptives rather than progestin-only versions.

The protective effect against attempted suicide increased further to 46% if ethinyl estradiol (EE)–containing preparations were used. Moreover, the beneficial effect of contraceptive use increased over time.

The main message is the “current use of hormonal contraceptives is not associated with an increased risk of attempted suicide in our population,” study presenter Elena Toffol, MD, PhD, department of public health, University of Helsinki, told meeting attendees at the European Psychiatric Association 2022 Congress.

Age range differences

Dr. Toffol said there could be “several reasons” why the results are different from those in previous studies, including that the researchers included a “larger age range.” She noted it is known that “older women have a lower rate of attempted suicide and use different types of contraceptives.”

Dr. Toffol said in an interview that, although it’s “hard to estimate any causality” because this is an observational study, it is “tempting to speculate, and it is plausible, that hormones partly play a role with some, but not all, women being more sensitive to hormonal influences.”

However, the results “may also reflect life choices or a protective life status; for example, more stable relationships or more conscious and health-focused behaviors,” she said.

“It may also be that the underlying characteristics of women who are prescribed or opt for certain types of contraceptives are somehow related to their suicidal risk,” she added.

In 2019, the global age-standardized suicide rate was 9.0 per 100,000, which translates into more than 700,000 deaths every year, Dr. Toffol noted.

However, she emphasized the World Health Organization has calculated that, for every adult who dies by suicide, more than 20 people attempt suicide. In addition, data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that attempted suicides are three times more common among young women than in men.

“What are the reasons for this gender gap?” Dr. Toffol asked during her presentation.

“It is known that the major risk factor for suicidal behavior is a psychiatric disorder, and in particular depression and mood disorders. And depression and mood disorders are more common in women than in men,” she said.

However, there is also “growing interest into the role of biological factors” in the risk for suicide, including hormones and hormonal contraception. Some studies have also suggested that there is an increased risk for depression and “both completed and attempted suicide” after starting hormonal contraception.

Dr. Toffol added that about 70% of European women use some form of contraception and, among Finnish women, 40% choose a hormonal contraceptive.

Nested analysis

The researchers conducted a nested case-control analysis combining 2017 national prescription data on 587,823 women aged 15-49 years with information from general and primary healthcare registers for the years 2018 to 2019.

They were able to identify 818 cases of attempted suicide among the women. These were matched 4:1 with 3,272 age-matched healthy women who acted as the control group. Use of hormonal contraceptives in the previous 180 days was determined for the whole cohort.

Among users of hormonal contraceptives, there were 344 attempted suicides in 2017, at an incidence rate of 0.59 per 1,000 person-years. This compared with 474 attempted suicides among nonusers, at an incidence rate of 0.81 per 1000 person-years.

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed there was a significant difference in rates for attempted suicide among hormonal contraceptive users versus nonusers, at an incidence rate ratio of 0.73 (P < .0001) – and the difference increased over time.

In addition, the incidence of attempted suicide decreased with increasing age, with the highest incidence rate in women aged 15-19 years (1.62 per 1,000 person-years).

Conditional logistic regression analysis that controlled for education, marital status, chronic disease, recent psychiatric hospitalization, and current use of psychotropic medication showed hormonal contraceptive use was not linked to an increased risk of attempted suicide overall, at an odds ratio of 0.79 (95% confidence interval, 0.56-1.11).

However, when they looked specifically at women without a history of psychiatric illness, the association became significant, at an OR of 0.73 for attempted suicide among hormonal contraceptive users (95% CI, 0.58-0.91), while the relationship remained nonsignificant in women with a history of psychiatric disorders.

Further analysis suggested the significant association was confined to women taking combined hormonal contraceptives, at an OR of 0.57 for suicide attempt versus nonusers (95% CI, 0.44-0.75), and those use EE-containing preparations (OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.40-0.73).

There was a suggestion in the data that hormonal contraceptives containing desogestrel or drospirenone alongside EE may offer the greatest reduction in attempted suicide risk, but that did not survive multivariate analysis.

Dr. Toffol also noted that they were not able to capture data on use of intrauterine devices in their analysis.

“There is a growing number of municipalities in Finland that are providing free-of-charge contraception to young women” that is often an intrauterine device, she said. The researchers hope to include these women in a future analysis.

‘Age matters’

Commenting on the findings, Alexis C. Edwards, PhD, Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, said the current study’s findings “made a lot of sense.” Dr. Edwards wasn’t involved with this study but conducted a previous study of 216,702 Swedish women aged 15-22 years that showed use of combination or progestin-only oral contraceptives was associated with an increased risk for suicidal behavior.

She agreed with Dr. Toffol that the “much larger age range” in the new study may have played a role in showing the opposite result.

“The trajectory that we saw if we had been able to continue following the women for longer – which we couldn’t, due to limitations of the registries – [was that] using hormonal contraceptives was going to end up being protective, so I do think that it matters what age you’re looking at,” she said.

Dr. Edwards noted the takeaway from both studies “is that, even if there is a slight increase in risk from using hormonal contraceptives, it’s short lived and it’s probably specific to young women, which is important.”

She suggested the hormonal benefit from extended contraceptive use could come from the regulation of mood, as it offers a “more stable hormonal course than what their body might be putting them through in the absence of using the pill.”

Overall, it is “really lovely to see very well-executed studies on this, providing more empirical evidence on this question, because it is something that’s relevant to anyone who’s potentially going to be using hormonal contraception,” Dr. Edwards said.

Clinical implications?

Andrea Fiorillo, MD, PhD, department of psychiatry, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli,” Naples, Italy, said in a press release that the “striking” findings of the current study need “careful evaluation.”

They also need to be replicated in “different cohorts of women and controlled for the impact of several psychosocial stressors, such as economic upheavals, social insecurity, and uncertainty due to the COVID pandemic,” said Dr. Fiorillo, who was not involved with the research.

Nevertheless, she believes the “clinical implications of the study are obvious and may help to destigmatize the use of hormonal contraceptives.”

The study was funded by the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, the Avohoidon Tsukimis äätiö (Foundation for Primary Care Research), the Yrj ö Jahnsson Foundation, and the Finnish Cultural Foundation. No relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Contrary to previous analyses, new research suggests.

In a study of more than 800 women younger than age 50 who attempted suicide and more than 3,000 age-matched peers, results showed those who took hormonal contraceptives had a 27% reduced risk for attempted suicide.

Further analysis showed this was confined to women without a history of psychiatric illness and the reduction in risk rose to 43% among those who took combined hormonal contraceptives rather than progestin-only versions.

The protective effect against attempted suicide increased further to 46% if ethinyl estradiol (EE)–containing preparations were used. Moreover, the beneficial effect of contraceptive use increased over time.

The main message is the “current use of hormonal contraceptives is not associated with an increased risk of attempted suicide in our population,” study presenter Elena Toffol, MD, PhD, department of public health, University of Helsinki, told meeting attendees at the European Psychiatric Association 2022 Congress.

Age range differences

Dr. Toffol said there could be “several reasons” why the results are different from those in previous studies, including that the researchers included a “larger age range.” She noted it is known that “older women have a lower rate of attempted suicide and use different types of contraceptives.”

Dr. Toffol said in an interview that, although it’s “hard to estimate any causality” because this is an observational study, it is “tempting to speculate, and it is plausible, that hormones partly play a role with some, but not all, women being more sensitive to hormonal influences.”

However, the results “may also reflect life choices or a protective life status; for example, more stable relationships or more conscious and health-focused behaviors,” she said.

“It may also be that the underlying characteristics of women who are prescribed or opt for certain types of contraceptives are somehow related to their suicidal risk,” she added.

In 2019, the global age-standardized suicide rate was 9.0 per 100,000, which translates into more than 700,000 deaths every year, Dr. Toffol noted.

However, she emphasized the World Health Organization has calculated that, for every adult who dies by suicide, more than 20 people attempt suicide. In addition, data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that attempted suicides are three times more common among young women than in men.