User login

Longitudinal course of atopic dermatitis often overlooked, expert says

In the opinion of Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, the longitudinal course of atopic dermatitis (AD) is an important yet overlooked clinical domain of the disease.

“We know that AD is associated with fluctuating severity, disease flares, long-term persistence, and periods of quiescence, but its longitudinal course is not routinely incorporated into guidelines or clinical trials,” Dr. Chovatiya, assistant professor in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said during the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. “Understanding the long-term course may improve our ability to phenotype, prognosticate, and personalize our care.”

The classic view of AD is that it starts in early childhood, follows a waxing and waning course for a few years, and burns out by adulthood. “I think we all know that this is generally false,” he said. “This was largely based on anecdotal clinical experience and large cross-sectional studies, not ones that consider the heterogeneity of AD.”

Results from a large-scale, prospective study of 7,157 children enrolled in the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), suggests that AD commonly persists beyond adulthood. PEER was a phase IV postmarketing safety study of children aged 12-17 with moderate to severe AD who were exposed to topical pimecrolimus and who were surveyed every 6 months (JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150[6]:593-600). The researchers found that more persistent disease was associated with self-reported disease activity, many environmental exposures, White race, history of AD, and an annual household income of less than $50,000. By age 20, 50% reported at least one 6-month symptom- and medication-free period. “The important takeaway was that at every age, greater than 80% reported active AD as defined by symptoms or medication use, meaning that persistence was extremely high – much higher than what was originally thought,” Dr. Chovatiya said. “If you take a look at the literature before this study, many were retrospective analyses, and persistence was estimated to be in the 40%-60% range.”

International prospective studies have provided a more conservative estimate of persistence. For example, the German Multicenter Allergy Study followed 1,314 from birth through age 7 (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113[5]:925-31). Of these, 22% had AD within the first 2 years of life. Of these, 43% were in remission by age 3, while 38% had intermittent AD, and 19% had symptoms every year of the study. “Studies of other birth cohorts in the world came out suggesting that the rates of AD persistence ranges in the single digits to the teens,” Dr. Chovatiya said.

To reconcile these heterogeneous estimates of AD persistence, researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 45 studies that included 110,651 subjects from 15 countries and spanned 434,992 patient-years (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:681-7.e11). They found that 80% of childhood AD had at least one observed period of disease clearance by 8 years of age. “Most importantly, less than 5% of childhood AD was persistent 20 years after diagnosis,” Dr. Chovatiya said. “However, interestingly, increased persistence was associated with later onset AD, more years of persistence, and more patient/caregiver-assessed disease.” He pointed out inherent limitations to all studies of AD persistence, including nonuniform methods of data collection, differing cohorts, different ways of diagnosing AD, different disease severity scales, and the fact that most don’t assess flares or recurrence beyond the initial period of disease clearance. “This can lead to a potential underestimation of longer-term persistence,” he said.

Childhood AD features unique predictors of persistence that may define AD trajectories. For example, in several existing studies, more persistent disease was associated with higher baseline severity, earlier-onset AD, personal history of atopy, family history of AD, AD genetic risk score (heritability, including common Filaggrin mutations), urban environment, non-White race, Hispanic ethnicity, female sex, lower household income, and overall poorer health status.

Dr. Chovatiya said. “I think that AD classification can take a lesson from asthma. When we think about how our allergy colleagues think about asthma, it is commonly classified as intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent, and severe persistent. Those that have intermittent disease get reactive treatment, while those with persistent disease get proactive treatment. Similarly, AD could be classified as mild intermittent, mild persistent, moderate to severe intermittent and moderate to severe persistent.”

He concluded his presentation by recommending that the fluctuating course of AD be better captured in clinical trials. “Current randomized, controlled trials use validated measures of AD signs and symptoms as inclusion criteria and measures of efficacy,” he said. “Static assessments may confound treatment effects, and assessment of prespecified time points are somewhat arbitrary in the context of disease subsets.” He proposes studies that examine aggregate measures of long-term disease control, such as number of itch-free days, weeks with clear skin, and flares experienced. “Long-term control assessment in RCTs should include signs, symptoms, health-related quality of life, and a patient global domain over time to better understand how AD is doing in the long run,” he said.

Dr. Chovatiya disclosed that he is a consultant to, a speaker for, and/or a member of the advisory board for AbbVie, Arcutis, Arena, Incyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme.

In the opinion of Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, the longitudinal course of atopic dermatitis (AD) is an important yet overlooked clinical domain of the disease.

“We know that AD is associated with fluctuating severity, disease flares, long-term persistence, and periods of quiescence, but its longitudinal course is not routinely incorporated into guidelines or clinical trials,” Dr. Chovatiya, assistant professor in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said during the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. “Understanding the long-term course may improve our ability to phenotype, prognosticate, and personalize our care.”

The classic view of AD is that it starts in early childhood, follows a waxing and waning course for a few years, and burns out by adulthood. “I think we all know that this is generally false,” he said. “This was largely based on anecdotal clinical experience and large cross-sectional studies, not ones that consider the heterogeneity of AD.”

Results from a large-scale, prospective study of 7,157 children enrolled in the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), suggests that AD commonly persists beyond adulthood. PEER was a phase IV postmarketing safety study of children aged 12-17 with moderate to severe AD who were exposed to topical pimecrolimus and who were surveyed every 6 months (JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150[6]:593-600). The researchers found that more persistent disease was associated with self-reported disease activity, many environmental exposures, White race, history of AD, and an annual household income of less than $50,000. By age 20, 50% reported at least one 6-month symptom- and medication-free period. “The important takeaway was that at every age, greater than 80% reported active AD as defined by symptoms or medication use, meaning that persistence was extremely high – much higher than what was originally thought,” Dr. Chovatiya said. “If you take a look at the literature before this study, many were retrospective analyses, and persistence was estimated to be in the 40%-60% range.”

International prospective studies have provided a more conservative estimate of persistence. For example, the German Multicenter Allergy Study followed 1,314 from birth through age 7 (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113[5]:925-31). Of these, 22% had AD within the first 2 years of life. Of these, 43% were in remission by age 3, while 38% had intermittent AD, and 19% had symptoms every year of the study. “Studies of other birth cohorts in the world came out suggesting that the rates of AD persistence ranges in the single digits to the teens,” Dr. Chovatiya said.

To reconcile these heterogeneous estimates of AD persistence, researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 45 studies that included 110,651 subjects from 15 countries and spanned 434,992 patient-years (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:681-7.e11). They found that 80% of childhood AD had at least one observed period of disease clearance by 8 years of age. “Most importantly, less than 5% of childhood AD was persistent 20 years after diagnosis,” Dr. Chovatiya said. “However, interestingly, increased persistence was associated with later onset AD, more years of persistence, and more patient/caregiver-assessed disease.” He pointed out inherent limitations to all studies of AD persistence, including nonuniform methods of data collection, differing cohorts, different ways of diagnosing AD, different disease severity scales, and the fact that most don’t assess flares or recurrence beyond the initial period of disease clearance. “This can lead to a potential underestimation of longer-term persistence,” he said.

Childhood AD features unique predictors of persistence that may define AD trajectories. For example, in several existing studies, more persistent disease was associated with higher baseline severity, earlier-onset AD, personal history of atopy, family history of AD, AD genetic risk score (heritability, including common Filaggrin mutations), urban environment, non-White race, Hispanic ethnicity, female sex, lower household income, and overall poorer health status.

Dr. Chovatiya said. “I think that AD classification can take a lesson from asthma. When we think about how our allergy colleagues think about asthma, it is commonly classified as intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent, and severe persistent. Those that have intermittent disease get reactive treatment, while those with persistent disease get proactive treatment. Similarly, AD could be classified as mild intermittent, mild persistent, moderate to severe intermittent and moderate to severe persistent.”

He concluded his presentation by recommending that the fluctuating course of AD be better captured in clinical trials. “Current randomized, controlled trials use validated measures of AD signs and symptoms as inclusion criteria and measures of efficacy,” he said. “Static assessments may confound treatment effects, and assessment of prespecified time points are somewhat arbitrary in the context of disease subsets.” He proposes studies that examine aggregate measures of long-term disease control, such as number of itch-free days, weeks with clear skin, and flares experienced. “Long-term control assessment in RCTs should include signs, symptoms, health-related quality of life, and a patient global domain over time to better understand how AD is doing in the long run,” he said.

Dr. Chovatiya disclosed that he is a consultant to, a speaker for, and/or a member of the advisory board for AbbVie, Arcutis, Arena, Incyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme.

In the opinion of Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, the longitudinal course of atopic dermatitis (AD) is an important yet overlooked clinical domain of the disease.

“We know that AD is associated with fluctuating severity, disease flares, long-term persistence, and periods of quiescence, but its longitudinal course is not routinely incorporated into guidelines or clinical trials,” Dr. Chovatiya, assistant professor in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said during the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. “Understanding the long-term course may improve our ability to phenotype, prognosticate, and personalize our care.”

The classic view of AD is that it starts in early childhood, follows a waxing and waning course for a few years, and burns out by adulthood. “I think we all know that this is generally false,” he said. “This was largely based on anecdotal clinical experience and large cross-sectional studies, not ones that consider the heterogeneity of AD.”

Results from a large-scale, prospective study of 7,157 children enrolled in the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), suggests that AD commonly persists beyond adulthood. PEER was a phase IV postmarketing safety study of children aged 12-17 with moderate to severe AD who were exposed to topical pimecrolimus and who were surveyed every 6 months (JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150[6]:593-600). The researchers found that more persistent disease was associated with self-reported disease activity, many environmental exposures, White race, history of AD, and an annual household income of less than $50,000. By age 20, 50% reported at least one 6-month symptom- and medication-free period. “The important takeaway was that at every age, greater than 80% reported active AD as defined by symptoms or medication use, meaning that persistence was extremely high – much higher than what was originally thought,” Dr. Chovatiya said. “If you take a look at the literature before this study, many were retrospective analyses, and persistence was estimated to be in the 40%-60% range.”

International prospective studies have provided a more conservative estimate of persistence. For example, the German Multicenter Allergy Study followed 1,314 from birth through age 7 (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113[5]:925-31). Of these, 22% had AD within the first 2 years of life. Of these, 43% were in remission by age 3, while 38% had intermittent AD, and 19% had symptoms every year of the study. “Studies of other birth cohorts in the world came out suggesting that the rates of AD persistence ranges in the single digits to the teens,” Dr. Chovatiya said.

To reconcile these heterogeneous estimates of AD persistence, researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 45 studies that included 110,651 subjects from 15 countries and spanned 434,992 patient-years (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:681-7.e11). They found that 80% of childhood AD had at least one observed period of disease clearance by 8 years of age. “Most importantly, less than 5% of childhood AD was persistent 20 years after diagnosis,” Dr. Chovatiya said. “However, interestingly, increased persistence was associated with later onset AD, more years of persistence, and more patient/caregiver-assessed disease.” He pointed out inherent limitations to all studies of AD persistence, including nonuniform methods of data collection, differing cohorts, different ways of diagnosing AD, different disease severity scales, and the fact that most don’t assess flares or recurrence beyond the initial period of disease clearance. “This can lead to a potential underestimation of longer-term persistence,” he said.

Childhood AD features unique predictors of persistence that may define AD trajectories. For example, in several existing studies, more persistent disease was associated with higher baseline severity, earlier-onset AD, personal history of atopy, family history of AD, AD genetic risk score (heritability, including common Filaggrin mutations), urban environment, non-White race, Hispanic ethnicity, female sex, lower household income, and overall poorer health status.

Dr. Chovatiya said. “I think that AD classification can take a lesson from asthma. When we think about how our allergy colleagues think about asthma, it is commonly classified as intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent, and severe persistent. Those that have intermittent disease get reactive treatment, while those with persistent disease get proactive treatment. Similarly, AD could be classified as mild intermittent, mild persistent, moderate to severe intermittent and moderate to severe persistent.”

He concluded his presentation by recommending that the fluctuating course of AD be better captured in clinical trials. “Current randomized, controlled trials use validated measures of AD signs and symptoms as inclusion criteria and measures of efficacy,” he said. “Static assessments may confound treatment effects, and assessment of prespecified time points are somewhat arbitrary in the context of disease subsets.” He proposes studies that examine aggregate measures of long-term disease control, such as number of itch-free days, weeks with clear skin, and flares experienced. “Long-term control assessment in RCTs should include signs, symptoms, health-related quality of life, and a patient global domain over time to better understand how AD is doing in the long run,” he said.

Dr. Chovatiya disclosed that he is a consultant to, a speaker for, and/or a member of the advisory board for AbbVie, Arcutis, Arena, Incyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme.

FROM REVOLUTIONIZING AD 2021

Benign adrenal tumors linked to hypertension, type 2 diabetes

In more than 15% of people with benign adrenal tumors, the growths produce clinically relevant levels of serum cortisol that are significantly linked with an increased prevalence of hypertension and, in 5% of those with Cushing syndrome (CS), an increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes, based on data from more than 1,300 people with benign adrenal tumors, the largest reported prospective study of the disorder.

The study results showed that mild autonomous cortisol secretion (MACS) from benign adrenal tumors “is very frequent and is an important risk condition for high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, especially in older women,” said Alessandro Prete, MD, lead author of the study which was published online Jan. 3, 2022, in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“The impact of MACS on high blood pressure and risk for type 2 diabetes has been underestimated until now,” said Dr. Prete, an endocrinologist at the University of Birmingham (England), in a written statement.

Results from previous studies “suggested that MACS is associated with poor health. Our study is the largest to establish conclusively the extent of the risk and severity of high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes in patients with MACS,” said Wiebke Arlt, MD, DSc, senior author and director of the Institute of Metabolism & Systems Research at the University of Birmingham.

All patients found to have a benign adrenal tumor should undergo testing for MACS and have their blood pressure and glucose levels measured regularly, Dr. Arlt advised in the statement released by the University of Birmingham.

MACS more common than previously thought

The new findings show that MACS “is more common and may have a more negative impact on health than previously thought, including increasing the risk for type 2 diabetes,” commented Lucy Chambers, PhD, head of research communications at Diabetes UK. “The findings suggest that screening for MACS could help identify people – particularly women, in whom the condition was found to be more common – who may benefit from support to reduce their risk of type 2 diabetes.”

The study included 1,305 people with newly diagnosed, benign adrenal tumors greater than 1 cm, a subset of patients prospectively enrolled in a study with the primary purpose of validating a novel way to diagnose adrenocortical carcinomas. Patients underwent treatment in 2011-2016 at any of 14 tertiary centers in 11 countries.

Researchers used a MACS definition of failure to suppress morning serum cortisol concentration to less than 50 nmol/L after treatment with 1 mg oral dexamethasone at 11 p.m. the previous evening in those with no clinical features of CS.

Roughly half of patients (n = 649) showed normal cortisol suppression with dexamethasone, identifying them as having nonfunctioning adrenal tumors, and about 35% showed possible MACS based on having moderate levels of excess cortisol.

Nearly 11% (n = 140) showed definitive MACS with more robust cortisol levels, and 5% (n = 65) received a diagnosis of clinically overt CS despite selection criteria meant to exclude people with clinical signs of CS.

There was a clear relationship between patient sex and severity of autonomous cortisol production. Among those with nonfunctioning adrenal tumors, 64% were women, which rose to 74% women in those with definitive MACS and 86% women among those with CS. The median age of participants was 60 years old.

Increasing cortisol levels linked with cardiometabolic disease

Analysis of the prevalence of hypertension and type 2 diabetes after adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index showed that, compared with people with nonfunctioning adrenal tumors, those with definitive MACS had a significant 15% higher rate of hypertension and those with overt CS had a 37% higher rate.

Higher levels of excess cortisol were also directly linked with an increased need for treatment with three or more antihypertensive agents to control blood pressure. Those with definitive MACS had a significant 31% higher rate of being on three or more drugs, and those with overt CS had a greater than twofold higher rate.

People with overt CS also had a significant 62% higher rate of type 2 diabetes, compared with those with a nonfunctioning tumor, but in those with definitive MACS the association was not significant. However, people with definitive MACS or overt CS who had type 2 diabetes and also had significantly increased rates of requiring insulin treatment.

The findings show that “people with definitive MACS carry an increased cardiometabolic burden similar to that seen in CS even if they do not display typical features of clinically overt cortisol excess,” the authors wrote in the report.

Even among those with apparently nonfunctioning tumors, each 10 nmol/L rise in cortisol level during a dexamethasone-suppression test was associated with a higher cardiometabolic disease burden. This observation suggests that current diagnostic cutoffs for the suppression test may miss some people with clinically relevant autonomous cortisol secretion, the report said. The study findings also suggest that people with benign adrenal tumors show a progressive continuum of excess cortisol with clinical consequences that increase as levels increase.

Determine the consequences of cortisol secretion

“These data clearly support the European Society of Endocrinology guideline recommendations that clinicians should determine precisely the cardiometabolic consequences of mild cortisol secretion in patients with adrenal lesions,” André Lacroix, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

But Dr. Lacroix included some caveats. He noted the “potential pitfalls in relying on a single total serum cortisol value after the 1-mg dexamethasone test.” He also wondered whether the analysis used optimal cortisol values to distinguish patient subgroups.

Plus, “even in patients with nonfunctioning adrenal tumors the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension is higher than in the general population, raising concerns about the cardiometabolic consequences of barely detectable cortisol excess,” wrote Dr. Lacroix, an endocrinologist at the CHUM Research Center and professor of medicine at the University of Montreal.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Prete, Dr. Chambers, and Dr. Lacroix have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Arlt is listed as an inventor on a patent on the use of steroid profiling as a biomarker tool for the differential diagnosis of adrenal tumors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In more than 15% of people with benign adrenal tumors, the growths produce clinically relevant levels of serum cortisol that are significantly linked with an increased prevalence of hypertension and, in 5% of those with Cushing syndrome (CS), an increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes, based on data from more than 1,300 people with benign adrenal tumors, the largest reported prospective study of the disorder.

The study results showed that mild autonomous cortisol secretion (MACS) from benign adrenal tumors “is very frequent and is an important risk condition for high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, especially in older women,” said Alessandro Prete, MD, lead author of the study which was published online Jan. 3, 2022, in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“The impact of MACS on high blood pressure and risk for type 2 diabetes has been underestimated until now,” said Dr. Prete, an endocrinologist at the University of Birmingham (England), in a written statement.

Results from previous studies “suggested that MACS is associated with poor health. Our study is the largest to establish conclusively the extent of the risk and severity of high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes in patients with MACS,” said Wiebke Arlt, MD, DSc, senior author and director of the Institute of Metabolism & Systems Research at the University of Birmingham.

All patients found to have a benign adrenal tumor should undergo testing for MACS and have their blood pressure and glucose levels measured regularly, Dr. Arlt advised in the statement released by the University of Birmingham.

MACS more common than previously thought

The new findings show that MACS “is more common and may have a more negative impact on health than previously thought, including increasing the risk for type 2 diabetes,” commented Lucy Chambers, PhD, head of research communications at Diabetes UK. “The findings suggest that screening for MACS could help identify people – particularly women, in whom the condition was found to be more common – who may benefit from support to reduce their risk of type 2 diabetes.”

The study included 1,305 people with newly diagnosed, benign adrenal tumors greater than 1 cm, a subset of patients prospectively enrolled in a study with the primary purpose of validating a novel way to diagnose adrenocortical carcinomas. Patients underwent treatment in 2011-2016 at any of 14 tertiary centers in 11 countries.

Researchers used a MACS definition of failure to suppress morning serum cortisol concentration to less than 50 nmol/L after treatment with 1 mg oral dexamethasone at 11 p.m. the previous evening in those with no clinical features of CS.

Roughly half of patients (n = 649) showed normal cortisol suppression with dexamethasone, identifying them as having nonfunctioning adrenal tumors, and about 35% showed possible MACS based on having moderate levels of excess cortisol.

Nearly 11% (n = 140) showed definitive MACS with more robust cortisol levels, and 5% (n = 65) received a diagnosis of clinically overt CS despite selection criteria meant to exclude people with clinical signs of CS.

There was a clear relationship between patient sex and severity of autonomous cortisol production. Among those with nonfunctioning adrenal tumors, 64% were women, which rose to 74% women in those with definitive MACS and 86% women among those with CS. The median age of participants was 60 years old.

Increasing cortisol levels linked with cardiometabolic disease

Analysis of the prevalence of hypertension and type 2 diabetes after adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index showed that, compared with people with nonfunctioning adrenal tumors, those with definitive MACS had a significant 15% higher rate of hypertension and those with overt CS had a 37% higher rate.

Higher levels of excess cortisol were also directly linked with an increased need for treatment with three or more antihypertensive agents to control blood pressure. Those with definitive MACS had a significant 31% higher rate of being on three or more drugs, and those with overt CS had a greater than twofold higher rate.

People with overt CS also had a significant 62% higher rate of type 2 diabetes, compared with those with a nonfunctioning tumor, but in those with definitive MACS the association was not significant. However, people with definitive MACS or overt CS who had type 2 diabetes and also had significantly increased rates of requiring insulin treatment.

The findings show that “people with definitive MACS carry an increased cardiometabolic burden similar to that seen in CS even if they do not display typical features of clinically overt cortisol excess,” the authors wrote in the report.

Even among those with apparently nonfunctioning tumors, each 10 nmol/L rise in cortisol level during a dexamethasone-suppression test was associated with a higher cardiometabolic disease burden. This observation suggests that current diagnostic cutoffs for the suppression test may miss some people with clinically relevant autonomous cortisol secretion, the report said. The study findings also suggest that people with benign adrenal tumors show a progressive continuum of excess cortisol with clinical consequences that increase as levels increase.

Determine the consequences of cortisol secretion

“These data clearly support the European Society of Endocrinology guideline recommendations that clinicians should determine precisely the cardiometabolic consequences of mild cortisol secretion in patients with adrenal lesions,” André Lacroix, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

But Dr. Lacroix included some caveats. He noted the “potential pitfalls in relying on a single total serum cortisol value after the 1-mg dexamethasone test.” He also wondered whether the analysis used optimal cortisol values to distinguish patient subgroups.

Plus, “even in patients with nonfunctioning adrenal tumors the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension is higher than in the general population, raising concerns about the cardiometabolic consequences of barely detectable cortisol excess,” wrote Dr. Lacroix, an endocrinologist at the CHUM Research Center and professor of medicine at the University of Montreal.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Prete, Dr. Chambers, and Dr. Lacroix have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Arlt is listed as an inventor on a patent on the use of steroid profiling as a biomarker tool for the differential diagnosis of adrenal tumors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In more than 15% of people with benign adrenal tumors, the growths produce clinically relevant levels of serum cortisol that are significantly linked with an increased prevalence of hypertension and, in 5% of those with Cushing syndrome (CS), an increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes, based on data from more than 1,300 people with benign adrenal tumors, the largest reported prospective study of the disorder.

The study results showed that mild autonomous cortisol secretion (MACS) from benign adrenal tumors “is very frequent and is an important risk condition for high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, especially in older women,” said Alessandro Prete, MD, lead author of the study which was published online Jan. 3, 2022, in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“The impact of MACS on high blood pressure and risk for type 2 diabetes has been underestimated until now,” said Dr. Prete, an endocrinologist at the University of Birmingham (England), in a written statement.

Results from previous studies “suggested that MACS is associated with poor health. Our study is the largest to establish conclusively the extent of the risk and severity of high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes in patients with MACS,” said Wiebke Arlt, MD, DSc, senior author and director of the Institute of Metabolism & Systems Research at the University of Birmingham.

All patients found to have a benign adrenal tumor should undergo testing for MACS and have their blood pressure and glucose levels measured regularly, Dr. Arlt advised in the statement released by the University of Birmingham.

MACS more common than previously thought

The new findings show that MACS “is more common and may have a more negative impact on health than previously thought, including increasing the risk for type 2 diabetes,” commented Lucy Chambers, PhD, head of research communications at Diabetes UK. “The findings suggest that screening for MACS could help identify people – particularly women, in whom the condition was found to be more common – who may benefit from support to reduce their risk of type 2 diabetes.”

The study included 1,305 people with newly diagnosed, benign adrenal tumors greater than 1 cm, a subset of patients prospectively enrolled in a study with the primary purpose of validating a novel way to diagnose adrenocortical carcinomas. Patients underwent treatment in 2011-2016 at any of 14 tertiary centers in 11 countries.

Researchers used a MACS definition of failure to suppress morning serum cortisol concentration to less than 50 nmol/L after treatment with 1 mg oral dexamethasone at 11 p.m. the previous evening in those with no clinical features of CS.

Roughly half of patients (n = 649) showed normal cortisol suppression with dexamethasone, identifying them as having nonfunctioning adrenal tumors, and about 35% showed possible MACS based on having moderate levels of excess cortisol.

Nearly 11% (n = 140) showed definitive MACS with more robust cortisol levels, and 5% (n = 65) received a diagnosis of clinically overt CS despite selection criteria meant to exclude people with clinical signs of CS.

There was a clear relationship between patient sex and severity of autonomous cortisol production. Among those with nonfunctioning adrenal tumors, 64% were women, which rose to 74% women in those with definitive MACS and 86% women among those with CS. The median age of participants was 60 years old.

Increasing cortisol levels linked with cardiometabolic disease

Analysis of the prevalence of hypertension and type 2 diabetes after adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index showed that, compared with people with nonfunctioning adrenal tumors, those with definitive MACS had a significant 15% higher rate of hypertension and those with overt CS had a 37% higher rate.

Higher levels of excess cortisol were also directly linked with an increased need for treatment with three or more antihypertensive agents to control blood pressure. Those with definitive MACS had a significant 31% higher rate of being on three or more drugs, and those with overt CS had a greater than twofold higher rate.

People with overt CS also had a significant 62% higher rate of type 2 diabetes, compared with those with a nonfunctioning tumor, but in those with definitive MACS the association was not significant. However, people with definitive MACS or overt CS who had type 2 diabetes and also had significantly increased rates of requiring insulin treatment.

The findings show that “people with definitive MACS carry an increased cardiometabolic burden similar to that seen in CS even if they do not display typical features of clinically overt cortisol excess,” the authors wrote in the report.

Even among those with apparently nonfunctioning tumors, each 10 nmol/L rise in cortisol level during a dexamethasone-suppression test was associated with a higher cardiometabolic disease burden. This observation suggests that current diagnostic cutoffs for the suppression test may miss some people with clinically relevant autonomous cortisol secretion, the report said. The study findings also suggest that people with benign adrenal tumors show a progressive continuum of excess cortisol with clinical consequences that increase as levels increase.

Determine the consequences of cortisol secretion

“These data clearly support the European Society of Endocrinology guideline recommendations that clinicians should determine precisely the cardiometabolic consequences of mild cortisol secretion in patients with adrenal lesions,” André Lacroix, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

But Dr. Lacroix included some caveats. He noted the “potential pitfalls in relying on a single total serum cortisol value after the 1-mg dexamethasone test.” He also wondered whether the analysis used optimal cortisol values to distinguish patient subgroups.

Plus, “even in patients with nonfunctioning adrenal tumors the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension is higher than in the general population, raising concerns about the cardiometabolic consequences of barely detectable cortisol excess,” wrote Dr. Lacroix, an endocrinologist at the CHUM Research Center and professor of medicine at the University of Montreal.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Prete, Dr. Chambers, and Dr. Lacroix have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Arlt is listed as an inventor on a patent on the use of steroid profiling as a biomarker tool for the differential diagnosis of adrenal tumors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

CDC panel recommends Pfizer COVID-19 boosters for ages 12-15

The CDC had already said 16- and 17-year-olds “may” receive a Pfizer booster but the new recommendation adds the 12- to 15-year-old group and strengthens the “may” to “should” for 16- and 17-year-olds.

The committee voted 13-1 to recommend the booster for ages 12-17. CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, must still approve the recommendation for it to take effect.

The vote comes after the FDA on Jan. 3 authorized the Pfizer vaccine booster dose for 12- to 15-year-olds.

The FDA action updated the authorization for the Pfizer vaccine, and the agency also shortened the recommended time between a second dose and the booster to 5 months or more (from 6 months). A third primary series dose is also now authorized for certain immunocompromised children between 5 and 11 years old. Full details are available in an FDA news release.

The CDC on Jan. 4 also backed the shortened time frame and a third primary series dose for some immunocompromised children 5-11 years old. But the CDC delayed a decision on a booster for 12- to 15-year-olds until it heard from its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices on Jan. 5.

The decision came as school districts nationwide are wrestling with decisions of whether to keep schools open or revert to a virtual format as cases surge, and as pediatric COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations reach new highs.

The only dissenting vote came from Helen Keipp Talbot, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

She said after the vote, “I am just fine with kids getting a booster. This is not me against all boosters. I just really want the U.S. to move forward with all kids.”

Dr. Talbot said earlier in the comment period, “If we divert our public health from the unvaccinated to the vaccinated, we are not going to make a big impact. Boosters are incredibly important but they won’t solve this problem of the crowded hospitals.”

She said vaccinating the unvaccinated must be the priority.

“If you are a parent out there who has not yet vaccinated your child because you have questions, please, please talk to a health care provider,” she said.

Among the 13 supporters of the recommendation was Oliver Brooks, MD, chief medical officer of Watts HealthCare Corporation in Los Angeles.

Dr. Brooks said extending the population for boosters is another tool in the toolbox.

“If it’s a hammer, we should hit that nail hard,” he said.

Sara Oliver, MD, ACIP’s lead for the COVID-19 work group, presented the case behind the recommendation.

She noted the soaring Omicron cases.

“As of Jan. 3, the 7-day average had reached an all-time high of nearly 500,000 cases,” Dr. Oliver noted.

Since this summer, she said, adolescents have had a higher rate of incidence than that of adults.

“The majority of COVID cases continue to occur among the unvaccinated,” she said, “with unvaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds having a 7-times-higher risk of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 compared to vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds. Unvaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have around 11 times higher risk of hospitalization than vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds.

“Vaccine effectiveness in adolescents 12-15 years old remains high,” Dr. Oliver said, but evidence shows there may be “some waning over time.”

Discussion of risk centered on myocarditis.

Dr. Oliver said myocarditis rates reported after the Pfizer vaccine in Israel across all populations as of Dec. 15 show that “the rates of myocarditis after a third dose are lower than what is seen after the second dose.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The CDC had already said 16- and 17-year-olds “may” receive a Pfizer booster but the new recommendation adds the 12- to 15-year-old group and strengthens the “may” to “should” for 16- and 17-year-olds.

The committee voted 13-1 to recommend the booster for ages 12-17. CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, must still approve the recommendation for it to take effect.

The vote comes after the FDA on Jan. 3 authorized the Pfizer vaccine booster dose for 12- to 15-year-olds.

The FDA action updated the authorization for the Pfizer vaccine, and the agency also shortened the recommended time between a second dose and the booster to 5 months or more (from 6 months). A third primary series dose is also now authorized for certain immunocompromised children between 5 and 11 years old. Full details are available in an FDA news release.

The CDC on Jan. 4 also backed the shortened time frame and a third primary series dose for some immunocompromised children 5-11 years old. But the CDC delayed a decision on a booster for 12- to 15-year-olds until it heard from its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices on Jan. 5.

The decision came as school districts nationwide are wrestling with decisions of whether to keep schools open or revert to a virtual format as cases surge, and as pediatric COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations reach new highs.

The only dissenting vote came from Helen Keipp Talbot, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

She said after the vote, “I am just fine with kids getting a booster. This is not me against all boosters. I just really want the U.S. to move forward with all kids.”

Dr. Talbot said earlier in the comment period, “If we divert our public health from the unvaccinated to the vaccinated, we are not going to make a big impact. Boosters are incredibly important but they won’t solve this problem of the crowded hospitals.”

She said vaccinating the unvaccinated must be the priority.

“If you are a parent out there who has not yet vaccinated your child because you have questions, please, please talk to a health care provider,” she said.

Among the 13 supporters of the recommendation was Oliver Brooks, MD, chief medical officer of Watts HealthCare Corporation in Los Angeles.

Dr. Brooks said extending the population for boosters is another tool in the toolbox.

“If it’s a hammer, we should hit that nail hard,” he said.

Sara Oliver, MD, ACIP’s lead for the COVID-19 work group, presented the case behind the recommendation.

She noted the soaring Omicron cases.

“As of Jan. 3, the 7-day average had reached an all-time high of nearly 500,000 cases,” Dr. Oliver noted.

Since this summer, she said, adolescents have had a higher rate of incidence than that of adults.

“The majority of COVID cases continue to occur among the unvaccinated,” she said, “with unvaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds having a 7-times-higher risk of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 compared to vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds. Unvaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have around 11 times higher risk of hospitalization than vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds.

“Vaccine effectiveness in adolescents 12-15 years old remains high,” Dr. Oliver said, but evidence shows there may be “some waning over time.”

Discussion of risk centered on myocarditis.

Dr. Oliver said myocarditis rates reported after the Pfizer vaccine in Israel across all populations as of Dec. 15 show that “the rates of myocarditis after a third dose are lower than what is seen after the second dose.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The CDC had already said 16- and 17-year-olds “may” receive a Pfizer booster but the new recommendation adds the 12- to 15-year-old group and strengthens the “may” to “should” for 16- and 17-year-olds.

The committee voted 13-1 to recommend the booster for ages 12-17. CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, must still approve the recommendation for it to take effect.

The vote comes after the FDA on Jan. 3 authorized the Pfizer vaccine booster dose for 12- to 15-year-olds.

The FDA action updated the authorization for the Pfizer vaccine, and the agency also shortened the recommended time between a second dose and the booster to 5 months or more (from 6 months). A third primary series dose is also now authorized for certain immunocompromised children between 5 and 11 years old. Full details are available in an FDA news release.

The CDC on Jan. 4 also backed the shortened time frame and a third primary series dose for some immunocompromised children 5-11 years old. But the CDC delayed a decision on a booster for 12- to 15-year-olds until it heard from its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices on Jan. 5.

The decision came as school districts nationwide are wrestling with decisions of whether to keep schools open or revert to a virtual format as cases surge, and as pediatric COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations reach new highs.

The only dissenting vote came from Helen Keipp Talbot, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

She said after the vote, “I am just fine with kids getting a booster. This is not me against all boosters. I just really want the U.S. to move forward with all kids.”

Dr. Talbot said earlier in the comment period, “If we divert our public health from the unvaccinated to the vaccinated, we are not going to make a big impact. Boosters are incredibly important but they won’t solve this problem of the crowded hospitals.”

She said vaccinating the unvaccinated must be the priority.

“If you are a parent out there who has not yet vaccinated your child because you have questions, please, please talk to a health care provider,” she said.

Among the 13 supporters of the recommendation was Oliver Brooks, MD, chief medical officer of Watts HealthCare Corporation in Los Angeles.

Dr. Brooks said extending the population for boosters is another tool in the toolbox.

“If it’s a hammer, we should hit that nail hard,” he said.

Sara Oliver, MD, ACIP’s lead for the COVID-19 work group, presented the case behind the recommendation.

She noted the soaring Omicron cases.

“As of Jan. 3, the 7-day average had reached an all-time high of nearly 500,000 cases,” Dr. Oliver noted.

Since this summer, she said, adolescents have had a higher rate of incidence than that of adults.

“The majority of COVID cases continue to occur among the unvaccinated,” she said, “with unvaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds having a 7-times-higher risk of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 compared to vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds. Unvaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have around 11 times higher risk of hospitalization than vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds.

“Vaccine effectiveness in adolescents 12-15 years old remains high,” Dr. Oliver said, but evidence shows there may be “some waning over time.”

Discussion of risk centered on myocarditis.

Dr. Oliver said myocarditis rates reported after the Pfizer vaccine in Israel across all populations as of Dec. 15 show that “the rates of myocarditis after a third dose are lower than what is seen after the second dose.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Who needs self-driving cars when we’ve got goldfish?

If a fish can drive …

Have you ever seen a sparrow swim? Have you ever seen an elephant fly? How about a goldfish driving a car? Well, one of these is not just something out of a children’s book.

In a recent study, investigators from Ben-Gurion University did the impossible and got a fish to drive a robotic car on land. How?

No, there wasn’t a tiny steering wheel inside the tank. The researchers created a tank with video recognition ability to sync with the fish. This video shows that the car, on which the tank sat, would navigate in the direction that the fish swam. The goal was to get the fish to “drive” toward a visual target, and with a little training the fish was successful regardless of start point, the researchers explained.

So what does that tell us about the brain and behavior? Shachar Givon, who was part of the research team, said the “study hints that navigational ability is universal rather than specific to the environment.”

The study’s domain transfer methodology (putting one species in the environment of another and have them cope with an unfamiliar task) shows that other animals also have the cognitive ability to transfer skills from one terrestrial environment to another.

That leads us to lesson two. Goldfish are much smarter than we think. So please don’t tap on the glass.

We prefer ‘It’s not writing a funny LOTME article’!

So many medical journals spend all their time grappling with such silly dilemmas as curing cancer or beating COVID-19. Boring! Fortunately, the BMJ dares to stand above the rest by dedicating its Christmas issue to answering the real issues in medicine. And what was the biggest question? Which is the more accurate idiom: “It’s not rocket science,” or “It’s not brain surgery”?

English researchers collected data from 329 aerospace engineers and 72 neurosurgeons who took the Great British Intelligence Test and compared the results against 18,000 people in the general public.

The engineers and neurosurgeons were basically identical in four of the six domains, but neurosurgeons had the advantage when it came to semantic problem solving and engineers had an edge at mental manipulation and attention. The aerospace engineers were identical to the public in all domains, but neurosurgeons held an advantage in problem-solving speed and a disadvantage in memory recall speed.

The researchers noted that exposure to Latin and Greek etymologies during their education gave neurosurgeons the advantage in semantic problem solving, while the aerospace engineers’ advantage in mental manipulation stems from skills taught during engineering training.

But is there a definitive answer to the question? If you’ve got an easy task in front of you, which is more accurate to say: “It’s not rocket science” or “It’s not brain surgery”? Can we get a drum roll?

It’s not brain surgery! At least, as long as the task doesn’t involve rapid problem solving. The investigators hedged further by saying that “It’s a walk in the park” is probably more accurate. Plus, “other specialties might deserve to be on that pedestal, and future work should aim to determine the most deserving profession,” they wrote. Well, at least we’ve got something to look forward to in BMJ’s next Christmas issue.

For COVID-19, a syringe is the sheep of things to come

The logical approach to fighting COVID-19 hasn’t really worked with a lot of people, so how about something more emotional?

People love animals, so they might be a good way to promote the use of vaccines and masks. Puppies are awfully cute, and so are koalas and pandas. And who can say no to a sea otter?

Well, forget it. Instead, we’ve got elephants … and sheep … and goats. Oh my.

First, elephant Santas. The Jirasartwitthaya school in Ayutthaya, Thailand, was recently visited by five elephants in Santa Claus costumes who handed out hand sanitizer and face masks to the students, Reuters said.

“I’m so glad that I got a balloon from the elephant. My heart is pounding very fast,” student Biuon Greham said. And balloons. The elephants handed out sanitizer and masks and balloons. There’s a sentence we never thought we’d write.

And those sheep and goats we mentioned? That was a different party.

Hanspeter Etzold, who “works with shepherds, companies, and animals to run team-building events in the northern German town of Schneverdingen,” according to Reuters, had an idea to promote the use of the COVID-19 vaccine. And yes, it involved sheep and goats.

Mr. Etzold worked with shepherd Wiebke Schmidt-Kochan, who arranged her 700 goats and sheep into the shape of a 100-meter-long syringe using bits of bread laying on the ground. “Sheep are such likable animals – maybe they can get the message over better,” Mr. Etzold told AP.

If those are the carrots in an animals-as-carrots-and-sticks approach, then maybe this golf-club-chomping crab could be the stick. We’re certainly not going to argue with it.

To be or not to be … seen

Increased Zoom meetings have been another side effect of the COVID-19 pandemic as more and more people have been working and learning from home.

A recent study from Washington State University looked at two groups of people who Zoomed on a regular basis: employees and students. Individuals who made the change to remote work/learning were surveyed in the summer and fall of 2020. They completed assessments with questions on their work/classes and their level of self-consciousness.

Those with low self-esteem did not enjoy having to see themselves on camera, and those with higher self-esteem actually enjoyed it more. “Most people believe that seeing yourself during virtual meetings contributes to making the overall experience worse, but that’s not what showed up in my data,” said Kristine Kuhn, PhD, the study’s author.

Dr. Kuhn found that having the choice of whether to have the camera on made a big difference in how the participants felt. Having that control made it a more positive experience. Most professors/bosses would probably like to see the faces of those in the Zoom meetings, but it might be better to let people choose for themselves. The unbrushed-hair club would certainly agree.

If a fish can drive …

Have you ever seen a sparrow swim? Have you ever seen an elephant fly? How about a goldfish driving a car? Well, one of these is not just something out of a children’s book.

In a recent study, investigators from Ben-Gurion University did the impossible and got a fish to drive a robotic car on land. How?

No, there wasn’t a tiny steering wheel inside the tank. The researchers created a tank with video recognition ability to sync with the fish. This video shows that the car, on which the tank sat, would navigate in the direction that the fish swam. The goal was to get the fish to “drive” toward a visual target, and with a little training the fish was successful regardless of start point, the researchers explained.

So what does that tell us about the brain and behavior? Shachar Givon, who was part of the research team, said the “study hints that navigational ability is universal rather than specific to the environment.”

The study’s domain transfer methodology (putting one species in the environment of another and have them cope with an unfamiliar task) shows that other animals also have the cognitive ability to transfer skills from one terrestrial environment to another.

That leads us to lesson two. Goldfish are much smarter than we think. So please don’t tap on the glass.

We prefer ‘It’s not writing a funny LOTME article’!

So many medical journals spend all their time grappling with such silly dilemmas as curing cancer or beating COVID-19. Boring! Fortunately, the BMJ dares to stand above the rest by dedicating its Christmas issue to answering the real issues in medicine. And what was the biggest question? Which is the more accurate idiom: “It’s not rocket science,” or “It’s not brain surgery”?

English researchers collected data from 329 aerospace engineers and 72 neurosurgeons who took the Great British Intelligence Test and compared the results against 18,000 people in the general public.

The engineers and neurosurgeons were basically identical in four of the six domains, but neurosurgeons had the advantage when it came to semantic problem solving and engineers had an edge at mental manipulation and attention. The aerospace engineers were identical to the public in all domains, but neurosurgeons held an advantage in problem-solving speed and a disadvantage in memory recall speed.

The researchers noted that exposure to Latin and Greek etymologies during their education gave neurosurgeons the advantage in semantic problem solving, while the aerospace engineers’ advantage in mental manipulation stems from skills taught during engineering training.

But is there a definitive answer to the question? If you’ve got an easy task in front of you, which is more accurate to say: “It’s not rocket science” or “It’s not brain surgery”? Can we get a drum roll?

It’s not brain surgery! At least, as long as the task doesn’t involve rapid problem solving. The investigators hedged further by saying that “It’s a walk in the park” is probably more accurate. Plus, “other specialties might deserve to be on that pedestal, and future work should aim to determine the most deserving profession,” they wrote. Well, at least we’ve got something to look forward to in BMJ’s next Christmas issue.

For COVID-19, a syringe is the sheep of things to come

The logical approach to fighting COVID-19 hasn’t really worked with a lot of people, so how about something more emotional?

People love animals, so they might be a good way to promote the use of vaccines and masks. Puppies are awfully cute, and so are koalas and pandas. And who can say no to a sea otter?

Well, forget it. Instead, we’ve got elephants … and sheep … and goats. Oh my.

First, elephant Santas. The Jirasartwitthaya school in Ayutthaya, Thailand, was recently visited by five elephants in Santa Claus costumes who handed out hand sanitizer and face masks to the students, Reuters said.

“I’m so glad that I got a balloon from the elephant. My heart is pounding very fast,” student Biuon Greham said. And balloons. The elephants handed out sanitizer and masks and balloons. There’s a sentence we never thought we’d write.

And those sheep and goats we mentioned? That was a different party.

Hanspeter Etzold, who “works with shepherds, companies, and animals to run team-building events in the northern German town of Schneverdingen,” according to Reuters, had an idea to promote the use of the COVID-19 vaccine. And yes, it involved sheep and goats.

Mr. Etzold worked with shepherd Wiebke Schmidt-Kochan, who arranged her 700 goats and sheep into the shape of a 100-meter-long syringe using bits of bread laying on the ground. “Sheep are such likable animals – maybe they can get the message over better,” Mr. Etzold told AP.

If those are the carrots in an animals-as-carrots-and-sticks approach, then maybe this golf-club-chomping crab could be the stick. We’re certainly not going to argue with it.

To be or not to be … seen

Increased Zoom meetings have been another side effect of the COVID-19 pandemic as more and more people have been working and learning from home.

A recent study from Washington State University looked at two groups of people who Zoomed on a regular basis: employees and students. Individuals who made the change to remote work/learning were surveyed in the summer and fall of 2020. They completed assessments with questions on their work/classes and their level of self-consciousness.

Those with low self-esteem did not enjoy having to see themselves on camera, and those with higher self-esteem actually enjoyed it more. “Most people believe that seeing yourself during virtual meetings contributes to making the overall experience worse, but that’s not what showed up in my data,” said Kristine Kuhn, PhD, the study’s author.

Dr. Kuhn found that having the choice of whether to have the camera on made a big difference in how the participants felt. Having that control made it a more positive experience. Most professors/bosses would probably like to see the faces of those in the Zoom meetings, but it might be better to let people choose for themselves. The unbrushed-hair club would certainly agree.

If a fish can drive …

Have you ever seen a sparrow swim? Have you ever seen an elephant fly? How about a goldfish driving a car? Well, one of these is not just something out of a children’s book.

In a recent study, investigators from Ben-Gurion University did the impossible and got a fish to drive a robotic car on land. How?

No, there wasn’t a tiny steering wheel inside the tank. The researchers created a tank with video recognition ability to sync with the fish. This video shows that the car, on which the tank sat, would navigate in the direction that the fish swam. The goal was to get the fish to “drive” toward a visual target, and with a little training the fish was successful regardless of start point, the researchers explained.

So what does that tell us about the brain and behavior? Shachar Givon, who was part of the research team, said the “study hints that navigational ability is universal rather than specific to the environment.”

The study’s domain transfer methodology (putting one species in the environment of another and have them cope with an unfamiliar task) shows that other animals also have the cognitive ability to transfer skills from one terrestrial environment to another.

That leads us to lesson two. Goldfish are much smarter than we think. So please don’t tap on the glass.

We prefer ‘It’s not writing a funny LOTME article’!

So many medical journals spend all their time grappling with such silly dilemmas as curing cancer or beating COVID-19. Boring! Fortunately, the BMJ dares to stand above the rest by dedicating its Christmas issue to answering the real issues in medicine. And what was the biggest question? Which is the more accurate idiom: “It’s not rocket science,” or “It’s not brain surgery”?

English researchers collected data from 329 aerospace engineers and 72 neurosurgeons who took the Great British Intelligence Test and compared the results against 18,000 people in the general public.

The engineers and neurosurgeons were basically identical in four of the six domains, but neurosurgeons had the advantage when it came to semantic problem solving and engineers had an edge at mental manipulation and attention. The aerospace engineers were identical to the public in all domains, but neurosurgeons held an advantage in problem-solving speed and a disadvantage in memory recall speed.

The researchers noted that exposure to Latin and Greek etymologies during their education gave neurosurgeons the advantage in semantic problem solving, while the aerospace engineers’ advantage in mental manipulation stems from skills taught during engineering training.

But is there a definitive answer to the question? If you’ve got an easy task in front of you, which is more accurate to say: “It’s not rocket science” or “It’s not brain surgery”? Can we get a drum roll?

It’s not brain surgery! At least, as long as the task doesn’t involve rapid problem solving. The investigators hedged further by saying that “It’s a walk in the park” is probably more accurate. Plus, “other specialties might deserve to be on that pedestal, and future work should aim to determine the most deserving profession,” they wrote. Well, at least we’ve got something to look forward to in BMJ’s next Christmas issue.

For COVID-19, a syringe is the sheep of things to come

The logical approach to fighting COVID-19 hasn’t really worked with a lot of people, so how about something more emotional?

People love animals, so they might be a good way to promote the use of vaccines and masks. Puppies are awfully cute, and so are koalas and pandas. And who can say no to a sea otter?

Well, forget it. Instead, we’ve got elephants … and sheep … and goats. Oh my.

First, elephant Santas. The Jirasartwitthaya school in Ayutthaya, Thailand, was recently visited by five elephants in Santa Claus costumes who handed out hand sanitizer and face masks to the students, Reuters said.

“I’m so glad that I got a balloon from the elephant. My heart is pounding very fast,” student Biuon Greham said. And balloons. The elephants handed out sanitizer and masks and balloons. There’s a sentence we never thought we’d write.

And those sheep and goats we mentioned? That was a different party.

Hanspeter Etzold, who “works with shepherds, companies, and animals to run team-building events in the northern German town of Schneverdingen,” according to Reuters, had an idea to promote the use of the COVID-19 vaccine. And yes, it involved sheep and goats.

Mr. Etzold worked with shepherd Wiebke Schmidt-Kochan, who arranged her 700 goats and sheep into the shape of a 100-meter-long syringe using bits of bread laying on the ground. “Sheep are such likable animals – maybe they can get the message over better,” Mr. Etzold told AP.

If those are the carrots in an animals-as-carrots-and-sticks approach, then maybe this golf-club-chomping crab could be the stick. We’re certainly not going to argue with it.

To be or not to be … seen

Increased Zoom meetings have been another side effect of the COVID-19 pandemic as more and more people have been working and learning from home.

A recent study from Washington State University looked at two groups of people who Zoomed on a regular basis: employees and students. Individuals who made the change to remote work/learning were surveyed in the summer and fall of 2020. They completed assessments with questions on their work/classes and their level of self-consciousness.

Those with low self-esteem did not enjoy having to see themselves on camera, and those with higher self-esteem actually enjoyed it more. “Most people believe that seeing yourself during virtual meetings contributes to making the overall experience worse, but that’s not what showed up in my data,” said Kristine Kuhn, PhD, the study’s author.

Dr. Kuhn found that having the choice of whether to have the camera on made a big difference in how the participants felt. Having that control made it a more positive experience. Most professors/bosses would probably like to see the faces of those in the Zoom meetings, but it might be better to let people choose for themselves. The unbrushed-hair club would certainly agree.

Experts disappointed by NICE’s decision to reject prostate cancer drug

In draft guidance, NICE rejected olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca) as a treatment option for hormone-relapsed metastatic prostate cancer with BRCA1/2 mutations.

The list price of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, at 37,491 pounds for an average cost of treatment, meant it was not cost effective to recommend for routine NHS use, the medicines regulator said.

The Institute of Cancer Research said the decision by NICE put patients in England and Wales at a disadvantage to those in Scotland where the regulator had approved olaparib for men with the same condition under a patient access scheme.

Kristian Helin, ICR chief executive, said: “I urge NICE and the manufacturer to come back to the table and try to find agreement on a way to make olaparib available at an agreeable price.”

Encouraging clinical evidence

Results from the PROfound trial, published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggested that progression-free survival for patients with prostate cancers who had faulty BRCA2, BRCA1, or ATM genes was significantly longer in the olaparib group than in a control group who received either enzalutamide or abiraterone.

Median survival in the Olaparib cohort was 7.4 months, compared with 3.6 months in the control group.

Retreatment with abiraterone or enzalutamide is not considered effective for men with this type of prostate cancer, and is not standard care in the NHS, NICE said.

Current treatment for metastatic hormone-relapsed prostate cancer is chemotherapy with docetaxel, cabazitaxel, or radium-223 dichloride.

NICE acknowledged that while an indirect comparison suggested that in men previously treated with docetaxel, olaparib increased survival, compared with cabazitaxel, there were no evidence directly comparing them.

Consultation period

Gillian Leng, CBE, NICE chief executive, said: “We know how important it is for people with this type of prostate cancer to have more treatment options that can help them live longer and enable them to maintain or improve their quality of life, as well as delay chemotherapy and its associated side effects.

“We’re therefore disappointed not to be able to recommend olaparib for use in this way. However, the company’s own economic model demonstrated that the drug does not offer enough benefit to justify the price it is asking.

“We’ll continue working with the company to try and address the issues highlighted by the committee.”

Johann De Bono, professor of experimental cancer medicine at the ICR, who leads the PROfound trial, said: “Olaparib is a precision drug that can extend life for men with some mutations in their tumors while sparing them the side effects of chemotherapy.

“I was delighted when olaparib was approved for NHS patients in Scotland earlier this year – and it’s disappointing that this decision means their counterparts in England and Wales will miss out on such a valuable new treatment option. It’s an example of the barriers that exist to making innovative drugs available at prices that the NHS can afford and is going to result in postcode prescribing across the U.K.”

The list price of olaparib is 2,317.50 pounds for a pack of 56 tablets covering 14 days of treatment. A confidential discount has been agreed by the manufacturer to make olaparib available to the NHS.

It is estimated that around 100 men would be eligible for treatment with olaparib if it was to be approved by NICE.

Consultation on the draft guidance closes on Jan. 31.

A version of this article first appeared on Univadis.com.

In draft guidance, NICE rejected olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca) as a treatment option for hormone-relapsed metastatic prostate cancer with BRCA1/2 mutations.

The list price of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, at 37,491 pounds for an average cost of treatment, meant it was not cost effective to recommend for routine NHS use, the medicines regulator said.

The Institute of Cancer Research said the decision by NICE put patients in England and Wales at a disadvantage to those in Scotland where the regulator had approved olaparib for men with the same condition under a patient access scheme.

Kristian Helin, ICR chief executive, said: “I urge NICE and the manufacturer to come back to the table and try to find agreement on a way to make olaparib available at an agreeable price.”

Encouraging clinical evidence

Results from the PROfound trial, published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggested that progression-free survival for patients with prostate cancers who had faulty BRCA2, BRCA1, or ATM genes was significantly longer in the olaparib group than in a control group who received either enzalutamide or abiraterone.

Median survival in the Olaparib cohort was 7.4 months, compared with 3.6 months in the control group.

Retreatment with abiraterone or enzalutamide is not considered effective for men with this type of prostate cancer, and is not standard care in the NHS, NICE said.

Current treatment for metastatic hormone-relapsed prostate cancer is chemotherapy with docetaxel, cabazitaxel, or radium-223 dichloride.

NICE acknowledged that while an indirect comparison suggested that in men previously treated with docetaxel, olaparib increased survival, compared with cabazitaxel, there were no evidence directly comparing them.

Consultation period

Gillian Leng, CBE, NICE chief executive, said: “We know how important it is for people with this type of prostate cancer to have more treatment options that can help them live longer and enable them to maintain or improve their quality of life, as well as delay chemotherapy and its associated side effects.

“We’re therefore disappointed not to be able to recommend olaparib for use in this way. However, the company’s own economic model demonstrated that the drug does not offer enough benefit to justify the price it is asking.

“We’ll continue working with the company to try and address the issues highlighted by the committee.”

Johann De Bono, professor of experimental cancer medicine at the ICR, who leads the PROfound trial, said: “Olaparib is a precision drug that can extend life for men with some mutations in their tumors while sparing them the side effects of chemotherapy.

“I was delighted when olaparib was approved for NHS patients in Scotland earlier this year – and it’s disappointing that this decision means their counterparts in England and Wales will miss out on such a valuable new treatment option. It’s an example of the barriers that exist to making innovative drugs available at prices that the NHS can afford and is going to result in postcode prescribing across the U.K.”

The list price of olaparib is 2,317.50 pounds for a pack of 56 tablets covering 14 days of treatment. A confidential discount has been agreed by the manufacturer to make olaparib available to the NHS.

It is estimated that around 100 men would be eligible for treatment with olaparib if it was to be approved by NICE.

Consultation on the draft guidance closes on Jan. 31.

A version of this article first appeared on Univadis.com.

In draft guidance, NICE rejected olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca) as a treatment option for hormone-relapsed metastatic prostate cancer with BRCA1/2 mutations.

The list price of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, at 37,491 pounds for an average cost of treatment, meant it was not cost effective to recommend for routine NHS use, the medicines regulator said.

The Institute of Cancer Research said the decision by NICE put patients in England and Wales at a disadvantage to those in Scotland where the regulator had approved olaparib for men with the same condition under a patient access scheme.

Kristian Helin, ICR chief executive, said: “I urge NICE and the manufacturer to come back to the table and try to find agreement on a way to make olaparib available at an agreeable price.”

Encouraging clinical evidence

Results from the PROfound trial, published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggested that progression-free survival for patients with prostate cancers who had faulty BRCA2, BRCA1, or ATM genes was significantly longer in the olaparib group than in a control group who received either enzalutamide or abiraterone.

Median survival in the Olaparib cohort was 7.4 months, compared with 3.6 months in the control group.

Retreatment with abiraterone or enzalutamide is not considered effective for men with this type of prostate cancer, and is not standard care in the NHS, NICE said.

Current treatment for metastatic hormone-relapsed prostate cancer is chemotherapy with docetaxel, cabazitaxel, or radium-223 dichloride.

NICE acknowledged that while an indirect comparison suggested that in men previously treated with docetaxel, olaparib increased survival, compared with cabazitaxel, there were no evidence directly comparing them.

Consultation period

Gillian Leng, CBE, NICE chief executive, said: “We know how important it is for people with this type of prostate cancer to have more treatment options that can help them live longer and enable them to maintain or improve their quality of life, as well as delay chemotherapy and its associated side effects.

“We’re therefore disappointed not to be able to recommend olaparib for use in this way. However, the company’s own economic model demonstrated that the drug does not offer enough benefit to justify the price it is asking.

“We’ll continue working with the company to try and address the issues highlighted by the committee.”

Johann De Bono, professor of experimental cancer medicine at the ICR, who leads the PROfound trial, said: “Olaparib is a precision drug that can extend life for men with some mutations in their tumors while sparing them the side effects of chemotherapy.

“I was delighted when olaparib was approved for NHS patients in Scotland earlier this year – and it’s disappointing that this decision means their counterparts in England and Wales will miss out on such a valuable new treatment option. It’s an example of the barriers that exist to making innovative drugs available at prices that the NHS can afford and is going to result in postcode prescribing across the U.K.”

The list price of olaparib is 2,317.50 pounds for a pack of 56 tablets covering 14 days of treatment. A confidential discount has been agreed by the manufacturer to make olaparib available to the NHS.

It is estimated that around 100 men would be eligible for treatment with olaparib if it was to be approved by NICE.

Consultation on the draft guidance closes on Jan. 31.

A version of this article first appeared on Univadis.com.

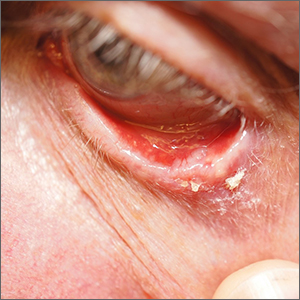

Growth on eyelid

A shave biopsy (performed carefully to avoid caustic hemostatic agents irritating the conjunctiva) confirmed the diagnosis of a micronodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

BCC is a common tumor occurring on the eyelids and in the periocular region. Any new growing papule on the eyelids, history of focal bleeding, irritation, or focal loss of eyelashes should cause suspicion for BCC. Patients are often unaware of any symptoms when lesions begin, highlighting the importance of close inspection of the eyelids when skin or eye exams are performed. The differential diagnosis includes benign lesions such as hidrocystomas and nevi, as well as malignancies, including sebaceous carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.1

Factors that come into play when exploring eyelid BCC treatment options include tumor removal, eyelid function, and appearance. The potential morbidity associated with tumor spread in the periorbital region highlights the importance of early detection of eyelid cancers. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a first choice for tumor removal of an eyelid BCC and offers a high cure rate with minimal tissue removal.

Removal of an eyelid BCC may be a multidisciplinary endeavor with MMS achieving a clear margin, and Ophthalmology or Oculoplastics following with repair and closure soon after. Patients who can’t tolerate surgery should consider vismodegib, a targeted chemotherapy, or radiotherapy.

The patient in this case opted for a single staged excision and repair with Oculoplastics and has had no recurrence. He subsequently underwent a revision procedure to improve ectropion.