User login

What makes a urinary tract infection complicated?

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

Anatomic approach

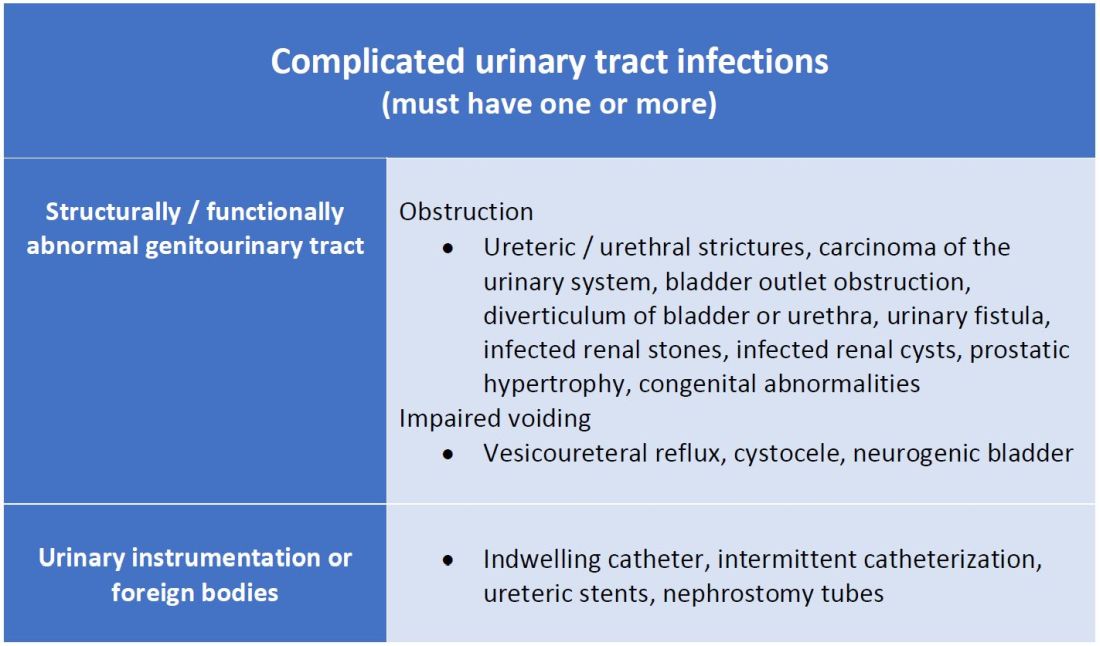

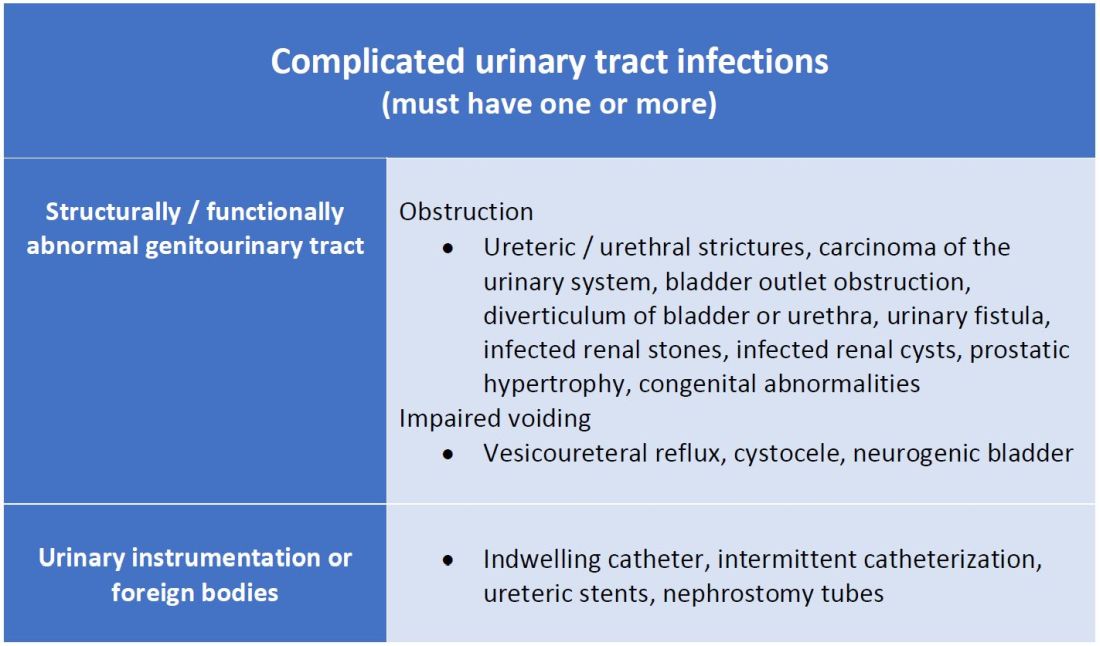

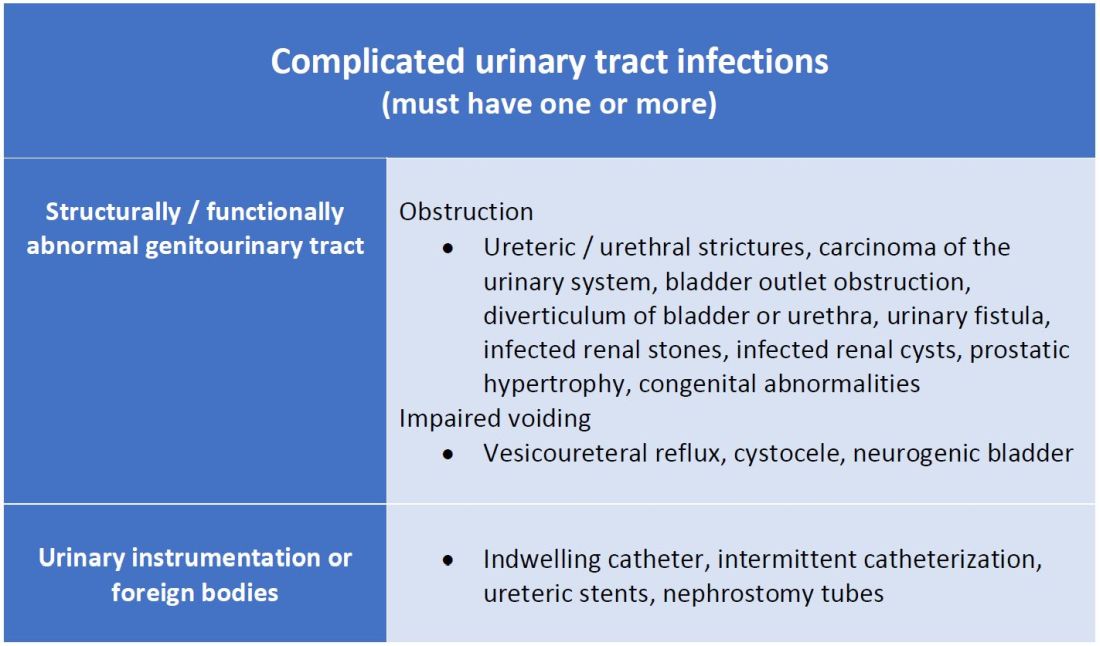

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.

This population of patients is at high risk of infections with more resistant bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli since they often lack the natural genitourinary barriers to infection. In addition, these patients more often undergo multiple antibiotic courses for their frequent infections, which also contributes to their risk of ESBL infections. Genitourinary abnormalities interfere with normal voiding, resulting in impaired flushing of bacteria. For instance, obstruction inhibits complete urinary drainage and increases the persistence of bacteria in biofilms, especially if there are stones or indwelling devices present. Biofilms usually contain a high concentration of organisms including Proteus mirabilis, Morgenella morganii, and Providencia spp.4 Keep in mind that, if there is an obstruction, the urinalysis might be without pyuria or bacteriuria.

Instrumentation increases infection risks through the direct introduction of bacteria into the genitourinary tract. Despite the efforts in maintaining sterility in urinary catheter placement, catheters provide a nidus for infection. Catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is defined by the Infectious Disease Society of America as UTIs that occur in patients with an indwelling catheter or who had a catheter removed for less than 48 hours who develop urinary symptoms and cultures positive for uropathogenic bacteria.4 Studies show that in general, patients with indwelling catheters will develop bacteriuria over time, with 10%-25% eventually developing symptoms.

Severity approach

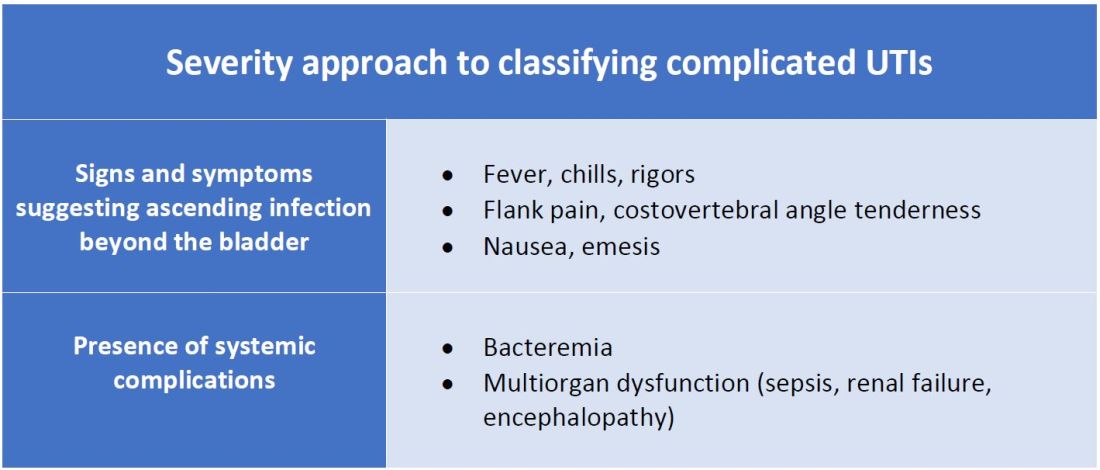

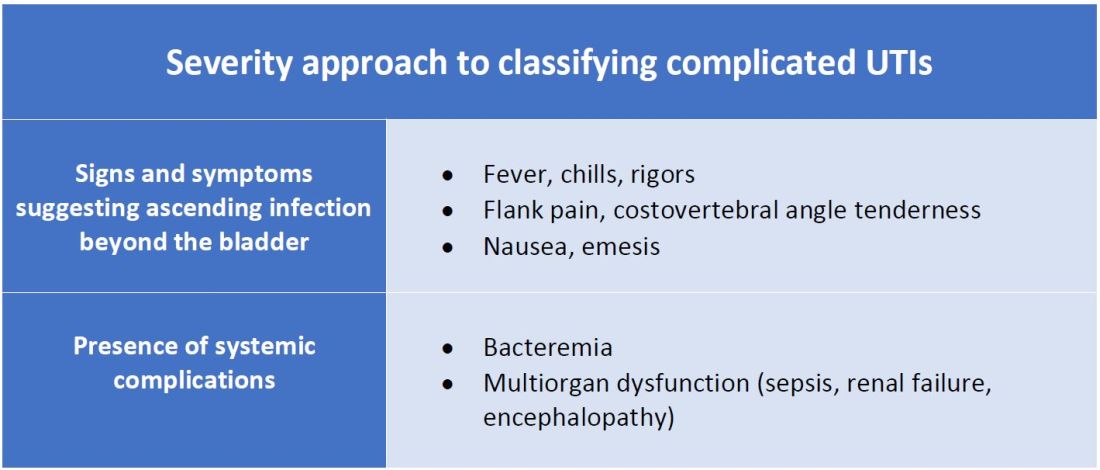

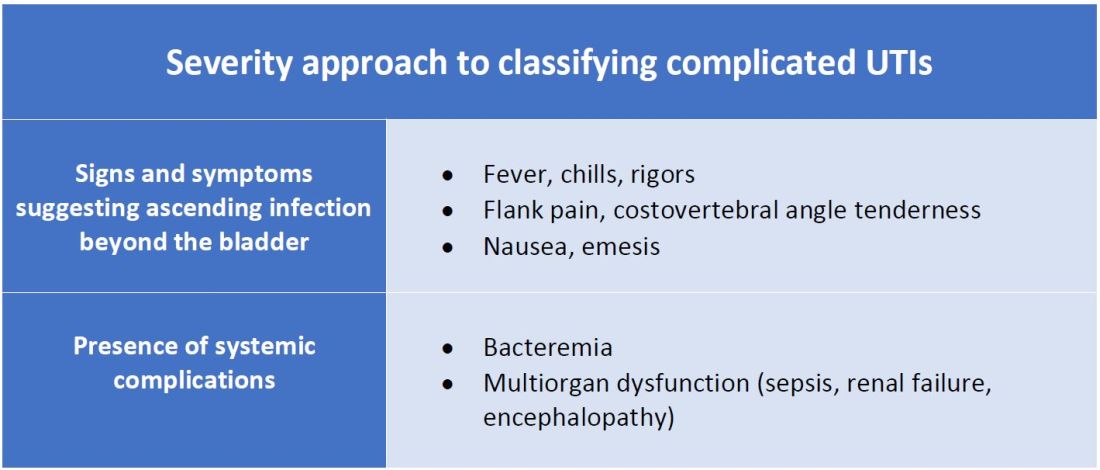

There are other schools of thought that categorize uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs based on the severity of presentation (see Table 2). An uncomplicated UTI would be classified as symptoms and signs of simple cystitis limited to dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. Using a symptom severity approach, systemic findings such as fever, chills, emesis, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or other findings of sepsis would be classified as a complicated UTI. These systemic findings would suggest an extension of infection beyond the bladder.

The argument for a symptomatic-based approach of classification is that the severity of symptoms should dictate the degree of management. Not all UTIs in the anatomic approach are severe. In fact, populations that are considered at risk for complicated UTIs by the AUA guidelines in Table 1 often have mild symptomatic cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the colonization of organisms in the urinary tract without active infection. For instance, bacteriuria is present in almost 100% of people with chronic indwelling catheters, 30%-40% of neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent catheterization, and 50% of elderly nursing home residents.4 Not all bacteriuria triggers enough of an inflammatory response to cause symptoms that require treatment.

Ultimate clinical judgment

Although there are multiple different society recommendations in distinguishing uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, considering both anatomical and severity risk factors can better aid in clinical decision-making rather than abiding by one classification method alone.

Uncomplicated UTIs from the AUA guidelines can cause severe infections that might require longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On the other hand, people with anatomic abnormalities can present with mild symptoms that can be treated with a narrow-spectrum antibiotic for a standard time course. Recognizing the severity of the infection and using clinical judgment aids in antibiotic stewardship.

Although the existence of algorithmic approaches can help guide clinical judgment, accounting for the spectrum of host and bacterial factors should ultimately determine the complexity of the disease and management.3 Using clinical suspicion to determine when a UTI should be treated as a complicated infection can ensure effective treatment and decrease the likelihood of sepsis, renal scarring, or end-stage disease.5

Back to the case

The case presents an elderly woman with diabetes presenting with sepsis from a UTI. Because of a normal urinary tract and no prior instrumentation, by the AUA definition, she would be classified as an uncomplicated UTI; however, we would classify her as a complicated UTI based on the severity of her presentation. She has a fever, tachycardia, flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness that are evidence of infection extending beyond the bladder. She has sepsis warranting inpatient management. Prior urine culture results could aid in determining empiric treatment while waiting for new cultures. In her case, an intravenous antibiotic with broad gram-negative coverage such as ceftriaxone would be appropriate.

Bottom line

There are multiple interpretations of complicated UTIs including both an anatomical and severity approach. Clinical judgment regarding infection severity should determine the depth of management.

Dr. Vu is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Gray is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky and the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

1. Folk CS. AUA Core Curriculum: Urinary Tract Infection (Adult). 2021 Mar 1. https://university.auanet.org/core_topic.cfm?coreid=92.

2. Gupta K et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257.

3. Johnson JR. Definition of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 February 15;64(4):529. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw751.

4. Nicolle LE, AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768.

5. Melekos MD and Naber KG. Complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15(4):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00168-0.

Key points

- The anatomical approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the presence of underlying, predisposing conditions such as structurally or functionally abnormal genitourinary tract or urinary instrumentation or foreign bodies.

- The severity approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the severity of presentation including the presence of systemic manifestations.

- Both approaches should consider populations that are at risk for recurrent or multidrug-resistant infections and infections that can lead to high morbidity.

- Either approach can be used as a guide, but neither should replace clinical suspicion and judgment in determining the depth of treatment.

Additional reading

Choe HS et al. Summary of the UAA‐AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018 Mar;25(3):175-85. doi:10.1111/iju.13493.

Nicolle LE et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;40(5):643-54. doi: 10.1086/427507.

Wagenlehner FME et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Oct;17:586-600. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0362-4.

Wallace DW et al. Urinalysis: A simple test with complicated interpretation. J Urgent Care Med. 2020 July-Aug;14(10):11-4.

Quiz

A 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with acute fever, chills, dysuria, frequency, and suprapubic pain. She has associated nausea, malaise, and fatigue. She takes metformin and denies recent antibiotic use. Her temperature is 102.8° F, heart rate 118 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/71 mm Hg, and her respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute. She is ill-appearing and has mild suprapubic tenderness. White blood cell count is 18 k/mcL. Urinalysis is positive for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria. Urine microscopy has 120 white blood cells per high power field. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Azithromycin

B. Ceftriaxone

C. Cefepime and vancomycin

D. Nitrofurantoin

The answer is B. The patient presents with sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Using the anatomic approach this would be classified as uncomplicated. Using the severity approach, this would be classified as a complicated urinary tract infection. With fever, chills, and signs of sepsis, it’s likely her infection extends beyond the bladder. Given the severity of her presentation, we’d favor treating her as a complicated urinary tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone. There is no suggestion of resistance or additional MRSA risk factors requiring intravenous vancomycin or cefepime. Nitrofurantoin, although a first-line treatment for uncomplicated cystitis, would not be appropriate if there is suspicion infection extends beyond the bladder. Azithromycin is a first-line option for chlamydia trachomatis, but not a urinary tract infection.

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

Anatomic approach

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.

This population of patients is at high risk of infections with more resistant bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli since they often lack the natural genitourinary barriers to infection. In addition, these patients more often undergo multiple antibiotic courses for their frequent infections, which also contributes to their risk of ESBL infections. Genitourinary abnormalities interfere with normal voiding, resulting in impaired flushing of bacteria. For instance, obstruction inhibits complete urinary drainage and increases the persistence of bacteria in biofilms, especially if there are stones or indwelling devices present. Biofilms usually contain a high concentration of organisms including Proteus mirabilis, Morgenella morganii, and Providencia spp.4 Keep in mind that, if there is an obstruction, the urinalysis might be without pyuria or bacteriuria.

Instrumentation increases infection risks through the direct introduction of bacteria into the genitourinary tract. Despite the efforts in maintaining sterility in urinary catheter placement, catheters provide a nidus for infection. Catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is defined by the Infectious Disease Society of America as UTIs that occur in patients with an indwelling catheter or who had a catheter removed for less than 48 hours who develop urinary symptoms and cultures positive for uropathogenic bacteria.4 Studies show that in general, patients with indwelling catheters will develop bacteriuria over time, with 10%-25% eventually developing symptoms.

Severity approach

There are other schools of thought that categorize uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs based on the severity of presentation (see Table 2). An uncomplicated UTI would be classified as symptoms and signs of simple cystitis limited to dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. Using a symptom severity approach, systemic findings such as fever, chills, emesis, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or other findings of sepsis would be classified as a complicated UTI. These systemic findings would suggest an extension of infection beyond the bladder.

The argument for a symptomatic-based approach of classification is that the severity of symptoms should dictate the degree of management. Not all UTIs in the anatomic approach are severe. In fact, populations that are considered at risk for complicated UTIs by the AUA guidelines in Table 1 often have mild symptomatic cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the colonization of organisms in the urinary tract without active infection. For instance, bacteriuria is present in almost 100% of people with chronic indwelling catheters, 30%-40% of neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent catheterization, and 50% of elderly nursing home residents.4 Not all bacteriuria triggers enough of an inflammatory response to cause symptoms that require treatment.

Ultimate clinical judgment

Although there are multiple different society recommendations in distinguishing uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, considering both anatomical and severity risk factors can better aid in clinical decision-making rather than abiding by one classification method alone.

Uncomplicated UTIs from the AUA guidelines can cause severe infections that might require longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On the other hand, people with anatomic abnormalities can present with mild symptoms that can be treated with a narrow-spectrum antibiotic for a standard time course. Recognizing the severity of the infection and using clinical judgment aids in antibiotic stewardship.

Although the existence of algorithmic approaches can help guide clinical judgment, accounting for the spectrum of host and bacterial factors should ultimately determine the complexity of the disease and management.3 Using clinical suspicion to determine when a UTI should be treated as a complicated infection can ensure effective treatment and decrease the likelihood of sepsis, renal scarring, or end-stage disease.5

Back to the case

The case presents an elderly woman with diabetes presenting with sepsis from a UTI. Because of a normal urinary tract and no prior instrumentation, by the AUA definition, she would be classified as an uncomplicated UTI; however, we would classify her as a complicated UTI based on the severity of her presentation. She has a fever, tachycardia, flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness that are evidence of infection extending beyond the bladder. She has sepsis warranting inpatient management. Prior urine culture results could aid in determining empiric treatment while waiting for new cultures. In her case, an intravenous antibiotic with broad gram-negative coverage such as ceftriaxone would be appropriate.

Bottom line

There are multiple interpretations of complicated UTIs including both an anatomical and severity approach. Clinical judgment regarding infection severity should determine the depth of management.

Dr. Vu is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Gray is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky and the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

1. Folk CS. AUA Core Curriculum: Urinary Tract Infection (Adult). 2021 Mar 1. https://university.auanet.org/core_topic.cfm?coreid=92.

2. Gupta K et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257.

3. Johnson JR. Definition of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 February 15;64(4):529. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw751.

4. Nicolle LE, AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768.

5. Melekos MD and Naber KG. Complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15(4):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00168-0.

Key points

- The anatomical approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the presence of underlying, predisposing conditions such as structurally or functionally abnormal genitourinary tract or urinary instrumentation or foreign bodies.

- The severity approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the severity of presentation including the presence of systemic manifestations.

- Both approaches should consider populations that are at risk for recurrent or multidrug-resistant infections and infections that can lead to high morbidity.

- Either approach can be used as a guide, but neither should replace clinical suspicion and judgment in determining the depth of treatment.

Additional reading

Choe HS et al. Summary of the UAA‐AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018 Mar;25(3):175-85. doi:10.1111/iju.13493.

Nicolle LE et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;40(5):643-54. doi: 10.1086/427507.

Wagenlehner FME et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Oct;17:586-600. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0362-4.

Wallace DW et al. Urinalysis: A simple test with complicated interpretation. J Urgent Care Med. 2020 July-Aug;14(10):11-4.

Quiz

A 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with acute fever, chills, dysuria, frequency, and suprapubic pain. She has associated nausea, malaise, and fatigue. She takes metformin and denies recent antibiotic use. Her temperature is 102.8° F, heart rate 118 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/71 mm Hg, and her respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute. She is ill-appearing and has mild suprapubic tenderness. White blood cell count is 18 k/mcL. Urinalysis is positive for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria. Urine microscopy has 120 white blood cells per high power field. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Azithromycin

B. Ceftriaxone

C. Cefepime and vancomycin

D. Nitrofurantoin

The answer is B. The patient presents with sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Using the anatomic approach this would be classified as uncomplicated. Using the severity approach, this would be classified as a complicated urinary tract infection. With fever, chills, and signs of sepsis, it’s likely her infection extends beyond the bladder. Given the severity of her presentation, we’d favor treating her as a complicated urinary tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone. There is no suggestion of resistance or additional MRSA risk factors requiring intravenous vancomycin or cefepime. Nitrofurantoin, although a first-line treatment for uncomplicated cystitis, would not be appropriate if there is suspicion infection extends beyond the bladder. Azithromycin is a first-line option for chlamydia trachomatis, but not a urinary tract infection.

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

Anatomic approach

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.

This population of patients is at high risk of infections with more resistant bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli since they often lack the natural genitourinary barriers to infection. In addition, these patients more often undergo multiple antibiotic courses for their frequent infections, which also contributes to their risk of ESBL infections. Genitourinary abnormalities interfere with normal voiding, resulting in impaired flushing of bacteria. For instance, obstruction inhibits complete urinary drainage and increases the persistence of bacteria in biofilms, especially if there are stones or indwelling devices present. Biofilms usually contain a high concentration of organisms including Proteus mirabilis, Morgenella morganii, and Providencia spp.4 Keep in mind that, if there is an obstruction, the urinalysis might be without pyuria or bacteriuria.

Instrumentation increases infection risks through the direct introduction of bacteria into the genitourinary tract. Despite the efforts in maintaining sterility in urinary catheter placement, catheters provide a nidus for infection. Catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is defined by the Infectious Disease Society of America as UTIs that occur in patients with an indwelling catheter or who had a catheter removed for less than 48 hours who develop urinary symptoms and cultures positive for uropathogenic bacteria.4 Studies show that in general, patients with indwelling catheters will develop bacteriuria over time, with 10%-25% eventually developing symptoms.

Severity approach

There are other schools of thought that categorize uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs based on the severity of presentation (see Table 2). An uncomplicated UTI would be classified as symptoms and signs of simple cystitis limited to dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. Using a symptom severity approach, systemic findings such as fever, chills, emesis, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or other findings of sepsis would be classified as a complicated UTI. These systemic findings would suggest an extension of infection beyond the bladder.

The argument for a symptomatic-based approach of classification is that the severity of symptoms should dictate the degree of management. Not all UTIs in the anatomic approach are severe. In fact, populations that are considered at risk for complicated UTIs by the AUA guidelines in Table 1 often have mild symptomatic cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the colonization of organisms in the urinary tract without active infection. For instance, bacteriuria is present in almost 100% of people with chronic indwelling catheters, 30%-40% of neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent catheterization, and 50% of elderly nursing home residents.4 Not all bacteriuria triggers enough of an inflammatory response to cause symptoms that require treatment.

Ultimate clinical judgment

Although there are multiple different society recommendations in distinguishing uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, considering both anatomical and severity risk factors can better aid in clinical decision-making rather than abiding by one classification method alone.

Uncomplicated UTIs from the AUA guidelines can cause severe infections that might require longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On the other hand, people with anatomic abnormalities can present with mild symptoms that can be treated with a narrow-spectrum antibiotic for a standard time course. Recognizing the severity of the infection and using clinical judgment aids in antibiotic stewardship.

Although the existence of algorithmic approaches can help guide clinical judgment, accounting for the spectrum of host and bacterial factors should ultimately determine the complexity of the disease and management.3 Using clinical suspicion to determine when a UTI should be treated as a complicated infection can ensure effective treatment and decrease the likelihood of sepsis, renal scarring, or end-stage disease.5

Back to the case

The case presents an elderly woman with diabetes presenting with sepsis from a UTI. Because of a normal urinary tract and no prior instrumentation, by the AUA definition, she would be classified as an uncomplicated UTI; however, we would classify her as a complicated UTI based on the severity of her presentation. She has a fever, tachycardia, flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness that are evidence of infection extending beyond the bladder. She has sepsis warranting inpatient management. Prior urine culture results could aid in determining empiric treatment while waiting for new cultures. In her case, an intravenous antibiotic with broad gram-negative coverage such as ceftriaxone would be appropriate.

Bottom line

There are multiple interpretations of complicated UTIs including both an anatomical and severity approach. Clinical judgment regarding infection severity should determine the depth of management.

Dr. Vu is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Gray is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky and the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

1. Folk CS. AUA Core Curriculum: Urinary Tract Infection (Adult). 2021 Mar 1. https://university.auanet.org/core_topic.cfm?coreid=92.

2. Gupta K et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257.

3. Johnson JR. Definition of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 February 15;64(4):529. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw751.

4. Nicolle LE, AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768.

5. Melekos MD and Naber KG. Complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15(4):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00168-0.

Key points

- The anatomical approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the presence of underlying, predisposing conditions such as structurally or functionally abnormal genitourinary tract or urinary instrumentation or foreign bodies.

- The severity approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the severity of presentation including the presence of systemic manifestations.

- Both approaches should consider populations that are at risk for recurrent or multidrug-resistant infections and infections that can lead to high morbidity.

- Either approach can be used as a guide, but neither should replace clinical suspicion and judgment in determining the depth of treatment.

Additional reading

Choe HS et al. Summary of the UAA‐AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018 Mar;25(3):175-85. doi:10.1111/iju.13493.

Nicolle LE et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;40(5):643-54. doi: 10.1086/427507.

Wagenlehner FME et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Oct;17:586-600. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0362-4.

Wallace DW et al. Urinalysis: A simple test with complicated interpretation. J Urgent Care Med. 2020 July-Aug;14(10):11-4.

Quiz

A 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with acute fever, chills, dysuria, frequency, and suprapubic pain. She has associated nausea, malaise, and fatigue. She takes metformin and denies recent antibiotic use. Her temperature is 102.8° F, heart rate 118 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/71 mm Hg, and her respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute. She is ill-appearing and has mild suprapubic tenderness. White blood cell count is 18 k/mcL. Urinalysis is positive for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria. Urine microscopy has 120 white blood cells per high power field. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Azithromycin

B. Ceftriaxone

C. Cefepime and vancomycin

D. Nitrofurantoin

The answer is B. The patient presents with sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Using the anatomic approach this would be classified as uncomplicated. Using the severity approach, this would be classified as a complicated urinary tract infection. With fever, chills, and signs of sepsis, it’s likely her infection extends beyond the bladder. Given the severity of her presentation, we’d favor treating her as a complicated urinary tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone. There is no suggestion of resistance or additional MRSA risk factors requiring intravenous vancomycin or cefepime. Nitrofurantoin, although a first-line treatment for uncomplicated cystitis, would not be appropriate if there is suspicion infection extends beyond the bladder. Azithromycin is a first-line option for chlamydia trachomatis, but not a urinary tract infection.

Lithium’s antisuicidal effects questioned

Adding lithium to usual care does not decrease the risk of suicide-related events in those with major depressive disorder (MDD) or bipolar disorder (BD) who have survived a recent suicidal event, new research shows.

The results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in veterans showed no apparent advantage of the drug in preventing self-injury, suicide attempts, or urgent hospitalization to prevent suicide.

“Lithium is an important therapy for bipolar disorders and depression subsets. Our study indicates that, in patients who are actively followed and treated in a system of care that the VA provides, simply adding lithium to their existing management, including medications, is unlikely to be effective for preventing a broad range of suicide-related events,” study investigator Ryan Ferguson, MPH, ScD, Boston Cooperative Studies Coordinating Center, VA Boston Healthcare System, told this news organization.

The study was published online JAMA Psychiatry.

Surprising findings

The results were somewhat surprising, Dr. Ferguson added. “Lithium showed little or no effect in our study, compared to observational data and results from previous trials. Many clinicians and practice guidelines had assumed that lithium was an effective agent in preventing suicide,” he said.

However, the authors of an accompanying editorial urge caution in concluding that lithium has no antisuicidal effects.

This “rigorously designed and conducted trial has much to teach but cannot be taken as evidence that lithium treatment is ineffective regarding suicidal risk,” write Ross Baldessarini, MD, and Leonardo Tondo, MD, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Study participants were veterans with MDD or BD receiving care at one of 29 Veterans Administration medical centers who survived a recent suicide-related event. In addition to usual care, they were randomly assigned to receive oral extended-release lithium carbonate starting at 600 mg/day or matching placebo for 52 weeks.

The primary outcome was time to the first repeated suicide-related event, including suicide attempts, interrupted attempts, hospitalizations specifically to prevent suicide, and deaths from suicide.

The trial was stopped for futility after 519 veterans (mean age, 42.8 years; 84% male) were randomly assigned to receive lithium (n = 255) or placebo (n = 264). At 3 months, mean lithium concentrations were 0.54 mEq/L for patients with BD and 0.46 mEq/L for those with MDD.

There was no significant difference in the primary outcome (hazard ratio, 1.10; 95% confidence interval, 0.77-1.55; P = .61).

One death occurred in the lithium group and three in the placebo group. There were no unanticipated drug-related safety concerns.

Caveats, cautionary notes

The researchers note that the study did not reach its original recruitment goal. “One of the barriers to recruitment was the perception of many of the clinicians caring for potential participants that the effectiveness of lithium was already established; in fact, this perception was supported by the VA/U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline,” they point out.

They also note that most veterans in the study had depression rather than BD, which is the most common indication for lithium use. Most also had substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, or both, which could influence outcomes.

As a result of small numbers, it wasn’t possible to evaluate outcomes for patients with BD, test whether outcomes differed among patients with BD and MDD, or assess whether comorbidities attenuated the effects of lithium.

The study’s protocol increased participants’ contacts with the VA, which also may have affected outcomes, the researchers note.

In addition, high rates of attrition and low rates of substantial adherence to lithium meant only about half (48.1%) of the study population achieved target serum lithium concentrations.

Editorial writers Dr. Baldessarini and Dr. Tondo note that the low circulating concentrations of lithium and the fact that adherence to assigned treatment was considered adequate in only 17% of participants are key limitations of the study.

“In general, controlled treatment trials aimed at detecting suicide preventive effects are difficult to design, perform, and interpret,” they point out.

Evidence supporting an antisuicidal effect of lithium treatment includes nearly three dozen observational trials that have shown fewer suicides or attempts with lithium treatment, as well as “marked, temporary” increases in suicidal behavior soon after stopping lithium treatment.

Dr. Baldessarini and Dr. Tondo note the current findings “cannot be taken as evidence that lithium lacks antisuicidal effects. An ironic final note is that recruiting participants to such trials may be made difficult by an evidently prevalent belief that the question of antisuicidal effects of lithium is already settled, which it certainly is not,” they write.

Dr. Ferguson “agrees that more work needs to be done to understand the antisuicidal effect of lithium.

The study received financial and material support from a grant from the Cooperative Studies Program, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Ferguson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original article.

Dr. Baldessarini and Dr. Tondo have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Their editorial was supported by grants from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation, the McLean Private Donors Fund for Psychiatric Research, and the Aretaeus Foundation of Rome.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adding lithium to usual care does not decrease the risk of suicide-related events in those with major depressive disorder (MDD) or bipolar disorder (BD) who have survived a recent suicidal event, new research shows.

The results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in veterans showed no apparent advantage of the drug in preventing self-injury, suicide attempts, or urgent hospitalization to prevent suicide.

“Lithium is an important therapy for bipolar disorders and depression subsets. Our study indicates that, in patients who are actively followed and treated in a system of care that the VA provides, simply adding lithium to their existing management, including medications, is unlikely to be effective for preventing a broad range of suicide-related events,” study investigator Ryan Ferguson, MPH, ScD, Boston Cooperative Studies Coordinating Center, VA Boston Healthcare System, told this news organization.

The study was published online JAMA Psychiatry.

Surprising findings

The results were somewhat surprising, Dr. Ferguson added. “Lithium showed little or no effect in our study, compared to observational data and results from previous trials. Many clinicians and practice guidelines had assumed that lithium was an effective agent in preventing suicide,” he said.

However, the authors of an accompanying editorial urge caution in concluding that lithium has no antisuicidal effects.

This “rigorously designed and conducted trial has much to teach but cannot be taken as evidence that lithium treatment is ineffective regarding suicidal risk,” write Ross Baldessarini, MD, and Leonardo Tondo, MD, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Study participants were veterans with MDD or BD receiving care at one of 29 Veterans Administration medical centers who survived a recent suicide-related event. In addition to usual care, they were randomly assigned to receive oral extended-release lithium carbonate starting at 600 mg/day or matching placebo for 52 weeks.

The primary outcome was time to the first repeated suicide-related event, including suicide attempts, interrupted attempts, hospitalizations specifically to prevent suicide, and deaths from suicide.

The trial was stopped for futility after 519 veterans (mean age, 42.8 years; 84% male) were randomly assigned to receive lithium (n = 255) or placebo (n = 264). At 3 months, mean lithium concentrations were 0.54 mEq/L for patients with BD and 0.46 mEq/L for those with MDD.

There was no significant difference in the primary outcome (hazard ratio, 1.10; 95% confidence interval, 0.77-1.55; P = .61).

One death occurred in the lithium group and three in the placebo group. There were no unanticipated drug-related safety concerns.

Caveats, cautionary notes

The researchers note that the study did not reach its original recruitment goal. “One of the barriers to recruitment was the perception of many of the clinicians caring for potential participants that the effectiveness of lithium was already established; in fact, this perception was supported by the VA/U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline,” they point out.

They also note that most veterans in the study had depression rather than BD, which is the most common indication for lithium use. Most also had substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, or both, which could influence outcomes.

As a result of small numbers, it wasn’t possible to evaluate outcomes for patients with BD, test whether outcomes differed among patients with BD and MDD, or assess whether comorbidities attenuated the effects of lithium.

The study’s protocol increased participants’ contacts with the VA, which also may have affected outcomes, the researchers note.

In addition, high rates of attrition and low rates of substantial adherence to lithium meant only about half (48.1%) of the study population achieved target serum lithium concentrations.

Editorial writers Dr. Baldessarini and Dr. Tondo note that the low circulating concentrations of lithium and the fact that adherence to assigned treatment was considered adequate in only 17% of participants are key limitations of the study.

“In general, controlled treatment trials aimed at detecting suicide preventive effects are difficult to design, perform, and interpret,” they point out.

Evidence supporting an antisuicidal effect of lithium treatment includes nearly three dozen observational trials that have shown fewer suicides or attempts with lithium treatment, as well as “marked, temporary” increases in suicidal behavior soon after stopping lithium treatment.

Dr. Baldessarini and Dr. Tondo note the current findings “cannot be taken as evidence that lithium lacks antisuicidal effects. An ironic final note is that recruiting participants to such trials may be made difficult by an evidently prevalent belief that the question of antisuicidal effects of lithium is already settled, which it certainly is not,” they write.

Dr. Ferguson “agrees that more work needs to be done to understand the antisuicidal effect of lithium.

The study received financial and material support from a grant from the Cooperative Studies Program, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Ferguson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original article.

Dr. Baldessarini and Dr. Tondo have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Their editorial was supported by grants from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation, the McLean Private Donors Fund for Psychiatric Research, and the Aretaeus Foundation of Rome.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adding lithium to usual care does not decrease the risk of suicide-related events in those with major depressive disorder (MDD) or bipolar disorder (BD) who have survived a recent suicidal event, new research shows.

The results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in veterans showed no apparent advantage of the drug in preventing self-injury, suicide attempts, or urgent hospitalization to prevent suicide.

“Lithium is an important therapy for bipolar disorders and depression subsets. Our study indicates that, in patients who are actively followed and treated in a system of care that the VA provides, simply adding lithium to their existing management, including medications, is unlikely to be effective for preventing a broad range of suicide-related events,” study investigator Ryan Ferguson, MPH, ScD, Boston Cooperative Studies Coordinating Center, VA Boston Healthcare System, told this news organization.

The study was published online JAMA Psychiatry.

Surprising findings

The results were somewhat surprising, Dr. Ferguson added. “Lithium showed little or no effect in our study, compared to observational data and results from previous trials. Many clinicians and practice guidelines had assumed that lithium was an effective agent in preventing suicide,” he said.

However, the authors of an accompanying editorial urge caution in concluding that lithium has no antisuicidal effects.

This “rigorously designed and conducted trial has much to teach but cannot be taken as evidence that lithium treatment is ineffective regarding suicidal risk,” write Ross Baldessarini, MD, and Leonardo Tondo, MD, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Study participants were veterans with MDD or BD receiving care at one of 29 Veterans Administration medical centers who survived a recent suicide-related event. In addition to usual care, they were randomly assigned to receive oral extended-release lithium carbonate starting at 600 mg/day or matching placebo for 52 weeks.

The primary outcome was time to the first repeated suicide-related event, including suicide attempts, interrupted attempts, hospitalizations specifically to prevent suicide, and deaths from suicide.

The trial was stopped for futility after 519 veterans (mean age, 42.8 years; 84% male) were randomly assigned to receive lithium (n = 255) or placebo (n = 264). At 3 months, mean lithium concentrations were 0.54 mEq/L for patients with BD and 0.46 mEq/L for those with MDD.

There was no significant difference in the primary outcome (hazard ratio, 1.10; 95% confidence interval, 0.77-1.55; P = .61).

One death occurred in the lithium group and three in the placebo group. There were no unanticipated drug-related safety concerns.

Caveats, cautionary notes

The researchers note that the study did not reach its original recruitment goal. “One of the barriers to recruitment was the perception of many of the clinicians caring for potential participants that the effectiveness of lithium was already established; in fact, this perception was supported by the VA/U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline,” they point out.

They also note that most veterans in the study had depression rather than BD, which is the most common indication for lithium use. Most also had substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, or both, which could influence outcomes.

As a result of small numbers, it wasn’t possible to evaluate outcomes for patients with BD, test whether outcomes differed among patients with BD and MDD, or assess whether comorbidities attenuated the effects of lithium.

The study’s protocol increased participants’ contacts with the VA, which also may have affected outcomes, the researchers note.

In addition, high rates of attrition and low rates of substantial adherence to lithium meant only about half (48.1%) of the study population achieved target serum lithium concentrations.

Editorial writers Dr. Baldessarini and Dr. Tondo note that the low circulating concentrations of lithium and the fact that adherence to assigned treatment was considered adequate in only 17% of participants are key limitations of the study.

“In general, controlled treatment trials aimed at detecting suicide preventive effects are difficult to design, perform, and interpret,” they point out.

Evidence supporting an antisuicidal effect of lithium treatment includes nearly three dozen observational trials that have shown fewer suicides or attempts with lithium treatment, as well as “marked, temporary” increases in suicidal behavior soon after stopping lithium treatment.

Dr. Baldessarini and Dr. Tondo note the current findings “cannot be taken as evidence that lithium lacks antisuicidal effects. An ironic final note is that recruiting participants to such trials may be made difficult by an evidently prevalent belief that the question of antisuicidal effects of lithium is already settled, which it certainly is not,” they write.

Dr. Ferguson “agrees that more work needs to be done to understand the antisuicidal effect of lithium.

The study received financial and material support from a grant from the Cooperative Studies Program, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Ferguson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original article.

Dr. Baldessarini and Dr. Tondo have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Their editorial was supported by grants from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation, the McLean Private Donors Fund for Psychiatric Research, and the Aretaeus Foundation of Rome.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

FDA puts clozapine REMS requirements on temporary hold

U.S. regulators have put some of the new clozapine risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program on temporary hold because of start-up difficulties, including long telephone wait times.

In a Nov. 19 statement, the Food and Drug Administration announced it is temporarily suspending certain aspects of the program because of challenges reported by medical professionals who were trying to meet the original Nov. 15 deadline.

In response, the FDA has conceded that pharmacists can dispense clozapine without a REMS dispense authorization (RDA). Wholesalers can continue to ship clozapine to pharmacies and health care settings without confirming enrollment in the REMS, the FDA also said.

“We encourage pharmacists and prescribers to continue working with the clozapine REMS to complete certification and patient enrollment,” the FDA said in a statement.

In July, the FDA approved modifications to the clozapine REMS strategy. Clozapine is used to treat schizophrenia that is not well controlled with standard antipsychotics. It is also prescribed to patients with recurrent suicidal behavior associated with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Although it is highly effective in some patients, it also carries serious risks. Specifically, it can decrease the neutrophil count, which can lead to severe neutropenia, serious infections, and death.

As a result, those taking the drug must undergo regular absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring. Clozapine REMS is intended to maximize the benefits of the drug and minimize risk.

HCP frustration

, including a high call volume and long call wait times for stakeholders.

“We understand that this has caused frustration and has led to patient access issues for clozapine,” the FDA said in a statement.

“Continuity of care, patient access to clozapine, and patient safety are our highest priorities,” the FDA added. “We are working closely with the clozapine REMS program administrators to address these challenges and avoid interruptions in patient care.”

Abrupt discontinuation of clozapine can result in significant complications, the FDA said. The agency urged use of “clinical judgment” with respect to prescribing and dispensing clozapine to patients with an absolute neutrophil count within the acceptable range.

As previously reported by this news organization, the American Psychiatric Association and other national groups in a September letter asked the FDA to delay the implementation of a new REMS program until after Jan. 1, 2022.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. regulators have put some of the new clozapine risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program on temporary hold because of start-up difficulties, including long telephone wait times.

In a Nov. 19 statement, the Food and Drug Administration announced it is temporarily suspending certain aspects of the program because of challenges reported by medical professionals who were trying to meet the original Nov. 15 deadline.

In response, the FDA has conceded that pharmacists can dispense clozapine without a REMS dispense authorization (RDA). Wholesalers can continue to ship clozapine to pharmacies and health care settings without confirming enrollment in the REMS, the FDA also said.

“We encourage pharmacists and prescribers to continue working with the clozapine REMS to complete certification and patient enrollment,” the FDA said in a statement.

In July, the FDA approved modifications to the clozapine REMS strategy. Clozapine is used to treat schizophrenia that is not well controlled with standard antipsychotics. It is also prescribed to patients with recurrent suicidal behavior associated with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Although it is highly effective in some patients, it also carries serious risks. Specifically, it can decrease the neutrophil count, which can lead to severe neutropenia, serious infections, and death.

As a result, those taking the drug must undergo regular absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring. Clozapine REMS is intended to maximize the benefits of the drug and minimize risk.

HCP frustration

, including a high call volume and long call wait times for stakeholders.

“We understand that this has caused frustration and has led to patient access issues for clozapine,” the FDA said in a statement.

“Continuity of care, patient access to clozapine, and patient safety are our highest priorities,” the FDA added. “We are working closely with the clozapine REMS program administrators to address these challenges and avoid interruptions in patient care.”

Abrupt discontinuation of clozapine can result in significant complications, the FDA said. The agency urged use of “clinical judgment” with respect to prescribing and dispensing clozapine to patients with an absolute neutrophil count within the acceptable range.

As previously reported by this news organization, the American Psychiatric Association and other national groups in a September letter asked the FDA to delay the implementation of a new REMS program until after Jan. 1, 2022.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. regulators have put some of the new clozapine risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program on temporary hold because of start-up difficulties, including long telephone wait times.

In a Nov. 19 statement, the Food and Drug Administration announced it is temporarily suspending certain aspects of the program because of challenges reported by medical professionals who were trying to meet the original Nov. 15 deadline.

In response, the FDA has conceded that pharmacists can dispense clozapine without a REMS dispense authorization (RDA). Wholesalers can continue to ship clozapine to pharmacies and health care settings without confirming enrollment in the REMS, the FDA also said.

“We encourage pharmacists and prescribers to continue working with the clozapine REMS to complete certification and patient enrollment,” the FDA said in a statement.

In July, the FDA approved modifications to the clozapine REMS strategy. Clozapine is used to treat schizophrenia that is not well controlled with standard antipsychotics. It is also prescribed to patients with recurrent suicidal behavior associated with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Although it is highly effective in some patients, it also carries serious risks. Specifically, it can decrease the neutrophil count, which can lead to severe neutropenia, serious infections, and death.

As a result, those taking the drug must undergo regular absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring. Clozapine REMS is intended to maximize the benefits of the drug and minimize risk.

HCP frustration

, including a high call volume and long call wait times for stakeholders.

“We understand that this has caused frustration and has led to patient access issues for clozapine,” the FDA said in a statement.

“Continuity of care, patient access to clozapine, and patient safety are our highest priorities,” the FDA added. “We are working closely with the clozapine REMS program administrators to address these challenges and avoid interruptions in patient care.”

Abrupt discontinuation of clozapine can result in significant complications, the FDA said. The agency urged use of “clinical judgment” with respect to prescribing and dispensing clozapine to patients with an absolute neutrophil count within the acceptable range.

As previously reported by this news organization, the American Psychiatric Association and other national groups in a September letter asked the FDA to delay the implementation of a new REMS program until after Jan. 1, 2022.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Schools, pediatricians look to make up lost ground on non–COVID-19 vaccinations

WESTMINSTER, COLO. – Melissa Blatzer was determined to get her three children caught up on their routine immunizations on a recent Saturday morning at a walk-in clinic in this Denver suburb. It had been about a year since the kids’ last shots, a delay Ms. Blatzer chalked up to the pandemic.

Two-year-old Lincoln Blatzer, in his fleece dinosaur pajamas, waited anxiously in line for his hepatitis A vaccine. His siblings, 14-year-old Nyla Kusumah and 11-year-old Nevan Kusumah, were there for their TDAP, HPV and meningococcal vaccines, plus a COVID-19 shot for Nyla.

“You don’t have to make an appointment and you can take all three at once,” said Ms. Blatzer, who lives several miles away in Commerce City. That convenience outweighed the difficulty of getting everyone up early on a weekend.

Child health experts hope community clinics like this – along with the return to in-person classes, more well-child visits, and the rollout of COVID shots for younger children – can help boost routine childhood immunizations, which dropped during the pandemic. Despite a rebound, immunization rates are still lower than in 2019, and disparities in rates between racial and economic groups, particularly for Black children, have been exacerbated.

“We’re still not back to where we need to be,” said Sean O’Leary, MD, a pediatric infectious disease doctor at Children’s Hospital Colorado and a professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Routine immunizations protect children against 16 infectious diseases, including measles, diphtheria and chickenpox, and inhibit transmission to the community.

The rollout of COVID shots for younger kids is an opportunity to catch up on routine vaccinations, said Dr. O’Leary, adding that children can receive these vaccines together. Primary care practices, where many children are likely to receive the COVID shots, usually have other childhood vaccines on hand.

“It’s really important that parents and health care providers work together so that all children are up to date on these recommended vaccines,” said Malini DeSilva, MD, an internist and pediatrician at HealthPartners in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area. “Not only for the child’s health but for our community’s health.”

People were reluctant to come out for routine immunizations at the height of the pandemic, said Karen Miller, an immunization nurse manager for the Denver area’s Tri-County Health Department, which ran the Westminster clinic. National and global data confirm what Ms. Miller saw on the ground.

Global vaccine coverage in children fell from 2019 to 2020, according to a recent study by scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, and UNICEF. Reasons included reduced access, lack of transportation, worries about COVID exposure and supply chain interruptions, the study said.

Third doses of the DTP vaccine and of the polio vaccine decreased from 86% of all eligible children in 2019 to 83% in 2020, according to the study. Worldwide, 22.7 million children had not had their third dose of DTP in 2020, compared with 19 million in 2019. Three doses are far more effective than one or two at protecting children and communities.

In the United States, researchers who studied 2019 and 2020 data on routine vaccinations in California, Colorado, Minnesota, Oregon, Washington, and Wisconsin found substantial disruptions in vaccination rates during the pandemic that continued into September 2020. For example, the percentage of 7-month-old babies who were up to date on vaccinations decreased from 81% in September 2019 to 74% a year later.

The proportion of Black children up to date on immunizations in almost all age groups was lower than that of children in other racial and ethnic groups. This was most pronounced in those turning 18 months old: Only 41% of Black children that age were caught up on vaccinations in September 2020, compared with 57% of all children at 18 months, said Dr. DeSilva, who led that study.

A CDC study of data from the National Immunization Surveys found that race and ethnicity, poverty, and lack of insurance created the greatest disparities in vaccination rates, and the authors noted that extra efforts are needed to counter the pandemic’s disruptions.

In addition to the problems caused by COVID, Ms. Miller said, competing life priorities like work and school impede families from keeping up with shots. Weekend vaccination clinics can help working parents get their children caught up on routine immunizations while they get a flu or COVID shot. Ms. Miller and O’Leary also said reminders via phone, text or email can boost immunizations.

“Vaccines are so effective that I think it’s easy for families to put immunizations on the back burner because we don’t often hear about these diseases,” she said.

It’s a long and nasty list that includes hepatitis A and B, measles, mumps, whooping cough, polio, rubella, rotavirus, pneumococcus, tetanus, diphtheria, human papillomavirus, and meningococcal disease, among others. Even small drops in vaccination coverage can lead to outbreaks. And measles is the perfect example that worries experts, particularly as international travel opens up.

“Measles is among the most contagious diseases known to humankind, meaning that we have to keep very high vaccination coverage to keep it from spreading,” said Dr. O’Leary.

In 2019, 22 measles outbreaks occurred in 17 states in mostly unvaccinated children and adults. Dr. O’Leary said outbreaks in New York City were contained because surrounding areas had high vaccination coverage. But an outbreak in an undervaccinated community still could spread beyond its borders.

In some states a significant number of parents were opposed to routine childhood vaccines even before the pandemic for religious or personal reasons, posing another challenge for health professionals. For example, 87% of Colorado kindergartners were vaccinated against measles, mumps, and rubella during the 2018-19 school year, one of the nation’s lowest rates.

Those rates bumped up to 91% in 2019-20 but are still below the CDC’s target of 95%.

Dr. O’Leary said he does not see the same level of hesitancy for routine immunizations as for COVID. “There has always been vaccine hesitancy and vaccine refusers. But we’ve maintained vaccination rates north of 90% for all routine childhood vaccines for a long time now,” he said.

Dr. DeSilva said the “ripple effects” of missed vaccinations earlier in the pandemic continued into 2021. As children returned to in-person learning this fall, schools may have been the first place families heard about missed vaccinations. Individual states set vaccination requirements, and allowable exemptions, for entry at schools and child care facilities. In 2020, Colorado passed a school entry immunization law that tightened allowable exemptions.

“Schools, where vaccination requirements are generally enforced, are stretched thin for a variety of reasons, including COVID,” said Dr. O’Leary, adding that managing vaccine requirements may be more difficult for some, but not all, schools.

Anayeli Dominguez, 13, was at the Westminster clinic for a Tdap vaccine because her middle school had noticed she was not up to date.

“School nurses play an important role in helping identify students in need of immunizations, and also by connecting families to resources both within the district and in the larger community,” said Denver Public Schools spokesperson Will Jones.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

WESTMINSTER, COLO. – Melissa Blatzer was determined to get her three children caught up on their routine immunizations on a recent Saturday morning at a walk-in clinic in this Denver suburb. It had been about a year since the kids’ last shots, a delay Ms. Blatzer chalked up to the pandemic.

Two-year-old Lincoln Blatzer, in his fleece dinosaur pajamas, waited anxiously in line for his hepatitis A vaccine. His siblings, 14-year-old Nyla Kusumah and 11-year-old Nevan Kusumah, were there for their TDAP, HPV and meningococcal vaccines, plus a COVID-19 shot for Nyla.

“You don’t have to make an appointment and you can take all three at once,” said Ms. Blatzer, who lives several miles away in Commerce City. That convenience outweighed the difficulty of getting everyone up early on a weekend.

Child health experts hope community clinics like this – along with the return to in-person classes, more well-child visits, and the rollout of COVID shots for younger children – can help boost routine childhood immunizations, which dropped during the pandemic. Despite a rebound, immunization rates are still lower than in 2019, and disparities in rates between racial and economic groups, particularly for Black children, have been exacerbated.

“We’re still not back to where we need to be,” said Sean O’Leary, MD, a pediatric infectious disease doctor at Children’s Hospital Colorado and a professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Routine immunizations protect children against 16 infectious diseases, including measles, diphtheria and chickenpox, and inhibit transmission to the community.

The rollout of COVID shots for younger kids is an opportunity to catch up on routine vaccinations, said Dr. O’Leary, adding that children can receive these vaccines together. Primary care practices, where many children are likely to receive the COVID shots, usually have other childhood vaccines on hand.

“It’s really important that parents and health care providers work together so that all children are up to date on these recommended vaccines,” said Malini DeSilva, MD, an internist and pediatrician at HealthPartners in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area. “Not only for the child’s health but for our community’s health.”

People were reluctant to come out for routine immunizations at the height of the pandemic, said Karen Miller, an immunization nurse manager for the Denver area’s Tri-County Health Department, which ran the Westminster clinic. National and global data confirm what Ms. Miller saw on the ground.

Global vaccine coverage in children fell from 2019 to 2020, according to a recent study by scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, and UNICEF. Reasons included reduced access, lack of transportation, worries about COVID exposure and supply chain interruptions, the study said.

Third doses of the DTP vaccine and of the polio vaccine decreased from 86% of all eligible children in 2019 to 83% in 2020, according to the study. Worldwide, 22.7 million children had not had their third dose of DTP in 2020, compared with 19 million in 2019. Three doses are far more effective than one or two at protecting children and communities.

In the United States, researchers who studied 2019 and 2020 data on routine vaccinations in California, Colorado, Minnesota, Oregon, Washington, and Wisconsin found substantial disruptions in vaccination rates during the pandemic that continued into September 2020. For example, the percentage of 7-month-old babies who were up to date on vaccinations decreased from 81% in September 2019 to 74% a year later.

The proportion of Black children up to date on immunizations in almost all age groups was lower than that of children in other racial and ethnic groups. This was most pronounced in those turning 18 months old: Only 41% of Black children that age were caught up on vaccinations in September 2020, compared with 57% of all children at 18 months, said Dr. DeSilva, who led that study.

A CDC study of data from the National Immunization Surveys found that race and ethnicity, poverty, and lack of insurance created the greatest disparities in vaccination rates, and the authors noted that extra efforts are needed to counter the pandemic’s disruptions.

In addition to the problems caused by COVID, Ms. Miller said, competing life priorities like work and school impede families from keeping up with shots. Weekend vaccination clinics can help working parents get their children caught up on routine immunizations while they get a flu or COVID shot. Ms. Miller and O’Leary also said reminders via phone, text or email can boost immunizations.

“Vaccines are so effective that I think it’s easy for families to put immunizations on the back burner because we don’t often hear about these diseases,” she said.

It’s a long and nasty list that includes hepatitis A and B, measles, mumps, whooping cough, polio, rubella, rotavirus, pneumococcus, tetanus, diphtheria, human papillomavirus, and meningococcal disease, among others. Even small drops in vaccination coverage can lead to outbreaks. And measles is the perfect example that worries experts, particularly as international travel opens up.

“Measles is among the most contagious diseases known to humankind, meaning that we have to keep very high vaccination coverage to keep it from spreading,” said Dr. O’Leary.

In 2019, 22 measles outbreaks occurred in 17 states in mostly unvaccinated children and adults. Dr. O’Leary said outbreaks in New York City were contained because surrounding areas had high vaccination coverage. But an outbreak in an undervaccinated community still could spread beyond its borders.

In some states a significant number of parents were opposed to routine childhood vaccines even before the pandemic for religious or personal reasons, posing another challenge for health professionals. For example, 87% of Colorado kindergartners were vaccinated against measles, mumps, and rubella during the 2018-19 school year, one of the nation’s lowest rates.

Those rates bumped up to 91% in 2019-20 but are still below the CDC’s target of 95%.

Dr. O’Leary said he does not see the same level of hesitancy for routine immunizations as for COVID. “There has always been vaccine hesitancy and vaccine refusers. But we’ve maintained vaccination rates north of 90% for all routine childhood vaccines for a long time now,” he said.

Dr. DeSilva said the “ripple effects” of missed vaccinations earlier in the pandemic continued into 2021. As children returned to in-person learning this fall, schools may have been the first place families heard about missed vaccinations. Individual states set vaccination requirements, and allowable exemptions, for entry at schools and child care facilities. In 2020, Colorado passed a school entry immunization law that tightened allowable exemptions.

“Schools, where vaccination requirements are generally enforced, are stretched thin for a variety of reasons, including COVID,” said Dr. O’Leary, adding that managing vaccine requirements may be more difficult for some, but not all, schools.

Anayeli Dominguez, 13, was at the Westminster clinic for a Tdap vaccine because her middle school had noticed she was not up to date.

“School nurses play an important role in helping identify students in need of immunizations, and also by connecting families to resources both within the district and in the larger community,” said Denver Public Schools spokesperson Will Jones.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

WESTMINSTER, COLO. – Melissa Blatzer was determined to get her three children caught up on their routine immunizations on a recent Saturday morning at a walk-in clinic in this Denver suburb. It had been about a year since the kids’ last shots, a delay Ms. Blatzer chalked up to the pandemic.

Two-year-old Lincoln Blatzer, in his fleece dinosaur pajamas, waited anxiously in line for his hepatitis A vaccine. His siblings, 14-year-old Nyla Kusumah and 11-year-old Nevan Kusumah, were there for their TDAP, HPV and meningococcal vaccines, plus a COVID-19 shot for Nyla.

“You don’t have to make an appointment and you can take all three at once,” said Ms. Blatzer, who lives several miles away in Commerce City. That convenience outweighed the difficulty of getting everyone up early on a weekend.

Child health experts hope community clinics like this – along with the return to in-person classes, more well-child visits, and the rollout of COVID shots for younger children – can help boost routine childhood immunizations, which dropped during the pandemic. Despite a rebound, immunization rates are still lower than in 2019, and disparities in rates between racial and economic groups, particularly for Black children, have been exacerbated.

“We’re still not back to where we need to be,” said Sean O’Leary, MD, a pediatric infectious disease doctor at Children’s Hospital Colorado and a professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.