User login

What is the real risk of smart phones in medicine?

Over the 10 years we’ve been writing this column, we have often found inspiration for topics while traveling – especially while flying. This is not just because of the idle time spent in the air, but instead because of the many ways that air travel and health care experiences are similar. Both industries focus heavily on safety, are tightly regulated, and employ highly trained individuals.

Consumers may recognize the similarities as well – health care and air travel are both well-known for long waits, uncertainty, and implicit risk. Both sectors are also notorious drivers of innovation, constantly leveraging new technologies in pursuit of better outcomes and experiences. Occasionally, however, advancements in technology can present unforeseen challenges and even compromise safety, with the potential to produce unexpected consequences.

A familiar reminder of this potential was provided to us at the commencement of a recent flight, when we were instructed to turn off our personal electronic devices or flip them into “airplane mode.” This same admonishment is often given to patients and visitors in health care settings – everywhere from clinic waiting rooms to intensive care units – though the reason for this is typically left vague. This got us thinking. More importantly, what other emerging technologies have the potential to create issues we may not have anticipated?

Mayo Clinic findings on radio communication used by mobile phones

Once our flight landed, we did some research to answer our initial question about personal communication technology and its ability to interfere with sensitive electronic devices. Specifically, we wanted to know whether radio communication used by mobile phones could affect the operation of medical equipment, potentially leading to dire consequences for patients. Spoiler alert: There is very little evidence that this can occur. In fact, a well-documented study performed by the Mayo Clinic in 2007 found interference in 0 out of 300 tests performed. To quote the authors, “the incidence of clinically important interference was 0%.”

We could find no other studies since 2007 that strongly contradict Mayo’s findings, except for several anecdotal reports and articles that postulate the theoretical possibility.

This is confirmed by the American Heart Association, who maintains a list of devices that may interfere with ICDs and pacemakers on their website. According to the AHA, “wireless transmissions from the antennae of phones available in the United States are a very small risk to ICDs and even less of a risk for pacemakers.” And in case you’re wondering, the story is quite similar for airplanes as well.

The latest publication from NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) documents incidents related to personal electronic devices during air travel. Most involve smoke production – or even small fires – caused by malfunctioning phone batteries during charging. Only a few entries reference wireless interference, and these were all minor and unconfirmed events. As with health care environments, airplanes don’t appear to face significant risks from radio interference. But that doesn’t mean personal electronics are completely harmless to patients.

Smartphones’ risks to patient with cardiac devices

On May 13 of 2021, the FDA issued a warning to cardiac patients about their smart phones and smart watches. Many current personal electronic devices and accessories are equipped with strong magnets, such as those contained in the “MagSafe” connector on the iPhone 12, that can deactivate pacemakers and implanted cardiac defibrillators. These medical devices are designed to be manipulated by magnets for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, but strong magnetic fields can disable them unintentionally, leading to catastrophic results.

Apple and other manufacturers have acknowledged this risk and recommend that smartphones and other devices be kept at least 6 inches from cardiac devices. Given the ubiquity of offending products, it is also imperative that we warn our patients about this risk to their physical wellbeing.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

Over the 10 years we’ve been writing this column, we have often found inspiration for topics while traveling – especially while flying. This is not just because of the idle time spent in the air, but instead because of the many ways that air travel and health care experiences are similar. Both industries focus heavily on safety, are tightly regulated, and employ highly trained individuals.

Consumers may recognize the similarities as well – health care and air travel are both well-known for long waits, uncertainty, and implicit risk. Both sectors are also notorious drivers of innovation, constantly leveraging new technologies in pursuit of better outcomes and experiences. Occasionally, however, advancements in technology can present unforeseen challenges and even compromise safety, with the potential to produce unexpected consequences.

A familiar reminder of this potential was provided to us at the commencement of a recent flight, when we were instructed to turn off our personal electronic devices or flip them into “airplane mode.” This same admonishment is often given to patients and visitors in health care settings – everywhere from clinic waiting rooms to intensive care units – though the reason for this is typically left vague. This got us thinking. More importantly, what other emerging technologies have the potential to create issues we may not have anticipated?

Mayo Clinic findings on radio communication used by mobile phones

Once our flight landed, we did some research to answer our initial question about personal communication technology and its ability to interfere with sensitive electronic devices. Specifically, we wanted to know whether radio communication used by mobile phones could affect the operation of medical equipment, potentially leading to dire consequences for patients. Spoiler alert: There is very little evidence that this can occur. In fact, a well-documented study performed by the Mayo Clinic in 2007 found interference in 0 out of 300 tests performed. To quote the authors, “the incidence of clinically important interference was 0%.”

We could find no other studies since 2007 that strongly contradict Mayo’s findings, except for several anecdotal reports and articles that postulate the theoretical possibility.

This is confirmed by the American Heart Association, who maintains a list of devices that may interfere with ICDs and pacemakers on their website. According to the AHA, “wireless transmissions from the antennae of phones available in the United States are a very small risk to ICDs and even less of a risk for pacemakers.” And in case you’re wondering, the story is quite similar for airplanes as well.

The latest publication from NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) documents incidents related to personal electronic devices during air travel. Most involve smoke production – or even small fires – caused by malfunctioning phone batteries during charging. Only a few entries reference wireless interference, and these were all minor and unconfirmed events. As with health care environments, airplanes don’t appear to face significant risks from radio interference. But that doesn’t mean personal electronics are completely harmless to patients.

Smartphones’ risks to patient with cardiac devices

On May 13 of 2021, the FDA issued a warning to cardiac patients about their smart phones and smart watches. Many current personal electronic devices and accessories are equipped with strong magnets, such as those contained in the “MagSafe” connector on the iPhone 12, that can deactivate pacemakers and implanted cardiac defibrillators. These medical devices are designed to be manipulated by magnets for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, but strong magnetic fields can disable them unintentionally, leading to catastrophic results.

Apple and other manufacturers have acknowledged this risk and recommend that smartphones and other devices be kept at least 6 inches from cardiac devices. Given the ubiquity of offending products, it is also imperative that we warn our patients about this risk to their physical wellbeing.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

Over the 10 years we’ve been writing this column, we have often found inspiration for topics while traveling – especially while flying. This is not just because of the idle time spent in the air, but instead because of the many ways that air travel and health care experiences are similar. Both industries focus heavily on safety, are tightly regulated, and employ highly trained individuals.

Consumers may recognize the similarities as well – health care and air travel are both well-known for long waits, uncertainty, and implicit risk. Both sectors are also notorious drivers of innovation, constantly leveraging new technologies in pursuit of better outcomes and experiences. Occasionally, however, advancements in technology can present unforeseen challenges and even compromise safety, with the potential to produce unexpected consequences.

A familiar reminder of this potential was provided to us at the commencement of a recent flight, when we were instructed to turn off our personal electronic devices or flip them into “airplane mode.” This same admonishment is often given to patients and visitors in health care settings – everywhere from clinic waiting rooms to intensive care units – though the reason for this is typically left vague. This got us thinking. More importantly, what other emerging technologies have the potential to create issues we may not have anticipated?

Mayo Clinic findings on radio communication used by mobile phones

Once our flight landed, we did some research to answer our initial question about personal communication technology and its ability to interfere with sensitive electronic devices. Specifically, we wanted to know whether radio communication used by mobile phones could affect the operation of medical equipment, potentially leading to dire consequences for patients. Spoiler alert: There is very little evidence that this can occur. In fact, a well-documented study performed by the Mayo Clinic in 2007 found interference in 0 out of 300 tests performed. To quote the authors, “the incidence of clinically important interference was 0%.”

We could find no other studies since 2007 that strongly contradict Mayo’s findings, except for several anecdotal reports and articles that postulate the theoretical possibility.

This is confirmed by the American Heart Association, who maintains a list of devices that may interfere with ICDs and pacemakers on their website. According to the AHA, “wireless transmissions from the antennae of phones available in the United States are a very small risk to ICDs and even less of a risk for pacemakers.” And in case you’re wondering, the story is quite similar for airplanes as well.

The latest publication from NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) documents incidents related to personal electronic devices during air travel. Most involve smoke production – or even small fires – caused by malfunctioning phone batteries during charging. Only a few entries reference wireless interference, and these were all minor and unconfirmed events. As with health care environments, airplanes don’t appear to face significant risks from radio interference. But that doesn’t mean personal electronics are completely harmless to patients.

Smartphones’ risks to patient with cardiac devices

On May 13 of 2021, the FDA issued a warning to cardiac patients about their smart phones and smart watches. Many current personal electronic devices and accessories are equipped with strong magnets, such as those contained in the “MagSafe” connector on the iPhone 12, that can deactivate pacemakers and implanted cardiac defibrillators. These medical devices are designed to be manipulated by magnets for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, but strong magnetic fields can disable them unintentionally, leading to catastrophic results.

Apple and other manufacturers have acknowledged this risk and recommend that smartphones and other devices be kept at least 6 inches from cardiac devices. Given the ubiquity of offending products, it is also imperative that we warn our patients about this risk to their physical wellbeing.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

Mobile stroke teams treat patients faster and reduce disability

Having a mobile interventional stroke team (MIST) travel to treat stroke patients soon after stroke onset may improve patient outcomes, according to a new study. A retrospective analysis of a pilot program in New York found that

“The use of a Mobile Interventional Stroke Team (MIST) traveling to Thrombectomy Capable Stroke Centers to perform endovascular thrombectomy has been shown to be significantly faster with improved discharge outcomes,” wrote lead author Jacob Morey, a doctoral Candidate at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and coauthors in the paper. Prior to this study, “the effect of the MIST model stratified by time of presentation” had yet to be studied.

The findings were published online on Aug. 5 in Stroke.

MIST model versus drip-and-ship

The researchers analyzed 226 patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy between January 2017 and February 2020 at four hospitals in the Mount Sinai health system using the NYC MIST Trial and a stroke database. At baseline, all patients were functionally independent as assessed by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS, score of 0-2). 106 patients were treated by a MIST team – staffed by a neurointerventionalist, a fellow or physician assistant, and radiologic technologist – that traveled to the patient’s location. A total of 120 patients were transferred to a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) or a hospital with endovascular thrombectomy expertise. The analysis was stratified based on whether the patient presented in the early time window (≤ 6 hours) or late time window (> 6 hours).

Patients treated in the early time window were significantly more likely to be mobile and able to perform daily tasks (mRS ≤ 2) 90 days after the procedure in the MIST group (54%), compared with the transferred group (28%, P < 0.01). Outcomes did not differ significantly between groups in the late time window (35% vs. 41%, P = 0.77).

Similarly, early-time-window patients in the MIST group were more likely to have higher functionality at discharge, compared with transferred patients, based on the on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (median score of 5.0 vs. 12.0, P < 0.01). There was no significant difference between groups treated in the late time window (median score of 5.0 vs. 11.0, P = 0.11).

“Ischemic strokes often progress rapidly and can cause severe damage because brain tissue dies quickly without oxygen, resulting in serious long-term disabilities or death,“ said Johanna Fifi, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine, said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “Assessing and treating stroke patients in the early window means that a greater number of fast-progressing strokes are identified and treated.”

Time is brain

Endovascular thrombectomy is a time-sensitive surgical procedure to remove large blood clots in acute ischemic stroke that has “historically been limited to comprehensive stroke centers,” the authors wrote in their paper. It is considered the standard of care in ischemic strokes, which make up 90% of all strokes. “Less than 50% of Americans have direct access to endovascular thrombectomy, the others must be transferred to a thrombectomy-capable hospital for treatment, often losing over 2 hours of time to treatment,” said Dr. Fifi. “Every minute is precious in treating stroke, and getting to a center that offers thrombectomy is very important. The MIST model would address this by providing faster access to this potentially life-saving, disability-reducing procedure.”

Access to timely endovascular thrombectomy is gradually improving as “more institutions and cities have implemented the [MIST] model.” Dr. Fifi said.

“This study stresses the importance of ‘time is brain,’ especially for patients in the early time window. Although the study is limited by the observational, retrospective design and was performed at a single integrated center, the findings are provocative,” said Louise McCullough, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “The use of a MIST model highlights the potential benefit of early and urgent treatment for patients with large-vessel stroke. Stroke systems of care need to take advantage of any opportunity to treat patients early, wherever they are.”

The study was partly funded by a Stryker Foundation grant.

Having a mobile interventional stroke team (MIST) travel to treat stroke patients soon after stroke onset may improve patient outcomes, according to a new study. A retrospective analysis of a pilot program in New York found that

“The use of a Mobile Interventional Stroke Team (MIST) traveling to Thrombectomy Capable Stroke Centers to perform endovascular thrombectomy has been shown to be significantly faster with improved discharge outcomes,” wrote lead author Jacob Morey, a doctoral Candidate at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and coauthors in the paper. Prior to this study, “the effect of the MIST model stratified by time of presentation” had yet to be studied.

The findings were published online on Aug. 5 in Stroke.

MIST model versus drip-and-ship

The researchers analyzed 226 patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy between January 2017 and February 2020 at four hospitals in the Mount Sinai health system using the NYC MIST Trial and a stroke database. At baseline, all patients were functionally independent as assessed by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS, score of 0-2). 106 patients were treated by a MIST team – staffed by a neurointerventionalist, a fellow or physician assistant, and radiologic technologist – that traveled to the patient’s location. A total of 120 patients were transferred to a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) or a hospital with endovascular thrombectomy expertise. The analysis was stratified based on whether the patient presented in the early time window (≤ 6 hours) or late time window (> 6 hours).

Patients treated in the early time window were significantly more likely to be mobile and able to perform daily tasks (mRS ≤ 2) 90 days after the procedure in the MIST group (54%), compared with the transferred group (28%, P < 0.01). Outcomes did not differ significantly between groups in the late time window (35% vs. 41%, P = 0.77).

Similarly, early-time-window patients in the MIST group were more likely to have higher functionality at discharge, compared with transferred patients, based on the on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (median score of 5.0 vs. 12.0, P < 0.01). There was no significant difference between groups treated in the late time window (median score of 5.0 vs. 11.0, P = 0.11).

“Ischemic strokes often progress rapidly and can cause severe damage because brain tissue dies quickly without oxygen, resulting in serious long-term disabilities or death,“ said Johanna Fifi, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine, said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “Assessing and treating stroke patients in the early window means that a greater number of fast-progressing strokes are identified and treated.”

Time is brain

Endovascular thrombectomy is a time-sensitive surgical procedure to remove large blood clots in acute ischemic stroke that has “historically been limited to comprehensive stroke centers,” the authors wrote in their paper. It is considered the standard of care in ischemic strokes, which make up 90% of all strokes. “Less than 50% of Americans have direct access to endovascular thrombectomy, the others must be transferred to a thrombectomy-capable hospital for treatment, often losing over 2 hours of time to treatment,” said Dr. Fifi. “Every minute is precious in treating stroke, and getting to a center that offers thrombectomy is very important. The MIST model would address this by providing faster access to this potentially life-saving, disability-reducing procedure.”

Access to timely endovascular thrombectomy is gradually improving as “more institutions and cities have implemented the [MIST] model.” Dr. Fifi said.

“This study stresses the importance of ‘time is brain,’ especially for patients in the early time window. Although the study is limited by the observational, retrospective design and was performed at a single integrated center, the findings are provocative,” said Louise McCullough, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “The use of a MIST model highlights the potential benefit of early and urgent treatment for patients with large-vessel stroke. Stroke systems of care need to take advantage of any opportunity to treat patients early, wherever they are.”

The study was partly funded by a Stryker Foundation grant.

Having a mobile interventional stroke team (MIST) travel to treat stroke patients soon after stroke onset may improve patient outcomes, according to a new study. A retrospective analysis of a pilot program in New York found that

“The use of a Mobile Interventional Stroke Team (MIST) traveling to Thrombectomy Capable Stroke Centers to perform endovascular thrombectomy has been shown to be significantly faster with improved discharge outcomes,” wrote lead author Jacob Morey, a doctoral Candidate at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and coauthors in the paper. Prior to this study, “the effect of the MIST model stratified by time of presentation” had yet to be studied.

The findings were published online on Aug. 5 in Stroke.

MIST model versus drip-and-ship

The researchers analyzed 226 patients who underwent endovascular thrombectomy between January 2017 and February 2020 at four hospitals in the Mount Sinai health system using the NYC MIST Trial and a stroke database. At baseline, all patients were functionally independent as assessed by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS, score of 0-2). 106 patients were treated by a MIST team – staffed by a neurointerventionalist, a fellow or physician assistant, and radiologic technologist – that traveled to the patient’s location. A total of 120 patients were transferred to a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) or a hospital with endovascular thrombectomy expertise. The analysis was stratified based on whether the patient presented in the early time window (≤ 6 hours) or late time window (> 6 hours).

Patients treated in the early time window were significantly more likely to be mobile and able to perform daily tasks (mRS ≤ 2) 90 days after the procedure in the MIST group (54%), compared with the transferred group (28%, P < 0.01). Outcomes did not differ significantly between groups in the late time window (35% vs. 41%, P = 0.77).

Similarly, early-time-window patients in the MIST group were more likely to have higher functionality at discharge, compared with transferred patients, based on the on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (median score of 5.0 vs. 12.0, P < 0.01). There was no significant difference between groups treated in the late time window (median score of 5.0 vs. 11.0, P = 0.11).

“Ischemic strokes often progress rapidly and can cause severe damage because brain tissue dies quickly without oxygen, resulting in serious long-term disabilities or death,“ said Johanna Fifi, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine, said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “Assessing and treating stroke patients in the early window means that a greater number of fast-progressing strokes are identified and treated.”

Time is brain

Endovascular thrombectomy is a time-sensitive surgical procedure to remove large blood clots in acute ischemic stroke that has “historically been limited to comprehensive stroke centers,” the authors wrote in their paper. It is considered the standard of care in ischemic strokes, which make up 90% of all strokes. “Less than 50% of Americans have direct access to endovascular thrombectomy, the others must be transferred to a thrombectomy-capable hospital for treatment, often losing over 2 hours of time to treatment,” said Dr. Fifi. “Every minute is precious in treating stroke, and getting to a center that offers thrombectomy is very important. The MIST model would address this by providing faster access to this potentially life-saving, disability-reducing procedure.”

Access to timely endovascular thrombectomy is gradually improving as “more institutions and cities have implemented the [MIST] model.” Dr. Fifi said.

“This study stresses the importance of ‘time is brain,’ especially for patients in the early time window. Although the study is limited by the observational, retrospective design and was performed at a single integrated center, the findings are provocative,” said Louise McCullough, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston said in a statement to the American Heart Association. “The use of a MIST model highlights the potential benefit of early and urgent treatment for patients with large-vessel stroke. Stroke systems of care need to take advantage of any opportunity to treat patients early, wherever they are.”

The study was partly funded by a Stryker Foundation grant.

FROM STROKE

Injectable monoclonal antibodies prevent COVID-19 in trial

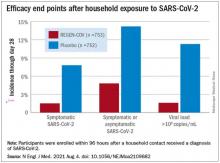

according to results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial published online August 4, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The cocktail of the monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab (REGEN-COV, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) reduced participants’ relative risk of infection by 72%, compared with placebo within the first week. After the first week, risk reduction increased to 93%.

“Long after you would be exposed by your household, there is an enduring effect that prevents you from community spread,” said David Wohl, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was a site investigator for the trial but not a study author.

Participants were enrolled within 96 hours after someone in their household tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1,200 mg of REGEN-COV subcutaneously or a placebo. Based on serologic testing, study participants showed no evidence of current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median age of participants was 42.9, but 45% were male teenagers (ages 12-17).

In the group that received REGEN-COV, 11 out of 753 participants developed symptomatic COVID-19, compared with 59 out of 752 participants who received placebo. The relative risk reduction for the study’s 4-week period was 81.4% (P < .001). Of the participants that did develop a SARS-CoV-2 infection, those that received REGEN-COV were less likely to be symptomatic. Asymptomatic infections developed in 25 participants who received REGEN-COV versus 48 in the placebo group. The relative risk of developing any SARS-CoV-2 infection, symptomatic or asymptomatic, was reduced by 66.4% with REGEN-COV (P < .001).

Among the patients who were symptomatic, symptoms subsided within a median of 1.2 weeks for the group that received REGEN-COV, 2 weeks earlier than the placebo group. These patients also had a shorter duration of a high viral load (>104 copies/mL). Few adverse events were reported in the treatment or placebo groups. Monoclonal antibodies “seem to be incredibly safe,” Dr. Wohl said.

“These monoclonal antibodies have proven they can reduce the viral replication in the nose,” said study author Myron Cohen, MD, an infectious disease specialist and professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina.

The Food and Drug Administration first granted REGEN-COV emergency use authorization (EUA) in November 2020 for use in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 who were also at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19. At that time, the cocktail of monoclonal antibodies was delivered by a single intravenous infusion.

In January, Regeneron first announced the success of this trial of the subcutaneous injection for exposed household contacts based on early results, and in June of 2021, the FDA expanded the EUA to include a subcutaneous delivery when IV is not feasible. On July 30, the EUA was expanded again to include prophylactic use in exposed patients based on these trial results.

The U.S. government has purchased approximately 1.5 million doses of REGEN-COV from Regeneron and has agreed to make the treatments free of charge to patients.

But despite being free, available, and backed by promising data, monoclonal antibodies as a therapeutic answer to COVID-19 still hasn’t really taken off. “The problem is, it first requires knowledge and awareness,” Dr. Wohl said. “A lot [of people] don’t know this exists. To be honest, vaccination has taken up all the oxygen in the room.”

Dr. Cohen agreed. One reason for the slow uptake may be because the drug supply is owned by the government and not a pharmaceutical company. There hasn’t been a typical marketing push to make physicians and consumers aware. Additionally, “the logistics are daunting,” Dr. Cohen said. The office spaces where many physicians care for patients “often aren’t appropriate for patients who think they have SARS-CoV-2.”

“Right now, there’s not a mechanism” to administer the drug to people who could benefit from it, Dr. Wohl said. Eligible patients are either immunocompromised and unlikely to mount a sufficient immune response with vaccination, or not fully vaccinated. They should have been exposed to an infected individual or have a high likelihood of exposure due to where they live, such as in a prison or nursing home. Local doctors are unlikely to be the primary administrators of the drug, Dr. Wohl added. “How do we operationalize this for people who fit the criteria?”

There’s also an issue of timing. REGEN-COV is most effective when given early, Dr. Cohen said. “[Monoclonal antibodies] really only work well in the replication phase.” Many patients who would be eligible delay care until they’ve had symptoms for several days, when REGEN-COV would no longer have the desired effect.

Eventually, Dr. Wohl suspects demand will increase when people realize REGEN-COV can help those with COVID-19 and those who have been exposed. But before then, “we do have to think about how to integrate this into a workflow people can access without being confused.”

The trial was done before there was widespread vaccination, so it’s unclear what the results mean for people who have been vaccinated. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Wohl said there are ongoing conversations about whether monoclonal antibodies could be complementary to vaccination and if there’s potential for continued monthly use of these therapies.

Cohen and Wohl reported no relevant financial relationships. The trial was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial published online August 4, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The cocktail of the monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab (REGEN-COV, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) reduced participants’ relative risk of infection by 72%, compared with placebo within the first week. After the first week, risk reduction increased to 93%.

“Long after you would be exposed by your household, there is an enduring effect that prevents you from community spread,” said David Wohl, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was a site investigator for the trial but not a study author.

Participants were enrolled within 96 hours after someone in their household tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1,200 mg of REGEN-COV subcutaneously or a placebo. Based on serologic testing, study participants showed no evidence of current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median age of participants was 42.9, but 45% were male teenagers (ages 12-17).

In the group that received REGEN-COV, 11 out of 753 participants developed symptomatic COVID-19, compared with 59 out of 752 participants who received placebo. The relative risk reduction for the study’s 4-week period was 81.4% (P < .001). Of the participants that did develop a SARS-CoV-2 infection, those that received REGEN-COV were less likely to be symptomatic. Asymptomatic infections developed in 25 participants who received REGEN-COV versus 48 in the placebo group. The relative risk of developing any SARS-CoV-2 infection, symptomatic or asymptomatic, was reduced by 66.4% with REGEN-COV (P < .001).

Among the patients who were symptomatic, symptoms subsided within a median of 1.2 weeks for the group that received REGEN-COV, 2 weeks earlier than the placebo group. These patients also had a shorter duration of a high viral load (>104 copies/mL). Few adverse events were reported in the treatment or placebo groups. Monoclonal antibodies “seem to be incredibly safe,” Dr. Wohl said.

“These monoclonal antibodies have proven they can reduce the viral replication in the nose,” said study author Myron Cohen, MD, an infectious disease specialist and professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina.

The Food and Drug Administration first granted REGEN-COV emergency use authorization (EUA) in November 2020 for use in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 who were also at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19. At that time, the cocktail of monoclonal antibodies was delivered by a single intravenous infusion.

In January, Regeneron first announced the success of this trial of the subcutaneous injection for exposed household contacts based on early results, and in June of 2021, the FDA expanded the EUA to include a subcutaneous delivery when IV is not feasible. On July 30, the EUA was expanded again to include prophylactic use in exposed patients based on these trial results.

The U.S. government has purchased approximately 1.5 million doses of REGEN-COV from Regeneron and has agreed to make the treatments free of charge to patients.

But despite being free, available, and backed by promising data, monoclonal antibodies as a therapeutic answer to COVID-19 still hasn’t really taken off. “The problem is, it first requires knowledge and awareness,” Dr. Wohl said. “A lot [of people] don’t know this exists. To be honest, vaccination has taken up all the oxygen in the room.”

Dr. Cohen agreed. One reason for the slow uptake may be because the drug supply is owned by the government and not a pharmaceutical company. There hasn’t been a typical marketing push to make physicians and consumers aware. Additionally, “the logistics are daunting,” Dr. Cohen said. The office spaces where many physicians care for patients “often aren’t appropriate for patients who think they have SARS-CoV-2.”

“Right now, there’s not a mechanism” to administer the drug to people who could benefit from it, Dr. Wohl said. Eligible patients are either immunocompromised and unlikely to mount a sufficient immune response with vaccination, or not fully vaccinated. They should have been exposed to an infected individual or have a high likelihood of exposure due to where they live, such as in a prison or nursing home. Local doctors are unlikely to be the primary administrators of the drug, Dr. Wohl added. “How do we operationalize this for people who fit the criteria?”

There’s also an issue of timing. REGEN-COV is most effective when given early, Dr. Cohen said. “[Monoclonal antibodies] really only work well in the replication phase.” Many patients who would be eligible delay care until they’ve had symptoms for several days, when REGEN-COV would no longer have the desired effect.

Eventually, Dr. Wohl suspects demand will increase when people realize REGEN-COV can help those with COVID-19 and those who have been exposed. But before then, “we do have to think about how to integrate this into a workflow people can access without being confused.”

The trial was done before there was widespread vaccination, so it’s unclear what the results mean for people who have been vaccinated. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Wohl said there are ongoing conversations about whether monoclonal antibodies could be complementary to vaccination and if there’s potential for continued monthly use of these therapies.

Cohen and Wohl reported no relevant financial relationships. The trial was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial published online August 4, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The cocktail of the monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab (REGEN-COV, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) reduced participants’ relative risk of infection by 72%, compared with placebo within the first week. After the first week, risk reduction increased to 93%.

“Long after you would be exposed by your household, there is an enduring effect that prevents you from community spread,” said David Wohl, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was a site investigator for the trial but not a study author.

Participants were enrolled within 96 hours after someone in their household tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1,200 mg of REGEN-COV subcutaneously or a placebo. Based on serologic testing, study participants showed no evidence of current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median age of participants was 42.9, but 45% were male teenagers (ages 12-17).

In the group that received REGEN-COV, 11 out of 753 participants developed symptomatic COVID-19, compared with 59 out of 752 participants who received placebo. The relative risk reduction for the study’s 4-week period was 81.4% (P < .001). Of the participants that did develop a SARS-CoV-2 infection, those that received REGEN-COV were less likely to be symptomatic. Asymptomatic infections developed in 25 participants who received REGEN-COV versus 48 in the placebo group. The relative risk of developing any SARS-CoV-2 infection, symptomatic or asymptomatic, was reduced by 66.4% with REGEN-COV (P < .001).

Among the patients who were symptomatic, symptoms subsided within a median of 1.2 weeks for the group that received REGEN-COV, 2 weeks earlier than the placebo group. These patients also had a shorter duration of a high viral load (>104 copies/mL). Few adverse events were reported in the treatment or placebo groups. Monoclonal antibodies “seem to be incredibly safe,” Dr. Wohl said.

“These monoclonal antibodies have proven they can reduce the viral replication in the nose,” said study author Myron Cohen, MD, an infectious disease specialist and professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina.

The Food and Drug Administration first granted REGEN-COV emergency use authorization (EUA) in November 2020 for use in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 who were also at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19. At that time, the cocktail of monoclonal antibodies was delivered by a single intravenous infusion.

In January, Regeneron first announced the success of this trial of the subcutaneous injection for exposed household contacts based on early results, and in June of 2021, the FDA expanded the EUA to include a subcutaneous delivery when IV is not feasible. On July 30, the EUA was expanded again to include prophylactic use in exposed patients based on these trial results.

The U.S. government has purchased approximately 1.5 million doses of REGEN-COV from Regeneron and has agreed to make the treatments free of charge to patients.

But despite being free, available, and backed by promising data, monoclonal antibodies as a therapeutic answer to COVID-19 still hasn’t really taken off. “The problem is, it first requires knowledge and awareness,” Dr. Wohl said. “A lot [of people] don’t know this exists. To be honest, vaccination has taken up all the oxygen in the room.”

Dr. Cohen agreed. One reason for the slow uptake may be because the drug supply is owned by the government and not a pharmaceutical company. There hasn’t been a typical marketing push to make physicians and consumers aware. Additionally, “the logistics are daunting,” Dr. Cohen said. The office spaces where many physicians care for patients “often aren’t appropriate for patients who think they have SARS-CoV-2.”

“Right now, there’s not a mechanism” to administer the drug to people who could benefit from it, Dr. Wohl said. Eligible patients are either immunocompromised and unlikely to mount a sufficient immune response with vaccination, or not fully vaccinated. They should have been exposed to an infected individual or have a high likelihood of exposure due to where they live, such as in a prison or nursing home. Local doctors are unlikely to be the primary administrators of the drug, Dr. Wohl added. “How do we operationalize this for people who fit the criteria?”

There’s also an issue of timing. REGEN-COV is most effective when given early, Dr. Cohen said. “[Monoclonal antibodies] really only work well in the replication phase.” Many patients who would be eligible delay care until they’ve had symptoms for several days, when REGEN-COV would no longer have the desired effect.

Eventually, Dr. Wohl suspects demand will increase when people realize REGEN-COV can help those with COVID-19 and those who have been exposed. But before then, “we do have to think about how to integrate this into a workflow people can access without being confused.”

The trial was done before there was widespread vaccination, so it’s unclear what the results mean for people who have been vaccinated. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Wohl said there are ongoing conversations about whether monoclonal antibodies could be complementary to vaccination and if there’s potential for continued monthly use of these therapies.

Cohen and Wohl reported no relevant financial relationships. The trial was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Half abandon metformin within a year of diabetes diagnosis

Nearly half of adults prescribed metformin after a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes have stopped taking it by 1 year, new data show.

The findings, from a retrospective analysis of administrative data from Alberta, Canada, during 2012-2017, also show that the fall-off in metformin adherence was most dramatic during the first 30 days, and in most cases, there was no concomitant substitution of another glucose-lowering drug.

While the majority with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes were prescribed metformin as first-line therapy, patients started on other agents incurred far higher medication and health care costs.

The data were recently published online in Diabetic Medicine by David J. T. Campbell, MD, PhD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), and colleagues.

“We realized that even if someone is prescribed metformin that doesn’t mean they’re staying on metformin even for a year ... the drop-off rate is really quite abrupt,” Dr. Campbell said in an interview. Most who discontinued had A1c levels above 7.5%, so it wasn’t that they no longer needed glucose-lowering medication, he noted.

People don’t understand chronic use; meds don’t make you feel better

One reason for the discontinuations, he said, is that patients might not realize they need to keep taking the medication.

“When a physician is seeing a person with newly diagnosed diabetes, I think it’s important to remember that they might not know the implications of having a chronic condition. A lot of times we’re quick to prescribe metformin and forget about it. ... Physicians might write a script for 3 months and three refills and not see the patient again for a year ... We may need to keep a closer eye on these folks and have more regular follow-up, and make sure they’re getting early diabetes education.”

Side effects are an issue, but not for most. “Any clinician who prescribes metformin knows there are side effects, such as upset stomach, diarrhea, and nausea. But certainly, it’s not half [who experience these]. ... A lot of people just aren’t accepting of having to take it lifelong, especially since they probably don’t feel any better on it,” Dr. Campbell said.

James Flory, MD, an endocrinologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said in an interview that about 25% of patients taking metformin experience gastrointestinal side effects.

Moreover, he noted that the drop-off in adherence is also seen with antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs that have fewer side effects than those of metformin. He pointed to a “striking example” of this, a 2011 randomized trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine, and as reported by this news organization, showing overall rates of adherence to these medications was around 50%, even among people who had already had a myocardial infarction.

“People really don’t want to be on these medications. ... They have an aversion to being medicalized and taking pills. If they’re not being pretty consistently prompted and reminded and urged to take them, I think people will find rationalizations, reasons for stopping. ... I think people want to handle things through lifestyle and not be on a drug,” noted Dr. Flory, who has published on the subject of metformin adherence.

“These drugs don’t make people feel better. None of them do. At best they don’t make you feel worse. You have to really believe in the chronic condition and believe that it’s hurting you and that you can’t handle it without the drugs to motivate you to keep taking them,” Dr. Flory explained.

Communication with the patient is key, he added.

“I don’t have empirical data to support this, but I feel it’s helpful to acknowledge the downsides to patients. I tell them to let me know [if they’re having side effects] and we’ll work on it. Don’t just stop taking the drug and never circle back.” At the same time, he added, “I think it’s important to emphasize metformin’s safety and effectiveness.”

For patients experiencing gastrointestinal side effects, options including switching to extended-release metformin or lowering the dose.

Also, while patients are typically advised to take metformin with food, some experience diarrhea when they do that and prefer to take it at bedtime than with dinner. “If that’s what works for people, that’s what they should do,” Dr. Flory advised.

“It doesn’t take a lot of time to emphasize to patients the safety and this level of flexibility and control they should be able to exercise over how much they take and when. These things should really help.”

Metformin usually prescribed, but not always taken

Dr. Campbell and colleagues analyzed 17,932 individuals with incident type 2 diabetes diagnosed between April 1, 2012, and March 31, 2017. Overall, 89% received metformin monotherapy as their initial diabetes prescription, 7.6% started metformin in combination with another glucose-lowering drug, and 3.3% were prescribed a nonmetformin diabetes medication. (Those prescribed insulin as their first diabetes medication were excluded.)

The most commonly coprescribed drugs with metformin were sulfonylureas (in 47%) and DPP-4 inhibitors (28%). Of those initiated with only nonmetformin medications, sulfonylureas were also the most common (53%) and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors second (21%).

The metformin prescribing rate of 89% reflects current guidelines, Dr. Campbell noted.

“In hypertension, clinicians weren’t really following the guidelines ... they were prescribing more expensive drugs than the guidelines say. ... We showed that in diabetes, contrary to hypertension, clinicians really are generally following the clinical practice guidelines. ... The vast majority who are started on metformin are started on monotherapy. That was reassuring to us. We’re not paying for a bunch of expensive drugs when metformin would do just as well,” he said.

However, the proportion who had been dispensed metformin to cover the prescribed number of days dropped by about 10% after 30 days, by a further 10% after 90 days, and yet again after 100 days, resulting in just 54% remaining on the drug by 1 year.

Factors associated with higher adherence included older age, presence of comorbidities, and highest versus lowest neighborhood income quintile.

Those who had been prescribed nonmetformin monotherapy had about twice the total health care costs of those initially prescribed metformin monotherapy. Higher health care costs were seen among patients who were younger, had lower incomes, had higher baseline A1c, had more comorbidities, and were men.

How will the newer type 2 diabetes drugs change prescribing?

Dr. Campbell noted that “a lot has changed since 2017. ... At least in Canada, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists were supposed to be reserved as second-line agents in patients with cardiovascular disease, but more and more they’re being thought of as first-line agents in high-risk patients.”

“I suspect as those guidelines are transmitted to primary care colleagues who are doing the bulk of the prescribing we’ll see more and more uptake of these agents.”

Indeed, Dr. Flory said, “The metformin data at this point are very dated and the body of trials showing health benefits for it is actually very weak compared to the big trials that have been done for the newer agents, to the point where you can imagine a consensus gradually forming where people start to recommend something other than metformin for nearly everybody with type 2 diabetes. The cost implications are just huge, and I think the safety implications as well.”

According to Dr. Flory, the SGLT2 inhibitors “are fundamentally not as safe as metformin. I think they’re very safe drugs – large good studies have established that – but if you’re going to give drugs to a large number of people who are pretty healthy at baseline the safety standards have to be pretty high.”

Just the elevated risk of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis alone is reason for pause, Dr. Flory said. “Even though it’s manageable ... metformin just doesn’t have a safety problem like that. I’m very comfortable prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors, but If I’m going to give a drug to a million people and have nothing go wrong with any of them, that would be metformin, not an SGLT2 [inhibitor].”

Dr. Campbell and colleagues will be conducting a follow-up of prescribing data through 2019, which will of course include the newer agents. They’ll also investigate reasons for drug discontinuation and outcomes of those who discontinue versus continue metformin.

Dr. Campbell has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Flory consults for a legal firm on litigation related to insulin analog pricing issues, not for or pertaining to a specific company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly half of adults prescribed metformin after a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes have stopped taking it by 1 year, new data show.

The findings, from a retrospective analysis of administrative data from Alberta, Canada, during 2012-2017, also show that the fall-off in metformin adherence was most dramatic during the first 30 days, and in most cases, there was no concomitant substitution of another glucose-lowering drug.

While the majority with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes were prescribed metformin as first-line therapy, patients started on other agents incurred far higher medication and health care costs.

The data were recently published online in Diabetic Medicine by David J. T. Campbell, MD, PhD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), and colleagues.

“We realized that even if someone is prescribed metformin that doesn’t mean they’re staying on metformin even for a year ... the drop-off rate is really quite abrupt,” Dr. Campbell said in an interview. Most who discontinued had A1c levels above 7.5%, so it wasn’t that they no longer needed glucose-lowering medication, he noted.

People don’t understand chronic use; meds don’t make you feel better

One reason for the discontinuations, he said, is that patients might not realize they need to keep taking the medication.

“When a physician is seeing a person with newly diagnosed diabetes, I think it’s important to remember that they might not know the implications of having a chronic condition. A lot of times we’re quick to prescribe metformin and forget about it. ... Physicians might write a script for 3 months and three refills and not see the patient again for a year ... We may need to keep a closer eye on these folks and have more regular follow-up, and make sure they’re getting early diabetes education.”

Side effects are an issue, but not for most. “Any clinician who prescribes metformin knows there are side effects, such as upset stomach, diarrhea, and nausea. But certainly, it’s not half [who experience these]. ... A lot of people just aren’t accepting of having to take it lifelong, especially since they probably don’t feel any better on it,” Dr. Campbell said.

James Flory, MD, an endocrinologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said in an interview that about 25% of patients taking metformin experience gastrointestinal side effects.

Moreover, he noted that the drop-off in adherence is also seen with antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs that have fewer side effects than those of metformin. He pointed to a “striking example” of this, a 2011 randomized trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine, and as reported by this news organization, showing overall rates of adherence to these medications was around 50%, even among people who had already had a myocardial infarction.

“People really don’t want to be on these medications. ... They have an aversion to being medicalized and taking pills. If they’re not being pretty consistently prompted and reminded and urged to take them, I think people will find rationalizations, reasons for stopping. ... I think people want to handle things through lifestyle and not be on a drug,” noted Dr. Flory, who has published on the subject of metformin adherence.

“These drugs don’t make people feel better. None of them do. At best they don’t make you feel worse. You have to really believe in the chronic condition and believe that it’s hurting you and that you can’t handle it without the drugs to motivate you to keep taking them,” Dr. Flory explained.

Communication with the patient is key, he added.

“I don’t have empirical data to support this, but I feel it’s helpful to acknowledge the downsides to patients. I tell them to let me know [if they’re having side effects] and we’ll work on it. Don’t just stop taking the drug and never circle back.” At the same time, he added, “I think it’s important to emphasize metformin’s safety and effectiveness.”

For patients experiencing gastrointestinal side effects, options including switching to extended-release metformin or lowering the dose.

Also, while patients are typically advised to take metformin with food, some experience diarrhea when they do that and prefer to take it at bedtime than with dinner. “If that’s what works for people, that’s what they should do,” Dr. Flory advised.

“It doesn’t take a lot of time to emphasize to patients the safety and this level of flexibility and control they should be able to exercise over how much they take and when. These things should really help.”

Metformin usually prescribed, but not always taken

Dr. Campbell and colleagues analyzed 17,932 individuals with incident type 2 diabetes diagnosed between April 1, 2012, and March 31, 2017. Overall, 89% received metformin monotherapy as their initial diabetes prescription, 7.6% started metformin in combination with another glucose-lowering drug, and 3.3% were prescribed a nonmetformin diabetes medication. (Those prescribed insulin as their first diabetes medication were excluded.)

The most commonly coprescribed drugs with metformin were sulfonylureas (in 47%) and DPP-4 inhibitors (28%). Of those initiated with only nonmetformin medications, sulfonylureas were also the most common (53%) and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors second (21%).

The metformin prescribing rate of 89% reflects current guidelines, Dr. Campbell noted.

“In hypertension, clinicians weren’t really following the guidelines ... they were prescribing more expensive drugs than the guidelines say. ... We showed that in diabetes, contrary to hypertension, clinicians really are generally following the clinical practice guidelines. ... The vast majority who are started on metformin are started on monotherapy. That was reassuring to us. We’re not paying for a bunch of expensive drugs when metformin would do just as well,” he said.

However, the proportion who had been dispensed metformin to cover the prescribed number of days dropped by about 10% after 30 days, by a further 10% after 90 days, and yet again after 100 days, resulting in just 54% remaining on the drug by 1 year.

Factors associated with higher adherence included older age, presence of comorbidities, and highest versus lowest neighborhood income quintile.

Those who had been prescribed nonmetformin monotherapy had about twice the total health care costs of those initially prescribed metformin monotherapy. Higher health care costs were seen among patients who were younger, had lower incomes, had higher baseline A1c, had more comorbidities, and were men.

How will the newer type 2 diabetes drugs change prescribing?

Dr. Campbell noted that “a lot has changed since 2017. ... At least in Canada, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists were supposed to be reserved as second-line agents in patients with cardiovascular disease, but more and more they’re being thought of as first-line agents in high-risk patients.”

“I suspect as those guidelines are transmitted to primary care colleagues who are doing the bulk of the prescribing we’ll see more and more uptake of these agents.”

Indeed, Dr. Flory said, “The metformin data at this point are very dated and the body of trials showing health benefits for it is actually very weak compared to the big trials that have been done for the newer agents, to the point where you can imagine a consensus gradually forming where people start to recommend something other than metformin for nearly everybody with type 2 diabetes. The cost implications are just huge, and I think the safety implications as well.”

According to Dr. Flory, the SGLT2 inhibitors “are fundamentally not as safe as metformin. I think they’re very safe drugs – large good studies have established that – but if you’re going to give drugs to a large number of people who are pretty healthy at baseline the safety standards have to be pretty high.”

Just the elevated risk of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis alone is reason for pause, Dr. Flory said. “Even though it’s manageable ... metformin just doesn’t have a safety problem like that. I’m very comfortable prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors, but If I’m going to give a drug to a million people and have nothing go wrong with any of them, that would be metformin, not an SGLT2 [inhibitor].”

Dr. Campbell and colleagues will be conducting a follow-up of prescribing data through 2019, which will of course include the newer agents. They’ll also investigate reasons for drug discontinuation and outcomes of those who discontinue versus continue metformin.

Dr. Campbell has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Flory consults for a legal firm on litigation related to insulin analog pricing issues, not for or pertaining to a specific company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly half of adults prescribed metformin after a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes have stopped taking it by 1 year, new data show.

The findings, from a retrospective analysis of administrative data from Alberta, Canada, during 2012-2017, also show that the fall-off in metformin adherence was most dramatic during the first 30 days, and in most cases, there was no concomitant substitution of another glucose-lowering drug.

While the majority with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes were prescribed metformin as first-line therapy, patients started on other agents incurred far higher medication and health care costs.

The data were recently published online in Diabetic Medicine by David J. T. Campbell, MD, PhD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.), and colleagues.

“We realized that even if someone is prescribed metformin that doesn’t mean they’re staying on metformin even for a year ... the drop-off rate is really quite abrupt,” Dr. Campbell said in an interview. Most who discontinued had A1c levels above 7.5%, so it wasn’t that they no longer needed glucose-lowering medication, he noted.

People don’t understand chronic use; meds don’t make you feel better

One reason for the discontinuations, he said, is that patients might not realize they need to keep taking the medication.

“When a physician is seeing a person with newly diagnosed diabetes, I think it’s important to remember that they might not know the implications of having a chronic condition. A lot of times we’re quick to prescribe metformin and forget about it. ... Physicians might write a script for 3 months and three refills and not see the patient again for a year ... We may need to keep a closer eye on these folks and have more regular follow-up, and make sure they’re getting early diabetes education.”

Side effects are an issue, but not for most. “Any clinician who prescribes metformin knows there are side effects, such as upset stomach, diarrhea, and nausea. But certainly, it’s not half [who experience these]. ... A lot of people just aren’t accepting of having to take it lifelong, especially since they probably don’t feel any better on it,” Dr. Campbell said.

James Flory, MD, an endocrinologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said in an interview that about 25% of patients taking metformin experience gastrointestinal side effects.

Moreover, he noted that the drop-off in adherence is also seen with antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs that have fewer side effects than those of metformin. He pointed to a “striking example” of this, a 2011 randomized trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine, and as reported by this news organization, showing overall rates of adherence to these medications was around 50%, even among people who had already had a myocardial infarction.

“People really don’t want to be on these medications. ... They have an aversion to being medicalized and taking pills. If they’re not being pretty consistently prompted and reminded and urged to take them, I think people will find rationalizations, reasons for stopping. ... I think people want to handle things through lifestyle and not be on a drug,” noted Dr. Flory, who has published on the subject of metformin adherence.

“These drugs don’t make people feel better. None of them do. At best they don’t make you feel worse. You have to really believe in the chronic condition and believe that it’s hurting you and that you can’t handle it without the drugs to motivate you to keep taking them,” Dr. Flory explained.

Communication with the patient is key, he added.

“I don’t have empirical data to support this, but I feel it’s helpful to acknowledge the downsides to patients. I tell them to let me know [if they’re having side effects] and we’ll work on it. Don’t just stop taking the drug and never circle back.” At the same time, he added, “I think it’s important to emphasize metformin’s safety and effectiveness.”

For patients experiencing gastrointestinal side effects, options including switching to extended-release metformin or lowering the dose.

Also, while patients are typically advised to take metformin with food, some experience diarrhea when they do that and prefer to take it at bedtime than with dinner. “If that’s what works for people, that’s what they should do,” Dr. Flory advised.

“It doesn’t take a lot of time to emphasize to patients the safety and this level of flexibility and control they should be able to exercise over how much they take and when. These things should really help.”

Metformin usually prescribed, but not always taken

Dr. Campbell and colleagues analyzed 17,932 individuals with incident type 2 diabetes diagnosed between April 1, 2012, and March 31, 2017. Overall, 89% received metformin monotherapy as their initial diabetes prescription, 7.6% started metformin in combination with another glucose-lowering drug, and 3.3% were prescribed a nonmetformin diabetes medication. (Those prescribed insulin as their first diabetes medication were excluded.)

The most commonly coprescribed drugs with metformin were sulfonylureas (in 47%) and DPP-4 inhibitors (28%). Of those initiated with only nonmetformin medications, sulfonylureas were also the most common (53%) and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors second (21%).

The metformin prescribing rate of 89% reflects current guidelines, Dr. Campbell noted.

“In hypertension, clinicians weren’t really following the guidelines ... they were prescribing more expensive drugs than the guidelines say. ... We showed that in diabetes, contrary to hypertension, clinicians really are generally following the clinical practice guidelines. ... The vast majority who are started on metformin are started on monotherapy. That was reassuring to us. We’re not paying for a bunch of expensive drugs when metformin would do just as well,” he said.

However, the proportion who had been dispensed metformin to cover the prescribed number of days dropped by about 10% after 30 days, by a further 10% after 90 days, and yet again after 100 days, resulting in just 54% remaining on the drug by 1 year.

Factors associated with higher adherence included older age, presence of comorbidities, and highest versus lowest neighborhood income quintile.

Those who had been prescribed nonmetformin monotherapy had about twice the total health care costs of those initially prescribed metformin monotherapy. Higher health care costs were seen among patients who were younger, had lower incomes, had higher baseline A1c, had more comorbidities, and were men.

How will the newer type 2 diabetes drugs change prescribing?

Dr. Campbell noted that “a lot has changed since 2017. ... At least in Canada, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists were supposed to be reserved as second-line agents in patients with cardiovascular disease, but more and more they’re being thought of as first-line agents in high-risk patients.”

“I suspect as those guidelines are transmitted to primary care colleagues who are doing the bulk of the prescribing we’ll see more and more uptake of these agents.”

Indeed, Dr. Flory said, “The metformin data at this point are very dated and the body of trials showing health benefits for it is actually very weak compared to the big trials that have been done for the newer agents, to the point where you can imagine a consensus gradually forming where people start to recommend something other than metformin for nearly everybody with type 2 diabetes. The cost implications are just huge, and I think the safety implications as well.”

According to Dr. Flory, the SGLT2 inhibitors “are fundamentally not as safe as metformin. I think they’re very safe drugs – large good studies have established that – but if you’re going to give drugs to a large number of people who are pretty healthy at baseline the safety standards have to be pretty high.”

Just the elevated risk of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis alone is reason for pause, Dr. Flory said. “Even though it’s manageable ... metformin just doesn’t have a safety problem like that. I’m very comfortable prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors, but If I’m going to give a drug to a million people and have nothing go wrong with any of them, that would be metformin, not an SGLT2 [inhibitor].”

Dr. Campbell and colleagues will be conducting a follow-up of prescribing data through 2019, which will of course include the newer agents. They’ll also investigate reasons for drug discontinuation and outcomes of those who discontinue versus continue metformin.

Dr. Campbell has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Flory consults for a legal firm on litigation related to insulin analog pricing issues, not for or pertaining to a specific company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

IBD risk rises with higher ultraprocessed food intake

Individuals who consumed more ultraprocessed foods had a significantly increased risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) than those who consumed less, according to data from more than 100,000 adults.

“Diet alters the microbiome and modifies the intestinal immune response and so could play a role in the pathogenesis of IBD,” Neeraj Narula, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and colleagues wrote. Although previous studies have investigated the impact of dietary risk factors on IBD, an association with ultraprocessed foods (defined as foods containing additives and preservatives) in particular has not been examined, they wrote.

In a study published in BMJ, the researchers examined data from 116,087 adults aged 35-70 years from 21 countries between 2003 and 2016 who were part of the large Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Cohort. Participants completed baseline food frequency questionnaires and were followed at least every 3 years; the median follow-up time was 9.7 years. The primary outcome was the development of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. In this study, ultraprocessed food included all packaged and formulated foods and beverages that contained food additives, artificial flavors or colors, or other chemical ingredients.

The categories of ultraprocessed foods included processed meat, cold breakfast cereal, various sauces, soft drinks, and fruit drinks, and refined sweetened foods such as candy, chocolate, jam, jelly, and brownies.

Overall, 467 participants developed IBD, including 90 with Crohn’s disease and 377 with ulcerative colitis.

After controlling for confounding factors, the investigators found that increased consumption of ultraprocessed foods was significantly associated with an increased risk of incident IBD. Compared with individuals who consumed less than 1 serving per day of ultraprocessed foods, the hazard ratio was 1.82 for those who consumed 5 or more servings and 1.67 for those who consumed 1-4 servings daily (P = .006).

“The pattern of increased ultraprocessed food intake and higher risk of IBD persisted within each of the regions examined, and effect estimates were generally similar, with overlapping confidence intervals and no significant heterogeneity,” the researchers noted.

The risk of IBD increased among individuals who consumed 1 serving per week or more of processed meat, compared with those who consumed less than 1 serving per week, and the risk increased with the amount consumed (HR, 2.07 for 1 or more servings per day). Similarly, IBD risk was higher among individuals who consumed 100 g/day or more of refined sweetened foods compared with no intake of these foods (HR, 2.58).

Individuals who consumed at least one serving of fried foods per day had the highest risk of IBD (HR, 3.02), the researchers noted. The reason for the association is uncertain, but may occur not only because many fried foods are also processed but also because the action of frying food and the processing of oil, as well as type and quality of oil, might modify the nutrients.

In the subgroup analysis, higher consumption of salty snacks and soft drinks also was associated with higher risk for IBD. However, the researchers found no association between increased risk of IBD and consumption of white meat, unprocessed red meat, dairy, starchy foods, and fruit/vegetables/legumes.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the relatively small number of individuals with Crohn’s disease, potential lack of generalizability to those who develop IBD in childhood or young adulthood, and possible confounding from unmeasured variables. The study also did not account for dietary changes over time, the investigators reported. However, the longitudinal design allowed them “to focus on people with incident IBD and to use medical record review and central adjudication to validate a sample of the diagnoses.”

The results suggest that the way food is processed or ultraprocessed, rather than the food itself, may be what confers the risk for IBD, given the lack of association between IBD and other food categories such as unprocessed red meat and dairy, the researchers concluded.

Next steps: Pin down driving factors

“There is significant interest in the apparent increase in the incidence and prevalence of IBD, particularly in previously low incidence areas,” Edward L. Barnes, MD, MPH, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill said in an interview.

“Many research groups and clinicians suspect that environmental exposures, including dietary exposures, may play a critical role in these trends,” said Dr. Barnes. “This study utilized a large, multinational prospective cohort design to assess the influence of diet on the risk of developing IBD,” which is particularly important considering the potential for processed foods and food additives to impact the gastrointestinal tract.

“The strong associations demonstrated by the authors were impressive, particularly given that the authors performed multiple subanalyses, including evaluations by participant age and evaluations of particular food groups/types [e.g., processed meat, soft drinks, and refined sweet foods],” he noted. Dr. Barnes also found the lack of association with intake of white meat and unprocessed red meat interesting. “In my opinion, these subanalyses strengthen the overall associations demonstrated by the authors given their prospective study design and their attention to evaluating all potential associations that may be driving the relationships present in this cohort.

“At this point, the take-home message for clinicians treating patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis should be that this association exists,” said Dr. Barnes. “One question that remains is whether the same risk factors that are present for developing disease also influence the disease course, given that the primary outcome of this study was the development of IBD. Given that much of our data with regard to the interplay between diet and IBD are still emerging, physicians treating patients with IBD can make patients aware of these associations and the potential benefit of limiting ultraprocessed foods in their diet.”

For these important results to become actionable, “further research is likely necessary to identify the factors that are driving this association,” Dr. Barnes explained. “This would likely build on prior animal models that have demonstrated an association between food additives such as emulsifiers and changes in the gastrointestinal tract that could ultimately lead to increased inflammation and the development of IBD.” Such information about specific drivers “would then allow clinicians to determine which population would benefit most from dietary changes/recommendations.”

The overall PURE study was supported by the Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton Health Sciences Research Institute, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, CIHR’s Strategy for Patient Oriented Research through the Ontario SPOR Support Unit, and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care. PURE also was supported in part by unrestricted grants from several pharmaceutical companies, notably AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Servier, and GlaxoSmithKline. The researchers had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Barnes disclosed serving as a consultant for AbbVie, Gilead, Pfizer, Takeda, and Target RWE.

Help your patients better understand their IBD treatment options by sharing AGA’s patient education, “Living with IBD,” in the AGA GI Patient Center at www.gastro.org/IBD.

Individuals who consumed more ultraprocessed foods had a significantly increased risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) than those who consumed less, according to data from more than 100,000 adults.