User login

A Case Series of Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis With Mechanical Thrombectomy for Treating Severe Deep Vein Thrombosis

Two cases of extensive symptomatic deep vein thrombosis without phlegmasia cerulea dolens were successfully treated with an endovascular technique that combines catheter-directed thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a frequently encountered medical condition with about 1 in 1,000 adults diagnosed annually.1,2 Up to one-half of patients who receive a diagnosis will experience long-term complications in the affected limb.1 Anticoagulation is the treatment of choice for DVT in the absence of any contraindications.3 Thrombolytic therapies (eg, systemic thrombolysis, catheter-directed thrombolysis with or without thrombectomy) historically have been reserved for patients who present with phlegmasia cerulea dolens (PCD), a severe condition involving venous obstruction within the extremities that causes impaired arterial blood supply and cyanosis that can lead to limb loss and death.4

The role of thrombolytic therapy is less clear in patients without PCD who present with extensive or symptomatic lower extremity DVT that causes significant pain, edema, and functional disability. Proximal lower extremity DVT (thrombus above the knee and above the popliteal vein) and particularly those involving the iliac or common femoral vein (ie, iliofemoral DVT) carry a significant risk of recurrent thromboembolism as well as postthrombotic syndrome (PTS), a complication of DVT resulting in chronic leg pain, edema, skin discoloration, and venous ulcers.5

The goal of thrombolytic therapy is to prevent thrombus propagation, recurrent thromboembolism, and PTS, in addition to providing more rapid pain relief and improvement in limb function.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis can be combined with catheter-directed thrombectomy using the same endovascular technique. This combination is called a pharmacomechanical thrombectomy or a pharmacomechanical thromobolysis and can offer more rapid removal of thrombus and decreased infusion times of thrombolytic drug.8 Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis is a relatively new technique, so the choice of thrombolytic therapy will depend on procedural expertise and resource availability. Early interventional radiology consultation (or vascular surgery in some centers) can assist in determining appropriate candidates for thrombolytic therapies. Here we present 2 cases of extensive symptomatic DVT successfully treated with catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis.

Case 1

A 61-year-old male current smoker with a history of obesity and hypertension presented to the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center emergency department (ED) with 2 days of progressive pain and swelling in the right lower extremity (RLE) after sustaining a calf injury the preceding week. The patient rated pain as 9 on a 10-point scale and reported no other symptoms. He reported no prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs and normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive RLE edema below the knee with tenderness to palpation and shiny taut skin. The neurovascular examination of the RLE was normal. Laboratory studies were notable only for a mild leukocytosis. Compression ultrasound with Doppler of the RLE demonstrated an acute thrombus of the right femoral vein extending to the popliteal vein.

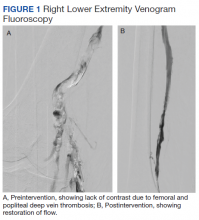

The patient was prescribed enoxaparin 90 mg every 12 hours for anticoagulation. After 36 hours of anticoagulation, he continued to experience severe RLE pain and swelling limiting ambulation. Interventional radiology was consulted, and catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis of the RLE was pursued given the persistence of significant symptoms. Intraprocedure venogram demonstrated thrombi filling the entirety of the right femoral and popliteal veins (Figure 1A). This was treated with catheter-directed pulse-spray thrombolysis with 12 mg of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA).

After a 20-minute incubation period, a thrombectomy was performed several times along the femoral vein and popliteal vein, using an AngioJet device. A follow-up venogram revealed a small amount of residual thrombi in the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein. This entire segment was further treated with angioplasty, and a postintervention venogram demonstrated patency of the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein with minimal residual thrombi and with brisk venous flow (Figure 1B). Immediately after the procedure, the patient’s RLE pain significantly improved. On day 2 postprocedure, the patient’s RLE edema resolved, and the patient was able to resume normal ambulation. There were no bleeding complications. The patient was discharged with oral anticoagulation therapy.

Case 2

A male aged 78 years with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and benign prostatic hypertrophy presented to the ED with 10 days of progressive pain and swelling in the left lower extremity (LLE). The patient noted decreased mobility over recent months and was using a front wheel walker while recovering from surgical repair of a hamstring tendon injury. He reported taking a transcontinental flight around the same time that his LLE pain began. The patient reported no prior history of VTE or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs with a normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive LLE edema up to the proximal thigh without erythema or cyanosis, and his skin was taut and tender. Neurovascular examination of the LLE was normal. Laboratory studies were unremarkable. Compression ultrasonography with Doppler of the LLE demonstrated an extensive acute occlusive thrombus within the left common femoral, entire left femoral, and left popliteal veins.

After evaluating the patient, the Vascular Surgery service did not feel there was evidence of compartment syndrome nor PCD. The patient received unfractionated heparin anticoagulation therapy and the LLE was elevated continuously. After 24 hours of anticoagulation therapy, the patient continued to have significant pain and was unable to ambulate. The case was presented in a joint Interventional Radiology/Vascular Surgery conference and the decision was made to pursue pharmacomechanic thrombolysis given the significant extent of thrombotic burden.

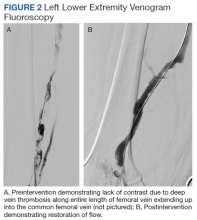

The patient underwent successful catheter-directed pharmacomechanic thrombolysis via pulse-spray thrombolysis of 15 mg of tPA using the Boston Scientific AngioJet Thrombectomy System, and angioplasty with no immediate complications (Figure 2). The patient noted dramatic improvement in LLE pain and swelling 1 day postprocedure and was able to ambulate. He developed mild asymptomatic hematuria, which resolved within 12 hours and without an associated drop in hemoglobin. The patient was transitioned to oral anticoagulation and discharged to an acute rehabilitation unit on postprocedure day 2.

Discussion

Anticoagulation is the preferred therapy for most patients with acute uncomplicated lower extremity DVT. PCD is the only widely accepted indication for thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute lower extremity DVT. However, in the absence of PCD, management of complicated DVT where there are either significant symptoms, extensive clot burden, or proximal location is less clear due to the paucity of clinical data. For example, in the case of iliofemoral DVT, thrombosis of the iliofemoral region is associated with an increased risk of pulmonary embolism, limb malperfusion, and PTS when compared with other types of DVT.5,6

Earlier retrospective observational studies in patients with acute DVT found that the addition of either systemic thrombolysis or catheter-directed thrombolysis to anticoagulation increased rates of clot lysis but did not lead to a reduction in clinical outcomes such as recurrent thromboembolism, mortality, or the rate of PTS.10-12 Additionally, both systemic thrombolytic therapy and catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy were associated with higher rates of major bleeding. However, these studies included all patients with acute DVT without selecting for criteria, such as proximal location of DVT, severe symptoms, or extensive clot burden. Because thrombolytic therapy is proven to provide more rapid and immediate clot lysis (whereas conventional anticoagulation prevents thrombus extension and recurrence but does not dissolve the clot), it is reasonable to suggest that a subpopulation of patients with extensive or symptomatic DVT may benefit from immediate clot lysis, thereby restoring limb perfusion and avoiding limb gangrene while preserving venous function and preventing PTS.

Mixed Study Results

The 2012 CaVenT study is one of the few randomized controlled trials to assess outcomes comparing conventional anticoagulation alone to anticoagulation with catheter-directed thrombolysis in patients with acute lower extremity DVT.13 Study patients did not undergo catheter-directed mechanical thrombectomy. Patients in this study consisted solely of those with first-time iliofemoral DVT. Long-term outcomes at 24-month follow-up showed that additional catheter-directed thrombolysis reduced the risk of PTS when compared with those who were treated with anticoagulation alone (41.1% vs 55.6%, P = .047). The difference in PTS corresponded to an absolute risk reduction of 14.4% (95% CI, 0.2-27.9), and the number needed to treat was 7 (95% CI, 4-502). There was a clinically relevant bleeding complication rate of 8.9% in the thrombolysis group with none leading to a permanently impaired outcome.

These results could not be confirmed by a more recent randomized control trial in 2017 conducted by Vedantham and colleagues.14 In this trial, patients with acute proximal DVT (femoral and iliofemoral DVT) were randomized to receive either anticoagulation alone or anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis. In the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group, the overall incidence of PTS and recurrent VTE was not reduced over the 24-month follow-up period. Those who developed PTS in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group had lower severity scores, as there was a significant reduction in moderate-to-severe PTS in this group. There also were more early major bleeds in the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group (1.7%, with no fatal or intracranial bleeds) when compared with the control group; however, this bleeding complication rate was much less than what was noted in the CaVenT study. Additionally, there was a significant decrease in both lower extremity pain and edema in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group at 10 days and 30 days postintervention.

Given the mixed results of these 2 randomized controlled trials, further studies are warranted to clarify the role of thrombolytic therapies in preventing major events such as recurrent VTE and PTS, especially given the increased risk of bleeding observed with thrombolytic therapies. The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines recommend anticoagulation as monotherapy vs thrombolytics, systemic or catheter-directed thrombolysis as designated treatment modalities.3 These guidelines are rated “Grade 2C”, which reflect a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. While these recommendations do not comment on additional considerations, such as DVT clot burden, location, or severity of symptoms, the guidelines do state that patients who attach a high value to the prevention of PTS and a lower value to the risk of bleeding with catheter-directed therapy are likely to choose catheter-directed therapy over anticoagulation alone.

Case Studies Analyses

In our first case presentation, pharma-comechanic thrombolysis was pursued because the patient presented with severesymptoms and did not experience any symptomatic improvement after 36 hours of anticoagulation. It is unclear whether a longer duration of anticoagulation might have improved the severity of his symptoms. When considering the level of pain, edema, and inability to ambulate, thrombolytic therapy was considered the most appropriate choice for treatment. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was successful, resulting in complete clot lysis, significant decrease in pain and edema with total recovery of ambulatory abilities, no bleeding complications, and prevention of any potential clinical deterioration, such as phlegmasia cerulea dolens. The patient is now 12 months postprocedure without symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events. Continued follow-up that monitors the development of PTS will be necessary for at least 2 years postprocedure.

In the second case, our patient experienced some improvement in pain after 24 hours of anticoagulation alone. However, considering the extensive proximal clot burden involving the entire femoral and common femoral veins, the treatment teams believed it was likely that this patient would experience a prolonged recovery time and increased morbidity on anticoagulant therapy alone. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was again successful with almost immediate resolution of pain and edema, and recovery of ambulatory abilities on postprocedure day 1. The patient is now 6 months postprocedure without any symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events.

In both case presentations, the presenting symptoms, methods of treatment, and immediate symptomatic improvement postintervention were similar. The patient in Case 2 had more extensive clot burden, a more proximal location of clot, and was classified as having an iliofemoral DVT because the thrombus included the common femoral vein; the decision for intervention in this case was more weighted on clot burden and location rather than on the significant symptoms of severe pain and difficulty with ambulation seen in Case 1. However, it is noteworthy that in Case 2 our patient also experienced significant improvement in pain, swelling, and ambulation postintervention. Complications were minimal and limited to Case 2 where our patient experienced mild asymptomatic hematuria likely related to the catheter-directed tPA that resolved spontaneously within hours and did not cause further complications. Additionally, it is likely that the length of hospital stay was decreased significantly in both cases given the rapid improvement in symptoms and recovery of ambulatory abilities.

High-Risk Patients

Given the successful treatment results in these 2 cases, we believe that there is a subset of higher-risk patients with severe symptomatic proximal DVT but without PCD that may benefit from the addition of thrombolytic therapies to anticoagulation. These patients may present with significant pain, difficulty ambulating, and will likely have extensive proximal clot burden. Immediate thrombolytic intervention can achieve rapid symptom relief, which, in turn, can decrease morbidity by decreasing length of hospitalization, improving ambulation, and possibly decreasing the incidence or severity of future PTS. Positive outcomes may be easier to predict for those with obvious features of pain, edema, and difficulty ambulating, which may be more readily reversed by rapid clot reversal/removal.

These patients should be considered on a case-by-case basis. For example, the severity of pain can be balanced against the patient’s risk factors for bleeding because rapid thrombus lysis or immediate thrombus removal will likely reduce the pain. Patients who attach a high value to functional quality (eg, both patients in this case study experienced significant difficulty ambulating), quicker recovery, and decreased hospitalization duration may be more likely to choose the addition of thrombolytic therapies over anticoagulation alone and accept the higher risk of bleed.

Finally, additional studies involving variations in methodology should be examined, including whether pharmacomechanic thrombolysis may be safer in terms of bleeding than catheter-directed thrombolysis alone, as suggested by the lower bleeding rates seen in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedantham and colleagues when compared with the CaVenT study.13,14 Patients in the CaVenT study received an infusion of 20 mg of alteplase over a maximum of 96 hours. Patients in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedanthem and colleagues received either a rapid pulsed delivery of alteplase over a single procedural session (

Conclusions

There is a relative lack of high-quality data examining thrombolytic therapies in the setting of acute lower extremity DVT. Recent studies have prioritized evaluation of the posttreatment incidence of PTS, recurrent thromboembolism, and risk of bleeding caused by thrombolytic therapies. Results are mixed thus far, and further studies are necessary to clarify a more definitive role for thrombolytic therapies, particularly in established higher-risk populations with proximal DVT. In this case series, we highlighted 2 patients with extensive proximal DVT burden with significant symptoms who experienced almost complete resolution of symptoms immediately following thrombolytic therapies. We postulate that even in the absence of PCD, there is a subset of patients with severe symptoms in the setting of acute proximal lower extremity DVT that clearly benefit from thrombolytic therapies.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous Thromboembolism (Blood Clots). Updated February 7, 2020. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/data.html

2. White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I4-I8. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66

3. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report [published correction appears in Chest. 2016 Oct;150(4):988]. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

4. Sarwar S, Narra S, Munir A. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens. Tex Heart Inst J. 2009;36(1):76-77.

5. Nyamekye I, Merker L. Management of proximal deep vein thrombosis. Phlebology. 2012;27 Suppl 2:61-72. doi:10.1258/phleb.2012.012s37

6. Abhishek M, Sukriti K, Purav S, et al. Comparison of catheter-directed thrombolysis vs systemic thrombolysis in pulmonary embolism: a propensity match analysis. Chest. 2017;152(4): A1047. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.1080

7. Sista AK, Kearon C. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism: where do we stand? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(10):1393-1395. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2015.06.009

8. Robertson L, McBride O, Burdess A. Pharmacomechanical thrombectomy for iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD011536. Published 2016 Nov 4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011536.pub2

9. Kahn SR, Shbaklo H, Lamping DL, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life during the 2 years following deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(7):1105-1112. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03002.x

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Chest. 2012 Dec;142(6):1698-1704]. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-e496S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2301

11. Bashir R, Zack CJ, Zhao H, Comerota AJ, Bove AA. Comparative outcomes of catheter-directed thrombolysis plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone to treat lower-extremity proximal deep vein thrombosis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1494-1501. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3415

12. Watson L, Broderick C, Armon MP. Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD002783. Published 2016 Nov 10. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002783.pub4

13. Enden T, Haig Y, Kløw NE, et al; CaVenT Study Group. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):31-38. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61753-4

14. Vedantham S, Goldhaber SZ, Julian JA, et al; ATTRACT Trial Investigators. Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2240-2252. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1615066

Two cases of extensive symptomatic deep vein thrombosis without phlegmasia cerulea dolens were successfully treated with an endovascular technique that combines catheter-directed thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy.

Two cases of extensive symptomatic deep vein thrombosis without phlegmasia cerulea dolens were successfully treated with an endovascular technique that combines catheter-directed thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a frequently encountered medical condition with about 1 in 1,000 adults diagnosed annually.1,2 Up to one-half of patients who receive a diagnosis will experience long-term complications in the affected limb.1 Anticoagulation is the treatment of choice for DVT in the absence of any contraindications.3 Thrombolytic therapies (eg, systemic thrombolysis, catheter-directed thrombolysis with or without thrombectomy) historically have been reserved for patients who present with phlegmasia cerulea dolens (PCD), a severe condition involving venous obstruction within the extremities that causes impaired arterial blood supply and cyanosis that can lead to limb loss and death.4

The role of thrombolytic therapy is less clear in patients without PCD who present with extensive or symptomatic lower extremity DVT that causes significant pain, edema, and functional disability. Proximal lower extremity DVT (thrombus above the knee and above the popliteal vein) and particularly those involving the iliac or common femoral vein (ie, iliofemoral DVT) carry a significant risk of recurrent thromboembolism as well as postthrombotic syndrome (PTS), a complication of DVT resulting in chronic leg pain, edema, skin discoloration, and venous ulcers.5

The goal of thrombolytic therapy is to prevent thrombus propagation, recurrent thromboembolism, and PTS, in addition to providing more rapid pain relief and improvement in limb function.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis can be combined with catheter-directed thrombectomy using the same endovascular technique. This combination is called a pharmacomechanical thrombectomy or a pharmacomechanical thromobolysis and can offer more rapid removal of thrombus and decreased infusion times of thrombolytic drug.8 Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis is a relatively new technique, so the choice of thrombolytic therapy will depend on procedural expertise and resource availability. Early interventional radiology consultation (or vascular surgery in some centers) can assist in determining appropriate candidates for thrombolytic therapies. Here we present 2 cases of extensive symptomatic DVT successfully treated with catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis.

Case 1

A 61-year-old male current smoker with a history of obesity and hypertension presented to the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center emergency department (ED) with 2 days of progressive pain and swelling in the right lower extremity (RLE) after sustaining a calf injury the preceding week. The patient rated pain as 9 on a 10-point scale and reported no other symptoms. He reported no prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs and normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive RLE edema below the knee with tenderness to palpation and shiny taut skin. The neurovascular examination of the RLE was normal. Laboratory studies were notable only for a mild leukocytosis. Compression ultrasound with Doppler of the RLE demonstrated an acute thrombus of the right femoral vein extending to the popliteal vein.

The patient was prescribed enoxaparin 90 mg every 12 hours for anticoagulation. After 36 hours of anticoagulation, he continued to experience severe RLE pain and swelling limiting ambulation. Interventional radiology was consulted, and catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis of the RLE was pursued given the persistence of significant symptoms. Intraprocedure venogram demonstrated thrombi filling the entirety of the right femoral and popliteal veins (Figure 1A). This was treated with catheter-directed pulse-spray thrombolysis with 12 mg of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA).

After a 20-minute incubation period, a thrombectomy was performed several times along the femoral vein and popliteal vein, using an AngioJet device. A follow-up venogram revealed a small amount of residual thrombi in the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein. This entire segment was further treated with angioplasty, and a postintervention venogram demonstrated patency of the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein with minimal residual thrombi and with brisk venous flow (Figure 1B). Immediately after the procedure, the patient’s RLE pain significantly improved. On day 2 postprocedure, the patient’s RLE edema resolved, and the patient was able to resume normal ambulation. There were no bleeding complications. The patient was discharged with oral anticoagulation therapy.

Case 2

A male aged 78 years with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and benign prostatic hypertrophy presented to the ED with 10 days of progressive pain and swelling in the left lower extremity (LLE). The patient noted decreased mobility over recent months and was using a front wheel walker while recovering from surgical repair of a hamstring tendon injury. He reported taking a transcontinental flight around the same time that his LLE pain began. The patient reported no prior history of VTE or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs with a normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive LLE edema up to the proximal thigh without erythema or cyanosis, and his skin was taut and tender. Neurovascular examination of the LLE was normal. Laboratory studies were unremarkable. Compression ultrasonography with Doppler of the LLE demonstrated an extensive acute occlusive thrombus within the left common femoral, entire left femoral, and left popliteal veins.

After evaluating the patient, the Vascular Surgery service did not feel there was evidence of compartment syndrome nor PCD. The patient received unfractionated heparin anticoagulation therapy and the LLE was elevated continuously. After 24 hours of anticoagulation therapy, the patient continued to have significant pain and was unable to ambulate. The case was presented in a joint Interventional Radiology/Vascular Surgery conference and the decision was made to pursue pharmacomechanic thrombolysis given the significant extent of thrombotic burden.

The patient underwent successful catheter-directed pharmacomechanic thrombolysis via pulse-spray thrombolysis of 15 mg of tPA using the Boston Scientific AngioJet Thrombectomy System, and angioplasty with no immediate complications (Figure 2). The patient noted dramatic improvement in LLE pain and swelling 1 day postprocedure and was able to ambulate. He developed mild asymptomatic hematuria, which resolved within 12 hours and without an associated drop in hemoglobin. The patient was transitioned to oral anticoagulation and discharged to an acute rehabilitation unit on postprocedure day 2.

Discussion

Anticoagulation is the preferred therapy for most patients with acute uncomplicated lower extremity DVT. PCD is the only widely accepted indication for thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute lower extremity DVT. However, in the absence of PCD, management of complicated DVT where there are either significant symptoms, extensive clot burden, or proximal location is less clear due to the paucity of clinical data. For example, in the case of iliofemoral DVT, thrombosis of the iliofemoral region is associated with an increased risk of pulmonary embolism, limb malperfusion, and PTS when compared with other types of DVT.5,6

Earlier retrospective observational studies in patients with acute DVT found that the addition of either systemic thrombolysis or catheter-directed thrombolysis to anticoagulation increased rates of clot lysis but did not lead to a reduction in clinical outcomes such as recurrent thromboembolism, mortality, or the rate of PTS.10-12 Additionally, both systemic thrombolytic therapy and catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy were associated with higher rates of major bleeding. However, these studies included all patients with acute DVT without selecting for criteria, such as proximal location of DVT, severe symptoms, or extensive clot burden. Because thrombolytic therapy is proven to provide more rapid and immediate clot lysis (whereas conventional anticoagulation prevents thrombus extension and recurrence but does not dissolve the clot), it is reasonable to suggest that a subpopulation of patients with extensive or symptomatic DVT may benefit from immediate clot lysis, thereby restoring limb perfusion and avoiding limb gangrene while preserving venous function and preventing PTS.

Mixed Study Results

The 2012 CaVenT study is one of the few randomized controlled trials to assess outcomes comparing conventional anticoagulation alone to anticoagulation with catheter-directed thrombolysis in patients with acute lower extremity DVT.13 Study patients did not undergo catheter-directed mechanical thrombectomy. Patients in this study consisted solely of those with first-time iliofemoral DVT. Long-term outcomes at 24-month follow-up showed that additional catheter-directed thrombolysis reduced the risk of PTS when compared with those who were treated with anticoagulation alone (41.1% vs 55.6%, P = .047). The difference in PTS corresponded to an absolute risk reduction of 14.4% (95% CI, 0.2-27.9), and the number needed to treat was 7 (95% CI, 4-502). There was a clinically relevant bleeding complication rate of 8.9% in the thrombolysis group with none leading to a permanently impaired outcome.

These results could not be confirmed by a more recent randomized control trial in 2017 conducted by Vedantham and colleagues.14 In this trial, patients with acute proximal DVT (femoral and iliofemoral DVT) were randomized to receive either anticoagulation alone or anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis. In the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group, the overall incidence of PTS and recurrent VTE was not reduced over the 24-month follow-up period. Those who developed PTS in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group had lower severity scores, as there was a significant reduction in moderate-to-severe PTS in this group. There also were more early major bleeds in the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group (1.7%, with no fatal or intracranial bleeds) when compared with the control group; however, this bleeding complication rate was much less than what was noted in the CaVenT study. Additionally, there was a significant decrease in both lower extremity pain and edema in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group at 10 days and 30 days postintervention.

Given the mixed results of these 2 randomized controlled trials, further studies are warranted to clarify the role of thrombolytic therapies in preventing major events such as recurrent VTE and PTS, especially given the increased risk of bleeding observed with thrombolytic therapies. The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines recommend anticoagulation as monotherapy vs thrombolytics, systemic or catheter-directed thrombolysis as designated treatment modalities.3 These guidelines are rated “Grade 2C”, which reflect a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. While these recommendations do not comment on additional considerations, such as DVT clot burden, location, or severity of symptoms, the guidelines do state that patients who attach a high value to the prevention of PTS and a lower value to the risk of bleeding with catheter-directed therapy are likely to choose catheter-directed therapy over anticoagulation alone.

Case Studies Analyses

In our first case presentation, pharma-comechanic thrombolysis was pursued because the patient presented with severesymptoms and did not experience any symptomatic improvement after 36 hours of anticoagulation. It is unclear whether a longer duration of anticoagulation might have improved the severity of his symptoms. When considering the level of pain, edema, and inability to ambulate, thrombolytic therapy was considered the most appropriate choice for treatment. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was successful, resulting in complete clot lysis, significant decrease in pain and edema with total recovery of ambulatory abilities, no bleeding complications, and prevention of any potential clinical deterioration, such as phlegmasia cerulea dolens. The patient is now 12 months postprocedure without symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events. Continued follow-up that monitors the development of PTS will be necessary for at least 2 years postprocedure.

In the second case, our patient experienced some improvement in pain after 24 hours of anticoagulation alone. However, considering the extensive proximal clot burden involving the entire femoral and common femoral veins, the treatment teams believed it was likely that this patient would experience a prolonged recovery time and increased morbidity on anticoagulant therapy alone. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was again successful with almost immediate resolution of pain and edema, and recovery of ambulatory abilities on postprocedure day 1. The patient is now 6 months postprocedure without any symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events.

In both case presentations, the presenting symptoms, methods of treatment, and immediate symptomatic improvement postintervention were similar. The patient in Case 2 had more extensive clot burden, a more proximal location of clot, and was classified as having an iliofemoral DVT because the thrombus included the common femoral vein; the decision for intervention in this case was more weighted on clot burden and location rather than on the significant symptoms of severe pain and difficulty with ambulation seen in Case 1. However, it is noteworthy that in Case 2 our patient also experienced significant improvement in pain, swelling, and ambulation postintervention. Complications were minimal and limited to Case 2 where our patient experienced mild asymptomatic hematuria likely related to the catheter-directed tPA that resolved spontaneously within hours and did not cause further complications. Additionally, it is likely that the length of hospital stay was decreased significantly in both cases given the rapid improvement in symptoms and recovery of ambulatory abilities.

High-Risk Patients

Given the successful treatment results in these 2 cases, we believe that there is a subset of higher-risk patients with severe symptomatic proximal DVT but without PCD that may benefit from the addition of thrombolytic therapies to anticoagulation. These patients may present with significant pain, difficulty ambulating, and will likely have extensive proximal clot burden. Immediate thrombolytic intervention can achieve rapid symptom relief, which, in turn, can decrease morbidity by decreasing length of hospitalization, improving ambulation, and possibly decreasing the incidence or severity of future PTS. Positive outcomes may be easier to predict for those with obvious features of pain, edema, and difficulty ambulating, which may be more readily reversed by rapid clot reversal/removal.

These patients should be considered on a case-by-case basis. For example, the severity of pain can be balanced against the patient’s risk factors for bleeding because rapid thrombus lysis or immediate thrombus removal will likely reduce the pain. Patients who attach a high value to functional quality (eg, both patients in this case study experienced significant difficulty ambulating), quicker recovery, and decreased hospitalization duration may be more likely to choose the addition of thrombolytic therapies over anticoagulation alone and accept the higher risk of bleed.

Finally, additional studies involving variations in methodology should be examined, including whether pharmacomechanic thrombolysis may be safer in terms of bleeding than catheter-directed thrombolysis alone, as suggested by the lower bleeding rates seen in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedantham and colleagues when compared with the CaVenT study.13,14 Patients in the CaVenT study received an infusion of 20 mg of alteplase over a maximum of 96 hours. Patients in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedanthem and colleagues received either a rapid pulsed delivery of alteplase over a single procedural session (

Conclusions

There is a relative lack of high-quality data examining thrombolytic therapies in the setting of acute lower extremity DVT. Recent studies have prioritized evaluation of the posttreatment incidence of PTS, recurrent thromboembolism, and risk of bleeding caused by thrombolytic therapies. Results are mixed thus far, and further studies are necessary to clarify a more definitive role for thrombolytic therapies, particularly in established higher-risk populations with proximal DVT. In this case series, we highlighted 2 patients with extensive proximal DVT burden with significant symptoms who experienced almost complete resolution of symptoms immediately following thrombolytic therapies. We postulate that even in the absence of PCD, there is a subset of patients with severe symptoms in the setting of acute proximal lower extremity DVT that clearly benefit from thrombolytic therapies.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a frequently encountered medical condition with about 1 in 1,000 adults diagnosed annually.1,2 Up to one-half of patients who receive a diagnosis will experience long-term complications in the affected limb.1 Anticoagulation is the treatment of choice for DVT in the absence of any contraindications.3 Thrombolytic therapies (eg, systemic thrombolysis, catheter-directed thrombolysis with or without thrombectomy) historically have been reserved for patients who present with phlegmasia cerulea dolens (PCD), a severe condition involving venous obstruction within the extremities that causes impaired arterial blood supply and cyanosis that can lead to limb loss and death.4

The role of thrombolytic therapy is less clear in patients without PCD who present with extensive or symptomatic lower extremity DVT that causes significant pain, edema, and functional disability. Proximal lower extremity DVT (thrombus above the knee and above the popliteal vein) and particularly those involving the iliac or common femoral vein (ie, iliofemoral DVT) carry a significant risk of recurrent thromboembolism as well as postthrombotic syndrome (PTS), a complication of DVT resulting in chronic leg pain, edema, skin discoloration, and venous ulcers.5

The goal of thrombolytic therapy is to prevent thrombus propagation, recurrent thromboembolism, and PTS, in addition to providing more rapid pain relief and improvement in limb function.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis can be combined with catheter-directed thrombectomy using the same endovascular technique. This combination is called a pharmacomechanical thrombectomy or a pharmacomechanical thromobolysis and can offer more rapid removal of thrombus and decreased infusion times of thrombolytic drug.8 Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis is a relatively new technique, so the choice of thrombolytic therapy will depend on procedural expertise and resource availability. Early interventional radiology consultation (or vascular surgery in some centers) can assist in determining appropriate candidates for thrombolytic therapies. Here we present 2 cases of extensive symptomatic DVT successfully treated with catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis.

Case 1

A 61-year-old male current smoker with a history of obesity and hypertension presented to the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center emergency department (ED) with 2 days of progressive pain and swelling in the right lower extremity (RLE) after sustaining a calf injury the preceding week. The patient rated pain as 9 on a 10-point scale and reported no other symptoms. He reported no prior history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs and normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive RLE edema below the knee with tenderness to palpation and shiny taut skin. The neurovascular examination of the RLE was normal. Laboratory studies were notable only for a mild leukocytosis. Compression ultrasound with Doppler of the RLE demonstrated an acute thrombus of the right femoral vein extending to the popliteal vein.

The patient was prescribed enoxaparin 90 mg every 12 hours for anticoagulation. After 36 hours of anticoagulation, he continued to experience severe RLE pain and swelling limiting ambulation. Interventional radiology was consulted, and catheter-directed pharmacomechanical thrombolysis of the RLE was pursued given the persistence of significant symptoms. Intraprocedure venogram demonstrated thrombi filling the entirety of the right femoral and popliteal veins (Figure 1A). This was treated with catheter-directed pulse-spray thrombolysis with 12 mg of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA).

After a 20-minute incubation period, a thrombectomy was performed several times along the femoral vein and popliteal vein, using an AngioJet device. A follow-up venogram revealed a small amount of residual thrombi in the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein. This entire segment was further treated with angioplasty, and a postintervention venogram demonstrated patency of the right suprageniculate popliteal vein and right femoral vein with minimal residual thrombi and with brisk venous flow (Figure 1B). Immediately after the procedure, the patient’s RLE pain significantly improved. On day 2 postprocedure, the patient’s RLE edema resolved, and the patient was able to resume normal ambulation. There were no bleeding complications. The patient was discharged with oral anticoagulation therapy.

Case 2

A male aged 78 years with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and benign prostatic hypertrophy presented to the ED with 10 days of progressive pain and swelling in the left lower extremity (LLE). The patient noted decreased mobility over recent months and was using a front wheel walker while recovering from surgical repair of a hamstring tendon injury. He reported taking a transcontinental flight around the same time that his LLE pain began. The patient reported no prior history of VTE or family history of thrombophilia.

A physical examination was notable for stable vital signs with a normal cardiopulmonary examination. There was extensive LLE edema up to the proximal thigh without erythema or cyanosis, and his skin was taut and tender. Neurovascular examination of the LLE was normal. Laboratory studies were unremarkable. Compression ultrasonography with Doppler of the LLE demonstrated an extensive acute occlusive thrombus within the left common femoral, entire left femoral, and left popliteal veins.

After evaluating the patient, the Vascular Surgery service did not feel there was evidence of compartment syndrome nor PCD. The patient received unfractionated heparin anticoagulation therapy and the LLE was elevated continuously. After 24 hours of anticoagulation therapy, the patient continued to have significant pain and was unable to ambulate. The case was presented in a joint Interventional Radiology/Vascular Surgery conference and the decision was made to pursue pharmacomechanic thrombolysis given the significant extent of thrombotic burden.

The patient underwent successful catheter-directed pharmacomechanic thrombolysis via pulse-spray thrombolysis of 15 mg of tPA using the Boston Scientific AngioJet Thrombectomy System, and angioplasty with no immediate complications (Figure 2). The patient noted dramatic improvement in LLE pain and swelling 1 day postprocedure and was able to ambulate. He developed mild asymptomatic hematuria, which resolved within 12 hours and without an associated drop in hemoglobin. The patient was transitioned to oral anticoagulation and discharged to an acute rehabilitation unit on postprocedure day 2.

Discussion

Anticoagulation is the preferred therapy for most patients with acute uncomplicated lower extremity DVT. PCD is the only widely accepted indication for thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute lower extremity DVT. However, in the absence of PCD, management of complicated DVT where there are either significant symptoms, extensive clot burden, or proximal location is less clear due to the paucity of clinical data. For example, in the case of iliofemoral DVT, thrombosis of the iliofemoral region is associated with an increased risk of pulmonary embolism, limb malperfusion, and PTS when compared with other types of DVT.5,6

Earlier retrospective observational studies in patients with acute DVT found that the addition of either systemic thrombolysis or catheter-directed thrombolysis to anticoagulation increased rates of clot lysis but did not lead to a reduction in clinical outcomes such as recurrent thromboembolism, mortality, or the rate of PTS.10-12 Additionally, both systemic thrombolytic therapy and catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy were associated with higher rates of major bleeding. However, these studies included all patients with acute DVT without selecting for criteria, such as proximal location of DVT, severe symptoms, or extensive clot burden. Because thrombolytic therapy is proven to provide more rapid and immediate clot lysis (whereas conventional anticoagulation prevents thrombus extension and recurrence but does not dissolve the clot), it is reasonable to suggest that a subpopulation of patients with extensive or symptomatic DVT may benefit from immediate clot lysis, thereby restoring limb perfusion and avoiding limb gangrene while preserving venous function and preventing PTS.

Mixed Study Results

The 2012 CaVenT study is one of the few randomized controlled trials to assess outcomes comparing conventional anticoagulation alone to anticoagulation with catheter-directed thrombolysis in patients with acute lower extremity DVT.13 Study patients did not undergo catheter-directed mechanical thrombectomy. Patients in this study consisted solely of those with first-time iliofemoral DVT. Long-term outcomes at 24-month follow-up showed that additional catheter-directed thrombolysis reduced the risk of PTS when compared with those who were treated with anticoagulation alone (41.1% vs 55.6%, P = .047). The difference in PTS corresponded to an absolute risk reduction of 14.4% (95% CI, 0.2-27.9), and the number needed to treat was 7 (95% CI, 4-502). There was a clinically relevant bleeding complication rate of 8.9% in the thrombolysis group with none leading to a permanently impaired outcome.

These results could not be confirmed by a more recent randomized control trial in 2017 conducted by Vedantham and colleagues.14 In this trial, patients with acute proximal DVT (femoral and iliofemoral DVT) were randomized to receive either anticoagulation alone or anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis. In the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group, the overall incidence of PTS and recurrent VTE was not reduced over the 24-month follow-up period. Those who developed PTS in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group had lower severity scores, as there was a significant reduction in moderate-to-severe PTS in this group. There also were more early major bleeds in the pharmacomechanic thrombolysis group (1.7%, with no fatal or intracranial bleeds) when compared with the control group; however, this bleeding complication rate was much less than what was noted in the CaVenT study. Additionally, there was a significant decrease in both lower extremity pain and edema in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group at 10 days and 30 days postintervention.

Given the mixed results of these 2 randomized controlled trials, further studies are warranted to clarify the role of thrombolytic therapies in preventing major events such as recurrent VTE and PTS, especially given the increased risk of bleeding observed with thrombolytic therapies. The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines recommend anticoagulation as monotherapy vs thrombolytics, systemic or catheter-directed thrombolysis as designated treatment modalities.3 These guidelines are rated “Grade 2C”, which reflect a weak recommendation based on low-quality evidence. While these recommendations do not comment on additional considerations, such as DVT clot burden, location, or severity of symptoms, the guidelines do state that patients who attach a high value to the prevention of PTS and a lower value to the risk of bleeding with catheter-directed therapy are likely to choose catheter-directed therapy over anticoagulation alone.

Case Studies Analyses

In our first case presentation, pharma-comechanic thrombolysis was pursued because the patient presented with severesymptoms and did not experience any symptomatic improvement after 36 hours of anticoagulation. It is unclear whether a longer duration of anticoagulation might have improved the severity of his symptoms. When considering the level of pain, edema, and inability to ambulate, thrombolytic therapy was considered the most appropriate choice for treatment. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was successful, resulting in complete clot lysis, significant decrease in pain and edema with total recovery of ambulatory abilities, no bleeding complications, and prevention of any potential clinical deterioration, such as phlegmasia cerulea dolens. The patient is now 12 months postprocedure without symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events. Continued follow-up that monitors the development of PTS will be necessary for at least 2 years postprocedure.

In the second case, our patient experienced some improvement in pain after 24 hours of anticoagulation alone. However, considering the extensive proximal clot burden involving the entire femoral and common femoral veins, the treatment teams believed it was likely that this patient would experience a prolonged recovery time and increased morbidity on anticoagulant therapy alone. Pharmacomechanic thrombolysis was again successful with almost immediate resolution of pain and edema, and recovery of ambulatory abilities on postprocedure day 1. The patient is now 6 months postprocedure without any symptoms of PTS or recurrent thromboembolic events.

In both case presentations, the presenting symptoms, methods of treatment, and immediate symptomatic improvement postintervention were similar. The patient in Case 2 had more extensive clot burden, a more proximal location of clot, and was classified as having an iliofemoral DVT because the thrombus included the common femoral vein; the decision for intervention in this case was more weighted on clot burden and location rather than on the significant symptoms of severe pain and difficulty with ambulation seen in Case 1. However, it is noteworthy that in Case 2 our patient also experienced significant improvement in pain, swelling, and ambulation postintervention. Complications were minimal and limited to Case 2 where our patient experienced mild asymptomatic hematuria likely related to the catheter-directed tPA that resolved spontaneously within hours and did not cause further complications. Additionally, it is likely that the length of hospital stay was decreased significantly in both cases given the rapid improvement in symptoms and recovery of ambulatory abilities.

High-Risk Patients

Given the successful treatment results in these 2 cases, we believe that there is a subset of higher-risk patients with severe symptomatic proximal DVT but without PCD that may benefit from the addition of thrombolytic therapies to anticoagulation. These patients may present with significant pain, difficulty ambulating, and will likely have extensive proximal clot burden. Immediate thrombolytic intervention can achieve rapid symptom relief, which, in turn, can decrease morbidity by decreasing length of hospitalization, improving ambulation, and possibly decreasing the incidence or severity of future PTS. Positive outcomes may be easier to predict for those with obvious features of pain, edema, and difficulty ambulating, which may be more readily reversed by rapid clot reversal/removal.

These patients should be considered on a case-by-case basis. For example, the severity of pain can be balanced against the patient’s risk factors for bleeding because rapid thrombus lysis or immediate thrombus removal will likely reduce the pain. Patients who attach a high value to functional quality (eg, both patients in this case study experienced significant difficulty ambulating), quicker recovery, and decreased hospitalization duration may be more likely to choose the addition of thrombolytic therapies over anticoagulation alone and accept the higher risk of bleed.

Finally, additional studies involving variations in methodology should be examined, including whether pharmacomechanic thrombolysis may be safer in terms of bleeding than catheter-directed thrombolysis alone, as suggested by the lower bleeding rates seen in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedantham and colleagues when compared with the CaVenT study.13,14 Patients in the CaVenT study received an infusion of 20 mg of alteplase over a maximum of 96 hours. Patients in the pharmacomechanic study by Vedanthem and colleagues received either a rapid pulsed delivery of alteplase over a single procedural session (

Conclusions

There is a relative lack of high-quality data examining thrombolytic therapies in the setting of acute lower extremity DVT. Recent studies have prioritized evaluation of the posttreatment incidence of PTS, recurrent thromboembolism, and risk of bleeding caused by thrombolytic therapies. Results are mixed thus far, and further studies are necessary to clarify a more definitive role for thrombolytic therapies, particularly in established higher-risk populations with proximal DVT. In this case series, we highlighted 2 patients with extensive proximal DVT burden with significant symptoms who experienced almost complete resolution of symptoms immediately following thrombolytic therapies. We postulate that even in the absence of PCD, there is a subset of patients with severe symptoms in the setting of acute proximal lower extremity DVT that clearly benefit from thrombolytic therapies.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous Thromboembolism (Blood Clots). Updated February 7, 2020. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/data.html

2. White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I4-I8. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66

3. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report [published correction appears in Chest. 2016 Oct;150(4):988]. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

4. Sarwar S, Narra S, Munir A. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens. Tex Heart Inst J. 2009;36(1):76-77.

5. Nyamekye I, Merker L. Management of proximal deep vein thrombosis. Phlebology. 2012;27 Suppl 2:61-72. doi:10.1258/phleb.2012.012s37

6. Abhishek M, Sukriti K, Purav S, et al. Comparison of catheter-directed thrombolysis vs systemic thrombolysis in pulmonary embolism: a propensity match analysis. Chest. 2017;152(4): A1047. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.1080

7. Sista AK, Kearon C. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism: where do we stand? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(10):1393-1395. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2015.06.009

8. Robertson L, McBride O, Burdess A. Pharmacomechanical thrombectomy for iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD011536. Published 2016 Nov 4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011536.pub2

9. Kahn SR, Shbaklo H, Lamping DL, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life during the 2 years following deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(7):1105-1112. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03002.x

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Chest. 2012 Dec;142(6):1698-1704]. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-e496S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2301

11. Bashir R, Zack CJ, Zhao H, Comerota AJ, Bove AA. Comparative outcomes of catheter-directed thrombolysis plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone to treat lower-extremity proximal deep vein thrombosis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1494-1501. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3415

12. Watson L, Broderick C, Armon MP. Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD002783. Published 2016 Nov 10. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002783.pub4

13. Enden T, Haig Y, Kløw NE, et al; CaVenT Study Group. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):31-38. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61753-4

14. Vedantham S, Goldhaber SZ, Julian JA, et al; ATTRACT Trial Investigators. Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2240-2252. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1615066

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous Thromboembolism (Blood Clots). Updated February 7, 2020. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/data.html

2. White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I4-I8. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66

3. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report [published correction appears in Chest. 2016 Oct;150(4):988]. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

4. Sarwar S, Narra S, Munir A. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens. Tex Heart Inst J. 2009;36(1):76-77.

5. Nyamekye I, Merker L. Management of proximal deep vein thrombosis. Phlebology. 2012;27 Suppl 2:61-72. doi:10.1258/phleb.2012.012s37

6. Abhishek M, Sukriti K, Purav S, et al. Comparison of catheter-directed thrombolysis vs systemic thrombolysis in pulmonary embolism: a propensity match analysis. Chest. 2017;152(4): A1047. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.1080

7. Sista AK, Kearon C. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism: where do we stand? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(10):1393-1395. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2015.06.009

8. Robertson L, McBride O, Burdess A. Pharmacomechanical thrombectomy for iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD011536. Published 2016 Nov 4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011536.pub2

9. Kahn SR, Shbaklo H, Lamping DL, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life during the 2 years following deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(7):1105-1112. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03002.x

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Chest. 2012 Dec;142(6):1698-1704]. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-e496S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2301

11. Bashir R, Zack CJ, Zhao H, Comerota AJ, Bove AA. Comparative outcomes of catheter-directed thrombolysis plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone to treat lower-extremity proximal deep vein thrombosis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1494-1501. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3415

12. Watson L, Broderick C, Armon MP. Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD002783. Published 2016 Nov 10. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002783.pub4

13. Enden T, Haig Y, Kløw NE, et al; CaVenT Study Group. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):31-38. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61753-4

14. Vedantham S, Goldhaber SZ, Julian JA, et al; ATTRACT Trial Investigators. Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2240-2252. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1615066

Management of Do Not Resuscitate Orders Before Invasive Procedures

In January 2017, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), led by the National Center of Ethics in Health Care, created the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative (LSTDI). The VA gradually implemented the LSTDI in its facilities nationwide. In a format similar to the standardized form of portable medical orders, provider orders for life-sustaining treatments (POLST), the initiative promotes discussions with veterans and encourages but does not require health care professionals (HCPs) to complete a template for documentation (life-sustaining treatment [LST] note) of a patient’s preferences.1 The HCP enters a code status into the electronic health record (EHR), creating a portable and durable note and order.

With a new durable code status, the HCPs performing these procedures (eg, colonoscopies, coronary catheterization, or percutaneous biopsies) need to acknowledge and can potentially rescind a do not resuscitate (DNR) order. Although the risk of cardiac arrest or intubation is low, all invasive procedures carry these risks to some degree.2,3 Some HCPs advocate the automatic discontinuation of DNR orders before any procedure, but multiple professional societies recommend that patients be included in these discussions to honor their wishes.4-7 Although no procedures at the VA require the suspension of a DNR status, it is important to establish which life-sustaining measures are acceptable to patients.

As part of the informed consent process, proceduralists (HCPs who perform a procedure) should discuss the option of temporary suspension of DNR in the periprocedural period and document the outcome of this discussion (eg, rescinded DNR, acknowledgment of continued DNR status). These discussions need to be documented clearly to ensure accurate communication with other HCPs, particularly those caring for the patient postprocedure. Without the documentation, the risk that the patient’s wishes will not be honored is high.8 Code status is usually addressed before intubation of general anesthesia; however, nonsurgical procedures have a lower likelihood of DNR acknowledgment.

This study aimed to examine and improve the rate of acknowledgment of DNR status before nonsurgical procedures. We hypothesized that the rate of DNR acknowledgment before nonsurgical invasive procedures is low; and the rate can be raised with an intervention designed to educate proceduralists and improve and simplify this documentation.9

Methods

This was a single center, before/after quasi-experimental study. The study was considered clinical operations and institutional review board approval was unnecessary.

A retrospective chart review was performed of patients who underwent an inpatient or outpatient, nonsurgical invasive procedure at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center in Minnesota. The preintervention period was defined as the first 6 months after implementation of the LSTDI between May 8, 2018 and October 31, 2018. The intervention was presented in December 2018 and January 2019. The postintervention period was from February 1, 2019 to April 30, 2019.

Patients who underwent a nonsurgical invasive procedure were reviewed in 3 procedural areas. These areas were chosen based on high patient volumes and the need for rapid patient turnover, including gastroenterology, cardiology, and interventional radiology. An invasive procedure was defined as any procedure requiring patient consent. Those patients who had a completed LST note and who had a DNR order were recorded.

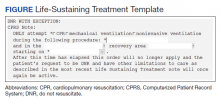

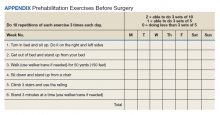

The intervention was composed of 2 elements: (1) an addendum to the LST note, which temporarily suspended resuscitation orders (Figure). We developed the addendum based on templates and orders in use before LSTDI implementation. Physicians from the procedural areas reviewed the addendum and provided feedback and the facility chief-of-staff provided approval. Part 2 was an educational presentation to proceduralists in each procedural area. The presentation included a brief introduction to the LSTDI, where to find a life-sustaining treatment note, code status, the importance of addressing code status, and a description of the addendum. The proceduralists were advised to use the addendum only after discussion with the patient and obtaining verbal consent for DNR suspension. If the patient elected to remain DNR, proceduralists were encouraged to document the conversation acknowledging the DNR.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was proceduralist acknowledgment of DNR status before nonsurgical invasive procedures. DNR status was considered acknowledged if the proceduralist provided any type of documentation.

Statistical Analysis

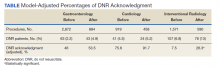

Model predicted percentages of DNR acknowledgment are reported from a logistic regression model with both procedural area, time (before vs after) and the interaction between these 2 variables in the model. The simple main effects comparing before vs after within the procedural area based on post hoc contrasts of the interaction term also are shown.

Results

During the first 6 months following LSTDI implementation (the preintervention phase), 5,362 invasive procedures were performed in gastroenterology, interventional radiology, and cardiology. A total of 211 procedures were performed on patients who had a prior LST note indicating DNR. Of those, 68 (32.2%) had documentation acknowledging their DNR status. The educational presentation was given to each of the 3 departments with about 75% faculty attendance in each department. After the intervention, 1,932 invasive procedures were performed, identifying 143 LST notes with a DNR status. Sixty-five (45.5%) had documentation of a discussion regarding their DNR status.

The interaction between procedural areas and time (before, after) was examined. Of the 3 procedural areas, only interventional radiology had significant differences before vs after, 7.5% vs 26.3%, respectively (P = .01). Model-adjusted percentages before vs after for cardiology were 75.6% vs 91.7% (P = .12) and for gastroenterology were 46% vs 53.5% (P = .40) (Table). When all 3 procedural areas were combined, there was a significant improvement in the overall percentage of DNR acknowledgment postintervention from 38.6% to 61.1.% (P = .01).

Discussion

With the LSTDI, DNR orders remain in place and are valid in the inpatient and outpatient setting until reversed by the patient. This creates new challenges for proceduralists. Before our intervention, only about one-third of proceduralists’ recognized DNR status before procedures. This low rate of preprocedural DNR acknowledgments is not unique to the VA. A pilot study assessing rate of documentation of code status discussions in patients undergoing venting gastrostomy tube for malignant bowel obstruction showed documentation in only 22% of cases before the procedure.10 Another simulation-based study of anesthesiologist showed only 57% of subjects addressed resuscitation before starting the procedure.11

Despite the low initial rates of DNR acknowledgment, our intervention successfully improved these rates, although with variation between procedural areas. Prior studies looking at improving adherence to guidelines have shown the benefit of physician education.12,13 Improving code status acknowledgment before an invasive procedure not only involves increasing awareness of a preexisting code status, but also developing a system to incorporate the documentation process efficiently into the procedural workflow and ensuring that providers are aware of the appropriate process. Although the largest improvement was in interventional radiology, many patients postintervention still did not have their DNR orders acknowledged. Confusion is created when the patient is cared for by a different HCP or when the resuscitation team is called during a cardiac arrest. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation may be started or withheld incorrectly if the patient’s most recent wishes for resuscitation are unclear.14

Outside of using education to raise awareness, other improvements could utilize informatics solutions, such as developing an alert on opening a patient chart if a DNR status exists (such as a pop-up screen) or adding code status as an item to a preprocedural checklist. Similar to our study, previous studies also have found that a systematic approach with guidelines and templates improved rates of documentation of code status and DNR decisions.15,16 A large proportion of the LST notes and procedures done on patients with a DNR in our study occurred in the inpatient setting without any involvement of the primary care provider in the discussion. Having an automated way to alert the primary care provider that a new LST note has been completed may be helpful in guiding future care. Future work could identify additional systematic methods to increase acknowledgment of DNR.

Limitations

Our single-center results may not be generalizable. Although the interaction between procedural area and time was tested, it is possible that improvement in DNR acknowledgment was attributable to secular trends and not the intervention. Other limitations included the decreased generalizability of a VA health care initiative and its unique electronic health record, incomplete attendance rates at our educational sessions, and a lack of patient-centered outcomes.

Conclusions

A templated addendum combined with targeted staff education improved the percentage of DNR acknowledgments before nonsurgical invasive procedures, an important step in establishing patient preferences for life-sustaining treatment in procedures with potential complications. Further research is needed to assess whether these improvements also lead to improved patient-centered outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable help of Dr. Kathryn Rice and Dr. Anne Melzer for their guidance in the manuscript revision process

1. Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment Paradigm. Honoring the wishes of those with serious illness and frailty. Accessed January 11, 2021.

2. Arepally A, Oechsle D, Kirkwood S, Savader S. Safety of conscious sedation in interventional radiology. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2001;24(3):185-190. doi:10.1007/s002700002549

3. Arrowsmith J, Gertsman B, Fleischer D, Benjamin S. Results from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy/U.S. Food and Drug Administration collaborative study on complication rates and drug use during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37(4):421-427. doi:10.1016/s0016-5107(91)70773-6

4. Burkle C, Swetz K, Armstrong M, Keegan M. Patient and doctor attitudes and beliefs concerning perioperative do not resuscitate orders: anesthesiologists’ growing compliance with patient autonomy and self-determination guidelines. BMC Anesthesiol. 2013;13:2. doi:10.1186/1471-2253-13-2

5. American College of Surgeons. Statement on advance directives by patients: “do not resuscitate” in the operative room. Published January 3, 2014. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://bulletin.facs.org/2014/01/statement-on-advance-directives-by-patients-do-not-resuscitate-in-the-operating-room

6. Association of periOperative Registered Nurses. AORN position statement on perioperative care of patients with do-not-resuscitate or allow-natural death orders. Reaffirmed February 2020. Accessed June 16, 2020. https://www.aorn.org/guidelines/clinical-resources/position-statements

7. Bastron DR. Ethical guidelines for the anesthesia care of patients with do-not-resuscitate orders or other directives that limit treatment. Published 1996. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article/85/5/1190/35862/Ethical-Concerns-in-Anesthetic-Care-for-Patients

8. Baxter L, Hancox J, King B, Powell A, Tolley T. Stop! Patients receiving CPR despite valid DNACPR documentation. Eur J Pall Car. 2018;23(3):125-127.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Practice facilitation handbook, module 10: academic detailing as a quality improvement tool. Last reviewed May 2013. Accessed January 11, 2021. 2021. https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/pf-handbook/mod10.html

10. Urman R, Lilley E, Changala M, Lindvall C, Hepner D, Bader A. A pilot study to evaluate compliance with guidelines for preprocedural reconsideration of code status limitations. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(8):1152-1156. doi:10.1089/jpm.2017.0601

11. Waisel D, Simon R, Truog R, Baboolal H, Raemer D. Anesthesiologist management of perioperative do-not-resuscitate orders: a simulation-based experiment. Simul Healthc. 2009;4(2):70-76. doi:10.1097/SIH.0b013e31819e137b

12. Lozano P, Finkelstein J, Carey V, et al. A multisite randomized trial of the effects of physician education and organizational change in chronic-asthma care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(9):875-883. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.9.875

13. Brunström M, Ng N, Dahlström J, et al. Association of physician education and feedback on hypertension management with patient blood pressure and hypertension control. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1918625. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18625

14. Wong J, Duane P, Ingraham N. A case series of patients who were do not resuscitate but underwent cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2020;146:145-146. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.11.020

15. Mittelberger J, Lo B, Martin D, Uhlmann R. Impact of a procedure-specific do not resuscitate order form on documentation of do not resuscitate orders. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(2):228-232.

16. Neubauer M, Taniguchi C, Hoverman J. Improving incidence of code status documentation through process and discipline. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):e263-266. doi:10.1200/JOP.2014.001438

In January 2017, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), led by the National Center of Ethics in Health Care, created the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative (LSTDI). The VA gradually implemented the LSTDI in its facilities nationwide. In a format similar to the standardized form of portable medical orders, provider orders for life-sustaining treatments (POLST), the initiative promotes discussions with veterans and encourages but does not require health care professionals (HCPs) to complete a template for documentation (life-sustaining treatment [LST] note) of a patient’s preferences.1 The HCP enters a code status into the electronic health record (EHR), creating a portable and durable note and order.

With a new durable code status, the HCPs performing these procedures (eg, colonoscopies, coronary catheterization, or percutaneous biopsies) need to acknowledge and can potentially rescind a do not resuscitate (DNR) order. Although the risk of cardiac arrest or intubation is low, all invasive procedures carry these risks to some degree.2,3 Some HCPs advocate the automatic discontinuation of DNR orders before any procedure, but multiple professional societies recommend that patients be included in these discussions to honor their wishes.4-7 Although no procedures at the VA require the suspension of a DNR status, it is important to establish which life-sustaining measures are acceptable to patients.

As part of the informed consent process, proceduralists (HCPs who perform a procedure) should discuss the option of temporary suspension of DNR in the periprocedural period and document the outcome of this discussion (eg, rescinded DNR, acknowledgment of continued DNR status). These discussions need to be documented clearly to ensure accurate communication with other HCPs, particularly those caring for the patient postprocedure. Without the documentation, the risk that the patient’s wishes will not be honored is high.8 Code status is usually addressed before intubation of general anesthesia; however, nonsurgical procedures have a lower likelihood of DNR acknowledgment.

This study aimed to examine and improve the rate of acknowledgment of DNR status before nonsurgical procedures. We hypothesized that the rate of DNR acknowledgment before nonsurgical invasive procedures is low; and the rate can be raised with an intervention designed to educate proceduralists and improve and simplify this documentation.9

Methods

This was a single center, before/after quasi-experimental study. The study was considered clinical operations and institutional review board approval was unnecessary.

A retrospective chart review was performed of patients who underwent an inpatient or outpatient, nonsurgical invasive procedure at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center in Minnesota. The preintervention period was defined as the first 6 months after implementation of the LSTDI between May 8, 2018 and October 31, 2018. The intervention was presented in December 2018 and January 2019. The postintervention period was from February 1, 2019 to April 30, 2019.

Patients who underwent a nonsurgical invasive procedure were reviewed in 3 procedural areas. These areas were chosen based on high patient volumes and the need for rapid patient turnover, including gastroenterology, cardiology, and interventional radiology. An invasive procedure was defined as any procedure requiring patient consent. Those patients who had a completed LST note and who had a DNR order were recorded.