User login

ZUMA-12 study shows frontline axi-cel has substantial activity in high-risk large B-cell lymphoma

Axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) can be safely administered and has substantial clinical benefit as part of first-line therapy in patients with high-risk large B-cell lymphoma, according to an investigator in a phase 2 study.

The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy had a “very high” overall response rate (ORR) of 85% and a complete response (CR) rate of 74% in the ZUMA-12 study, said investigator Sattva S. Neelapu, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Nearly three-quarters of responses were ongoing with a median of follow-up of about 9 months, Dr. Neelapu said in interim analysis of ZUMA-12 presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, which was held virtually.

While axi-cel is approved for treatment of certain relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphomas (LBCLs), Dr. Neelapu said this is the first-ever study evaluating a CAR T-cell therapy as a first-line treatment for patients with LBCL that is high risk as defined by histology or International Prognostic Index (IPI) scoring.

Treatment with axi-cel was guided by dynamic risk assessment, Dr. Neelapu explained, meaning that patients received the CAR T-cell treatment if they had a positive interim positron emission tomography (PET) scan after two cycles of an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and anthracycline-containing regimen.

Longer follow-up needed

The interim efficacy analysis is based on 27 evaluable patients out of 40 patients planned to be enrolled, meaning that the final analysis is needed, and longer follow-up is needed to ensure that durability is maintained, Dr. Neelapu said in a question-and-answer session following his presentation.

Nevertheless, the 74% complete response rate in the frontline setting is “quite encouraging” compared to historical data in high-risk LBCL, where CR rates have generally been less than 50%, Dr. Neelapu added.

“Assuming that long-term data in the final analysis confirms this encouraging activity, I think we likely would need a randomized phase 3 trial to compare (axi-cel) head-to-head with frontline therapy,” he said.

Without mature data available, it’s hard to say in this single-arm study how much axi-cel is improving outcomes at the cost of significant toxicity, said Catherine M. Diefenbach, MD, director of the clinical lymphoma program at NYU Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York.

Adverse events as reported by Dr. Neelapu included grade 3 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in 9% of patients, and 25% grade 3 or greater neurologic events in 25%.

“It appears as though it may be salvaging some patients, as the response rate is higher than that expected for chemotherapy alone in this setting,” Dr. Diefenbach said in an interview, “but toxicity is not trivial, so the long-term data will provide better clarity as to the degree of benefit.”

Ongoing responses at 9 months

The phase 2 ZUMA-12 study includes patients classified as high risk based on MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 translocations, or by an International Prognostic Indicator score of 3 or greater.

Patients initially received two cycles of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy plus an anthracycline containing regimen. Those with a positive interim PET (score of 4 or 5 on the 5-point Deauville scale) received fludarabine/cyclophosphamide conditioning plus axi-cel as a single intravenous infusion of 2 x 106 CAR T cells per kg of body weight.

As of the report at the ASH meeting, 32 patient had received axi-cel, of whom 32 were evaluable for safety and 27 were evaluable for efficacy.

The ORR was 85% (23 of 27 patients), and the CR rate was 74% (20 of 27 patients), Dr. Neelapu reported, noting that with a median follow-up of 9.3 months, 70% of responders (19 of 27) were in ongoing response.

Median duration of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival have not been reached, he added.

Encephalopathy was the most common grade 3 or greater adverse event related to axi-cel, occurring in 16% of patients, while increased alanine aminotransferase and decreased neutrophil count were each seen in 9% of patients, Dr. Neelapu said.

All 32 patients experienced CRS, including grade 3 CRS in 3 patients (9%), according to the reported data. Neurologic events were seen in 22 patients (69%) including grade 3 or greater in 8 (25%). There were 2 grade 4 neurologic events – both encephalopathies that resolved, according to Dr. Neelapu – and no grade 5 neurologic events.

ZUMA-12 is sponsored by Kite, a Gilead Company. Dr. Neelapu reported disclosures related to Acerta, Adicet Bio, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Kite, and various other pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

SOURCE: Neelapu SS et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 405.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) can be safely administered and has substantial clinical benefit as part of first-line therapy in patients with high-risk large B-cell lymphoma, according to an investigator in a phase 2 study.

The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy had a “very high” overall response rate (ORR) of 85% and a complete response (CR) rate of 74% in the ZUMA-12 study, said investigator Sattva S. Neelapu, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Nearly three-quarters of responses were ongoing with a median of follow-up of about 9 months, Dr. Neelapu said in interim analysis of ZUMA-12 presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, which was held virtually.

While axi-cel is approved for treatment of certain relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphomas (LBCLs), Dr. Neelapu said this is the first-ever study evaluating a CAR T-cell therapy as a first-line treatment for patients with LBCL that is high risk as defined by histology or International Prognostic Index (IPI) scoring.

Treatment with axi-cel was guided by dynamic risk assessment, Dr. Neelapu explained, meaning that patients received the CAR T-cell treatment if they had a positive interim positron emission tomography (PET) scan after two cycles of an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and anthracycline-containing regimen.

Longer follow-up needed

The interim efficacy analysis is based on 27 evaluable patients out of 40 patients planned to be enrolled, meaning that the final analysis is needed, and longer follow-up is needed to ensure that durability is maintained, Dr. Neelapu said in a question-and-answer session following his presentation.

Nevertheless, the 74% complete response rate in the frontline setting is “quite encouraging” compared to historical data in high-risk LBCL, where CR rates have generally been less than 50%, Dr. Neelapu added.

“Assuming that long-term data in the final analysis confirms this encouraging activity, I think we likely would need a randomized phase 3 trial to compare (axi-cel) head-to-head with frontline therapy,” he said.

Without mature data available, it’s hard to say in this single-arm study how much axi-cel is improving outcomes at the cost of significant toxicity, said Catherine M. Diefenbach, MD, director of the clinical lymphoma program at NYU Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York.

Adverse events as reported by Dr. Neelapu included grade 3 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in 9% of patients, and 25% grade 3 or greater neurologic events in 25%.

“It appears as though it may be salvaging some patients, as the response rate is higher than that expected for chemotherapy alone in this setting,” Dr. Diefenbach said in an interview, “but toxicity is not trivial, so the long-term data will provide better clarity as to the degree of benefit.”

Ongoing responses at 9 months

The phase 2 ZUMA-12 study includes patients classified as high risk based on MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 translocations, or by an International Prognostic Indicator score of 3 or greater.

Patients initially received two cycles of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy plus an anthracycline containing regimen. Those with a positive interim PET (score of 4 or 5 on the 5-point Deauville scale) received fludarabine/cyclophosphamide conditioning plus axi-cel as a single intravenous infusion of 2 x 106 CAR T cells per kg of body weight.

As of the report at the ASH meeting, 32 patient had received axi-cel, of whom 32 were evaluable for safety and 27 were evaluable for efficacy.

The ORR was 85% (23 of 27 patients), and the CR rate was 74% (20 of 27 patients), Dr. Neelapu reported, noting that with a median follow-up of 9.3 months, 70% of responders (19 of 27) were in ongoing response.

Median duration of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival have not been reached, he added.

Encephalopathy was the most common grade 3 or greater adverse event related to axi-cel, occurring in 16% of patients, while increased alanine aminotransferase and decreased neutrophil count were each seen in 9% of patients, Dr. Neelapu said.

All 32 patients experienced CRS, including grade 3 CRS in 3 patients (9%), according to the reported data. Neurologic events were seen in 22 patients (69%) including grade 3 or greater in 8 (25%). There were 2 grade 4 neurologic events – both encephalopathies that resolved, according to Dr. Neelapu – and no grade 5 neurologic events.

ZUMA-12 is sponsored by Kite, a Gilead Company. Dr. Neelapu reported disclosures related to Acerta, Adicet Bio, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Kite, and various other pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

SOURCE: Neelapu SS et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 405.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) can be safely administered and has substantial clinical benefit as part of first-line therapy in patients with high-risk large B-cell lymphoma, according to an investigator in a phase 2 study.

The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy had a “very high” overall response rate (ORR) of 85% and a complete response (CR) rate of 74% in the ZUMA-12 study, said investigator Sattva S. Neelapu, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Nearly three-quarters of responses were ongoing with a median of follow-up of about 9 months, Dr. Neelapu said in interim analysis of ZUMA-12 presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, which was held virtually.

While axi-cel is approved for treatment of certain relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphomas (LBCLs), Dr. Neelapu said this is the first-ever study evaluating a CAR T-cell therapy as a first-line treatment for patients with LBCL that is high risk as defined by histology or International Prognostic Index (IPI) scoring.

Treatment with axi-cel was guided by dynamic risk assessment, Dr. Neelapu explained, meaning that patients received the CAR T-cell treatment if they had a positive interim positron emission tomography (PET) scan after two cycles of an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and anthracycline-containing regimen.

Longer follow-up needed

The interim efficacy analysis is based on 27 evaluable patients out of 40 patients planned to be enrolled, meaning that the final analysis is needed, and longer follow-up is needed to ensure that durability is maintained, Dr. Neelapu said in a question-and-answer session following his presentation.

Nevertheless, the 74% complete response rate in the frontline setting is “quite encouraging” compared to historical data in high-risk LBCL, where CR rates have generally been less than 50%, Dr. Neelapu added.

“Assuming that long-term data in the final analysis confirms this encouraging activity, I think we likely would need a randomized phase 3 trial to compare (axi-cel) head-to-head with frontline therapy,” he said.

Without mature data available, it’s hard to say in this single-arm study how much axi-cel is improving outcomes at the cost of significant toxicity, said Catherine M. Diefenbach, MD, director of the clinical lymphoma program at NYU Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York.

Adverse events as reported by Dr. Neelapu included grade 3 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in 9% of patients, and 25% grade 3 or greater neurologic events in 25%.

“It appears as though it may be salvaging some patients, as the response rate is higher than that expected for chemotherapy alone in this setting,” Dr. Diefenbach said in an interview, “but toxicity is not trivial, so the long-term data will provide better clarity as to the degree of benefit.”

Ongoing responses at 9 months

The phase 2 ZUMA-12 study includes patients classified as high risk based on MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 translocations, or by an International Prognostic Indicator score of 3 or greater.

Patients initially received two cycles of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy plus an anthracycline containing regimen. Those with a positive interim PET (score of 4 or 5 on the 5-point Deauville scale) received fludarabine/cyclophosphamide conditioning plus axi-cel as a single intravenous infusion of 2 x 106 CAR T cells per kg of body weight.

As of the report at the ASH meeting, 32 patient had received axi-cel, of whom 32 were evaluable for safety and 27 were evaluable for efficacy.

The ORR was 85% (23 of 27 patients), and the CR rate was 74% (20 of 27 patients), Dr. Neelapu reported, noting that with a median follow-up of 9.3 months, 70% of responders (19 of 27) were in ongoing response.

Median duration of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival have not been reached, he added.

Encephalopathy was the most common grade 3 or greater adverse event related to axi-cel, occurring in 16% of patients, while increased alanine aminotransferase and decreased neutrophil count were each seen in 9% of patients, Dr. Neelapu said.

All 32 patients experienced CRS, including grade 3 CRS in 3 patients (9%), according to the reported data. Neurologic events were seen in 22 patients (69%) including grade 3 or greater in 8 (25%). There were 2 grade 4 neurologic events – both encephalopathies that resolved, according to Dr. Neelapu – and no grade 5 neurologic events.

ZUMA-12 is sponsored by Kite, a Gilead Company. Dr. Neelapu reported disclosures related to Acerta, Adicet Bio, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Kite, and various other pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

SOURCE: Neelapu SS et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 405.

FROM ASH 2020

Highly effective in Ph-negative B-cell ALL: Hyper-CVAD with sequential blinatumomab

Hyper-CVAD (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) with sequential blinatumomab is highly effective as frontline therapy for Philadelphia Chromosome (Ph)–negative B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to results of a phase 2 study reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Favorable minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity and overall survival with low higher-grade toxicities suggest that reductions in chemotherapy in this setting are feasible, said Nicholas J. Short, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

While complete response rates with current ALL therapy are 80%-90%, long-term overall survival is only 40%-50%. Blinatumomab, a bispecific T-cell–engaging CD3-CD19 antibody, has been shown to be superior to chemotherapy in relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL, and to produce high rates of MRD eradication, the most important prognostic factor in ALL, Dr. Short said at the meeting, which was held virtually.

The hypothesis of the current study was that early incorporation of blinatumomab with hyper-CVAD in patients with newly diagnosed Ph-negative B-cell ALL would decrease the need for intensive chemotherapy and lead to higher efficacy and cure rates with less myelosuppression. Patients were required to have a performance status of 3 or less, total bilirubin 2 mg/dL or less and creatinine 2 mg/dL or less. Investigators enrolled 38 patients (mean age, 37 years,; range, 17-59) with most (79%) in performance status 0-1. The primary endpoint was relapse-free survival (RFS).

Study details

Patients received hyper-CVAD alternating with high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine for up to four cycles followed by four cycles of blinatumomab at standard doses. Those with CD20-positive disease (1% or greater percentage of the cells) received eight doses of ofatumumab or rituximab, and prophylactic intrathecal chemotherapy was given eight times in the first four cycles. Maintenance consisted of alternating blocks of POMP (6-mercaptopurine, vincristine, methotrexate, prednisone) and blinatumomab. When two patients with high-risk features experienced early relapse, investigators amended the protocol to allow blinatumomab after only two cycles of hyper-CVAD in those with high-risk features (e.g., CRLF2 positive by flow cytometry, complex karyotype, KMT2A rearranged, low hypodiploidy/near triploidy, TP53 mutation, or persistent MRD). Nineteen patients (56%) had at least one high-risk feature, and 82% received ofatumumab or rituximab. Six patients were in complete remission at the start of the study (four of them MRD negative).

Complete responses

After induction, complete responses were achieved in 81% (26/32), with all patients achieving a complete response at some point, according to Dr. Short. The MRD negativity rate was 71% (24/34) after induction and 97% (33/34) at any time. Among the 38 patients, all with complete response at median follow-up of 24 months (range, 2-45), relapses occurred only in those 5 patients with high-risk features. Twelve patients underwent transplant in the first remission. Two relapsed, both with high-risk features. The other 21 patients had ongoing complete responses.

RFS at 1- and 2-years was 80% and 71%, respectively. Five among seven relapses were without hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and 2 were post HSCT. Two deaths occurred in patients with complete responses (one pulmonary embolism and one with post-HSCT complications). Overall survival at 1 and 2 years was 85% and 80%, respectively, with the 2-year rate comparable with prior reports for hyper-CVAD plus ofatumumab, Dr. Short said.

The most common nonhematologic grade 3-4 adverse events with hyper-CVAD plus blinatumomab were ALT/AST elevation (24%) and hyperglycemia (21%). The overall cytokine release syndrome rate was 13%, with 3% for higher-grade reactions. The rate for blinatumomab-related neurologic events was 45% overall and 13% for higher grades, with 1 discontinuation attributed to grade 2 encephalopathy and dysphasia.

“Overall, this study shows the potential benefit of incorporating frontline blinatumomab into the treatment of younger adults with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome–negative B-cell lymphoma, and shows, as well, that reduction of chemotherapy in this context is feasible,” Dr. Short stated.

“Ultimately, often for any patients with acute leukemias and ALL, our only chance to cure them is in the frontline setting, so our approach is to include all of the most effective agents we have. So that means including blinatumomab in all of our frontline regimens in clinical trials – and now we’ve amended that to add inotuzumab ozogamicin with the goal of deepening responses and increasing cure rates,” he added.

Dr. Short reported consulting with Takeda Oncology and Astrazeneca, and receiving research funding and honoraria from Amgen, Astella, and Takeda Oncology.

SOURCE: Short NG et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 464.

Hyper-CVAD (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) with sequential blinatumomab is highly effective as frontline therapy for Philadelphia Chromosome (Ph)–negative B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to results of a phase 2 study reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Favorable minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity and overall survival with low higher-grade toxicities suggest that reductions in chemotherapy in this setting are feasible, said Nicholas J. Short, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

While complete response rates with current ALL therapy are 80%-90%, long-term overall survival is only 40%-50%. Blinatumomab, a bispecific T-cell–engaging CD3-CD19 antibody, has been shown to be superior to chemotherapy in relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL, and to produce high rates of MRD eradication, the most important prognostic factor in ALL, Dr. Short said at the meeting, which was held virtually.

The hypothesis of the current study was that early incorporation of blinatumomab with hyper-CVAD in patients with newly diagnosed Ph-negative B-cell ALL would decrease the need for intensive chemotherapy and lead to higher efficacy and cure rates with less myelosuppression. Patients were required to have a performance status of 3 or less, total bilirubin 2 mg/dL or less and creatinine 2 mg/dL or less. Investigators enrolled 38 patients (mean age, 37 years,; range, 17-59) with most (79%) in performance status 0-1. The primary endpoint was relapse-free survival (RFS).

Study details

Patients received hyper-CVAD alternating with high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine for up to four cycles followed by four cycles of blinatumomab at standard doses. Those with CD20-positive disease (1% or greater percentage of the cells) received eight doses of ofatumumab or rituximab, and prophylactic intrathecal chemotherapy was given eight times in the first four cycles. Maintenance consisted of alternating blocks of POMP (6-mercaptopurine, vincristine, methotrexate, prednisone) and blinatumomab. When two patients with high-risk features experienced early relapse, investigators amended the protocol to allow blinatumomab after only two cycles of hyper-CVAD in those with high-risk features (e.g., CRLF2 positive by flow cytometry, complex karyotype, KMT2A rearranged, low hypodiploidy/near triploidy, TP53 mutation, or persistent MRD). Nineteen patients (56%) had at least one high-risk feature, and 82% received ofatumumab or rituximab. Six patients were in complete remission at the start of the study (four of them MRD negative).

Complete responses

After induction, complete responses were achieved in 81% (26/32), with all patients achieving a complete response at some point, according to Dr. Short. The MRD negativity rate was 71% (24/34) after induction and 97% (33/34) at any time. Among the 38 patients, all with complete response at median follow-up of 24 months (range, 2-45), relapses occurred only in those 5 patients with high-risk features. Twelve patients underwent transplant in the first remission. Two relapsed, both with high-risk features. The other 21 patients had ongoing complete responses.

RFS at 1- and 2-years was 80% and 71%, respectively. Five among seven relapses were without hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and 2 were post HSCT. Two deaths occurred in patients with complete responses (one pulmonary embolism and one with post-HSCT complications). Overall survival at 1 and 2 years was 85% and 80%, respectively, with the 2-year rate comparable with prior reports for hyper-CVAD plus ofatumumab, Dr. Short said.

The most common nonhematologic grade 3-4 adverse events with hyper-CVAD plus blinatumomab were ALT/AST elevation (24%) and hyperglycemia (21%). The overall cytokine release syndrome rate was 13%, with 3% for higher-grade reactions. The rate for blinatumomab-related neurologic events was 45% overall and 13% for higher grades, with 1 discontinuation attributed to grade 2 encephalopathy and dysphasia.

“Overall, this study shows the potential benefit of incorporating frontline blinatumomab into the treatment of younger adults with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome–negative B-cell lymphoma, and shows, as well, that reduction of chemotherapy in this context is feasible,” Dr. Short stated.

“Ultimately, often for any patients with acute leukemias and ALL, our only chance to cure them is in the frontline setting, so our approach is to include all of the most effective agents we have. So that means including blinatumomab in all of our frontline regimens in clinical trials – and now we’ve amended that to add inotuzumab ozogamicin with the goal of deepening responses and increasing cure rates,” he added.

Dr. Short reported consulting with Takeda Oncology and Astrazeneca, and receiving research funding and honoraria from Amgen, Astella, and Takeda Oncology.

SOURCE: Short NG et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 464.

Hyper-CVAD (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) with sequential blinatumomab is highly effective as frontline therapy for Philadelphia Chromosome (Ph)–negative B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to results of a phase 2 study reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Favorable minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity and overall survival with low higher-grade toxicities suggest that reductions in chemotherapy in this setting are feasible, said Nicholas J. Short, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

While complete response rates with current ALL therapy are 80%-90%, long-term overall survival is only 40%-50%. Blinatumomab, a bispecific T-cell–engaging CD3-CD19 antibody, has been shown to be superior to chemotherapy in relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL, and to produce high rates of MRD eradication, the most important prognostic factor in ALL, Dr. Short said at the meeting, which was held virtually.

The hypothesis of the current study was that early incorporation of blinatumomab with hyper-CVAD in patients with newly diagnosed Ph-negative B-cell ALL would decrease the need for intensive chemotherapy and lead to higher efficacy and cure rates with less myelosuppression. Patients were required to have a performance status of 3 or less, total bilirubin 2 mg/dL or less and creatinine 2 mg/dL or less. Investigators enrolled 38 patients (mean age, 37 years,; range, 17-59) with most (79%) in performance status 0-1. The primary endpoint was relapse-free survival (RFS).

Study details

Patients received hyper-CVAD alternating with high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine for up to four cycles followed by four cycles of blinatumomab at standard doses. Those with CD20-positive disease (1% or greater percentage of the cells) received eight doses of ofatumumab or rituximab, and prophylactic intrathecal chemotherapy was given eight times in the first four cycles. Maintenance consisted of alternating blocks of POMP (6-mercaptopurine, vincristine, methotrexate, prednisone) and blinatumomab. When two patients with high-risk features experienced early relapse, investigators amended the protocol to allow blinatumomab after only two cycles of hyper-CVAD in those with high-risk features (e.g., CRLF2 positive by flow cytometry, complex karyotype, KMT2A rearranged, low hypodiploidy/near triploidy, TP53 mutation, or persistent MRD). Nineteen patients (56%) had at least one high-risk feature, and 82% received ofatumumab or rituximab. Six patients were in complete remission at the start of the study (four of them MRD negative).

Complete responses

After induction, complete responses were achieved in 81% (26/32), with all patients achieving a complete response at some point, according to Dr. Short. The MRD negativity rate was 71% (24/34) after induction and 97% (33/34) at any time. Among the 38 patients, all with complete response at median follow-up of 24 months (range, 2-45), relapses occurred only in those 5 patients with high-risk features. Twelve patients underwent transplant in the first remission. Two relapsed, both with high-risk features. The other 21 patients had ongoing complete responses.

RFS at 1- and 2-years was 80% and 71%, respectively. Five among seven relapses were without hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and 2 were post HSCT. Two deaths occurred in patients with complete responses (one pulmonary embolism and one with post-HSCT complications). Overall survival at 1 and 2 years was 85% and 80%, respectively, with the 2-year rate comparable with prior reports for hyper-CVAD plus ofatumumab, Dr. Short said.

The most common nonhematologic grade 3-4 adverse events with hyper-CVAD plus blinatumomab were ALT/AST elevation (24%) and hyperglycemia (21%). The overall cytokine release syndrome rate was 13%, with 3% for higher-grade reactions. The rate for blinatumomab-related neurologic events was 45% overall and 13% for higher grades, with 1 discontinuation attributed to grade 2 encephalopathy and dysphasia.

“Overall, this study shows the potential benefit of incorporating frontline blinatumomab into the treatment of younger adults with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome–negative B-cell lymphoma, and shows, as well, that reduction of chemotherapy in this context is feasible,” Dr. Short stated.

“Ultimately, often for any patients with acute leukemias and ALL, our only chance to cure them is in the frontline setting, so our approach is to include all of the most effective agents we have. So that means including blinatumomab in all of our frontline regimens in clinical trials – and now we’ve amended that to add inotuzumab ozogamicin with the goal of deepening responses and increasing cure rates,” he added.

Dr. Short reported consulting with Takeda Oncology and Astrazeneca, and receiving research funding and honoraria from Amgen, Astella, and Takeda Oncology.

SOURCE: Short NG et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 464.

FROM ASH 2020

IBD: Fecal calprotectin’s role in guiding treatment debated

Questions on fecal calprotectin’s usefulness as a measure of intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) dominated the viewer chat after the opening session of Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2020 Annual Meeting.

The measure is often used to differentiate irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) from IBD.

Panelists differed on how predictive fecal calprotectin is for disease status and what information the stool concentration of calprotectin imparts. Several experts discussed calprotectin cutoffs for when disease would be considered in remission or when a colonoscopy is needed for evaluation.

Bruce E. Sands, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said about the noninvasive test: “It can be very tricky to use.”

Variation by time of day, by person

He explained that there can be individual differences, and that the concentration may be different in the first stool of the day compared with the last.

“There’s a lot of variation, which makes the cutoffs good on average for populations but a little bit more difficult to apply to individuals,” he said.

Dr. Sands said the marker has more merit for people with large-bowel inflammation but is not quite as accurate a marker for patients with exclusively small-bowel inflammation.

Moderator Steven Hanauer, MD, professor of medicine, gastroenterology, and hepatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, asked Dr. Sands what his next move would be if a patient had a concentration of 160 mcg/mg.

Sands called concentrations between 150 and 250 mcg/mg “a gray zone.”

“That usually indicates for me a need to evaluate with a colonoscopy,” he said.

“If we’re talking about using fecal calprotectin to rule out IBS, the cutoff there is more like 50, 55. But that isn’t how we’re generally using it as IBD practitioners.”

Sunanda V. Kane, MD, MSPH, a gastroenterologist with the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview that 160 mcg/mg in a patient with IBD “means to me likely some minimal disease but not enough for me to make drastic changes to a medical regimen.”

She said about the measure, “We need to understand its limitations as well as strengths. Right now, insurance companies consider it ‘experimental’ and a lot of companies will not cover it. Ironically, they will cover the cost of a colonoscopy but not a stool test.”

Use as a benchmark

Dr. Sands said if he’s doing a colonoscopy to establish that the patient is in remission and knows what the fecal calprotectin level is at the time, he uses it as a benchmark for the future to judge whether the patient is deviating from remission.

He added that the negative predictive value of fecal calprotectin with a cutoff of 100 mcg/mg is “actually pretty good so you can avoid a number of unnecessary colonoscopies to look for recurrence.”

William J. Sandborn, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, said about the marker, “We use it some, but a cutoff of 50 is very specific. You can think of that as equivalent to a Mayo endoscopy score of 0 in ulcerative colitis and probably histologic remission.”

Cutoffs above 50 mcg/mg are “not very clear,” he said.

He said given the lack of consensus on the panel, “others might take some pause about that discomfort.”

Dr. Sandborn pointed out that little is known about elevated calprotectin in ulcerative proctitis and whether it is elevated in Crohn’s ileitis.

Dr. Kane said other factors will affect fecal calprotectin levels.

“We have some data to say that if you are on a proton pump inhibitor that that changes fecal calprotectin levels. Patients who have inflamed pseudopolyps may have quiescent disease around the pseudopolyps that may elevate the fecal calprotectin.”

But it can have particular benefit in some patient populations, she said.

She pointed to a study that concluded calprotectin levels can be used in pregnant ulcerative colitis patients to gauge disease activity noninvasively.

Dr. Sands, Dr. Sandborn, Dr. Kane, and Dr. Hanauer have disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Questions on fecal calprotectin’s usefulness as a measure of intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) dominated the viewer chat after the opening session of Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2020 Annual Meeting.

The measure is often used to differentiate irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) from IBD.

Panelists differed on how predictive fecal calprotectin is for disease status and what information the stool concentration of calprotectin imparts. Several experts discussed calprotectin cutoffs for when disease would be considered in remission or when a colonoscopy is needed for evaluation.

Bruce E. Sands, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said about the noninvasive test: “It can be very tricky to use.”

Variation by time of day, by person

He explained that there can be individual differences, and that the concentration may be different in the first stool of the day compared with the last.

“There’s a lot of variation, which makes the cutoffs good on average for populations but a little bit more difficult to apply to individuals,” he said.

Dr. Sands said the marker has more merit for people with large-bowel inflammation but is not quite as accurate a marker for patients with exclusively small-bowel inflammation.

Moderator Steven Hanauer, MD, professor of medicine, gastroenterology, and hepatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, asked Dr. Sands what his next move would be if a patient had a concentration of 160 mcg/mg.

Sands called concentrations between 150 and 250 mcg/mg “a gray zone.”

“That usually indicates for me a need to evaluate with a colonoscopy,” he said.

“If we’re talking about using fecal calprotectin to rule out IBS, the cutoff there is more like 50, 55. But that isn’t how we’re generally using it as IBD practitioners.”

Sunanda V. Kane, MD, MSPH, a gastroenterologist with the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview that 160 mcg/mg in a patient with IBD “means to me likely some minimal disease but not enough for me to make drastic changes to a medical regimen.”

She said about the measure, “We need to understand its limitations as well as strengths. Right now, insurance companies consider it ‘experimental’ and a lot of companies will not cover it. Ironically, they will cover the cost of a colonoscopy but not a stool test.”

Use as a benchmark

Dr. Sands said if he’s doing a colonoscopy to establish that the patient is in remission and knows what the fecal calprotectin level is at the time, he uses it as a benchmark for the future to judge whether the patient is deviating from remission.

He added that the negative predictive value of fecal calprotectin with a cutoff of 100 mcg/mg is “actually pretty good so you can avoid a number of unnecessary colonoscopies to look for recurrence.”

William J. Sandborn, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, said about the marker, “We use it some, but a cutoff of 50 is very specific. You can think of that as equivalent to a Mayo endoscopy score of 0 in ulcerative colitis and probably histologic remission.”

Cutoffs above 50 mcg/mg are “not very clear,” he said.

He said given the lack of consensus on the panel, “others might take some pause about that discomfort.”

Dr. Sandborn pointed out that little is known about elevated calprotectin in ulcerative proctitis and whether it is elevated in Crohn’s ileitis.

Dr. Kane said other factors will affect fecal calprotectin levels.

“We have some data to say that if you are on a proton pump inhibitor that that changes fecal calprotectin levels. Patients who have inflamed pseudopolyps may have quiescent disease around the pseudopolyps that may elevate the fecal calprotectin.”

But it can have particular benefit in some patient populations, she said.

She pointed to a study that concluded calprotectin levels can be used in pregnant ulcerative colitis patients to gauge disease activity noninvasively.

Dr. Sands, Dr. Sandborn, Dr. Kane, and Dr. Hanauer have disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Questions on fecal calprotectin’s usefulness as a measure of intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) dominated the viewer chat after the opening session of Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2020 Annual Meeting.

The measure is often used to differentiate irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) from IBD.

Panelists differed on how predictive fecal calprotectin is for disease status and what information the stool concentration of calprotectin imparts. Several experts discussed calprotectin cutoffs for when disease would be considered in remission or when a colonoscopy is needed for evaluation.

Bruce E. Sands, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said about the noninvasive test: “It can be very tricky to use.”

Variation by time of day, by person

He explained that there can be individual differences, and that the concentration may be different in the first stool of the day compared with the last.

“There’s a lot of variation, which makes the cutoffs good on average for populations but a little bit more difficult to apply to individuals,” he said.

Dr. Sands said the marker has more merit for people with large-bowel inflammation but is not quite as accurate a marker for patients with exclusively small-bowel inflammation.

Moderator Steven Hanauer, MD, professor of medicine, gastroenterology, and hepatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, asked Dr. Sands what his next move would be if a patient had a concentration of 160 mcg/mg.

Sands called concentrations between 150 and 250 mcg/mg “a gray zone.”

“That usually indicates for me a need to evaluate with a colonoscopy,” he said.

“If we’re talking about using fecal calprotectin to rule out IBS, the cutoff there is more like 50, 55. But that isn’t how we’re generally using it as IBD practitioners.”

Sunanda V. Kane, MD, MSPH, a gastroenterologist with the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview that 160 mcg/mg in a patient with IBD “means to me likely some minimal disease but not enough for me to make drastic changes to a medical regimen.”

She said about the measure, “We need to understand its limitations as well as strengths. Right now, insurance companies consider it ‘experimental’ and a lot of companies will not cover it. Ironically, they will cover the cost of a colonoscopy but not a stool test.”

Use as a benchmark

Dr. Sands said if he’s doing a colonoscopy to establish that the patient is in remission and knows what the fecal calprotectin level is at the time, he uses it as a benchmark for the future to judge whether the patient is deviating from remission.

He added that the negative predictive value of fecal calprotectin with a cutoff of 100 mcg/mg is “actually pretty good so you can avoid a number of unnecessary colonoscopies to look for recurrence.”

William J. Sandborn, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, said about the marker, “We use it some, but a cutoff of 50 is very specific. You can think of that as equivalent to a Mayo endoscopy score of 0 in ulcerative colitis and probably histologic remission.”

Cutoffs above 50 mcg/mg are “not very clear,” he said.

He said given the lack of consensus on the panel, “others might take some pause about that discomfort.”

Dr. Sandborn pointed out that little is known about elevated calprotectin in ulcerative proctitis and whether it is elevated in Crohn’s ileitis.

Dr. Kane said other factors will affect fecal calprotectin levels.

“We have some data to say that if you are on a proton pump inhibitor that that changes fecal calprotectin levels. Patients who have inflamed pseudopolyps may have quiescent disease around the pseudopolyps that may elevate the fecal calprotectin.”

But it can have particular benefit in some patient populations, she said.

She pointed to a study that concluded calprotectin levels can be used in pregnant ulcerative colitis patients to gauge disease activity noninvasively.

Dr. Sands, Dr. Sandborn, Dr. Kane, and Dr. Hanauer have disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

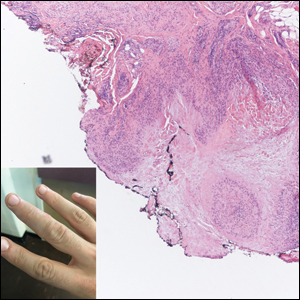

Multiple Nontender Subcutaneous Nodules on the Finger

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Granuloma Annulare

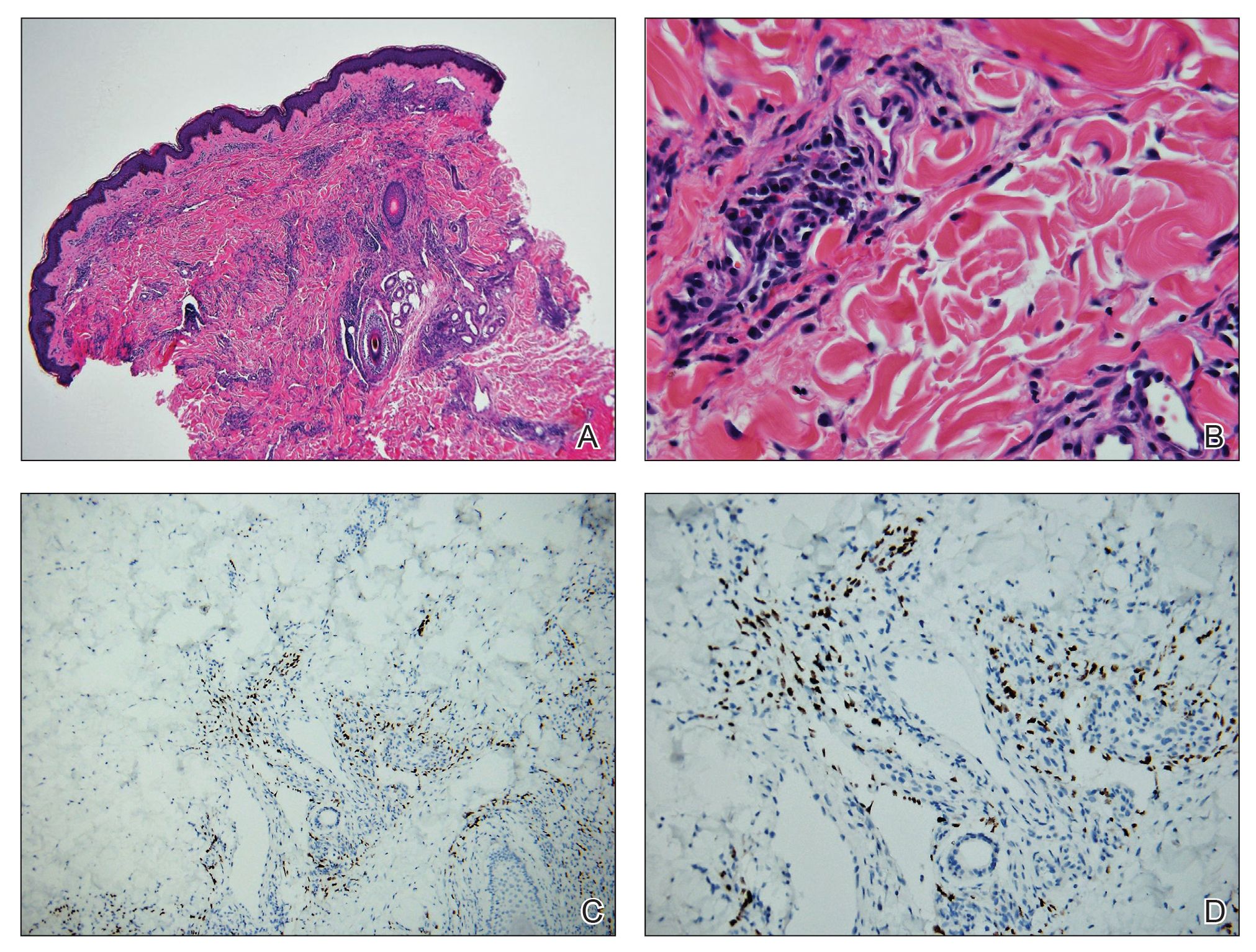

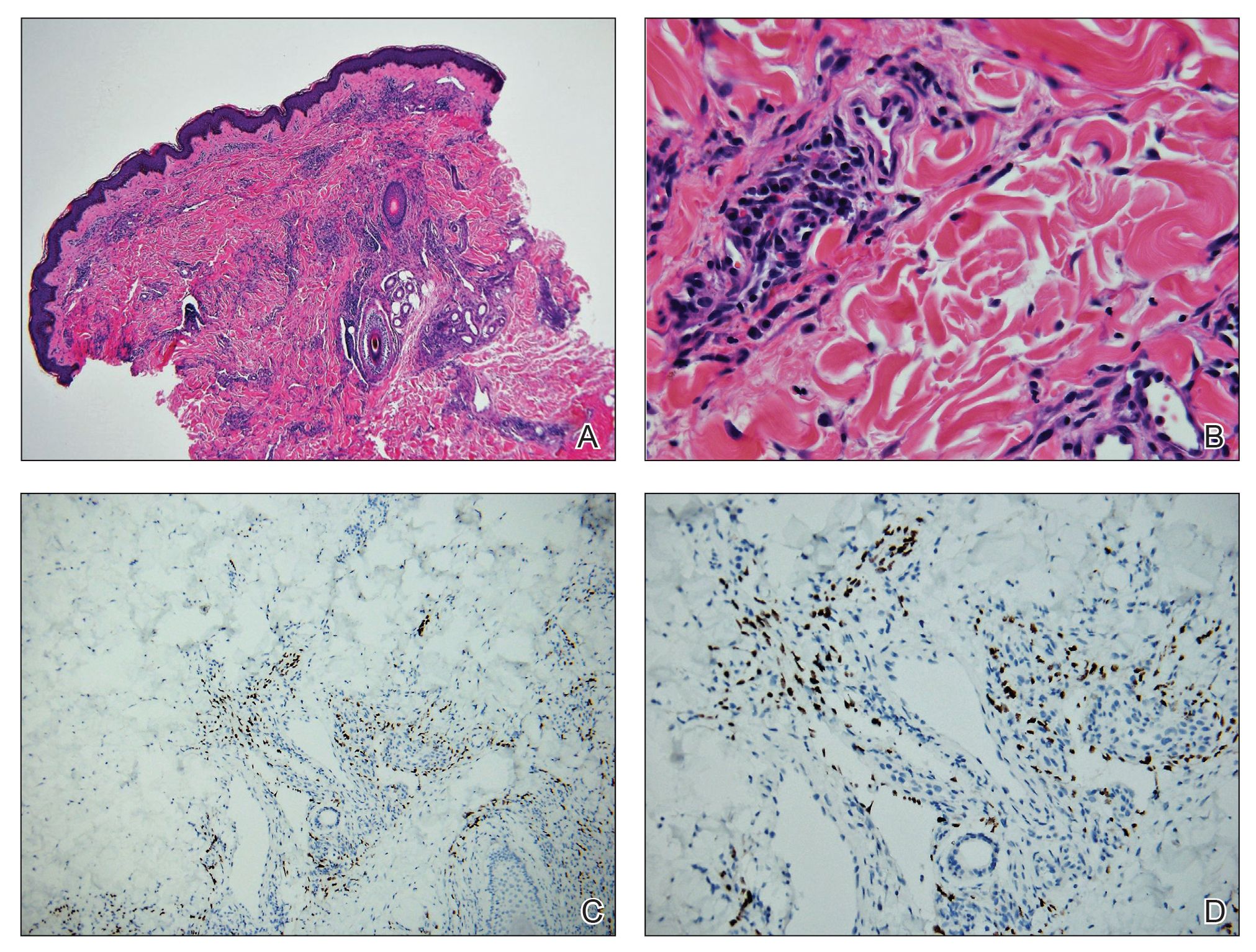

Subcutaneous granuloma annulare (SGA), also known as deep GA, is a rare variant of GA that usually occurs in children and young adults. It presents as single or multiple, nontender, deep dermal and/or subcutaneous nodules with normal-appearing skin usually on the anterior lower legs, dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers, scalp, or buttocks.1-3 The pathogenesis of SGA as well as GA is not fully understood, and proposed inciting factors include trauma, insect bite reactions, tuberculin skin testing, vaccines, UV exposure, medications, and viral infections.3-6 A cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an unknown antigen also has been postulated as a possible mechanism.7 Treatment usually is not necessary, as the nature of the condition is benign and the course often is self-limited. Spontaneous resolution occurs within 2 years in 50% of patients with localized GA.4,8 Surgery usually is not recommended due to the high recurrence rate (40%-75%).4,9

Absence of epidermal change in this entity obfuscates clinical recognition, and accurate diagnosis often depends on punch or excisional biopsies revealing characteristic histopathology. The histology of SGA consists of palisaded granulomas with central areas of necrobiosis composed of degenerated collagen, mucin deposition, and nuclear dust from neutrophils that extend into the deep dermis and subcutis.2 The periphery of the granulomas is lined by palisading epithelioid histiocytes with occasional multinucleated giant cells.10,11 Eosinophils often are present.12 Colloidal iron and Alcian blue stains can be used to highlight the abundant connective tissue mucin of the granulomas.4

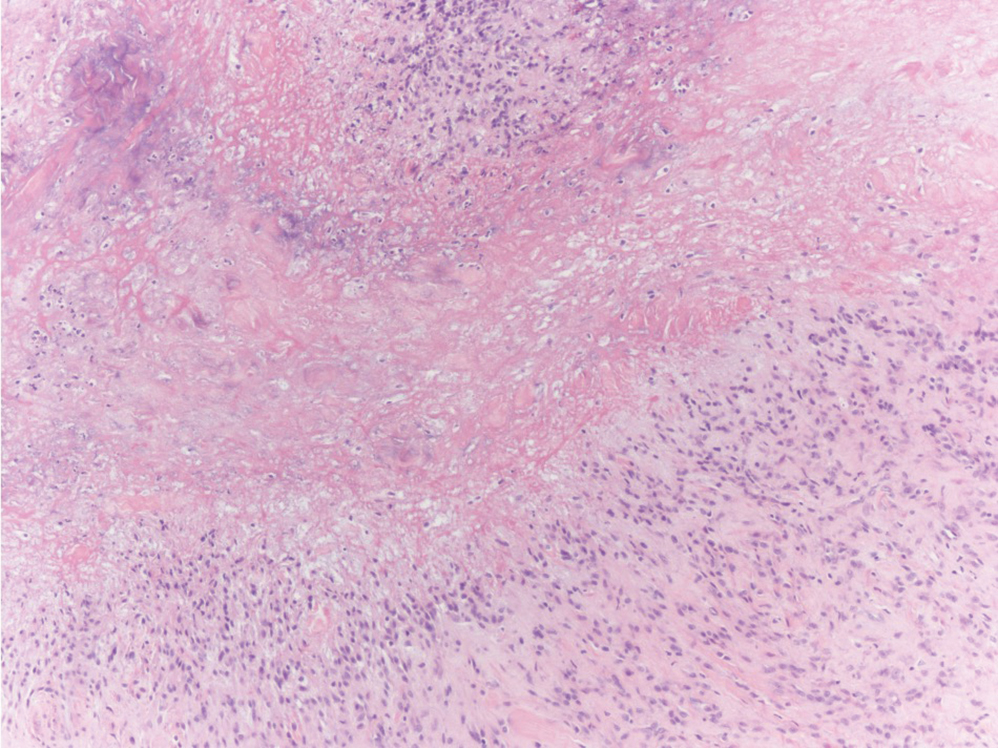

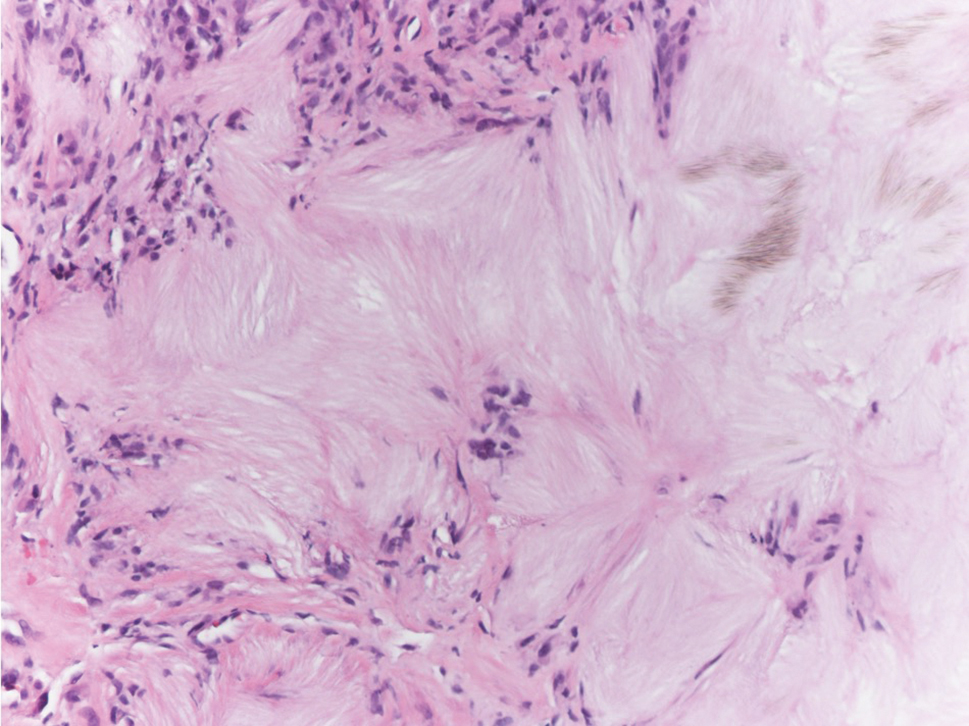

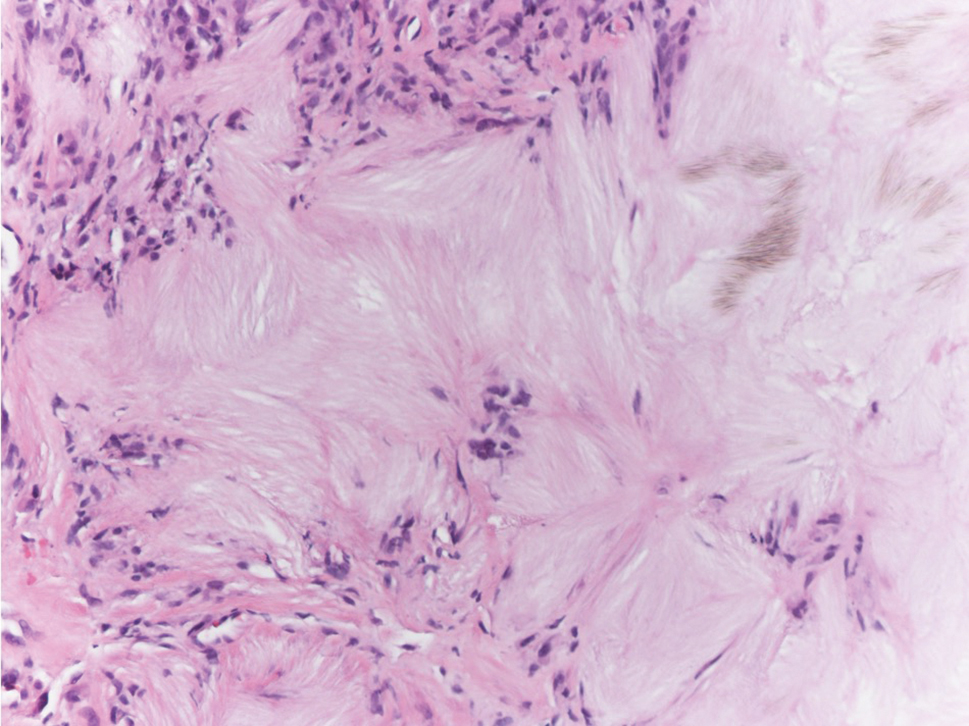

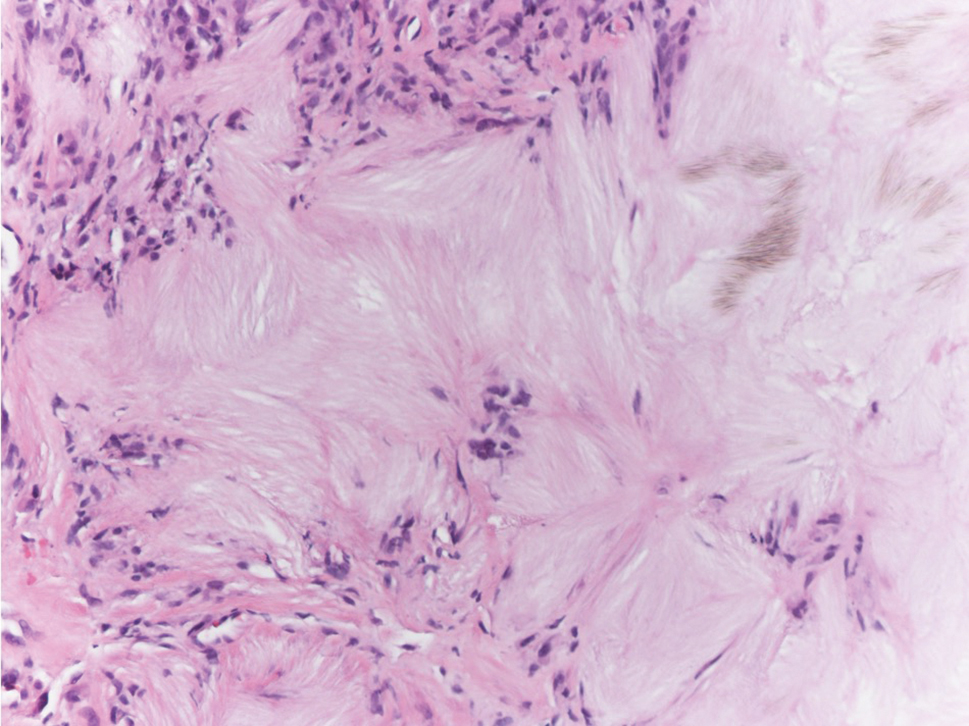

The histologic differential diagnosis of SGA includes rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, epithelioid sarcoma, and tophaceous gout.2 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common dermatologic presentation of rheumatoid arthritis and are found in up to 30% to 40% of patients with the disease.13-15 They present as firm, painless, subcutaneous papulonodules on the extensor surfaces and at sites of trauma or pressure. Histologically, rheumatoid nodules exhibit a homogenous and eosinophilic central area of necrobiosis with fibrin deposition and absent mucin deep within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). In contrast, granulomas in SGA usually are pale and basophilic with abundant mucin.2

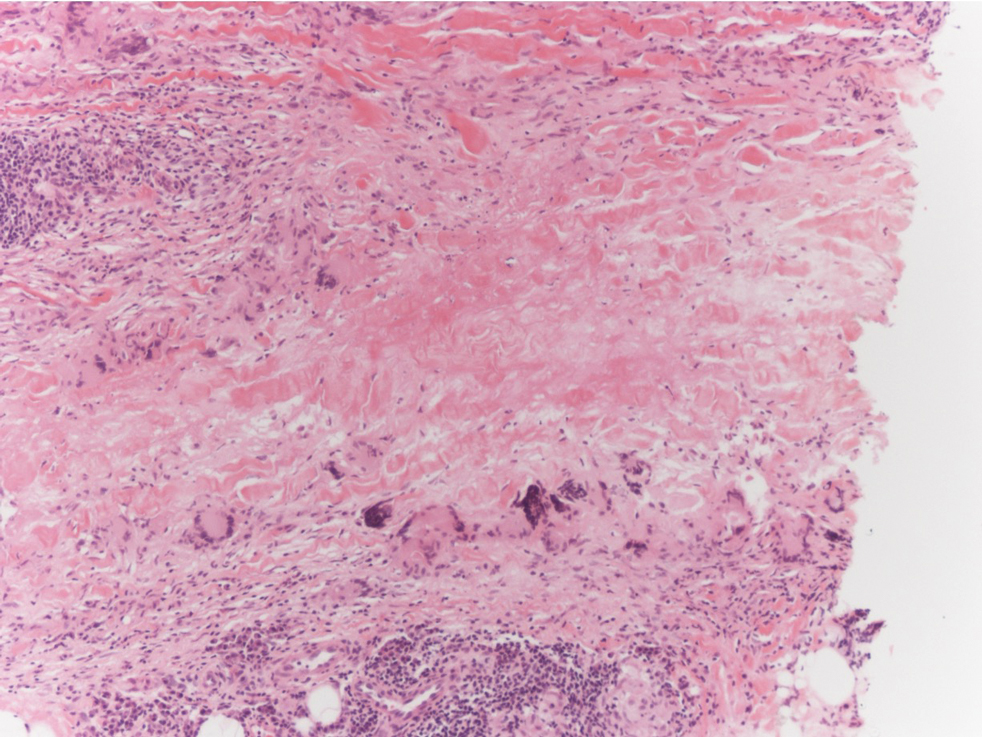

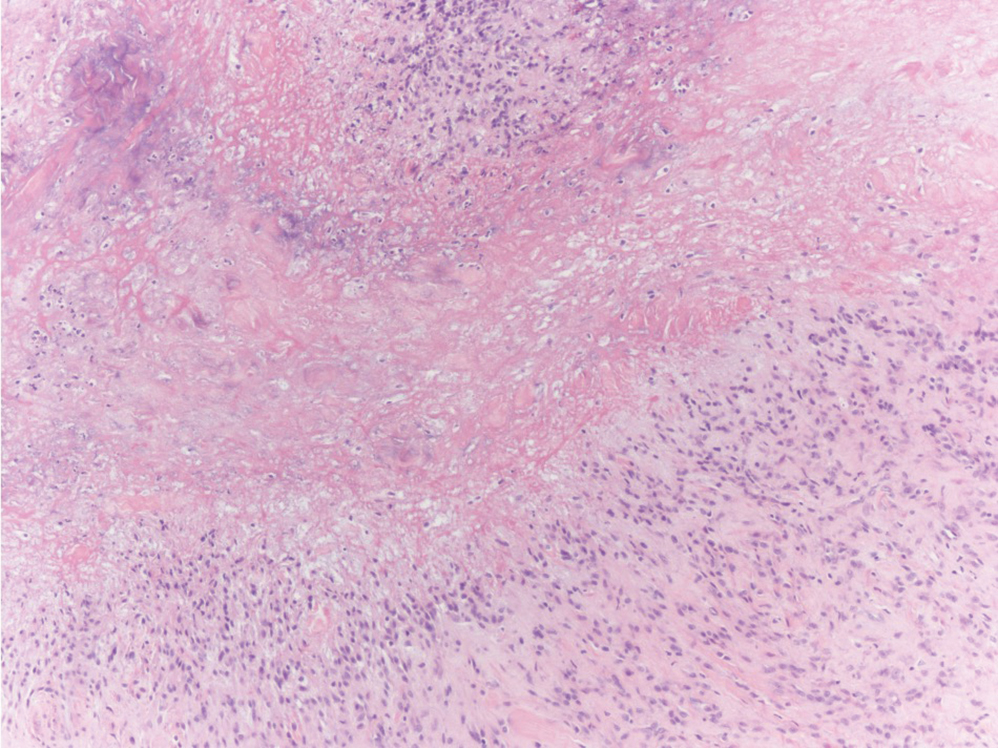

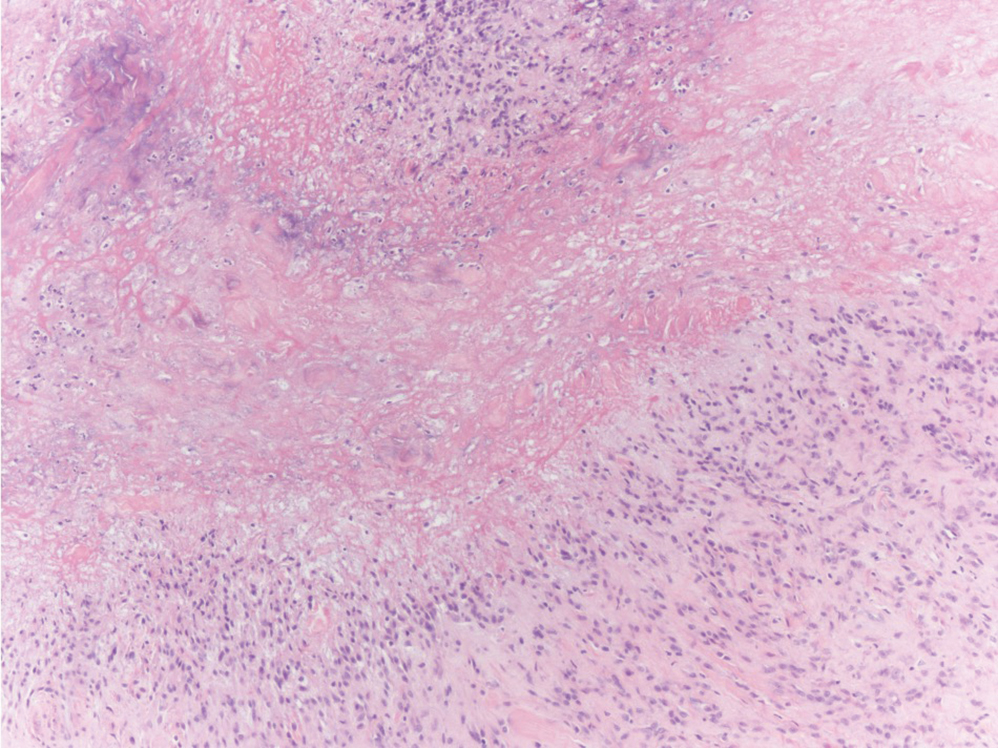

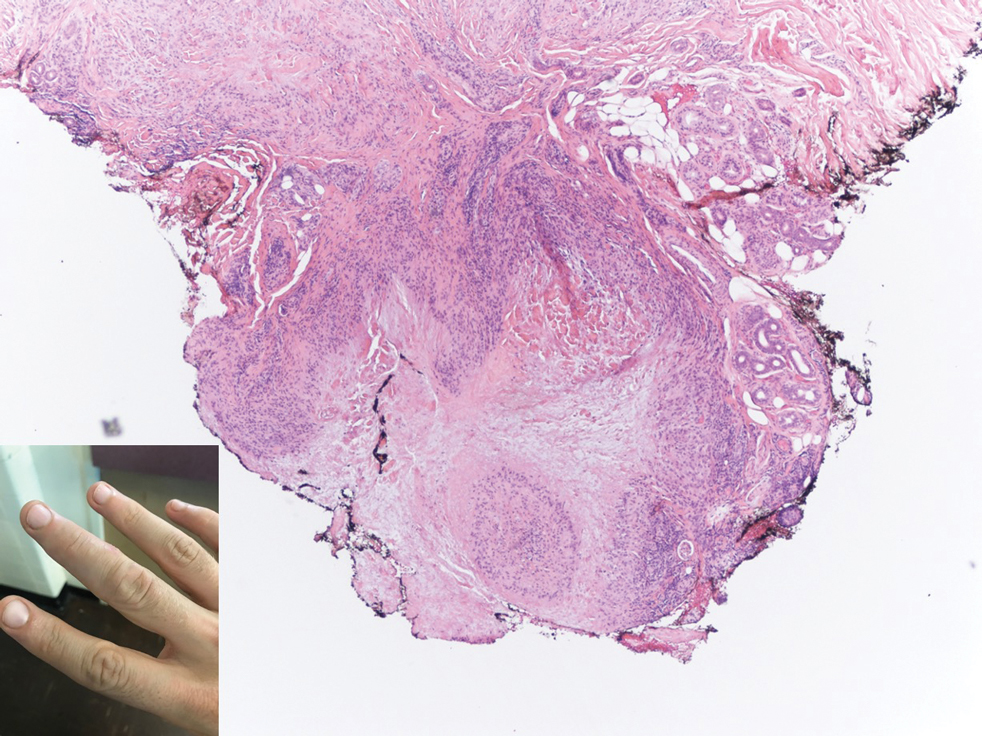

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease of the skin that most commonly occurs in young to middle-aged adults and is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus.16 It clinically presents as yellow to red-brown papules and plaques with a peripheral erythematous to violaceous rim usually on the pretibial area. Over time, lesions become yellowish atrophic patches and plaques that sometimes can ulcerate. Histopathology reveals areas of horizontally arranged, palisaded, and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis intermixed with areas of degenerated collagen and widespread fibrosis extending from the superficial dermis into the subcutis (Figure 2).2 These areas lack mucin and have an increased number of plasma cells. Eosinophils and/or lymphoid nodules occasionally can be seen.17,18

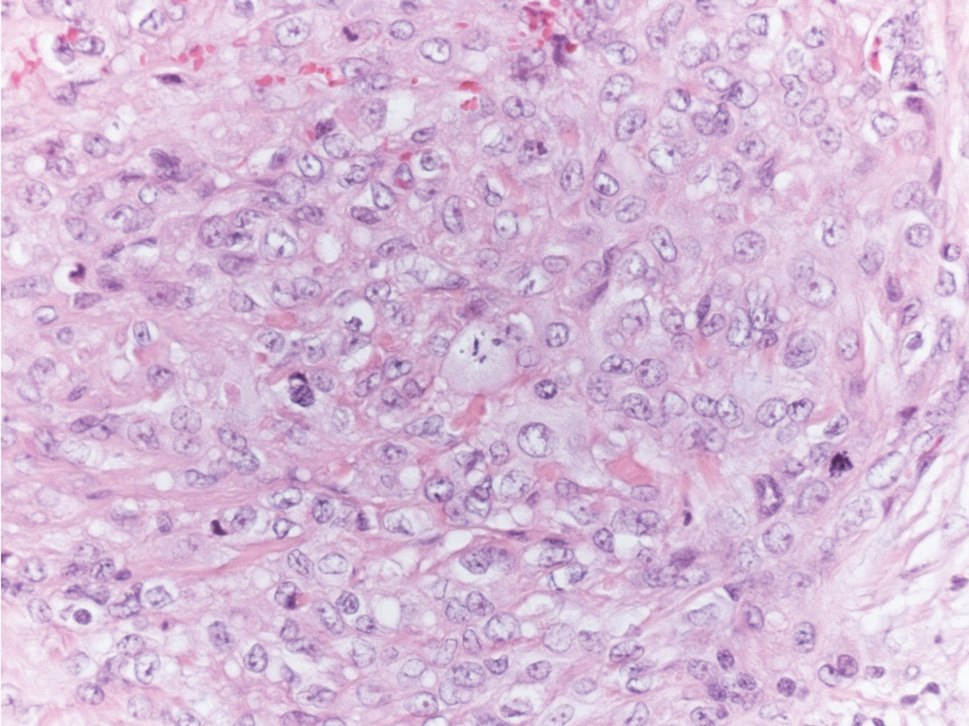

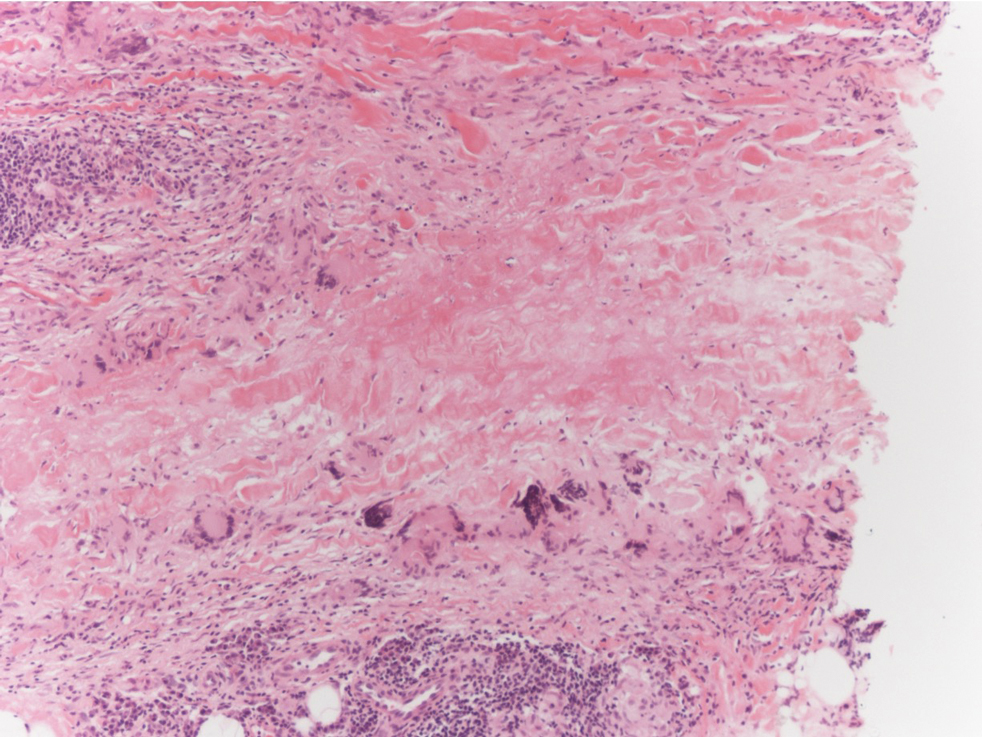

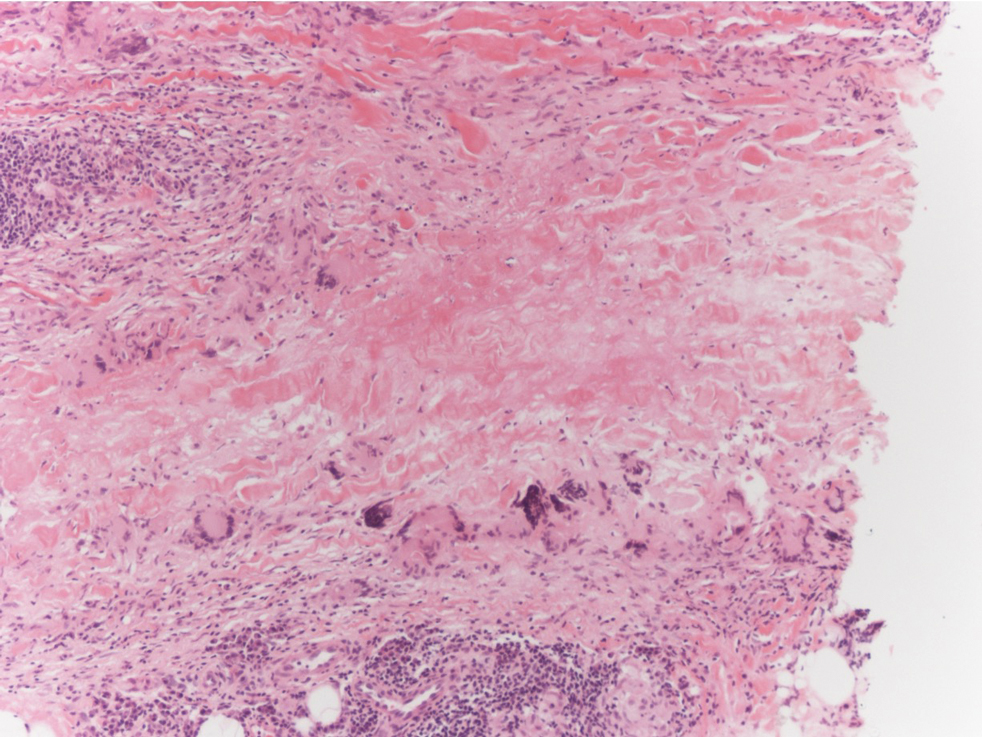

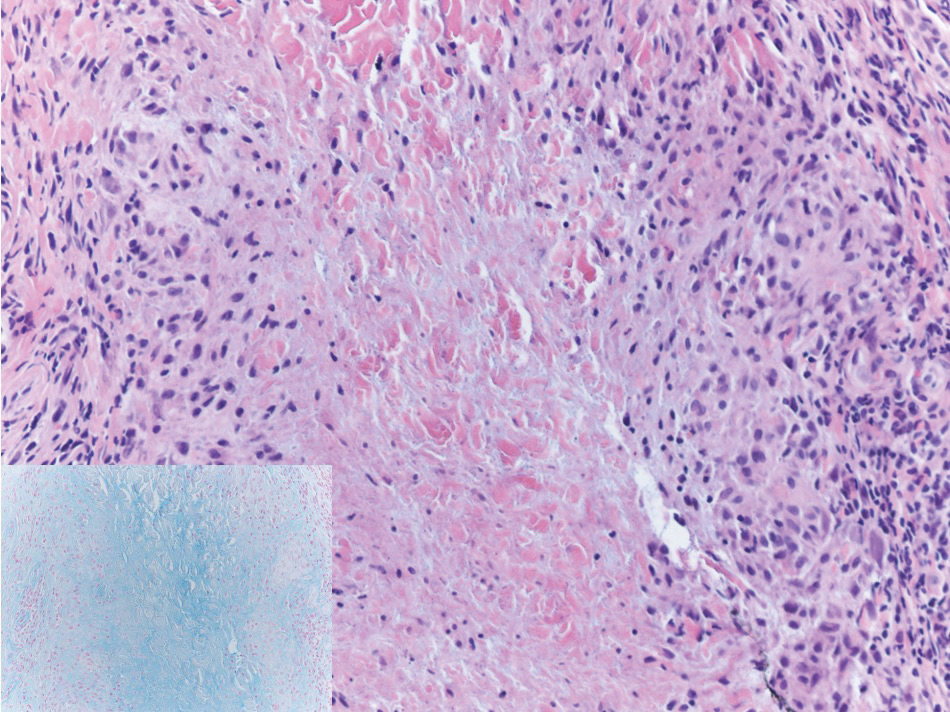

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare malignant soft tissue sarcoma that tends to occur on the distal extremities in younger patients, typically aged 20 to 40 years, often with preceding trauma to the area. It usually presents as a solitary, poorly defined, hard, subcutaneous nodule. Histologic analysis shows central areas of necrosis and degenerated collagen surrounded by epithelioid and spindle cells with hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei and mitoses (Figure 3).2 These tumor cells express positivity for keratins, vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, and CD34, while they usually are negative for desmin, S-100, and FLI-1 nuclear transcription factor.2,4,19

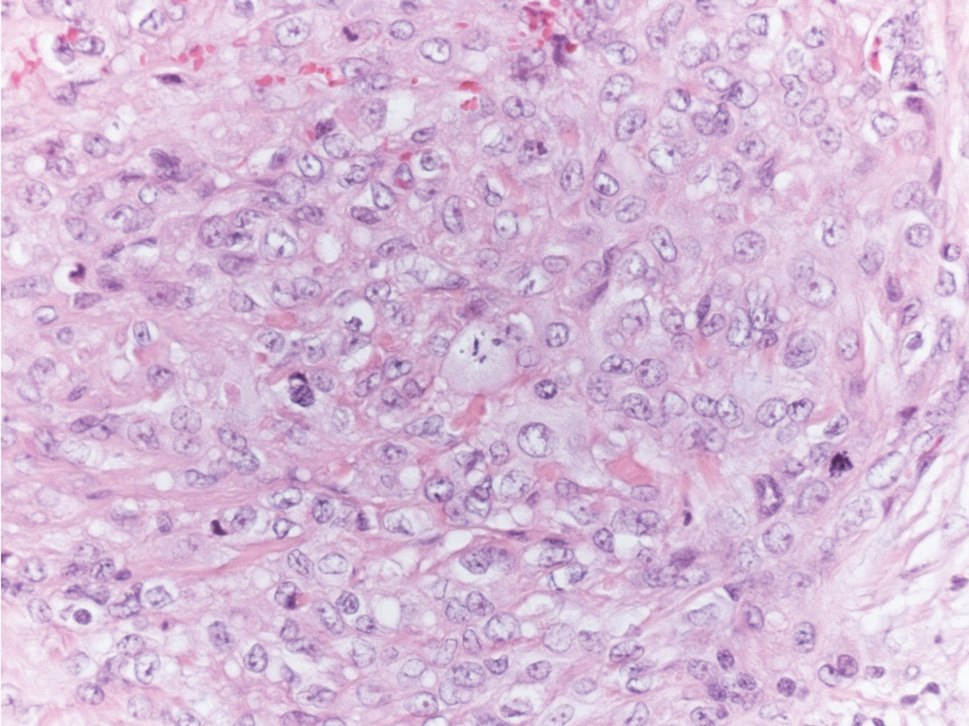

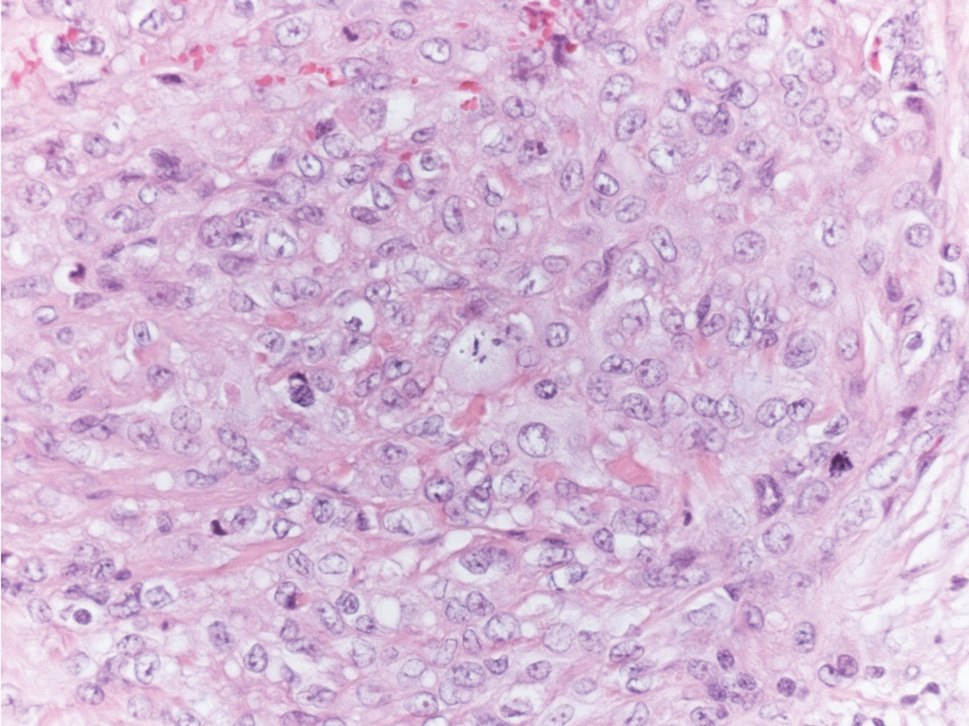

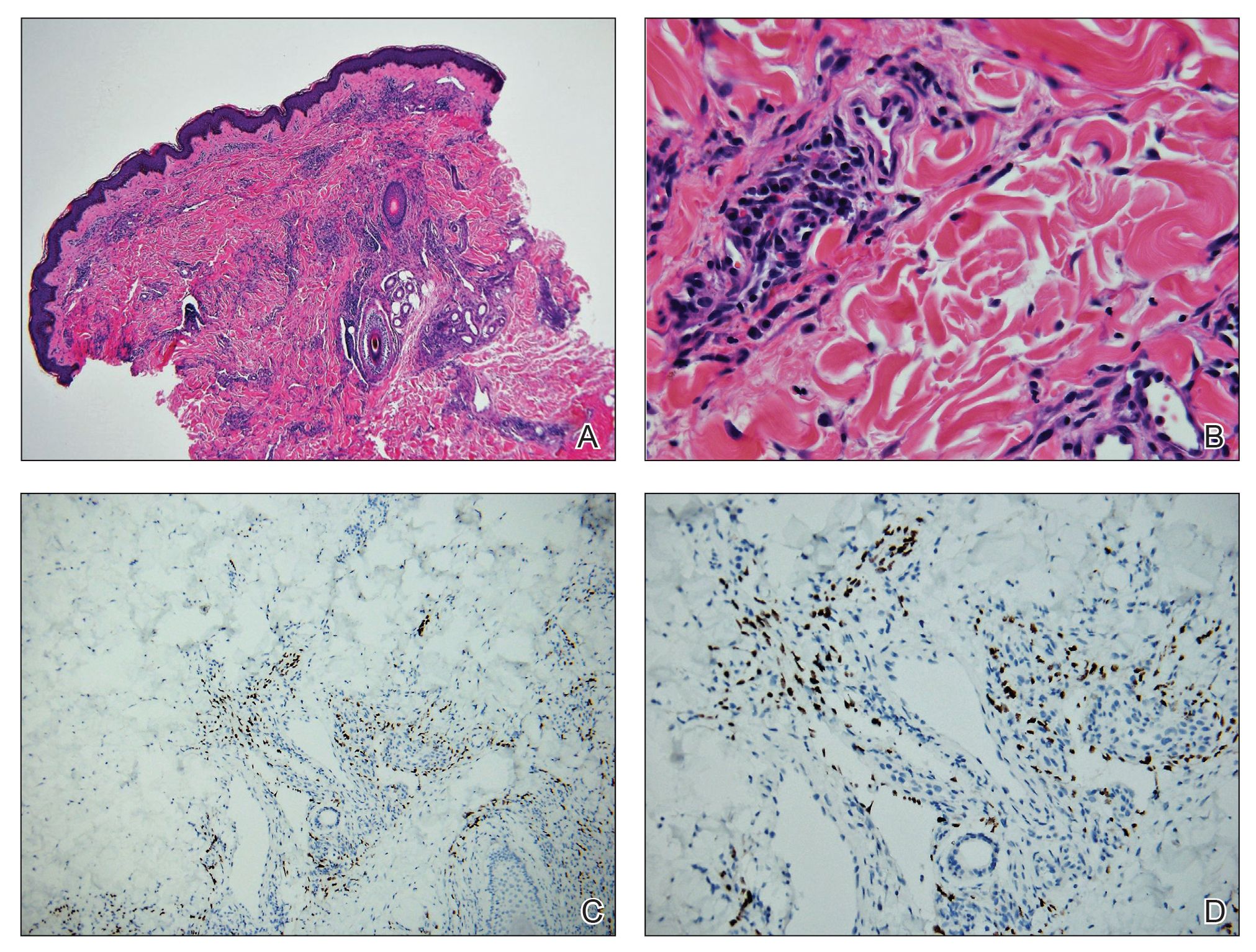

Tophaceous gout results from the accumulation of monosodium urate crystals in the skin. It clinically presents as firm, white-yellow, dermal and subcutaneous papulonodules on the helix of the ear and the skin overlying joints. Histopathology reveals palisaded granulomas surrounding an amorphous feathery material that corresponds to the urate crystals that were destroyed with formalin fixation (Figure 4). When the tissue is fixed with ethanol or is incompletely fixed in formalin, birefringent urate crystals are evident with polarization.20

- Felner EI, Steinberg JB, Weinberg AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a review of 47 cases. Pediatrics. 1997;100:965-967.

- Requena L, Fernández-Figueras MT. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:96-99.

- Taranu T, Grigorovici M, Constantin M, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:292-294.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare: a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199.

- Davids JR, Kolman BH, Billman GF, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: recognition and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:582-586.

- Evans MJ, Blessing K, Gray ES. Pseudorheumatoid nodule (deep granuloma annulare) of childhood: clinicopathologic features of twenty patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:6-9.

- Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

- Weedon D. Granuloma annulare. Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill-Livingstone; 1997:167-170.

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209.

- Highton J, Hessian PA, Stamp L. The rheumatoid nodule: peripheral or central to rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1385-1387.

- Turesson C, Jacobsson LT. Epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:65-72.

- Erfurt-Berge C, Dissemond J, Schwede K, et al. Updated results of 100 patients on clinical features and therapeutic options in necrobiosis lipoidica in a retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:595-601.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Alegre VA, Winkelmann RK. A new histopathologic feature of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: lymphoid nodules. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:75-77.

- Armah HB, Parwani AV. Epithelioid sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:814-819.

- Shidham V, Chivukula M, Basir Z, et al. Evaluation of crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections for the differential diagnosis pseudogout, gout, and tumoral calcinosis. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:806-810.

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Granuloma Annulare

Subcutaneous granuloma annulare (SGA), also known as deep GA, is a rare variant of GA that usually occurs in children and young adults. It presents as single or multiple, nontender, deep dermal and/or subcutaneous nodules with normal-appearing skin usually on the anterior lower legs, dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers, scalp, or buttocks.1-3 The pathogenesis of SGA as well as GA is not fully understood, and proposed inciting factors include trauma, insect bite reactions, tuberculin skin testing, vaccines, UV exposure, medications, and viral infections.3-6 A cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an unknown antigen also has been postulated as a possible mechanism.7 Treatment usually is not necessary, as the nature of the condition is benign and the course often is self-limited. Spontaneous resolution occurs within 2 years in 50% of patients with localized GA.4,8 Surgery usually is not recommended due to the high recurrence rate (40%-75%).4,9

Absence of epidermal change in this entity obfuscates clinical recognition, and accurate diagnosis often depends on punch or excisional biopsies revealing characteristic histopathology. The histology of SGA consists of palisaded granulomas with central areas of necrobiosis composed of degenerated collagen, mucin deposition, and nuclear dust from neutrophils that extend into the deep dermis and subcutis.2 The periphery of the granulomas is lined by palisading epithelioid histiocytes with occasional multinucleated giant cells.10,11 Eosinophils often are present.12 Colloidal iron and Alcian blue stains can be used to highlight the abundant connective tissue mucin of the granulomas.4

The histologic differential diagnosis of SGA includes rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, epithelioid sarcoma, and tophaceous gout.2 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common dermatologic presentation of rheumatoid arthritis and are found in up to 30% to 40% of patients with the disease.13-15 They present as firm, painless, subcutaneous papulonodules on the extensor surfaces and at sites of trauma or pressure. Histologically, rheumatoid nodules exhibit a homogenous and eosinophilic central area of necrobiosis with fibrin deposition and absent mucin deep within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). In contrast, granulomas in SGA usually are pale and basophilic with abundant mucin.2

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease of the skin that most commonly occurs in young to middle-aged adults and is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus.16 It clinically presents as yellow to red-brown papules and plaques with a peripheral erythematous to violaceous rim usually on the pretibial area. Over time, lesions become yellowish atrophic patches and plaques that sometimes can ulcerate. Histopathology reveals areas of horizontally arranged, palisaded, and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis intermixed with areas of degenerated collagen and widespread fibrosis extending from the superficial dermis into the subcutis (Figure 2).2 These areas lack mucin and have an increased number of plasma cells. Eosinophils and/or lymphoid nodules occasionally can be seen.17,18

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare malignant soft tissue sarcoma that tends to occur on the distal extremities in younger patients, typically aged 20 to 40 years, often with preceding trauma to the area. It usually presents as a solitary, poorly defined, hard, subcutaneous nodule. Histologic analysis shows central areas of necrosis and degenerated collagen surrounded by epithelioid and spindle cells with hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei and mitoses (Figure 3).2 These tumor cells express positivity for keratins, vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, and CD34, while they usually are negative for desmin, S-100, and FLI-1 nuclear transcription factor.2,4,19

Tophaceous gout results from the accumulation of monosodium urate crystals in the skin. It clinically presents as firm, white-yellow, dermal and subcutaneous papulonodules on the helix of the ear and the skin overlying joints. Histopathology reveals palisaded granulomas surrounding an amorphous feathery material that corresponds to the urate crystals that were destroyed with formalin fixation (Figure 4). When the tissue is fixed with ethanol or is incompletely fixed in formalin, birefringent urate crystals are evident with polarization.20

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Granuloma Annulare

Subcutaneous granuloma annulare (SGA), also known as deep GA, is a rare variant of GA that usually occurs in children and young adults. It presents as single or multiple, nontender, deep dermal and/or subcutaneous nodules with normal-appearing skin usually on the anterior lower legs, dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers, scalp, or buttocks.1-3 The pathogenesis of SGA as well as GA is not fully understood, and proposed inciting factors include trauma, insect bite reactions, tuberculin skin testing, vaccines, UV exposure, medications, and viral infections.3-6 A cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an unknown antigen also has been postulated as a possible mechanism.7 Treatment usually is not necessary, as the nature of the condition is benign and the course often is self-limited. Spontaneous resolution occurs within 2 years in 50% of patients with localized GA.4,8 Surgery usually is not recommended due to the high recurrence rate (40%-75%).4,9

Absence of epidermal change in this entity obfuscates clinical recognition, and accurate diagnosis often depends on punch or excisional biopsies revealing characteristic histopathology. The histology of SGA consists of palisaded granulomas with central areas of necrobiosis composed of degenerated collagen, mucin deposition, and nuclear dust from neutrophils that extend into the deep dermis and subcutis.2 The periphery of the granulomas is lined by palisading epithelioid histiocytes with occasional multinucleated giant cells.10,11 Eosinophils often are present.12 Colloidal iron and Alcian blue stains can be used to highlight the abundant connective tissue mucin of the granulomas.4

The histologic differential diagnosis of SGA includes rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, epithelioid sarcoma, and tophaceous gout.2 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common dermatologic presentation of rheumatoid arthritis and are found in up to 30% to 40% of patients with the disease.13-15 They present as firm, painless, subcutaneous papulonodules on the extensor surfaces and at sites of trauma or pressure. Histologically, rheumatoid nodules exhibit a homogenous and eosinophilic central area of necrobiosis with fibrin deposition and absent mucin deep within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). In contrast, granulomas in SGA usually are pale and basophilic with abundant mucin.2

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease of the skin that most commonly occurs in young to middle-aged adults and is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus.16 It clinically presents as yellow to red-brown papules and plaques with a peripheral erythematous to violaceous rim usually on the pretibial area. Over time, lesions become yellowish atrophic patches and plaques that sometimes can ulcerate. Histopathology reveals areas of horizontally arranged, palisaded, and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis intermixed with areas of degenerated collagen and widespread fibrosis extending from the superficial dermis into the subcutis (Figure 2).2 These areas lack mucin and have an increased number of plasma cells. Eosinophils and/or lymphoid nodules occasionally can be seen.17,18

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare malignant soft tissue sarcoma that tends to occur on the distal extremities in younger patients, typically aged 20 to 40 years, often with preceding trauma to the area. It usually presents as a solitary, poorly defined, hard, subcutaneous nodule. Histologic analysis shows central areas of necrosis and degenerated collagen surrounded by epithelioid and spindle cells with hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei and mitoses (Figure 3).2 These tumor cells express positivity for keratins, vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, and CD34, while they usually are negative for desmin, S-100, and FLI-1 nuclear transcription factor.2,4,19

Tophaceous gout results from the accumulation of monosodium urate crystals in the skin. It clinically presents as firm, white-yellow, dermal and subcutaneous papulonodules on the helix of the ear and the skin overlying joints. Histopathology reveals palisaded granulomas surrounding an amorphous feathery material that corresponds to the urate crystals that were destroyed with formalin fixation (Figure 4). When the tissue is fixed with ethanol or is incompletely fixed in formalin, birefringent urate crystals are evident with polarization.20

- Felner EI, Steinberg JB, Weinberg AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a review of 47 cases. Pediatrics. 1997;100:965-967.

- Requena L, Fernández-Figueras MT. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:96-99.

- Taranu T, Grigorovici M, Constantin M, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:292-294.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare: a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199.

- Davids JR, Kolman BH, Billman GF, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: recognition and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:582-586.

- Evans MJ, Blessing K, Gray ES. Pseudorheumatoid nodule (deep granuloma annulare) of childhood: clinicopathologic features of twenty patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:6-9.

- Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

- Weedon D. Granuloma annulare. Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill-Livingstone; 1997:167-170.

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209.

- Highton J, Hessian PA, Stamp L. The rheumatoid nodule: peripheral or central to rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1385-1387.

- Turesson C, Jacobsson LT. Epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:65-72.

- Erfurt-Berge C, Dissemond J, Schwede K, et al. Updated results of 100 patients on clinical features and therapeutic options in necrobiosis lipoidica in a retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:595-601.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Alegre VA, Winkelmann RK. A new histopathologic feature of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: lymphoid nodules. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:75-77.

- Armah HB, Parwani AV. Epithelioid sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:814-819.

- Shidham V, Chivukula M, Basir Z, et al. Evaluation of crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections for the differential diagnosis pseudogout, gout, and tumoral calcinosis. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:806-810.

- Felner EI, Steinberg JB, Weinberg AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a review of 47 cases. Pediatrics. 1997;100:965-967.

- Requena L, Fernández-Figueras MT. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:96-99.

- Taranu T, Grigorovici M, Constantin M, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:292-294.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare: a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199.

- Davids JR, Kolman BH, Billman GF, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: recognition and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:582-586.

- Evans MJ, Blessing K, Gray ES. Pseudorheumatoid nodule (deep granuloma annulare) of childhood: clinicopathologic features of twenty patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:6-9.

- Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

- Weedon D. Granuloma annulare. Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill-Livingstone; 1997:167-170.

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209.

- Highton J, Hessian PA, Stamp L. The rheumatoid nodule: peripheral or central to rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1385-1387.

- Turesson C, Jacobsson LT. Epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:65-72.

- Erfurt-Berge C, Dissemond J, Schwede K, et al. Updated results of 100 patients on clinical features and therapeutic options in necrobiosis lipoidica in a retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:595-601.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Alegre VA, Winkelmann RK. A new histopathologic feature of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: lymphoid nodules. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:75-77.

- Armah HB, Parwani AV. Epithelioid sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:814-819.

- Shidham V, Chivukula M, Basir Z, et al. Evaluation of crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections for the differential diagnosis pseudogout, gout, and tumoral calcinosis. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:806-810.

Getting to secure text messaging in health care

Health care teams are searching for solutions

Hospitalists and health care teams struggle with issues related to text messaging in the workplace. “It’s happening whether an institution has a secure text messaging platform or not,” said Philip Hagedorn, MD, MBI, associate chief medical information officer at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

“Many places reacted to this reality by procuring a solution – take your pick of secure text messaging platforms – and implementing it, but bypassed an opportunity to think about how we tailor the use of this culturally ubiquitous medium to the health care setting,” he said.It doesn’t work to just drop a secure text messaging platform into clinical systems and expect that health care practitioners will know how to use them appropriately, Dr. Hagedorn says. “The way we use text messaging in our lives outside health care inevitably bleeds into how we use the medium at work, but it shouldn’t. The needs are different and the stakes are higher for communication in the health care setting.”

In a paper looking at the issue, Dr. Hagedorn and co-authors laid out critical areas of concern, such as text messaging becoming a form of alarm fatigue and also increasing the likelihood of communication error.

“It’s my hope that fellow hospitalists can use this as an opportunity to think deeply about how we communicate in health care,” he said. “If we don’t think critically about how and where something like text messaging should be used in medicine, we risk facing unintended consequences for our patients.”The article discusses several steps for mitigating the risks laid out, including proactive surveillance and targeted training. “These are starting points, and I’m sure there are plenty of other creative solutions out there. We wanted to get the conversation going. We’d love to hear from others who face similar issues or have come up with interesting solutions.”

Reference

1. Hagedorn PA, et al. Secure Text Messaging in Healthcare: Latent Threats and Opportunities to Improve Patient Safety. J Hosp Med. 2020 June;15(6):378-380. Published Online First 2019 Sept 18. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3305

Health care teams are searching for solutions

Health care teams are searching for solutions

Hospitalists and health care teams struggle with issues related to text messaging in the workplace. “It’s happening whether an institution has a secure text messaging platform or not,” said Philip Hagedorn, MD, MBI, associate chief medical information officer at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

“Many places reacted to this reality by procuring a solution – take your pick of secure text messaging platforms – and implementing it, but bypassed an opportunity to think about how we tailor the use of this culturally ubiquitous medium to the health care setting,” he said.It doesn’t work to just drop a secure text messaging platform into clinical systems and expect that health care practitioners will know how to use them appropriately, Dr. Hagedorn says. “The way we use text messaging in our lives outside health care inevitably bleeds into how we use the medium at work, but it shouldn’t. The needs are different and the stakes are higher for communication in the health care setting.”

In a paper looking at the issue, Dr. Hagedorn and co-authors laid out critical areas of concern, such as text messaging becoming a form of alarm fatigue and also increasing the likelihood of communication error.

“It’s my hope that fellow hospitalists can use this as an opportunity to think deeply about how we communicate in health care,” he said. “If we don’t think critically about how and where something like text messaging should be used in medicine, we risk facing unintended consequences for our patients.”The article discusses several steps for mitigating the risks laid out, including proactive surveillance and targeted training. “These are starting points, and I’m sure there are plenty of other creative solutions out there. We wanted to get the conversation going. We’d love to hear from others who face similar issues or have come up with interesting solutions.”

Reference

1. Hagedorn PA, et al. Secure Text Messaging in Healthcare: Latent Threats and Opportunities to Improve Patient Safety. J Hosp Med. 2020 June;15(6):378-380. Published Online First 2019 Sept 18. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3305

Hospitalists and health care teams struggle with issues related to text messaging in the workplace. “It’s happening whether an institution has a secure text messaging platform or not,” said Philip Hagedorn, MD, MBI, associate chief medical information officer at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

“Many places reacted to this reality by procuring a solution – take your pick of secure text messaging platforms – and implementing it, but bypassed an opportunity to think about how we tailor the use of this culturally ubiquitous medium to the health care setting,” he said.It doesn’t work to just drop a secure text messaging platform into clinical systems and expect that health care practitioners will know how to use them appropriately, Dr. Hagedorn says. “The way we use text messaging in our lives outside health care inevitably bleeds into how we use the medium at work, but it shouldn’t. The needs are different and the stakes are higher for communication in the health care setting.”

In a paper looking at the issue, Dr. Hagedorn and co-authors laid out critical areas of concern, such as text messaging becoming a form of alarm fatigue and also increasing the likelihood of communication error.

“It’s my hope that fellow hospitalists can use this as an opportunity to think deeply about how we communicate in health care,” he said. “If we don’t think critically about how and where something like text messaging should be used in medicine, we risk facing unintended consequences for our patients.”The article discusses several steps for mitigating the risks laid out, including proactive surveillance and targeted training. “These are starting points, and I’m sure there are plenty of other creative solutions out there. We wanted to get the conversation going. We’d love to hear from others who face similar issues or have come up with interesting solutions.”

Reference

1. Hagedorn PA, et al. Secure Text Messaging in Healthcare: Latent Threats and Opportunities to Improve Patient Safety. J Hosp Med. 2020 June;15(6):378-380. Published Online First 2019 Sept 18. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3305

Just under three million will get COVID-19 vaccine in first week

The federal government says it will distribute only enough doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine to immunize 2.9 million Americans in the first week after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorizes it, far less than the initially discussed 6.4 million doses.

Theoretically, states have already formulated plans for distribution based on the revised lower amount. But in a briefing with reporters on December 9, officials from Operation Warp Speed and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) didn’t make clear exactly what the states were expecting.

Vaccine will be shipped to and allocated by 64 jurisdictions and five federal agencies — the Bureau of Prisons, the Department of Defense, the Department of State, the Indian Health Service, and the Veterans Health Administration — according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 Vaccination Program Interim Playbook.

It will be up to states — which will receive a supply prorated to population — and these agencies to determine how to prioritize distribution of the 2.9 million doses. Each state and agency has its own plan. Gen. Gustave Perna, the chief operating officer for Operation Warp Speed, said in the briefing that 30 states have told the federal government they will prioritize initial doses for residents and staff of long-term care facilities.

The distribution is contingent on FDA authorization, which could happen soon. The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biologics Advisory Committee weighed the effectiveness data for the Pfizer vaccine on December 10 and recommended that the agency grant emergency authorization. The FDA could issue a decision at any time.

Fewer doses out of the gate

Perna said the federal government will begin shipping the Pfizer vaccine within 24 hours of an FDA authorization.

He said those shipments will include a total of 2.9 million doses — not the 6.4 million that will be available. The government is holding 500,000 doses in reserve and another 2.9 million to guarantee that the first few million people who are vaccinated will be able to receive a second dose 21 days later, said Perna.

In part, that is because the FDA labeling will require that a first dose be followed by a second exactly 21 days later, said HHS Secretary Alex Azar in the briefing.

Federal officials have calculated how much to hold back on the basis of Pfizer’s production, said Azar. At least initially, “we will not distribute a vaccine knowing that the booster will not be available either from reserve supply by us or ongoing expected predicted production,” he said.

Even with Pfizer having reduced its estimates of how much vaccine it can deliver in December, Azar said, “There will be enough vaccine available for 20 million first vaccinations in the month of December.”

That estimate is predicated, however, on the idea that a vaccine under development by Moderna will receive clearance shortly after the FDA assesses that vaccine’s safety and effectiveness on December 17.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The federal government says it will distribute only enough doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine to immunize 2.9 million Americans in the first week after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorizes it, far less than the initially discussed 6.4 million doses.

Theoretically, states have already formulated plans for distribution based on the revised lower amount. But in a briefing with reporters on December 9, officials from Operation Warp Speed and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) didn’t make clear exactly what the states were expecting.

Vaccine will be shipped to and allocated by 64 jurisdictions and five federal agencies — the Bureau of Prisons, the Department of Defense, the Department of State, the Indian Health Service, and the Veterans Health Administration — according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 Vaccination Program Interim Playbook.

It will be up to states — which will receive a supply prorated to population — and these agencies to determine how to prioritize distribution of the 2.9 million doses. Each state and agency has its own plan. Gen. Gustave Perna, the chief operating officer for Operation Warp Speed, said in the briefing that 30 states have told the federal government they will prioritize initial doses for residents and staff of long-term care facilities.

The distribution is contingent on FDA authorization, which could happen soon. The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biologics Advisory Committee weighed the effectiveness data for the Pfizer vaccine on December 10 and recommended that the agency grant emergency authorization. The FDA could issue a decision at any time.

Fewer doses out of the gate

Perna said the federal government will begin shipping the Pfizer vaccine within 24 hours of an FDA authorization.

He said those shipments will include a total of 2.9 million doses — not the 6.4 million that will be available. The government is holding 500,000 doses in reserve and another 2.9 million to guarantee that the first few million people who are vaccinated will be able to receive a second dose 21 days later, said Perna.

In part, that is because the FDA labeling will require that a first dose be followed by a second exactly 21 days later, said HHS Secretary Alex Azar in the briefing.

Federal officials have calculated how much to hold back on the basis of Pfizer’s production, said Azar. At least initially, “we will not distribute a vaccine knowing that the booster will not be available either from reserve supply by us or ongoing expected predicted production,” he said.

Even with Pfizer having reduced its estimates of how much vaccine it can deliver in December, Azar said, “There will be enough vaccine available for 20 million first vaccinations in the month of December.”

That estimate is predicated, however, on the idea that a vaccine under development by Moderna will receive clearance shortly after the FDA assesses that vaccine’s safety and effectiveness on December 17.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The federal government says it will distribute only enough doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine to immunize 2.9 million Americans in the first week after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorizes it, far less than the initially discussed 6.4 million doses.

Theoretically, states have already formulated plans for distribution based on the revised lower amount. But in a briefing with reporters on December 9, officials from Operation Warp Speed and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) didn’t make clear exactly what the states were expecting.

Vaccine will be shipped to and allocated by 64 jurisdictions and five federal agencies — the Bureau of Prisons, the Department of Defense, the Department of State, the Indian Health Service, and the Veterans Health Administration — according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 Vaccination Program Interim Playbook.

It will be up to states — which will receive a supply prorated to population — and these agencies to determine how to prioritize distribution of the 2.9 million doses. Each state and agency has its own plan. Gen. Gustave Perna, the chief operating officer for Operation Warp Speed, said in the briefing that 30 states have told the federal government they will prioritize initial doses for residents and staff of long-term care facilities.

The distribution is contingent on FDA authorization, which could happen soon. The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biologics Advisory Committee weighed the effectiveness data for the Pfizer vaccine on December 10 and recommended that the agency grant emergency authorization. The FDA could issue a decision at any time.

Fewer doses out of the gate

Perna said the federal government will begin shipping the Pfizer vaccine within 24 hours of an FDA authorization.

He said those shipments will include a total of 2.9 million doses — not the 6.4 million that will be available. The government is holding 500,000 doses in reserve and another 2.9 million to guarantee that the first few million people who are vaccinated will be able to receive a second dose 21 days later, said Perna.

In part, that is because the FDA labeling will require that a first dose be followed by a second exactly 21 days later, said HHS Secretary Alex Azar in the briefing.