User login

P3SONG: Evaluation for autism spectrum disorder

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by impairments in communication and social interactions, along with repetitive and perseverant behaviors.1 It has a prevalence of 0.75% to 1.1% among the general population.1 The presentation of ASD can vary, and patients may have a wide range of comorbidities, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), neurologic disorders, and genetic disorders.1 Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation needs to include a multidisciplinary assessment by clinicians from several specialties, including primary care, psychiatry, psychology, and neurology. Here I offer psychiatrists 3 Ps and the mnemonic SONG to describe a multidisciplinary approach to assessing a patient with suspected or confirmed ASD.

Primary care evaluation of patients with ASD is important for the diagnosis and treatment of any co-existing medical conditions. Primary care physicians are often the source of referrals to psychiatry, although the reason for the referral may not always be suspicion of autism. In my clinical practice, almost all referrals from primary care involve a chief complaint of anger or behavioral problems, or even obsessive-compulsive behaviors.

Psychiatric evaluation should include obtaining a detailed history of the patient’s conception, birth, development, and social life, and his/her family history of genetic conditions. In my practice, ADHD and elimination disorders are common comorbidities in patients with ASD. Consider communicating with daycare staff or teachers and auxiliary staff, such as guidance counselors, because doing so can help elucidate the diagnosis. Also, ask adult family members, preferably a parent, for collateral information to help establish an accurate diagnosis in your adult patients.

Psychological evaluation should include testing to rule out intellectual disability and learning disorders, which are common in patients with ASD.2 Tests commonly used for evaluation of ASD include the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), and Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R).

Speech evaluation. Deficits in language and communication are commonly observed in patients with ASD, especially in younger patients.3 A study of the relationship between early language skills (age of first word production) and later functioning in children with ASD indicated that earlier age of first word acquisition was associated with higher cognitive ability and adaptive skills when measured later in childhood.3 Therefore, timely intervention following speech evaluation can result in favorable outcomes.

Occupational evaluation. Approximately 69% to 93% of children and adults with ASD exhibit sensory symptoms (hyperresponsive, hyporesponsive, and sensory-seeking behaviors).4 Patients with sensory symptoms often experience limitations in multiple areas of their life. Early intervention by an occupational therapist can help improve long-term outcomes.4

Neurologic evaluation is important because ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder. Patients with ASD often have comorbid seizure disorders.1 The estimated prevalence of epilepsy in these patients ranges from 2.7% to 44.4%.1 A baseline EEG and neuroimaging can help improve your understanding of the relationship between ASD and seizure disorders, and guide treatment.

Genetic testing. Between 10% to 15% of individuals with ASD have a medical condition, such as cytogenetic or single-gene disorder, that causes ASD.5 Fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, and Prader-Willi syndrome are a few common examples of genetic disorders associated with ASD.5 Autism spectrum disorder has also been known to have a strong genetic basis with high probability of heritability in families.5 Genetic testing can help to detect any underlying genetic disorders in your patients as well as their family members. Chromosomal microarray analysis has become more accessible due to improved insurance coverage, and is convenient to perform by collection of a buccal mucosa sample in the office setting.

1. Strasser L, Downes M, Kung J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for autism spectrum disorder in epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(1):19-29.

2. Schwatrz CE, Neri G. Autism and intellectual disability: two sides of the same coin. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet. 2012;160C(2):89-89.

3. Mayo J, Chlebowski C, Fein DA, et al. Age of first words predicts cognitive ability and adaptive skills in children with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(2):253-264.

4. McCormick C, Hepburn S, Young GS, et al. Sensory symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder, other developmental disorders and typical development: a longitudinal study. Autism. 2016;20(5):572-579.

5. Balasubramanian B, Bhatt CV, Goyel NA. Genetic studies in children with intellectual disability and autistic spectrum of disorders. Indian J Hum Genet. 2009;15(3):103-107.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by impairments in communication and social interactions, along with repetitive and perseverant behaviors.1 It has a prevalence of 0.75% to 1.1% among the general population.1 The presentation of ASD can vary, and patients may have a wide range of comorbidities, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), neurologic disorders, and genetic disorders.1 Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation needs to include a multidisciplinary assessment by clinicians from several specialties, including primary care, psychiatry, psychology, and neurology. Here I offer psychiatrists 3 Ps and the mnemonic SONG to describe a multidisciplinary approach to assessing a patient with suspected or confirmed ASD.

Primary care evaluation of patients with ASD is important for the diagnosis and treatment of any co-existing medical conditions. Primary care physicians are often the source of referrals to psychiatry, although the reason for the referral may not always be suspicion of autism. In my clinical practice, almost all referrals from primary care involve a chief complaint of anger or behavioral problems, or even obsessive-compulsive behaviors.

Psychiatric evaluation should include obtaining a detailed history of the patient’s conception, birth, development, and social life, and his/her family history of genetic conditions. In my practice, ADHD and elimination disorders are common comorbidities in patients with ASD. Consider communicating with daycare staff or teachers and auxiliary staff, such as guidance counselors, because doing so can help elucidate the diagnosis. Also, ask adult family members, preferably a parent, for collateral information to help establish an accurate diagnosis in your adult patients.

Psychological evaluation should include testing to rule out intellectual disability and learning disorders, which are common in patients with ASD.2 Tests commonly used for evaluation of ASD include the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), and Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R).

Speech evaluation. Deficits in language and communication are commonly observed in patients with ASD, especially in younger patients.3 A study of the relationship between early language skills (age of first word production) and later functioning in children with ASD indicated that earlier age of first word acquisition was associated with higher cognitive ability and adaptive skills when measured later in childhood.3 Therefore, timely intervention following speech evaluation can result in favorable outcomes.

Occupational evaluation. Approximately 69% to 93% of children and adults with ASD exhibit sensory symptoms (hyperresponsive, hyporesponsive, and sensory-seeking behaviors).4 Patients with sensory symptoms often experience limitations in multiple areas of their life. Early intervention by an occupational therapist can help improve long-term outcomes.4

Neurologic evaluation is important because ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder. Patients with ASD often have comorbid seizure disorders.1 The estimated prevalence of epilepsy in these patients ranges from 2.7% to 44.4%.1 A baseline EEG and neuroimaging can help improve your understanding of the relationship between ASD and seizure disorders, and guide treatment.

Genetic testing. Between 10% to 15% of individuals with ASD have a medical condition, such as cytogenetic or single-gene disorder, that causes ASD.5 Fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, and Prader-Willi syndrome are a few common examples of genetic disorders associated with ASD.5 Autism spectrum disorder has also been known to have a strong genetic basis with high probability of heritability in families.5 Genetic testing can help to detect any underlying genetic disorders in your patients as well as their family members. Chromosomal microarray analysis has become more accessible due to improved insurance coverage, and is convenient to perform by collection of a buccal mucosa sample in the office setting.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by impairments in communication and social interactions, along with repetitive and perseverant behaviors.1 It has a prevalence of 0.75% to 1.1% among the general population.1 The presentation of ASD can vary, and patients may have a wide range of comorbidities, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), neurologic disorders, and genetic disorders.1 Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation needs to include a multidisciplinary assessment by clinicians from several specialties, including primary care, psychiatry, psychology, and neurology. Here I offer psychiatrists 3 Ps and the mnemonic SONG to describe a multidisciplinary approach to assessing a patient with suspected or confirmed ASD.

Primary care evaluation of patients with ASD is important for the diagnosis and treatment of any co-existing medical conditions. Primary care physicians are often the source of referrals to psychiatry, although the reason for the referral may not always be suspicion of autism. In my clinical practice, almost all referrals from primary care involve a chief complaint of anger or behavioral problems, or even obsessive-compulsive behaviors.

Psychiatric evaluation should include obtaining a detailed history of the patient’s conception, birth, development, and social life, and his/her family history of genetic conditions. In my practice, ADHD and elimination disorders are common comorbidities in patients with ASD. Consider communicating with daycare staff or teachers and auxiliary staff, such as guidance counselors, because doing so can help elucidate the diagnosis. Also, ask adult family members, preferably a parent, for collateral information to help establish an accurate diagnosis in your adult patients.

Psychological evaluation should include testing to rule out intellectual disability and learning disorders, which are common in patients with ASD.2 Tests commonly used for evaluation of ASD include the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), and Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R).

Speech evaluation. Deficits in language and communication are commonly observed in patients with ASD, especially in younger patients.3 A study of the relationship between early language skills (age of first word production) and later functioning in children with ASD indicated that earlier age of first word acquisition was associated with higher cognitive ability and adaptive skills when measured later in childhood.3 Therefore, timely intervention following speech evaluation can result in favorable outcomes.

Occupational evaluation. Approximately 69% to 93% of children and adults with ASD exhibit sensory symptoms (hyperresponsive, hyporesponsive, and sensory-seeking behaviors).4 Patients with sensory symptoms often experience limitations in multiple areas of their life. Early intervention by an occupational therapist can help improve long-term outcomes.4

Neurologic evaluation is important because ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder. Patients with ASD often have comorbid seizure disorders.1 The estimated prevalence of epilepsy in these patients ranges from 2.7% to 44.4%.1 A baseline EEG and neuroimaging can help improve your understanding of the relationship between ASD and seizure disorders, and guide treatment.

Genetic testing. Between 10% to 15% of individuals with ASD have a medical condition, such as cytogenetic or single-gene disorder, that causes ASD.5 Fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, and Prader-Willi syndrome are a few common examples of genetic disorders associated with ASD.5 Autism spectrum disorder has also been known to have a strong genetic basis with high probability of heritability in families.5 Genetic testing can help to detect any underlying genetic disorders in your patients as well as their family members. Chromosomal microarray analysis has become more accessible due to improved insurance coverage, and is convenient to perform by collection of a buccal mucosa sample in the office setting.

1. Strasser L, Downes M, Kung J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for autism spectrum disorder in epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(1):19-29.

2. Schwatrz CE, Neri G. Autism and intellectual disability: two sides of the same coin. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet. 2012;160C(2):89-89.

3. Mayo J, Chlebowski C, Fein DA, et al. Age of first words predicts cognitive ability and adaptive skills in children with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(2):253-264.

4. McCormick C, Hepburn S, Young GS, et al. Sensory symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder, other developmental disorders and typical development: a longitudinal study. Autism. 2016;20(5):572-579.

5. Balasubramanian B, Bhatt CV, Goyel NA. Genetic studies in children with intellectual disability and autistic spectrum of disorders. Indian J Hum Genet. 2009;15(3):103-107.

1. Strasser L, Downes M, Kung J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for autism spectrum disorder in epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(1):19-29.

2. Schwatrz CE, Neri G. Autism and intellectual disability: two sides of the same coin. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet. 2012;160C(2):89-89.

3. Mayo J, Chlebowski C, Fein DA, et al. Age of first words predicts cognitive ability and adaptive skills in children with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(2):253-264.

4. McCormick C, Hepburn S, Young GS, et al. Sensory symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder, other developmental disorders and typical development: a longitudinal study. Autism. 2016;20(5):572-579.

5. Balasubramanian B, Bhatt CV, Goyel NA. Genetic studies in children with intellectual disability and autistic spectrum of disorders. Indian J Hum Genet. 2009;15(3):103-107.

How to handle negative online reviews

Online reviews have become a popular method for patients to rate their psychiatrists. Patients’ online reviews can help other patients make more informed decisions about pursuing treatment, offer us valuable feedback on our performance, and help improve standards of care.1 However, during the course of our careers, we may receive negative online reviews. These reviews may range from mild dissatisfaction to abusive comments, and they could have adverse personal and professional consequences.2 For example, online discussions might make current patients question your practices or consider ending their treatment with you.2 Also, potential patients might decide to not inquire about your services.2 Here I offer suggestions for approaching negative online reviews, and point out some potential pitfalls of responding to them.

Remain professional. You might become upset or frazzled after reading online criticisms about your performance, particularly if the information is erroneous or deceptive. As much as you would like to immediately respond, a public tit-for-tat could prolong or fuel a conflict, or make you come across as angry.2

There may be occasions, however, when it would be appropriate to respond. If you choose to respond to a negative online review, you need to have a methodical plan. Avoid reacting in a knee-jerk manner because this is usually unproductive. In addition, ensure that your response is professional and polite, because an intemperate response could undermine the public’s confidence in our profession.2

Maintain patient confidentiality. Although patients are free to post anything they desire, psychiatrists must maintain confidentiality. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) applies to online reviews, which prevents us from disclosing information about patients without their permission, including even acknowledging that someone is our patient.3 Your patients’ disclosures are not permission to disclose their health information. Potential patients might avoid us or existing patients may end their treatment with us if they believe their personal information could be disclosed online without their consent. To avoid such concerns, reply to online reviews with generic comments about your practice’s general policies without violating confidentiality. Also, to avoid violating HIPAA rules, you may want to contact your malpractice carrier or your facility’s legal department before replying.1

Invite patients to discuss their grievances. If your patients identify themselves in a review, or if you are able to identify them, consider inviting them to discuss their concerns with you (over the phone, face-to-face, or via video conferencing). During such conversations, thank the patient for their review, and do not ask them to delete it.2 Focus on addressing their concerns and resolving any problems they experienced during treatment; doing so can help improve your practice. This approach also might lead a patient to remove their negative review or to write a review that lets other patients know that you are listening to them.

Even if you choose not to invite your patients to air their concerns, do not entirely dismiss negative reviews. Instead, try to step back from your emotions and take an objective look at such reviews so you can determine what steps to take to improve your practices. Improving your communication with patients could decrease the likelihood that they will write negative reviews in the first place.

Take action on fake reviews. If a negative review is fake (not written by one of your patients) or blatantly untrue, contact the web site administrator and provide evidence to support having the review deleted, especially if it violates the site’s terms of service.1 However, this approach may not be fruitful. Web sites can be manipulated, and many do not require users to authenticate that they are actual patients.1 Although most web sites would not want their reputation damaged by users posting fake reviews, more dramatic reviews could help lead to increased traffic, which lowers an administrator’s incentive to remove negative reviews.1

Continue to: Consider legal repercussions

Consider legal repercussions. Stay up-to-date with online reviews about you by conducting internet searches once every 3 months.1 Consider notifying your malpractice carrier or facility’s legal department if a review suggests a patient or family might initiate legal action against you or the facility.1 You might consider pursuing legal action if an online review is defamatory, but such claims often are difficult to prove in court.1 Even if you win, such a case could later be repeatedly mentioned in articles and journals, thus creating a permanent record of the negative review in the literature.1

Enlist help with your online image. If financially feasible, hire a professional service to help improve your online image or assist in responding to negative reviews.1 Build your profile on review web sites to help frame your online image, and include information that mentions the pertinent steps you are taking to address any legitimate concerns your patients raise in their reviews. Encourage your patients to post reviews because that could produce a more equitable sample and paint a more accurate picture of your practice.

Lobby professional medical organizations to take action to protect psychiatrists from negative online reviews by creating legislation that holds web sites accountable for their content.1

Stay positive. Unfounded or not, negative online reviews are an inevitable part of a psychiatrist’s professional life.2 One negative review (or even several) is not going to destroy your reputation or career. Do not feel alone if you receive a negative review. Seek advice from colleagues who have received negative reviews; in addition to offering advice, they can also provide a listening ear.2

1. Kendall L, Botello T. Internet sabotage: negative online reviews of psychiatrists. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(12):715-716, 718-719.

2. Rimmer A. A patient has complained about me online. What should I do? BMJ. 2019;366:I5705. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I5705.

3. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), S 1028, 104th Cong, Public Law No. 104-191, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-104publ191/pdf/PLAW-104publ191.pdf. Accessed Novermber 16, 2020.

Online reviews have become a popular method for patients to rate their psychiatrists. Patients’ online reviews can help other patients make more informed decisions about pursuing treatment, offer us valuable feedback on our performance, and help improve standards of care.1 However, during the course of our careers, we may receive negative online reviews. These reviews may range from mild dissatisfaction to abusive comments, and they could have adverse personal and professional consequences.2 For example, online discussions might make current patients question your practices or consider ending their treatment with you.2 Also, potential patients might decide to not inquire about your services.2 Here I offer suggestions for approaching negative online reviews, and point out some potential pitfalls of responding to them.

Remain professional. You might become upset or frazzled after reading online criticisms about your performance, particularly if the information is erroneous or deceptive. As much as you would like to immediately respond, a public tit-for-tat could prolong or fuel a conflict, or make you come across as angry.2

There may be occasions, however, when it would be appropriate to respond. If you choose to respond to a negative online review, you need to have a methodical plan. Avoid reacting in a knee-jerk manner because this is usually unproductive. In addition, ensure that your response is professional and polite, because an intemperate response could undermine the public’s confidence in our profession.2

Maintain patient confidentiality. Although patients are free to post anything they desire, psychiatrists must maintain confidentiality. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) applies to online reviews, which prevents us from disclosing information about patients without their permission, including even acknowledging that someone is our patient.3 Your patients’ disclosures are not permission to disclose their health information. Potential patients might avoid us or existing patients may end their treatment with us if they believe their personal information could be disclosed online without their consent. To avoid such concerns, reply to online reviews with generic comments about your practice’s general policies without violating confidentiality. Also, to avoid violating HIPAA rules, you may want to contact your malpractice carrier or your facility’s legal department before replying.1

Invite patients to discuss their grievances. If your patients identify themselves in a review, or if you are able to identify them, consider inviting them to discuss their concerns with you (over the phone, face-to-face, or via video conferencing). During such conversations, thank the patient for their review, and do not ask them to delete it.2 Focus on addressing their concerns and resolving any problems they experienced during treatment; doing so can help improve your practice. This approach also might lead a patient to remove their negative review or to write a review that lets other patients know that you are listening to them.

Even if you choose not to invite your patients to air their concerns, do not entirely dismiss negative reviews. Instead, try to step back from your emotions and take an objective look at such reviews so you can determine what steps to take to improve your practices. Improving your communication with patients could decrease the likelihood that they will write negative reviews in the first place.

Take action on fake reviews. If a negative review is fake (not written by one of your patients) or blatantly untrue, contact the web site administrator and provide evidence to support having the review deleted, especially if it violates the site’s terms of service.1 However, this approach may not be fruitful. Web sites can be manipulated, and many do not require users to authenticate that they are actual patients.1 Although most web sites would not want their reputation damaged by users posting fake reviews, more dramatic reviews could help lead to increased traffic, which lowers an administrator’s incentive to remove negative reviews.1

Continue to: Consider legal repercussions

Consider legal repercussions. Stay up-to-date with online reviews about you by conducting internet searches once every 3 months.1 Consider notifying your malpractice carrier or facility’s legal department if a review suggests a patient or family might initiate legal action against you or the facility.1 You might consider pursuing legal action if an online review is defamatory, but such claims often are difficult to prove in court.1 Even if you win, such a case could later be repeatedly mentioned in articles and journals, thus creating a permanent record of the negative review in the literature.1

Enlist help with your online image. If financially feasible, hire a professional service to help improve your online image or assist in responding to negative reviews.1 Build your profile on review web sites to help frame your online image, and include information that mentions the pertinent steps you are taking to address any legitimate concerns your patients raise in their reviews. Encourage your patients to post reviews because that could produce a more equitable sample and paint a more accurate picture of your practice.

Lobby professional medical organizations to take action to protect psychiatrists from negative online reviews by creating legislation that holds web sites accountable for their content.1

Stay positive. Unfounded or not, negative online reviews are an inevitable part of a psychiatrist’s professional life.2 One negative review (or even several) is not going to destroy your reputation or career. Do not feel alone if you receive a negative review. Seek advice from colleagues who have received negative reviews; in addition to offering advice, they can also provide a listening ear.2

Online reviews have become a popular method for patients to rate their psychiatrists. Patients’ online reviews can help other patients make more informed decisions about pursuing treatment, offer us valuable feedback on our performance, and help improve standards of care.1 However, during the course of our careers, we may receive negative online reviews. These reviews may range from mild dissatisfaction to abusive comments, and they could have adverse personal and professional consequences.2 For example, online discussions might make current patients question your practices or consider ending their treatment with you.2 Also, potential patients might decide to not inquire about your services.2 Here I offer suggestions for approaching negative online reviews, and point out some potential pitfalls of responding to them.

Remain professional. You might become upset or frazzled after reading online criticisms about your performance, particularly if the information is erroneous or deceptive. As much as you would like to immediately respond, a public tit-for-tat could prolong or fuel a conflict, or make you come across as angry.2

There may be occasions, however, when it would be appropriate to respond. If you choose to respond to a negative online review, you need to have a methodical plan. Avoid reacting in a knee-jerk manner because this is usually unproductive. In addition, ensure that your response is professional and polite, because an intemperate response could undermine the public’s confidence in our profession.2

Maintain patient confidentiality. Although patients are free to post anything they desire, psychiatrists must maintain confidentiality. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) applies to online reviews, which prevents us from disclosing information about patients without their permission, including even acknowledging that someone is our patient.3 Your patients’ disclosures are not permission to disclose their health information. Potential patients might avoid us or existing patients may end their treatment with us if they believe their personal information could be disclosed online without their consent. To avoid such concerns, reply to online reviews with generic comments about your practice’s general policies without violating confidentiality. Also, to avoid violating HIPAA rules, you may want to contact your malpractice carrier or your facility’s legal department before replying.1

Invite patients to discuss their grievances. If your patients identify themselves in a review, or if you are able to identify them, consider inviting them to discuss their concerns with you (over the phone, face-to-face, or via video conferencing). During such conversations, thank the patient for their review, and do not ask them to delete it.2 Focus on addressing their concerns and resolving any problems they experienced during treatment; doing so can help improve your practice. This approach also might lead a patient to remove their negative review or to write a review that lets other patients know that you are listening to them.

Even if you choose not to invite your patients to air their concerns, do not entirely dismiss negative reviews. Instead, try to step back from your emotions and take an objective look at such reviews so you can determine what steps to take to improve your practices. Improving your communication with patients could decrease the likelihood that they will write negative reviews in the first place.

Take action on fake reviews. If a negative review is fake (not written by one of your patients) or blatantly untrue, contact the web site administrator and provide evidence to support having the review deleted, especially if it violates the site’s terms of service.1 However, this approach may not be fruitful. Web sites can be manipulated, and many do not require users to authenticate that they are actual patients.1 Although most web sites would not want their reputation damaged by users posting fake reviews, more dramatic reviews could help lead to increased traffic, which lowers an administrator’s incentive to remove negative reviews.1

Continue to: Consider legal repercussions

Consider legal repercussions. Stay up-to-date with online reviews about you by conducting internet searches once every 3 months.1 Consider notifying your malpractice carrier or facility’s legal department if a review suggests a patient or family might initiate legal action against you or the facility.1 You might consider pursuing legal action if an online review is defamatory, but such claims often are difficult to prove in court.1 Even if you win, such a case could later be repeatedly mentioned in articles and journals, thus creating a permanent record of the negative review in the literature.1

Enlist help with your online image. If financially feasible, hire a professional service to help improve your online image or assist in responding to negative reviews.1 Build your profile on review web sites to help frame your online image, and include information that mentions the pertinent steps you are taking to address any legitimate concerns your patients raise in their reviews. Encourage your patients to post reviews because that could produce a more equitable sample and paint a more accurate picture of your practice.

Lobby professional medical organizations to take action to protect psychiatrists from negative online reviews by creating legislation that holds web sites accountable for their content.1

Stay positive. Unfounded or not, negative online reviews are an inevitable part of a psychiatrist’s professional life.2 One negative review (or even several) is not going to destroy your reputation or career. Do not feel alone if you receive a negative review. Seek advice from colleagues who have received negative reviews; in addition to offering advice, they can also provide a listening ear.2

1. Kendall L, Botello T. Internet sabotage: negative online reviews of psychiatrists. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(12):715-716, 718-719.

2. Rimmer A. A patient has complained about me online. What should I do? BMJ. 2019;366:I5705. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I5705.

3. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), S 1028, 104th Cong, Public Law No. 104-191, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-104publ191/pdf/PLAW-104publ191.pdf. Accessed Novermber 16, 2020.

1. Kendall L, Botello T. Internet sabotage: negative online reviews of psychiatrists. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(12):715-716, 718-719.

2. Rimmer A. A patient has complained about me online. What should I do? BMJ. 2019;366:I5705. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I5705.

3. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), S 1028, 104th Cong, Public Law No. 104-191, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-104publ191/pdf/PLAW-104publ191.pdf. Accessed Novermber 16, 2020.

2020 Peer Reviewers

Aparna Atluru, MD, MBA

Stanford Medicine

Sandra Barker, PhD

Virginia Commonwealth University

Kamal Bhatia, MD

MedStar Georgetown University Hospital

Charles F. Caley, PharmD

Western New England University Pharmacy Practice

Khushminder Chahal, MD

Homewood Health Centre

Craig Chepke, MD, FAPA

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine

O. Greg Deardorff, PharmD, BCPP

Fulton State Hospital

Parikshit Deshmukh, MD, FAPA, FASAM

Oxford, FL

David Dunner, MD

Center for Anxiety and Depression

Lee Flowers, MD, MPH

Aspire Locums LLC

Melissa D. Grady, PhD, MSW

Catholic University, National Catholic School of Social Services

Staci Gruber, PhD

McLean Hospital

Vikas Gupta, MD, MPH

South Carolina Department of Mental Health

Susan Hatters-Friedman, MD

Case Western Reserve University

Robert Hendren, DO

University of California, San Francisco

Veeraraghavan Iyer, MD

Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

Abigail Kay, MD

Thomas Jefferson University

Rebecca Klisz-Hulbert, MD

Wayne State University

Gaurav Kulkarni, MD

Compass Health Network Psychiatry

Jill Levenson, PhD

Barry University

Steven B. Lippmann, MD

University of Louisville

Muhammad Hassan Majeed, MD

Lehigh Valley Health Network

David N. Neubauer, MD

Johns Hopkins University

John Onate, MD

UC Davis Health

Joel Paris, MD

McGill University

Brett Parmenter, PhD

VA Puget Sound Health Care System American Lake Division, Mental Health Clinic

Andrew Penn, RN, MS, NP

University of California, San Francisco

Fady Rachid, MD

Private Practice Geneva, Switzerland

Eduardo Rueda Vasquez, MD

Williamsport, PA

Marsal Sanches, MD, PhD, FAPA

University of Texas John P. and Kathrine G. McGovern Medical School

Matthew A. Schreiber, MD, PhD

Puget Sound VA Health Care System University of Washington School of Medicine

Mary Seeman, MD

University of Toronto

Ravi Shankar, MD

University of Missouri

Ashish Sharma, MD

University of Nebraska Medical Center

James Shore, MD, MPH/MSPH

University of Colorado Denver

Tawny Smith, PharmD, BCPP

University of Texas at Austin

Renee Sorrentino, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital

Cornel Stanciu, MD

Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine

Justin Strickland, PhD

Johns Hopkins University

Yilang Tang, MD, PhD

Emory University

Robyn Thom, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital

Katherine Unverferth, MD

University of California, Los Angeles

Amy M. VandenBerg, PharmD, BCPP

University of Michigan

Shikha Verma, MD

Rogers Behavioral Health

Roopma Wadhwa, MD, MHA

South Carolina Department of Mental Health

Patricia Westmoreland, MD

Eating Recovery Center

Glen Xiong, MD

University of California at Davis

Aparna Atluru, MD, MBA

Stanford Medicine

Sandra Barker, PhD

Virginia Commonwealth University

Kamal Bhatia, MD

MedStar Georgetown University Hospital

Charles F. Caley, PharmD

Western New England University Pharmacy Practice

Khushminder Chahal, MD

Homewood Health Centre

Craig Chepke, MD, FAPA

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine

O. Greg Deardorff, PharmD, BCPP

Fulton State Hospital

Parikshit Deshmukh, MD, FAPA, FASAM

Oxford, FL

David Dunner, MD

Center for Anxiety and Depression

Lee Flowers, MD, MPH

Aspire Locums LLC

Melissa D. Grady, PhD, MSW

Catholic University, National Catholic School of Social Services

Staci Gruber, PhD

McLean Hospital

Vikas Gupta, MD, MPH

South Carolina Department of Mental Health

Susan Hatters-Friedman, MD

Case Western Reserve University

Robert Hendren, DO

University of California, San Francisco

Veeraraghavan Iyer, MD

Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

Abigail Kay, MD

Thomas Jefferson University

Rebecca Klisz-Hulbert, MD

Wayne State University

Gaurav Kulkarni, MD

Compass Health Network Psychiatry

Jill Levenson, PhD

Barry University

Steven B. Lippmann, MD

University of Louisville

Muhammad Hassan Majeed, MD

Lehigh Valley Health Network

David N. Neubauer, MD

Johns Hopkins University

John Onate, MD

UC Davis Health

Joel Paris, MD

McGill University

Brett Parmenter, PhD

VA Puget Sound Health Care System American Lake Division, Mental Health Clinic

Andrew Penn, RN, MS, NP

University of California, San Francisco

Fady Rachid, MD

Private Practice Geneva, Switzerland

Eduardo Rueda Vasquez, MD

Williamsport, PA

Marsal Sanches, MD, PhD, FAPA

University of Texas John P. and Kathrine G. McGovern Medical School

Matthew A. Schreiber, MD, PhD

Puget Sound VA Health Care System University of Washington School of Medicine

Mary Seeman, MD

University of Toronto

Ravi Shankar, MD

University of Missouri

Ashish Sharma, MD

University of Nebraska Medical Center

James Shore, MD, MPH/MSPH

University of Colorado Denver

Tawny Smith, PharmD, BCPP

University of Texas at Austin

Renee Sorrentino, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital

Cornel Stanciu, MD

Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine

Justin Strickland, PhD

Johns Hopkins University

Yilang Tang, MD, PhD

Emory University

Robyn Thom, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital

Katherine Unverferth, MD

University of California, Los Angeles

Amy M. VandenBerg, PharmD, BCPP

University of Michigan

Shikha Verma, MD

Rogers Behavioral Health

Roopma Wadhwa, MD, MHA

South Carolina Department of Mental Health

Patricia Westmoreland, MD

Eating Recovery Center

Glen Xiong, MD

University of California at Davis

Aparna Atluru, MD, MBA

Stanford Medicine

Sandra Barker, PhD

Virginia Commonwealth University

Kamal Bhatia, MD

MedStar Georgetown University Hospital

Charles F. Caley, PharmD

Western New England University Pharmacy Practice

Khushminder Chahal, MD

Homewood Health Centre

Craig Chepke, MD, FAPA

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine

O. Greg Deardorff, PharmD, BCPP

Fulton State Hospital

Parikshit Deshmukh, MD, FAPA, FASAM

Oxford, FL

David Dunner, MD

Center for Anxiety and Depression

Lee Flowers, MD, MPH

Aspire Locums LLC

Melissa D. Grady, PhD, MSW

Catholic University, National Catholic School of Social Services

Staci Gruber, PhD

McLean Hospital

Vikas Gupta, MD, MPH

South Carolina Department of Mental Health

Susan Hatters-Friedman, MD

Case Western Reserve University

Robert Hendren, DO

University of California, San Francisco

Veeraraghavan Iyer, MD

Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

Abigail Kay, MD

Thomas Jefferson University

Rebecca Klisz-Hulbert, MD

Wayne State University

Gaurav Kulkarni, MD

Compass Health Network Psychiatry

Jill Levenson, PhD

Barry University

Steven B. Lippmann, MD

University of Louisville

Muhammad Hassan Majeed, MD

Lehigh Valley Health Network

David N. Neubauer, MD

Johns Hopkins University

John Onate, MD

UC Davis Health

Joel Paris, MD

McGill University

Brett Parmenter, PhD

VA Puget Sound Health Care System American Lake Division, Mental Health Clinic

Andrew Penn, RN, MS, NP

University of California, San Francisco

Fady Rachid, MD

Private Practice Geneva, Switzerland

Eduardo Rueda Vasquez, MD

Williamsport, PA

Marsal Sanches, MD, PhD, FAPA

University of Texas John P. and Kathrine G. McGovern Medical School

Matthew A. Schreiber, MD, PhD

Puget Sound VA Health Care System University of Washington School of Medicine

Mary Seeman, MD

University of Toronto

Ravi Shankar, MD

University of Missouri

Ashish Sharma, MD

University of Nebraska Medical Center

James Shore, MD, MPH/MSPH

University of Colorado Denver

Tawny Smith, PharmD, BCPP

University of Texas at Austin

Renee Sorrentino, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital

Cornel Stanciu, MD

Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine

Justin Strickland, PhD

Johns Hopkins University

Yilang Tang, MD, PhD

Emory University

Robyn Thom, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital

Katherine Unverferth, MD

University of California, Los Angeles

Amy M. VandenBerg, PharmD, BCPP

University of Michigan

Shikha Verma, MD

Rogers Behavioral Health

Roopma Wadhwa, MD, MHA

South Carolina Department of Mental Health

Patricia Westmoreland, MD

Eating Recovery Center

Glen Xiong, MD

University of California at Davis

Treating insomnia, anxiety in a pandemic

Since the start of the pandemic, we have been conducting an extra hour of Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health. Virtual Rounds has been an opportunity to discuss cases around a spectrum of clinical management issues with respect to depression, bipolar disorder, and a spectrum of anxiety disorders like obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and generalized anxiety disorder. How to apply the calculus of risk-benefit decision-making around management of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period has been the cornerstone of the work at our center for over 2 decades.

When we went virtual at our center in the early Spring, we decided to keep the format of our faculty rounds the way they have been for years and to sustain cohesiveness of our program during the pandemic. But we thought the needs of pregnant and postpartum women warranted being addressed in a context more specific to COVID-19, and also that reproductive psychiatrists and other clinicians could learn from each other about novel issues coming up for this group of patients during the pandemic. With that backdrop, Marlene Freeman, MD, and I founded “Virtual Rounds at the Center” to respond to queries from our colleagues across the country; we do this just after our own rounds on Wednesdays at 2:00 p.m.

As the pandemic has progressed, Virtual Rounds has blossomed into a virtual community on the Zoom platform, where social workers, psychologists, nurse prescribers, psychiatrists, and obstetricians discuss the needs of pregnant and postpartum women specific to COVID-19. Frequently, our discussions involve a review of the risks and benefits of treatment before, during, and after pregnancy.

Seemingly, week to week, more and more colleagues raise questions about the treatment of anxiety and insomnia during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I’ve spoken in previous columns about the enhanced use of telemedicine. Telemedicine not only facilitates efforts like Virtual Rounds and our ability to reach out to colleagues across the country and share cases, but also has allowed us to keep even closer tabs on the emotional well-being of our pregnant and postpartum women during COVID-19.

The question is not just about the effects of a medicine that a woman might take to treat anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy, but the experience of the pandemic per se, which we are measuring in multiple studies now using a variety of psychological instruments that patients complete. The pandemic is unequivocally taking a still unquantified toll on the mental health of Americans and potentially on the next generation to come.

Midcycle awakening during pregnancy

Complaints of insomnia and midcycle awakening during pregnancy are not new – it is the rule, rather than the exception for many pregnant women, particularly later in pregnancy. We have unequivocally seen a worsening of complaints of sleep disruption including insomnia and midcycle awakening during the pandemic that is greater than what we have seen previously. Both patients and colleagues have asked us the safest ways to manage it. One of the first things we consider when we hear about insomnia is whether it is part of an underlying mood disorder. While we see primary insomnia clinically, it really is important to remember that insomnia can be part and parcel of an underlying mood disorder.

With that in mind, what are the options? During the pandemic, we’ve seen an increased use of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) for patients who cannot initiate sleep, which has a very strong evidence base for effectiveness as a first-line intervention for many.

If a patient has an incomplete response to CBT-I, what might be pursued next? In our center, we have a low threshold for using low doses of benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam or clonazepam, because the majority of data do not support an increased risk of major congenital malformations even when used in the first trimester. It is quite common to see medicines such as newer nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotics such as Ambien CR (zolpidem) or Lunesta (eszopiclone) used by our colleagues in ob.gyn. The reproductive safety data on those medicines are particularly sparse, and they may have greater risk of cognitive side effects the next day, so we tend to avoid them.

Another sometimes-forgotten option to consider is using low doses of tricyclic antidepressants (i.e., 10-25 mg of nortriptyline at bedtime), with tricyclics having a 40-year history and at least one pooled analysis showing the absence of increased risk for major congenital malformations when used. This may be a very easy way of managing insomnia, with low-dose tricyclics having an anxiolytic effect as well.

Anxiety during pregnancy

The most common rise in symptoms during COVID-19 for women who are pregnant or post partum has been an increase in anxiety. Women present with a spectrum of concerns leading to anxiety symptoms in the context of the pandemic. Earlier on in the pandemic, concerns focused mostly on how to stay healthy, and how to mitigate risk and not catch SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy, as well as the very complex issues that were playing out in real time as hospital systems were figuring out how to manage pregnant women in labor and to keep both them and staff safe. Over time, anxiety has shifted to still staying safe during the pandemic and the potential impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on pregnancy outcomes. The No. 1 concern is what the implications of COVID-19 disease are on mother and child. New mothers also are anxious about how they will practically navigate life with a newborn in the postpartum setting.

Early on in the pandemic, some hospital systems severely limited who was in the room with a woman during labor, potentially impeding the wishes of women during delivery who would have wanted their loved ones and/or a doula present, as an example. With enhanced testing available now, protocols have since relaxed in many hospitals to allow partners – but not a team – to remain in the hospital during the labor process. Still, the prospect of delivering during a pandemic is undoubtedly a source of anxiety for some women.

This sort of anxiety, particularly in patients with preexisting anxiety disorders, can be particularly challenging. Fortunately, there has been a rapid increase over the last several years of digital apps to mitigate anxiety. While many of them have not been systematically studied, the data on biobehavioral intervention for anxiety is enormous, and this should be used as first-line treatment for patients with mild to moderate symptoms; so many women would prefer to avoid pharmacological intervention during pregnancy, if possible, to avoid fetal drug exposure. For patients who meet criteria for frank anxiety disorder, other nonpharmacologic interventions such as CBT have been shown to be effective.

Frequently, we see women who are experiencing levels of anxiety where nonpharmacological interventions have an incomplete response, and colleagues have asked about the safest way to treat these patients. As has been discussed in multiple previous columns, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) should be thought of sooner rather than later, particularly with medicines with good reproductive safety data such as sertraline, citalopram, or fluoxetine.

We also reported over 15 years ago that at least 30%-40% of women presenting with histories of recurrent major depression at the beginning of pregnancy had comorbid anxiety disorders, and that the use of benzodiazepines in that population in addition to SSRIs was exceedingly common, with doses of approximately 0.5-1.5 mg of clonazepam or lorazepam being standard fare. Again, this is very appropriate treatment to mitigate anxiety symptoms because now have enough data as a field that support the existence of adverse outcomes associated with untreated anxiety during pregnancy in terms of both adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes, higher rates of preterm birth, and other obstetric complications. Hence, managing anxiety during pregnancy should be considered like managing a toxic exposure – the same way that one would be concerned about anything else that a pregnant woman could be exposed to.

Lastly, although no atypical antipsychotic has been approved for the treatment of anxiety, its use off label is extremely common. More and more data support the absence of a signal of teratogenicity across the family of molecules including atypical antipsychotics. Beyond potential use of atypical antipsychotics, at Virtual Rounds last week, a colleague asked about the use of gabapentin in a patient who was diagnosed with substance use disorder and who had inadvertently conceived on gabapentin, which was being used to treat both anxiety and insomnia. We have typically avoided the use of gabapentin during pregnancy because prospective data have been limited to relatively small case series and one report, with a total of exposures in roughly the 300 range.

However, our colleagues at the Harvard School of Public Health have recently published an article that looked at the United States Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) dataset, which has been used to publish other articles addressing atypical antipsychotics, SSRIs, lithium, and pharmacovigilance investigations among other important topics. In this study, the database was used to look specifically at 4,642 pregnancies with gabapentin exposure relative to 1,744,447 unexposed pregnancies, without a significant finding for increased risk for major congenital malformations.

The question of an increased risk of cardiac malformations and of increased risk for obstetric complications are difficult to untangle from anxiety and depression, as they also are associated with those same outcomes. With that said, the analysis is a welcome addition to our knowledge base for a medicine used more widely to treat symptoms such as anxiety and insomnia in the general population, with a question mark around where it may fit into the algorithm during pregnancy.

In our center, gabapentin still would not be used as a first-line treatment for the management of anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy. But these new data still are reassuring for patients who come in, frequently with unplanned pregnancies. It is an important reminder to those of us taking care of patients during the pandemic to review use of contraception, because although data are unavailable specific to the period of the pandemic, what is clear is that, even prior to COVID-19, 50% of pregnancies in America were unplanned. Addressing issues of reliable use of contraception, particularly during the pandemic, is that much more important.

In this particular case, our clinician colleague in Virtual Rounds decided to continue gabapentin across pregnancy in the context of these reassuring data, but others may choose to discontinue or pursue some of the other treatment options noted above.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Since the start of the pandemic, we have been conducting an extra hour of Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health. Virtual Rounds has been an opportunity to discuss cases around a spectrum of clinical management issues with respect to depression, bipolar disorder, and a spectrum of anxiety disorders like obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and generalized anxiety disorder. How to apply the calculus of risk-benefit decision-making around management of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period has been the cornerstone of the work at our center for over 2 decades.

When we went virtual at our center in the early Spring, we decided to keep the format of our faculty rounds the way they have been for years and to sustain cohesiveness of our program during the pandemic. But we thought the needs of pregnant and postpartum women warranted being addressed in a context more specific to COVID-19, and also that reproductive psychiatrists and other clinicians could learn from each other about novel issues coming up for this group of patients during the pandemic. With that backdrop, Marlene Freeman, MD, and I founded “Virtual Rounds at the Center” to respond to queries from our colleagues across the country; we do this just after our own rounds on Wednesdays at 2:00 p.m.

As the pandemic has progressed, Virtual Rounds has blossomed into a virtual community on the Zoom platform, where social workers, psychologists, nurse prescribers, psychiatrists, and obstetricians discuss the needs of pregnant and postpartum women specific to COVID-19. Frequently, our discussions involve a review of the risks and benefits of treatment before, during, and after pregnancy.

Seemingly, week to week, more and more colleagues raise questions about the treatment of anxiety and insomnia during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I’ve spoken in previous columns about the enhanced use of telemedicine. Telemedicine not only facilitates efforts like Virtual Rounds and our ability to reach out to colleagues across the country and share cases, but also has allowed us to keep even closer tabs on the emotional well-being of our pregnant and postpartum women during COVID-19.

The question is not just about the effects of a medicine that a woman might take to treat anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy, but the experience of the pandemic per se, which we are measuring in multiple studies now using a variety of psychological instruments that patients complete. The pandemic is unequivocally taking a still unquantified toll on the mental health of Americans and potentially on the next generation to come.

Midcycle awakening during pregnancy

Complaints of insomnia and midcycle awakening during pregnancy are not new – it is the rule, rather than the exception for many pregnant women, particularly later in pregnancy. We have unequivocally seen a worsening of complaints of sleep disruption including insomnia and midcycle awakening during the pandemic that is greater than what we have seen previously. Both patients and colleagues have asked us the safest ways to manage it. One of the first things we consider when we hear about insomnia is whether it is part of an underlying mood disorder. While we see primary insomnia clinically, it really is important to remember that insomnia can be part and parcel of an underlying mood disorder.

With that in mind, what are the options? During the pandemic, we’ve seen an increased use of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) for patients who cannot initiate sleep, which has a very strong evidence base for effectiveness as a first-line intervention for many.

If a patient has an incomplete response to CBT-I, what might be pursued next? In our center, we have a low threshold for using low doses of benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam or clonazepam, because the majority of data do not support an increased risk of major congenital malformations even when used in the first trimester. It is quite common to see medicines such as newer nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotics such as Ambien CR (zolpidem) or Lunesta (eszopiclone) used by our colleagues in ob.gyn. The reproductive safety data on those medicines are particularly sparse, and they may have greater risk of cognitive side effects the next day, so we tend to avoid them.

Another sometimes-forgotten option to consider is using low doses of tricyclic antidepressants (i.e., 10-25 mg of nortriptyline at bedtime), with tricyclics having a 40-year history and at least one pooled analysis showing the absence of increased risk for major congenital malformations when used. This may be a very easy way of managing insomnia, with low-dose tricyclics having an anxiolytic effect as well.

Anxiety during pregnancy

The most common rise in symptoms during COVID-19 for women who are pregnant or post partum has been an increase in anxiety. Women present with a spectrum of concerns leading to anxiety symptoms in the context of the pandemic. Earlier on in the pandemic, concerns focused mostly on how to stay healthy, and how to mitigate risk and not catch SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy, as well as the very complex issues that were playing out in real time as hospital systems were figuring out how to manage pregnant women in labor and to keep both them and staff safe. Over time, anxiety has shifted to still staying safe during the pandemic and the potential impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on pregnancy outcomes. The No. 1 concern is what the implications of COVID-19 disease are on mother and child. New mothers also are anxious about how they will practically navigate life with a newborn in the postpartum setting.

Early on in the pandemic, some hospital systems severely limited who was in the room with a woman during labor, potentially impeding the wishes of women during delivery who would have wanted their loved ones and/or a doula present, as an example. With enhanced testing available now, protocols have since relaxed in many hospitals to allow partners – but not a team – to remain in the hospital during the labor process. Still, the prospect of delivering during a pandemic is undoubtedly a source of anxiety for some women.

This sort of anxiety, particularly in patients with preexisting anxiety disorders, can be particularly challenging. Fortunately, there has been a rapid increase over the last several years of digital apps to mitigate anxiety. While many of them have not been systematically studied, the data on biobehavioral intervention for anxiety is enormous, and this should be used as first-line treatment for patients with mild to moderate symptoms; so many women would prefer to avoid pharmacological intervention during pregnancy, if possible, to avoid fetal drug exposure. For patients who meet criteria for frank anxiety disorder, other nonpharmacologic interventions such as CBT have been shown to be effective.

Frequently, we see women who are experiencing levels of anxiety where nonpharmacological interventions have an incomplete response, and colleagues have asked about the safest way to treat these patients. As has been discussed in multiple previous columns, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) should be thought of sooner rather than later, particularly with medicines with good reproductive safety data such as sertraline, citalopram, or fluoxetine.

We also reported over 15 years ago that at least 30%-40% of women presenting with histories of recurrent major depression at the beginning of pregnancy had comorbid anxiety disorders, and that the use of benzodiazepines in that population in addition to SSRIs was exceedingly common, with doses of approximately 0.5-1.5 mg of clonazepam or lorazepam being standard fare. Again, this is very appropriate treatment to mitigate anxiety symptoms because now have enough data as a field that support the existence of adverse outcomes associated with untreated anxiety during pregnancy in terms of both adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes, higher rates of preterm birth, and other obstetric complications. Hence, managing anxiety during pregnancy should be considered like managing a toxic exposure – the same way that one would be concerned about anything else that a pregnant woman could be exposed to.

Lastly, although no atypical antipsychotic has been approved for the treatment of anxiety, its use off label is extremely common. More and more data support the absence of a signal of teratogenicity across the family of molecules including atypical antipsychotics. Beyond potential use of atypical antipsychotics, at Virtual Rounds last week, a colleague asked about the use of gabapentin in a patient who was diagnosed with substance use disorder and who had inadvertently conceived on gabapentin, which was being used to treat both anxiety and insomnia. We have typically avoided the use of gabapentin during pregnancy because prospective data have been limited to relatively small case series and one report, with a total of exposures in roughly the 300 range.

However, our colleagues at the Harvard School of Public Health have recently published an article that looked at the United States Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) dataset, which has been used to publish other articles addressing atypical antipsychotics, SSRIs, lithium, and pharmacovigilance investigations among other important topics. In this study, the database was used to look specifically at 4,642 pregnancies with gabapentin exposure relative to 1,744,447 unexposed pregnancies, without a significant finding for increased risk for major congenital malformations.

The question of an increased risk of cardiac malformations and of increased risk for obstetric complications are difficult to untangle from anxiety and depression, as they also are associated with those same outcomes. With that said, the analysis is a welcome addition to our knowledge base for a medicine used more widely to treat symptoms such as anxiety and insomnia in the general population, with a question mark around where it may fit into the algorithm during pregnancy.

In our center, gabapentin still would not be used as a first-line treatment for the management of anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy. But these new data still are reassuring for patients who come in, frequently with unplanned pregnancies. It is an important reminder to those of us taking care of patients during the pandemic to review use of contraception, because although data are unavailable specific to the period of the pandemic, what is clear is that, even prior to COVID-19, 50% of pregnancies in America were unplanned. Addressing issues of reliable use of contraception, particularly during the pandemic, is that much more important.

In this particular case, our clinician colleague in Virtual Rounds decided to continue gabapentin across pregnancy in the context of these reassuring data, but others may choose to discontinue or pursue some of the other treatment options noted above.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Since the start of the pandemic, we have been conducting an extra hour of Virtual Rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health. Virtual Rounds has been an opportunity to discuss cases around a spectrum of clinical management issues with respect to depression, bipolar disorder, and a spectrum of anxiety disorders like obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and generalized anxiety disorder. How to apply the calculus of risk-benefit decision-making around management of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period has been the cornerstone of the work at our center for over 2 decades.

When we went virtual at our center in the early Spring, we decided to keep the format of our faculty rounds the way they have been for years and to sustain cohesiveness of our program during the pandemic. But we thought the needs of pregnant and postpartum women warranted being addressed in a context more specific to COVID-19, and also that reproductive psychiatrists and other clinicians could learn from each other about novel issues coming up for this group of patients during the pandemic. With that backdrop, Marlene Freeman, MD, and I founded “Virtual Rounds at the Center” to respond to queries from our colleagues across the country; we do this just after our own rounds on Wednesdays at 2:00 p.m.

As the pandemic has progressed, Virtual Rounds has blossomed into a virtual community on the Zoom platform, where social workers, psychologists, nurse prescribers, psychiatrists, and obstetricians discuss the needs of pregnant and postpartum women specific to COVID-19. Frequently, our discussions involve a review of the risks and benefits of treatment before, during, and after pregnancy.

Seemingly, week to week, more and more colleagues raise questions about the treatment of anxiety and insomnia during pregnancy and the postpartum period. I’ve spoken in previous columns about the enhanced use of telemedicine. Telemedicine not only facilitates efforts like Virtual Rounds and our ability to reach out to colleagues across the country and share cases, but also has allowed us to keep even closer tabs on the emotional well-being of our pregnant and postpartum women during COVID-19.

The question is not just about the effects of a medicine that a woman might take to treat anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy, but the experience of the pandemic per se, which we are measuring in multiple studies now using a variety of psychological instruments that patients complete. The pandemic is unequivocally taking a still unquantified toll on the mental health of Americans and potentially on the next generation to come.

Midcycle awakening during pregnancy

Complaints of insomnia and midcycle awakening during pregnancy are not new – it is the rule, rather than the exception for many pregnant women, particularly later in pregnancy. We have unequivocally seen a worsening of complaints of sleep disruption including insomnia and midcycle awakening during the pandemic that is greater than what we have seen previously. Both patients and colleagues have asked us the safest ways to manage it. One of the first things we consider when we hear about insomnia is whether it is part of an underlying mood disorder. While we see primary insomnia clinically, it really is important to remember that insomnia can be part and parcel of an underlying mood disorder.

With that in mind, what are the options? During the pandemic, we’ve seen an increased use of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) for patients who cannot initiate sleep, which has a very strong evidence base for effectiveness as a first-line intervention for many.

If a patient has an incomplete response to CBT-I, what might be pursued next? In our center, we have a low threshold for using low doses of benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam or clonazepam, because the majority of data do not support an increased risk of major congenital malformations even when used in the first trimester. It is quite common to see medicines such as newer nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotics such as Ambien CR (zolpidem) or Lunesta (eszopiclone) used by our colleagues in ob.gyn. The reproductive safety data on those medicines are particularly sparse, and they may have greater risk of cognitive side effects the next day, so we tend to avoid them.

Another sometimes-forgotten option to consider is using low doses of tricyclic antidepressants (i.e., 10-25 mg of nortriptyline at bedtime), with tricyclics having a 40-year history and at least one pooled analysis showing the absence of increased risk for major congenital malformations when used. This may be a very easy way of managing insomnia, with low-dose tricyclics having an anxiolytic effect as well.

Anxiety during pregnancy

The most common rise in symptoms during COVID-19 for women who are pregnant or post partum has been an increase in anxiety. Women present with a spectrum of concerns leading to anxiety symptoms in the context of the pandemic. Earlier on in the pandemic, concerns focused mostly on how to stay healthy, and how to mitigate risk and not catch SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy, as well as the very complex issues that were playing out in real time as hospital systems were figuring out how to manage pregnant women in labor and to keep both them and staff safe. Over time, anxiety has shifted to still staying safe during the pandemic and the potential impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on pregnancy outcomes. The No. 1 concern is what the implications of COVID-19 disease are on mother and child. New mothers also are anxious about how they will practically navigate life with a newborn in the postpartum setting.

Early on in the pandemic, some hospital systems severely limited who was in the room with a woman during labor, potentially impeding the wishes of women during delivery who would have wanted their loved ones and/or a doula present, as an example. With enhanced testing available now, protocols have since relaxed in many hospitals to allow partners – but not a team – to remain in the hospital during the labor process. Still, the prospect of delivering during a pandemic is undoubtedly a source of anxiety for some women.

This sort of anxiety, particularly in patients with preexisting anxiety disorders, can be particularly challenging. Fortunately, there has been a rapid increase over the last several years of digital apps to mitigate anxiety. While many of them have not been systematically studied, the data on biobehavioral intervention for anxiety is enormous, and this should be used as first-line treatment for patients with mild to moderate symptoms; so many women would prefer to avoid pharmacological intervention during pregnancy, if possible, to avoid fetal drug exposure. For patients who meet criteria for frank anxiety disorder, other nonpharmacologic interventions such as CBT have been shown to be effective.

Frequently, we see women who are experiencing levels of anxiety where nonpharmacological interventions have an incomplete response, and colleagues have asked about the safest way to treat these patients. As has been discussed in multiple previous columns, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) should be thought of sooner rather than later, particularly with medicines with good reproductive safety data such as sertraline, citalopram, or fluoxetine.

We also reported over 15 years ago that at least 30%-40% of women presenting with histories of recurrent major depression at the beginning of pregnancy had comorbid anxiety disorders, and that the use of benzodiazepines in that population in addition to SSRIs was exceedingly common, with doses of approximately 0.5-1.5 mg of clonazepam or lorazepam being standard fare. Again, this is very appropriate treatment to mitigate anxiety symptoms because now have enough data as a field that support the existence of adverse outcomes associated with untreated anxiety during pregnancy in terms of both adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes, higher rates of preterm birth, and other obstetric complications. Hence, managing anxiety during pregnancy should be considered like managing a toxic exposure – the same way that one would be concerned about anything else that a pregnant woman could be exposed to.

Lastly, although no atypical antipsychotic has been approved for the treatment of anxiety, its use off label is extremely common. More and more data support the absence of a signal of teratogenicity across the family of molecules including atypical antipsychotics. Beyond potential use of atypical antipsychotics, at Virtual Rounds last week, a colleague asked about the use of gabapentin in a patient who was diagnosed with substance use disorder and who had inadvertently conceived on gabapentin, which was being used to treat both anxiety and insomnia. We have typically avoided the use of gabapentin during pregnancy because prospective data have been limited to relatively small case series and one report, with a total of exposures in roughly the 300 range.

However, our colleagues at the Harvard School of Public Health have recently published an article that looked at the United States Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) dataset, which has been used to publish other articles addressing atypical antipsychotics, SSRIs, lithium, and pharmacovigilance investigations among other important topics. In this study, the database was used to look specifically at 4,642 pregnancies with gabapentin exposure relative to 1,744,447 unexposed pregnancies, without a significant finding for increased risk for major congenital malformations.

The question of an increased risk of cardiac malformations and of increased risk for obstetric complications are difficult to untangle from anxiety and depression, as they also are associated with those same outcomes. With that said, the analysis is a welcome addition to our knowledge base for a medicine used more widely to treat symptoms such as anxiety and insomnia in the general population, with a question mark around where it may fit into the algorithm during pregnancy.

In our center, gabapentin still would not be used as a first-line treatment for the management of anxiety or insomnia during pregnancy. But these new data still are reassuring for patients who come in, frequently with unplanned pregnancies. It is an important reminder to those of us taking care of patients during the pandemic to review use of contraception, because although data are unavailable specific to the period of the pandemic, what is clear is that, even prior to COVID-19, 50% of pregnancies in America were unplanned. Addressing issues of reliable use of contraception, particularly during the pandemic, is that much more important.

In this particular case, our clinician colleague in Virtual Rounds decided to continue gabapentin across pregnancy in the context of these reassuring data, but others may choose to discontinue or pursue some of the other treatment options noted above.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

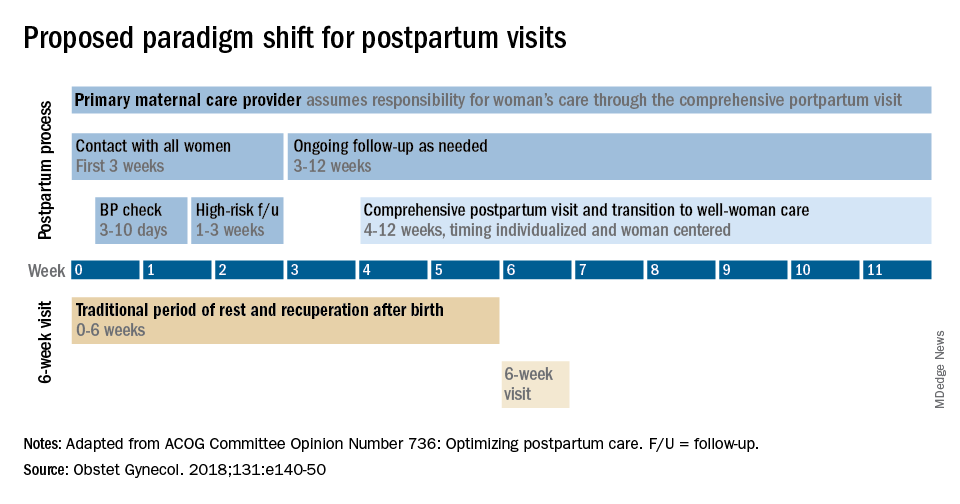

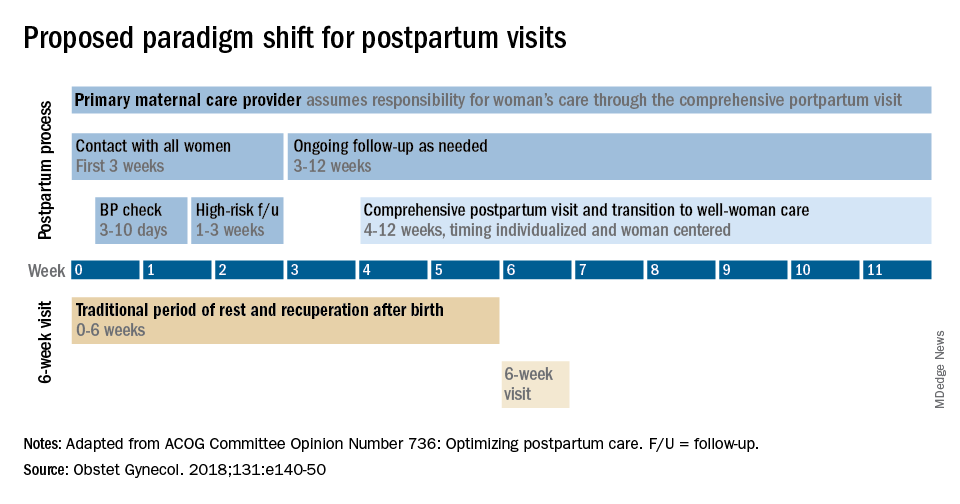

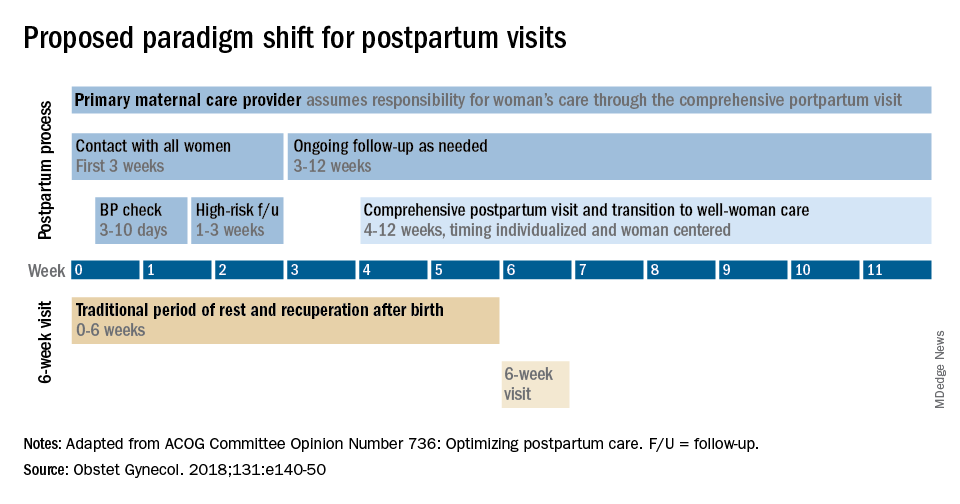

The fourth trimester: Achieving improved postpartum care

The field of ob.gyn. has long focused significantly more attention on the prenatal period – on determining the optimal frequency of ultrasound examinations, for instance, and on screening for diabetes and other conditions – than on women’s health and well-being after delivery.

The traditional 6-week postpartum visit has too often been a quick and cursory visit, with new mothers typically navigating the preceding postpartum transitions on their own.

The need to redefine postpartum care was a central message of Haywood Brown, MD, who in 2017 served as the president of the America College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dr. Brown established a task force whose work resulted in important guidance for taking a more comprehensive and patient-centered approach to postpartum care.1

Improved care in the “fourth trimester,” as it has come to be known, is comprehensive and includes ensuring that our patients have a solid transition to health care beyond the pregnancy. We also hope that it will help us to reduce maternal mortality, given that more than half of pregnancy-related deaths occur after delivery.

Timing and frequency of contact