User login

Adjunctive pimavanserin looks promising for anxious depression

Adjunctive pimavanserin brought clinically meaningful improvement in patients with anxious major depressive disorder inadequately responsive to standard antidepressants alone in a post hoc analysis of the CLARITY trial, Bryan Dirks, MD, reported at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

This is an intriguing observation, because it’s estimated that roughly 50% of individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) have comorbid anxiety disorders or a high level of anxiety symptoms. Moreover, anxious depression has been associated with increased risk of suicidality, high unemployment, and impaired functioning.

CLARITY was a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial whose positive results for the primary outcome have been published (J Clin Psychiatry. 2019 Sep 24;80[6]:19m12928. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19m12928). Because the encouraging findings regarding pimavanserin’s impact on anxious depression came from a post hoc analysis, the results need replication. That’s ongoing in a phase 3 trial of adjunctive pimavanserin versus placebo in patients with MDD, according to Dr. Dirks, director of clinical research at Acadia Pharmaceuticals, San Diego.

The CLARITY post hoc analysis included 104 patients with baseline MDD inadequately responsive to an SSRI or a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and anxious depression as defined by a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17) anxiety/somatization factor subscale score of 7 or more. Twenty-nine of the patients were randomized to 34 mg of adjunctive oral pimavanserin once daily, and 75 to placebo. At 5 weeks, the HAMD-17 anxiety/somatization factor score in the pimavanserin group had dropped by a mean of 5 points from a baseline of 8.8, a significantly greater effect than the 2.8-point drop in placebo-treated controls.

By week 5, the treatment response rate as defined by at least a 50% reduction in HAMD-17 total score from baseline was 55% with pimavanserin and 22% with placebo. The remission rate as indicated by a HAMD-17 total score below 7 was 24% in the pimavanserin group, compared with 5% with placebo. These results translated into an effect size of 0.78, considered by statisticians to be on the border between medium and large. Those response and remission rates in patients with anxious depression were higher with pimavanserin and lower with placebo than in the overall CLARITY trial.

as defined by a HAMD-17 total score of 24 or more plus an anxiety/somatization factor score of 7 or greater. Seventeen such patients were randomized to adjunctive pimavanserin, 36 to placebo. At 5 weeks, the mean HAMD total score had dropped by 17.4 points from a baseline of 27.6 in the pimavanserin group, compared with a 9.3-point reduction in controls.

“Of note, significant differences from placebo were observed as early as week 2 with pimavanserin,” Dr. Dirks said.

Pimavanserin is a novel selective serotonin inverse agonist with a high affinity for 5-HT2A receptors and low affinity for 5-HT2C receptors. At present pimavanserin is Food Drug Administration–approved as Nuplazid only for treatment of hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease psychosis, but because of the drug’s unique mechanism of action it is under study for a variety of other mental disorders. Indeed, pimavanserin is now under FDA review for a possible expanded indication for treatment of dementia-related psychosis. The drug is also under study for schizophrenia as well as for MDD.

The CLARITY trial and this post hoc analysis were sponsored by Acadia Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Dirks B. ECNP 2020. Abstract P 094.

Adjunctive pimavanserin brought clinically meaningful improvement in patients with anxious major depressive disorder inadequately responsive to standard antidepressants alone in a post hoc analysis of the CLARITY trial, Bryan Dirks, MD, reported at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

This is an intriguing observation, because it’s estimated that roughly 50% of individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) have comorbid anxiety disorders or a high level of anxiety symptoms. Moreover, anxious depression has been associated with increased risk of suicidality, high unemployment, and impaired functioning.

CLARITY was a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial whose positive results for the primary outcome have been published (J Clin Psychiatry. 2019 Sep 24;80[6]:19m12928. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19m12928). Because the encouraging findings regarding pimavanserin’s impact on anxious depression came from a post hoc analysis, the results need replication. That’s ongoing in a phase 3 trial of adjunctive pimavanserin versus placebo in patients with MDD, according to Dr. Dirks, director of clinical research at Acadia Pharmaceuticals, San Diego.

The CLARITY post hoc analysis included 104 patients with baseline MDD inadequately responsive to an SSRI or a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and anxious depression as defined by a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17) anxiety/somatization factor subscale score of 7 or more. Twenty-nine of the patients were randomized to 34 mg of adjunctive oral pimavanserin once daily, and 75 to placebo. At 5 weeks, the HAMD-17 anxiety/somatization factor score in the pimavanserin group had dropped by a mean of 5 points from a baseline of 8.8, a significantly greater effect than the 2.8-point drop in placebo-treated controls.

By week 5, the treatment response rate as defined by at least a 50% reduction in HAMD-17 total score from baseline was 55% with pimavanserin and 22% with placebo. The remission rate as indicated by a HAMD-17 total score below 7 was 24% in the pimavanserin group, compared with 5% with placebo. These results translated into an effect size of 0.78, considered by statisticians to be on the border between medium and large. Those response and remission rates in patients with anxious depression were higher with pimavanserin and lower with placebo than in the overall CLARITY trial.

as defined by a HAMD-17 total score of 24 or more plus an anxiety/somatization factor score of 7 or greater. Seventeen such patients were randomized to adjunctive pimavanserin, 36 to placebo. At 5 weeks, the mean HAMD total score had dropped by 17.4 points from a baseline of 27.6 in the pimavanserin group, compared with a 9.3-point reduction in controls.

“Of note, significant differences from placebo were observed as early as week 2 with pimavanserin,” Dr. Dirks said.

Pimavanserin is a novel selective serotonin inverse agonist with a high affinity for 5-HT2A receptors and low affinity for 5-HT2C receptors. At present pimavanserin is Food Drug Administration–approved as Nuplazid only for treatment of hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease psychosis, but because of the drug’s unique mechanism of action it is under study for a variety of other mental disorders. Indeed, pimavanserin is now under FDA review for a possible expanded indication for treatment of dementia-related psychosis. The drug is also under study for schizophrenia as well as for MDD.

The CLARITY trial and this post hoc analysis were sponsored by Acadia Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Dirks B. ECNP 2020. Abstract P 094.

Adjunctive pimavanserin brought clinically meaningful improvement in patients with anxious major depressive disorder inadequately responsive to standard antidepressants alone in a post hoc analysis of the CLARITY trial, Bryan Dirks, MD, reported at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

This is an intriguing observation, because it’s estimated that roughly 50% of individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) have comorbid anxiety disorders or a high level of anxiety symptoms. Moreover, anxious depression has been associated with increased risk of suicidality, high unemployment, and impaired functioning.

CLARITY was a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial whose positive results for the primary outcome have been published (J Clin Psychiatry. 2019 Sep 24;80[6]:19m12928. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19m12928). Because the encouraging findings regarding pimavanserin’s impact on anxious depression came from a post hoc analysis, the results need replication. That’s ongoing in a phase 3 trial of adjunctive pimavanserin versus placebo in patients with MDD, according to Dr. Dirks, director of clinical research at Acadia Pharmaceuticals, San Diego.

The CLARITY post hoc analysis included 104 patients with baseline MDD inadequately responsive to an SSRI or a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and anxious depression as defined by a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17) anxiety/somatization factor subscale score of 7 or more. Twenty-nine of the patients were randomized to 34 mg of adjunctive oral pimavanserin once daily, and 75 to placebo. At 5 weeks, the HAMD-17 anxiety/somatization factor score in the pimavanserin group had dropped by a mean of 5 points from a baseline of 8.8, a significantly greater effect than the 2.8-point drop in placebo-treated controls.

By week 5, the treatment response rate as defined by at least a 50% reduction in HAMD-17 total score from baseline was 55% with pimavanserin and 22% with placebo. The remission rate as indicated by a HAMD-17 total score below 7 was 24% in the pimavanserin group, compared with 5% with placebo. These results translated into an effect size of 0.78, considered by statisticians to be on the border between medium and large. Those response and remission rates in patients with anxious depression were higher with pimavanserin and lower with placebo than in the overall CLARITY trial.

as defined by a HAMD-17 total score of 24 or more plus an anxiety/somatization factor score of 7 or greater. Seventeen such patients were randomized to adjunctive pimavanserin, 36 to placebo. At 5 weeks, the mean HAMD total score had dropped by 17.4 points from a baseline of 27.6 in the pimavanserin group, compared with a 9.3-point reduction in controls.

“Of note, significant differences from placebo were observed as early as week 2 with pimavanserin,” Dr. Dirks said.

Pimavanserin is a novel selective serotonin inverse agonist with a high affinity for 5-HT2A receptors and low affinity for 5-HT2C receptors. At present pimavanserin is Food Drug Administration–approved as Nuplazid only for treatment of hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease psychosis, but because of the drug’s unique mechanism of action it is under study for a variety of other mental disorders. Indeed, pimavanserin is now under FDA review for a possible expanded indication for treatment of dementia-related psychosis. The drug is also under study for schizophrenia as well as for MDD.

The CLARITY trial and this post hoc analysis were sponsored by Acadia Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Dirks B. ECNP 2020. Abstract P 094.

FROM ECNP 2020

Key clinical point: Pimavanserin may have a future as a novel treatment for anxious depression.

Major finding: Twenty-four percent of patients with anxious major depressive disorder inadequately responsive to standard antidepressant therapy achieved remission with 5 weeks of adjunctive pimavanserin, compared with 5% with placebo.

Study details: This was a post hoc analysis of the phase 2, multicenter, randomized, double-blind CLARITY trial.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Acadia Pharmaceuticals and presented by a company employee.

Source: Dirks B. ECNP 2020. Abstract P 094.

MitraClip effective for post-MI acute mitral regurgitation with cardiogenic shock

Percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip appears to be a safe, effective, and life-saving new treatment for severe acute mitral regurgitation (MR) secondary to MI in surgical noncandidates, even when accompanied by cardiogenic shock, according to data from the international IREMMI registry.

“Cardiogenic shock, when adequately supported, does not seem to influence short- and mid-term outcomes, so the development of cardiogenic shock should not preclude percutaneous mitral valve repair in this scenario,” Rodrigo Estevez-Loureiro, MD, PhD, said in presenting the IREMMI (International Registry of MitraClip in Acute Myocardial Infarction) findings reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

Commentators hailed the prospective IREMMI data as potentially practice changing in light of the dire prognosis of such patients when surgery is deemed unacceptably high risk because medical management, the traditionally the only alternative, has a 30-day mortality of up to 50%.

Severe acute MR occurs in an estimated 3% of acute MIs, and in roughly 10% of patients who present with acute MI complicated by cardiogenic shock (CS). The impact of intervening with the MitraClip in an effort to correct the acute MR arising from MI with CS has previously been addressed only in sparse case reports. The new IREMMI study is easily the largest dataset to date detailing clinical and echocardiographic outcomes, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro of Alvaro Cunqueiro Hospital in Vigo, Spain, said at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

He reported on 93 consecutive patients who underwent MitraClip implantation for acute MR arising in the setting of MI, including 50 patients in CS at the time of the procedure. All 93 patients had been turned down by their surgical team because of extreme surgical risk. Three-quarters of the MIs showed ST-segment elevation. Only six patients had a papillary muscle rupture; in the rest, the mechanism of acute MR involved left ventricular global remodeling associated with mitral valve leaflet tethering. Percutaneous valve repair was performed at 18 expert valvular heart centers in the United States, Canada, Israel, and five European countries.

Procedural success

Time from MI to MitraClip implantation averaged 24 days in the CS patients and 33 days in the comparator arm without CS.

“These patients had been turned down for surgery, so the attending physicians generally followed a strategy of trying to cool them down with mechanical circulatory support and vasopressors. MitraClip wasn’t an option at the beginning, but after two or three failed weanings from all the possible therapies, then MitraClip becomes an option. This is one of the reasons why the time lapse between MI and the clip is so large,” the cardiologist explained.

Procedural success rates were similar in the two groups: 90% in those with CS and 93% in those without. However, average procedure time was significantly longer in the CS patients: 143 minutes versus 83 minutes in the patients without CS.

At baseline, 86% of the CS group had grade 4+ MR, similar to the 79% rate in the non-CS patients. Postprocedurally, 60% of the CS group were MR grade 0/1 and 34% were grade 2, comparable to the rates of 65% and 23% in the non-CS group.

At 3 months’ follow-up, 83.4% of the CS group had MR grade 2 or less, again not significantly different from the 90.5% rate in non-CS patients. Systolic pulmonary artery pressure was also similar: 39.6 mm Hg in the CS patients, 44 mm Hg in those without. While everyone was New York Heart Association functional class IV preprocedurally, 79.5% of the CS group were NYHA class I or II at 3 months, not significantly different from the 86.5% prevalence in the comparator arm.

Longer-term clinical outcomes

At a median follow-up of 7 months, the composite primary clinical outcome composed of all-cause mortality or heart failure rehospitalization did not differ between the two groups: a 28% rate in the CS group and 25.6% in non-CS patients. All-cause mortality occurred in 16% with CS and 9.3% without, again not a significant difference.

In a Cox regression analysis, neither surgical risk score, patient age, left ventricular geometry, nor CS was independently associated with the primary composite endpoint. Indeed, the only independent predictor of freedom from mortality or heart failure readmission at follow-up was procedural success, which is very much a function of the experience of the heart team, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro continued.

Michael A. Borger, MD, PhD, who comoderated the late-breaking clinical science session, was wowed by the IREMMI results.

“The mortality rates, I can tell you, compared to traditional surgical series of acute MR in the face of ACS [acute cardiogenic shock] are very, very respectable,” commented Dr. Borger, director of the cardiac surgery clinic at the Leipzig (Ger.) University Heart Center.

“Extremely impressive,” agreed discussant Vinayak N. Bapat, MD, a cardiothoracic surgeon and valve scientist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation. He posed a practical question: “Should we take from this presentation that patients should be stabilized with something like ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or Impella [left ventricular assist device], then transferred to an expert center for the procedure?”

“I think that the stabilization is essential in the patients with cardiogenic shock,” Dr. Estevez-Loureiro replied. “Unlike with surgery, it’s very difficult to establish a MitraClip procedure in a couple of hours in the middle of the night. You have to stabilize them and then treat for shock with ECMO, Impella, or both. I think they should be transferred to a center than can deliver the best treatment. In centers with less experience, patients can be put on mechanical support and transferred to an expert valve center, not only for MitraClip implantation, but for discussion of all the treatment possibilities, including surgery.”

At a press conference in which Dr. Estevez-Loureiro presented highlights of the IREMMI study, discussant Dee Dee Wang, MD, said the international coinvestigators “need to be applauded” for this study.

“Having these outcomes is incredible,” declared Dr. Wang, a structural heart disease specialist at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit.

While this is an observational study, it’s a high-quality dataset with excellent methodology. And conducting a randomized trial in patients with such high surgical risk scores – the CS group had an average EuroSCORE II of 21 – would be extremely difficult, according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Estevez-Loureiro reported receiving research grants from Abbott and serving as a consultant to that company as well as Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Estevez-Loureiro, R. TCT 2020, LBCS session IV.

Percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip appears to be a safe, effective, and life-saving new treatment for severe acute mitral regurgitation (MR) secondary to MI in surgical noncandidates, even when accompanied by cardiogenic shock, according to data from the international IREMMI registry.

“Cardiogenic shock, when adequately supported, does not seem to influence short- and mid-term outcomes, so the development of cardiogenic shock should not preclude percutaneous mitral valve repair in this scenario,” Rodrigo Estevez-Loureiro, MD, PhD, said in presenting the IREMMI (International Registry of MitraClip in Acute Myocardial Infarction) findings reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

Commentators hailed the prospective IREMMI data as potentially practice changing in light of the dire prognosis of such patients when surgery is deemed unacceptably high risk because medical management, the traditionally the only alternative, has a 30-day mortality of up to 50%.

Severe acute MR occurs in an estimated 3% of acute MIs, and in roughly 10% of patients who present with acute MI complicated by cardiogenic shock (CS). The impact of intervening with the MitraClip in an effort to correct the acute MR arising from MI with CS has previously been addressed only in sparse case reports. The new IREMMI study is easily the largest dataset to date detailing clinical and echocardiographic outcomes, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro of Alvaro Cunqueiro Hospital in Vigo, Spain, said at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

He reported on 93 consecutive patients who underwent MitraClip implantation for acute MR arising in the setting of MI, including 50 patients in CS at the time of the procedure. All 93 patients had been turned down by their surgical team because of extreme surgical risk. Three-quarters of the MIs showed ST-segment elevation. Only six patients had a papillary muscle rupture; in the rest, the mechanism of acute MR involved left ventricular global remodeling associated with mitral valve leaflet tethering. Percutaneous valve repair was performed at 18 expert valvular heart centers in the United States, Canada, Israel, and five European countries.

Procedural success

Time from MI to MitraClip implantation averaged 24 days in the CS patients and 33 days in the comparator arm without CS.

“These patients had been turned down for surgery, so the attending physicians generally followed a strategy of trying to cool them down with mechanical circulatory support and vasopressors. MitraClip wasn’t an option at the beginning, but after two or three failed weanings from all the possible therapies, then MitraClip becomes an option. This is one of the reasons why the time lapse between MI and the clip is so large,” the cardiologist explained.

Procedural success rates were similar in the two groups: 90% in those with CS and 93% in those without. However, average procedure time was significantly longer in the CS patients: 143 minutes versus 83 minutes in the patients without CS.

At baseline, 86% of the CS group had grade 4+ MR, similar to the 79% rate in the non-CS patients. Postprocedurally, 60% of the CS group were MR grade 0/1 and 34% were grade 2, comparable to the rates of 65% and 23% in the non-CS group.

At 3 months’ follow-up, 83.4% of the CS group had MR grade 2 or less, again not significantly different from the 90.5% rate in non-CS patients. Systolic pulmonary artery pressure was also similar: 39.6 mm Hg in the CS patients, 44 mm Hg in those without. While everyone was New York Heart Association functional class IV preprocedurally, 79.5% of the CS group were NYHA class I or II at 3 months, not significantly different from the 86.5% prevalence in the comparator arm.

Longer-term clinical outcomes

At a median follow-up of 7 months, the composite primary clinical outcome composed of all-cause mortality or heart failure rehospitalization did not differ between the two groups: a 28% rate in the CS group and 25.6% in non-CS patients. All-cause mortality occurred in 16% with CS and 9.3% without, again not a significant difference.

In a Cox regression analysis, neither surgical risk score, patient age, left ventricular geometry, nor CS was independently associated with the primary composite endpoint. Indeed, the only independent predictor of freedom from mortality or heart failure readmission at follow-up was procedural success, which is very much a function of the experience of the heart team, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro continued.

Michael A. Borger, MD, PhD, who comoderated the late-breaking clinical science session, was wowed by the IREMMI results.

“The mortality rates, I can tell you, compared to traditional surgical series of acute MR in the face of ACS [acute cardiogenic shock] are very, very respectable,” commented Dr. Borger, director of the cardiac surgery clinic at the Leipzig (Ger.) University Heart Center.

“Extremely impressive,” agreed discussant Vinayak N. Bapat, MD, a cardiothoracic surgeon and valve scientist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation. He posed a practical question: “Should we take from this presentation that patients should be stabilized with something like ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or Impella [left ventricular assist device], then transferred to an expert center for the procedure?”

“I think that the stabilization is essential in the patients with cardiogenic shock,” Dr. Estevez-Loureiro replied. “Unlike with surgery, it’s very difficult to establish a MitraClip procedure in a couple of hours in the middle of the night. You have to stabilize them and then treat for shock with ECMO, Impella, or both. I think they should be transferred to a center than can deliver the best treatment. In centers with less experience, patients can be put on mechanical support and transferred to an expert valve center, not only for MitraClip implantation, but for discussion of all the treatment possibilities, including surgery.”

At a press conference in which Dr. Estevez-Loureiro presented highlights of the IREMMI study, discussant Dee Dee Wang, MD, said the international coinvestigators “need to be applauded” for this study.

“Having these outcomes is incredible,” declared Dr. Wang, a structural heart disease specialist at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit.

While this is an observational study, it’s a high-quality dataset with excellent methodology. And conducting a randomized trial in patients with such high surgical risk scores – the CS group had an average EuroSCORE II of 21 – would be extremely difficult, according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Estevez-Loureiro reported receiving research grants from Abbott and serving as a consultant to that company as well as Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Estevez-Loureiro, R. TCT 2020, LBCS session IV.

Percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip appears to be a safe, effective, and life-saving new treatment for severe acute mitral regurgitation (MR) secondary to MI in surgical noncandidates, even when accompanied by cardiogenic shock, according to data from the international IREMMI registry.

“Cardiogenic shock, when adequately supported, does not seem to influence short- and mid-term outcomes, so the development of cardiogenic shock should not preclude percutaneous mitral valve repair in this scenario,” Rodrigo Estevez-Loureiro, MD, PhD, said in presenting the IREMMI (International Registry of MitraClip in Acute Myocardial Infarction) findings reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

Commentators hailed the prospective IREMMI data as potentially practice changing in light of the dire prognosis of such patients when surgery is deemed unacceptably high risk because medical management, the traditionally the only alternative, has a 30-day mortality of up to 50%.

Severe acute MR occurs in an estimated 3% of acute MIs, and in roughly 10% of patients who present with acute MI complicated by cardiogenic shock (CS). The impact of intervening with the MitraClip in an effort to correct the acute MR arising from MI with CS has previously been addressed only in sparse case reports. The new IREMMI study is easily the largest dataset to date detailing clinical and echocardiographic outcomes, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro of Alvaro Cunqueiro Hospital in Vigo, Spain, said at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

He reported on 93 consecutive patients who underwent MitraClip implantation for acute MR arising in the setting of MI, including 50 patients in CS at the time of the procedure. All 93 patients had been turned down by their surgical team because of extreme surgical risk. Three-quarters of the MIs showed ST-segment elevation. Only six patients had a papillary muscle rupture; in the rest, the mechanism of acute MR involved left ventricular global remodeling associated with mitral valve leaflet tethering. Percutaneous valve repair was performed at 18 expert valvular heart centers in the United States, Canada, Israel, and five European countries.

Procedural success

Time from MI to MitraClip implantation averaged 24 days in the CS patients and 33 days in the comparator arm without CS.

“These patients had been turned down for surgery, so the attending physicians generally followed a strategy of trying to cool them down with mechanical circulatory support and vasopressors. MitraClip wasn’t an option at the beginning, but after two or three failed weanings from all the possible therapies, then MitraClip becomes an option. This is one of the reasons why the time lapse between MI and the clip is so large,” the cardiologist explained.

Procedural success rates were similar in the two groups: 90% in those with CS and 93% in those without. However, average procedure time was significantly longer in the CS patients: 143 minutes versus 83 minutes in the patients without CS.

At baseline, 86% of the CS group had grade 4+ MR, similar to the 79% rate in the non-CS patients. Postprocedurally, 60% of the CS group were MR grade 0/1 and 34% were grade 2, comparable to the rates of 65% and 23% in the non-CS group.

At 3 months’ follow-up, 83.4% of the CS group had MR grade 2 or less, again not significantly different from the 90.5% rate in non-CS patients. Systolic pulmonary artery pressure was also similar: 39.6 mm Hg in the CS patients, 44 mm Hg in those without. While everyone was New York Heart Association functional class IV preprocedurally, 79.5% of the CS group were NYHA class I or II at 3 months, not significantly different from the 86.5% prevalence in the comparator arm.

Longer-term clinical outcomes

At a median follow-up of 7 months, the composite primary clinical outcome composed of all-cause mortality or heart failure rehospitalization did not differ between the two groups: a 28% rate in the CS group and 25.6% in non-CS patients. All-cause mortality occurred in 16% with CS and 9.3% without, again not a significant difference.

In a Cox regression analysis, neither surgical risk score, patient age, left ventricular geometry, nor CS was independently associated with the primary composite endpoint. Indeed, the only independent predictor of freedom from mortality or heart failure readmission at follow-up was procedural success, which is very much a function of the experience of the heart team, Dr. Estevez-Loureiro continued.

Michael A. Borger, MD, PhD, who comoderated the late-breaking clinical science session, was wowed by the IREMMI results.

“The mortality rates, I can tell you, compared to traditional surgical series of acute MR in the face of ACS [acute cardiogenic shock] are very, very respectable,” commented Dr. Borger, director of the cardiac surgery clinic at the Leipzig (Ger.) University Heart Center.

“Extremely impressive,” agreed discussant Vinayak N. Bapat, MD, a cardiothoracic surgeon and valve scientist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation. He posed a practical question: “Should we take from this presentation that patients should be stabilized with something like ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or Impella [left ventricular assist device], then transferred to an expert center for the procedure?”

“I think that the stabilization is essential in the patients with cardiogenic shock,” Dr. Estevez-Loureiro replied. “Unlike with surgery, it’s very difficult to establish a MitraClip procedure in a couple of hours in the middle of the night. You have to stabilize them and then treat for shock with ECMO, Impella, or both. I think they should be transferred to a center than can deliver the best treatment. In centers with less experience, patients can be put on mechanical support and transferred to an expert valve center, not only for MitraClip implantation, but for discussion of all the treatment possibilities, including surgery.”

At a press conference in which Dr. Estevez-Loureiro presented highlights of the IREMMI study, discussant Dee Dee Wang, MD, said the international coinvestigators “need to be applauded” for this study.

“Having these outcomes is incredible,” declared Dr. Wang, a structural heart disease specialist at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit.

While this is an observational study, it’s a high-quality dataset with excellent methodology. And conducting a randomized trial in patients with such high surgical risk scores – the CS group had an average EuroSCORE II of 21 – would be extremely difficult, according to the cardiologist.

Dr. Estevez-Loureiro reported receiving research grants from Abbott and serving as a consultant to that company as well as Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Estevez-Loureiro, R. TCT 2020, LBCS session IV.

FROM TCT 2020

IL-23 plays key roles in antimicrobial macrophage activity

Interleukin-23 optimizes antimicrobial macrophage activity, which is reduced among persons harboring an IL-23 receptor variant that helps protect against inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), recent research has found.

“These [findings] highlight that the susceptibility to infections with therapeutic blockade of the IL-23/IL-12 pathways may be owing in part to the essential role for IL-23 in mediating antimicrobial functions in macrophages. They further highlight that carriers of the IL-23R–Q381 variant, who are relatively protected from IBD and other immune-mediated diseases, may be at increased risk for bacterial infection,” Rui Sun and Clara Abraham, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

IL-23 is key to the pathogenesis of IBD and is being studied as a therapeutic target, both alone and in combination with IL-12 blocking. Although human macrophages express low levels of IL-23 receptor, recent research reveals that IL-23R is up-regulated “within minutes of exposure to IL-23,” which promotes signaling and cytokine secretion, the investigators wrote. However, the extent to which IL-23 supports macrophage antimicrobial activity was unknown. To characterize protein expression, signaling, and bacterial uptake and clearance of bacteria by human macrophages derived from monocytes, the investigators tested these cells with Western blot, flow cytometry, and gentamicin protection, which involved coculturing human macrophages with bacteria, adding gentamicin solution, and then lysing and plating the cells onto agar to assess the extent to which the macrophages had taken up the bacteria.

After 48 hours of exposure to IL-23 or IL-12, macrophages increased their intracellular clearance of clinically relevant bacteria, including Enterococcus faecalis, adherent invasive Escherichia coli, and Salmonella typhimurium. Notably, this did not occur when the investigators reduced (“knocked down”) macrophage expression of either IL-23R or IL-12 receptor alpha 2. Additional investigations showed that in macrophages, IL-23 promotes bacterial uptake, clearance, and autophagy by inducing a pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1)–dependent pathway mediated by Janus kinase 2/tyrosine kinase 2 and by inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) pathways. IL-23 also activates two key proteins involved in autophagy (ATG5 and ATG16L1), the researchers reported. “ROS, RNS, and autophagy cooperate to mediate IL-23-induced bacterial clearance. Reduction of each ROS, RNS, and autophagy pathway partially reversed the enhanced bacterial clearance observed with chronic IL-23 treatment.”

Further tests found that IL-23 mediates antimicrobial pathways through the Janus kinase 2, tyrosine kinase 2, and STAT3 pathways, which “cooperate to mediate optimal IL-23-induced intracellular bacterial clearance in human macrophages.” Importantly, human macrophages showed less antimicrobial activity when transfected with the IL-23R–Q381 variant than with IL-23R–R381. The IL-23R-Q381 variant, which reduces susceptibility to IBD, “decreased IL-23-induced and NOD2-induced antimicrobial pathways and intracellular bacterial clearance in monocyte-derived macrophages,” the researchers explained. Evaluating actual carriers of these variants showed the same results – macrophages harboring IBD-protective IL-23R–R381/Q381 exhibited lower antimicrobial activity and less intracellular bacterial clearance compared with macrophages from carriers of IL-23R–R381/R381.

“Taken together, IL-23 promotes increased bacterial uptake and then induces a more rapid and effective clearance of these intracellular bacteria in human monocyte-derived macrophages,” the researchers wrote. “The reduced inflammatory responses observed in IL-23R Q381 carriers are associated with protection from multiple immune-mediated diseases. This would imply that loss-of-function observed with the common IL-23R–R381Q variant may lead to a disadvantage in select infectious diseases, including through [this variant’s] now identified role in promoting antimicrobial pathways in macrophages.”

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sun R, Abraham C. Cell Molec Gastro Hepatol. 2020 May 28. doi.: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.05.007.

Both genetic studies in humans and functional studies in mice have pinpointed interleukin-23 and its receptor as a key pathway in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). IL-23 is released from myeloid cells in response to sensing of invading pathogens or danger-associated molecular patterns, where it drives induction of Th17, innate lymphoid cell responses, and inflammation.

Alison Simmons, FRCP, PhD, is professor of gastroenterology, honorary consultant gastroenterologist, MRC human immunology unit, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford (England), and translational gastroenterology unit, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust. She has consultancies from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Janssen, and is a cofounder and equity holder in TRexBio.

Both genetic studies in humans and functional studies in mice have pinpointed interleukin-23 and its receptor as a key pathway in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). IL-23 is released from myeloid cells in response to sensing of invading pathogens or danger-associated molecular patterns, where it drives induction of Th17, innate lymphoid cell responses, and inflammation.

Alison Simmons, FRCP, PhD, is professor of gastroenterology, honorary consultant gastroenterologist, MRC human immunology unit, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford (England), and translational gastroenterology unit, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust. She has consultancies from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Janssen, and is a cofounder and equity holder in TRexBio.

Both genetic studies in humans and functional studies in mice have pinpointed interleukin-23 and its receptor as a key pathway in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). IL-23 is released from myeloid cells in response to sensing of invading pathogens or danger-associated molecular patterns, where it drives induction of Th17, innate lymphoid cell responses, and inflammation.

Alison Simmons, FRCP, PhD, is professor of gastroenterology, honorary consultant gastroenterologist, MRC human immunology unit, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford (England), and translational gastroenterology unit, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust. She has consultancies from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Janssen, and is a cofounder and equity holder in TRexBio.

Interleukin-23 optimizes antimicrobial macrophage activity, which is reduced among persons harboring an IL-23 receptor variant that helps protect against inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), recent research has found.

“These [findings] highlight that the susceptibility to infections with therapeutic blockade of the IL-23/IL-12 pathways may be owing in part to the essential role for IL-23 in mediating antimicrobial functions in macrophages. They further highlight that carriers of the IL-23R–Q381 variant, who are relatively protected from IBD and other immune-mediated diseases, may be at increased risk for bacterial infection,” Rui Sun and Clara Abraham, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

IL-23 is key to the pathogenesis of IBD and is being studied as a therapeutic target, both alone and in combination with IL-12 blocking. Although human macrophages express low levels of IL-23 receptor, recent research reveals that IL-23R is up-regulated “within minutes of exposure to IL-23,” which promotes signaling and cytokine secretion, the investigators wrote. However, the extent to which IL-23 supports macrophage antimicrobial activity was unknown. To characterize protein expression, signaling, and bacterial uptake and clearance of bacteria by human macrophages derived from monocytes, the investigators tested these cells with Western blot, flow cytometry, and gentamicin protection, which involved coculturing human macrophages with bacteria, adding gentamicin solution, and then lysing and plating the cells onto agar to assess the extent to which the macrophages had taken up the bacteria.

After 48 hours of exposure to IL-23 or IL-12, macrophages increased their intracellular clearance of clinically relevant bacteria, including Enterococcus faecalis, adherent invasive Escherichia coli, and Salmonella typhimurium. Notably, this did not occur when the investigators reduced (“knocked down”) macrophage expression of either IL-23R or IL-12 receptor alpha 2. Additional investigations showed that in macrophages, IL-23 promotes bacterial uptake, clearance, and autophagy by inducing a pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1)–dependent pathway mediated by Janus kinase 2/tyrosine kinase 2 and by inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) pathways. IL-23 also activates two key proteins involved in autophagy (ATG5 and ATG16L1), the researchers reported. “ROS, RNS, and autophagy cooperate to mediate IL-23-induced bacterial clearance. Reduction of each ROS, RNS, and autophagy pathway partially reversed the enhanced bacterial clearance observed with chronic IL-23 treatment.”

Further tests found that IL-23 mediates antimicrobial pathways through the Janus kinase 2, tyrosine kinase 2, and STAT3 pathways, which “cooperate to mediate optimal IL-23-induced intracellular bacterial clearance in human macrophages.” Importantly, human macrophages showed less antimicrobial activity when transfected with the IL-23R–Q381 variant than with IL-23R–R381. The IL-23R-Q381 variant, which reduces susceptibility to IBD, “decreased IL-23-induced and NOD2-induced antimicrobial pathways and intracellular bacterial clearance in monocyte-derived macrophages,” the researchers explained. Evaluating actual carriers of these variants showed the same results – macrophages harboring IBD-protective IL-23R–R381/Q381 exhibited lower antimicrobial activity and less intracellular bacterial clearance compared with macrophages from carriers of IL-23R–R381/R381.

“Taken together, IL-23 promotes increased bacterial uptake and then induces a more rapid and effective clearance of these intracellular bacteria in human monocyte-derived macrophages,” the researchers wrote. “The reduced inflammatory responses observed in IL-23R Q381 carriers are associated with protection from multiple immune-mediated diseases. This would imply that loss-of-function observed with the common IL-23R–R381Q variant may lead to a disadvantage in select infectious diseases, including through [this variant’s] now identified role in promoting antimicrobial pathways in macrophages.”

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sun R, Abraham C. Cell Molec Gastro Hepatol. 2020 May 28. doi.: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.05.007.

Interleukin-23 optimizes antimicrobial macrophage activity, which is reduced among persons harboring an IL-23 receptor variant that helps protect against inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), recent research has found.

“These [findings] highlight that the susceptibility to infections with therapeutic blockade of the IL-23/IL-12 pathways may be owing in part to the essential role for IL-23 in mediating antimicrobial functions in macrophages. They further highlight that carriers of the IL-23R–Q381 variant, who are relatively protected from IBD and other immune-mediated diseases, may be at increased risk for bacterial infection,” Rui Sun and Clara Abraham, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

IL-23 is key to the pathogenesis of IBD and is being studied as a therapeutic target, both alone and in combination with IL-12 blocking. Although human macrophages express low levels of IL-23 receptor, recent research reveals that IL-23R is up-regulated “within minutes of exposure to IL-23,” which promotes signaling and cytokine secretion, the investigators wrote. However, the extent to which IL-23 supports macrophage antimicrobial activity was unknown. To characterize protein expression, signaling, and bacterial uptake and clearance of bacteria by human macrophages derived from monocytes, the investigators tested these cells with Western blot, flow cytometry, and gentamicin protection, which involved coculturing human macrophages with bacteria, adding gentamicin solution, and then lysing and plating the cells onto agar to assess the extent to which the macrophages had taken up the bacteria.

After 48 hours of exposure to IL-23 or IL-12, macrophages increased their intracellular clearance of clinically relevant bacteria, including Enterococcus faecalis, adherent invasive Escherichia coli, and Salmonella typhimurium. Notably, this did not occur when the investigators reduced (“knocked down”) macrophage expression of either IL-23R or IL-12 receptor alpha 2. Additional investigations showed that in macrophages, IL-23 promotes bacterial uptake, clearance, and autophagy by inducing a pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1)–dependent pathway mediated by Janus kinase 2/tyrosine kinase 2 and by inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) pathways. IL-23 also activates two key proteins involved in autophagy (ATG5 and ATG16L1), the researchers reported. “ROS, RNS, and autophagy cooperate to mediate IL-23-induced bacterial clearance. Reduction of each ROS, RNS, and autophagy pathway partially reversed the enhanced bacterial clearance observed with chronic IL-23 treatment.”

Further tests found that IL-23 mediates antimicrobial pathways through the Janus kinase 2, tyrosine kinase 2, and STAT3 pathways, which “cooperate to mediate optimal IL-23-induced intracellular bacterial clearance in human macrophages.” Importantly, human macrophages showed less antimicrobial activity when transfected with the IL-23R–Q381 variant than with IL-23R–R381. The IL-23R-Q381 variant, which reduces susceptibility to IBD, “decreased IL-23-induced and NOD2-induced antimicrobial pathways and intracellular bacterial clearance in monocyte-derived macrophages,” the researchers explained. Evaluating actual carriers of these variants showed the same results – macrophages harboring IBD-protective IL-23R–R381/Q381 exhibited lower antimicrobial activity and less intracellular bacterial clearance compared with macrophages from carriers of IL-23R–R381/R381.

“Taken together, IL-23 promotes increased bacterial uptake and then induces a more rapid and effective clearance of these intracellular bacteria in human monocyte-derived macrophages,” the researchers wrote. “The reduced inflammatory responses observed in IL-23R Q381 carriers are associated with protection from multiple immune-mediated diseases. This would imply that loss-of-function observed with the common IL-23R–R381Q variant may lead to a disadvantage in select infectious diseases, including through [this variant’s] now identified role in promoting antimicrobial pathways in macrophages.”

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sun R, Abraham C. Cell Molec Gastro Hepatol. 2020 May 28. doi.: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.05.007.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Intravascular lithotripsy hailed as ‘game changer’ for coronary calcification

aimed at gaining U.S. regulatory approval.

The technology is basically the same as in extracorporeal lithotripsy, used for the treatment of kidney stones for more than 30 years: namely, transmission of pulsed acoustic pressure waves in order to fracture calcium. For interventional cardiology purposes, however, the transmitter is located within a balloon angioplasty catheter, Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, explained in presenting the study results at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

In Disrupt CAD III, intravascular lithotripsy far exceeded the procedural success and 30-day freedom from major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) performance targets set in conjunction with the Food and Drug Administration. In so doing, the intravascular lithotripsy device developed by Shockwave Medical successfully addressed one of the banes of contemporary interventional cardiology: heavily calcified coronary lesions.

Currently available technologies targeting such lesions, including noncompliant high-pressure balloons, intravascular lasers, cutting balloons, and orbital and rotational atherectomy, often yield suboptimal results, noted Dr. Kereiakes, medical director of the Christ Hospital Heart and Cardiovascular Center in Cincinnati.

Severe vascular calcifications are becoming more common, due in part to an aging population and the growing prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and renal insufficiency. Severely calcified coronary lesions complicate percutaneous coronary intervention. They’re associated with increased risks of dissection, perforation, and periprocedural MI. Moreover, heavily calcified lesions impede stent delivery and expansion – and stent underexpansion is the leading predictor of restenosis and stent thrombosis, he observed at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Disrupt CAD III was a prospective single-arm study of 384 patients at 47 sites in the United States and several European countries. All participants had de novo coronary calcifications graded as severe by core laboratory assessment, with a mean calcified length of 47.9 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean calcium angle and thickness of 292.5 degrees and 0.96 mm by optical coherence tomography.

“It’s staggering, the level of calcification these patients had. It’s jaw dropping,” Dr. Kereiakes observed.

Intravascular lithotripsy was used to prepare these severely calcified lesions for stenting. The intervention entailed transmission of acoustic waves circumferentially and transmurally at 1 pulse per second through tissue at an effective pressure of about 50 atm. Patients received an average of 69 pulses.

This was not a randomized trial; there was no sham-treated control arm. Instead, the comparator group selected under regulatory guidance was comprised of patients who had received orbital atherectomy for severe coronary calcifications in the earlier, similarly designed ORBIT II trial, which led to FDA marketing approval of that technology.

Key outcomes

The procedural success rate, defined as successful stent delivery with less than a 50% residual stenosis and no in-hospital MACE, was 92.4% in Disrupt CAD III, compared to 83.4% for orbital atherectomy in ORBIT II. The primary safety endpoint of freedom from cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization at 30 days was achieved in 92.2% of patients in the intravascular lithotripsy trial, versus 84.4% in ORBIT II.

The 30-day MACE rate of 7.8% in Disrupt CAD III was primarily driven by periprocedural MIs, which occurred in 6.8% of participants. Only one-third of the MIs were clinically relevant by the Society for Coronary Angiography and Intervention definition. There were two cardiac deaths and three cases of stent thrombosis, all of which were associated with known predictors of the complication. There was 1 case each of dissection, abrupt closure, and perforation, but no instances of slow flow or no reflow at the procedure’s end. Transient lithotripsy-induced left ventricular capture occurred in 41% of patients, but they were benign events with no lasting consequences.

The device was able to cross and deliver acoustic pressure wave therapy to 98.2% of lesions. The mean diameter stenosis preprocedure was 65.1%, dropping to 37.2% post lithotripsy, with a final in-stent residual stenosis diameter of 11.9%, with a 1.7-mm acute gain. The average stent expansion at the site of maximum calcification was 102%, with a minimum stent area of 6.5 mm2.

Optical coherence imaging revealed that 67% of treated lesions had circumferential and transmural fractures of both deep and superficial calcium post lithotripsy. Yet outcomes were the same regardless of whether fractures were evident on imaging.

At 30-day follow-up, 72.9% of patients had no angina, up from just 12.6% of participants pre-PCI. Follow-up will continue for 2 years.

Outcomes were similar for the first case done at each participating center and all cases thereafter.

“The ease of use was remarkable,” Dr. Kereiakes recalled. “The learning curve is virtually nonexistent.”

The reaction

At a press conference where Dr. Kereiakes presented the Disrupt CAD III results, discussant Allen Jeremias, MD, said he found the results compelling.

“The success rate is high, I think it’s relatively easy to use, as demonstrated, and I think the results are spectacular,” said Dr. Jeremias, director of interventional cardiology research and associate director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at St. Francis Hospital in Roslyn, N.Y.

Cardiologists “really don’t do a good job most of the time” with severely calcified coronary lesions, added Dr. Jeremias, who wasn’t involved in the trial.

“A lot of times these patients have inadequate stent outcomes when we do intravascular imaging. So to do something to try to basically crack the calcium and expand the stent is, I think, critically important in these patients, and this is an amazing technology that accomplishes that,” the cardiologist said.

Juan F. Granada, MD, of Columbia University, New York, who moderated the press conference, said, “Some of the debulking techniques used for calcified stenoses actually require a lot of training, knowledge, experience, and hospital infrastructure.

I really think having a technology that is easy to use and familiar to all interventional cardiologists, such as a balloon, could potentially be a disruptive change in our field.”

“It’s an absolute game changer,” agreed Dr. Jeremias.

Dr. Kereiakes reported serving as a consultant to a handful of medical device companies, including Shockwave Medical, which sponsored Disrupt CAD III.

SOURCE: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

aimed at gaining U.S. regulatory approval.

The technology is basically the same as in extracorporeal lithotripsy, used for the treatment of kidney stones for more than 30 years: namely, transmission of pulsed acoustic pressure waves in order to fracture calcium. For interventional cardiology purposes, however, the transmitter is located within a balloon angioplasty catheter, Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, explained in presenting the study results at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

In Disrupt CAD III, intravascular lithotripsy far exceeded the procedural success and 30-day freedom from major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) performance targets set in conjunction with the Food and Drug Administration. In so doing, the intravascular lithotripsy device developed by Shockwave Medical successfully addressed one of the banes of contemporary interventional cardiology: heavily calcified coronary lesions.

Currently available technologies targeting such lesions, including noncompliant high-pressure balloons, intravascular lasers, cutting balloons, and orbital and rotational atherectomy, often yield suboptimal results, noted Dr. Kereiakes, medical director of the Christ Hospital Heart and Cardiovascular Center in Cincinnati.

Severe vascular calcifications are becoming more common, due in part to an aging population and the growing prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and renal insufficiency. Severely calcified coronary lesions complicate percutaneous coronary intervention. They’re associated with increased risks of dissection, perforation, and periprocedural MI. Moreover, heavily calcified lesions impede stent delivery and expansion – and stent underexpansion is the leading predictor of restenosis and stent thrombosis, he observed at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Disrupt CAD III was a prospective single-arm study of 384 patients at 47 sites in the United States and several European countries. All participants had de novo coronary calcifications graded as severe by core laboratory assessment, with a mean calcified length of 47.9 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean calcium angle and thickness of 292.5 degrees and 0.96 mm by optical coherence tomography.

“It’s staggering, the level of calcification these patients had. It’s jaw dropping,” Dr. Kereiakes observed.

Intravascular lithotripsy was used to prepare these severely calcified lesions for stenting. The intervention entailed transmission of acoustic waves circumferentially and transmurally at 1 pulse per second through tissue at an effective pressure of about 50 atm. Patients received an average of 69 pulses.

This was not a randomized trial; there was no sham-treated control arm. Instead, the comparator group selected under regulatory guidance was comprised of patients who had received orbital atherectomy for severe coronary calcifications in the earlier, similarly designed ORBIT II trial, which led to FDA marketing approval of that technology.

Key outcomes

The procedural success rate, defined as successful stent delivery with less than a 50% residual stenosis and no in-hospital MACE, was 92.4% in Disrupt CAD III, compared to 83.4% for orbital atherectomy in ORBIT II. The primary safety endpoint of freedom from cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization at 30 days was achieved in 92.2% of patients in the intravascular lithotripsy trial, versus 84.4% in ORBIT II.

The 30-day MACE rate of 7.8% in Disrupt CAD III was primarily driven by periprocedural MIs, which occurred in 6.8% of participants. Only one-third of the MIs were clinically relevant by the Society for Coronary Angiography and Intervention definition. There were two cardiac deaths and three cases of stent thrombosis, all of which were associated with known predictors of the complication. There was 1 case each of dissection, abrupt closure, and perforation, but no instances of slow flow or no reflow at the procedure’s end. Transient lithotripsy-induced left ventricular capture occurred in 41% of patients, but they were benign events with no lasting consequences.

The device was able to cross and deliver acoustic pressure wave therapy to 98.2% of lesions. The mean diameter stenosis preprocedure was 65.1%, dropping to 37.2% post lithotripsy, with a final in-stent residual stenosis diameter of 11.9%, with a 1.7-mm acute gain. The average stent expansion at the site of maximum calcification was 102%, with a minimum stent area of 6.5 mm2.

Optical coherence imaging revealed that 67% of treated lesions had circumferential and transmural fractures of both deep and superficial calcium post lithotripsy. Yet outcomes were the same regardless of whether fractures were evident on imaging.

At 30-day follow-up, 72.9% of patients had no angina, up from just 12.6% of participants pre-PCI. Follow-up will continue for 2 years.

Outcomes were similar for the first case done at each participating center and all cases thereafter.

“The ease of use was remarkable,” Dr. Kereiakes recalled. “The learning curve is virtually nonexistent.”

The reaction

At a press conference where Dr. Kereiakes presented the Disrupt CAD III results, discussant Allen Jeremias, MD, said he found the results compelling.

“The success rate is high, I think it’s relatively easy to use, as demonstrated, and I think the results are spectacular,” said Dr. Jeremias, director of interventional cardiology research and associate director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at St. Francis Hospital in Roslyn, N.Y.

Cardiologists “really don’t do a good job most of the time” with severely calcified coronary lesions, added Dr. Jeremias, who wasn’t involved in the trial.

“A lot of times these patients have inadequate stent outcomes when we do intravascular imaging. So to do something to try to basically crack the calcium and expand the stent is, I think, critically important in these patients, and this is an amazing technology that accomplishes that,” the cardiologist said.

Juan F. Granada, MD, of Columbia University, New York, who moderated the press conference, said, “Some of the debulking techniques used for calcified stenoses actually require a lot of training, knowledge, experience, and hospital infrastructure.

I really think having a technology that is easy to use and familiar to all interventional cardiologists, such as a balloon, could potentially be a disruptive change in our field.”

“It’s an absolute game changer,” agreed Dr. Jeremias.

Dr. Kereiakes reported serving as a consultant to a handful of medical device companies, including Shockwave Medical, which sponsored Disrupt CAD III.

SOURCE: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

aimed at gaining U.S. regulatory approval.

The technology is basically the same as in extracorporeal lithotripsy, used for the treatment of kidney stones for more than 30 years: namely, transmission of pulsed acoustic pressure waves in order to fracture calcium. For interventional cardiology purposes, however, the transmitter is located within a balloon angioplasty catheter, Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, explained in presenting the study results at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics virtual annual meeting.

In Disrupt CAD III, intravascular lithotripsy far exceeded the procedural success and 30-day freedom from major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) performance targets set in conjunction with the Food and Drug Administration. In so doing, the intravascular lithotripsy device developed by Shockwave Medical successfully addressed one of the banes of contemporary interventional cardiology: heavily calcified coronary lesions.

Currently available technologies targeting such lesions, including noncompliant high-pressure balloons, intravascular lasers, cutting balloons, and orbital and rotational atherectomy, often yield suboptimal results, noted Dr. Kereiakes, medical director of the Christ Hospital Heart and Cardiovascular Center in Cincinnati.

Severe vascular calcifications are becoming more common, due in part to an aging population and the growing prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and renal insufficiency. Severely calcified coronary lesions complicate percutaneous coronary intervention. They’re associated with increased risks of dissection, perforation, and periprocedural MI. Moreover, heavily calcified lesions impede stent delivery and expansion – and stent underexpansion is the leading predictor of restenosis and stent thrombosis, he observed at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Disrupt CAD III was a prospective single-arm study of 384 patients at 47 sites in the United States and several European countries. All participants had de novo coronary calcifications graded as severe by core laboratory assessment, with a mean calcified length of 47.9 mm by quantitative coronary angiography and a mean calcium angle and thickness of 292.5 degrees and 0.96 mm by optical coherence tomography.

“It’s staggering, the level of calcification these patients had. It’s jaw dropping,” Dr. Kereiakes observed.

Intravascular lithotripsy was used to prepare these severely calcified lesions for stenting. The intervention entailed transmission of acoustic waves circumferentially and transmurally at 1 pulse per second through tissue at an effective pressure of about 50 atm. Patients received an average of 69 pulses.

This was not a randomized trial; there was no sham-treated control arm. Instead, the comparator group selected under regulatory guidance was comprised of patients who had received orbital atherectomy for severe coronary calcifications in the earlier, similarly designed ORBIT II trial, which led to FDA marketing approval of that technology.

Key outcomes

The procedural success rate, defined as successful stent delivery with less than a 50% residual stenosis and no in-hospital MACE, was 92.4% in Disrupt CAD III, compared to 83.4% for orbital atherectomy in ORBIT II. The primary safety endpoint of freedom from cardiac death, MI, or target vessel revascularization at 30 days was achieved in 92.2% of patients in the intravascular lithotripsy trial, versus 84.4% in ORBIT II.

The 30-day MACE rate of 7.8% in Disrupt CAD III was primarily driven by periprocedural MIs, which occurred in 6.8% of participants. Only one-third of the MIs were clinically relevant by the Society for Coronary Angiography and Intervention definition. There were two cardiac deaths and three cases of stent thrombosis, all of which were associated with known predictors of the complication. There was 1 case each of dissection, abrupt closure, and perforation, but no instances of slow flow or no reflow at the procedure’s end. Transient lithotripsy-induced left ventricular capture occurred in 41% of patients, but they were benign events with no lasting consequences.

The device was able to cross and deliver acoustic pressure wave therapy to 98.2% of lesions. The mean diameter stenosis preprocedure was 65.1%, dropping to 37.2% post lithotripsy, with a final in-stent residual stenosis diameter of 11.9%, with a 1.7-mm acute gain. The average stent expansion at the site of maximum calcification was 102%, with a minimum stent area of 6.5 mm2.

Optical coherence imaging revealed that 67% of treated lesions had circumferential and transmural fractures of both deep and superficial calcium post lithotripsy. Yet outcomes were the same regardless of whether fractures were evident on imaging.

At 30-day follow-up, 72.9% of patients had no angina, up from just 12.6% of participants pre-PCI. Follow-up will continue for 2 years.

Outcomes were similar for the first case done at each participating center and all cases thereafter.

“The ease of use was remarkable,” Dr. Kereiakes recalled. “The learning curve is virtually nonexistent.”

The reaction

At a press conference where Dr. Kereiakes presented the Disrupt CAD III results, discussant Allen Jeremias, MD, said he found the results compelling.

“The success rate is high, I think it’s relatively easy to use, as demonstrated, and I think the results are spectacular,” said Dr. Jeremias, director of interventional cardiology research and associate director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at St. Francis Hospital in Roslyn, N.Y.

Cardiologists “really don’t do a good job most of the time” with severely calcified coronary lesions, added Dr. Jeremias, who wasn’t involved in the trial.

“A lot of times these patients have inadequate stent outcomes when we do intravascular imaging. So to do something to try to basically crack the calcium and expand the stent is, I think, critically important in these patients, and this is an amazing technology that accomplishes that,” the cardiologist said.

Juan F. Granada, MD, of Columbia University, New York, who moderated the press conference, said, “Some of the debulking techniques used for calcified stenoses actually require a lot of training, knowledge, experience, and hospital infrastructure.

I really think having a technology that is easy to use and familiar to all interventional cardiologists, such as a balloon, could potentially be a disruptive change in our field.”

“It’s an absolute game changer,” agreed Dr. Jeremias.

Dr. Kereiakes reported serving as a consultant to a handful of medical device companies, including Shockwave Medical, which sponsored Disrupt CAD III.

SOURCE: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

FROM TCT 2020

Key clinical point: Intravascular lithotripsy was safe and effective for treatment of severely calcified coronary stenoses in a pivotal trial.

Major finding: The 30-day rate of freedom from major adverse cardiovascular events was 92.2%, well above the prespecified performance goal of 84.4%.

Study details: Disrupt CAD III study is a multicenter, single-arm, prospective study of intravascular lithotripsy in 384 patients with severe coronary calcification.

Disclosures: The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Shockwave Medical Inc., the study sponsor, as well as several other medical device companies.

Source: Kereiakes DJ. TCT 2020. Late Breaking Clinical Science session 2.

Paraneoplastic Pemphigus With Cicatricial Nail Involvement

To the Editor:

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP), also known as paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome, is an autoimmune mucocutaneous blistering disease that typically occurs secondary to a lymphoproliferative disorder. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is characterized by severe erosive stomatitis, polymorphous skin lesions, and potential bronchiolitis obliterans that can mimic a wide array of conditions. The exact pathogenesis is unknown but is thought to be due to a combination of humoral and cell-mediated immunity. The condition usually confers a poor prognosis, with morbidity from 38% to upwards of 90%.1

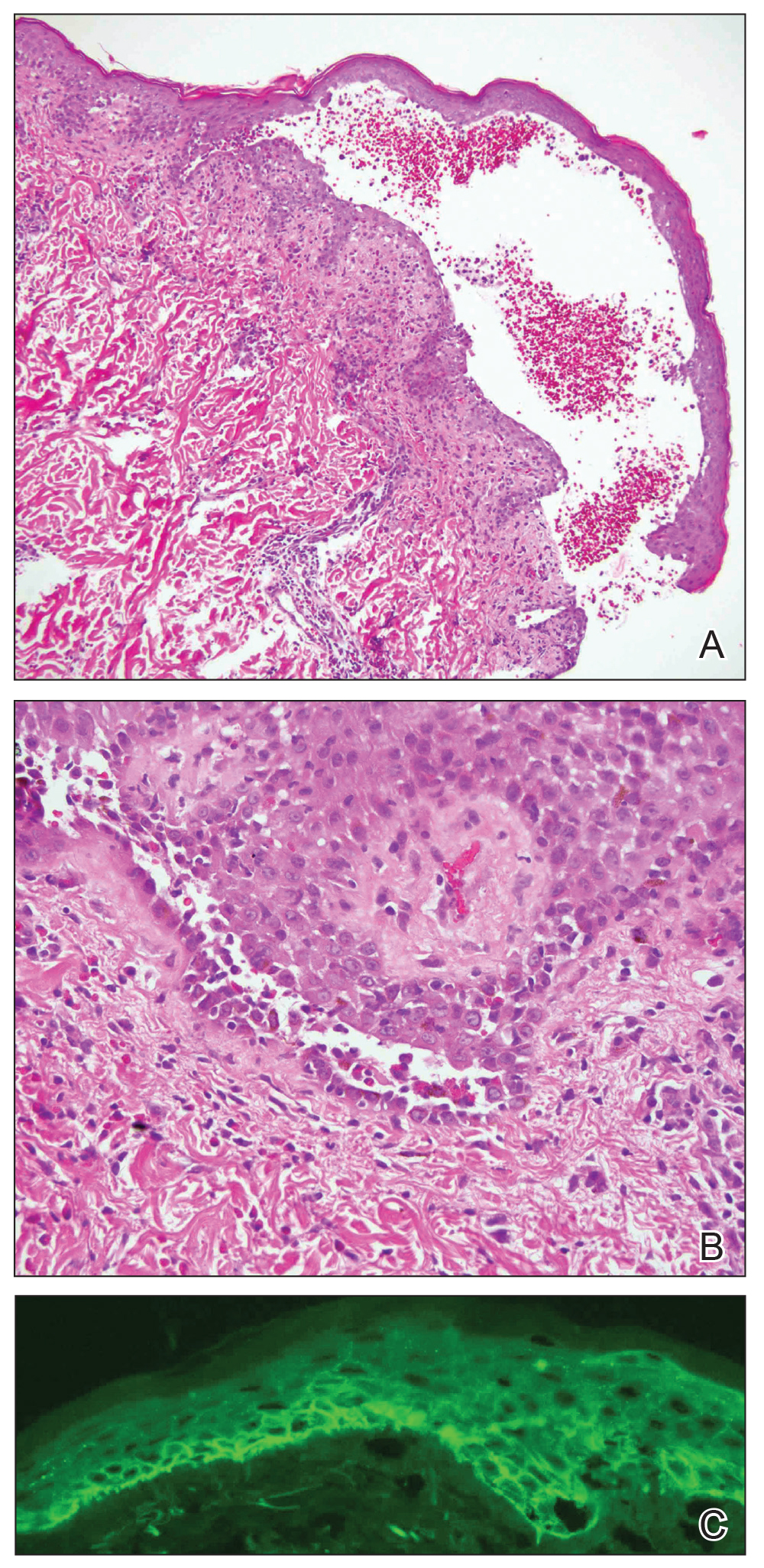

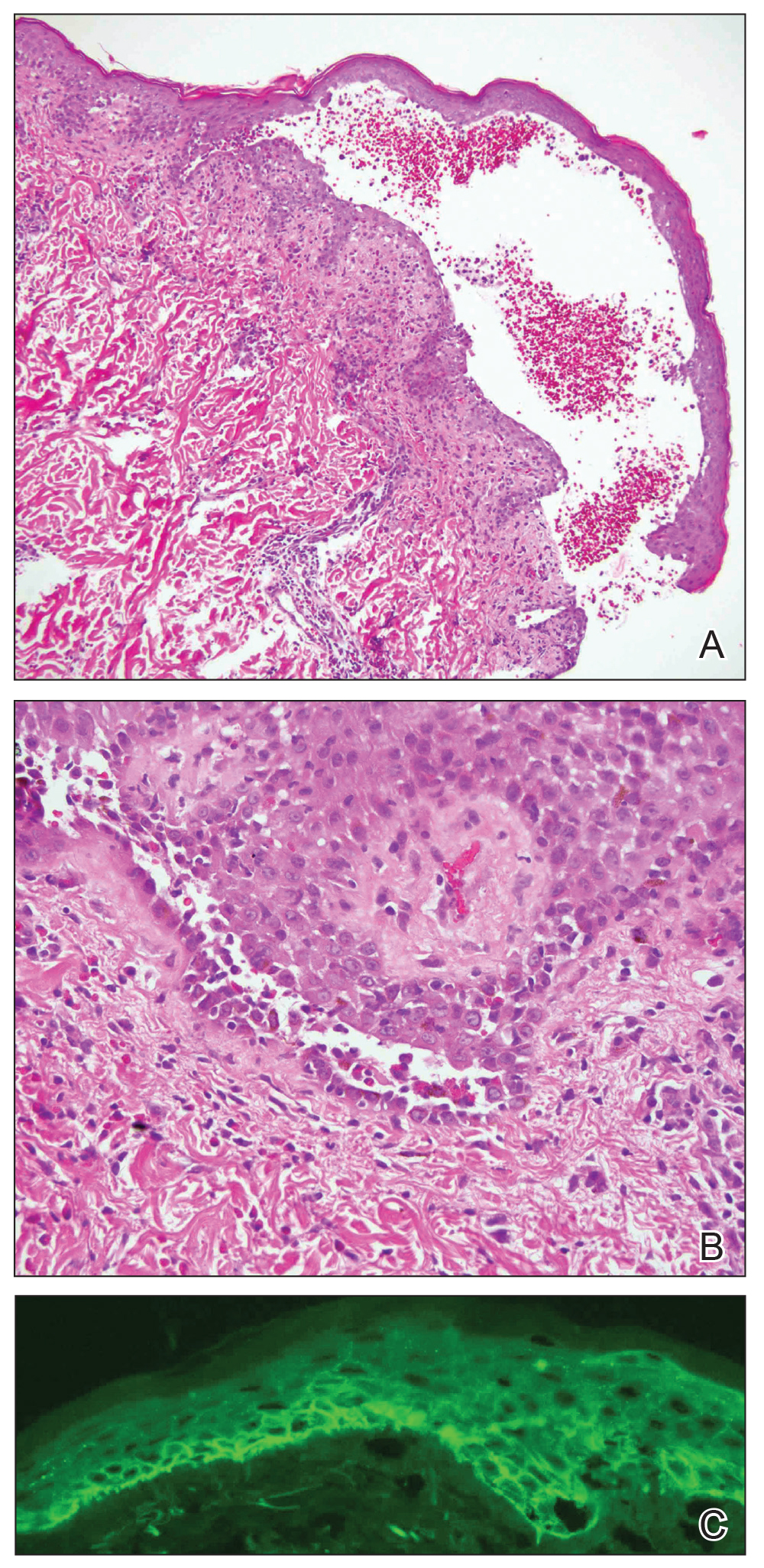

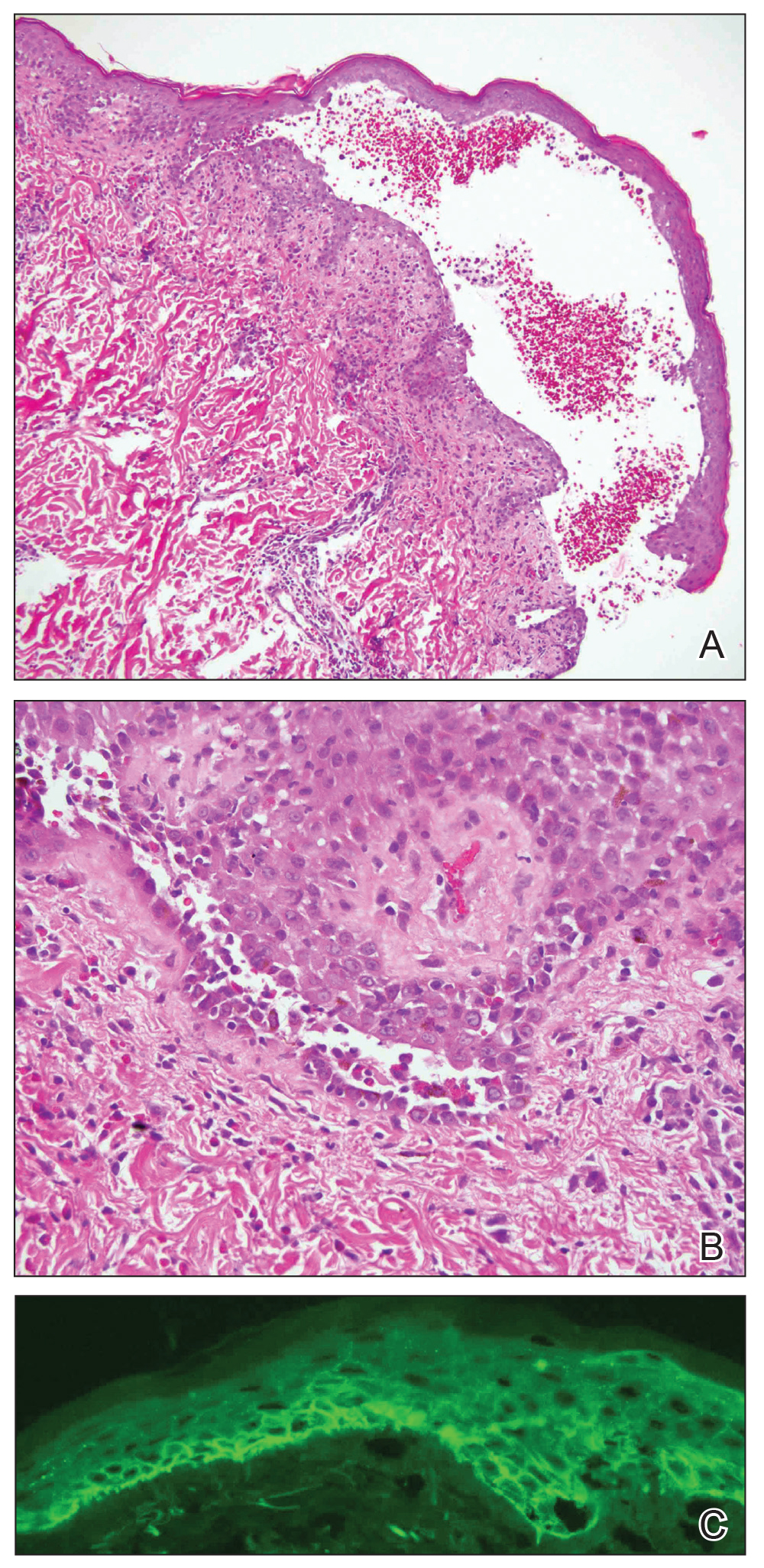

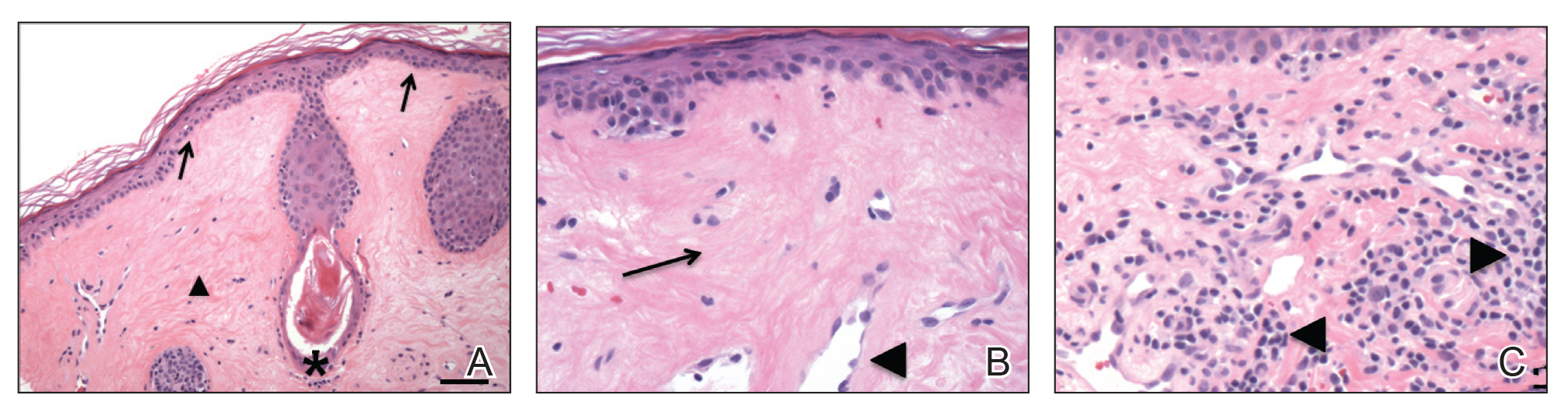

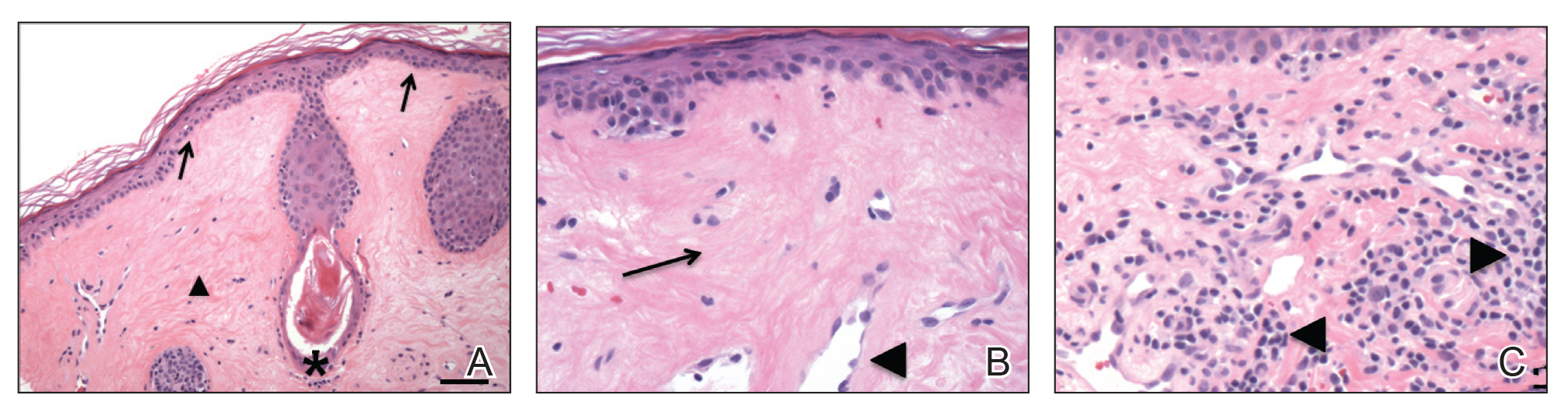

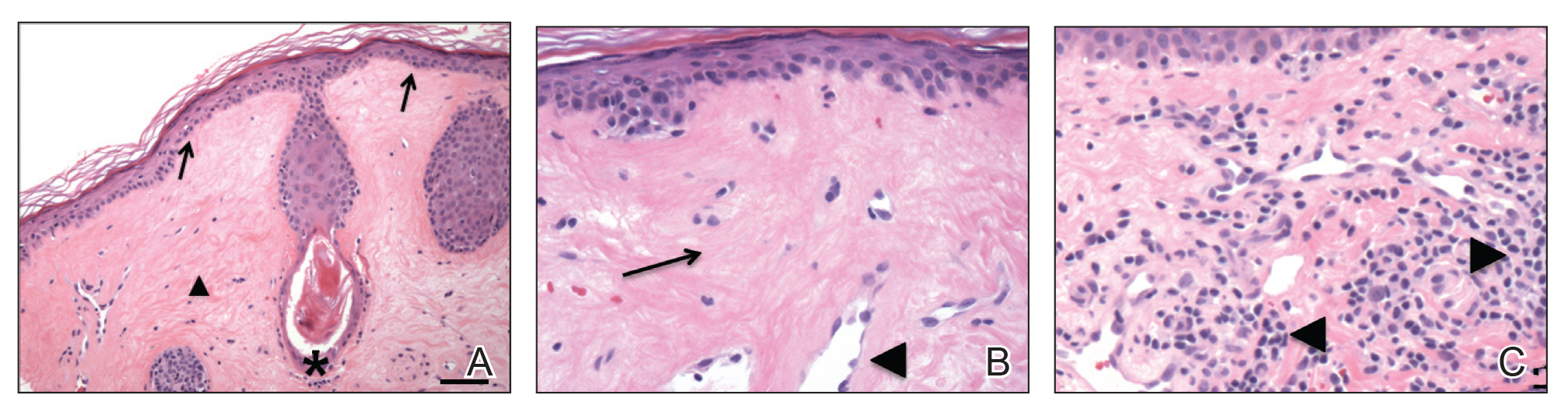

A 47-year-old man developed prominent pink to dusky, ill-defined, targetoid, coalescing papules over the back; violaceous macules over the palms and soles; and numerous crusted oral erosions while hospitalized for an infection. He had a history of stage IVB follicular lymphoma (double-hit type immunoglobulin heavy chain/BCL2 fusion and rearrangement of BCL6) complicated by extensive erosive skin lesions and multiple lines of infections. The clinical differential diagnosis included Stevens-Johnson syndrome vs erythema multiforme (EM) major secondary to administration of oxacillin vs PNP. Herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction and Mycoplasma titers were negative. Skin biopsies from the back and right abdomen revealed severe lichenoid interface dermatitis (IFD) with numerous dyskeratotic cells mimicking EM and eosinophils; however, direct immunofluorescence of the abdomen biopsy revealed an apparent suprabasal acantholysis with intercellular C3 in the lower half of the epidermis. Histologically, PNP was favored, but indirect immunofluorescence with monkey esophagus IgG was negative.

The skin lesions progressed, and an additional skin biopsy from the left arm performed 1 month later revealed similar histologic features with intercellular IgG and C3 in the lower half of the epidermis with weak basement membrane C3 (Figure 1). Serology also confirmed elevated serum antidesmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies. Thus, in the clinical setting of an erosive mucositis with EM-like and pemphigoidlike eruptions associated with B-cell lymphoma, the patient was diagnosed with PNP.

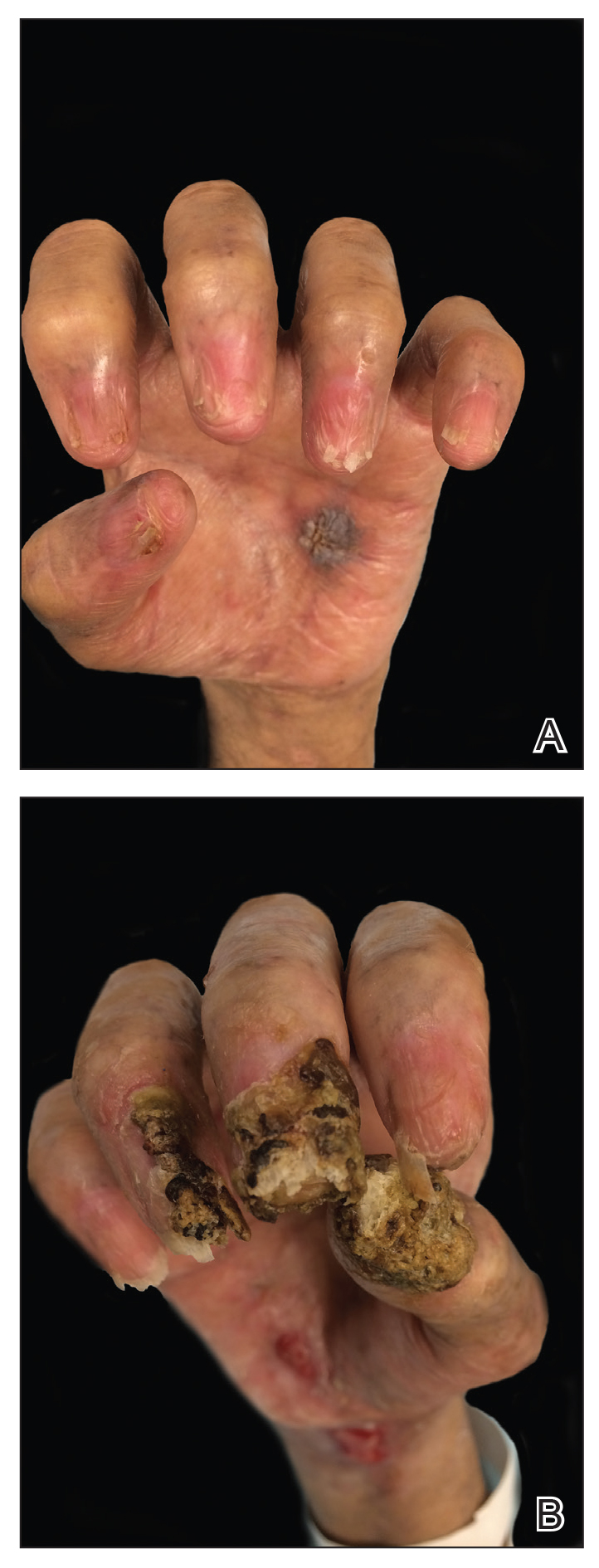

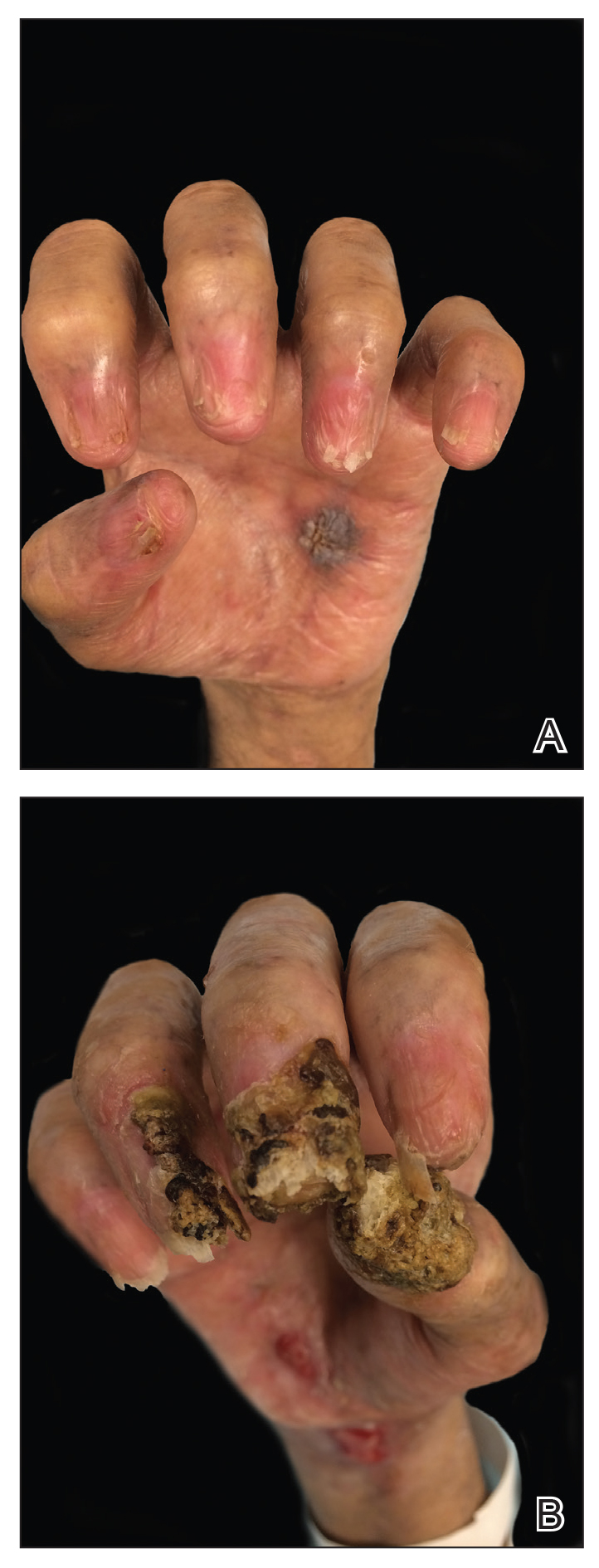

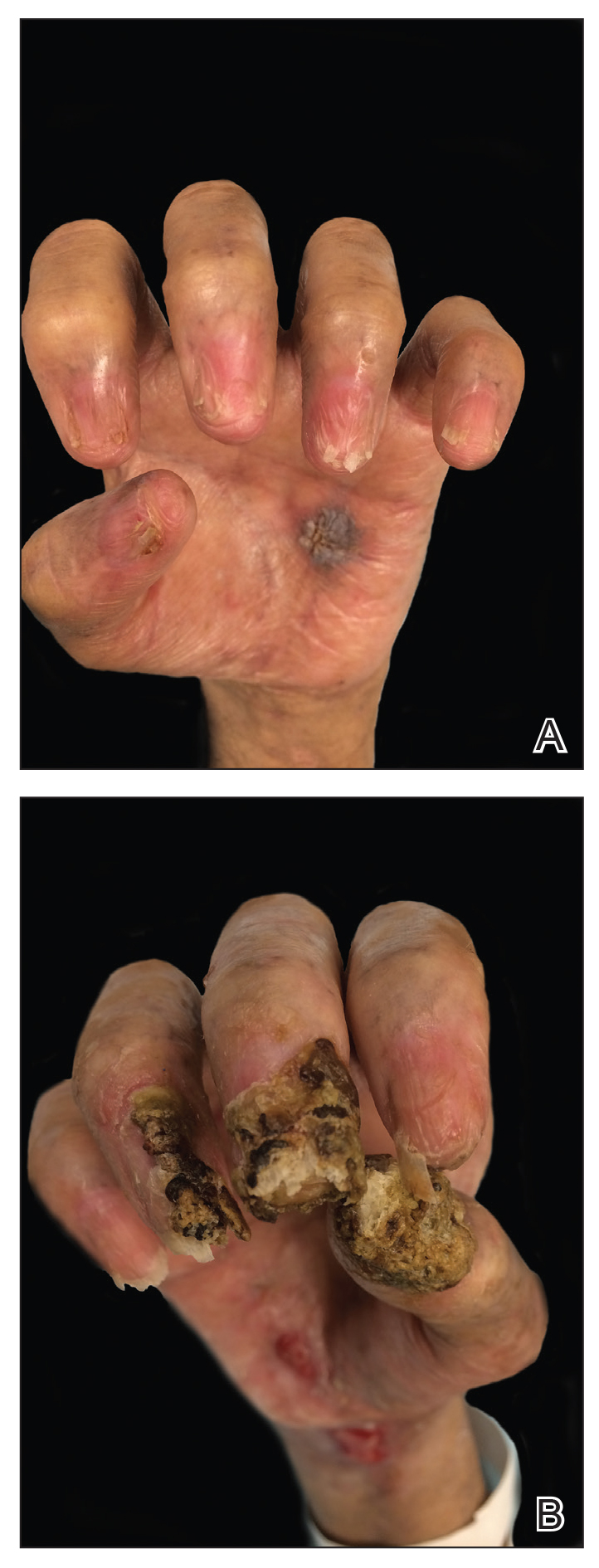

Despite multiple complications followed by intermittent treatments, the initial therapy with rituximab induction and subsequent cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone) for the B-cell lymphoma was done during his hospital stay. Toward the end of his 8-week hospitalization, the patient was noted to have new lesions involving the hands, digits, and nails. The left hand showed anonychia of several fingers with prominent scarring (Figure 2A). There were large, verrucous, crusted plaques on the distal phalanges of several fingers on the right hand (Figure 2B). At that time, he was taking 20 mg daily of prednisone (for 10 months) and had completed his 6th cycle of R-CHOP, which resulted in improvement of the skin lesions. Oral steroids were tapered, and he was maintained on rituximab infusions every 8 weeks but has since been lost to follow-up.

Paraneoplastic lymphoma is a rare condition that affects 0.012% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients.2 Reports of PNP involving the nails are even more rare, with 3 reports in the setting of underlying Castleman disease3-5 and 2 reports in patients with underlying non-Hodgkin6 and follicular1 lymphoma. These studies describe variable nail findings ranging from periungual erosions and edema, formation of dorsal pterygium, onycholysis with longitudinal furrowing, and destruction of the nail plate leading to onychomadesis and/or anonychia. These nail changes typically are seen in lichen planus or in bullous diseases affecting the basement membrane (eg, bullous pemphigoid, acquired epidermolysis bullosa) but not known in pemphigus, which is characterized by nonscarring nail changes.7

Although antidesmoglein 3 antibody was shown to be a pathologic driver in PNP, there is a weak correlation between antibody profiles and clinical presentation.8 In one case of PNP, antidesmoglein 3 antibody was negative, suggesting that lichenoid IFD may cause the phenotypic findings in PNP.9 Thus, the development of nail scarring in PNP may be explained by the presence of lichenoid IFD that is characteristic of PNP. However, the variation in antibody profile in PNP likely is a consequence of epitope spreading.

- Miest RY, Wetter DA, Drage LA, et al. A mucocutaneous eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1425-1427.

- Anhalt GJ, Mimouni D. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. In: LA G, Katz SI, Gilchrest, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine 8th Edition. Vol 1. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012:600.

- Chorzelski T, Hashimoto T, Maciejewska B, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman tumor, myasthenia gravis and bronchiolitis obliterans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:393-400.

- Lemon MA, Weston WL, Huff JC. Childhood paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman’s tumour. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:115-117.

- Tey HL, Tang MB. A case of paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman’s disease presenting as erosive lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e754-e756.

- Liang JJ, Cordes SF, Witzig TE. More than skin-deep. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013;80:632-633.

- Tosti A, Andre M, Murrell DF. Nail involvement in autoimmune bullous disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:511-513, xi.

- Ohyama M, Amagai M, Hashimoto T, et al. Clinical phenotype and anti-desmoglein autoantibody profile in paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:593-598.

- Kanwar AJ, Vinay K, Varma S, et al. Anti-desmoglein antibody-negative paraneoplastic pemphigus successfully treated with rituximab. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:576-579.

To the Editor:

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP), also known as paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome, is an autoimmune mucocutaneous blistering disease that typically occurs secondary to a lymphoproliferative disorder. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is characterized by severe erosive stomatitis, polymorphous skin lesions, and potential bronchiolitis obliterans that can mimic a wide array of conditions. The exact pathogenesis is unknown but is thought to be due to a combination of humoral and cell-mediated immunity. The condition usually confers a poor prognosis, with morbidity from 38% to upwards of 90%.1

A 47-year-old man developed prominent pink to dusky, ill-defined, targetoid, coalescing papules over the back; violaceous macules over the palms and soles; and numerous crusted oral erosions while hospitalized for an infection. He had a history of stage IVB follicular lymphoma (double-hit type immunoglobulin heavy chain/BCL2 fusion and rearrangement of BCL6) complicated by extensive erosive skin lesions and multiple lines of infections. The clinical differential diagnosis included Stevens-Johnson syndrome vs erythema multiforme (EM) major secondary to administration of oxacillin vs PNP. Herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction and Mycoplasma titers were negative. Skin biopsies from the back and right abdomen revealed severe lichenoid interface dermatitis (IFD) with numerous dyskeratotic cells mimicking EM and eosinophils; however, direct immunofluorescence of the abdomen biopsy revealed an apparent suprabasal acantholysis with intercellular C3 in the lower half of the epidermis. Histologically, PNP was favored, but indirect immunofluorescence with monkey esophagus IgG was negative.

The skin lesions progressed, and an additional skin biopsy from the left arm performed 1 month later revealed similar histologic features with intercellular IgG and C3 in the lower half of the epidermis with weak basement membrane C3 (Figure 1). Serology also confirmed elevated serum antidesmoglein 1 and 3 antibodies. Thus, in the clinical setting of an erosive mucositis with EM-like and pemphigoidlike eruptions associated with B-cell lymphoma, the patient was diagnosed with PNP.

Despite multiple complications followed by intermittent treatments, the initial therapy with rituximab induction and subsequent cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone) for the B-cell lymphoma was done during his hospital stay. Toward the end of his 8-week hospitalization, the patient was noted to have new lesions involving the hands, digits, and nails. The left hand showed anonychia of several fingers with prominent scarring (Figure 2A). There were large, verrucous, crusted plaques on the distal phalanges of several fingers on the right hand (Figure 2B). At that time, he was taking 20 mg daily of prednisone (for 10 months) and had completed his 6th cycle of R-CHOP, which resulted in improvement of the skin lesions. Oral steroids were tapered, and he was maintained on rituximab infusions every 8 weeks but has since been lost to follow-up.