User login

High infantile spasm risk should contraindicate sodium channel blocker antiepileptics

BALTIMORE – “This is scary and warrants caution,” said senior investigator and pediatric neurologist Shaun Hussain, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA. Because of the findings, “we are avoiding the use of voltage-gated sodium channel blockade in any child at risk for infantile spasms. More broadly, we are avoiding [them] in any infant if there is a good alternative medication, of which there are many in most cases.”

There have been a few previous case reports linking voltage-gated sodium channel blockers (SCBs) – which include oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, lacosamide, and phenytoin – to infantile spasms, but they are still commonly used for infant seizures. There was some disagreement at UCLA whether there really was a link, so Dr. Hussain and his team took a look at the university’s experience. They matched 50 children with nonsyndromic epilepsy who subsequently developed video-EEG confirmed infantile spasms (cases) to 50 children who also had nonsyndromic epilepsy but did not develop spasms, based on follow-up duration and age and date of epilepsy onset.

The team then looked to see what drugs they had been on; it turned out that cases and controls were about equally as likely to have been treated with any specific antiepileptic, including SCBs. Infantile spasms were substantially more likely with SCB exposure in children with spasm risk factors, which also include focal cortical dysplasia, Aicardi syndrome, and other problems (HR 7.0; 95%; CI 2.5-19.8; P less than .001). Spasms were also more likely among even low-risk children treated with SCBs, although the trend was not statistically significant.

In the end, “we wonder how many cases of infantile spasms could [have been] prevented entirely if we had avoided sodium channel blockade,” Dr. Hussain said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

With so many other seizure options available – levetiracetam, topiramate, and phenobarbital, to name just a few – maybe it would be best “to stay away from” SCBs entirely in “infants with any form of epilepsy,” said lead investigator Jaeden Heesch, an undergraduate researcher who worked with Dr. Hussain.

It is unclear why SCBs increase infantile spasm risk; maybe nonselective voltage-gated sodium channel blockade interferes with proper neuron function in susceptible children, similar to the effects of sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 1 mutations in Dravet syndrome, Dr. Hussain said. Perhaps the findings will inspire drug development. “If nonselective sodium channel blockade is bad, perhaps selective modulation of voltage-gated sodium currents [could be] beneficial or protective,” he said.

The age of epilepsy onset in the study was around 2 months. Children who went on to develop infantile spasms had an average of almost two seizures per day, versus fewer than one among controls, and were on an average of two, versus about 1.5 antiepileptics. The differences were not statistically significant.

The study looked at SCB exposure overall, but it’s possible that infantile spasm risk differs among the various class members.

The work was funded by the Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. The investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Heesch J et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.234.

BALTIMORE – “This is scary and warrants caution,” said senior investigator and pediatric neurologist Shaun Hussain, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA. Because of the findings, “we are avoiding the use of voltage-gated sodium channel blockade in any child at risk for infantile spasms. More broadly, we are avoiding [them] in any infant if there is a good alternative medication, of which there are many in most cases.”

There have been a few previous case reports linking voltage-gated sodium channel blockers (SCBs) – which include oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, lacosamide, and phenytoin – to infantile spasms, but they are still commonly used for infant seizures. There was some disagreement at UCLA whether there really was a link, so Dr. Hussain and his team took a look at the university’s experience. They matched 50 children with nonsyndromic epilepsy who subsequently developed video-EEG confirmed infantile spasms (cases) to 50 children who also had nonsyndromic epilepsy but did not develop spasms, based on follow-up duration and age and date of epilepsy onset.

The team then looked to see what drugs they had been on; it turned out that cases and controls were about equally as likely to have been treated with any specific antiepileptic, including SCBs. Infantile spasms were substantially more likely with SCB exposure in children with spasm risk factors, which also include focal cortical dysplasia, Aicardi syndrome, and other problems (HR 7.0; 95%; CI 2.5-19.8; P less than .001). Spasms were also more likely among even low-risk children treated with SCBs, although the trend was not statistically significant.

In the end, “we wonder how many cases of infantile spasms could [have been] prevented entirely if we had avoided sodium channel blockade,” Dr. Hussain said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

With so many other seizure options available – levetiracetam, topiramate, and phenobarbital, to name just a few – maybe it would be best “to stay away from” SCBs entirely in “infants with any form of epilepsy,” said lead investigator Jaeden Heesch, an undergraduate researcher who worked with Dr. Hussain.

It is unclear why SCBs increase infantile spasm risk; maybe nonselective voltage-gated sodium channel blockade interferes with proper neuron function in susceptible children, similar to the effects of sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 1 mutations in Dravet syndrome, Dr. Hussain said. Perhaps the findings will inspire drug development. “If nonselective sodium channel blockade is bad, perhaps selective modulation of voltage-gated sodium currents [could be] beneficial or protective,” he said.

The age of epilepsy onset in the study was around 2 months. Children who went on to develop infantile spasms had an average of almost two seizures per day, versus fewer than one among controls, and were on an average of two, versus about 1.5 antiepileptics. The differences were not statistically significant.

The study looked at SCB exposure overall, but it’s possible that infantile spasm risk differs among the various class members.

The work was funded by the Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. The investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Heesch J et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.234.

BALTIMORE – “This is scary and warrants caution,” said senior investigator and pediatric neurologist Shaun Hussain, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA. Because of the findings, “we are avoiding the use of voltage-gated sodium channel blockade in any child at risk for infantile spasms. More broadly, we are avoiding [them] in any infant if there is a good alternative medication, of which there are many in most cases.”

There have been a few previous case reports linking voltage-gated sodium channel blockers (SCBs) – which include oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, lacosamide, and phenytoin – to infantile spasms, but they are still commonly used for infant seizures. There was some disagreement at UCLA whether there really was a link, so Dr. Hussain and his team took a look at the university’s experience. They matched 50 children with nonsyndromic epilepsy who subsequently developed video-EEG confirmed infantile spasms (cases) to 50 children who also had nonsyndromic epilepsy but did not develop spasms, based on follow-up duration and age and date of epilepsy onset.

The team then looked to see what drugs they had been on; it turned out that cases and controls were about equally as likely to have been treated with any specific antiepileptic, including SCBs. Infantile spasms were substantially more likely with SCB exposure in children with spasm risk factors, which also include focal cortical dysplasia, Aicardi syndrome, and other problems (HR 7.0; 95%; CI 2.5-19.8; P less than .001). Spasms were also more likely among even low-risk children treated with SCBs, although the trend was not statistically significant.

In the end, “we wonder how many cases of infantile spasms could [have been] prevented entirely if we had avoided sodium channel blockade,” Dr. Hussain said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

With so many other seizure options available – levetiracetam, topiramate, and phenobarbital, to name just a few – maybe it would be best “to stay away from” SCBs entirely in “infants with any form of epilepsy,” said lead investigator Jaeden Heesch, an undergraduate researcher who worked with Dr. Hussain.

It is unclear why SCBs increase infantile spasm risk; maybe nonselective voltage-gated sodium channel blockade interferes with proper neuron function in susceptible children, similar to the effects of sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 1 mutations in Dravet syndrome, Dr. Hussain said. Perhaps the findings will inspire drug development. “If nonselective sodium channel blockade is bad, perhaps selective modulation of voltage-gated sodium currents [could be] beneficial or protective,” he said.

The age of epilepsy onset in the study was around 2 months. Children who went on to develop infantile spasms had an average of almost two seizures per day, versus fewer than one among controls, and were on an average of two, versus about 1.5 antiepileptics. The differences were not statistically significant.

The study looked at SCB exposure overall, but it’s possible that infantile spasm risk differs among the various class members.

The work was funded by the Elsie and Isaac Fogelman Endowment, the Hughes Family Foundation, and the UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. The investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Heesch J et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.234.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Fast-tracking psilocybin for refractory depression makes sense

A significant proportion of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) either do not respond or have partial responses to the currently available Food and Drug Administration–approved antidepressants.

In controlled clinical trials, there is about a 40%-60% symptom remission rate with a 20%-40% remission rate in community-based treatment settings. Not only do those medications lack efficacy in treating MDD, but there are currently no cures for this debilitating illness. As a result, many patients with MDD continue to suffer.

In response to those poor outcomes, researchers and clinicians have developed algorithms aimed at diagnosing the condition of treatment-resistant depression (TRD),1 which enable opportunities for various treatment methods.2 Several studies underway across the United States are testing what some might consider medically invasive procedures, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), deep brain stimulation (DBS), and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). ECT often is considered the gold standard of treatment response, but it requires anesthesia, induces a convulsion, and needs a willing patient and clinician. DBS has been used more widely in neurological treatment of movement disorders. Pioneering neurosurgical treatment for TRD reported recently in the American Journal of Psychiatry found that DBS of an area in the brain called the subcallosal cingulate produces clear and apparently sustained antidepressant effects.3 VNS4 remains an experimental treatment for MDD. TMS is safe, noninvasive, and approved by the FDA for depression, but responses appear similar to those with usual antidepressants.

It is not surprising, given those outcomes, that ketamine was fast-tracked in 2016. The enthusiasm related to ketamine’s effect on MDD and TRD has grown over time as more research findings reach the public. While it is unknown how ketamine affects the biological neural network, a single intravenous dose of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) in patients diagnosed with TRD can lead to improved depression symptoms outcomes within a few hours – and those effects were sustained in 65%-70% of patients at 24 hours. Antidepressants take many weeks to show effects. Ketamine’s exciting findings also offered hope to clinicians and patients trying to manage suicidal thoughts and plans. Ketamine was quickly approved by the FDA as a nasal spray medication.

Now, in another encouraging development, the FDA has granted the Usona Institute Breakthrough Therapy designation for psilocybin for the treatment of MDD. The medical benefits of psilocybin, or “magic mushrooms,” has a long empirical history in our literature. Most recently, psilocybin was featured on “60 Minutes,”5 and in his book, “How to Change Your Mind,”6Michael Pollan details how psychedelic drugs where used to investigate and treat psychiatric disorders until the 1960s, when street use and unsupervised administration led to restrictions on their research and clinical use.

With protocol-driven specific trials, they might become critical medications for a wide range of psychiatric disorders, such as depression, PTSD, anxiety, and addictions. Exciting findings are coming from Roland R. Griffiths, PhD, and his team at Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research. In a recent study8 with cancer patients suffering from depression and anxiety, carefully administered, specific and supervised high doses of psilocybin produced decreases in depression and anxiety, and increases in quality of life and life meaning attitudes. Those improved attitudes, behavior, and responses were sustained by 80% of the sample 6 months post treatment.

Dr. Griffiths’ center is collaborating with Usona, and this collaboration should result in specific guidelines for dose, safety, and protection against abuse and diversion,9 as the study and FDA trials for ketamine have as well.10 It is very encouraging that psychedelic drugs are receiving fast-track designations, and this development reflects a shift in the risk-benefit considerations taking place in our society. Changing attitudes about depression and other psychiatric diseases are encouraging new approaches and new treatments. Psychiatric suffering and pain are being prioritized in research and appreciated by the general public as devastating. Serious, random assignment placebo-controlled and double- blind research studies will define just how valuable these medications might be, what is the safe dose and duration, and for whom they might prove more effective than existing treatments.

The process will take some time. And it is worth remembering that, although research has been promising,11 the number of patients studied, research design, and outcomes are not yet proven for psilosybin.12 The FDA fast-track makes sense, and the agency should continue supporting these efforts for psychedelics. In fact, we think the FDA also should support the promising trials of nitrous oxide13 (laughing gas), and other safe and novel approaches to successfully treat refractory depression. While we wait for personalized psychiatric medicines to be developed and validated through the long process of FDA approval, we will at least have a larger suite of treatment options to match patients with, along with some new algorithms that treat MDD,* TRD, and other disorders just are around the corner.

Dr. Patterson Silver Wolf is an associate professor at Washington University in St. Louis’s Brown School of Social Work. He is a training faculty member for two National Institutes of Health–funded (T32) training programs and serves as the director of the Community Academic Partnership on Addiction (CAPA). He’s chief research officer at the new CAPA Clinic, a teaching addiction treatment facility that is incorporating and testing various performance-based practice technology tools to respond to the opioid crisis and improve addiction treatment outcomes. Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University, St. Louis. He is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville. For more than 40 years, Dr. Gold has worked on developing models for understanding the effects of opioid, tobacco, cocaine, and other drugs, as well as food, on the brain and behavior. He has written several books and published more than 1,000 peer-reviewed scientific articles, texts, and practice guidelines.

References

1. Sackeim HA et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2019 Jun;113:125-36.

2. Conway CR et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 25 Nov;76(11):1569-70.

3. Crowell AL et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Oct 4. doi: 10.1176.appi.ajp.2019.18121427.

4. Kumar A et al. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019 Feb 13;15:457-68.

5. Psilocybin sessions: Psychedelics could help people with addiction and anxiety. “60 Minutes” CBS News. 2019 Oct 13.

6. Pollan M. How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence (Penguin Random House, 2018).

7. Nutt D. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2019;21(2):139-47.

8. Griffiths RR et al. J Psychopharmacol 2016 Dec;30(12):1181-97.

9. Johnson MW et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018 Nov;142:143-66.

10. Schwenk ES et al. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018 Jul;43(5):456-66.

11. Johnson MW et al. Neurotherapeutics. 2017 Jul;14(3):734-40.

12. Mutonni S et al. J Affect Disord. 2019 Nov.1;258:11-24.

13. Nagele P et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Apr;38(2):144-8.

*Correction, 1/9/2020: An earlier version of this story misidentified the intended disease state.

A significant proportion of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) either do not respond or have partial responses to the currently available Food and Drug Administration–approved antidepressants.

In controlled clinical trials, there is about a 40%-60% symptom remission rate with a 20%-40% remission rate in community-based treatment settings. Not only do those medications lack efficacy in treating MDD, but there are currently no cures for this debilitating illness. As a result, many patients with MDD continue to suffer.

In response to those poor outcomes, researchers and clinicians have developed algorithms aimed at diagnosing the condition of treatment-resistant depression (TRD),1 which enable opportunities for various treatment methods.2 Several studies underway across the United States are testing what some might consider medically invasive procedures, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), deep brain stimulation (DBS), and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). ECT often is considered the gold standard of treatment response, but it requires anesthesia, induces a convulsion, and needs a willing patient and clinician. DBS has been used more widely in neurological treatment of movement disorders. Pioneering neurosurgical treatment for TRD reported recently in the American Journal of Psychiatry found that DBS of an area in the brain called the subcallosal cingulate produces clear and apparently sustained antidepressant effects.3 VNS4 remains an experimental treatment for MDD. TMS is safe, noninvasive, and approved by the FDA for depression, but responses appear similar to those with usual antidepressants.

It is not surprising, given those outcomes, that ketamine was fast-tracked in 2016. The enthusiasm related to ketamine’s effect on MDD and TRD has grown over time as more research findings reach the public. While it is unknown how ketamine affects the biological neural network, a single intravenous dose of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) in patients diagnosed with TRD can lead to improved depression symptoms outcomes within a few hours – and those effects were sustained in 65%-70% of patients at 24 hours. Antidepressants take many weeks to show effects. Ketamine’s exciting findings also offered hope to clinicians and patients trying to manage suicidal thoughts and plans. Ketamine was quickly approved by the FDA as a nasal spray medication.

Now, in another encouraging development, the FDA has granted the Usona Institute Breakthrough Therapy designation for psilocybin for the treatment of MDD. The medical benefits of psilocybin, or “magic mushrooms,” has a long empirical history in our literature. Most recently, psilocybin was featured on “60 Minutes,”5 and in his book, “How to Change Your Mind,”6Michael Pollan details how psychedelic drugs where used to investigate and treat psychiatric disorders until the 1960s, when street use and unsupervised administration led to restrictions on their research and clinical use.

With protocol-driven specific trials, they might become critical medications for a wide range of psychiatric disorders, such as depression, PTSD, anxiety, and addictions. Exciting findings are coming from Roland R. Griffiths, PhD, and his team at Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research. In a recent study8 with cancer patients suffering from depression and anxiety, carefully administered, specific and supervised high doses of psilocybin produced decreases in depression and anxiety, and increases in quality of life and life meaning attitudes. Those improved attitudes, behavior, and responses were sustained by 80% of the sample 6 months post treatment.

Dr. Griffiths’ center is collaborating with Usona, and this collaboration should result in specific guidelines for dose, safety, and protection against abuse and diversion,9 as the study and FDA trials for ketamine have as well.10 It is very encouraging that psychedelic drugs are receiving fast-track designations, and this development reflects a shift in the risk-benefit considerations taking place in our society. Changing attitudes about depression and other psychiatric diseases are encouraging new approaches and new treatments. Psychiatric suffering and pain are being prioritized in research and appreciated by the general public as devastating. Serious, random assignment placebo-controlled and double- blind research studies will define just how valuable these medications might be, what is the safe dose and duration, and for whom they might prove more effective than existing treatments.

The process will take some time. And it is worth remembering that, although research has been promising,11 the number of patients studied, research design, and outcomes are not yet proven for psilosybin.12 The FDA fast-track makes sense, and the agency should continue supporting these efforts for psychedelics. In fact, we think the FDA also should support the promising trials of nitrous oxide13 (laughing gas), and other safe and novel approaches to successfully treat refractory depression. While we wait for personalized psychiatric medicines to be developed and validated through the long process of FDA approval, we will at least have a larger suite of treatment options to match patients with, along with some new algorithms that treat MDD,* TRD, and other disorders just are around the corner.

Dr. Patterson Silver Wolf is an associate professor at Washington University in St. Louis’s Brown School of Social Work. He is a training faculty member for two National Institutes of Health–funded (T32) training programs and serves as the director of the Community Academic Partnership on Addiction (CAPA). He’s chief research officer at the new CAPA Clinic, a teaching addiction treatment facility that is incorporating and testing various performance-based practice technology tools to respond to the opioid crisis and improve addiction treatment outcomes. Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University, St. Louis. He is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville. For more than 40 years, Dr. Gold has worked on developing models for understanding the effects of opioid, tobacco, cocaine, and other drugs, as well as food, on the brain and behavior. He has written several books and published more than 1,000 peer-reviewed scientific articles, texts, and practice guidelines.

References

1. Sackeim HA et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2019 Jun;113:125-36.

2. Conway CR et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 25 Nov;76(11):1569-70.

3. Crowell AL et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Oct 4. doi: 10.1176.appi.ajp.2019.18121427.

4. Kumar A et al. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019 Feb 13;15:457-68.

5. Psilocybin sessions: Psychedelics could help people with addiction and anxiety. “60 Minutes” CBS News. 2019 Oct 13.

6. Pollan M. How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence (Penguin Random House, 2018).

7. Nutt D. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2019;21(2):139-47.

8. Griffiths RR et al. J Psychopharmacol 2016 Dec;30(12):1181-97.

9. Johnson MW et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018 Nov;142:143-66.

10. Schwenk ES et al. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018 Jul;43(5):456-66.

11. Johnson MW et al. Neurotherapeutics. 2017 Jul;14(3):734-40.

12. Mutonni S et al. J Affect Disord. 2019 Nov.1;258:11-24.

13. Nagele P et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Apr;38(2):144-8.

*Correction, 1/9/2020: An earlier version of this story misidentified the intended disease state.

A significant proportion of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) either do not respond or have partial responses to the currently available Food and Drug Administration–approved antidepressants.

In controlled clinical trials, there is about a 40%-60% symptom remission rate with a 20%-40% remission rate in community-based treatment settings. Not only do those medications lack efficacy in treating MDD, but there are currently no cures for this debilitating illness. As a result, many patients with MDD continue to suffer.

In response to those poor outcomes, researchers and clinicians have developed algorithms aimed at diagnosing the condition of treatment-resistant depression (TRD),1 which enable opportunities for various treatment methods.2 Several studies underway across the United States are testing what some might consider medically invasive procedures, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), deep brain stimulation (DBS), and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). ECT often is considered the gold standard of treatment response, but it requires anesthesia, induces a convulsion, and needs a willing patient and clinician. DBS has been used more widely in neurological treatment of movement disorders. Pioneering neurosurgical treatment for TRD reported recently in the American Journal of Psychiatry found that DBS of an area in the brain called the subcallosal cingulate produces clear and apparently sustained antidepressant effects.3 VNS4 remains an experimental treatment for MDD. TMS is safe, noninvasive, and approved by the FDA for depression, but responses appear similar to those with usual antidepressants.

It is not surprising, given those outcomes, that ketamine was fast-tracked in 2016. The enthusiasm related to ketamine’s effect on MDD and TRD has grown over time as more research findings reach the public. While it is unknown how ketamine affects the biological neural network, a single intravenous dose of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) in patients diagnosed with TRD can lead to improved depression symptoms outcomes within a few hours – and those effects were sustained in 65%-70% of patients at 24 hours. Antidepressants take many weeks to show effects. Ketamine’s exciting findings also offered hope to clinicians and patients trying to manage suicidal thoughts and plans. Ketamine was quickly approved by the FDA as a nasal spray medication.

Now, in another encouraging development, the FDA has granted the Usona Institute Breakthrough Therapy designation for psilocybin for the treatment of MDD. The medical benefits of psilocybin, or “magic mushrooms,” has a long empirical history in our literature. Most recently, psilocybin was featured on “60 Minutes,”5 and in his book, “How to Change Your Mind,”6Michael Pollan details how psychedelic drugs where used to investigate and treat psychiatric disorders until the 1960s, when street use and unsupervised administration led to restrictions on their research and clinical use.

With protocol-driven specific trials, they might become critical medications for a wide range of psychiatric disorders, such as depression, PTSD, anxiety, and addictions. Exciting findings are coming from Roland R. Griffiths, PhD, and his team at Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research. In a recent study8 with cancer patients suffering from depression and anxiety, carefully administered, specific and supervised high doses of psilocybin produced decreases in depression and anxiety, and increases in quality of life and life meaning attitudes. Those improved attitudes, behavior, and responses were sustained by 80% of the sample 6 months post treatment.

Dr. Griffiths’ center is collaborating with Usona, and this collaboration should result in specific guidelines for dose, safety, and protection against abuse and diversion,9 as the study and FDA trials for ketamine have as well.10 It is very encouraging that psychedelic drugs are receiving fast-track designations, and this development reflects a shift in the risk-benefit considerations taking place in our society. Changing attitudes about depression and other psychiatric diseases are encouraging new approaches and new treatments. Psychiatric suffering and pain are being prioritized in research and appreciated by the general public as devastating. Serious, random assignment placebo-controlled and double- blind research studies will define just how valuable these medications might be, what is the safe dose and duration, and for whom they might prove more effective than existing treatments.

The process will take some time. And it is worth remembering that, although research has been promising,11 the number of patients studied, research design, and outcomes are not yet proven for psilosybin.12 The FDA fast-track makes sense, and the agency should continue supporting these efforts for psychedelics. In fact, we think the FDA also should support the promising trials of nitrous oxide13 (laughing gas), and other safe and novel approaches to successfully treat refractory depression. While we wait for personalized psychiatric medicines to be developed and validated through the long process of FDA approval, we will at least have a larger suite of treatment options to match patients with, along with some new algorithms that treat MDD,* TRD, and other disorders just are around the corner.

Dr. Patterson Silver Wolf is an associate professor at Washington University in St. Louis’s Brown School of Social Work. He is a training faculty member for two National Institutes of Health–funded (T32) training programs and serves as the director of the Community Academic Partnership on Addiction (CAPA). He’s chief research officer at the new CAPA Clinic, a teaching addiction treatment facility that is incorporating and testing various performance-based practice technology tools to respond to the opioid crisis and improve addiction treatment outcomes. Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University, St. Louis. He is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville. For more than 40 years, Dr. Gold has worked on developing models for understanding the effects of opioid, tobacco, cocaine, and other drugs, as well as food, on the brain and behavior. He has written several books and published more than 1,000 peer-reviewed scientific articles, texts, and practice guidelines.

References

1. Sackeim HA et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2019 Jun;113:125-36.

2. Conway CR et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 25 Nov;76(11):1569-70.

3. Crowell AL et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Oct 4. doi: 10.1176.appi.ajp.2019.18121427.

4. Kumar A et al. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019 Feb 13;15:457-68.

5. Psilocybin sessions: Psychedelics could help people with addiction and anxiety. “60 Minutes” CBS News. 2019 Oct 13.

6. Pollan M. How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence (Penguin Random House, 2018).

7. Nutt D. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2019;21(2):139-47.

8. Griffiths RR et al. J Psychopharmacol 2016 Dec;30(12):1181-97.

9. Johnson MW et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018 Nov;142:143-66.

10. Schwenk ES et al. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018 Jul;43(5):456-66.

11. Johnson MW et al. Neurotherapeutics. 2017 Jul;14(3):734-40.

12. Mutonni S et al. J Affect Disord. 2019 Nov.1;258:11-24.

13. Nagele P et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Apr;38(2):144-8.

*Correction, 1/9/2020: An earlier version of this story misidentified the intended disease state.

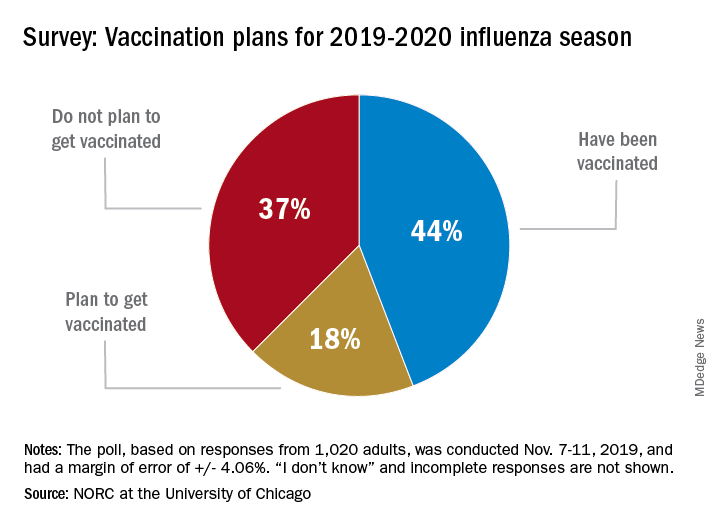

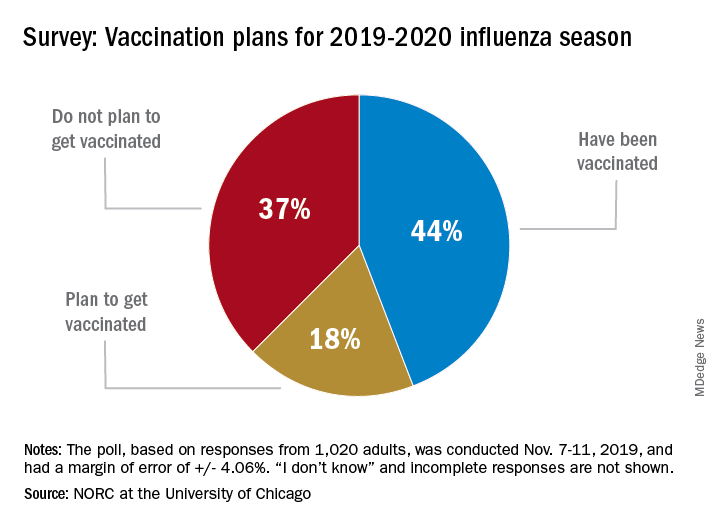

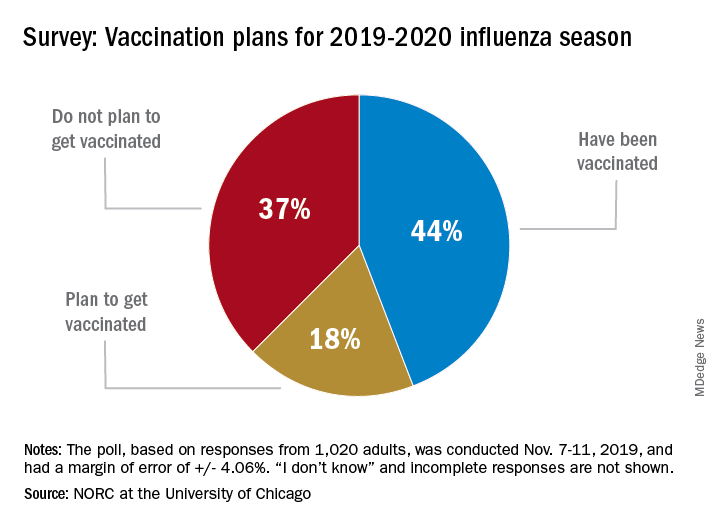

Many Americans planning to avoid flu vaccination

As the 2019-20 flu season got underway, more than half of American adults had not yet been vaccinated, according to a survey from the research organization NORC at the University of Chicago.

Only 44% of the 1,020 adults surveyed said that they had already received the vaccine as of Nov. 7-11, when the poll was conducted. Another the NORC reported. About 1% of those surveyed said they didn’t know or skipped the question.

Age was a strong determinant of vaccination status: 35% of those aged 18-29 years had gotten their flu shot, along with 36% of respondents aged 30-44 years and 34% of those aged 45- 59 years, compared with 65% of those aged 60 years and older. Of the respondents with children under age 18 years, 43% said that they were not planning to have the children vaccinated, the NORC said.

Concern about side effects, mentioned by 37% of those who were not planning to get vaccinated, was the most common reason given to avoid a flu shot, followed by belief that the vaccine doesn’t work very well (36%) and “never get the flu” (26%), the survey results showed.

“Widespread misconceptions exist regarding the safety and efficacy of flu shots. Because of the way the flu spreads in a community, failing to get a vaccination not only puts you at risk but also others for whom the consequences of the flu can be severe. Policymakers should focus on changing erroneous beliefs about immunizing against the flu,” said Caitlin Oppenheimer, who is senior vice president of public health research for the NORC, which has conducted the National Immunization Survey for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 2005.

As the 2019-20 flu season got underway, more than half of American adults had not yet been vaccinated, according to a survey from the research organization NORC at the University of Chicago.

Only 44% of the 1,020 adults surveyed said that they had already received the vaccine as of Nov. 7-11, when the poll was conducted. Another the NORC reported. About 1% of those surveyed said they didn’t know or skipped the question.

Age was a strong determinant of vaccination status: 35% of those aged 18-29 years had gotten their flu shot, along with 36% of respondents aged 30-44 years and 34% of those aged 45- 59 years, compared with 65% of those aged 60 years and older. Of the respondents with children under age 18 years, 43% said that they were not planning to have the children vaccinated, the NORC said.

Concern about side effects, mentioned by 37% of those who were not planning to get vaccinated, was the most common reason given to avoid a flu shot, followed by belief that the vaccine doesn’t work very well (36%) and “never get the flu” (26%), the survey results showed.

“Widespread misconceptions exist regarding the safety and efficacy of flu shots. Because of the way the flu spreads in a community, failing to get a vaccination not only puts you at risk but also others for whom the consequences of the flu can be severe. Policymakers should focus on changing erroneous beliefs about immunizing against the flu,” said Caitlin Oppenheimer, who is senior vice president of public health research for the NORC, which has conducted the National Immunization Survey for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 2005.

As the 2019-20 flu season got underway, more than half of American adults had not yet been vaccinated, according to a survey from the research organization NORC at the University of Chicago.

Only 44% of the 1,020 adults surveyed said that they had already received the vaccine as of Nov. 7-11, when the poll was conducted. Another the NORC reported. About 1% of those surveyed said they didn’t know or skipped the question.

Age was a strong determinant of vaccination status: 35% of those aged 18-29 years had gotten their flu shot, along with 36% of respondents aged 30-44 years and 34% of those aged 45- 59 years, compared with 65% of those aged 60 years and older. Of the respondents with children under age 18 years, 43% said that they were not planning to have the children vaccinated, the NORC said.

Concern about side effects, mentioned by 37% of those who were not planning to get vaccinated, was the most common reason given to avoid a flu shot, followed by belief that the vaccine doesn’t work very well (36%) and “never get the flu” (26%), the survey results showed.

“Widespread misconceptions exist regarding the safety and efficacy of flu shots. Because of the way the flu spreads in a community, failing to get a vaccination not only puts you at risk but also others for whom the consequences of the flu can be severe. Policymakers should focus on changing erroneous beliefs about immunizing against the flu,” said Caitlin Oppenheimer, who is senior vice president of public health research for the NORC, which has conducted the National Immunization Survey for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 2005.

Health benefits of TAVR over SAVR sustained at 1 year

SAN FRANCISCO – Among patients with severe aortic stenosis at low surgical risk, both transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement resulted in substantial health status benefits at 1 year despite most patients having New York Heart Association class I or II symptoms at baseline.

However, when compared with surgical replacement,

The findings come from an analysis of patients enrolled in the randomized PARTNER 3 trial, which showed that transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) with the SAPIEN 3 valve. At 1 year post procedure, the rate of the primary composite endpoint comprising death, stroke, or cardiovascular rehospitalization was 8.5% in the TAVR group and 15.1% with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), for a highly significant 46% relative risk reduction (N Engl J Med 2019 May 2;380:1695-705).

“The PARTNER 3 and Evolut Low Risk trials have demonstrated that transfemoral TAVR is both safe and effective when compared with SAVR in patients with severe aortic stenosis at low surgical risk,” Suzanne J. Baron, MD, MSc, said at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting. “While prior studies have demonstrated improved early health status with transfemoral TAVR, compared with SAVR in intermediate and high-risk patients, there is little evidence of any late health status benefit with TAVR.”

To address this gap in knowledge, Dr. Baron, director of interventional cardiology research at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., and associates performed a prospective study alongside the PARTNER 3 randomized trial to understand the impact of valve replacement strategy on early and late health status in aortic stenosis patients at low surgical risk. She reported results from 449 low-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis who were assigned to transfemoral TAVR using a balloon-expandable valve, and 449 who were assigned to surgery in PARTNER 3. At baseline, the mean age of patients was 73 years, 69% were male, and the average STS (Society of Thoracic Surgeons) Risk Score was 1.9%. Rates of other comorbidities were generally low.

Patients in both groups reported a mild baseline impairment in health status. The mean Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire–Overall Summary (KCCQ-OS) score was 70, “which corresponds to only New York Heart Association Class II symptoms,” Dr. Baron said. “The SF-36 [Short Form 36] physical summary score was 44 for both groups, which is approximately half of a standard deviation below the population mean.”

As expected, patients who underwent TAVR showed substantially improved health status at 1 month based on the KCCQ-OS (mean difference,16 points; P less than .001). However, in contrast to prior studies, the researchers observed a persistent, although attenuated, benefit of TAVR over SAVR in disease-specific health status at 6 and 12 months (mean difference in KCCQ-OS of 2.6 and 1.8 points respectively; P less than .04 for both).

Dr. Baron said that a sustained benefit of TAVR over SAVR at 6 months and 1 year was observed on several KCCQ subscales, but a similar benefit was not noted on the generic health status measures such as the SF-36 physical summary score. “That’s likely reflective of the fact that, as a disease-specific measure, the KCCQ is much more sensitive in detecting meaningful differences in this population,” she explained. When change in health status was analyzed as an ordinal variable, with death as the worst outcome and large clinical improvement, which was defined as a 20-point or greater increase in the KCCQ-OS score, TAVR showed a significant benefit, compared with surgery at all time points (P less than .05).

In an effort to better understand the mechanism underlying this persistent albeit small late benefit in disease-specific health status with TAVR, the researchers generated cumulative distribution curves to display the proportion of patients who achieved a given change on the KCCQ-OS. A clear separation of the curves emerged, with 5.2% more patients in the TAVR group experiencing a change of at least 20 points, compared with the surgery group. “This suggests that the difference in late health status between the two groups is driven by this 5.2% absolute risk difference in the proportion of patients who experienced a large clinical improvement,” Dr. Baron said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Next, the researchers performed subgroup analyses to examine the interaction between the 1-year health status benefit of TAVR over surgery and prespecified baseline characteristics including age, gender, STS risk score, ejection fraction, atrial fibrillation, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. They observed a significant interaction between NYHA class and treatment effect such that patients who had NYHA class III or IV symptoms at baseline derived greater benefit from TAVR, compared with those who had NYHA class I or II symptoms at baseline.

“This finding suggests that it’s the patients with worse functional impairment at baseline who may be that subset of patients on the cumulative responder curves who gained better health status outcomes with TAVR, compared with surgery in the low-risk population,” Dr. Baron said.

Suzanne V. Arnold, MD, a cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo., who was an invited discussant, said that it was “remarkable” that patients in the substudy were not particularly symptomatic and yet they still experienced close to a 20-point improvement in the KCCQ-OS score following TAVR, and asked whether frailty may have played a role in the 1.8-point adjusted difference in the KCCQ-OS score between TAVR and surgery at 1 year. Dr. Baron responded that she and her colleagues performed a subgroup analysis of patients who had two or more markers of frailty versus those who had one or less. Noting that there were only 20 patients in that subgroup, she said there was a significant signal that patients who were considered have two or more frail measures were considered to do much better with TAVR.

Dr. Baron concluded that the study’s overall findings, taken together with the clinical outcomes of the PARTNER 3 trial, “further support the use of TAVR in patients with severe [aortic stenosis] at low surgical risk. Longer-term follow up is needed (and ongoing) to determine whether the health status benefits of TAVR at 1 year are durable.”

The content of the study was published online at the time of presentation (J Am Coll Cardiol 2019 Sep 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.09.007). The PARTNER 3 quality of life substudy was funded by Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Baron disclosed research funding and advisory board compensation from Boston Scientific Corp and consulting fees from Edwards Lifesciences.

SAN FRANCISCO – Among patients with severe aortic stenosis at low surgical risk, both transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement resulted in substantial health status benefits at 1 year despite most patients having New York Heart Association class I or II symptoms at baseline.

However, when compared with surgical replacement,

The findings come from an analysis of patients enrolled in the randomized PARTNER 3 trial, which showed that transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) with the SAPIEN 3 valve. At 1 year post procedure, the rate of the primary composite endpoint comprising death, stroke, or cardiovascular rehospitalization was 8.5% in the TAVR group and 15.1% with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), for a highly significant 46% relative risk reduction (N Engl J Med 2019 May 2;380:1695-705).

“The PARTNER 3 and Evolut Low Risk trials have demonstrated that transfemoral TAVR is both safe and effective when compared with SAVR in patients with severe aortic stenosis at low surgical risk,” Suzanne J. Baron, MD, MSc, said at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting. “While prior studies have demonstrated improved early health status with transfemoral TAVR, compared with SAVR in intermediate and high-risk patients, there is little evidence of any late health status benefit with TAVR.”

To address this gap in knowledge, Dr. Baron, director of interventional cardiology research at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., and associates performed a prospective study alongside the PARTNER 3 randomized trial to understand the impact of valve replacement strategy on early and late health status in aortic stenosis patients at low surgical risk. She reported results from 449 low-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis who were assigned to transfemoral TAVR using a balloon-expandable valve, and 449 who were assigned to surgery in PARTNER 3. At baseline, the mean age of patients was 73 years, 69% were male, and the average STS (Society of Thoracic Surgeons) Risk Score was 1.9%. Rates of other comorbidities were generally low.

Patients in both groups reported a mild baseline impairment in health status. The mean Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire–Overall Summary (KCCQ-OS) score was 70, “which corresponds to only New York Heart Association Class II symptoms,” Dr. Baron said. “The SF-36 [Short Form 36] physical summary score was 44 for both groups, which is approximately half of a standard deviation below the population mean.”

As expected, patients who underwent TAVR showed substantially improved health status at 1 month based on the KCCQ-OS (mean difference,16 points; P less than .001). However, in contrast to prior studies, the researchers observed a persistent, although attenuated, benefit of TAVR over SAVR in disease-specific health status at 6 and 12 months (mean difference in KCCQ-OS of 2.6 and 1.8 points respectively; P less than .04 for both).

Dr. Baron said that a sustained benefit of TAVR over SAVR at 6 months and 1 year was observed on several KCCQ subscales, but a similar benefit was not noted on the generic health status measures such as the SF-36 physical summary score. “That’s likely reflective of the fact that, as a disease-specific measure, the KCCQ is much more sensitive in detecting meaningful differences in this population,” she explained. When change in health status was analyzed as an ordinal variable, with death as the worst outcome and large clinical improvement, which was defined as a 20-point or greater increase in the KCCQ-OS score, TAVR showed a significant benefit, compared with surgery at all time points (P less than .05).

In an effort to better understand the mechanism underlying this persistent albeit small late benefit in disease-specific health status with TAVR, the researchers generated cumulative distribution curves to display the proportion of patients who achieved a given change on the KCCQ-OS. A clear separation of the curves emerged, with 5.2% more patients in the TAVR group experiencing a change of at least 20 points, compared with the surgery group. “This suggests that the difference in late health status between the two groups is driven by this 5.2% absolute risk difference in the proportion of patients who experienced a large clinical improvement,” Dr. Baron said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Next, the researchers performed subgroup analyses to examine the interaction between the 1-year health status benefit of TAVR over surgery and prespecified baseline characteristics including age, gender, STS risk score, ejection fraction, atrial fibrillation, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. They observed a significant interaction between NYHA class and treatment effect such that patients who had NYHA class III or IV symptoms at baseline derived greater benefit from TAVR, compared with those who had NYHA class I or II symptoms at baseline.

“This finding suggests that it’s the patients with worse functional impairment at baseline who may be that subset of patients on the cumulative responder curves who gained better health status outcomes with TAVR, compared with surgery in the low-risk population,” Dr. Baron said.

Suzanne V. Arnold, MD, a cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo., who was an invited discussant, said that it was “remarkable” that patients in the substudy were not particularly symptomatic and yet they still experienced close to a 20-point improvement in the KCCQ-OS score following TAVR, and asked whether frailty may have played a role in the 1.8-point adjusted difference in the KCCQ-OS score between TAVR and surgery at 1 year. Dr. Baron responded that she and her colleagues performed a subgroup analysis of patients who had two or more markers of frailty versus those who had one or less. Noting that there were only 20 patients in that subgroup, she said there was a significant signal that patients who were considered have two or more frail measures were considered to do much better with TAVR.

Dr. Baron concluded that the study’s overall findings, taken together with the clinical outcomes of the PARTNER 3 trial, “further support the use of TAVR in patients with severe [aortic stenosis] at low surgical risk. Longer-term follow up is needed (and ongoing) to determine whether the health status benefits of TAVR at 1 year are durable.”

The content of the study was published online at the time of presentation (J Am Coll Cardiol 2019 Sep 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.09.007). The PARTNER 3 quality of life substudy was funded by Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Baron disclosed research funding and advisory board compensation from Boston Scientific Corp and consulting fees from Edwards Lifesciences.

SAN FRANCISCO – Among patients with severe aortic stenosis at low surgical risk, both transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement resulted in substantial health status benefits at 1 year despite most patients having New York Heart Association class I or II symptoms at baseline.

However, when compared with surgical replacement,

The findings come from an analysis of patients enrolled in the randomized PARTNER 3 trial, which showed that transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) with the SAPIEN 3 valve. At 1 year post procedure, the rate of the primary composite endpoint comprising death, stroke, or cardiovascular rehospitalization was 8.5% in the TAVR group and 15.1% with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), for a highly significant 46% relative risk reduction (N Engl J Med 2019 May 2;380:1695-705).

“The PARTNER 3 and Evolut Low Risk trials have demonstrated that transfemoral TAVR is both safe and effective when compared with SAVR in patients with severe aortic stenosis at low surgical risk,” Suzanne J. Baron, MD, MSc, said at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting. “While prior studies have demonstrated improved early health status with transfemoral TAVR, compared with SAVR in intermediate and high-risk patients, there is little evidence of any late health status benefit with TAVR.”

To address this gap in knowledge, Dr. Baron, director of interventional cardiology research at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., and associates performed a prospective study alongside the PARTNER 3 randomized trial to understand the impact of valve replacement strategy on early and late health status in aortic stenosis patients at low surgical risk. She reported results from 449 low-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis who were assigned to transfemoral TAVR using a balloon-expandable valve, and 449 who were assigned to surgery in PARTNER 3. At baseline, the mean age of patients was 73 years, 69% were male, and the average STS (Society of Thoracic Surgeons) Risk Score was 1.9%. Rates of other comorbidities were generally low.

Patients in both groups reported a mild baseline impairment in health status. The mean Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire–Overall Summary (KCCQ-OS) score was 70, “which corresponds to only New York Heart Association Class II symptoms,” Dr. Baron said. “The SF-36 [Short Form 36] physical summary score was 44 for both groups, which is approximately half of a standard deviation below the population mean.”

As expected, patients who underwent TAVR showed substantially improved health status at 1 month based on the KCCQ-OS (mean difference,16 points; P less than .001). However, in contrast to prior studies, the researchers observed a persistent, although attenuated, benefit of TAVR over SAVR in disease-specific health status at 6 and 12 months (mean difference in KCCQ-OS of 2.6 and 1.8 points respectively; P less than .04 for both).

Dr. Baron said that a sustained benefit of TAVR over SAVR at 6 months and 1 year was observed on several KCCQ subscales, but a similar benefit was not noted on the generic health status measures such as the SF-36 physical summary score. “That’s likely reflective of the fact that, as a disease-specific measure, the KCCQ is much more sensitive in detecting meaningful differences in this population,” she explained. When change in health status was analyzed as an ordinal variable, with death as the worst outcome and large clinical improvement, which was defined as a 20-point or greater increase in the KCCQ-OS score, TAVR showed a significant benefit, compared with surgery at all time points (P less than .05).

In an effort to better understand the mechanism underlying this persistent albeit small late benefit in disease-specific health status with TAVR, the researchers generated cumulative distribution curves to display the proportion of patients who achieved a given change on the KCCQ-OS. A clear separation of the curves emerged, with 5.2% more patients in the TAVR group experiencing a change of at least 20 points, compared with the surgery group. “This suggests that the difference in late health status between the two groups is driven by this 5.2% absolute risk difference in the proportion of patients who experienced a large clinical improvement,” Dr. Baron said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Next, the researchers performed subgroup analyses to examine the interaction between the 1-year health status benefit of TAVR over surgery and prespecified baseline characteristics including age, gender, STS risk score, ejection fraction, atrial fibrillation, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. They observed a significant interaction between NYHA class and treatment effect such that patients who had NYHA class III or IV symptoms at baseline derived greater benefit from TAVR, compared with those who had NYHA class I or II symptoms at baseline.

“This finding suggests that it’s the patients with worse functional impairment at baseline who may be that subset of patients on the cumulative responder curves who gained better health status outcomes with TAVR, compared with surgery in the low-risk population,” Dr. Baron said.

Suzanne V. Arnold, MD, a cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo., who was an invited discussant, said that it was “remarkable” that patients in the substudy were not particularly symptomatic and yet they still experienced close to a 20-point improvement in the KCCQ-OS score following TAVR, and asked whether frailty may have played a role in the 1.8-point adjusted difference in the KCCQ-OS score between TAVR and surgery at 1 year. Dr. Baron responded that she and her colleagues performed a subgroup analysis of patients who had two or more markers of frailty versus those who had one or less. Noting that there were only 20 patients in that subgroup, she said there was a significant signal that patients who were considered have two or more frail measures were considered to do much better with TAVR.

Dr. Baron concluded that the study’s overall findings, taken together with the clinical outcomes of the PARTNER 3 trial, “further support the use of TAVR in patients with severe [aortic stenosis] at low surgical risk. Longer-term follow up is needed (and ongoing) to determine whether the health status benefits of TAVR at 1 year are durable.”

The content of the study was published online at the time of presentation (J Am Coll Cardiol 2019 Sep 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.09.007). The PARTNER 3 quality of life substudy was funded by Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Baron disclosed research funding and advisory board compensation from Boston Scientific Corp and consulting fees from Edwards Lifesciences.

REPORTING FROM TCT 2019

PT-Cy bests conventional GVHD prophylaxis

ORLANDO – Posttransplant cyclophosphamide may be superior to conventional immunosuppression as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis, according to findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

A phase 3 trial showed that posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy) reduced graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) without affecting relapse. Rates of acute and chronic GVHD were significantly lower among patients who received PT-Cy than among those who received conventional immunosuppression (CIS). Rates of progression/relapse, progression-free survival, and overall survival were similar between the PT-Cy and CIS arms.

These results suggest PT-Cy provides a “long-term benefit and positive impact on quality of life” for patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, according to Annoek E.C. Broers, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Medical Center Cancer Institute in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Dr. Broers presented the results during the plenary session at ASH 2019.

The trial enrolled 160 patients with leukemias, lymphomas, myelomas, and other hematologic malignancies. All patients had a matched, related donor or an 8/8 or greater matched, unrelated donor.

The patients were randomized to receive CIS (n = 55) or PT-Cy (n = 105) as GVHD prophylaxis. The CIS regimen consisted of cyclosporine A (from day –3 to 180) and mycophenolic acid (from day 0 to 84). Patients in the PT-Cy arm received cyclophosphamide at 50 mg/kg (days 3 and 4) and cyclosporine A (from day 5 to 70).

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was 58 years in the CIS arm and 57 years in the PT-Cy arm. A majority of patients were men – 63% and 67%, respectively.

Two patients in the CIS arm received myeloablative conditioning, but all other patients received reduced-intensity conditioning. Most patients in the CIS arm (67%) and the PT-Cy arm (70%) had a matched, unrelated donor. All patients in the CIS arm and 96% in the PT-Cy arm received peripheral blood cell grafts.

PT-Cy significantly reduced the cumulative incidence of acute and chronic GVHD. The incidence of grade 2-4 acute GVHD at 6 months was 48% in the CIS arm and 32% in the PT-Cy arm (P = .014). The incidence of chronic extensive GVHD at 24 months was 50% and 19%, respectively (P = .001).

There were no significant between-arm differences for any other individual endpoint assessed.

“With a median follow-up of 3.2 years, so far, there’s no difference in the cumulative incidence of progression or relapse, nor is there a difference in progression-free or overall survival,” Dr. Broers said.

At 60 months, the rate of relapse/progression was 32% in the PT-Cy arm and 26% in the CIS arm (P = .36). The rate of nonrelapse mortality was 11% and 14%, respectively (P = .53).

At 60 months, the progression-free survival was 60% in the CIS arm and 58% in the PT-Cy arm (P = .67). The overall survival was 69% and 63%, respectively (P = .63).

In addition to assessing endpoints that “determine the success of our transplant strategy,” Dr. Broers said she and her colleagues also looked at a combined endpoint to account for “the effect GVHD has on morbidity and quality of life.” That endpoint is GVHD- and relapse-free survival.

The researchers found that PT-Cy improved GVHD- and relapse-free survival at 12 months. It was 22% in the CIS arm and 45% in the PT-Cy arm (P = .001). PT-Cy conferred this benefit irrespective of donor type, Dr. Broers noted.

Overall, the incidence of adverse events was somewhat higher in the PT-Cy arm (60%) than in the CIS arm (42%). The incidence of infections also was higher in the PT-Cy arm (41%) than in the CIS arm (21%), and this was largely caused by a greater incidence of neutropenic fever with PT-Cy (25% vs. 15%).

The study was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society, and Novartis provided the mycophenolic acid used in the study. Dr. Broers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Broers AEC et al. ASH 2019, Abstract 1.

ORLANDO – Posttransplant cyclophosphamide may be superior to conventional immunosuppression as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis, according to findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

A phase 3 trial showed that posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy) reduced graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) without affecting relapse. Rates of acute and chronic GVHD were significantly lower among patients who received PT-Cy than among those who received conventional immunosuppression (CIS). Rates of progression/relapse, progression-free survival, and overall survival were similar between the PT-Cy and CIS arms.

These results suggest PT-Cy provides a “long-term benefit and positive impact on quality of life” for patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, according to Annoek E.C. Broers, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Medical Center Cancer Institute in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Dr. Broers presented the results during the plenary session at ASH 2019.

The trial enrolled 160 patients with leukemias, lymphomas, myelomas, and other hematologic malignancies. All patients had a matched, related donor or an 8/8 or greater matched, unrelated donor.

The patients were randomized to receive CIS (n = 55) or PT-Cy (n = 105) as GVHD prophylaxis. The CIS regimen consisted of cyclosporine A (from day –3 to 180) and mycophenolic acid (from day 0 to 84). Patients in the PT-Cy arm received cyclophosphamide at 50 mg/kg (days 3 and 4) and cyclosporine A (from day 5 to 70).

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was 58 years in the CIS arm and 57 years in the PT-Cy arm. A majority of patients were men – 63% and 67%, respectively.

Two patients in the CIS arm received myeloablative conditioning, but all other patients received reduced-intensity conditioning. Most patients in the CIS arm (67%) and the PT-Cy arm (70%) had a matched, unrelated donor. All patients in the CIS arm and 96% in the PT-Cy arm received peripheral blood cell grafts.

PT-Cy significantly reduced the cumulative incidence of acute and chronic GVHD. The incidence of grade 2-4 acute GVHD at 6 months was 48% in the CIS arm and 32% in the PT-Cy arm (P = .014). The incidence of chronic extensive GVHD at 24 months was 50% and 19%, respectively (P = .001).

There were no significant between-arm differences for any other individual endpoint assessed.

“With a median follow-up of 3.2 years, so far, there’s no difference in the cumulative incidence of progression or relapse, nor is there a difference in progression-free or overall survival,” Dr. Broers said.

At 60 months, the rate of relapse/progression was 32% in the PT-Cy arm and 26% in the CIS arm (P = .36). The rate of nonrelapse mortality was 11% and 14%, respectively (P = .53).

At 60 months, the progression-free survival was 60% in the CIS arm and 58% in the PT-Cy arm (P = .67). The overall survival was 69% and 63%, respectively (P = .63).

In addition to assessing endpoints that “determine the success of our transplant strategy,” Dr. Broers said she and her colleagues also looked at a combined endpoint to account for “the effect GVHD has on morbidity and quality of life.” That endpoint is GVHD- and relapse-free survival.

The researchers found that PT-Cy improved GVHD- and relapse-free survival at 12 months. It was 22% in the CIS arm and 45% in the PT-Cy arm (P = .001). PT-Cy conferred this benefit irrespective of donor type, Dr. Broers noted.

Overall, the incidence of adverse events was somewhat higher in the PT-Cy arm (60%) than in the CIS arm (42%). The incidence of infections also was higher in the PT-Cy arm (41%) than in the CIS arm (21%), and this was largely caused by a greater incidence of neutropenic fever with PT-Cy (25% vs. 15%).

The study was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society, and Novartis provided the mycophenolic acid used in the study. Dr. Broers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Broers AEC et al. ASH 2019, Abstract 1.

ORLANDO – Posttransplant cyclophosphamide may be superior to conventional immunosuppression as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis, according to findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

A phase 3 trial showed that posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PT-Cy) reduced graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) without affecting relapse. Rates of acute and chronic GVHD were significantly lower among patients who received PT-Cy than among those who received conventional immunosuppression (CIS). Rates of progression/relapse, progression-free survival, and overall survival were similar between the PT-Cy and CIS arms.

These results suggest PT-Cy provides a “long-term benefit and positive impact on quality of life” for patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, according to Annoek E.C. Broers, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Medical Center Cancer Institute in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Dr. Broers presented the results during the plenary session at ASH 2019.

The trial enrolled 160 patients with leukemias, lymphomas, myelomas, and other hematologic malignancies. All patients had a matched, related donor or an 8/8 or greater matched, unrelated donor.

The patients were randomized to receive CIS (n = 55) or PT-Cy (n = 105) as GVHD prophylaxis. The CIS regimen consisted of cyclosporine A (from day –3 to 180) and mycophenolic acid (from day 0 to 84). Patients in the PT-Cy arm received cyclophosphamide at 50 mg/kg (days 3 and 4) and cyclosporine A (from day 5 to 70).

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was 58 years in the CIS arm and 57 years in the PT-Cy arm. A majority of patients were men – 63% and 67%, respectively.

Two patients in the CIS arm received myeloablative conditioning, but all other patients received reduced-intensity conditioning. Most patients in the CIS arm (67%) and the PT-Cy arm (70%) had a matched, unrelated donor. All patients in the CIS arm and 96% in the PT-Cy arm received peripheral blood cell grafts.

PT-Cy significantly reduced the cumulative incidence of acute and chronic GVHD. The incidence of grade 2-4 acute GVHD at 6 months was 48% in the CIS arm and 32% in the PT-Cy arm (P = .014). The incidence of chronic extensive GVHD at 24 months was 50% and 19%, respectively (P = .001).

There were no significant between-arm differences for any other individual endpoint assessed.

“With a median follow-up of 3.2 years, so far, there’s no difference in the cumulative incidence of progression or relapse, nor is there a difference in progression-free or overall survival,” Dr. Broers said.

At 60 months, the rate of relapse/progression was 32% in the PT-Cy arm and 26% in the CIS arm (P = .36). The rate of nonrelapse mortality was 11% and 14%, respectively (P = .53).

At 60 months, the progression-free survival was 60% in the CIS arm and 58% in the PT-Cy arm (P = .67). The overall survival was 69% and 63%, respectively (P = .63).

In addition to assessing endpoints that “determine the success of our transplant strategy,” Dr. Broers said she and her colleagues also looked at a combined endpoint to account for “the effect GVHD has on morbidity and quality of life.” That endpoint is GVHD- and relapse-free survival.

The researchers found that PT-Cy improved GVHD- and relapse-free survival at 12 months. It was 22% in the CIS arm and 45% in the PT-Cy arm (P = .001). PT-Cy conferred this benefit irrespective of donor type, Dr. Broers noted.

Overall, the incidence of adverse events was somewhat higher in the PT-Cy arm (60%) than in the CIS arm (42%). The incidence of infections also was higher in the PT-Cy arm (41%) than in the CIS arm (21%), and this was largely caused by a greater incidence of neutropenic fever with PT-Cy (25% vs. 15%).

The study was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society, and Novartis provided the mycophenolic acid used in the study. Dr. Broers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Broers AEC et al. ASH 2019, Abstract 1.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2019

Study delineates spectrum of Dravet syndrome phenotypes

BALTIMORE – , researchers said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. About half of patients have an afebrile seizure as their first seizure, and it is common for patients to present with seizures before age 5 months. Patients also may have seizure onset after age 18 months, said Wenhui Li, a researcher affiliated with Children’s Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai and University of Melbourne, and colleagues.

“Subtle differences in Dravet syndrome phenotypes lead to delayed diagnosis,” the researchers said. “Understanding key features within the phenotypic spectrum will assist clinicians in evaluating whether a child has Dravet syndrome, facilitating early diagnosis for precision therapies.”

Typically, Dravet syndrome is thought to begin with prolonged febrile hemiclonic or generalized tonic-clonic seizures at about age 6 months in normally developing infants. Multiple seizure types occur during subsequent years, including focal impaired awareness, bilateral tonic-clonic, absence, and myoclonic seizures.

Patients often do not receive a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome until they are older than 3 years, after “developmental plateau or regression occurs in the second year,” the investigators said. “Earlier diagnosis is critical for optimal management.”

To outline the range of phenotypes, researchers analyzed the clinical histories of 188 patients with Dravet syndrome and pathogenic SCN1A variants. They excluded from their analysis patients with SCN1A-positive genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+).

In all, 53% of the patients were female, and 2% had developmental delay prior to the onset of seizures. Age at seizure onset ranged from 1.5 months to 21 months (median, 5.75 months). Three patients had seizure onset after age 12 months, the authors noted.

In cases where the first seizure type could be classified, 52% had generalized tonic-clonic seizures at onset, 37% had hemiclonic seizures, 4% myoclonic seizures, 4% focal impaired awareness seizures, and 0.5% absence seizures. In addition, 1% had hemiclonic and myoclonic seizures, and 2% had tonic-clonic and myoclonic seizures.

Fifty-four percent of patients were febrile during their first seizure, and 46% were afebrile.

Status epilepticus as the first seizure occurred in about 44% of cases, while 35% of patients had a first seizure duration of 5 minutes or less.

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Li W et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.116.

BALTIMORE – , researchers said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. About half of patients have an afebrile seizure as their first seizure, and it is common for patients to present with seizures before age 5 months. Patients also may have seizure onset after age 18 months, said Wenhui Li, a researcher affiliated with Children’s Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai and University of Melbourne, and colleagues.

“Subtle differences in Dravet syndrome phenotypes lead to delayed diagnosis,” the researchers said. “Understanding key features within the phenotypic spectrum will assist clinicians in evaluating whether a child has Dravet syndrome, facilitating early diagnosis for precision therapies.”

Typically, Dravet syndrome is thought to begin with prolonged febrile hemiclonic or generalized tonic-clonic seizures at about age 6 months in normally developing infants. Multiple seizure types occur during subsequent years, including focal impaired awareness, bilateral tonic-clonic, absence, and myoclonic seizures.

Patients often do not receive a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome until they are older than 3 years, after “developmental plateau or regression occurs in the second year,” the investigators said. “Earlier diagnosis is critical for optimal management.”

To outline the range of phenotypes, researchers analyzed the clinical histories of 188 patients with Dravet syndrome and pathogenic SCN1A variants. They excluded from their analysis patients with SCN1A-positive genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+).

In all, 53% of the patients were female, and 2% had developmental delay prior to the onset of seizures. Age at seizure onset ranged from 1.5 months to 21 months (median, 5.75 months). Three patients had seizure onset after age 12 months, the authors noted.

In cases where the first seizure type could be classified, 52% had generalized tonic-clonic seizures at onset, 37% had hemiclonic seizures, 4% myoclonic seizures, 4% focal impaired awareness seizures, and 0.5% absence seizures. In addition, 1% had hemiclonic and myoclonic seizures, and 2% had tonic-clonic and myoclonic seizures.

Fifty-four percent of patients were febrile during their first seizure, and 46% were afebrile.

Status epilepticus as the first seizure occurred in about 44% of cases, while 35% of patients had a first seizure duration of 5 minutes or less.

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Li W et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.116.

BALTIMORE – , researchers said at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. About half of patients have an afebrile seizure as their first seizure, and it is common for patients to present with seizures before age 5 months. Patients also may have seizure onset after age 18 months, said Wenhui Li, a researcher affiliated with Children’s Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai and University of Melbourne, and colleagues.

“Subtle differences in Dravet syndrome phenotypes lead to delayed diagnosis,” the researchers said. “Understanding key features within the phenotypic spectrum will assist clinicians in evaluating whether a child has Dravet syndrome, facilitating early diagnosis for precision therapies.”

Typically, Dravet syndrome is thought to begin with prolonged febrile hemiclonic or generalized tonic-clonic seizures at about age 6 months in normally developing infants. Multiple seizure types occur during subsequent years, including focal impaired awareness, bilateral tonic-clonic, absence, and myoclonic seizures.

Patients often do not receive a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome until they are older than 3 years, after “developmental plateau or regression occurs in the second year,” the investigators said. “Earlier diagnosis is critical for optimal management.”

To outline the range of phenotypes, researchers analyzed the clinical histories of 188 patients with Dravet syndrome and pathogenic SCN1A variants. They excluded from their analysis patients with SCN1A-positive genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+).

In all, 53% of the patients were female, and 2% had developmental delay prior to the onset of seizures. Age at seizure onset ranged from 1.5 months to 21 months (median, 5.75 months). Three patients had seizure onset after age 12 months, the authors noted.

In cases where the first seizure type could be classified, 52% had generalized tonic-clonic seizures at onset, 37% had hemiclonic seizures, 4% myoclonic seizures, 4% focal impaired awareness seizures, and 0.5% absence seizures. In addition, 1% had hemiclonic and myoclonic seizures, and 2% had tonic-clonic and myoclonic seizures.

Fifty-four percent of patients were febrile during their first seizure, and 46% were afebrile.

Status epilepticus as the first seizure occurred in about 44% of cases, while 35% of patients had a first seizure duration of 5 minutes or less.

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Li W et al. AES 2019. Abstract 2.116.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Bariatric surgery tied to fewer cerebrovascular events

PHILADELPHIA – Obese people living in the United Kingdom who underwent bariatric surgery had a two-thirds lower rate of major cerebrovascular events than that of a matched group of obese residents who did not undergo bariatric surgery, in a retrospective study of 8,424 people followed for a mean of just over 11 years.