User login

Treating AKs with PDT, other options

SEATTLE – While David Pariser, MD, said during a presentation at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

“My personal view is that, no matter how good other treatments are eventually going to be, we’re never going to give that up,” Dr. Pariser, professor of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said at the meeting, jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education.

During the presentation, he emphasized that it isn’t always clear which actinic keratosis (AK) should be treated and which can be left alone, since most AKs don’t progress to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). “We know that most squamous cell carcinomas arise near AKs, and many of them have histologic evidence” of AK/SCC continuum at the periphery, he said. Sun protection reduces the incidence of AKs and the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer, “so it’s a logical conclusion that treating AKs reduces the development of SCCs, but there are no data to show that.”

Generally, treatment decisions are made based on the presence of symptoms, location, or appearance; if the area is irritated; or there is a progressive or unusual appearance, especially if hyperkeratotic. Physician or patient concerns about cancer can prompt treatment, as should a history of multiple skin cancers or the presence of immunosuppression, he said.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, surgery, topical agents, and photodynamic therapy (PDT); Dr. Pariser focused on the latter because it is a special interest of his.

Field cancerization is based on the idea that a broad area of cells may be at risk for developing into SCC, rather than just individual AKs. Treatment with methyl 5-aminolevulinate (MAL) can reveal the extent of a problem. In some patients, “you can see a lot of fluorescence in areas that look reasonably clinically normal. So this is a piece of evidence of this field cancerization, that maybe we shouldn’t be treating individual AKs, but larger areas,” Dr. Pariser said.

With PDT, there has been some debate about how long to leave the photosensitizer on the skin before applying the light. The longer it remains, the more it spreads to nerves, which can lead to pain during the procedure. A clinical trial comparing 1-, 2-, and 3-hour wait times showed no difference in efficacy. “So 1 hour is what I do for AKs, that’s it,” Dr. Pariser said.

There are two Food and Drug Administration–approved PDT systems, a blue-light system combined with aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and a newer red-light system combined with a nanoemulsion of ALA 7.8% and a proprietary 635-nm red LED light. The nanoemulsion has the theoretical advantage in that it can penetrate more deeply into the epidermis, though this isn’t really an issue when treating AKs, according to Dr. Pariser.

A study comparing nanoemulsion of ALA, compared with a MAL cream, found the nanoemulsion to be superior in achieving complete clearance of all lesions at 12 weeks (78.2% vs. 64.2%; P less than .05). Both treatments achieved best efficacy with LED lamps, and the proprietary red light may reduce pain by allowing use of lower light intensity (Br J Dermatol. 2012 Jan; 166[1]:137-46).

Another study, Dr. Pariser said, looked at whether occlusion during drug incubation improves outcomes of blue light ALA-PDT (J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11[12]:1483-9). Patients underwent split occlusion on the upper extremities before undergoing blue-light treatment. The median clearance rate of AKs at 8 weeks was higher with occlusion, compared with the nonoccluded areas (75% vs. 47%; P = .006), and at 12 weeks, after a second treatment (89% vs. 70%; P = .00029). There was a higher efficacy with a 3-hour incubation period, compared with studies using a 2-hour incubation period.

Application of heat can also boost success rates by increasing the synthesis of the photoactive agent, Dr. Pariser said. One study found that a simple heating pad applied to the area treated with ALA-PDT and blue light led to an 88% reduction in lesions at 8 and 24 weeks, compared with a reduction of 71% at 8 weeks and 68% at 24 weeks without heat (P less than .0001). “So if you want to give PDT a little extra oomph, add occlusion and heat,” he commented.

He also pointed out the availability of a new 4% 5-fluorouracil cream that contains peanut oil, which has similar efficacy to 5% 5-fluorouracil cream but has been associated with less pruritus, stinging/burning, edema, crusting, scaling/dryness, erosion, and erythema (J Drugs Dermatol. 2016 Oct 1;15[10]: 1218-24).

Dr. Pariser is an investigator and consultant for DUSA/Sun Pharma, Photocure, LEO Pharma, and Biofrontera. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

SEATTLE – While David Pariser, MD, said during a presentation at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

“My personal view is that, no matter how good other treatments are eventually going to be, we’re never going to give that up,” Dr. Pariser, professor of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said at the meeting, jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education.

During the presentation, he emphasized that it isn’t always clear which actinic keratosis (AK) should be treated and which can be left alone, since most AKs don’t progress to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). “We know that most squamous cell carcinomas arise near AKs, and many of them have histologic evidence” of AK/SCC continuum at the periphery, he said. Sun protection reduces the incidence of AKs and the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer, “so it’s a logical conclusion that treating AKs reduces the development of SCCs, but there are no data to show that.”

Generally, treatment decisions are made based on the presence of symptoms, location, or appearance; if the area is irritated; or there is a progressive or unusual appearance, especially if hyperkeratotic. Physician or patient concerns about cancer can prompt treatment, as should a history of multiple skin cancers or the presence of immunosuppression, he said.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, surgery, topical agents, and photodynamic therapy (PDT); Dr. Pariser focused on the latter because it is a special interest of his.

Field cancerization is based on the idea that a broad area of cells may be at risk for developing into SCC, rather than just individual AKs. Treatment with methyl 5-aminolevulinate (MAL) can reveal the extent of a problem. In some patients, “you can see a lot of fluorescence in areas that look reasonably clinically normal. So this is a piece of evidence of this field cancerization, that maybe we shouldn’t be treating individual AKs, but larger areas,” Dr. Pariser said.

With PDT, there has been some debate about how long to leave the photosensitizer on the skin before applying the light. The longer it remains, the more it spreads to nerves, which can lead to pain during the procedure. A clinical trial comparing 1-, 2-, and 3-hour wait times showed no difference in efficacy. “So 1 hour is what I do for AKs, that’s it,” Dr. Pariser said.

There are two Food and Drug Administration–approved PDT systems, a blue-light system combined with aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and a newer red-light system combined with a nanoemulsion of ALA 7.8% and a proprietary 635-nm red LED light. The nanoemulsion has the theoretical advantage in that it can penetrate more deeply into the epidermis, though this isn’t really an issue when treating AKs, according to Dr. Pariser.

A study comparing nanoemulsion of ALA, compared with a MAL cream, found the nanoemulsion to be superior in achieving complete clearance of all lesions at 12 weeks (78.2% vs. 64.2%; P less than .05). Both treatments achieved best efficacy with LED lamps, and the proprietary red light may reduce pain by allowing use of lower light intensity (Br J Dermatol. 2012 Jan; 166[1]:137-46).

Another study, Dr. Pariser said, looked at whether occlusion during drug incubation improves outcomes of blue light ALA-PDT (J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11[12]:1483-9). Patients underwent split occlusion on the upper extremities before undergoing blue-light treatment. The median clearance rate of AKs at 8 weeks was higher with occlusion, compared with the nonoccluded areas (75% vs. 47%; P = .006), and at 12 weeks, after a second treatment (89% vs. 70%; P = .00029). There was a higher efficacy with a 3-hour incubation period, compared with studies using a 2-hour incubation period.

Application of heat can also boost success rates by increasing the synthesis of the photoactive agent, Dr. Pariser said. One study found that a simple heating pad applied to the area treated with ALA-PDT and blue light led to an 88% reduction in lesions at 8 and 24 weeks, compared with a reduction of 71% at 8 weeks and 68% at 24 weeks without heat (P less than .0001). “So if you want to give PDT a little extra oomph, add occlusion and heat,” he commented.

He also pointed out the availability of a new 4% 5-fluorouracil cream that contains peanut oil, which has similar efficacy to 5% 5-fluorouracil cream but has been associated with less pruritus, stinging/burning, edema, crusting, scaling/dryness, erosion, and erythema (J Drugs Dermatol. 2016 Oct 1;15[10]: 1218-24).

Dr. Pariser is an investigator and consultant for DUSA/Sun Pharma, Photocure, LEO Pharma, and Biofrontera. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

SEATTLE – While David Pariser, MD, said during a presentation at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

“My personal view is that, no matter how good other treatments are eventually going to be, we’re never going to give that up,” Dr. Pariser, professor of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said at the meeting, jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education.

During the presentation, he emphasized that it isn’t always clear which actinic keratosis (AK) should be treated and which can be left alone, since most AKs don’t progress to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). “We know that most squamous cell carcinomas arise near AKs, and many of them have histologic evidence” of AK/SCC continuum at the periphery, he said. Sun protection reduces the incidence of AKs and the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer, “so it’s a logical conclusion that treating AKs reduces the development of SCCs, but there are no data to show that.”

Generally, treatment decisions are made based on the presence of symptoms, location, or appearance; if the area is irritated; or there is a progressive or unusual appearance, especially if hyperkeratotic. Physician or patient concerns about cancer can prompt treatment, as should a history of multiple skin cancers or the presence of immunosuppression, he said.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, surgery, topical agents, and photodynamic therapy (PDT); Dr. Pariser focused on the latter because it is a special interest of his.

Field cancerization is based on the idea that a broad area of cells may be at risk for developing into SCC, rather than just individual AKs. Treatment with methyl 5-aminolevulinate (MAL) can reveal the extent of a problem. In some patients, “you can see a lot of fluorescence in areas that look reasonably clinically normal. So this is a piece of evidence of this field cancerization, that maybe we shouldn’t be treating individual AKs, but larger areas,” Dr. Pariser said.

With PDT, there has been some debate about how long to leave the photosensitizer on the skin before applying the light. The longer it remains, the more it spreads to nerves, which can lead to pain during the procedure. A clinical trial comparing 1-, 2-, and 3-hour wait times showed no difference in efficacy. “So 1 hour is what I do for AKs, that’s it,” Dr. Pariser said.

There are two Food and Drug Administration–approved PDT systems, a blue-light system combined with aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and a newer red-light system combined with a nanoemulsion of ALA 7.8% and a proprietary 635-nm red LED light. The nanoemulsion has the theoretical advantage in that it can penetrate more deeply into the epidermis, though this isn’t really an issue when treating AKs, according to Dr. Pariser.

A study comparing nanoemulsion of ALA, compared with a MAL cream, found the nanoemulsion to be superior in achieving complete clearance of all lesions at 12 weeks (78.2% vs. 64.2%; P less than .05). Both treatments achieved best efficacy with LED lamps, and the proprietary red light may reduce pain by allowing use of lower light intensity (Br J Dermatol. 2012 Jan; 166[1]:137-46).

Another study, Dr. Pariser said, looked at whether occlusion during drug incubation improves outcomes of blue light ALA-PDT (J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11[12]:1483-9). Patients underwent split occlusion on the upper extremities before undergoing blue-light treatment. The median clearance rate of AKs at 8 weeks was higher with occlusion, compared with the nonoccluded areas (75% vs. 47%; P = .006), and at 12 weeks, after a second treatment (89% vs. 70%; P = .00029). There was a higher efficacy with a 3-hour incubation period, compared with studies using a 2-hour incubation period.

Application of heat can also boost success rates by increasing the synthesis of the photoactive agent, Dr. Pariser said. One study found that a simple heating pad applied to the area treated with ALA-PDT and blue light led to an 88% reduction in lesions at 8 and 24 weeks, compared with a reduction of 71% at 8 weeks and 68% at 24 weeks without heat (P less than .0001). “So if you want to give PDT a little extra oomph, add occlusion and heat,” he commented.

He also pointed out the availability of a new 4% 5-fluorouracil cream that contains peanut oil, which has similar efficacy to 5% 5-fluorouracil cream but has been associated with less pruritus, stinging/burning, edema, crusting, scaling/dryness, erosion, and erythema (J Drugs Dermatol. 2016 Oct 1;15[10]: 1218-24).

Dr. Pariser is an investigator and consultant for DUSA/Sun Pharma, Photocure, LEO Pharma, and Biofrontera. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM COASTAL DERM

‘Forward-Oriented’ Vector Holds Potential for Sickle Cell Cure

About 100,000 people in America have sickle cell disease. Of those, an estimated 27 people have undergone experimental gene therapy using conventional vectors—virus-based vehicles for delivering “therapeutic genes.” Now National Institutes of Health researchers have taken the vector idea and revved it up, bringing the possibility of curing sickle cell disease a bit closer.

With gene therapy, doctors add a normal copy of the β-globin gene to the patient’s hematopoietic stem cells, then reinfuse the modified stem cells into the patient to produce normal disc-shaped red blood cells. In animal studies, the new vector was up to 10 times more efficient at incorporating corrective genes into bone marrow stem cells with a carrying capacity of up to 6 times greater viral load than current vectors. The new vectors also can be produced in much higher amounts, saving time and lowering costs.

The researchers call it a “forward-oriented” vector because it changes the usual direction of how gene sequences in globin-containing vectors are read: from right to left. That backward orientation—globin-containing vectors are the only therapeutic vectors in clinical development that use it—the researchers say, “has remained unchallenged for decades despite its negative impacts on efficiency.”

The right-to-left orientation was dictated by the need to prevent the loss of a key molecular component, intron 2, by RNA splicing during the vector preparation. The redesigned forward-reading method crucially leaves intron 2 intact and makes the gene-translation approach less complicated, says John Tisdale, MD, chief of the Cellular and Molecular Therapeutic Branch at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, who, with Naoya Uchida, MD, PhD, came up with the idea.

In testing, the new vectors also proved longer lasting, remaining in place 4 years after transplantation.

National Institutes of Health is working to accelerate research and development through the Cure Sickle Cell Initiative, launched by NHLBI in 2018 to identify and support the most promising genetic therapies for the more than 20 million people worldwide who have sickle cell disease. NIH holds the patent for the new vector, which still will need clinical testing in humans. Clinical trials are actively enrolling.

About 100,000 people in America have sickle cell disease. Of those, an estimated 27 people have undergone experimental gene therapy using conventional vectors—virus-based vehicles for delivering “therapeutic genes.” Now National Institutes of Health researchers have taken the vector idea and revved it up, bringing the possibility of curing sickle cell disease a bit closer.

With gene therapy, doctors add a normal copy of the β-globin gene to the patient’s hematopoietic stem cells, then reinfuse the modified stem cells into the patient to produce normal disc-shaped red blood cells. In animal studies, the new vector was up to 10 times more efficient at incorporating corrective genes into bone marrow stem cells with a carrying capacity of up to 6 times greater viral load than current vectors. The new vectors also can be produced in much higher amounts, saving time and lowering costs.

The researchers call it a “forward-oriented” vector because it changes the usual direction of how gene sequences in globin-containing vectors are read: from right to left. That backward orientation—globin-containing vectors are the only therapeutic vectors in clinical development that use it—the researchers say, “has remained unchallenged for decades despite its negative impacts on efficiency.”

The right-to-left orientation was dictated by the need to prevent the loss of a key molecular component, intron 2, by RNA splicing during the vector preparation. The redesigned forward-reading method crucially leaves intron 2 intact and makes the gene-translation approach less complicated, says John Tisdale, MD, chief of the Cellular and Molecular Therapeutic Branch at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, who, with Naoya Uchida, MD, PhD, came up with the idea.

In testing, the new vectors also proved longer lasting, remaining in place 4 years after transplantation.

National Institutes of Health is working to accelerate research and development through the Cure Sickle Cell Initiative, launched by NHLBI in 2018 to identify and support the most promising genetic therapies for the more than 20 million people worldwide who have sickle cell disease. NIH holds the patent for the new vector, which still will need clinical testing in humans. Clinical trials are actively enrolling.

About 100,000 people in America have sickle cell disease. Of those, an estimated 27 people have undergone experimental gene therapy using conventional vectors—virus-based vehicles for delivering “therapeutic genes.” Now National Institutes of Health researchers have taken the vector idea and revved it up, bringing the possibility of curing sickle cell disease a bit closer.

With gene therapy, doctors add a normal copy of the β-globin gene to the patient’s hematopoietic stem cells, then reinfuse the modified stem cells into the patient to produce normal disc-shaped red blood cells. In animal studies, the new vector was up to 10 times more efficient at incorporating corrective genes into bone marrow stem cells with a carrying capacity of up to 6 times greater viral load than current vectors. The new vectors also can be produced in much higher amounts, saving time and lowering costs.

The researchers call it a “forward-oriented” vector because it changes the usual direction of how gene sequences in globin-containing vectors are read: from right to left. That backward orientation—globin-containing vectors are the only therapeutic vectors in clinical development that use it—the researchers say, “has remained unchallenged for decades despite its negative impacts on efficiency.”

The right-to-left orientation was dictated by the need to prevent the loss of a key molecular component, intron 2, by RNA splicing during the vector preparation. The redesigned forward-reading method crucially leaves intron 2 intact and makes the gene-translation approach less complicated, says John Tisdale, MD, chief of the Cellular and Molecular Therapeutic Branch at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, who, with Naoya Uchida, MD, PhD, came up with the idea.

In testing, the new vectors also proved longer lasting, remaining in place 4 years after transplantation.

National Institutes of Health is working to accelerate research and development through the Cure Sickle Cell Initiative, launched by NHLBI in 2018 to identify and support the most promising genetic therapies for the more than 20 million people worldwide who have sickle cell disease. NIH holds the patent for the new vector, which still will need clinical testing in humans. Clinical trials are actively enrolling.

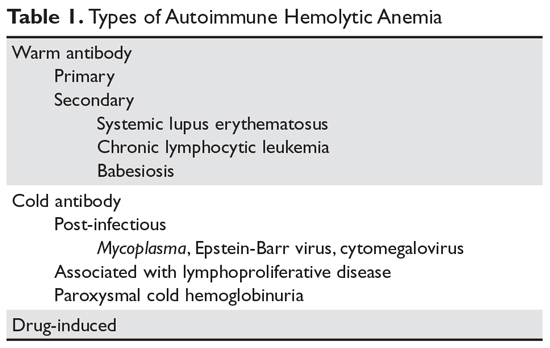

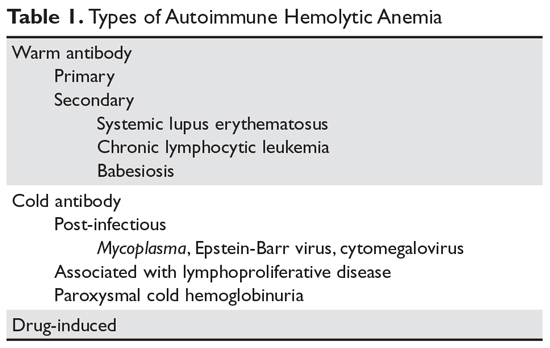

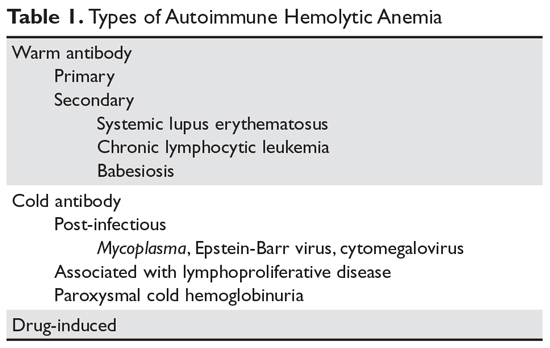

Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia: Treatment of Common Types

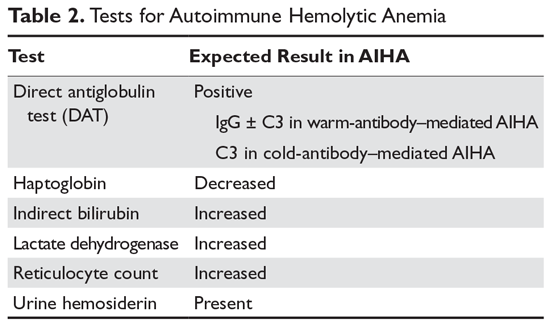

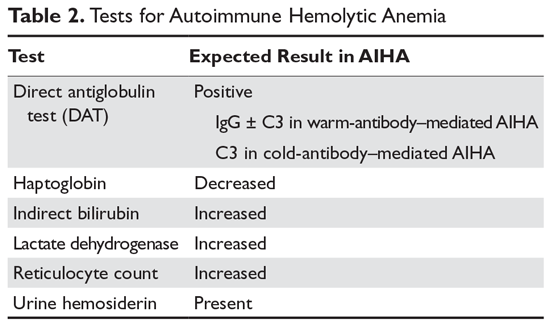

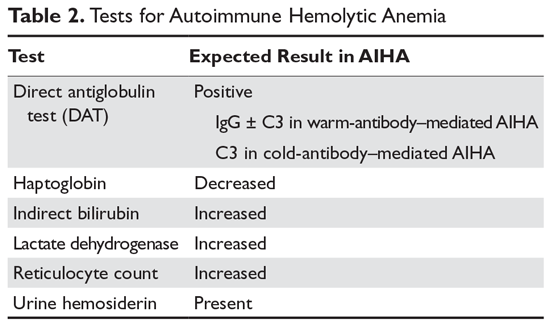

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is mediated by antibodies, and in most cases immunoglobulin (Ig) G is the mediating antibody. This type of AIHA is referred to as "warm" AIHA because IgG antibodies bind best at body temperature. "Cold" AIHA is mediated by IgM antibodies, which bind maximally at temperatures below 37°C. AIHA caused by a drug reaction is rare, with an estimated annual incidence of 1:1,000,000 for severe drug-related AIHA.1 This article reviews the management of the more common types of AIHA, with a focus on warm, cold, and drug-induced AIHA; the evaluation and diagnosis of AIHA is reviewed in a separate article.

Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

In AIHA, hemolysis is mediated by antibodies that bind to the surface of red blood cells. AIHA in which IgG antibodies are the offending antibodies is referred to as warm AIHA. “Warm” refers to the fact that the antibody binds best at body temperature (37°C). In warm AIHA, testing will show IgG molecules attached to the surface of the red cells, with 50% of patients also showing C3. Between 50% and 90% of AIHA cases are due to warm antibodies.2,3 The incidence of warm AIHA varies by series but is approximately 1 case per 100,000 patients per year; this form of hemolysis affects women more frequently than men.4,5

Therapeutic Options

First Line

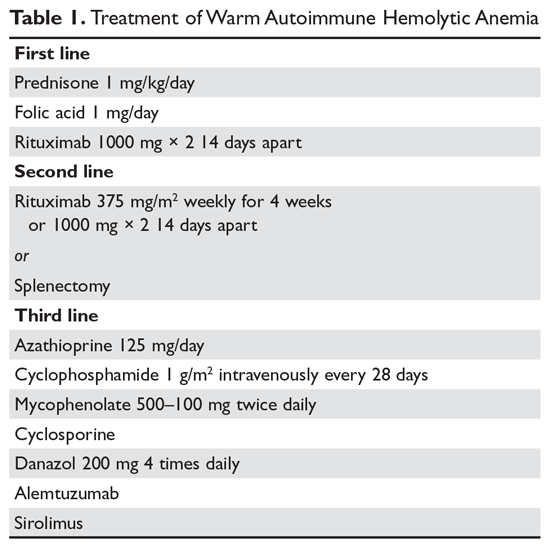

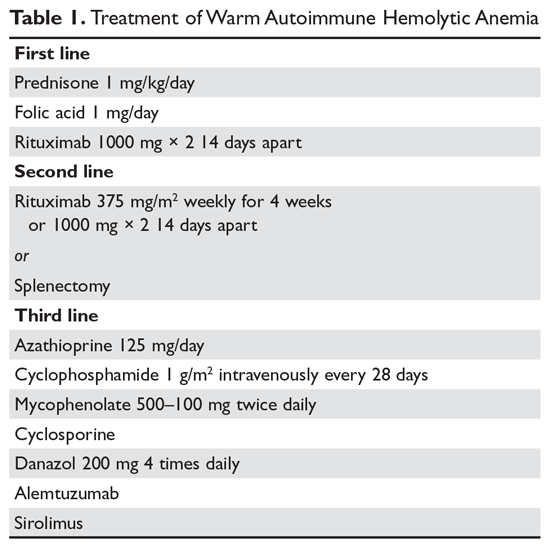

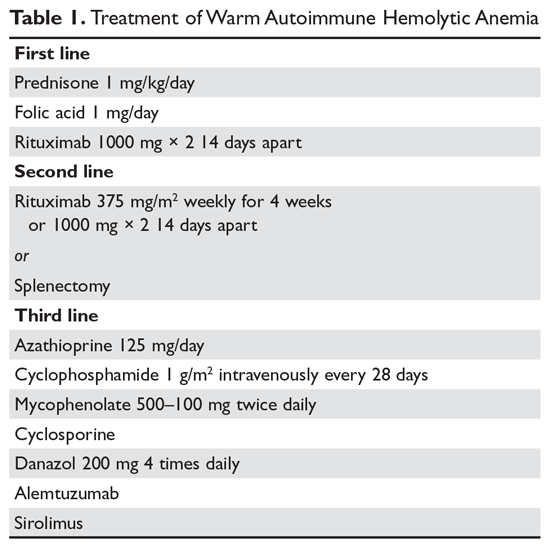

Steroids. The goal of therapy in warm AIHA can be hard to define. However, most would agree that a hematocrit above 30% (or higher to prevent symptoms) with a minimal increase in the reticulocyte count—reflective of a significantly slowed hemolytic process—is a reasonable goal. Initial management of warm AIHA is prednisone at a standard dose of 1 mg/kg daily (Table 1).6,7 Patients should be also started on proton-pump inhibitors to prevent ulcers. It can take up to 3 weeks for patients to respond to prednisone therapy. Once the patient’s hematocrit is above 30%, the prednisone is slowly tapered. Although approximately 80% of patients will respond to steroids, only 30% can be fully tapered off steroids. For patients who can be maintained on a daily steroid dose of 10 mg or less, steroids may be the most reasonable long-term therapy. In addition, because active hemolysis leads to an increased demand for folic acid, patients with warm AIHA are often prescribed folic acid 1 mg daily to prevent megaloblastic anemia due to folic acid deficiency.

Rituximab. Increasingly, rituximab (anti-CD20) therapy is added to the initial steroids. Two clinical trials showed both increased long-term and short-term responses with the use of rituximab.8,9 An important consideration is that most patients respond gradually to rituximab over weeks, so a rapid response should not be expected. Most studies have used the traditional dosing of 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks. These responses appear to be durable, but as in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), repeat treatment with rituximab is effective.

The major side effects of rituximab are infusion reactions, which are often worse with the first dose. These reactions can be controlled with antihistamines, steroids, and, for severe rigors, meperidine. Rarely, patients can develop neutropenia (approximately 1:500) that appears to be autoimmune in nature. Infections appear to be only minimally increased with the use of rituximab.10 One group at risk is chronic carriers of hepatitis B virus, who may experience a reactivation of the virus that can be fatal. Thus, patients being considered for rituximab need to be screened for hepatitis B virus carrier state.11 Patients receiving rituximab are at very slight risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, which is more common in patients with cancer and in heavily immunosuppressed patients. The overall risk is unknown but is less than 1:50,000.

Second Line

Splenectomy. For patients who cannot be weaned from steroids or in whom steroid therapy fails, there is no standard therapy. Currently, the 2 main choices are splenectomy or rituximab (anti-CD20) therapy if the patient did not receive it first line. Splenectomy is the classic therapy for warm AIHA. Reported response rates in the literature range from 50% to 80%, with 50% to 60% remaining in remission.12-16 Timing of the procedure is a balance between allowing time for the steroids to work and the risk of toxicity of steroids. In a patient who has low presurgical risk and has either refractory disease or cannot be weaned from high doses of steroids, splenectomy should be done sooner. Splenectomy can be delayed or other therapy tried first in patients who require lower doses of steroids or have medical risk factors for surgery. Most splenectomies are performed via laparoscopy. The small incisions allow for quicker healing, and the laparoscopic approach provides better visualization of the abdomen to find and remove accessory spleens. When splenectomy is performed by experienced surgeons, the mortality rate is low (< 0.5%).17

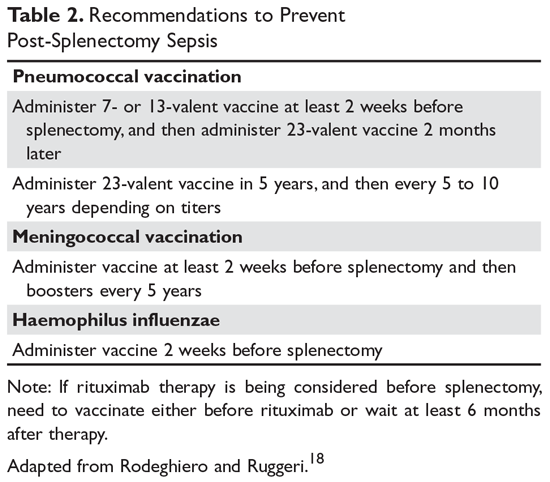

The most concerning complication of splenectomy is overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI).18 In adults, the spleen appears to play a minimal role in immunity except for protecting against certain encap-sulated organisms. Splenectomized patients infected with an encapsulated organism (eg, Pneumococcus) will develop overwhelming sepsis within hours. These patients will often have disseminated intravascular coagulation and will rapidly progress to purpura fulminans. Approximately 40% to 50% of patients will die of sepsis even when the infection is detected early. The overall lifetime risk of sepsis may be as high as 1:500. The organism that most commonly causes sepsis in splenectomized patients is Streptococcus pneumoniae, reported in over 50% of cases. Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae have also been implicated in many cases.19 Overwhelming sepsis after dog bites has been reported due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus infections. Patients are also at increased risk of developing severe malaria and severe babesiosis.18

Patients who have undergone splenectomy need to be warned about the risk of OPSI and instructed to report to the emergency department readily if they develop a fever greater than 101°F (38.3°C) or shaking chills. Once in the emergency department, blood cultures should be obtained rapidly and the patient started on antibiotic coverage with vancomycin and ceftriaxone (or levofloxacin if allergic to beta-lactams).20 For patients in remote areas, some physicians will prescribe prophylactic antibiotics to take while they are traveling to a health care provider or even recommend a “standby” antibiotic dose to take while traveling to health care.5 This usually consists of amoxicillin or a macrolide for penicillin-allergic patients.

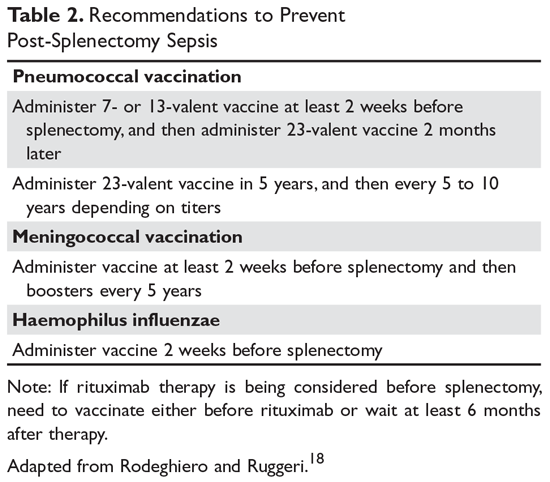

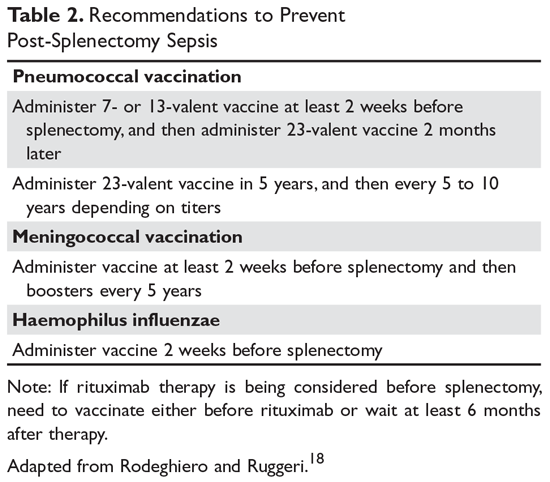

Patients in whom splenectomy is being planned or considered should be vaccinated for pneumococcal, meningococcal, and influenza infections (Table 2).18 If there is a plan to treat with rituximab, patients should first be vaccinated since they will not be able to mount an immune response after being treated with rituximab.

Third Line

The therapeutic options for patients who do not respond to either splenectomy or rituximab are much less certain.5,6 Although intravenous immune globulin is a standard therapy for ITP, response rates are low in warm AIHA.17 Numerous therapies have been reported in small series, but no clear approach has emerged. Options include azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, cyclosporine, danazol, and alemtuzumab. Our approach has been to use mycophenolate for patients requiring high doses of steroids or transfusions. Patients who respond to lower doses of steroids may be good candidates for danazol to help wean them off steroids.

Treatment of Warm AIHA with Associated Diseases

Warm AIHA can complicate several diseases. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can develop warm AIHA as part of their disease complex. The initial treatment approach is the same, but data suggest that splenectomy may not be as effective.13,17 Also, many SLE patients have complex medical conditions, making surgeries riskier. For SLE patients who are refractory or cannot be weaned from steroids, rituximab may be the better choice. Babesiosis, particularly in asplenic patients, has been associated with the development of AIHA.21,22

Of the malignances associated with AIHA, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has the strongest association.4,23 Series show that 5% to 10% of patients with CLL will have warm AIHA. AIHA can appear concurrent with CLL or develop during the course of the disease. The introduction of purine analogs such as fludarabine led to a dramatic increase in the incidence of warm AIHA in treated patients.24 It is speculated that these powerful agents reduce the number and effectiveness of T cells that hold in check the autoantibody response, leading to warm AIHA.25 However, when these purine analogs are used in com-bination with agents such as cyclophosphamide or rituximab (with their immunosuppressive effects), the rates of warm AIHA have been lower.23

The approach to patients with CLL and warm AIHA depends on the state of their CLL.23 For patients who have low-stage CLL that does not need treatment, the standard approach to warm AIHA should be steroids, splenectomy, and rituximab.24 For patients with higher-stage CLL, the treatment for the leukemia will often provide therapy for the warm AIHA. The combination of rituximab-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone has been reported to be effective for both the AIHA and CLL components.26 The use of ibrutinib has also been reported to be effective.27

A rare but important variant of warm AIHA is Evans syndrome.28,29 This is the combination of AIHA and ITP. Approximately 1% to 3% of AIHA cases are the Evans variant. The ITP can precede, be concurrent with, or develop after the AIHA. The diagnosis of Evans syndrome should raise concern for underlying disorders. In young adults, immunodeficiency disorders such as autoimmune lymphoproliferative disease (ALPS) need to be considered. In older patients, Evans syndrome is often associated with T cell lymphomas. The sparse literature on Evans syndrome suggests that it can be more refractory to standard therapy, with response rates to splenectomy in the 50% range.28,30 In patients with lymphoma, antineoplastic therapy is crucial. There is increasing data showing that mycophenolate or sirolimus may be effective for patients with ALPS in whom splenectomy or rituximab therapy is unsuccessful.31

Warm AIHA with IgA or IgM Antibodies

In rare patients with warm AIHA, IgA or IgM is the implicated antibody. The literature suggests that patients with IgA AIHA may have more severe hemolysis.32 Patients with IgM AIHA often have a severe course with a fatal outcome.33 In such cases, the patient’s plasma may show spontaneous hemolysis and agglutination. The DAT may not be strongly positive or may show C3 reactivity only. The clinical clues are C3 reactivity with no cold agglutinins and severe hemolysis, sometimes with an intravascular component. Treatment is the same as for warm AIHA, including the use of rituximab.34

Cold Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

In cold AIHA, the hemolysis is mediated by IgM antibodies directed against red cells.35 As discussed earlier, the term “cold” refers to the fact that the antibody binds maximally at temperatures below 37°C. The most efficient temperature for binding is called the “thermal amplitude,” and, in theory, the higher the thermal amplitude, the more virulent the antibody. An antibody titer can be calculated at each reaction temperature from 4°C to 37°C by serial dilutions of the patient’s serum prior to incubating with reagent red cells. Rarely, the IgM can fix complement rapidly, leading to intravascular hemolysis. In most patients, complement is fixed through C3, and the C3-coated red cells are taken up by macrophages in the mononuclear phagocyte system, primarily in the liver.3

The DAT in patients with cold AIHA will show cells coated with C3. The blood smear will often show ag-glutination of the blood, and if the blood cools before being analyzed, the agglutination will interfere with the analysis. Titers of cold agglutinin can range from 1:1000 to over 1 million. The IgM autoantibodies are most often directed against the I/i antigens on the red blood cell membrane, with 90% against I antigen.35 The I antigen specificity is typical with primary cold agglutinin disease and after Mycoplasma infection. The i antigen specificity is most typical of Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus infections in children. In young patients, cold AIHA often occurs following an infection, including viral and Mycoplasma infections, and the course is self-limited.35,36 The hemolysis usually starts 2 to 3 weeks after the illness and will last for 4 to 6 weeks. In older patients, the etiology in over 90% of cases is a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, usually with monoclonal kappa B-cells.37 The most common disorders are marginal zone lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma.3

Therapeutic Options

It is important to diagnose cold AIHA because the standard therapy for warm AIHA (steroids) is ineffective in cold AIHA. Because C3-coated red cells are taken up primarily in the liver, removing the spleen is also an ineffective therapy. Simple measures to help with cold AIHA should be employed.37 Patients should be kept in a warm environment and should try to avoid the cold. If transfusions are needed, they should be infused via blood warmers to prevent hemolysis. In rare patients with severe hemolysis, therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) can be considered.38 Given that the culprit antibody is IgM—mostly intravascular—use of TPE may slow the hemolysis to give time for other therapies to take effect.

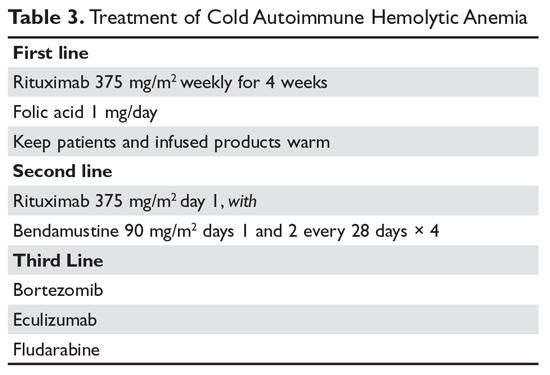

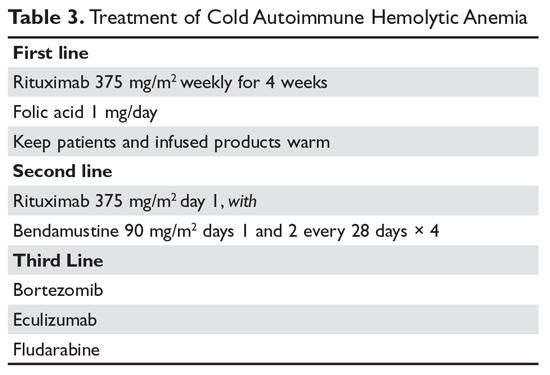

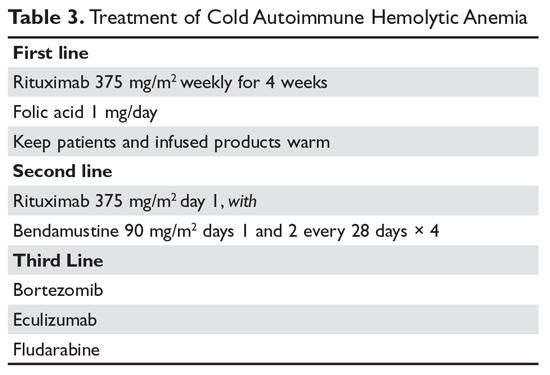

Treatment of cold AIHA remains difficult (Table 3). Because most patients with primary AIHA have underlying lymphoproliferative diseases, chlorambucil has been used in the past to treat cold AIHA. However, responses were rare and the drug could worsen the anemia.38 Currently, the drug of choice is rituximab. Response is seen in 45% to 75% of patients, but is almost always a partial response and retreatment is often necessary.17,37,39 As with other autoimmune hematologic diseases, there can be a delay in response that ranges from 2 weeks to 4 months (median time, 1.5 months).37 Given the lack of robust response (complete and durable) with rituximab, the Berentsen group has explored adding bendamustine to rituximab.40 In a prospective trial, 71% of patients responded with a 40% complete response rate. Therapy was well tolerated, with only 29% of patients needing dose reduction Although more toxic, this combination can be considered in patients with aggressive disease. A small study of the use of bortezomib showed a good response in one-third of patients.41 There is increasing use of the C5 complement inhibitor eculizumab to halt the hemolysis, but further study of this agent is also required.36,42,43 Blockers of C1s complement, which block hemolysis by preventing complement activation, are currently being studied in clinical trials.44

Since most patients with cold AIHA are older, a frequent issue that must be considered is cardiac surgery. The concern is that the hypothermia involved with most heart bypass procedures will lead to agglutination and hemolysis. The development of normothermic bypass has expanded treatment options. A recommended approach in patients who have known cold agglutinins is to measure the thermal amplitude of the antibody preoperatively. If the thermal amplitude is above 18°C, normothermic bypass should be done, if feasible.45 If not feasible, preoperative TPE should be considered.

Paroxysmal Cold Hemoglobinuria

A unique cold AIHA is paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria (PCH).3,46 This cold hemolytic syndrome most often occurs in children following a viral infection, but in the past it complicated any stage of syphilis.47 The mediating antibody in PCH is an IgG antibody directed against the P antigen on the red blood cell. This antibody binds best at temperatures below 37°C, fixing complement at cold temperatures, but then activates the complement cascade at body temperature.48 Because this antibody can fix complement, hemolysis can be rapid and severe, leading to extreme anemia. The DAT is often weakly positive but can be negative. The diagnostic test for PCH is the Donath–Landsteiner test. This complex test is performed by incubating 3 blood samples, 1 at 0° to 4°C, another at 37°C, and a third at 0° to 4°C and then at 37°C. The diagnosis of PCH is made if only the third tube shows hemolysis.35 PCH can persist for 1 to 3 months but is almost always self-limiting. In severe case, steroids may be of benefit.

Drug-Induced Hemolytic Anemia

AIHA caused by a drug reaction is rare, with a lower incidence than drug-related ITP. The rate of severe drug-related AIHA is estimated at 1:1,000,000, but less severe cases may be missed.1 Most patients will have a positive DAT without signs of hemolysis, but in rare cases patients will have relentless hemolysis resulting in death.

Mechanisms

Multiple mechanisms for drug-induced immune hemolysis have been proposed, including drug-absorption (hapten-induced) and immune complex mechanisms.1,49 The hapten mechanism is most often associated with the use of high-dose penicillin.50 High doses of penicillin or similar drugs such as piperacillin lead to incorporation of the drug into the red cell membrane by binding to proteins. Patients will manifest a positive DAT with IgG antibody but not complement.51 The patient’s plasma will be reactive only with penicillin-coated red cells and not with normal cells. As mentioned, very few patients will have hemolysis, and if they have hemolysis, it will resolve in a few days after discontinuation of the offending drug.52

Binding of a drug-antibody complex to the red cell membrane may cause hemolysis via the immune com-plex mechanism.53 Again, most often the patient will have just a positive DAT, but rarely patients will have life-threatening hemolysis upon exposure or reexposure to the drug. The onset of hemolysis is rapid, with signs of acute illness and intravascular hemolysis. The paradigm drug is quinine, but many other drugs have been implicated. Testing shows a positive Coombs test with anti-complement but not anti-IgG.50 This pattern is due to the effectiveness of the tertiary complex at fixing complement. The patient’s plasma reacts with red cells only when the drug is added.

A form of immune complex hemolysis associated with both disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and brisk hemolysis has been recognized. Patients who receive certain second- and third-generation cephalosporins (especially cefotetan and ceftriaxone.53,54) have developed this syndrome.50,55-59 The clinical symptoms start 7 to 10 days after the drug is administered; often the patient has only received the antibiotic for surgical prophylaxis. Immune hemolysis with acute hematocrit drop, hypotension, and DIC ensues. The patients are often believed to have sepsis and are often reexposed to the cephalosporin, resulting in worsening of the clinical status. The outcome is often fatal due to massive hemolysis and thrombosis.56,60,62

Finally, 8% to 36% of patients taking methyldopa will develop a positive DAT after 6 months of therapy, with less than 1% showing hemolysis.52,63 The hemolysis in these patients is indistinguishable from warm AIHA, consistent with the notion that methyldopa induces an AIHA. The hemolysis often resolves rapidly after the methyldopa is stopped, but the Coombs test may remain positive for months.63 This type of drug-induced hemolytic anemia has been reported with levodopa, procainamide, and chlorpromazine, but fludarabine is the most common cause currently. This form of AIHA is now being seen with increased use of checkpoint inhibitors.64

Diagnosis

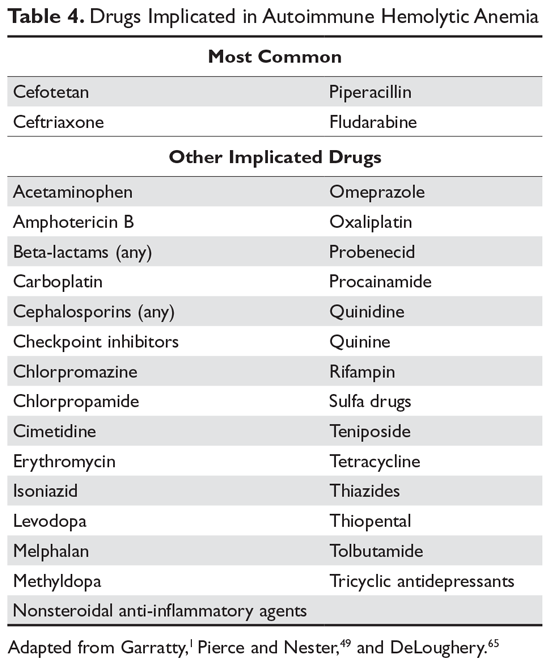

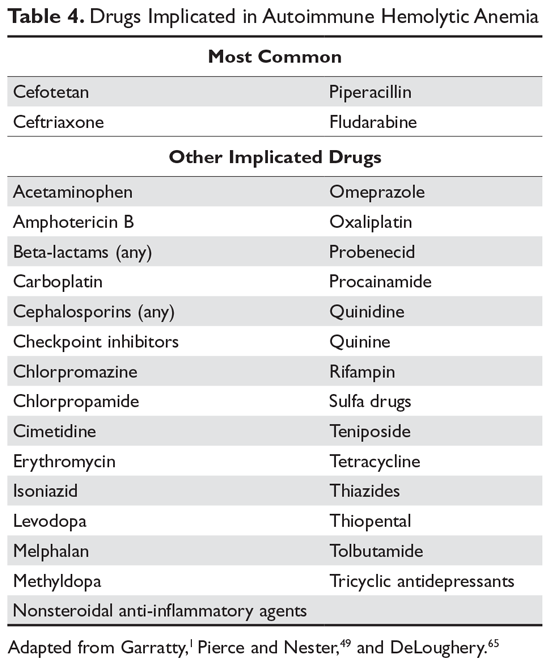

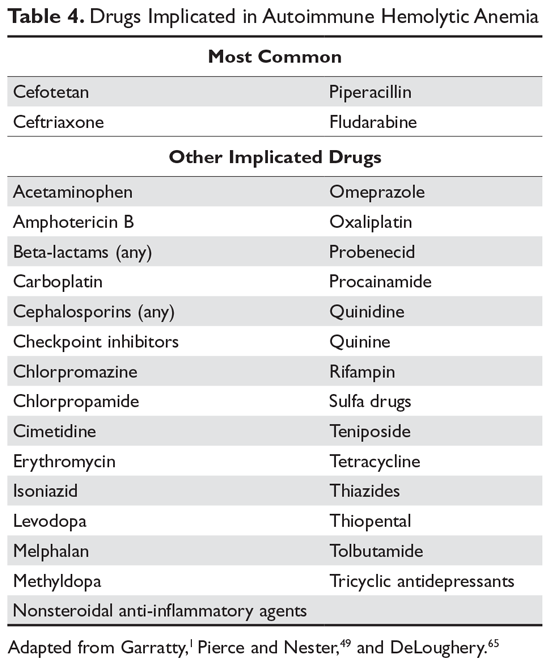

In many patients, the first clue to the presence of drug AIHA is the finding of a positive DAT. Rarely, patients will have severe hemolysis, but in many patients the hemolytic process is mild and may be wrongly assumed to be part of the underlying illness. Finding the offending drug can be a challenge, unless a patient has recently started a new drug; in a hospitalized patient on multiple agents, identifying the problem drug is difficult. Patients recently started on “suspect drugs,” especially the most common agents cefotetan, ceftriaxone, and piperacillin, should have these agents stopped (Table 4).1,49,65 Specialty laboratories such as the Blood Center of Wisconsin or the Los Angeles Red Cross can perform in vitro studies of drug interactions that can confirm the clinical diagnosis of drug-induced AIHA.

Treatment

Therapy for patients with positive DAT without signs of hemolysis is uncertain. If the drug is essential, then the patient can be observed. If the patient has hemolysis, the drug needs to be stopped and the patient observed for signs of end-organ damage. It is doubtful that steroids or other autoimmune-directed therapy is effective. For patients with the DIC-hemolysis syndrome, there are anecdotal reports that TPE may be helpful.1

Summary

AIHA can range from an abnormal laboratory test (positive DAT and signs of hemolysis) to an acute, life-threatening illness. Treatment is guided by the laboratory work-up and evaluation of the patient’s clinical status. While rituximab is promising for many patients, the lack of robust clinical trials hinders the treatment of patients who fail standard therapies.

1. Garratty G. Immune hemolytic anemia associated with drug therapy. Blood Rev. 2010;24:143-150.

2. Ness PM. How do I encourage clinicians to transfuse mismatched blood to patients with autoimmune hemolytic anemia in urgent situations? Transfusion. 2006;46:1859-1862.

3. Berentsen S. Cold agglutinin disease. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016:226-231.

4. Liebman HA, Weitz IC. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Med Clin North Am. 2017;101:351-359.

5. Barros MM, Blajchman MA, Bordin JO. Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia: recent progress in understanding the immunobiology and the treatment. Transfus Med Rev. 2010;24:195–210.

6. Kyrle PA, Rosendaal FR, Eichinger S. Risk assessment for re¬current venous thrombosis. Lancet. 2010;376:2032-2039.

7. Go RS, Winters JL, Kay NE. How I treat autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood. 2017;129:2971-2979.

8. Birgens H, Frederiksen H, Hasselbalch HC, et al. A phase III randomized trial comparing glucocorticoid monotherapy versus glucocorticoid and rituximab in patients with autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2013;163:393-399

9. Michel M, Terriou L, Roudot-Thoraval F, et al. A randomized and double-blind controlled trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of rituximab for warm auto-immune hemolytic anemia in adults (the RAIHA study). Am J Hematol. 2017;92:23-27.

10. Gea-Banacloche JC. Rituximab-associated infections. Semin Hematol. 2010;47:187-198.

11. Loomba R, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B reactivation associated with immune suppressive and biological modifier therapies: current concepts, management strategies, and future directions. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1297-1309.

12. Coon WW. Splenectomy in the treatment of hemolytic anemia. Arch Surg. 1985;120:625-628.

13. Akpek G, McAneny D, Weintraub L. Comparative response to splenectomy in coombs-positive autoimmune hemolytic anemia with or without associated disease. Am J Hematol. 1999;61:98-102.

14. Patel NY, Chilsen AM, Mathiason MA, et al. Outcomes and complications after splenectomy for hematologic disorders. Am J Surg. 2012;204:1014-1020.

15. Crowther M, Chan YL, Garbett IK, et al. Evidence-based focused review of the treatment of idiopathic warm immune hemolytic anemia in adults. Blood. 2011;118:4036-4040.

16. Giudice V, Rosamilio R, Ferrara I, et al. Efficacy and safety of splenectomy in adult autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Open Med (Wars). 2016;11:374-380.

17. Lechner K, Jager U. How I treat autoimmune hemolytic anemias in adults. Blood. 2010;116:1831-1838.

18. Rodeghiero F, Ruggeri M. Short- and long-term risks of splenectomy for benign haematological disorders: should we revisit the indications? Br J Haematol. 2012;158:16-29.

19. Ahmed N, Bialowas C, Kuo YH, Zawodniak L. Impact of preinjury anticoagulation in patients with traumatic brain injury. South Med J. 2009;102:476-480.

20. Morgan TL, Tomich EB. Overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI): a case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:758-763.

21. Woolley AE, Montgomery MW, Savage WJ, et al. Post-babesiosis warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:939-946.

22. Shatzel JJ, Donohoe K, Chu NQ, et al. Profound autoimmune hemolysis and Evans syndrome in two asplenic patients with babesiosis. Transfusion. 2015;55:661-665.

23. Hodgson K, Ferrer G, Montserrat E, Moreno C. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and autoimmunity: a systematic review. Haematologica. 2011;96:752-761.

24. Hamblin TJ. Autoimmune complications of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:230-239.

25. Tertian G, Cartron J, Bayle C, et al. Fatal intravascular au¬toimmune hemolytic anemia after fludarabine treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol Cell Ther. 1996;38:359-360.

26. Rossignol J, Michallet AS, Oberic L, et al. Rituximab-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone combination in the management of autoimmune cytopenias associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:473-478.

27. Hampel PJ, Larson MC, Kabat B, et al. Autoimmune cytopenias in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia treated with ibrutinib in routine clinical practice at an academic medical centre. Br J Haematol. 2018;183:421-427.

28. Michel M, Chanet V, Dechartres A, et al. The spectrum of Evans syndrome in adults: new insight into the disease based on the analysis of 68 cases. Blood. 2009;114:3167-3172.

29. Jaime-Pérez JC, Aguilar-Calderón PE, Salazar-Cavazos L, Gómez-Almaguer D. Evans syndrome: clinical perspectives, biological insights and treatment modalities. J Blood Med. 2018;9:171-184.

30. Dhingra KK, Jain D, Mandal S, et al. Evans syndrome: a study of six cases with review of literature. Hematology. 2008;13:356-360.

31. Bride KL, Vincent T, Smith-Whitley K, et al. Sirolimus is effective in relapsed/refractory autoimmune cytopenias: results of a prospective multi-institutional trial. Blood. 2016;127:17-28.

32. Sokol RJ, Booker DJ, Stamps R, et al. IgA red cell au¬toantibodies and autoimmune hemolysis. Transfusion. 1997;37:175-181.

33. Garratty G, Arndt P, Domen R, et al. Severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with IgM warm autoantibodies directed against determinants on or associated with glycophorin A. Vox Sang. 1997;72:124-130.

34. Wakim M, Shah A, Arndt PA, et al. Successful anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment of severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia due to warm reactive IgM autoantibody in a child with common variable immunodeficiency. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:152-155.

35. Gehrs BC, Friedberg RC. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Am J Hematol. 2002;69:258-271.

36. Berentsen S, Tjonnfjord GE. Diagnosis and treatment of cold agglutinin mediated autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood Rev. 2012;26:107-115.

37. Berentsen S. How I manage cold agglutinin disease. Br J Haematol. 2011;153:309-317.

38. King KE, Ness PM. Treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Semin Hematol. 2005;42:131136.

39. Barcellini W, Zaja F, Zaninoni A, et al. Low-dose rituximab in adult patients with idiopathic autoimmune hemolytic anemia: clinical efficacy and biologic studies. Blood. 2012;119:3691-3697.

40. Berentsen S, Randen U, Oksman M, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab for chronic cold agglutinin disease: results of a Nordic prospective multicenter trial. Blood. 2017;130:537-541.

41. Rossi G, Gramegna D, Paoloni F, et al. Short course of bortezomib in anemic patients with relapsed cold agglutinin disease: a phase 2 prospective GIMEMA study. Blood. 2018;132:547-550.

42. Makishima K, Obara N, Ishitsuka K, et al. High efficacy of eculizumab treatment for fulminant hemolytic anemia in primary cold agglutinin disease. Ann Hematol. 2019;98:1031-1032.

43. Roth A, Huttmann A, Rother RP, et al. Long-term efficacy of the complement inhibitor eculizumab in cold agglutinin disease. Blood. 2009;113:38853886.

44. Jäger U, D'Sa S, Schörgenhofer C, et al. Inhibition of complement C1s improves severe hemolytic anemia in cold agglutinin disease: a first-in-human trial. Blood. 2019;133:893-901.

45. Agarwal SK, Ghosh PK, Gupta D. Cardiac surgery and cold-reactive proteins. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1143-1150.

46. Shanbhag S, Spivak J. Paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2015;29:473-478.

47. Kumar ND, Sethi S, Pandhi RK. Paroxysmal cold haemoglobinuria in syphilis patients. Genitourin Med. 1993;69:76.

48. Zantek ND, Koepsell SA, Tharp DR Jr, Cohn CS. The direct antiglobulin test: a critical step in the evaluation of hemolysis. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:707-709.

49. Pierce A, Nester T. Pathology consultation on drug-induced hemolytic anemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:7-12.

50. Garratty G. Immune cytopenia associated with antibiotics. Transfusion Med Rev. 1993;7:255-267.

51. Petz LD, Mueller-Eckhardt C. Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia. Transfusion. 1992;32:202-204.

52. Packman CH, Leddy JP. Drug-related immune hemolytic anemia. In: Beutler E, Lichtman MA, Coller BS, Kipps TJ, eds. William’s Hematology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995:691-704.

53. Garratty G. Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;73-79.

54. Leicht HB, Weinig E, Mayer B, et al. Ceftriaxone-induced hemolytic anemia with severe renal failure: a case report and review of literature. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;19:67.

55. Chenoweth CE, Judd WJ, Steiner EA, Kauffman CA. Cefotetan-induced immune hemolytic anemia. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:863-865.

56. Garratty G, Nance S, Lloyd M, Domen R. Fatal im¬mune hemolytic anemia due to cefotetan. Transfusion. 1992;32:269-271.

57. Endoh T, Yagihashi A, Sasaki M, Watanabe N. Ceftizoxime-induced hemolysis due to immune complexes: case report and determination of the epitope responsible for immune complex-mediated hemolysis. Transfusion. 1999;39:306-309.

58. Arndt PA, Leger RM, Garratty G. Serology of antibodies to second- and third-generation cephalosporins associated with immune hemolytic anemia and/or positive direct antiglobulin tests. Transfusion. 1999;39:1239-1246.

59. Martin ME, Laber DA. Cefotetan-induced hemolytic anemia after perioperative prophylaxis. Am J Hematol. 2006;81:186-188.

60. Bernini JC, Mustafa MM, Sutor LJ, Buchanan GR. Fatal hemolysis induced by ceftriaxone in a child with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr. 1995;126(5 Pt 1):813-815.

61. Borgna-Pignatti C, Bezzi TM, Reverberi R. Fatal ceftriaxone-induced hemolysis in a child with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:1116-1117.

62. Lascari AD, Amyot K. Fatal hemolysis caused by ceftriaxone [see comments]. J Pediatr. 1995;126(5 Pt 1):816-817.

63. Petz LD. Drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Transfusion Med Rev. 1993;7:242-254.

64. Leaf RK, Ferreri C, Rangachari D, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:563-574.

65. DeLoughery T. Drug induced immune hematological disease. Allerg Immunol Clin. 1998;18:829-841.

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is mediated by antibodies, and in most cases immunoglobulin (Ig) G is the mediating antibody. This type of AIHA is referred to as "warm" AIHA because IgG antibodies bind best at body temperature. "Cold" AIHA is mediated by IgM antibodies, which bind maximally at temperatures below 37°C. AIHA caused by a drug reaction is rare, with an estimated annual incidence of 1:1,000,000 for severe drug-related AIHA.1 This article reviews the management of the more common types of AIHA, with a focus on warm, cold, and drug-induced AIHA; the evaluation and diagnosis of AIHA is reviewed in a separate article.

Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

In AIHA, hemolysis is mediated by antibodies that bind to the surface of red blood cells. AIHA in which IgG antibodies are the offending antibodies is referred to as warm AIHA. “Warm” refers to the fact that the antibody binds best at body temperature (37°C). In warm AIHA, testing will show IgG molecules attached to the surface of the red cells, with 50% of patients also showing C3. Between 50% and 90% of AIHA cases are due to warm antibodies.2,3 The incidence of warm AIHA varies by series but is approximately 1 case per 100,000 patients per year; this form of hemolysis affects women more frequently than men.4,5

Therapeutic Options

First Line

Steroids. The goal of therapy in warm AIHA can be hard to define. However, most would agree that a hematocrit above 30% (or higher to prevent symptoms) with a minimal increase in the reticulocyte count—reflective of a significantly slowed hemolytic process—is a reasonable goal. Initial management of warm AIHA is prednisone at a standard dose of 1 mg/kg daily (Table 1).6,7 Patients should be also started on proton-pump inhibitors to prevent ulcers. It can take up to 3 weeks for patients to respond to prednisone therapy. Once the patient’s hematocrit is above 30%, the prednisone is slowly tapered. Although approximately 80% of patients will respond to steroids, only 30% can be fully tapered off steroids. For patients who can be maintained on a daily steroid dose of 10 mg or less, steroids may be the most reasonable long-term therapy. In addition, because active hemolysis leads to an increased demand for folic acid, patients with warm AIHA are often prescribed folic acid 1 mg daily to prevent megaloblastic anemia due to folic acid deficiency.

Rituximab. Increasingly, rituximab (anti-CD20) therapy is added to the initial steroids. Two clinical trials showed both increased long-term and short-term responses with the use of rituximab.8,9 An important consideration is that most patients respond gradually to rituximab over weeks, so a rapid response should not be expected. Most studies have used the traditional dosing of 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks. These responses appear to be durable, but as in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), repeat treatment with rituximab is effective.

The major side effects of rituximab are infusion reactions, which are often worse with the first dose. These reactions can be controlled with antihistamines, steroids, and, for severe rigors, meperidine. Rarely, patients can develop neutropenia (approximately 1:500) that appears to be autoimmune in nature. Infections appear to be only minimally increased with the use of rituximab.10 One group at risk is chronic carriers of hepatitis B virus, who may experience a reactivation of the virus that can be fatal. Thus, patients being considered for rituximab need to be screened for hepatitis B virus carrier state.11 Patients receiving rituximab are at very slight risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, which is more common in patients with cancer and in heavily immunosuppressed patients. The overall risk is unknown but is less than 1:50,000.

Second Line

Splenectomy. For patients who cannot be weaned from steroids or in whom steroid therapy fails, there is no standard therapy. Currently, the 2 main choices are splenectomy or rituximab (anti-CD20) therapy if the patient did not receive it first line. Splenectomy is the classic therapy for warm AIHA. Reported response rates in the literature range from 50% to 80%, with 50% to 60% remaining in remission.12-16 Timing of the procedure is a balance between allowing time for the steroids to work and the risk of toxicity of steroids. In a patient who has low presurgical risk and has either refractory disease or cannot be weaned from high doses of steroids, splenectomy should be done sooner. Splenectomy can be delayed or other therapy tried first in patients who require lower doses of steroids or have medical risk factors for surgery. Most splenectomies are performed via laparoscopy. The small incisions allow for quicker healing, and the laparoscopic approach provides better visualization of the abdomen to find and remove accessory spleens. When splenectomy is performed by experienced surgeons, the mortality rate is low (< 0.5%).17

The most concerning complication of splenectomy is overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI).18 In adults, the spleen appears to play a minimal role in immunity except for protecting against certain encap-sulated organisms. Splenectomized patients infected with an encapsulated organism (eg, Pneumococcus) will develop overwhelming sepsis within hours. These patients will often have disseminated intravascular coagulation and will rapidly progress to purpura fulminans. Approximately 40% to 50% of patients will die of sepsis even when the infection is detected early. The overall lifetime risk of sepsis may be as high as 1:500. The organism that most commonly causes sepsis in splenectomized patients is Streptococcus pneumoniae, reported in over 50% of cases. Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae have also been implicated in many cases.19 Overwhelming sepsis after dog bites has been reported due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus infections. Patients are also at increased risk of developing severe malaria and severe babesiosis.18

Patients who have undergone splenectomy need to be warned about the risk of OPSI and instructed to report to the emergency department readily if they develop a fever greater than 101°F (38.3°C) or shaking chills. Once in the emergency department, blood cultures should be obtained rapidly and the patient started on antibiotic coverage with vancomycin and ceftriaxone (or levofloxacin if allergic to beta-lactams).20 For patients in remote areas, some physicians will prescribe prophylactic antibiotics to take while they are traveling to a health care provider or even recommend a “standby” antibiotic dose to take while traveling to health care.5 This usually consists of amoxicillin or a macrolide for penicillin-allergic patients.

Patients in whom splenectomy is being planned or considered should be vaccinated for pneumococcal, meningococcal, and influenza infections (Table 2).18 If there is a plan to treat with rituximab, patients should first be vaccinated since they will not be able to mount an immune response after being treated with rituximab.

Third Line

The therapeutic options for patients who do not respond to either splenectomy or rituximab are much less certain.5,6 Although intravenous immune globulin is a standard therapy for ITP, response rates are low in warm AIHA.17 Numerous therapies have been reported in small series, but no clear approach has emerged. Options include azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, cyclosporine, danazol, and alemtuzumab. Our approach has been to use mycophenolate for patients requiring high doses of steroids or transfusions. Patients who respond to lower doses of steroids may be good candidates for danazol to help wean them off steroids.

Treatment of Warm AIHA with Associated Diseases

Warm AIHA can complicate several diseases. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can develop warm AIHA as part of their disease complex. The initial treatment approach is the same, but data suggest that splenectomy may not be as effective.13,17 Also, many SLE patients have complex medical conditions, making surgeries riskier. For SLE patients who are refractory or cannot be weaned from steroids, rituximab may be the better choice. Babesiosis, particularly in asplenic patients, has been associated with the development of AIHA.21,22

Of the malignances associated with AIHA, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has the strongest association.4,23 Series show that 5% to 10% of patients with CLL will have warm AIHA. AIHA can appear concurrent with CLL or develop during the course of the disease. The introduction of purine analogs such as fludarabine led to a dramatic increase in the incidence of warm AIHA in treated patients.24 It is speculated that these powerful agents reduce the number and effectiveness of T cells that hold in check the autoantibody response, leading to warm AIHA.25 However, when these purine analogs are used in com-bination with agents such as cyclophosphamide or rituximab (with their immunosuppressive effects), the rates of warm AIHA have been lower.23

The approach to patients with CLL and warm AIHA depends on the state of their CLL.23 For patients who have low-stage CLL that does not need treatment, the standard approach to warm AIHA should be steroids, splenectomy, and rituximab.24 For patients with higher-stage CLL, the treatment for the leukemia will often provide therapy for the warm AIHA. The combination of rituximab-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone has been reported to be effective for both the AIHA and CLL components.26 The use of ibrutinib has also been reported to be effective.27

A rare but important variant of warm AIHA is Evans syndrome.28,29 This is the combination of AIHA and ITP. Approximately 1% to 3% of AIHA cases are the Evans variant. The ITP can precede, be concurrent with, or develop after the AIHA. The diagnosis of Evans syndrome should raise concern for underlying disorders. In young adults, immunodeficiency disorders such as autoimmune lymphoproliferative disease (ALPS) need to be considered. In older patients, Evans syndrome is often associated with T cell lymphomas. The sparse literature on Evans syndrome suggests that it can be more refractory to standard therapy, with response rates to splenectomy in the 50% range.28,30 In patients with lymphoma, antineoplastic therapy is crucial. There is increasing data showing that mycophenolate or sirolimus may be effective for patients with ALPS in whom splenectomy or rituximab therapy is unsuccessful.31

Warm AIHA with IgA or IgM Antibodies

In rare patients with warm AIHA, IgA or IgM is the implicated antibody. The literature suggests that patients with IgA AIHA may have more severe hemolysis.32 Patients with IgM AIHA often have a severe course with a fatal outcome.33 In such cases, the patient’s plasma may show spontaneous hemolysis and agglutination. The DAT may not be strongly positive or may show C3 reactivity only. The clinical clues are C3 reactivity with no cold agglutinins and severe hemolysis, sometimes with an intravascular component. Treatment is the same as for warm AIHA, including the use of rituximab.34

Cold Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

In cold AIHA, the hemolysis is mediated by IgM antibodies directed against red cells.35 As discussed earlier, the term “cold” refers to the fact that the antibody binds maximally at temperatures below 37°C. The most efficient temperature for binding is called the “thermal amplitude,” and, in theory, the higher the thermal amplitude, the more virulent the antibody. An antibody titer can be calculated at each reaction temperature from 4°C to 37°C by serial dilutions of the patient’s serum prior to incubating with reagent red cells. Rarely, the IgM can fix complement rapidly, leading to intravascular hemolysis. In most patients, complement is fixed through C3, and the C3-coated red cells are taken up by macrophages in the mononuclear phagocyte system, primarily in the liver.3

The DAT in patients with cold AIHA will show cells coated with C3. The blood smear will often show ag-glutination of the blood, and if the blood cools before being analyzed, the agglutination will interfere with the analysis. Titers of cold agglutinin can range from 1:1000 to over 1 million. The IgM autoantibodies are most often directed against the I/i antigens on the red blood cell membrane, with 90% against I antigen.35 The I antigen specificity is typical with primary cold agglutinin disease and after Mycoplasma infection. The i antigen specificity is most typical of Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus infections in children. In young patients, cold AIHA often occurs following an infection, including viral and Mycoplasma infections, and the course is self-limited.35,36 The hemolysis usually starts 2 to 3 weeks after the illness and will last for 4 to 6 weeks. In older patients, the etiology in over 90% of cases is a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, usually with monoclonal kappa B-cells.37 The most common disorders are marginal zone lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma.3

Therapeutic Options

It is important to diagnose cold AIHA because the standard therapy for warm AIHA (steroids) is ineffective in cold AIHA. Because C3-coated red cells are taken up primarily in the liver, removing the spleen is also an ineffective therapy. Simple measures to help with cold AIHA should be employed.37 Patients should be kept in a warm environment and should try to avoid the cold. If transfusions are needed, they should be infused via blood warmers to prevent hemolysis. In rare patients with severe hemolysis, therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) can be considered.38 Given that the culprit antibody is IgM—mostly intravascular—use of TPE may slow the hemolysis to give time for other therapies to take effect.

Treatment of cold AIHA remains difficult (Table 3). Because most patients with primary AIHA have underlying lymphoproliferative diseases, chlorambucil has been used in the past to treat cold AIHA. However, responses were rare and the drug could worsen the anemia.38 Currently, the drug of choice is rituximab. Response is seen in 45% to 75% of patients, but is almost always a partial response and retreatment is often necessary.17,37,39 As with other autoimmune hematologic diseases, there can be a delay in response that ranges from 2 weeks to 4 months (median time, 1.5 months).37 Given the lack of robust response (complete and durable) with rituximab, the Berentsen group has explored adding bendamustine to rituximab.40 In a prospective trial, 71% of patients responded with a 40% complete response rate. Therapy was well tolerated, with only 29% of patients needing dose reduction Although more toxic, this combination can be considered in patients with aggressive disease. A small study of the use of bortezomib showed a good response in one-third of patients.41 There is increasing use of the C5 complement inhibitor eculizumab to halt the hemolysis, but further study of this agent is also required.36,42,43 Blockers of C1s complement, which block hemolysis by preventing complement activation, are currently being studied in clinical trials.44

Since most patients with cold AIHA are older, a frequent issue that must be considered is cardiac surgery. The concern is that the hypothermia involved with most heart bypass procedures will lead to agglutination and hemolysis. The development of normothermic bypass has expanded treatment options. A recommended approach in patients who have known cold agglutinins is to measure the thermal amplitude of the antibody preoperatively. If the thermal amplitude is above 18°C, normothermic bypass should be done, if feasible.45 If not feasible, preoperative TPE should be considered.

Paroxysmal Cold Hemoglobinuria

A unique cold AIHA is paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria (PCH).3,46 This cold hemolytic syndrome most often occurs in children following a viral infection, but in the past it complicated any stage of syphilis.47 The mediating antibody in PCH is an IgG antibody directed against the P antigen on the red blood cell. This antibody binds best at temperatures below 37°C, fixing complement at cold temperatures, but then activates the complement cascade at body temperature.48 Because this antibody can fix complement, hemolysis can be rapid and severe, leading to extreme anemia. The DAT is often weakly positive but can be negative. The diagnostic test for PCH is the Donath–Landsteiner test. This complex test is performed by incubating 3 blood samples, 1 at 0° to 4°C, another at 37°C, and a third at 0° to 4°C and then at 37°C. The diagnosis of PCH is made if only the third tube shows hemolysis.35 PCH can persist for 1 to 3 months but is almost always self-limiting. In severe case, steroids may be of benefit.

Drug-Induced Hemolytic Anemia

AIHA caused by a drug reaction is rare, with a lower incidence than drug-related ITP. The rate of severe drug-related AIHA is estimated at 1:1,000,000, but less severe cases may be missed.1 Most patients will have a positive DAT without signs of hemolysis, but in rare cases patients will have relentless hemolysis resulting in death.

Mechanisms

Multiple mechanisms for drug-induced immune hemolysis have been proposed, including drug-absorption (hapten-induced) and immune complex mechanisms.1,49 The hapten mechanism is most often associated with the use of high-dose penicillin.50 High doses of penicillin or similar drugs such as piperacillin lead to incorporation of the drug into the red cell membrane by binding to proteins. Patients will manifest a positive DAT with IgG antibody but not complement.51 The patient’s plasma will be reactive only with penicillin-coated red cells and not with normal cells. As mentioned, very few patients will have hemolysis, and if they have hemolysis, it will resolve in a few days after discontinuation of the offending drug.52

Binding of a drug-antibody complex to the red cell membrane may cause hemolysis via the immune com-plex mechanism.53 Again, most often the patient will have just a positive DAT, but rarely patients will have life-threatening hemolysis upon exposure or reexposure to the drug. The onset of hemolysis is rapid, with signs of acute illness and intravascular hemolysis. The paradigm drug is quinine, but many other drugs have been implicated. Testing shows a positive Coombs test with anti-complement but not anti-IgG.50 This pattern is due to the effectiveness of the tertiary complex at fixing complement. The patient’s plasma reacts with red cells only when the drug is added.

A form of immune complex hemolysis associated with both disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and brisk hemolysis has been recognized. Patients who receive certain second- and third-generation cephalosporins (especially cefotetan and ceftriaxone.53,54) have developed this syndrome.50,55-59 The clinical symptoms start 7 to 10 days after the drug is administered; often the patient has only received the antibiotic for surgical prophylaxis. Immune hemolysis with acute hematocrit drop, hypotension, and DIC ensues. The patients are often believed to have sepsis and are often reexposed to the cephalosporin, resulting in worsening of the clinical status. The outcome is often fatal due to massive hemolysis and thrombosis.56,60,62

Finally, 8% to 36% of patients taking methyldopa will develop a positive DAT after 6 months of therapy, with less than 1% showing hemolysis.52,63 The hemolysis in these patients is indistinguishable from warm AIHA, consistent with the notion that methyldopa induces an AIHA. The hemolysis often resolves rapidly after the methyldopa is stopped, but the Coombs test may remain positive for months.63 This type of drug-induced hemolytic anemia has been reported with levodopa, procainamide, and chlorpromazine, but fludarabine is the most common cause currently. This form of AIHA is now being seen with increased use of checkpoint inhibitors.64

Diagnosis

In many patients, the first clue to the presence of drug AIHA is the finding of a positive DAT. Rarely, patients will have severe hemolysis, but in many patients the hemolytic process is mild and may be wrongly assumed to be part of the underlying illness. Finding the offending drug can be a challenge, unless a patient has recently started a new drug; in a hospitalized patient on multiple agents, identifying the problem drug is difficult. Patients recently started on “suspect drugs,” especially the most common agents cefotetan, ceftriaxone, and piperacillin, should have these agents stopped (Table 4).1,49,65 Specialty laboratories such as the Blood Center of Wisconsin or the Los Angeles Red Cross can perform in vitro studies of drug interactions that can confirm the clinical diagnosis of drug-induced AIHA.

Treatment

Therapy for patients with positive DAT without signs of hemolysis is uncertain. If the drug is essential, then the patient can be observed. If the patient has hemolysis, the drug needs to be stopped and the patient observed for signs of end-organ damage. It is doubtful that steroids or other autoimmune-directed therapy is effective. For patients with the DIC-hemolysis syndrome, there are anecdotal reports that TPE may be helpful.1

Summary

AIHA can range from an abnormal laboratory test (positive DAT and signs of hemolysis) to an acute, life-threatening illness. Treatment is guided by the laboratory work-up and evaluation of the patient’s clinical status. While rituximab is promising for many patients, the lack of robust clinical trials hinders the treatment of patients who fail standard therapies.

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is mediated by antibodies, and in most cases immunoglobulin (Ig) G is the mediating antibody. This type of AIHA is referred to as "warm" AIHA because IgG antibodies bind best at body temperature. "Cold" AIHA is mediated by IgM antibodies, which bind maximally at temperatures below 37°C. AIHA caused by a drug reaction is rare, with an estimated annual incidence of 1:1,000,000 for severe drug-related AIHA.1 This article reviews the management of the more common types of AIHA, with a focus on warm, cold, and drug-induced AIHA; the evaluation and diagnosis of AIHA is reviewed in a separate article.

Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

In AIHA, hemolysis is mediated by antibodies that bind to the surface of red blood cells. AIHA in which IgG antibodies are the offending antibodies is referred to as warm AIHA. “Warm” refers to the fact that the antibody binds best at body temperature (37°C). In warm AIHA, testing will show IgG molecules attached to the surface of the red cells, with 50% of patients also showing C3. Between 50% and 90% of AIHA cases are due to warm antibodies.2,3 The incidence of warm AIHA varies by series but is approximately 1 case per 100,000 patients per year; this form of hemolysis affects women more frequently than men.4,5

Therapeutic Options

First Line

Steroids. The goal of therapy in warm AIHA can be hard to define. However, most would agree that a hematocrit above 30% (or higher to prevent symptoms) with a minimal increase in the reticulocyte count—reflective of a significantly slowed hemolytic process—is a reasonable goal. Initial management of warm AIHA is prednisone at a standard dose of 1 mg/kg daily (Table 1).6,7 Patients should be also started on proton-pump inhibitors to prevent ulcers. It can take up to 3 weeks for patients to respond to prednisone therapy. Once the patient’s hematocrit is above 30%, the prednisone is slowly tapered. Although approximately 80% of patients will respond to steroids, only 30% can be fully tapered off steroids. For patients who can be maintained on a daily steroid dose of 10 mg or less, steroids may be the most reasonable long-term therapy. In addition, because active hemolysis leads to an increased demand for folic acid, patients with warm AIHA are often prescribed folic acid 1 mg daily to prevent megaloblastic anemia due to folic acid deficiency.

Rituximab. Increasingly, rituximab (anti-CD20) therapy is added to the initial steroids. Two clinical trials showed both increased long-term and short-term responses with the use of rituximab.8,9 An important consideration is that most patients respond gradually to rituximab over weeks, so a rapid response should not be expected. Most studies have used the traditional dosing of 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks. These responses appear to be durable, but as in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), repeat treatment with rituximab is effective.

The major side effects of rituximab are infusion reactions, which are often worse with the first dose. These reactions can be controlled with antihistamines, steroids, and, for severe rigors, meperidine. Rarely, patients can develop neutropenia (approximately 1:500) that appears to be autoimmune in nature. Infections appear to be only minimally increased with the use of rituximab.10 One group at risk is chronic carriers of hepatitis B virus, who may experience a reactivation of the virus that can be fatal. Thus, patients being considered for rituximab need to be screened for hepatitis B virus carrier state.11 Patients receiving rituximab are at very slight risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, which is more common in patients with cancer and in heavily immunosuppressed patients. The overall risk is unknown but is less than 1:50,000.

Second Line