User login

Real world responses mirror TOURMALINE-MM1 data

Glasgow – Patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) who were treated with a combination of the oral protease inhibitor ixazomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (IRd) in routine clinical practice had similar responses to clinical trial patients, according to a global observational study.

Real-world progression-free survival (PFS) and overall response (OR) rates closely approximated data from the TOURMALINE‑MM1 trial, reported lead author Gordon Cook, MB ChB, PhD, clinical director of hematology at the University of Leeds (England).

Tolerability appeared slightly higher in routine clinical practice, and in agreement with previous real-world studies for RRMM, patients who received IRd in earlier lines of therapy had better outcomes than did those who received IRd in later lines of therapy. “The translation of clinical trial data into the real world is really important because we practice in the real world,” Dr. Cook said at the annual meeting of the British Society for Haematology. “We know that trials are really important for establishing efficacy and safety of drugs so they can get licensed and market access, but [clinical trials] often don’t tell us about the true effectiveness of the drugs and tolerability because the populations in trials are often different from [patients in] the real world.”

This situation leads to an evidence gap, which the present trial, dubbed INSIGHT MM aims to fill. INSIGHT is the largest global, prospective, observational trial for multiple myeloma conducted to date, with ongoing enrollment of about 4,200 patients from 15 countries with newly diagnosed or refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma. Dr. Cook estimated that recruitment would be complete by June of 2019.

“The aim of [INSIGHT MM] is to evaluate real-world treatment and outcomes [in multiple myeloma] over 5 years and beyond,” Dr. Cook said.

In combination with interim data from INSIGHT MM (n = 50), Dr. Cook reported patient outcomes from the Czech Registry of Monoclonal Gammopathies (n = 113), a similar database. Unlike INSIGHT MM, which includes patients treated with between one and three prior lines of therapy, the Czech registry does not cap the number of prior therapies. Overall, in the data presented by Dr. Cook, nine countries were represented; about 90% of which were European, although approximately 10% of patients were treated in the United States and about 1% were treated in Taiwan.

The median age of diagnosis was 67 years, with about 14% of patients over the age of 75 years. Median time from diagnosis to initiation of IRd was about 3.5 years (42.6 months), at which point 71% of patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of at least 1.

About two-thirds of the patients (65%) had IgG multiple myeloma, and 14% had extramedullary disease. The most common prior therapy was bortezomib (89%), followed by transplant (61%), thalidomide (42%), lenalidomide (21%), carfilzomib (11%), daratumumab (3%), and pomalidomide (2%).

Half of the patients received IRd as second-line therapy, while the other half received the treatment third-line (30%), or fourth-line or later (20%). Median duration of therapy was just over 1 year (14 months), with 62% of patients still receiving therapy at data cutoff.

Dr. Cook cautioned that with a median follow-up of 9.3 months, data are still immature. However, the results so far suggest strong similarities in tolerability and efficacy when comparing real-world and clinical trial administration of IRd.

Routine clinical use was associated with an overall response rate of 74%, compared with 78% in the TOURMALINE‑MM1 trial. Again, showing high similarity, median PFS rates were 20.9 months and 20.6 months for the present data set and the TOURMALINE‑MM1 trial, respectively.

Just 4% of patients permanently discontinued ixazomib in the real-world study, compared with 17% in the clinical trial, suggesting that IRd may be better tolerated in routine clinical practice than the trial data indicated.

“IRd is effective in this setting,” Dr. Cook said. “Bear in mind that patients in the real-world database were further down the line in terms of the treatment pathway, they had prior heavier exposure to bortezomib and lenalidomide, and their performance status was slightly less impressive than it was in [TOURMALINE‑MM1]; therefore, to see this level of response in the real world is very pleasing.”

When asked by an attendee if clinical trials should push for inclusion of patients more representative of real-world populations, Dr. Cook said no. “I think the way we conduct phase 3 clinical trials, in particular, has to be the way it is in order for us to ensure that we can actually get the absolute efficacy and the safety, and that has to be done by a refined population, I’m afraid,” he said.

However, Dr. Cook supported efforts to improve reliability of data for clinicians at the time of drug licensing.

“We should be running real-world exposure in parallel with phase 3 studies, which is harder to do but just requires a bit of imagination,” Dr. Cook said.

The study was funded by Takeda. The investigators reported financial relationships with Takeda and other companies.

SOURCE: Cook G et al. BSH 2019, Abstract OR-018.

Glasgow – Patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) who were treated with a combination of the oral protease inhibitor ixazomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (IRd) in routine clinical practice had similar responses to clinical trial patients, according to a global observational study.

Real-world progression-free survival (PFS) and overall response (OR) rates closely approximated data from the TOURMALINE‑MM1 trial, reported lead author Gordon Cook, MB ChB, PhD, clinical director of hematology at the University of Leeds (England).

Tolerability appeared slightly higher in routine clinical practice, and in agreement with previous real-world studies for RRMM, patients who received IRd in earlier lines of therapy had better outcomes than did those who received IRd in later lines of therapy. “The translation of clinical trial data into the real world is really important because we practice in the real world,” Dr. Cook said at the annual meeting of the British Society for Haematology. “We know that trials are really important for establishing efficacy and safety of drugs so they can get licensed and market access, but [clinical trials] often don’t tell us about the true effectiveness of the drugs and tolerability because the populations in trials are often different from [patients in] the real world.”

This situation leads to an evidence gap, which the present trial, dubbed INSIGHT MM aims to fill. INSIGHT is the largest global, prospective, observational trial for multiple myeloma conducted to date, with ongoing enrollment of about 4,200 patients from 15 countries with newly diagnosed or refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma. Dr. Cook estimated that recruitment would be complete by June of 2019.

“The aim of [INSIGHT MM] is to evaluate real-world treatment and outcomes [in multiple myeloma] over 5 years and beyond,” Dr. Cook said.

In combination with interim data from INSIGHT MM (n = 50), Dr. Cook reported patient outcomes from the Czech Registry of Monoclonal Gammopathies (n = 113), a similar database. Unlike INSIGHT MM, which includes patients treated with between one and three prior lines of therapy, the Czech registry does not cap the number of prior therapies. Overall, in the data presented by Dr. Cook, nine countries were represented; about 90% of which were European, although approximately 10% of patients were treated in the United States and about 1% were treated in Taiwan.

The median age of diagnosis was 67 years, with about 14% of patients over the age of 75 years. Median time from diagnosis to initiation of IRd was about 3.5 years (42.6 months), at which point 71% of patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of at least 1.

About two-thirds of the patients (65%) had IgG multiple myeloma, and 14% had extramedullary disease. The most common prior therapy was bortezomib (89%), followed by transplant (61%), thalidomide (42%), lenalidomide (21%), carfilzomib (11%), daratumumab (3%), and pomalidomide (2%).

Half of the patients received IRd as second-line therapy, while the other half received the treatment third-line (30%), or fourth-line or later (20%). Median duration of therapy was just over 1 year (14 months), with 62% of patients still receiving therapy at data cutoff.

Dr. Cook cautioned that with a median follow-up of 9.3 months, data are still immature. However, the results so far suggest strong similarities in tolerability and efficacy when comparing real-world and clinical trial administration of IRd.

Routine clinical use was associated with an overall response rate of 74%, compared with 78% in the TOURMALINE‑MM1 trial. Again, showing high similarity, median PFS rates were 20.9 months and 20.6 months for the present data set and the TOURMALINE‑MM1 trial, respectively.

Just 4% of patients permanently discontinued ixazomib in the real-world study, compared with 17% in the clinical trial, suggesting that IRd may be better tolerated in routine clinical practice than the trial data indicated.

“IRd is effective in this setting,” Dr. Cook said. “Bear in mind that patients in the real-world database were further down the line in terms of the treatment pathway, they had prior heavier exposure to bortezomib and lenalidomide, and their performance status was slightly less impressive than it was in [TOURMALINE‑MM1]; therefore, to see this level of response in the real world is very pleasing.”

When asked by an attendee if clinical trials should push for inclusion of patients more representative of real-world populations, Dr. Cook said no. “I think the way we conduct phase 3 clinical trials, in particular, has to be the way it is in order for us to ensure that we can actually get the absolute efficacy and the safety, and that has to be done by a refined population, I’m afraid,” he said.

However, Dr. Cook supported efforts to improve reliability of data for clinicians at the time of drug licensing.

“We should be running real-world exposure in parallel with phase 3 studies, which is harder to do but just requires a bit of imagination,” Dr. Cook said.

The study was funded by Takeda. The investigators reported financial relationships with Takeda and other companies.

SOURCE: Cook G et al. BSH 2019, Abstract OR-018.

Glasgow – Patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) who were treated with a combination of the oral protease inhibitor ixazomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (IRd) in routine clinical practice had similar responses to clinical trial patients, according to a global observational study.

Real-world progression-free survival (PFS) and overall response (OR) rates closely approximated data from the TOURMALINE‑MM1 trial, reported lead author Gordon Cook, MB ChB, PhD, clinical director of hematology at the University of Leeds (England).

Tolerability appeared slightly higher in routine clinical practice, and in agreement with previous real-world studies for RRMM, patients who received IRd in earlier lines of therapy had better outcomes than did those who received IRd in later lines of therapy. “The translation of clinical trial data into the real world is really important because we practice in the real world,” Dr. Cook said at the annual meeting of the British Society for Haematology. “We know that trials are really important for establishing efficacy and safety of drugs so they can get licensed and market access, but [clinical trials] often don’t tell us about the true effectiveness of the drugs and tolerability because the populations in trials are often different from [patients in] the real world.”

This situation leads to an evidence gap, which the present trial, dubbed INSIGHT MM aims to fill. INSIGHT is the largest global, prospective, observational trial for multiple myeloma conducted to date, with ongoing enrollment of about 4,200 patients from 15 countries with newly diagnosed or refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma. Dr. Cook estimated that recruitment would be complete by June of 2019.

“The aim of [INSIGHT MM] is to evaluate real-world treatment and outcomes [in multiple myeloma] over 5 years and beyond,” Dr. Cook said.

In combination with interim data from INSIGHT MM (n = 50), Dr. Cook reported patient outcomes from the Czech Registry of Monoclonal Gammopathies (n = 113), a similar database. Unlike INSIGHT MM, which includes patients treated with between one and three prior lines of therapy, the Czech registry does not cap the number of prior therapies. Overall, in the data presented by Dr. Cook, nine countries were represented; about 90% of which were European, although approximately 10% of patients were treated in the United States and about 1% were treated in Taiwan.

The median age of diagnosis was 67 years, with about 14% of patients over the age of 75 years. Median time from diagnosis to initiation of IRd was about 3.5 years (42.6 months), at which point 71% of patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of at least 1.

About two-thirds of the patients (65%) had IgG multiple myeloma, and 14% had extramedullary disease. The most common prior therapy was bortezomib (89%), followed by transplant (61%), thalidomide (42%), lenalidomide (21%), carfilzomib (11%), daratumumab (3%), and pomalidomide (2%).

Half of the patients received IRd as second-line therapy, while the other half received the treatment third-line (30%), or fourth-line or later (20%). Median duration of therapy was just over 1 year (14 months), with 62% of patients still receiving therapy at data cutoff.

Dr. Cook cautioned that with a median follow-up of 9.3 months, data are still immature. However, the results so far suggest strong similarities in tolerability and efficacy when comparing real-world and clinical trial administration of IRd.

Routine clinical use was associated with an overall response rate of 74%, compared with 78% in the TOURMALINE‑MM1 trial. Again, showing high similarity, median PFS rates were 20.9 months and 20.6 months for the present data set and the TOURMALINE‑MM1 trial, respectively.

Just 4% of patients permanently discontinued ixazomib in the real-world study, compared with 17% in the clinical trial, suggesting that IRd may be better tolerated in routine clinical practice than the trial data indicated.

“IRd is effective in this setting,” Dr. Cook said. “Bear in mind that patients in the real-world database were further down the line in terms of the treatment pathway, they had prior heavier exposure to bortezomib and lenalidomide, and their performance status was slightly less impressive than it was in [TOURMALINE‑MM1]; therefore, to see this level of response in the real world is very pleasing.”

When asked by an attendee if clinical trials should push for inclusion of patients more representative of real-world populations, Dr. Cook said no. “I think the way we conduct phase 3 clinical trials, in particular, has to be the way it is in order for us to ensure that we can actually get the absolute efficacy and the safety, and that has to be done by a refined population, I’m afraid,” he said.

However, Dr. Cook supported efforts to improve reliability of data for clinicians at the time of drug licensing.

“We should be running real-world exposure in parallel with phase 3 studies, which is harder to do but just requires a bit of imagination,” Dr. Cook said.

The study was funded by Takeda. The investigators reported financial relationships with Takeda and other companies.

SOURCE: Cook G et al. BSH 2019, Abstract OR-018.

Reporting from BSH 2019

Powerful breast-implant testimony constrained by limited evidence

What’s the role of anecdotal medical histories in the era of evidence-based medicine?

But the anecdotal histories fell short of producing a clear committee consensus on dramatic, immediate changes in FDA policy, such as joining a renewed ban on certain types of breast implants linked with a rare lymphoma, a step recently taken by 38 other countries, including 33 European countries acting in concert through the European Union.

The disconnect between gripping testimony and limited panel recommendations was most stark for a complication that’s been named Breast Implant Illness (BII) by patients on the Internet. Many breast implant recipients have reported life-changing symptoms that appeared after implant placement, most often fatigue, joint and muscle pain, brain fog, neurologic symptoms, immune dysfunction, skin manifestations, and autoimmune disease or symptoms. By my count, 22 people spoke about their harrowing experiences with BII symptoms out of the 77 who stepped to the panel’s public-comment mic during 4 hours of public testimony over 2-days of hearings, often saying that they had experienced dramatic improvements after their implants came out. The meeting of the General and Plastic Surgery Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee also heard presentations from two experts who ran some of the first reported studies on BII, or a BII-like syndrome called Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Adjuvants (ASIA) described by Jan W.C. Tervaert, MD, professor of medicine and director of rheumatology at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Dr. Tervaert and his associates published their findings about ASIA in the rheumatology literature last year (Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Feb;37[2]:483-93), and during his talk before the FDA panel, he said that silicone breast implants and the surgical mesh often used with them could be ASIA triggers.

Panel members seemed to mostly believe that the evidence they heard about BII did no more than hint at a possible association between breast implants and BII symptoms that required additional study. Many agreed on the need to include mention of the most common BII-linked patient complaints in informed consent material, but some were reluctant about even taking that step.

“I do not mention BII to patients. It’s not a disease; it’s a constellation of symptoms,” said panel member and plastic surgeon Pierre M. Chevray, MD, from Houston Methodist Hospital. The evidence for BII “is extremely anecdotal,” he said in an interview at the end of the 2-day session. Descriptions of BII “have been mainly published on social media. One reason why I don’t tell patients [about BII as part of informed consent] is because right now the evidence of a link is weak. We don’t yet even have a definition of this as an illness. A first step is to define it,” said Dr. Chevray, who has a very active implant practice. Other plastic surgeons were more accepting of BII as a real complication, although they agreed it needs much more study. During the testimony period, St. Louis plastic surgeon Patricia A. McGuire, MD, highlighted the challenge of teasing apart whether real symptoms are truly related to implants or are simply common ailments that accumulate during middle-age in many women. Dr. McGuire and some of her associates published an assessment of the challenges and possible solutions to studying BII that appeared shortly before the hearing (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 March;143[3S]:74S-81S),

Consensus recommendations from the panel to the FDA to address BII included having a single registry that would include all U.S. patients who receive breast implants (recently launched as the National Breast Implant Registry), inclusion of a control group, and collection of data at baseline and after regular follow-up intervals that includes a variety of measures relevant to autoimmune and rheumatologic disorders. Several panel members cited inadequate postmarketing safety surveillance by manufacturers in the years since breast implants returned to the U.S. market, and earlier in March, the FDA issued warning letters to two of the four companies that market U.S. breast implants over their inadequate long-term safety follow-up.

The panel’s decisions about the other major implant-associated health risk it considered, breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), faced a different sort of challenge. First described as linked to breast implants in 2011, today there is little doubt that BIA-ALCL is a consequence of breast implants, what several patients derisively called a “man-made cancer.” The key issue the committee grappled with was whether the calculated incidence of BIA-ALCL was at a frequency that warranted a ban on at least selected breast implant types. Mark W. Clemens, MD, a plastic surgeon at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, told the panel that he calculated the Allergan Biocell group of implants, which have textured surfaces that allows for easier and more stable placement in patients, linked with an incidence of BIA-ALCL that was sevenfold to eightfold higher than that with smooth implants. That’s against a background of an overall incidence of about one case for every 20,000 U.S. implant recipients, Dr. Clemens said.

Many testifying patients, including several of the eight who described a personal history of BIA-ALCL, called for a ban on the sale of at least some breast implants because of their role in causing lymphoma. That sentiment was shared by Dr. Chevray, who endorsed a ban on “salt-loss” implants (the method that makes Biocell implants) during his closing comments to his fellow panel members. But earlier during panel discussions, others on the committee pushed back against implant bans, leaving the FDA’s eventual decision on this issue unclear. Evidence presented during the hearings suggests that implants cause ALCL by triggering a local “inflammatory milieu” and that different types of implants can have varying levels of potency for producing this milieu.

Perhaps the closest congruence between what patients called for and what the committee recommended was on informed consent. “No doubt, patients feel that informed consent failed them,” concluded panel member Karen E. Burke, MD, a New York dermatologist who was one of two panel discussants for the topic.

In addition to many suggestions on how to improve informed consent and public awareness lobbed at FDA staffers during the session by panel members, the final public comment of the 2 days came from Laurie A. Casas, MD, a Chicago plastic surgeon affiliated with the University of Chicago and a member of the board of directors of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (also know as the Aesthetic Society). During her testimony, Dr. Casas said “Over the past 2 days, we heard that patients need a structured educational checklist for informed consent. The Aesthetic Society hears you,” and promised that the website of the Society’s publication, the Aesthetic Surgery Journal, will soon feature a safety checklist for people receiving breast implants that will get updated as new information becomes available. She also highlighted the need for a comprehensive registry and long-term follow-up of implant recipients by the plastic surgeons who treated them.

In addition to better informed consent, patients who came to the hearing clearly also hoped to raise awareness in the general American public about the potential dangers from breast implants and the need to follow patients who receive implants. The 2 days of hearing accomplished that in part just by taking place. The New York Times and The Washington Post ran at least a couple of articles apiece on implant safety just before or during the hearings, while a more regional paper, the Philadelphia Inquirer, ran one article, as presumably did many other newspapers, broadcast outlets, and websites across America. Much of the coverage focused on compelling and moving personal stories from patients.

Women who have been having adverse effects from breast implants “have felt dismissed,” noted panel member Natalie C. Portis, PhD, a clinical psychologist from Oakland, Calif., and the patient representative on the advisory committee. “We need to listen to women that something real is happening.”

Dr. Tervaert, Dr. Chevray, Dr. McGuire, Dr. Clemens, Dr. Burke, Dr. Casas, and Dr. Portis had no relevant commercial disclosures.

What’s the role of anecdotal medical histories in the era of evidence-based medicine?

But the anecdotal histories fell short of producing a clear committee consensus on dramatic, immediate changes in FDA policy, such as joining a renewed ban on certain types of breast implants linked with a rare lymphoma, a step recently taken by 38 other countries, including 33 European countries acting in concert through the European Union.

The disconnect between gripping testimony and limited panel recommendations was most stark for a complication that’s been named Breast Implant Illness (BII) by patients on the Internet. Many breast implant recipients have reported life-changing symptoms that appeared after implant placement, most often fatigue, joint and muscle pain, brain fog, neurologic symptoms, immune dysfunction, skin manifestations, and autoimmune disease or symptoms. By my count, 22 people spoke about their harrowing experiences with BII symptoms out of the 77 who stepped to the panel’s public-comment mic during 4 hours of public testimony over 2-days of hearings, often saying that they had experienced dramatic improvements after their implants came out. The meeting of the General and Plastic Surgery Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee also heard presentations from two experts who ran some of the first reported studies on BII, or a BII-like syndrome called Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Adjuvants (ASIA) described by Jan W.C. Tervaert, MD, professor of medicine and director of rheumatology at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Dr. Tervaert and his associates published their findings about ASIA in the rheumatology literature last year (Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Feb;37[2]:483-93), and during his talk before the FDA panel, he said that silicone breast implants and the surgical mesh often used with them could be ASIA triggers.

Panel members seemed to mostly believe that the evidence they heard about BII did no more than hint at a possible association between breast implants and BII symptoms that required additional study. Many agreed on the need to include mention of the most common BII-linked patient complaints in informed consent material, but some were reluctant about even taking that step.

“I do not mention BII to patients. It’s not a disease; it’s a constellation of symptoms,” said panel member and plastic surgeon Pierre M. Chevray, MD, from Houston Methodist Hospital. The evidence for BII “is extremely anecdotal,” he said in an interview at the end of the 2-day session. Descriptions of BII “have been mainly published on social media. One reason why I don’t tell patients [about BII as part of informed consent] is because right now the evidence of a link is weak. We don’t yet even have a definition of this as an illness. A first step is to define it,” said Dr. Chevray, who has a very active implant practice. Other plastic surgeons were more accepting of BII as a real complication, although they agreed it needs much more study. During the testimony period, St. Louis plastic surgeon Patricia A. McGuire, MD, highlighted the challenge of teasing apart whether real symptoms are truly related to implants or are simply common ailments that accumulate during middle-age in many women. Dr. McGuire and some of her associates published an assessment of the challenges and possible solutions to studying BII that appeared shortly before the hearing (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 March;143[3S]:74S-81S),

Consensus recommendations from the panel to the FDA to address BII included having a single registry that would include all U.S. patients who receive breast implants (recently launched as the National Breast Implant Registry), inclusion of a control group, and collection of data at baseline and after regular follow-up intervals that includes a variety of measures relevant to autoimmune and rheumatologic disorders. Several panel members cited inadequate postmarketing safety surveillance by manufacturers in the years since breast implants returned to the U.S. market, and earlier in March, the FDA issued warning letters to two of the four companies that market U.S. breast implants over their inadequate long-term safety follow-up.

The panel’s decisions about the other major implant-associated health risk it considered, breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), faced a different sort of challenge. First described as linked to breast implants in 2011, today there is little doubt that BIA-ALCL is a consequence of breast implants, what several patients derisively called a “man-made cancer.” The key issue the committee grappled with was whether the calculated incidence of BIA-ALCL was at a frequency that warranted a ban on at least selected breast implant types. Mark W. Clemens, MD, a plastic surgeon at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, told the panel that he calculated the Allergan Biocell group of implants, which have textured surfaces that allows for easier and more stable placement in patients, linked with an incidence of BIA-ALCL that was sevenfold to eightfold higher than that with smooth implants. That’s against a background of an overall incidence of about one case for every 20,000 U.S. implant recipients, Dr. Clemens said.

Many testifying patients, including several of the eight who described a personal history of BIA-ALCL, called for a ban on the sale of at least some breast implants because of their role in causing lymphoma. That sentiment was shared by Dr. Chevray, who endorsed a ban on “salt-loss” implants (the method that makes Biocell implants) during his closing comments to his fellow panel members. But earlier during panel discussions, others on the committee pushed back against implant bans, leaving the FDA’s eventual decision on this issue unclear. Evidence presented during the hearings suggests that implants cause ALCL by triggering a local “inflammatory milieu” and that different types of implants can have varying levels of potency for producing this milieu.

Perhaps the closest congruence between what patients called for and what the committee recommended was on informed consent. “No doubt, patients feel that informed consent failed them,” concluded panel member Karen E. Burke, MD, a New York dermatologist who was one of two panel discussants for the topic.

In addition to many suggestions on how to improve informed consent and public awareness lobbed at FDA staffers during the session by panel members, the final public comment of the 2 days came from Laurie A. Casas, MD, a Chicago plastic surgeon affiliated with the University of Chicago and a member of the board of directors of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (also know as the Aesthetic Society). During her testimony, Dr. Casas said “Over the past 2 days, we heard that patients need a structured educational checklist for informed consent. The Aesthetic Society hears you,” and promised that the website of the Society’s publication, the Aesthetic Surgery Journal, will soon feature a safety checklist for people receiving breast implants that will get updated as new information becomes available. She also highlighted the need for a comprehensive registry and long-term follow-up of implant recipients by the plastic surgeons who treated them.

In addition to better informed consent, patients who came to the hearing clearly also hoped to raise awareness in the general American public about the potential dangers from breast implants and the need to follow patients who receive implants. The 2 days of hearing accomplished that in part just by taking place. The New York Times and The Washington Post ran at least a couple of articles apiece on implant safety just before or during the hearings, while a more regional paper, the Philadelphia Inquirer, ran one article, as presumably did many other newspapers, broadcast outlets, and websites across America. Much of the coverage focused on compelling and moving personal stories from patients.

Women who have been having adverse effects from breast implants “have felt dismissed,” noted panel member Natalie C. Portis, PhD, a clinical psychologist from Oakland, Calif., and the patient representative on the advisory committee. “We need to listen to women that something real is happening.”

Dr. Tervaert, Dr. Chevray, Dr. McGuire, Dr. Clemens, Dr. Burke, Dr. Casas, and Dr. Portis had no relevant commercial disclosures.

What’s the role of anecdotal medical histories in the era of evidence-based medicine?

But the anecdotal histories fell short of producing a clear committee consensus on dramatic, immediate changes in FDA policy, such as joining a renewed ban on certain types of breast implants linked with a rare lymphoma, a step recently taken by 38 other countries, including 33 European countries acting in concert through the European Union.

The disconnect between gripping testimony and limited panel recommendations was most stark for a complication that’s been named Breast Implant Illness (BII) by patients on the Internet. Many breast implant recipients have reported life-changing symptoms that appeared after implant placement, most often fatigue, joint and muscle pain, brain fog, neurologic symptoms, immune dysfunction, skin manifestations, and autoimmune disease or symptoms. By my count, 22 people spoke about their harrowing experiences with BII symptoms out of the 77 who stepped to the panel’s public-comment mic during 4 hours of public testimony over 2-days of hearings, often saying that they had experienced dramatic improvements after their implants came out. The meeting of the General and Plastic Surgery Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee also heard presentations from two experts who ran some of the first reported studies on BII, or a BII-like syndrome called Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Adjuvants (ASIA) described by Jan W.C. Tervaert, MD, professor of medicine and director of rheumatology at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Dr. Tervaert and his associates published their findings about ASIA in the rheumatology literature last year (Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Feb;37[2]:483-93), and during his talk before the FDA panel, he said that silicone breast implants and the surgical mesh often used with them could be ASIA triggers.

Panel members seemed to mostly believe that the evidence they heard about BII did no more than hint at a possible association between breast implants and BII symptoms that required additional study. Many agreed on the need to include mention of the most common BII-linked patient complaints in informed consent material, but some were reluctant about even taking that step.

“I do not mention BII to patients. It’s not a disease; it’s a constellation of symptoms,” said panel member and plastic surgeon Pierre M. Chevray, MD, from Houston Methodist Hospital. The evidence for BII “is extremely anecdotal,” he said in an interview at the end of the 2-day session. Descriptions of BII “have been mainly published on social media. One reason why I don’t tell patients [about BII as part of informed consent] is because right now the evidence of a link is weak. We don’t yet even have a definition of this as an illness. A first step is to define it,” said Dr. Chevray, who has a very active implant practice. Other plastic surgeons were more accepting of BII as a real complication, although they agreed it needs much more study. During the testimony period, St. Louis plastic surgeon Patricia A. McGuire, MD, highlighted the challenge of teasing apart whether real symptoms are truly related to implants or are simply common ailments that accumulate during middle-age in many women. Dr. McGuire and some of her associates published an assessment of the challenges and possible solutions to studying BII that appeared shortly before the hearing (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 March;143[3S]:74S-81S),

Consensus recommendations from the panel to the FDA to address BII included having a single registry that would include all U.S. patients who receive breast implants (recently launched as the National Breast Implant Registry), inclusion of a control group, and collection of data at baseline and after regular follow-up intervals that includes a variety of measures relevant to autoimmune and rheumatologic disorders. Several panel members cited inadequate postmarketing safety surveillance by manufacturers in the years since breast implants returned to the U.S. market, and earlier in March, the FDA issued warning letters to two of the four companies that market U.S. breast implants over their inadequate long-term safety follow-up.

The panel’s decisions about the other major implant-associated health risk it considered, breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), faced a different sort of challenge. First described as linked to breast implants in 2011, today there is little doubt that BIA-ALCL is a consequence of breast implants, what several patients derisively called a “man-made cancer.” The key issue the committee grappled with was whether the calculated incidence of BIA-ALCL was at a frequency that warranted a ban on at least selected breast implant types. Mark W. Clemens, MD, a plastic surgeon at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, told the panel that he calculated the Allergan Biocell group of implants, which have textured surfaces that allows for easier and more stable placement in patients, linked with an incidence of BIA-ALCL that was sevenfold to eightfold higher than that with smooth implants. That’s against a background of an overall incidence of about one case for every 20,000 U.S. implant recipients, Dr. Clemens said.

Many testifying patients, including several of the eight who described a personal history of BIA-ALCL, called for a ban on the sale of at least some breast implants because of their role in causing lymphoma. That sentiment was shared by Dr. Chevray, who endorsed a ban on “salt-loss” implants (the method that makes Biocell implants) during his closing comments to his fellow panel members. But earlier during panel discussions, others on the committee pushed back against implant bans, leaving the FDA’s eventual decision on this issue unclear. Evidence presented during the hearings suggests that implants cause ALCL by triggering a local “inflammatory milieu” and that different types of implants can have varying levels of potency for producing this milieu.

Perhaps the closest congruence between what patients called for and what the committee recommended was on informed consent. “No doubt, patients feel that informed consent failed them,” concluded panel member Karen E. Burke, MD, a New York dermatologist who was one of two panel discussants for the topic.

In addition to many suggestions on how to improve informed consent and public awareness lobbed at FDA staffers during the session by panel members, the final public comment of the 2 days came from Laurie A. Casas, MD, a Chicago plastic surgeon affiliated with the University of Chicago and a member of the board of directors of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (also know as the Aesthetic Society). During her testimony, Dr. Casas said “Over the past 2 days, we heard that patients need a structured educational checklist for informed consent. The Aesthetic Society hears you,” and promised that the website of the Society’s publication, the Aesthetic Surgery Journal, will soon feature a safety checklist for people receiving breast implants that will get updated as new information becomes available. She also highlighted the need for a comprehensive registry and long-term follow-up of implant recipients by the plastic surgeons who treated them.

In addition to better informed consent, patients who came to the hearing clearly also hoped to raise awareness in the general American public about the potential dangers from breast implants and the need to follow patients who receive implants. The 2 days of hearing accomplished that in part just by taking place. The New York Times and The Washington Post ran at least a couple of articles apiece on implant safety just before or during the hearings, while a more regional paper, the Philadelphia Inquirer, ran one article, as presumably did many other newspapers, broadcast outlets, and websites across America. Much of the coverage focused on compelling and moving personal stories from patients.

Women who have been having adverse effects from breast implants “have felt dismissed,” noted panel member Natalie C. Portis, PhD, a clinical psychologist from Oakland, Calif., and the patient representative on the advisory committee. “We need to listen to women that something real is happening.”

Dr. Tervaert, Dr. Chevray, Dr. McGuire, Dr. Clemens, Dr. Burke, Dr. Casas, and Dr. Portis had no relevant commercial disclosures.

Scientific Abstracts; Skin Disease Education Foundation’s 43rd Annual Hawaii Dermatology Seminar

Despite failed primary endpoint, MI alert device has predictive value

WASHINGTON –Although an implantable device for detecting myocardial infarction missed the primary composite outcome endpoint in a controlled trial, a newly completed extended analysis associated the device with a higher positive predictive value and a lower false positive rate when compared to sham control, according to data presented at CRT 2019, sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

“Among high risk patients, this system may be beneficial in the identification of both symptomatic and asymptomatic coronary events,” reported C. Michael Gibson, MD, chief of clinical research in the cardiology division at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston.

The implantable device (AngelMed Guardian System), which received Food and Drug Administration approval in April 2018, is designed to identify MI through detection of ST-segment elevations in the absence of an elevated heart rate. When the system detects an event during continuous monitoring, it sends a signal (internal vibration and auditory signal to an external monitor) designed to tell the patient to seek medical care.

The previously published multicenter and randomized ALERTS (AngelMed for Early Recognition and Treatment of STEMI) trial that tested this device was negative for primary composite endpoint of cardiac or unexplained death, new Q-wave MI, or presentation at the emergency department (ED) more than 2 hours after symptom onset (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Feb 25. pii: S0735-1097[19]30237-2). In that trial 907 patients were fitted with the device and then randomized to having the device switched on or left off.

At 7 days, a primary endpoint was reached by 3.8% of those in the device-on group versus 4.9% of those in the device-off group, which was not significantly different.

Although the primary endpoint was not met, there were promising results. For example, in those who did have an occlusive event, patients in the device-on group had better preserved left ventricular function when evaluated after the event, a result consistent with earlier presentation in the ED and earlier treatment. In fact, 85% of patients with an MI in the device-on group presented to a hospital within 2 hours, compared with just 5% of those in the device-off control group during the initial study period.

More evidence of a potential clinical role for the device has now been generated in a new extended analysis. This analysis was made possible because patients in both of the randomized groups continue to wear the device, including those in the device-off group who had their devices activated after 6 months. There are now 3 more years of data of follow-up from those initially in the device-on group and those switched from the device-off group.

“So we started the clock over with a new statistical analysis plan and new endpoints,” Dr. Gibson explained. The FDA was consulted in selecting endpoints, particularly regarding evidence that the device did not increase false-positive ED visits.

There were numerous encouraging findings. One was that 42 silent MIs, which would otherwise have been missed, were detected over the extended follow-up. Another was that the annualized false-positive rate was lower in those with an activated device (0.164/year) when compared to the original device-off group (0.678/year; P less than .001). Lastly, the positive predictive value of an alarm during the extended follow-up was higher than that of symptoms alone among the original device-off group (25.8% vs. 18.2%).

The device was found safe. The rate of system-related complications was under 4%, which Dr. Gibson said is noninferior to that associated with pacemakers.

One of the potential explanations for the failure of the device to achieve the primary endpoint in the original trial was an unexpectedly low event rate, according to Dr. Gibson.

Even before this extended analysis, the FDA had accepted the potential benefits of this device as demonstrated in the approval last year. In the labeling, the device is called “a more accurate predictor of acute coronary syndrome events when compared to patient recognized symptoms alone and demonstrates a reduced rate over time of patient presentations without ACS events.”

“About 50% of patients wait more than 3 hours after the onset of symptoms before reaching an emergency room,” observed Dr. Gibson. Emphasizing the evidence that delay is an important predictor of adverse outcomes, he suggested the alarm device might be useful in accelerating care in some high risk groups.

WASHINGTON –Although an implantable device for detecting myocardial infarction missed the primary composite outcome endpoint in a controlled trial, a newly completed extended analysis associated the device with a higher positive predictive value and a lower false positive rate when compared to sham control, according to data presented at CRT 2019, sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

“Among high risk patients, this system may be beneficial in the identification of both symptomatic and asymptomatic coronary events,” reported C. Michael Gibson, MD, chief of clinical research in the cardiology division at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston.

The implantable device (AngelMed Guardian System), which received Food and Drug Administration approval in April 2018, is designed to identify MI through detection of ST-segment elevations in the absence of an elevated heart rate. When the system detects an event during continuous monitoring, it sends a signal (internal vibration and auditory signal to an external monitor) designed to tell the patient to seek medical care.

The previously published multicenter and randomized ALERTS (AngelMed for Early Recognition and Treatment of STEMI) trial that tested this device was negative for primary composite endpoint of cardiac or unexplained death, new Q-wave MI, or presentation at the emergency department (ED) more than 2 hours after symptom onset (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Feb 25. pii: S0735-1097[19]30237-2). In that trial 907 patients were fitted with the device and then randomized to having the device switched on or left off.

At 7 days, a primary endpoint was reached by 3.8% of those in the device-on group versus 4.9% of those in the device-off group, which was not significantly different.

Although the primary endpoint was not met, there were promising results. For example, in those who did have an occlusive event, patients in the device-on group had better preserved left ventricular function when evaluated after the event, a result consistent with earlier presentation in the ED and earlier treatment. In fact, 85% of patients with an MI in the device-on group presented to a hospital within 2 hours, compared with just 5% of those in the device-off control group during the initial study period.

More evidence of a potential clinical role for the device has now been generated in a new extended analysis. This analysis was made possible because patients in both of the randomized groups continue to wear the device, including those in the device-off group who had their devices activated after 6 months. There are now 3 more years of data of follow-up from those initially in the device-on group and those switched from the device-off group.

“So we started the clock over with a new statistical analysis plan and new endpoints,” Dr. Gibson explained. The FDA was consulted in selecting endpoints, particularly regarding evidence that the device did not increase false-positive ED visits.

There were numerous encouraging findings. One was that 42 silent MIs, which would otherwise have been missed, were detected over the extended follow-up. Another was that the annualized false-positive rate was lower in those with an activated device (0.164/year) when compared to the original device-off group (0.678/year; P less than .001). Lastly, the positive predictive value of an alarm during the extended follow-up was higher than that of symptoms alone among the original device-off group (25.8% vs. 18.2%).

The device was found safe. The rate of system-related complications was under 4%, which Dr. Gibson said is noninferior to that associated with pacemakers.

One of the potential explanations for the failure of the device to achieve the primary endpoint in the original trial was an unexpectedly low event rate, according to Dr. Gibson.

Even before this extended analysis, the FDA had accepted the potential benefits of this device as demonstrated in the approval last year. In the labeling, the device is called “a more accurate predictor of acute coronary syndrome events when compared to patient recognized symptoms alone and demonstrates a reduced rate over time of patient presentations without ACS events.”

“About 50% of patients wait more than 3 hours after the onset of symptoms before reaching an emergency room,” observed Dr. Gibson. Emphasizing the evidence that delay is an important predictor of adverse outcomes, he suggested the alarm device might be useful in accelerating care in some high risk groups.

WASHINGTON –Although an implantable device for detecting myocardial infarction missed the primary composite outcome endpoint in a controlled trial, a newly completed extended analysis associated the device with a higher positive predictive value and a lower false positive rate when compared to sham control, according to data presented at CRT 2019, sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

“Among high risk patients, this system may be beneficial in the identification of both symptomatic and asymptomatic coronary events,” reported C. Michael Gibson, MD, chief of clinical research in the cardiology division at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston.

The implantable device (AngelMed Guardian System), which received Food and Drug Administration approval in April 2018, is designed to identify MI through detection of ST-segment elevations in the absence of an elevated heart rate. When the system detects an event during continuous monitoring, it sends a signal (internal vibration and auditory signal to an external monitor) designed to tell the patient to seek medical care.

The previously published multicenter and randomized ALERTS (AngelMed for Early Recognition and Treatment of STEMI) trial that tested this device was negative for primary composite endpoint of cardiac or unexplained death, new Q-wave MI, or presentation at the emergency department (ED) more than 2 hours after symptom onset (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Feb 25. pii: S0735-1097[19]30237-2). In that trial 907 patients were fitted with the device and then randomized to having the device switched on or left off.

At 7 days, a primary endpoint was reached by 3.8% of those in the device-on group versus 4.9% of those in the device-off group, which was not significantly different.

Although the primary endpoint was not met, there were promising results. For example, in those who did have an occlusive event, patients in the device-on group had better preserved left ventricular function when evaluated after the event, a result consistent with earlier presentation in the ED and earlier treatment. In fact, 85% of patients with an MI in the device-on group presented to a hospital within 2 hours, compared with just 5% of those in the device-off control group during the initial study period.

More evidence of a potential clinical role for the device has now been generated in a new extended analysis. This analysis was made possible because patients in both of the randomized groups continue to wear the device, including those in the device-off group who had their devices activated after 6 months. There are now 3 more years of data of follow-up from those initially in the device-on group and those switched from the device-off group.

“So we started the clock over with a new statistical analysis plan and new endpoints,” Dr. Gibson explained. The FDA was consulted in selecting endpoints, particularly regarding evidence that the device did not increase false-positive ED visits.

There were numerous encouraging findings. One was that 42 silent MIs, which would otherwise have been missed, were detected over the extended follow-up. Another was that the annualized false-positive rate was lower in those with an activated device (0.164/year) when compared to the original device-off group (0.678/year; P less than .001). Lastly, the positive predictive value of an alarm during the extended follow-up was higher than that of symptoms alone among the original device-off group (25.8% vs. 18.2%).

The device was found safe. The rate of system-related complications was under 4%, which Dr. Gibson said is noninferior to that associated with pacemakers.

One of the potential explanations for the failure of the device to achieve the primary endpoint in the original trial was an unexpectedly low event rate, according to Dr. Gibson.

Even before this extended analysis, the FDA had accepted the potential benefits of this device as demonstrated in the approval last year. In the labeling, the device is called “a more accurate predictor of acute coronary syndrome events when compared to patient recognized symptoms alone and demonstrates a reduced rate over time of patient presentations without ACS events.”

“About 50% of patients wait more than 3 hours after the onset of symptoms before reaching an emergency room,” observed Dr. Gibson. Emphasizing the evidence that delay is an important predictor of adverse outcomes, he suggested the alarm device might be useful in accelerating care in some high risk groups.

REPORTING FROM CRT 2019

Whole-genome sequencing demonstrates clinical relevance

GLASGOW – Whole genome sequencing (WGS) appears capable of replacing cytogenetic testing and next generation sequencing (NGS) for the detection of clinically relevant molecular abnormalities in hematological malignancies, according to investigators.

A comparison of WGS with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) showed that WGS caught all the same significant structural variants, plus some abnormalities that FISH had not detected, reported lead author Shirley Henderson, PhD, lead for cancer molecular diagnostics at Genomics England in Oxford.

Although further validation is needed, these findings, reported at the annual meeting of the British Society for Haematology, support an ongoing effort to validate the clinical reliability of WGS, which is currently reserved for research purposes.

“It’s vitally important that the clinical community engage with this and understand both the power and the limitations of this technique and how this work is going to be interpreted for the benefit of patients,” said Adele Fielding, PhD, session chair from University College London’s Cancer Institute.

The investigators compared WGS with FISH for detection of clinically significant structural variants (SVs) and copy number variants (CNVs) in tumor samples from 34 patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The 252 standard of care FISH tests – conducted at three separate clinical diagnostic centers in the United Kingdom – included 138 SVs and 114 CNVs. WGS relied on a combination of bioinformatics and visual inspection of Circos plots. WGS confirmed all of the SVs detected by FISH with high confidence; WGS detected four additional SVs, also with high confidence, including an ETV6-RUNX1 fusion not detected by FISH because of probe limitations.

Results for CNVs were similar, with WGS detecting 78 out of 85 positive CNVs. Six of the missed positives were associated with low quality samples or low level mutations in the FISH test, suggesting that at least some positives may have been detected with better samples. Only one negative CNV from FISH was missed by WGS.

Overall, WGS had a false positive rate of less than 5% and a positive percentage agreement with FISH that exceeded 90%.

“Further work is required to fully validate all aspects of the WGS analysis pipeline,” Dr. Henderson said. “But these results indicate that WGS has the potential to reliably detect SVs and CNVs in these conditions while offering the advantage of detecting all SVs and CNVs present without the need for additional interrogation of the sample by multiple tests or probes.”

Dr. Henderson noted that there is really no “perfect method” for identifying structural and copy number variants at the present time.

Small variants are relatively easy to detect with techniques such as karyotyping and gene banding, but these tests have shortcomings, namely, that they require live cells and have “fairly high failure rates for various reasons,” Dr. Henderson said.

“FISH is an incredibly useful test and it has higher resolution than gene banding, but the problem with FISH is that you only find what you’re looking at,” Dr. Henderson said. “It’s not genome wide; it’s very targeted.”

Similarly, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), including next generation sequencing (NGS), can detect molecular abnormalities, but only those that are targeted, which may necessitate multiple tests, she said.

“If you start looking for all of the structural variants [with existing techniques], then you’re going to be doing an awful lot of tests,” Dr. Henderson said.

Another potential benefit of WGS is that it is “future resistant,” Dr. Henderson said. “As new biomarkers are discovered, you don’t have to redesign a new targeted test. It will also detect emerging biomarkers, such as mutational signatures and burden.”

The study was sponsored by NHS England. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Henderson S et al. BSH 2019, Abstract OR-002.

GLASGOW – Whole genome sequencing (WGS) appears capable of replacing cytogenetic testing and next generation sequencing (NGS) for the detection of clinically relevant molecular abnormalities in hematological malignancies, according to investigators.

A comparison of WGS with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) showed that WGS caught all the same significant structural variants, plus some abnormalities that FISH had not detected, reported lead author Shirley Henderson, PhD, lead for cancer molecular diagnostics at Genomics England in Oxford.

Although further validation is needed, these findings, reported at the annual meeting of the British Society for Haematology, support an ongoing effort to validate the clinical reliability of WGS, which is currently reserved for research purposes.

“It’s vitally important that the clinical community engage with this and understand both the power and the limitations of this technique and how this work is going to be interpreted for the benefit of patients,” said Adele Fielding, PhD, session chair from University College London’s Cancer Institute.

The investigators compared WGS with FISH for detection of clinically significant structural variants (SVs) and copy number variants (CNVs) in tumor samples from 34 patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The 252 standard of care FISH tests – conducted at three separate clinical diagnostic centers in the United Kingdom – included 138 SVs and 114 CNVs. WGS relied on a combination of bioinformatics and visual inspection of Circos plots. WGS confirmed all of the SVs detected by FISH with high confidence; WGS detected four additional SVs, also with high confidence, including an ETV6-RUNX1 fusion not detected by FISH because of probe limitations.

Results for CNVs were similar, with WGS detecting 78 out of 85 positive CNVs. Six of the missed positives were associated with low quality samples or low level mutations in the FISH test, suggesting that at least some positives may have been detected with better samples. Only one negative CNV from FISH was missed by WGS.

Overall, WGS had a false positive rate of less than 5% and a positive percentage agreement with FISH that exceeded 90%.

“Further work is required to fully validate all aspects of the WGS analysis pipeline,” Dr. Henderson said. “But these results indicate that WGS has the potential to reliably detect SVs and CNVs in these conditions while offering the advantage of detecting all SVs and CNVs present without the need for additional interrogation of the sample by multiple tests or probes.”

Dr. Henderson noted that there is really no “perfect method” for identifying structural and copy number variants at the present time.

Small variants are relatively easy to detect with techniques such as karyotyping and gene banding, but these tests have shortcomings, namely, that they require live cells and have “fairly high failure rates for various reasons,” Dr. Henderson said.

“FISH is an incredibly useful test and it has higher resolution than gene banding, but the problem with FISH is that you only find what you’re looking at,” Dr. Henderson said. “It’s not genome wide; it’s very targeted.”

Similarly, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), including next generation sequencing (NGS), can detect molecular abnormalities, but only those that are targeted, which may necessitate multiple tests, she said.

“If you start looking for all of the structural variants [with existing techniques], then you’re going to be doing an awful lot of tests,” Dr. Henderson said.

Another potential benefit of WGS is that it is “future resistant,” Dr. Henderson said. “As new biomarkers are discovered, you don’t have to redesign a new targeted test. It will also detect emerging biomarkers, such as mutational signatures and burden.”

The study was sponsored by NHS England. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Henderson S et al. BSH 2019, Abstract OR-002.

GLASGOW – Whole genome sequencing (WGS) appears capable of replacing cytogenetic testing and next generation sequencing (NGS) for the detection of clinically relevant molecular abnormalities in hematological malignancies, according to investigators.

A comparison of WGS with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) showed that WGS caught all the same significant structural variants, plus some abnormalities that FISH had not detected, reported lead author Shirley Henderson, PhD, lead for cancer molecular diagnostics at Genomics England in Oxford.

Although further validation is needed, these findings, reported at the annual meeting of the British Society for Haematology, support an ongoing effort to validate the clinical reliability of WGS, which is currently reserved for research purposes.

“It’s vitally important that the clinical community engage with this and understand both the power and the limitations of this technique and how this work is going to be interpreted for the benefit of patients,” said Adele Fielding, PhD, session chair from University College London’s Cancer Institute.

The investigators compared WGS with FISH for detection of clinically significant structural variants (SVs) and copy number variants (CNVs) in tumor samples from 34 patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The 252 standard of care FISH tests – conducted at three separate clinical diagnostic centers in the United Kingdom – included 138 SVs and 114 CNVs. WGS relied on a combination of bioinformatics and visual inspection of Circos plots. WGS confirmed all of the SVs detected by FISH with high confidence; WGS detected four additional SVs, also with high confidence, including an ETV6-RUNX1 fusion not detected by FISH because of probe limitations.

Results for CNVs were similar, with WGS detecting 78 out of 85 positive CNVs. Six of the missed positives were associated with low quality samples or low level mutations in the FISH test, suggesting that at least some positives may have been detected with better samples. Only one negative CNV from FISH was missed by WGS.

Overall, WGS had a false positive rate of less than 5% and a positive percentage agreement with FISH that exceeded 90%.

“Further work is required to fully validate all aspects of the WGS analysis pipeline,” Dr. Henderson said. “But these results indicate that WGS has the potential to reliably detect SVs and CNVs in these conditions while offering the advantage of detecting all SVs and CNVs present without the need for additional interrogation of the sample by multiple tests or probes.”

Dr. Henderson noted that there is really no “perfect method” for identifying structural and copy number variants at the present time.

Small variants are relatively easy to detect with techniques such as karyotyping and gene banding, but these tests have shortcomings, namely, that they require live cells and have “fairly high failure rates for various reasons,” Dr. Henderson said.

“FISH is an incredibly useful test and it has higher resolution than gene banding, but the problem with FISH is that you only find what you’re looking at,” Dr. Henderson said. “It’s not genome wide; it’s very targeted.”

Similarly, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), including next generation sequencing (NGS), can detect molecular abnormalities, but only those that are targeted, which may necessitate multiple tests, she said.

“If you start looking for all of the structural variants [with existing techniques], then you’re going to be doing an awful lot of tests,” Dr. Henderson said.

Another potential benefit of WGS is that it is “future resistant,” Dr. Henderson said. “As new biomarkers are discovered, you don’t have to redesign a new targeted test. It will also detect emerging biomarkers, such as mutational signatures and burden.”

The study was sponsored by NHS England. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Henderson S et al. BSH 2019, Abstract OR-002.

REPORTING FROM BSH 2019

Bothersome Blisters: Localized Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex

To the Editor:

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) was first described in 1886, with the first classification scheme proposed in 1962 utilizing transmission electron microscopy (TEM) findings to delineate categories: epidermolytic (EB simplex [EBS]), lucidolytic (junctional EB), and dermolytic (dystrophic EB).1 Localized EBS (EBS-loc) is an autosomal-dominant disorder caused by negative mutations in keratin-5 and keratin-14, proteins expressed in the intermediate filaments of basal keratinocytes, which result in fragility of the skin in response to minor trauma.2 The incidence of EBS-loc is approximately 10 to 30 cases per million live births, with the age of presentation typically between the first and third decades of life.3,4 Because EBS-loc is the most common and often mildest form of EB, not all patients present for medical evaluation and true prevalence may be underestimated.4 We report a case of EBS-loc.

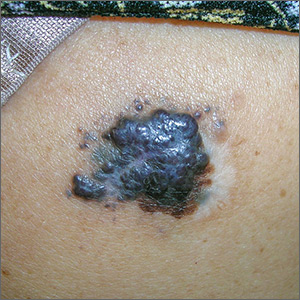

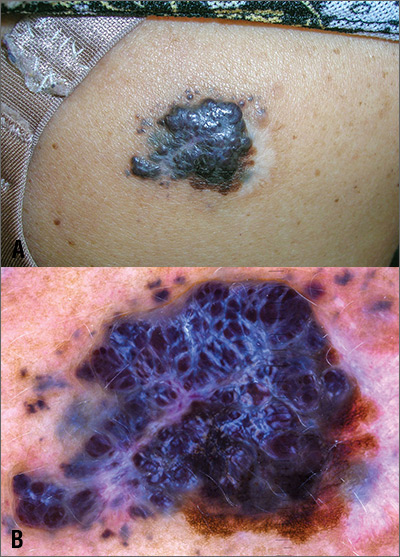

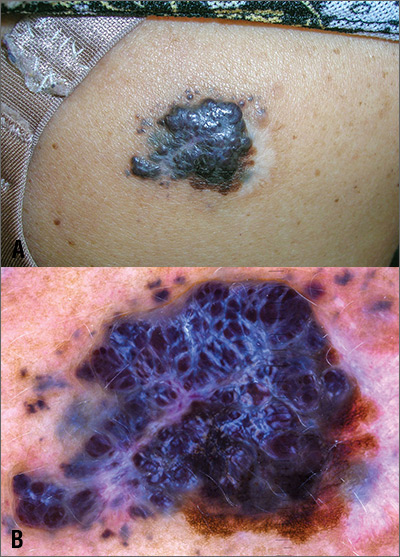

A 26-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of skin blisters that had been intermittently present since infancy. The blisters primarily occurred on the feet, but she did occasionally develop blisters on the hands, knees, and elbows and at sites of friction or trauma (eg, bra line, medial thighs) following exercise. The blisters were worsened by heat and tight-fitting shoes. Because of the painful nature of the blisters, she would lance them with a needle. On the medial thighs, she utilized nonstick and gauze bandage roll dressings to minimize friction. A review of systems was positive for hyperhidrosis. Her family history revealed multiple family members with blisters involving the feet and areas of friction or trauma for 4 generations with no known diagnosis.

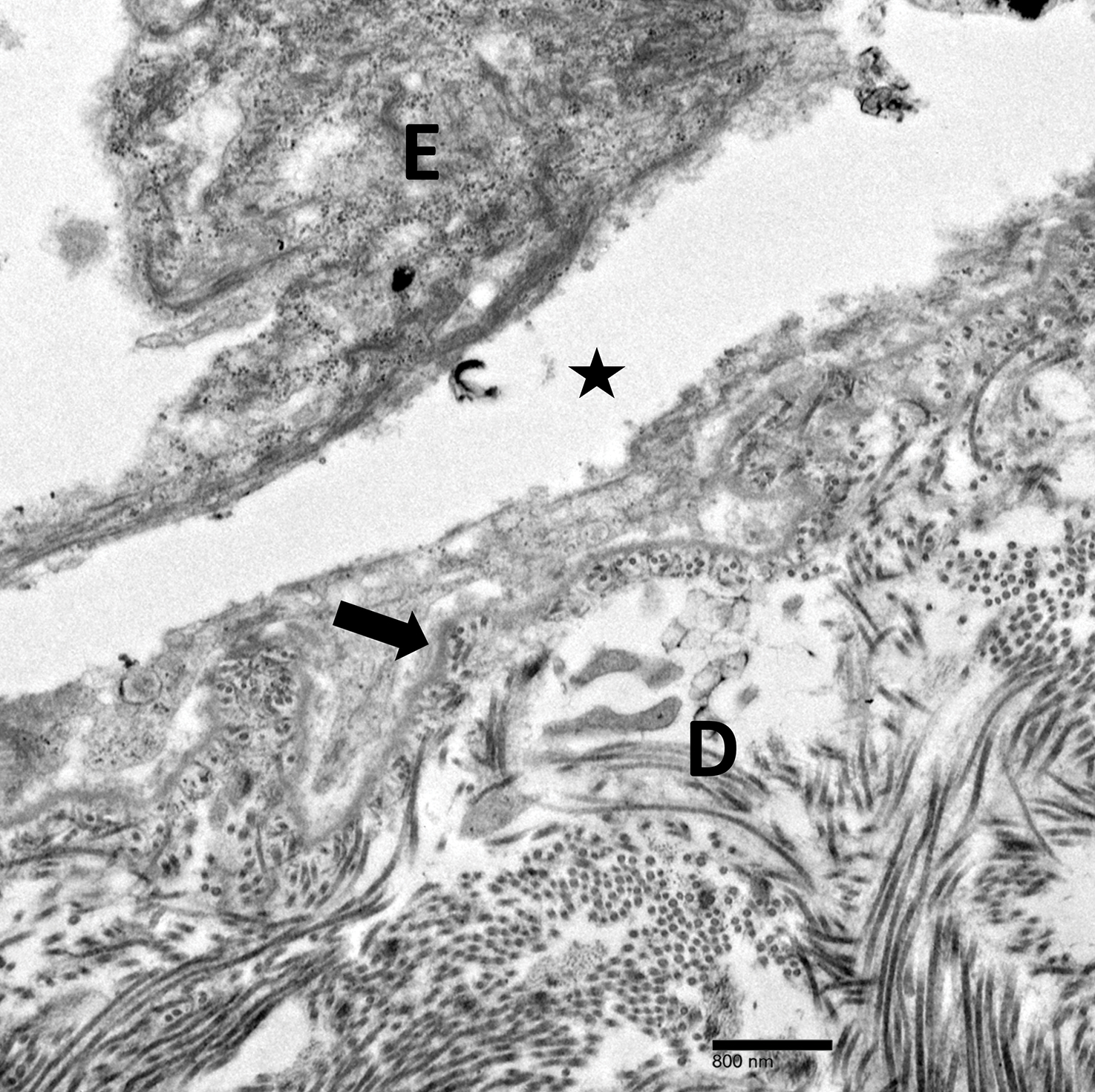

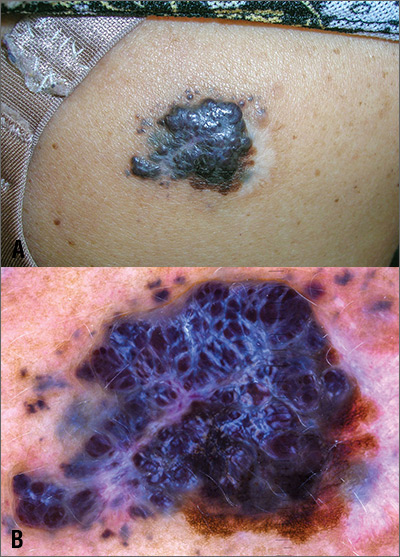

Physical examination revealed multiple tense bullae and calluses scattered over the bilateral plantar and distal dorsal feet with a few healing, superficially eroded, erythematous papules and plaques on the bilateral medial thighs (Figure 1). A biopsy from an induced blister on the right dorsal second toe was performed and sent in glutaraldehyde to the Epidermolysis Bullosa Clinic at Stanford University (Redwood City, California) for electron microscopy, which revealed lysis within the basal keratinocytes through the tonofilaments with continuous and intact lamina densa and lamina lucida (Figure 2). In this clinical context with the relevant family history, the findings were consistent with the diagnosis of EBS-loc (formerly Weber-Cockayne syndrome).2

Skin manifestations of EBS-loc typically consist of friction-induced blisters, erosions, and calluses primarily on the palms and soles, often associated with hyperhidrosis and worsening of symptoms in summer months and hot temperatures.3 Milia, atrophic scarring, and dystrophic nails are uncommon.1 Extracutaneous involvement is rare with the exception of oral cavity erosions, which typically are asymptomatic and usually are only seen during infancy.1

Light microscopy does not have a notable role in diagnosis of classic forms of inherited EB unless another autoimmune blistering disorder is suspected.2,5 Both TEM and immunofluorescence mapping are used to diagnose EB.1 DNA mutational analysis is not considered a first-line diagnostic test for EB given it is a costly labor-intensive technique with limited access at present, but it may be considered in settings of prenatal diagnosis or in vitro fertilization.1 Biopsy of a freshly induced blister should be performed, as early reepithelialization of an existing blister makes it difficult to establish the level of cleavage.5 Applying firm pressure using a pencil eraser and rotating it on intact skin induces a subclinical blister. Two punch biopsies (4 mm) at the edge of the blister with one-third lesional and two-thirds perilesional skin should be obtained, with one biopsy sent for immunofluorescence mapping in Michel fixative and the other for TEM in glutaraldehyde.3,5 Transmission electron microscopy of an induced blister in EBS-loc shows cleavage within the most inferior portion of the basilar keratinocyte.2 Immunofluorescence mapping with anti–epidermal basement membrane monoclonal antibodies can distinguish between EB subtypes and assess expression of specific skin-associated proteins on both a qualitative or semiquantitative basis, providing insight on which structural protein is mutated.1,5

No specific treatments are available for EBS-loc. Mainstays of treatment include prevention of mechanical trauma and secondary infection. Hyperhidrosis of thepalms and soles may be treated with topical aluminum chloride hexahydrate or injections of botulinum toxin type A.2,6 Patients have normal life expectancy, though some cases may have complications with substantial morbidity.1 Awareness of this disease, its clinical course, and therapeutic options will allow physicians to more appropriately counsel patients on the disease process.

Localized EBS may be more common than previously thought, as not all patients seek medical care. Given its impact on patient quality of life, it is important for clinicians to recognize EBS-loc. Although no specific treatments are available, wound care counseling and explanation of the genetics of the disease should be provided to patients.

- Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA, et al. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:931-950.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes EF, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- Spitz JL. Genodermatoses: A Clinical Guide to Genetic Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- Epidermolysis bullosa. Stanford Medicine website. http://med.stanford.edu/dermatopathology/dermpath-services/epiderm.html. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- Abitbol RJ, Zhou LH. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa simplex, Weber-Cockayne type, with botulinum toxin type A. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:13-15.

To the Editor:

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) was first described in 1886, with the first classification scheme proposed in 1962 utilizing transmission electron microscopy (TEM) findings to delineate categories: epidermolytic (EB simplex [EBS]), lucidolytic (junctional EB), and dermolytic (dystrophic EB).1 Localized EBS (EBS-loc) is an autosomal-dominant disorder caused by negative mutations in keratin-5 and keratin-14, proteins expressed in the intermediate filaments of basal keratinocytes, which result in fragility of the skin in response to minor trauma.2 The incidence of EBS-loc is approximately 10 to 30 cases per million live births, with the age of presentation typically between the first and third decades of life.3,4 Because EBS-loc is the most common and often mildest form of EB, not all patients present for medical evaluation and true prevalence may be underestimated.4 We report a case of EBS-loc.

A 26-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of skin blisters that had been intermittently present since infancy. The blisters primarily occurred on the feet, but she did occasionally develop blisters on the hands, knees, and elbows and at sites of friction or trauma (eg, bra line, medial thighs) following exercise. The blisters were worsened by heat and tight-fitting shoes. Because of the painful nature of the blisters, she would lance them with a needle. On the medial thighs, she utilized nonstick and gauze bandage roll dressings to minimize friction. A review of systems was positive for hyperhidrosis. Her family history revealed multiple family members with blisters involving the feet and areas of friction or trauma for 4 generations with no known diagnosis.

Physical examination revealed multiple tense bullae and calluses scattered over the bilateral plantar and distal dorsal feet with a few healing, superficially eroded, erythematous papules and plaques on the bilateral medial thighs (Figure 1). A biopsy from an induced blister on the right dorsal second toe was performed and sent in glutaraldehyde to the Epidermolysis Bullosa Clinic at Stanford University (Redwood City, California) for electron microscopy, which revealed lysis within the basal keratinocytes through the tonofilaments with continuous and intact lamina densa and lamina lucida (Figure 2). In this clinical context with the relevant family history, the findings were consistent with the diagnosis of EBS-loc (formerly Weber-Cockayne syndrome).2

Skin manifestations of EBS-loc typically consist of friction-induced blisters, erosions, and calluses primarily on the palms and soles, often associated with hyperhidrosis and worsening of symptoms in summer months and hot temperatures.3 Milia, atrophic scarring, and dystrophic nails are uncommon.1 Extracutaneous involvement is rare with the exception of oral cavity erosions, which typically are asymptomatic and usually are only seen during infancy.1

Light microscopy does not have a notable role in diagnosis of classic forms of inherited EB unless another autoimmune blistering disorder is suspected.2,5 Both TEM and immunofluorescence mapping are used to diagnose EB.1 DNA mutational analysis is not considered a first-line diagnostic test for EB given it is a costly labor-intensive technique with limited access at present, but it may be considered in settings of prenatal diagnosis or in vitro fertilization.1 Biopsy of a freshly induced blister should be performed, as early reepithelialization of an existing blister makes it difficult to establish the level of cleavage.5 Applying firm pressure using a pencil eraser and rotating it on intact skin induces a subclinical blister. Two punch biopsies (4 mm) at the edge of the blister with one-third lesional and two-thirds perilesional skin should be obtained, with one biopsy sent for immunofluorescence mapping in Michel fixative and the other for TEM in glutaraldehyde.3,5 Transmission electron microscopy of an induced blister in EBS-loc shows cleavage within the most inferior portion of the basilar keratinocyte.2 Immunofluorescence mapping with anti–epidermal basement membrane monoclonal antibodies can distinguish between EB subtypes and assess expression of specific skin-associated proteins on both a qualitative or semiquantitative basis, providing insight on which structural protein is mutated.1,5

No specific treatments are available for EBS-loc. Mainstays of treatment include prevention of mechanical trauma and secondary infection. Hyperhidrosis of thepalms and soles may be treated with topical aluminum chloride hexahydrate or injections of botulinum toxin type A.2,6 Patients have normal life expectancy, though some cases may have complications with substantial morbidity.1 Awareness of this disease, its clinical course, and therapeutic options will allow physicians to more appropriately counsel patients on the disease process.

Localized EBS may be more common than previously thought, as not all patients seek medical care. Given its impact on patient quality of life, it is important for clinicians to recognize EBS-loc. Although no specific treatments are available, wound care counseling and explanation of the genetics of the disease should be provided to patients.

To the Editor: