User login

At what diameter does a scar form after a full-thickness wound?

DENVER – A clinically identifiable scar occurs after full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter, while wounds of smaller diameter heal with no clinically perceptible scar.

The findings come from a “The broader purpose of this work is to contribute to the development of techniques for harvesting skin tissue with less morbidity than conventional methods,” lead study author Amanda H. Champlain, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The size threshold at which a full-thickness skin wound can heal without scarring had not been determined prior to this study.”

Dr. Champlain, a fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital and The Wellman Center for Photomedicine, both in Boston, and her colleagues designed a way to evaluate healing responses and safety after collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin. According to the study abstract, the concept “is based on fractional photothermolysis in which a multitude of small, full-thickness thermal burns are produced by a laser on the skin with rapid healing and no scarring.” Measures included the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS), donor site pain scale, subject satisfaction survey, and an assessment of side effects, clinical photographs, and histology.

Preliminary data are available for five subjects. The POSAS-Observer scale ranges from 5 to 50 while the POSAS-Patient scale ranges from 6 to 60. The researchers observed that average final POSAS-Observer scores were 5.6 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 5.2 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 7.0 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.8 for scars 600 mcm in diameter, 8.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 9.6 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 13.2 for those 2 mm in diameter. Meanwhile, the average final POSAS-Subject scores were 6.0 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 6.0 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 6.6 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.4 for those 600 mcm in diameter, 7.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 7.4 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 10.0 for those 2 mm in diameter.

The maximum donor site pain reported was 4 out of 10 in one subject. “The procedure was very well tolerated by the subjects,” Dr. Champlain said. “They healed quickly, and the majority were happy with the cosmetic outcome regardless of the diameter of the microbiopsy used.”

The most common side effects of the study procedures included mild bleeding, scabbing, redness, and hyper/hypopigmentation. “The majority of study participants strongly agree that the study procedure was safe, tolerable, and cosmetically sound,” she said.

Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

DENVER – A clinically identifiable scar occurs after full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter, while wounds of smaller diameter heal with no clinically perceptible scar.

The findings come from a “The broader purpose of this work is to contribute to the development of techniques for harvesting skin tissue with less morbidity than conventional methods,” lead study author Amanda H. Champlain, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The size threshold at which a full-thickness skin wound can heal without scarring had not been determined prior to this study.”

Dr. Champlain, a fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital and The Wellman Center for Photomedicine, both in Boston, and her colleagues designed a way to evaluate healing responses and safety after collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin. According to the study abstract, the concept “is based on fractional photothermolysis in which a multitude of small, full-thickness thermal burns are produced by a laser on the skin with rapid healing and no scarring.” Measures included the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS), donor site pain scale, subject satisfaction survey, and an assessment of side effects, clinical photographs, and histology.

Preliminary data are available for five subjects. The POSAS-Observer scale ranges from 5 to 50 while the POSAS-Patient scale ranges from 6 to 60. The researchers observed that average final POSAS-Observer scores were 5.6 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 5.2 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 7.0 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.8 for scars 600 mcm in diameter, 8.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 9.6 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 13.2 for those 2 mm in diameter. Meanwhile, the average final POSAS-Subject scores were 6.0 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 6.0 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 6.6 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.4 for those 600 mcm in diameter, 7.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 7.4 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 10.0 for those 2 mm in diameter.

The maximum donor site pain reported was 4 out of 10 in one subject. “The procedure was very well tolerated by the subjects,” Dr. Champlain said. “They healed quickly, and the majority were happy with the cosmetic outcome regardless of the diameter of the microbiopsy used.”

The most common side effects of the study procedures included mild bleeding, scabbing, redness, and hyper/hypopigmentation. “The majority of study participants strongly agree that the study procedure was safe, tolerable, and cosmetically sound,” she said.

Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

DENVER – A clinically identifiable scar occurs after full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter, while wounds of smaller diameter heal with no clinically perceptible scar.

The findings come from a “The broader purpose of this work is to contribute to the development of techniques for harvesting skin tissue with less morbidity than conventional methods,” lead study author Amanda H. Champlain, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The size threshold at which a full-thickness skin wound can heal without scarring had not been determined prior to this study.”

Dr. Champlain, a fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital and The Wellman Center for Photomedicine, both in Boston, and her colleagues designed a way to evaluate healing responses and safety after collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin. According to the study abstract, the concept “is based on fractional photothermolysis in which a multitude of small, full-thickness thermal burns are produced by a laser on the skin with rapid healing and no scarring.” Measures included the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS), donor site pain scale, subject satisfaction survey, and an assessment of side effects, clinical photographs, and histology.

Preliminary data are available for five subjects. The POSAS-Observer scale ranges from 5 to 50 while the POSAS-Patient scale ranges from 6 to 60. The researchers observed that average final POSAS-Observer scores were 5.6 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 5.2 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 7.0 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.8 for scars 600 mcm in diameter, 8.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 9.6 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 13.2 for those 2 mm in diameter. Meanwhile, the average final POSAS-Subject scores were 6.0 for scars 200 mcm in diameter, 6.0 for scars 400 mcm in diameter, 6.6 for scars 500 mcm in diameter, 6.4 for those 600 mcm in diameter, 7.2 for scars 800 mcm in diameter, 7.4 for scars 1 mm in diameter, and 10.0 for those 2 mm in diameter.

The maximum donor site pain reported was 4 out of 10 in one subject. “The procedure was very well tolerated by the subjects,” Dr. Champlain said. “They healed quickly, and the majority were happy with the cosmetic outcome regardless of the diameter of the microbiopsy used.”

The most common side effects of the study procedures included mild bleeding, scabbing, redness, and hyper/hypopigmentation. “The majority of study participants strongly agree that the study procedure was safe, tolerable, and cosmetically sound,” she said.

Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

REPORTING FROM ASLMS 2019

Key clinical point: Collecting skin microbiopsies of different sizes from preabdominoplasty skin is safe and highly tolerable.

Major finding: Full-thickness skin wounds greater than 400-500 mcm in diameter heal with a clinically identifiable scar.

Study details: A pilot trial in five individuals that set out to determine the biopsy size limit at which healing occurs without a scar, as well as demonstrate the safety of performing multiple skin microbiopsies.

Disclosures: Dr. Champlain does not have any disclosures, but she said that the study was funded by the Department of Defense.

Implementation of a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system

Cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is potentially preventable. Antiviral treatment in patients with cirrhosis-related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus can prevent complications.1-3 Beta-blockers and endoscopic treatments of esophageal varices are effective in primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage.4 Surveillance for hepatocellular cancer is associated with increased detection of early-stage cancer and improved survival.5 However, many patients with cirrhosis are either not diagnosed in a primary care setting, or even when diagnosed, not seen or referred to specialty clinics to receive disease-specific care,6 and thus remain at high risk for complications.

Our goal was to implement a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system (P-CIMS) to allow identification of all patients with potential cirrhosis in the health care system and to facilitate their linkage to specialty liver care. We describe the implementation of P-CIMS at a large Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospital and present initial results about its impact on patient care.

P-CIMS Intervention

P-CIMS is a multicomponent intervention that includes a secure web-based tracking system, standardized communication templates, and care coordination protocols.

Web-based tracking system

An interdisciplinary team of clinicians, programmers, and informatics experts developed the P-CIMS software program by extending an existing comprehensive care tracking system.7 The P-CIMS program (referred to as cirrhosis tracker) extracts information from VHA’s national corporate data warehouse. VHA corporate data warehouse includes diagnosis codes, laboratory test results, vital status, and pharmacy data for each encounter in the VA since October 1999. We designed the cirrhosis tracker program to identify patients who had outpatient or inpatient encounters in the last 3 years with either at least 1 cirrhosis diagnosis (defined as any instance of previously validated International Classification of Diseases-9 and -10 codes)8; or possible cirrhosis (defined as either aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index greater than 2.0 or Fibrosis-4 above 3.24 in patients with active HCV infection9 [defined based on positive HCV RNA or genotype test results]).

The user interface of the cirrhosis tracker is designed for easy patient lookup with live links to patient information extracted from the corporate data warehouse (recent laboratory test results, recent imaging studies, and appointments). The tracker also includes free-text fields that store follow-up information and alerting functions that remind the end user when to follow up with a patient. Supplementary Figure 1 shows screen-shots from the program.

We refined the program through an iterative process to ensure accuracy and completeness of data. Each data element (e.g., cirrhosis diagnosis, laboratory tests, clinic appointments) was validated using the full electronic medical record as the reference standard; this process occurred over a period of 9 months. The program can run to update patient data on a daily basis.

Standardized communication templates and care coordination protocols

Our interdisciplinary team created chart review note templates for use in the VHA electronic medical record to verify diagnosis of cirrhosis and to facilitate accurate communication with primary care providers (PCPs) and other specialty clinicians. We also designed standard patient letters to communicate the recommendations with patients. We established protocols for initial clinical reviews, patient outreach, scheduling, and follow-ups. These care coordination protocols were modified in an iterative manner during the implementation phase of P-CIMS.

Setting and patients

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston provides care to more than 111,000 veterans, including more than 3,800 patients with cirrhosis. At the time of P-CIMS implementation, there were three hepatologists and four advanced practice providers (APP) who provided liver-related care at the MEDVAMC.

The primary goal of the initial phase of implementation was to link patients with cirrhosis to regular liver-related care. Thus, the sample was limited to patients who did not have ongoing specialty care (i.e., no liver clinic visits in the last 6 months, including patients who were never seen in liver clinics).

Implementation strategy

We used implementation facilitation (IF), an evidence-based strategy, to implement P-CIMS.10 The IF team included facilitators (F.K., D.S.), local champions (S.M., K.H.), and technical support personnel (e.g., tracker programmers). Core components of IF were leadership engagement, creation of and regular engagement with a local stakeholder group of clinicians, educational outreach to clinicians and support staff, and problem solving. The IF activities took part in two phases: preimplementation and implementation.

Preimplementation phase

We interviewed key stakeholders to identify facilitators and barriers to P-CIMS implementation. One of the implementation facilitators (F.K.) obtained facility and clinical section’s leadership support, engaged key stakeholders, and devised a local implementation plan. Stakeholders included leadership in several disciplines: hepatology, infectious diseases, and primary care. We developed a map of clinical workflow processes to describe optimal integration of P-CIMS into existing workflow (Supplementary Figure 2).

Implementation phase

The facilitators met regularly (biweekly for the first year) with the stakeholder group including local champions and clinical staff. One of the facilitators (D.S.) served as the liaison between the P-CIMS team (F.K., A.M., R.M., T.T.) and the clinic staff to ensure that no patients were getting missed and to follow through on patient referrals to care. The programmers troubleshot technical issues that arose, and both facilitators worked with clinical staff to modify workflow as needed. At the start of IF, the facilitator conducted an initial round of trainings through in-person training or with the use of screen-sharing software. The impact of P-CIMS on patient care was tracked and feedback was provided to clinical staff on a quarterly basis.

Implementation results: Linkage to liver specialty care

P-CIMS was successfully implemented at the MEDVAMC. Patient data were first extracted in October 2015 with five updates through March 2017. In total, four APP, one MD, and the facilitator used the cirrhosis tracker on a regular basis. The clinical team (APP) conducted the initial review, triage, and outreach. It took on average 7 minutes (range, 2–20 minutes) for the initial review and outreach. The APPs entered each follow-up reminder in the tracker. For example, if they negotiated a liver clinic appointment with the patient, then they entered a reminder to follow up with the date by which this step (patient seen in liver clinic) should be completed. The tracker has a built-in alerting function. The implementation team was notified (via the tracker) when these tasks were due to ensure timely receipt of recommended care processes.

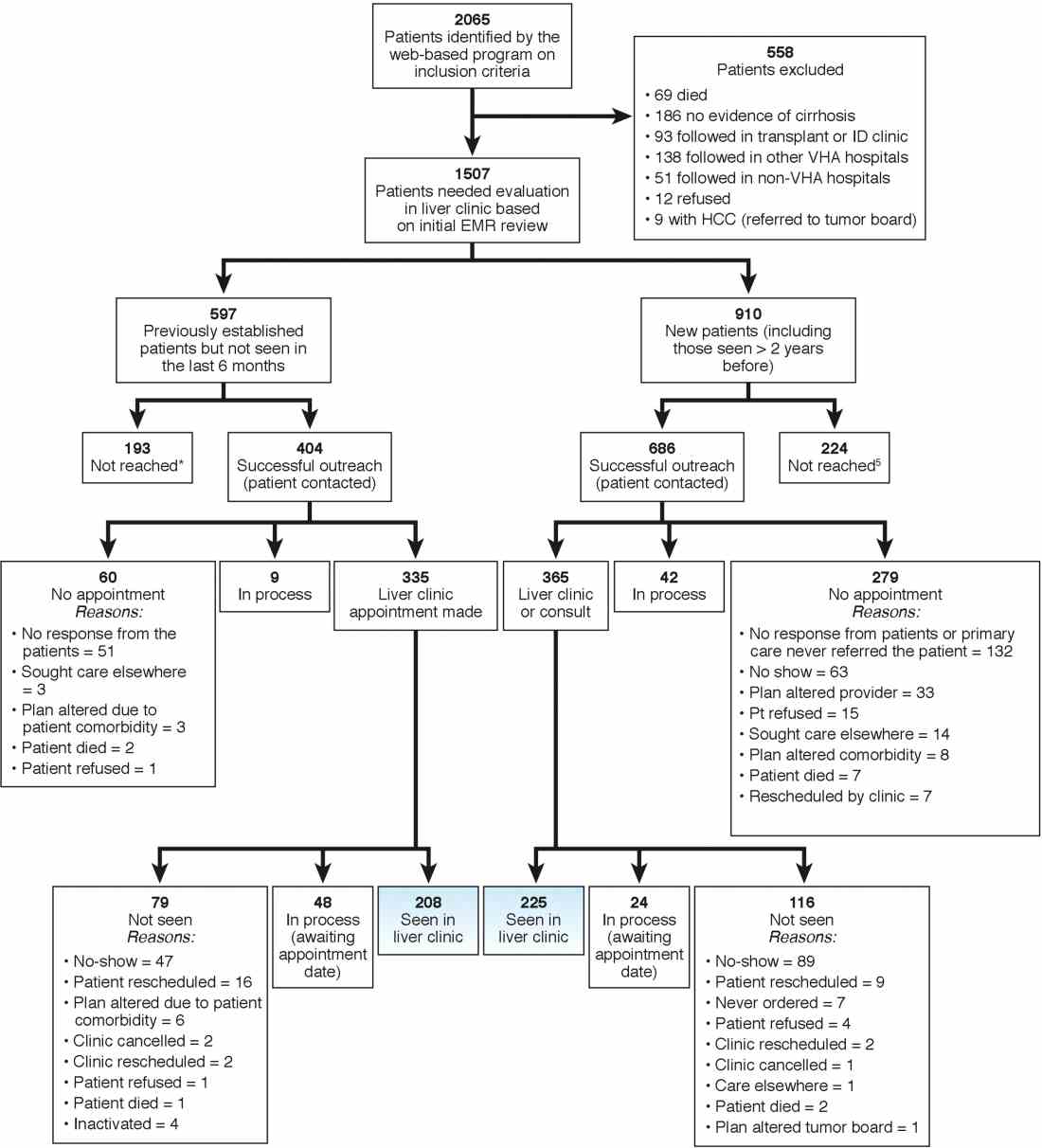

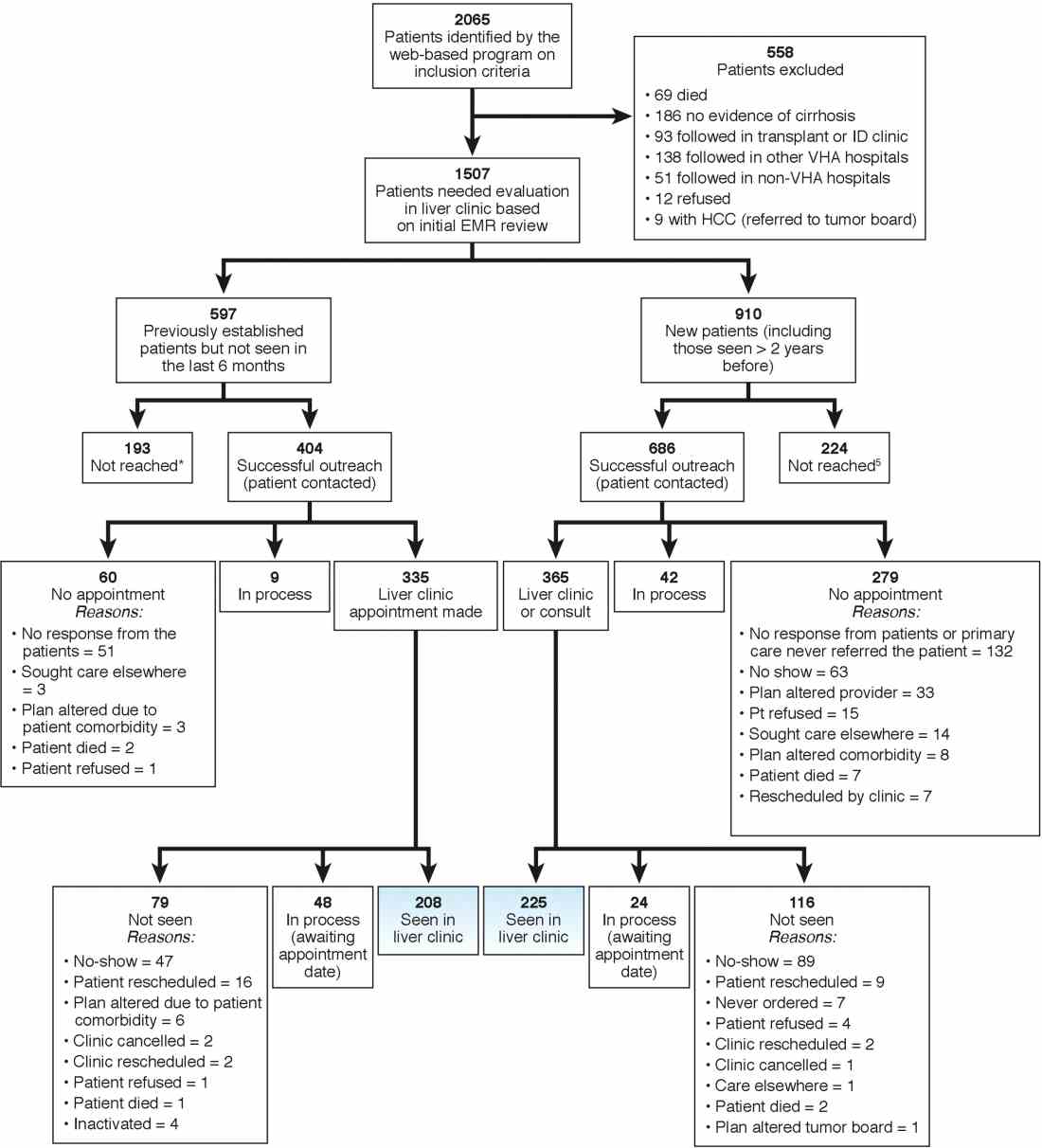

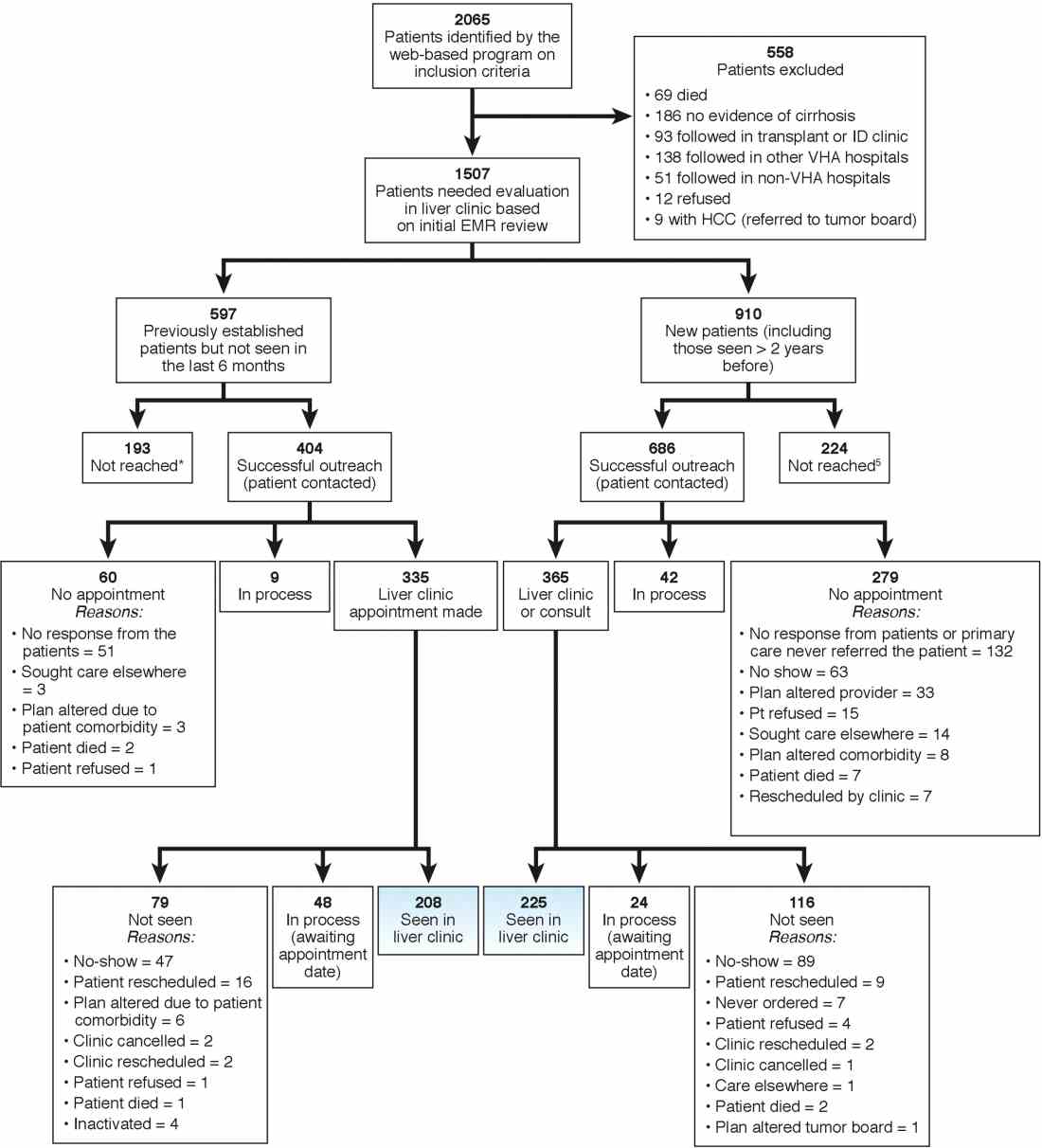

We identified 2,065 patients who met the case definition of cirrhosis (diagnosed and potentially undiagnosed) and were not in regular liver care. Based on initial review, 1,507 patients had an indication to be seen in the liver clinic. Among the remaining 558, the most common reasons for not requiring liver clinic follow-up were: being seen in other facilities (138 in other VHA and 51 in outside hospitals), followed in other specialty clinics (e.g., liver transplant or infectious disease, n = 93), or absence of cirrhosis based on initial review (n = 165) (see Figure 1 for other reasons).

We used two different strategies to reach out to the patients. Of the 1,507 patients, 597 were previously seen in the liver clinics but were lost to follow-up. These patients were contacted directly by the liver clinic staff. The other 910 patients with cirrhosis (of 1,507) had never been seen in the ambulatory liver clinics (n = 559) or were seen more than 2 years before the implementation of cirrhosis tracker (n = 351). These patients were reached through their PCPs. We used standard electronic medical record templates to request PCP’s assistance in reviewing patients' records and submitting a liver consultation after they discussed the need for liver evaluation with the patient.

Of the 597 patients who were previously seen but lost to follow-up, we successfully contacted 404 (67.7%) patients via telephone and/or letters (for the latter, success was defined when patients called back); of these 335 (82.9%) patients had clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 208 (51.5% of 404; 34.8% of 597) patients were subsequently seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. As shown in Figure 1, the most common reasons for inability to successfully link patients to the clinic were at the patient level, including no show, cancellation, and noninterest in seeking liver care. It took on average 1.5 attempts (range, 1–4) to link 214 patients to the liver clinic.

Of the other 910 patients with cirrhosis, 686 (75.4%) were successfully contacted; and of these 365 (53.2%) patients had liver clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 225 (61.7% of 365; 24.7% of 910) patients were seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. The reasons underlying inability to link patients to liver specialty clinics are listed in Figure 1 and included shortfalls at the PCP and the patient levels. It took on average 2.4 attempts (range, 1–5) to link 225 patients to the liver clinic.

A total of 124 patients were initiated on direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV treatment and 18 new hepatocellular carcinoma cases were diagnosed as part of P-CIMS.

Discussion and future directions

We learned several lessons during this initiative. First, it was critical to allow time to iteratively revise the cirrhosis tracker program, with input from key stakeholders, including clinician end users. For example, based on feedback, the program was modified to exclude patients who had died or those who were seeking primary care at other VHA facilities. Second, merely having a program that accurately identifies patients with cirrhosis is not the same as knowing how to get organizations and providers to use it. We found that it was critical to involve local leadership and key stakeholders in the preimplementation phase to foster active ownership of P-CIMS and to encourage the rise of natural champions. Additionally, we focused on integrating P-CIMS in the existing workflow. We also had to be cognizant of the needs of patients, such as potential problems with communication relating to notification and appointments for evaluation. Third, several elements at the facility level played a key role in the successful implementation of P-CIMS, including the culture of the facility (commitment to quality improvement); leadership engagement; and perceived need for and relative priority of identifying and managing patients with cirrhosis, especially those with chronic HCV. We also had strong buy-in from the VHA National Program Office tasked with improving care for those with liver disease, which provided support for development of the cirrhosis tracker.

Overall, our early results show that about 30% of patients with cirrhosis without ongoing linkage to liver care were seen in the liver specialty clinics because of P-CIMS. This proportion should be interpreted in the context of the patient population and setting. Cirrhosis disproportionately affects vulnerable patients, including those who are impoverished, homeless, and with drug- and alcohol-related problems; a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. Most patients in our sample had no linkage with specialty care. It is plausible that some patients with cirrhosis would have been seen in the liver clinics, regardless of P-CIMS. However, we expect this proportion would have been substantially lower than the 30% observed with P-CIMS.

We found several barriers to successful linkage and identified possible solutions. Our results suggest that a direct outreach to patients (without going through PCP) may result in fewer failures to linkage. In total, about 35% of patients who were contacted directly by the liver clinic met the endpoint compared with about 25% of patients who were contacted via their PCP. Future iterations of P-CIMS will rely on direct outreach for most patients. We also found that many patients were unable to keep scheduled appointments; some of this was because of inability to come on specific days and times. Open-access clinics may be one way to accommodate these high-risk patients. Although a full cost-effectiveness analysis is beyond the scope of this report, annual cost of maintaining P-CIMS was less than $100,000 (facilitator and programming support), which is equivalent to antiviral treatment cost of four to five HCV patients, suggesting that P-CIMS (with ability to reach out to hundreds of patients) may indeed be cost effective (if not cost saving).

In summary, we built and successfully implemented a population-based health management system with a structured care coordination strategy to facilitate identification and linkage to care of patients with cirrhosis. Our initial results suggest modest success in managing a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. The next steps include comparing the rates of linkage to specialty care with rates in comparable facilities that did not use the tracker; broadening the scope to ensure patients are retained in care and receive guideline-concordant care over time. We will share these results in a subsequent manuscript. To our knowledge, cirrhosis tracker is the first informatics tool that leverages data from the electronic medical records with other tools and strategies to improve quality of cirrhosis care. We believe that the lessons that we learned can also help inform efforts to design programs that encourage use of administrative data–based risk screeners to identify patients with other chronic conditions who are at risk for suboptimal outcomes.

References

1. Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, et al. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:509-16.

2. Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:996-1005.

3. Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521-31.

4. Gluud LL, Klingenberg S, Nikolova D, et al. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers as primary prophylaxis in esophageal varices: systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2842-8.

5. Singal AG, Mittal S, Yerokun OA, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening associated with early tumor detection and improved survival among patients with cirrhosis in the US. Am J Med. 2017;130:1099-106.

6. Kanwal F, Volk M, Singal A, et al. Improving quality of health care for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1204-7.

7. Taddei T, Hunnibell L, DeLorenzo A, et al. EMR-linked cancer tracker facilitates lung and liver cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:77.

8. Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, et al. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:274-82.

9. Chou R, Wasson N. Blood tests to diagnose fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:807-20.

10. Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, et al. Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:904-12.

Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Mapakshi is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Centerof Excellence, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Smith is project manager at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Taddei is director of the HCC Initiative, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, associate professor of medicine, digestive diseases, Yale University School of Medicine, director, liver cancer team, Smilow Cancer Hospital at Yale New Haven Hospital; Dr. Hussain is assistant professor, Baylor College of Medicine, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Madu is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Duong is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. White is assistant professor of medicine, health services research, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Cao is a statistical analyst at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Mehta is in Health Services Research at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven; Dr. El-Serag is Chairman and Professor Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Asch is chief of health service research, director of HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System , Palo Alto, Calif., professor of medicine, primary care and population health, Stanford, Calif.; Dr. Midboe is co-implementation research coordinator, HIV/Hepatitis QUERI, director VA patient safety center of inquiry, HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, Calif. The authors disclose no conflicts. This material is based on work supported by Department of Veterans Affairs, QUERI Program, QUE 15-284, VA HIV, Hepatitis C, and Related Conditions Program, and VA National Center for Patient Safety. The work is also supported in part by the Veterans Administration Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13-413); Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Tex.; and the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is potentially preventable. Antiviral treatment in patients with cirrhosis-related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus can prevent complications.1-3 Beta-blockers and endoscopic treatments of esophageal varices are effective in primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage.4 Surveillance for hepatocellular cancer is associated with increased detection of early-stage cancer and improved survival.5 However, many patients with cirrhosis are either not diagnosed in a primary care setting, or even when diagnosed, not seen or referred to specialty clinics to receive disease-specific care,6 and thus remain at high risk for complications.

Our goal was to implement a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system (P-CIMS) to allow identification of all patients with potential cirrhosis in the health care system and to facilitate their linkage to specialty liver care. We describe the implementation of P-CIMS at a large Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospital and present initial results about its impact on patient care.

P-CIMS Intervention

P-CIMS is a multicomponent intervention that includes a secure web-based tracking system, standardized communication templates, and care coordination protocols.

Web-based tracking system

An interdisciplinary team of clinicians, programmers, and informatics experts developed the P-CIMS software program by extending an existing comprehensive care tracking system.7 The P-CIMS program (referred to as cirrhosis tracker) extracts information from VHA’s national corporate data warehouse. VHA corporate data warehouse includes diagnosis codes, laboratory test results, vital status, and pharmacy data for each encounter in the VA since October 1999. We designed the cirrhosis tracker program to identify patients who had outpatient or inpatient encounters in the last 3 years with either at least 1 cirrhosis diagnosis (defined as any instance of previously validated International Classification of Diseases-9 and -10 codes)8; or possible cirrhosis (defined as either aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index greater than 2.0 or Fibrosis-4 above 3.24 in patients with active HCV infection9 [defined based on positive HCV RNA or genotype test results]).

The user interface of the cirrhosis tracker is designed for easy patient lookup with live links to patient information extracted from the corporate data warehouse (recent laboratory test results, recent imaging studies, and appointments). The tracker also includes free-text fields that store follow-up information and alerting functions that remind the end user when to follow up with a patient. Supplementary Figure 1 shows screen-shots from the program.

We refined the program through an iterative process to ensure accuracy and completeness of data. Each data element (e.g., cirrhosis diagnosis, laboratory tests, clinic appointments) was validated using the full electronic medical record as the reference standard; this process occurred over a period of 9 months. The program can run to update patient data on a daily basis.

Standardized communication templates and care coordination protocols

Our interdisciplinary team created chart review note templates for use in the VHA electronic medical record to verify diagnosis of cirrhosis and to facilitate accurate communication with primary care providers (PCPs) and other specialty clinicians. We also designed standard patient letters to communicate the recommendations with patients. We established protocols for initial clinical reviews, patient outreach, scheduling, and follow-ups. These care coordination protocols were modified in an iterative manner during the implementation phase of P-CIMS.

Setting and patients

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston provides care to more than 111,000 veterans, including more than 3,800 patients with cirrhosis. At the time of P-CIMS implementation, there were three hepatologists and four advanced practice providers (APP) who provided liver-related care at the MEDVAMC.

The primary goal of the initial phase of implementation was to link patients with cirrhosis to regular liver-related care. Thus, the sample was limited to patients who did not have ongoing specialty care (i.e., no liver clinic visits in the last 6 months, including patients who were never seen in liver clinics).

Implementation strategy

We used implementation facilitation (IF), an evidence-based strategy, to implement P-CIMS.10 The IF team included facilitators (F.K., D.S.), local champions (S.M., K.H.), and technical support personnel (e.g., tracker programmers). Core components of IF were leadership engagement, creation of and regular engagement with a local stakeholder group of clinicians, educational outreach to clinicians and support staff, and problem solving. The IF activities took part in two phases: preimplementation and implementation.

Preimplementation phase

We interviewed key stakeholders to identify facilitators and barriers to P-CIMS implementation. One of the implementation facilitators (F.K.) obtained facility and clinical section’s leadership support, engaged key stakeholders, and devised a local implementation plan. Stakeholders included leadership in several disciplines: hepatology, infectious diseases, and primary care. We developed a map of clinical workflow processes to describe optimal integration of P-CIMS into existing workflow (Supplementary Figure 2).

Implementation phase

The facilitators met regularly (biweekly for the first year) with the stakeholder group including local champions and clinical staff. One of the facilitators (D.S.) served as the liaison between the P-CIMS team (F.K., A.M., R.M., T.T.) and the clinic staff to ensure that no patients were getting missed and to follow through on patient referrals to care. The programmers troubleshot technical issues that arose, and both facilitators worked with clinical staff to modify workflow as needed. At the start of IF, the facilitator conducted an initial round of trainings through in-person training or with the use of screen-sharing software. The impact of P-CIMS on patient care was tracked and feedback was provided to clinical staff on a quarterly basis.

Implementation results: Linkage to liver specialty care

P-CIMS was successfully implemented at the MEDVAMC. Patient data were first extracted in October 2015 with five updates through March 2017. In total, four APP, one MD, and the facilitator used the cirrhosis tracker on a regular basis. The clinical team (APP) conducted the initial review, triage, and outreach. It took on average 7 minutes (range, 2–20 minutes) for the initial review and outreach. The APPs entered each follow-up reminder in the tracker. For example, if they negotiated a liver clinic appointment with the patient, then they entered a reminder to follow up with the date by which this step (patient seen in liver clinic) should be completed. The tracker has a built-in alerting function. The implementation team was notified (via the tracker) when these tasks were due to ensure timely receipt of recommended care processes.

We identified 2,065 patients who met the case definition of cirrhosis (diagnosed and potentially undiagnosed) and were not in regular liver care. Based on initial review, 1,507 patients had an indication to be seen in the liver clinic. Among the remaining 558, the most common reasons for not requiring liver clinic follow-up were: being seen in other facilities (138 in other VHA and 51 in outside hospitals), followed in other specialty clinics (e.g., liver transplant or infectious disease, n = 93), or absence of cirrhosis based on initial review (n = 165) (see Figure 1 for other reasons).

We used two different strategies to reach out to the patients. Of the 1,507 patients, 597 were previously seen in the liver clinics but were lost to follow-up. These patients were contacted directly by the liver clinic staff. The other 910 patients with cirrhosis (of 1,507) had never been seen in the ambulatory liver clinics (n = 559) or were seen more than 2 years before the implementation of cirrhosis tracker (n = 351). These patients were reached through their PCPs. We used standard electronic medical record templates to request PCP’s assistance in reviewing patients' records and submitting a liver consultation after they discussed the need for liver evaluation with the patient.

Of the 597 patients who were previously seen but lost to follow-up, we successfully contacted 404 (67.7%) patients via telephone and/or letters (for the latter, success was defined when patients called back); of these 335 (82.9%) patients had clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 208 (51.5% of 404; 34.8% of 597) patients were subsequently seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. As shown in Figure 1, the most common reasons for inability to successfully link patients to the clinic were at the patient level, including no show, cancellation, and noninterest in seeking liver care. It took on average 1.5 attempts (range, 1–4) to link 214 patients to the liver clinic.

Of the other 910 patients with cirrhosis, 686 (75.4%) were successfully contacted; and of these 365 (53.2%) patients had liver clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 225 (61.7% of 365; 24.7% of 910) patients were seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. The reasons underlying inability to link patients to liver specialty clinics are listed in Figure 1 and included shortfalls at the PCP and the patient levels. It took on average 2.4 attempts (range, 1–5) to link 225 patients to the liver clinic.

A total of 124 patients were initiated on direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV treatment and 18 new hepatocellular carcinoma cases were diagnosed as part of P-CIMS.

Discussion and future directions

We learned several lessons during this initiative. First, it was critical to allow time to iteratively revise the cirrhosis tracker program, with input from key stakeholders, including clinician end users. For example, based on feedback, the program was modified to exclude patients who had died or those who were seeking primary care at other VHA facilities. Second, merely having a program that accurately identifies patients with cirrhosis is not the same as knowing how to get organizations and providers to use it. We found that it was critical to involve local leadership and key stakeholders in the preimplementation phase to foster active ownership of P-CIMS and to encourage the rise of natural champions. Additionally, we focused on integrating P-CIMS in the existing workflow. We also had to be cognizant of the needs of patients, such as potential problems with communication relating to notification and appointments for evaluation. Third, several elements at the facility level played a key role in the successful implementation of P-CIMS, including the culture of the facility (commitment to quality improvement); leadership engagement; and perceived need for and relative priority of identifying and managing patients with cirrhosis, especially those with chronic HCV. We also had strong buy-in from the VHA National Program Office tasked with improving care for those with liver disease, which provided support for development of the cirrhosis tracker.

Overall, our early results show that about 30% of patients with cirrhosis without ongoing linkage to liver care were seen in the liver specialty clinics because of P-CIMS. This proportion should be interpreted in the context of the patient population and setting. Cirrhosis disproportionately affects vulnerable patients, including those who are impoverished, homeless, and with drug- and alcohol-related problems; a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. Most patients in our sample had no linkage with specialty care. It is plausible that some patients with cirrhosis would have been seen in the liver clinics, regardless of P-CIMS. However, we expect this proportion would have been substantially lower than the 30% observed with P-CIMS.

We found several barriers to successful linkage and identified possible solutions. Our results suggest that a direct outreach to patients (without going through PCP) may result in fewer failures to linkage. In total, about 35% of patients who were contacted directly by the liver clinic met the endpoint compared with about 25% of patients who were contacted via their PCP. Future iterations of P-CIMS will rely on direct outreach for most patients. We also found that many patients were unable to keep scheduled appointments; some of this was because of inability to come on specific days and times. Open-access clinics may be one way to accommodate these high-risk patients. Although a full cost-effectiveness analysis is beyond the scope of this report, annual cost of maintaining P-CIMS was less than $100,000 (facilitator and programming support), which is equivalent to antiviral treatment cost of four to five HCV patients, suggesting that P-CIMS (with ability to reach out to hundreds of patients) may indeed be cost effective (if not cost saving).

In summary, we built and successfully implemented a population-based health management system with a structured care coordination strategy to facilitate identification and linkage to care of patients with cirrhosis. Our initial results suggest modest success in managing a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. The next steps include comparing the rates of linkage to specialty care with rates in comparable facilities that did not use the tracker; broadening the scope to ensure patients are retained in care and receive guideline-concordant care over time. We will share these results in a subsequent manuscript. To our knowledge, cirrhosis tracker is the first informatics tool that leverages data from the electronic medical records with other tools and strategies to improve quality of cirrhosis care. We believe that the lessons that we learned can also help inform efforts to design programs that encourage use of administrative data–based risk screeners to identify patients with other chronic conditions who are at risk for suboptimal outcomes.

References

1. Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, et al. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:509-16.

2. Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:996-1005.

3. Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521-31.

4. Gluud LL, Klingenberg S, Nikolova D, et al. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers as primary prophylaxis in esophageal varices: systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2842-8.

5. Singal AG, Mittal S, Yerokun OA, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening associated with early tumor detection and improved survival among patients with cirrhosis in the US. Am J Med. 2017;130:1099-106.

6. Kanwal F, Volk M, Singal A, et al. Improving quality of health care for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1204-7.

7. Taddei T, Hunnibell L, DeLorenzo A, et al. EMR-linked cancer tracker facilitates lung and liver cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:77.

8. Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, et al. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:274-82.

9. Chou R, Wasson N. Blood tests to diagnose fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:807-20.

10. Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, et al. Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:904-12.

Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Mapakshi is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Centerof Excellence, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Smith is project manager at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Taddei is director of the HCC Initiative, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, associate professor of medicine, digestive diseases, Yale University School of Medicine, director, liver cancer team, Smilow Cancer Hospital at Yale New Haven Hospital; Dr. Hussain is assistant professor, Baylor College of Medicine, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Madu is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Duong is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. White is assistant professor of medicine, health services research, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Cao is a statistical analyst at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Mehta is in Health Services Research at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven; Dr. El-Serag is Chairman and Professor Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Asch is chief of health service research, director of HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System , Palo Alto, Calif., professor of medicine, primary care and population health, Stanford, Calif.; Dr. Midboe is co-implementation research coordinator, HIV/Hepatitis QUERI, director VA patient safety center of inquiry, HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, Calif. The authors disclose no conflicts. This material is based on work supported by Department of Veterans Affairs, QUERI Program, QUE 15-284, VA HIV, Hepatitis C, and Related Conditions Program, and VA National Center for Patient Safety. The work is also supported in part by the Veterans Administration Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13-413); Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Tex.; and the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is potentially preventable. Antiviral treatment in patients with cirrhosis-related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus can prevent complications.1-3 Beta-blockers and endoscopic treatments of esophageal varices are effective in primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage.4 Surveillance for hepatocellular cancer is associated with increased detection of early-stage cancer and improved survival.5 However, many patients with cirrhosis are either not diagnosed in a primary care setting, or even when diagnosed, not seen or referred to specialty clinics to receive disease-specific care,6 and thus remain at high risk for complications.

Our goal was to implement a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system (P-CIMS) to allow identification of all patients with potential cirrhosis in the health care system and to facilitate their linkage to specialty liver care. We describe the implementation of P-CIMS at a large Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospital and present initial results about its impact on patient care.

P-CIMS Intervention

P-CIMS is a multicomponent intervention that includes a secure web-based tracking system, standardized communication templates, and care coordination protocols.

Web-based tracking system

An interdisciplinary team of clinicians, programmers, and informatics experts developed the P-CIMS software program by extending an existing comprehensive care tracking system.7 The P-CIMS program (referred to as cirrhosis tracker) extracts information from VHA’s national corporate data warehouse. VHA corporate data warehouse includes diagnosis codes, laboratory test results, vital status, and pharmacy data for each encounter in the VA since October 1999. We designed the cirrhosis tracker program to identify patients who had outpatient or inpatient encounters in the last 3 years with either at least 1 cirrhosis diagnosis (defined as any instance of previously validated International Classification of Diseases-9 and -10 codes)8; or possible cirrhosis (defined as either aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index greater than 2.0 or Fibrosis-4 above 3.24 in patients with active HCV infection9 [defined based on positive HCV RNA or genotype test results]).

The user interface of the cirrhosis tracker is designed for easy patient lookup with live links to patient information extracted from the corporate data warehouse (recent laboratory test results, recent imaging studies, and appointments). The tracker also includes free-text fields that store follow-up information and alerting functions that remind the end user when to follow up with a patient. Supplementary Figure 1 shows screen-shots from the program.

We refined the program through an iterative process to ensure accuracy and completeness of data. Each data element (e.g., cirrhosis diagnosis, laboratory tests, clinic appointments) was validated using the full electronic medical record as the reference standard; this process occurred over a period of 9 months. The program can run to update patient data on a daily basis.

Standardized communication templates and care coordination protocols

Our interdisciplinary team created chart review note templates for use in the VHA electronic medical record to verify diagnosis of cirrhosis and to facilitate accurate communication with primary care providers (PCPs) and other specialty clinicians. We also designed standard patient letters to communicate the recommendations with patients. We established protocols for initial clinical reviews, patient outreach, scheduling, and follow-ups. These care coordination protocols were modified in an iterative manner during the implementation phase of P-CIMS.

Setting and patients

Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston provides care to more than 111,000 veterans, including more than 3,800 patients with cirrhosis. At the time of P-CIMS implementation, there were three hepatologists and four advanced practice providers (APP) who provided liver-related care at the MEDVAMC.

The primary goal of the initial phase of implementation was to link patients with cirrhosis to regular liver-related care. Thus, the sample was limited to patients who did not have ongoing specialty care (i.e., no liver clinic visits in the last 6 months, including patients who were never seen in liver clinics).

Implementation strategy

We used implementation facilitation (IF), an evidence-based strategy, to implement P-CIMS.10 The IF team included facilitators (F.K., D.S.), local champions (S.M., K.H.), and technical support personnel (e.g., tracker programmers). Core components of IF were leadership engagement, creation of and regular engagement with a local stakeholder group of clinicians, educational outreach to clinicians and support staff, and problem solving. The IF activities took part in two phases: preimplementation and implementation.

Preimplementation phase

We interviewed key stakeholders to identify facilitators and barriers to P-CIMS implementation. One of the implementation facilitators (F.K.) obtained facility and clinical section’s leadership support, engaged key stakeholders, and devised a local implementation plan. Stakeholders included leadership in several disciplines: hepatology, infectious diseases, and primary care. We developed a map of clinical workflow processes to describe optimal integration of P-CIMS into existing workflow (Supplementary Figure 2).

Implementation phase

The facilitators met regularly (biweekly for the first year) with the stakeholder group including local champions and clinical staff. One of the facilitators (D.S.) served as the liaison between the P-CIMS team (F.K., A.M., R.M., T.T.) and the clinic staff to ensure that no patients were getting missed and to follow through on patient referrals to care. The programmers troubleshot technical issues that arose, and both facilitators worked with clinical staff to modify workflow as needed. At the start of IF, the facilitator conducted an initial round of trainings through in-person training or with the use of screen-sharing software. The impact of P-CIMS on patient care was tracked and feedback was provided to clinical staff on a quarterly basis.

Implementation results: Linkage to liver specialty care

P-CIMS was successfully implemented at the MEDVAMC. Patient data were first extracted in October 2015 with five updates through March 2017. In total, four APP, one MD, and the facilitator used the cirrhosis tracker on a regular basis. The clinical team (APP) conducted the initial review, triage, and outreach. It took on average 7 minutes (range, 2–20 minutes) for the initial review and outreach. The APPs entered each follow-up reminder in the tracker. For example, if they negotiated a liver clinic appointment with the patient, then they entered a reminder to follow up with the date by which this step (patient seen in liver clinic) should be completed. The tracker has a built-in alerting function. The implementation team was notified (via the tracker) when these tasks were due to ensure timely receipt of recommended care processes.

We identified 2,065 patients who met the case definition of cirrhosis (diagnosed and potentially undiagnosed) and were not in regular liver care. Based on initial review, 1,507 patients had an indication to be seen in the liver clinic. Among the remaining 558, the most common reasons for not requiring liver clinic follow-up were: being seen in other facilities (138 in other VHA and 51 in outside hospitals), followed in other specialty clinics (e.g., liver transplant or infectious disease, n = 93), or absence of cirrhosis based on initial review (n = 165) (see Figure 1 for other reasons).

We used two different strategies to reach out to the patients. Of the 1,507 patients, 597 were previously seen in the liver clinics but were lost to follow-up. These patients were contacted directly by the liver clinic staff. The other 910 patients with cirrhosis (of 1,507) had never been seen in the ambulatory liver clinics (n = 559) or were seen more than 2 years before the implementation of cirrhosis tracker (n = 351). These patients were reached through their PCPs. We used standard electronic medical record templates to request PCP’s assistance in reviewing patients' records and submitting a liver consultation after they discussed the need for liver evaluation with the patient.

Of the 597 patients who were previously seen but lost to follow-up, we successfully contacted 404 (67.7%) patients via telephone and/or letters (for the latter, success was defined when patients called back); of these 335 (82.9%) patients had clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 208 (51.5% of 404; 34.8% of 597) patients were subsequently seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. As shown in Figure 1, the most common reasons for inability to successfully link patients to the clinic were at the patient level, including no show, cancellation, and noninterest in seeking liver care. It took on average 1.5 attempts (range, 1–4) to link 214 patients to the liver clinic.

Of the other 910 patients with cirrhosis, 686 (75.4%) were successfully contacted; and of these 365 (53.2%) patients had liver clinic appointments scheduled. In total, 225 (61.7% of 365; 24.7% of 910) patients were seen in the liver clinics during a median of 12-month follow-up. The reasons underlying inability to link patients to liver specialty clinics are listed in Figure 1 and included shortfalls at the PCP and the patient levels. It took on average 2.4 attempts (range, 1–5) to link 225 patients to the liver clinic.

A total of 124 patients were initiated on direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV treatment and 18 new hepatocellular carcinoma cases were diagnosed as part of P-CIMS.

Discussion and future directions

We learned several lessons during this initiative. First, it was critical to allow time to iteratively revise the cirrhosis tracker program, with input from key stakeholders, including clinician end users. For example, based on feedback, the program was modified to exclude patients who had died or those who were seeking primary care at other VHA facilities. Second, merely having a program that accurately identifies patients with cirrhosis is not the same as knowing how to get organizations and providers to use it. We found that it was critical to involve local leadership and key stakeholders in the preimplementation phase to foster active ownership of P-CIMS and to encourage the rise of natural champions. Additionally, we focused on integrating P-CIMS in the existing workflow. We also had to be cognizant of the needs of patients, such as potential problems with communication relating to notification and appointments for evaluation. Third, several elements at the facility level played a key role in the successful implementation of P-CIMS, including the culture of the facility (commitment to quality improvement); leadership engagement; and perceived need for and relative priority of identifying and managing patients with cirrhosis, especially those with chronic HCV. We also had strong buy-in from the VHA National Program Office tasked with improving care for those with liver disease, which provided support for development of the cirrhosis tracker.

Overall, our early results show that about 30% of patients with cirrhosis without ongoing linkage to liver care were seen in the liver specialty clinics because of P-CIMS. This proportion should be interpreted in the context of the patient population and setting. Cirrhosis disproportionately affects vulnerable patients, including those who are impoverished, homeless, and with drug- and alcohol-related problems; a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. Most patients in our sample had no linkage with specialty care. It is plausible that some patients with cirrhosis would have been seen in the liver clinics, regardless of P-CIMS. However, we expect this proportion would have been substantially lower than the 30% observed with P-CIMS.

We found several barriers to successful linkage and identified possible solutions. Our results suggest that a direct outreach to patients (without going through PCP) may result in fewer failures to linkage. In total, about 35% of patients who were contacted directly by the liver clinic met the endpoint compared with about 25% of patients who were contacted via their PCP. Future iterations of P-CIMS will rely on direct outreach for most patients. We also found that many patients were unable to keep scheduled appointments; some of this was because of inability to come on specific days and times. Open-access clinics may be one way to accommodate these high-risk patients. Although a full cost-effectiveness analysis is beyond the scope of this report, annual cost of maintaining P-CIMS was less than $100,000 (facilitator and programming support), which is equivalent to antiviral treatment cost of four to five HCV patients, suggesting that P-CIMS (with ability to reach out to hundreds of patients) may indeed be cost effective (if not cost saving).

In summary, we built and successfully implemented a population-based health management system with a structured care coordination strategy to facilitate identification and linkage to care of patients with cirrhosis. Our initial results suggest modest success in managing a complex population who often have difficulty staying in care. The next steps include comparing the rates of linkage to specialty care with rates in comparable facilities that did not use the tracker; broadening the scope to ensure patients are retained in care and receive guideline-concordant care over time. We will share these results in a subsequent manuscript. To our knowledge, cirrhosis tracker is the first informatics tool that leverages data from the electronic medical records with other tools and strategies to improve quality of cirrhosis care. We believe that the lessons that we learned can also help inform efforts to design programs that encourage use of administrative data–based risk screeners to identify patients with other chronic conditions who are at risk for suboptimal outcomes.

References

1. Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, et al. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:509-16.

2. Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:996-1005.

3. Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521-31.

4. Gluud LL, Klingenberg S, Nikolova D, et al. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers as primary prophylaxis in esophageal varices: systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2842-8.

5. Singal AG, Mittal S, Yerokun OA, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening associated with early tumor detection and improved survival among patients with cirrhosis in the US. Am J Med. 2017;130:1099-106.

6. Kanwal F, Volk M, Singal A, et al. Improving quality of health care for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1204-7.

7. Taddei T, Hunnibell L, DeLorenzo A, et al. EMR-linked cancer tracker facilitates lung and liver cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:77.

8. Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, et al. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:274-82.

9. Chou R, Wasson N. Blood tests to diagnose fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:807-20.

10. Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, et al. Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:904-12.

Dr. Kanwal is professor of medicine, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Mapakshi is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Centerof Excellence, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Smith is project manager at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. Taddei is director of the HCC Initiative, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, associate professor of medicine, digestive diseases, Yale University School of Medicine, director, liver cancer team, Smilow Cancer Hospital at Yale New Haven Hospital; Dr. Hussain is assistant professor, Baylor College of Medicine, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Madu is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Duong is in gastroenterology and hepatology, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Dr. White is assistant professor of medicine, health services research, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Cao is a statistical analyst at Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Ms. Mehta is in Health Services Research at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven; Dr. El-Serag is Chairman and Professor Margaret M. and Albert B. Alkek, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Asch is chief of health service research, director of HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System , Palo Alto, Calif., professor of medicine, primary care and population health, Stanford, Calif.; Dr. Midboe is co-implementation research coordinator, HIV/Hepatitis QUERI, director VA patient safety center of inquiry, HSR&D Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, Calif. The authors disclose no conflicts. This material is based on work supported by Department of Veterans Affairs, QUERI Program, QUE 15-284, VA HIV, Hepatitis C, and Related Conditions Program, and VA National Center for Patient Safety. The work is also supported in part by the Veterans Administration Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13-413); Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Tex.; and the Center for Gastrointestinal Development, Infection and Injury (NIDDK P30 DK 56338).

Top AGA Community patient cases

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses.

In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical discussions shared in the forum recently:

1. Refractory lymphocytic colitis and diarrhea

An elderly female with lymphocytic colitis wasn’t responding to any treatment provided by her physician, who was trying to avoid a colectomy due to her advanced age. The GI community shared their support with recommendations for therapy options and next steps.

2. Atypical case of enteropathy

This physician found mild erosive gastritis, villous blunting and mucosal accumulation of eosinophils up to 55/hpf in an 18-year-old female with a history of nausea, vomiting, nonbloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss over the past year. She tested negative for celiac disease and a gluten-free diet only provided partial improvement. The conversation in the Community forum covered potential diagnoses to be considered and recommendations for therapy.

3. Eosinophilic esophagitis with aperistalsis

A 21-year-old male presented with progressive dysphagia due to eosinophilic esophagitis with a weight loss of 17 pounds in two months. A panendoscopy revealed a hiatal hernia and aperistalsis of the esophagus, with normal inferior and superior sphincter pressures. No changes were observed recently; he is being managed with prokinetics and remains asymptomatic.

More clinical cases and discussions are at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses.

In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical discussions shared in the forum recently:

1. Refractory lymphocytic colitis and diarrhea

An elderly female with lymphocytic colitis wasn’t responding to any treatment provided by her physician, who was trying to avoid a colectomy due to her advanced age. The GI community shared their support with recommendations for therapy options and next steps.

2. Atypical case of enteropathy

This physician found mild erosive gastritis, villous blunting and mucosal accumulation of eosinophils up to 55/hpf in an 18-year-old female with a history of nausea, vomiting, nonbloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss over the past year. She tested negative for celiac disease and a gluten-free diet only provided partial improvement. The conversation in the Community forum covered potential diagnoses to be considered and recommendations for therapy.

3. Eosinophilic esophagitis with aperistalsis

A 21-year-old male presented with progressive dysphagia due to eosinophilic esophagitis with a weight loss of 17 pounds in two months. A panendoscopy revealed a hiatal hernia and aperistalsis of the esophagus, with normal inferior and superior sphincter pressures. No changes were observed recently; he is being managed with prokinetics and remains asymptomatic.

More clinical cases and discussions are at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses.

In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical discussions shared in the forum recently:

1. Refractory lymphocytic colitis and diarrhea

An elderly female with lymphocytic colitis wasn’t responding to any treatment provided by her physician, who was trying to avoid a colectomy due to her advanced age. The GI community shared their support with recommendations for therapy options and next steps.

2. Atypical case of enteropathy

This physician found mild erosive gastritis, villous blunting and mucosal accumulation of eosinophils up to 55/hpf in an 18-year-old female with a history of nausea, vomiting, nonbloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss over the past year. She tested negative for celiac disease and a gluten-free diet only provided partial improvement. The conversation in the Community forum covered potential diagnoses to be considered and recommendations for therapy.

3. Eosinophilic esophagitis with aperistalsis

A 21-year-old male presented with progressive dysphagia due to eosinophilic esophagitis with a weight loss of 17 pounds in two months. A panendoscopy revealed a hiatal hernia and aperistalsis of the esophagus, with normal inferior and superior sphincter pressures. No changes were observed recently; he is being managed with prokinetics and remains asymptomatic.

More clinical cases and discussions are at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

Continuing board certification vision report includes many sound recommendations on MOC

Five key wins will help lay the foundation for new assessment pathway to maintaining board certification.

The Continuing Board Certification: Vision for the Future Commission submitted its final report to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) Board of Directors. The draft reflected many of the issues AGA has raised with ABIM over the years and our comments on the draft report.

Having this report in hand puts AGA in a position of strength as we begin working with ABIM and the other GI societies to explore the development of a new assessment pathway through which gastroenterologists and hepatologists can maintain board certification.

Here’s a link to the full report: https://visioninitiative.org/commission/final-report/

Key wins:

- Commission recommended the term “Maintenance of Certification” be abandoned.

- “Emphasis on continuing certification must be focused on the availability of curated information that helps diplomates deliver improved clinical care ... traditional infrequent high-stakes assessments no matter how psychometrically valid, is viewed as inappropriate as the future direction for continuing certification.”

- The Commission believes ABMS Boards need to engage with diplomates on an ongoing basis instead of every 2, 5, or 10 years.

- The ABMS Board must offer an alternative to burdensome highly secure, point-in-time examinations of knowledge.

- ABMS and ABMS Boards must facilitate and encourage independent research to build on the existing evidence base about the value of continuing certification.

MOC and AGA’s approach to reform are topics of much discussion on the AGA Community.

Five key wins will help lay the foundation for new assessment pathway to maintaining board certification.

The Continuing Board Certification: Vision for the Future Commission submitted its final report to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) Board of Directors. The draft reflected many of the issues AGA has raised with ABIM over the years and our comments on the draft report.

Having this report in hand puts AGA in a position of strength as we begin working with ABIM and the other GI societies to explore the development of a new assessment pathway through which gastroenterologists and hepatologists can maintain board certification.

Here’s a link to the full report: https://visioninitiative.org/commission/final-report/

Key wins:

- Commission recommended the term “Maintenance of Certification” be abandoned.

- “Emphasis on continuing certification must be focused on the availability of curated information that helps diplomates deliver improved clinical care ... traditional infrequent high-stakes assessments no matter how psychometrically valid, is viewed as inappropriate as the future direction for continuing certification.”

- The Commission believes ABMS Boards need to engage with diplomates on an ongoing basis instead of every 2, 5, or 10 years.

- The ABMS Board must offer an alternative to burdensome highly secure, point-in-time examinations of knowledge.

- ABMS and ABMS Boards must facilitate and encourage independent research to build on the existing evidence base about the value of continuing certification.

MOC and AGA’s approach to reform are topics of much discussion on the AGA Community.

Five key wins will help lay the foundation for new assessment pathway to maintaining board certification.

The Continuing Board Certification: Vision for the Future Commission submitted its final report to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) Board of Directors. The draft reflected many of the issues AGA has raised with ABIM over the years and our comments on the draft report.

Having this report in hand puts AGA in a position of strength as we begin working with ABIM and the other GI societies to explore the development of a new assessment pathway through which gastroenterologists and hepatologists can maintain board certification.

Here’s a link to the full report: https://visioninitiative.org/commission/final-report/

Key wins:

- Commission recommended the term “Maintenance of Certification” be abandoned.

- “Emphasis on continuing certification must be focused on the availability of curated information that helps diplomates deliver improved clinical care ... traditional infrequent high-stakes assessments no matter how psychometrically valid, is viewed as inappropriate as the future direction for continuing certification.”

- The Commission believes ABMS Boards need to engage with diplomates on an ongoing basis instead of every 2, 5, or 10 years.

- The ABMS Board must offer an alternative to burdensome highly secure, point-in-time examinations of knowledge.

- ABMS and ABMS Boards must facilitate and encourage independent research to build on the existing evidence base about the value of continuing certification.

MOC and AGA’s approach to reform are topics of much discussion on the AGA Community.

Sperm quality linked to some recurrent pregnancy loss

NEW ORLEANS – Couples with recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) might benefit from seminal parameter testing, based on results from a study presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Sperm quality was more likely to be impaired in the 50 male partners of women with recurrent pregnancy loss than it was in a control group of 63 similar-age men, reported Anastasia P. Dimakopoulou, MBBS, a clinical research fellow at Imperial College, London.

Recurrent pregnancy loss is defined as three pregnancy losses before 20 weeks of gestation.

The reported prevalence of RPL has been estimated at less than 2% in couples attempting pregnancy. About half of those cases are considered to be idiopathic, she said.

Sperm DNA plays a role in placentation, and previous study findings have shown that men in RPL couples are more likely to have higher rates of DNA fragmentation in their sperm. Male partners are not routinely evaluated when seeking a cause for RPL, however.

In this study, 50 men from RPL couples and 63 control men were screened for factors known to affect sperm quality, such as previous testicular surgery, sexually transmitted diseases, alcohol intake, and smoking. In patients and controls, semen reactive oxidative stress, a novel biomarker of sperm function, was measured with a chemiluminescence luminol assay.

The proportion of men with abnormal sperm morphology, although modest in both groups, was significantly more common in men from RPL couples than in controls (4.5% vs. 3.4%, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, the mean reactive oxidative stress levels were four times greater in the RPL men (9.3 vs. 2.3 relative light units/sec per 106 sperm; P less than .05).

Consistent with the higher median reactive oxidative stress levels, the median DNA fragmentation index, which is likely to be linked to increased reactive oxidative stress, was more than twice as high in the RPL men, compared with the controls (16.3 vs. 7.4; P less than .0001).

In addition, the sperm volume was significantly lower in men from the RPL couples, compared with controls. The levels of morning serum testosterone also were lower in men from RPL couples, but the difference did not reach significance relative to controls.

There has been relatively little attention directed toward the male partner in the evaluation and treatment of RPL, but that should change, according to Dr. Dimakopoulou. She said data encourage a new direction of study, including the effort to look for treatable causes of RPL in the male partner.

“By pursuing drugs that stop sperm DNA damage, it may be possible to identify new therapeutic pathways for couples who experience RPL,” Dr. Dimakopoulou maintained. However, even in advance of targeted therapies, she suggested these data encourage investigation of male partners in couples with RPL. Although evidence of reactive oxidative stress may not define a cause, it broadens the scope of investigation and might have value when counseling patients.

Dr. Dimakopoulou reported no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Dimakopoulou AP et al. ENDO 2019, Session OR18-5.

NEW ORLEANS – Couples with recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) might benefit from seminal parameter testing, based on results from a study presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Sperm quality was more likely to be impaired in the 50 male partners of women with recurrent pregnancy loss than it was in a control group of 63 similar-age men, reported Anastasia P. Dimakopoulou, MBBS, a clinical research fellow at Imperial College, London.