User login

FDA chief calls for release of all data tracking problems with medical devices

Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced in a tweet Wednesday that the agency plans to

“We’re now prioritizing making ALL of this data available,” Dr. Gottlieb tweeted.

A recent Kaiser Health News investigation revealed the scope of a hidden reporting pathway for device makers, with the agency accepting more than 1.1 million such reports since the start of 2016.

Device makers for nearly 20 years were able to quietly seek an “exemption” from standard, public harm-reporting rules. Devices with such exemptions have included surgical staplers and balloon pumps used in the vessels of heart-surgery patients.

Dr. Gottlieb’s tweet also referenced the challenge in opening the database, saying it “wasn’t easily accessible electronically owing to the system’s age. But it’s imperative that all safety information be available to the public.”

The agency made changes to the “alternative summary reporting” program in mid-2017 to require a public report summarizing data filed within the FDA. But nearly two decades of data remained cordoned off from doctors, patients, and device-safety researchers who say they could use it to detect problems.

Dr. Gottlieb’s announcement was welcomed by Madris Tomes, who has testified to FDA device-review panels about the importance of making summary data on patient harm open to the public.

“That’s the best news I’ve heard in years,” said Ms. Tomes, president of Device Events, which makes the FDA device-harm data more user-friendly. “I’m really happy that they’re taking notice and realizing that physicians who couldn’t see this data before were using devices that they wouldn’t have used if they had this data in front of them.”

Since September, KHN has filed Freedom of Information Act requests for parts or all of the “alternative summary reporting” database and for other special “exemption” reports, to little effect. A request to expedite delivery of those records was denied, and the FDA cited the lack of “compelling need” for the public to have the information. Officials noted that it might take up to 2 years to get such records through the FOIA process.

As recently as March 22, though, the agency began publishing previously undisclosed reports of harm, suddenly updating the numbers of breast implant malfunctions or injuries submitted over the years. The new data was presented to an FDA advisory panel, which is reviewing the safety of such devices. The panel, which met March 25 and 26, saw a chart showing hundreds of thousands more accounts of harm or malfunctions than had previously been acknowledged.

Michael Carome, MD, director of Public Citizen’s health research group, said his initial reaction to the news is “better late than never.”

“If [Dr. Gottlieb] follows through with his pledge to make all this data public, then that’s certainly a positive development,” he said. “But this is safety information that should have been made available years ago.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced in a tweet Wednesday that the agency plans to

“We’re now prioritizing making ALL of this data available,” Dr. Gottlieb tweeted.

A recent Kaiser Health News investigation revealed the scope of a hidden reporting pathway for device makers, with the agency accepting more than 1.1 million such reports since the start of 2016.

Device makers for nearly 20 years were able to quietly seek an “exemption” from standard, public harm-reporting rules. Devices with such exemptions have included surgical staplers and balloon pumps used in the vessels of heart-surgery patients.

Dr. Gottlieb’s tweet also referenced the challenge in opening the database, saying it “wasn’t easily accessible electronically owing to the system’s age. But it’s imperative that all safety information be available to the public.”

The agency made changes to the “alternative summary reporting” program in mid-2017 to require a public report summarizing data filed within the FDA. But nearly two decades of data remained cordoned off from doctors, patients, and device-safety researchers who say they could use it to detect problems.

Dr. Gottlieb’s announcement was welcomed by Madris Tomes, who has testified to FDA device-review panels about the importance of making summary data on patient harm open to the public.

“That’s the best news I’ve heard in years,” said Ms. Tomes, president of Device Events, which makes the FDA device-harm data more user-friendly. “I’m really happy that they’re taking notice and realizing that physicians who couldn’t see this data before were using devices that they wouldn’t have used if they had this data in front of them.”

Since September, KHN has filed Freedom of Information Act requests for parts or all of the “alternative summary reporting” database and for other special “exemption” reports, to little effect. A request to expedite delivery of those records was denied, and the FDA cited the lack of “compelling need” for the public to have the information. Officials noted that it might take up to 2 years to get such records through the FOIA process.

As recently as March 22, though, the agency began publishing previously undisclosed reports of harm, suddenly updating the numbers of breast implant malfunctions or injuries submitted over the years. The new data was presented to an FDA advisory panel, which is reviewing the safety of such devices. The panel, which met March 25 and 26, saw a chart showing hundreds of thousands more accounts of harm or malfunctions than had previously been acknowledged.

Michael Carome, MD, director of Public Citizen’s health research group, said his initial reaction to the news is “better late than never.”

“If [Dr. Gottlieb] follows through with his pledge to make all this data public, then that’s certainly a positive development,” he said. “But this is safety information that should have been made available years ago.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced in a tweet Wednesday that the agency plans to

“We’re now prioritizing making ALL of this data available,” Dr. Gottlieb tweeted.

A recent Kaiser Health News investigation revealed the scope of a hidden reporting pathway for device makers, with the agency accepting more than 1.1 million such reports since the start of 2016.

Device makers for nearly 20 years were able to quietly seek an “exemption” from standard, public harm-reporting rules. Devices with such exemptions have included surgical staplers and balloon pumps used in the vessels of heart-surgery patients.

Dr. Gottlieb’s tweet also referenced the challenge in opening the database, saying it “wasn’t easily accessible electronically owing to the system’s age. But it’s imperative that all safety information be available to the public.”

The agency made changes to the “alternative summary reporting” program in mid-2017 to require a public report summarizing data filed within the FDA. But nearly two decades of data remained cordoned off from doctors, patients, and device-safety researchers who say they could use it to detect problems.

Dr. Gottlieb’s announcement was welcomed by Madris Tomes, who has testified to FDA device-review panels about the importance of making summary data on patient harm open to the public.

“That’s the best news I’ve heard in years,” said Ms. Tomes, president of Device Events, which makes the FDA device-harm data more user-friendly. “I’m really happy that they’re taking notice and realizing that physicians who couldn’t see this data before were using devices that they wouldn’t have used if they had this data in front of them.”

Since September, KHN has filed Freedom of Information Act requests for parts or all of the “alternative summary reporting” database and for other special “exemption” reports, to little effect. A request to expedite delivery of those records was denied, and the FDA cited the lack of “compelling need” for the public to have the information. Officials noted that it might take up to 2 years to get such records through the FOIA process.

As recently as March 22, though, the agency began publishing previously undisclosed reports of harm, suddenly updating the numbers of breast implant malfunctions or injuries submitted over the years. The new data was presented to an FDA advisory panel, which is reviewing the safety of such devices. The panel, which met March 25 and 26, saw a chart showing hundreds of thousands more accounts of harm or malfunctions than had previously been acknowledged.

Michael Carome, MD, director of Public Citizen’s health research group, said his initial reaction to the news is “better late than never.”

“If [Dr. Gottlieb] follows through with his pledge to make all this data public, then that’s certainly a positive development,” he said. “But this is safety information that should have been made available years ago.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Cimzia becomes first FDA-approved treatment for nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis

, with objective evidence of inflammation, making it the first treatment approved by the agency for the condition.

The FDA approved the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor based on results from a randomized clinical trial in 317 adult patients with nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) who had elevated C-reactive protein levels and/or sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joints) on MRI.

The trial entailed 52 weeks of double-blind therapy with certolizumab at a starting dose of 400 mg on weeks 0, 2, and 4 followed by 200 mg every 2 weeks, or placebo. The Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score Major Improvement rate, defined as at least a 2-point improvement from baseline, was 47% in the active treatment arm, compared with 7% on placebo. The Assessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis International Society 40% response rate, a more patient-reported outcome measure, was 57% in the certolizumab group and 16% in controls (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 March 8. doi: 10.1002/art.40866).

The overall safety profile observed in the Cimzia treatment group was consistent with the known safety profile of certolizumab.

Cimzia was first approved in 2008 and has FDA-approved indications for adult patients with Crohn’s disease, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, active ankylosing spondylitis and moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy.

, with objective evidence of inflammation, making it the first treatment approved by the agency for the condition.

The FDA approved the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor based on results from a randomized clinical trial in 317 adult patients with nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) who had elevated C-reactive protein levels and/or sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joints) on MRI.

The trial entailed 52 weeks of double-blind therapy with certolizumab at a starting dose of 400 mg on weeks 0, 2, and 4 followed by 200 mg every 2 weeks, or placebo. The Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score Major Improvement rate, defined as at least a 2-point improvement from baseline, was 47% in the active treatment arm, compared with 7% on placebo. The Assessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis International Society 40% response rate, a more patient-reported outcome measure, was 57% in the certolizumab group and 16% in controls (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 March 8. doi: 10.1002/art.40866).

The overall safety profile observed in the Cimzia treatment group was consistent with the known safety profile of certolizumab.

Cimzia was first approved in 2008 and has FDA-approved indications for adult patients with Crohn’s disease, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, active ankylosing spondylitis and moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy.

, with objective evidence of inflammation, making it the first treatment approved by the agency for the condition.

The FDA approved the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor based on results from a randomized clinical trial in 317 adult patients with nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) who had elevated C-reactive protein levels and/or sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joints) on MRI.

The trial entailed 52 weeks of double-blind therapy with certolizumab at a starting dose of 400 mg on weeks 0, 2, and 4 followed by 200 mg every 2 weeks, or placebo. The Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score Major Improvement rate, defined as at least a 2-point improvement from baseline, was 47% in the active treatment arm, compared with 7% on placebo. The Assessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis International Society 40% response rate, a more patient-reported outcome measure, was 57% in the certolizumab group and 16% in controls (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 March 8. doi: 10.1002/art.40866).

The overall safety profile observed in the Cimzia treatment group was consistent with the known safety profile of certolizumab.

Cimzia was first approved in 2008 and has FDA-approved indications for adult patients with Crohn’s disease, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, active ankylosing spondylitis and moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy.

Four biomarkers could distinguish psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis

A panel of four biomarkers of cartilage metabolism, metabolic syndrome, and inflammation could help physicians to distinguish between osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis, new research suggests.

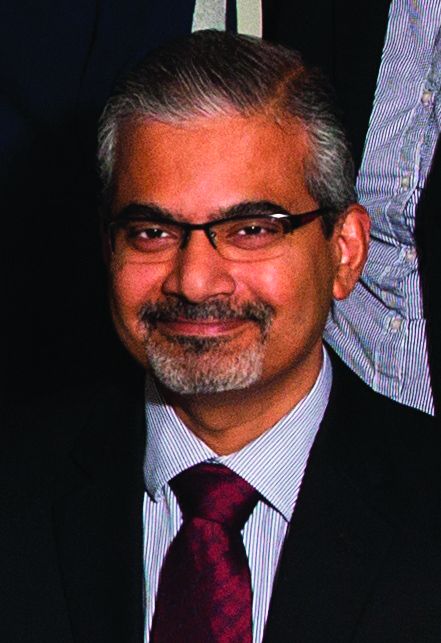

Such a test for distinguishing between the two conditions, which have “similarities in the distribution of joints involved,” could offer a way to make earlier diagnoses and avoid inappropriate treatment, according to Vinod Chandran, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at the University of Toronto and Toronto Western Hospital and his colleagues. Dr. Chandran was first author on a study published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases that analyzed serum samples from the University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program and University Health Network Arthritis Program for differences in certain biomarkers from 201 individuals with osteoarthritis, 77 with psoriatic arthritis, and 76 healthy controls.

The samples were tested for 15 biomarkers, including those related to cartilage metabolism (cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and hyaluronan), to metabolic syndrome (adiponectin, adipsin, resistin, hepatocyte growth factor, insulin, and leptin), and to inflammation (C-reactive protein, interleukin-1-beta, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, tumor necrosis factor alpha, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor).

Researchers found that levels of 12 of these markers were different in patients with psoriatic arthritis, osteoarthritis, or controls, and 9 markers showed altered expression in psoriatic arthritis, compared with osteoarthritis.

Further analysis showed that levels of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, resistin, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor were significantly different between patients with psoriatic arthritis and those with osteoarthritis. The ROC curve for a model based on these four biomarkers that also incorporated age and sex had an area under the curve of 0.9984.

Researchers then validated the four biomarkers in an independent set of 75 patients with osteoarthritis and 73 with psoriatic arthritis and found these biomarkers were able to discriminate between the two conditions beyond what would be achieved based on age and sex alone.

The authors noted that previous research has observed high expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 and resistin in patients with psoriatic arthritis when compared with those with osteoarthritis.

Nerve growth factor has been seen at elevated levels in the synovial fluid of individuals with osteoarthritis and is known to play a role in the chronic pain associated with that disease.

Similarly, higher cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels are associated with a higher risk of knee osteoarthritis.

However, the authors noted that individuals with osteoarthritis in the study were all undergoing joint replacement surgery and therefore may not be typical of patients presenting to family practices or rheumatology clinics.

The University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program is supported by the Krembil Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Chandran V et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214737.

A panel of four biomarkers of cartilage metabolism, metabolic syndrome, and inflammation could help physicians to distinguish between osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis, new research suggests.

Such a test for distinguishing between the two conditions, which have “similarities in the distribution of joints involved,” could offer a way to make earlier diagnoses and avoid inappropriate treatment, according to Vinod Chandran, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at the University of Toronto and Toronto Western Hospital and his colleagues. Dr. Chandran was first author on a study published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases that analyzed serum samples from the University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program and University Health Network Arthritis Program for differences in certain biomarkers from 201 individuals with osteoarthritis, 77 with psoriatic arthritis, and 76 healthy controls.

The samples were tested for 15 biomarkers, including those related to cartilage metabolism (cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and hyaluronan), to metabolic syndrome (adiponectin, adipsin, resistin, hepatocyte growth factor, insulin, and leptin), and to inflammation (C-reactive protein, interleukin-1-beta, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, tumor necrosis factor alpha, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor).

Researchers found that levels of 12 of these markers were different in patients with psoriatic arthritis, osteoarthritis, or controls, and 9 markers showed altered expression in psoriatic arthritis, compared with osteoarthritis.

Further analysis showed that levels of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, resistin, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor were significantly different between patients with psoriatic arthritis and those with osteoarthritis. The ROC curve for a model based on these four biomarkers that also incorporated age and sex had an area under the curve of 0.9984.

Researchers then validated the four biomarkers in an independent set of 75 patients with osteoarthritis and 73 with psoriatic arthritis and found these biomarkers were able to discriminate between the two conditions beyond what would be achieved based on age and sex alone.

The authors noted that previous research has observed high expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 and resistin in patients with psoriatic arthritis when compared with those with osteoarthritis.

Nerve growth factor has been seen at elevated levels in the synovial fluid of individuals with osteoarthritis and is known to play a role in the chronic pain associated with that disease.

Similarly, higher cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels are associated with a higher risk of knee osteoarthritis.

However, the authors noted that individuals with osteoarthritis in the study were all undergoing joint replacement surgery and therefore may not be typical of patients presenting to family practices or rheumatology clinics.

The University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program is supported by the Krembil Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Chandran V et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214737.

A panel of four biomarkers of cartilage metabolism, metabolic syndrome, and inflammation could help physicians to distinguish between osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis, new research suggests.

Such a test for distinguishing between the two conditions, which have “similarities in the distribution of joints involved,” could offer a way to make earlier diagnoses and avoid inappropriate treatment, according to Vinod Chandran, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at the University of Toronto and Toronto Western Hospital and his colleagues. Dr. Chandran was first author on a study published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases that analyzed serum samples from the University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program and University Health Network Arthritis Program for differences in certain biomarkers from 201 individuals with osteoarthritis, 77 with psoriatic arthritis, and 76 healthy controls.

The samples were tested for 15 biomarkers, including those related to cartilage metabolism (cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and hyaluronan), to metabolic syndrome (adiponectin, adipsin, resistin, hepatocyte growth factor, insulin, and leptin), and to inflammation (C-reactive protein, interleukin-1-beta, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, tumor necrosis factor alpha, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor).

Researchers found that levels of 12 of these markers were different in patients with psoriatic arthritis, osteoarthritis, or controls, and 9 markers showed altered expression in psoriatic arthritis, compared with osteoarthritis.

Further analysis showed that levels of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, resistin, monocyte chemoattractant protein–1, and nerve growth factor were significantly different between patients with psoriatic arthritis and those with osteoarthritis. The ROC curve for a model based on these four biomarkers that also incorporated age and sex had an area under the curve of 0.9984.

Researchers then validated the four biomarkers in an independent set of 75 patients with osteoarthritis and 73 with psoriatic arthritis and found these biomarkers were able to discriminate between the two conditions beyond what would be achieved based on age and sex alone.

The authors noted that previous research has observed high expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 and resistin in patients with psoriatic arthritis when compared with those with osteoarthritis.

Nerve growth factor has been seen at elevated levels in the synovial fluid of individuals with osteoarthritis and is known to play a role in the chronic pain associated with that disease.

Similarly, higher cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels are associated with a higher risk of knee osteoarthritis.

However, the authors noted that individuals with osteoarthritis in the study were all undergoing joint replacement surgery and therefore may not be typical of patients presenting to family practices or rheumatology clinics.

The University of Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Program is supported by the Krembil Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Chandran V et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214737.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

The paclitaxel paradox

As medical editor of Vascular Specialist, it has always been my hope to use our excellent reporters and rapid production schedule to keep readers abreast of the latest news in vascular surgery. While my colleagues at the Journal of Vascular Surgery publish studies that will drive treatment, my goal is to drive discussion.

With topics like burnout, workforce shortages, and electronic medical records, I feel we have been successful. The downside of staying current is we sometimes find ourselves publishing contradictory stories. This has been the case with paclitaxel. Let’s take a break from the fray and review where we are, and where we might go from here.

In 2012, the Zilver PTX became the first drug-eluting stent (DES) to gain Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of peripheral vascular disease. Two years later, the FDA approved the Lutonix 035 as the first drug-coated balloon (DCB) for use in the femoral-popliteal arteries. The Lutonix would also gain a second indication for failing dialysis fistulas. Medtronic and Spectranetics received authorizations for their DCBs in 2015 and 2017, respectively.

While the safety of paclitaxel-coated devices in the coronary system had previously been called into question, the drug was generally considered safe and effective in the peripheral arterial system. The controversy began in December 2018, when Katsanos et al.1 published a meta-analysis of 28 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) investigating paclitaxel-coated devices in the femoral-popliteal arteries. While all-cause patient mortality was similar at 1 year between paclitaxel-coated devices and controls (2.3% in each), at 2 years the risk of death was significantly higher in those treated with paclitaxel (7.2% vs. 3.8%). The 5-year data were available for three trials where there was a continued significantly increased risk of mortality with paclitaxel (14.7% vs. 8.1%).

Opposition to these findings was prompt from both physicians and industry. Weaknesses of the analysis, both perceived and real, were hammered. The meta-analysis did not include individual patient data, and the actual cause of death was unknown in most of the included trials. The study was not adequately powered to eliminate the risk of type 1 error when comparing mortality after 2 years. Individuals assigned to the control group may have received paclitaxel treatment at some point in their follow-up. The DCB and DES treatment groups were combined. The methods employed by the authors, however, stood up reasonably well to scrutiny.

On Jan. 17, 2019, the FDA issued their first response stating, “the FDA believes that the benefits continue to outweigh the risks for approved paclitaxel-coated balloons and paclitaxel-eluting stents when used in accordance with their indications for use.”2

Later that month, Peter Schneider, MD, and associates published a patient-level meta-analysis in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.3 The study included 1,980 patients and found no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality between DCB (9.3%) and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) (11.2%) through 5 years. Shortly after that, however, a correction was issued.

On Feb. 15, 2019, Medtronic reported an error in the 2- and 3-year follow-up periods for the IN.PACT Global postmarket study. The company stated, “Due to a programming error, mortality data were inadvertently omitted from the summary tables included in the statistical analysis.” The mortality in the DCB cohort was corrected from 9.30% to 15.12%. The authors stated that this new mortality rate was still not significantly higher than the PTA group (P = .09).4

Less than 1 week later, another device company issued a correction. And once again, the error had been made in favor of the paclitaxel-treated group. In 2016, the 5-year data from Cook Medical’s Zilver PTX trial were published in Circulation. The study reported a mortality of 10.2% in the DES group and 16.9% in the PTA cohort. Regrettably, these numbers were reversed and significantly higher in the paclitaxel-treated group (16.9% vs. 10.2%, P = .03).5

On Feb. 12, 2019, another response to the Katsanos meta-analysis was published in JAMA Cardiology.6 In this study, Secemsky et al. analyzed patient-level data from a Medicare database. The authors reported finding no evidence of paclitaxel- related deaths in 16,560 patients. Unfortunately, the mean follow-up time was only 389 days, which may have been insufficient to detect the late mortality reported in the Katsanos meta-analysis.

On March 15, 2019, the FDA issued a second statement, this time with a much stronger tone.7 The agency reported an ongoing analysis of the long-term survival data from the pivotal randomized trials. In the three studies with 5-year data available, each showed a significantly higher mortality in the paclitaxel group.

When pooled, there were 975 patients, and the risk of death was 20.1% in the paclitaxel group versus 13.4 % in the controls. The FDA recommended discussing the increased risk of mortality with all patients receiving paclitaxel therapy as part of the informed consent process. They also stated that for most patients alternative options should generally be used until additional analysis of the mortality risk is performed.

Industry bristled at this new, strongly worded statement. Becton Dickinson, makers of the Lutonix balloon, asserted that the FDA recommendation was based on “a limited review of data from less than 1,000 patients.”8 The company noted that its LEVANT 2 trial did not see a signal of increased mortality at 5 years. Although they did acknowledge that, among the randomized patients, there was a significantly higher mortality at 5 years for those treated with paclitaxel.

How do we make sense of this? Pac-litaxel is a cytotoxic drug. Its pharmacokinetics vary significantly based on the preparation and administration. The FDA label for the injectable form (Taxol) warns of anaphylaxis and severe hypersensitivity reactions, but there is no mention of long-term mortality. In the coronary vessels, paclitaxel-coated devices have been associated with myocardial infarction and death. Obviously it is easy to comprehend how local vessel effects in the coronary system can lead to increased mortality. The pathway is less clear with femoral-popliteal interventions. If the association of paclitaxel with death is truly causation there must be some systemic effects. The dose delivered with femoral- popliteal interventions is much higher than that seen with coronary devices.

The mortality may be associated with the platform used or even the formulation (crystalline formularies have a longer half-life). Could it be something more benign? Paclitaxel-treated patients see less recurrence of their femoral-popliteal disease. Are the control group patients with more recurrences seeing their interventionalist more often and therefore receiving more frequent reminders to comply with medical therapy?

At this point, we have few answers. After an all-day town hall at the recent Cardiovascular Research Technologies conference,9 one moderator said, “I came in with uncertainty and now I’m going away with uncertainty, but we made tremendous progress.” His comoderator added, “I know I don’t know.” Well then, glad we cleared that up!

In any event, changes are coming. The BASIL-3 trial has suspended recruitment. Physicians using paclitaxel-coated devices are now advised by the FDA to inform patients of the increased risk of death and to use alternatives in most cases. Therefore, if you employ these devices routinely in the femoral-popliteal vessels you are seemingly doing so in opposition to the recommendations of the FDA. Legal peril may follow.

The time for nitpicking the Katsanos analysis has ended. Our industry partners must be compelled to supply the data and finances needed to settle this issue. The signal seems real and it is time to find answers. Research initiatives are underway through the SVS, the VIVA group, the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, and the FDA.

Going forward, the SVS has formed a Paclitaxel Safety Task Force under the leadership of President-elect Kim Hodgson. Their mission is to facilitate the performance and interpretation of an Individual Patient Data meta-analysis using patient-level RCT data from industry partners. The task force states: “We remain troubled by the recent reports of reanalysis of existing datasets, pooled analyses of RCTs, and other ‘series’, as we believe that the findings of these statistically inferior analyses bring no additional clarity, cannot be relied upon for guidance, and distract us from the analysis that needs to be performed.”

References

1. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Dec 18;7(24):e011245.

2. www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/letterstohealthcareproviders/ucm629589.htm.

3. J Am Coll Cardiol. Jan 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.013.

4. Circulation. 2019;139:e42.

5. https://evtoday.com/2019/02/20/zilver-ptx-trial-5-year-mortality-data-corrected-in-circulation.

6. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Feb 12. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0325.

7. www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/LetterstoHealthCareProviders/ucm633614.htm.

8. www.med-technews.com/news/bud-defends-safety-of-drug-coated-device-following-fda-warnin/.

9. www.crtonline.org/news-detail/paclitaxel-device-safety-thoroughly-discussed-at-c.

As medical editor of Vascular Specialist, it has always been my hope to use our excellent reporters and rapid production schedule to keep readers abreast of the latest news in vascular surgery. While my colleagues at the Journal of Vascular Surgery publish studies that will drive treatment, my goal is to drive discussion.

With topics like burnout, workforce shortages, and electronic medical records, I feel we have been successful. The downside of staying current is we sometimes find ourselves publishing contradictory stories. This has been the case with paclitaxel. Let’s take a break from the fray and review where we are, and where we might go from here.

In 2012, the Zilver PTX became the first drug-eluting stent (DES) to gain Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of peripheral vascular disease. Two years later, the FDA approved the Lutonix 035 as the first drug-coated balloon (DCB) for use in the femoral-popliteal arteries. The Lutonix would also gain a second indication for failing dialysis fistulas. Medtronic and Spectranetics received authorizations for their DCBs in 2015 and 2017, respectively.

While the safety of paclitaxel-coated devices in the coronary system had previously been called into question, the drug was generally considered safe and effective in the peripheral arterial system. The controversy began in December 2018, when Katsanos et al.1 published a meta-analysis of 28 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) investigating paclitaxel-coated devices in the femoral-popliteal arteries. While all-cause patient mortality was similar at 1 year between paclitaxel-coated devices and controls (2.3% in each), at 2 years the risk of death was significantly higher in those treated with paclitaxel (7.2% vs. 3.8%). The 5-year data were available for three trials where there was a continued significantly increased risk of mortality with paclitaxel (14.7% vs. 8.1%).

Opposition to these findings was prompt from both physicians and industry. Weaknesses of the analysis, both perceived and real, were hammered. The meta-analysis did not include individual patient data, and the actual cause of death was unknown in most of the included trials. The study was not adequately powered to eliminate the risk of type 1 error when comparing mortality after 2 years. Individuals assigned to the control group may have received paclitaxel treatment at some point in their follow-up. The DCB and DES treatment groups were combined. The methods employed by the authors, however, stood up reasonably well to scrutiny.

On Jan. 17, 2019, the FDA issued their first response stating, “the FDA believes that the benefits continue to outweigh the risks for approved paclitaxel-coated balloons and paclitaxel-eluting stents when used in accordance with their indications for use.”2

Later that month, Peter Schneider, MD, and associates published a patient-level meta-analysis in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.3 The study included 1,980 patients and found no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality between DCB (9.3%) and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) (11.2%) through 5 years. Shortly after that, however, a correction was issued.

On Feb. 15, 2019, Medtronic reported an error in the 2- and 3-year follow-up periods for the IN.PACT Global postmarket study. The company stated, “Due to a programming error, mortality data were inadvertently omitted from the summary tables included in the statistical analysis.” The mortality in the DCB cohort was corrected from 9.30% to 15.12%. The authors stated that this new mortality rate was still not significantly higher than the PTA group (P = .09).4

Less than 1 week later, another device company issued a correction. And once again, the error had been made in favor of the paclitaxel-treated group. In 2016, the 5-year data from Cook Medical’s Zilver PTX trial were published in Circulation. The study reported a mortality of 10.2% in the DES group and 16.9% in the PTA cohort. Regrettably, these numbers were reversed and significantly higher in the paclitaxel-treated group (16.9% vs. 10.2%, P = .03).5

On Feb. 12, 2019, another response to the Katsanos meta-analysis was published in JAMA Cardiology.6 In this study, Secemsky et al. analyzed patient-level data from a Medicare database. The authors reported finding no evidence of paclitaxel- related deaths in 16,560 patients. Unfortunately, the mean follow-up time was only 389 days, which may have been insufficient to detect the late mortality reported in the Katsanos meta-analysis.

On March 15, 2019, the FDA issued a second statement, this time with a much stronger tone.7 The agency reported an ongoing analysis of the long-term survival data from the pivotal randomized trials. In the three studies with 5-year data available, each showed a significantly higher mortality in the paclitaxel group.

When pooled, there were 975 patients, and the risk of death was 20.1% in the paclitaxel group versus 13.4 % in the controls. The FDA recommended discussing the increased risk of mortality with all patients receiving paclitaxel therapy as part of the informed consent process. They also stated that for most patients alternative options should generally be used until additional analysis of the mortality risk is performed.

Industry bristled at this new, strongly worded statement. Becton Dickinson, makers of the Lutonix balloon, asserted that the FDA recommendation was based on “a limited review of data from less than 1,000 patients.”8 The company noted that its LEVANT 2 trial did not see a signal of increased mortality at 5 years. Although they did acknowledge that, among the randomized patients, there was a significantly higher mortality at 5 years for those treated with paclitaxel.

How do we make sense of this? Pac-litaxel is a cytotoxic drug. Its pharmacokinetics vary significantly based on the preparation and administration. The FDA label for the injectable form (Taxol) warns of anaphylaxis and severe hypersensitivity reactions, but there is no mention of long-term mortality. In the coronary vessels, paclitaxel-coated devices have been associated with myocardial infarction and death. Obviously it is easy to comprehend how local vessel effects in the coronary system can lead to increased mortality. The pathway is less clear with femoral-popliteal interventions. If the association of paclitaxel with death is truly causation there must be some systemic effects. The dose delivered with femoral- popliteal interventions is much higher than that seen with coronary devices.

The mortality may be associated with the platform used or even the formulation (crystalline formularies have a longer half-life). Could it be something more benign? Paclitaxel-treated patients see less recurrence of their femoral-popliteal disease. Are the control group patients with more recurrences seeing their interventionalist more often and therefore receiving more frequent reminders to comply with medical therapy?

At this point, we have few answers. After an all-day town hall at the recent Cardiovascular Research Technologies conference,9 one moderator said, “I came in with uncertainty and now I’m going away with uncertainty, but we made tremendous progress.” His comoderator added, “I know I don’t know.” Well then, glad we cleared that up!

In any event, changes are coming. The BASIL-3 trial has suspended recruitment. Physicians using paclitaxel-coated devices are now advised by the FDA to inform patients of the increased risk of death and to use alternatives in most cases. Therefore, if you employ these devices routinely in the femoral-popliteal vessels you are seemingly doing so in opposition to the recommendations of the FDA. Legal peril may follow.

The time for nitpicking the Katsanos analysis has ended. Our industry partners must be compelled to supply the data and finances needed to settle this issue. The signal seems real and it is time to find answers. Research initiatives are underway through the SVS, the VIVA group, the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, and the FDA.

Going forward, the SVS has formed a Paclitaxel Safety Task Force under the leadership of President-elect Kim Hodgson. Their mission is to facilitate the performance and interpretation of an Individual Patient Data meta-analysis using patient-level RCT data from industry partners. The task force states: “We remain troubled by the recent reports of reanalysis of existing datasets, pooled analyses of RCTs, and other ‘series’, as we believe that the findings of these statistically inferior analyses bring no additional clarity, cannot be relied upon for guidance, and distract us from the analysis that needs to be performed.”

References

1. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Dec 18;7(24):e011245.

2. www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/letterstohealthcareproviders/ucm629589.htm.

3. J Am Coll Cardiol. Jan 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.013.

4. Circulation. 2019;139:e42.

5. https://evtoday.com/2019/02/20/zilver-ptx-trial-5-year-mortality-data-corrected-in-circulation.

6. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Feb 12. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0325.

7. www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/LetterstoHealthCareProviders/ucm633614.htm.

8. www.med-technews.com/news/bud-defends-safety-of-drug-coated-device-following-fda-warnin/.

9. www.crtonline.org/news-detail/paclitaxel-device-safety-thoroughly-discussed-at-c.

As medical editor of Vascular Specialist, it has always been my hope to use our excellent reporters and rapid production schedule to keep readers abreast of the latest news in vascular surgery. While my colleagues at the Journal of Vascular Surgery publish studies that will drive treatment, my goal is to drive discussion.

With topics like burnout, workforce shortages, and electronic medical records, I feel we have been successful. The downside of staying current is we sometimes find ourselves publishing contradictory stories. This has been the case with paclitaxel. Let’s take a break from the fray and review where we are, and where we might go from here.

In 2012, the Zilver PTX became the first drug-eluting stent (DES) to gain Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of peripheral vascular disease. Two years later, the FDA approved the Lutonix 035 as the first drug-coated balloon (DCB) for use in the femoral-popliteal arteries. The Lutonix would also gain a second indication for failing dialysis fistulas. Medtronic and Spectranetics received authorizations for their DCBs in 2015 and 2017, respectively.

While the safety of paclitaxel-coated devices in the coronary system had previously been called into question, the drug was generally considered safe and effective in the peripheral arterial system. The controversy began in December 2018, when Katsanos et al.1 published a meta-analysis of 28 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) investigating paclitaxel-coated devices in the femoral-popliteal arteries. While all-cause patient mortality was similar at 1 year between paclitaxel-coated devices and controls (2.3% in each), at 2 years the risk of death was significantly higher in those treated with paclitaxel (7.2% vs. 3.8%). The 5-year data were available for three trials where there was a continued significantly increased risk of mortality with paclitaxel (14.7% vs. 8.1%).

Opposition to these findings was prompt from both physicians and industry. Weaknesses of the analysis, both perceived and real, were hammered. The meta-analysis did not include individual patient data, and the actual cause of death was unknown in most of the included trials. The study was not adequately powered to eliminate the risk of type 1 error when comparing mortality after 2 years. Individuals assigned to the control group may have received paclitaxel treatment at some point in their follow-up. The DCB and DES treatment groups were combined. The methods employed by the authors, however, stood up reasonably well to scrutiny.

On Jan. 17, 2019, the FDA issued their first response stating, “the FDA believes that the benefits continue to outweigh the risks for approved paclitaxel-coated balloons and paclitaxel-eluting stents when used in accordance with their indications for use.”2

Later that month, Peter Schneider, MD, and associates published a patient-level meta-analysis in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.3 The study included 1,980 patients and found no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality between DCB (9.3%) and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) (11.2%) through 5 years. Shortly after that, however, a correction was issued.

On Feb. 15, 2019, Medtronic reported an error in the 2- and 3-year follow-up periods for the IN.PACT Global postmarket study. The company stated, “Due to a programming error, mortality data were inadvertently omitted from the summary tables included in the statistical analysis.” The mortality in the DCB cohort was corrected from 9.30% to 15.12%. The authors stated that this new mortality rate was still not significantly higher than the PTA group (P = .09).4

Less than 1 week later, another device company issued a correction. And once again, the error had been made in favor of the paclitaxel-treated group. In 2016, the 5-year data from Cook Medical’s Zilver PTX trial were published in Circulation. The study reported a mortality of 10.2% in the DES group and 16.9% in the PTA cohort. Regrettably, these numbers were reversed and significantly higher in the paclitaxel-treated group (16.9% vs. 10.2%, P = .03).5

On Feb. 12, 2019, another response to the Katsanos meta-analysis was published in JAMA Cardiology.6 In this study, Secemsky et al. analyzed patient-level data from a Medicare database. The authors reported finding no evidence of paclitaxel- related deaths in 16,560 patients. Unfortunately, the mean follow-up time was only 389 days, which may have been insufficient to detect the late mortality reported in the Katsanos meta-analysis.

On March 15, 2019, the FDA issued a second statement, this time with a much stronger tone.7 The agency reported an ongoing analysis of the long-term survival data from the pivotal randomized trials. In the three studies with 5-year data available, each showed a significantly higher mortality in the paclitaxel group.

When pooled, there were 975 patients, and the risk of death was 20.1% in the paclitaxel group versus 13.4 % in the controls. The FDA recommended discussing the increased risk of mortality with all patients receiving paclitaxel therapy as part of the informed consent process. They also stated that for most patients alternative options should generally be used until additional analysis of the mortality risk is performed.

Industry bristled at this new, strongly worded statement. Becton Dickinson, makers of the Lutonix balloon, asserted that the FDA recommendation was based on “a limited review of data from less than 1,000 patients.”8 The company noted that its LEVANT 2 trial did not see a signal of increased mortality at 5 years. Although they did acknowledge that, among the randomized patients, there was a significantly higher mortality at 5 years for those treated with paclitaxel.

How do we make sense of this? Pac-litaxel is a cytotoxic drug. Its pharmacokinetics vary significantly based on the preparation and administration. The FDA label for the injectable form (Taxol) warns of anaphylaxis and severe hypersensitivity reactions, but there is no mention of long-term mortality. In the coronary vessels, paclitaxel-coated devices have been associated with myocardial infarction and death. Obviously it is easy to comprehend how local vessel effects in the coronary system can lead to increased mortality. The pathway is less clear with femoral-popliteal interventions. If the association of paclitaxel with death is truly causation there must be some systemic effects. The dose delivered with femoral- popliteal interventions is much higher than that seen with coronary devices.

The mortality may be associated with the platform used or even the formulation (crystalline formularies have a longer half-life). Could it be something more benign? Paclitaxel-treated patients see less recurrence of their femoral-popliteal disease. Are the control group patients with more recurrences seeing their interventionalist more often and therefore receiving more frequent reminders to comply with medical therapy?

At this point, we have few answers. After an all-day town hall at the recent Cardiovascular Research Technologies conference,9 one moderator said, “I came in with uncertainty and now I’m going away with uncertainty, but we made tremendous progress.” His comoderator added, “I know I don’t know.” Well then, glad we cleared that up!

In any event, changes are coming. The BASIL-3 trial has suspended recruitment. Physicians using paclitaxel-coated devices are now advised by the FDA to inform patients of the increased risk of death and to use alternatives in most cases. Therefore, if you employ these devices routinely in the femoral-popliteal vessels you are seemingly doing so in opposition to the recommendations of the FDA. Legal peril may follow.

The time for nitpicking the Katsanos analysis has ended. Our industry partners must be compelled to supply the data and finances needed to settle this issue. The signal seems real and it is time to find answers. Research initiatives are underway through the SVS, the VIVA group, the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, and the FDA.

Going forward, the SVS has formed a Paclitaxel Safety Task Force under the leadership of President-elect Kim Hodgson. Their mission is to facilitate the performance and interpretation of an Individual Patient Data meta-analysis using patient-level RCT data from industry partners. The task force states: “We remain troubled by the recent reports of reanalysis of existing datasets, pooled analyses of RCTs, and other ‘series’, as we believe that the findings of these statistically inferior analyses bring no additional clarity, cannot be relied upon for guidance, and distract us from the analysis that needs to be performed.”

References

1. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Dec 18;7(24):e011245.

2. www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/letterstohealthcareproviders/ucm629589.htm.

3. J Am Coll Cardiol. Jan 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.013.

4. Circulation. 2019;139:e42.

5. https://evtoday.com/2019/02/20/zilver-ptx-trial-5-year-mortality-data-corrected-in-circulation.

6. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Feb 12. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0325.

7. www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/LetterstoHealthCareProviders/ucm633614.htm.

8. www.med-technews.com/news/bud-defends-safety-of-drug-coated-device-following-fda-warnin/.

9. www.crtonline.org/news-detail/paclitaxel-device-safety-thoroughly-discussed-at-c.

Ticagrelor reversal agent looks promising

NEW ORLEANS – A novel targeted ticagrelor reversal agent demonstrated rapid and sustained reversal of the potent antiplatelet agent in a phase 1 proof-of-concept study, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Hopefully the FDA will view this as something that really is a breakthrough,” commented Dr. Bhatt, executive director of interventional cardiology programs at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard University, both in Boston.

Why a breakthrough? Because despite recent major advances in the ability to reverse the action of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants and thereby greatly improve their safety margin, there have been no parallel developments with regard to the potent antiplatelet agents ticagrelor (Brilinta), prasugrel (Effient), and clopidogrel. The effects of these antiplatelet drugs take 3-5 days to dissipate after they’ve been stopped, which is highly problematic when they’ve induced catastrophic bleeding or a patient requires emergent or urgent surgery, the cardiologist explained.

“The ability to reverse tigracelor’s antiplatelet effects rapidly could distinguish it from other antiplatelet agents such as prasugrel or even generic clopidogrel and, for that matter, even aspirin,” Dr. Bhatt said.

The ticagrelor reversal agent, known for now as PB2452, is an intravenously administered recombinant human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody antigen-binding fragment. It binds specifically and with high affinity to ticagrelor and its active metabolite. In the phase 1, placebo-controlled, double-blind study conducted in 64 healthy volunteers pretreated with ticagrelor for 48 hours, it reversed oral ticagrelor’s antiplatelet effects within 5 minutes and, with prolonged infusion, showed sustained effect for at least 20 hours.

The only adverse events observed in blinded assessment were minor injection site issues.

PB2452 is specific to ticagrelor and will not reverse the activity of other potent antiplatelet agents. Indeed, because of their chemical structure, neither prasugrel nor clopidogrel is reversible, according to Dr. Bhatt.

He said the developmental game plan for the ticagrelor reversal agent is initially to get it approved by the Food and Drug Administration for ticagrelor-related catastrophic bleeding, such as intracranial hemorrhage, since there is a recognized major unmet need in such situations. But as shown in the phase 1 study, BP2452 is potentially titratable by varying the size of the initial bolus dose and the dosing and duration of the subsequent infusion. So after initial approval for catastrophic bleeding, it makes sense to branch out and conduct further studies establishing the reversal agent’s value for prevention of bleeding complications caused by ticagrelor. An example might be a patient on ticagrelor because she recently received a stent in her left main coronary artery who falls and breaks her hip, and her surgeon says she needs surgery right away.

“If someone on ticagrelor came in with an intracranial hemorrhage, you’d want rapid reversal and have it sustained for as many days as the neurologist advises, whereas maybe if someone came in on ticagrelor after placement of a left main stent and you needed to do a lumbar puncture, you’d want to reverse the antiplatelet effect for the LP, and then if things go smoothly you’d want to get the ticagrelor back on board so the stent doesn’t thrombose. But that type of more precise dosing will require further work,” according to the cardiologist.

Discussant Barbara S. Wiggins, PharmD, commented, “We’ve been fortunate to have reversal agents come out for oral anticoagulants, but in terms of antiplatelet activity we’ve not been able to be successful with platelet transfusions. So having a reversal agent added to our armamentarium certainly is something that’s desirable.”

The phase 1 study of PB2452 indicates the monoclonal antibody checks the key boxes one looks for in a reversal agent: quick onset, long duration of effect, lack of a rebound in platelet activity after drug cessation, and potential for tailored titration. Of course, data on efficacy outcomes will also be necessary, noted Dr. Wiggins, a clinical pharmacologist at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

She added that she was favorably impressed that Dr. Bhatt and his coinvestigators went to the trouble of convincingly demonstrating reversal of ticagrelor’s antiplatelet effects using three different assays: light transmission aggregometry, which is considered the standard, as well as the point-of-care VerifyNow P2Y12 assay and the modified CY-QUANT assay.

The phase 1 study was funded by PhaseBio Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Bhatt reported the company provided a research grant directly to Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Simultaneous with Dr. Bhatt’s presentation, the study results were published online (N Engl J Med. 2019 Mar 17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901778).

NEW ORLEANS – A novel targeted ticagrelor reversal agent demonstrated rapid and sustained reversal of the potent antiplatelet agent in a phase 1 proof-of-concept study, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Hopefully the FDA will view this as something that really is a breakthrough,” commented Dr. Bhatt, executive director of interventional cardiology programs at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard University, both in Boston.

Why a breakthrough? Because despite recent major advances in the ability to reverse the action of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants and thereby greatly improve their safety margin, there have been no parallel developments with regard to the potent antiplatelet agents ticagrelor (Brilinta), prasugrel (Effient), and clopidogrel. The effects of these antiplatelet drugs take 3-5 days to dissipate after they’ve been stopped, which is highly problematic when they’ve induced catastrophic bleeding or a patient requires emergent or urgent surgery, the cardiologist explained.

“The ability to reverse tigracelor’s antiplatelet effects rapidly could distinguish it from other antiplatelet agents such as prasugrel or even generic clopidogrel and, for that matter, even aspirin,” Dr. Bhatt said.

The ticagrelor reversal agent, known for now as PB2452, is an intravenously administered recombinant human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody antigen-binding fragment. It binds specifically and with high affinity to ticagrelor and its active metabolite. In the phase 1, placebo-controlled, double-blind study conducted in 64 healthy volunteers pretreated with ticagrelor for 48 hours, it reversed oral ticagrelor’s antiplatelet effects within 5 minutes and, with prolonged infusion, showed sustained effect for at least 20 hours.

The only adverse events observed in blinded assessment were minor injection site issues.

PB2452 is specific to ticagrelor and will not reverse the activity of other potent antiplatelet agents. Indeed, because of their chemical structure, neither prasugrel nor clopidogrel is reversible, according to Dr. Bhatt.

He said the developmental game plan for the ticagrelor reversal agent is initially to get it approved by the Food and Drug Administration for ticagrelor-related catastrophic bleeding, such as intracranial hemorrhage, since there is a recognized major unmet need in such situations. But as shown in the phase 1 study, BP2452 is potentially titratable by varying the size of the initial bolus dose and the dosing and duration of the subsequent infusion. So after initial approval for catastrophic bleeding, it makes sense to branch out and conduct further studies establishing the reversal agent’s value for prevention of bleeding complications caused by ticagrelor. An example might be a patient on ticagrelor because she recently received a stent in her left main coronary artery who falls and breaks her hip, and her surgeon says she needs surgery right away.

“If someone on ticagrelor came in with an intracranial hemorrhage, you’d want rapid reversal and have it sustained for as many days as the neurologist advises, whereas maybe if someone came in on ticagrelor after placement of a left main stent and you needed to do a lumbar puncture, you’d want to reverse the antiplatelet effect for the LP, and then if things go smoothly you’d want to get the ticagrelor back on board so the stent doesn’t thrombose. But that type of more precise dosing will require further work,” according to the cardiologist.

Discussant Barbara S. Wiggins, PharmD, commented, “We’ve been fortunate to have reversal agents come out for oral anticoagulants, but in terms of antiplatelet activity we’ve not been able to be successful with platelet transfusions. So having a reversal agent added to our armamentarium certainly is something that’s desirable.”

The phase 1 study of PB2452 indicates the monoclonal antibody checks the key boxes one looks for in a reversal agent: quick onset, long duration of effect, lack of a rebound in platelet activity after drug cessation, and potential for tailored titration. Of course, data on efficacy outcomes will also be necessary, noted Dr. Wiggins, a clinical pharmacologist at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

She added that she was favorably impressed that Dr. Bhatt and his coinvestigators went to the trouble of convincingly demonstrating reversal of ticagrelor’s antiplatelet effects using three different assays: light transmission aggregometry, which is considered the standard, as well as the point-of-care VerifyNow P2Y12 assay and the modified CY-QUANT assay.

The phase 1 study was funded by PhaseBio Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Bhatt reported the company provided a research grant directly to Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Simultaneous with Dr. Bhatt’s presentation, the study results were published online (N Engl J Med. 2019 Mar 17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901778).

NEW ORLEANS – A novel targeted ticagrelor reversal agent demonstrated rapid and sustained reversal of the potent antiplatelet agent in a phase 1 proof-of-concept study, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“Hopefully the FDA will view this as something that really is a breakthrough,” commented Dr. Bhatt, executive director of interventional cardiology programs at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard University, both in Boston.

Why a breakthrough? Because despite recent major advances in the ability to reverse the action of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants and thereby greatly improve their safety margin, there have been no parallel developments with regard to the potent antiplatelet agents ticagrelor (Brilinta), prasugrel (Effient), and clopidogrel. The effects of these antiplatelet drugs take 3-5 days to dissipate after they’ve been stopped, which is highly problematic when they’ve induced catastrophic bleeding or a patient requires emergent or urgent surgery, the cardiologist explained.

“The ability to reverse tigracelor’s antiplatelet effects rapidly could distinguish it from other antiplatelet agents such as prasugrel or even generic clopidogrel and, for that matter, even aspirin,” Dr. Bhatt said.

The ticagrelor reversal agent, known for now as PB2452, is an intravenously administered recombinant human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody antigen-binding fragment. It binds specifically and with high affinity to ticagrelor and its active metabolite. In the phase 1, placebo-controlled, double-blind study conducted in 64 healthy volunteers pretreated with ticagrelor for 48 hours, it reversed oral ticagrelor’s antiplatelet effects within 5 minutes and, with prolonged infusion, showed sustained effect for at least 20 hours.

The only adverse events observed in blinded assessment were minor injection site issues.

PB2452 is specific to ticagrelor and will not reverse the activity of other potent antiplatelet agents. Indeed, because of their chemical structure, neither prasugrel nor clopidogrel is reversible, according to Dr. Bhatt.

He said the developmental game plan for the ticagrelor reversal agent is initially to get it approved by the Food and Drug Administration for ticagrelor-related catastrophic bleeding, such as intracranial hemorrhage, since there is a recognized major unmet need in such situations. But as shown in the phase 1 study, BP2452 is potentially titratable by varying the size of the initial bolus dose and the dosing and duration of the subsequent infusion. So after initial approval for catastrophic bleeding, it makes sense to branch out and conduct further studies establishing the reversal agent’s value for prevention of bleeding complications caused by ticagrelor. An example might be a patient on ticagrelor because she recently received a stent in her left main coronary artery who falls and breaks her hip, and her surgeon says she needs surgery right away.

“If someone on ticagrelor came in with an intracranial hemorrhage, you’d want rapid reversal and have it sustained for as many days as the neurologist advises, whereas maybe if someone came in on ticagrelor after placement of a left main stent and you needed to do a lumbar puncture, you’d want to reverse the antiplatelet effect for the LP, and then if things go smoothly you’d want to get the ticagrelor back on board so the stent doesn’t thrombose. But that type of more precise dosing will require further work,” according to the cardiologist.

Discussant Barbara S. Wiggins, PharmD, commented, “We’ve been fortunate to have reversal agents come out for oral anticoagulants, but in terms of antiplatelet activity we’ve not been able to be successful with platelet transfusions. So having a reversal agent added to our armamentarium certainly is something that’s desirable.”

The phase 1 study of PB2452 indicates the monoclonal antibody checks the key boxes one looks for in a reversal agent: quick onset, long duration of effect, lack of a rebound in platelet activity after drug cessation, and potential for tailored titration. Of course, data on efficacy outcomes will also be necessary, noted Dr. Wiggins, a clinical pharmacologist at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

She added that she was favorably impressed that Dr. Bhatt and his coinvestigators went to the trouble of convincingly demonstrating reversal of ticagrelor’s antiplatelet effects using three different assays: light transmission aggregometry, which is considered the standard, as well as the point-of-care VerifyNow P2Y12 assay and the modified CY-QUANT assay.

The phase 1 study was funded by PhaseBio Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Bhatt reported the company provided a research grant directly to Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Simultaneous with Dr. Bhatt’s presentation, the study results were published online (N Engl J Med. 2019 Mar 17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901778).

REPORTING FROM ACC 19

Key clinical point: Oral ticagrelor’s antiplatelet effect was reversed within 5 minutes by a novel targeted monoclonal antibody.

Major finding: A novel targeted monoclonal antibody reversed oral ticagrelor’s antiplatelet effects within 5 minutes and, with prolonged infusion, showed sustained effect for at least 20 hours.

Study details: This phase 1 study included 64 healthy subjects pretreated with 48 hours of ticagrelor before receiving various doses of the reversal agent or placebo.

Disclosures: The study was funded by PhaseBio Pharmaceuticals, which provided a research grant directly to Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

FDA proposes updates to mammography regulations

Proposed changes to federal mammography regulations aim to provide more information for doctors and patients, as well as standardize patient information on breast density’s impact on screening.

The Food and Drug Administration posted a new proposed rule online March 27 that would “expand the information mammography facilities must provide to patients and health care professionals, allowing for more informed medical decision making,” the agency said in a statement. “It would also modernize mammography quality standards and better position the FDA to enforce regulations that apply to the safety and quality of mammography services.”

Key among the proposed changes is the addition of breast density information to the summary letter provided to patients and to the medical report provided to referring health care professionals.

“The FDA is proposing specific language that would explain how breast density can influence the accuracy of mammography and would recommend patients with dense breasts talk to their health care provider about high breast density and how it relates to breast cancer risk and their individual situation,” the agency said in a statement.

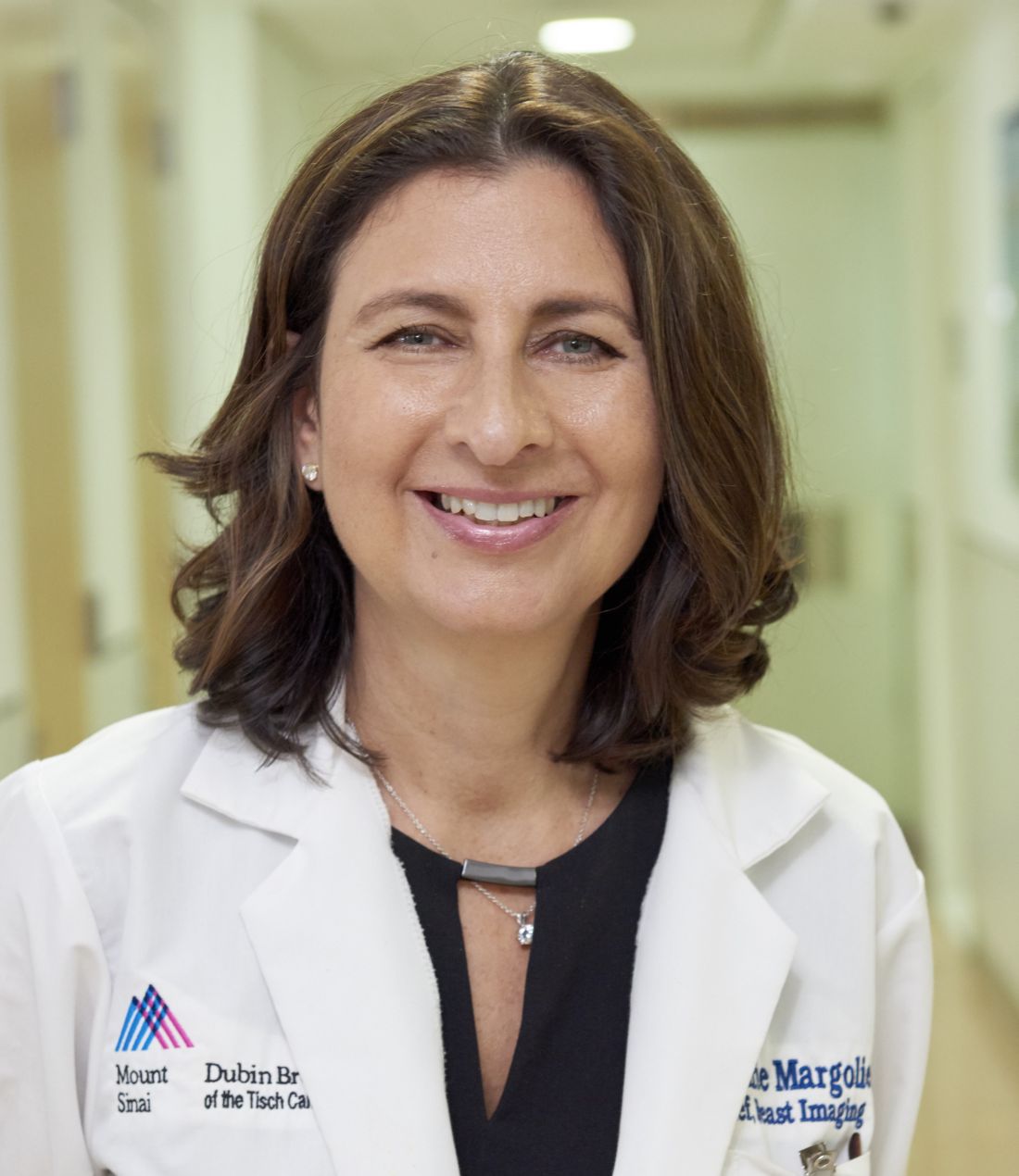

Laurie Margolies, MD, section chief of breast imaging at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said the regulations would bring some uniformity to the communication process.

“It builds on the experience of the 37 states and the District of Columbia, all of whom have passed dense breast notification laws, and can serve to unify those disparate regulations into one that would be uniform throughout the country to give one clear message to women and health care providers,” Dr. Margolies said in an interview.

She noted that dense breasts are very common and communicating issues that are related to them, including the potential need for supplemental screening, are important.

“Almost half of American women have dense breasts and why that is significant is because the dense breast issue not only increases one’s risk of getting breast cancer, but it also can hide small breast cancers on the mammogram,” she said.

If you take 1,000 women with dense breasts and then do a breast ultrasound as a supplemental screening measure, “you will find three more small node-negative breast cancers that would not have come to light if you didn’t do the extra supplemental screening,” underscoring the importance of communicating dense breast information, she continued.

FDA also is seeking to enhance information provided to health care professionals by codifying three additional categories for mammogram assessments, including the addition of the “known biopsy proven malignancy” category, which the agency says would help identify which scans were being used to evaluate treatment of already diagnosed cancers.

Both patients and health care professionals would receive more detailed information about the mammography facility under the proposed rule.

FDA is proposing modernization of quality standards to help the agency enforce regulations, including giving the agency the authority to notify patients and health care professionals directly if a mammography facility does not meet quality standards and that a reevaluation or repeat of the exam at a different facility may be needed. The proposed amendments also include requiring that only digital accessory components specifically FDA approved or cleared for mammography be used or that facilities use components that otherwise meet the requirements, and stronger record-keeping requirements.

Dr. Margolies did note one potential deficiency in the proposed rule – the lack of any information on health insurance coverage of supplemental screening for women with dense breasts, though she noted this may not fall under the FDA’s authority.

“It would do the most good if everybody could get the supplemental screening without regards to their ability to pay for it out of pocket,” she said.

The proposal amends regulations issued under the Mammography Quality Standards Act of 1992, which gives FDA oversight authority over mammography facilities, including accreditation, certification, annual inspection, and enforcement of standards.

Comments on the proposal are due 90 days after the proposed rule is published in the Federal Register, which is scheduled for March 28.

Proposed changes to federal mammography regulations aim to provide more information for doctors and patients, as well as standardize patient information on breast density’s impact on screening.

The Food and Drug Administration posted a new proposed rule online March 27 that would “expand the information mammography facilities must provide to patients and health care professionals, allowing for more informed medical decision making,” the agency said in a statement. “It would also modernize mammography quality standards and better position the FDA to enforce regulations that apply to the safety and quality of mammography services.”

Key among the proposed changes is the addition of breast density information to the summary letter provided to patients and to the medical report provided to referring health care professionals.

“The FDA is proposing specific language that would explain how breast density can influence the accuracy of mammography and would recommend patients with dense breasts talk to their health care provider about high breast density and how it relates to breast cancer risk and their individual situation,” the agency said in a statement.

Laurie Margolies, MD, section chief of breast imaging at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said the regulations would bring some uniformity to the communication process.

“It builds on the experience of the 37 states and the District of Columbia, all of whom have passed dense breast notification laws, and can serve to unify those disparate regulations into one that would be uniform throughout the country to give one clear message to women and health care providers,” Dr. Margolies said in an interview.

She noted that dense breasts are very common and communicating issues that are related to them, including the potential need for supplemental screening, are important.

“Almost half of American women have dense breasts and why that is significant is because the dense breast issue not only increases one’s risk of getting breast cancer, but it also can hide small breast cancers on the mammogram,” she said.

If you take 1,000 women with dense breasts and then do a breast ultrasound as a supplemental screening measure, “you will find three more small node-negative breast cancers that would not have come to light if you didn’t do the extra supplemental screening,” underscoring the importance of communicating dense breast information, she continued.

FDA also is seeking to enhance information provided to health care professionals by codifying three additional categories for mammogram assessments, including the addition of the “known biopsy proven malignancy” category, which the agency says would help identify which scans were being used to evaluate treatment of already diagnosed cancers.

Both patients and health care professionals would receive more detailed information about the mammography facility under the proposed rule.

FDA is proposing modernization of quality standards to help the agency enforce regulations, including giving the agency the authority to notify patients and health care professionals directly if a mammography facility does not meet quality standards and that a reevaluation or repeat of the exam at a different facility may be needed. The proposed amendments also include requiring that only digital accessory components specifically FDA approved or cleared for mammography be used or that facilities use components that otherwise meet the requirements, and stronger record-keeping requirements.

Dr. Margolies did note one potential deficiency in the proposed rule – the lack of any information on health insurance coverage of supplemental screening for women with dense breasts, though she noted this may not fall under the FDA’s authority.

“It would do the most good if everybody could get the supplemental screening without regards to their ability to pay for it out of pocket,” she said.

The proposal amends regulations issued under the Mammography Quality Standards Act of 1992, which gives FDA oversight authority over mammography facilities, including accreditation, certification, annual inspection, and enforcement of standards.

Comments on the proposal are due 90 days after the proposed rule is published in the Federal Register, which is scheduled for March 28.

Proposed changes to federal mammography regulations aim to provide more information for doctors and patients, as well as standardize patient information on breast density’s impact on screening.

The Food and Drug Administration posted a new proposed rule online March 27 that would “expand the information mammography facilities must provide to patients and health care professionals, allowing for more informed medical decision making,” the agency said in a statement. “It would also modernize mammography quality standards and better position the FDA to enforce regulations that apply to the safety and quality of mammography services.”

Key among the proposed changes is the addition of breast density information to the summary letter provided to patients and to the medical report provided to referring health care professionals.

“The FDA is proposing specific language that would explain how breast density can influence the accuracy of mammography and would recommend patients with dense breasts talk to their health care provider about high breast density and how it relates to breast cancer risk and their individual situation,” the agency said in a statement.

Laurie Margolies, MD, section chief of breast imaging at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said the regulations would bring some uniformity to the communication process.

“It builds on the experience of the 37 states and the District of Columbia, all of whom have passed dense breast notification laws, and can serve to unify those disparate regulations into one that would be uniform throughout the country to give one clear message to women and health care providers,” Dr. Margolies said in an interview.

She noted that dense breasts are very common and communicating issues that are related to them, including the potential need for supplemental screening, are important.

“Almost half of American women have dense breasts and why that is significant is because the dense breast issue not only increases one’s risk of getting breast cancer, but it also can hide small breast cancers on the mammogram,” she said.

If you take 1,000 women with dense breasts and then do a breast ultrasound as a supplemental screening measure, “you will find three more small node-negative breast cancers that would not have come to light if you didn’t do the extra supplemental screening,” underscoring the importance of communicating dense breast information, she continued.