User login

Pregnant women commonly refuse the influenza vaccine

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Although almost all ob.gyns. recommend the influenza and Tdap vaccines for pregnant women, both commonly are refused.

Major finding: A total of 62% of ob.gyns. reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine; 32% reported this for Tdap vaccine.

Study details: An email and mail survey sent to a national network of ob.gyns. between March and June 2016.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

QOL is poorer for young women after mastectomy than BCS

SAN ANTONIO – , according to investigators for a multicenter cross-sectional cohort study reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Women aged 40 or younger make up about 7% of all newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer in the United States, according to lead author, Laura S. Dominici, MD, of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Despite the fact that there is equivalent local-regional control with breast conservation and mastectomy, the rates of mastectomy and particularly bilateral mastectomy are increasing in young women, with a 10-fold increase seen from 1998 to 2011,” she noted in a press conference. “Young women are at particular risk for poorer psychosocial outcomes following a breast cancer diagnosis and in survivorship. However, little is known about the impact of surgery, particularly in the era of increasing bilateral mastectomy, on the quality of life of young survivors.”

Nearly three-fourths of the 560 young breast cancer survivors studied had undergone mastectomy, usually with some kind of reconstruction. Roughly 6 years later, compared with peers who had undergone breast-conserving surgery, women who had undergone unilateral or bilateral mastectomy had significantly poorer adjusted BREAST-Q scores for satisfaction with the appearance and feel of their breasts (beta, –8.7 and –9.3 points) and psychosocial well-being (–8.3 and –10.5 points). The latter also had poorer adjusted scores for sexual well-being (–8.1 points). Physical well-being, which captures aspects such as pain and range of motion, did not differ significantly by type of surgery.

“Local therapy decisions are associated with a persistent impact on quality of life in young breast cancer survivors,” Dr. Dominici concluded. “Knowledge of the potential long-term impact of surgery and quality of life is of critical importance for counseling young women about surgical decisions.”

Moving away from mastectomy

“The data are, to me anyway, more disconcerting when you consider the high mastectomy rate in this country relative to Europe, and this urge to have bilateral mastectomies, which, pardon the expression, is ridiculous in some cases because it doesn’t improve your outcome. And yet, it does have deleterious effects that last for years psychologically,” commented SABCS codirector and press conference moderator C. Kent Osborne, MD, who is director of the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “What can we do about that?” he asked.

“It’s a really challenging problem,” Dr. Dominici replied. “Part of what we are missing in the conversation that we have with our patients is this kind of information. We can certainly tell patients that the outcomes are equivalent, but if they don’t know that the long-term [quality of life] impact is potentially worse, then that may not affect their decision. The more prospective data that we generate to help us figure out which patients are going to have better or worse outcomes with these different types of surgery, the better we will be able to counsel patients with things that will be meaningful to them in the long run.”

The study was not designed to tease out the specific role of anxiety about a recurrence or a new breast cancer, which is a major driver of the decision to have mastectomy and also needs to be addressed during counseling, Dr. Dominici and Dr. Osborne agreed. “I think I spend more time talking patients out of bilateral mastectomy or mastectomy at all than anything,” he commented.

Study details

The women studied were participants in the prospective Young Women’s Breast Cancer Study (YWS) and had a mean age of 37 years at diagnosis. Most (86%) had stage 0-2 breast cancer. (Those with metastatic disease at diagnosis or a recurrence during follow-up were excluded.)

Overall, 52% of the women underwent bilateral mastectomy, 20% underwent unilateral mastectomy, and 28% underwent breast-conserving surgery, Dr. Dominici reported. Within the mastectomy group, most underwent implant-based reconstruction (69%) or flap reconstruction (12%), while some opted for no reconstruction (11%).

Multivariate analyses showed that, in addition to mastectomy, other significant predictors of poorer breast satisfaction were receipt of radiation therapy (beta, –7.5 points) and having a financially uncomfortable status as compared with a comfortable one (–5.4 points).

Additional significant predictors of poorer psychosocial well-being were receiving radiation (beta, –6.0 points), being financially uncomfortable (–7 points), and being overweight or obese (–4.2 points), and additional significant predictors of poorer sexual well-being were being financially uncomfortable (–6.8 points), being overweight or obese (–5.3 points), and having lymphedema a year after diagnosis (–3.8 points).

The only significant predictors of poorer physical health were financially uncomfortable status (beta, –4.8 points) and lymphedema (–6.4 points), whereas longer time since surgery (more than 5 years) predicted better physical health (+6.0 points), according to Dr. Dominici.

Age, race, marital status, work status, education level, disease stage, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy did not significantly predict any of the outcomes studied.

“This was a one-time survey of women who were enrolled in an observational cohort study, and we know that preoperative quality of life likely drives surgical choices,” she commented, addressing the study’s limitations. “Our findings may have limited generalizability to a more diverse population in that the majority of our participants were white and of high socioeconomic status.”

Dr. Dominici disclosed that she had no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Susan G. Komen, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and The Pink Agenda.

SOURCE: Dominici LS et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS6-06,

SAN ANTONIO – , according to investigators for a multicenter cross-sectional cohort study reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Women aged 40 or younger make up about 7% of all newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer in the United States, according to lead author, Laura S. Dominici, MD, of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Despite the fact that there is equivalent local-regional control with breast conservation and mastectomy, the rates of mastectomy and particularly bilateral mastectomy are increasing in young women, with a 10-fold increase seen from 1998 to 2011,” she noted in a press conference. “Young women are at particular risk for poorer psychosocial outcomes following a breast cancer diagnosis and in survivorship. However, little is known about the impact of surgery, particularly in the era of increasing bilateral mastectomy, on the quality of life of young survivors.”

Nearly three-fourths of the 560 young breast cancer survivors studied had undergone mastectomy, usually with some kind of reconstruction. Roughly 6 years later, compared with peers who had undergone breast-conserving surgery, women who had undergone unilateral or bilateral mastectomy had significantly poorer adjusted BREAST-Q scores for satisfaction with the appearance and feel of their breasts (beta, –8.7 and –9.3 points) and psychosocial well-being (–8.3 and –10.5 points). The latter also had poorer adjusted scores for sexual well-being (–8.1 points). Physical well-being, which captures aspects such as pain and range of motion, did not differ significantly by type of surgery.

“Local therapy decisions are associated with a persistent impact on quality of life in young breast cancer survivors,” Dr. Dominici concluded. “Knowledge of the potential long-term impact of surgery and quality of life is of critical importance for counseling young women about surgical decisions.”

Moving away from mastectomy

“The data are, to me anyway, more disconcerting when you consider the high mastectomy rate in this country relative to Europe, and this urge to have bilateral mastectomies, which, pardon the expression, is ridiculous in some cases because it doesn’t improve your outcome. And yet, it does have deleterious effects that last for years psychologically,” commented SABCS codirector and press conference moderator C. Kent Osborne, MD, who is director of the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “What can we do about that?” he asked.

“It’s a really challenging problem,” Dr. Dominici replied. “Part of what we are missing in the conversation that we have with our patients is this kind of information. We can certainly tell patients that the outcomes are equivalent, but if they don’t know that the long-term [quality of life] impact is potentially worse, then that may not affect their decision. The more prospective data that we generate to help us figure out which patients are going to have better or worse outcomes with these different types of surgery, the better we will be able to counsel patients with things that will be meaningful to them in the long run.”

The study was not designed to tease out the specific role of anxiety about a recurrence or a new breast cancer, which is a major driver of the decision to have mastectomy and also needs to be addressed during counseling, Dr. Dominici and Dr. Osborne agreed. “I think I spend more time talking patients out of bilateral mastectomy or mastectomy at all than anything,” he commented.

Study details

The women studied were participants in the prospective Young Women’s Breast Cancer Study (YWS) and had a mean age of 37 years at diagnosis. Most (86%) had stage 0-2 breast cancer. (Those with metastatic disease at diagnosis or a recurrence during follow-up were excluded.)

Overall, 52% of the women underwent bilateral mastectomy, 20% underwent unilateral mastectomy, and 28% underwent breast-conserving surgery, Dr. Dominici reported. Within the mastectomy group, most underwent implant-based reconstruction (69%) or flap reconstruction (12%), while some opted for no reconstruction (11%).

Multivariate analyses showed that, in addition to mastectomy, other significant predictors of poorer breast satisfaction were receipt of radiation therapy (beta, –7.5 points) and having a financially uncomfortable status as compared with a comfortable one (–5.4 points).

Additional significant predictors of poorer psychosocial well-being were receiving radiation (beta, –6.0 points), being financially uncomfortable (–7 points), and being overweight or obese (–4.2 points), and additional significant predictors of poorer sexual well-being were being financially uncomfortable (–6.8 points), being overweight or obese (–5.3 points), and having lymphedema a year after diagnosis (–3.8 points).

The only significant predictors of poorer physical health were financially uncomfortable status (beta, –4.8 points) and lymphedema (–6.4 points), whereas longer time since surgery (more than 5 years) predicted better physical health (+6.0 points), according to Dr. Dominici.

Age, race, marital status, work status, education level, disease stage, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy did not significantly predict any of the outcomes studied.

“This was a one-time survey of women who were enrolled in an observational cohort study, and we know that preoperative quality of life likely drives surgical choices,” she commented, addressing the study’s limitations. “Our findings may have limited generalizability to a more diverse population in that the majority of our participants were white and of high socioeconomic status.”

Dr. Dominici disclosed that she had no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Susan G. Komen, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and The Pink Agenda.

SOURCE: Dominici LS et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS6-06,

SAN ANTONIO – , according to investigators for a multicenter cross-sectional cohort study reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Women aged 40 or younger make up about 7% of all newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer in the United States, according to lead author, Laura S. Dominici, MD, of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Despite the fact that there is equivalent local-regional control with breast conservation and mastectomy, the rates of mastectomy and particularly bilateral mastectomy are increasing in young women, with a 10-fold increase seen from 1998 to 2011,” she noted in a press conference. “Young women are at particular risk for poorer psychosocial outcomes following a breast cancer diagnosis and in survivorship. However, little is known about the impact of surgery, particularly in the era of increasing bilateral mastectomy, on the quality of life of young survivors.”

Nearly three-fourths of the 560 young breast cancer survivors studied had undergone mastectomy, usually with some kind of reconstruction. Roughly 6 years later, compared with peers who had undergone breast-conserving surgery, women who had undergone unilateral or bilateral mastectomy had significantly poorer adjusted BREAST-Q scores for satisfaction with the appearance and feel of their breasts (beta, –8.7 and –9.3 points) and psychosocial well-being (–8.3 and –10.5 points). The latter also had poorer adjusted scores for sexual well-being (–8.1 points). Physical well-being, which captures aspects such as pain and range of motion, did not differ significantly by type of surgery.

“Local therapy decisions are associated with a persistent impact on quality of life in young breast cancer survivors,” Dr. Dominici concluded. “Knowledge of the potential long-term impact of surgery and quality of life is of critical importance for counseling young women about surgical decisions.”

Moving away from mastectomy

“The data are, to me anyway, more disconcerting when you consider the high mastectomy rate in this country relative to Europe, and this urge to have bilateral mastectomies, which, pardon the expression, is ridiculous in some cases because it doesn’t improve your outcome. And yet, it does have deleterious effects that last for years psychologically,” commented SABCS codirector and press conference moderator C. Kent Osborne, MD, who is director of the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “What can we do about that?” he asked.

“It’s a really challenging problem,” Dr. Dominici replied. “Part of what we are missing in the conversation that we have with our patients is this kind of information. We can certainly tell patients that the outcomes are equivalent, but if they don’t know that the long-term [quality of life] impact is potentially worse, then that may not affect their decision. The more prospective data that we generate to help us figure out which patients are going to have better or worse outcomes with these different types of surgery, the better we will be able to counsel patients with things that will be meaningful to them in the long run.”

The study was not designed to tease out the specific role of anxiety about a recurrence or a new breast cancer, which is a major driver of the decision to have mastectomy and also needs to be addressed during counseling, Dr. Dominici and Dr. Osborne agreed. “I think I spend more time talking patients out of bilateral mastectomy or mastectomy at all than anything,” he commented.

Study details

The women studied were participants in the prospective Young Women’s Breast Cancer Study (YWS) and had a mean age of 37 years at diagnosis. Most (86%) had stage 0-2 breast cancer. (Those with metastatic disease at diagnosis or a recurrence during follow-up were excluded.)

Overall, 52% of the women underwent bilateral mastectomy, 20% underwent unilateral mastectomy, and 28% underwent breast-conserving surgery, Dr. Dominici reported. Within the mastectomy group, most underwent implant-based reconstruction (69%) or flap reconstruction (12%), while some opted for no reconstruction (11%).

Multivariate analyses showed that, in addition to mastectomy, other significant predictors of poorer breast satisfaction were receipt of radiation therapy (beta, –7.5 points) and having a financially uncomfortable status as compared with a comfortable one (–5.4 points).

Additional significant predictors of poorer psychosocial well-being were receiving radiation (beta, –6.0 points), being financially uncomfortable (–7 points), and being overweight or obese (–4.2 points), and additional significant predictors of poorer sexual well-being were being financially uncomfortable (–6.8 points), being overweight or obese (–5.3 points), and having lymphedema a year after diagnosis (–3.8 points).

The only significant predictors of poorer physical health were financially uncomfortable status (beta, –4.8 points) and lymphedema (–6.4 points), whereas longer time since surgery (more than 5 years) predicted better physical health (+6.0 points), according to Dr. Dominici.

Age, race, marital status, work status, education level, disease stage, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy did not significantly predict any of the outcomes studied.

“This was a one-time survey of women who were enrolled in an observational cohort study, and we know that preoperative quality of life likely drives surgical choices,” she commented, addressing the study’s limitations. “Our findings may have limited generalizability to a more diverse population in that the majority of our participants were white and of high socioeconomic status.”

Dr. Dominici disclosed that she had no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Susan G. Komen, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and The Pink Agenda.

SOURCE: Dominici LS et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS6-06,

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2018

Key clinical point: More extensive breast surgery has a long-term negative impact on QOL for young breast cancer survivors.

Major finding: Compared with peers who underwent breast-conserving surgery, young women who underwent unilateral or bilateral mastectomy had significantly poorer adjusted scores for breast satisfaction (beta, –8.7 and –9.3 points) and psychosocial well-being (beta, –8.3 and –10.5 points).

Study details: A multicenter cross-sectional cohort study of 560 women with a mean age of 37 years at breast cancer diagnosis who completed the BREAST-Q questionnaire a median of 5.8 years later.

Disclosures: Dr. Dominici disclosed that she had no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Susan G. Komen, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and The Pink Agenda.

Source: Dominici LS et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS6-06.

Untreated OSA linked to resistant hypertension in black patients

according to findings published in Circulation.

In an analysis of 664 patients with hypertension, those with moderate to severe OSA had twofold higher odds of resistant hypertension, compared with those with no or mild OSA (odds ratio, 2.04; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-3.67), reported Dayna A. Johnson, PhD, of the Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and coauthors.

Participants were enrolled in the JHSS, an ancillary trial conducted during December 2012 – May 2016 as part of the Jackson Heart Study, a longitudinal study of 5,306 black adults aged 21-95 years in Jackson, Miss. Patients included in the analysis had hypertension (defined as high blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication, or self-reported diagnosis). Those without a valid in-home sleep apnea test and with missing data on hypertension, measured blood pressure, or use of antihypertensive medications and diuretics were excluded from analysis.

Sleep apnea was assessed using measures of nasal pressure, thoracic and abdominal inductance plethysmography, finger pulse oximetry, body position, and electrocardiography with a validated Type 3 home sleep apnea device. Obstructive apneas were identified as a flat or nearly flat amplitude of the nasal pressure signal for greater than 10 seconds, accompanied by respiratory effort on the abdominal or thoracic inductance plethysmography bands. Severity was defined by the standard Respiratory Event Index (REI) categories: fewer than 5 events (unaffected), greater than or equal to 5 events to fewer than 15 events (mild), greater than or equal to 15 events to fewer than 30 events (moderate), and greater than or equal to 30 events (severe), the authors reported.

High blood pressure (BP) was defined as systolic BP greater than or equal to 130 mm Hg or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 80 mm Hg. Controlled hypertension was defined as systolic BP less than 130 mmHg and diastolic BP less than 80 mm Hg.

Uncontrolled BP was defined as high BP with use of one or two classes of antihypertensive medications; resistant hypertension was defined as having high BP while on greater than or equal to three classes of antihypertensive medications with one being a diuretic or as using of greater than four classes of antihypertensive medications regardless of BP control, Dr. Johnson and colleagues reported.

A total of 25.7% of hypertension patients had moderate or severe OSA, though only 6% of these patients had an OSA diagnosis from a physician. In addition, 48.2% of patients had uncontrolled hypertension, and 14.5% had resistant hypertension.

Moderate or severe OSA was associated with nearly twofold higher unadjusted odds of resistant hypertension (OR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.15-3.20). In adjusted models, moderate or severe OSA and nocturnal hypoxemia were not associated with uncontrolled hypertension but were associated with resistant hypertension (OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.14-3.67; OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.01-1.55, respectively).

Compared with no OSA, severe OSA was associated with more than three times higher odds of resistant hypertension (OR, 3.50; 95% CI, 1.54-7.91). This association was even higher after adjustment for covariates (OR, 3.58; 95% CI, 1.39-9.19).

“These data suggest that untreated OSA may contribute to the high burden of resistant hypertension in blacks,” Dr. Johnson and coauthors wrote. “Future studies should test whether diagnosis and treatment of OSA may be interventions for improving BP control” and reducing this burden, they added.

“These findings are particularly important given that most adults with OSA are undiagnosed and untreated.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. One of the authors reported receiving funding from Amgen. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Johnson D et al. Circulation. 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036675.

according to findings published in Circulation.

In an analysis of 664 patients with hypertension, those with moderate to severe OSA had twofold higher odds of resistant hypertension, compared with those with no or mild OSA (odds ratio, 2.04; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-3.67), reported Dayna A. Johnson, PhD, of the Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and coauthors.

Participants were enrolled in the JHSS, an ancillary trial conducted during December 2012 – May 2016 as part of the Jackson Heart Study, a longitudinal study of 5,306 black adults aged 21-95 years in Jackson, Miss. Patients included in the analysis had hypertension (defined as high blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication, or self-reported diagnosis). Those without a valid in-home sleep apnea test and with missing data on hypertension, measured blood pressure, or use of antihypertensive medications and diuretics were excluded from analysis.

Sleep apnea was assessed using measures of nasal pressure, thoracic and abdominal inductance plethysmography, finger pulse oximetry, body position, and electrocardiography with a validated Type 3 home sleep apnea device. Obstructive apneas were identified as a flat or nearly flat amplitude of the nasal pressure signal for greater than 10 seconds, accompanied by respiratory effort on the abdominal or thoracic inductance plethysmography bands. Severity was defined by the standard Respiratory Event Index (REI) categories: fewer than 5 events (unaffected), greater than or equal to 5 events to fewer than 15 events (mild), greater than or equal to 15 events to fewer than 30 events (moderate), and greater than or equal to 30 events (severe), the authors reported.

High blood pressure (BP) was defined as systolic BP greater than or equal to 130 mm Hg or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 80 mm Hg. Controlled hypertension was defined as systolic BP less than 130 mmHg and diastolic BP less than 80 mm Hg.

Uncontrolled BP was defined as high BP with use of one or two classes of antihypertensive medications; resistant hypertension was defined as having high BP while on greater than or equal to three classes of antihypertensive medications with one being a diuretic or as using of greater than four classes of antihypertensive medications regardless of BP control, Dr. Johnson and colleagues reported.

A total of 25.7% of hypertension patients had moderate or severe OSA, though only 6% of these patients had an OSA diagnosis from a physician. In addition, 48.2% of patients had uncontrolled hypertension, and 14.5% had resistant hypertension.

Moderate or severe OSA was associated with nearly twofold higher unadjusted odds of resistant hypertension (OR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.15-3.20). In adjusted models, moderate or severe OSA and nocturnal hypoxemia were not associated with uncontrolled hypertension but were associated with resistant hypertension (OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.14-3.67; OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.01-1.55, respectively).

Compared with no OSA, severe OSA was associated with more than three times higher odds of resistant hypertension (OR, 3.50; 95% CI, 1.54-7.91). This association was even higher after adjustment for covariates (OR, 3.58; 95% CI, 1.39-9.19).

“These data suggest that untreated OSA may contribute to the high burden of resistant hypertension in blacks,” Dr. Johnson and coauthors wrote. “Future studies should test whether diagnosis and treatment of OSA may be interventions for improving BP control” and reducing this burden, they added.

“These findings are particularly important given that most adults with OSA are undiagnosed and untreated.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. One of the authors reported receiving funding from Amgen. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Johnson D et al. Circulation. 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036675.

according to findings published in Circulation.

In an analysis of 664 patients with hypertension, those with moderate to severe OSA had twofold higher odds of resistant hypertension, compared with those with no or mild OSA (odds ratio, 2.04; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-3.67), reported Dayna A. Johnson, PhD, of the Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and coauthors.

Participants were enrolled in the JHSS, an ancillary trial conducted during December 2012 – May 2016 as part of the Jackson Heart Study, a longitudinal study of 5,306 black adults aged 21-95 years in Jackson, Miss. Patients included in the analysis had hypertension (defined as high blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication, or self-reported diagnosis). Those without a valid in-home sleep apnea test and with missing data on hypertension, measured blood pressure, or use of antihypertensive medications and diuretics were excluded from analysis.

Sleep apnea was assessed using measures of nasal pressure, thoracic and abdominal inductance plethysmography, finger pulse oximetry, body position, and electrocardiography with a validated Type 3 home sleep apnea device. Obstructive apneas were identified as a flat or nearly flat amplitude of the nasal pressure signal for greater than 10 seconds, accompanied by respiratory effort on the abdominal or thoracic inductance plethysmography bands. Severity was defined by the standard Respiratory Event Index (REI) categories: fewer than 5 events (unaffected), greater than or equal to 5 events to fewer than 15 events (mild), greater than or equal to 15 events to fewer than 30 events (moderate), and greater than or equal to 30 events (severe), the authors reported.

High blood pressure (BP) was defined as systolic BP greater than or equal to 130 mm Hg or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 80 mm Hg. Controlled hypertension was defined as systolic BP less than 130 mmHg and diastolic BP less than 80 mm Hg.

Uncontrolled BP was defined as high BP with use of one or two classes of antihypertensive medications; resistant hypertension was defined as having high BP while on greater than or equal to three classes of antihypertensive medications with one being a diuretic or as using of greater than four classes of antihypertensive medications regardless of BP control, Dr. Johnson and colleagues reported.

A total of 25.7% of hypertension patients had moderate or severe OSA, though only 6% of these patients had an OSA diagnosis from a physician. In addition, 48.2% of patients had uncontrolled hypertension, and 14.5% had resistant hypertension.

Moderate or severe OSA was associated with nearly twofold higher unadjusted odds of resistant hypertension (OR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.15-3.20). In adjusted models, moderate or severe OSA and nocturnal hypoxemia were not associated with uncontrolled hypertension but were associated with resistant hypertension (OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.14-3.67; OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.01-1.55, respectively).

Compared with no OSA, severe OSA was associated with more than three times higher odds of resistant hypertension (OR, 3.50; 95% CI, 1.54-7.91). This association was even higher after adjustment for covariates (OR, 3.58; 95% CI, 1.39-9.19).

“These data suggest that untreated OSA may contribute to the high burden of resistant hypertension in blacks,” Dr. Johnson and coauthors wrote. “Future studies should test whether diagnosis and treatment of OSA may be interventions for improving BP control” and reducing this burden, they added.

“These findings are particularly important given that most adults with OSA are undiagnosed and untreated.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. One of the authors reported receiving funding from Amgen. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Johnson D et al. Circulation. 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036675.

FROM CIRCULATION

Key clinical point: Untreated moderate or severe obstructive sleep apnea was associated with greater odds of resistant hypertension.

Major finding: In patients with hypertension, those with moderate to severe OSA had twofold higher odds of resistant hypertension, compared with those with no or mild OSA.

Study details: A total of 664 participants were enrolled in the JHSS, an ancillary trial as part of the Jackson Heart Study, a longitudinal study of 5,306 black adults.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. One of the authors reported receiving funding from Amgen. No other disclosures were reported.

Source: Johnson D et al. Circulation. 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036675.

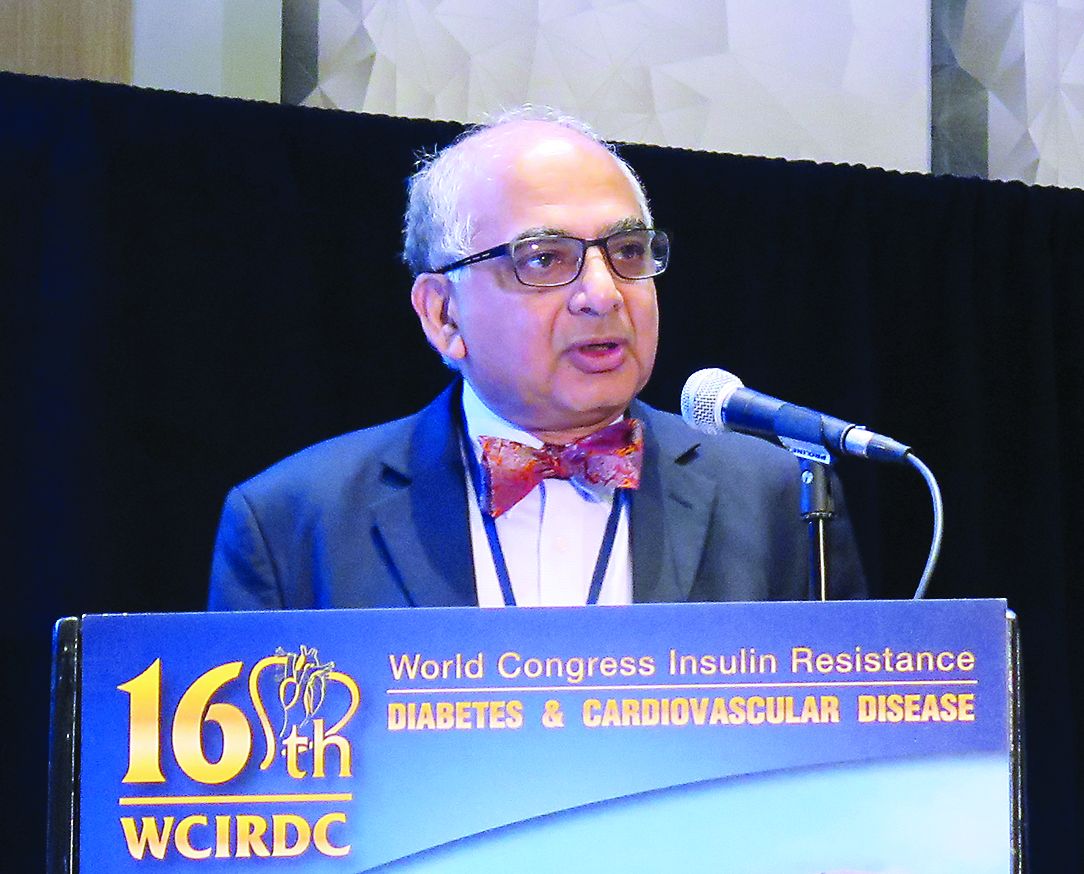

New risk-prediction model for diabetes under development

LOS ANGELES – Clinicians treating patients with diabetes rely heavily on the U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Risk Engine and the Framingham Risk Score to predict outcomes, but the populations used for developing these tools differ significantly from the current U.S. diabetes population.

“All these risk engines have various degrees of accuracy along with several limitations, including that they are derived from data from various populations,” Vivian A. Fonseca, MD, said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Cardiovascular Disease. “Sometimes the results may not be generalizable. That’s one of the big problems with the risk engines we’re using.”

To address these shortcomings, Dr. Fonseca, Hui Shao, PhD, and Lizheng Shi, PhD, have developed the Building, Relating, Assessing, Validating Outcomes (BRAVO) of Diabetes Model, a patient-level microsimulation model based on data from the ACCORD trial. The model predicts both primary and secondary CVD events, microvascular events, the progress of hemoglobin A1c and other key biomarkers over time, quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) function decrements associated with complications, and an ability to predict outcomes in patients from other regions in the world. The risk engine contains three modules for 17 equations in total, including angina, blindness, and hypoglycemia (Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36[9]:1125-34). “There are lots of data now showing that if you get hypoglycemia, your risk of a cardiovascular event goes up greatly over the subsequent 2 years,” said Dr. Fonseca, who is chief of the section of endocrinology at Tulane University Health Science Center, New Orleans. “No other risk engine has that.”

When he and his associates applied the UKPDS Risk Engine to the ACCORD cohort, they found that the UPKDS Risk Engine overpredicted the risk of stroke (2.3% vs. 1.4% observed), MI (6.5% vs. 4.9% observed), and all-cause mortality (10.3% vs. 4% observed); yet it underpredicted congestive heart failure (2.2% vs. 4% observed), end-stage renal disease (0.5% vs. 3% observed), and blindness (1.35% vs. 8.1% observed). In the ACCORD cohort, baseline duration varied from 0 to 35 years. “Using left truncated regression, we can piece together the segmented follow-up times for 10,251 patients to a complete diabetes progression track from 0 years to 40 years after diabetes onset,” he said.

Dr. Fonseca said that Internal validations studies found that BRAVO predicted outcomes from the ACCORD trial, including congestive heart failure, MI, stroke, angina, blindness, end-stage renal disease, and neuropathy. Data from the ASPEN, CARDS, and ADVANCE trials were used to conduct external validation, and the incidence rates of 28 endpoints correlated with that of BRAVO “extremely well.” In addition, BRAVO has been calibrated against 18 large randomized, controlled trials conducted after the year 2000. “Regional variation in CVD [cardiovascular disease] outcomes were included as an important risk factor in the simulation,” said Dr. Fonseca, who is also assistant dean for clinical research at Tulane. Results to date show a high prediction accuracy (R-squared value = .91).

He and his associates are currently examining ways to apply BRAVO in clinical practice, including for risk stratification. “Let’s say you have a large health system, and you want to separate out your patients who have high, medium, or low risk for diabetes and make sure they get they get the right care according to their stratification,” he explained. “A couple of large health systems are trying this out right now.”

BRAVO can also be used as a tool for cost-effectiveness analysis and program evaluation. In fact, he and his colleagues at five medical centers are working with the American Diabetes Association “to see what effect a certain intervention will have on outcomes in people with diabetes over a number of years, and how cost effective it might be.”

Finally, BRAVO can be used for diabetes management in clinical practice. “Based on an individual’s characteristics, the BRAVO model potentially simulates future outcomes such as complications and mortality, providing a transparent platform for shared decision making,” he said.

Dr. Fonseca disclosed that he has an ownership interest in the development of BRAVO.

LOS ANGELES – Clinicians treating patients with diabetes rely heavily on the U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Risk Engine and the Framingham Risk Score to predict outcomes, but the populations used for developing these tools differ significantly from the current U.S. diabetes population.

“All these risk engines have various degrees of accuracy along with several limitations, including that they are derived from data from various populations,” Vivian A. Fonseca, MD, said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Cardiovascular Disease. “Sometimes the results may not be generalizable. That’s one of the big problems with the risk engines we’re using.”

To address these shortcomings, Dr. Fonseca, Hui Shao, PhD, and Lizheng Shi, PhD, have developed the Building, Relating, Assessing, Validating Outcomes (BRAVO) of Diabetes Model, a patient-level microsimulation model based on data from the ACCORD trial. The model predicts both primary and secondary CVD events, microvascular events, the progress of hemoglobin A1c and other key biomarkers over time, quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) function decrements associated with complications, and an ability to predict outcomes in patients from other regions in the world. The risk engine contains three modules for 17 equations in total, including angina, blindness, and hypoglycemia (Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36[9]:1125-34). “There are lots of data now showing that if you get hypoglycemia, your risk of a cardiovascular event goes up greatly over the subsequent 2 years,” said Dr. Fonseca, who is chief of the section of endocrinology at Tulane University Health Science Center, New Orleans. “No other risk engine has that.”

When he and his associates applied the UKPDS Risk Engine to the ACCORD cohort, they found that the UPKDS Risk Engine overpredicted the risk of stroke (2.3% vs. 1.4% observed), MI (6.5% vs. 4.9% observed), and all-cause mortality (10.3% vs. 4% observed); yet it underpredicted congestive heart failure (2.2% vs. 4% observed), end-stage renal disease (0.5% vs. 3% observed), and blindness (1.35% vs. 8.1% observed). In the ACCORD cohort, baseline duration varied from 0 to 35 years. “Using left truncated regression, we can piece together the segmented follow-up times for 10,251 patients to a complete diabetes progression track from 0 years to 40 years after diabetes onset,” he said.

Dr. Fonseca said that Internal validations studies found that BRAVO predicted outcomes from the ACCORD trial, including congestive heart failure, MI, stroke, angina, blindness, end-stage renal disease, and neuropathy. Data from the ASPEN, CARDS, and ADVANCE trials were used to conduct external validation, and the incidence rates of 28 endpoints correlated with that of BRAVO “extremely well.” In addition, BRAVO has been calibrated against 18 large randomized, controlled trials conducted after the year 2000. “Regional variation in CVD [cardiovascular disease] outcomes were included as an important risk factor in the simulation,” said Dr. Fonseca, who is also assistant dean for clinical research at Tulane. Results to date show a high prediction accuracy (R-squared value = .91).

He and his associates are currently examining ways to apply BRAVO in clinical practice, including for risk stratification. “Let’s say you have a large health system, and you want to separate out your patients who have high, medium, or low risk for diabetes and make sure they get they get the right care according to their stratification,” he explained. “A couple of large health systems are trying this out right now.”

BRAVO can also be used as a tool for cost-effectiveness analysis and program evaluation. In fact, he and his colleagues at five medical centers are working with the American Diabetes Association “to see what effect a certain intervention will have on outcomes in people with diabetes over a number of years, and how cost effective it might be.”

Finally, BRAVO can be used for diabetes management in clinical practice. “Based on an individual’s characteristics, the BRAVO model potentially simulates future outcomes such as complications and mortality, providing a transparent platform for shared decision making,” he said.

Dr. Fonseca disclosed that he has an ownership interest in the development of BRAVO.

LOS ANGELES – Clinicians treating patients with diabetes rely heavily on the U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Risk Engine and the Framingham Risk Score to predict outcomes, but the populations used for developing these tools differ significantly from the current U.S. diabetes population.

“All these risk engines have various degrees of accuracy along with several limitations, including that they are derived from data from various populations,” Vivian A. Fonseca, MD, said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Cardiovascular Disease. “Sometimes the results may not be generalizable. That’s one of the big problems with the risk engines we’re using.”

To address these shortcomings, Dr. Fonseca, Hui Shao, PhD, and Lizheng Shi, PhD, have developed the Building, Relating, Assessing, Validating Outcomes (BRAVO) of Diabetes Model, a patient-level microsimulation model based on data from the ACCORD trial. The model predicts both primary and secondary CVD events, microvascular events, the progress of hemoglobin A1c and other key biomarkers over time, quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) function decrements associated with complications, and an ability to predict outcomes in patients from other regions in the world. The risk engine contains three modules for 17 equations in total, including angina, blindness, and hypoglycemia (Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36[9]:1125-34). “There are lots of data now showing that if you get hypoglycemia, your risk of a cardiovascular event goes up greatly over the subsequent 2 years,” said Dr. Fonseca, who is chief of the section of endocrinology at Tulane University Health Science Center, New Orleans. “No other risk engine has that.”

When he and his associates applied the UKPDS Risk Engine to the ACCORD cohort, they found that the UPKDS Risk Engine overpredicted the risk of stroke (2.3% vs. 1.4% observed), MI (6.5% vs. 4.9% observed), and all-cause mortality (10.3% vs. 4% observed); yet it underpredicted congestive heart failure (2.2% vs. 4% observed), end-stage renal disease (0.5% vs. 3% observed), and blindness (1.35% vs. 8.1% observed). In the ACCORD cohort, baseline duration varied from 0 to 35 years. “Using left truncated regression, we can piece together the segmented follow-up times for 10,251 patients to a complete diabetes progression track from 0 years to 40 years after diabetes onset,” he said.

Dr. Fonseca said that Internal validations studies found that BRAVO predicted outcomes from the ACCORD trial, including congestive heart failure, MI, stroke, angina, blindness, end-stage renal disease, and neuropathy. Data from the ASPEN, CARDS, and ADVANCE trials were used to conduct external validation, and the incidence rates of 28 endpoints correlated with that of BRAVO “extremely well.” In addition, BRAVO has been calibrated against 18 large randomized, controlled trials conducted after the year 2000. “Regional variation in CVD [cardiovascular disease] outcomes were included as an important risk factor in the simulation,” said Dr. Fonseca, who is also assistant dean for clinical research at Tulane. Results to date show a high prediction accuracy (R-squared value = .91).

He and his associates are currently examining ways to apply BRAVO in clinical practice, including for risk stratification. “Let’s say you have a large health system, and you want to separate out your patients who have high, medium, or low risk for diabetes and make sure they get they get the right care according to their stratification,” he explained. “A couple of large health systems are trying this out right now.”

BRAVO can also be used as a tool for cost-effectiveness analysis and program evaluation. In fact, he and his colleagues at five medical centers are working with the American Diabetes Association “to see what effect a certain intervention will have on outcomes in people with diabetes over a number of years, and how cost effective it might be.”

Finally, BRAVO can be used for diabetes management in clinical practice. “Based on an individual’s characteristics, the BRAVO model potentially simulates future outcomes such as complications and mortality, providing a transparent platform for shared decision making,” he said.

Dr. Fonseca disclosed that he has an ownership interest in the development of BRAVO.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE WCIRCD 2018

Risk-based testing missed 35% of HCV-positive prison inmates

Routine testing for hepatitis C virus at inmate entry should be considered by U.S. state prisons, according to Sabrina A. Assoumou, MD, of the Boston Medical Center and her colleagues.

The researchers performed a retrospective analysis of individuals entering the Washington state prison system, which routinely offers hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing, in order to compare routine opt-out testing with current risk-based and one-time testing for individuals born between 1945 and 1965. Additionally, liver fibrosis stage was characterized in blood samples from HCV-positive individuals, the investigators wrote in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine.

Between 2012 and 2016, 24,567 (83%) individuals were tested for HCV antibody, and of these, 4,921 (20%) tested positive. A total of 2,403 (49%) of those testing positive had subsequent hepatitis HCV RNA testing, with 1,727 (72%) of these showing chronic infection.

As expected, Dr. Assoumou and her colleagues found that reactive antibodies was more prevalent in individuals born between 1945 and 1965, compared with other years (44% vs. 17%). However, in actual case numbers, most (72%) were outside of this age bracket. Overall, they calculated that up to 35% of positive HCV tests would be missed using testing targeted by birth cohort and risk behavior alone. Among the chronically infected individuals, 23% had showed at least moderate liver fibrosis.

“Routine opt-out testing identified a substantial number of HCV cases that would have been missed by targeted testing. Almost one-quarter of individuals with chronic HCV had significant liver fibrosis and thus a more urgent need for treatment to prevent complications,” Dr Assoumou and her colleagues concluded.

The researchers reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Assoumou SA et al, Am J Prev Med. 2019;56:8-16.

Routine testing for hepatitis C virus at inmate entry should be considered by U.S. state prisons, according to Sabrina A. Assoumou, MD, of the Boston Medical Center and her colleagues.

The researchers performed a retrospective analysis of individuals entering the Washington state prison system, which routinely offers hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing, in order to compare routine opt-out testing with current risk-based and one-time testing for individuals born between 1945 and 1965. Additionally, liver fibrosis stage was characterized in blood samples from HCV-positive individuals, the investigators wrote in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine.

Between 2012 and 2016, 24,567 (83%) individuals were tested for HCV antibody, and of these, 4,921 (20%) tested positive. A total of 2,403 (49%) of those testing positive had subsequent hepatitis HCV RNA testing, with 1,727 (72%) of these showing chronic infection.

As expected, Dr. Assoumou and her colleagues found that reactive antibodies was more prevalent in individuals born between 1945 and 1965, compared with other years (44% vs. 17%). However, in actual case numbers, most (72%) were outside of this age bracket. Overall, they calculated that up to 35% of positive HCV tests would be missed using testing targeted by birth cohort and risk behavior alone. Among the chronically infected individuals, 23% had showed at least moderate liver fibrosis.

“Routine opt-out testing identified a substantial number of HCV cases that would have been missed by targeted testing. Almost one-quarter of individuals with chronic HCV had significant liver fibrosis and thus a more urgent need for treatment to prevent complications,” Dr Assoumou and her colleagues concluded.

The researchers reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Assoumou SA et al, Am J Prev Med. 2019;56:8-16.

Routine testing for hepatitis C virus at inmate entry should be considered by U.S. state prisons, according to Sabrina A. Assoumou, MD, of the Boston Medical Center and her colleagues.

The researchers performed a retrospective analysis of individuals entering the Washington state prison system, which routinely offers hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing, in order to compare routine opt-out testing with current risk-based and one-time testing for individuals born between 1945 and 1965. Additionally, liver fibrosis stage was characterized in blood samples from HCV-positive individuals, the investigators wrote in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine.

Between 2012 and 2016, 24,567 (83%) individuals were tested for HCV antibody, and of these, 4,921 (20%) tested positive. A total of 2,403 (49%) of those testing positive had subsequent hepatitis HCV RNA testing, with 1,727 (72%) of these showing chronic infection.

As expected, Dr. Assoumou and her colleagues found that reactive antibodies was more prevalent in individuals born between 1945 and 1965, compared with other years (44% vs. 17%). However, in actual case numbers, most (72%) were outside of this age bracket. Overall, they calculated that up to 35% of positive HCV tests would be missed using testing targeted by birth cohort and risk behavior alone. Among the chronically infected individuals, 23% had showed at least moderate liver fibrosis.

“Routine opt-out testing identified a substantial number of HCV cases that would have been missed by targeted testing. Almost one-quarter of individuals with chronic HCV had significant liver fibrosis and thus a more urgent need for treatment to prevent complications,” Dr Assoumou and her colleagues concluded.

The researchers reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Assoumou SA et al, Am J Prev Med. 2019;56:8-16.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Canakinumab reduces arthroplasty rates

CHICAGO – Canakinumab, a human monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-1 beta, was associated with an eye-popping 45% relative risk reduction in the rate of total knee or hip replacement in a prespecified secondary analysis of the landmark CANTOS trial, Matthias Schieker, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

For the broader composite endpoint of all osteoarthritis-related adverse events, including new-onset OA or worsening of symptoms in those with OA at baseline, the relative risk reduction was 23% in patients randomized to canakinumab rather than placebo. For CANTOS participants who already had OA at baseline, the relative risk reduction was 31%, according to Dr. Schieker, who is head of the joint, bone, and tendon disease group at the Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research in Basel, Switzerland, and professor of regenerative medicine at the University of Munich.

CANTOS (the Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study) was designed as a massive phase 3 secondary cardiovascular prevention trial. It included 10,061 patients with a history of acute MI and an elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) level of 2 mg/L or more who were randomized double blind to subcutaneous canakinumab at 50, 150, or 300 mg or placebo given once every 3 months. During a median 3.7 years of prospective follow-up, patients in the 150-mg group had a highly significant 17% reduction relative to placebo in the risk of the composite efficacy endpoint comprising cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina resulting in urgent coronary revascularization (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21;377[12]:1119-31).

Since this result was achieved with a 39% reduction in CRP, compared with placebo, and involved no lipid-lowering effect, it was hailed in the cardiology world as the long-awaited proof of the inflammatory hypothesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

CANTOS has proved to be the gift that keeps on giving. Secondary analyses of the study data have found statistically significant reductions in the incidence of and mortality caused by lung cancer in the coronary disease patients on canakinumab, as well as a decreased risk of developing gout. Moreover, the CANTOS investigators, well aware that there are no approved therapies to prevent disease progression in OA, had the foresight to prospectively collect data on OA-related symptoms and outcomes.

At baseline, 15.6% of CANTOS participants had a history of OA. During follow-up, patients in that subgroup had a 3.4% incidence of total knee replacement or total hip replacement if they had been assigned to canakinumab, compared with a 6.3% incidence if they got placebo. In the full 10,000-plus CANTOS cohort, the arthroplasty rates were 0.8% and 1.4%, respectively.

The combined rate of OA-related adverse events in the full CANTOS cohort was 5.4% with canakinumab and 7.0% with placebo. In the subgroup with baseline OA, the rates were 14.5% and 20.8%.

Canakinumab is marketed by Novartis as Ilaris and is already approved for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes, familial Mediterranean fever, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and other rare autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Based upon the positive primary outcomes of the CANTOS trial, Novartis applied to the Food and Drug Administration for a major expanded indication of the IL-1B inhibitor for cardiovascular risk reduction. However, the regulatory agency has turned down that bid.

Although the CANTOS OA-related outcomes data caused quite a stir at the meeting, Dr. Schieker said in an interview that the impressive findings didn’t really come as a surprise to him.

“I think everyone in the field has assumed that IL-1 plays a role in OA. That idea has been around for quite a long time, but until now no effects could be shown in OA. We were lucky to have an enriched population with elevated hsCRP that was so large and followed for so long that we could finally show these relative risk reductions,” he explained.

SOURCE: Schieker M et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10), Abstract 445.

CHICAGO – Canakinumab, a human monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-1 beta, was associated with an eye-popping 45% relative risk reduction in the rate of total knee or hip replacement in a prespecified secondary analysis of the landmark CANTOS trial, Matthias Schieker, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

For the broader composite endpoint of all osteoarthritis-related adverse events, including new-onset OA or worsening of symptoms in those with OA at baseline, the relative risk reduction was 23% in patients randomized to canakinumab rather than placebo. For CANTOS participants who already had OA at baseline, the relative risk reduction was 31%, according to Dr. Schieker, who is head of the joint, bone, and tendon disease group at the Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research in Basel, Switzerland, and professor of regenerative medicine at the University of Munich.

CANTOS (the Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study) was designed as a massive phase 3 secondary cardiovascular prevention trial. It included 10,061 patients with a history of acute MI and an elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) level of 2 mg/L or more who were randomized double blind to subcutaneous canakinumab at 50, 150, or 300 mg or placebo given once every 3 months. During a median 3.7 years of prospective follow-up, patients in the 150-mg group had a highly significant 17% reduction relative to placebo in the risk of the composite efficacy endpoint comprising cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina resulting in urgent coronary revascularization (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21;377[12]:1119-31).

Since this result was achieved with a 39% reduction in CRP, compared with placebo, and involved no lipid-lowering effect, it was hailed in the cardiology world as the long-awaited proof of the inflammatory hypothesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

CANTOS has proved to be the gift that keeps on giving. Secondary analyses of the study data have found statistically significant reductions in the incidence of and mortality caused by lung cancer in the coronary disease patients on canakinumab, as well as a decreased risk of developing gout. Moreover, the CANTOS investigators, well aware that there are no approved therapies to prevent disease progression in OA, had the foresight to prospectively collect data on OA-related symptoms and outcomes.

At baseline, 15.6% of CANTOS participants had a history of OA. During follow-up, patients in that subgroup had a 3.4% incidence of total knee replacement or total hip replacement if they had been assigned to canakinumab, compared with a 6.3% incidence if they got placebo. In the full 10,000-plus CANTOS cohort, the arthroplasty rates were 0.8% and 1.4%, respectively.

The combined rate of OA-related adverse events in the full CANTOS cohort was 5.4% with canakinumab and 7.0% with placebo. In the subgroup with baseline OA, the rates were 14.5% and 20.8%.

Canakinumab is marketed by Novartis as Ilaris and is already approved for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes, familial Mediterranean fever, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and other rare autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Based upon the positive primary outcomes of the CANTOS trial, Novartis applied to the Food and Drug Administration for a major expanded indication of the IL-1B inhibitor for cardiovascular risk reduction. However, the regulatory agency has turned down that bid.

Although the CANTOS OA-related outcomes data caused quite a stir at the meeting, Dr. Schieker said in an interview that the impressive findings didn’t really come as a surprise to him.

“I think everyone in the field has assumed that IL-1 plays a role in OA. That idea has been around for quite a long time, but until now no effects could be shown in OA. We were lucky to have an enriched population with elevated hsCRP that was so large and followed for so long that we could finally show these relative risk reductions,” he explained.

SOURCE: Schieker M et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10), Abstract 445.

CHICAGO – Canakinumab, a human monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-1 beta, was associated with an eye-popping 45% relative risk reduction in the rate of total knee or hip replacement in a prespecified secondary analysis of the landmark CANTOS trial, Matthias Schieker, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

For the broader composite endpoint of all osteoarthritis-related adverse events, including new-onset OA or worsening of symptoms in those with OA at baseline, the relative risk reduction was 23% in patients randomized to canakinumab rather than placebo. For CANTOS participants who already had OA at baseline, the relative risk reduction was 31%, according to Dr. Schieker, who is head of the joint, bone, and tendon disease group at the Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research in Basel, Switzerland, and professor of regenerative medicine at the University of Munich.

CANTOS (the Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study) was designed as a massive phase 3 secondary cardiovascular prevention trial. It included 10,061 patients with a history of acute MI and an elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) level of 2 mg/L or more who were randomized double blind to subcutaneous canakinumab at 50, 150, or 300 mg or placebo given once every 3 months. During a median 3.7 years of prospective follow-up, patients in the 150-mg group had a highly significant 17% reduction relative to placebo in the risk of the composite efficacy endpoint comprising cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina resulting in urgent coronary revascularization (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21;377[12]:1119-31).

Since this result was achieved with a 39% reduction in CRP, compared with placebo, and involved no lipid-lowering effect, it was hailed in the cardiology world as the long-awaited proof of the inflammatory hypothesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

CANTOS has proved to be the gift that keeps on giving. Secondary analyses of the study data have found statistically significant reductions in the incidence of and mortality caused by lung cancer in the coronary disease patients on canakinumab, as well as a decreased risk of developing gout. Moreover, the CANTOS investigators, well aware that there are no approved therapies to prevent disease progression in OA, had the foresight to prospectively collect data on OA-related symptoms and outcomes.

At baseline, 15.6% of CANTOS participants had a history of OA. During follow-up, patients in that subgroup had a 3.4% incidence of total knee replacement or total hip replacement if they had been assigned to canakinumab, compared with a 6.3% incidence if they got placebo. In the full 10,000-plus CANTOS cohort, the arthroplasty rates were 0.8% and 1.4%, respectively.

The combined rate of OA-related adverse events in the full CANTOS cohort was 5.4% with canakinumab and 7.0% with placebo. In the subgroup with baseline OA, the rates were 14.5% and 20.8%.

Canakinumab is marketed by Novartis as Ilaris and is already approved for cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes, familial Mediterranean fever, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and other rare autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Based upon the positive primary outcomes of the CANTOS trial, Novartis applied to the Food and Drug Administration for a major expanded indication of the IL-1B inhibitor for cardiovascular risk reduction. However, the regulatory agency has turned down that bid.

Although the CANTOS OA-related outcomes data caused quite a stir at the meeting, Dr. Schieker said in an interview that the impressive findings didn’t really come as a surprise to him.

“I think everyone in the field has assumed that IL-1 plays a role in OA. That idea has been around for quite a long time, but until now no effects could be shown in OA. We were lucky to have an enriched population with elevated hsCRP that was so large and followed for so long that we could finally show these relative risk reductions,” he explained.

SOURCE: Schieker M et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10), Abstract 445.

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients on the IL-1B inhibitor canakinumab for secondary cardiovascular prevention also experienced a 45% risk reduction in total knee or total hip replacement, compared with placebo.

Study details: This was a prespecified secondary analysis of OA-related outcomes in the 10,061 participants in the randomized, double-blind CANTOS trial.

Disclosures: The presenter is an employee of Novartis, which markets canakinumab and sponsored CANTOS.

Source: Schieker M et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10), Abstract 445.

Hospice liability

Question: Hospice liability may exist in which of the following?

A. False claims in violation of Medicare rules regarding eligible beneficiaries.

B. False claims for continuous home care services.

C. Negligent billing practices.

D. Only A and B are correct.

E. A, B, and C are correct.

Answer: D. With an aging population and better end-of-life care, the United States has in the last decade witnessed about a 50% increase in the number of hospices. Hospice care is a Medicare-covered benefit, and most hospices operate on a for-profit basis. Although occasionally institution based, services are more often offered as an outpatient or home-care option. In 2016, hospice care reached 1.4 million beneficiaries, with total Medicare expenditure of $16.7 billion.1

There are two broad categories of legal jeopardy that hospices face: Medicare fraud and malpractice lawsuits. This article will address these two issues. In addition, hospices, like all health care institutions, face numerous other liabilities, such as negligent hiring, breach of confidentiality, premise liability, HIPAA violations, sexual harassment, vicarious liability, and many others.

Medicare fraud

The False Claims Act (FCA) is an old law enacted by Congress way back in 1863. It imposes liability for submitting a payment demand to the federal government where there is actual or constructive knowledge that the claim is false.2

Intent to defraud is not a required element. But knowing or reckless disregard of the truth or material misrepresentation are required, although negligence is insufficient to constitute a violation. Penalties include treble damages, costs and attorney fees, and fines of $11,000 per false claim – as well as possible imprisonment. The FCA is the most prominent health care antifraud statute.3 Two others are the federal Anti-Kickback Statute and the Stark Law.

A recent example of hospice fraud involved Ohio’s Chemed and Vitas Hospice Services, which were accused of knowingly billing for hospice-ineligible patients and inflated levels of care.4

The government alleged that the defendants rewarded employees with bonuses based on the number of patients receiving hospice services, irrespective of whether they were actually terminally ill or needed continuous home care services (CHCS). CHCS commands the highest Medicare daily rate and is meant only for the temporary treatment of acute symptoms constituting a medical crisis.