User login

Insulin loses its starting spot

, fewer migraines in women are linked to increased type 2 diabetes risk, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force looks to prevent opioid abuse in primary care, and there’s an uncomfortable truth in new guidelines for posttraumatic stress disorder.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

, fewer migraines in women are linked to increased type 2 diabetes risk, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force looks to prevent opioid abuse in primary care, and there’s an uncomfortable truth in new guidelines for posttraumatic stress disorder.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

, fewer migraines in women are linked to increased type 2 diabetes risk, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force looks to prevent opioid abuse in primary care, and there’s an uncomfortable truth in new guidelines for posttraumatic stress disorder.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Drug may be new option for transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia

SAN DIEGO—Luspatercept can produce “clinically meaningful” results in transfusion-dependent adults with β-thalassemia, according to a speaker at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting.

In the phase 3 BELIEVE trial, β-thalassemia patients were significantly more likely to experience a reduction in transfusion burden if they were treated with luspatercept rather than placebo.

“Luspatercept showed a statistically significant and clinically meaningful . . . reduction in transfusion burden compared with placebo at any 12- or 24-week [period] along this study,” said Maria Domenica Cappellini, MD, of the University of Milan in Italy.

“At this point, we believe [luspatercept] is a potential new treatment for adult patients with β-thalassemia who are requiring regular blood transfusions.”

Dr. Cappellini presented these results at ASH as abstract 163.

The BELIEVE trial (NCT02604433) enrolled 336 patients from 65 sites in 15 countries. All patients had β-thalassemia or hemoglobin E/β‑thalassemia. They required regular transfusions of six to 20 red blood cell (RBC) units in the 24 weeks prior to randomization, and none had a transfusion-free period lasting 35 days or more.

The patients were randomized 2:1 to receive luspatercept—at a starting dose of 1.0 mg/kg with titration up to 1.25 mg/kg—(n=224) or placebo (n=112) subcutaneously every 3 weeks for at least 48 weeks.

All patients continued to receive RBC transfusions and iron chelation therapy as necessary (so they maintained the same baseline hemoglobin level).

The median age was 30 in both treatment arms (range, 18-66). More than half of patients were female—58.9% in the luspatercept arm and 56.3% in the placebo arm.

A similar percentage of patients in both arms had the β0, β0 genotype—30.4% in the luspatercept arm and 31.3% in the placebo arm.

The median hemoglobin level at baseline was 9.31 g/dL in the luspatercept arm and 9.15 g/dL in the placebo arm. The median RBC transfusion burden was 6.12 units/12 weeks and 6.27 units/12 weeks, respectively.

Other baseline characteristics were similar as well.

Efficacy

“[L]uspatercept showed a statistically significant improvement in the primary endpoint,” Dr. Cappellini noted.

The primary endpoint was at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden—of at least two RBC units—from week 13 to week 24, as compared to the 12-week baseline period.

This endpoint was achieved by 21.4% (n=48) of patients in the luspatercept arm and 4.5% (n=5) in the placebo arm (odds ratio=5.79; P<0.0001).

“Statistical significance was also demonstrated with luspatercept versus placebo for all the key secondary endpoints,” Dr. Cappellini said.

There were more patients in the luspatercept arm than the placebo arm who achieved at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden from week 37 to 48—19.6% and 3.6%, respectively (P<0.0001).

Similarly, there were more patients in the luspatercept arm than the placebo arm who achieved at least a 50% reduction in transfusion burden from week 13 to 24—7.6% and 1.8%, respectively (P=0.0303)—and from week 37 to 48—10.3% and 0.9%, respectively (P=0.0017).

During any 12-week interval, 70.5% of luspatercept-treated patients and 29.5% of placebo-treated patients achieved at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden (P<0.0001), and 40.2% and 6.3%, respectively (P<0.0001), achieved at least a 50% reduction in transfusion burden.

During any 24-week interval, 41.1% of luspatercept-treated patients and 2.7% of placebo-treated patients achieved at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden (P<0.0001), and 16.5% and 0.9%, respectively (P<0.0001), achieved at least a 50% reduction in transfusion burden.

Safety

Ninety-six percent of patients in the luspatercept arm and 92.7% in the placebo arm had at least one treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE).

Grade 3 or higher TEAEs occurred in 29.1% of patients in the luspatercept arm and 15.6% of those in the placebo arm. Serious TEAEs occurred in 15.2% and 5.5%, respectively.

One patient in the placebo arm had a TEAE-related death (acute cholecystitis), but there were no treatment-related deaths in the luspatercept arm.

TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 5.4% of luspatercept-treated patients and 0.9% of placebo-treated patients.

TEAEs that occurred more frequently in the luspatercept arm than in the placebo arm (respectively) included bone pain (19.7% and 8.3%), arthralgia (19.3% and 11.9%), and dizziness (11.2% and 4.6%).

Grade 3/4 TEAEs (in the luspatercept and placebo arms, respectively) included anemia (3.1% and 0%), increased liver iron concentration (2.7% and 0.9%), hyperuricemia (2.7% and 0%), hypertension (1.8% and 0%), syncope (1.8% and 0%), back pain (1.3% and 0.9%), bone pain (1.3% and 0%), blood uric acid increase (1.3% and 0%), increased aspartate aminotransferase (1.3% and 0%), increased alanine aminotransferase (0.9% and 2.8%), and thromboembolic events (0.9% and 0%).

Dr. Cappellini noted that thromboembolic events occurred in eight luspatercept-treated patients and one placebo-treated patient. In all cases, the patients had multiple risk factors for thrombosis.

This study was sponsored by Celgene Corporation and Acceleron Pharma. Dr. Cappellini reported relationships with Novartis, Celgene, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Vifor.

SAN DIEGO—Luspatercept can produce “clinically meaningful” results in transfusion-dependent adults with β-thalassemia, according to a speaker at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting.

In the phase 3 BELIEVE trial, β-thalassemia patients were significantly more likely to experience a reduction in transfusion burden if they were treated with luspatercept rather than placebo.

“Luspatercept showed a statistically significant and clinically meaningful . . . reduction in transfusion burden compared with placebo at any 12- or 24-week [period] along this study,” said Maria Domenica Cappellini, MD, of the University of Milan in Italy.

“At this point, we believe [luspatercept] is a potential new treatment for adult patients with β-thalassemia who are requiring regular blood transfusions.”

Dr. Cappellini presented these results at ASH as abstract 163.

The BELIEVE trial (NCT02604433) enrolled 336 patients from 65 sites in 15 countries. All patients had β-thalassemia or hemoglobin E/β‑thalassemia. They required regular transfusions of six to 20 red blood cell (RBC) units in the 24 weeks prior to randomization, and none had a transfusion-free period lasting 35 days or more.

The patients were randomized 2:1 to receive luspatercept—at a starting dose of 1.0 mg/kg with titration up to 1.25 mg/kg—(n=224) or placebo (n=112) subcutaneously every 3 weeks for at least 48 weeks.

All patients continued to receive RBC transfusions and iron chelation therapy as necessary (so they maintained the same baseline hemoglobin level).

The median age was 30 in both treatment arms (range, 18-66). More than half of patients were female—58.9% in the luspatercept arm and 56.3% in the placebo arm.

A similar percentage of patients in both arms had the β0, β0 genotype—30.4% in the luspatercept arm and 31.3% in the placebo arm.

The median hemoglobin level at baseline was 9.31 g/dL in the luspatercept arm and 9.15 g/dL in the placebo arm. The median RBC transfusion burden was 6.12 units/12 weeks and 6.27 units/12 weeks, respectively.

Other baseline characteristics were similar as well.

Efficacy

“[L]uspatercept showed a statistically significant improvement in the primary endpoint,” Dr. Cappellini noted.

The primary endpoint was at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden—of at least two RBC units—from week 13 to week 24, as compared to the 12-week baseline period.

This endpoint was achieved by 21.4% (n=48) of patients in the luspatercept arm and 4.5% (n=5) in the placebo arm (odds ratio=5.79; P<0.0001).

“Statistical significance was also demonstrated with luspatercept versus placebo for all the key secondary endpoints,” Dr. Cappellini said.

There were more patients in the luspatercept arm than the placebo arm who achieved at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden from week 37 to 48—19.6% and 3.6%, respectively (P<0.0001).

Similarly, there were more patients in the luspatercept arm than the placebo arm who achieved at least a 50% reduction in transfusion burden from week 13 to 24—7.6% and 1.8%, respectively (P=0.0303)—and from week 37 to 48—10.3% and 0.9%, respectively (P=0.0017).

During any 12-week interval, 70.5% of luspatercept-treated patients and 29.5% of placebo-treated patients achieved at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden (P<0.0001), and 40.2% and 6.3%, respectively (P<0.0001), achieved at least a 50% reduction in transfusion burden.

During any 24-week interval, 41.1% of luspatercept-treated patients and 2.7% of placebo-treated patients achieved at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden (P<0.0001), and 16.5% and 0.9%, respectively (P<0.0001), achieved at least a 50% reduction in transfusion burden.

Safety

Ninety-six percent of patients in the luspatercept arm and 92.7% in the placebo arm had at least one treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE).

Grade 3 or higher TEAEs occurred in 29.1% of patients in the luspatercept arm and 15.6% of those in the placebo arm. Serious TEAEs occurred in 15.2% and 5.5%, respectively.

One patient in the placebo arm had a TEAE-related death (acute cholecystitis), but there were no treatment-related deaths in the luspatercept arm.

TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 5.4% of luspatercept-treated patients and 0.9% of placebo-treated patients.

TEAEs that occurred more frequently in the luspatercept arm than in the placebo arm (respectively) included bone pain (19.7% and 8.3%), arthralgia (19.3% and 11.9%), and dizziness (11.2% and 4.6%).

Grade 3/4 TEAEs (in the luspatercept and placebo arms, respectively) included anemia (3.1% and 0%), increased liver iron concentration (2.7% and 0.9%), hyperuricemia (2.7% and 0%), hypertension (1.8% and 0%), syncope (1.8% and 0%), back pain (1.3% and 0.9%), bone pain (1.3% and 0%), blood uric acid increase (1.3% and 0%), increased aspartate aminotransferase (1.3% and 0%), increased alanine aminotransferase (0.9% and 2.8%), and thromboembolic events (0.9% and 0%).

Dr. Cappellini noted that thromboembolic events occurred in eight luspatercept-treated patients and one placebo-treated patient. In all cases, the patients had multiple risk factors for thrombosis.

This study was sponsored by Celgene Corporation and Acceleron Pharma. Dr. Cappellini reported relationships with Novartis, Celgene, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Vifor.

SAN DIEGO—Luspatercept can produce “clinically meaningful” results in transfusion-dependent adults with β-thalassemia, according to a speaker at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting.

In the phase 3 BELIEVE trial, β-thalassemia patients were significantly more likely to experience a reduction in transfusion burden if they were treated with luspatercept rather than placebo.

“Luspatercept showed a statistically significant and clinically meaningful . . . reduction in transfusion burden compared with placebo at any 12- or 24-week [period] along this study,” said Maria Domenica Cappellini, MD, of the University of Milan in Italy.

“At this point, we believe [luspatercept] is a potential new treatment for adult patients with β-thalassemia who are requiring regular blood transfusions.”

Dr. Cappellini presented these results at ASH as abstract 163.

The BELIEVE trial (NCT02604433) enrolled 336 patients from 65 sites in 15 countries. All patients had β-thalassemia or hemoglobin E/β‑thalassemia. They required regular transfusions of six to 20 red blood cell (RBC) units in the 24 weeks prior to randomization, and none had a transfusion-free period lasting 35 days or more.

The patients were randomized 2:1 to receive luspatercept—at a starting dose of 1.0 mg/kg with titration up to 1.25 mg/kg—(n=224) or placebo (n=112) subcutaneously every 3 weeks for at least 48 weeks.

All patients continued to receive RBC transfusions and iron chelation therapy as necessary (so they maintained the same baseline hemoglobin level).

The median age was 30 in both treatment arms (range, 18-66). More than half of patients were female—58.9% in the luspatercept arm and 56.3% in the placebo arm.

A similar percentage of patients in both arms had the β0, β0 genotype—30.4% in the luspatercept arm and 31.3% in the placebo arm.

The median hemoglobin level at baseline was 9.31 g/dL in the luspatercept arm and 9.15 g/dL in the placebo arm. The median RBC transfusion burden was 6.12 units/12 weeks and 6.27 units/12 weeks, respectively.

Other baseline characteristics were similar as well.

Efficacy

“[L]uspatercept showed a statistically significant improvement in the primary endpoint,” Dr. Cappellini noted.

The primary endpoint was at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden—of at least two RBC units—from week 13 to week 24, as compared to the 12-week baseline period.

This endpoint was achieved by 21.4% (n=48) of patients in the luspatercept arm and 4.5% (n=5) in the placebo arm (odds ratio=5.79; P<0.0001).

“Statistical significance was also demonstrated with luspatercept versus placebo for all the key secondary endpoints,” Dr. Cappellini said.

There were more patients in the luspatercept arm than the placebo arm who achieved at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden from week 37 to 48—19.6% and 3.6%, respectively (P<0.0001).

Similarly, there were more patients in the luspatercept arm than the placebo arm who achieved at least a 50% reduction in transfusion burden from week 13 to 24—7.6% and 1.8%, respectively (P=0.0303)—and from week 37 to 48—10.3% and 0.9%, respectively (P=0.0017).

During any 12-week interval, 70.5% of luspatercept-treated patients and 29.5% of placebo-treated patients achieved at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden (P<0.0001), and 40.2% and 6.3%, respectively (P<0.0001), achieved at least a 50% reduction in transfusion burden.

During any 24-week interval, 41.1% of luspatercept-treated patients and 2.7% of placebo-treated patients achieved at least a 33% reduction in transfusion burden (P<0.0001), and 16.5% and 0.9%, respectively (P<0.0001), achieved at least a 50% reduction in transfusion burden.

Safety

Ninety-six percent of patients in the luspatercept arm and 92.7% in the placebo arm had at least one treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE).

Grade 3 or higher TEAEs occurred in 29.1% of patients in the luspatercept arm and 15.6% of those in the placebo arm. Serious TEAEs occurred in 15.2% and 5.5%, respectively.

One patient in the placebo arm had a TEAE-related death (acute cholecystitis), but there were no treatment-related deaths in the luspatercept arm.

TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 5.4% of luspatercept-treated patients and 0.9% of placebo-treated patients.

TEAEs that occurred more frequently in the luspatercept arm than in the placebo arm (respectively) included bone pain (19.7% and 8.3%), arthralgia (19.3% and 11.9%), and dizziness (11.2% and 4.6%).

Grade 3/4 TEAEs (in the luspatercept and placebo arms, respectively) included anemia (3.1% and 0%), increased liver iron concentration (2.7% and 0.9%), hyperuricemia (2.7% and 0%), hypertension (1.8% and 0%), syncope (1.8% and 0%), back pain (1.3% and 0.9%), bone pain (1.3% and 0%), blood uric acid increase (1.3% and 0%), increased aspartate aminotransferase (1.3% and 0%), increased alanine aminotransferase (0.9% and 2.8%), and thromboembolic events (0.9% and 0%).

Dr. Cappellini noted that thromboembolic events occurred in eight luspatercept-treated patients and one placebo-treated patient. In all cases, the patients had multiple risk factors for thrombosis.

This study was sponsored by Celgene Corporation and Acceleron Pharma. Dr. Cappellini reported relationships with Novartis, Celgene, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Vifor.

CHMP backs dasatinib for kids with newly diagnosed ALL

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the marketing authorization for dasatinib (Sprycel).

The CHMP’s recommendation is to approve dasatinib in combination with chemotherapy to treat pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The CHMP’s recommendation will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC), which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The EC usually makes a decision within 67 days of a CHMP recommendation.

Dasatinib is already EC-approved to treat:

- Adults with newly diagnosed, Ph+ chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in the chronic phase

- Adults with chronic, accelerated, or blast phase CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy including imatinib

- Adults with Ph+ ALL and lymphoid blast CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy

- Pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Ph+ CML in chronic phase

- Pediatric patients with Ph+ CML in chronic phase that is resistant or intolerant to prior therapy including imatinib.

Phase 2 trial

The CHMP’s recommendation to approve dasatinib in pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Ph+ ALL is based on data from a phase 2 trial (NCT01460160). In this trial, researchers are evaluating dasatinib in combination with a chemotherapy regimen modeled on a Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster high-risk backbone.

Results from the trial were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

At that time, 106 patients had been treated. They received continuous daily dasatinib (60 mg/m2) beginning at day 15 of induction chemotherapy. All treated patients achieved complete remission.

Patients who had evidence of minimal residual disease (MRD) ≥ 0.05% at the end of the first block of treatment (day 78) and those with MRD 0.005% to 0.05% who remained MRD-positive at any detectable level after three additional high-risk chemotherapy blocks were eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in first remission.

Nineteen patients met these criteria, and 15 (14.2%) received HSCT. The remaining 85.8% of patients received dasatinib plus chemotherapy for two years.

The 3-year event-free survival rate was 65.5%, and the 3-year overall survival rate was 91.5%.

Two patients discontinued dasatinib due to toxicity—one due to allergy and one due to prolonged thrombocytopenia.

Grade 3/4 adverse events attributed to dasatinib included elevated alanine aminotransferase (21.7%), elevated aspartate transaminase (10.4%), pleural effusion (3.8%), edema (2.8%), hemorrhage (5.7%), and cardiac failure (0.8%).

Five patients died while receiving chemotherapy (three from sepsis, one due to pneumonia, and one of an unknown cause). Two deaths were HSCT-related.

This trial was sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the marketing authorization for dasatinib (Sprycel).

The CHMP’s recommendation is to approve dasatinib in combination with chemotherapy to treat pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The CHMP’s recommendation will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC), which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The EC usually makes a decision within 67 days of a CHMP recommendation.

Dasatinib is already EC-approved to treat:

- Adults with newly diagnosed, Ph+ chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in the chronic phase

- Adults with chronic, accelerated, or blast phase CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy including imatinib

- Adults with Ph+ ALL and lymphoid blast CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy

- Pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Ph+ CML in chronic phase

- Pediatric patients with Ph+ CML in chronic phase that is resistant or intolerant to prior therapy including imatinib.

Phase 2 trial

The CHMP’s recommendation to approve dasatinib in pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Ph+ ALL is based on data from a phase 2 trial (NCT01460160). In this trial, researchers are evaluating dasatinib in combination with a chemotherapy regimen modeled on a Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster high-risk backbone.

Results from the trial were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

At that time, 106 patients had been treated. They received continuous daily dasatinib (60 mg/m2) beginning at day 15 of induction chemotherapy. All treated patients achieved complete remission.

Patients who had evidence of minimal residual disease (MRD) ≥ 0.05% at the end of the first block of treatment (day 78) and those with MRD 0.005% to 0.05% who remained MRD-positive at any detectable level after three additional high-risk chemotherapy blocks were eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in first remission.

Nineteen patients met these criteria, and 15 (14.2%) received HSCT. The remaining 85.8% of patients received dasatinib plus chemotherapy for two years.

The 3-year event-free survival rate was 65.5%, and the 3-year overall survival rate was 91.5%.

Two patients discontinued dasatinib due to toxicity—one due to allergy and one due to prolonged thrombocytopenia.

Grade 3/4 adverse events attributed to dasatinib included elevated alanine aminotransferase (21.7%), elevated aspartate transaminase (10.4%), pleural effusion (3.8%), edema (2.8%), hemorrhage (5.7%), and cardiac failure (0.8%).

Five patients died while receiving chemotherapy (three from sepsis, one due to pneumonia, and one of an unknown cause). Two deaths were HSCT-related.

This trial was sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended expanding the marketing authorization for dasatinib (Sprycel).

The CHMP’s recommendation is to approve dasatinib in combination with chemotherapy to treat pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The CHMP’s recommendation will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC), which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

The EC usually makes a decision within 67 days of a CHMP recommendation.

Dasatinib is already EC-approved to treat:

- Adults with newly diagnosed, Ph+ chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in the chronic phase

- Adults with chronic, accelerated, or blast phase CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy including imatinib

- Adults with Ph+ ALL and lymphoid blast CML with resistance or intolerance to prior therapy

- Pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Ph+ CML in chronic phase

- Pediatric patients with Ph+ CML in chronic phase that is resistant or intolerant to prior therapy including imatinib.

Phase 2 trial

The CHMP’s recommendation to approve dasatinib in pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Ph+ ALL is based on data from a phase 2 trial (NCT01460160). In this trial, researchers are evaluating dasatinib in combination with a chemotherapy regimen modeled on a Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster high-risk backbone.

Results from the trial were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

At that time, 106 patients had been treated. They received continuous daily dasatinib (60 mg/m2) beginning at day 15 of induction chemotherapy. All treated patients achieved complete remission.

Patients who had evidence of minimal residual disease (MRD) ≥ 0.05% at the end of the first block of treatment (day 78) and those with MRD 0.005% to 0.05% who remained MRD-positive at any detectable level after three additional high-risk chemotherapy blocks were eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in first remission.

Nineteen patients met these criteria, and 15 (14.2%) received HSCT. The remaining 85.8% of patients received dasatinib plus chemotherapy for two years.

The 3-year event-free survival rate was 65.5%, and the 3-year overall survival rate was 91.5%.

Two patients discontinued dasatinib due to toxicity—one due to allergy and one due to prolonged thrombocytopenia.

Grade 3/4 adverse events attributed to dasatinib included elevated alanine aminotransferase (21.7%), elevated aspartate transaminase (10.4%), pleural effusion (3.8%), edema (2.8%), hemorrhage (5.7%), and cardiac failure (0.8%).

Five patients died while receiving chemotherapy (three from sepsis, one due to pneumonia, and one of an unknown cause). Two deaths were HSCT-related.

This trial was sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Food allergies linked to increased MS relapses, lesions

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) and food allergies had more relapses and gadolinium-enhancing lesions than patients with MS but no food allergies, according to a recent analysis of a longitudinal study.

Patients with food allergies had a 1.3-times higher rate for cumulative number of attacks and a 2.5-times higher likelihood of enhancing lesions on brain MRI in the analysis of patients enrolled in the Comprehensive Longitudinal Investigation of Multiple Sclerosis at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (CLIMB).

By contrast, there were no significant differences in relapse or lesion rates for patients with environmental or drug allergies when compared with those without allergies, reported Tanuja Chitnis, MD, of Partners Multiple Sclerosis Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her coinvestigators.

“Our findings suggest that MS patients with allergies have more active disease than those without allergies, and that this effect is driven by food allergies,” Dr. Tanuja and her coauthors wrote in their report, which appeared in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

Previous investigations have looked at whether allergy history increases risk of developing MS, with conflicting results, they added, noting a meta-analysis of 10 observational studies suggesting no such link.

By contrast, whether allergies lead to more or less intense MS activity has not been addressed, according to investigators, who said this is the first study tying allergy history to MS disease course using clinical and MRI variables.

Their study was based on a subset of 1,349 patients with a diagnosis of MS who were enrolled in CLIMB and completed a self-administered questionnaire on food, environmental, and drug allergies. Of those patients, 922 reported allergies, while 427 reported no known allergies.

Patients with food allergies had a significantly increased rate of cumulative number of attacks, compared with those with no allergies, according to investigators, even after adjusting the analysis for gender, age at symptom onset, disease category, and time on treatment (relapse rate ratio, 1.274; 95% confidence interval, 1.023-1.587; P = .0305).

Food allergy patients were more than twice as likely as no-allergy patients were to have gadolinium-enhancing lesions on brain MRI after adjusting for other covariates (odds ratio, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.25-5.11; P = .0096), they added.

Patients with environmental and drug allergies also appeared to have more relapses, compared with patients with no allergies, in univariate analysis, but the differences were not significant in the adjusted analysis, investigators said. Likewise, there were trends toward a link between number of lesions and presence of environmental or drug allergies that did not hold up on multivariate analysis.

It is unknown what underlying biological mechanisms might potentially link food allergies to MS disease severity; however, findings of experimental studies support the hypothesis that gut microbiota might affect the risk and course of MS, Dr. Chitnis and her coauthors wrote in their report.

The CLIMB study was supported by Merck Serono and the National MS Society Nancy Davis Center Without Walls. Dr. Chitnis reported consulting fees from Biogen Idec, Novartis, Sanofi, Bayer, and Celgene outside the submitted work. Coauthors provided additional disclosures related to Merck Serono, Genentech, Verily Life Sciences, EMD Serono, Biogen, Teva, Sanofi, and Novartis, among others.

SOURCE: Fakih R et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 18. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-319301.

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) and food allergies had more relapses and gadolinium-enhancing lesions than patients with MS but no food allergies, according to a recent analysis of a longitudinal study.

Patients with food allergies had a 1.3-times higher rate for cumulative number of attacks and a 2.5-times higher likelihood of enhancing lesions on brain MRI in the analysis of patients enrolled in the Comprehensive Longitudinal Investigation of Multiple Sclerosis at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (CLIMB).

By contrast, there were no significant differences in relapse or lesion rates for patients with environmental or drug allergies when compared with those without allergies, reported Tanuja Chitnis, MD, of Partners Multiple Sclerosis Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her coinvestigators.

“Our findings suggest that MS patients with allergies have more active disease than those without allergies, and that this effect is driven by food allergies,” Dr. Tanuja and her coauthors wrote in their report, which appeared in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

Previous investigations have looked at whether allergy history increases risk of developing MS, with conflicting results, they added, noting a meta-analysis of 10 observational studies suggesting no such link.

By contrast, whether allergies lead to more or less intense MS activity has not been addressed, according to investigators, who said this is the first study tying allergy history to MS disease course using clinical and MRI variables.

Their study was based on a subset of 1,349 patients with a diagnosis of MS who were enrolled in CLIMB and completed a self-administered questionnaire on food, environmental, and drug allergies. Of those patients, 922 reported allergies, while 427 reported no known allergies.

Patients with food allergies had a significantly increased rate of cumulative number of attacks, compared with those with no allergies, according to investigators, even after adjusting the analysis for gender, age at symptom onset, disease category, and time on treatment (relapse rate ratio, 1.274; 95% confidence interval, 1.023-1.587; P = .0305).

Food allergy patients were more than twice as likely as no-allergy patients were to have gadolinium-enhancing lesions on brain MRI after adjusting for other covariates (odds ratio, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.25-5.11; P = .0096), they added.

Patients with environmental and drug allergies also appeared to have more relapses, compared with patients with no allergies, in univariate analysis, but the differences were not significant in the adjusted analysis, investigators said. Likewise, there were trends toward a link between number of lesions and presence of environmental or drug allergies that did not hold up on multivariate analysis.

It is unknown what underlying biological mechanisms might potentially link food allergies to MS disease severity; however, findings of experimental studies support the hypothesis that gut microbiota might affect the risk and course of MS, Dr. Chitnis and her coauthors wrote in their report.

The CLIMB study was supported by Merck Serono and the National MS Society Nancy Davis Center Without Walls. Dr. Chitnis reported consulting fees from Biogen Idec, Novartis, Sanofi, Bayer, and Celgene outside the submitted work. Coauthors provided additional disclosures related to Merck Serono, Genentech, Verily Life Sciences, EMD Serono, Biogen, Teva, Sanofi, and Novartis, among others.

SOURCE: Fakih R et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 18. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-319301.

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) and food allergies had more relapses and gadolinium-enhancing lesions than patients with MS but no food allergies, according to a recent analysis of a longitudinal study.

Patients with food allergies had a 1.3-times higher rate for cumulative number of attacks and a 2.5-times higher likelihood of enhancing lesions on brain MRI in the analysis of patients enrolled in the Comprehensive Longitudinal Investigation of Multiple Sclerosis at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (CLIMB).

By contrast, there were no significant differences in relapse or lesion rates for patients with environmental or drug allergies when compared with those without allergies, reported Tanuja Chitnis, MD, of Partners Multiple Sclerosis Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her coinvestigators.

“Our findings suggest that MS patients with allergies have more active disease than those without allergies, and that this effect is driven by food allergies,” Dr. Tanuja and her coauthors wrote in their report, which appeared in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

Previous investigations have looked at whether allergy history increases risk of developing MS, with conflicting results, they added, noting a meta-analysis of 10 observational studies suggesting no such link.

By contrast, whether allergies lead to more or less intense MS activity has not been addressed, according to investigators, who said this is the first study tying allergy history to MS disease course using clinical and MRI variables.

Their study was based on a subset of 1,349 patients with a diagnosis of MS who were enrolled in CLIMB and completed a self-administered questionnaire on food, environmental, and drug allergies. Of those patients, 922 reported allergies, while 427 reported no known allergies.

Patients with food allergies had a significantly increased rate of cumulative number of attacks, compared with those with no allergies, according to investigators, even after adjusting the analysis for gender, age at symptom onset, disease category, and time on treatment (relapse rate ratio, 1.274; 95% confidence interval, 1.023-1.587; P = .0305).

Food allergy patients were more than twice as likely as no-allergy patients were to have gadolinium-enhancing lesions on brain MRI after adjusting for other covariates (odds ratio, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.25-5.11; P = .0096), they added.

Patients with environmental and drug allergies also appeared to have more relapses, compared with patients with no allergies, in univariate analysis, but the differences were not significant in the adjusted analysis, investigators said. Likewise, there were trends toward a link between number of lesions and presence of environmental or drug allergies that did not hold up on multivariate analysis.

It is unknown what underlying biological mechanisms might potentially link food allergies to MS disease severity; however, findings of experimental studies support the hypothesis that gut microbiota might affect the risk and course of MS, Dr. Chitnis and her coauthors wrote in their report.

The CLIMB study was supported by Merck Serono and the National MS Society Nancy Davis Center Without Walls. Dr. Chitnis reported consulting fees from Biogen Idec, Novartis, Sanofi, Bayer, and Celgene outside the submitted work. Coauthors provided additional disclosures related to Merck Serono, Genentech, Verily Life Sciences, EMD Serono, Biogen, Teva, Sanofi, and Novartis, among others.

SOURCE: Fakih R et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 18. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-319301.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY, NEUROSURGERY, AND PSYCHIATRY

Clinical trial: The Sinai Robotic Surgery Trial in HPV Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The Sinai Robotic Surgery Trial in HPV Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma trial is an interventional study recruiting patients with human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive oropharyngeal cancer.

Patients who are recruited will undergo robotic surgery after being screened for poor prognosis. Patients with good prognosis will be followed without receiving postoperative radiation. Those in this group who experience a recurrence will receive either more surgery and postoperative radiotherapy or postoperative chemoradiotherapy alone. Patients with poor prognosis will receive reduced-dose radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy based on pathology.

Few trials have examined deescalation using surgery alone in intermediate- and early-stage HPV-positive cancer, the investigators noted, adding that they expect more than half of participants will undergo curative treatment with surgery alone and that withholding radiation in these patients will not noticeably affect their long-term survival.

Patients are eligible for the study if they have early- or intermediate-stage, resectable, HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. Patients must be at aged at least 18 years; cannot be pregnant; cannot have active alcohol addiction or tobacco usage; must have adequate bone marrow, hepatic, and renal functions; have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1; have a limiting serious illness; and have had previous surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma other than biopsy or tonsillectomy.

The primary outcome measures of the study are disease-free survival and local regional control after 3 and 5 years. Secondary outcome measures include overall survival, toxicity rates, quality of life outcomes after 3 and 5 years, and local regional control after 5 years.

Recruitment for the study ends in March 2019. About 200 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information on the study page at Clinicaltrials.gov.

The Sinai Robotic Surgery Trial in HPV Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma trial is an interventional study recruiting patients with human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive oropharyngeal cancer.

Patients who are recruited will undergo robotic surgery after being screened for poor prognosis. Patients with good prognosis will be followed without receiving postoperative radiation. Those in this group who experience a recurrence will receive either more surgery and postoperative radiotherapy or postoperative chemoradiotherapy alone. Patients with poor prognosis will receive reduced-dose radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy based on pathology.

Few trials have examined deescalation using surgery alone in intermediate- and early-stage HPV-positive cancer, the investigators noted, adding that they expect more than half of participants will undergo curative treatment with surgery alone and that withholding radiation in these patients will not noticeably affect their long-term survival.

Patients are eligible for the study if they have early- or intermediate-stage, resectable, HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. Patients must be at aged at least 18 years; cannot be pregnant; cannot have active alcohol addiction or tobacco usage; must have adequate bone marrow, hepatic, and renal functions; have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1; have a limiting serious illness; and have had previous surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma other than biopsy or tonsillectomy.

The primary outcome measures of the study are disease-free survival and local regional control after 3 and 5 years. Secondary outcome measures include overall survival, toxicity rates, quality of life outcomes after 3 and 5 years, and local regional control after 5 years.

Recruitment for the study ends in March 2019. About 200 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information on the study page at Clinicaltrials.gov.

The Sinai Robotic Surgery Trial in HPV Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma trial is an interventional study recruiting patients with human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive oropharyngeal cancer.

Patients who are recruited will undergo robotic surgery after being screened for poor prognosis. Patients with good prognosis will be followed without receiving postoperative radiation. Those in this group who experience a recurrence will receive either more surgery and postoperative radiotherapy or postoperative chemoradiotherapy alone. Patients with poor prognosis will receive reduced-dose radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy based on pathology.

Few trials have examined deescalation using surgery alone in intermediate- and early-stage HPV-positive cancer, the investigators noted, adding that they expect more than half of participants will undergo curative treatment with surgery alone and that withholding radiation in these patients will not noticeably affect their long-term survival.

Patients are eligible for the study if they have early- or intermediate-stage, resectable, HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. Patients must be at aged at least 18 years; cannot be pregnant; cannot have active alcohol addiction or tobacco usage; must have adequate bone marrow, hepatic, and renal functions; have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1; have a limiting serious illness; and have had previous surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma other than biopsy or tonsillectomy.

The primary outcome measures of the study are disease-free survival and local regional control after 3 and 5 years. Secondary outcome measures include overall survival, toxicity rates, quality of life outcomes after 3 and 5 years, and local regional control after 5 years.

Recruitment for the study ends in March 2019. About 200 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information on the study page at Clinicaltrials.gov.

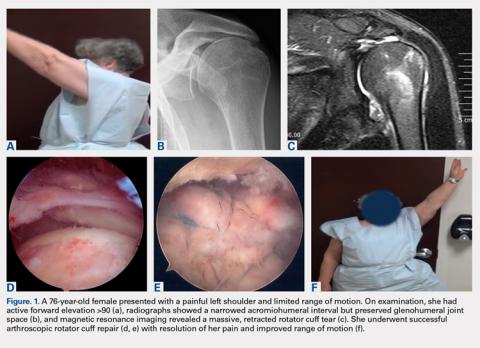

Massive Rotator Cuff Tears in Patients Older Than Sixty-five: Indications for Cuff Repair versus Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

ABSTRACT

The decision to perform rotator cuff repair (RCR) versus reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) for massive rotator cuff tear (MCT) without arthritis can be difficult. Our aim was to identify preoperative variables that are influential in a surgeon's decision to choose one of the two procedures and evaluate outcomes.

We retrospectively reviewed 181 patients older than 65 who underwent RCR or rTSA for MCT without arthritis. Clinical and radiographic data were collected and used to evaluate the preoperative variables in each of these two patient populations and assess outcomes.

Ninety-five shoulders underwent RCR and 92 underwent rTSA with an average followup of 44 and 47 months, respectively. Patients selected for RCR had greater preoperative flexion (113 vs 57), abduction (97 vs 53), and external rotation (42 vs 32), higher SST (3.1 vs 1.9) and ASES scores (43.8 vs 38.6), and were less likely to have had previous cuff surgery (6.3% vs 35.9%). Patients selected for rTSA had a smaller acromiohumeral interval (4.8 vs 8.7) and more superior subluxation (50.6% vs 14.1%). Similar preoperative characteristics included pain, comorbidities, and BMI. Patients were satisfied in both groups and had significant improvement in motion and function postoperatively.

Both RCR and rTSA can result in significant functional improvement and patient satisfaction in the setting of MCT without arthritis in patients older than 65. At our institution, patients who underwent rTSA had less pre-operative motion, lower function, more evidence of superior migration, and were more likely to have had previous rotator cuff surgery.

Continue to: The treatment of patients...

The treatment of patients with massive rotator cuff tears (MCTs) without osteoarthritis is challenging. This population is of considerable interest, as the prevalence of MCT has been reported to be as high as 40% of all rotator cuff tears.1Options for surgical treatment in patients who have failed conservative management are numerous and include tendon debridement, partial or complete arthroscopic or open rotator cuff repair (RCR), tendon transfers, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA), arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction (ASCR), and other grafting procedures.2 Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction shows promise as a novel technique, but it is not yet well studied. Other procedures such as tendon transfers fit into the treatment algorithm for only a small subset of patients. Open rotator cuff repair and rTSA are the 2 most commonly utilized procedures for MCT, and both have been shown to reliably achieve significant functional improvement and patient satisfaction.3–6

The dilemma for the treating surgeon is deciding which patients to treat with RCR and who to treat with rTSA. Predicting which surgical procedure will provide a better functional result is difficult and controversial.7 The RCR method is a bone-conserving procedure with relatively low surgical risk and allows the option for rTSA to be performed as a salvage surgery should repair fail. It also may be less costly in the appropriate population.8 However, large rotator cuff tears in elderly patients have low healing potential, and the prospect of participating in a lengthy rehabilitation after an operation that may not prove successful can be deterring.9,10 In the elderly population, rTSA may be a reliable option, as tendon healing of the cuff is not necessary to restore function. However, rTSA does not conserve bone, provides a non-anatomic solution, and has had historically high complication rates.4,5

In an effort to aid in the decision-making process when considering these 2 surgical options, we compared RCR and rTSA performed at a single institution for MCT in patients >65 years. Our aim was to identify preoperative patient variables that influence a surgeon’s decision to proceed with 1 of the 2 procedures. Moreover, we evaluated clinical outcomes in these 2 patient populations. We hypothesized that (1) patients selected for rTSA would have worse preoperative function, less range of motion, more comorbidities, more evidence of radiographic subluxation, and a higher likelihood of having undergone previous RCR than those selected for RCR, and (2) both RCR and rTSA would be successful and result in improved clinical outcomes with high patient satisfaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PATIENT SELECTION

We performed a retrospective chart review using our practice database of all patients undergoing arthroscopic RCR and rTSA for any indication by the senior author (M.A.F.) between January 2004 and April 2015. A total of 1503 RCRs and 1973 rTSAs were conducted during the study period. Patient medical records were reviewed, and those meeting the following criteria were included in the study: >65 years at the time of surgery, MCT, no preoperative glenohumeral arthritis, minimum follow-up of 12 months, functional deltoid muscle on physical examination, and no prior shoulder surgery except for RCR or diagnostic arthroscopy. A total of 92 patients who underwent arthroscopic RCR and 89 patients who underwent rTSA met the inclusion criteria. For patients with bilateral shoulder surgery, we measured each shoulder independently. Three patients underwent bilateral rTSA, and 3 patients underwent bilateral RCR, leaving 95 shoulders in the RCR group and 92 in the rTSA group. The Western Institutional Review Board determined this study to be exempt from review.

RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION

All patient charts included a radiology report and documented interpretation of the images by the treating surgeon prior to surgery. Radiographs were assessed to assure the absence of preoperative glenohumeral osteoarthritis. The images were also graded based on the Hamada classification.11 Stage 1 is associated with minimal radiographic change with an acromiohumeral interval (AHI) >6 mm; stage 2 is characterized by narrowing of the AHI <6 mm; and Stage 3 is defined by narrowing of the AHI with radiographic changes of the acromion. Stages 4 and higher include arthritic changes to the glenohumeral joint, and they were not included in the study population. The AHI measurements and the presence or absence of glenohumeral subluxation were documented.

Continue to: MASSIVE CUFF TEAR DETERMINATION...

MASSIVE CUFF TEAR DETERMINATION

We defined MCT on the basis of previously described criteria of tears involving ≥2 tendons or tears measuring ≥5 cm in greatest dimension.12,13 Patient charts were screened, and those whose clinical notes or radiology reports indicated an absence of MCT were excluded. Preoperative imaging of the remaining patients was then evaluated by 3 fellowship-trained shoulder surgeons to confirm MCT in all patients with a clinically documented MCT, as well as to assess those who had insufficient documentation of tear size in the notes.

Advanced imaging was evaluated for fatty atrophy of the rotator cuff musculature, and Goutallier classification was assigned.14,15 Length of retraction was measured from the tendon end to the medial aspect of the footprint on coronal imaging, and the subscapularis and teres minor were assessed and documented as torn or intact.16,17

DATA COLLECTION

We reviewed clinical charts and patient questionnaire forms from both the preoperative and follow-up visits. Clinical data collected included gender, age at surgery, active range of motion (forward elevation, abduction, external rotation, and internal rotation), comorbidities, smoking status, BMI, history of shoulder surgery, and any postoperative complications or need for secondary surgery. All patients completed patient-centered questionnaires regarding shoulder pain and dysfunction at each visit or via telephone communication with clinic staff. Outcome measurements used for analysis included American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Score, simple shoulder test (SST), visual analog score (VAS) pain scale, and patient-reported satisfaction (Graded 1-10; 1 = poor outcome; 4 = satisfactory outcome; 7 = good outcome; 10 = excellent outcome).

DATA ANALYSIS AND STATISTICAL METHODS

Statistical tests were selected based on the result of Shapiro–Wilk test for normality. Continuous variables were evaluated with either independent t test or Mann–Whitney U test. Dependent t test was used to evaluate outcome variables. For categorical variables, either Pearson’s χ2or Fisher’s exact test was performed depending on the sample size. Alpha was set at P =.05.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

PREOPERATIVE CHARACTERISTICS

Of the 187 shoulders in the study group, 95 had RCR and 92 had rTSA. Demographic information and preoperative variables for both groups are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2. Patients in the RCR group had greater preoperative forward elevation, abduction, and external rotation and higher preoperative functional scores than those in the rTSA group. Patients in the rTSA group were older and more likely to be female than those in the RCR group. More patients in the rTSA group had undergone prior RCR compared with those in the RCR group. Each of these differences was statistically significant. Subjective pain scores, BMI, and comorbidities were similar between the 2 groups.

Table 1. Patient demographics

| RCR | rTSA | P value |

Age (yr; mean ± SD) | 71 ± 5 | 74 ± 6 | <.0001 |

Gender *male (no.; %) *female (no.; %) | 57 (60%) 38 (40%) | 30 (33%) 62 (67%) | <.0001 |

BMI (mean ± SD) | 28.5 ± 4.4 | 28.1 ± 4.5 | .578 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; RCR, rotator cuff repair; rTSA, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

Table 2. Preoperative variables

| RCR (n=95) | rTSA (n=92) | P value |

Radiographic parameters | |||

AB interval | 9 ± 3 | 5 ± 3 | <.0001 |

Humeral escape | 14.1% | 50.6% | <.0001 |

Hamada 1 | 76.1% | 15.6% | <.0001 |

Hamada 2 | 13.0% | 50.6% | |

Hamada 3 | 10.9% | 33.8% | |

Goutallier grade 1 | 7.8% | 19.3% | .227 |

Goutallier grade 2 | 66.7% | 52.6% | |

Goutallier grade 3 | 21.6% | 19.3% | |

Goutallier grade 4 | 3.9% | 8.8% | |

Clinical measures | |||

Preop FE | 113 ± 50 | 57 ± 34 | <.0001 |

Preop AB | 97 ± 45 | 53 ± 35 | <.0001 |

Preop ER | 42 ± 25 | 32 ± 28 | .029 |

Preop IR | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 1.8 | .247 |

Preop pain | 5.7 ± 2.3 | 5.6 ± 2.5 | .927 |

Preop ASES | 44 ± 17 | 39 ± 16 | .04 |

Preop SST | 3.1 ± 2.6 | 1.9 ± 1.7 | .001 |

Patients parameters | |||

Previous cuff surgery | 6.3% | 35.9% | <.0001 |

Comorbidity count | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 2.7 | .126 |

Abbreviations: AB, abduction; ASES, American Shoulder and Elbow Society score; ER, external rotation; FE, forward elevation; IR, internal rotation; preop, preoperative; SST, simple shoulder test.

Radiographically, patients selected to undergo rTSA had a smaller AHI (4.8 vs 8.7, P < .0001) and more evidence of superior subluxation (50.6% vs 14.1%, P < .0001) than those in the RCR group. Average Hamada grade was 1.4 ± 0.7 and 2.2 ± 0.7 for the RCR and rTSA groups, respectively (P < .0001). Average Goutallier grade was similar between the groups (2.2 ± 0.6 for RCR vs 2.2 ± 0.8 for rTSA, P =.227), and 25.5% of the RCR group had Grade 3 or 4 atrophy compared with 28.1% of the rTSA group.

POSTOPERATIVE OUTCOMES

The average follow-up time was 44 months for RCR and 47 months for rTSA. Patients in the RCR and rTSA groups were highly satisfied with the surgery (8.5 ± 2.6 vs 8.2 ± 2.6, P = .461) and had significantly increased range of motion in all planes and improved functional scores (Table 3). The rTSA group had greater net improvement in forward elevation, abduction, and external rotation than the RCR group. Both groups demonstrated similar improvement in ASES, SST, and VAS pain scores.

Table 3. Postoperative outcomes

| RCR (n=95) | P value | rTSA (n=92) | P value | ||

Preoperative | Postoperative | Preoperative | Postoperative | |||

FE | 113 ± 50 | 166 ± 26 | <.0001 | 57 ± 34 | 136 ± 46 | <.0001 |

AB | 97 ± 45 | 155 ± 37 | <.0001 | 53 ± 35 | 129 ± 44 | <.0001 |

ER | 42 ± 25 | 48 ± 20 | .033 | 32 ± 28 | 57 ± 32 | <.0001 |

IR | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 4.6 ± 1.6 | <.0001 | 2.6 ± 1.8 | 4.7 ± 2.4 | <.0001 |

VAS pain | 5.7 ± 2.3 | 1.7 ± 2.4 | <.0001 | 5.6 ± 2.5 | 1.6 ± 2.5 | <.0001 |

ASES | 44 ± 17 | 83 ± 18 | <.0001 | 39 ± 16 | 77 ± 22 | <.0001 |

SST | 3.1 ± 2.6 | 9.3 ± 2.9 | <.0001 | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 7.1 ± 3.4 | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: AB, abduction; ASES, American Shoulder and Elbow Society score; ER, external rotation; FE, forward elevation; IR, internal rotation; SST, simple shoulder test; VAS – visual analog score.

In the RCR group, 5 patients (5.3%) required reoperation: 3 patients underwent conversion to rTSA, 1 patient underwent biceps tenotomy with subacromial decompression, and 1 patient underwent arthroscopic irrigation and debridement for a postoperative Propionibacterium acnes infection. In the rTSA group, 2 patients (2.2%) required reoperation: 1 patient underwent open reduction internal fixation for a scapula fracture that failed conservative management, and 1 patient had an open irrigation and debridement with polyethylene exchange for an acute postoperative infection of unknown source.

DISCUSSION

Massive, retracted rotator cuff tears are a common and difficult problem.1 The treatment options are numerous and depend on a variety of preoperative factors including patient-specific characteristics and factors specific to the tear. For certain patients, nonoperative management may be a reasonable first step, as an MCT does not necessarily preclude painless, functional shoulder motion. Elderly, lower demand individuals have been shown to do well with physical rehabilitation.18 Similarly, for the same category of elderly patients who do not respond to conservative measures, arthroscopic tendon debridement with or without subacromial decompression and/or biceps tenotomy may be effective.1,19 This technique has been described as “limited goals surgery;” despite some mixed results in the literature, multiple studies have reported symptomatic and functional improvement after simple debridement.2,19–21The consensus among several authors has been that this procedure continues to play a role for elderly, low-demand patients whose functional goals are limited and whose primary complaint is pain.1,2,20

For the majority of patients with MCT who desire pain relief and a restoration of shoulder function, RCR remains the gold standard of treatment and should be the primary aim if feasible. Complete RCR has consistently outperformed both partial repair and debridement in multiple studies in terms of pain relief and functional improvement.10,21,22However, elderly patients with chronic, massive tears, particularly in the setting of muscle atrophy, are at high risk of failure with attempted cuff repair.9,23 Novel techniques such as superior capsular reconstruction and subacromial balloon spacer implantation may offer a minimally invasive method of re-centering the humeral head and stabilizing the glenohumeral joint; however, these new treatment options lack any long-term data in the literature to support their widespread use.24–26 Alternatively, rTSA has been shown to be a reliable option to restore shoulder function in the setting of a massive irreparable rotator cuff tear, even in the absence of arthritis.5,27-31

Continue to: The decision-making process...

The decision-making process for selecting RCR or rTSA in the setting of MCT without arthritis in the older population (age >65 years) remains challenging. We attempted to quantify the data of a high-volume surgeon and identify the differences and similarities between those patients selected for either procedure. At our institution, we generally performed rTSA on patients with low preoperative range of motion, poor function based on SST and ASES scores, small AHI, and strong evidence of superior subluxation. We were also more likely to perform rTSA if the patient had a history of rotator cuff surgery. There was a predilection for older age and female gender in those who underwent rTSA.

For our study, we elected to focus on patients >65 years. In our experience, the choice of which surgical procedure to perform is generally easier in younger patients. Most surgeons appropriately opt for an arthroscopic procedure or tendon transfer to preserve bone and maintain the option of rTSA as a salvage procedure if necessary in the future. Studies have reported that <60 years is a predictor of poor outcome with rTSA, and patients <65 years who undergo rTSA have been shown to have high complication rates.30-32 Furthermore, the longevity of the implant in young patients is a significant concern, and revision surgery after rTSA is technically demanding and known to result in poor functional outcomes.32,33

Although the indications for rTSA are expanding, attempts at RCR in the setting of MCT remain largely appropriate. Preserved preoperative anterior elevation >90° has been associated with loss of motion after rTSA and poor satisfaction, and one should exercise caution when considering rTSA in this setting.3 The current study confirmed that even older patients with MCT may be very satisfied with arthroscopic RCR (Figure 1). Both range of motion and function significantly improved, and patients were largely satisfied with the procedure with an average self-reported outcome of good to excellent. At the time of final follow-up for this study, only 3 shoulders in the RCR group had undergone conversion to rTSA. This number may be expected to rise with long follow-up periods, and we feel that prolonging the time before arthroplasty is generally in the best interest of the patient.

Our results were consistent with several reported studies in which RCR has been shown to be successful in the setting of MCT.34–37 Henry and colleagues36 performed a systematic review that evaluated 954 patients who underwent partial or complete anatomic RCR for MCT. Although the average age was 63 years (range, 37–87), functional outcome scores, VAS pain score, and overall range of motion consistently and significantly improved.

rTSA may be a “more reliable” option than RCR in treating MCT in the older population because it does not rely on tendon healing. However, the relationship between tendon healing and clinical outcomes after RCR is unclear. The aforementioned systematic review reported re-tear rates to be as high as 79%, but several studies have reported high satisfaction even in the setting of retear.36 Yoo and colleagues38 and Chung and colleagues9 reported re-tear rates of 45.5% and 39.8%, respectively, but both studies noted that there was no difference in outcome measures between those patients with and without re-tears. In particular, for patients who have had no prior rotator cuff surgery, an attempt at arthroscopic repair may be a prudent option with relatively low risk.

Although certain patients may clinically improve despite suffering a re-tear (or inability to heal in the first place), others continue to experience pain and dysfunction that negatively affect their quality of life.39–41 These patients are more often appropriate candidates for rTSA. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated a higher re-tear rate in patients with a history of surgery than in those without.23,31,38,42 Shamsudin and colleagues43 found revision arthroscopic RCR, even in a younger age group with tears of all sizes, to be twice as likely to re-tear. Notably, re-tear after revision repair may be more likely to be symptomatic, as these re-tears are routinely associated with pain, stiffness, and loss of function. Even in the hands of experienced surgeons in a younger population, revision repair has only been able to reverse pseudoparalysis in 43% of patients, leading to only 39% return to sport or full activity.44 In examining our data, we were much less likely to perform an RCR in patients who had a history of cuff repair surgery than in those without this history.

Continue to: Overall, those patients selected for rTSA...

Overall, those patients selected for rTSA in our study population performed well postoperatively (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Vast improvements were noted in range of motion, function, and pain scores at final follow up. Moreover, no patients in the study group required revision arthroplasty during the follow-up period. Although the average follow-up period was only 47 months, these results suggested that elderly patients with MCT without arthritis may be particularly ideal candidates for rTSA with regard to implant survival and anticipated revision rate when chosen appropriately.

Several weaknesses were noted within this paper. First, the study was retrospective, precluding randomization of treatment groups and standardization of data collection and follow-up. The outcomes of RCR and rTSA could not be compared directly due to the inherent selection bias. The groups clearly differed in many respects, and these preoperative factors likely played a role in postoperative outcomes. However, the primary goal of this study was not to compare outcomes of the treatment groups but to analyze the patterns of patient selection by an experienced treating surgeon and contribute to published data that each surgery can be successful in this patient population when chosen appropriately.

Second, our data were based on a single surgeon’s decisions, and results may not be generalizable. Furthermore, the senior author has had a longstanding interest in reverse shoulder arthroplasty and has published data illustrating successful outcomes for rTSA in patients with MCT. For this reason, one could presume that there may have been some bias toward treating patients with rTSA. However, we feel that the senior author’s unique and longstanding experience in treating MCT allows for a thorough evaluation and comparison of preoperative variables and outcomes declared within this study. Indeed, many patients included in this study were referred from outside institutions specifically for rTSA but instead were deemed more appropriate candidates for RCR and underwent successful arthroscopic repair, a common scenario which served as an impetus for this study.

CONCLUSION

RCR and rTSA are both viable options for patients >65 years with MCT without arthritis. Treatment must be individualized for each patient with careful consideration of a number of preoperative variables and patient characteristics. At our institution, patients with previous RCR, decreased range of motion, poor function, and strong radiographic evidence of subluxation are more likely to undergo rTSA. When chosen appropriately, both RCR and rTSA can result in improved range of motion, function, and high patient satisfaction in this patient population.

- Bedi A, Dines J, Warren RF, Dines DM. Massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1894-1908. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.01531.

- Greenspoon JA, Petri M, Warth RJ, Millett PJ. Massive rotator cuff tears: pathomechanics, current treatment options, and clinical outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1493-1505. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.04.005.

- Boileau P, Gonzalez JF, Chuinard C, Bicknell R, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty after failed rotator cuff surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:600-606. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.03.011.

- Cuff D, Pupello D, Virani N, Levy J, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of rotator cuff deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1244-1251. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00775.

- Mulieri P, Dunning P, Klein S, Pupello D, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tear without glenohumeral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2544-2556.doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00912.

- Wall B, Nove-Josserand L, O'Connor DP, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1476-1485. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00666.

- Pill SG, Walch G, Hawkins RJ, Kissenberth MJ. The role of the biceps tendon in massive rotator cuff tears. Instr Course Lect. 2012;61:113-120.

- Makhni EC, Swart E, Steinhaus ME, Mather RC 3rd, Levine WN, Bach BR Jr et al. Cost-effectiveness of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty versus arthroscopic rotator cuff repair for symptomatic large and massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(9):1771-1780. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2016.01.063.

- Chung SW, Kim JY, Kim MH, Kim SH, Oh JH. Arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears: outcome and analysis of factors associated with healing failure or poor postoperative function. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:1674-1683. doi:10.1177/0363546513485719.

- Holtby R, Razmjou H. Relationship between clinical and surgical findings and reparability of large and massive rotator cuff tears: a longitudinal study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:180. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-180.

- Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobayashi Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:92-96.

- DeOrio JK, Cofield RH. Results of a second attempt at surgical repair of a failed initial rotator-cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:563-567.

- Gerber C, Fuchs B, Hodler J. The results of repair of massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:505-515.

- Fuchs B, Weishaupt D, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Gerber C. Fatty degeneration of the muscles of the rotator cuff: assessment by computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:599-605.

- Goutallier D, Bernageau J, Patte D. Assessment of the trophicity of the muscles of the ruptured rotator cuff by CT scan. In: Post M, Morrey B, Hawkins R, eds. Surgery of the Shoulder. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1990;11-13.

- Meyer DC, Farshad M, Amacker NA, Gerber C, Wieser K. Quantitative analysis of muscle and tendon retraction in chronic rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):606-610.

- Meyer DC, Wieser K, Farshad M, Gerber C. Retraction of supraspinatus muscle and tendon as predictors of success of rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2242-2247.

- Williams GR Jr, Rockwood CA Jr, Bigliani LU, Ianotti JP, Stanwood W. Rotator cuff tears: why do we repair them? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(12):2764-2776.

- Rockwood CA Jr, Williams GR Jr, Burkhead WZ Jr. Debridement of degenerative, irreparable lesions of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:857-866.

- Berth A, Neumann W, Awiszus F, Pap G. Massive rotator cuff tears: functional outcome after debridement or arthroscopic partial repair. J Orthopaed Traumatol. 2010;11:13-20. doi 10.1007/s10195-010-0084-0.

- Heuberer PR, Kolblinger R, Buchleitner S, Pauzenberger L, Laky B, Auffarth A, et al. Arthroscopic management of massive rotator cuff tears: an evaluation of debridement, complete, and partial repair with and without force couple restoration. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:3828-3837.

- Moser M, Jablonski MV, Horodyski M, Wright TW. Functional outcome of surgically treated massive rotator cuff tears: a comparison of complete repair, partial repair, and debridement. Orthopedics.2007;30(6):479-482.

- Rhee YG, Cho NS, Yoo JH. Clinical outcome and repair integrity after rotator cuff repair in patients older than 70 years versus patients younger than 70 years. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:546-554. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2014.02.006.

- Denard PJ, Brady PC, Adams CR, Tokish JM, Burkhart SS. Preliminary results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction with dermal allograft. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(1):93-99. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.08.265.

- Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, Fukunishi K, Ohue M, Tsujimura T, Kinoshita M. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy.2013;29:459-70.

- Piekaar RSM, Bouman ICE, van Kampen PM, van Eijk F, Huijsmans PE. Early promising outcome following arthroscopic implantation of the subacromial balloon spacer for treating massive rotator cuff tear. Musculoskelet Surg. 2018;102(3):247-255. doi: 10.1007/s12306-017-0525-5.

- Al-Hadithy N, Domos P, Sewell MD, Pandit R. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty in 41 patients with cuff tear arthropathy with a mean follow-up period of 5 years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1662-1668. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.03.001.

- Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM, Balg F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:147S-161S. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.10.006.

- Grammont PM, Baulot E. Delta shoulder prosthesis for rotator cuff rupture. Orthopedics 1993;16:65-68. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19930101-11.

- Hartzler RU, Steen BM, Hussey MM, Cusick MC, Cottrell BJ, Clark RE, Frankle MA. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for massive rotator cuff tear: risk factors for poor functional improvement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1698-1706. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.04.015.

- Kim HM, Caldwell JM, Buza JA, Fink LA, Ahmad CS, Bigliani LU, Levine WN. Factors affecting satisfaction and shoulder function in patients with a recurrent rotator cuff tear. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:106-112. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.01649.

- Ek ET, Neukom L, Catanzaro S, Gerber C. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears in patients younger than 65 years old: results after five to fifteen years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:1199-1208. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.11.016.

- Sershon RA, Van Thiel GS, Lin EC, McGill KC, Cole BJ, Verma NN, et al. Clinical outcomes of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients aged younger than 60 years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg.2014;23:395-400. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.047.

- Denard PJ, Ladermann A, Jiwani AZ, Burkhart SS. Functional outcome after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears in individuals with pseudoparalysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:1214-1219. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2012.02.026.

- Denard PJ, Ladermann A, Brady PC, Narbona P, Adams CR, Arrigoni P, et al. Pseudoparalysis from a massive rotator cuff tear is reliably reversed with an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in patients without preoperative glenohumeral arthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2373-2378. doi: 10.1177/0363546515597486.

- Henry P, Wasserstein D, Park S, Dwyer T, Chahal J, Slobogean G, Schemitsch E. Arthroscopic repair for chronic massive rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:2472-2480. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2015.06.038.

- Oh JH, Kim SH, Shin SH, Chung SW, Kim JY, Kim SJ. Outcome of rotator cuff repair in large-to-massive tear with pseudoparalysis: a comparative study with propensity score matching. Am J Sports Med.2011;39:1413-1420.

- Yoo JC, Ahn JH, Koh KH, Lim KS. Rotator cuff integrity after arthroscopic repair for large tears with less-than-optimal footprint coverage. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:1093-1100. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2009.07.010.

- Jost B, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C, Switzerland Z. Clinical outcome after structural failure of rotator cuff repairs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:304-314.

- Klepps S, Bishop J, Lin J, Cahlon O, Strauss A, Hayes P, Flatow EL Prospective evaluation of the effect of rotator cuff integrity on the outcome of open rotator cuff repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1716-1722.

- Liu SH, Baker CL. Arthroscopically assisted rotator cuff repair: correlation of functional results with integrity of the cuff. Arthroscopy. 1994;10:54-60.

- Papadopoulos P, Karataglis D, Boutsiadis A, Fotiadou A, Christoforidis J, Christodoulou A. Functional outcome and structural integrity following mini-open repair of large and massive rotator cuff tears: a 3-5 year follow-up study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:131-137. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.05.026.

- Shamsudin A, Lam PH, Peters K, Rubenis I, Hackett L, Murrell GA. Revision versus primary arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a 2-year analysis of outcomes in 360 patients. Am J Sports Med.2015;43:557-564. doi:10.1177/0363546514560729.

- Ladermann A, Denard PJ, Burkhart SS. Midterm outcome of arthroscopic revision repair of massive and nonmassive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:1620-1627. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2011.08.290.

ABSTRACT

The decision to perform rotator cuff repair (RCR) versus reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) for massive rotator cuff tear (MCT) without arthritis can be difficult. Our aim was to identify preoperative variables that are influential in a surgeon's decision to choose one of the two procedures and evaluate outcomes.

We retrospectively reviewed 181 patients older than 65 who underwent RCR or rTSA for MCT without arthritis. Clinical and radiographic data were collected and used to evaluate the preoperative variables in each of these two patient populations and assess outcomes.

Ninety-five shoulders underwent RCR and 92 underwent rTSA with an average followup of 44 and 47 months, respectively. Patients selected for RCR had greater preoperative flexion (113 vs 57), abduction (97 vs 53), and external rotation (42 vs 32), higher SST (3.1 vs 1.9) and ASES scores (43.8 vs 38.6), and were less likely to have had previous cuff surgery (6.3% vs 35.9%). Patients selected for rTSA had a smaller acromiohumeral interval (4.8 vs 8.7) and more superior subluxation (50.6% vs 14.1%). Similar preoperative characteristics included pain, comorbidities, and BMI. Patients were satisfied in both groups and had significant improvement in motion and function postoperatively.

Both RCR and rTSA can result in significant functional improvement and patient satisfaction in the setting of MCT without arthritis in patients older than 65. At our institution, patients who underwent rTSA had less pre-operative motion, lower function, more evidence of superior migration, and were more likely to have had previous rotator cuff surgery.

Continue to: The treatment of patients...

The treatment of patients with massive rotator cuff tears (MCTs) without osteoarthritis is challenging. This population is of considerable interest, as the prevalence of MCT has been reported to be as high as 40% of all rotator cuff tears.1Options for surgical treatment in patients who have failed conservative management are numerous and include tendon debridement, partial or complete arthroscopic or open rotator cuff repair (RCR), tendon transfers, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA), arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction (ASCR), and other grafting procedures.2 Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction shows promise as a novel technique, but it is not yet well studied. Other procedures such as tendon transfers fit into the treatment algorithm for only a small subset of patients. Open rotator cuff repair and rTSA are the 2 most commonly utilized procedures for MCT, and both have been shown to reliably achieve significant functional improvement and patient satisfaction.3–6