User login

ASCO 2018: Less is more as ‘tailoring’ takes on new meaning

A record-setting 40,000-plus oncology professionals attended this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago. The outstanding education and scientific program, with the theme of Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, was planned and led by ASCO President Dr Bruce Johnson, professor and director of Thoracic Oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and chaired by Sarah Cannon’s Dr David Spigel and Harvard’s Dr Ann Partridge. A recurring finding throughout the meeting was that “less is more” in several key areas of cancer therapy. From small molecules targeting driver mutations across various tumors to the application of immunotherapy in subsets of common cancers, it is clear that more patients are experiencing dramatic results from novel approaches.

A featured plenary session trial was TAILORx, a study of 10,273 women with hormone-receptor–positive, surgically resected breast cancer that had not spread to the lymph nodes, was less than 5 cm, and was not positive for the HER2 gene amplification. This clinical trial was sponsored by the NCI and initiated in 2006. It used the OncotypeDX genetic test to stratify patients into groups of low, intermediate, or high risk for recurrence. The low-risk patients received only hormonal therapy, and the high-risk patients were treated with hormonal therapy plus chemotherapy.

Dr Joseph Sparano, professor of Medicine and Women’s Health at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, presented the results from the group of 6,700 intermediate risk women who were randomized to receive hormonal therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy. After 9 years of follow-up, 83.3% of the volunteers, as Dr Sparano appropriately referred to them, who were treated with hormonal therapy were still cancer free, compared with 84.3% of those who also received chemotherapy, demonstrating no statistical benefit for the addition of chemotherapy. Of note, breast cancer experts discussing the trial, including Dr Lisa Carey, professor of Breast Cancer Research at the UNC Lineberger Cancer Institute in Chapel Hill, urged that younger women, under the age of 50, with recurrence scores (RS) toward the higher end of the intermediate risk group (RS, 16-25) should still discuss and consider chemotherapy with their physicians. In summary, all patients fitting the study criteria with low (

These landmark and practice changing results mean that each year about 60,000 women in the United States will be spared the side effects of toxic drugs. These 10,273 study volunteers are true heroes to the women who will be diagnosed with breast cancer in coming years.

In the field of lung cancer, many new trial results using immunotherapy were presented, with the most talked about being single-agent pembrolizumab, a PD1 inhibitor, improving survival over traditional chemotherapy in patients with PD-L1 positive tumors, which comprise the majority of squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the lung. Also in the plenary, Dr Gilberto Lopes of the Sylvester Cancer Center at the University of Miami, presented these results from the KEYNOTE-042 study. In patients with PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) of >1%, the benefit in overall survival (OS) of pembrolizumab compared with chemotherapy was 16.7 versus 12.1 months, respectively (HR, 0.81). In those patients with a TPS of >20%, the OS benefit was 17.7 versus 1.0 months (HR, 0.77), and in the group with a TPS of >50%, the benefit was 20.0 versus 12.2 months (HR, 0.69). Overall, the quality of life and the occurrence of side effects were substantially better for those patients receiving immunotherapy alone. Other findings presented at the meeting demonstrated the benefit of adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy and of treating with combination immunotherapy (PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors). Many options now exist, much work remains to be done, and accrual to clinical trials is more important than ever.

Another plenary session trial evaluated the benefit of performing a nephrectomy in patients with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC), a long-held and practiced standard of care. Dr Arnaud Mejean of Paris Descartes University presented findings from the CARMENA trial, which randomized 450 patients with metastatic clear cell RCC to receive cytoreductive nephrectomy followed by sunitinib, or sunitinib alone. The OS results of 18.4 versus 13.9 months, respectively (HR, 0.89) favored sunitinib alone in this noninferiority analysis. Other endpoints lined up in favor of not removing the cancerous kidney, and the presenter and discussants were united in their opinion of the results and the resulting change in doing less surgery in these patients.

In a step away from less therapy, the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study showed that adding 6 months of low-dose maintenance chemotherapy after standard intensive therapy improves survival in children with high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma. The addition of a vinorelbine and cyclophosphamide low-dose regimen improved 5-year disease-free survival from 69.8% to 77.6% (HR, 0.68) and OS from 73.7% to 86.5% (HR, 0.52) as presented by Dr Gianni Bisogno, University of Padovani, Italy. The maintenance regimen showed no increase in toxicity and actually fewer infections were noted.

In the area of molecular profiling, multiple studies at the meeting demonstrated the importance of assessing cancers for mutations as outstanding results were seen with therapies for NTRK, RET, ROS, and MSI-high driven tumors. In a debate on the role of molecular profiling, I had the opportunity to declare and support our position at Sarah Cannon that all patients with relapsed or metastatic cancers should have this testing performed. It will be through better understanding of the biology of these cancers that we will advance the field for all patients while sometimes finding a target or mutation that will dramatically change the life of a patient.

In keeping with the meeting’s theme, Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, the presentations and the discussions clearly demonstrated that through the use of precision medicine techniques such as prognostic gene assays and molecular profiling, patients can receive the best therapy, even “tailored” therapy, which may often actually be less therapy. It is an exciting time in cancer research, and I have never been more optimistic about the future of cancer treatment for our patients.

A record-setting 40,000-plus oncology professionals attended this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago. The outstanding education and scientific program, with the theme of Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, was planned and led by ASCO President Dr Bruce Johnson, professor and director of Thoracic Oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and chaired by Sarah Cannon’s Dr David Spigel and Harvard’s Dr Ann Partridge. A recurring finding throughout the meeting was that “less is more” in several key areas of cancer therapy. From small molecules targeting driver mutations across various tumors to the application of immunotherapy in subsets of common cancers, it is clear that more patients are experiencing dramatic results from novel approaches.

A featured plenary session trial was TAILORx, a study of 10,273 women with hormone-receptor–positive, surgically resected breast cancer that had not spread to the lymph nodes, was less than 5 cm, and was not positive for the HER2 gene amplification. This clinical trial was sponsored by the NCI and initiated in 2006. It used the OncotypeDX genetic test to stratify patients into groups of low, intermediate, or high risk for recurrence. The low-risk patients received only hormonal therapy, and the high-risk patients were treated with hormonal therapy plus chemotherapy.

Dr Joseph Sparano, professor of Medicine and Women’s Health at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, presented the results from the group of 6,700 intermediate risk women who were randomized to receive hormonal therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy. After 9 years of follow-up, 83.3% of the volunteers, as Dr Sparano appropriately referred to them, who were treated with hormonal therapy were still cancer free, compared with 84.3% of those who also received chemotherapy, demonstrating no statistical benefit for the addition of chemotherapy. Of note, breast cancer experts discussing the trial, including Dr Lisa Carey, professor of Breast Cancer Research at the UNC Lineberger Cancer Institute in Chapel Hill, urged that younger women, under the age of 50, with recurrence scores (RS) toward the higher end of the intermediate risk group (RS, 16-25) should still discuss and consider chemotherapy with their physicians. In summary, all patients fitting the study criteria with low (

These landmark and practice changing results mean that each year about 60,000 women in the United States will be spared the side effects of toxic drugs. These 10,273 study volunteers are true heroes to the women who will be diagnosed with breast cancer in coming years.

In the field of lung cancer, many new trial results using immunotherapy were presented, with the most talked about being single-agent pembrolizumab, a PD1 inhibitor, improving survival over traditional chemotherapy in patients with PD-L1 positive tumors, which comprise the majority of squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the lung. Also in the plenary, Dr Gilberto Lopes of the Sylvester Cancer Center at the University of Miami, presented these results from the KEYNOTE-042 study. In patients with PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) of >1%, the benefit in overall survival (OS) of pembrolizumab compared with chemotherapy was 16.7 versus 12.1 months, respectively (HR, 0.81). In those patients with a TPS of >20%, the OS benefit was 17.7 versus 1.0 months (HR, 0.77), and in the group with a TPS of >50%, the benefit was 20.0 versus 12.2 months (HR, 0.69). Overall, the quality of life and the occurrence of side effects were substantially better for those patients receiving immunotherapy alone. Other findings presented at the meeting demonstrated the benefit of adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy and of treating with combination immunotherapy (PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors). Many options now exist, much work remains to be done, and accrual to clinical trials is more important than ever.

Another plenary session trial evaluated the benefit of performing a nephrectomy in patients with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC), a long-held and practiced standard of care. Dr Arnaud Mejean of Paris Descartes University presented findings from the CARMENA trial, which randomized 450 patients with metastatic clear cell RCC to receive cytoreductive nephrectomy followed by sunitinib, or sunitinib alone. The OS results of 18.4 versus 13.9 months, respectively (HR, 0.89) favored sunitinib alone in this noninferiority analysis. Other endpoints lined up in favor of not removing the cancerous kidney, and the presenter and discussants were united in their opinion of the results and the resulting change in doing less surgery in these patients.

In a step away from less therapy, the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study showed that adding 6 months of low-dose maintenance chemotherapy after standard intensive therapy improves survival in children with high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma. The addition of a vinorelbine and cyclophosphamide low-dose regimen improved 5-year disease-free survival from 69.8% to 77.6% (HR, 0.68) and OS from 73.7% to 86.5% (HR, 0.52) as presented by Dr Gianni Bisogno, University of Padovani, Italy. The maintenance regimen showed no increase in toxicity and actually fewer infections were noted.

In the area of molecular profiling, multiple studies at the meeting demonstrated the importance of assessing cancers for mutations as outstanding results were seen with therapies for NTRK, RET, ROS, and MSI-high driven tumors. In a debate on the role of molecular profiling, I had the opportunity to declare and support our position at Sarah Cannon that all patients with relapsed or metastatic cancers should have this testing performed. It will be through better understanding of the biology of these cancers that we will advance the field for all patients while sometimes finding a target or mutation that will dramatically change the life of a patient.

In keeping with the meeting’s theme, Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, the presentations and the discussions clearly demonstrated that through the use of precision medicine techniques such as prognostic gene assays and molecular profiling, patients can receive the best therapy, even “tailored” therapy, which may often actually be less therapy. It is an exciting time in cancer research, and I have never been more optimistic about the future of cancer treatment for our patients.

A record-setting 40,000-plus oncology professionals attended this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago. The outstanding education and scientific program, with the theme of Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, was planned and led by ASCO President Dr Bruce Johnson, professor and director of Thoracic Oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and chaired by Sarah Cannon’s Dr David Spigel and Harvard’s Dr Ann Partridge. A recurring finding throughout the meeting was that “less is more” in several key areas of cancer therapy. From small molecules targeting driver mutations across various tumors to the application of immunotherapy in subsets of common cancers, it is clear that more patients are experiencing dramatic results from novel approaches.

A featured plenary session trial was TAILORx, a study of 10,273 women with hormone-receptor–positive, surgically resected breast cancer that had not spread to the lymph nodes, was less than 5 cm, and was not positive for the HER2 gene amplification. This clinical trial was sponsored by the NCI and initiated in 2006. It used the OncotypeDX genetic test to stratify patients into groups of low, intermediate, or high risk for recurrence. The low-risk patients received only hormonal therapy, and the high-risk patients were treated with hormonal therapy plus chemotherapy.

Dr Joseph Sparano, professor of Medicine and Women’s Health at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, presented the results from the group of 6,700 intermediate risk women who were randomized to receive hormonal therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy. After 9 years of follow-up, 83.3% of the volunteers, as Dr Sparano appropriately referred to them, who were treated with hormonal therapy were still cancer free, compared with 84.3% of those who also received chemotherapy, demonstrating no statistical benefit for the addition of chemotherapy. Of note, breast cancer experts discussing the trial, including Dr Lisa Carey, professor of Breast Cancer Research at the UNC Lineberger Cancer Institute in Chapel Hill, urged that younger women, under the age of 50, with recurrence scores (RS) toward the higher end of the intermediate risk group (RS, 16-25) should still discuss and consider chemotherapy with their physicians. In summary, all patients fitting the study criteria with low (

These landmark and practice changing results mean that each year about 60,000 women in the United States will be spared the side effects of toxic drugs. These 10,273 study volunteers are true heroes to the women who will be diagnosed with breast cancer in coming years.

In the field of lung cancer, many new trial results using immunotherapy were presented, with the most talked about being single-agent pembrolizumab, a PD1 inhibitor, improving survival over traditional chemotherapy in patients with PD-L1 positive tumors, which comprise the majority of squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the lung. Also in the plenary, Dr Gilberto Lopes of the Sylvester Cancer Center at the University of Miami, presented these results from the KEYNOTE-042 study. In patients with PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) of >1%, the benefit in overall survival (OS) of pembrolizumab compared with chemotherapy was 16.7 versus 12.1 months, respectively (HR, 0.81). In those patients with a TPS of >20%, the OS benefit was 17.7 versus 1.0 months (HR, 0.77), and in the group with a TPS of >50%, the benefit was 20.0 versus 12.2 months (HR, 0.69). Overall, the quality of life and the occurrence of side effects were substantially better for those patients receiving immunotherapy alone. Other findings presented at the meeting demonstrated the benefit of adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy and of treating with combination immunotherapy (PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors). Many options now exist, much work remains to be done, and accrual to clinical trials is more important than ever.

Another plenary session trial evaluated the benefit of performing a nephrectomy in patients with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC), a long-held and practiced standard of care. Dr Arnaud Mejean of Paris Descartes University presented findings from the CARMENA trial, which randomized 450 patients with metastatic clear cell RCC to receive cytoreductive nephrectomy followed by sunitinib, or sunitinib alone. The OS results of 18.4 versus 13.9 months, respectively (HR, 0.89) favored sunitinib alone in this noninferiority analysis. Other endpoints lined up in favor of not removing the cancerous kidney, and the presenter and discussants were united in their opinion of the results and the resulting change in doing less surgery in these patients.

In a step away from less therapy, the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study showed that adding 6 months of low-dose maintenance chemotherapy after standard intensive therapy improves survival in children with high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma. The addition of a vinorelbine and cyclophosphamide low-dose regimen improved 5-year disease-free survival from 69.8% to 77.6% (HR, 0.68) and OS from 73.7% to 86.5% (HR, 0.52) as presented by Dr Gianni Bisogno, University of Padovani, Italy. The maintenance regimen showed no increase in toxicity and actually fewer infections were noted.

In the area of molecular profiling, multiple studies at the meeting demonstrated the importance of assessing cancers for mutations as outstanding results were seen with therapies for NTRK, RET, ROS, and MSI-high driven tumors. In a debate on the role of molecular profiling, I had the opportunity to declare and support our position at Sarah Cannon that all patients with relapsed or metastatic cancers should have this testing performed. It will be through better understanding of the biology of these cancers that we will advance the field for all patients while sometimes finding a target or mutation that will dramatically change the life of a patient.

In keeping with the meeting’s theme, Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, the presentations and the discussions clearly demonstrated that through the use of precision medicine techniques such as prognostic gene assays and molecular profiling, patients can receive the best therapy, even “tailored” therapy, which may often actually be less therapy. It is an exciting time in cancer research, and I have never been more optimistic about the future of cancer treatment for our patients.

Tumor heterogeneity: a central foe in the war on cancer

A major challenge to effective cancer treatment is the astounding level of heterogeneity that tumors display on many different fronts. Here, we discuss how a deeper appreciation of this heterogeneity and its impact is driving research efforts to better understand and tackle it and a radical rethink of treatment paradigms.

A complex and dynamic disease

The nonuniformity of cancer has long been appreciated, reflected most visibly in the variation of response to the same treatment across patients with the same type of tumor (inter-tumor heterogeneity). The extent of tumor heterogeneity is being fully realized only now, with the advent of next-generation sequencing technologies. Even within the same tumor, there can be significant heterogeneity from cell to cell (intra-tumor heterogeneity), yielding substantial complexity in cancer.

Heterogeneity reveals itself on many different levels. Histologically speaking, tumors are composed of a nonhomogenous mass of cells that vary in type and number. In terms of their molecular make-up, there is substantial variation in the types of molecular alterations observed, all the way down to the single cell level. In even more abstract terms, beyond the cancer itself, the microenvironment in which it resides can be highly heterogeneous, composed of a plethora of different supportive and tumor-infiltrating normal cells.

Heterogeneity can manifest spatially, reflecting differences in the composition of the primary tumor and tumors at secondary sites or across regions of the same tumor mass and temporally, at different time points across a tumor’s natural history. Evocative of the second law of thermodynamics, cancers generally become more diverse and complex over time.1-3

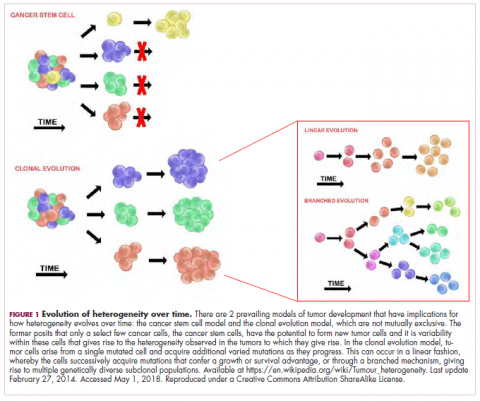

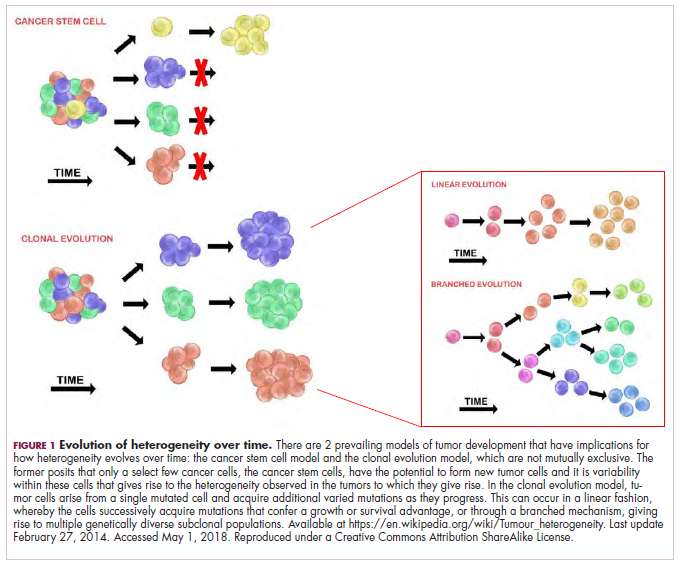

A tale of 2 models

It is widely accepted that the transformation of a normal cell into a malignant one occurs with the acquisition of certain “hallmark” abilities, but there are myriad ways in which these can be attained.

The clonal evolution model

As cells divide, they randomly acquire mutations as a result of DNA damage. The clonal evolution model posits that cancer develops as the result of a multistep accumulation of a series of “driver” mutations that confer a promalignant advantage to the cell and ultimately fuel a cancerous hallmark.

This evolution can occur in a linear fashion, whereby the emergence of a new driver mutation conveys such a potent evolutionary advantage that it outcompetes all previous clones. There is limited evidence for linear evolution in most advanced human cancers; instead, they are thought to evolve predominantly through a process of branching evolution, in which multiple clones can diverge in parallel from a common ancestor through the acquisition of different driver mutations. This results in common clonal mutations that form the trunk of the cancer’s evolutionary tree and are shared by all cells and subclonal mutations, which make up the branches and differ from cell to cell.

More recently, several other mechanisms of clonal evolution have been proposed, including neutral evolution, a type of branching evolution in which there are no selective pressures and evolution occurs by random mutations occurring over time that lead to genetic drift, and punctuated evolution, in which there are short evolutionary bursts of hypermutation.4,5

The CSC model

This model posits that the ability to form and sustain a cancer is restricted to a single cell type – the cancer stem cells – which have the unique capacity for self-renewal and differentiation. Although the forces of evolution are still involved in this model, they act on a hierarchy of cells, with stem cells sitting at the top. A tumor is derived from a single stem cell that has acquired a mutation, and the heterogeneity observed results both from the differentiation and the accumulation of mutations in CSCs.

Accumulated experimental evidence suggests that these models are not mutually exclusive and that they can all contribute to heterogeneity in varied amounts across different tumor types. What is clear is that heterogeneity and evolution are intricately intertwined in cancer development.1,2,6

An unstable genome

Heterogeneity and evolution are fueled by genomic alterations and the genome instability that they foster. This genome instability can range from single base pair substitutions to a doubling of the entire genome and results from both exposure to exogenous mutagens (eg, chemicals and ultraviolet radiation) and genomic alterations that have an impact on important cellular processes (eg, DNA repair or replication).

Among the most common causes of genome instability are mutations in the DNA mismatch repair pathway proteins or in the proofreading polymerase enzymes. Genome instability is often associated with unique mutational signatures – characteristic combinations of mutations that arose as the result of the specific biological processes underlying them.7

Genome-wide analyses have begun to reveal these mutational signatures across the spectrum of human cancers. The Wellcome Sanger Institute’s Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database has generated a set of 30 mutational signatures based on analysis of almost 11,000 exomes and more than 1,000 whole genomes spanning 40 different cancer types, some of which have been linked with specific mutagenic processes, such as tobacco, UV radiation, and DNA repair deficiency (Table 1).8

Fueling resistance

Arguably, heterogeneity presents one of the most significant barriers to effective cancer therapy, and this has become increasingly true in the era of personalized medicine in which targeted therapies take aim at specific molecular abnormalities.

It is vital that drugs target the truncal alterations that are present in all cancer cells to ensure that the entire cancer is eradicated. However, it is not always possible to target these alterations, for example, at the present time tumor suppressor proteins like p53 are not druggable.

Even when truncal alterations have been targeted successfully, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) chromosomal rearrangements in non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and BRAF mutations in melanoma, the long-term efficacy of these drugs is almost invariably limited by the development of resistance.

Tumor heterogeneity and the clonal evolution it fuels are central drivers of resistance. Because tumors are dynamic and continue to evolve, anticancer treatments can act as a strong selective pressure and drive the emergence of drug-resistant subclones that allow the tumor to persist. In fact, study findings have revealed that small populations of resistant cells may be present before treatment. Thus, resistance may also occur as a result of the outgrowth of preexisting treatment-resistant cells that suddenly find that they acquire a survival advantage in the presence of a drug.1,6

Tackling heterogeneity

Despite extensive clinical documentation of the existence of heterogeneity and its underlying mechanisms across a range of tumor types, the development of novel clinical trial designs and therapeutic strategies that account for its effects have only recently begun to be explored.

For the most part, this was because of a lack of effective methods for evaluating intratumor heterogeneity. Multiregion biopsies, in which tissue derived from multiple different regions of a single tumor mass or from distinct cancerous lesions within the same patient, give a snapshot of tumor heterogeneity at a single point in time. The repeated longitudinal sampling required to gain a deeper appreciation of tumor heterogeneity over the course of tumor evolution is often not possible because of the morbidity associated with repeated surgical procedures.

Liquid biopsies, in which DNA sequencing can be performed on tumor components that are found circulating in the blood of cancer patients (including circulating tumor cells and cell-free circulating tumor DNA) have rapidly gained traction in the past several decades and offer an unprecedented opportunity for real-time assessment of evolving tumor heterogeneity.

They have proved to be highly sensitive and specific, with a high degree of concordance with tissue biopsy, they can identify both clonal and subclonal mutations, and they can detect resistance substantially earlier than radiographic imaging, which could permit earlier intervention.10,11 The first liquid biopsy-based companion diagnostic test was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2016, for the detection of EGFR mutations associated with NSCLC.

Yet, even liquid biopsy alone is not able to fully dissect the extent of tumor heterogeneity, especially because it is limited in its ability to assess spatial heterogeneity. Truly effective assessment of tumor heterogeneity is likely to require a combination of liquid biopsy, carefully selected tumor tissue biopsies, imaging diagnostics, and biomarkers.

The ongoing TRACERx (Tracking cancer evolution through therapy [Rx]) trials are evaluating a combination of approaches to follow tumor evolution across the course of treatment. The study in NSCLC began in 2014 with a target enrollment of 842 patients and will follow patients over 6 years. Preliminary data from the first 100 patients were recently published and demonstrated that increased intratumor heterogeneity correlated with increased risk of recurrence or death.12

If patients consent, the TRACERx trials also feed into the PEACE (Posthumous evaluation of advanced cancer environment) trials, which are collecting postmortem biopsies to further evaluate tumor heterogeneity and evolution. TRACERx trials in several other cancer types are now also underway.

Cutting off the source

The main therapeutic strategies for overcoming tumor heterogeneity are focused on the mechanisms of resistance that it drives. It is becoming increasingly apparent that rationally designed combinations of drugs are likely to be required and might need to be administered early in the course of disease to prevent resistance.

However, according to mathematical modeling studies, combinations of at least 3 drugs may be necessary.13 In many cases, this is unlikely to be feasible owing to the unavailability of drugs for certain targets and issues of toxicity, as well as the high cost.

An alternative strategy is to use immunotherapy, because a single treatment can target multiple neoantigens simultaneously. Although immunotherapy has proved to be a highly effective treatment paradigm in multiple tumor types, resistance still arises through varied mechanisms with tumor heterogeneity at their core.14,15

A promising avenue for drug development is to cut off the source of tumor heterogeneity – genomic instability and the mutagenic processes that foster it (Table 2). This is exemplified by the success of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in patients with breast cancer susceptibility (BRCA1/2) gene mutations.

Both germline and somatic mutations in the BRCA1/2 genes are observed in 10% to 15% of patients with ovarian cancer and a substantial number of patients with other types of cancer, including breast, pancreatic, and prostate cancers.16,17

These genes play a central role in the homologous recombination (HR) pathway of DNA repair, which repairs double-strand breaks in DNA. PARP inhibitors target a different DNA repair pathway, base excision repair, which repairs single-strand breaks. The use of PARP inhibitors in patients with BRCA1/2 mutations is designed to create irreparable damage to the DNA repair processes and drive an unsustainable level of genome instability that leads to cell death, whereas normal cells without HR deficiency can survive.18

A growing number of PARP inhibitors are now approved for use in the United States for the treatment of ovarian cancer. In January, olaparib became the first PARP inhibitor approved for patients with BRCA1/2-mutant breast cancer, based on data from the OlympiAD trial in which 302 patients were randomized to receive olaparib 300 mg twice daily or physician’s choice of chemotherapy. Olaparib improved progression-free survival from 4.2 months to 7.0 months (hazard ratio, 0.58; P = .0009), and the most common adverse events included anemia, nausea, fatigue, and vomiting.19

Tumors with other defects in HR have also shown susceptibility to PARP inhibition, shifting interest toward identifying and treating these tumors as a group, independent of histology – about a quarter of all tumors display HR deficiency.20 This novel strategy of targeting mutational processes across a range of tumor types has also been exploited in the development of immunotherapies.

Patients with defects in the mismatch repair (MMR) pathway and microsatellite instability (MSI) – multiple alterations in the length of microsatellite markers within the DNA – are more sensitive to immunotherapy, likely because they are predisposed to a high level of somatic mutations that can serve as neoantigens to provoke a strong anti-tumor immune response.

In 2017, 2 immune checkpoint inhibitors were approved for use in patients with MSI-high or defective MMR (dMMR) cancers. The indication for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) was independent of tumor histology, the first approval of its kind. It was based on the results of 5 clinical trials in which 149 patients with MSI-H or dMMR cancers were given pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks or 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks for a maximum of 24 months. The overall response rate was 39.6%, including 11 complete responses and 48 partial responses.21

A new paradigm

Treatment of a tumor is one of the major selective pressures that shapes its evolution and recent evidence has emerged that these selective pressures can be highly dynamic. Study findings have shown that there is a cost associated with evolution of resistant subclones and, if the selective pressure of therapy is removed, that cost may become too high, such that resistant subclones are then outcompeted by drug-sensitive ones. There have been reports of reversal of drug resistance when drug treatment is interrupted.

The current treatment paradigm is to try to eliminate tumors by hitting them hard and fast with the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of a drug. However, there is increasing appreciation that this may be inadvertently fostering more rapid disease progression because it selects for the emergence of resistant cells and eliminates all their competitors (Figure 2).

This is driving a potential paradigm shift, in which researchers are applying concepts from evolutionary biology and the control of invasive species to the treatment of cancer. Instead of completely eliminating a cancer, a strategy of adaptive therapy could be used to set up competition between different subclones and keep tumor growth in check by exploiting the high cost of resistance.22

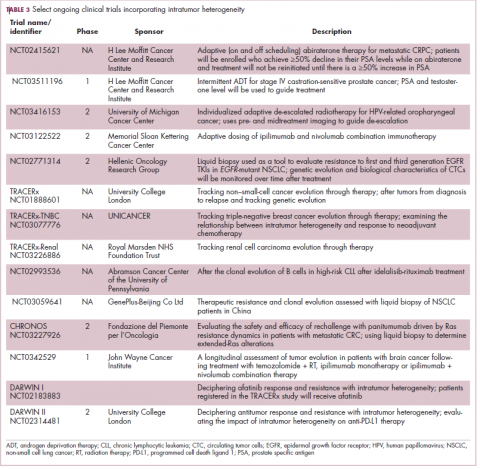

Adaptive therapy involves the use of treatment holidays, intermittent dosing schedules or reduced drug doses, rather than using the MTD. Adaptive therapy was tested recently in mice with triple-negative and estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. The standard maximum dose of chemotherapy was compared with adaptive therapy with either reduced doses or skipped doses as the tumor responded. Tumor growth initially decreased with all 3 treatment scenarios, but then regrew when chemotherapy was stopped or doses were skipped. However, adaptive therapy with lower doses resulted in long-term stabilization of the tumor where treatment was eventually able to be withdrawn.23 Clinical trials of several different types of adaptive therapy strategies are ongoing (Table 3).

1. Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(2):81-94.

2. Dzobo K, Senthebane DA, Thomford NE, Rowe A, Dandara C, Parker MI. Not everyone fits the mold: intratumor and intertumor heterogeneity and innovative cancer drug design and development. OMICS. 2018;22(1):17-34.

3. McGranahan N, Swanton C. Clonal heterogeneity and tumor evolution: past, present, and the future. Cell. 2017;168(4):613-628.

4. Davis A, Gao R, Navin N. Tumor evolution: linear, branching, neutral or punctuated? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1867(2):151-161.

5. Amirouchene-Angelozzi N, Swanton C, Bardelli A. Tumor evolution as a therapeutic target. Cancer Discov. Published online first July 20, 2017. Accessed May 23, 2018. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0343

6. Wu D, Wang DC, Cheng Y, et al. Roles of tumor heterogeneity in the development of drug resistance: a call for precision therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017;42:13-19.

7. Ferguson LR, Chen H, Collins AR, et al. Genomic instability in human cancer: molecular insights and opportunities for therapeutic attack and prevention through diet and nutrition. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35(suppl):S5-S24.

8. Forbes SA, Beare D, Gunasekaran P, et al. COSMIC: exploring the world’s knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D805-811.

9. Rosenthal R, McGranahan N, Herrero J, Swanton C. Deciphering genetic intratumor heterogeneity and its impact on cancer evolution. Ann Rev Cancer Biol. 2017;1(1):223-240.

10. Esposito A, Criscitiello C, Locatelli M, Milano M, Curigliano G. Liquid biopsies for solid tumors: understanding tumor heterogeneity and real time monitoring of early resistance to targeted therapies. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;157:120-124.

11. Venesio T, Siravegna G, Bardelli A, Sapino A. Liquid biopsies for monitoring temporal genomic heterogeneity in breast and colon cancers. Pathobiology. 2018;85(1-2):146-154.

12. Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, McGranahan N, et al. Tracking the evolution of non–small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2109-2121.

13. Bozic I, Reiter JG, Allen B, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of cancer in response to targeted combination therapy. Elife. 2013;2:e00747.

14. Zugazagoitia J, Guedes C, Ponce S, Ferrer I, Molina-Pinelo S, Paz-Ares L. Current challenges in cancer treatment. Clin Ther. 2016;38(7):1551-1566.

15. Ventola CL. Cancer immunotherapy, Part 3: challenges and future trends. PT. 2017;42(8):514-521.

16. Cavanagh H, Rogers KMA. The role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in prostate, pancreatic and stomach cancers. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2015;13:16.

17. Moschetta M, George A, Kaye SB, Banerjee S. BRCA somatic mutations and epigenetic BRCA modifications in serous ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(8):1449-1455.

18. Brown JS, O’Carrigan B, Jackson SP, Yap TA. Targeting DNA repair in cancer: beyond PARP inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(1):20-37.

19. Robson M, Im S-A, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(6):523-533.

20. Williers H, Pfaffle HN, Zou L. Targeting homologous recombination repair in cancer: molecular targets and clinical applications. In: Kelley M, Fishel M, eds. DNA repair in cancer therapy. 2nd ed: Academic Press; 2016:119-160.

21. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for first tissue/site agnostic indication. 2017; https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ ApprovedDrugs/ucm560040.htm. Accessed May 1st,, 2018.

22. Gallaher JA, Enriquez-Navas PM, Luddy KA, Gatenby RA, Anderson ARA. Adaptive Therapy For Heterogeneous Cancer: Exploiting Space And Trade-Offs In Drug Scheduling. bioRxiv. 2017.

23. Enriquez-Navas PM, Kam Y, Das T, et al. Exploiting evolutionary principles to prolong tumor control in preclinical models of breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(327):327ra24.

A major challenge to effective cancer treatment is the astounding level of heterogeneity that tumors display on many different fronts. Here, we discuss how a deeper appreciation of this heterogeneity and its impact is driving research efforts to better understand and tackle it and a radical rethink of treatment paradigms.

A complex and dynamic disease

The nonuniformity of cancer has long been appreciated, reflected most visibly in the variation of response to the same treatment across patients with the same type of tumor (inter-tumor heterogeneity). The extent of tumor heterogeneity is being fully realized only now, with the advent of next-generation sequencing technologies. Even within the same tumor, there can be significant heterogeneity from cell to cell (intra-tumor heterogeneity), yielding substantial complexity in cancer.

Heterogeneity reveals itself on many different levels. Histologically speaking, tumors are composed of a nonhomogenous mass of cells that vary in type and number. In terms of their molecular make-up, there is substantial variation in the types of molecular alterations observed, all the way down to the single cell level. In even more abstract terms, beyond the cancer itself, the microenvironment in which it resides can be highly heterogeneous, composed of a plethora of different supportive and tumor-infiltrating normal cells.

Heterogeneity can manifest spatially, reflecting differences in the composition of the primary tumor and tumors at secondary sites or across regions of the same tumor mass and temporally, at different time points across a tumor’s natural history. Evocative of the second law of thermodynamics, cancers generally become more diverse and complex over time.1-3

A tale of 2 models

It is widely accepted that the transformation of a normal cell into a malignant one occurs with the acquisition of certain “hallmark” abilities, but there are myriad ways in which these can be attained.

The clonal evolution model

As cells divide, they randomly acquire mutations as a result of DNA damage. The clonal evolution model posits that cancer develops as the result of a multistep accumulation of a series of “driver” mutations that confer a promalignant advantage to the cell and ultimately fuel a cancerous hallmark.

This evolution can occur in a linear fashion, whereby the emergence of a new driver mutation conveys such a potent evolutionary advantage that it outcompetes all previous clones. There is limited evidence for linear evolution in most advanced human cancers; instead, they are thought to evolve predominantly through a process of branching evolution, in which multiple clones can diverge in parallel from a common ancestor through the acquisition of different driver mutations. This results in common clonal mutations that form the trunk of the cancer’s evolutionary tree and are shared by all cells and subclonal mutations, which make up the branches and differ from cell to cell.

More recently, several other mechanisms of clonal evolution have been proposed, including neutral evolution, a type of branching evolution in which there are no selective pressures and evolution occurs by random mutations occurring over time that lead to genetic drift, and punctuated evolution, in which there are short evolutionary bursts of hypermutation.4,5

The CSC model

This model posits that the ability to form and sustain a cancer is restricted to a single cell type – the cancer stem cells – which have the unique capacity for self-renewal and differentiation. Although the forces of evolution are still involved in this model, they act on a hierarchy of cells, with stem cells sitting at the top. A tumor is derived from a single stem cell that has acquired a mutation, and the heterogeneity observed results both from the differentiation and the accumulation of mutations in CSCs.

Accumulated experimental evidence suggests that these models are not mutually exclusive and that they can all contribute to heterogeneity in varied amounts across different tumor types. What is clear is that heterogeneity and evolution are intricately intertwined in cancer development.1,2,6

An unstable genome

Heterogeneity and evolution are fueled by genomic alterations and the genome instability that they foster. This genome instability can range from single base pair substitutions to a doubling of the entire genome and results from both exposure to exogenous mutagens (eg, chemicals and ultraviolet radiation) and genomic alterations that have an impact on important cellular processes (eg, DNA repair or replication).

Among the most common causes of genome instability are mutations in the DNA mismatch repair pathway proteins or in the proofreading polymerase enzymes. Genome instability is often associated with unique mutational signatures – characteristic combinations of mutations that arose as the result of the specific biological processes underlying them.7

Genome-wide analyses have begun to reveal these mutational signatures across the spectrum of human cancers. The Wellcome Sanger Institute’s Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database has generated a set of 30 mutational signatures based on analysis of almost 11,000 exomes and more than 1,000 whole genomes spanning 40 different cancer types, some of which have been linked with specific mutagenic processes, such as tobacco, UV radiation, and DNA repair deficiency (Table 1).8

Fueling resistance

Arguably, heterogeneity presents one of the most significant barriers to effective cancer therapy, and this has become increasingly true in the era of personalized medicine in which targeted therapies take aim at specific molecular abnormalities.

It is vital that drugs target the truncal alterations that are present in all cancer cells to ensure that the entire cancer is eradicated. However, it is not always possible to target these alterations, for example, at the present time tumor suppressor proteins like p53 are not druggable.

Even when truncal alterations have been targeted successfully, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) chromosomal rearrangements in non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and BRAF mutations in melanoma, the long-term efficacy of these drugs is almost invariably limited by the development of resistance.

Tumor heterogeneity and the clonal evolution it fuels are central drivers of resistance. Because tumors are dynamic and continue to evolve, anticancer treatments can act as a strong selective pressure and drive the emergence of drug-resistant subclones that allow the tumor to persist. In fact, study findings have revealed that small populations of resistant cells may be present before treatment. Thus, resistance may also occur as a result of the outgrowth of preexisting treatment-resistant cells that suddenly find that they acquire a survival advantage in the presence of a drug.1,6

Tackling heterogeneity

Despite extensive clinical documentation of the existence of heterogeneity and its underlying mechanisms across a range of tumor types, the development of novel clinical trial designs and therapeutic strategies that account for its effects have only recently begun to be explored.

For the most part, this was because of a lack of effective methods for evaluating intratumor heterogeneity. Multiregion biopsies, in which tissue derived from multiple different regions of a single tumor mass or from distinct cancerous lesions within the same patient, give a snapshot of tumor heterogeneity at a single point in time. The repeated longitudinal sampling required to gain a deeper appreciation of tumor heterogeneity over the course of tumor evolution is often not possible because of the morbidity associated with repeated surgical procedures.

Liquid biopsies, in which DNA sequencing can be performed on tumor components that are found circulating in the blood of cancer patients (including circulating tumor cells and cell-free circulating tumor DNA) have rapidly gained traction in the past several decades and offer an unprecedented opportunity for real-time assessment of evolving tumor heterogeneity.

They have proved to be highly sensitive and specific, with a high degree of concordance with tissue biopsy, they can identify both clonal and subclonal mutations, and they can detect resistance substantially earlier than radiographic imaging, which could permit earlier intervention.10,11 The first liquid biopsy-based companion diagnostic test was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2016, for the detection of EGFR mutations associated with NSCLC.

Yet, even liquid biopsy alone is not able to fully dissect the extent of tumor heterogeneity, especially because it is limited in its ability to assess spatial heterogeneity. Truly effective assessment of tumor heterogeneity is likely to require a combination of liquid biopsy, carefully selected tumor tissue biopsies, imaging diagnostics, and biomarkers.

The ongoing TRACERx (Tracking cancer evolution through therapy [Rx]) trials are evaluating a combination of approaches to follow tumor evolution across the course of treatment. The study in NSCLC began in 2014 with a target enrollment of 842 patients and will follow patients over 6 years. Preliminary data from the first 100 patients were recently published and demonstrated that increased intratumor heterogeneity correlated with increased risk of recurrence or death.12

If patients consent, the TRACERx trials also feed into the PEACE (Posthumous evaluation of advanced cancer environment) trials, which are collecting postmortem biopsies to further evaluate tumor heterogeneity and evolution. TRACERx trials in several other cancer types are now also underway.

Cutting off the source

The main therapeutic strategies for overcoming tumor heterogeneity are focused on the mechanisms of resistance that it drives. It is becoming increasingly apparent that rationally designed combinations of drugs are likely to be required and might need to be administered early in the course of disease to prevent resistance.

However, according to mathematical modeling studies, combinations of at least 3 drugs may be necessary.13 In many cases, this is unlikely to be feasible owing to the unavailability of drugs for certain targets and issues of toxicity, as well as the high cost.

An alternative strategy is to use immunotherapy, because a single treatment can target multiple neoantigens simultaneously. Although immunotherapy has proved to be a highly effective treatment paradigm in multiple tumor types, resistance still arises through varied mechanisms with tumor heterogeneity at their core.14,15

A promising avenue for drug development is to cut off the source of tumor heterogeneity – genomic instability and the mutagenic processes that foster it (Table 2). This is exemplified by the success of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in patients with breast cancer susceptibility (BRCA1/2) gene mutations.

Both germline and somatic mutations in the BRCA1/2 genes are observed in 10% to 15% of patients with ovarian cancer and a substantial number of patients with other types of cancer, including breast, pancreatic, and prostate cancers.16,17

These genes play a central role in the homologous recombination (HR) pathway of DNA repair, which repairs double-strand breaks in DNA. PARP inhibitors target a different DNA repair pathway, base excision repair, which repairs single-strand breaks. The use of PARP inhibitors in patients with BRCA1/2 mutations is designed to create irreparable damage to the DNA repair processes and drive an unsustainable level of genome instability that leads to cell death, whereas normal cells without HR deficiency can survive.18

A growing number of PARP inhibitors are now approved for use in the United States for the treatment of ovarian cancer. In January, olaparib became the first PARP inhibitor approved for patients with BRCA1/2-mutant breast cancer, based on data from the OlympiAD trial in which 302 patients were randomized to receive olaparib 300 mg twice daily or physician’s choice of chemotherapy. Olaparib improved progression-free survival from 4.2 months to 7.0 months (hazard ratio, 0.58; P = .0009), and the most common adverse events included anemia, nausea, fatigue, and vomiting.19

Tumors with other defects in HR have also shown susceptibility to PARP inhibition, shifting interest toward identifying and treating these tumors as a group, independent of histology – about a quarter of all tumors display HR deficiency.20 This novel strategy of targeting mutational processes across a range of tumor types has also been exploited in the development of immunotherapies.

Patients with defects in the mismatch repair (MMR) pathway and microsatellite instability (MSI) – multiple alterations in the length of microsatellite markers within the DNA – are more sensitive to immunotherapy, likely because they are predisposed to a high level of somatic mutations that can serve as neoantigens to provoke a strong anti-tumor immune response.

In 2017, 2 immune checkpoint inhibitors were approved for use in patients with MSI-high or defective MMR (dMMR) cancers. The indication for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) was independent of tumor histology, the first approval of its kind. It was based on the results of 5 clinical trials in which 149 patients with MSI-H or dMMR cancers were given pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks or 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks for a maximum of 24 months. The overall response rate was 39.6%, including 11 complete responses and 48 partial responses.21

A new paradigm

Treatment of a tumor is one of the major selective pressures that shapes its evolution and recent evidence has emerged that these selective pressures can be highly dynamic. Study findings have shown that there is a cost associated with evolution of resistant subclones and, if the selective pressure of therapy is removed, that cost may become too high, such that resistant subclones are then outcompeted by drug-sensitive ones. There have been reports of reversal of drug resistance when drug treatment is interrupted.

The current treatment paradigm is to try to eliminate tumors by hitting them hard and fast with the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of a drug. However, there is increasing appreciation that this may be inadvertently fostering more rapid disease progression because it selects for the emergence of resistant cells and eliminates all their competitors (Figure 2).

This is driving a potential paradigm shift, in which researchers are applying concepts from evolutionary biology and the control of invasive species to the treatment of cancer. Instead of completely eliminating a cancer, a strategy of adaptive therapy could be used to set up competition between different subclones and keep tumor growth in check by exploiting the high cost of resistance.22

Adaptive therapy involves the use of treatment holidays, intermittent dosing schedules or reduced drug doses, rather than using the MTD. Adaptive therapy was tested recently in mice with triple-negative and estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. The standard maximum dose of chemotherapy was compared with adaptive therapy with either reduced doses or skipped doses as the tumor responded. Tumor growth initially decreased with all 3 treatment scenarios, but then regrew when chemotherapy was stopped or doses were skipped. However, adaptive therapy with lower doses resulted in long-term stabilization of the tumor where treatment was eventually able to be withdrawn.23 Clinical trials of several different types of adaptive therapy strategies are ongoing (Table 3).

A major challenge to effective cancer treatment is the astounding level of heterogeneity that tumors display on many different fronts. Here, we discuss how a deeper appreciation of this heterogeneity and its impact is driving research efforts to better understand and tackle it and a radical rethink of treatment paradigms.

A complex and dynamic disease

The nonuniformity of cancer has long been appreciated, reflected most visibly in the variation of response to the same treatment across patients with the same type of tumor (inter-tumor heterogeneity). The extent of tumor heterogeneity is being fully realized only now, with the advent of next-generation sequencing technologies. Even within the same tumor, there can be significant heterogeneity from cell to cell (intra-tumor heterogeneity), yielding substantial complexity in cancer.

Heterogeneity reveals itself on many different levels. Histologically speaking, tumors are composed of a nonhomogenous mass of cells that vary in type and number. In terms of their molecular make-up, there is substantial variation in the types of molecular alterations observed, all the way down to the single cell level. In even more abstract terms, beyond the cancer itself, the microenvironment in which it resides can be highly heterogeneous, composed of a plethora of different supportive and tumor-infiltrating normal cells.

Heterogeneity can manifest spatially, reflecting differences in the composition of the primary tumor and tumors at secondary sites or across regions of the same tumor mass and temporally, at different time points across a tumor’s natural history. Evocative of the second law of thermodynamics, cancers generally become more diverse and complex over time.1-3

A tale of 2 models

It is widely accepted that the transformation of a normal cell into a malignant one occurs with the acquisition of certain “hallmark” abilities, but there are myriad ways in which these can be attained.

The clonal evolution model

As cells divide, they randomly acquire mutations as a result of DNA damage. The clonal evolution model posits that cancer develops as the result of a multistep accumulation of a series of “driver” mutations that confer a promalignant advantage to the cell and ultimately fuel a cancerous hallmark.

This evolution can occur in a linear fashion, whereby the emergence of a new driver mutation conveys such a potent evolutionary advantage that it outcompetes all previous clones. There is limited evidence for linear evolution in most advanced human cancers; instead, they are thought to evolve predominantly through a process of branching evolution, in which multiple clones can diverge in parallel from a common ancestor through the acquisition of different driver mutations. This results in common clonal mutations that form the trunk of the cancer’s evolutionary tree and are shared by all cells and subclonal mutations, which make up the branches and differ from cell to cell.

More recently, several other mechanisms of clonal evolution have been proposed, including neutral evolution, a type of branching evolution in which there are no selective pressures and evolution occurs by random mutations occurring over time that lead to genetic drift, and punctuated evolution, in which there are short evolutionary bursts of hypermutation.4,5

The CSC model

This model posits that the ability to form and sustain a cancer is restricted to a single cell type – the cancer stem cells – which have the unique capacity for self-renewal and differentiation. Although the forces of evolution are still involved in this model, they act on a hierarchy of cells, with stem cells sitting at the top. A tumor is derived from a single stem cell that has acquired a mutation, and the heterogeneity observed results both from the differentiation and the accumulation of mutations in CSCs.

Accumulated experimental evidence suggests that these models are not mutually exclusive and that they can all contribute to heterogeneity in varied amounts across different tumor types. What is clear is that heterogeneity and evolution are intricately intertwined in cancer development.1,2,6

An unstable genome

Heterogeneity and evolution are fueled by genomic alterations and the genome instability that they foster. This genome instability can range from single base pair substitutions to a doubling of the entire genome and results from both exposure to exogenous mutagens (eg, chemicals and ultraviolet radiation) and genomic alterations that have an impact on important cellular processes (eg, DNA repair or replication).

Among the most common causes of genome instability are mutations in the DNA mismatch repair pathway proteins or in the proofreading polymerase enzymes. Genome instability is often associated with unique mutational signatures – characteristic combinations of mutations that arose as the result of the specific biological processes underlying them.7

Genome-wide analyses have begun to reveal these mutational signatures across the spectrum of human cancers. The Wellcome Sanger Institute’s Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database has generated a set of 30 mutational signatures based on analysis of almost 11,000 exomes and more than 1,000 whole genomes spanning 40 different cancer types, some of which have been linked with specific mutagenic processes, such as tobacco, UV radiation, and DNA repair deficiency (Table 1).8

Fueling resistance

Arguably, heterogeneity presents one of the most significant barriers to effective cancer therapy, and this has become increasingly true in the era of personalized medicine in which targeted therapies take aim at specific molecular abnormalities.

It is vital that drugs target the truncal alterations that are present in all cancer cells to ensure that the entire cancer is eradicated. However, it is not always possible to target these alterations, for example, at the present time tumor suppressor proteins like p53 are not druggable.

Even when truncal alterations have been targeted successfully, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) chromosomal rearrangements in non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and BRAF mutations in melanoma, the long-term efficacy of these drugs is almost invariably limited by the development of resistance.

Tumor heterogeneity and the clonal evolution it fuels are central drivers of resistance. Because tumors are dynamic and continue to evolve, anticancer treatments can act as a strong selective pressure and drive the emergence of drug-resistant subclones that allow the tumor to persist. In fact, study findings have revealed that small populations of resistant cells may be present before treatment. Thus, resistance may also occur as a result of the outgrowth of preexisting treatment-resistant cells that suddenly find that they acquire a survival advantage in the presence of a drug.1,6

Tackling heterogeneity

Despite extensive clinical documentation of the existence of heterogeneity and its underlying mechanisms across a range of tumor types, the development of novel clinical trial designs and therapeutic strategies that account for its effects have only recently begun to be explored.

For the most part, this was because of a lack of effective methods for evaluating intratumor heterogeneity. Multiregion biopsies, in which tissue derived from multiple different regions of a single tumor mass or from distinct cancerous lesions within the same patient, give a snapshot of tumor heterogeneity at a single point in time. The repeated longitudinal sampling required to gain a deeper appreciation of tumor heterogeneity over the course of tumor evolution is often not possible because of the morbidity associated with repeated surgical procedures.

Liquid biopsies, in which DNA sequencing can be performed on tumor components that are found circulating in the blood of cancer patients (including circulating tumor cells and cell-free circulating tumor DNA) have rapidly gained traction in the past several decades and offer an unprecedented opportunity for real-time assessment of evolving tumor heterogeneity.

They have proved to be highly sensitive and specific, with a high degree of concordance with tissue biopsy, they can identify both clonal and subclonal mutations, and they can detect resistance substantially earlier than radiographic imaging, which could permit earlier intervention.10,11 The first liquid biopsy-based companion diagnostic test was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2016, for the detection of EGFR mutations associated with NSCLC.

Yet, even liquid biopsy alone is not able to fully dissect the extent of tumor heterogeneity, especially because it is limited in its ability to assess spatial heterogeneity. Truly effective assessment of tumor heterogeneity is likely to require a combination of liquid biopsy, carefully selected tumor tissue biopsies, imaging diagnostics, and biomarkers.

The ongoing TRACERx (Tracking cancer evolution through therapy [Rx]) trials are evaluating a combination of approaches to follow tumor evolution across the course of treatment. The study in NSCLC began in 2014 with a target enrollment of 842 patients and will follow patients over 6 years. Preliminary data from the first 100 patients were recently published and demonstrated that increased intratumor heterogeneity correlated with increased risk of recurrence or death.12

If patients consent, the TRACERx trials also feed into the PEACE (Posthumous evaluation of advanced cancer environment) trials, which are collecting postmortem biopsies to further evaluate tumor heterogeneity and evolution. TRACERx trials in several other cancer types are now also underway.

Cutting off the source

The main therapeutic strategies for overcoming tumor heterogeneity are focused on the mechanisms of resistance that it drives. It is becoming increasingly apparent that rationally designed combinations of drugs are likely to be required and might need to be administered early in the course of disease to prevent resistance.

However, according to mathematical modeling studies, combinations of at least 3 drugs may be necessary.13 In many cases, this is unlikely to be feasible owing to the unavailability of drugs for certain targets and issues of toxicity, as well as the high cost.

An alternative strategy is to use immunotherapy, because a single treatment can target multiple neoantigens simultaneously. Although immunotherapy has proved to be a highly effective treatment paradigm in multiple tumor types, resistance still arises through varied mechanisms with tumor heterogeneity at their core.14,15

A promising avenue for drug development is to cut off the source of tumor heterogeneity – genomic instability and the mutagenic processes that foster it (Table 2). This is exemplified by the success of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in patients with breast cancer susceptibility (BRCA1/2) gene mutations.

Both germline and somatic mutations in the BRCA1/2 genes are observed in 10% to 15% of patients with ovarian cancer and a substantial number of patients with other types of cancer, including breast, pancreatic, and prostate cancers.16,17

These genes play a central role in the homologous recombination (HR) pathway of DNA repair, which repairs double-strand breaks in DNA. PARP inhibitors target a different DNA repair pathway, base excision repair, which repairs single-strand breaks. The use of PARP inhibitors in patients with BRCA1/2 mutations is designed to create irreparable damage to the DNA repair processes and drive an unsustainable level of genome instability that leads to cell death, whereas normal cells without HR deficiency can survive.18

A growing number of PARP inhibitors are now approved for use in the United States for the treatment of ovarian cancer. In January, olaparib became the first PARP inhibitor approved for patients with BRCA1/2-mutant breast cancer, based on data from the OlympiAD trial in which 302 patients were randomized to receive olaparib 300 mg twice daily or physician’s choice of chemotherapy. Olaparib improved progression-free survival from 4.2 months to 7.0 months (hazard ratio, 0.58; P = .0009), and the most common adverse events included anemia, nausea, fatigue, and vomiting.19

Tumors with other defects in HR have also shown susceptibility to PARP inhibition, shifting interest toward identifying and treating these tumors as a group, independent of histology – about a quarter of all tumors display HR deficiency.20 This novel strategy of targeting mutational processes across a range of tumor types has also been exploited in the development of immunotherapies.

Patients with defects in the mismatch repair (MMR) pathway and microsatellite instability (MSI) – multiple alterations in the length of microsatellite markers within the DNA – are more sensitive to immunotherapy, likely because they are predisposed to a high level of somatic mutations that can serve as neoantigens to provoke a strong anti-tumor immune response.

In 2017, 2 immune checkpoint inhibitors were approved for use in patients with MSI-high or defective MMR (dMMR) cancers. The indication for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) was independent of tumor histology, the first approval of its kind. It was based on the results of 5 clinical trials in which 149 patients with MSI-H or dMMR cancers were given pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks or 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks for a maximum of 24 months. The overall response rate was 39.6%, including 11 complete responses and 48 partial responses.21

A new paradigm

Treatment of a tumor is one of the major selective pressures that shapes its evolution and recent evidence has emerged that these selective pressures can be highly dynamic. Study findings have shown that there is a cost associated with evolution of resistant subclones and, if the selective pressure of therapy is removed, that cost may become too high, such that resistant subclones are then outcompeted by drug-sensitive ones. There have been reports of reversal of drug resistance when drug treatment is interrupted.

The current treatment paradigm is to try to eliminate tumors by hitting them hard and fast with the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of a drug. However, there is increasing appreciation that this may be inadvertently fostering more rapid disease progression because it selects for the emergence of resistant cells and eliminates all their competitors (Figure 2).

This is driving a potential paradigm shift, in which researchers are applying concepts from evolutionary biology and the control of invasive species to the treatment of cancer. Instead of completely eliminating a cancer, a strategy of adaptive therapy could be used to set up competition between different subclones and keep tumor growth in check by exploiting the high cost of resistance.22

Adaptive therapy involves the use of treatment holidays, intermittent dosing schedules or reduced drug doses, rather than using the MTD. Adaptive therapy was tested recently in mice with triple-negative and estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. The standard maximum dose of chemotherapy was compared with adaptive therapy with either reduced doses or skipped doses as the tumor responded. Tumor growth initially decreased with all 3 treatment scenarios, but then regrew when chemotherapy was stopped or doses were skipped. However, adaptive therapy with lower doses resulted in long-term stabilization of the tumor where treatment was eventually able to be withdrawn.23 Clinical trials of several different types of adaptive therapy strategies are ongoing (Table 3).

1. Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(2):81-94.

2. Dzobo K, Senthebane DA, Thomford NE, Rowe A, Dandara C, Parker MI. Not everyone fits the mold: intratumor and intertumor heterogeneity and innovative cancer drug design and development. OMICS. 2018;22(1):17-34.

3. McGranahan N, Swanton C. Clonal heterogeneity and tumor evolution: past, present, and the future. Cell. 2017;168(4):613-628.

4. Davis A, Gao R, Navin N. Tumor evolution: linear, branching, neutral or punctuated? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1867(2):151-161.

5. Amirouchene-Angelozzi N, Swanton C, Bardelli A. Tumor evolution as a therapeutic target. Cancer Discov. Published online first July 20, 2017. Accessed May 23, 2018. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0343

6. Wu D, Wang DC, Cheng Y, et al. Roles of tumor heterogeneity in the development of drug resistance: a call for precision therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017;42:13-19.

7. Ferguson LR, Chen H, Collins AR, et al. Genomic instability in human cancer: molecular insights and opportunities for therapeutic attack and prevention through diet and nutrition. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35(suppl):S5-S24.

8. Forbes SA, Beare D, Gunasekaran P, et al. COSMIC: exploring the world’s knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D805-811.

9. Rosenthal R, McGranahan N, Herrero J, Swanton C. Deciphering genetic intratumor heterogeneity and its impact on cancer evolution. Ann Rev Cancer Biol. 2017;1(1):223-240.

10. Esposito A, Criscitiello C, Locatelli M, Milano M, Curigliano G. Liquid biopsies for solid tumors: understanding tumor heterogeneity and real time monitoring of early resistance to targeted therapies. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;157:120-124.

11. Venesio T, Siravegna G, Bardelli A, Sapino A. Liquid biopsies for monitoring temporal genomic heterogeneity in breast and colon cancers. Pathobiology. 2018;85(1-2):146-154.

12. Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, McGranahan N, et al. Tracking the evolution of non–small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2109-2121.

13. Bozic I, Reiter JG, Allen B, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of cancer in response to targeted combination therapy. Elife. 2013;2:e00747.

14. Zugazagoitia J, Guedes C, Ponce S, Ferrer I, Molina-Pinelo S, Paz-Ares L. Current challenges in cancer treatment. Clin Ther. 2016;38(7):1551-1566.

15. Ventola CL. Cancer immunotherapy, Part 3: challenges and future trends. PT. 2017;42(8):514-521.

16. Cavanagh H, Rogers KMA. The role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in prostate, pancreatic and stomach cancers. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2015;13:16.

17. Moschetta M, George A, Kaye SB, Banerjee S. BRCA somatic mutations and epigenetic BRCA modifications in serous ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(8):1449-1455.

18. Brown JS, O’Carrigan B, Jackson SP, Yap TA. Targeting DNA repair in cancer: beyond PARP inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(1):20-37.

19. Robson M, Im S-A, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(6):523-533.

20. Williers H, Pfaffle HN, Zou L. Targeting homologous recombination repair in cancer: molecular targets and clinical applications. In: Kelley M, Fishel M, eds. DNA repair in cancer therapy. 2nd ed: Academic Press; 2016:119-160.

21. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for first tissue/site agnostic indication. 2017; https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ ApprovedDrugs/ucm560040.htm. Accessed May 1st,, 2018.

22. Gallaher JA, Enriquez-Navas PM, Luddy KA, Gatenby RA, Anderson ARA. Adaptive Therapy For Heterogeneous Cancer: Exploiting Space And Trade-Offs In Drug Scheduling. bioRxiv. 2017.

23. Enriquez-Navas PM, Kam Y, Das T, et al. Exploiting evolutionary principles to prolong tumor control in preclinical models of breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(327):327ra24.

1. Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(2):81-94.

2. Dzobo K, Senthebane DA, Thomford NE, Rowe A, Dandara C, Parker MI. Not everyone fits the mold: intratumor and intertumor heterogeneity and innovative cancer drug design and development. OMICS. 2018;22(1):17-34.

3. McGranahan N, Swanton C. Clonal heterogeneity and tumor evolution: past, present, and the future. Cell. 2017;168(4):613-628.

4. Davis A, Gao R, Navin N. Tumor evolution: linear, branching, neutral or punctuated? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1867(2):151-161.

5. Amirouchene-Angelozzi N, Swanton C, Bardelli A. Tumor evolution as a therapeutic target. Cancer Discov. Published online first July 20, 2017. Accessed May 23, 2018. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0343

6. Wu D, Wang DC, Cheng Y, et al. Roles of tumor heterogeneity in the development of drug resistance: a call for precision therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017;42:13-19.

7. Ferguson LR, Chen H, Collins AR, et al. Genomic instability in human cancer: molecular insights and opportunities for therapeutic attack and prevention through diet and nutrition. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35(suppl):S5-S24.

8. Forbes SA, Beare D, Gunasekaran P, et al. COSMIC: exploring the world’s knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D805-811.

9. Rosenthal R, McGranahan N, Herrero J, Swanton C. Deciphering genetic intratumor heterogeneity and its impact on cancer evolution. Ann Rev Cancer Biol. 2017;1(1):223-240.

10. Esposito A, Criscitiello C, Locatelli M, Milano M, Curigliano G. Liquid biopsies for solid tumors: understanding tumor heterogeneity and real time monitoring of early resistance to targeted therapies. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;157:120-124.

11. Venesio T, Siravegna G, Bardelli A, Sapino A. Liquid biopsies for monitoring temporal genomic heterogeneity in breast and colon cancers. Pathobiology. 2018;85(1-2):146-154.

12. Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, McGranahan N, et al. Tracking the evolution of non–small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2109-2121.

13. Bozic I, Reiter JG, Allen B, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of cancer in response to targeted combination therapy. Elife. 2013;2:e00747.

14. Zugazagoitia J, Guedes C, Ponce S, Ferrer I, Molina-Pinelo S, Paz-Ares L. Current challenges in cancer treatment. Clin Ther. 2016;38(7):1551-1566.

15. Ventola CL. Cancer immunotherapy, Part 3: challenges and future trends. PT. 2017;42(8):514-521.

16. Cavanagh H, Rogers KMA. The role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in prostate, pancreatic and stomach cancers. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2015;13:16.

17. Moschetta M, George A, Kaye SB, Banerjee S. BRCA somatic mutations and epigenetic BRCA modifications in serous ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(8):1449-1455.

18. Brown JS, O’Carrigan B, Jackson SP, Yap TA. Targeting DNA repair in cancer: beyond PARP inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(1):20-37.

19. Robson M, Im S-A, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(6):523-533.

20. Williers H, Pfaffle HN, Zou L. Targeting homologous recombination repair in cancer: molecular targets and clinical applications. In: Kelley M, Fishel M, eds. DNA repair in cancer therapy. 2nd ed: Academic Press; 2016:119-160.

21. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for first tissue/site agnostic indication. 2017; https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ ApprovedDrugs/ucm560040.htm. Accessed May 1st,, 2018.

22. Gallaher JA, Enriquez-Navas PM, Luddy KA, Gatenby RA, Anderson ARA. Adaptive Therapy For Heterogeneous Cancer: Exploiting Space And Trade-Offs In Drug Scheduling. bioRxiv. 2017.

23. Enriquez-Navas PM, Kam Y, Das T, et al. Exploiting evolutionary principles to prolong tumor control in preclinical models of breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(327):327ra24.

No strong evidence linking vitamin D levels and preeclampsia