User login

White House pushes transparency in drug price plan

The Trump administration believes it is a “right that, when you are sitting there with your doctor, you ought to be able to know what your out-of-pocket [cost] is for drug you are going to be prescribed under your precise drug plan. And you ought to have information on what competing drugs are that your doctor is not prescribing and what you would pay out of pocket for that.”

Price transparency is a key theme to the broad package of proposals called American Patients First that the White House released May 11. The plan includes changes that can be made immediately as well as some upon which the administration will seek public comment, according to the plan.

Another tactic the administration is considering for quick action is requiring a drug’s list prices to be included in all direct-to-consumer advertising.

The plan also calls for the banning of gag rules that prevent pharmacists from alerting patients when it would be cheaper to buy a prescribed drug without going through their insurance coverage, as well as moving certain drugs from Medicare Part B to Medicare Part D to improve the government’s ability to negotiations for lower prices.

The overall strategy is laid out across four areas:

- Increasing competition though policy measures that prevent manufacturers from gaming the patent system and promoting innovation and competition among biologics.

- Improving negotiation abilities, including doing more with value-based purchasing; allowing for more substitution, especially in the case of single-source generics; and further examination of the competitive acquisition program for Part B.

- Providing incentives to manufacturers to lower their list prices.

- Lowering out-of-pocket costs.

Currently, there is no incentive to lower drug prices, Mr. Azar noted. He called out pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) for financially benefiting from both manufacturers and the insurers they represent and said HHS is looking into banning financial compensation to PBMs from the manufacturers. He also said the agency will be releasing a request for information on the feasibility of doing away with rebates as a means of driving manufacturers to lower their prices.

PhRMA, the lobbying group representing pharmaceutical manufacturers, said in a statement that some of the changes related to Part D “could undermine the existing structure of the program that has successfully held down costs and provided seniors with access to comprehensive prescription drug coverage. We also must avoid changes to Medicare Part B that could raise costs for seniors and limit their access to lifesaving treatments.”

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the lobbying group for pharmacy benefit managers, also spoke out against the idea of eliminating rebates, noting in a statement that getting rid of them “and other price concessions would leave patients and payers, including Medicaid and Medicare, at the mercy of drug manufacturer pricing strategies. PBMs have long encouraged manufacturers to offer payers alternative ways to reduce net costs. Simply put, the easiest way to lower costs would be for drug companies to lower their prices.”

The American Medical Association voiced support for the plan.

“The AMA is pleased the Trump administration is moving forward with its effort to address seemingly arbitrary pricing for prescription drugs,” President David Barbe, MD, said in a statement “Physicians see the impact of skyrocketing prices every day as patients are often unable to afford the most medically appropriate medications – even those that have effectively controlled their medical condition for years. No one can understand the logic behind the high and fluctuating prices. We hope the administration can bring some transparency – and relief – to patients.”

During a Rose Garden ceremony to introduce the initiative, President Trump said he is targeting foreign countries that require manufacturers to sell their products well below list prices as a condition of selling in their country, forcing Americans to absorb the research and development costs via higher prices for drugs.

“It’s time to end the global freeloading once and for all,” President Trump said. “I have directed U.S. Trade Representative Bob Lighthizer to make fixing this injustice a top priority with every trading partner.”

One proposal President Trump campaigned on – giving the federal government the power to directly negotiate for drug prices – was not included in the plan.

“I am very disappointed that he has apparently dropped his support for allowing Medicare to negotiate the price of prescription drugs,” Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.) said in a statement.

Also absent from the plan: a direct negotiation tactic for Part B drugs supported by Mr. Azar during his confirmation hearings.

The Trump administration believes it is a “right that, when you are sitting there with your doctor, you ought to be able to know what your out-of-pocket [cost] is for drug you are going to be prescribed under your precise drug plan. And you ought to have information on what competing drugs are that your doctor is not prescribing and what you would pay out of pocket for that.”

Price transparency is a key theme to the broad package of proposals called American Patients First that the White House released May 11. The plan includes changes that can be made immediately as well as some upon which the administration will seek public comment, according to the plan.

Another tactic the administration is considering for quick action is requiring a drug’s list prices to be included in all direct-to-consumer advertising.

The plan also calls for the banning of gag rules that prevent pharmacists from alerting patients when it would be cheaper to buy a prescribed drug without going through their insurance coverage, as well as moving certain drugs from Medicare Part B to Medicare Part D to improve the government’s ability to negotiations for lower prices.

The overall strategy is laid out across four areas:

- Increasing competition though policy measures that prevent manufacturers from gaming the patent system and promoting innovation and competition among biologics.

- Improving negotiation abilities, including doing more with value-based purchasing; allowing for more substitution, especially in the case of single-source generics; and further examination of the competitive acquisition program for Part B.

- Providing incentives to manufacturers to lower their list prices.

- Lowering out-of-pocket costs.

Currently, there is no incentive to lower drug prices, Mr. Azar noted. He called out pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) for financially benefiting from both manufacturers and the insurers they represent and said HHS is looking into banning financial compensation to PBMs from the manufacturers. He also said the agency will be releasing a request for information on the feasibility of doing away with rebates as a means of driving manufacturers to lower their prices.

PhRMA, the lobbying group representing pharmaceutical manufacturers, said in a statement that some of the changes related to Part D “could undermine the existing structure of the program that has successfully held down costs and provided seniors with access to comprehensive prescription drug coverage. We also must avoid changes to Medicare Part B that could raise costs for seniors and limit their access to lifesaving treatments.”

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the lobbying group for pharmacy benefit managers, also spoke out against the idea of eliminating rebates, noting in a statement that getting rid of them “and other price concessions would leave patients and payers, including Medicaid and Medicare, at the mercy of drug manufacturer pricing strategies. PBMs have long encouraged manufacturers to offer payers alternative ways to reduce net costs. Simply put, the easiest way to lower costs would be for drug companies to lower their prices.”

The American Medical Association voiced support for the plan.

“The AMA is pleased the Trump administration is moving forward with its effort to address seemingly arbitrary pricing for prescription drugs,” President David Barbe, MD, said in a statement “Physicians see the impact of skyrocketing prices every day as patients are often unable to afford the most medically appropriate medications – even those that have effectively controlled their medical condition for years. No one can understand the logic behind the high and fluctuating prices. We hope the administration can bring some transparency – and relief – to patients.”

During a Rose Garden ceremony to introduce the initiative, President Trump said he is targeting foreign countries that require manufacturers to sell their products well below list prices as a condition of selling in their country, forcing Americans to absorb the research and development costs via higher prices for drugs.

“It’s time to end the global freeloading once and for all,” President Trump said. “I have directed U.S. Trade Representative Bob Lighthizer to make fixing this injustice a top priority with every trading partner.”

One proposal President Trump campaigned on – giving the federal government the power to directly negotiate for drug prices – was not included in the plan.

“I am very disappointed that he has apparently dropped his support for allowing Medicare to negotiate the price of prescription drugs,” Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.) said in a statement.

Also absent from the plan: a direct negotiation tactic for Part B drugs supported by Mr. Azar during his confirmation hearings.

The Trump administration believes it is a “right that, when you are sitting there with your doctor, you ought to be able to know what your out-of-pocket [cost] is for drug you are going to be prescribed under your precise drug plan. And you ought to have information on what competing drugs are that your doctor is not prescribing and what you would pay out of pocket for that.”

Price transparency is a key theme to the broad package of proposals called American Patients First that the White House released May 11. The plan includes changes that can be made immediately as well as some upon which the administration will seek public comment, according to the plan.

Another tactic the administration is considering for quick action is requiring a drug’s list prices to be included in all direct-to-consumer advertising.

The plan also calls for the banning of gag rules that prevent pharmacists from alerting patients when it would be cheaper to buy a prescribed drug without going through their insurance coverage, as well as moving certain drugs from Medicare Part B to Medicare Part D to improve the government’s ability to negotiations for lower prices.

The overall strategy is laid out across four areas:

- Increasing competition though policy measures that prevent manufacturers from gaming the patent system and promoting innovation and competition among biologics.

- Improving negotiation abilities, including doing more with value-based purchasing; allowing for more substitution, especially in the case of single-source generics; and further examination of the competitive acquisition program for Part B.

- Providing incentives to manufacturers to lower their list prices.

- Lowering out-of-pocket costs.

Currently, there is no incentive to lower drug prices, Mr. Azar noted. He called out pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) for financially benefiting from both manufacturers and the insurers they represent and said HHS is looking into banning financial compensation to PBMs from the manufacturers. He also said the agency will be releasing a request for information on the feasibility of doing away with rebates as a means of driving manufacturers to lower their prices.

PhRMA, the lobbying group representing pharmaceutical manufacturers, said in a statement that some of the changes related to Part D “could undermine the existing structure of the program that has successfully held down costs and provided seniors with access to comprehensive prescription drug coverage. We also must avoid changes to Medicare Part B that could raise costs for seniors and limit their access to lifesaving treatments.”

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the lobbying group for pharmacy benefit managers, also spoke out against the idea of eliminating rebates, noting in a statement that getting rid of them “and other price concessions would leave patients and payers, including Medicaid and Medicare, at the mercy of drug manufacturer pricing strategies. PBMs have long encouraged manufacturers to offer payers alternative ways to reduce net costs. Simply put, the easiest way to lower costs would be for drug companies to lower their prices.”

The American Medical Association voiced support for the plan.

“The AMA is pleased the Trump administration is moving forward with its effort to address seemingly arbitrary pricing for prescription drugs,” President David Barbe, MD, said in a statement “Physicians see the impact of skyrocketing prices every day as patients are often unable to afford the most medically appropriate medications – even those that have effectively controlled their medical condition for years. No one can understand the logic behind the high and fluctuating prices. We hope the administration can bring some transparency – and relief – to patients.”

During a Rose Garden ceremony to introduce the initiative, President Trump said he is targeting foreign countries that require manufacturers to sell their products well below list prices as a condition of selling in their country, forcing Americans to absorb the research and development costs via higher prices for drugs.

“It’s time to end the global freeloading once and for all,” President Trump said. “I have directed U.S. Trade Representative Bob Lighthizer to make fixing this injustice a top priority with every trading partner.”

One proposal President Trump campaigned on – giving the federal government the power to directly negotiate for drug prices – was not included in the plan.

“I am very disappointed that he has apparently dropped his support for allowing Medicare to negotiate the price of prescription drugs,” Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.) said in a statement.

Also absent from the plan: a direct negotiation tactic for Part B drugs supported by Mr. Azar during his confirmation hearings.

Open Clinical Trials for Patients With Colorectal Cancer (FULL)

Providing access to clinical trials for veteran and active-duty military patients can be a challenge, but a significant number of trials are now recruiting patients from those patient populations. Many trials explicitly recruit patients from the VA, the military, and IHS. The VA Office of Research and Development alone sponsors > 300 research initiatives, and many more are sponsored by Walter Reed National Medical Center and other major defense and VA facilities. The clinical trials listed below are all open as of April 1, 2017; have at least 1 VA, DoD, or IHS location recruiting patients; and are focused on treatment for colorectal cancer. For additional information and full inclusion/exclusion criteria, please consult clinicaltrials.gov.

Impact of Family History and Decision Support on High-Risk Cancer Screening

There is no standardized system for collecting and updating family health history, using this information to determine a patient’s disease risk level, and providing screening recommendations to patients and providers. Patients will enter their family health history into a program that will produce screening recommendations tailored to the patient’s family health history. The investigators will examine whether this process increases physician referrals for, and patient uptake of, guideline-recommended screening for colorectal cancer.

ID: NCT02247336

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Location (contact): Durham VAMC, North Carolina (Jamiyla Bolton, Susan B. Armstrong); William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin (Corrine Voils)

Colonoscopy Versus Fecal Immunochemical Test in Reducing Mortality From Colorectal Cancer

The investigators propose to perform a large, simple, multicenter, randomized, parallel-group trial directly comparing screening colonoscopy with annual fecal immunochemical test screening in average risk individuals. The hypothesis is that colonoscopy will be superior to fecal immunochemical testing in the prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC) mortality measured over 10 years. The primary study endpoint will be CRC mortality within 10 years of enrollment.

ID: NCT01239082

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Locations: 48 current locations

S0820, Adenoma and Second Primary Prevention Trial (PACES)

The investigators hypothesize that the combination of eflornithine and sulindac will be effective in reducing a 3-year event rate of adenomas and second primary colorectal cancers in patients previously treated for Stages 0 through III colon cancer.

ID: NCT01349881

Sponsor: Southwest Oncology Group

Location (contact): VA Connecticut Healthcare System-West Haven Campus (Michal Rose); Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital, Hines, Illinois (Abdul Choudhury); Kansas City VAMC, Missouri (Joaquina Baranda); White River Junction VAMC, Vermont (Nancy Kuemmerle); Eisenhower Army Medical Center, Fort Gordon, Georgia (Andrew Delmas); Tripler Army Medical Center, Honolulu, Hawaii (Jeffrey Berenberg); Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas (John Renshaw)

Irinotecan Hydrochloride and Cetuximab With or Without Ramucirumab in Treating Patients With Advanced Colorectal Cancer With Progressive Disease After Treatment With Bevacizumab

This randomized phase II trial is studying the adverse effects and how well giving cetuximab and irinotecan hydrochloride with or without ramucirumab work in treating patients with advanced colorectal cancer with progressive disease after treatment with bevacizumab-containing chemotherapy.

ID: NCT01079780

Sponsor: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Location (contact): Atlanta VAMC, Decatur, Georgia (Samuel Chan); VA New Jersey Health Care System East Orange Campus (Basil Kasimis)

Cancer Associated Thrombosis and Isoquercetin

This research study is evaluating a drug called isoquercetin to prevent venous thrombosis (blood clots) in participants who have pancreas, non-small cell lung cancer or colorectal cancer.

ID: NCT02195232

Sponsor: Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Location (contact): Washington DC VAMC (Anita Aggarwal); Boston VA Healthcare System, Massachusetts (Kenneth Bauer); White River Junction VAMC, Vermont (Nancy Kuemmerle)

Studying Lymph Nodes in Patients With Stage II Colon Cancer

Diagnostic procedures that look for micrometastases in lymph nodes removed during surgery for colon cancer may help doctors learn the extent of disease. This phase I trial is studying lymph nodes in patients with stage II colon cancer.

ID: NCT00949312

Sponsor: John Wayne Cancer Institute

Location: Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC

Click here to read the digital edition.

Providing access to clinical trials for veteran and active-duty military patients can be a challenge, but a significant number of trials are now recruiting patients from those patient populations. Many trials explicitly recruit patients from the VA, the military, and IHS. The VA Office of Research and Development alone sponsors > 300 research initiatives, and many more are sponsored by Walter Reed National Medical Center and other major defense and VA facilities. The clinical trials listed below are all open as of April 1, 2017; have at least 1 VA, DoD, or IHS location recruiting patients; and are focused on treatment for colorectal cancer. For additional information and full inclusion/exclusion criteria, please consult clinicaltrials.gov.

Impact of Family History and Decision Support on High-Risk Cancer Screening

There is no standardized system for collecting and updating family health history, using this information to determine a patient’s disease risk level, and providing screening recommendations to patients and providers. Patients will enter their family health history into a program that will produce screening recommendations tailored to the patient’s family health history. The investigators will examine whether this process increases physician referrals for, and patient uptake of, guideline-recommended screening for colorectal cancer.

ID: NCT02247336

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Location (contact): Durham VAMC, North Carolina (Jamiyla Bolton, Susan B. Armstrong); William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin (Corrine Voils)

Colonoscopy Versus Fecal Immunochemical Test in Reducing Mortality From Colorectal Cancer

The investigators propose to perform a large, simple, multicenter, randomized, parallel-group trial directly comparing screening colonoscopy with annual fecal immunochemical test screening in average risk individuals. The hypothesis is that colonoscopy will be superior to fecal immunochemical testing in the prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC) mortality measured over 10 years. The primary study endpoint will be CRC mortality within 10 years of enrollment.

ID: NCT01239082

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Locations: 48 current locations

S0820, Adenoma and Second Primary Prevention Trial (PACES)

The investigators hypothesize that the combination of eflornithine and sulindac will be effective in reducing a 3-year event rate of adenomas and second primary colorectal cancers in patients previously treated for Stages 0 through III colon cancer.

ID: NCT01349881

Sponsor: Southwest Oncology Group

Location (contact): VA Connecticut Healthcare System-West Haven Campus (Michal Rose); Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital, Hines, Illinois (Abdul Choudhury); Kansas City VAMC, Missouri (Joaquina Baranda); White River Junction VAMC, Vermont (Nancy Kuemmerle); Eisenhower Army Medical Center, Fort Gordon, Georgia (Andrew Delmas); Tripler Army Medical Center, Honolulu, Hawaii (Jeffrey Berenberg); Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas (John Renshaw)

Irinotecan Hydrochloride and Cetuximab With or Without Ramucirumab in Treating Patients With Advanced Colorectal Cancer With Progressive Disease After Treatment With Bevacizumab

This randomized phase II trial is studying the adverse effects and how well giving cetuximab and irinotecan hydrochloride with or without ramucirumab work in treating patients with advanced colorectal cancer with progressive disease after treatment with bevacizumab-containing chemotherapy.

ID: NCT01079780

Sponsor: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Location (contact): Atlanta VAMC, Decatur, Georgia (Samuel Chan); VA New Jersey Health Care System East Orange Campus (Basil Kasimis)

Cancer Associated Thrombosis and Isoquercetin

This research study is evaluating a drug called isoquercetin to prevent venous thrombosis (blood clots) in participants who have pancreas, non-small cell lung cancer or colorectal cancer.

ID: NCT02195232

Sponsor: Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Location (contact): Washington DC VAMC (Anita Aggarwal); Boston VA Healthcare System, Massachusetts (Kenneth Bauer); White River Junction VAMC, Vermont (Nancy Kuemmerle)

Studying Lymph Nodes in Patients With Stage II Colon Cancer

Diagnostic procedures that look for micrometastases in lymph nodes removed during surgery for colon cancer may help doctors learn the extent of disease. This phase I trial is studying lymph nodes in patients with stage II colon cancer.

ID: NCT00949312

Sponsor: John Wayne Cancer Institute

Location: Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC

Click here to read the digital edition.

Providing access to clinical trials for veteran and active-duty military patients can be a challenge, but a significant number of trials are now recruiting patients from those patient populations. Many trials explicitly recruit patients from the VA, the military, and IHS. The VA Office of Research and Development alone sponsors > 300 research initiatives, and many more are sponsored by Walter Reed National Medical Center and other major defense and VA facilities. The clinical trials listed below are all open as of April 1, 2017; have at least 1 VA, DoD, or IHS location recruiting patients; and are focused on treatment for colorectal cancer. For additional information and full inclusion/exclusion criteria, please consult clinicaltrials.gov.

Impact of Family History and Decision Support on High-Risk Cancer Screening

There is no standardized system for collecting and updating family health history, using this information to determine a patient’s disease risk level, and providing screening recommendations to patients and providers. Patients will enter their family health history into a program that will produce screening recommendations tailored to the patient’s family health history. The investigators will examine whether this process increases physician referrals for, and patient uptake of, guideline-recommended screening for colorectal cancer.

ID: NCT02247336

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Location (contact): Durham VAMC, North Carolina (Jamiyla Bolton, Susan B. Armstrong); William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin (Corrine Voils)

Colonoscopy Versus Fecal Immunochemical Test in Reducing Mortality From Colorectal Cancer

The investigators propose to perform a large, simple, multicenter, randomized, parallel-group trial directly comparing screening colonoscopy with annual fecal immunochemical test screening in average risk individuals. The hypothesis is that colonoscopy will be superior to fecal immunochemical testing in the prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC) mortality measured over 10 years. The primary study endpoint will be CRC mortality within 10 years of enrollment.

ID: NCT01239082

Sponsor: VA Office of Research and Development

Locations: 48 current locations

S0820, Adenoma and Second Primary Prevention Trial (PACES)

The investigators hypothesize that the combination of eflornithine and sulindac will be effective in reducing a 3-year event rate of adenomas and second primary colorectal cancers in patients previously treated for Stages 0 through III colon cancer.

ID: NCT01349881

Sponsor: Southwest Oncology Group

Location (contact): VA Connecticut Healthcare System-West Haven Campus (Michal Rose); Edward Hines Jr. VA Hospital, Hines, Illinois (Abdul Choudhury); Kansas City VAMC, Missouri (Joaquina Baranda); White River Junction VAMC, Vermont (Nancy Kuemmerle); Eisenhower Army Medical Center, Fort Gordon, Georgia (Andrew Delmas); Tripler Army Medical Center, Honolulu, Hawaii (Jeffrey Berenberg); Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas (John Renshaw)

Irinotecan Hydrochloride and Cetuximab With or Without Ramucirumab in Treating Patients With Advanced Colorectal Cancer With Progressive Disease After Treatment With Bevacizumab

This randomized phase II trial is studying the adverse effects and how well giving cetuximab and irinotecan hydrochloride with or without ramucirumab work in treating patients with advanced colorectal cancer with progressive disease after treatment with bevacizumab-containing chemotherapy.

ID: NCT01079780

Sponsor: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Location (contact): Atlanta VAMC, Decatur, Georgia (Samuel Chan); VA New Jersey Health Care System East Orange Campus (Basil Kasimis)

Cancer Associated Thrombosis and Isoquercetin

This research study is evaluating a drug called isoquercetin to prevent venous thrombosis (blood clots) in participants who have pancreas, non-small cell lung cancer or colorectal cancer.

ID: NCT02195232

Sponsor: Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Location (contact): Washington DC VAMC (Anita Aggarwal); Boston VA Healthcare System, Massachusetts (Kenneth Bauer); White River Junction VAMC, Vermont (Nancy Kuemmerle)

Studying Lymph Nodes in Patients With Stage II Colon Cancer

Diagnostic procedures that look for micrometastases in lymph nodes removed during surgery for colon cancer may help doctors learn the extent of disease. This phase I trial is studying lymph nodes in patients with stage II colon cancer.

ID: NCT00949312

Sponsor: John Wayne Cancer Institute

Location: Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC

Click here to read the digital edition.

Group calls on WHO to help fight HTLV-1

A group of scientists and activists are calling on the World Health Organization (WHO) to fight the spread of human T-cell leukemia virus subtype 1 (HTLV-1).

The group has written a letter to the WHO highlighting the global prevalence of HTLV-1 infection and recommending strategies to prevent the transmission of HTLV-1.

An abbreviated version of the letter was published in The Lancet. The full letter is available on the Global Virus Network (GVN)* website.

“Since my colleagues and I discovered HTLV-1 . . ., we have learned that this destructive and lethal virus is causing much devastation in communities with high prevalence,” said Robert C. Gallo, MD, co-founder and director of GVN and a professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

“During the GVN meeting last September, I was astounded to learn of the hyper-endemic numbers in the Aboriginal population of Australia. HTLV-1 is endemic in other regions, including several islands of the Caribbean, and in countries such as Brazil, Iran, Japan, and Peru. We hope that the WHO will agree with us and begin to take action in promoting prevention strategies against HTLV-1.”

HTLV-1 prevalence

In their letter, Dr Gallo and his colleagues cite statistics of HTLV-1 prevalence around the world.

The authors note that, in a hospital-based cohort study conducted in Central Australia, 33.6% of Indigenous people tested HTLV-1 positive, with the incidence rate reaching 48.5% in older men.

Research has suggested that, in Brazil, the HTLV-1 prevalence rate is 1.8% in the general population, 1.3% in blood donors in certain regions, and 1.05% in pregnant women.

It is estimated that nearly 1 million people are HTLV-1-positive in Japan, and 850,000 to 1.7 million people in Nigeria are infected with the virus.

In Gabon, the HTLV-1 prevalence in adults is believed to be 5% to 10%. And in Central African Republic, 7% of older, female Pygmies in the southern region were found to be infected with HTLV-1.

Studies have indicated that 6.1% of the general population in Jamaica is positive for HTLV-1, and other Caribbean islands have similar prevalence rates.

The authors note that HTLV-1 and -2 have also been detected in non-endemic areas due to migration and sexual transmission.

It is estimated that 20,000 to 30,000 people are infected with HTLV-1 in the UK, and 10,000 to 25,000 people are infected in metropolitan France.

Other estimates suggest that 266,000 people are infected with HTLV-1 or -2 in the US, and 3600 people with HTLV-1 associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) remain undiagnosed.

“The general neglect, globally, of the importance of HTLV-1 as a sexually transmitted infection that causes a range of debilitating inflammatory diseases does our patients, who request a sexual health screen, a disservice,” said Graham P. Taylor, MDMB, DSc, a professor at Imperial College London in the UK.

“It is also important to recognize the importance of mother-to-child transmission of HTLV-1 in the development of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) decades later. Despite the availability of highly sensitive and specific diagnostic tests for infection and a proven intervention, except for Japan, there are no antenatal screening programs. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of such programs should now be a priority.”

“To prevent mother-to-child infection, the Japanese government has been offering HTLV-1 screening for all pregnant women without cost,” noted Yoshi Yamano, MD, PhD, a professor at St. Marianna University School of Medicine in Kawasaki, Japan.

“Taking a leadership role to promote research, it also provides grants for clinical trials and patient registries focused on ATLL and HAM/TSP.”

Preventing transmission

The letter outlines 5 strategies to prevent or reduce transmission of HTLV-1. The authors recommend:

- Protecting the sexually active population with routine HTLV-1 testing in sexual health clinics and through promotion of CMPC—Counsel & Monitor HTLV-1-positive patients, notify Partners, and promote Condom usage

- Protecting blood and organ donors and recipients by testing for HTLV, avoiding use of products that may be infected, and promoting CMPC

- Protecting mothers, babies, and fathers via routine antenatal care testing, advising HTLV-1-positive mothers against breastfeeding (when feasible), and promoting CMPC

- Protecting injectable drug users by promoting HTLV-1 testing, providing safe needles through needle exchange program, and promoting CMPC

- Supporting the general population and healthcare providers by providing access to an up-to-date WHO HTLV-1 Fact Sheet that can help healthcare providers diagnose HTLV-1 and related diseases and help patients protect themselves from HTLV-1.

“This virus has been underestimated since the time of its discovery perhaps because it is restricted to certain regions or because it is not terribly infectious,” said William Hall, MD, PhD, co-founder of GVN and a professor at the University College Dublin in Ireland.

“However, for decades, it has been known that HTLV-1 is highly carcinogenic and causes severe paralytic neurologic disease and immune disorders that can lead to bacterial infections. It is time that the WHO publicize prevention strategies against this devastating virus.”

*GVN is an international coalition of medical virologists dedicated to identifying, researching, fighting, and preventing current and emerging pandemic viruses that pose a threat to public health.

A group of scientists and activists are calling on the World Health Organization (WHO) to fight the spread of human T-cell leukemia virus subtype 1 (HTLV-1).

The group has written a letter to the WHO highlighting the global prevalence of HTLV-1 infection and recommending strategies to prevent the transmission of HTLV-1.

An abbreviated version of the letter was published in The Lancet. The full letter is available on the Global Virus Network (GVN)* website.

“Since my colleagues and I discovered HTLV-1 . . ., we have learned that this destructive and lethal virus is causing much devastation in communities with high prevalence,” said Robert C. Gallo, MD, co-founder and director of GVN and a professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

“During the GVN meeting last September, I was astounded to learn of the hyper-endemic numbers in the Aboriginal population of Australia. HTLV-1 is endemic in other regions, including several islands of the Caribbean, and in countries such as Brazil, Iran, Japan, and Peru. We hope that the WHO will agree with us and begin to take action in promoting prevention strategies against HTLV-1.”

HTLV-1 prevalence

In their letter, Dr Gallo and his colleagues cite statistics of HTLV-1 prevalence around the world.

The authors note that, in a hospital-based cohort study conducted in Central Australia, 33.6% of Indigenous people tested HTLV-1 positive, with the incidence rate reaching 48.5% in older men.

Research has suggested that, in Brazil, the HTLV-1 prevalence rate is 1.8% in the general population, 1.3% in blood donors in certain regions, and 1.05% in pregnant women.

It is estimated that nearly 1 million people are HTLV-1-positive in Japan, and 850,000 to 1.7 million people in Nigeria are infected with the virus.

In Gabon, the HTLV-1 prevalence in adults is believed to be 5% to 10%. And in Central African Republic, 7% of older, female Pygmies in the southern region were found to be infected with HTLV-1.

Studies have indicated that 6.1% of the general population in Jamaica is positive for HTLV-1, and other Caribbean islands have similar prevalence rates.

The authors note that HTLV-1 and -2 have also been detected in non-endemic areas due to migration and sexual transmission.

It is estimated that 20,000 to 30,000 people are infected with HTLV-1 in the UK, and 10,000 to 25,000 people are infected in metropolitan France.

Other estimates suggest that 266,000 people are infected with HTLV-1 or -2 in the US, and 3600 people with HTLV-1 associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) remain undiagnosed.

“The general neglect, globally, of the importance of HTLV-1 as a sexually transmitted infection that causes a range of debilitating inflammatory diseases does our patients, who request a sexual health screen, a disservice,” said Graham P. Taylor, MDMB, DSc, a professor at Imperial College London in the UK.

“It is also important to recognize the importance of mother-to-child transmission of HTLV-1 in the development of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) decades later. Despite the availability of highly sensitive and specific diagnostic tests for infection and a proven intervention, except for Japan, there are no antenatal screening programs. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of such programs should now be a priority.”

“To prevent mother-to-child infection, the Japanese government has been offering HTLV-1 screening for all pregnant women without cost,” noted Yoshi Yamano, MD, PhD, a professor at St. Marianna University School of Medicine in Kawasaki, Japan.

“Taking a leadership role to promote research, it also provides grants for clinical trials and patient registries focused on ATLL and HAM/TSP.”

Preventing transmission

The letter outlines 5 strategies to prevent or reduce transmission of HTLV-1. The authors recommend:

- Protecting the sexually active population with routine HTLV-1 testing in sexual health clinics and through promotion of CMPC—Counsel & Monitor HTLV-1-positive patients, notify Partners, and promote Condom usage

- Protecting blood and organ donors and recipients by testing for HTLV, avoiding use of products that may be infected, and promoting CMPC

- Protecting mothers, babies, and fathers via routine antenatal care testing, advising HTLV-1-positive mothers against breastfeeding (when feasible), and promoting CMPC

- Protecting injectable drug users by promoting HTLV-1 testing, providing safe needles through needle exchange program, and promoting CMPC

- Supporting the general population and healthcare providers by providing access to an up-to-date WHO HTLV-1 Fact Sheet that can help healthcare providers diagnose HTLV-1 and related diseases and help patients protect themselves from HTLV-1.

“This virus has been underestimated since the time of its discovery perhaps because it is restricted to certain regions or because it is not terribly infectious,” said William Hall, MD, PhD, co-founder of GVN and a professor at the University College Dublin in Ireland.

“However, for decades, it has been known that HTLV-1 is highly carcinogenic and causes severe paralytic neurologic disease and immune disorders that can lead to bacterial infections. It is time that the WHO publicize prevention strategies against this devastating virus.”

*GVN is an international coalition of medical virologists dedicated to identifying, researching, fighting, and preventing current and emerging pandemic viruses that pose a threat to public health.

A group of scientists and activists are calling on the World Health Organization (WHO) to fight the spread of human T-cell leukemia virus subtype 1 (HTLV-1).

The group has written a letter to the WHO highlighting the global prevalence of HTLV-1 infection and recommending strategies to prevent the transmission of HTLV-1.

An abbreviated version of the letter was published in The Lancet. The full letter is available on the Global Virus Network (GVN)* website.

“Since my colleagues and I discovered HTLV-1 . . ., we have learned that this destructive and lethal virus is causing much devastation in communities with high prevalence,” said Robert C. Gallo, MD, co-founder and director of GVN and a professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

“During the GVN meeting last September, I was astounded to learn of the hyper-endemic numbers in the Aboriginal population of Australia. HTLV-1 is endemic in other regions, including several islands of the Caribbean, and in countries such as Brazil, Iran, Japan, and Peru. We hope that the WHO will agree with us and begin to take action in promoting prevention strategies against HTLV-1.”

HTLV-1 prevalence

In their letter, Dr Gallo and his colleagues cite statistics of HTLV-1 prevalence around the world.

The authors note that, in a hospital-based cohort study conducted in Central Australia, 33.6% of Indigenous people tested HTLV-1 positive, with the incidence rate reaching 48.5% in older men.

Research has suggested that, in Brazil, the HTLV-1 prevalence rate is 1.8% in the general population, 1.3% in blood donors in certain regions, and 1.05% in pregnant women.

It is estimated that nearly 1 million people are HTLV-1-positive in Japan, and 850,000 to 1.7 million people in Nigeria are infected with the virus.

In Gabon, the HTLV-1 prevalence in adults is believed to be 5% to 10%. And in Central African Republic, 7% of older, female Pygmies in the southern region were found to be infected with HTLV-1.

Studies have indicated that 6.1% of the general population in Jamaica is positive for HTLV-1, and other Caribbean islands have similar prevalence rates.

The authors note that HTLV-1 and -2 have also been detected in non-endemic areas due to migration and sexual transmission.

It is estimated that 20,000 to 30,000 people are infected with HTLV-1 in the UK, and 10,000 to 25,000 people are infected in metropolitan France.

Other estimates suggest that 266,000 people are infected with HTLV-1 or -2 in the US, and 3600 people with HTLV-1 associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) remain undiagnosed.

“The general neglect, globally, of the importance of HTLV-1 as a sexually transmitted infection that causes a range of debilitating inflammatory diseases does our patients, who request a sexual health screen, a disservice,” said Graham P. Taylor, MDMB, DSc, a professor at Imperial College London in the UK.

“It is also important to recognize the importance of mother-to-child transmission of HTLV-1 in the development of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) decades later. Despite the availability of highly sensitive and specific diagnostic tests for infection and a proven intervention, except for Japan, there are no antenatal screening programs. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of such programs should now be a priority.”

“To prevent mother-to-child infection, the Japanese government has been offering HTLV-1 screening for all pregnant women without cost,” noted Yoshi Yamano, MD, PhD, a professor at St. Marianna University School of Medicine in Kawasaki, Japan.

“Taking a leadership role to promote research, it also provides grants for clinical trials and patient registries focused on ATLL and HAM/TSP.”

Preventing transmission

The letter outlines 5 strategies to prevent or reduce transmission of HTLV-1. The authors recommend:

- Protecting the sexually active population with routine HTLV-1 testing in sexual health clinics and through promotion of CMPC—Counsel & Monitor HTLV-1-positive patients, notify Partners, and promote Condom usage

- Protecting blood and organ donors and recipients by testing for HTLV, avoiding use of products that may be infected, and promoting CMPC

- Protecting mothers, babies, and fathers via routine antenatal care testing, advising HTLV-1-positive mothers against breastfeeding (when feasible), and promoting CMPC

- Protecting injectable drug users by promoting HTLV-1 testing, providing safe needles through needle exchange program, and promoting CMPC

- Supporting the general population and healthcare providers by providing access to an up-to-date WHO HTLV-1 Fact Sheet that can help healthcare providers diagnose HTLV-1 and related diseases and help patients protect themselves from HTLV-1.

“This virus has been underestimated since the time of its discovery perhaps because it is restricted to certain regions or because it is not terribly infectious,” said William Hall, MD, PhD, co-founder of GVN and a professor at the University College Dublin in Ireland.

“However, for decades, it has been known that HTLV-1 is highly carcinogenic and causes severe paralytic neurologic disease and immune disorders that can lead to bacterial infections. It is time that the WHO publicize prevention strategies against this devastating virus.”

*GVN is an international coalition of medical virologists dedicated to identifying, researching, fighting, and preventing current and emerging pandemic viruses that pose a threat to public health.

FDA expands fingolimod's indications to treat relapsing MS in pediatric patients

Pediatric patients with

The Food and Drug Administration approved on May 11 an expanded indication of the drug to allow it to be used to treat relapsing MS in children and adolescents age 10 and older. Gilenya was first approved by FDA to treat adults with relapsing MS in 2010.

“For the first time, we have an FDA-approved treatment specifically for children and adolescents with multiple sclerosis,” Billy Dunn, MD, director of the Division of Neurology Products in the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “This represents an important and needed advance in the care of pediatric patients with multiple sclerosis.”

Side effects for fingolimod in pediatric trial participants were similar to those experienced in adults, the most common of which include headache, liver enzyme elevation, diarrhea, cough, flu, sinusitis, back pain, abdominal pain, and pain in extremities. The drug must be dispensed with a medication guide that describes the product’s more serious risks.

The FDA, which granted the product a priority review and breakthrough designation for this indication, noted that 2%-5% of people with MS have symptoms onset before age 18 and suggested that 8,000-10,000 children and adolescents in the United States suffer from the disease.

The clinical trial evaluating the drug included 214 patients aged 10-17 years and compared fingolimod with interferon beta-1a. In that study, the FDA stated that 86% of patients receiving fingolimod remained relapse-free after 24 months of treatment, compared with 46% of those treated with interferon beta-1a.

Pediatric patients with

The Food and Drug Administration approved on May 11 an expanded indication of the drug to allow it to be used to treat relapsing MS in children and adolescents age 10 and older. Gilenya was first approved by FDA to treat adults with relapsing MS in 2010.

“For the first time, we have an FDA-approved treatment specifically for children and adolescents with multiple sclerosis,” Billy Dunn, MD, director of the Division of Neurology Products in the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “This represents an important and needed advance in the care of pediatric patients with multiple sclerosis.”

Side effects for fingolimod in pediatric trial participants were similar to those experienced in adults, the most common of which include headache, liver enzyme elevation, diarrhea, cough, flu, sinusitis, back pain, abdominal pain, and pain in extremities. The drug must be dispensed with a medication guide that describes the product’s more serious risks.

The FDA, which granted the product a priority review and breakthrough designation for this indication, noted that 2%-5% of people with MS have symptoms onset before age 18 and suggested that 8,000-10,000 children and adolescents in the United States suffer from the disease.

The clinical trial evaluating the drug included 214 patients aged 10-17 years and compared fingolimod with interferon beta-1a. In that study, the FDA stated that 86% of patients receiving fingolimod remained relapse-free after 24 months of treatment, compared with 46% of those treated with interferon beta-1a.

Pediatric patients with

The Food and Drug Administration approved on May 11 an expanded indication of the drug to allow it to be used to treat relapsing MS in children and adolescents age 10 and older. Gilenya was first approved by FDA to treat adults with relapsing MS in 2010.

“For the first time, we have an FDA-approved treatment specifically for children and adolescents with multiple sclerosis,” Billy Dunn, MD, director of the Division of Neurology Products in the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “This represents an important and needed advance in the care of pediatric patients with multiple sclerosis.”

Side effects for fingolimod in pediatric trial participants were similar to those experienced in adults, the most common of which include headache, liver enzyme elevation, diarrhea, cough, flu, sinusitis, back pain, abdominal pain, and pain in extremities. The drug must be dispensed with a medication guide that describes the product’s more serious risks.

The FDA, which granted the product a priority review and breakthrough designation for this indication, noted that 2%-5% of people with MS have symptoms onset before age 18 and suggested that 8,000-10,000 children and adolescents in the United States suffer from the disease.

The clinical trial evaluating the drug included 214 patients aged 10-17 years and compared fingolimod with interferon beta-1a. In that study, the FDA stated that 86% of patients receiving fingolimod remained relapse-free after 24 months of treatment, compared with 46% of those treated with interferon beta-1a.

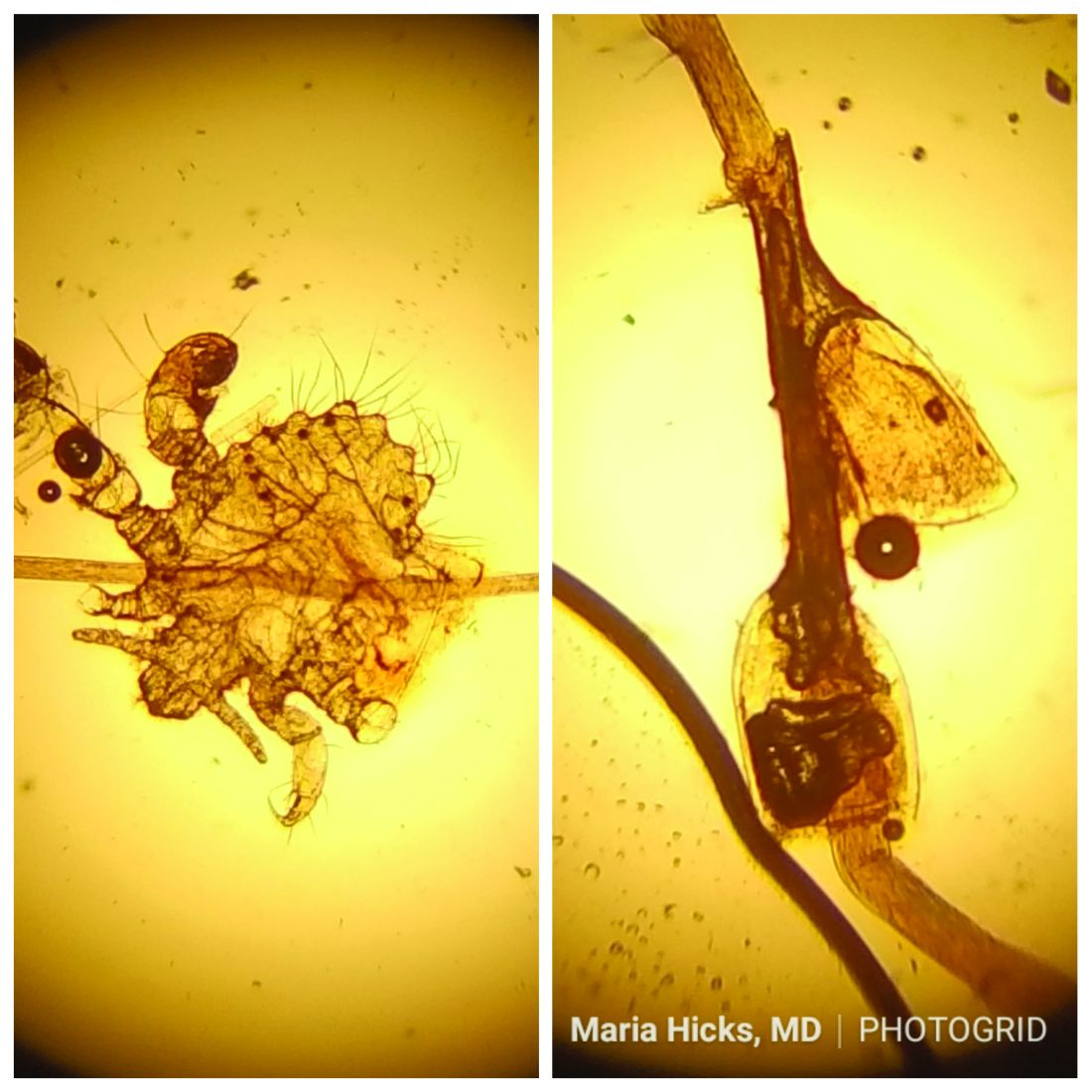

Make the Diagnosis - May 2018

and through close skin contact, as well as contaminated clothes and bedding. Adult lice can live up to 36 hours away from its host. Pubic areas most commonly are affected, although other hair-bearing parts of the body often are affected, including eyelashes.

Pruritus can be severe. Secondary bacterial infections may occur as maculae ceruleae, or blue-colored macules, on the skin. The lice are visible to the naked eye and are approximately 1 mm in length. They have a crablike appearance, six legs, and a wide body. Nits may be present on the hair shaft. Unlike hair casts, which can be moved up and down along the hair shaft, nits firmly adhere to the hair. Diagnosis should prompt a workup for other sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.

Treatment for patients and their sexual partners include permethrin topically; and laundering of clothing and bedding. Lice on the eyelashes can be treated with 8 days of twice-daily applications of petrolatum. Ivermectin can be used when topical therapy fails, although this is an off-label treatment (not approved by the Food and Drug Administration).

Pediculosis corporis – body lice or clothing lice – is also known as “vagabond’s disease” and is caused by Pediculus humanus var corporis. Body lice lay their eggs in clothing seams and can live in clothing for up to 1 month without feeding on human blood. Often homeless individuals and those living in overcrowded areas can be affected. The louse and nits also are visible to the naked eye. They have a longer, narrower body than Phthirus pubis and are more similar in appearance to head lice. They rarely are found on the skin.

Body lice may carry disease such as epidemic typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever or endocarditis. Permethrin is the most widely used treatment to kill both lice and ova. Other treatments include Malathion, Lindane, and Crotamiton. Clothing and bedding should be laundered.

Scabies is a mite infestation caused by Sarcoptes scabiei. Unlike lice, scabies often affects the hands and feet. Characteristic linear burrows may be seen in the finger web spaces. The circle of Hebra describes the areas commonly infected by mites: axillae, antecubital fossa, wrists, hands, and the groin. Pruritus may be severe and worse at night. Patients may be afflicted with both lice and scabies at the same time. Mites are not visible to the naked eye but can be seen microscopically. Topical permethrin cream is used most often for treatment. All household contacts should be treated at the same time. As in louse infestations, clothing and bedding should be laundered. Ivermectin can be used for crusted scabies, although this is an off-label treatment.

This case and photo were submitted by Maria Hicks, MD, Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery, Tampa, and Dr. Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

and through close skin contact, as well as contaminated clothes and bedding. Adult lice can live up to 36 hours away from its host. Pubic areas most commonly are affected, although other hair-bearing parts of the body often are affected, including eyelashes.

Pruritus can be severe. Secondary bacterial infections may occur as maculae ceruleae, or blue-colored macules, on the skin. The lice are visible to the naked eye and are approximately 1 mm in length. They have a crablike appearance, six legs, and a wide body. Nits may be present on the hair shaft. Unlike hair casts, which can be moved up and down along the hair shaft, nits firmly adhere to the hair. Diagnosis should prompt a workup for other sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.

Treatment for patients and their sexual partners include permethrin topically; and laundering of clothing and bedding. Lice on the eyelashes can be treated with 8 days of twice-daily applications of petrolatum. Ivermectin can be used when topical therapy fails, although this is an off-label treatment (not approved by the Food and Drug Administration).

Pediculosis corporis – body lice or clothing lice – is also known as “vagabond’s disease” and is caused by Pediculus humanus var corporis. Body lice lay their eggs in clothing seams and can live in clothing for up to 1 month without feeding on human blood. Often homeless individuals and those living in overcrowded areas can be affected. The louse and nits also are visible to the naked eye. They have a longer, narrower body than Phthirus pubis and are more similar in appearance to head lice. They rarely are found on the skin.

Body lice may carry disease such as epidemic typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever or endocarditis. Permethrin is the most widely used treatment to kill both lice and ova. Other treatments include Malathion, Lindane, and Crotamiton. Clothing and bedding should be laundered.

Scabies is a mite infestation caused by Sarcoptes scabiei. Unlike lice, scabies often affects the hands and feet. Characteristic linear burrows may be seen in the finger web spaces. The circle of Hebra describes the areas commonly infected by mites: axillae, antecubital fossa, wrists, hands, and the groin. Pruritus may be severe and worse at night. Patients may be afflicted with both lice and scabies at the same time. Mites are not visible to the naked eye but can be seen microscopically. Topical permethrin cream is used most often for treatment. All household contacts should be treated at the same time. As in louse infestations, clothing and bedding should be laundered. Ivermectin can be used for crusted scabies, although this is an off-label treatment.

This case and photo were submitted by Maria Hicks, MD, Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery, Tampa, and Dr. Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

and through close skin contact, as well as contaminated clothes and bedding. Adult lice can live up to 36 hours away from its host. Pubic areas most commonly are affected, although other hair-bearing parts of the body often are affected, including eyelashes.

Pruritus can be severe. Secondary bacterial infections may occur as maculae ceruleae, or blue-colored macules, on the skin. The lice are visible to the naked eye and are approximately 1 mm in length. They have a crablike appearance, six legs, and a wide body. Nits may be present on the hair shaft. Unlike hair casts, which can be moved up and down along the hair shaft, nits firmly adhere to the hair. Diagnosis should prompt a workup for other sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.

Treatment for patients and their sexual partners include permethrin topically; and laundering of clothing and bedding. Lice on the eyelashes can be treated with 8 days of twice-daily applications of petrolatum. Ivermectin can be used when topical therapy fails, although this is an off-label treatment (not approved by the Food and Drug Administration).

Pediculosis corporis – body lice or clothing lice – is also known as “vagabond’s disease” and is caused by Pediculus humanus var corporis. Body lice lay their eggs in clothing seams and can live in clothing for up to 1 month without feeding on human blood. Often homeless individuals and those living in overcrowded areas can be affected. The louse and nits also are visible to the naked eye. They have a longer, narrower body than Phthirus pubis and are more similar in appearance to head lice. They rarely are found on the skin.

Body lice may carry disease such as epidemic typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever or endocarditis. Permethrin is the most widely used treatment to kill both lice and ova. Other treatments include Malathion, Lindane, and Crotamiton. Clothing and bedding should be laundered.

Scabies is a mite infestation caused by Sarcoptes scabiei. Unlike lice, scabies often affects the hands and feet. Characteristic linear burrows may be seen in the finger web spaces. The circle of Hebra describes the areas commonly infected by mites: axillae, antecubital fossa, wrists, hands, and the groin. Pruritus may be severe and worse at night. Patients may be afflicted with both lice and scabies at the same time. Mites are not visible to the naked eye but can be seen microscopically. Topical permethrin cream is used most often for treatment. All household contacts should be treated at the same time. As in louse infestations, clothing and bedding should be laundered. Ivermectin can be used for crusted scabies, although this is an off-label treatment.

This case and photo were submitted by Maria Hicks, MD, Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery, Tampa, and Dr. Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 40-year-old HIV-positive male presented with a 1-month history of severely pruritic papules on his chest. The patient reported that he "removes bugs" from his skin. Microscopic examination of a hair clipping was performed.

Make the Diagnosis:

Structured PPH management cuts severe hemorrhage

AUSTIN, TEX. – Taking a page from critical care, an obstetrical team that implemented a checklist-based management protocol for postpartum hemorrhage saw a significant drop in severe obstetric hemorrhage, with numeric reductions in other maternal outcomes.

The protocol, piloted in a single hospital, is now being rolled out in all 28 hospitals of a large, multistate health care system.

“Our medical critical care colleagues long ago abandoned the notion that physician judgment should guide the provision of basic and advanced cardiac life support in favor of highly specific and uniform protocols,” wrote first author Rachael Smith, DO, and her coauthors in the poster accompanying the presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“While existing guidelines outlining a general approach to postpartum hemorrhage are useful, recent data suggest that greater specificity is necessary to significantly impact morbidity and mortality,” they wrote.

When comparing outcomes for 9 matched months before and after implementation of the protocol, Dr. Smith and her collaborators found that rates of severe postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), defined as estimated blood loss (EBL) of at least 2,500 cc, were halved, dropping from 18% to 9% (P = .035).

“Patients with life-threatening illnesses seem to do better when their providers are following very structured, regimented protocols, and [advanced cardiac life support protocols] is probably the best example of that,” said Ms. Hermann.

They then produced a training video to educate nursing and house staff and attending physicians about the new checklist-based protocol. In this way, each team member would understand the rationale behind the checklist, know the steps in the care pathway, and understand his or her specific role.

The protocol, which begins when uterine atony is suspected, first calls the physician to the patient room, along with a second nurse to be the recorder and timekeeper. Among other duties, this individual tracks blood loss during a maternal bleeding event, weighing linens and sponges, and alerting the team when EBL exceeds 500, 1,000, and 1,500 cc, or when pulse or blood pressure fall outside of designated parameters.

“Having a second nurse in the room who is keeping the team on track, saying ‘Hey, we’re at this much blood loss; these are the next steps,’ and who is recording everything” can avert the sense of chaos that sometimes occurs in critical scenarios, said Ms. Hermann.

When stage 1 PPH (EBL of at least 500 cc) has occurred, a team lead is called. At this point, a PPH cart containing necessary equipment and medication, including uterotonics, is brought to the room.

Having the uterotonic kit in the room, said Ms. Hermann, is a key component of the protocol. “Having a kit you can wheel into the room, and having everything you need to manage PPH” saves critical time, she said. “The nurses aren’t running back and forth to the Pyxis to get the next uterotonic that you need.”

If EBL of at least 1,500 cc is reached, a third nurse is called and the obstetric rapid-response team is activated, meaning that a code cart and additional supportive equipment are also brought to the patient.

The checklist paperwork lays out all interventions, including uterotonic dosing, timing, and contraindications. It also includes differential diagnoses for PPH, and provides directions for visual estimation of blood loss.

Finally, a structured debrief takes place after each PPH, said Ms. Hermann.

The study included women who experienced PPH during matched 9-month periods before and after the PPH protocol implementation. PPH was defined as EBL of at least 500 cc for vaginal delivery, and 1,000 cc for cesarean delivery. Women were excluded if they delivered before 22 weeks’ gestation, or if there was a diagnosis of or suspicion for placenta accreta, increta, or percreta.

A total of 147 women were in the preintervention group; of these, 98 (66%) had vaginal deliveries. In the postintervention group, 110 out of150 women (73%) had vaginal deliveries.

In addition to the significant reduction in severe PPH that followed implementation of the protocol, numeric reductions were also seen in other surrogate measures of maternal morbidity, including stage 1 hemorrhage, the need for transfusion, surgical interventions, intensive care admissions, and length of stay.

“Across all of these surrogates, we saw an improvement in our postprotocol patients,” said Ms. Hermann. “We think that the reason the rest of them weren’t statistically significant was due to lack of power” in the single-center study, she said. “The clinical trend speaks for itself.”

Once the protocol is rolled out in all 28 hospitals, she anticipates seeing statistics that confirm what the investigators are already seeing clinically.

SOURCE: Smith R et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 26R.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Taking a page from critical care, an obstetrical team that implemented a checklist-based management protocol for postpartum hemorrhage saw a significant drop in severe obstetric hemorrhage, with numeric reductions in other maternal outcomes.

The protocol, piloted in a single hospital, is now being rolled out in all 28 hospitals of a large, multistate health care system.

“Our medical critical care colleagues long ago abandoned the notion that physician judgment should guide the provision of basic and advanced cardiac life support in favor of highly specific and uniform protocols,” wrote first author Rachael Smith, DO, and her coauthors in the poster accompanying the presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“While existing guidelines outlining a general approach to postpartum hemorrhage are useful, recent data suggest that greater specificity is necessary to significantly impact morbidity and mortality,” they wrote.

When comparing outcomes for 9 matched months before and after implementation of the protocol, Dr. Smith and her collaborators found that rates of severe postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), defined as estimated blood loss (EBL) of at least 2,500 cc, were halved, dropping from 18% to 9% (P = .035).

“Patients with life-threatening illnesses seem to do better when their providers are following very structured, regimented protocols, and [advanced cardiac life support protocols] is probably the best example of that,” said Ms. Hermann.

They then produced a training video to educate nursing and house staff and attending physicians about the new checklist-based protocol. In this way, each team member would understand the rationale behind the checklist, know the steps in the care pathway, and understand his or her specific role.

The protocol, which begins when uterine atony is suspected, first calls the physician to the patient room, along with a second nurse to be the recorder and timekeeper. Among other duties, this individual tracks blood loss during a maternal bleeding event, weighing linens and sponges, and alerting the team when EBL exceeds 500, 1,000, and 1,500 cc, or when pulse or blood pressure fall outside of designated parameters.

“Having a second nurse in the room who is keeping the team on track, saying ‘Hey, we’re at this much blood loss; these are the next steps,’ and who is recording everything” can avert the sense of chaos that sometimes occurs in critical scenarios, said Ms. Hermann.

When stage 1 PPH (EBL of at least 500 cc) has occurred, a team lead is called. At this point, a PPH cart containing necessary equipment and medication, including uterotonics, is brought to the room.

Having the uterotonic kit in the room, said Ms. Hermann, is a key component of the protocol. “Having a kit you can wheel into the room, and having everything you need to manage PPH” saves critical time, she said. “The nurses aren’t running back and forth to the Pyxis to get the next uterotonic that you need.”

If EBL of at least 1,500 cc is reached, a third nurse is called and the obstetric rapid-response team is activated, meaning that a code cart and additional supportive equipment are also brought to the patient.

The checklist paperwork lays out all interventions, including uterotonic dosing, timing, and contraindications. It also includes differential diagnoses for PPH, and provides directions for visual estimation of blood loss.

Finally, a structured debrief takes place after each PPH, said Ms. Hermann.

The study included women who experienced PPH during matched 9-month periods before and after the PPH protocol implementation. PPH was defined as EBL of at least 500 cc for vaginal delivery, and 1,000 cc for cesarean delivery. Women were excluded if they delivered before 22 weeks’ gestation, or if there was a diagnosis of or suspicion for placenta accreta, increta, or percreta.

A total of 147 women were in the preintervention group; of these, 98 (66%) had vaginal deliveries. In the postintervention group, 110 out of150 women (73%) had vaginal deliveries.

In addition to the significant reduction in severe PPH that followed implementation of the protocol, numeric reductions were also seen in other surrogate measures of maternal morbidity, including stage 1 hemorrhage, the need for transfusion, surgical interventions, intensive care admissions, and length of stay.

“Across all of these surrogates, we saw an improvement in our postprotocol patients,” said Ms. Hermann. “We think that the reason the rest of them weren’t statistically significant was due to lack of power” in the single-center study, she said. “The clinical trend speaks for itself.”

Once the protocol is rolled out in all 28 hospitals, she anticipates seeing statistics that confirm what the investigators are already seeing clinically.

SOURCE: Smith R et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 26R.

AUSTIN, TEX. – Taking a page from critical care, an obstetrical team that implemented a checklist-based management protocol for postpartum hemorrhage saw a significant drop in severe obstetric hemorrhage, with numeric reductions in other maternal outcomes.

The protocol, piloted in a single hospital, is now being rolled out in all 28 hospitals of a large, multistate health care system.

“Our medical critical care colleagues long ago abandoned the notion that physician judgment should guide the provision of basic and advanced cardiac life support in favor of highly specific and uniform protocols,” wrote first author Rachael Smith, DO, and her coauthors in the poster accompanying the presentation at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“While existing guidelines outlining a general approach to postpartum hemorrhage are useful, recent data suggest that greater specificity is necessary to significantly impact morbidity and mortality,” they wrote.

When comparing outcomes for 9 matched months before and after implementation of the protocol, Dr. Smith and her collaborators found that rates of severe postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), defined as estimated blood loss (EBL) of at least 2,500 cc, were halved, dropping from 18% to 9% (P = .035).

“Patients with life-threatening illnesses seem to do better when their providers are following very structured, regimented protocols, and [advanced cardiac life support protocols] is probably the best example of that,” said Ms. Hermann.

They then produced a training video to educate nursing and house staff and attending physicians about the new checklist-based protocol. In this way, each team member would understand the rationale behind the checklist, know the steps in the care pathway, and understand his or her specific role.

The protocol, which begins when uterine atony is suspected, first calls the physician to the patient room, along with a second nurse to be the recorder and timekeeper. Among other duties, this individual tracks blood loss during a maternal bleeding event, weighing linens and sponges, and alerting the team when EBL exceeds 500, 1,000, and 1,500 cc, or when pulse or blood pressure fall outside of designated parameters.

“Having a second nurse in the room who is keeping the team on track, saying ‘Hey, we’re at this much blood loss; these are the next steps,’ and who is recording everything” can avert the sense of chaos that sometimes occurs in critical scenarios, said Ms. Hermann.

When stage 1 PPH (EBL of at least 500 cc) has occurred, a team lead is called. At this point, a PPH cart containing necessary equipment and medication, including uterotonics, is brought to the room.

Having the uterotonic kit in the room, said Ms. Hermann, is a key component of the protocol. “Having a kit you can wheel into the room, and having everything you need to manage PPH” saves critical time, she said. “The nurses aren’t running back and forth to the Pyxis to get the next uterotonic that you need.”

If EBL of at least 1,500 cc is reached, a third nurse is called and the obstetric rapid-response team is activated, meaning that a code cart and additional supportive equipment are also brought to the patient.

The checklist paperwork lays out all interventions, including uterotonic dosing, timing, and contraindications. It also includes differential diagnoses for PPH, and provides directions for visual estimation of blood loss.

Finally, a structured debrief takes place after each PPH, said Ms. Hermann.

The study included women who experienced PPH during matched 9-month periods before and after the PPH protocol implementation. PPH was defined as EBL of at least 500 cc for vaginal delivery, and 1,000 cc for cesarean delivery. Women were excluded if they delivered before 22 weeks’ gestation, or if there was a diagnosis of or suspicion for placenta accreta, increta, or percreta.

A total of 147 women were in the preintervention group; of these, 98 (66%) had vaginal deliveries. In the postintervention group, 110 out of150 women (73%) had vaginal deliveries.

In addition to the significant reduction in severe PPH that followed implementation of the protocol, numeric reductions were also seen in other surrogate measures of maternal morbidity, including stage 1 hemorrhage, the need for transfusion, surgical interventions, intensive care admissions, and length of stay.

“Across all of these surrogates, we saw an improvement in our postprotocol patients,” said Ms. Hermann. “We think that the reason the rest of them weren’t statistically significant was due to lack of power” in the single-center study, she said. “The clinical trend speaks for itself.”

Once the protocol is rolled out in all 28 hospitals, she anticipates seeing statistics that confirm what the investigators are already seeing clinically.

SOURCE: Smith R et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 26R.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2018

Key clinical point: Indicators of maternal morbidity decreased after a postpartum hemorrhage checklist was implemented.

Major finding: Severe postpartum hemorrhage rates fell from 18% to 9% (P = .035).

Study details: A prospective pre/post implementation study of 297 women experiencing postpartum hemorrhage.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Source: Smith R et al. ACOG 2018, Abstract 26R.

Children with Down syndrome and ALL have good outcomes today

PITTSBURGH – In the current era, children with Down syndrome who have standard risk B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia have event-free and overall survival rates nearly as good as those of other children with standard-risk B–ALL, results of a Children’s Oncology Group study show.

Among 5,311 children enrolled in the COG AALL0331 trial, a study of combination chemotherapy for young patients with newly diagnosed ALL, the 5-year event-free survival (EFS) rate for children with Down syndrome was 86%, compared with 89% for children without Down syndrome (P = .025).

Although the differences in EFS and OS were significant, ”overall in this study, Down syndrome ALL had an excellent outcome that was similar to those patients without Down syndrome,” she said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology.

The trial confirmed her group’s previous finding that there is a low rate of favorable cytogenetic features in patients with Down syndrome ALL; nonetheless, in the current study, 5-year continuous complete remission rates for standard-risk average, low, and high in patients with Down syndrome were similar to those for patients without Down syndrome, she said.

In the trial, patients were treated with a three-drug induction regimen, and following induction were assigned to standard-risk low, average, or high groups based on leukemia genetics and initial response to therapy.

Of the 5,311 children enrolled, 141 (2.7%) had Down syndrome, and these patients received risk-stratified therapy with additional supportive care guidelines, including leucovorin rescue after intrathecal methotrexate until maintenance. The care team strongly encouraged hospitalizations during high-risk blocks for this subgroup of patients until they experienced neutrophil recovery.

At the end of induction, patients who were judged to be standard-risk average were then randomized in a 2x2 design to either standard or intensified consolidation, and to standard interim maintenance with delayed intensification, or to intensified interim maintenance with delayed intensification.

The intensified interim maintenance with delayed intensification randomization was closed in 2008 because of superior results with escalating intravenous methotrexate during interim maintenance for standard-risk ALL patients treated in the CCG 1991 trial. Subsequently, all patients enrolled in AALL0331 received escalating intravenous methotrexate during interim maintenance.

Also in AALL0331, patients with Down syndrome who had standard-high ALL were given intensified consolidation and a single vs. double intensified interim maintenance with delayed intensification; patients without Down syndrome and standard risk high received the double intensified interim maintenance regimen.

Standard-risk low Down syndrome patients and non–Down syndrome patients participated in a randomization to additional pegaspargase doses during consolidation and interim maintenance.

There were no significant differences between patients with or without Down syndrome in the proportion of either rapid or slow early responses. Significantly fewer patients with Down syndrome had standard-risk low disease, and significantly more had average or high-risk disease.