User login

Cooperation can drive T-ALL, study shows

Overexpression of HOXA9 and activated JAK/STAT signaling cooperate to drive the development of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to researchers.

The team found that JAK3 mutations are significantly associated with elevated HOXA9 expression in T-ALL, and co-expression of HOXA9 and JAK3 mutations prompt “rapid” leukemia development in mice.

In addition, STAT5 and HOXA9 occupy similar genetic loci, which results in increased JAK-STAT signaling in leukemia cells.

These discoveries, and results of subsequent experiments, suggested that PIM1 and JAK1 are potential therapeutic targets for T-ALL.

Jan Cools, PhD, of VIB-KU Leuven Center for Cancer Biology in Leuven, Belgium, and his colleagues described this research in Cancer Discovery.

“JAK3/STAT5 mutations are important in ALL since they stimulate the growth of the cells,” Dr Cools said. “[W]e found that JAK3/STAT5 mutations frequently occur together with HOXA9 mutations.”

In analyzing data from 2 cohorts of T-ALL patients, the researchers found that IL7R/JAK/STAT5 mutations were more frequent in HOXA+ cases, and HOXA9 was “the most important upregulated gene of the HOXA cluster.” (HOXA9 expression levels were significantly higher than HOXA10 or HOXA11 levels.)

“We examined the cooperation between JAK3/STAT5 mutation and HOXA9, [and] we observed that HOXA9 boosts the effects of other genes, leading to tumor development,” said study author Charles de Bock, PhD, of VIB-KU Leuven.

“As a result, when JAK3/STAT5 mutations and HOXA9 are both present, leukemia develops more rapidly and aggressively.”

The researchers found that co-expression of HOXA9 and the JAK3 M511I mutation led to rapid leukemia development in mice. Animals with co-expression of HOXA9 and JAK3 (M511I) developed leukemia that was characterized by an increase in peripheral white blood cell counts that exceeded 10,000 cells/mm3 within 30 days.

In addition, these mice had a significant decrease in disease-free survival compared to mice with JAK3 (M511I) alone. The median disease-free survival was 25 days and 126.5 days, respectively (P<0.0001).

Further analysis revealed co-localization of HOXA9 and STAT5. The researchers also found that HOXA9 enhances transcriptional activity of STAT5 in leukemia cells.

The team said this reconfirms STAT5 as “a major central player” in T-ALL, and it suggests that STAT5 target genes such as PIM1 could be therapeutic targets for T-ALL.

To test this theory, the researchers inhibited both PIM1 and JAK1 in JAK/STAT mutant T-ALL. The PIM1 inhibitor AZD1208 and the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib demonstrated synergy and significantly reduced leukemia burden in vivo.

Overexpression of HOXA9 and activated JAK/STAT signaling cooperate to drive the development of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to researchers.

The team found that JAK3 mutations are significantly associated with elevated HOXA9 expression in T-ALL, and co-expression of HOXA9 and JAK3 mutations prompt “rapid” leukemia development in mice.

In addition, STAT5 and HOXA9 occupy similar genetic loci, which results in increased JAK-STAT signaling in leukemia cells.

These discoveries, and results of subsequent experiments, suggested that PIM1 and JAK1 are potential therapeutic targets for T-ALL.

Jan Cools, PhD, of VIB-KU Leuven Center for Cancer Biology in Leuven, Belgium, and his colleagues described this research in Cancer Discovery.

“JAK3/STAT5 mutations are important in ALL since they stimulate the growth of the cells,” Dr Cools said. “[W]e found that JAK3/STAT5 mutations frequently occur together with HOXA9 mutations.”

In analyzing data from 2 cohorts of T-ALL patients, the researchers found that IL7R/JAK/STAT5 mutations were more frequent in HOXA+ cases, and HOXA9 was “the most important upregulated gene of the HOXA cluster.” (HOXA9 expression levels were significantly higher than HOXA10 or HOXA11 levels.)

“We examined the cooperation between JAK3/STAT5 mutation and HOXA9, [and] we observed that HOXA9 boosts the effects of other genes, leading to tumor development,” said study author Charles de Bock, PhD, of VIB-KU Leuven.

“As a result, when JAK3/STAT5 mutations and HOXA9 are both present, leukemia develops more rapidly and aggressively.”

The researchers found that co-expression of HOXA9 and the JAK3 M511I mutation led to rapid leukemia development in mice. Animals with co-expression of HOXA9 and JAK3 (M511I) developed leukemia that was characterized by an increase in peripheral white blood cell counts that exceeded 10,000 cells/mm3 within 30 days.

In addition, these mice had a significant decrease in disease-free survival compared to mice with JAK3 (M511I) alone. The median disease-free survival was 25 days and 126.5 days, respectively (P<0.0001).

Further analysis revealed co-localization of HOXA9 and STAT5. The researchers also found that HOXA9 enhances transcriptional activity of STAT5 in leukemia cells.

The team said this reconfirms STAT5 as “a major central player” in T-ALL, and it suggests that STAT5 target genes such as PIM1 could be therapeutic targets for T-ALL.

To test this theory, the researchers inhibited both PIM1 and JAK1 in JAK/STAT mutant T-ALL. The PIM1 inhibitor AZD1208 and the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib demonstrated synergy and significantly reduced leukemia burden in vivo.

Overexpression of HOXA9 and activated JAK/STAT signaling cooperate to drive the development of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to researchers.

The team found that JAK3 mutations are significantly associated with elevated HOXA9 expression in T-ALL, and co-expression of HOXA9 and JAK3 mutations prompt “rapid” leukemia development in mice.

In addition, STAT5 and HOXA9 occupy similar genetic loci, which results in increased JAK-STAT signaling in leukemia cells.

These discoveries, and results of subsequent experiments, suggested that PIM1 and JAK1 are potential therapeutic targets for T-ALL.

Jan Cools, PhD, of VIB-KU Leuven Center for Cancer Biology in Leuven, Belgium, and his colleagues described this research in Cancer Discovery.

“JAK3/STAT5 mutations are important in ALL since they stimulate the growth of the cells,” Dr Cools said. “[W]e found that JAK3/STAT5 mutations frequently occur together with HOXA9 mutations.”

In analyzing data from 2 cohorts of T-ALL patients, the researchers found that IL7R/JAK/STAT5 mutations were more frequent in HOXA+ cases, and HOXA9 was “the most important upregulated gene of the HOXA cluster.” (HOXA9 expression levels were significantly higher than HOXA10 or HOXA11 levels.)

“We examined the cooperation between JAK3/STAT5 mutation and HOXA9, [and] we observed that HOXA9 boosts the effects of other genes, leading to tumor development,” said study author Charles de Bock, PhD, of VIB-KU Leuven.

“As a result, when JAK3/STAT5 mutations and HOXA9 are both present, leukemia develops more rapidly and aggressively.”

The researchers found that co-expression of HOXA9 and the JAK3 M511I mutation led to rapid leukemia development in mice. Animals with co-expression of HOXA9 and JAK3 (M511I) developed leukemia that was characterized by an increase in peripheral white blood cell counts that exceeded 10,000 cells/mm3 within 30 days.

In addition, these mice had a significant decrease in disease-free survival compared to mice with JAK3 (M511I) alone. The median disease-free survival was 25 days and 126.5 days, respectively (P<0.0001).

Further analysis revealed co-localization of HOXA9 and STAT5. The researchers also found that HOXA9 enhances transcriptional activity of STAT5 in leukemia cells.

The team said this reconfirms STAT5 as “a major central player” in T-ALL, and it suggests that STAT5 target genes such as PIM1 could be therapeutic targets for T-ALL.

To test this theory, the researchers inhibited both PIM1 and JAK1 in JAK/STAT mutant T-ALL. The PIM1 inhibitor AZD1208 and the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib demonstrated synergy and significantly reduced leukemia burden in vivo.

Emotional regulation training lowers risk of adolescents having sex

Emotional regulation (ER) skills training lowers the likelihood that young adolescents with mental health symptoms will have vaginal sex.

“The inclusion of ER training in a small-group behavioral intervention reduced sexual risk behaviors among seventh-graders with suspected mental health symptoms over a 2.5-year follow-up beyond that achieved with more traditional health education,” wrote Chistopher Houck, PhD, and his colleagues at Bradley Hasbro Children’s Research Center, Providence, R.I., in Pediatrics. “This was true across a range of behaviors, such as engaging in fewer condom-less sex acts, being less likely to have multiple partners, and being less likely to use substances before sex.”

Students in the study participated in one of two after school intervention programs, either ER or health promotion (HP). Both programs consisted of 12 twice-weekly, hour-long sessions composed of single-sex groups of 4-8 adolescents. Two follow-up sessions were provided for both groups at 6 and 12 months. Both interventions used identical techniques, such as interactive games, videos, group discussions, and workbook assignments. ER sessions focused more on recognizing feelings, strategies for reducing momentary emotional arousal, and sexual health topics. HP exclusively focused on health topics like sexual risk and substance abuse but did not include emotional education.

During the 30-month study, 63 in the ER group (31%) and 68 students in the HP group (39%) reported having vaginal sex for the first time. This equated to an adjusted hazard ratio that indicated a delay in vaginal sex in the ER group (0.61; 95% confidence interval,0.42-0.89). Overall, students in the ER group were much less likely to endorse risky sexual behaviors than did participants in the HP group: Students in the ER group were less likely to endorse any risky sexual behavior (adjusted odds ratio, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.32-0.84), to support having multiple partners within 6 months (aOR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.30-0.99), and to support the use of drugs before sex (aOR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.23-0.75). Students in the ER group also reported fewer condom-less sex acts, compared with students in the HP group (adjusted rate ratio, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.14-0.90).

According to Dr. Houck and his colleagues, this study had several limitations that are common to sexual risk studies. One limitation is the reliance on self-report data, which can be biased. Dr. Houck and his associates utilized computer-assisted self-interviews to minimize biases. Another, and potentially larger, limitation is that the study was powered to assess delay of vaginal sex. Part of the patient sample was not sexually experienced, which provided less power for comparisons to other sexual behaviors.

Dr. Houck and his colleagues also spoke to the potential that ER training has in reducing risky behaviors of adolescents, as well as the issues in implementing it.

“Because ER is a skill that could influence other adolescent risk behaviors, such as substance use, violence, and truancy, addressing ER during this sensitive period in adolescent development promises significant public health benefits,” they wrote. “The challenge is the scale-up and dissemination of ER interventions. Increasing the reach of programs in which health education is enhanced with emotion education may be an important step toward improving the lives of adolescents because they are prone to beginning risk behavior.”

Dr. Houck and his associates have no relevant financial disclosures. This study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research.

SOURCE: Houck C et al. Pediatrics. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2525.

The work of Houck et al. provides an important contribution in understanding strategies to reduce sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV in adolescents by utilizing emotional regulation skills.

By helping young people understand their emotions and how that relates to behavior in the context of a sexual encounter, the after school intervention program helped teens regulate positive and negative emotions. Specifically, it utilized three strategies: get out, let it out, and think it out. Games and role playing gave teens a chance to practice these strategies in scenarios of varying risk.

Teenagers who underwent emotional regulation training, rather than simply being taught about adolescent health topics, fared much better in reducing the transition to vaginal sex over a 30-month period.

Carol Ford, MD, and her colleague James Jaccard, PhD, pointed out the superiority of the emotional training, compared with just sexual health information.

“Together, these findings reveal the importance of gearing more attention toward emotions and the regulation of emotions when developing interventions aimed at influencing adolescent sexual behavior,” they wrote. “Behavioral decision theory implicates the role of adolescent cognitions about engaging in sex, norms and peer pressure, and adolescent image prototypes surrounding sex.”

More broadly, Dr. Ford and Dr. Jaccard, believe that this research is the beginning to designing better interventions.

“As we come to understand the types of cognitions and emotions that dominate working memory in high-risk sexual situations, we can effectively design interventions that help shape cognitive and affective appraisals and how youth process those appraisals when making choices.”

Carol Ford, MD, is the chief of the Craig-Dalsimer Division of Adolescent Medicine at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; she holds the Orton P. Jackson Endowed Chair in Adolescent Medicine. James Jaccard, PhD, is a professor of social work at New York University Silver School of Social Work. This is a summary of their commentary that accompanied the article by Houck et al. (Pediatrics. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4143). They had no financial disclosures, and there was no external funding.

The work of Houck et al. provides an important contribution in understanding strategies to reduce sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV in adolescents by utilizing emotional regulation skills.

By helping young people understand their emotions and how that relates to behavior in the context of a sexual encounter, the after school intervention program helped teens regulate positive and negative emotions. Specifically, it utilized three strategies: get out, let it out, and think it out. Games and role playing gave teens a chance to practice these strategies in scenarios of varying risk.

Teenagers who underwent emotional regulation training, rather than simply being taught about adolescent health topics, fared much better in reducing the transition to vaginal sex over a 30-month period.

Carol Ford, MD, and her colleague James Jaccard, PhD, pointed out the superiority of the emotional training, compared with just sexual health information.

“Together, these findings reveal the importance of gearing more attention toward emotions and the regulation of emotions when developing interventions aimed at influencing adolescent sexual behavior,” they wrote. “Behavioral decision theory implicates the role of adolescent cognitions about engaging in sex, norms and peer pressure, and adolescent image prototypes surrounding sex.”

More broadly, Dr. Ford and Dr. Jaccard, believe that this research is the beginning to designing better interventions.

“As we come to understand the types of cognitions and emotions that dominate working memory in high-risk sexual situations, we can effectively design interventions that help shape cognitive and affective appraisals and how youth process those appraisals when making choices.”

Carol Ford, MD, is the chief of the Craig-Dalsimer Division of Adolescent Medicine at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; she holds the Orton P. Jackson Endowed Chair in Adolescent Medicine. James Jaccard, PhD, is a professor of social work at New York University Silver School of Social Work. This is a summary of their commentary that accompanied the article by Houck et al. (Pediatrics. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4143). They had no financial disclosures, and there was no external funding.

The work of Houck et al. provides an important contribution in understanding strategies to reduce sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV in adolescents by utilizing emotional regulation skills.

By helping young people understand their emotions and how that relates to behavior in the context of a sexual encounter, the after school intervention program helped teens regulate positive and negative emotions. Specifically, it utilized three strategies: get out, let it out, and think it out. Games and role playing gave teens a chance to practice these strategies in scenarios of varying risk.

Teenagers who underwent emotional regulation training, rather than simply being taught about adolescent health topics, fared much better in reducing the transition to vaginal sex over a 30-month period.

Carol Ford, MD, and her colleague James Jaccard, PhD, pointed out the superiority of the emotional training, compared with just sexual health information.

“Together, these findings reveal the importance of gearing more attention toward emotions and the regulation of emotions when developing interventions aimed at influencing adolescent sexual behavior,” they wrote. “Behavioral decision theory implicates the role of adolescent cognitions about engaging in sex, norms and peer pressure, and adolescent image prototypes surrounding sex.”

More broadly, Dr. Ford and Dr. Jaccard, believe that this research is the beginning to designing better interventions.

“As we come to understand the types of cognitions and emotions that dominate working memory in high-risk sexual situations, we can effectively design interventions that help shape cognitive and affective appraisals and how youth process those appraisals when making choices.”

Carol Ford, MD, is the chief of the Craig-Dalsimer Division of Adolescent Medicine at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; she holds the Orton P. Jackson Endowed Chair in Adolescent Medicine. James Jaccard, PhD, is a professor of social work at New York University Silver School of Social Work. This is a summary of their commentary that accompanied the article by Houck et al. (Pediatrics. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4143). They had no financial disclosures, and there was no external funding.

Emotional regulation (ER) skills training lowers the likelihood that young adolescents with mental health symptoms will have vaginal sex.

“The inclusion of ER training in a small-group behavioral intervention reduced sexual risk behaviors among seventh-graders with suspected mental health symptoms over a 2.5-year follow-up beyond that achieved with more traditional health education,” wrote Chistopher Houck, PhD, and his colleagues at Bradley Hasbro Children’s Research Center, Providence, R.I., in Pediatrics. “This was true across a range of behaviors, such as engaging in fewer condom-less sex acts, being less likely to have multiple partners, and being less likely to use substances before sex.”

Students in the study participated in one of two after school intervention programs, either ER or health promotion (HP). Both programs consisted of 12 twice-weekly, hour-long sessions composed of single-sex groups of 4-8 adolescents. Two follow-up sessions were provided for both groups at 6 and 12 months. Both interventions used identical techniques, such as interactive games, videos, group discussions, and workbook assignments. ER sessions focused more on recognizing feelings, strategies for reducing momentary emotional arousal, and sexual health topics. HP exclusively focused on health topics like sexual risk and substance abuse but did not include emotional education.

During the 30-month study, 63 in the ER group (31%) and 68 students in the HP group (39%) reported having vaginal sex for the first time. This equated to an adjusted hazard ratio that indicated a delay in vaginal sex in the ER group (0.61; 95% confidence interval,0.42-0.89). Overall, students in the ER group were much less likely to endorse risky sexual behaviors than did participants in the HP group: Students in the ER group were less likely to endorse any risky sexual behavior (adjusted odds ratio, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.32-0.84), to support having multiple partners within 6 months (aOR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.30-0.99), and to support the use of drugs before sex (aOR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.23-0.75). Students in the ER group also reported fewer condom-less sex acts, compared with students in the HP group (adjusted rate ratio, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.14-0.90).

According to Dr. Houck and his colleagues, this study had several limitations that are common to sexual risk studies. One limitation is the reliance on self-report data, which can be biased. Dr. Houck and his associates utilized computer-assisted self-interviews to minimize biases. Another, and potentially larger, limitation is that the study was powered to assess delay of vaginal sex. Part of the patient sample was not sexually experienced, which provided less power for comparisons to other sexual behaviors.

Dr. Houck and his colleagues also spoke to the potential that ER training has in reducing risky behaviors of adolescents, as well as the issues in implementing it.

“Because ER is a skill that could influence other adolescent risk behaviors, such as substance use, violence, and truancy, addressing ER during this sensitive period in adolescent development promises significant public health benefits,” they wrote. “The challenge is the scale-up and dissemination of ER interventions. Increasing the reach of programs in which health education is enhanced with emotion education may be an important step toward improving the lives of adolescents because they are prone to beginning risk behavior.”

Dr. Houck and his associates have no relevant financial disclosures. This study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research.

SOURCE: Houck C et al. Pediatrics. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2525.

Emotional regulation (ER) skills training lowers the likelihood that young adolescents with mental health symptoms will have vaginal sex.

“The inclusion of ER training in a small-group behavioral intervention reduced sexual risk behaviors among seventh-graders with suspected mental health symptoms over a 2.5-year follow-up beyond that achieved with more traditional health education,” wrote Chistopher Houck, PhD, and his colleagues at Bradley Hasbro Children’s Research Center, Providence, R.I., in Pediatrics. “This was true across a range of behaviors, such as engaging in fewer condom-less sex acts, being less likely to have multiple partners, and being less likely to use substances before sex.”

Students in the study participated in one of two after school intervention programs, either ER or health promotion (HP). Both programs consisted of 12 twice-weekly, hour-long sessions composed of single-sex groups of 4-8 adolescents. Two follow-up sessions were provided for both groups at 6 and 12 months. Both interventions used identical techniques, such as interactive games, videos, group discussions, and workbook assignments. ER sessions focused more on recognizing feelings, strategies for reducing momentary emotional arousal, and sexual health topics. HP exclusively focused on health topics like sexual risk and substance abuse but did not include emotional education.

During the 30-month study, 63 in the ER group (31%) and 68 students in the HP group (39%) reported having vaginal sex for the first time. This equated to an adjusted hazard ratio that indicated a delay in vaginal sex in the ER group (0.61; 95% confidence interval,0.42-0.89). Overall, students in the ER group were much less likely to endorse risky sexual behaviors than did participants in the HP group: Students in the ER group were less likely to endorse any risky sexual behavior (adjusted odds ratio, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.32-0.84), to support having multiple partners within 6 months (aOR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.30-0.99), and to support the use of drugs before sex (aOR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.23-0.75). Students in the ER group also reported fewer condom-less sex acts, compared with students in the HP group (adjusted rate ratio, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.14-0.90).

According to Dr. Houck and his colleagues, this study had several limitations that are common to sexual risk studies. One limitation is the reliance on self-report data, which can be biased. Dr. Houck and his associates utilized computer-assisted self-interviews to minimize biases. Another, and potentially larger, limitation is that the study was powered to assess delay of vaginal sex. Part of the patient sample was not sexually experienced, which provided less power for comparisons to other sexual behaviors.

Dr. Houck and his colleagues also spoke to the potential that ER training has in reducing risky behaviors of adolescents, as well as the issues in implementing it.

“Because ER is a skill that could influence other adolescent risk behaviors, such as substance use, violence, and truancy, addressing ER during this sensitive period in adolescent development promises significant public health benefits,” they wrote. “The challenge is the scale-up and dissemination of ER interventions. Increasing the reach of programs in which health education is enhanced with emotion education may be an important step toward improving the lives of adolescents because they are prone to beginning risk behavior.”

Dr. Houck and his associates have no relevant financial disclosures. This study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research.

SOURCE: Houck C et al. Pediatrics. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2525.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Emotional regulation (ER) training reduces the likelihood adolescents will have sex.

Major finding: There was a delay in vaginal sex in the ER group (adusted hazard ratio, 0.61; 95% confidence interval, 0.42-0.89), compared with the health promotion group.

Study details: The study included 420 seventh grade students aged 12-14 years from five urban Rhode Island middle schools between September 2009 and February 2012.

Disclosures: Dr. Houck and his associates have no relevant financial disclosures. This study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research.

Source: Houck C et al. Pediatrics. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2525.

Growing mole on breast

The FP recognized this lesion as a congenital nevus.

He was aware that nevi might become more raised during early adulthood, though this was not necessarily a sign of malignant degeneration. He looked at the nevus carefully and saw that it was relatively symmetrical with one predominant color and a light brown coloration on the left edge. (The patient stated it had always been this way.) The surface texture, which could be described as mamillated, was not unusual for congenital nevi. The FP examined the nevus using a dermatoscope and did not see any melanoma-specific structures.

The FP encouraged the patient to monitor the nevus and return for further evaluation if there were any changes or symptoms. He also offered her the option of a biopsy, but stated that it was not medically required. The patient noted that the changes of increased height of the congenital nevus had been very slow over the past 2 years, and she was willing to keep an eye on it. The patient returned in 6 months, and there were no visible changes to the congenital nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this lesion as a congenital nevus.

He was aware that nevi might become more raised during early adulthood, though this was not necessarily a sign of malignant degeneration. He looked at the nevus carefully and saw that it was relatively symmetrical with one predominant color and a light brown coloration on the left edge. (The patient stated it had always been this way.) The surface texture, which could be described as mamillated, was not unusual for congenital nevi. The FP examined the nevus using a dermatoscope and did not see any melanoma-specific structures.

The FP encouraged the patient to monitor the nevus and return for further evaluation if there were any changes or symptoms. He also offered her the option of a biopsy, but stated that it was not medically required. The patient noted that the changes of increased height of the congenital nevus had been very slow over the past 2 years, and she was willing to keep an eye on it. The patient returned in 6 months, and there were no visible changes to the congenital nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this lesion as a congenital nevus.

He was aware that nevi might become more raised during early adulthood, though this was not necessarily a sign of malignant degeneration. He looked at the nevus carefully and saw that it was relatively symmetrical with one predominant color and a light brown coloration on the left edge. (The patient stated it had always been this way.) The surface texture, which could be described as mamillated, was not unusual for congenital nevi. The FP examined the nevus using a dermatoscope and did not see any melanoma-specific structures.

The FP encouraged the patient to monitor the nevus and return for further evaluation if there were any changes or symptoms. He also offered her the option of a biopsy, but stated that it was not medically required. The patient noted that the changes of increased height of the congenital nevus had been very slow over the past 2 years, and she was willing to keep an eye on it. The patient returned in 6 months, and there were no visible changes to the congenital nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Congenital nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:953-957.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Screening blood donations for Zika proved costly, low yield

Testing donated blood for Zika virus in the United States confirmed just 8 authentic cases and cost nearly $42 million over a period of 15 months, investigators reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

That price did not reflect a commercial price hike, said Paula Saá, PhD, of the American Red Cross in Gaithersburg, MD, and her associates. Furthermore, more than half of the Zika cases had a low viral level that might not be infectious.

Among more than 4 million screened donations, 9% were tested in pools. All pooled tests were negative. The other 3.9 million donations were screened individually. Only 160 were positive, and just 6 were confirmed positive on repeat TMA. Two of these six confirmed positives also were RNA-positive on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, while two were equivocal and two were negative. The positive and equivocal donations were negative for Zika immunoglobulin M on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, which indicated acute infections. The RNA-negative infections were IgM-positive, indicating prior infections.

Three more donations were initially positive on TMA, were negative on repeat TMA, and were IgM-positive, bringing the total case count to nine. Among these, two donors had been infected in Florida, six had traveled to Zika-endemic areas, and one had received an experimental Zika vaccine, according to the researchers.

For each detection of authentic Zika virus RNA infection in U.S.-donated blood, testing had cost $5.3 million, they concluded. They called the current FDA recommendation to individually screen all U.S. blood donations for Zika virus “low-yield” and “high cost.” Of three acute infections with enough sample left for pooled testing, all were positive, they noted.

The American Red Cross and Grifols Diagnostic Solutions provided funding. Dr. Saá disclosed research support from Grifols, which makes the TMA test used in the study. She had no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Saá P et al. New Engl J Med. 2018;378:1778-88.

Despite these findings, it would be premature to stop testing U.S. blood donations for Zika virus, wrote Evan M. Bloch, MBChB; Paul M. Ness, MD; Aaron A.R. Tobian, MD, PhD; and Jeremy Sugarman, MD, MPH, in an editorial accompanying the study.

Nonetheless, “actual and perceived risks to the blood supply seem to be conflated,” the experts wrote. They noted that the United States currently has no active areas of Zika virus transmission and that confirmed mosquito-borne, locally acquired infections fell from 226 in 2016 to two the following year.

There is no historical precedent for ending a policy of testing blood donations for pathogens, they added. Consequently, ending widespread screening “may actually prove to be far more challenging than the decision to start.” For now, a precautionary, risk-based approach should entail “continuous review” of screening policies and “reassessment as new data emerge.”

The editorialists are with Johns Hopkins University and Johns Hopkins University’s Bergman Institute of Bioethics, both in Baltimore. They reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments are from their editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018;378:19:1837-41).

Despite these findings, it would be premature to stop testing U.S. blood donations for Zika virus, wrote Evan M. Bloch, MBChB; Paul M. Ness, MD; Aaron A.R. Tobian, MD, PhD; and Jeremy Sugarman, MD, MPH, in an editorial accompanying the study.

Nonetheless, “actual and perceived risks to the blood supply seem to be conflated,” the experts wrote. They noted that the United States currently has no active areas of Zika virus transmission and that confirmed mosquito-borne, locally acquired infections fell from 226 in 2016 to two the following year.

There is no historical precedent for ending a policy of testing blood donations for pathogens, they added. Consequently, ending widespread screening “may actually prove to be far more challenging than the decision to start.” For now, a precautionary, risk-based approach should entail “continuous review” of screening policies and “reassessment as new data emerge.”

The editorialists are with Johns Hopkins University and Johns Hopkins University’s Bergman Institute of Bioethics, both in Baltimore. They reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments are from their editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018;378:19:1837-41).

Despite these findings, it would be premature to stop testing U.S. blood donations for Zika virus, wrote Evan M. Bloch, MBChB; Paul M. Ness, MD; Aaron A.R. Tobian, MD, PhD; and Jeremy Sugarman, MD, MPH, in an editorial accompanying the study.

Nonetheless, “actual and perceived risks to the blood supply seem to be conflated,” the experts wrote. They noted that the United States currently has no active areas of Zika virus transmission and that confirmed mosquito-borne, locally acquired infections fell from 226 in 2016 to two the following year.

There is no historical precedent for ending a policy of testing blood donations for pathogens, they added. Consequently, ending widespread screening “may actually prove to be far more challenging than the decision to start.” For now, a precautionary, risk-based approach should entail “continuous review” of screening policies and “reassessment as new data emerge.”

The editorialists are with Johns Hopkins University and Johns Hopkins University’s Bergman Institute of Bioethics, both in Baltimore. They reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments are from their editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018;378:19:1837-41).

Testing donated blood for Zika virus in the United States confirmed just 8 authentic cases and cost nearly $42 million over a period of 15 months, investigators reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

That price did not reflect a commercial price hike, said Paula Saá, PhD, of the American Red Cross in Gaithersburg, MD, and her associates. Furthermore, more than half of the Zika cases had a low viral level that might not be infectious.

Among more than 4 million screened donations, 9% were tested in pools. All pooled tests were negative. The other 3.9 million donations were screened individually. Only 160 were positive, and just 6 were confirmed positive on repeat TMA. Two of these six confirmed positives also were RNA-positive on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, while two were equivocal and two were negative. The positive and equivocal donations were negative for Zika immunoglobulin M on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, which indicated acute infections. The RNA-negative infections were IgM-positive, indicating prior infections.

Three more donations were initially positive on TMA, were negative on repeat TMA, and were IgM-positive, bringing the total case count to nine. Among these, two donors had been infected in Florida, six had traveled to Zika-endemic areas, and one had received an experimental Zika vaccine, according to the researchers.

For each detection of authentic Zika virus RNA infection in U.S.-donated blood, testing had cost $5.3 million, they concluded. They called the current FDA recommendation to individually screen all U.S. blood donations for Zika virus “low-yield” and “high cost.” Of three acute infections with enough sample left for pooled testing, all were positive, they noted.

The American Red Cross and Grifols Diagnostic Solutions provided funding. Dr. Saá disclosed research support from Grifols, which makes the TMA test used in the study. She had no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Saá P et al. New Engl J Med. 2018;378:1778-88.

Testing donated blood for Zika virus in the United States confirmed just 8 authentic cases and cost nearly $42 million over a period of 15 months, investigators reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

That price did not reflect a commercial price hike, said Paula Saá, PhD, of the American Red Cross in Gaithersburg, MD, and her associates. Furthermore, more than half of the Zika cases had a low viral level that might not be infectious.

Among more than 4 million screened donations, 9% were tested in pools. All pooled tests were negative. The other 3.9 million donations were screened individually. Only 160 were positive, and just 6 were confirmed positive on repeat TMA. Two of these six confirmed positives also were RNA-positive on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, while two were equivocal and two were negative. The positive and equivocal donations were negative for Zika immunoglobulin M on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, which indicated acute infections. The RNA-negative infections were IgM-positive, indicating prior infections.

Three more donations were initially positive on TMA, were negative on repeat TMA, and were IgM-positive, bringing the total case count to nine. Among these, two donors had been infected in Florida, six had traveled to Zika-endemic areas, and one had received an experimental Zika vaccine, according to the researchers.

For each detection of authentic Zika virus RNA infection in U.S.-donated blood, testing had cost $5.3 million, they concluded. They called the current FDA recommendation to individually screen all U.S. blood donations for Zika virus “low-yield” and “high cost.” Of three acute infections with enough sample left for pooled testing, all were positive, they noted.

The American Red Cross and Grifols Diagnostic Solutions provided funding. Dr. Saá disclosed research support from Grifols, which makes the TMA test used in the study. She had no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Saá P et al. New Engl J Med. 2018;378:1778-88.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Individually screening all blood donations for Zika virus was low yield and costly.

Major finding: Testing confirmed only 8 authentic cases and cost nearly $42 million over 15 months.

Study details: Screening and confirmatory testing of 4,325,889 donations of blood in the United States during 2016-2017.

Disclosures: American Red Cross and Grifols Diagnostic Solutions provided funding. Grifols makes a test used in the study. Dr. Saá disclosed research support from Grifols but had no other conflicts of interest.

Source: Saá P et al. New Engl J Med. 2018;378:1778-88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714977

Perianal Extramammary Paget Disease Treated With Topical Imiquimod and Oral Cimetidine

Case Report

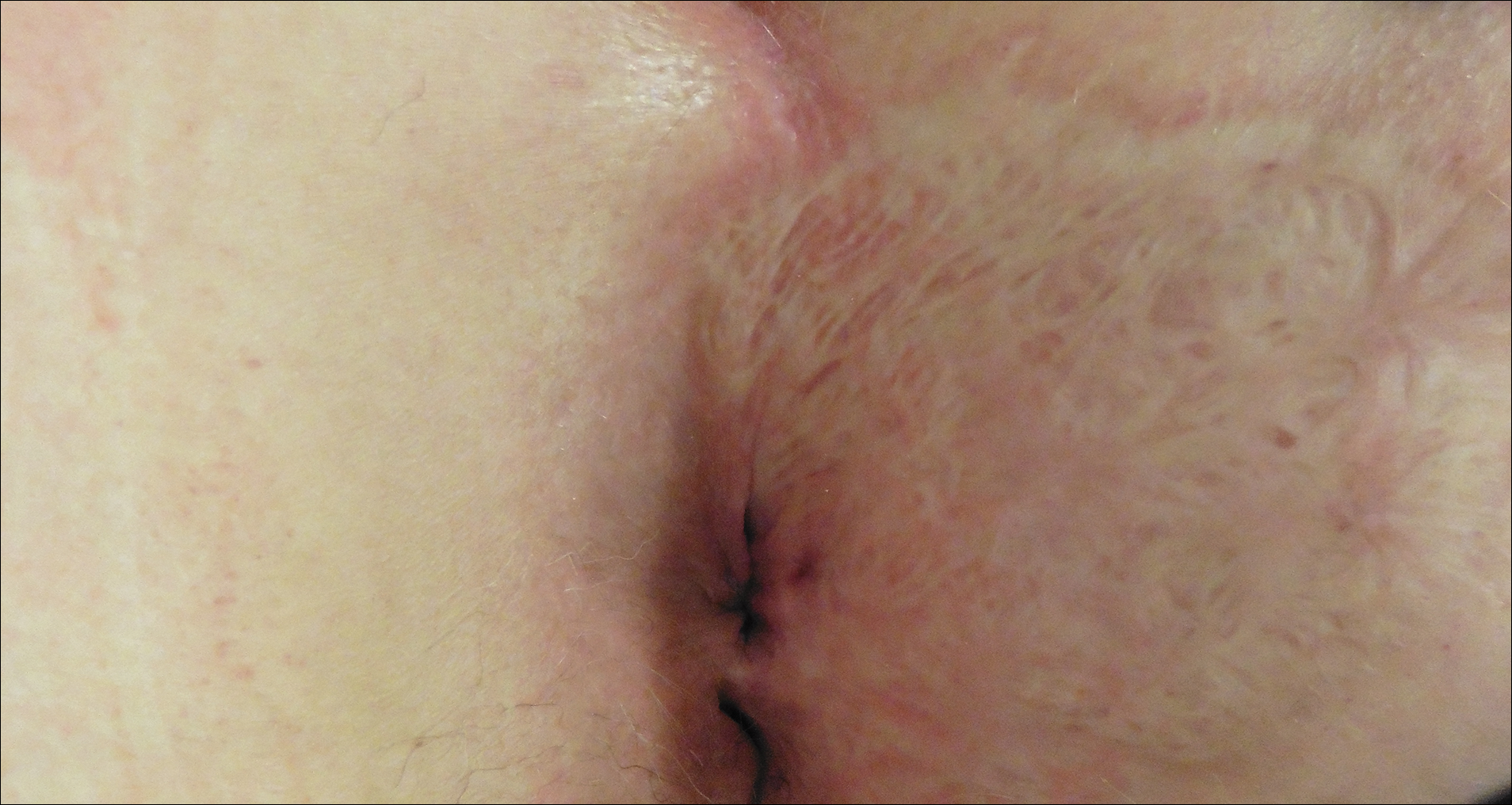

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

Resident Pearls

- Topical imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine can be a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with perianal extramammary Paget disease (EMPD).

- Its antineoplastic and immunomodulatory properties may suggest a role for oral cimetidine as an adjuvant therapy in the treatment of perianal EMPD.

Female physicians face enduring wage gap

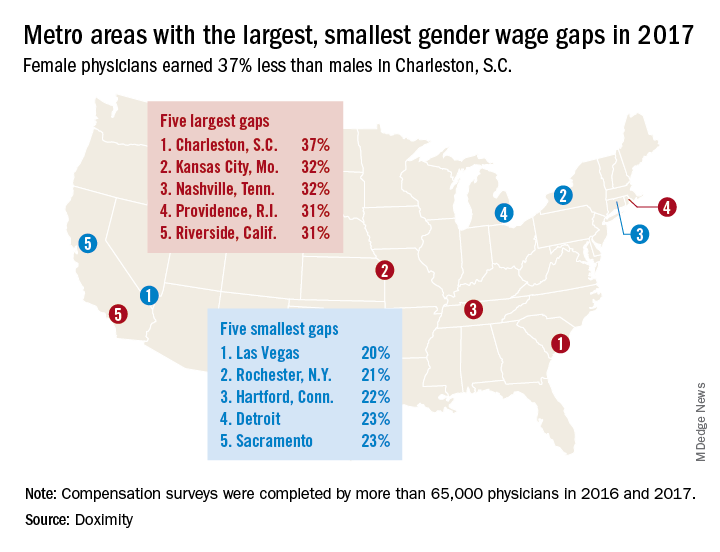

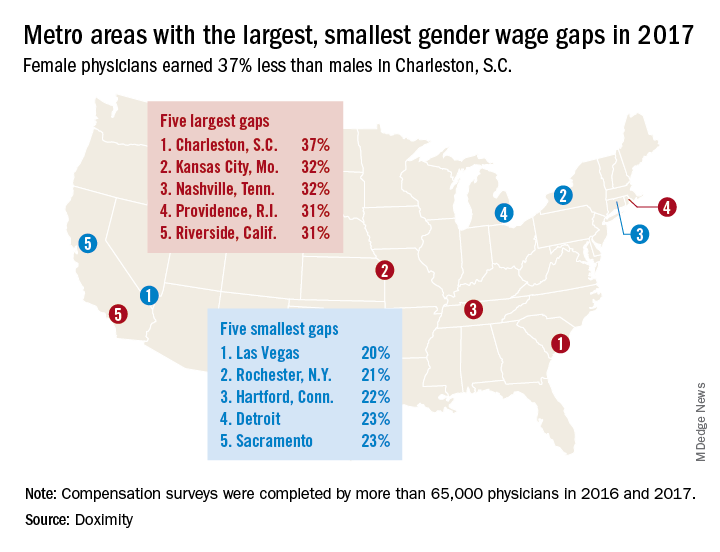

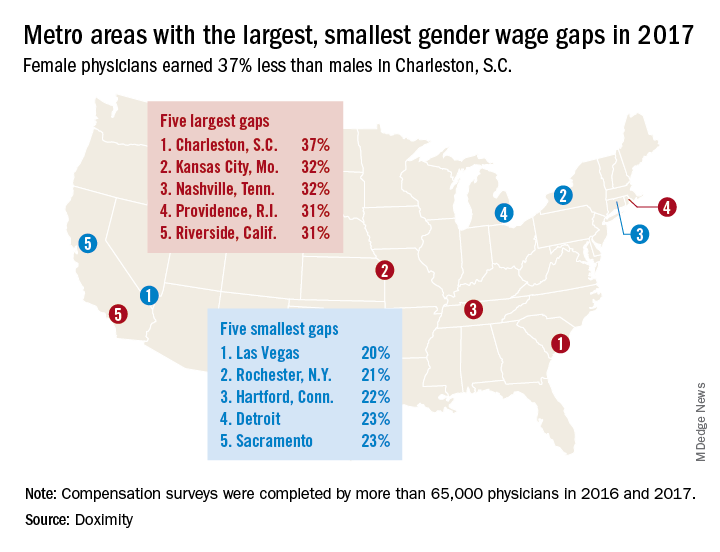

Male physicians make more money than female physicians, and that seems to be a rule with few exceptions. Among the 50 largest metro areas, there were none where women earn as much as men, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.

The metro area that comes the closest is Las Vegas, where female physicians earned 20% less – that works out to $73,654 – than their male counterparts in 2017. Rochester, N.Y., had the smallest gap in terms of dollars ($68,758) and the second-smallest percent difference (21%), Doximity said in its 2018 Physician Compensation Report.

The largest wage gap on both measures can be found in Charleston, S.C., where women earned 37%, or $134,499, less than men in 2017. The other members of the largest-wage-gap club are as follows: Kansas City, Mo., and Nashville, Tenn., both had differences of 32%, and Providence, R.I., and Riverside, Calif., had differences of 31%, Doximity said in the report, which was based on data from “compensation surveys completed in 2016 and 2017 by more than 65,000 full-time, licensed U.S. physicians who practice at least 40 hours per week.”

A quick look at the 2016 data shows that the wage gap between female and male physicians increased from 26.5% to 27.7% in 2017, going from more than $92,000 to $105,000. “Medicine is a highly trained field, and as such, one might expect the gender wage gap to be less prominent here than in other industries. However, the gap endures, despite the level of education required to practice medicine and market forces suggesting that this gap should shrink,” Doximity said.

In a recent issue of AGA Perspectives, Ellen M. Zimmermann, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Women’s Committee, wrote about the need for transparent policies at institutions to help close the gender gap. Read more at http://ow.ly/43If30jTlEc.

Male physicians make more money than female physicians, and that seems to be a rule with few exceptions. Among the 50 largest metro areas, there were none where women earn as much as men, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.

The metro area that comes the closest is Las Vegas, where female physicians earned 20% less – that works out to $73,654 – than their male counterparts in 2017. Rochester, N.Y., had the smallest gap in terms of dollars ($68,758) and the second-smallest percent difference (21%), Doximity said in its 2018 Physician Compensation Report.

The largest wage gap on both measures can be found in Charleston, S.C., where women earned 37%, or $134,499, less than men in 2017. The other members of the largest-wage-gap club are as follows: Kansas City, Mo., and Nashville, Tenn., both had differences of 32%, and Providence, R.I., and Riverside, Calif., had differences of 31%, Doximity said in the report, which was based on data from “compensation surveys completed in 2016 and 2017 by more than 65,000 full-time, licensed U.S. physicians who practice at least 40 hours per week.”

A quick look at the 2016 data shows that the wage gap between female and male physicians increased from 26.5% to 27.7% in 2017, going from more than $92,000 to $105,000. “Medicine is a highly trained field, and as such, one might expect the gender wage gap to be less prominent here than in other industries. However, the gap endures, despite the level of education required to practice medicine and market forces suggesting that this gap should shrink,” Doximity said.

In a recent issue of AGA Perspectives, Ellen M. Zimmermann, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Women’s Committee, wrote about the need for transparent policies at institutions to help close the gender gap. Read more at http://ow.ly/43If30jTlEc.

Male physicians make more money than female physicians, and that seems to be a rule with few exceptions. Among the 50 largest metro areas, there were none where women earn as much as men, according to a new survey by the medical social network Doximity.

The metro area that comes the closest is Las Vegas, where female physicians earned 20% less – that works out to $73,654 – than their male counterparts in 2017. Rochester, N.Y., had the smallest gap in terms of dollars ($68,758) and the second-smallest percent difference (21%), Doximity said in its 2018 Physician Compensation Report.

The largest wage gap on both measures can be found in Charleston, S.C., where women earned 37%, or $134,499, less than men in 2017. The other members of the largest-wage-gap club are as follows: Kansas City, Mo., and Nashville, Tenn., both had differences of 32%, and Providence, R.I., and Riverside, Calif., had differences of 31%, Doximity said in the report, which was based on data from “compensation surveys completed in 2016 and 2017 by more than 65,000 full-time, licensed U.S. physicians who practice at least 40 hours per week.”

A quick look at the 2016 data shows that the wage gap between female and male physicians increased from 26.5% to 27.7% in 2017, going from more than $92,000 to $105,000. “Medicine is a highly trained field, and as such, one might expect the gender wage gap to be less prominent here than in other industries. However, the gap endures, despite the level of education required to practice medicine and market forces suggesting that this gap should shrink,” Doximity said.

In a recent issue of AGA Perspectives, Ellen M. Zimmermann, MD, AGAF, chair of the AGA Women’s Committee, wrote about the need for transparent policies at institutions to help close the gender gap. Read more at http://ow.ly/43If30jTlEc.

Responsive parenting intervention slows weight gain in infancy

TORONTO – Teaching parents of newborns to respond to eating and satiety cues in ways that promote self-regulation was associated with improvements in some weight outcomes at 3 years in a randomized clinical trial.

For the primary outcome of body mass index (BMI) z score at 3 years, a significant difference favoring the responsive parenting (RP) intervention was seen (–0.13 vs. 0.15 for controls; absolute difference, –0.28; P = .04). A longitudinal analysis examining the entire intervention period confirmed that the mean BMI group differences across seven study visits confirmed the effect of the RP intervention on BMI (P less than .001).

“We felt that the BMI z score and longitudinal growth analysis are probably the most sustained effects for an early-life intervention that have been recorded to date,” reported Ian M. Paul, MD, MSc, of Penn State University, Hershey. “While the differences between study groups were modest and not all achieved statistical significance, all favored the responsive-parenting intervention.”

Mean BMI percentile, a secondary outcome, was 47th for the RP group and 54th for controls, narrowly missing statistical significance (P = .07). Similarly, the percent of children deemed overweight at 3 years was 11.2% for the RP group and 19.8% for controls (P = .07), while 2.6% and 7.8%, respectively, were obese (P = .08).

No significant differences were seen in growth-related adverse events, such a weight-for-age less than the 5th percentile. The issue of “inducing” failure-to-thrive with a feeding intervention is a concern, said Dr. Paul, but there was no evidence for it in their study.

“One could question whether [the small differences seen between groups] are clinically significant, but if we look at how small differences have changed in the population over time and how those equate as far as longitudinal risk for cardiovascular outcomes and metabolic syndrome, etc., the small differences [we saw] might be important on a population level,” said Dr. Paul at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

Study details

With upwards of one-quarter of U.S. children aged 2-5 years being overweight or obese, interventions to prevent rapid weight gain and reduce risk for overweight status in infancy are needed, noted Dr. Paul. Another reason to consider very early intervention, he added, is that infancy is a time of both “metabolic and behavioral plasticity.” However, most efforts to intervene early have, thus far, had limited success.

“Our responses to a baby crying are to feed that baby,” said Dr. Paul. This urge, along with others (such as “clear your plate”), evolved during times of food scarcity but persist now that we have inexpensive and palatable food, and promote rapid infant weight gain and increased obesity risk.

An alternative to those traditional parenting practices are responsive feeding and responsive parenting, he explained. “Responsive feeding and parenting requires prompt, developmentally appropriate responses to a child’s behaviors including hunger and satiety cues.”

In other studies, RP has been shown to foster cognitive, social, and emotional development. “The question we had was: Can responsive parenting reduce obesity risk?” he said.

The INSIGHT (Intervention Nurses Start Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories) study is an ongoing, randomized clinical trial started in January 2012 comparing an RP intervention designed to prevent childhood obesity with a safety control, with the interventions matched on intensity and length.