User login

A Peek at Our May 2018 Issue

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Gone but Not Forgotten: Acute Appendicitis Postappendectomy

Acute appendicitis is a common condition emergency physicians (EPs) encounter in the ED, and it is also one of the most common general surgeries.1Although stump appendicitis is a rare, long-term complication of appendectomy, it should always be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with right-sided abdominal pain and a history of appendectomy. Delays in diagnosing stump appendicitis can lead to perforation, gangrene, and sepsis.2

Case

A 33-year-old previously healthy man, whose medical history was significant for an appendectomy 6 months earlier, presented to the ED with progressive and worsening right lower quadrant abdominal pain that radiated to his right testicle. The patient stated that the pain started 3 days prior while he was lifting a bale of hay. He further noted having a fever of 102oF, nausea, and vomiting hours prior to his arrival at the ED.

Upon presentation, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 89 beats/min; respiratory rate, 17 breaths/min; blood pressure, 132/84 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.9°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Physical examination revealed exquisite tenderness in the right lower quadrant and suprapubic region. The testicular examination and the remainder of the physical examination were normal. Laboratory evaluation included a complete blood count and urinalysis, the results of which were significant for an elevated white blood cell count of 17 x 109/Lmicroscopic hematuria, trace leukocyte esterase, and ketones.

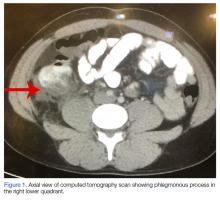

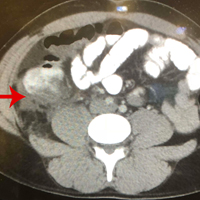

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast demonstrated a phlegmonous process surrounding the surgical site, which was concerning for stump appendicitis. The terminal ilium and colon were noted to be normal (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was started on IV fluids and IV antibiotics, and received Zosyn in the ED. Surgical service was consulted, and the patient was admitted to the hospital where he continued nonoperative treatment with IV ciprofloxacin and metronidazole. The patient was discharged home on hospital day 3 without further complication. A repeat CT scan was taken of the abdomen and pelvis 3 weeks after discharge, and demonstrated complete resolution of the inflammatory process at the appendiceal stump with chronic scarring.

Discussion

Approximately 7% of patients who present to the ED with abdominal pain are diagnosed with appendicitis.3 Although appendectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures, stump appendicitis is a rare postsurgical complication, with a reported incidence of 1 in 50,000 cases.4,5

Stump appendicitis is an acute inflammation of the residual appendicular stump; the incidence of stump perforation is approximately 60% to 70%.4,6 Thus, stump appendicitis has a high morbidity and complication rate. Unfortunately, though stump appendicitis is a condition in which timely diagnosis and intervention are essential to prevent morbidity, due to its rarity and low occurrence, there is often a delay in diagnosis. It is therefore important that EPs include stump appendicitis in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with right-sided abdominal pain and a history of appendectomy.

Stump appendicitis was initially described by Rose et al in 1945.2 This condition is underreported, and the exact causes are still unclear.Of the reported cases of stump appendicitis, approximately 66% developed following an open surgical appendectomy;5 therefore, complicated surgery or difficult dissection of the appendix is considered a risk factor for stump appendicitis. Conversely, adequate visualization of the appendiceal base during appendectomy and a stump measuring less than 3 to 5 mm1,4 are associated with a lower risk for stump appendicitis.

Stump appendicitis can develop as early as a few days postappendectomy or as late as 50 years postappendectomy. Patients with stump appendicitis present with signs and symptoms similar to that of acute appendicitis.2,4,7 Diagnosis can be made through ultrasound or CT studies, though CT is the preferred modality due to its higher specificity and ability to exclude other causes of right-sided abdominal pain.4

Management

Surgical intervention to remove the appendiceal stump is typically the preferred treatment. However, as with our patient, cases of successful and uncomplicated medical management have been reported.1,2,4

Conclusion

While stump appendicitis is rare, there has been a rise in the number of reported cases over the past few years due to the increasing use and availability of CT.4 The diagnosis of stump appendicitis is time-critical to prevent associated complications of stump perforation, gangrene, and sepsis. It is therefore imperative that EPs consider this

1. Shah T, Gupta RK, Karkee RJ, Agarwal CS. Recurrent pain abdomen following appendectomy: stump appendicitis, a surgeon’s dilemma. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(3):215-217. doi:10.1002/ccr3.781.

2. Giwa A, Reyes M. Three times a charm…a case of repeat appendicitis status post two prior appendectomies. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(3):528.e1-528.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.12.024.

3. Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910-925.

4. Hendahewa R, Shekhar A, Ratnayake S. The dilemma of stump appendicitis—a case report and literature review. Int J Surg. Case Rep. 2015;14:101-103. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.017.

5. Liang MK, Lo HG, Marks JL. Stump appendicitis: a comprehensive review of literature. Am Surg. 2006;72(2):162-166.

6. Parthsarathi R, Jankar SV, Chittawadgi B, et al. Laraposcopic management of symptomatic residual appendicular tip: a rare case report. J Minim Access Surg. 2017;13(2):154-156. doi:10.4103/0972-9941.199610.

7. Kanona H, Al Samaraee A, Nice C, Bhattacharya V. Stump appendicitis: a review. Int J Surg. 2012;10(9):425-428. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.07.007.

Acute appendicitis is a common condition emergency physicians (EPs) encounter in the ED, and it is also one of the most common general surgeries.1Although stump appendicitis is a rare, long-term complication of appendectomy, it should always be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with right-sided abdominal pain and a history of appendectomy. Delays in diagnosing stump appendicitis can lead to perforation, gangrene, and sepsis.2

Case

A 33-year-old previously healthy man, whose medical history was significant for an appendectomy 6 months earlier, presented to the ED with progressive and worsening right lower quadrant abdominal pain that radiated to his right testicle. The patient stated that the pain started 3 days prior while he was lifting a bale of hay. He further noted having a fever of 102oF, nausea, and vomiting hours prior to his arrival at the ED.

Upon presentation, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 89 beats/min; respiratory rate, 17 breaths/min; blood pressure, 132/84 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.9°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Physical examination revealed exquisite tenderness in the right lower quadrant and suprapubic region. The testicular examination and the remainder of the physical examination were normal. Laboratory evaluation included a complete blood count and urinalysis, the results of which were significant for an elevated white blood cell count of 17 x 109/Lmicroscopic hematuria, trace leukocyte esterase, and ketones.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast demonstrated a phlegmonous process surrounding the surgical site, which was concerning for stump appendicitis. The terminal ilium and colon were noted to be normal (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was started on IV fluids and IV antibiotics, and received Zosyn in the ED. Surgical service was consulted, and the patient was admitted to the hospital where he continued nonoperative treatment with IV ciprofloxacin and metronidazole. The patient was discharged home on hospital day 3 without further complication. A repeat CT scan was taken of the abdomen and pelvis 3 weeks after discharge, and demonstrated complete resolution of the inflammatory process at the appendiceal stump with chronic scarring.

Discussion

Approximately 7% of patients who present to the ED with abdominal pain are diagnosed with appendicitis.3 Although appendectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures, stump appendicitis is a rare postsurgical complication, with a reported incidence of 1 in 50,000 cases.4,5

Stump appendicitis is an acute inflammation of the residual appendicular stump; the incidence of stump perforation is approximately 60% to 70%.4,6 Thus, stump appendicitis has a high morbidity and complication rate. Unfortunately, though stump appendicitis is a condition in which timely diagnosis and intervention are essential to prevent morbidity, due to its rarity and low occurrence, there is often a delay in diagnosis. It is therefore important that EPs include stump appendicitis in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with right-sided abdominal pain and a history of appendectomy.

Stump appendicitis was initially described by Rose et al in 1945.2 This condition is underreported, and the exact causes are still unclear.Of the reported cases of stump appendicitis, approximately 66% developed following an open surgical appendectomy;5 therefore, complicated surgery or difficult dissection of the appendix is considered a risk factor for stump appendicitis. Conversely, adequate visualization of the appendiceal base during appendectomy and a stump measuring less than 3 to 5 mm1,4 are associated with a lower risk for stump appendicitis.

Stump appendicitis can develop as early as a few days postappendectomy or as late as 50 years postappendectomy. Patients with stump appendicitis present with signs and symptoms similar to that of acute appendicitis.2,4,7 Diagnosis can be made through ultrasound or CT studies, though CT is the preferred modality due to its higher specificity and ability to exclude other causes of right-sided abdominal pain.4

Management

Surgical intervention to remove the appendiceal stump is typically the preferred treatment. However, as with our patient, cases of successful and uncomplicated medical management have been reported.1,2,4

Conclusion

While stump appendicitis is rare, there has been a rise in the number of reported cases over the past few years due to the increasing use and availability of CT.4 The diagnosis of stump appendicitis is time-critical to prevent associated complications of stump perforation, gangrene, and sepsis. It is therefore imperative that EPs consider this

Acute appendicitis is a common condition emergency physicians (EPs) encounter in the ED, and it is also one of the most common general surgeries.1Although stump appendicitis is a rare, long-term complication of appendectomy, it should always be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with right-sided abdominal pain and a history of appendectomy. Delays in diagnosing stump appendicitis can lead to perforation, gangrene, and sepsis.2

Case

A 33-year-old previously healthy man, whose medical history was significant for an appendectomy 6 months earlier, presented to the ED with progressive and worsening right lower quadrant abdominal pain that radiated to his right testicle. The patient stated that the pain started 3 days prior while he was lifting a bale of hay. He further noted having a fever of 102oF, nausea, and vomiting hours prior to his arrival at the ED.

Upon presentation, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 89 beats/min; respiratory rate, 17 breaths/min; blood pressure, 132/84 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.9°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Physical examination revealed exquisite tenderness in the right lower quadrant and suprapubic region. The testicular examination and the remainder of the physical examination were normal. Laboratory evaluation included a complete blood count and urinalysis, the results of which were significant for an elevated white blood cell count of 17 x 109/Lmicroscopic hematuria, trace leukocyte esterase, and ketones.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast demonstrated a phlegmonous process surrounding the surgical site, which was concerning for stump appendicitis. The terminal ilium and colon were noted to be normal (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was started on IV fluids and IV antibiotics, and received Zosyn in the ED. Surgical service was consulted, and the patient was admitted to the hospital where he continued nonoperative treatment with IV ciprofloxacin and metronidazole. The patient was discharged home on hospital day 3 without further complication. A repeat CT scan was taken of the abdomen and pelvis 3 weeks after discharge, and demonstrated complete resolution of the inflammatory process at the appendiceal stump with chronic scarring.

Discussion

Approximately 7% of patients who present to the ED with abdominal pain are diagnosed with appendicitis.3 Although appendectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures, stump appendicitis is a rare postsurgical complication, with a reported incidence of 1 in 50,000 cases.4,5

Stump appendicitis is an acute inflammation of the residual appendicular stump; the incidence of stump perforation is approximately 60% to 70%.4,6 Thus, stump appendicitis has a high morbidity and complication rate. Unfortunately, though stump appendicitis is a condition in which timely diagnosis and intervention are essential to prevent morbidity, due to its rarity and low occurrence, there is often a delay in diagnosis. It is therefore important that EPs include stump appendicitis in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with right-sided abdominal pain and a history of appendectomy.

Stump appendicitis was initially described by Rose et al in 1945.2 This condition is underreported, and the exact causes are still unclear.Of the reported cases of stump appendicitis, approximately 66% developed following an open surgical appendectomy;5 therefore, complicated surgery or difficult dissection of the appendix is considered a risk factor for stump appendicitis. Conversely, adequate visualization of the appendiceal base during appendectomy and a stump measuring less than 3 to 5 mm1,4 are associated with a lower risk for stump appendicitis.

Stump appendicitis can develop as early as a few days postappendectomy or as late as 50 years postappendectomy. Patients with stump appendicitis present with signs and symptoms similar to that of acute appendicitis.2,4,7 Diagnosis can be made through ultrasound or CT studies, though CT is the preferred modality due to its higher specificity and ability to exclude other causes of right-sided abdominal pain.4

Management

Surgical intervention to remove the appendiceal stump is typically the preferred treatment. However, as with our patient, cases of successful and uncomplicated medical management have been reported.1,2,4

Conclusion

While stump appendicitis is rare, there has been a rise in the number of reported cases over the past few years due to the increasing use and availability of CT.4 The diagnosis of stump appendicitis is time-critical to prevent associated complications of stump perforation, gangrene, and sepsis. It is therefore imperative that EPs consider this

1. Shah T, Gupta RK, Karkee RJ, Agarwal CS. Recurrent pain abdomen following appendectomy: stump appendicitis, a surgeon’s dilemma. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(3):215-217. doi:10.1002/ccr3.781.

2. Giwa A, Reyes M. Three times a charm…a case of repeat appendicitis status post two prior appendectomies. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(3):528.e1-528.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.12.024.

3. Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910-925.

4. Hendahewa R, Shekhar A, Ratnayake S. The dilemma of stump appendicitis—a case report and literature review. Int J Surg. Case Rep. 2015;14:101-103. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.017.

5. Liang MK, Lo HG, Marks JL. Stump appendicitis: a comprehensive review of literature. Am Surg. 2006;72(2):162-166.

6. Parthsarathi R, Jankar SV, Chittawadgi B, et al. Laraposcopic management of symptomatic residual appendicular tip: a rare case report. J Minim Access Surg. 2017;13(2):154-156. doi:10.4103/0972-9941.199610.

7. Kanona H, Al Samaraee A, Nice C, Bhattacharya V. Stump appendicitis: a review. Int J Surg. 2012;10(9):425-428. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.07.007.

1. Shah T, Gupta RK, Karkee RJ, Agarwal CS. Recurrent pain abdomen following appendectomy: stump appendicitis, a surgeon’s dilemma. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(3):215-217. doi:10.1002/ccr3.781.

2. Giwa A, Reyes M. Three times a charm…a case of repeat appendicitis status post two prior appendectomies. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(3):528.e1-528.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.12.024.

3. Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910-925.

4. Hendahewa R, Shekhar A, Ratnayake S. The dilemma of stump appendicitis—a case report and literature review. Int J Surg. Case Rep. 2015;14:101-103. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.017.

5. Liang MK, Lo HG, Marks JL. Stump appendicitis: a comprehensive review of literature. Am Surg. 2006;72(2):162-166.

6. Parthsarathi R, Jankar SV, Chittawadgi B, et al. Laraposcopic management of symptomatic residual appendicular tip: a rare case report. J Minim Access Surg. 2017;13(2):154-156. doi:10.4103/0972-9941.199610.

7. Kanona H, Al Samaraee A, Nice C, Bhattacharya V. Stump appendicitis: a review. Int J Surg. 2012;10(9):425-428. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.07.007.

FDA approves anti-CD38 with VMP in myeloma

The who are ineligible for autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT).

The drug is approved in combination with a standard VMP regimen – bortezomib (Velcade), melphalan, and prednisone. The FDA had granted priority review to the drug application in January 2018 based on the results of the phase 3 ALCYONE study (NCT02195479).

Daratumumab, an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 50%, compared with VMP alone in the ALCYONE study. The median progression-free survival had not yet been reached in the daratumumab arm; the median progression-free survival was 18.1 months in the VMP-only arm (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:518-28).

Daratumumab is marketed by Janssen Biotech as Darzalex.

The who are ineligible for autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT).

The drug is approved in combination with a standard VMP regimen – bortezomib (Velcade), melphalan, and prednisone. The FDA had granted priority review to the drug application in January 2018 based on the results of the phase 3 ALCYONE study (NCT02195479).

Daratumumab, an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 50%, compared with VMP alone in the ALCYONE study. The median progression-free survival had not yet been reached in the daratumumab arm; the median progression-free survival was 18.1 months in the VMP-only arm (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:518-28).

Daratumumab is marketed by Janssen Biotech as Darzalex.

The who are ineligible for autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT).

The drug is approved in combination with a standard VMP regimen – bortezomib (Velcade), melphalan, and prednisone. The FDA had granted priority review to the drug application in January 2018 based on the results of the phase 3 ALCYONE study (NCT02195479).

Daratumumab, an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 50%, compared with VMP alone in the ALCYONE study. The median progression-free survival had not yet been reached in the daratumumab arm; the median progression-free survival was 18.1 months in the VMP-only arm (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:518-28).

Daratumumab is marketed by Janssen Biotech as Darzalex.

Tower Health teams with SHM as first health system institutional partner

Reading Health System has had a long-standing relationship with the Society of Hospital Medicine. Walter R. Bohnenblust Jr., MD, SFHM, the former medical director of hospitalist services at Reading Hospital, West Reading, Pa., had been an SHM member since 2002. He worked together with his dyad partner, who was trained in the SHM Leadership Academy curriculum, for 20 years. Together at Reading Hospital, they participated in several SHM Center for Quality Improvement mentored implementation programs on topics including opioid management, care transitions, glycemic control, and VTE treatment.

Today, Reading Health System is known as Tower Health, and recently acquired five hospitals in the southeastern Pennsylvania region. John K. Derderian, DO, FHM, director of hospitalist services, is leading the growth of the hospitalist programs and made the strategic decision to become an SHM institutional partner by enrolling his entire staff, which consists of 70 physicians and 20 nurse practitioners and physician assistants who provide acute care in a 711-bed hospital, as members of SHM.

“I am proud to say the hospitalist group at Reading Hospital is committed to continuous improvement and the providers recognize that the partnership will be an effective tool to achieve their goals,” Dr. Derderian said. “The team at Tower Health is excited about the opportunity to partner with SHM and the potential for our providers to have a single source for all of their career needs – continuing medical education and professional development, to name a few.”

Reading Hospital has also enrolled in SHM’s Optimizing Neurovascular Intervention Care for Stroke Patients Mentored Implementation program, which provides resources and training to equip practitioners with the skills needed to ensure continuous quality of care for stroke patients.

Defining the value of the hospital medicine program for Tower Health’s leadership is a topic that is also important to Dr. Derderian. “SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine [SoHM] Report provides exquisite detail of programs around the country, giving Tower Health’s providers invaluable insight into the changes of the hospital medicine landscape occurring across the country and the value of the hospitalist team,” he said.

Eric Howell, MD, MHM, who serves as senior physician adviser to SHM, traveled to Reading Hospital to share his experience as chief of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore. Dr. Howell shared his metrics dashboard with the Reading hospital medicine staff to provide insight into how to measure the effectiveness of the hospitalist team.

“This was an excellent example of how these institutional partnerships create important dialogue between SHM and our partner members, resulting in customized benefits,” said Kristin Scott, director of business development at SHM.

For more information about SHM’s institutional partnerships, please contact Debra Beach, SHM Customer Experience Manager, at 267-702-2644 or [email protected].

Reading Health System has had a long-standing relationship with the Society of Hospital Medicine. Walter R. Bohnenblust Jr., MD, SFHM, the former medical director of hospitalist services at Reading Hospital, West Reading, Pa., had been an SHM member since 2002. He worked together with his dyad partner, who was trained in the SHM Leadership Academy curriculum, for 20 years. Together at Reading Hospital, they participated in several SHM Center for Quality Improvement mentored implementation programs on topics including opioid management, care transitions, glycemic control, and VTE treatment.

Today, Reading Health System is known as Tower Health, and recently acquired five hospitals in the southeastern Pennsylvania region. John K. Derderian, DO, FHM, director of hospitalist services, is leading the growth of the hospitalist programs and made the strategic decision to become an SHM institutional partner by enrolling his entire staff, which consists of 70 physicians and 20 nurse practitioners and physician assistants who provide acute care in a 711-bed hospital, as members of SHM.

“I am proud to say the hospitalist group at Reading Hospital is committed to continuous improvement and the providers recognize that the partnership will be an effective tool to achieve their goals,” Dr. Derderian said. “The team at Tower Health is excited about the opportunity to partner with SHM and the potential for our providers to have a single source for all of their career needs – continuing medical education and professional development, to name a few.”

Reading Hospital has also enrolled in SHM’s Optimizing Neurovascular Intervention Care for Stroke Patients Mentored Implementation program, which provides resources and training to equip practitioners with the skills needed to ensure continuous quality of care for stroke patients.

Defining the value of the hospital medicine program for Tower Health’s leadership is a topic that is also important to Dr. Derderian. “SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine [SoHM] Report provides exquisite detail of programs around the country, giving Tower Health’s providers invaluable insight into the changes of the hospital medicine landscape occurring across the country and the value of the hospitalist team,” he said.

Eric Howell, MD, MHM, who serves as senior physician adviser to SHM, traveled to Reading Hospital to share his experience as chief of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore. Dr. Howell shared his metrics dashboard with the Reading hospital medicine staff to provide insight into how to measure the effectiveness of the hospitalist team.

“This was an excellent example of how these institutional partnerships create important dialogue between SHM and our partner members, resulting in customized benefits,” said Kristin Scott, director of business development at SHM.

For more information about SHM’s institutional partnerships, please contact Debra Beach, SHM Customer Experience Manager, at 267-702-2644 or [email protected].

Reading Health System has had a long-standing relationship with the Society of Hospital Medicine. Walter R. Bohnenblust Jr., MD, SFHM, the former medical director of hospitalist services at Reading Hospital, West Reading, Pa., had been an SHM member since 2002. He worked together with his dyad partner, who was trained in the SHM Leadership Academy curriculum, for 20 years. Together at Reading Hospital, they participated in several SHM Center for Quality Improvement mentored implementation programs on topics including opioid management, care transitions, glycemic control, and VTE treatment.

Today, Reading Health System is known as Tower Health, and recently acquired five hospitals in the southeastern Pennsylvania region. John K. Derderian, DO, FHM, director of hospitalist services, is leading the growth of the hospitalist programs and made the strategic decision to become an SHM institutional partner by enrolling his entire staff, which consists of 70 physicians and 20 nurse practitioners and physician assistants who provide acute care in a 711-bed hospital, as members of SHM.

“I am proud to say the hospitalist group at Reading Hospital is committed to continuous improvement and the providers recognize that the partnership will be an effective tool to achieve their goals,” Dr. Derderian said. “The team at Tower Health is excited about the opportunity to partner with SHM and the potential for our providers to have a single source for all of their career needs – continuing medical education and professional development, to name a few.”

Reading Hospital has also enrolled in SHM’s Optimizing Neurovascular Intervention Care for Stroke Patients Mentored Implementation program, which provides resources and training to equip practitioners with the skills needed to ensure continuous quality of care for stroke patients.

Defining the value of the hospital medicine program for Tower Health’s leadership is a topic that is also important to Dr. Derderian. “SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine [SoHM] Report provides exquisite detail of programs around the country, giving Tower Health’s providers invaluable insight into the changes of the hospital medicine landscape occurring across the country and the value of the hospitalist team,” he said.

Eric Howell, MD, MHM, who serves as senior physician adviser to SHM, traveled to Reading Hospital to share his experience as chief of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore. Dr. Howell shared his metrics dashboard with the Reading hospital medicine staff to provide insight into how to measure the effectiveness of the hospitalist team.

“This was an excellent example of how these institutional partnerships create important dialogue between SHM and our partner members, resulting in customized benefits,” said Kristin Scott, director of business development at SHM.

For more information about SHM’s institutional partnerships, please contact Debra Beach, SHM Customer Experience Manager, at 267-702-2644 or [email protected].

HHS says no to lifetime limits on Medicaid

The Trump administration’s promise of unprecedented flexibility to states in running their Medicaid programs hit its limit on May 7.

“We seek to create a pathway out of poverty, but we also understand that people’s circumstances change, and we must ensure that our programs are sustainable and available to them when they need and qualify for them,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said May 7 at an American Hospital Association meeting in Washington.

Arizona, Utah, Maine and Wisconsin have also requested lifetime limits on Medicaid.

This marked the first time the Trump administration has rejected a state’s Medicaid waiver request regarding who is eligible for the program.

Critics of time limits, who say such a change would unfairly burden people who struggle financially throughout their lives, cheered the decision.

“This is good news,” said Joan Alker, executive director of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families, a Medicaid advocate. “This was a bridge too far for this CMS.”

Ms. Alker’s enthusiasm, though, was tempered because Ms. Verma did not also reject Kansas’ effort to place work requirements on some adult enrollees. That decision is still pending.

CMS has approved work requirements for adults in four states – the latest, New Hampshire, winning approval May 7. The other states are Kentucky, Indiana, and Arkansas.

All these states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to cover everyone with incomes of more than 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,753 for an individual). The work requirements would apply only to adults added through that ACA expansion.

Kansas and a handful of states, including Alabama and Mississippi – which did not expand the program – want to add the work requirement for some of their adult enrollees, many of whom have incomes well below the poverty level. In Kansas, an individual qualifying for Medicaid can earn no more than $4,600.

Adding work requirements to Medicaid has also been controversial. The National Health Law Program, an advocacy group, has filed suit against CMS and Kentucky to block the work requirement from taking effect, saying it violates federal law.

The Kansas proposal would have imposed a cumulative 3-year maximum benefit only on Medicaid recipients deemed able to work. It would have applied to about 12,000 low-income parents who make up a tiny fraction of the 400,000 Kansans who receive Medicaid.

Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer, a Republican, responded to the announcement saying state officials decided in April to no longer pursue the lifetime limits after CMS indicated it would not be approved.

“While we will not be moving forward with lifetime caps, we are pleased that the Administration has been supportive of our efforts to include a work requirement in the [Medicaid] waiver,” Gov. Colyer said in a statement. “This important provision will help improve outcomes and ensure that Kansans are empowered to achieve self-sufficiency.”

Eliot Fishman, senior director of health policy for the advocacy group Families USA, applauded Ms. Verma’s decision.

“The decision on the Kansas time limits proposal that Seema Verma announced today is the right one. CMS should apply this precedent to all state requests to impose time limits on any group of people who get health coverage through Medicaid – including adults who are covered through Medicaid expansion,” he said. “Time limits in Medicaid are bad law and bad policy, harming people who rely on the program for lifesaving health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The Trump administration’s promise of unprecedented flexibility to states in running their Medicaid programs hit its limit on May 7.

“We seek to create a pathway out of poverty, but we also understand that people’s circumstances change, and we must ensure that our programs are sustainable and available to them when they need and qualify for them,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said May 7 at an American Hospital Association meeting in Washington.

Arizona, Utah, Maine and Wisconsin have also requested lifetime limits on Medicaid.

This marked the first time the Trump administration has rejected a state’s Medicaid waiver request regarding who is eligible for the program.

Critics of time limits, who say such a change would unfairly burden people who struggle financially throughout their lives, cheered the decision.

“This is good news,” said Joan Alker, executive director of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families, a Medicaid advocate. “This was a bridge too far for this CMS.”

Ms. Alker’s enthusiasm, though, was tempered because Ms. Verma did not also reject Kansas’ effort to place work requirements on some adult enrollees. That decision is still pending.

CMS has approved work requirements for adults in four states – the latest, New Hampshire, winning approval May 7. The other states are Kentucky, Indiana, and Arkansas.

All these states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to cover everyone with incomes of more than 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,753 for an individual). The work requirements would apply only to adults added through that ACA expansion.

Kansas and a handful of states, including Alabama and Mississippi – which did not expand the program – want to add the work requirement for some of their adult enrollees, many of whom have incomes well below the poverty level. In Kansas, an individual qualifying for Medicaid can earn no more than $4,600.

Adding work requirements to Medicaid has also been controversial. The National Health Law Program, an advocacy group, has filed suit against CMS and Kentucky to block the work requirement from taking effect, saying it violates federal law.

The Kansas proposal would have imposed a cumulative 3-year maximum benefit only on Medicaid recipients deemed able to work. It would have applied to about 12,000 low-income parents who make up a tiny fraction of the 400,000 Kansans who receive Medicaid.

Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer, a Republican, responded to the announcement saying state officials decided in April to no longer pursue the lifetime limits after CMS indicated it would not be approved.

“While we will not be moving forward with lifetime caps, we are pleased that the Administration has been supportive of our efforts to include a work requirement in the [Medicaid] waiver,” Gov. Colyer said in a statement. “This important provision will help improve outcomes and ensure that Kansans are empowered to achieve self-sufficiency.”

Eliot Fishman, senior director of health policy for the advocacy group Families USA, applauded Ms. Verma’s decision.

“The decision on the Kansas time limits proposal that Seema Verma announced today is the right one. CMS should apply this precedent to all state requests to impose time limits on any group of people who get health coverage through Medicaid – including adults who are covered through Medicaid expansion,” he said. “Time limits in Medicaid are bad law and bad policy, harming people who rely on the program for lifesaving health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The Trump administration’s promise of unprecedented flexibility to states in running their Medicaid programs hit its limit on May 7.

“We seek to create a pathway out of poverty, but we also understand that people’s circumstances change, and we must ensure that our programs are sustainable and available to them when they need and qualify for them,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said May 7 at an American Hospital Association meeting in Washington.

Arizona, Utah, Maine and Wisconsin have also requested lifetime limits on Medicaid.

This marked the first time the Trump administration has rejected a state’s Medicaid waiver request regarding who is eligible for the program.

Critics of time limits, who say such a change would unfairly burden people who struggle financially throughout their lives, cheered the decision.

“This is good news,” said Joan Alker, executive director of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families, a Medicaid advocate. “This was a bridge too far for this CMS.”

Ms. Alker’s enthusiasm, though, was tempered because Ms. Verma did not also reject Kansas’ effort to place work requirements on some adult enrollees. That decision is still pending.

CMS has approved work requirements for adults in four states – the latest, New Hampshire, winning approval May 7. The other states are Kentucky, Indiana, and Arkansas.

All these states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to cover everyone with incomes of more than 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,753 for an individual). The work requirements would apply only to adults added through that ACA expansion.

Kansas and a handful of states, including Alabama and Mississippi – which did not expand the program – want to add the work requirement for some of their adult enrollees, many of whom have incomes well below the poverty level. In Kansas, an individual qualifying for Medicaid can earn no more than $4,600.

Adding work requirements to Medicaid has also been controversial. The National Health Law Program, an advocacy group, has filed suit against CMS and Kentucky to block the work requirement from taking effect, saying it violates federal law.

The Kansas proposal would have imposed a cumulative 3-year maximum benefit only on Medicaid recipients deemed able to work. It would have applied to about 12,000 low-income parents who make up a tiny fraction of the 400,000 Kansans who receive Medicaid.

Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer, a Republican, responded to the announcement saying state officials decided in April to no longer pursue the lifetime limits after CMS indicated it would not be approved.

“While we will not be moving forward with lifetime caps, we are pleased that the Administration has been supportive of our efforts to include a work requirement in the [Medicaid] waiver,” Gov. Colyer said in a statement. “This important provision will help improve outcomes and ensure that Kansans are empowered to achieve self-sufficiency.”

Eliot Fishman, senior director of health policy for the advocacy group Families USA, applauded Ms. Verma’s decision.

“The decision on the Kansas time limits proposal that Seema Verma announced today is the right one. CMS should apply this precedent to all state requests to impose time limits on any group of people who get health coverage through Medicaid – including adults who are covered through Medicaid expansion,” he said. “Time limits in Medicaid are bad law and bad policy, harming people who rely on the program for lifesaving health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Guiding Resuscitation in the Emergency Department

Resuscitation of critically ill patients in shock from cardiogenic, hypovolemic, obstructive, distributive, or neurogenic etiology is a cornerstone of the care delivered by emergency physicians (EPs).1 Regardless of the etiology, it is essential that the treating EP initiate resuscitative measures in a timely manner and closely trend the patient’s response to these interventions.

The early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) initially proposed by Rivers et al2 in 2001 demonstrated a bundled approach to fluid resuscitation by targeting end points for volume resuscitation, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), oxygen (O2) delivery/extraction (mixed venous O2 saturation, [SvO2]), hemoglobin (Hgb) concentration, and cardiac contractility. Since then, advancements in laboratory testing and hemodynamic monitoring (HDM) devices further aid and guide resuscitative efforts, and are applicable to any etiology of shock.

In addition to these advancements, the growing evidence of the potential harm from improper fluid resuscitation, such as the administration of excessive intravascular fluid (IVF),3 underscores the importance of a precise, targeted, and individualized approach to care. This article reviews the background, benefits, and limitations of some of the common and readily available tools in the ED that the EP can employ to guide fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients.

Physical Examination

Background

The rapid recognition and treatment of septic shock in the ED is associated with lower rates of in-hospital morbidity and mortality.4 The physical examination by the EP begins immediately upon examining the patient. The acquisition of vital signs and recognition of physical examination findings suggestive of intravascular volume depletion allows the EP to initiate treatment immediately.

In this discussion, hypotension is defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) of less than 95 mm Hg, MAP of less than 65 mm Hg, or a decrease in SBP of more than 40 mm Hg from baseline measurements. Subsequently, shock is defined as hypotension with evidence of tissue hypoperfusion-induced dysfunction.5,6 Although the use of findings from the physical examination to guide resuscitation allows for rapid patient assessment and treatment, the predictive value of the physical examination to assess hemodynamic status is limited.

Visual inspection of the patient’s skin and mucous membranes can serve as an indicator of volume status. The patient’s tongue should appear moist with engorged sublingual veins; a dry tongue and diminished veins may suggest the need for volume resuscitation. On examination of the skin, delayed capillary refill of the digits and cool, clammy extremities suggest the shunting of blood by systemic circulation from the skin to central circulation. Patients who progress to more severe peripheral vasoconstriction develop skin mottling, referred to as livedo reticularis (Figure 1).

Benefits

The major benefit of the physical examination as a tool to evaluate hemodynamic status is its ease and rapid acquisition. The patient’s vital signs and physical examination can be obtained in the matter of moments upon presentation, without the need to wait on results of laboratory evaluation or additional equipment. Additionally, serial examinations by the same physician can be helpful to monitor a patient’s response to resuscitative efforts. The negative predictive value (NPV) of the physical examination in evaluating for hypovolemia may be helpful, but only when it is taken in the appropriate clinical context and is used in conjunction with other diagnostic tools. The physical examination can exclude hypovolemic volume status with an NPV of approximately 70%.7

A constellation of findings from the physical examination may include altered mentation, hypotension, tachycardia, and decreased urinary output by 30% to 40% intravascular volume loss.8,9Findings from the physical examination to assess fluid status should be used with caution as interobserver reliability has proven to be poor and the prognostic value is limited.

Limitations

The literature shows the limited prognostic value of the physical examination in determining a patient’s volume status and whether fluid resuscitation is indicated. For example, in one meta-analysis,10 supine hypotension and tachycardia were frequently absent on examination—even in patients who underwent large volume phlebotomy.8 This study also showed postural dizziness to be of no prognostic value.

Another study by Saugel et al7 that compared the physical examination (skin assessment, lung auscultation, and percussion) to transpulmonary thermodilution measurements of the cardiac index, global end-diastolic volume index, and extravascular lung water index, found poor interobserver correlation and agreement among physicians.

The physical examination is also associated with weak predictive capabilities for the estimation of volume status compared to the device measurements. Another contemporary study by Saugel et al9 evaluated the predictive value of the physical examination to accurately identify volume responsiveness replicated these results, and reported poor interobserver correlation (κ coefficient 0.01; 95% caval index [CI] -0.39-0.42) among physical examination findings, with a sensitivity of only 71%, specificity of 23.5%, positive predictive value of 27.8%, and negative predictive value of 66.7%.9

Serum Lactate Levels

Background

In the 1843 book titled, Investigations of Pathological Substances Obtained During the Epidemic of Puerperal Fever, Johann Joseph Scherer described the cases of seven young peripartum female patients who died from a clinical picture of what is now understood to be septic shock.11 In his study of these cases, Scherer demonstrated the presence of lactic acid in patients with pathological conditions. Prior to this discovery, lactic acid had never been isolated in a healthy individual. These results were recreated in 1851 by Scherer and Virchow,11 who demonstrated the presence of lactic acid in the blood of a patient who died from leukemia. The inference based on Scherer and Virchow’s work correlated the presence of excessive lactic acid with bodily deterioration and severe disease. Since this finding, there has been a great deal of interest in measuring serum lactic acid as a means to identify and manage critical illness.

In a 2001 groundbreaking study of EGDT for severe sepsis and septic shock, Rivers et al2 studied lactic acid levels as a marker for severe disease. Likewise, years later, the 2014 Protocol-Based Care for Early Septic Shock (PROCESS), Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE), and Australasian Resuscitation in Sepsis Evaluation (ARISE) trials used lactate levels in a similar manner to identify patients appropriate for randomization.12-14 While the purpose of measuring lactic acid was only employed in these studies to identify patients at risk for critical illness, the 2012 Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines recommended serial measurement of lactate, based on the assumption that improved lactate levels signified better tissue perfusion.15

Although much of the studies on lactate levels appear to be based on the treatment and management of septic patients, findings can be applied to any etiology of shock. For example, a serum lactate level greater than 2 mmol/L is considered abnormal, and a serum lactate greater than 4 mmol/L indicates a significantly increased risk for in-hospital mortality.16

Benefits

It is now a widely accepted belief that the rapid identification, triage, and treatment of critically ill patients has a dramatic effect on morbidity and mortality.4 As previously noted, lactate has been extensively studied and identified as a marker of severe illness.17,18 A serum lactate level, which can be rapidly processed in the ED, can be easily obtained from a minimally invasive venous, arterial, or capillary blood draw.18 The only risk associated with serum lactate testing is that of any routine venipuncture; the test causes minimal, if any, patient discomfort.

Thanks to advances in point-of-care (POC) technology, the result of serum lactate assessment can be available within 10 minutes from blood draw. This technology is inexpensive and can be easily deployed in the prehospital setting or during the initial triage assessment of patients arriving at the ED.19 These POC instruments have been well correlated with whole blood measurements and permit for the rapid identification and treatment of at risk patients.

Limitations

The presence of elevated serum lactate levels is believed to represent the presence of cellular anaerobic metabolism due to impaired O2 delivery in the shock state. Abnormal measurements therefore prompt aggressive interventions aimed at maximizing O2 delivery to the tissues, such as intravenous fluid boluses, vasopressor therapy, or even blood product administration.

A return to a normalized serum lactate level is assumed to represent a transition back to aerobic metabolism. Lactate elevations, however, are not solely an indication of anaerobic metabolism and may only represent a small degree of lactate production.20 While the specific cellular mechanics are out of the scope of this article, it has been postulated that the increase in plasma lactate concentration is primarily driven by β-2 receptor stimulation from increased circulating catecholamines leading to increased aerobic glycolysis. Increased lactate levels could therefore be an adaptive mechanism of energy production—aggressive treatment and rapid clearance may, in fact, be harmful. Type A lactic acidosis is categorized as elevated serum levels due to tissue hypoperfusion.21

However, lactate elevations do not exclusively occur in severe illness. The use of β-2 receptor agonists such as continuous albuterol treatments or epinephrine may cause abnormal lactate levels.22 Other medications have also been associated with elevated serum lactate levels, including, but not limited to linezolid, metformin, and propofol.23-25 Additionally, lactate levels may be elevated after strenuous exercise, seizure activity, or in liver and kidney disease.26 These “secondary” causes of lactic acidosis that are not due to tissue hypoperfusion are referred to as type B lactic acidosis. Given these multiple etiologies and lack of specificity for this serum measurement, a failure to understand these limitations may result in over aggressive or unnecessary medical treatments.

Central Venous Pressure

Background

Central venous pressure (CVP) measurements can be obtained through a catheter, the distal tip of which transduces pressure of the superior vena cava at the entrance of the right atrium (RA). Thus, CVP is often used as a representation of RA pressure (RAP) and therefore an estimate of right ventricular (RV) preload. While CVP is used to diagnose and determine the etiology of shock, evidence and controversy regarding the use of CVP as a marker for resuscitation comes largely from sepsis-focused literature.5 Central venous pressure is meant to represent preload, which is essential for stroke volume as described by the Frank-Starling mechanism; however, its use as a target in distributive shock, a state in which it is difficult to determine a patient’s volume status, has been popularized by EGDT since 2001.2

Since the publication of the 2004 Surviving Sepsis Guidelines, CVP monitoring has been in the spotlight of sepsis resuscitation, albeit with some controversy.27 Included as the result of two studies, this recommendation has been removed in the most recent guidelines after 12 years of further study and scrutiny.2,27,28

Hypovolemic and hemorrhagic shock are usually diagnosed clinically and while a low CVP can be helpful in the diagnosis, the guidelines do not support CVP as a resuscitation endpoint. Obstructive and cardiogenic shock will both result in elevated CVP; however, treatment of obstructive shock is generally targeted at the underlying cause. While cardiogenic shock can be preload responsive, the mainstay of therapy in the ED is identification of patients for revascularization and inotropic support.29

Benefits

The CVP has been used as a surrogate for RV preload volume. If a patient’s preload volume is low, the treating physician can administer fluids to improve stroke volume and cardiac output (CO). Clinically, CVP measurements are easy to obtain provided a central venous line has been placed with the distal tip at the entrance to the RA. Central venous pressure is measured by transducing the pressure via manometry and connecting it to the patient’s bedside monitor. This provides an advantage of being able to provide serial or even continuous measurements. The “normal” RAP should be a low value (1-5 mm Hg, mean of 3 mm Hg), as this aids in the pressure gradient to drive blood from the higher pressures of the left ventricle (LV) and aorta through the circulation back to the low-pressure of the RA.30 The value of the CVP is meant to correspond to the physical examination findings of jugular venous distension.31,32 Thus, a low CVP may be “normal” and seen in patients with hypovolemic shock, whereas an elevated CVP can suggest volume overload or obstructive shock. However, this is of questionable value in distributive shock cases.

Aside from the two early studies on CVP monitoring during treatment of septic patients, there are few data to support the use of CVP measurement in the early resuscitation of patients with shock.2,28 More recent trials (PROMISE, ARISE, PROCESS) that compared protocolized sepsis care to standard care showed no benefit to bundles including CVP measurements.12-14 However, a subsequent, large observational trial spanning 7.5 years demonstrated improvements in sepsis-related mortality in patients who received a central venous catheter (CVC) and CVP-targeted therapy.33 Thus, it is possible that protocols including CVP are still beneficial in combination with other therapies even though CVP in isolation is not.

Limitations

The traditional two assumptions in CVP monitoring are CVP value represents the overall volume status of the patient, and the LV is able to utilize additional preload volume. The latter assumption, however, may be hampered by the presence of sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction, which may be present in up to 40% of critically ill patients.34 The former assumption does not always hold true due to processes that change filling pressures independent of intravascular volume—eg, acute or chronic pulmonary hypertension, cardiac tamponade, intra-abdominal hypertension, or LV failure. Even before the landmark EGDT study, available data suggested that CVP was not a reliable marker for resuscitation management.35 A recent systematic review by Gottlieb and Hunter36 showed that the area under the receiver-operator curve for low, mid-range, or high CVPs was equivocal at best. In addition to its unreliability and lack of specificity, another significant drawback to using CVP to guide resuscitation therapy in the ED is that it necessitates placement of a CVC, which can be time-consuming and, if not otherwise indicated, lead to complications of infection, pneumothorax, and/or thrombosis.37

Mixed Venous Oxygen

Background

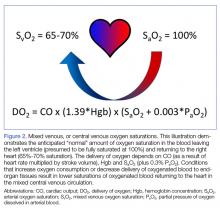

Most EPs are familiar with the use of ScvO2 in EGDT protocols to guide volume resuscitation of septic patients.2 A patient’s ScvO2 represents the O2 saturation of venous blood obtained via a CVC at the confluence of the superior vena cava and the RA, and thus it reflects tissue O2 consumption as a surrogate for tissue perfusion. The measurement parallels the SvO2 obtained from the pulmonary artery. In a healthy patient, SvO2 is around 65% to 70% and includes blood returning from both the superior and inferior vena cava (IVC). As such, ScvO2 values are typically 3% to 5% lower than SvO2 owing to the lower O2 extracted by tissues draining into the IVC compared to the mixed venous blood sampled from the pulmonary artery.38

Though a debate over the benefit of EGDT in treating sepsis continues, understanding the physiology of ScvO2 measurements is another potential tool the EP can use to guide the resuscitation of critically ill patients.39 A patient’s SvO2 and, by extension, ScvO2 represents the residual O2 saturation after the tissues have extracted the amount of O2 necessary to meet metabolic demands (Figure 2).

Conversely, cellular dysfunction, which can occur in certain toxicities or in severe forms of sepsis, can lead to decreased tissue O2 consumption with a concomitant rise in ScvO2 to supernormal values.38 The EP should take care, however, to consider whether ScvO2 values exceeding 80% represent successful therapeutic intervention or impaired tissue O2 extraction and utilization. There are data from ED patients suggesting an increased risk of mortality with both extremely low and extremely high values of ScvO2.40

Benefits

A critically ill patient’s ScvO2 can potentially provide EPs with insight into the patient’s global tissue perfusion and the source of any mismatch between O2 delivery and consumption. Using additional tools and measurements (physical examination, serum Hgb levels, and pulse oximetry) in conjunction with an ScvO2 measurement, assists EPs in identifying targets for therapeutic intervention. The effectiveness of this intervention can then be assessed using serial ScvO2 measurements, as described in Rivers et al2 EGDT protocol. Importantly, EPs should take care to measure serial ScvO2 values to maximize its utility.38 Similar to a CVP measurement, ScvO2is easily obtained from blood samples for serial laboratory measurements, assuming the patient already has a CVC with the distal tip at the entrance to the RA (ScvO2) or a pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) (SvO2).

Limitations

Serial measurements provide the most reliable information, which may be more useful in patients who spend extended periods of their resuscitation in the ED. In comparison to other measures of global tissue hypoxia, work by Jones et al41 suggests non-inferiority of peripherally sampled, serial lactate measurements as an alternative to ScvO2. This, in conjunction with the requirement for an internal jugular CVC, subclavian CVC, or PAC with their associated risks, may make ScvO2 a less attractive guide for the resuscitation of critically ill patients in the ED.

Monitoring Devices

Background

As noted throughout this review, it is important not only to identify and rapidly treat shock, but to also correctly identify the type of shock, such that treatment can be appropriately directed at its underlying cause. However, prior work suggests that EPs are unable to grossly estimate CO or systemic vascular resistance when compared to objective measurements of these parameters.42 This is in agreement with the overall poor performance of physical examination and clinical evaluation as a means of predicting volume responsiveness or guiding resuscitation, as discussed previously. Fortunately, a wide variety of devices to objectively monitor hemodynamics are now available to the EP.

In 1970, Swan et al43 published their initial experience with pulmonary artery catheterization at the bedside, using a balloon-tipped, flow-guided PAC in lieu of fluoroscopy, which had been mandated by earlier techniques. The ability to measure CO, right heart pressures, pulmonary arterial pressures, and estimate LV end diastolic pressure ushered in an era of widespread PAC use, despite an absence of evidence for causation of improved patient outcomes. The utilization of PACs has fallen, as the literature suggests that the empiric placement of PACs in critically ill patients does not improve mortality, length of stay, or cost, and significant complication rates have been reported in large trials.44,45Subsequently, a number of non-invasive or less-invasive HDM devices have been developed. Amongst the more commonly encountered modern devices, the techniques utilized for providing hemodynamic assessments include thermodilution and pulse contour analysis (PiCCOTM), pulse contour analysis (FloTrac/VigileoTM), and lithium chemodilution with pulse power analysis (LiDCOplusTM).46 The primary utility of these devices for the EP lies in the ability to quantify CO, stroke volume, and stroke volume or pulse pressure variation (PPV) to predict or assess response to resuscitative interventions (volume administration, vasopressors, inotropes, etc).

Benefits

Many of these devices require placement of an arterial catheter. Some require the addition of a CVC. Both of these procedures are well within the clinical scope of the EP, and are performed with fair frequency on critically ill patients. This is a distinct advantage when compared to pulmonary artery catheterization, a higher risk procedure that is rarely performed outside of the intensive care unit or cardiac catheterization laboratory. In addition, all of the devices below present hemodynamic data in a graphical, easy-to-read format, in real time. All of the devices discussed report stroke volume variation (SVV) or PPV continuously.

Limitations

Though these measures have validated threshold values that predict volume responsiveness, they require the patient to be intubated with a set tidal volume of greater than or equal to 8 mL/kg without spontaneous respirations and cardiac arrhythmias, in order to accurately do so. All of the HDM devices that rely on pulse contour analysis as the primary means of CO measurement cannot be used in the presence of significant cardiac arrhythmias (ie, atrial fibrillation), or mechanical circulatory assistance devices (ie, intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation). None of these devices are capable of monitoring microcirculatory changes, felt to be of increasing clinical importance in the critically ill.

The use of HDM devices to monitor CO with a reasonable degree of accuracy, trend CO, and assess for volume responsiveness using a number of previously validated parameters such as SVV is now in little doubt. However, these devices are still invasive, if less so than a pulmonary artery. The crux of the discussion of HDM devices for use in ED resuscitation revolves around whether or not the use of such devices to drive previously validated, protocolized care results in better outcomes for patients. The EP can now have continuous knowledge of a large number of hemodynamic parameters at their fingertips with relatively minimal additional efforts. At the time of this writing, though, this is both untested and unproven, with respect to the ED population.

Point-of-Care Ultrasound

Background

Over the past two decades, ultrasound (US) has become an integral part of the practice of emergency medicine (EM), and is now included in all United States Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Emergency Medicine Residency Programs.47,48 It has emerged as a very important bedside tool performed by the clinician to identify type of shock and guide resuscitation, and has been endorsed by both EM and critical care societies.49-51 This section reviews the utility of US as a modality in identifying shock and guiding resuscitation, in addition to the pitfalls and limitations of this important tool.

In 2010, Perera et al47 described in their landmark article the Rapid Ultrasound in SHock (RUSH) examination, which describes a stepwise (the pump, tank, pipes) approach to identify the type of shock (cardiogenic, hypovolemic, obstructive, or distributive) in the crashing, hypotensive ED patient. We do not describe the full RUSH examination in this review, but discuss key elements of it as examples of how POCUS can assist the EP to make a rapid diagnosis and aid in the management of patients in shock. The “pump” is the heart, which is assessed in four different views to identify a pericardial effusion and possible tamponade, assess contractility or ejection fraction of the LV (severely decreased, decreased, normal, or hyperdynamic), and right heart strain which is identified by an RV that is larger than the LV, indicative of a potential pulmonary embolus.

The “tank” is then assessed by visualizing the IVC in the subxiphoid plane, and is evaluated for respiratory collapsibility (CI) and maximum size. This has been quite the debated topic over the last two decades. In 1988, Simonson and Schiller52 were the first to describe a correlation in spontaneously breathing patients between IVC caliber (measured 2 cm from the cavoatrial junction) and variation and RAP, where a larger IVC diameter and less respiratory variation correlated with a high RAP. Kircher et al53 later went on to describe that a CI greater than 50% correlated with an RAP of less than 10 mm Hg and vice versa in spontaneously breathing patients. Since then there have been more studies attempting to verify these findings in both spontaneously breathing and mechanically ventilated patients.54-56 The purpose of performing these measurements is not to estimate CVP, but to assess fluid responsiveness (ie, a blood pressure response to a fluid challenge). It can be assumed in states of shock that a small IVC, or one with a high CI, in the presence of a hyperdynamic heart is indicative of an underfilled ventricle and fluid responsiveness, especially if the IVC size increases with fluid.55,57 However, there are several caveats to this. First, in mechanically ventilated patients, the IVC is already plethoric due to positive pressure ventilation, and increases in diameter with inspiration and decreases with expiration as compared to spontaneously breathing patients. Second, the CI value to predict volume responsiveness in ventilated patients is set at 15% instead of 50%.55 Third, it is important to always take the clinical scenario in context; a dilated IVC with small CI is not necessarily only due to volume overload and congestive heart failure, but can be due to elevated RAP from obstructive shock due to cardiac tamponade or massive pulmonary embolus, which is why it is important to assess the “pump” first.47,58 It is also crucial to not forget to assess the abdominal and thoracic cavities, as intraperitoneal or pleural fluid with a collapsed IVC can potentially make a diagnosis of hemorrhagic or hypovolemic shock depending on the clinical scenario.47 The final part of the RUSH protocol is to evaluate the “pipes,” inclusive of the lower extremity deep venous system for evaluation of potential thrombosis that could increase suspicion for a pulmonary embolism causing obstructive shock, and the aorta with the common iliac arteries if there is concern for aortic dissection or aneurysmal rupture.

Benefits

Some of the most significant advantages to the use of POCUS to guide resuscitation is that it is quick, non-invasive, does not use ionizing radiation, and can be easily repeated. As noted above, it is a requirement for EM residencies to teach its use, so that contemporary graduates are entering the specialty competent in applying it to the care of their patients. Furthermore, POCUS is done at the bedside, limiting the need to potentially transport unstable patients.

In the most basic applications, POCUS provides direct visualization of a patient’s cardiac function, presence or absence of lung sliding to suggest a pneumothorax, presence of pulmonary edema, assessment of CVP pressures or potential for fluid responsiveness, as well as identification of potential thoracic, peritoneal, or pelvic cavity fluid accumulation that may suggest hemorrhage. There is literature to support that these assessments performed by the EP have been shown to be comparable to those of cardiologists.59,60 With continued practice and additional training, it is possible for EPs to even perform more “advanced” hemodynamic assessments to both diagnose and guide therapy to patients in shock (Figures 3 and 4).61

Limitations

Although POCUS has been shown as a remarkable tool to help assist the EP in making rapid decisions regarding resuscitation, it is always important to remember its limitations. Most of the studies regarding its use are of very small sample sizes, and further prospective studies have to be performed in order for this modality to be fully relied on.62Compared to some of the previously mentioned HDM devices that may provide continuous data, POCUS needs to be performed by the treating physician, thereby occurring intermittently. Emergency physicians need to be aware of their own experience and limitations with this modality, as errors in misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary procedures, with resulting significant morbidity and mortality. Blanco and Volpicelli63 describe several common errors that include misdiagnosing the stomach as a peritoneal effusion, assuming adequate volume resuscitation when the IVC is seen to be plethoric in the setting of cardiac tamponade, or mistaking IVC movement as indicative of collapsibility, amongst other described misinterpretations. Several other studies have shown that, despite adequate performance of EPs in POCUS, diagnostic sensitivities remained higher when performed by radiologists.64-67 Thus it remains important for the EPs to be vigilant and not anchor on a diagnosis when in doubt, and to consult early with radiology, particularly if there is any question, to avoid potential adverse patient outcomes.

Summary

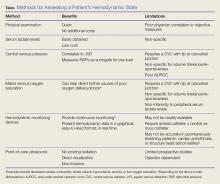

There are several ways to diagnose and track resuscitation in the ED, which include physical examination, assessment of serum laboratory values, monitoring of hemodynamic status, and use of POCUS. Unfortunately, none of these methods provides a perfect assessment, and no method has been proven superior and effective over the others. Therefore, it is important for EPs treating patients in shock to be aware of the strengths and limitations of each assessment method (Table).

1. Richards JB, Wilcox SR. Diagnosis and management of shock in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2014;16(3):1-22; quiz 22-23.

2. Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al; Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368-1377.

3. Boyd JH, Forbes J, Nakada TA, Walley KR, Russell JA. Fluid resuscitation in septic shock: a positive fluid balance and elevated central venous pressure are associated with increased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:259-265. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feeb15.

4. Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, et al. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2235-2244. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1703058.

5. Cecconi M, De Backer D, Antonelli M, et al. Consensus on circulatory shock and hemodynamic monitoring. Task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(12):1795-1815. doi:10.1007/s00134-014-3525-z.

6. Vincent JL, De Backer D. Circulatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1726-1734. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1208943.

7. Saugel B, Ringmaier S, Holzapfel K, et al. Physical examination, central venous pressure, and chest radiography for the prediction of transpulmonary thermodilution-derived hemodynamic parameters in critically ill patients: a prospective trial. J Crit Care. 2011;26(4):402-410. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.11.001.

8. American College of Surgeons. Committee on Trauma. Shock. In: American College of Surgeons. Committee on Trauma, ed. Advanced Trauma Life Support: Student Course Manual. 9th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012:69.

9. Saugel B, Kirsche SV, Hapfelmeier A, et al. Prediction of fluid responsiveness in patients admitted to the medical intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2013:28(4):537.e1-e9. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.10.008.

10. McGee S, Abernethy WB 3rd, Simel DV. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient hypovolemic? JAMA. 1999;281(11):1022-1029.

11. Kompanje EJ, Jansen TC, van der Hoven B, Bakker J. The first demonstration of lactic acid in human blood in shock by Johann Joseph Scherer (1814-1869) in January 1843. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(11):1967-1971. doi:10.1007/s00134-007-0788-7.

12. The ProCESS Investigators. A Randomized Trial of Protocol-Based Care for Early Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370:1683-1693. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1401602.

13. Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, et al. Protocolised Management In Sepsis (ProMISe): a multicentre randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of early, goal-directed, protocolised resuscitation for emerging septic shock. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(97):i-xxv, 1-150. doi:10.3310/hta19970.

14. ARISE Investigators; ANZICS Clinical Trials Group; Peake SL, Delaney A, Bailey M, et al. Goal-directed resuscitation for patients with early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1496-1506. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1404380.

15. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including The Pediatric Group. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(2):165-228. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8.

16. Casserly B, Phillips GS, Schorr C, et al: Lactate measurements in sepsis-induced tissue hypoperfusion: results from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign database. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(3):567-573. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000742.

17. Bakker J, Nijsten MW, Jansen TC. Clinical use of lactate monitoring in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3(1):12. doi:10.1186/2110-5820-3-12.

18. Kruse O, Grunnet N, Barfod C. Blood lactate as a predictor for in-hospital mortality in patients admitted acutely to hospital: a systematic review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19:74. doi:10.1186/1757-7241-19-74.

19. Gaieski DF, Drumheller BC, Goyal M, Fuchs BD, Shofer FS, Zogby K. Accuracy of handheld point-of-care fingertip lactate measurement in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14(1):58-62. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.5.6706.

20. Marik PE, Bellomo R. Lactate clearance as a target of therapy in sepsis: a flawed paradigm. OA Critical Care. 2013;1(1):3.

21. Kreisberg RA. Lactate homeostasis and lactic acidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92(2 Pt 1):227-237.

22. Dodda VR, Spiro P. Can albuterol be blamed for lactic acidosis? Respir Care. 2012; 57(12):2115-2118. doi:10.4187/respcare.01810.

23. Scale T, Harvey JN. Diabetes, metformin and lactic acidosis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;74(2):191-196. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03891.x.

24. Velez JC, Janech MG. A case of lactic acidosis induced by linezolid. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6(4):236-242. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2010.20.

25. Kam PC, Cardone D. Propofol infusion syndrome. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(7):690-701.

26. Griffith FR Jr, Lockwood JE, Emery FE. Adrenalin lactacidemia: proportionality with dose. Am J Physiol. 1939;127(3):415-421.

27. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304-377. doi:10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6.

28. Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group of Zhejiang Province. The effect of early goal-directed therapy on treatment of critical patients with severe sepsis/ septic shock: a multi-center, prospective, randomised, controlled study. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2010;22(6):331-334.

29. Thiele H, Ohman EM, Desch S, Eitel I, de Waha S. Management of cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(20):1223-1230. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv051.

30. Lee M, Curley GF, Mustard M, Mazer CD. The Swan-Ganz catheter remains a critically important component of monitoring in cardiovascular critical care. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(1):142-147. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2016.10.026.

31. Morgan BC, Abel FL, Mullins GL, Guntheroth WG. Flow patterns in cavae, pulmonary artery, pulmonary vein, and aorta in intact dogs. Am J Physiol. 1966;210(4):903-909. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.210.4.903.

32. Brecher GA, Hubay CA. Pulmonary blood flow and venous return during spontaneous respiration. Circ Res. 1955;3(2):210-214.

33. Levy MM, Rhodes A, Phillips GS, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5-year study. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(11):1623-1633. doi:10.1007/s00134-014-3496-0.

34. Fernandes CJ Jr, Akamine N, Knobel E. Cardiac troponin: a new serum marker of myocardial injury in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(10):1165-1168. doi:10.1007/s001340051030.

35. Rady MY, Rivers EP, Nowak RM. Resuscitation of the critically III in the ED: responses of blood pressure, heart rate, shock index, central venous oxygen saturation, and lactate. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(2):218-225. doi:10.1016/s0735-6757(96)90136-9.

36. Gottlieb M, Hunter B. Utility of central venous pressure as a predictor of fluid responsiveness. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(1):114-116. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.02.009.

37. Kornbau C, Lee KC, Hughes GD, Firstenberg MS. Central line complications. Int J Critical Illn Inj Sci. 2015;5(3):170-178. doi:10.4103/2229-5151.164940.

38. Walley KR. Use of central venous oxygen saturation to guide therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(5):514-520. doi:10.1164/rccm.201010-1584CI.

39. PRISM Investigators, Rowan KM, Angus DC, et al. Early, goal-directed therapy for septic shock - a patient-level meta-analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2223-2234. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1701380.